Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Phase-Level Analysis and Forecasting of System Resources in Edge Device Cryptographic Algorithms

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Seoul National University of Science and Technology, Seoul, 01811, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Computer Engineering (AI-ML), Marwadi University, Rajkot, 360003, Gujarat, India

3 School of Computer Science and Engineering, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, 06974, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Yongseok Son. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Cutting-Edge Security and Privacy Solutions for Next-Generation Intelligent Mobile Internet Technologies and Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 2761-2785. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070888

Received 26 July 2025; Accepted 20 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

With the accelerated growth of the Internet of Things (IoT), real-time data processing on edge devices is increasingly important for reducing overhead and enhancing security by keeping sensitive data local. Since these devices often handle personal information under limited resources, cryptographic algorithms must be executed efficiently. Their computational characteristics strongly affect system performance, making it necessary to analyze resource impact and predict usage under diverse configurations. In this paper, we analyze the phase-level resource usage of AES variants, ChaCha20, ECC, and RSA on an edge device and develop a prediction model. We apply these algorithms under varying parallelism levels and execution strategies across key generation, encryption, and decryption phases. Based on the analysis, we train a unified Random Forest model using execution context and temporal features, achieving R2 values up to 0.994 for power and 0.988 for temperature. Furthermore, the model maintains practical predictive performance even for cryptographic algorithms not included during training, demonstrating its ability to generalize across distinct computational characteristics. Our proposed approach reveals how execution characteristics and resource usage interacts, supporting proactive resource planning and efficient deployment of cryptographic workloads on edge devices. As our approach is grounded in phase-level computational characteristics rather than in any single algorithm, it provides generalizable insights that can be extended to a broader range of cryptographic algorithms that exhibit comparable phase-level execution patterns and to heterogeneous edge architectures.Keywords

The Internet of Things (IoT) is widely used in various fields such as autonomous driving [1], smart cities [2], healthcare [3], and industrial automation [4]. IoT systems collect and process real-time data from sensors and devices to enable context awareness [5], decision-making [6], and automated control [7]. The data often contains sensitive information such as location, biometrics, images, and device logs, and is used in environments like autonomous vehicles, remote healthcare, and smart homes, where rapid processing is essential. To reduce latency and protect personal information, edge devices are increasingly used to process data locally before transferring it to central storage systems (e.g., the cloud or a data lake) [8–10]. In addition, as sensitive data is directly handled at the edge, ensuring its confidentiality, integrity, and availability has become even more important, with cryptographic mechanisms playing a key role in meeting these requirements [11–13].

Cryptographic algorithms are classified into symmetric-key algorithms (e.g., AES, ChaCha20) and asymmetric-key algorithms (e.g., RSA, ECC), each with different computational structures, key management methods, and resource requirements [14–16]. For example, AES is widely used in low-power wireless protocols such as Zigbee [17] and Bluetooth [18], while ChaCha20 is adopted in mobile environments and TLS due to its efficient software implementation [19]. In addition, RSA and ECC are used for key exchange and initial authentication in systems like smart cards, vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) communication, and IoT authentication [20]. However, the structure and execution characteristics of cryptographic algorithms have a significant impact on how many system resources they consume. Specifically, resource usage varies depending on factors such as processing capacity, available energy, and application context. The impact of these factors becomes more critical when edge devices face tight constraints in CPU power, battery life, memory, and thermal management [21,22]. As a result, edge devices such as autonomous vehicles, wearables, and sensors are highly sensitive to the resource demands of cryptographic algorithms, which can directly affect overall system performance. Therefore, algorithms used in such environments must minimize computational overhead to ensure stable and efficient operation under constrained resources.

When cryptographic operations are executed on edge devices, the system can become unstable due to increased CPU usage, power consumption, and heat generation [13,23]. To address these limitations, parallel execution is often employed to reduce latency and improve efficiency [24–26]. However, the effectiveness and impact of such optimizations can vary depending on algorithmic characteristics and resource constraints. In some cases, improvements in execution time may be offset by increased overhead or unpredictable resource behavior, making it difficult to maintain real-time responsiveness [27]. To ensure stable operation in constrained environments, edge devices require detailed analysis of execution characteristics, along with a systematic approach to predict associated resource usage.

To address these constraints, many studies have analyzed the performance of cryptographic algorithms on edge devices from various perspectives. Makarenko et al. [28] examined CPU and memory usage of lightweight cryptographic algorithms. Panahi et al. [29] investigated the throughput and memory consumption of block ciphers. Sultan et al. [30] measured the power consumption of AES variants. However, most studies focus on overall performance without analyzing how resource usage changes across phases such as key generation, encryption, and decryption. They also rarely consider how parallel execution and scalability affect efficiency, especially in terms of power and thermal behavior. In this paper, we conduct a detailed phase-level analysis under different parallel execution settings, and additionally propose a prediction method to estimate resource usage across phases and configurations, supporting proactive and informed system-level decisions.

In this paper, we propose a phase-level resource analysis and prediction method for cryptographic workloads on edge devices. We first extract real-world license plate texts using a YOLOv8-based detection model and apply various cryptographic algorithms (AES-CBC, AES-CTR, AES-EAX, ChaCha20, ECC, and RSA) on an edge device. Each algorithm is evaluated across three execution phases under different parallel execution strategies. We monitor system resource usage during phases and train a Random Forest model using execution context and temporal features to predict resource demands under varying configurations. Our main contributions are as follows:

• We conduct a phase-level analysis of cryptographic algorithms by dividing operations into key generation, encryption, and decryption. For each phase, we systematically analyze resource usage under varying degrees of parallelism and execution strategies, identifying distinct usage patterns across algorithms and configurations.

• Building on our analysis, we propose a unified Random Forest-based prediction model that captures execution context and temporal resource dynamics to accurately forecast CPU, memory, power, and temperature usage across diverse configurations.

• Our proposed model achieves high accuracy for power (R2 = 0.994) and temperature (R2 = 0.988), two critical metrics for real-time control in edge devices, and enables proactive execution planning and overload prevention.

Cryptographic algorithms can be categorized into symmetric and asymmetric types, each offering different trade-offs in terms of performance, security, and computational overhead. Symmetric algorithms encrypt and decrypt data using a shared secret key and are typically faster and more lightweight, making them suitable for high-throughput or low-resource environments. In contrast, asymmetric algorithms use a public-private key pair and are widely employed for secure key exchange and authentication, albeit with higher computational cost [31,32].

AES (Advanced Encryption Standard). AES [33] is a symmetric block cipher that operates on 128-bit blocks and supports key sizes of 128, 192, and 256 bits. It uses a fixed number of iterative rounds depending on the key length to achieve strong confusion and diffusion. Due to its balance of high security and computational efficiency, AES has become a standard in various applications, including secure communications and data storage. AES-CBC (Cipher Block Chaining) [34] encrypts each block by combining it with the previous ciphertext block. This mode ensures ciphertext variability but introduces error propagation and limits parallelizability due to block dependency. AES-CTR (Counter Mode) encrypts a counter value and XORs it with the plaintext, making blocks independent and enabling parallel processing. It avoids error propagation and provides consistent encryption throughput. AES-EAX (Encrypt-then-Authenticate) [35] is an authenticated encryption mode that ensures both confidentiality and integrity. It performs encryption and tag generation concurrently, offering strong security guarantees with additional computational cost.

ChaCha20. ChaCha20 [15] is a stream cipher that generates a keystream by repeatedly applying a pseudorandom function to a combination of a secret key, a counter, and a nonce. Its core function consists of a series of simple arithmetic operations: modular addition, bitwise XOR, and bit rotation. These operations are uniformly applied over a fixed-size internal state, allowing for efficient and consistent performance across platforms, especially in software-only environments. Since the keystream blocks are generated independently, the encryption of different segments can proceed without inter-block dependency, contributing to its suitability for high-throughput and low-latency applications in constrained environments.

ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography). ECC [16] is a public-key cryptosystem that relies on the mathematical structure of elliptic curves over finite fields. Its security is based on the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem, which allows shorter keys to provide equivalent strength to longer RSA keys. The main computation involves scalar multiplication, where a point on the curve is repeatedly added to itself. This operation is typically implemented using iterative techniques such as the double-and-add method, where sub-steps like point doubling and point addition can be organized to minimize data dependencies. These characteristics enable implementation strategies that are well-suited for efficient processing in performance-sensitive or resource-constrained environments.

RSA (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman). RSA [36] is a public-key cryptosystem whose security is based on the computational difficulty of factoring large integers. Its primary operations are modular exponentiation for encryption and decryption, typically involving large integers and repeated squaring and multiplication. During these computations, intermediate steps such as individual modular multiplications do not rely on the outcomes of adjacent steps, making them structurally separable. This inherent modularity allows for efficient implementation techniques where sub-operations can be independently optimized or scheduled.

2.2 Resource Constraints on Edge Devices

Edge devices serve as critical components in the IoT ecosystem by processing and analyzing data near the source, thereby reducing latency and network bandwidth usage [37]. However, these devices are typically constrained in processing power, memory capacity, energy availability, and thermal management capabilities. Ensuring reliable real-time performance thus requires careful management of limited system resources. Additionally, the integration of cryptographic algorithms adds further computational overhead. Algorithms such as RSA or AES with long key lengths require considerable CPU and memory resources, potentially increasing latency, power consumption, and device temperature [38]. Since edge devices are responsible for handling sensitive information securely, it is important to understand how different cryptographic algorithms affect system resources to ensure that security measures can be deployed without compromising performance or stability. Given these considerations, characterizing how system metrics behave under different execution settings is essential. Resource usage not only varies across algorithm types and phases, but also exhibits interdependent behavior. For example, high CPU usage can lead to increased power consumption and thermal output, while memory utilization often fluctuates with parallelization strategies. Understanding these interactions is important to prevent system overload, ensure real-time responsiveness, and maintain secure operation under constrained conditions.

Several strategies have been pursued to mitigate these limitations. Algorithm optimization reduces per-operation cost by adopting lightweight or parallelizable schemes and adjusting parameters such as key length [39–41]. Edge-cloud collaboration alleviates local bottlenecks by offloading compute- or memory-intensive operations to cloud resources through secure communication channels (e.g., TLS [42]) [43–45]. Hardware acceleration and architectural enhancements, including secure enclaves, cryptographic hardware accelerators, and energy-efficient SoCs, improve throughput and stability at the system level [46–48]. While effective, these strategies largely rely on static design choices or infrastructure support. However, cryptographic algorithms on edge devices involve distinct operational stages such as key generation, encryption, and decryption, and thus often exhibit highly variable resource behavior per stage at runtime. Such variability cannot be fully anticipated by optimization, offloading, or hardware enhancement alone. Understanding these dynamics is therefore essential to ensure that additional strategies can be applied effectively under constrained conditions.

To predict the resource usage of cryptographic algorithms, it is crucial to understand their characteristics and how they behave under diverse execution conditions. Based on this analysis, we design a predictive model to estimate system-level metrics such as CPU and memory utilization, power consumption, and temperature. For the analysis and prediction, we used a System-on-Chip (SoC) device, the Jetson Orin Nano, equipped with a 6-core Arm Cortex-A78AE CPU and 8 GB of memory. The device runs Ubuntu 20.04.5 LTS with Linux kernel version 5.10.104. For cryptographic modules, we used PyCryptodome 3.20.0 [49] (AES-CBC, AES-CTR, AES-EAX, ChaCha20, and RSA with PKCS1_OAEP) and ecdsa 0.19.0 [50] (ECC with the NIST256p curve). All implementations were executed under Python 3.8.10.

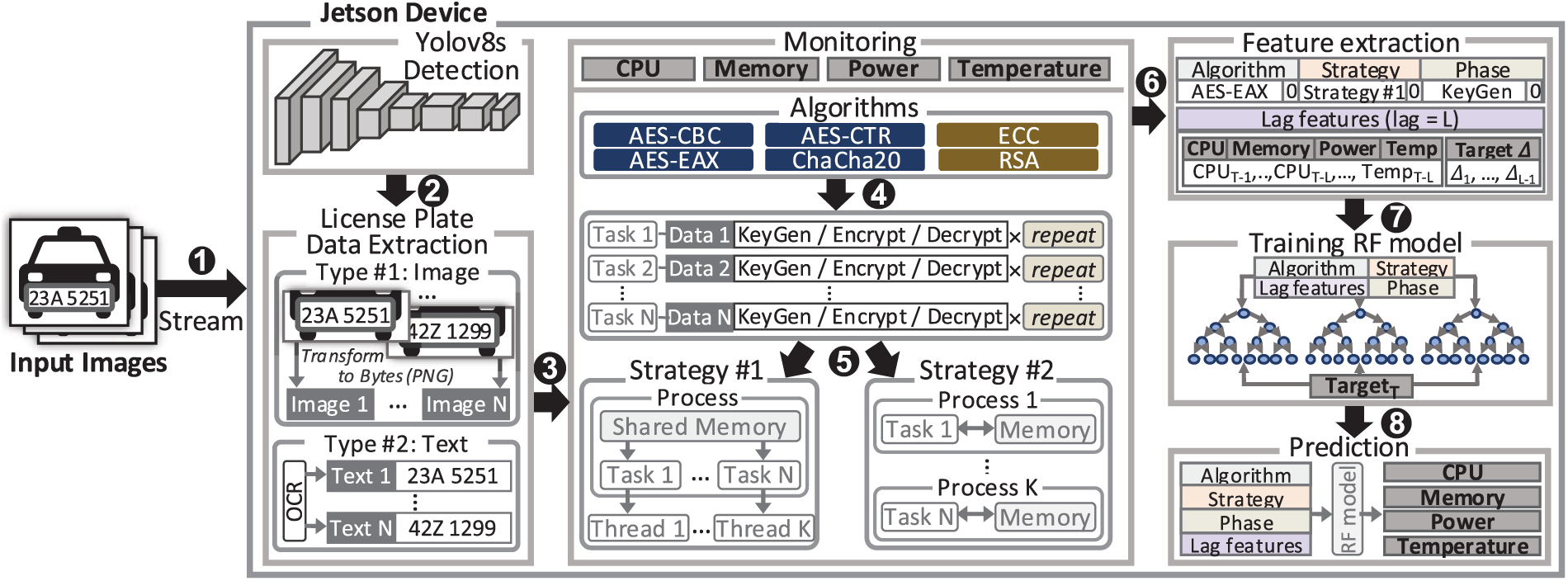

Fig. 1 shows the overall procedure for data collection, processing, and modeling on an edge device. We used 368 vehicle license plate images from Kaggle [51] and applied a YOLOv8s-based detection model to extract license plate regions (❶). From each region, we extracted two data types: cropped bounding box images in PNG byte format (Image 1,

Figure 1: Overall procedure

For prediction, the extracted data was preprocessed by encoding categorical features (algorithm, execution strategy, and phase) and by generating lag features at each prediction time step T (❻). Each lag feature included the L most recent values of the resource usage metrics (from

To understand the overall computational cost and scalability of cryptographic algorithms on edge devices, we first analyze how each algorithm behaves across the three fundamental phases (i.e., key generation, encryption, and decryption) under varying levels and types of parallelism and across different data types (i.e., text and image), based on the observed resource consumption.

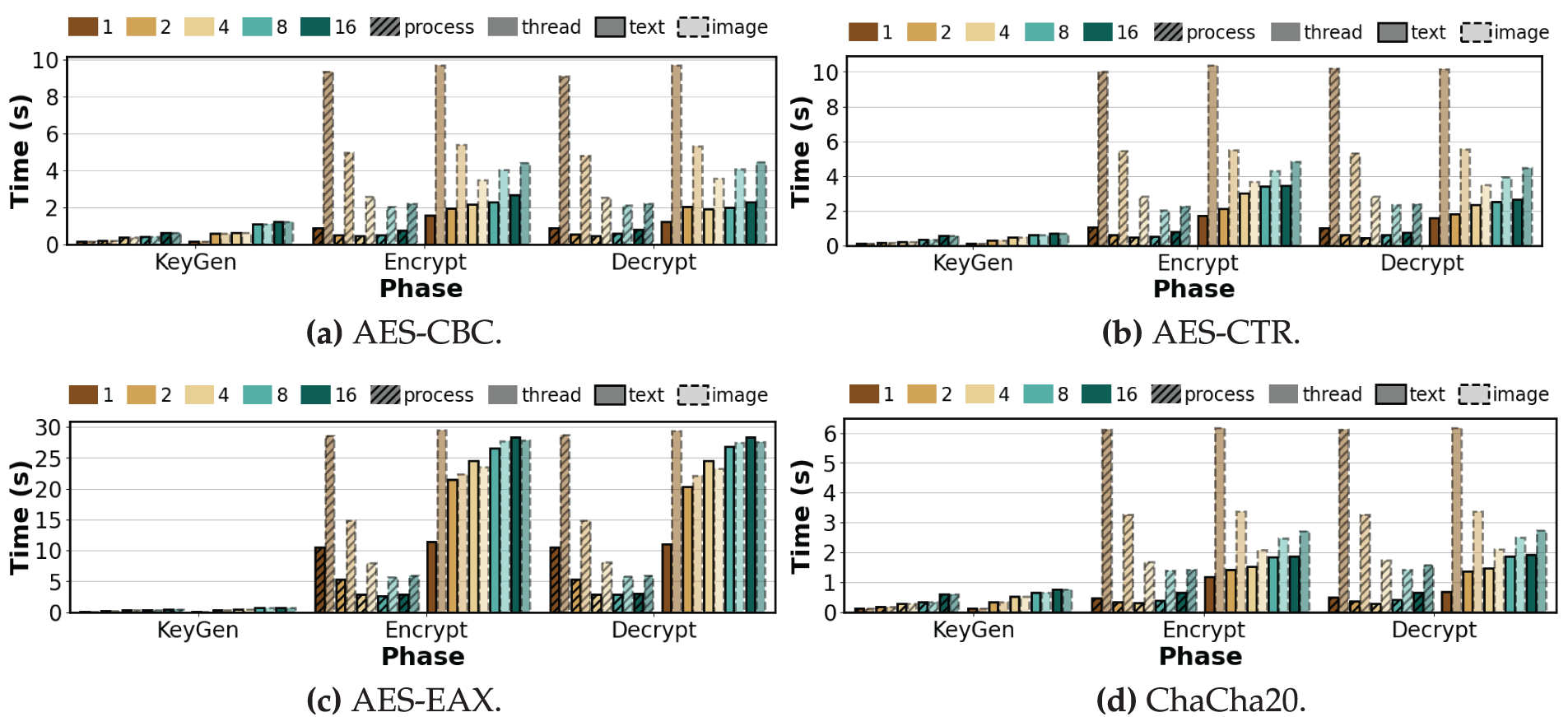

In this section, we compare the phase-level execution time trends of key generation, encryption, and decryption across cryptographic algorithms for different data types under varying levels of parallelism (K = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16) and execution strategies (process-level, thread-level). Figs. 2 and 3 show these trends according to algorithm characteristics.

Figure 2: Total execution time per phase of symmetric algorithms under varying degrees of process-level and thread-level parallelism (repeat count = 100, K = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16)

Figure 3: Total execution time per phase of asymmetric algorithms under varying degrees of process-level and thread-level parallelism (repeat count = 100, K = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16)

Key Generation. As shown in Fig. 2, AES variants and ChaCha20 complete within approximately one second for both text and image data. This is because key generation involves only the creation of cryptographic keys and does not process the input payload itself, making the operation identical regardless of data type. Due to the lightweight computation, benefits from parallelism are limited, and execution time increases with larger K values, both in process-level and thread-level parallelism, due to synchronization and context-switching overheads. As shown in Fig. 3, ECC and RSA also maintain similar characteristics across data types due to identical operation: ECC benefits significantly from process-level parallelism (time decreasing from 37.29 s to 8.79 s,

Encryption. Unlike text data, image data requires several seconds in the encryption phase due to larger input sizes. For example, AES-CBC at

Decryption. Decryption results generally mirror encryption, but with heavier absolute costs for images. Symmetric algorithms and ECC show similar trends, with process-level parallelism scaling effectively up to

Observation 1: On edge devices, the effectiveness of parallelism depends on the operations in each phase, input size, and available cores. Lightweight phases gain little from parallelism and suffer from thread-level overhead, while heavy phases expose severe slowdowns for large inputs under thread-level parallelism due to cache contention, making process-level isolation more scalable.

