Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Applications of AI and Blockchain in Origin Traceability and Forensics: A Review of ICs, Pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and Robotics

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung City, 40227, Taiwan

2 Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, Chaoyang University of Technology, Taichung City, 41349, Taiwan

* Corresponding Authors: Der-Chen Huang. Email: ; Chin-Ling Chen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Key Technologies and Applications of Blockchain Technology in Supply Chain Intelligence and Trust Establishment)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 67-126. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070944

Received 28 July 2025; Accepted 25 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

This study presents a systematic review of applications of artificial intelligence (abbreviated as AI) and blockchain in supply chain provenance traceability and legal forensics cover five sectors: integrated circuits (abbreviated as ICs), pharmaceuticals, electric vehicles (abbreviated as EVs), drones (abbreviated as UAVs), and robotics—in response to rising trade tensions and geopolitical conflicts, which have heightened concerns over product origin fraud and information security. While previous literature often focuses on single-industry contexts or isolated technologies, this review comprehensively surveys these sectors and categorizes 116 peer-reviewed studies by application domain, technical architecture, and functional objective. Special attention is given to traceability control mechanisms, data integrity, and the use of forensic technologies to detect origin fraud. The study further evaluates real-world implementations, including blockchain-enabled drug tracking systems, EV battery raw material traceability, and UAV authentication frameworks, demonstrating the practical value of these technologies. By identifying technological challenges and policy implications, this research provides a comprehensive foundation for future academic inquiry, industrial adoption, and regulatory development aimed at enhancing transparency, resilience, and trust in global supply chains.Keywords

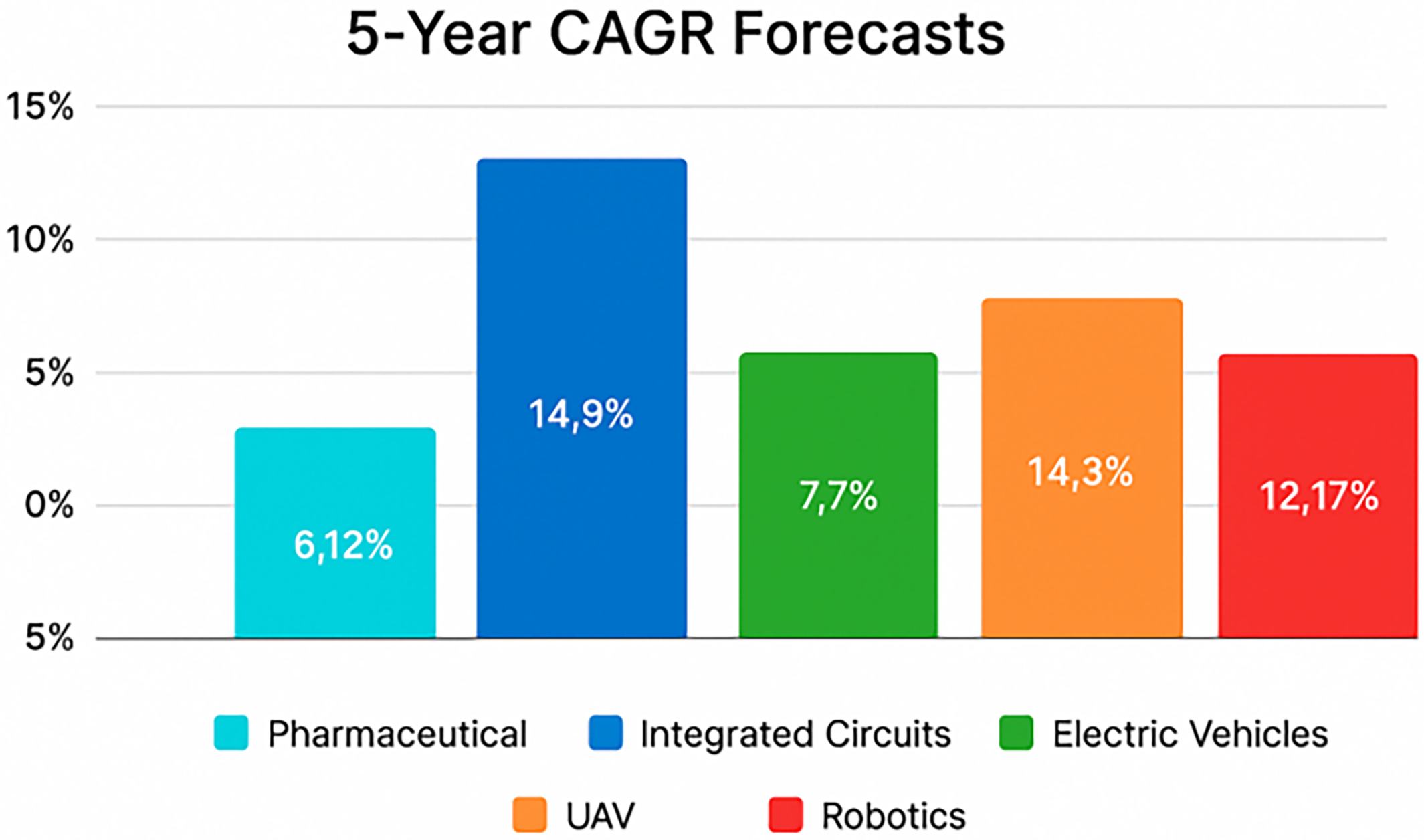

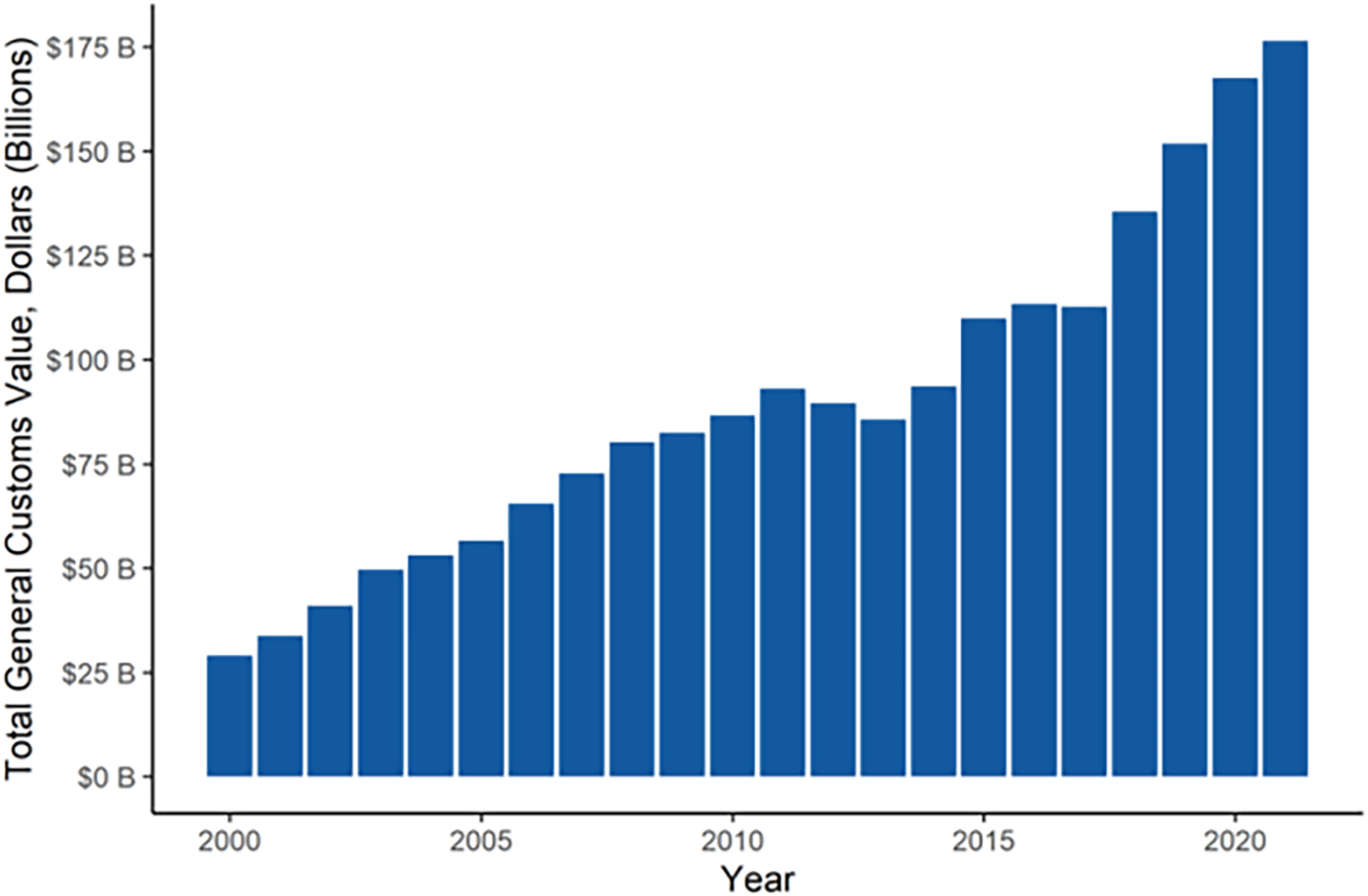

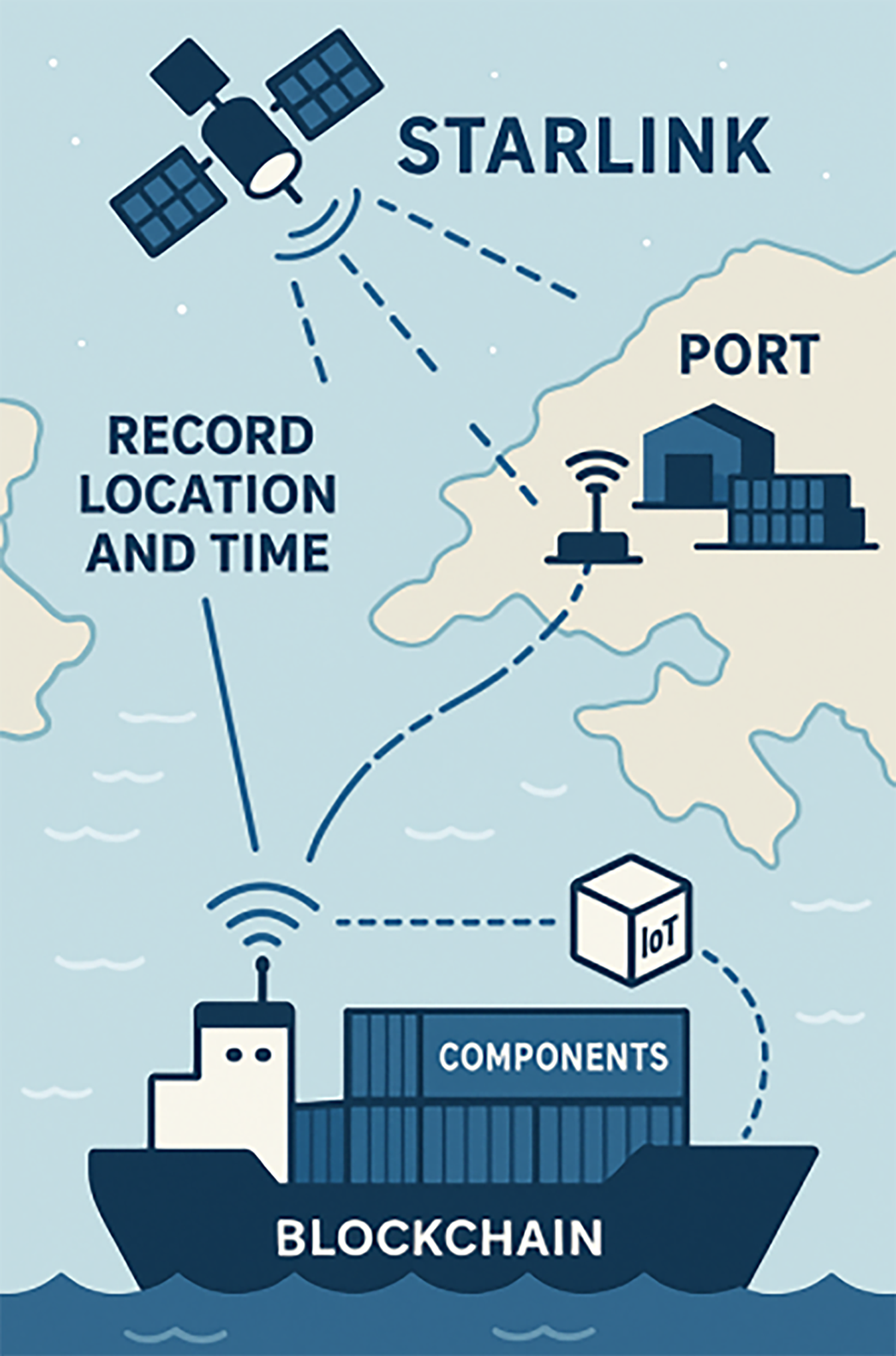

In the late 20th century, a surge in free trade and economic globalization prompted U.S. corporations to pursue “maximum profit and minimum cost” by outsourcing key functions—including procurement, manufacturing, and R&D—to multinational suppliers with greater price competitiveness. This shift gave rise to global value chains and a complex system of international labor divisions that span multiple countries and production stages. However, it also incurred significant economic repercussions, such as a mounting U.S. trade deficit, domestic industrial hollowing, and widespread job displacement, leading to trade frictions. Furthermore, the broader geographical span and growing complexity of goods flows have intensified concerns about opacity in supply chain processes. In recent years, the Russia-Ukraine war has leveraged unmanned aerial vehicles and the Starlink satellite system to reshape military operations, significantly increasing demand for related technologies and underscoring the imperative of securing critical supply chains during geopolitical conflicts. Key industries—including pharmaceuticals, electric vehicles, drones, robotics, and ICs—have become central to technological development and are projected to gain strategic influence ([1–5], see Fig. 1 below). Nevertheless, their production remains highly dependent on imported raw materials ([6], see Fig. 2 below), posing national security risks. In response, the U.S. government has sought to reshore these industries and, amid rising concerns over information security, has intensified efforts to combat illicit practices such as origin fraud. These efforts involve enhancing component traceability and strengthening legal and forensic safeguards.

Figure 1: Annual growth rates projected for the five industries over the next five years

Figure 2: Continued increase in U.S. pharmaceutical import value

(a) ICs are essential components of all electronic products and constitute one of the most critical points of cybersecurity vulnerability. If malicious code is embedded and activated at a crucial moment, it can take over system control, thereby posing severe security risks to a wide range of electronic systems. For example, the Spanish cybersecurity firm Tarlogic Security has identified hidden instructions in Chinese-manufactured ESP32 chips, which could function as backdoors, potentially allowing the covert remote control of millions of IoT devices [7], including EVs, UAVs, and robotics systems.

(b) The prevalence of counterfeit pharmaceuticals poses a critical threat to global public health, resulting in an estimated 110,000 deaths in the United States in 2023 alone [8] and approximately one million deaths worldwide each year [9]. In developing countries, one in ten medical products is counterfeit or substandard [10], with up to 30% of pharmaceuticals in regions such as Africa, Asia, and Latin America failing to meet regulatory standards [11]. Likewise, major disasters and widespread infectious disease outbreaks frequently lead to drug shortages, heightening social anxiety and unrest [12]. This vulnerability is further exacerbated under intensified geopolitical tensions, prompting governments around the world to enact pharmaceutical traceability regulations aimed at enhancing transparency across supply chains [13–16].

(c) Instability in component supply can lead to significant disruptions in automotive production activities [17], with amplified implications for national security during periods of geopolitical conflict. Furthermore, EVs, which possess integrated capabilities for data collection and surveillance, may be vulnerable to exploitation or remote manipulation by adversarial entities. Consequently, the stability and transparency of the sourcing of EV components have emerged as critical strategic concerns. Among all components, the battery is arguably the most vital; however, its supply chains of raw materials have been repeatedly linked to violations of human rights and environmental degradation [18]. In response, leading nations have implemented legislative frameworks mandating traceability and strict regulatory oversight of EV components and raw materials, aiming to prevent fraudulent practices such as country-of-origin misrepresentation [19–21].

(d) Currently, large UAVs are primarily deployed for military and governmental purposes. In particular, during the Russia-Ukraine war, UAVs have demonstrated significant effectiveness in striking tanks and air defense systems, as well as in executing reconnaissance and electronic warfare missions. As such, UAV-based tactics are increasingly regarded as a critical component of future warfare strategies. However, if these systems are compromised or remotely controlled by adversarial actors, they could become offensive weapons against their own forces. In response to these risks, countries such as the United States, the European Union, and Japan have increased the regulatory oversight of the supply of UAV components and the integrity of the system [22–25].

(e) Robots are widely deployed across a wide range of sectors, including manufacturing lines, seaports, automated warehouses, customer service, and even personal companionship. Designed for continuous and long-term operation, these systems are inherently vulnerable to cyber intrusions, rendering them potential targets for adversarial infiltration. If backdoors are implanted or remote attacks initiated by hostile actors, robots can be able to immediately disrupt port logistics, cripple factory operations, damage medical infrastructure, or even target specific individuals. Such scenarios pose serious threats to public safety and economic stability and may ultimately influence the outcomes of geopolitical conflicts. In response, leading countries such as the United States, the European Union, and Japan have introduced legislation aimed at reinforcing supply chain autonomy and enhancing cybersecurity in the robotics sector [22–25].

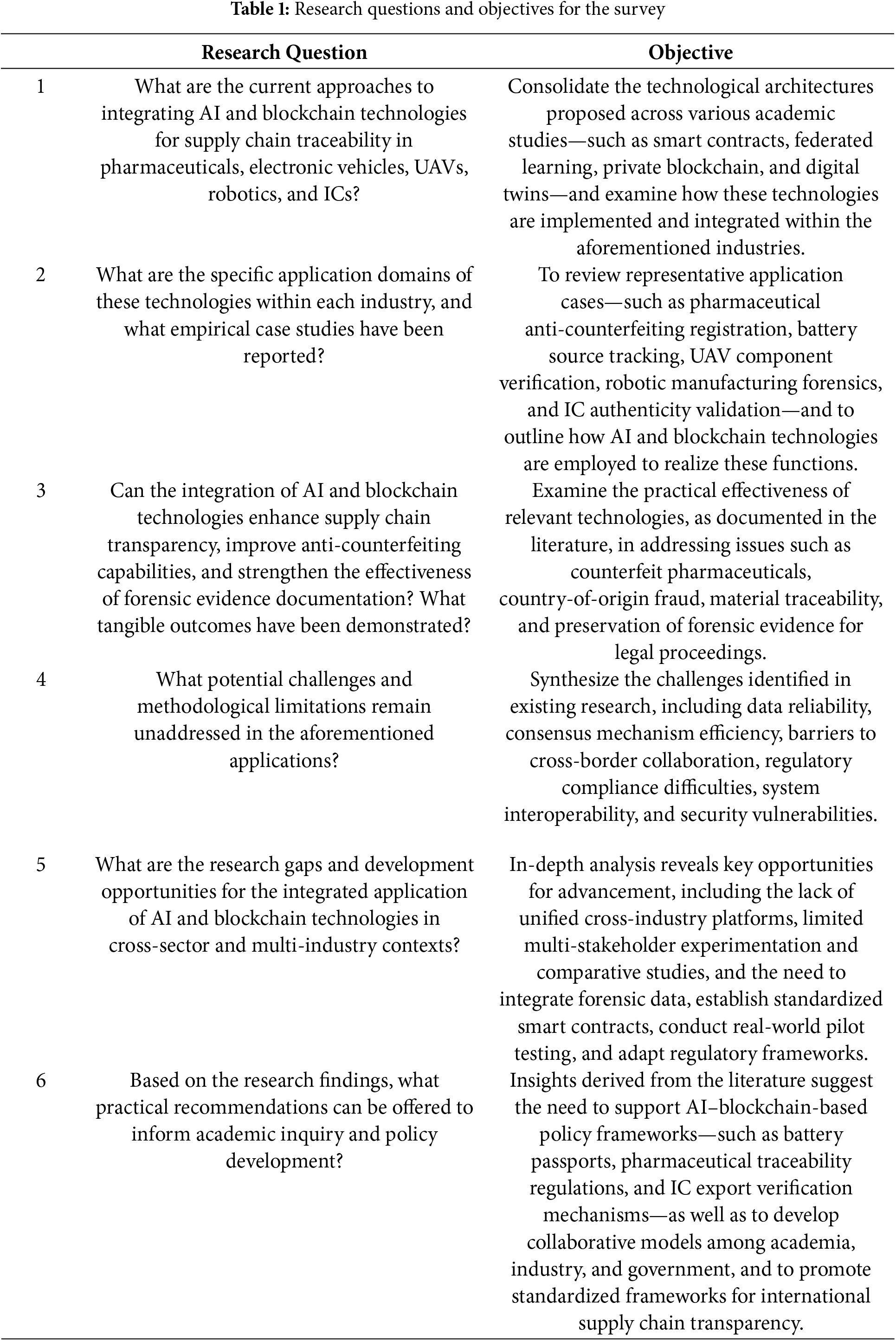

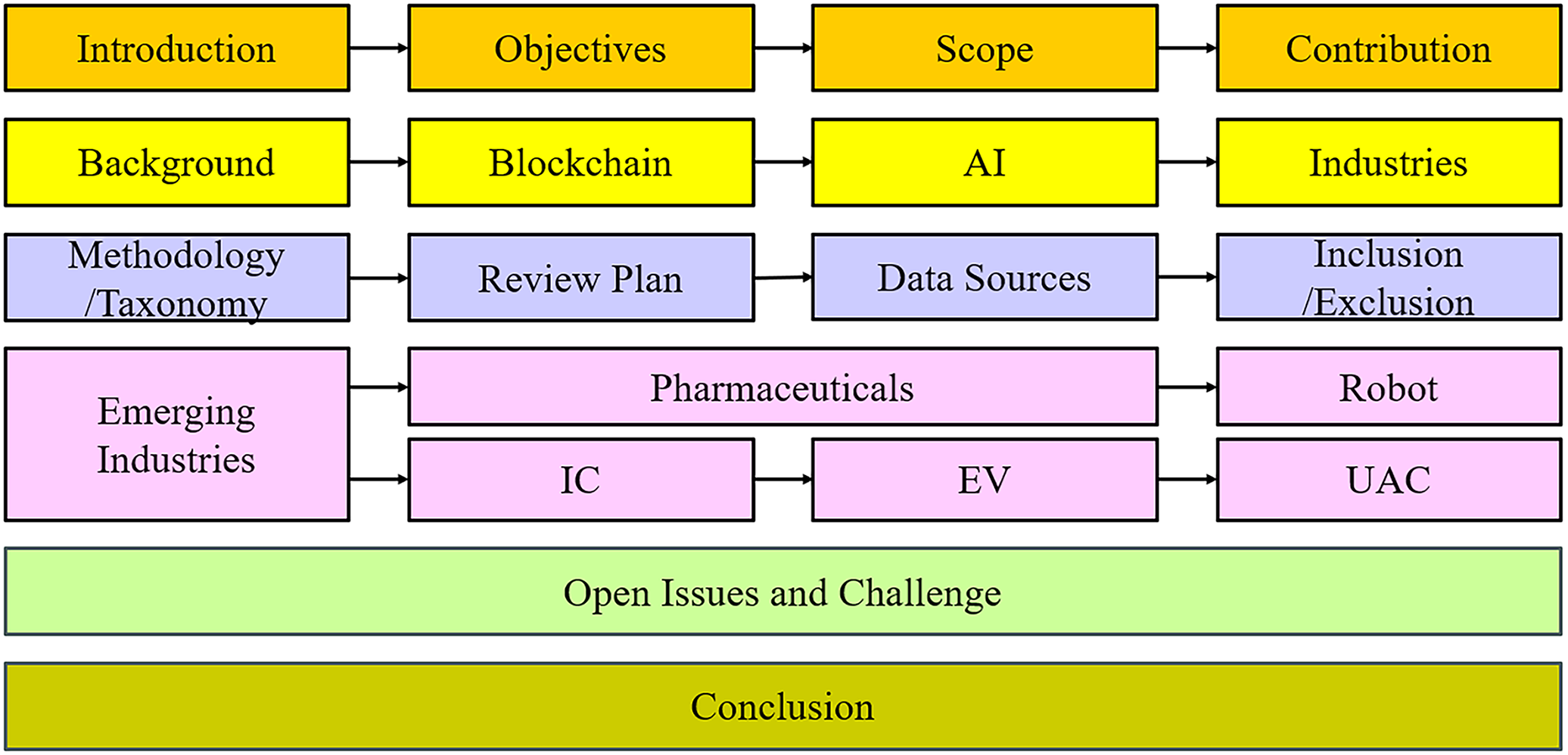

The supply chains of these industries are inherently complex and globally distributed, presenting significant challenges in the identification and traceability of the origin of material. Addressing these issues increasingly relies on the adoption of emerging technologies, particularly blockchain and AI. In recent years, the integration of AI and blockchain in supply chain management has expanded considerably. AI contributes to a wide range of operational improvements, including forecasting market demand, inventory and warehouse optimization, transportation and logistics efficiency, risk analysis of disruptions, anomaly detection, and intelligent procurement. In parallel, blockchain technology—characterized by its decentralized architecture and immutability—ensures the authenticity and integrity of provenance data, while facilitating the automated execution of smart contracts and inter-node protocols across distributed systems. Therefore, the integration of AI and blockchain technologies into key sectors—such as ICs, pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and robotics—can substantially strengthen the control and verification of product provenance. Similarly, country-of-origin fraud is considered a criminal offense under both criminal and tax legislation, and has been subject to increasingly stringent legal penalties and enforcement measures in many jurisdictions. As a result, the role of forensic technologies in supporting legal investigations and evidence collection has gained increasing importance. Among these sectors, ICs—given their central role in the electronics industry and their critical implications for information security—have become a primary focus of traceability enforcement and serve as vital media for recording provenance evidence through forensic methodologies. In light of these developments, the objectives of this study are as follows (see Table 1 below):

(a) Conduct a systematic review of the literature on the current applications of AI and blockchain technologies in supply chain management and product provenance traceability, with a particular focus on high-risk and high-sensitivity industries such as ICs, pharmaceuticals, electric vehicles, UAVs, and robotics.

(b) Examine traceability control mechanisms for ICs and explore how forensic technologies can be used to record provenance evidence and detect country-of-origin fraud.

This study synthesizes existing academic research by describing technological architectures, key application domains, and the prevailing research trends. In addition, it evaluates the practical effectiveness and challenges of these technologies in enhancing supply chain transparency, preventing origin-related fraud, improving security resilience, and preserving legal forensic evidence. The goal is to provide an integrated knowledge base and practice-oriented recommendations to support future research and policy development.

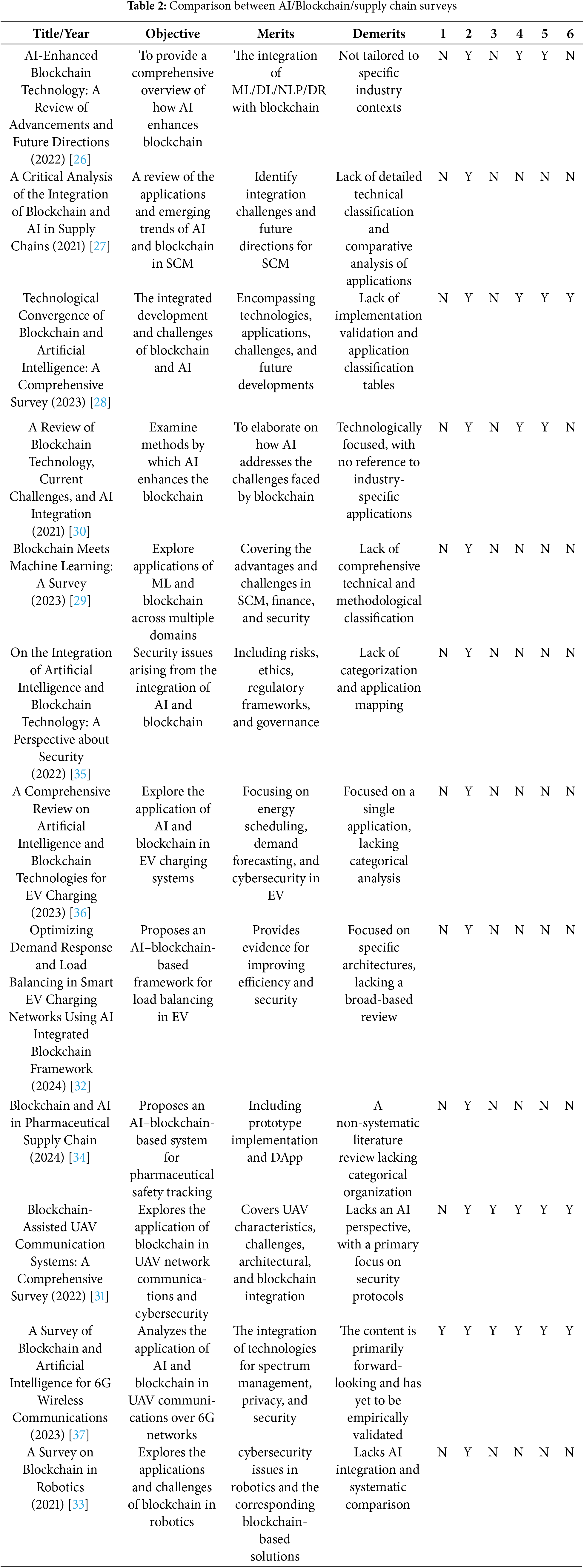

In recent years, the integrated application of AI and blockchain has attracted growing academic interest, with supply chain management emerging as a particularly critical domain. This technological convergence addresses multiple core challenges, including data transparency, product traceability, transactional trust, security, and regulatory compliance. The existing literatures have thoroughly examined the architectural models and potential benefits of AI–blockchain integration (see Table 2 below). For example, studies such as [26,27] provide systematic reviews of how these technologies enhance security, intelligent decision-making, and operational transparency. Nevertheless, much of the current research remains confined to single-industry contexts or narrowly focused technical perspectives. Some studies emphasize how AI can improve blockchain efficiency—through improvements in consensus mechanisms or data privacy protection [28]—while others are limited to applications in specific sectors, such as healthcare and finance [29,30]. Despite increasing scholarly interest in AI and blockchain technologies, there still have a notable lack of comprehensive review studies that address their integrated application within the supply chains of five geopolitically sensitive and security-critical industries: ICs, pharmaceuticals, electronic vehicles, UAVs, and robotics. Specifically, current literatures have not offered a consolidated overview of how these technologies can be used to enhance data reliability, provenance traceability, anomaly detection, and access control in these high-risk sectors. In addition, the role of forensic technologies in detecting and preventing country-of-origin fraud has received insufficient academic attention.

Taking UAVs as an example, prior research, such as Ref. [31], has conducted in-depth analyses on the application of blockchain in drone communications and cybersecurity. In the context of EVs, Ref. [32] explores the integration of AI and blockchain for charging optimization and energy distribution. The study [33] investigates the use of blockchain to improve security and transparency within the robotics supply chain. In the pharmaceutical sector, Ref. [34] examines the challenges and potential of applying these technologies to combat counterfeit drugs and ensure traceability. Building on these efforts, this study aims to comprehensively review and synthesize academic research on the integration of AI and blockchain in the supply chains of five geopolitically sensitive and security-critical industries: ICs, pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and robotics. Particular attention paid to the technological integration methods, representative application scenarios, and the challenges encountered in real-world implementations. In doing so, this study addresses current gaps in the literature concerning cross-sectoral applications, systematic knowledge consolidation, supply chain traceability, cybersecurity, and forensic verification. The purpose of this project is to provide a conceptual foundation for future academic research and to inform practical policy development.

Although numerous studies have conducted comprehensive reviews on the integration of AI and blockchain—highlighting their potential in supply chain security, privacy protection, and intelligent decision-making—most of the existing literature remains focused on individual technological aspects, individual industries, or specific data processing techniques. To date, there has been no holistic synthesis that addresses the application of AI and blockchain in supply chain traceability and legal forensics in high-sensitivity sectors such as ICs, pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and robotics. Consequently, the main contributions of this study are as follows.

(a) Consolidate the roles of AI and blockchain within the supply chains of ICs, pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and robotics. This study aims to establish a comprehensive, cross-sectoral research framework that addresses the fragmented and siloed nature of the existing literature.

(b) Identify the predominant integration models and critical applications of AI and blockchain in these industries. Prior studies are systematically categorized according to their application domains, core technological architectures (e.g., smart contracts, federated learning, private blockchains), and functional objectives (e.g., provenance traceability, criminal forensics, information transparency, anomaly detection, and privacy protection).

(c) Propose future research directions and key challenges for the integrated application of AI and blockchain in high-risk supply chains. This study also critically examines the methodological, practical, and structural limitations identified in representative works—for example, the lack of longitudinal traceability in high-risk supply networks or the absence of industry-specific integration strategies, as observed in [31,33,34].

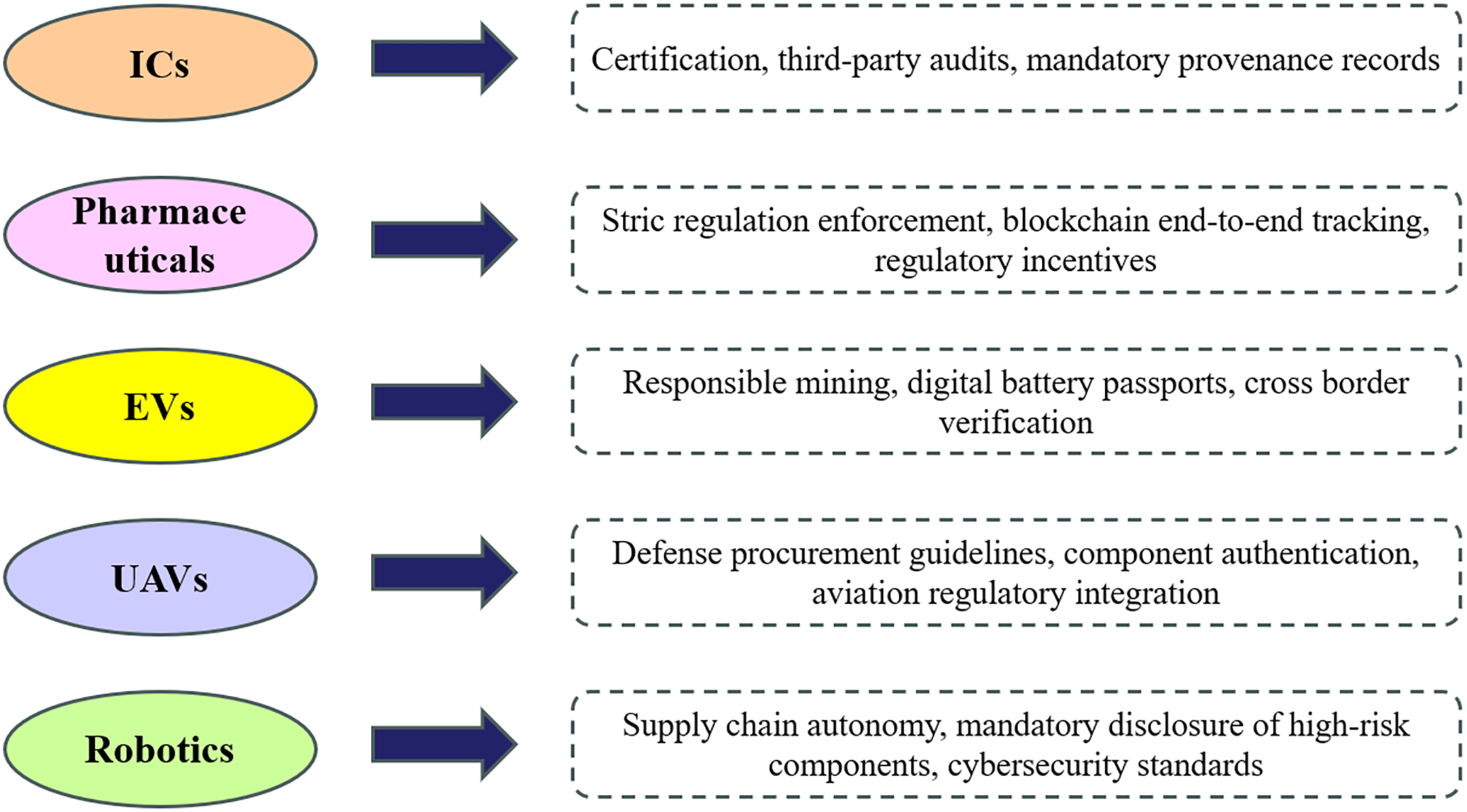

For policy implications, beyond its academic contributions, this study also carries several important policy implications for industries, regulators, and governments. First, the five sectors examined in this review—ICs, pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and robotics—share common vulnerabilities in origin opacity, which can result in national security risks, counterfeit circulation, and reduced trust in global value chains. Policymakers should therefore prioritize the establishment of standardized provenance frameworks that enable transparent, interoperable, and verifiable records of component origins. Second, regulatory authorities such as the FDA, EU Commission, and civil aviation agencies must consider adopting blockchain-based provenance models (e.g., drug traceability under DSCSA or EV “battery passports”) as enforceable compliance tools, ensuring that traceability requirements are consistently met across jurisdictions. Third, governments should encourage cross-industry collaboration in setting data standards, since heterogeneous supply chains often face fragmented reporting practices and inconsistent provenance requirements. Finally, by embedding AI-driven anomaly detection and blockchain-enabled forensic verification into legal frameworks, states can strengthen their ability to deter illicit practices such as origin fraud, adversarial component insertion, and counterfeit drug distribution. These policy insights underscore that AI–blockchain integration is not only a technical solution but also a regulatory enabler, with direct relevance to national security, public health, and industrial resilience.

1.3 Organization and Reading Map

The structure of this study and the organization of the remaining sections are as follows (see Fig. 3 below):

Figure 3: Structure and organization of this study

Section 2 reviews the background of AI and blockchain applications in supply chain management, and of 5 security-critical industries: ICs, pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and robotics to provide a technical overview and outline the key challenges facing each sector.

Section 3 describes the research methodology used in this study, which is grounded in a Systematic Literature Review (abbreviated as SLR). This section details the database search procedures, Boolean query formulations, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the classification dimensions and processing workflow used for analysis.

Section 4 synthesizes the current academic literature on AI and blockchain integration in the supply chains of the aforementioned industries, highlighting development trends and representative applications in various domains.

Section 5 discusses unresolved research issues and practical barriers identified in the existing literature, and proposes potential future research directions and development strategies.

Section 6 concludes the study by summarizing its key contributions and emphasizing the academic and practical implications of integrating AI and blockchain in the supply chains of high-sensitivity industries.

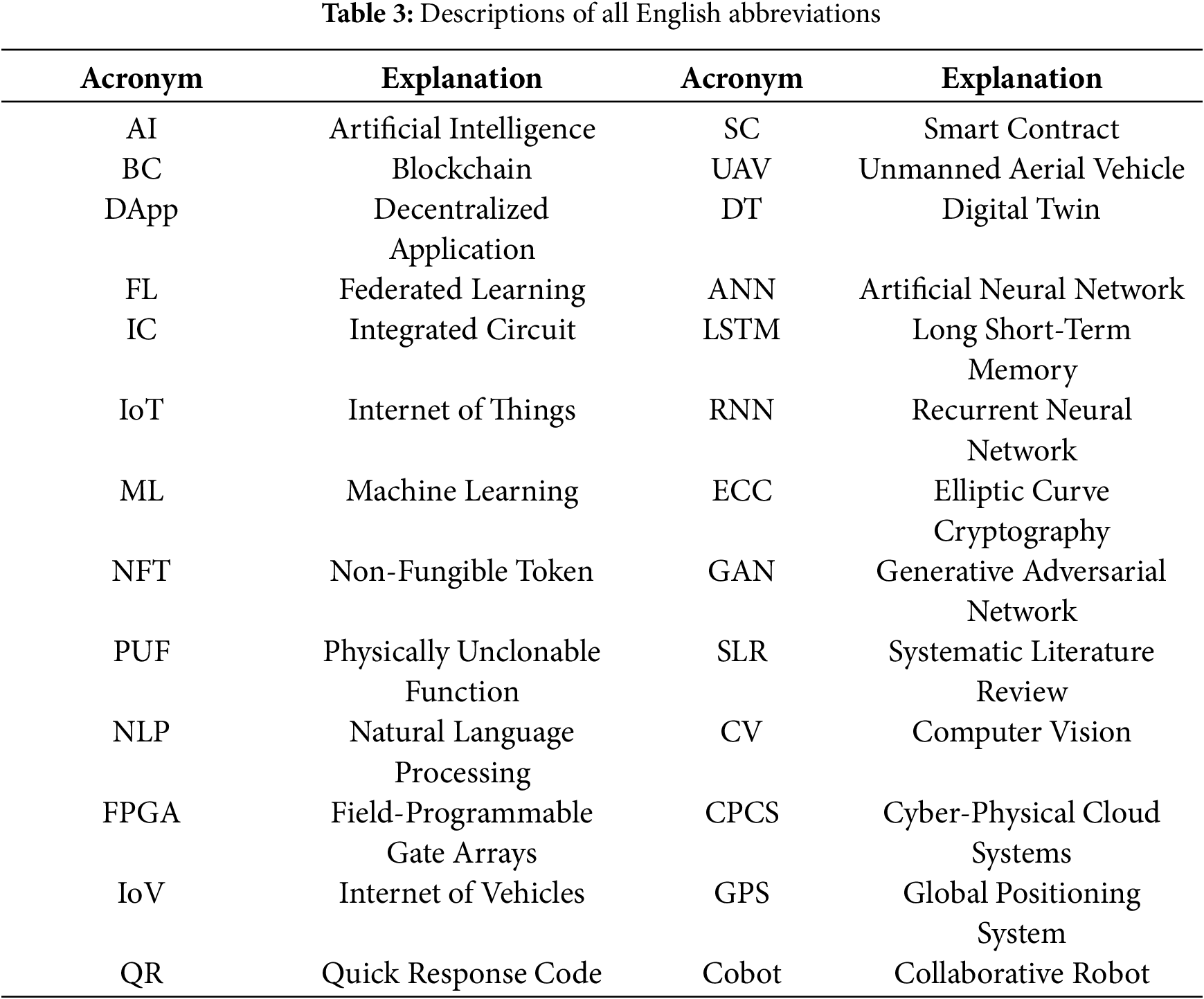

The primary abbreviations used in this study and their corresponding meanings are summarized in Table 3 (see Table 3 below).

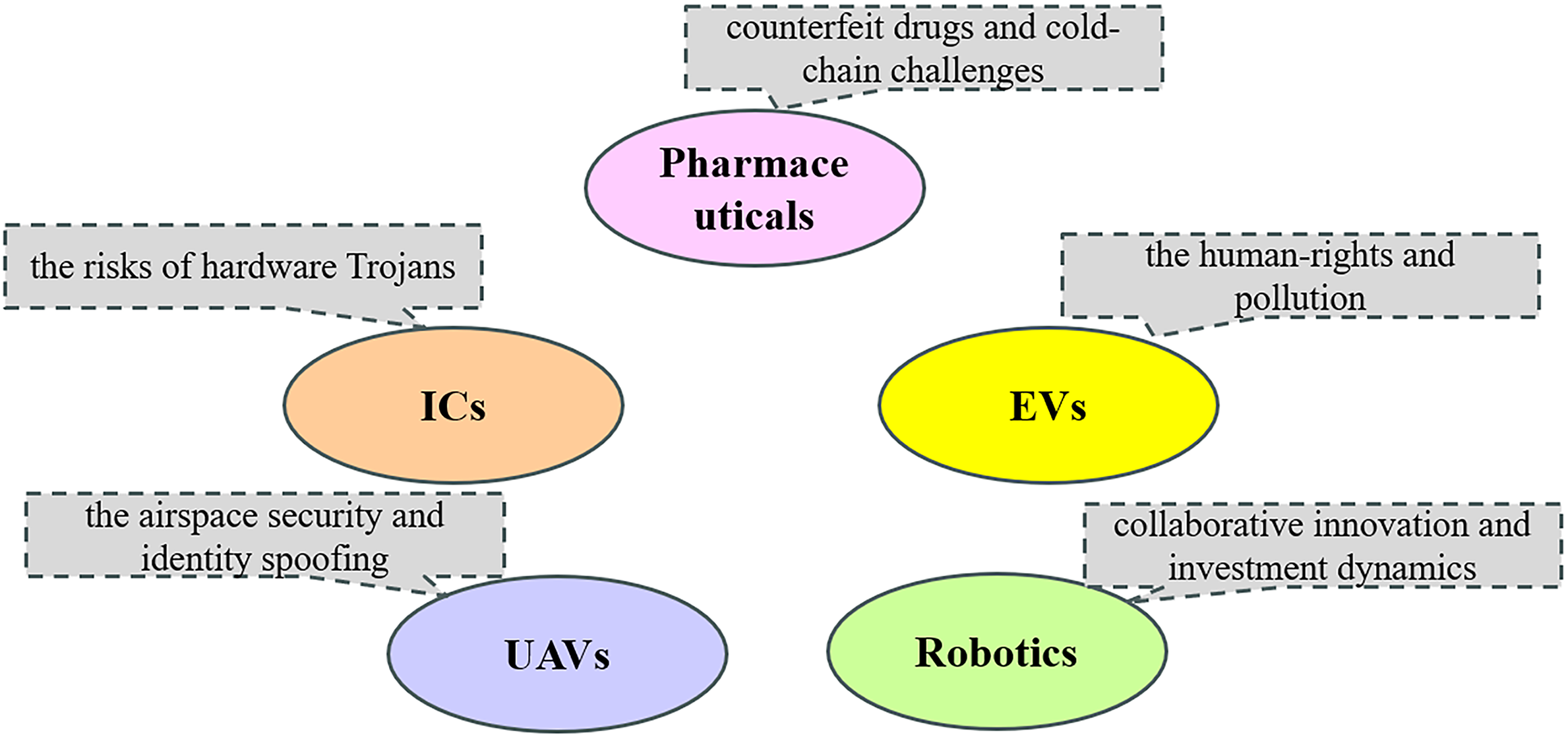

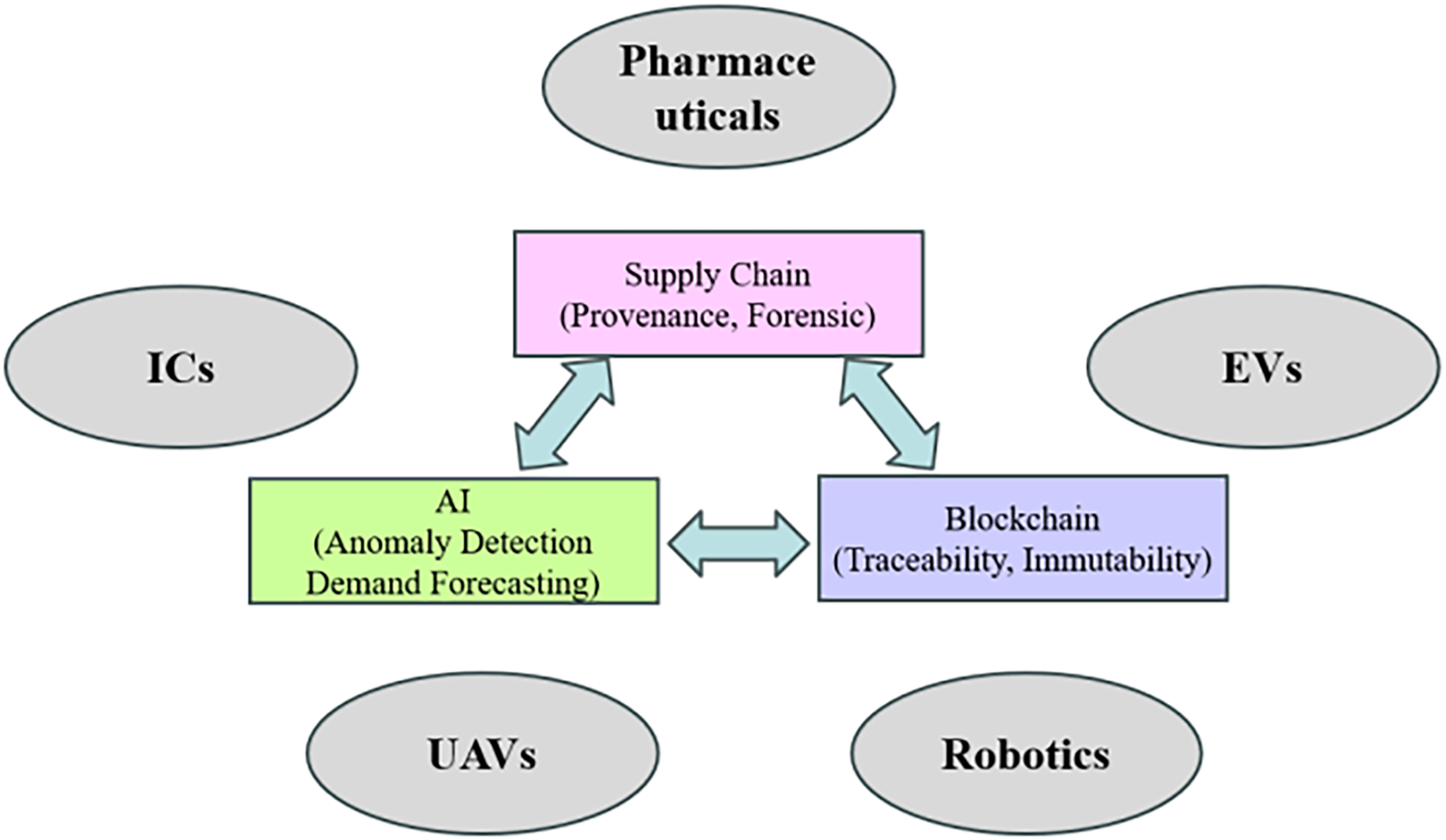

This section explores the background of blockchain and AI applications in supply chain management and outlines the development landscape of key sectors—ICs, pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and robotics—as foundational knowledge for this study (see Fig. 4 below).

Figure 4: Sector-specific challenges in supply chain traceability

2.1 Blockchain and Supply Chain

Blockchain is a decentralized and distributed ledger technology initially introduced by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008 [38] to address the trust and anti-counterfeiting challenges associated with Bitcoin. Data immutability is typically guaranteed through cryptographic mechanisms and facilitate consensus among network participants using algorithms such as Proof of Work, Proof of Stake, and Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance. Although blockchain was originally developed for applications in cryptocurrency, the advancement of smart contracts has significantly broadened its utility. Today, blockchain is increasingly adopted in various diverse sectors, including financial technology, supply chain management, healthcare information systems, and smart manufacturing [39].

In supply chain applications, blockchain offers key advantages such as enhanced transparency, traceability, and non-repudiation. Notable implementations include IBM Food Trust and Walmart’s blockchain-based supply chain tracking systems, which leverage blockchain to enable data integration between companies and source verification. Practical benefits have been realized in areas such as logistics tracking, digital certification, provenance verification of critical products (e.g., diamonds, cocoa, pharmaceuticals), and legal forensics. Meanwhile, blockchain can be integrated with IoT and decentralized storage systems, such as the Inter Planetary File System (abbreviated as IPFS), to strengthen the integrity and credibility of preserved forensic evidence [39].

AI, encompassing machine learning (abbreviated as ML), deep learning (abbreviated as DL), natural language processing (abbreviated as NLP), and computer vision (abbreviated as CV), has been widely adopted in supply chain management for a range of functions, including demand forecasting, intelligent scheduling, route optimization, warehouse management, and anomaly detection. Using historical data for predictive modeling, AI enables enterprises to assess supply risks, analyze demand–supply dynamics, and anticipate future trends—thereby facilitating dynamic adjustments to inventory levels and resource allocation [40]. In advancing supply chain transparency, AI can be combined with sensor data and edge computing to support real-time monitoring of production processes and logistics operations. AI-driven analytics can also identify anomalous supplier behavior, detect fraudulent activities or information obfuscation, and assist in developing risk mitigation strategies. In addition, recent research has introduced Explainable AI (XAI) to enhance the interpretability and trustworthiness of AI-based decisions, particularly in highly regulated environments such as healthcare and finance [41].

ICs are foundational components of modern electronic systems and critical infrastructure, with extensive applications spanning the communications, computing, autonomous vehicles, aerospace, and defense sectors. Due to their strategic importance and high sensitivity, ICs are indeed critical for national security and economic competitiveness. However, global fragmentation of IC design and manufacturing introduces a spectrum of security vulnerabilities [42]:

(a) Complex supply chain structure: The IC supply chain involves multi-national collaboration across several stages—including front-end design, wafer fabrication, packaging, testing, and system integration. Each stage may involve different vendors, and the lack of verifiable mechanisms at any point may expose the system to exploitation.

(b) Risk of hardware Trojans: Malicious actors can be embedded in circuits during design or manufacturing processes, which, when triggered under specific conditions, can cause data breaches, system failures, or unauthorized access. These hardware Trojans are notoriously difficult to detect using conventional testing methods, posing severe threats to high-security domains such as defense, finance, and healthcare.

(c) Challenges in provenance verification and counterfeit detection: Due to the geographically dispersed nature of IC production, issues such as counterfeiting, tampering, and “country-of-origin laundering” are widespread. Addressing these challenges requires robust forensic technologies capable of tracing chip origins and authenticating complete supply histories.

To counter these risks, both academia and industry have invested in a range of countermeasures, including Physical Unclonable Functions (abbreviated as PUF), chip fingerprinting, blockchain-based provenance tracking, and AI-assisted forensic analysis. Collectively, these approaches aim to establish a secure and trustworthy IC supply chain infrastructure that ensures verifiability, resilience, and forensic accountability.

The pharmaceutical supply chain is inherently complex and encompasses multiple stages that include raw material procurement, manufacturing, storage, transportation, and distribution. Each stage is subject to stringent regulatory and quality requirements. The industry currently faces several critical challenges [8,9]:

(a) Counterfeit pharmaceuticals: According to the World Health Organization (abbreviated as WHO), more than 10% of medicines distributed globally are counterfeit, with prevalence even higher in developing countries. These counterfeit drugs may contain incorrect dosages, inactive substances, or harmful ingredients, posing severe risks to public health [10].

(b) Cold chain logistics management: Many pharmaceuticals—particularly vaccines and biologics—are highly sensitive to temperature fluctuations. They must be transported and stored within tightly controlled thermal ranges. Any deviation can compromise drug efficacy, resulting in financial losses and heightened patient safety concerns.

(c) Supply disruptions and drug shortages: Globalization of pharmaceutical production has led to increased dependency on specific geographic regions, particularly for active pharmaceutical ingredients, which are often concentrated in a small number of supplier countries. Geopolitical tensions, natural disasters, and pandemics can rapidly disrupt supply continuity, leading to widespread shortages [12].

To mitigate these challenges, the industry is increasingly investing in advanced logistics management systems, enhancing supply chain transparency, and diversifying sourcing strategies. These efforts aim not only to improve operational resilience but also to safeguard regulatory compliance and protect public health on a global scale.

The EV industry has witnessed rapid growth in recent years. According to the International Energy Agency, global EV sales are projected to reach 17 million units by 2025, representing more than 20 percent of new vehicle sales [43]. Key trends driving this expansion include the following.

(a) Sustained market growth: The EV market is expected to increase from USD 396.49 billion in 2024 to USD 620.33 billion by 2030, with a compound annual growth rate of approximately 7.7 percent [3].

(b) Cost reduction and technological advancement: Improvements in technology and economies of scale are reducing EV production costs and enhancing affordability. At the same time, advances in driving range, charging speed, and intelligent features are expanding the consumer base.

(c) Policy support and infrastructure development: Governments around the world are promoting the adoption of EV through subsidies, tax incentives, and investments in charging infrastructure, further accelerating market momentum.

This rapid industry transformation is reshaping the automotive sector and has profound implications for energy systems, environmental protection, and urban planning.

UAVs have found widespread application in diverse sectors, demonstrating exceptional flexibility and operational efficiency [44]:

(a) Agricultural management: UAVs enable crop health monitoring, pesticide/fertilizer application, and precision agriculture—contributing to increased yields and optimized resource use.

(b) Infrastructure inspection: UAVs routinely inspect critical infrastructure—such as transmission lines, bridges, and wind turbines—providing high-resolution imagery while reducing labor demands and enhancing safety.

(c) Disaster response: In the event of natural disasters like earthquakes and floods, UAVs can quickly surveys affected areas, assist in search-and-rescue operations, and enhance situational awareness.

(d) Environmental protection: UAVs support air quality monitoring, wildlife population surveys, and early detection of forest fires, providing accurate and real-time environmental data.

(e) Logistics and delivery: UAVs are increasingly being tested and deployed for delivering medical supplies, e-commerce packages, and other small payloads, especially in remote or hard-to-reach regions.

As regulatory frameworks mature and technological advancements—particularly in AI and blockchain—continue to evolve, the potential application domains of UAVs are expected to grow substantially.

Robotic technologies are rapidly advancing and being increasingly adopted in industries such as manufacturing, logistics, and healthcare, positioning them as a fundamental element of Industry 4.0 and automation efforts [45]:

(a) Collaborative robots: Engineered to work alongside humans, collaborative robots enhance productivity and flexibility—particularly in manufacturing environments with diverse task requirements.

(b) Humanoid robots: With human-like form and movement, these robots excel in applications requiring adaptability and nuanced interaction, such as caregiving and service roles.

(c) Specialized robots: Designed for specific functions, including security, firefighting, sanitation, and surveillance patrols.

(d) Market growth and investment: In the first quarter of 2025, the global robotics sector attracted more than USD 2.26 billion in investment, underscoring strong market interest and high expectations for innovation [46].

With ongoing advancements in AI, sensor technologies, and materials science, robotics is poised to assume an increasingly central role across diverse domains—ultimately becoming a cornerstone of future intelligent and autonomous societies.

3 Survey Methodologies and Taxonomy

This study employs a SLR methodology [47] to investigate the application of AI and blockchain in provenance traceability and forensic verification across the supply chains of ICs, pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and robotics. The methodological framework comprises data sources, keywords/Boolean logic, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and classification methods.

The data sources of this survey include:

(a) IEEE Xplore

(b) ScienceDirect

(c) SpringerLink

(d) ACM Digital Library

(e) Web of Science

(f) arXiv

3.2 Keywords and Boolean Logic

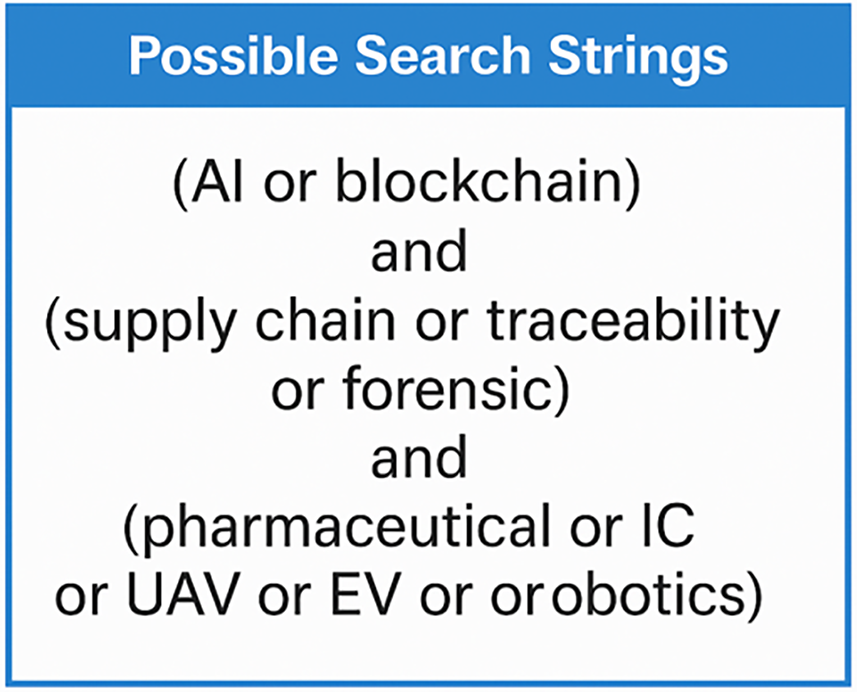

To comprehensively map the academic research landscape related to the use of AI and blockchain for provenance traceability and forensic verification within the supply chains of ICs, pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and robotics, this study employed compound Boolean search queries. The search strategy targeted key themes—such as supply chain traceability, origin authentication, source credibility, risk detection, and intelligent management—through combined keyword logic (see Fig. 5 below):

Figure 5: The compound Boolean logic queries employed in this study for literature retrieval

(a) IC: (“blockchain” or “artificial intelligence”) and (“supply chain” or “traceability” or “forensic”) and “IC or semiconductor”

(b) Pharmaceuticals: (“blockchain” or “artificial intelligence”) and (“supply chain” or “traceability” or “forensic”) and “pharmaceutical”

(c) EV: (“blockchain” or “artificial intelligence”) and (“supply chain” or “traceability” or “forensic”) and (“electric vehicle” or “EV”)

(d) UAV: (“blockchain” or “artificial intelligence”) and (“supply chain” or “traceability” or “forensic”) and (“UAV” or “drone”)

(e) Robotics: (“blockchain” or “artificial intelligence”) and (“supply chain” or “traceability” or “forensic”) and “robotics”

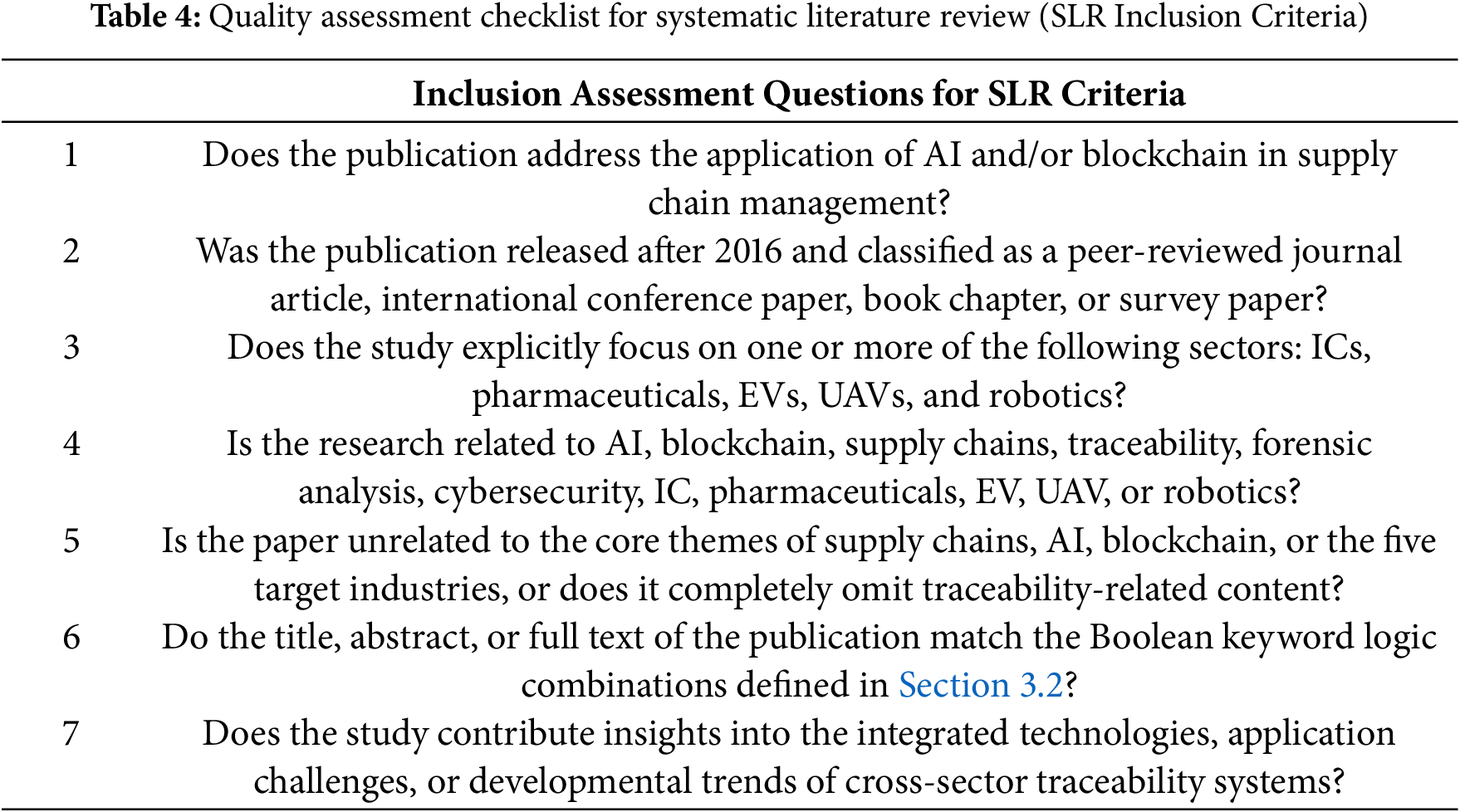

3.3 Criteria of Inclusion and Exclusion

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the literature reviewed in this study are defined as follows.

(a) Inclusion criteria: peer-reviewed journal articles, international conference papers, book chapters, and survey/review studies published from 2016 downwards. In addition, the works address the application of AI and/or blockchain in supply chain management or forensic verification and focus on IC, pharmaceuticals, EV, UAV, or robotics.

(b) Exclusion criteria: publications that are unrelated to AI, blockchain, the specified industrial sectors (ICs, pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and robotics), supply chain processes, or forensic applications were omitted from the review.

3.4 Data Processing and Classification Methods

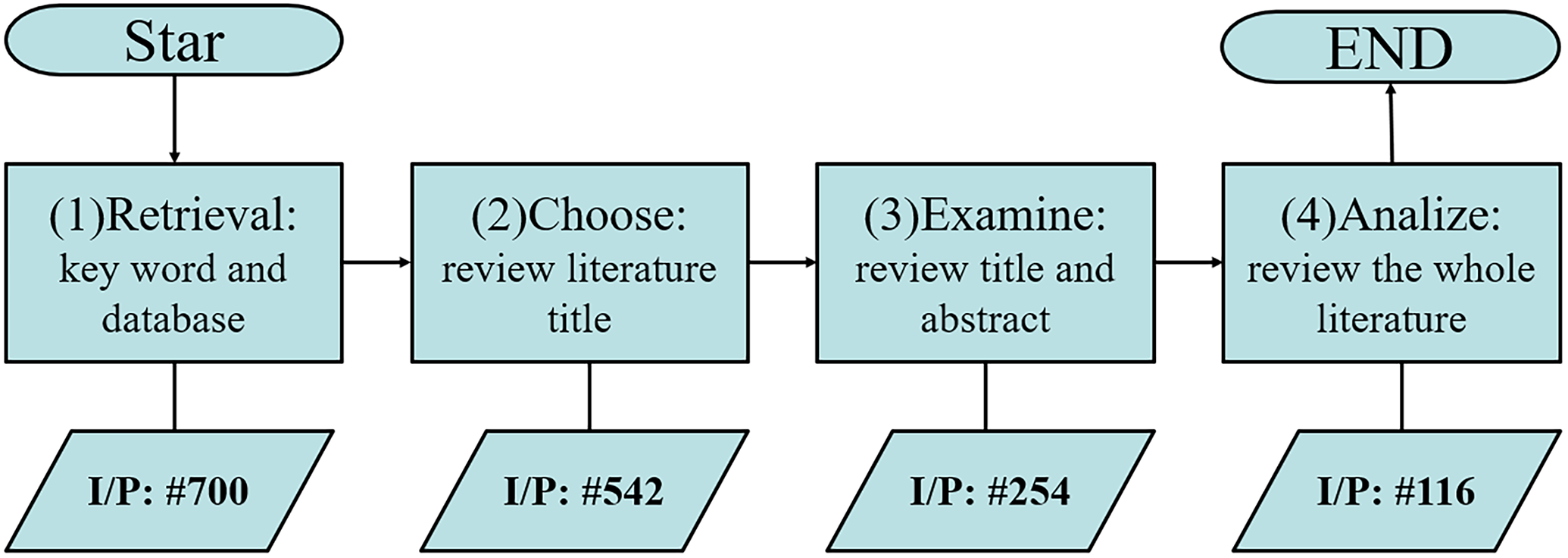

This study adopts a topic-oriented literature review to examine AI and blockchain applications for provenance traceability and forensic verification within the supply chains of ICs, pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and robotics. We sourced literature from six major databases—IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, ACM Digital Library, Web of Science, and arXiv—using compound Boolean keyword searches. The retrieved records were then filtered through a four-step screening process (see Fig. 6 below):

Figure 6: The Process and Criteria of inclusion and exclusion for the literatures of Survey Papers

(a) Initial Retrieval: Keyword searches across all databases yielded 700 records.

(b) Title Selection: Title review narrowed the data set to 542 potentially relevant studies.

(c) Abstract Selection: Abstract reviews excluded low-relevance items, reducing the pool to 254 articles.

(d) Full-Text Analysis: Detailed examination of abstracts, conclusions, and relevant sections resulted in a final sample of 116 studies for in-depth analysis.

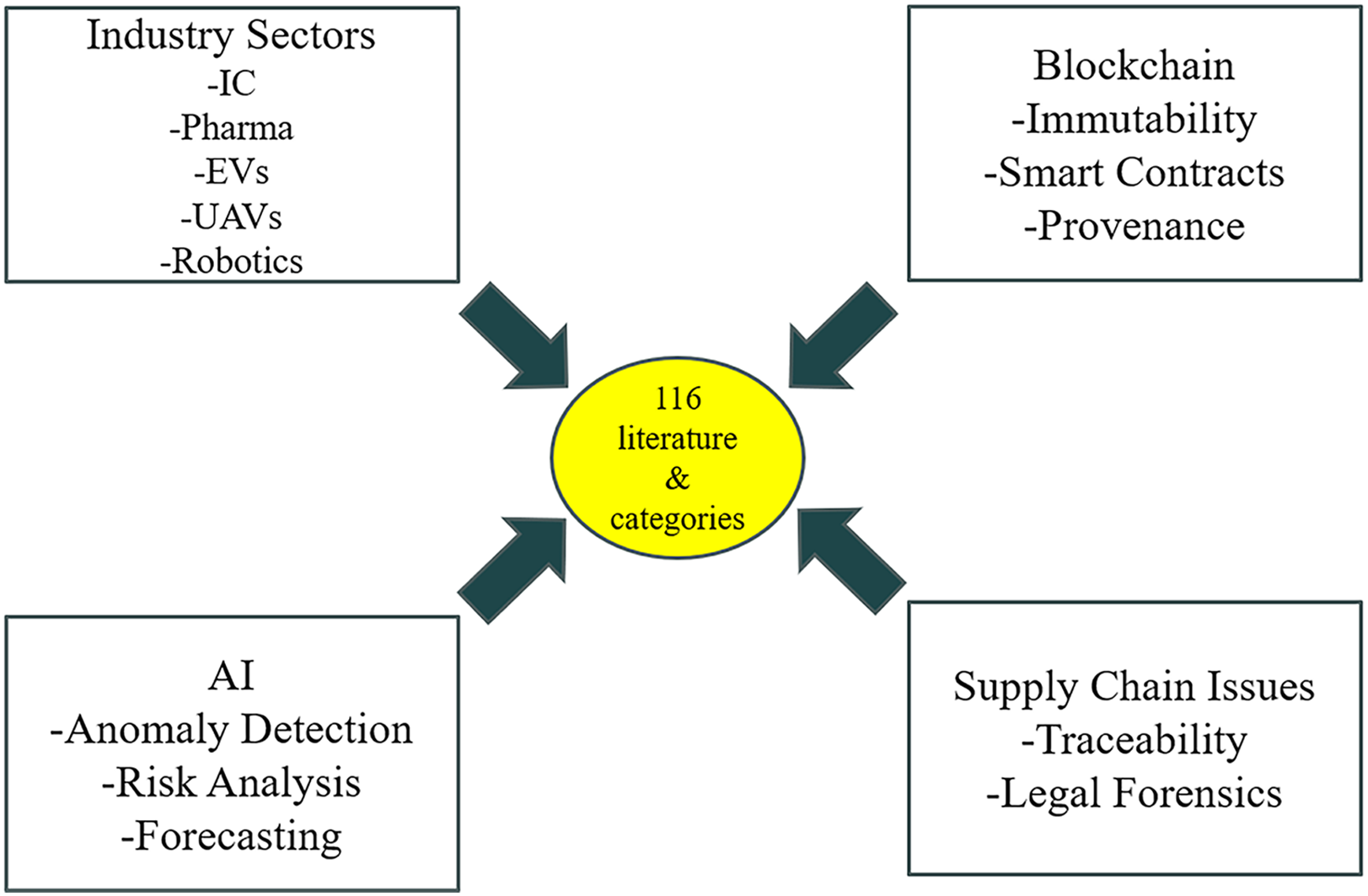

For clarity and reproducibility, Fig. 7 below presents a baseline schematic diagram summarizing the overall data-processing workflow of this study. It captures the progression from literature retrieval and screening to thematic classification and synthesis, complementing the detailed selection process already shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 7: High-level schematic diagram for how the 116 studies be selected and categorized

Although this study does not employ systematic bibliographic analysis, representativeness and relevance are maintained through manual selection and thematic selection (see Table 4 below). A final set of 116 academically significant and application-oriented publications was selected (refer to Section 4), and their content was synthesized to delineate the current landscape of AI and blockchain applications. The selected studies were categorized along three analytical dimensions:

(a) Application Domain: Industry-specific contexts, including ICs, pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and robotics.

(b) Core Technology: AI models (e.g., machine learning, deep learning, and federated learning) and blockchain architectures (e.g., private chains, consortium chains, IPFS, and smart contracts).

(c) Functional Objective: Targeted outcomes such as supply chain provenance traceability, legal forensic applications, cybersecurity protection, and risk detection.

In addition, to highlight the novelty of this study’s methodological framework, we emphasize that the classification scheme goes beyond conventional survey structures by introducing a three-dimensional taxonomy that integrates:

(a) Industry-specific contexts (cross-sector comparison across ICs, pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and robotics);

(b) Core technological layers (AI models and blockchain frameworks);

(c) Functional objectives (traceability, forensic verification, cybersecurity, and risk detection).

This multi-dimensional classification and cross-sector integration, combined with a forensic perspective, differentiates our review from existing surveys and provides a unique contribution to the literature.

4 Blockchain and AI Applications for Provenance Traceability

Geopolitical tensions and trade disputes have increased the importance of traceability of the supply chain. Sensitive electronic products can be hijacked by adversaries during crises for offensive purposes or become national vulnerabilities due to shortages during conflicts [48,49]. In response, the United States has enhanced efforts to combat illegal practices such as country-of-origin laundering, with particular focus on high risk categories including ICs, pharmaceuticals, EVs, UAVs, and robotics. To mitigate long-term security vulnerabilities and prevent tax evasion through falsified origins, deploying technologies such as AI and blockchain is essential to enable provenance tracking and preserve forensic evidence across supply chains (see Fig. 8 below). These technologies not only improve operational efficiency, but also align with national security objectives. Similar efforts are being observed in regions such as the European Union and Japan. The following subsections review current research developments and applications in each of these domains.

Figure 8: AI + blockchain synergy for supply chain traceability & forensics

4.1 Blockchain, AI, and Supply Chain

Blockchain—a form of decentralized Distributed Ledger Technology—provides immutable, traceable, and tamper resistant record keeping, and has been widely implemented in areas such as supply chain management, IoTs, edge computing, pharmaceutical traceability, communication security, digital identity verification, and legal forensics and evidence preservation [39]. Beyond using cryptographic mechanisms and consensus algorithms to ensure data accuracy, integrity, and transparency, blockchain leverages smart contracts—self executing agreements embedded in the ledger—to automate operations upon predefined conditions, thereby reducing intermediary costs and minimizing human intervention. This makes blockchain a key technology for building a highly trustworthy digital infrastructure [50].

AI refers to the collective set of technologies that emulate human cognitive behaviors, encompassing ML, DL, NLP, and CV. Trained in large datasets, AI models possess capabilities in classification, recognition, predictive analytics, and automated decision-making. These models are widely applied in various domains—including voice assistants, medical diagnostics, financial, intelligent manufacturing, and smart city—acting as the main drivers of digital transformation and smart infrastructure development [40].

AI is driving digital transformation across industries, and its integration with blockchain technology can enhance system autonomy, trustworthiness, and efficiency [41]. Blockchain offers traceability and anti-counterfeiting to log transactions and promote transparency; however, traditional consensus mechanisms can suffer from inefficiencies. To address this, Ref. [51] introduced a Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy cognitive map–artificial neural network as the inference core of a Traceability Chain Algorithm, significantly accelerating traceability decision-making. In addition, Refs. [52,53] demonstrated that adopting the blockchain Proof of Relationship algorithm as an activation function within neural network models substantially enhances AI’s ability to detect maliciously distorted supply-chain information. Moreover, Ref. [54] used ML for inventory allocation in cloud-based supply-chain frameworks, and empirical results show 13%–16% improvement in allocation accuracy over conventional methods. Except the examples noted earlier, further scholarly research and applied studies support the synergistic potential of blockchain and AI [41], including:

(a) For EV smart-charging networks, blockchain enables decentralized energy trading, reducing operational costs and enhancing trust among stakeholders [36].

(b) In intelligent vehicular networks, by leveraging blockchain’s immutability and anonymization properties, data security is maintained, fostering trustworthy interactions among vehicles, users, and service providers [55].

(c) For supply chain management, blockchain mitigates the asymmetry between the upstream and downstream information asymmetry information, and AI facilitates predictive analytics of sales data to support automated decision-making [27].

(d) In the healthcare and pharmaceutical fields, blockchain ensures drug safety and traceability, and AI uncovers latent informational patterns to support drug-related decision-making [34].

In summary, prior studies provide a foundation on the roles of blockchain and AI across supply chain–related domains. Blockchain has been shown to ensure immutability, traceability, and trust through decentralized architectures, while AI contributes predictive analytics, anomaly detection, and decision support across diverse applications. Building on this groundwork, the following section turns specifically to their applications in supply chain traceability.

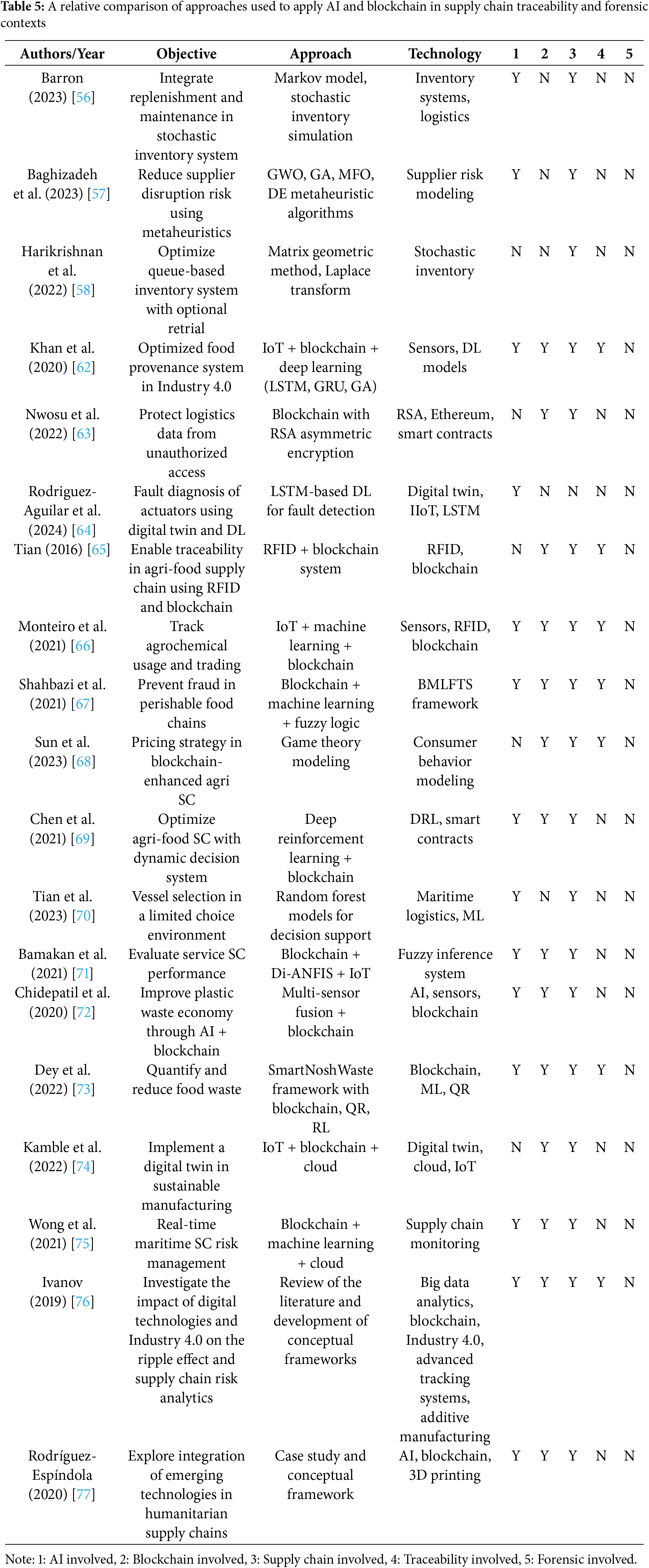

4.1.2 Blockchain and AI for Supply Chain Traceability

The traceability and transparency of inventory and components have long been critical research topics in supply chain management (see Table 5 below). For example, Ref. [56] investigates warehouse allocation in a dual-warehouse inventory system. Using Markov processes and stochastic arrival models, the study captures real-world demand fluctuations. This dynamic analysis improves forecasting and responsiveness, and integrates replenishment decisions with maintenance services to reduce resource waste. In addition, Ref. [57] examines the management of spare inventory management under supplier disruptions by employing four metaheuristic algorithms—Grey Wolf Optimizer, Genetic Algorithm, Moth Flame Optimization, and Differential Evolution—to identify inventory strategies that minimize total cost. The study suggests that incorporating alternative supply sources can effectively mitigate stockout risks. Additionally, Ref. [58] addresses variability in demand and inventory levels by applying optimization methods based on the Neuts’ matrix-geometric approach and Laplace transforms. Performance is evaluated using key inventory metrics such as the average inventory level, repurchase rate, and the service waiting time.

In recent years, increasing social concerns about health, environmental sustainability, human rights, and safety have driven the adoption of emerging technologies—particularly AI and blockchain—in supply chain management. These technologies are being leveraged to enhance component traceability and legal forensics, especially in high-sensitivity industries including the following:

(a) As the foundational components of all electronic devices, ICs represent a major security vulnerability if embedded with malicious code capable of seizing control during critical operations—an issue with heightened significance amid geopolitical tensions. For instance, the Spanish cybersecurity firm Tarlogic Security reported that Chinese-manufactured ESP32 chips contain undocumented hidden instructions that may serve as backdoors, potentially allowing remote control over millions of IoT devices [7].

(b) Counterfeit medications were responsible for over 110,000 deaths in the United States alone in 2023 [8], and globally, they contribute to an estimated 1 million deaths annually [9]. In developing countries, one out of every ten medicines are either counterfeit or substandard [10], and up to 30% of pharmaceuticals in regions such as Africa, Asia, and Latin America fail to meet regulatory standards [11]. In response, numerous governments have introduced pharmaceutical traceability regulations to strengthen supply chain transparency [13–15], mandating full end-to-end electronic tracking capabilities within pharmaceutical distribution systems [16].

(c) Geopolitical conflicts have revealed critical vulnerabilities in global component supply chains, resulting in disruptions in automotive manufacturing activities [17] and posing potential threats to national security. In particular, EV may be exposed to adversarial control, enabling malicious surveillance or attacks. This has raised significant concerns over the transparency and stability of component sourcing. Batteries are the most critical components for EV. However, the extraction and supply of battery raw materials have been repeatedly associated with violations of human rights and environmental degradation [18]. As a result, leading nations have enacted legislation requiring traceability and rigorous oversight of EV components and raw materials to combat fraudulent practices such as origin laundering [19–21].

(d) The Russia-Ukraine conflict has highlighted the strategic importance of UAVs, which are expected to play a central role in future warfare. However, if UAVs are compromised and remotely controlled by hostile states, they could be transformed into offensive weapons. Similarly, robots are now widely deployed in various supply chain environments. If these systems are embedded with backdoors and activated remotely, they could disable port logistics, sabotage factory production lines, damage healthcare infrastructure, or even target individuals. In response, countries such as the United States, the European Union, and Japan have introduced legislation to enhance the autonomy of the supply chain and cybersecurity of the robotics industry [22–25]. These regulations are broadly applicable to IoT devices as well.

In addition, food contamination not only poses serious public health risks, but also triggers regulatory mandates requiring end-to-end traceability across all participants in the supply chain [59,60]. When well-established brands experience food safety scandals, consumer trust can be profoundly undermined and may remain difficult to restore even after years of remediation efforts [61]. This erosion of confidence has become a major impetus for corporate investment in traceability technologies powered by AI and blockchain. In this context, Industry 4.0 has emerged as a transformative industrial paradigm that integrates smart manufacturing, digital technologies, and interconnected systems. Therefore, Ref. [62] proposes a traceability system for the food supply chain in the Industry 4.0 framework, integrating IoTs, blockchain, and Advanced DL. The system is built upon LSTM architecture, further enhanced through the incorporation of Gated Recurrent Units and Genetic Algorithms to improve prediction accuracy and model stability. And then Ref. [63] tackles the problem of unauthorized access to private customer data in multi-party sharing environments within Logistics 4.0, presenting a logistics management framework based on Ethereum blockchain and smart contracts. The system adopts RSA asymmetric encryption to ensure data confidentiality and system integrity, and demonstrates its effectiveness in safeguarding logistics processes and customer information against cyber threats. In addition, Ref. [64] investigates fault diagnosis in industrial equipment within the cloud-based IOT architectures of Industry 4.0 and 5.0. By employing an LSTM deep learning model, the study enhances the decision-making abilities of digital twins in identifying failure patterns and technical diagnostics, with the proposed approach validated through simulation and real-world datasets.

In the area of Radio Frequency Identification (abbreviated as RFID), Ref. [65] proposed a food supply chain traceability system that integrates RFID with blockchain to allow the collection and sharing of authentic data at all stages of the supply chain—from agricultural production to storage, distribution, and retail. The system improves food safety and transparency. Likewise, Ref. [66] integrated sensors, microcontrollers, RFID, ML, and blockchain to develop the Agrochemical Pervasive Traceability Model, which is designed to monitor the use, recycling, and trading of agrochemicals. This model addresses pesticide misuse, environmental pollution, and illegal distribution.

For agriculture, Ref. [67] proposed a food traceability system for perishable supply chains by integrating blockchain, ML, and fuzzy logic to prevent shelf-life manipulation and product data falsification. In addition, Ref. [68] applied game theory to investigate the factors influencing consumer preferences for traceability in fresh agricultural products. Then a pricing decision model was developed to help firms implement blockchain under competitive market conditions, enabling optimal pricing and profit maximization. Furthermore, Ref. [69] introduced a framework that combines blockchain with deep reinforcement learning to dynamically adjust agricultural goods production and storage in response to market demand and cost fluctuations, thus improving overall profitability.

In logistics and service, Ref. [70] examined the selection of vessels within logistics management. Faced with limited shipping options, the study used the Random Forest algorithm to develop multiple predictive models to optimize vessel selection strategies. The goal was to avoid potentially non-compliant ships and, in turn, enhance the efficiency of Port State Control inspections and improve maritime safety. In addition, Ref. [71] proposed a decentralized intelligent diagnostic and evaluation framework with integrating blockchain, neuro-fuzzy, and IoT. This framework supports performance assessment and forecasting within service supply chains, ultimately fostering greater transparency and trust among stakeholders.

For sustainability and circular economy, Ref. [72] developed a plastic classification system by integrating blockchain-based smart contracts with multi-sensor AI data fusion algorithms. The system supports the exchange of information between sorting facilities, recycling companies, and manufacturers, thus improving the transparency and precision of plastic waste classification. In addition, Ref. [73] introduced the SmartNoshWaste framework, which combines blockchain, cloud computing, QR code, and reinforcement learning to quantify food waste, resulting in a 9.46% reduction in food waste. To add further, Ref. [74] highlighted that the integration of IoT, cloud computing, and blockchain within a digital twin system—linking physical and virtual environments—can enable high-quality, rapid, and customized smart manufacturing supply chains across sectors. These innovations ultimately improve operational performance and contribute to broader sustainability objectives.

For disruption risk, Ref. [75] proposed an integrated architecture that combines blockchain, ML, and cloud computing to meet the increasing demand for immutable transaction records. The framework demonstrates real-time detection and decision-making capabilities in maritime risk management. In addition, Ref. [76] developed a supply chain risk analysis framework that emphasizes the importance of digital transformation in enhancing the predictive capacity for disruption risks, while also highlighting the potential of cyber-physical supply chains in mitigating such risks. Not only that, Ref. [77] introduced a comprehensive framework that integrates blockchain, AI, and 3D printing to enhance the effectiveness of humanitarian supply chains during large-scale disaster events, supported by in-depth analysis of empirical cases.

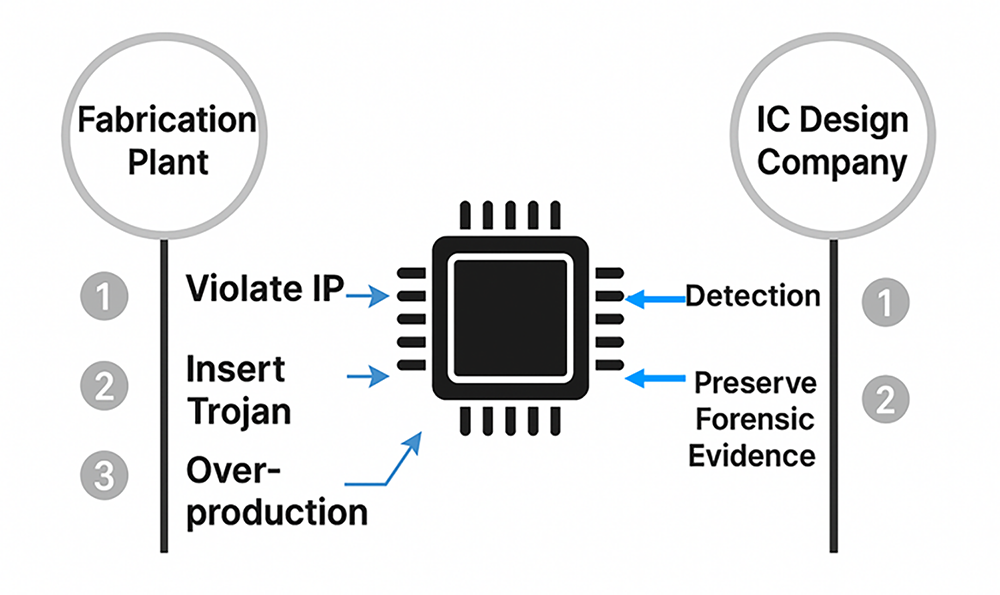

4.2 IC Traceability and Forensics

ICs are the foundational components of all electronic industries. However, the increasing globalization and fragmentation of the semiconductor design and manufacturing sectors over the past two decades have significantly intensified hardware security concerns. Infiltration of counterfeit electronic components into the supply chain has resulted in failures of critical infrastructure and financial losses for end-users of essential systems, which presents a widespread global challenge [42]. In the same manner, the common practice of outsourcing chip fabrication by IC design firms has exposed supply chains to hardware Trojan threats [7]. In response, IC traceability and forensic technologies have emerged as vital research areas, with the aim at tracking the origin and distribution of chips and to prevent illicit activities such as origin laundering and tax evasion—thereby reinforcing the integrity of the supply chain and supporting national security efforts (see Fig. 9 below).

Figure 9: The Blockchain-based Forensic Procedure for fragmentation of IC design and manufacturing sectors

4.2.1 IC Traceability and Legal Forensics

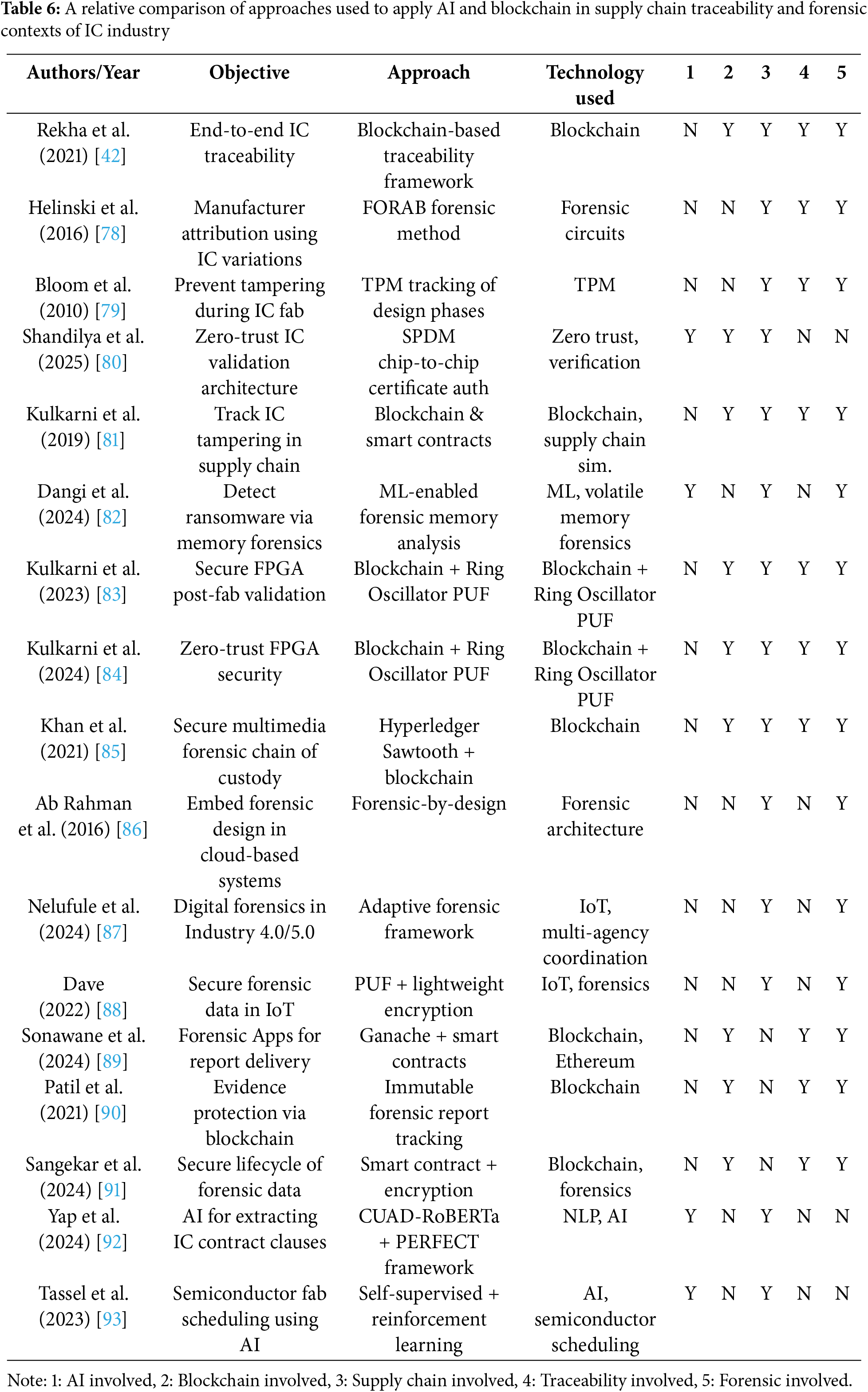

Blockchain is increasingly adopted to enhance IC traceability and the preservation of forensic evidence, owing to its inherent features of immutability, decentralization, and transparency. Meanwhile, AI is leveraged to improve supply chain efficiency and to track carbon footprints (see Table 6 below). According to [42], the infiltration of counterfeit IC into the supply chain has become a global challenge. Most existing blockchain-based traceability methods focus on post-sale tracking—that is, after IC design companies deliver chips to customers. However, before chips are shipped, traceability becomes more complex due to the involvement of multiple foundries. To address this issue, the study proposes a comprehensive IC traceability framework that spans the entire process, from manufacturing and testing to sales. This enables IC design firms to precisely monitor chip origin and distribution, thereby enhancing supply chain transparency and resistance to counterfeiting. Furthermore, Ref. [78] investigated the risks of counterfeiting and tampering in the increasingly globalized IC supply chain, noting that current methods often fail to effectively verify the true origin of chips. To overcome this limitation, the study introduced a forensic identification circuit, which utilizes intrinsic process variations within ICs to identify and trace their manufacturing origins. For experimental validation, the researchers fabricated 159 ICs incorporating three different circuit types. The proposed method achieved identification accuracy rates of up to 98% for both foundry recognition and production batch identification.

For IP infringement and malicious modifications, when chip fabrication is outsourced, IC design companies must submit confidential GDS-II layout files, which introduces risks of IP tampering, theft, and counterfeiting. To mitigate these risks, Ref. [79] proposed a forensic mechanism based on the Trusted Platform Module that records changes and operations across three stages in the foundry: GDS-II editing, mask conversion, and mask printing. This mechanism ensures full traceability throughout the process. In IC design, companies can later extract these records from the physical chip and compare them with the original manufacturing process to verify whether unauthorized modifications, duplications, or overproduction has occurred. These records can also serve as legal evidence for prosecution and counterfeit traceability. In addition to that, Ref. [80] introduced a certificate-based Security Protocol and Data Model to establish a “chip-to-chip” authentication framework. Adhering to the zero-trust principle, every chip must undergo verification prior to deployment to ensure authenticity and provenance. Similarly, Ref. [81] examined the security vulnerabilities introduced by globalization of the IC supply chain, such as counterfeit chips and insertion of hardware Trojans. The study proposed a framework enabled by blockchain and smart contract to monitor chip integrity during both manufacturing and transportation. At each stage, relevant parameters and test results are logged, and each participant independently updates the blockchain. In the event of malicious activity, the system can precisely identify the stage and responsible party through timestamped records and change logs, thereby providing reliable forensic evidence. The feasibility of this approach was validated using a simulated supply chain network built on the IBM platform.

With respect to memory forensics, semiconductor manufacturing functions as a highly automated supply chain system that integrates ML, sensors, UAVs, and big data. While improving efficiency, these technologies increase the risks of ransomware and fileless malware attacks. Sensitive data are often stored in volatile memory, which is lost upon system shutdown, making it difficult for forensic investigators to determine the nature of the attack or identify the specific type of malicious software involved. To address this challenge, Ref. [82] proposed a Live Memory Forensics approach that enables the extraction and analysis of volatile memory in real-time. ML is incorporated to enhance both the efficiency and accuracy of the memory acquisition and analysis.

4.2.2 FPGA Traceability and Legal Forensics

With the growing demand for field-programmable gate arrays (abbreviated as FPGA) across various sectors, counterfeit and recycled FPGA chips have increasingly infiltrated supply chains, posing risks to critical infrastructure and raising concerns about hardware Trojans. To address these threats, Ref. [83] proposed a security method that integrates PUF with blockchain to strengthen verification mechanisms in the downstream FPGA supply chain. The method was simulated using the Ganache framework provided by the Truffle suite, demonstrating its effectiveness in authenticating the integrity of the FPGA and tracking.

In the same way, to counter threats such as intellectual property theft, counterfeiting, and bitstream tampering that undermine the trustworthiness of FPGA, Ref. [84] introduced a zero-trust architecture that combines blockchain with PUF based on ring oscillator. Using theArtix-7 Xilinx FPGA as a test case, the framework was evaluated through a series of targeted attack scenarios aligned with zero-trust principles. The experimental results confirmed its effectiveness in mitigating potential security breaches.

Together, these studies highlight the growing importance of blockchain-integrated hardware security frameworks in ensuring the authenticity, traceability, and resilience of programmable logic devices within global supply chains.

4.2.3 Blockchain and Legal Forensics in Supply Chains

The exchange of multimedia data over the Internet often involves multiple institutions that share, modify, and reuse information, which can compromise the integrity, reliability, and credibility of digital forensic investigations. To address this issue, Ref. [85] proposed the MF-Ledger blockchain framework based on Hyperledger Sawtooth. This architecture enables digital forensic processes to record protocols and evidence securely within a private network, using encrypted private blockchain ledgers to prevent evidence tampering. By the same token, as supply chain operations increasingly migrate to cloud environments, cyber-physical cloud systems (abbreviated as CPCS) are exposed to elevated risks of cyberattacks. In response, Ref. [86] examined the security challenges posed by threats related to CPCS and emphasized the importance of incorporating a forensic design approach during the development phase of the system.

With the advent of Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0, the increasing complexity of emerging technologies and data environments in supply chain IoT systems has introduced significant challenges to digital forensics. To mitigate these risks, Ref. [87] proposed an adaptive digital forensic framework that incorporates cross-border judicial collaboration and integration of industrial system. This framework brings together dynamic evidence collection techniques, advanced data analytics tools, and multi-stakeholder cooperation mechanisms to ensure the integrity, reliability, and admissibility of forensic evidence. In the same way, IoT devices used in supply chain management are typically resource-constrained, limiting their capacity to support advanced cybersecurity mechanisms. As a result, they are highly susceptible to threats such as Trojans, malicious code, and reverse engineering. Therefore, Ref. [88] implemented lightweight cryptographic techniques in conjunction with PUF to enhance device-level protection and secure data essential for IoT forensics. This approach contributes to faster, and more accurate cybercrime investigations.

For the preservation of forensic evidence, Ref. [85] emphasized that modern criminal investigations are highly dependent on the secure management of forensic evidence, which requires both robust storage mechanisms and comprehensive documentation throughout the evidence transfer process. To address this challenge, Ref. [89] utilized Ganache developed by Truffle Suite to build a private Ethereum blockchain environment to rapidly deploy smart contracts and DApp. This environment was used to simulate the multi-stage transmission of forensic reports within the forensic evidence chain. Similarly, traditional methods of transmitting forensic evidence—such as physical delivery or email—are vulnerable to tampering, which can jeopardize the integrity of the court. To address these threats, Ref. [90] proposed a blockchain-based solution on the Ethereum platform to establish an immutable and traceable digital forensic reporting system. This system improves transparency and ensures high-integrity handling of forensic data throughout criminal investigations. Consequently, Ref. [91] introduced a new blockchain-enabled forensic preservation framework that integrates cryptographic mechanisms with smart contracts to support transparent, secure, and verifiable lifecycle management of forensic evidence.

4.2.4 Blockchain and Legal Forensics in Supply Chains

Companies such as Microsoft and Infineon frequently need to identify critical clauses—such as delivery deadlines, warranty periods, and payment terms—within long IC supply contracts. Traditionally, this task has relied on manual processes that are time-consuming and error-prone. To improve efficiency, Ref. [92] proposed the use of a pre-trained language model CUAD-RoBERTa in combination with the PERFECT few-shot learning framework to improve the accuracy and speed of contract clause extraction. The model was trained and validated using 138 contracts signed by Infineon since 1990, demonstrating consistent F1-score performance across diverse clause types.

Inclusion, Ref. [93] introduced a semiconductor process scheduling method that integrates self-supervised learning with reinforcement learning. This approach addresses the complex, continuous, stochastic, and dynamic nature of modern semiconductor manufacturing scheduling challenges. The results indicate a significant reduction in order delays and completion times, along with a more efficient allocation of processing resources.

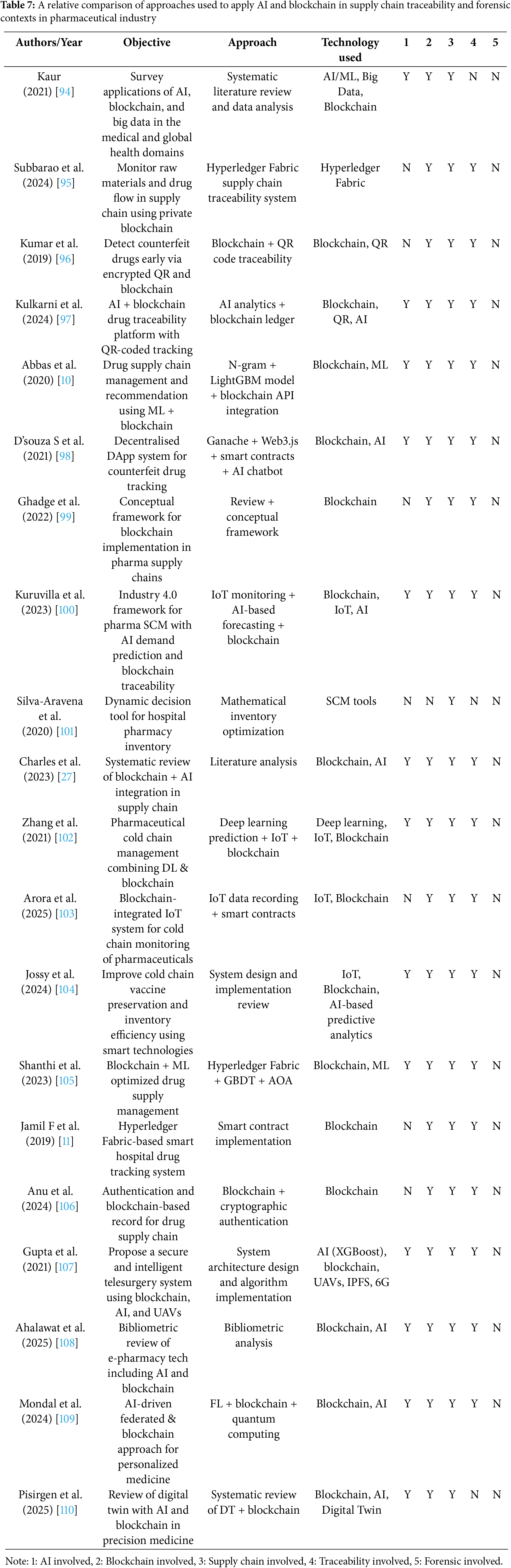

Approximately one million people die each year due to counterfeit medications [9], and up to 30% of pharmaceutical products in regions such as Africa, Asia, and Latin America fail to meet regulatory standards [11]. This widespread issue is largely attributed to the complexity and fragmentation of the pharmaceutical supply chain, where illicit practices such as origin laundering hinder transparency and make traceability highly challenging. To address these issues, an intelligent pharmaceutical supply chain system that integrates blockchain’s immutability with AI’s analytical and predictive capabilities is needed to ensure verifiability, transparency, and traceability [94]. In much the same way, Drug shortages can also trigger social unrest, prompting many governments to implement pharmaceutical traceability regulations [13–15]. These laws require comprehensive, end-to-end electronic traceability throughout the supply chain [16], creating a favorable environment for the adoption of blockchain and AI in pharmaceutical supply chain management (see Table 7 below).

4.3.1 AI and Blockchain Applications in Pharmaceutical Traceability

Hyperledger Fabric is a private enterprise blockchain platform developed under the Linux Foundation. Based on this framework, Ref. [95] designed a blockchain system capable of continuously monitoring and tracking the origins of raw materials and the distribution of pharmaceutical products throughout the supply chain, thus enhancing traceability and anti-counterfeiting capabilities. The system has been tested and validated for feasibility and effectiveness.

A core challenge in combating counterfeit drugs lies in the inability to verify the authenticity of raw materials in the early stages of pharmaceutical production. Therefore, Ref. [96] proposed a mechanism that combines blockchain with encrypted QR codes to improve the verification of the authenticity of ingredients during manufacturing, strengthening the detection of counterfeit drugs. In addition to that, Ref. [97] introduced an integrated traceability and anti-counterfeiting framework for the pharmaceutical supply chain that leverages both blockchain and AI. In this system, all pharmaceutical items are registered on the blockchain from the raw material stage and are assigned unique QR codes to record and retrieve complete distribution histories, allowing identification of counterfeit sources. AI is also used to analyze certification documents and laboratory test reports, improving the credibility and reliability of the supply chain.

For the widespread distribution of counterfeit and substandard pharmaceuticals, Ref. [10] proposed an integrated blockchain and ML system to enable the complete tracking of raw material sources and the drug distribution pathways. It incorporates an N-gram model combined with Light Gradient Boosting Machine to train a pharmaceutical recommendation model. The model was developed and validated using data from Irvine Machine Learning Repository of the University of California, and integrated into a blockchain framework via a Representational State Transfer Application Programming Interface. Building on similar objectives, Ref. [98] developed a blockchain–AI hybrid system with all components deployed on a local Ganache blockchain. Integration with Truffle was achieved using Web3.js. The DApp was built using the React framework. The mobile frontend was developed using Flutter and a Rasa-based chatbot supported interactive communication. Smart contracts were used to ensure verifiability and traceability for all transactions within the supply chain, providing an effective mechanism to identify and investigate counterfeit pharmaceutical circulation. Furthermore, Ref. [99] reviewed recent studies on key challenges in traditional pharmaceutical supply chains—including drug counterfeiting, product recalls, patient privacy, and clinical trials. The study underscored the potential of blockchain to improve transparency and information reliability, thereby strengthening the authenticity of pharmaceutical products and curbing the spread of counterfeit drugs.

Industry 4.0 is a concept of cross-technological integration that extends beyond AI and robotics to encompass a comprehensive intelligent supply chain platform incorporating AI, blockchain, IoT, and big data analytics. This integrated architecture not only enhances the intelligence and automation of healthcare supply chains but also enables effective pharmaceutical inventory management. In this context, Ref. [100] proposed an Industry 4.0–based framework that applies blockchain to trace the origins of raw materials and the distribution routes of pharmaceutical products, thus preventing counterfeit drugs from infiltrating the supply chain. AI models are also utilized to forecast pharmaceutical demand and mitigate risks of shortages or overstocking, while Industrial IoT is used to monitor drug storage conditions and enhance procurement transparency. In addition to that, Ref. [101] developed an algorithmic decision support tool geared for pharmacy inventory management. This tool optimizes the procurement and storage planning of pharmaceutical products. Empirical validation showed that the proposed approach reduces costs by more than 7% compared to traditional methods and provides more effective maintenance of critical drug inventories.

4.3.2 AI and Blockchain Applications in SCM

In logistics and cold chain management, Ref. [27] conducted a systematic review of existing studies on the integration of blockchain and AI in supply chain applications. The review highlighted that these technologies contribute to improved supply chain stability and operational efficiency, accelerate logistics processes, reduce costs, and improve both information transparency and traceability of product origins. Given that pharmaceutical cold chains involve significantly higher storage and transportation costs, the need for accurate demand forecasting becomes critical for cost control. Addressing this, Ref. [102] developed a deep learning–based model to predict demand for cold chain pharmaceuticals and integrated blockchain, cloud storage, and IoT to track supply chain activities, thus improving transparency and quality assurance. Not only that, Ref. [103] proposed a system that integrates blockchain with IoT-based environmental sensors to monitor and log real-time temperature and humidity data throughout the cold chain logistics process. This approach ensures the safety and integrity of temperature-sensitive pharmaceutical products. Using the immutability of blockchain and the automated execution of smart contracts, the system improves both transparency and trust throughout the pharmaceutical cold chain. In a similar manner, conventional vaccine tracking methods are often inefficient and prone to spoilage. To address this challenge, Ref. [104] introduced a cold chain storage solution incorporating IoT technology, capable of issuing real-time alerts when vaccine inventory is low or nears expiration. The system can also be integrated with cloud platforms and AI-driven forecasting models to further optimize vaccine storage and management.

Regarding Hyperledger Fabric, Ref. [105] proposed a pharmaceutical supply chain management approach that integrates blockchain with ML to achieve traceability of drug distribution. The system is developed on the Hyperledger Fabric framework and employs Gradient Boosting Decision Trees to generate drug recommendations. To optimize model performance, the Archimedes Optimization Algorithm is used for hyperparameter tuning. Experimental validation using a standard dataset demonstrated high effectiveness in multiple evaluation metrics. Equally important, Ref. [11] implemented a blockchain-based pharmaceutical supply chain platform built on the Hyperledger Fabric architecture. Smart contracts are deployed to enable authorized access to electronic drug records, ensuring data immutability and improving system transparency. Performance evaluation using Hyperledger Caliper confirmed the efficiency of the platform in terms of transaction throughput, latency, and resource utilization. To build on this, Ref. [106] introduced a blockchain architecture that incorporates an authentication mechanism to document the entire life cycle of pharmaceuticals—from the sourcing of raw materials through manufacturing, storage and distribution. The system balances transparency with the protection of sensitive information and enables users to verify records through unique identifiers and cryptographic techniques. Any anomalies detected in the data may signal the presence of counterfeit drugs.

For last-mile delivery of pharmaceuticals, Ref. [107] proposed the Blockchain and AI-empowered Telesurgery System for 6G, which integrates UAVs to establish temporary and rapid pharmaceutical logistics networks. This system addresses transportation bottlenecks in emergency medical scenarios by enabling efficient and timely delivery of critical medications. Currently, Ref. [108] examined trends in technological adoption in the online pharmacy sector and identified the integration of emerging technologies—particularly AI and blockchain—as a critical driver of innovation. These technologies are transforming both the technical capabilities and the managerial models of online pharmaceutical services, fostering greater efficiency, transparency, and responsiveness within digital healthcare ecosystems.

4.3.3 Blockchain and Federated Learning

Federated learning has rapidly emerged as a prominent research domain in recent years. Ref. [109] proposed an integrated architecture that combines AI-driven federated learning, blockchain, and quantum computing to enhance data privacy protection, facilitate real-time analytics, and share secure patient data between distributed nodes. This approach supports improved diagnostic accuracy, more efficient treatment planning, and improved disease prediction in healthcare settings. Simultaneously, Ref. [110] examined the application of federated ML within digital twin systems, emphasizing the prevalent use of hybrid algorithms that blend supervised and unsupervised learning to improve the accuracy and performance of the digital twin. The study also further observed that integrating blockchain with generative AI can enhance both the functionality and data security of digital twin platforms.

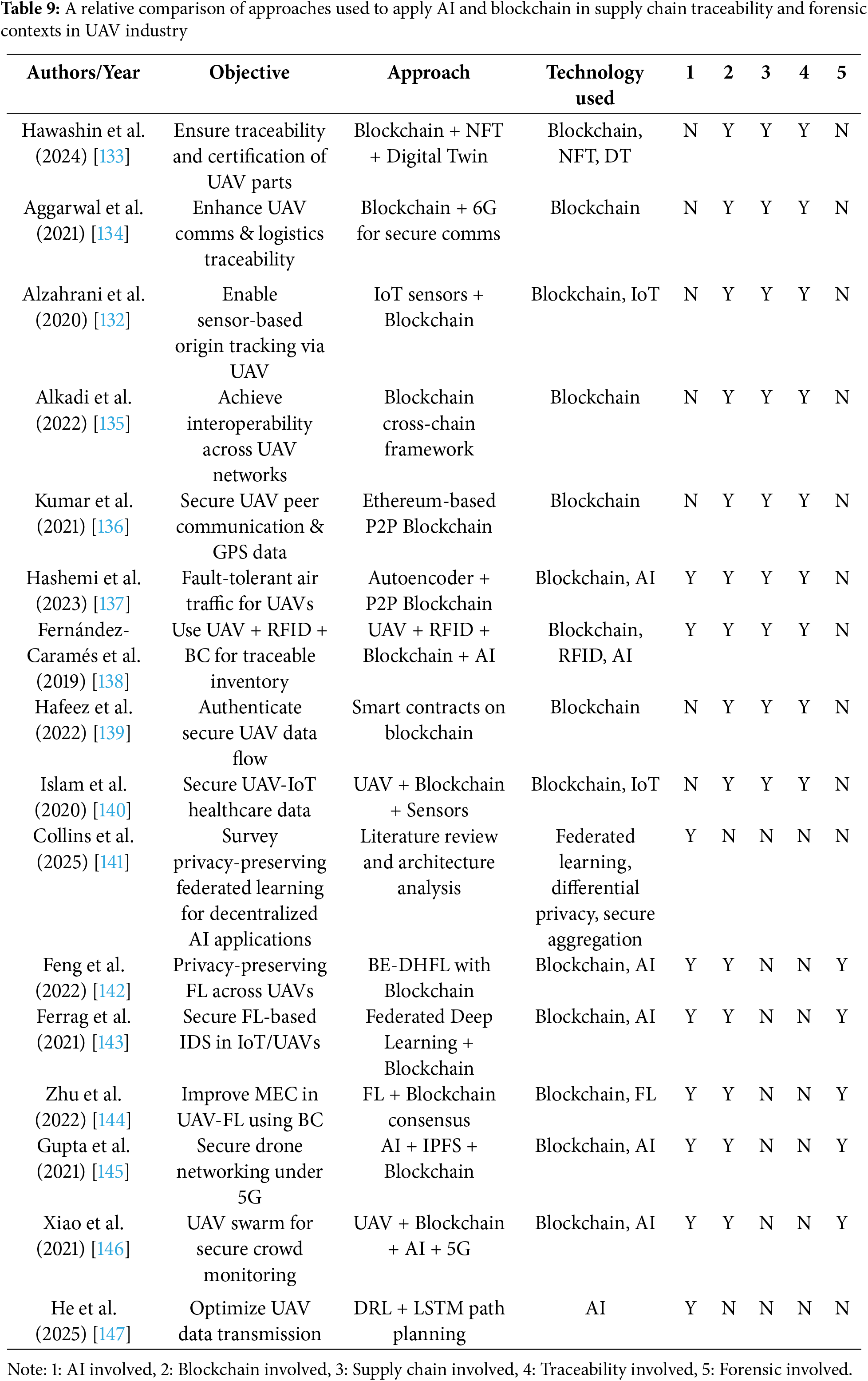

With the rapid development of EVs, related supply chain challenges have attracted increasing attention. Disruptions in component supply can stop vehicle production [17], and EVs can be compromised for surveillance or attacks. In the meantime, sourcing the procurement of battery raw materials has been implicated in human rights abuses and environmental pollution [18], prompting major countries to legislate traceability and strict regulation of EV components and raw materials to prevent activities such as origin laundering and falsified provenance [19–21]. Consequently, emerging technologies such as blockchain and AI are applied to EV supply chains (see Table 8 below) to improve transparency, prevent counterfeiting, reduce environmental impact, support sustainability goals and ensure compliance with international regulations. For example, Ref. [111] highlighted blockchain’s immutability, transparency, traceability, and decentralization as key enablers to improve the security and credibility of EV-related data. Current research has identified three main application areas:

(a) EV charging infrastructure: Blockchain facilitates recording and validation of charging transactions to ensure transaction transparency and prevent fraudulent behaviors.

(b) Battery supply chains: Blockchain allows tracking of material provenance and distribution flows, improving component traceability and compliance with sustainability policies.

(c) Vehicle connectivity: Blockchain integration supports demand-response management and enhances data privacy

Besides, regulatory initiatives such as the EU’s upcoming “battery passport” framework can leverage blockchain as a digital ledger platform to meet policy requirements and strengthen consumer trust.

4.4.1 AI and Blockchain for EV Component Traceability

In applying AI and blockchain to component traceability and data security in EV supply chains, Ref. [112] classified suppliers into three categories: chassis, drivetrain, and battery. The study initially deployed ANN, LSTM, and RNN algorithms to detect potentially malicious behavior among suppliers. Once identified, smart contracts were used to record component-related data on a blockchain. The immutability of the blockchain prevents any unauthorized alterations to component records, thus improving the transparency and traceability of the supply chain.

In response to traceability for lithium-ion battery raw materials, Ref. [113] proposed a theoretical framework based on a blockchain ecosystem to support future implementation and scholarly research on battery component traceability and recycling. Addressing risks such as child labor and environmental pollution in small-scale and artisanal mining regions, Ref. [114] demonstrated a blockchain-enabled system that tracks every stage of cobalt extraction by recording data such as mining locations, mining identities, working conditions, and ore sale and transport records. Data from mines, smelters, and markets are immutably logged on the blockchain ledger, enhancing both transparency and traceability. Synchronously, AI are proposed to analyze mining operations and identify potential legal or ethical violations. In a related application, Ref. [115] implemented a combination of blockchain and QR code technologies in EV the production of EVs. Batteries are laser-engraved with unique QR codes linked to a Traceability System that records raw materials and production data at each stage. The system leverages blockchain connectivity to document critical traceability points, such as material mixing, splitting, or transformation, in real time, thus preventing data loss or untraceable gaps. AI-driven modeling and data analysis are also used to predict product defects and enhance manufacturing quality.

In the context of circular economy and sustainable management, Ref. [116] examined the application of blockchain to monitor battery supply chains. The study demonstrated that blockchain enhances transparency and traceability throughout the life cycle of lithium-ion batteries—from resource extraction and manufacturing to recycling—thereby preventing environmental pollution and supporting sustainability objectives. Specifically, the blockchain records critical data at each stage, including mineral origin, processing parameters, transport logs, chemical composition, and pollution metrics. Meanwhile, Ref. [117] implemented a blockchain–based system to trace raw materials, production, and usage information throughout the full life cycle of lithium-ion EV batteries. This decentralized approach prevents unauthorized data modification and implements a Digital Battery Passport on the chain, which logs the battery health status (State of Health), material composition, and recycling records—enhancing supply chain traceability and promoting circular economy principles. Furthermore, Ref. [118] integrated blockchain with QR-code by laser-etching a unique QR code onto each battery during manufacturing. Suppliers register information—such as the origins of hazardous materials (e.g., lead, tin, sulfuric acid)—on the blockchain ledger. Each logistics transfer is digitally signed and recorded, allowing verification by third-party auditors and strengthening regulatory oversight. In addition to this, AI-driven analytics can be employed to evaluate recycling processes and improve circular economy management.

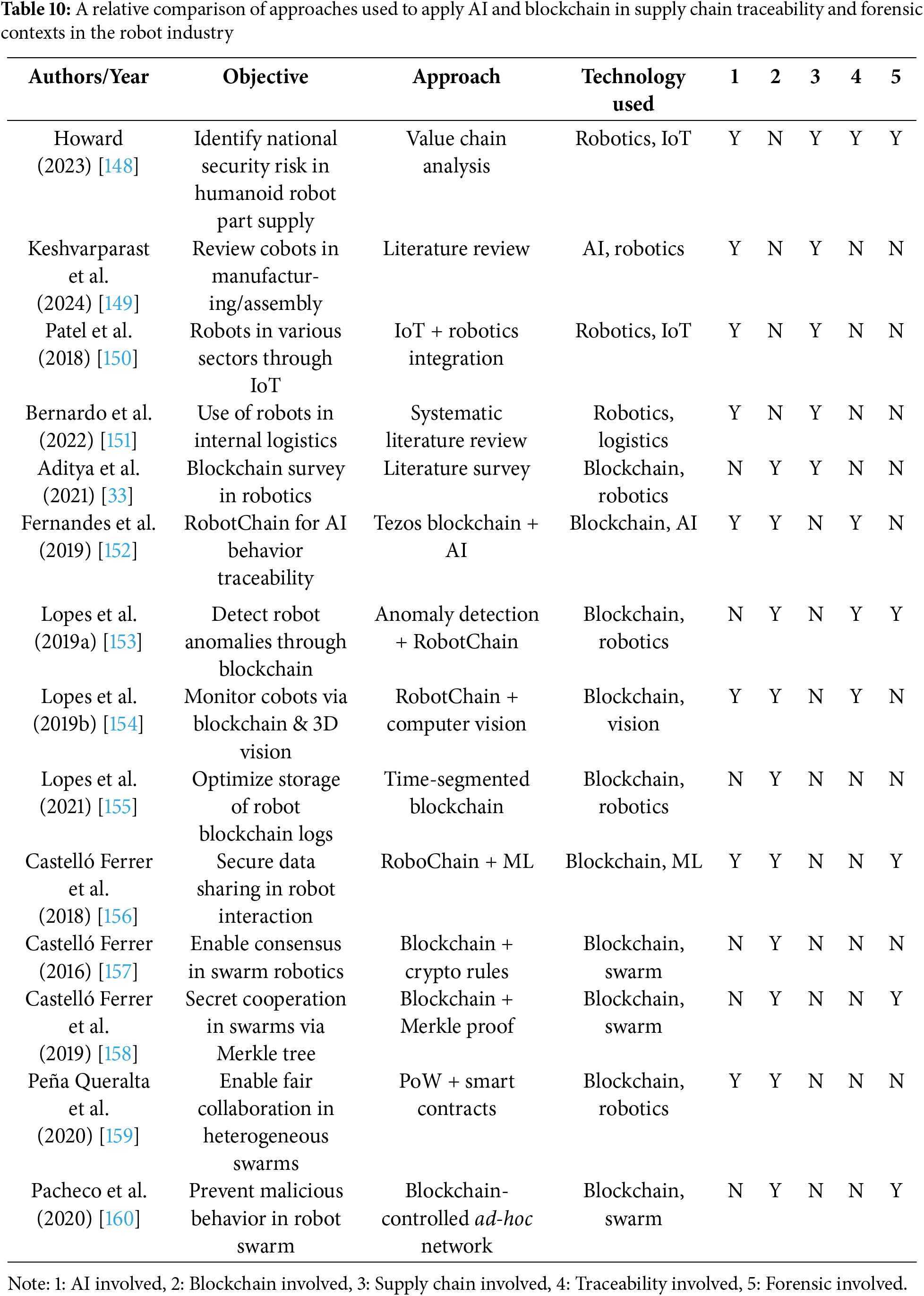

4.4.2 AI and Blockchain Apply to SCM of EVs