Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

AI-Enabled Perspective for Scaling Consortium Blockchain

Software College, Northeastern University, Shenyang, 110819, China

* Corresponding Author: Jie Song. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 3087-3131. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.074378

Received 10 October 2025; Accepted 14 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

As consortium blockchains scale and complexity grow, scalability presents a critical bottleneck hindering broader adoption. This paper meticulously extracted 150 primary references from IEEE Xplore, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and other reputable databases and websites, providing a comprehensive and structured overview of consortium blockchain scalability research. We propose a scalability framework that combines a four-layer architectural model with a four-dimensional cost model to analyze scalability trade-offs. Applying this framework, we conduct a comprehensive review of scaling approaches and reveal the inherent costs they introduce. Furthermore, we map the artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled methods to the scaling approaches and analyze their effectiveness in enhancing scalability and mitigating these inherent costs. Based on this analysis, we identify the root causes of the remaining costs unresolved by AI and the new trade-offs introduced by AI integration, and propose promising research opportunities for AI-enabled consortium blockchain scalability, guiding future work toward more adaptive, intelligent, and cost-efficient consortium blockchain systems.Keywords

As a distributed ledger technology paradigm, blockchain’s applications have evolved beyond its initial open and permissionless form. To meet the complex requirements of multi-party collaborative systems for compliance, performance, and governance, the consortium blockchain emerged as a permissioned architecture. Consortium blockchains are ideal for multi-party, regulated applications: improving supply chain traceability and resilience [1], ensuring auditable and controlled data sharing in healthcare [2,3], and governing multi-party transactions in finance and operations management [4]. However, trade finance platforms1 and supply chains2 require processing millions of transactions daily. By comparison, the throughput of mainstream consortium blockchains still primarily remains at a few thousand transactions per second (TPS) [5]. This significant gap highlights the urgent need for enhanced scalability.

To bridge this performance gap, a multitude of scaling approaches have been proposed that can be systematically categorized based on the architectural layer: the data, network, execution, and consensus layers. The approaches at the data and execution layers focus on increasing the number of transactions that can be processed in parallel. For example, the data layer employs sharding or directed acyclic graphs to enable parallel transaction confirmations [6,7], while the execution layer uses parallel and off-chain processing to increase the number of transactions handled per cycle [8,9]. In contrast, approaches at the network and consensus layers aim to reduce the consensus time and minimize propagation delays [10–12]. Designed for identity-based governance and selective information transparency, consortium blockchains sacrifice a degree of decentralization for higher performance. These scaling approaches take further measures to maximize throughput while maintaining security, which inevitably introduces costs in other dimensions, as we will discuss in more detail in Section 2.2. Meanwhile, these scaling approaches are often reliant on static pre-configurations. They cannot adapt to dynamic workloads and changing network conditions, leading to suboptimal performance.

With the widespread use of artificial intelligence (AI) for complex systems optimization, many studies have proposed AI-enabled enhancements to these scaling approaches [13]. The distinct advantage of AI-enabled scaling lies in its ability to learn and implement optimal policies in real-time and dynamic environments. For example, reinforcement learning is applied to dynamically tune network and consensus parameters [14,15], while unsupervised learning helps optimize data sharding by discovering underlying transaction patterns [16]. These intelligent methods aim to further enhance scalability through dynamic and adaptive control while also actively mitigating the inherent costs of the scaling approaches, thus seeking a better balance between performance and its associated costs. Despite the promising outlook, the path of AI enablement is not without its own challenges. On one hand, the integration of AI has not entirely eliminated all costs. On the other hand, AI technology itself brings new trade-offs, such as the resource overhead for model training and the transparency of the decision-making process.

Although previous surveys have explored scalability approaches for general blockchains [17–19], the interaction between AI and blockchain [20–23], and the performance analysis of consortium blockchains [24], a holistic analysis shows that their research relationship is absent. Those surveys on scalability often overlook the potential of AI, while those on the interaction between AI and blockchain do not focus on specific performance bottlenecks. This survey is stimulated by the impressive recent developments in scaling approaches, the rapid advances in AI-driven system optimization, and the increasing demand for high-performance consortium blockchain applications. Therefore, to bridge this gap, this study conducts a comprehensive survey that systematically maps AI-enabled enhancements to scaling approaches for consortium blockchains and systematically evaluates the associated costs. This synthesis of scaling approaches, their inherent costs, and their AI-enabled enhancements distinguishes our work from the existing surveys. Ultimately, this paper compares the performance and inherent costs of scaling approaches and the corresponding AI-enabled enhancements for the four layers, and reveals that while AI effectively reduces inherent costs and enhances performance, it often introduces new trade-offs. The foremost contributions in this study are enumerated as follows:

• Proposing a unified scalability framework that combines a four-layer architectural model with a four-dimensional cost model to systematically analyze scalability trade-offs.

• Conducting a comprehensive review of scaling approaches, using our scalability metrics to analyze their performance and inherent costs.

• Systematically mapping AI-enabled enhancements to the scaling approaches, analyzing how they enhance performance while mitigating associated costs.

• Identifying promising research opportunities to address remaining costs and analyze trade-offs for the integration of AI.

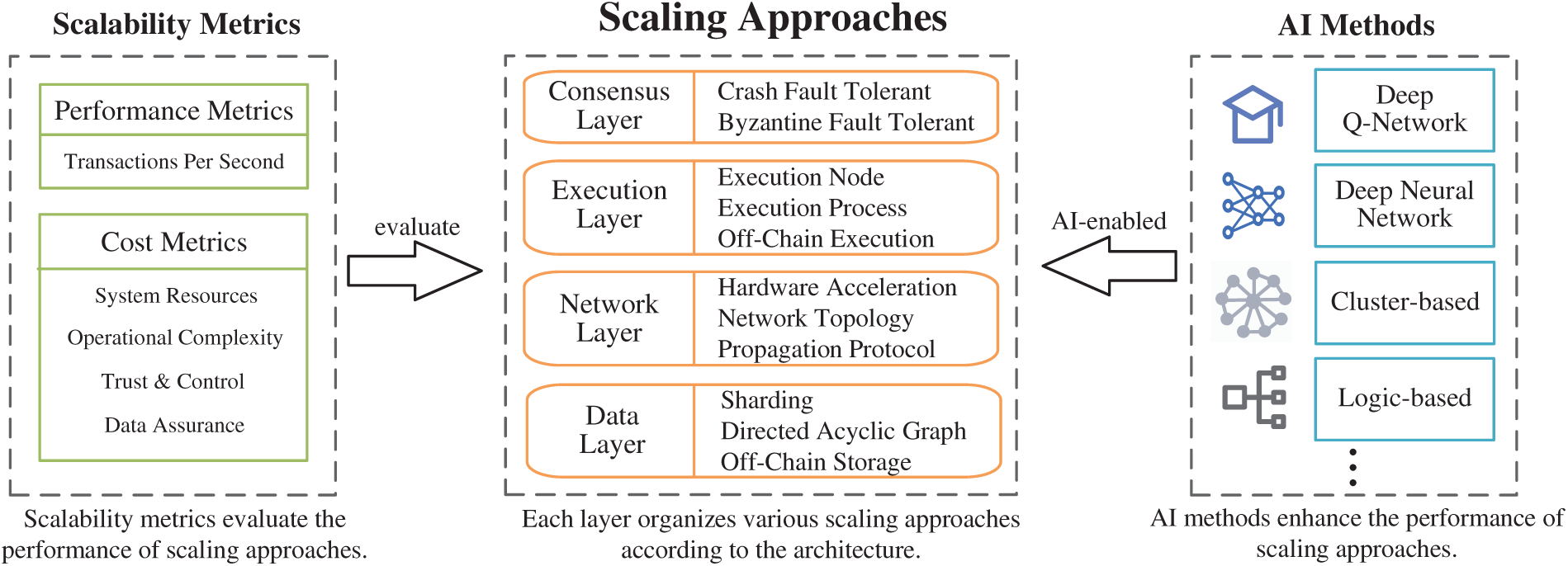

To realize the contributions mentioned above, we organize our survey based on four primary aspects. First, we propose the architecture of consortium blockchains and present the scalability metrics for evaluation. Second, guided by this architecture, we categorize the scaling approaches at each layer of the consortium blockchain and evaluate the approaches using our scalability metrics. Third, we analyze the state-of-the-art AI-enabled methods that further enhance these scaling approaches. Finally, based on the analysis above, we propose future research opportunities for AI-enabled consortium blockchain scalability. Fig. 1 illustrates the organizational structure of this paper.

Figure 1: The organizational structure of this paper connecting AI methods, scaling approaches, and evaluation metrics. The figure highlights how AI methods enhance scaling approaches across four blockchain layers, whose effectiveness is evaluated through performance and cost metrics

2.1 Consortium Blockchain Architecture

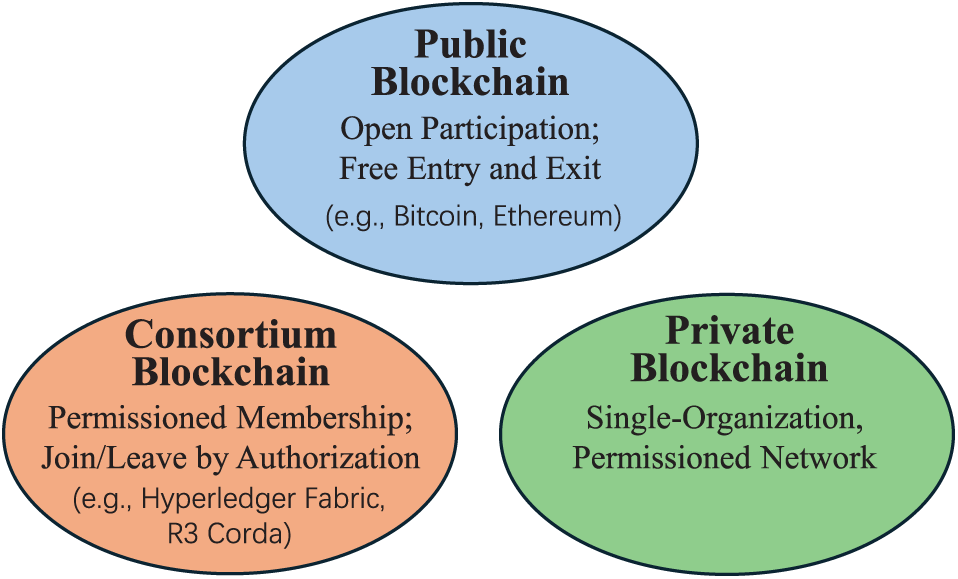

Blockchain, a revolutionary distributed ledger technology, has garnered widespread attention and applications globally in recent years [25]. Its core lies in the use of cryptographic principles and consensus mechanisms to ensure data security, immutability, and consistency, thus constructing a decentralized trust system [26]. Blockchain is categorized into three main types: public blockchains, private blockchains, and consortium blockchains [27]. Fig. 2 illustrates the differences among the three blockchains. Consortium blockchains, positioned between public and private chains, achieve more efficient transaction confirmation and more flexible permission management through pre-defined node admission mechanisms and consensus algorithms. Currently, various consortium blockchain systems have emerged, each optimized and designed for different application scenarios. Some of the well-known consortium blockchain systems include Hyperledger Fabric [28], R3 Corda [29], Quorum [30], Hyperledger Besu, and so on.

Figure 2: The three main types of blockchain are distinguished by their participation and access control models: public blockchains feature open participation, consortium blockchains operate on permissioned membership, and private blockchains are controlled by a single organization

Although these consortium blockchain systems have different focuses in their specific implementations, such as differences in consensus algorithms, data storage, and smart contract engines, they all follow similar design principles and have a common four-layer architectural model, including the data layer, network layer, consensus layer, execution layer, and application layer.

• Data layer is the foundation of the consortium blockchain architecture, responsible for storing data on the blockchain. The main function of this layer is to provide a secure and reliable data storage mechanism, ensuring data integrity and durability. The data layer needs to support efficient data access and querying, and be able to adapt to the ever-growing amount of data.

• Network layer is responsible for communication and data propagation between consortium blockchain nodes. The consortium blockchain network needs to provide efficient and stable communication protocols to ensure that nodes can synchronize data on time. The network layer also needs to have node discovery and management functions to facilitate the addition of new nodes and the maintenance of existing nodes.

• Execution layer is responsible for executing smart contracts and processing transactions. The consortium blockchain needs to provide a secure and trustworthy execution environment to support the deployment and execution of smart contracts. The execution layer is responsible for processing transactions, executing smart contract code, and updating the blockchain state.

• Consensus layer is the core of the consortium blockchain, responsible for reaching consensus on the state of the blockchain. Unlike public blockchains, consortium blockchains typically employ more efficient consensus algorithms to achieve faster transaction confirmation. The consensus layer is responsible for verifying the validity of new blocks and resolving any forks that may occur, ensuring the consistency of the blockchain.

Consortium blockchains are typically applied in scenarios with high-performance requirements [31]. Examples include complex supply chain networks that may generate hundreds of thousands or even millions of transactions daily, and financial applications like cross-border payments and trade finance that have extremely high demands for transaction speed and throughput. Therefore, scalability is a crucial performance indicator for consortium blockchains. The essence of a blockchain is a distributed, immutable write-only database or ledger. Its primary operation is packaging new transaction data into blocks and appending them to the end of the chain. Therefore, the most intuitive performance metric for assessing its scalability is throughput, i.e., the number of transactions the system can process per unit of time (TPS) [32,33], which is defined as:

where

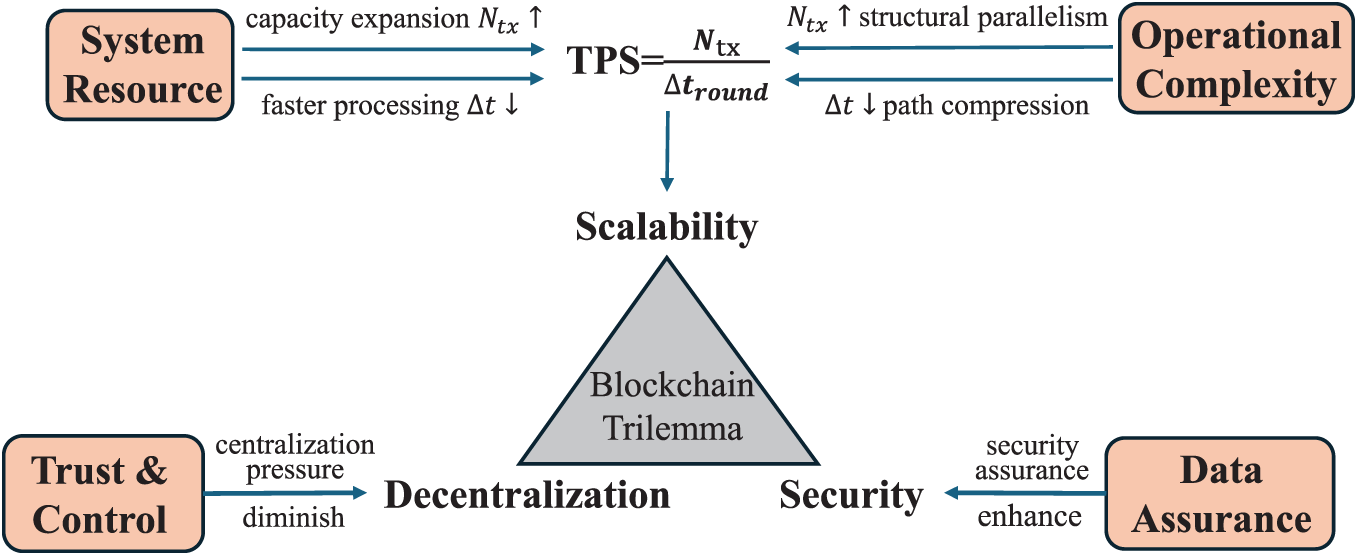

Blockchain faces a well-known challenge known as the Trilemma [34,35]. This trilemma posits that it is difficult for a blockchain system to simultaneously optimize three core attributes: Decentralization, Security, and Scalability, as at most only two can be prioritized. Traditional public blockchains prioritize maximizing decentralization and security [36,37], which comes at the direct cost of limited scalability. To meet the demands of high-performance scenarios, consortium blockchains make a fundamentally different strategic trade-off within this trilemma: prioritizing security and scalability while sacrificing a degree of decentralization. However, to satisfy the needs of increasingly demanding scenarios, researchers are pushing the boundaries of performance while striving to maintain or even strengthen the inherent security model of consortium blockchains. This intensified pursuit of scalability forces deeper compromises on decentralization and security. For instance, this pursuit often requires direct investments in system infrastructure and the management of more intricate operational processes. These actions, in turn, create consequences in other domains: control may become concentrated onto fewer components, while novel designs can introduce new challenges for guaranteeing data integrity and availability across a distributed system. We introduce a four-dimensional cost framework that measures the costs incurred to enhance scalability. Fig. 3 presents the relationship between the blockchain trilemma and our four-dimensional cost framework.

Figure 3: The relationship between the blockchain trilemma and our four-dimensional cost framework. The pursuit of higher scalability (TPS) involves increasing system resources to expand transaction capacity (

• System Resources: Measures the direct investment in foundational infrastructure required for scalability. This investment aims to either increase the number of transactions per round (

• Operational Complexity: Measures the management burden required for scalability. This burden arises from implementing and maintaining intricate architectures designed to either increase transaction throughput (

• Trust & Control: Quantifies the consequential cost to decentralization, measuring the additional governance and oversight mechanisms required to diminish centralization pressure when scalable designs delegate critical responsibilities to a minority of roles or specialized components. For instance, to accelerate consensus, a system might rely on a small, fixed committee of high-performance nodes. This design concentrates power, thus incurring a trust & control cost as the system must now introduce rotation policies and heightened monitoring to manage the risks of this centralization.

• Data Assurance: Quantifies the consequential cost to security, measuring the additional cryptographic and protocol mechanisms required to enhance security assurance when scalable architectures physically or logically separate data and validation processes. For instance, an off-chain execution solution improves scalability by moving computation off the main chain. To ensure the results are correct and verifiable, the system must now bear the cost of generating and verifying cryptographic proofs. This additional computational and protocol overhead is the data assurance cost.

As established in the previous section, enhancing scalability is a critical objective for consortium blockchains, but achieving it introduces significant costs across system resources, operational complexity, trust & control, and data assurance. This section provides a systematic and comprehensive review of the scaling approaches from four layers: data layer, network layer, execution layer, and consensus layer.

The data layer serves as the foundation of the consortium blockchain, responsible for storing transaction records and world states, and supporting the execution, consensus, and network layers. The organization of the data layer directly affects concurrency, conflict detection, and the complexity of consensus, thereby exerting a direct impact on the scalability of the consortium blockchain. However, most traditional consortium blockchains adopt a linear chain structure, where block generation and commitment must be globally serialized, resulting in low transaction-level parallelism and becoming a critical bottleneck to scalability. To overcome these limitations, researchers have proposed various improvements at the data layer, which can be categorized into three types: sharding, which partition the global ledger into multiple parallel shards; directed acyclic graph, which allow multiple transactions or blocks to be committed concurrently to break the restriction of linearity; and off-chain storage, which move part of the transaction data or states off-chain to reduce the workload on the main chain.

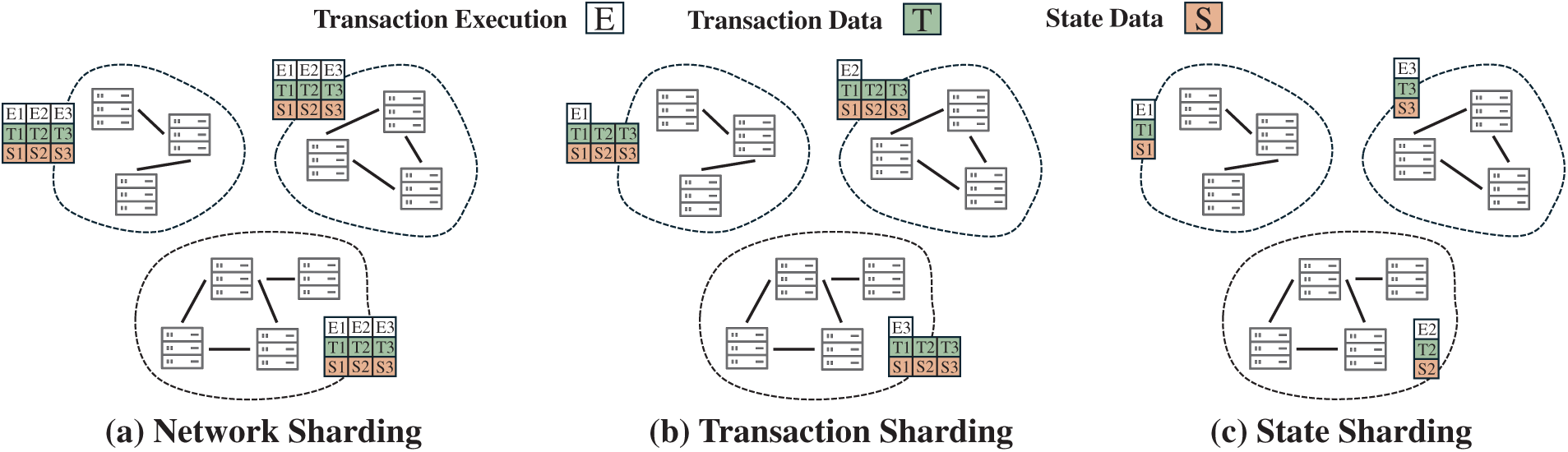

Sharding is a scaling technique that partitions a blockchain system into multiple parallel shards so that different subsets of work can be handled concurrently [38]. In practice, sharding can target different objects: network sharding partitions nodes as illustrated in Fig. 4a, transaction sharding routes execution to different shards as shown in Fig. 4b, and state sharding assigns the world state to specific shards as depicted in Fig. 4c [39]. In fact, network sharding and transaction sharding primarily affect other layers, such as execution scheduling, parallelism, and peer-to-peer (P2P) propagation, and do not change the storage structure in the data layer. They will be discussed in later sections. By contrast, only state sharding directly impacts the data layer.

Figure 4: Schematic diagram of (a) Network Sharding, (b) Transaction Sharding, and (c) State Sharding, illustrating how transaction execution, transaction data, and state data are distributed across shards

State sharding partitions the global world state across shards and routes each transaction to the shards that own the touched keys, so that shards maintain and update only their local slice of the ledger [6,40–42]. A representative baseline in consortium blockchains is SharPer, proposed by Amiri et al. [6], which maps data shards to pre-formed clusters. Each cluster executes intra-shard transactions locally and stores only its local view. This design reduces the storage footprint and communication overhead for each node and allows multiple clusters to process disjoint workloads in parallel. Building on SharPer, Matani et al. [40] balance nodes into shards and then organize each shard into level groups in a hierarchical tree. This structure minimizes both the storage and communication overhead by localizing data and consensus, enabling each shard to process its workload with high autonomy. To address the high overhead of cross-shard transactions, Hong et al. [41] propose Pyramid, a layered sharding system. Instead of complete isolation, Pyramid introduces specialized bridge shards that store the full records of multiple internal shards. This design enables cross-shard transactions to be processed internally within a single bridge shard, committing them in one consensus round and significantly boosting throughput.

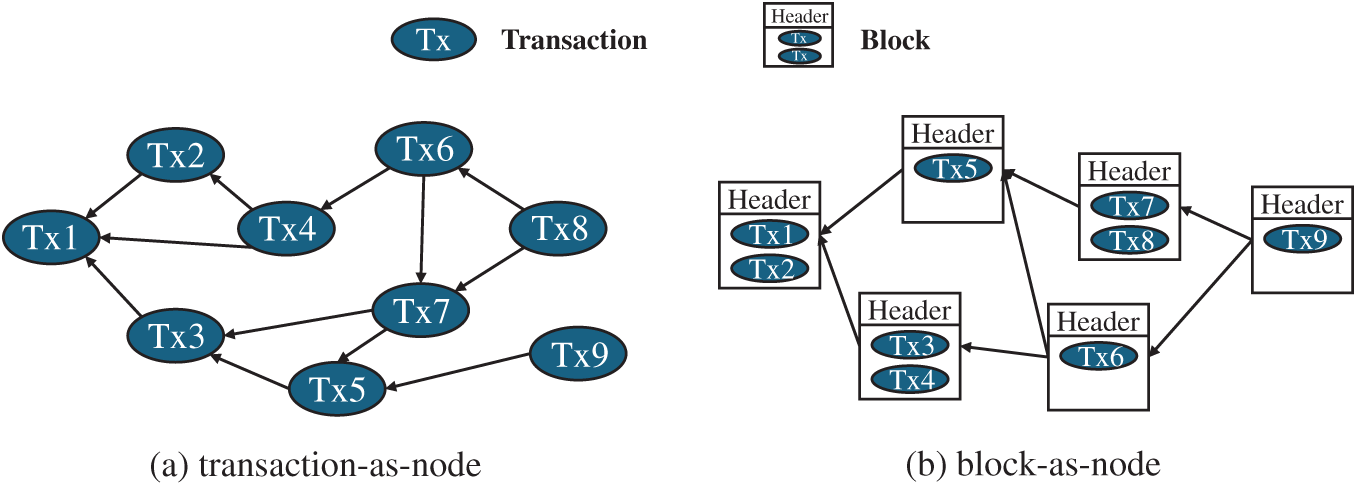

Unlike the traditional linear blockchain, Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)-based approaches allow multiple nodes to be appended concurrently, avoiding the strict serialization bottleneck and thereby significantly enhancing system concurrency and throughput [43]. By maintaining partial order within the graph, these designs preserve consistency while supporting higher parallelism. Depending on what each DAG node represents, such approaches can be broadly classified into two categories: block-as-node DAG, where each node is a block containing multiple transactions and scalability is achieved through concurrent block generation to improve consensus efficiency; and transaction-as-node DAG, where each node corresponds to a single transaction and edges capture dependency relations, enabling fine-grained parallel execution.

For a transaction-as-node DAG, as shown in Fig. 5a, each transaction is represented as a node, with edges encoding dependencies or conflicts. Nexus proposed by Zhang et al. [7] builds on this by combining local and global DAGs: each shard maintains a local DAG to execute non-conflicting transactions in parallel, while the global DAG guarantees cross-shard consistency and conflict-equivalence to sequential execution. This directly increases concurrency in the execution layer and also impacts the sharding and consensus layers, ensuring global correctness across shards and ultimately enhancing system throughput.

Figure 5: A comparison of the two primary DAG models: (a) a transaction-as-node DAG, where each vertex represents a single transaction, and (b) a block-as-node DAG, where each vertex is a block containing multiple transactions

For a block-as-node DAG, as shown in Fig. 5b, each node represents a block containing multiple transactions, with edges denoting inter-block references [44–47]. JointGraph, introduced by Xiang et al. [46], exemplifies this category by integrating the DAG structure with an efficient consensus mechanism, enabling multiple blocks to be confirmed in parallel within the same round. This directly improves block production in the consensus layer and indirectly accelerates transaction validation and state updates in the execution layer, thereby reducing end-to-end latency.

Off-chain storage approaches refer to moving part of the blockchain’s transaction data or states off the chain, delegating them to external storage nodes or multi-chain structures, while retaining only lightweight indexes or commitments on-chain [48–52]. It alleviates on-chain data load, making block generation and validation more efficient, and it allows compute- or storage-intensive tasks to be handled off-chain, shortening the on-chain critical path and increasing throughput.

Feng and Deng [48] propose a hot/cold data separation scheme, migrating cold blocks to an off-chain file system and keeping only hot blocks and essential index information on-chain. By reducing the on-chain storage footprint, this scheme alleviates the I/O and memory pressure on nodes, allowing them to validate and commit new blocks more efficiently. SlimChain designed by Xu et al. [49] adopts a stateless blockchain design that moves contract execution and state storage entirely off-chain, with only state roots and commitments retained on-chain. This stateless design drastically reduces the on-chain storage requirements and simplifies the data validation process, as nodes only need to verify lightweight commitments instead of re-executing transactions against a large state. This layered approach is validated by recent public blockchain engineering, such as the Ethereum Dencun upgrade [53]. This upgrade introduced Blobs, a dedicated and low-cost data availability layer specifically to support Layer 2 Rollups, a form of off-chain execution. This real-world deployment demonstrates the scalability benefits of separating data assurance from state execution, validating it as a promising direction for reducing on-chain data load and the associated system resources cost for high-throughput consortium chains.

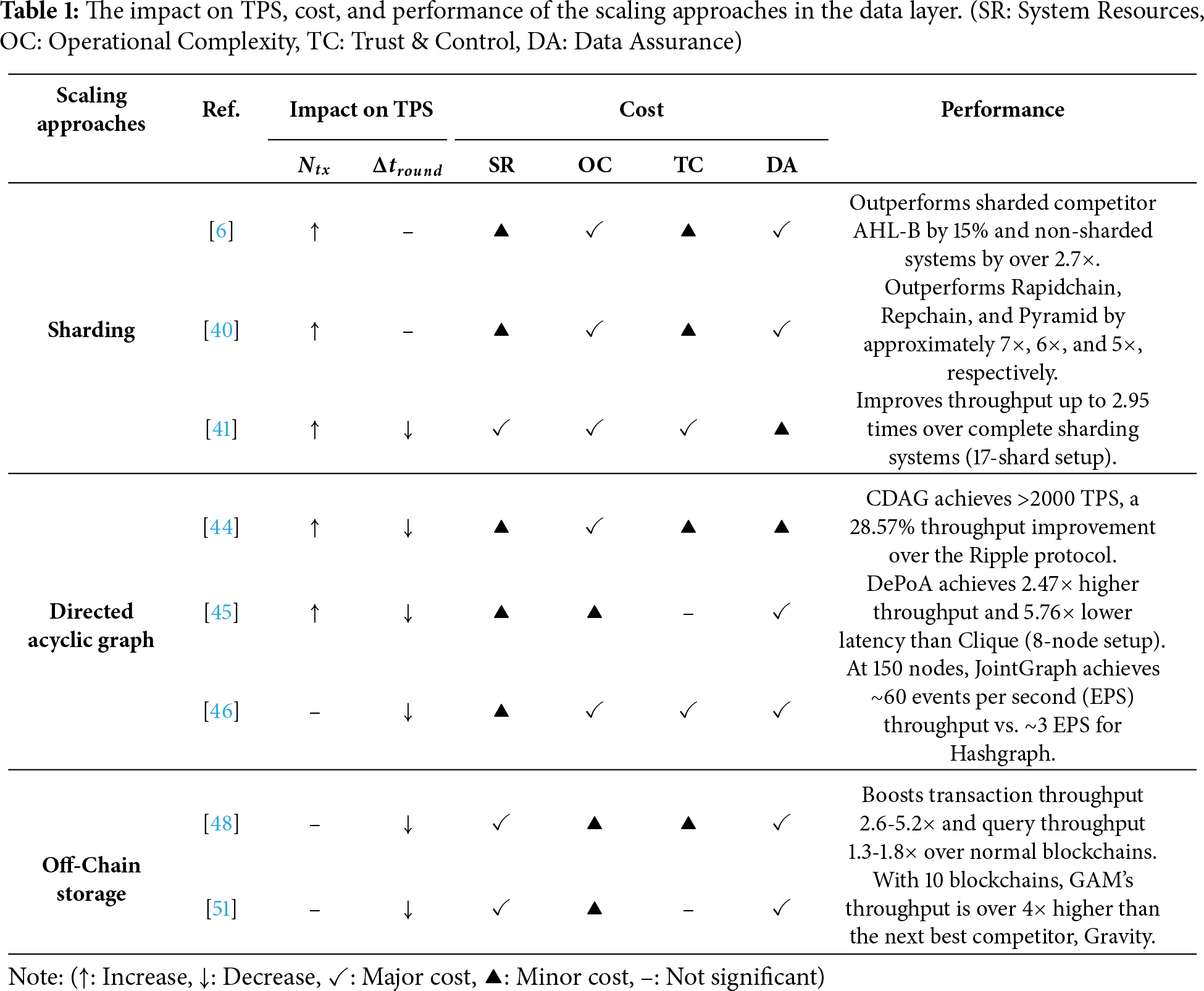

Key insight: Table 1 summarizes the effectiveness of scaling approaches in the data layer. The scaling approaches achieve significant scalability improvements by restructuring the ledger to break serial bottlenecks. Regarding the impact on TPS, Sharding and DAG directly increase the number of transactions processed per unit of time (

AI-enabled methods offer a promising direction to mitigate these costs. AI can automate the discovery of optimal data partitions, which significantly reduces operational complexity. This intelligent partitioning also leads to more efficient workload distribution and lower system resource requirements. Furthermore, AI can enhance data assurance by assessing node trustworthiness to ensure the integrity of data within shards, thereby reducing the reliance on costly verification protocols.

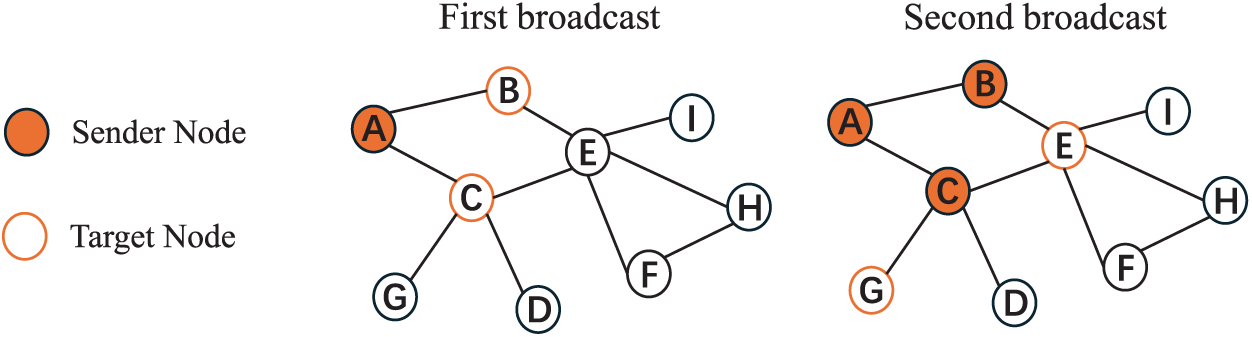

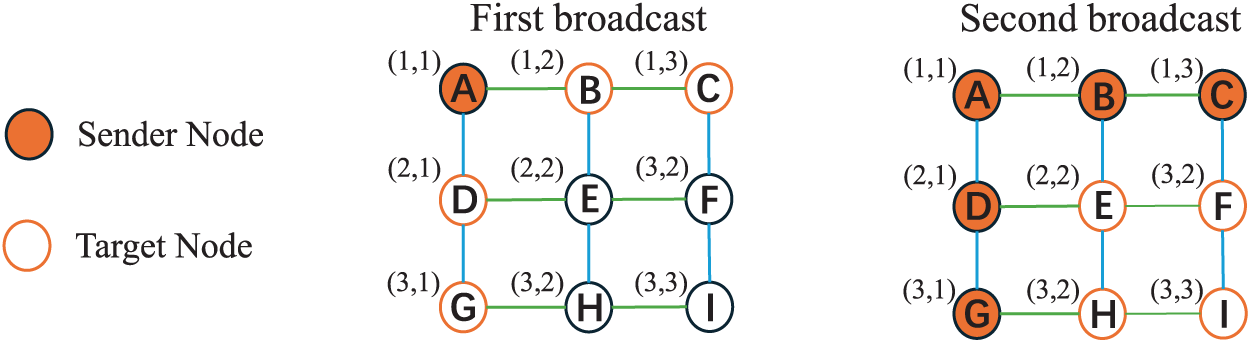

In consortium blockchains, the network layer, as the fundamental component for data propagation and node interaction, plays a critical role in system scalability. It not only determines the efficiency of transaction and block propagation among nodes but also affects the speed and stability of consensus. Based on existing studies, this paper categorizes scalability approaches at the network layer into three main types: hardware acceleration, network topology, and propagation protocol. Among these, network topology and the propagation protocol interact closely to influence overall propagation efficiency. For instance, an inefficient combination, such as a random P2P overlay combined with the basic Gossip protocol as shown in Fig. 6, can lead to significant block transmission delays and redundant messaging. Conversely, optimizing these two aspects in tandem yields substantial gains. Fig. 7 shows that an effective synergy based on the Hyperclique overlay coupled with a clique-based relaying protocol [54] achieves efficient propagation.

Figure 6: Message propagation on a random P2P overlay, where nodes connect arbitrarily, using the Gossip protocol, where nodes randomly forward messages to neighbors. After two broadcasts, 5 out of 9 nodes are informed, showing a gradual and potentially redundant spread

Figure 7: Message propagation on a Hyperclique overlay, where nodes form fully connected cliques based on coordinates, using the clique-based relaying protocol, where nodes relay messages to their neighbors in other cliques [54]. After two broadcasts, all 9 nodes are informed, achieving structured full network coverage

Beyond topology and protocol-level improvements, hardware acceleration has emerged as an important means of enhancing scalability. In datacenter and cloud environments, high-bandwidth, low-latency interconnects and efficient memory primitives can substantially reduce communication and copying overhead, enabling higher concurrency and throughput [55–57].

Bidl introduced by Qi et al. [55] leverages large batching, zero-copy transfers, and parallel processing in datacenter settings to cut redundant messaging costs. By reducing per-transaction overhead, it allows significantly more transactions to be processed within a given time window. In contrast, another line of work focuses more directly on high-performance interconnects.

CloudChain proposed by Xu et al. [57] combines a shared-memory model with RDMA in cloud environments. By treating inter-node communication as direct memory access (reads/writes) rather than traditional network packet exchanges, it minimizes the overhead of data serialization and network protocol processing. This results in lower per-transaction communication latency, which is crucial in the closely-coupled environment of a cloud.

Network topology strongly affects propagation efficiency and scalability in the network layer, and its optimization can be considered from two aspects: structural design and policy control. Structural design concerns the connection patterns and overall layout of nodes, which define transmission paths and redundancy, while policy control focuses on dynamic neighbor selection and forwarding strategies within a given structure to improve efficiency and resource use. The former reflects static layout, whereas the latter emphasizes dynamic adjustment. Accordingly, this paper classifies network topology approaches into structural design optimization and policy control optimization.

In terms of structural design optimization, approaches fall into two types: overlay-centric broadcast [10,54,58,59] and network sharding [60]. For the former, the overlay is engineered as the dissemination plane. Blocks follow planned overlay routes rather than flood gossip, which bounds fan-out and shortens network diameter. vCubeChain [10] uses vCube’s failure detection for leader election and an

In terms of policy control optimization, different studies have proposed two methods from the node side [61,62] and the network control side [63,64]. On one hand, Hao et al. [61] design a trust-aware P2P topology in which nodes dynamically select reliable neighbors and remove inactive or low-trust peers. This strategy optimizes data propagation paths in real-time, reduces message redundancy, and mitigates network congestion, leading to lower and more stable block broadcast latency. From a centralized control perspective, Deshpande et al. [63] apply the Software-Defined Networking (SDN) paradigm. An SDN controller maintains a global view of the P2P network, allowing it to dynamically reconfigure the topology and optimize routing paths based on real-time traffic conditions. This centralized orchestration prevents network bottlenecks and ensures high propagation rates.

The block propagation protocol directly determines the efficiency of block and transaction dissemination, making it a critical factor affecting throughput and latency. Existing studies optimize propagation from two complementary directions: relay node selection optimization, which focuses on selecting appropriate relay nodes to reduce redundancy and congestion; and block broadcast method optimization, which emphasizes improving how blocks are transmitted and combined to shorten critical paths and reduce communication complexity.

For relay node selection optimization, since consortium blockchains commonly rely on Gossip for block propagation, most existing works focus on enhancing Gossip-based protocols. Some methods aim to reduce redundancy and improve load balancing. For example, Matching-Gossip [65] and Fair Gossip [66] employ refined neighbor discovery and push strategies. These methods reduce redundant message transmissions and alleviate network congestion, ensuring a more uniform and rapid block delivery across the network. Another line of research introduces hierarchical and trust-based control. DC-SoC proposed by Dong et al. [67] partitions peers into a structured skeleton via density clustering and social credibility. This design creates more deterministic and efficient dissemination paths, reducing the number of redundant transmissions and shortening the average block propagation latency.

For block broadcast method optimization, studies aim to reduce the payload size and the complexity of asynchronous protocols [68–72]. The method proposed by Zhao et al. [68] broadcasts only block metadata first. This approach allows peers to pre-validate headers and fetch full block bodies on demand, which cuts redundant data transmission and shortens the critical path for block validation across the network. Another method proposed by Bai et al. [69] leverages scalable multi-secret sharing with proxy re-encryption to reduce asynchronous reliable broadcast complexity from

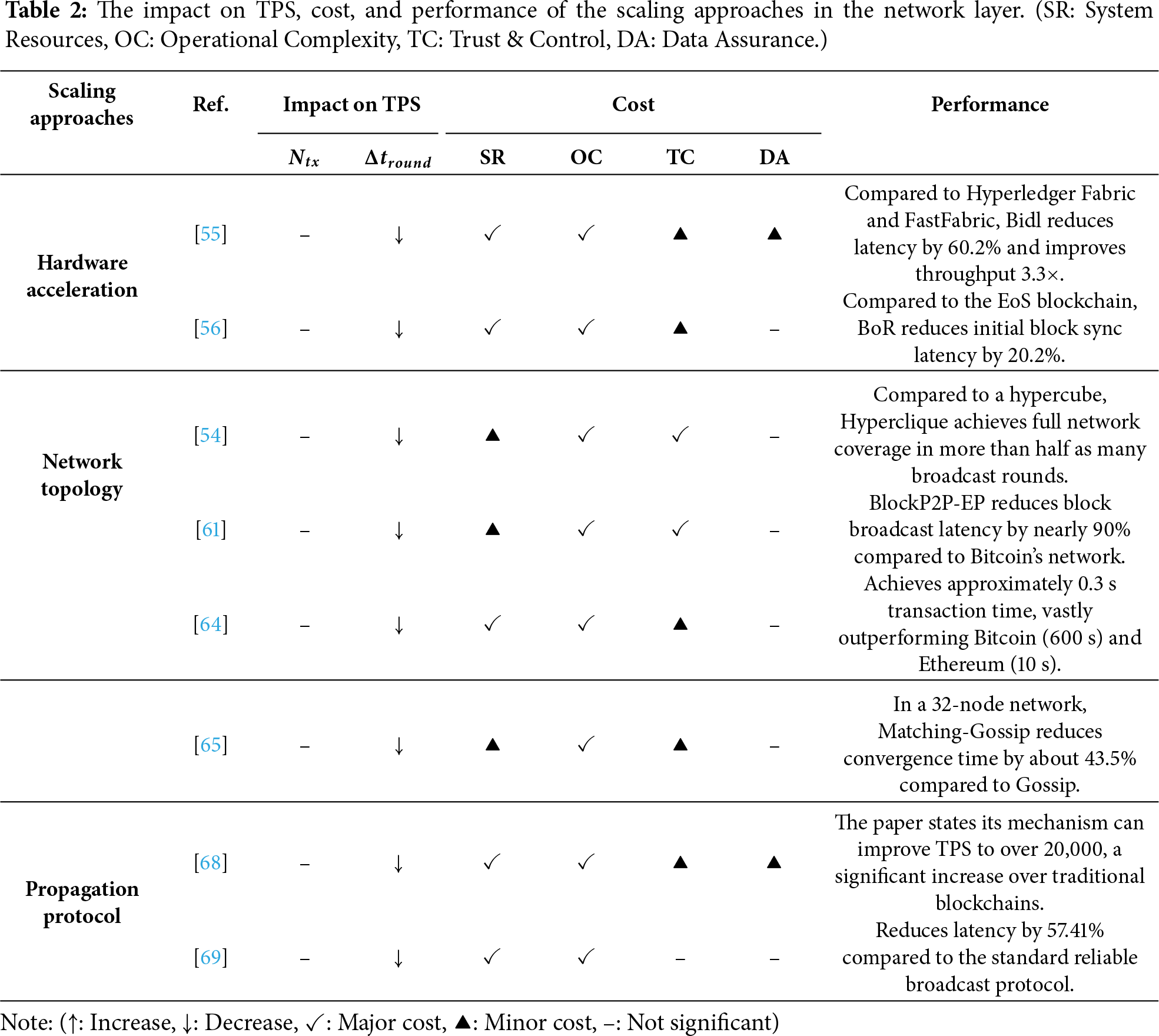

Key insight: Table 2 presents the effectiveness of the scaling approaches in the network layer. The scaling approaches enhance scalability by reducing communication latency and accelerating data propagation. Regarding the impact on TPS, all three approaches focus on reducing the time per round (

3.3 Execution Layer Approaches

In consortium blockchains, the execution layer is primarily responsible for running smart contract logic on received transaction requests to produce execution results and read-write sets. Its performance directly determines the number of transactions that can be successfully processed and committed to the ledger per unit of time, and thus has a significant impact on throughput. On the one hand, the selection of execution nodes and the distribution of workloads affect overall resource utilization and efficiency, so unreasonable allocation or redundant execution can noticeably constrain TPS. On the other hand, the computational cost and concurrency capability of the execution layer determine the speed of transaction processing; excessive latency or conflicts can reduce effective throughput. To address these challenges, existing studies propose three main scalability approaches at the execution layer: execution node selection, which focuses on allocating nodes and balancing workloads; execution process optimization, which enhances concurrency and reduces redundant operations; and off-chain execution, which migrates part of the execution workload to external environments and only performs result verification on-chain.

3.3.1 Execution Node Selection

In some consortium blockchains, transaction requests are typically distributed through static configuration or random selection. This often results in certain execution nodes becoming overloaded under high concurrency, while others remain idle, leading to performance bottlenecks. To address this issue, researchers usually move in two directions. One improves scalability by directing requests to executors with lighter loads, which balances resource utilization across nodes and sustains higher throughput under heavy concurrency. The other enhances scalability by distributing requests to a group of executors that work in parallel, allowing the system to process more transactions simultaneously and expand capacity in proportion to the level of concurrency. Following this intuition, we discuss load-aware routing and transaction sharding as two approaches.

For load-aware routing, the key to scalability lies in preventing a few execution nodes from becoming persistent hotspots [73,74]. By steering requests toward nodes whose resources are less utilized, the system balances workloads across the network and reduces the chance of bottlenecks. Liu et al. [73] compute a load indicator from metrics such as CPU usage, memory consumption, and endorsement latency to guide request routing, while Cao et al. [74] rely on a ZooKeeper-based monitoring service that continuously collects node status and enables clients to select nodes dynamically. Both methods simplify the client’s decision process and ensure a more balanced distribution of endorsement tasks, which prevents individual execution nodes from becoming bottlenecks under high concurrency.

For transaction sharding, scalability is achieved by decomposing the execution workload across multiple groups of nodes, so that each group only processes a portion of the transaction stream. This design reduces contention within any single group and enables parallel execution across shards, effectively expanding the system’s processing capacity as the number of shards grows. Meepo proposed by Zheng et al. [75] introduces multiple execution environments per organization. Meepo enables the parallel dispatch and execution of transactions within a single organization, directly breaking the sequential processing bottleneck at the endorsement stage.

3.3.2 Execution Process Optimization

The execution stage directly determines the compute and I/O resources consumed by each transaction, the probability of conflicts and rollbacks, and the latency on the critical path. Therefore, it has the most direct impact on system throughput and end-to-end confirmation time: the faster the execution and the fewer the conflicts, the more valid transactions can be committed per unit time. We categorize execution optimizations into two classes: (1) transaction batch execution, which aggregates multiple transactions into batches to amortize per-transaction fixed costs and consolidate verification; and (2) transaction parallel execution, which increases concurrency at the execution layer through dependency analysis, conflict detection, and concurrency control.

The transaction batch execution process can be divided into batch formation [76,77] and intra-batch execution [78–80]. The former focuses on how transactions are aggregated and scheduled into batches. For example, Carbon proposed by Camaioni et al. [76] groups payment transactions into batches. This approach amortizes the fixed overhead costs associated with each transaction’s execution and validation, allowing more transactions to be processed with the same amount of computational resources. The latter emphasizes how to efficiently process transactions once the batch has been formed. A representative work proposed by Thakkar et al. [78] optimizes Hyperledger Fabric’s execution pipeline by enabling parallel verification and adopting batched read/write interfaces, which significantly reduces redundant computation within the execution phase.

The transaction parallel execution process can be divided into conflict detection before execution and execution control during parallel processing [8,81–84]. For example, SP-PoR introduced by Wang et al. [8] performs conflict detection by classifying transactions into normal and contract types. It then uses a clustered DAG structure for execution control, which allows non-conflicting transactions to be executed concurrently within the same epoch, thereby achieving partial parallelism at the execution layer while ensuring correctness. Jin et al. [81] conduct conflict detection by concurrently executing transactions and recording their read-write sets to build a dependency graph. During the validation phase, nodes deterministically replay these independent subgraphs in parallel, which maximizes the degree of concurrent execution while maintaining serializability and consistency.

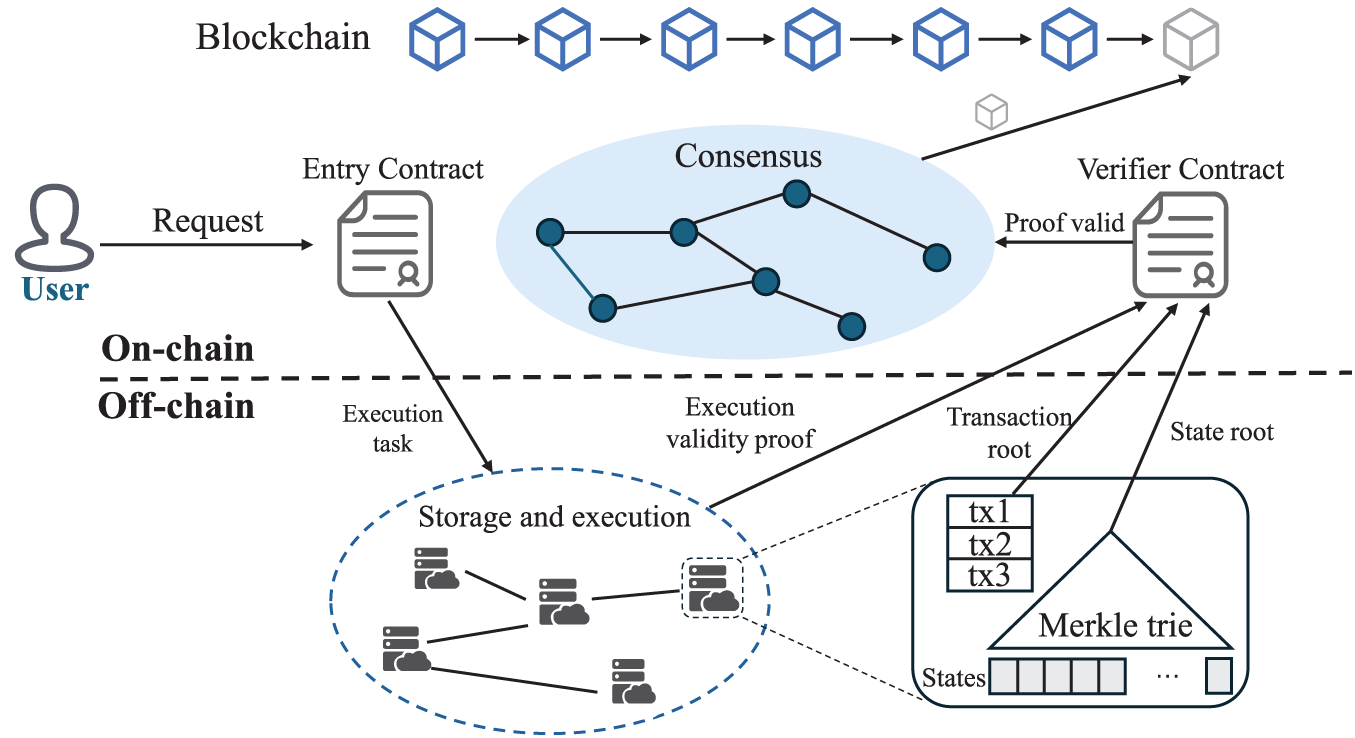

Off-chain execution refers to performing part of transaction processing or state storage outside the main blockchain, while only committing necessary results, summaries, or proofs back on-chain. Fig. 8 illustrates this general architecture for off-chain execution. This approach reduces the computational and storage burden on on-chain execution nodes, which alleviates block congestion and consensus overhead, and thereby significantly improves system throughput. Depending on application scenarios and design objectives, existing off-chain execution methods can be broadly divided into two categories: payment-oriented off-chain execution, which leverages payment channels or dedicated settlement mechanisms to improve the efficiency of high-frequency payments; and general-purpose off-chain execution, which typically adopts batching, off-chain storage, and proof verification to scale smart contracts and diverse transaction types.

Figure 8: General architecture for off-chain execution. User requests, initiated via an on-chain Entry Contract, trigger execution and state updates within an off-chain cluster. The cluster processes these tasks and submits state roots and transaction roots along with a validity proof back to an on-chain Verifier Contract. Final commitment to the main blockchain ledger occurs after successful verification and subsequent on-chain consensus

In payment-oriented off-chain execution, the goal of off-chain execution is to reduce the overhead of frequent on-chain transfers. Xiao et al. [85] introduce multi-party payment channels, where most payments are settled off-chain. This removes a large volume of simple payment logic from the on-chain execution pipeline, freeing up resources for more complex transactions. CBOP introduced by Yang et al. [9] adopts a dynamic partitioning algorithm to decide whether transactions should be executed on-chain or off-chain. By moving a significant portion of the payment processing workload off-chain, these methods effectively reduce contention and processing load on the on-chain execution layer.

In general-purpose off-chain execution, the goal of off-chain execution is to reduce on-chain computation and storage overhead. ScorpioBase designed by Sui et al. [86] targets supply chain traceability by performing batch processing and storage off-chain. This design minimizes the on-chain execution to only verifying batch summaries, rather than processing each traceability record individually. SlimChain proposed by Xu et al. [49] introduces a stateless blockchain framework that moves contract execution and state storage entirely off-chain. This fundamentally transforms the role of the on-chain execution layer from complex computation to lightweight proof verification, which drastically reduces the computational resources required per transaction.

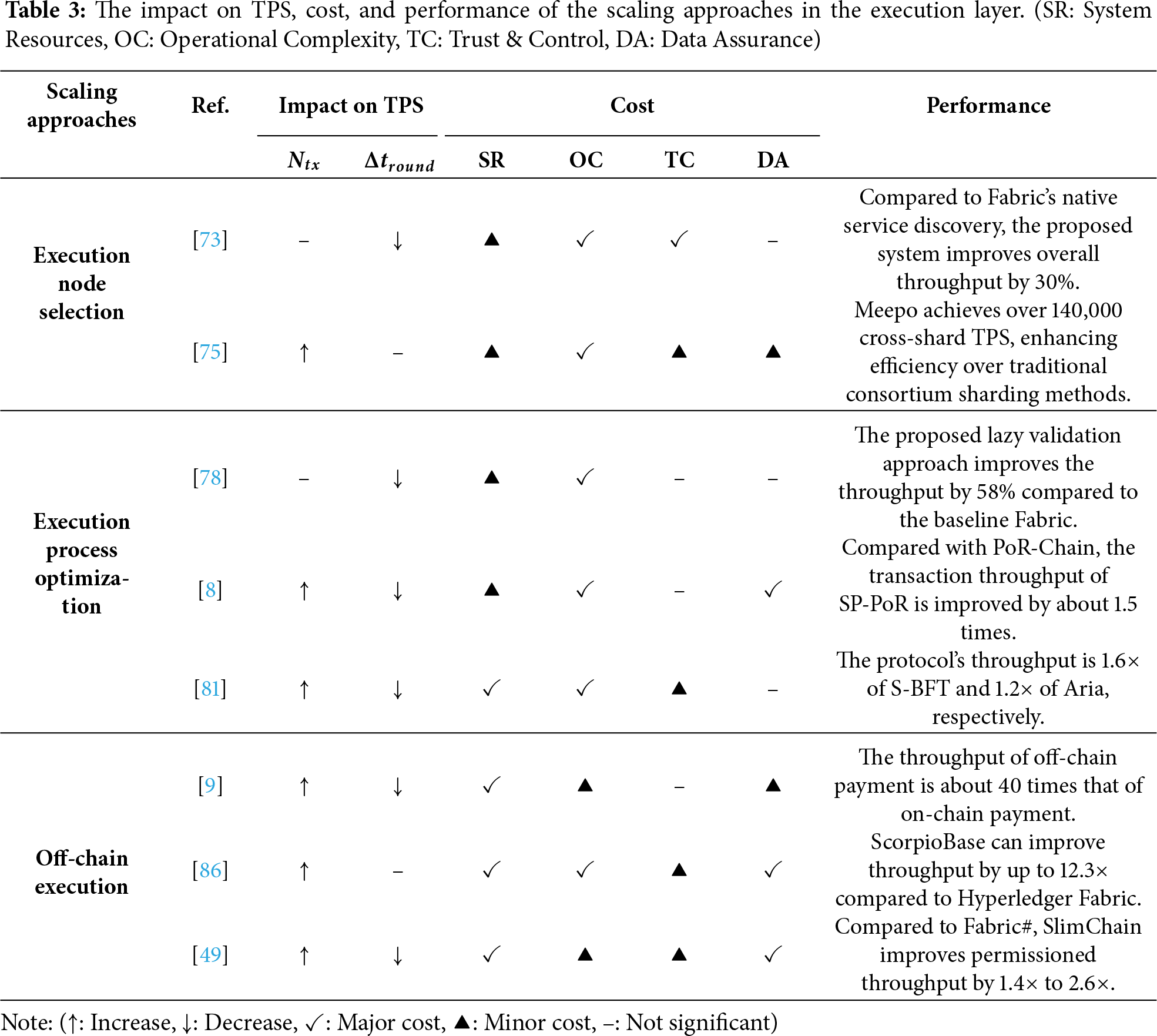

Key insight: Table 3 illustrates the effectiveness of the scaling approaches in execution layer. Execution layer approaches offer diverse strategies to enhance throughput, ranging from optimizing workload distribution to fundamentally altering the execution model itself. Regarding the impact on TPS, execution node selection improves throughput by efficiently routing workloads to avoid bottlenecks; execution process optimization directly boosts the number of valid transactions (

Alleviating these resulting costs is a prime opportunity for AI-driven optimization. By automating the sophisticated logic for workload distribution and intelligently determining which tasks to offload in real-time, AI directly addresses the challenge of high operational complexity. This dynamic management also ensures more efficient use of the underlying infrastructure, thereby reducing system resource demands.

3.4 Consensus Layer Approaches

The consensus layer is a crucial component primarily responsible for achieving agreement among participating nodes. As the scale of consortium blockchains continues to expand, designing a consensus protocol that ensures system consistency while improving performance has become crucial for addressing scalability. In some scenarios, failures are limited to node crashes, and thus consensus algorithms only need to tolerate crash faults while maintaining efficiency. In other scenarios, however, consortium blockchains involve sensitive data and may face malicious or Byzantine behaviors, which place higher demands on security and consistency. Therefore, the choice of consensus algorithm for consortium blockchains must strike a balance between scalability and security. Based on these considerations, existing approaches can be broadly classified into two categories: Crash Fault Tolerant (CFT) algorithms and Byzantine Fault Tolerant (BFT) algorithms.

3.4.1 Crash Fault Tolerant Algorithms

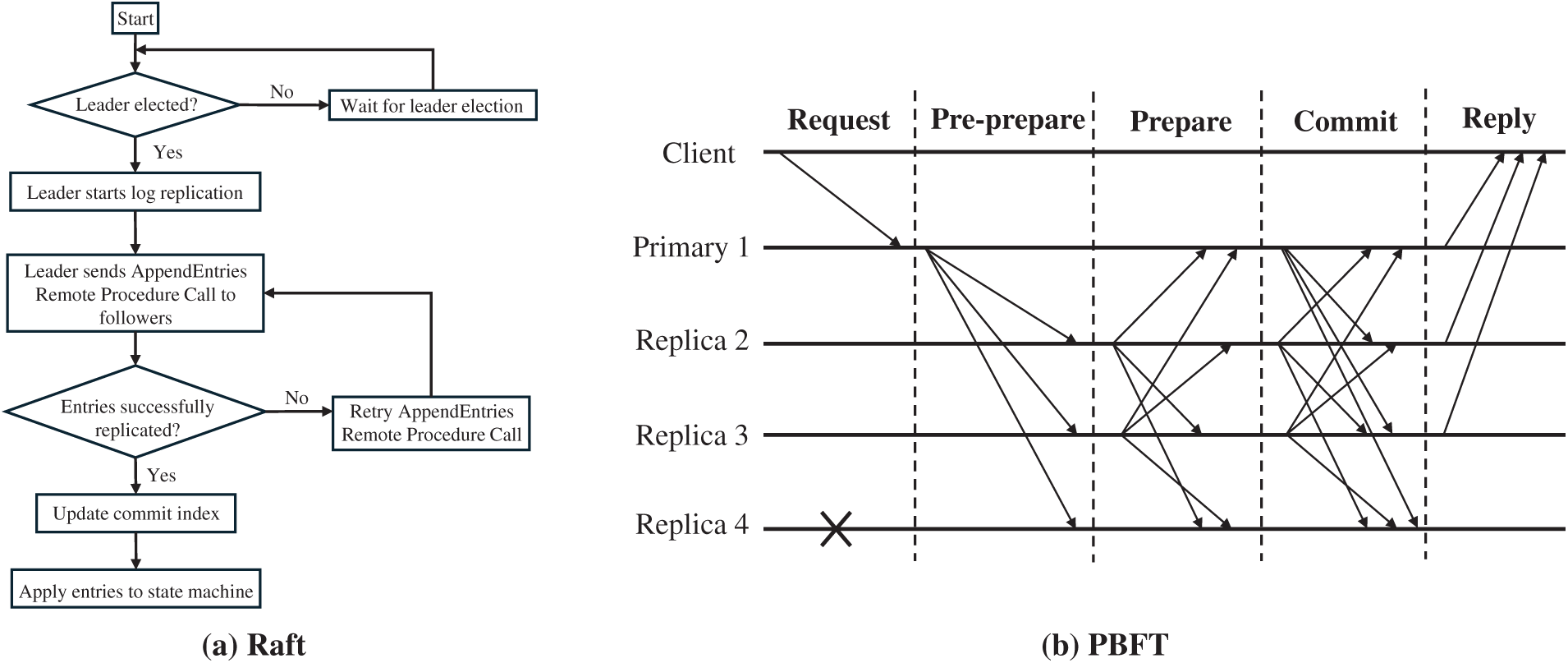

When the scale of a consortium blockchain is larger and the trust level among nodes is higher, focusing primarily on issues related to node crashes due to failures, CFT algorithms are more appropriate. A representative CFT algorithm is Raft. Fig. 9a presents the leader-based log replication of Raft. Raft divides node roles into leader, follower, and candidate. During the consensus process, Raft selects the leader through an election mechanism. Following this, the leader node processes all write requests and replicates these requests to followers in the form of log entries to achieve global consistency. The efficiency of the leader node’s log replication and election process is a core factor that restricts the scalability of the Raft algorithm. Therefore, existing CFT research is focused on optimizing Raft in two areas: leader election and log replication, to enhance scalability.

Figure 9: Schematic diagram of (a) Raft and (b) PBFT, illustrating the leader-based log replication and Byzantine consensus message flow, respectively

For the leader election optimization, the impact of elections on scalability manifests in two aspects: (1) the latency generated by the election process [87,88] and (2) the performance of the elected nodes [89–91]. The former focuses on optimizing the election process. PB-Raft [87] employs a weighted PageRank algorithm to shorten the election timeout for high-ranking nodes, thereby accelerating the convergence of the leader election process. Fu et al. [88] minimize the probability of split votes and subsequent election rounds by adjusting the affiliation of peers based on voting results, which reduces the overall latency of the election phase. The latter aspect aims to enhance the scalability of subsequent consensus processes by selecting high-performance leaders. P-Raft proposed by Lu et al. [89] ensures the elected leader has the necessary computational and network capacity to efficiently handle log replication through real-time assessment of each node’s machine performance. RaftOptima introduced by Kondru and Rajiakodi [90] incorporates a proxy leader, alleviating the leader’s communication bottleneck by delegating command distribution and response collection tasks.

For the log replication optimization, existing research has proposed various methods to reduce the log replication cost for the leader node. SRaft proposed by Ye et al. [92] splits the consensus mechanism into replication and ordering phases. In SRaft, the replication phase utilizes an adaptive leaderless replication method, which distributes the network load across multiple nodes, thus mitigating the single-point bottleneck of the leader during log propagation. LRD-Raft [93] reduces the leader’s bandwidth consumption and processing overhead by delegating part of the log replication tasks to follower nodes. Fu et al. [88] introduced a distribution mechanism during the log replication process, which parallelizes the log dissemination process and effectively reduces the communication complexity of the leader node.

3.4.2 Byzantine Fault Tolerant Algorithms

When the scale of a consortium blockchain is relatively small and there is a high demand for security, allowing for a certain proportion of malicious nodes, BFT algorithms [94–96] are the ideal choice. A representative BFT algorithm is Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT). Fig. 9b shows the Byzantine consensus message flow of PBFT. BFT algorithms ensure that the system can still reach consensus and prevent data tampering even in the presence of malicious nodes. The practical maturity of BFT algorithms for enterprise environments is confirmed by recent platform adoption. A significant validation is the integration of SmartBFT [94] as a production-ready ordering service in Hyperledger Fabric v3.0 [97]. This adoption underscores the viability of modern BFT protocols for consortiums demanding high security and resilience, moving beyond foundational algorithms like PBFT. BFT algorithms mainly include three stages: proposal, voting, and confirmation. Each stage involves significant communication and message exchanges between nodes, so these three processes affect the scalability of the consortium blockchain. To improve the scalability of BFT algorithms, optimizations can be made for these three stages. Therefore, the methods can be classified into proposal stage optimization, voting stage optimization, and confirmation stage optimization.

In terms of the proposal stage optimization, the main goals are to reduce sequential dependency and alleviate the leader bottleneck. Multi-pipeline HotStuff proposed by Cheng et al. [98] allows multiple leaders to propose blocks concurrently and utilizes pipelining to reduce idle time during the proposal phase, which improves the efficiency of the consensus process by increasing block production parallelism. Votes-as-a-Proof (VaaP) proposed by Fu et al. [12] allows nodes to propose blocks and vote concurrently, which reduces the serial dependency between the proposal and voting phases in traditional consensus protocols, thus shortening the time for a block to be confirmed.

In terms of the voting stage optimization, throughput can be improved by reducing redundant voting and mitigating the impact of malicious nodes [11,99–101]. For example, dynamically selecting high-reputation nodes for voting based on their performance and classifying nodes using the ID3 decision tree [11] or clustering mechanism [99] can reduce the communication overhead in the voting stage by shrinking the size of the consensus committee and avoid the performance degradation caused by slow or malicious nodes. TSBFT introduced by Tian et al. [100] uses the gossip protocol to disseminate voting messages and employs threshold signatures to aggregate vote results. The combination of these two mechanisms significantly reduces the communication overhead and message complexity during the voting phase.

In terms of the confirmation stage optimization, the main goal is to reduce confirmation latency [102–104]. Lyra proposed by Zarbafian and Gramoli [102] employs the commit-reveal mechanism to prevent reordering or front-running attacks, thereby reducing the overhead caused by invalid transactions; at the same time, it adopts a leaderless consensus mechanism that enables multiple nodes to advance confirmation in parallel. Together, these two features reduce the communication burden and latency in the confirmation stage.

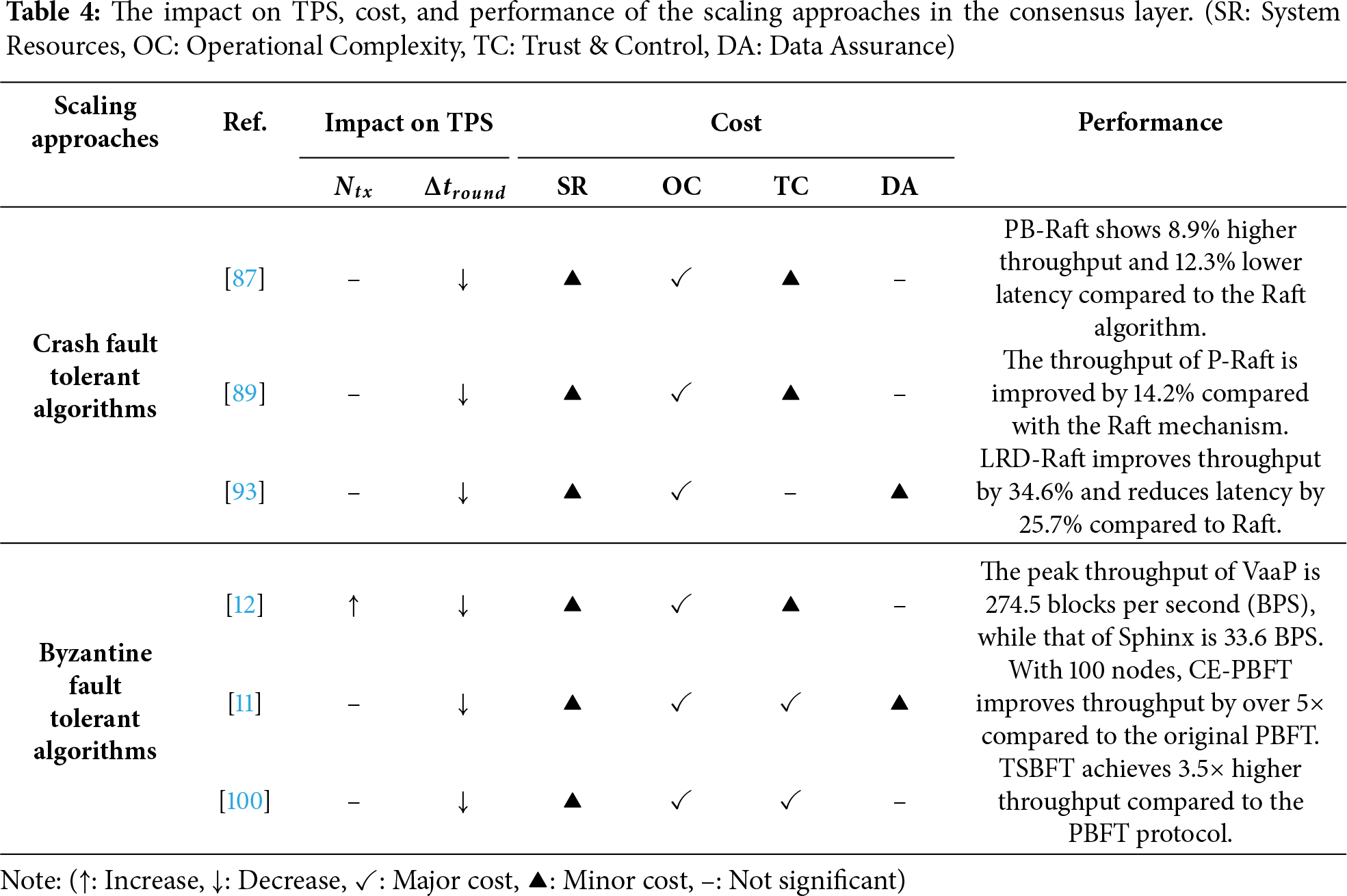

Key insight: Table 4 analyzes the effectiveness of the scaling approaches in consensus layer. Consensus layer approaches enhance scalability by optimizing the agreement process itself to make it faster and more efficient. Regarding the impact on TPS, both CFT and BFT algorithms primarily focus on reducing the time per round (

However, The substantial costs in operational complexity and system resources, present an opportunity for AI-driven optimization. AI can streamline the intricate management of consensus protocols, which directly tackles the high operational complexity. This intelligent, real-time adaptation also curtails unnecessary cryptographic overhead, leading to a more efficient use of system resources.

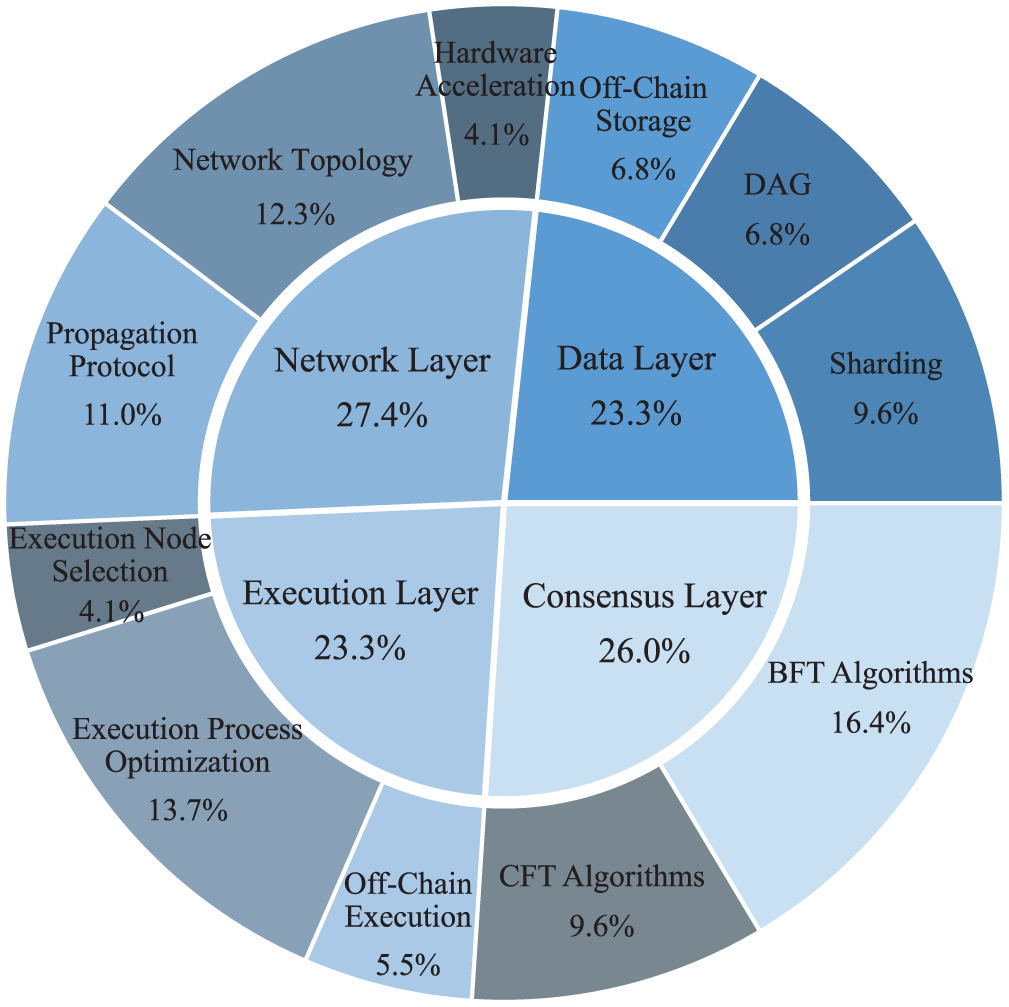

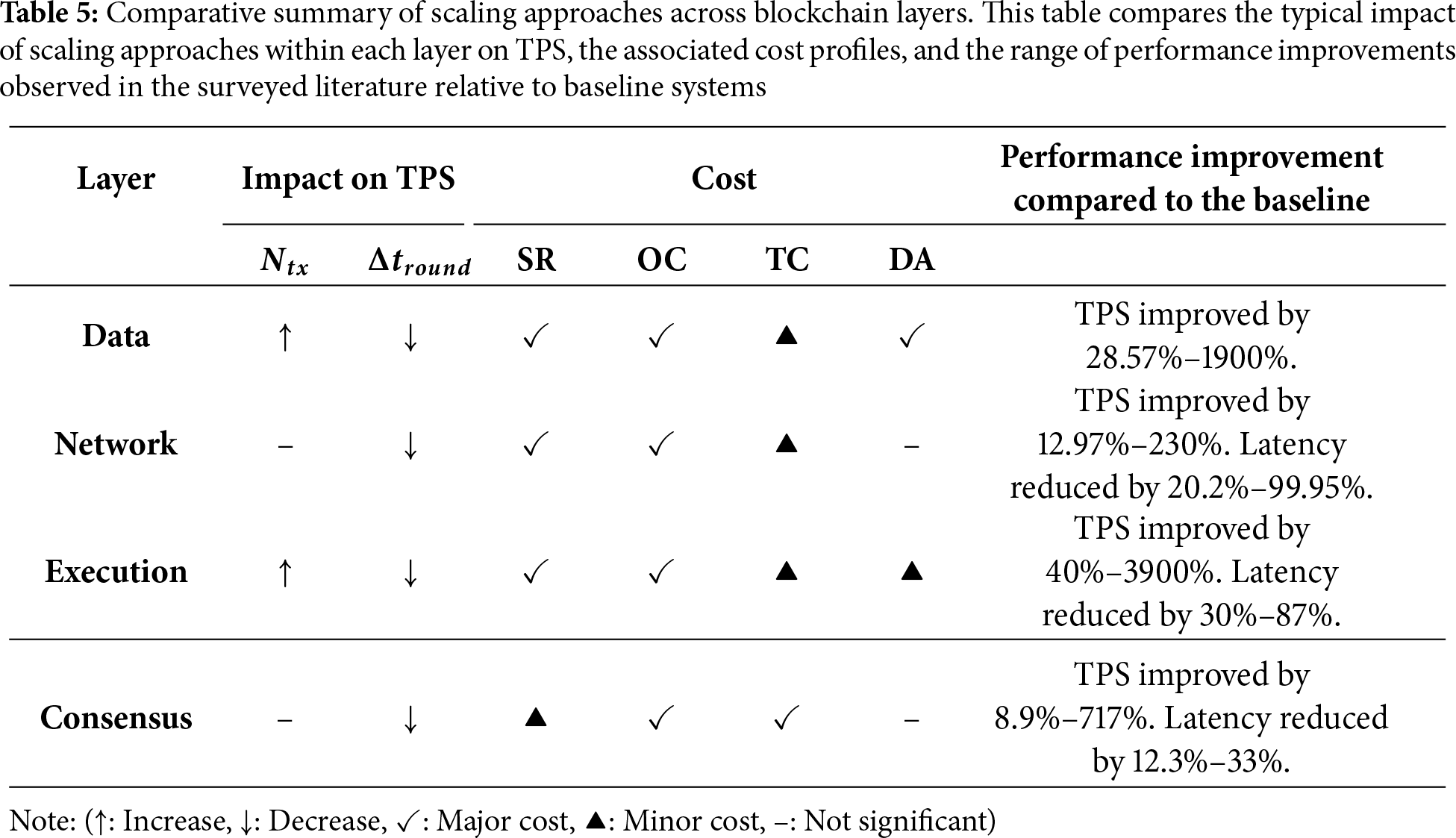

Fig. 10 presents the distribution of scaling approaches across four layers. It illustrates the relative attention given to each layer and the specific techniques within them. Table 5 synthesizes the typical impact of approaches within these layers on performance metrics and cost dimensions. Data layer and execution layer offer the most significant potential for scalability enhancement. They provide multiplicative gains by directly expanding the system’s concurrency to increase

Figure 10: Distribution of research on scaling approaches for consortium blockchains. Research attention appears relatively balanced across the four layers, with slightly more emphasis on the network 27.4% and consensus 26.0% layers

However, as shown in Table 5, these performance gains come with significant trade-offs, with each layer presenting a distinct cost profile. 1) In the data layer, complex cross-domain protocols and verification increase data assurance; new data structures raise operational complexity and system resources; and dependency on special nodes introduces trust & control. 2) The network layer’s costs arise as specialized hardware and maintenance increase system resources and operational complexity, while centralized controllers or backbone nodes increase trust & control. 3) In the execution layer, the sophisticated logic required for scheduling and parallel processing raises operational complexity; the introduction of off-chain components and verifiable proofs increases system resources and major data assurance costs; and the dependency on centralized schedulers or specialized nodes introduces trust & control risks. 4) Consensus layer sees increased operational complexity from complex protocol pipelines, higher system resources from cryptographic overhead, and elevated trust & control from a dependency on small committees or sequencers. Overall, the costs of system resources, operational complexity, and trust & control are present in all four layers. In addition, there are also data assurance costs in the data layer and the execution layer.

As established in the previous section, scaling approaches of consortium blockchains introduce significant costs across four key dimensions. AI-enabled methods offer a new perspective. By leveraging data-driven learning and real-time adaptation, they seek to discover more efficient system configurations and operational policies, thereby pushing scalability boundaries while reducing the associated costs. This section provides a systematic review of these AI-enabled methods, exploring how various methodologies are applied across the Data, Network, Execution, and Consensus layers to achieve this dual objective.

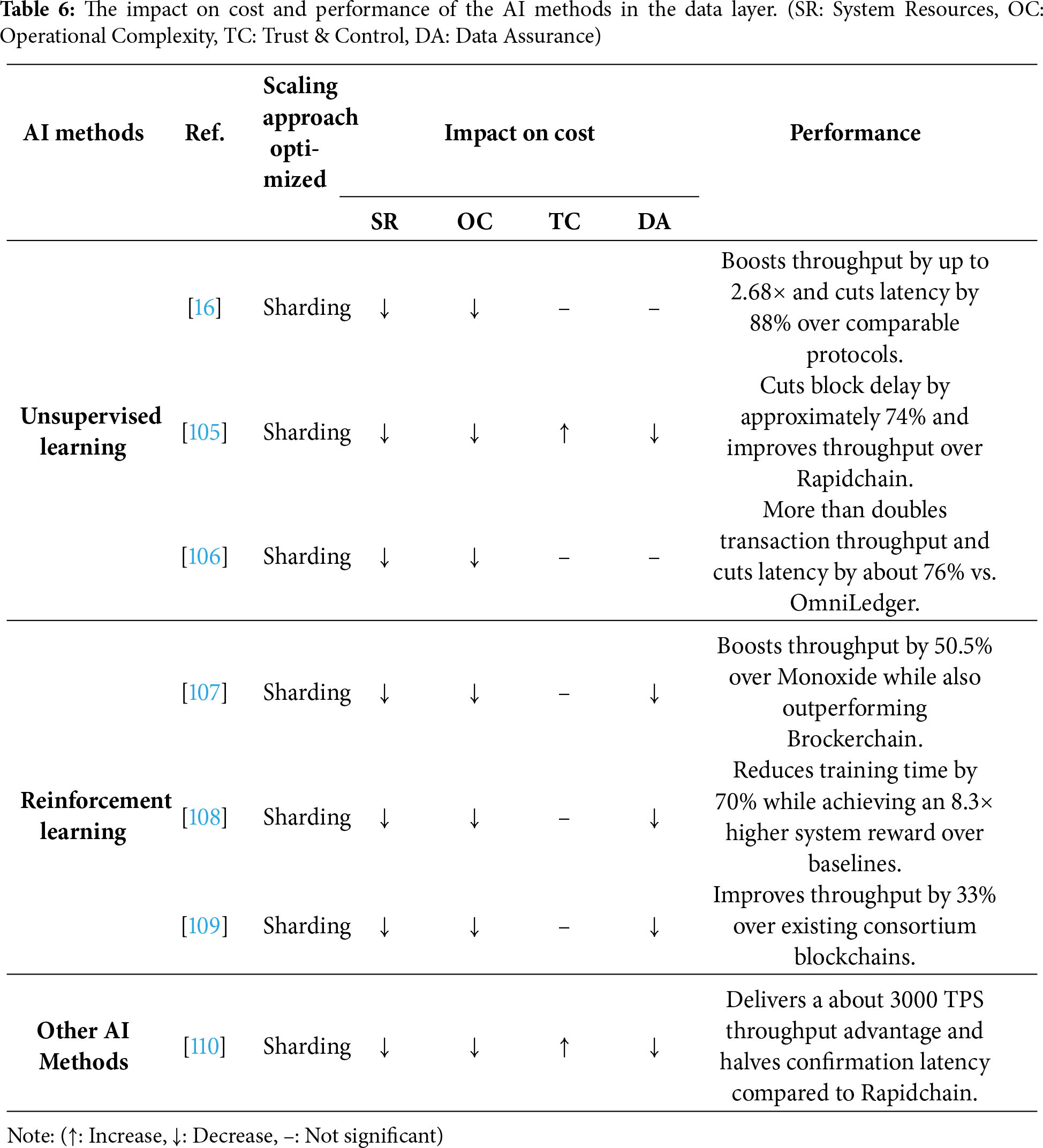

Section 3.1 introduces three primary scaling approaches for the data layer: DAG, sharding, and off-chain storage. Among them, sharding is the only category where AI-enabled enhancements have been actively explored. Sharding technology faces two core challenges: first, how to optimize the static partitioning of accounts or data to reduce cross-shard interactions; and second, how to dynamically adjust shard parameters to adapt to changing system loads. These two challenges naturally align with the characteristics of different AI methods. For the former, unsupervised learning excels at discovering underlying community structures from transaction data to guide shard partitioning. For the latter, reinforcement learning is adept at continuous decision-making and adaptive control in dynamic environments. Furthermore, to address specific issues like node heterogeneity and unreliability, Other AI methods are used to assess node trustworthiness to ensure the security and integrity of data within shards. Consequently, AI methods in sharding are categorized as follows: reinforcement learning, unsupervised learning, and other AI methods (Table 6).

Unsupervised learning methods, particularly clustering, graph methods, and probabilistic modeling, are highly suitable for optimizing the static partitioning of accounts in sharding. Their core strength lies in uncovering hidden patterns and relationships within transaction data to identify communities of accounts. By partitioning closely related accounts into the same shard, these methods maximize intra-shard transaction locality. This locality reduces the reliance on high-latency, low-concurrency cross-shard communication protocols, thereby maximizing the system’s parallel processing capability.

Various unsupervised models have been applied in this domain [16,105,106,109]. DBSRP-ML [16] proposes a label graph network to represent account states and utilizes a multi-label community detection algorithm for account partitioning. By ensuring that the vast majority of transactions can be processed entirely within a single shard, this method maximizes the system’s parallel processing capability. MSLShard [105] considers network distance, node credibility, and access frequency, using a spectral clustering algorithm to partition nodes. By creating an optimized topology where nodes within a shard have low-latency connections, this method accelerates intra-shard consensus and transaction processing. HMMDShard [106] takes a different method by constructing a dynamic transaction graph and employing a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) for dynamic, fine-grained incremental sharding. By proactively adapting the data partitions to predicted transaction flows, this method allows the system to sustain a high degree of parallel execution.

Reinforcement learning methods are highly suitable for the dynamic adaptive control of a sharded architecture, especially in dynamic environments where transaction loads and network conditions are constantly changing [111,112]. Their core advantage is the ability to continuously adjust sharding parameters based on real-time feedback. This dynamic adjustment is crucial for increasing TPS as it prevents individual shards from becoming overloaded due to load variations, thereby ensuring the entire system can consistently engage in efficient parallel processing.

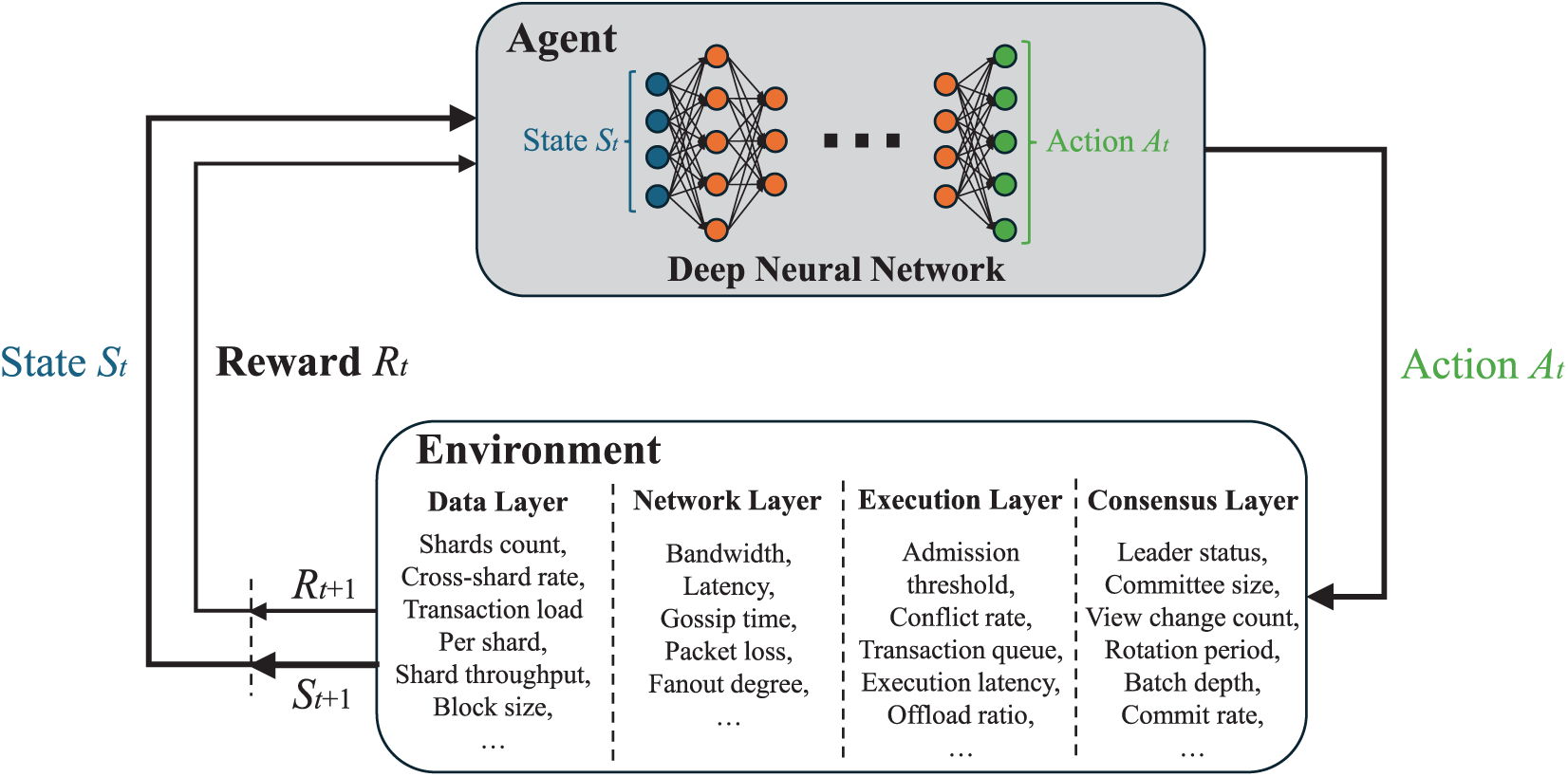

Several works highlight this direction [106–108,113]. DSSBD [107] models the optimal block generation problem as a markov decision process (MDP) and uses deep reinforcement learning to dynamically adjust the number of shards, block interval, and block size. By optimizing these parameters in real time, this method ensures that each shard can process transactions at maximum efficiency, avoiding backlogs caused by parameter mismatches. Similarly, DSPO-CB [106] also employs a Deep Q-Network (DQN) to select optimal sharding and consensus parameters. This dynamic enhancement avoids the performance bottlenecks that static configurations can create under changing loads, ensuring the sharded system operates efficiently. Fig. 11 illustrates the deep reinforcement learning (DRL) framework, where an agent learns to optimize the system by observing states and taking actions across all four layers.

Figure 11: An overall framework illustrating how a deep reinforcement learning (DRL) optimizes the scalability of the four layers. The agent observes a comprehensive state from all four layers and takes actions to dynamically tune system parameters, creating a feedback loop (state

Beyond the primary learning paradigms, other AI Methods, such as trust models from probabilistic logic, are used to address specific challenges in sharding [109,110,114]. The core of these methods is to model the heterogeneity and reliability of nodes quantitatively. A stable and reliable shard is a prerequisite for continuous and efficient parallel processing.

MSLTChain [110] is a representative study. It introduces a trust model based on multi-dimensional subjective logic within a tree sharding structure. This model does not directly optimize data partitioning or dynamic parameters but rather guides shard composition and maintenance by assessing and filtering nodes based on their credibility. By dynamically filtering out low-reputation nodes, the system ensures the stable operation of each shard, avoiding processing interruptions caused by node failures or malicious activities, thereby providing the foundation for sustained high TPS.

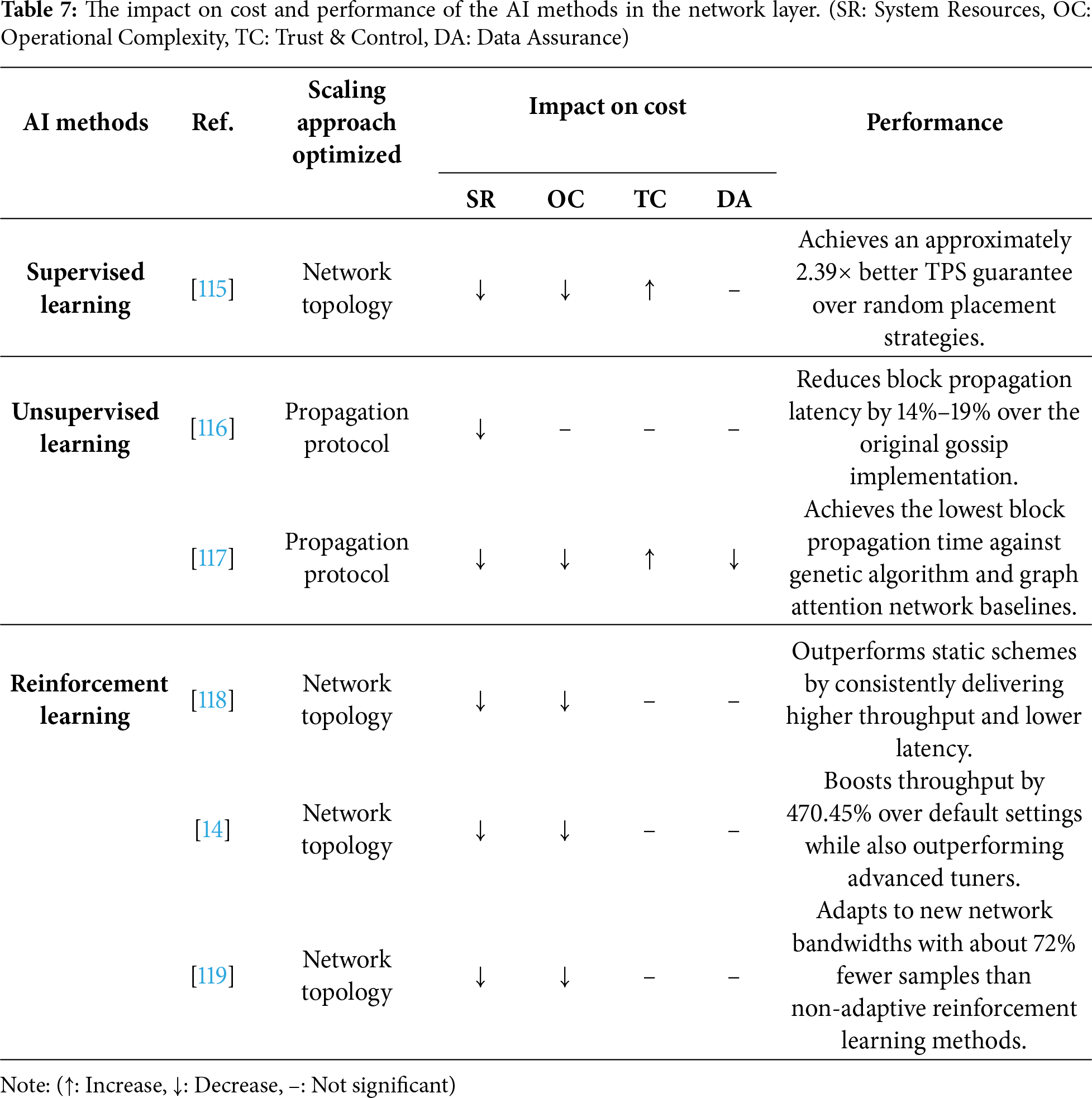

Building upon the classification outlined in Section 3.2, the approaches of the network layer are primarily divided into three main types: hardware acceleration, network topology, and propagation protocol. Currently, AI methods have not yet been significantly applied in the hardware acceleration domain. However, AI has emerged as a powerful tool to elevate the enhancement of the other two categories. On one hand, for tasks involving the static structural design of the network, supervised learning can be used to predict optimal node placements, while unsupervised learning is excellent at discovering natural, efficient topologies and propagation paths from network data. On the other hand, for tasks that require dynamic policy control and real-time adjustment of network parameters, the adaptive, feedback-driven nature of reinforcement learning is an ideal fit. Consequently, this section categorizes AI methods in the network layer into three main types: reinforcement learning, supervised learning, and unsupervised learning (Table 7).

Supervised learning are employed to optimize the structural design of the network topology before deployment [115,120–122]. By training a model on data that maps network configurations to performance outcomes, these predictive methods can determine the optimal placement of nodes in a geo-distributed environment. This data-driven foresight helps in constructing a network topology that is inherently efficient, thereby improving scalability from the ground up.

A representative study by Lee et al. [115] demonstrates this method. They build a TPS predictor by comparing various supervised models, including random forest, gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT), deep neural network (DNN), and support vector machine (SVM). This predictor is used to select the optimal node placement strategy before the system is launched, which ensures an efficient initial network topology and guarantees high-speed data dissemination pathways from the start.

Unsupervised learning is highly effective for optimizing both the network topology and the propagation protocol by discovering efficient, underlying structures from network data without predefined labels. Clustering methods can partition nodes into geographically or logically proximal groups to optimize the topology, while graph-based and generative methods can learn the most efficient data broadcast paths to improve the propagation protocol.

Several studies exemplify these methods [116,117]. To optimize the propagation protocol, Xu et al. [116] introduce density clustering in Hyperledger Fabric’s broadcast mechanism. This method constructs a highly dense and connected topology, which reduces redundant message transmissions and lowers overall block propagation latency. In a more advanced application, Kang et al. [117] use a Graph Refusion model, which combines a graph neural network with a diffusion model, to generate the optimal propagation trajectory. This generative method learns complex spatial relationships within the network to devise the most efficient path for block dissemination, minimizing latency.

Reinforcement learning methods are particularly well-suited for the dynamic policy control aspect of network topology and propagation protocol optimization. In environments with fluctuating conditions like network bandwidth, a reinforcement learning agent can learn an optimal policy to continuously adjust system parameters through interaction and feedback. This enables the network to self-optimize and maintain high message propagation rates, a key factor for scalability.

Several DRL methods have been proposed to achieve this [14,118,119]. The work by Liu et al. [118] uses DRL to dynamically select and adjust parameters such as block producers, block size, and interval. This allows the system to adapt the network’s data traffic and load in real time, preventing propagation bottlenecks. Athena, proposed by Li et al. [14], introduces a multi-agent DRL algorithm for adaptive parameter tuning in Hyperledger Fabric, which improves the overall message dissemination speed across the network. Going a step further, Pei et al. [119] use meta-reinforcement learning (Meta-RL) to create a tuning agent that can quickly adapt to unknown network bandwidth changes. This method minimizes performance degradation due to network fluctuations and maintains high propagation rates.

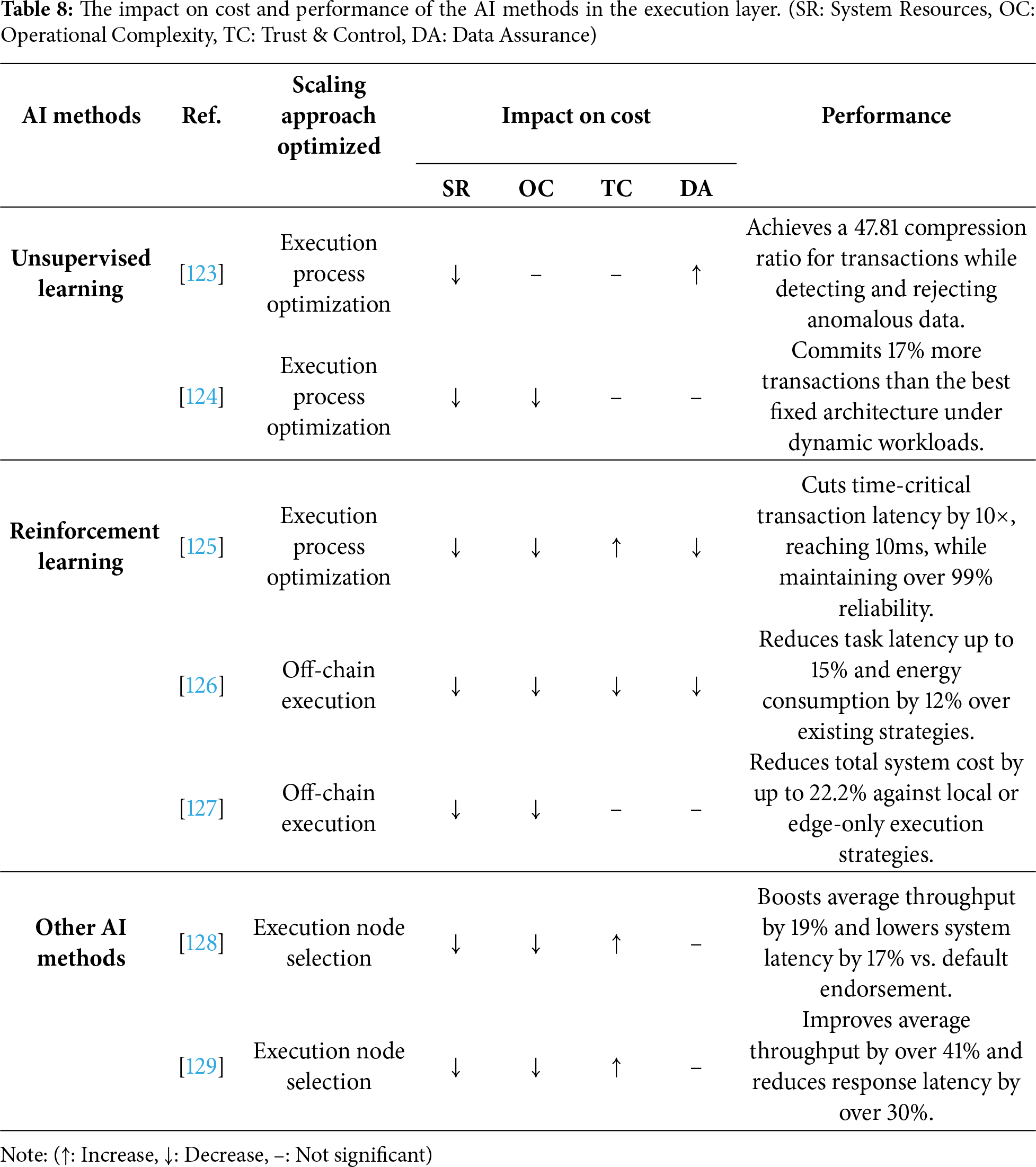

Execution layer scaling approaches mainly include three categories in Section 3.3: execution node selection, execution process optimization, and off-chain execution. AI has been applied to all three areas to enhance scalability. The suitability of each AI method corresponds to the specific challenges of these tasks. For dynamic control problems like execution process optimization and off-chain execution, the capacity of reinforcement learning to learn optimal decision-making policies through continuous interaction with the environment makes it an ideal fit. For execution process optimization, unsupervised learning can identify and filter anomalous transactions without explicit labels. Finally, for complex execution node selection problems that require balancing multiple real-time metrics, Other AI methods like computational intelligence are highly suitable. Consequently, AI methods in the execution layer can be summarized into three categories: reinforcement learning, unsupervised learning, and other AI methods (Table 8).

Unsupervised learning methods contribute to execution process optimization by identifying patterns, such as anomalies, from unlabeled data. This capability is particularly valuable for pre-filtering transactions before they enter the resource-intensive execution and endorsement stages, thereby reducing the workload on the execution nodes.

A DNN-based contract policy proposed by Sapkota et al. [123] exemplifies this method. It uses a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) autoencoder, a type of unsupervised model, to identify anomalous Internet of Things (IoT) transactions based on reconstruction error. By identifying and filtering these anomalous transactions before they enter the execution pipeline, the framework reduces the computational load on endorsing peers, resulting in a faster and more efficient execution process.

Reinforcement learning methods are highly versatile for enhancing execution layer scalability, addressing challenges in both on-chain process optimization and off-chain execution. By continuously interacting with the system to learn dynamic strategies, reinforcement learning can adjust key parameters in real time. For on-chain optimization, it excels at adapting transaction scheduling and execution parameters. In off-chain execution, it is particularly effective for managing complex task offloading decisions in dynamic environments.

For on-chain execution process optimization [124,125,130,131], AdaChain introduced by Wu et al. [124] models the selection of blockchain architecture and parameters as a contextual multi-armed bandit problem. By learning to choose the best execution configuration for the current workload, it ensures the system operates with optimal efficiency, avoiding processing bottlenecks. PBRL-TChain designed by Zhang et al. [125] introduces deep reinforcement learning to continuously optimize key aspects such as transaction admission and priority scheduling. This optimization of the transaction pipeline reduces execution conflicts and re-processing overhead.

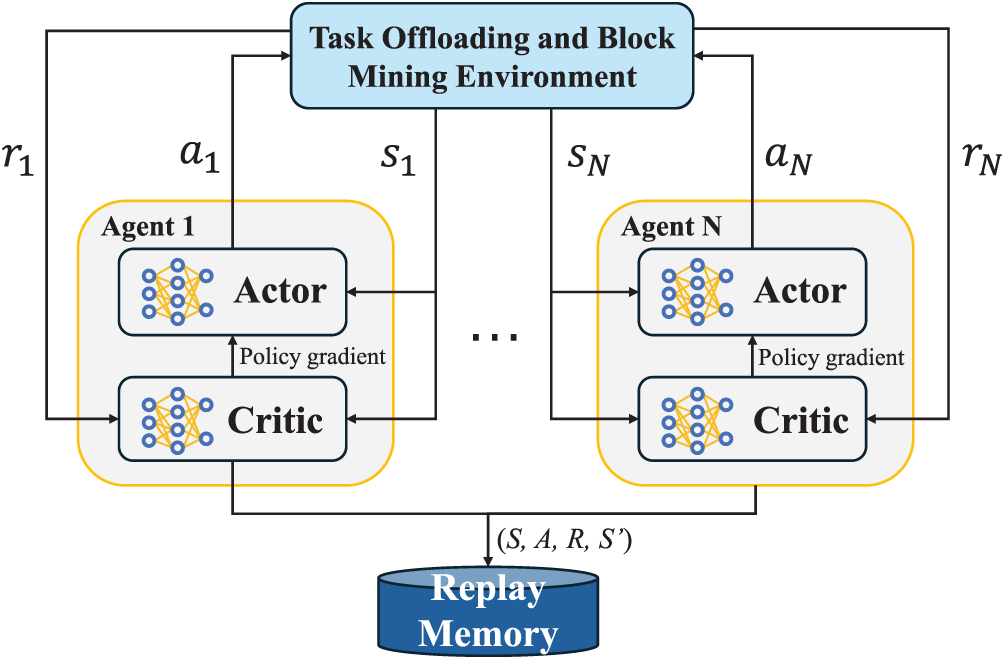

For off-chain execution [126,127,132–134], Li et al. [126] employ Independent Deep Q-Networks to intelligently decide where to execute tasks based on security and resource constraints. This efficient management of off-chain tasks reduces the computational burden on the blockchain network, allowing it to scale more effectively for security-critical operations. Nguyen et al. [132] employ Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MADDPG), a cooperative reinforcement learning approach illustrated in Fig. 12, to jointly optimize task offloading and block mining decisions. By finding optimal offloading strategies, this method frees up on-chain execution resources, allowing the blockchain to process other transactions with lower latency and higher concurrency.

Figure 12: Simplified architecture of the MADDPG algorithm. Agents interact with the environment, storing experiences in a shared Replay Memory. Each agent uses an Actor and a Critic network, with the Critic guiding the Actor’s updates via policy gradients learned from sampled experiences

Beyond traditional machine learning paradigms, other AI methods, such as computational intelligence methods, are used for execution node selection. These methods excel at multi-criteria decision-making without requiring a model to be trained on historical data. They can dynamically evaluate and rank endorsement nodes based on multiple real-time resource metrics, ensuring a balanced workload distribution across execution nodes.

Two studies highlight this direction. Dra-Fabric, introduced by Wu et al. [128], uses the multi-criteria decision making (MCDM)-based methods to rank candidate endorsement nodes based on their real-time computational, storage, and network resource utilization. This intelligent allocation avoids overloading individual nodes and reduces endorsement latency. Similarly, Pdo-Fabric, proposed by Yu et al. [129], uses fuzzy logic to evaluate the resource status of endorsement nodes. This evaluation then guides a scheduling algorithm to dynamically distribute transaction proposals across different organizations, which improves resource utilization during the endorsement phase and leads to faster parallel execution of transaction proposals.

In addition, a prominent production-level example demonstrating the principle of off-chain computation with on-chain governance is the Ritual Infernet network [135]. This system operationalizes the off-chain execution model for the specific task of AI inference. In this architecture, on-chain smart contracts submit inference requests to the decentralized off-chain network, which performs the computation and returns the result. This model directly aligns with the off-chain execution principle of outsourcing intensive tasks while retaining on-chain governance, where the smart contract defines the request and verifies the outcome provided by the decentralized network.

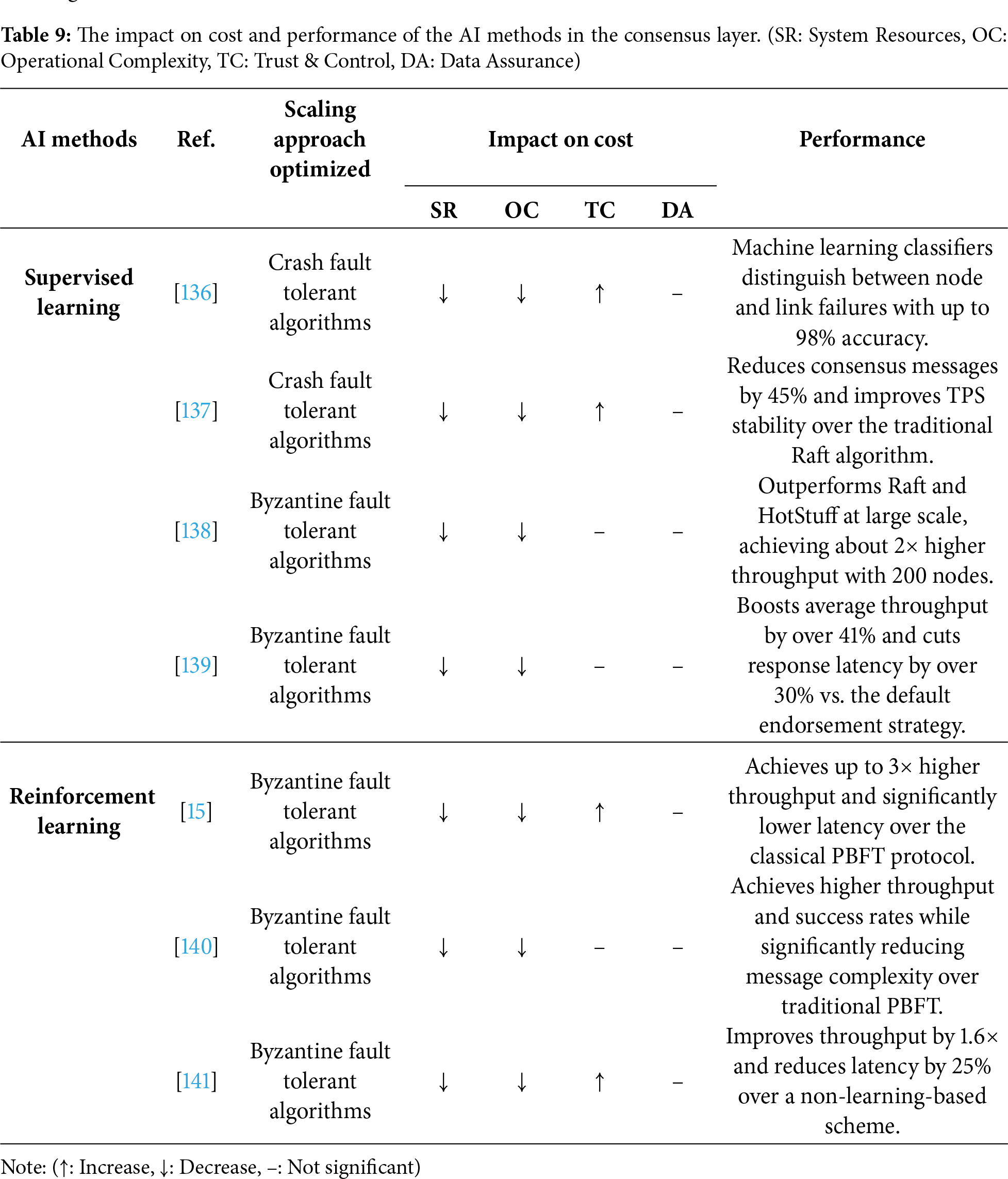

Section 3.4 categorizes the scaling approaches in the consensus layer of consortium blockchains into two categories: CFT and BFT. AI-driven enhancements have been applied to both categories. CFT protocols such as Raft focus on tolerating benign failures, and their performance bottlenecks in leader election and log replication can often be modeled as classification or regression problems, making them an excellent fit for supervised learning. In contrast, BFT protocols such as PBFT must maintain performance in complex, dynamic environments with potentially malicious actors. This process requires strategies that can be continuously and adaptively optimized. Reinforcement learning methods are an excellent fit for such a task. Consequently, AI methods in the consensus layer can be grouped into reinforcement learning and supervised learning (Table 9).

Supervised learning is well-suited for consensus protocols where performance can be improved by making data-driven predictions that reduce operational overhead. For BFT protocols, these methods can be used to build reputation models that evaluate node performance based on historical data, enabling the selection of more efficient committee members. For CFT protocols, they can classify system events to avoid unnecessary protocol actions or predict optimal parameters to improve processes like log replication.

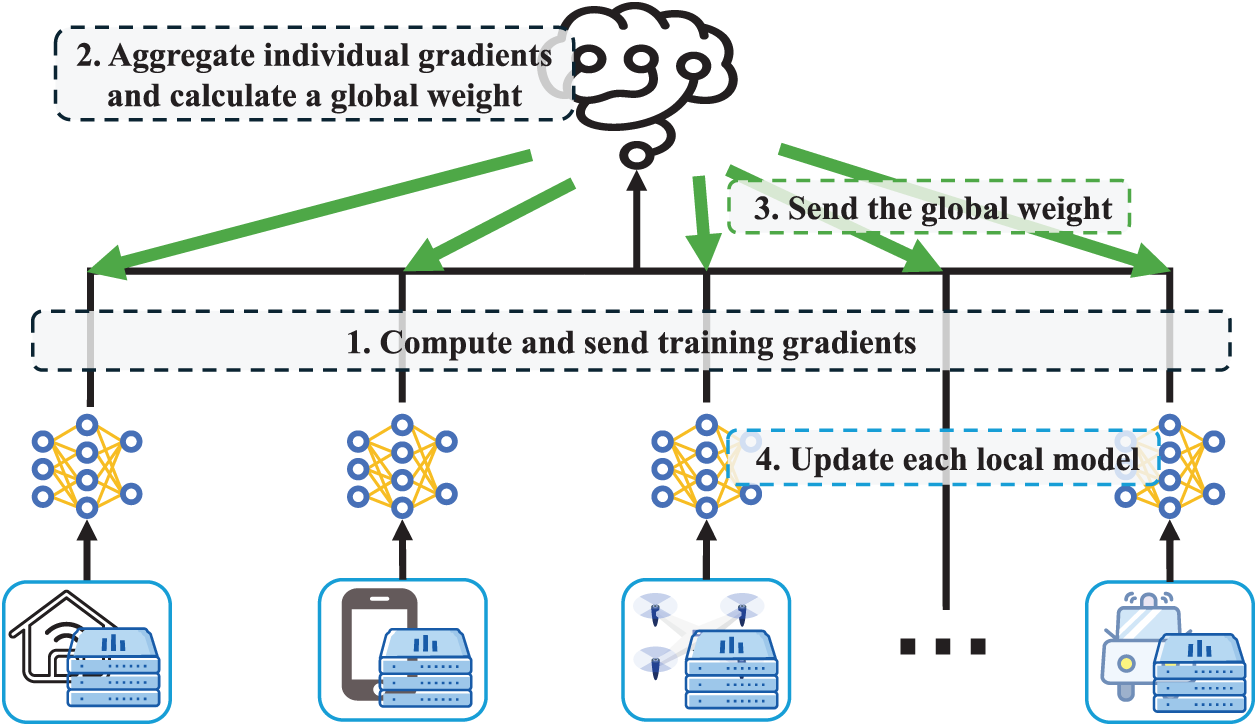

For CFT optimization, Choumas and Korakis [136] use supervised classifiers to determine whether a leader election in Raft is triggered by a genuine node failure or a temporary link failure. By preventing unnecessary leadership transitions, this method enhances the operational stability and availability of the Raft protocol. In another CFT work, the Cell-Based Raft algorithm [137] uses a federated learning paradigm to determine the optimal transaction batch size. As shown in Fig. 13, by predicting the best configuration, this method maximizes the efficiency of the log replication phase in their Raft-based algorithm.

Figure 13: Basic architecture and process of federated learning, employed by Cell-Based Raft to determine optimal cell size. Consensus nodes (clients, bottom) compute local gradients based on performance with different cell sizes and send them to a central server (cloud, top). The server aggregates gradients and sends back the global model update. Nodes then update their local models to predict the optimal cell size for maximizing throughput

For BFT optimization [138,139,142–144], Deng et al. [138] employ a backpropagation neural network to build a dynamic reputation model for nodes. By ensuring the consensus committee is composed of high-performance nodes, this method accelerates the multi-stage validation process inherent in BFT algorithms. The work by Riahi et al. [139] uses multi-task learning to simultaneously classify multiple node attributes, such as honesty and availability. This allows for a more holistic selection of committee members, which enhances the efficiency of the PBFT voting stage.

Reinforcement learning methods are particularly effective for optimizing complex BFT protocols, which often operate in dynamic environments. BFT protocols involve multiple configurable parameters, and finding the optimal settings becomes challenging when transaction loads and network conditions constantly change. Through direct interaction with the system and performance-based rewards, a reinforcement learning agent can learn an optimal policy for dynamically adjusting these key parameters, allowing the BFT protocol to maintain high performance in fluctuating workloads.

Recent works demonstrate this with both modern and classic reinforcement learning methods [15,140,141,145]. Li et al. [15] employ Double Dueling DQN to build a PBFT enhancement model. This continuous adaptation ensures the PBFT protocol’s parameters are always optimized for the current network conditions, resulting in more efficient consensus rounds. Similarly, Qiu et al. [140] model view switching, access selection, and resource allocation as an MDP. Their Dueling DQN agent learns an optimal strategy that improves the efficiency of leader selection and resource allocation within the BFT process. Representing a classic distributed reinforcement learning paradigm, Ameri and Meybodi [141] use a Learning Automata and Goore Game method. This game-theoretic model streamlines the block verification process, aiming to achieve faster convergence to a consensus decision than traditional BFT protocols.

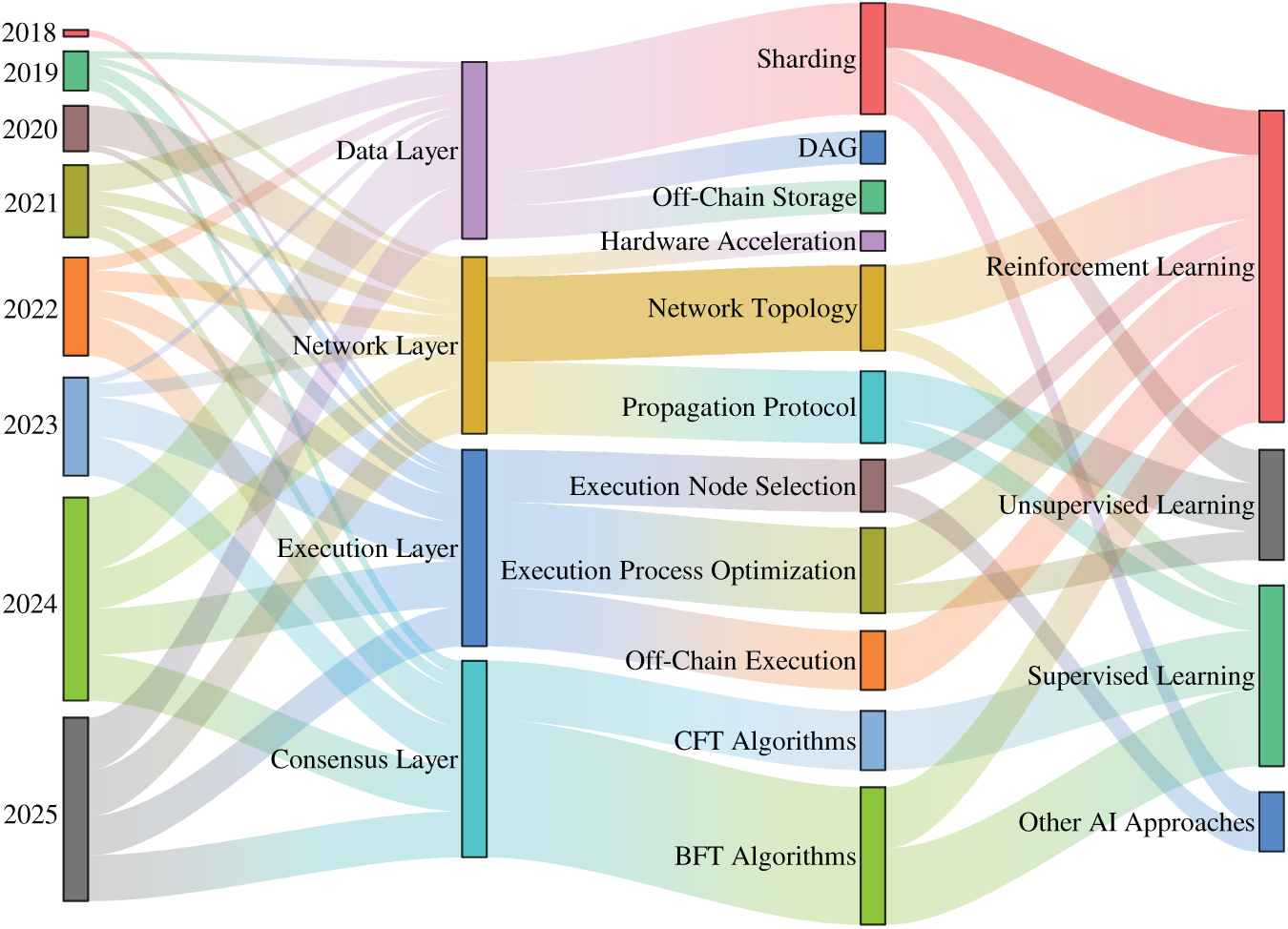

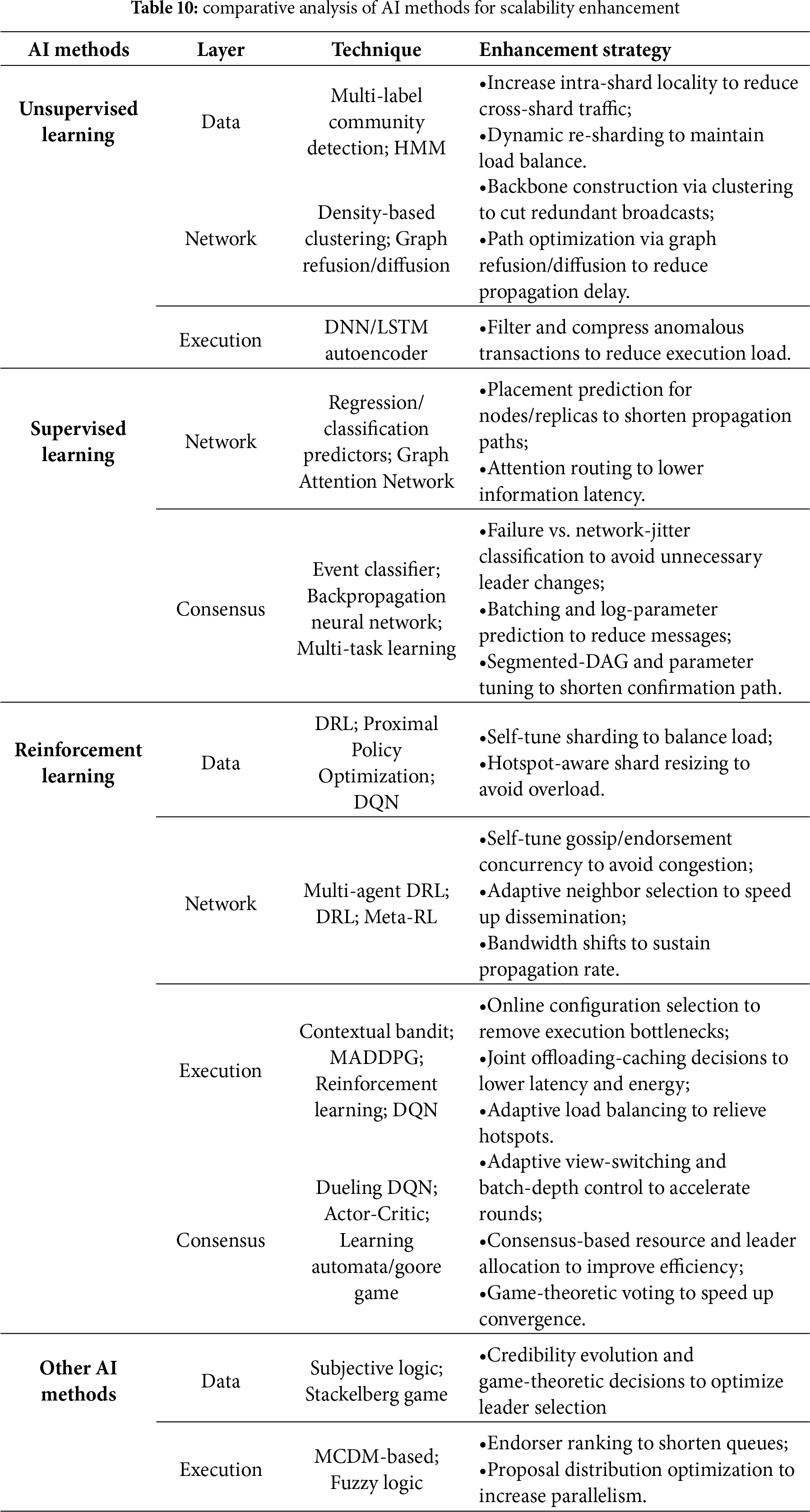

Fig. 14 maps the application of AI methods to scaling approaches across the four architectural layers. AI-enabled methods have significantly improved the performance of scaling approaches. Table 10 provides a comprehensive overview of these AI-enabled methods, categorized by AI type and the specific blockchain layer they target. For each combination, the table highlights representative techniques and outlines the core enhancement strategy. Reinforcement learning has proven to be the most impactful, providing dynamic, adaptive control for sharding locality and parameter adaptation in the data layer, online tuning of network topologies and propagation paths in the network layer, adaptive admission, scheduling, and task offloading in the execution layer, and self-adjusting consensus mechanisms such as leader rotation, view change timing, and batching depth in the consensus layer. Complementing this, supervised and unsupervised learning play crucial roles in more predictive or static tasks, such as consensus layer event discrimination and reputation modeling, and pre-filtering anomalous transactions in the execution layer.

Figure 14: A Sankey diagram illustrating the evolution and interconnection of research from 2018 to 2025. It maps AI methodologies (right column) to specific scaling approaches within the four architectural layers (middle column) over time (left column). The width of the flows indicates the relative research focus connecting these areas

While our analysis is organized by layer, many AI models operate across these boundaries, introducing two cross-layer challenges. On one hand, data from different layers and organizations is often heterogeneous, and its patterns can change over time, making it difficult for AI models to perform consistently. On the other hand, the black-box of many AI models poses a transparency problem, which can hinder the auditability and governance essential for blockchain systems. These challenges motivate privacy-preserving coordination (e.g., federated learning) and transparency mechanisms (e.g., explainable AI) as complementary enablers for cross-layer enhancement.

Despite the optimizations provided by AI, significant costs persist across all layers. AI methods are highly effective at reducing system resources and operational complexity, but the cost of trust & control often increases, and the data assurance costs in the data and execution layers are not fully mitigated. The root cause is that AI’s core advantage lies in transforming optimization problems that previously relied on manual and static configuration into dynamic and adaptive policies based on real-time observation. This shift significantly reduces resource waste from wrong configurations and automates the operational burden, thereby generally lowering system resources and operational complexity. However, the AI model concentrates the power of making decisions and system responsibilities onto a few intelligent nodes. This intensifies the dependency on a minority of components, leading to an increase in trust & control costs. In addition, the data assurance costs in the data and execution layers stem from the structural data separation introduced by architectures like sharding and off-chain execution, which must be underwritten by cryptographic proofs and protocol-level rollback mechanisms. While AI can reduce the frequency at which these mechanisms are triggered, it cannot eliminate the fundamental need for them, and thus, the associated data assurance costs remain significant.

Finally, the integration of AI itself is not without costs, creating new trade-offs that mirror the four dimensions of concern. AI models can increase system resources due to computational demands for training and inference, and add new components that raise operational complexity. Furthermore, a complex AI model can become a new centralized point of failure, introducing trust & control risks, while its black-box nature may pose challenges to the auditability required for data assurance.

Although AI-enabled methods have made significant strides in mitigating the inherent costs of scaling consortium blockchains, there remains considerable room for enhancement. The remaining costs and the new trade-offs introduced by AI integration represent key opportunities for future research. This chapter delves into these opportunities. First, we analyze how AI, acting as an optimizer and coordinator, can further reduce the persistent Trust & Control costs across the four layers. We then provide a systematic analysis of the new trade-offs that arise from integrating AI itself, proposing corresponding mitigation strategies for the four cost dimensions.

5.1 Addressing Remaining Costs: Trust & Control

In Section 4.5, we discuss the remaining trust & control and data assurance costs after the optimizations of AI-enabled methods. Although AI offers powerful optimization tools, it is essential to recognize that several costs in blockchain scalability are rooted in domains where AI is not the primary method. For instance, to reduce the high data assurance costs in the data layer and lower system resource costs in the network layer, it requires designing lightweight forensic proofs and managing offline cryptographic material pre-generation. These depend on cryptographic innovation, not AI models. Similarly, to reduce data assurance in the execution layer, it is necessary to guarantee formally verifiable conflict rules, which is a matter of strict protocol and semantic design. For the trust & control cost, AI’s role in the blockchain can act as an optimizer and coordinator. The key research opportunities in each layer where AI can fulfill this role are as follows.

Data Layer. The Trust & Control cost in the data layer primarily originates from the introduction of critical central nodes like sorters and aggregators, which are necessary for cross-shard or off-chain interactions. These nodes control the entire data channel, leading to a concentration of power. A key optimization opportunity lies in decoupling data availability from transaction ordering, which disperses the control over data processing across multiple stages, including encoding/distribution, consensus on digests, and subsequent forensics. As a result, the power of any single role is significantly diminished. The core idea is to first reach consensus on data digests and then pull the full data in parallel. In this model, the sorter/aggregator no longer controls the complete data flow, and retrieval/forensics are parallelized into later stages, thus reducing the bottleneck risk of central nodes. Research in this area can draw inspiration from DispersedLedger [146], which uses verifiable information dispersal to achieve near-optimal communication efficiency and significantly alleviates the centralization pressure caused by slow nodes.