Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Small Object Detection in UAV Scenarios Based on YOLOv5

1 Information Center, Jilin University of Chemical Technology, Jilin, 132022, China

2 Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Chongqing, 400065, China

3 Beijing Chaitin Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, 100101, China

4 School of Information and Control Engineering, Jilin University of Chemical Technology, Jilin, 132022, China

* Corresponding Author: Shuangyuan Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Image Segmentation and Object Detection: Innovations, Challenges, and Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 3993-4011. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.073896

Received 28 September 2025; Accepted 11 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

Object detection plays a crucial role in the field of computer vision, and small object detection has long been a challenging issue within this domain. In order to improve the performance of object detection on small targets, this paper proposes an enhanced structure for YOLOv5, termed ATC-YOLOv5. Firstly, a novel structure, AdaptiveTrans, is introduced into YOLOv5 to facilitate efficient communication between the encoder and the detector. Consequently, the network can better address the adaptability challenge posed by objects of different sizes in object detection. Additionally, the paper incorporates the CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module) attention mechanism, which dynamically adjusts the weights of different channels in the feature map by introducing a channel attention mechanism. Finally, the paper addresses small object detection by increasing the number of detection heads, specifically designed for detecting high-resolution and minute target objects. Experimental results demonstrate that on the VisDrone2019 dataset, ATC-YOLOv5 outperforms the original YOLOv5, with an improvement in mAP@0.5 from 34.32% to 42.72% and an increase in mAP@[0.5:0.95] from 18.93% to 24.48%.Keywords

Since the 20th century, target detection has witnessed extensive development and application in domains such as intelligent transportation, pedestrian detection, and unmanned driving. With the improvement in the accuracy of image classification, target detection algorithms based on convolutional neural networks have gradually become a focal point in current research [1–4].

As deep learning and target detection technologies continue to advance, small object detection has emerged as a crucial research area in the field of target recognition [5]. Small objects are those that occupy only a few pixels in an image. The performance of small object detection has continually improved with the enhancement of high-precision sensor technologies and the evolution of image techniques, finding widespread applications in areas like camera surveillance and unmanned aerial vehicles [6–8]. Detection devices are typically equipped with high-definition cameras for image acquisition, offering advantages such as operational simplicity, flexible monitoring, stability, and cost-effectiveness [9,10]. In recent years, small object detection applications based on computer vision detection technology have garnered increasing attention among researchers both domestically and internationally.

For small object detection, the complexity of backgrounds and the small proportion of detected targets are the primary challenges leading to the difficulty of target detection [11]. Additionally, each small object dataset exhibits unique characteristics, requiring algorithm adjustments when conducting small object detection on multiple datasets to adapt to diverse scenarios [12]. This not only demands algorithmic flexibility but also necessitates models with strong generalization capabilities.

Presently, the majority of target detection algorithms are typically designed for normal-sized objects. While these algorithms perform well on most publicly available datasets such as Pascal VOC, Common Objects In Context, and ImageNet, these datasets mainly comprise medium or large-sized targets, falling short of meeting the requirements for small object detection [13]. To address this issue, applications focused on small object detection datasets have emerged, such as VisDrone 2019, UAV 123, and others [14–17]. The VisDrone dataset can be found at http://aiskyeye.com.

In the current field of computer vision, significant progress has been made in the research of target detection for unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) image datasets. Researchers have employed diverse methods and models to enhance detection performance, with some introducing novel network architectures and techniques.

Liu et al. [18] proposed the Multi-Branch Parallel Feature Pyramid Network (MPFPN) on the VisDrone UAV image dataset, incorporating a Supervised Spatial Attention Module (SSAM) and a cascading architecture [19]. This method achieved a 2.05% improvement in mAP compared to the original FPN method, reaching the state-of-the-art performance on the dataset. However, the method relies on multiple branches and a complex architecture, which may lead to increased computational overhead, potentially affecting the efficiency in real-time applications. Kostiv et al. [20] introduced the DBNet model based on Cascade R-CNN, enhancing localization performance through a cascading box approach, achieving a mAP of 39.43 on the VisDrone-DET2021 test set. Although the method provides some improvement in localization, there is still a risk of performance degradation when handling small object detection and fast-moving targets, as the cascading mechanism may introduce delays or produce inaccurate detection results in certain complex scenarios. Nikouei et al. [21] proposed the TPH-YOLOv5 model based on the YOLOv5 structure, addressing challenges related to target scale variation and motion blur [22–24] by replacing convolutional blocks with transformers and adding additional prediction heads, ultimately achieving a mAP of 39.18. The method improves detection performance to some extent by introducing transformers to handle complex feature representations, but it still faces the challenge of better handling objects of different scales. Ale et al., on the VisDrone dataset, utilized RetinaNet as the base model, introducing an anchor box optimization method tailored for the dataset. They employed the crow search [25] algorithm to search for optimal anchor box scales and ratios, maximizing the overlap area between predicted and ground truth boxes. Experimental results showed that optimized anchor boxes reduced false negatives, improving mAP from 0.249 to 0.295. Although the method significantly improves detection accuracy by optimizing anchor boxes, it may still be limited by anchor box selection, especially when dealing with large variations in object scales or complex scenes, potentially facing a performance bottleneck.

Despite significant progress in UAV image target detection, there are still some major drawbacks, particularly in the detection of small objects. Current models face challenges when handling small objects, primarily manifested in two aspects. Firstly, due to their small size and low resolution, small objects are prone to occlusion or confusion, leading to inaccurate detection results [26,27]. Existing detection methods require further targeted approaches to address this issue and enhance the accuracy of small object detection. Secondly, limited detailed information poses a challenge in the feature representation of small objects, making it difficult for existing models to effectively extract crucial features and impacting detection accuracy [28]. Additionally, the low signal-to-noise ratio and background interference of small objects can also affect the performance of current models [29].

This study introduces the AdaptiveTrans module, acting as a bridge between the Backbone and Neck in YOLOv5, improving the performance of PANet with lower computational costs and higher accuracy [30,31]. This structural design demonstrates superior performance in experiments, offering computational efficiency compared to overall neck structure modifications. Furthermore, to enhance small object detection performance, this paper introduces the CBAM block [32], focusing on extracting critical feature information from small objects. This design, more practical than methods introducing Transformer layers, holds promise for achieving better performance in large-scale image detection. Therefore, combining the main structure of YOLOv5 with previous work, the proposed improvement algorithm in this study is experimentally validated to achieve excellent results in small object detection. The following are the contributions to the theme of this article:

(1) A lightweight AdaptiveTrans module is designed and embedded at the Backbone–Neck interface of YOLOv5, wholly replacing the original Conv-C3 stack. via four parallel branches—adaptive pooling, 1 × 1 squeeze, ReLU, and Hard-Sigmoid channel re-weighting—it generates multi-scale fusion weights on-the-fly with negligible extra cost, boosting overall detection accuracy.

(2) By embedding the CBAM attention module into the backbone, the model’s focus on images is improved: it markedly amplifies low-contrast small-object responses, suppresses complex background noise, alleviates the loss of fine details in deep feature maps, and thus enhances overall detection accuracy.

(3) The added P2 head (4× resolution) operates on high-resolution features, markedly boosting spatial localization accuracy for small objects and simultaneously improving recall and positioning of 4 × 4-pixel targets in cluttered scenes, thereby strengthening overall multi-scale detection capability.

The YOLO (You Only Look Once) series constitutes a deep learning-based object detection framework known for its unique ability to efficiently detect all objects in a single forward pass. YOLOv5, as a milestone version within this series, demonstrates outstanding computational efficiency and precision. Compared to its predecessors, YOLOv5 exhibits quicker characteristics in both training and inference, coupled with lower memory usage, making it more advantageous in image detection applications.

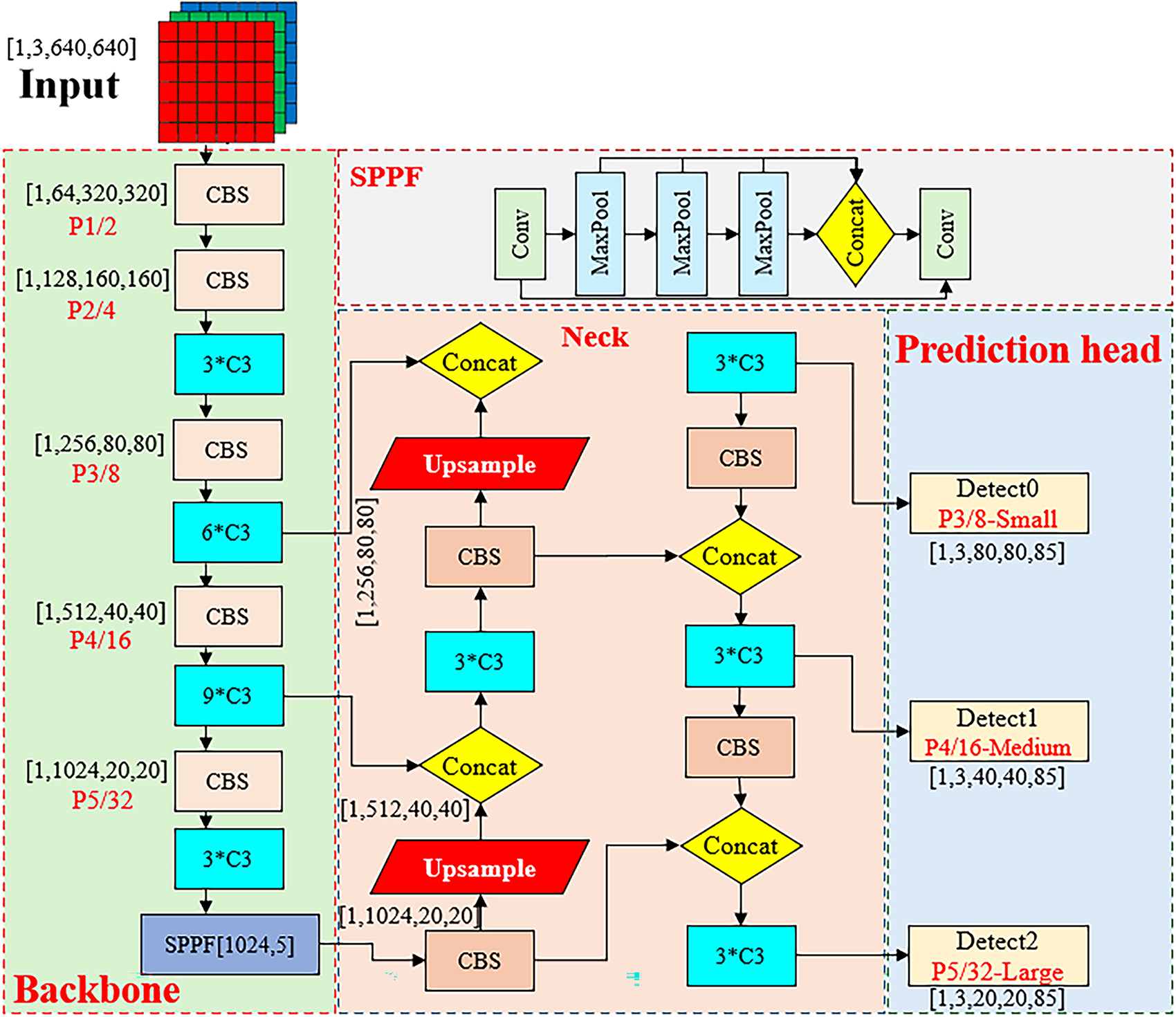

The network architecture of YOLOv5 is illustrated in Fig. 1 designed to address the requirement of simultaneously handling multiple objects in a single forward pass. This design philosophy enables the model to complete object detection tasks in a shorter timeframe, enhancing real-time performance. Additionally, YOLOv5 strikes a well-balanced compromise between network depth and parameter count, ensuring high detection accuracy without sacrificing computational efficiency.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of YOLOv5s network structure

In image detection scenarios, the advantages of YOLOv5 become evident. Its rapid inference speed and lower memory requirements enable efficient operation even on resource-constrained platforms, meeting the demands of practical applications. Therefore, YOLOv5 has not only garnered widespread attention in the field of deep learning but has also demonstrated robust potential in real-world image detection tasks.

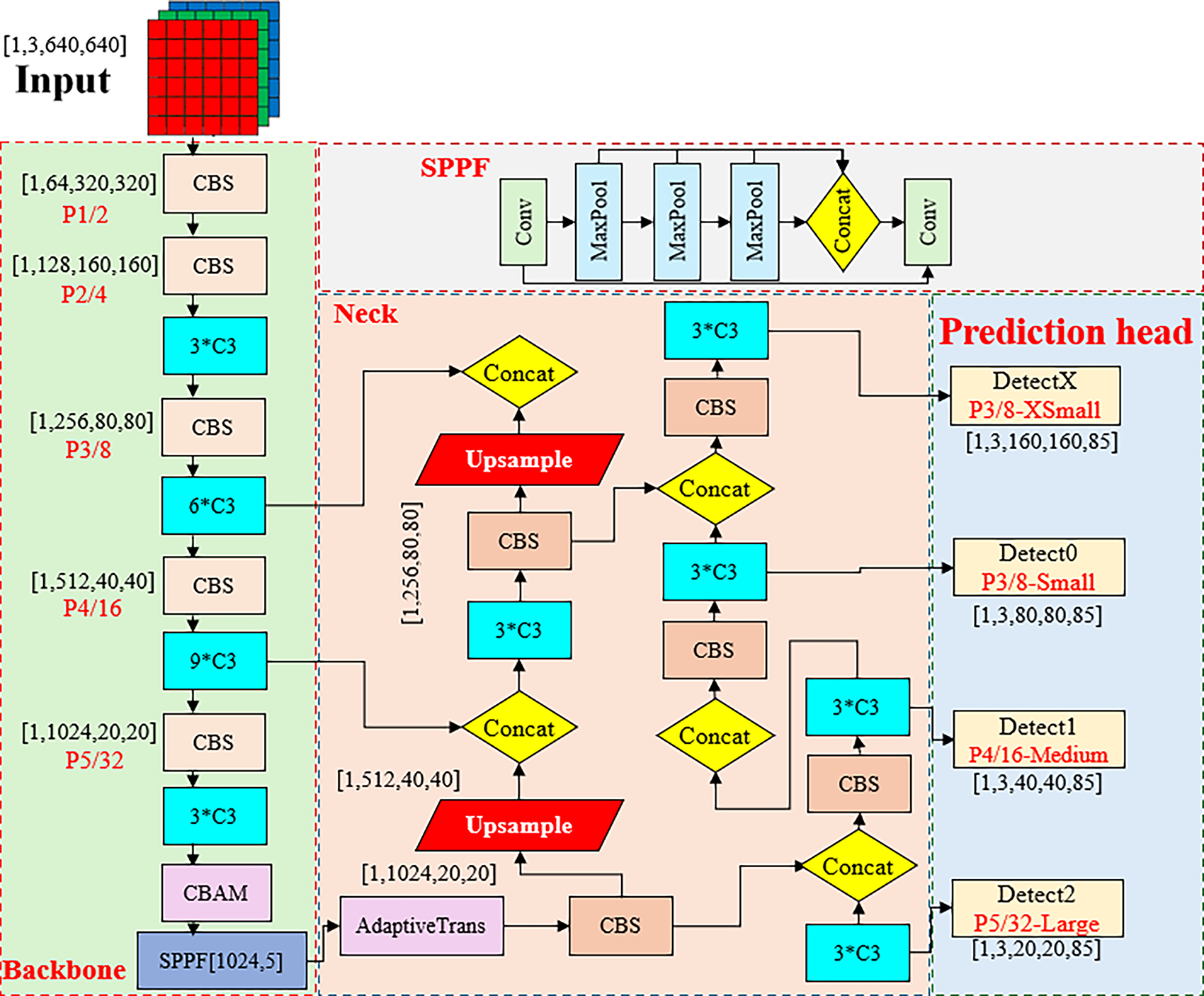

In summary, this paper proposes the ATC-YOLOv5 algorithm based on the YOLOv5s version. The network architecture of the algorithm is illustrated in Fig. 2. Initially, at the input of the bottleneck network, an Adaptive Transposing Module (AdaptiveTrans) is introduced to perform downsampling on the feature map and increase the number of channels. Through this step, channel information is enhanced and shared, effectively reducing information loss in the initial stages of the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN). This improvement plays a significant role in enhancing the performance of FPN, particularly aiding in the detection of smaller-sized targets.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of ATC-YOLOv5 network structure

Introduction of the Adaptive Transposing Module allows the network to better adapt to targets of different sizes, simultaneously enhancing detection accuracy while reducing computational burden. This improvement is expected to bring about more robust and efficient detection performance in practical applications. In summary, the ATC-YOLOv5 algorithm achieves significant improvements in object detection tasks through the optimization of the network structure.

In the neck section of the algorithm, this paper introduces the Spatial Pyramid Convolutional Module, designating the 160 × 160 layer specifically for the detection of extremely small targets. The role of this module is to provide a detection mechanism more sensitive to minute targets, enabling the algorithm to intricately capture and analyze the features of these small-sized targets. Simultaneously, by utilizing the 160 × 160 layer as a detection head for specific targets, this paper further optimizes the network structure, making it more suitable for small target detection tasks. Lastly, convolutional operations are introduced to add detection heads with even smaller resolutions, enhancing spatial localization information. The purpose of this step is to improve the accuracy of target positioning through higher-resolution detection heads, thereby enhancing the overall performance of target detection. Through this design, this paper achieves more significant results in handling small targets, providing the algorithm with increased capabilities for target detection in complex scenarios. The overall architecture is designed to comprehensively optimize the performance of target detection, particularly making notable advancements in the detection of small targets. By introducing these improvement modules in the neck section, the paper aims to enhance the algorithm’s responsiveness to targets of different sizes and complexities.

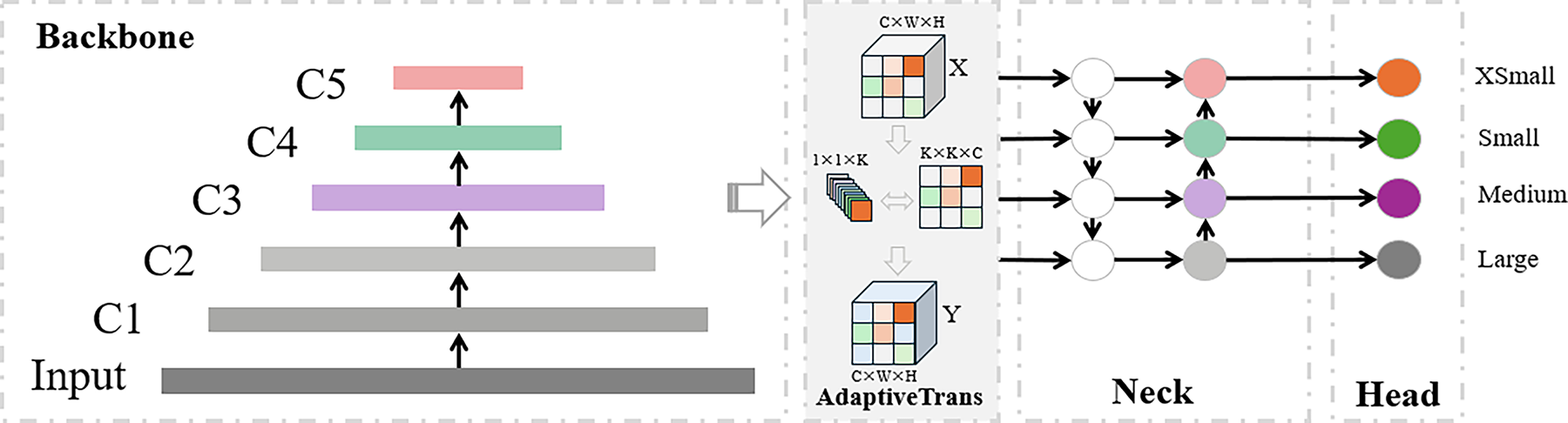

Integrating the AdaptiveTrans module into the YOLOv5 framework effectively addresses two key issues in small object detection: insufficient feature extraction and low contrast between the target and background. Small objects tend to lose details on deep feature maps due to their small size, making it difficult for traditional convolutional neural networks to extract their features effectively. Current research on small object detection focuses on how to enhance small object performance through multi-scale feature fusion. The AdaptiveTrans module tackles this by enhancing features adaptively and aggregating information across scales. It uses adaptive pooling and feature fusion techniques to integrate features from different scales, enhancing the representation of small object details and preventing them from being lost through multiple convolutions.

At the same time, current research highlights the importance of attention mechanisms, especially spatial and channel attention, in small object detection, as they can effectively improve the contrast between the target and the background, reducing interference from background noise. The AdaptiveTrans module leverages spatial attention mechanisms to dynamically focus on regions containing small objects, boosting the contrast between the target features and the background, thus improving the model’s ability to distinguish small objects. Additionally, the task-aware feature selection within the module adjusts the weights of feature channels, further enhancing the response of small object regions, which aligns with the current trend of adaptive feature processing in small object detection. With these innovations, the AdaptiveTrans module provides YOLOv5 with stronger small object detection capabilities, improving its performance in complex backgrounds and varying scales.

The AdaptiveTrans module optimizes the transmission and fusion of feature maps through a series of operations. First, the module performs adaptive average pooling on the input feature map to automatically adjust the pooling region based on the feature map’s different scales, ensuring that multi-scale information is preserved in the output feature map. Next, the feature map, after adaptive pooling, is processed through a 1 × 1 convolution, which helps integrate information from different channels and reduces redundant features, thereby lowering the computational burden. Then, the ReLU activation function is applied to the convolved feature map for non-linear transformation, further enhancing the effective feature responses. Finally, the module uses a Hard Sigmoid activation function to scale each channel of the feature map, dynamically adjusting the weights of each channel to amplify key feature channels while suppressing irrelevant ones. This series of operations enables the AdaptiveTrans module to generate feature maps with dynamic weights, effectively transmitting and fusing multi-scale features between the backbone and neck networks, thus improving the model’s ability to handle small targets and complex backgrounds, ultimately enhancing overall object detection accuracy and performance.

The introduction of the AdaptiveTrans block between the Backbone and Neck represents a critical improvement. The incorporation of this block aids in enhancing and sharing channel information, effectively reducing information loss in the initial stages of the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN).

This optimization plays a pivotal role in improving the performance of FPN, particularly demonstrating more significant enhancements when detecting smaller-sized targets.

The AdaptiveTrans block exhibits superior performance in adapting to different visual patterns, demonstrating a broader applicability from various spatial perspectives. The introduction of AdaptiveTrans plays a pivotal role not only in the improvement of channel information but also showcases stronger adaptability in processing information from different spatial positions. Such enhancements contribute to elevating the overall perceptual capability of the model, enabling it to be more flexible and effectively adapt to diverse visual scenes, particularly resulting in a significant performance boost in the detection of small-sized targets.

The structure of the AdaptiveTrans, as depicted in Fig. 3, is designed to present adaptive transformations in both spatial and channel domains, showcasing multi-channel attributes. Here, and represent the height and width of the feature map, respectively, while denotes the convolutional kernel size, with each group sharing the same AdaptiveTrans convolutional kernel. This design not only optimizes the handling of channel information but also achieves adaptability transformations in the spatial domain. The utilization of shared convolutional kernels helps reduce model parameterization, improving training efficiency and maintaining adaptability to different channel information.

Figure 3: AdaptiveTrans structure in YOLOv5

Overall, the introduction of AdaptiveTrans brings significant advantages in both structure and performance, providing a robust foundation for better adaptability and performance improvement in the model.

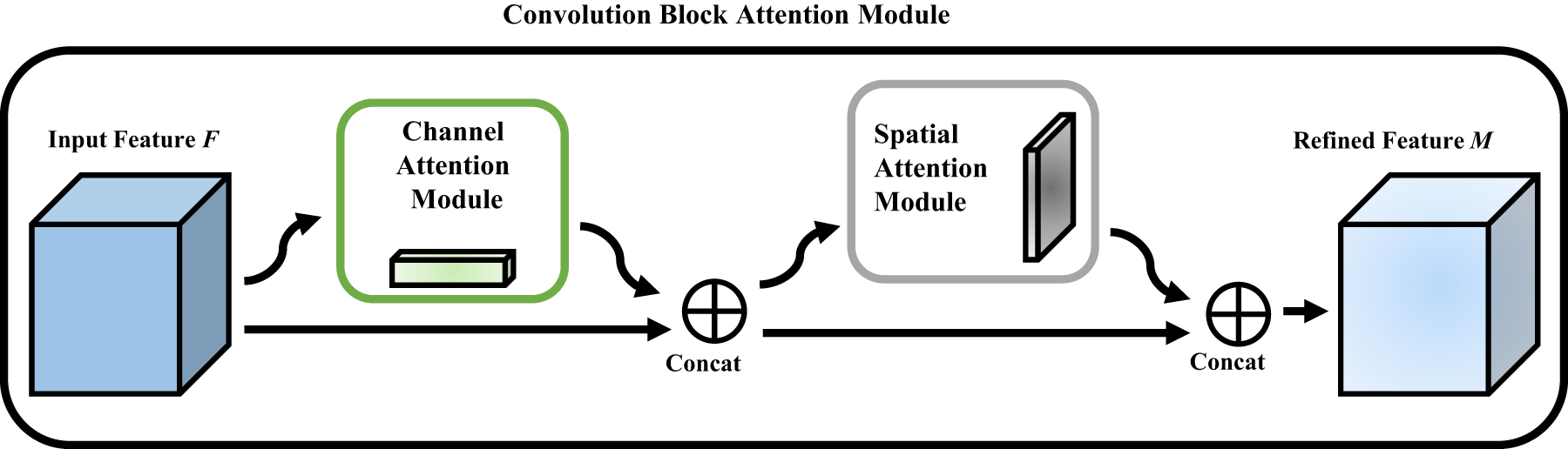

CBAM-CBAM is an effective attention-based model that can be seamlessly integrated into CNN architectures. The model consists of two key modules, namely, the channel attention module and the spatial attention module, as illustrated in Fig. 4. In the channel attention component, the feature map is initially pooled into a vector along the channel dimension through global average pooling. Subsequently, channel attention weights are obtained through two fully connected layers.

Figure 4: Convolution block attention module architecture

In the spatial attention component, channel information of a feature map is aggregated through two pooling operations, generating two 2D maps:

Rather than learning a fresh set of convolution kernels for every input pixel, our channel-attention branch first squeezes each channel into a single scalar through parallel global average- and max-pooling, fuses the two statistics with a shared fully-connected layer, and produces a 1 × 1 × C vector that is simply multiplied channel-wise with the original feature map; analogously, the spatial-attention branch pools only along the channel axis (yielding two H × W maps), concatenates them, applies one 7 × 7 convolution, and generates an H × W mask that is pixel-wise multiplied with the input. This “pool–fuse–scale” pipeline re-weights existing features instead of synthesising new kernels, so it introduces no extra convolutional parameters at inference time and avoids the heavy computational overhead inherent in dynamic convolution, while still allowing the network to emphasise informative channels and locations on a per-sample basis.

All experiments were conducted on the VisDrone 2019 dataset. To ensure the fairness of ablation experiments, algorithms such as GBS-YOLOv5 and YOLOv3 were tested based on the VisDrone dataset. The experimental results indicate that the proposed ATC-YOLOv5 exhibits excellent performance in terms of detection accuracy.

A. Datasets

With the widespread application of drones in agriculture, transportation, aerial photography, and other fields, the requirements for collecting visual data with drones have become more stringent. To conduct experiments more convincingly, this study chooses to use the VisDrone open dataset. The VisDrone dataset is collected by the AISKYEYE team from the Machine Learning and Data Mining Laboratory at Tianjin University. The dataset analyzed in the current research can be obtained from the VisDrone dataset repository (https://github.com/VisDrone/VisDrone-Dataset, accessed on 10 November 2025), which includes 26,908 frames and 10,209 images.

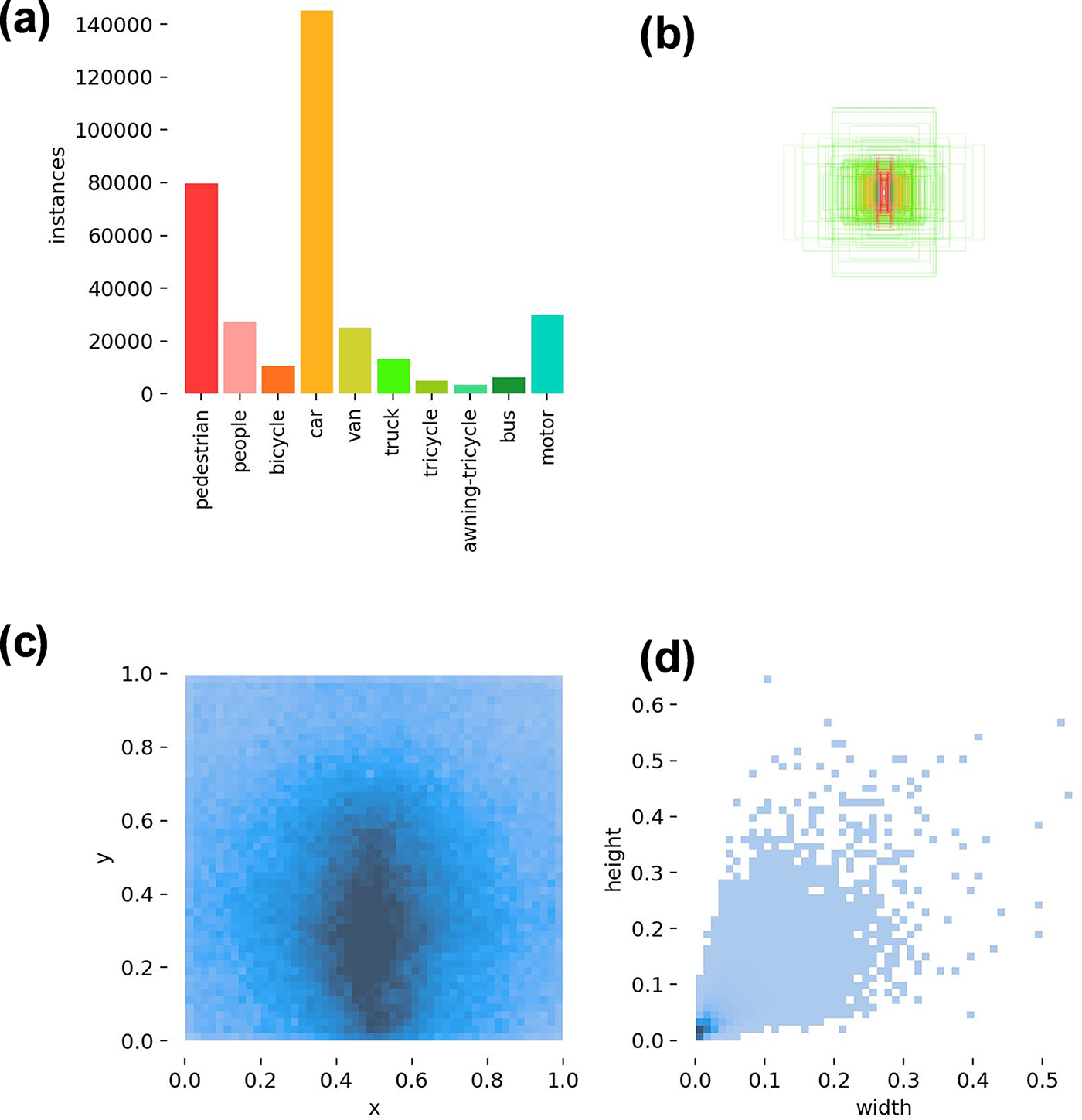

These data are captured by drone cameras, covering diverse regions, including 14 different cities in China, spanning thousands of kilometers. The covered environments include urban and rural areas, featuring various objects such as pedestrians, vehicles, and bicycles, in both sparse and crowded scenes. Additionally, the dataset is collected using different drone platforms (i.e., different drone models) in various scenes, weather conditions, and lighting conditions. The dataset predefines bounding boxes for 10 categories, including pedestrians, humans, cars, trucks, buses, vans, motorcycles, bicycles, canopies of tricycles, and tricycles. In the experiments, 10,209 static images are used, and the dataset is divided into training, validation, and test sets according to official predefined splits. This dataset contains small targets, severe target occlusion, and a diverse range of detected objects. Sample data is shown in Fig. 5. The label information and category count of the VisDrone dataset in this scenario are illustrated in Fig. 6.

Figure 5: Datasets examples in (a) country road, (b) night situation, (c) parking area

Figure 6: (a) Instances. Information of 10 classes in VisDrone-2019. (b) Anchor boxes, distribution of box sizes in the dataset. (c) Locations. The locations of objects in an image, whose height and width are assumed to be 1. (d) Size, the size of the data image, the width and height are normalized to between 0

We adopted evaluation metrics based on the confusion matrix, using mAP (mean Average Precision), Recall, and Precision as indicators to assess the model’s performance.

In the confusion matrix, positive and negative instances represent positive and negative samples, respectively. True Positive (TP) indicates that the sample’s true class is positive, and the model’s prediction is also positive. True Negative (TN) indicates that the sample’s true class is negative, and the model’s prediction is also negative. False Positive (FP) represents a scenario where the sample’s true class is negative, but the model predicts it as positive. False Negative (FN) represents a situation where the sample’s true class is positive, but the model predicts it as negative.

Recall represents the proportion of correctly identified positive sample pixels to the total number of positive sample pixels. The calculation formula for Recall is shown in Eq. (3).

Precision is a crucial performance metric that gauges the accuracy of the model in segmentation tasks. Specifically, it indicates the proportion of pixels correctly segmented by the model out of all segmented pixels. This metric is pivotal, particularly in tasks such as image segmentation and object detection. The calculation for precision is illustrated in Formula (4).

mAP is a metric that averages the accuracy values across multiple validation sets for individual instances. It is employed to measure the detection accuracy in object detection. There are two main indicators within mAP. When the Intersection over Union (IoU) is set to 0.5, it is denoted as mAP@0.5. Additionally, the average mAP across IoU values ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step size of 0.05 is represented as mAP@0.5:0.95.

The loss function utilized in this experiment is as follows:

In this scenario, the training loss encompasses three primary components: the bounding box loss

In addition to the primary evaluation metrics presented earlier in this paper, we further assess the performance of the proposed model using three additional metrics: Parameters, Inference Time, and FPS (batch size = 1). First, Parameters reflect the model’s complexity and capacity; more parameters typically indicate greater expressive power, but also lead to higher computational and storage demands. Next, Inference Time refers to the time the model takes to process a single input sample. A lower inference time signifies that the model can make predictions faster, which is particularly important for real-time applications. Lastly, FPS (batch size = 1) measures the number of frames the model can process per second when the batch size is set to 1. Higher FPS indicates that the model can process more samples within the same time frame, thereby improving the system’s efficiency and real-time performance. By incorporating these additional metrics, we can offer a more comprehensive evaluation of the model’s balance between accuracy, efficiency, and computational resource requirements.

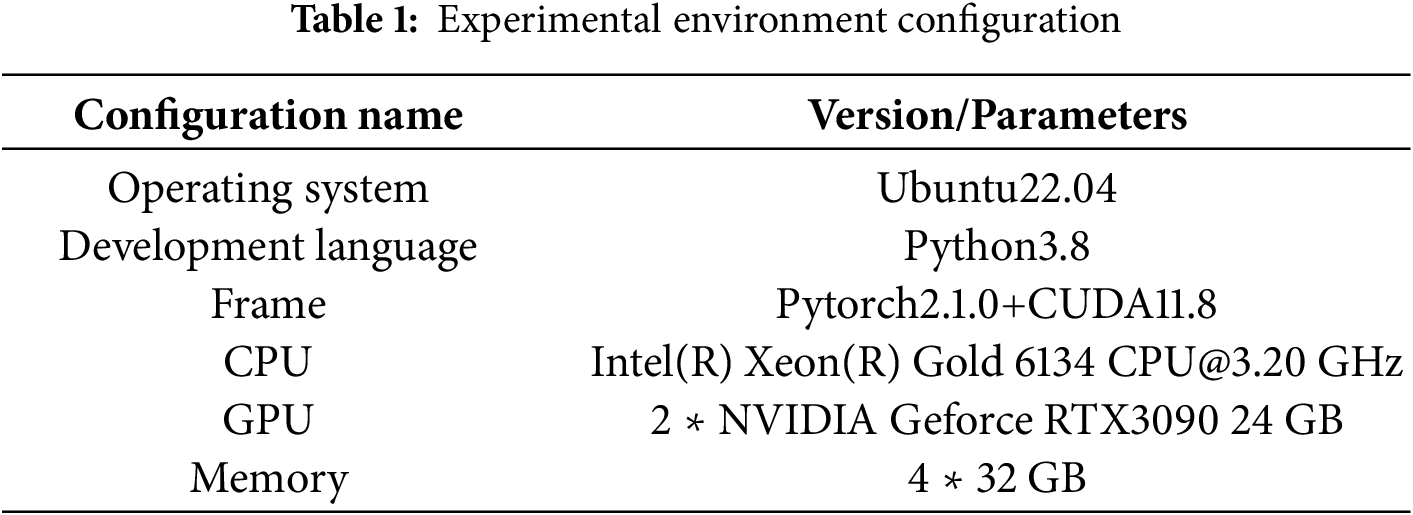

The operating system utilized in our experiments was Ubuntu 22.04, running on a system equipped with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6134 CPU@3.20 GHz processor, 128 GB of RAM, and two NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 graphics cards, each possessing 24 ∗ 2 GB of video memory. Detailed specifications of the hardware configuration are presented in Table 1.

In the experiments, this study configured training weights using hyperparameters without utilizing official pre-trained weights. The number of training iterations (Epoch) was set to 300, batch size to 16, and input size to 640 × 640. The training hyperparameters were set as follows: initial learning rate (Lr) at 0.01, utilizing stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with a rate of 1 × 10−2, and the Adam optimizer with a rate of 1 × 10−3. The loss function during training is defined by Eq. (7). To address potential overfitting, data augmentation was applied specifically to the VisDrone dataset with the following hyperparameters: mosaic data augmentation set to 1.0, scaling factor at 0.5, flipping factor at 0.1, image HSV (Hue, Saturation, Value) value enhancement at 0.4, image HSV saturation enhancement at 0.7, and image HSV hue enhancement at 0.015.

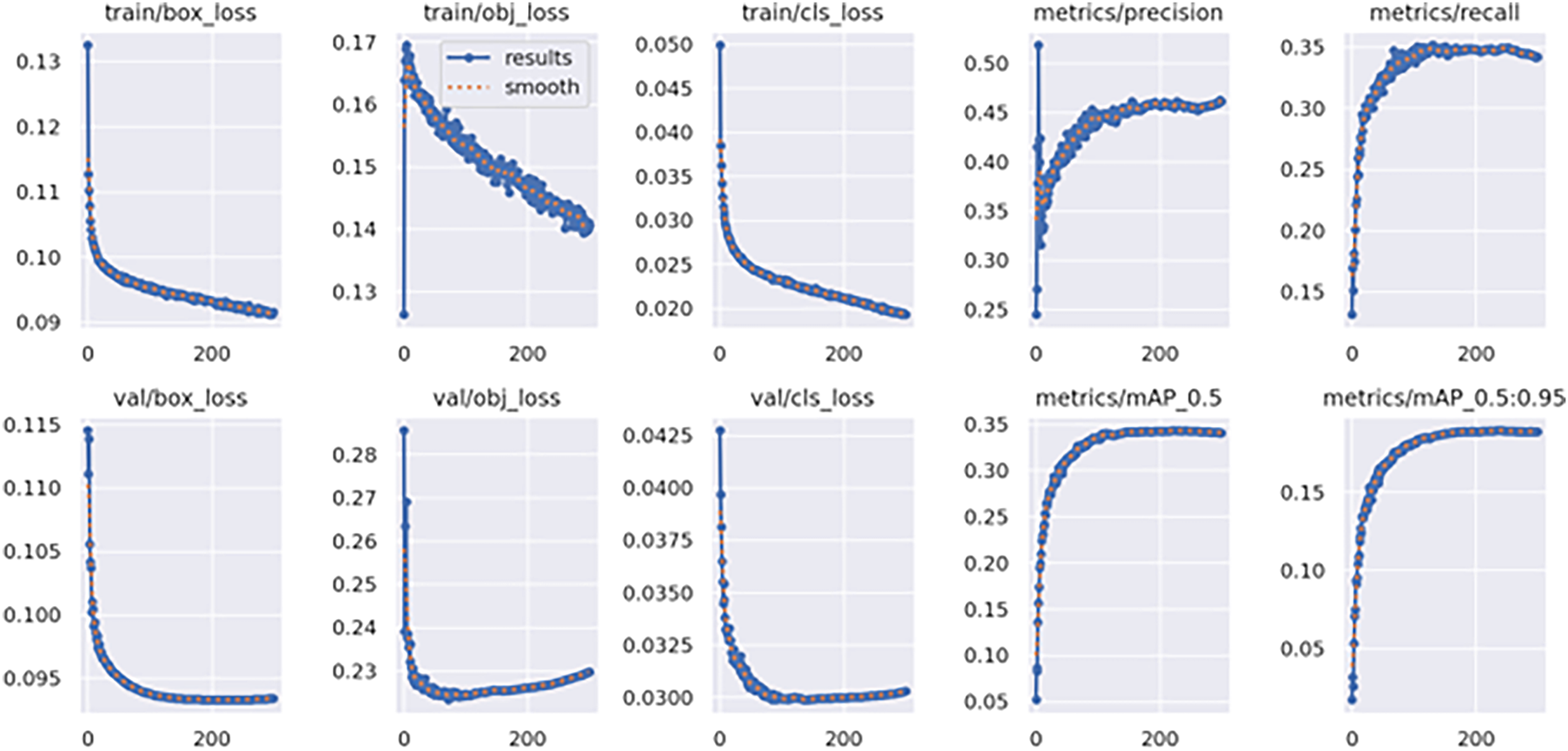

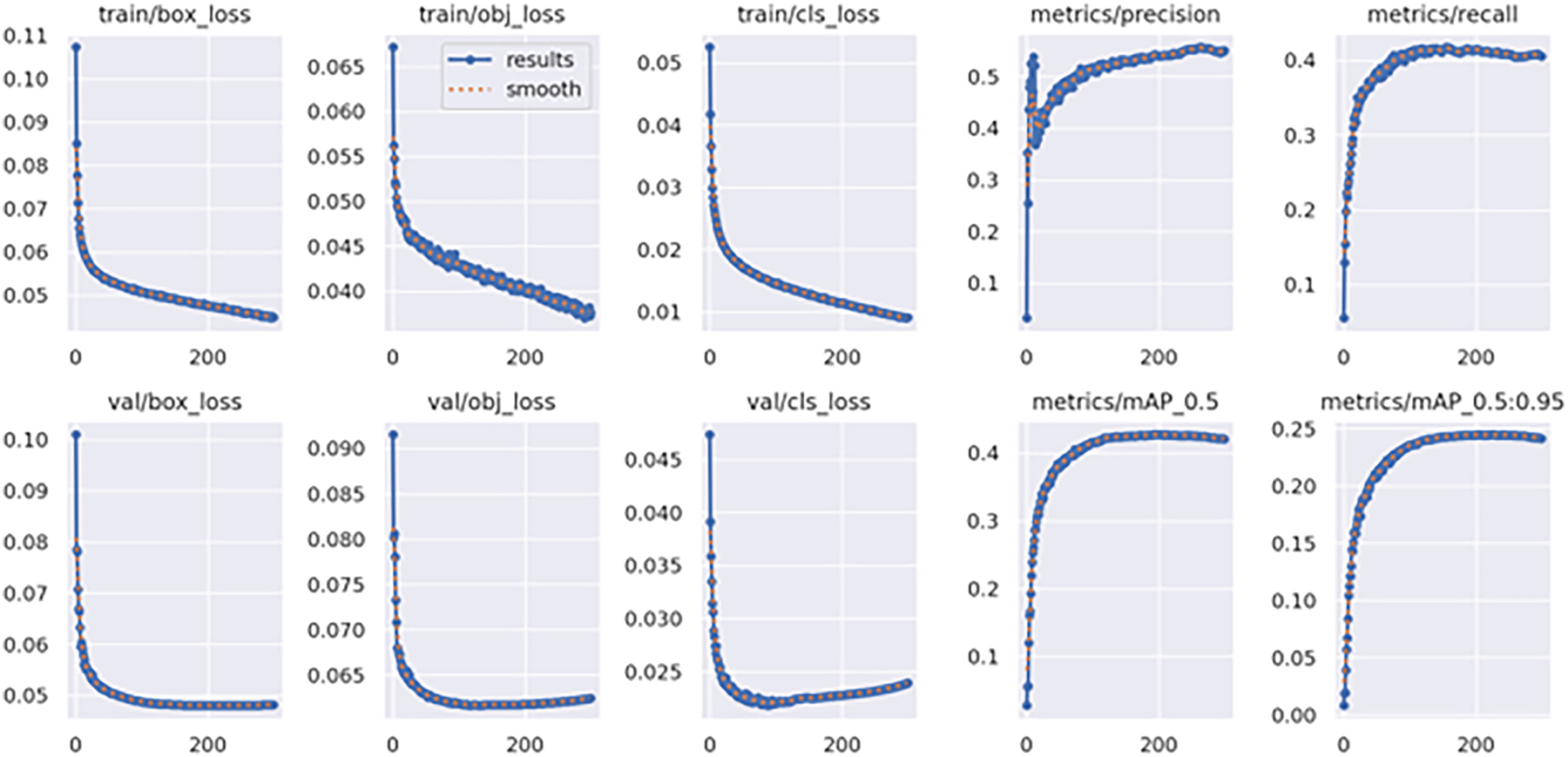

We conducted training on YOLOv5 and ATC-YOLOv5 using the VisDrone 2019 dataset. The optimization of the models during training employed the stochastic gradient descent method. The training batch size was adjusted to 300, and the image input size was set to 640 × 640. The learning rate was configured to be 0.01. Additionally, data augmentation techniques such as mosaic and flipping were applied during the training process to enhance the diversity of the dataset. The training processes for YOLOv5 and ATC-YOLOv5 are illustrated in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: YOLOv5 and ATC-YOLOv5 training process

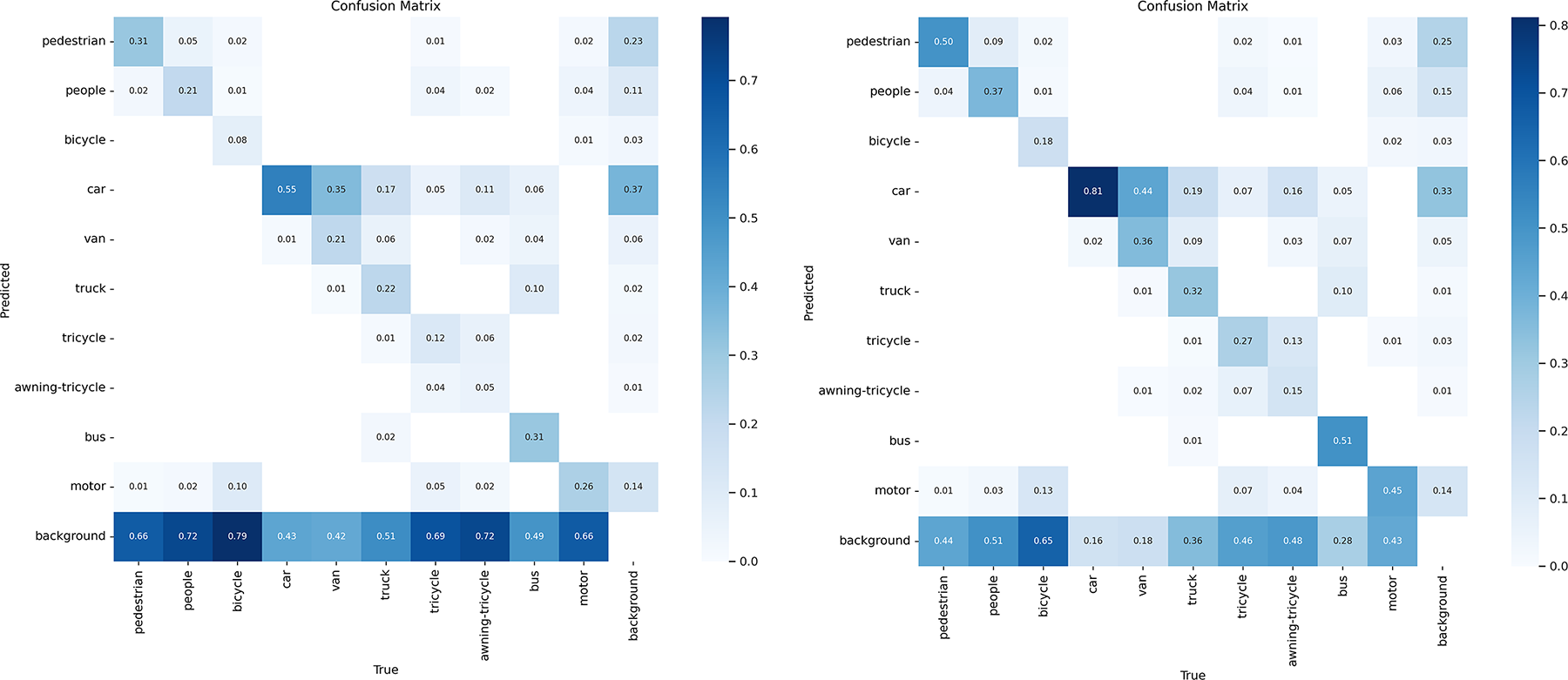

Through the observation of Fig. 8, it is evident that the proposed algorithm demonstrates varying degrees of improvement in precision (P) across all categories, averaging a 16% enhancement. Additionally, the recall rate (R) exhibits an average increase of 14.6% for each category, with a corresponding improvement of 13.1% in mAP@0.5. Compared to the traditional YOLOv5s, our algorithm shows a substantial performance boost.

Figure 8: YOLOv5 and ATC-YOLOv5 confusion matrix

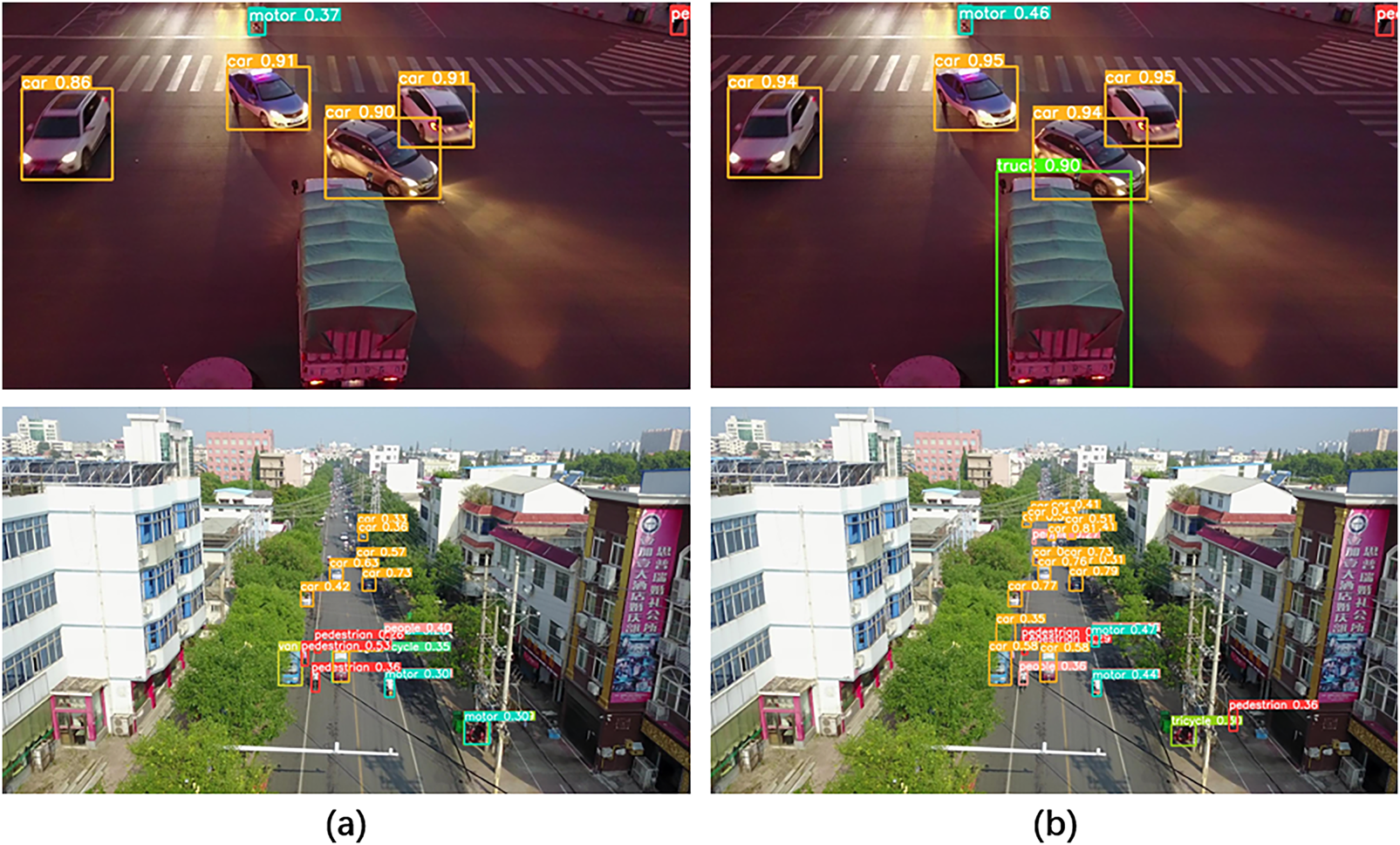

Further examination of Fig. 9 reveals that, by adopting the proposed improvements, the ATC-YOLOv5 algorithm can more effectively detect a greater number of small targets. This observation suggests that the introduced enhancements, such as the AdeptiveTrans module and CBAM structure, play a significant role in handling small targets, providing the algorithm with more robust performance in complex scenarios.

Figure 9: Part of the detection results of the ATC-YOLOv5 algorithm on the Visdrone data set, (a) is the YOLOv5 algorithm, (b) is the ATC-YOLOv5 algorithm

These significant performance improvements are not only reflected in precision but also yield satisfactory results in crucial metrics such as recall rate and mAP@0.5. Overall, the ATC-YOLOv5 algorithm proposed in this study demonstrates outstanding performance in object detection tasks, surpassing the current YOLOv5 algorithm, particularly in the detection of small targets.

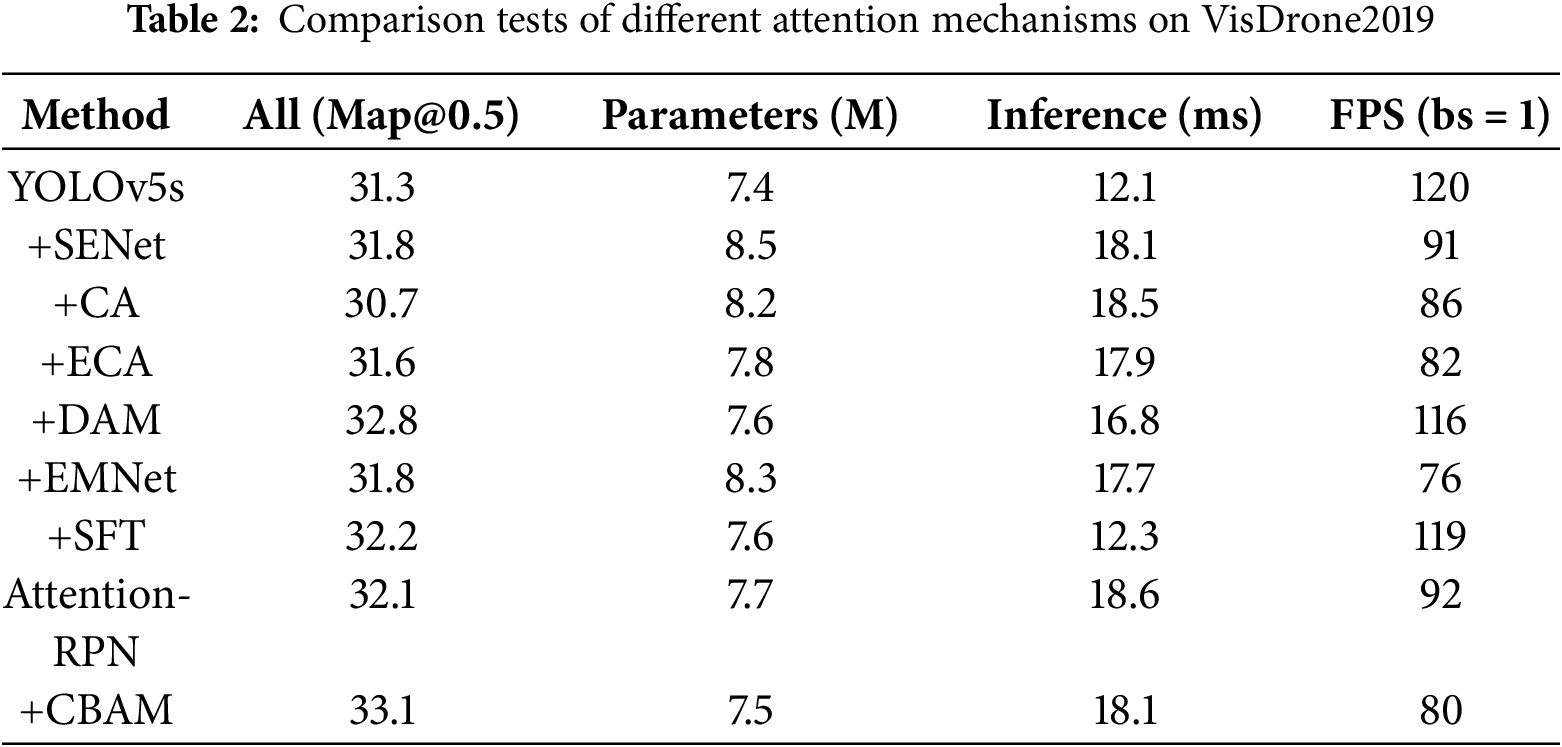

Table 2 shows the comparison of common attention mechanisms. Including Deformable Attention Module (DAM) [33], Entangled Multi-task Network (EMNet) [34], SFT [35], Attention-RPN [36], SENet [37], CA [38], ECA [39]. The experimental results indicate that when CBAM is added to YOLOv5s, there is a significant improvement in mAP@0.5, reaching 33.1, which demonstrates the effectiveness of CBAM in enhancing feature representation. Although CBAM introduces additional computational overhead, increasing the Inference time to 18.1 ms and decreasing the FPS to 80, it provides the most notable improvement in mAP@0.5, with a relatively small increase in Parameters from 7.4 M to 7.5 M. This indicates that CBAM can maintain a low model complexity while increasing computational load. Overall, CBAM enhances the detection accuracy of YOLOv5s in small object detection and complex scenes, effectively balancing performance and computational efficiency.

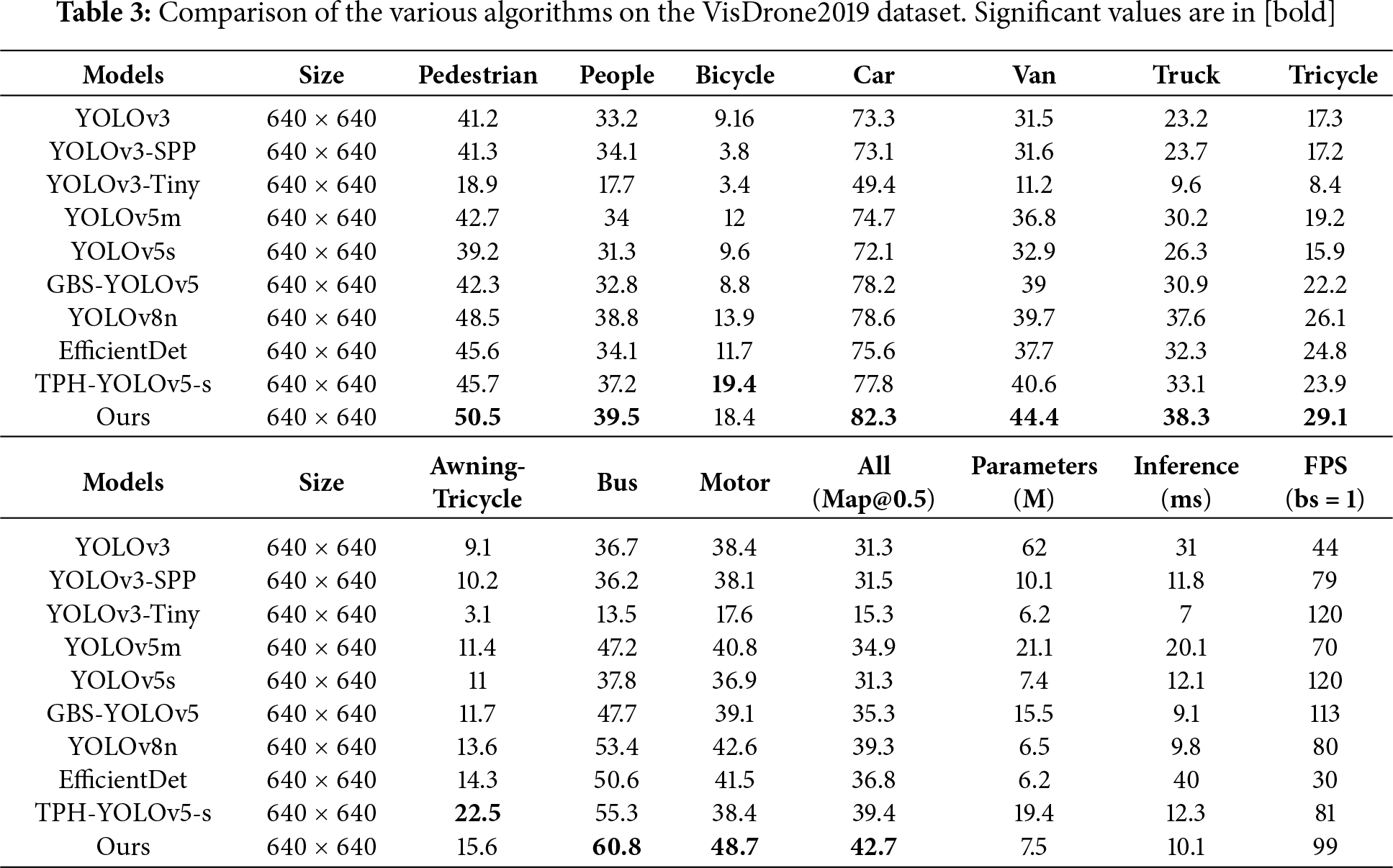

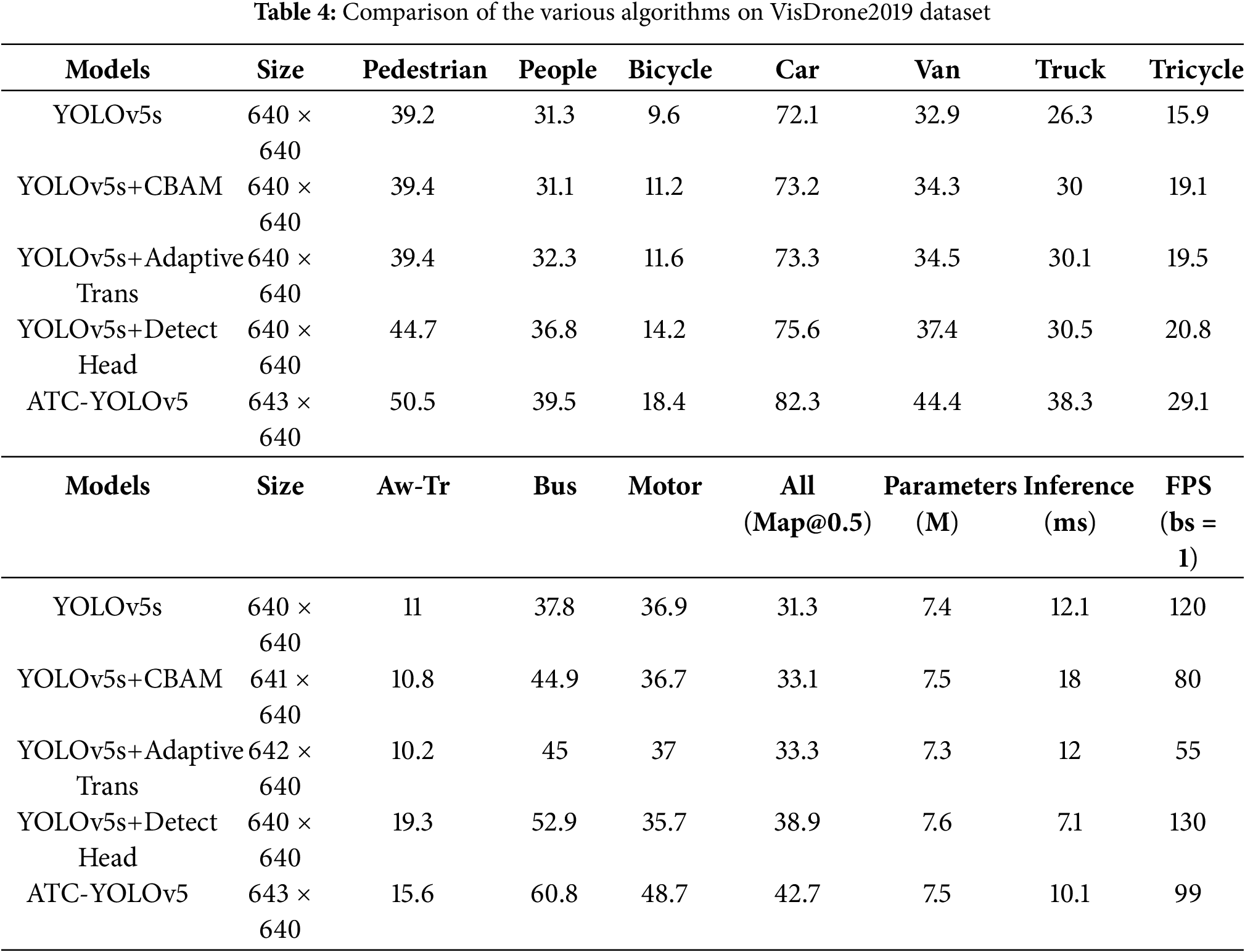

In addition, we conducted various algorithm comparison experiments on the VisDrone dataset. To facilitate a more intuitive comparison of the performance between ATC-YOLOv5 and other algorithms, mAP@0.5 was selected as the performance metric. Furthermore, efforts were made to adjust the training parameters of the compared models as much as possible to ensure fair competition among the models. The detailed experimental results for each algorithm are presented in Table 3.

Upon reviewing Table 3, the ATC-YOLOv5 model achieved superior accuracy compared to other detection models. Specifically, the drone detection accuracy of ATC-YOLOv5 is 7.8% higher than that of YOLOv5m. Additionally, compared to YOLOv3, YOLOv3-spp, YOLOv3-tiny, and ATC-YOLOv5, it has improved by 11.4%, 11.2%, 27.4%, and 7.4%, respectively. These comparative results clearly demonstrate the outstanding performance of ATC-YOLOv5 on the VisDrone dataset, particularly exhibiting a significant improvement in drone detection tasks compared to other algorithms. This not only confirms the effectiveness of the improvements introduced in this paper but also indicates that ATC-YOLOv5 possesses stronger adaptability and robustness in practical applications.

At the same time, ATC-YOLOv5 also has significant advantages in Parameters, Inference Time, and FPS.

First, in terms of Parameters (M), the OUR algorithm has 7.5 M parameters, which is significantly lower than YOLOv3 (62 M) and YOLOv3-SPP (31 M), as well as YOLOv5m (21.1 M). It is slightly higher than YOLOv5s (7.4 M) and GBS-YOLOv5 (15.5 M) but remains relatively small. A lower parameter count means the model is more lightweight, requiring less computational power and memory, making it more suitable for deployment on resource-constrained devices or in edge computing environments.

In terms of Inference Time (ms), the OUR algorithm has an inference time of 10.1 ms, which is significantly faster than YOLOv3 (31 ms) and YOLOv3-SPP (44 ms). It is also comparable to YOLOv5s (12.1 ms) and GBS-YOLOv5 (9.1 ms). The OUR algorithm thus provides a substantial advantage in inference speed, making it highly suitable for real-time applications such as video streaming, autonomous driving, and intelligent surveillance, where low latency is crucial for fast response times.

Finally, in terms of FPS (batch size = 1), OUR algorithm achieves 99 FPS, which is higher than YOLOv3 (44 FPS) and YOLOv3-SPP (31 FPS), and comparable to YOLOv5s (142 FPS) and GBS-YOLOv5 (113 FPS). Although its FPS is slightly lower than YOLOv5s and GBS-YOLOv5, it still maintains a high processing speed, capable of handling nearly 100 frames per second. This high FPS allows the OUR algorithm to efficiently process high-throughput applications with real-time performance.

In conclusion, ATC-YOLOv5 strikes an excellent balance across these key performance metrics. Its lower parameter count makes it lightweight and more deployable in resource-constrained environments, while its fast inference time and high FPS ensure its real-time capability for high-throughput tasks. These advantages make ATC-YOLOv5 a strong competitor in scenarios that require efficient inference and low latency, offering superior performance in practical applications.

By introducing the CBAM and AdaptiveTrans structures and making adjustments to YOLOv5s, the YOLOv5s+CBAM and YOLOv5s+AdaptiveTrans models exhibit slight improvements across multiple categories, achieving overall mAP@0.5 values of 33.1% and 33.3%, respectively. However, the significant modifications in the model structure of ATC-YOLOv5 lead to a notable enhancement in object detection performance, reaching a high-precision level of 42.7% in overall mAP@0.5 across all categories. Its performance is particularly outstanding in detecting small targets. Therefore, ATC-YOLOv5 demonstrates a more robust capability in object detection on the VisDrone 2019 dataset. The specific results of ablation experiments are presented in Table 4.

We propose the ATC-YOLOv5 algorithm based on YOLOv5, contributing to three primary aspects. First, the introduction of the AdaptiveTrans structure addresses the adaptability issues of the network’s feature representation concerning targets of varying sizes. This structure efficiently generates adaptive convolutional kernel weights to enhance the network’s ability to represent features for different-sized targets. Second, the utilization of the CBAM attention mechanism adjusts the weights of different channels in the feature map through channel attention, increasing the network’s focus on small target regions. This resolves the performance degradation issue caused by the absence of local detailed information. Third, an increase in the number of detection heads is implemented, specifically designed for detecting high-resolution and minute target objects.

Experimental results on the VisDrone 2019 dataset demonstrate a significant improvement in ATC-YOLOv5 compared to the original YOLOv5. The mAP@0.5 and mAP@ [0.5:0.95] metrics have notably increased from 34.32% to 42.72% and from 18.93% to 24.48%, respectively. These findings underscore the exceptional performance of ATC-YOLOv5 in small object detection.

Nevertheless, the algorithm still has room for improvement in extreme environmental conditions, especially in scenarios with uneven lighting and adverse weather. Additionally, in complex backgrounds (e.g., urban streets or crowded areas), the algorithm may be affected by background noise, leading to false or missed detections. For future research, the following directions could be explored: First, introducing advanced image preprocessing techniques to enhance the model’s target detection performance in extreme environments. Second, investigating Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-based image augmentation methods to generate more diverse training data. Third, exploring model compression techniques or designing more efficient network architectures to reduce computational complexity, enabling the algorithm to run on resource-limited devices. Finally, developing background suppression methods, such as deep learning-based background modeling, to reduce the impact of background noise, as well as exploring multimodal data fusion (e.g., combining infrared or radar data) to improve detection performance in complex backgrounds.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank the VisDrone dataset maintainers for providing high-quality open-access data, and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. All volunteers who participated in the data annotation and validation stages are gratefully acknowledged for their time and effort. No patients or members of the public were involved in the study design, analysis or reporting.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Shuangyuan Li, Zhengwei Wang; Data collection: Jiaming Liang; Analysis and interpretation of results: Shuangyuan Li, Zhengwei Wang, Yichen Wang; Draft manuscript preparation: Jiaming Liang, Yichen Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets supporting the conclusions of this study are publicly available. The VisDrone dataset can be downloaded from the official repository (http://www.aiskyeye.com/).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yang Z. Pedestrian detection for intelligent vehicle based on bilayer difference features algorithm. In: Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety (ICTIS); 2015 Jun 25–28; Wuhan, China. p. 337–40. doi:10.1109/ictis.2015.7232047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chen C, Liu B, Wan S, Qiao P, Pei Q. An edge traffic flow detection scheme based on deep learning in an intelligent transportation system. IEEE Trans Intell Transport Syst. 2021;22(3):1840–52. doi:10.1109/tits.2020.3025687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ye T, Zhao Z, Zhang J, Chai X, Zhou F. Low-altitude small-sized object detection using lightweight feature-enhanced convolutional neural network. J Syst Eng Electron. 2021;32(4):841–53. doi:10.23919/jsee.2021.000073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Prajwal P, Prajwal D, Harish DH, Gajanana R, Jayasri BS, Lokesh S. Object detection in self driving cars using deep learning. In: Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Innovative Computing, Intelligent Communication and Smart Electrical Systems (ICSES); 2021 Sep 24–25; Chennai, India. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/icses52305.2021.9633965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang X, Bai X, Liu W, Latecki LJ. Feature context for image classification and object detection. In: Proceedings of the CVPR 2011; 2011 Jun 20–25; Colorado Springs, CO, USA. p. 961–8. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2011.5995696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kim H, Lee Y, Yim B, Park E, Kim H. On-road object detection using deep neural network. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics-Asia (ICCE-Asia); 2016 Oct 26–28; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/ICCE-Asia.2016.7804765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Boyuk M, Duvar R, Urhan O. Deep learning based vehicle detection with images taken from unmanned air vehicle. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Innovations in Intelligent Systems and Applications Conference (ASYU); 2020 Oct 15–17; Istanbul, Turkey. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/asyu50717.2020.9259868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Jonnalagadda M, Taduri S, Reddy R. RealTime traffic management system using object detection based signal logic. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Applied Imagery Pattern Recognition Workshop (AIPR); 2020 Oct 13–15; Washington, DC, USA. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/aipr50011.2020.9425070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang X, Zhu X. Vehicle detection in the aerial infrared images via an improved Yolov3 network. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 4th International Conference on Signal and Image Processing (ICSIP); 2019 Jul 19–21; Wuxi, China. p. 372–6. doi:10.1109/siprocess.2019.8868430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Avola D, Cinque L, Foresti GL, Martinel N, Pannone D, Piciarelli C. A UAV video dataset for mosaicking and change detection from low-altitude flights. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 2020;50(6):2139–49. doi:10.1109/tsmc.2018.2804766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Du D, Zhu P, Wen L, Bian X, Lin H, Hu Q, et al. VisDrone-DET2019: the vision meets drone object detection in image challenge results. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops; 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 213–26. [Google Scholar]

12. Borji A. Complementary datasets to COCO for object detection. arXiv:2206.11473. 2022. [Google Scholar]

13. Everingham M, Van Gool L, Williams CKI, Winn J, Zisserman A. The pascal visual object classes (VOC) challenge. Int J Comput Vis. 2010;88(2):303–38. doi:10.1007/s11263-009-0275-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lin TY, Maire M, Belongie S, Hays J, Perona P, Ramanan D, et al. Microsoft COCO: common objects in context. In: Computer vision—ECCV 2014. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2014. p. 740–55. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-10602-1_48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Deng J, Dong W, Socher R, Li LJ, Li K, Li FF. ImageNet: a large-scale hierarchical image database. In: Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2009 Jun 20–25; Miami, FL, USA. p. 248–55. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2009.5206848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Xing C, Liang X, Yang R. Compact one-stage object detection network. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 8th International Conference on Computer Science and Network Technology (ICCSNT); 2020 Nov 20–22; Dalian, China. p. 115–8. doi:10.1109/iccsnt50940.2020.9304979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Luo J, Yang Z, Li S, Wu Y. FPCB surface defect detection: a decoupled two-stage object detection framework. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2021;70:1–11. doi:10.1109/tim.2021.3092510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu Y, Yang F, Hu P. Small-object detection in UAV-captured images via multi-branch parallel feature pyramid networks. IEEE Access. 2020;8:145740–50. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3014910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Li S, Lin J, Lv Y, Li T. Deep learning-based algorithm for complex small target detection in UAV aerial images. Int J Innov Comput Inf Control. 2025;21(1):135–52. [Google Scholar]

20. Kostiv M, Adamovskyi A, Cherniavskyi Y, Varenyk M, Viniavskyi O, Krashenyi I, et al. Self-supervised real-time tracking of military vehicles in low-FPS UAV footage. In: Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Military Communication and Information Systems (ICMCIS); 2025 May 13–14; Oerias, Portugal. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/icmcis64378.2025.11047873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Nikouei M, Baroutian B, Nabavi S, Taraghi F, Aghaei A, Sajedi A, et al. Small object detection: a comprehensive survey on challenges, techniques and real-world applications. Intell Syst Appl. 2025;27(1):200561. doi:10.1016/j.iswa.2025.200561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang Z, Lu X, Cao G, Yang Y, Jiao L, Liu F. ViT-YOLO: transformer-based YOLO for object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW); 2021 Oct 11–17; Montreal, BC, Canada. p. 2799–808. doi:10.1109/iccvw54120.2021.00314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Guo Z, Wang C, Yang G, Huang Z, Li G. MSFT-YOLO: improved YOLOv5 based on transformer for detecting defects of steel surface. Sensors. 2022;22(9):3467. doi:10.3390/s22093467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Dai Y, Liu W, Wang H, Xie W, Long K. YOLO-former: marrying YOLO and transformer for foreign object detection. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2022;71:1–14. doi:10.1109/tim.2022.3219468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ale L, Zhang N, Li L. Road damage detection using RetinaNet. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data); 2018 Dec 10–13; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 5197–200. doi:10.1109/bigdata.2018.8622025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. He K, Gkioxari G, Dollár P, Girshick R. Mask R-CNN. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2980–8. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Minaee S, Boykov YY, Porikli F, Plaza AJ, Kehtarnavaz N, Terzopoulos D. Image segmentation using deep learning: a survey. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;44(7):3523–42. doi:10.1109/tpami.2021.3059968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Qiu M, Huang L, Tang BH. ASFF-YOLOv5: multielement detection method for road traffic in UAV images based on multiscale feature fusion. Remote Sens. 2022;14(14):3498. doi:10.3390/rs14143498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sudars K, Namatevs I, Judvaitis J, Balass R, Nikulins A, Peter A, et al. YOLOv5 deep neural network for quince and raspberry detection on RGB images. In: Proceedings of the 2022 Workshop on Microwave Theory and Techniques in Wireless Communications (MTTW); 2022 Oct 5–7; Riga, Latvia. p. 19–22. doi:10.1109/mttw56973.2022.9942550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Liu W, Quijano K, Crawford MM. YOLOv5-tassel: detecting tassels in RGB UAV imagery with improved YOLOv5 based on transfer learning. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2022;15:8085–94. doi:10.1109/jstars.2022.3206399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhu X, Lyu S, Wang X, Zhao Q. TPH-YOLOv5: improved YOLOv5 based on transformer prediction head for object detection on drone-captured scenarios. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW); 2021 Oct 11–17; Montreal, BC, Canada. p. 2778–88. doi:10.1109/iccvw54120.2021.00312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wang CY, Bochkovskiy A, Liao HM. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 7464–75. doi:10.1109/cvpr52729.2023.00721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Dai X, Chen Y, Yang J, Zhang P, Yuan L, Zhang L. Dynamic DETR: end-to-end object detection with dynamic attention. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 2968–77. doi:10.1109/iccv48922.2021.00298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wan Y, Cheng Y, Shao M, Gonzàlez J. Image rain removal and illumination enhancement done in one go. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;252:109244. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wan Y, Shao M, Cheng Y, Meng D, Zuo W. Progressive convolutional transformer for image restoration. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;125:106755. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Fan Q, Zhuo W, Tang CK, Tai YW. Few-shot object detection with attention-RPN and multi-relation detector. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 4012–21. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Hu J, Shen L, Sun G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 7132–41. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2018.00745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Gu R, Wang G, Song T, Huang R, Aertsen M, Deprest J, et al. CA-net: comprehensive attention convolutional neural networks for explainable medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2021;40(2):699–711. doi:10.1109/TMI.2020.3035253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Wang Q, Wu B, Zhu P, Li P, Zuo W, Hu Q. ECA-net: efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 11531–9. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.01155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools