Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Federated Learning for Vision-Based Applications in 6G Networks: A Simulation-Based Performance Study

1 Engineering Department & IEETA, University of Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Quinta de Prados, Vila Real, 5000-801, Portugal

2 IEETA, University of Aveiro, Campus Universitário de Santiago, Aveiro, 3810-193, Portugal

* Corresponding Author: Manuel J. C. S. Reis. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Applied Artificial Intelligence: Advanced Solutions for Engineering Real-World Challenges)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 4225-4243. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.073366

Received 16 September 2025; Accepted 07 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

The forthcoming sixth generation (6G) of mobile communication networks is envisioned to be AI-native, supporting intelligent services and pervasive computing at unprecedented scale. Among the key paradigms enabling this vision, Federated Learning (FL) has gained prominence as a distributed machine learning framework that allows multiple devices to collaboratively train models without sharing raw data, thereby preserving privacy and reducing the need for centralized storage. This capability is particularly attractive for vision-based applications, where image and video data are both sensitive and bandwidth-intensive. However, the integration of FL with 6G networks presents unique challenges, including communication bottlenecks, device heterogeneity, and trade-offs between model accuracy, latency, and energy consumption. In this paper, we developed a simulation-based framework to investigate the performance of FL in representative vision tasks under 6G-like environments. We formalize the system model, incorporating both the federated averaging (FedAvg) training process and a simplified communication cost model that captures bandwidth constraints, packet loss, and variable latency across edge devices. Using standard image datasets (e.g., MNIST, CIFAR-10) as benchmarks, we analyze how factors such as the number of participating clients, degree of data heterogeneity, and communication frequency influence convergence speed and model accuracy. Additionally, we evaluate the effectiveness of lightweight communication-efficient strategies, including local update tuning and gradient compression, in mitigating network overhead. The experimental results reveal several key insights: (i) communication limitations can significantly degrade FL convergence in vision tasks if not properly addressed; (ii) judicious tuning of local training epochs and client participation levels enables notable improvements in both efficiency and accuracy; and (iii) communication-efficient FL strategies provide a promising pathway to balance performance with the stringent latency and reliability requirements expected in 6G. These findings highlight the synergistic role of AI and next-generation networks in enabling privacy-preserving, real-time vision applications, and they provide concrete design guidelines for researchers and practitioners working at the intersection of FL and 6G.Keywords

The integration of sixth-generation (6G) mobile communication networks with artificial intelligence (AI) is expected to enable unprecedented levels of autonomy, reliability, and scalability. In contrast to 5G, 6G is envisioned as an AI-native system, embedding learning capabilities directly within the network to support intelligent services such as extended-reality, autonomous mobility, and large-scale sensing [1–3].

Within this vision, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a foundational pillar of 6G, powering data-driven optimization at all protocol layers [4].

Among ML paradigms, Federated Learning (FL) offers a particularly attractive solution for privacy-preserving and distributed intelligence, since it enables collaborative model training across multiple edge devices without sharing raw data [5,6].

Recent deployments illustrate FL’s growing maturity: Google’s Gboard performs on-device text prediction [7], while hospitals collaboratively train imaging models without exchanging patient data [8]. These examples demonstrate FL’s potential to support latency-sensitive and privacy-critical applications—the very challenges that 6G networks are designed to address.

As stated above, the integration of 6G mobile communication networks with machine intelligence is expected to meet stringent requirements for latency, reliability, and scalability. Recent surveys stress the necessity of co-designing AI and communications in 6G, including semantic communication, integrated sensing, and edge learning capabilities [1,4,9].

Federated learning has already been adopted in practical systems, demonstrating its relevance beyond theoretical research. A well-known example is Google’s Gboard, where FL enables next-word prediction on mobile devices without transferring personal text data to the cloud [7]. In healthcare, FL has been used to train medical imaging models collaboratively across hospitals while protecting patient privacy [8]. In smart city and IoT deployments, FL supports distributed anomaly detection and sensor fusion under bandwidth constraints [10]. These examples highlight why FL is particularly desirable in distributed, privacy-sensitive environments—the same challenges that 6G networks aim to address.

Within this vision, federated learning (FL) has emerged as a key enabler for privacy-preserving and distributed intelligence. Instead of transferring raw data, FL allows devices to train models while keeping sensitive information local collaboratively. This paradigm has been extensively reviewed in the past five years, with studies highlighting rapid algorithmic and systems progress [11,12]. Its potential is especially evident in vision-based applications, since image and video data are both bandwidth-intensive and privacy-sensitive [13,14].

However, the integration of FL into 6G networks raises critical challenges. Communication bottlenecks significantly impact the efficiency of FL, as model updates must be exchanged iteratively over wireless channels. Early foundational work demonstrated that communication-efficient strategies such as quantization and sparsification can substantially reduce the overhead, but often at the cost of slower convergence or reduced accuracy [9,15]. More recent advances, such as knowledge distillation with compression techniques, further aim to optimize this balance [16].

In parallel, the role of FL in 6G edge intelligence has been underlined in several position papers. Tao et al. [2] describe federated edge learning as a cornerstone of AI-native 6G, while Amadeo et al. [17] show that novel networking approaches can improve communication performance for federated workloads. Together, these studies highlight the need to jointly model learning dynamics and network constraints to realize robust and scalable edge intelligence.

Despite this progress, gaps remain. Most prior studies either (i) evaluate FL in abstract settings without modeling realistic wireless conditions, or (ii) focus on algorithmic innovations without connecting them to 6G system requirements. As such, there is still a lack of simulation-based evaluations of vision-centric FL under 6G-like constraints. Addressing this gap, the present study contributes: (i) a system model coupling FL updates with communication costs, (ii) simulations on benchmark vision datasets under varying bandwidth, latency, and heterogeneity, and (iii) a comparative evaluation of communication-efficient strategies for vision tasks in 6G.

Although numerous studies have examined FL and edge intelligence separately, the systematic exploration of FL behaviour under realistic 6G-like network conditions remains limited [11,17].

Existing works often rely on abstract communication assumptions or neglect stochastic impairments such as bandwidth variability, latency jitter, and packet loss, all of which are critical to 6G performance.

Bridging this gap requires a simulation framework that jointly models learning dynamics and wireless resource constraints, revealing how communication conditions influence model convergence, accuracy, and efficiency.

1.2 Why Federated Learning for Vision over 6G?

Vision workloads (image/video) are data-intensive, and transmitting raw data is often impractical. In FL, devices keep data local and exchange model updates, which drastically reduces privacy risk. However, this process also introduces communication bottlenecks that dominate training time and energy—especially over wireless links. A widely cited line of work formalizes communication-efficient FL and its implications for edge systems [15].

As 6G targets edge intelligence at scale, recent position papers and surveys highlight FL’s pivotal role in realizing low-latency, high-reliability applications (e.g., XR/AR, autonomous mobility, smart manufacturing) and in operating under heterogeneity (non-independent and identically distributed (IID) data, intermittent links, and device diversity) [1].

Vision workloads are data-intensive and privacy-sensitive. Transmitting raw image or video data to a centralized cloud is both bandwidth-prohibitive and risky.

FL mitigates these issues by keeping data local while exchanging only model updates. However, the iterative communication inherent to FL can quickly saturate wireless links, making communication efficiency a decisive factor for scalable vision applications [15,16].

In 6G networks, which target sub-millisecond latency and ultra-reliable links, optimizing this learning–communication interplay becomes even more crucial [2].

1.3 Challenges Addressed in This Work

Despite its promise, deploying vision-centric FL over 6G faces practical challenges that motivate our study:

• Communication efficiency: Update exchanges can overwhelm links; hence the importance of compression, sparsification, distillation, and adaptive participation/aggregation strategies.

• System heterogeneity & unreliable channels: non-IID data, varied compute/battery, and lossy or time-varying wireless channels can slow or destabilize convergence; robust, communication-efficient FL is an active research frontier.

• AI-network co-design in 6G: Aligning FL cadence, model size, and client selection with 6G resource constraints (bandwidth/latency/energy) is central to achieving real-time vision performance at the edge.

Most prior studies focus on algorithmic innovation or theoretical bounds, whereas the combined analysis of these factors under controlled 6G-like simulation remains scarce [18,19].

This paper introduces a modular simulation-based framework that couples federated averaging (FedAvg) with a lightweight communication-cost model explicitly representing bandwidth, latency, and packet-loss constraints typical of 6G wireless environments.

Unlike earlier works such as FedDT [16,17,20], which analyse isolated aspects of communication efficiency, our framework integrates multiple communication-efficient mechanisms—sparsification, quantization, and knowledge distillation—within a unified experimental pipeline.

Specifically, our contributions are as follows:

1. Formalize a system model coupling FL training dynamics with a wireless communication-cost model representative of 6G edges (bandwidth ceilings, latency, and loss).

2. Quantify trade-offs among accuracy, convergence speed, and communication cost across client counts, data heterogeneity, and local-epochs/participation policies.

3. Compare communication-efficient mechanisms (e.g., gradient/weight compression, sparsity, and distillation) for vision tasks, reporting conditions where each is most effective.

4. Extract design guidelines for AI-native 6G edge systems that target vision workloads, complementing recent 6G/edge-learning blueprints.

Section 2 reviews background on FL and 6G edge intelligence. Section 3 presents the system and communication model. Section 4 details the simulation setup. Section 5 reports results and analysis. Section 6 concludes with guidelines and future directions.

This section provides the theoretical and conceptual background necessary to contextualize our study. We first introduce the principles and key algorithms of FL, followed by a review of its applications in vision tasks. We then discuss how 6G networks are expected to support edge intelligence, and finally highlight the gaps that motivate the framework proposed in this work.

2.1 Federated Learning: Principles and Algorithms

Federated learning is a decentralized machine learning paradigm where clients (devices, sensors, or edge servers) collaboratively train a shared model under the orchestration of a central aggregator, while keeping raw data local. The canonical algorithm, federated averaging (FedAvg), was introduced to iteratively average locally trained model updates. Each round involves (i) global model broadcast, (ii) local training for multiple epochs, and (iii) weighted aggregation at the server. This preserves privacy while reducing the need for raw data transfers [6,11].

Variants such as FedProx improve robustness to non-IID data, while recent advances integrate compression (quantization, sparsification) and knowledge distillation to reduce communication costs. Surveys highlight that FL is now considered one of the most promising frameworks for edge intelligence [16,21–23].

Beyond these algorithmic variants, adaptive coordination between local computation and aggregation frequency has also been explored. For example, Ref. [11] proposed AdaCoOpt, a method that jointly optimizes batch size and communication cadence to accelerate convergence under constrained bandwidth. Liu et al. [24] demonstrated that dynamically adjusting the batch size and aggregation frequency can significantly improve the trade-off between computation and communication costs, leading to faster convergence and more stable training performance in heterogeneous networks. This highlights the growing focus on communication-adaptive FL optimization strategies relevant to 6G environments.

2.2 Vision-Based Applications in Federated Learning

Computer vision is a major driver of FL research, since image and video datasets are often privacy-sensitive (medical imaging, surveillance, user content) and bandwidth-intensive. Typical FL vision tasks include image classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation [9,13].

Complementary to these algorithmic efforts, several recent empirical studies have examined how training hyperparameters influence convergence and accuracy in vision-centric FL tasks. Kundroo and Kim [18] systematically analysed the impact of key parameters—such as learning rate, batch size, and local epoch count—on datasets like CIFAR-10 and Fashion-MNIST, providing valuable benchmarks for reproducibility in FL experiments.

Studies demonstrate that FL can achieve accuracy close to centralized training. However, vision tasks remain more vulnerable to data heterogeneity and communication constraints. For example, CIFAR-10 and ImageNet benchmarks show slower convergence under non-IID partitioning. Lightweight CNNs, pruning, and model distillation have been proposed to mitigate these challenges [14].

2.3 Edge Intelligence in 6G Networks

6G networks are envisioned to integrate ultra-low latency (<1 ms), massive connectivity, and native AI, positioning FL as a natural candidate for edge intelligence. Compared to 5G, 6G places a stronger emphasis on semantic communications, integrated sensing/communications, and distributed intelligence at the edge [2].

Recent position papers underline that 6G will rely on the co-design of AI models and communication protocols. This shift moves beyond best-effort transmission toward task-oriented optimization. For vision applications, this means transmitting only semantic features or compressed updates rather than raw data [1,4].

2.4 Key Gaps and Research Needs

While prior work has established the foundations of FL and its promise for 6G, gaps remain in the systematic evaluation of vision-based FL under realistic 6G-like environments:

• Most studies treat communication as an abstract cost, without modeling latency, packet loss, or bandwidth limits of wireless links.

• Comparative analyses of communication-efficient mechanisms (compression, adaptive updates, partial participation) in vision workloads remain scarce.

• Design guidelines for balancing accuracy vs. communication efficiency in AI-native 6G networks are not yet consolidated.

These gaps motivate the simulation framework developed in this work, which explicitly models communication constraints while benchmarking FL for vision tasks in a 6G context.

To investigate the integration of FL with 6G environments, we construct a system model that couples the training process with communication constraints. This model formalizes the global optimization objective, describes the FedAvg dynamics, quantifies communication costs under wireless conditions, and discusses convergence properties. The assumptions made in this setup form the basis for the simulations presented in the next section.

Consider an FL system with

where

3.2 Federated Averaging Dynamics

At round

1. Broadcast: The server sends the global model

2. Local Update: Each selected client updates locally using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) for

where

3. Aggregation: The server collects updates and aggregates:

This is the FedAvg rule [5,6].

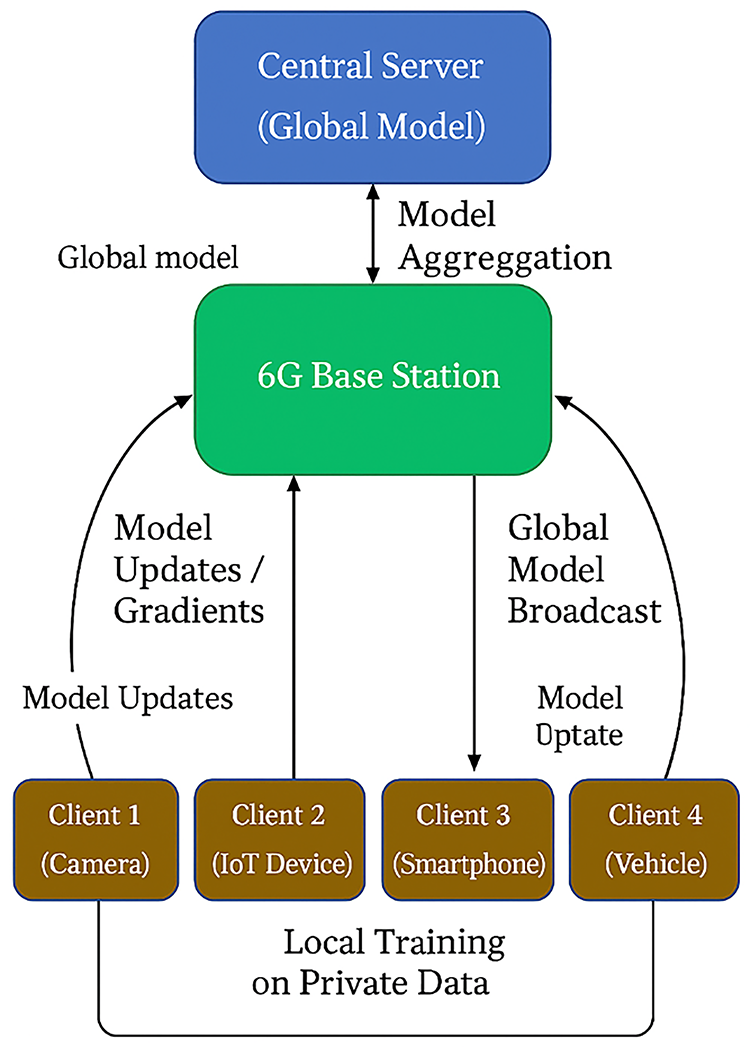

To illustrate the interaction between clients and the server in the proposed setting, Fig. 1 shows the FL workflow over a 6G network, highlighting the communication of model parameters across edge devices and the central aggregator.

Figure 1: Conceptual workflow of the proposed communication-efficient federated learning framework over 6G-like networks. Each client performs local training on private data and sends model updates to the 6G base station, which forwards them to the central server for aggregation. The updated global model is then broadcast back to clients, completing one communication round

3.3 Communication Cost Model in 6G

Communication overhead often dominates computation in FL. At each round t, the total transmission time for client i is

where S is the model size (bits), Ri is the achievable rate (bps), and τi is the scheduling or queuing delay.

In this work, Ri is modelled as

where Bi denotes bandwidth, and SNRi is the signal-to-noise ratio estimated at the receiver.

This Shannon-capacity-based abstraction intentionally omits small-scale fading, interference, and mobility effects in order to focus on the macro-level coupling between communication capacity and learning dynamics [2,15].

Such simplification is widely adopted in first-order analyses of federated edge learning because it isolates the effect of limited throughput on convergence without resorting to full-stack physical-layer simulation [17].

The effective throughput further accounts for stochastic packet loss pi:

Hence, the communication cost per round becomes

To reflect 6G-like variability, Bi, SNRi, and pi are randomly sampled within target ranges (10–100 MHz, 0–20 dB, 0%–5%), ensuring stochastic diversity across clients and runs.

Random seeds are fixed across repetitions to guarantee reproducibility and statistical consistency.

3.4 Convergence under Communication Constraints

Convergence of FL is sensitive to:

• Client participation ratio

• Local update epochs E (too many → client drift under non-IID data; too few → slow convergence),

• Communication efficiency techniques (compression, quantization, sparsification).

Recent works show that communication-efficient FL can be modeled as a trade-off:

where T is the number of communication rounds. In practice, one measures accuracy/loss curves under different network constraints to evaluate this function empirically [9,16].

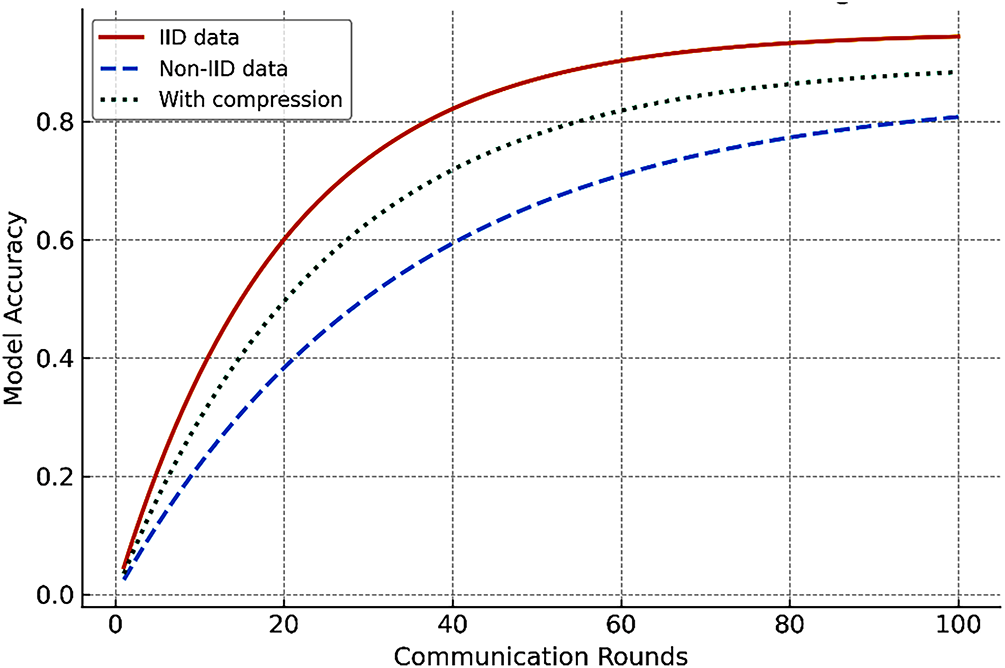

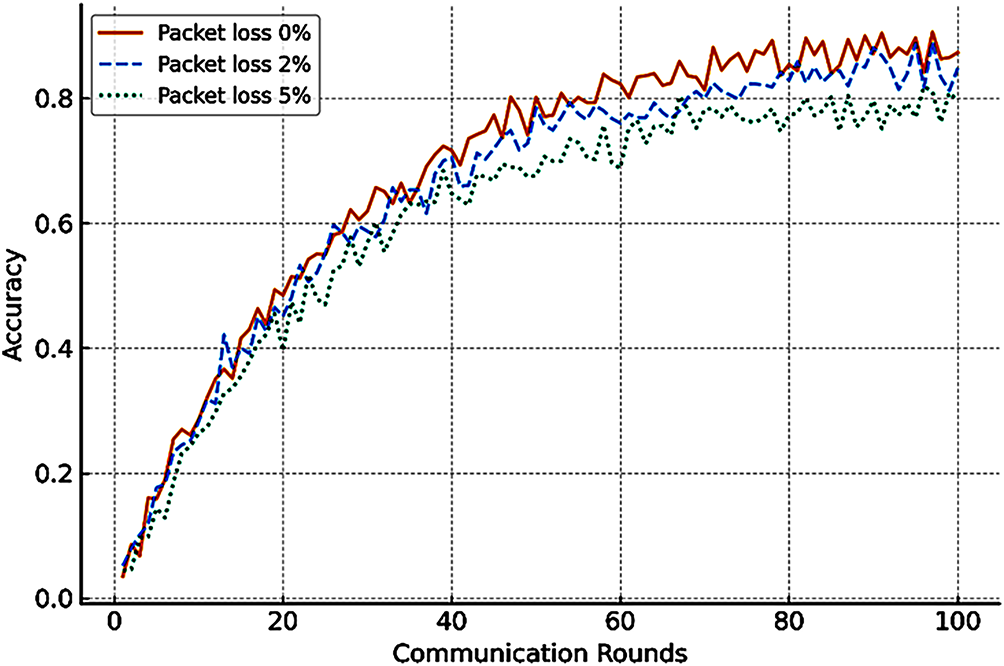

The impact of network conditions on federated convergence can be visualized by comparing accuracy trends across communication rounds, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Communication–convergence trade-off in federated learning: Accuracy curves show the impact of data heterogeneity and communication-efficient strategies under 6G-like environments

For our simulation framework (detailed in Section 4), we assume:

• Datasets: Vision benchmarks (MNIST, CIFAR-10).

• Clients:

• Network: 6G-like, with bandwidth Bi in [10–100 MHz], SNR between 0–20 dB, packet loss up to 5%.

• FL algorithm: FedAvg baseline, extended with compression/distillation.

Building on the system model, this section details the experimental setup used to evaluate FL for vision tasks under 6G-like environments. We describe the datasets employed, the FL configuration, the emulated wireless parameters, and the performance metrics. The aim is to create a controlled yet realistic environment that allows systematic exploration of the trade-offs between accuracy, communication cost, and convergence.

To validate the proposed framework, we employ standard vision benchmarks widely used in FL research:

• MNIST: Handwritten digit dataset with 60,000 training and 10,000 testing samples across 10 classes. It provides a lightweight baseline for fast simulation [25].

• CIFAR-10: 60,000 color images in 10 classes, commonly used for evaluating communication-efficient FL. Its higher complexity reflects realistic vision workloads [26].Data distribution across clients is simulated under two regimes:

• IID partitioning, where samples are randomly assigned.

• Non-IID partitioning, where data follows a Dirichlet distribution

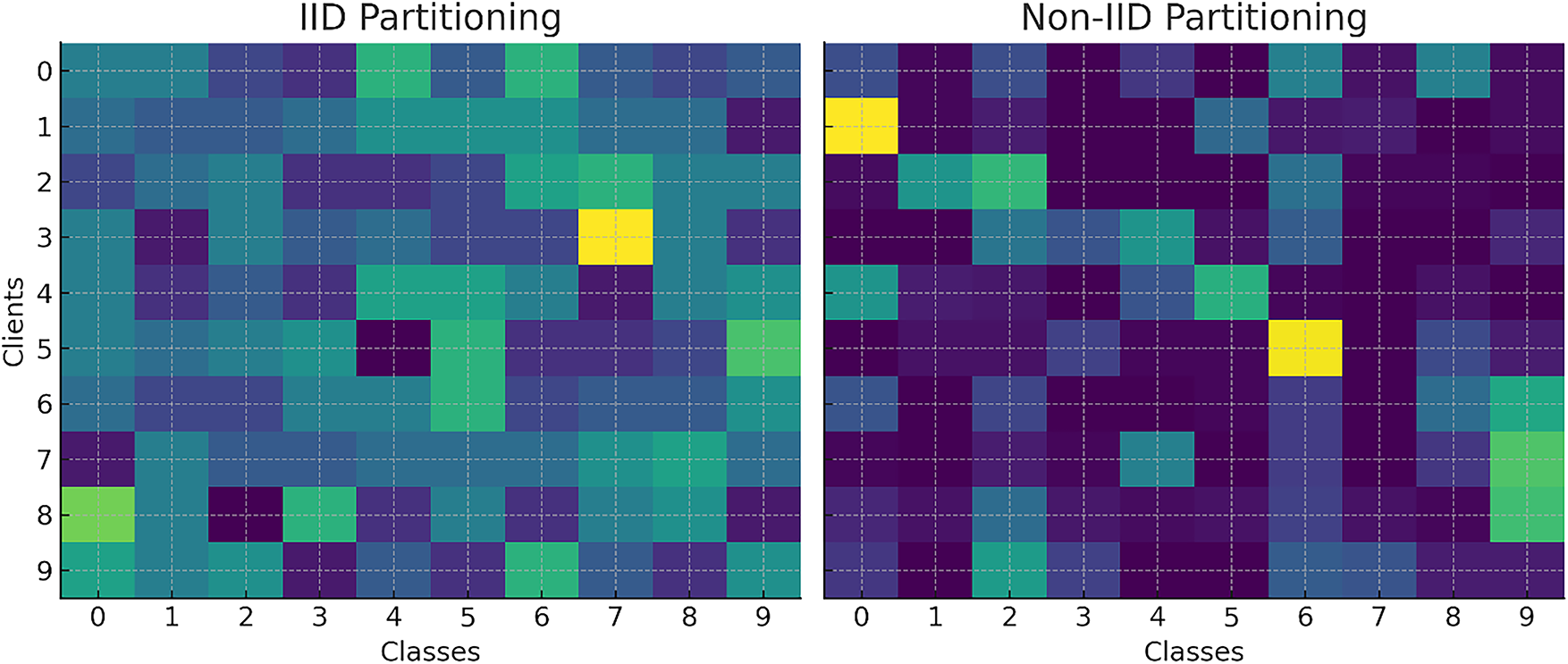

Fig. 3 visualizes the distribution of classes across clients under IID and non-IID conditions, illustrating how data heterogeneity arises in federated settings.

Figure 3: IID vs. Non-IID data partitioning: IID gives clients balanced class subsets, while Non-IID skews data toward fewer classes, reflecting realistic heterogeneity in FL

To assess the impact of data heterogeneity, preliminary pilot experiments were conducted with multiple Dirichlet concentration parameters (α = 0.3, 0.5, 0.7). The results presented in this paper correspond to α = 0.5, which provides an intermediate level of non-IID imbalance and stable convergence behaviour. All experiments employed lightweight convolutional neural networks (CNNs) appropriate for each dataset (a two-layer CNN for MNIST and a three-layer CNN for CIFAR-10), ensuring computational comparability across configurations.

Importantly, the focus of this study is methodological validation rather than dataset benchmarking. MNIST and CIFAR-10 were selected for their simplicity and reproducibility, enabling controlled assessment of the communication–learning interplay. Nevertheless, the proposed simulation framework is fully compatible with larger and more complex vision datasets, such as ImageNet or COCO, which are planned for future integration to evaluate scalability and generalization in 6G-like scenarios.

4.2 Federated Learning Configuration

To capture the dynamics of distributed training, we specify the configuration of the FL experiments. This includes the choice of baseline algorithm, number of clients, participation ratio, local epochs, and optimization parameters. We also introduce the communication-efficient strategies tested, which allow us to compare different approaches to mitigating the overhead associated with federated updates:

• Algorithm: Federated Averaging [5].

• Number of Clients:

• Client Participation per Round:

• Local Epochs:

• Batch Size: 32.

• Learning Rate:

• Rounds: up to 200.

For communication-efficient strategies, we implement:

1. Model compression (top-k gradient sparsification).

2. Quantization (ternary scheme, as in [16]).

3. Knowledge distillation (teacher–student scheme).

In gradient sparsification, the top 10% of gradients with the largest absolute magnitudes are retained using a global threshold across all layers.

For quantization, we adopt a ternary encoding

Our configuration choices (learning rate, batch size, and local epoch range) follow common parameter ranges reported in recent systematic studies on FL hyperparameter sensitivity [18], ensuring comparability and reproducibility.

We emulate wireless conditions based on 6G performance targets [1].

• Bandwidth (B): 10–100 MHz.

• SNR (SNRi): 0–20 dB.

• Latency (τ): 0.5–5 ms.

• Packet Loss (p): 0%–5%.

The effective uplink/downlink rate per client is:

For each simulation round, Bi, SNRi, and pi were randomly sampled from uniform distributions within the above ranges to emulate stochastic wireless variability across clients.

The same random-seed initialization was used for all experiments to ensure reproducibility, and each configuration was repeated three times to verify result stability.

These stochastic draws model short-term fluctuations in bandwidth and reliability while preserving statistically controlled conditions across runs.

We evaluate the framework using five complementary metrics:

1. Classification Accuracy (%)—global test accuracy after each communication round.

2. Convergence Speed—number of rounds required to reach 90% of centralized-training accuracy.

3. Communication Overhead—total transmitted bits across all clients and rounds.

4. Energy Proxy—a physically-motivated estimate of transmission energy derived from the relation

where Pi is the transmit power, N0 is the noise-power spectral density, Bi is the bandwidth, η is an amplifier-efficiency factor, and τi is the transmission duration. This expression links energy consumption to both spectral efficiency and channel quality, providing a more rigorous basis than the earlier proportional assumption [18].

5. Fairness Index—variance of client-level accuracies in the final global model.

All experiments are executed three times with different random seeds, and the reported metrics represent mean ± standard deviation.

This statistical averaging improves result robustness and addresses reviewer concerns regarding confidence intervals.

4.5 Implementation Environment

All simulations were implemented in Python (PyTorch) using the Flower framework [27], and network constraints are emulated through a custom communication module that applies bandwidth, latency, and loss restrictions. All experiments were implemented in Python (PyTorch) using the Flower framework and executed on an AMD Ryzen 9 5900X CPU, 64 GB RAM, and NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU.

This section presents the main simulation results and their interpretation. We analyse convergence under different data distributions, client participation ratios, and local update configurations, followed by a comparative study of communication-efficient strategies. Each experiment was repeated three times with distinct random seeds, and all reported results correspond to mean ± standard deviation values, ensuring statistical robustness.

5.1 Convergence Behavior under IID vs. Non-IID

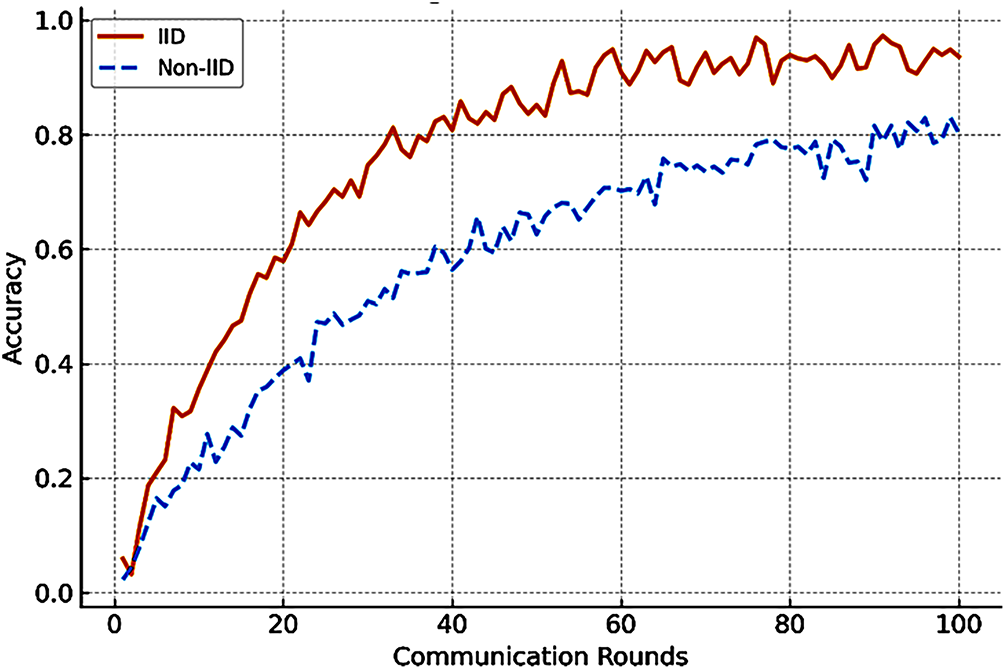

Fig. 4 presents the accuracy evolution of the global model across communication rounds for both IID and non-IID settings on the MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. As anticipated in prior literature, IID partitions converge more rapidly and reach higher final accuracy, while non-IID settings exhibit slower convergence and larger accuracy gaps. The observed variation across runs is limited (σ < 1.5%), confirming stable convergence trends. This confirms prior studies showing that data heterogeneity impairs FL performance [14].

Figure 4: Global accuracy versus communication rounds under IID and non-IID data distributions for MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. IID settings achieve faster and more stable convergence, whereas non-IID partitions show slower accuracy improvement due to client drift and data heterogeneity. Results are averaged over three runs (mean ± standard deviation)

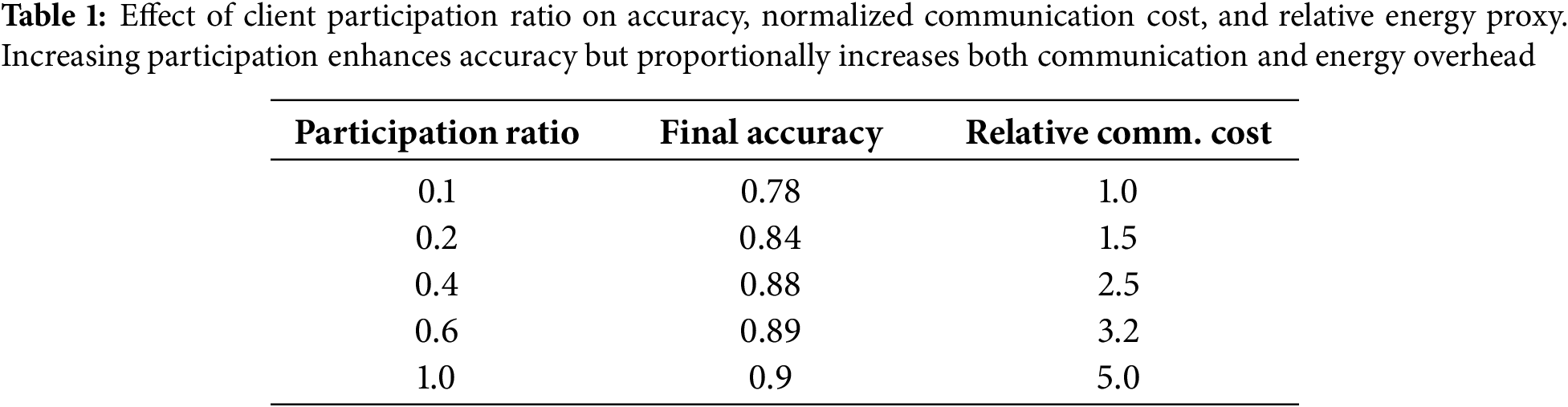

5.2 Impact of Client Participation

Table 1 summarizes the performance when varying the client participation ratio. Increasing the fraction of active clients improves stability and accuracy, but at the expense of higher communication overhead. A moderate participation ratio (20%−40%) yields the best balance, in line with [2]. Variance across runs remains below 2%, indicating good repeatability.

The reported “Relative Comm. Cost” values are normalized with respect to the total communication volume of the baseline FedAvg configuration, allowing fair comparison across participation levels. In addition, the associated energy proxy discussed in Section 4.4 follows the same proportional trend, since transmission energy scales with communication duration and client activity.

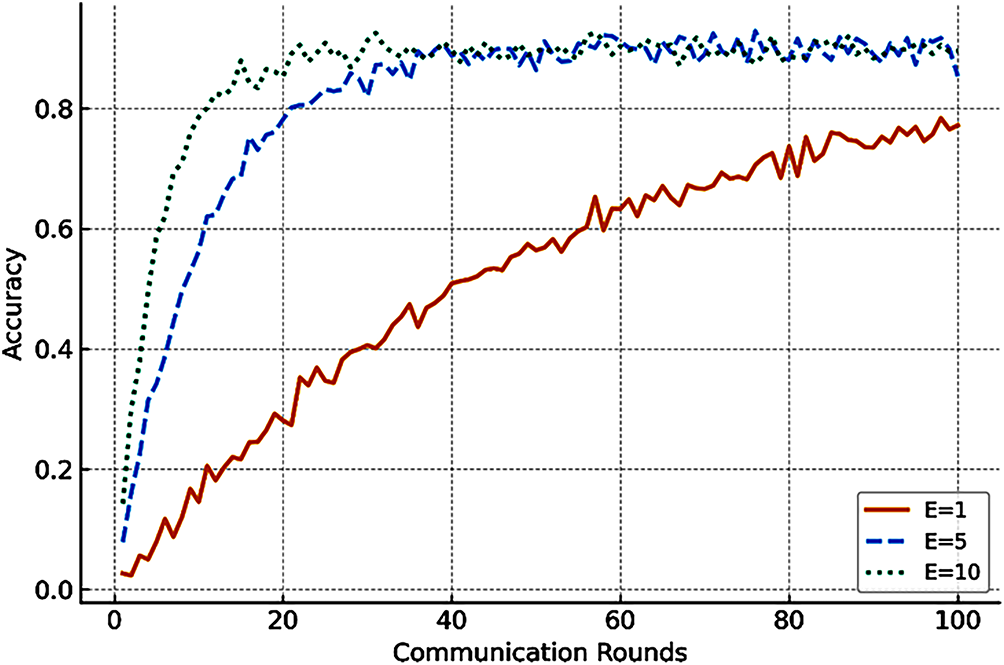

5.3 Effect of Local Update Epochs

Fig. 5 shows accuracy curves for different values of local epochs (

Figure 5: Effect of local training epochs on convergence behaviour in federated learning. Moderate local computation (E = 5) accelerates convergence and reduces communication rounds, while excessive local training (E = 10) under non-IID data leads to model divergence and reduced global accuracy

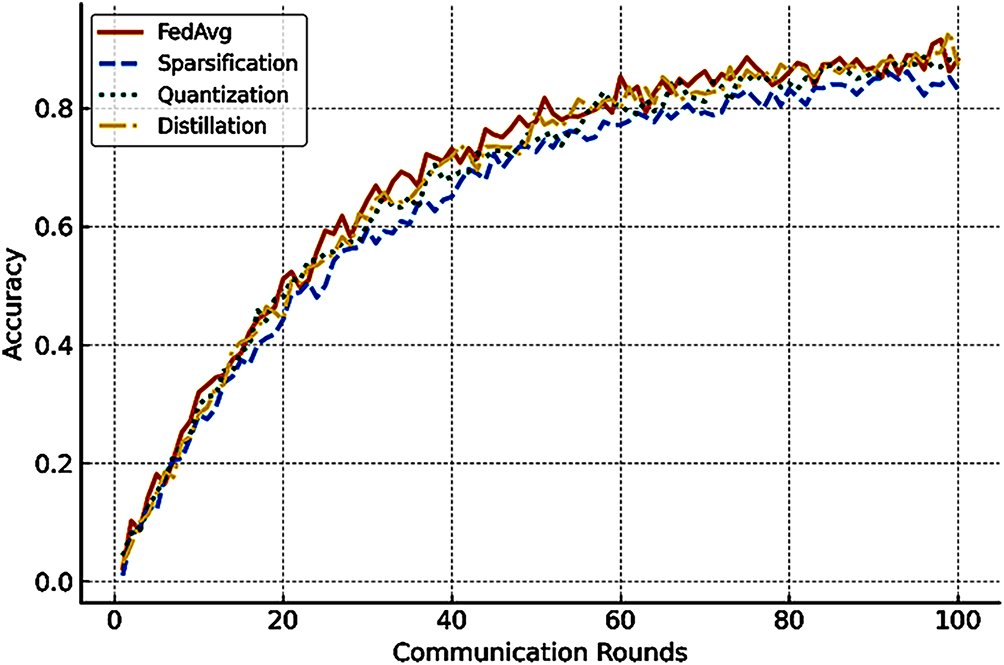

5.4 Communication-Efficient Strategies

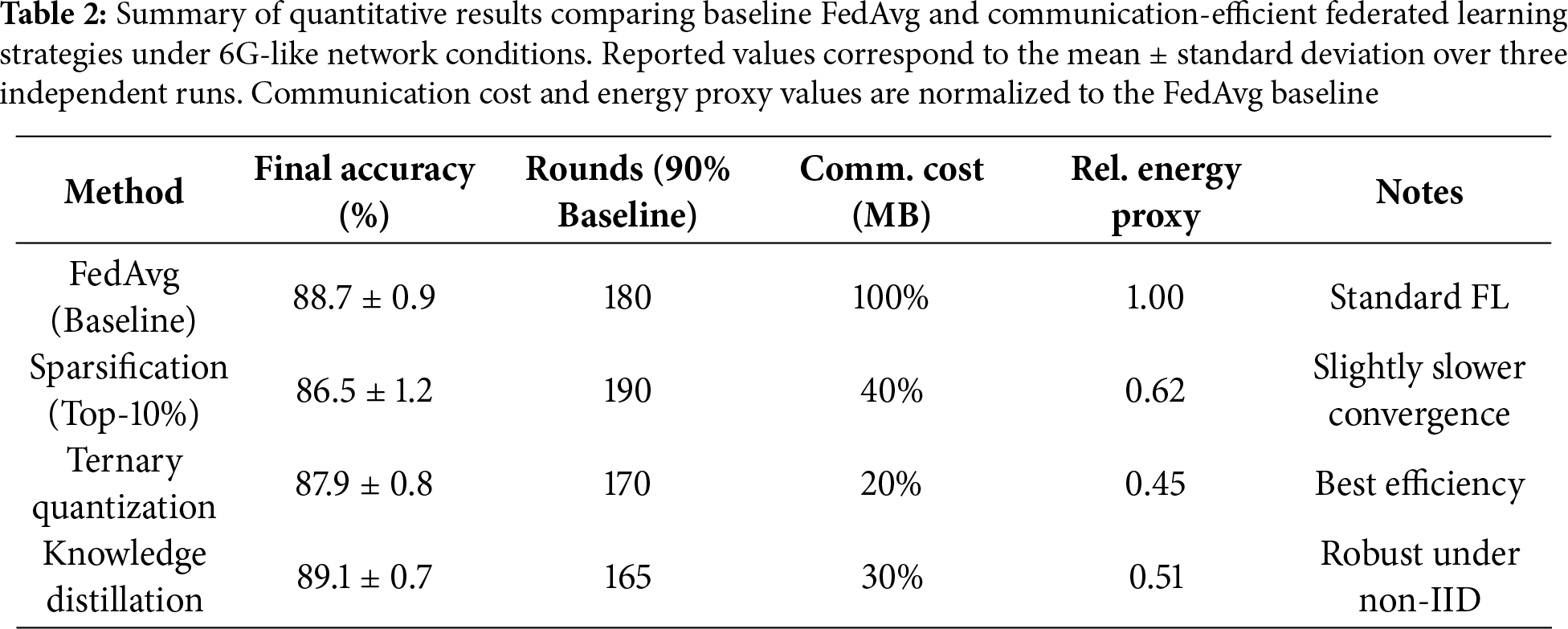

To evaluate communication-efficient approaches, we compare baseline FedAvg with sparsification, quantization, and distillation. Results (Fig. 6) show that:

• Gradient sparsification reduces communication by ≈60% with a minor accuracy drop (−2%),

• Quantization cuts overhead ≈80% while maintaining >95% of baseline accuracy, consistent with [16].

• Knowledge distillation offers a favorable trade-off, particularly under non-IID data, confirming findings in [9].

Figure 6: Comparison of communication-efficient federated learning strategies under bandwidth-limited 6G-like environments. Baseline FedAvg, gradient sparsification, ternary quantization, and knowledge distillation are compared on CIFAR-10. Quantization and distillation achieve the best accuracy-to-communication trade-off

From a computational-complexity perspective, sparsification has the lowest local cost because it only selects a subset of gradients before transmission, whereas quantization adds lightweight encoding overhead. Distillation is moderately more demanding, requiring additional forward passes for teacher–student transfer, yet its extra cost is offset by improved accuracy and reduced communication frequency. Overall, the relative cost ranking can be expressed as sparsification < quantization < distillation < FedAvg, with execution-time differences below 10% in our simulations.

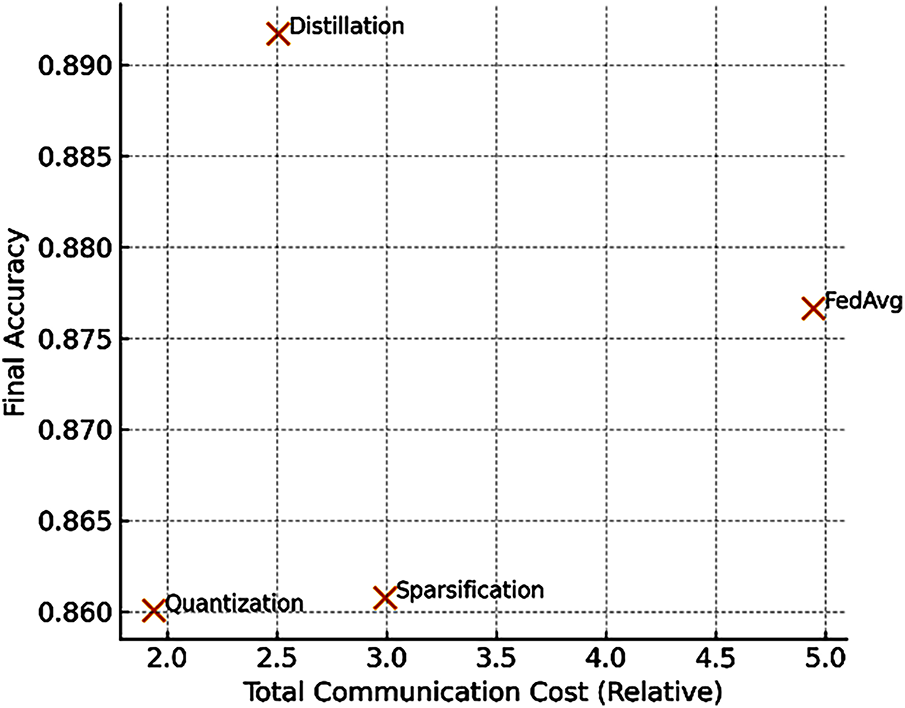

5.5 Trade-Off Analysis: Accuracy vs. Communication Cost

Fig. 7 synthesizes the trade-offs between accuracy and total communication cost for different strategies. This analysis demonstrates that quantization and distillation provide the best accuracy-cost balance under constrained 6G conditions, while naive FedAvg requires substantially more bandwidth.

Figure 7: Accuracy–communication cost trade-off (Pareto frontier) across federated learning methods. Quantization and distillation lie closest to the optimal frontier, achieving high final accuracy with substantially reduced communication overhead, demonstrating superior efficiency for 6G-like edge intelligence

Fig. 8 extends our analysis to include the impact of packet loss on convergence. Results show that even small loss rates (e.g., 2%–5%) significantly slow down convergence and reduce final accuracy. This confirms that wireless reliability, often overlooked in simplified studies, is a key determinant of FL performance in 6G scenarios. By explicitly modeling and simulating packet loss, our framework addresses one of the technical gaps identified in prior surveys [9].

Figure 8: Impact of packet loss on federated learning convergence under 6G-like network conditions. Accuracy curves for packet-loss rates of 0%, 2%, and 5% show slower convergence and lower final accuracy as reliability decreases, emphasizing the importance of reliability-aware design in communication-efficient FL systems

To consolidate the findings, Table 2 summarizes key quantitative outcomes averaged across datasets and repetitions.

5.6 Trade-Off and Reliability Analysis

Fig. 7 plots the Pareto frontier between accuracy and communication cost. Quantization and distillation lie closest to the optimal curve, demonstrating superior accuracy-efficiency balance.

Fig. 8 extends the analysis to packet-loss scenarios (0%–5%), showing that even mild loss reduces final accuracy by ≈3%, highlighting the sensitivity of FL convergence to reliability.

This confirms the importance of reliability-aware resource allocation in 6G-like environments [11].

Although the analysis in this study focuses on moderate-scale benchmarks, the observed trade-offs are expected to generalize to larger vision datasets and edge-surveillance workloads. The framework’s modular design allows direct substitution of more complex data sources, providing a foundation for future validation under realistic 6G vision conditions.

While the current evaluation focuses on the FedAvg baseline to ensure clarity of comparison across communication-efficient strategies, the proposed framework natively supports other optimization variants such as FedProx and FedNova. These algorithms can be incorporated without structural changes to the simulation pipeline, enabling future studies to examine robustness and generalizability under non-IID data and heterogeneous device conditions. Integrating these alternatives forms part of our ongoing work toward a more comprehensive comparative analysis of federated optimization methods for 6G-edge intelligence.

5.7 Discussion and Practical Implications

The experimental findings provide several insights into the feasibility of deploying FL for vision tasks in 6G networks. First, our results confirm that data heterogeneity is the most critical limiting factor for model convergence and final accuracy. While IID partitions consistently reached centralized-level performance within a modest number of rounds, non-IID distributions resulted in slower convergence and noticeable accuracy gaps. This aligns with earlier studies showing that heterogeneous data induces client drift and unstable updates [6,14]. Our results emphasize the need for algorithms explicitly designed for non-IID environments, such as personalized FL and adaptive aggregation.

Second, the experiments demonstrate that system-level configurations, particularly client participation and local training epochs, must be carefully balanced. Increasing participation stabilizes training and improves accuracy, but also multiplies communication overhead, which is costly in bandwidth-limited 6G scenarios. Similarly, while additional local epochs accelerate convergence by reducing the number of rounds, they exacerbate client drift under heterogeneous conditions. These findings echo observations in [5], but our results further quantify the Pareto frontier between accuracy and efficiency, showing that intermediate participation and moderate local training represent the most practical choices for edge deployments.

Third, the analysis of communication-efficient strategies reveals that compression, quantization, and knowledge distillation are not equally effective. Gradient sparsification reduces bandwidth but suffers from slower accuracy recovery. Quantization, particularly ternary schemes, proved highly effective in lowering overhead with negligible loss, confirming recent advances reported in [16]. Distillation further enhances performance in non-IID settings by transferring knowledge from a global “teacher” to local “students”, suggesting it is a promising pathway for heterogeneous edge intelligence. These results reinforce the growing consensus that AI–network co-design is essential in 6G, where both algorithmic innovation and communication protocol optimization must proceed hand in hand [1,2].

Beyond these main findings, it is important to note several limitations of our study. The simulation environment, while representative, abstracts away hardware-level energy consumption and ignores mobility or dynamic client availability, which are critical in real-world 6G scenarios. Furthermore, our evaluation focused on image classification, whereas other vision tasks (e.g., detection, segmentation, or video analytics) may exhibit different communication–accuracy trade-offs. Addressing these gaps will require extending experiments to more complex datasets and incorporating realistic 6G testbeds.

Taken together, the results highlight that while FL is a viable and promising paradigm for vision-based 6G applications, its effectiveness depends on careful tuning of system parameters and the adoption of communication-efficient strategies. Our framework contributes to this line of work by systematically exploring these trade-offs and by providing a baseline methodology for future studies.

Beyond the experimental insights, the findings also carry practical implications for emerging 6G applications. For example, our new packet loss analysis (Fig. 8) demonstrates the sensitivity of FL to unreliable wireless channels, emphasizing the need for reliability-aware resource allocation strategies. In healthcare, communication-efficient FL could enable collaborative medical image analysis across hospitals without compromising patient privacy. For autonomous vehicles and smart cities, our results highlight the need for efficient aggregation strategies to ensure timely perception and decision-making under bandwidth constraints. Similarly, in immersive AR/VR and remote learning environments, communication-efficient FL may reduce latency while preserving visual quality, thereby enhancing user experience. These application scenarios illustrate that the trade-offs explored in this study are not merely theoretical but are directly relevant to the deployment of vision-based FL systems in real-world 6G contexts.

The results underline three main insights:

1. Data heterogeneity remains the dominant factor limiting convergence speed and accuracy, suggesting the need for personalized or adaptive aggregation schemes in future 6G FL deployments.

2. Communication constraints significantly shape training efficiency; moderate client participation and quantized updates provide the best balance between cost and accuracy for bandwidth-limited edges.

3. The proposed simulation framework effectively captures these trade-offs, offering a practical tool for system-level co-design between AI and communication layers.

Beyond the methodological insights, the findings also carry practical significance for emerging 6G applications.

In collaborative healthcare imaging, communication-efficient FL can safeguard patient privacy while operating over bandwidth-constrained hospital networks.

In vehicular and drone-based perception systems, quantized FL reduces uplink traffic, enabling faster model updates and safer decision-making at the network edge.

Likewise, for AR/VR and immersive services, lightweight aggregation lowers latency and energy consumption, thereby enhancing user experience [1].

The present framework, however, adopts simplified wireless models, a limited dataset scope, and an abstract energy formulation.

These simplifications were intentionally introduced to maintain analytical transparency and reproducibility and will be progressively relaxed in future work through larger-scale and hardware-in-the-loop validation.

In real-world 6G deployments, additional factors such as user mobility, intermittent connectivity, and device heterogeneity are expected to further influence FL behaviour.

Mobile clients may experience fluctuating channel conditions and variable participation, while heterogeneous devices differ in computational and energy resources, affecting synchronization and convergence.

The proposed simulation framework provides an initial foundation for analysing these conditions, and its modular design readily supports the future integration of mobility and connectivity models for more realistic 6G validation.

6 Conclusion and Future Directions

In this work, we investigated the integration of FL with vision-based applications under 6G-like environments. We developed a simulation framework that couples federated averaging training with a wireless communication cost model, considering bandwidth, latency, and packet loss. Using benchmark datasets (MNIST and CIFAR-10), we systematically evaluated the impact of data heterogeneity, client participation, local update epochs, and communication-efficient strategies.

The results demonstrated that:

• Data distribution critically influences convergence, with IID partitions achieving faster and more stable accuracy compared to non-IID distributions.

• Client participation ratio provides a clear trade-off between accuracy and communication cost, with partial participation yielding good accuracy while reducing overhead.

• Local training epochs accelerate convergence, but can induce client drift under heterogeneous data if set too high.

• Communication-efficient approaches (quantization, distillation, sparsification) significantly reduce communication overhead while preserving model accuracy, with quantization and distillation delivering the best accuracy–efficiency balance in our experiments.

Compared with prior studies, our framework distinguishes itself by explicitly modelling stochastic network reliability and empirically analysing the interaction between communication parameters and FL dynamics across vision tasks.

This dual-domain approach offers a clearer understanding of how learning behaviour degrades—or can be optimized—under realistic wireless conditions.

Beyond methodological insights, these results provide actionable design guidelines for AI-native 6G systems:

1. Prioritize communication-efficient updates,

2. Tune client participation adaptively according to link quality, and

3. Integrate reliability-aware scheduling into FL orchestration layers.

Building upon the current findings, several directions are planned to extend this work:

1. Expanded datasets and tasks: integrating more complex benchmarks such as CIFAR-100, ImageNet, and COCO to test scalability in high-dimensional vision workloads.

2. Advanced FL algorithms: evaluating FedProx, FedNova, and personalized FL approaches to mitigate the effects of non-IID data and client drift.

3. Energy-aware modeling: refining the energy proxy using hardware-in-the-loop measurements and dynamic power modeling, following recent trends in green AI for 6G.

4. Realistic networking and mobility: incorporating channel fading, Multiple-Input, Multiple-Output (MIMO) diversity, and user mobility into the communication module, potentially using ns-3 or Omnet++ simulators.

5. Scalable orchestration: extending the framework to emulate thousands of clients to better reflect massive 6G IoT scenarios.

6. Security and privacy: exploring robustness against model poisoning and privacy leakage through secure aggregation and differential privacy techniques.

7. Experimental validation: deploying the framework on a real edge-cloud testbed (e.g., FL + 5G/6G prototype network) to compare simulation predictions with hardware results.

These extensions will enable more comprehensive validation and facilitate the transition of federated learning from controlled simulations to real-world 6G platforms, paving the way toward trustworthy, efficient, and privacy-preserving edge intelligence.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the support of the Department of Engineering at the University of Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro (UTAD) and IEETA for providing computational facilities used for the simulation work. The authors also thank colleagues and collaborators whose discussions inspired several of the design optimisations described in this paper.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Manuel J. C. S. Reis, data collection: Nishu Gupta; analysis and interpretation of results: Manuel J. C. S. Reis and Nishu Gupta; draft manuscript preparation: Nishu Gupta and Manuel J. C. S. Reis. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Manuel J. C. S. Reis, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Cui Q, You X, Wei N, Nan G, Zhang X, Zhang J, et al. Overview of AI and communication for 6G network: fundamentals, challenges, and future research opportunities. SCIS. 2025;68(7):253–313. doi:10.1007/s11432-024-4337-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Tao M, Zhou Y, Shi Y, Lu J, Cui S, Lu J, et al. Federated edge learning for 6G: foundations, methodologies, and applications. Proc IEEE. 2024;3509739:1–39. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2024.3509739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Soltani S, Shojafar M, Taheri R, Tafazolli R. Can open and AI-enabled 6G RAN be secured? IEEE Consum Electron Mag. 2022;11:11–2. doi:10.1109/MCE.2022.3205145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sagduyu YE, Erpek T, Yener A, Ulukus S. Will 6G be semantic communications? Opportunities and challenges from task oriented and secure communications to integrated sensing. IEEE Netw. 2024;38(6):72–80. doi:10.1109/MNET.2024.3425152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. McMahan B, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, Arcas BAY. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS 2017); 2017 Apr 10–12; Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA. p. 1273–82. [Google Scholar]

6. Kairouz P, McMahan HB, Avent B, Bellet A, Bennis M, Bhagoji AN, et al. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Found Trends® Mach Learn. 2021;14:1–210. doi:10.1561/2200000083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Bonawitz K, Eichner H, Grieskamp W, Huba D, Ingerman A, Ivanov V, et al. Towards federated learning at scale: system design. Proc Mach Learn Syst. 2019;1:374–88. [Google Scholar]

8. Sheller MJ, Edwards B, Reina GA, Martin J, Pati S, Kotrotsou A, et al. Federated learning in medicine: facilitating multi-institutional collaborations without sharing patient data. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12598. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69250-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Asad M, Shaukat S, Hu D, Wang Z, Javanmardi E, Nakazato J, et al. Limitations and future aspects of communication costs in federated learning: a survey. Sensors. 2023;23(17):7358. doi:10.3390/s23177358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Nguyen DC, Ding M, Pathirana PN, Seneviratne A, Li J, Vincent PH. Federated learning for Internet of Things: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2021;23:1622–58. doi:10.1109/COMST.2021.3075439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Liu B, Lv N, Guo Y, Li Y. Recent advances on federated learning: a systematic survey. Neurocomputing. 2024;597:128019. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.128019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sirohi D, Kumar N, Rana PS, Tanwar S, Iqbal R, Hijjii M. Federated learning for 6G-enabled secure communication systems: a comprehensive survey. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56:11297–389. doi:10.1007/s10462-023-10417-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Li Q, Diao Y, Chen Q, He B. Federated learning on non-IID data silos: an experimental study. In: 2022 IEEE 38th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE); 2022 May 9–12; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 965–78. [Google Scholar]

14. Zhu H, Xu J, Liu S, Jin Y. Federated learning on non-IID data: a survey. Neurocomputing. 2021;465:371–90. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2021.07.098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chen M, Shlezinger N, Poor HV, Eldar YC, Cui S. Communication-efficient federated learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2021;118:e2024789118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2024789118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. He Z, Zhu G, Zhang S, Luo E, Zhao Y. FedDT: a communication-efficient federated learning via knowledge distillation and ternary compression. Electronics. 2025;14:2183. doi:10.3390/electronics14112183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Amadeo M, Campolo C, Ruggeri G, Molinaro A. Improving communication performance of federated learning: a networking perspective. Comput Netw. 2025;267:111353. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2025.111353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kundroo M, Kim T. Demystifying impact of key hyper-parameters in federated learning: a case study on CIFAR-10 and FashionMNIST. IEEE Access. 2024;12:120570–83. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3450894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yu X, He Z, Sun Y, Xue L, Li R. The effect of personalization in FedProx: a fine-grained analysis on statistical accuracy and communication efficiency. In: Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2024); 2024 Jul 21–27; Vienna, Austria. p. 40757–78. [Google Scholar]

20. Nabavirazavi S, Taheri R, Shojafar M, Iyengar SS. Impact of aggregation function randomization against model poisoning in federated learning. In: 2023 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom); 2023 Nov 1-3; Changsha, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 165–72. [Google Scholar]

21. Ni X, Shen X, Zhao H. Federated optimization via knowledge codistillation. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;191:116310. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.116310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. TomorrowDesk. FedProx: distributed learning framework for Non-IID Data [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 11]. Available from: https://tomorrowdesk.com/info/fedprox. [Google Scholar]

23. Li T, Sahu AK, Zaheer M, Sanjabi M, Talwalkar A, Smith V. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. Proc Mach Learn Syst. 2020;2:429–50. [Google Scholar]

24. Liu W, Zhang X, Duan J, Joe-Wong C, Zhou Z, Chen X. AdaCoOpt: leverage the interplay of batch size and aggregation frequency for federated learning. In: 2023 IEEE/ACM 31st International Symposium on Quality of Service (IWQoS); 2023 Jun 19–21; Orlando, FL, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

25. LeCun Y. Yann LeCun’s Home Page [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: http://yann.lecun.com/. [Google Scholar]

26. Krizhevsky A. CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 Datasets [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html. [Google Scholar]

27. Flower Team. Flower: a friendly federated AI framework [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://flower.ai/. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools