Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Optimization of Truss Structures Using Nature-Inspired Algorithms with Frequency and Stress Constraints

1 Department of Civil Engineering, Sharda University, Knowledge Park III, Greater Noida, 201310, India

2 Nepal Research and Collaboration Center, Bhakti Thapa Sadak, Baneshwor, Kathmandu, 44600, Nepal

3 Department of Civil, Environmental, Aerospace and Materials Engineering, University of Palermo, Palermo, 90128, Italy

4 Department of Civil Engineering, Pashchimanchal Campus, Institute of Engineering, Tribhuvan University, Pokhara, 33700, Nepal

5 Department of Structural Engineering, School of Engineering and Technology, Asian Institute of Technology, Pathum Thani, 12120, Thailand

6 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Nevada, 1664 N Virginia St., Reno, NV 89557, USA

7 Computational Mechanics Laboratory, School of Pedagogical and Technological Education, Marousi, Athens, 15122, Greece

* Corresponding Authors: Panagiotis G. Asteris. Email: ,

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Meta-heuristic Algorithms in Materials Science and Engineering)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 14 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.069691

Received 28 June 2025; Accepted 28 November 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

Optimization is the key to obtaining efficient utilization of resources in structural design. Due to the complex nature of truss systems, this study presents a method based on metaheuristic modelling that minimises structural weight under stress and frequency constraints. Two new algorithms, the Red Kite Optimization Algorithm (ROA) and Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA), are utilized on five benchmark trusses with 10, 18, 37, 72, and 200-bar trusses. Both algorithms are evaluated against benchmarks in the literature. The results indicate that SBOA always reaches a lighter optimal. Designs with reducing structural weight ranging from 0.02% to 0.15% compared to ROA, and up to 6%–8% as compared to conventional algorithms. In addition, SBOA can achieve 15%–20% faster convergence speed and 10%–18% reduction in computational time with a smaller standard deviation over independent runs, which demonstrates its robustness and reliability. It is indicated that the adaptive exploration mechanism of SBOA, especially its Levy flight–based search strategy, can obviously improve optimization performance for low- and high-dimensional trusses. The research has implications in the context of promoting bio-inspired optimization techniques by demonstrating the viability of SBOA, a reliable model for large-scale structural design that provides significant enhancements in performance and convergence behavior.Keywords

Topology optimization represents the most versatile form of structural optimization, permitting the addition or removal of material from any location within the design domain [1]. This approach optimizes both structural connectivity and material distribution simultaneously, often leading to the discovery of innovative and high-performing structures [2]. However, solutions obtained through deterministic optimization methods can prove impractical or less than optimal when considering real-world engineering scenarios characterized by inherent variabilities, such as those found in fabrication processes and operational conditions [3]. These variabilities introduce uncertainties in structural geometry and material properties, potentially resulting in significant uncertainties in structural stiffness. The necessity of a new and highly capable method to effectively integrate such uncertainties into the optimization process to produce robust topology-optimized designs becomes imperative to optimize structures [4].

Trusses have been widely used in vital infrastructures, including bridges, transmission towers, buildings, aerospace, and other essential engineering structures [5]. Their simple design, consisting of pin joints and linked straight sections constructed from a single material, has made them very appealing in structural optimization. Further, the truss can be optimized for topology, shape, and size. Topology optimization involves figuring out the most efficient arrangements of the members by deciding which members to include or exclude without compromising the structural integrity of the overall geometric design [6]. Similarly, shape optimization produces the most efficient structure arrangement within a predetermined layout. In contrast, size optimization determines the most efficient cross-section for the truss members without altering the structure’s layout [7].

Truss layout optimization has a rich history, tracing back to Michell’s seminal work in 1904 [8]. Dorn et al. [9] later introduced a numerical method employing linear programming to find optimal truss configurations. Subsequent research has delved into plastic design under various loading conditions [10,11]. Building upon these foundations, Gilbert and Tyas [12] proposed a “member adding” technique to enhance computational efficiency while maintaining solution optimality. In addition, there has been development in geometry optimization methods to simplify optimized structures derived from layout optimization [13,14]. Recently, there has been attention given to layout optimization considering global stability constraints [15]. However, there’s a scarcity of research focusing on repetitive modular design in truss layout optimization. A recent investigation [16] explored a modular tall building skeleton system constructed from tetrahedral units, although the arrangement of basic modular units was predetermined rather than optimized. Further exploration in this domain is necessary to fully harness the potential of modular design in truss layout optimization.

Several techniques can be utilized to solve the truss optimization problems, among which the use of meta-heuristic algorithms is significant [17,18]. Meta-heuristic algorithms have undergone significant advancements in recent years, leading to the development of numerous new algorithms and their corresponding improved variants [19–21]. The meta-heuristic algorithms can be categorized into nine classes: biology-based algorithms, physics-based algorithms, social-based algorithms, music-based algorithms, chemistry-based algorithms, swarm intelligence algorithms, sports algorithms, mathematics algorithms, and hybrid algorithms [22–24]. Numerous studies have used the algorithms to find the optimum size and layout of truss structures using advanced multi-objective topology design [25]. The truss optimization problems can have different constraints depending on the type of structure and nature of optimization design, including nonlinear geometrical optimization [26]. Stress constraint and natural frequency constraint are two common types of constraints used for benchmarking the structural optimization performance of algorithms [27]. Various algorithms have been utilized to solve stress-constraint truss optimization problems. Rahami et al. [28] employed force and complementary energy methods with Genetic Algorithm (GA) to find an optimal member size and topology of truss structures. Azad et al. [29] used the Mutation-Based Real-Coded Genetic Algorithm (MBRCGA). Gholizadeh [30] proposed Sequential Cellular Particle Swarm Optimization (SCPSO), a hybrid optimization algorithm of Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Cellular Automata (CA) algorithms. Ho-Huu et al. [31] worked on variations of an Improved Constrained Differential Evolution (ICDE): Round-Off ICDE (R-ICDE) and Discrete-ICDE (D-ICDE). Similarly, Mortazavi et al. [32] used an integrated Particle Swarm Optimizer (iPSO) algorithm to optimize two and three-dimensional truss structures. Kaveh and Khosravian [33] studied truss structure optimization by using the Vibrating Particles System (VPS).

In addition to stress constraint optimizations, several studies on truss optimization have been conducted by constraining natural frequencies. Sedaghati et al. [34] employed an integrated Finite Element Force Method (FEFM) to perform the frequency analysis and minimize the weight of truss and frame structures. Lingyun et al. [35] applied a Niche Hybrid Genetic Algorithm (NHGA). Miguel and Miguel [36] utilized Harmony Search (HS) and a Firefly Algorithm (FA) for layout and weight optimization of truss structures with frequency constraints. Kaveh and Zolghadr [37] proposed hybridization of the charged system search (CSS) and the Big Bang–Big Crunch (BBBC) algorithms, CSS-BBBC, and employed the algorithm for truss optimization. Kaveh and Javadi [38] used Harmony Search and a Ray Optimizer to enhance the particle swarm optimization algorithm (HRPSO). Kaveh and Zolghadr [39] proposed Democratic Particle Swarm Optimization (DPSO) to address premature convergence and to boost the global search of PSO. Kaveh and Ghazaan [40] combined PSO with the Aging Leader and Challengers (ALC) algorithm and the harmonic search-based ALC algorithm (HALC) to form ALC-PSO and HALC-PSO, respectively, to handle variable constraints. The two algorithms, ALC-PSO, HALC-PSO, and PSO, were utilized to tackle truss optimization problems. Farshchin et al. [41] modified and applied Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO) within a collaborative framework, and presented an advanced version known as School-Based Optimization (SBO). In addition, Farshchin et al. [42] introduced Multi-Class Teaching–Learning-Based Optimization (MC-TLBO), a multi-class approach that improves the initial exploration capability of TLBO. Kaveh and Ilchi Ghazaan [43] evaluated the performance of Vibrating Particles System (VPS), a physically inspired non-gradient algorithm, in truss design problems. Tejani et al. [44] employed the Symbiotic Organisms Search (SOS) algorithm to tackle non-convex, nonlinear, and implicit characteristics of truss optimization problems. In addition, Tejani et al. [45] proposed an improved SOS (ISOS) to improve the performance of SOS. Lieu et al. [46] combined Differential Evolution (DE) and Firefly algorithm (FA) to form Adaptive Hybrid Evolutionary Firefly Algorithm (AHEFA). Lee et al. [6] used truss structures to benchmark optimization capability of Modified Simulated Annealing Algorithm (MSAA). Huynh et al. [47] suggested Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm with Q-learning (qIDE), and reported that the convergence speed for optimization was improved. Khodadadi et al. [48] adopted the Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (AOA), introduced a dynamic version of AOA (DAOA), and the optimization performance of the algorithms was accessed with several weight minimization problems.

This study examines the optimization performance of two recent nature-inspired algorithms: the Red Kite Optimization Algorithm (ROA) and the Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA). The two algorithms are applied to solve different shape and weight truss optimization problems involving stress or natural frequency constraints. Five truss optimization problems are studied, and the outcomes are compared to those of other algorithms. This paper is outlined as follows: Section 2 introduces the research significance, and Section 3 employs nature-inspired algorithms. Likewise, Section 4 discusses the formulation of optimization problems and covers the optimization of four distinct truss structures with ROA and SBOA. Convergence analysis and Statistical analysis are done in Section 5, conclusions are drawn in Section 6, and finally, limitations and future directions are discussed in Section 7.

This study presents a unique and technically efficient approach that employs two contemporary metaheuristic algorithms, ROA as well as SBOA, to address complex truss optimization problems. Although such algorithms have been studied in general optimization settings, their applicability to structural expedients for design problems of stress and frequency constraints has not been much investigated. The algorithms are linked to OpenSeesPy, which is a finite element (FE) program developed in Python, and together they form an integrated system to conduct accurate stress analysis and modal analysis for each optimization cycle. The direct association of optimization with a structural analysis tool guarantees that the method not only looks for (lightweight) designs but also ensures safety and performance from realistic loadings. The performance of the algorithms is tested on five benchmark truss designs, which range from a 10-bar structure to an increasingly complex 18-bar, 37-bar, 72-bar, and finally the largest 200-bar structure. These comprise both planar and space trusses, which facilitate a broad evaluation of performance with different design scales and constraint types. The presented work is aimed at carrying out a broad validation of the capabilities that ROA and SBOA must quickly solve both size and shape optimization problems, satisfying various design goals. Another advantage of using OpenSeesPy is that the optimization algorithm appropriately considers the physical behavior of the structure, such as stress spread throughout its surface and natural frequency caps. One of the major contributions is the discussion as well as comparison of SBOA and ROA with some popular metaheuristic algorithms such as PSO, TLBO, and MC-TLBO. It is demonstrated that SBOA yields better or similar performance with respect to convergence rate, robustness, and computational complexity. This progress is mainly attributed to its adaptive search strategy based on the Levy Flight, which can add the global exploration ability and avoid premature convergence.

3.1 Nature-Inspired Algorithms

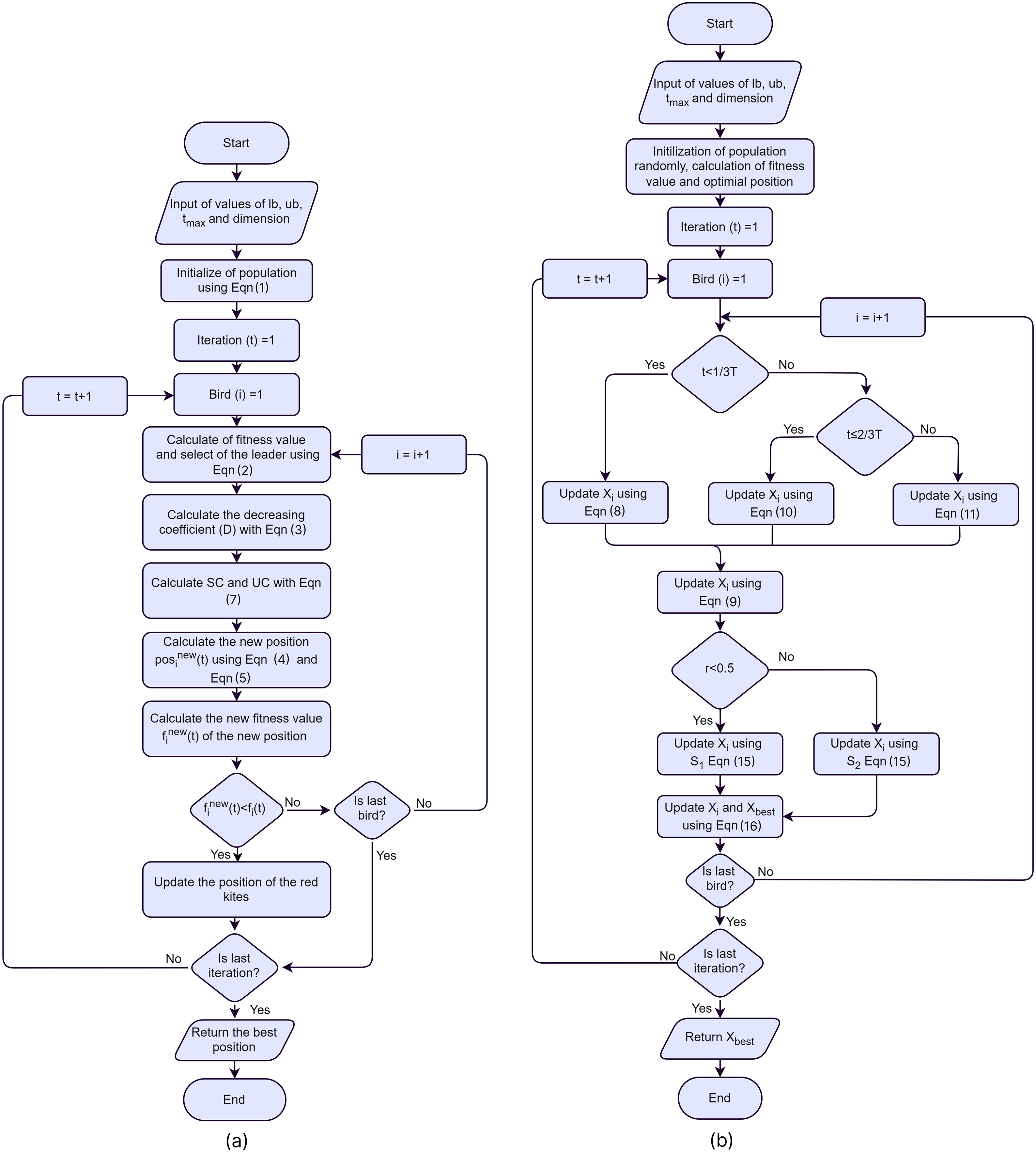

Nature-inspired algorithms are a subset of metaheuristic algorithms that draw inspiration from natural phenomena and biological processes, such as finding food, hunting, evading, reproducing, and adapting to environmental changes. The flowchart of the adopted algorithm is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Flowchart of (a) Red Kite Optimization Algorithm (ROA) and (b) Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA)

Mathematical models of these phenomena and methods are utilized to tackle a variety of problems in science and engineering. This study utilizes the Red Kite Optimization Algorithm (ROA) and the Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA), inspired by nature by the behaviors of secretary birds and red kites.

3.2 Red Kite Optimization Algorithm (ROA)

ROA is a nature-inspired metaheuristics algorithm developed by Raeisi-Gahruei and Beheshti [49]. It is based on the social behavior of red kites [50]. Red kites typically construct nests in wooded areas and lakes conducive to foraging. They coexist in adversity, influencing the other’s positions during flight. Although hunting, they operate at rapid velocities. The sound of unity generates results from migration, birth, water sources, and finding suitable lures. The sounds of peril include the noises associated with danger, such as the demise of another animal, a hostile attack, an earthquake, and a disruption. The position and value of evaluation of each avian can be defined to replicate the behavior of a red kite in its search for nutrition. The behavior of a red kite is represented mathematically by the initial position of the bird, the value of the objective function, the displacement of points, the sound of peril (in the direction of the individual component), the sound of unity (in the direction of the social component), the new avian position, and a new value of the objective function [46]. ROA effectively explores the problem search space and then transitions from the exploration to the exploitation phase, utilizing the most effective solution in the most recent iteration. The flowchart of ROA is presented in Fig. 1a. The formulation is expressed in Eqs. (1)–(7). Initialization of the red kites is the first stage; the position of

where

where

where

3.3 Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA)

SBOA is a metaheuristic algorithm developed by Fu et al. [51]. This population-based algorithm is based on the continuous hunting and predator-evading behavior of a secretary bird. The flowchart of SBOA is shown in Fig. 1b. The behavior of the bird is modeled in two phases: the exploration and exploitation phase.

In the exploration phase, the hunting process of the bird is divided into three stages: searching, consuming, and attacking, with equal time intervals. The searching for prey stage is modeled mathematically by Eqs. (8) and (9).

where

where

The new position is calculated as Eq. (11) and updated using Eq. (9).

where

After the exploration phase comes an exploitation phase; there are two evasion strategies adopted by a secretary bird in the exploitation phase. The first strategy is to camouflage to hide from the predators (

where

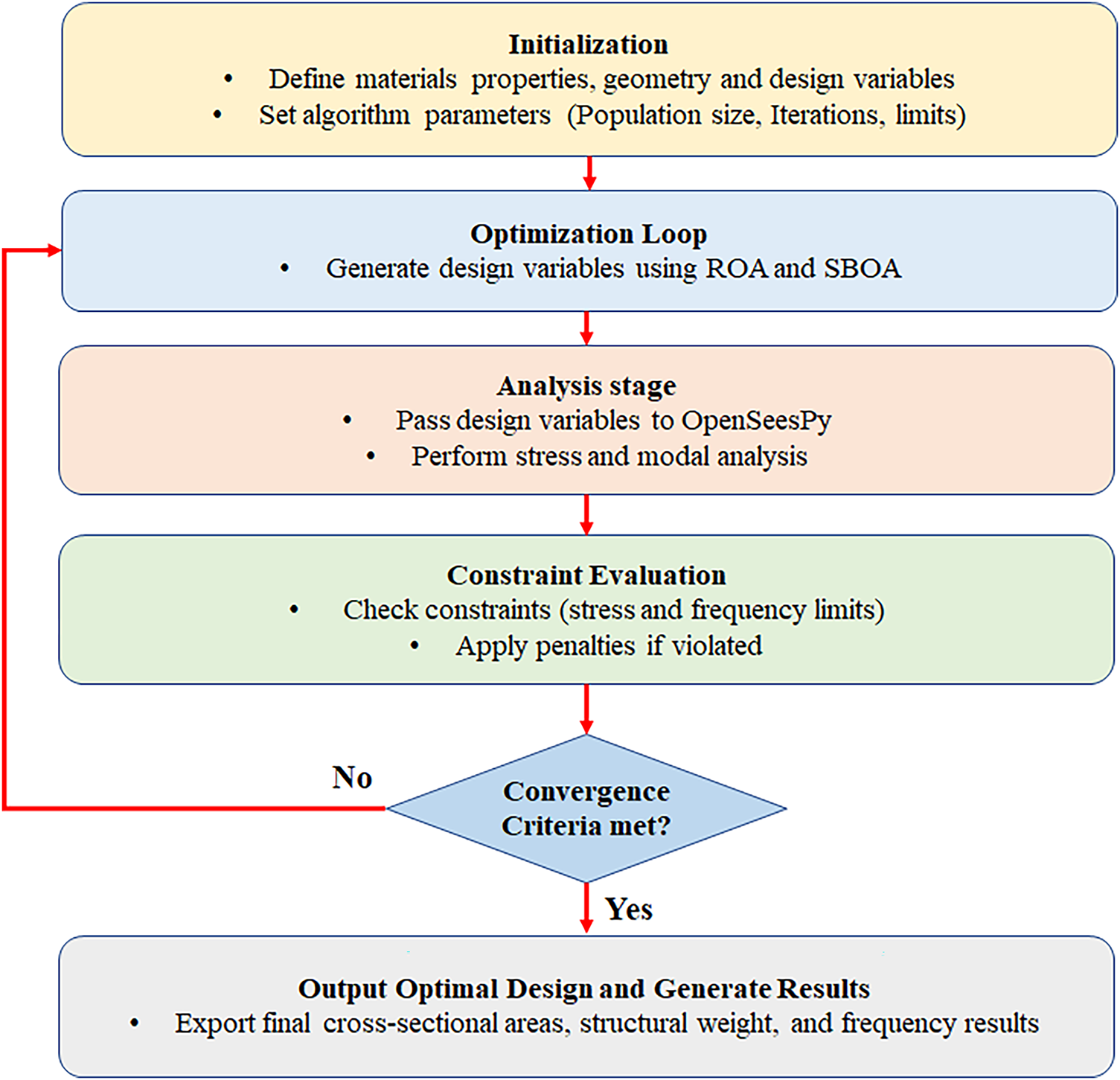

The general procedure, presented in Fig. 2, is initiated by a pre-processing stage during which material properties and geometric descriptions, as well as design variables such as cross-sectional areas, are specified. ROA and SBOA are the methodologies implemented to form an effective optimization framework for trusses. Population size, iteration numbers, and bound constraints are also determined in this stage by means of the algorithm parameters. These are parameters that set the design space, or basis for optimization. After starting the optimization, initialization is performed. In this stage, the ROA and SBOA are utilized to produce candidate design variables. Every design is an embodiment of one of the many possible instances of trusses spread across the span, and a design is pushed to the analysis phase. The analysis is conducted using OpenSeesPy with stress and modal analysis. The member stresses are checked to be within allowable limits by the stress analysis, and dynamic constraints are checked by modal analysis of the natural frequencies.

Figure 2: Computational framework adopted in the current study

For each iteration, a constraint check occurs to ensure that the design satisfies the stress and frequency specifications. Then any constraint violations should be penalized within the objective, leading to an objective function that, if one designs infeasible solutions, is discouraged and makes the optimization focus on feasible designs. This iterative calculation repeats until the required criterion is achieved, i.e., when the improvement between two steps is too small or the number of iterations reaches a limit. When convergence is reached, the algorithm generates the final optimized design. Results contain the optimum cross-sectional areas of all members, the minimal area weight of the structure, and the corresponding natural frequencies. This last process makes certain that the end design is structurally sound as well as lightweight. Accordingly, this integrated process that combines the searching effectiveness of ROA and SBOA with the computational accuracy of OpenSeesPy leads to a robust and efficient approach to size-and-shape optimization of stress-and-frequency constrained truss structures.

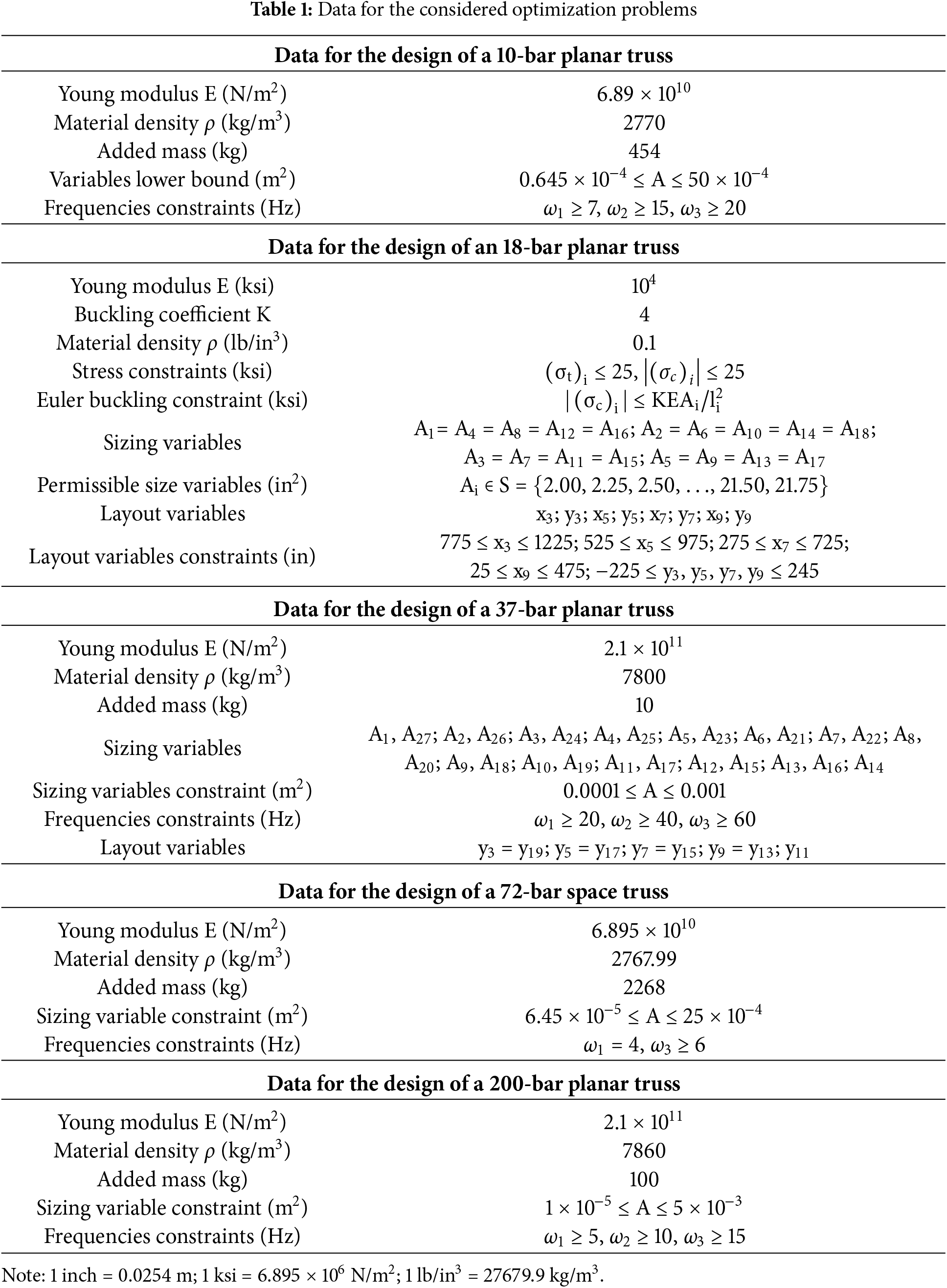

The optimization performance of ROA and SBOA is assessed by five truss models: 10-bar, 18-bar, 37-bar, 72-bar, and 200-bar trusses. The 72-bar truss is a space truss, and the rest are planar. 10-bar, 72-bar, and 200-bar truss optimization are section size optimization problems, whereas 18-bar and 37-bar truss optimization are sizing (weight) and layout optimization problems. The optimization examples are investigated with 30 independent trials for ROA and SBOA to consider the stochastic nature of metaheuristic algorithms.

In this study, OpenSeesPy (Zhu et al. [52]), a Python implementation of OpenSees (McKenna et al. [53]), was utilized to model the truss structures and to perform modal analysis and stress calculation.

4.1 Formulation of the Truss Optimization Problems

A truss optimization problem aims to minimize the member size of the truss structure while adhering to multiple constraints. In this study, 10-bar, 37-bar, 72-bar, and 200-bar trusses are constrained by multiple natural frequencies, while the 18-bar truss is constrained by stress limits. The truss optimization problem can be represented in Eq. (17).

where W is the total weight of a truss structure with m numbers of members.

where

For the frequency constraint problem, any

A penalty function is utilized to account for the designs that do not conform to the constraints. The total weight is multiplied by a factor that is proportionate to frequency or stress limit violation.

where

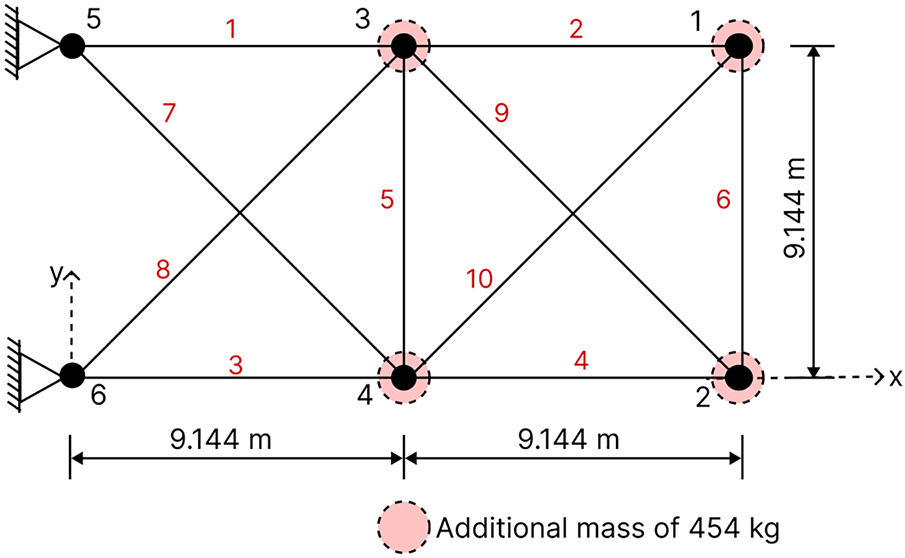

4.2 The 10-Bar Planar Truss Structure

This is the first truss optimization problem constrained by natural frequencies. This is a weight optimization problem. Fig. 3 depicts the geometry of a 10-bar truss structure. It indicates that 454 kg of non-structural mass is added to free nodes 1, 2, 3, and 4. The cross-sections of the truss elements are considered as continuous design variables [34,35,38]. Similar approaches have also been adopted in [39,41,42]. Limits of the sizing variables, constraints, and material properties of the truss are listed in Table 1. Population size of 20 (number of birds) and maximum iteration of 500 are taken for both ROA and SBOA. The penalty factor

where t is the current iteration number and T is the total number of iterations.

Figure 3: Schematic of the planar 10-bar truss structure with added mass

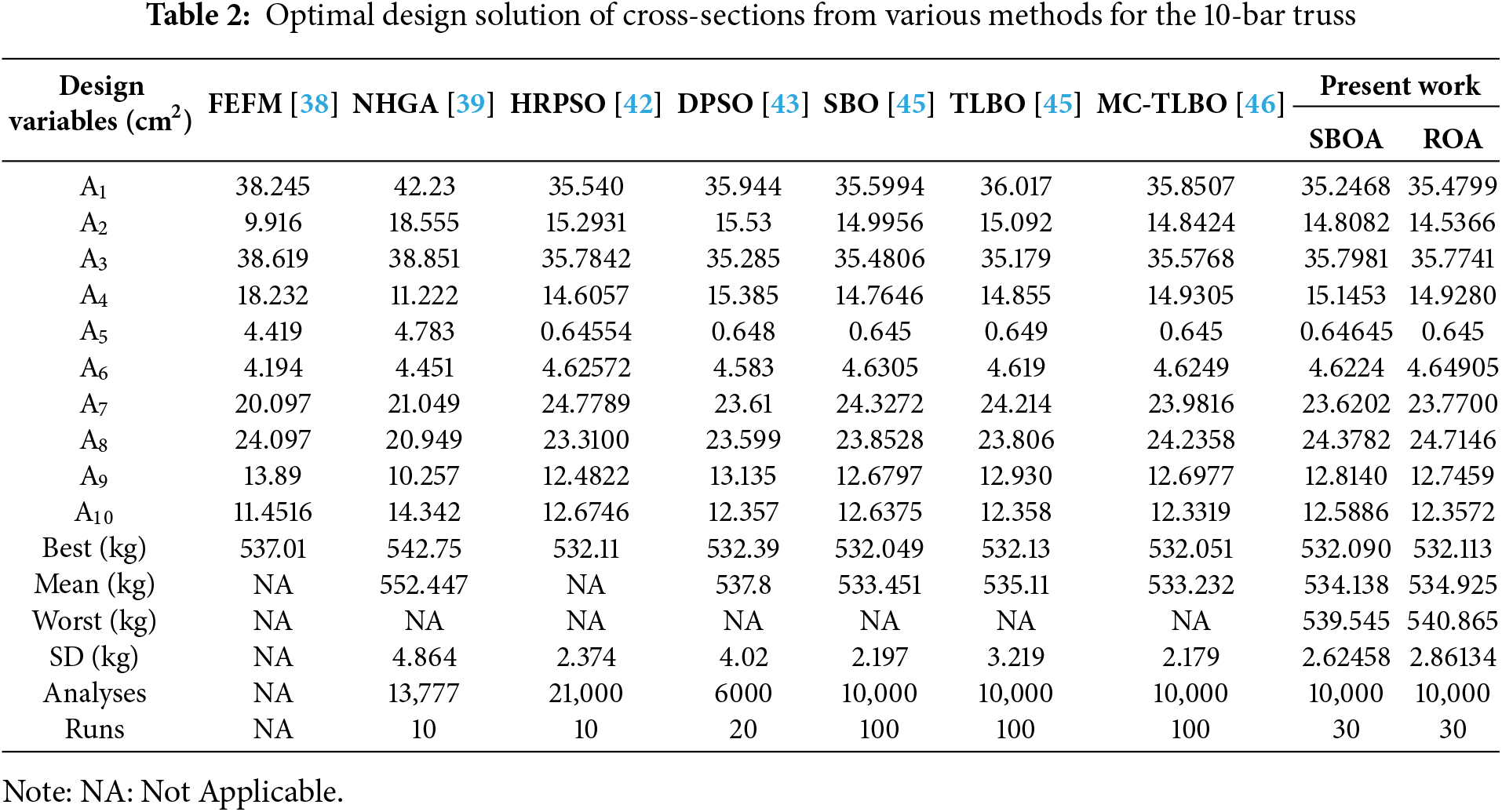

The results obtained from the employed algorithms are listed in Table 2. SBOA had a smaller total weight of the structure than ROA. In addition, the standard deviation of weight when utilizing SBOA is smaller than that of ROA. The results given by SBOA (532.09006 kg) and ROA (532.11392 kg) are comparable to the best results: SBO (532.0496 kg) and MC-TLBO (532.051 kg). In addition, the SBOA and ROA produced the results in 30 optimization runs, whereas SBO and MC-TLBO were conducted for 100 independent runs. Between SBOA and ROA, SBOA performed better in terms of overall performance and efficiency with lower weight, mean, and standard deviation values. In addition, SBOA converged to its optimum solution in just about 150 iterations, whereas ROA took more than 350 iterations.

This further shows the better performance of SBOA. Table 3 lists the first eight natural frequencies of the optimal structure, and both ROA and SBOA adhered to the imposed frequency constraints. Studies have optimized this truss structure with variations in values of material density and modulus of elasticity [54–57].

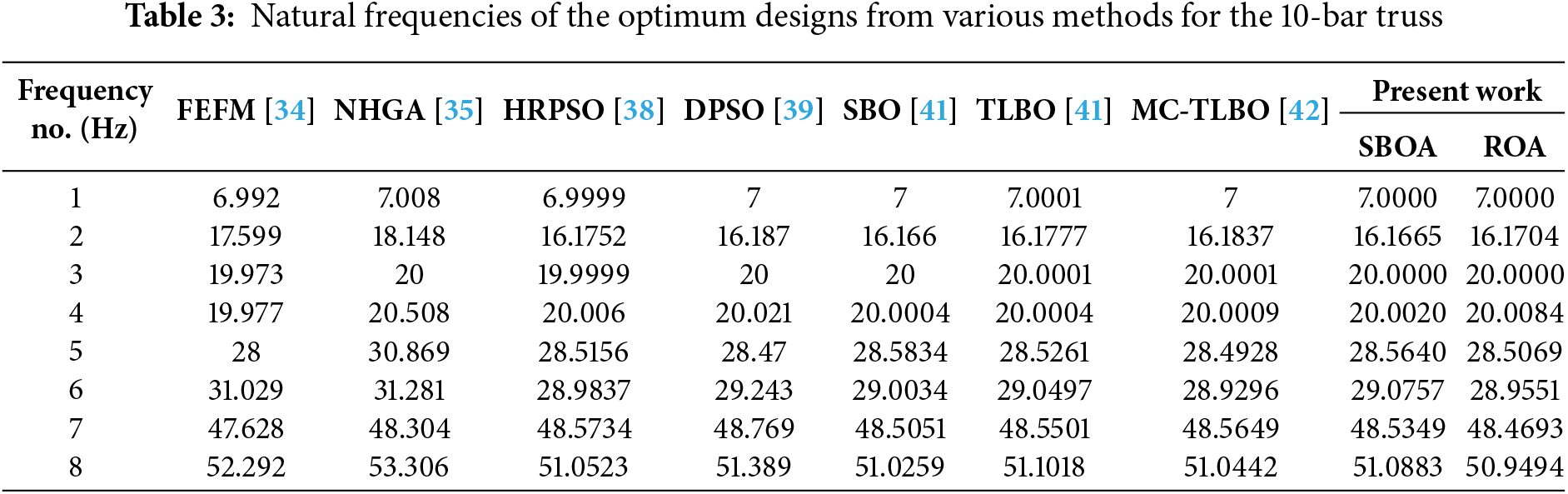

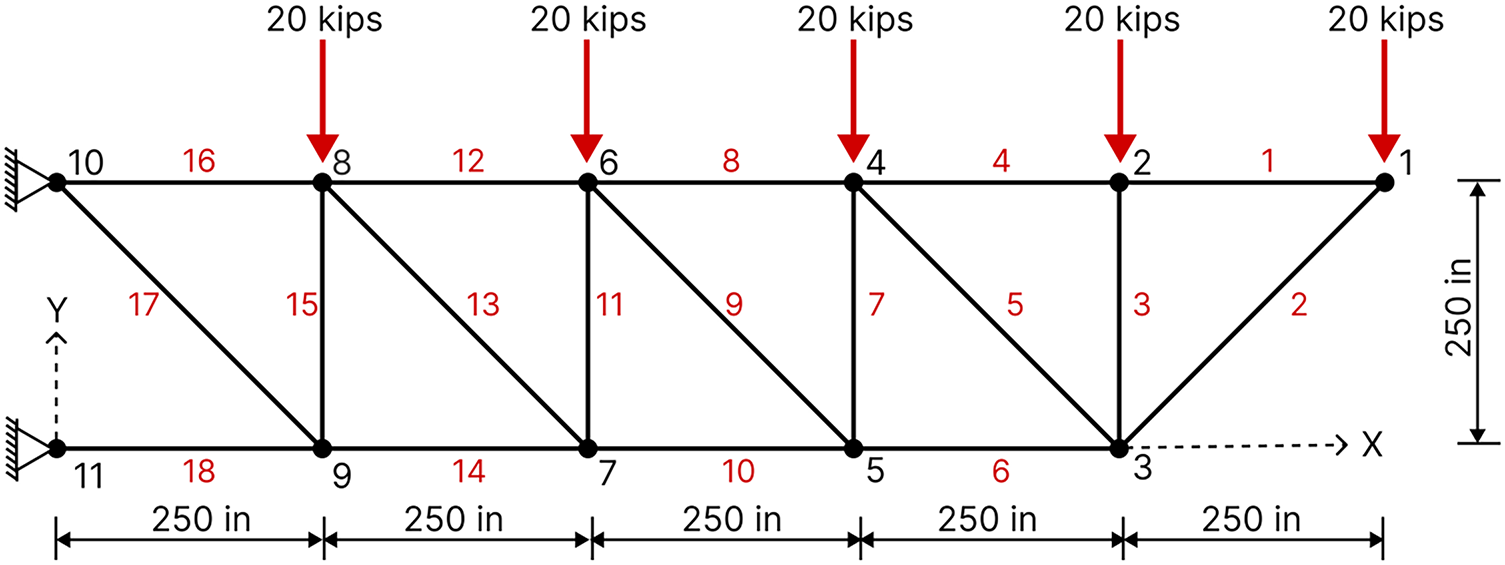

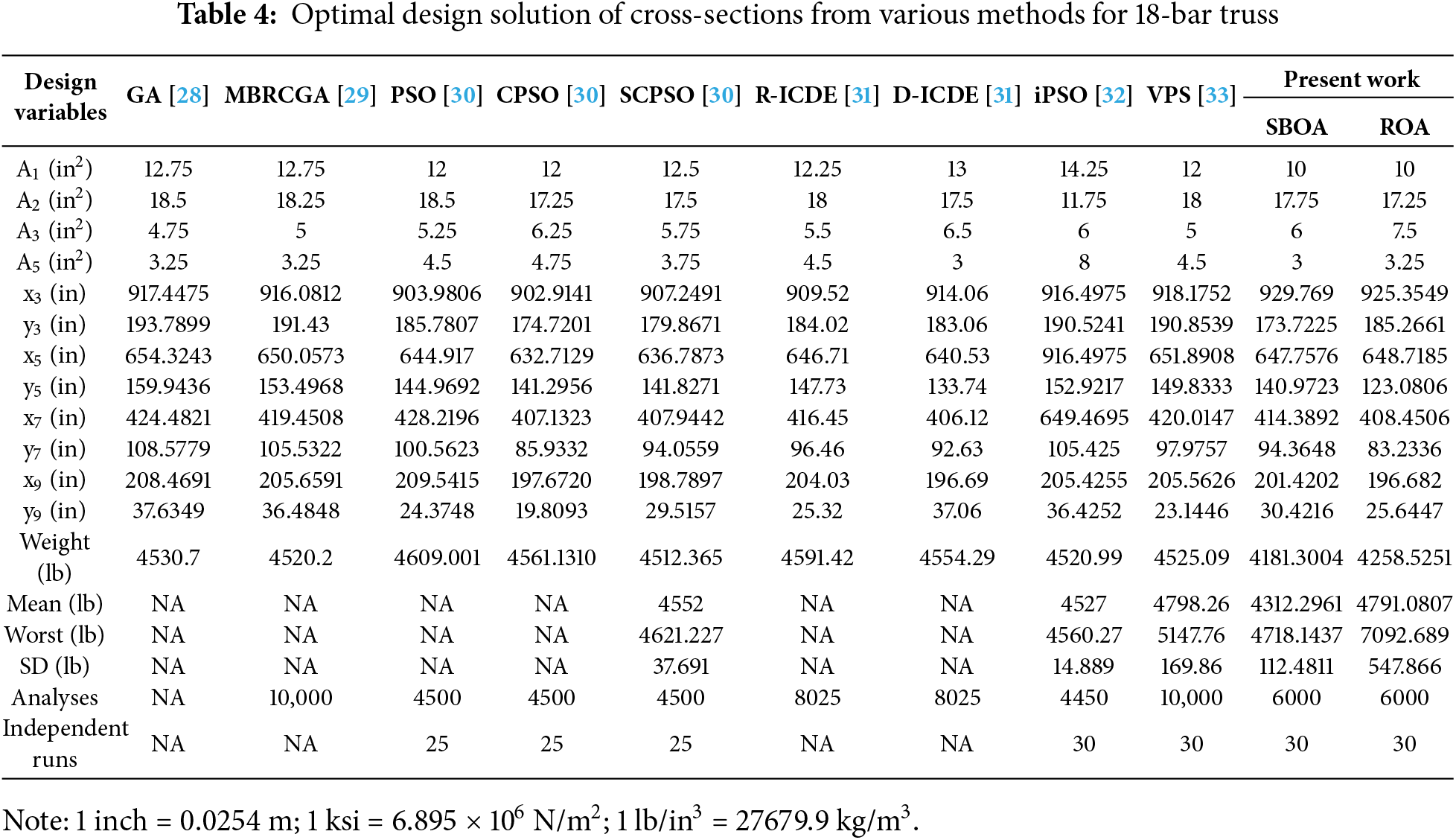

4.3 The 18-Bar Planar Truss Structure

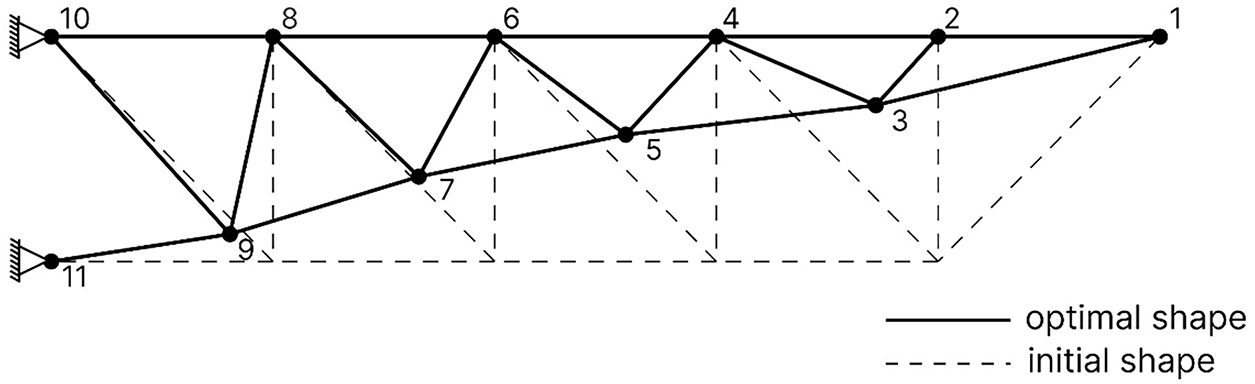

An 18-bar planar truss structure is illustrated in Fig. 4. This is a shape and size optimization problem, using four sizing variables and eight layout variables, as detailed in Table 1. The adopted problem was also conducted using the imperial system to ensure easy comparison of results. The unit conversions are as follows: 1 inch = 0.0254 m, 1 ksi = 6.895 × 106 N/m2, and 1 lb/in3 = 27679.9 kg/m3.

Figure 4: Schematic of the 18-bar planar truss structure with external loading

The truss bars have a material density of 0.1 lb/in3, a modulus of elasticity (E) of 10,000 ksi, and are subjected to a stress limit of 25 ksi in compression and tension. In addition, compression members are also constrained by a maximum Euler buckling stress of 4EA/L2, where A and L are the bar’s area and length, respectively. A point load of 20 kips is applied on nodes 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8. For this optimization example, the population size and the maximum iteration are taken as 20 and 300, respectively. The penalty factors

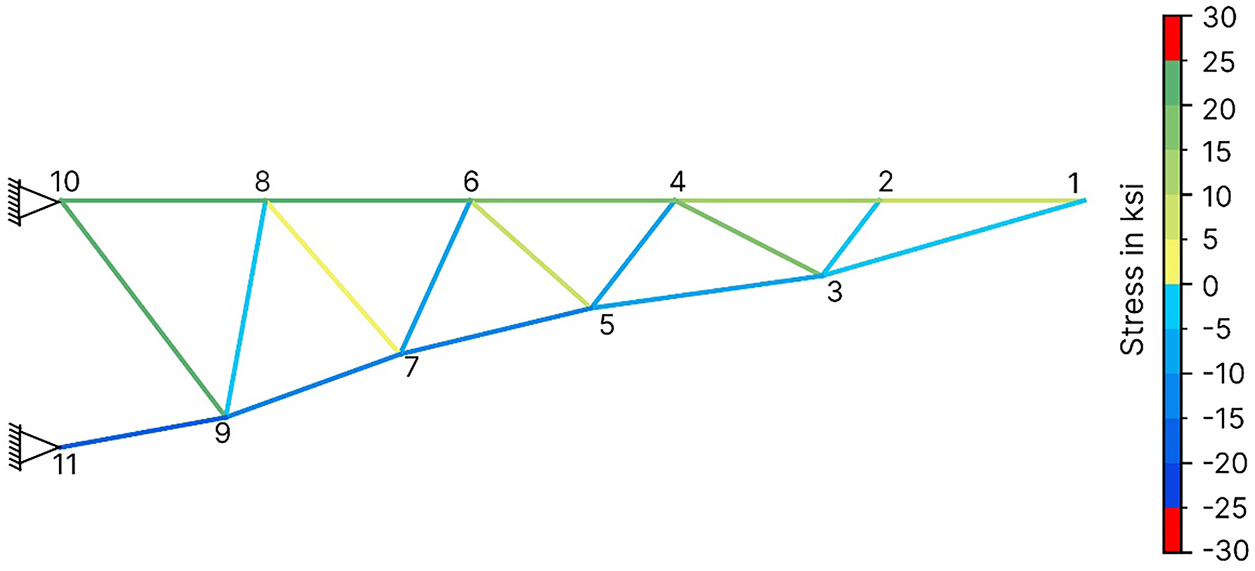

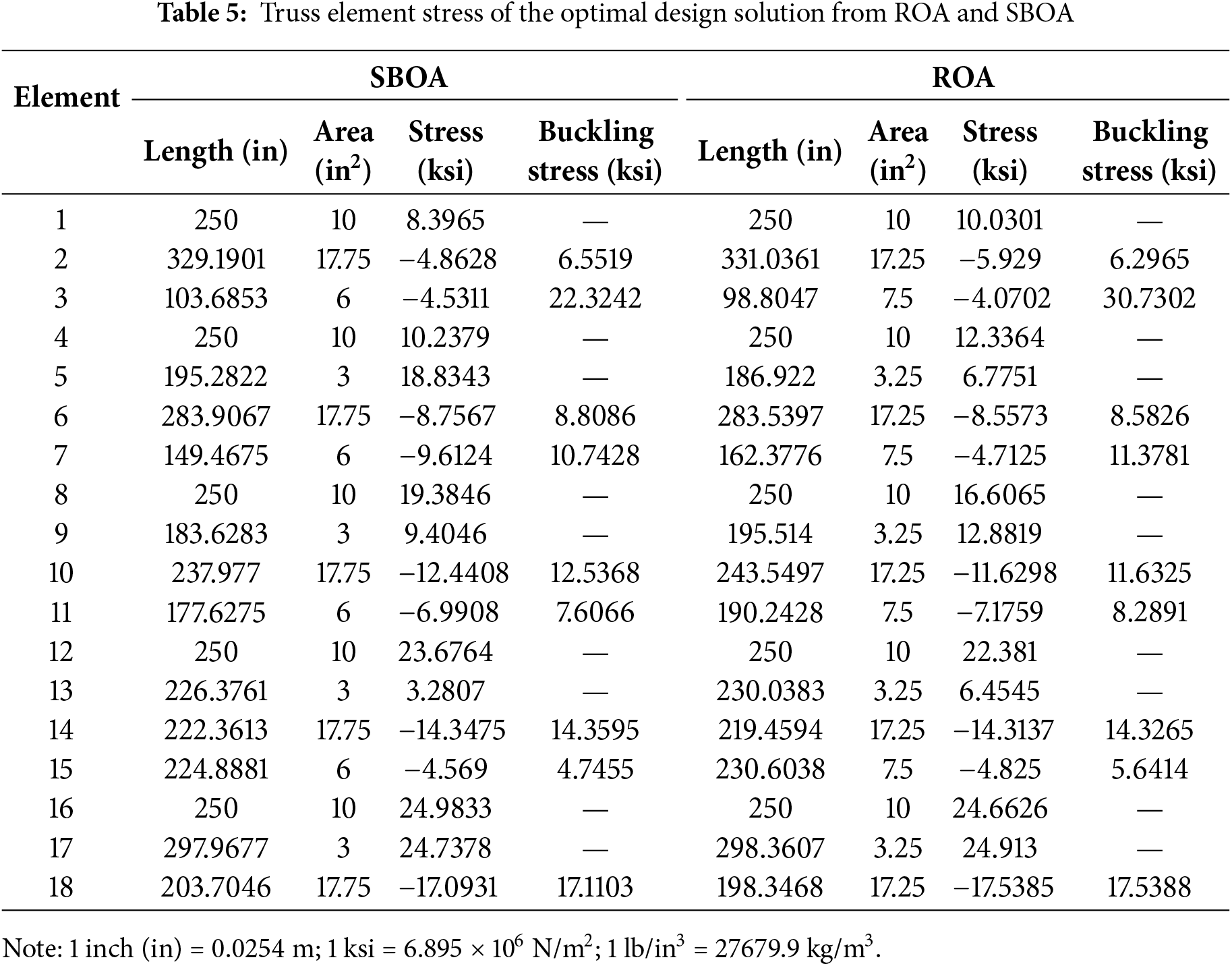

The value of the best design variables given by the employed algorithms is provided in Table 4 along with optimization results from other methods. The table shows that both ROA and SBOA performed better in this optimization problem, with total optimum weights of 4181.3004 lb. and 4258.5251 lb., respectively, outperforming other algorithms. The best optimum layout, given by SBOA, Figs. 5 and 6, shows the stress on the best-optimized truss designs. Elements did not violate stress constraints, with the stresses remaining within the limit of ±25 ksi. This is also evident in Table 5. In addition, Table 5 lists the values of optimum bar area, length, and limiting Euler buckling. The table indicates that all bars under compression have stresses below their respective allowable maximum buckling stress.

Figure 5: Schematic of the optimized 18-bar planar truss structure

Figure 6: Schematic of the optimized 18-bar planar truss structure (SBOA) with element stress

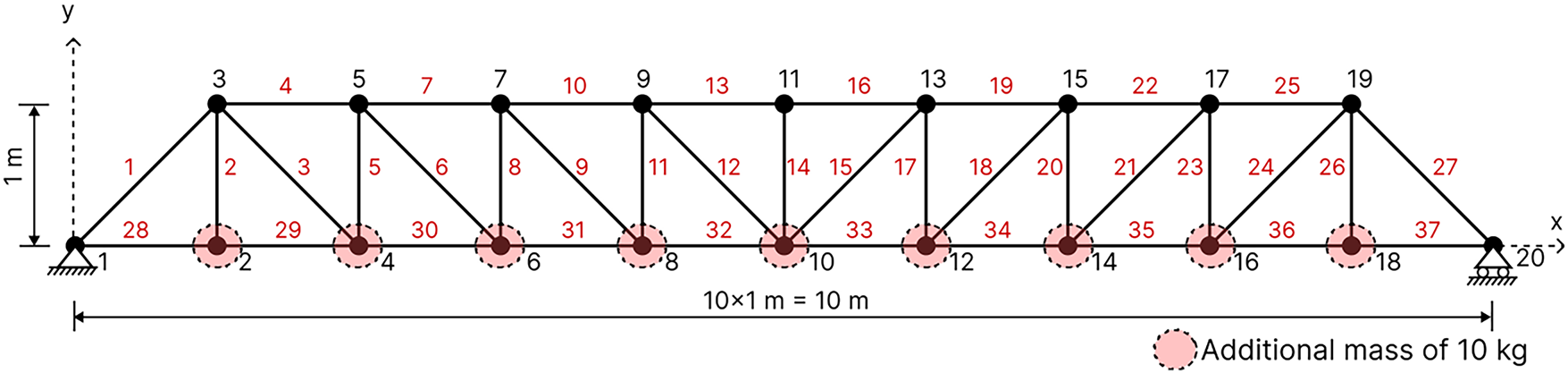

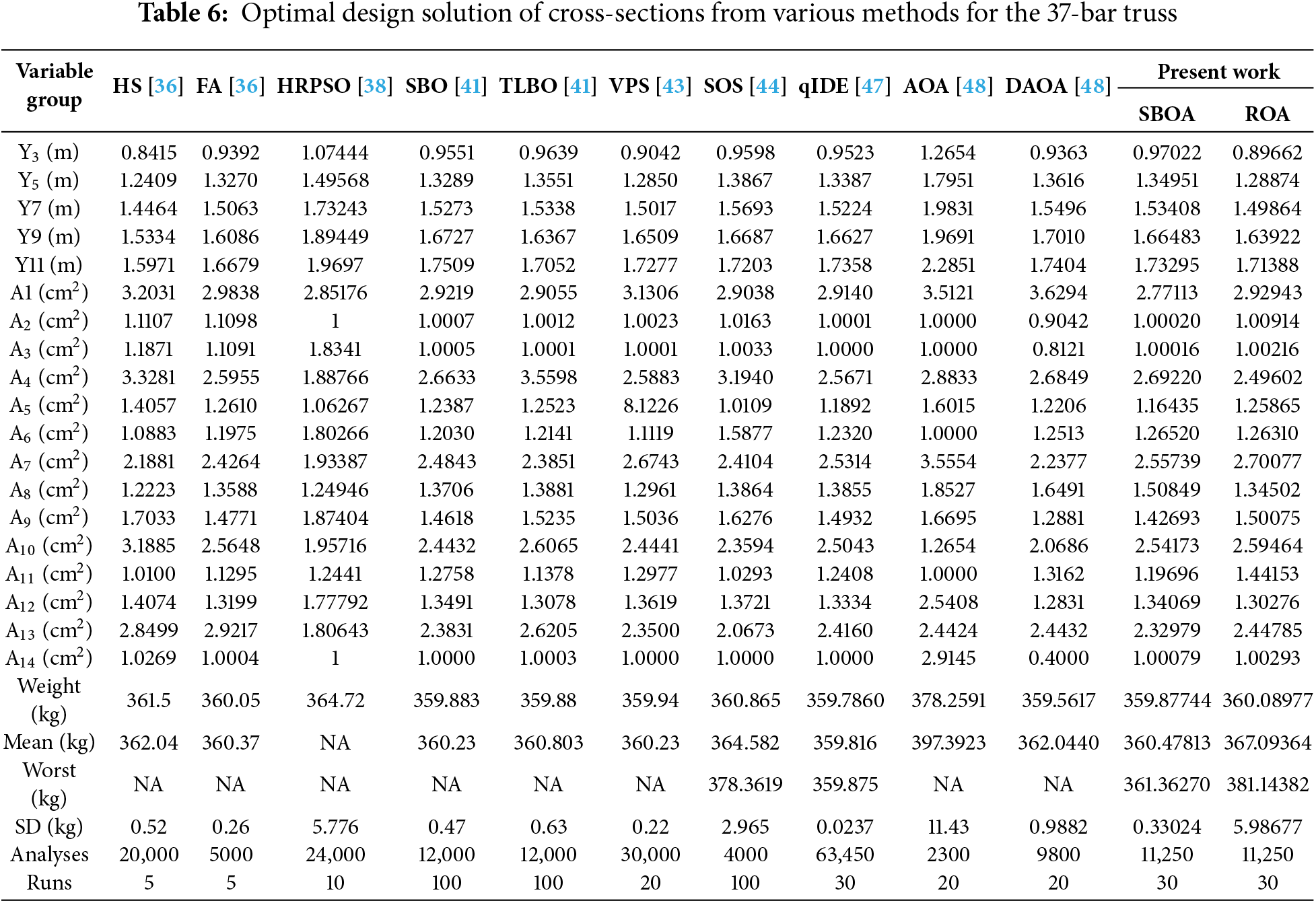

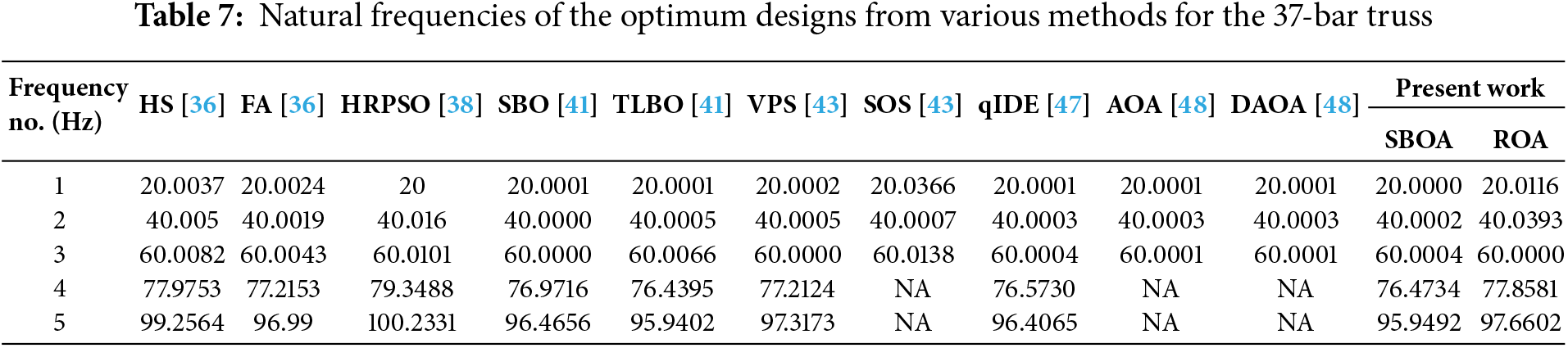

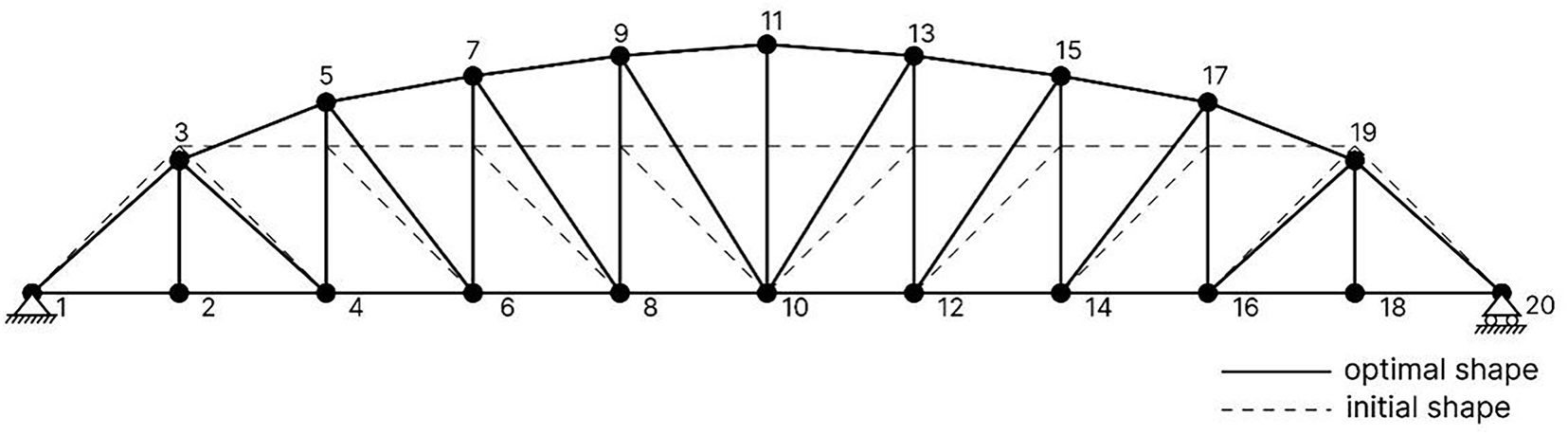

4.4 The 37-Bar Planar Truss Structure

A 37-bar planar truss structure is illustrated in Fig. 7. This optimization problem includes layout optimization and section size optimization. The planar bridge truss is a simply supported structure, with a fixed support at node 1 and a roller support at node 20. Fig. 7 indicates that free nodes at lower chords are subjected to a constant non-structural mass of 10 kg [36,38,41,43]. Similar approaches have also been adopted in [45,47,48] as presented in Table 6. The lower chords have an area of 4 × 10−3 m2 and are taken as constant, whereas the areas of other bars are taken as variables. This truss example has five layout variables and fourteen sizing variables. The coordinates of the lower chords are fixed, but the y-axis coordinates of the upper nodes are taken as variables and are bounded in the range of −0.5 to 2.5 m [47]. The variable groups and corresponding design variables, material properties, and constraints are presented in Table 1. For this problem, penalty factors

Figure 7: Schematic of the 37-bar simply-supported planar truss structure with added mass

SBOA (359.87744 kg) performed slightly better than ROA (360.08977 kg). The optimum value obtained by SBOA is comparable with that of DAOA (359.5617 kg) and qIDE (359.7860 kg). The mean and standard deviation of SBOA are 360.47813 and 0.33024 kg, respectively, which are lower than those of DAOA. This indicates that SBOA can produce more consistent results than DAOA. The natural frequencies of the optimal truss designs are presented in Table 7. The first three frequencies are above the values of 20, 40, and 60 Hz, conforming to their respective constraints. The best optimum layout, which is given by SBOA, is shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Schematic of the optimized 37-bar simply-supported planar truss structure

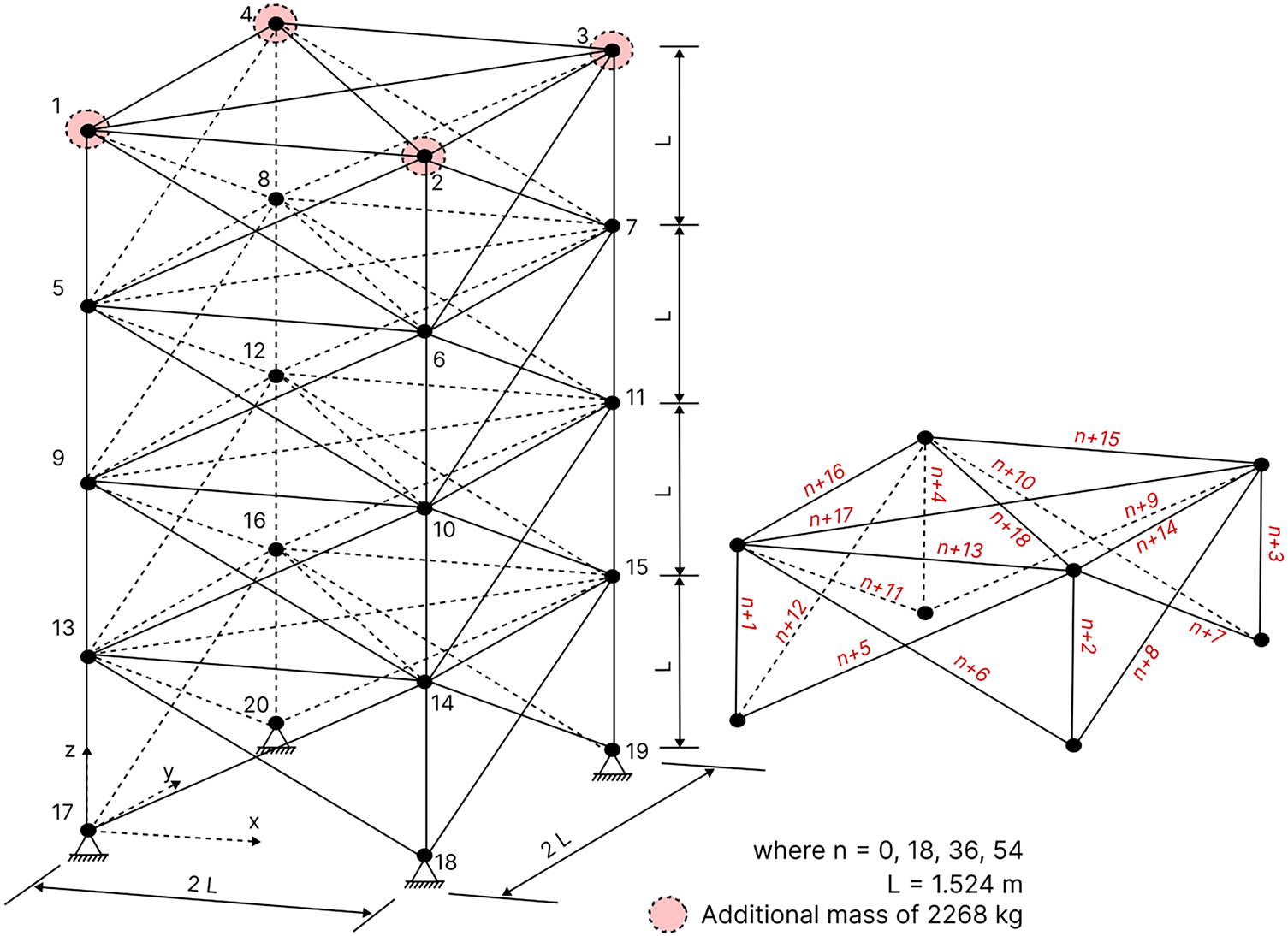

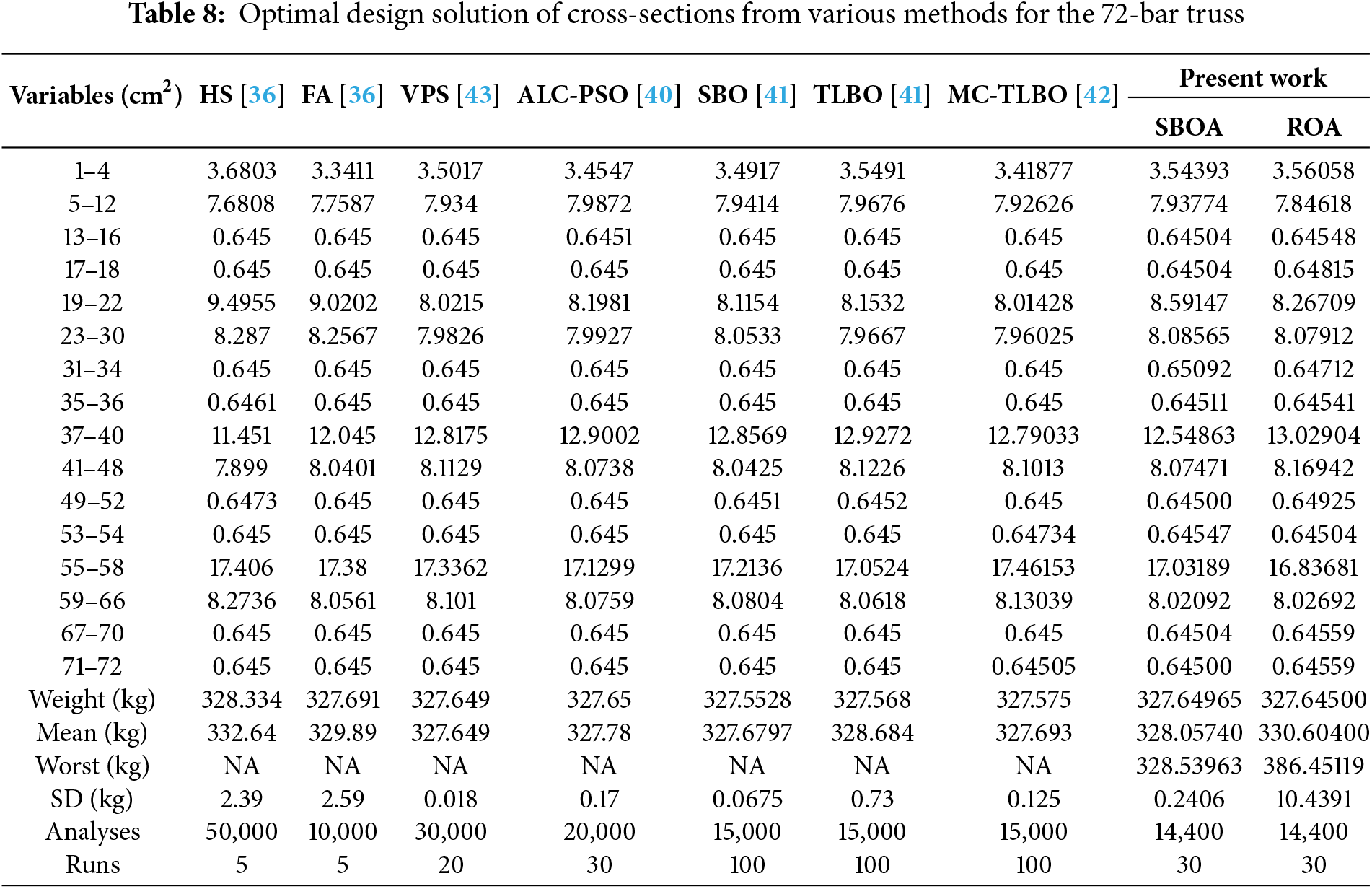

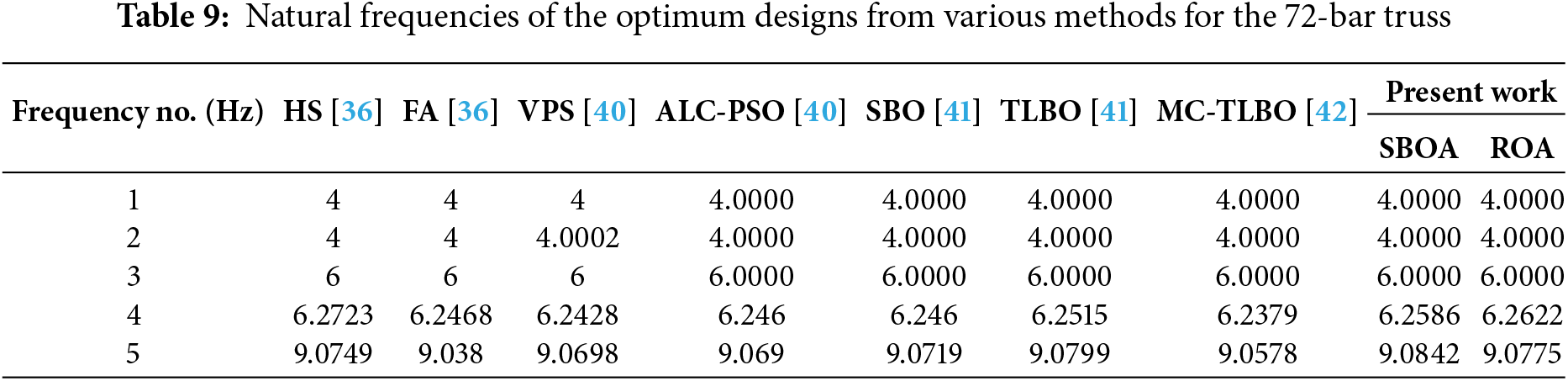

4.5 The 72-Bar Space Truss Structure

Fig. 9 illustrates the topology of a 72-bar space truss. It indicates that an additional mass of 2268 kg is added to nodes 1, 2, 3, and 4. The 72 bars are divided into 16 sizing variable groups to ensure symmetry of the structure [36,40–43]. Table 1 lists the material properties of the truss element, sizing variables constraints, and frequency constraints. During optimization, the population size and the total number of iterations are kept at 20 and 720, respectively, while the penalty factor

Figure 9: Schematic of the 72-bar space truss structure with added mass

The results of ROA and SBOA for this truss structure are listed in Table 8, and the corresponding frequencies are detailed in Table 9. Both the employed optimization algorithms gave similar optimal weights. In this optimization example, ROA achieved a lower final weight than SBOA. However, the mean weight and the standard deviation given by SBOA are lower. The optimized weights were greater than those of SBO, TLBO, and MC-TLBO, but they were more optimized than the rest of the algorithms. Table 9 shows that the frequencies of the optimal designs are greater than the lower limits as mentioned in Table 1, satisfying their constraints. Studies have solved this truss optimization with different values of non-structural mass, material density, and modulus of elasticity [47,48,56,58,59].

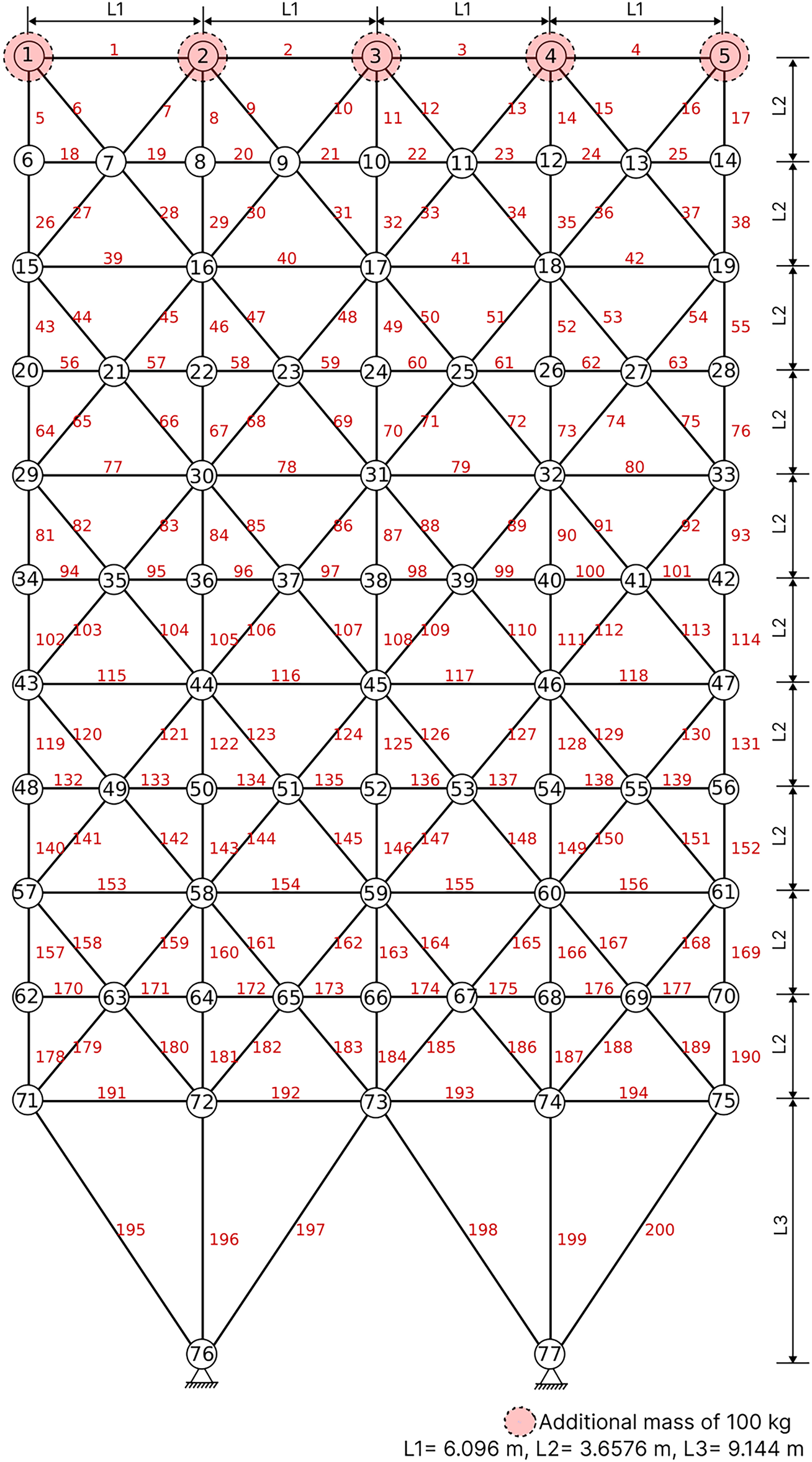

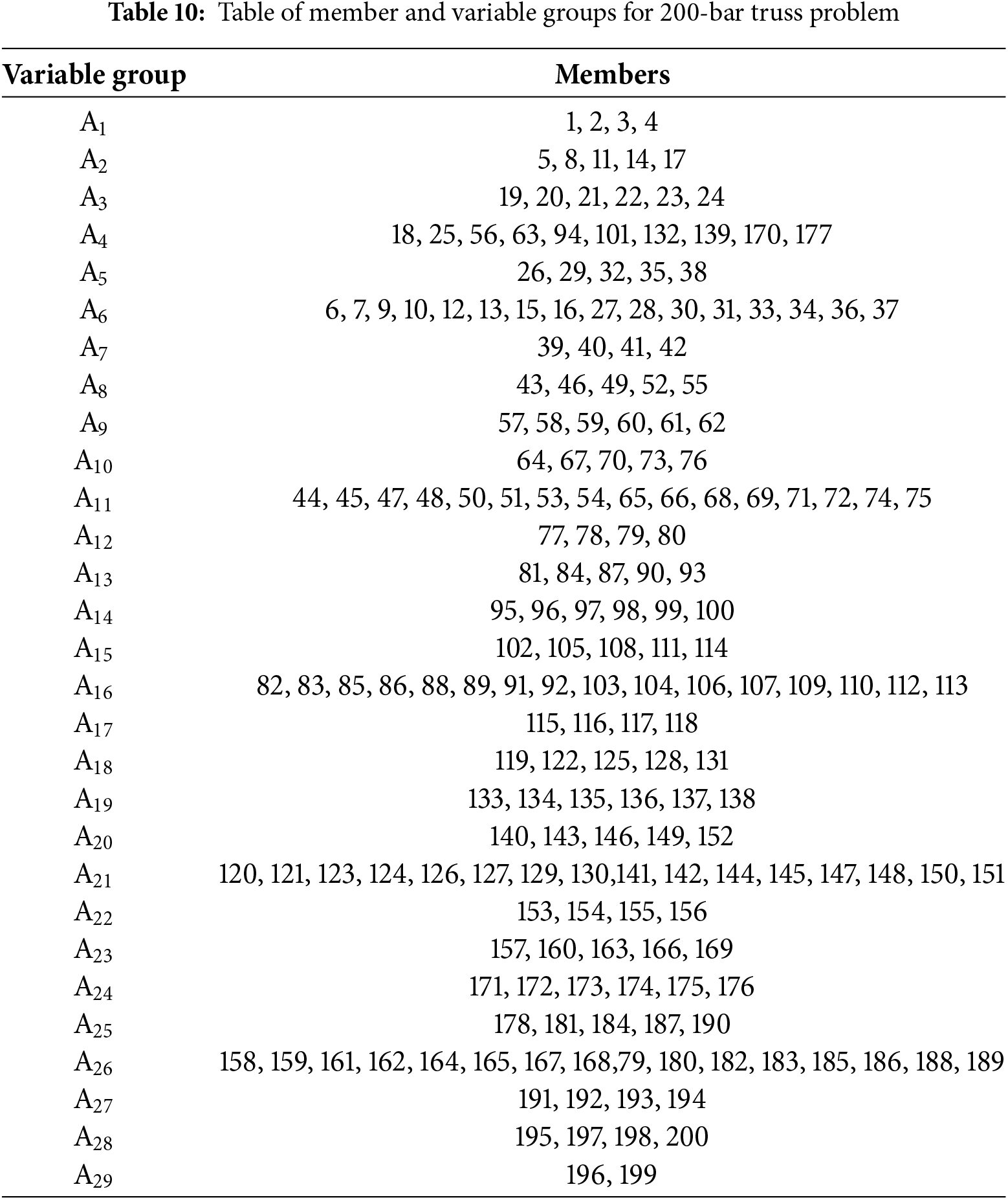

4.6 The 200-Bar Planar Truss Structure

Fig. 10 shows the topology of a 200-bar planar truss. This is an example of size optimization with frequency constraints. A non-structural mass of 100 kg is added to nodes 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, which are at the top of the structure. Table 1 lists the material properties of the truss element, sizing variables constraints, and frequency constraints. The truss members are divided into 29 groups as shown in Table 10. During optimization, for SBOA, the population size and the total number of iterations are kept at 18 and 500, while the penalty factors

Figure 10: Schematic of the 200-bar planar truss structure with added mass

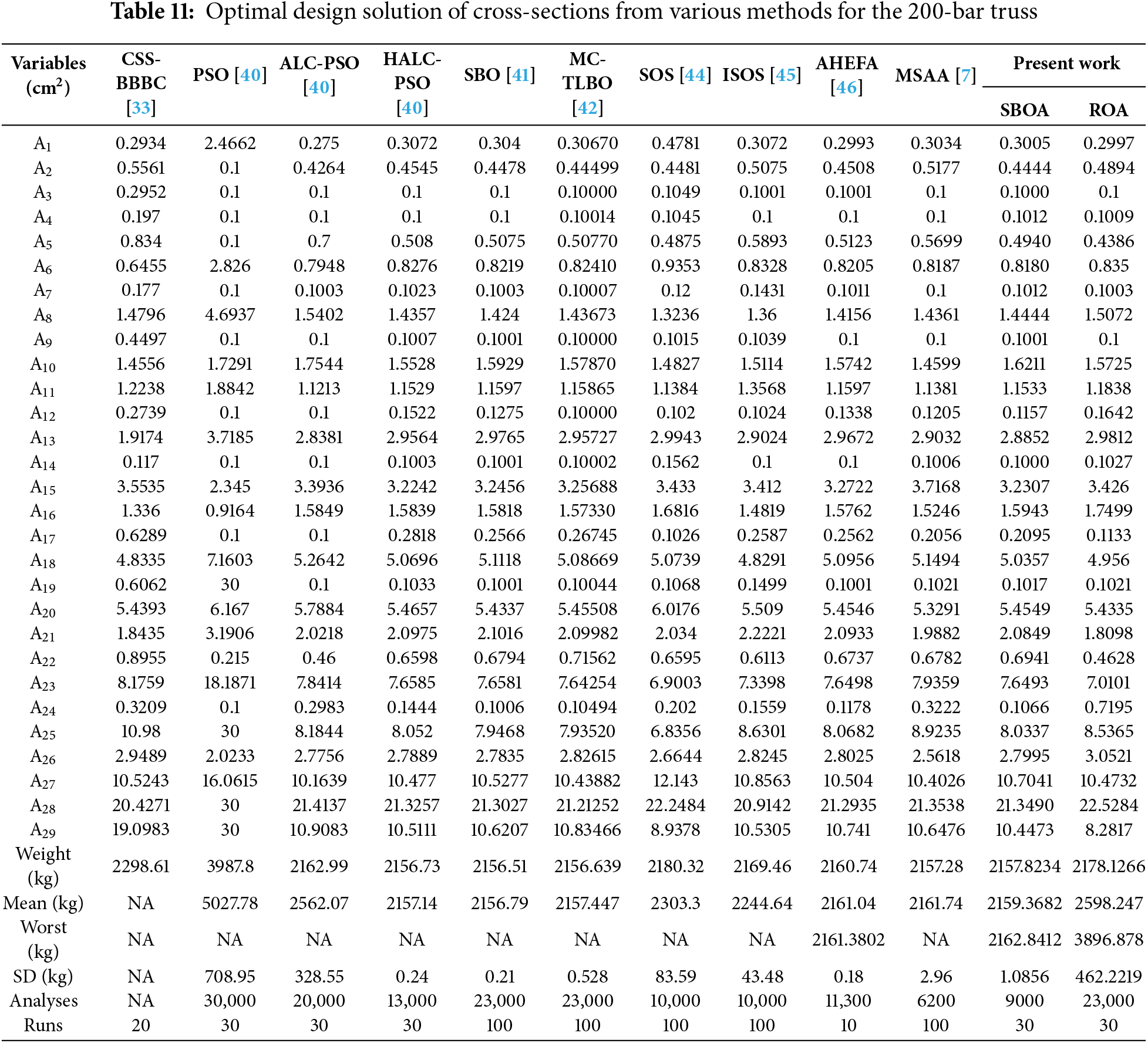

The optimization results are listed in Table 11. The weight obtained by SBOA (2157.8234 kg) is less than that given by CSS-BBBC (2298.61 kg), PSO (3987.8 kg), ALC-PSO (2162.99 kg), SOS (2162.99 kg), ISOS (2169.46 kg), AHEFA (2160.74 kg), and ROA (2178.1266 kg). However, the optimal design given by SBOA is 1.0934, 1.3134, 1.1844, and 0.5434 kg heavier than HALC-PSO, SBO, MC-TLBO, and MSAA, respectively. ROA, however, did not perform well in this example. SBOA exhibited stable performance with an SD of 1.2379 kg and a mean of 2158.3575 kg. Table 12 lists the natural frequencies. It indicates that the designs adhered to the frequency constraints.

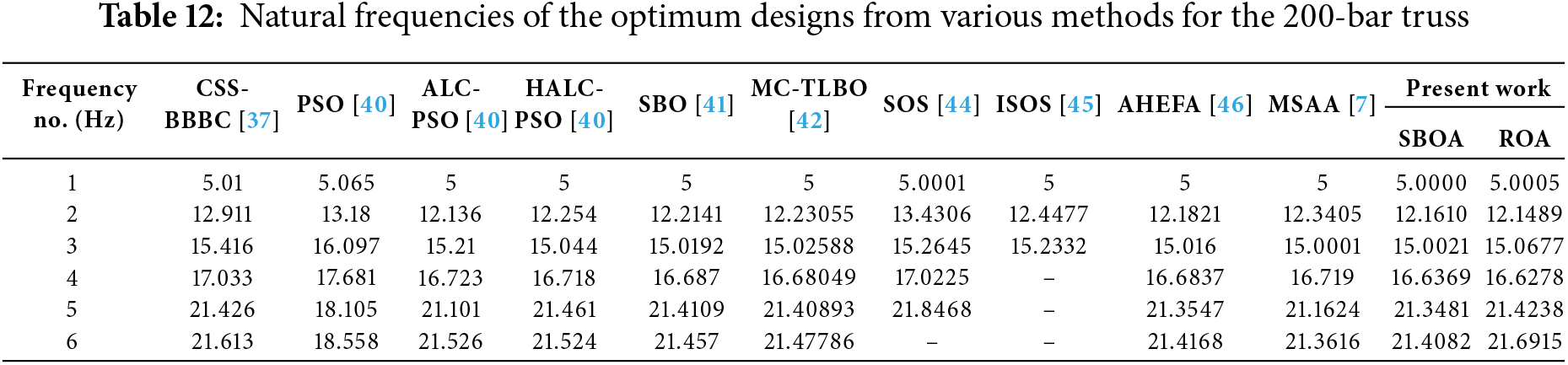

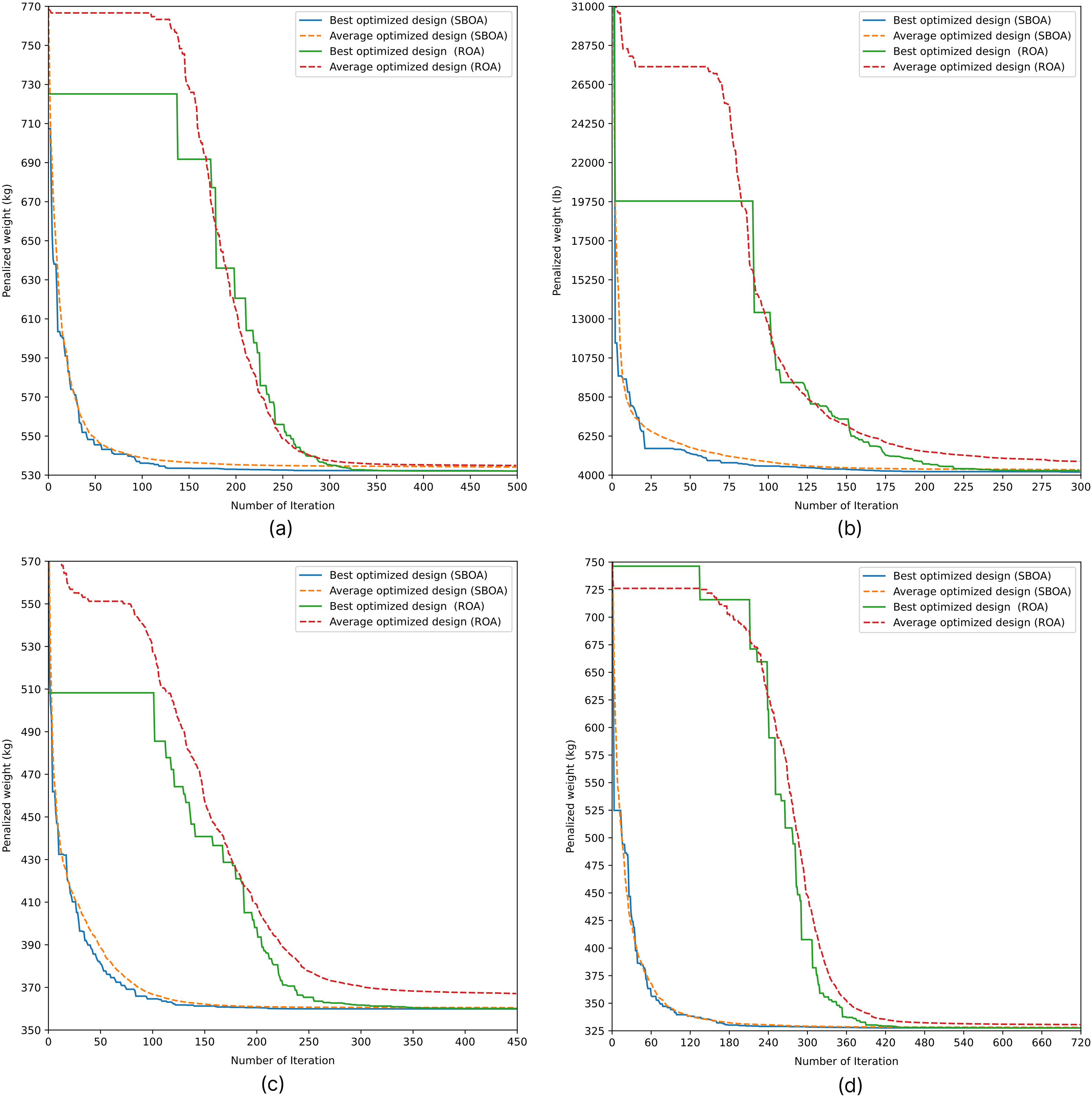

The convergence patterns for the 10-bar, 18-bar, 37-bar, and 72-bar truss structures are showcased in Fig. 11a–d, respectively. Similarly, the convergence curve for the 200-bar truss using SBOA and ROA is shown in Fig. 12a,b, respectively. It can be observed that ROA and SBOA have their distinct convergence patterns. Convergence plots show the competitive nature of SBOA and ROA for minimizing the penalized weight of simple, moderate, and complex truss structures. This penalized weight is the summation of the total structure’s weight with penalties for constraint violations (as it is the primary objective). The iterations on the x-axis show how fast each algorithm converges toward an optimal design. Both a smooth and steep decrease of the penalized weight reflects good convergence speed, stability, and computational efficiency.

Figure 11: Convergence curve of (a) 10-bar truss, (b) 18-bar truss, (c) 37-bar truss and (d) 72-bar truss

Figure 12: Convergence curve of 200-bar truss with (a) SBOA and (b) ROA

SBOA converges faster and more stably than ROA for 10-, 18-, 37-, and 72-bar trusses. The value of the penalized weight in SBOA is much smaller than that of ROA, and it drops significantly in the first 150–250 iterations. The plots for the SBOA best and average optimized designs are close to each other, reflecting small variance between runs and robust performance. Analogously, on the other hand, ROA’s convergence curves present a series of plateaus and oscillations, which are interpreted as local minima at which the algorithm freezes temporarily before continuing. The discrepancy is primarily due to the internal search mechanism of SBOA, which assumes Lévy flight-type random walks and a hierarchical movement manner motivated by the hunting process of secretary birds.

For SBOA, the Lévy flight mechanism permits different step sizes in the search. The early large jumps allow for exploring the whole design search space by ‘jumping out’ of local minima or plateaus, avoiding premature convergence and enhancing global exploration. With any increase in iterations, the step size continues to decrease, promoting exploitation within promising regions. This inherited robust adaptation for dynamic strategy balancing and based on it, the non-uniform strategy selection makes SBOA to have a better trade-off between exploration and exploitation, which can lead to a faster convergence rate with stable performance. ROA instead uses a fixed or limited random range of movement based on the flock behavior, and this can lead to slower convergence speed and a higher possibility of being stuck in a local optimum.

For the 200-bar truss, these benefits are even more significant. In the optimization curve for penalized weight of SBOA, the latter keeps a quick and monotonic decrease to reach optimal solutions after 100–150 iterations. ROA has a much slower convergence with longer periods of plateaus, particularly in the middle of the optimization. The small separation between SBOA’s best and average curves reflects the ability of its Lévy flight strategy to foster population diversity while preventing over-concentration in suboptimal areas, which makes the method produce more stable results even in high-dimensional search spaces. This is also indicated by the standard deviations mentioned in the result tables (Tables 2, 4, 6, 8, 11).

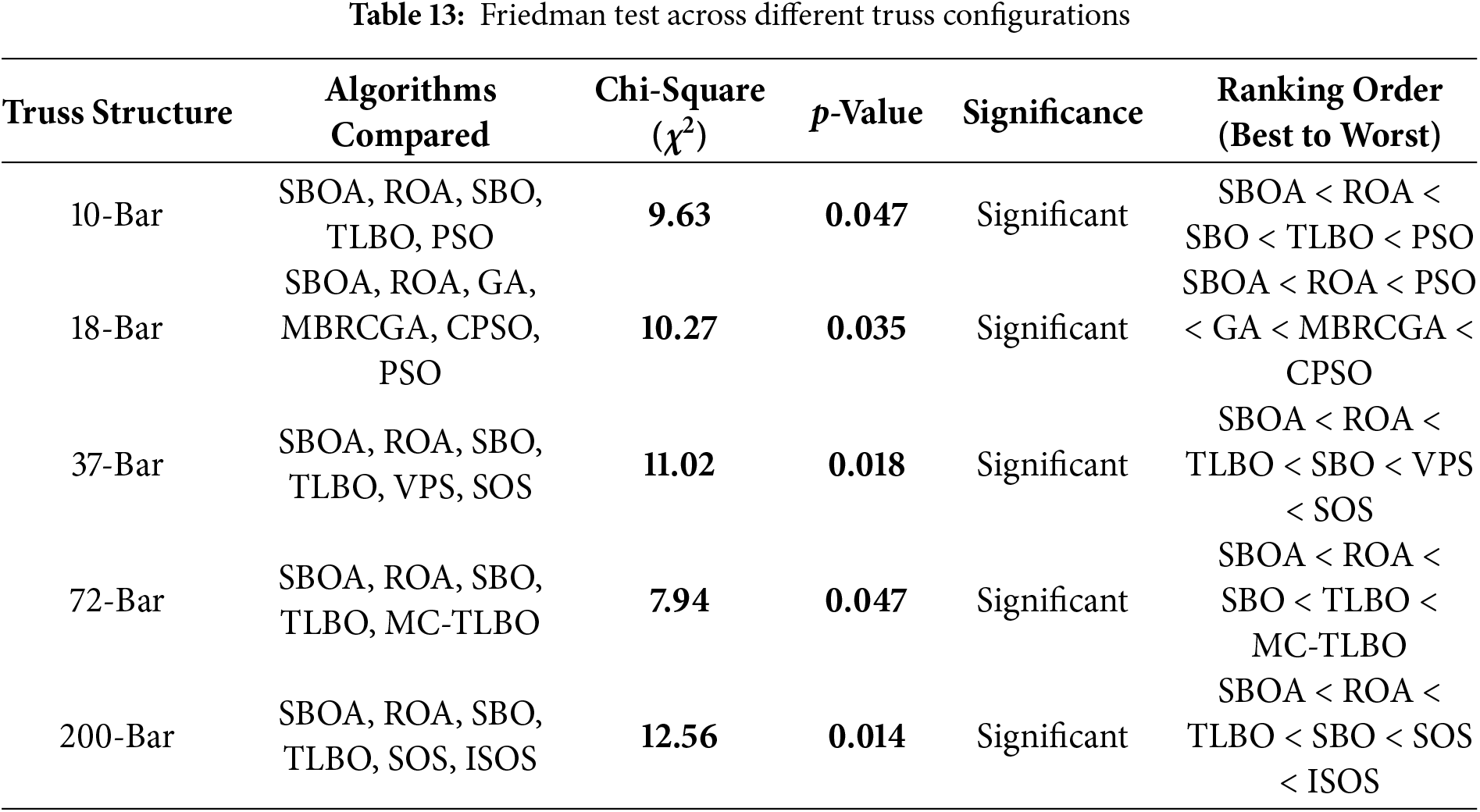

A Friedman test was performed to check if any observed differences between the optimization approaches were significant over all the trusses. This non-parametric test relies on the ranking of the algorithm rather than numerical differences, and therefore fits particularly well to engineering optimization studies where trends in convergence and variability are at least as significant as actual objective values. The Chi-Square measure χ2 indicates how much the observed rankings differ from what will be predicted when it is presumed that all algorithms have equal performance. The p-value for the χ2 statistic is a measure of the probability that these differences are merely chance. It was such, therefore, when p < 0.05, the null hypothesis that all algorithms run equivalent was rejected, indicating significant variability was yielded.

The results of the Friedman test for each truss structure are shown in Table 13. The results also reveal that for the 10-bar truss, a χ2 value of 9.63 and p-value of 0.047 are observed, indicating the difference between the algorithms’ performance is statistically significant. The ranking order (SBOA < ROA < SBO < TLBO < PSO) provides evidence that the proposed algorithms perform better than some established methods. This improvement is attributed to their well-developed exploration–exploitation strategies and the modified Levy flight strategy in SBOA, which can provide greater global search diversity, as a result making it less prone to early convergence in low-dimensional design space.

For the 18-bar truss, the Friedman test has χ2 = 10.27 (p = 0.035), so differences are again statistically significant. Although the classical methods GA, MBRCGA, and CPSO also behave properly, they exhibit slower convergence and less ability to adapt themselves to the nonlinear constraint manifold in contrast to SBOA and ROA. Therefore, in comparison to the multi-factorial evolutionary algorithm (MFEA-II), it is noticed that the Levy flight–based randomization within SBOA and the adaptive reflection behavior of ROA allow these two models to retain multiple solution diversity while extracting elite solutions so as to ensure better stability and lighter optimal weights. For the 37-bar, χ2 = 11.02 with p = 0.018 validates the superiority of SBOA, ROA over SBO, TLBO, VPS, and SOS. With the increase of dimensionality, exploration plays a more important role in algorithms, and traditional algorithms such as TLBO and VPS cause local trapping to be inefficient. On the other hand, stochastic step-length control utilizing Levy distribution jumps employed by SBOA provides the agent with more flexibility in searching throughout the solution space, and ROA (due to its oscillatory exploitation mechanism) helps optimize around near-optimal solutions.

The 72-bar truss obtains χ2 = 7.94 (p = 0.047), demonstrating a significant difference in performance, but with algorithms having somewhat closer competition. In medium- to high-dimensions, SBOA ranks first again, followed by ROA and SBO. TLBO and MC-TLBO show good results in the experimental study but do not exhibit adaptive behavior to cope with constraint-induced changes in design. The stability of both SBOA and ROA can imply that they can also act as an adaptive mode to modulate search pressure to keep feasible solutions during the dynamic evaluation of boundaries in OpenSeesPy. The upper bound case, the 200-bar truss, has the highest Chi-Square (χ2 = 12.56, p = 0.014), thus indicating a strong difference in algorithm performance as problem complexity increases. SBOA and ROA also show their supremacy over SBO, TLBO, SOS, and ISOS. This result stresses the fact that the two proposed algorithms operate efficiently and robustly in terms of large-scale structural optimization. The enhancement is attributed to long-term exploration due to Levy flight and adaptive parameter adjusting, which can lead to the convergence stability and prevent it from falling into a local optimal solution quickly in a high-dimensional multimodal search space. Such mechanisms become vital for performance maintenance on the way up in truss dimensionality, and this is why classical swarm optimizers, including PSO and TLBO, lose their effectiveness.

Two modern nature-inspired algorithms, specifically bird-inspired, the Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA) and the Red Kite Optimization Algorithm (ROA), are evaluated for solving truss optimization problems. Four frequency-constrained and one stress-constrained trusses are optimized with the algorithms. The optimization problems are diverse; some are weight optimization, while others are weight and layout optimization. The optimum results are compared to different studies. In the truss problems, except for the 72-bar truss optimization, SBOA performed better than ROA. SBOA converged faster than ROA in all examples; this better performance of SBOA can be attributed to the use of the Levy flight, which mitigates the risk of being trapped in a local solution and enhances the convergence precision. When compared to other algorithms, ROA and SBOA perform well. In 10-bar and 37-bar trusses, the employed algorithms perform comparably to the best-performing algorithms, whereas in the 18-bar truss with stress constraint, the algorithms achieve the lowest weights, outperforming other algorithms.

The comparison results of all truss structures show that the SBOA is better than the ROA in convergence rate, stability, and computational efficiency. Both approaches generated structurally sound, lightweight truss designs, and the improvement is evident when using the SBOA. The average weight savings of SBOA compared to the ROA are between 0.02% and 0.15%, smaller in low-dimensional trusses (10-bar, 18-bar) and higher in high-dimensional models (72-bar, 200-bar).

Such excellent performance is mainly because SBOA follows a variable operation strategy based on the Levy flight mechanism, which brings in long-range exploration when it is young and thus effectively enhances its global search ability. The Levy distribution allows the algorithm to escape from local basins and is particularly useful for large truss spaces with nonlinear stress and frequency constraints. ROA is built on the social foraging and reflects the behavior of red kites, which adapts a locally convergent oscillation manner that efficiently intensifies searching regions but is deprived of stochastic reach to get out of sub-optimal regions once convergence happens. Thus, the ROA tends to converge soon around local optima when constraint coupling is strong, especially for large trusses. In terms of convergence, SBOA generally achieves a stable optimal solution 15%–20% faster than ROA. For the smaller problems (10- and 18-bar trusses), SBOA stabilizes at about 60%–70% of total iterations, while ROA needs 75%–85%. For the more complex 72- and 200-bar trusses, convergence is achieved at around iteration numbers between 8000–8500 out of 10,000 using SBOA, while for ROA, iteration numbers go up to about 9000–9200. This efficiency results in a decrease of 10%–18% for the computing time, which is credited to the optimal proportionality ratio of global exploration and local exploitation due to dynamic control coefficients in SBOA. Standard deviation (SD) results also confirm the better reliability of SBOA. In most truss topologies, the SD in the last objective (structural weight) under SBOA is at 0.20–0.33 kg for small-sized trusses and 0.33–1.09 kg for larger ones, as compared to that in ROA with higher values of 0.28–0.38 kg and 0.90–1.45 kg, respectively. This shows that SBOA not only discovers superior solutions but also does so more often in independent runs. The computational convergence curves also illustrate the advantage of SBOA. In iterative curves, SBOA exhibits a highly rapid initial descent in objective value behavior (acts more aggressively but stably during the global search stage). ROA has a delayed early decline with a slower and plateauing convergence track indicative of progressive refinement. The dual nature that SBOA strikes between the Levy-driven global moves and adaptive local search enables it to dynamically adjust the response on constraint feedback for each iteration. In the practical engineering sense, this also implies that SBOA’s adaptive motion scheme enables it to be more effective in exploring complex constraint surfaces and large trusses where frequency and stress constraints interact nonlinearly with design frequency. ROA is competitive for mid-scale problems, exhibiting good exploitation accuracy now, with a weakness of being more sensitive to parameters.

Although SBOA and ROA proved to perform well for all trusses, this research has some shortcomings that consider future work in terms of its improvement. The present design variable strategy has concentrated only on the structural weight minimization subject to frequency and stress limits. However, being a single-objective approach to algorithm evaluation, this fails to account for other critical engineering factors, including cost of material, ease of realization, and manufacturability. In the future, more advanced optimization models, such as multi-objective or cost-integrated ones that consider weight saving together with practical design variables and sustainability measures, can be developed based on the proposed method. Another shortcoming is the absence of a thorough computational efficiency analysis. Although the algorithms are compared statistically and their convergence is examined, the study does not report a standardized measure of computation time or how performance scales with problem size, i.e., for large trusses such as those in the 200-bar configuration. Therefore, the future work should include a thorough runtime and scalability analysis, certainly benchmarking all algorithms under the same computational settings. It will be more meaningful if the results can also be compared in terms of efficiency, i.e., convergence rate (iteration time) and energy. In addition, the reliability of SBOA and ROA for different levels of constraints, such as tightening the stress or displacement bounds, was not explored in this study. Many of these computations will also provide insight into how each algorithm responds to limiting design envelopes or variable loading cases. Future research can be conducted on robust or reliability-based optimization problems, such that both algorithms are compared under uncertainty and in conditions to provide a more reliable structural design.

Another shortcoming is the lack of experimental confirmation. All the results are obtained based on numerical experiments by the finite element method, and no experimental test is conducted. Though validating simulation is useful, experimental validation of the optimized truss structures or comparison to actual field-measured data will significantly improve the practical credibility of such optimization methodologies. It is also recommended for the future to have experimental or hybrid digital twin models included to validate and improve computational predictions. Lastly, the use of no standardized performance metrics, including unified time to computation or normalized measures of convergence, despite the study using a Friedman test for determining significance in results, greatly limits our ability to directly evaluate how efficiently each algorithm can solve problems across approaches such as TLBO, PSO, and SBO. This process should provide a benchmarking scheme for metaheuristic algorithms in structural optimization and rules for: (a) the efforts of computation, (b) the convergence characteristic, and (c) the repeatability among several independent runs.

Accordingly, this study validates that the SBOA can achieve significantly better optimization performances in comparison to both ROA and other state-of-the-art benchmark algorithms; however, generalization of its performance across wider engineering applications still remains to be addressed. Future work should be devoted to further improving scalability, adopting hybrid optimization that combines SBOA’s Levy flight–based exploration and ROA’s reflection refinement, as well as integrating parameter adaptation based on machine learning for greater flexibility. Hence, the model is also applicable to dynamic loading, geometric nonlinearities, and composite material properties, which increases its usefulness for design and engineering. In addition, with multi-objective and data-validated optimization methodologies employed in the investigation work, an approach bridging computational efficiency and real-world design reliability will be developed towards next-generation structural engineering problems so that bio-inspired algorithms become more applicable.

Acknowledgement: The authors express their sincere gratitude to NRCC, Nepal, for providing the necessary resources, technical support, and guidance throughout this research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Sanjog Chhetri Sapkota: Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Software, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—Review and Editing, Investigation; Liborio Cavaleri: Data Curation, Methodology, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision; Ajaya Khatri: Writing—Original Draft, Data Curation, Validation, Investigation, Visualization, Software; Siddhi Pandey: Writing—Review and Editing, Investigation, Validation, Data Curation; Satish Paudel: Writing—Review and Editing, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Supervision; Panagiotis G. Asteris: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Software, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—Review and Editing, Investigation, Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All the datasets in this study are generated using codes developed by the authors. The full datasets, as well as the source codes, can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that can have appeared to influence the work reported.

References

1. Li LJ, Huang ZB, Liu F, Wu QH. A heuristic particle swarm optimizer for optimization of pin-connected structures. Comput Struct. 2007;85(7–8):340–9. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2006.11.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hsu YL. A review of structural shape optimization. Comput Ind. 1994;25(1):3–13. doi:10.1016/0166-3615(94)90028-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kaveh A, Khayatazad M. Ray optimization for size and shape optimization of truss structures. Comput Struct. 2013;117:82–94. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2012.12.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Grubits P, Cucuzza R, Habashneh M, Domaneschi M, Aela P, Movahedi Rad M. Structural topology optimization for plastic-limit behavior of I-beams, considering various beam-column connections. Mech Based Des Struct Mach. 2024;53(4):2719–43. doi:10.1080/15397734.2024.2412757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Carvalho JPG, Vargas DE, Jacob BP, Lima BS, Hallak PH, Lemonge AC. Multi-objective structural optimization for the automatic member grouping of truss structures using evolutionary algorithms. Comput Struct. 2024;292:107230. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2023.107230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lee D, Shon S, Lee S, Ha J. Size and topology optimization of truss structures using quantum-based HS algorithm. Buildings. 2023;13(6):1436. doi:10.3390/buildings13061436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Millan-Paramo C, Abdalla Filho JE. Size and shape optimization of truss structures with natural frequency constraints using modified simulated annealing algorithm. Arab J Sci Eng. 2020;45(5):3511–25. doi:10.1007/s13369-019-04138-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Michell AGM LVIII. The limits of economy of material in frame-structures. Lond Edinb Dubl Philos Mag J Sci. 1904;8(47):589–97. doi:10.1080/14786440409463229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Dorn WC, Gomory RE, Greenberg H. Automatic design of optimal structures. J Mech Phys Solids. 1964;12(3):179–88. [Google Scholar]

10. Hemp WS, Chan HSY. Optimum structures. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 1965 [cited 2025 Aug 28]. Available from: https://reports.aerade.cranfield.ac.uk/handle/1826.2/4320. [Google Scholar]

11. Rozvany GIN, Sokół T, Pomezanski V. Fundamentals of exact multi-load topology optimization: stress-based least-volume trusses (generalized Michell structures)—part I: plastic design. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2014;50:1051–78. doi:10.1007/s00158-014-1118-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Gilbert M, Tyas A. Layout optimization of large-scale pin-jointed frames. Eng Comput. 2003;20(8):1044–64. doi:10.1108/02644400310503017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ye J, Kyvelou P, Gilardi F, Lu H, Gilbert M, Gardner L. An end-to-end framework for the additive manufacture of optimized tubular structures. IEEE Access. 2021;9:165476–89. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3132797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. He L, Gilbert M, Johnson T, Pritchard T. Conceptual design of AM components using layout and geometry optimization. Comput Math Appl. 2019;78(7):2308–24. doi:10.1016/j.camwa.2018.07.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Weldeyesus AG, Gondzio J, He L, Gilbert M, Shepherd P, Tyas A. Truss geometry and topology optimization with global stability constraints. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2020;62:1721–37. doi:10.1007/s00158-020-02634-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Angelucci G, Mollaioli F, Tardocchi R. A new modular structural system for tall buildings based on tetrahedral configuration. Buildings. 2020;10(12):240. doi:10.3390/buildings10120240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhou H, Yang X, Tao R, Chen H. Improved sine-cosine algorithm for the optimization design of truss structures. KSCE J Civ Eng. 2024;28(2):687–98. doi:10.1007/s12205-023-0314-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yücel M, Nigdeli SM, Bekdaş G. Optimization of truss structures by using a hybrid population-based metaheuristic algorithm. Arab J Sci Eng. 2024;49(4):5011–26. doi:10.1007/s13369-023-08319-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Rezk H, Olabi AG, Wilberforce T, Sayed ET. Metaheuristic optimization algorithms for real-world electrical and civil engineering application, a review. Results Eng. 2024;23:102437. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Shaikh MS, Raj S, Zheng G, Xie S, Wang C, Dong X, et al. Applications, classifications, and challenges: a comprehensive evaluation of recently developed metaheuristics for search and analysis. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(12):390. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11377-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sanjalawe Y, Al-E’mari S, Abualhaj M, Makhadmeh SN, Alsharaiah MA, Hijazi DH. Recent advances in secretary bird optimization algorithm, its variants and applications. Evol Intell. 2025;18:65. doi:10.1007/s12065-025-01054-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Das A, Rai R, Sasmal B, Dhal KG, Khurma RA, Saha R. Metaheuristic algorithms since 2020, development, taxonomy, analysis, and applications. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2025;267:66. doi:10.1007/s11831-025-10408-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Rabie AH, Mansour NA, Saleh AI. Leopard seal optimization (LSOa natural inspired meta-heuristic algorithm. Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul. 2023;125:107338. doi:10.1016/j.cnsns.2023.107338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Rajwar K, Deep K, Das S. An exhaustive review of the metaheuristic algorithms for search and optimization: taxonomy, applications, and open challenges. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56:13187–257. doi:10.1007/s10462-023-10470-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Jiang X, Ma J, Teng X. A modified bi-directional evolutionary structural optimization procedure with variable evolutionary volume ratio applied to multi-objective topology optimization problem. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;135(1):511–26. doi:10.32604/cmes.2022.022785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Grubits P, Movahedi Rad M. Automated elasto-plastic design of truss structures based on residual plastic deformations using a geometrical nonlinear optimization framework. Comput Struct. 2025;316:107855. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2025.107855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Tao R, Yang X, Zhou H, Meng Z. Shape and size optimization of truss structures under frequency constraints based on hybrid sine cosine firefly algorithm. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;134(1):405–28. doi:10.32604/cmes.2022.020824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Rahami H, Kaveh A, Gholipour Y. Sizing, geometry and topology optimization of trusses via force method and genetic algorithm. Eng Struct. 2008;30(9):2360–9. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2008.01.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Azad SK, Azad SK, Kulkarni AJ. Structural optimization using a mutation-based genetic algorithm. Int J Optim Civ Eng. 2012;2(1):80–100. [Google Scholar]

30. Gholizadeh S. Layout optimization of truss structures by hybridizing cellular automata and particle swarm optimization. Comput Struct. 2013;125:86–99. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2013.04.024.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ho-Huu V, Nguyen-Thoi T, Nguyen-Thoi M, Le-Anh L. An improved constrained differential evolution using discrete variables (D-ICDE) for layout optimization of truss structures. Expert Syst Appl. 2015;42(20):7057–69. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2015.04.072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Mortazavi A, Toğan V, Nuhoğlu A. Weight minimization of truss structures with sizing and layout variables using integrated particle swarm optimizer. J Civ Eng Manage. 2017;23(8):985–1001. doi:10.3846/13923730.2017.1348982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kaveh A, Khosravian M. Size/layout optimization of truss structures using vibrating particles system meta-heuristic algorithm and its improved version. Period Polytech Civ Eng. 2022;66(1):1–17. doi:10.3311/PPci.18670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Sedaghati R, Suleman A, Tabarrok B. Structural optimization with frequency constraints using the finite element force method. AIAA J. 2002;40(2):382–8. doi:10.2514/2.1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wei LY, Zhao M, Wu GM, Meng G. Truss optimization on shape and sizing with frequency constraints based on genetic algorithm. Comput Mech. 2005;35:361–8. doi:10.1007/s00466-004-0623-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Miguel LFF, Miguel LFF. Shape and size optimization of truss structures considering dynamic constraints through modern metaheuristic algorithms. Expert Syst Appl. 2012;39(10):9458–67. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2012.02.113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kaveh A, Zolghadr A. Truss optimization with natural frequency constraints using a hybridized CSS-BBBC algorithm with trap recognition capability. Comput Struct. 2012;102:14–27. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2012.03.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Kaveh A, Javadi S. Shape and size optimization of trusses with multiple frequency constraints using harmony search and ray optimizer for enhancing the particle swarm optimization algorithm. Acta Mech. 2014;225(6):1595–605. doi:10.1007/s00707-013-1006-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kaveh A, Zolghadr A. Democratic PSO for truss layout and size optimization with frequency constraints. Comput Struct. 2014;130:10–21. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2013.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Kaveh A, Ghazaan MI. Hybridized optimization algorithms for design of trusses with multiple natural frequency constraints. Adv Eng Softw. 2015;79:137–47. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2014.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Farshchin M, Camp CV, Maniat M. Optimal design of truss structures for size and shape with frequency constraints using a collaborative optimization strategy. Expert Syst Appl. 2016;66:203–18. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2016.09.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Farshchin M, Camp C, Maniat M. Multi-class teaching-learning-based optimization for truss design with frequency constraints. Eng Struct. 2016;106:355–69. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2015.10.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kaveh A, Ilchi Ghazaan M. Vibrating particles system algorithm for truss optimization with multiple natural frequency constraints. Acta Mech. 2017;228:307–22. doi:10.1007/s00707-016-1725-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Tejani GG, Savsani VJ, Patel VK. Adaptive symbiotic organisms search (SOS) algorithm for structural design optimization. J Comput Des Eng. 2016;3(3):226–49. doi:10.1016/j.jcde.2016.02.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Tejani GG, Savsani VJ, Patel VK, Mirjalili S. Truss optimization with natural frequency bounds using improved symbiotic organisms search. Knowl Based Syst. 2018;143:162–78. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2017.12.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Lieu QX, Do DT, Lee J. An adaptive hybrid evolutionary firefly algorithm for shape and size optimization of truss structures with frequency constraints. Comput Struct. 2018;195:99–112. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2017.06.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Huynh TN, Do DT, Lee J. Q-Learning-based parameter control in differential evolution for structural optimization. Appl Soft Comput. 2021;107:107464. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Khodadadi N, Snasel V, Mirjalili S. Dynamic arithmetic optimization algorithm for truss optimization under natural frequency constraints. IEEE Access. 2022;10:16188–208. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3146374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Raeisi-Gahruei J, Beheshti Z. The electricity consumption prediction using hybrid red kite optimization algorithm with multi-layer perceptron neural network. J Intell Proced Electr Technol. 2022;15(60):19–40. [Google Scholar]

50. Alshareef SM, Fathy A. Efficient red kite optimization algorithm for integrating renewable sources and electric vehicle fast charging stations in radial distribution networks. Mathematics. 2023;11(15):3305. doi:10.3390/math11153305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Fu Y, Liu D, Chen J, He L. Secretary bird optimization algorithm: a new metaheuristic for solving global optimization problems. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(5):123. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10729-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Zhu M, McKenna F, Scott MH. OpenSeesPy: Python library for the OpenSees finite element framework. SoftwareX. 2018;7:6–11. doi:10.1016/j.softx.2017.10.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. McKenna F, Scott MH, Fenves GL. Nonlinear finite-element analysis software architecture using object composition. J Comput Civ Eng. 2010;24(1):95–107. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)CP.1943-5487.0000002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Grandhi R, Venkayya V. Structural optimization with frequency constraints. AIAA J. 1988;26(7):858–66. doi:10.2514/3.9979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wang D, Zhang W, Jiang J. Truss optimization on shape and sizing with frequency constraints. AIAA J. 2004;42(3):622–30. doi:10.2514/1.1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Gomes HM. Truss optimization with dynamic constraints using a particle swarm algorithm. Expert Syst Appl. 2011;38(1):957–68. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2010.07.086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Khatibinia M, Naseralavi SS. Truss optimization on shape and sizing with frequency constraints based on orthogonal multi-gravitational search algorithm. J Sound Vib. 2014;333(24):6349–69. doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2014.07.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Ho-Huu V, Vo-Duy T, Luu-Van T, Le-Anh L, Nguyen-Thoi T. Optimal design of truss structures with frequency constraints using improved differential evolution algorithm based on an adaptive mutation scheme. Autom Constr. 2016;68:81–94. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2016.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Khodadadi N, Harati E, De Caso F, Nanni A. Optimizing truss structures using composite materials under natural frequency constraints with a new hybrid algorithm based on cuckoo search and stochastic paint optimizer (CSSPO). Buildings. 2023;13(6):1551. doi:10.3390/buildings13061551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools