Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Computer Modeling Approaches for Blockchain-Driven Supply Chain Intelligence: A Review on Enhancing Transparency, Security, and Efficiency

1 Department of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, Malla Reddy University, Hyderabad, 500043, India

2 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Vardhaman College of Engineering, Hyderabad, 501218, India

3 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Symbiosis Institute of Technology, Hyderabad, 509217, India

4Versa Networks, Santa Clara, CA 95054, USA

5 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Koneru Lakshmaiah Education Foundation, Vaddeswaram, 522302, India

6 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh, 174103, India

7 Division of Research & innovation, Uttaranchal University, Dehradun, 248007, India

8 Division of Research and Development, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, 144411, India

9 School of Built Environment, Engineering and Computing, Leeds Beckett University, Leeds, LS6 3HF, UK

10 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Chennai Institute of Technology, Chennai, 600069, India

11 Centre for Research Impact & Outcome, Chitkara University Institute of Engineering and Technology, Chitkara University, Rajpura, 140401, India

* Corresponding Author: Shitharth Selvarajan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Key Technologies and Applications of Blockchain Technology in Supply Chain Intelligence and Trust Establishment)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(3), 2779-2818. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.066365

Received 07 April 2025; Accepted 15 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Blockchain Technology (BT) has emerged as a transformative solution for improving the efficacy, security, and transparency of supply chain intelligence. Traditional Supply Chain Management (SCM) systems frequently have problems such as data silos, a lack of visibility in real time, fraudulent activities, and inefficiencies in tracking and traceability. Blockchain’s decentralized and irreversible ledger offers a solid foundation for dealing with these issues; it facilitates trust, security, and the sharing of data in real-time among all parties involved. Through an examination of critical technologies, methodology, and applications, this paper delves deeply into computer modeling based-blockchain framework within supply chain intelligence. The effect of BT on SCM is evaluated by reviewing current research and practical applications in the field. As part of the process, we delved through the research on blockchain-based supply chain models, smart contracts, Decentralized Applications (DApps), and how they connect to other cutting-edge innovations like Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the Internet of Things (IoT). To quantify blockchain’s performance, the study introduces analytical models for efficiency improvement , security enhancement , and scalability , enabling computational assessment and simulation of supply chain scenarios. These models provide a structured approach to predicting system performance under varying parameters. According to the results, BT increases efficiency by automating transactions using smart contracts, increases security by using cryptographic techniques, and improves transparency in the supply chain by providing immutable records. Regulatory concerns, challenges with interoperability, and scalability all work against broad adoption. To fully automate and intelligently integrate blockchain with AI and the IoT, additional research is needed to address blockchain’s current limitations and realize its potential for supply chain intelligence.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileSupply Chain Management (SCM) is the process of transferring products from the producer to the consumer [1]. Members of this network include those directly and indirectly engaged in the production and distribution of goods, including manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, and consumers. It encompasses everything from the enhancement of products to the source of materials, development of content, coordination, and the data structures that are necessary to allow these activities. Supply chains have been in existence since the beginning of time, beginning with the first product or service that was created and released for sale [2]. Globalization of the economy and intense market competitiveness have both contributed to the increasing complexity and variability of supply networks [3,4]. This is largely attributable to the fact that modern consumers are pickier than ever before, seeking higher-quality, more personalized goods and services at reasonable prices and with reasonable turnaround times. Companies are shifting their focus to their core function and embracing collaborative efforts like outsourcing, developing advanced value chains, and open innovation [5] to efficiently respond to market changes and stay competitive. So, the number of participants in a supply chain has grown substantially. Information is sometimes highly fragmented because these members are often distributed geographically. Quality systems, production standards, and other forms of increased coordination cost are necessary for the effective management and facilitation of information sharing among the participants in a complicated supply chain.

However, there is still an imbalance of information in the current supply line. In transaction cost economics, opportunism is commonly associated with information asymmetry [6]. This occurs when participants in a collaboration do not completely share knowledge with one another, which leaves potential for dishonesty. This interpretation is not the subject of the paper that is being discussed. Information asymmetry, as we understand it, is characterized as hidden information [7]. This information could be intentionally or unintentionally hidden. This occurs when there is a lack of uniform and equitable access to product information among supply chain participants. In most cases, product manufacturers have an advantage when it comes to managing and concealing the amount, precision, and categories of data that they share with other members and even with consumers [8]. One of the most common justifications for keeping information from other members secret is a potential conflict of interest [9]. The trust among members and the efficiency of a supply chain are both diminished by the lack of flexibility and the highly restricted flow of information. In this setting, “data trust” is having faith in the accuracy of data and information supplied by supply chain or central authority partners. A catalyst to improve supply chain efficiency can be accurate data confidence in information exchange [10].

One key technique to lower the transaction cost is to share information. When people in a supply chain share information, it might be ranging from product specs to its current status to ownership details to data locations to environmental impacts [11]. Beyond the decision-making process, information exchange is critical for businesses in areas like logistical planning and profit maximization. Improving members’ ability to work together is another important goal. Nevertheless, data undergoes continual transformations across the supply chain, and its volume grows at an exponential rate. In light of the deluge of data available, businesses and consumers may be confused about which pieces of information to believe, since the data’s veracity cannot be confirmed. So, to improve performing supply chains, prevent fraud and theft, and improve information sharing, a better tool is required [12].

This issue can be resolved through the utilization of BT, which possesses a single trusted ledger that has the potential to transform the concept of trust. Providing a lasting digital footprint to all participants of the network, this distributed ledger technology type can be a solution to trustworthy information exchange. This ensures that a tamper-evidence environment records all authorized transactions that take place along the supply chain. Any deliberate effort to change the data will be easily detectable. Integrating smart devices and the IoT can further digitize and automate processes, allowing members of a supply chain to collect and share information in real-time. This enhances transparency and efficiency. Many researchers have taken an interest in these possible effects on the supply chain.

Evolution of Blockchain

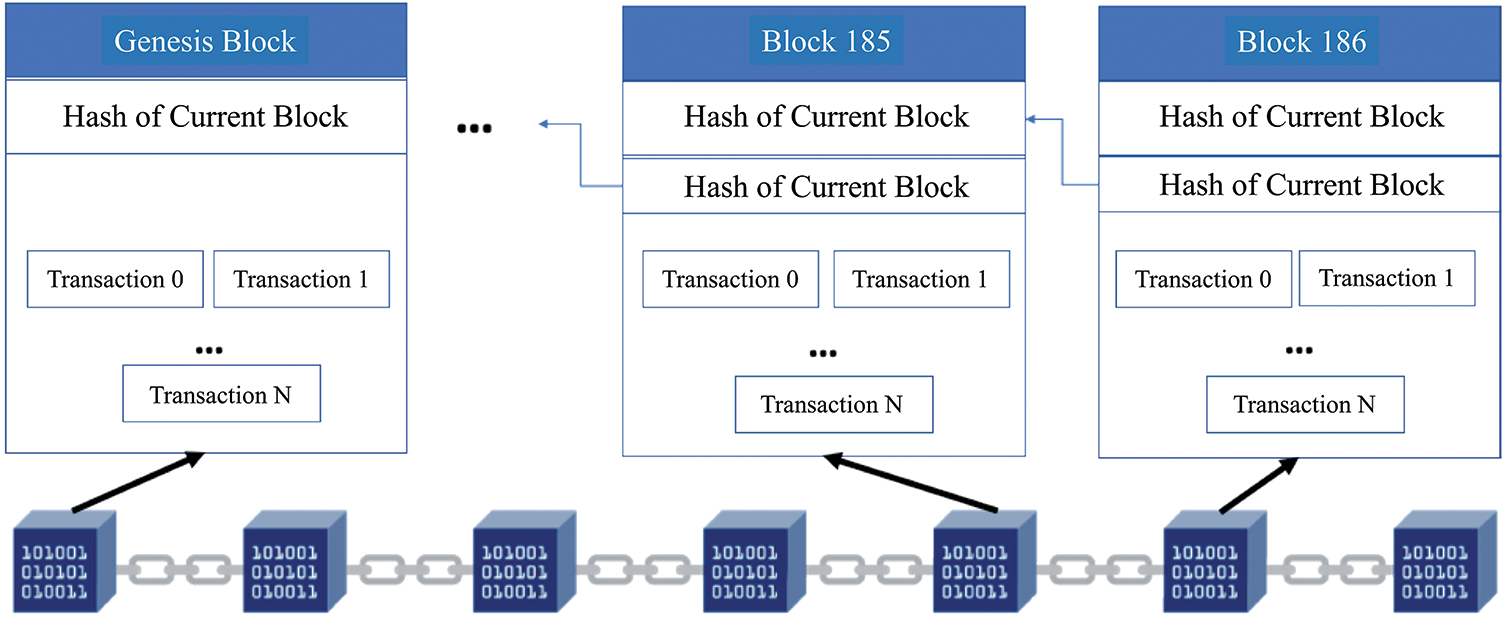

The first digital currencies and distributed ledger technologies were introduced in the early 1990s, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The idea of a safe chain of blocks is not new. In 1991 [13], came up with the idea in order to prevent the manipulation of electronic data. Data encryption is the study of creating a level of data security that allows for its transmission between two or more nodes that are not trusted. A cypher with a secret key can encrypt and decrypt data. Bitcoin, a decentralised digital currency founded on BT, was introduced by [14]. In 2012 and 2013, disruptive technologies were widely used in e-commerce platforms, which paved the way for the creation of smart contracts and their subsequent use in non-monetary financial areas. In recent years, BT has been utilised in the process of safeguarding quantum data. This is due to the fact that blockchain transactions are extremely trustworthy. Public, private, permission, and consortium blockchains are the three main categories [15] of this network technology.

Figure 1: The advancement of blockchain technology [11]

All participants in a public blockchain can see the data and transactions that have taken place. Bitcoin, Ethereum, Dash, and Factom are a few well-known cryptocurrencies that were built on the public blockchain [16]. Participation in the operations of a public blockchain, such as bitcoin, is open to each and every individual. On the other hand, it has insufficient security features, consumes a lot of processing resources, and doesn’t make transactions private. A private blockchain network is one in which a single company acts as administrator for its customers, setting participation guidelines, overseeing the consensus process, and updating the distributed ledger. Everyone involved in a private blockchain is familiar with each other and works for the same company. As a result, nobody saves the administrator has access to the details of each transaction [17]. Multichain and block stack are two instances of private blockchains. Permission blockchain makes transactions partly private by limiting their visibility to specific participants. We have identified all of the players, and their profiles are identical to their real-life counterparts. Namely, Hyperledger, r3, and ripple are permission blockchains. Multiple companies work together to oversee a common blockchain. All transactions and ledger access for this blockchain are overseen by a small set of reliable individuals. A consortium blockchain is ideal when all members of the consortium require blockchain access and will be held accountable for its maintenance [18].

Nevertheless, the overall contribution of blockchain-enabled information exchange inside a supply chain as well as the obstacles that it presents must to be determined. So, the purpose of this article is to explore and comprehend the ways in which BT can alter the present state of information exchange in a supply chain. To better understand the present state of knowledge about supply chain information sharing, a systematic study is necessary [19]. By highlighting the knowledge gap in this area, the obstacles to BT progress, and the unrealised potential benefits, this has the opportunity to give a more thorough insight. We have performed an extensive literature evaluation to address this research topic.

• This study thoroughly investigates the function of blockchain technology (BT) in supply chain intelligence, with a focus on security, operational efficiency, and transparency.

• It also delves into blockchain-based frameworks, such as smart contracts and decentralised applications (DApps), and how they interact with new technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and the internet of things (IoT).

• Analyses current research and industry uses of blockchain technology to show how it can improve supply chain management.

• Draws attention to the pros and cons of using blockchain technology, including issues with scalability, interoperability, and regulations. Suggests ways to improve blockchain integration for a smarter, more automated supply chain.

In Section 2 of this study, the basic ideas of BT are introduced, and its function in improving supply chain intelligence is discussed. The methodology is detailed in Section 3. The section 4 delves into the various blockchain-powered supply chain models, including permissioned and permissionless frameworks, smart contracts, and decentralised applications (DApps). Section 5 explores how blockchain frameworks, smart contracts, and applications in SCM will integrate with new technologies like the IoT and AI. Detailed algorithms and computer modeling approaches for blockchain-driven SCM are highlighted in Section 6, which offers an exhaustive examination of industry implementations. Section 7 outlines the key takeaways, obstacles, and areas for potential further study. In Section 8, the report comes to a close by reviewing the main points, discussing current issues including scalability and interoperability, and recommending areas for further study to improve blockchain integration in Supply Chain Intelligence (SCI).

Blockchain gained global attention when its spinoff, bitcoin, exploded the financial industry [20], and additional spinoffs in other fields are emerging quickly, such as healthcare [21], oil and gas [22], and tele-communications [23]. One of the most important ways in which the circular economy makes use of SCM is through this IR4.0 technology [24]. Worldwide participation and extensive interorganizational cooperation are two ways in which globalization has made SCM more complex [25]. For focused enterprises involved in international business operations in particular, this increases the cost of SCM [26]. In contrast to the way Block Chain Technology (BCT) disrupts traditional SCM [27], one of the major crucial and dominant barriers for Blockchain in supply chain management [28] is technology, which could be problematic for companies that are wary of adopting new technologies. To show how brick-and-mortar stores (like Macy’s, J.C. Penny, Toys R Us, etc.), cable TV companies (like Direct TV, Dish, etc.), and traditional news outlets (like local newspapers, etc.) are all facing challenges with technology adoption, a common feeling known as FOMO (fear of missing out). Consequently, the Blockchain’s advent immediately captivated the public’s attention, and companies rushed to adopt the technology without hesitation. According to reports, 92% of Blockchain ventures fail due to the unreasonable rush for technological adoption and the sheer complexity of Bitcoin and Blockchain [29,30]. While it comes to BCT for SCM, the most prominent technologies are the IoT and smart contracts [31]. Smart contracts have allowed the electric power business to integrate BCT more quickly than other sectors [32]. In addition, BCT presents a promising opportunity to promote long-term SCM [33]. However, there is a dark side to BCT as well; their research shows five related shortcomings: inefficiency, lack of standardization, GIGO, lack of privacy, and the black box effect [34].

The complexity of supply chains increases, nevertheless, as they grow in size [35]. As a result, typical supply chains aren’t really transparent or traceable, which is a problem for the whole business because it leads to terrible inefficiencies, mistakes, and higher costs. A unified perspective of data that allows for independent and private verification of transactions (such as production, shipment, delivery, and sales) is necessary for supply chain actors to tackle this challenge. The four iterations and methodology steps of the literature review process are shown in Fig. 2. We began by compiling all 2291 studies that used the terms “SCM” or “BT” in their analysis of published articles between 2013 to 2025 [36–38].

Figure 2: Represents four iterations and the methodology steps

The second step is to narrow the papers down to those with a “Final” publication status and authored in “English” using four criteria. This publication falls into one of six categories: “Business, Management, and Accounting,” “Computer Science,” “Social Sciences,” “Decision Sciences,” “Economics, Econometrics, and Finance,” or “Environmental Sciences.” For the purpose of understanding the current state of the literature, descriptive statistics were employed. Third, utilizing the results of step 2—the abstracts, titles, and keywords—we combed through 2265 papers [39,40]. The dataset had 9553 distinct phrases after eliminating stop words and certain irrelevant terms (such as article, abstract, report, etc.). To avoid including irrelevant terms, we limited our inclusion to 250 terms that appear 10 times or more out of 2265 abstracts (See Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Flow diagram of the literature review process for blockchain-based supply chain studies

To further understand the terms’ relationships, frequency of occurrence, and top clusters, a network analysis was built using the 250 terms that met the criterion. Google Trends study was also executed simultaneously to ascertain the pattern of occurrence of BT, Bitcoin, and Metaverse across various countries since 2015. The PRISMA Checklists can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

3 Methodologies Used in Blockchain-Based Supply Chain Management

As part of the research technique for the proposed survey, a systematic analysis and study were carried out to provide a full analysis of the adoption of BC in SCM. We started the study by analyzing review articles on BC-based supply chains from reputable conferences and databases such as Springer, ScienceDirect, ACM, Taylor & Francis, Wiley, IEEE Xplore, and Google Scholar [10]. After that, we looked at several BC-based system applications. This research aims to see how BC technology may be used to improve current supply chain networks. For this purpose, keyword searches were conducted using terms such as BC Technology, Supply Chain Management, BC Use in SCM, Provenance, and Supply Chain Traceability. Finally, we examined the abstracts and conclusions of the collected publications and determined the relevant techniques and ideas for the proposed survey.

The key objectives of this study include:

• Evaluating how Blockchain Technology (BT) enhances efficiency, security, and transparency in supply chain systems;

• Identifying the integration potential of BT with advanced technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the Internet of Things (IoT);

• Analyzing current trends, applications, and research gaps in BT-driven supply chain intelligence;

• Highlighting limitations in scalability, interoperability, and regulation, and suggesting future directions for fully automated and intelligent supply chains.

The main contributions of this work are:

• A detailed synthesis of BT’s role in addressing traditional SCM problems such as data silos, fraud, and lack of real-time visibility.

• A comprehensive review of smart contracts, DApps, and blockchain models that automate transactions and ensure immutable tracking.

• Integration analysis of BT with AI and IoT for intelligent supply chain automation.

• Insights into methodological approaches like probabilistic modeling, algebraic modeling, and metaheuristics for solving uncertainty in decentralized SCM systems.

In addition to identifying application areas, we analyzed the methodologies used in literature to address blockchain-enabled supply chain challenges. Several studies incorporate multi-objective optimization, probabilistic modeling, and metaheuristic algorithms to handle uncertainties, environmental sustainability, and cost-efficiency in decentralized networks. For instance, a multi-attribute closed-loop supply chain model using self-healing polymers was developed in [9], which applies a weighted goal programming technique along with three metaheuristic approaches to optimize profit and minimize carbon emissions under budget and storage constraints. This study also highlighted the impact of the single-setup-multi-delivery (SSMD) policy, which improved profitability and efficiency compared to the conventional single-setup-single-delivery (SSSD) policy.

Similarly, in [10], the authors presented a two-stage supply chain model that recycles food-waste into livestock feed, achieving zero-waste through circular economy integration. The model utilizes an algebraic optimization approach and SSMD shipment policy to manage demand, deterioration, and carbon footprint reduction, thus demonstrating effective cost and waste management. These studies demonstrate how optimization methods, including fuzzy logic, stochastic modeling, and algebraic decision models, are applied in blockchain-augmented supply chains to manage probabilistic behavior, system constraints, and multi-layered decisions. Such methodological insights are essential to enrich the current study’s scope beyond technological factors by offering a problem-solving lens aligned with real-world SCM challenges.

The goal for doing this research is to comprehend and assess BC technology, as well as to investigate its usefulness in tackling the issues of existing supply chain systems in a cost-effective manner. Several study problems prompted us to investigate the potentials of BC in secure SCM. These are as follows:

RQ1: What are the advantages of implementing BC-based supply chain systems?

RQ2: Recently, have there been any BC uses in the supply chain industry?

RQ3: What primary issues has BC adoption brought to supply chains?

RQ4: Is BC usage in SCM likely to grow in the future?

We studied standard reviewed journal databases, i.e., IEEE Xplore, Elsevier, ScienceDirect, Springer to find the current literary studies and the information available on the Internet. We also took advantage of other resources, i.e., technical books related to the case, concessions, envisioning websites, and online journals pertinent to the current survey.

4 Technology and Its Role in Enhancing Supply Chain Intelligence

The importance of electronic integration in the supply chain has been highlighted by [41]. Enterprises, workers, and customers all benefit when supply chain innovation is facilitated by new technologies. The advent of truly globalized trade has coincided with a surge of ground-breaking inventions aimed at making operations more resilient and long-lasting. The following technologies and tools are used to digitally connect the supply chain.

4.1 Traditional Supply Chain Management

The supply chain is the series of interconnected entities that begin with raw materials and continue through the production, distribution, sale, and consumption of a product. A company’s ability to control the flow of goods and services among its stakeholders is greatly enhanced by efficient SCM [42]. A hierarchically organized framework has long been the standard operating procedure in the field of supply chain management [43]. The orders placed by customers are the first step in this framework because they constitute the demand for products. Following the transformation of demand into manufacturing feeds, the production phase is initiated. After manufacturing is finished, the products are sent out to different stores for sale. The regional offices gather information, analyses it, and then share the results with the relevant parties; they are the nerve centers of the decision-making process [44,45]. The supply chain, however, is vulnerable to the model’s many flaws [46]. For example, it causes instability and insecurity because it isn’t transparent, auditable, and involves stakeholders. From a convenience standpoint, it’s clear that our present supply chain has become much more centralized. Fig. 4 shows the typical centralization found in traditional supply chain management systems [47]. Logistics, distribution, and procurement experts run the production out of a central office and warehouse in this setup. The day-to-day operations of their specific portions of the supply chain are supervised and operationalized by these managers. Data collection and administration are both made easier with the help of a single database. There are downsides to this strategy, despite the fact that it has been effective in some areas [48,49]. The possibility of covert distortion of firm data is one of the main issues frequently encountered with this arrangement. This is of utmost importance when the misrepresentation has the potential to impede the company’s attempts to expand. Because of this, companies may start to distrust one another, which in turn makes communication more difficult and expensive [50].

Figure 4: Understanding the transit of goods and services within the supply chain

In traditional supply chain management, the overall cost of operations is influenced by procurement, production, transportation, and inventory decisions across multiple echelons of the chain [51]. A general cost model for a basic three-stage supply chain can be defined as:

where:

•

•

•

•

These components capture the integrated cost elements in a traditional supply chain. While this model simplifies real-world complexities, it serves as a more representative framework for analyzing cost flows across the supply chain than standalone EOQ-based inventory models.

In addition, the existence of intermediaries within the supply chain might be a barrier to the creation of transparent and efficient pricing for products and services [52]. The different parts of the supply line often can’t share the same data. As a result, there may be delays and other problems when trying to monitor and control the flow of products [53,54]. The possibility of data manipulation occurring within the supply chain is of utmost importance. It has the potential to cause major problems with the product tracking process, which in turn can reduce the company’s efficiency and bottom line. On the other hand, it also results in a great deal of difficulties that certainly cannot be ignored. The high expenses of running a centralized supply chain are a major cause for worry, since they have the potential to affect product prices in the market [55]. Finding insights that can optimize the supply chain network can be challenging with such a system’s absence of useful market analysis tools. Lack of visibility and auditability in the present supply chain architecture is another major problem that need addressing. Coordination, stock control, dependency on personnel, order supervision, stock administration, end-of-life control, and other issues plague the current supply chain system [56,57]. Demand assessment and storage capacity optimization become more difficult in the face of these challenges, which can have far-reaching effects on stakeholders and consumers [58]. Product fraud, delays, and counterfeiting are problems that can affect the traditional supply chain management approach and have far-reaching effects. Therefore, it is of the utmost importance to address these difficulties and establish a supply chain network that is more efficient and effective, offering benefits to all of the parties involved [59]. Consequently, there is a rising demand for more advanced SCM systems that can tackle these issues and promote supply chain accountability and transparency. To guarantee a fair, transparent, and safe supply chain, firms should take a more holistic approach to SCM, involving all stakeholders at every level [60].

A network of interconnected devices that automatically collects and transmits data is known as the IoT. Supply chain management has been deeply affected by the rise of the IoT [61,62]. We have gone a long way in comprehending the location, method of storage, and anticipated arrival time of various things at various locations. This means that the IoT could make use of technologies like Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) to equip inanimate objects with senses and the capacity to react to their environment [63]. Given that technology has the ability to be applied across the whole supply chain, the Internet of Things is clearly appealing. As a result, businesses are able to boost their productivity, reduce their downtime, improve their ability to anticipate the needs and desires of their customers, and boost their return on investment [64]. In loT enabled supply chains (See Fig. 5), the efficiency of sensor network is measured using latency

Figure 5: Generic illustration of the IoT-empowered logistics and supply chain management

The energy consumption

4.3 Integration of Blockchain with AI and IoT

AI and Machine Learning (ML) technologies can assist organisations in predicting changes in client demand. Artificial intelligence has the ability to mitigate the effects of misconduct and pandemics on supply chains. The capacity of digital technology to enable real-time data interchange among the many links in the supply chain might be advantageous to the entire system [66]. Fig. 6 illustrate the AI powered forecasting solutions can help SCM save time and money. To guarantee supply chains can endure interruptions, data is needed by Industry 5.0’s AI and ML algorithms [67,68]. The IoT plays a pivotal role in bolstering supply chain resilience by facilitating data interchange, which improves visibility and cooperation in the face of challenges. Improved intelligence, interactive data visualisation, and real-time reporting are all benefits of integrating these centralised technology into business platforms [69]. Forecasting analytics and ML-based techniques provide various improvements to scheduling and decision-making tools, as well as the detection of purchasing trends and the automation of tedious warehouse duties [70]. In Artificial Intelligence (Al)-powtrod supply chains, demand forecasting accuracy

Figure 6: Benefits resulted from the integration of deep learning and blockchain technology

Al based optimization of supply chain efficiency

The integration of blockchain with Al and IoT technologies introduces a layered computational model to enable predictive intelligence, autonomous operations, and real-time traceability [72,73]. IoT sensors embedded in supply chain endpoints continuously generate time-series data

The LSTM equations are defined as follows [74]:

These models are deployed on-chain (using platforms like Chainlink oracles) or off-chain (via federated nodes) to predict disruptions, delays, and fraudulent behavior. For instance, anomaly detection in blockchain-based cold chains can use an LSTM-Autoencoder trained on sensor sequences

4.4 Blockchain-Driven Supply Chain Models

Blockchain-driven supply chain models leverage decentralization, immutability, and transparency to improve coordination, tracking, and accountability across stakeholders. These models often include mechanisms for managing inventory, verifying authenticity, automating payments, and securing sensitive logistics data through smart contracts. Sectors such as pharmaceuticals, agriculture, food distribution, and healthcare have adopted such blockchain solutions. One specific application of blockchain in healthcare is in blood supply chain management, where traceability, data integrity, and access control are critical. The following model presents how blockchain can be used to ensure secure and efficient blood donation and distribution.

Blockchain-Enabled Blood Supply Chain Management

Blockchain technology is proposed by [77] as a means of improving blood donation management systems in order to guarantee both efficiency and safety. The system takes care of important details including collecting, delivering, requesting, and transferring blood units. Traceability, immutability, transparency, secrecy, auditability, and safety are often missing from conventional blood donation systems. To overcome these limitations, the proposed approach employs a secure and private Ethereum blockchain with two key smart contracts—production and consumption—accessible through DApps and APIs such as Infura and JSON Remote Procedure Call (RPC) [78]. In Blockchain for Blood Donation, the donor verification process is modeled using trust scone

The security of blockchain transactions in blood donation depends on the transaction verification probability

The smart contract system incorporates various components to maintain secure and authorized access [79]. An Ethereum address, restricted to blood bank technicians and phlebotomists, ensures that only authorized personnel can handle and transport blood units [80]. Additionally, a transporter mapping system is embedded to prevent unauthorized access and facilitate safe and efficient transportation. A critical element of the smart contract is the Blood Unit Status (BUS) variable, which tracks the different stages of a blood unit:

• Not Ready (NR)—Blood unit not yet prepared

• Ready for Delivery (RD)—Blood unit ready for transport

• Start Delivery (SD)—Delivery process initiated

• End Delivery (ED)—Delivery completed

• Blood Unit Received (BUR)—Blood unit successfully delivered

The Blood Component Type (BCT) variable, represented as an 8-bit unsigned integer, classifies blood components as follows [81,82]:

• 0—Red Blood Cells (RBC)

• 1—Plasma

• 2—Platelets

This classification ensures that the correct blood type is delivered to the appropriate recipient. The tracking process begins once a phlebotomist draws a blood unit and marks it as RD [83]. An authorized transporter then retrieves it and initiates the delivery process. Upon arrival at the blood bank, a technician verifies the blood unit, records its component type, quantity, and expiration date, and updates the blockchain. Hospitals and blood banks manage these transactions through smart contract consumption, which maps transporters, physicians, and nurses via Ethereum addresses [84]. Only authorized transporters can deliver blood units to hospitals, ensuring secure and controlled distribution. The study provides a detailed security analysis, entity-relationship diagrams, and sequence diagrams to validate the system’s effectiveness [85]. The integration of blockchain technology ensures a transparent, immutable, and efficient blood donation management system.

