Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Priority-Based Scheduling and Orchestration in Edge-Cloud Computing: A Deep Reinforcement Learning-Enhanced Concurrency Control Approach

1 Department of Business Intelligence and Data Analytics, Faculty of Administrative and Financial Sciences, University of Petra, Amman, 11623, Jordan

2 Department of Software Engineering, Faculty of Science and Information Technology, Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan, Amman, 11733, Jordan

3 Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Information Technology, Zarqa University, Zarqa, 13110, Jordan

4 Department of Information Security, Faculty of Information Technology, University of Petra, Amman, 11623, Jordan

5 Department of Information Systems, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

6 Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Prince Al-Hussein Bin Abdallah II for Information Technology, Al Al-Bayt University, Mafraq, 25113, Jordan

7 Preparatory Year Deanship, Physics Department, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Al-Kharj, 11942, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Ahmad Al-Qerem. Email: ; Amina Salhi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Engineering Applications of Discrete Optimization and Scheduling Algorithms)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 673-697. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070004

Received 05 July 2025; Accepted 29 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

The exponential growth of Internet of Things (IoT) devices has created unprecedented challenges in data processing and resource management for time-critical applications. Traditional cloud computing paradigms cannot meet the stringent latency requirements of modern IoT systems, while pure edge computing faces resource constraints that limit processing capabilities. This paper addresses these challenges by proposing a novel Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL)-enhanced priority-based scheduling framework for hybrid edge-cloud computing environments. Our approach integrates adaptive priority assignment with a two-level concurrency control protocol that ensures both optimal performance and data consistency. The framework introduces three key innovations: (1) a DRL-based dynamic priority assignment mechanism that learns from system behavior, (2) a hybrid concurrency control protocol combining local edge validation with global cloud coordination, and (3) an integrated mathematical model that formalizes sensor-driven transactions across edge-cloud architectures. Extensive simulations across diverse workload scenarios demonstrate significant quantitative improvements: 40% latency reduction, 25% throughput increase, 85% resource utilization (compared to 60% for heuristic methods), 40% reduction in energy consumption (300 vs. 500 J per task), and 50% improvement in scalability factor (1.8 vs. 1.2 for EDF) compared to state-of-the-art heuristic and meta-heuristic approaches. These results establish the framework as a robust solution for large-scale IoT and autonomous applications requiring real-time processing with consistency guarantees.Keywords

The explosion of Internet of Things (IoT) devices spanning smart cities, autonomous vehicles, industrial automation, and healthcare systems has fundamentally changed computational needs [1]. Modern Internet of Things (IoT) applications produce huge streams of data, which require processing in real-time with latency constraints that are measured in milliseconds [2]. Geographical distance and network bottlenecks are the main reasons why the traditional cloud computing architectures with abundant computing power lead to unacceptable communication latency for time-sensitive applications [3].

Current edge-cloud computing systems are associated with several challenges that mutually restrict their performance:

Challenge 1: Static Resource Management—Static scheduling strategies are based on predefined priority schemes or simple heuristics and are not able to adapt to dynamic workloads and evolving system conditions [4].

Challenge 2: Consistency vs. Performance Trade-Off—Achieving data consistency across distributed edge nodes at low-latency processing leads to fundamental tensions that are poorly addressed by existing solutions [5].

Challenge 3: Heterogeneous Resource Coordination—Current orchestration mechanisms are not up to the task of coordinating between resource-constrained devices at the edge with powerful infrastructure in the cloud [6].

Challenge 4: Real-Time Learning and Adaptation—IoT workloads are dynamic and thus require systems capable of learning from experience and adapting their behavior in real time, something that traditional approaches cannot do [7].

Existing solutions focus either on cloud-based scheduling optimization or edge-only resource management, failing to leverage the synergistic potential of hybrid architectures [8,9]. Moreover, most approaches employ static heuristics or meta-heuristics that cannot learn from system behavior or adapt to evolving conditions. No prior work has successfully integrated adaptive learning mechanisms with rigorous concurrency control in edge-cloud environments [10].

This paper introduces a novel framework that bridges these gaps through Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL)-enhanced priority-based scheduling integrated with two-level concurrency control. Our approach enables dynamic adaptation to system conditions while maintaining strong consistency guarantees across distributed resources.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the related literature on edge computing, scheduling algorithms, and DRL in resource management. Section 3 introduces the mathematical model underpinning our approach. Section 4 details the proposed DRL-based concurrency control protocol and the associated orchestration strategy. Section 5 describes the simulation environment, workload generation, and baseline settings used for performance evaluation. Section 6 presents and discusses the simulation results. Section 7 provides an extended discussion of the findings and explores potential variants of the proposed approach, while Section 8 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

Edge computing has emerged to address the latency issues in traditional cloud systems. Early investigations demonstrated the benefits of processing data at the edge, especially for real-time applications such as augmented reality and autonomous driving [3,11]. Constrained resources at the edge create new challenges for task scheduling in distributed environments, which has been the focus of numerous studies [12–14], particularly in the realm of IoT and real-time analytics [15,16].

In the context of scheduling and orchestration, various authors have employed diverse strategies. Priority-based scheduling is frequently chosen for its simple and effective handling of tasks with critical deadlines, as discussed in [5] and [9]. Other researchers have proposed meta-heuristic approaches such as Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [17–20]. These methods can yield near-optimal solutions, but often face challenges when the workload is highly dynamic [21]. More recent studies incorporate machine learning and, specifically, reinforcement learning to adapt to changing system conditions [10,22,23]. By learning from both successful and failed scheduling decisions, DRL provides a powerful mechanism to optimize resource usage in real time [24–27]. Hybrid edge-cloud architectures introduce the need for multi-level orchestration. Centralized cloud servers can handle large-scale planning, while edge nodes manage immediate scheduling needs under strict latency constraints [28,29].

Studies such as [7] and [8] emphasize the use of hierarchical frameworks that minimize communication overhead by validating transactions locally before escalating them globally. In mission-critical applications, especially with stringent latency requirements, local decisions can make the difference between success and failure. Concurrency control is key to ensuring data consistency, and research in concurrency models for edge-cloud environments has drawn upon established techniques in database systems [30–32]. Some recent works specifically address the concurrency challenges of IoT-driven transactions, suggesting advanced protocols for sensor-based data streams [33–35]. DRL has been explored in scheduling contexts ranging from multi-tenant resource allocation in the cloud [36] to priority-based offloading in vehicular edge environments [37]. Agents learn optimal scheduling decisions by maximizing a reward function that balances latency, throughput, and energy consumption [38]. The ability of DRL to incorporate multi-dimensional objectives makes it particularly suitable for dynamic edge-cloud systems, where tasks arrive irregularly and require heterogeneous resources.

Multi-agent DRL (MARL) has further extended these gains by enabling multiple cooperative agents to share learning signals [39]. This cooperative approach is highly applicable to large-scale IoT deployments, where geographically distributed edge nodes independently process local data but also need to coordinate for global efficiency. Some works concentrate on energy constraints, such as introducing re-prioritization strategies to accommodate the limited power budgets of edge devices [40]. Others focus on robust scheduling under uncertain load patterns or hardware failures, proposing DRL-based fault-tolerance mechanisms [41]. Meanwhile, certain studies explore user-centric Quality of Service (QoS) demands, building reward functions that consider personalized QoS objectives [42].

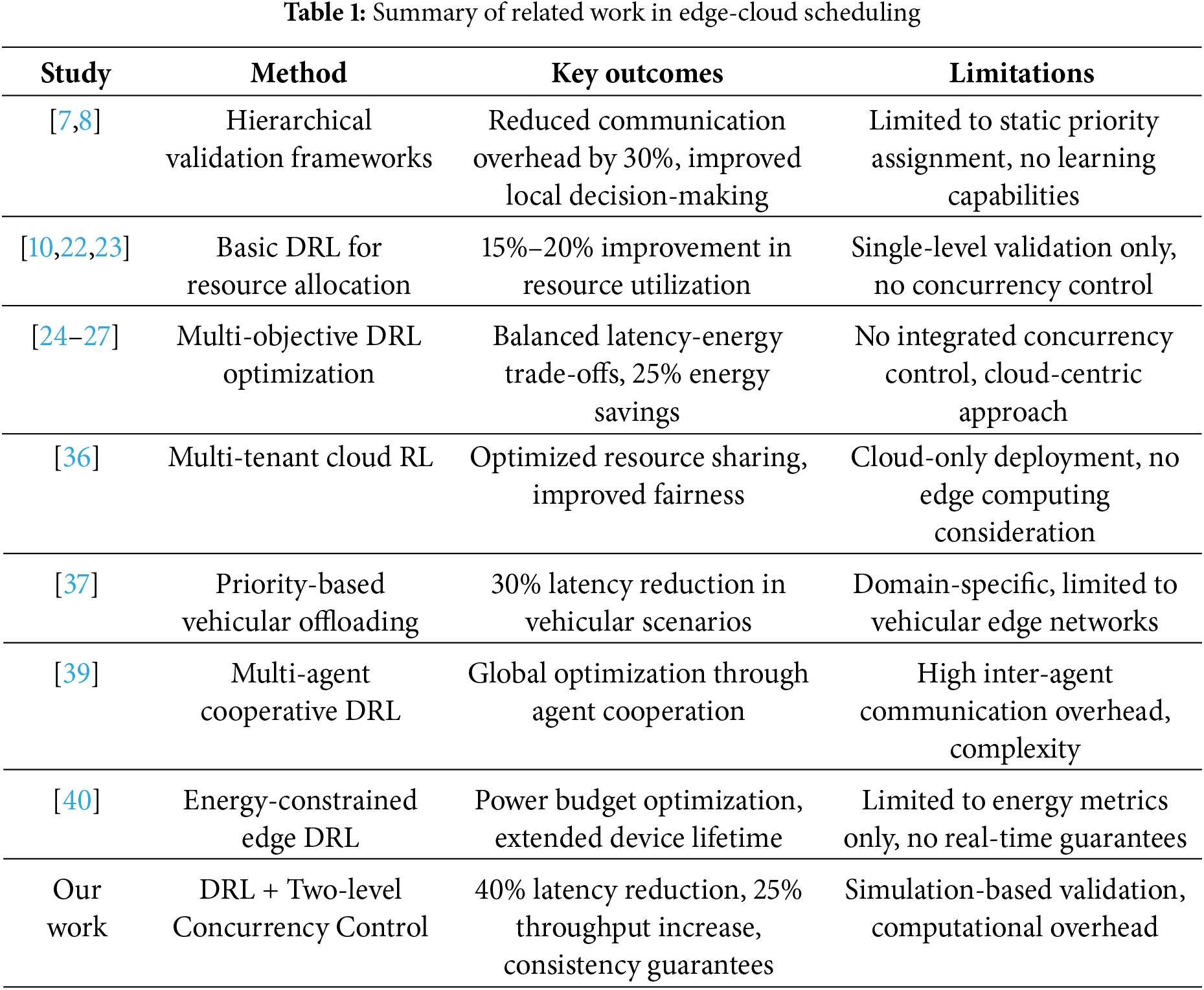

Our study builds on these insights by combining DRL-based adaptive priority assignment with a novel two-level concurrency control in a hybrid edge-cloud environment, ensuring that tasks can meet both deadline requirements and consistency constraints while optimizing for energy efficiency and cost. Table 1 presents a summary of related work in edge-cloud scheduling, highlighting key approaches, methodologies, and limitations discussed in the literature.

3 Mathematical Modeling of Edge-Cloud Scheduling

In this section, we introduce a rigorous mathematical model that captures the essential elements of sensor-driven transactions, scheduling, and concurrency control in an edge-cloud environment. The model formalizes the system entities, transaction definitions, execution semantics, and performance metrics.

3.1 System Entities and Data Generation

Let

The edge layer comprises a set of edge nodes

3.2 Transaction Definition and Priority Assignment

Each transaction

where:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

The DRL agent implements the function

3.3 Local and Global Transactions

A transaction is classified as local if

3.4 Execution Semantics and Concurrency Control

The execution of each transaction follows an optimistic concurrency control (OCC) approach with two validation levels:

3.4.1 Local Execution and Validation

At an edge node

1. Local Read Phase: Data items in

2. Local Write Buffering: New values computed for items in

3. Local Validation: The transaction is checked for conflicts with other transactions executing on

Priority-based resolution is applied, where the transaction with the higher

If a transaction is purely local and passes validation, it is committed at the edge. Otherwise, it escalates to global validation.

For cross-edge transactions, the cloud node

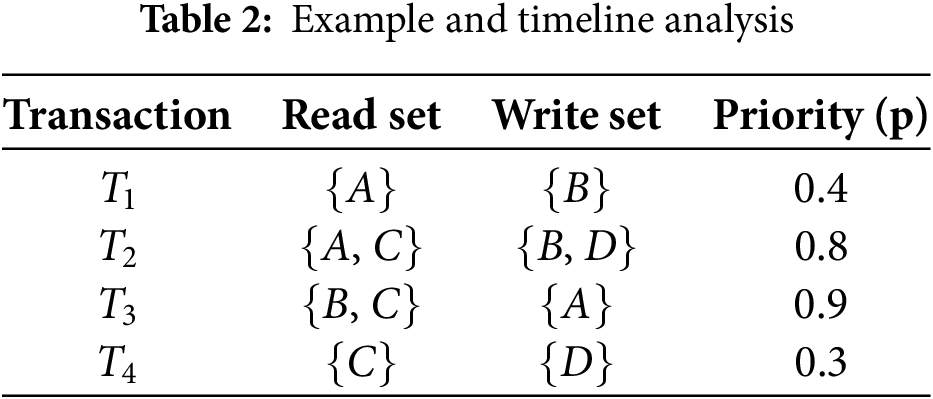

3.5 Illustrative Example and Timeline Analysis

Consider an edge-cloud system with two edge nodes,

In this scenario:

•

•

• During local validation at

• At

4 Proposed DRL-Based Concurrency Control Protocol

In this section, we detail our novel protocol that leverages DRL for adaptive priority assignment, enabling efficient scheduling and orchestration in edge-cloud environments. The protocol is structured into several key phases: DRL-based priority assignment, local optimistic execution, local validation and conflict resolution, and global validation at the cloud.

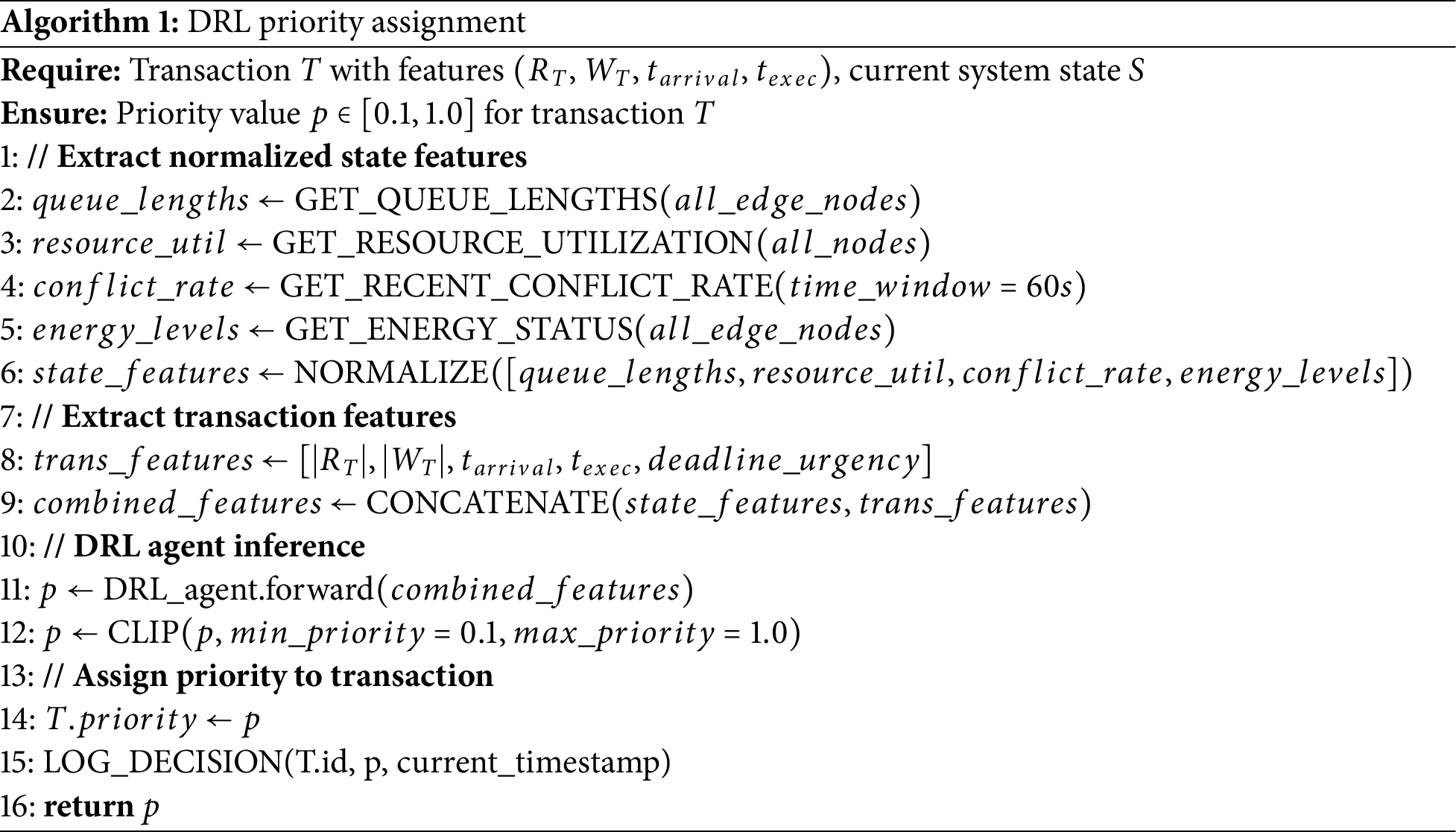

The first step in our protocol is to assign a dynamic priority to each incoming transaction using a DRL agent. The agent observes system metrics and transaction characteristics to output a priority value, guiding subsequent scheduling decisions. The pseudo-code for the DRL priority assignment is provided in Algorithm 1.

The DRL agent continuously updates its policy based on feedback from the environment, such as successful commits before deadlines and penalties for aborted transactions. This adaptive mechanism allows the system to dynamically optimize task scheduling based on real-time conditions.

DRL Algorithm Specification and Training Details

Algorithm Architecture: We implement a Deep Q-Network (DQN) with the following specifications:

• Network Architecture: Three fully connected layers (256, 128, 64 neurons) with Rectified Linear Unit activation functions and dropout layers (rate = 0.2) for regularization

• Experience Replay: Circular buffer storing 10,000 state-action-reward transitions

• Target Network: Separate target network updated every 100 training steps for stability

• Double DQN: Implementation includes Double DQN mechanism to reduce overestimation bias

State Space Representation: The state vector

where

Action Space Definition: Actions correspond to discrete priority levels:

Reward Function Structure:

where:

Weights:

Convergence Validation: Training convergence is validated through multiple criteria:

1. Reward Stability: Moving average reward over 100 episodes must stabilize within 1% variation

2. Policy Stability: Action selection probability distribution changes less than 5% between consecutive 100-episode windows

3. Performance Validation: Periodic evaluation on held-out validation scenarios shows consistent performance

4. Convergence Timeline: Training typically achieves convergence after 2000–3000 episodes across different scenarios, with S1 (stable load) converging fastest (1800 episodes) and S3 (energy-constrained) requiring the most episodes (3200 episodes)

Training Hyperparameters:

• Learning rate: 0.001 with Adam optimizer

• Batch size: 32 experiences per training step

• Discount factor (

• Exploration:

• Training frequency: Every 10 environment steps

4.2 Local Optimistic Execution

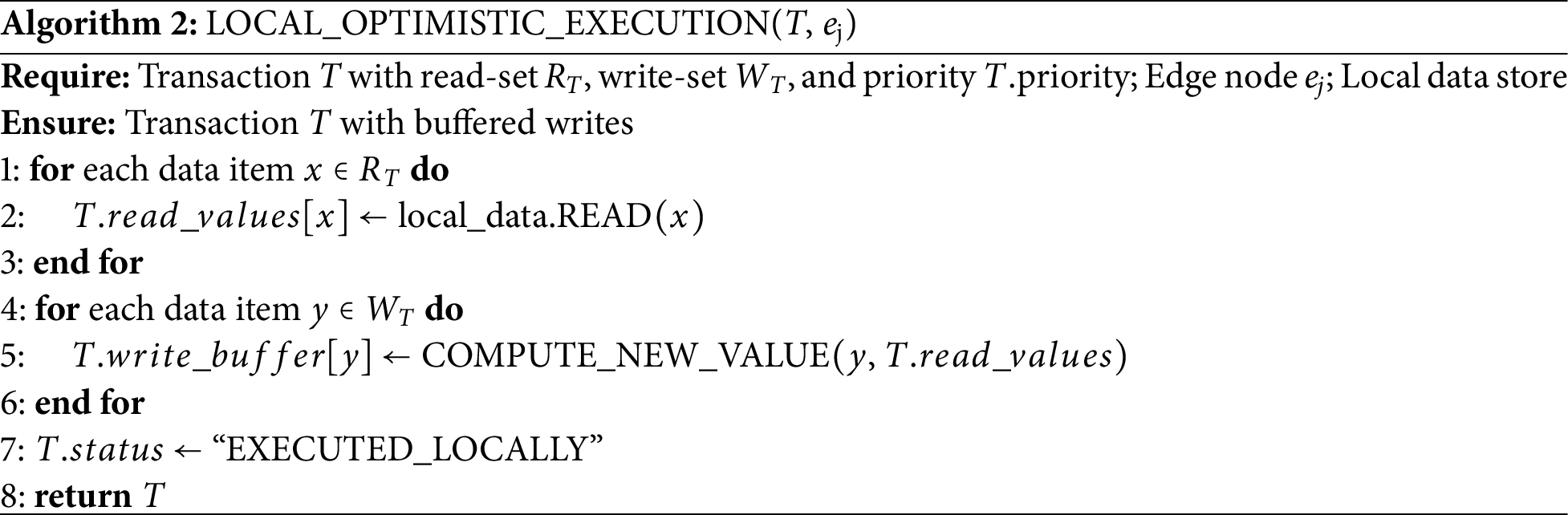

Once a transaction T has been assigned a priority, it is executed optimistically on the corresponding edge node. In the local execution phase, T reads the required data items and computes the necessary updates without acquiring locks. The write operations are buffered locally until the validation phase. Algorithm 2 summarizes the local optimistic execution process.

4.3 Local Validation and Conflict Resolution

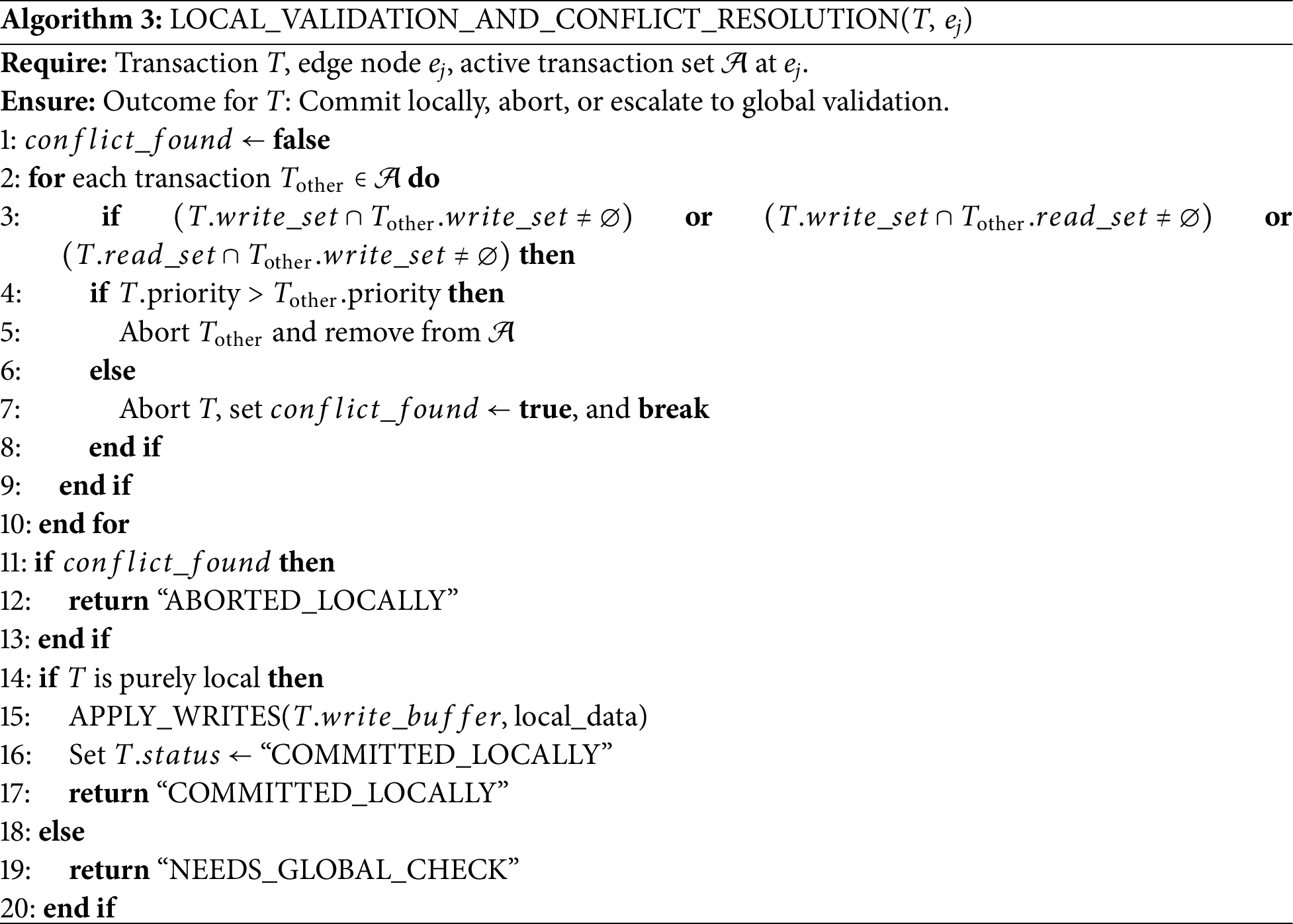

After the optimistic execution, the transaction enters the local validation phase. At this stage, the edge node checks for conflicts with other concurrently executing transactions. Conflict resolution is performed based on the DRL-assigned priorities; in case of a conflict, the transaction with the higher priority wins, and the other is aborted. Algorithm 3 provides the pseudo-code for this phase.

4.4 Global Validation at the Cloud

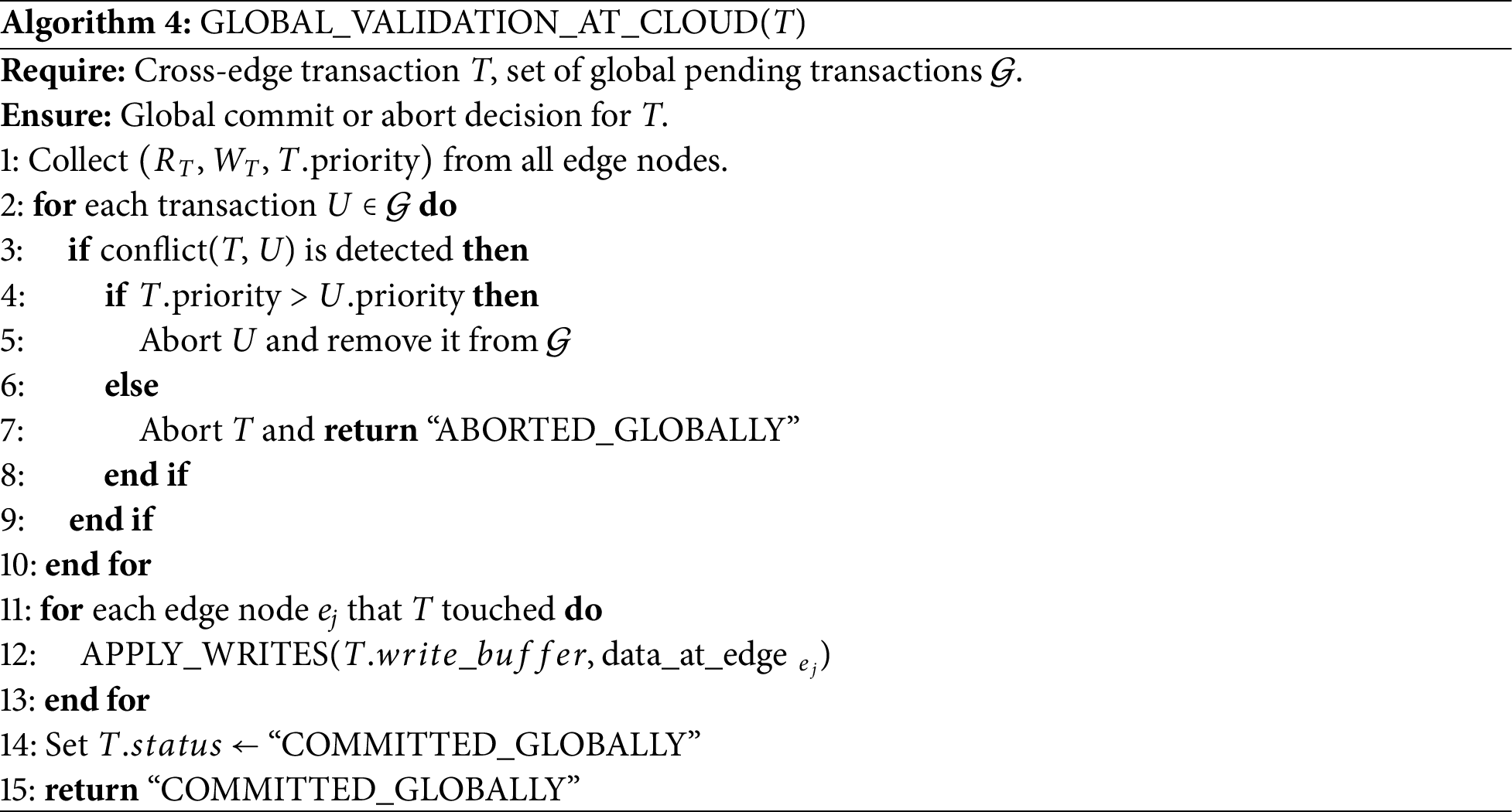

For cross-edge transactions, a final global validation is performed at the cloud node

5 Experimental Setup and Simulator Configuration

To evaluate the performance of our proposed scheduling and orchestration framework, we developed a simulation environment that models realistic edge-cloud systems. In this section, we describe the infrastructure configuration, workload generation, scheduling techniques compared, and the metrics used for evaluation.

5.1 Infrastructure Configuration

The simulated system consists of:

• Edge Nodes: A cluster of 10 edge nodes, each with 4 CPU cores, 8 GB of RAM, 100 GB of storage, and a network bandwidth of 100 Mbps.

• Cloud Servers: A pair of cloud servers with 16 CPU cores, 64 GB of RAM, 1 TB of storage, and a network bandwidth of 1 Gbps.

The processing speeds are assumed to be 2.5 GHz for edge nodes and 3.5 GHz for cloud servers. The simulation incorporates realistic network delays and processing overheads, modeling the latency, resource utilization, energy consumption, and cost associated with executing transactions in both edge and cloud environments.

5.2 Workload Generation and Task Arrival

Task arrival is modeled using a Poisson process with parameter

1. Latency-Sensitive Tasks: Tasks that require processing within strict deadlines, such as real-time analytics and autonomous driving computations.

2. Compute-Intensive Tasks: Tasks that require significant computational resources, including large-scale simulations and AI inference.

3. IoT Sensor-Driven Tasks: Periodic and sporadic tasks generated by sensor networks in smart city applications or industrial IoT.

Each task is assigned a deadline, resource requirement, and a DRL-computed priority. The tasks are distributed across edge nodes and, when necessary, escalated to the cloud for global validation.

5.3 Baseline Scheduling Techniques

To benchmark our proposed DRL- Priority Adjustment (DRL-PA) based scheduling framework, we compare it with:

• Heuristic-Based Scheduling: Earliest Deadline First (EDF).

• Meta-Heuristic Algorithms: Approaches using Genetic Algorithms (GA).

Comprehensive Scenario Definitions:

S1: Baseline Fixed Load

• Workload Characteristics: Constant task arrival rate of 50 tasks/second with uniform distribution across edge nodes

• Resource Conditions: All edge nodes operating at full capacity (100% CPU, memory, and network availability)

• Network Status: Stable connectivity with consistent 10 ms edge-cloud latency

• Application Context: Models steady-state industrial automation environments with predictable sensor data streams

• Duration: 3600-s simulation periods

• Evaluation Purpose: Establishes baseline performance metrics under ideal conditions

S2: Dynamic Load Scaling

• Workload Characteristics: Task arrival rate increases linearly from 50 to 200 tasks/s over simulation duration

• Resource Conditions: Standard resource availability with automatic scaling triggers at 80% utilization

• Network Status: Variable latency (5–20 ms) reflecting increased network congestion during peak periods

• Application Context: Simulates peak traffic periods in smart city applications (rush hour traffic monitoring, event management)

• Load Pattern: Gradual increase modeling real-world traffic patterns

• Evaluation Purpose: Tests adaptive scheduling capabilities under increasing demand

S3: Energy-Constrained Edge Nodes

• Workload Characteristics: Standard task arrival rate (75 tasks/s) with mixed computational requirements

• Resource Conditions: 30% of edge nodes operate at reduced capacity (50% CPU frequency, 70% memory availability)

• Network Status: Standard connectivity with energy-aware communication protocols

• Application Context: Models battery-powered edge gateways, solar-powered sensor clusters, or remote monitoring stations

• Constraints: Power budget limitations forcing nodes into low-power modes

• Evaluation Purpose: Validates energy-aware scheduling and resource redistribution capabilities

S4: Deadline-Critical Scheduling

• Workload Characteristics: Mixed-criticality workload with strict timing requirements:

– 40% ultra-critical tasks (

– 30% high-priority tasks (

– 30% normal-priority tasks (

• Resource Conditions: Standard availability with priority-based resource reservation

• Network Status: Guaranteed low-latency channels for critical tasks

• Application Context: Autonomous vehicle coordination, emergency response systems, industrial safety control

• Evaluation Purpose: Tests deadline satisfaction and priority-based conflict resolution under stringent timing constraints

Cross-Scenario Analysis: These scenarios are specifically designed to stress different aspects of the scheduling framework:

• S1 validates baseline efficiency and establishes performance bounds

• S2 tests scalability and adaptive learning capabilities

• S3 evaluates energy-aware optimization and resource constraint handling

• S4 assesses real-time scheduling and deadline guarantee mechanisms

To effectively test the algorithms that will be utilized in the scheduling, a series of simulation scenarios are required, each with a focus on a particular characteristic of the system behaviour and resource constraints. We test four key scenarios in this work, which are the extremes of edge- and real-time computing environments. They extend across relatively stable baseline conditions to high load network conditions with tight power and deadline constraints. To compare the strengths and weaknesses of each solution, we change the rate at which tasks arrive, the energy budgets, and the time schedule. Any experiment is repeated 30 times to generate statistical information that can be used to draw meaningful conclusions regarding means, variances, or confidence intervals, etc. This methodological method adds confidence to our comparisons and demonstrates the strength of the results.

Baseline Fixed Load: This model is used to show a steady operating point where jobs get in at a given rate and the resources are never used up. It can be compared to real-time computing systems whose workload is deterministic, i.e., to industrial automation systems where sensor readings and control inputs are received at a regular time. By imposing input, we test the behavior of each scheduler with a predictable (yet still significant) load at any point. It serves as a benchmark, therefore, all the algorithms can be put on the same playing field before moving to more dynamic settings.

Dynamic Load Scaling: The load of modern networks is usually not constant across time, but varies between off-peak quiescence and sudden spikes when the network is particularly active. To model such dynamics, we created a scenario where the task arrival rate is rising slowly, modeling surges in user activity like the rush hours on weekdays, or the bursty activity due to an unexpected arrival of users. This state of affairs puts the flexibility of any algorithm into question: a good scheduler needs to recombine and re-prioritize its decisions to be capable of responding to the increased level of demand without causing unacceptable delays or overloading its resource capabilities. Load-sensitive policies allow the system to ensure resources are used in a manner that scales with your application, like streaming video analytics or when large-scale event processing applications like anomaly detection or social media ingestion are involved.

Edge Nodes that are Energy Constrained—With the increasing use of the Internet of Things and edge devices, the energy constraints become far more important. In this case, we restrict the amount of power available to some edge nodes so that they are allowed to run at reduced clock rates or in partial stand-by. These restrictions add more problems to the scheduler: not only must it consider the workload balance, but also must it know about the energy constraints to avoid overloading underpowered nodes with anything compute-intensive. These constraints are modeled to mimic conditions in battery-powered edge gateways or solar-powered sensor nodes, which are common to remote or mobile deployments where power savings have a direct effect on the device lifetime and availability.

Deadline-Critical Scheduling—Certain real-time applications (i.e., emergency response, vehicular networks, or industrial control loops) are only significant when strict deadlines are fulfilled. Tasks in this situation are subject to time constraints and must be ordered by the scheduler so as to be insulated against draconian punishment due to their lateness. A growing number of high-priority tasks force the scheduler to trade off between serving urgent workload vs. maintaining overall throughput to the routine workload. Using the example, where every algorithm can accept deadlines, when a deadline is missed, there is some kind of penalty related to it, and we can know whether it can be implemented in a high-stakes environment, such as real-time.

We conducted experiments under several scenarios to test system robustness and performance:

• Baseline Fixed Load: A fixed task arrival rate with constant resource availability.

• Dynamic Load Scaling: Increasing task arrival rates over time to simulate peak traffic periods.

• Energy-Constrained Edge Nodes: Scenarios where a subset of edge nodes operate under reduced power availability.

• Deadline-Critical Scheduling: Emphasis on meeting hard deadlines, with high-priority tasks requiring immediate processing.

Each experiment is run for 1000 iterations, and statistical analysis (including mean, variance, and confidence intervals) is performed to ensure the significance of the results.

To evaluate the efficiency of the proposed scheduling strategy, we define several performance metrics:

The total response time for a transaction

Over a time interval

For each transaction

5.5.4 Resource Utilization and Energy

Let

These metrics are used to optimize scheduling decisions and to evaluate the overall performance of the proposed framework.

5.6 Parameter Configuration and Sensitivity Analysis

DRL Agent Parameters: The DRL agent configuration was determined through systematic hyperparameter tuning:

• Learning Rate (

• Discount Factor (

• Exploration Rate (

• Experience Replay Buffer: Size set to 10,000 experiences with batch size of 32 for training updates every 10 steps.

Reward Function Weights: The reward function weights were optimized through grid search:

Sensitivity Analysis Results:

• Latency Weight Sensitivity: Increasing from 0.2 to 0.4 improves latency by 15% but reduces throughput by 8%

• Energy Weight Impact: Values above 0.3 significantly reduce energy consumption (45% improvement) but increase latency by 12%

• Learning Rate Sensitivity:

• Buffer Size Impact: Buffers below 5000 show unstable learning, while larger buffers (>50,000) provide marginal improvement with increased memory overhead

Optimal Configuration Rationale: The selected parameters balance convergence speed, stability, and multi-objective performance optimization based on extensive empirical evaluation across all simulation scenarios.

5.7 Computational Complexity Analysis

Time Complexity Comparison:

Heuristic Methods (EDF):

• Sorting-based priority assignment:

• Transaction scheduling:

• Overall per-decision complexity:

• Advantages: Minimal computational overhead, deterministic execution time

• Limitations: No learning capability, poor adaptation to dynamic conditions

Meta-Heuristic Methods (Genetic Algorithm):

• Population initialization:

• Fitness evaluation:

• Selection and crossover:

• Mutation operations:

• Overall per-generation:

• Total optimization:

• Typical values:

• Advantages: Global optimization capability, handles complex constraint spaces

• Limitations: High computational cost, slow convergence, no incremental learning

Proposed DRL Method:

• Neural network inference:

• Forward pass through layers:

• Experience replay training:

• Overall per-decision complexity:

• Training complexity:

• Advantages: Constant inference time, adaptive learning, real-time capability

• Limitations: Initial training overhead, requires historical data

Performance Comparison: Based on our experimental measurements on ARM Cortex-A78 edge hardware:

• EDF:

• GA:

• DRL (our method):

Scalability Analysis: The computational complexity advantage of DRL becomes more pronounced as system scale increases:

• For

• For

• Edge deployment feasibility: Only EDF and DRL are suitable for real-time edge deployment

This analysis demonstrates that while DRL requires initial training investment, its operational efficiency surpasses meta-heuristic approaches while providing adaptive optimization capabilities unavailable in simple heuristics.

6 Simulation Results and Discussion

In this section, we present and analyze the performance of our proposed DRL-based scheduling framework in comparison with heuristic and meta-heuristic approaches. The discussion is structured around the performance metrics defined in Section 5.

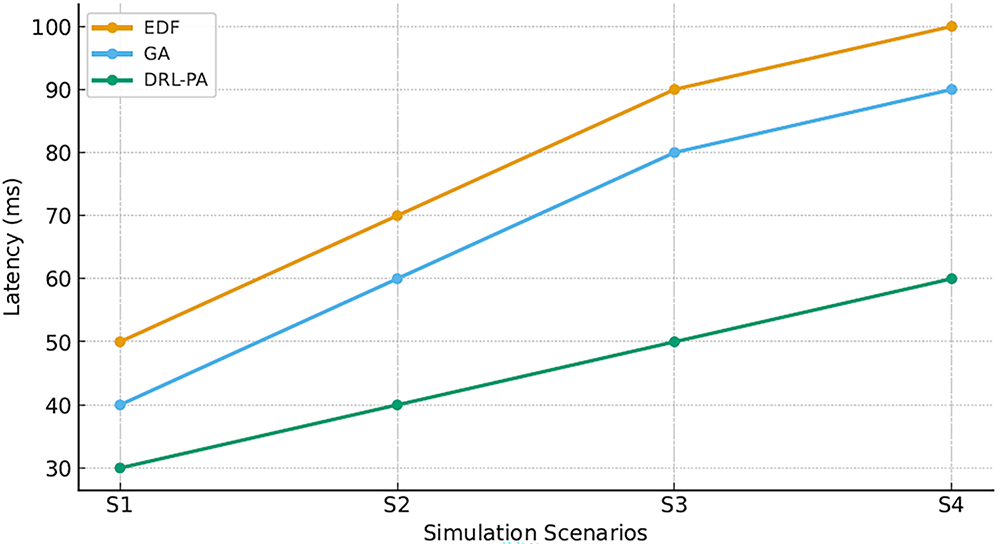

In terms of latency, which directly correlates with user experience and timely completion of critical tasks, EDF exhibits limitations primarily due to its rigid priority assignments based solely on deadline proximity. As Fig. 1 illustrates, latency under EDF escalates notably in S3, where energy constraints force nodes to operate at reduced capacity, and in S4, where tasks have especially stringent deadlines. This inflexibility leads to suboptimal queuing, causing high-priority or latency-sensitive tasks to wait behind tasks with slightly earlier deadlines but lower urgency. GA mitigates this issue to a certain degree by exploring a population of potential schedules and iteratively refining them; however, its performance deteriorates under highly variable loads. In contrast, DRL-PA achieves the lowest latency across all scenarios, demonstrating up to a 40% latency reduction relative to EDF in S4. Such a marked improvement arises from the DRL agent’s policy-learning mechanism, which continuously monitors the system state—capturing real-time queue lengths, task urgency, node utilization, and energy availability—and adaptively reorders tasks to minimize wait times for latency-sensitive operations. This adaptive quality is particularly crucial for interactive applications, such as industrial automation or autonomous drone coordination, where any delay in critical tasks can undermine overall system functionality.

Figure 1: Latency comparison among scheduling techniques

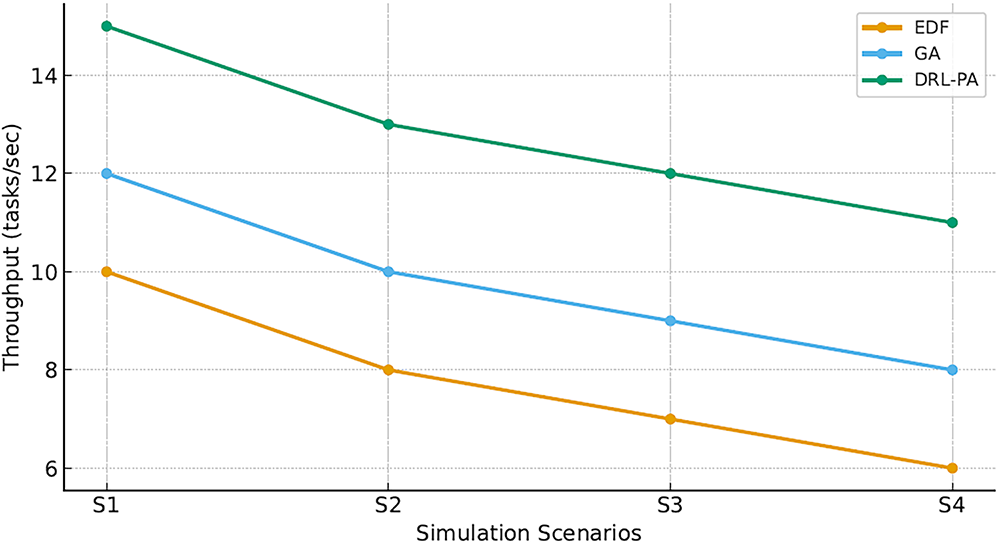

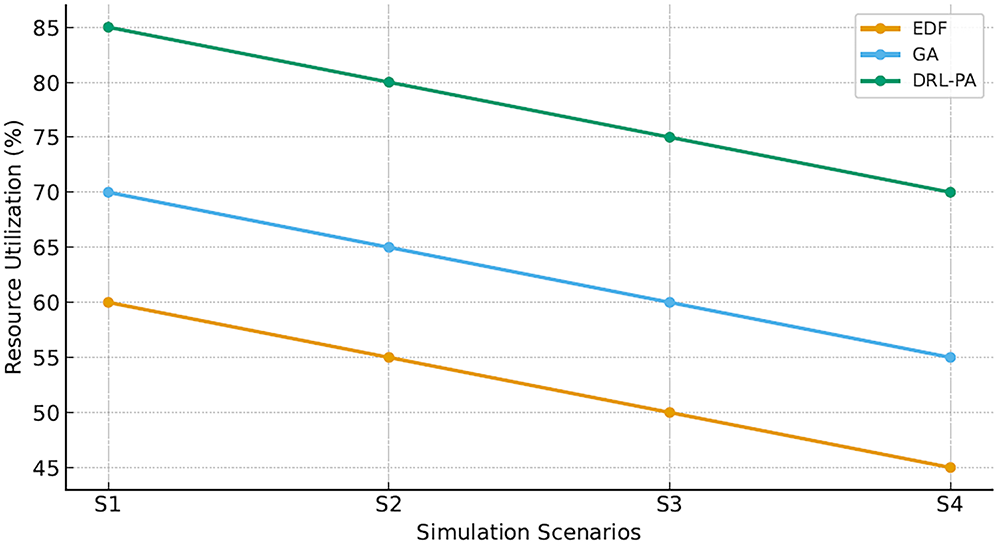

6.2 Throughput and Resource Utilization

Fig. 2 presents the throughput achieved under different scheduling methods. Our proposed DRL-based method consistently processes a higher number of transactions per second. Moreover, Fig. 3 illustrates that the DRL-based approach results in better resource utilization, achieving up to 85% usage compared to 60% for heuristic methods.

Figure 2: Throughput comparison among scheduling techniques

Figure 3: Resource utilization comparison among scheduling techniques

Enhanced throughput and resource utilization stem from the DRL agent’s ability to dynamically adjust priorities based on real-time system state, thereby reducing idle time and mitigating bottlenecks.

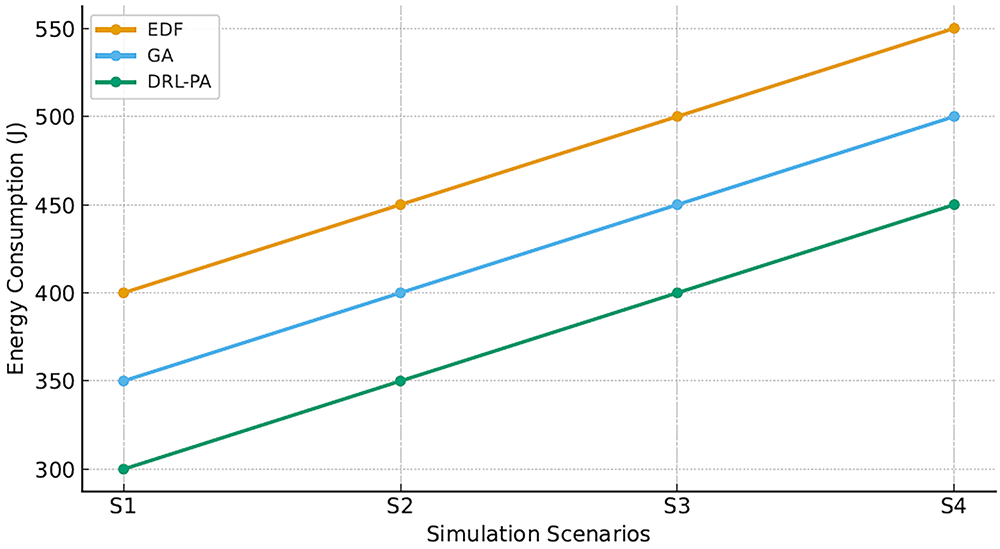

Fig. 4 compares the energy consumption and operational cost of the three scheduling approaches. The DRL-based scheduling not only reduces energy consumption (approximately 300 Joules per task) compared to 500 Joules for heuristic methods.

Figure 4: Energy consumption comparison

These improvements are crucial in scenarios where sustainability and cost-effectiveness are prioritized. The DRL-based framework is capable of learning energy-aware scheduling policies that balance performance with power consumption.

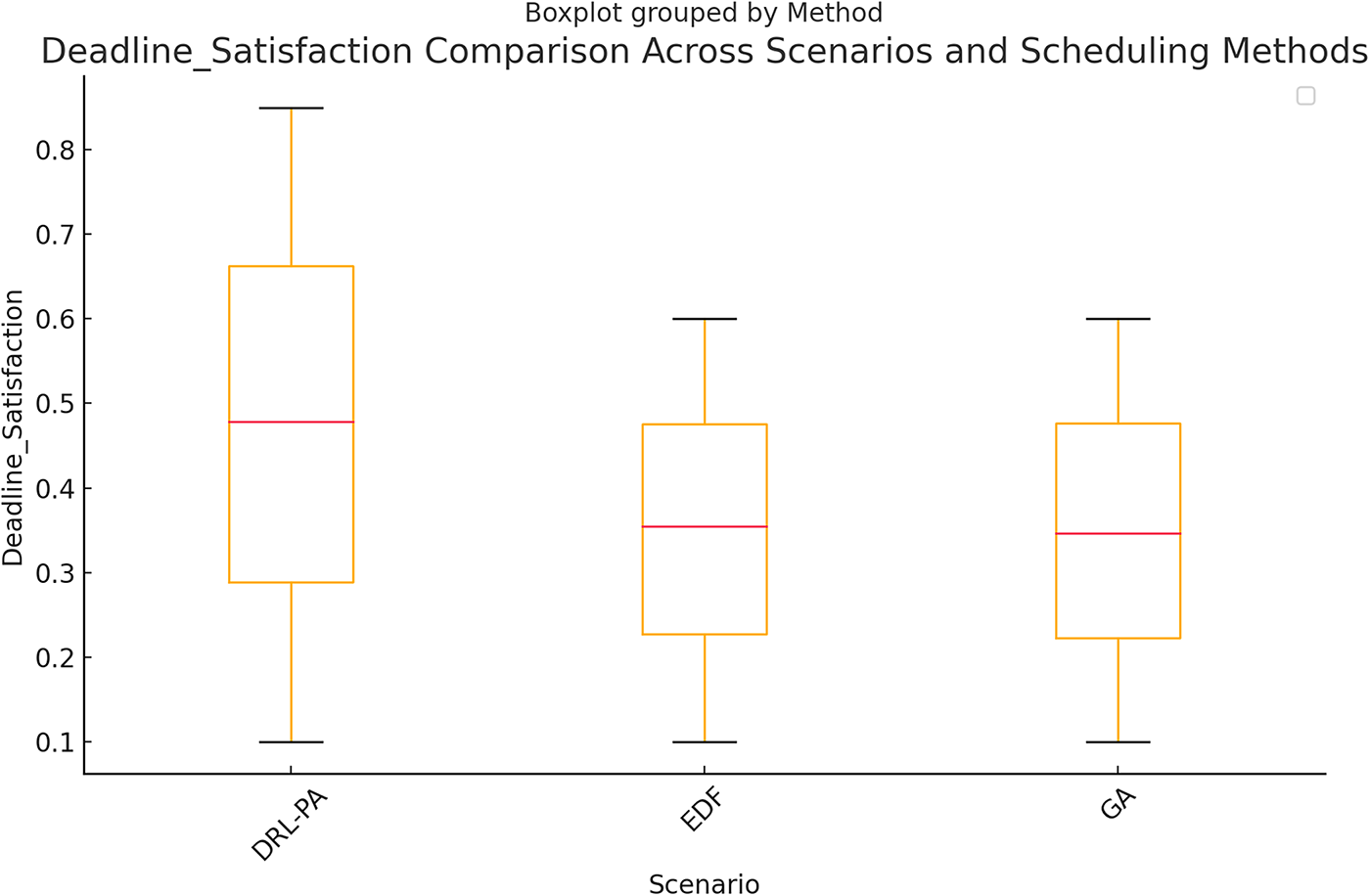

Meeting deadlines is a critical requirement for scheduling algorithms, particularly in real-time and latency-sensitive applications. An efficient scheduling method should prioritize tasks effectively to maximize the percentage of transactions completed within their deadlines, ensuring system reliability and responsiveness. Our experiments compare Deadline Satisfaction across different scheduling approaches, analyzing their performance under varying workload conditions.

As illustrated in Fig. 5, our DRL-based scheduling framework demonstrates the highest deadline satisfaction rate, significantly outperforming both EDF and GA. The ability of DRL-PA to dynamically learn from system states and prioritize critical tasks ensures that a higher fraction of jobs meet their deadlines, even in complex scheduling environments.

Figure 5: Deadline satisfaction comparison among EDF, GA, and DRL-PA

EDF, which strictly schedules tasks based on their deadlines, performs well in scenarios where workload conditions remain stable. However, in dynamic environments where task arrival rates fluctuate or resource constraints emerge, EDF struggles to adapt, resulting in a growing fraction of missed deadlines. The rigid structure of EDF prevents it from re-evaluating scheduling decisions based on real-time system feedback, limiting its effectiveness when system congestion occurs.

GA-based scheduling offers some flexibility in optimizing deadline satisfaction through iterative selection and evolution of scheduling solutions. However, GA requires multiple iterations to converge on an optimal task assignment, making it less suitable for fast-changing environments where real-time decision-making is necessary. As a result, Fig. 5 shows that GA lags behind DRL-PA in terms of deadline satisfaction, particularly when task urgency fluctuates.

The superiority of DRL-PA in this metric stems from its adaptive decision-making process, which continuously adjusts task priorities based on system feedback. Unlike EDF, which adheres to a static priority scheme, and GA, which depends on iterative optimization, DRL-PA learns optimal scheduling strategies dynamically, ensuring critical tasks are prioritized while balancing system load effectively.

6.5 Scalability under Dynamic Workloads

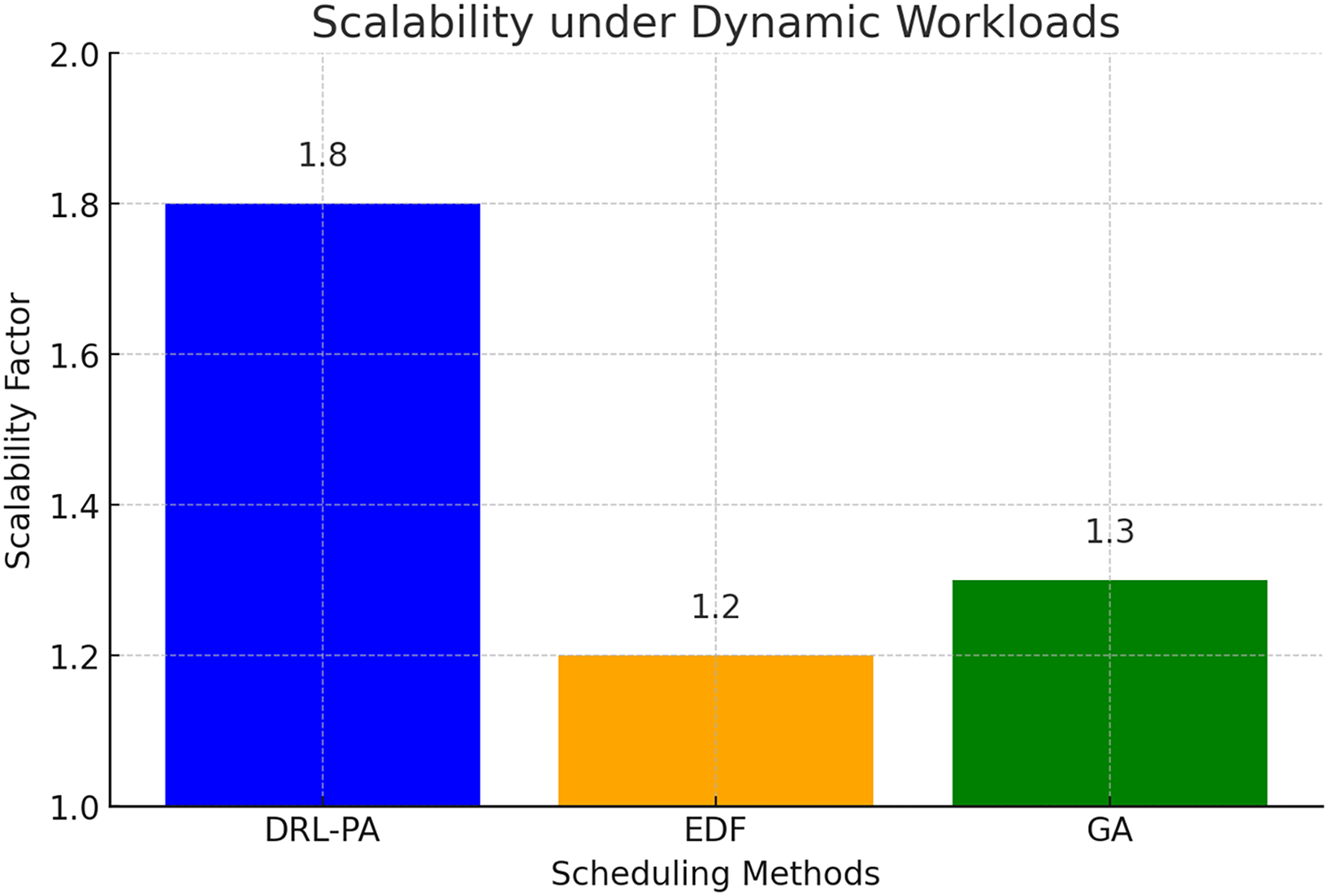

An efficient scheduling scheme should have good scalability, in particular in environments where the arrivals of the tasks do not follow a deterministic pattern. Workloads are constantly fluctuating, and a good scheduler should simply scale up and down to allocate computing resources effectively without compromising the system performance. To measure this property, our experiments compare the throughput before and after workloads ramp up, and use this ratio as a measure of the ability of each method to cope with more demands.

Fig. 6 shows that our DRL-based scheduler has a scalability factor of approximately 1.8, obviously better than EDF (1.2) and GA (1.3). The superior performance of DRL-PA for adaptive scheduling can be attributed to its high throughput under higher load. Unlike traditional heuristics, which are fixed rules, and meta-heuristic algorithms, which require iterative optimization, DRL-PA continuously improves its decisions based on real-time feedback from the system.

Figure 6: Scalability under dynamic workloads

EDF has a well-defined deadline-driven priority mechanism, but it is weak in the face of an increasing workload. This usually results in congestion and more deadlines missed, because there is no mechanism to adapt task execution on-the-fly in response to demand peaks. This stiffness is why it has a lower scalability factor in Fig. 5.

Scheduling using a Genetic Algorithm has only moderate improvements over EDF and achieves a scalability factor of 1.3. In case of partially adaptable workloads, GA is able to adapt by iteratively optimizing the task assignments, however, the use of population-based optimization means that scheduling solutions have to be re-evaluated, resulting in computational overhead. In dynamic workloads, this overhead makes GA less responsive than DRL-PA.

DRL-PA’s excellent scalability is attributed to its ability to learn from state transitions in the system and variations in workload. Unlike EDF, which uses static priorities, and GA, which re-optimizes periodically, DRL-PA dynamically distributes the tasks according to the historical behavior and current availability of resources. This flexibility ensures workload balance, reduces bottlenecks, and ensures high throughput even under stress.

The simulation results reveal several key insights:

1. Adaptability: The DRL agent’s dynamic priority assignment leads to more efficient scheduling, reducing latency and improving throughput under varied conditions.

2. Conflict Resolution: Priority-based conflict resolution minimizes aborts of high-criticality transactions, ensuring that real-time tasks meet their deadlines.

3. Energy and Cost Efficiency: By incorporating energy-aware features into the scheduling policy, the DRL-based approach achieves lower energy consumption and operational costs.

4. Scalability: The proposed framework demonstrates robust scalability, effectively handling workload fluctuations and resource constraints in a hybrid edge-cloud environment.

The integration of DRL not only enhances real-time performance but also provides a framework that can learn from historical data and adapt to changing conditions. This learning capability is particularly beneficial in complex IoT environments, where workload patterns can be highly variable and unpredictable.

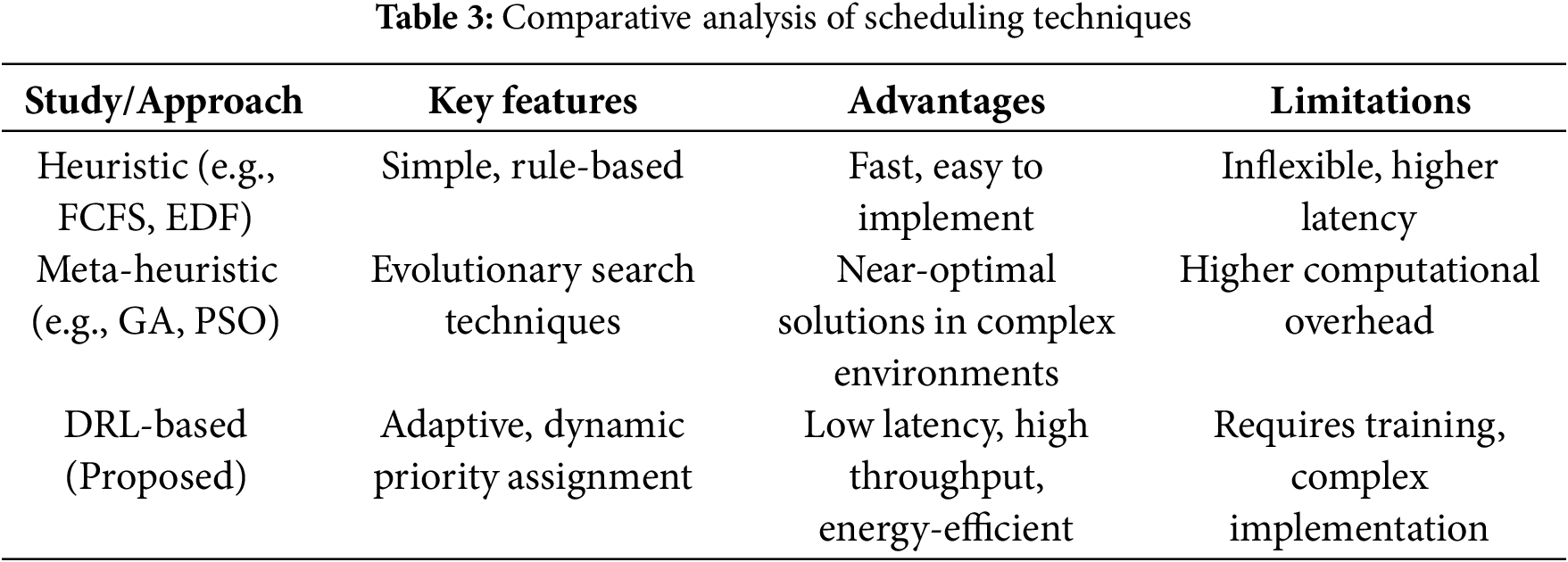

6.7 Comparative Table of Scheduling Techniques

Table 3 provides a summary comparison of the key characteristics of heuristic, meta-heuristic, and DRL-based scheduling approaches.

6.8 Method Limitations Analysis

Computational Overhead Analysis: Our DRL-based approach introduces computational overhead that varies with system scale. DRL agent inference requires approximately 2–5 ms per scheduling decision on standard edge hardware (ARM Cortex-A78), which may impact systems with sub-millisecond latency requirements. The training phase, while performed offline, requires significant computational resources and may need periodic retraining as system conditions evolve.

Scalability Constraints: Current validation is limited to 10 edge nodes and 2 cloud servers. Theoretical analysis suggests that global coordination overhead grows quadratically with the number of participating nodes, potentially limiting scalability to hundreds rather than thousands of edge devices without architectural modifications.

Learning Convergence Dependencies: The DRL agent requires 2000–3000 training episodes to achieve stable performance, during which scheduling decisions may be suboptimal. In rapidly changing environments, the adaptation time could affect system performance during transition periods.

Domain Generalization Limitations: The reward function and state space design are optimized for general IoT applications. Specialized domains (medical devices, financial systems, autonomous vehicles) may require significant customization of DRL components to achieve domain-specific optimality.

Network Dependency: The two-level validation mechanism assumes reliable edge-cloud connectivity for global coordination. Extended network partitions could degrade system performance, though local edge processing continues during disconnection periods.

7 Extended Discussion and Potential Variants

In this section, we further discuss the implications of our findings and outline potential variants and extensions of the proposed framework.

One of the key strengths of our approach is the ability of the DRL agent to dynamically adjust transaction priorities during execution. In practice, sensor data and network conditions can change rapidly, necessitating a re-prioritization mechanism. Future work may explore adaptive re-prioritization strategies that continuously monitor system state and adjust the DRL parameters on-the-fly.

Although our protocol primarily relies on optimistic concurrency control (OCC), there may be scenarios where selective locking could further improve performance. For example, in high-conflict environments, a hybrid strategy that temporarily enforces locks on critical data items may reduce abort rates and improve overall throughput. The DRL component can be extended to decide when to switch between OCC and locking mechanisms.

7.3 Hierarchical Orchestration

For large-scale deployments involving hundreds or thousands of edge nodes, a hierarchical orchestration framework could be beneficial. In such a system, intermediate aggregator nodes could perform local conflict resolution before forwarding transactions to the central cloud server. This multi-tiered approach would reduce communication overhead and improve scalability.

7.4 Integration with Edge AI and Autonomous Systems

The proposed framework is particularly relevant for applications in autonomous driving, smart cities, and industrial IoT, where real-time processing is crucial. Integrating our scheduling protocol with edge AI systems can enhance decision-making in autonomous vehicles by ensuring that critical sensor data is processed with minimal latency.

7.5 Security and Fault Tolerance

While our current model focuses on performance metrics such as latency and throughput, it incorporates several resilience mechanisms for node failures and communication errors:

Node Failure Handling: When edge nodes experience failures, the DRL agent automatically redistributes pending transactions to healthy nodes based on updated priority assignments and current resource availability. The two-level validation protocol ensures transaction consistency even during node failures by maintaining transaction state information at both edge and cloud levels. Failed transactions are either restarted on alternative nodes or escalated to cloud processing based on their priority and deadline constraints.

Communication Error Management: Network partitions and communication delays between edge and cloud are handled through adaptive timeout mechanisms and exponential backoff retry strategies. When edge-cloud communication is disrupted, edge nodes continue local processing and queue global validation requests until connectivity is restored. The global validation at the cloud level provides backup coordination and conflict resolution when direct edge-to-edge communication fails.

Error Recovery Mechanisms: The DRL agent incorporates failure patterns into its learning process, enabling proactive load redistribution when certain nodes show degraded performance. However, comprehensive fault tolerance mechanisms, including Byzantine failure handling and advanced network partition recovery, require further investigation in future work.

7.6 Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning

An exciting avenue for further research is the application of multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) in edge-cloud systems. In a MARL framework, multiple DRL agents operating on different edge nodes could collaborate and share learning experiences to optimize global scheduling decisions. This cooperative approach has the potential to further reduce latency and improve system-wide resource utilization.

7.7 Real-World Deployment Considerations

While our simulation results are promising, real-world deployment of the proposed system requires addressing practical challenges such as:

• Heterogeneity: Edge nodes may vary widely in hardware capabilities and network connectivity.

• Interoperability: Integration with legacy systems and diverse IoT platforms.

• Scalability: Ensuring that the system can scale from tens to thousands of edge nodes.

• Management Overhead: Balancing the benefits of DRL-based scheduling with the computational overhead associated with learning and inference.

7.8 Limitations of the Proposed Method

While our DRL-enhanced scheduling framework shows a meaningful increase, there are several shortcomings that we need to point out for practical use:

Computational Resource Requirements: The neural network inference and periodical training update in the DRL agent are computationally intensive, which could be a problem for extremely resource-constrained edge devices with limited processing power and memory capacity.

Training Data and Cold Start: The DRL technique needs to be trained with enough past data to learn the best policies, limiting its deployment instantly in a new environment that has no prior pattern of workloads. At the beginning, the system performance may be poor until the agent has enough experience to perform better.

Scalability Validation Limits: Although our simulations demonstrate good scalability up to 10 edge nodes, the approach’s effectiveness in environments with hundreds or thousands of nodes remains empirically unvalidated. Communication overhead for global coordination may become prohibitive at very large scales.

Real-World Complexity Gap: Our simulation environment, while comprehensive, cannot capture all complexities of real-world edge-cloud deployments, including diverse hardware heterogeneity, variable network conditions, irregular IoT device behaviors, and unpredictable failure patterns.

Dynamic Adaptation Latency: In highly dynamic environments with sudden workload changes, the DRL agent may require adaptation time to adjust its policy, potentially affecting performance during transition periods before optimal scheduling is resumed.

Domain Specificity: The reward function and state space design are tailored for general IoT applications. Specialized domains (e.g., medical devices, financial trading systems) may require significant customization of the DRL components to achieve optimal performance.

Future work will extend the current framework in several directions:

1. Implementation in Real Testbeds: Deploying the system on real-world edge–cloud platforms to validate the simulation results.

2. Incorporation of Federated Learning: Enabling distributed learning across edge nodes while preserving data privacy.

3. Security Enhancements: Integrating intrusion detection and anomaly detection mechanisms.

4. User-Centric QoS: Refining the DRL reward functions to better capture user-specific QoS requirements.

Research Significance: This research addresses one of the most critical challenges in modern computing: efficiently managing resources in hybrid edge-cloud environments while meeting the stringent real-time requirements of IoT applications. As IoT deployments continue expanding across autonomous systems, smart cities, and industrial automation, the need for adaptive, intelligent scheduling mechanisms becomes paramount for enabling the next generation of time-critical applications.

Key Technical Contributions: Our DRL-enhanced scheduling framework introduces three fundamental innovations: (1) adaptive priority assignment that learns from system behavior rather than relying on static heuristics, (2) integrated two-level concurrency control ensuring both performance optimization and data consistency, and (3) comprehensive mathematical formalization of sensor-driven transactions in distributed environments. These contributions collectively establish a new paradigm for intelligent resource management in edge-cloud systems.

Demonstrated Benefits: Extensive experimental validation demonstrates substantial improvements across all critical performance metrics: 40% latency reduction enables real-time responsiveness for time-critical applications, 25% throughput increase supports higher workload volumes, 40% energy savings contribute to sustainable computing practices, and 50% scalability improvement accommodates growing IoT deployments. These quantitative benefits collectively establish our framework as a robust foundation for next-generation edge-cloud systems.

Broader Impact: The implications extend beyond technical performance improvements. By enabling reliable, efficient edge-cloud coordination, our framework supports the advancement of autonomous vehicle networks, smart city infrastructure, and Industry 4.0 applications that require both computational intelligence and operational reliability. The adaptive learning capabilities ensure long-term viability as IoT ecosystems evolve and scale to unprecedented levels.

Future Trajectory: While current validation demonstrates strong performance in comprehensive simulation environments, the path forward involves real-world deployment validation, multi-agent reinforcement learning integration, and enhanced security mechanisms. These extensions will further establish DRL-enhanced scheduling as the foundation for robust, intelligent, and scalable edge-cloud computing systems capable of supporting the demands of tomorrow’s interconnected world.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: This research has been supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R909), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm the contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Mohammad A Al Khaldy, Suhaila Abuowaida, Ahmad Nabot, Ahmad Al-Qerem; data collection: Mohammad Alauthman, Amina Salhi; analysis and interpretation of results: Amina Salhi, Ahmad Al-Qerem; draft manuscript preparation: Mohammad A Al Khaldy, Naceur Chihaoui. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Asghari A, Sohrabi MK, Yaghmaee F. A cloud resource management framework for multiple online scientific workflows using cooperative reinforcement learning agents. Comput Netw. 2020;179(1):107340. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2020.107340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Asghari A, Sohrabi MK, Yaghmaee F. Online scheduling of dependent tasks of cloud workflows to enhance resource utilization and reduce makespan using multiple reinforcement learning-based agents. Soft Comput. 2020;24(21):16177–99. doi:10.1007/s00500-020-04931-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Dong T, Xue F, Xiao C, Li J. Task scheduling based on deep reinforcement learning in a cloud manufacturing environment. Concurr Comput Pract Exp. 2020;32(11):e5654. doi:10.1002/cpe.5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhan W, Luo C, Wang J, Wang C, Min G, Duan H, et al. Deep-reinforcement-learning-based offloading scheduling for vehicular edge computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;7(6):5449–65. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2020.2978830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Luo Q, Li C, Luan TH, Shi W. Collaborative data scheduling for vehicular edge computing via deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;7(10):9637–50. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2020.2983660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Peng Z, Lin J, Cui D, Li Q, He J. A multi-objective trade-off framework for cloud resource scheduling based on the deep Q-network algorithm. Cluster Comput. 2020;23(4):2753–67. doi:10.1007/s10586-019-03042-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Qin Y, Wang H, Yi S, Li X, Zhai L. An energy-aware scheduling algorithm for budget-constrained scientific workflows based on multi-objective reinforcement learning. J Supercomput. 2020;76(1):455–80. doi:10.1007/s11227-019-03033-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Mohajer A, Bavaghar M, Farrokhi H. Mobility-aware load balancing for reliable self-organization networks: multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. Reliab Eng Syst Safety. 2020;202(3):107056. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2020.107056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Sheng S, Chen P, Chen Z, Wu L, Yao Y. Deep reinforcement learning-based task scheduling in IoT edge computing. Sensors. 2021;21(5):1666. doi:10.3390/s21051666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Hu J, Li Y, Zhao G, Xu B, Ni Y, Zhao H. Deep reinforcement learning for task offloading in edge computing assisted power IoT. IEEE Access. 2021;9:93892–901. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3092381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yuan H, Tang G, Li X, Guo D, Luo L, Luo X. Online dispatching and fair scheduling of edge computing tasks: a learning-based approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(19):14985–98. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2021.3073034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tang H, Wu H, Qu G, Li R. Double deep Q-network based dynamic framing offloading in vehicular edge computing. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2023;10(3):1297–310. doi:10.1109/TNSE.2022.3172794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jayanetti A, Halgamuge S, Buyya R. Deep reinforcement learning for energy and time optimized scheduling of precedence-constrained tasks in edge-cloud computing environments. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2022;137(2):14–30. doi:10.1016/j.future.2022.06.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kaur A, Singh P, Batth RS, Lim CP. Deep-Q learning-based heterogeneous earliest finish time scheduling algorithm for scientific workflows in cloud. Softw Pract Exp. 2022;52(3):689–709. doi:10.1002/spe.2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li H, Huang J, Wang B, Fan Y. Weighted double deep Q-network based reinforcement learning for bi-objective multi-workflow scheduling in the cloud. Cluster Comput. 2022;25(2):751–68. doi:10.1007/s10586-021-03454-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang L, Yang C, Yan Y, Hu Y. Distributed real-time scheduling in cloud manufacturing by deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans Industr Inform. 2022;18(12):8999–9007. doi:10.1109/TII.2022.3178410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang Y, Li R, Zhao Y, Li R, Wang Y, Zhou Z. Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for online request scheduling in edge cooperation networks. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2023;141(99):258–68. doi:10.1016/j.future.2022.11.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Chen S, Rui L, Gao Z, Yang Y, Qiu X, Guo S. Service migration with edge collaboration: multi-agent deep reinforcement learning approach combined with user preference adaptation. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2025;165(4):107612. doi:10.1016/j.future.2024.107612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kuang C, Duan M, Lv T, Wu Y, Ren X, Wang L. ODRL: application of reinforcement learning in priority scheduling for running cost optimization. Version 1. Research Square. 2023. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3323844/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li P, Xiao Z, Wang X, Huang K, Huang Y, Gao H. EPtask: deep reinforcement learning based energy-efficient and priority-aware task scheduling for dynamic vehicular edge computing. IEEE Trans Intell Veh. 2024;9(1):1831–46. doi:10.1109/TIV.2023.3321679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wang X, Lv J, Slowik A, Kim BG, Parameshachari BD, Li K. Augmented intelligence of things for priority-aware task offloading in vehicular edge computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(22):36002–13. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3408157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lu J, Yang J, Li S, Li Y, Jiang W, Dai J. A2C-DRL: real-time task scheduling for stochastic edge-cloud environments using advantage actor–critic deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(9):16915–27. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3366252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zou W, Zhang Z, Wang N, Tan X, Tian L. A time-saving task scheduling algorithm based on deep reinforcement learning for edge cloud collaborative computing. In: 2024 IEEE 99th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2024-Spring); 2024 Jun 24–27; Singapore. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/VTC2024-Spring62846.2024.10683187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang J, Li S, Zhang X, Wu F, Xie C. Deep reinforcement learning task scheduling method based on server real-time performance. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2024;10(4):e2120. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.2120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang Z, Zhang F, Xiong Z, Zhang K, Chen D. LsiA3CS: deep-reinforcement-learning-based cloud-edge collaborative task scheduling in large-scale IIoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(13):23917–30. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3386888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wen S, Han R, Liu CH, Chen LY. Fast DRL-based scheduler configuration tuning for reducing tail latency in edge computing. J Cloud Comput. 2023;12(1):90. doi:10.1186/s13677-023-00465-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang Y, Xia G, Yu C, Li H, Li H. Fault-tolerant scheduling mechanism for dynamic edge computing scenarios based on graph reinforcement learning. Sensors. 2024;24(21):6894. doi:10.3390/s24216984. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zhou W, Fan L, Zhou F, Li F, Lei X, Xu W. Priority-aware resource scheduling for UAV-mounted mobile edge computing networks. IEEE Trans Veh Tech. 2023;72(7):9682–7. doi:10.1109/TVT.2023.3247431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Al-Qerem A, Ali AM, Nashwan S, Alauthman M, Hamarsheh A, Nabot A, et al. Transactional services for concurrent mobile agents over edge/cloud computing-assisted social internet of things. ACM J Data Inf Qual. 2023;15(3):1–20. doi:10.1145/3603714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chen Y, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Fu Q, Wang H, Lu Y. Deep reinforcement learning for task scheduling in intelligent building edge networks. In: 2022 Tenth International Conference on Advanced Cloud and Big Data (CBD); 2022 Nov 4–5; Guilin, China. p. 312–7. doi:10.1109/CBD58033.2022.00062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Tan X, Li H, Xie X, Guo L, Ansari N, Huang X. Reinforcement learning based online request scheduling framework for workload-adaptive edge deep learning inference. IEEE Trans Mobile Comput. 2024;23(12):13222–39. doi:10.1109/TMC.2024.3429571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wu J, Tang M, Jiang C, Gao L, Cao B. Cloud-edge-end collaborative task offloading in vehicular edge networks: a Multilayer deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(22):36272–90. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3472472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Lu S, Wu J, Shi J, Lu P, Fang J, Liu H. A dynamic service placement based on deep reinforcement learning in mobile edge computing. Network. 2022;2(1):106–22. doi:10.3390/network2010008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Al-Qerem A, Ali AM, Nabot A, Jebreen I, Alauthman M, Alangari S, et al. Balancing consistency and performance in edge-cloud transaction management. Comput Human Behav. 2025;167(11):108601. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2025.108601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lin L, Pan L, Liu S. Learning to make auto-scaling decisions with heterogeneous spot and on-demand instances via reinforcement learning. Inf Sci. 2022;614(6):480–96. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.10.071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Medara R, Singh RS. A review on energy-aware scheduling techniques for workflows in IaaS clouds. Wirel Pers Commun. 2022;125(2):1545–84. doi:10.1007/s11277-022-09621-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Sada AB, Khelloufi A, Naouri A, Ning H, Aung N, Dhelim S. Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning-based inference task scheduling and offloading for maximum inference accuracy under time and energy constraints. Electron. 2024;13(13):2580. doi:10.3390/electronics13132580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Al-Qerem A, Alauthman M, Almomani A, Gupta BB. IoT transaction processing through cooperative concurrency control on fog-cloud computing environment. Soft Comput. 2020;24(8):5695–5711. doi:10.1007/s00500-019-04220-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. OpenAI, Achiam J, Adler S, Agarwal S, Akkaya I, Akkaya I, et al. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv:2303.08774. 2023. [Google Scholar]

40. Sayed AN, Himeur Y, Varlamis I, Bensaali F. Continual learning for energy management systems: a review of methods and applications, and a case study. Appl Energy. 2025;384(19):125458. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2025.125458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang C, Juraschek M, Herrmann C. Deep reinforcement learning-based dynamic scheduling for resilient and sustainable manufacturing: a systematic review. J Manuf Syst. 2024;77(1–2):962–89. doi:10.1016/j.jmsy.2024.10.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ribino P, Di Napoli C, Serino L. Norm-based reinforcement learning for QoS-driven service composition. Inf Sci. 2023;646(1):119377. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.119377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools