Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Augmented Deep-Feature-Based Ear Recognition Using Increased Discriminatory Soft Biometrics

Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Computing and Information Technology, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 21589, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Emad Sami Jaha. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Machine Learning and Deep Learning-Based Pattern Recognition)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(3), 3645-3678. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068681

Received 04 June 2025; Accepted 11 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

The human ear has been substantiated as a viable nonintrusive biometric modality for identification or verification. Among many feasible techniques for ear biometric recognition, convolutional neural network (CNN) models have recently offered high-performance and reliable systems. However, their performance can still be further improved using the capabilities of soft biometrics, a research question yet to be investigated. This research aims to augment the traditional CNN-based ear recognition performance by adding increased discriminatory ear soft biometric traits. It proposes a novel framework of augmented ear identification/verification using a group of discriminative categorical soft biometrics and deriving new, more perceptive, comparative soft biometrics for feature-level fusion with hard biometric deep features. It conducts several identification and verification experiments for performance evaluation, analysis, and comparison while varying ear image datasets, hard biometric deep-feature extractors, soft biometric augmentation methods, and classifiers used. The experimental work yields promising results, reaching up to 99.94% accuracy and up to 14% improvement using the AMI and AMIC datasets, along with their corresponding soft biometric label data. The results confirm the proposed augmented approaches’ superiority over their standard counterparts and emphasize the robustness of the new ear comparative soft biometrics over their categorical peers.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Biometric recognition technologies have been optimal automated solutions for human identification and verification/authentication for decades, especially in security-conscious societies around the globe. Numerous dependable systems and practical applications have been influentially deployed, ranging from personal-level, e.g., securing handheld devices, to universal-level, e.g., international border control. Such biometric recognition systems and applications are developed employing a variety of discriminative biometric modalities, which can mostly be physiological, such as a person’s fingerprint, iris, face, and ear, or behavioral, such as a person’s voice, gait, signature, and keystroke [1]. Notably, physiological and behavioral biometric modalities are also known as traditional hard biometrics [2]. Amongst those discriminant hard biometrics, the human ear has recently attracted increased research attention, highlighting its efficacy as a nonintrusive biometric modality for many beneficial applications in various scenarios [3].

Several computer vision algorithms have been devoted to ear biometric recognition tasks, utilizing effective machine and deep learning techniques [4]. Nevertheless, deep learning models based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have frequently tended to be more capable than other techniques for comprehensive image analysis, informative representations, and accurate visual recognition [5]. Other than hard biometrics, soft biometrics is a high-level semantic form of traits recently introduced as a new biometric modality. Soft biometric traits are more impervious to changes in viewpoint, pose, occlusion, illumination, and other variable environmental aspects [6]. For instance, age, gender, colors, verbally describable sizes, dimensions, ratios, and many other feasible soft biometrics can be less vulnerable to losing value in challenging scenarios, and they can be deployed where traditional biometrics cannot [7]. Furthermore, such soft biometrics can provide highly invariant feature observability, extraction, and generalizability [8].

Although soft biometrics are insufficiently unique and less distinctive when used alone, they are more efficacious and helpful as supplementary information when used in conjunction with other hard biometrics [6,8]. Therefore, soft biometrics are likely to be nominated for fusion with hard biometrics to enhance their recognition performance. Here comes an unanswered research question and an open research gap to be filled in this study. It mainly aims to propose robust soft biometrics for the person’s ear and investigate their capabilities in augmenting the performance of traditional hard biometric deep features extracted using efficient CNN models. Even though there is very little relevant research concerning ear soft biometrics [1,9–11], the current scope of soft biometrics and deep feature fusion to augment ear recognition has yet to be explored based on existing literature. The main contribution of this research can be outlined as follows:

• A novel framework for augmenting CNN-based ear biometric recognition by feature-level fusion of hard biometric deep features with proposed increased discriminatory soft biometrics;

• A new group of more perceptive comparative soft biometrics, derived automatically via pairwise comparative labeling, ranking ears by attributes, and mapping to refined relative measurements;

• Several CNN deep-feature-based ear recognition approaches augmented by different combinations of proposed categorical and comparative soft biometric traits;

• Extended performance evaluation, analysis, and comparison of traditional vs. augmented ear biometric identification and verification using various ear image datasets, hard biometric CNN deep-feature extractors, and employed classifiers.

In the remainder of this research paper, Section 2 provides a brief background and a review of related studies, Section 3 describes the detailed research methodology, Section 4 illustrates the conducted experimental work and performance result analyses and comparisons, and finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and indicates potential future venues.

2 Background and Related Studies

The human ear as a nonintrusive biometric modality is still an emerging research field with little interest compared to other well-researched and extensively analyzed biometric modalities, such as the human face. Yet, unlike the face, the ear is a rigid organ considered relatively less vulnerable to variations in illumination, poses, occlusions, aging, and visual or emotional states as in facial expressions [5]. Practical biometrics are expected to satisfy several essential requirements like universality, measurability, collectability, permanence, and uniqueness, which can be satisfiable by ear biometric traits [1]. Furthermore, the ear modality has additional advantages of being stable over time [12], easy to acquire with low/no user-sensor interaction [3], conductible in mere image-based unimodal/multimodal biometric systems [13], and immune to privacy issues and hygiene concerns [5]. Such advantages make ear biometrics acceptable to the public as a typical contactless means to identify/verify a person, involving minimal naked-eye-identifiable information compared to other biometrics like the face [9,12].

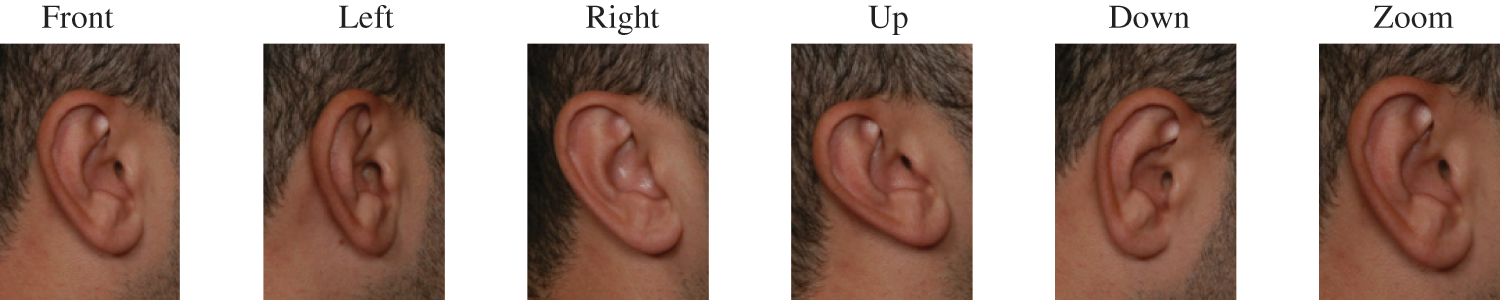

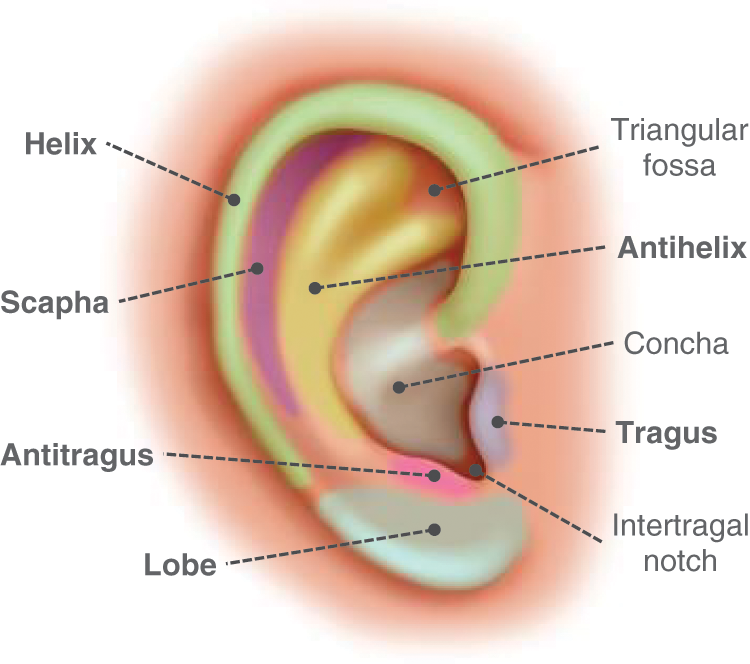

Traditional ear biometric recognition can be defined as the automatic process of human recognition using physical ear characteristics [14]. It has been reliably and effectively deployed in diverse applications, including forensics, surveillance, identification, verification, and securing personal devices [3,10]. Unique ear biometric traits can be extracted by analyzing several primary ear morphological parts, such as the ear’s lobe, scapha, helix, antihelix, tragus, antitragus, and their subcomponents, which were found to be powerful even for challenging tasks like identical twin discrimination or kinship verification [15]. Fig. A1 in the Appendix A illustrates the general anatomical structure of the human ear. From a biometrics perspective, the overlay-colored with bolded annotations are the principal different ear parts that are significant not only for physical feature extraction as hard biometrics but also the most discriminative, describable, comparable, and thus more likely for inferring viable soft biometrics. Table 1 provides a glossary of key terminology in the current research context to help enrich readability and understanding.

2.1 Traditional Ear Biometric Recognition

For human recognition using ear biometric modality, many computer vision and machine/deep learning algorithms have been devoted to developing robust systems with high accuracy [3]. Most earlier research studies commenced working on the ear recognition domain using standard machine learning methods and handcrafted features [16]. However, most recent ear biometrics-related approaches have dramatically shifted from classical feature extraction and handcrafted feature engineering to deep learning models [17]. Moreover, exploiting ear biometric recognition capabilities in multimodal biometric systems has attracted some research interest. For instance, a new multimodal biometric feature-level fusion was introduced for selecting optimized feature sets from ear, iris, palm, and fingerprint, with a kernelized multiclass support vector machine (MSVM) to improve the security and performance of human authentication [13].

Deep learning methods were employed in effective ear vision-based feature extraction and successful human identification/verification in unimodal/multimodal biometric systems [4]. A multimodal biometric identification was offered, combining transfer learning with sample expansion before feeding face and ear images to the VGG-16 network to enhance accuracy and address the problem of single-sample face and ear datasets [18]. On the other hand, a unimodal ear identification was explored on the AMI ear dataset, using a Pix2Pix generative adversarial network (GAN) to augment the ear data by generating corresponding left ear images for right ear images and vice versa, and improve the EarNet model performance [19]. In [20], a framework was developed based on deep convolutional generative adversarial networks (DCGAN) to enhance the ear recognition performance of AlexNet, VGG-16, and VGG-19 on benchmark AMI and AWE ear datasets. MDFNet was introduced as an unsupervised single-layer model for ear print recognition [21].

Different CNN-based deep learning architectures have attained exceptional performance and boosted ear identification capabilities, utilizing reliable deep features to be used as discriminative hard biometric traits [3,4]. Ensemble classifiers for score-level fusion were suggested for improving ear identification on AMI and IIT Delhi1 ear datasets, using a machine learning technique of discrete curvelet transform (DCT) and also deep learning CNNs of ResNet-50, AlexNet, and GoogleNet [22]. In [5], multiple VGG-based network topologies (VGG-11/13/16/19) were examined in ear identification using AMI, AMIC, and WPUT datasets. Ablation experiments with comparative analysis were conducted for scratch training, deep feature extraction, fine-tuning, and, eventually, multimodal ensembles, which outperformed the other three strategies by averaging posterior probabilities of the VGG-(13, 16, and 19) configuration. Meanwhile, in [5], the performance of training and using every single network alone, especially on more challenging datasets like AMIC, led to much lower performance than ensembles, which are computationally costly and time-consuming. In a later related study, further CNNs, including AlexNet, VGG-16/19, InceptionV3, ResNet-50/101, and ResNeXt-50/101, were separately experimented with and compared in unconstrained ear identification using the EarVN1.0 dataset [14]. Another research was conducted on AMI and EarVN1.0 while boosting the performance of VGG-16/19, ResNet-50, MobileNet, and EfficientNet-B7 for deep feature extraction by vision-based preprocessing like zooming, contour detection, and different data augmentations [12]. A feature-level fusion method was proposed based on channel features and dynamic convolution (CFDCNet) based on an adapted DenseNet-121 model, which outperforms the standard DenseNet-121 benchmark performance on AMI and AWE datasets [23]. Focusing on independently training the left and right ears for ear side-specific person identification can remarkably enhance ResNet-50 model accuracy and vary in performance between left and right as they need not be identical [24].

2.2 Soft Biometrics for Augmented Biometric Recognition

Modern soft biometrics has recently emerged as a new alternative or supplementary means for human recognition [25]. Numerous research efforts have been booming in various domains and scenarios, leading to robust and practical systems for person identification, verification, and retrieval, especially using soft biometrics inferred from the face [26] and body, alongside other body-related supplemental characteristics, such as clothing [7]. A variety of possible soft biometrics attributes can be derived to semantically describe different personal identity aspects: global aspect, e.g., gender and age; facial aspect, e.g., eye size and nose length; body aspect, e.g., height and arm length; and clothing aspects, e.g., clothes category and sleeve length [25,27]. They can be annotated using any conventional, namable, and understandable group of semantic labels in different categorical, relative, and comparative labeling forms [8], as in Table 1.

Soft biometric traits have been considerably helpful in empowering functional biometrics systems for various purposes, such as surveillance and forensic applications [28]. In some challenging cases, manual or automatic soft biometric traits can be the only observable cues for identity [6]. In other scenarios, they can be viable where the traditional vision-based traits alone are impractical or degrade performance due to poor data quality or environmental conditions, e.g., distance, viewpoint, illumination, and occlusions [7].

Soft biometrics have been proven as powerful supplemental traits to augment the performance of many standard vision-based hard traits of different biometric modalities. Instead of relying solely on standard hard biometrics, they can be integrated by soft biometrics using different schemes, such as feature-level, score-level, and decision-level, for effective fusion of hard-soft biometric information and enhanced recognition [26]. The feature-level fusion represents the most interaction between facial hard and soft biometrics. It can augment deep CNNs in a challenging scenario where training is limited to front-face images, enabling zero-shot side-face identification and verification [8]. The hard-soft face biometrics fusion is feasible in their original forms and their cancellable biometric hard and soft bio-hashing formats, as their score-level fusion can attain enhanced prompt face image match and retrieval in large-scale datasets [29].

Only a few relevant research explorations have been conducted on soft biometrics in fusion with vision-based hard biometrics using machine learning for human ear biometric identification or verification [1,9,11]. In [1], a set of twenty categorical and thirteen relative ear soft biometric traits were proposed, which led to augmenting identification and verification on AMI-cropped (AMIC) ear images. Different feature-level fusion approaches were applied to combine them with hard biometric features derived using local binary pattern (LBP) and principal component analysis (PCA). For newborn baby identification, four soft biometrics, comprising two categorical traits, gender and blood group, in addition to two relative traits, weight and height, were combined in the score level with different vision-based features to enhance their performance, including PCA, HAAR, fisher linear discriminant analysis (FLDA), independent component analysis (ICA), and geometrical feature extraction (GF) [9].

Another approach was proposed to explore the potency of skin color, hair color, and mole location as soft biometric traits to improve local Gabor binary pattern (LGBP) identification performance in score-level fusion [11]. The study of [10] was dedicated to statistically investigating potential morphological features of the external ear, which can be candidate soft biometric traits. To the best of our knowledge, the comparative form of ear soft biometrics has never been investigated or analyzed as per the existing literature, suggesting the current research study to pioneer this research gap-filling in the ear biometric domain. This research is motivated by several significant limitations in existing related work. Most studies have focused on face and body modalities for soft biometrics analysis and utilization, either in isolation or in fusion with hard biometrics. In contrast, the ear modality has rarely been considered for soft biometric applications. Additionally, those few studies that do incorporate ear soft biometrics tend to use only categorical and relative forms of labeling, which are often less discriminative than comparative labeling. Another limitation is the lack of automated systems for categorical or comparative soft biometric annotations. There is also an excessive reliance on traditional crowdsourcing methods using human annotators, which, while still a standard predominant practice for acquiring manual labels in face and body soft biometrics, is not ideal.

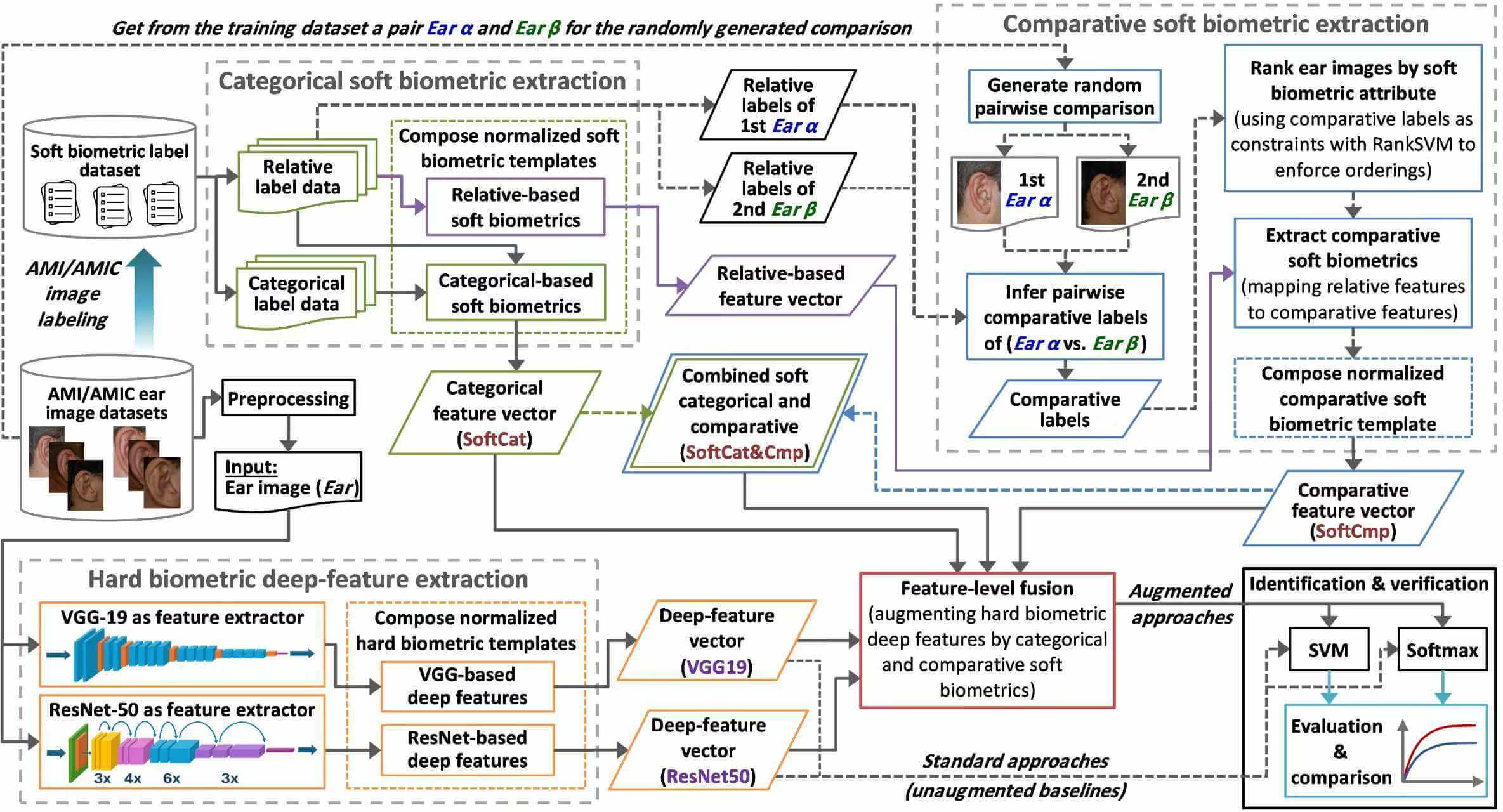

This research proposed a novel methodology framework to achieve augmented ear biometric recognition by fusing increased discriminatory soft biometric traits with reliable hard biometric deep features. It investigated the capabilities of effective categorical and further perceptive comparative soft biometrics in enhancing human identification and verification performance. Fig. 1 shows a brief overview of the proposed research methodology framework and clarifies the process workflow.

Figure 1: Framework overview of the proposed research methodology

The framework starts with preprocessing an input ear image (Ear) from the AMI/AMIC dataset and preparing categorical/relative label input from the soft biometric label dataset. SoftCat is extracted as the first normalized categorical soft biometric template, comprising categorical and relative traits in the categorical soft biometric extraction phase. A relative-based only feature vector is additionally extracted to be mapped to a corresponding comparative feature vector. Thus, in the comparative soft biometric extraction phase, random pairwise (Ear α and Ear β) comparisons are generated between AMI/AMIC training samples only, where their relative labels are fetched and compared per attribute to infer comparative labels. Comparative labels are used as constraints with RankSVM to rank all ear images by each attribute. After mapping, SoftCmp is extracted as the second normalized comparative soft biometric template. The third soft biometric template (SoftCat&Cmp) is derived as the combination of both SoftCat and SoftCmp. In the hard biometric extraction phase, each input ear image undergoes CNN deep feature extraction using VGG-19 and ResNet-50. Extracted deep-feature vectors are normalized to compose two hard biometric templates (VGG19 and ResNet50), where each is fused with the three soft biometric templates. The final module evaluates and compares the identification and verification performance of two standard hard biometric approaches, as unaugmented baselines, and six soft biometric-based augmented approaches when using SVM and Softmax classifiers. The framework modules will be elaborated in the following sections.

3.1 Ear Image and Label Datasets

This research used two ear image datasets and a soft biometric label dataset: AMI, its cropped image version AMIC, and their corresponding soft biometric labels. These AMI-based datasets were adopted due to their suitability to the objectives and compliance with the requirements of this research context and methodology, besides the availability of pre-acquired categorical soft labels. They allowed systematic evaluation and comparison of proposed augmentation approaches in different biometric recognition scenarios.

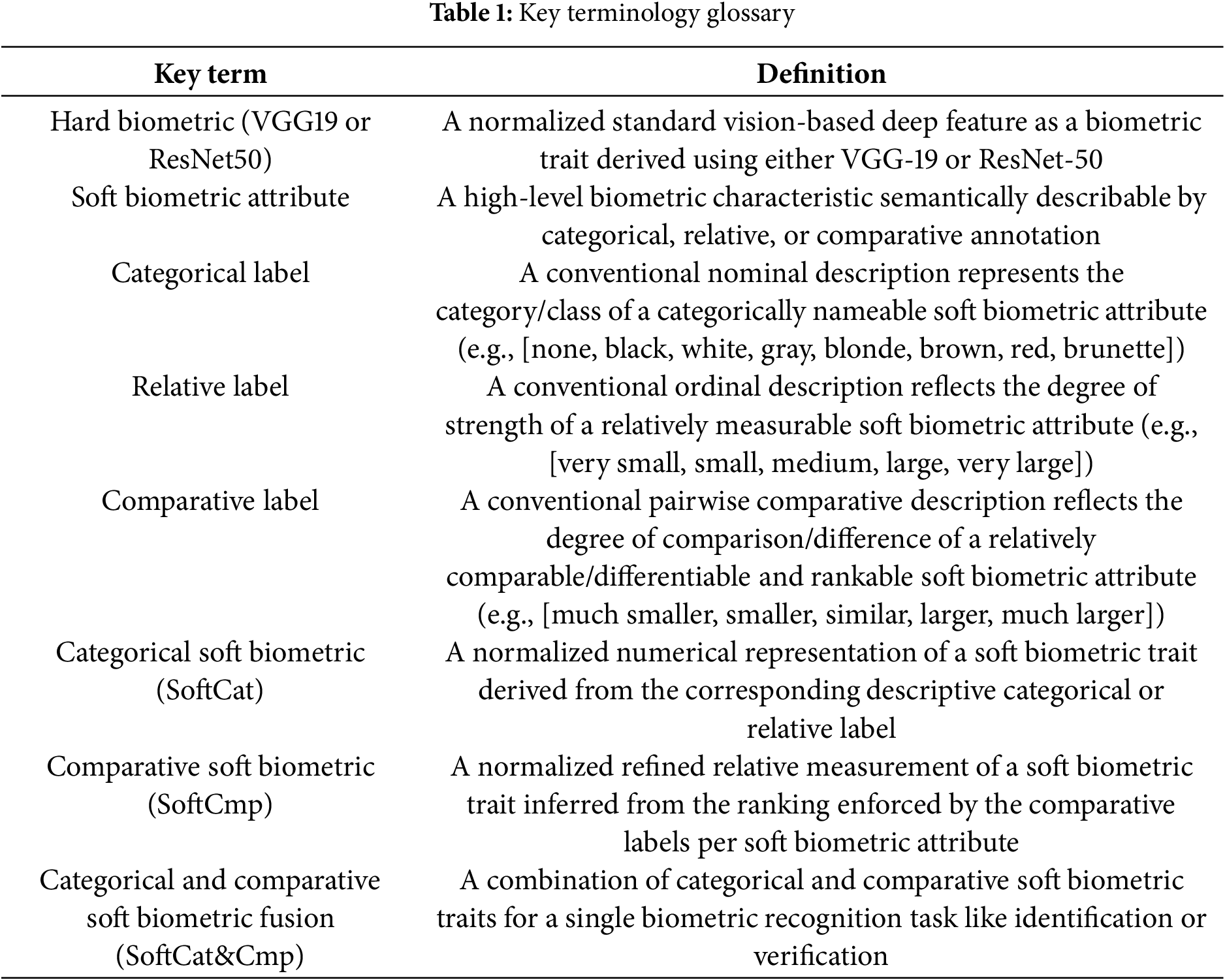

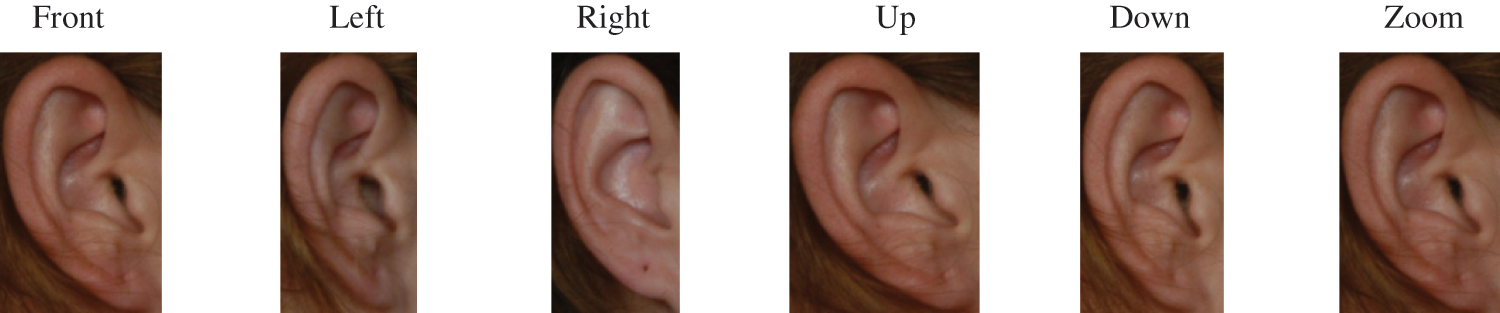

The AMI ear database is a standard image dataset for ear biometric recognition experimentation [30]. It comprises 700 ear image samples, in JPEG format with 492 × 702 pix, belonging to a hundred male/female subjects of ages ranging from nineteen to 65. Each subject has seven image samples, representing six different viewpoints: “front”, “left”, “right”, “up”, “down”, and “zoom”, of the right ear, in addition to a seventh image showing the left ear annotated as “back”. In this research, the seventh was excluded, and only six images representing the same ear per subject were included in all experimental work since left and right ears are naturally not necessarily identical, as substantiated and recommended for accurate performance by [24]. Fig. 2 exhibits these six images for a male subject from the AMI dataset of the 600 adopted images. As such, 400 were randomly selected as a training dataset, and the remaining 200 were held out as a testing dataset. Namely, each subject had four random images for training vs. two others for testing.

Figure 2: Human ear image samples from the raw AMI dataset represent six various perspectives for a mele subject

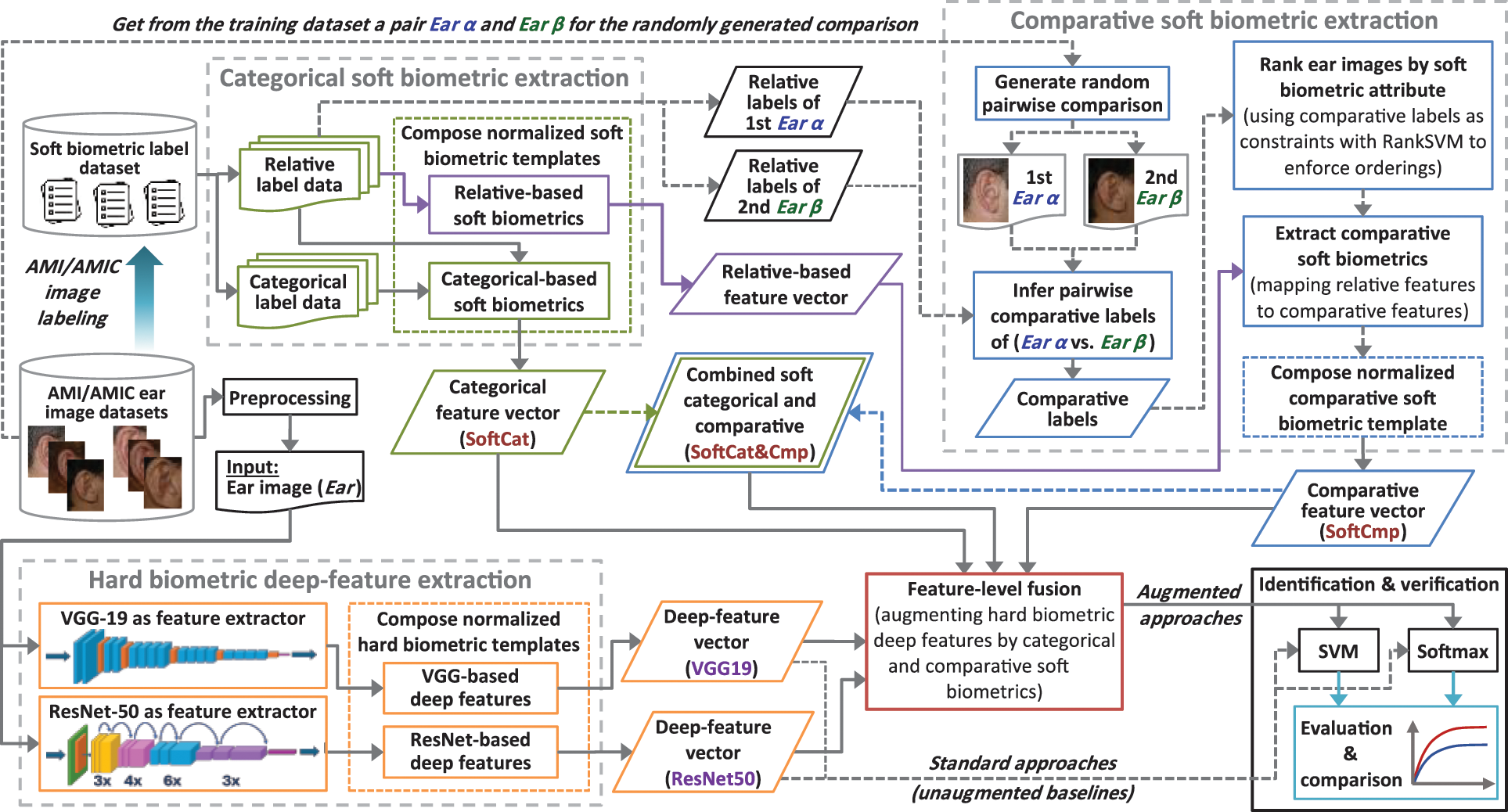

3.1.2 AMI-Cropped (AMIC) Ear Image Dataset

A dataset derived from AMI, containing a cropped version of all AMI images, has been repeatedly used in the literature and known as AMI-Cropped (AMIC) [1,5]. In AMIC, each AMI’s raw image, like those shown in Fig. 2, was cropped tightly, surrounding the ear. As a result, the cropping process discarded all partial regions of hair, face, and neck around the ear, and it kept only the ear within a minimal ear bounding-box as the only region-of-interest (ROI). Fig. 3 illustrates six AMIC’s cropped ear images for a female subject. In this research, the adopted AMIC dataset consists of a cropped version of the same original 600 ear image samples in the AMI. Likewise, AMIC was split into 400 and 200 random images for training and testing. This dataset was meant to investigate the variability in ear recognition performance in more challenging scenarios, offering more confusable data images and minimal usable biometric information.

Figure 3: More challenging six cropped ear images in various perspectives for a female subject from the AMIC dataset

3.1.3 AMI-Based Dataset of Ear Categorical Soft Biometric Labels

The AMI-based dataset of ear categorical soft biometric labels [1] was crowdsourced for all image samples of the hundred subjects in the AMI dataset. It consists of 2900 multi-label annotations provided by 666 annotators. The label data were acquired using categorical and relative labeling forms for 33 fine-grained soft biometric attributes of the human ear grouped into eight zones, as listed in Table A1 in the Appendix A, where the attributes described with relative label form are bolded, as they will be used in the next section for inferring comparative soft biometric labels. Multiple, two to five, crowdsourcing annotators annotated each ear image by assigning the most suited categorical label from a given label group to best describe each attribute. Other than “can’t see”, each label was assigned a representative numerical value ranging from 1 to 8. These values were arbitrarily assigned to categorical label groups, whereas they worked for each relative label group as a bipolar scale, indicating a compatible numeral rating for each relative label.

In this research, “gender” was labeled with (male/female), likewise, and added to the categorical label data as a global 34th soft biometric attribute, appended in italics at the end of Table A1. The raw label dataset was thoroughly analyzed for data cleansing, outlier removal, and noise mitigation. Moreover, from 1934 relevant annotations, the categorical and relative labels were used to derive a unique categorical soft biometric trait per attribute for each ear image sample in the training dataset. Each trait was deduced as the median value of all categorical/relative labels acquired from several annotators to describe the same ear image sample specifically. The nascent traits for all attributes were used to compose a 34-value feature vector of categorical soft biometrics (SoftCat) for each of the 400 AMI/AMIC training samples. Also, utilizing randomly selected 200 out of 966 relevant annotations, a similar feature vector was composed for each of the 200 testing samples; however, it comprises 34 raw categorical/relative labels provided by a single annotator, reflecting their categorical soft biometrics to be used as a query to recognize a person-of-interest.

3.2 Proposed Ear Comparative Soft Biometrics

Among dozens of practical soft biometric attributes, many can be mere nominal, which can only be semantically annotated using a group of categorical labels as absolute types, such as the “scapha shape” (A6) trait in Table A1 in the Appendix A described using the categorical label-group (flat, convex, other) that do not reflect any sortable information. Dissimilarly, some other attributes can be ordinal, which can be further annotated using a group of relative labels as a scalar, such as the “scapha size” (A5) trait in Table A1 described using the relative label-group (very small, small, medium, large, very large), reflecting sortable information of the degree of strength of this attribute. Such ordinal soft biometric attributes are not only relatively describable but also comparable and consequently rankable, which enables the derivation of comparative soft biometrics with increased discriminatory capabilities for augmenting human recognition.

Table 2 outlines the proposed comparable and differentiable ear soft biometric attributes and corresponding comparative label groups. Thus, thirteen ordinal attributes were adapted, and their descriptive relative labels were extended to their corresponding comparative label form. The resulting comparative labels represent the degree of comparison/difference between two ears per attribute rather than the degree of strength per attribute for a single ear. Each label group comprises five labels, numerically represented consecutively from the lowest to the highest by a 5-point bipolar scale of the integer values from 1 to 5 as their codes, e.g., (much lower = 1, lower = 2, similar = 3, higher = 4, much higher = 5). The following subsections explain how comparative labels were inferred for soft biometric attributes, how ear image ranking was enforced using the comparative labels, and how comparative soft biometrics were eventually extracted.

3.2.1 Inferring AMI-Based Ear Comparative Soft Biometric Labels

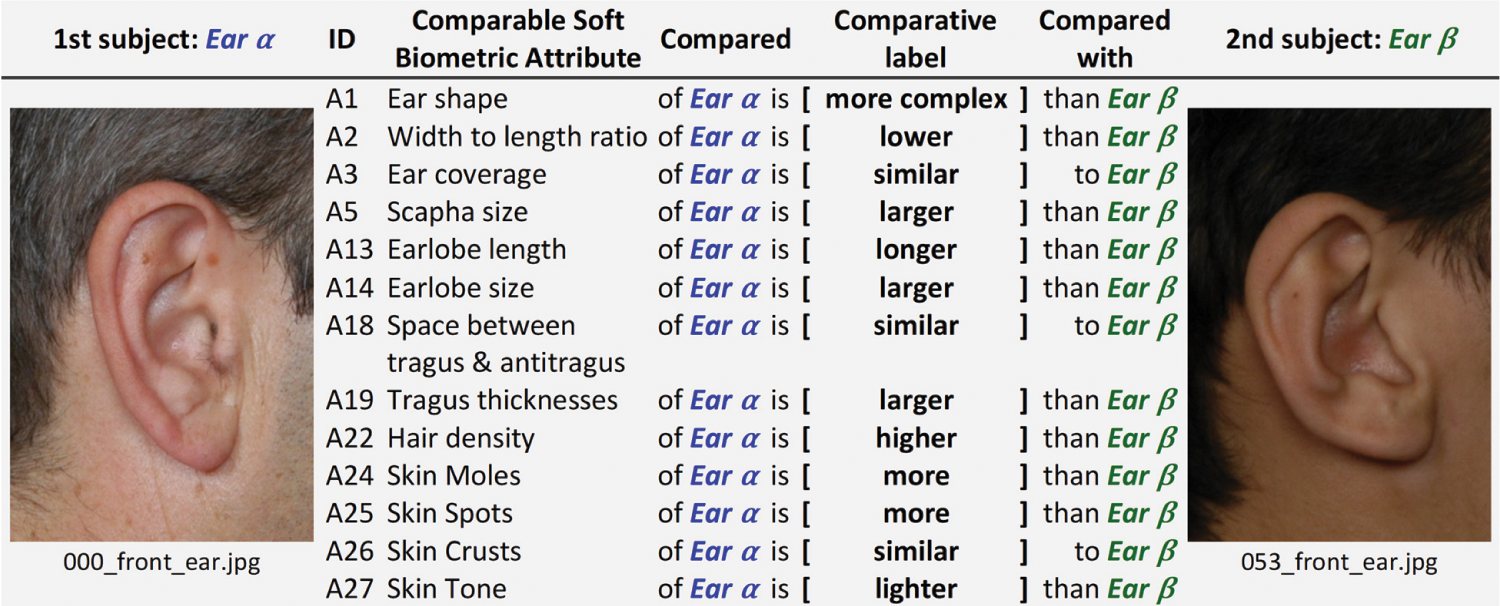

An automatic ear soft biometric labeling technique was developed to infer comparative label information for AMI/AMIC ear images by comparing their relative label information. For each comparable soft biometric attribute in Table 2, multiple pairwise comparisons were generated between ear images to compare their relative labels and assign the most applicable comparative label accordingly. Such an automated process enables mimicking human perception to detect the nuanced difference between a subject pair compared in a particular attribute [6,27]. Fig. 4 displays an automatic pairwise comparison between two subjects’ ear images in the AMI training dataset, resulting in thirteen inferred soft biometric comparative labels.

Figure 4: Example of nascent comparative labels for ear soft biometric attributes inferred by the proposed automatic comparative labeling technique based on a pairwise comparison between two subjects’ ear images (Ear α) and (Ear β)

Each inferred comparative label describes the degree of similarity/dissimilarity between two relative labels of the same soft biometric attribute for two compared training samples of different subjects in AMI/AMIC. For each pairwise comparison per attribute, associated relative labels were fetched from the AMI-based categorical label dataset and compared to assign a comparative label that best reflects the degree of comparison. This comparative labeling was implemented using a function [6], adapted to suit the ear biometric recognition context. It decides the applicable comparative label code (1–5) for each attribute

For each ear pair α and β to be compared per attribute and for ranking, several considerations can ensure the practicality and accuracy for learning a ranking function while also mimicking real-life scenarios. Each (α and β) pair is selected only from the training dataset to maintain generalizability, holding out the test dataset as unseen data to recognize. It is randomly chosen without restrictions on which subject should be compared with whom and in what order to avoid bias and reveal robustness against such randomness.

3.2.2 Ranking Ears by Comparable Soft Biometric Attribute

The ability to compare ears in a soft biometric attribute further enables a more meaningful capability of ranking them by that attribute. Such ranking by comparable attributes is a pivotal process prior to extracting viable comparative soft biometrics. Therefore, numerous pairwise comparisons by attribute were generated and annotated with comparative labels primarily for ranking purposes. The goal of the ranking process was to anchor those comparisons and use them as constraints of resemblance and contrast to enforce the desired ordering per attribute on all training samples [25,31]. Hence, all ears were ranked by each attribute, resulting in a list of ordered subjects per attribute. Based on the imposed ordering rules, the thirteen relative-based categorical soft biometrics, which describe only the comparable attributes, were mapped to their corresponding comparative soft biometrics. The resultant comparative soft biometrics are refined relative measurements describing a subject’s ear in relation to all remaining subjects in the dataset.

This research used an operative soft-margin RankSVM model [31] that was redevised here to rank ears by attribute. The generated comparison information was employed as similarity/dissimilarity constraints and ordering rules to impose coveted ranking per attribute. The role of the RankSVM model was to learn

where

The total possible pairwise comparisons per attribute can be inferred as the number of all possible two-sample combinations of n samples, calculated by n!/2(n − 2)!. Here, since the AMI/AMIC training dataset has multiple samples per same subject, they did not necessarily need to be compared with each other, as the comparisons between samples of different subjects are more significant towards discriminative biometric recognition capabilities. Moreover, generating only a subset of valid pairwise comparisons can be sufficient to learn a successful ranking function [31]. Therefore, a comprehensive subset of about 25% of all possible combinations was generated per attribute. In this subset, only those satisfying particular criteria were selected as a minimal proportion of only about 20% to learn a robust ranking function. Table 3 gives a statistical synopsis of generated and included/excluded comparative label data for ranking purposes.

The criteria for selecting a subset of comparisons for ranking were applied for each attribute

where C is the hyperparameter to balance maximizing the margin vs. minimizing the error, which decreases as the ranking better complies with enforced constraints. Unlike standard SVMs, RankSVM aims to separate the differences between data points rather than separating the data points themselves. In this context, the margin is the smallest difference between the nearest two ranks among all ranks of the ear sample points.

3.2.3 Extracting Ear Comparative Soft Biometrics

This research proposed and extracted a novel set of thirteen ear comparative soft biometrics (SoftCmp) to investigate their capabilities in augmenting ear recognition. These comparative traits were automatically derived after inferring comparative labels and then using them in learning to rank by attribute, described in Sections 3.2.1 and 3.2.2. Each learned ranking function

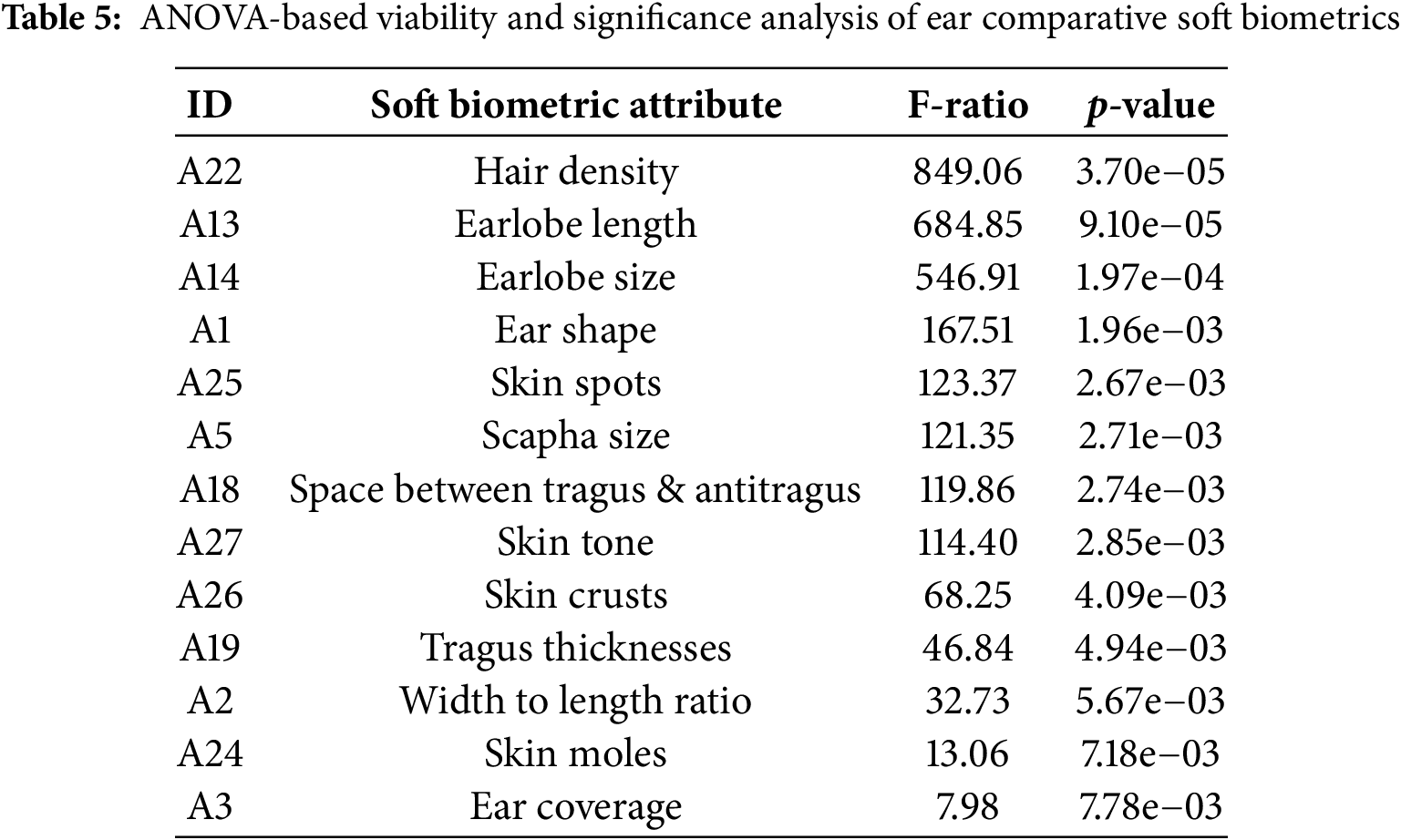

3.2.4 Significance Analysis of Ear Comparative Soft Biometrics

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used as a standard statistical tool to analyze the viability of the newly proposed and most significant comparative soft biometric traits in terms of discriminatory and separability, reflecting how significant and well each trait contributes to person recognition. Table 5 shows the comparative soft biometrics in order based on their significance and capability to differentiate between groups and contribute to successful person identification or verification. It can be observed that all proposed comparative soft biometrics gained significant F-ratios and corresponding small p-values, according to the significance level of p < 0.05. These results emphasized their potential and potency as discriminative soft biometric traits for augmenting hard biometric traits and improving recognition accuracy. Interestingly, “Hair density” (A22), “Earlobe length” (A13), and “Earlobe size” (A14) distinctly showed the most significance among traits, signifying their efficacy for person recognition purposes.

The F-ratio, together with the resultant p-value, was deduced for each trait using the one-way ANOVA as follows [8]:

where each group, in the human recognition context, comprises all samples of the same subject (person).

3.3 Pre-Trained Deep Learning Models for Biometric Feature Extraction

Convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures have been well-established as versatile deep learning models for various image analysis and computer vision purposes [4,32–34]. Such pre-trained CNN models can be effectively used as deep-feature extractors for image-based recognition tasks like human identification/verification. Since they have already been sufficiently trained on large-scale datasets, their pre-trained weights can be utilized to initialize these models when transferring learning to a new task instead of random reinitializations [5]. In this research, VGG-19 and ResNet-50 models were adapted as deep-feature extractors. The extracted vision-based deep features composed two feature vectors for ear biometric recognition, denoted as (VGG19 and ResNet50). The two feature vectors represented the ear hard biometrics to be fused and augmented by the proposed ear soft biometrics (i.e., SoftCat, SoftCmp, and SoftCat&Cmp).

3.3.1 VGG-19 as Deep-Feature Extractor

The VGG-19 model is a CNN-based deep learning architecture designed as a visual geometry group (VGG) version with a uniform structure of nineteen hidden layers: sixteen convolutional (conv) and three fully connected (FC) [33]. It was successfully pre-trained for generic image recognition on the sizable ImageNet dataset. Thus, it offers functional transferable learning by slight fine-tuning, even using a small dataset of a new target task [5]. This research adopted the strategy of using the pre-trained VGG-19 as a deep-feature extractor. Hence, the standard architecture was adapted to suit the context of augmenting deep-feature-based ear recognition with soft biometrics. Table 6a illustrates the architecture components of the VGG-19 adapted and used as a deep-feature extractor.

The ImageNet-based pre-trained weights were used for model initialization. The original input size 224 × 224 was replaced by the full size 492 × 702 of the raw RGB ear data image in the AMI dataset, as it was empirically found to be the optimal size, maintaining the most informative vision-based deep features for biometric recognition on both AMI and AMIC. As such, the AMIC’s cropped ear images were rescaled to fit the required input size. The model used 3 × 3 convolution kernels with a stride of 1 and 2 × 2 max pooling operations with a stride of 2 across all five architecture blocks. A one-pixel zero padding was enforced to preserve the spatial dimensions of the output feature map after each convolution. A rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function was used with each convolution. The last three FC layers were replaced with a global average pooling layer to derive a fixed-size deep-feature output of 512 values, representing the VGG19 feature vector of hard biometrics for each image in both AMI/AMIC training and testing datasets.

3.3.2 ResNet-50 as Deep-Feature Extractor

The ResNet-50 is a 50-layer version of the residual network (ResNet) devised based on CNN deep learning architecture with 49 convolutional layers and one average pooling layer [32]. ResNet-50 was also intensively pre-trained using ImageNet for generic image recognition tasks. It allows learning transfer and generalization by utilizing its reliable pre-trained weights for target task-specific network initialization or fine-tuning. The inherent power of ResNets lies in exploiting increased depth for more perceptive feature extraction and addressing likely grain vanishing or overproduction issues [12]. Since ResNets are equipped with skip connections to avoid possible loss of image information along the network’s depth increase [14]. This research adjusted the standard ResNet-50 architecture to transfer its learned deep features to ear biometric recognition to be augmented by soft biometrics. Table 6b presents the ResNet-50 architecture and its modules adapted and employed in this research as a ResNet-based deep-feature extractor.

Here, the adjusted ResNet-based model for AMI and AMIC was also initialized using the ImageNet-based pre-trained weights, and the original ResNet-50 input size was changed from 224 × 224 to 492 × 702 because it was also here the optimal empirically found input size for best ear biometric signature representation in this research. Accordingly, the AMIC’s variant-size cropped images were rescaled to the new input size. As shown in Table 6b, the adapted model used a 7 × 7 kernel with a stride of 2 and three-pixel zero padding in the first conv layer. In the subsequent multi-block conv layers, each block of three convolutions used two 1 × 1 kernels with a stride of 1 for the top and bottom convolutions. However, a 3 × 3 kernel was used for the middle convolution, where one-pixel zero padding was applied. A stride of 1 was used for all 3 × 3 kernels except Conv3_block1, Conv4_block1, and Conv5_block1, where it was a stride of 2 to downsample the feature maps. The last FC layer was substituted with a global average pooling layer, which derives a fixed-size deep-feature output of 2048 values, representing the ResNet50 feature vector of hard biometrics for each training and testing ear image sample in AMI/AMIC.

3.4 Biometric Trait Normalization and Feature-Level Fusion

Using the proposed hard and soft biometric feature extraction methods, for each ear image data sample in both AMI and AMIC datasets, all hard biometric deep features and corresponding soft biometrics were extracted and normalized using min-max normalization to rescale all biometric trait values between zero and one. Across the entire experimental work, the same procedure was applied to all AMI, AMIC, and soft biometrics original datasets by splitting each into two disjoint 66.67% training and 33.33% test subsets.

For augmenting deep-feature-based ear recognition by soft biometrics, feature-level fusion was adopted to investigate the ultimate capabilities of the proposed soft biometrics and their potency in this endeavor. Feature-level fusion was selected over other fusion strategies, e.g., classifier-level and decision-level, because it empowers most interaction and synergy between augmented hard and augmenting soft biometrics in achieving enhanced recognition performance. Moreover, it enables feature viability analysis and benefits from the best qualities of biometric modalities, and has often been proven as an effective fusion strategy for integrating diverse biometric traits or modalities for significantly improved recognition [34].

Consequently, eight biometric templates were composed for each ear image to be ready for use in further training and testing for ear identification and verification. Two represented unaugmented standard hard biometric templates of VGG-based and ResNet-based deep-feature vectors, which were used as benchmark baselines for performance comparison purposes. The remaining six represented soft biometric-based augmented templates, where each standard template was concatenated with each of the three proposed soft biometric feature vectors, SoftCat, SoftCmp, and SoftCat&Cmp. Table 7 shows VGG and ResNet unaugmented standard ear biometric templates and their soft-based counterparts augmented by categorical and comparative soft biometrics. These two VGG-based and ResNet-based traditional deep-feature approaches and their six augmented counterparts were evaluated and compared in eight ear biometric identification and verification experiments that will be described in Section 4.

3.5 Effective Classifiers for Ear Recognition

The methodology employed two efficacious SVM-based and Softmax-based classifiers to streamline extended analysis and performance variation investigation using machine learning-based vs. deep learning-based classifiers. Thus, all proposed augmented approaches were extensively explored and comprehensively assessed using different biometric datasets, scenarios, and tasks with different classification methods.

Support vector machines (SVMs) are reliable and practical methods widely deployed for diverse classification problems and pattern recognition endeavors, including human identification and verification [1,8]. Their key role is to find an optimal hyperplane that efficiently differentiates between classes with max hard/soft margin and min misclassification. SVM-based classification can be applied to data points even if nonlinearly separable via mapping the classification problem to a higher-dimensional feature space, where they became linearly separable [11,13]. The desired mapping can be accomplished by utilizing helpful kernel functions, such as linear, sigmoid, polynomial, and radial basis.

A soft-margin SVM classifier was separately trained for each approach in Table 7, using its designated training AMI/AMIC dataset. The input of each per-approach SVM-based classifier varies based on its biometric template size, ensuing from the preceding hard/soft biometric feature extraction phases, as shown in Table 7. The grid-search strategy was applied to enforce three-fold cross-validation on the training dataset to decide the following optimal model parameter values empirically. The model could choose between four kernel functions: linear, sigmoid, polynomial (poly), and radial basis function (RBF). The tuning of the regularization hyperparameter C was allowed to vary between six logarithmically spaced values 10−2 to 103, whereas the decision boundary was controlled by the gamma (γ) hyperparameter, ranging between five values 10−3 to 10. In addition, weight coefficients for the categorical and comparative soft biometric traits were used, ranging from 0.1 to 1.5, to control their significance level of the extent they were allowed to contribute to sample representation, feature-level fusion, and thus performance augmentation. Such weight coefficients can be empirically decided to better achieve augmented performance by enforcing a form of regularization on soft biometric traits [8]. They can also balance their influences on the recognition task to exploit their maximum capabilities and avoid possible adverse dominance in the feature space [1].

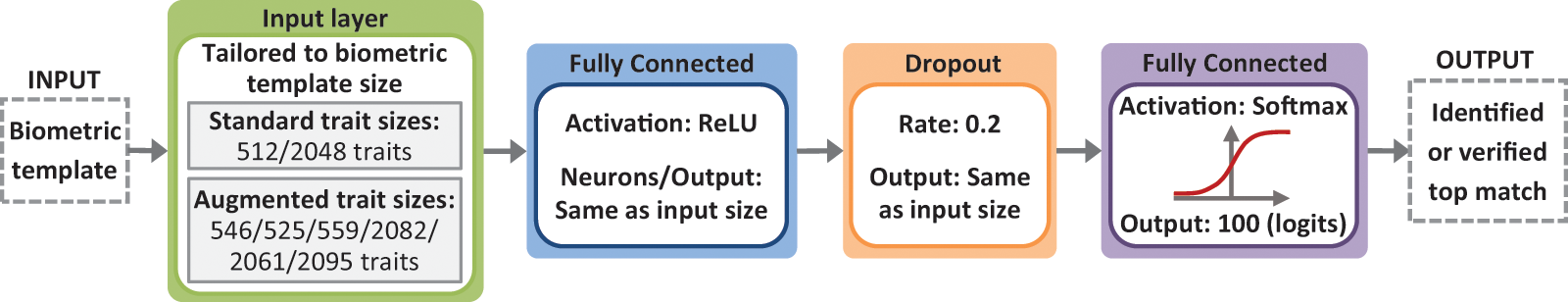

3.5.2 Softmax-Based Classifier

Softmax-based classifiers have been proven to be high-performing integral configurations in various functional deep-learning architectures for generic image recognition [32,33] or biometric template matching and recognition [5,14,18,23]. In this research, a softmax-based feedforward neural network (FFNN) was constructed to be independently trained and used as a classifier for each approach in identification and verification. The Adam optimizer was used with a learning rate of 10−3, where the number of epochs and batch size were 100 and 10 for VGG-based approaches and 100 and 50 for ResNet-based approaches. The input layer was tailored to each approach, matching the number of features in its biometric template. Next, an FC layer is added with a compatible matching of the input layer size, where ReLU was used as the activation function, followed by a 20% dropout rate as a regularization layer. Another FC layer with a hundred neurons was appended to provide class probabilities (logits) for the hundred unique subjects in the dataset. Here, the Softmax activation function played a focal role in accurate classification, and is defined as follows [35]:

where

Figure 5: Separately trained and used Softmax-based FFNN as a classifier per biometric approach

Performance evaluation, analysis, and comparison of ear recognition approaches were carried out in two primary target biometric tasks: identification and verification. Therefore, this research used variant standard statistical evaluation metrics along with analytical visual representations of those suited to each target biometric task, as follows:

Ear identification performance evaluation: cumulative match characteristic (CMC) curves per experiment, enabling visual identification performance representation and comparison between different used approaches; area under the CMC-curve (CMC-AUC); CMC-based accuracy at the top-match rank 1 (R1), with its 95% confidence interval (CI), and rank 5 (R5), and the average accuracy of the first five ranks R1–R5; precision; and recall.

Ear verification performance evaluation: receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves per experiment to visualize and compare verification performance representatives while gradually varying the identity accept/reject decision thresholds from 0 to 1 along the curve and accordingly updating the true accept rate (TAR) vs. the false accept rate (FAR); the area under the ROC-curve (ROC-AUC); the equal error rate (EER) of which both accept and reject error rates (FAR and FRR) are equal; the resulting verification accuracy inferred as (1 − EER), with its 95% confidence interval (CI); the decidability index (d′) to characterize the separability between the genuine and imposter distributions.

4 Experimental Work and Results

As proof of concept, various experiments were conducted and analyzed to investigate the capabilities of the proposed ear soft biometrics in augmenting standard deep features for ear recognition purposes. Both identification and verification tasks were experimented on AMI and AMIC datasets, using SVM-based (SVM) and Softmax-based (Softmax) classifiers to evaluate and compare the performance of eight approaches. Two standard (hard biometric) deep-feature approaches, VGG-19 and ResNet-50, served as baselines for benchmarking, along with three proposed counterparts for each baseline that were augmented by different soft biometrics (i.e., SoftCat, SoftCmp, and SoftCat&Cmp). The two VGG-based and ResNet-based traditional deep-feature approaches, as well as their six augmented counterparts, listed in Table 7, were evaluated and compared in each of eight ear biometric identification and verification experiments.

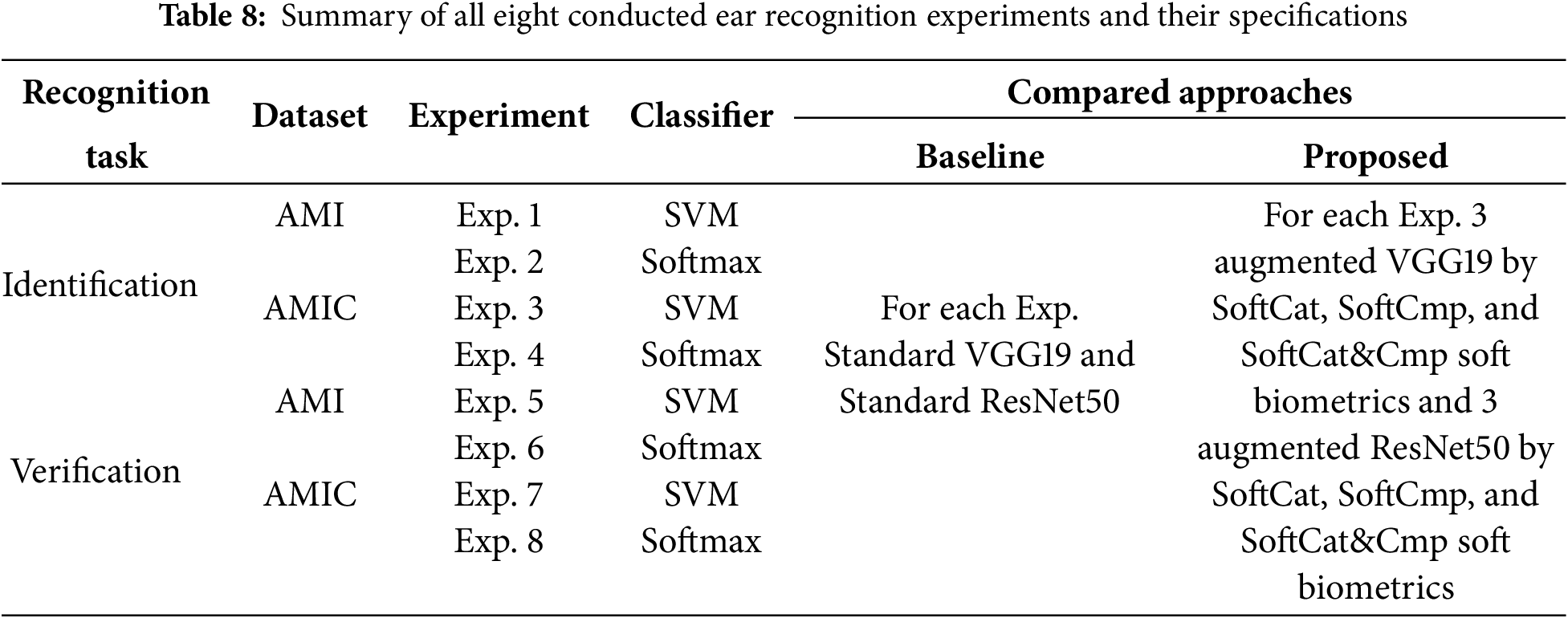

As such, eight experiments were designed to vary between target biometric recognition tasks, classifiers, datasets, and posed data challenges. They were evaluated and compared in each experiment to explore, characterize, and confirm the efficacy of the proposed augmented approaches over their unaugmented baselines. Their identification and verification performance was evaluated using different metrics and compared from different aspects to show their superiority in such enforced scenarios. Table 8 summarizes all experiments conducted in this research, which will be demonstrated in detail in the following subsections.

4.1 Ear Biometric Identification

The first group of experiments (Exp. 1 to 4) was accomplished on the ear biometric identification task, considering the scenario deployed in many real-life systems for human identification purposes. As a one-to-many recognition problem, identification uses an unknown ear sample as an unseen query biometric template to probe a gallery [1]. The system should respond to the query by deciding whether this biometric template belongs to a known subject and retrieving the top-match identity from the enrolled individuals in the gallery/training set, if any. Several standard evaluation metrics suited for identification, described in Section 3.6, besides the improvement rate (improve) as the percentile difference of R1 between the baseline and the augmented performance, were used here to investigate the potency of the proposed soft biometric-based augmented approaches and benchmark them against the traditional hard biometric deep features.

4.1.1 Augmented Ear Identification Using AMI Dataset

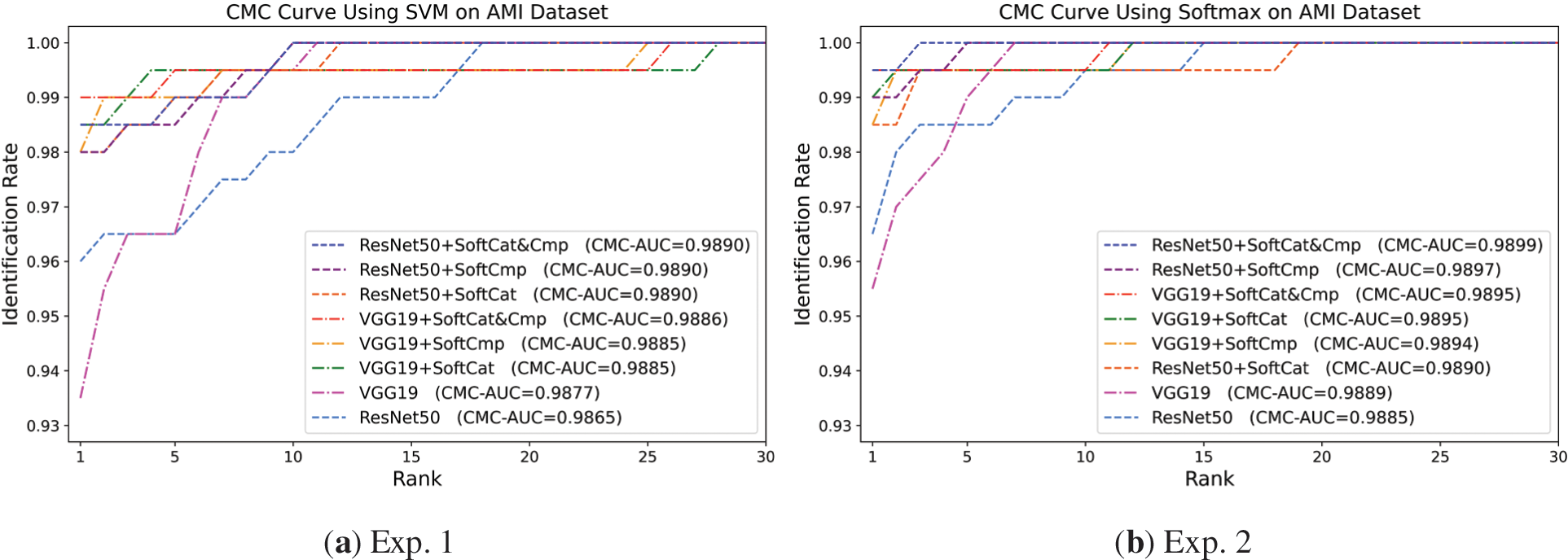

Exp. 1 and 2 were conducted on the AMI dataset using SVM and Softmax for augmenting ear identification. Table 9 presents the identification performance of Exp. 1 and 2, along with Fig. 6, which shows their corresponding CMC curves in (a) and (b), respectively. In the overview, it is evident that in both experiments, the proposed fusion of SoftCat&Cmp yielded the highest augmented identification for VGG19 and ResNet50 in all ways when used with SVM-based and Softmax-based classifiers, improving the baselines’ accuracy with rates ranging from 2.5% to 5.5%, as bolded in Table 9.

Figure 6: CMC performance of VGG19-based and ResNet50-based baseline and augmented approaches for ear biometric identification on AMI dataset. (a) Exp. 1 using the SVM classifier; (b) Exp. 2 using the Softmax-based classifier

Focusing on Exp. 1 using SVM, VGG19 + SoftCat&Cmp achieved the highest accuracy of 99% at R1, followed by ResNet50 + SoftCat&Cmp and VGG19 + SoftCat with the same 98.5% accuracy. Despite the VGG19-based augmented approaches receiving higher CMC scores in initial ranks 1–5, the ResNet50-based augmented approaches attained higher CMC-AUC scores, as shown in Fig. 6a. Still, all augmented approaches demonstrated greater CMC-AUC than the VGG19 and ResNet50 baselines. The SoftCat traits slightly outperformed the SoftCmp traits in augmenting VGG19 and ResNet50 in some metrics, signifying that such categorical soft biometrics were more functional and interactive with VGG19 deep features and SVM. Nevertheless, SoftCat and SoftCmp performed more similarly in augmenting ResNet50 in Exp. 1.

In Exp. 2 using Softmax, ResNet50 + SoftCat&Cmp was the top-performing in all means, with an R1 accuracy of 99.5% and the greatest CMC-AUC of 98.99%. Interestingly, ResNet50 + SoftCmp came second, gaining a better CMC curve and higher CMC-AUC and R5 scores than VGG19 + SoftCat&Cmp. Besides, it was the only augmented approach that achieved 100% accuracy at R5 in addition to the top-performing ResNet50 + SoftCat&Cmp. Here, once again, SoftCat was better in augmenting VGG19 identification performance. Dissimilarly, SoftCmp remarkably surpassed SoftCat by all better scores in augmenting ResNet50 identification performance, suggesting that such comparative soft biometrics (SoftCmp) was more successfully integrative and interactive with ResNet50 deep features together with Softmax for achieving augmented identification performance, despite using only about a third of the number of SoftCat traits. In Fig. 6b, all augmented approaches attained greater CMC and CMC-AUC compared to their baselines.

Table 9, together with Fig. 6, shows that soft biometrics effectively augment CNN deep features on AMI. All augmented approaches improve the baselines in identification. Adding SoftCat to deep features yields better synergistic effects when using the SVM classifier, whereas the integration between SoftCat and deep features is higher when using the Softmax classifier. The SoftCat&Cmp combination achieves the best augmentation and maximum interaction because it integrates the potencies of both Cat and Cmp soft traits.

4.1.2 Augmented Ear Identification Using AMIC Dataset

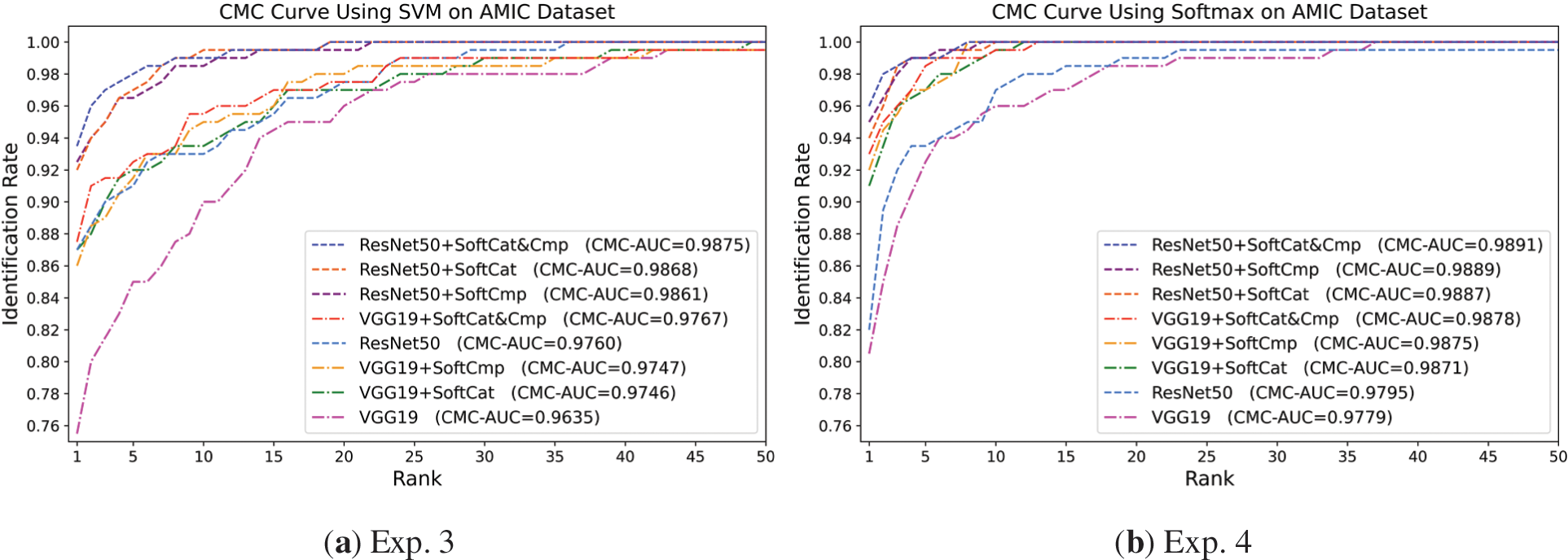

Two further ear identification experiments Exp. 3 and 4 were conducted on AMIC, which comprised more challenging cropped ear images. Exp. 3 used SVM as a classifier, whereas Exp. 4 used Softmax instead. Table 10 reports Exp. 3 and 4 identification performance results on the AMIC dataset. Fig. 7 illustrates CMC curves, enabling a visual performance comparison. Generally, SoftCat&Cmp-based augmented approaches were superior in augmenting the performance of VGG19 and ResNet50 baseline approaches using both SVM-based and Softmax-based classifiers, receiving their highest accuracy of 93% and 96%, respectively, with significant improvement rates reaching up to 14%. All SoftCmp-based augmented approaches, except VGG19 + SoftCmp with SVM, outperformed their SoftCat-based augmented counterparts and obtained higher results and more prosperous identification augmentation on the more challenging AMIC data.

Figure 7: CMC performance of VGG19-based and ResNet50-based baseline and augmented approaches for ear biometric identification on AMIC dataset. (a) Exp. 3 using the SVM classifier; (b) Exp. 4 using the Softmax-based classifier

Table 10 and Fig. 7 confirm the contribution to significantly augmenting CNN deep features with soft biometrics in identification. SoftCmp appears more significant than SoftCat in augmenting deep features, reflecting its higher perceptual capabilities on challenging AMIC. Their SoftCat&Cmp integration attains the highest overall improvement. Augmented ResNet50 approaches outperform augmented VGG19 counterparts, as they incorporate more features that more effectively interact with soft biometrics in the fusion.

Concerning Exp. 3 using SVM, VGG19 + SoftCat&Cmp attained the highest performance among the other VGG19-based approaches and was the only one to exceed the ResNet50 baseline, as in Table 10 and Fig. 7a, which performed better than the VGG19 as a baseline. Although, VGG19 + SoftCat&Cmp and ResNet50 + SoftCat&Cmp were the most superior among their corresponding VGG19-based and ResNet50-based peers, VGG19 + SoftCat and ResNet50 + SoftCmp scored the highest precisions amongst the VGG19-based and ResNet50-based approaches, respectively. Based on the CMC performance representation in Fig. 7a, all ResNet50-based augmented approaches surpassed all VGG19-based augmented approaches, with higher CMC-AUC ranging between 98.61% to 98.75%.

In Exp. 4 using Softmax, as consistently observed in Table 10 and Fig. 7b, the performance improvement was more systematic, such that the SoftCat&Cmp, SoftCmp, and SoftCat traits consecutively augmented the ResNet50 then VGG19 deep features, for all metrics. ResNet50 + SoftCat&Cmp significantly augmented identification to jump from 82% to 96% on a more challenging scenario using only available soft/hard biometric information, limited to AMIC’s cropped ear images. VGG19 + SoftCmp and ResNet50 + SoftCmp, which were equipped with fewer discriminative comparative traits, consistently achieved higher performance in all aspects than VGG19 + SoftCat and ResNet50 + SoftCat augmented with categorical traits of around triple the number of the comparative traits.

4.2 Ear Biometric Verification

The second group of experiments (Exp. 5 to 8) was carried out on the ear biometric verification task concerning the scenario enforced in numerous real-life applications for human verification. In this task, an unseen ear sample for a claimed identity is used as a query biometric template to probe a gallery as a one-to-one recognition problem [1]. The system should consider the query by confirming whether the biometric template truly belongs to the claimed subject’s identity and deciding whether to accept or reject it based on its authenticity to the previously enrolled templates for that claimed subject in the gallery/training set, as per the confidence level control. Verification standard performance evaluation metrics, described in Section 3.6, and the improvement rate (improve) deduced as the percentile difference of (1 − EER) between the baseline and the augmented performance, were used here to explore the proposed soft biometric augmentation capabilities and benchmark them against the traditional hard biometric deep features in isolation. The degree of confidence in accepting or rejecting a claimed identity was determined by varying the decision thresholds between 0 and 1 along the ROC curve while recalculating both TAR and FAR for each threshold.

4.2.1 Augmented Ear Verification Using AMI Dataset

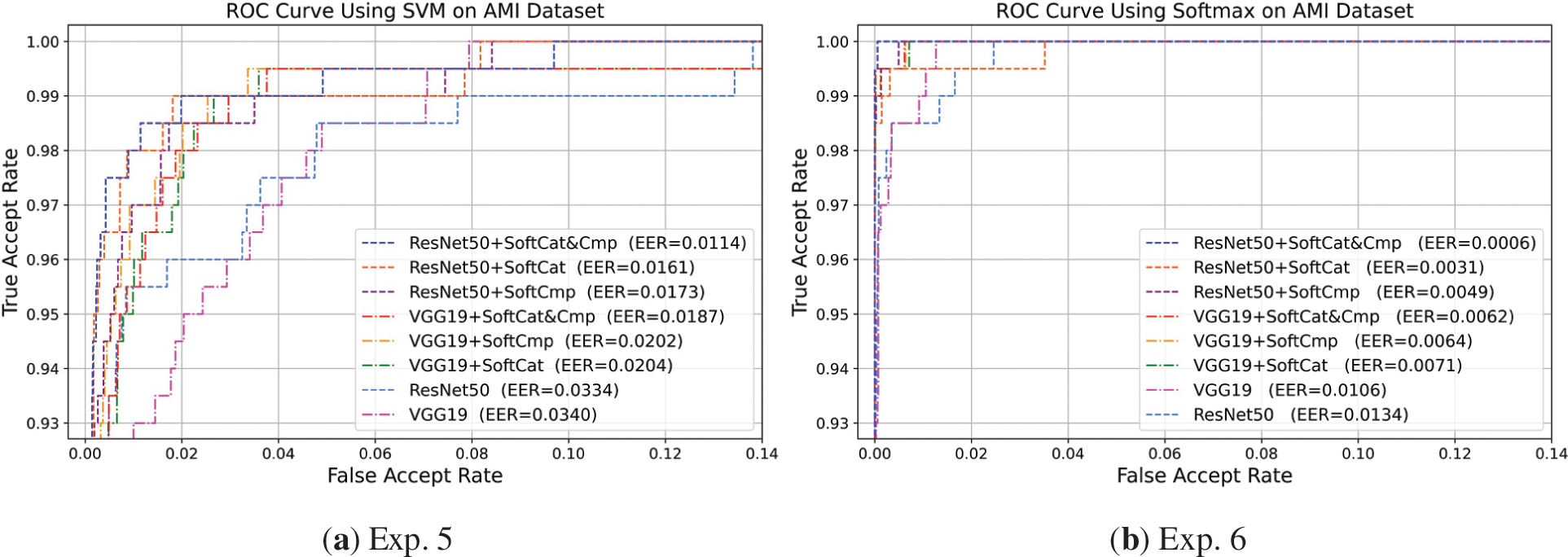

Augmenting ear verification was enforced when using SVM in Exp. 5 and Softmax in Exp. 6 classifiers on the AMI dataset. Ear verification performance is reported in Table 11 for Exp. 5 and 6, characterizing and comparing all standard and augmented approaches. Also, ROC performance representations are illustrated in Fig. 8a for SVM-based approaches of Exp. 5 and Fig. 8b for Softmax-based approaches of Exp. 6.

Figure 8: ROC performance of VGG19-based and ResNet50-based baseline and augmented approaches for ear biometric verification on the AMI dataset. (a) Exp. 5 using the SVM classifier; (b) Exp. 5 using the Softmax-based classifier

In Exp. 5 using SVM, ResNet50 + SoftCat&Cmp attained the highest ROC-AUC of 99.89% and accuracy (1 − EER) of 98.86% with the lowest EER of 0.011 scores over all augmented approaches. Whilst ResNet50 + SoftCmp obtained the highest d′ score overall. All proposed soft biometric traits augmented the performance of VGG19; however, the SoftCmp traits enhanced ROC-AUC better, the SoftCmp then SoftCat traits improved d′ better, and their combination in SoftCat&Cmp reduced EER better. As in Fig. 8a, the ResNet50-based augmented approaches offered better verification performance with greater ROC-AUC and lower EER rates than the VGG19-based augmented approaches.

Table 11, along with Fig. 8, provides supportive performance results for the contribution to augmenting deep features with soft biometrics in verification on the AMI dataset. SoftCat&Cmp enforces the best augmented verification utilizing all possible viability of Cat and Cmp traits. All augmented approaches surpass the verification performance of the baselines. Here, SoftCat improves the ResNet50 performance better, whereas SoftCmp improves VGG19 better, due to the variability posed by different biometric scenarios.

4.2.2 Augmented Ear Verification Using AMIC Dataset

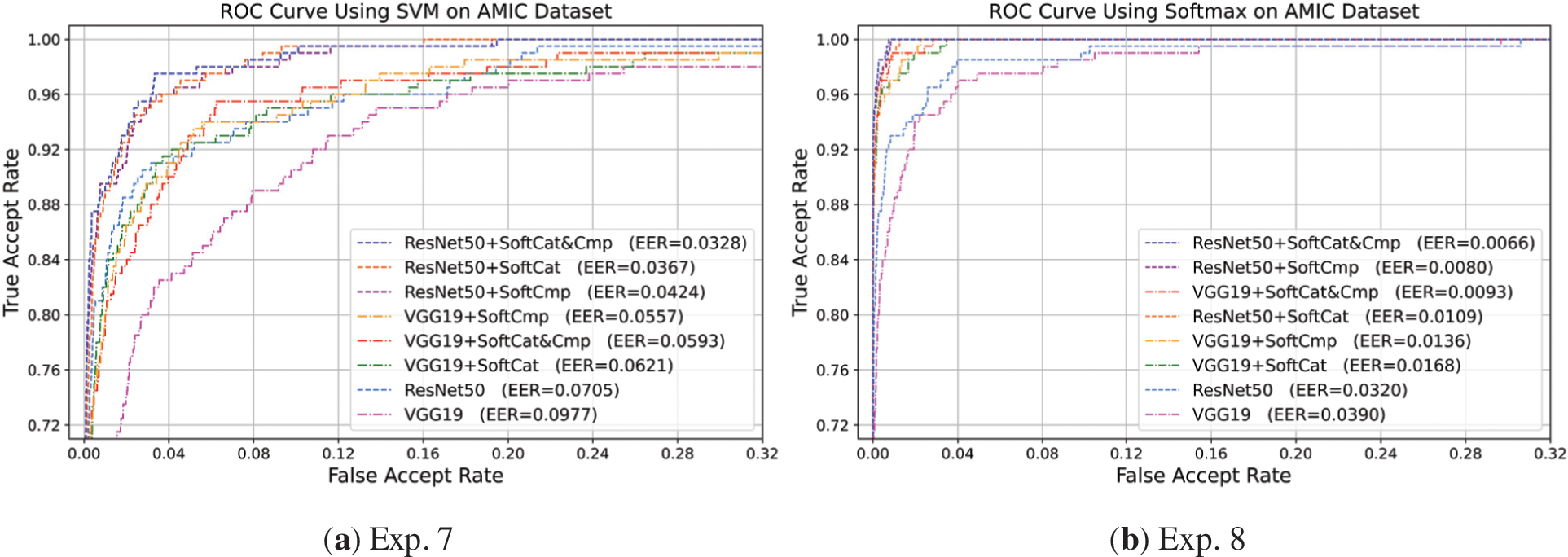

Additional ear verification experiments Exp. 7 and 8 were performed on the AMIC’s more challenging data. Table 12 provides ear verification performance results for VGG19-based and ResNet50-based baselines and proposed approaches on the AMIC dataset, using SVM in Exp. 7 and Softmax in Exp. 8 as classifiers. Accordingly, the corresponding ROC performance for Exp. 7 and 8 are shown in Fig. 9a,b.

Figure 9: ROC performance of VGG19-based and ResNet50-based baseline and augmented approaches for ear biometric verification on the AMIC dataset. (a) Exp. 7 using the SVM classifier; (b) Exp. 8 using the Softmax-based classifier

The results in Table 12 and Fig. 9 emphasize that SoftCat&Cmp enforces the most augmentation for CNN deep features and best performance in challenging verification on AMIC. SoftCmp is the second-best performer, revealing increased discrimination with the highest genuine-imposter separability. SoftCmp traits offer several advantages over SoftCat traits, especially in verification, as they can detect and characterize subtle differences between compared individuals based on specific soft biometric attributes.

In Exp. 7, using SVM, ResNet50 + SoftCat&Cmp received the greatest ROC-AUC of 99.51% and accuracy (1 − EER) of 96.72% associated with the lowest EER of 0.0328, though ResNet50 + SoftCmp scored a higher d′ of 0.394 and VGG19 + SoftCmp scored the highest d′ of 0.528. Notably, the SoftCmp traits showed their efficient capabilities in augmenting verification performance, where VGG19 + SoftCmp surpassed VGG19 + SoftCat&Cmp with a lower EER and higher d′ score, while VGG19 + SoftCat&Cmp still had a larger ROC-AUC. Fig. 9a visually characterizes and compares the ROC curves of all approaches using SVM on AMIC. It can also be observed here that the ResNet50-based approaches outperformed the VGG19-based approaches. This finding indicates that the proposed ResNet50-based augmented approaches are more reliable for robust ear verification systems.

In Exp. 8, using Softmax, the SoftCat&Cmp traits continuously attained the highest augmented verification results involving ROC-AUC, accuracy (1 − EER), and EER. However, SoftCmp was superior in gaining the highest genuine/imposter separability by d′ of 5.56 for VGG19 + SoftCmp and 5.05 for ResNet50 + SoftCmp. Hence, this nominated the SoftCmp traits as more viable discriminative traits for augmenting biometric verification than SoftCat. As shown in Fig. 9b and Table 12 results, ResNet50 + SoftCat&Cmp achieved the best-augmented performance with a 99.98% ROC-AUC, 99.34% accuracy, and 0.0066 EER, followed by ResNet50 + SoftCmp then VGG19 + SoftCat&Cmp.

4.3 Overall Performance Summary and Comparison with Related Studies

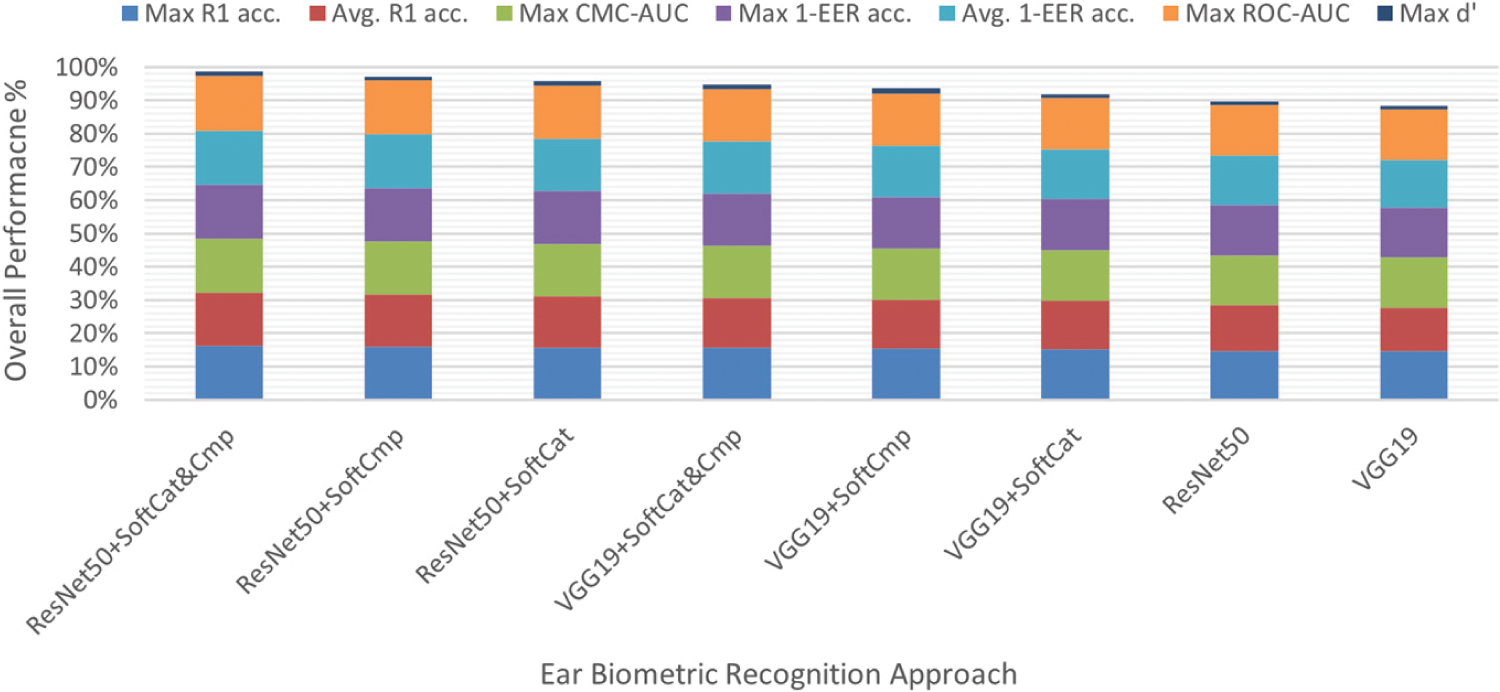

The overall ear identification and verification performance for all approaches used across the extended experimental work can be summarized as follows. Table 13 highlights selected key performance indicators for ear identification and verification, using both SVM and Softmax classifiers on both AMI and AMIC datasets, where the eight approaches are ranked by their overall performance measured by all major evaluation metrics. Furthermore, Fig. 10 accordingly visualizes the overall performance comparison of CMC-based metrics for identification and ROC-based metrics for verification and emphasizes the concluded overall rank of all eight approaches. Besides, Table 14 compares this research with several related studies.

Figure 10: Overall performance summary of CMC-based identification metrics and ROC-based verification metrics on AMI and AMIC using SVM and Softmax, where approaches are ranked from the highest to the lowest performance

Based on the overall performance reported in Table 13 and Fig. 10, regardless of which SVM or Softmax was used, all six proposed augmented approaches successfully enhanced the deep-feature performance. Consequently, the standard VGG19 and ResNet50 approaches without augmentation ranked last as seventh and eighth overall, stressing the effectiveness of all augmented approaches. Where either the AMI or AMIC dataset was used, as shown in Table 13, all R1 accuracy max scores were gained using Softmax as the classifier. As such, Softmax is better-performing and more efficient than SVM in such ear recognition problems.

All three ResNet50-based augmented approaches were assigned overall ranks from 1st to 3rd since they outperformed all three VGG19-based approaches, which were assigned lower overall ranks from 4th to 6th. Hence, compared to VGG19, the ResNet50 deep features are more reliable and discriminative in the ear identification/verification context, especially when fused with soft biometrics. VGG19 + SoftCat&Cmp and ResNet50 + SoftCat&Cmp were the top performers within their respective VGG19-based and ResNet50-based groups. ResNet50 + SoftCat&Cmp ranked first among all, owing to its supremacy in all evaluations. Thus, SoftCat&Cmp can enforce the utmost augmentation for VGG19 and ResNet50 deep features by combining both categorical and comparative soft biometric capabilities.

ResNet50 + SoftCmp was ranked second-best, indicating that SoftCmp empowers more perceptive and informative comparative soft biometrics than those categorical soft biometrics used in SoftCat. Exceptionally, VGG19 + SoftCmp obtained the highest overall d′ in verification, enabling increased separability between the genuine and imposter populations for more confident accept/reject thresholding. The SoftCmp traits augmented the ResNet50 deep features better, whereas the SoftCat traits were better in augmenting the VGG19 deep features. That means the comparative soft biometric traits (SoftCmp) are more viable and contribute most to augmenting ResNet50. In contrast, the categorical soft biometric traits (SoftCat) are more efficacious and integrate most with VGG19 for augmenting performance.

The primary focus of this research is to investigate the capabilities of newly proposed ear soft biometrics in augmenting the performance of traditional hard biometric CNN-based deep features. Hence, as an initial novel study, all experiments were conducted using AMI and AMIC datasets along with their available raw soft labels, while varying recognition scenarios, hard biometric deep-feature extractors, soft biometric augmentation methods, and matching classifiers. Through these variations, the performance variability and generalizability were evaluated, with all results confirming the robustness and superiority of the proposed augmented approaches in all respects. AMI and AMIC were utilized as different variants of widely used standard benchmark datasets, posing various difficulty levels and challenge aspects [1,3,5,21,23]. They were chosen over others due to the availability of their raw soft labels, making them most suited for the current research context and initial study. However, they still can be replaced with any other datasets after soft label annotation for all ear images. In terms of maximizing dataset generalizability, the variations in illumination, occlusion, deformation, and ear accessories pose further challenging conditions to consider in a forthcoming extended exploration of the proposed framework using other datasets that incorporate such conditions, e.g., WPUT, EarVN1.0, and USTB, for extensive cross-dataset performance validation and comparison.

Several remarks are noteworthy in the overview of the computational complexity anticipated for the proposed augmented approaches. In all six augmented approaches, given that both VGG-19 and ResNet-50 pre-trained models are used merely as backbones for deep feature extraction, which is the most computationally intensive. Then, the extracted 512 VGG-19-based and 2048 ResNet-50-based deep features are supplemented by fusing them with different combinations of either 13, 34, or 47 soft biometrics. As such, each augmented approach introduces moderate computational complexity, which primarily relies on the conventional processes for deep feature extraction. Namely, the additional fusion process of low-dimensional soft biometric groups poses only a negligible footprint in comparison. RankSVM is conducted only once for each of the 13 comparable soft biometric attributes as a separate prior process needed to learn a ranking function. However, its computational complexity is considerably minimized by generating only about 20% of all possible pairwise comparisons and then using them to enforce the desired ordering, while using those learned ranking functions for mapping relative features to extract comparative soft biometrics is also negligible. Thus, all newly added processes in our proposed augmented approaches yield a tractable representation that enables scalable ear biometric recognition with minimal impact on runtime. The overall architecture offers high discriminative power, achieving significant performance improvements with manageable memory and computational demands, particularly during identification and verification.

Eventually, the current research study was further compared with several related studies to gain a deeper understanding and differentiation. Table 14 compares the different characteristics and performance aspects of this research with other most relevant studies. The comparisons highlight its contributions and advantages over existing literature. They also accentuate the promising ear recognition results of the proposed soft biometric-based augmented approaches, which offer competitive performance to earlier relevant hard and soft biometric approaches utilizing machine learning or deep learning technologies.

This research study introduces a novel framework empowered by increased discriminatory soft biometrics to augment CNN-based ear biometric recognition. The framework extracts a group of fine-grained categorical and newly proposed comparative soft biometrics as more perceptive traits. It also extracts VGG and ResNet deep features as traditional hard biometric traits. It then enforces feature-level fusion of hard biometric deep features with different combinations of categorical and comparative soft biometric traits, resulting in several augmented approaches. It finally conducts multiple human identification and verification experiments to evaluate, analyze, and compare the performance of augmented vs. unaugmented approaches while varying ear image datasets, hard biometric deep-feature extractors, and classifiers.

Indeed, soft biometrics can effectively augment CNN deep features for enhanced ear recognition. Comparative soft biometric traits can offer increased discrimination and augmentation capabilities compared to categorical traits, even when fewer comparative traits are used in isolation. Combining both categorical and comparative soft biometrics and integrating their capabilities can improve recognition even further. The experimental investigation reveals significantly augmented identification and verification and promising performance results, which reach up to 99.94% accuracy and improve up to 14%.

The availability of categorical soft biometrics for large-scale ear image datasets is a possible limitation facing this study, signifying a priority initiative to also automate the categorical soft biometric labeling process as potential future work. Such an initiative is motivated by this study, and its pursuance can be inspired by the practical automatic comparative soft biometric labeling and feature extraction by the proposed framework to advance this promising domain. Another limitation to consider in future work is investigating the expected invariance capabilities of the proposed comparative-based soft biometrics on other challenging datasets, such as WPUT, EarVN1.0, and USTB, with various deformations, occlusions, illuminations, and ear accessories. The proposed method can also supplement other ear-dedicated methods and compare with their standard performance.

In future venues, the proposed augmented ear biometric approaches can be extended to further helpful applications and more problem-specific biometric scenarios for various person identification, verification, re-identification, and retrieval. They can also be devoted to contributing to multimodal biometric fields, such as using them as hard-soft ear biometrics along with face biometrics for augmenting side/profile face recognition. Further extended analysis of potential correlations between the fusible soft and hard features may provide a better understanding and practical insights for future investigations.

Acknowledgement: The author acknowledges with thanks KAU Endowment (WAQF) and the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University (KAU), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, for financial support for this research publication. The author would also like to thank Ms. Ghoroub Talal Bostaji for collaborating in an earlier related research study, yielding the raw soft label data utilized in this research.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by WAQF at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used in this article are available in the AMI Ear Database [30] and the AMI-Based AMIC and Ear Categorical Soft Biometric Labels datasets [1].

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Figure A1: Human ear anatomical structure, where the overlay-colored parts are the significant for physical feature extraction (hard biometrics) and the most discriminative, describable, and comparable for practical soft biometrics

References

1. Talal Bostaji G, Sami Jaha E. Fine-grained soft ear biometrics for augmenting human recognition. Comput Syst Sci Eng. 2023;47(2):1571–91. doi:10.32604/csse.2023.039701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Nelufule N, Mabuza-Hocquet G, de Kock A. Circular interpolation techniques towards accurate segmentation of iris biometric images for infants. In: Proceedings of the 2020 International SAUPEC/RobMech/PRASA Conference; 2020 Jan 29–31; Cape Town, South Africa. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/saupec/robmech/prasa48453.2020.9041135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Benzaoui A, Khaldi Y, Bouaouina R, Amrouni N, Alshazly H, Ouahabi A. A comprehensive survey on ear recognition: databases, approaches, comparative analysis, and open challenges. Neurocomputing. 2023;537(1–3):236–70. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.03.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kamboj A, Rani R, Nigam A. A comprehensive survey and deep learning-based approach for human recognition using ear biometric. Vis Comput. 2022;38(7):2383–416. doi:10.1007/s00371-021-02119-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Alshazly H, Linse C, Barth E, Martinetz T. Ensembles of deep learning models and transfer learning for ear recognition. Sensors. 2019;19(19):4139. doi:10.3390/s19194139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Jaha ES, Nixon MS. From clothing to identity: manual and automatic soft biometrics. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2016;11(10):2377–90. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2016.2584001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hassan B, Izquierdo E, Piatrik T. Soft biometrics: a survey: benchmark analysis, open challenges and recommendations. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(5):15151–94. doi:10.1007/s11042-021-10622-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Alsubhi AH, Jaha ES. Front-to-side hard and soft biometrics for augmented zero-shot side face recognition. Sensors. 2025;25(6):1638. doi:10.3390/s25061638. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Tiwari S. Fusion of ear and soft-biometrics for recognition of newborn. Signal Image Process. 2012;3(3):103–16. doi:10.5121/sipij.2012.3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Purkait R. Application of external ear in personal identification: a somatoscopic study in families. Ann Forensic Res Anal. 2015;2(1):1015. [Google Scholar]

11. Saeed U, Khan MM. Combining ear-based traditional and soft biometrics for unconstrained ear recognition. J Electron Imag. 2018;27(5):051220. doi:10.1117/1.jei.27.5.051220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mohamed Y, Youssef Z, Heakl A, Zaky AB. Advancing ear biometrics: enhancing accuracy and robustness through deep learning. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Intelligent Methods, Systems, and Applications (IMSA); 2024 Jul 13–14; Giza, Egypt. p. 437–42. doi:10.1109/IMSA61967.2024.10652851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Sharma R, Sandhu J, Bharti V. Improved multimodal biometric security: OAWG-MSVM for optimized feature-level fusion and human authentication. In: Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Cybersecurity (ISCS); 2024 May 3–4; Gurugram, India. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/ISCS61804.2024.10581400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Alshazly H, Linse C, Barth E, Martinetz T. Deep convolutional neural networks for unconstrained ear recognition. IEEE Access. 2020;8:170295–310. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3024116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Toygar Ö, Alqaralleh E, Afaneh A. Symmetric ear and profile face fusion for identical twins and non-twins recognition. Signal Image Video Process. 2018;12(6):1157–64. doi:10.1007/s11760-018-1263-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Emeršič Ž, Štruc V, Peer P. Ear recognition: more than a survey. Neurocomputing. 2017;255(3):26–39. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2016.08.139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Korichi A, Slatnia S, Aiadi O. TR-ICANet: a fast unsupervised deep-learning-based scheme for unconstrained ear recognition. Arab J Sci Eng. 2022;47(8):9887–98. doi:10.1007/s13369-021-06375-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Tomar V, Kumar N, Deshmukh M, Singh M. Single sample face and ear recognition using transfer learning and sample expansion. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computer, Electronics, Electrical Engineering & Their Applications (IC2E3); 2024 Jun 6–7; Srinagar, India. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/IC2E362166.2024.10827249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Alomari EAM, Yang S, Hoque S, Deravi F. Ear-based person recognition using Pix2Pix GAN augmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference of the Biometrics Special Interest Group (BIOSIG); 2024 Sep 25–27; Darmstadt, Germany. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/BIOSIG61931.2024.10786744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Khaldi Y, Benzaoui A. A new framework for grayscale ear images recognition using generative adversarial networks under unconstrained conditions. Evol Syst. 2021;12(4):923–34. doi:10.1007/s12530-020-09346-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Aiadi O, Khaldi B, Saadeddine C. MDFNet: an unsupervised lightweight network for ear print recognition. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2023;14(10):13773–86. doi:10.1007/s12652-022-04028-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Sharkas M. Ear recognition with ensemble classifiers: a deep learning approach. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022;81(30):43919–45. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-13252-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Xu X, Liu Y, Liu C, Lu L. A feature fusion human ear recognition method based on channel features and dynamic convolution. Symmetry. 2023;15(7):1454. doi:10.3390/sym15071454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Resmi K, Raju G, Padmanabha V, Mani J. Person identification by models trained using left and right ear images independently. In: Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Innovation in Information Technology and Business (ICIITB 2022); 2022 Nov 9–10; Muscat, Oman. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Atlantis Press; 2022. p. 281–8. [Google Scholar]

25. Nixon MS, Jaha ES. Soft biometrics for human identification. In: Ahad MAR, Mahbub U, Turk M, Hartley R, editors. Computer vision. New York, NY, USA: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2024. p. 33–60. doi: 10.1201/9781003328957-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ezichi S. A comparative study of soft biometric traits and fusion systems for face-based person recognition. Int J Image Graph Signal Process. 2021;13(6):45–53. doi:10.5815/ijigsp.2021.06.05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Jaha ES, Nixon MS. Soft biometrics for subject identification using clothing attributes. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Joint Conference on Biometrics; 2014 Sep 29–Oct 2; Clearwater, FL, USA. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/BTAS.2014.6996278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]