Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Acoustic Noise-Based Scroll Compressor Diagnosis during the Manufacturing Process

1 Department of Industrial Engineering, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon, 16419, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Systems Management Engineering, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon, 16419, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Daeil Kwon. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Data-Driven and Physics-Informed Machine Learning for Digital Twin, Surrogate Modeling, and Model Discovery, with An Emphasis on Industrial Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(3), 3329-3342. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.069402

Received 22 June 2025; Accepted 04 September 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Nondestructive testing (NDT) methods such as visual inspection and ultrasonic testing are widely applied in manufacturing quality control, but they remain limited in their ability to detect defect characteristics. Visual inspection depends strongly on operator experience, while ultrasonic testing requires physical contact and stable coupling conditions that are difficult to maintain in production lines. These constraints become more pronounced when defect-related information is scarce or when background noise interferes with signal acquisition in manufacturing processes. This study presents a non-contact acoustic method for diagnosing defects in scroll compressors during the manufacturing process. The diagnostic approach leverages Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCC), and short-time Fourier transform (STFT) parameters to capture the rotational frequency and harmonic characteristics of the scroll compressor. These parameters enable the extraction of defect-related features even in the presence of background noise. A convolutional neural network (CNN) model was constructed using MFCCs and spectrograms as image inputs. The proposed method was validated using acoustic data collected from compressors operated at a fixed rotational speed under real manufacturing process. The method identified normal operation and three defect types. These results demonstrate the applicability of this method in noise-prone manufacturing environments and suggest its potential for improving product quality, manufacturing reliability and productivity.Keywords

As product complexity increases and quality demands grow, ensuring product quality during the manufacturing process becomes crucial. Unexpected defects may occur during the manufacturing process, such as the assembly of defective parts or the intrusion of foreign matter into the product. These defects degrade product quality and reduce productivity. Defect diagnosis improves quality and productivity by enabling the efficient allocation of resources and time to non-defective products [1,2].

Defect detection in manufacturing processes can be categorized as a form of nondestructive testing (NDT), including techniques such as visual inspection and ultrasonic testing. Aust et al. [3] analyzed visual and visual-tactile inspection methods for defects in aircraft engine blades. Katunin et al. [4] compared four NDT techniques as alternatives to X-ray computed tomography (XCT) for diagnosing internal defects in composite material disks, recommending infrared thermography testing (IRT) and ultrasonic testing (UT) as effective solutions. Mian et al. [5] used acoustic signals for bearing fault diagnosis in rotating machinery and developed a self-adaptive fault diagnostic method using Head and Torso Simulator (HATS)-based data acquisition and a support vector machine (SVM). Farag et al. [6] utilized eddy current-based sensors to detect defects such as voids, cracks, and lack of fusion in additively manufactured titanium and stainless steel components. Existing diagnostic methods rely on human judgment, which leads to inconsistencies in diagnostic criteria and an inability to identify defect characteristics when defect-related information is insufficient and background noise is present. These factors limit diagnostic performance [7–9]. Addressing this issue requires a methodology capable of identifying defect characteristics in signals mixed with background noise.

Numerous studies have aimed to remove background noise from signals and identify defect characteristics. Yao et al. [10] proposed a recursive denoising learning-based adaptive tracking method for removing abnormal industrial background noise. Zou et al. [11] presented a method for simulating noise interference through dynamic erasure, which allows a diagnostic model to learn the characteristics of error signals in noisy environments. Yang et al. [12] extracted fault features from noise-containing signals using a general multi-objective optimized wavelet filter. Senanayaka et al. [13] applied a DEMUCS-based source separation technique to isolate defect characteristics from complex acoustic signals in industrial machinery. These methods remove background noise and separate defect-related features. Most require knowledge of defect conditions and use signals from controlled environments. Application in manufacturing remains limited due to variable background noise.

Deep learning-based methods can extract defect-related features in environments with background noise [14–18]. Munir et al. [19] proposed a convolutional neural network (CNN)-based method that processes noisy ultrasonic signals directly and improves defect classification without prior signal processing or manual feature extraction. Zhang et al. [20] proposed a method that integrates a Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG) edge operator and a ResNet-based CNN to suppress background texture and extract features under industrial imaging conditions with noise. Hong and Kim [21] proposed a 1D CNN-based adaptive tracking algorithm that combines signal feature extraction, system condition diagnosis, and data generation using a variational autoencoder (VAE) and a generative adversarial network (GAN) to process vibration and noise signals from machines in industrial environments. These methods assume sufficient training data and stable environmental conditions, which can cause a drop in performance in real manufacturing processes with variability.

Some studies have attempted to improve the robustness of feature extraction by reflecting the frequency patterns or domain characteristics of rotating machinery [22–25]. Li et al. [26] proposed a frequency-domain fusing CNN (FFCNN) that uses dilated convolutions to fuse multi-scale frequency-band features and integrates domain adaptation to extract fault-related features under various operating conditions. Yu et al. [27] proposed an attention-based CNN that fuses time- and frequency-domain features to improve fault diagnosis accuracy under different signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions. Yu et al. [28] proposed an adaptive high-resolution order spectrum method that combines multi–order probabilistic approach (MOPA)-based speed estimation, time-varying filtering, and surrogate testing to extract true fault-related harmonic components under nonstationary operating conditions. These approaches were evaluated in controlled environments with artificially added noise. Verification under real manufacturing conditions, where both noise levels and defect characteristics vary unpredictably, is required [29,30].

Previous studies on rotating machinery fault diagnosis have mainly focused on scenarios with variable operating conditions such as changes in speed, load, or machine-to-machine variability [31,32]. In such cases, domain adaptation methods and deep learning approaches have been developed to maintain diagnostic performance across different domains. These approaches have shown strong results on benchmark vibration datasets and are generally oriented toward operational monitoring.

In the manufacturing process, scroll compressors are tested under controlled speed and load. The main challenges in this stage are the lack of defect information for model training and the overlap between defect signals and background noise. These constraints limit the applicability of large-scale supervised learning approaches.

This study addresses these challenges by proposing a non-contact method for defect diagnosis during the manufacturing process of scroll compressors. The method incorporates rotational frequency and its harmonics into STFT and MFCC feature extraction, guiding the model toward signal regions linked to mechanical behavior. The extracted features are then classified with a compact CNN to achieve robust diagnosis under background noise and limited data.

The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows.

1. Non-contact acoustic diagnosis framework: A microphone-based approach was used without sensor attachment.

2. Rotational frequency-based feature extraction: Rotational frequency and harmonic bands were incorporated into the STFT and MFCC feature extraction process.

3. Validation with manufacturing data: Data collected from a manufacturing process were used.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the proposed methodology. Section 3 describes the experimental setup and presents the results validating the proposed approach. Finally, Section 4 presents the conclusions of this study.

The methodology for diagnosing product defects in manufacturing processes involves identifying the main acoustic frequencies of the normal and defective conditions.

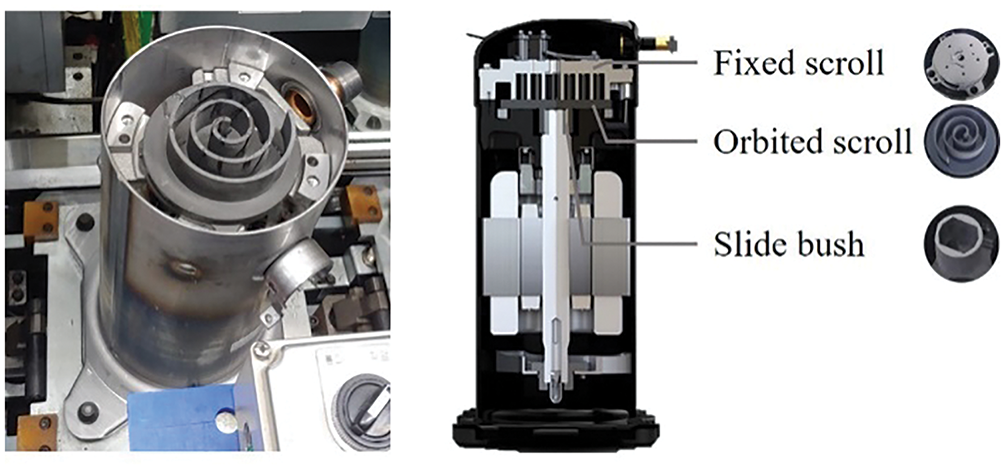

The scroll compressor used in this study is shown in Fig. 1. This compressor operates by combining two spiral scroll elements that compress air through rotational and reciprocating motions. The orbiting and fixed scrolls performed eccentric rotations to minimize the gaps between them, thereby gradually compressing the gas. During this process, the scrolls, slide bushes, and crankshafts functioned organically in an integrated manner.

Figure 1: Appearance and configuration of the scroll compressor

The quality and performance of scroll compressors were affected by component tolerances and defects during assembly. For example, scrolls with uneven surface finishes may have been used, some scrolls may have been contaminated by welding spatter, and some parts may not have been assembled correctly. When such defective compressors were assembled, they did not function as designed, and abnormal rattling noise was observed during operation [33,34].

2.2 Extraction of Time-Frequency Domain Features

Time-frequency domain features were extracted from signals obtained under various operating conditions. These features captured the variation of frequency over time and have been widely used in defect diagnosis research [35–37]. The parameters of STFT and MFCC were set based on the known rotational frequency of the scroll compressor under test. Rotational frequency and its harmonics determined the window size and sampling frequency according to the Nyquist theorem.

In the field of sound recognition, STFT has been used as an input feature for machine learning models and has achieved high classification accuracy [38,39]. STFT divided the signal into short overlapping segments, applied the Fourier transform to each segment, and recombined the results to create a time-frequency representation. The window function

where

The sampling frequency and window size follow the Nyquist theorem to ensure that the harmonic bands of interest are represented without aliasing. To ensure that the rotational frequency components were distinguishable in the time-frequency spectrum,

The MFCC is a time-frequency domain feature that simulates the mechanism of the human ear’s response to sound. Because defective scroll compressors produce audible human noise, the MFCC was an appropriate feature for representing defect conditions. In the MFCC, the horizontal axis represents time information, and the vertical axis represents the magnitude of the frequency component in decibels. MFCC was generated using several signal-processing methods. First, a one-dimensional sound signal was divided into frames of predetermined length, and then the frequency spectrum was obtained by applying a Fourier transform.

where

Frequency resolution was important for distinguishing low-frequency components, such as the operating frequency of rotating machinery. An appropriate configuration of frequency resolution in the STFT process improved the representational effectiveness of MFCC features.

Human hearing does not recognize frequencies in a linear manner. It transforms the frequency axis to a mel scale to mimic the human auditory system.

A Mel spectrogram was generated by mapping the frequency spectrum onto a Mel scale. The Mel filter bank comprises multiple triangular bandpass filters. In this filter bank, narrow triangular filters were placed in the low-frequency region, whereas wider triangular filters were placed in the high-frequency region.

where

where

The feature extraction process captures the rotational frequency and its harmonics. The rotational speed of scroll compressor determines the rotational frequency and the corresponding harmonic bands. Each band contains signal components generated by mechanical activity. Signal components appear consistently in the frequency domain, independent of the number of samples.

Mechanical defects affect the rotational behavior of the scroll compressor. Defect-induced disturbances produce signal components in the rotational frequency and harmonic bands. The proposed method applies feature extraction with parameter settings that reflect the rotational frequency and its harmonics. The method does not apply any noise removal to the acoustic data. Background noise does not concentrate in harmonic bands, reducing the impact of noise variation across recordings. The diagnostic process does not depend on the type of defect.

2.3 Diagnosis Using Convolutional Neural Network

A CNN model was developed for product condition diagnosis. The model used AlexNet, proposed by Krizhevsky et al. [40]. The model consisted of five convolutional layers and three fully connected layers, with a softmax classifier used for classification. AlexNet was capable of automatically extracting relevant features from input images, distinguishing important patterns even in the presence of extraneous signals such as background noise. This capability enabled the model to automatically detect abnormal features during defect diagnosis, eliminating the need for manual feature selection, thereby enhancing its applicability in manufacturing environments. The shallow network structure of AlexNet results in short training and detection times, further enhancing its suitability for manufacturing processes [41,42].

3.1 Data Collection and Augmentation

The experimental data were collected during the operational testing stage of the scroll compressor manufacturing process. This stage refers to a functional test in which each compressor is operated under rated speed and load conditions to verify the presence of defects. Each compressor was operated at a rotational speed of 3600 revolutions per minute (rpm), corresponding to a fundamental frequency of 60 Hz.

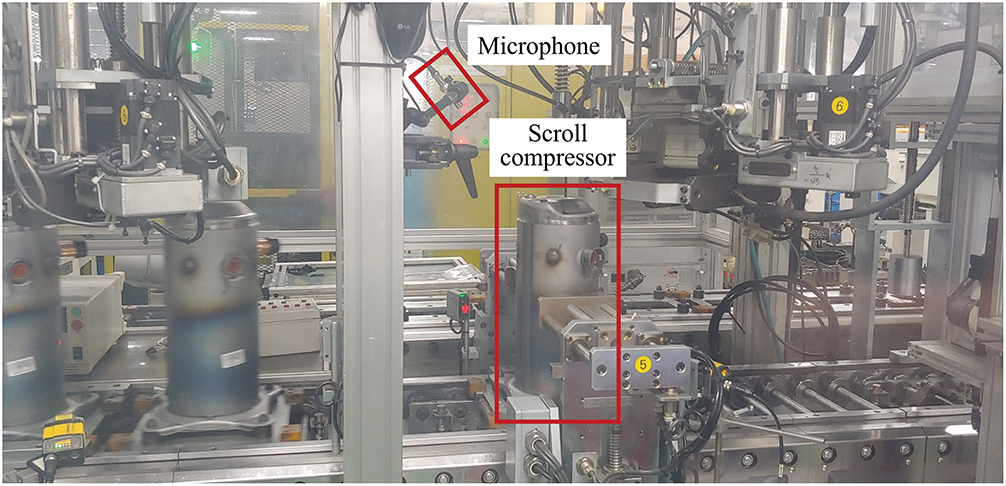

The operational test setup is shown in Fig. 2. A CRY331 microphone was positioned above the compressor at a fixed distance, without physical contact, to record acoustic signals generated during this test operation. Acoustic signals were collected with a sampling rate of 51.2 kHz. Acoustic data were collected for 2 s from each compressor. The collected signals included background noise from the manufacturing process. Noise sources included other machines in operation, alarm sounds, and human activity. The recordings were used without additional noise filtering. The acoustic signals contained variations in noise profiles across measurements.

Figure 2: Operational testing of scroll compressor

A total of 103 compressors were tested, including 100 normal compressors and 3 defective compressors, with one compressor assigned to each defect condition. Scroll machining defect was defined as a dimensional error in the scroll component. Spatter contamination was defined as welding spatter present between the fixed and orbiting scrolls. Missing component was defined as the omission of a slide bush in the assembly. For the normal condition, recordings were obtained from 100 compressors, resulting in 100 samples. For the defective condition, three recordings were obtained from one compressor with scroll machining defect, and two recordings each were obtained from compressors with spatter contamination and missing component. In total, the dataset contained 107 recordings.

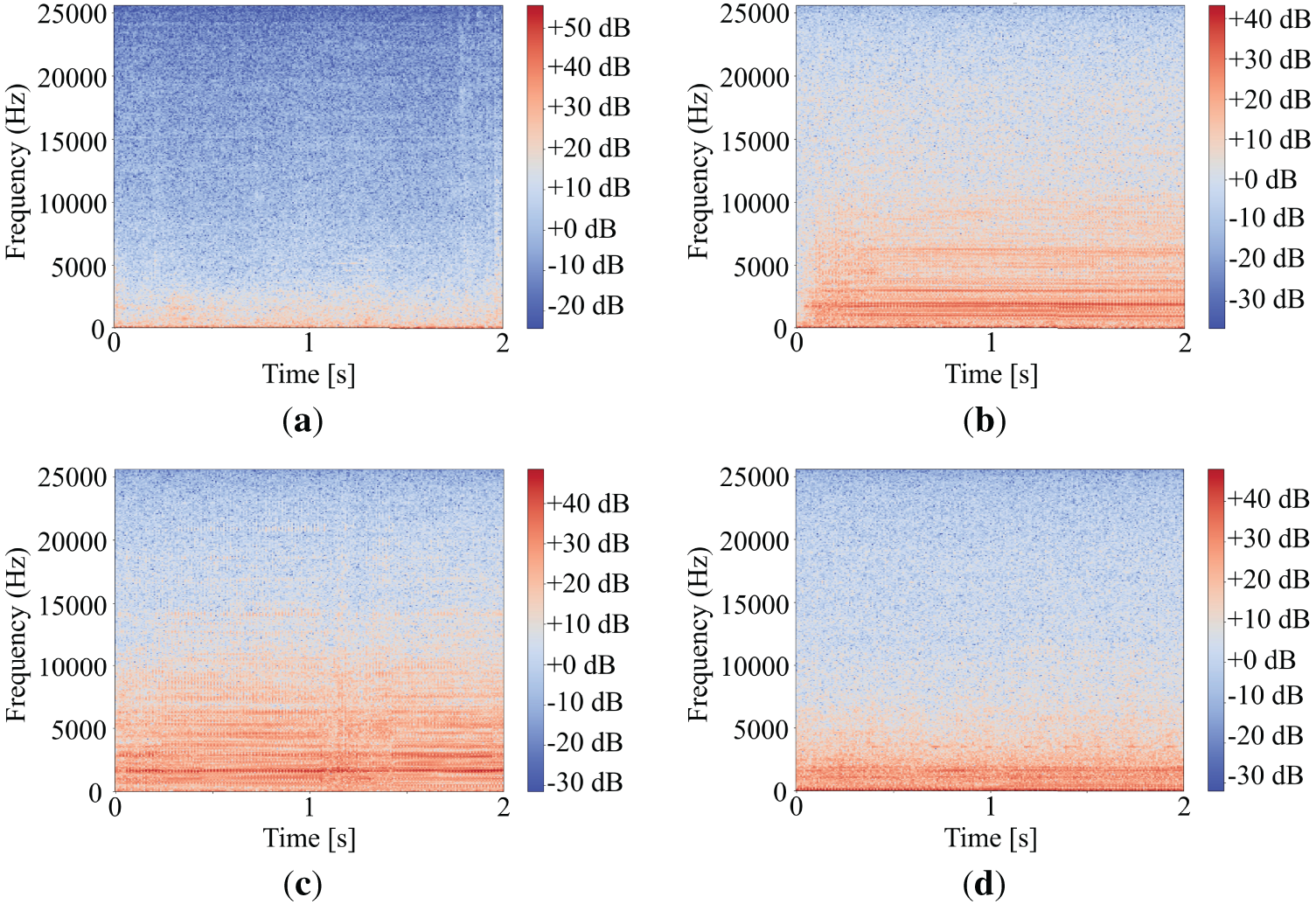

The dataset contained few defect samples and was imbalanced across classes. The synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) generated synthetic data points to increase the number of samples in the minority classes. The sample count was equalized across conditions. The data augmentation did not change the feature extraction or model structure. The dataset was expanded to 400 samples per condition, resulting in 1600 total samples. Table 1 presents the data.

3.2 Image Extraction with Time-Frequency Domain Features

The rotational frequency band must be identified to diagnose defects in scroll compressors. In this study, the scroll compressor was operated at 3600 rpm, corresponding to a fundamental rotational frequency of 60 Hz. While these spectral components reflect normal operational behavior, defects introduce additional high-frequency components due to contact between the scroll and other components, such as spatter or additional mechanical parts. Accordingly, the STFT was implemented with selected parameters to ensure sufficient resolution around the 60 Hz rotational frequency and its harmonics. The sampling rate was set to 51.2 kHz, based on the Nyquist theorem and the frequency range of defect-related signals. The window length was set to 854 samples, corresponding to the 60 Hz rotational frequency of the scroll compressor. This setting allows observation of the rotational frequency and its harmonics. A 50% overlap was applied between windows to retain signal continuity and reduce repeated computation. The number of fast Fourier transform (FFT) points was set to 854, equal to the window length, to maintain frequency resolution and control computational load.

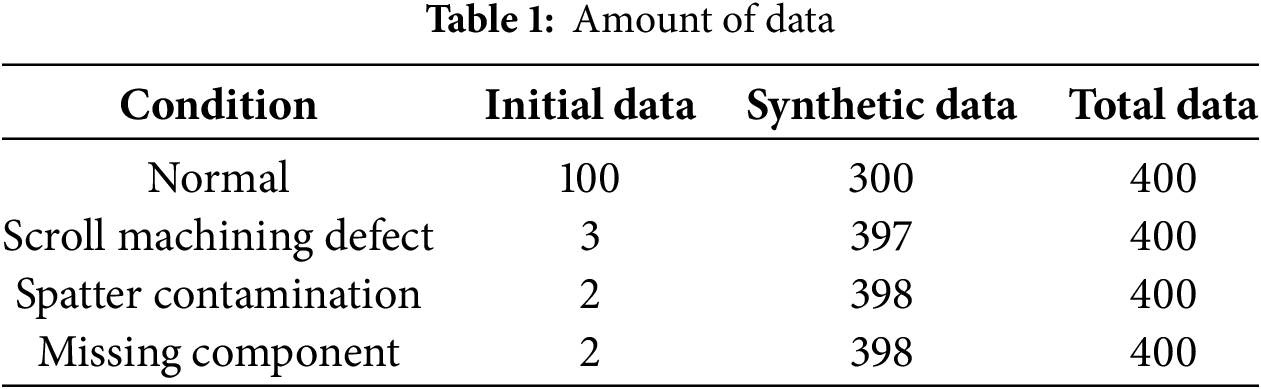

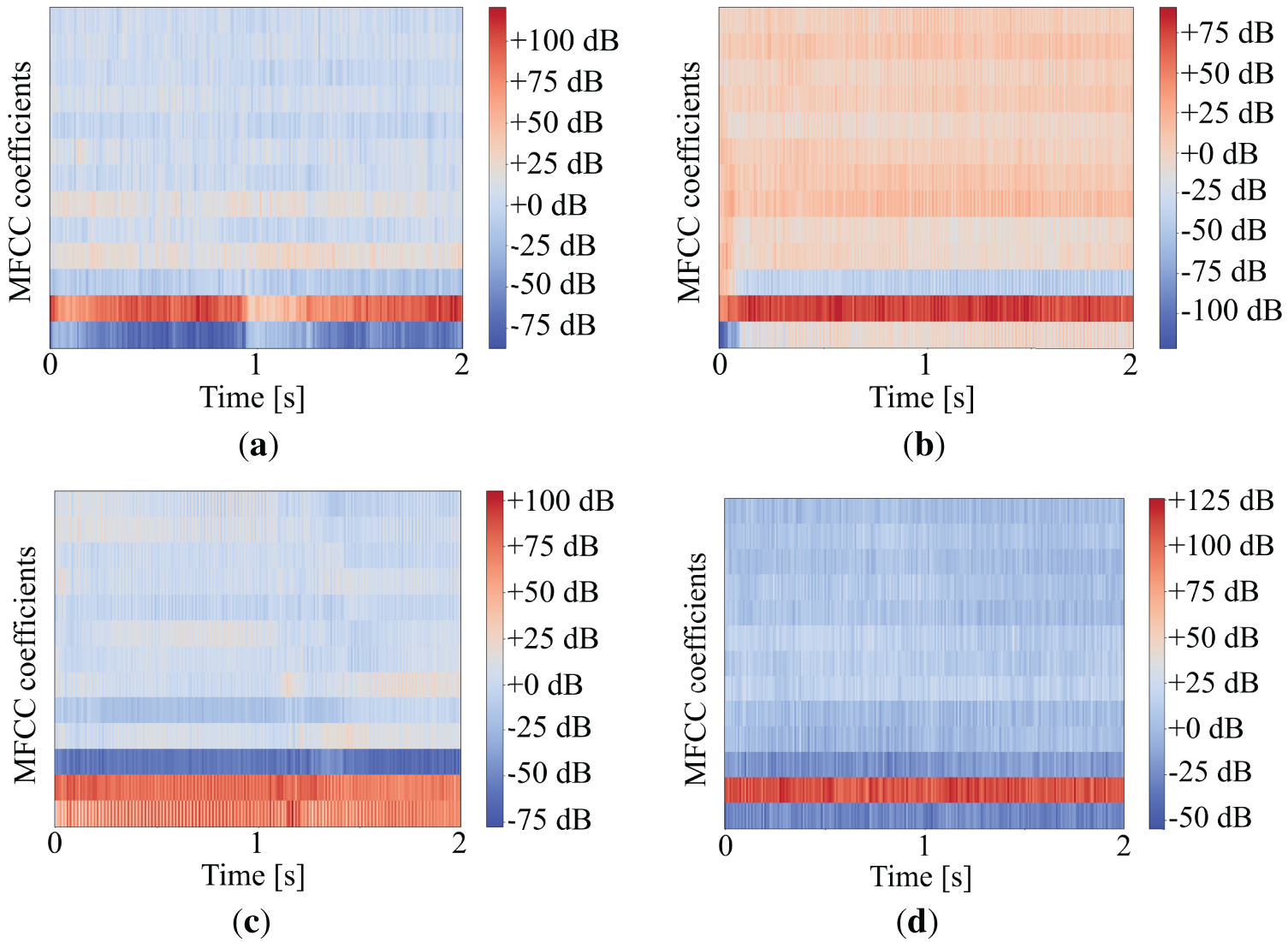

As shown in Fig. 3, the STFT was applied to the acoustic signals for each state of the scroll compressor to extract the 428 × 240 spectrograms, which were used as image inputs. These spectrograms visually represented frequency and amplitude variations over time. The spectrogram for a normal compressor showed frequency components in the low-frequency range, with minimal presence in the high-frequency regions. This pattern is characteristic of a properly functioning scroll compressor, where the acoustic signal is mainly generated at the rotational frequency and its harmonics. In contrast, the spectrograms of defective compressors showed strong components not only at the rotational and harmonic frequencies but also at a broader range of low-frequency bands. Significant components also appeared in the high-frequency range, from several hundred hertz to several kilohertz, caused by structural defects or frictional interactions, which generated continuous acoustic signals. A spectrogram can be used to distinguish between normal and defective conditions.

Figure 3: Spectrograms of scroll compressor acoustic signals: (a) Normal: frequency components are concentrated in the low-frequency band at the rotational frequency and its harmonics; (b) Scroll machining defect: additional frequency components appear in the band below 5 kHz; (c) Spatter contamination: similar to scroll machining defect but with more distinct frequency components below 5 kHz; and (d) Missing component: frequency components near 5 kHz are weak, while low-frequency components are stronger than in the normal condition

MFCCs were extracted using the following parameter settings. The sampling rate was set to 51.2 kHz, based on the Nyquist theorem and the frequency range of defect-related signals. The window length was set to 854 samples to achieve sufficient resolution near the 60 Hz operational frequency. An overlap of 50% was applied between frames to retain signal continuity and reduce repeated computation. The number of FFT points was set to 854, equal to the window length, to preserve frequency resolution and manage computational load. The Mel filter bank consisted of 40 filters, which reflect human auditory scaling and increase resolution in higher frequency bands. Thirteen cepstral coefficients were selected, following standard practice in MFCC extraction.

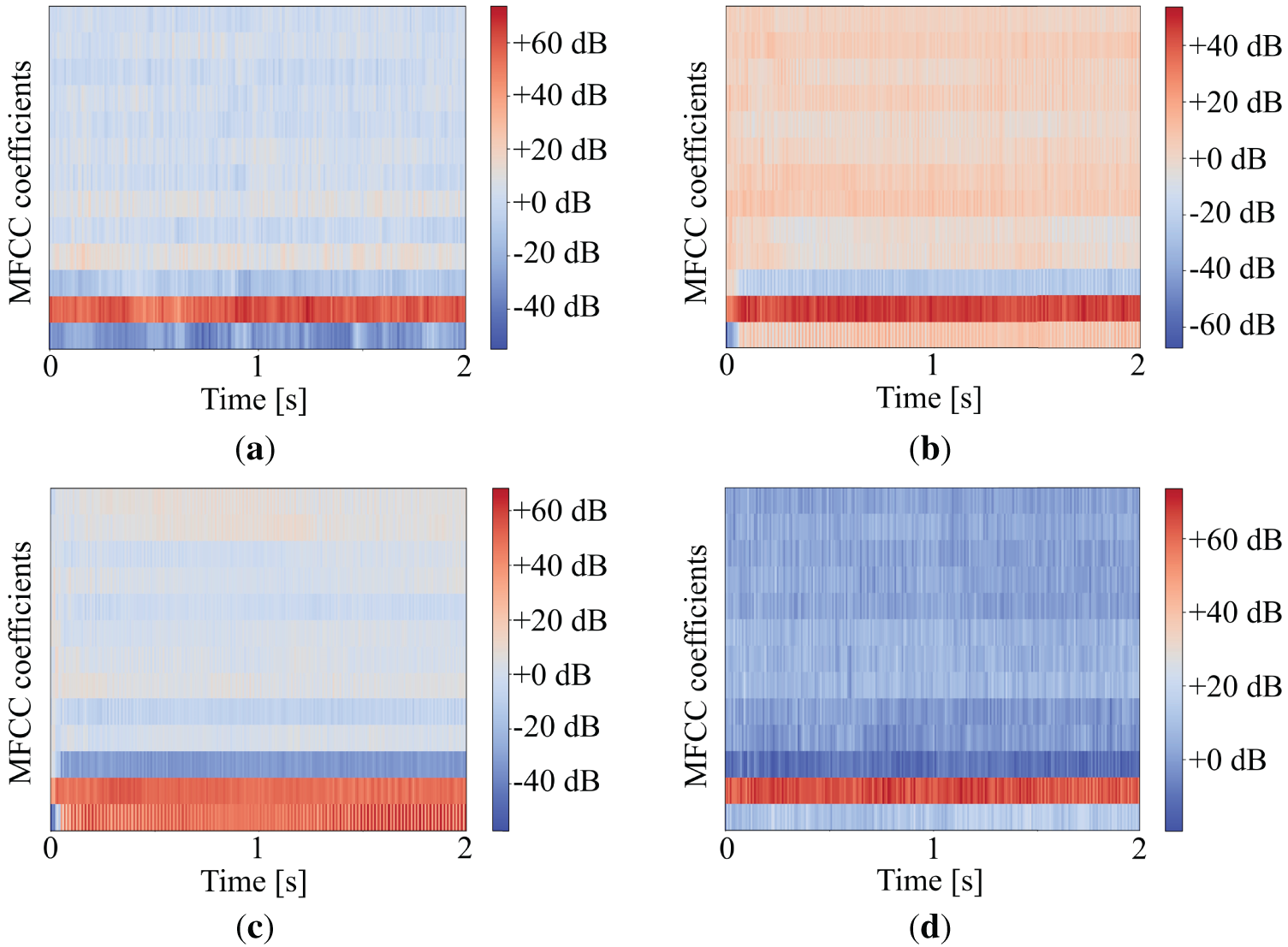

As shown in Fig. 4, the MFCCs were extracted from the sound signals for each state of the scroll compressor. The MFCC of a normal compressor primarily captured frequency components in the low-frequency range and exhibited minimal components in the high-frequency range. This pattern is expected, as the sound signal in a normally operating scroll compressor is generated mainly at the rotational frequency and its harmonics. The MFCC of scroll machining defects showed strong components not only in the low-frequency regions but also across most of the high-frequency bands. The MFCC of the spatter contamination exhibited frequency components in the low-frequency range. The MFCC of missing component condition represents frequency components in the low-frequency range and is minimally present in the high-frequency range.

Figure 4: Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCC) of scroll compressor acoustic signals: (a) Normal: coefficients are stable in the lower bands with minimal variation in the higher bands; (b) Scroll machining defect: strong coefficients appear across both lower and higher bands; (c) Spatter contamination: coefficients are dominant in the lower bands; and (d) Missing component: coefficients are strong in the lower bands with minimal values in the higher bands

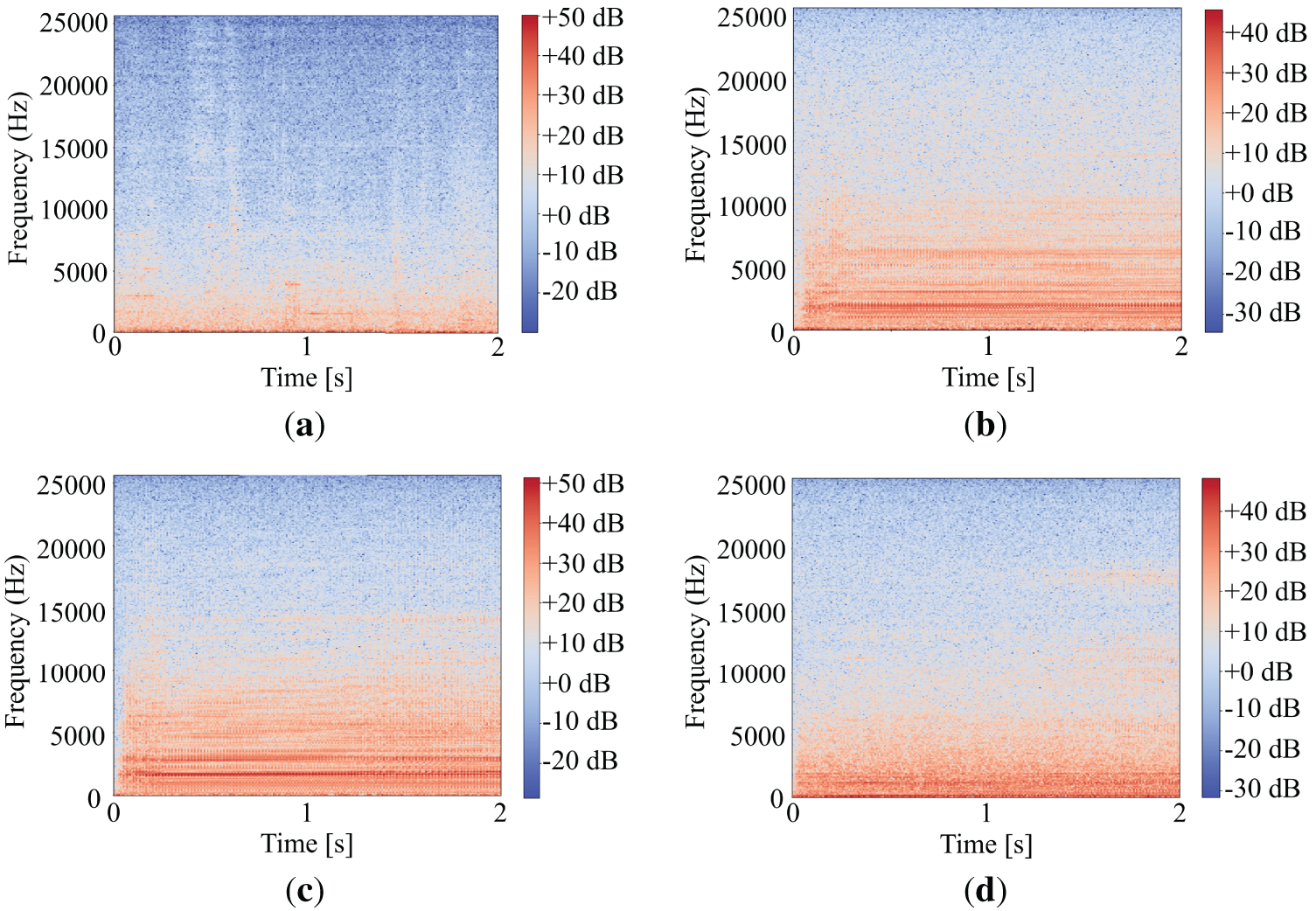

Fig. 5 shows the STFT spectrograms of the SMOTE-generated synthetic samples. This comparison is used to confirm whether the frequency components extracted from the synthetic data reflect the same patterns as those in the real data. Frequency components appear near the 60 Hz rotational frequency and its harmonics. In defective conditions, additional frequency components are observed below 5 kHz. These patterns are similar to those in Fig. 3.

Figure 5: Spectrograms of synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE)-generated synthetic scroll compressor acoustic signals: (a) Normal: frequency components are concentrated around the rotational frequency and its harmonics, with minimal high-frequency components; (b) Scroll machining defect: additional frequency components are observed below 5 kHz; (c) Spatter contamination: broader activation is observed in the low-frequency band below 5 kHz; and (d) Missing component: frequency components increases in the low-frequency band

Fig. 6 shows the MFCCs of synthetic samples. This comparison is used to examine whether the mel-frequency coefficients in the synthetic data follow the distribution seen in the real data. Coefficients are distributed in the lower mel-frequency bands. In defective conditions, coefficients appear across a wider range of mel-frequency bands. The overall patterns correspond to those in Fig. 4.

Figure 6: MFCC of SMOTE-generated synthetic scroll compressor acoustic signals: (a) Normal: coefficients are dominant in the lower bands with minimal values in the higher bands; (b) Scroll machining defect: coefficients are strong across both lower and higher bands; (c) Spatter contamination: coefficients are dominant in the lower bands with some variation in the higher bands; and (d) Missing component: coefficients are strong in the lower bands and minimal in the higher bands

Baseline models were defined by varying the feature extraction process. STFT and MFCC were applied with and without incorporation of rotational frequency and harmonic information. The same AlexNet-based CNN structure was used across all configurations. This allowed evaluation of the effect of incorporating rotational frequency information. Seventy percent of the data were used for training, and the remaining thirty percent of the data were used for testing.

Model performance was evaluated using accuracy, Macro-precision, Macro-recall, and Macro-F1. In this study,

where

For multi-condition evaluation, precision, recall, and F1-score were averaged across all conditions using the macro-averaging scheme.

This formulation ensures that each class, including the minority defect classes, contributes equally to the final evaluation. The experimental results are listed in Table 2.

For the STFT-based model, the version incorporating the rotational frequency achieved an accuracy of 95.00%. This result is attributed to the ability of the model to capture the harmonic components related to the operating characteristics of the compressor. In contrast, the model without rotational frequency consideration showed a reduced accuracy of 79.17%, likely due to its failure to extract defect-related information or its increased susceptibility to background noise.

For the MFCC-based model, all the performance metrics reached 100%, regardless of whether the rotational frequency was incorporated. The frequency components associated with defects were effectively captured due to the configuration of the Mel filter bank, which provides higher resolution in the lower frequency range where rotational harmonics are present. Parameter tuning based on the rotational frequency guides feature extraction toward spectral regions less affected by background noise unrelated to mechanical defects, especially under conditions with large noise variation. The absence of such tuning may lead the model to rely on unstable components, which reduce robustness under actual operating conditions.

This study proposed a non-contact method to diagnose scroll compressor defects during manufacturing. STFT and MFCC parameters were adjusted using the scroll compressor’s rotational frequency to extract defect features under background noise. The optimized features were input into a CNN to construct a diagnostic model. Experimental data were collected during manufacturing processes.

MFCC achieved 100% accuracy with or without rotational frequency input. STFT showed 95% accuracy when rotational frequency was used and 79.17% when it was not used. These results confirm that configuring feature extraction based on rotational frequency improves diagnostic performance.

Rotational frequency and harmonic bands were defined from the rotational speed, which led the model to focus on signal regions linked to mechanical behavior. This design supports consistent diagnostic features across defect types and reduces the risk of overfitting in cases with limited defect samples.

The proposed non-contact method minimizes issues related to sensor installation and equipment interference, making it suitable for scroll compressor testing in manufacturing processes. The method maintained reliability under background noise conditions, supporting integration into factory testing lines.

This study did not evaluate real-time performance. The use of fixed parameter settings and compact CNN architecture enables short training and detection times, supporting integration into manufacturing systems. Future work will include prototype implementation and latency testing in production scenarios. In addition, further studies could extend the framework by addressing variations in operating conditions such as speed and load, and by incorporating domain adaptation strategies to improve generalizability across different equipment and operating environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2023-00239657), in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00423772).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Geunil Lee and Daeil Kwon; Data curation: Geunil Lee; Methodology: Geunil Lee and Daeil Kwon; Project administration: Daeil Kwon; Resources: Daeil Kwon; Software: Geunil Lee; Validation: Geunil Lee and Daeil Kwon; Visualization: Geunil Lee; Writing—original draft: Geunil Lee; Writing—review and editing: Daeil Kwon. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, the data cannot be shared publicly as it is subject to commercial confidentiality agreements.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang T, Chen Y, Qiao M, Snoussi H. A fast and robust convolutional neural network-based defect detection model in product quality control. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2018;94(9):3465–71. doi:10.1007/s00170-017-0882-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yang J, Li S, Wang Z, Dong H, Wang J, Tang S. Using deep learning to detect defects in manufacturing: a comprehensive survey and current challenges. Materials. 2020;13(24):5755. doi:10.3390/ma13245755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Aust J, Mitrovic A, Pons D. Comparison of visual and visual–tactile inspection of aircraft engine blades. Aerospace. 2021;8(11):313. doi:10.3390/aerospace8110313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Katunin A, Dragan K, Nowak T, Chalimoniuk M. Quality control approach for the detection of internal lower density areas in composite disks in industrial conditions based on a combination of NDT techniques. Sensors. 2021;21(21):7174. doi:10.3390/s21217174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Mian T, Choudhary A, Fatima S. An efficient diagnosis approach for bearing faults using sound quality metrics. Appl Acoust. 2022;195(1):108839. doi:10.1016/j.apacoust.2022.108839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Farag HE, Toyserkani E, Khamesee MB. Non-destructive testing using eddy current sensors for defect detection in additively manufactured titanium and stainless-steel parts. Sensors. 2022;22(14):5440. doi:10.3390/s22145440. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Kim JH. Time frequency image and artificial neural network based classification of impact noise for machine fault diagnosis. Int J Precis Eng Manuf. 2018;19(6):821–7. doi:10.1007/s12541-018-0098-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wu X, Peng Z, Ren J, Cheng C, Zhang W, Wang D. Rub-impact fault diagnosis of rotating machinery based on 1-D convolutional neural networks. IEEE Sens J. 2019;20(15):8349–63. doi:10.1109/jsen.2019.2944157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yuan Y, Ge Z, Su X, Guo X, Suo T, Liu Y, et al. Crack length measurement using convolutional neural networks and image processing. Sensors. 2021;21(17):5894. doi:10.3390/s21175894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Yao Y, Gui G, Yang S, Zhang S. A recursive denoising learning for gear fault diagnosis based on acoustic signal in real industrial noise condition. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2021;70:1–15. doi:10.1109/tim.2021.3108216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zou L, Li Y, Xu F. An adversarial denoising convolutional neural network for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery under noisy environment and limited sample size case. Neurocomputing. 2020;407(3):105–20. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2020.04.074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yang S, Gu X, Liu Y, Hao R, Li S. A general multi-objective optimized wavelet filter and its applications in fault diagnosis of wheelset bearings. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2020;145(2):106914. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.106914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Senanayaka A, Lee P, Lee N, Dickerson C, Netchaev A, Mun S. Enhancing the accuracy of machinery fault diagnosis through fault source isolation of complex mixture of industrial sound signals. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2024;133(11–12):5627–42. doi:10.1007/s00170-024-14080-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Shin J, Lee S. Robust and lightweight deep learning model for industrial fault diagnosis in low-quality and noisy data. Electronics. 2023;12(2):409. doi:10.3390/electronics12020409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kumar A, Gandhi CP, Zhou Y, Kumar R, Xiang J. Improved deep convolution neural network (CNN) for the identification of defects in the centrifugal pump using acoustic images. Appl Acoust. 2020;167:107399. doi:10.1016/j.apacoust.2020.107399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Gu J, Peng Y, Lu H, Chang X, Chen G. A novel fault diagnosis method of rotating machinery via VMD, CWT and improved CNN. Measurement. 2022;200(5):111635. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Jiang W, Wang C, Zou J, Zhang S. Application of deep learning in fault diagnosis of rotating machinery. Processes. 2021;9(6):919. doi:10.3390/pr9060919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang Y, Yu Y, Yang Z, Liu Q. Rolling bearing fault identification with acoustic emission signal based on variable-pooling multiscale convolutional neural networks. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):15644. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-00573-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Munir N, Kim HJ, Park J, Song SJ, Kang SS. Convolutional neural network for ultrasonic weldment flaw classification in noisy conditions. Ultrasonics. 2019;94(2):74–81. doi:10.1016/j.ultras.2018.12.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang H, Zhou J, Wang Q, Zhu C, Shao H. Classification-detection of metal surfaces under lower edge sharpness using a deep learning-based approach combined with an enhanced log operator. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;137(2):1551–72. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.027035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hong D, Kim B. 1D convolutional neural network-based adaptive algorithm structure with system fault diagnosis and signal feature extraction for noise and vibration enhancement in mechanical systems. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2023;197(10):110395. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2023.110395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lee J-G, Kim KS, Lee JH. Sound-based unsupervised fault diagnosis of industrial equipment considering environmental noise. Sensors. 2024;24(22):7319. doi:10.3390/s24227319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Ye L, Ma X, Wen C. Rotating machinery fault diagnosis method by combining time-frequency domain features and CNN knowledge transfer. Sensors. 2021;21(24):8168. doi:10.3390/s21248168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Jin T, Yan C, Chen C, Yang Z, Tian H, Guo J. New domain adaptation method in shallow and deep layers of the CNN for bearing fault diagnosis under different working conditions. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2021;124(11–12):3701–12. doi:10.1007/s00170-021-07385-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bienefeld C, Becker-Dombrowsky FM, Shatri E, Kirchner E. Investigation of feature engineering methods for domain-knowledge-assisted bearing fault diagnosis. Entropy. 2023;25(9):1278. doi:10.3390/e25091278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Li X, Zheng J, Li M, Ma W, Hu Y. Frequency-domain fusing convolutional neural network: a unified architecture improving effect of domain adaptation for fault diagnosis. Sensors. 2021;21(2):450. doi:10.3390/s21020450. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Yu M, Liu H, Wang R, Kong X, Hu Z, Li X. An improved CNN based on attention mechanism with multi-domain feature fusion for bearing fault diagnosis. In: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Prognostics and Health Management (ICPHM); 2021 Jun 7–9; Online. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

28. Yu X, Chen X, Du M, Yang Y, Feng Z. Rotating machinery fault diagnosis under time–varying speed conditions based on adaptive identification of order structure. Processes. 2024;12(4):752. doi:10.3390/pr12040752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Tran T, Lundgren J. Drill fault diagnosis based on the scalogram and mel spectrogram of sound signals using artificial intelligence. IEEE Access. 2020;8:203655–66. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3036769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jang GB, Cho SB. Feature space transformation for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery under different working conditions. Sensors. 2021;21(4):1417. doi:10.3390/s21041417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Yu S, Song L, Pang S, Wang M, He X, Xie P. M-Net: a novel unsupervised domain adaptation framework based on multi-kernel maximum mean discrepancy for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery. Complex Intell Syst. 2024;10(3):3259–72. doi:10.1007/s40747-023-01320-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yu S, Pang S, Ning J, Wang M, Song L. ANC-Net: a novel multi-scale active noise cancellation network for rotating machinery fault diagnosis based on discrete wavelet transform. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;265(1):125937. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Oh JH, Kim CG, Cho YM. Diagnostics and prognostics based on adaptive time-frequency feature discrimination. KSME Int J. 2004;18(9):1537–48. doi:10.1007/BF02990368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Song Y, Ma Q, Zhang T, Li F, Yu Y. Research on vibration and noise characteristics of scroll compressor with condenser blockage fault based on signal demodulation. Int J Refrig. 2023;154:9–18. doi:10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2023.07.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wang J, Mo Z, Zhang H, Miao Q. a deep learning method for bearing fault diagnosis based on time-frequency image. IEEE Access. 2019;7:42373–83. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2907131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Nakamura H, Asano K, Usuda S, Mizuno Y. A diagnosis method of bearing and stator fault in motor using rotating sound based on deep learning. Energies. 2021;14(5):1319. doi:10.3390/en14051319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yao Y, Wang H, Li S, Liu Z, Gui G, Dan Y, et al. End-to-end convolutional neural network model for gear fault diagnosis based on sound signals. Appl Sci. 2018;8(9):1584. doi:10.3390/app8091584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Deng L, Seltzer ML, Yu D, Acero A, Mohamed A, Hinton G. Binary coding of speech spectrograms using a deep auto-encoder. In: Eleventh Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association; 2010 Sep 26–30; Chiba, Japan. p. 1692–5. [Google Scholar]

39. Zhang J, Tian J, Cao Y, Yang Y, Xu X. Deep time–frequency representation and progressive decision fusion for ECG classification. Knowl-Based Syst. 2020;190(3):105402. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2019.105402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun ACM. 2017;60(6):84–90. doi:10.1145/3065386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang H, Wu Q, Tang W, Yang J. Acoustic signal-based defect identification for directed energy deposition-arc using wavelet time-frequency diagrams. Sensors. 2024;24(13):4397. doi:10.3390/s24134397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Prasshanth CV, Naveen Venkatesh S, Mahanta TK, Sakthivel NR, Sugumaran V. Fault diagnosis of monoblock centrifugal pumps using pre-trained deep learning models and scalogram images. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;136(7):109022. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.109022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools