Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Hybrid Pythagorean Fuzzy Decision-Making Framework for Sustainable Urban Planning under Uncertainty

1 Department of Business Administration, College of Business Administration, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

2 Sustainability Competence Centre, Széchenyi István University, Egyetem tér 1, Gyor, 9026, Hungary

3 Department of Computer Science and Information Systems, College of Applied Sciences, AlMaarefa University, Diriyah, Riyadh, 13713, Saudi Arabia

4 Research Center, Deanship of Scientific Research and Post-Graduate Studies, AlMaarefa University, Dariyah, Riyadh, 13713, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Computer Engineering, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, 202002, India

6 Department of Operations Research and Statistics, Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, 11000, Serbia

7 Faculty of Engineering, Dogus University, Umraniye, Istanbul, 34775, Türkiye

8 Department of Applied Mathematical Science, College of Science and Technology, Korea University, Sejong, 30019, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Vladimir Simic. Email: ; Mohd Anjum. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 29 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.073945

Received 29 September 2025; Accepted 01 November 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

Environmental problems are intensifying due to the rapid growth of the population, industry, and urban infrastructure. This expansion has resulted in increased air and water pollution, intensified urban heat island effects, and greater runoff from parks and other green spaces. Addressing these challenges requires prioritizing green infrastructure and other sustainable urban development strategies. This study introduces a novel Integrated Decision Support System that combines Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets with the Advanced Alternative Ranking Order Method allowing for Two-Step Normalization (AAROM-TN), enhanced by a dual weighting strategy. The weighting approach integrates the Criteria Importance Through Intercriteria Correlation (CRITIC) method with the Criteria Importance through Means and Standard Deviation (CIMAS) technique. The originality of the proposed framework lies in its ability to objectively quantify criteria importance using CRITIC, incorporate decision-makers’ preferences through CIMAS, and capture the uncertainty and hesitation inherent in human judgment via Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets. A case study evaluating green infrastructure alternatives in metropolitan regions demonstrates the applicability and effectiveness of the framework. A sensitivity analysis is conducted to examine how variations in criteria weights affect the rankings and to evaluate the robustness of the results. Furthermore, a comparative analysis highlights the practical and financial implications of each alternative by assessing their respective strengths and weaknesses.Keywords

The rapid spread of civilization and urbanization has created new challenges for cities worldwide in the pursuit of sustainable development [1]. The global emphasis on sustainable urban development has spurred a re-evaluation of city dynamics and the adoption of diverse techniques [2]. Theoretical foundations in economics, the environment, and society underpin this research. Cities must rethink and reconstruct the complex relationships among people, the environment, the economy, politics, and society to meet the expectations of diverse stakeholders. Prioritizing the unique qualities and opportunities of urban life is essential for adapting to the evolving context of sustainable development [3]. Mao et al. [4] highlighted how firm-level perceptions of risk and uncertainty influence real estate decisions, reinforcing the importance of structured decision-making in urban infrastructure investment. Beyond fulfilling physical requirements such as air quality, the ratio of green space to population, and resource utilization, a prosperous city must also prioritize social well-being [5]. Human connections play a central role in this process. Yang et al. [6] demonstrated how urban parks contribute to thermal regulation, underscoring the environmental benefits of green infrastructure. Thriving in sustainable development represents the pinnacle of environmental and social advancement. Xu et al. [7] examined how smart city policies affect

The multidisciplinary field of sustainable urban planning seeks to balance the social, economic, and environmental dimensions of city development and administration. It involves creating cities that can withstand natural disasters, utilize resources efficiently, and support prosperous communities. Key principles include walkability, open-space preservation, and transit-oriented, compact development, which are emphasized to curb uncontrolled urban sprawl. Natural systems, such as urban forests, parks, and green roofs, can also be integrated into city design. These elements enhance ecosystem functions, regulate stormwater runoff, and improve air quality. To ensure the sustainable use of resources, priority must be given to conserving energy, water, and managing waste. At the same time, addressing open space, affordable housing, and community participation in planning ensures that urban growth benefits all residents. Such measures also strengthen resilience to social and environmental shocks, including economic downturns, natural disasters, and climate change. There is growing recognition that the complex challenges of urbanization cannot be resolved without sustainable urban planning. Implementing these initiatives requires the use of systematic techniques to evaluate and rank alternative strategies.

Environmental impact reduction in urban planning refers to strategies designed to minimize the adverse effects of urbanization on the environment [8]. In a similar sustainability-focused initiative, Chen et al. [9] applied AI tools to address carbon neutrality, offering a precedent for integrating advanced technologies into decision-making. A common objective of these initiatives is to reduce pollution in the air, water, and soil through stricter regulations, environmentally friendly technologies, and improved waste management. Green infrastructure solutions, such as permeable pavements and rain gardens, help manage stormwater and reduce pollution. Various approaches also exist to mitigate the urban heat island effect, including the installation of green roofs, the use of cool roofing materials, and the expansion of urban vegetation [10,11]. Encouraging walking, cycling, and the use of public transportation instead of private vehicles can further reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Transit-oriented development is one such land-use–transportation strategy. Preserving and enhancing natural habitats during urban expansion benefits local wildlife and helps maintain ecological balance. The creation of urban woodlands and green spaces plays an important role in protecting biodiversity. Urban planning can also reduce energy demand by incorporating insulation, passive solar design, and renewable energy sources [12]. Energy-efficient building codes and upgrades are key strategies for lowering energy consumption and emissions [13].

Recent evaluations of green infrastructure increasingly emphasize its broader implications for sustainability and quality of life. Wang et al. [14] advocate for a life-cycle approach to assessing the overall performance of green infrastructure, highlighting environmental, technical, socio-economic, and human-centric factors. Stangierska et al. [15] examine the impact of urban green areas on residents’ quality of life in Warsaw, emphasizing psychological health, environmental aesthetics, and community satisfaction. Building on this, Takano et al. [16] propose a structured evaluation framework for sustainable urban development, incorporating indicators directly related to human well-being and accessibility. This study defines quality of life as a multidimensional concept encompassing physical and mental health, environmental satisfaction, access to green spaces, and community cohesion. Our assessment model operationalizes this concept through specific criteria, including public health benefits, aesthetic improvements, and community acceptance. These indicators effectively capture the crucial yet intangible contributions of green infrastructure to urban livability and social sustainability. The reviewed studies address a wide range of decision-making areas with varying levels of importance, carefully weighing and ranking alternatives according to predefined standards. To address these complex decision-making challenges, urban planners often apply methods such as the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), and the Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL). In addition, Spatial Decision-Making Tools support urban planning by analyzing geographic data, visualizing decision impacts, evaluating land-use patterns, and optimizing infrastructure site selection [17].

Life Cycle Assessment evaluates the environmental impact of a project or product from raw material extraction through to final disposal. In urban planning, it is used to assess the sustainability of building materials, infrastructure projects, and policies. By incorporating trends, policies, and technological assumptions, this approach allows planners to create and evaluate future scenarios. Scenario planning helps urban planners anticipate and adapt to a wide range of potential outcomes. Cost-Benefit Analysis identifies the most financially feasible urban planning projects by weighing their benefits against their costs. It is often used in conjunction with Environmental and Social Impact Assessments to provide a more comprehensive evaluation. A key advantage of these tools lies in their ability to provide a holistic assessment of complex urban planning options. Increasingly, it is essential to integrate such approaches with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to ensure that planning decisions benefit both society and the environment. The reviewed studies also demonstrate that Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) models are highly effective and adaptable across diverse sectors and operational conditions. Collectively, this body of research illustrates the broad applicability of MCDM models in both commercial and operational contexts.

MCDM is a key technique in decision science that aims to identify optimal solutions by considering a wide variety of factors. To achieve this, a group of experts evaluates each alternative according to multiple criteria and then communicates their conclusions clearly. However, uncertainty affects nearly every decision-making process in today’s complex and dynamic world. Consequently, it is essential to account for potential discrepancies during interpretation. Data managers often face challenges in providing precise responses when dealing with imprecise, erroneous, or poorly defined data. Such difficulties can occur in a variety of real-world contexts, including decision-making, classification, and supplier assessment. Traditional data analysis techniques are often insufficient for handling ambiguous or unclear knowledge. To address these challenges, several theoretical frameworks have been developed: Molodtsov (1999) introduced Soft Set Theory; Pawlak (1980) developed Rough Set Theory; and Zadeh (1965) proposed Fuzzy Set Theory and the concept of Membership Degree (MBSD) [18]. Atanassov (1986) later introduced Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets (IFSs) [19], which are characterized by the MBSD and the non-MBSD, constrained such that their sum does not exceed one. IFSs effectively capture the fuzziness and ambiguity inherent in real-world events, making them a widely adopted approach in this field. Building on this, Yager (2013) proposed the Pythagorean Fuzzy Set (PyFS) as an extension of IFS [20]. In a PyFS, the squared sum of the MBSD and non-MBSD cannot exceed one. This feature allows PyFSs to better handle the ambiguity and imprecision of data arising from real-world problems. In recent years, a substantial body of research has explored PyFSs from various perspectives [21,22]. Wang and Khalil (2022) [23] introduced the concept of a Generalized Pythagorean Fuzzy Soft Set by combining Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets and Fuzzy Soft Sets to enhance the modeling of uncertainty in decision-making.

Information aggregation for decision-making can benefit many sectors, including administration, intelligent systems, technology, psychology, social work, and medicine. Traditionally, alternative opinions have been treated as fixed quantities or linguistic values. However, due to the inherent variability of data, aggregating these opinions is often challenging [24]. Since the primary objective of multi-attribute decision-making problems is to consolidate multiple inputs into a single output, alternative opinions play a particularly important role. The Best–Worst Method was introduced by Moslem (2020) [25] to evaluate transit mode choices. Abbasi et al. (2022) [26] developed a novel decision-making approach by introducing Pythagorean Fuzzy Einstein aggregation operators, integrated with Z-numbers, to better model uncertainty and reliability in complex decision environments. Al-Quran et al. (2023) [27] proposed a novel approach to enhance tropical artificial forests using cubic picture fuzzy aggregation operators. Their study addressed the inherent uncertainties in ecological data by employing an advanced fuzzy logic framework, enabling a more nuanced aggregation of expert opinions.

The literature highlights a variety of noteworthy applications of decision-making methods, including efficient risk management in distribution operations, environmentally friendly hydrogen production, phone selection, and general decision-making. Ali et al. [28] proposed a norm-based distance measure, while Ali [29] introduced Minkowski-type distance measures for cubic q-rung orthopair fuzzy sets. Taylan et al. [30] conducted an integrated decision-making study using fuzzy AHP, fuzzy TOPSIS, and fuzzy VIKOR to assess different energy system options under uncertainty. A new and powerful hybrid model was presented within this approach; it effectively utilized linguistic and imprecise information. The framework provided a more robust and transparent multi-criteria assessment model by combining subjective and objective evaluations. The model was applied to renewable energy system selection and demonstrated higher accuracy and consistency than classical MCDM approaches.

Diakoulaki et al. [31] developed the Criteria Importance Through Intercriteria Correlation (CRITIC) methodology—a robust and reliable approach for assigning weights to multiple criteria in complex MCDM problems. This comparative, ratio-based method performs pairwise comparisons to determine the relative importance of each criterion, providing a consistent and credible weighting mechanism. From a land-use planning perspective, Yu et al. [32] examined how administrative reforms enhance urban land-use efficiency, a critical factor in evaluating infrastructure alternatives.

The extensive body of research demonstrates the CRITIC methodology’s flexibility and applicability across diverse domains. This approach offers a nuanced, human-like evaluation of criteria that goes beyond basic mathematical calculations, making it a key tool in decision-making processes. Kaur et al. [33] extended the CRITIC methodology within a neutrosophic environment and applied it to aircraft selection, demonstrating its adaptability to complex decision-making scenarios. Sleem et al. [34] employed neutrosophic CRITIC–MCDM to rank variables and client preferences in the virtual-reality metaverse, illustrating CRITIC’s applicability to emerging technologies. Mishra et al. [35] introduced a novel scoring function for Fermatean fuzzy numbers in MCDM, integrating it with the Grey-Level Decision System and CRITIC approaches, thereby enhancing decision-making processes through advanced scoring mechanisms. Wei et al. [36] investigated how urban economic activity spatially influences airport throughput, highlighting the interconnectedness of urban systems.

Jusufbašić [37] reviewed multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) approaches for equipment selection in logistics, emphasizing their effectiveness in optimizing operations. Zulqarnain et al. [38] proposed an intelligent multi-criteria group decision-making model for green supplier selection using interactional aggregation operators under interval-valued Pythagorean fuzzy soft sets (IVPyFSSs). Chen et al. [39] examined the ecological consequences of landscape design on spontaneous flora in urban parks, further supporting the prioritization of green spaces. These studies demonstrate how MCDM methods are applied in emerging technologies and urban sustainability contexts. Keršulienė et al. [40] applied the Step-wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (SWARA) technique to achieve equitable conflict resolution. Stević et al. [41] investigated the fuzzy SWARA approach for MCDM, conducting a detailed analysis and identifying several limitations. Li et al. [42] introduced predictive modeling using structural urban imagery to derive multi-level socioeconomic indicators, which are valuable for prioritizing infrastructure projects. Deveci et al. [43] utilized Fermatean fuzzy scoring functions to analyze and evaluate risks associated with sustainable mining practices. In the automotive industry, intuitionistic fuzzy numbers have been applied effectively, as demonstrated by Amoozad et al. [44]. Eroğlu and Gencer [45] enhanced decision-making processes by categorizing the SWARA approach and proposing an application utilizing Stochastic Multicriteria Acceptability Analysis–2 (SMAA–2). Alrasheedi et al. [46] introduced a group decision-making framework with multiple criteria to further improve decision-making effectiveness.

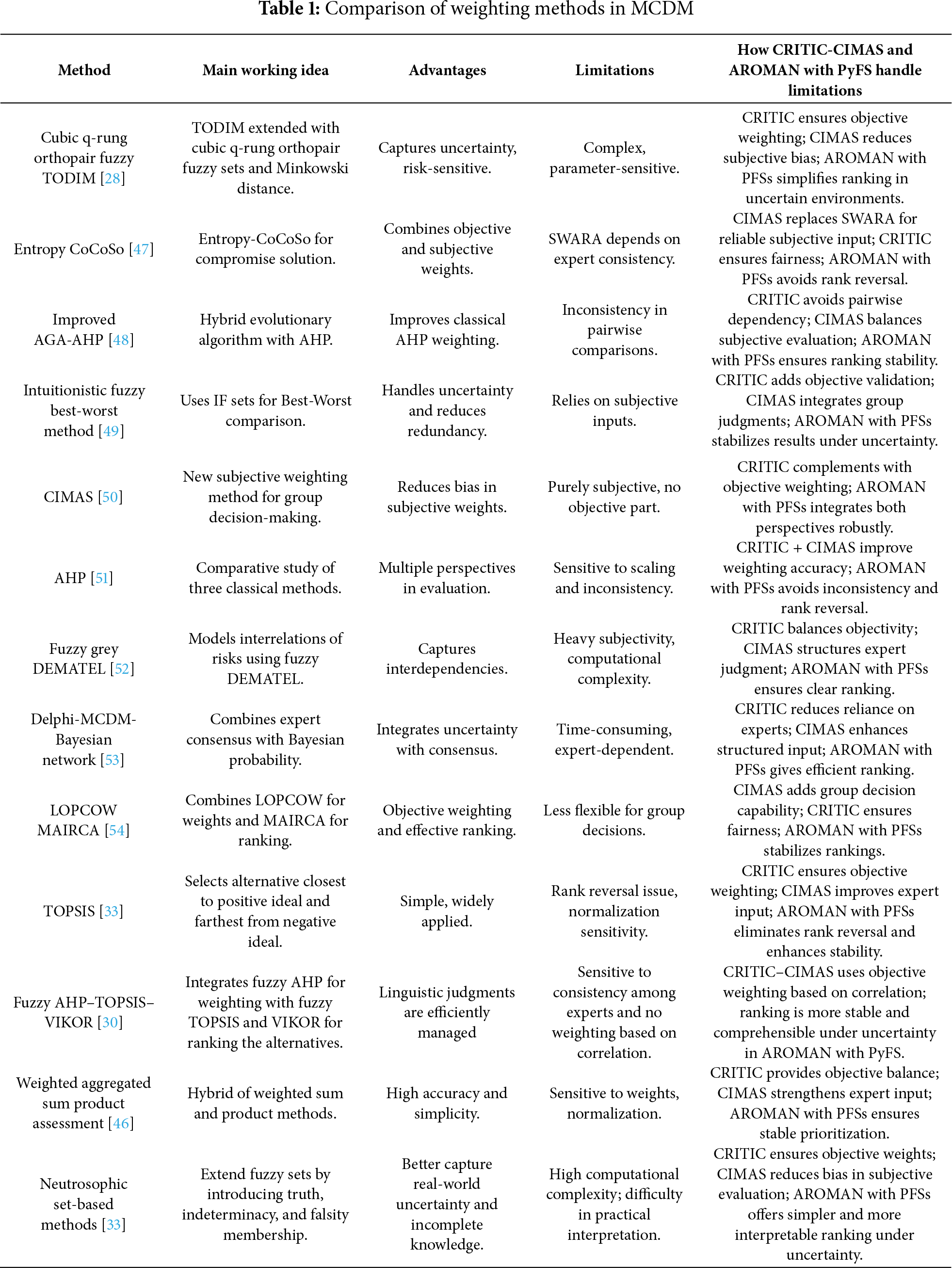

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of commonly used weighting and ranking methods in MCDM. It highlights the principal working mechanisms, advantages, and limitations of each method, as well as how the proposed integration of the CRITIC, Criteria Importance through Means and Standard Deviation (CIMAS), and the Alternative Ranking Order Method Allowing for Two-Step Normalization (AROMAN) with PyFSs addresses these limitations. The table demonstrates that classical, hybrid, and fuzzy MCDM methods often face challenges such as parameter sensitivity, reliance on subjective judgments, rank reversal, and computational complexity. By combining CRITIC, CIMAS, and AROMAN with PyFSs, the proposed framework ensures objective weighting, reduces subjective bias, stabilizes rankings, and enhances interpretability in uncertain and socially inclusive urban planning contexts.

Zafar et al. [55] developed a blockchain evaluation system that integrates the entropy–CRITIC weighting approach with MCDM methodologies, making a valuable contribution to blockchain technology assessment. Bączkiewicz et al. [56] examined the methodological aspects of MCDM in an e-commerce recommender system, highlighting its significance in designing recommendation algorithms. Hassan et al. [57] applied a CRITIC–TOPSIS technique to optimize site selection for a solar photovoltaic farm, demonstrating the applicability of MCDM in renewable energy planning. Kumar and Singh [58] employed an integrated MCDM technique to optimize powder-mixed green electrical discharge machining parameters, illustrating its utility in industrial processes. Vadivel et al. [59] used the CRITIC method for selecting sustainable green suppliers, emphasizing the role of MCDM in promoting sustainability within supply chain management.

Collectively, these studies demonstrate the extensive application of the CRITIC approach and MCDM methods across diverse sectors, highlighting their adaptability and effectiveness in addressing complex decision-making problems. This body of research contributes both to theoretical advancements and practical applications, reflecting the ongoing evolution of MCDM approaches across multiple disciplines. In 2023, Bošković et al. [60] proposed the AROMAN, introducing a new perspective on decision-making in cargo bike delivery models. Their emphasis on flexibility and adaptability paved the way for broader applications in the sector and facilitated the development of novel decision-support techniques. Kara et al. [61] subsequently combined the Method Based on the Removal Effects of Criteria with AROMAN to evaluate sustainable competitiveness levels. Through a case study conducted in Turkey, this integrated approach provided practical insights into socioeconomic planning and sustainability assessment.

While the literature on sustainable urban planning and decision-making methods is substantial, several gaps remain. First, there is a lack of comprehensive frameworks that integrate multiple decision-making tools to address the complex and multifaceted nature of urban sustainability. Most studies focus on specific methodologies rather than combining them to provide a holistic assessment of urban planning options. Second, there is limited research on the practical application of decision-making tools in real-world urban planning projects, particularly in developing countries where resources and data availability are often constrained. This highlights the need for adaptive and scalable solutions that can be applied across diverse urban contexts. Third, existing research frequently overlooks the importance of community engagement and social equity in decision-making processes. While environmental and economic aspects are regularly considered, social dimensions of sustainability—such as inclusion and community acceptability—are less frequently addressed.

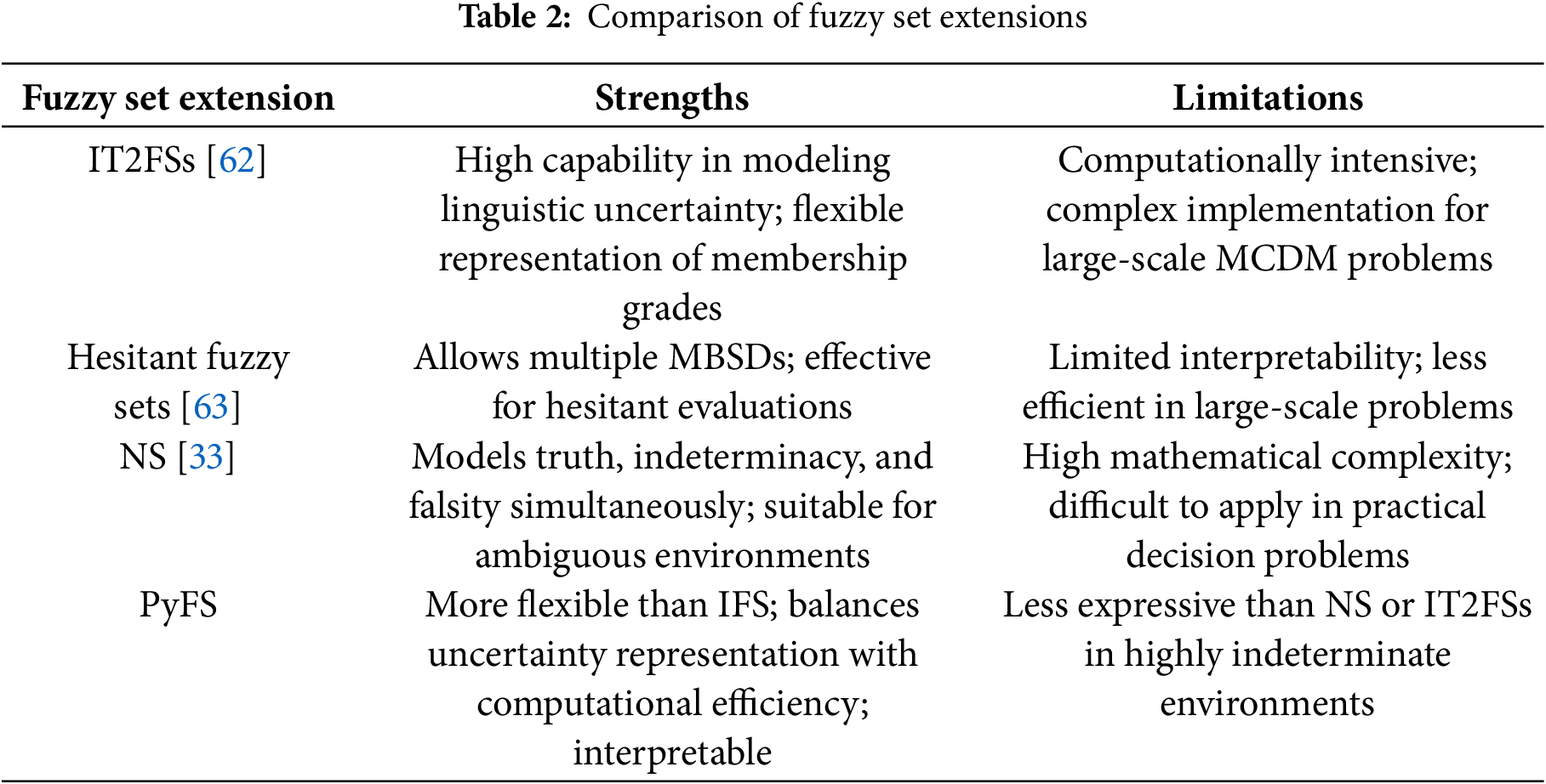

In recent years, several extensions of fuzzy set theory have been developed to more effectively capture uncertainty in multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM). For instance, Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Sets (IT2FSs) can model linguistic uncertainty with high granularity; however, they are computationally intensive and less practical for large-scale problems [62]. Hesitant Fuzzy Sets allow decision-makers to assign multiple membership degrees, thereby offering greater flexibility in situations involving hesitation; nevertheless, their interpretability and scalability remain limited [63]. Neutrosophic Sets [33] incorporate truth, indeterminacy, and falsity within a unified framework, making them suitable for highly ambiguous environments, yet their mathematical complexity often restricts practical use. In comparison, Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets (PyFSs), introduced by Yager and further refined in subsequent research, provide a balanced trade-off between expressiveness and computational simplicity. PyFSs extend IFSs by relaxing the membership–nonmembership constraint, thereby enabling decision-makers to represent higher degrees of uncertainty without incurring the computational burden of IT2FSs or the interpretability challenges of NSs. Accordingly, PyFSs were selected in this study as the most suitable tool for enhancing the robustness and interpretability of the proposed CRITIC–CIMAS–AROMAN framework.

Table 2 presents a comparative overview of common extensions of fuzzy sets used in MCDM. It summarizes the strengths and limitations of each method, emphasizing their suitability for managing uncertainty in complex decision-making scenarios. While IT2FSs and Neutrosophic Sets offer high expressiveness for modeling ambiguous data, they are often computationally intensive or mathematically complex. Hesitant Fuzzy Sets provide flexibility for hesitant evaluations but exhibit limited interpretability. Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets (PyFSs) strike a practical balance between uncertainty representation and computational efficiency, making them particularly well-suited for integration within the CRITIC-CIMAS-AROMAN framework applied in this study.

2.1 Motivation and Contribution

Rapid urbanization, population growth, and industrial expansion have significantly intensified environmental challenges in cities, including air and water pollution, the urban heat island effect, and the depletion of natural ecosystems. These issues pose serious threats to the long-term sustainability of urban environments and their capacity to support human life. Traditional urban planning models have largely prioritized economic growth, often at the expense of ecological balance and social well-being. Consequently, there is an urgent need for integrative approaches that embed sustainability, resilience, and community welfare into contemporary urban decision-making frameworks.

To address such multidimensional and often conflicting objectives, MCDM methods have been widely applied. Classical techniques such as the AHP [51] and Step-wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (SWARA) are simple and interpretable; however, they suffer from subjectivity and inconsistency in expert judgments. Recent extensions, including the Entropy–Combined Compromise Solution (CoCoSO) [47] and the Improved Adaptive Genetic Algorithm–AHP model [48], attempt to integrate objective and subjective weighting approaches but remain sensitive to inconsistencies and the reliability of expert assessments. Similarly, the Intuitionistic Fuzzy Best–Worst Method [49] and the fuzzy-grey Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL) [52] more effectively capture uncertainty and interdependencies, yet they are computationally complex and still heavily dependent on subjective expert input.

Several hybrid and advanced MCDM approaches have also been proposed. For instance, the Delphi-MCDM framework integrated with Bayesian methods [53] and the Logarithmic Percentage Change–Driven Objective Weighting (LOPCOW)–Multi-Attribute Ideal-Real Comparative Analysis (MAIRCA) method [54] combine probabilistic reasoning and objective weighting to enhance robustness; however, they are often time-consuming and less flexible for group decision-making. Ranking-oriented models such as the TOPSIS [33], the fuzzy AHP-TOPSIS-VIKOR hybrid approach [30], and the WASPAS method [46] are widely applied owing to their simplicity and ability to facilitate trade-offs. Nonetheless, they frequently encounter challenges such as rank reversal, parameter sensitivity, and dependence on normalization procedures, which can limit their reliability in complex urban planning contexts. Furthermore, Neutrosophic set-based approaches [33] extend fuzzy and intuitionistic fuzzy logic by incorporating indeterminacy to better represent real-world ambiguity; yet, their computational complexity and limited interpretability continue to pose significant challenges.

Motivated by these limitations, this study proposes an integrated decision-support framework that combines the CRITIC, CIMAS and AROMAN approaches within a PyFS environment. The CRITIC method provides objective, correlation-aware weighting of criteria, minimizing inconsistencies and reducing bias. The CIMAS technique structures subjective evaluations, thereby enhancing group decision-making and mitigating dependence on individual expert opinions. The AROMAN method ensures robust, rank-reversal-free prioritization of alternatives, promoting stability and fairness in evaluation. By embedding this hybrid framework within a PyFS environment, the proposed model effectively balances objectivity, subjectivity, and uncertainty, offering a comprehensive and resilient tool for sustainable urban planning decision-making.

The study identifies a critical research gap in the absence of an integrated decision-making framework that incorporates both objective and subjective assessment criteria for evaluating green infrastructure solutions in urban planning. Although numerous studies have analyzed individual green infrastructure alternatives, few have employed MCDM approaches that simultaneously balance environmental, economic, and social dimensions. Furthermore, conventional methodologies often fail to adequately address the inherent uncertainty and complexity of urban environmental planning, particularly when multiple, and at times conflicting, criteria must be considered concurrently. This research addresses these limitations by integrating the CRITIC, CIMAS, and AROMAN techniques within a PyFS environment. The proposed framework provides a comprehensive and data-driven approach for evaluating and ranking green infrastructure alternatives, thereby supporting sustainable urban development through more informed, transparent, and balanced decision-making.

Despite the growing emphasis on green infrastructure in urban planning, several significant research gaps remain:

• Existing studies predominantly analyze individual green infrastructure alternatives, lacking a holistic framework that simultaneously evaluates multiple options across diverse and often conflicting criteria.

• Many existing models emphasize either expert judgment (subjective) or quantitative data (objective), leading to insufficient integration between the two perspectives.

• Urban planning decisions inherently involve uncertainty arising from diverse stakeholder preferences, dynamic environmental conditions, and limited data availability. Conventional approaches often fail to adequately address this uncertainty.

• Although multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) techniques are widely applied, few studies employ hybrid frameworks—such as the integration of CRITIC, CIMAS, AROMAN, and Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets (PyFSs)—that can effectively manage both uncertainty and complexity.

• There remains a pressing need for decision-support tools tailored to the practical requirements of urban planners and policymakers, facilitating sustainable, socially inclusive, and cost-efficient urban development decisions.

The primary objectives of this study are as follows:

• To develop a comprehensive multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) framework for evaluating green infrastructure alternatives in urban planning.

• To apply the Criteria Importance Through Intercriteria Correlation (CRITIC) method to determine objective criterion weights, the Criteria Importance through Mean and Standard Deviation (CIMAS) technique for subjective criterion weights, and the Alternative Ranking Order Method Allowing for Two-Step Normalization (AROMAN) integrated with Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets (PyFSs) for ranking alternatives.

• To construct a robust decision-support framework for urban planners and policymakers to identify sustainable and effective green infrastructure solutions that balance environmental protection, economic viability, public health enhancement, and community acceptance.

• To facilitate informed and equitable decision-making by integrating environmental, economic, and social criteria into a unified evaluation process.

• To strengthen decision-making under uncertain conditions by leveraging the uncertainty-handling capabilities of PyFSs.

• To promote sustainable urban development by minimizing environmental impacts, ensuring economic feasibility, improving public health outcomes, and fostering community engagement.

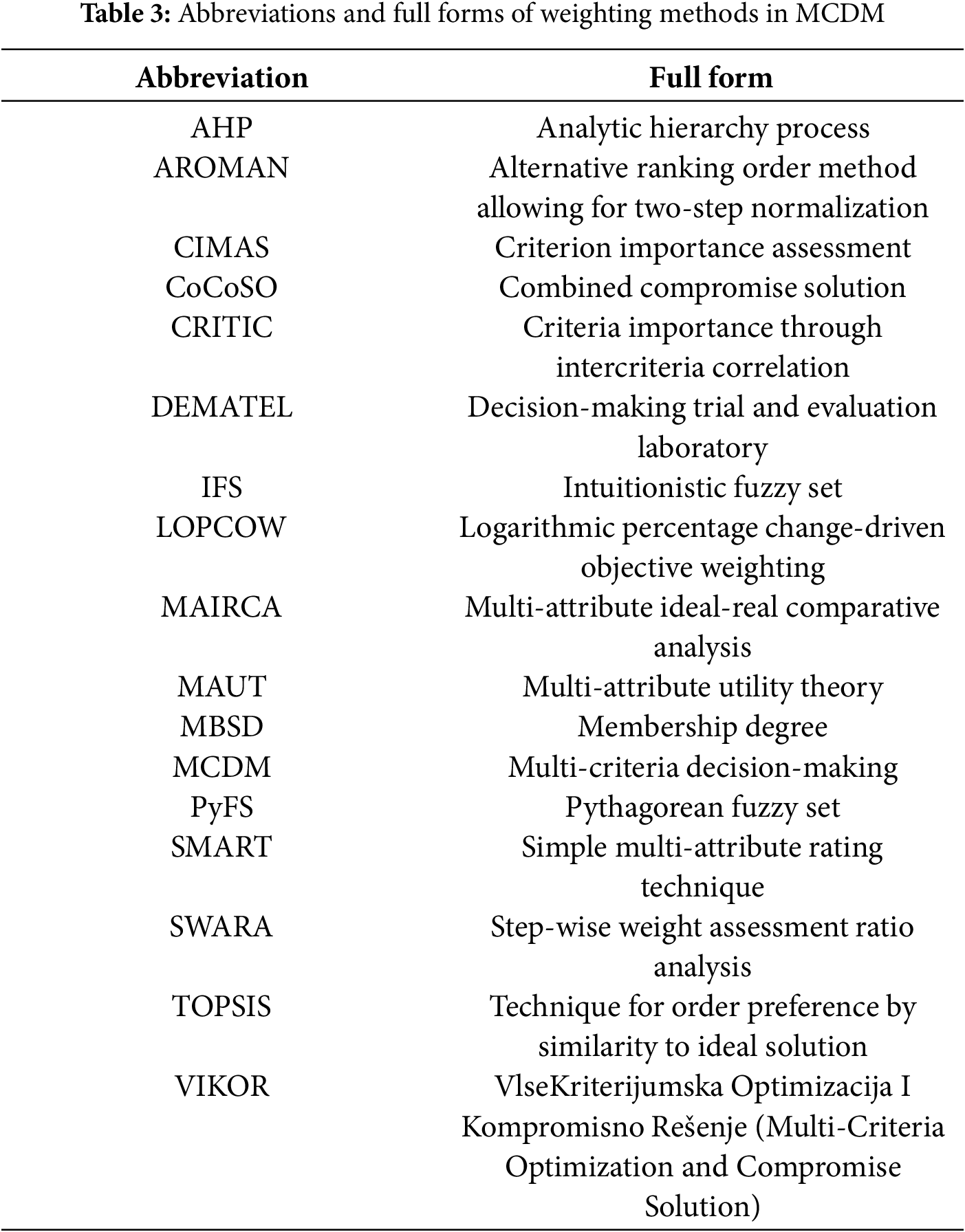

A summary of PyFS and their fundamental concepts is provided in Section 2, with an emphasis on their application in addressing decision-making uncertainty. Section 3 focuses on the development of the AROMAN for alternative ranking, as well as the CRITIC and CIMAS methods for criterion weighting. In Section 4, a case study demonstrates the practical application of the proposed framework for evaluating technical devices. Section 5 presents the sensitivity and comparative analyses conducted to ensure the validity, robustness, and stability of the proposed methodology. Finally, Section 6 concludes the study by summarizing the key findings, discussing their implications for practitioners, and suggesting avenues for further research on fuzzy decision-making and smart manufacturing. The abbreviations used throughout this study are summarized in Table 3.

Definition 1. [18] Let

where

Definition 2. [19] An IFS in

where

Definition 3. [20,64,65] Consider, a PyFS

where

Furthermore,

Definition 4. [20] Let

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

(7)

Definition 5. [20] Consider

Definition 6. Consider

Definition 7. Let

(1) If

(2) If

if

if

Always remember that the value of the scoring function lies between

Step 1: For each

Step 2: Use the scoring function in Eq. (2) to determine the weights of the decision-makers. Once the scores are obtained, substitute them into Eq. (3). This procedure involves a detailed evaluation in accordance with the proposed decision-making framework.

Step 3: In this step, experts assess a set of alternatives using a predefined linguistic scale, which is subsequently converted into PyFNs to accurately capture the uncertainty and vagueness inherent in human judgment. All participating experts are assumed to be independent, competent, and equipped with the necessary domain knowledge to provide reliable evaluations. The constructed decision matrix is complete, containing no missing values. The evaluation criteria are considered mutually exclusive and positively oriented, meaning that higher values correspond to better performance across all criteria. The complete decision matrix is obtained using Eq. (4) and is represented as

Step 4: CRITIC Method

The CRITIC method is a robust technique in MCDM for determining the relative importance of criteria. The following steps provide a structured framework to guide the calculation process, enabling a systematic examination and comparison of variables throughout decision-making. This approach is particularly useful when multiple criteria are involved, as it offers a methodical and objective way to evaluate their significance and establish their relative weights.

Step 4.1: To obtain the scores for the combined decision matrix, Eq. (5) is applied. This calculation systematically uses the specified formula to the combined decision matrix, producing a numerical representation of the overall performance of each alternative.

Step 4.2: Normalization is a critical step in the CRITIC method, as it enables comparability among criteria that are measured using different scales or units. This process transforms the original decision matrix into a dimensionless format, allowing for a consistent evaluation of all criteria. The normalization formulas for benefit-type and cost-type criteria are presented in Eq. (6).

where

Step 4.3: The standard deviations for each criterion are calculated using Eq. (7).

where

Step 4.4: Eq. (8) is used to calculate the correlation coefficients among the criteria, providing a standardized approach to assess the interrelationships within the dataset. Applying this formula ensures a consistent and reliable method for measuring the degree of correlation.

Step 4.5: Eq. (9) is used to evaluate the information content for each criterion. This procedure helps determine the significance of the data and the interrelationships within the dataset. The formula provides a systematic approach for a comprehensive analysis of the criteria.

Step 4.6: The weight for each criterion is determined using Eq. (10).

CIMAS Method

Step 5: The normalized decision matrix is multiplied by the weight of each expert, as calculated using Eq. (11).

Step 6: The primary objective of this step is to determine the maximum and minimum values for each criterion within the expert-weighted matrix.

Step 7: In this step, Eq. (14) is used to calculate the difference between the maximum and minimum values obtained in the previous phase.

Next, the weights are normalized using Eq. (15).

Step 8: Eq. (16) is used to integrate the criteria weights obtained from the CIMAS method with the objective weights calculated using the CRITIC technique. Subsequently, Eq. (17) is applied to determine the final criterion weights.

AROMAN

Step 9: Normalization is applied to standardize the input data in the decision-making matrix. Once the input matrix is constructed, the next step involves structuring the data into intervals ranging from 0 to 1. Two distinct techniques, as described in Eqs. (18) and 19, are used to achieve this standardization.

Step 9.1: Normalization 1 (Linear):

Step 9.2: Normalization 2 (Vector):

Step 10: To normalize the given data, the Averaged Aggregation Normalization method is applied. This systematic approach ensures consistent and meaningful comparisons across all criteria throughout the normalization process. The aggregated averaging procedure is carried out using Eq. (20).

In this context, the aggregated average normalization result is denoted as

Step 11: According to Eq. (21), the aggregated averaged normalized decision-making matrix is multiplied by the criterion weights to obtain the weighted decision-making matrix.

Step 12: Eq. (22) is used to calculate the normalized weighted values for the criteria types

Step 13: After incorporating all relevant data and evaluations, the final ranking of the alternatives is determined. This ranking provides a clear order that reflects the overall performance and acceptability of each option in the decision-making process. It presents a comprehensive assessment of the alternatives based on the established methodology and criteria:

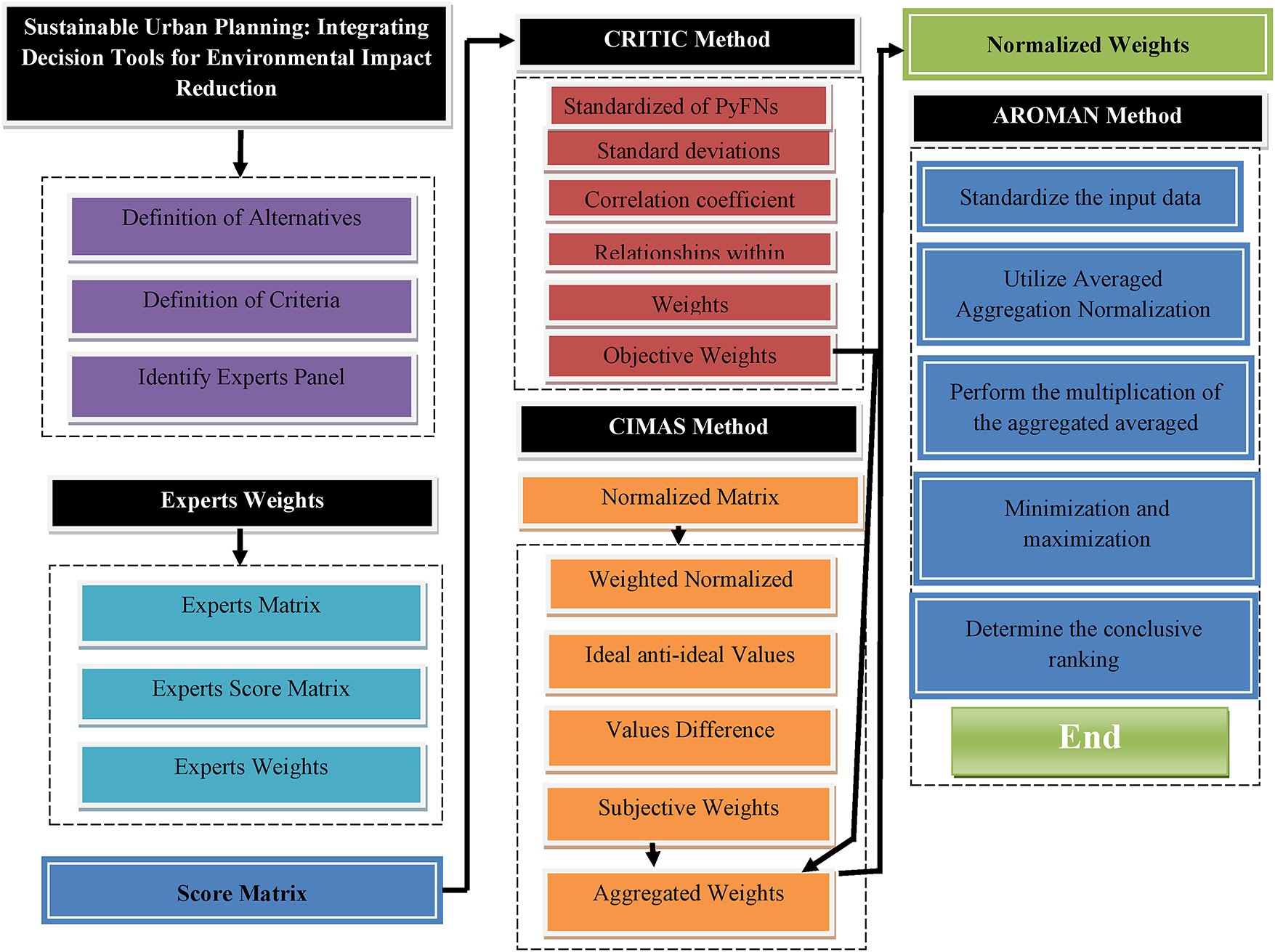

Fig. 1 illustrates the methodology, outlining the procedures required to address the problem.

Figure 1: Algorithm flowchart outlining key steps

Rapid urbanization, industrialization, and population growth exert considerable pressure on metropolitan environments, leading to air and water pollution, urban heat island effects, the depletion of natural green spaces, and increased stormwater runoff. Traditional urban planning frameworks have often prioritized infrastructure development and economic growth at the expense of ecological sustainability, resulting in long-term risks to human health and environmental stability. Green infrastructure has emerged as a key strategy within sustainable urban planning, helping to mitigate adverse environmental impacts while providing multiple co-benefits, including improved public health, biodiversity conservation, climate resilience, and enhanced community well-being. In recognition of this, numerous international and institutional guidelines—such as the European Commission’s Green Infrastructure Strategy and UN-Habitat’s Sustainable Urban Development Framework—highlight green infrastructure as a critical component of contemporary urban planning. This study evaluates five green infrastructure alternatives within the context of metropolitan urban planning. These options were selected based on their widespread inclusion in international planning guidelines and their demonstrated effectiveness in alleviating environmental stressors in urban areas [66,67]. By assessing these alternatives across multiple criteria, the study aims to provide decision support for policymakers, urban planners, and stakeholders in identifying sustainable strategies tailored to urban needs.

5.1 Definition of Alternatives

The selected alternatives for evaluation follow established practices in sustainable urban planning and provide a range of environmental, social, and economic benefits:

• Urban Forests (UF):

Comprising trees and vegetation within residential areas, parks, and roadways, urban forests reduce stormwater runoff, regulate temperature, sequester carbon, and filter air pollutants. They enhance biodiversity and aesthetic quality, serving as a fundamental component of resilient urban ecosystems [66].

• Green Roofs (GR):

Consisting of waterproof membranes, soil, and vegetation installed on rooftops, green roofs mitigate urban heat island effects, regulate stormwater, and improve building insulation. They enhance energy efficiency, air quality, and provide habitats for various species [67].

• Green Walls (GW):

Vertical vegetation systems, also known as living walls, are implemented on building facades. They improve air purification, reduce noise, provide insulation, and enhance visual aesthetics. Green walls are versatile, applicable in both indoor and outdoor settings [68].

• Rain Gardens (RG):

Shallow vegetated basins designed to capture and filter stormwater from roofs, roads, and pavements. Rain gardens reduce flooding risks, remove pollutants, provide habitats for local wildlife, and promote the use of native plants [66].

• Permeable Pavements (PP):

Materials such as porous asphalt, pervious concrete, and interlocking pavers facilitate water infiltration. Permeable pavements manage stormwater, replenish groundwater, and mitigate the urban heat island effect on surfaces like roads, sidewalks, and parking lots [69].

The evaluation criteria were adapted from sustainable urban planning guidelines and existing literature on green infrastructure, ensuring relevance to both environmental and socio-economic dimensions:

• Environmental impact reduction (EIR):

Measures the capacity to minimize habitat destruction, mitigate urban heat island effects, reduce air and water pollution, and promote biodiversity.

• Cost-effectiveness (CE):

Assesses installation and maintenance costs alongside long-term financial benefits, including reduced energy consumption and infrastructure upkeep.

• Aesthetic improvement (AI):

Evaluates enhancements in visual quality, urban livability, and architectural harmony with surrounding environments.

• Public health benefits (PHB):

Analyses the impact of reduced air pollution, decreased heat stress, noise reduction, and the availability of recreational areas on mental and physical health.

• Energy efficiency (EE):

Examines reductions in energy usage due to improved insulation and decreased cooling requirements.

• Scalability (S):

Considers the adaptability of solutions to diverse urban contexts, availability of resources, and potential for large-scale implementation.

• Community Acceptance (CA):

Evaluates societal and political support, including integration into policy frameworks, public endorsement, and sustained stakeholder involvement.

• Implementation time (IT):

Accounts for the time required for design, construction, approvals, and resolution of logistical or regulatory challenges.

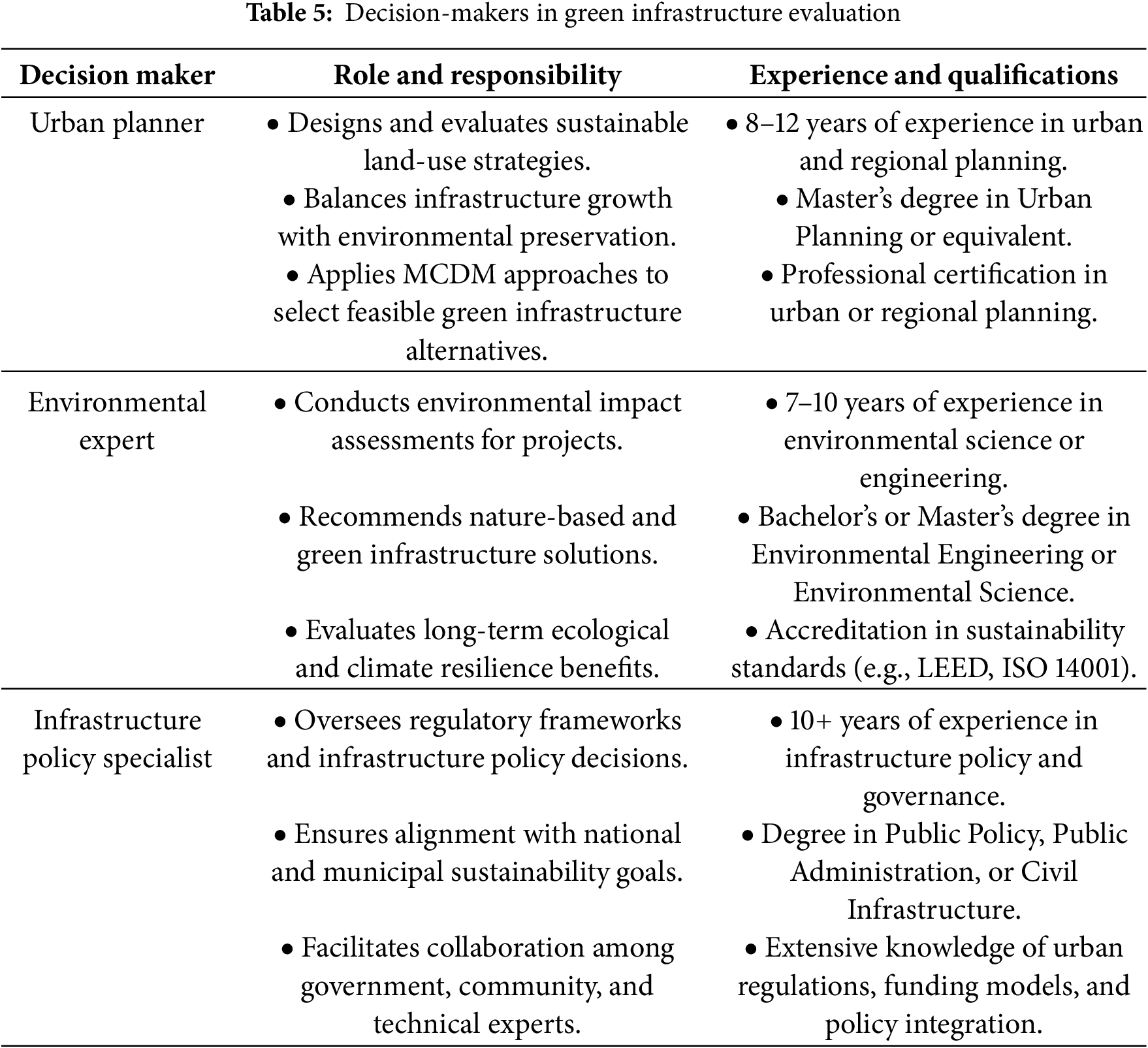

Three decision-makers were involved in this study, representing key stakeholder groups: (1) urban planners, (2) environmental experts, and (3) infrastructure policy specialists. Their participation ensures that technical feasibility, ecological sustainability, and policy alignment are all adequately considered in the evaluation process. Expert preferences were captured using linguistic scales, while the proposed CRITIC–CIMAS hybrid method objectively balances these subjective inputs, reducing bias and enhancing the credibility of the analysis. Detailed information about each decision-maker is provided in Table 5.

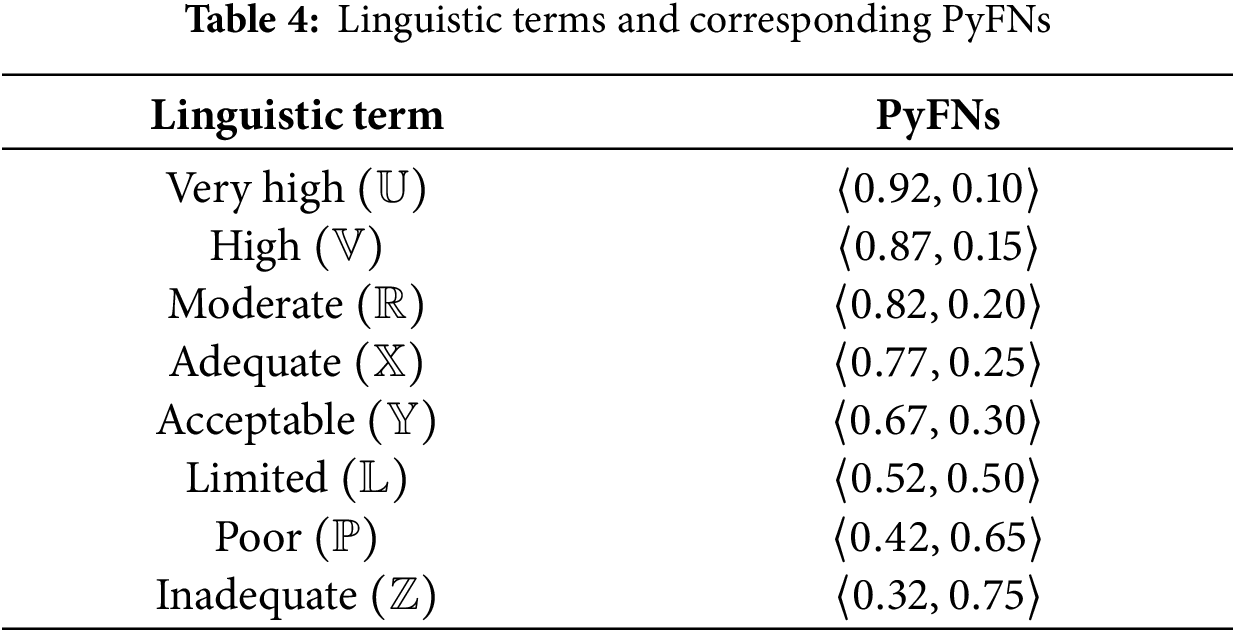

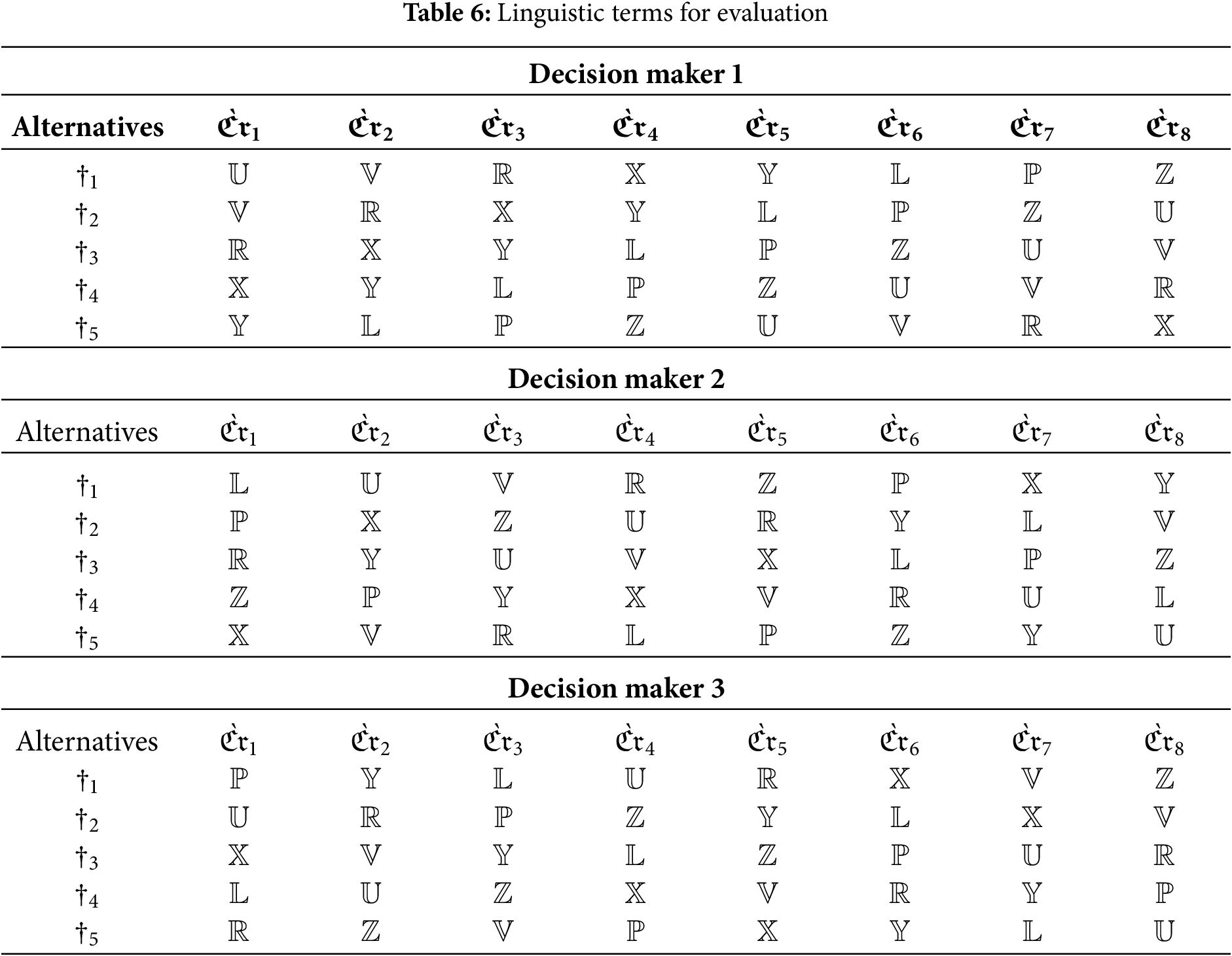

Step 1: For each alternative, experts utilize the PyFNs dataset and apply the linguistic terms listed in Table 4 to evaluate

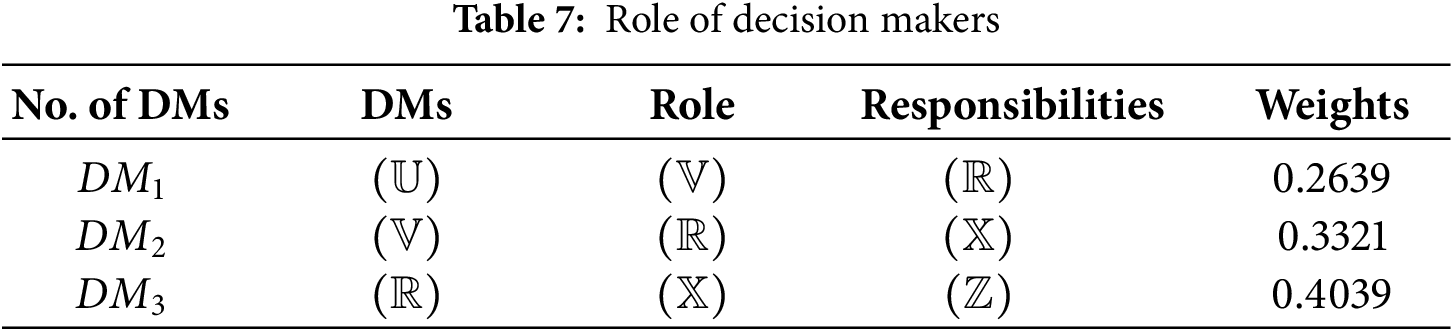

Step 2: Eq. (2) provides the scoring function used to evaluate the weights of decision-makers (DMs) and determine their relative significance. The resulting scores are then applied in Eq. (4) to calculate the overall influence of each DM. The outcomes are presented in a clear and informative format in Table 7. This systematic approach ensures a comprehensive understanding of the contributions of each decision-maker within the given context.

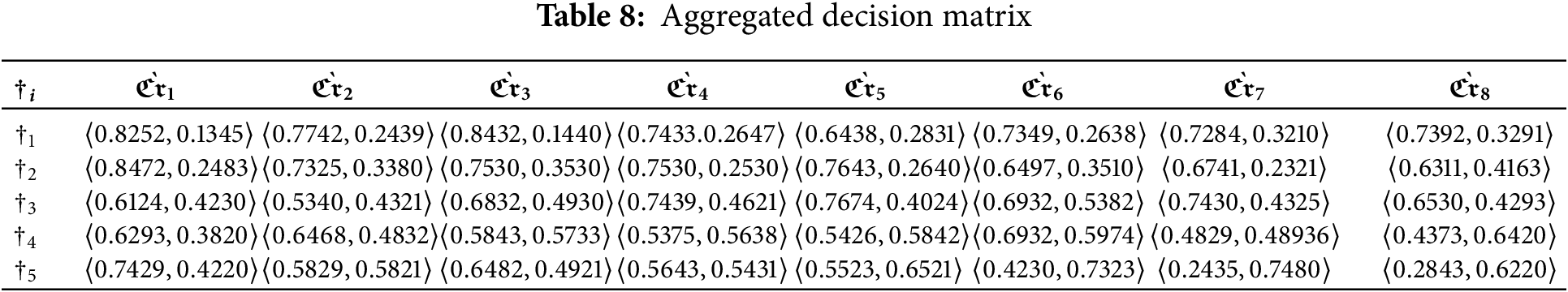

Step 3: The aggregated decision matrix, denoted as

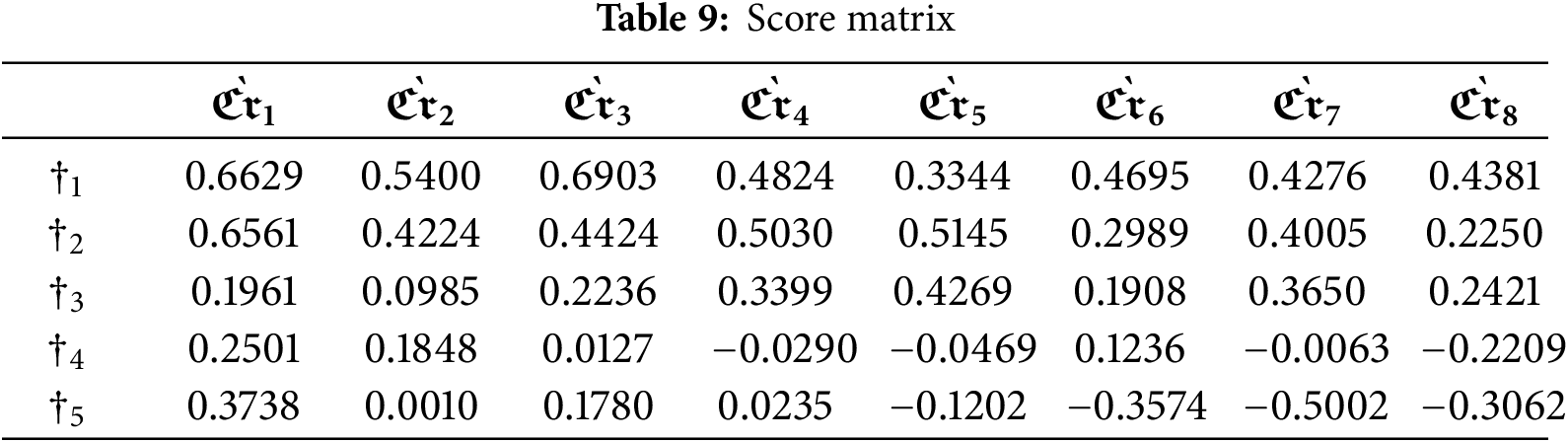

Step 4.1: The score of the decision matrix is calculated using Eq. (5), as presented in Table 9.

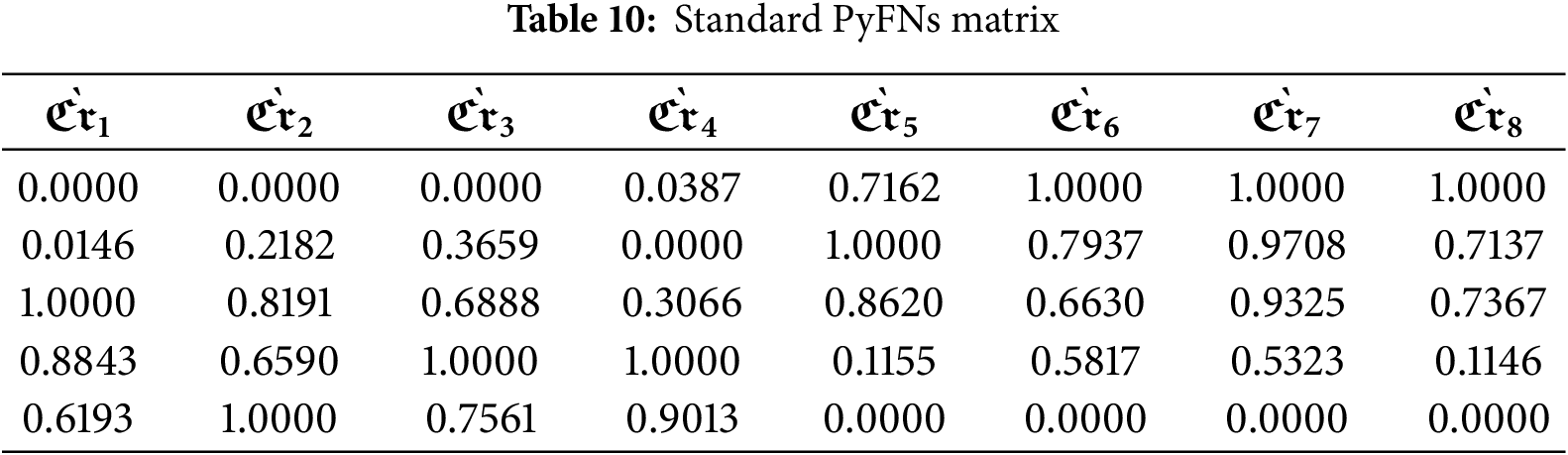

Step 4.2: Using Eq. (6) from Table 10, the matrix

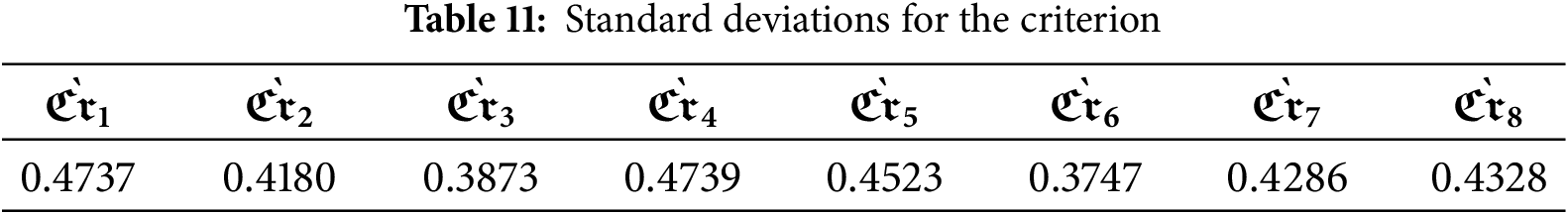

Step 4.3 The standard deviation for each criterion is calculated using Eq. (7) provided in Table 11.

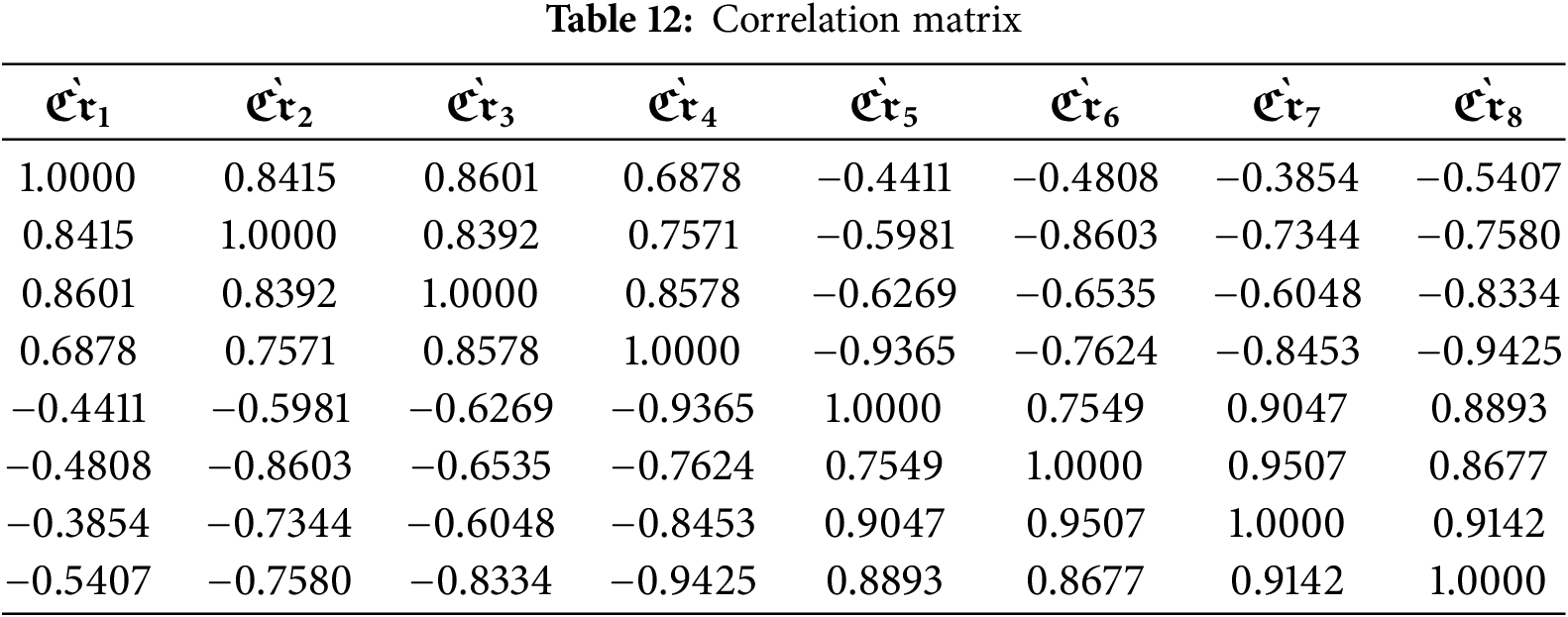

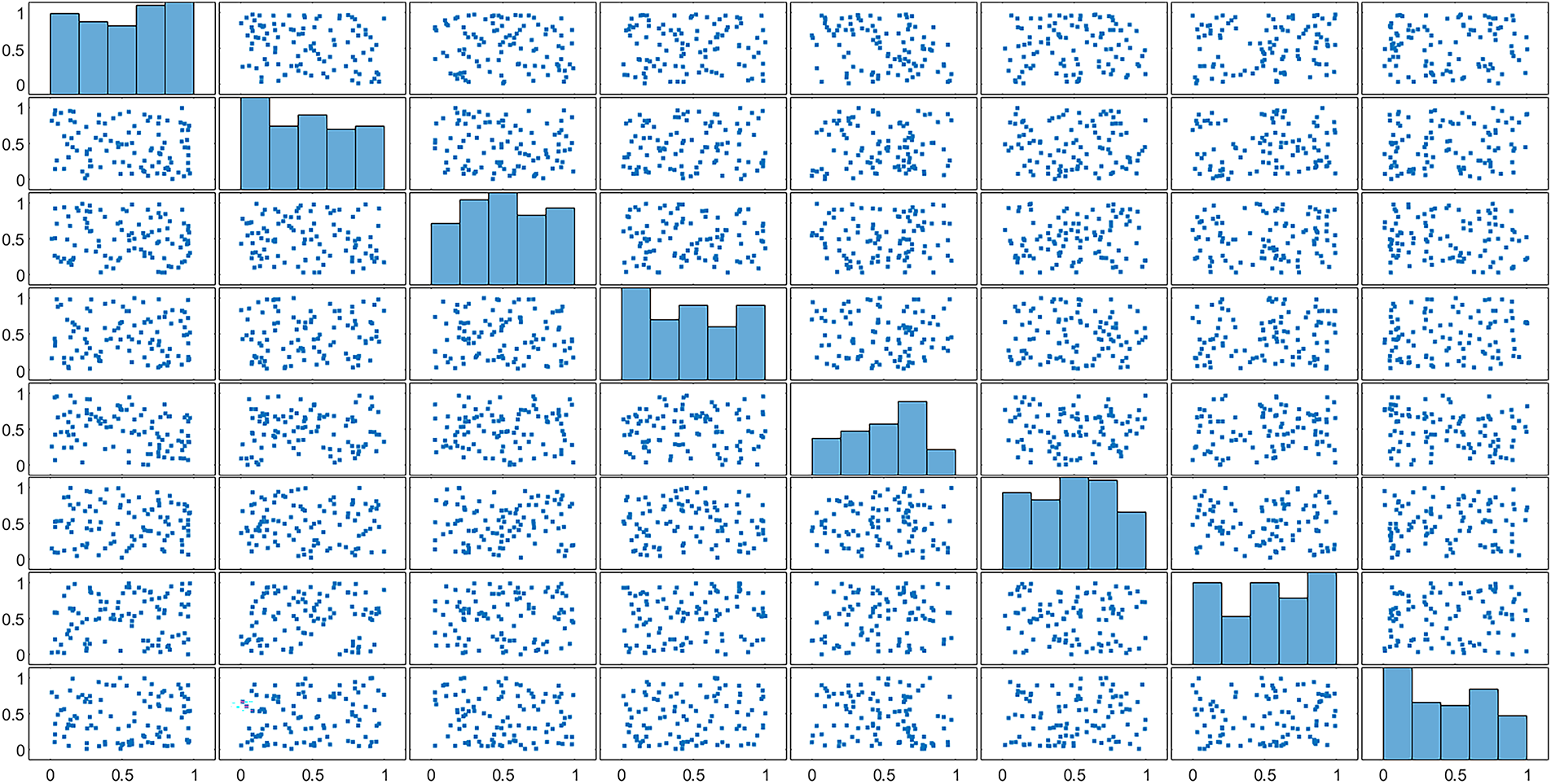

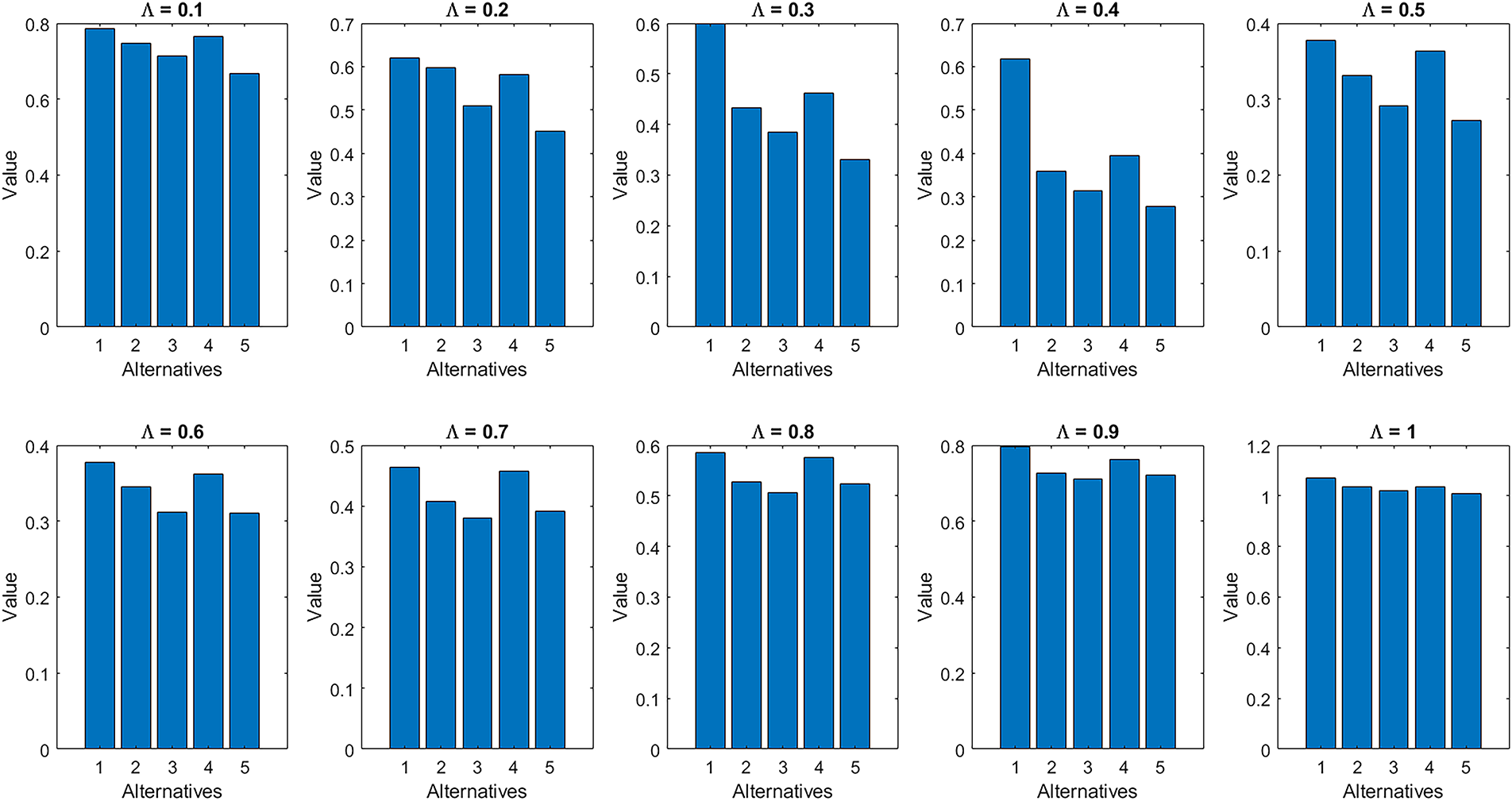

Step 4.4: Using Eq. (8), the correlation coefficients for the criteria listed in Table 12 are determined. The scatterplot matrix shown in Fig. 2 illustrates the distribution of individual criteria and their pairwise relationships. The plots reveal that most criteria are largely independent, indicating that each contributes unique value to the decision-making process without substantial overlap. This visualization also highlights potential trade-offs—for example, enhancing cost-effectiveness may reduce environmental benefits, whereas performance and reliability may reinforce each other. Understanding these relationships is essential for assigning appropriate weights, avoiding double-counting of correlated factors, and ensuring a balanced and robust final evaluation. Additionally, Fig. 3 presents the distribution and frequency of pairwise comparisons among the criteria, emphasizing their relative importance and potential influence on the decision-making outcomes.

Figure 2: Pairwise scatter matrix all pairs of criteria

Figure 3: Histogram showing the behavior of the parameter on weights

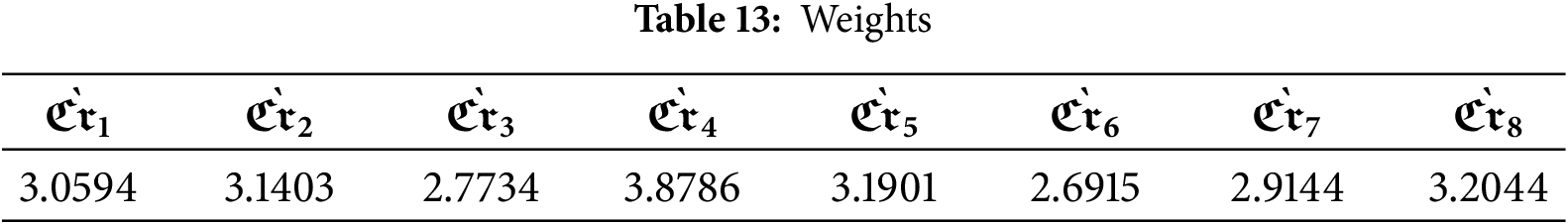

Step 4.5: Examine the details of each criterion using Eq. (9), as presented in Table 13.

Step 4.6: As shown in Table 14, compute the objective weight for each criterion using Eq. (10) to determine the corresponding weights.

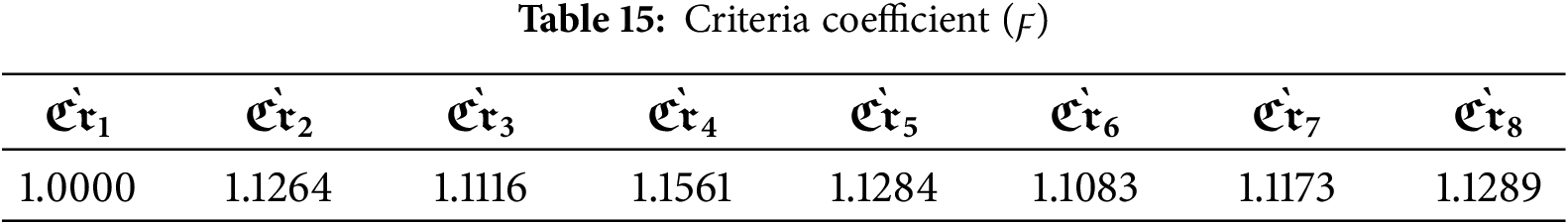

Step 5: Using Eq. (11), calculate the criteria coefficient (

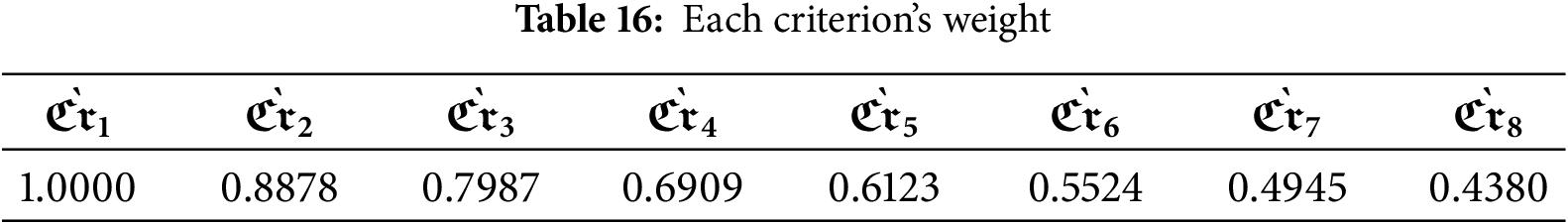

Step 6: Compute the weight for each criterion using Eq. (12), as detailed in Table 16.

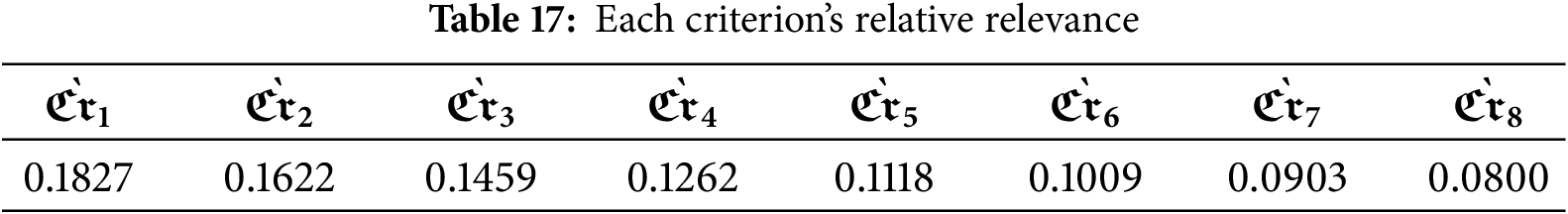

Step 7 Determine the relative importance of each criterion by applying Eq. (15), as presented in Table 17.

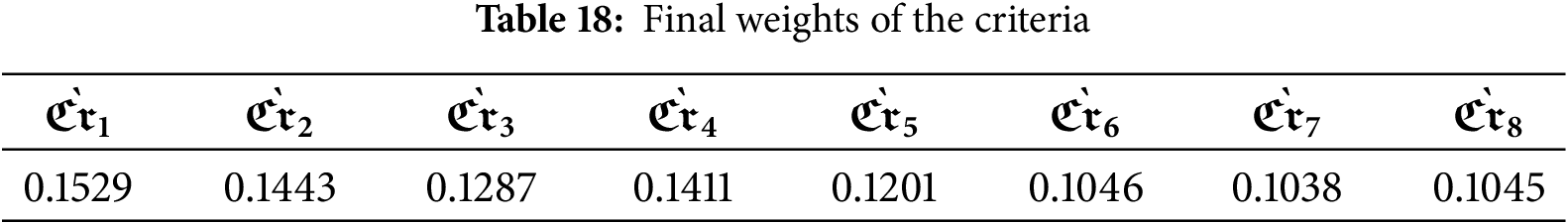

Step 8: Compute the final weights of the criteria using Eq. (17), as presented in Table 18.

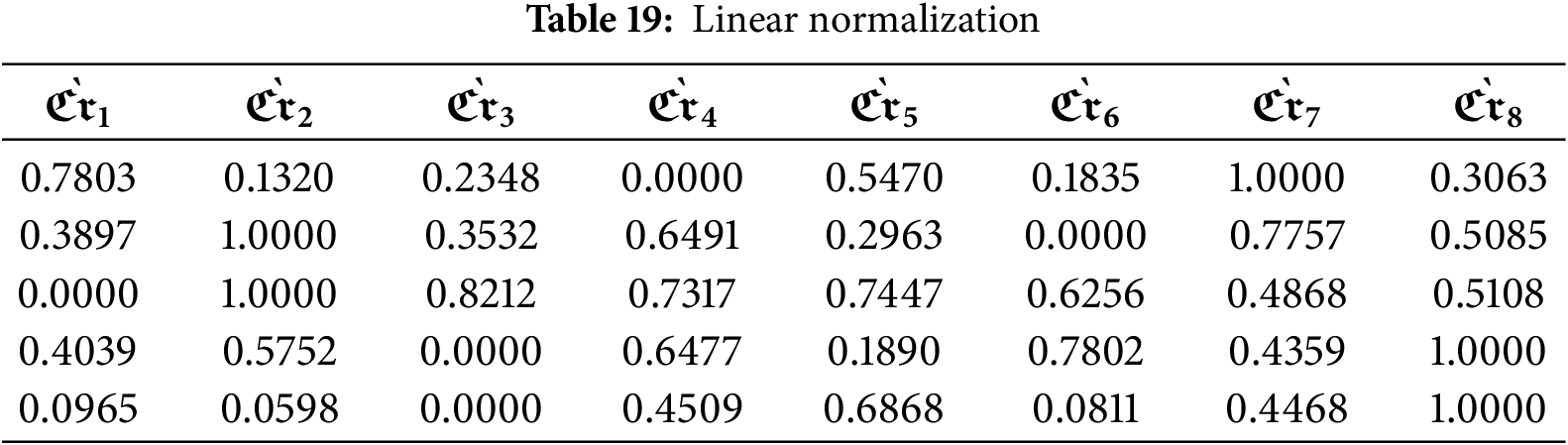

Step 9.1: For linear normalization (Normalization 1), apply Eq. (18) as presented in Table 19.

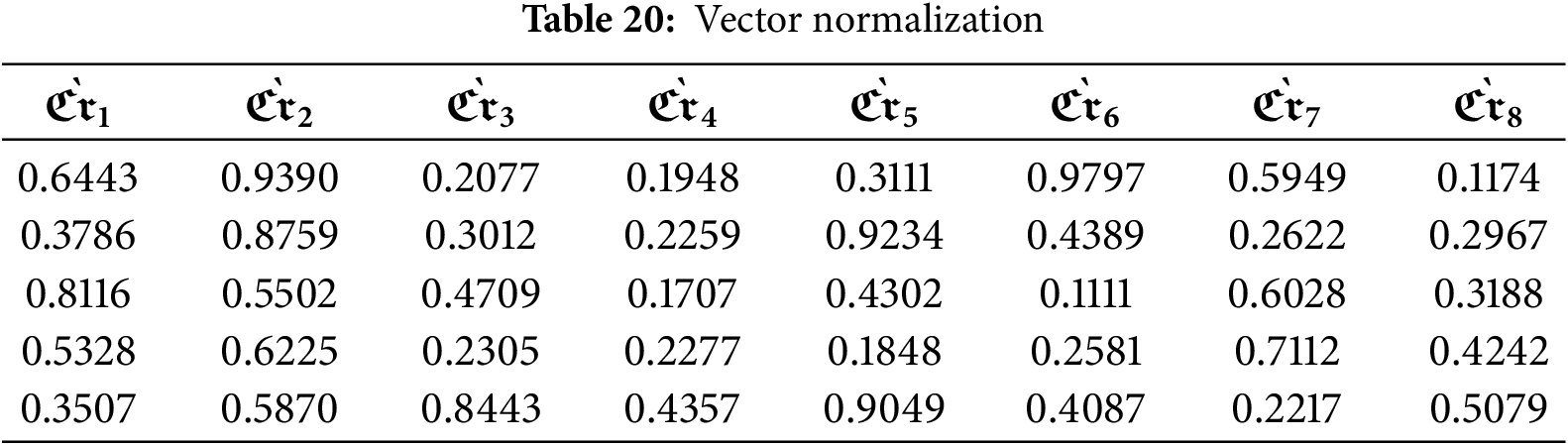

Step 9.2: For vector normalization (Normalization 2), apply Eq. (19) as shown in Table 20.

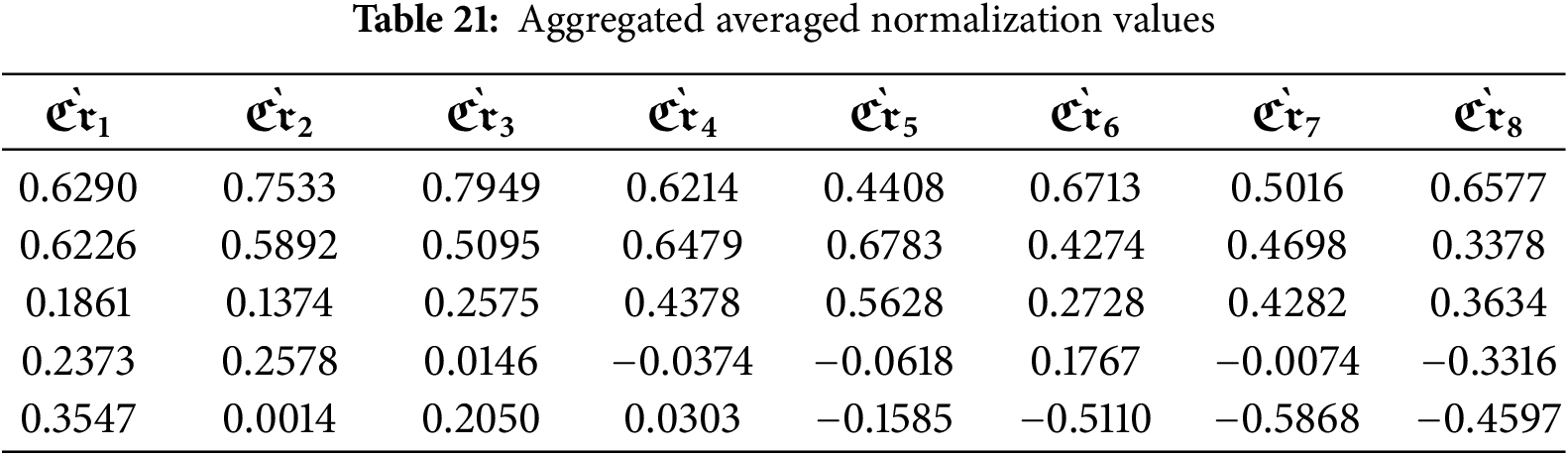

Step 10: The aggregated averaged normalization is performed using Eq. (20) as provided in Table 21.

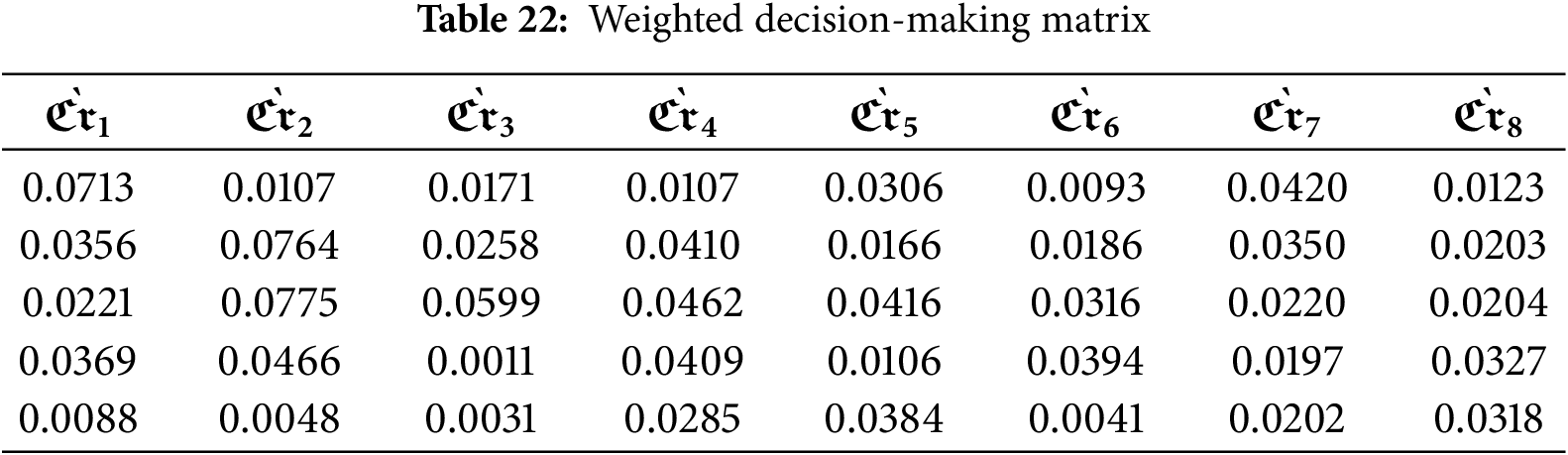

Step 11: The weighted decision-making matrix is obtained by multiplying the aggregated averaged normalized decision-making matrix by the criterion weights, as described in Eq. (21) (Table 22). This formula produces a weighted matrix that reflects both the normalized performance values and the relative importance of each criterion.

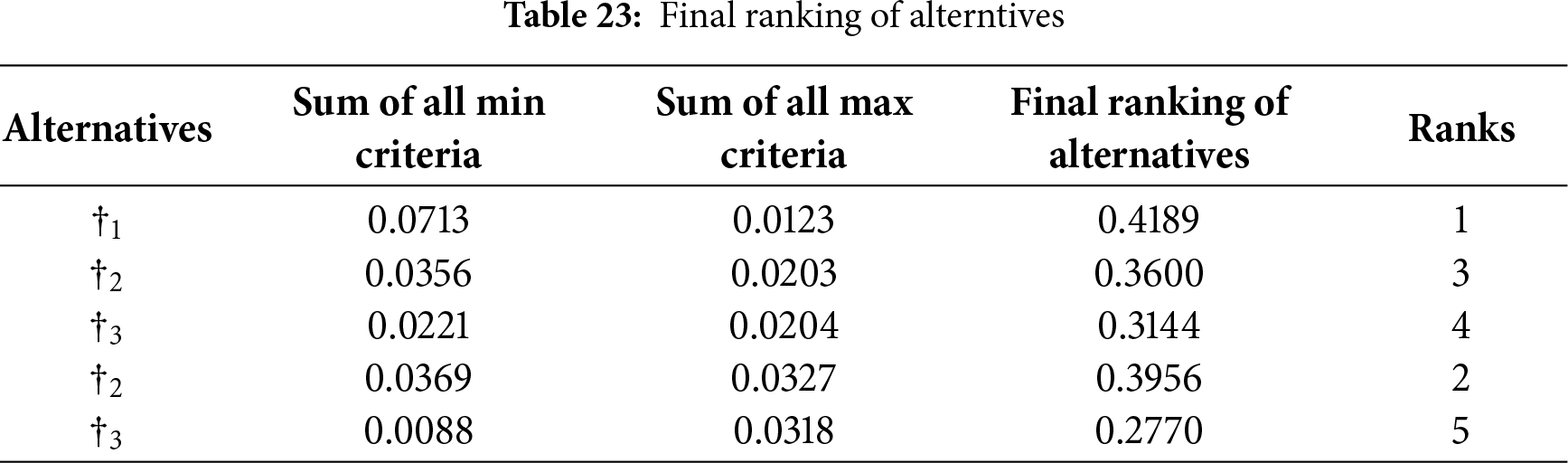

Steps 12, 13: Use Eq. (22) to calculate the normalized weighted values for criteria of types

6 Sensitivity Analysis and Comparative Analysis

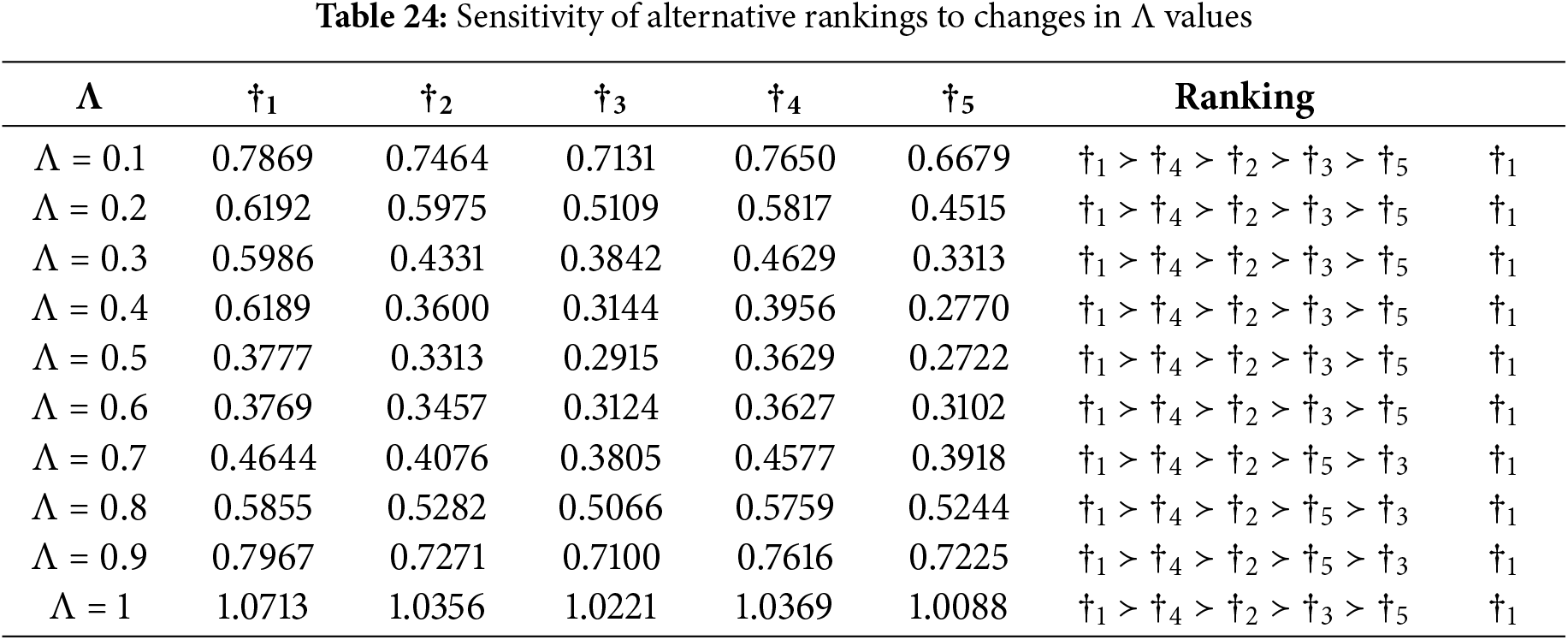

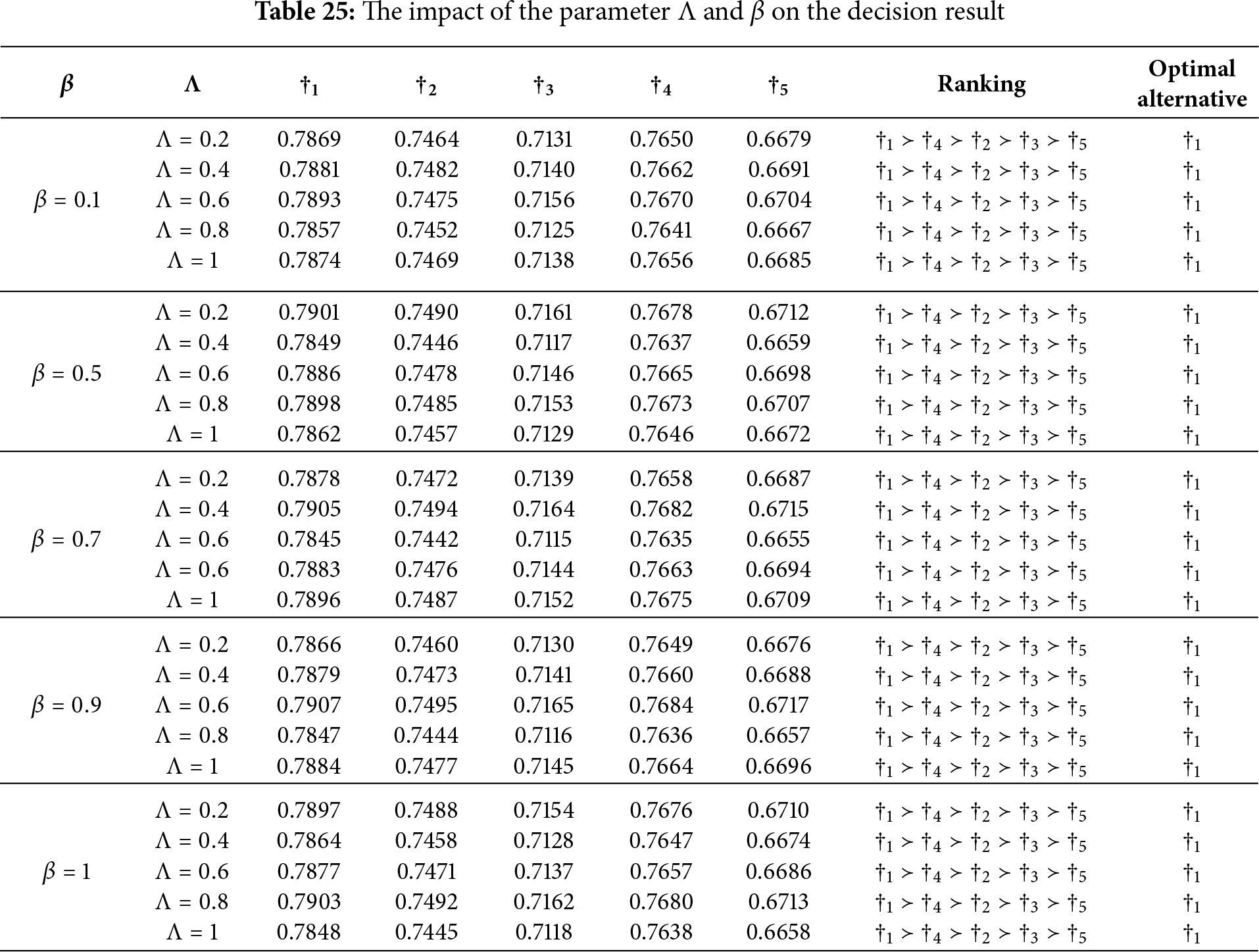

Sensitivity analysis is a crucial component of the decision-making process, particularly when applying the CRITIC and CIMAS–AROMAN techniques within a Pythagorean fuzzy (PyF) environment. Conducting sensitivity analysis helps evaluate the stability and responsiveness of decision results by examining how changes in key parameters influence rankings. To ensure robustness and empirical validation, a two-stage sensitivity analysis was performed.

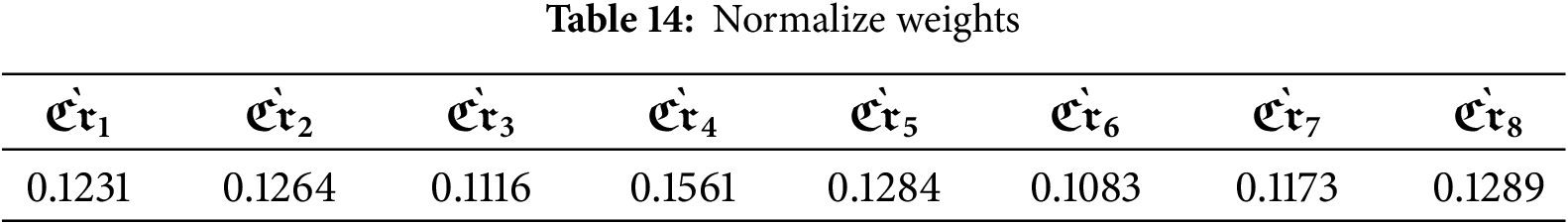

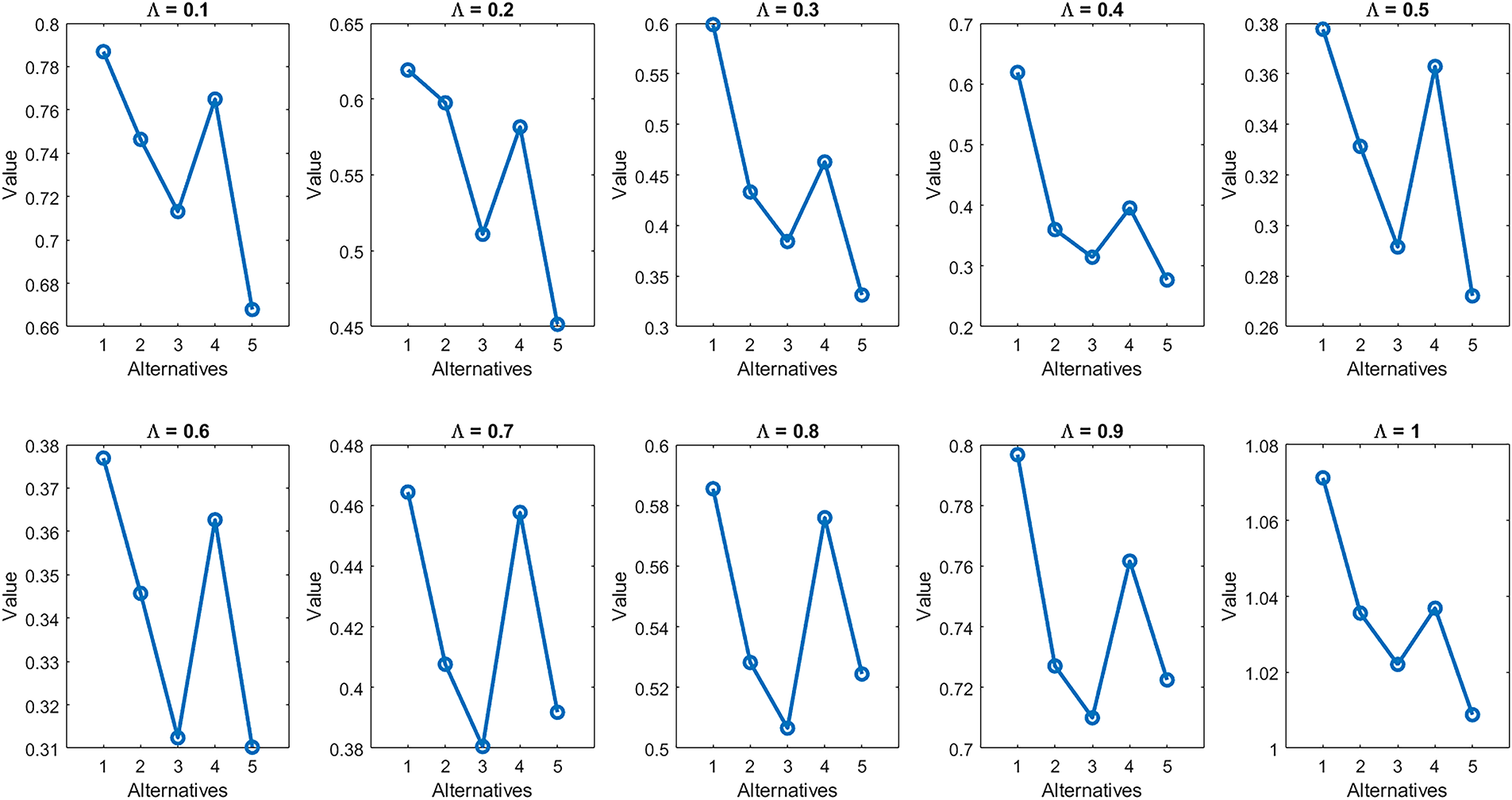

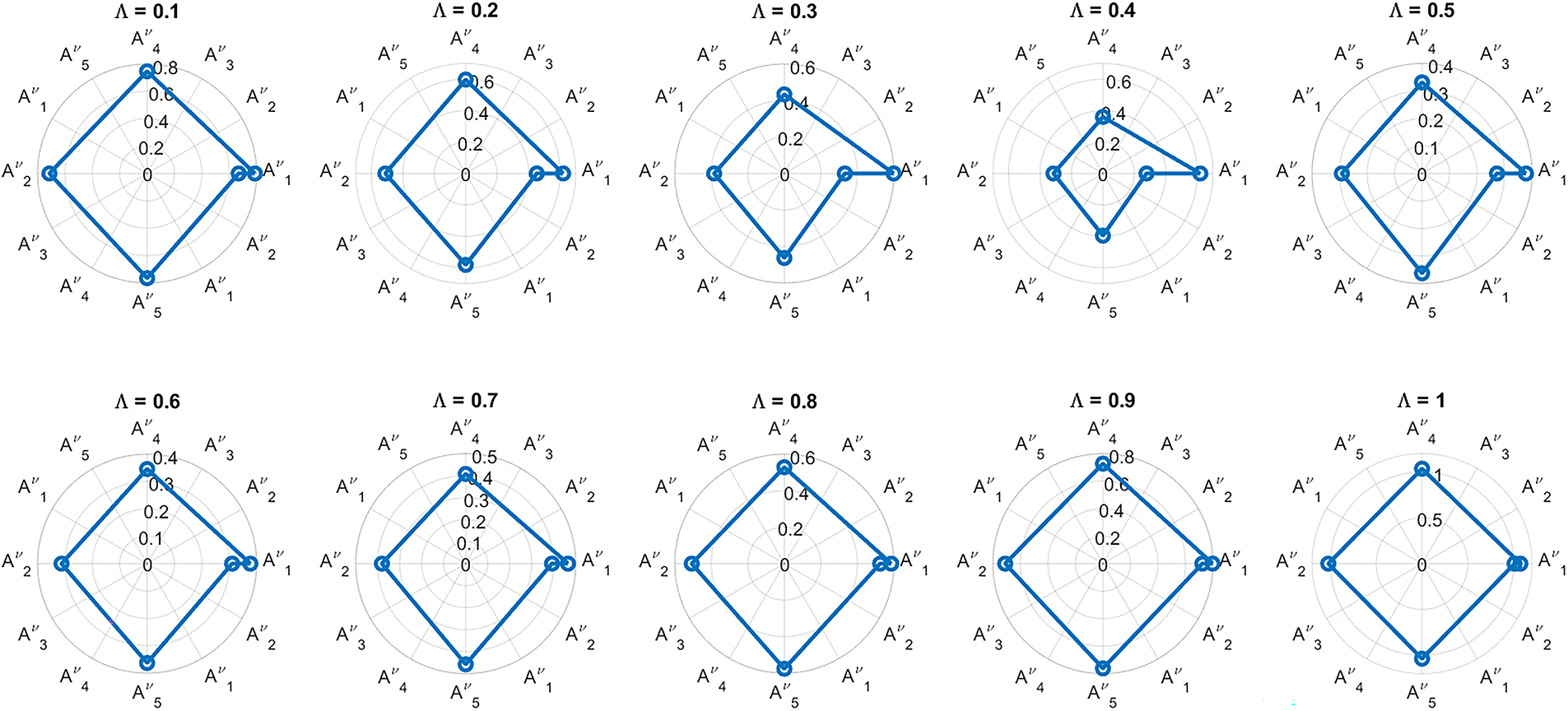

In the first stage, the impact of varying the parameter

These outcomes indicate that the proposed framework is stable under parameter adjustments, enhancing the reliability and credibility of the results. Statistical validation using Kendall’s W and Spearman’s rank correlation further confirmed consistency among rankings. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients, when compared with established MCDM methods such as AHP, TOPSIS, and VIKOR, consistently exceeded 0.85, demonstrating strong alignment in ranking patterns. Additionally, Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (

Overall, the findings suggest that the derived rankings are methodologically robust and statistically consistent with expert consensus and comparable decision-making methods. Consequently, the framework produces reliable and valid outcomes suitable for practical application in urban planning contexts. Figs. 4 and 5 provide visual representations of these results.

Figure 4: Ranking of alternatives based on varying parameter (

Figure 5: Radar charts representing the evaluation of alternatives for each

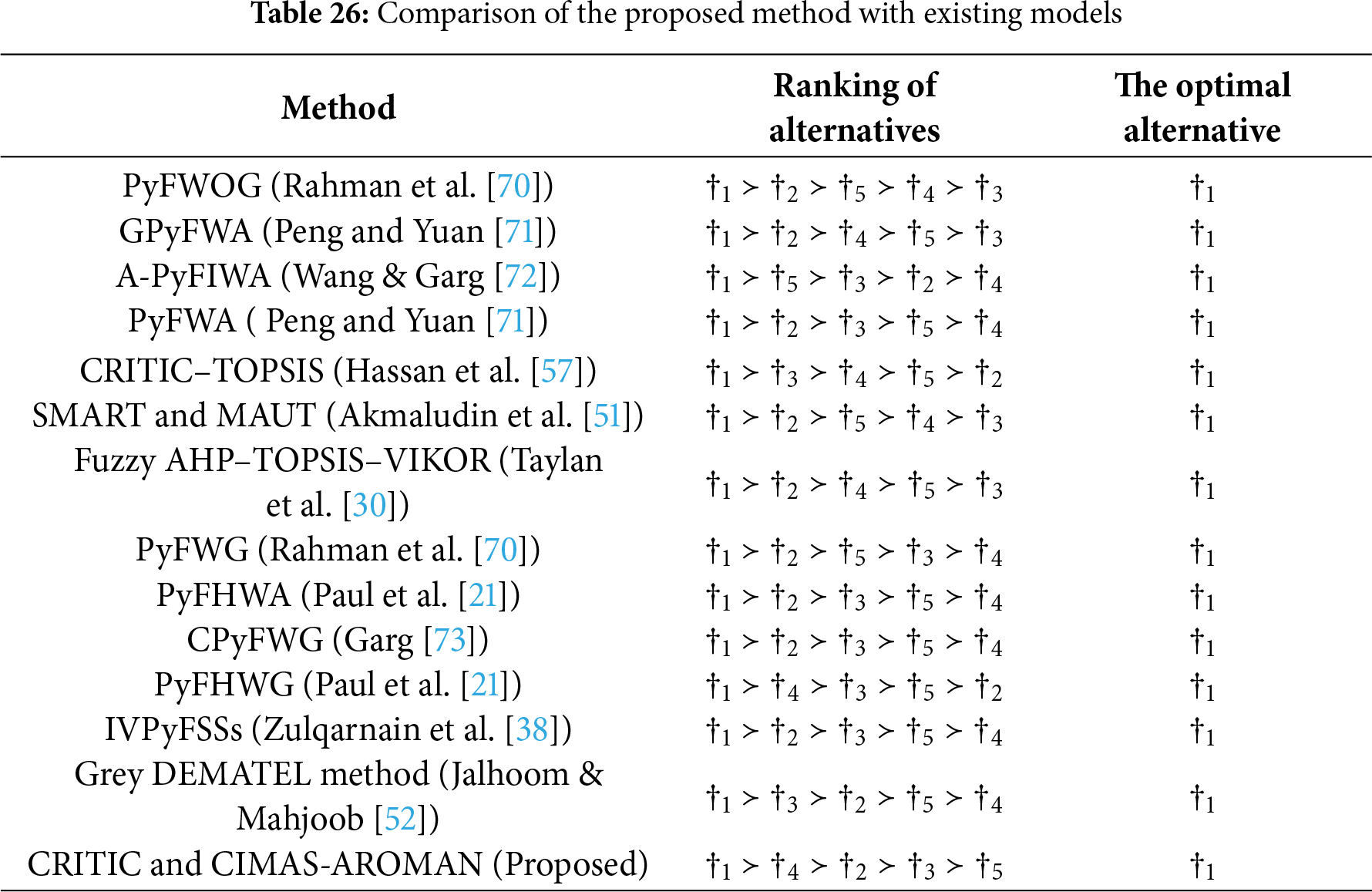

Table 26 presents a comparative evaluation of the proposed CRITIC–CIMAS–AROMAN framework against several established decision-making models. Across all benchmark methods, including classical and fuzzy aggregation operators such as PyFWOG [70], GPyFWA [71], A-PyFIWA [72], and PyFWA [71], the top-ranked alternative consistently corresponds to

Other classical MCDM approaches, including CRITIC–TOPSIS [57], Step-Wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (SMART) and Multi-Attribute Utility Theory (MAUT) [51], and Fuzzy AHP-TOPSIS-VIKOR [30], also identified

The proposed CRITIC-CIMAS-AROMAN model produces a ranking sequence of

6.1 Marginal Limitations of the Model

The accuracy of the CRITIC method depends heavily on the availability and quality of objective data. Variations in data across different metropolitan regions may affect the reliability of the results. Similarly, the effectiveness of the CIMAS approach relies on selecting a panel of experts who are both competent and diverse. A lack of sufficient diversity or expertise among participants may introduce bias into the weighting process. Furthermore, the combined use of CRITIC, CIMAS, and AROMAN techniques, particularly when integrated with PyFS, may pose challenges for real-time decision-making due to their computational complexity. Another limitation lies in the potential for rankings to become less relevant when external factors—such as environmental conditions or public preferences—change over time. Finally, while the framework emphasizes technical and community-oriented dimensions of green infrastructure deployment, it places less focus on political or legal barriers that may significantly hinder implementation.

Rapid industrialization, population growth, and infrastructure development have created major environmental challenges in cities worldwide. These issues are particularly pronounced in rapidly expanding metropolitan regions, where urban heat islands, air and water pollution, environmental degradation, and the loss of green spaces have significantly worsened public health conditions. Traditional urban planning strategies, which often prioritize economic growth, have failed to provide adequate long-term solutions.

To address these challenges, urban planners increasingly rely on green infrastructure solutions aimed at enhancing livability while reducing environmental impacts. Green infrastructure can be broadly classified into five categories: urban forests, permeable pavements, green walls, green roofs, and rain gardens. In this study, several case studies were examined to explore the applicability and effectiveness of these five green infrastructure options. These approaches were selected for their proven ability to improve stormwater management, mitigate pollution, and enhance biodiversity in urban environments.

Each alternative was evaluated against multiple criteria, including community acceptance, energy efficiency, scalability, cost-effectiveness, aesthetic value, public health benefits, and implementation time. The case study framework provided a practical foundation for applying decision-making methodologies to prioritize green infrastructure alternatives. Within this framework, the CRITIC and CIMAS methods were employed as complementary weighting techniques: CRITIC captured objective weights by analyzing the variability and interrelationships among criteria, while CIMAS incorporated expert judgments to balance subjective inputs.

Through a two-stage normalization process, urban environmental planning challenges were systematically assessed, and the AROMAN technique, combined with PyFS, was applied to generate robust and practical rankings. This integrative approach offered actionable insights and highlighted viable solutions for promoting sustainable urban development.

In the case study, the application of the proposed framework to Urban Forests demonstrated clear advantages. Urban forests consistently emerged as the top priority alternative, as they effectively reduce air pollutants, enhance biodiversity, regulate stormwater runoff, and mitigate the impacts of urban heat islands. In addition to their environmental benefits, urban forests improve aesthetic value and foster positive community response, thereby increasing public acceptance of sustainable urban interventions. These findings highlight that urban tree-planting initiatives represent one of the most sustainable and effective strategies for addressing environmental challenges in metropolitan regions. Consequently, the integration of ecologically friendly infrastructure, such as urban forests, into urban development is essential for advancing sustainability goals and improving the overall quality of life for city residents.

Despite the strengths of the proposed model, several limitations must be acknowledged. The evaluation process relies heavily on expert judgments, which introduces subjectivity and the possibility of bias. Furthermore, the CRITIC method, while effective for objective weighting, may undervalue certain criteria that exhibit low variability, leading to their underrepresentation in the final outcomes. The framework also assumes a complete, consistent, and positively oriented decision matrix, an assumption that may not always hold true in real-world contexts where data are often incomplete, uncertain, or inconsistent.

Additionally, the incorporation of PyFS in conjunction with dual-stage normalization increases computational complexity, potentially limiting the scalability of the model to larger decision-making problems. The findings are derived from a single case study, making them context-specific and less readily generalizable to other urban settings without suitable adaptation. Finally, the framework presumes the availability of comprehensive qualitative and quantitative data, a condition that may not be feasible in every decision-making environment.

The proposed decision-making framework extends beyond theoretical evaluation by offering direct and practical implications for urban planning and policy design. It serves as a decision-support tool for urban planners, municipal authorities, and policy specialists by systematically evaluating and ranking green infrastructure alternatives under diverse scenarios. The outputs provide a clear prioritization of alternatives, enabling seamless integration into policy discussions and guiding infrastructure investment strategies.

In terms of computational performance, the framework demonstrates both efficiency and scalability. The weighting and ranking procedures rely on closed-form mathematical operations that require minimal computational resources, even when applied to larger sets of criteria or alternatives. This ensures the model’s applicability to complex urban systems while maintaining both accuracy and usability. Furthermore, its adaptability supports scalability by accommodating new criteria—such as social, economic, or resilience-related factors—as well as expanded datasets. Such flexibility allows policymakers to tailor the analysis to specific contexts, thereby enhancing its relevance across different metropolitan regions.

The framework also strengthens usability by generating outputs that are easily interpretable through rankings, sensitivity analyses, and comparative scenarios. These clear and transparent results enable stakeholders to engage meaningfully in the decision-making process without requiring extensive technical expertise, thus encouraging adoption in collaborative planning environments. By linking evaluation outcomes to practical decision pathways, the framework enhances the policy relevance of urban planning strategies and promotes evidence-based prioritization of sustainable infrastructure investments.

This study establishes an MCDM framework to evaluate a range of urban green infrastructure options. By integrating PyFSs with the CRITIC, CIMAS, and AROMAN approaches for alternative ranking, the framework provides a comprehensive decision-support tool that incorporates community acceptance, public health benefits, cost-effectiveness, and environmental impact. Findings from the case study indicates that urban forests represent the most suitable alternative, as they effectively mitigate urban heat island effects, enhance public health, promote biodiversity, reduce air pollution, and strengthen community acceptance.

Despite these contributions, several limitations remain, including reliance on subjective expert opinions, the context-specific nature of the case study, and the computational complexity of the proposed framework. Nevertheless, the research offers urban planners and policymakers a valuable, data-driven tool for guiding decisions on sustainable metropolitan development. As urban systems evolve, the framework can contribute to building cities that are more resilient and environmentally sustainable.

The following points outline potential future directions for this research:

• Develop automated or data-driven techniques to minimise subjectivity in the CIMAS method.

• Integrate dynamic temporal factors, such as evolving public preferences and environmental conditions, to strengthen long-term applicability.

• Evaluate the scalability of the framework across metropolitan contexts with diverse social, economic, and ecological characteristics.

• Incorporate real-time data sources, such as environmental monitoring sensors, to support adaptive and responsive urban planning systems.

• Enhance the framework’s adaptability to address a broader range of global urban planning challenges.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2026R259) for their support, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Ashit Kumar Dutta would like to thank AlMaarefa University for supporting this research under project number MHIRSP2025017.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2026R259), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Ashit Kumar Dutta would like to thank AlMaarefa University for supporting this research under project number MHIRSP2025017.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Sana Shahab and Vladimir Simic; methodology, Ashit Kumar Dutta and Mohd Anjum; software, Sana Shahab and Mohd Anjum; validation, Sana Shahab and Dragan Pamucar; formal analysis, Mohd Anjum and Dragan Pamucar; resources, Sana Shahab, Vladimir Simic and Ashit Kumar Dutta; data curation, Mohd Anjum and Dragan Pamucar; writing—original draft preparation, Sana Shahab, Vladimir Simic and Mohd Anjum; writing—review and editing, Ashit Kumar Dutta and Dragan Pamucar; visualization, Sana Shahab and Dragan Pamucar; funding acquisition, Sana Shahab, Ashit Kumar Dutta and Dragan Pamucar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data used in this study are included within the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Marans RW. Quality of urban life & environmental sustainability studies: future linkage opportunities. Habitat Int. 2015;45:47–52. [Google Scholar]

2. Bakar AHA, Cheen KS. A framework for assessing sustainable urban development. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci. 2013;85(1):484–92. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhang X, Hes D, Wu Y, Hafkamp W, Lu W, Bayulken B, et al. Catalyzing sustainable urban transformations towards smarter, healthier cities through urban ecological infrastructure, regenerative development, eco towns and regional prosperity. J Clean Produc. 2016;122(3):2–4. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mao F, Yuan Y, Zhang F. Firm-level perception of uncertainty, risk aversion, and corporate real estate investment: evidence from China’s listed firms. Econ Anal Policy. 2025;85:1428–41. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2025.02.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Turkoglu H. Sustainable development and quality of urban life. Procedia-Soci Behav Sci. 2015;202(1):10–4. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.08.203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yang Y, Lv Y, Zhou D. The impact of urban parks on the thermal environment of built-up areas and an optimization method. PLoS One. 2025;20(3):e0318633. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

7. Xu A, Wang W, Zhu Y. Does smart city pilot policy reduce CO2 emissions from industrial firms? Insights from China. J Innov Knowl. 2023;8(3):100367. doi:10.1016/j.jik.2023.100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Moktadir MA, Paul SK, Bai C, Gonzalez S. The current and future states of MCDM methods in sustainable supply chain risk assessment. Environ Develop Sustain. 2025;27:7435–80. [Google Scholar]

9. Chen Y, Li Q, Liu J. Innovating sustainability: VQA-based AI for carbon neutrality challenges. J Organ End User Comput. 2024;36(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

10. Cao J, Li M, Yang X, Zhang R, Wang M. The impact of urban dry island on building energy consumption is overlooked compared to urban heat island in cold climate. Energy Build. 2024;320:114655. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2024.114655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhao F, Zhang M, Zhu S, Zhang X, Ma S, Gao Y, et al. Spatiotemporal patterns of the urban thermal environment and the impact of human activities in low-latitude plateau cities. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf. 2025;142(4):104703. doi:10.1016/j.jag.2025.104703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Meng Q, Xu J, Luo F, Jin X, Xu L, Yao W, et al. Collaborative and effective scheduling of integrated energy systems with consideration of carbon restrictions. IET Gen Trans Distrib. 2023;17(18):4134–45. [Google Scholar]

13. Amaripadath D, Sailor DJ. Reassessing energy-efficient passive retrofits in terms of indoor environmental quality in residential buildings in the United States. Energy Build. 2024;319(7):114564. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2024.114564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang M, Zhong X, Sun C, Chen T, Su J, Li J. Comprehensive performance of green infrastructure through a life-cycle perspective: a review. Sustainability. 2023;15(14):10857. [Google Scholar]

15. Stangierska D, Kowalczuk I, Juszczak-Szelągowska K, Widera K, Ferenc W. Urban environment, green urban areas, and life quality of citizens—the case of Warsaw. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17):10943. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

16. Takano T, Morita H, Nakamura S, Togawa T, Kachi N, Kato H, et al. Evaluating the quality of life for sustainable urban development. Cities. 2023;142:104561. [Google Scholar]

17. Pan J, Deng Y, Yang Y, Zhang Y. Location-allocation modelling for rational health planning: applying a two-step optimization approach to evaluate the spatial accessibility improvement of newly added tertiary hospitals in a metropolitan city of China. Soc Sci Med. 2023;338(12):116296. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zadeh LA. Fuzzy sets. Inf Control. 1965;8:338–53. [Google Scholar]

19. Atanassov KT. Intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Ans Systems. 1986;20(1):87–96. doi:10.1016/s0165-0114(86)80034-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yager RR, Abbasov AM. Pythagorean membership grades, complex numbers, and decision making. Int J Intell Syst. 2013;28(5):436–52. doi:10.1002/int.21584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Paul TK, Jana C, Pal M. Enhancing multi-attribute decision making with Pythagorean fuzzy Hamacher aggregation operators. J Ind Intell. 2023;1(1):30–54. doi:10.56578/jii010103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Alam L. A robust road image defogging framework integrating Pythagorean fuzzy aggregation, Gaussian Mixture Models, and level-set segmentation. Mechatron Intell Transp Syst. 2024;3(4):254–63. doi:10.56578/mits030405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wang X, Khalil AM. A new kind of generalized pythagorean fuzzy soft set and its application in decision-making. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;136(3):2861–71. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.026021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yang Y, Liu J, Meng W, Zhuo Y, Wu Z. An integrated consensus reaching process for product appearance design decision-making: combining trust and empathy relationships. Adv Eng Inform. 2025;67:103562. [Google Scholar]

25. Moslem S. A novel parsimonious best worst method for evaluating travel mode choice. IEEE Access. 2023;11:16768–73. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3242120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Abbasi SN, Ashraf, Hameed SMS, Eldin SM. Pythagorean fuzzy einstein aggregation operators with Z-Numbers: application in complex decision aid systems. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;137(3):2795–844. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.028963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Al-Quran A, Kausar R, Jameel T, Riaz M. Enhancing tropical artificial forests with cubic picture fuzzy fairly aggregation operators. IEEE Access. 2023;11:112362–83. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3322652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ali J, Bashir Z, Rashid T. A cubic q-rung orthopair fuzzy TODIM method based on Minkowski-type distance measures and entropy weight. Soft Comput. 2023;27(20):15199–223. doi:10.1007/s00500-023-08552-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ali J. Norm-based distance measure of q-rung orthopair fuzzy sets and its application in decision-making. Comput Appl Math. 2023;42(4):184. doi:10.1007/s40314-023-02313-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Taylan O, Alamoudi R, Bajaba S, Kabli MR, Al-Harbi KM. An integrated fuzzy AHP-TOPSIS–VIKOR methodology for energy system selection under uncertainty. Sustainability. 2020;12(7):2745. [Google Scholar]

31. Diakoulaki D, Mavrotas G, Papayannakis L. Determining objective weights in multiple criteria problems: the CRITIC method. Comput Operat Res. 1995;22(7):763–77. [Google Scholar]

32. Yu B, Hu Y, Zhou X. Can administrative division adjustment improve urban land use efficiency? Evidence from “Revoke County to Urban District” in China. Environ Plan B Urban Anal City Sci. 2025. doi:10.1177/23998083251325638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kaur G, Dhara A, Majumder A, Sandhu BS, Puhan A, Adhikari MS. A CRITIC-TOPSIS MCDM technique under the neutrosophic environment with application on aircraft selection. Contemp Math. 2023;4(4):1180–203. doi:10.37256/cm.4420232963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Sleem A, Mostafa N, Elhenawy I. Neutrosophic CRITIC MCDM methodology for ranking factors and needs of customers in product’s target demographic in virtual reality metaverse. Neutrosophic Syst Appl. 2023;2:55–65. doi:10.61356/j.nswa.2023.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Mishra AR, Chen SM, Rani P. Multicriteria decision making based on novel score function of Fermatean fuzzy numbers, the CRITIC method, and the GLDS method. Inf Sci. 2023;623(1):915–31. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.12.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wei M, Xiong Y, Sun B. Spatial effects of urban economic activities on airports’ passenger throughputs: a case study of thirteen cities and nine airports in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, China. J Air Transp Manag. 2025;125(2):102765. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2025.102765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Jusufbašić A. MCDM methods for selection of handling equipment in logistics: a brief review. Spect Eng Manage Sci. 2023;1(1):13–24. doi:10.31181/sems1120232j. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zulqarnain RM, Ma W-X, Siddique I, Ahmad H, Askar S. An intelligent MCGDM model in green suppliers selection using interactional aggregation operators for interval-valued pythagorean fuzzy soft sets. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;139(2):1829–62. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.030687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Chen C, Wang R, Chen M, Zhao J, Li H, Ignatieva M, et al. The post-effects of landscape practices on spontaneous plants in urban parks. Urban Forest Urban Green. 2025;107:128744. [Google Scholar]

40. Keršuliene V, Zavadskas EK, Turskis Z. Selection of rational dispute resolution method by applying new step-wise weight assessment ratio analysis (SWARA). J Bus Econom Manage. 2010;11(2):243–58. doi:10.3846/jbem.2010.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Stević ž, Das DK, Tešić R, Vidas M, Vojinović D. Objective SWARAism and negative conclusions on using the fuzzy SWARA method in multi-criteria decision making. Mathematics. 2022;10(4):635. doi:10.3390/math10040635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Li T, Xin S, Xi Y, Tarkoma S, Hui P, Li Y. Predicting multi-level socioeconomic indicators from structural urban imagery. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management (CIKM ’22); 2022 Oct 17–21; Atlanta, GA, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2022. p. 3282–91. [Google Scholar]

43. Deveci M, Varouchakis EA, Brito-Parada PR, Mishra AR, Rani P, Bolgkoranou M, et al. Evaluation of risks impeding sustainable mining using Fermatean fuzzy score function based SWARA method. Appl Soft Comput. 2023;139(1):110220. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2023.110220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Amoozad Mahdiraji H, Zavadskas EK, Arab A, Turskis Z, Sahebi IG. Formulation of manufacturing strategies based on an extended Swara method with intuitionistic fuzzy numbers: an automotive industry application. Transform Bus Econom. 2021;20(2):346–74. [Google Scholar]

45. Eroğlu Ö, Gencer C. Classification on SWARA method and an application with SMAA-2. Politeknik Dergisi. 2021;24(4):1707–18. [Google Scholar]

46. Alrasheedi AF, Mishra AR, Rani P, Zavadskas EK, Cavallaro F. Multicriteria group decision-making approach based on an improved distance measure, the SWARA method, and the WASPAS method. Granul Comput. 2023;8(6):1867–85. doi:10.1007/s41066-023-00413-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Jameel T, Riaz M, Aslam M, Pamucar D. Sustainable renewable energy systems with entropy based step-wise weight assessment ratio analysis and combined compromise solution. Renew Energy. 2024;235(2):121310. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2024.121310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Zhou K. Comprehensive evaluation on water resources carrying capacity based on improved AGA-AHP method. Appl Water Sci. 2022;12(5):103. doi:10.1007/s13201-022-01626-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Cheng X, Chen C. Decision making with intuitionistic fuzzy best-worst method. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;237(Part A):121215. [Google Scholar]

50. Bošković S, Jovčić S, Simic V, švadlenka L, Dobrodolac M, Bacanin N. A new criteria importance assessment (Cimas) method in multi-criteria group decision-making: criteria evaluation for supplier selection. Facta Univ Series Mec Eng. 2023;23(2):335–49. doi:10.22190/fume230730050b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Akmaludin A, Sihombing EG, Dewi LS, Arisawati E. Comparison of selection for employee position recommended MCDM-AHP, SMART and MAUT method. Sinkron: Jurnal Dan Penelitian Teknik Informatika. 2023;7(2):603–16. doi:10.33395/sinkron.v8i2.11843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Jalhoom RJK, Mahjoob AMR. An MCDM approach for evaluating construction-related risks using a combined fuzzy grey DEMATEL method. Eng Technol Appl Sci Res. 2024;14(2):13572–7. doi:10.48084/etasr.6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Dohale V, Gunasekaran A, Akarte M, Verma P. An integrated Delphi-MCDM-Bayesian Network framework for production system selection. Int J Prod Econ. 2021;242:108296. [Google Scholar]

54. Öztaş T, Öztaş GZ. Innovation performance analysis of G20 countries: a novel integrated LOPCOW-MAIRCA MCDM approach including the COVID-19 period. Verimlilik Dergisi. 2024;1–20. doi:10.51551/verimlilik.1320794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Zafar S, Alamgir Z, Rehman MH. An effective blockchain evaluation system based on entropy-CRITIC weight method and MCDM techniques. Peer Peer Netw Appl. 2021;14(5):3110–23. [Google Scholar]

56. Bączkiewicz A, Kizielewicz B, Shekhovtsov A, Wątróbski J, Sałabun W. Methodical aspects of MCDM based E-commerce recommender system. J Theor Appl Electron Commer Res. 2021;16(6):2192–29. [Google Scholar]

57. Hassan I, Alhamrouni I, Azhan NH. A CRITIC-TOPSIS multi-criteria decision-making approach for optimum site selection for solar PV farm. Energies. 2023;16(10):4245. doi:10.3390/en16104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Kumar S, Singh A. Multi-objective optimization of powder mixed green-EDM parameters on machining of HcHcr steel using an integrated MCDM approach. In: Advances in Modern Machining Processes: Proceedings of AIMTDR. Singapore: Springer; 2021. p. 199–214. [Google Scholar]

59. Vadivel SM, Shetty DS, Sequeira AH, Nagaraj E, Sakthivel V. A sustainable green supplier selection using CRITIC method. In: Intelligent Systems Design and Applications: 22nd International Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and Applications (ISDA 2022). Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 308–15. [Google Scholar]

60. Bošković S, švadlenka L, Dobrodolac M, Jovčić S, Zanne M. An extended AROMAN method for cargo bike delivery concept selection. Decis Mak Adv. 2023;1(1):1–9. doi:10.31181/v120231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Kara K, Yalçın GC, Acar AZ, Simic V, Konya S, Pamucar D. The MEREC-AROMAN method for determining sustainable competitiveness levels: a case study for Turkey. Socioecon Plann Sci. 2024;91(48):101762. doi:10.1016/j.seps.2023.101762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Amartya PS, Kabir S, Babu SC, Jahan M. An interval creation approach to construct interval type-2 fuzzy sets. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

63. Boulaaras S, Mostafa GE, Jan R, Mekawy I. Applications of distance measure between dual hesitant fuzzy sets in medical diagnosis and weighted dual hesitant fuzzy sets in making decision. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):26214. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-75687-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Yager RR. Pythagorean fuzzy subsets. In: IFSA World Congress and NAFIPS Annual Meeting (IFSA/NAFIPS). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2013. p. 57–61. [Google Scholar]

65. Yager RR. Pythagorean membership grades in multi criteria decision-making. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2014;22(4):958–65. doi:10.1109/tfuzz.2013.2278989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. O’Brien LE, Urbanek RE, Gregory JD. Ecological functions and human benefits of urban forests. Urban Forest Urban Green. 2022;75:127707. [Google Scholar]

67. Desouki M, Madkour M, Abdeen A, Elboshy B. Multicriteria decision-making tool for investigating the feasibility of green roof systems in Egypt. Sustain Environ Res. 2024;34(2):1–16. [Google Scholar]

68. Ysebaert T, Koch K, Samson R, Denys S. Green walls for mitigating urban particulate matter pollution—a review. Urban Forest Urban Green. 2021;59:127014. [Google Scholar]

69. Zhou J, Pang Y, Du W, Huang T, Wang H, Zhou M, et al. Review of the development and research of permeable pavements. Hydrol Process. 2024;38(6):e15179. [Google Scholar]

70. Rahman K, Abdullah S, Husain F, Khan MSA. Approaches to Pythagorean fuzzy geometric aggregation operators. Int J Comput Sci Inform Secur. 2016;14(9):174–200. [Google Scholar]

71. Peng XD, Yuan H. Fundamental properties of Pythagorean fuzzy aggregation operators. Fundam Inform. 2016;147(4):415–46. doi:10.3233/fi-2016-1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Wang L, Garg H. Algorithm for multiple attribute decision-making with interactive archimedean norm operations under pythagorean fuzzy uncertainty. Int J Comput Intell Syst. 2021;14(1):503– 527. [Google Scholar]

73. Garg H. Confidence levels based Pythagorean fuzzy aggregation operators and its application to decision-making process. Comput Math Organ Theory. 2017;23(4):546–71. doi:10.1007/s10588-017-9242-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools