Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Flexible Decision Method for Holonic Smart Grids

De Vinci Higher Education, De Vinci Research Center, Paris La Defense Cedex, 92916, France

* Corresponding Author: Guillaume Guerard. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Methods Applied to Energy Systems)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 597-619. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070517

Received 18 July 2025; Accepted 29 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Isolated power systems, such as those on islands, face acute challenges in balancing energy demand with limited generation resources, making them particularly vulnerable to disruptions. This paper addresses these challenges by proposing a novel control and simulation framework based on a holonic multi-agent architecture, specifically developed as a digital twin for the Mayotte island grid. The primary contribution is a multi-objective optimization model, driven by a genetic algorithm, designed to enhance grid resilience through intelligent, decentralized decision-making. The efficacy of this architecture is validated through three distinct simulation scenarios: (1) a baseline scenario establishing nominal grid operation; (2) a critical disruption involving the failure of a major power plant; and (3) a localized fault resulting in the complete disconnection of a regional sub-grid. The major results demonstrate the system’s dual resilience mechanisms. In the plant failure scenario, the top-level holon successfully managed a global energy deficit by optimally reallocating shared resources, prioritizing grid stability over complete demand satisfaction. In the disconnection scenario, the affected holon demonstrated true autonomy, transitioning seamlessly into a self-sufficient islanded microgrid to prevent a cascading failure. Collectively, these findings validate the holonic model as a robust decision-support tool capable of managing both systemic and localized faults, thereby significantly enhancing the operational resilience and stability of isolated smart grids.Keywords

The evolution of electrical grids since their inception in the late 19th century has been a cornerstone of modern technological progress. Early grid systems enabled breakthroughs in numerous fields—ranging from medicine and chemistry to computing—and provided essential services such as lighting and Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning (HVAC). However, as these systems expanded, their environmental impact became increasingly evident. Global

In response to these challenges, the energy landscape has undergone a significant transformation with the emergence of RES technologies. This shift has resulted in an increasingly diversified energy mix in which intermittent sources such as solar and wind power play a dominant role. Such changes have introduced new complexities into grid management. In particular, the integration of RES brings variability and uncertainty to the power supply. Addressing these issues requires not only robust real-time balancing strategies to prevent blackouts and reduce dependency on backup power plants, but also clear and precise control methodologies that can manage both supply and demand dynamically.

To design and improve these control methodologies, the simulation of current energy systems is indispensable. Multi-Agent System (MAS) offers a powerful tool for modeling complex interactions and behaviors within (SGs). By simulating a variety of scenarios—ranging from normal operational conditions to extreme events or faults—MAS enables researchers and grid operators to systematically analyze, understand, and subsequently enhance grid performance. Such simulations facilitate a deeper understanding of the interdependencies between various grid components, thereby enabling the identification of weaknesses and the testing of innovative management strategies under controlled and virtual conditions prior to real-world deployment.

A promising solution to address these issues is the adoption of a holonic architecture within SGs. Holarchies structure the grid into autonomous yet cooperative units—called holons—that can act independently or as part of a larger coordinated network. This dual capability enhances flexibility and supports decentralized decision-making while still benefiting from centralized oversight [2,3]. Multi-agent modeling, in particular, allows for the dynamic simulation of various scenarios and provides tailored recommendations for grid operations, an approach that is essential in environments where grid stability is critical.

Despite these advancements, the implementation of SGs still faces both functional and behavioral challenges. On the functional side, building a truly “smart” grid requires a layered approach, starting with granular data collection and culminating in complex, coordinated control. This begins with sophisticated measurement systems to accurately monitor the energy usage of individuals and devices, a foundational requirement detailed by the National Energy Technology Laboratory [4]. This raw data must then be aggregated into historical datasets—a significant big data management challenge, as discussed by Zainab et al. [5]—which are essential for developing the accurate load forecasts reviewed by Khan et al. [6]. These forecasts, in turn, are critical inputs for Energy Management System (EMS), which, as Yassim et al. demonstrate, are responsible for optimizing grid operations [7]. The entire functional chain is interconnected by the secure, bidirectional communication channels whose architectures have been thoroughly surveyed by Wang et al. [8].

Meanwhile, from a behavioral perspective, SGs must exhibit a suite of interconnected capabilities to adapt to fluctuating energy demands and effectively integrate diverse power sources. Central to this is flexibility, which, as reviewed by Hussain et al., is the grid’s capacity to adjust generation and consumption to manage the intermittency of renewable energy [9]. This adaptability directly supports resilience—the ability to withstand and recover from disruptions. As Fan et al. review, smart grid technologies are key to accelerating post-fault restoration, a critical aspect of self-healing [10]. The concept of self-healing is advanced further by holonic architectures, which enable sections of the grid to operate autonomously, thereby localizing faults and ensuring continuous operation [11]. However, as grids become more autonomous, robust security becomes paramount. The comprehensive surveys by Zibaeirad et al. detail the numerous cyber-physical threats and essential mitigation strategies required to protect the grid’s integrity [12]. Finally, overarching challenges of interoperability and scalability, as highlighted by Salkuti, must be addressed to ensure that diverse technologies can work together seamlessly and that the grid can expand to meet future needs [13].

A pertinent example of these challenges is found in geographically isolated regions, such as Mayotte. Mayotte lacks external energy interconnections, making it especially susceptible to energy shortages and operational disruptions. In such contexts, an SG that can adapt dynamically using simulation-driven recommendations becomes critical to ensuring both energy reliability and sustainability. In this paper, and in the context of the MAESHA project1, a decision model capable of adapting to various situations in the SG is proposed. This work builds upon the architecture previously proposed in [14].

In summary, the research presented in this paper aims to bridge existing gaps in SG management by proposing a novel decision model grounded in a holonic MAS framework. The objectives are threefold: to develop an adaptive decision model that manages real-time fluctuations in energy supply and demand; to optimize the integration of RES while minimizing environmental impacts; and to ensure economic efficiency through reduced operational costs. Addressing these objectives involves answering critical research questions regarding the balance of energy equilibrium, environmental sustainability, and economic feasibility in dynamic grid environments, particularly in isolated regions like Mayotte.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of related work in holonic SGs. Section 3 introduces the holonic architecture adopted in this study and details the proposed multi-objective optimization model for decision and control. Section 4 presents simulation results that validate the proposed approach, following by a discussion in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and suggests directions for future research.

This section reviews recent advances in SG management and control, focusing on two key areas: EMS and Multi-Agent Holonic Systems. These components are critical for addressing the increasing variability in energy supply and the challenges of integrating RESes into modern grid infrastructures.

The evolution of EMS began in earnest with the inception of SGs around 2005 [15]. EMS architectures are designed to reduce dependence on thermal power plants by leveraging advanced Demand Side Management (DSM) techniques and facilitating the large-scale integration of RESes. However, the very nature of renewable energy—exemplified by Photovoltaic (PV) systems that require sunlight and wind turbines that are subject to fluctuating conditions [16]—introduces significant challenges to maintaining grid stability, reliability, and efficiency.

To overcome these challenges, a broad array of innovative technologies and methodologies have been proposed. For instance, blockchain technology has emerged as a transformative tool, decentralizing energy transactions within microgrids and enhancing both the security and reliability of peer-to-peer energy trading networks [17,18]. Simultaneously, the development of Digital Twins (DT) provides a powerful means to replicate physical grid behaviors in a virtual environment. Frameworks like the OKDD (Ontology-body, Knowledge-body, Data-body, and Digital-portal) model facilitate real-time monitoring, predictive control, and dynamic simulation of EMS operations, ultimately contributing to more informed and proactive decision-making [19,20].

Optimization remains a core pillar of EMS, where sophisticated techniques are employed to address the multi-objective challenges inherent to dynamic grid operations. Evolutionary game theory has been successfully applied in both single-game and multi-game frameworks, enabling the modeling of competitive and cooperative interactions among grid entities under varying operational conditions [21,22]. These game-theoretical strategies are increasingly being combined with reinforcement learning methods, such as Q-Learning, which refine decision-making processes and enhance adaptive control strategies across the grid [23]. Complementing these methods is the emerging concept of the Internet of Energy (IoE), which reconceptualizes the grid as an interconnected network of energy flows, thereby improving situational awareness and bolstering operational command over distributed resources [24,25].

In addition to these technological advancements, recent research has increasingly focused on hybrid EMS architectures that integrate both centralized and decentralized control schemes [26]. This synthesis allows operators to combine the high-level oversight provided by traditional centralized systems with the responsiveness and resilience of distributed, agent-based approaches. Such hybrid models are particularly valuable in managing the complexity of modern grids, where rapid adaptation to variable conditions is essential for maintaining performance and reliability.

Collectively, these advancements in blockchain and DT technologies, optimization algorithms, and the IoE paradigm form a comprehensive toolkit for modern EMS. This integrated approach not only mitigates the uncertainties associated with RES intermittency but also paves the way for a more resilient, efficient, and future-proof grid infrastructure. By harnessing these innovations, EMS can better adapt to both anticipated and unforeseen changes in energy demand and supply, thereby ensuring a robust framework for sustainable energy management.

The integration of these advanced EMS concepts is particularly relevant for the modeling and simulation of the SG in Mayotte. As Mayotte represents a unique energy landscape, characterized by an isolated grid system and a high penetration of RESes, the deployment of tools such as DT can play a critical role in enhancing grid monitoring and decision-making processes. Simulation environments that incorporate these technologies allow for detailed scenario testing under various conditions, ensuring that both intermittent renewable generation and load variability are realistically captured.

Furthermore, hybrid EMS architectures that combine centralized and decentralized control are well-suited to addressing the operational challenges of Mayotte’s grid. By leveraging detailed simulation models that incorporate both traditional optimization techniques and MAS strategies, stakeholders can systematically evaluate the performance of different management strategies. Such simulations not only facilitate the identification of potential bottlenecks and vulnerabilities but also assist in formulating tailored strategies to improve energy distribution and reliability across the island.

2.2 Multi-Agent Holonic Systems

Parallel to advancements in EMS, research into MAS and holonic architectures has gained significant momentum. This approach offers an effective paradigm for managing the escalating complexity of modern energy networks, which are increasingly decentralized and dynamic. The core concept, derived from Arthur Koestler’s philosophy, involves partitioning a complex system into autonomous yet cooperative entities known as holons. Each holon—representing anything from a single smart appliance to a substation or a microgrid—functions as a self-contained whole while simultaneously acting as an integral part of a larger, coordinated system. This dual nature allows for a “holarchy,” a flexible control structure that combines the robustness of decentralized systems with the strategic coherence of centralized ones, thereby enhancing overall grid responsiveness, scalability, and resilience.

2.2.1 State of the Art in Holonic Grid Management

The body of literature on holonic systems for SGs can be thematically organized into key research pillars: architectural design, operational optimization, hierarchical control, and advanced resilience applications.

A primary focus of research has been the development of robust architectural frameworks that ensure stability and interoperability among diverse energy assets. The work of Negeri et al. [2] is instrumental in this area. The authors successfully implemented a Service Oriented Architecture within a holonic framework, which treats grid functions as discoverable services. This design promotes loose coupling between agents, allowing for a “plug-and-play” capability where new Distributed Energy Rerouces (DERs) can be integrated with minimal system disruption. While architectural modularity ensures stability, capturing the system’s dynamic behavior is equally vital. Ferreira et al. [27] addressed this by developing models that explicitly account for the non-linear interactions and feedback loops inherent in SG environments, which is fundamental for creating reliable control strategy simulations.

With a stable architecture, the central challenge becomes optimization. The hierarchical structure of holonic systems is particularly well-suited to decomposition-based optimization. Ansari et al. [28] provided a compelling demonstration by employing Lagrangian Relaxation to break a large, complex problem into smaller sub-problems solvable by individual holons. In a complementary approach, Wallis et al. [29] proposed a strategy-based framework where agents are guided by predefined rules to achieve near-optimal solutions, trading absolute optimality for computational efficiency.

The practical implementation of these concepts relies on layered control structures. The literature extensively documents the pivotal role of aggregators and multi-level EMS architectures—from Grid EMS (GEMS) down to Home EMS (HEMS)—in harmonizing grid-wide energy flows [30]. In the holonic paradigm, aggregators function as crucial intermediary holons, bundling the capacities of numerous DERs to provide essential ancillary services and align the actions of low-level holons with higher-level grid objectives.

Beyond routine operation, a significant driver for adopting holonic architectures is the promise of enhanced resilience. This resilience is explored from two critical angles. The first is self-healing, which focuses on automated recovery from physical faults. As reviewed by Abdel-Fattah et al. [11], holonic systems are ideally suited for this task. Their decentralized intelligence allows for rapid fault detection, isolation, and service restoration by autonomously reconfiguring the grid around the damaged area, thereby minimizing outage duration and impact. The second angle addresses the growing threat of cyber-attacks. Modern grids are vulnerable to malicious actors who can compromise system integrity. Research by Tian et al. [31] highlights this by investigating targeted Adversarial False Data Injection attacks designed to corrupt state estimation—a critical function for grid monitoring and control. This research underscores the need for sophisticated defense mechanisms to secure the data and communication layers upon which MAS depend.

2.2.2 Research Gap and Contributions

While this extensive body of work provides robust models for holonic architecture, optimization, and advanced resilience against physical faults and cyber threats, its application remains largely focused on well-interconnected, continental grids. A significant gap persists in addressing the unique operational resilience challenges of isolated island grids.

The existing literature on resilience is heavily oriented toward recovery from external, event-driven shocks like equipment failure or cyber-attacks. In contrast, the primary challenge for an island grid like Mayotte’s is maintaining stability during routine, yet highly volatile, operating conditions. This requires a different kind of resilience—one focused on proactively managing extreme resource variability and competing internal objectives under severe physical and economic constraints. Current models do not adequately address the need to simultaneously balance supply security, economic cost, renewable energy utilization, and carbon emissions in such a constrained and isolated environment.

This manuscript addresses this specific gap through the following primary contributions:

• The design and implementation of a multi-agent holonic architecture specifically tailored to the characteristics of the Mayotte grid, modeling its distinct control layers and integrating its diverse portfolio of DERs.

• The introduction of a multi-phase genetic algorithm designed to balance four competing objectives: supply/demand equilibrium, economic cost, RES utilization, and carbon impact within the holonic framework.

• A comprehensive simulation-based analysis to validate the proposed system under diverse scenarios, including emergency conditions and high renewable output variability, thereby identifying concrete strategies to enhance the operational resilience and performance of Mayotte’s SG.

3.1 Materials’ Context and Contents

Mayotte, a French tropical island with an area of 374

The data used in this study, obtained from Mayotte’s official electricity provider (EDM), encompass comprehensive historical records of both electrical load and generation. These datasets include measurements at granular intervals, alongside ancillary information such as holiday calendars and weather forecasts. Such multi-dimensional data are essential for capturing load variability, seasonality, and the impacts of renewable energy intermittency. Detailed data preprocessing procedures—including interpolation, normalization (via Z-score normalization), and wavelet transform-based denoising—were applied to smooth out abrupt variations and uncover the underlying trends necessary for accurate modeling, as presented in prior work [32].

Furthermore, the spatial distribution of generation sources on the island, illustrated on an open data website2, reinforces the importance of incorporating geographic and infrastructural details into the modeling framework. This material forms the backbone of the simulation environment, enabling a robust representation of Mayotte’s energy system. By integrating these comprehensive datasets and tailored preprocessing techniques, the developed model is designed to effectively address both the operational challenges and the sustainability objectives specific to isolated grid systems like that of Mayotte.

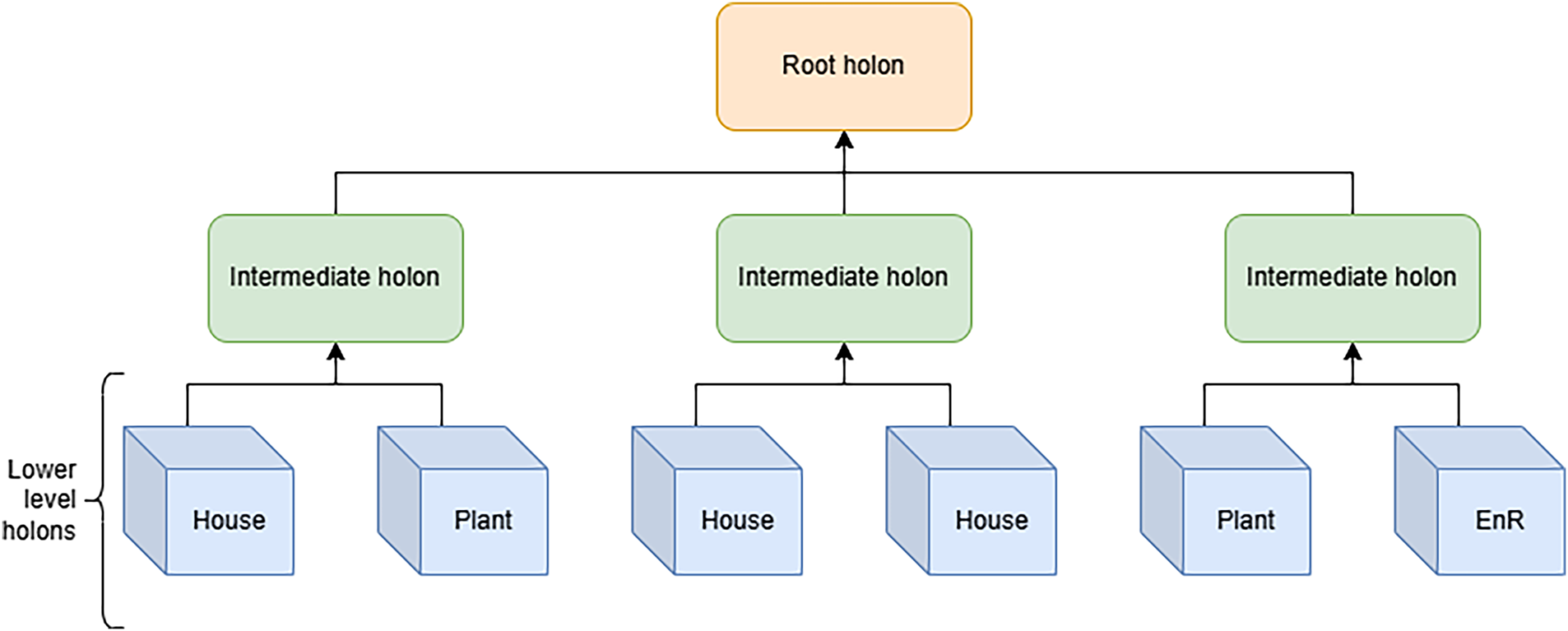

Holonic architectures organize energy systems as hierarchies of autonomous yet coordinated entities called holons—a concept inspired by biological systems where components maintain independence while contributing to systemic stability [3]. As shown in Fig. 1, holons form a bidirectional rooted tree (holarchy) where each node represents a grid segment (from individual consumers to regional clusters) through a 3-tuple (

Figure 1: Three-level holarchy with bidirectional communication. Lower levels (blue) aggregate data, middle levels (green) optimize regional flows, and the root holon (orange) acts as system-wide EMS

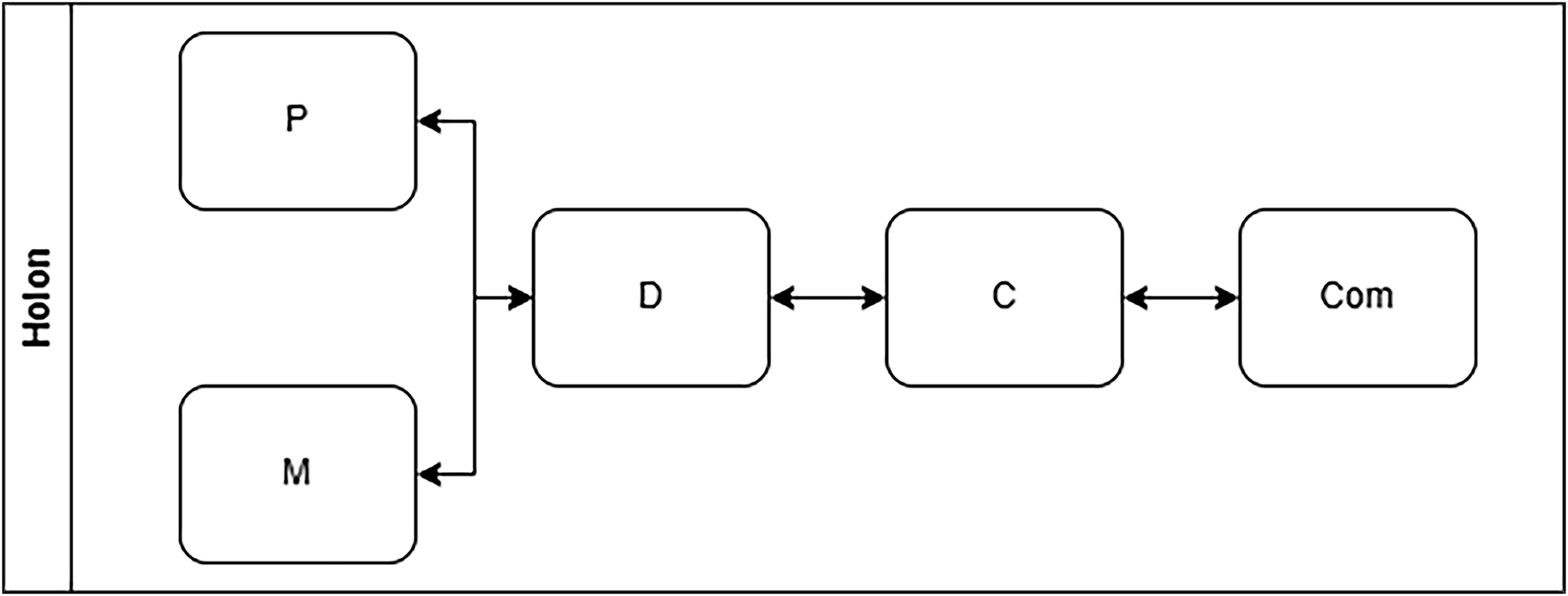

Each holon comprises five interworking agents (Fig. 2):

Figure 2: Agent interaction workflow within a holon. Arrows indicate data flows between measurement (M), data (D), prediction (P), control (C), and communication (Com) agents

Measurement Agent

Interfaces with physical devices (Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, smart meters) to collect real-time generation/demand data. While the current implementation simulates input via Excel files for testing, the architecture supports direct IoT integration through standard protocols like IEC 61850.

Data Agent

Acts as a temporal database, storing both historical measurements and forecasts. It employs ring buffers for time-series data to balance memory efficiency with low-latency access during optimizations.

Prediction Agent

Executes a hybrid deep learning model adapted from [33], combining temporal convolutional networks with attention mechanisms. This enables multi-scale forecasting:

• Spatially: Predictions at island-wide (10 MW resolution) or building-cluster (100 kW) levels

• Temporally: Real-time (15-min), daily (24-h), and weekly (168-h) horizons

Communication Agent

Manages bidirectional Agent Communication Language (ACL) messaging using FIPA standards. It implements priority queues to handle simultaneous uplink (aggregated data to parent holons) and downlink (control signals to subholons), with timeout thresholds for fault detection.

Control Agent

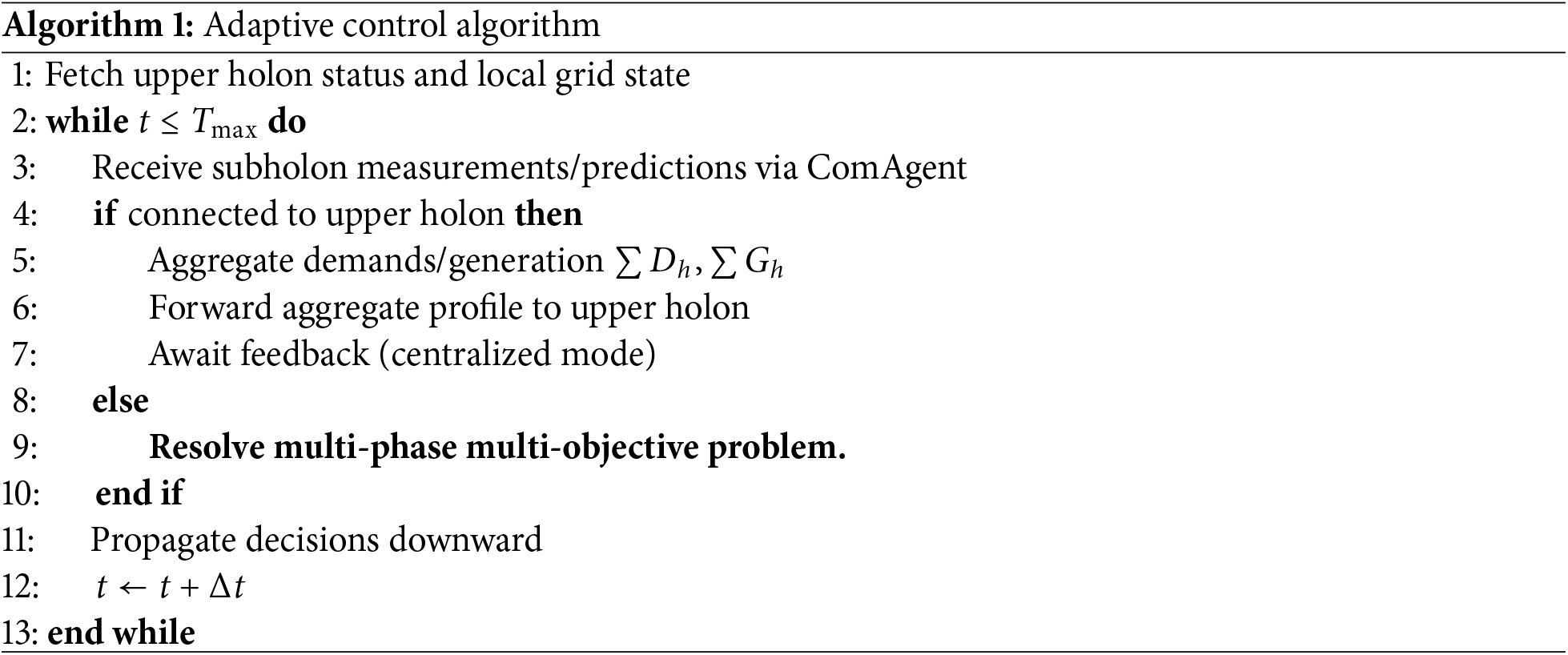

The decision engine orchestrates two operational modes based on network connectivity as shown in Algorithm 1.

The control agent solves the following multi-objective optimization problem across time periods

where:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Constraints (1)–(4) ensure operational feasibility while preserving:

• Real-time power balance (Eq. (1))

• Temporal storage state relationships (Eq. (2))

• Equipment safe operating limits (Eqs. (3) and (4))

During faults (e.g., regional blackouts), disconnected subholons switch to autonomous control, prioritizing critical loads and storage reserves to prevent cascading failures. The architecture’s resilience stems from three properties:

• Decentralized Autonomy: Subholons optimize locally when communication fails

• Hierarchical Coordination: Upper holons override suboptimal decisions during normal operation

• State Awareness: Real-time monitoring of storage SOC and generation margin prevents overscheduling

The next section describes the optimization process to solve the multi-phase multi-objective problem.

3.3 Multi-Phase Multi-Objective Optimization

This section presents the adaptive decision-making method used by the control agent. To adapt to changing grid conditions, the architecture employs a multi-phase, multi-objective optimization model inspired by the Cascaded Weighted Sum method [34]. The process is structured as a sequence of three optimization phases, each addressing objectives in descending order of priority. The first priority is to maintain grid stability (supply-demand equilibrium). Subsequent phases optimize for environmental, economic, and operational objectives, with each phase being constrained by the optimal solution of the preceding one. This iterative approach ensures that lower-priority goals are pursued only after critical higher-priority requirements have been met.

To govern the transitions between optimization phases and to evaluate the grid’s performance, three key indicators are defined. The Satisfaction and RES Utilization ratios serve as conditional thresholds within the optimization logic, while the Carbon Impact is used for post-simulation performance analysis.

Satisfaction Ratio (SR): This indicator assesses the grid’s ability to meet energy demand, reflecting overall supply reliability. A ratio approaching 1 indicates high stability.

RES Utilization: This metric tracks the proportion of energy generated from RES relative to the total generation.

where

Carbon Impact (CI): This indicator measures the total carbon emissions associated with energy generation and storage activities.

where

3.3.2 State-Transition Optimization Model

The decision-making process is formally modeled as a sequential, three-phase optimization. Let the set of decision variables at time

Phase 1: Equilibrium Optimization

The primary objective is to ensure grid stability by minimizing load curtailment. This establishes the maximum possible load that can be served under the current conditions.

• Objective (

• Constraints: Subject to

The solution from this phase,

Phase 2: Environmental Optimization

This phase is executed only if a high level of grid stability was achieved in Phase 1, determined by the Satisfaction Ratio (SR). The objective is to minimize the environmental cost without compromising the previously established stability.

• State Transition Condition: Execute if

• Objective (

• Constraints: Subject to

The solution

Phase 3: Techno-Economic Optimization

The final phase is executed only if the solution from Phase 2 demonstrates high utilization of RES. It performs a holistic optimization of economic costs and battery usage, constrained by the stability and environmental performance levels already secured.

• State Transition Condition: Execute if

• Objective (

where the first term corresponds to the economic cost objective and

• Constraints: Subject to

The final operational decision is the solution

3.3.3 Implementation via Genetic Algorithm

The sequential optimization model is solved at each time step using a Genetic Algorithm (GA) implemented via the Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms (MOEA) framework [36]. For each phase, the GA is applied to find the optimal solution for that phase’s specific objective function and constraints.

The algorithm is configured with a population size of 100 and uses a linear dominance comparator. The fitness function for the GA corresponds to the objective function (

4 Simulation Framework and Use Cases

The simulation was implemented using the JAVA programming language, leveraging the JAVA Agent DEvelopment Framework (JADE) for the creation of holons and their constituent agents. JADE provides a robust, FIPA-compliant environment well-suited for developing complex MAS. The core decision-making logic of the system is driven by the multi-objective optimization model detailed in Section 3.3.

4.1 System Setup, Control Architecture, and Economic Model

This study is grounded in a realistic model of the island of Mayotte, utilizing data from the MAESHA project. The simulation framework integrates real-world datasets, a hierarchical control architecture, and a strategic economic model to guide decision-making.

4.1.1 System and Data Foundation

The energy infrastructure modeled for Mayotte comprises two thermal power plants, multiple RESes (specifically PV parks), and two Battery Energy Storage System (BESS). The simulation operates on historical data with a 60-min time granularity, which includes weather forecasts, public holiday schedules, and records of energy demand and renewable generation.

To account for the stochastic variability inherent in real-world operations, the system’s performance is tested in a stochastically generated environment. Before the “ground truth” historical data is fed into the optimization model, a stochastic variable is applied to the weather-dependent inputs (i.e., solar irradiance forecasts). This perturbs the baseline forecast to create a plausible scenario reflecting common prediction errors. By running numerous simulations with different random perturbations, the robustness of the control logic can be assessed across a wide range of potential conditions.

Regarding the fidelity of the BESS model, the current implementation utilizes a simplified model with a constant charging and discharging efficiency. A model for battery degradation and state-of-health (SOH) is not incorporated. This simplification is justified by the study’s focus on short-term operational simulations (spanning hours to days), where the immediate effects of long-term degradation are negligible. The inclusion of a formal SOH degradation model and dynamic, state-dependent efficiencies would be a critical extension for future research focused on long-term asset management, lifecycle cost analysis, and strategic investment planning.

In this simulation framework, fault tolerance is assessed through the system’s response to stochastic variations, which act as proxies for unexpected operational dysfunctions. The random perturbations applied to renewable generation and demand forecasts create realistic operational challenges. For instance, a sudden, unforecasted drop in solar output reduces the energy available in Phase 1, forcing a greater reliance on Phase 2 and potentially triggering Phase 3 (diesel or curtailment). The model’s robustness and fault tolerance are measured by its ability to navigate these events while minimizing the activation of the high-cost, last-resort actions in Phase 3.

4.1.2 Holonic Control Architecture

The system’s control logic is implemented as a three-level holarchy, ensuring both coordinated global optimization and localized operational autonomy:

• Level 1: The root holon functions as the island-wide EMS, holding a global view of the grid.

• Level 2: Seventeen regional holons represent geographical subdivisions. These holons aggregate major assets, including thermal plants, PV parks, large consumers, and BESS.

• Level 3: Village holons act as local aggregators, primarily representing the cumulative demand of smaller residential and commercial users.

The operational data flows bottom-up: demand data from Level 3 is aggregated at Level 2, combined with regional generation and storage data, and then transmitted to the Level 1 EMS. Following optimization, the EMS issues top-down control commands to ensure coordinated dispatch, strategic BESS management, and grid stability.

4.1.3 Case Study Selection and Contribution

Due to the large number of holons, simulation results are presented for the Mamoudzou region. This holon was chosen as a representative case because its local PV park and BESS enable it to demonstrate autonomous capabilities.

This research significantly enhances the scenarios from previous work by the authors in [37] by applying a more sophisticated, multi-objective control algorithm. The new model provides a more flexible and realistic simulation by integrating strategic cost optimization, advanced energy storage management, and controlled load curtailment.

4.2 Scenario 1: Baseline Performance under Nominal Conditions

The first scenario establishes a performance baseline by simulating the system under nominal operating conditions. This configuration serves as the reference benchmark against which the system’s resilience in subsequent fault scenarios is measured. In this baseline case, all holons within the 3-level hierarchy are fully connected and all grid assets, including thermal generation and RESes, are operational. The BESS are assumed to begin with a sufficient state of charge to meet their operational mandates.

The system executes its designed communication and optimization logic, as described in Section 3. Energy demands propagate from lower-level holons upwards to the central EMS, which then computes a grid-wide optimal dispatch. Control commands, including energy allocation confirmations and BESS charging/discharging instructions, are subsequently issued down the hierarchy.

The primary objective of this scenario is to validate the system’s fundamental capability to satisfy all user demands when resource and network availability are unconstrained. As expected, the simulation confirms that the proposed control method achieves a 100% demand satisfaction ratio across all holons, thereby demonstrating the model’s effectiveness in maintaining optimal grid stability and performance under ideal circumstances.

4.3 Scenario 2: Resilience to a Major Generation Fault

This scenario is designed to test the resilience and adaptive capabilities of the holonic EMS in response to a critical generation fault. The simulation introduces an unplanned outage of the thermal power plant located in Koungou, which is taken offline between time-steps 5 and 14. The objective is to evaluate the system’s ability to autonomously re-dispatch its remaining assets—the Badamiers thermal plant, distributed PV parks, and BESS—to maintain grid stability and mitigate the impact on consumers. The system’s response is analyzed across three distinct operational phases.

Phase 1: Compensatory Response (Time-Steps 5-10)

Upon the instantaneous loss of the Koungou plant, the control algorithm immediately mitigates the generation deficit. It orchestrates a coordinated response by dispatching energy from the BESS while simultaneously maximizing output from the Badamiers plant and all available PV resources. During this initial phase, the system successfully maintains a 100% demand satisfaction ratio, demonstrating its ability to dynamically leverage energy storage to preserve energy equilibrium and service quality.

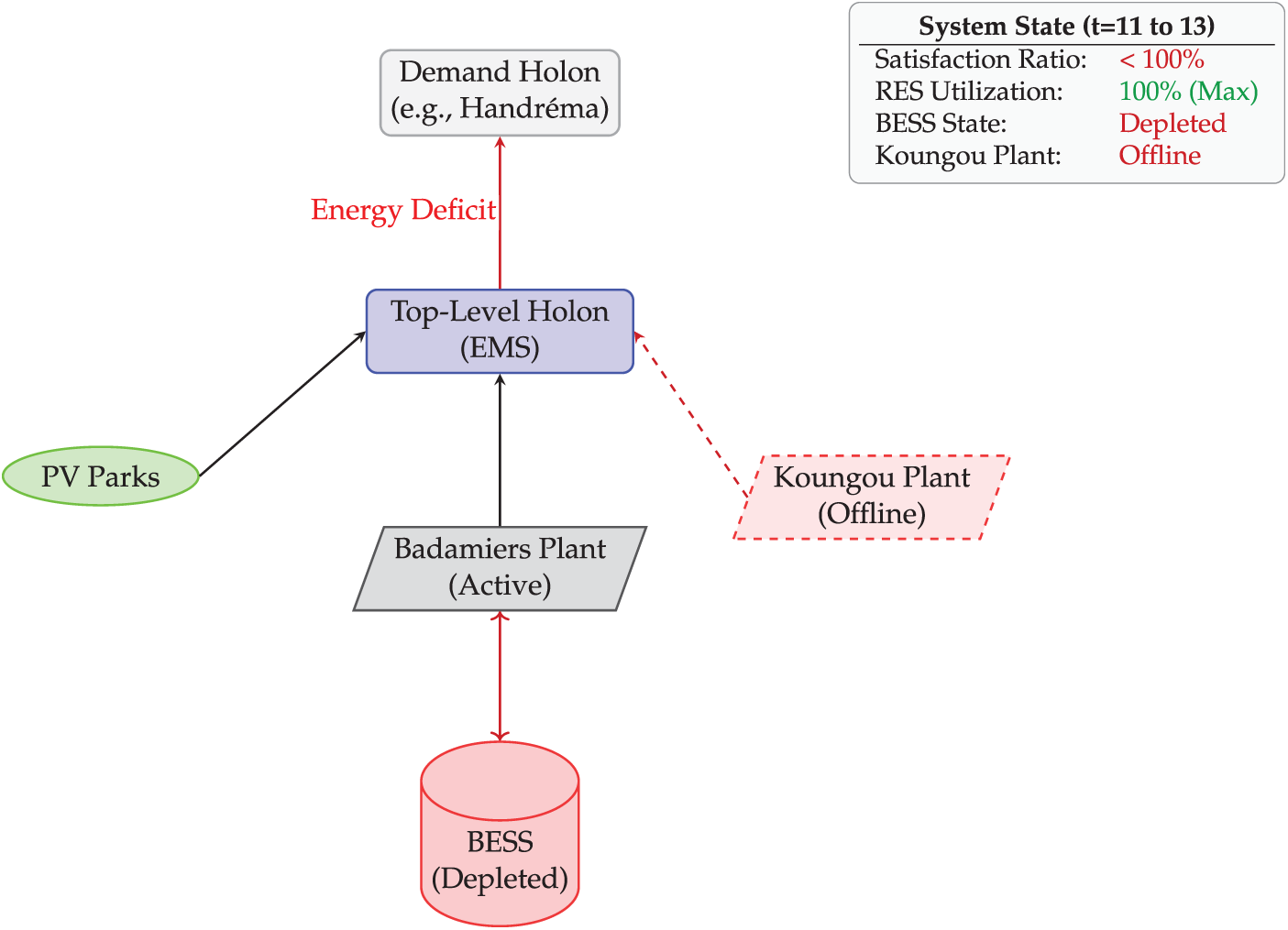

Phase 2: System Strain and Controlled Load Shedding (Time-steps 11-13)

At time-step 11, the scenario enters a critical stage as the prolonged outage depletes the BESS to their minimum allowable state of charge. With its primary backup exhausted and a major generation asset still offline, the system’s available power is no longer sufficient to meet the aggregate demand. This triggers a necessary, albeit partial, load curtailment.

A key validation of the optimization model occurs during this phase, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Even as the consumer satisfaction ratio falls below 100%, the RES utilization is maintained at 100%. This result confirms that the control algorithm is operating exactly as designed, correctly prioritizing the complete utilization of zero-marginal-cost renewable energy before resorting to the high-cost penalty of load shedding.

Figure 3: Conceptual diagram of the generation fault scenario during the critical phase (time-steps 11-13). With the Koungou plant offline and BESS reserves exhausted, the EMS cannot fully meet the demand of subordinate holons. The key outcome is the system’s adherence to its economic model: prioritizing 100% RES utilization even when load curtailment is unavoidable

Phase 3: System Recovery and Service Restoration (Post Time-step 14)

Once the Koungou plant is brought back online, the system initiates an immediate recovery sequence. The EMS algorithm re-optimizes the grid-wide dispatch, prioritizing the restoration of full service to all consumers. Once demand is met, surplus generation is allocated to recharging the BESS, thereby rebuilding the system’s energy reserves and restoring its resilience for future contingencies. Throughout the event, the holonic architecture remained stable, and post-recovery, the system’s performance converged with the baseline scenario, confirming its ability to return to a globally optimal state.

4.4 Scenario 3: Autonomous Islanding and Re-Synchronization

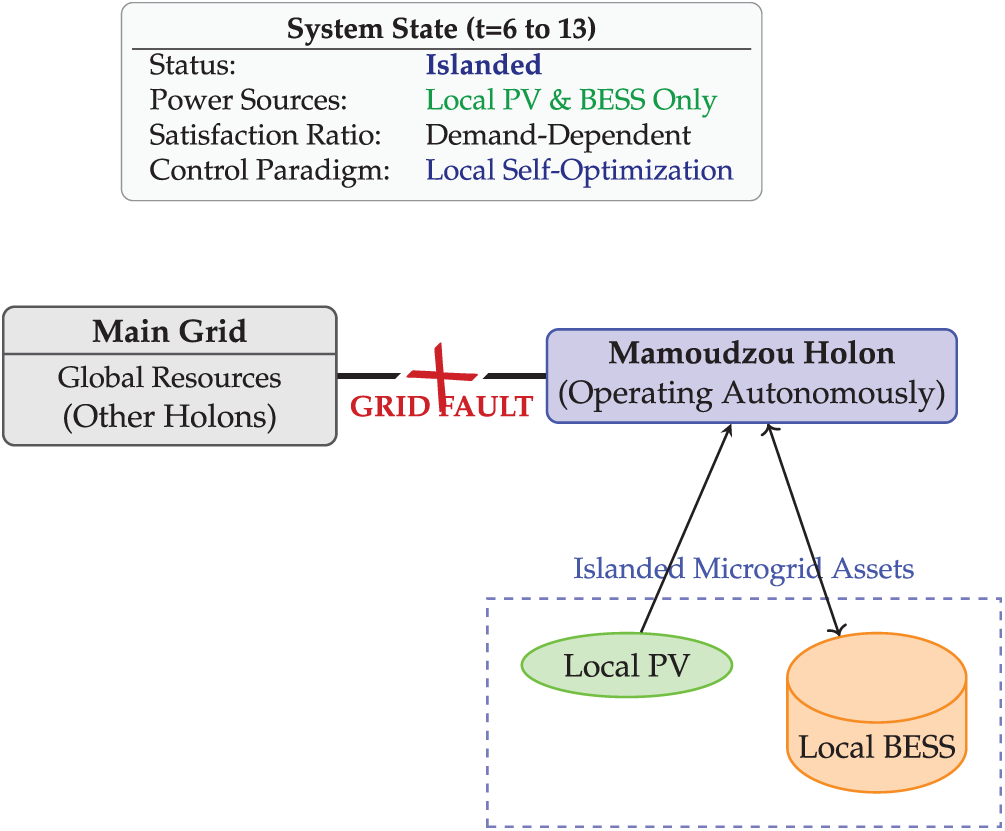

This scenario evaluates one of the most critical capabilities of the proposed architecture: the ability of a regional holon to autonomously manage a complete physical disconnection from the main grid. The objective is to validate that the holon can operate as a stable, self-sufficient islanded microgrid and subsequently execute an automated re-synchronization once the grid connection is restored. The conceptual architecture for this test is depicted in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Conceptual validation of the disconnected region scenario. The grid fault severs the connection, forcing the Mamoudzou holon to transition to an autonomous control state. It forms a self-sufficient microgrid, relying exclusively on its local assets to maintain stability, demonstrating the core principle of holonic resilience

At time-step 6, a simulated grid fault isolates the Mamoudzou holon. The system’s response, managed entirely by its internal logic, is analyzed across three phases.

Phase 1: Fault Detection and Autonomous Islanding (Time-steps 6-13)

Upon disconnection, the Mamoudzou holon’s internal EMS immediately detects the loss of the upstream connection and transitions its operational mode from a regional aggregator to a fully autonomous microgrid controller. In this islanded state, its optimization objective dynamically shifts from participating in the global grid economy to ensuring local stability and self-preservation. It manages its local resources—a dedicated PV array and a BESS—to serve its internal demand. Any demand exceeding the available local generation and stored energy is systematically curtailed, validating the holon’s capacity to maintain internal equilibrium during a crisis.

Phase 2: Automated Re-Synchronization (Time-step 14)

When the external grid fault is cleared at time-step 14, the holon’s EMS detects the availability of the main grid and initiates an automated re-synchronization protocol. This action seamlessly transitions the holon’s role back from an autonomous controller to a subordinate aggregator within the main holarchy. Access to grid power immediately restores the ability to satisfy 100% of local consumer demand.

Phase 3: Resilience Restoration (Post Time-step 14)

Following re-synchronization, the system enters the final recovery stage. The algorithm leverages the restored grid connection to systematically recharge the local BESS. This proactive measure restores the holon’s energy reserves, thereby rebuilding its resilience and ensuring it is prepared for future contingencies.

The successful execution of this entire fault lifecycle—from islanding to autonomous recovery—validates the architecture’s capacity for “plug-and-play” resilience. This test confirms the model’s ability to not only survive a critical failure but also to manage its own recovery and return to an optimal, fully-integrated state without necessitating external command or intervention.

4.5 Synthesis and Resilience Mechanisms

The experimental results validate the proposed holonic architecture’s capacity to deliver multi-faceted resilience, a capability elucidated through the contrasting outcomes of the simulated fault scenarios. The architecture demonstrates both top-down systemic management and bottom-up autonomous response, providing a comprehensive strategy for grid stability.

The Disrupted Plant Scenario demonstrates systemic resilience, managed from the apex of the holarchy. The failure was global in scope, inducing a grid-wide supply-demand deficit. In response, the top-level EMS optimally re-dispatched the entire portfolio of remaining shared assets. The crucial insight from this scenario is the system’s execution of a strategic trade-off: when resources became critically scarce, the control logic prioritized the pre-defined objectives of maximizing RES utilization and maintaining grid stability over guaranteeing 100% consumer satisfaction. This outcome is not a system failure but a validation of intelligent, centralized resource management, showcasing a capacity for graceful service degradation under duress.

Conversely, the Disconnected Region Scenario highlights the architecture’s capacity for subsidiarity and decentralized autonomy. Here, the fault was localized, requiring the affected subsystem to operate independently. The Mamoudzou holon successfully transitioned into a self-sufficient islanded microgrid, a feat that monolithic, purely centralized control systems cannot readily replicate without complex, pre-programmed contingency protocols. This demonstrates the inherent modularity and fault-containment of the holonic paradigm; the failure was managed at the lowest possible level, preventing a local issue from cascading into a systemic blackout.

Synthesizing these findings reveals a comprehensive and layered resilience strategy. The architecture can manage a global resource deficit via intelligent, centralized degradation (Scenario 2) while simultaneously handling a complete loss of local connectivity through autonomous islanding (Scenario 3). Furthermore, the consistent post-fault logic of prioritizing BESS recharging in both scenarios is a critical design feature. It confirms that resilience—defined as the capacity to recover and prepare for subsequent events—is an integral component of the control logic, not merely an emergent property. This multi-modal approach to fault management provides a robust and adaptive solution uniquely suited to the operational realities of an isolated island grid like Mayotte’s, whose survival depends entirely on its internal capacity to withstand and recover from disruptions.

5.1 Overview of the Proposed Model

The approach is based on a holonic architecture that integrates advanced simulation, forecasting, and optimization techniques to enhance the performance of SGs. This section provides an overview of the methodology, discusses the strengths and innovations of the model, and benchmarks it against existing approaches in the literature.

Summary of Methodology:

This approach is fundamentally built upon a holonic modeling architecture that decomposes the SG into discrete, autonomous yet cooperative units. Each holon encapsulates a subset of generation assets, BESS, and local demand profiles, enabling localized decision-making while preserving a coordinated overall grid operation. This structure facilitates scalable and modular system design, which is particularly beneficial when addressing the complexities of isolated or region-specific grids.

In parallel with the holonic framework, a hybrid forecasting mechanism is implemented that integrates real-time data and historical trends. This forecasting model is pivotal for predicting both renewable energy output and consumption patterns, thereby supporting proactive decision-making. Key performance indicators such as carbon impact, RES utilization, and satisfaction ratio are defined to monitor grid performance. The carbon impact indicator quantifies the environmental cost by measuring associated emissions; the RES utilization indicator assesses the penetration of renewable energy in the grid; and the satisfaction ratio evaluates the grid’s effectiveness in balancing supply with demand.

Model Strengths and Innovations:

One of the major innovations of this approach lies in its combination of a holonic structure with modern optimization and simulation techniques. The model’s flexibility and reusability stem from its modular holonic design, which directly addresses limitations found in more centralized or monolithic grid management strategies. Additionally, a genetic optimization algorithm is integrated that optimizes multi-objective criteria—ranging from energy balancing to environmental and economic costs. This algorithm enables the model to efficiently explore a wide solution space and determine optimal configurations under varying scenarios.

Furthermore, the incorporation of a DT framework represents a significant leap forward in terms of realistic simulation and scenario analysis. The DT not only mirrors the real-time operational status of the grid but also allows for the testing and validation of control strategies in a virtual environment. This dual approach of real-time optimization combined with DT -based simulation ensures that the model remains robust and adaptive under both normal and fault conditions.

Benchmarking against Existing Approaches:

Given that this work represents the first DT developed specifically for the Mayotte grid, establishing a direct benchmark against existing methods is not feasible. Unlike typical studies that aim to outperform current optimization techniques through quantitative comparisons, the model is primarily intended to simulate scenarios that reveal both the strengths and limitations of the grid. The insight provided by these simulations is used to understand the operational dynamics, such as the trade-offs between renewable integration and grid stability, as opposed to claiming superiority over traditional optimization methods. This exploratory approach ensures that the model serves as a comprehensive decision support tool to evaluate diverse scenarios rather than a competitive optimization framework.

5.2 Simulation of Scenarios via a Digital Twin

Digital Twin Integration:

The DT framework was designed to accurately mirror the Mayotte SG environment by integrating real-world data with a virtual representation of the grid’s physical, operational, and geographic characteristics. Data collected from Mayotte’s official electricity provider—including historical consumption records, renewable generation statistics, and ancillary inputs such as weather forecasts and holiday schedules—are fed into the DT. This continuous data synchronization ensures that the simulation environment remains current and reflective of the evolving grid dynamics. The DT serves as a dynamic platform where the interactions among various holons, energy sources, and storage devices can be observed and analyzed in near real-time.

Scenario Simulation:

A diverse range of scenarios was simulated through the DT to encompass the variability prevalent in the Mayotte grid. Among these, peak demand periods were modeled to assess how the grid adapts during times of high energy demand and prioritizes resource allocation. In addition, the simulation examined periods of RES variability, such as fluctuations in solar irradiance or wind conditions, to evaluate the effectiveness of renewable energy integration. Furthermore, fault conditions were simulated by introducing grid faults or outages in specific regions, allowing for an in-depth study of resilience strategies and the role of energy storage in mitigating interruptions. The simulation setup is built upon a holonic architecture, where each holon represents a distinct operational unit of the grid, thus enabling scenario-specific testing that meticulously examines the interactions between local decisions and overall grid behavior.

In addition to these primary cases, other scenarios were explored to further stress-test the grid under a broader set of challenges. One such category focused on demand response events, where dynamic changes in consumer behavior were incorporated to mimic the rapid shifts in power consumption that can occur during economic fluctuations or sudden behavioral shifts. This allowed the simulation to capture the grid’s response to unexpected load variations and assess the effectiveness of DSM strategies. Another set of scenarios introduced forecasting uncertainties by integrating errors in both meteorological inputs and load predictions, which helped reveal potential vulnerabilities in decision-making processes when predictions deviate from actual conditions. Moreover, extreme weather scenarios, including prolonged high temperatures, severe storms, and other adverse environmental events, were simulated to evaluate the grid’s performance and stability under environmental stress.

A key strength of the DT lies in its holonic architecture, which is inherently adaptable to the wide range of scenarios outlined. By design, each holon functions as an autonomous, modular unit representing distinct operational segments of the grid. This modularity allows for rapid configuration and reconfiguration, making it straightforward to incorporate variations. The decentralized control inherent in the holonic system enables each unit to engage in local decision-making, thereby reducing bottlenecks and ensuring swift, targeted responses to localized disruptions. At the same time, because these holons are designed to seamlessly interact within a larger framework, the architecture ensures that individual adjustments are harmonized with overall grid performance.

Use of Performance Indicators:

Key performance indicators were systematically monitored during each simulation scenario. Emission levels, evaluated through the carbon impact indicator, were tracked to assess the environmental performance of various operational strategies, thereby highlighting the balance between conventional and renewable energy generation. The RES utilization indicator measured the proportion of renewable energy generation, determining how effectively the grid incorporated RESes under different conditions. Similarly, the satisfaction ratio, which reflects the balance between energy supply and demand, was continuously assessed to gauge service reliability and consumer satisfaction. By tracking these indicators, the simulation framework provided a comprehensive evaluation of grid performance under both standard and adverse conditions, ultimately informing decision-makers about potential areas for improvement.

It is important to note that while a range of additional indicators—such as dynamic load forecasting errors, long-term economic performance metrics, and resilience to cyber-physical disturbances—exists, they are typically not incorporated into this type of DT implementation. The purpose of this streamlined DT is to present an immediate and practical view of the grid’s current strengths and weaknesses, rather than offering a full spectrum of in-depth, forward-looking analyses. Consequently, these more complex indicators, which could provide valuable insights in a more integrated and data-rich framework, remain outside the scope of this implementation, which focuses on current operational pros and cons.

Comparative Analysis:

The grid’s performance was compared across various simulated scenarios to understand how different operational strategies affect grid behavior. The DT analysis revealed several key observations. Under peak demand, the model underscored the necessity for robust DSM techniques in order to maintain acceptable satisfaction ratios. In situations characterized by renewable variability, the RES utilization indicator highlighted a dependency on energy storage systems to buffer against the intermittency of RESes. Additionally, during fault conditions, the DT was instrumental in determining the thresholds at which the grid shifts its operating mode to optimize energy dispatch in response to disturbances. This comparative overview confirms the model’s capability to simulate and elucidate the complex dynamics of grid operations, thereby guiding the development of targeted recommendations for enhancing overall grid resilience and sustainability.

5.3 Recommendations Based on Simulation Outcomes

Operational Limits and Indicator Thresholds:

The simulation outcomes provide valuable insights into critical thresholds across various performance indicators. For instance, the carbon impact indicator reveals the point at which emission levels may jeopardize environmental targets, while the RES utilization metric exposes the limitations in renewable capacity utilization under adverse weather conditions. The satisfaction ratio, reflecting the balance between supply and demand, serves as a proxy for overall grid reliability and consumer service level. By analyzing the trends and statistical patterns observed during simulations, it is possible to identify specific thresholds-such as maximum permissible carbon emissions, minimum acceptable RES contribution, or a critical satisfaction ratio—that signal when the grid is approaching its operational limits. Such thresholds can be used to trigger automated control interventions, alert operators, or suggest a need for load curtailment and DSM enhancements.

Control Strategies and Optimization:

Based on insights derived from the simulations, several control strategies and optimization measures can be recommended to improve grid performance. Adaptive control strategies should be developed that dynamically recalibrate resource allocation in response to real-time variations in load demand or renewable generation. These adaptive algorithms would enable the grid to flexibly shift between energy sources and reallocate energy storage utilization, maintaining operational stability under changing conditions. In parallel, resource re-allocation routines can be implemented to facilitate the dynamic rebalancing of generation assets and storage capacity. This approach includes the proactive re-dispatch of energy from more stable sources during periods of peak demand or in fault conditions, thereby reducing reliance on non-renewable sources. Additionally, improvements in demand side management should be pursued by introducing enhanced demand response programs that align consumer usage patterns with grid capabilities.

Policy and Investment Implications:

The DT framework offers a unique capability to simulate the effects of prospective structural investments before they are implemented in the physical grid. By virtually modeling changes—such as infrastructure upgrades, the addition of renewable generation units, or the integration of advanced control systems—the simulation provides early insights into the potential performance and resilience of the grid. This simulation feedback plays a crucial role in informing investment decisions, allowing stakeholders to understand the economic and operational impacts of various scenarios. Such foresight enables the identification of projects with the most significant benefits, helping to optimize capital allocation while minimizing risks. Consequently, by translating simulation outcomes into data-driven investment strategies, decision-makers can ensure that expenditure in grid modernization aligns with long-term resilience, efficiency, and sustainability objectives.

5.4 Limitations and Future Directions

While this study successfully validates the core principles of the proposed holonic architecture, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations, which in turn define clear pathways for future research.

Model Fidelity and Physical Grid Constraints:

The current DT operates primarily as a high-level systemic model, focusing on energy balance, economic dispatch, and strategic decision-making. It simplifies the underlying power system physics, such as AC power flow, voltage stability, and frequency regulation. A dispatch schedule that is optimal from an energy-balance perspective may not be feasible in the real world without causing physical grid violations.

Future Work:A significant next step is to integrate this holonic control framework with a high-fidelity power systems simulator (e.g., PowerFactory, PSCAD, or OPAL-RT). Such a co-simulation environment would allow for the validation of dispatch commands against real-time physical constraints, ensuring that the holonic system’s strategies are not only economically optimal but also physically viable and conducive to grid stability. Crucially, this would enable the incorporation of quantitative stability and resilience metrics (e.g., voltage stability indices, frequency response, and fault ride-through capabilities) to rigorously validate the EMS’s performance during grid faults and fluctuations, moving beyond the current operational and economic-based evaluation.

Resilience to Cyber-Physical Disruptions:

The scenarios presented focus on physical faults: the failure of a generator and the disconnection of a transmission line. However, a distributed control architecture like a holonic system relies heavily on a communication network. The current model implicitly assumes this network is perfectly reliable and secure. In practice, communication links can suffer from latency, packet loss, or malicious cyberattacks, which could compromise the coordination between holons.

Future Work:Future research should explicitly model the cyber-physical nature of the grid. This involves simulating communication network failures and testing the system’s resilience to cyberattacks (e.g., false data injection). Developing fallback control logic that allows holons to operate safely with intermittent or untrusted communication is a critical research direction.

Validation Beyond Pure Simulation:

The findings of this paper are based entirely on a simulated environment. While the DT is data-driven, it cannot capture all the unmodeled dynamics and emergent behaviors of the real-world grid. The true efficacy of the control strategies remains to be proven in a physical setting.

Future Work: A phased validation approach is necessary. The next logical step would be Controller-Hardware-in-the-Loop (C-HIL) testing, where the developed holonic control software interacts with real hardware emulating grid components. Success at this stage would pave the way for a pilot deployment on a small, contained subsection of the Mayotte grid to validate performance with real-world assets and constraints.

Advanced Optimization under Uncertainty:

The use of a genetic algorithm is effective for navigating the multi-objective problem space, but as a heuristic, it does not guarantee mathematical optimality and can be computationally intensive. Furthermore, while the simulation tested scenarios with forecast errors, the optimization algorithm itself treats the forecasts as deterministic inputs.

Future Work: It would be valuable to benchmark the genetic algorithm against other optimization techniques, such as Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP), which can provide provably optimal solutions for linearized models. More importantly, future iterations should incorporate stochastic or robust optimization methods. These techniques explicitly account for forecast uncertainty within the decision-making process, producing strategies that are more resilient to prediction errors and inherently less risky.

6 Conclusion and Future Perspectives

This paper addressed the critical challenge of ensuring operational resilience in isolated power grids by proposing and validating a novel decision and control method based on a holonic multi-agent architecture. A primary contribution is the development of a multi-phase, multi-objective optimization model that empowers decentralized holons to make intelligent, adaptive decisions. This approach moves beyond traditional centralized control, offering a more robust framework specifically tailored to the unique vulnerabilities of islanded systems like Mayotte’s. The core strength of the model was demonstrated through a series of rigorous simulation scenarios, which validated its dual-mode resilience. In the face of a system-wide disruption (a major plant failure), the hierarchical holonic structure effectively coordinated a global response, managing the energy deficit by prioritizing critical loads and optimizing shared resources. Conversely, during a localized fault (a regional disconnection), the affected holon showcased true autonomy, seamlessly transitioning into a self-sufficient islanded microgrid. This ability to act both collectively during systemic stress and independently during localized failures is a key finding of this work and a significant advantage over monolithic control paradigms. The implications of these findings are substantial. This work provides a strong case for the adoption of decentralized, agent-based control systems as a viable and superior strategy for enhancing the energy security of vulnerable, isolated communities. The proposed architecture serves as a blueprint for developing DT capable of not only optimizing day-to-day operations but also stress-testing the grid against potential crises, thereby improving preparedness and minimizing economic and social impact. Looking forward, this research opens several promising avenues for future work. The model’s performance could be further enhanced by incorporating stochastic optimization methods to more formally manage the uncertainty inherent in renewable energy forecasts. Secondly, while the simulations provide a robust proof-of-concept, the next logical step involves hardware-in-the-loop testing to validate the model’s interaction with real-world physical components and communication latencies. Finally, future research should explore the scalability of this architecture for larger, more complex island systems or even for managing microgrids within a larger continental grid. In conclusion, by successfully integrating advanced optimization with a flexible holonic architecture, this paper represents a significant step toward creating smarter, more resilient, and more autonomous power systems. The proposed method offers a robust and adaptable solution that can pave the way for a more secure and sustainable energy future for isolated grids worldwide.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received funding for this study from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 957843. The research was supported by the MAESHA project. More information can be found at the Horizon 2020 website: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/957843/fr (accessed on 28 September 2025).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Ihab Taleb, Guillaume Guerard; Methodology: Ihab Taleb, Guillaume Guerard; Software: Ihab Taleb, Guillaume Guerard; Validation: Nga Nguyen; Formal Analysis: Ihab Taleb, Guillaume Guerard; Resources: Ihab Taleb; Data Curation: Ihab Taleb; Writing—Original Draft: Ihab Taleb, Guillaume Guerard; Writing—Review & Editing: Guillaume Guerard; Visualization: Guillaume Guerard; Supervision: Guillaume Guerard, Frédéric Fauberteau, Nga Nguyen; Project Administration: Pascal Clain; Funding Acquisition: Pascal Clain. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and materials that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to their sensitive nature and are restricted to internal use by the project members.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/957843/fr (accessed on 28 September 2025)

2https://opendata.electricitedemayotte.com/explore/dataset/registre-des-installations-de-production-et-de-stockage/map/?basemap=jawg.streets&location=11,-12.816,45.15917 (accessed on 28 September 2025)

References

1. Spencer T, Berghmans N, Sartor O. Coal transitions in China’s power sector: a plant-level assessment of stranded assets and retirement pathways. Coal Transitions. 2017;12:21. [Google Scholar]

2. Negeri E, Baken N, Popov M. Holonic architecture of the smart grid. Smart Grid Renew Energy. 2013;4(2):202–12. doi:10.4236/sgre.2013.42025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Howell S, Rezgui Y, Hippolyte JL, Jayan B, Li H. Towards the next generation of smart grids: semantic and holonic multi-agent management of distributed energy resources. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;77:193–214. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Advanced metering infrastructure. 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.smartgrid.gov/document/netl_modern_grid_strategy_powering_our_21st_century_economy_advanced_metering_infrastructur. [Google Scholar]

5. Zainab A, Ghrayeb A, Syed D, Abu-Rub H, Refaat SS, Bouhali O. Big data management in smart grids: technologies and challenges. IEEE Access. 2021;9:73046–59. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3080433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Khan AR, Mahmood A, Safdar A, Khan ZA, Khan NA. Load forecasting, dynamic pricing and DSM in smart grid: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2016;54(31):1311–22. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Yassim HM, Abdullah MN, Gan CK, Ahmed A. A review of hierarchical energy management system in networked microgrids for optimal inter-microgrid power exchange. Elect Power Syst Res. 2024;231(14):110329. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2024.110329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang W, Xu Y, Khanna M. A survey on the communication architectures in smart grid. Comput Netw. 2011;55(15):3604–29. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2011.07.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hussain S, Lai C, Eicker U. Flexibility: literature review on concepts, modeling, and provision method in smart grid. Sustain Energy Grids Netw. 2023;35(1):101113. doi:10.1016/j.segan.2023.101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Fan D, Ren Y, Feng Q, Liu Y, Wang Z, Lin J. Restoration of smart grids: current status, challenges, and opportunities. Renew Sustain Energ Rev. 2021;143(5):110909. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.110909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Abdel-Fattah M, Kohler H, Rotenberger P, Scholer L. A review of the holonic architecture for the smart grids and the self-healing application. In: Proceedings of the 21st International Scientific Conference on Electric Power Engineering (EPE); 2020 Oct 19–21; Prague, Czech Republic. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

12. Zibaeirad A, Koleini F, Bi S, Hou T, Wang T. A comprehensive survey on the security of smart grid: challenges, mitigations, and future research opportunities. arXiv:2407.07966. 2024. [Google Scholar]

13. Salkuti SR. Challenges, issues and opportunities for the development of smart grid. Int J Elec Comput Eng (IJECE). 2020;10(2):1179–86. doi:10.11591/ijece.v10i2.pp1179-1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Taleb I, Guerard G, Fauberteau F, Nguyen N. Holonic energy management systems: towards flexible and resilient smart grids. In: Rocha AP, Steels L, van den Herik J, editors. Agents and artificial intelligence. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 95–112. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-55326-4_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Amin SM, Wollenberg BF. Toward a smart grid: power delivery for the 21st century. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2005;3(5):34–41. doi:10.1109/mpae.2005.1507024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ramchurn S, Vytelingum P, Rogers A, Jennings N. Putting the ‘Smarts’ into the smart grid: a grand challenge for artificial intelligence. Commun ACM. 2012;55(4):86–97. doi:10.1145/2133806.2133825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Guo Y, Wan Z, Cheng X. When blockchain meets smart grids: a comprehensive survey. High-Confid Comput. 2022;2(2):100059. doi:10.1016/j.hcc.2022.100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Nehai Z, Guérard G. Integration of the blockchain in a smart grid model. In: The 14th International Conference of Young Scientists on Energy Issues (CYSENI) 2017; 2017 May 25–26; Kaunas, Lithuania. p. 127–34. [Google Scholar]

19. Liu M, Fang S, Dong H, Xu C. Review of digital twin about concepts, technologies, and industrial applications. J Manuf Syst. 2020;58(B):346–61. doi:10.1016/j.jmsy.2020.06.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Jiang Z, Lv H, Li Y, Guo Y. A novel application architecture of digital twin in smart grid. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2022;13(8):3819–35. doi:10.1007/s12652-021-03329-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Weibull JW. An introduction to evolutionary game theory. In: IUI working paper. Stockholm, Sweden: The Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IUI); 1992. No. 347. [Google Scholar]

22. Gokhale C, Traulsen A. Evolutionary games in the multiverse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(12):5500–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.0912214107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Chica-Pedraza G, Mojica-Nava E, Cadena-Muñoz E. Boltzmann distributed replicator dynamics: population games in a microgrid context. Games. 2021;12(1):8. doi:10.3390/g12010008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Hussain SS, Nadeem F, Aftab MA, Ali I, Ustun TS. The emerging energy internet: architecture, benefits, challenges, and future prospects. Electronics. 2019;8(9):1037. doi:10.3390/electronics8091037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mahmud K, Khan B, Ravishankar J, Ahmadi A, Siano P. An internet of energy framework with distributed energy resources, prosumers and small-scale virtual power plants: an overview. Renew Sustain Energ Rev. 2020;127(3):109840. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2020.109840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kudzin A, Takayama S, Ishigame A. Energy management systems (EMS) for a decentralized grid: a review and analysis of the generation and control methods impact on EMS type and topology. IET Renew Power Gener. 2025;19(1):e70008. doi:10.1049/rpg2.70008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ferreira A, Ferreira Â, Cardin O, Leitão P. Extension of holonic paradigm to smart grids. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2015;48(3):1099–104. doi:10.1016/j.ifacol.2015.06.230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ansari J, Kazemi A, Gholami A. Holonic structure: a state-of-the-art control architecture based on multi-agent systems for optimal reactive power dispatch in smart grids. IET Gener Transm Distrib. 2015;9(14):1922–34. doi:10.1049/iet-gtd.2014.1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wallis A, Hauke S, Egert R, Mühlhäuser M. A framework for strategy selection of atomic entities in the holonic smart grid. In: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Smart Grids, Green Communications and IT Energy-Aware Technologies; 2020 Sep 27–Oct 1; Lisbon, Portugal. p. 11–6. [Google Scholar]

30. Hussain S, El-Bayeh CZ, Lai C, Eicker U. Multi-level energy management systems toward a smarter grid: a review. IEEE Access. 2021;9:71994–2016. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3078082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Tian J, Shen C, Wang B, Ren C, Xia X, Dong R, et al. EVADE: targeted adversarial false data injection attacks for state estimation in smart grid. IEEE Trans Sustain Comput. 2025;10(3):534–46. doi:10.1109/tsusc.2024.3492290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Guerard G, Pousseur H, Taleb I. Isolated areas consumption short-term forecasting method. Energies. 2021;14(23):7914. doi:10.3390/en14237914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Taleb I, Guerard G, Fauberteau F, Nguyen N. A flexible deep learning method for energy forecasting. Energies. 2022;15(11):3926. doi:10.3390/en15113926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Jakob W, Blume C. Pareto optimization or cascaded weighted sum: a comparison of concepts. Algorithms. 2014;7(1):166–85. doi:10.3390/a7010166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Fotopoulou M, Rakopoulos D, Petridis S. Development of a multi-dimensional key performance indicators’ framework for the holistic performance assessment of smart grids. In: Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Efficiency, Cost, Optimization, Simulation and Environmental Impact of Energy Systems ECOS; 2022 Jul 3–7; Copenhagen, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

36. Hadka D. MOEA framework: a java library for multi-objective evolutionary algorithms; 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 17]. Available from: http://moeaframework.org/index.html. [Google Scholar]

37. Taleb I, Guerard G, Fauberteau F, Nguyen N. A holonic multi-agent architecture for smart grids. In: Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence—Volume 1: ICAART. INSTICC. Setúbal, Portugal: SciTePress; 2023. p. 126–34. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools