Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Deep Learning and Federated Learning in Human Activity Recognition with Sensor Data: A Comprehensive Review

Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology, University Putra Malaysia (UPM), Serdang, 43400, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Farhad Mortezapour Shiri. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 1389-1485. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.071858

Received 13 August 2025; Accepted 06 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

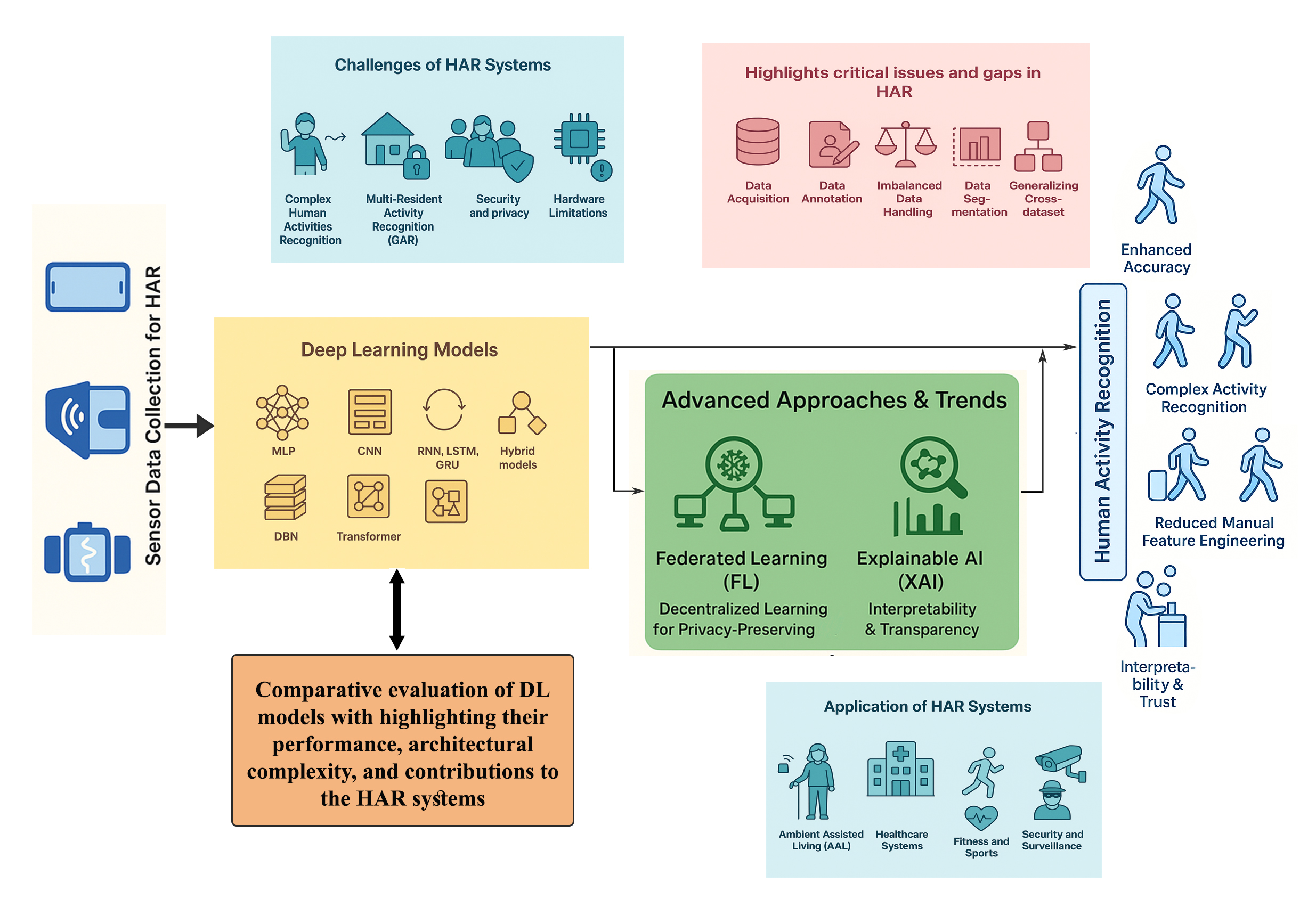

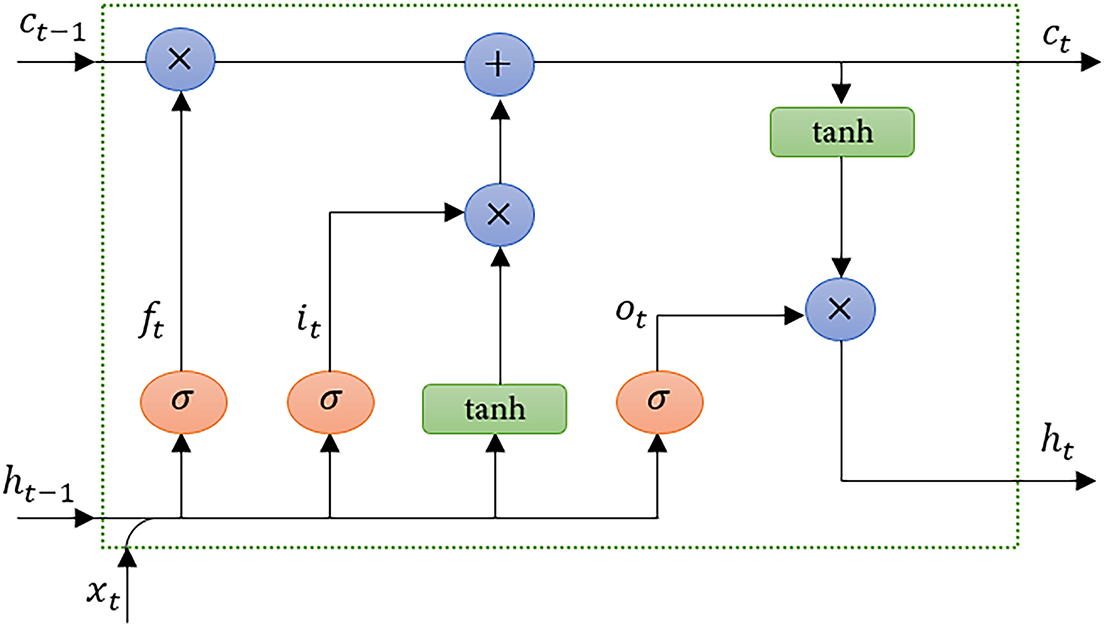

Human Activity Recognition (HAR) represents a rapidly advancing research domain, propelled by continuous developments in sensor technologies and the Internet of Things (IoT). Deep learning has become the dominant paradigm in sensor-based HAR systems, offering significant advantages over traditional machine learning methods by eliminating manual feature extraction, enhancing recognition accuracy for complex activities, and enabling the exploitation of unlabeled data through generative models. This paper provides a comprehensive review of recent advancements and emerging trends in deep learning models developed for sensor-based human activity recognition (HAR) systems. We begin with an overview of fundamental HAR concepts in sensor-driven contexts, followed by a systematic categorization and summary of existing research. Our survey encompasses a wide range of deep learning approaches, including Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTM), Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), Transformers, Deep Belief Networks (DBN), and hybrid architectures. A comparative evaluation of these models is provided, highlighting their performance, architectural complexity, and contributions to the field. Beyond Centralized deep learning models, we examine the role of Federated Learning (FL) in HAR, highlighting current applications and research directions. Finally, we discuss the growing importance of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in sensor-based HAR, reviewing recent studies that integrate interpretability methods to enhance transparency and trustworthiness in deep learning-based HAR systems.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The recent advancements on the Internet of Things (IoT) have led to the proliferation of embedded sensors across a vast array of applications, enabling the collection of massive volumes of real-world data. These developments facilitate the monitoring and control of various IoT-enabled devices, enhancing the interactivity between physical objects and digital data platforms. [1] The IoT encompasses a network of interconnected physical entities ranging from vehicles and buildings to everyday objects, equipped with sensors, electronics, and network connectivity, which collectively gather and exchange data [2]. A significant application of IoT technology is in Human Activity Recognition (HAR), which involves the identification and classification of human actions using data sourced from multiple sensors and devices such as Wi-Fi signals, cameras, radar, and wearable sensors. HAR aims to detect a wide range of human motions, including, but not limited to, running, walking, stair climbing, falling, sitting, and standing [3]. The primary goal of HAR is to analyze and understand human interactions with their surroundings, focusing on detailed movements of the whole body and individual limbs. By interpreting these activities, it is possible to predict outcomes, infer intentions, and assess the psychological state of individuals involved [4].

Researchers in the field of Human Activity Recognition (HAR) are developing methods to observe and analyze the actions of individuals to identify the types of activities being performed. HAR systems are broadly classified into two categories: sensor-based and video-based systems [5]. Video-based HAR systems utilize one or more cameras to record videos of human activities, capturing multiple perspectives to detect movements. However, these systems face significant challenges related to privacy concerns, as individuals may be reluctant to be continuously recorded during their daily activities. Additionally, processing video data for HAR can be computationally intensive, posing another significant barrier to the widespread adoption of video-based systems [6]. In contrast, sensor-based HAR has gained popularity among both users and researchers due to its numerous advantages over video-based systems. Sensor-based systems involve the automatic recognition of human activities using data collected from various sensing devices, including wearable and ambient sensors [7]. These sensors are advantageous as they are less susceptible to environmental disturbances, capturing continuous and precise motion signals. This robustness enhances the reliability and applicability of sensor-based HAR across diverse environments, significantly improving the efficiency and accuracy of activity recognition [3]. Overall, the choice between sensor-based and video-based HAR systems depends on the specific requirements of the application, balancing factors such as accuracy, privacy, and computational demands.

Machine learning (ML) approaches are commonly employed to address human activity recognition in smart environments, categorized into conventional machine learning (CML) models and deep learning (DL) models. While CML models have been historically utilized for HAR, they exhibit several limitations that have spurred the shift towards the adoption of deep learning methods. CML techniques require the manual extraction of features, which depend heavily on domain-specific expertise or human experience. This necessity for heuristic feature design not only restricts these models to environments where expert knowledge is available but also limits their applicability to more generalized scenarios and diverse tasks [8]. Furthermore, CML models are typically constrained to learn shallow features that align with human expertise, which predominantly facilitate the recognition of basic activities such as running or walking. They often struggle to recognize high-level or context-aware activities due to their inability to interpret complex data patterns without explicit feature guidance.

In contrast, DL models overcome these limitations by eliminating the need for manual feature extraction, thus allowing for more scalable and robust activity recognition systems. Deep learning (DL) is the process of learning hierarchical data representations by using architectures with several hidden layers that make up the depth of a neural network. In DL algorithms, data flows through these layers in a cascading fashion, with each layer gradually extracting complex features and passing crucial information to its successor. Low-level features are captured by the first layers, and these fundamental features are then combined and improved upon by later layers to provide a thorough and complex data representation [9]. In fact, deep learning architectures inherently learn to identify intricate patterns and features directly from raw data, enabling them to discern more complex, high-level activities. This capability significantly enhances the accuracy and adaptiveness of HAR systems. Moreover, while CML methods generally require extensive labeled datasets for training, deep generative networks can effectively learn from unlabeled data, offering substantial benefits for developing efficient HAR systems. DL models also demonstrate superior performance in handling variability in data due to different individuals, device models, and device poses, making them more versatile and effective in practical applications [10].

In this study, we offer concise, high-level overviews of pivotal deep learning techniques that have significantly influenced sensor-based Human Activity Recognition (HAR) systems. For detailed insights into specific methods or fundamental deep learning procedures, we encourage our readers to consult specialized research papers, comprehensive surveys, textbooks, and tutorials. Below, we outline the contributions of our study:

1. Related Review Works on Sensor-Based HAR: We begin by examining several review papers that focus on deep learning applications in sensor-based human activity recognition. This provides a foundational understanding of the current research landscape and identifies key advancements and methodologies.

2. Background of Human Activity Recognition: We present an overview of the human activity recognition field, discussing its established and emerging applications, challenges, and the sensors utilized. Additionally, we highlight popular publicly available datasets that are instrumental in the development and benchmarking of HAR systems.

3. Evaluation of Deep Learning Models in HAR: Following a brief introduction to prevalent deep learning models, we delve into recent studies that have employed these models for recognizing human activities from sensor data. We discuss various architectures, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), Deep Belief Networks (DBN), and Transformer. Lastly, we categorize recent articles in our domain based on the deployment of different models and assess these models based on their accuracy on publicly available datasets, deployment characteristics, architectural details, and overall achievements in the field.

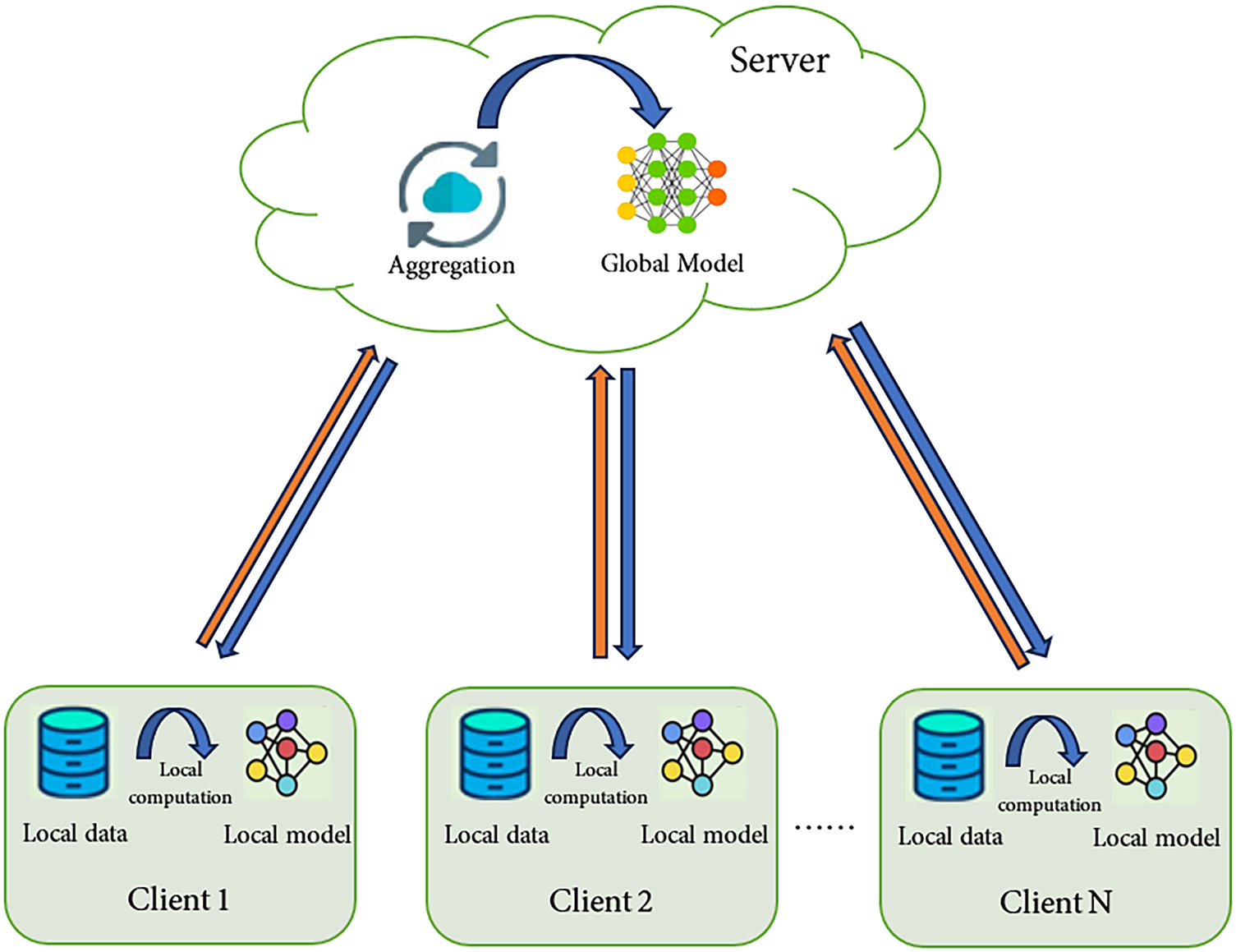

4. Federated Learning (FL) in HAR: introducing the fundamental concepts of Federated Learning (FL), highlighting its key design considerations, architectures, and optimization algorithms. Subsequently, we review the applications of FL in Human Activity Recognition (HAR) and provide a summary of recent research efforts that have employed FL in HAR systems.

5. Use of Explainable AI (XAI) in HAR: Discuss the necessity of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in sensor-based HAR systems that rely on deep learning and give an overview of current studies that have used XAI methods in HAR.

This structured approach not only encapsulates the state of the art in sensor-based HAR using deep learning but also sets the stage for future research directions in this rapidly evolving field. The article is organized as follows: The research method including research questions and research scope is explained in Section 2. The related existing review works in the field of HAR using deep learning are discussed in Section 3. Section 4 provides an in-depth overview of HAR concepts, including applications, challenges, sensor data, and datasets, aligning these elements with the posed research questions. Section 5 introduces significant deep learning contributions to HAR, detailing specific models and their roles in advancing the field. Section 6 provides an overview of the applications of Federated Learning (FL) in HAR systems. The application of XAI models in DL-based HAR systems is discussed in Section 7. Research directions and future aspects are covered in Section 8. The paper concludes with Section 9.

In this study, we address several critical research questions that explore various facets of Human Activity Recognition (HAR) systems.

• Q1: What are the real-world applications of HAR systems?

This question seeks to identify and explain the diverse practical implementations of HAR technologies across different sectors.

• Q2: What challenges are we facing in this field, and what potential solutions may exist?

Here, we explore the current obstacles impeding HAR development and effectiveness, along with innovative strategies that might overcome these challenges.

• Q3: What are the mainstream sensors and major public datasets in this field?

This inquiry focuses on detailing the sensors predominantly used in HAR systems and highlighting the key datasets that facilitate research and development in this area.

• Q4: What deep learning approaches are employed in the field of HAR, and what are the pros and cons of each?

We aim to review the various deep learning models applied to HAR, assessing their strengths and limitations in context.

• Q5: What are the applications of Federated Learning (FL) in Human Activity Recognition (HAR)?

Investigating the benefits of FL in addressing key challenges of real-world HAR systems, including privacy, communication costs, scalability, and latency.

• Q6: What is the necessity of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) for HAR systems?

Examining the Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) models that can be used in sensor-based HAR systems that rely on deep learning.

This article is organized to systematically address the research questions and provide a comprehensive review of the state-of-the-art in HAR using deep learning.

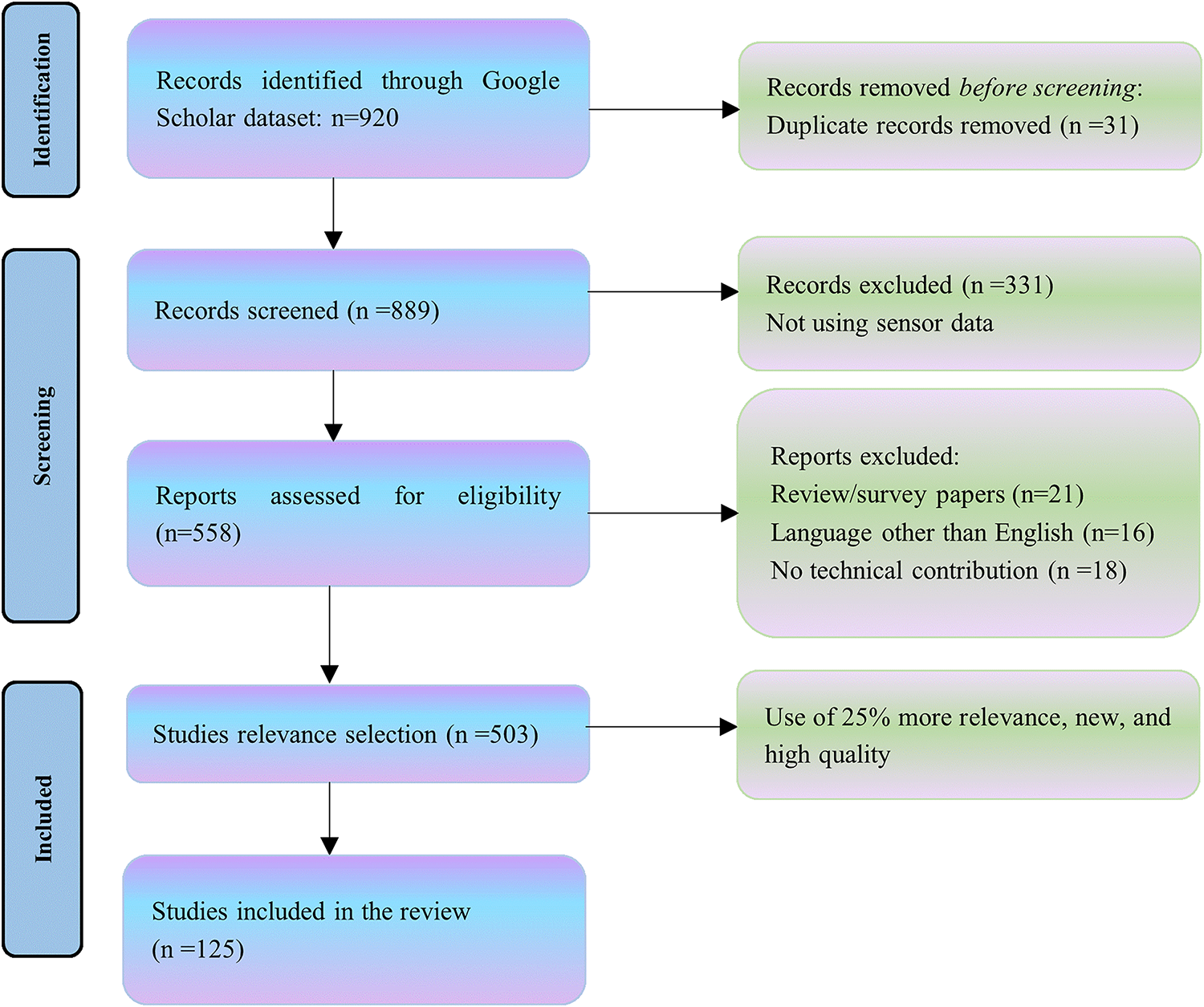

In this paper, we conduct a comprehensive systematic review of the field of human activity recognition (HAR) utilizing deep learning methodologies. We conducted a targeted search on the Google Scholar database. Our search strategy employed a carefully selected set of keywords pertinent to HAR, including “human activity recognition”, “HAR”, “action detection”, “multi-resident activity recognition”, and “fall detection”. These were combined with terms related to deep learning terms including “deep learning”, “CNN”, “convolutional neural network”, “RNN”, “ recurrent neural network”, “LSTM”, “ long short-term memory”, “GRU”, “gated recurrent unit”, “MLP”, “multi-layer perceptron”, “DBN”, and “deep belief network”. Initially, 920 papers were identified through our keyword-based search. Subsequent screening processes involved the exclusion of duplicates, papers using visual data for activity recognition, non-English papers, and non-technical studies. The final selection focused on 125 recent high-quality papers that are most relevant to advancements in HAR. The methodological flow of article selection is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Steps performed for selection of articles

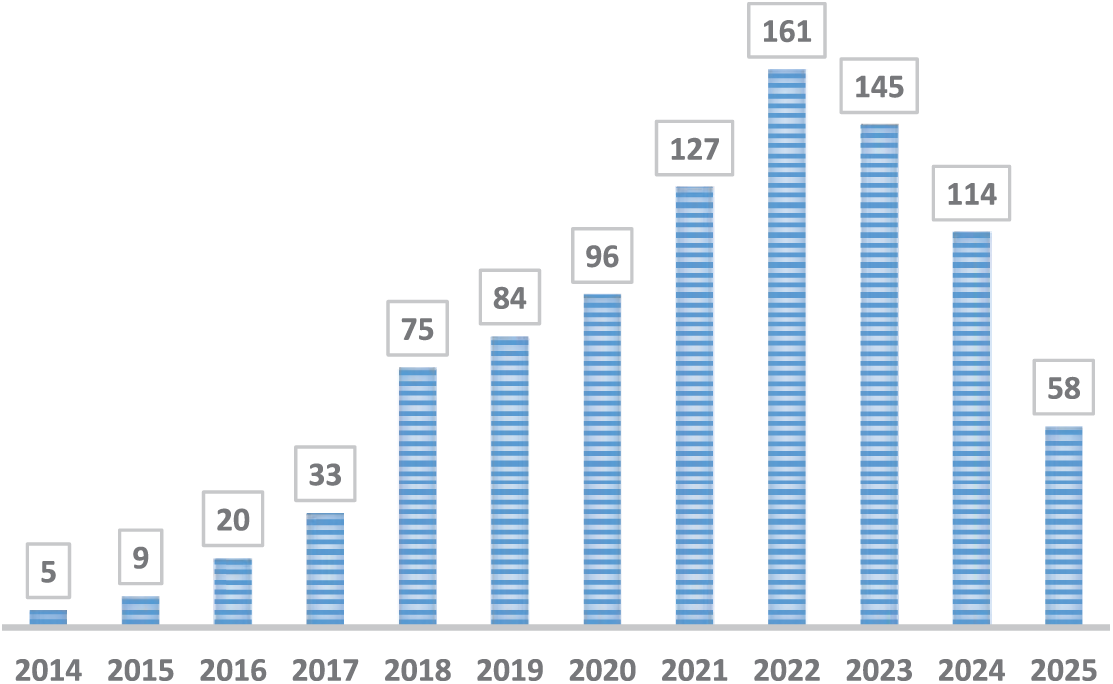

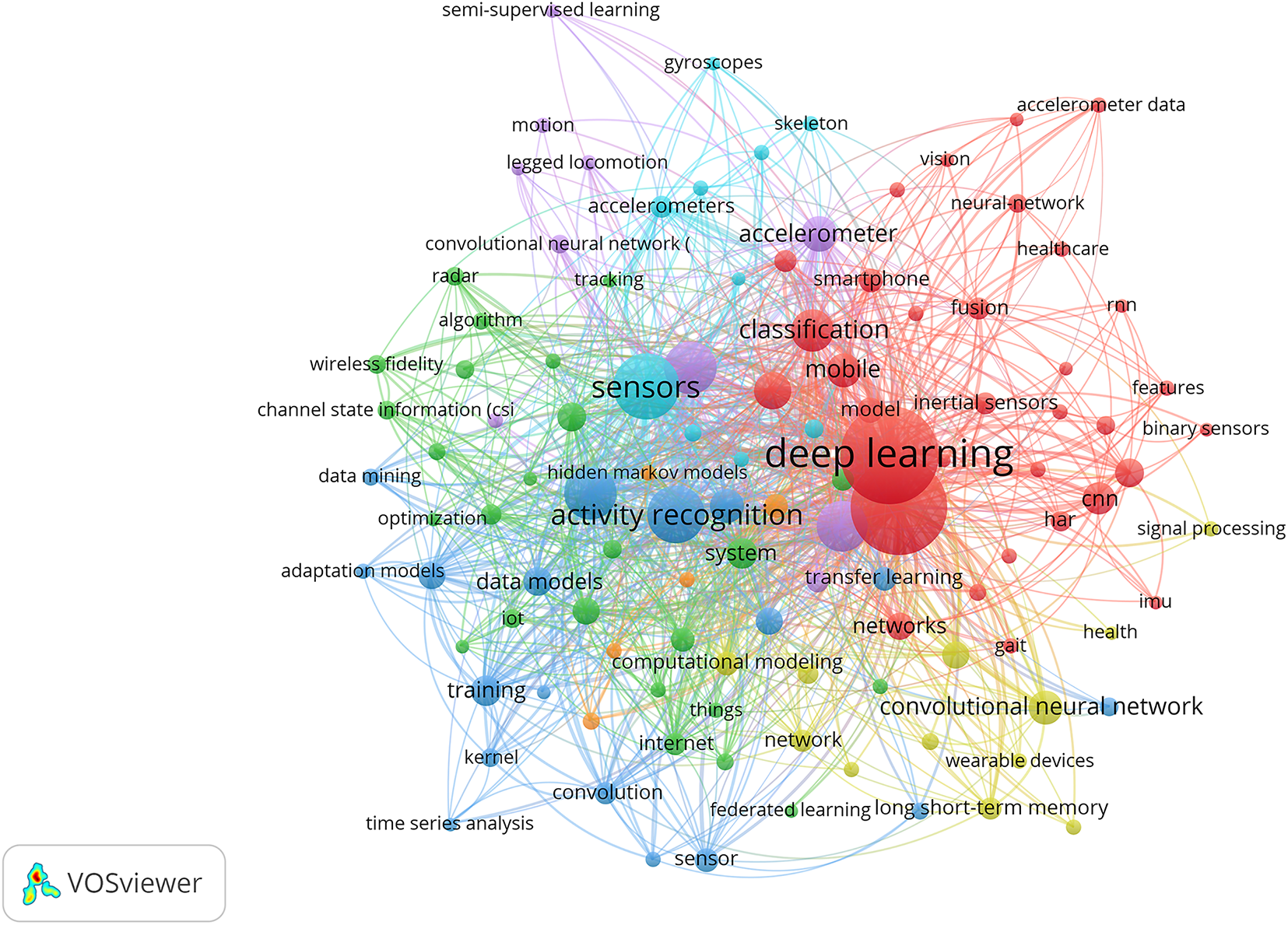

The author co-citation network and recurrent keywords were analyzed and shown using VOS Viewer, a free and open-source visualization software. Fig. 2 illustrates the distribution of scholarly articles focused on human activity recognition (HAR) utilizing deep learning models over recent years. The chart depicts a significant uptick in research within this area, particularly highlighting the robust growth throughout this decade. This trend clearly demonstrates the increasing reliance on deep learning methodologies in developing HAR systems, reflecting both a growing academic interest and advancements in technological applications.

Figure 2: The number of articles in the field of HAR using deep learning during recent decades

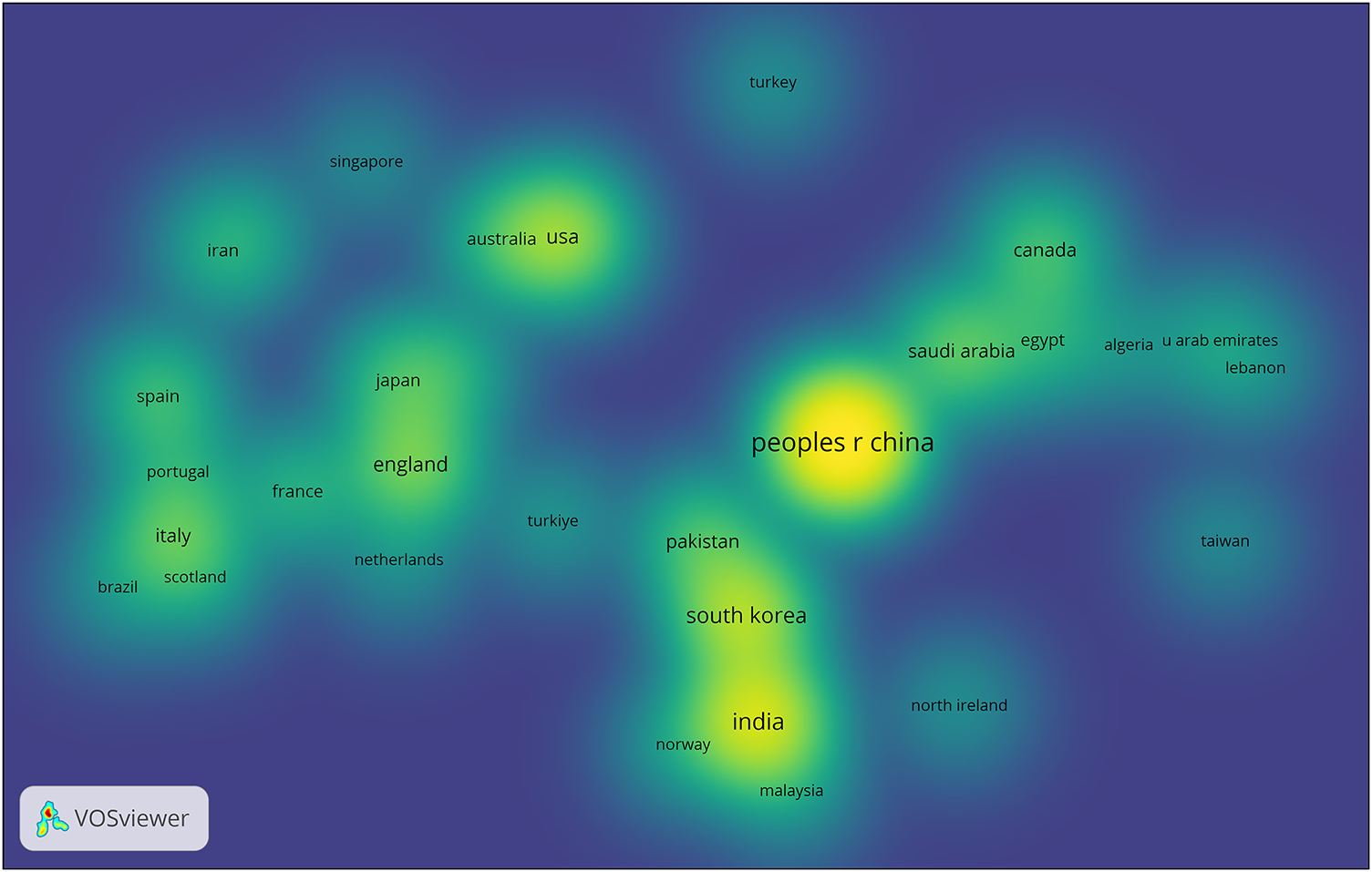

A thorough breakdown of the publishing output distribution per nation is shown in Fig. 3. The analysis of publication output by nation revealed that the countries with the largest publication output in this discipline were China, India, South Korea, and the United States.

Figure 3: Distributions of publication output by countries in the field of sensor-based human activity recognition

Finding research trends in a particular field of study is made easier with the help of keyword analysis. The density of keyword occurrences in the chosen documents was visualized in this experiment using VOS Viewer as the tool. The most often used keywords are deep learning, activity recognition, sensors, classification, mobile, and accelerometer. To view the keyword density graphically, please refer to Fig. 4. The density of the identified keywords is shown visually in the figure.

Figure 4: The density visualization of the identified keywords

Numerous studies have been conducted on human activity recognition (HAR), yet the bulk of these have centered on delineating the taxonomy of HAR and evaluating the most sophisticated systems that utilize traditional machine learning techniques [11–14]. While there have been reviews on the use of deep learning models for HAR, these studies often focus on a narrow selection of deep learning architectures and their variants, providing a somewhat limited perspective on the field.

A significant advancement in this domain is provided by [15], which detailed advanced deep learning approaches for sensor-based HAR. This review illuminated the multimodal nature of sensory data and discussed publicly available datasets that facilitate the assessment of HAR systems under various challenges. The authors proposed a new taxonomy to categorize deep learning approaches based on the specific challenges they address, providing a structured overview of the state of research by summarizing and analyzing the challenges and corresponding deep learning approaches.

Ramanujam et al. [16] focused on deep learning methods used in wearable and smartphone sensor-based systems. They distinguished between traditional and hybrid deep learning models, discussing each in terms of their advantages, limitations, and unique characteristics. The review also covered benchmark datasets commonly used in the field, concluding with a list of unresolved issues and challenges that warrant further investigation.

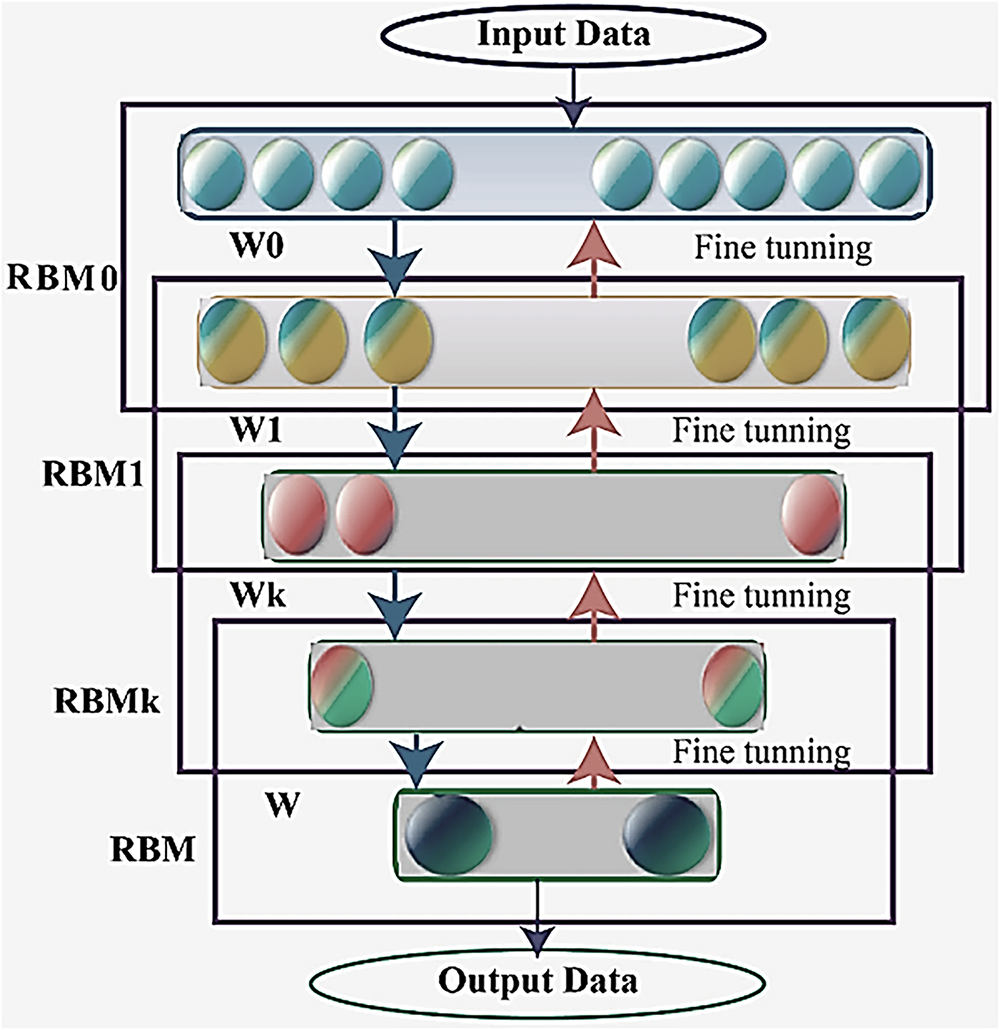

Gu et al. [10] delivered a comprehensive review on recent advancements and challenges in deep learning for HAR. They categorized deep learning models into generative, discriminative, and hybrid types. Notably, they discussed popular generative models like Restricted Boltzmann Machines (RBMs), autoencoders [17], and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [18], as well as discriminative models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and their variants. Their analysis of hybrid models highlighted how outputs from generative models could be utilized as inputs for discriminative models to enhance classification or regression tasks.

Zhang et al. [19] provided a thorough examination of the latest developments, emerging trends, and significant challenges in wearable-based HAR. Their review started with an overview of common sensors, real-world applications, and accessible HAR datasets. Following an assessment of each deep learning technique’s strengths and weaknesses, they discussed the advancements in wearable HAR and provided guidance on selecting optimal deep learning strategies. The review concluded with a discussion on current challenges from data, label, and model perspectives, each offering potential research opportunities.

Despite the growing body of work on human activity recognition (HAR) using deep learning, there remains a critical need for a comprehensive and in-depth exploration of the latest deep learning techniques applied to HAR. Our study aims to fill this gap by focusing on state-of-the-art deep learning methods tailored for sensor-based HAR, which distinguishes our work from other publications currently available. We extend our analysis beyond single-sensor systems to include a variety of sensor types, such as ambient and wearable sensors, thereby broadening the scope of our review.

Furthermore, our research delves into the latest advancements aimed at overcoming existing barriers and challenges within the field. We provide insights into potential areas for future research, emphasizing the complexity of HAR systems, especially in environments with multiple residents. This aspect is particularly challenging, yet crucial for the advancement of HAR systems. We include a review of significant studies that have addressed the issue of activity recognition in multi-resident scenarios, highlighting their methodologies and findings. Our aim is to provide a comprehensive overview that not only summarizes the current state of HAR technologies but also sets the stage for future innovations and applications in this dynamic field.

Human Activity Recognition (HAR) utilizing sensor data has been extensively deployed across various research domains, significantly enhancing capabilities in ambient assisted living (AAL), healthcare systems, behavior analysis, and security frameworks. Furthermore, HAR technologies are integral in facilitating human-robot interactions and in the accurate recognition of sport-specific movements.

Ambient Assisted Living (AAL) is an emerging communication technology designed to support the elderly in maintaining independence and activity in their daily lives [20]. HAR systems integrated into AAL environments play a crucial role in ensuring the safety and well-being of elderly or disabled individuals by monitoring daily activities and alerting caregivers to potential issues [21].

The demographic shift towards an older population has become more pronounced, with a notable increase in the average lifespan leading to a larger proportion of seniors living with various disabilities. Statistics reveal that the global population of individuals aged 65 and older has surged by over 360 million, now representing more than 8.5% of the worldwide population. This demographic change has significantly impacted community needs, escalating demand for home assistance, rehabilitation, and physical support, thereby driving up healthcare costs [22].

HAR is an integral component of smart home technologies that enable seniors to live autonomously, thereby enhancing their quality of life and standard of care. The primary function of these smart home environments, also known as AAL systems, is to remotely monitor and evaluate the health and safety of elderly individuals, those with dementia, and others with relevant disabilities [23]. Moreover, the integration of HAR in smart homes facilitates a transparent representation of the surrounding context, allowing for the implementation of various health technology applications. These applications range from monitoring disease progression and recovery to detecting anomalies, such as falls, highlighting the versatility and critical importance of HAR in modern healthcare technology [24].

Human Activity Recognition (HAR) systems are increasingly utilized within healthcare settings to monitor and manage patients, particularly the elderly and disabled. These e-health systems encompass a wide range of applications, including remote patient care, respiratory biofeedback, comprehensive activity monitoring, mental stress evaluation, both physical and mental rehabilitation, weight training, as well as real-time assessment of posture, vision, and movement [13]. The capability of HAR systems to accurately recognize human activities is pivotal in identifying various health disorders such as cardiovascular issues and Alzheimer’s disease. Early detection through HAR can facilitate timely medical interventions, significantly enhancing patient outcomes [25].

Furthermore, HAR plays a critical role in maintaining the overall physical and mental health of the population. For chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders, physicians can leverage HAR to continuously monitor patients’ daily activities. This continuous monitoring allows for the strict management of dietary and exercise regimes essential for disease control [26]. For example, individuals affected by these conditions are often required to maintain a balanced diet and engage in regular physical activity [27]. HAR systems provide a way to record daily activities, supplying clinicians with up-to-date information and offering patients real-time feedback on their progress. Additionally, for those suffering from mental health issues or cognitive decline, HAR systems are crucial for the continuous observation necessary to promptly identify any abnormal behavior, thereby preventing potential adverse outcomes [11].

The implementation of activity recognition systems empowers patients to take charge of their health and enables healthcare providers to monitor their patients’ conditions more effectively and tailor their recommendations. By facilitating continuous monitoring, HAR systems can reduce the length of hospital stays, enhance diagnostic accuracy, and ultimately improve patients’ quality of life [28].

Human Activity Recognition (HAR) systems are revolutionizing the fitness industry by enabling individuals to monitor their physical activities, such as walking, running, cycling, and swimming, through advanced wearable technologies like smartwatches and fitness bands [29]. These systems provide valuable data on the duration, intensity, and caloric expenditure of physical activities. Recognized as a crucial paradigm, physical activity (PA) recognition is linked to significant benefits for both physical and mental health and is integral to various fitness and rehabilitation programs [30].

Physical activity is vital for reducing the risk of numerous chronic and non-communicable diseases including diabetes, hypertension, depression, obesity, as well as cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disorders [31]. Furthermore, regular physical activity physiologically improves mood, supports active lifestyles in older adults, enhances self-esteem, and helps in managing blood pressure, anxiety, stress levels, and weight. It also reduces the risk of cognitive disorders like Alzheimer’s disease in the elderly [32].

Traditionally, dietitians and medical professionals have relied on self-completed questionnaire methods, asking participants to log their daily activities. These questionnaires are then analyzed to assess the individual’s physical activity level and provide tailored feedback. However, the analysis of self-reported data is time-consuming and labor-intensive, especially with large populations. To overcome these challenges, recent advances have seen the adoption of sensor-based technologies that provide a more effective means of capturing and compiling daily contextual data and life logs [33,34].

Moreover, in the realm of elite sports, the objective evaluation of an athlete’s performance is crucial. Automated sport-specific movement detection and recognition systems, facilitated by sensor-based HAR technologies, provide significant improvements over manual performance analysis methods [35]. These systems are employed during training sessions and competitions across various sports [36], including ski jumping [37,38], tennis [39–41], running [42–44], Boxing [45,46], Golf [47–49], volleyball [50–52], swimming [53–55], cricket [56–58], skateboard [59–61], and other. The adoption of HAR in these contexts eliminates the inaccuracies associated with traditional performance analysis, enabling detailed and precise assessments that are essential for optimizing athlete training and competitive performance.

4.1.4 Security and Surveillance

In the realm of security and surveillance, the urgency for immediate action is pronounced in situations involving suspect behaviors, such as extended periods of loitering, sudden running, theft of mobile devices, confrontational arguments, suspicious activities towards others, or potential threats of suicide bombing. These scenarios require a robust intelligent surveillance system capable of not only detecting but also swiftly responding to potential threats through timely alerts. In the current global context, where numerous attacks are attributed to terrorism, the ability to predict and preemptively address such threats can significantly mitigate or even prevent loss of life [62].

HAR systems have become integral to surveillance strategies that utilize both sensor and visual data. These systems are adept at continuous monitoring, detecting unauthorized entries, and identifying abnormal activities. The effective deployment of HAR in these contexts is crucial for enhancing situational awareness and enabling rapid response to potential security incidents, thereby playing a critical role in safeguarding public safety [13].

Human Activity Recognition (HAR) has emerged as a crucial field with diverse applications ranging from healthcare to security. Despite significant research advancements, HAR systems continue to face substantial challenges that hinder their full potential.

4.2.1 Security and Surveillance

A fundamental aspect of HAR research is data collection, which often faces issues such as unlabeled datasets, absence of temporal context, uncertain class labels, and restrictive data conditions. These challenges need to be addressed to improve the accuracy of activity anticipation and recognition [63,64].

Hardware Limitations: Hardware forms the backbone of HAR endeavors, especially in scenarios dealing with large volumes of data. Commonly used hardware includes smartphones, smartwatches, and various sensors. However, limitations related to hardware capabilities, computational costs, and algorithmic constraints remain a concern and can hinder the scalability and effectiveness of HAR systems [12].

4.2.3 Complex Human Activities (CHA) Recognition

Recognizing complex human activities (CHAs) poses significant challenges in the field of Human Activity Recognition (HAR). CHAs often encompass multiple concurrent or overlapping actions sustained over extended periods. Examples include cooking, which may simultaneously involve multiple tasks such as chopping vegetables, monitoring cooking progress, and cleaning dishes, or writing, which can involve organizing thoughts, typing, and reviewing text concurrently. These are contrasted with simple human activities (SHAs), which are defined as singular, brief actions such as sitting or standing. The difficulty lies in accurately identifying and distinguishing CHAs from SHAs, given the complexity and duration of CHAs compared to the more transient nature of SHAs [65]. Moreover, CHAs can occur in both concurrent and interleaved modes. For instance, an individual might engage in cooking and cleaning dishes in an alternating sequence, or cook while listening to music, and also manage these tasks independently but simultaneously. The capability to model these dynamic and overlapping actions accurately remains a formidable challenge in HAR, necessitating advanced algorithms capable of capturing the nuanced intricacies of human behavior [5]. The literature on Human Activity Recognition (HAR) identifies three primary methodologies for recognizing complex human activities (CHAs), each with distinct approaches and limitations.

SHA-Based Recognition: This method involves applying simple human activity (SHA) identification techniques to CHAs, essentially treating complex activities as if they were simple ones. The primary limitation here is that the features extractable from SHAs, which are inherently less complex, do not adequately capture the nuances of CHAs. Consequently, this approach may not accurately represent the intricacies of complex activities, leading to potential inaccuracies in activity recognition [66].

Composite SHA Representation: In this approach, CHAs are modeled as combinations of multiple SHAs that have been meticulously labeled and predefined. While this method benefits from leveraging detailed SHA insights, it heavily depends on domain expertise to define and label the SHAs accurately. Additionally, this method is constrained by the nature of SHAs themselves, which may not fully encompass the non-semantic and unlabeled components frequently present in CHAs, thereby limiting the recognition capability of truly complex activities [67,68].

Latent Semantic Analysis: The third approach utilizes topic models to identify latent semantics in sensor data, which are presumed to reflect the characteristics of CHAs. This method can potentially uncover underlying patterns and structures in activity data that are not explicitly labeled. However, its major drawback is that topic models generally focus on the distribution of data and often neglect the sequential aspects of activities. This oversight can lead to a significant gap in recognizing the temporal dynamics that are critical for accurately modeling and understanding CHAs [69–71].

Each of these methods provides a framework for addressing the challenges posed by CHA recognition but also illustrates the complexity and the need for further refinement to enhance accuracy and applicability in real-world scenarios.

4.2.4 Multi-Resident Activity Recognition

Recognizing activities within systems that house multiple residents introduces unique challenges. Unlike single-resident systems, where activities can be directly attributed to the sole inhabitant, multi-resident systems must discern which individual is responsible for which activity. This complexity is heightened by the residents’ ability to engage in both solitary and collaborative activities, often influenced by the dynamics of social interactions. A particularly critical issue in multi-resident environments is data association, which is the process of accurately linking each environmental sensor-detected event, such as the opening of a refrigerator door, to the initiating individual [72]. The ambiguity of sensor readings, compounded by events triggered in close temporal and spatial proximity, significantly complicates this task. For example, if two sensors in different rooms are activated simultaneously, it becomes challenging to accurately determine which individual is in which room [73]. To address these challenges, research suggests three main approaches including wearable-based approaches, data-driven approaches, and single-model approaches [74].

Wearable-Based Approaches: These methods require residents to wear personal sensors, like smart jewelry or wristbands, which can provide precise data to associate activities with specific individuals [72,75].

Data-Driven Approaches: These techniques treat data association as a distinct learning task that precedes activity classification, allowing for more a nuanced understanding and categorization of activities [76,77].

Single-Model Approaches: Leveraging raw ambient sensor data, these models implicitly learn data associations during the training process, aiming to integrate and correlate data without explicit labeling [78,79].

4.2.5 Group Activity Recognition (GAR)

Recognizing group activities within HAR systems poses another significant challenge. GAR often begins with the recognition of individual activities, which are then synthesized to infer group behavior. However, the structural differences between individual and group actions, along with the variability in behaviors exhibited by individuals within the same group setting, complicate the recognition process. Direct modeling of group dynamics is essential to understanding the roles and relationships among participants accurately. Currently, GAR systems struggle with precision and are limited by a lack of labeled data, which is crucial for training effective recognition algorithms [80].

In smart environments, the effective collection of raw data is crucial for the functionality and intelligence of Human Activity Recognition (HAR) systems. This data is gathered through a diverse array of sensors, actuators, and smart devices such as smartwatches, smart glasses, smartphones, and others. These components are essential for capturing a wide range of activities and interactions within these environments.

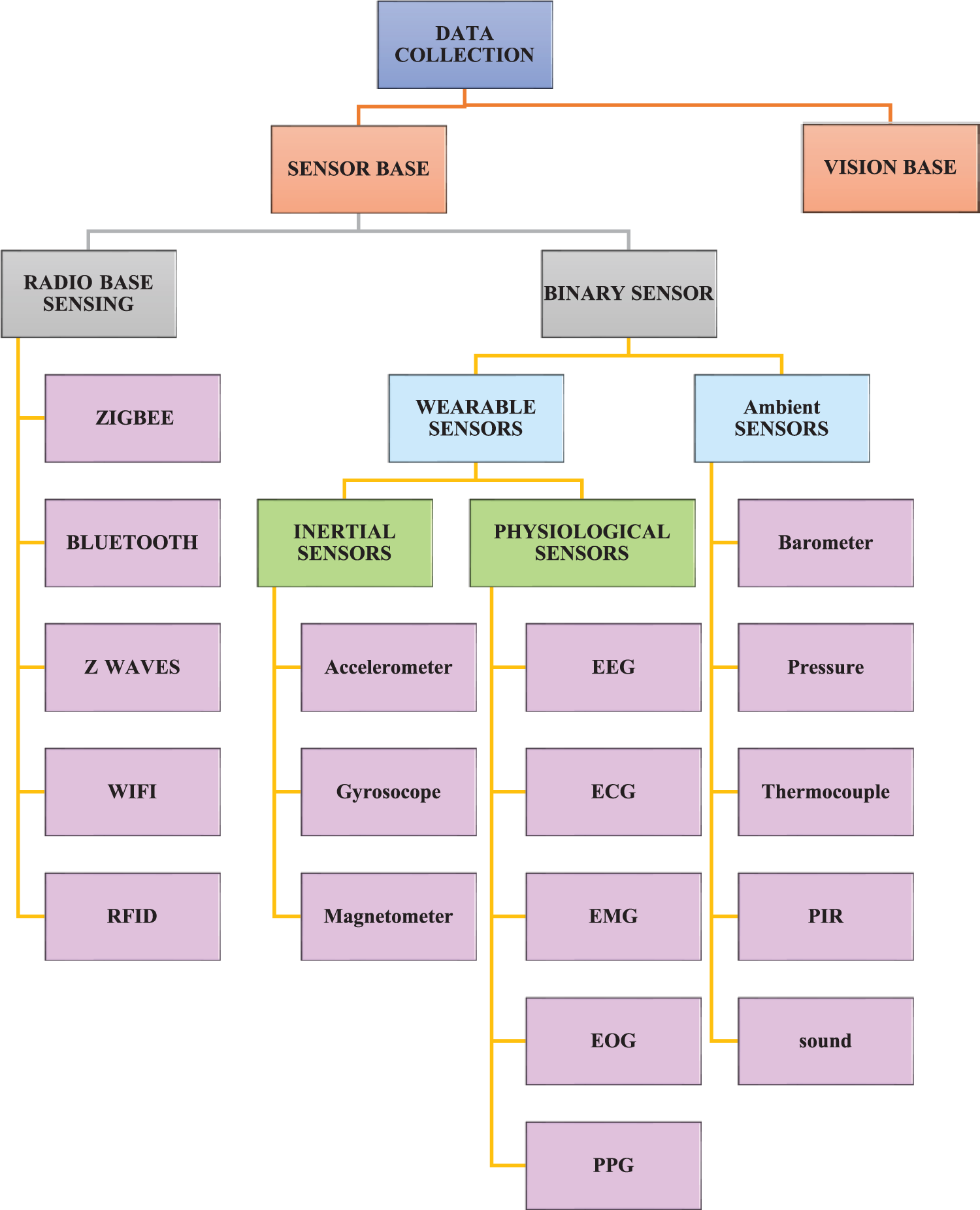

Fig. 5 provides an overview of the various sensors employed for data collection in Human Activity Recognition (HAR) systems. Sensors are generally classified into two categories including radio-based sensors and binary sensors. The most common radio-based sensing systems are Bluetooth, ZigBee, Z-waves, RFID, 6LoWPAN, and Wi-Fi. Binary sensors are divided into two groups: Ambient (Environmental) sensors and wearable sensors [73].

Figure 5: Various sensors for collecting data in HAR systems

Wearable sensors play a pivotal role in Human Activity Recognition (HAR) systems, providing critical data that allow for continuous monitoring of both physical activities and physiological states. These sensors are seamlessly integrated into everyday portable electronics such as glasses, helmets, smartwatches, smart bands, and smartphones, enabling unobtrusive and constant data acquisition. Inertial and physiological sensors are the two categories of wearable sensors. Inertial sensors provide data on movement and orientation, crucial for detecting physical activities like walking, running, or cycling.

The most common inertial sensors are magnetometers, gyroscopes, and accelerometers [81]. Meanwhile, physiological sensors offer insights into an individual’s internal state, such as stress levels, brain activity, and cardiac health, enabling a deeper understanding of the user’s overall health and activity patterns. The most often used physiological signals are electromyogram (EMG) [82], electroencephalogram (EEG) [83,84], electrocardiogram (ECG) [85], electrooculogram (EOG) [86], and photoplethysmography (PPG) [87].

Accelerometers: An accelerometer is a crucial motion sensor used extensively in Human Activity Recognition (HAR) systems to detect changes in the velocity of a moving object. This sensor measures acceleration in units of gravity (g) or meters per second squared (m/s²), providing insights into the intensity and direction of motion. Accelerometers typically operate at sampling frequencies ranging from tens to hundreds of Hz, enabling them to capture a wide range of human movements. They are equipped with three axes (X, Y, and Z), allowing them to generate a three-variate time series that offers a comprehensive view of the wearer’s movements in three-dimensional space. Accelerometers can be attached to multiple body parts, such as the arm, wrist, ankle, and waist, making them versatile tools for monitoring daily activities [88].

Gyroscopes: Gyroscopes complement accelerometers by measuring an object’s orientation and angular velocity rather than linear acceleration. Unlike accelerometers, gyroscopes are specifically designed to track the rotational movements around an axis [89]. A gyroscope consists of a rotating wheel fixed within a frame. The principle behind its operation is the conservation of angular momentum: the spinning wheel tends to maintain its orientation, remaining unaffected by external forces. When the direction of the gyroscope’s axis changes, a torque proportional to the rate of change in orientation is generated. This torque is crucial for calculating angular velocity, making gyroscopes essential for accurately determining orientation changes, such as tilts and turns [90].

Magnetometer: Magnetometers measure the strength and direction of magnetic fields, primarily those generated by the Earth. These sensors are vital for determining orientation by detecting the planet’s magnetic poles, complementing the data provided by accelerometers and gyroscopes. They operate by measuring the induction caused by moving charges or electrons, typically within the frequency range of tens to hundreds of Hz. Magnetometers also feature a triaxial setup, providing three-dimensional data on magnetic field orientation. In HAR, magnetometers are frequently used for tasks requiring precise [89].

Electromyogram (EMG): Electromyography (EMG) is a biomedical signal that reflects neuromuscular activity within the body. EMG signals are typically captured using specialized sensors known as electromyogram sensors. These signals serve various purposes, including tracking health irregularities, measuring muscle activation, and analyzing the biomechanics of movement [91].

Electroencephalogram (EEG): The Electroencephalogram (EEG) is a vital physiological sensor that detects electrical signals generated by the brain. EEG sensors record the activity of large populations of neurons near the brain’s surface over time. EEG signals provide insights into brain activity and are essential for understanding cognitive processes and neurological conditions [92,93].

Electrocardiogram (ECG): An ECG sensor records the electrical activity of the heart using electrodes placed on the skin. It provides valuable information about cardiac function and rhythm [94]. Heart rate (HR), derived from ECG signals, is a crucial indicator of physical and mental stress, making ECG a valuable tool for assessing human activities [95].

Electrooculogram (EOG): Electrooculography (EOG) measures the corneo-retinal standing potential, which reflects the electrical potential difference between the retina and the front of the eye [96]. EOG signals, captured using electrodes placed around the eyes, can identify sleep states [97], track eye movements [98], and detect human activity [99].

photoplethysmography (PPG): PPG offers an alternative method for monitoring heart rate and cardiovascular rhythm by detecting variations in vascular tissue’s light absorption during the cardiac cycle. PPG signals are commonly obtained using pulse oximeter sensors integrated into wearable devices like smartwatches [100,101]. PPG signals complement other sensor data, such as inertial measurement unit (IMU) or ECG signals, to enhance the accuracy of Human Activity Recognition (HAR) systems [102,103].

In smart environments, wearable devices offer a direct method for recognizing human activities. However, this method has notable limitations. Many users, especially in smart homes, may find these devices uncomfortable and inconvenient. Additionally, there’s a risk of forgetfulness in usage, particularly among elderly residents. Thus, ambient sensors present a preferable alternative for non-intrusive data collection in such settings. Ambient sensors are integrated into the environment, capturing interactions between humans and their surroundings without causing any disturbance [15]. These sensors include contact sensors, temperature sensors, pressure sensors, passive infrared (PIR) sensors, light sensors, sound sensors, and more. Although ambient sensors efficiently collect data, interpreting this data and resolving associated challenges requires advanced techniques.

Passive Infrared (PIR) Sensor: A passive infrared (PIR) sensor consists of two primary components: a Fresnel lens or mirror, which directs infrared signals toward the sensor, and a pyroelectric sensor, which measures the intensity of the infrared radiation. PIR sensors are typically classified into two categories: binary-based and signal-based. The binary type, commonly used in various applications, such as controlling lighting systems and triggering alarms, provides a simple binary output, indicating ‘1’ for detected motion and ‘0’ for no motion. This straightforward functionality makes PIR sensors a popular choice for motion detection in smart environments, enabling efficient monitoring and documentation of the presence of occupants in specific locations like bedrooms, kitchens, and bathrooms [104].

Pressure Sensors: These sensors measure the force exerted over an area to detect physical interactions like touch. They help monitor whether a person is sitting or lying down on furniture such as chairs or beds, thus discreetly logging their presence [4].

Contact Switch Sensors: These sensors can be attached to a variety of objects, including bedroom doors, living room furniture, kitchen cabinets, or refrigerators, to determine how residents interact with their surroundings. This setup enables a detailed understanding of user behavior within the environment [7].

Temperature and Humidity Sensors (TH): Monitoring changes in temperature and humidity is essential for recognizing activities within a smart home. Sensors that track these environmental factors are strategically positioned in locations like bathrooms and kitchens, where they can detect specific activities, such as cooking or showering. These activities usually cause increases in humidity and temperature, making such sensors valuable for providing insights into the home’s dynamics [105].

Light Intensity Sensors (L): These sensors measure the brightness of light within a specific area, playing a crucial role in understanding user behavior, such as determining if a user is asleep. While presence sensors can detect movement, they may not indicate whether someone is actually sleeping, especially during daylight hours. In contrast, a significant drop in light levels often suggests that the individual is likely asleep. Additionally, the use of light intensity sensors is beneficial in other areas like bathrooms, where changes in lighting can further inform about the activities and habits of residents. [105].

Sound (Acoustic) Sensors: These sensors employ sound waves to detect a variety of noises, such as footsteps, voices, or the sound of breaking glass. This capability allows them to play a crucial role in monitoring and security within areas where they are installed [4].

Floor Sensor: Floor sensing is pivotal in creating environments that are both sensitive and non-invasive. Floor sensors are integrated seamlessly beneath the surface, maintaining the appearance of a conventional floor while functioning to monitor activity. These sensors can be deployed across both private and public settings. In smart buildings, for example, floor sensors detect human presence, automating control of lighting and heating systems to enhance efficiency and comfort. In eldercare settings, they provide vital functionality by detecting falls and other emergencies, ensuring timely assistance. Additionally, these sensors are useful in public spaces for counting people and monitoring crowd dynamics during events, contributing to safety and operational management [106,107].

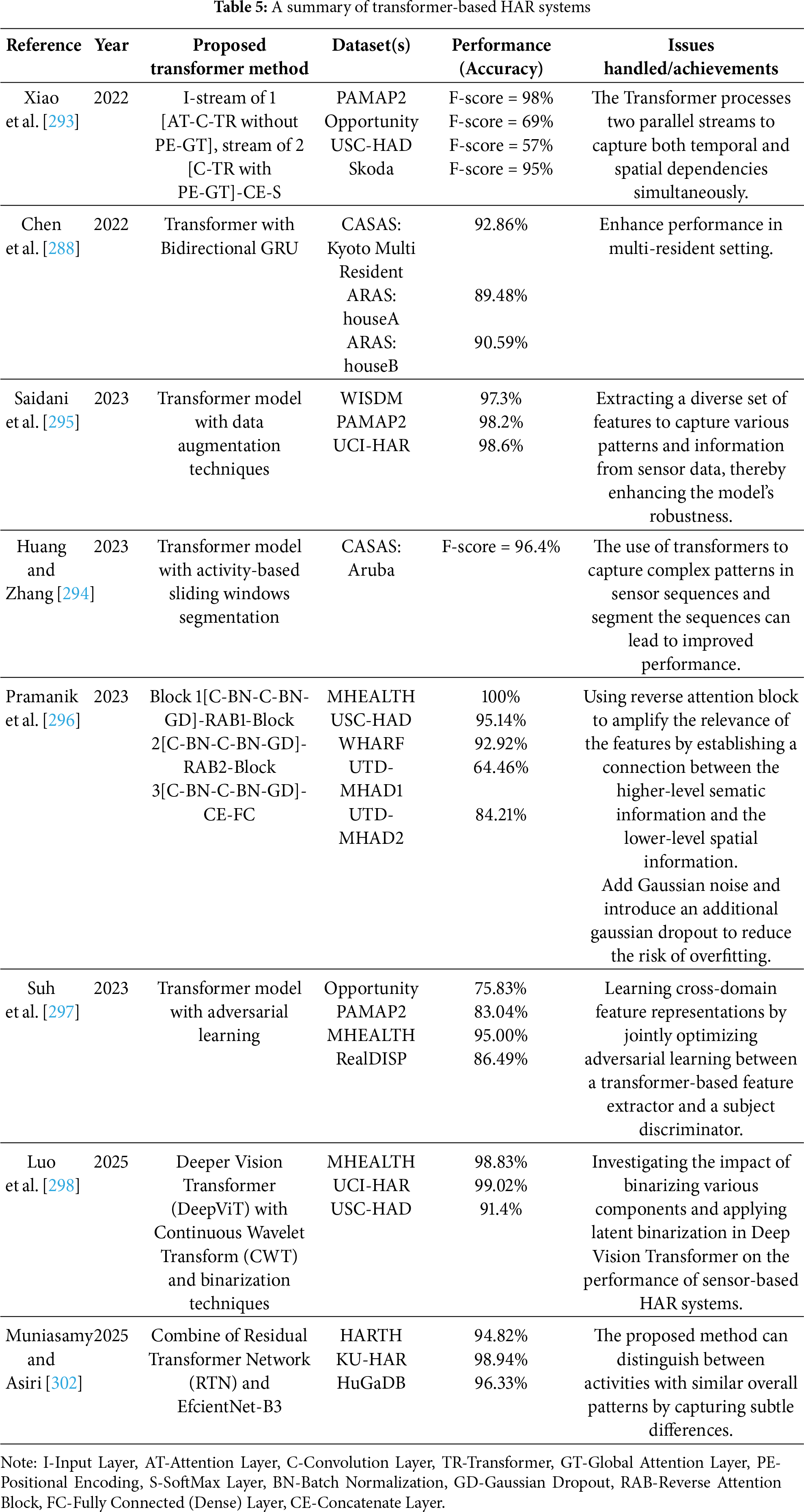

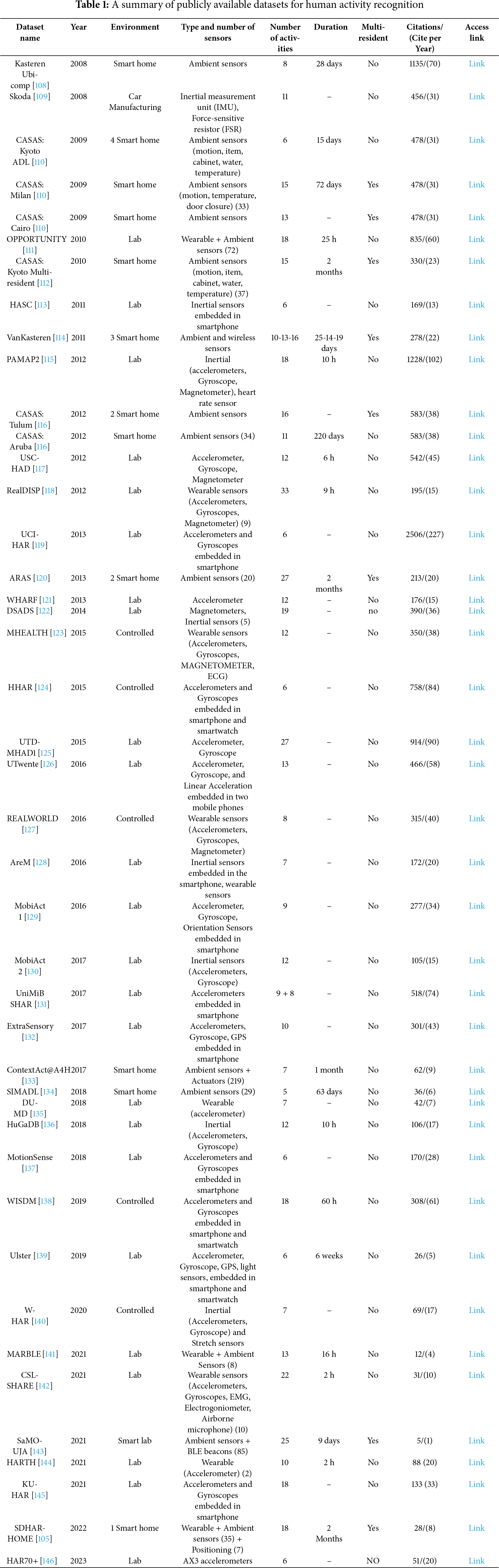

When selecting a dataset for smart living applications, it is crucial to consider the type of human activities represented. These activities should be relevant to the specific contexts of smart living, such as homes, offices, or urban settings, and should reflect the typical duties and routines of individuals. Activities in these datasets can generally be categorized into two types: simple activities, which include actions like walking, lying down, running, jogging, and climbing stairs; and complex activities, such as cooking, cleaning the kitchen, and washing clothes. Other vital factors to consider in choosing a Human Activity Recognition (HAR) dataset include the quality of the data, the types of sensors used, the number of sensors deployed, sensor placement, the duration of recorded activities, and the number of participants. These criteria are essential for ensuring the selected dataset is well-suited to the application, as they significantly influence the performance and reliability of HAR models. Table 1 lists the major publicly available datasets designed specifically for human activity recognition, providing a comprehensive overview to aid in the selection process.

The design and implementation of Human Activity Recognition (HAR) systems involve a systematic process encompassing data acquisition, preprocessing, model training, and deployment. This process begins with the collection of data through diverse sensors including ambient, radio-based, physiological, and inertial types. The data then undergo preprocessing steps such as cleaning, normalization, and feature extraction. Subsequently, an appropriate machine learning model is selected, trained, and utilized to predict activities based on processed data [147].

In recent years, deep learning (DL) approaches have surpassed traditional machine learning methods in various HAR tasks due to several key advancements. The widespread availability of large datasets has facilitated the development of models that effectively learn complex patterns and relationships, significantly enhancing performance. Moreover, advances in hardware acceleration technologies like Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) and Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) [148] have dramatically shortened model training times. These technologies enable more rapid computations and parallel processing, which accelerates the overall training process. Additionally, improvements in algorithmic techniques for optimization and training have boosted the speed and efficiency of deep learning models, enabling faster convergence and improved generalization capabilities [19].

The upcoming discussion explores numerous studies that employ deep learning techniques to recognize human activities. These studies illustrate the versatility and effectiveness of deep learning models in overcoming the challenges of human activity recognition, highlighting significant contributions to the field, and pointing towards future research directions.

5.1 Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP)

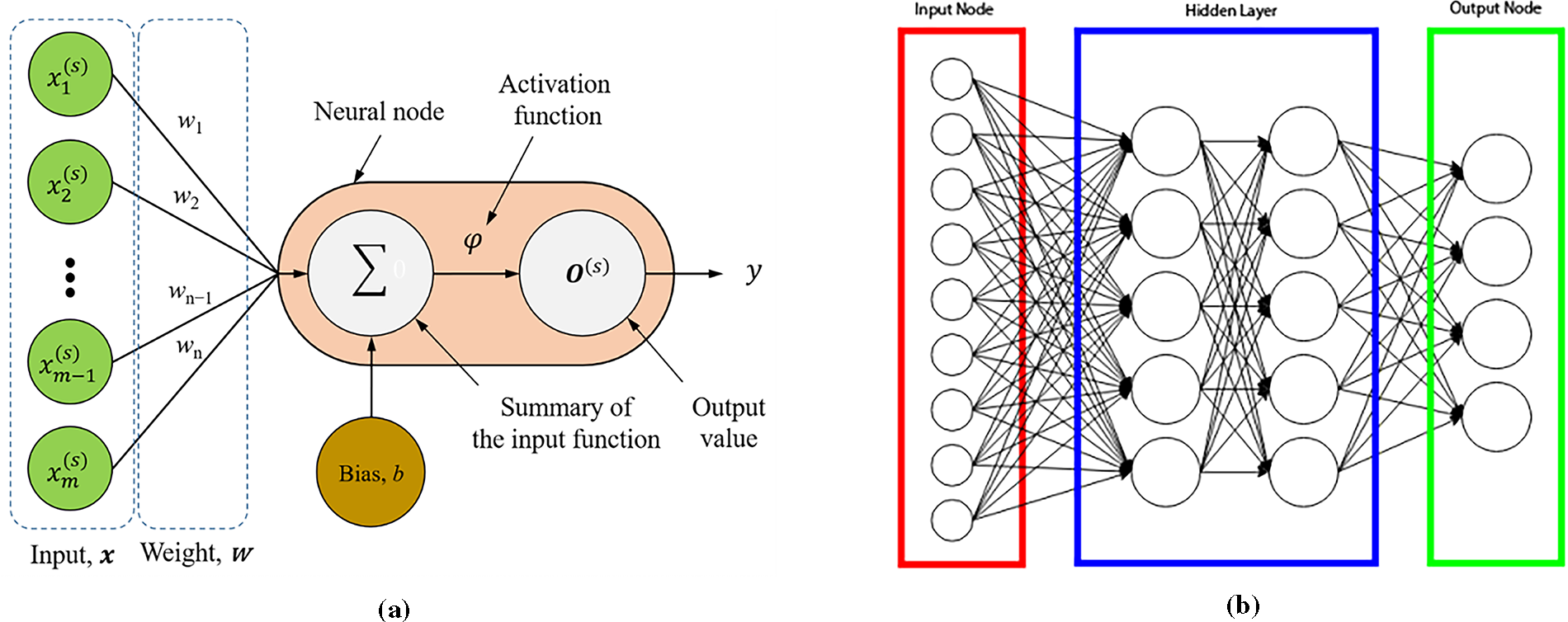

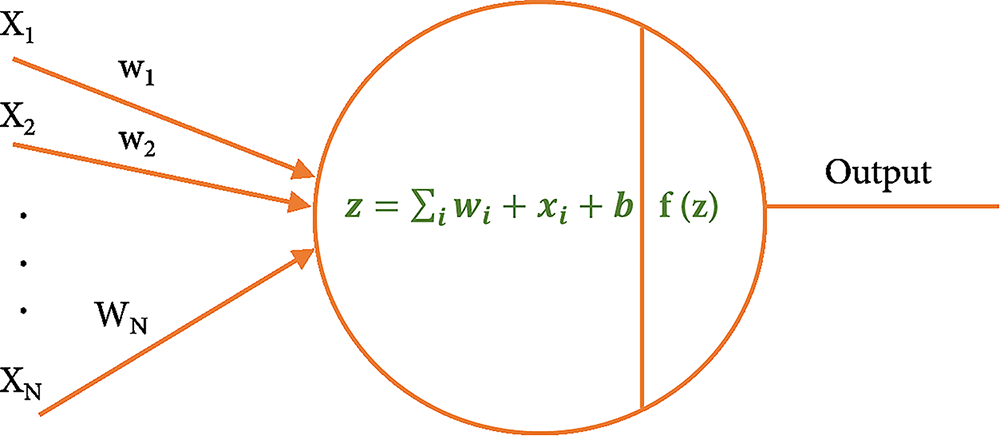

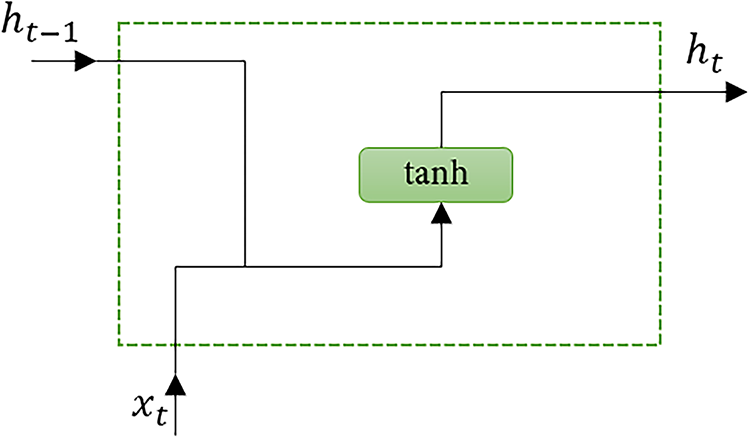

The Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) is a fundamental architecture underpinning deep learning and deep neural networks (DNNs). Classified within the sphere of feedforward artificial neural networks (ANNs), the MLP consists of three principal layer types: the input layer, one or more hidden layers, and the output layer. This configuration is pivotal for its role in supervised learning. In the MLP architecture, each neuron from one layer is fully interconnected with every neuron in the subsequent layer, ensuring a densely connected structure [149]. This architecture is critical for the effective propagation of information during the learning process, characterized by two main phases: forward and backward propagation. In forward propagation, input data are sequentially processed from the input layer through the hidden layers to the output layer, with each neuron’s output computed using a combination of incoming inputs and trainable parameters. In forward propagation, input data are sequentially processed from the input layer through the hidden layers to the output layer, with each neuron’s output computed using a combination of incoming inputs and trainable parameters [150]. The output at each neuron is given by the equation [151]:

where x represents the input vector, w denotes the weighting vector, b is the bias term, φ is a nonlinear activation function that introduces non-linearity into the model, enabling it to learn complex patterns, and y represents the output value. Fig. 6a exemplifies the operation of a single-neuron perceptron model, highlighting the computational mechanics involving the input vector, weighting factors, bias, and the resultant output through the activation function.

Figure 6: (a) Single-neuron perceptron model [151]. (b) Structure of the MLP [160]

Upon computing the final outputs, the network evaluates the prediction error, and backward propagation commences. During backward propagation, error gradients are transmitted back through the network from the output layer to the input layer. This process adjusts the weights and biases to minimize the error, refining the model’s predictions. The backward pass relies on gradient-based optimization techniques, such as stochastic gradient descent, to update the trainable parameters effectively.

The structural composition of the MLP is elucidated in Fig. 6b, which illustrates the interconnected layers and the directional flow of data within the network.

Activation functions, or transfer functions, are essential in shaping the output of an MLP (Multi-Layer Perceptron) network. Essential activation functions include Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) [152], hyperbolic tangent (Tanh), Sigmoid, and SoftMax [153,154]. These functions impart non-linearity to the network, enabling it to decipher complex patterns and relationships within the data. Throughout an MLP’s training phase, a variety of optimization methods are used to fine-tune network parameters and reduce the loss function. Notable among these methods are Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam) [155], Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) [156], adaptive gradient algorithm (ADAGRAD) [157], and Nesterov-accelerated Adaptive Moment Estimation (Nadam) [158]. These techniques are employed to iteratively adjust the weights and biases, thereby enhancing network performance [159].

Choosing the right hyperparameters is essential for constructing a neural network capable of achieving high accuracy. The performance of the network is significantly influenced by these hyperparameter settings. For example, if the number of training iterations is set too high, it may result in overfitting [161]. This occurs when the model is overly tuned to the training data, capturing noise and irrelevant patterns, and thus performs poorly on new, unseen data. Furthermore, the learning rate is a critical hyperparameter that influences the speed of convergence during training. A learning rate set too high can cause the network to converge too rapidly, potentially overlooking the global minimum of the loss function. Conversely, a learning rate set too low may lead to a protracted convergence process. Therefore, finding an optimal balance of hyperparameters is crucial to maximizing the network’s performance [150].

In the field of human activity recognition (HAR) within multi-resident smart environments, researchers have widely adopted the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) model for its efficacy in classification tasks, as evidenced by numerous studies [160,162].

In a novel approach, Rustam et al. [163] introduced the Deep Stacked Multilayered Perceptron (DS-MLP) model. This model leverages a meta-learning framework using a neural network as the meta-learner and five MLP models as base learners. The DS-MLP model was evaluated using the UCI-HAR and HHAR datasets, which comprise data collected from accelerometer and gyroscope sensors on smartphones. Experimental results demonstrated impressive accuracy rates of 99.4% and 97.3% for the respective datasets.

Further, another study [164] employed an MLP neural network to recognize various human activities using data from devices worn on the wrist and ankle. The authors proposed a novel data collection technique capable of distinguishing nine different activity categories. This technique utilizes an ultra-low-power STM32L4 series MCU, supplemented by various communication modules (including Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, NFC, Sub-RF, and a second Bluetooth module) and embedded Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) sensors. These sensors measure mechanical movements (such as rotation and acceleration) and environmental parameters (like temperature, humidity, and proximity) [165]. The study achieved a remarkable classification accuracy exceeding 98% across all activity categories.

Further, another study [164] employed an MLP neural network to recognize various human activities using data from devices worn on the wrist and ankle. The authors proposed a novel data collection technique capable of distinguishing nine different activity categories. This technique utilizes an ultra-low-power STM32L4 series MCU, supplemented by various communication modules (including Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, NFC, Sub-RF, and a second Bluetooth module) and embedded Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) sensors. These sensors measure mechanical movements (such as rotation and acceleration) and environmental parameters (like temperature, humidity, and proximity) [165]. The study achieved a remarkable classification accuracy exceeding 98% across all activity categories.

In a different exploration, Natani et al. [166] adapted the MLP architecture for multi-resident activity recognition in environments equipped with ambient sensors. By incorporating dual output layers in the MLP design, the modified architecture avoids the complexities of multi-label techniques or combined label strategies traditionally used in multi-resident activity modeling. The study, which utilized the ARAS dataset, reported accuracy rates of 69.92% for house A and 89.7% for house B.

Shi et al. [167] proposed a smartphone-assisted HAR method utilizing a residual MLP (Res-MLP) structure. This model features two linear layers with Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU) activation functions [168] and employs residual connections to enhance learning. Tested on the public UCI HAR dataset, the method achieved a high classification accuracy of 96.72%, underscoring the potential of Res-MLP in activity recognition tasks.

Mao et al. [169] presented a novel Human Activity Recognition (HAR) technique that incorporates an MLP neural network and extracts Euler angles from inertial measurement unit (IMU) sensors. This method initially calculates Euler angles for determining precise attitude angles, which are further refined using data from gyroscopes and magnetometers. To enhance data representation from a time domain to a frequency domain, the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is employed for feature extraction, thereby increasing the practical utility of the data. Moreover, the introduction of a Group Attention Module (GAM) facilitates enhanced feature fusion and information sharing. This module, termed the Feature Fusion Enrichment Multi-Layer Perceptron (GAM-MLP), effectively amalgamates features to yield accurate classification results. The technique demonstrated impressive accuracy rates of 93.96% and 96.13% on the self-created MultiportGAM and the publicly available PAMAP2 datasets, respectively.

Wang et al. [170] proposed an all-MLP lightweight network architecture tailored for HAR, which is distinguished by its simplicity and effectiveness in handling sensor data. Unlike Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), this architecture relies solely on MLP layers equipped with a gating unit, enabling straightforward processing of sensor data. By partitioning multi-channel sensor time series into non-overlapping patches, the model locally analyzes sensor patches to extract features, thereby reducing computational demands. Tested across four benchmark HAR datasets including WISDM, OPPORTUNITY, PAMAP2, and USC-HAD, showed that the model not only necessitated fewer Floating-Point Operations per Second (FLOPs), and parameters compared to convolutional architectures but also matched their classification performance.

Two MLP-based models, MLP-Mixer and gMLP, were utilized by Miyoshi et al. [171] for sensor-based human activity recognition. The MLP-Mixer construction [172] consists of Mixer layers that combine two different kinds of MLPs: channel-mixing MLP, and token-mixing MLP. Through the spatial mixing of information across several tokens, the token-mixing MLP can extract features. channel-mixing MLP is able to extract features by combining data in the channel direction into a single token. gMLP [173] comprises L blocks of uniform size and structure, integrating a Spatial Gating Unit (SGU) alongside conventional MLPs. The accuracy of both models was discovered in this study when the model parameters were gradually reduced, and the results indicated that accuracy is proportional to the model parameters. The experimental results show that MLP-based models can compete with current CNNs and do not perform worse.

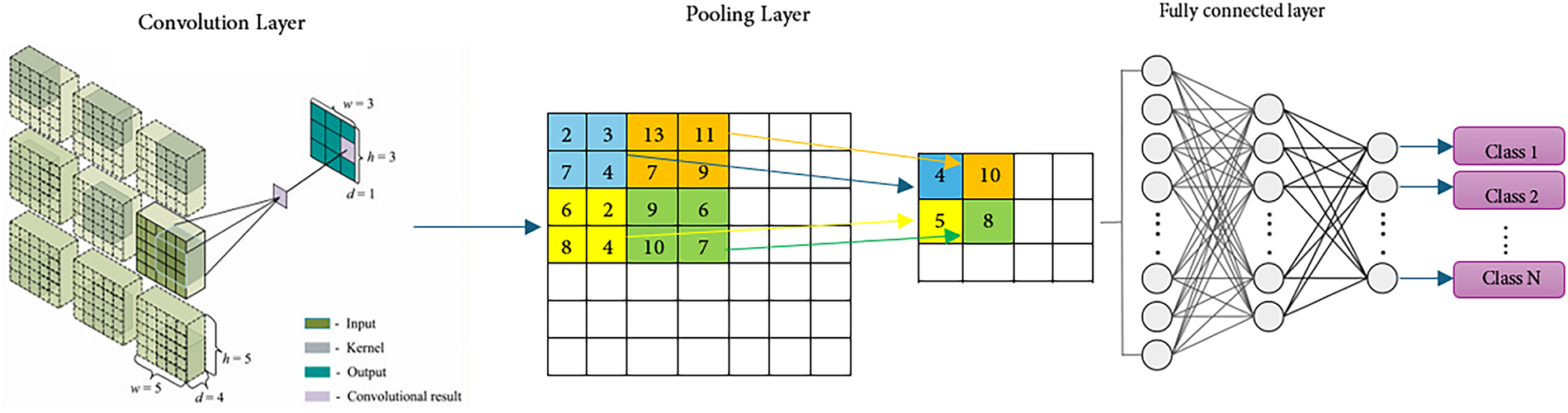

5.2 Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are distinguished as a leading class of deep learning algorithms, predominantly utilized for their robust performance in image processing and pattern recognition tasks. Unlike conventional machine learning techniques, CNNs excel at autonomously extracting features from unprocessed data and discerning patterns to classify behaviors [149]. The design of CNN draws significant inspiration from the mechanisms of visual perception observed in biological organisms [147]. The architecture of CNN is fundamentally characterized by its use of convolutional layers for feature extraction, distinguishing it from traditional Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs).

There are several pivotal advantages that set CNNs apart from ANNs: 1) Local Connections: In CNNs, each neuron is linked only to a small subset of neurons in the preceding layer, rather than to every neuron. This localized connectivity reduces the overall number of parameters, expediting the learning process and convergence. 2) Weight Sharing: This feature involves reusing the same weights for multiple connections within the network. By reducing the number of unique parameters, weight sharing simplifies the model and enhances its ability to generalize across different data sets. 3) Dimensionality Reduction via Pooling: CNNs integrate pooling layers to down sample the input data effectively. These layers capitalize on the principle of local correlation, reducing the spatial dimensions of feature maps while retaining essential information. By omitting less significant features, pooling also decreases the parameter count, contributing further to model efficiency [149,174].

These distinctive characteristics collectively position CNNs as highly efficient and capable algorithms within the realm of deep learning, making them particularly suitable for a variety of complex computational tasks. As illustrated in Fig. 7, a CNN typically comprises several layers including convolutional layers, pooling layers, fully connected layers, and nonlinear activation functions, each contributing to the streamlined and effective processing of data through the network.

Figure 7: The pipeline of a Convolutional Neural Network

Convolution Layer: The convolution layer is a pivotal component of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and plays a critical role in the extraction of spatially invariant features through the convolution operation, utilizing shared kernels. Unlike fully connected neural networks, the convolutional layers are adept at detecting local dependencies, with each filter targeting a specific receptive field. Although the kernel of each layer covers only a modest subset of input neurons, the deployment of multiple layers results in neurons in higher layers possessing larger and more expansive receptive fields.

This hierarchical arrangement facilitates the transformation of local, low-level features into abstract, high-level semantic information [19]. Convolution layers consist of learnable convolution kernels, typically structured as weight matrices that maintain equal length and width, and are commonly odd-numbered (e.g.,

Pooling Layer: Situated typically after the convolution layer within a CNN, the pooling layer is designed to perform dimensionality reduction and down-sampling, effectively minimizing the number of network connections. This reduction is crucial for alleviating computational demands and combating overfitting. By decreasing the spatial dimensions of the feature maps generated by the convolution layer, the pooling layer not only compresses the learned representations but also preserves essential features, enhancing the model’s efficiency and robustness [176]. Various pooling techniques exist, each with specific advantages and use cases. Some common pooling techniques including Max Pooling: Selects the maximum value from each patch of the input feature map, and captures prominent features. Average Pooling: Calculates the average value across each patch, providing a smoothed feature representation [177].

Mixed Pooling: Combines methods like max and average pooling to leverage the benefits of both [178]. Stochastic Pooling: Randomly selects a maximum value from the input patch, introducing variability and promoting exploration in learning [179]. Spatial Pyramid Pooling [180] and Multi-Scale Order-Less Pooling [181]. These advanced techniques adapt the pooling process to handle varying input sizes and capture features at multiple scales. Each of these pooling strategies offers unique benefits, allowing developers to tailor the approach to meet the demands of CNN architecture and the task at hand.

Fully Connected Layer: The fully connected (FC) layer, positioned at the end of the CNN architecture, is integral to the network’s decision-making process. Following the principles of a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), each neuron in the FC layer is interconnected with every neuron from the previous layer. The input to this layer typically comes from the last pooling or convolutional layer and involves a flattened vector of the feature maps. This layer synthesizes the extracted features into final outputs, forming the basis for high-level reasoning and classification in the CNN [149].

Activation Functions: Activation functions are essential components in Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), critical for introducing non-linearity into the network. This non-linearity is vital for CNN’s ability to model complex patterns and relationships within the data, enabling it to perform tasks beyond mere linear classification or regression. Without these non-linear activation functions, a CNN would merely perform linear operations, significantly limiting its capability to accurately represent the intricate, non-linear behaviors typical of many real-world phenomena [182].

Fig. 8 would typically illustrate how these activation functions modulate input signals to produce output, emphasizing the non-linear transformations applied to the input data across different regions of the function curve. In this figure,

Figure 8: The general structure of activation functions

Tanh and sigmoid functions are often referred to as saturating nonlinearities due to their behavior when inputs are very large or small. Specifically, the Sigmoid function approaches values of 0 or 1, whereas the Tanh function trends towards −1 or 1 as described in reference [174]. To mitigate issues related to these saturating effects, various alternative nonlinearities have been introduced, such as the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) [152], Leaky ReLU [183], Parametric Rectified Linear Units (PReLU) [184], Randomized Leaky ReLU (RReLU) [185], S-shaped ReLU (SReLU) [186], and Exponential Linear Units (ELUs) [187]. Among the activation functions, ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) is particularly popular in contemporary CNNs due to its simplicity and effectiveness in addressing the vanishing gradient problem during training. Mathematically, ReLU is defined as follows [188]:

In these definitions,

Conversely, the sigmoid function is defined as:

where

Similarly, the hyperbolic tangent (tanh) function, like sigmoid, maps real numbers to a range between −1 and 1, providing non-linearity to the model. However, it can also suffer from issues related to vanishing gradients in deep neural networks [182].

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) offer significant advantages for time series data classification in applications such as Human Activity Recognition (HAR). These advantages primarily arise from their ability to exploit local dependencies and achieve scale invariance. Local dependencies imply that neighboring time series data points are often correlated, enabling CNNs to effectively discern spatial relationships and patterns. Scale invariance, meanwhile, ensures consistent performance despite variations in scale or frequency within the input data [8].

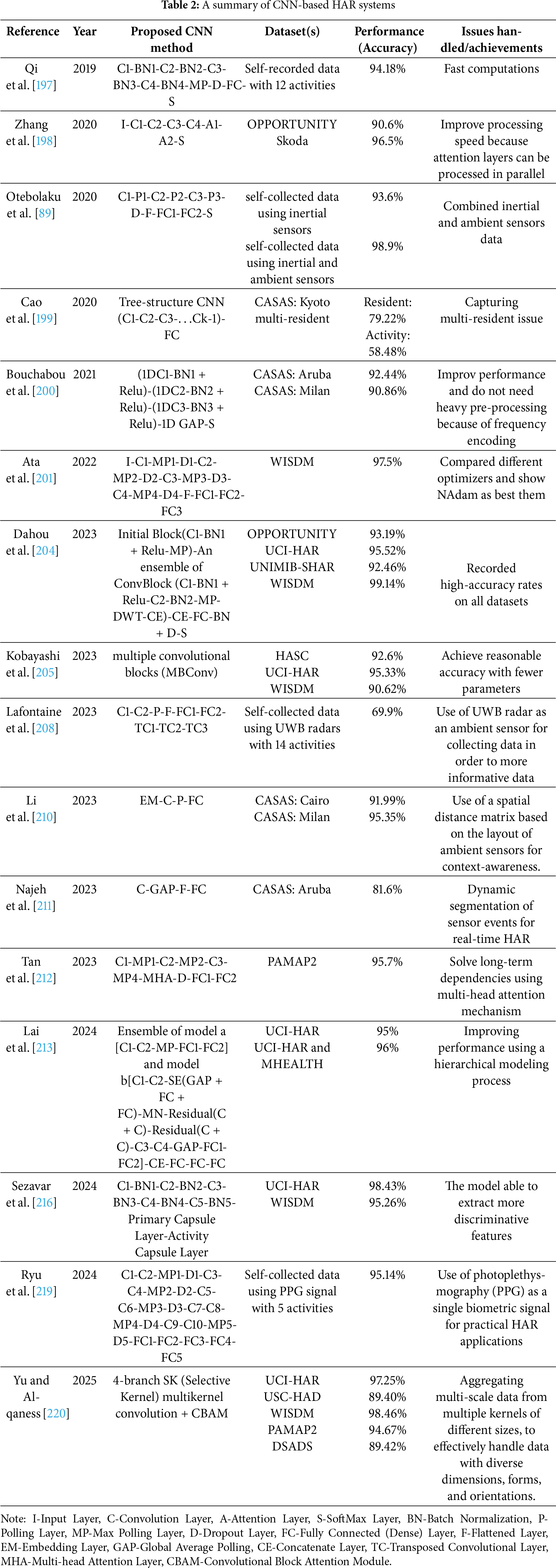

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have become highly effective deep learning tools for Human Activity Recognition (HAR) systems in sensor-based contexts, thanks to their capability to leverage local dependencies and maintain scale invariance. While some studies have employed the simple CNN models for HAR [189–191], others have explored advanced variants, including DenseNet [192], CNN-based autoencoders [193,194], and CNN models enhanced with attention mechanisms [195,196], among others.

Qi et al. [197] introduced a robust framework termed Fast and Robust Deep Convolutional Neural Network (FR-DCNN) designed for HAR using smartphone sensors. This framework enhances data efficiency through an integrated signal selection module and various signal processing algorithms, all operating on data from inertial measurement units (IMUs). A complementary data compression module facilitates a swifter construction of the DCNN classifier, significantly optimizing computational speed.

Another novel approach is the DeepConvAttn model developed by Zhang et al. [198], which merges the convolutional neural network with an attention mechanism. Building on the established DeepConvLSTM model, comparative studies on benchmark HAR datasets have shown that DeepConvAttn delivers superior performance, attributed to its parallel processing of attention mechanisms, thereby accelerating data throughput.

Otebolaku et al. [89] developed two distinct Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) models to address the challenges of class imbalance in Human Activity Recognition (HAR) systems. The first model processed only inertial sensor data, while the second model enhanced the input feature set by integrating both inertial and ambient sensor signals. This integration leverages the CNN’s inherent capabilities for scale invariance and local dependency to better capture the complex dynamics of the combined sensor data. Specifically, ambient sensor data, such as noise levels and lighting conditions, when fused with inertial sensor data, contribute significantly to the richness of the input features. This fusion leads to markedly improved recognition accuracy, as demonstrated through the evaluation and analysis of the system using datasets characterized by imbalanced class distributions. This study highlights the potential of multimodal sensor integration in enhancing the performance of HAR systems under challenging real-world conditions.

In the context of multi-resident activity recognition, Cao et al. [199] introduced an advanced end-to-end framework for Multi-Resident Activity Recognition utilizing Tree-Structured Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). This architecture is designed to capture temporal dependencies among sensor readings in close proximity, which facilitates the automatic extraction of relevant temporal features. The integration of a fully connected layer processes these features to concurrently classify both the residents and their activities. This comprehensive approach not only streamlines the recognition process but also enhances the accuracy of activity predictions across multiple residents within the same environment.

Bouchabou et al. [200] developed a novel HAR system for smart homes, employing an end-to-end architecture that merges frequency encoding with a fully convolutional network (FCN). This method eliminates the need for manual feature engineering and extensive preprocessing, leveraging frequency-based embedding to enhance input data representation directly from raw signals.

Ata et al. [201] introduced a novel Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model tailored for human activity recognition. They employed an innovative stream-based CNN architecture, incorporating various optimization techniques to enhance model performance. The focus of their research was on a spectrum of human activities, which were represented through signal data collected from gyroscope and accelerometer sensors attached to multiple body parts. This sensor data served as the input for the proposed networks. By using this approach, they were able to efficiently process the complex patterns inherent in the sensor signals, potentially leading to more accurate and reliable recognition of diverse human activities.

Ataseven et al. [202] have devised a sophisticated system for real-time physical activity recognition by employing deep transfer learning techniques. Utilizing acceleration data from Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs), they adapted a pre-trained GoogLeNet convolutional neural network model [203] to suit their needs. To effectively integrate IMU data into the GoogLeNet architecture, which was not originally designed for handling such data, they introduced three innovative data transform techniques based on continuous wavelet transform. These are Horizontal Concatenation (HC), which aligns data streams side-by-side; Acceleration-Magnitude (AM), which focuses on the magnitude of acceleration vectors; and Pixelwise Axes-Averaging (PA), which averages data across different sensor axes at each pixel point. These transformations are critical for rendering IMU data compatible with the input requirements of GoogLeNet, thereby enabling the refined model to process and recognize physical activities with enhanced accuracy. This approach not only leverages the powerful feature extraction capabilities of GoogLeNet but also tailors it to the unique characteristics of sensor-based activity data, significantly advancing the field of wearable technology-based activity recognition.

Another novel approach for Human Activity Recognition (HAR) named MLCNNwav was presented by Dahou et al. [204], which integrates the strengths of residual convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and one-dimensional trainable discrete wavelet transform (DWT). This innovative architecture utilizes a multilevel CNN to capture global features essential for recognizing a wide range of activities, while simultaneously employing the wavelet transformation to learn activity-specific features. The integration of DWT allows for a more refined feature extraction process, capturing both time and frequency domain information that is crucial for accurately classifying complex human movements. The synergy between the deep learning capabilities of residual CNNs and the precise feature delineation afforded by DWT enhances both the representation and generalization power of the model. This dual approach ensures that MLCNNwav effectively handles the variability and intricacies of sensor-based activity data, leading to significant improvements in HAR performance.

Kobayashi et al. [205] introduced MarNASNets, a deep learning model designed for sensor-based Human Activity Recognition (HAR), utilizing the innovative approach of Neural Architecture Search (NAS) [206,207]. They implemented Bayesian optimization to methodically explore various architectural options, focusing on optimal configurations for the convolution process. Key parameters varied included kernel size, types of skip operations, the number of convolutional layers, and the number of output filters. Experimental findings underscore the efficiency of MarNASNets, demonstrating that they achieve comparable accuracy to conventional CNN models while requiring fewer parameters. This attribute makes MarNASNets particularly suitable for on-device applications where computational resources are limited.

Lafontaine et al. [208] proposed an unsupervised deep convolutional autoencoder, utilized specifically for denoising the scattering matrix data from Ultra-WideBand (UWB) radar [209], an advanced ambient sensor technology. The autoencoder focuses on isolating and removing unique background noise patterns from the data, a critical step facilitated by the encoder’s restricted component. Following min-max normalization, the model employs a mean squared error (MSE) loss function during training, which aids in reconstructing the primary features from the noisy input. The effectiveness of this CNN-based autoencoder in enhancing HAR data quality through unsupervised filtering has been validated through rigorous testing.

A new analytical method called sensor data contribution significance analysis (CSA), which assesses the impact of various sensors on behavior recognition in HAR systems, was developed by Li et al. [210]. This approach utilizes a novel metric based on the frequency-inverse type frequency of sensor status. To enhance data reliability and context awareness, they also designed a spatial distance matrix that considers the physical arrangement of ambient sensors. The culmination of this research is the proposal of the HAR_WCNN algorithm, which integrates wide time-domain convolutional neural networks with data from multiple environmental sensors to recognize daily behaviors effectively.

Furthermore, an online HAR framework designed for real-time processing on streaming sensor data was presented by Najeh et al. [211]. This framework incorporates stigmergy-based encoding and CNN2D classification, paired with real-time dynamic segmentation. This segmentation process determines whether consecutive sensor events should be grouped as a single activity segment. The encoded features, structured in a multi-dimensional format suitable for CNN2D input, leverage a directed weighted network (DWN) to account for overlapping actions and capture the spatiotemporal trajectories of human movement, enhancing the real-time analytical capabilities of the system.

In another study, Tan et al. [212] developed a novel convolutional neural network architecture enhanced with a multi-head attention mechanism (CNN-MHA). This architecture features several attention heads, each autonomously determining the attention weights for different input segments. The integration of these weights occurs at a fully connected layer that synthesizes the final attention representation. The multi-head attention design enables the network to preserve long-term dependencies within the input data while focusing on salient features, significantly improving the precision and effectiveness of the processing.

A multi-input model for Human Activity Recognition (HAR) using hybrid CNNs was introduced by Lai et al. [213] that incorporates fundamental CNN structures with advanced squeeze-and-excitation (SE) blocks [214] and residual blocks [215]. The model uses multiple transformed datasets derived from the UCI-HAR and MHEALTH databases through fast Fourier, continuous wavelet, and Hilbert-Huang transform methods. These datasets serve as heterogeneous inputs to a system that synergizes one- and two-dimensional CNNs with SE and residual blocks, enhancing the model’s ability to handle complex time-frequency domain data effectively.

Sezavar et al. [216] proposed DCapsNet, a deep neural network that merges traditional convolutional layers with a capsule network (CapsNet) framework [217,218]. This architecture is specifically designed for classifying and extracting activity features from integrated sensor data. The convolutional layers of the model are better suited for processing temporal sequences, producing scalar outputs but not capturing equivariance. To enhance the model’s classification efficiency, a dynamic routing method is used to train the capsule network (CapsNet), enabling it to detect equivariance in terms of both magnitude and orientation.

The practical application of a HAR system based on photoplethysmography (PPG) signals was explored by Ryu et al. [219]. They collected PPG data from 40 participants engaged in daily activities to build a dataset, which was then used to train a 1D CNN model to classify five distinct activities. Their analysis determined that a 10-s window size was optimal for the input signal, showcasing the feasibility of PPG-based HAR systems for real-world applications through comprehensive performance evaluations.

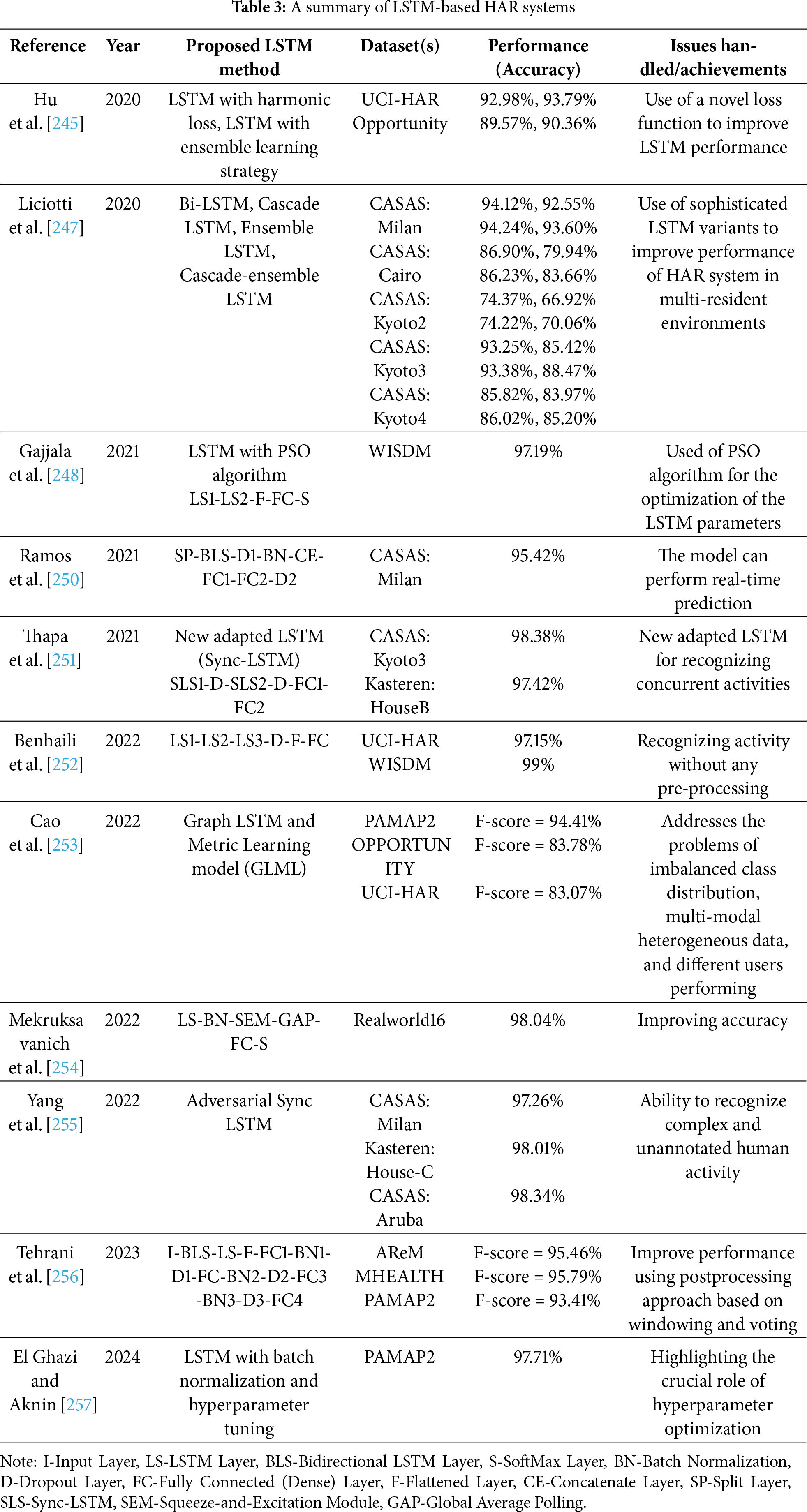

A novel HAR model proposed by Yu et al. [220], called ASK-HAR, makes use of several convolution kernels that offer reliable characteristics and enable each neuron to adaptively choose the right receptive field size based on the input content. Standard CNN architecture strives to keep the kernel size constant within the same feature layer. The suggested model, however, uses the softmax attention mechanism rather than linear splicing to merge several branches with different kernel sizes. Each layer’s convolution output is then integrated and supplied to the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [221]. The CBAM seeks to alleviate the limitations of traditional convolutional neural networks by handling data with different dimensions, shapes, and orientations.