Clouds are environments that are centralised for the storing and processing of a wide variety of data and information [86]. Data storage and processing through an external network of computers, rather than a local network, is known as Cloud Computing (CC). Several aspects of the supply chain might be affected by CC. These systems gather data from sensors, analyse it, and then display it to customers in a comprehensible online representation using CC as a desirable supply chain application. A number of benefits arise from integrating cloud computing into the supply chain. According to [87], the most significant benefit of CC is most likely its intelligence and automation components. CC analytics has the potential to radically alter the logistics system. By utilising cloud platforms, supply chain opportunities can be better understood. In CC enabled supply chains, the total processing time

Cloud based cost efficiency

4.6 Big Data and Modeling-Based Analysis of Industry Implementations

Big data describes an abundance of datasets that are too big to be handled by traditional methods. The millions of data sources that are available today are having a dizzying effect on the rate at which data is being produced. These centres of knowledge are located all across the world [88,89]. There are four main types of BDA: descriptive, diagnostic, predictive, and prescriptive functions. BDA is now a vital tool for companies across all industries and sizes. Businesses can gain insight into their customers and internal processes with the use of big data and a centralised data architecture.

Blockchain technology is an emerging field. As a result, further remarkable and perhaps revolutionary applications of this state-of-the-art instrument are expected to emerge in the future [90]. BDA may be utilised in a variety of contexts, including but not limited to risk management, the development of new products, enhanced internal decision-making, and the satisfaction of customers (See Fig. 7) [91]. In BDA, the accuracy of decision making

Figure 7: Incessant data processing method

The efficiency of real time analytics

To illustrate practical deployment, computational models of real-world systems are analyzed, particularly focusing on performance, reliability, and security [93]. For example, IBM Food Trust employs Hyperledger Fabric, which can be simulated using discrete event simulation (DES) to model asset tracking under different network loads. Smart contract execution time

where

Al-enhanced systems, such as SAP’s blockchain-enabled demand prediction tool, employ time-series forecasting models like Prophet or BiGRU trained on past blockchain-verified order data. Industrial deployments can also be evaluated using any logic-based simulations or tensor flow-based model serving [97]. Challenges such as network congestion, computational resource limitations, and interoperability can be modeled using queuing theory and graph-based representations [98].

4.7 Robotics Process Automation (RPA)

Robots assist humans in the supply chain to complete tasks more quickly and accurately, reducing the likelihood of human error. Robots are more efficient and dependable than humans [99]. Instead of replacing humans, robots augment human labour to increase productivity. Businesses can benefit from RPA in many ways. It can automate payroll, generate and distribute invoices, verify personnel histories, and extract data from media like Portable Document Formats (PDFs) and images of documents. In Robotic Process Automation (RPA), task efficiency

The reduction in human efforts

Profit maximisation is the ultimate aim of any business, and RPA shines during the Quote to Cash (Q2C) phase by improving and streamlining sales procedures. There is a possibility that robotic process automation (RPA) will not function as stated or produce the same results for every company. Furthermore, not all businesses have the personnel on staff with the right mix of expertise to make good use of RPA. Inadequate understanding of the project’s timetable, budget, resource requirements, and other constraints will cause RPA to fail.

5 Blockchain Frameworks, Smart Contracts, and Applications in Supply Chain Management

The most general blockchain classification is based on the requirements imposed on users to be able to transact on them [101]. In a permissioned or private blockchain network, access to the network and participation in the validation and verification of transactions are restricted to a specific group of authorized participants. These participants are typically identified and verified through some form of identity verification process. Permissioned blockchain networks are typically used in enterprise or government applications where privacy, security and compliance are critical operational requirements. In contrast, a permissionless or public blockchain network is open to anyone who wishes to participate in it, with no restrictions or identity verification requirements [102]. These networks are generally considered more decentralized and offer greater transparency, but may also be more susceptible to attacks or other malicious activity due to their open nature. Cryptocurrency blockchains are the straightforward example of permissionless networks, while, as indicated, enterprise blockchains would perhaps be the best example of permissioned networks [103]. The most relevant characteristics of these chains are discussed below.

5.1 Blockchain Frameworks in SCM

5.1.1 Permissionless Blockchains: Cryptocurrency

Digital currencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum rely on distributed ledger technology as a blockchain to record and monitor transactions. It is built to be safe, transparent, and unchangeable; it allows for peer-to-peer transactions without the involvement of intermediaries like banks or financial institutions. As a technology with the ability to disrupt established financial systems and change the way people buy and sell goods and services, cryptocurrencies gained immense popularity among both investors and the broader population. Each transaction in a cryptocurrency blockchain is added to the ledger in chronological order as a block [104]. The immutability, security, and tamper-proof ledger is created by linking each block to the preceding one using a unique cryptographic hash, as is the case with any blockchain [105]. Consensus mechanisms are rules and protocols that all participants in a network follow to guarantee that all transactions are legitimate and added to the blockchain in the correct sequence. This ensures the security and integrity of a cryptocurrency blockchain. All network peers may see the specifics of a transaction on a permissionless cryptocurrency blockchain because of the blockchain’s design, which makes it both transparent and auditable [106]. Cryptocurrency blockchains are scalable in that they can process a high number of transactions per second; however, scalability problems may arise if the network uses energy-intensive consensus processes like proof-of-work [107–109].

5.1.2 Permissioned Blockchains: Enterprise Chains

In contrast, enterprise blockchains are designed to facilitate the secure and transparent exchange of data and collaboration among different stakeholders of a business network, such as suppliers, customers, employees and partners [110]. Permissioned blockchains require authorization froma central entity or a consortium in order to operate, and are designed to support specific business applications. Unlike public blockchains used for cryptocurrencies, enterprise blockchains are typically designed for use by a specific group of participants and are not open to the public [111]. Enterprise blockchains offer several advantages to businesses, such as increased transparency, security and efficiency [112]. By using a shared and distributed database, participants can access and verify data in real time, which reduces the risk of errors, fraud and disputes. In addition, enterprise blockchains help streamline business activities and reduce costs by eliminating intermediaries, automating the flow of information and optimizing processes [113]. In permissioned blockchains, trust and reputation play a crucial role in validating transactions.

Common use cases for enterprise blockchains include supply chain management, digital identity verification, trade finance and payments [114,115]. For example, Fig. 8 represents a blockchained supply chain could enable manufacturers, distributors and retailers to track themovement of goods fromproduction to customer delivery, ensuring transparency and reducing the risk of product counterfeiting [116]. Similarly, a digital identity blockchain could enable secure and efficient identity verification for individuals and businesses, reducing the risk of fraud and identity theft [117]. Ultimately, enterprise blockchains offer companies a way to leverage the benefits of decentralized database technology, while addressing the challenges and requirements of specific use cases [118]. Enterprise blockchains can offer greater privacy and confidentiality, using techniques such as data encryption or selective information sharing. They also tend to scale better, as they can be designed with a specific application in mind. Besides, they do not need to support the same volume of transactions as a cryptocurrency blockchain [119]. In general, while both permissioned and permissionless blockchains use decentralized ledger technology, they have different design considerations and serve different purposes [120]. Permissionless blockchains, such as cryptocurrency blockchains, prioritize decentralization, transparency and security for peer-to-peer transactions, while permissioned blockchains prioritize scalability, privacy and interoperability for the secure and efficient exchange of data within a network composed of peers that, in turn, are explicitly given permission to operate on the network [121].

Figure 8: The architecture of a data chain in a blockchain network

5.2 Smart Contracts and Decentralized Applications (dApps) in SCM

5.2.1 Smart Contracts in Supply Chain

Goods monitoring and tracing was the primary focus of our initial scenario analysis of the corporate supply chain. Product tracing begins in the factory with the recording of data pertaining to the products and raw materials and continues until the products reach their final destination, the retail store, and ultimately the consumers [122]. In this light, we set out to create a system that would both help and update manufacturing companies by allowing them to track their products all the way through the supply chain and give consumers the ability to see what goes into their purchases and get a better sense of trust in the industry as a whole [123]. The VIOZOIS industry will be the site of application and validation of the technology we are creating. This sector manufactures and retails animal feed. The thirteen workstations and five use case scenarios that make up the Dog-Cat Feed production line are the real deal in this business scenario. Ultimately, they want to be able to track and identify their finished goods by using BC technology [124]. Here is the setup for the business case: Producers can now record details about the raw materials that come into the factory, including the type of raw material, production technique, metadata, and producer details, in a data log file that has been generated on the ledger. The BC program assigns a unique identifier (UID) to each raw material when this data is entered into the ledger trepresented in Figs. 9 and 10. During this process, any extra information is likewise recorded on the ledger in the same record that is identifiable by the UID number. The user of the factory app can then utilise the BC to choose which of the raw ingredients that were previously recorded on the ledger are utilised for feed preparation while the process is underway [125]. The user can narrow down the available raw materials to those that are relevant to their product by using a catalogue that is returned. Additionally, a record is created on the ledger where the product UID number is automatically allocated to the finished product [126]. Data about the components’ raw ingredients is also included in this record. Hence, the end result is a product with a special code that links to information on the raw materials (such as the loT of raw materials used, the amount of these materials, etc.) [127]. The DApp adds more information to the blockchain for each product as it is put into the truck to be transported to the points of sale (stores), such as the loading time and the truck’s identify. In addition, once the driver has acquired the finished goods and transported them to their designated location (the store), he notes this fact on the BC.

Figure 9: Raw materials and product logging

Figure 10: Product traceability

Along with any shipment metadata, the ledger also records a transaction that includes the truck’s and driver’s identification numbers [128]. The moment a product arrives at a retail store, the clerk updates the BC with the details of when the package was received, the product’s status, and any other pertinent information. It is the responsibility of the retailer to add on the BC that the product has been sold and includes information such as the time of sale, product status, and other relevant details. The buyer can verify the product’s details recorded on the ledger, such as the date of production, the expiration date, the provenance of the raw materials, and more, by scanning the unique code of the package with her mobile phone DApp. In exceptional circumstances, such as when the product’s components are determined to be harmful and the buyer is asked to return it, further information can be supplied to the client if she agrees to provide her personal details [129]. A digital application (DApp) enables all participants in the supply chain, including end users, to manage a plethora of product-related metadata, as we outlined at the user level. Manufacturing date, expiration date, lot number, and other details could be part of the product metadata. In this case, the desired outcomes centre on three main areas: a) helping supply chain stakeholders optimise product traceability; b) allowing consumers to identify finished items; and c) empowering stakeholders in terms of product availability and delivery schedules. The following graphics illustrate (See Fig. 11) the three main components of the aforementioned business scenario. According to the literature, supply chains encounter issues with trust, fraud, and falsification; this method employs BC to circumvent these issues and eliminate single points of failure [130]. For example, reference [131] highlights how asymmetric information in a green supply chain governed by cap-and-trade and carbon tax policies can affect coordination and profitability, with specific emphasis on deriving optimal service levels and RFID configurations through mathematical modeling. While it provides valuable insights into strategic and regulatory optimization, our research complements this by analyzing blockchain technology as a more holistic and decentralized infrastructure for enhancing information visibility, transparency, and trust across the supply chain.

Figure 11: Product verification

5.2.2 Smart Contracts and Decentralized Applications (dApps) in Supply Chain Management

Smart contracts are defined as self-executing digital contracts in which the terms of the agreemen between the parties are expressed directly in lines of software code. In other words, a smart contract (See Fig. 12) is an automatically triggerable piece of software that enforces the rules and terms of an agreement between two or more parties.

Figure 12: Supply chain used to demonstrate the dApp’s workflow

In the blockchain world, it manifests as a piece of code that, when loaded into a node in the network, can be set to execute certain operations or initiate certain transactions in response to certain criteria. Financial transactions, supply chain management, digital asset generation and transfer, and voting systems are just a few of the many possible uses for smart contracts Transparent and secure, they can lessen transaction costs, boost efficiency, and foster confidence among all parties participating in a blockchain. In a dApp, the application’s server logic is implemented as a smart contract or a set of smart contracts deployed on a blockchain network. Users interact with the dApp through a user interface, typically a web application or mobile app [132]. DApps represent a new paradigm for building and deploying decentralized applications, which exploits the advantages of blockchain networks for greater security, transparency and reliability, compared to traditional centralized applications or even distributed [133]. DApps are typically open source, meaning that the code is publicly available for anyone to view, use and modify. In addition, DApps are not controlled by any central authority, which makes them resistant to censorship and manipulation. According to their nature, the requirements of dApps are materialized through smart contracts, which are visible and transparent. DApps are protected by the underlying blockchain technology, which uses cryptography to protect data integrity and prevent unauthorized access.

5.3 Domain-Specific Applications of Blockchain in SCM

Now, BC technology is employed in nearly every industry that involves supply chains. This paper discusses two of the most prominent applications of BC in the supply chain, such as the Food supply chain and the Pharmaceutical supply chain [134].

5.3.1 Pharmaceutical Supply Chain

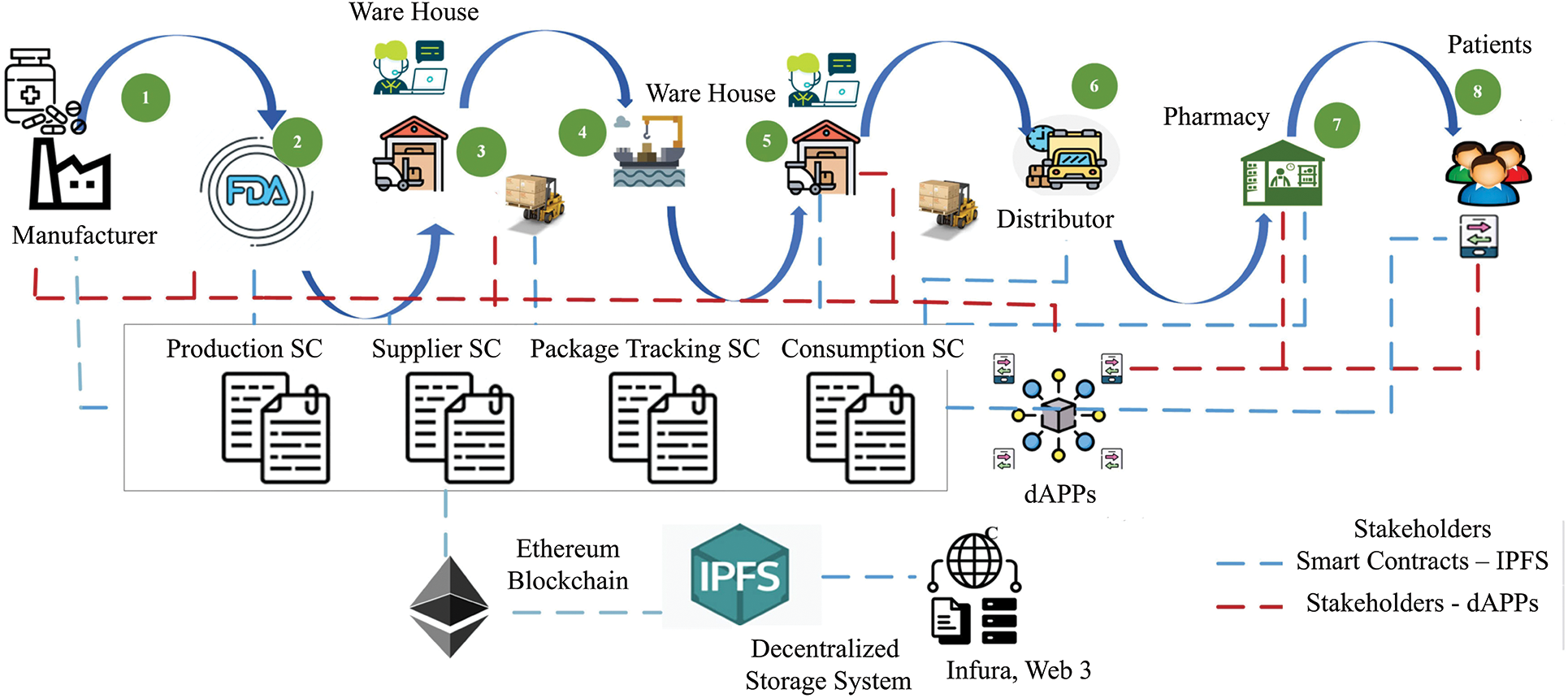

Medicines prescribed by doctors are distributed to patients through a system called the pharmaceutical supply chain as illustrated in Fig. 13. To make a medicine, the materials are usually gathered from several places before the final recipe is made. Distribution of the drug can commence upon the determination of the final formula. Along its journey through the supply chain, the medicine will pass through a number of hands, including those of the producer and the consumer [135]. The supply chain and manufacturing industry are vulnerable to the introduction of fake or altered goods with each transaction. Due to the intricate nature of the pharmaceutical sector, it is challenging to ensure that counterfeit drugs do not enter the distribution supply chain. Consequently, there is a high need for monitoring the production and distribution of fake, low-quality, counterfeit, or grey market medications while developing technology-based solutions for the pharmaceutical supply chain [136]. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), counterfeit pharmaceutical goods account for around 3.3% of the total in the global pharmaceutical medication trade. Experts agree that the sale of fake pharmaceuticals is a major cause for alarm. A distributed, shared data platform for an immutable, accountable, and transparent system might be built using BC-enabled medicine tracing in the pharmaceutical supply chain [137]. BC’s transparency, immutability, and auditability make it a promising tool for enhancing the pharmaceutical supply chain’s operational efficiency. Additionally, it can aid in inventory control and the reduction of supply chain theft and counterfeiting. The Modum.io system for pharmaceutical supply chain traceability, developed by [138], integrates the benefits of both the IoT and BC. The system’s architecture is built around IoT sensor devices, a back-end, and a user interface. The Ethereum blockchain and the server nodes that oversee it and execute smart contracts make up the backend. Private information can also be saved on this server. Connected to the server in the backend, the frontend consists of Android-powered mobile devices created Gcoin, a conceptual framework for tracking the shipment and distribution of medications that is enabled by BC in the pharmaceutical supply chain.

Figure 13: The use of blockchain technology in the pharmaceutical supply chain process

In order to optimise and enhance vaccine coverage in faraway places while keeping everything transparent, suggested using Internet of everything devices to monitor the location, temperature, and humidity of the carrier. Concerned about vaccine record fraud and expiration dates, created “vaccine BC” technology that leverages BC technology’s traceability and smart contracts. A comprehensive life cycle supply chain management (SCM) method for medical equipment is evaluated and developed by [139] with the use of BC technology. This approach encompasses the full process of production, supply, tendering, procurement, storage, application, export, usage, destruction, and traceability. The delivery of medicines amongst public health centres in Indonesia was predicted by [140] to be facilitated by a BC-enabled Medicine SCM system (MSCM). If the proposed solution is viable, it may be tested using the JMeter tool to see how the system performs in terms of latency, resource consumption, and transactions per second (TPS). A BC-enabled management system was developed by [141] to detect fake goods in the supply chain. The pharmaceutical supply chain and decentralised off-chain storage were developed by [142] as part of an Ethereum-based BC system for decentralised drug monitoring and tracing. It was said by [57], in terms of security, privacy, accessibility, and transparency, two possible BC-based decentralised architectures are Hyperledger Fabric and Hyperledger Besu.

5.3.2 Blood Donation Supply Chain Process

Blockchain technology has been suggested by the authors of [39] for the implementation of blood donation administration systems, as illustrated in Fig. 13. Efficiency and security were the two main metrics used to assess their method. Their proposed system integrates multiple components of blood donation systems, such as the collection, delivery, request, and transfer of blood units. Problems with traceability, immutability, transparency, secrecy, auditing, and safety are common in the present blood donation management systems. An approach to managing blood donations over a secure and private Ethereum blockchain is laid out in this paper. This page provides a detailed explanation of the structure, management strategies, entity-relationship diagrams, and sequence diagrams. In order to talk about how useful and successful the method is, we also do a comprehensive security examination. Fig. 14 depicts the entire architecture of the proposed system, which includes two smart contracts for production and consumption.

Figure 14: The process of blood donation supply chain using blockchain

These smart contracts can be accessed by authorised parties through DApps and APIs. Infura, JSON Remote Procedure Call (RPC), and Web3 are just a few of the APIs that provide access to smart contract functionality. An ethereum address that is available solely to the blood bank technician and phlebotomist is one of many factors in the intricate mechanism that is the asmart contract. Only authorised users will be able to access the system and transfer blood units from donation locations to blood banks using this address. One built-in element that makes sure that only authorised workers can transfer the blood units is the transporter mapping system. The blood units will be transported securely and effectively by means of this technology, which is also intended to deter unauthorised entry. Blood Unit Status (BUS) is an essential smart contract variable. Statuses such as Not Ready, Ready for Delivery, Start Delivery, End Delivery, and Blood Unit Received are tracked by this variable, which pertains to the collected blood unit. The efficient tracking and delivery of blood units to their intended recipients relies heavily on the “BUS” variable. Another important part of a smart contract is the enumeration variable BCT, which stands for Blood Component Type. An unsigned 8-bit integer containing the values “0” for “Red Blood Cells” (RBC), “1” for “plasma,” and “2” for “platelets” is supplied as the required variable. Making sure the correct blood type is given to the right people relies on this variable. It is also important to make sure the blood units are handled properly when they are being transported. To summarise, the smart contract is an extremely complex mechanism that was developed with the intention of ensuring that the blood units are carried in a manner that is both secure and effective. The smooth tracking and delivery of blood units is made possible by the several parts of the contract. In order to maintain track of the blood units that have been obtained, phlebotomists use smart contracts. Their Ethereum addresses, donor IDs, and those of blood bank staff are all part of the contract. The process of tracking blood units begins after they are activated. Reliable couriers will be entrusted with responsibilities pertaining to authorisation in the future. The process of monitoring a blood unit consists of five main steps. At the beginning, the phlebotomist will draw the whole blood unit and indicate that it’s RD. Initiation of the delivery process requires the designated transporter to retrieve the unit from the phlebotomist. The blood bank tech will make an announcement stating the BCT, quantity, and expiration date once the entire unit has been received. The consumption smart contract incorporates a wide range of types of variables, and the ethereum address covers hospital and blood bank administration. The consumption of smart contracts completes the mapping of transporters, doctors, and nurses.

Transporters must be authorised by the blood bank in order to deliver blood unit orders to the hospital. In this case, the consumption smart contract—which includes details like the initial state of the blood component unit, the starting time for deployment, and the hospital administration’s ethereum address—is owned by the blood bank administration. Once the smart contract is activated, the tracking of consumption begins. Reliable transporters are assigned by the blood bank management, and trustworthy doctors and nurses are assigned by the hospital administration. To guarantee the safety and efficacy of the process, there are six essential steps in the ingestion of blood components. To begin, a physician’s signature is required on a blood component request form that specifies the patient’s blood type, the quantity required, and the date of the request. Requests for red blood cell, plasma, or platelet units are acceptable. A designated carrier will collect the blood component unit and start the delivery process once the request is approved by the blood bank administration. The hospital is considered to have received the order, thereby ending the delivery process. A prescription for the blood unit, comprising the patient’s identification number, the kind of blood component unit, and the amount required, will then be written by the designated physician. The consummation surgery will be officially declared complete once the authorised nurse has transfused the blood component units. The safe and efficient delivery of blood components to those in need is guaranteed by these steps. A comprehensive analysis was conducted to guarantee that the authors’ proposed blood donation management system is resilient against any security threats and attacks. The efficacy of the strategy was also assessed by comparing it to other well-established approaches. The Ethereum network will manage the development and testing of the DApp.

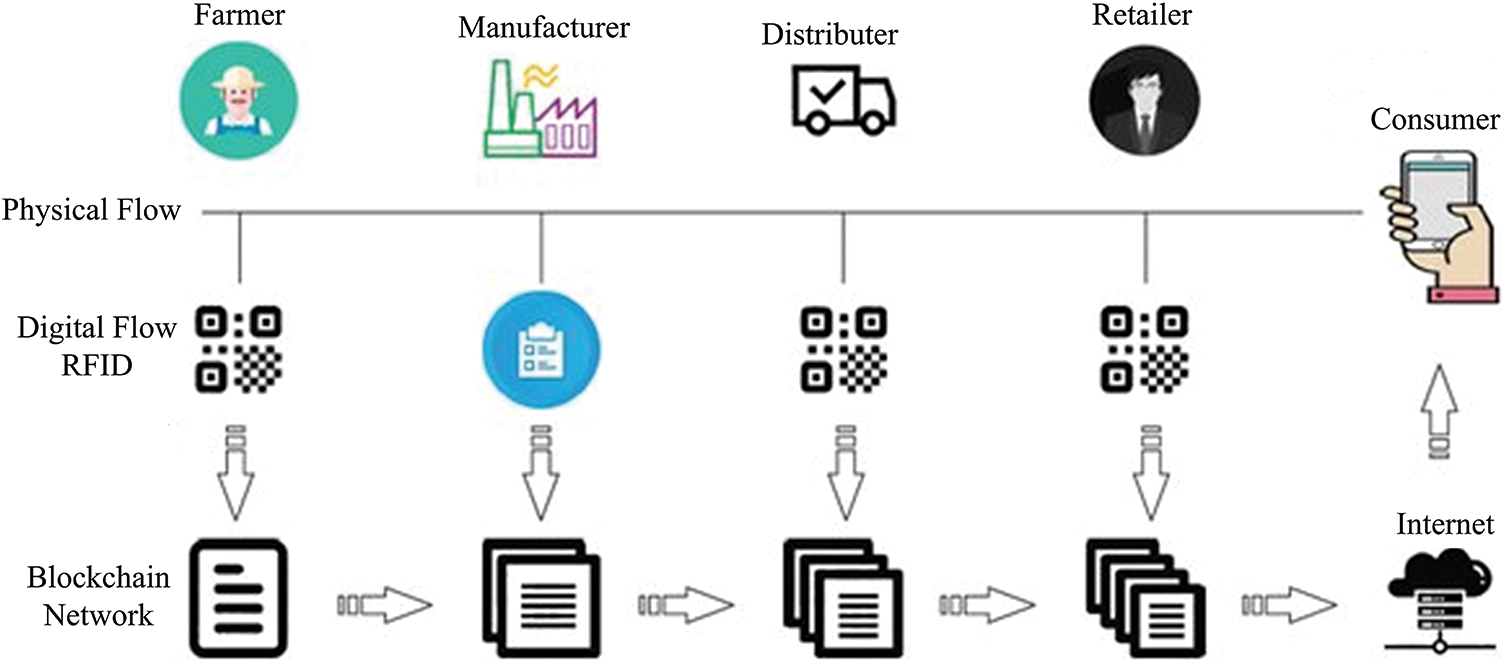

5.3.3 Supply Chain Management in Agriculture

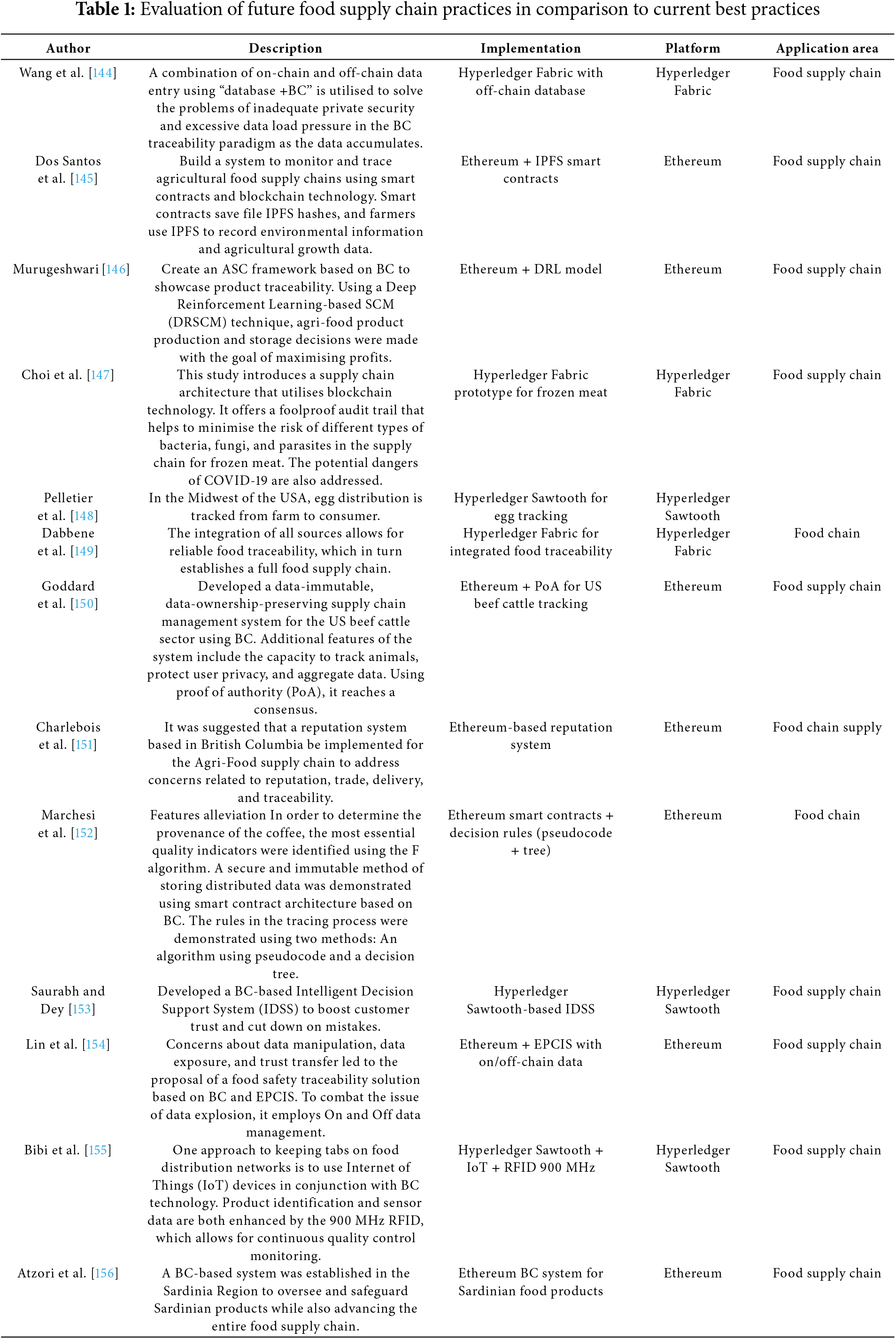

Despite the complexity of managing system architecture in the soybean supply chain, a beneficial approach is offered in an article [16]. Blockchain technology, distribution centres, bean classifiers, transporters, warehouses, retailers, and consumers are all integral parts of this system. Fig. 15 shows how the EVM runs a smart contract on the blockchain; to take part, everyone needs their own unique Ethereum address. To encrypt and validate transaction data and associate it with a particular account, private and public keys associated with an Ethereum address are essential. All parties involved in growing and harvesting the beans have their responsibilities, affiliations, and interactions detailed in the smart contract. Table 1 represents food supply chain practice to current best practice [143].

Figure 15: Utilizing blockchain for the agricultural supply chain process

Businesses, bean farmers, sorters, couriers, warehouse employees, sellers, and consumers are all part of this chain. Smart contracts facilitate the sale of seeds by seed firms to farmers. Thanks to the smart contract, the enrolment process for the farmer can only begin after the money is received in full. The contract will go to the “initiatedseedreq” state if the transaction goes through successfully. After that, the seed firm gets the green light, and the farmer patiently awaits additional instructions. The farmer notifies the business of their development and chooses a harvest date after sowing the seeds. After that, the contract will reflect the new status as “Crop Ready for Harvesting” (CRFH). The last step is to assign a distinct Ethereum address to each intermediary so that they can negotiate a fair price for the harvested goods. Once all parties involved have reached an agreement on a price, the intermediaries will update the smart contract with the new details, including the amount, date, and time of the crop purchase.

The subsequent stage of the process is then reached by the bean classification firm, which updates the information that the intermediaries had acquired. The workers at the bean classifier refine the beans, update the status to “Refining Completed” (RC), check for moisture (M), remove any “Extraneous Material” (EM), and begin labelling. Before being recorded and updated in the smart contract as “Quality Good” (QG) or “Quality Bad” (QB), the bean classification operator rates the beans’ quality and assigns them a rating between 1 and 2. The next stage is to assign distinct Ethereum addresses to vendors, like merchants. The customer’s “Trade Request” (TQ) and integers for “beanid” and “saleid” should be received. The status should be updated to “paid” once the customer makes the payment. It will return an error message if it does not. At long last, the shop must change the contract’s status to “sold” and include the time, date, and money. The authors laid forth a comprehensive strategy and methodology for tracking the origins of soybeans. To efficiently and accurately monitor and record company transactions, the approach makes use of smart contracts and the powerful features of Ethereum’s blockchain technology. To guarantee the openness and security of soybean supply chains, their novel approach seeks to construct a reliable and efficient system.

5.3.4 Inventory Supply Chain Process

In a groundbreaking development, a prestigious team of researchers [157] has unveiled a method that utilises the power of Ethereum smart contracts to revolutionise inventory sharing. Using decentralised data storage—the wave of the future—this novel approach is devoted to improving the trustworthiness, transparency, and dependability of supply chain transactions. The team has painstakingly created a safe framework for exchanging information that incorporates sophisticated algorithms to record all discussions in order to build credibility and confidence with all parties involved. The meticulous creation and verification of the smart contract using the REMIX IDE left no space for error, guaranteeing accuracy and efficacy. This method is set to shake up the supply chain industry thanks to its groundbreaking character, which has attracted a lot of attention.

As shown in Fig. 16, suppliers are crucial in the supply chain because they enable the effective delivery of goods to end consumers. In order to achieve this goal, suppliers need to research the market extensively to find out what items are popular. The process of calculating the amount of products required to fulfil client demand must also adhere to all applicable rules and regulations. Suppliers, on the other hand, need to be ready to deal with supply chain interruptions that nobody saw coming, including raw material delivery delays due to natural catastrophes or production backlogs caused by pandemics. Shops, on the other hand, must stock their shelves with products sourced from a wide variety of manufacturers, wholesalers, and suppliers. For this reason, it is crucial for retailers to have a firm grasp on inventory management and solid supplier connections in order to keep products in stock and satisfy customer demand. As the last stop in the supply chain, retailers bring products from producers all the way to customers’ doorsteps in a timely and effective manner.

Figure 16: Incorporating blockchain technology into the stocking process of the supply chain

Some have proposed the use of four separate intelligent contracts, each with a defined purpose, to simplify operations. While the stock level agreement details the products offered by each supplier and their current stock levels, the registration contract is meant to register all network members. Companies are evaluated in the supplier reputation agreement according to a number of criteria, such as the honesty, efficiency of delivery, and quality of products offered. The procedure for receiving and processing orders is detailed in the order management agreement. One way to make it easier for everyone on the network to access the same files is to use a peer-to-peer (P2P) distributed file system like Filecoin or IPFS. The time-stamped and cryptographically protected IPFS hashes are maintained by blockchain transactions, allowing authorised network users to store massive volumes of data on IPFS. The following steps will describe how supplier stock can build up. Counting the product, determining its pricing, and determining the quantity required are the initial values to be set. Since the design was an original modifying item, the owner’s choices will be taken into account. As a third stage, suppliers will be invited to join the smart contract. In the fourth stage, suppliers will execute a smart contract for storage. Step five of the storage contract process allows suppliers to provide product details. Using the product number as an input, construct the request function. Then, in step six, increase the quantity of a product and increment the product count. A new item will be added to the stock and its price will be established in step seven. Reconfirm the product’s price with the required function in step eight, and then confidently change the price.

Purchase by stores is the next step. First, make sure all the required details are in place, including the stock address, product number, and quantity required. The next step is to make a retailer-specific object modification. In the third phase, the merchant uses the smart contract for order management to submit a purchase order. Reverse the transaction in step four using the demand function if necessary. In the fifth step, you’ll need to access the stock smart contract to get the product quantity information. Deduct the amount from the supplier’s stock in step six if needed. Lastly, to emit the procurement without any complications, use the events function in step seven. Making adjustments to the supplier reliability ratings is the last stage. Step one is to input the Ethereum supply address. The next step is to verify that the supplier’s Ethereum address has been added to the trusted suppliers list by the smart contract. In the third step, you’ll need to let the store know if something is true or incorrect so they may move forward with the sale or cancel it. In order to boost their reputation, step four requires the provider to offer a real service. Lastly, in step five, the provider’s reputation will take a hit if they don’t provide genuine service. The suggested approach is remarkably effective in handling many circumstances and system properties, according to extensive experiments. The success of supply chain operations depends on the effective coordination and integration of all key partners. Achieving peak efficiency is all about setting up a smooth data exchange between the two parties, which will greatly increase production and efficiency in the long run.

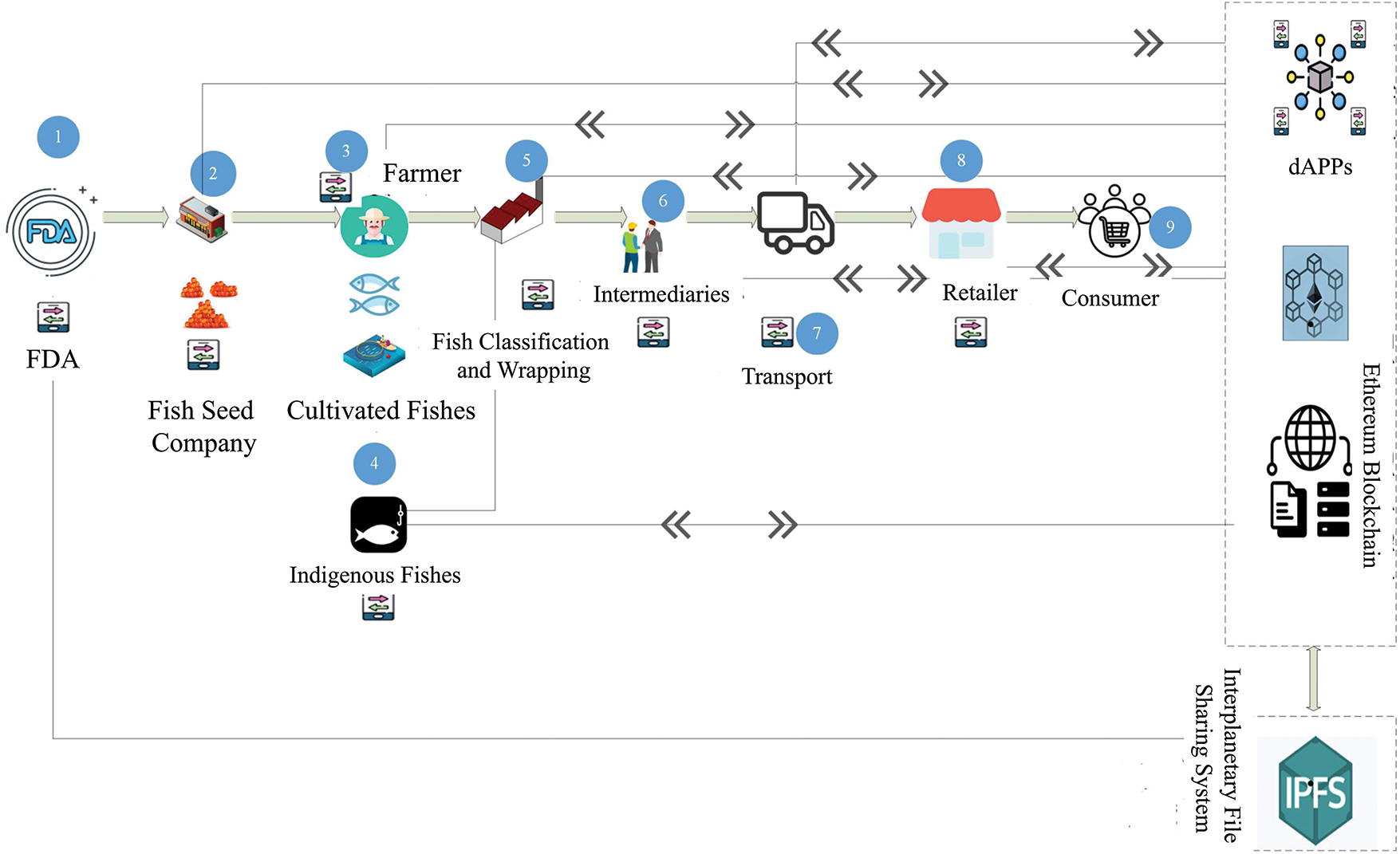

5.3.5 Fishery Supply Chain Process

In order to guarantee efficient supply chain management in the fishing sector, the concept stated in the study paper is of the utmost importance. This idea must be put into action without delay. The authors propose an Ethereum-based blockchain system to build a decentralised, accessible, secure, private, and dependable network with the goal of streamlining the aquaculture supply chain [158]. To do this, the suggested solution makes use of five smart contracts. The production and harvesting methods differentiate the farmed and indigenous categories in the fishing industry’s supply chain. In the seafood business, “indigenous” means taking fish straight from their water of origin, whether that’s the ocean or a river. Food safety and the prevention of fraud in the seafood supply chain can only be achieved through the establishment of traceability standards. Nevertheless, the accomplishment of this purpose continues to be a difficulty-filled endeavour.

Therefore, when buying seafood, the majority of people do not know what species of fish they are eating. In light of these difficulties, the authors suggested a blockchain-based system that could provide a workable answer by making the fishing supply chain more transparent and traceable. In many different sectors, cutting-edge tech has been an invaluable asset, especially for the establishment of reliable product tracing systems. Integrating blockchain technology, particularly Ethereum, can alleviate potential issues in fish tracing. The authors of this paper propose using the private Ethereum blockchain platform to oversee the procedures involved in the purchase and shipment of fish. Transparency, accountability, traceability, and privacy are all guaranteed by this approach. In addition to this, the authors give a framework that outlines the many actors and the relationships that exist between them throughout the supply chain. The EVM makes it easy for users to access these programs and conduct transactions decentralizedly. Smart contracts, which are the protocols that make this process work as it should, are the backbone of this capability. To guarantee a legitimate and risk-free supply chain for fish products, the system incorporates multiple components and actors, as seen in Fig. 17. An essential part of the FDA’s function is to record all business transactions on the blockchain and check that they are legal. The fish seed company uses captive breeding to generate fish eggs or seeds. To verify the species, they test the fish’s genetic makeup and store the results in an IPFS database. Aquaculturists buy fish eggs and then watch them develop in aquariums while keeping an eye on the conditions. As the fish grow older, they also post pictures and profiles of them online for inspection. Before selling their fish to fish classifiers, local fishermen update data connected to native fish and exclusively cultivate fish in natural areas.

Figure 17: The process of supply chain in the fishery industry utilizing blockchain technology

The fish classifier sorts fish species according on where they came from and how they were caught. The fish is prepared for filleting after the processor takes off the scales, fins, and skin. For the sake of future validation, they save the findings of the genetic testing on IPFS for the fish products. Merchants that have agreed to sell the items receive them from the supplier, who then ships them to the customers. Distributors distribute classified fish packets to retailers, who resell them to consumers. Afterwards, the consumer buys and eats the seafood. It has already been said that the solution’s creators have come up with a revolutionary method that can be readily integrated into different supply chain processes. Extensive testing and correct solution implementation on the Ethereum network are part of their next strategies, which they view with great optimism. Furthermore, they aim to create customised DApps that meet the specific needs of all the different parties involved in these processes.

6 Algorithms and Computer Modeling Approaches for Blockchain-Driven SCM

To bridge the gap between conceptual adoption and practical deployment, blockchain implementations in SCM must be assessed using rigorous computer modeling techniques. This section introduces analytical and algorithmic approaches for evaluating blockchain performance, security, and scalability in supply chain contexts.

6.1 Analytical Modeling of Blockchain Efficiency

Efficiency in blockchain-enabled Supply Chain Management (SCM) refers to the ability to reduce operational delays and minimize transaction costs while maintaining the same or improved quality of service. In this paper, efficiency improvement is quantified using the efficiency improvement coefficient

where:

This equation is a weighted sum of relative time reduction and relative cost reduction, enabling flexible adaptation to different industrial priorities. For example, in high-value logistics chains,

Modeling Approach: By simulating different values of

6.2 Security Modeling Using Cryptographic Algorithms (δ)

Security in blockchain-driven SCM ensures that data cannot be altered without detection, thereby preventing fraud and improving trust among participants. The security enhancement degree

where:

This model assumes that security benefits scale with the reduction in tampering probability and the number of participants validating the ledger. The cryptographic coefficient

Modeling Approach: The equation can be used to evaluate the effect of different cryptographic algorithms (e.g., SHA-256, SHA-3, elliptic-curve cryptography) on network security. Simulations can incorporate attack scenarios (e.g., doublespending attempts, Sybil attacks) to estimate

6.3 Scalability Modeling and Simulation (

Scalability measures the blockchain network’s ability to process a growing number of transactions without significant performance degradation. The scalability metric

where:

This formulation provides a normalized measure of transaction throughput per unit of block capacity and processing time. Higher

Modeling Approach: By varying

7 Main Findings, Challenges and Future Research Directions

In this section, we will go over a few of the key advantages of BC when it comes to safe supply chain management. Due to its distinctive properties, for instance, real-time data interchange, transparency, reliability, traceability, immutability, and visibility, BC has emerged as the instrument of the modern-day [139]. By 2030, the worldwide supply chain market in British Columbia will have grown by 80.2%, predicts Allied Market Research. By 2030, the worldwide market for supply chains that are enabled by BC is predicted to reach $9.8 billion, according to Market Watch. The supply chain sector predicts that by 2023, British Columbia will have contributed $424 million globally. Among the most promising applications of BC technology in the next five to ten years will be supply chain management (SCM), and BC is on track to become the de facto standard in SCM [159]. The SWOT analysis of using BC in the supply chain is displayed in Fig. 10.

7.1 Reduced Anti-Counterfeiting Problem