Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Inverse Design of Composite Materials Based on Latent Space and Bayesian Optimization

Department of Structural Engineering, College of Civil Engineering, Tongji University, Shanghai, 200092, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaodan Ren. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI-Enhanced Computational Methods in Engineering and Physical Science)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 1 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.074388

Received 10 October 2025; Accepted 01 December 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

Inverse design of advanced materials represents a pivotal challenge in materials science. Leveraging the latent space of Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) for material optimization has emerged as a significant advancement in the field of material inverse design. However, VAEs are inherently prone to generating blurred images, posing challenges for precise inverse design and microstructure manufacturing. While increasing the dimensionality of the VAE latent space can mitigate reconstruction blurriness to some extent, it simultaneously imposes a substantial burden on target optimization due to an excessively high search space. To address these limitations, this study adopts a Variational Autoencoder guided Conditional Diffusion Generative Model (VAE-CDGM) framework integrated with Bayesian optimization to achieve the inverse design of composite materials with targeted mechanical properties. The VAE-CDGM model synergizes the strengths of VAEs and Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPM), enabling the generation of high-quality, sharp images while preserving a manipulable latent space. To accommodate varying dimensional requirements of the latent space, two optimization strategies are proposed. When the latent space dimensionality is excessively high, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) sensitivity analysis is employed to identify critical latent features for optimization within a reduced subspace. Conversely, direct optimization is performed in the low-dimensional latent space of VAE-CDGM when dimensionality is modest. The results demonstrate that both strategies accurately achieve the targeted design of composite materials while circumventing the blurred reconstruction flaws of VAEs, which offers a novel pathway for the precise design of advanced materials.Keywords

Composite materials, renowned for their high strength, toughness, and multifunctionality, have found extensive applications across aerospace, new energy vehicles, and high-end manufacturing sectors [1–4]. As quintessential multiphase materials, their macroscopic properties, such as mechanical strength, thermal conductivity, and fatigue resistance, are governed not only by the intrinsic attributes of the matrix and reinforcement but also by microstructural features, including reinforcement distribution density, size distribution, and spatial orientation [5,6]. For instance, a regular arrangement of reinforcement within the matrix can significantly enhance the strain hardening rate and flow stress, while a gradient arrangement, particularly when aligned parallel to the applied load, effectively mitigates damage propagation. Conversely, clustered microstructures may induce stress concentrations and precipitate premature failure [7]. Consequently, the precise design of microstructures to achieve targeted performance constitutes a pivotal objective in advanced materials engineering [8].

Inverse design, a critical pathway bridging performance targets and microstructure, aims to infer optimal microstructural configurations from predefined macroscopic properties, with its efficiency and accuracy directly influencing the development cycle and engineering value of novel materials. Traditional inverse design methodologies rely on microstructure characterization techniques [9], employing physical descriptors [10], such as fiber volume fraction, average diameter, and spacing distribution [11–14], to reduce the high-dimensional microstructural space to a lower-dimensional representation for optimization. However, these descriptors are often constrained by empirically defined rules, exhibiting limitations such as restricted spatial dimensionality and incomplete information representation. For example, volume fraction alone fails to capture localized clustering features, resulting in the inability to perform precise microstructure inverse design. As material systems continue to increase in complexity, conventional inverse design methodologies face growing challenges in simultaneously capturing both global microstructural patterns and localized features, emerging as a significant bottleneck in enhancing inverse design precision.

In recent years, deep generative models have ushered in a transformative paradigm for the precise characterization and inverse design of microstructures [9]. The pixel-based representation of microstructures fundamentally constitutes a high-dimensional random field. Meanwhile, the core objective of generative models which is high-dimensional probability density estimation [15], aligns intrinsically with the representational needs of microstructures, enabling the capture of higher-order statistical properties thereby providing a more comprehensive depiction of their complex information. Among these models, the Variational Autoencoder (VAE) emerges as a classical approach [16], employing an encoder to map high-dimensional microstructures into a low-dimensional latent space and a decoder to reconstruct the structures, demonstrating robust dimensionality reduction and generative capabilities. VAE has been extensively applied in the microstructure reconstruction of composite materials, metallic alloys, sandstones, and other material systems [17–19], offering efficient tools for material characterization and design.

Leveraging the latent space of VAE for optimization design has emerged as a frontier strategy for inverse materials design. Recent studies have demonstrated its applicability across diverse material systems, aiming to generate materials with desired properties through latent space exploration and optimization. For instance, Wang et al. [20] demonstrated that VAE latent spaces provide a meaningful distance metric for assessing shape similarity, enabling vector operations to adjust mechanical properties and manipulate complex microstructures. Lew and Buehler [21] focused on compliance optimization of cantilever designs, encoding cantilever structures into a 2D latent space using a VAE and employing a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network to learn optimization trajectories within that space. Kusampudi and Diehl [22] trained a VAE to identify descriptors from synthetic dual-phase steel microstructures, utilizing Bayesian optimization to determine optimal descriptor combinations that yield microstructures with specific yield strengths and reduced damage initiation sensitivity. Xue et al. [23] employed the VAE to compress the low-resolution (

Nevertheless, VAEs exhibit inherent limitations in microstructure generation. Their objective function primarily optimizes for latent distribution regularization and pixel-wise reconstruction error, which often leads to decoded microstructures with lost details, such as blurred edges [26]. Although increasing the dimensionality of the latent space can partially alleviate reconstruction inaccuracies, it does not fully eliminate the blurring effect, while substantially increasing computational cost and complicating downstream inverse design tasks. As noted by Peng et al. [27], selecting an appropriate latent dimension requires balancing reconstruction quality against the curse of dimensionality. An undersized latent space lacks sufficient representational capacity, resulting in high reconstruction loss, whereas an oversized space introduces diminishing returns in accuracy while exponentially expanding the search space. This trade-off is particularly consequential when VAEs are coupled with Bayesian optimization (BO). Since BO is typically applicable to dimensions below 20, the microstructures generated by VAEs within this range are often blurry and inadequate for precise design and manufacturing objectives. Therefore, maintaining a low latent space dimension without compromising microstructural fidelity is essential to fully leverage Bayesian optimization in VAE-based inverse design frameworks.

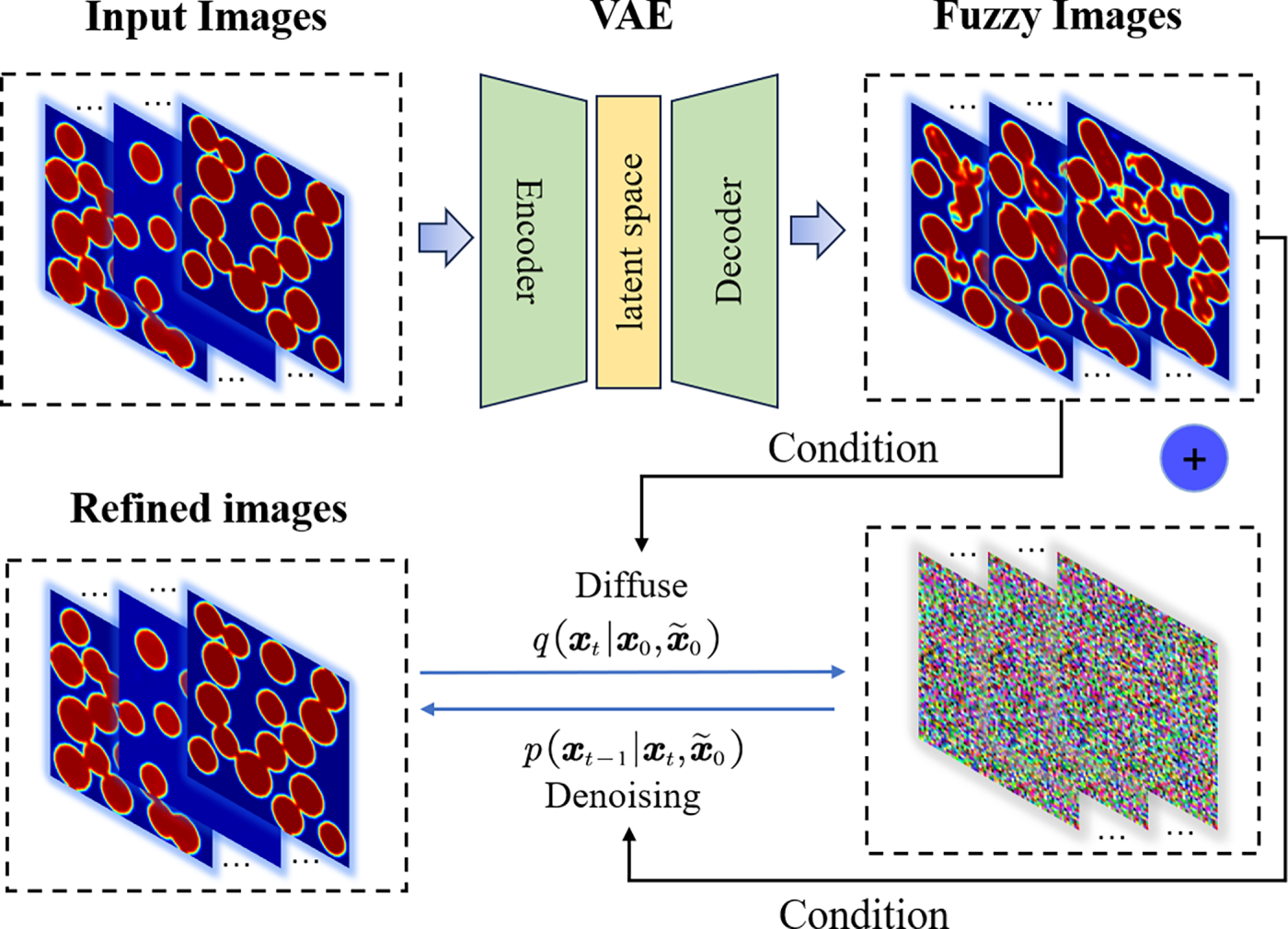

To overcome this bottleneck, our research group previously introduced a Variational Autoencoder guided Conditional Diffusion Generative Model (VAE-CDGM) tailored for material design [28], integrating the low-dimensional mapping capabilities of VAEs with the high-fidelity generative attributes of Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPM). This model uses the blurred image generated by the VAE as a conditional input to restructure the forward diffusion process of DDPM. It then employs multi-step denoising iterations to progressively refine the microstructural details. This approach thus achieves high-fidelity microstructure reconstruction while maintaining a continuous and controllable latent space.

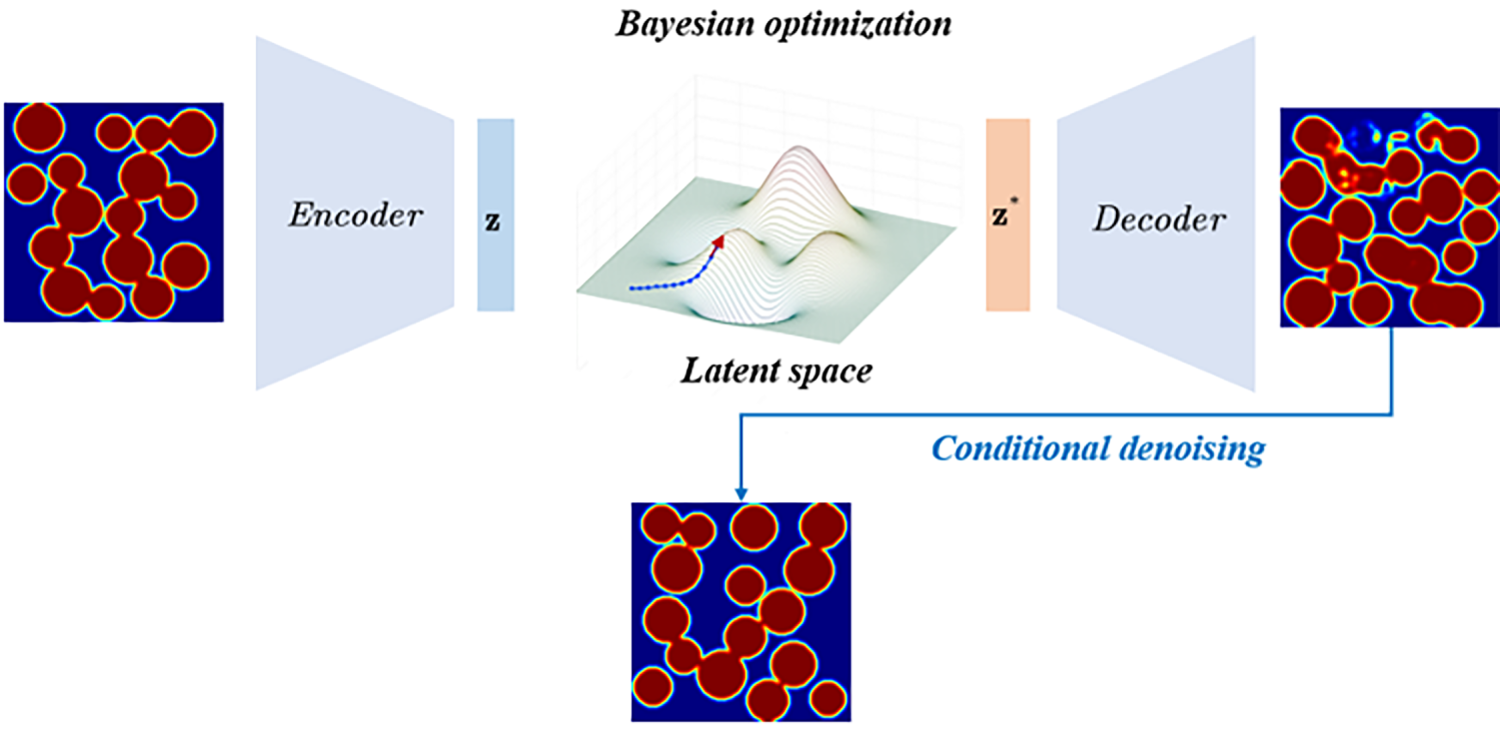

For the inverse design of composite materials, this study builds upon the VAE-CDGM framework, balancing latent space manipulability with high-quality generation, and proposes a dual-strategy inverse design approach integrated with Bayesian optimization. When higher latent space dimensionality is required, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) sensitivity analysis is employed to identify the most impactful dimensions for performance, enabling Bayesian optimization within a reduced subspace. Conversely, for lower-dimensional spaces, direct Bayesian optimization is performed in VAE-CDGM’s latent space. Both strategies utilize VAE-CDGM to map optimized latent vectors back to the pixel space, generating high-quality microstructure images providing guidance for subsequent manufacturing processes. The material design framework proposed in the study is shown in Fig. 1. The subsequent sections are organized as follows: Section 2 elaborates the construction principles of the VAE-CDGM model; Section 3 validates the latent space properties and reconstruction quality of VAE-CDGM; Section 4 experimentally confirms the model’s generative performance and the efficacy of the inverse design strategy; Section 5 summarizes the findings, discusses the method’s advantages and future improvement directions.

Figure 1: Material design framework based on VAE-CDGM and Bayesian optimization

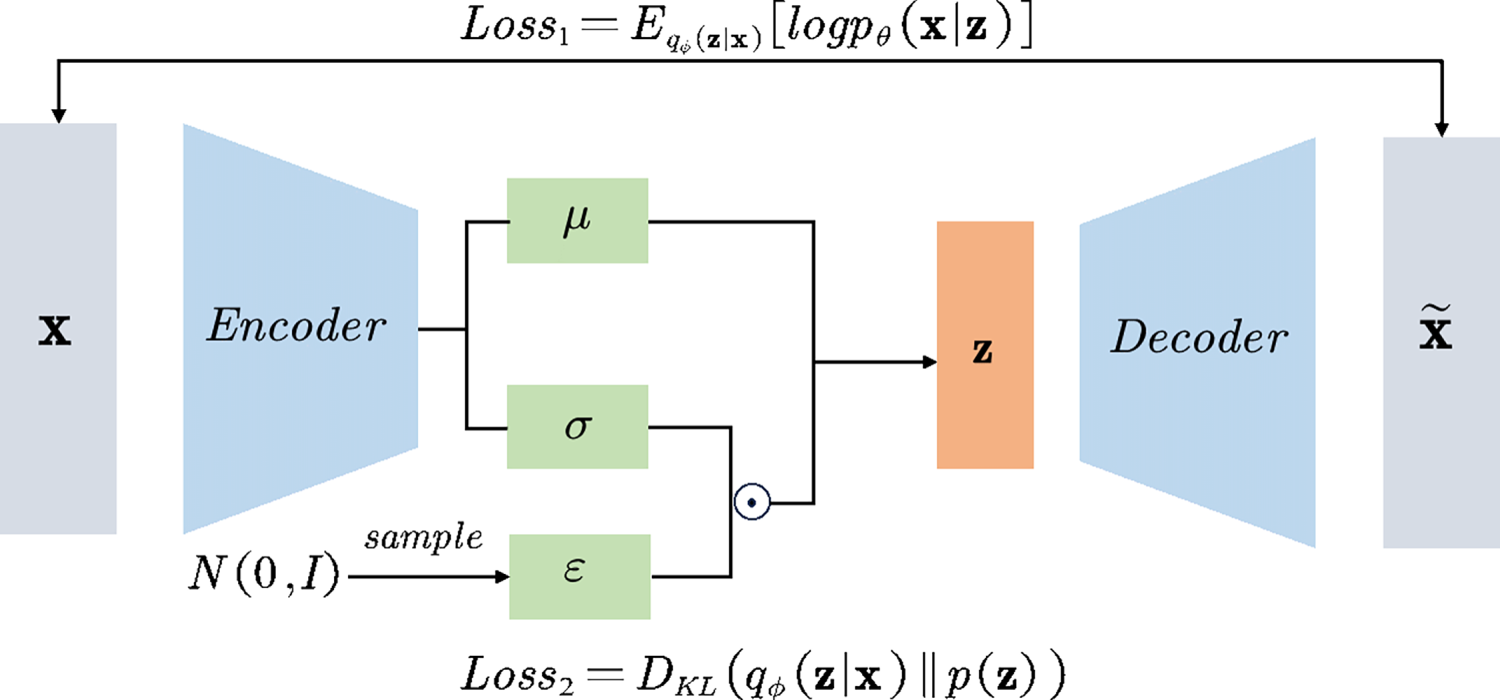

The Variational Autoencoder, a generative model integrating probabilistic modeling with deep learning, was pioneered by Kingma and Welling [16]. Its core innovation lies in employing variational inference to establish a probabilistic mapping between high-dimensional data and a low-dimensional latent space, facilitating the representation, generation, and reconstruction of microstructure images. Distinct from traditional autoencoders [29], VAE introduces regularization in the latent space, endowing it with continuity and interpretability, which lays a theoretical foundation for interpolation-based generation and optimization-driven design in materials engineering.

The generative process assumes that observed data

To address this, VAE employs variational inference and Jensen’s inequality to avoid direct integration. By introducing an approximate posterior distribution, the marginal log-likelihood can be expressed as:

here, since

The expectation term on the right side of the above equation is the core of VAE, the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO),

By applying Jensen’s inequality, the intractable log-likelihood

Splitting the logarithmic terms in Eq. (4) and substituting them into the expectation-based definition of the ELBO yields:

Since machine learning typically minimizes loss functions via gradient descent, while the objective of VAE is to maximize the ELBO, this is equivalent to minimizing the negative ELBO (−ELBO). The VAE optimization objective can ultimately be written in the following form,

where

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of VAE architecture

In materials science, VAE’s robust non-linear dimensionality reduction and generative capabilities have been widely leveraged for microstructure characterization and reconstruction across diverse material systems. Its probabilistic framework enables interpolation and optimization operations within the continuous latent space, providing a foundation for target-oriented material design. Despite these advantages, VAE-generated outputs often suffer from blurriness due to the loss’s emphasis on mean-field approximations. Moreover, the choice of latent space dimensionality critically influences both generation quality and computational complexity. Low-dimensional spaces may result in the loss of essential microstructural features, whereas high-dimensional spaces, while potentially reducing blurriness, significantly increase the computational burden and optimization challenges in subsequent inverse design tasks.

2.2 Introduction to Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM)

The Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM), a deep learning framework rooted in probabilistic generative processes, was initially proposed by Sohl-Dickstein et al. in 2015 [30] and subsequently developed by Ho et al. in 2020 [31]. DDPM achieves high-precision modeling of complex high-dimensional data distributions by simulating a stepwise noising and denoising process. Compared to VAEs, DDPM excels in generating high-quality samples, demonstrating significant advantages in image generation and microstructure reconstruction [32–34].

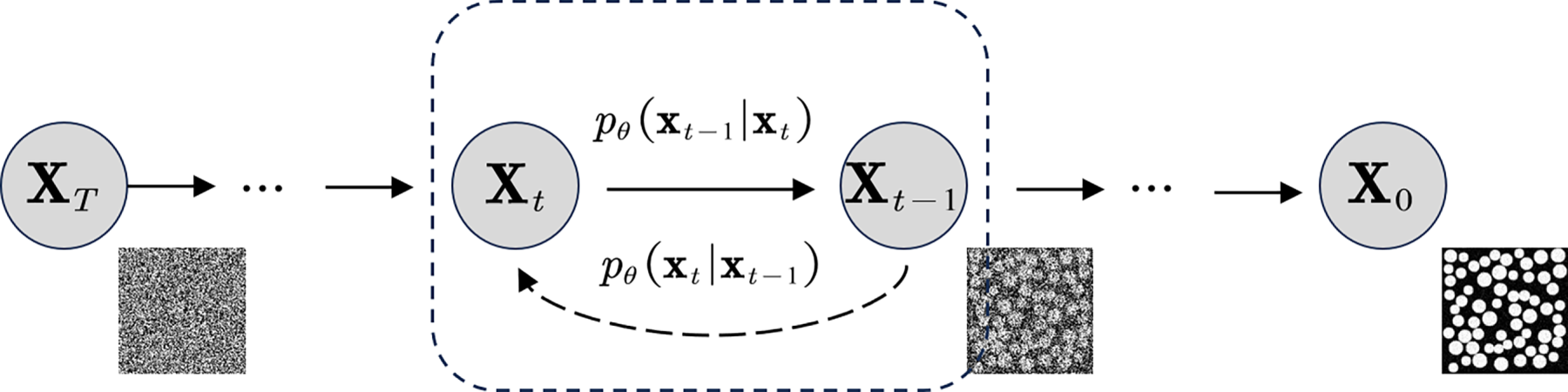

The core concept of DDPM revolves around a forward diffusion process and a reverse denoising process to model the data probability distribution, as shown in Fig. 3. The forward process incrementally adds Gaussian noise to the original data

where

where

Figure 3: The forward and reverse processes of diffusion model

The reverse process aims to recover the original data from noise,

where

The objective of DDPM is to minimize the KL divergence between the true posterior distribution

Moreover, since,

Substituting the above equation into the optimization objective, the objective becomes:

Removing the coefficient yields the final loss function of DDPM,

where

Compared to the blurred images generated by VAEs, DDPM’s multi-step denoising process markedly enhances detail fidelity, providing reliable samples for material performance prediction and reverse design. However, the diffusion model does not undergo dimensionality reduction during implementation, resulting in its latent space and pixel space being the same dimensions, making it impossible to use it as a search space for target optimization.

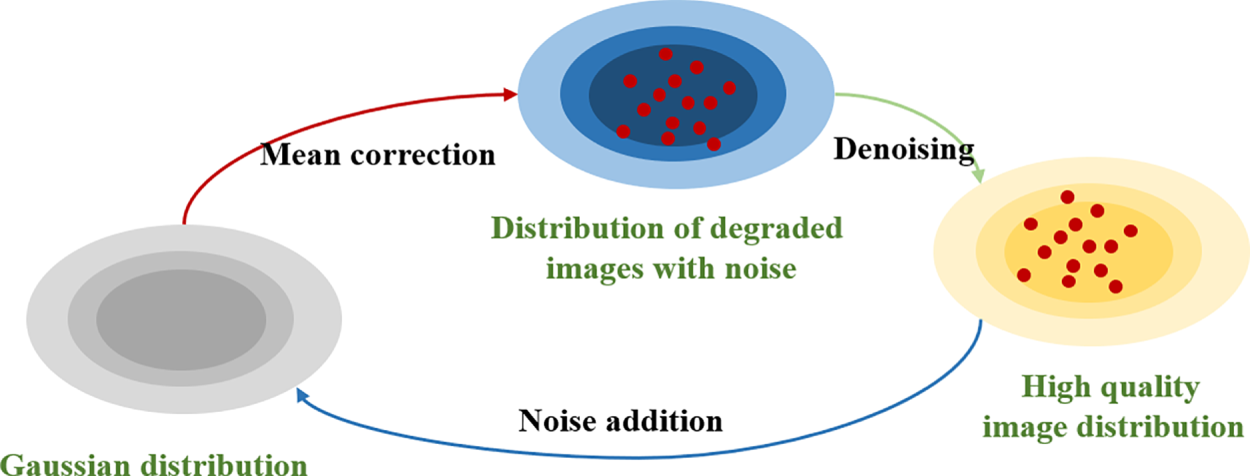

The preceding analyses highlight that while VAEs offer a low-dimensional, continuous latent space conducive to optimization, they are prone to producing blurred reconstructions. Conversely, DDPM excels in high-quality image reconstruction but lacks a manipulable latent space for material optimization. To address these complementary limitations, the VAE-CDGM integrates the strengths of VAEs and DDPMs, ensuring the presence of a continuous latent space while enhancing microstructure reconstruction quality [28].

Unlike standard DDPM, VAE-CDGM incorporates a conditional diffusion process during the forward process:

where

Figure 4: Mean correction process of VAE-CDGM

Subsequently, based on Bayesian inference, the reverse process can be expressed as:

with the posterior mean and variance derived from the forward process as:

where

Traditional conditional diffusion models typically employ a standard diffusion process, incrementally adding Gaussian noise to images until they degenerate into pure noise, with conditional information (e.g., low-quality images) appended as input to the noise prediction network. In contrast, VAE-CDGM explicitly models the image degradation process, progressively degrading high-quality images

The VAE-CDGM model adopts a two-phase training strategy [35], fully decoupling the training parameters of its constituent components. In the first phase, the model focuses on training the VAE component, where the encoder network maps input microstructure images

Figure 5: Schematic diagram of VAE-CDGM framework

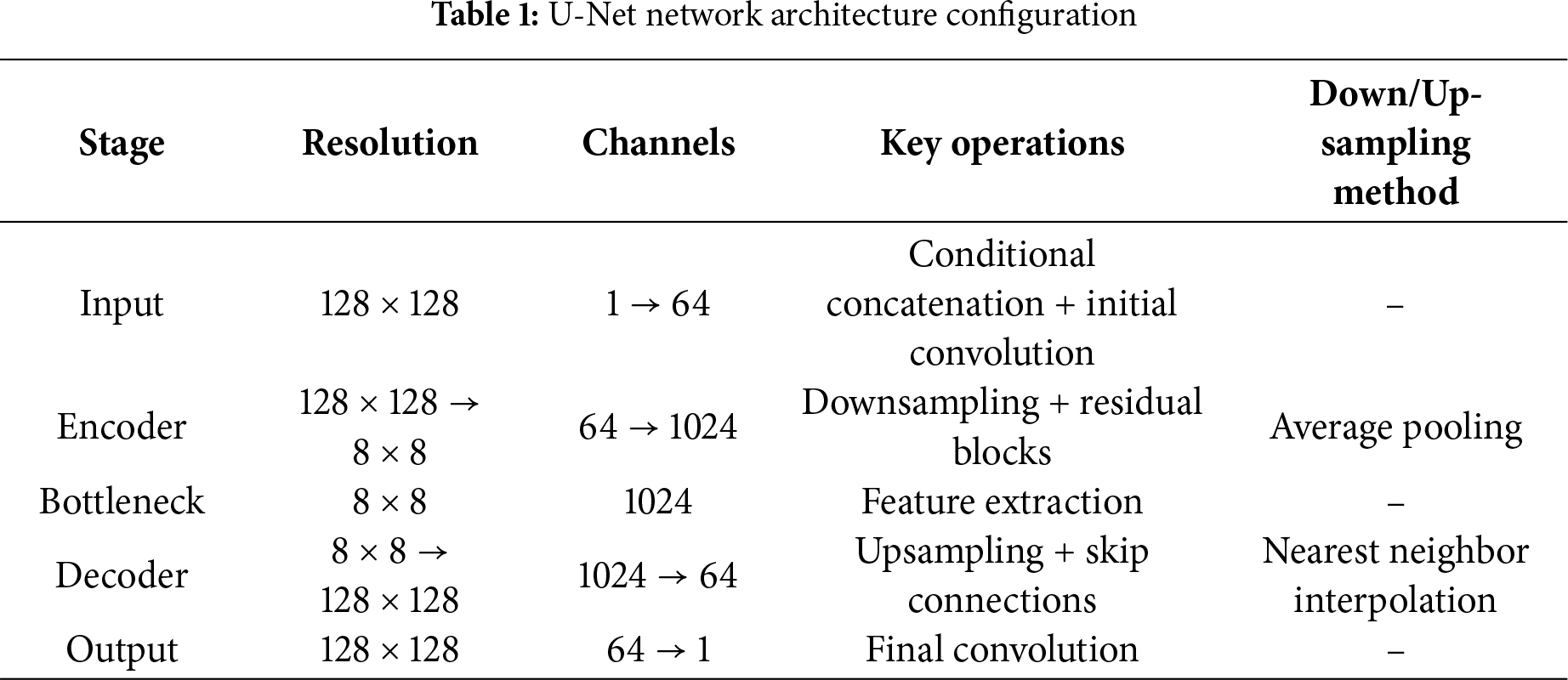

The model’s first branch comprises a convolutional VAE network. The encoder employs a five-layer downsampling module, each consisting of a Conv2d, BatchNorm2d, and ReLU combination, compressing a

3 Characterization and Reconstruction of Composites Based on VAE-CDGM

This study generates two-dimensional microstructure images of composite materials with randomly distributed circular inclusions to simulate diverse inclusion patterns. The images are synthesized at a resolution of

3.2 Generation Quality Validation

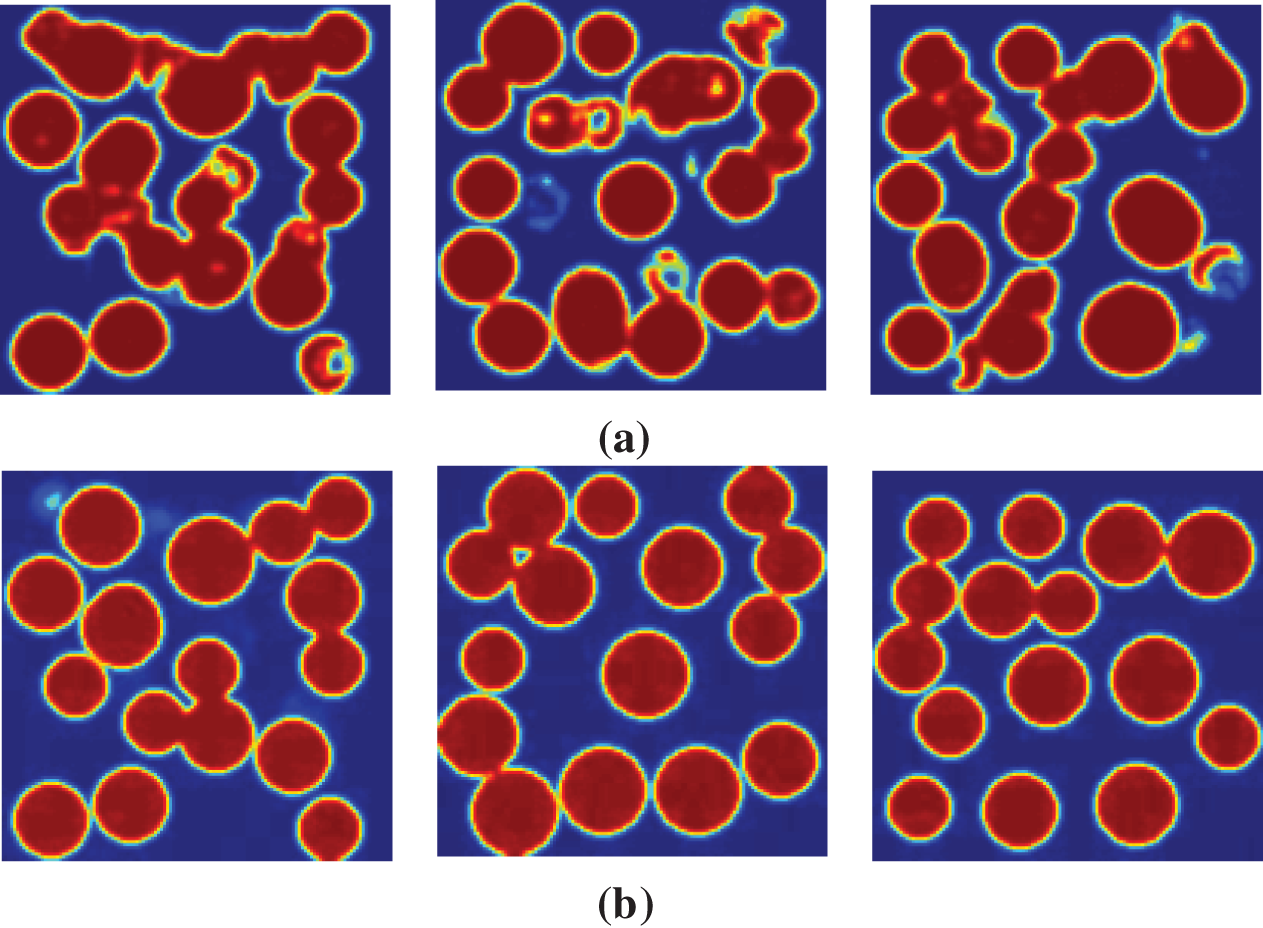

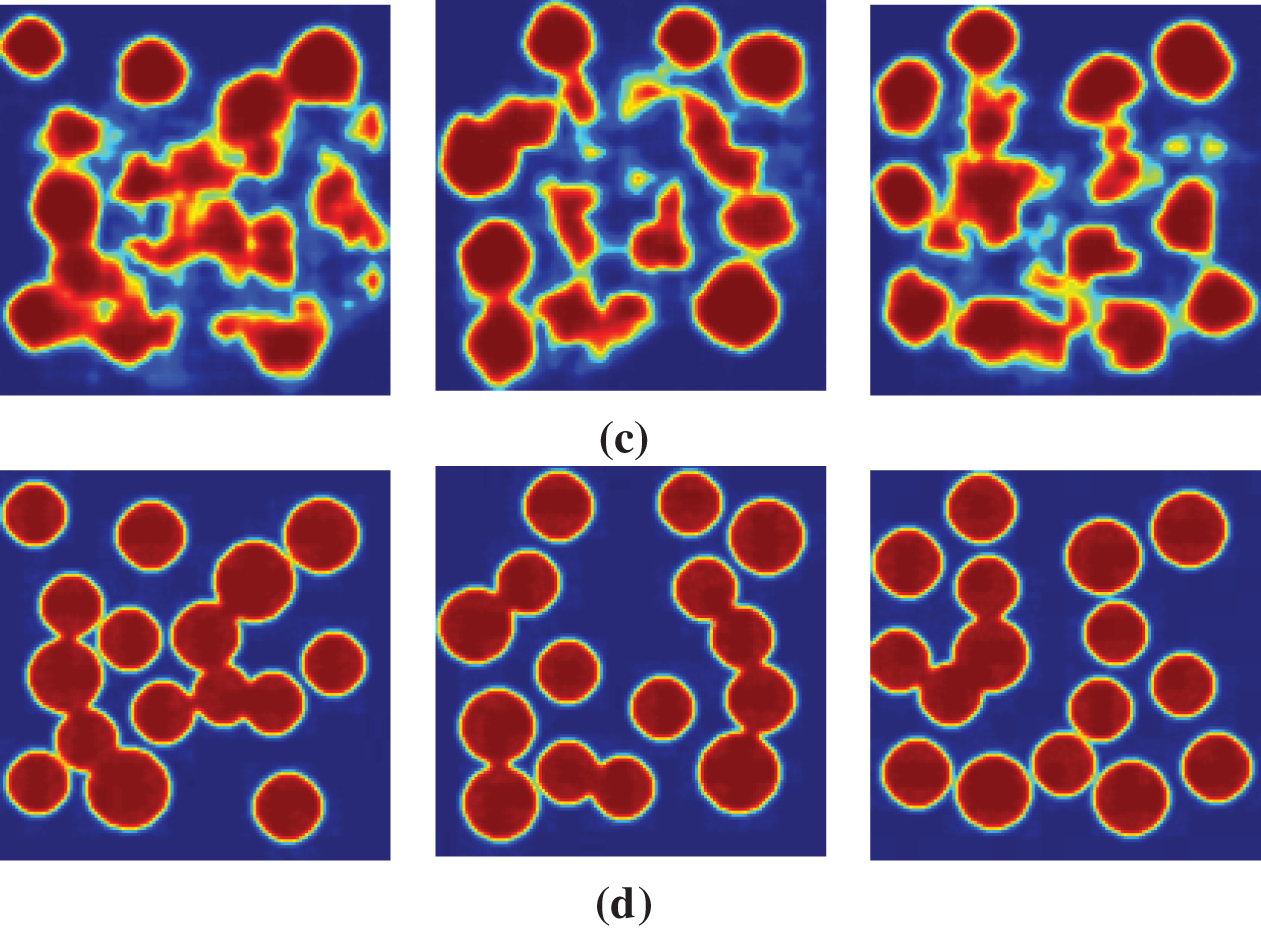

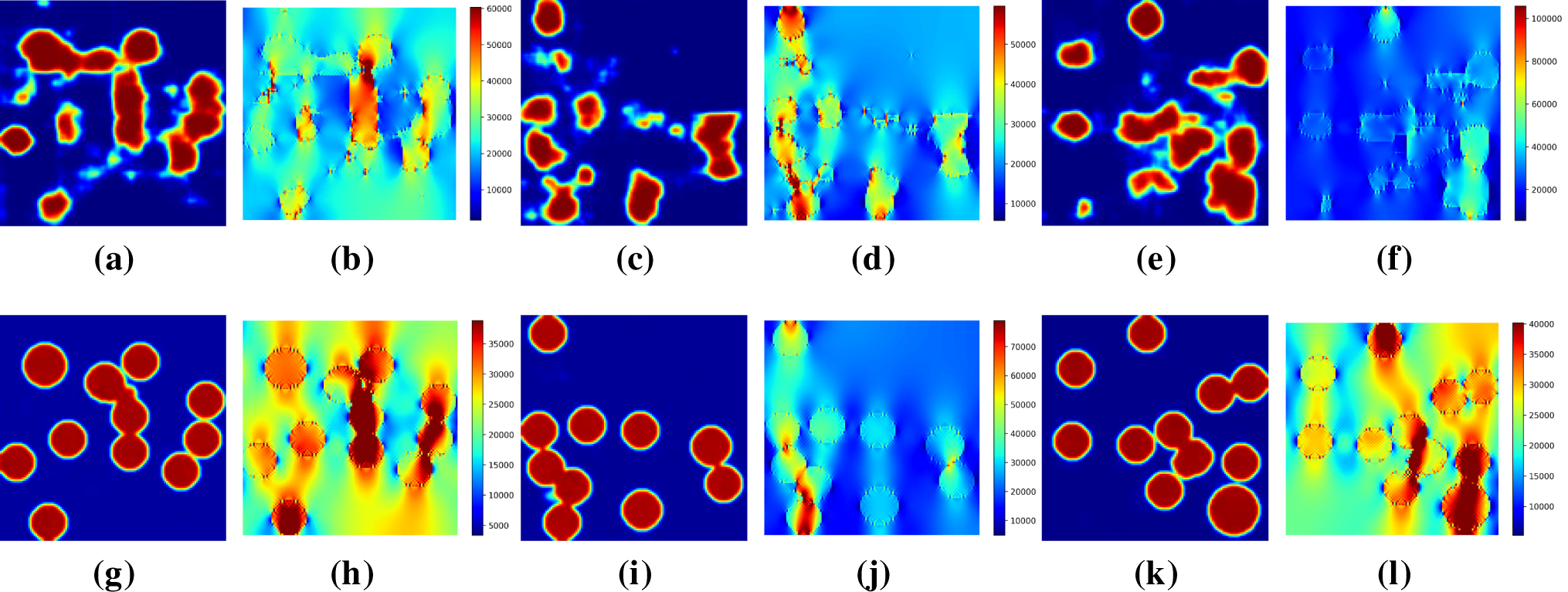

In this study, we conducted a comparative analysis of the microstructure generation quality for composite materials with circular inclusions, using VAE and the proposed VAE-CDGM model at latent space dimensions of 256 and 16, as sown in Fig. 6. For the 256-dimensional latent space, the VAE generated microstructures with improved detail retention compared to its 16-dimensional counterpart, capturing finer geometric features such as inclusion boundaries and spatial distributions. However, the VAE outputs still exhibited noticeable blurriness, particularly in boundary regularity and inclusion size accuracy. In contrast, the VAE-CDGM model at 256 dimensions significantly enhanced generation quality, producing microstructures with sharper boundaries and higher fidelity. When reducing the latent space to 16 dimensions, the VAE suffered from substantial information loss, resulting in overly blurry microstructures with diminished topological accuracy. Conversely, the VAE-CDGM model maintained superior generation quality even at 16 dimensions, leveraging the iterative denoising process of DDPM to reconstruct detailed microstructures while preserving the low-dimensional latent representation of VAE. These results underscore the VAE-CDGM model’s ability to balance latent space dimensionality and high-fidelity microstructure generation, making it a robust tool for inverse design applications in composite materials.

Figure 6: Comparison of VAE and VAE-CDGM generation quality under different latent spaces (a) VAE-256; (b) VAE-CDGM-256; (c) VAE-16; (d) VAE-CDGM-16

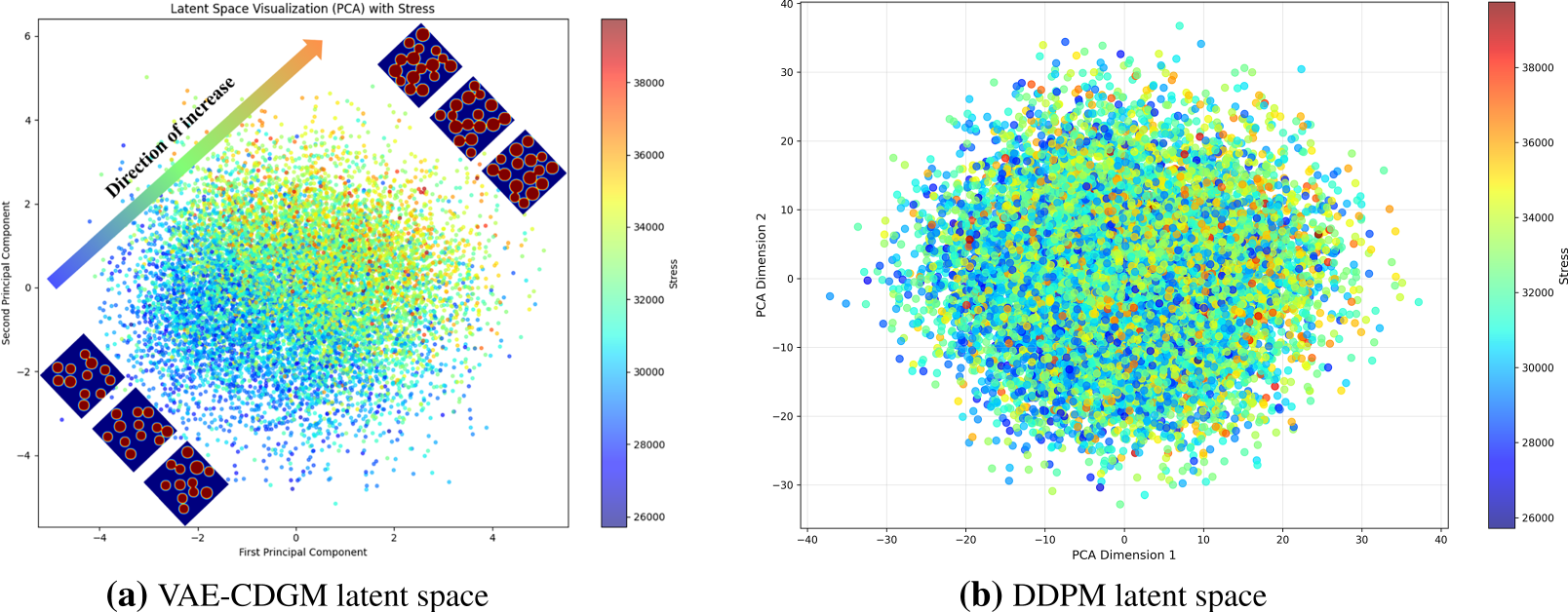

To gain deeper insights into the latent space properties of the VAE-CDGM model, we conducted a detailed analysis of the 16-dimensional latent space. To facilitate visualization, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed to reduce the dimensionality to three principal components, enabling the projection of the latent space onto the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2). The label assigned to each data point represents the homogenized stress of the composite material under uniaxial compression. The finite element model configuration, including mesh discretization and boundary conditions, is depicted in Fig. 7. Each microstructure image was directly converted into a corresponding finite element model using the python script that maps pixel intensities to material properties, with each pixel corresponding to one CPS4R finite element. The model simulates the mechanical behavior of the composite using two linearly elastic materials: Material- matrix with a Young’s modulus

Figure 7: Microstructure image and finite element setup of composite material (a) Microstructure image of composite material; (b) Mesh discretization and boundary setting

The PCA visualization results, presented in Fig. 8a, reveal that the 16-dimensional latent space retains significant structural characteristics post-reduction. In stark contrast to the diffusion model’s latent space, which exhibits a disordered and unstructured distribution under identical PCA conditions (Fig. 8b), the homogenized stress exhibits a pronounced clustered distribution within the PC1-PC2 plane. Low-stress microstructures concentrated in the lower-left region and high-stress microstructures in the upper-right region, accompanied by a smooth gradient along the diagonal. This clustering in the PCA space indicates that the VAE-CDGM model successfully compresses high-dimensional microstructural information into a low-dimensional representation while preserving critical features correlated with mechanical performance. The smooth gradient further reflects the continuity of the latent space, enabling interpolation or optimization to explore performance variations, which is conducive to efficient inverse design. This structured latent space not only validates the superior representational capability of the VAE-CDGM model but also provides a reliable design space for target-oriented material optimization.

Figure 8: Distribution characteristics of composite materials in (a) VAE-CDGM latent space and (b) DDPM latent space

4 Inverse Design of Composites Based on Bayesian Optimization

4.1 Introduction to Bayesian Optimization

Bayesian Optimization (BO) represents an efficient global optimization methodology that constructs a probabilistic surrogate model of the target function and leverages an acquisition function to guide the search process, thereby significantly reducing the number of evaluations required for parameter optimization. In the realm of materials science, BO has been extensively adopted for inverse design applications [36–40].

The primary objective of Bayesian optimization is to identify the global optimum of a target function

The Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function stands as a widely adopted choice in Bayesian optimization, renowned for its effective balance between exploration and exploitation [43,44]. EI quantifies the anticipated improvement in the objective function

where

where

This process iterates iteratively until the predetermined number of evaluations or convergence conditions are reached. However, the computational complexity of GP regression, coupled with the sparsity of data in high-dimensional spaces, poses significant challenges, typically constraining its effectiveness to low-dimensional problems (

To address these limitations, the proposed VAE-CDGM model integrates the low-dimensional representation capabilities of VAE with the high-fidelity image generation prowess of DDPM, enabling the generation of detailed microstructures for composite materials while maintaining an efficient latent space. Theoretically, the model’s capacity to produce high-quality microstructure images from low-dimensional latent spaces (<20 dimensions) suggests that Bayesian optimization can be directly applied to such spaces to efficiently search for microstructures with target mechanical performance. Nevertheless, to reconcile the practical trade-offs among representational completeness, computational efficiency, and optimization robustness, we devised two tailored optimization strategies. For high-dimensional latent spaces (dimensionality > 20), we conducted SHAP analysis using a fully connected neural network (FCN) to quantify feature importance, subsequently selecting the top 16 most influential dimensions according to their mean absolute SHAP values. This dimension reduction ensures that Bayesian optimization, guided by the EI acquisition function, operates within a compact yet informative subspace, enhancing convergence speed and robustness. Conversely, for low-dimensional latent spaces (<20 dimensions), the VAE-CDGM model provides a concise representation, enabling direct Bayesian optimization without further reduction. By proposing this dual-strategy framework, we address the distinct computational and representational demands of high- and low-dimensional latent spaces, harnessing the VAE-CDGM to facilitate efficient and robust inverse design of composite microstructures.

4.2 Bayesian Optimization under 256 Dimensional Latent Space

The VAE-CDGM framework employs a decoupled training strategy for its VAE and DDPM components, which enhances compatibility with pre-trained VAE models across diverse tasks. This architecture offers significant flexibility by enabling the integration of existing VAEs without requiring computationally expensive retraining. However, when merging pre-trained VAEs for design tasks, especially those with high-dimensional latent spaces where retraining is prohibitively costly, a critical challenge is the efficient optimization of targets in such high-dimensional spaces. This challenge is further compounded by stringent requirements for reconstruction fidelity of VAE or the need to model intricate high-order statistical correlations. However, direct optimization in such high-dimensional spaces introduces substantial challenges. To mitigate these issues, we employed SHAP [45] sensitivity analysis to identify the 16 most influential dimensions based on mean absolute SHAP values, enabling Bayesian optimization to operate within a compact yet information-rich subspace that preserves critical features while significantly reducing computational overhead.

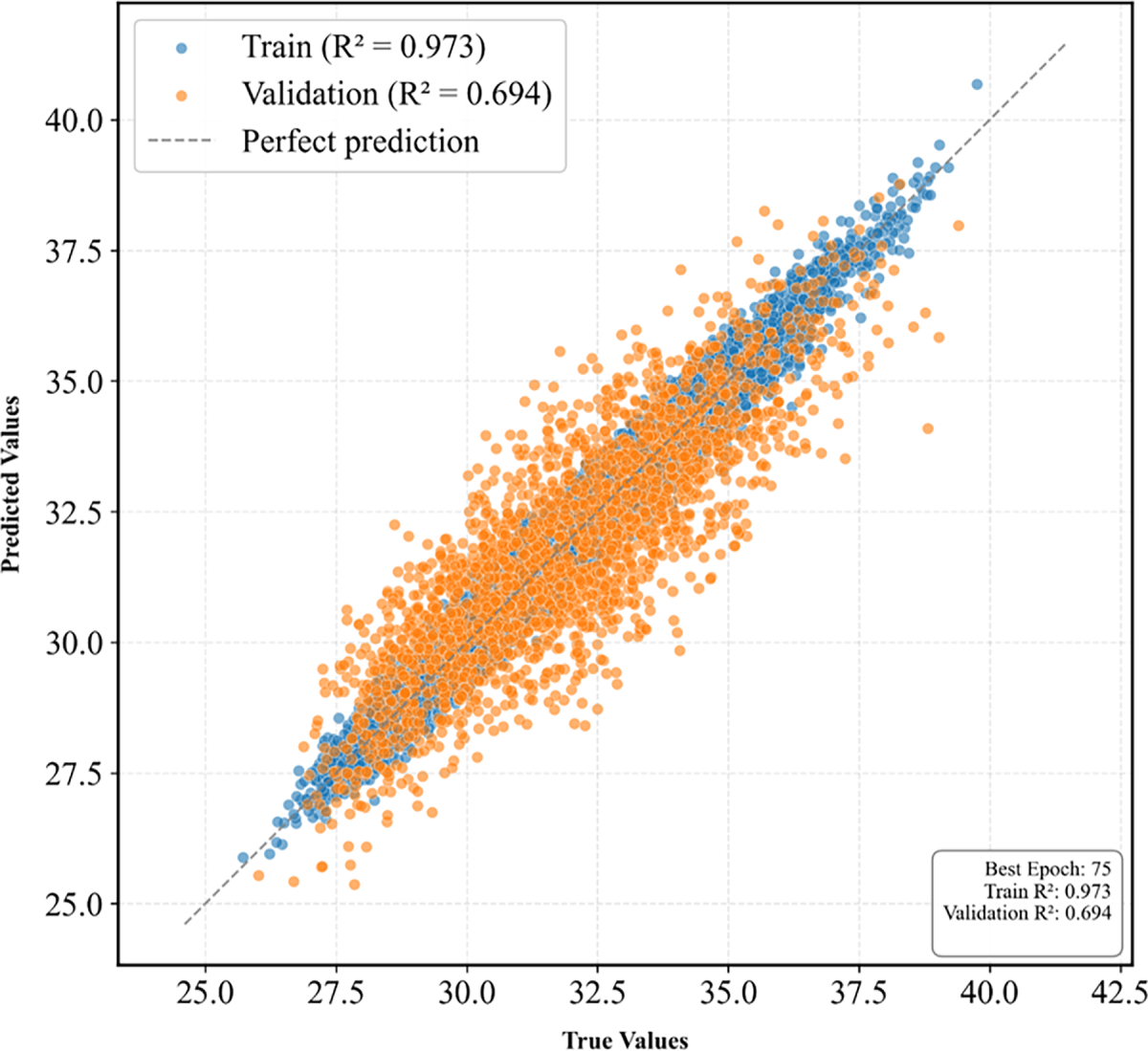

To perform sensitivity analysis and identify critical latent features governing mechanical properties, we first developed a surrogate mapping model between the latent space and material performance. This approach is fundamentally similar to CNN-based methods [46,47], which also operate by extracting abstract low-dimensional features from high-dimensional images and then mapping them to physical properties via a fully connected neural network. In the present study, the VAE encoder replaces the CNN as the feature extractor. Specifically, we constructed a FCN to predict homogenized stress from 256-dimensional latent vectors. The network architecture comprised an input layer (256 dimensions), followed by hidden layers with dimensions of 512, 256, 128, and 64, each employing ReLU activation functions, and a final single-output linear layer. The model was trained on a dataset of 11,893 samples, randomly partitioned into an 80% training set (9514 samples) and a 20% validation set (2379 samples). Training was performed using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 and mean squared error (MSE) loss. The selection of the above hyperparameters was determined through ablation experiments and trial and error. Meanwhile, we added dropout layers (p = 0.1) after each hidden layer. Early stopping was enforced with a patience of 10 epochs and a minimum validation improvement of

Figure 9: Performance of the surrogate model on the training and testing sets

To identify the latent dimensions most critical for homogenized stress prediction, we conducted a comprehensive sensitivity analysis using SHAP implemented through the DeepExplainer. SHAP is a framework rooted in cooperative game theory, specifically the Shapley Value, which aims to fairly allocate the prediction output for a single instance to each of its features. The SHAP value

here, N is the set of all features, S is a subset of features excluding

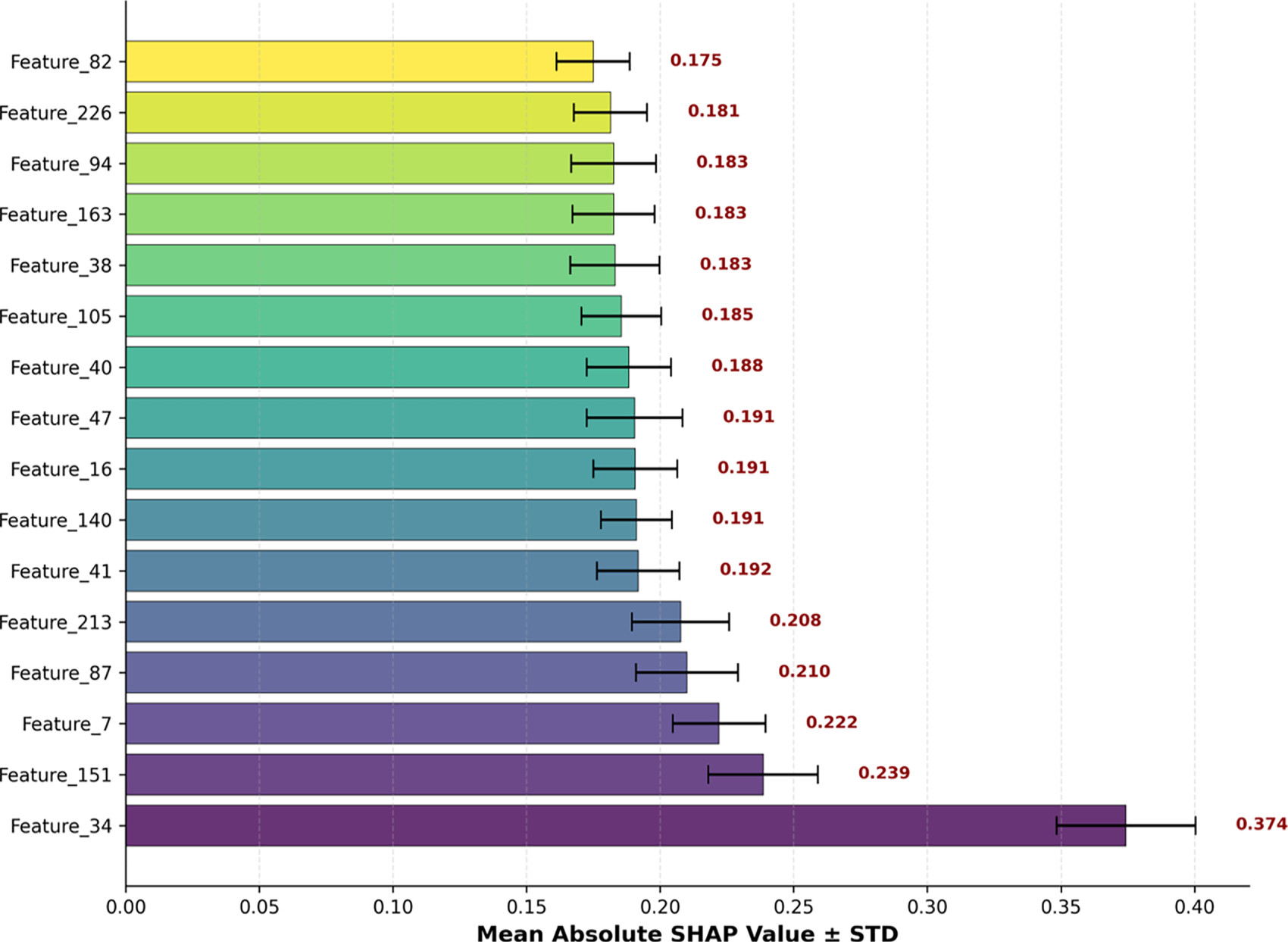

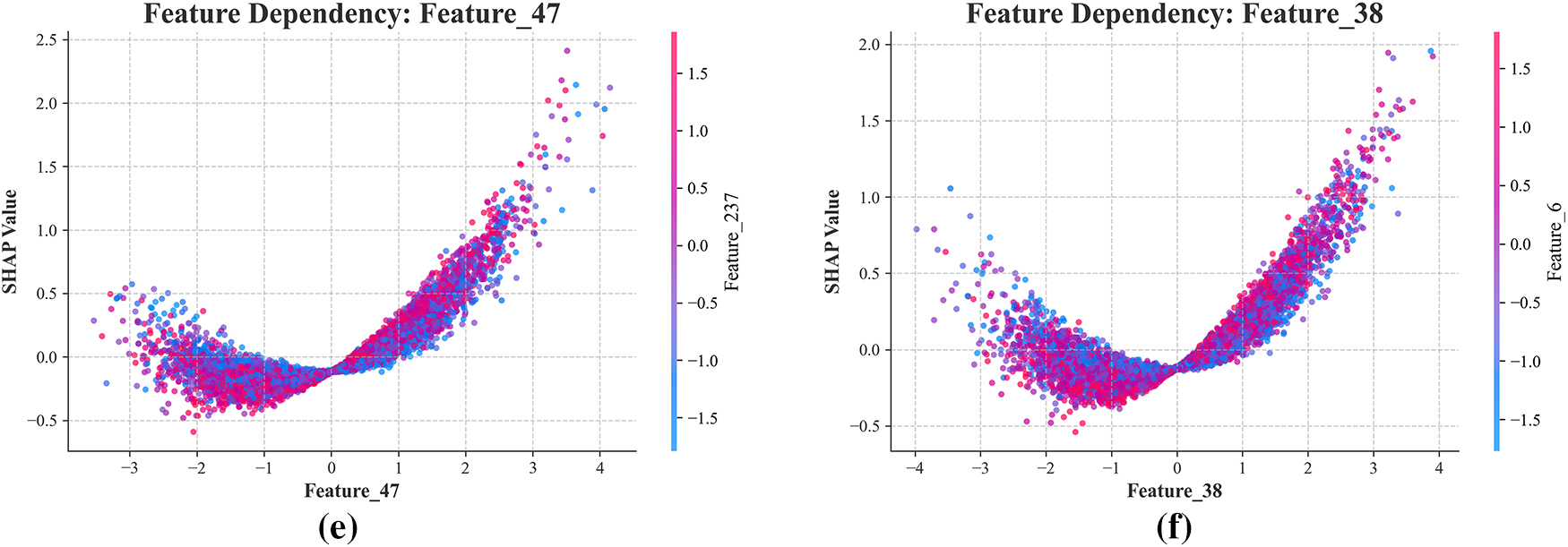

This approach quantitatively evaluated the contribution of each latent dimension to the predictions generated by our FCN by computing SHAP values. The mean absolute SHAP values were ranked, and the top 16 dimensions were selected, as they captured the majority of the predictive influence. To ensure the stability and reliability of the SHAP analysis, this study performed multiple random splits of the dataset (3 splits

Figure 10: Top 16 feature importance ranking based on mean absolute SHAP values

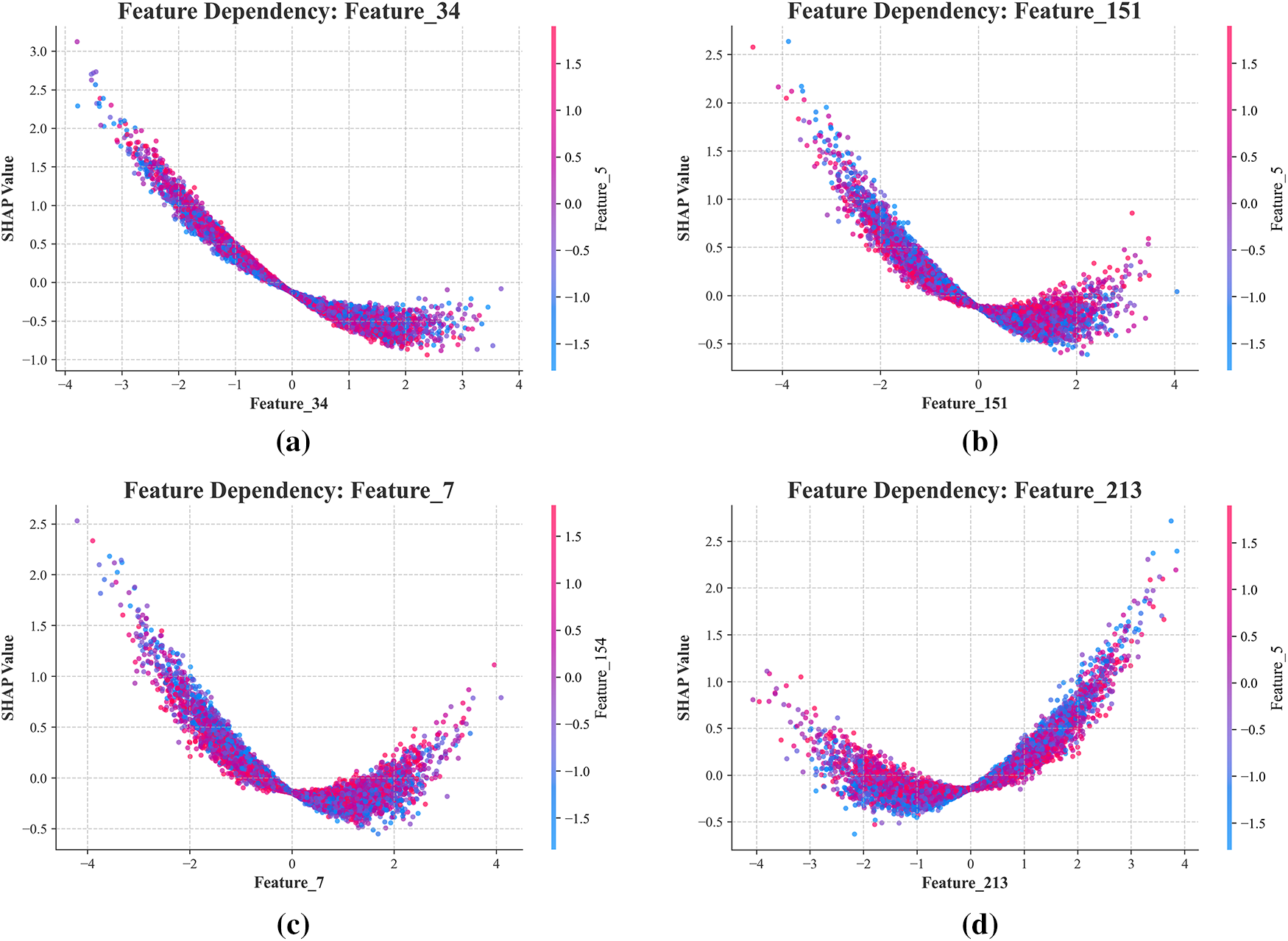

Figure 11: SHAP dependency plots for homogenized stress predictions (a) Feature 34; (b) Feature 151; (c) Feature 7; (d) Feature 213; (e) Feature 47; (f) Feature 38

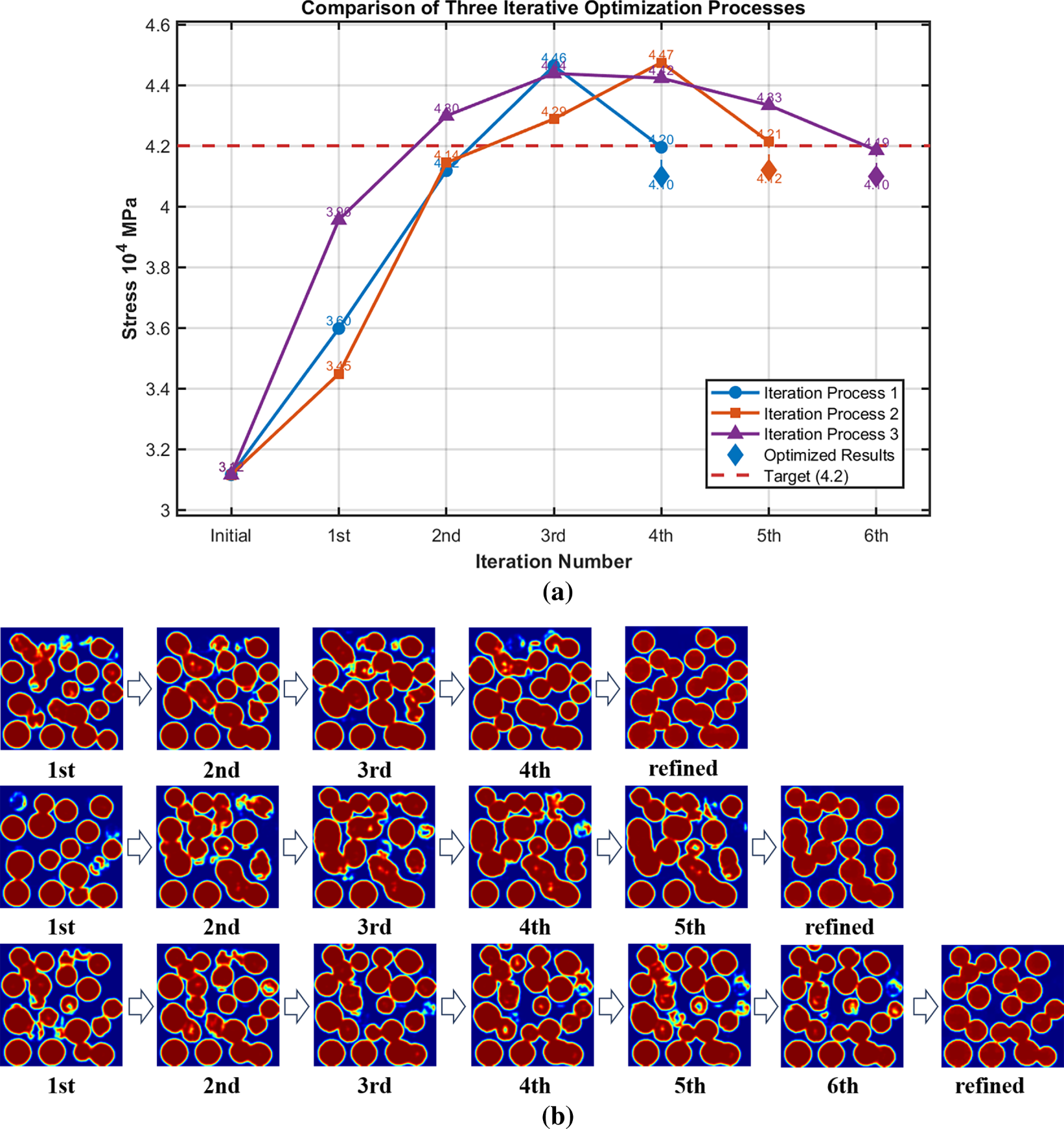

Subsequently, Bayesian optimization was performed within the 16-dimensional subspace to identify latent vectors corresponding to a target homogenized stress of

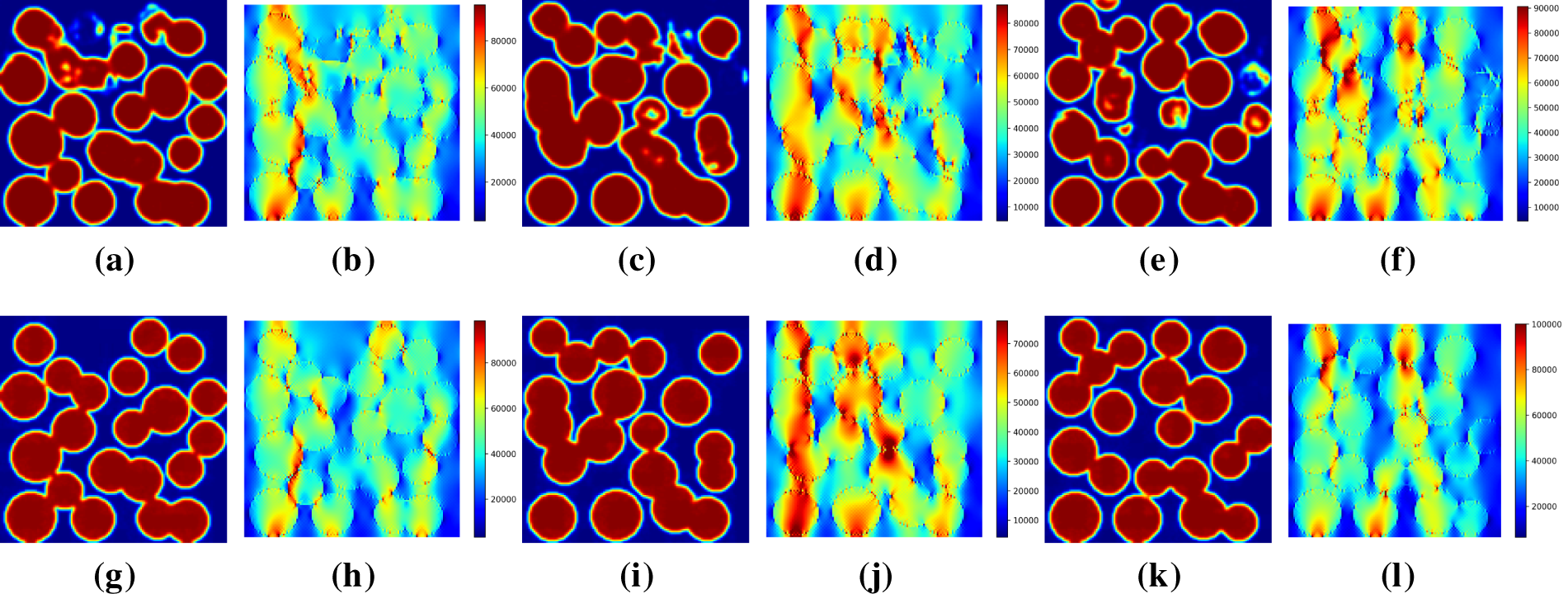

Figure 12: Bayesian optimization iteration process (a) Homogenized stress changes during the iteration process; (b) Microstructure changes during the iterative process

Figure 13: Bayesian optimization results: (a,c,e) VAE decoded microstructure; (b,d,f) FEM verification of VAE; (g,i,k) VAE-CDGM decoded microstructure; (h,j,l) FEM verification of VAE-CDGM

4.3 Bayesian Optimization under 16 Dimensional Latent Space

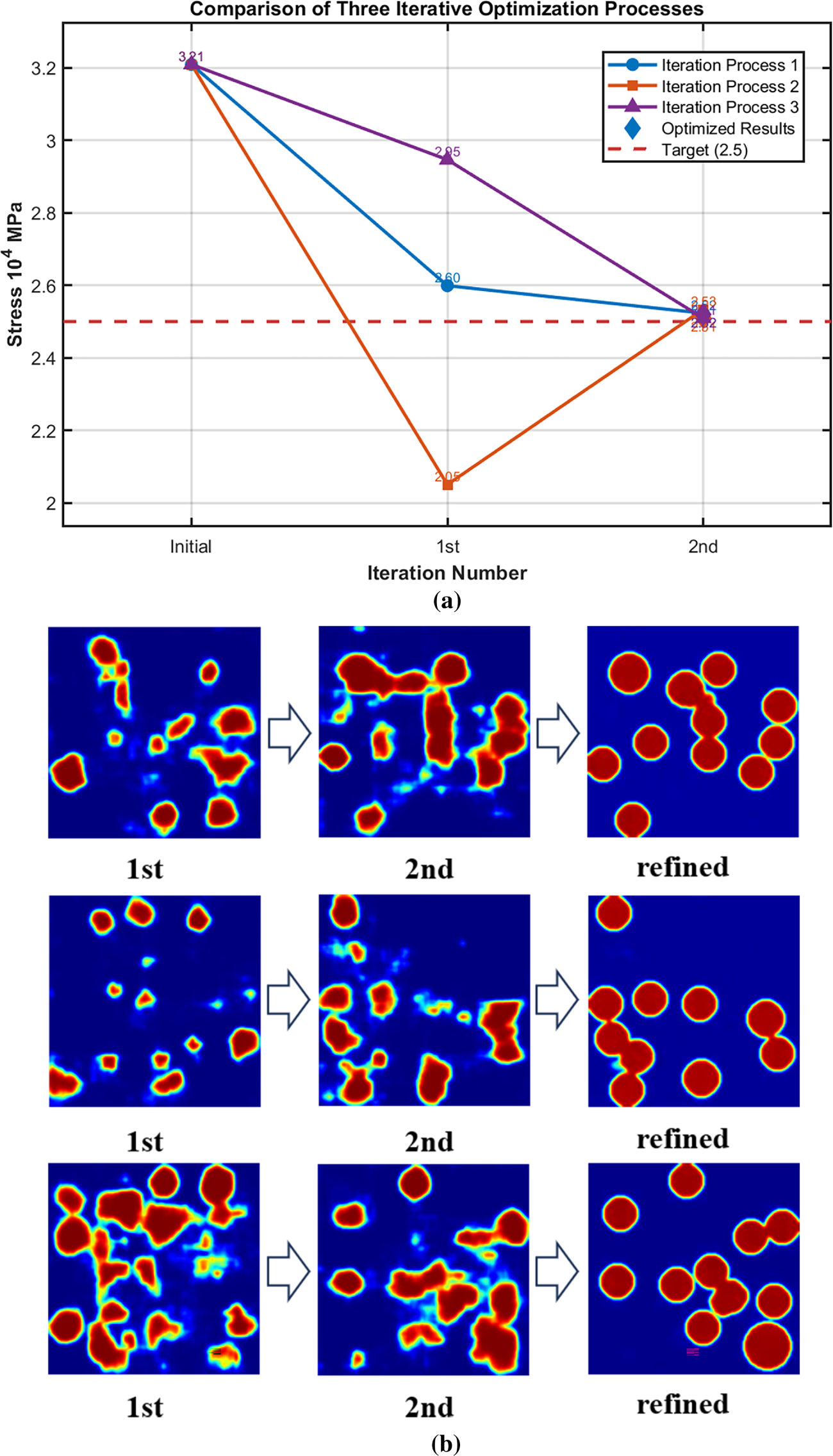

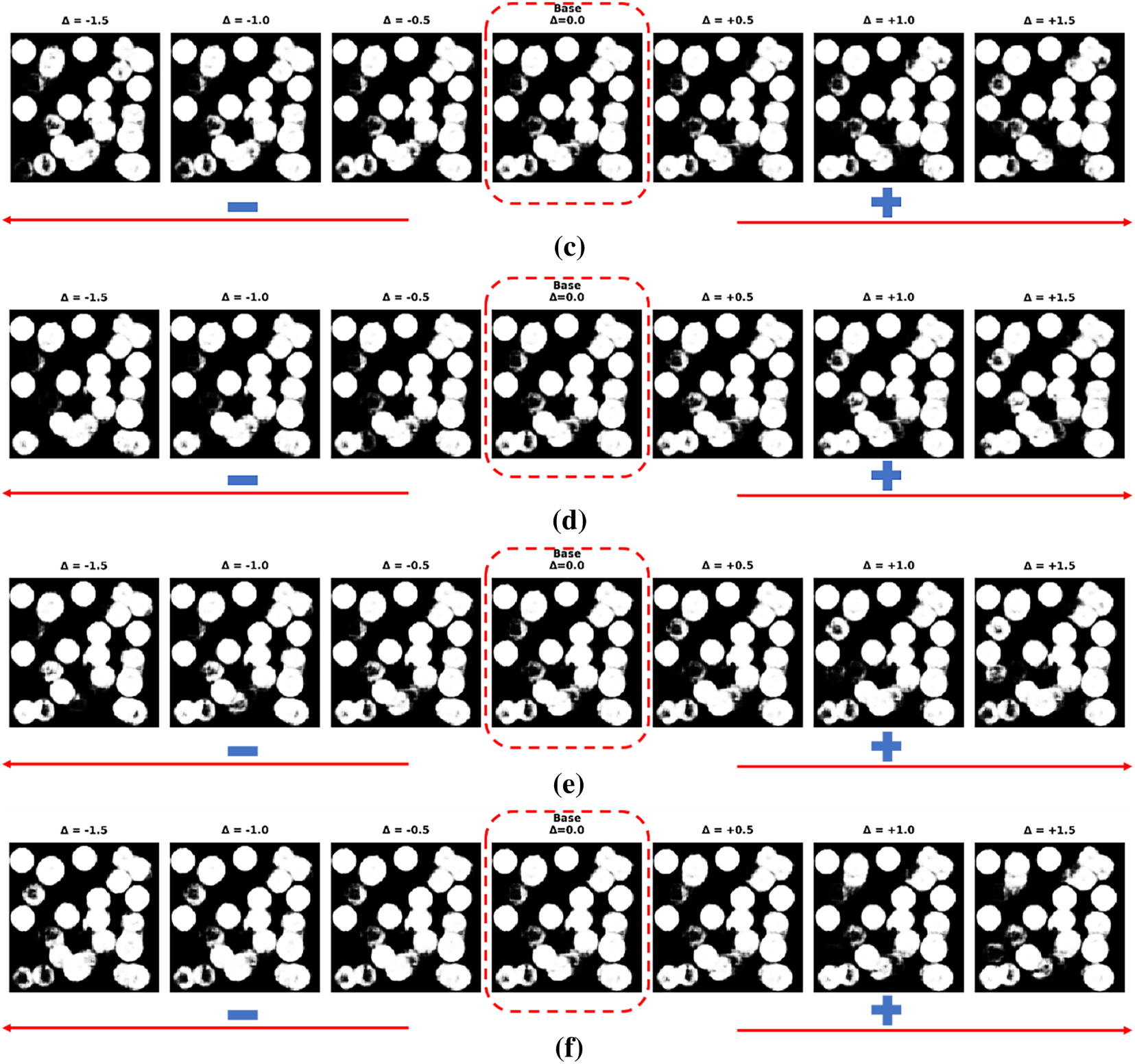

A 16-dimensional latent space is preferentially selected when computational efficiency and rapid optimization are prioritized, or when prior analyses demonstrate that a compact representation adequately captures the key microstructural features and statistical information. This latent space is derived from the VAE-CDGM model, where prior PCA visualization reveals a structured distribution characterized by distinct clusters of homogenized stress values along smooth gradients. This organized topology, coupled with the VAE-CDGM model’s capacity to generate high-fidelity microstructure images supports direct optimization without necessitating additional dimensionality reduction. A Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model was initialized using a random sample of latent vectors from the 16-dimensional space, with the EI acquisition function guiding the search process. The EI function strategically balances exploration of regions with high predictive uncertainty and exploitation of areas with superior predicted performance, iteratively optimizing the latent vectors to achieve the target homogenized stress of

As illustrated in Fig. 14, Bayesian optimization achieved convergence to the target performance after merely 2 iterations, requiring only 10 finite element evaluations, demonstrating remarkable efficiency in the optimization process. The optimized 16-dimensional latent vector was subsequently decoded into realistic microstructure images using both the VAE and VAE-CDGM models, with the results presented in Fig. 15. The VAE-decoded images, constrained by significant information loss inherent to the 16-dimensional representation, exhibited blurred features with indistinct circular inclusions, limiting their fidelity to the target microstructure. In contrast, the VAE-CDGM-decoded images displayed enhanced clarity and detailed characteristics, including well-defined circular inclusions, reflecting its superior generative capacity. FEA quantification of mechanical performance yielded homogenized stress of

Figure 14: Bayesian optimization iteration process (a) Homogenized stress changes during the iteration process; (b) Microstructure changes during the iterative process

Figure 15: Bayesian optimization results: (a,c,e) VAE decoded microstructure; (b,d,f) FEM verification of VAE; (g,i,k) VAE-CDGM decoded microstructure; (h,j,l) FEM verification of VAE-CDGM

This study proposes a inverse design framework for composite materials that integrates the VAE-CDGM with Bayesian optimization. The VAE-CDGM model addresses the blurriness of VAE reconstructions while providing a continuous and differentiable latent space. Bayesian optimization, leveraging a probabilistic surrogate model and acquisition function, achieves convergence to target performance with minimal finite element evaluations. To accommodate varying dimensional requirements of the latent space, two distinct optimization strategies are introduced. For high-dimensional latent spaces, a fully connected neural network was developed to model the relationship between input features and target properties. Subsequently, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis was employed to quantify the contribution of individual input features to the model’s predictions, identifying key factors influencing target performance, and Bayesian optimization was performed within the subspace defined by these critical features. For low-dimensional latent spaces, optimization was conducted directly within the design space provided by VAE-CDGM. In the case study targeting the mechanical property of composite materials, convergence to the target performance was achieved with only 2–6 iterations, corresponding to 10–30 finite element analyses, respectively. Notably, microstructures decoded by VAE-CDGM exhibited superior clarity and fidelity compared to those from VAE. Collectively, this inverse design framework achieves both high efficiency and precise microstructure reconstruction, offering an innovative and viable pathway for the inverse design of advanced materials.

It is noteworthy that in this study, while VAE-CDGM refines the blurred images generated by the VAE, it also tends to mitigate stress concentrations induced by fine inclusions present in the VAE-generated blurry images. As a result, the homogenized stress of the microstructures refined by VAE-CDGM may be slightly lower than the target stress. Although this outcome is both predictable and acceptable, future work could explore performing VAE-CDGM refinement on the decoded VAE images at each iteration to address this discrepancy. Meanwhile, while the selection of key latent dimensions through SHAP analysis enables effective integration with Bayesian optimization, it does entail a partial loss of the full latent space’s representational capacity for microstructures. Future work will explore hierarchical optimization strategies, commencing with preliminary exploration in low-dimensional spaces before progressively expanding to refined searches in higher dimensions. Additionally, the integration of Bayesian optimization with diffusion models within the latent space represents a promising direction for future research.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The financial support provided by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52478198) and Shanghai Municipal Commission of Science and Technology (Grant No. 24510711500) is greatly appreciated.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, methodology and writing—original draft preparation: Xianrui Lyu; supervision, funding acquisition and writing—review and editing: Xiaodan Ren. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A

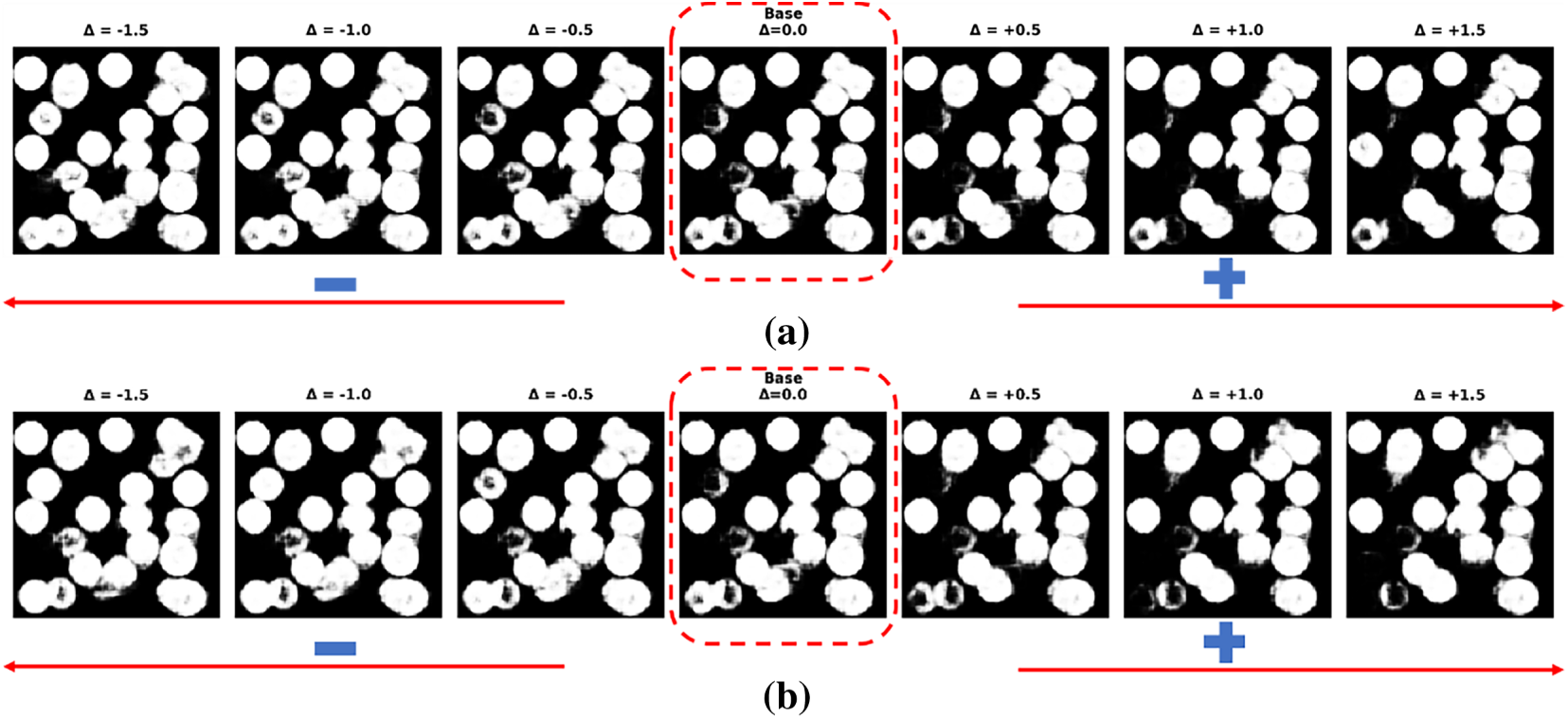

To elucidate the physical significance of the SHAP-identified latent features, we conducted a systematic sensitivity analysis by perturbing individual dimensions while holding others constant. The procedure was as follows: a baseline latent vector was first randomly sampled from the latent space to serve as the origin. For each of the 16 SHAP-ranked dimensions, we generated a sequence of seven latent vectors by varying the target coordinate in increments of 0.5, spanning the range

The results demonstrate a remarkable consistency with the SHAP-based sensitivity analysis. As illustrated in Fig. A1a, an increase in the value of Feature 34 leads to a pronounced reduction in the volume fraction of circular inclusions, which also become more sparsely distributed. Conversely, a decrease in Feature 34 results in a substantial increase in inclusion volume fraction. It is worth noting that while variations in Feature 34 also induce other microstructural changes (e.g., inclusion arrangement), the alteration in volume fraction is the most visually salient effect. This visualization directly validates the negative correlation between Feature 34 identified by the SHAP analysis and homogenized stress.

Figure A1: Microstructural evolution induced by variations in latent features identified through SHAP analysis (a) Effect of Features 34 variation on microstructure; (b) Effect of Features 151 variation on microstructure; (c) Effect of Features 7 variation on microstructure; (d) Effect of Features 213 variation on microstructure; (e) Effect of Features 47 variation on microstructure; (f) Effect of Features 38 variation on microstructure

Similarly, as shown in Fig. A1d, an increase in Feature 213 leads to a marked increase in the volume fraction of inclusions, which aligns perfectly with the positive correlation identified by the SHAP analysis. These findings confirm that the latent representations learned by the VAE encapsulate physically interpretable microstructural characteristics, and that the SHAP-identified dimensions correspond to meaningful geometric controls. The strong agreement between the perturbation-based visualizations and the SHAP dependency plots validates the reliability of the interpretability framework and underscores the utility of the latent space for guiding microstructure-sensitive design.

References

1. Barile C, Casavola C, De Cillis F. Mechanical comparison of new composite materials for aerospace applications. Compos Part B Eng. 2019;162:122–8. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.10.101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Cheng P, Peng Y, Li S, Rao Y, Le Duigou A, Wang K, et al. 3D printed continuous fiber reinforced composite lightweight structures: a review and outlook. Compos Part B Eng. 2023;250:110450. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.110450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Jiao JK, Cheng XY, Wang JL, Sheng LY, Zhang YM, Xu JH, et al. A review of research progress on machining carbon fiber-reinforced composites with lasers. Micromachines. 2023;14(1):24. doi:10.3390/mi14010024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Li J, Durandet Y, Huang X, Sun G, Ruan D. Additively manufactured fiber-reinforced composites: a review of mechanical behavior and opportunities. J Mater Sci Technol. 2022;119:219–44. doi:10.1016/j.jmst.2021.11.063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Brockenbrough JR, Suresh S, Wienecke HA. Deformation of metal-matrix composites with continuous fibers: geometrical effects of fiber distribution and shape. Acta Metall Mater. 1991;39(5):735–52. doi:10.1016/0956-7151(91)90274-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Christman T, Needleman A, Suresh S. An experimental and numerical study of deformation in metal-ceramic composites. Acta Metall. 1989;37(11):3029–50. doi:10.1016/0001-6160(89)90339-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Mishnaevsky JL. Computational mesomechanics of composites. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

8. Liu C, Zhang X, Liu X, Yang Q. Mechanical field guiding structure design strategy for meta-fiber reinforced hydrogel composites by deep learning. Adv Sci. 2024;11(22):2310141. doi:10.1002/advs.202310141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Bostanabad R, Zhang Y, Li X, Kearney T, Brinson LC, Apley DW, et al. Computational microstructure characterization and reconstruction: review of the state-of-the-art techniques. Prog Mater Sci. 2018;95(4):1–41. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2018.01.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Torquato SA, Haslach JHW. Random heterogeneous materials: microstructure and macroscopic properties. Appl Mech Rev. 2002;55(4):B62–3. doi:10.1115/1.1483342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kenney B, Valdmanis M, Baker C, Pharoah JG, Karan K. Computation of TPB length, surface area and pore size from numerical reconstruction of composite solid oxide fuel cell electrodes. J Power Sources. 2009;189(2):1051–9. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2008.12.145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Pattan PC, Mytri V, Hiremath P. Classification of cast iron based on graphite grain morphology using neural network approach. In: SPIE—the international society for optical engineering. Washington, DC, USA: SPIE; 2010. 75462S p. [Google Scholar]

13. Tewari A, Gokhale AM. Nearest-neighbor distances between particles of finite size in three-dimensional uniform random microstructures. Mater Sci Eng A. 2004;385(1–2):332–41. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2004.06.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Xu H, Li Y, Brinson C, Chen W. A descriptor-based design methodology for developing heterogeneous microstructural materials system. J Mech Des. 2014;136(5):051007. doi:10.1115/1.4026649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Goodfellow IJ, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial networks. arXiv:1406.2661. 2014. [Google Scholar]

16. Kingma DP, Welling M. Auto-encoding variational bayes. arXiv:1312.6114. 2013. [Google Scholar]

17. Cang R, Li H, Yao H, Jiao Y, Ren Y. Improving direct physical properties prediction of heterogeneous materials from imaging data via convolutional neural network and a morphology-aware generative model. Comput Mater Sci. 2018;150(1):212–21. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2018.03.074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sardeshmukh A, Reddy S, Gautham B, Bhattacharyya P. Material microstructure design using VAE-regression with multimodal prior. arXiv:2402.17806. 2024. [Google Scholar]

19. Zhang Y, Seibert P, Otto A, Raßloff A, Ambati M, Kästner M. DA-VEGAN: differentiably augmenting VAE-GAN for microstructure reconstruction from extremely small data sets. Comput Mater Sci. 2024;232(1):112661. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2023.112661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang L, Chan YC, Ahmed F, Liu Z, Zhu P, Chen W. Deep generative modeling for mechanistic-based learning and design of metamaterial systems. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2020;372:113377. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2020.113377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Lew AJ, Buehler MJ. Encoding and exploring latent design space of optimal material structures via a VAE-LSTM model. Forces Mech. 2021;5:100054. doi:10.1016/j.finmec.2021.100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kusampudi N, Diehl M. Inverse design of dual-phase steel microstructures using generative machine learning model and Bayesian optimization. Int J Plast. 2023;171:103776. doi:10.1016/j.ijplas.2023.103776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Xue T, Wallin TJ, Menguc Y, Adriaenssens S, Chiaramonte M. Machine learning generative models for automatic design of multi-material 3D printed composite solids. Extrem Mech Lett. 2020;41:100992. doi:10.1016/j.eml.2020.100992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sun H, Wang X, Li J, Li Z, Guan Z. Efficient property-oriented design of composite layups via controllable latent features using generative VAE. Compos Sci Technol. 2025;259:110936. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2024.110936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Park SM, Yoon HG, Lee DB, Choi JW, Kwon HY, Won C. Optimization of physical quantities in the autoencoder latent space. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):9003. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-13007-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Prince SJD. Understanding deep learning. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2023. [Google Scholar]

27. Peng B, Wei Y, Qin Y, Dai J, Li Y, Liu A, et al. Machine learning-enabled constrained multi-objective design of architected materials. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):6630. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-42415-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Lyu X, Ren X. Variational autoencoder guided conditional diffusion generative model for material microstructure reconstruction and inverse design. Mater Today Commun. 2025;48(1):113087. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2025.113087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Michelucci U. An introduction to autoencoders. arXiv:2201.03898. 2022. [Google Scholar]

30. Sohl-Dickstein J, Weiss EA, Maheswaranathan N, Ganguli S. Deep unsupervised learning using nonequilibrium thermodynamics. arXiv:1503.03585. 2015. [Google Scholar]

31. Ho J, Jain A, Abbeel P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. arXiv:2006.11239. 2020. [Google Scholar]

32. Düreth C, Seibert P, Rücker D, Handford S, Kästner M, Gude M. Conditional diffusion-based microstructure reconstruction. Mater Today Commun. 2023;35:105608. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.105608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Lyu X, Ren X. Microstructure reconstruction of 2D/3D random materials via diffusion-based deep generative models. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):5041. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-54861-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Vlassis NN, Sun W. Denoising diffusion algorithm for inverse design of microstructures with fine-tuned nonlinear material properties. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2023;413(1):116126. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2023.116126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Pandey K, Mukherjee A, Rai P, Kumar A. DiffuseVAE: efficient, controllable and high-fidelity generation from low-dimensional latents. arXiv:2201.00308. 2022. [Google Scholar]

36. Honarmandi P, Attari V, Arroyave R. Accelerated materials design using batch Bayesian optimization: a case study for solving the inverse problem from materials microstructure to process specification. Comput Mater Sci. 2022;210(1):111417. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2022.111417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Matsuda Y, Ookawara S, Yasuda T, Yoshikawa S, Matsumoto H. Framework for discovering porous materials: structural hybridization and Bayesian optimization of conditional generative adversarial network. Digit Chem Eng. 2022;5:100058. doi:10.1016/j.dche.2022.100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Shahriari B, Swersky K, Wang Z, Adams RP, de Freitas N. Taking the human out of the loop: a review of bayesian optimization. Proc IEEE. 2016;104(1):148–75. doi:10.1109/jproc.2015.2494218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhang W, Tang M, Mu H, Yang X, Zeng X, Tuo R, et al. Inverse design of nonlinear mechanics of bio-inspired materials through interface engineering and Bayesian optimization. Extrem Mech Lett. 2025;78:102359. doi:10.1016/j.eml.2025.102359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhao Y, Altschuh P, Santoki J, Griem L, Tosato G, Selzer M, et al. Characterization of porous membranes using artificial neural networks. Acta Mater. 2023;253:118922. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2023.118922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wang X, Jin Y, Schmitt S, Olhofer M. Recent advances in Bayesian optimization. arXiv:2206.03301. 2022. [Google Scholar]

42. Rasmussen CE. Gaussian processes in machine learning. In: Advanced lectures on machine learning. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2003. p. 63–71. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-28650-9_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Močkus J. On Bayesian methods for seeking the extremum. In: IFIP technical conference on optimizationtechniques. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1974. p. 400–4. [Google Scholar]

44. Zhan D, Xing H. Expected improvement for expensive optimization: a review. J Glob Optim. 2020;78(3):507–44. doi:10.1007/s10898-020-00923-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Lundberg S, Lee SI. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. arXiv:1705.07874. 2017. [Google Scholar]

46. Kondo R, Yamakawa S, Masuoka Y, Tajima S, Asahi R. Microstructure recognition using convolutional neural networks for prediction of ionic conductivity in ceramics. Acta Mater. 2017;141:29–38. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2017.09.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Prifling B, Röding M, Townsend P, Neumann M, Schmidt V. Large-scale statistical learning for mass transport prediction in porous materials using 90,000 artificially generated microstructures. Front Mater. 2021;8:786502. doi:10.3389/fmats.2021.786502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Song J, Meng C, Ermon S. Denoising diffusion implicit models. arXiv:2010.02502. 2020. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools