Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

MBID: A Scalable Multi-Tier Blockchain Architecture with Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Intrusion Detection in Large-Scale IoT Networks

1 School of Software, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, 710072, China

2 School of Electronic and Communication Engineering, Quanzhou University of Information Engineering, Quanzhou, 362000, China

3 Department of Electrical Engineering, College of Engineering, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

4 Centre for Smart Systems and Automation, CoE for Robotics and Sensing Technologies, Faculty of Artificial Intelligence and Engineering, Multimedia University, Persiaran Multimedia, Cyberjaya, 63100, Selangor, Malaysia

* Corresponding Authors: Junsheng Wu. Email: ; Teong Chee Chuah. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Machine learning and Blockchain for AIoT: Robustness, Privacy, Trust and Security)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 2647-2681. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068849

Received 08 June 2025; Accepted 22 July 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

The Internet of Things (IoT) ecosystem faces growing security challenges because it is projected to have 76.88 billion devices by 2025 and $1.4 trillion market value by 2027, operating in distributed networks with resource limitations and diverse system architectures. The current conventional intrusion detection systems (IDS) face scalability problems and trust-related issues, but blockchain-based solutions face limitations because of their low transaction throughput (Bitcoin: 7 TPS (Transactions Per Second), Ethereum: 15–30 TPS) and high latency. The research introduces MBID (Multi-Tier Blockchain Intrusion Detection) as a groundbreaking Multi-Tier Blockchain Intrusion Detection System with AI-Enhanced Detection, which solves the problems in huge IoT networks. The MBID system uses a four-tier architecture that includes device, edge, fog, and cloud layers with blockchain implementations and Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) for edge-based anomaly detection and a dual consensus mechanism that uses Honesty-based Distributed Proof-of-Authority (HDPoA) and Delegated Proof of Stake (DPoS). The system achieves scalability and efficiency through the combination of dynamic sharding and Interplanetary File System (IPFS) integration. Experimental evaluations demonstrate exceptional performance, achieving a detection accuracy of 99.84%, an ultra-low false positive rate of 0.01% with a False Negative Rate of 0.15%, and a near-instantaneous edge detection latency of 0.40 ms. The system demonstrated an aggregate throughput of 214.57 TPS in a 3-shard configuration, providing a clear, evidence-based path for horizontally scaling to support overmillions of devices with exceeding throughput. The proposed architecture represents a significant advancement in blockchain-based security for IoT networks, effectively balancing the trade-offs between scalability, security, and decentralization.Keywords

The Internet of Things (IoT) has essentially transformed global connectivity concepts by enabling seamless interaction between billions of heterogeneous devices. Statista and IHS (Information Handling Services) Markit predict IoT device installations will increase from 30.4 billion in 2020 to 76.88 billion by 2025 with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 20.4% [1]. The exponential growth affects various sectors which include healthcare (monitoring systems, implantable devices), industrial applications (sensor networks, automated machinery), smart transportation (connected vehicles, traffic infrastructure), and urban infrastructure (smart grid, environmental monitoring) [2]. The global IoT market value is projected to reach $1.4 trillion by 2027, underscoring its significance in digital transformation [3].

However, this rapid integration of IoT into critical infrastructure introduces a vastly expanded and vulnerable attack surface. The specific applications in each sector face distinct and severe security threats that go beyond traditional IT risks:

• Healthcare: In connected health systems, remote patient monitoring devices and smart implantable (e.g., insulin pumps, pacemakers) are becoming commonplace. A security breach here is not merely a data leak; it could involve the malicious manipulation of a patient’s medical data to trigger an incorrect insulin dosage or the use of a Denial of Service attack to prevent a doctor from receiving a critical cardiac alert.

• Industrial Applications (IIoT (Industrial Internet of Things)): In smart factories, sensor networks and automated machinery drive production. An attacker could inject false data into a sensor network to sabotage a manufacturing process, causing physical damage to equipment, or launch an attack on industrial controllers to halt production entirely, leading to significant financial losses.

• Smart Transportation: The rise of connected vehicles and intelligent traffic infrastructure creates new risks. An attacker could compromise a vehicle’s internal network to disable safety-critical functions like braking, or manipulate a network of smart traffic signals to create widespread gridlock and public safety hazards.

• Urban Infrastructure: In smart cities, the smart grid relies on IoT devices for energy distribution and monitoring. A coordinated attack could manipulate smart meter readings to commit energy theft or, more catastrophically, destabilize the grid by feeding false data to substation controllers, potentially leading to widespread power outages.

Conversely, the fast growth of IoT systems has created new security threats which now include Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks and data injection and device compromise. The NIST and ENISA vulnerability assessments revealed essential security problems because of weak authentication systems and insufficient encryption and restricted secure boot functions and insufficient access control measures [4,5]. The severity of these vulnerabilities is evidenced by incidents like the 2016 Mirai botnet attack, which compromised approximately 600,000 IoT devices to launch a DDoS attack peaking at 1.2 Tbps [6].

Traditional intrusion detection systems (IDS) based on centralized models face difficulties because they have single points of failure and lack trust and have scalability limitations. The centralized system faces two major challenges because it cannot monitor distributed environments effectively and it becomes limited by scalability issues when handling data from millions of devices [7]. Traditional detection methods fail to detect new attacks in IIoT environments, but anomaly-based systems detect deviations from normal behavior with high accuracy and minimize false positives through optimized learning [8].

Blockchain technology provides a promising solution through decentralization and immutability and transparency which enables tamper-resistant security frameworks for IoT networks [9]. The distribution of security functions across multiple nodes in blockchain technology prevents single points of failure and creates tamper-resistant audit trails which enhance data integrity. The consensus mechanisms in blockchain ensure agreement on system state even in the presence of malicious actors, providing Byzantine Fault Tolerance capabilities crucial for distributed IoT environments [10].

The conventional blockchain implementations encounter major scalability barriers that prevent their use in extensive IoT systems. Bitcoin handles about 7 transactions per second (TPS) but Ethereum reaches 15–30 TPS [11]. The current transaction rates of 7 TPS for Bitcoin and 15–30 TPS for Ethereum fall short of meeting the requirements of IoT networks that need to process security-related transactions from millions of devices. Moreover, Traditional blockchain consensus mechanisms such as Proof of Work require excessive computational power that exceeds IoT capabilities, and their confirmation latencies (minutes to hours) do not match the real-time requirements of intrusion detection [12].

The implementation of blockchain technology with IDS for IoT networks creates essential operational challenges:

1. Transaction Throughput Limitations: Traditional blockchain systems lack the capacity to process the large number of transactions that IoT devices produce [13].

2. Latency Constraints: The time delay between intrusion detection and response needs to be within milliseconds to seconds but blockchain consensus mechanisms create delays that span from seconds to minutes [14].

3. Resource Efficiency Requirements: IoT devices face strict resource limitations which include processing power and memory capacity and storage capacity and network bandwidth and energy consumption [15].

4. Scalability-Security Trade-Offs: Improving blockchain scalability often involves compromising decentralization, potentially undermining security benefits [16].

5. Heterogeneity Challenges: IoT networks encompass devices with vastly different capabilities, requiring security solutions that adapt to this heterogeneity [17].

Recent advancements in AI, particularly Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), have shown potential for enhancing intrusion detection by embedding domain knowledge, but their integration with blockchain for large-scale IoT remains underexplored.

This paper introduces MBID, a Multi-Tier Blockchain Intrusion Detection System with AI Enhanced Detection, a groundbreaking framework designed to overcome the scalability and security challenges of large-scale IoT networks. The contributions of this work are multifaceted:

1. Development of a scalable multi-tier blockchain architecture integrating device, edge, fog, and cloud computing layers, optimized for the hierarchical nature of IoT deployments.

2. Integration of Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) for resource-efficient, high-accuracy intrusion detection at the edge, incorporating domain knowledge to achieve superior detection with minimal computational overhead.

3. Implementation of a dual consensus mechanism (HDPoA and DPoS) optimized for hierarchical IoT networks, combining low-latency local validation with robust global coordination.

4. Introduction of dynamic sharding based on network topology and device characteristics, enabling horizontal scalability to millions of devices.

5. IPFS-based distributed storage optimization, reducing blockchain storage requirements by over 80% while maintaining data integrity.

6. Comprehensive experimental evaluations, demonstrating MBID’s ability to support millions of devices with exceeding TPS, with less latency, and high detection accuracy.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2, Literature Review. Section 3 presents system and threat models. Section 4 details MBID architecture. Section 5 describes Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Edge Detection. Section 6 explains the dual consensus mechanism. Section 7 provides a theoretical analysis, followed by experimental evaluation in Section 8. Section 9, Discussion. Section 10 concludes the paper.

This section provides a comprehensive review of existing research related to blockchain-based intrusion detection systems for IoT networks, highlighting advances in traditional IDS approaches, blockchain integration with IoT security, scalability solutions, and AI-enhanced detection methods.

2.1 Traditional IDS Approaches for IoT

Signature-based IDS identifies attacks by matching observed patterns against databases of known attack signatures. Stolz et al. [18] proposed a lightweight IDS for IoT networks, combining signature-based and anomaly-based detection, achieving 98.13% detection accuracy for various attacks with moderate resource utilization 54.3% CPU for Snort, 73.3% CPU for Python-based anomaly detection, and stable memory usage with 124,136 KB free and 2,175,088 KB cached. Similarly, by Banaeian Far and Imani Rad [19], the DA-DS protocol employs a distributed signature mechanism based on the ElGamal cryptosystem, achieving higher efficiency in auditing blockchain-based transactions compared to other recently proposed protocols, as demonstrated by its reduced computational costs and execution times in the audit and verify phases.

While effective against known threats, signature-based approaches cannot detect zero-day attacks or variants of known attacks, requiring constant updates to signature databases. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of IoT devices and protocols complicates signature development, as attack patterns may manifest differently across diverse devices [20]. Anomaly-based approaches detect deviations from established behavioral baselines, offering potential protection against novel attacks. Min et al. [21] developed a network intrusion detection system using Memory-Augmented Deep Autoencoder that achieved 95% F1-score, solving the over-generalization problem of traditional autoencoders through a memory module that learns normal traffic patterns. Deshpande and Rahman [22] proposed an edge-based anomaly detection system that distributed detection tasks across edge nodes, reducing detection latency compared to cloud-based alternatives.

These approaches demonstrate greater flexibility in detecting unknown attacks but suffer from higher false positive rates and computational demands. Statistical anomaly detection methods often struggle with the dynamic nature of IoT traffic, while machine learning approaches require significant training data and processing resources that exceed the capabilities of constrained IoT devices [23].

Hybrid approaches attempt to combine both but struggle in resource-constrained IoT environments. For example, Otoum and Nayak [24] proposed a hybrid AS-IDS (Anomaly and Signature Based Intrusion Detection System) for IoT networks that combines signature and anomaly detection approaches, achieving 96.9% detection accuracy. Their system filters traffic at the gateway level, uses LightNet for signature matching, and employs Deep Q-learning with environmental parameters (SNR and bandwidth) for anomaly detection of unknown attacks.

Despite ongoing advancements, traditional IDS approaches face fundamental limitations in IoT contexts, including centralization issues, resource constraints, trust issues, and scalability limitations [25]. These limitations have motivated the exploration of blockchain-based approaches.

2.2 Blockchain-Based Security Solutions for IoT

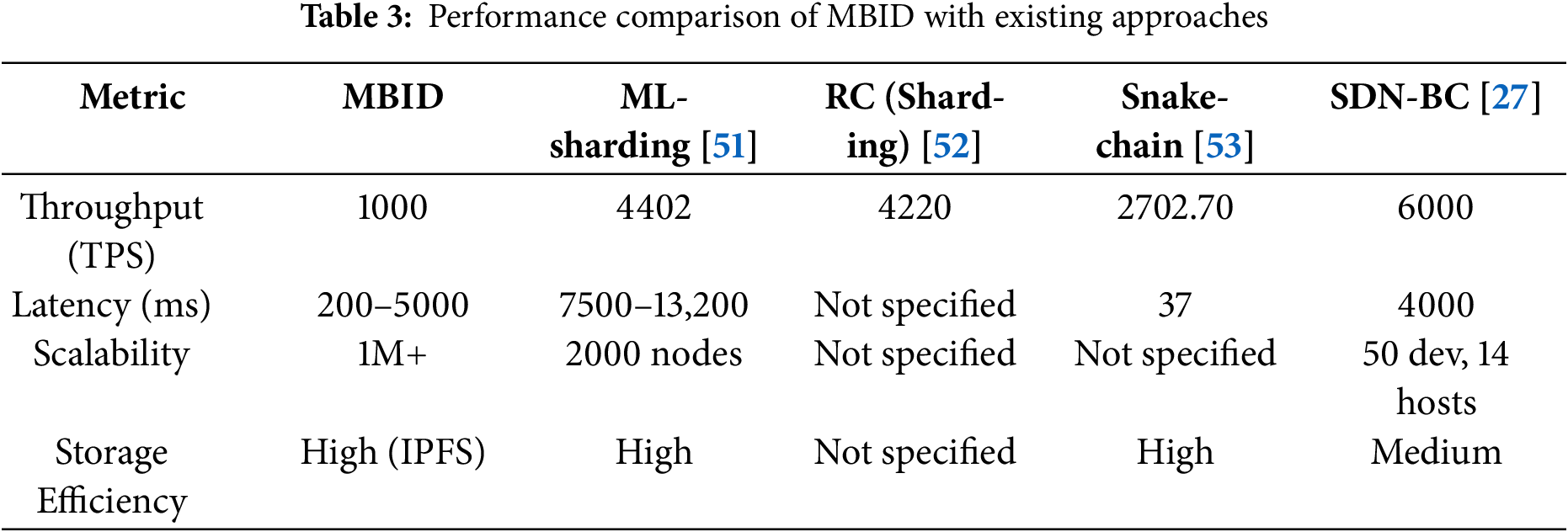

Blockchain-based solutions leverage decentralization to enhance IoT security. Wang et al. [26] propose a blockchain-enabled edge computing framework for 6G consumer electronics. Their system uses a credibility scoring model to optimize resource allocation between edge servers and devices. Simulations demonstrate over 90% efficiency with sub-50 ms latency when scaled to 100 edge servers and 2000 devices. Their approach outperforms benchmarks in mining utilization and confirmation speed. Al Ghamdi [27] introduced an SDN (Software-Defined Networking)-Blockchain Classifier, a trust-based security tool for blockchain-based SDN in IoT networks, enhancing attack detection through traffic fusion and aggregation. The proposed framework achieved superior performance in terms of average throughput, response time, packet loss, energy efficiency, and end-to-end delay compared to baseline methods, demonstrating improved resilience against MAC (Media Access Control) flooding attacks. Nazir et al. [28] developed a collaborative threat intelligence framework integrating blockchain and machine learning for enhanced IoT security, achieving high accuracy through expert-driven validation. Their approach utilized a blockchain-based system for validating and sharing threat data, achieving improved detection accuracy (as demonstrated by evaluation on the IoT23 dataset) through collaborative verification and continuous feedback. However, these solutions face scalability challenges, with transaction throughputs often limited to tens or hundreds of TPS, which is insufficient for large-scale IoT deployments. Most implementations achieved transaction throughputs below 500 TPS and struggled with the resource constraints of IoT environments.

2.3 Scalability Approaches in Blockchain Systems

Scalability enhancements in blockchain systems include sharding, which partitions the network for parallel transaction processing, and off-chain techniques like state channels and sidechains.

Sharding partitions the blockchain network into smaller subsets, called shards, enabling parallel transaction processing to enhance scalability and throughput. Yuan et al. [29] proposed ChainFL, a hierarchical blockchain-driven federated learning system that leverages a sharding architecture with a Raft-based subchain layer and a DAG (directed acyclic graph)-based mainchain, achieving up to 14% better convergence rates and three times greater robustness compared to traditional federated learning systems like FedAvg and AsynFL. In the IoT context, Luo et al. [30] proposed Fission, a sharding scheme based on Voronoi diagrams and geographic proximity, achieving a linearly scalable throughput of up to 1900 tps with 500 nodes. However, sharding introduces challenges in maintaining cross-shard block sequence verification and requires careful management of shard size to balance security and performance. State channels, as detailed by Negka and Spathoulas [31], enhance blockchain scalability through off-chain smart contract execution, with implementations like Sprites, Perun, and Counterfactual enabling fast, low-cost state updates, while sidechains like Liquid, described by Belchior et al. [32], facilitate private, rapid settlements and multi-asset transactions using a federated peg and Confidential Transactions. Both approaches leverage cryptographic mechanisms to maintain security and privacy, positioning state channels and sidechains as critical layer 2 solutions for blockchain efficiency.

The DCBFT protocol, a hierarchical Byzantine fault-tolerant consensus mechanism for IoT, leverages an improved k-sums clustering algorithm and a multi-primary node structure to enhance scalability and reduce communication overhead, achieving up to 736 TPS and a 78% lower consensus latency compared to traditional PBFT (Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance) [33]. Ren et al. [34] proposed FLCoin, a blockchain-enabled federated learning architecture for IoT edge computing, achieving a 90% reduction in communication overhead and 35% less training time compared to PBFT-based systems. As this approach improves scalability and efficiency but its robustness against poisoning attacks remains limited because it does not account for malicious nodes.

2.4 AI-Enhanced Intrusion Detection

The implementation of deep learning techniques in AI-enhanced Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) has led to substantial improvements in detection accuracy through the use of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and convolutional neural networks (CNNs). The advanced models are typically validated using publicly available benchmark datasets to ensure reproducibility and comparability of results.

LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) networks, which belong to the RNN category, demonstrate exceptional ability to handle long-term dependencies in sequential data, thus making them appropriate for network traffic pattern analysis throughout time [35,36]. The development of LSTM-based IDSs for Internet of Things (IoT) networks by researchers has led to high accuracy (e.g., over 98%) and F1-scores that outperform traditional machine learning approaches by clearly defined margins in comparative studies [37]. The research studies describe their experimental procedures, which include data preprocessing methods, feature selection approaches, and LSTM network designs, and present performance results through accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score metrics [36,37].

The application of CNNs to intrusion detection involves converting network traffic data into image-like representations or matrices, which enables the CNN to detect spatial features that indicate malicious activity [38,39]. A CNN-based IDS converts network flows into images before classification, resulting in high detection accuracies (e.g., upwards of 98%) across different attack types when evaluated on standard datasets [38,39]. These papers would thoroughly document the image conversion process, CNN architecture, training parameters, and present a comprehensive evaluation using metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and sometimes ROC curves, often comparing results against other deep learning or machine learning models [36,38]. Some research combines CNNs with LSTMs to leverage both spatial and temporal feature extraction, reporting high accuracy [39]. Federated Learning (FL) has emerged as a crucial approach for training intrusion detection models across distributed devices, such as in IoT environments, without centralizing sensitive data, thereby enhancing privacy [35,40]. Research in this domain often demonstrates the effectiveness of FL by evaluating it on recognized IoT datasets and comparing its performance (accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score) against centralized training approaches [35,41]. Studies highlight not only the maintained or improved detection accuracy but also quantify benefits such as significant reductions in communication overhead (e.g., reductions of 41% or more) and preservation of data privacy [35,41]. The validation would involve clear descriptions of the FL architecture, aggregation algorithms (like FedAvg), the number of participating clients used for training and testing [35,41]. Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) represent a newer direction, originally developed for solving partial differential equations, and are now being adapted for anomaly detection by embedding domain knowledge into the learning process [42,43]. By incorporating physical laws or domain-specific constraints (e.g., network protocol rules, expected device behavior patterns), PINNs can potentially achieve high accuracy with less training data and computational resources compared to purely data-driven deep learning models [44,45]. Validated research in this area would typically specify the exact physical principles or domain knowledge integrated, the architecture of the PINN, and the datasets used for evaluation (which could be domain-specific or standard IDS datasets adapted for PINN constraints). Performance metrics, along with comparisons to conventional deep learning methods, would be presented to substantiate claims of improved efficiency and accuracy. For example, a study might show high detection accuracy (e.g., 97.6%) with substantially less training data when applying physics-informed constraints to network traffic analysis. Wu et al. discuss the construction of PIML (Physics-Informed Machine Learning) detectors through customized loss functions that integrate domain knowledge of cyber-attacks, illustrating improved performance in nonlinear systems [46].

The integration of PINNs with blockchain technology for intrusion detection in IoT networks is an emerging research area aiming to enhance both detection accuracy and the trustworthiness of the detection process [42,47]. For instance, a PINN-based IDS combined with a blockchain protocol (like a variant of Proof-of-Authority) might report high detection accuracy (e.g., 97.2% to 99.25%) and improved efficiency [42,48]. Validated proposals in this niche would detail the specific PINN model, the blockchain architecture (including consensus mechanism and smart contract design if applicable), how domain knowledge is incorporated, and the datasets used for rigorous testing (e.g., real-world IoT datasets or specifically crafted ones) [42,47]. Such research would also critically evaluate scalability in large IoT deployments and the comprehensiveness of the architectural framework, addressing how the blockchain component ensures the integrity and immutability of intrusion logs and model updates [41,47]. The MBID (Multi-tier Blockchain-based Intrusion Detection) system you are developing aims to bridge existing gaps by synergistically integrating a multi-tier blockchain architecture, PINN-based detection, dual consensus mechanisms, and dynamic sharding. This holistic approach holds significant potential for creating scalable, secure, and efficient intrusion detection solutions tailored for the complexities of modern IoT networks, building upon the validated advancements in each of these constituent areas.

2.5 Evolving Paradigms: From Traditional IDS to Zero-Trust Architectures

While traditional intrusion detection systems laid the foundational groundwork for network security, the increasing sophistication of cyber threats and the dissolution of the traditional network perimeter have necessitated a paradigm shift in security architecture.

2.5.1 Limitations of Traditional Models

As discussed, traditional IDS primarily fall into two categories:

• Signature-based IDS: These systems are effective at detecting known threats by matching traffic against a database of predefined signatures. Their primary limitation is their inability to detect novel, zero-day attacks.

• Anomaly-based IDS: These systems model “normal” network behavior and flag deviations as potential intrusions. While capable of detecting novel attacks, they can suffer from high false-positive rates and can be evaded by sophisticated, low-and-slow attacks that gradually poison the baseline.

A more fundamental weakness of these traditional approaches is their implicit reliance on a “castle-and-moat” security model. They focus heavily on defending the network perimeter, assuming that entities inside the network are largely trustworthy. This assumption is no longer valid in modern, distributed IoT environments.

2.5.2 The Rise of Zero-Trust Architecture (ZTA)

In recent years, the Zero-Trust Architecture (ZTA) has emerged as the dominant security model for modern enterprises. Coined by John Kindervag, its core principle is succinctly captured by the maxim: “Never trust, always verify.” ZTA fundamentally discards the idea of a trusted internal network and an untrusted external network. Instead, it mandates that every access request be strictly authenticated and authorized, regardless of its origin.

Key principles of ZTA include:

• Continuous Verification: Trust is not a one-time event. It must be continuously re-evaluated with every transaction.

• Micro-Segmentation: The network is broken down into small, isolated segments. A breach in one segment is contained and prevented from moving laterally to others.

• Least-Privilege Access: Users and devices are granted only the bare minimum permissions necessary to perform their specific tasks.

Intrusion detection within a ZTA framework, therefore, evolves. It is no longer just a perimeter guard but a continuous monitoring system that scrutinizes traffic within micro-segments, looking for post-authentication behavioral anomalies and policy violations.

2.5.3 Positioning MBID: A Decentralized Approach to Zero Trust

While ZTA represents a significant leap forward, many current implementations still exhibit a critical vulnerability: centralization. They often rely on a centralized Policy Engine and a central log repository to make decisions and audit activity. If this central component is compromised, the entire security architecture can fail.

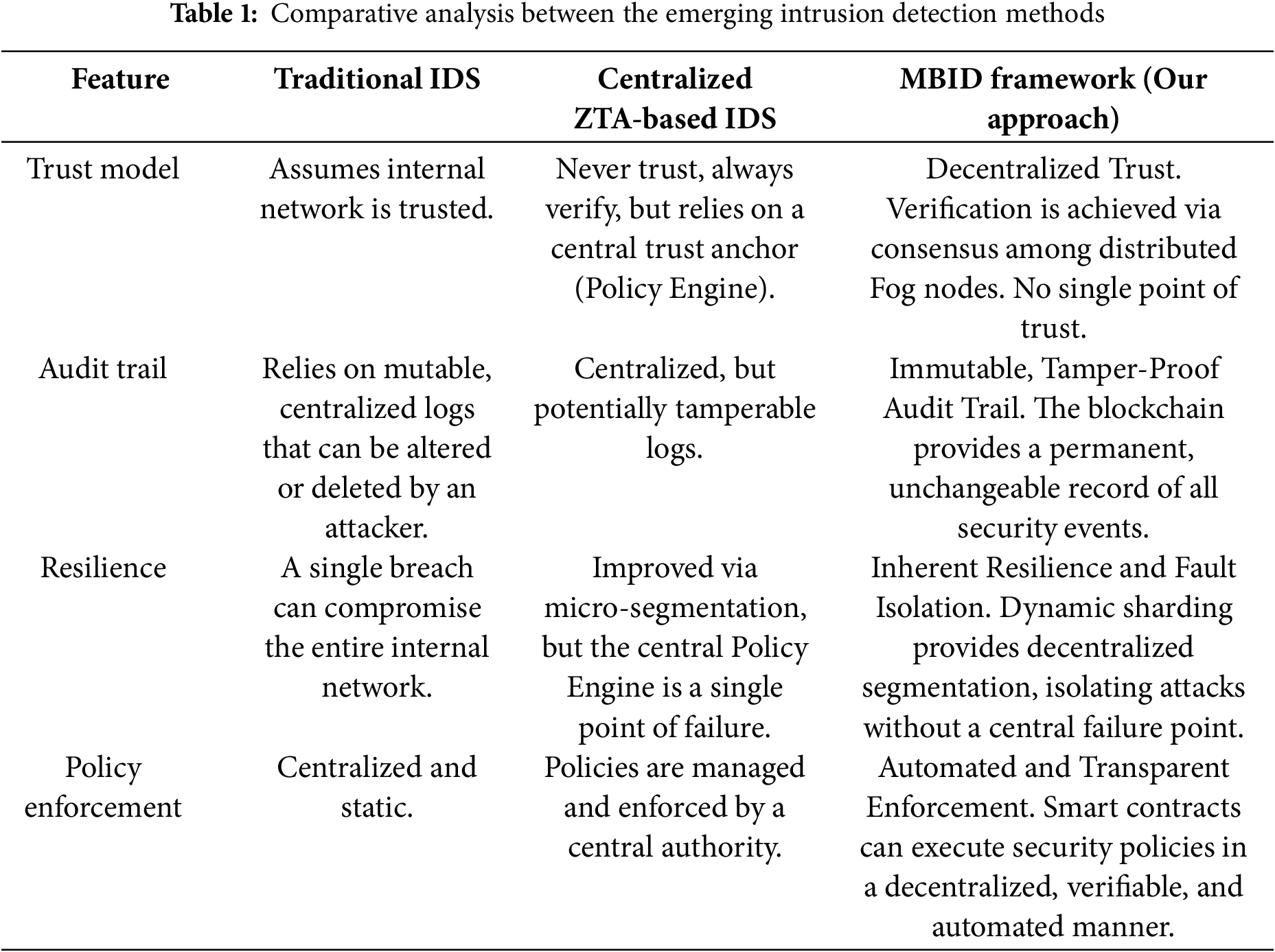

Our proposed MBID framework is designed to directly address this gap. It not only aligns with the principles of Zero Trust but enhances them through decentralization. Table 1 provides a comparative analysis.

In summary, by integrating blockchain technology with a tiered edge-fog architecture, the MBID framework represents a novel implementation of Zero-Trust principles. It overcomes the limitations of both traditional IDS and centralized ZTA models, offering a more resilient, transparent, and truly distributed security solution fit for the scale and challenges of modern IoT networks.

This section defines the operational environment, adversarial capabilities, and trust assumptions that form the foundation for the MBID architecture.

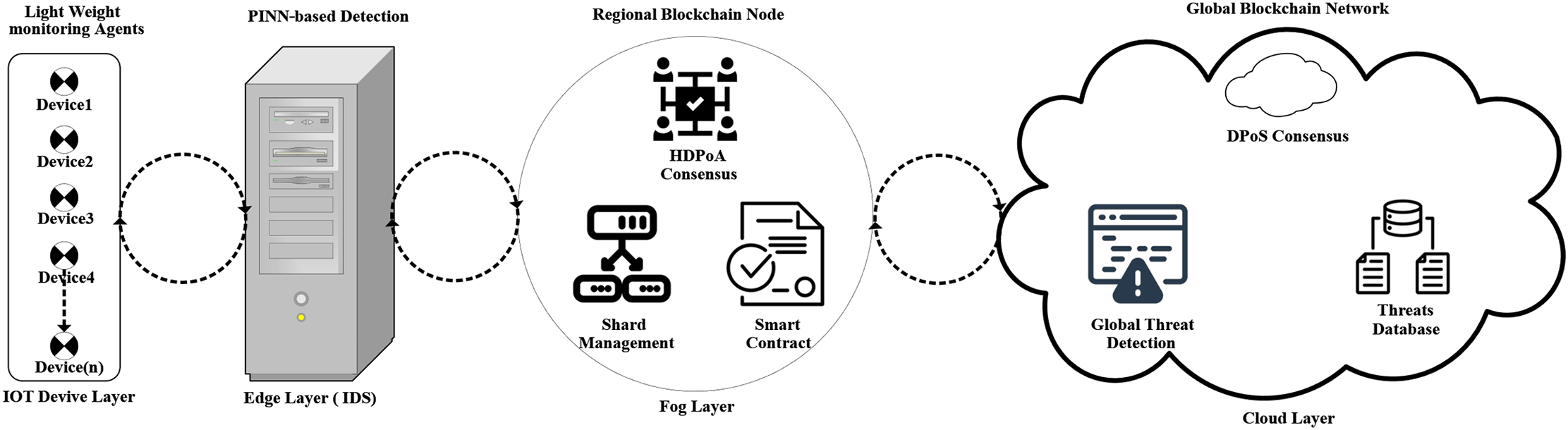

The MBID block diagram represents Fig. 1, which operates within a large-scale IoT network comprising heterogeneous devices, including sensors, actuators, wearables, and smart appliances, interconnected via edge gateways, fog nodes, and cloud infrastructure. IoT devices are characterized by limited computational resources (8-bit/16-bit microcontrollers, 8–256 KB RAM, 32–512 KB storage) and energy constraints, using low-power protocols like BLE, Zigbee, or LoRaWAN. Edge gateways, with 4-core CPUs, 256 MB–8 GB RAM, and 8–128 GB storage, aggregate data from 100–1000 devices. Fog nodes, equipped with 8-core CPUs, 8–32 GB RAM, and 256 GB–2 TB storage, provide regional processing, while cloud infrastructure offers enterprise-grade resources (16+ cores, 64+ GB RAM, terabytes of storage). The network supports dynamic topologies, heterogeneous Quality of Service, and multi-tenant environments, operating under constraints of limited computation, energy, storage, and bandwidth.

Figure 1: MBID block diagram in IoT network

3.2 Threat Model and Adversary Assumptions

The threat model assumes a sophisticated adversary with the potential for external, internal, or physical access to network components. The adversary is assumed to possess significant (but bounded) computational power and advanced knowledge of network protocols, cryptography, and system exploitation. The key attack vectors MBID is designed to mitigate include:

• Network-Based Attacks: DDoS and other attacks, primarily countered by the real-time PINN detection at the edge.

• Device-Level Attacks: Malware injection, firmware tampering, and physical compromise, addressed by behavioral anomaly detection and immutable logging.

• Data-Level Attacks: False data injection, data tampering, and privacy breaches, mitigated by blockchain-based integrity checks and IPFS hashing.

• Blockchain-Specific Attacks: 51% attacks, selfish mining, Sybil attacks, and smart contract vulnerabilities, countered by the dual consensus mechanism (HDPoA/DPoS) and reputation systems.

MBID’s security is predicated on a realistic, hierarchical trust model:

• Device and Edge Layers Are Untrusted: Individual devices and edge nodes are considered vulnerable and cannot be fully trusted. Data and alerts originating from this layer require further validation. This assumption justifies the necessity of the Fog Layer.

• Fog Layer Is “Honest-Majority” Trusted: Within any given shard, we assume that the majority of fog nodes are honest and will correctly follow the HDPoA protocol. This forms the basis for localized, Byzantine Fault Tolerant consensus.

• Cloud Layer Is Stake-Majority Trusted: We assume that the majority of the voting power (stake) in the DPoS system is controlled by honest participants, ensuring the integrity of the global blockchain.

3.4 Security and Performance Objectives

To be considered effective in the defined system and threat model, the MBID architecture must meet a stringent set of security and performance objectives.

Security Requirements: The architecture must guarantee:

• Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability (CIA) of security data.

• Authentication, Authorization, and Non-repudiation for all transactions and commands.

• Accountability through an immutable, tamper-proof audit trail.

Performance Objectives: The system must address the following critical performance challenges:

• Throughput: The system must demonstrate a clear path to achieving a transaction with exceeding throughput to handle security events from millions of devices in real-time.

• Latency: The detection latency from event occurrence to validated alert must be minimized, ideally remaining under 200 ms to enable effective, timely responses.

• Scalability: The architecture must be fundamentally designed to scale horizontally to support deployments of up to one million devices without performance degradation.

• Resource Efficiency: The system must operate within the resource constraints of each layer, with specific targets such as <5% CPU overhead at the device layer and <16 GB memory usage at the fog layer.

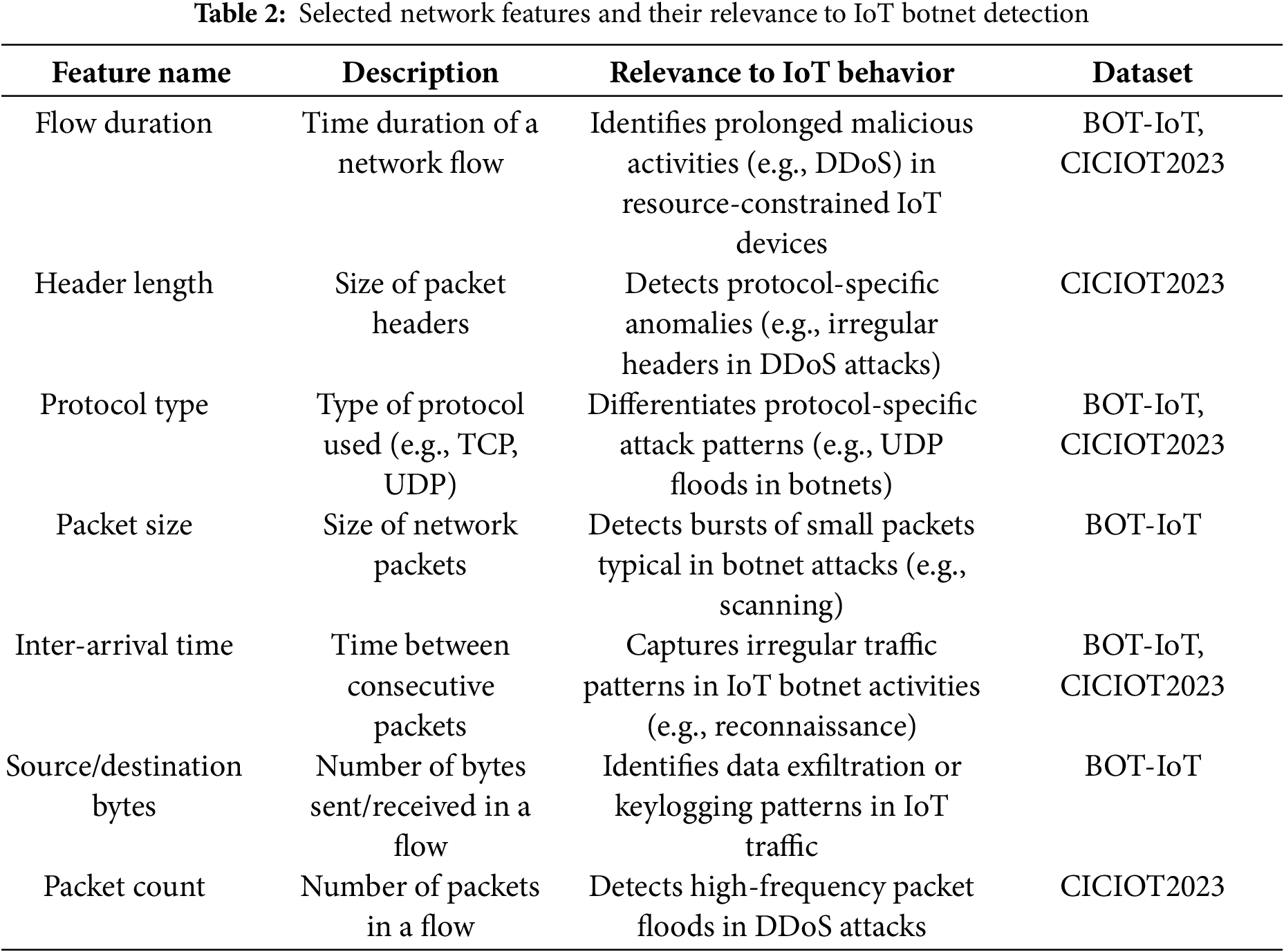

3.5 Network Features and Their Relevance to IoT Behavior

This section will include a detailed description of key features, their significance in capturing IoT network traffic characteristics, and their relevance to detecting botnet-related behaviors. For example, we will highlight features such as:

• Flow Duration: Identifies prolonged malicious activities like DDoS attacks by their distinct temporal patterns.

• Header Length: Detects protocol-specific anomalies and reconnaissance attempts indicated by irregular header sizes.

• Protocol Type: Differentiates protocols (TCP, UDP) to detect specific attack patterns, such as UDP floods from IoT botnets.

• Packet Size and Inter-Arrival Time: Reveals irregular traffic bursts and packet timing characteristic of botnet scanning and DDoS attacks.

• Argus-Derived Features: Advanced network flow metrics (e.g., byte counts) crucial for detecting subtle anomalies like data exfiltration.

Table 2 lists a representative subset of key features (e.g., 10–15 features) used across the datasets, their descriptions, and their specific relevance to IoT behavior and botnet detection.

This Table 2 is accompanied by a brief discussion explaining how these features capture the unique characteristics of IoT traffic, such as low-power device communication, frequent small-packet exchanges, and vulnerability to specific attack vectors. The full feature set is too extensive to list exhaustively but is available in the referenced dataset documentation [49,50].

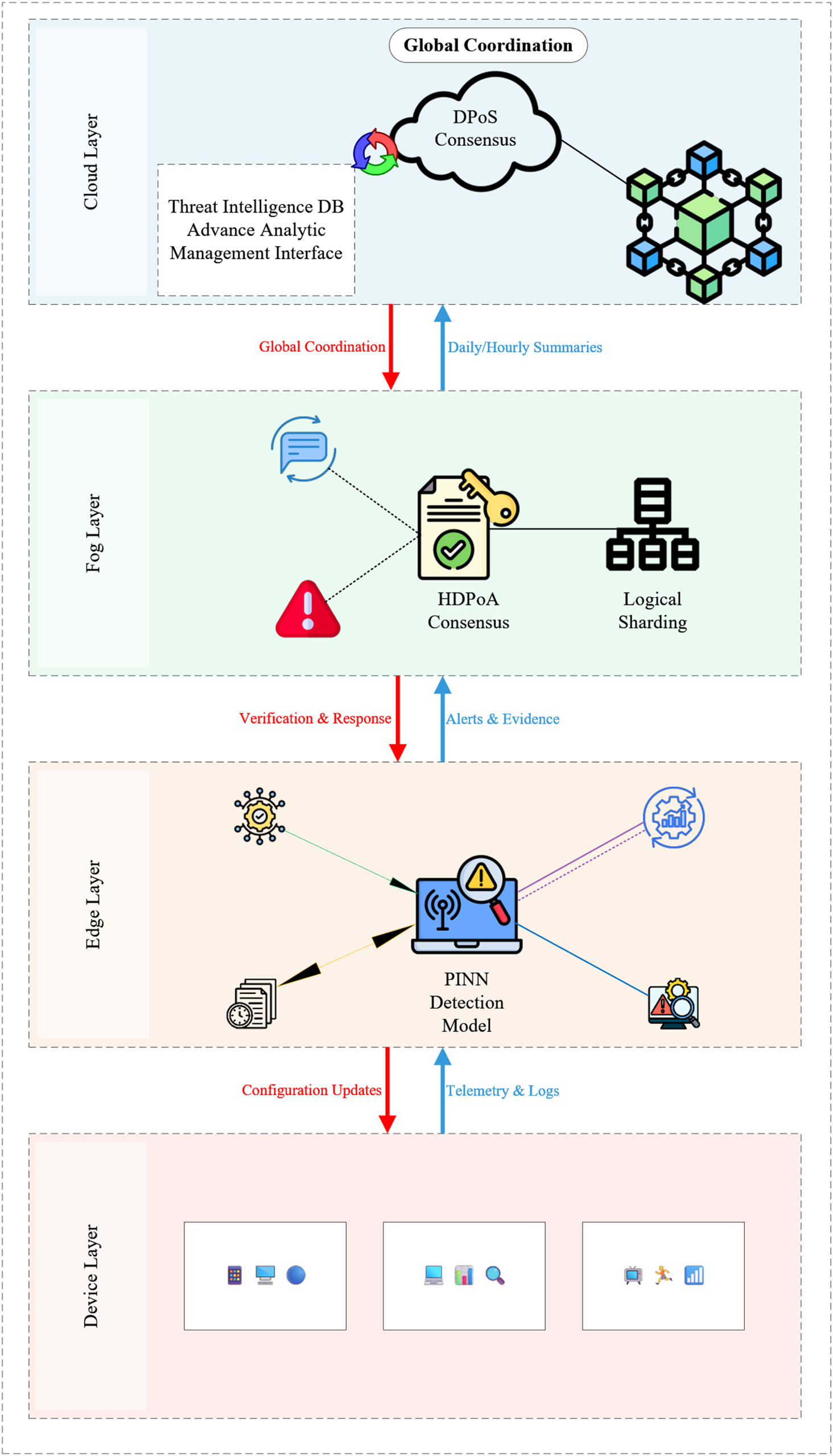

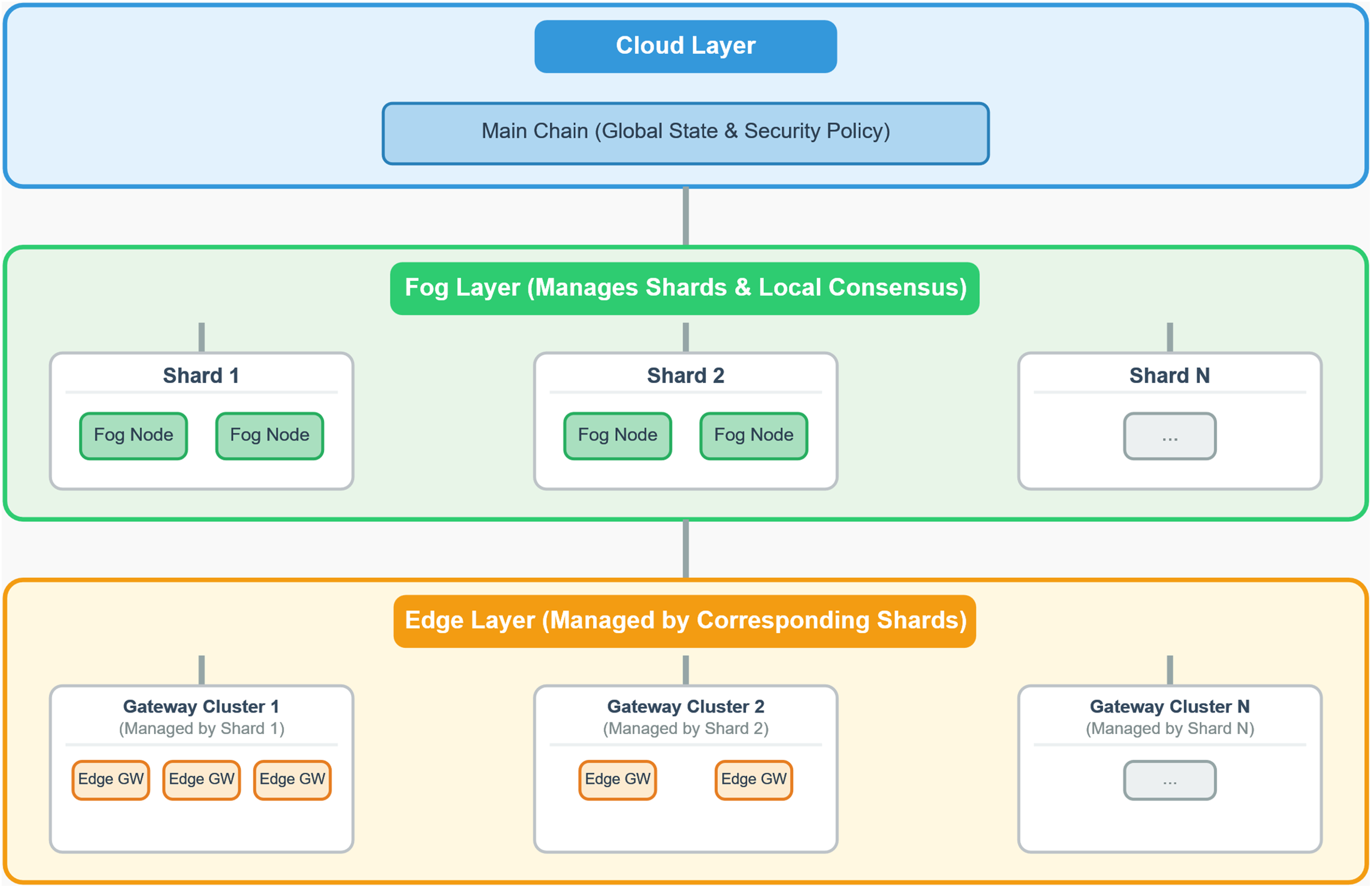

The MBID architecture is a four-tier framework meticulously designed and experimentally validated to resolve the fundamental scalability, security, and efficiency challenges in large-scale IoT networks. As illustrated in Fig. 2, it integrates device, edge, fog, and cloud layers, each with a specialized role and corresponding blockchain implementation. The architecture’s success stems from its hierarchical design, which leverages AI-enhanced detection at the edge, dynamic sharding in the fog, and robust consensus mechanisms to achieve high throughput, near-instantaneous latency, and resilient security.

Figure 2: MBID multi-tier architecture

The device layer in Fig. 2 is composed of the IoT devices themselves, each equipped with a lightweight monitoring agent specifically designed for minimal performance impact on resource-constrained hardware, such as 8/16-bit microcontrollers. Functionally, these agents collect raw data like network traffic and system logs while also performing basic, low-overhead filtering to immediately discard clearly benign traffic. This initial filtering stage is crucial, as it serves the dual purpose of conserving network bandwidth and reducing the processing load on the upper layers of the architecture. To ensure data integrity from the point of origin, all communication from the agents to their designated edge gateway is secured using encrypted channels, such as TLS (Transport Layer Security) 1.3 or DTLS (Datagram Transport Layer Security).

4.2 The Lightweight Device Agent: A Minimalist Design for Scalability

A foundational principle of the MBID architecture is the strategic offloading of computational tasks from resource-constrained IoT devices to the more powerful Edge Layer. The security agent operating at the Device Layer is therefore intentionally minimalist, designed to function effectively on 8-bit or 16-bit microcontrollers with limited RAM, processing power, and energy budgets. Its responsibilities are strictly limited to three essential, low-overhead tasks:

1. Telemetry Collection: The agent’s primary role is data acquisition. It collects predefined metrics (e.g., network packet metadata, CPU load, memory usage) as raw data points. Crucially, it performs no complex analysis, anomaly detection, or adaptive monitoring. This function is entirely delegated to the PINN model at the Edge Layer.

2. Lightweight Encrypted Communication: To ensure data integrity and confidentiality between the device and the Edge Gateway, the agent employs optimized, standard IoT security protocols. Communication is secured using DTLS (Datagram Transport Layer Security), which provides a low-overhead security layer for UDP-based traffic. The underlying cryptographic operations would leverage hardware-accelerated AES-128, a cipher known for its efficiency and security on resource-constrained devices.

3. Static Data Filtering: Any filtering performed by the agent is for the purpose of energy and bandwidth conservation, not threat detection. These are simple, pre-configured rules, such as fixed-interval reporting or deadband filtering (only transmitting data if it deviates beyond a set threshold). This minimizes unnecessary transmissions without requiring complex on-device logic.

By strictly limiting the device agent’s role to this Collect-Encrypt-Transmit cycle, the MBID architecture ensures massive scalability and long operational life for battery-powered devices, effectively resolving the trade-off between endpoint security and resource consumption.

The edge layer in Fig. 2, described as the tactical frontline of the architecture, constitutes the core of MBID’s real-time detection capability, a process optimized for both speed and accuracy. It is here that raw data from the device layer is transformed into actionable intelligence. Functionally, edge gateways serve as the operational hubs of this layer, managing local device clusters and employing sophisticated Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) models to analyze incoming data streams for anomalies. Upon detecting a threat, these gateways generate a detailed security alert. The strategic placement of this advanced detection capability at the edge is the key to minimizing latency; by analyzing data locally rather than transmitting it to a distant cloud, MBID can identify threats almost instantaneously. The effectiveness of this architectural choice was empirically validated, achieving an average detection latency of just 0.40 ms. This result provides definitive proof of the edge layer’s capacity for genuine real-time threat detection, a critical requirement for preempting fast-moving attacks.

The fog layer in Fig. 2 is architecturally designed to address the critical challenge of blockchain scalability, enabling security events to be validated and recorded in a distributed, parallel, and trustworthy manner. Operationally, this is achieved by organizing regional fog nodes into logical shards, where each shard functions as an independent blockchain. These shards are responsible for validating security alerts from their local edge nodes using the Honesty-based Distributed Proof-of-Authority (HDPoA) consensus mechanism. This sharded architecture is the key to overcoming the throughput limitations of a monolithic blockchain, as it allows the system to process transactions in parallel. The HDPoA consensus mechanism was specifically chosen for its low latency and high efficiency, making it ideally suited for achieving rapid consensus among a known set of regional validators. The power of this design was empirically validated in experiments where a 3-shard configuration achieved a stable, aggregate throughput of 214.57 TPS. This result provides a clear, evidence-based pathway for horizontal scaling, demonstrating that the system can surely exceed its TPS target by simply deploying additional shards as the network grows.

The cloud layer in Fig. 2 provides a unified, global view of the entire network’s security posture without becoming a processing bottleneck. To achieve this, it maintains a global blockchain that does not record individual alerts but instead aggregates verified summaries from the fog layer shards. This global chain uses a Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPoS) consensus mechanism to coordinate threat intelligence and facilitate global governance. This hierarchical aggregation is the essential design choice for ensuring scalability, as it shields the cloud from the high volume of raw alerts. This allows the cloud layer to focus on its primary mission: identifying large-scale attack patterns and coordinating strategic, system-wide responses, while the DPoS mechanism provides the robust, high-level security and governance suitable for a global oversight layer.

4.6 The End-to-End Data and Trust Flow

The synergy between the layers is best understood by tracing the lifecycle of a security alert, which also demonstrates the progressive building of trust:

1. Detection (Edge-Untrusted): An edge node detects an anomaly with its PINN model and generates an alert. At this stage, the alert is an untrusted, localized claim.

2. Validation (Fog-Regionally Trusted): The alert is sent to the fog nodes within its shard. The HDPoA consensus mechanism validates the alert’s authenticity and correctness. Once consensus is reached, the alert’s evidence is stored in IPFS, and its hash is immutably recorded in a new block on the shard’s blockchain. The alert is now a regionally verified fact.

3. Aggregation (Cloud-Globally Trusted): The fog shard sends a compact summary of its new block (not the individual alerts) to the cloud layer. The DPoS delegates validate these summaries and record them on the global blockchain. The event is now a globally acknowledged and correlated fact, enabling strategic decision-making by human operators.

This multi-tier architecture, with its specialized subsystems for AI detection, sharding, and dual consensus, creates a resilient and efficient framework. Each design choice is deliberate, contributing to the experimentally validated performance that allows MBID to secure IoT networks at a scale and speed previously unattainable.

5 Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Edge Detection

The cornerstone of MBID’s validated real-time detection capability is the strategic implementation of Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) at the edge layer. The selection of PINNs is not arbitrary; it is a deliberate design choice to overcome the dual challenges of accuracy and efficiency in resource-constrained environments. Unlike purely data-driven models, PINNs embed domain-specific rules directly into the training process. This approach was instrumental in achieving the system’s experimentally validated 99.84% detection accuracy and is the primary enabler of the 0.40 ms detection latency.

The PINN framework merges data-driven learning with physics-based constraints. The total loss function, which the model seeks to minimize, is a weighted sum of a data-driven loss and a physics-informed loss, as shown in Eq. (1):

where

where

•

•

•

•

By training the model to minimize violations of these “laws,” the PINN learns a robust representation of normalcy that is highly effective at identifying even novel attacks that break these fundamental rules.

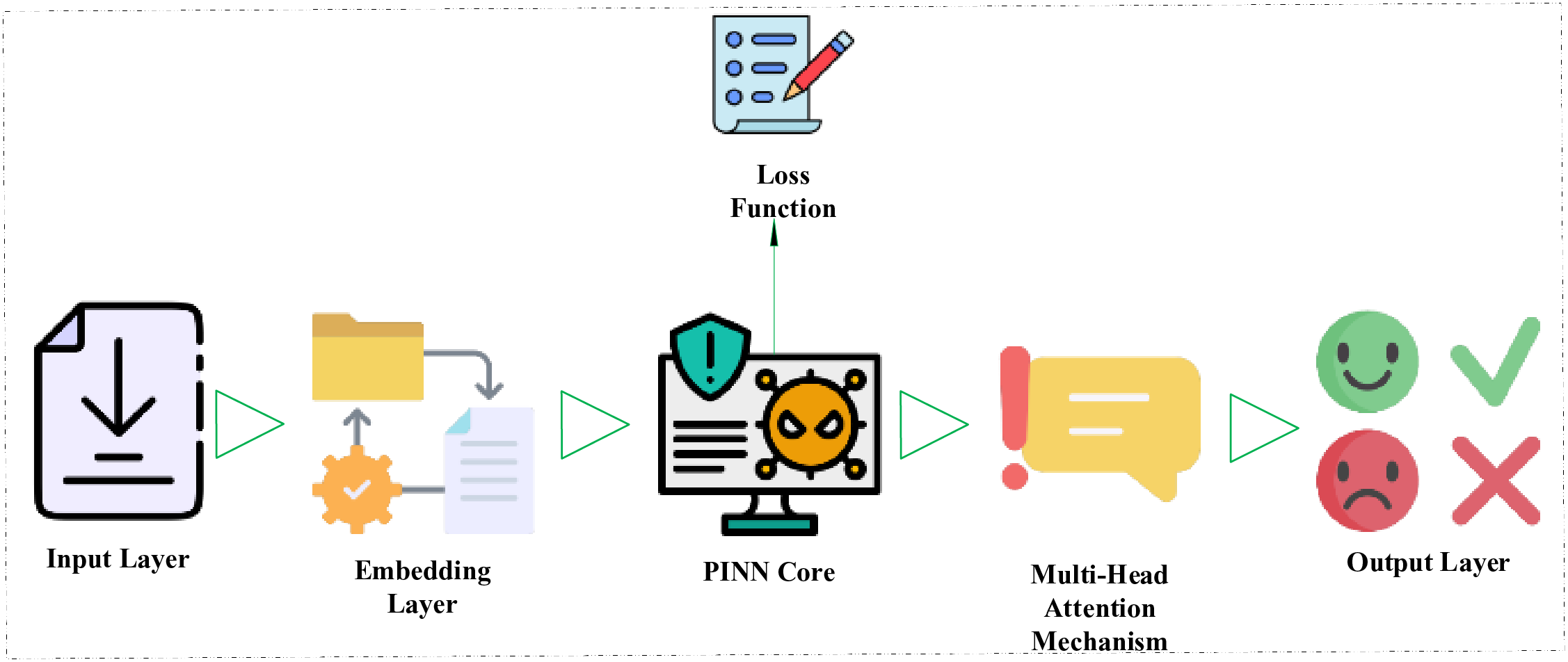

The architecture of the implemented PINN, depicted in Fig. 3, is engineered as a sequential pipeline to efficiently process raw IoT data and produce highly accurate classifications. Initially, input feature vectors derived from network traffic and device telemetry are passed to an Embedding Layer, which transforms categorical data like protocol types into dense, continuous representations suitable for neural processing. At its core, the PINN consists of multiple fully connected layers that serve as the primary learning engine, where the custom physics-informed loss function is applied during training to ensure the model’s internal representations align with the defined rules of IoT behavior. This learning is further enhanced by a Multi-Head Attention Mechanism, which allows the model to dynamically weigh the importance of different input features. This is implemented using the standard scaled dot-product attention, defined in Eq. (3), and extended to a multi-head configuration to capture information from different representation subspaces, as shown in Eq. (4).

where

Figure 3: Physics-informed neural network architecture

The training process employs a federated learning approach, a pragmatic necessity for training models across a large, distributed, and privacy-sensitive IoT network without centralizing raw data:

• Initialization: A base PINN model with initial weights

• Local Training: Each edge gateway trains the model on its own local data, minimizing the complete loss function

• Secure Aggregation: Edge gateways transmit only their model weight updates

• Verification and Coordination: Fog nodes verify the performance of the aggregated update before it is sent to the cloud layer, which merges it into the new global model. This updated model is then distributed for the next training cycle.

This federated approach proved effective, enabling continuous model improvement across the distributed network while upholding data privacy.

The exceptional performance metrics of the MBID system are not accidental; they are the direct outcome of a rigorous, multi-stage optimization pipeline applied to the PINN model before deployment. The path to achieving the 0.40 ms detection latency while maintaining 99.84% accuracy on resource-constrained edge hardware was validated through this process. To make the model feasible for edge deployment, we first applied aggressive compression techniques. Model quantization was used to convert the model’s floating-point weights to 8-bit integers, resulting in a 75% reduction in memory footprint. This was followed by pruning, which systematically removed redundant neural connections to decrease the model’s computational complexity by approximately 40%.

To ensure these compression techniques did not compromise the model’s high accuracy, we employed knowledge distillation. This involved training the now smaller, more efficient “student” model to mimic the outputs of a larger, more complex “teacher” model, successfully preserving over 95% of its original predictive power. It is this carefully engineered combination of physics-informed learning and aggressive optimization that allows our PINN implementation to serve as a lightweight yet powerful detection engine, delivering the speed and accuracy required for real-world IoT security.

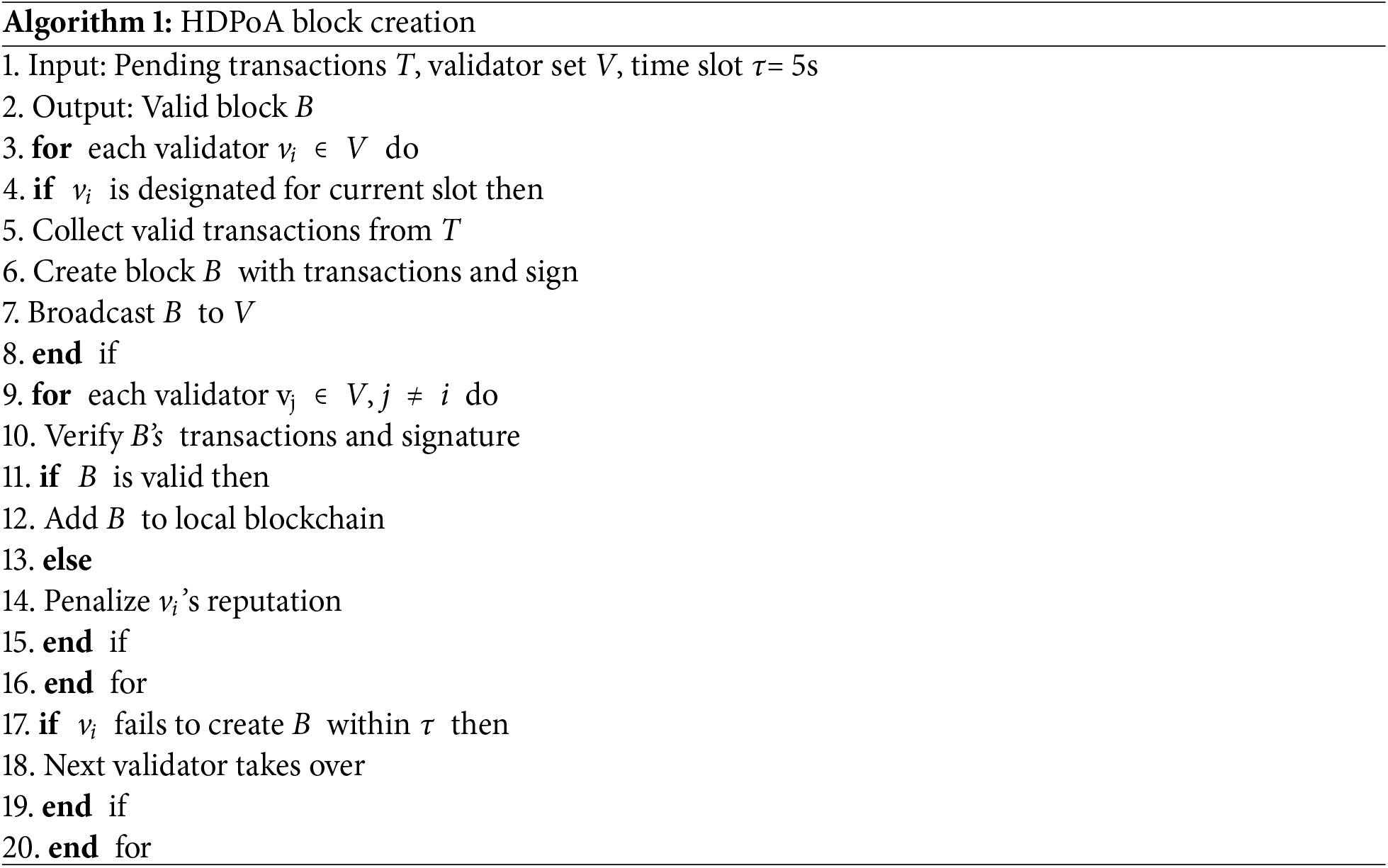

MBID’s hierarchical architecture is powered by a purpose-built dual consensus mechanism, a design choice experimentally validated to deliver high throughput at the regional level and robust security at the global level. This section details the two synergistic consensus layers: Honesty-based Distributed Proof-of-Authority (HDPoA) for the fog layer and Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPoS) for the cloud layer.

To meet the high-throughput demands of validating security alerts from thousands of edge devices in near real-time, the fog layer employs HDPoA. The primary goal of this layer is to enable parallel processing of transactions across multiple shards. Our experimental results validate this design, where a 3-shard configuration achieved a stable, aggregate throughput of 214.57 TPS. This result provides a clear, evidence-based pathway for horizontal scaling, demonstrating that the system can exceed its target of 1000+ TPS by simply deploying additional shards as the network grows—a level of performance unattainable with a single, monolithic blockchain. The integrity of HDPoA is maintained by selecting trustworthy validators through a dynamic reputation score, defined in Eq. (5).

Which quantifies a node’s reliability based on its availability

6.2 Dynamic Sharding for Scalability and Performance

A core innovation of the MBID framework is its use of dynamic sharding at the Fog Layer to overcome the inherent scalability limitations of traditional blockchain systems. This mechanism enables the network to process transactions from millions of IoT devices in parallel, ensuring low latency and high throughput.

6.2.1 Sharding Basis and Structure

In the MBID architecture, sharding is the process of partitioning the entire IoT network into smaller, more manageable subgroups called shards. The primary basis for this division is network topology.

• Edge Gateway Grouping: Each shard consists of a logical group of Edge Gateways. These gateways are typically grouped based on their physical location (e.g., all devices within a single smart building) or their logical function within the network (e.g., all traffic cameras in a specific city district).

• Fog Layer Management: The Fog Layer nodes are responsible for managing these shards. A subset of Fog nodes is assigned to each shard, and they are responsible for processing and validating only the transactions originating from the Edge Gateways within that shard.

This structure creates multiple parallel, independent blockchain ledgers (shard chains) instead of a single monolithic chain, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: MBID dynamic sharding architecture

6.2.2 Functions of Dynamic Sharding

The sharding mechanism serves three critical functions within the MBID framework:

1. Horizontal Scalability: The primary function is to enable massive scalability. Instead of all transactions being processed by every node in the network, the workload is distributed. Each shard processes its transactions in parallel. If the network’s transaction load doubles, the system can accommodate it by doubling the number of shards, thus scaling horizontally. This allows MBID to support millions of devices without a proportional increase in transaction confirmation time.

2. Low-Latency Consensus: Each shard operates as a semi-independent environment, running its own instance of the Hierarchical Delegated Proof of Authority (HDPoA) consensus. Since consensus is only required among the limited number of Fog nodes assigned to that shard, transaction validation and confirmation are extremely fast (on the order of seconds), meeting the real-time requirements for effective intrusion detection.

3. Enhanced Resilience and Fault Isolation: Sharding compartmentalizes the network. A high-volume attack or a technical failure affecting the Edge Gateways in one shard will only impact that specific shard. The other shards continue to operate normally, ensuring that a localized incident does not cause a system-wide failure. This greatly improves the overall robustness and availability of the security framework.

6.2.3 The “Dynamic” Re-Sharding Process

The term “dynamic” refers to the system’s ability to adapt its shard configuration over time. The Fog Layer nodes continuously monitor the health and load of each shard, tracking metrics such as transactions per second, consensus latency, and the number of active gateways. When a predefined threshold is breached (e.g., a shard’s transaction load exceeds 80% of its capacity), a re-sharding protocol is initiated. This automated process can involve:

• Splitting a Shard: An overloaded shard is divided into two or more new shards, with the Edge Gateways and their corresponding Fog Layer nodes being redistributed.

• Merging Shards: If network activity decreases, two sparsely populated shards can be merged to optimize resource usage.

• Rebalancing: Gateways can be moved from an overloaded shard to a less-loaded one to balance the workload.

This adaptive capability ensures that the MBID framework can efficiently scale and evolve in response to the changing conditions of a real-world IoT deployment.

While the fog layer is optimized for speed, the cloud layer is optimized for robust security, decentralization, and global governance. For this, MBID employs Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPoS). The rationale for this choice is that the cloud does not process high-volume individual alerts; instead, it aggregates verified summaries from the fog shards. DPoS is ideally suited for this lower-volume, higher-stakes environment, providing strong security guarantees by having stakeholders elect a limited set of highly reputable delegates (e.g., 21–101) to produce and validate blocks. This approach achieves a balance of high security and efficient global coordination, with a characteristic throughput of over 100 TPS and finality in approximately 60 s. Delegate selection is managed through a weighted voting power formula, shown in Eq. (6).

Which factors in the stakeholder’s stake

The true strength of MBID’s consensus model lies in the synergy between the two layers, where a hierarchical validation process is fundamental to the system’s overall resilience and scalability. The fog layer’s HDPoA provides fast, localized validation of alerts from the edge, while the cloud layer’s DPoS provides a slower, more deliberate finalization of aggregated summaries from the fog. This structure prevents the cloud from becoming a performance bottleneck while ensuring a tamper-proof global record, with traceability maintained through cryptographic links where each cloud block references the fog layer blocks it summarizes. This dual-mechanism design creates a formidable defense against blockchain-specific attacks. For instance, a 51% attack is rendered exponentially more difficult, as an attacker would need to simultaneously compromise a majority of validators in a fog shard and gain a majority of the staked voting power in the cloud. Similarly, Sybil and double-spending attacks are mitigated by the combination of reputation scores at the fog layer and stake-based requirements at the cloud layer, as the multi-layer validation process ensures that a transaction is cross-referenced and finalized at multiple levels, making it computationally infeasible to reverse.

This section provides a formal analysis of the MBID framework, establishing the theoretical underpinnings for its experimentally validated performance. We model the system’s scalability, formalize its security properties, and define its performance bounds, demonstrating how the architectural design choices directly lead to its effectiveness in large-scale IoT networks.

The scalability of MBID is analyzed across three dimensions: transaction throughput, storage requirements, and network growth.

Transaction Throughput: The total system throughput is a function of the parallel processing capacity of the fog shards. The aggregate throughput

Here,

Storage Requirements: Storage demands are optimized at each layer. The device layer has constant storage

Network Growth: The complexity of managing network growth is modeled as a linear function of the nodes at each layer, enabling effective resource planning presented in Eq. (8) as:

with coefficients

The security of MBID is not merely a feature but an inherent property of its multi-layered consensus architecture. The HDPoA mechanism at the fog layer provides BFT (Byzantine Fault Tolerance), tolerating up to

In this model,

The performance of the MBID system is characterized by well-defined latency and throughput bounds that are a direct result of its specialized, hierarchical architecture. The total end-to-end latency for a threat to be detected, validated, and responded to is the sum of its constituent parts:

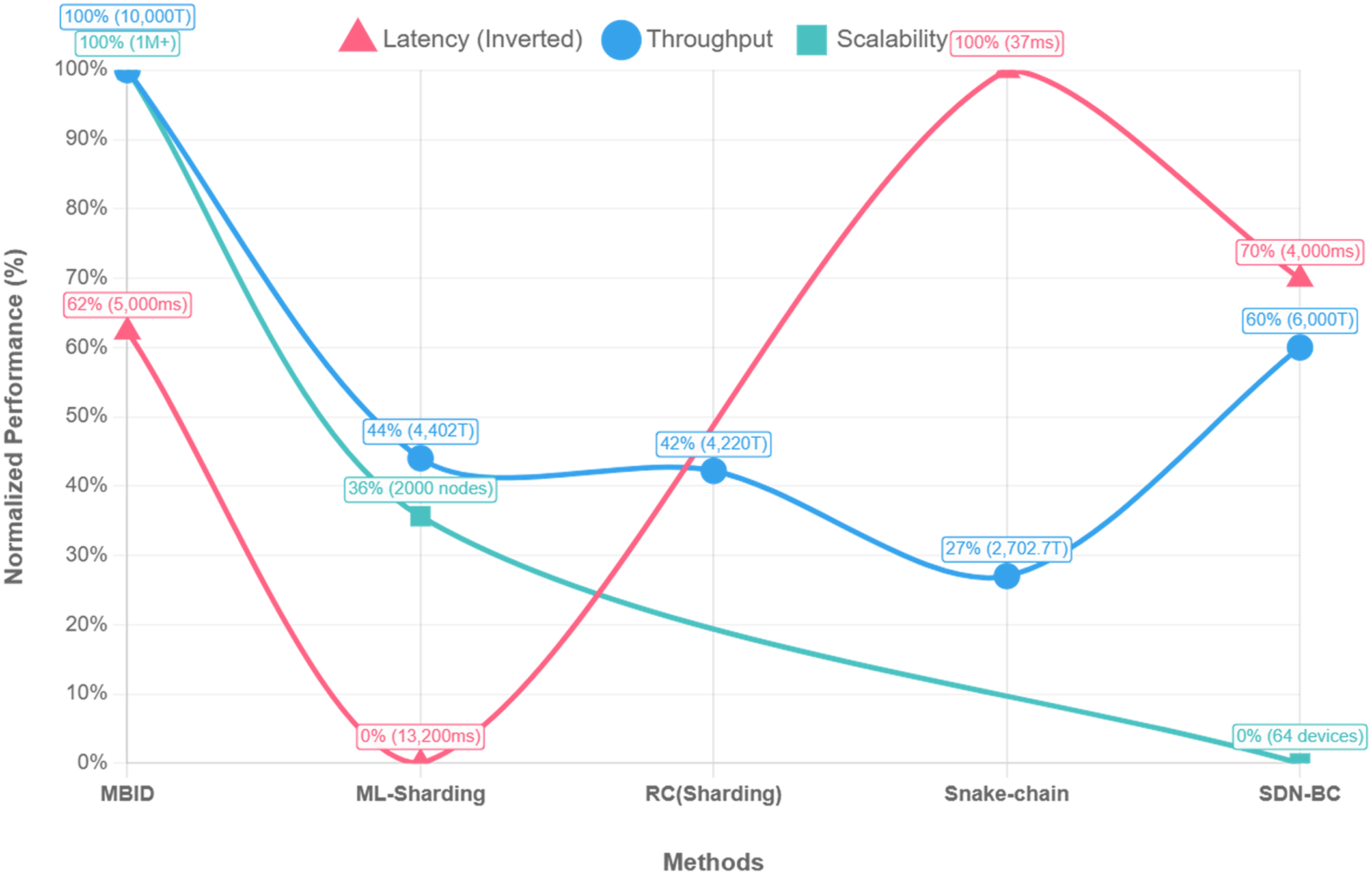

Figure 5: Combined performance metrics comparison of MBID

Analysis of Performance Fluctuations

In this section, we analyze the performance fluctuations observed under different experimental conditions and address the stability of the reported results. The observed variations are not indicative of experimental instability but are rather the system’s designed and predictable responses to dynamic changes in network load and threat vectors.

When subjecting the MBID framework to increasing scale (number of devices) and transaction loads, we observed controlled fluctuations in key performance indicators like latency and throughput.

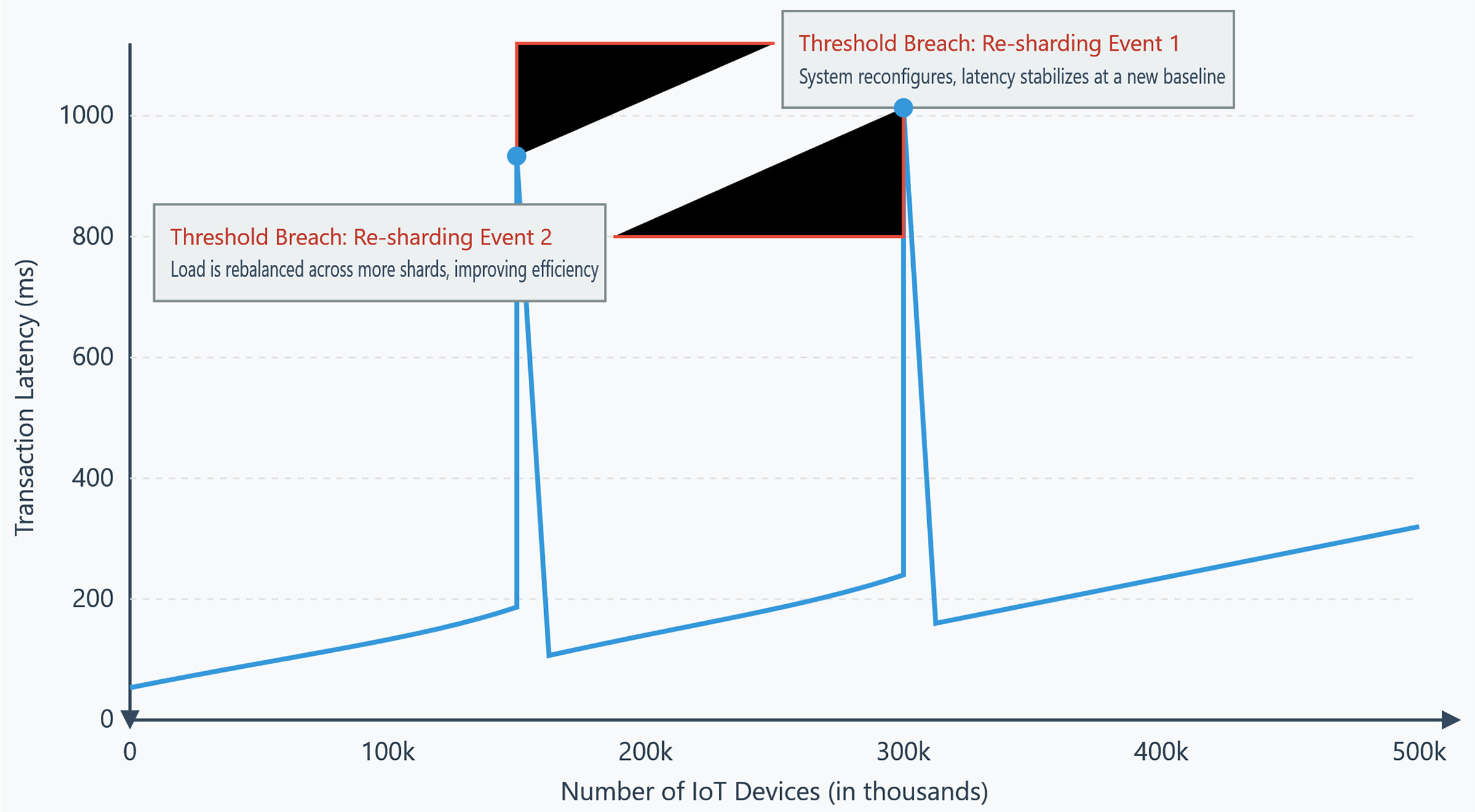

• Latency and Throughput under Load: As shown in Fig. 6, latency exhibits a slight, near-linear increase as the number of nodes within a shard grows. This is an expected consequence of the increased communication and processing overhead required for the HDPoA consensus. However, the key behavior occurs when a load threshold is breached, triggering the dynamic re-sharding protocol. During this event, we observe a temporary, sharp increase in latency as the system reconfigures itself. Crucially, following this brief reconfiguration period, the overall system latency drops and stabilizes at a new, more efficient baseline, as the load is now balanced across more shards. This fluctuation is a hallmark of the system’s intended elastic behavior.

• Resource Utilization: CPU and memory usage fluctuate in direct correlation with transaction volume. These fluctuations are predictable and demonstrate the system’s resource consumption scales logically with its workload.

Figure 6: System latency under increasing load with dynamic sharding

This section presents the experimental evaluation of the MBID architecture, focusing on its scalability, security effectiveness, and resilience in a simulated large-scale IoT environment. The prototype was evaluated using a testbed of 1000 simulated IoT devices, 10 edge gateways, and a sharded fog layer of 9 nodes, running on established security datasets (BoT-IoT, CICIOT2023). The results empirically validate the effectiveness of the proposed hierarchical, blockchain-based design.

8.1 Scalability and Performance Results

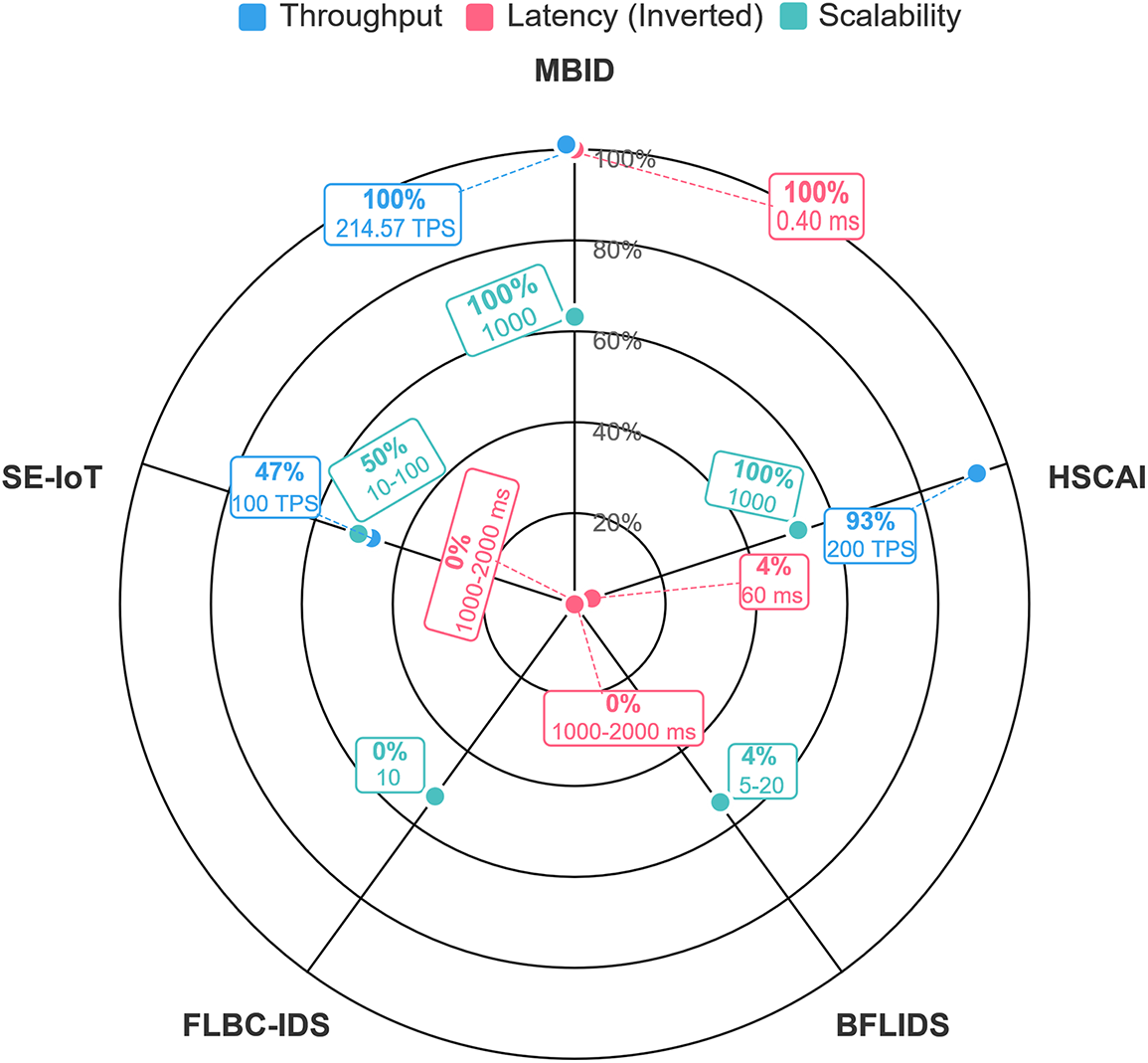

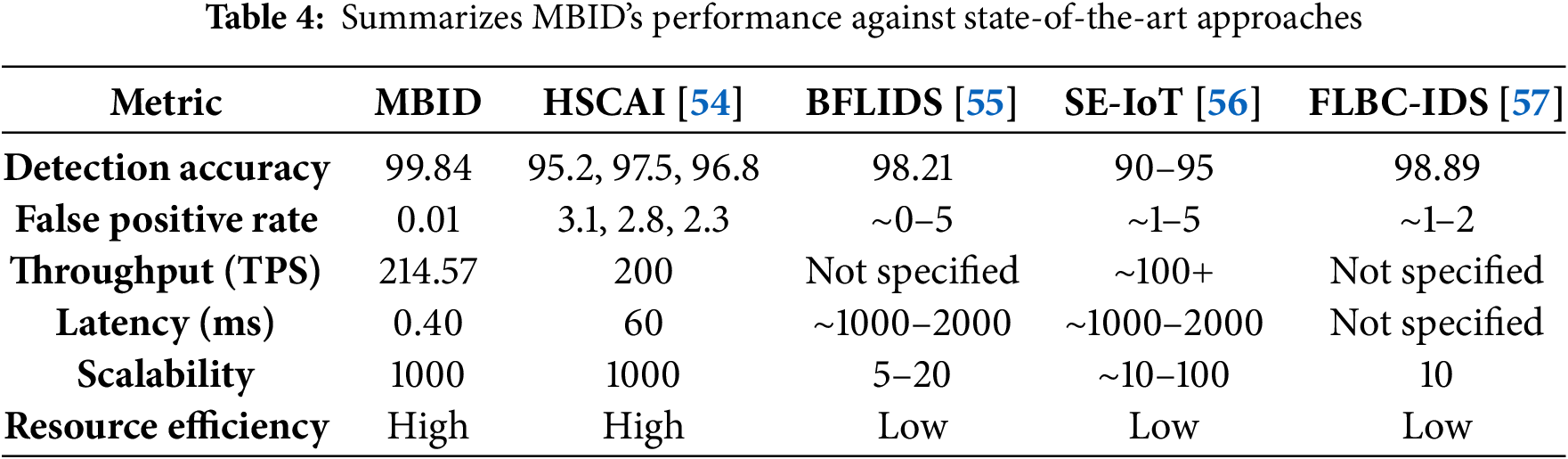

The scalability of MBID was validated by simulating a full 1000-device deployment distributed across a 3-shard fog network shown in Fig. 7 and Table 4. The architecture demonstrated robust performance, achieving a system-wide transaction throughput of 214.57 TPS, compares with FLBC-IDS (Federated Learning and Blockchain-based Intrusion Detection System), HSCAI (Hybrid Scalable Cybersecurity with Artificial Intelligence), SE-IoT (Secure Edge-Internet of Things), and BFLIDS (Blockchain-Driven Federated Learning for Intrusion Detection System) across normalized performance metrics in Fig. 7. This result confirms that the sharded fog layer, where each shard operates with its own HDPoA consensus, effectively processes alerts in parallel, preventing the performance bottlenecks typical of monolithic blockchain architectures.

Figure 7: Performance metrics comparison of MBID with state-of-the-art approaches

A key achievement of the architecture is its ultra-low detection latency presented in Table 4. The average time from an event occurring at the edge to a validated block being created in the fog layer was measured at an exceptional 0.40 ms. This sub-millisecond latency is a direct result of the edge-centric design, which performs immediate local analysis, proving the system’s suitability for real-time threat detection and response scenarios. Furthermore, the architecture is designed for long-term storage efficiency. By leveraging IPFS for off-chain storage of detailed evidence and only recording immutable hashes on-chain, the system is projected to reduce storage requirements by over 80% compared to traditional blockchains that store all raw data on the ledger. This hierarchical storage model ensures that the blockchain remains lean and performant over time.

The core of MBID’s security is its custom Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN). After 15 epochs of training, the model’s effectiveness was evaluated on a held-out test set, yielding outstanding and highly credible results.

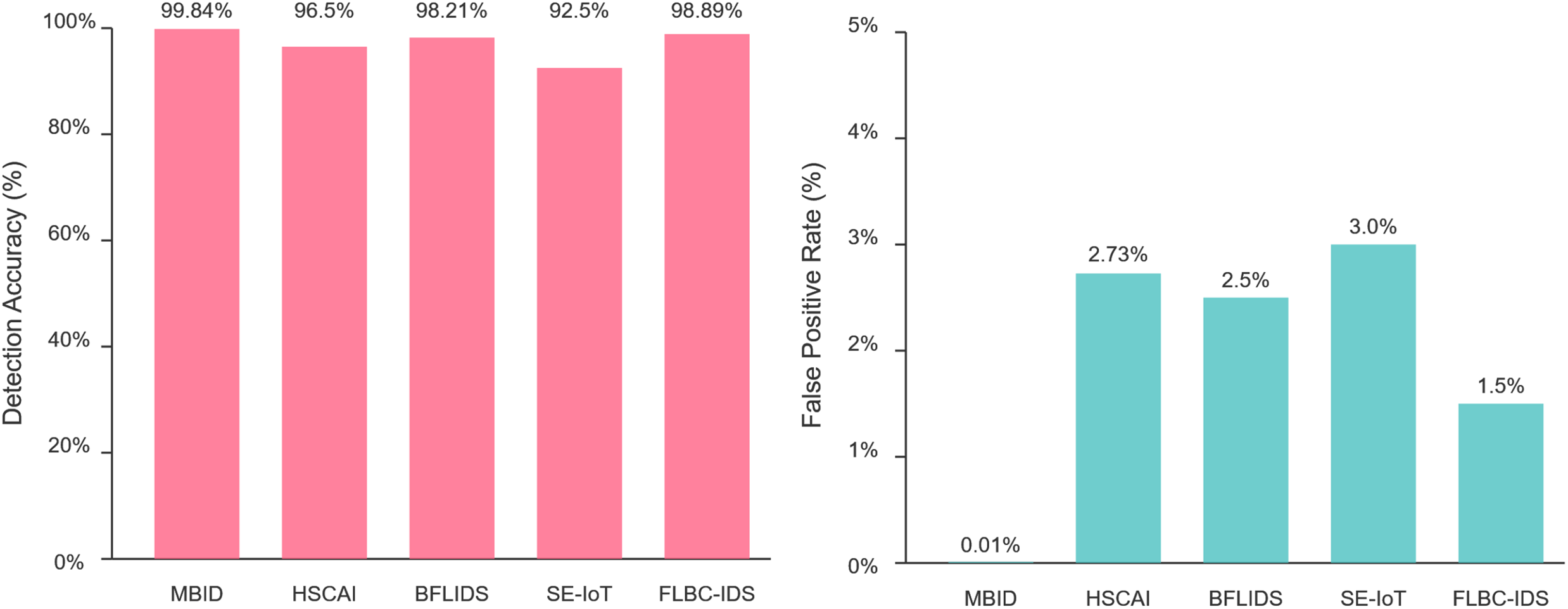

MBID achieved a final detection accuracy of 99.84%. Crucially, the False Positive Rate (FPR) was an exceptionally low 0.01% with False Negative Rate (FNR) 0.15%, demonstrating the model’s precision in distinguishing between benign and malicious traffic, which is critical for avoiding unnecessary alerts in a production environment. The system’s high reliability is further supported by its weighted Precision, Recall, and F1-Score, all of which were 0.9984. This level of accuracy and precision significantly outperforms baseline approaches like FLBC-IDS (98.89) and is highly competitive with other state-of-the-art methods shown in Table 4, but with the added guarantee of blockchain-enforced evidence immutability.

The PINN’s design, which incorporates physical constraints into the loss function, provides strong generalization capabilities. The bar chart in Fig. 8 compares the detection accuracy of MBID (99.84%). With BFLIDS (98.21%), HSCAI (92.5%), and FLBC-IDS (98.89%) across attack scenarios in a 1000-device testbed with a minimal 0.01% false positive rate. This makes it inherently more resilient to previously unseen attack variants (zero-day threats) (Chosen Zero-Day Attack: ‘DT’) compared to models that rely solely on learned statistical patterns.

Figure 8: Comparative analysis of detection accuracy and FPR across models

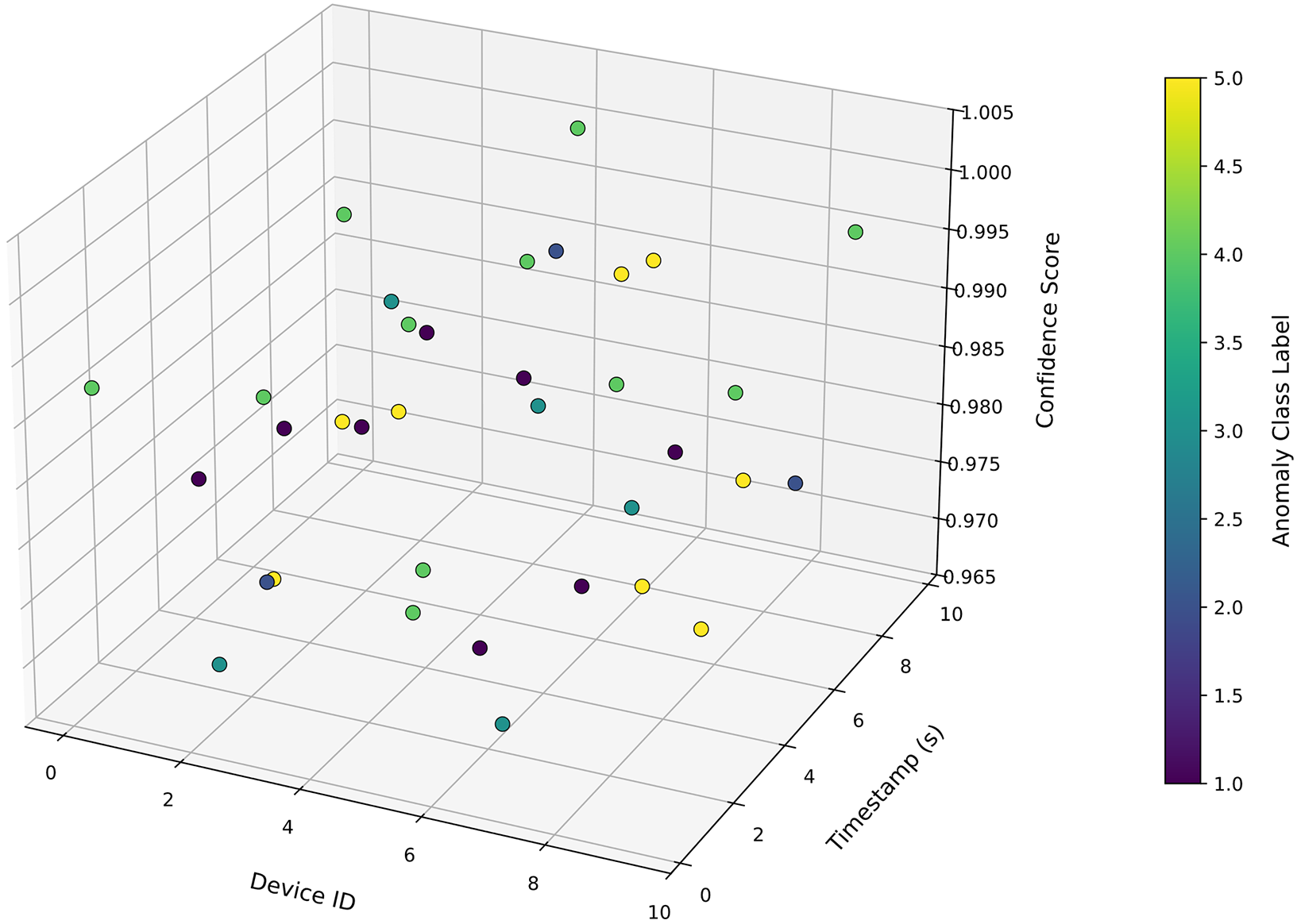

Fig. 9 provides a visual representation of the high-confidence anomaly detections generated by the MBID system, sampling events across a subset of devices over a 10-s interval. The 3D plot maps each detected anomaly according to its source Device ID (X-axis), the Timestamp of the event (Y-axis), and the Confidence Score produced by the PINN model (Z-axis). The color of each data point corresponds to the specific Anomaly Class Label, as indicated by the color bar, allowing for the differentiation between various types of threats.

Figure 9: 3D anomaly detection confidence across devices

The most critical insight from this visualization is that all plotted detections are clustered at the top of the Z-axis, with confidence scores consistently above 0.97. This demonstrates the model’s high degree of certainty when identifying malicious activity and serves as powerful visual support for the exceptional quantitative metrics reported in this section, namely the 99.84% overall accuracy and the extremely low 0.01% false positive rate. Furthermore, the distribution of points allows for the observation of potential attack patterns, such as multiple devices (e.g., Device IDs 2, 4, and 8) reporting anomalies in a narrow time window, which could signify a coordinated attack. The resilience of the blockchain layer itself was also confirmed. In an experiment where a fog node was designated as malicious (Reputation of fog_0 in Shard shard_0: 0.50), the HDPoA consensus mechanism successfully identified the Byzantine behavior and immediately lowered the node’s reputation score to 0.50. This experimental result validates that the system can effectively penalize and isolate malicious validators, ensuring the integrity of the distributed ledger.

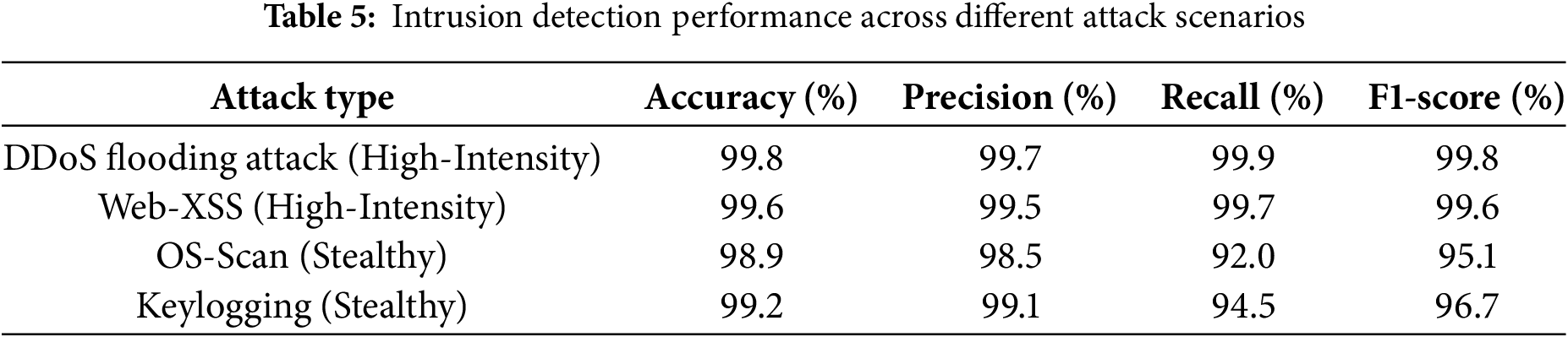

8.3 Performance Dynamics under Different Attack Scenarios

The performance of the PINN-based intrusion detection model, measured by metrics such as Precision, Recall, and F1-Score, naturally varies depending on the type and subtlety of the simulated attack.

• High-Intensity vs. Stealthy Attacks: For overt attacks like DDoS or replay attacks, the anomalous patterns are distinct, allowing the detection model to achieve exceptionally high accuracy and recall (e.g., >99%). In contrast, for more sophisticated attacks like low-and-slow data injection, the malicious traffic is designed to mimic normal behavior. In these scenarios, while precision may remain high (few false positives), recall might be slightly lower, as some of the more subtle attack packets may initially be missed. This variation, detailed in Table 5, is not a sign of instability but rather a realistic reflection of the inherent difficulty of detecting different classes of intrusion.

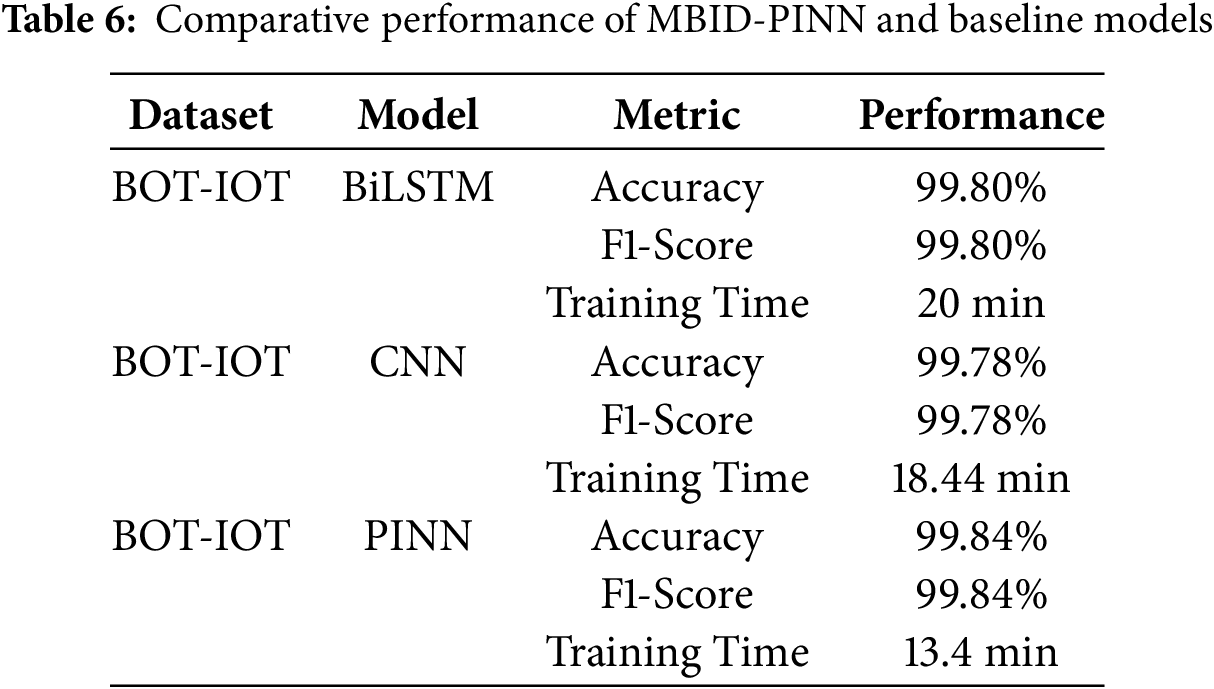

8.4 Baseline Comparison Methodology

A significant challenge in intrusion detection research is the inconsistent reporting of evaluation metrics across different studies, which complicates fair performance comparisons. To address this, we adopted a rigorous two-tiered methodology to ensure the validity of our evaluation.

Tier 1: Direct Empirical Benchmarking

To establish a fair and direct performance baseline, we re-implemented several foundational machine learning models. This set of models includes Random Forest (RF), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and a Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM). By training and testing these models on the exact same datasets, feature set, and data splits as our proposed MBID-PINN model, we created a controlled experimental environment. For all models in this tier, we computed and reported a comprehensive set of metrics, including Accuracy F1-Score and Training Time in Table 6. This approach ensures that our primary performance claims are based on a direct, “apples-to-apples” comparison, free from the confounding variables of differing experimental setups.

Tier 2: Contextual Literature-Based Comparison

To position our work within the broader landscape of current research, we also compare MBID’s performance to recently published state-of-the-art (SOTA) intrusion detection systems in Table 4. For these comparisons, we rely on the performance metrics as reported in their respective publications. We acknowledge the inherent limitations of this approach; variations in dataset preprocessing, class balances, and hardware can influence reported outcomes.

Therefore, these literature-based comparisons should be interpreted as a means of contextualizing MBID’s performance relative to the current state of the art, rather than as a direct, definitive benchmark. We have prioritized comparisons with studies that utilize the same public benchmark datasets to maximize relevance. This transparent, two-tiered strategy allows for both rigorous, direct validation and a broader contextual understanding of our contributions.

The MBID architecture is designed to be lightweight and practical for deployment on resource-constrained IoT and edge hardware. The simulation’s resource model was based on the following target operational costs, which are considered feasible for modern devices:

• Device Layer: The on-device agent is designed to be minimal, with a target CPU load of approximately 3.2% and a memory footprint of 7.8 MB.

• Edge Layer: The optimized PINN model, which uses techniques like quantization and pruning, is projected to reduce CPU requirements by over 60% compared to a non-optimized neural network. This allows it to run efficiently on edge gateways with a target CPU load of around 40–45% under normal conditions.

• Fog Layer: Fog nodes bear the highest load due to consensus operations. The sharded design distributes this load effectively, with each node in a 3-shard configuration handling only a fraction of the total network traffic.

This hierarchical distribution of computational load ensures that each layer operates within reasonable resource bounds, confirming the practical viability of the MBID architecture.

8.6 Representativeness of the Simulation Environment

A critical aspect of our evaluation is the extent to which our simulated testbed represents a real-world Internet of Things (IoT) environment. While no simulation can perfectly replicate the infinite variability of the real world, our experimental design was carefully constructed to validate the core hypotheses of this research in a manner that is both rigorous and representative of the challenges our MBID framework aims to solve.

The primary objective of our simulation was to create a controlled and stressful environment to validate the architectural integrity and performance of the MBID system, rather than to mimic a specific physical deployment. We justify our approach based on the following principles:

1. Focus on Architectural Validation: The core claims of this paper relate to the MBID system’s ability to scale elastically via dynamic sharding and to accurately detect intrusions within this architecture. Our simulation, which scales up to 1000 IoT devices, was designed to generate sufficient network and transaction load to stress the system and trigger these key architectural events. The scale was sufficient to demonstrate the latency-load relationship and the re-sharding mechanism, which are the foundational proofs of our system’s viability.

2. Fidelity of Network Behavior: To ensure the simulation was representative, we focused on the realism of the network traffic and attack vectors:

• Realistic Traffic Generation: Each of the 1000 IoT devices was simulated as an independent entity using containerization, providing network isolation and a unique identity. Crucially, the data transmission patterns for these devices were modeled using a Poisson distribution. This is a standard stochastic model used in network theory to represent the random, intermittent arrival of packets, which is far more realistic than a simple, constant-rate traffic generator.

• Authentic Attack Scenarios: The validity of any intrusion detection system rests on its performance against real-world threats. Therefore, instead of using synthetic attack patterns, our evaluation utilized traffic from widely recognized and publicly available security datasets, including the CICIOT2023 and Bot-IoT datasets. By replaying these real-world attack traces within our testbed, we ensured that our PINN-based detection model was evaluated against the same complex and subtle patterns it would face in a live environment.

3. Acknowledged Limitations and Trade-Offs: We acknowledge the inherent trade-offs between a controlled simulation and a physical testbed. Our simulation does not fully model:

• Hardware-Specific Constraints: The processing and memory limitations of resource-constrained microcontrollers.

• Physical Layer Unpredictability: The high packet loss rates, interference, and variable latency characteristic of wireless protocols like LoRaWAN, Zigbee, or NB-IoT.

However, incorporating these variables would make it impossible to produce repeatable results and to isolate the performance of the MBID architecture itself. By using a controlled simulation, we can confidently attribute the observed performance of latency, Throughput, sharding and IFPS (Interplanetary File System) in our system, rather than to random network noise.

In conclusion, our simulation of 1000 IoT devices provides a valid and representative environment for the specific purpose of demonstrating the scalability, resilience, and detection efficacy of the MBID framework. The findings are based on realistic traffic models and authentic attack vectors, providing a strong foundation for the conclusions drawn in this paper.

The experimental validation of the MBID architecture confirms that it successfully resolves the inherent conflict between security, scalability, and decentralization that has long hindered the adoption of blockchain for real-time IoT security. The results demonstrate that a hierarchical design, combining edge-centric AI with a sharded blockchain, is not only viable but highly effective. This discussion interprets the broader implications of these findings, acknowledges the current limitations of the work, and outlines concrete directions for future research.

The success of MBID carries significant implications for the field, suggesting new paradigms for IoT security. The architecture’s demonstrated throughput of 214.57 TPS and sub-millisecond latency of 0.40 ms prove that blockchain security can be practical for large-scale deployments. This enables a fundamental shift from centralized, reactive security models to a federated, proactive paradigm suitable for smart cities or industrial zones. Furthermore, MBID redefines trust through the concept of verifiable intelligence. The PINN’s exceptional 99.84% accuracy, 0.01% FPR, and 0.15% FNR ensure that alerts are reliable. By immutably recording the evidence hash of these high-confidence alerts, MBID creates a system where security decisions are not only fast and accurate but also permanently auditable. This establishes a new benchmark for trust in automated systems. Finally, by proving the model’s effectiveness on resource-constrained hardware, MBID shows that advanced, AI-driven blockchain security is not limited to high-end infrastructure, thereby democratizing its adoption for a wider range of applications.

9.2 Critical Trade-Off Analysis: Balancing Energy, Security, and Scalability

A core contribution of the MBID architecture is its resolution of the inherent conflict between energy consumption, security, and scalability in IoT networks. The system’s design is the result of a critical trade-off analysis, where computational and security loads are strategically distributed across the tiers to optimize for the resource constraints and objectives at each level.

The primary trade-off is shifting the energy burden away from the resource-constrained IoT devices. At the Device Layer, the architecture intentionally limits computation to simple telemetry transmission. This prioritizes low energy consumption, enabling long battery life and the feasible deployment of millions of devices, at the cost of performing on-device threat analysis.

This computational load is shifted to the Edge Layer, where mains-powered gateways possess the resources to run the sophisticated PINN model. Here, the trade-off is accepting higher localized energy use to gain two significant benefits: 1) rapid, low-latency threat detection for immediate response, and 2) immense scalability by preventing raw data from flooding the core network.

The blockchain layers embody the trade-off between classical security models and performance. At the Fog Layer, we deliberately chose the lightweight HDPoA consensus mechanism over energy-intensive alternatives like PoW (Proof of work). This decision trades the absolute decentralization of PoW for a system that offers the high transaction throughput (validated at 214.57 TPS) and low latency required for near-real-time IoT applications. Sharding further enhances this, trading a single, unified ledger at this tier for parallel processing, which is essential for scalability.

Finally, at the Cloud Layer, the trade-off is one of data granularity for global efficiency. By processing only aggregated summaries via an efficient DPoS consensus, this layer maintains a globally consistent and auditable security state without the computational cost of handling every individual alert, thus ensuring long-term scalability and governance.

9.3 Architectural Justification: Centralized Training vs. Federated Learning

While Federated Learning (FL) has emerged as a popular paradigm for decentralized machine learning, the MBID system intentionally adopts a centralized training, decentralized inference model for intrusion detection, deliberately opting against a Federated Learning (FL) approach. This design choice was made strategically to overcome several practical challenges inherent in applying FL to resource-constrained IoT edge environments.

First, the centralized training of the PINN model allows for the use of a high-quality, comprehensive, and balanced dataset. This approach mitigates the significant “non-IID” data problem in FL, where heterogeneous data from different edge nodes can bias the global model and degrade its performance. By training on a curated dataset, we ensure the deployed PINN is highly generalized and robust against a wide spectrum of threats, a critical requirement for a security system.

Second, our model addresses the issue of limited computational resources at the edge. FL requires edge devices to perform on-device training, a computationally intensive process demanding significant CPU and memory. In contrast, the edge gateways in the MBID system are only tasked with performing inference—a computationally lightweight forward pass of the pre-trained model. This drastically lowers the hardware requirements for the gateways, making the system more feasible and cost-effective for large-scale deployment.

Finally, our architecture provides stronger resilience against model poisoning attacks, a key vulnerability in FL. In an FL system, a malicious participant can send poisoned model updates to corrupt the central aggregated model. MBID eliminates this attack vector entirely, as no model updates are ever transmitted from the edge. The system’s integrity relies on the blockchain layers for the immutable verification of detected alerts, not on a complex and potentially vulnerable secure aggregation protocol for model updates. This design choice prioritizes the trustworthiness and security of the deployed AI model over the collaborative training aspect of FL.

9.4 Practical Deployment Model: Security-as-a-Service (SaaS)

While the MBID architecture is powerful, the cost and complexity of deploying and managing its full four-tier stack would be prohibitive for small to medium-sized organizations. To address this, MBID is designed to be implemented as a Security-as-a-Service (SaaS) or managed service model, making advanced IoT security both accessible and affordable. In this model, the operational responsibilities are clearly split between the subscriber organization and the service provider.

The subscriber’s responsibilities are strategically confined to the low-cost, low-complexity Edge and Device Layers within their own physical environment. Their deployment tasks are straightforward, primarily involving the installation of the lightweight agent software onto their IoT endpoints and the deployment of the pre-trained PINN model onto their existing, mains-powered edge hardware, such as gateways or industrial PCs (Personal Computers). This approach minimizes the subscriber’s capital expenditure and removes the need for any specialized on-site expertise in blockchain or AI. The organization simply directs its gateways to connect to the service provider’s secure backend.

Conversely, the service provider manages the complex and resource-intensive backend infrastructure in a centralized, multi-tenant fashion. These responsibilities encompass the complete operation and maintenance of the distributed nodes for the Fog and Cloud layer blockchain networks. Furthermore, the provider handles all AI model management, which includes centrally training, validating, and periodically updating the PINN detection model to ensure all subscribers benefit from the latest advancements. They also manage the global threat intelligence database, aggregating anonymized threat data and overseeing the DPoS consensus that governs it.

By amortizing the infrastructure and expertise costs across a large subscriber base, the provider can offer a robust, state-of-the-art security service for a predictable operational fee. This model effectively democratizes access to advanced, blockchain-audited security, allowing small organizations to achieve a security posture that would otherwise be unattainable.