3.2.2 Hardware Utilization Analysis

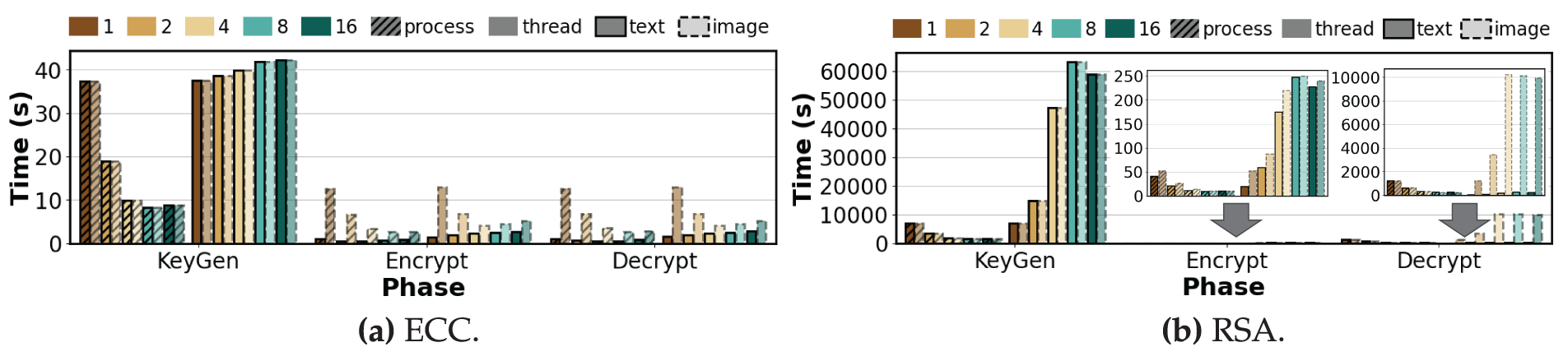

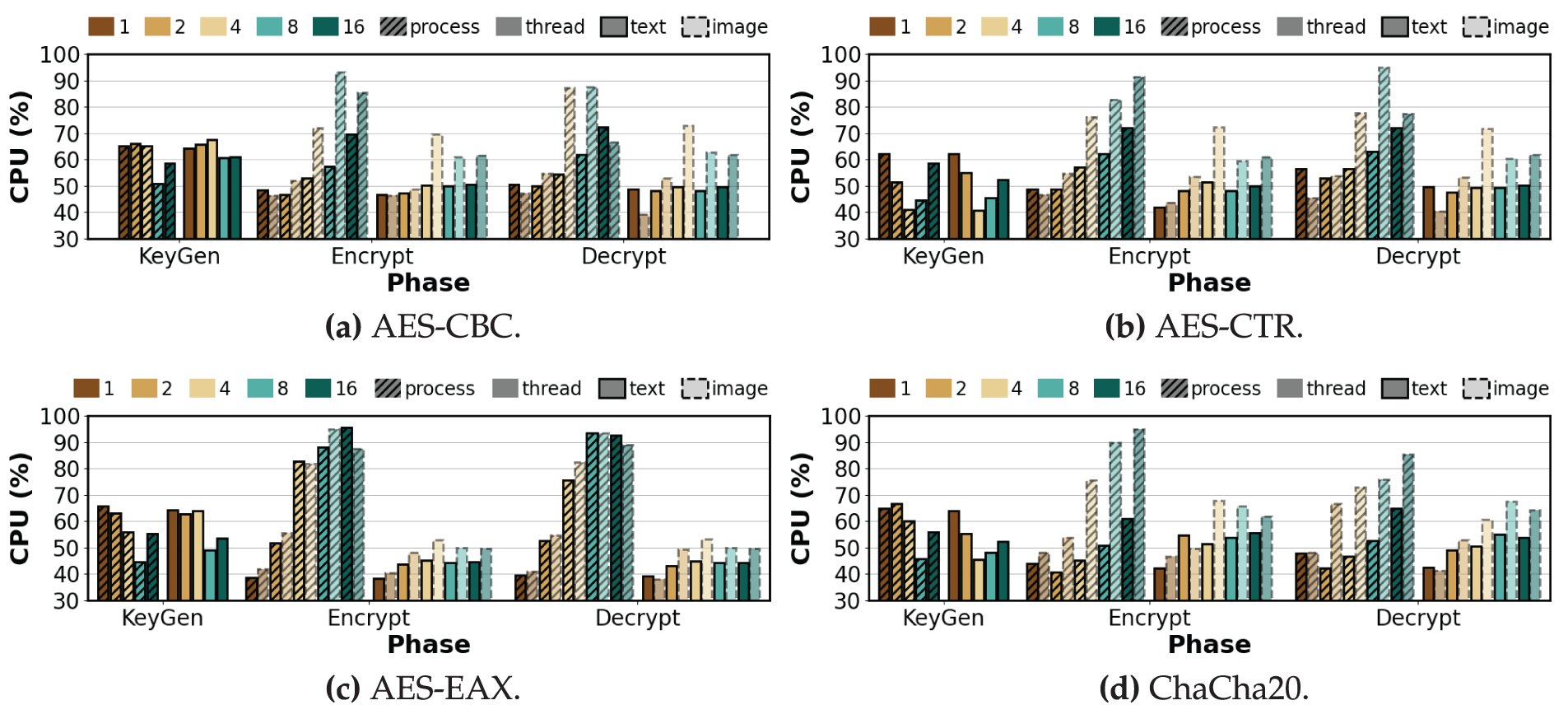

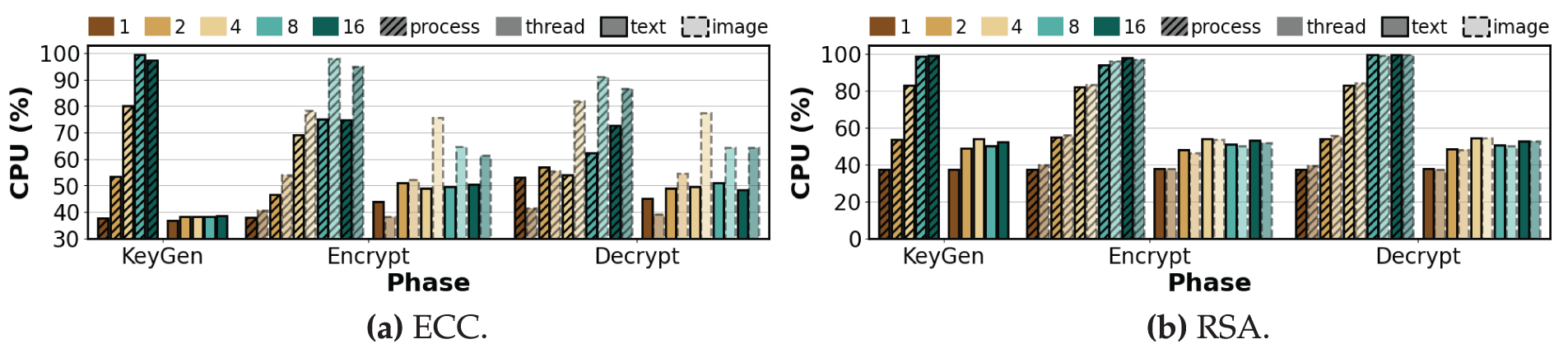

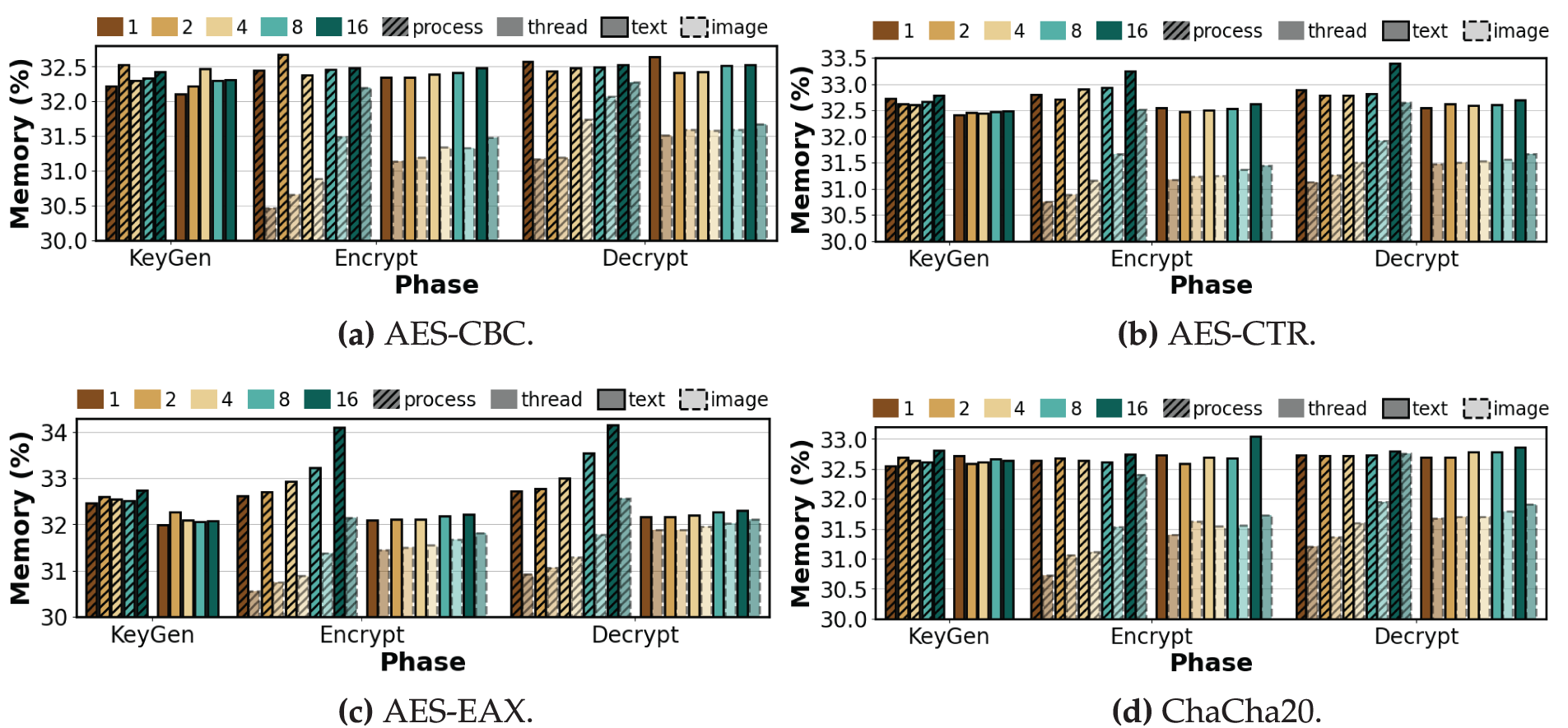

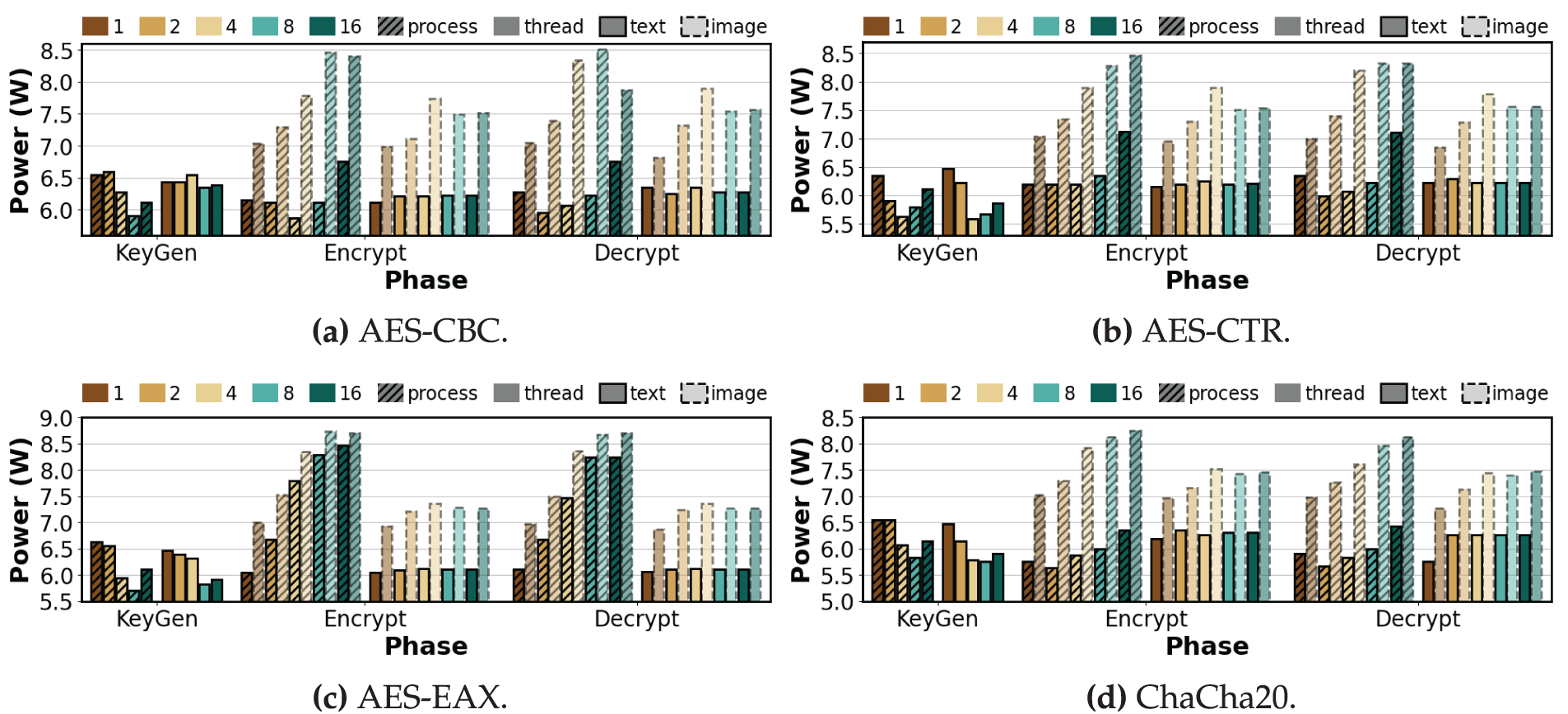

In this section, we analyze CPU and memory usage by phase under varying degrees of parallelism (

Figure 4: Average CPU utilization per phase of symmetric algorithms under varying degrees of process-level and thread-level parallelism (repeat count = 100, K = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16)

Figure 5: Average CPU utilization per phase of asymmetric algorithms under varying degrees of process-level and thread-level parallelism (repeat count = 100, K = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16)

Figure 6: Average memory utilization per phase of symmetric algorithms under varying degrees of process-level and thread-level parallelism (repeat count = 100, K = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16)

Figure 7: Average memory utilization per phase of asymmetric algorithms under varying degrees of process-level and thread-level parallelism (repeat count = 100, K = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16)

Key Generation. Since key generation is independent of the input, the following trends apply equally to text and image data. As shown in Figs. 4 and 6, the AES variants and ChaCha20 showed decreases in CPU usage as K increased, while RAM remained essentially flat with minimal drift. For example, the process-level CPU usage of AES-CBC decreased by 14.33% from

Encryption. Across all ciphers, the trend of CPU usage relative to K is similar for both text and image data. Image data primarily results in a higher magnitude of usage at high K under process-level execution because per-process input handling and buffer staging are repeated in each process, whereas threads share buffers, which reduces per-thread overhead. As shown in Fig. 4a,b, under process-level execution AES-CBC and AES-CTR increase in CPU usage with K for text. At

Decryption.As in encryption, CPU usage for both input types increases with K, but processing image data amplifies process-level CPU growth—especially from

Observation 2:In process-level decryption, RSA is the most demanding, with CPU usage reaching 99.5% and RAM usage increasing by 2.63%. Processing image data mainly amplifies the magnitude of this usage at high parallelism: process-level CPU usage for images grows about 20%–30% more than for text, and process-level RAM usage rises modestly by about 1%–2% across ciphers, while thread-level changes remain below 0.24%.

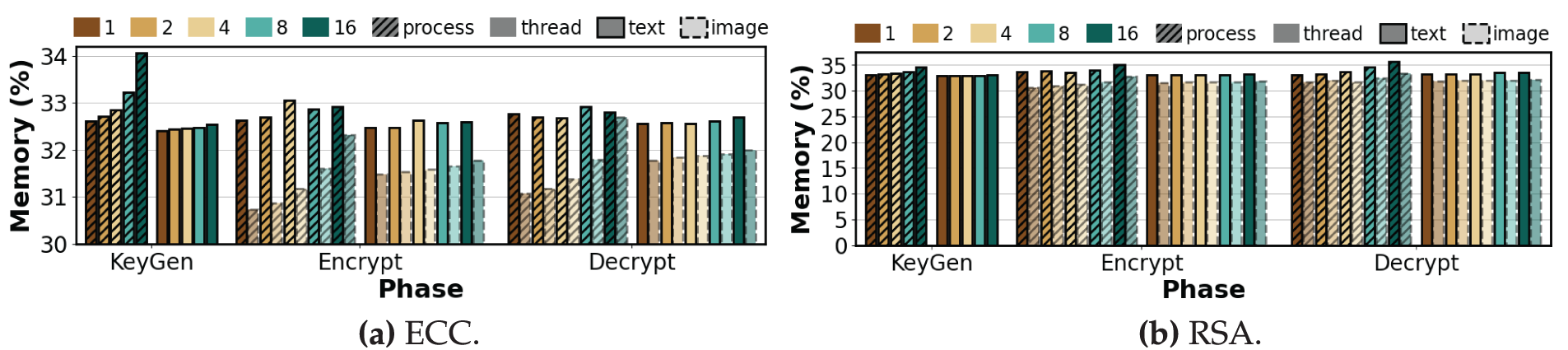

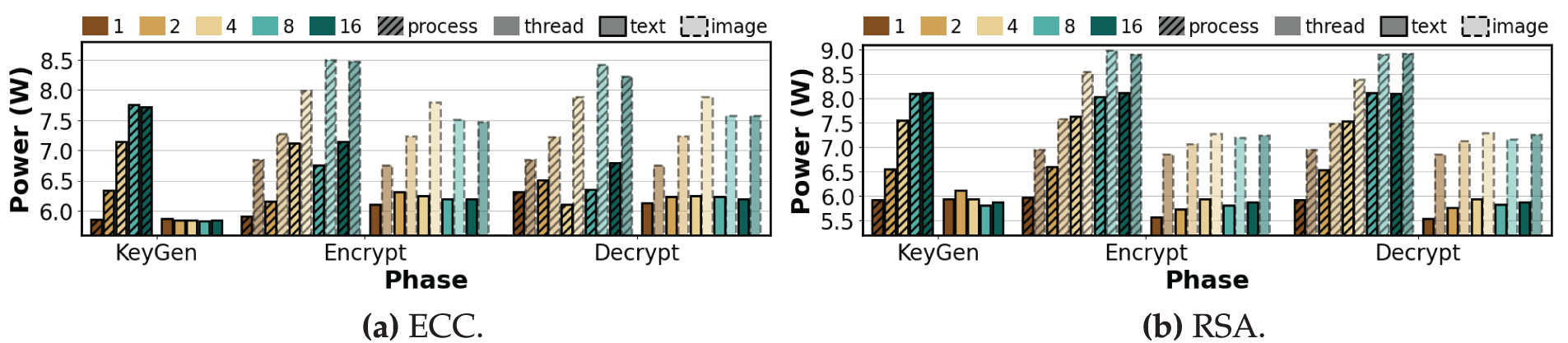

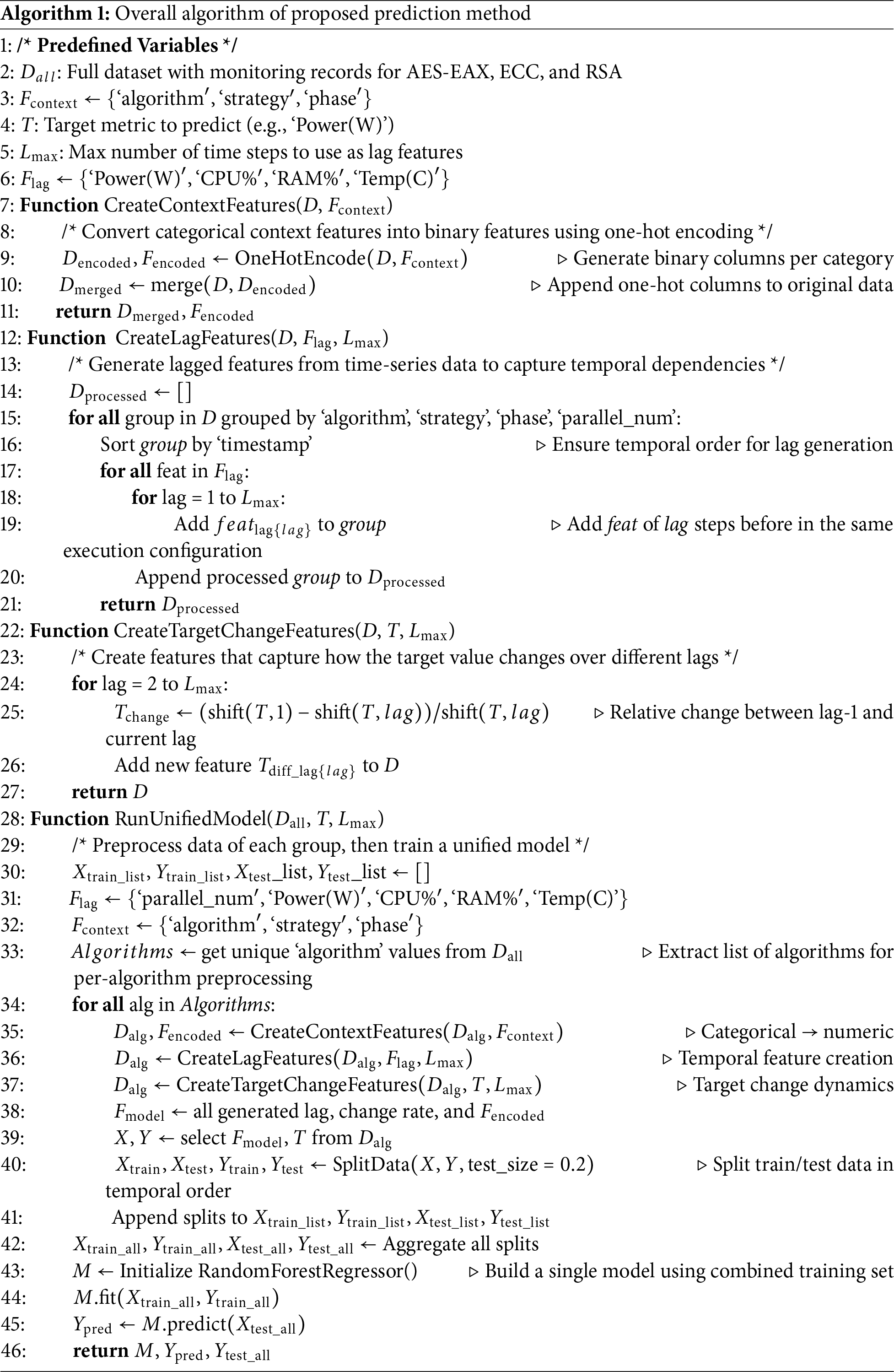

In this section, we analyze the average power consumption (W) for the different phases across different levels of parallelism (K = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16) and execution strategies (process-level, thread-level). Since the key generation phase is input-independent and does not consume input data, power consumption is identical for text and images; we therefore report only text results, with image runs following the same trend. Figs. 8 and 9 show the power consumption trends per phase, strategy, and degree of parallelism.

Figure 8: Average power consumption per phase of symmetric algorithms under varying degrees of process-level and thread-level parallelism (repeat count = 100, K = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16)

Figure 9: Average power consumption per phase of asymmetric algorithms under varying degrees of process-level and thread-level parallelism (repeat count = 100, K = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16)

Key Generation. As shown in Fig. 8a, AES-CBC under process-level execution shows a slight increase from 6.55 to 6.59 W as K increases, followed by a decrease to 6.27 and 5.91 W, then a rise again to 6.11 W at

Encryption. As shown in Fig. 8a, AES-CBC under process-level execution first decreases from 6.15 to 5.87 W, then increases to 6.11 and 6.75 W at

Decryption. AES-CBC and AES-CTR both show an increase in process-level power from 5.95 to 6.75 W and from 5.99 to 7.11 W, respectively, excluding the value at

Observation 3:Process-level parallelism increases power. Power consumption for AES variants and ChaCha20 grows mainly during encryption, with little or even reduced power in key generation; among symmetric modes, AES-EAX rises the most. Power consumption for ECC and RSA increases steadily across all phases, indicating higher sensitivity in compute-intensive algorithms. Power consumption trends for text and image data are similar; image data chiefly amplifies the magnitude at high parallelism under process-level runs, while thread-level power stays within a narrow band.

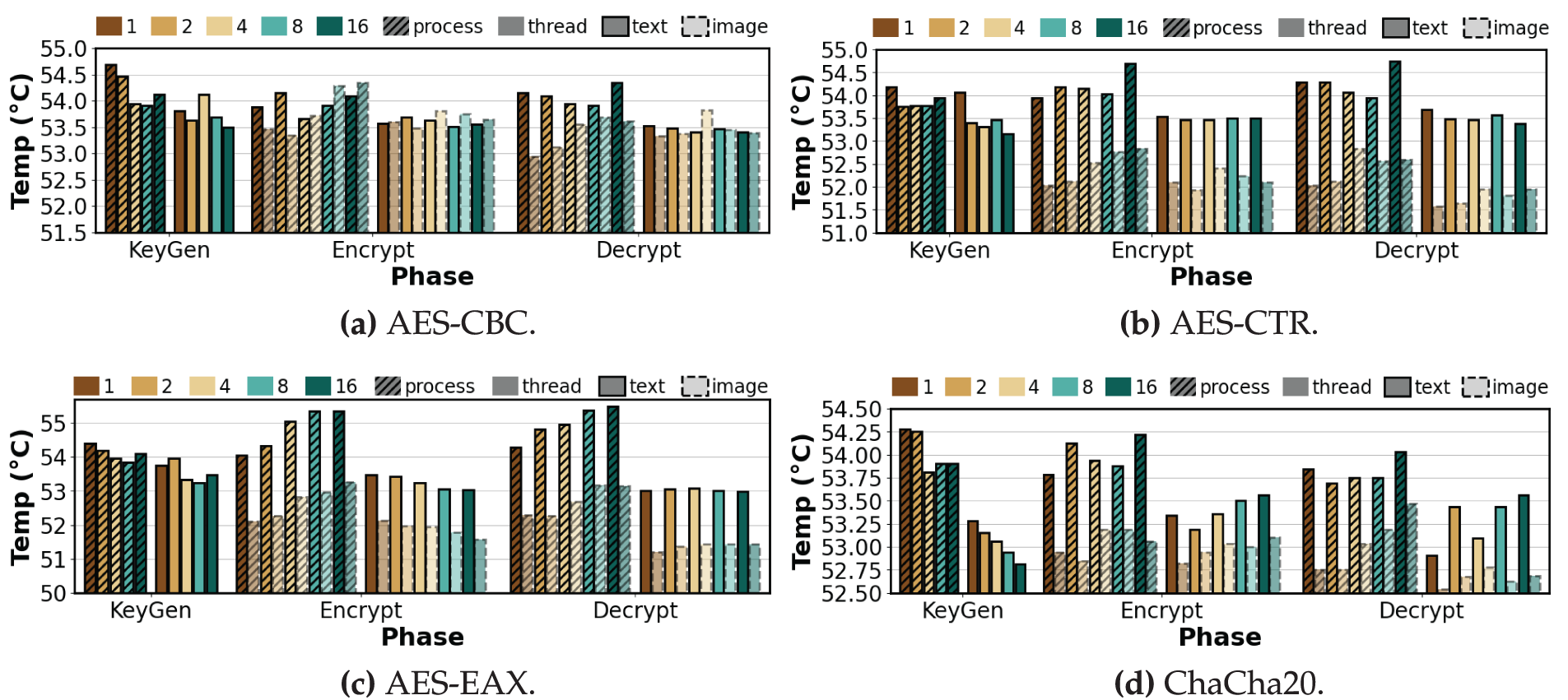

In this section, we analyze the average temperature

Figure 10: Average temperature per phase of symmetric algorithms under varying degrees of process-level and thread-level parallelism (repeat count = 100, K = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16)

Figure 11: Average temperature per phase of asymmetric algorithms under varying degrees of process-level and thread-level parallelism (repeat count = 100, K = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16)

Key Generation. As shown in Fig. 10, symmetric algorithms exhibited minimal and stable temperature fluctuations despite increasing K. In the case of AES-CBC, the temperature under process-level execution decreased from 54.69°C at K = 1 to 53.94°C at K = 4, and then slightly increased to 54.12°C at K = 16. Under thread-level execution, the temperature ranged between 53.50°C and 53.81°C, with a marginal difference of 0.3°C. AES-CTR maintained temperatures between 53.75°C and 54.19°C in process-level execution. In thread-level execution, the temperature dropped from 54.06°C to 53.31°C at K = 4, increased slightly to 53.47°C at K = 8, and then dropped again to 53.16°C at K = 16. For AES-EAX, the temperature in process-level execution decreased from 54.41°C to 53.84°C up to K = 8, and then rose to 54.09°C at K = 16. In thread-level execution, it increased from 53.75°C to 53.97°C at K = 2, decreased to 52.94°C at K = 8, and rose again to 53.47°C at K = 16. ChaCha20 showed a decreasing trend from 54.28°C to 53.91°C in process-level execution and from 53.28°C to 52.81°C in thread-level execution. In contrast, as shown in Fig. 11, asymmetric algorithms exhibited larger temperature variations, especially in process-level execution, where the temperature increased with higher K values. In ECC, the temperature under process-level execution increased from 53.96°C to 55.04°C, whereas under thread-level execution, it decreased from 53.56°C to 52.49°C. RSA showed the largest temperature difference, with an increase of 4.6°C from 48.21°C to 52.81°C in process-level execution. In thread-level execution, the temperature remained more stable, ranging from 51.17°C to 51.96°C, indicating lower thermal variation compared to process-level execution.

Encryption. As shown in Fig. 10a, the temperature for AES-CBC with text is nearly flat across K, with a net increase of

Decryption. AES-CBC shows a process-level temperature increase of 0.33% from

Observation 4:Process-level temperatures rise with increasing K, whereas thread-level temperatures stay flat or slightly decreases. RSA shows the largest process-level increase in decryption, up to

In this section, we present our feature generation method and unified prediction model, which are designed to learn from the diverse resource usage patterns identified in our analysis. For training and evaluation, we focus on AES-EAX, ECC, and RSA, as they exhibit the most distinct system resource consumption behaviors across phases and configurations.

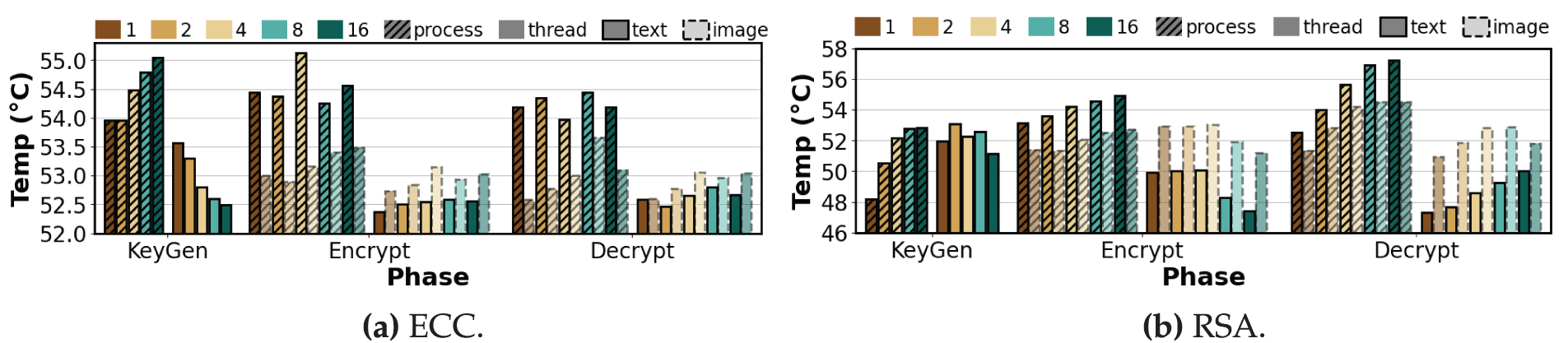

In Algorithm 1, we show the simplified process of generating features from resource monitoring data and a training a unified prediction model for cryptographic algorithms. As shown in the algorithm, our method consists of four functions: CreateContextFeatures, CreateLag Features, CreateTargetChangeFeatures, and RunUnifiedModel. First, input data and variables used throughout the algorithm are initialized (Lines 1–6).

CreateContextFeatures encodes categorical execution contexts as binary features using one-hot encoding and merges them into the original dataframe (Lines 7–11). These context features capture differences in resource behavior based on algorithm type and execution phase. For example, AES-EAX is a symmetric block cipher with AEAD support, while ECC and RSA are asymmetric algorithms. RSA, in particular, tends to show higher computation and power demands in the encryption and decryption phases under process-level parallelism compared to ECC. Thus, even within the same algorithm, resource usage patterns differ significantly depending on the execution strategy (process-level vs. thread-level) and the phase (e.g., key generation vs. encryption). To reflect these variations, we encode algorithm, strategy, and phase as binary vectors so that the model can learn resource usage patterns under different execution configurations.

CreateLagFeatures generates time-lagged features based on system metrics (Lines 12–21). For each algorithm-strategy-phase-parallelism group, monitoring records are sorted by timestamp, and past values from

Here,

RunUnifiedModel handles the end-to-end training process for resource usage prediction (Lines 28–46). Given a merged dataframe containing context features, configuration, and resource usage features, it iterates through each cryptographic algorithm, generates lag features and context features (Lines 35–37), and splits data into training and testing sets in temporal order (Line 40). These sets are then merged into a single training pool (Line 42). A unified RandomForestRegressor is trained on this combined dataset to capture generalized resource usage patterns across algorithms and configurations (Lines 43–44). The function returns the trained model M, predicted values

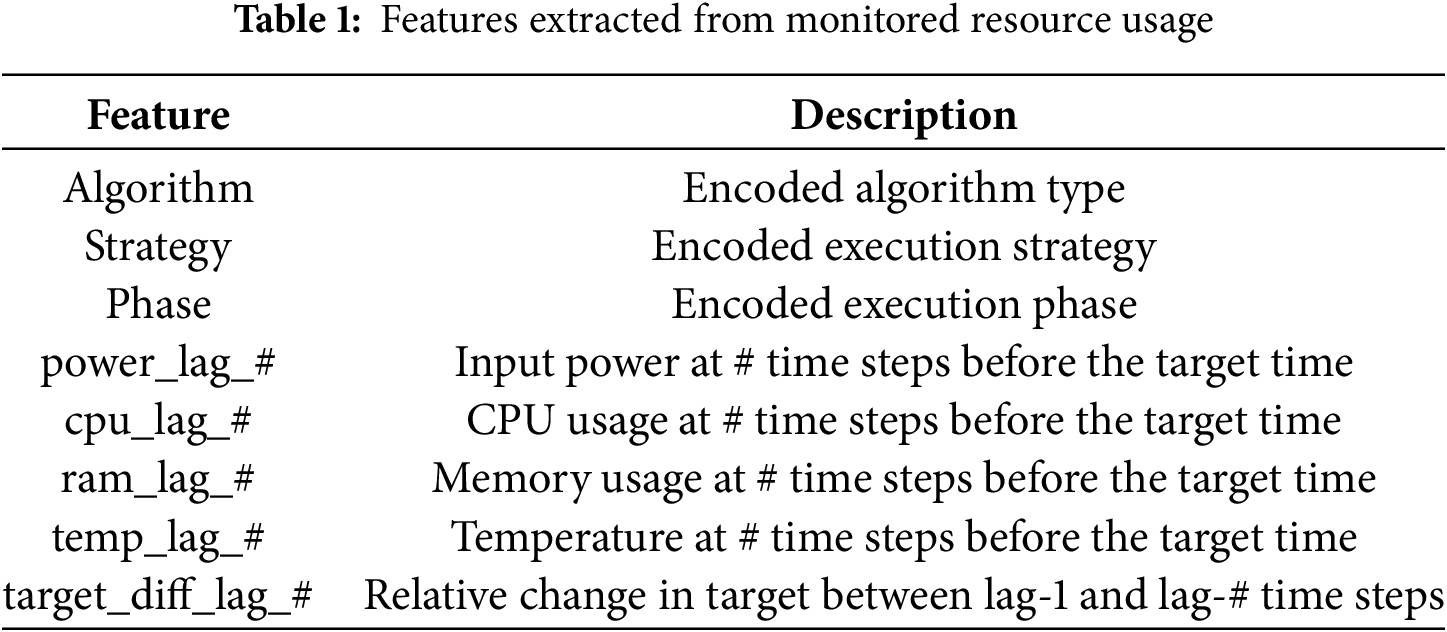

Table 1 shows the features used in Algorithm 1. The functions CreateContextFeatures, CreateLagFeatures, and CreateTargetChangeFeatures generate features for execution context (algorithm, strategy, and phase), time-series resource usage ([power/cpu/memory/temp]_lag_#), and changes in the target metric (target_diff_lag_#). In particular, lag features use past values to help predict future resource usage, while change features reflect usage trends.

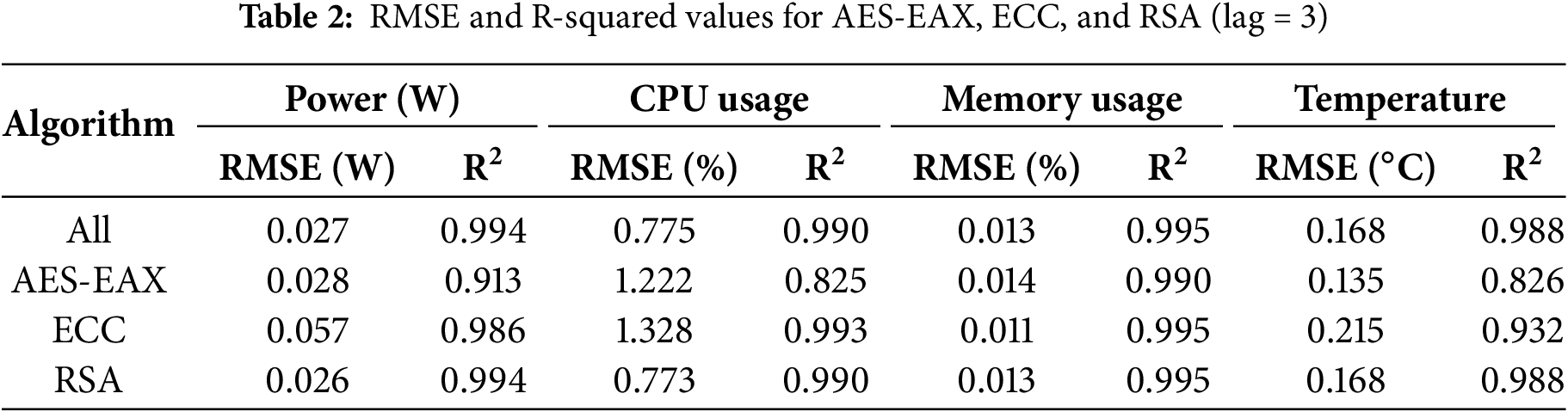

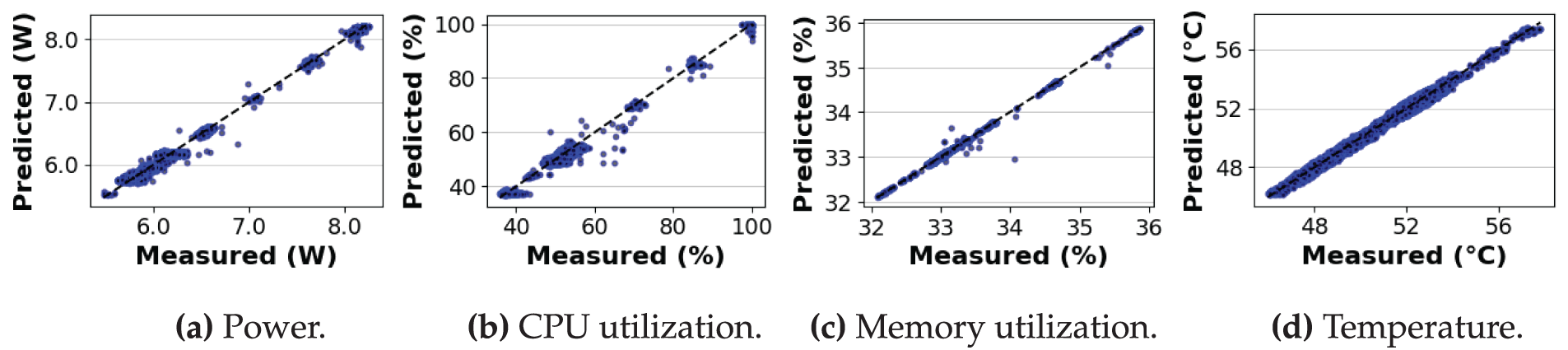

Table 2 presents the prediction results for the algorithms AES-EAX, ECC, and RSA with a lag of 3. As shown in the table, the root mean square error (RMSE) and the coefficient of determination (R2) for four system metrics are reported: power in W, CPU usage in %, memory usage in %, and temperature in °C. Fig. 12a–d shows the predicted values compared to the actual monitored measurements using scatter plots. As shown in the figures, the black dotted line indicates the case of a perfect prediction, where the predicted value is equal to the measured value.

Figure 12: Resource usage prediction results for AES-EAX, ECC, and RSA (lag = 3)

Power. For power, the model achieved an overall RMSE of 0.027 W and R2 of 0.994 across all algorithms. Among the three algorithms, ECC had the highest RMSE of 0.057 W. AES-EAX and RSA showed similar errors, with RMSE values of 0.028 and 0.026 W, respectively. These correspond to approximately 0.49%, 0.98%, and 0.47% of the minimum average power consumption for AES-EAX, ECC, and RSA, respectively. In terms of R2, RSA and ECC showed high accuracy with values of 0.994 and 0.986, respectively, while AES-EAX recorded a lower R2 of 0.913. This lower value is mainly due to the limited power variation of AES-EAX across different phases and levels of parallelism, which resulted in lower variance and a corresponding decrease in R2 despite the small RMSE.

Hardware utilization. For CPU utilization, the prediction was also highly accurate, with an overall R2 of 0.990. However, AES-EAX had the lowest R2 of 0.825. This is because CPU utilization for AES-EAX during encryption and decryption under thread-level execution remained in the mid-20% range and showed little variation. ECC, in contrast, exhibited larger differences across phases and execution types, particularly with high CPU load during encryption and decryption when process-level parallelism was used. As a result, ECC recorded the highest RMSE of 1.328% but also achieved a high R2 of 0.993. RSA showed high variability in CPU utilization with a clear and predictable pattern. This led to an RMSE of 0.773% and an R2 of 0.990. In this case, the clear difference between process-level and thread-level execution helped distinguish CPU utilization patterns and improved the prediction performance. For memory utilization, the prediction was highly accurate for all algorithms. The average RMSE was 0.013% and R2 was 0.995. This strong performance is due to the stable and low variation of memory utilization, regardless of the algorithm or phase. Since the differences across algorithms were minimal, the results suggest that memory utilization is largely governed by consistent system-level behavior rather than the characteristics of each algorithm.

Temperature. For temperature, the overall prediction was also highly accurate, with an R2 of 0.988. AES-EAX had the lowest RMSE of 0.135°C, but also the lowest R2 of 0.826. The relatively low

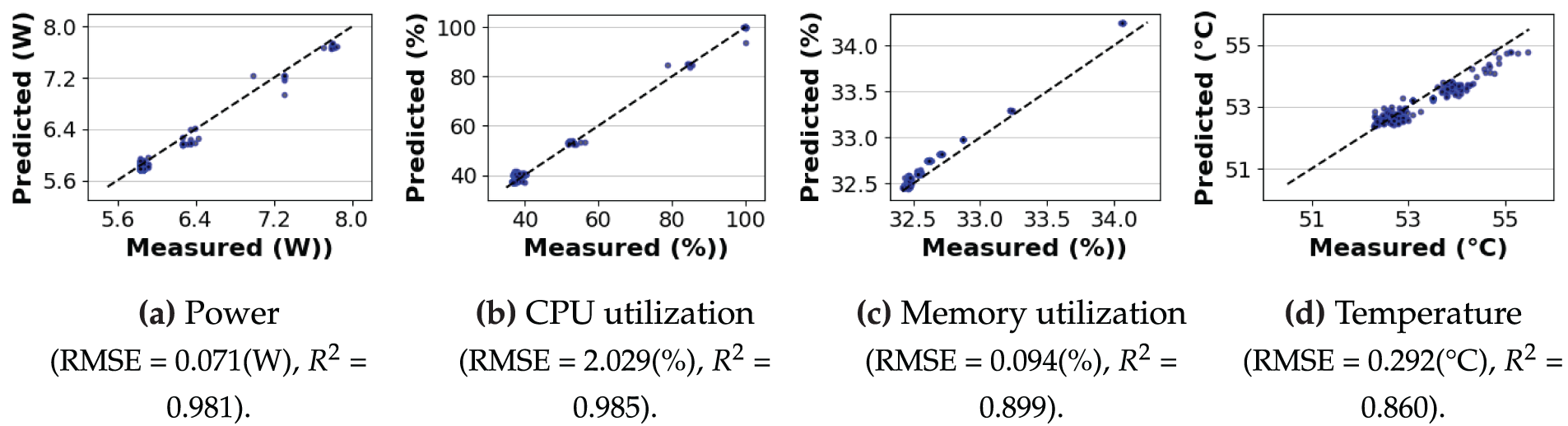

Generalization to an unseen algorithm. Fig. 13 shows the resource usage prediction results for a unified Random Forest model trained on AES-EAX and RSA and evaluated on ECC, which exhibits a distinct resource-usage trend relative to the a training algorithms. Compared to AES-EAX and RSA, ECC shows lower average CPU utilization during encryption and decryption at high parallelism. Additionally, it exhibits lower process-level power in those phases (

Figure 13: ECC resource usage prediction using a model trained on AES-EAX and RSA (lag = 3)

Observation 5: Prediction performance is not solely determined by algorithm complexity but by the interaction between phase-level behaviors and the intrinsic variability of each resource. Low variation can hinder R2, even with small RMSE, whereas structured fluctuations improve predictability.

4.1 Cryptography Performance on Resource-Constrained Edge Devices

Several studies have analyzed the resource usage of cryptographic algorithms to optimize their performance under the constrained hardware conditions of edge devices. Makarenko et al. [28] measured key performance indicators such as energy consumption, power usage, memory footprint, and throughput through simulation-based evaluation of symmetric encryption algorithms. Panahi et al. [29] evaluated lightweight block ciphers on widely used IoT platforms, showing that algorithms optimized for hardware environments can be inefficient when deployed in software contexts. Fotovvat et al. [55] analyzed various lightweight encryption algorithms on embedded systems and demonstrated that such designs can reduce memory usage compared to conventional approaches. Mohammed and Abdul Wahab [56] developed a lightweight blockchain system to reduce computational overhead. While their method shows significant performance gains, it requires deploying a new architecture rather than managing existing, widely-adopted cryptographic standards.

Our work contributes to this field by providing a detailed performance analysis of widely used cryptographic algorithms on edge devices. However, unlike prior work, we perform a phase-level analysis by separating each algorithm into key generation, encryption, and decryption, and evaluate how resource usage changes across these phases under different parallel execution strategies. Furthermore, we propose a prediction method that leverages execution context to estimate resource usage with high accuracy (

4.2 Power Consumption and Thermal Impact of Encryption on Edge Devices

Many studies have focused on analyzing the power consumption of encryption algorithms on edge devices, offering insights into the energy efficiency of lightweight cryptography. Sultan et al. [30] showed that reducing rounds in AES variants can improve power efficiency on constrained platforms. Muñoz et al. [57] emphasized the benefits of hardware acceleration in enhancing the energy performance of AES implementations. Maitra et al. [58] compared hardware and software AES with a lightweight alternative, concluding that while hardware-accelerated AES was most efficient, the lightweight option offered similar performance with lower memory overhead.

Our paper aligns with prior studies in examining the power characteristics of cryptographic algorithms on edge devices. However, we incorporate temperature as a key system metric and analyze the impact of execution strategies and parallelism levels on both power and thermal behavior. This broader perspective clarifies how algorithm type and execution configuration jointly affect power and temperature patterns under resource-constrained conditions. Additionally, by modeling these patterns, our proposed method enables accurate prediction of power and temperature, two critical factors for real-time control, and supports informed planning and overload avoidance in edge devices.

We acknowledge that our analysis remains limited in scope, as it is based on a restricted set of cryptographic algorithms and a single edge device platform. Monitoring granularity is also constrained, since production-suited tools report aggregated rather than per-operation signals. External factors such as ambient conditions, background tasks, and system-level scheduling may also contribute to variability, but capturing all of them in real time is not feasible. These constraints indicate that the present findings should be interpreted with caution, particularly when extrapolated beyond the evaluated environment.

Nevertheless, our phase-level analysis and prediction show that separating cryptographic workloads into phases reveals structural resource usage trends that aggregated measurements cannot capture. Although we used a subset of algorithms and a single edge device with a specific OS and kernel, this setup ensured reproducibility and stable driver support. The observed trends are rooted in algorithm structure rather than in artifacts of a particular software stack. In compute paths dominated by large-number arithmetic and complex control flow, thread-level parallelism can trigger lock contention and cache interference. In contrast, process-level execution isolates parallel jobs and reduces synchronization pressure. In block-parallel stages with independent per-chunk work, thread-level parallelism can be effective when synchronization is modest and data paths are vectorized. With respect to power and thermal behavior, higher degrees of process-level concurrency in compute-intensive stages increase aggregate activity and can elevate power draw and temperature depending on duty cycle and scheduling. Phases with light per-unit work show weaker sensitivity, which indicates that resource usage is highly phase-dependent rather than uniform. For prediction, phases with minimal thermal variability naturally yield lower

Building on these observations, our approach offers a basis for extension along several directions. It can be extended to a broader range of cryptographic algorithms by applying the same phase-level characterization and monitoring procedure to additional algorithms, including symmetric, asymmetric, and authenticated encryption schemes. This allows new algorithms to be analyzed under a consistent methodology without redesigning the pipeline. It can also be applied to heterogeneous SoCs and kernels by reusing the phase-aware collection and prediction pipeline, which remains valid even when absolute performance values shift across platforms. In this way, our proposed method not only supports portability but also enhances its generalizability. Moreover, the same design enables throttling-aware models that adapt predictions under varying workload conditions, and it provides a foundation for implementing the hybrid execution strategy end to end with library-level controls and core-affinity policies to reduce overhead while maintaining stability. In addition, the model can incorporate lightweight context features, such as ambient temperature or background load, while preserving the core pipeline. This would allow predictions to adapt more effectively to fluctuating workloads and environmental variation in real deployments. Taken together, these directions demonstrate how the proposed analysis provides practical grounds for developing generalizable and deployable cryptographic workloads on diverse edge devices.

In this paper, we present a phase-level resource analysis and prediction method for cryptographic algorithms on edge devices. Using AES variants, ChaCha20, ECC, and RSA on the Jetson Orin Nano, we applied the algorithms to two data types and monitored execution time, CPU and memory usage, power consumption, and temperature across key generation, encryption, and decryption phases under varying levels of parallelism. Furthermore, our unified prediction model achieved

Acknowledgement: This research was supported by the Chung-Ang University research grant in 2024 (Corresponding Author: Yongseok Son).

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (No. RS-2025-00554650).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Ehan Sohn, Sangmyung Lee and Kiwook Sohn; methodology, Ehan Sohn, Sangmyung Lee and Sunggon Kim; software, Ehan Sohn and Manish Kumar; validation, Ehan Sohn, Sangmyung Lee and Yongseok Son; formal analysis, Ehan Sohn and Sangmyung Lee; investigation, Ehan Sohn and Kiwook Sohn; resources, Kiwook Sohn, Sunggon Kim and Yongseok Son; data curation, Ehan Sohn, Sangmyung Lee and Manish Kumar; writing—original draft preparation, Ehan Sohn; review and editing, Sangmyung Lee, Sunggon Kim, Kiwook Sohn, Manish Kumar and Yongseok Son; visualization, Ehan Sohn; supervision, Sunggon Kim and Yongseok Son; project administration, Yongseok Son; funding acquisition, Yongseok Son. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1This paper is an extended version of our paper published at the 8th International Conference on Mobile Internet Security (Mobisec 2024), Sapporo, Japan, December 2024.

References

1. Wang J, Liu J, Kato N. Networking and communications in autonomous driving: a survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2018;21(2):1243–74. [Google Scholar]

2. Zanella A, Bui N, Castellani A, Vangelista L, Zorzi M. Internet of things for smart cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2014;1(1):22–32. doi:10.1109/jiot.2014.2306328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Islam SR, Kwak D, Kabir MH, Hossain M, Kwak KS. The internet of things for health care: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Access. 2015;3:678–708. doi:10.1109/access.2015.2437951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Da Xu L, He W, Li S. Internet of things in industries: a survey. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2014;10(4):2233–43. doi:10.1109/tii.2014.2300753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Perera C, Zaslavsky A, Christen P, Georgakopoulos D. Context aware computing for the internet of things: a survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2013;16(1):414–54. [Google Scholar]

6. Gubbi J, Buyya R, Marusic S, Palaniswami M. Internet of Things (IoTa vision, architectural elements, and future directions. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2013;29(7):1645–60. doi:10.1016/j.future.2013.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Al-Fuqaha A, Guizani M, Mohammadi M, Aledhari M, Ayyash M. Internet of things: a survey on enabling technologies, protocols, and applications. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2015;17(4):2347–76. [Google Scholar]

8. Shi W, Cao J, Zhang Q, Li Y, Xu L. Edge computing: vision and challenges. IEEE Interne Things J. 2016;3(5):637–46. doi:10.1109/jiot.2016.2579198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Mao Y, You C, Zhang J, Huang K, Letaief KB. A survey on mobile edge computing: the communication perspective. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2017;19(4):2322–58. [Google Scholar]

10. Weber RH. Internet of Things-New security and privacy challenges. Comput Law Secur Rev. 2010;26(1):23–30. [Google Scholar]

11. Chandu Y, Kumar KR, Prabhukhanolkar NV, Anish A, Rawal S. Design and implementation of hybrid encryption for security of IOT data. In: 2017 International Conference on Smart Technologies for Smart Nation (SmartTechCon); 2017 Aug 17–19. Bengaluru, India. p. 1228–31. [Google Scholar]

12. Bhandari R, Kirubanand V. Enhanced encryption technique for secure IoT data transmission. Int J Electr Comput Eng. 2019;9(5):3732. doi:10.11591/ijece.v9i5.pp3732-3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Singh S, Sharma PK, Moon SY, Park JH. Advanced lightweight encryption algorithms for IoT devices: survey, challenges and solutions. J Am Intell Humanized Comput. 2024;15(2):1625–42. doi:10.1007/s12652-017-0494-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Katz J, Lindell Y. Introduction to modern cryptography: principles and protocols. Boca Raton, FL, USA: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

15. Bernstein DJ. ChaCha, a variant of Salsa20. In: Workshop record of SASC. Easton, PA, USA: Citeseer; 2008. Vol. 8, p. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

16. Hankerson D, Menezes AJ, Vanstone S. Guide to elliptic curve cryptography. New York, NY, USA: Springer Science & Business Media; 2004. [Google Scholar]

17. Alliance. Zigbee alliance. WPAN industry group; 2010. [cited 2025 Sep 19]. Available form: https://csa-iot.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/05-3474-23-csg-zigbee-specification-compressed.pdf. p. 297. [Google Scholar]

18. Bluetooth SIG. Bluetooth core specification version 5.4, Specifies AES-CCM as a mandatory feature for LE Secure Connections; 2023. [Google Scholar]

19. Nir Y, Langley A. RFC 8439: ChaCha20 and Poly1305 for IETF Protocols. USA: RFC Editor; 2018. [Google Scholar]

20. Gura N, Patel A, Wander A, Eberle H, Shantz SC. Comparing elliptic curve cryptography and RSA on 8-bit CPUs. In: Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems-CHES 2004: 6th International Workshop. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2004. p. 119–32. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-28632-5_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Dhanda SS, Singh B, Jindal P. Lightweight cryptography: a solution to secure IoT. Wireless Personal Commun. 2020;112(3):1947–80. doi:10.1007/s11277-020-07134-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Aslan B, Yavuzer Aslan F, Sakallı MT. Energy consumption analysis of lightweight cryptographic algorithms that can be used in the security of Internet of Things applications. Secur Commun Netw. 2020;2020(1):8837671–15. doi:10.1155/2020/8837671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ledwaba LP, Hancke GP, Venter HS, Isaac SJ. Performance costs of software cryptography in securing new-generation Internet of energy endpoint devices. IEEE Access. 2018;6:9303–23. doi:10.1109/access.2018.2793301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mochurad L, Shchur G. Parallelization of cryptographic algorithm based on different parallel computing technologies. In: IT&AS’2021: Symposium on Information Technologies & Applied Sciences; 2021 Mar 5; Bratislava, Slovakia. p. 20–9. [Google Scholar]

25. Wang X, Feng L, Zhao H. Fast image encryption algorithm based on parallel computing system. Inform Sci. 2019;486:340–58. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2019.02.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Song W, Zheng Y, Fu C, Shan P. A novel batch image encryption algorithm using parallel computing. Inform Sci. 2020;518:211–24. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2020.01.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Samie F, Tsoutsouras V, Bauer L, Xydis S, Soudris D, Henkel J. Computation offloading and resource allocation for low-power IoT edge devices. In: 2016 IEEE 3rd World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT); 2016 Dec 12–14; Reston, VA, USA. p. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

28. Makarenko I, Semushin S, Suhai S, Kazmi SA, Oracevic A, Hussain R. A comparative analysis of cryptographic algorithms in the internet of things. In: 2020 International Scientific and Technical Conference Modern Computer Network Technologies (MoNeTeC); 2020 Oct 27–29; Moscow, Russia. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

29. Panahi P, Bayılmış C, Çavuşoğlu U, Kaçar S. Performance evaluation of lightweight encryption algorithms for IoT-based applications. Arab J Sci Eng. 2021;46(4):4015–37. doi:10.1007/s13369-021-05358-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Sultan I, Mir BJ, Banday MT. Analysis and optimization of advanced encryption standard for the internet of things. In: 2020 7th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN); 2020 Feb 27–28. Noida, India. p. 571–5. [Google Scholar]

31. Chandra S, Paira S, Alam SS, Sanyal G. A comparative survey of symmetric and asymmetric key cryptography. In: 2014 International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Computational Engineering (ICECCE); 2014 Nov 17–18. Hosur, India. p. 83–93. [Google Scholar]

32. Yassein MB, Aljawarneh S, Qawasmeh E, Mardini W, Khamayseh Y. Comprehensive study of symmetric key and asymmetric key encryption algorithms. In: 2017 International Conference on Engineering and Technology (ICET); 2017 Aug 21–23. Antalya, Turkey. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

33. Daemen J, Rijmen V. AES proposal: Rijndael. In: The Rijndael block cipher; 1999. [Google Scholar]

34. Frankel S, Glenn R, Kelly S. The aes-cbc cipher algorithm and its use with ipsec. In: Standards track. Reston, VA, USA: The Internet Society; 2003. [Google Scholar]

35. Bellare M, Rogaway P, Wagner D. The EAX mode of operation. In: International Workshop on Fast Software Encryption. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2004. p. 389–407. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-25937-4_25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Milanov E. The RSA algorithm. Hebron, CT, USA: RSA Laboratories; 2009. [Google Scholar]

37. Xiao Y, Jia Y, Liu C, Cheng X, Yu J, Lv W. Edge computing security: state of the art and challenges. Proc IEEE. 2019;107(8):1608–31. doi:10.1109/jproc.2019.2918437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Khan N, Sakib N, Jerin I, Quader S, Chakrabarty A. Performance analysis of security algorithms for IoT devices. In: 2017 IEEE Region 10 Humanitarian Technology Conference (R10-HTC); 2017 Dec 21–23. Dhaka, Bangladesh. p. 130–3. [Google Scholar]

39. Kim H, Seo H. Optimizing AES-GCM on 32-Bit ARM Cortex-M4 Microcontrollers: fixslicing and FACE-based approach. ACM Trans Embed Comput Syst. 2025;24(6):168–24. doi:10.1145/3766074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Ahmed S, Ahmad N, Shah NA, Abro GEM, Wijayanto A, Hirsi A, et al. Lightweight aes design for iot applications: optimizations in fpga and asic with dfa countermeasure strategies. IEEE Access. 2025;13:22489–509. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3533611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Cheng PY, Su YC, Chao PCP. Novel high throughput-to-area efficiency and strong-resilience datapath of AES for lightweight implementation in IoT devices. IEEE Internet of Things J. 2024;11(10):17678–87. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3359714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Dierks T, Allen C. RFC2246: the TLS protocol version 1.0. Marina del Rey, CA, USA: RFC Editor; 1999. [Google Scholar]

43. Nanos A, Mainas C, Papazafeiropoulos K, Giannousas A, Lagomatis I, Kretsis A. MLIoT: transparent and secure ML offloading in the cloud-edge-IoT continuum. In: 2025 IEEE 25th International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Internet Computing Workshops (CCGridW); 2025 May 19–22. Tromsø, Norway. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

44. Zhou J, Kondo M. An edge-cloud collaboration framework for graph processing in smart society. IEEE Trans Emerg Topics Comput. 2023;11(4):985–1001. doi:10.1109/tetc.2023.3297066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Gaikwad B, Karmakar A. End-to-end person re-identification: real-time video surveillance over edge-cloud environment. Comput Electr Eng. 2022;99:107824. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.107824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Puckett S, Liu J, Yoo SM, Morris TH. A secure and efficient protocol for lora using cryptographic hardware accelerators. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(24):22143–52. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3304175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Nguyen KD, Dang TK, Kieu-Do-Nguyen B, Le DH, Pham CK, Hoang TT. Asic implementation of ascon lightweight cryptography for IoT applications. IEEE Trans Circ Syst II Express Briefs. 2025;72(1):278–82. doi:10.1109/tcsii.2024.3483214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. He P, Bao T, Xie J, Amin M. FPGA implementation of compact hardware accelerators for ring-binary-LWE-based post-quantum cryptography. ACM Trans Reconfigurable Technol Syst. 2023;16(3):1–23. doi:10.1145/3569457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Legrand S. Pycryptodome. [cited 2025 Sep 19]. Available from: https://pypi.org/project/pycryptodome/. [Google Scholar]

50. Warner B. Ecdsa. [cited 2025 Sep 19]. Available from: https://pypi.org/project/ecdsa/. [Google Scholar]

51. Open Source License A. Kaggle License plate image [Online]. [cited 2025 Sep 19]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/code/tustunkok/license-plate-detection. [Google Scholar]

52. Foundation PS. Pytesseract. 2024 Aug 16 [cited 2025 Sep 19]. Available from: https://pypi.org/project/pytesseract/. [Google Scholar]

53. Corporation N. NVIDIA Jetson Stats [Online]. [cited 2025 Sep 19]. Available from: https://developer.nvidia.com/embedded/community/jetson-projects/jetson_stats. [Google Scholar]

54. Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

55. Fotovvat A, Rahman GM, Vedaei SS, Wahid KA. Comparative performance analysis of lightweight cryptography algorithms for IoT sensor nodes. IEEE Internet of Things J. 2020;8(10):8279–90. doi:10.1109/jiot.2020.3044526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Mohammed MA, Abdul Wahab HB. Enhancing IoT data security with lightweight blockchain and Okamoto Uchiyama homomorphic encryption. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;138(2):1731–48. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.030528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Munoz PS, Tran N, Craig B, Dezfouli B, Liu Y. Analyzing the resource utilization of AES encryption on IoT devices. In: 2018 Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC); 2018 Nov 12–15. Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 1200–7. [Google Scholar]

58. Maitra S, Richards D, Abdelgawad A, Yelamarthi K. Performance evaluation of IoT encryption algorithms: memory, timing, and energy. In: 2019 IEEE Sensors Applications Symposium (SAS); 2019 Mar 11–13. Sophia Antipolis, France. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools