Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Hybrid CNN Architecture for Hot Spot Detection in Photovoltaic Panels Using Fast R-CNN and GoogleNet

1 HCTLab Research Group, Electronics and Communications Technology Department, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, 28049, Spain

2 Ingenium Research Group, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Ciudad Real, 13071, Spain

3 Department of Engineering, School of Architecture, Engineering and Design, Universidad Europea de Madrid, Villaviciosa de Odon, 28670, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Fausto Pedro García Márquez. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Data Analysis Techniques in Renewable Energy)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(3), 3369-3386. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.069225

Received 18 June 2025; Accepted 11 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Due to the continuous increase in global energy demand, photovoltaic solar energy generation and associated maintenance requirements have significantly expanded. One critical maintenance challenge in photovoltaic installations is detecting hot spots, localized overheating defects in solar cells that drastically reduce efficiency and can lead to permanent damage. Traditional methods for detecting these defects rely on manual inspections using thermal imaging, which are costly, labor-intensive, and impractical for large-scale installations. This research introduces an automated hybrid system based on two specialized convolutional neural networks deployed in a cascaded architecture. The first convolutional neural network efficiently detects and isolates individual solar panels from high-resolution aerial thermal images captured by drones. Subsequently, a second, more advanced convolutional neural network accurately classifies each isolated panel as either defective or healthy, effectively distinguishing genuine thermal anomalies from false positives caused by reflections or glare. Experimental validation on a real-world dataset comprising thousands of thermal images yielded exceptional accuracy, significantly reducing inspection time, costs, and the likelihood of false defect detections. This proposed system enhances the reliability and efficiency of photovoltaic plant inspections, thus contributing to improved operational performance and economic viability.Keywords

The rapid expansion of photovoltaic (PV) installations globally reflects the growing demand for renewable and sustainable energy sources. Solar PV panels, being the core component of these installations, require continuous and reliable performance to maximize energy production and ensure economic viability. However, photovoltaic panels are susceptible to various operational challenges, such as environmental degradation, dirt accumulation, and particularly, the formation of hot spots. These hot spots result from individual solar cells malfunctioning or degrading, leading to overheating due to energy absorption rather than its conversion into electricity [1]. If left undetected, these localized overheating issues can cause significant efficiency losses, damage the photovoltaic modules irreversibly, and reduce the overall lifespan of the installation [2].

Traditionally, inspection and maintenance tasks aimed at detecting hot spots and other panel defects have been carried out manually by specialized technicians using handheld thermal imaging cameras. This approach is not only costly but also labor-intensive and time-consuming, especially given the large-scale and often remote nature of modern solar power plants [3]. In recent years, technological advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), particularly in the fields of computer vision and machine learning, have presented viable alternatives to automate and significantly enhance the efficiency of such inspections.

Thermal imaging cameras mounted on UAVs have recently emerged as a highly effective solution for large-scale and efficient inspection of photovoltaic installations [4]. UAVs equipped with thermal cameras capture aerial images of entire solar fields, clearly highlighting overheated cells as bright spots. These images provide substantial datasets that can be leveraged by convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and other deep learning models to autonomously detect and accurately classify solar panel defects [5]. Furthermore, integrating these AI-based detection methods with geographic information systems (GIS) or Internet of Things (IoT) platforms allows for real-time monitoring, precise localization, and efficient scheduling of maintenance tasks.

This research proposes a novel approach combining two specialized convolutional neural networks arranged in a cascaded structure. The first neural network is designed specifically for accurately detecting and isolating individual photovoltaic panels from aerial images obtained by drone-based thermal imaging. Subsequently, the second neural network classifies the isolated panels to identify the presence or absence of defects, specifically targeting hot spot detection. This specialized cascading method aims to enhance detection accuracy, significantly reduce false-positive detections, particularly those caused by sun reflections, and streamline the overall inspection process.

The specific objectives of this work are as follows:

• To create a comprehensive database of thermal images captured by drones from operational solar installations.

• To manually annotate and prepare these images, distinguishing solar panels from background noise and classifying them based on their condition.

• To select, design, and train a specialized region-based CNN (Fast R-CNN) model to identify and isolate individual photovoltaic panels effectively.

• To design and train a robust and precise classification CNN (e.g., GoogleNet) to detect panels with hot spot defects, accurately distinguishing them from healthy panels and false-positive cases due to reflections.

• To integrate these two CNN models into a unified, automated algorithm capable of performing high-precision, real-time detection and classification tasks.

By deploying this integrated and automated AI-driven inspection methodology, the proposed system significantly reduces the reliance on manual inspections, optimizes maintenance operations, and substantially lowers associated operational costs. Consequently, this work contributes directly to the improvement of photovoltaic plant productivity, sustainability, and economic competitiveness.

2.1 Overview of Photovoltaic System Maintenance

Solar photovoltaic (PV) energy represents one of the most promising and rapidly evolving renewable energy sources today, involving the direct conversion of sunlight into electricity through solar cells. Recent advancements have significantly reduced the cost of solar cells while simultaneously improving their conversion efficiency [6]. Additionally, developments in battery technologies and energy storage systems have made solar photovoltaic installations more reliable and practical, leading to rapid global adoption across diverse applications, from residential rooftops to large-scale solar power plants [7]. Despite these advancements, challenges such as sunlight variability and limited large-scale storage remain, necessitating continued research and innovation [8].

In contrast to traditional non-renewable sources, photovoltaic technology offers substantial environmental benefits, emitting no greenhouse gases and significantly reducing the harmful effects associated with global warming [9]. Solar technologies can be broadly classified based on their function and energy conversion processes into photovoltaics (directly converting solar radiation to electricity), thermal collectors (capturing solar energy to heat fluids for industrial or domestic use), and hybrid systems (combining both electrical and thermal energy production) [10]. This research specifically addresses photovoltaic panels, focusing on their operational challenges and defects that negatively impact their efficiency and reliability.

2.2 Hot Spot Formation and Effects

One of the major operational issues with photovoltaic panels is the accumulation of dirt and contaminants. External pollutants such as dust, leaves, branches, and bird droppings significantly obstruct the absorption of solar radiation, potentially causing efficiency losses of up to 50%. Consequently, regular and effective cleaning strategies are critical for maintaining optimal photovoltaic panel performance [11].

Another critical issue impacting photovoltaic panel efficiency is the occurrence of hot spots. Hot spots are localized overheating defects caused by cell malfunctions or degradation. Affected cells cease to convert solar radiation into electrical energy, instead absorbing radiation and overheating. This phenomenon reduces panel efficiency and may lead to permanent cell damage [12,13]. Regular inspection and proactive maintenance are essential to identify and repair these defective cells before significant damage occurs. Various innovative methodologies have been developed to automate hot spot detection. For example, in [14], the authors propose a deep learning method specifically designed for accurately segmenting hot spots from thermal images of photovoltaic panels. A different and complementary approach is presented in [15], where the authors develop a real-time detection platform suitable for practical deployment in photovoltaic power plants.

2.3 Non-Destructive Testing Methods

Non-destructive testing (NDT) techniques have emerged as critical methods for diagnosing photovoltaic panel conditions without causing any physical damage. Among these, thermal imaging has become prominent due to its cost-effectiveness, speed, and adaptability [16]. Thermal imaging identifies hot spots by capturing temperature anomalies caused by solar cell malfunctions or degradation. This method allows for early-stage defect identification, significantly reducing maintenance costs and downtime [17–20].

Significant research efforts have aimed to enhance the precision and reliability of thermal imaging methodologies. In the work [21], the authors propose advanced deep learning frameworks to improve the early detection of hot spots, offering superior accuracy compared to traditional thermal imaging methods. In a related effort, Ref. [22] presents an unsupervised clustering method to segment and accurately detect malfunctioning photovoltaic modules, thereby enhancing detection speed and reliability.

2.4 Deep Learning in Solar Panel Inspection

More recently, sophisticated computer vision and deep learning techniques have been introduced to overcome common limitations of thermal image analysis, such as false positives induced by solar reflections. A notable contribution in this area is found in [23]. Here, the authors developed unsupervised sensing algorithms that differentiate actual deterioration from reflection-induced artifacts, substantially reducing false-positive detections [24].

Moreover, the integration of deep learning techniques with UAVs has further revolutionized photovoltaic inspection processes. UAV-based thermal imaging systems combined with convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and vision transformers have provided highly accurate and automated defect detection capabilities. For instance, Ref. [25] compares state-of-the-art machine learning methods applied to drone-captured thermal imagery, concluding that modern vision transformer models can significantly enhance detection accuracy compared to conventional CNN-based methods. In this context, Ref. [26] proposed TransPV, a hybrid architecture combining U-Net and Vision Transformer mechanisms, which incorporates Mix Transformer blocks for global context modeling and a PointRend module for refining segmentation boundaries. Their model achieved superior performance in PV segmentation tasks, particularly in hetergeneous environments, reporting an accuracy of 87.6% and demonstrating strong generalization capabilities across diverse datasets. This work highlights the potential of transformer-based architectures for improving semantic segmentation in complex photovoltaic scenarios.

Additionally, Ref. [27] introduced an innovative self-supervised learning approach. This method effectively isolates hotspots from thermal images without extensive labeled data, significantly reducing annotation costs and improving the generalization capability of hotspot detection algorithms. Likewise, Ref. [28] leveraged supervised contrastive learning techniques to robustly distinguish actual defects from non-defective anomalies, providing superior results compared to traditional binary classification approaches.

In the context of integrated frameworks combining multiple technologies, Ref. [29] introduced an advanced artificial intelligence approach. This method optimizes photovoltaic power generation efficiency by integrating solar photovoltaic systems with wind turbines and fuel cells, employing AI-driven point tracking techniques for enhanced overall performance.

The advancement of convolutional neural networks has significantly improved the accuracy and efficiency of defect detection in photovoltaic systems. Recent studies highlight CNN-based approaches specifically tailored for solar panel defect recognition and hot spot detection. For instance, in the study [30], CNN architectures were applied to aerial imagery, achieving high accuracy in recognizing and segmenting photovoltaic panels within large-scale solar plants. Similarly, the research [31] introduced a specialized CNN framework to effectively analyze infrared images, significantly enhancing hotspot detection performance in diverse environmental conditions.

In contrast to the cascaded architecture employed in this work, several studies have explored single-network approaches based on You Only Look One (YOLO) architectures for photovoltaic panel and defect detection. For instance, Yin et al. (2023) proposed PV-YOLO, a network that enhances YOLOX by integrating Vision Transformer (PVTv2) features, achieving a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 92.56%, which represents a 10.46% improvement over YOLOX in the detection of small photovoltaic objects [32].

Similarly, Ghahremani et al. (2025) conducted a comparative evaluation of YOLOv9, YOLOv10, and YOLOv11 for hot spot detection, showing that YOLOv11-X achieved 89.7% precision, 87.7% recall, 92.7% mAP, and an F1-score of 90% on their custom dataset [33].

Beyond these purely detection-oriented models, other researchers have proposed hybrid solutions that integrate segmentation and detection in a unified framework. In [34], the authors introduced Deeplab-YOLO, which combines semantic segmentation and object detection, yielding a 2.6% increase in segmentation accuracy and a 0.7% improvement in hot spot detection compared to baseline detectors.

While these approaches demonstrate the potential of unified or single-stage systems in terms of accuracy and computational efficiency, the modular nature of our cascaded architecture offers distinct advantages. By decoupling the panel detection and defect classification tasks, our method enables independent optimization at each stage, enhancing interpretability and adaptability to diverse inspection scenarios.

2.5 UAV and IoT-Based Monitoring Solutions

Another key innovation has been the integration of CNN models with Internet of Things (IoT) technology. The research [35] presents a novel autonomous system that combines CNN-based fault detection algorithms with IoT-enabled sensor networks. Their proposed framework enables real-time monitoring and predictive maintenance of photovoltaic modules, ensuring early-stage fault identification and improving the operational reliability and efficiency of solar power systems.

The combination of UAV technology with advanced machine learning methods continues to expand the capabilities of solar panel inspections. The study [36] demonstrated the effectiveness of real-time defect detection using YOLO-based algorithms integrated with UAV platforms, significantly reducing the time required for manual inspections. Similarly, the work [37] highlights improvements achieved through the fusion of UAV thermal imaging and deep learning methods, resulting in more accurate and cost-effective defect identification.

Numerous field studies further support the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of UAV-based inspections in operational PV settings. Gallardo-Saavedra et al. (2020) [38] reported that thermal inspections using UAVs were approximately 97% faster than manual methods, translating to a cost reduction of €1.07 per kWp. Similarly, Zefri et al. (2018) [39] found that inspection time was reduced by up to 85% using drone-mounted cameras in large solar farms. In a large-scale deployment, Pruthviraj et al. (2023) [3] used UAV thermal imaging to inspect over 230,000 panels, detecting thousands of defects more efficiently than by manual surveys. In other work [40], the authors demonstrated that UAV-based efficiency assessment using high-resolution thermal orthomosaics enables rapid and detailed evaluation of solar fields, supporting real-time maintenance decisions and scalability in large installations.

Fault classification and localization methods have also seen considerable progress. For example, Ref. [41] introduced efficient CNN architectures combined with UAV thermal imaging, enabling precise localization and classification of defects.

Looking forward, further research efforts are expected to explore advanced neural network architectures, including transformer-based models, as demonstrated in [25]. This comparative study confirmed that vision transformers hold great promise for further enhancing detection performance, outperforming traditional CNN approaches in certain tasks. Ongoing innovations combining CNNs, IoT technology, UAVs, and emerging deep learning models have significantly advanced the state-of-the-art in photovoltaic defect detection, contributing to increased efficiency, reduced maintenance costs, and enhanced system reliability. Continuous research in these areas is essential for addressing existing challenges and ensuring the long-term sustainability and competitiveness of solar photovoltaic energy.

3 Materials and Data Collection

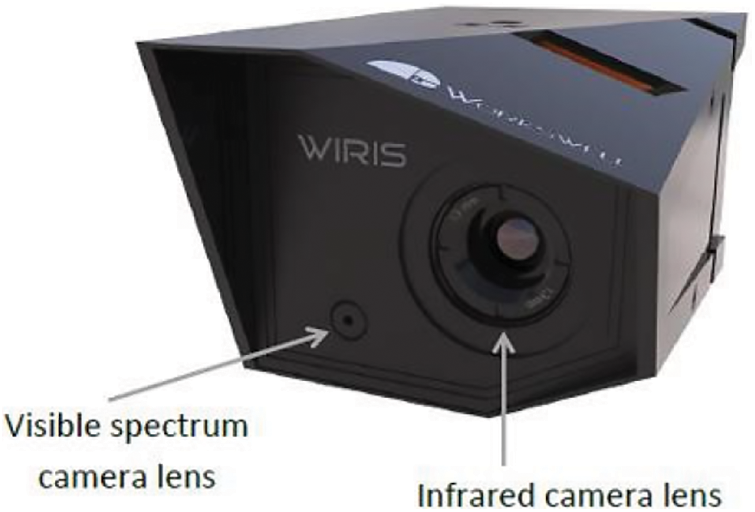

The thermal images utilized in this research were captured using a Workswell WIRIS 640 thermal imaging camera mounted on a DJI S900 drone. The Workswell WIRIS 640 camera is specifically designed for drone-based inspections, providing high-quality radiometric images capable of accurately measuring temperature variations at the pixel level. The camera incorporates advanced thermographic sensors, supporting functionalities such as full remote control, radiometric data acquisition, continuous digital zoom, adjustable manual temperature ranges, Global Positioning System (GPS) positioning, thermal image analysis software, and the capability to generate 3D models from the captured data. The camera weighs less than 400 g and features a temperature measurement range of up to 1500°C, internal memory of 32 GB, dimensions of 135 mm × 77 mm × 69 mm, and connectivity via HDMI and USB ports (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Radiometric camera Workswel WIRIS

The DJI S900 drone employed for data collection is a professional-grade octocopter designed for stable flight and high payload capacity, capable of carrying specialized equipment such as thermal imaging cameras. It features a collapsible carbon fiber frame for portability, eight motors with corresponding propellers providing significant lift and stability, and a precision flight controller suitable for accurate maneuvering even in windy conditions. The drone integrates both GPS and visual positioning systems, ensuring reliable flight stability and precise image capture. With a flight autonomy ranging from 15 to 20 min per battery charge, the DJI S900 is suitable for professional aerial imaging applications (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Octocopter DJI S900 mounted with WIRIS camera

Data collection was performed at a large-scale photovoltaic power plant located in the province of Albacete, Spain. This facility spans approximately 8 hectares and has an installed capacity of 15 MW, producing around 28,000 MWh annually, sufficient to meet the energy requirements of approximately 11,200 households. The installation includes roughly 70,000 polycrystalline silicon photovoltaic modules (CS6P-P series manufactured by Canadian Solar) arranged in around 7000 horizontal single-axis tracking structures. Each tracking structure supports 10 modules organized in two rows of five panels. This solar power plant has been in continuous operation since its commissioning in 2008 and is maintained through a centralized monitoring system.

The drone-mounted thermal imaging system captured aerial video sequences of photovoltaic modules from diverse angles and elevations, including multiple panels within single frames. The radiometric images provided clear visualization of temperature differences, distinctly highlighting hot spots on defective solar cells. However, some captured images included bright areas caused by sunlight reflections rather than genuine defects, complicating straightforward tonal filtering methods.

Raw thermal video sequences were processed frame by frame into individual images during a dedicated pre-processing stage. Frames exhibiting motion blur, primarily resulting from drone turns and rapid movements, were automatically discarded due to sensitivity limitations of thermal imaging cameras operating at lower frame rates. Additional image filtering was conducted to remove frames captured from steep viewing angles or those exhibiting significant geometric distortion of panel structures (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Discarded images due to improper viewing angles

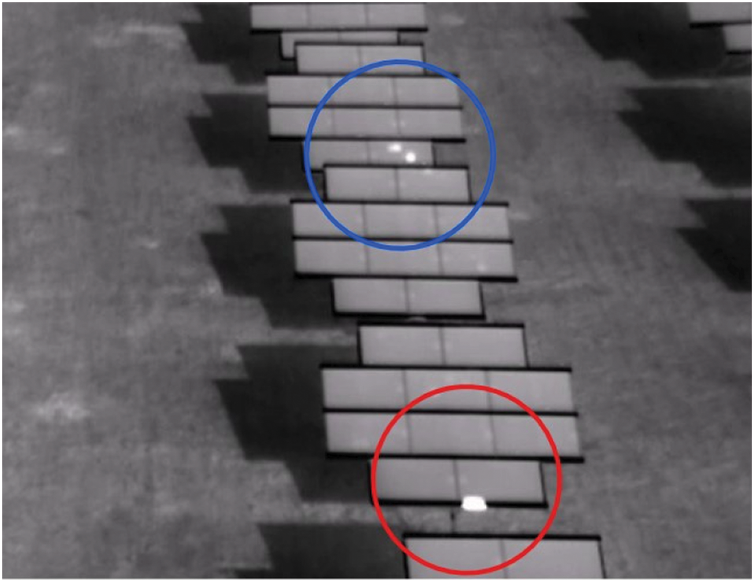

Following initial filtering, the remaining images were manually reviewed and annotated. Panels exhibiting actual defects were labeled with assistance from semi-automated tracking algorithms, facilitating accurate and efficient identification of hot spots across image sequences. Special attention was directed toward identifying and excluding false positives caused by solar reflections on the panels or their frames. These challenging scenarios were carefully addressed in the annotation stage, ensuring the training dataset enabled neural networks to differentiate genuine thermal anomalies from reflection effectively (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Panels annotated with ground truth: hot spots are marked in blue, while sun-induced reflections (potential sources of false positives) are highlighted in red

After rigorous pre-processing and annotation, a total of 3718 valid thermal images were compiled into the final dataset, ready for subsequent training and evaluation of the proposed defect detection system.

The proposed system integrates two specialized convolutional neural networks (CNNs) arranged in a cascaded architecture to optimize computational efficiency and accuracy. Instead of processing high-resolution images entirely with a single deep neural network, this cascading approach separates the tasks into distinct stages: initial detection of photovoltaic (PV) panels in aerial images, followed by detailed defect classification within each detected panel.

4.1 Data Input and Preprocessing

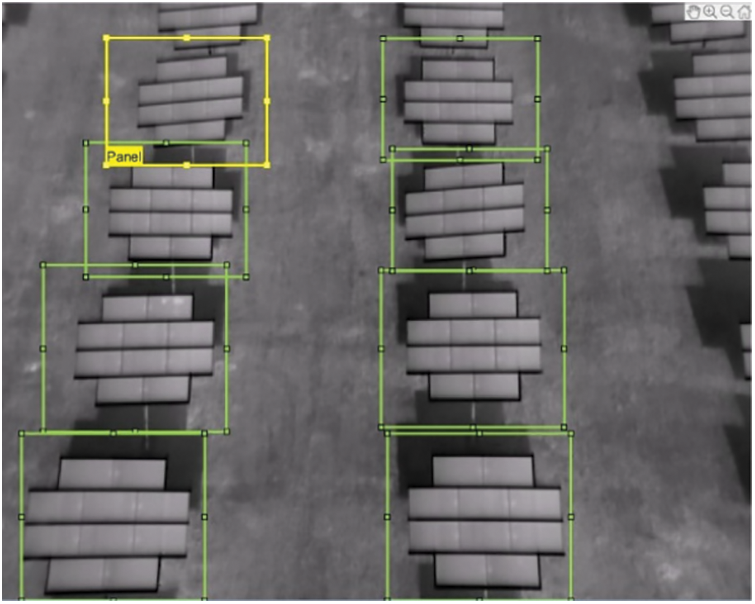

A critical preliminary step was the creation of a precise ground truth dataset through manual annotation. Aerial thermal images were manually labeled by placing bounding boxes exclusively around fully visible, non-overlapping solar panels. Labeling only complete panels prevented erroneous detections of partial or overlapping panels by the model [42]. To accelerate the labeling process, particularly for video data, a point-tracker-based labeling tool was employed (Fig. 5). This tool allowed marking panels in the first frame of a video sequence and automatically tracking these panels across subsequent frames, significantly expediting dataset preparation [43]. In the interface, yellow bounding boxes indicate the currently selected or tracked object, while green boxes represent successfully tracked objects that are not currently selected.

Figure 5: Semi-automated video annotation using the point tracker tool in MATLAB video labeler

4.2 Panel Detection Stage (Fast R-CNN)

The first stage of the proposed system utilizes a Fast Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (Fast R-CNN) to detect solar panels within aerial thermal images [44]. The network consists of 11 layers and is intentionally lightweight, as panel detection primarily relies on simple visual patterns such as rectangular contours and thermal intensity profiles, which are recognizable at moderate resolutions.

Unlike classical R-CNN, which applies a separate convolutional network to each candidate region, Fast R-CNN first extracts a global feature map from the entire input image using convolutional, ReLU, and MaxPooling layers. Externally defined Regions of Interest (RoIs), obtained from annotated bounding boxes, are then projected onto this map and resized via RoI Pooling to fixed-size vectors (32 × 32 × 3). These are subsequently classified by fully connected layers as either “Panel” or “Background”.

To train the detector, a Ground Truth dataset was generated by manually labeling only complete, non-overlapping panels in a set of aerial thermal images, preventing the network from learning ambiguous or partial patterns. Labels were defined by rectangular coordinates and linked to image filenames. The detector was trained using this annotated dataset, which included bounding boxes propagated from video sequences using semi-automated tools.

Training on high-resolution images (1280 × 1024 pixels) posed memory constraints and risks of information loss if downsampled excessively. Reducing input to 28 × 28 pixels, for instance, would remove critical spatial detail [45]. Fast R-CNN mitigates this by processing the full image once and performing detection through RoI mapping and classification, as shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Fast R-CNN object detector structure

Using labeled RoIs, the network was trained via backpropagation to discriminate panels from background. Convolutional layers extract shared features, while RoI Pooling and dense layers perform classification. After training on thousands of examples, the model consistently localized panels with high confidence [46], assigning scores between 0 and 1 to each detection.

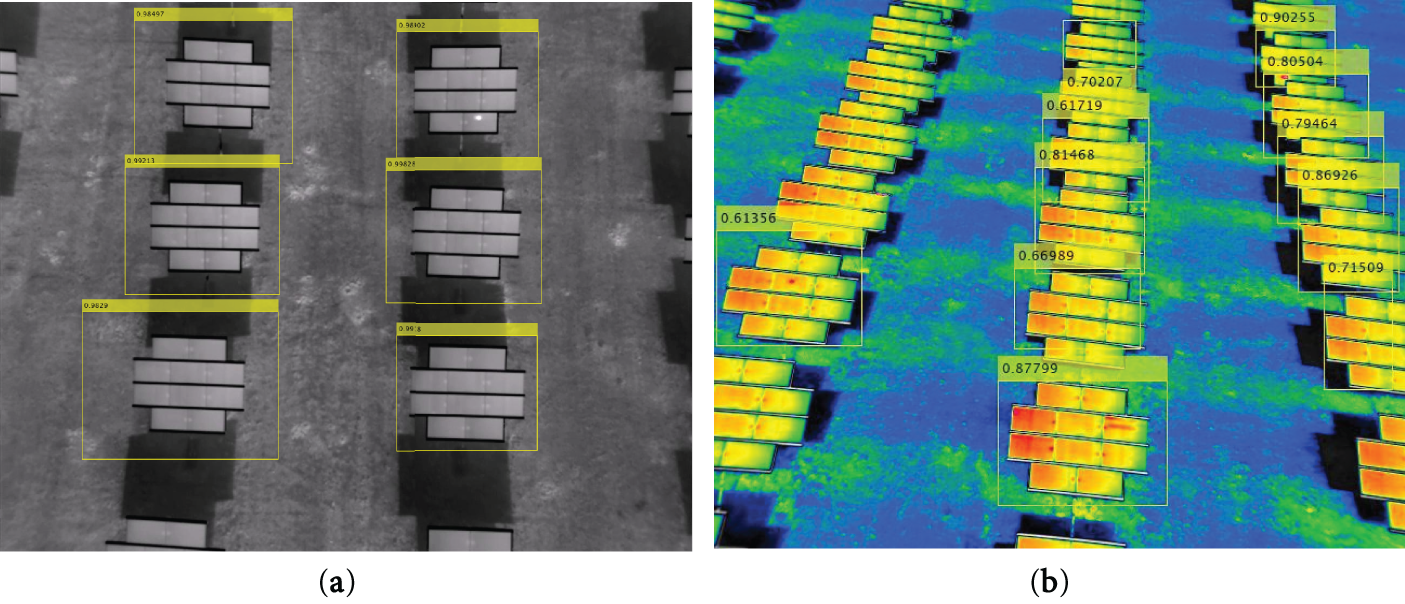

Validation on unseen images confirmed the detector’s effectiveness. As shown in Fig. 7, fully visible panels are correctly identified and framed in yellow boxes, while partial or overlapping panels tend to be ignored due to lower confidence scores. This conservative behavior reflects the impact of a strict annotation strategy and reduces false positives in subsequent classification.

Figure 7: Panel detection examples using Fast R-CNN: (a) grayscale thermal image with high-confidence detections, and (b) pseudo-color thermal map showing detection scores for each panel

This approach ensures that only clearly defined panels are passed to the next stage, improving reliability and minimizing ambiguity, particularly near image edges or in densely packed arrays.

4.3 Defect Classification Stage (GoogleNet)

After panels were successfully detected and cropped from original high-resolution images, the next step was to classify each panel individually as either defective or healthy. This required creating a detailed, balanced dataset, obtained by manually categorizing each cropped panel image as “Defect” (indicating thermal anomalies, primarily hot spots) or “Healthy” (normal thermal signatures). This manual labeling ensured high accuracy of training data, facilitating the subsequent classification task.

Due to the inherent complexity in distinguishing genuine thermal anomalies from false positives caused by solar reflections or glare, a robust pre-trained convolutional neural network, GoogleNet (Inception v1), was selected for this classification stage [47]. Originally trained on ImageNet, GoogleNet incorporates hierarchical feature extraction across its 22 core layers (or 144 layers counting auxiliary branches), making it highly suitable for fine-grained classification tasks involving subtle thermal patterns [48].

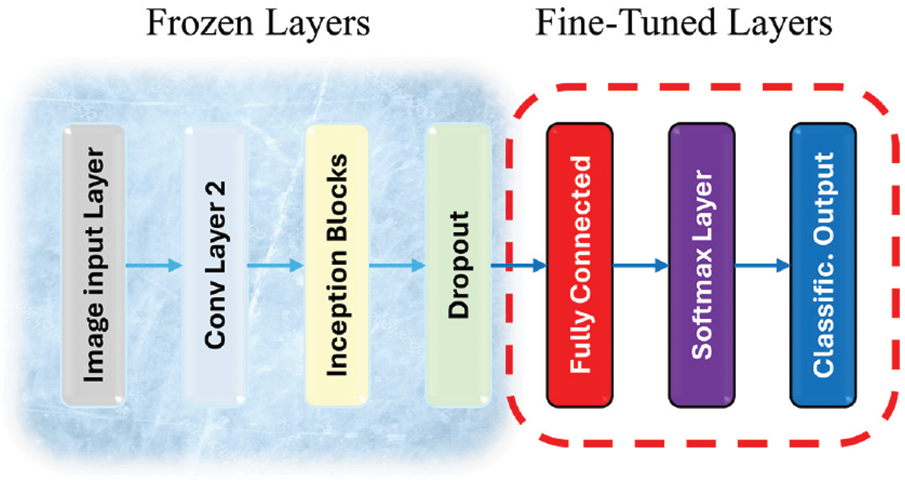

To adapt GoogleNet to our specific binary classification task (“Defect” vs. “No Defect”), we applied transfer learning by freezing all layers up to the “pool5-drop_7x7_s1” dropout layer. This approach preserved the general feature extraction capabilities learned from ImageNet and reduced the risk of overfitting. Only the final classification layers were retrained using our domain-specific dataset. Additionally, to improve generalization and increase training data variability, data augmentation techniques were applied. These included random horizontal reflections as well as random pixel translations in both the X and Y directions, implemented using MATLAB’s imageDataAugmenter with appropriate settings.

Transfer learning was applied to adapt GoogleNet to our binary classification problem (“Defect” vs. “No Defect”). This involved freezing early convolutional layers to preserve general features previously learned, significantly reducing the amount of training data and computation required. New, task-specific Fully Connected layers were added and trained specifically on the prepared dataset of panel images (Fig. 8). After fine-tuning these layers, GoogleNet achieved an outstanding validation accuracy of 99.86%, demonstrating exceptional proficiency in differentiating between defective and healthy panels.

Figure 8: Modified GoogleNet structure with frozen and trainable layer blocks for defect classification

4.4 Integrated Pipeline and System Operation

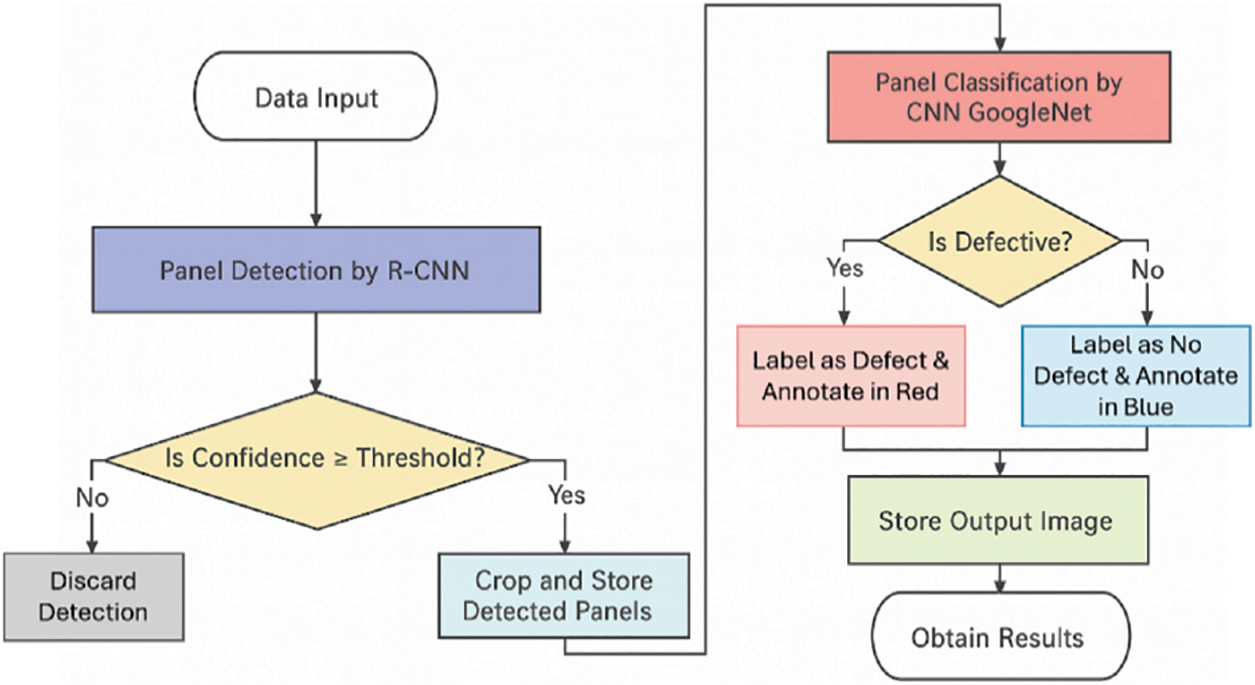

Finally, the trained Fast R-CNN panel detector and the GoogleNet-based defect classifier were integrated into a unified, automated pipeline designed for practical and scalable photovoltaic panel inspection (Fig. 9). The detailed operation of this integrated system follows a structured inference pipeline:

Figure 9: Flowchart of the integrated hybrid system

• Data Input: Users provide paths to directories containing new images and stored models, enabling modularity and easy updates of the neural networks.

• Panel Detection: Fast R-CNN processes each input image, outputs bounding boxes around detected panels, and provides confidence scores. Panels below a confidence threshold are automatically discarded, enhancing the reliability of subsequent classification.

• Defect Classification: Cropped panels identified by the detection stage are individually analyzed by the GoogleNet model, which classifies each panel as either “Defect” or “No Defect”, also outputting associated confidence scores.

• Result Annotation and Output: Results from both stages are consolidated, and original images are annotated with bounding boxes clearly color-coded according to panel status—red boxes indicating defects and blue indicating healthy panels. Annotated images are then saved in an output directory, facilitating straightforward and accurate maintenance interventions.

This comprehensive and detailed methodological framework effectively addresses practical challenges in photovoltaic panel inspection, significantly reducing manual inspection time, minimizing false detections, and substantially improving the overall efficiency and reliability of solar plant maintenance operations.

After training the two-stage system, we evaluated its performance on both detection and classification tasks using a held-out test dataset and qualitative analysis of sample images. The dataset for defect classification was split into 60% of the images for training, 20% for validation, and 20% for final testing. The test set consisted of 743 thermal images of individual panels (with an equal balance of faulty and healthy panels).

Solar Panel Detection Performance: The Fast R-CNN panel detector proved highly effective at localizing solar panels in diverse images. In a typical example, the network successfully detected and delineated all fully visible panels in the image while completely ignoring those panels that were only partially visible. Each detected panel is marked with a bounding box and an associated confidence score. The detection confidences ranged from about 98.5% up to 99.8%, indicating a very high level of certainty in the recognitions. Importantly, the detector did not flag any incomplete panel fragments, a direct benefit of our training strategy that excluded partial panels from the ground truth.

The detector’s performance was robust not only on the monochromatic (grayscale or thermal) images it was primarily trained on, but also generalized to color images. As shown in Fig. 7b, Fast R-CNN is able to identify solar panels in color photographs as well, though with somewhat lower confidence levels compared to the thermal images. This reduction in confidence is attributed to the greater variability in appearance of panels across different color images and the relatively smaller size of the color image subset in the training data. In practice, enlarging the training dataset with more varied color images and retraining would likely improve the detector’s confidence on color imagery. Overall, the first-stage panel detection exhibited high precision in finding complete panels and produced very few false positives, providing a reliable set of inputs for the subsequent classification stage.

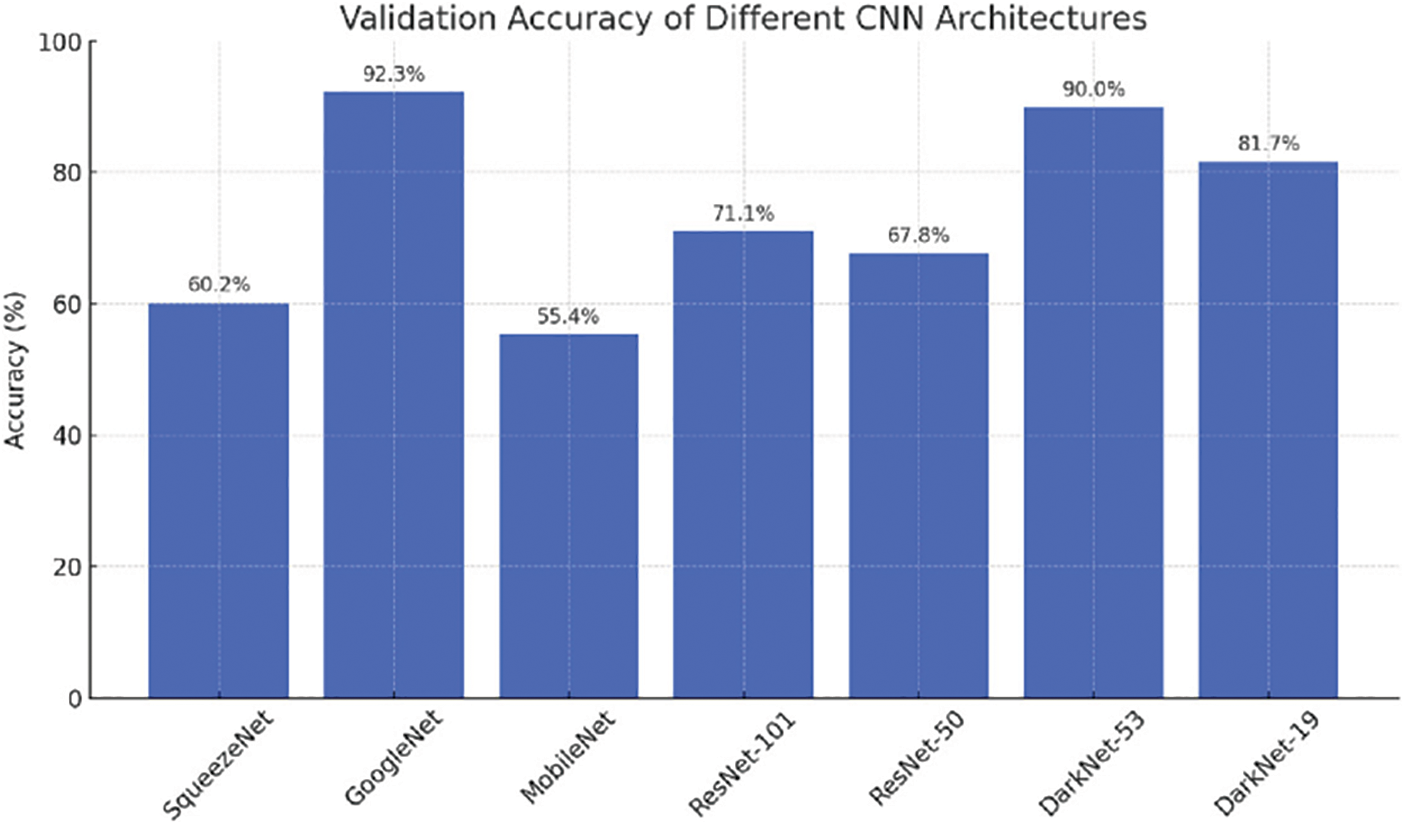

To select the most appropriate architecture for the defect classification stage, a comparative study was conducted using the same set of input images across several state-of-the-art convolutional neural network models. Architectures evaluated included SqueezeNet, MobileNet, ResNet-50, ResNet-101, DarkNet-19, DarkNet-53, and GoogleNet. Each model was trained and validated under identical baseline conditions using the same dataset of cropped panel images. As shown in Fig. 10, GoogleNet achieved the highest validation accuracy in this initial comparison, reaching 92.3%, and offered a good balance between classification performance and computational efficiency. This motivated its selection as the backbone for the final defect classification stage.

Figure 10: Performance comparison between different CNN Architectures for this task

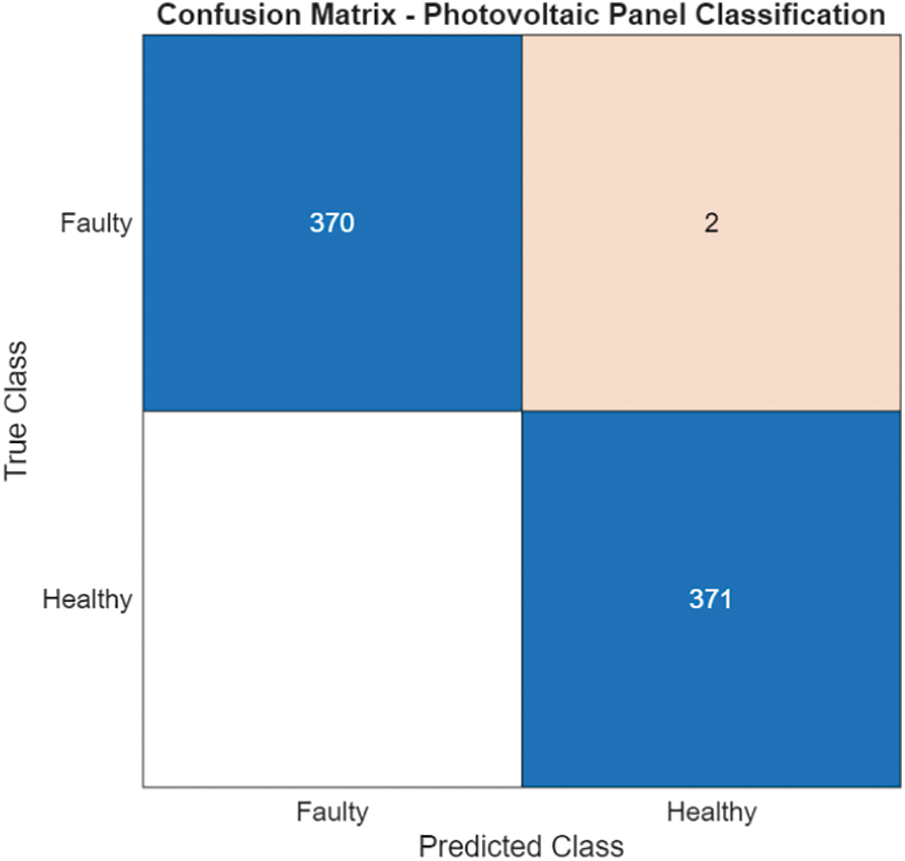

Defect Classification Performance: After integrating GoogleNet into the two-stage cascaded system and applying a dedicated fine-tuning process, the adapted classifier achieved significantly improved results. Evaluated on an independent test set of 743 panel images, the model demonstrated excellent classification performance (Fig. 11).

Figure 11: Confusion Matix of the Fine-tuned GoogleNet

The resulting confusion matrix showed outstanding metrics: an overall accuracy of 99.73%, a precision of 100.00%, a recall of 99.46%, and an F1-score of 99.73%. In fact, out of 743 panels, only two were misclassified. These two errors were false negatives, cases where panels that did contain a hot-spot defect were incorrectly labeled as “No Defect”. These panels exhibited very subtle anomalies, such as low-contrast hot spots or reflection artifacts, which made them particularly challenging to detect. Importantly, no false positives were observed.

Such high precision is particularly valuable in real-world operations, as it means the system would rarely trigger unnecessary maintenance checks on healthy panels. Meanwhile, the near-perfect recall indicates that the vast majority of actual defects were correctly detected, with only those extremely subtle cases being missed. These outcomes demonstrate the reliability and robustness of the proposed hybrid system for practical photovoltaic inspection scenarios.

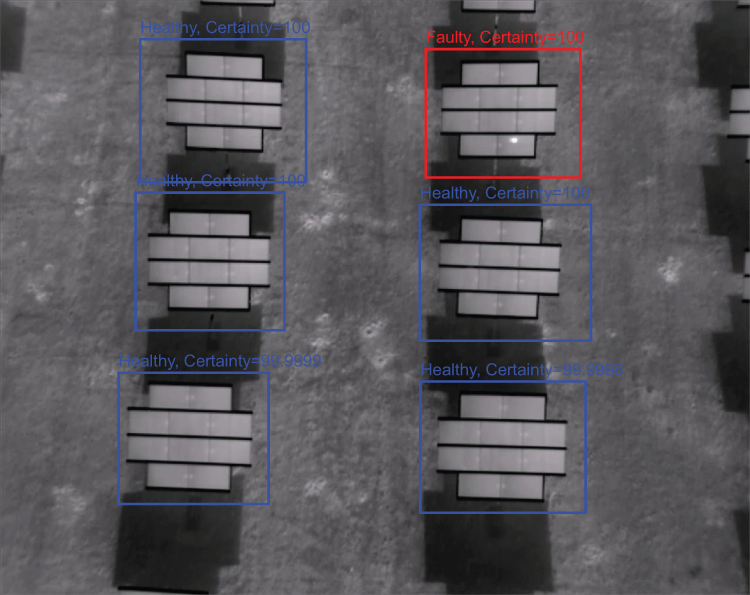

To illustrate the end-to-end performance of the system, Fig. 12 presents a final output where each detected panel in a sample image has been classified and annotated. Panels that contain a hot-spot defect are enclosed in red boxes labeled “Defect”, and panels without any issues are enclosed in blue boxes labeled “No Defect”, each accompanied by the model’s confidence percentage. As shown, the model identifies the defective panels with near absolute certainty (in many cases 99.9% confidence) and clearly marks them, thereby successfully completing the hot-spot detection process.

Figure 12: Detection and classification of defective and non-defective solar panels

Red bounding boxes indicate panels with hot-spot defects (“Faulty”), and blue boxes indicate healthy panels (“Healthy”), each with the model’s confidence score.

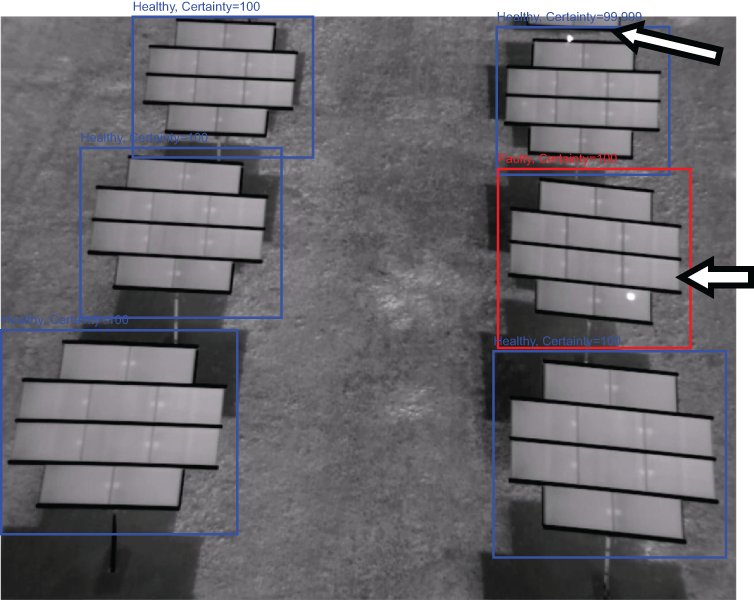

Finally, the Fig. 13 demonstrates a scenario containing both a true defect and a strong reflection on different panels. The center-right panel in Fig. 13 has an actual hot-spot defect, while a neighboring panel shows a bright reflection from the sun.

Figure 13: Correct rejection of false positives caused by reflections. The model identifies a true hot-spot defect (red box) and correctly classifies a neighboring panel affected by sunlight reflection as healthy (blue box), avoiding a false positive thanks to spatial context analysis

The trained GoogleNet classifier correctly distinguishes between the two: the hot-spot defect is identified and labeled in red (with a high confidence score), whereas the reflected glare is correctly ignored, and that panel is labeled as “No Defect”. The confidence for the reflection panel being healthy is also very high, indicating the model’s strong certainty that the bright reflection is not a fault. This result confirms that the cascaded system can overcome one of the main challenges noted in the state of the art. It can reliably tell apart genuine panel faults from false positives caused by reflections, thereby minimizing false alarms and ensuring that maintenance efforts are directed only at panels that truly require attention.

This research successfully demonstrates an innovative approach to the autonomous detection and classification of defects in photovoltaic panels using convolutional neural networks (CNNs). The main contributions and achievements of this study are summarized as follows:

• An effective hybrid CNN-based system was developed for autonomous detection of solar panels, demonstrating high accuracy in identifying panels within aerial images.

• A robust defect classification model utilizing a fine-tuned GoogleNet architecture was successfully trained, achieving a validation accuracy of 99.89%. This model reliably distinguishes between healthy panels and those exhibiting thermal anomalies or hot spots.

• The integration of the two specialized neural networks into a comprehensive software solution provides an efficient and scalable system capable of accurately identifying and classifying defects, significantly streamlining the monitoring and maintenance processes.

• The proposed system is versatile, using a Fast R-CNN architecture that can process images of varying resolutions and sizes, facilitating the analysis of large-area images captured at higher altitudes. This capability greatly optimizes the image acquisition process, enabling coverage of extensive solar farms in a shorter timeframe.

• The automation provided by the developed solution significantly reduces the time, costs, and operational complexity associated with traditional manual inspection methods. By employing drones equipped with advanced thermal imaging cameras, inspections can now be conducted rapidly, safely, and economically, greatly enhancing the overall competitiveness and sustainability of solar power plants.

However, this study presents certain limitations. The system’s performance has been validated on a specific dataset collected under particular environmental and lighting conditions, which may not fully represent the diversity of operational scenarios in other geographic locations or seasons. Additionally, although the classifier demonstrated excellent accuracy, when applied to a new dataset, the model must be retrained in two stages: first, to detect the new panel types present in the images; and second, to classify potential defects, accounting for false positives that may arise due to specific features of the new panels, particularly their frames or edges.

Future research directions include the analysis of motion patterns in aerial video footage captured during drone flights, with the aim of distinguishing transient reflections from true hot spots. Reflections tend to shift across frames due to changes in viewing angle and sunlight position, whereas actual defects remain fixed in the same region of the panel. Optimizing drone flight paths to maintain consistent imaging angles, along with incorporating real-time GPS coordinates into the inspection data, would further enhance detection precision and localization accuracy. Additionally, Vision Transformer architectures will be explored to improve feature representation and increase the model’s ability to generalize across diverse inspection scenarios. These improvements would enable solar plant operators to quickly obtain precise locations of defective panels, reducing response time and maintenance efforts. Ultimately, these advances aim to create a fully automated, remotely manageable solar panel inspection system, significantly improving reliability, maintenance efficiency, and economic viability.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades through the research grant RTC2019-007364-3, and by the the project “ICARUS—Inspección y Control Automatizado con Redes Neuronales y UAVs en Sistemas Fotovoltaicos” with reference [ref. SI4/PJI/2024-00233] which is funded by the Comunidad de Madrid through the direct grant agreement for the promotion of research and technology transfer at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, grant number RTC2019-007364-3 (FPGM), and by the Comunidad de Madrid through the direct grant with ref. SI4/PJI/2024-00233 for the promotion of research and technology transfer at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Carlos Quiterio Gómez Muñoz and Fausto Pedro García Márquez; methodology, Carlos Quiterio Gómez Muñoz and Jorge Bernabé Sanjuán; software, Jorge Bernabé Sanjuán; validation, Jorge Bernabé Sanjuán; formal analysis, Jorge Bernabé Sanjuán and Carlos Quiterio Gómez Muñoz; investigation, Carlos Quiterio Gómez Muñoz and Fausto Pedro García Márquez; resources, Fausto Pedro García Márquez; data curation, Jorge Bernabé Sanjuán; writing—original draft preparation, Jorge Bernabé Sanjuán; writing—review and editing, Carlos Quiterio Gómez Muñoz and Fausto Pedro García Márquez; visualization, Carlos Quiterio Gómez Muñoz and Fausto Pedro García Márquez; supervision, Fausto Pedro García Márquez; project administration, Fausto Pedro García Márquez and Carlos Quiterio Gómez Muñoz. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yang H, Yin Y, Abu-Siada A. A comprehensive review of solar panel performance degradation and adaptive mitigation strategies. IET Control Theory Appl. 2025;19(1):e70040. doi:10.1049/cth2.70040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Aboagye B, Gyamfi S, Ofosu EA, Djordjevic S. Investigation into the impacts of design, installation, operation and maintenance issues on performance and degradation of installed solar photovoltaic (PV) systems. Energy Sustain Dev. 2022;66(5):165–76. doi:10.1016/j.esd.2021.12.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Pruthviraj U, Kashyap Y, Baxevanaki E, Kosmopoulos P. Solar photovoltaic hotspot inspection using unmanned aerial vehicle thermal images at a solar field in south India. Remote Sens. 2023;15(7):1914. doi:10.3390/rs15071914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bemposta Rosende S, Sánchez-Soriano J, Gómez Muñoz CQ, Fernández Andrés J. Remote management architecture of UAV fleets for maintenance, surveillance, and security tasks in solar power plants. Energies. 2020;13(21):5712. [Google Scholar]

5. Abdelsattar M, Abdelmoety A, ISMEil MA, Emad-Eldeen A. Automated defect detection in solar cell images using deep learning algorithms. IEEE Access. 2025;13(2):4136–57. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3525183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Pse A. Photovoltaics report. Freiburg, Germany: Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE; 2022. [Google Scholar]

7. Europe SJSEB. Global market outlook for solar power 2023–2027 [Internet]; 2023. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.solarpowereurope.org/insights/outlooks/global-market-outlook-for-solar-power-2023-2027/detail. [Google Scholar]

8. Mann M, Babinec S, Putsche V. Energy storage grand challenge: energy storage market report. Golden, CO, USA: National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL); 2020. [Google Scholar]

9. Kim M, Drury S, Altermatt P, Wang L, Zhang Y, Chan C, et al. Identifying methods to reduce emission intensity of centralised Photovoltaic deployment for net zero by 2050: life cycle assessment case study of a 30 MW PV plant. Prog Photovolt Res Appl. 2023;31(12):1493–502. doi:10.1002/pip.3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Muñoz del Rio A, Segovia Ramírez I, García Mñrquez FP. Performance rate analysis in photovoltaic solar plants by machine learning. Advanced Energy and Sustainability Research. 2025;253:154–74. doi:10.1002/aesr.202500144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chaichan MT, Kazem HA. Experimental evaluation of dust composition impact on photovoltaic performance in Iraq. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util Environ Eff. 2024;46(1):7018–39. doi:10.1080/15567036.2020.1746444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dhimish M, Theristis M, D’Alessandro V. Photovoltaic hotspots: a mitigation technique and its thermal cycle. Optik. 2024;300(3):171627. doi:10.1016/j.ijleo.2024.171627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Dhimish M, Tyrrell AM. Power loss and hotspot analysis for photovoltaic modules affected by potential induced degradation. NPJ Mater Degrad. 2022;6(1):11. doi:10.1038/s41529-022-00221-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang F, Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhu D, Gong X, Cong W. An edge-guided deep learning solar panel hotspot thermal image segmentation algorithm. Appl Sci. 2023;13(19):11031. doi:10.3390/app131911031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ab Hamid MZ, Daud K, Che Soh ZH, Osman MK, Isa IS, Jadin MS. Deep learning-driven thermal imaging hotspot detection in solar photovoltaic arrays using YOLOv10. ESTEEM Acad J. 2024;20:77–90. doi:10.24191/esteem.v20iseptember.1861.g1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Gupta M, Khan MA, Butola R, Singari RM. Advances in applications of non-destructive testing (NDTa review. Adv Mater Process Technol. 2022;8(2):2286–307. doi:10.1080/2374068x.2021.1909332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Su Y, Tao F, Jin J, Zhang C. Automated overheated region object detection of photovoltaic module with thermography image. IEEE J Photovolt. 2021;11(2):535–44. doi:10.1109/JPHOTOV.2020.3045680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Hantula R. How Do Solar Panels Work? New York, NY, USA: Infobase Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

19. Raj B, Jayakumar T, Thavasimuthu M. Practical non-destructive testing. Oxford, UK: Woodhead Publishing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

20. Gomez CQ, Garcia FP, Arcos A, Cheng L, Kogia M, Papelias M. Calculus of the defect severity with EMATs by analysing the attenuation curves of the guided waves. Smart Struct Syst. 2017;19(2):195–202. doi:10.12989/sss.2017.19.2.195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ali MU, Saleem S, Masood H, Kallu KD, Masud M, Alvi MJ, et al. Early hotspot detection in photovoltaic modules using color image descriptors: an infrared thermography study. Int J Energy Res. 2022;46(2):774–85. doi:10.1002/er.7201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Dwivedi D, Yemula PK, MJapa P. Detection of malfunctioning modules in photovoltaic power plants using unsupervised feature clustering segmentation algorithm. arXiv:2212.14653. 2022. [Google Scholar]

23. Oulefki A, Himeur Y, Trongtirakul T, Amara K, Agaian S, Benbelkacem S, et al. Detection and analysis of deteriorated areas in solar PV modules using unsupervised sensing algorithms and 3D augmented reality. Heliyon. 2024;10(6):e27973. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27973. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Gómez Muñoz CQ, García Márquez FP. Future maintenance management in renewable energies. In: Renewable energies. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 149–59. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-45364-4_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Memari A, Debich T. Drone-assisted infrared thermography and machine learning for enhanced photovoltaic defect detection: a comparative study of vision transformers and YOLOv8. In: Artificial intelligence XLI. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 59–72. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-77918-3_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Guo Z, Lu J, Chen Q, Liu Z, Song C, Tan H, et al. TransPV: refining photovoltaic panel detection accuracy through a vision transformer-based deep learning model. Appl Energy. 2024;355:122282. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.122282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Goyal S, Rajapakse JC. Self-supervised learning for hotspot detection and isolation from thermal images. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;237(2):121566. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Bommes L, Hoffmann M, Buerhop-Lutz C, Pickel T, Hauch J, Brabec C, et al. Anomaly detection in IR images of PV modules using supervised contrastive learning. Prog Photovolt Res Appl. 2022;30(6):597–614. doi:10.1002/pip.3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Khan MJ, Kumar D, Narayan Y, Malik H, García Márquez FP, Gómez Muñoz CQ. A novel artificial intelligence maximum power point tracking technique for integrated PV-WT-FC frameworks. Energies. 2022;15(9):3352. doi:10.3390/en15093352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ramírez IS, Márquez FPG, Chaparro JP. Automated CNN-based semantic segmentation for thermal image of solar photovoltaic (PV) panel. In: Convolutional neural networks and Internet of Things for fault detection by aerial monitoring of photovoltaic solar plants. Measurement, 2024;234:114861. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.114861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Niu X, Liu C, Liu W, Liu S, Wang X, Kang J. Heat spot detection method of photovoltaic infrared image based on deep learning. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024;45(11):212–81. doi:10.19912/j.0254-0096.tynxb.2023-1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wang Y, Shen L, Li M, Sun Q, Li X. PV-YOLO: lightweight YOLO for photovoltaic panel fault detection. IEEE Access. 2023;11:10966–76. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3240894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ghahremani A, Adams SD, Norton M, Khoo SY, Kouzani AZ. Detecting defects in solar panels using the YOLO v10 and v11 algorithms. Electronics. 2025;14(2):344. doi:10.3390/electronics14020344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Lei Y, Wang X, An A, Guan H. Deeplab-YOLO: a method for detecting hot-spot defects in infrared image PV panels by combining segmentation and detection. J Real Time Image Process. 2024;21(2):52. doi:10.1007/s11554-024-01415-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Cardinale-Villalobos L, Jimenez-Delgado E, García-Ramírez Y, Araya-Solano L, Solís-García LA, Méndez-Porras A, et al. IoT system based on artificial intelligence for hot spot detection in photovoltaic modules for a wide range of irradiances. Sensors. 2023;23(15):6749. doi:10.3390/s23156749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Huang J, Zeng K, Zhang Z, Zhong W. Solar panel defect detection design based on YOLO v5 algorithm. Heliyon. 2023;9(8):e18826. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18826. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Majid Ali Al Risi AR, Khamis Al-Zaabi FH, Salim Al Washahi AM, Mohammed Al-Maaini RK, Boddu MK. Advancing solar PV component inspection: early defect detection with UAV based thermal imaging and machine learning. In: Proceedings of the 2023 Middle East and North Africa Solar Conference (MENA-SC); 2023 Nov 15–18; Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 1–3. doi:10.1109/MENA-SC54044.2023.10374464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Gallardo-Saavedra S, Hernández-Callejo L, Alonso-García MDC, Muñoz-Cruzado-Alba J, Ballestín-Fuertes J. Infrared thermography for the detection and characterization of photovoltaic defects: comparison between illumination and dark conditions. Sensors. 2020;20(16):4395. doi:10.3390/s20164395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zefri Y, ElKettani A, Sebari I, Ait Lamallam S. Thermal infrared and visual inspection of photovoltaic installations by UAV photogrammetry—application case: morocco. Drones. 2018;2(4):41. doi:10.3390/drones2040041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Akay SS, Özcan O, Özcan O, Yetemen Ö. Efficiency analysis of solar farms by UAV-based thermal monitoring. Eng Sci Technol Int J. 2024;53(1):101688. doi:10.1016/j.jestch.2024.101688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wang ZF, Yu YF, Wang J, Zhang JQ, Zhu HL, Li P, et al. Convolutional neural-network-based automatic dam-surface seepage defect identification from thermograms collected from UAV-mounted thermal imaging camera. Constr Build Mater. 2022;323(1–4):126416. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Gong S, Liu C, Ji Y, Zhong B, Li Y, Dong H. Image and video understanding based on deep learning. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2018. p. 513–53. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-77223-3_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Saponara S, Elhanashi A, Gagliardi A. Exploiting R-CNN for video smoke/fire sensing in antifire surveillance indoor and outdoor systems for smart cities. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing (SMARTCOMP); 2020 Sep 14–17; Bologna, Italy. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 392–7. doi:10.1109/smartcomp50058.2020.00083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Dalai R, Senapati KK. Comparison of various RCNN techniques for classification of object from image. Int Res J Eng Technol. 2017;4(7):3147–50. [Google Scholar]

45. Paluszek M, Thomas S. Machine learning examples in MATLAB. New York, NY, USA: Apress; 2016. p. 85–8. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4842-2250-8_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ciaburro G. MATLAB for machine learning. Birmingham, UK: Packt Publishing Ltd.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

47. Beale MH, Hagan MT, Demuth HB. Neural network toolbox. User’s Guide MathWorks. 2010;2:77–81. [Google Scholar]

48. Frniak M, Kamencay P, Markovic M, Dubovan J, Dado M. Comparison of vehicle categorisation by convolutional neural networks using MATLAB. In: Proceedings of the 2020 ELEKTRO; 2020 May 25–28; Taormina, Italy. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/elektro49696.2020.9130238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools