Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancement of Medical Imaging Technique for Diabetic Retinopathy: Realistic Synthetic Image Generation Using GenAI

1 Department of Information Technology, Marwadi University, Rajkot, 360003, India

2 Engineering Cluster, Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore, 828608, Singapore

3 Electronics and Communication Engineering Department, Sapthagiri NPS University, Bangalore, 560057, India

4 School of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, SR University, Warangal, 506371, India

5 Electronics Telecommunication Engineering, J D College of Engineering Management, Nagpur, 441501, India

6 College of Computer Science, King Khalid University, Abha, 61421, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Naim Ahmad. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 4107-4127. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.073387

Received 17 September 2025; Accepted 11 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

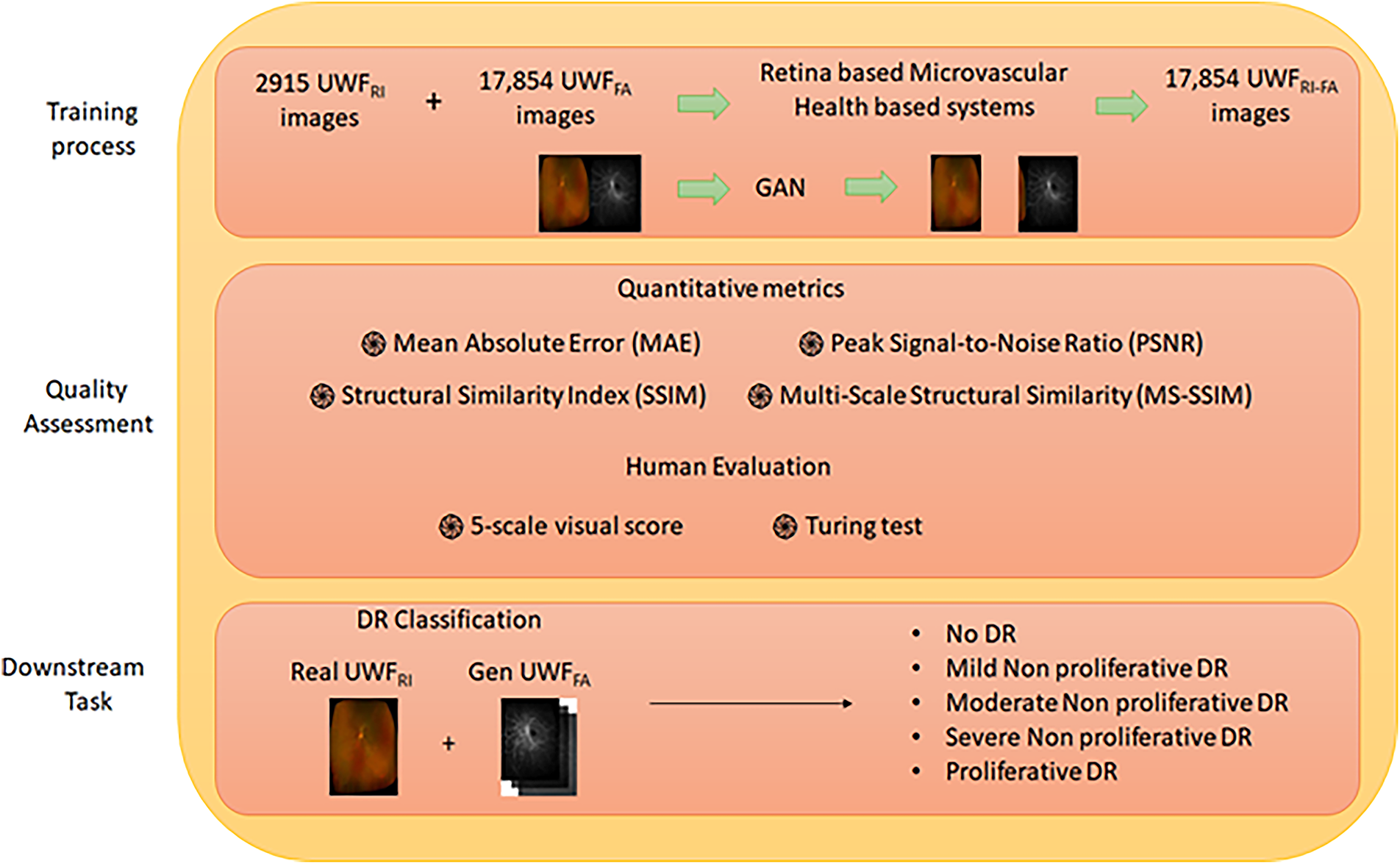

A phase-aware cross-modal framework is presented that synthesizes UWF_FA from non-invasive UWF_RI for diabetic retinopathy (DR) stratification. A curated cohort of 1198 patients (2915 UWF_RI and 17,854 UWF_FA images) with strict registration quality supports training across three angiographic phases (initial, mid, final). The generator is based on a modified pix2pixHD with an added Gradient Variance Loss to better preserve microvasculature, and is evaluated using MAE, PSNR, SSIM, and MS-SSIM on held-out pairs. Quantitatively, the mid phase achieves the lowest MAE (98.76Keywords

As a a common and deadly complication of diabetes mellitus, diabetic retinopathy (DR) is one of the leading causes of vision loss and blindness globally. According to the International Diabetes Federation, over 100 million people are currently affected by DR, and this number is expected to rise with the global diabetes burden, making early detection and management a public health priority. People in their middle years and later years seem to have it more often than younger generations [1]. People with diabetes often notice a gradual blurring of vision as the disease progresses; if left untreated, this might lead to permanent irreversible impairment. Diabetic retinopathy (DR) manifests itself in a variety of ways, but one of the most important is the development of microvascular abnormalities, which can have a major impact on retinal function [2]. Depending on the degree of damage, there are two main kinds of diabetic retinopathy (DR): non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). In order to effectively treat and prevent vision loss, it is crucial to diagnose these phases early and accurately.

Ophthalmologists with extensive training are required to perform medical imaging procedures such as fundus photography and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), which are the backbone of the traditional diagnostic approach. However, due to the complexity and variation in image quality of retinal photographs, manual screening is both laborious and error prone. Moreover, fluorescein angiography (FA) the gold standard for visualizing retinal vasculature requires intravenous dye injection, which can cause side effects such as nausea, skin discoloration, and in rare cases severe allergic reactions; these risks limit routine use, especially in large-scale screening programs. Automating the diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy (DR) from raw retinal images has been made possible in recent years by ML techniques like Bayesian classifiers, K-Means clustering, Probabilistic Neural Networks (PNN), and Support Vector Machines (SVM) [3]. Methods such as these make use of blood vessels, haemorrhages, and exudates. Support vector machines (SVM) outperformed Bayes (94.4%) and PNN (89.6%), according to a comparative study that used 350 fundus pictures (100 for training and 250 for testing). This resulted in the highest classification accuracy (97.6%) [4]. Another evaluation using 130 images from the DIARETDB0 dataset gave more evidence of SVM’s superior performance (95.38%) [5]. Despite these advancements, limitations in dataset diversity, imbalance, or data scarcity might occasionally impair the efficacy of deep learning and machine learning models. With this issue in mind, generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has been getting a lot of attention, with a focus on GANs and diffusion models in particular. Generating synthetic images that closely resemble real patient data is within the capabilities of these AI kinds [6]. You may utilise these artificial images to enhance model generalisation, increase DR diagnosis accuracy, and refresh training datasets; they also solve big problems with data availability, privacy, and imbalance [7]. Plus, you can use them to make DR diagnostics work better.

Additionally, common image preprocessing techniques like denoising, edge detection, and contrast enhancement can miss small retinal features associated with DR. Modern DR classification methods are based on deep learning models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). A limitation of these models is their reliance on massive annotated datasets, which limits their scalability [8]. The ability to generate varied and realistic retinal images across all stages of DR has led to the emergence of GenAI models, including conditional GANs (cGANs), CycleGANs, and diffusion models, as game-changing tools [9]. The training of diagnostic systems powered by artificial intelligence has been improved as a result [10]. Generative models not only enhance model training, but they also allow for the modelling of disease progression. For a better understanding of the disease, this allows researchers to build prediction models for DR staging and severity assessment. The ability to do so offers up new avenues for personalised and preventive treatment options [11]. Furthermore, synthetic data helps to allay privacy concerns, which in turn allows for more data interchange and collaboration among ophthalmic researchers, all while patients’ confidentiality is preserved [12].

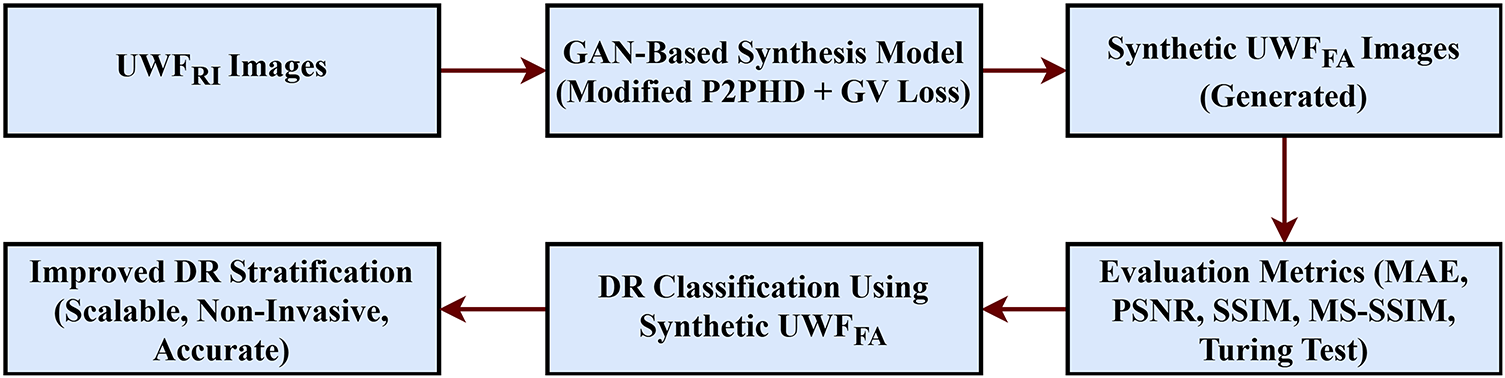

In this work, we propose a GAN-based cross modal translation framework that synthesizes ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography (UWF_FA) directly from ultra widefield retinal images (UWF_RI). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to generate multi-phase synthetic UWF_FA (initial, mid, and final angiographic phases) and to validate both perceptual realism and clinical utility using quantitative metrics (MAE, PSNR, SSIM) and ophthalmologist Turing tests while integrating the synthetic phases with a Swin Transformer classifier for improved DR stratification. An overview of the proposed pipeline is shown in Fig. 1. By eliminating the risks of dye injection and preserving angiographic cues (nonperfusion, leakage, peripheral vasculature), our approach offers a scalable, non-invasive pathway to safer DR screening and triage.

Figure 1: Block diagram of the proposed cross-modal framework. UWF–RI = ultra-widefield retinal imaging; UWF–FA = ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography. The framework performs preprocessing and registration of UWF–RI, phase-aware GAN synthesis of UWF–FA (initial, mid, final), and fusion with a Swin Transformer classifier for DR stratification

Overall, DR screening methods might be improved by combining generative models with traditional and modern AI-based diagnostic techniques. This could lead to more accessible, efficient, and accurate screenings. Our study addresses a critical gap by delivering high fidelity, phase-aware synthetic angiography from non-invasive inputs, demonstrating measurable gains in downstream DR grading and pointing toward broader clinical deployment.

Research on automated diabetic retinopathy (DR) analysis has evolved from classical feature engineering on colour fundus photographs to powerful deep models that segment vessels and lesions, grade disease severity, and increasingly aim to recreate angiography like information from non-invasive inputs [13]. Ultra widefield (UWF) modalities and angiography (FA, OCTA) capture nonperfusion, leakage, and peripheral pathology that standard views can miss, which is clinically important for risk stratification and treatment decisions [14]. This has motivated cross-modal synthesis (fundus or UWF retinal images to FA-like outputs) to support safer, scalable screening and triage while preserving clinically salient vascular cues [15].

2.1 Traditional DR Classification Approaches

Early automated systems extracted hand-crafted descriptors vessel maps, microaneurysms, haemorrhages, and exudates from colour fundus images and applied SVMs, kNN, or Bayesian models to estimate DR severity. These pipelines required heavy preprocessing, were sensitive to illumination and device shifts, and often struggled on heterogeneous cohorts [16]. To alleviate data scarcity, works explored contrast enhancement and GAN-based augmentation to stabilise prognostication [17], but such strategies still operated on fundus-only inputs and lacked direct angiographic signals unless dye-based FA or OCTA was acquired [18]. Robust learning under imperfect labels (loss correction and noise-aware training) was also studied [19], and objective image-quality metrics such as SSIM, PSNR, MSE, and FSIM became standard for screening inputs and evaluating restorations [20].

2.2 Deep Learning for DR Screening and Grading

Modern screening is dominated by convolutional and transformer-based architectures, spanning segmentation (vessel/lesion localisation) and end-to-end grading [21]. Lesion aware and multi-loss designs improved microvasculature delineation and robustness [22], while hybrid pipelines with vision transformers strengthened representation learning for synthesis and predict workflows [23]. Transfer learning and representation pretraining trends (including vision–language supervision) further enhanced feature reuse across cohorts [24]. Persistent challenges include large annotation demands, class imbalance, and domain shift [25]. Diffusion models recently emerged as strong priors for denoising and augmentation on retinal imagery, improving fidelity and training stability [26]. Nevertheless, most pipelines are fundus-only and cannot directly model nonperfusion or leakage patterns that are best visualised on FA or OCTA; studies using UWF-FA demonstrate grading value but still require invasive dye [27].

2.3 Cross-Modal Translation and Generative Models for Retinal Imaging

Cross-modal retinal synthesis aims to recover angiography-like information from non-invasive images. Foundational conditional adversarial frameworks established paired image-to-image translation, and ophthalmic variants adapted architectures, objectives, and priors to encode retinal structure [28]. UWAT-GAN introduced an ultra-wide-angle, multi-scale generator to map UWF-RI to UWF-FA, but relied on only a few dozen matched pairs, limiting generalisation and phase modelling [29]. UWAFA-GAN increased data scale and integrated attention and registration enhancement to sharpen vasculature fidelity; however, it produced a single venous-phase frame and did not quantify downstream DR stratification gains. Other directions focused on targeted synthesis or controllability: lesion-centric DR-LL-GAN, Wasserstein-based retinal synthesis, controllable StyleGAN variants, and high-fidelity semantic manipulation. Some explored grading via the generative prior itself, but comprehensive multi-phase UWF-FA generation coupled with an integrated classifier and validated on downstream clinical tasks remains uncommon [30].

2.4 Generative AI in Broader Medical Imaging

Beyond ophthalmology, adversarial and diffusion paradigms matured for translation and restoration. Unsupervised adversarial diffusion enabled cross modality mapping without dense pairing [31], while image-to-image diffusion provided stable, controllable synthesis [32]. Disentangled and regularised GANs promoted factorised latent structure and interpretable controls [33]; surveys chart diffusion advantages in likelihood training, diversity, and perceptual quality [34]. At the same time, the community cautioned against overreliance on single realism metrics, advocating multi metric assessment [35] and task based validation principles directly relevant to retinal synthesis and evaluation [36]. Recent hybrid generative–classification frameworks have further demonstrated the synergy between image synthesis and diagnostic modeling in diabetic retinopathy [37]. Gencer et al. (2025) combined GAN-based augmentation with denoising autoencoders and an EfficientNet-B0 classifier, achieving 99% accuracy, recall, and specificity on a high-resolution OCT dataset [38].

2.5 Clinical Context and Motivation

UWF imaging expands coverage to the periphery, where clinically significant lesions and nonperfusion can alter staging and management. Widefield OCTA studies link nonperfusion areas with DR severity and progression, underscoring the value of angiographic signals beyond colour fundus. Deep-learning pipelines trained directly on UWF-FA demonstrate strong grading potential, yet FA requires dye injection, with workflow implications and rare adverse reactions. These factors motivate non-invasive synthesis that preserves diagnostic utility while improving accessibility [39].

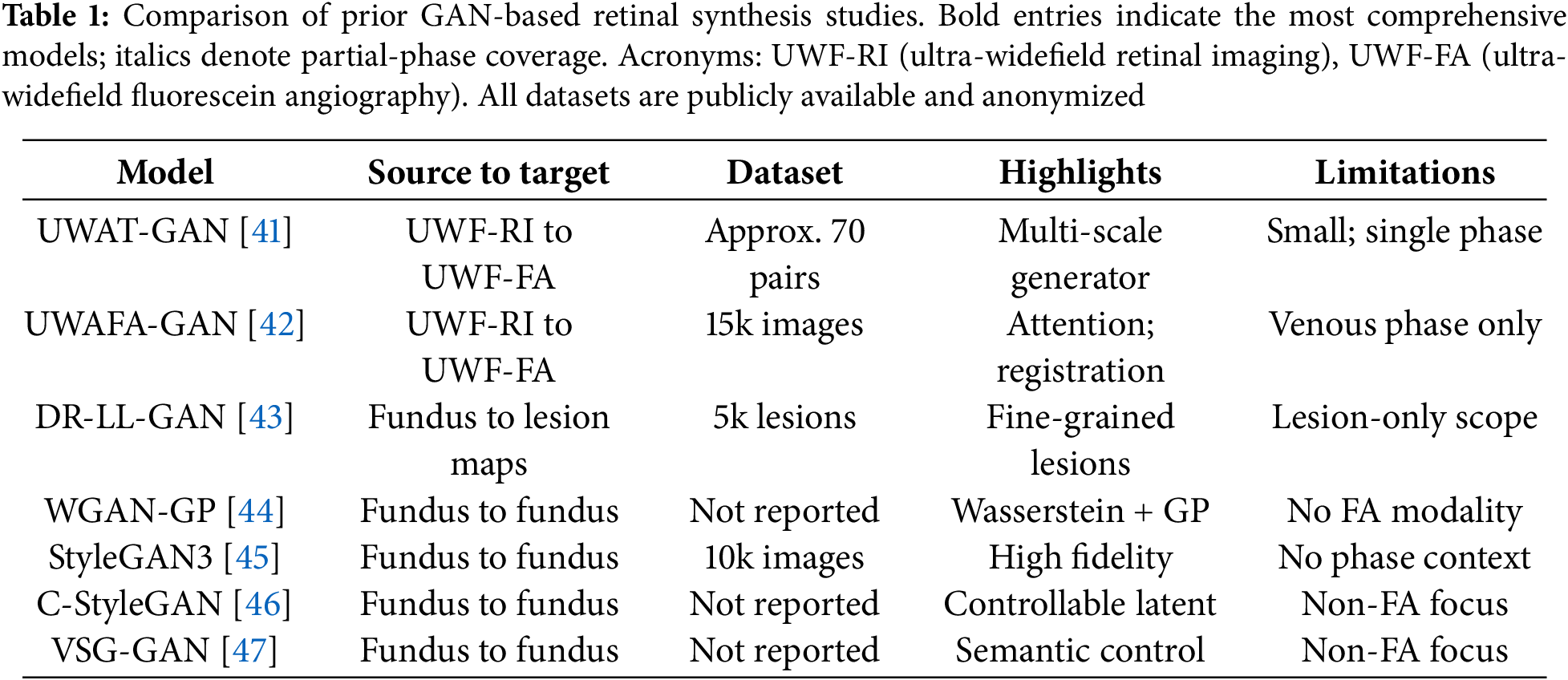

In summary, existing retinal synthesis studies often train on limited paired data, restrict outputs to a single angiographic phase (Table 1), or focus on narrow fields and lesion slices; few quantify downstream diagnostic gains with an integrated classifier. Registration errors and domain shift further hinder generalisation at UWF resolution [40]. Our work addresses these gaps with a large paired UWF-RI and UWF-FA corpus, a phase aware generator that synthesises initial, mid, and final FA frames from a single UWF-RI input, and an integrated Swin Transformer classifier; we evaluate both multi metric image quality and downstream DR stratification, linking image realism to clinical performance while avoiding dye related risks.

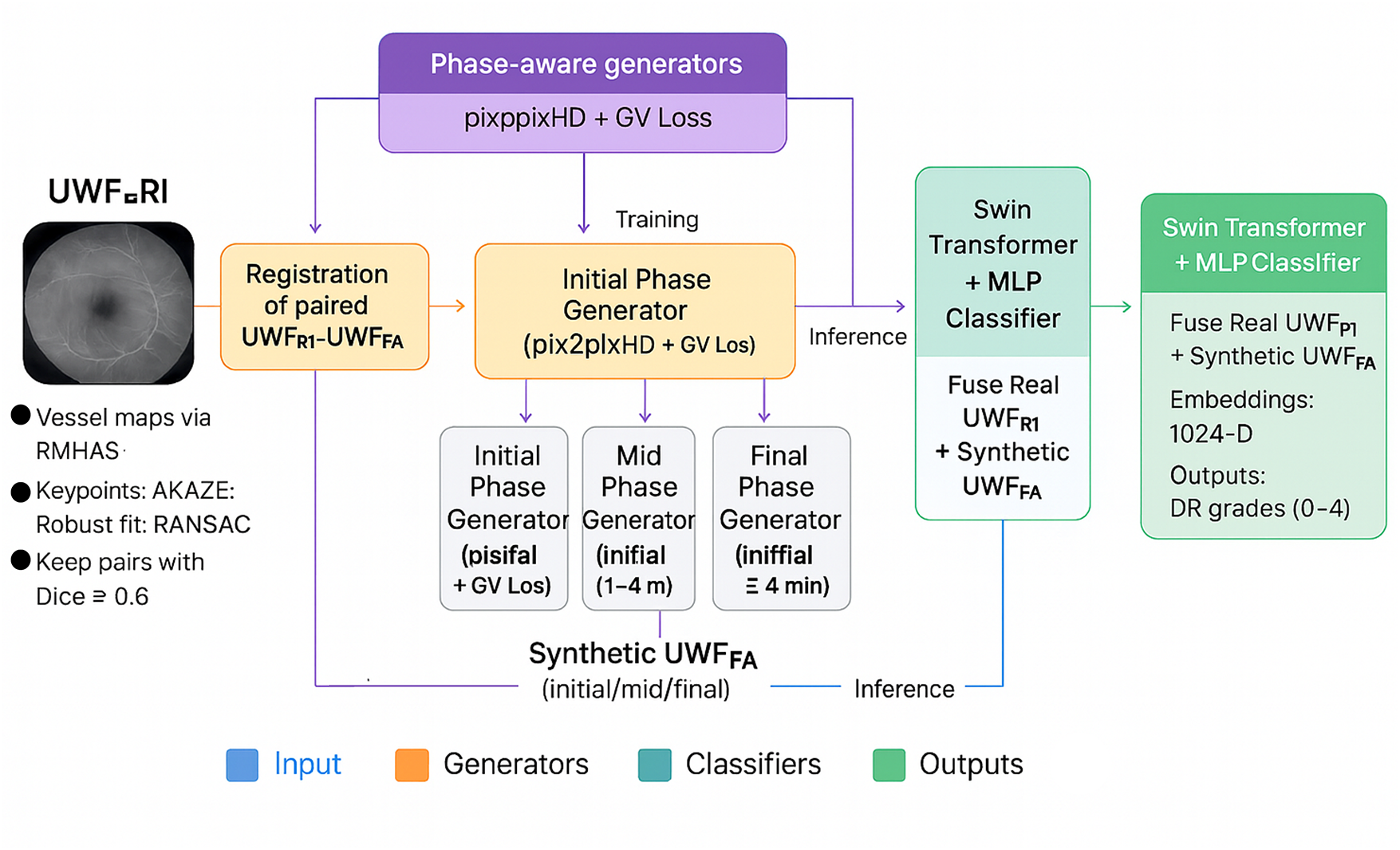

This section details the datasets, acquisition context, splits, preprocessing, training protocols, and evaluation procedures used in our study. Algorithmic design and formulas are deferred to Section 4. A step-by-step view of the experimental workflow is summarized in Algorithm 1.

While Table 1 qualitatively summarizes prior GAN-based retinal synthesis studies, quantitative cross-model benchmarking was also performed to contextualize our framework. Metrics such as SSIM, PSNR, and AUC were collated from published baselines (UWAT-GAN, UWAFA-GAN, DR-LL-GAN) where available and compared against our proposed phase-aware model. Our approach achieved notably higher SSIM (0.85 vs. 0.79–0.83) and PSNR (

3.1 Datasets and Acquisition Context

We used two datasets that play complementary roles in development and external validation. The primary ultra-widefield (UWF) cohort comprising 1198 patients (2915

• Primary development dataset (ODIR). For training and tuning the cross-modal generator, we used 3800 ultra widefield retinal images UWF_RI and 1100 ultra widefield fluorescein angiography images UWF_FA. Images were captured at 3500

• External evaluation dataset (Messidor-2). For downstream DR stratification, we used Messidor-2, labeled on the international clinical DR scale: 0 (no DR), 1 (mild NPDR), 2 (moderate NPDR), 3 (severe NPDR), 4 (PDR) [49].

Angiographic timing was organized in three phases for UWF_FA: initial (20–50 s post-injection), mid (1–4 min), and final (>4 min). Unless noted, training emphasized post-venous frames, while validation and testing covered all phases.

3.2 Inclusion, Exclusion, and Privacy

Frames with severe eyelid/iris occlusion, motion blur, or illumination artifacts were excluded during quality review. For paired UWF_RI–UWF_FA sequences (same eye and visit), only pairs passing stringent registration (see Section 4) were retained. Pairs with Dice below 0.6 were discarded, removing approximately 7.3% of candidates. All data were de-identified and used solely for research purposes.

3.3 Data Partitions and Sampling

Patient-level splitting (3:1:1 train:validation:test) was utilized to avoid leakage, maintaining DR class balance and FA phase balance. The same policy was used for Messidor-2. All test results reflect a single held-out set with no overlap with training.

3.4 Preprocessing and Normalization

Preprocessing included mask-based cropping to suppress periocular artifacts, resolution harmonization, intensity normalization to [0, 1], and optional histogram matching for cross-session consistency. For generation, UWF_RI and UWF_FA were resized to 1080

3.5 Training Protocols: Generation

Training was performed on three phase specific generators (initial, mid, final) to produce UWF_FA from UWF_RI. Data augmentation included random resized cropping (scale 0.4–3.0), horizontal/vertical flips, and random rotations within 0–30 degrees. Each generator trained for 45 epochs (batch size 6, learning rate

3.6 Training Protocols: Classification

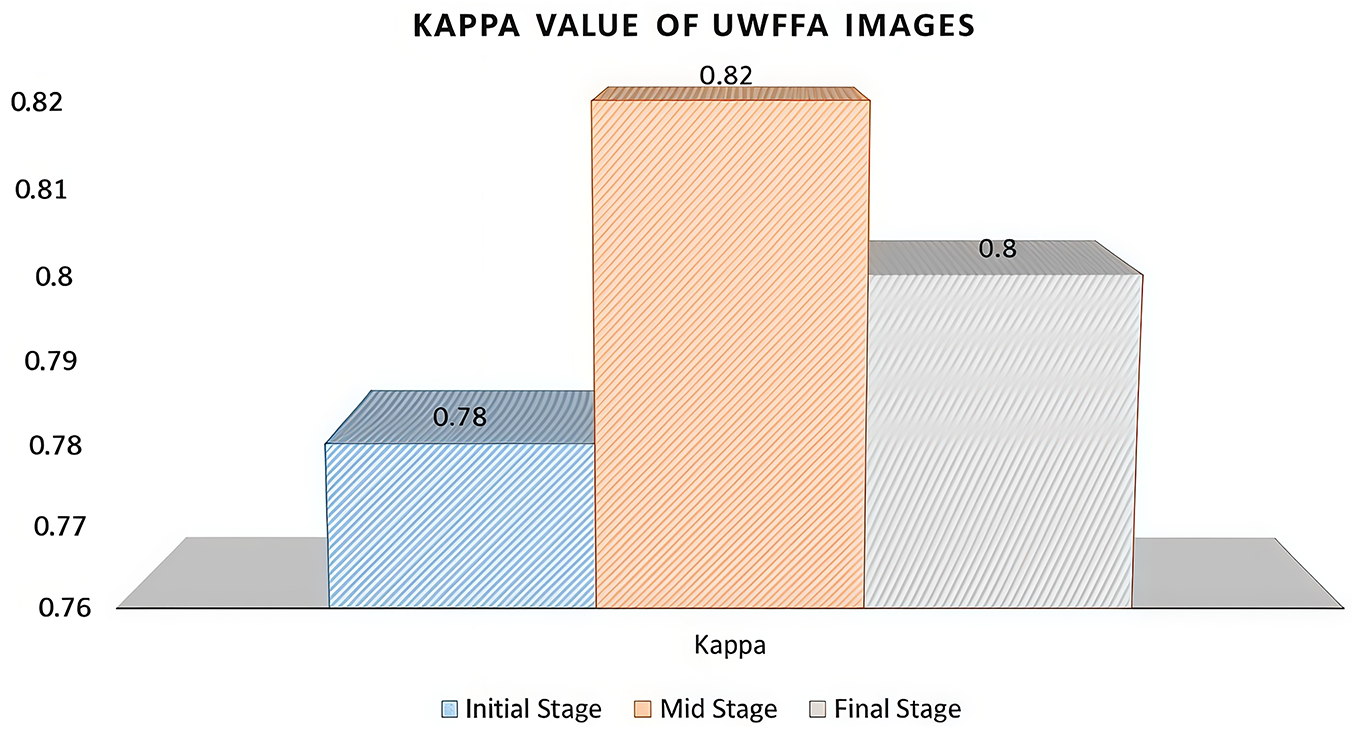

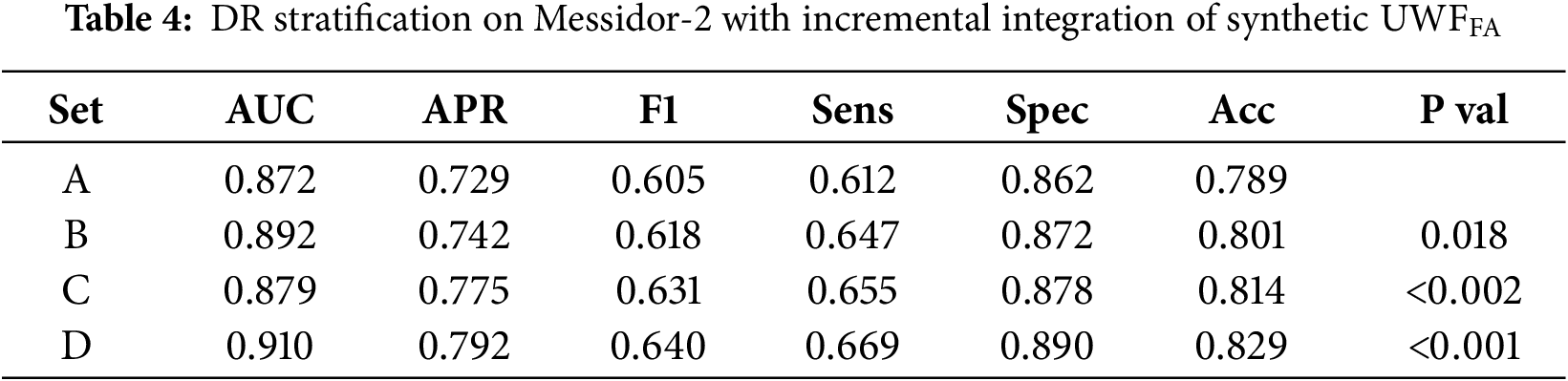

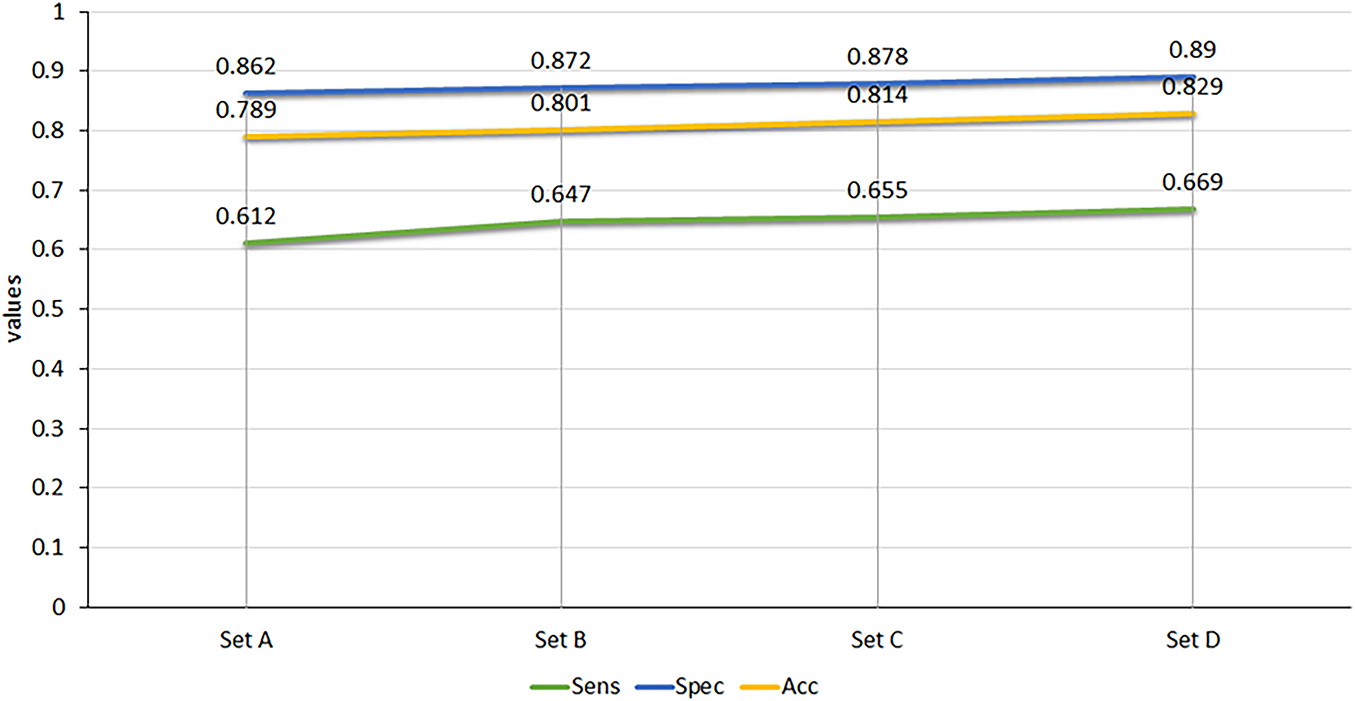

To quantify downstream value of synthetic angiography, a Swin Transformer with an MLP head was trained on four compositions:

• Set A: Real UWF_RI only (baseline).

• Set B: UWF_RI plus synthetic initial-phase UWF_FA.

• Set C: UWF_RI plus synthetic initial and mid phases.

• Set D: UWF_RI plus synthetic initial, mid, and final phases.

All runs used identical splits, ImageNet initialization, and class balancing. Swin features were reduced to 1024-dimensional embeddings and passed to a fully connected layer with softmax. We used Adam (learning rate (1

The Gradient Variance Loss (GVL) term encourages local edge consistency and is defined as:

where

3.8 Evaluation Protocols and Endpoints

For synthesis, we report MAE, PSNR, SSIM, and MS-SSIM between generated and ground-truth UWF_FA on the held-out test set. For DR classification, we report AUC, APR, F1, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy, indicating statistical significance relative to Set A.

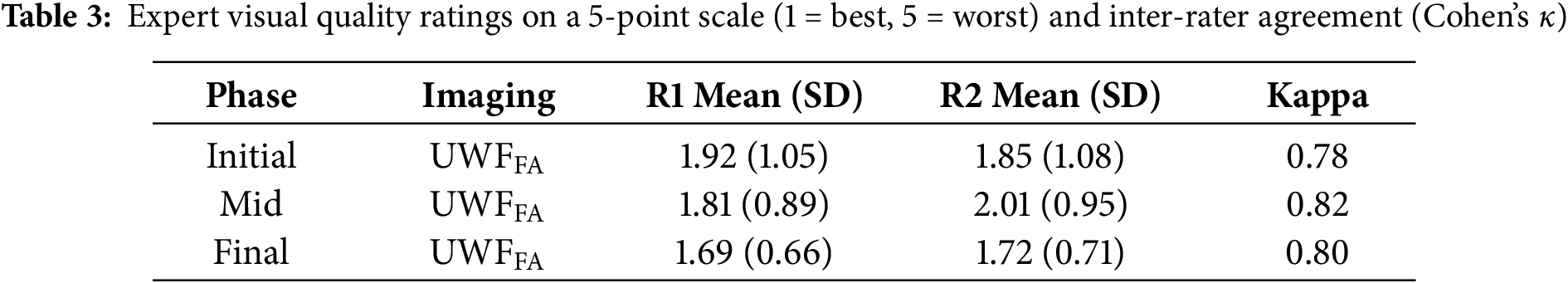

3.9 Expert Reading and Turing-Style Assessment

This subjective assessment followed a double-blind, within-subject design where experts were unaware of image origin (synthetic vs. real). Two ophthalmologists independently rated 50 test pairs across FA phases on a 5-point quality scale (1 best, 5 worst). Inter-rater reliability used Cohen’s weighted kappa. A Turing-style task asked readers to label 25 FA images as real or synthetic; a third adjudicator resolved disagreements. The resulting kappa of 0.74 indicates substantial agreement. In total, 50 unique UWF-FA test pairs were presented per reader across three angiographic phases (initial, mid, final), including both real and synthesized samples balanced in equal proportion. For the Turing-style evaluation, each ophthalmologist reviewed 25 randomly sampled FA images—12 synthetic and 13 real—under blinded conditions. Images were classified as “synthetic” if they exhibited any atypical vessel branching, inconsistent dye diffusion, or unnatural texture patterns not characteristic of genuine angiograms. These predefined visual cues, established prior to reading, ensured consistent interpretation criteria across experts.

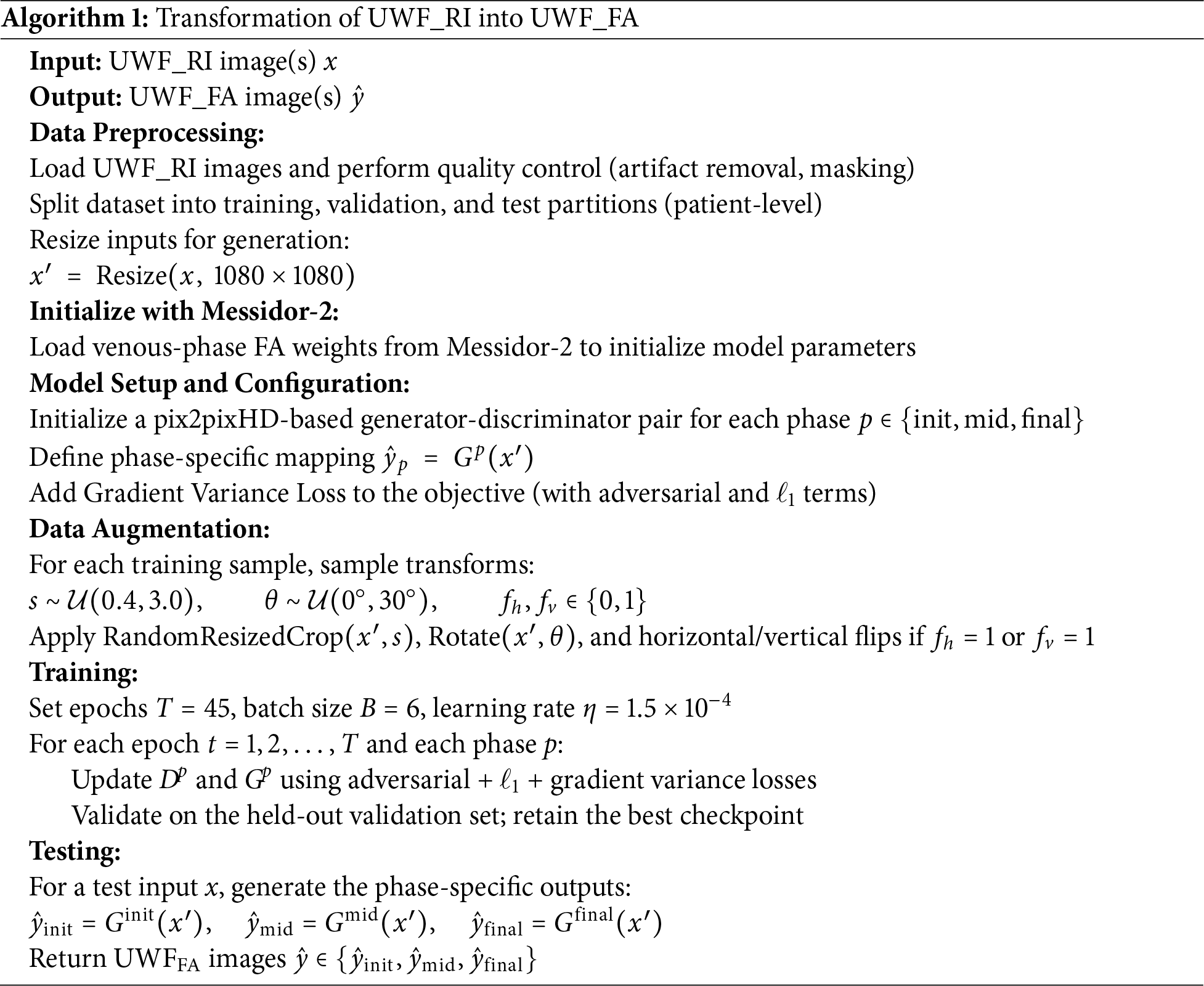

A phase-aware cross-modal translation framework is proposed to synthesize ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography UWF_FA from ultra widefield retinal images UWF_RI, followed by an integrated classifier for diabetic retinopathy (DR) stratification. The pipeline comprises: (i) robust trans modal registration to align paired UWF_RI – UWF_FA, (ii) three phase specific generators for initial, mid, and final angiographic frames, (iii) an adversarial reconstruction objective augmented with gradient variance loss to sharpen vascular detail, and (iv) a Swin Transformer head that fuses real UWF_RI with synthetic UWF_FA phases for downstream grading. See Fig. 2 for an overview.

Figure 2: Proposed model workflow: registration of paired UWF_RI – UWF_FA, phase-aware generators for initial/mid/final UWF_FA, and a Swin Transformer classifier that fuses real UWF_RI with synthetic UWF_FA

Accurate alignment between

4.2 Phase-Aware Image-to-Image Translation

Separate generators (

4.2.1 Adversarial Objective (LSGAN Form)

For phase

4.2.2 Pixel Reconstruction Objective

Absolute deviations are penalized to preserve tone and coarse structure:

4.2.3 Gradient Variance Loss for Vascular Fidelity

To emphasize high-frequency retinal structures (vessel trunks, capillary beds, microaneurysm borders), we augment supervision with gradient variance loss (

with

Intuitively, (

4.2.4 Full Generator Objective

For each phase

while the discriminator minimizes

4.3 Integrated Classifier for DR Stratification

To quantify diagnostic utility of synthetic angiography, integrates a Swin Transformer classifier that fuses real UWF_RI with zero to three synthetic UWF_FA phases (Sets A–D in Section 3). Each available image (RI or FA phase) is fed through a shared Swin backbone

and the cross-entropy;

is minimized over DR classes

At test time, a single UWF_RI image is mapped by the three phase-specific generators to produce (

Generators and discriminators follow common residual and multi-scale design choices for high-resolution translation. Training uses the protocols in Section 3 (phase-specific models; 45 epochs; batch size 6; learning rate 0.00015; augmentations: random resized crop, flips, rotations). The classifier employs ImageNet initialization, Adam optimization with learning rate (

5.1 Cohort Curation and Phase Distribution

After quality screening and registration filtering, the final cohort comprised 1198 patients contributing 2915 UWF_RI images and 17,854 UWF_FA images. On average, each subject contributed approximately two UWF_RI frames and fifteen UWF_FA frames collected at a single clinical visit, ensuring phase consistency for paired supervision. Demographically, 689 patients (57.5%) were male, with a median age of 56.34 years (range: 44.12–66.89 years). By angiographic stage, the dataset contained 1927 initial, 9892 mid, and 6035 final phase pairings, reflecting distinct circulation states exploited by our phase-aware generators. The overall workflow for data preparation, model training, and evaluation is summarized in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Proposed workflow for data curation and model evaluation

To enhance reproducibility across splits, all images underwent the same preprocessing sequence: normalization, optional histogram matching, resizing 512

5.3 Image Quality and Fidelity Metrics

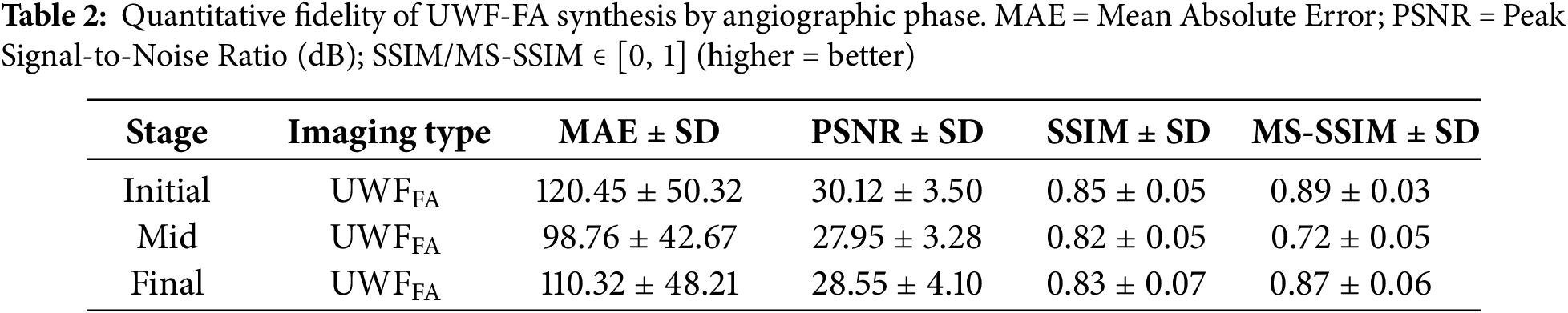

Per-phase reconstruction quality is reported, using MAE, PSNR, SSIM, and MS-SSIM on the held-out test pairs (Table 2). All fidelity metrics (MAE, PSNR, SSIM, MS-SSIM) were computed on the 8-bit [0–255] intensity scale prior to normalization, explaining the magnitude of MAE values near 100 despite normalized preprocessing. Differences reported in Table 2 are statistically significant at

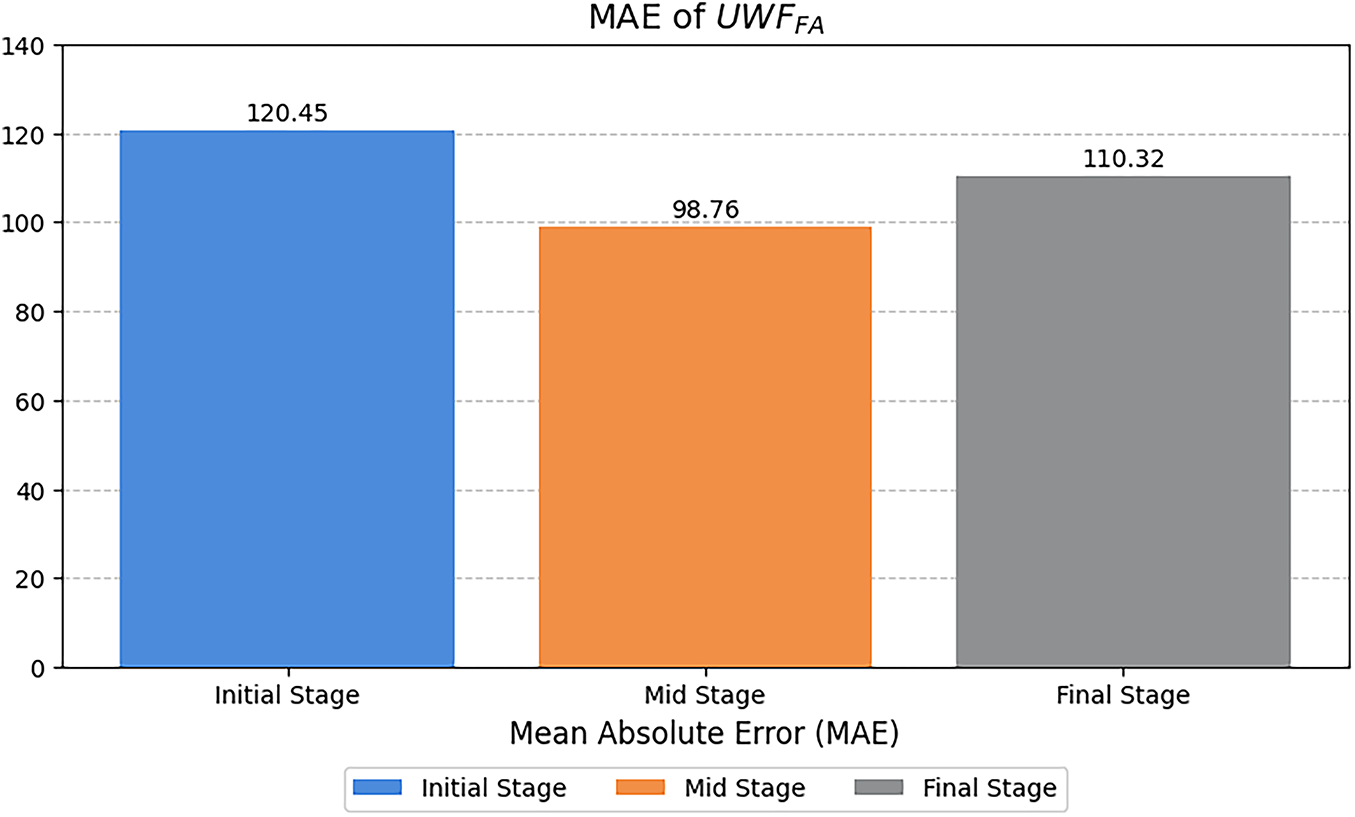

Figure 4: Mean Absolute Error (MAE, computed on 8-bit scale) across angiographic phases for synthesized

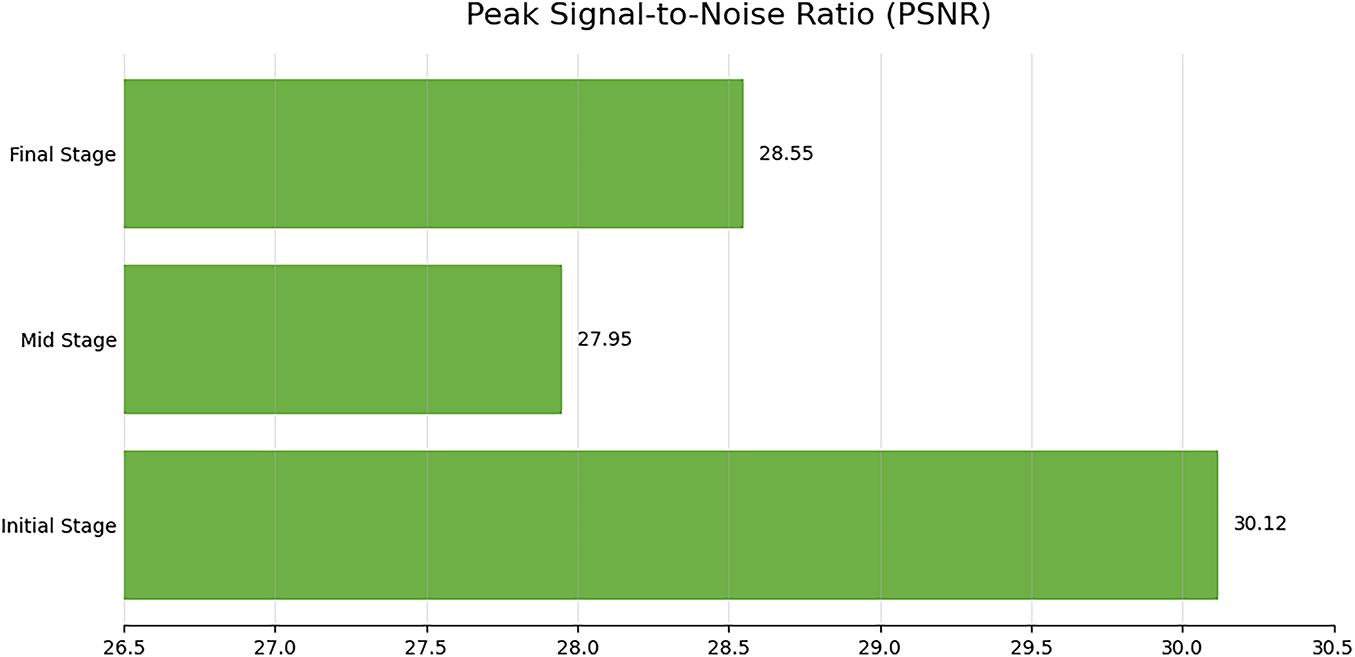

Figure 5: Peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR, in dB) across angiographic phases for synthesized UWF-FA; higher values indicate better fidelity

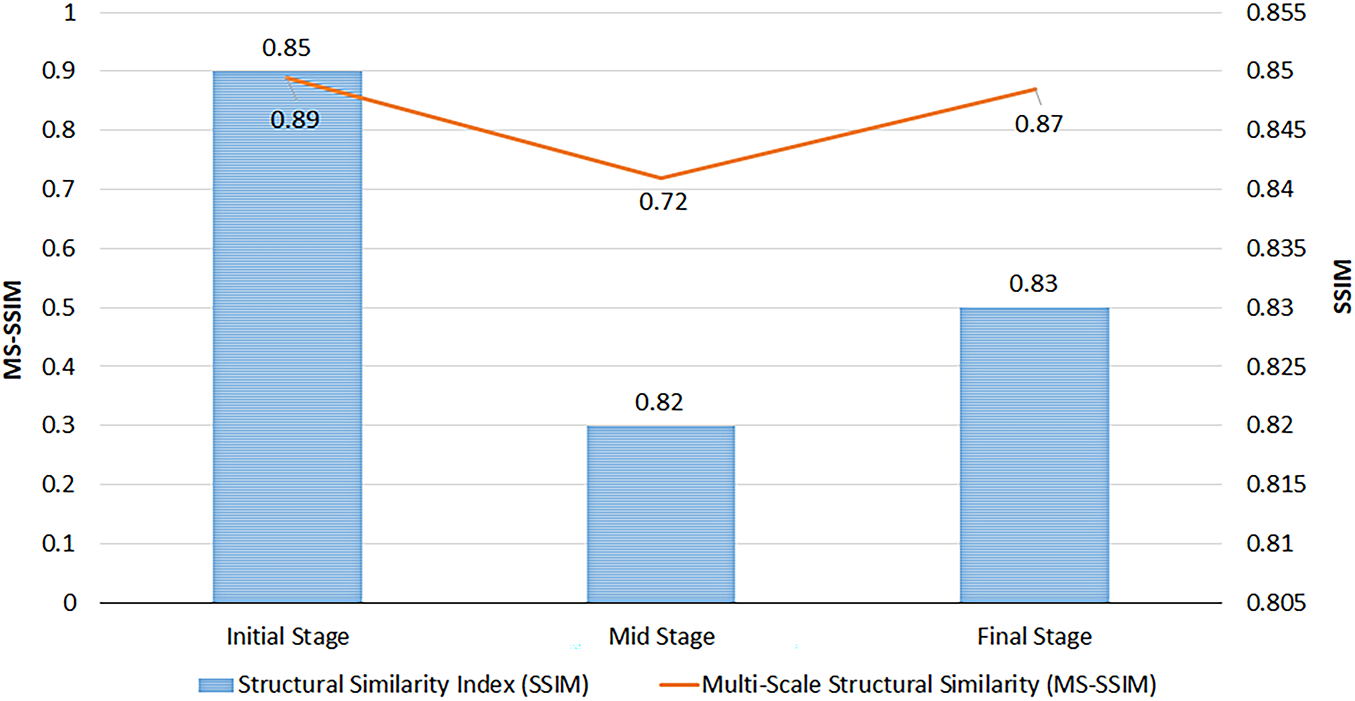

Figure 6: Structural Similarity (SSIM) and Multi-Scale SSIM (MS-SSIM) for synthesized UWF-FA by phase; range [0, 1], higher scores denote closer perceptual similarity to real FA images

The mid stage attained the lowest MAE (Table 2), indicating the most faithful pixel-level reconstruction. A slight PSNR decrease from initial to final phase (Fig. 5) suggests modest noise or contrast dispersion later in circulation, yet absolute PSNR values remain high. SSIM values are stable (Fig. 6), while MS-SSIM dips in mid phase and rebounds in final, indicating transient loss of fine multi-scale structures during mid-phase contrast dynamics.

5.4 Expert Visual Assessment and Turing-Style Realism

Two ophthalmologists achieved substantial inter-rater agreement (Cohen’s weighted

Figure 7: Inter-rater agreement (Cohen’s

5.5 Downstream DR Stratification with Synthetic FA

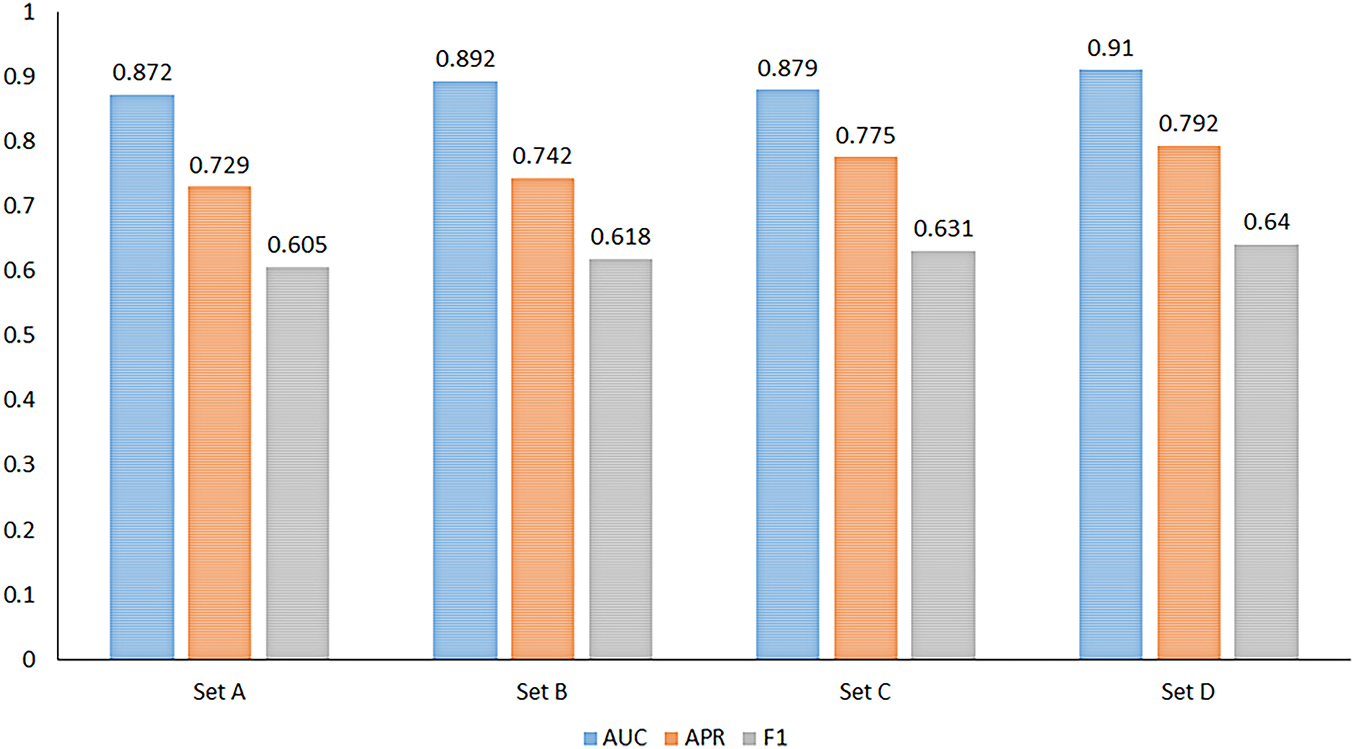

Diagnostic utility was quantified by training a Swin-based classifier on four dataset compositions (Sets A–D; see Section 3). Performance metrics (AUC, APR, F1, sensitivity, specificity, accuracy) are reported in Table 4 with visual summaries in Figs. 8 and 9. Adding synthetic FA improved all task metrics relative to baseline (Set A), with full multi-phase integration (Set D) achieving the best overall performance (AUC 0.910, APR 0.792, accuracy 0.829). Significance tests indicate these gains are unlikely due to chance (Table 4). The monotonic rise in sensitivity from Sets A to D suggests that angiographic cues—nonperfusion, leakage, peripheral vasculature—provide complementary information to UWF_RI.

Figure 8: Sensitivity (Sens), Specificity (Spec), and Accuracy (Acc) across Sets A–D for synthetic UWF-FA integration

Figure 9: Area Under Curve (AUC), Average Precision Rate (APR), and F1-score across Sets A–D showing consistent improvement with multi-phase synthetic inputs

5.6 Qualitative Comparisons across Phases and Pathologies

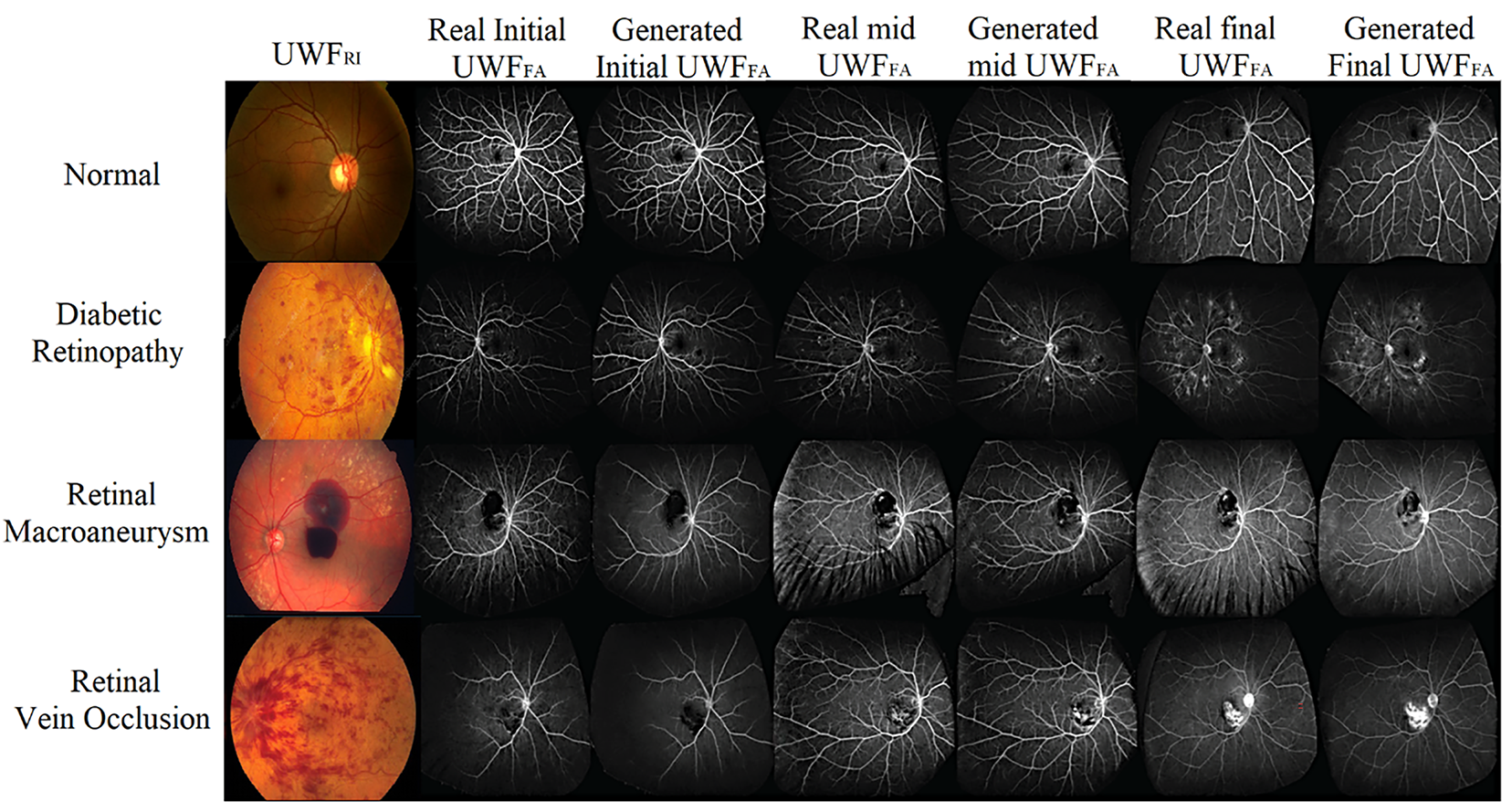

Fig. 10 illustrates side-by-side comparisons of real and synthesized UWF_FA across initial, mid, and final phases for representative conditions (retinal macroaneurysm, normal retina, DR, and retinal vein occlusion). The synthesized images preserve macrovessel topology and lesion boundaries while reproducing phase-dependent contrast filling, supporting both perceptual realism and clinical interpretability.

Figure 10: Qualitative gallery: real vs. synthetic

Across quantitative metrics, expert review, and downstream classification, the proposed phase-aware synthesis yields high-fidelity UWF_FA that enhances DR stratification when combined with UWF_RI. Mid-phase reconstructions exhibit the lowest MAE; multi-scale structure is transiently reduced during mid-phase but recovers in final-phase views; and multi-phase synthetic integration delivers the strongest end-task performance.

Presenting a phase-aware cross-modal translation framework that synthesizes ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography (UWF_FA) from non-invasive ultra widefield retinal images (UWF_RI), and demonstrated its clinical utility by integrating synthetic angiography into downstream diabetic retinopathy (DR) stratification. Across quantitative fidelity metrics, expert visual reading, and task performance, the multi phase design produced high quality angiograms that improved classification when fused with UWF_RI. See Section 5, Tables 2 and 4, and Fig. 10.

6.1 Comparison with Prior Work

Our study advances beyond earlier UWF translation approaches by scaling paired data, enforcing strict registration quality, and learning phase-specific generators. Prior systems such as UWAT-GAN focused on single venous-phase synthesis with limited paired samples, which constrains generalization and fails to model temporal angiographic dynamics. In contrast, we produce initial, mid, and final phases under a unified training and evaluation protocol, enabling richer depiction of nonperfusion and leakage patterns. This broader temporal coverage and the integration with a modern classifier strengthen the link between perceptual realism and clinical task performance.

6.2 Clinical Relevance of Non-Invasive Multi-Phase FA

UWF imaging captures peripheral pathology that can shift disease staging and management. Angiographic information remains the gold standard for visualizing capillary dropout and leakage but requires dye injection with workflow burden and rare adverse reactions. Our results show that synthetic UWF_FA can complement UWF_RI to improve DR stratification (Set D vs. Set A in Table 4), suggesting a practical path to safer, scalable screening and triage where invasive FA is unavailable or contraindicated.

6.3 Interpreting Quantitative Trends

The mid phase achieved the lowest MAE (Table 2), indicating the most faithful pixel-level reconstruction during peak circulation contrast. The slight PSNR decline from initial to final phase (Fig. 5) likely reflects dispersion and noise accumulation later in the sequence, yet absolute values remain high. SSIM is stable across phases (Fig. 6); the MS-SSIM dip in the mid phase suggests transient loss of very fine multi-scale structure during dynamic filling, which is restored by the final phase. These patterns are consistent with the known temporal physiology of FA and the trade-offs between global fidelity and micro-structure preservation at high resolution.

6.4 Expert Reading and Turing-Style Realism

Two ophthalmologists provided consistent quality ratings with substantial agreement (

6.5 Downstream Utility: Why Multi-Phase Helps

Integrating synthetic FA incrementally improved all classification metrics relative to a UWF_RI only baseline, with the full multi-phase setting (Set D) yielding the best AUC, APR, sensitivity, and accuracy (Table 4 and Figs. 8 and 9). The monotonic gain in sensitivity from Sets A to D indicates that angiographic cues provide complementary information to color imaging particularly for detecting nonperfusion and peripheral vascular pathology not fully captured by UWF_RI. This supports the design choice of phase-specific generators and late-fusion classification.

6.6 Limitations and Threats to Validity

First, despite stringent registration (Section 4), peripheral distortion and residual artifacts can degrade synthesis near the edges of UWF fields, potentially affecting lesion depiction. Second, although we curated large paired data, domain shift across devices and sites may persist; prospective multi-center validation is needed. Third, Messidor-2 served as external data for classification with synthetic FA derived from UWF_RI, which may not fully reflect clinical deployment where heterogeneous imaging protocols are common. Fourth, our evaluation focused on DR; generalization to other retinal diseases (e.g., RVO, RAM) is suggested by qualitative examples (Fig. 10) but requires dedicated studies. Finally, reader studies included a limited number of experts; expanding to larger, geographically diverse panels will improve confidence intervals and reduce annotation bias.

Several directions can further raise clinical readiness. (i) Data and domain expansion: incorporate additional vendors, populations, and pathologies, with patient-level temporal follow-up to study progression. (ii) Robust learning: add domain adaptation and self-supervised pretraining to mitigate shift, and uncertainty estimation to flag unreliable synthesis. (iii) Architectural advances: explore diffusion or hybrid adversarial–diffusion objectives for sharper microvasculature while retaining stability. (iv) Lesion-aware evaluation: augment global metrics with vessel-wise and lesion-level endpoints, calibration, and decision-curve analysis to connect image quality with patient benefit. (v) Prospective trials: assess impact on referral decisions and treatment planning, compare against dye-based FA when ethically feasible, and evaluate operational benefits in teleophthalmology workflows. In summary, phase-aware synthesis of UWF_FA from UWF_RI yields high-fidelity, perceptually convincing angiograms and confers measurable gains in DR stratification when integrated with a transformer-based classifier. By reducing reliance on dye injection while preserving angiographic insight, the approach offers a scalable path to safer, more accessible screening. Continued work on domain robustness, lesion-aware validation, and prospective clinical studies will be key to realizing translational impact at scale.

A phase-aware cross-modal framework was presented that synthesizes ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography (UWF_FA) from non-invasive UWF_RI and demonstrated clinical utility for diabetic retinopathy (DR) stratification. The approach combines strict trans-modal registration, three phase-specific generators (initial, mid, final), and a composite objective augmented with gradient variance loss to better preserve vascular detail. When fused with a transformer-based classifier, multi-phase synthetic angiography consistently outperformed a UWF_RI only baseline, with the full-phase setting (Set D) achieving the strongest end task metrics. See Table 4 and Figs. 8 and 9. From a fidelity standpoint, mid-phase synthesis attained the lowest MAE while SSIM remained stable and MS-SSIM exhibited a transient mid-phase dip consistent with dynamic contrast filling; expert review showed substantial agreement and frequent real-synthetic confusions, supporting perceptual realism. See Tables 2 and 3 and Figs. 4–7. Limitations include residual peripheral distortions, potential domain shift across devices/centers, and a modest reader cohort; broader disease coverage beyond DR also warrants formal evaluation. Future work will target robustness via domain adaptation and self/weak supervision, hybrid adversarial-diffusion objectives for sharper microvasculature, uncertainty calibration to flag unreliable synthesis, lesion/vessel-level endpoints with decision-curve analysis, and prospective multi center studies to quantify impact on referral and treatment workflows. In sum, phase aware UWF_FA synthesis offers a scalable, dye-free pathway to enrich screening and triage, improving DR stratification while mitigating risks of invasive angiography, and holds promise for safe, accessible retinal care at scale.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/417/46.

Funding Statement: The work was funded by the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University through Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/417/46.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: major contribution to the writing of the article, model building, data extraction and main writer: Damodharan Palaniappan, Tan Kuan Tak and K. Vijayan; overall design and execution: Damodharan Palaniappan, Tan Kuan Tak, K. Vijayan, Balajee Maram, Pravin R Kshirsagar and Naim Ahmad; technical support in data processing and analysis: Damodharan Palaniappan, Tan Kuan Tak and K. Vijayan; overall design and execution: Damodharan Palaniappan, Tan Kuan Tak, K. Vijayan, Balajee Maram, Pravin R Kshirsagar and Naim Ahmad. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Naim Ahmad, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional review board. All 1198 patient images were fully de-identified before analysis. Public datasets (ODIR, Messidor-2) are open-access and anonymized; therefore, no additional consent was required.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chatterjee S, Fruhling A, Kotiadis K, Gartner D. Towards new frontiers of healthcare systems research using artificial intelligence and generative AI. Health Syst. 2024;13(4):263–73. doi:10.1080/20476965.2024.2402128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Bajenaru L, Tomescu M, Grigorovici-Toganel I. Leveraging generative Artificial Intelligence for advanced healthcare solutions. Rom J Inf Technol Autom Control. 2024;34(3):149–64. [Google Scholar]

3. Bennani T. Advancing healthcare with generativeAI: a multifaceted approach to reliable medical information and innovation [Ph.D. thesis]. Cambridge, MA, USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2024. [Google Scholar]

4. Sai S, Gaur A, Sai R, Chamola V, Guizani M, Rodrigues JJPC. Generative AI for transformative healthcare: a comprehensive study of emerging models, applications, case studies, and limitations. IEEE Access. 2024;12:31078–106. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3367715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yim D, Khuntia J, Parameswaran V, Meyers A. Preliminary evidence of the use of generative AI in health care clinical services: systematic narrative review. JMIR Med Inform. 2024;12(1):e52073. doi:10.2196/52073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Ling Ong JC, Michael C, Ng N, Elangovan K, Ting Tan NY, Jin L, et al. Generative AI and large language models in reducing medication related harm and adverse drug events—a scoping review. MedRxiv. 2024. doi:10.1101/2024.09.13.24313606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Teo ZL, Quek CWN, Wong JLY, Ting DSW. Cybersecurity in the generative artificial intelligence era. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol. 2024;13(4):100091. doi:10.1016/j.apjo.2024.100091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Chen R, Zhang W, Liu B, Chen X, Xu P, Liu S, et al. EyeDiff: text-to-image diffusion model improves rare eye disease diagnosis. arXiv:2411.10004. 2024. [Google Scholar]

9. Ahmed T, Choudhury S. An integrated approach to AI-generated content in e-health. arXiv:2501.16348. 2025. [Google Scholar]

10. Gupta M, Gupta S, Palanisamy G, Nisha JS, Goutham V, Kumar SA, et al. A comprehensive survey on detection of ocular and non-ocular diseases using color fundus images. IEEE Access. 2024;12:194296–321. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3517700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mochan A, Farinha J, Bailey G, Rodriguez L, Zanca F, Pólvora A, et al. Imaging the Future-Horizon scanning for emerging technologies and breakthrough innovations in the field of medical imaging and AI. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2024. [Google Scholar]

12. Casu M, Guarnera L, Caponnetto P, Battiato S. GenAI mirage: the impostor bias and the deepfake detection challenge in the era of artificial illusions. Forensic Sci Int Digit Investig. 2024;50(3):301795. doi:10.1016/j.fsidi.2024.301795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kawai K, Murakami T, Mori Y, Ishihara K, Dodo Y, Terada N, et al. Clinically significant nonperfusion areas on widefield OCT angiography in diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmol Sci. 2023;3(1):100241. doi:10.1016/j.xops.2022.100241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Ashraf M, Shokrollahi S, Salongcay RP, Aiello LP, Silva PS. Diabetic retinopathy and ultrawide field imaging. Semin Ophthalmol. 2020;35(1):56–65. doi:10.1080/08820538.2020.1729818. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wang X, Ji Z, Ma X, Zhang Z, Yi Z, Zheng H, et al. Automated grading of diabetic retinopathy with ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography and deep learning. J Diabetes Res. 2021;2021(1):2611250. doi:10.1155/2021/2611250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Akram MU, Khalid S, Tariq A, Khan SA, Azam F. Detection and classification of retinal lesions for grading of diabetic retinopathy. Comput Biol Med. 2014;45(2):161–71. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2013.11.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Alwakid G, Gouda W, Humayun M. Enhancement of diabetic retinopathy prognostication using deep learning, CLAHE, and ESRGAN. Diagnostics. 2023;13(14):2375. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13142375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Khan MH, Mungloo-Dilmohamud Z, Jhumka K, Mungloo NZ, Pena-Reyes C. Investigating on data augmentation and generative adversarial networks (GAN s) for diabetic retinopathy. In: 2022 International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME); 2022 Nov 16–18; Maldives. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

19. Patrini G, Rozza A, Krishna Menon A, Nock R, Qu L. Making deep neural networks robust to label noise: a loss correction approach. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 1944–52. [Google Scholar]

20. Dgani Y, Greenspan H, Goldberger J. Training a neural network based on unreliable human annotation of medical images. In: 2018 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2018). Piscataway, NJ, USA: Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 39–42. [Google Scholar]

21. Mehralian M, Karasfi B. RDCGAN: unsupervised representation learning with regularized deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. In: 2018 9th Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Robotics and 2nd Asia-Pacific International Symposium. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 31–8. [Google Scholar]

22. Park KB, Choi SH, Lee JY. M-GAN: retinal blood vessel segmentation by balancing losses through stacked deep fully convolutional networks. IEEE Access. 2020;8:146308–22. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3015108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kamran SA, Hossain KF, Tavakkoli A, Zuckerbrod SL, Baker SA. Vtgan: semi-supervised retinal image synthesis and disease prediction using vision transformers. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 3235–45. [Google Scholar]

24. Radford A, Kim JW, Hallacy C, Ramesh A, Goh G, Agarwal S, et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2021. p. 8748–63. [Google Scholar]

25. Kong L, Lian C, Huang D, Li Z, Hu Y, Zhou Q. Breaking the dilemma of medical image-to-image translation. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2021;34:1964–78. [Google Scholar]

26. Nichol AQ, Dhariwal P. Improved denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2021. p. 8162–71. [Google Scholar]

27. Nichol A, Dhariwal P, Ramesh A, Shyam P, Mishkin P, McGrew B, et al. Glide: towards photorealistic image generation and editing with text-guided diffusion models. arXiv:2112.10741. 2021. [Google Scholar]

28. Krichen M. Generative adversarial networks. In: 2023 14th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

29. Isola P, Zhu JY, Zhou T, Efros AA. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 1125–34. [Google Scholar]

30. Poles I, D’arnese E, Cellamare LG, Santambrogio MD, Yi D. Repurposing the image generative potential: exploiting GANs to grade diabetic retinopathy. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 2305–14. [Google Scholar]

31. Chen X, Duan Y, Houthooft R, Schulman J, Sutskever I, Abbeel P. Infogan: interpretable representation learning by information maximizing generative adversarial nets. In: NIPS’16: Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2016 Dec 5–10; Barcelona Spain. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc. p. 2180–8. [Google Scholar]

32. Yang L, Zhang Z, Song Y, Hong S, Xu R, Zhao Y, et al. Diffusion models: a comprehensive survey of methods and applications. ACM Comput Surv. 2023;56(4):1–39. doi:10.1145/3626235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Saharia C, Chan W, Chang H, Lee C, Ho J, Salimans T, et al. Palette: image-to-image diffusion models. In: ACM SIGGRAPH 2022 Conference Proceedings. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2022. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

34. Ozbey M, Dalmaz O, Dar SUH, Bedel HA, Ozturk S, Gungor A, et al. Unsupervised medical image translation with adversarial diffusion models. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2023;42(12):3524–39. doi:10.1109/tmi.2023.3290149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Binkowski M, Sutherland DJ, Arbel M, Gretton A. Demystifying mmd gans. arXiv:1801.01401. 2018. [Google Scholar]

36. Chong MJ, Forsyth D. Effectively unbiased fid and inception score and where to find them. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 6070–9. [Google Scholar]

37. Sara U, Akter M, Uddin MS. Image quality assessment through FSIM, SSIM, MSE and PSNR—a comparative study. J Comput Commun. 2019;7(3):8–18. doi:10.4236/jcc.2019.73002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Gencer K, Gencer G, Ceran TH, Bilir AE, Doǧan M. Photodiagnosis with deep learning: a GAN and autoencoder-based approach for diabetic retinopathy detection. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2025;53(22):104552. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2025.104552. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Kalisapudi SSA, Raj VD, Vanam S, Anne JC. Synthesizing realistic ARMD fundus images using generative adversarial networks (GANs). In: International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Communication. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 587–99. [Google Scholar]

40. Alghamdi M, Abdel-Mottaleb M. Retinal image augmentation using composed GANs. Eng Technol Appl Sci Res. 2024;14(6):18525–31. doi:10.48084/etasr.8964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Fang Z, Chen Z, Wei P, Li W, Zhang S, Elazab A, et al. Uwat-gan: fundus fluorescein angiography synthesis via ultra-wide-angle transformation multi-scale gan. In: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. p. 745–55. [Google Scholar]

42. Ge R, Fang Z, Wei P, Chen Z, Jiang H, Elazab A, et al. UWAFA-GAN: ultra-wide-angle fluorescein angiography transformation via multi-scale generation and registration enhancement. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2024;28(8):4820–9. doi:10.1109/jbhi.2024.3394597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Abbood SH, Abdull Hamed HN, Mohd Rahim MS, Alaidi AHM, Salim ALRikabi HTH. DR-LL Gan: diabetic retinopathy lesions synthesis using generative adversarial network. Int J Online Biomed Eng. 2022;18(3):151–63. doi:10.3991/ijoe.v18i03.28005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Das S, Walia P. Enhancing early diabetic retinopathy detection through synthetic DR1 image generation: a StyleGAN3 approach. arXiv:2501.00954. 2025. [Google Scholar]

45. Anaya-Sanchez H, Altamirano-Robles L, Diaz-Hernandez R, Zapotecas-Martinez S. Wgan-gp for synthetic retinal image generation: enhancing sensor-based medical imaging for classification models. Sensors. 2024;25(1):167. doi:10.3390/s25010167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Pakdelmoez S, Omidikia S, Seyyedsalehi SA, Seyyedsalehi SZ. Controllable retinal image synthesis using conditional StyleGAN and latent space manipulation for improved diagnosis and grading of diabetic retinopathy. arXiv:2409.07422. 2024. [Google Scholar]

47. Liu J, Xu S, He P, Wu S, Luo X, Deng Y, et al. VSG-GAN: a high-fidelity image synthesis method with semantic manipulation in retinal fundus image. Biophys J. 2024;123(17):2815–29. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2024.02.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Pour AM, Seyedarabi H, Jahromi SHA, Javadzadeh A. Automatic detection and monitoring of diabetic retinopathy using efficient convolutional neural networks and contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization. IEEE Access. 2020;8:136668–73. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3005044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Kaur J, Kaur P. UNIConv: an enhanced U-Net based InceptionV3 convolutional model for DR semantic segmentation in retinal fundus images. Concurr Comput Pract Exp. 2022;34(21):e7138. doi:10.1002/cpe.7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Shi D, He S, Yang J, Zheng Y, He M. One-shot retinal artery and vein segmentation via cross-modality pretraining. Ophthalmol Sci. 2024;4(2):100363. doi:10.1016/j.xops.2023.100363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Alcantarilla PF, Nuevo J, Bartoli A. Fast explicit diffusion for accelerated features in nonlinear scale spaces. In: Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC); 2011 Aug 29–Sep 2; Dundee, UK. Durham, UK: BMVA Press; 2011. p. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

52. Fischler MA, Bolles RC. Random sample consensus: a paradigm for model fitting with applications to image analysis and automated cartography. Commun ACM. 1981;24(6):381–95. doi:10.1145/358669.358692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Abrahamyan L, Truong AM, Philips W, Deligiannis N. Gradient variance loss for structure-enhanced image super-resolution. In: ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 3219–23. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools