Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Shock-Boundary Layer Interaction in Transonic Flows: Evaluation of Grid Resolution and Turbulence Modeling Effects on Numerical Predictions

Faculty of Engineering, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Necmettin Erbakan University, Konya, 42090, Türkiye

* Corresponding Author: Mehmet Numan Kaya. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 327-343. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072000

Received 17 August 2025; Accepted 15 October 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

This study investigates the influence of mesh resolution and turbulence model selection on the accuracy of numerical simulations for transonic flow, with particular emphasis on shock-boundary layer interaction phenomena. Accurate prediction of such flows is notoriously difficult due to the sensitivity to near-wall resolution, global mesh density, and turbulence model assumptions, and this problem motivates the present work. Two solvers were employed, rhoCentralFoam (unsteady) and TSLAeroFoam (steady-state), both are compressible and density-based and implemented within the OpenFOAM framework. The investigation focuses on three different non-dimensional wall distance (y+) values of 1, 2.5 and 5, each implemented with both moderate and fine mesh resolutions. Three turbulence models—Spalart-Allmaras (SA), k-ω Shear Stress Transport (SST), and k-ε Realizable—were evaluated at M = 0.74, Re = 2.7 × 106, and α = 3.19°. Results showed that while both solvers achieved good overall agreement with experimental data, particularly in terms of pressure distribution, lift coefficient, and shock location, noticeable differences still emerged. The k-ω SST model consistently delivered the most robust performance across all cases, capturing the shock position on meshes with deviations below 0.02 compared to the experiment, and maintaining accuracy even at y+ ≈ 5. The k-ε Realizable model was highly sensitive to near-wall resolution, displacing shocks downstream at higher y+ values, whereas Spalart-Allmaras remained broadly comparable to the k-ω SST model in predictive performance. The rhoCentralFoam solver achieved consistently better lift predictions, staying within about 2% of the experimental value on average, whereas TSLAeroFoam overpredicted it by around 4%. For transonic Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) simulations, unsteady k-ω SST with y+ ≈ 1 is recommended for maximum fidelity, whereas steady k-ω SST or SA simulations offer a practical option for quick and reasonably accurate aerodynamic predictions.Keywords

Transonic flow simulation remains one of the most challenging areas in computational fluid dynamics (CFD) due to the complex physics involved, particularly the shock wave/boundary layer interactions. These interactions are critical in determining the aerodynamic performance of various aerospace applications, from aircraft wings to turbomachinery components [1,2]. The accurate prediction of such flows is therefore essential for efficient design optimization and performance assessment.

A significant body of research has focused on mesh resolution as a key factor in improving the accuracy of transonic flow simulations. High-resolution meshes are essential for accurately resolving intricate flow features, particularly in regions where shock waves are present. Widiawaty et al. [3] emphasized that mesh resolution plays a crucial role in CFD, directly impacting result accuracy, and highlighted the necessity of refining meshes in critical flow regions. Kulkarni et al. [4] demonstrated that the choice of mesh significantly influences flow characteristics and turbulence model performance, finding that coarser meshes failed to accurately capture shock positions. Hashimoto et al. [5] investigated unsteady transonic buffet and reported that accurate prediction of shock location remains challenging even with fine grids unless appropriate wall modeling is used.

The selection of turbulence models represents another decisive factor for the accurate simulation of transonic flows. Different models exhibit varying capabilities in capturing the complexities of transonic phenomena. The Spalart-Allmaras (SA) and

The interaction between mesh resolution and turbulence modeling has also been explored in several contexts. Galpin et al. [12] validated CFD simulations against experimental data from a transonic axial compressor, assessing sensitivity to mesh size, turbulence models, and other factors, and showed that accurate prediction of shock-boundary layer interactions required both appropriate turbulence modeling and sufficient mesh resolution. Hosangadi et al. [13] presented simulations for transonic diffuser-volute configurations using unstructured CFD and achieved good agreement with experimental data by employing multi-element unstructured frameworks that provided better resolution around critical geometry features. Coratger et al. [14] developed a hybrid lattice-Boltzmann method for complex transonic flows that combined grid refinement with subgrid turbulence models, demonstrating good predictive capability.

In parallel, machine learning approaches have recently emerged as promising tools for transonic flow prediction. Zhou et al. [15] developed a deep learning framework using residual networks that accurately captured essential physical features such as shock strength, location, flow separation, and boundary layer characteristics in transonic regimes. Jia et al. [16] created a hybrid method fusing deep learning with reduced-order modeling that reduced prediction errors in nonlinear flow regions by 13%–66%, while maintaining computational efficiency. Complementary to these developments, Mufti et al. [17] proposed a domain-informed probabilistic deep learning framework for predicting transonic flow fields, achieving 6.4% error in shock strength and 1% error in shock location prediction, and outperforming traditional reduced-order models by 60%. Al-Rbaihat et al. [18] combined RANS/DES-based CFD with Gaussian process regression (GPR) to demonstrate the effectiveness of hybrid CFD-Machine Learning (CFD-ML) methodologies in handling complex shock-dominated flows.

Despite these advances in transonic flow simulation, the review of the literature reveals a gap: there is a notable absence of comprehensive studies that systematically investigate the combined effects of mesh resolution and turbulence model selection. Most prior work has either optimized mesh resolution with a fixed turbulence model or compared turbulence models on a single mesh, with little attention to how steady and unsteady solvers behave under these combined conditions. This fragmented approach overlooks key interdependencies that directly influence prediction accuracy. In particular, the interaction between different non-dimensional wall distance (

2.1 RAE2822 Data Airfoil and Experimental Data

The experimental dataset for this study is taken from the Advisory Group for Aerospace Research and Development (AGARD) AR-138 report on the RAE2822 airfoil [19]. Case 13A was selected, corresponding to a Mach number of 0.74, a Reynolds number of 2.7

2.2 Computational Domain and Mesh Generation

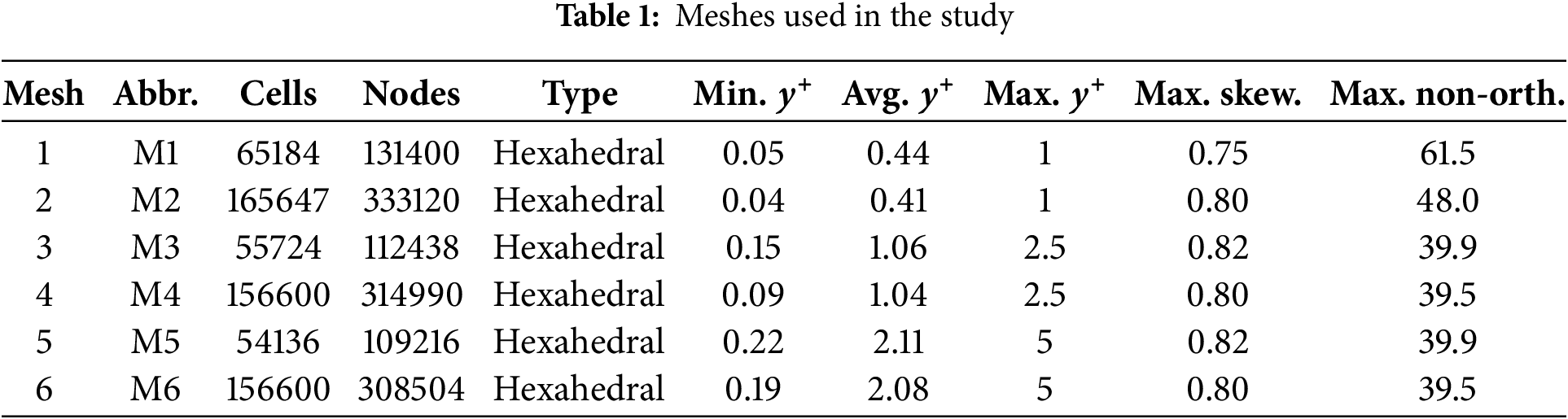

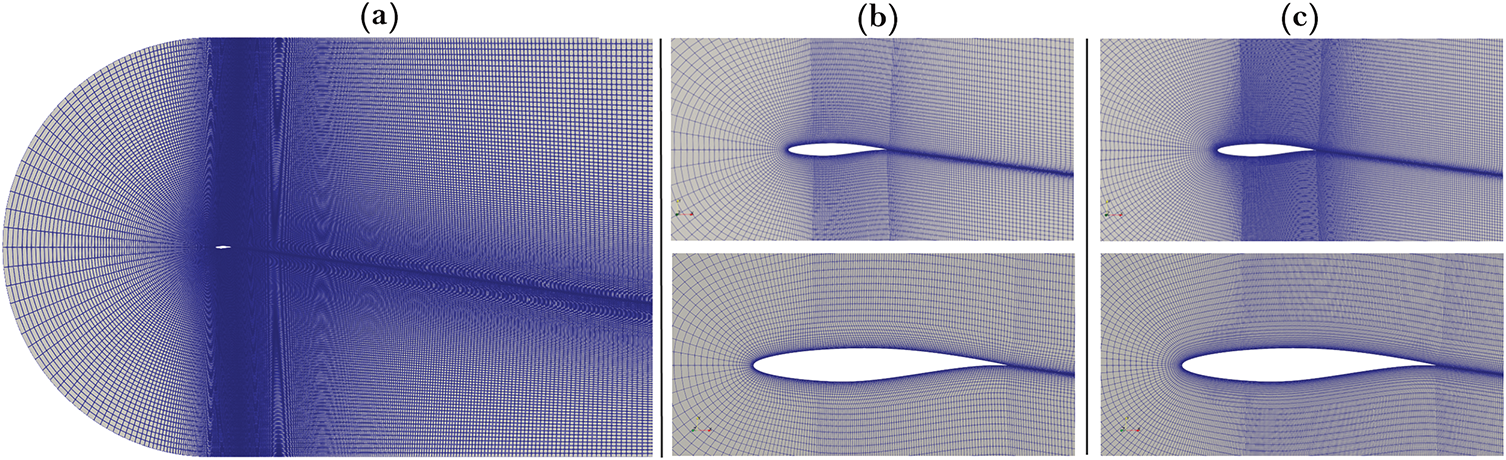

The computational domain employs a C-grid topology surrounding the RAE2822 airfoil, extending 20 chord lengths in all directions to minimize far-field boundary effects. The mesh was generated using OpenFOAM’s native blockMesh utility, with the blockMesh dictionary was configured to enhance cell distribution, particularly near the shock region for accurate boundary layer resolution. The first cell height was calculated to achieve target

Fig. 1 presents the representative mesh pairs, showing (a) the complete domain configuration of the fine grid, with close-up views comparing (b) moderate and (c) fine resolutions. This systematic approach of varying both near-wall resolution (

Figure 1: Computational mesh visualization: (a) Complete domain view of the fine-resolution C-grid configuration (M2); (b) Close-up views from the moderate-resolution mesh (M1); (c) Close-up views from the fine-resolution mesh (M2)

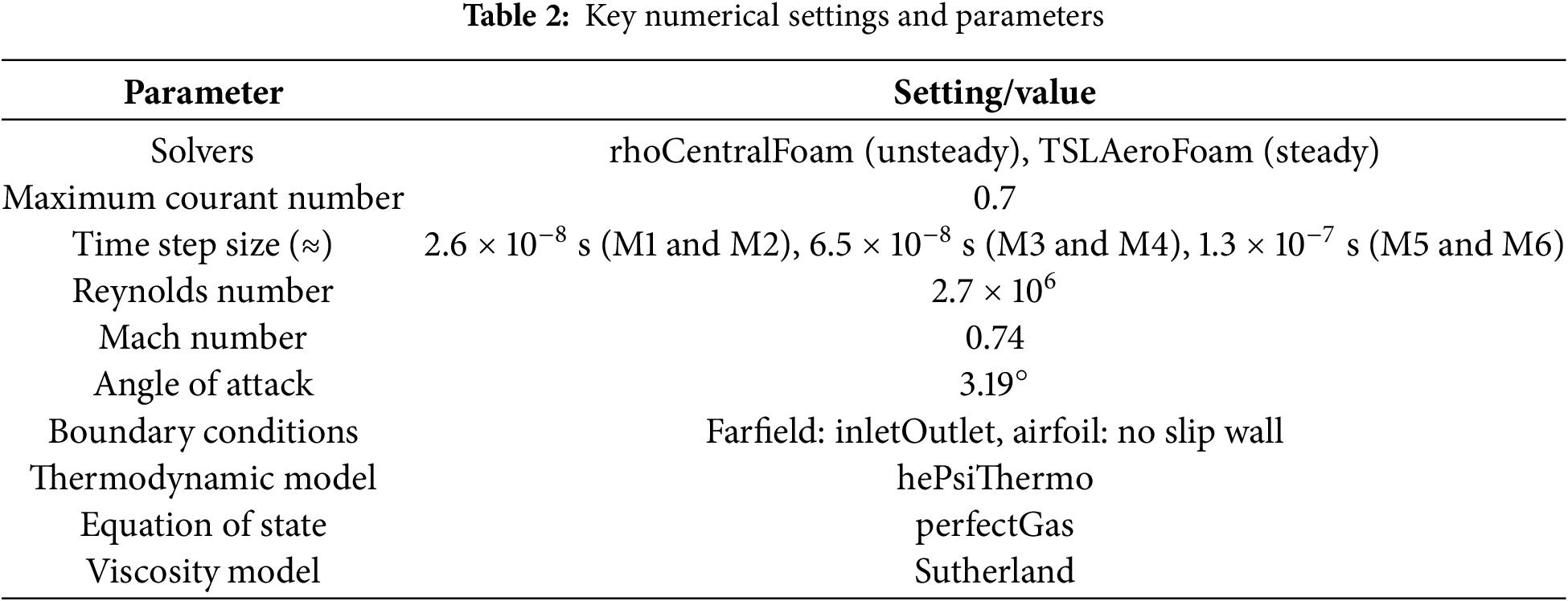

Two solvers are used for steady and unsteady simulations: TSLAerofoam and rhoCentralFoam, both based on the OpenFOAM framework.

The rhoCentralFoam is an unsteady density-based solver for high-speed compressible flow included in the standard OpenFOAM distribution. As described by Greenshields et al. [25], this solver implements a semi-discrete, non-staggered central scheme developed by Kurganov and Tadmor [26]. The CFD solver discretizes the continuity, momentum, and energy equations separately to obtain three linear systems [27].

where

with dynamic viscosity

This central-upwind scheme offers an alternative approach to traditional Riemann solvers, combining central-difference and upwind schemes, making it particularly effective for flows with shocks and discontinuities in transonic regimes [28,29].

The second solver, TSLAeroFoam, is a steady-state, density-based compressible flow solver developed within the OpenFOAM-based NextFOAM framework. It employs the Lower–Upper Symmetric Gauss–Seidel (LU-SGS) algorithm for implicit time integration, which enables rapid convergence for steady computations. Tailored for aerospace applications, the solver incorporates Riemann-based boundary conditions, advanced near-wall treatment, and the thin shear layer (TSL) approximation, which improves efficiency in boundary layer-dominated transonic flows. In TSLAeroFoam, convective fluxes are computed using the Roe-FDS (flux difference splitting) scheme with VK-limited gradient reconstruction, while viscous fluxes are modeled with the TSL approximation. A second-order upwind scheme is consistently applied to both convective and turbulence terms [30,31].

The use of both steady and unsteady solvers allows a direct comparison in transonic simulations. The rhoCentralFoam enables the capture of possible transient effects associated with shock-boundary layer interaction in transonic conditions, while TSLAeroFoam provides an efficient steady-state baseline. This setup makes it possible to assess how mesh resolution and turbulence modeling influence solution accuracy differently in steady vs. unsteady frameworks.

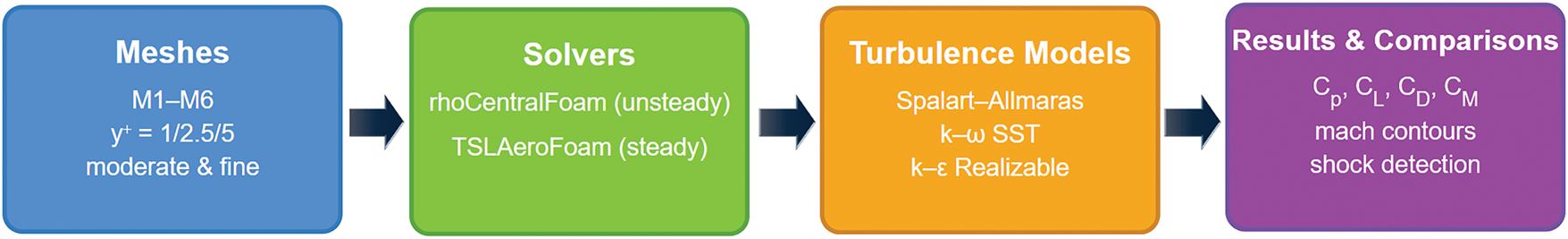

A comprehensive matrix of simulations was performed to systematically investigate the effects of mesh resolution,

• Spalart-Allmaras (SA)—A one-equation model known for its robustness in aerospace applications [32].

Here,

•

Here,

•

Here,

The unsteady simulations were performed using the rhoCentralFoam solver of OpenFOAM v2406. The maximum Courant number was set to 0.7, resulting in time step sizes of 2.6

Figure 2: Flowchart of the research workflow

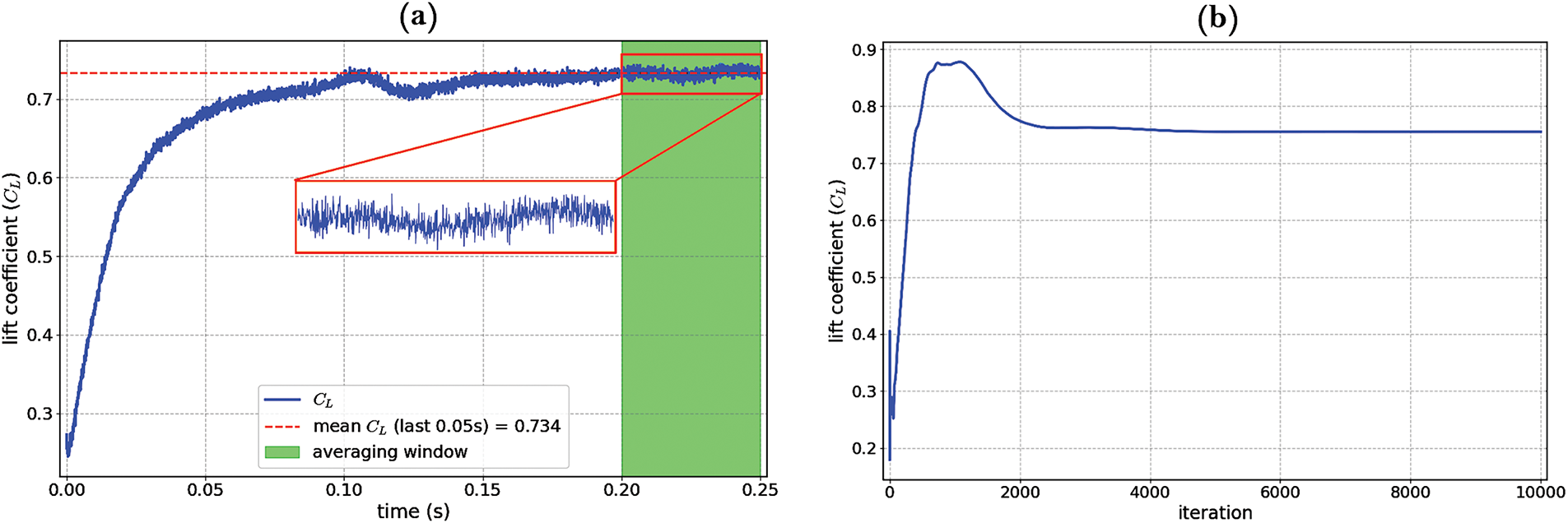

Figure 3: Representative convergence histories for the M3 mesh configuration: (a)

For the steady-state simulations with TSLAeroFoam, a maximum of 10,000 iterations was performed, and convergence was ensured by requiring all residuals to fall below

Fig. 4 compares rhoCentralFoam predictions with experimental data across turbulence models and mesh resolutions, revealing key findings about shock location sensitivity. While all models show some dependence on near-wall resolution, the

Figure 4: Comparison of CFD results obtained using different turbulence models with rhoCentralFoam on grids (a) M1, (b) M2, (c) M3, (d) M4, (e) M5, and (f) M6 against experimental data

Fig. 5 presents Mach number contours from the unsteady rhoCentralFoam solver across six mesh configurations and three turbulence models. The flow velocity reaches around M = 1.4 on the suction side and remains around M = 0.6 on the pressure side near the leading edge. When comparing the contours, two main trends can be observed. First, increasing global mesh density generally reduces the extent of low-Mach number regions while slightly expanding high-Mach zones. This effect is most evident near the shock formation area, where finer meshes yield more compact supersonic regions compared to their moderate-resolution counterparts. Second, reducing

Figure 5: Mach number contours obtained from the rhoCentralFoam solver for six mesh configurations using three turbulence models: Spalart-Allmaras,

Fig. 6 displays Mach contours from the steady-state TSLAeroFoam solver, revealing several key differences from the unsteady results. The steady solver demonstrates significantly reduced sensitivity to both mesh density and

Figure 6: Mach number contours obtained from the TSLAeroFoam solver for all six mesh configurations using three turbulence models: Spalart-Allmaras,

Fig. 7 compares TSLAeroFoam’s steady-state pressure distributions with experimental data across six mesh configurations and three turbulence models, revealing several important insights. The

Figure 7: Comparison of CFD results obtained using different turbulence models with TSLAeroFoam on grids (a) M1, (b) M2, (c) M3, (d) M4, (e) M5, and (f) M6 against experimental data

Fig. 8 presents a comparative visualization of pressure coefficient (

Figure 8: Pressure coefficient (

Fig. 9 compares the pressure distribution results of rhoCentralFoam and TSLAeroFoam using the

Figure 9: Comparison of pressure coefficient (

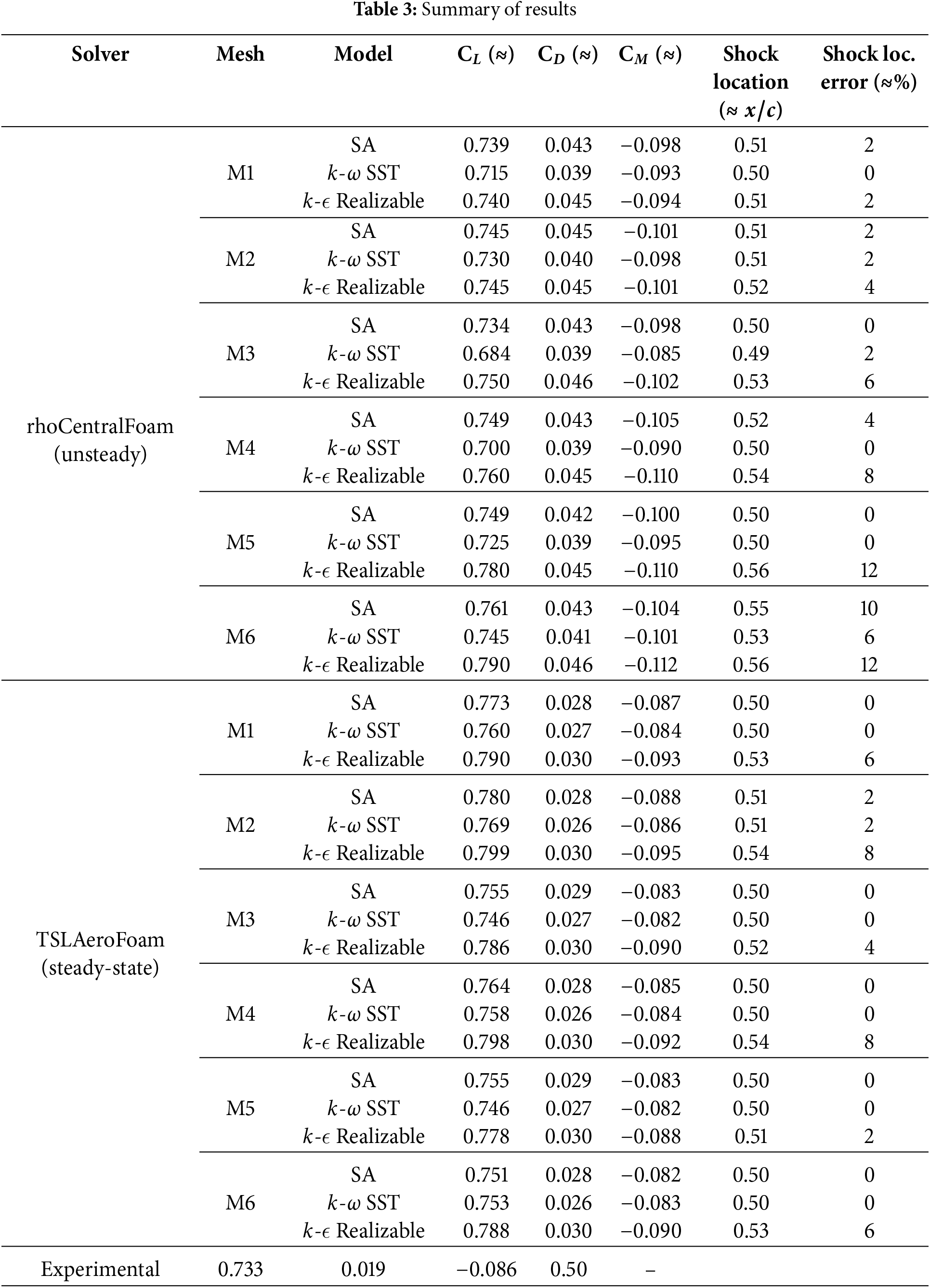

Table 3 summarizes the comprehensive results obtained in this study. The lift coefficient predictions from rhoCentralFoam generally show excellent agreement with the experimental value of

This study systematically evaluated the interdependent effects of near-wall resolution, mesh density, and turbulence model choice on transonic shock-boundary layer interaction predictions for the RAE2822 airfoil. The main findings are:

• The rhoCentralFoam solver achieved generally better lift predictions, staying within about 2% of the experimental value, while TSLAeroFoam tended to overpredict by around 4%.

• The

• Turbulence model choice plays the dominant role in predictive accuracy in transonic CFD simulations, and with appropriate near-wall resolution the influence of global mesh density remains secondary.

• The TSLAeroFoam solver showed generally better performance in terms of drag and moment coefficient predictions.

• The rhoCentralFoam solver captured unsteady lift-generating flow physics more accurately but required substantially higher computational cost. TSLAeroFoam achieved efficient convergence and provided reasonable predictions.

For maximum fidelity, unsteady rhoCentralFoam with

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Guo H, Zhang C, Lv B, Yu L. Numerical simulation research on static aeroelastic effect of the transonic aileron of a high aspect ratio aircraft. Comput Model En Sci. 2022;132(3):991–1010. doi:10.32604/cmes.2022.020638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Al-Rbaihat R, Saleh K, Malpress R, Buttsworth D. Experimental investigation of a novel variable geometry radial ejector. Appl Therm Eng. 2023;233(2):121143. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2023.121143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Widiawaty CD, Siswantara AI, Budiyanto MA, Andira MA, Adanta D, Syafei MHG, et al. Analysis of mesh resolution effect to numerical result of CFD-ROM: turbulent flow in stationary parallel plate. CFD Lett. 2024;16(8):1–17. doi:10.37934/cfdl.16.8.117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kulkarni S, Chapman C, Shah H. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) mesh independency study of a straight blade horizontal axis tidal turbine. Preprints. 2016:2016080008. doi:10.20944/preprints201608.0008.v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hashimoto A, Ishida T, Ohmichi Y, Aoyama T, Yamamoto T, Hayashi K. Current progress in unsteady transonic buffet simulation with unstructured grid CFD code. In: AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting; 2018 Jan 8–12; Kissimmee, FL, USA. doi:10.2514/6.2018-0788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Duggirala R, Roy CJ, Schetz JA. Analysis of interference drag for strut-strut interaction in transonic flow. AIAA J. 2011;49(3):449–62. doi:10.2514/1.45703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xie A, Yan W, Zhou J. Investigation of shockwave-turbulent boundary layer interaction in transonic compressor rotor37. In: First Aerospace Frontiers Conference (AFC 2024); 2024 Apr 12–15; Xi’an, China. p. 568–74. [Google Scholar]

8. Yi W, Ji L, Tian Y, Shao W, Li W, Xiao Y. An aerodynamic design and numerical investigation of transonic centrifugal compressor stage. J Therm Sci. 2011;20(3):211–7. doi:10.1007/s11630-011-0460-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Soda A. Numerical investigation of unsteady transonic shock/boundary-layer interaction for aeronautical applications. Tech Rep. DLR Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V.; 2007 [Google Scholar]

10. Petrocchi A, Barakos G. Transonic buffet simulation using a partially-averaged navier-stokes approach. Aerosp Sci Technol. 2024;149(5):109134. doi:10.1016/j.ast.2024.109134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Johnston LJ. Computational fluid dynamics analysis of multi-element, high-lift aerofoil sections at transonic manoeuvre conditions. Proc Institut Mech EngbPart G J Aerosp Eng. 2011;226(8):912–29. doi:10.1177/0954410011417541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Galpin P, Hansen T, Scheuerer G, Kelly R, Hickman A, Jemcov A, et al. Validation of transonic axial compressor stage unsteady-state rotor-stator simulations. In: Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2017: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition; 2017 Jun 26–30; Charlotte, NC, USA. doi:10.1115/GT2017-64786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Hosangadi A, Ahuja V, Lee YT. Simulations of transonic diffuser-volute system using hybrid unstructured CFD. In: ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition; 2000 Nov 5–10; Orlando, FL, USA. p. 55–62. doi:10.1115/IMECE2000-1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Coratger T, Farag G, Zhao S, Boivin P, Sagaut P. Large-eddy lattice-boltzmann modeling of transonic flows. Phys Fluids. 2021;33(11):115112. doi:10.1063/5.0064944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhou H, Xie F, Ji T, Zhang X, Zheng C, Zheng Y. Fast transonic flow prediction enables efficient aerodynamic design. Phys Fluids. 2023;35(2):026109. doi:10.1063/5.0138946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Jia X, Gong C, Ji W, Li C. An accuracy-enhanced transonic flow prediction method fusing deep learning and a reduced-order model. Phys Fluids. 2024;36(5):56101. doi:10.1063/5.0204152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Mufti B, Bhaduri A, Ghosh S, Wang L, Mavris DN. Shock wave prediction in transonic flow fields using domain-informed probabilistic deep learning. Phys Fluids. 2024;36(1):016121. doi:10.1063/5.0185370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Al-Rbaihat R, Saleh K, Malpress R, Buttsworth D, Alahmer H, Alahmer A. Performance evaluation of supersonic flow for variable geometry radial ejector through CFD models based on DES-turbulence models, GPR machine learning, and MPA optimization. Int J Thermofluids. 2023;20:100487. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2023.100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Cook PH, Firmin MCP, McDonald MA. Aerofoil RAE 2822: pressure distributions, and boundary layer and wake measurements. RAE; 1977. [Google Scholar]

20. Jinks E, Bruce P, Santer M. Optimisation of adaptive shock control bumps with structural constraints. Aerosp Sci Technol. 2018;77(1):332–43. doi:10.1016/j.ast.2018.03.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Modesti D, Pirozzoli S. A low-dissipative solver for turbulent compressible flows on unstructured meshes, with OpenFOAM implementation. Comput Fluids. 2017;152(1):14–23. doi:10.1016/j.compfluid.2017.03.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Rahman MM, Zhang X, Hasan K, Chen S. RANS flow computation around transonic RAE2822 airfoil with a new SST turbulence model. MIST Int J Sci Technol. 2024;12:23–8. doi:10.47981/j.mijst.12(02)2024.477(23-27). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yun TIA, Gao S, Liu P, Wang J. Transonic buffet control research with two types of shock control bump based on RAE2822 airfoil. Chin J Aeronaut. 2017;30(5):1681–96. doi:10.1016/j.cja.2017.08.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. NASA. RAE2822 transonic airfoil validation data. [cited 2025 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/wind/valid/raetaf/raetaf.html. [Google Scholar]

25. Greenshields CJ, Weller HG, Gasparini L, Reese JM. Implementation of semi-discrete, non-staggered central schemes in a colocated, polyhedral, finite volume framework, for high-speed viscous flows. Int J Numer Methods Fluids. 2010;63(1):1–21. doi:10.1002/fld.2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kurganov A, Tadmor E. New high-resolution central schemes for nonlinear conservation laws and convection-diffusion equations. J Comput Phys. 2000;160(1):241–82. doi:10.1006/jcph.2000.6459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Kumar M, Sahoo R, Behera S. Design and numerical investigation to visualize the fluid flow and thermal characteristics of non-axisymmetric convergent nozzle. Eng Sci Technol Int J. 2019;22(1):294–312. doi:10.1016/j.jestch.2018.10.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kaya MN, Satcunanathan S, Meinke M, Schröder W. Leading-edge noise mitigation on a rod-airfoil configuration using regular and irregular leading-edge serrations. Appl Sci. 2025;15(14):7822. doi:10.3390/app15147822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Canteros ML, Polanský J. Review and comparison of two OpenFOAM solvers: rhocentralfoam and sonicfoam. EPJ Web Conf. 2024;299:1005. doi:10.1051/epjconf/202429901005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kim J, Kim K. A development and verification of density based solver using LU-SGS algorithm in OpenFOAM. In: ICAS 2014, 29th Congress of the International Council of the Aeronautical Sciences; 2014 Sep 7–12; St. Petersburg, Russia. p. 375. [Google Scholar]

31. You KK, Ha JH, Lee SC. An automated aerodynamic analysis system in missile based on open-source software. Int J Aeronaut Space Sci. 2023;24(3):592–605. doi:10.1007/s42405-022-00558-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Spalart P, Allmaras S. A one-equation turbulence model for aerodynamic flows. In: 30th Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit; 1992 Jan 6–9; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 439. [Google Scholar]

33. Menter FR. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J. 1994;32(8):1598–1605. doi:10.2514/3.12149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Noorollahi Y, Ziabakhsh Ganji MJ, Rezaei M, Tahani M. Analysis of turbulent flow on tidal stream turbine by RANS and BEM. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2021;127(2):515–32. [Google Scholar]

35. Shih TH, Liou WW, Shabbir A, Yang Z, Zhu J. A new k-ϵ eddy viscosity model for high Reynolds number turbulent flows. Comput Fluids. 1995;24(3):227–38. [Google Scholar]

36. Fuhrman DR, Li Y. Instability of the realizable k-ϵ turbulence model beneath surface waves. Phys Fluids. 2020;32(11):115108. doi:10.1063/5.0029206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools