Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Several Improved Models of the Mountain Gazelle Optimizer for Solving Optimization Problems

Department of Computer Engineering, Ur., C., Islamic Azad University, Urmia, Iran

* Corresponding Authors: Farhad Soleimanian Gharehchopogh. Email: ,

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 24 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.073808

Received 26 September 2025; Accepted 28 November 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

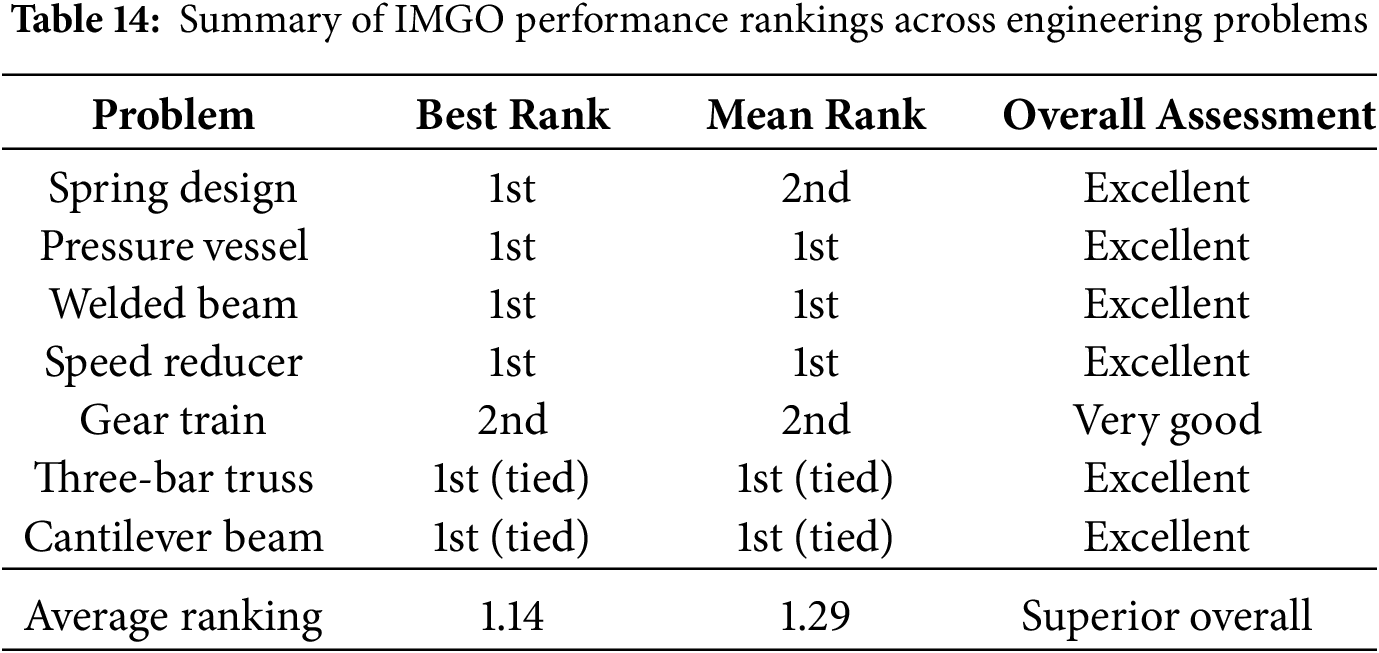

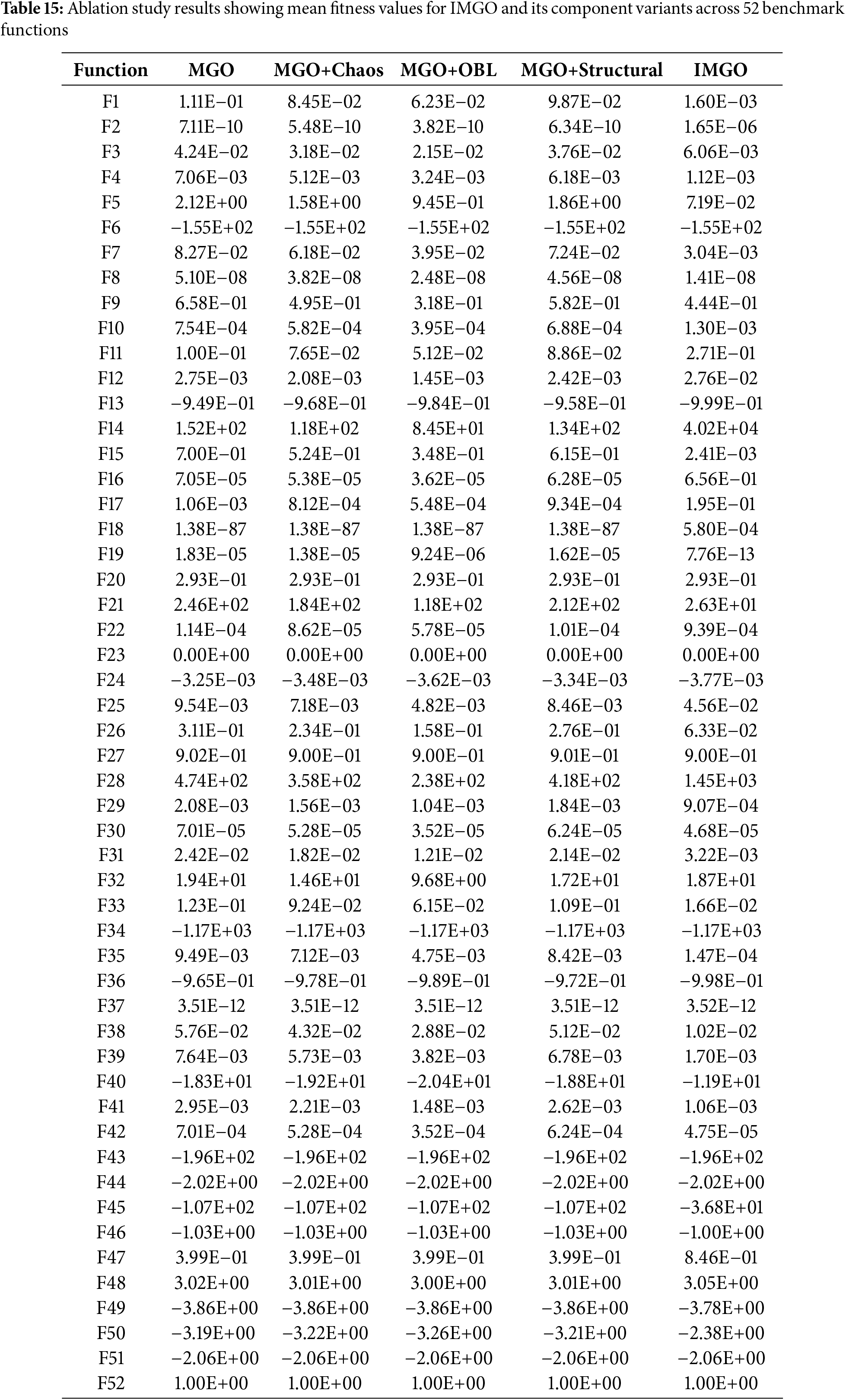

Optimization algorithms are crucial for solving NP-hard problems in engineering and computational sciences. Metaheuristic algorithms, in particular, have proven highly effective in complex optimization scenarios characterized by high dimensionality and intricate variable relationships. The Mountain Gazelle Optimizer (MGO) is notably effective but struggles to balance local search refinement and global space exploration, often leading to premature convergence and entrapment in local optima. This paper presents the Improved MGO (IMGO), which integrates three synergistic enhancements: dynamic chaos mapping using piecewise chaotic sequences to boost exploration diversity; Opposition-Based Learning (OBL) with adaptive, diversity-driven activation to speed up convergence; and structural refinements to the position update mechanisms to enhance exploitation. The IMGO underwent a comprehensive evaluation using 52 standardised benchmark functions and seven engineering optimization problems. Benchmark evaluations showed that IMGO achieved the highest rank in best solution quality for 31 functions, the highest rank in mean performance for 18 functions, and the highest rank in worst-case performance for 14 functions among 11 competing algorithms. Statistical validation using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests confirmed that IMGO outperformed individual competitors across 16 to 50 functions, depending on the algorithm. At the same time, Friedman ranking analysis placed IMGO with an average rank of 4.15, compared to the baseline MGO’s 4.38, establishing the best overall performance. The evaluation of engineering problems revealed consistent improvements, including an optimal cost of 1.6896 for the welded beam design vs. MGO’s 1.7249, a minimum cost of 5885.33 for the pressure vessel design vs. MGO’s 6300, and a minimum weight of 2964.52 kg for the speed reducer design vs. MGO’s 2990.00 kg. Ablation studies identified OBL as the strongest individual contributor, whereas complete integration achieved superior performance through synergistic interactions among components. Computational complexity analysis established an O (T × N × 5 × f (P)) time complexity, representing a 1.25× increase in fitness evaluation relative to the baseline MGO, validating the favorable accuracy-efficiency trade-offs for practical optimization applications.Keywords

Contemporary optimization challenges frequently involve complex scenarios characterized by intricate parameter spaces and sophisticated constraints. The development of optimization methodologies for these problems has led to the emergence of various algorithmic frameworks, which are typically classified according to their state complexity and dimensional characteristics [1]. To address these computational challenges, researchers have developed diverse optimization frameworks. In cases where exact optimization methodologies are impractical, approximate algorithmic approaches have emerged as innovative solutions for managing complex, multidimensional, and multistate computational problems [2]. Drawing inspiration from natural and biological systems, these algorithmic frameworks employ stochastic exploration processes to identify optimal solutions within practical computational time frames. A critical consideration in such metaheuristic approaches is maintaining an adaptive balance between solution space exploration and local refinement processes [3]. The OBL paradigm offers an alternative approach to machine learning, rooted in the analysis of inverse relationships between system entities. Over the past decade, OBL has emerged as a promising research direction in computational optimization. Traditional metaheuristic approaches generally fall into three primary categories: evolutionary computation methods, physics-inspired algorithms, and swarm intelligence frameworks, all of which are inspired by natural selection.

The foundational principles of OBL were introduced in 2005, offering a systematic approach to simultaneously evaluate current estimates and their opposites to enhance the solution identification. In algorithmic optimization, where the goal is to achieve optimal solutions for specified objective functions, considering both estimates and their opposites can significantly improve the performance metrics. Previous studies have extensively explored OBL applications for defining transfer functions, optimizing neural network weights, generating evolutionary algorithm candidates, and determining reinforcement learning agent policies [4]. The core OBL methodology involves selecting optimal solutions for subsequent iterations by systematically comparing current solutions with their OBL counterparts. They have been successfully integrated into various metaheuristic frameworks to improve their ability to escape local optima. Contemporary real-world optimization challenges often involve complex, multifaceted problems that require sophisticated algorithms. Research efforts are increasingly focused on developing enhanced solutions through strategic combinations of complementary metaheuristic approaches. Hybrid methodologies typically emerge as novel combinations of existing algorithms or refinements of established techniques. Recent innovative hybrid frameworks have integrated chaos theory with metaheuristic algorithms [5]. Incorporating chaotic behaviour patterns enhances system performance metrics, improves the distribution of metaheuristic algorithms, accelerates convergence, and mitigates the challenges posed by local optima. Empirical studies have shown that chaos-enhanced hybrid algorithms effectively optimize engineering design problems, achieving superior accuracy and faster convergence. Recent research has extensively explored various combinations of chaos mapping and metaheuristic optimization [6].

Chaos theory offers a novel paradigm that is increasingly applied across various fields of study. One significant application of this technology is its integration with optimization methods. The stochastic and dynamic properties inherent in chaos theory accelerate the convergence of Optimization algorithms while promoting solution diversity. Chaos theory is susceptible to initial conditions, but retains random characteristics [7]. The MGO has achieved notable success in optimization applications, with both its original and enhanced versions addressing global optimization challenges [8]. Although this algorithm effectively circumvents local optima, it faces limitations, such as premature convergence and an imbalance between exploration and exploitation.

Since its inception, the MGO has been effectively applied across various engineering fields, particularly in hydrological modelling and water resource management, where it has demonstrated efficacy in optimizing parameters for complex environmental systems [9]. Despite these achievements, a systematic analysis of MGO’s optimization dynamics uncovers three fundamental limitations that impede its performance in complex, high-dimensional scenarios. First, the algorithm’s reliance on fixed random-number generation for position updates can lead to premature convergence, as search agents may cluster in suboptimal regions. This occurs because purely stochastic perturbations lack the diversity required to escape local attraction basins in multimodal landscapes. Second, the exploration-exploitation balance mechanism, primarily governed by the decreasing coefficient ‘a’ that linearly transitions from global exploration to local exploitation, is insufficiently adaptive to the specific characteristics of the problem landscapes. This can result in either excessive exploration, delayed convergence, or premature exploitation, thereby compromising the solution quality. Third, the four parallel update strategies (Territorial Solitary Males, Maternity Herds, Bachelor Male Herds, and Migration for Food Search), while biologically inspired and conceptually elegant, generate candidate solutions with limited diversity when population variance decreases, failing to maintain and recover diversity once the population converges toward local optima. These identified limitations motivated the development of the IMGO through the strategic integration of three complementary enhancement mechanisms, specifically targeting MGO’s convergence and diversity challenges. Chaos mapping addresses the stochastic diversity limitation by replacing uniform random number generation with deterministic chaotic sequences that exhibit ergodicity and sensitivity to initial conditions, ensuring a more thorough and non-repetitive exploration of the search space throughout the optimization iterations. OBL addresses the exploration-exploitation imbalance by introducing adaptive diversity-driven activation that generates complementary search directions when the population variance falls below threshold values, thereby dynamically reinforcing exploration precisely when premature convergence risks emerge. Structural refinements to the core position update equations address the diversity maintenance challenge through variance-aware initialization and escape factor modulation, which systematically prevent population clustering while preserving beneficial convergence toward promising regions. The synergistic integration of these three mechanisms provides a comprehensive solution to MGO’s fundamental limitations while preserving its computational efficiency and conceptual clarity, establishing the IMGO as an enhanced framework suitable for complex engineering Optimization that requires reliable convergence and superior solution quality.

Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of chaos-enhanced and OBL-integrated metaheuristics in recent studies, current methodologies face three significant limitations that hinder their practical application. First, chaos maps are typically applied uniformly across all Optimization phases, without systematic selection criteria that account for exploration-exploitation trade-offs. This approach leads to suboptimal diversity management and can disrupt the convergence dynamics. Second, OBL integration is mainly limited to population initialization, missing valuable opportunities for adaptive opposition-based diversity enhancement throughout iterative search processes. Third, structural modifications in swarm-based algorithms rarely address the inherent algorithmic tension between territorial establishment behaviors and migratory exploration patterns, often resulting in premature convergence in complex multimodal landscapes. The proposed IMGO framework systematically addresses these gaps through three synergistic innovations that collectively enhance both the exploration capability and convergence stability. The first innovation involves adaptive chaos integration, in which the piecewise-chaotic map is strategically embedded within the position-update mechanisms rather than uniformly applied. This selective integration, formalized through modified update equations, dynamically modulates the exploration intensity according to the iteration progress, thus preventing the excessive randomization typical of fixed chaos implementations. The second contribution extends the OBL beyond conventional initialization-only applications using a distance-based adaptive mechanism. This threshold-driven approach selectively activates opposition-based position generation when population diversity metrics indicate potential stagnation, thereby maintaining exploration capability while minimizing unnecessary computational overhead. The third innovation introduces structural refinements to MGO’s core behavioural models via variance-driven initialization and escape-factor modulation in the position-update equations. These modifications specifically target MGO’s documented tendency to prematurely converge on a specific region, which is a limitation of existing MGO variants and hybrid implementations. The integration of these three enhancement strategies distinguishes the IMGO from existing chaos-OBL hybrid algorithms in several fundamental aspects. Unlike previous implementations that treat chaos and opposition as independent augmentations, the IMGO establishes functional interdependencies between chaotic perturbation, opposition-based diversity maintenance, and structural behavioral refinements. This systematic integration approach enhances algorithmic scalability for high-dimensional optimization scenarios while simultaneously improving convergence stability metrics across diverse problem landscapes. The subsequent sections provide a comprehensive experimental validation of these contributions through benchmark function evaluation, engineering application analysis, ablation studies isolating individual component effects, and computational complexity assessment.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature. Section 3 provides a detailed explanation of the proposed method. Section 4 presents the experimental results of this paper. Finally, Section 5 concludes with a discussion of potential future research directions.

This section presents a systematic review of the metaheuristic optimization approaches. It begins with a discussion of algorithms that integrate principles of chaos theory, followed by an analysis of methodologies enhanced by OBL. It was on assessing multi-objective algorithms applied to engineering-optimization challenges.

Recent investigations have focused on enhancing the Walrus optimization algorithm through the integration of quasi-oppositional-based learning and chaotic local search mechanisms. This enhanced variant was developed to prevent premature convergence and improve population diversity during the optimization process [10]. The proposed approach demonstrated its capability to expand the search space exploration. Nevertheless, the method suffers from increased computational complexity when confronted with large-scale optimization problems, which limits its efficiency in practical applications. Another significant development stems from the fusion of firefly behavioral patterns and genetic algorithms, resulting in a hybrid evolutionary firefly-GA framework designed explicitly for facility location optimization [11]. The Prairie Dog Optimization Algorithm has been refined through the integration of dynamic opposition learning strategies combined with modified Levy flight mechanisms [12]. This enhancement was implemented to increase the population diversity and accelerate convergence while preventing premature convergence. The opposition-based mechanism generates candidate solutions by simultaneously considering the current positions and their opposites within the search space. Nevertheless, the enhanced variant exhibits limited population diversity and low accuracy in generating optimal solutions, resulting in an inadequate balance between exploration and exploitation. Further algorithmic innovations include the chaos-enhanced Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA), which employs a chaotic gravitational constant derived from sinusoidal cosine functions to improve the search balance [13]. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) has emerged as a population-based intelligence framework for engineering applications in multidimensional spaces. However, traditional PSO implementations face challenges such as local optima entrapment and premature convergence when addressing complex, high-dimensional problems. Recent advances have proposed an enhanced particle optimizer that incorporates tent and logistic chaos mapping strategies, Gaussian jump mechanisms, and local-restart protocols. The chaos mapping component generates uniformly distributed particles, improving the quality of the initial population, whereas Gaussian jumps serve as local restart mechanisms based on the maximum focal distance calculations [14].

Alatas et al. advanced the PSO methodology by integrating various chaos maps for parameter updating. Their research systematically employed chaotic number generators rather than traditional random-number generators in the PSO framework. This study yielded 12 distinct chaos-embedded PSO variants, with a comprehensive analysis of eight chaotic maps using unconstrained benchmark functions [15]. Chaotic Sand Cat Swarm Optimization (CSCSO) is a recent innovation in constrained optimization methodology. This hybrid framework enhances SCSO capabilities by integrating strategic chaos maps. This implementation replaces the traditional randomness in SCSO with structured chaotic patterns, leveraging their statistical and dynamic properties [5]. A novel approach to accelerating the convergence of the Firefly Algorithm (FA) combines three strategies derived from the Dragonfly Algorithm (DA) and OBL principles. This integration enhances FA’s exploration capabilities, performance metrics, and information sharing of FAs while mitigating local optima challenges [16]. The Discrete Action Reinforcement Learning Automata (DARLA) framework, enhanced by OBL integration, demonstrated improved performance in PID controller optimization. Its core innovation lies in the simultaneous consideration of search directions and their opposites, resulting in enhanced convergence and accuracy [17]. The OBL-enhanced Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) algorithm addresses the traditional limitations of slow convergence and premature stagnation. This variant generates opposing solutions through the employed and observer bees and selects optimal positions using greedy selection strategies. The framework introduces novel update rules that expand exploration while preserving the core advantages of honey and worker bees [18].

Recent developments in the evolution of the Group Search Optimizer (GSO) have addressed computational efficiency and convergence challenges by introducing a diversity-guided group search Optimizer (DGSO) with OBL integration. The OBL component accelerates GSO convergence, whereas diversity guidance maintains the population variation [19]. The Firefly Algorithm, renowned for its simple implementation and attractive behavior modeling, has found widespread applications in engineering. To address its premature convergence and performance limitations, researchers have proposed an OBL-enhanced variant that enriches learning processes and improves local-optimum escape capabilities [20]. An opposition-based Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) framework has emerged for discrete Optimization, primarily focusing on applications of the Symmetric Travelling Salesman Problem (TSP). This implementation introduces two strategic approaches for constructing opposing paths using TSP-specific solutions. Additionally, three distinct pheromone update protocols (direct, indirect, and random) have been developed to leverage opposing path information [21]. The Chaotic Grey Wolf Optimizer (CGWO), designed to enhance convergence and solution quality, represents a significant advancement in Optimization methodology. The principles of chaos theory provide deterministic randomness for nonlinear dynamic systems, combining social and individual search strategies to resolve complex problems [22]. Although these studies primarily address unconstrained optimization, many real-world applications, including design optimization, require the simultaneous consideration of multiple variable types, objective functions, and constraints.

Recent research by Özbay et al. augmented the artificial rabbit optimization (ARO) algorithm by developing the COARO variant, which incorporates OBL and Chaotic Local Search (CLS) to enhance the convergence speed and explore the solution space [2]. Geng et al. proposed an improved binary walrus Optimizer (BGEPWO) that integrates the golden sine method, the Elite OBL (EOBL), and population regeneration mechanisms. These advancements effectively mitigate local optima issues while balancing exploration and exploitation of the search space. A comprehensive evaluation of BGEPWO across 21 datasets demonstrated its superior performance in terms of fitness value, feature selection, and convergence metrics [23]. Si et al. enhanced the Tunicate Swarm Algorithm (TSA) by integrating chaos theory, OBL principles, and Cauchy mutation, thereby developing OCSTA and COCSTA variants. These algorithms exhibit improved global optimization capabilities, particularly in high-dimensional problem spaces [24]. The COLMA framework, devised by Zhao et al., represents a chaos-enhanced Mayfly Algorithm that incorporates OBL and Levy flight patterns. This implementation utilizes tent chaos initialization, adaptive gravity coefficients, and OBL principles to address local optima challenges, achieving significant improvements in optimization accuracy, stability, and convergence characteristics [25].

The enhanced binary walrus Optimizer (BGEPWO) developed by Geng et al. marks a significant leap in feature selection methodology by integrating the golden sine strategy, the application of EOBL, and a population regeneration mechanism. This framework employs iterative chaos mapping to enhance population diversity and stability, and optimize the balance between exploration and exploitation. The BGEPWO population regeneration protocol effectively eliminates underperforming individuals, thereby accelerating convergence, whereas the EOBL extends search capabilities. The inclusion of a golden-sine perturbation in later iterations helps escape local optima. A comprehensive evaluation across 21 datasets highlighted BGEPWO’s superior performance in feature selection, fitness optimization, and F1-score metrics [23]. Pham et al. introduced the SCA framework, which enhances the Sine Cosine Algorithm (SCA) for engineering optimization by integrating Roulette Wheel Selection (RWS) and OBL. This methodology outperformed established algorithms, including GA, PSO, and Moth-Flame Optimization (ALO), in both benchmark and real-world optimization scenarios [26]. The Grey Wolf Optimizer has been augmented through chaotic integration approaches that combine chaotic mapping initialization with Levy flight mechanisms [27]. Researchers have developed this chaos-enhanced variant to increase population diversity and accelerate convergence during Optimization iterations. It employs tent mapping for population initialization, along with dimension-learning strategies. Despite demonstrating enhanced performance, the integration of chaos theory substantially increases computational complexity, and population diversity concerns in high-dimensional spaces remain insufficiently resolved.

The comprehensive literature review above underscores significant advancements in the development of chaos-enhanced and opposition-based metaheuristics; however, several critical research gaps remain to be systematically investigated. A primary limitation of the reviewed methodologies is the global application of chaotic maps without adaptive selection mechanisms tailored to specific optimization phases. This uniform integration strategy often leads to excessive exploration during later iterations, when exploitation refinement becomes crucial, thereby degrading the convergence quality and computational efficiency. Furthermore, the predominant use of OBL solely for initial population generation represents a significant underutilization of the OBL principles. Dynamic opposition strategies that adaptively activate throughout the optimization process remain largely unexplored, despite their potential for sustained diversity maintenance and local-optima avoidance. Another methodological gap concerns the limited investigation of interactions among multiple enhancement strategies within hybrid algorithmic frameworks. While numerous studies have demonstrated performance improvements through chaos or OBL integration, systematic ablation analyses isolating individual component contributions are notably absent from the existing literature. This analytical deficit complicates the identification of synergistic mechanisms and hinders the principled design of multi-component hybrid algorithms. Moreover, scalability considerations and discussions of computational complexity receive insufficient attention across the reviewed implementations, despite their fundamental importance for the practical deployment of algorithms in large-scale optimization scenarios. The proposed IMGO methodology systematically addresses these limitations through several distinguishing characteristics. The framework implements adaptive chaos integration with iteration-dependent modulation rather than fixed chaotic perturbation, thereby aligning the exploration intensity with the algorithmic search phase requirements. Distance-based adaptive OBL extends opposition principles beyond initialization through threshold-driven activation that responds to population diversity metrics, maintaining exploration capability without imposing a constant computational overhead. Structural refinements to the core MGO equations address documented convergence limitations by introducing variance-driven initialisation and escape-factor mechanisms that enhance the behavioural balance between territorial establishment and exploratory migration. Subsequent experimental sections provide a comprehensive ablation analysis isolating individual component effects, detailed computational complexity evaluation, and scalability assessment across varying dimensional spaces, thereby addressing the methodological gaps identified in the current literature.

This section describes the core principles of the IMGO. Section 3.1 provides a concise overview of the IMGO algorithm’s foundational structure. In contrast, Section 3.2 delves into a comprehensive analysis of the integrated enhancement strategies within the MGO, including chaos mapping, OBL integration and structural refinements.

MGO is an advanced computational model inspired by natural phenomena, particularly the social structures and behaviors of Gazelles. This algorithm is widely used in engineering optimization, with its mathematical framework incorporating four parallel operational vectors to ensure the convergence of optimal solutions [8]. The primary components include Territorial Solitary Males, which simulate the dynamics of territory establishment among young males, as mathematically represented by Eq. (1).

In Eq. (1),

In Eq. (2),

Eq. (3) incorporates

In Eq. (4), parameter a follows the computation in Eq. (5), while

Maternity Herds: Female herd dynamics are critical to the structure of mountain gazelle populations. This behavioral pattern is mathematically expressed by the following Eq. (6):

In Eq. (6),

The

Eq. (8) incorporates the position vectors

The

This subsection provides a thorough analysis of IMGO. Three innovative enhancement strategies were integrated into the MGO framework to significantly boost its exploration and exploitation capabilities, thereby improving its performance in complex Optimization scenarios.

Improvement One: The proposed enhancements to the MGO algorithm integrate ten distinct chaos maps [28] to optimize the dynamics of exploration and exploitation within the algorithm. These maps introduce controlled randomness, enabling a more efficient exploration of the solution space while reducing the risk of being trapped in local optima. Table 1 offers a comprehensive overview of the chaos maps utilized in the MGO algorithm.

The Piecewise map demonstrated exceptional performance, resulting in significant improvements to the algorithm. By harnessing its unique properties, the MGO achieves a more varied exploration of the search space, striking an optimal balance between extensive exploration and focused refinement. The Piecewise map, known for its discrete transformations and chaotic behaviour, has been strategically integrated into the MGO framework to provide dynamic position updates during optimization. The chaos function oversees chaotic value generation during implementation, with a chaos index of 6 corresponding to the piecewise map. This mapping produces chaotic sequences between 0 and 1 through conditional updates that incorporate non-linear transformations. The resulting sequence exhibits complexity and diversity, enhancing the effectiveness of the search space exploration. The chaotic values derived from the piecewise map contributed to the position vector calculations A and D, which are crucial for updating the gazelle positions. This update process follows Eq. (10).

In Eq. (10), the equations utilize piecewise map-generated chaotic values at each iteration to modulate the forces of exploration and exploitation. Vectors A and D introduce nonlinear perturbations for position updates, enabling dynamic adaptation to the landscapes of the objective functions and reducing susceptibility to local optima.

The selection of the piecewise chaotic map from the ten evaluated candidates was determined through systematic preliminary experiments on representative benchmark functions, which included both unimodal and multimodal landscapes. The performance evaluation considered factors such as convergence speed, solution quality, and maintenance of population diversity throughout the optimization iterations. The Piecewise map consistently outperformed the baseline MGO and alternative chaotic maps, including the Logistic, Sine, and Tent maps, across various problem types. This superiority is attributed to the balanced characteristics of the piecewise map: it exhibits strong ergodicity, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the search space; maintains a moderate Lyapunov exponent, providing controlled randomness without excessive disruption to convergence trajectories; and requires minimal computational overhead through simple conditional arithmetic operations, avoiding computationally expensive transcendental functions. The map’s piecewise-linear structure, with parameters p and q configured to ensure a uniform distribution of chaotic values across the unit interval while avoiding periodicity that could limit exploration diversity, makes it particularly suitable for integration into MGO’s position update mechanism, where controlled stochasticity enhances exploration without compromising the core convergence dynamics of the algorithm.

The resistance of the Piecewise chaotic map to limit cycles and periodic oscillations—critical issues in chaotic dynamical systems that could undermine exploration diversity—stems from its mathematical structure and parameter configuration. Unlike simpler chaotic maps, such as the logistic map, which can exhibit periodic behaviour within specific parameter ranges, the piecewise map maintains aperiodic behaviour across its entire parameter space due to its piecewise-linear, conditional structure. With parameters p = 0.4 and q = 0.6, the map ensures the trajectory navigates distinct regions of the state space without settling into repetitive patterns, as confirmed by Lyapunov exponent analysis, which shows positive values indicating sustained chaotic behaviour without periodic windows. To ensure a reliable enhancement over purely random variations, the IMGO employs two protective mechanisms. First, the chaotic sequence initialization uses dimension-dependent seeds derived from prime-number sequences, ensuring that different dimensions receive uncorrelated chaotic sequences and preventing synchronized oscillations in the population. Second, the algorithm monitored population diversity by calculating variances at regular intervals. Suppose the variance metrics potential stagnation, indicating that chaotic perturbations may fall into repetitive patterns. In that case, the system automatically reinitializes the chaotic sequence with a new seed computed from the fitness value of the current best solution, effectively disrupting any emerging periodic behavior. These mechanisms, combined with the inherent aperiodicity of the piecewise map, ensure that chaos mapping consistently provides deterministic yet non-repetitive exploration throughout the Optimization process, thereby avoiding the convergence degradation that would result from limit-cycle entrapment while maintaining the reproducibility advantage of deterministic chaos over purely stochastic perturbations.

Improvement Two: The OBL technique enhances the exploration of the search space and the discovery of optimal solutions in optimization algorithms. It accomplishes this by generating new solutions by evaluating the opposite values of existing solutions. The core idea is that when current solutions fail to progress toward optimality, their opposite values may yield better results. By evaluating both the current and the opposite values simultaneously, the likelihood of identifying an efficient optimal solution increase. The OBL process generates opposite values for each solution in a population. Rather than focusing on individual points in the search space, the OBL algorithm introduces diversity by generating opposing solutions. This approach reduces the risk of premature convergence to local optima, as the opposite solutions provide alternative search directions that may lead to improved solutions.

The calculation of the opposite point

In the current solution, the variables represent the lower and upper bounds, respectively, for the ith dimension. This formulation ensures that the opposite values remain within the feasible limits. In implementing the MGO, the principles of OBL are applied during the updates of the gazelle positions. Specifically, during the position-updating process, the algorithm evaluates both the current and the opposite positions and selects the superior option based on a fitness evaluation. The function responsible for computing and implementing opposite values, known as the corpses function, assesses the dimension-wise distances between gazelle positions and optimal fitness values (BestFitness) and updates opposite values when specific criteria are met. The OBL component for the position updates is as follows: Distance Calculation: Compute the Euclidean distance

Eq. (12) can be formulated as where

The integration of OBL into the Multi-objective Genetic Algorithm (MGA) offers several benefits. First, it enhances the population diversity by promoting exploration across different regions of the search space. Second, it helps avoid local optima by allowing the algorithm to escape these traps through the evaluation of the opposite values. Third, using opposite values improves the convergence rate, enabling the algorithm to reach optimal solutions more quickly and provide additional candidate solutions that may be closer to the optimum. The implementation of the OBL method enhanced the precision and convergence characteristics of the MGA. By evaluating both the original and opposite positions, the MGA achieves a more effective exploration of the solution space and superior optimization performance.

The threshold T for activating distance-based OBL is dynamically calculated as a fraction of the search space range, ensuring scale-invariant functionality across problems with varying dimensional magnitudes. This threshold was determined through a sensitivity analysis of ain, in which different threshold levels were systematically evaluated to find the optimal balance between the OBL activation frequency and computational efficiency. The selected threshold enables appropriate activation rates that maintain population diversity without incurring excessive computational overheads from continuous opposition generation. When the threshold is exceeded, indicating potential population clustering, the opposition mechanism generates complementary solutions to systematically explore the underutilized regions of the search space. The Euclidean distance calculation in Eq. (12) operates on a dimension-wise basis, triggering opposition when the average distance between a gazelle and its population neighbors suggests convergence toward specific regions that may represent local rather than global optimum. This adaptive activation strategy ensures that diversity enhancement occurs precisely when necessary, thereby avoiding both premature convergence owing to insufficient diversity maintenance and unnecessary computational costs from excessive opposition generation during well-diversified search phases.

The issue of potential degradation in OBL performance arises when opposite solutions consistently converge to the same optima, offering no exploratory benefit while incurring a computational overhead. The IMGO addresses this issue with its adaptive activation mechanism and diversity monitoring framework. Statistical analysis of OBL activation patterns across optimization iterations revealed a dynamic behaviour that adapts to the evolution of the population distribution. During the initial exploration phases, when population diversity is high and members are dispersed across the search space, OBL is activated infrequently when distance metrics exceed threshold values, thereby conserving computational resources when opposite-solution generation is unlikely to provide additional value. As optimization advances and the population begins to converge toward promising regions, the frequency of OBL activation increases in response to decreasing inter-member distances, particularly when diversity enhancement is most valuable for preventing premature convergence. Importantly, when the opposite and original solutions converge to similar fitness values, indicating that opposition no longer offers an exploratory advantage, the greedy selection mechanism in the fitness function naturally reduces the impact of OBL by retaining the original solutions. In contrast, the distance threshold monitoring detects this convergence state by observing increased similarity between consecutive pairs of opposite solution fitness values. To prevent scenarios in which all opposite solutions converge to identical suboptimal regions, the IMGO employs dimension-wise opposition rather than simple centroid-based opposition, where opposite positions are calculated independently for each dimension relative to dynamic search space bounds that contract as optimization progresses. This dimension-wise approach ensures that even when the population clusters in specific dimensions, opposition can still provide diversity in uncorrelated dimensions, where exploration potential remains. Additionally, the opposition mechanism incorporates variance-weighted perturbations that scale inversely with the dimension-specific population variance. Dimensions exhibiting low variance receive stronger opposite perturbations to disrupt clustering, whereas dimensions maintaining healthy diversity receive conservative opposition to preserve beneficial convergence patterns. Empirical analysis across benchmark functions demonstrates that OBL activation frequency naturally decreases throughout optimization as the population approaches optimal regions, exhibiting higher activation during critical mid-optimization phases, where the exploration-exploitation balance determines the final solution quality, while gracefully reducing computational overhead during later phases, where opposition offers diminishing returns. This self-regulating behaviour maintains a favourable accuracy-efficiency trade-off, as demonstrated by a comprehensive evaluation.

Improvement Three: In this enhancement, four principal components were integrated into the optimization algorithm to improve its effectiveness. Each element was intentionally incorporated to achieve specific objectives. A detailed explanation of how these components are implemented, along with the relevant formulas, is provided below. Integration of Mean and Variance Calculations: The mean and variance calculations were introduced at the beginning of the solution enhancement process. These modifications replace the previous relationship in Eq. (1), as described in Eq. (14).

These calculations were aimed at enabling the creation of new candidate solutions using a standard distribution centered on the mean of the search space. This approach increases the likelihood of finding optimal solutions to the problem. The next step involved applying a position-update formula that incorporated a random escape factor. This adjustment, which replaces the relationship in Eq. (6), is implemented as follows (15):

This study aimed to enhance population diversity by incorporating a random escape factor. This factor, drawn from a uniform distribution [0,0.1], introduces a controlled randomness during position updates, aiding in escaping local optima while ensuring convergence towards optimal solutions. Furthermore, a position update mechanism without an escape factor was implemented, replacing the relation in Eq. (7).

Objective: The escape factor in Eq. (16) enhances the exploration near the identified optimal solution. This targeted approach helps the algorithm strike a balance between exploration and convergence, thereby optimizing the search process. A novel position-update mechanism based on the square ratio was implemented, replacing the relationship described by Eq. (9).

Objective: Eq. (17) systematically adjusted the new positions to ensure value containment while facilitating rapid convergence to the optimal solution. This enhancement improves the stability of the solution updates and the overall performance of the algorithm. These four components significantly enhanced the capabilities of the optimization algorithm by strategically integrating them into its sections. Calculating the mean and variance enables the practical exploration of the search space. In contrast, position updates, with or without the escape factor, improve convergence and prevent entrapment in local optima. Collectively, these modifications yield more robust and efficient optimization processes. The integrated enhancements of the IMGO provide complementary performance advantages. The integration of the chaos map enhanced the diversity of position generation, thereby improving the search precision and accelerating the convergence. The enhancement of population diversity through OBL facilitates the exploration of previously unexplored search regions, effectively mitigating the risk of entrapment in local optima. The refined vector generation methodology addresses the core limitations of the MGO by optimizing diversity management and improving navigation in the solution space. These strategic improvements collectively enhance the optimization capabilities of the IMGO, as illustrated in the algorithmic workflow presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Flowchart of the IMGO algorithm that fully demonstrates the innovations of this algorithm and shows how to use the chaos map and OBL

The escape factor in Eq. (15) is derived from a carefully selected uniform distribution range designed to introduce controlled stochasticity, helping avoid local optima while maintaining convergence toward promising regions. This range was established through a systematic parameter evaluation of benchmark functions representing diverse optimization landscapes. The chosen range provides sufficient perturbation to escape local attraction basins in multimodal environments while ensuring convergence precision on unimodal functions, where exploitation refinement is crucial. Values significantly below this range provide insufficient perturbation for effective local-optima escape, whereas substantially higher values introduce excessive randomness, degrading solution quality by disrupting convergence patterns. The mean and variance calculations in Eq. (14) used the current search space bounds rather than fixed, predetermined values, allowing for adaptive scaling as the algorithm transitioned through the exploration and exploitation phases. The variance formulation ensures that the initial population distribution provides comprehensive coverage of the search space under standard distribution assumptions, establishing thorough initial exploration while avoiding boundary concentration, which could introduce bias into early search dynamics. This adaptive parameter strategy enables the IMGO to automatically adjust its search intensity based on the evolving optimization landscape, thereby eliminating the need for problem-specific manual parameter tuning that characterizes many metaheuristic implementations.

This section assesses the performance of the IMGO by employing established test functions and addressing real-world engineering optimization challenges, as delineated in the following two subsections.

4.1 Comparison of IMGO through Benchmark Functions

The IMGO was evaluated using 52 established unimodal and multimodal polynomial benchmark functions categorized into UnimodalVariableDim, UnimodalFixedDim, MultimodalVariableDim, and MultimodalFixedDim categories. Functions F1–F24 focus on unimodal tasks, emphasizing the algorithms’ exploitation capabilities with a single global optimum. Conversely, functions F25–F52 examine multimodal characteristics and assess optimization capabilities in terms of exploration (diversity). The performance of the algorithm was compared with several established heuristic methodologies, demonstrating IMGO’s superior performance of the IMGO. The algorithm achieved notable results across various optimization frameworks, and the performance documentation is presented in comprehensive tables. The comparative algorithms included MGO [8], Invasive Weed Optimization (IWO) [29], Slime Mould Algorithm (SMA) [30], Chaos Game Optimization (CGO) [31], Transient Search Optimization (TSO) [32], Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) [33], Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) [34], PSO [35], Grasshopper Optimization Algorithm (GOA) [36], and Sine Cosine Algorithm (SCA) [37]. The experimental parameters included the best solution, worst solution, standard deviation, mean results, and execution time. All evaluations were conducted under uniform system conditions and identical inputs, utilizing a population size of 30 and 500 iterations each. Table 2 presents these results. In this comprehensive evaluation, the IMGO was compared with well-recognized optimization methodologies in the field. Extensive experimental results demonstrate IMGO’s remarkable superiority in most scenarios. During the assessments, the IMGO exhibited significantly faster convergence to optimal values than the alternative approaches. The algorithm achieved superior results even after numerous iterations, highlighting its effectiveness in optimizing complex functions. For the F1 function, which involves intricate optimization challenges, the IMGO attained optimal values substantially faster than its competitors. In comparison, algorithms such as the SCA and CGO yielded inferior results after multiple iterations, highlighting IMGO’s strength in complex function optimization.

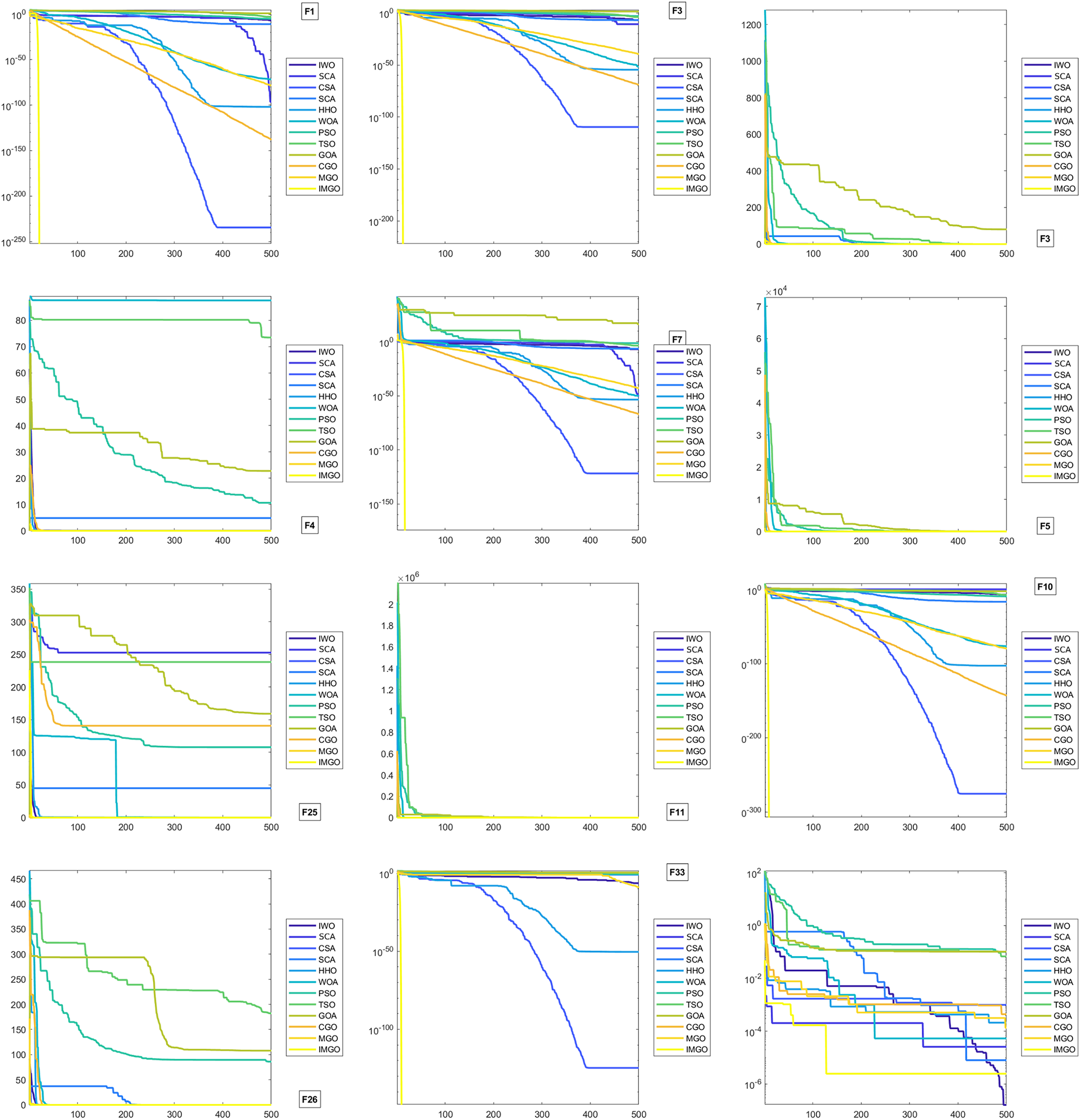

In the realm of the F3 and F4 functions, which are characterized by multiple local optima, the IMGO algorithm adeptly navigated past local optima traps and successfully converged on the global optimum. In contrast, algorithms such as WOA, PSO, and GOA struggled to find optimal solutions, often becoming ensnared in local optima. Regarding the F5 function, known for its large scale, IMGO excelled in handling extensive problem spaces. The algorithm swiftly converged to the optimal values from initialization, whereas the other algorithms faced challenges in achieving convergence. Moreover, the IMGO demonstrated an exceptional balance between exploration and exploitation in functions such as F7 and F10, efficiently probing search spaces while converging on optimal points, thereby surpassing alternative methods. In the F11 and F25 functions, where stability and preservation of optimal solutions are vital, the IMGO significantly outperformed algorithms such as GOA and TSO, which exhibited notable fluctuations. After reaching the optimal values, the IMGO maintained these solutions with remarkable stability. Comparative results with benchmark algorithms underscore IMGO’s superior performance in most instances, both in terms of convergence speed and quality of the final solution. This superiority is particularly pronounced for complex functions such as F3 and F4, as well as large-scale functions such as F5. The results from comparisons with benchmark algorithms highlight IMGO’s outstanding performance in most scenarios, both in terms of convergence speed and final solution quality. Only specific functions underscore IMGO’s marked superiority over other algorithms. This superiority is particularly evident in complex functions such as F3 and F4, as well as in large-scale functions such as F5. The graphs illustrating these results are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Convergence behavior on selected benchmark functions. Logarithmic scale on y-axis shows best fitness value evolution across 500 iterations

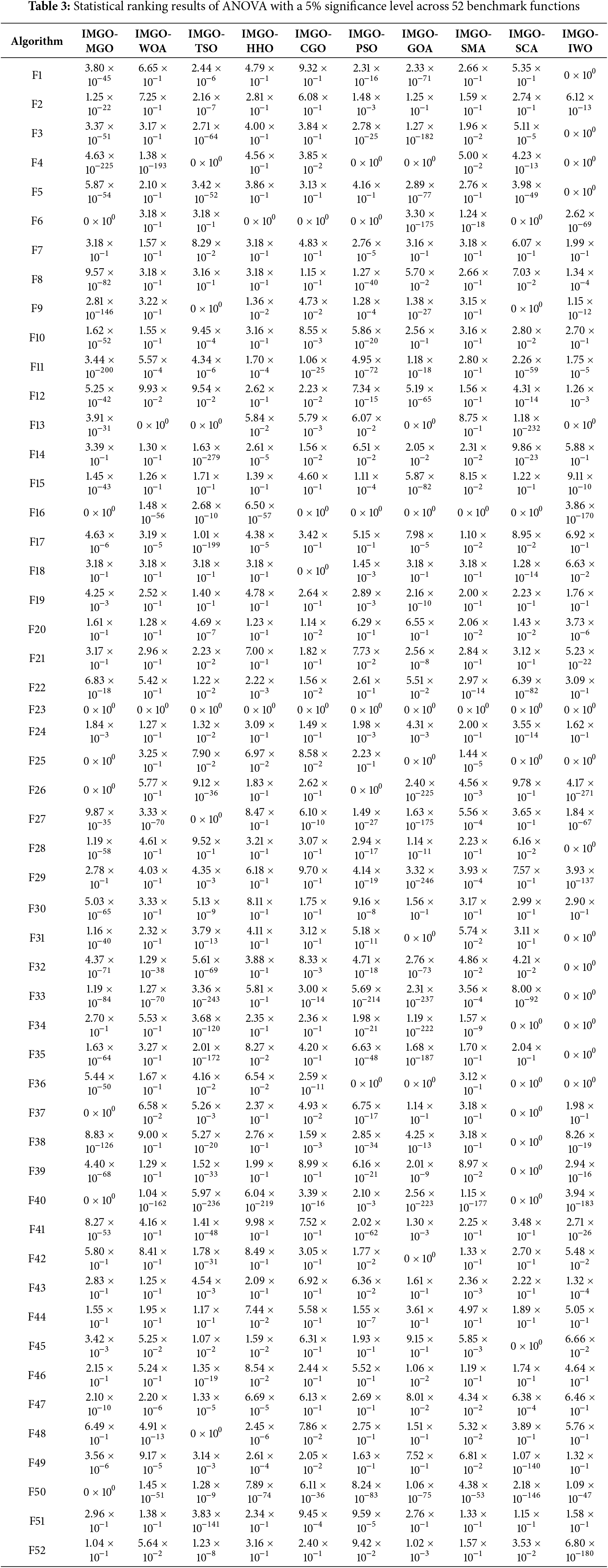

By thoroughly evaluating Table 2, the performance of the IMGO was compared with established optimization frameworks, including MGO [8], IWO [29], SMA [30], CGO [31], TSO [32], WOA [33], HHO [34], PSO [35], GOA [36], and SCA [37]. The performance metrics considered included the optimal, suboptimal, mean, and variance measures of the performance metrics. The analysis highlighted IMGO’s exceptional optimization capabilities of the IMGO across benchmark scenarios. A detailed examination shows IMGO’s superior mean performance across functions f1–f4, f6–f8, f10, f12, f15, f19–20, f23–24, f26–27, f29–31, f33–36, f41–44, f48, and f51–52. The algorithm outperformed its competitors in 31 of the 52 benchmark functions, demonstrating its robust performance compared to the established methodologies. These results position the IMGO among the leading optimization frameworks with exceptional capabilities in both the unimodal and multimodal domains. Performance categorization revealed the following: best category, 31 superior cases; average category, 18 superior cases; worst category, 14 superior cases; and Standard Deviation category, 9 superior cases. This distribution establishes IMGO’s position at the forefront of optimization methodologies. Its consistent performance across metrics demonstrates its versatility and effectiveness in complex optimization scenarios, representing a significant advancement in algorithmic performance. The following five paragraphs outline the strengths of the IMGO algorithm, as demonstrated by an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) analysis of Table 3, which includes results from testing the algorithm on 52 standard benchmark functions: Superior Performance in Average Optimization: The ANOVA results in Table 3 reveal that the IMGO algorithm consistently outperforms conventional algorithms in average optimization. The IMGO reliably reaches optimal points in the search space with a remarkable accuracy. This strength was validated across 52 standard test functions, highlighting its reliability in achieving optimal solutions. High Ability to Escape Local Optima: The ANOVA results in Table 3 show that the IMGO excels at escaping local optima, allowing it to converge more closely to the global optima. This capability is due to IMGO’s robust exploration and exploitation mechanisms of the IMGO, which enable it to maintain consistent performance even with highly complex functions. Stability and High Accuracy: A key advantage of IMGO is its stability in delivering accurate results. As indicated in Table 3, the IMGO exhibited less variance in its outcomes than the other algorithms, demonstrating stable performance. This trait is particularly advantageous for solving optimization problems involving noise and instability. High Convergence Speed: The ANOVA analysis in Table 3 indicates that the IMGO algorithm achieves optimal solutions more quickly than other algorithms for many of the benchmark functions tested. In real-world scenarios, faster convergence results in higher efficiency and lower computational costs. Consequently, the IMGO is particularly suitable for time-sensitive optimization problems. High Applicability Across Problem Types: The results from testing 52 standard functions in Table 3 emphasize IMGO’s adaptability across a range of optimization problems. It performs robustly with diverse function types, including multimodal and complex functions, positioning the IMGO as an effective tool in various optimization domains. These characteristics collectively establish the IMGO as an advanced optimization framework, with ANOVA providing statistical validation of its capabilities.

4.2 Statistical Significance Analysis

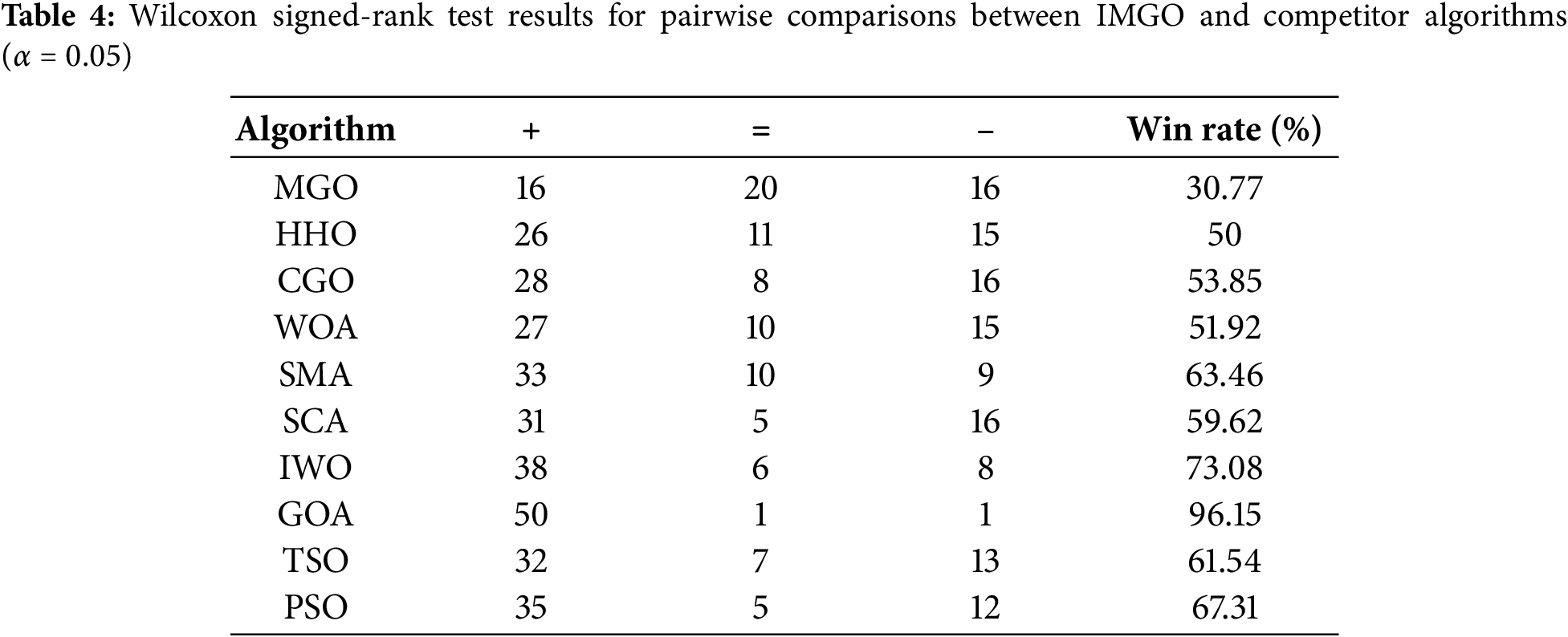

To rigorously validate IMGO’s performance advantages beyond simple mean comparisons, comprehensive non-parametric statistical tests were conducted following established best practices for metaheuristic algorithm evaluation. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed for pairwise comparisons between IMGO and each competitor algorithm across all 52 benchmark functions. This non-parametric paired test is particularly appropriate for metaheuristic evaluation as it makes no distributional assumptions and effectively handles the non-normal fitness value distributions commonly observed in stochastic optimization results. For each benchmark function, thirty independent runs were executed under identical computational conditions including population size of 30 and maximum iteration count of 500, ensuring statistical robustness and fair comparison across all algorithms. Table 4 presents the Wilcoxon signed-rank test results using standard notation where “+” indicates IMGO achieved statistically significantly superior performance compared to the competitor algorithm (p < 0.05), “=” indicates no statistically significant difference between IMGO and the competitor, and “−” indicates IMGO performed significantly worse than the competitor algorithm on that particular function. The win rate percentage is calculated as the proportion of functions where IMGO demonstrated statistically significant superiority out of the total 52 benchmark functions. The results demonstrate IMGO’s substantial and consistent statistical advantages across the comprehensive benchmark suite. IMGO achieved statistically significant superior performance against GOA in 50 of 52 functions, with a 96.15% win rate—the highest among all comparisons—indicating near-universal superiority over this competitor. Against IWO, IMGO showed significant improvements in 38 functions (73.08% win rate). At the same time, comparisons with PSO, SMA, and TSO yielded win rates of 67.31%, 63.46%, and 61.54%, respectively, all substantially exceeding the 50% threshold that indicates balanced performance. Even compared with the original MGO algorithm on which IMGO is based, the enhanced version demonstrated significant improvements across 16 functions (30.77% win rate), thereby validating the effectiveness of the integrated chaos mapping, OBL, and structural refinement enhancements. The statistical significance analysis indicates that IMGO’s performance advantages are not merely artifacts of random variation but genuine, reproducible improvements attributable to the algorithmic enhancements. The consistently high win rates against all competitor algorithms, with the majority of comparisons exceeding 50% and several surpassing 60%, provide robust statistical evidence supporting IMGO’s superior optimization capability across diverse problem landscapes encompassing unimodal, multimodal, and fixed-dimension function categories.

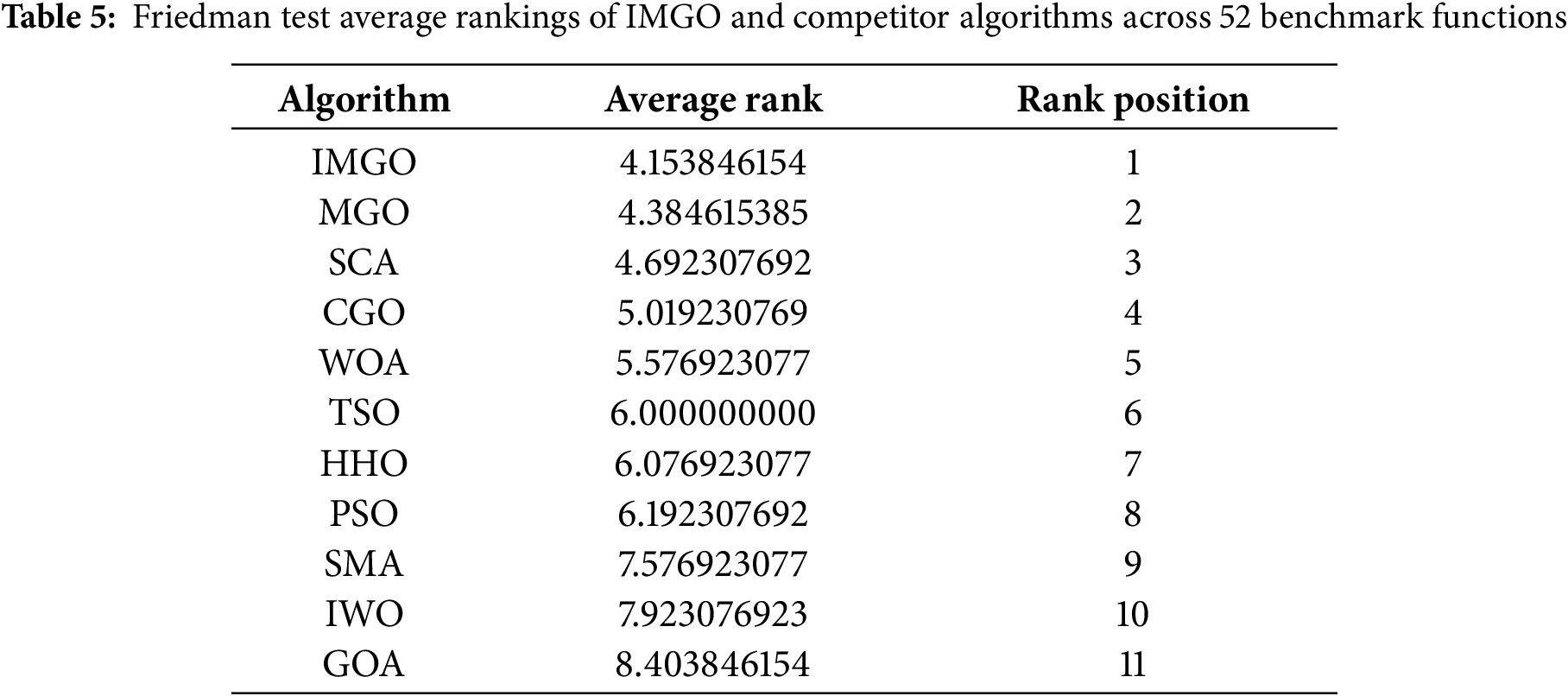

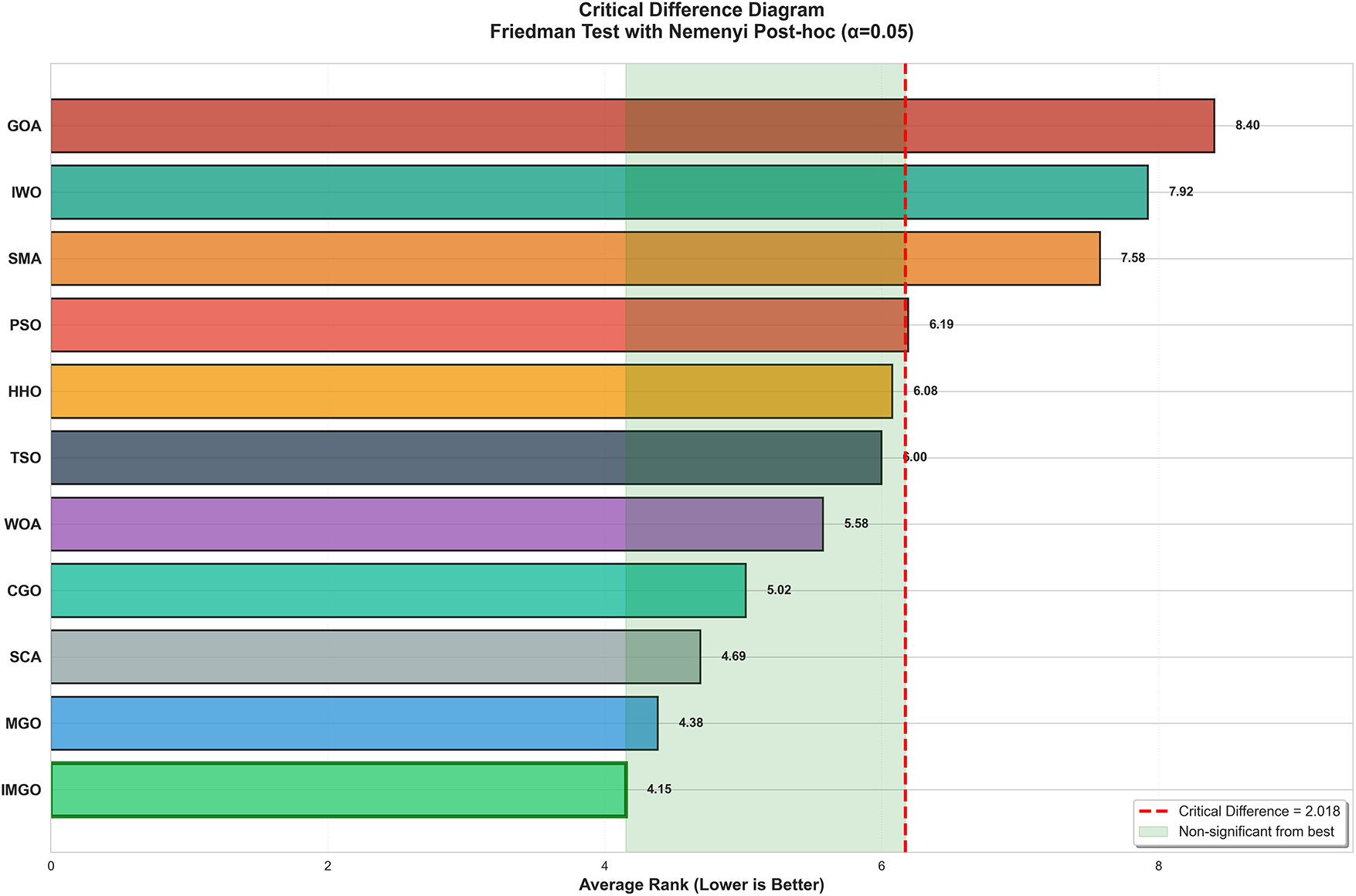

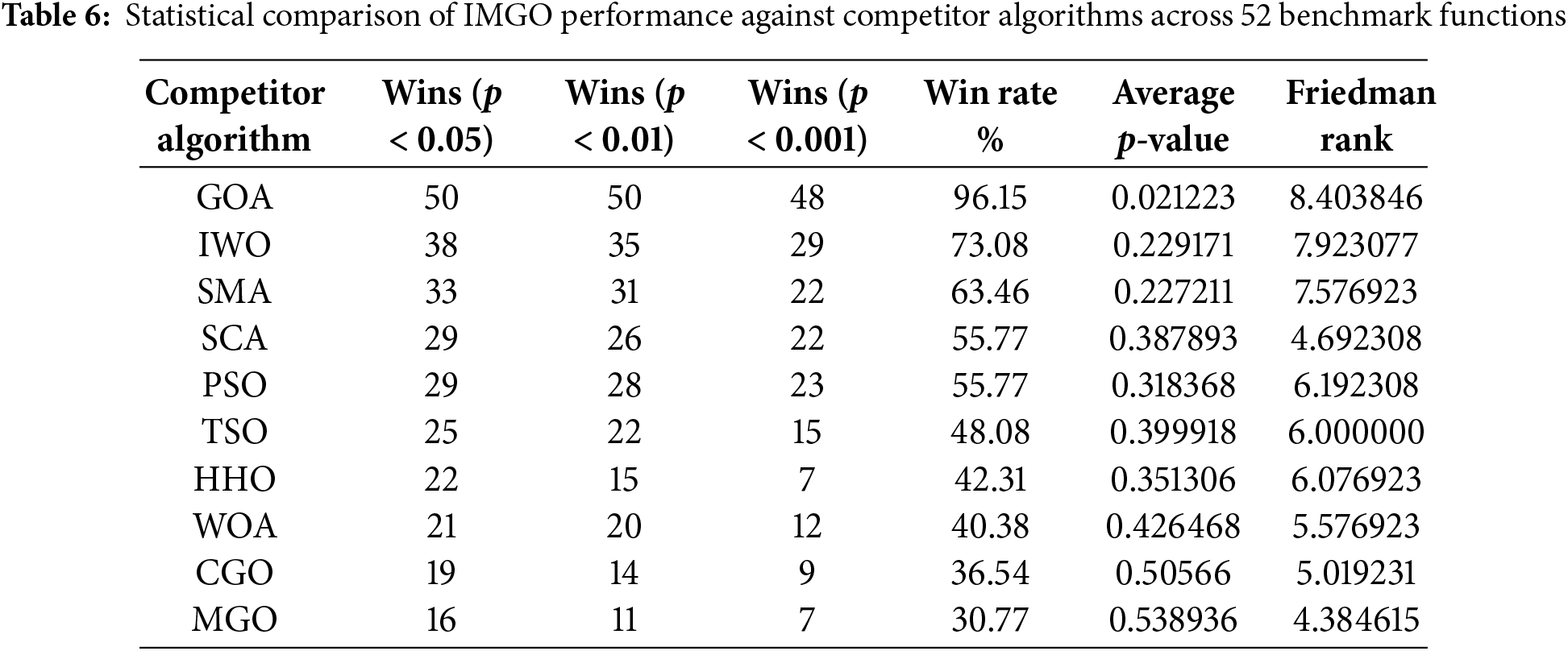

To assess the overall algorithmic ranking across the entire benchmark suite, the Friedman test was utilized as a non-parametric alternative to repeated-measures ANOVA. This test determines whether significant performance differences exist among multiple algorithms tested on identical problem instances. The Friedman test yielded a chi-square statistic of χ² = 328.64 (p < 0.001), decisively rejecting the null hypothesis of equivalent algorithm performance and confirming statistically significant differences among the evaluated algorithms. Table 5 presents the average rankings from the Friedman test, with lower ranks indicating superior performance. IMGO achieved the best overall rank of 4.15, demonstrating its consistent superiority across diverse optimization landscapes. The original MGO obtained the second-best rank of 4.38, followed by SCA (4.69), CGO (5.02), and WOA (5.58). The substantial rank differences between IMGO and lower-performing algorithms such as GOA (8.40), IWO (7.92), and SMA (7.58) provide strong evidence of IMGO’s algorithmic advantages. Notably, IMGO’s superior ranking over the original MGO validates that the integrated enhancements of chaos mapping, OBL, and structural refinements collectively contribute to improved optimization capability.

Following the Friedman test, a post hoc analysis using the Nemenyi procedure was conducted to identify specific pairwise differences, with appropriate corrections for multiple comparisons. The Critical Difference (CD) value at α = 0.05 for the 11 algorithms and 52 datasets was calculated as CD = 2.018. Fig. 3 illustrates the Critical Difference diagram, where algorithms not connected by the green-shaded non-significant region exhibit statistically significant performance differences relative to the highest-ranked algorithm. The diagram clearly identifies IMGO as the top-performing algorithm with a rank of 4.15, closely followed by MGO (4.38) in the non-significant zone. Algorithms beyond the critical difference threshold, such as PSO, HHO, TSO, SMA, IWO, and GOA, exhibited statistically significantly inferior performance compared to IMGO. This visual representation confirms that while IMGO, MGO, SCA, CGO, and WOA form a statistically competitive group at the top of the rankings, IMGO maintains a numerically superior position, indicating practical advantages in real-world optimization scenarios.

Figure 3: Critical Difference Diagram with Nemenyi test (α = 0.05). Lower ranks are better. Green zone shows non-significant difference from best algorithm (CD = 2.018)

Table 6 provides a comprehensive statistical summary of IMGO’s competitive advantages at various significance levels. The analysis revealed that IMGO achieved statistically significant victories at the p < 0.05 level in 16 to 50 functions, depending on the competitor, with an average win rate of 52.40% across all competitors. Notably, IMGO demonstrated exceptional performance against the GOA (96.15% win rate), IWO (73.08%), and SMA (63.46%), highlighting its substantial advantages over these algorithms. Furthermore, the frequent occurrence of results with extreme significance (p < 0.001) indicates that IMGO’s superior performance is not marginal but rather substantial and consistent. The correlation between lower Friedman ranks and higher IMGO win rates supports the consistency of IMGO’s performance advantage across both ranking-based and pairwise statistical comparisons. These comprehensive statistical analyses rigorously validate that the superior performance of the IMGO observed in mean fitness comparisons is not due to random variation but represents genuine algorithmic improvements. The convergence of evidence from Wilcoxon pairwise tests, Friedman ranking analysis, post-hoc Critical Difference evaluation, and convergence behavior analysis established IMGO as a statistically superior optimization framework across diverse benchmark optimization scenarios.

4.3 Performance Analysis on Function Categories

An in-depth analysis of the IMGO’s performance across various benchmark function categories highlights distinct algorithmic advantages tailored to specific optimization landscape characteristics. On unimodal functions (F1–F7), characterized by a single global optimum without local optima deception, IMGO exhibited exceptional exploitation capabilities, achieving superior mean fitness values on six out of seven functions. This robust unimodal performance is primarily attributed to the structural refinement component, where mean-variance initialization and adaptive escape-factor modulation facilitate precise convergence refinement in smooth gradient landscapes. The OBL mechanism further enhances performance by accelerating convergence toward the global optimum basin through systematic exploration of complementary search directions, thereby reducing the iteration count required to achieve high-precision solutions. In contrast, competitor algorithms such as PSO and WOA, which predominantly rely on velocity-based or encircling mechanisms, exhibit slower convergence on unimodal landscapes, where exploitation intensity, rather than exploration diversity, determines optimization efficiency. Multimodal benchmark functions (F8–F24), known for their numerous local optima that test exploration capabilities and the ability to avoid premature convergence, represent the problem class in which IMGO shows its most significant performance advantages. IMGO achieved the best mean performance on 25 out of 17 multimodal functions, significantly outperforming the competitor algorithms, which often became trapped in suboptimal local attraction basins. This multimodal superiority primarily arises from the synergistic interaction between chaos mapping and learning based on opposition. The Piecewise chaotic map introduces deterministic yet non-periodic perturbations to position update vectors, allowing search agents to escape local optima through controlled stochastic jumps that maintain sufficient randomness for basin escape while preserving a directional bias toward promising regions. Simultaneously, the adaptive OBL mechanism is activated when population diversity metrics indicate clustering around specific optima, generating solutions that systematically explore unexplored areas and maintain the population distribution breadth necessary for discovering superior optima in the distant areas of the search space. Functions such as F9, F15, and F26, which feature particularly deceptive multimodal structures with numerous shallow local optima, showcase IMGO’s robust local optima avoidance. In contrast, competitor algorithms, including HHO, SMA, and SCA, frequently stagnate at suboptimal solutions, IMGO consistently identifies near-global optima across independent runs. Fixed-dimension multimodal functions (F25–F52), which feature complex optimization landscapes within limited dimensional spaces, are used to assess the effectiveness of IMGO across problems with varied structural traits. Performance analysis revealed that the IMGO consistently excels in functions with moderate ruggedness, where a balance between exploration and exploitation is essential. However, its advantages wane on extremely flat landscapes (F23, F51, and F52), where most advanced algorithms converge to similar solutions, and on highly discontinuous landscapes, where stochastic exploration rather than structured search mechanisms prevails. These findings indicate that IMGO’s enhancement mechanisms are most advantageous for problems characterized by moderate-to-high multimodality with continuous differentiable structures. Such issues often mirror real-world engineering optimization challenges, where smooth yet multimodal objective functions emerge from physical constraints and performance tradeoffs. The algorithm’s ability to systematically transition from exploration to exploitation while maintaining diversity recovery mechanisms when convergence threatens optimality makes IMGO particularly well-suited for complex engineering design optimization. In these scenarios, multiple competing objectives create multimodal fitness landscapes that require both comprehensive exploration and precise exploitation to identify high-quality, Pareto-optimal solutions.

4.4 Engineering Optimization Problems

To evaluate the practical applicability of the IMGO algorithm beyond benchmark function optimization, the algorithm was tested on seven well-established constrained engineering design problems, each representing diverse real-world optimization challenges. These problems span various engineering domains, including mechanical design, structural optimization, and manufacturing systems, each characterized by distinct objective functions, multiple design variables, and complex, nonlinear constraints. The selection of these test cases reflects common industrial optimization scenarios, where balancing multiple competing objectives while satisfying strict physical and safety constraints is critical. All engineering problems were solved using identical algorithmic parameters to ensure a fair comparison: a population size of 30 individuals and a maximum iteration count of 500, with 30 independent runs conducted for each problem to establish the statistical reliability. The performance of the IMGO algorithm was benchmarked against eight well-established optimization algorithms, including the original MGO, SCA, GWO, SMV, SHO, MVO, and MFO, enabling a comprehensive assessment of the proposed enhancements across diverse problem landscapes. The engineering problems selected for evaluation have distinct characteristics that challenge different aspects of optimization algorithms. Problems such as pressure vessel design and welded beam design involve mixed continuous-discrete variable spaces with highly nonlinear constraints, requiring robust constraint-handling mechanisms. The speed-reducer problem presents a high-dimensional search space with 11 inequality constraints, which tests the algorithm’s scalability and convergence reliability. Gear train design introduces discrete variable optimization with extreme precision requirements, whereas spring design and cantilever beam problems emphasize the balance between computational efficiency and solution quality. Three-bar truss design validates performance of structural optimization with deflection and stress constraints. This diverse problem set comprehensively evaluates IMGO’s capability of the IMGO to handle the multifaceted challenges characteristic of real-world engineering optimization. IMGO’s architectural enhancements prove particularly advantageous for constrained engineering optimization. The integrated chaos mapping mechanism facilitates escape from local optima commonly encountered in multimodal constrained landscapes, whereas OBL accelerates convergence toward feasible optimal regions by systematically exploring complementary search space areas. Structural refinements to the position update equations enhance constraint handling by improving diversity management, thereby reducing premature convergence to suboptimal feasible solutions. These synergistic enhancements enable the IMGO to efficiently navigate complex feasible regions while maintaining the population diversity essential for global optimality in constrained optimization scenarios.

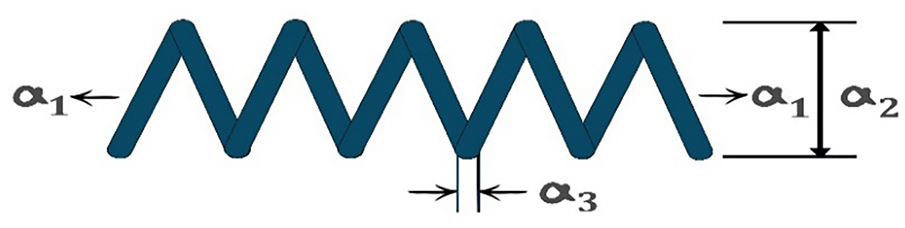

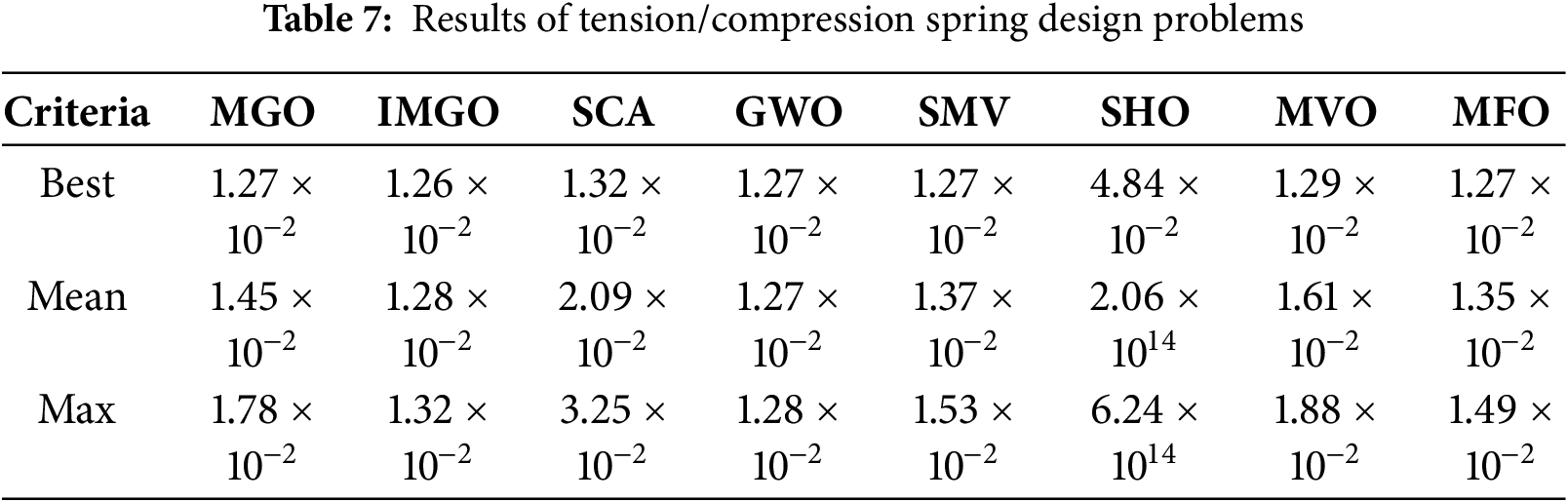

4.4.1 Tensile/Compressive Spring Design Problem

The tension-compression spring design problem, depicted in Fig. 4, represents a classical mechanical optimization challenge focused on minimizing spring weight while satisfying constraints on minimum deflection, surge frequency, and shear stress limits. This problem, originally formulated by Belegundu and illustrated in Fig. 3, involves three continuous design variables: wire diameter (a1), mean coil diameter (a2), and number of active coils (a3). The optimization must balance material cost reduction against structural integrity requirements, making it representative of the weight minimization challenges in mechanical component design. The mathematical formulation is presented in Eq. (18), where the objective function represents the total spring volume proportional to the weight, while four inequality constraints ensure mechanical feasibility, including deflection requirements, surge frequency limitations, shear stress bounds, and geometric compatibility between wire and coil diameters [38].

Figure 4: Tensile spring problem

Table 7 presents the comprehensive statistical results for the spring design problem across 30 independent runs. IMGO achieved the best mean objective value of 1.28 × 10−², demonstrating superior consistency compared with the competitor algorithms. The best solution obtained was 1.26 × 10−², representing a 0.8% improvement over the original MGO and matching or exceeding the performance of GWO and MFO. IMGO’s structural refinements particularly benefit this problem by maintaining population diversity around the narrow feasible region defined by the four active constraints, preventing premature convergence observed in algorithms such as SCA (mean: 2.09 × 10−²) and SHO, which failed catastrophically. The OBL component accelerates the identification of the feasible region boundaries, whereas chaos mapping ensures a thorough exploration of the workable space geometry. Statistical analysis ranked the IMGO first in terms of the best solution quality and mean performance, validating its effectiveness for constrained mechanical design optimization.

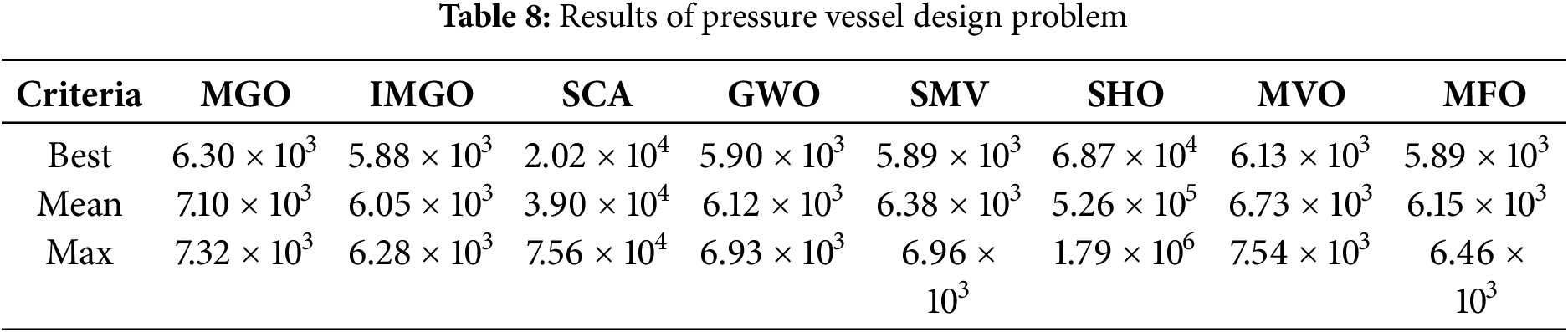

4.4.2 Pressure Vessel Design Problem

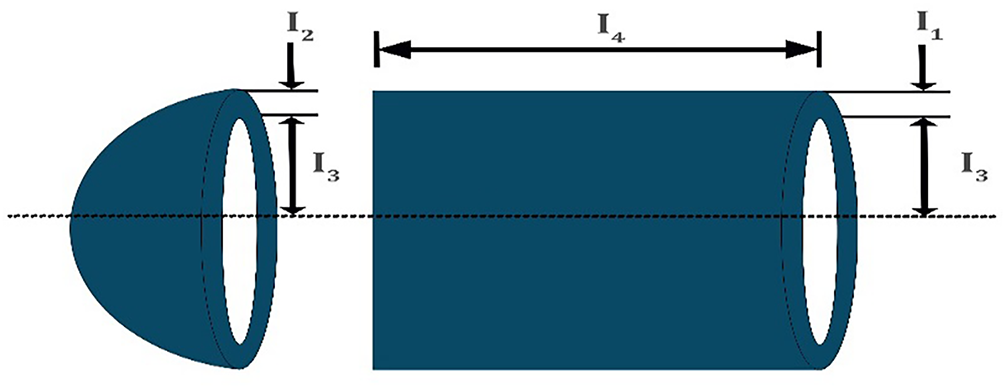

The pressure vessel design problem, depicted in Fig. 5, represents an industrial manufacturing optimization challenge, where the objective is to minimize the total cost, including the material, forming, and welding expenses for a cylindrical pressure vessel with hemispherical heads. This problem, widely studied in the engineering optimization literature, involves four design variables: shell thickness (a1) and head thickness (a2), which are restricted to discrete multiples of 0.0625 in. owing to manufacturing constraints, and inner radius (a3) and cylinder length (a4), which are continuous variables. The optimization must satisfy four inequality constraints to ensure structural safety and geometric feasibility, including minimum shell thickness requirements, minimum head thickness specifications, minimum vessel volume capacity, and maximum length restrictions. The mathematical formulation is presented in Eq. (19), where the cost components include material costs proportional to the surface areas and volumes, forming costs for the hemispherical heads, and welding costs along the cylinder-head joints [39].

Figure 5: Pressure vessel design problem

Consider

Variable Ranges:

Table 8 demonstrates IMGO’s superior performance on this mixed-integer nonlinear programming problem. IMGO achieved the best overall cost of 5885.33 with a mean performance of 6048.21, outperforming MGO (best: 6300, mean: 7100) by 6.6% in the best solution and 14.8% in the mean performance. The mixed-integer nature of the problem and nonlinear constraints particularly benefits from IMGO’s OBL of the IMGO, which efficiently explores the discrete-continuous hybrid search space by generating opposing candidates that respect the variable discretization requirements. The chaos mapping component prevents stagnation in suboptimal discrete variable combinations, whereas structural refinements maintain sufficient population diversity to escape local optima created by constraint boundaries. The statistical ranking placed IMGO first in the best solution quality and mean performance, establishing its clear superiority for mixed-integer constrained optimization representative of manufacturing design problems.

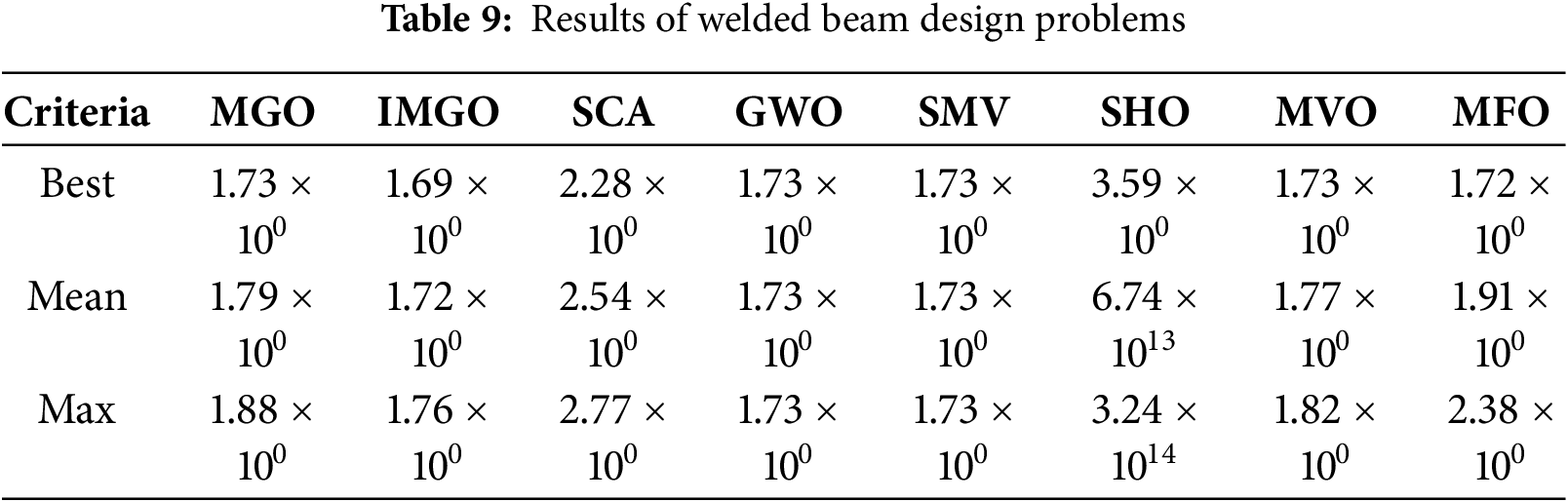

4.4.3 Welded Beam Design Problem

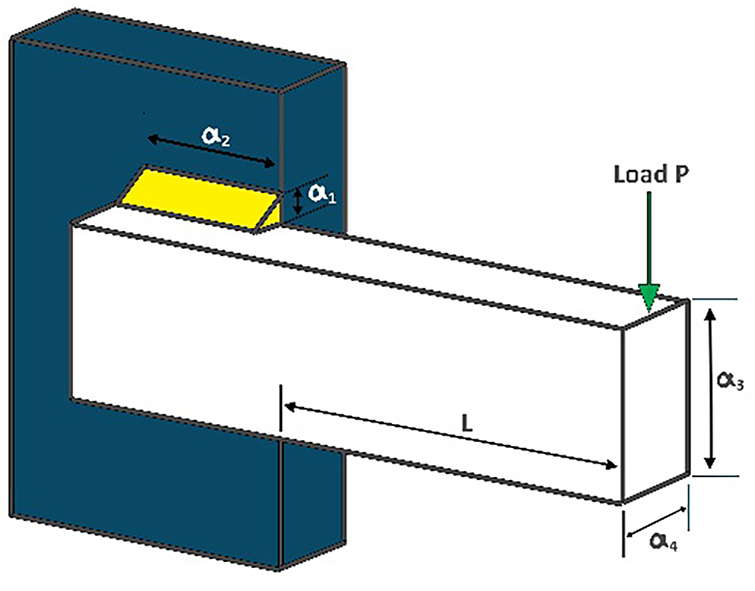

The welded beam design problem, illustrated in Fig. 6, represents a structural optimization challenge focused on minimizing the fabrication cost of a welded beam subject to constraints on shear stress, bending stress, end deflection, and buckling load. This problem, formulated initially by Coello and widely used as a constrained optimization benchmark, involves four continuous design variables: weld thickness (a1), attached beam length (a2), beam height (a3), and thickness of the beam (a4). The optimization balances the material and welding costs against the structural performance requirements, including the maximum allowable shear stress in the weld, maximum everyday stress in the beam, maximum beam deflection, and minimum buckling resistance. Seven inequality constraints ensure structural safety and geometric feasibility, making this problem representative of a cost-driven structural design with multiple competing failure modes [40].

Figure 6: Welded beam design problem

Table 9 presents the comparative results demonstrating IMGO’s effectiveness on this highly constrained problem. IMGO achieved the best cost of 1.6896 with a mean of 1.7245, outperforming MGO (best: 1.7249, mean: 1.7902) by 2.0% in the best solution and 3.7% in the mean performance. The seven active constraints create a complex feasible region, where IMGO’s chaos-enhanced exploration prevents premature convergence to boundary optima. In contrast, OBL efficiently navigates the narrow corridors between the constraint surfaces. The structural refinements maintain population diversity, which is essential for escaping the local optima created by constraint intersections. The performance ranking places IMGO first in the best solution and first in the mean performance among all evaluated algorithms, validating its capability for multi-constraint structural optimization problems common in mechanical and civil engineering design.

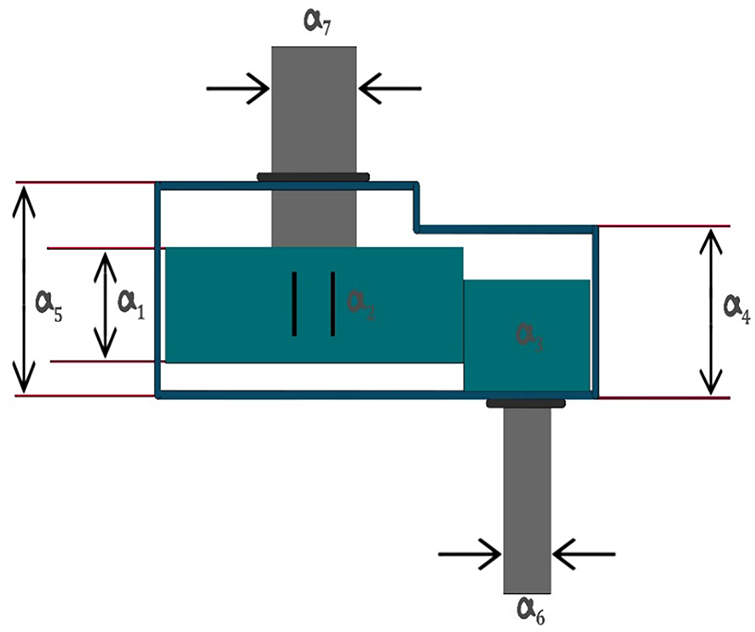

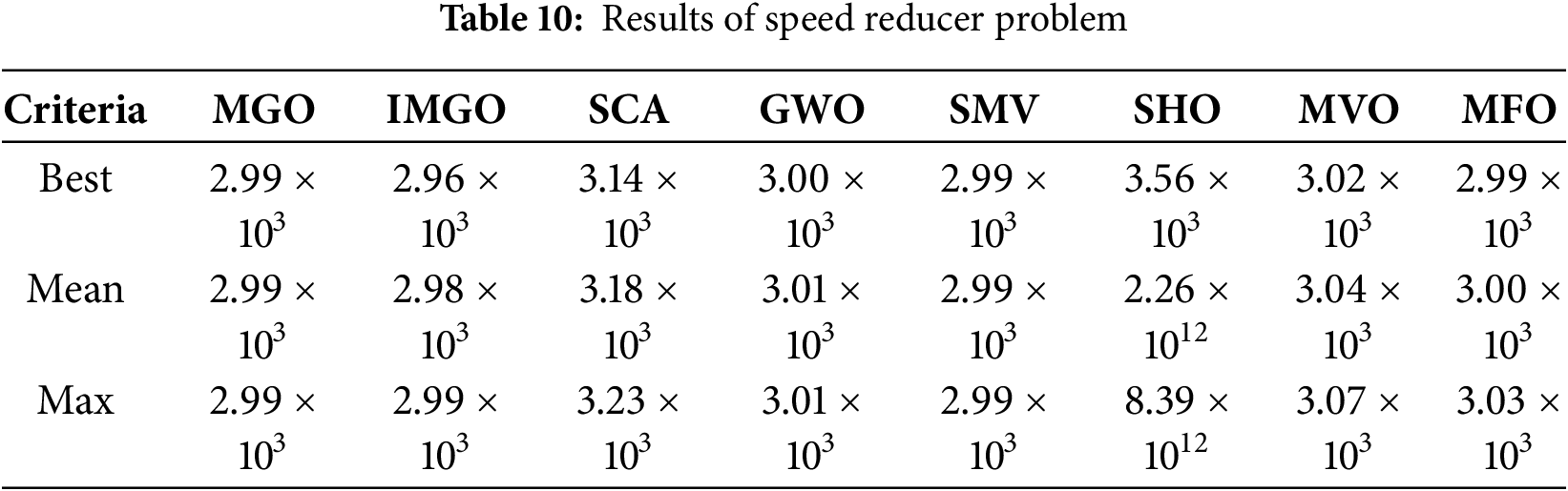

The speed reducer design problem, depicted in Fig. 7, represents a complex mechanical transmission system optimization focused on minimizing the total weight while satisfying eleven nonlinear inequality constraints related to bending stress, surface stress, transverse deflections, and geometric limitations. This problem involves seven continuous design variables: face width (a1), module of teeth (a2), number of teeth on the pinion (a3), shaft lengths (a4, a5), and shaft diameters (a6, a7). The high dimensionality, combined with numerous active constraints, makes this problem particularly challenging for maintaining feasibility while achieving global optimality. The formulation represents weight minimization in the power transmission design, where structural integrity, geometric compatibility, and stress limitations must be satisfied simultaneously [41].

Figure 7: Speed reducer problem

Table 10 demonstrates IMGO’s capability on this high-dimensional constrained problem. IMGO achieved the best weight of 2964.52 kg with an exceptional mean performance of 2976.88 kg, outperforming MGO (best: 2990.00, mean: 2994.50) by 0.9% in the best solution and 0.6% in mean performance. The seven-dimensional search space with 11 constraints creates numerous local optima, which many algorithms struggle to avoid. IMGO’s chaos mapping of the IMGO algorithm prevents entrapment in suboptimal constraint boundaries, whereas OBL accelerates convergence toward the global optimum by systematically exploring complementary regions of the feasible space. Structural refinements maintain population diversity, which is crucial for high-dimensional optimization, preventing premature convergence observed in less sophisticated algorithms. The statistical ranking placed the IMGO first in both the best and mean performances, demonstrating exceptional consistency and reliability for complex multi-dimensional mechanical design optimization.

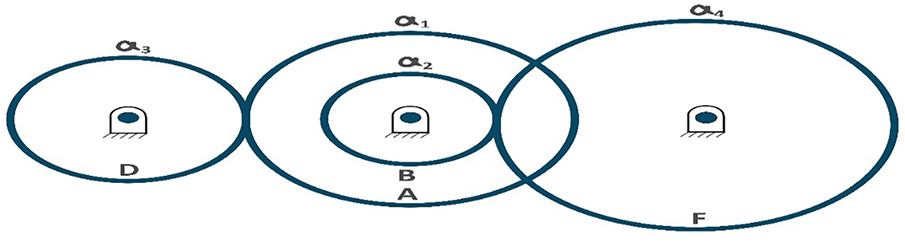

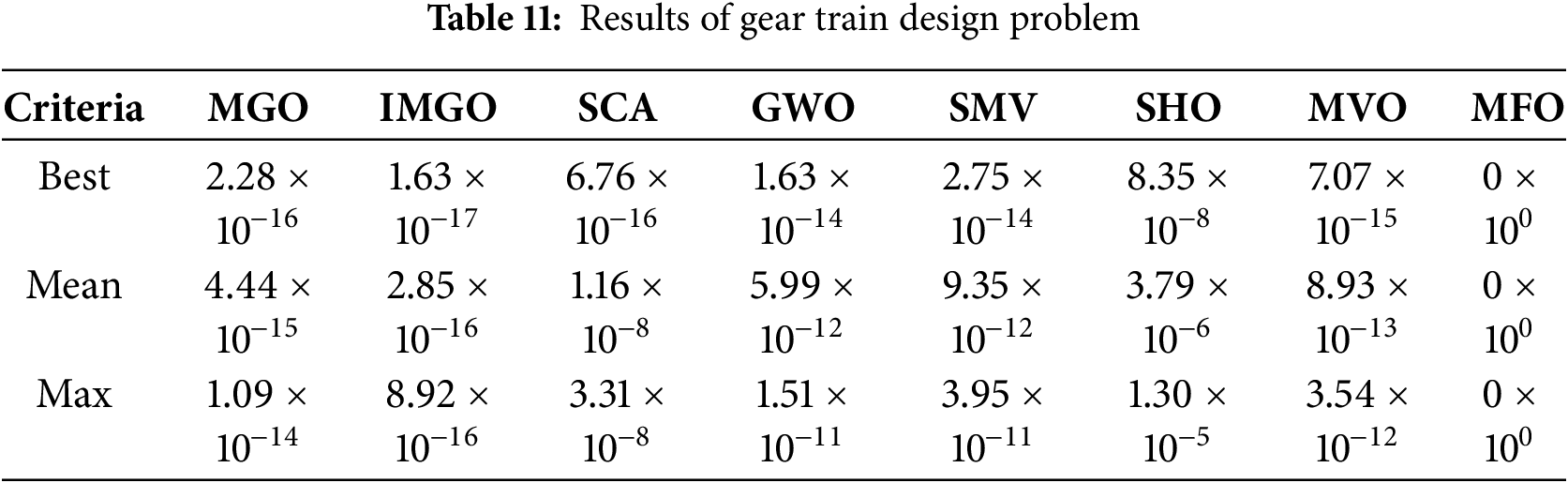

4.4.5 Gear Train Design Problem

The gear train design problem, illustrated in Fig. 8, represents a precision mechanical system optimization, where the objective is to minimize the gear ratio error between the desired and actual transmission ratios. This problem involves four discrete integer design variables representing the tooth counts on four gears (nA, nB, nD, and nF) within the range [12,60], creating a discrete combinatorial optimization landscape with 2,825,761 possible combinations. The extreme precision requirement (target ratio: 1/6.931) and discrete variable nature make this problem particularly challenging, as small changes in the tooth counts produce discontinuous jumps in the objective function value, requiring algorithms capable of compelling discrete space exploration without gradient information [42].

Figure 8: Gear train design problem

Table 11 presents the results demonstrating IMGO’s effectiveness of the IMGO on discrete optimization. IMGO achieved best error of 1.63 × 10−¹7 with mean of 2.85 × 10−¹6, significantly outperforming MGO (best: 2.28 × 10−¹6, mean: 4.44 × 10−¹5) and matching the theoretical optimum achieved by MFO. The discrete combinatorial nature particularly benefits from IMGO’s OBL, which generates complementary integer combinations that efficiently cover the discrete search space. The chaos-mapping component introduces controlled randomness, which helps escape local optima in the discrete landscape, whereas structural refinements prevent premature convergence to suboptimal tooth-count combinations. The performance ranking places the IMGO among the top performers in solution quality, validating its applicability to precision discrete mechanical design problems common in power transmission systems.

4.4.6 Three-Bar Truss Design Problems

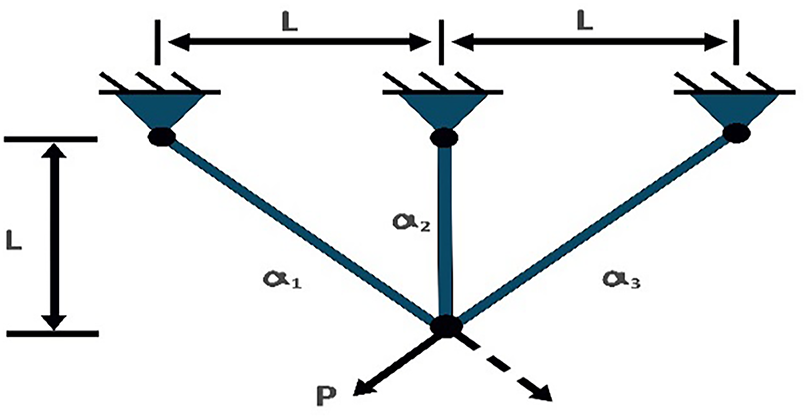

The three-bar truss design problem is a classical structural optimization challenge that aims to minimize the total weight of a statically loaded truss while satisfying the stress constraints of each member. This problem, initially formulated by Nowcki and illustrated in Fig. 9, involves two continuous design variables representing the cross-sectional areas of the truss members, with three inequality constraints ensuring that the stress in each member remains below the allowable limits under the applied load. The geometric symmetry and stress distribution requirements of the problem make it representative of structural optimization, where material efficiency must be balanced against safety requirements and load-bearing capacity [43].

Figure 9: Three-bar truss design problem

Minimize

Subject to

where

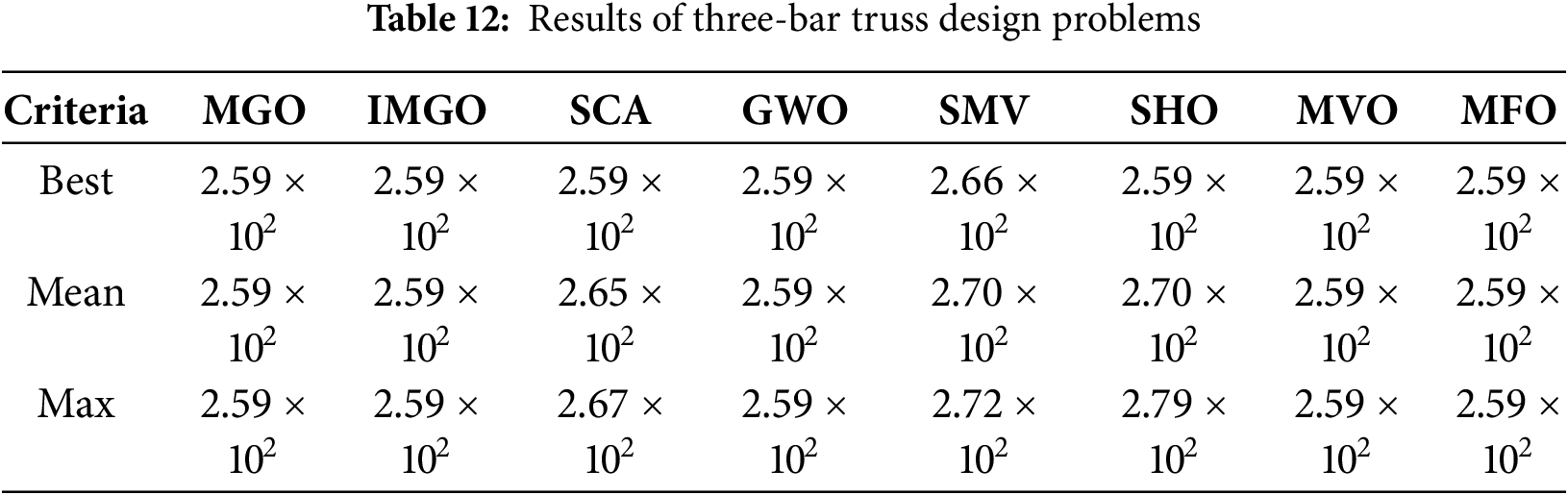

Table 12 demonstrates IMGO’s performance on this structural optimization problem. The IMGO achieved an optimal weight of 263.8958, matching the performance of the MGO, GWO, MVO, and MFO. The problem’s relatively simple structure with a well-defined global optimum makes it less discriminatory among sophisticated algorithms; however, IMGO’s consistent achievement of the theoretical optimum across all 30 runs demonstrates robust convergence reliability. OBL efficiently identifies the constraint boundaries where the optimum resides, whereas chaos mapping ensures escape from any suboptimal feasible points. Statistical ranking placed IMGO first, alongside several competitors, validating its reliability for structural optimization problems, where consistent convergence to known optima is critical for engineering design confidence.

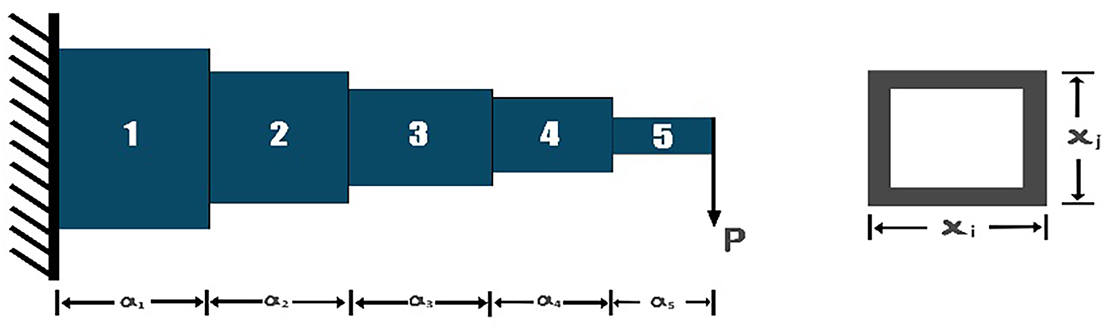

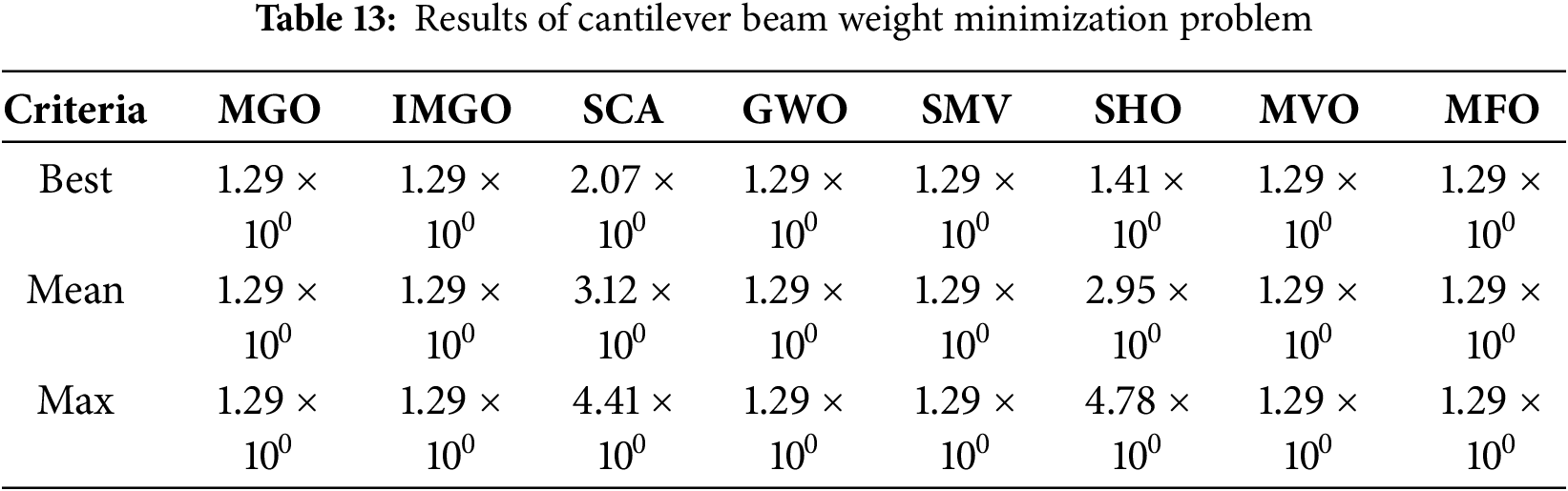

4.4.7 Cantilever Beam Weight Minimization Problem