Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Neuro-Symbolic Graph Learning for Causal Inference and Continual Learning in Mental-Health Risk Assessment

1 Department of Computer Science, Fakir Mohan University, Balasore, 756019, Odisha, India

2 Department of Architecture and Architectural Engineering, Yonsei University, Seoul, 03722, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Industrial Security, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, 06974, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Noman Khan. Email: ; Mi Young Lee. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 44 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.075119

Received 25 October 2025; Accepted 19 December 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

Mental-health risk detection seeks early signs of distress from social media posts and clinical transcripts to enable timely intervention before crises. When such risks go undetected, consequences can escalate to self-harm, long-term disability, reduced productivity, and significant societal and economic burden. Despite recent advances, detecting risk from online text remains challenging due to heterogeneous language, evolving semantics, and the sequential emergence of new datasets. Effective solutions must encode clinically meaningful cues, reason about causal relations, and adapt to new domains without forgetting prior knowledge. To address these challenges, this paper presents a Continual Neuro-Symbolic Graph Learning (CNSGL) framework that unifies symbolic reasoning, causal inference, and continual learning within a single architecture. Each post is represented as a symbolic graph linking clinically relevant tags to textual content, enriched with causal edges derived from directional Point-wise Mutual Information (PMI). A two-layer Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) encodes these graphs, and a Transformer-based attention pooler aggregates node embeddings while providing interpretable tag-level importances. Continual adaptation across datasets is achieved through the Multi-Head Freeze (MH-Freeze) strategy, which freezes a shared encoder and incrementally trains lightweight task-specific heads (small classifiers attached to the shared embedding). Experimental evaluations across six diverse mental-health datasets ranging from Reddit discourse to clinical interviews, demonstrate that MH-Freeze consistently outperforms existing continual-learning baselines in both discriminative accuracy and calibration reliability. Across six datasets, MH-Freeze achieves up to 0.925 accuracy and 0.923 F1-Score, with AUPRCKeywords

Mental-health disorders such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation are rising globally, posing serious risks to individuals and society [1,2]. With the growth of online platforms and clinical records, vast amounts of unstructured text now capture personal experiences and distress signals [3,4]. Automatically analyzing this text for early detection of psychological risk has become an urgent research problem. However, it remains highly challenging due to the ambiguity of natural language, and the subtlety of psychological cues [5,6]. Timely detection enables early intervention and targeted allocation of limited mental-health resources, and real-world deployment demands models that are not only accurate but also interpretable and well-calibrated so that clinicians and moderators can act on predictions with confidence [7].

In many real-world scenarios, posts and interviews carry implicit cues (e.g., hopelessness, insomnia, self-harm) that are difficult to capture with surface features alone [8]. Purely neural approaches can learn powerful representations but often lack interpretability and causal grounding; purely symbolic methods offer transparency but struggle with linguistic variability and generalization [9]. Moreover, data arrive over time from different communities and collection protocols, creating domain shift and exposing models to catastrophic forgetting when retrained sequentially [10,11]. These factors emphasize an integrated approach that can (i) structure free text into clinically meaningful graphs, (ii) model directional relations among risk factors, and (iii) learn continually across datasets without erasing earlier competencies. In addition, class imbalance, where rare but critical signals such as suicidal ideation are underrepresented, biases predictions and reduces reliability. Addressing these issues requires models that are both interpretable and adaptable, while retaining stability across evolving datasets.

Continual learning (CL), also referred to as lifelong or incremental learning, aims to enable models to acquire new knowledge over time without forgetting previously learned information [12]. Unlike traditional retraining approaches that require access to all past data, CL supports sequential learning across tasks or domains by reusing shared representations and adapting to new inputs efficiently. This paradigm is particularly valuable in mental-health applications, where new linguistic trends, populations, and annotation protocols continuously emerge. A robust continual learning mechanism ensures that models remain up to date while preserving earlier competencies, enabling sustainable and realistic deployment in evolving digital health environments.

To address these challenges, a Continual Neuro-Symbolic Graph Learning (CNSGL) framework is proposed in this work for causal inference and continual learning in mental-health risk assessment. CNSGL represents each post as a symbolic graph in which a post node connects to tag nodes derived from a risk lexicon. Beyond simple co-occurrence, graphs are enriched with directional edges using a variant of point-wise mutual information to reflect likely precursors and consequents among risk factors. A two-layer Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) propagates information over this structure, and a lightweight Transformer attention pooler, anchored by a learnable [CLS] token, aggregates node embeddings while producing tag-level importances for interpretability.

To enable continual adaptation, the proposed framework employs a Multi-Head Freeze (MH-Freeze) strategy that freezes the shared encoder after the first dataset and incrementally attaches lightweight task-specific heads for subsequent datasets. Here, “task-specific head” refers to a small linear-sigmoid classifier attached to the shared embedding for each dataset. This form is adopted to enable lightweight adaptation on a fixed embedding space: the frozen GCN-Transformer encoder produces a stable representation, and the head maps it directly to a calibrated probability via binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss. This keeps updates simple and efficient, reduces the risk of cross-task gradient interference, and preserves calibration. In contrast, deeper or non-linear heads introduce extra trainable layers that can overfit to a single dataset and reintroduce interference with previously learned tasks. Each dataset is treated as a separate task (T1-T6), allowing systematic evaluation of domain transfer and retention. Our evaluation further incorporates both discrimination and calibration metrics (AUROC, AUPRC, Brier score, and Expected Calibration Error) to quantify predictive reliability under domain shift and sequential learning conditions.

In mental health risk assessment and monitoring, systems are deployed in dynamic and evolving scenarios. In many real world scenarios, diverse signals (clinical notes, social media text, speech, and wearable biosignals) are used to detect risk states such as depression, anxiety, self-harm intent, and acute stress. However, most pipelines are trained on static datasets with fixed labels and vocabularies. When new expressions, populations, or risk patterns appear, performance is often degraded. In practice, full retraining on new data is often required, while incremental updates risk catastrophic forgetting that overwrites previously learned knowledge [13]. Therefore, continual learning is increasingly regarded as important for mental health tasks. Rather than retraining from scratch, new risk categories or domains can be incorporated as they arise while preserving recognition of earlier ones [14].

Despite rapid progress, Several unresolved challenges continue to hinder dependable mental-health risk detection from text:

• Missing causal structure: Most models treat symptoms as flat labels; they do not encode directed tag

• Limited interpretability: Explanations are often post-hoc for text tokens, not concept-level (symbolic tags) nor pathway-level (causal paths).

• Catastrophic forgetting: Models struggle to retain prior knowledge as new datasets arrive, while simple, deployable continual-learning solutions are still lacking.

• Opaque pooling: Mean/max pooling blurs which symbolic tags matter per post; attention over concept nodes is rarely leveraged.

In light of the above, we propose a continual neuro-symbolic framework that builds per-post symbolic tag graphs with directed links, encodes them via a two-layer GCN, and uses a lightweight attention head to form calibrated, interpretable post representations. For sequential datasets, we adopt a frozen-encoder, multi-head protocol to prevent forgetting while keeping adaptation lightweight. The key contributions of this work are summarized below:

• A neuro-symbolic graph learning framework is proposed that combines symbolic reasoning, causal inference, graph-based neural encoding, and continual learning for mental-health risk assessment.

• Symbolic graphs are constructed from text using risk-related tags, ensuring interpretability by grounding predictions in clinically meaningful indicators.

• A causal-aware enrichment mechanism introduces directed tag–tag edges, capturing potential causal influences among symptoms rather than simple co-occurrence.

• A graph convolutional encoder is employed to propagate symbolic and causal features, followed by a lightweight Transformer-based attention head weights the post–tag embeddings and a classifier that outputs binary risk predictions through probability estimation and thresholding.

• A continual learning strategy (multi-head frozen-encoder) is implemented to preserve knowledge across datasets while enabling adaptation to new domains, mitigating catastrophic forgetting.

• Extensive experiments are conducted on multiple datasets, and results are compared against strong continual learning baselines, demonstrating improved robustness, interpretability, and adaptability.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents an extensive survey of related research and methods relevant to this work, Section 3 presents the proposed CNSGL framework, including symbolic graph construction, causal enrichment, the GCN–Transformer encoder, and the MH-Freeze continual-learning strategy. Section 4 describes the experimental details, and evaluation metrics. Section 5 presents the ablation study analyzing the contribution of each component. Section 6 concludes the paper and highlights future directions.

Detecting mental-health risk from text is a challenging and active area with direct applications to screening, risk stratification, and clinical decision support. This section reviews related research across the categories listed in the subsections, aligning each category of methods pertinent to this work.

2.1 Mental-Health Risk Detection from Text

This subsection reviews key efforts on detecting mental-health signals from social-media text, ranging from traditional machine learning (ML) to deep learning (DL). Hemmatirad et al. [15] showed that lexicon and handcrafted features paired with support vector machine or logistic regression classifiers can distinguish high-risk users using linguistic and emotional cues. With the advent of contextual embeddings, hybrid models such as BERT+BiLSTM have been proposed by Zhou and Mohd [16] to better handle informal language, emojis, and sequential patterns in depression-related posts.

Prior surveys consolidate the literature and shed light on persistent challenges. Garg [17] reviewed 92 studies, introduced an updatable suicide-detection repository, and emphasized the need for real-time, responsible AI. Skaik and Inkpen [18] surveyed NLP/ML approaches for public mental-health surveillance, summarizing data collection strategies, modeling tools, and remaining gaps. Other studies explore emotion-aware and efficiency-focused systems. Benrouba and Boudour [19] proposed an emotion-aware content-filtering framework that classifies posts into basic emotions and compares them with an “ideal” lexicon to flag potentially harmful content. Ding et al. [20] compared ML models (logistic regression, random forest, LightGBM) with DL models (ALBERT, GRU) for binary and multi-class mental-health classification, finding that ML methods offer better interpretability and efficiency on medium-sized datasets, whereas DL models better capture complex linguistic patterns.

Causal reasoning in language means modeling directional influence (

Zhang et al. [22] proposed a causal framework based on a counterfactual neural temporal point process (TPP) to estimate the individual treatment effect (ITE) of misinformation on user beliefs and actions at scale, using a neural TPP with Gaussian mixtures for efficient inference. Experiments on synthetic data and a real COVID-19 vaccine dataset showed identifiable causal effects of misinformation, including negative shifts in users’ vaccine-related sentiments. Cheng et al. [23] surveyed Event Causality Identification (ECI) and proposed a systematic taxonomy split into sentence-level ECI (SECI) and document-level ECI (DECI) tasks, reviewing approaches from feature/ML methods to deep semantic encoding, event-graph reasoning, and prompt/causal-knowledge pretraining, with notes on multilingual, cross-lingual, and zero-shot large language model settings.

2.3 Neural Encoders: Graph + Attention

GCN encoders capture relational structure for text via message passing on graphs, benefiting settings with explicit concept relations [24]. Hamilton et al. [25] proposed GraphSAGE, an inductive framework that extended GCNs to unsupervised learning and introduced trainable aggregation functions beyond simple convolutions. The method generated embeddings for unseen nodes by sampling and aggregating neighborhood features, leveraging node attributes for generalization. Yao et al. [26] introduced Text GCN, which built a corpus-level graph from word co-occurrence and document-word relations to jointly learn word and document embeddings. Without relying on external embeddings, Text GCN outperformed state-of-the-art methods on multiple benchmarks and showed strong robustness with limited training data.

Transformers, driven by self-attention, excel at weighting inputs and can be used as interpretable pooling over concept embeddings [27]. Vaswani et al. [28] proposed the Transformer, a sequence transduction architecture based solely on attention mechanisms, removing recurrence and convolutions. The model achieved state-of-the-art results on Workshop on Machine Translation 2014 English to German and English to French translation tasks, while being more parallelizable and significantly faster to train than prior approaches.

Devlin et al. [29] introduced Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT), a bidirectional Transformer-based model pre-trained on unlabeled text by jointly conditioning on left and right context. With simple fine-tuning, BERT achieved state-of-the-art results on eleven NLP tasks. Yang et al. [30] proposed a hierarchical attention network (HAN) for document classification, which reflected the hierarchical structure of documents and applied attention at both word and sentence levels. The model outperformed prior methods on six large-scale benchmarks and provided interpretable document representations by highlighting informative words and sentences.

2.4 Continual Learning for Mental Health

Continual learning addresses time-varying, patient-specific data in mental-health scenarios by incrementally updating models from electronic health records, speech/text, and wearable streams while preserving prior knowledge. Although the CL for mental health literature remains limited, we highlight a few representative systems that show feasibility under practical constraints. Gamel and Talaat [31] proposed SleepSmart, an Internet of Things (IoT) enabled continual learning framework for intelligent sleep enhancement. The system employed wearable biosensors to capture physiological signals during sleep, which were processed via an IoT platform to deliver personalized recommendations. By leveraging continual learning, SleepSmart improved recommendation accuracy over time, and a pilot study demonstrated its effectiveness in enhancing sleep quality and reducing disturbances.

Lee and Lee [32] explored the role of continual learning in medicine, where models adapt to new patient data without forgetting prior knowledge. They emphasized challenges such as catastrophic forgetting and regulatory constraints, but argued that continual learning offers advantages over non-adaptive Food and Drug Administration approved systems by incrementally improving diagnostic and decision-support performance. Li and Jha [33] proposed DOCTOR, a continual-learning framework for multi-disease detection on wearable medical sensors at the edge. The system used a multi-headed deep neural network with replay-based CL, via exemplar data preservation or synthetic data generation to mitigate catastrophic forgetting while sequentially adding tasks with new classes and distributions. In experiments, a single model maintained high accuracy, yielding up to 43% higher test accuracy, 25% higher F1 score, and 0.41 higher backward transfer over naive fine-tuning.

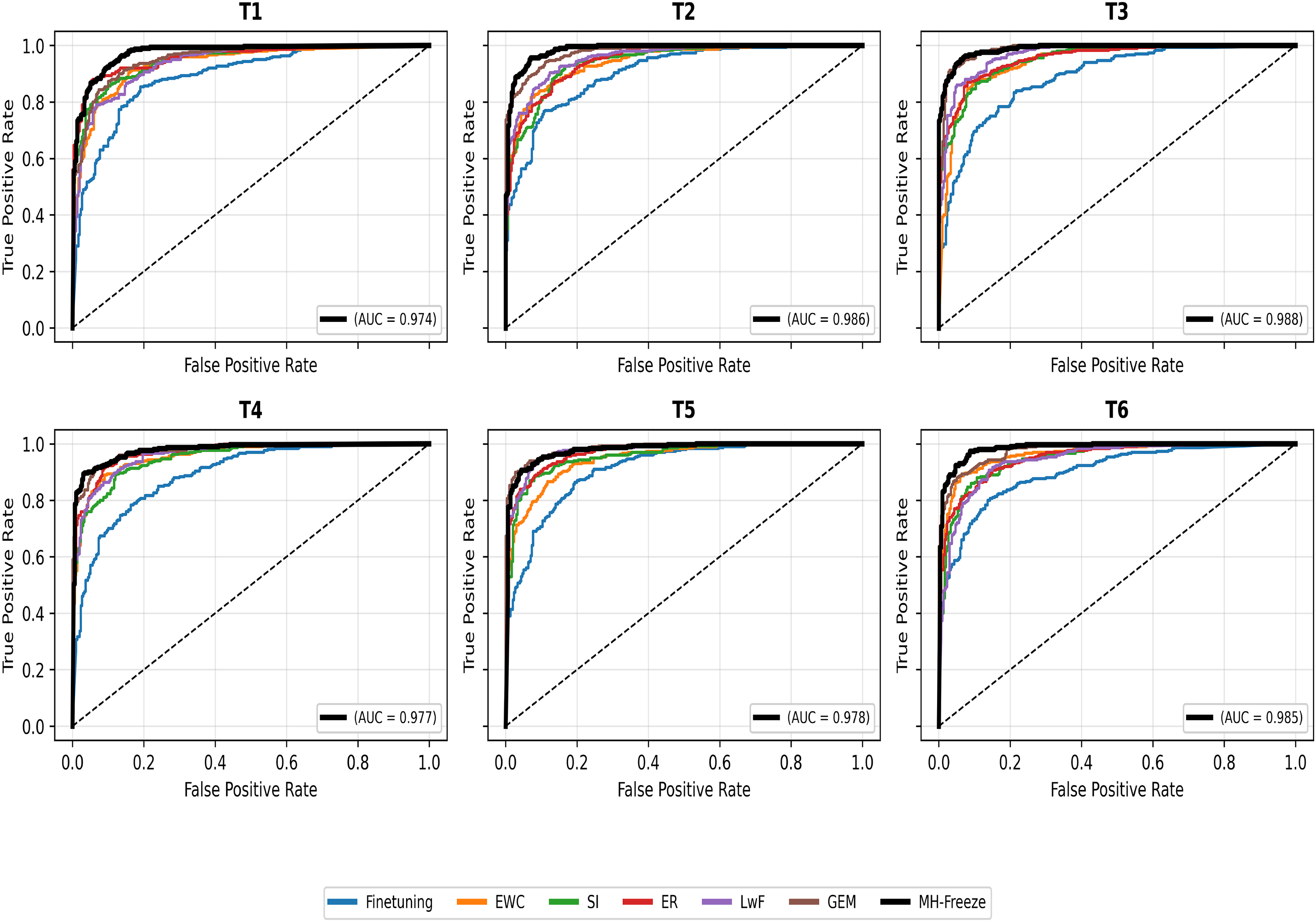

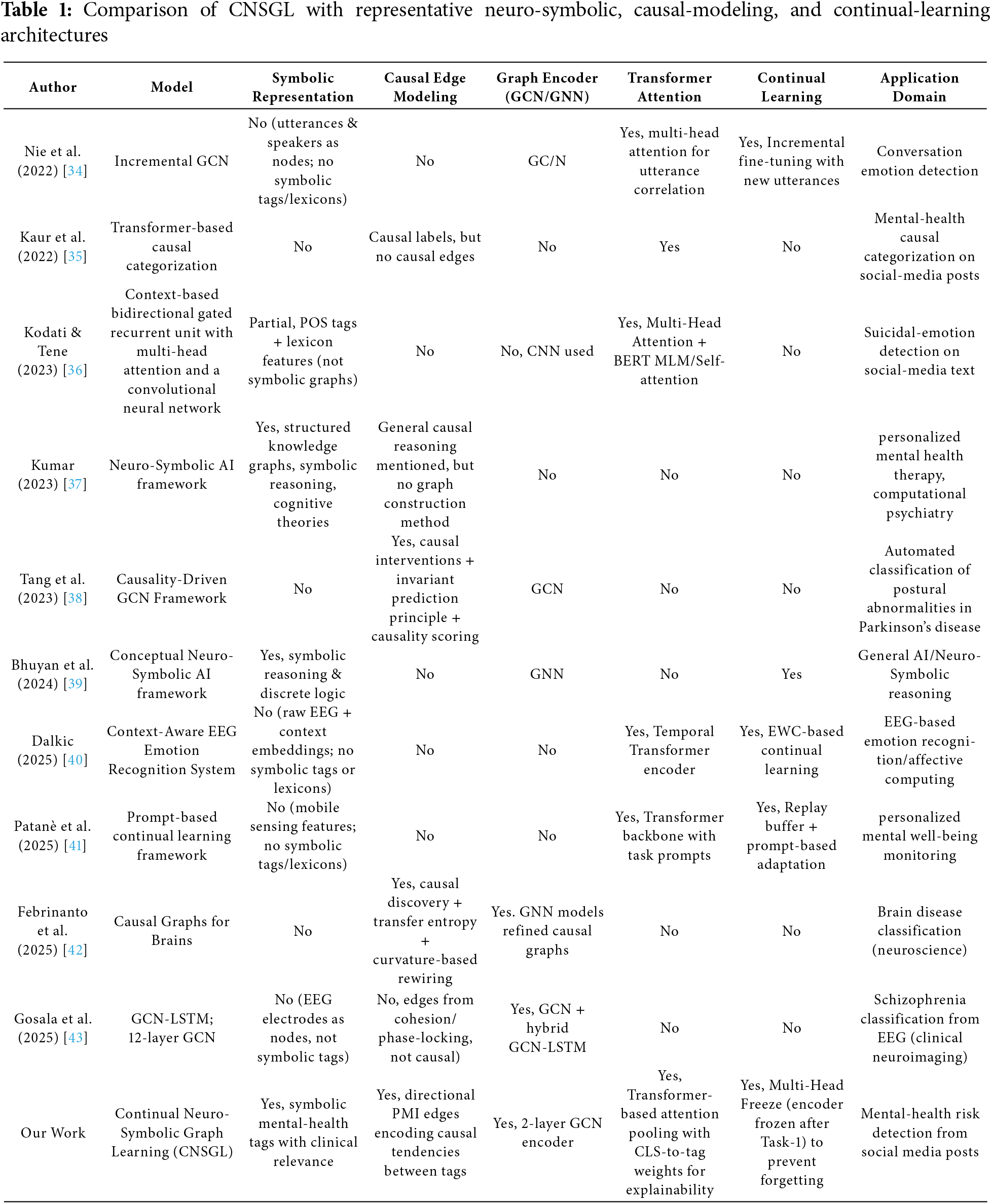

A structured comparison is presented in Table 1 to more clearly contextualize CNSGL within existing work. Prior methods typically incorporate only one or two of the components, symbolic representations, causal edge modeling, graph-based encoders, Transformer attention mechanisms, or continual-learning strategies, rather than unifying all of them within a single framework. As shown in Table 1, approaches that employ symbolic reasoning rarely integrate GNN encoders or explicit causal edge construction; causal GNN models generally do not use symbolic tag vocabularies or Transformer-based pooling; and continual-learning systems commonly operate without symbolic graphs or causal modeling. In contrast, CNSGL combines directional PMI-derived causal edges, a symbolic tag graph, a two-layer GCN encoder, a Transformer attention pooler, and a multi-head freeze continual-learning strategy within one architecture tailored for mental-health risk detection. This integrated design forms the central novelty of the approach and demonstrates how CNSGL extends beyond existing component-wise methods.

A Continual Neuro-Symbolic Graph Learning (CNSGL) framework is proposed for causal inference and continual learning in mental-health risk assessment. In this framework, symbolic reasoning, causal graph construction, graph neural encoding, and continual learning are combined within a single architecture. The details of the proposed work are presented in the following subsections.

3.1 Symbolic Graph Construction

Mental-health text from online platforms or clinical records is largely unstructured and often contains implicit cues about psychological conditions that are difficult to analyze directly. To impose structure and enhance interpretability, each post is represented as a symbolic graph that captures both semantic content and clinically meaningful indicators. A compact set of ten symbolic tags, sleep, anxiety, depression, stress, anger, lonely, health, fear, coping, and suicidal, was constructed based on well-established constructs in computational mental-health research and their frequent annotation in benchmark datasets. The vocabulary was further validated through manual inspection and an expert-informed review to ensure clinical relevance. A small, consistent set was intentionally maintained to minimize noise and support stable directional PMI estimation during causal graph construction. Let

where each

The symbolic graph is defined as

• Nodes:

• Edges:

• Features: Node attributes encode symbolic and semantic information. Tag node features use Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) scores [44] of the tag

while the post node

At this stage,

3.2 Causal-Aware Graph Enrichment

Edges based solely on co-occurrence capture statistical associations but cannot distinguish whether one factor precedes or influences another. For example, sleep deprivation may frequently appear with stress, yet in many cases it precedes and contributes to suicidal ideation. To incorporate such directional relationships, graphs are enriched with causal edges in addition to co-occurrence links. To quantify how strongly tags co-occur in the input space, point-wise mutual information (PMI) is used here. Consider the tags sleep and anxiety. These tags may frequently appear together in posts, which would yield a symmetric, undirected edge in a standard co-occurrence graph. Directional PMI instead focuses on ordered pairs and estimates whether one tag is more likely to appear before the other. If ordered counts show that mentions of sleep problems systematically precede anxiety indicators more often than the reverse, then

Probabilities were estimated by counting how often each tag and each tag pair appeared within the same post and then normalizing by the total. A small smoothing constant was applied so that rare tags didn’t get zero probability. Because PMI treats a pair the same in either order, it captures association only and does not encode direction. Let

where,

A directed edge,

where

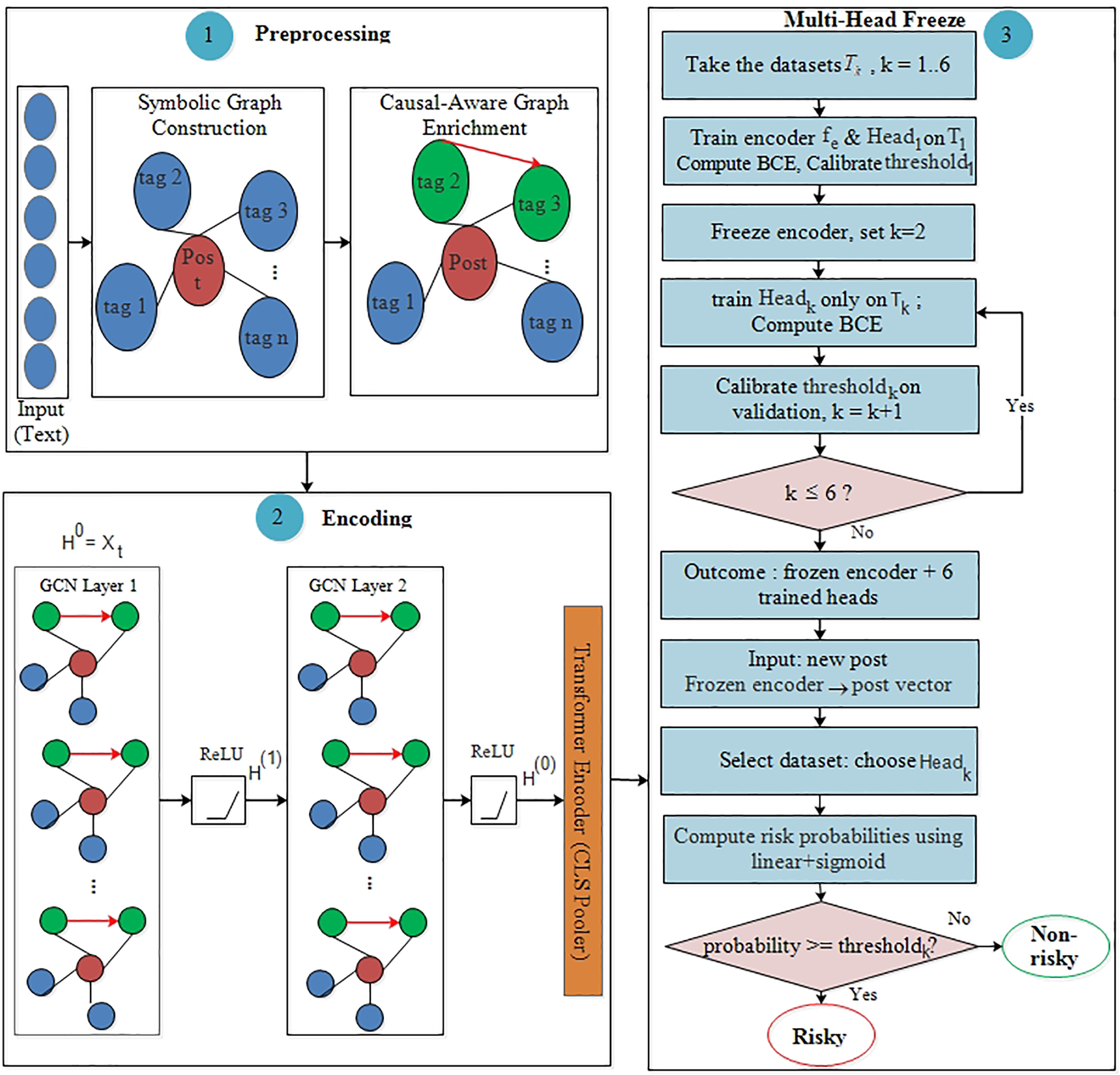

The proposed CNSGL framework is depicted as an end-to-end architecture in Fig. 1, emphasizing the left-to-right progression from symbolic/causal structuring to representation learning and, then to sequential adaptation. The diagram marks where the shared encoder is frozen and where dataset-specific heads are attached, making clear how prior knowledge is preserved while new tasks are added. The Transformer Encoder used for graph-level pooling in the encoding stage is described separately in Fig. 2.

Figure 1: Proposed CNSGL framework consisting of three key components: (1) Preprocessing, where a post-tag graph is built and enriched with directional causal edges (red), and causal tag nodes (green). (2) Encoding, consisting of two-layer GCN followed by a light-weight Transformer [CLS] pooler, produces a post vector and tag importances.(3) Continual learning (MH-Freeze): the encoder and

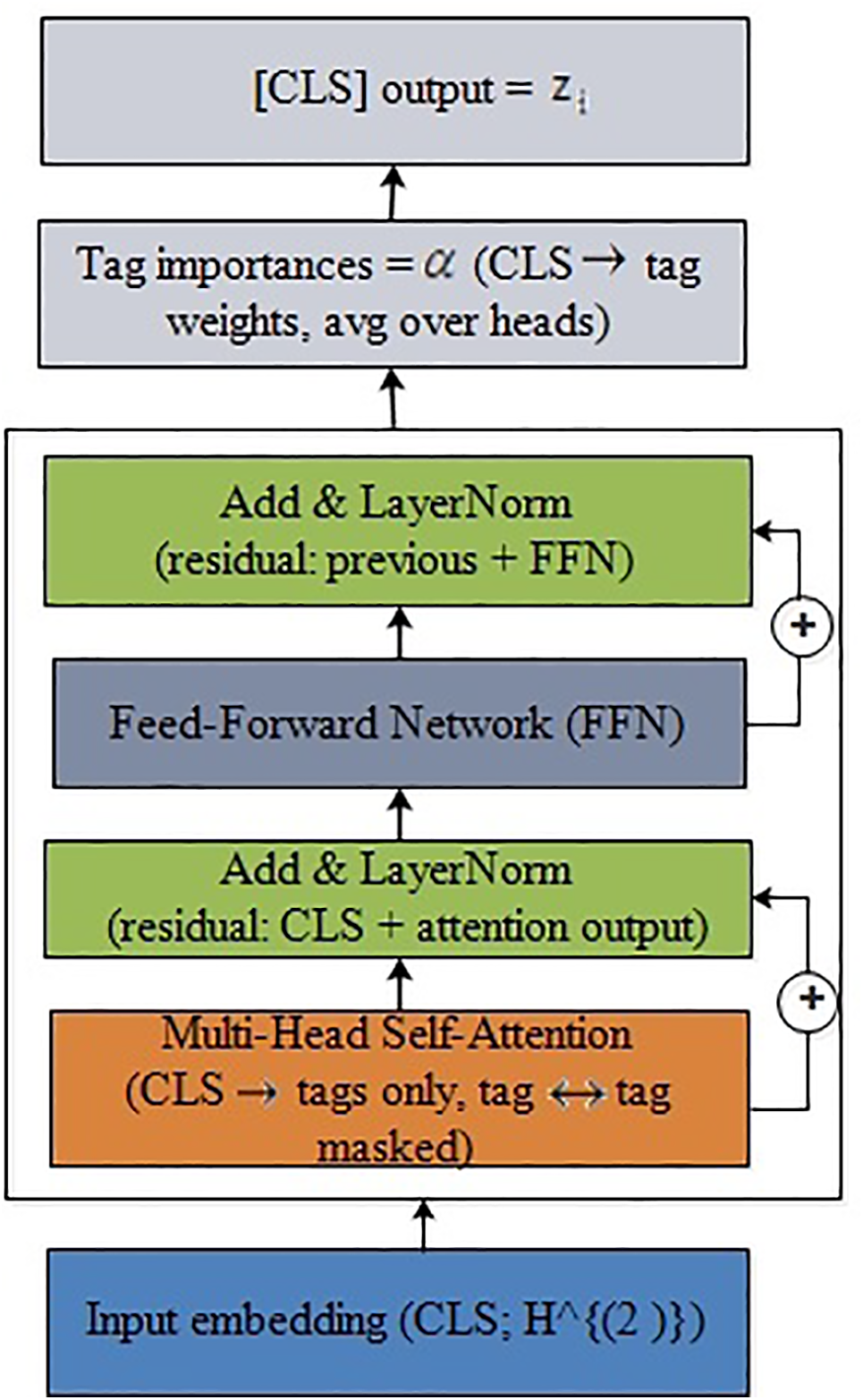

Figure 2: Architecture of the encoder-only Transformer used as an attention pooler. The CLS token and tag embeddings are fed into a single Transformer block, where multi-head attention computes CLS

The symbolic graphs enriched with causal relations are processed by a two-layer GCN. The GCN propagates information across connected nodes so that each representation reflects both its own features and those of neighboring nodes. In this way, a post node aggregates signals from its tags, while tag nodes incorporate both symbolic and causal context. Eq. (3) shows how the node representations are updated at layer

where

Although the final GCN uses a symmetrized adjacency matrix for stable message passing, the causal interpretability of the framework is retained because symmetrization occurs only after causal tendencies have been encoded in the edge-selection stage. Directional PMI determines which tag pairs are connected and the strength of those connections, thereby shaping the underlying causal structure even if the GCN operates on an undirected form of the graph. The interpretability comes from this directed edge construction and from the subsequent analysis of causal paths and attention weights, whereas symmetrization serves primarily as a computational requirement of the canonical GCN rather than a removal of causal information. After two layers, the node embeddings

3.4 Transformer-Based Attention

While mean pooling provides a simple mechanism for aggregating node embeddings into a graph-level representation, it treats all nodes equally and fails to highlight which risk factors are more influential in a particular post. To address this limitation, the node embeddings produced by the GCN are passed through a Transformer encoder to perform attention-based pooling [47]. Fig. 2 illustrates the Transformer encoder block employed as an attention pooler over GCN-derived node embeddings. The [CLS] token attends to tag embeddings to produce a pooled representation while simultaneously providing interpretable tag-level importance scores through attention weights.

Let

where [CLS] is a learnable pooling token. The encoder computes linear projections

with trainable

These are then used to form a weighted sum of the values for [CLS] (computed per head, concatenated, and projected). Each encoder block applies Add&LayerNorm around multi-head attention and a Feed-Forward Network (FFN). The final [CLS] vector is taken as the pooled embedding

The weights

The pooling module is implemented as a single Transformer-style encoder block with multi-head self-attention and a position-wise feed-forward network (FFN). In practice, the CLS attention Pooler uses an embedding dimension of

To illustrate how the Transformer attention pooler provides qualitative interpretability, two example posts are shown below. In each case, the model highlights the most influential tags and their causal relations when producing a risk prediction.

Example 1 (High-risk post): “I have not slept properly for days, and the constant anxiety is making everything feel overwhelming. Lately I keep thinking that things would be easier if I just disappeared.” The attention pooler assigns high importance to the tags sleep, anxiety, and suicidal, with a strong causal pathway sleep

Example 2 (Low-risk post): “Feeling a bit stressed about exams next week, but talking to friends has helped and I’m trying to stay positive.” The model focuses primarily on stress, with low attention weights on other tags and no causal escalation toward depression or suicidal. The attention pattern reflects a non-escalatory emotional state, leading to a low-risk prediction.

3.5 Continual Learning Strategy

In real-world applications, data arrive in stages

where

For dataset

with parameters

MH-Freeze

At first, the shared encoder

The shared encoder

After convergence, the encoder parameters

For each subsequent dataset

As

The experiments were conducted on a high-performance workstation equipped with an AMD Ryzen Threadripper 2950X (16 cores, 3.50 GHz) and 32 GB RAM. The experiments were implemented in Python 3.11 using key libraries such as PyTorch 2.2, PyTorch Geometric 2.5, NumPy, Scikit–learn, and Matplotlib. All codes were executed in a Jupyter Notebook environment configured on Windows 11, ensuring a consistent and reproducible experimental setup.

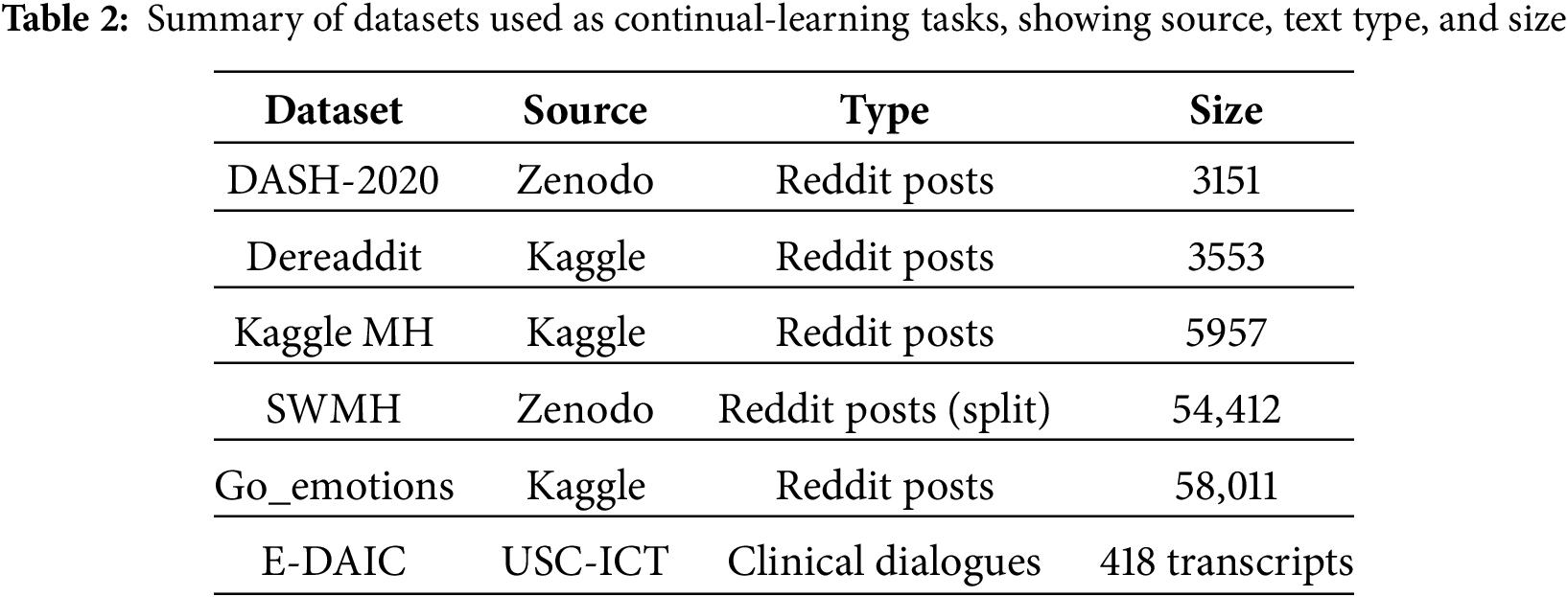

To evaluate the effectiveness and generalizability of the proposed Continual Neuro-Symbolic Graph Learning framework, six diverse datasets were used spanning Reddit-based mental health discourse and clinician-guided interviews. A brief summary is provided in Table 2. These corpora differ in annotation protocols, linguistic style, and risk indicators, enabling a comprehensive assessment of both the symbolic reasoning components and the graph-based learning modules.

• Data Analytics for Smart Health (DASH-2020) [49]: It consists of reddit posts annotated for substance use, addiction, and recovery. For our binary setup, we merged all recovery-related categories into a single non-addicted class, while posts explicitly labeled as addicted are retained as the positive class.

• Go_emotions [50]: It is a reddit-based dataset annotated with 27 fine-grained emotion categories plus neutral. It contains about 58,000 unique comments collected from diverse subreddits. For binary mental-health risk classification in our work, all emotion categories associated with distress (e.g., sadness, anger, fear, anxiety) were grouped as risky, while the rest were treated as non-risky.

• Kaggle Mental Health [51]: This dataset sourced from Kaggle repository, contains Reddit posts labeled across five mental health conditions. For binary classification, all risk-associated categories were merged into a single risky class, while the remaining category was treated as non-risky.

• Dreaddit [52]: This dataset also sourced from Kaggle, consists of reddit corpus for stress detection across five community categories. The authors collected around 190 K posts and crowd-sourced stress labels for around 3.5 K text segments. The public release provides official splits (

• Reddit SuicideWatch and Mental Health Collection (SWMH) [53]: This is a Reddit-derived dataset released via Zenodo, combining posts from the SuicideWatch subreddit and other mental health communities. Posts from SuicideWatch are categorized as the risky class, while those from broader mental health forums are assigned to the non-risky class.

• Extended DAIC (E-DAIC) [54]: E-DAIC is an extended version of the original Distress Analysis Interview Corpus with Wizard-of-Oz (DAIC-WOZ) corpus [55]. The dataset, sourced from University of Southern California-Institute for Creative Technologies (USC-ICT), includes semi-structured interviews conducted by a virtual agent named Ellie, controlled either by a human wizard or an autonomous AI system. It contains transcribed clinical interviews annotated using PHQ-8 scores.

4.2 Continual Learning Baselines

The proposed MH-Freeze framework is compared with several representative continual learning techniques, each reflecting a distinct strategy for mitigating catastrophic forgetting in sequential task scenarios.

• Elastic Weight Consolidation (EWC) [56]: EWC addresses catastrophic forgetting in sequential learning by estimating the importance of each parameter for previously learned tasks (via a Fisher-based approximation) and selectively slowing changes to those important weights when learning a new task. This preserves prior expertise while allowing plasticity on less critical parameters.

• Gradient Episodic Memory (GEM) [57]: GEM uses an episodic memory of past tasks and projects the current gradient to satisfy inequality constraints that do not increase loss on stored past-task examples. This enforces update compatibility with earlier tasks and can yield positive backward transfer when gradients align. In our experiments, we adopt the efficient A-GEM variant with the same memory protocol as ER and apply projection at every step before the optimizer update.

• Learning without Forgetting (LWF) [58]: LWF adapts a network to new tasks using only new-task data while preserving prior capabilities via knowledge distillation: the current model is trained to match the frozen previous model’s outputs on the new data, alongside the new-task loss. This avoids storing old datasets, competes with multitask training that has access to old data, and often outperforms plain feature extraction or finetuning when old and new tasks are similar.

• Experience Replay (ER) [59]: It mitigates forgetting by maintaining a small episodic memory of past-task examples and interleaving them with current-task batches during training. This simple rehearsal stabilizes prior decision boundaries while preserving plasticity on new data, yielding a strong, low-complexity baseline. We have kept a fixed-size, class-balanced buffer. Each minibatch mixes current-task samples with buffer samples at a fixed ratio. Buffer size and ratio are tuned on validation.

• Finetuning: The finetuning (Sequential Learning) across tasks without any anti-forgetting mechanism serves as a lower-bound baseline [60]. In this work, a single shared head and encoder are updated sequentially across tasks under the same optimizer/schedule and validation-based thresholding; no replay or regularization terms are added.

• Synaptic Intelligence (SI) [61]: This CL technique assigns an ‘importance’ score to each weight based on how much it contributed during training on a task. At the end of a task, those importance scores are retained as a summary of what mattered most. When the next task arrives, SI adds a lightweight penalty that discourages large changes to previously important weights while leaving the others free to adapt. We applied SI to the encoder (and pooler), snapshot parameters at each task boundary, and tune the overall regularization strength and a small stabilizer constant on the validation split.

The effectiveness of the proposed framework and the baseline continual learning techniques is evaluated using multiple performance metrics. These metrics capture not only classification accuracy but also robustness under class imbalance and calibration of probabilistic outputs.

Accuracy measures the proportion of correctly classified instances, as computed in Eq. (10). It reflects how effectively each continual-learning method distinguishes risky posts from non-risky ones across sequential mental-health datasets:

where TP, TN, FP, and FN denote true positive, true negative, false positive, and false negative instances, respectively.

It is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, rewarding models that balance both low false positives and low false negatives, as shown in Eq. (11). Precision is the proportion of predicted positives that are correct, recall is the proportion of actual positives that are correctly identified. F1 score reflects how well each continual-learning method maintains balanced risky vs. non-risky decisions across sequential datasets.:

4.3.3 Area under ROC Curve (AUROC)

The AUROC evaluates the trade-off between true positive rate (TPR) and false positive rate (FPR) across varying thresholds. It is defined as the probability that a randomly chosen positive is ranked higher than a randomly chosen negative.

4.3.4 Area under Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC)

The AUPRC integrates the precision- recall curve, which is more informative under class imbalance. It summarizes the trade-off between precision and recall across thresholds.

The Brier score evaluates the accuracy of probabilistic predictions by measuring the mean squared error between predicted probabilities

4.3.6 Expected Calibration Error (ECE)

ECE measures the alignment between predicted probabilities and observed accuracy. Predictions are partitioned into M bins according to confidence, and the weighted average gap between accuracy and confidence is reported. It can be computed using Eq. (13). In our work, ECE is computed per task (dataset) to assess whether MH-Freeze and the baselines produce well-calibrated risk probabilities after threshold calibration in the continual-learning sequence.

where

4.3.7 Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC)

MCC quantifies how well the classifier balances positive/negative decisions across sequential tasks and shifting, imbalanced class distributions, penalizing asymmetric error patterns that F1 or accuracy may hide. A higher value of MCC indicates better predictive performance. The MCC is computed in Eq. (14) [62].

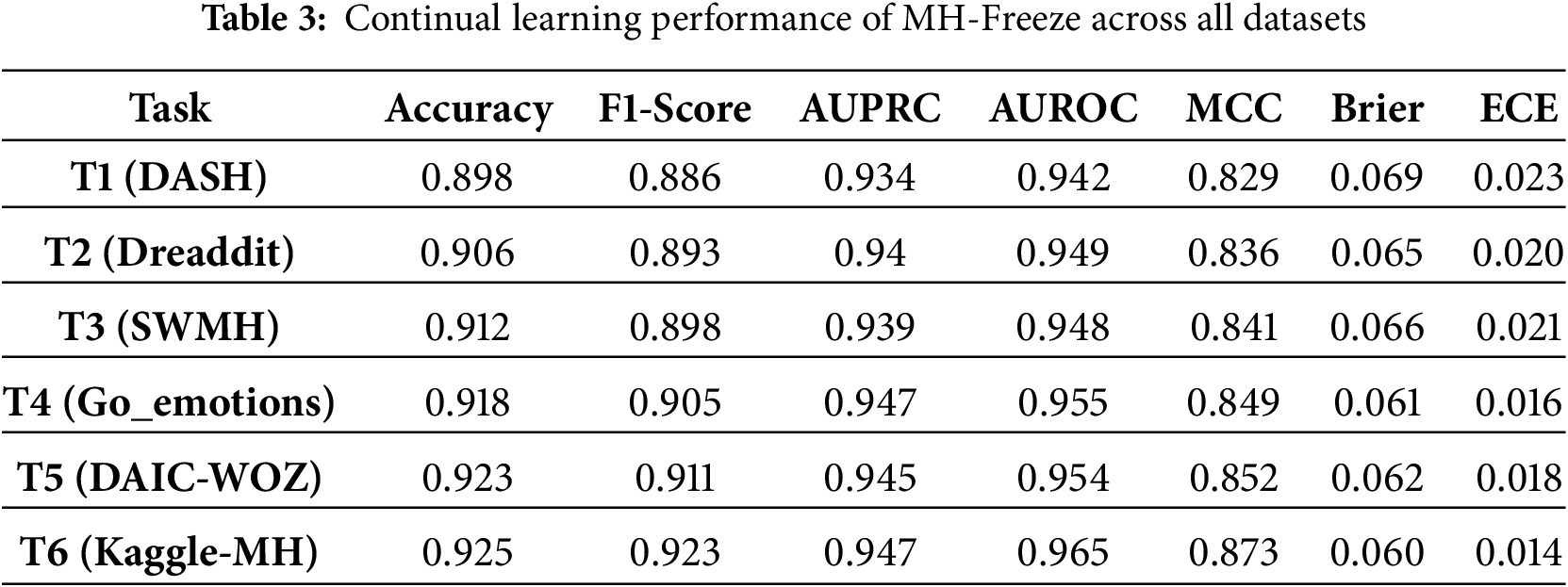

The proposed MH-Freeze framework demonstrates strong continual-learning behavior across heterogeneous datasets as seen in Table 3. MH-Freeze performs continual learning by freezing a shared GCN-Transformer encoder and training lightweight, task-specific heads as new tasks arrive. MH-Freeze is compared against six continual-learning baselines across six tasks, where each task corresponds to a different dataset in a fixed sequential order. The six tasks correspond to distinct datasets: T1 = DASH, T2 = Dreaddit, T3 = SWMH, T4 = Go_emotions, T5 = DAIC-WOZ, and T6 = Kaggle-MH. For brevity and consistency, these datasets are referenced as T1-T6 throughout the remainder of the paper. In all experiments, tasks are encountered in the fixed order T1-T6; balanced mini-batches are used to counter dataset-level imbalance, and the MH-Freeze architecture prevents dominance by any single dataset due to differing label distributions. The discriminative capability remains uniformly high, with AUPRC

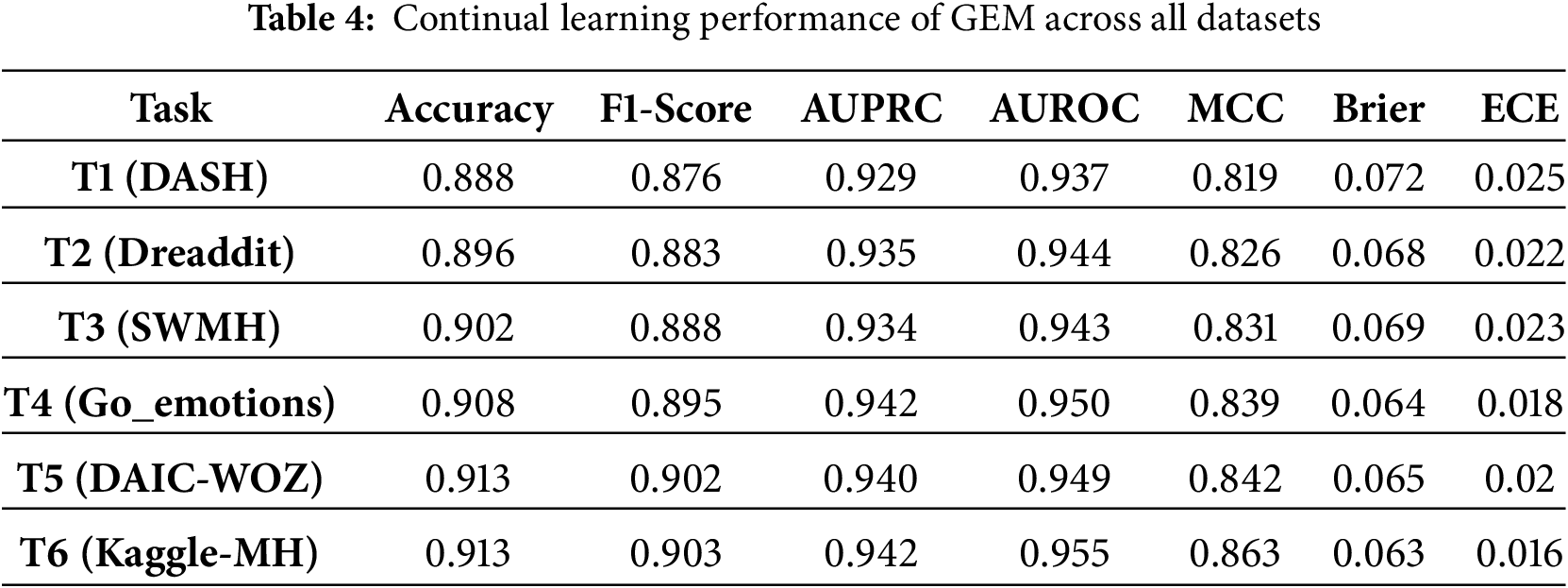

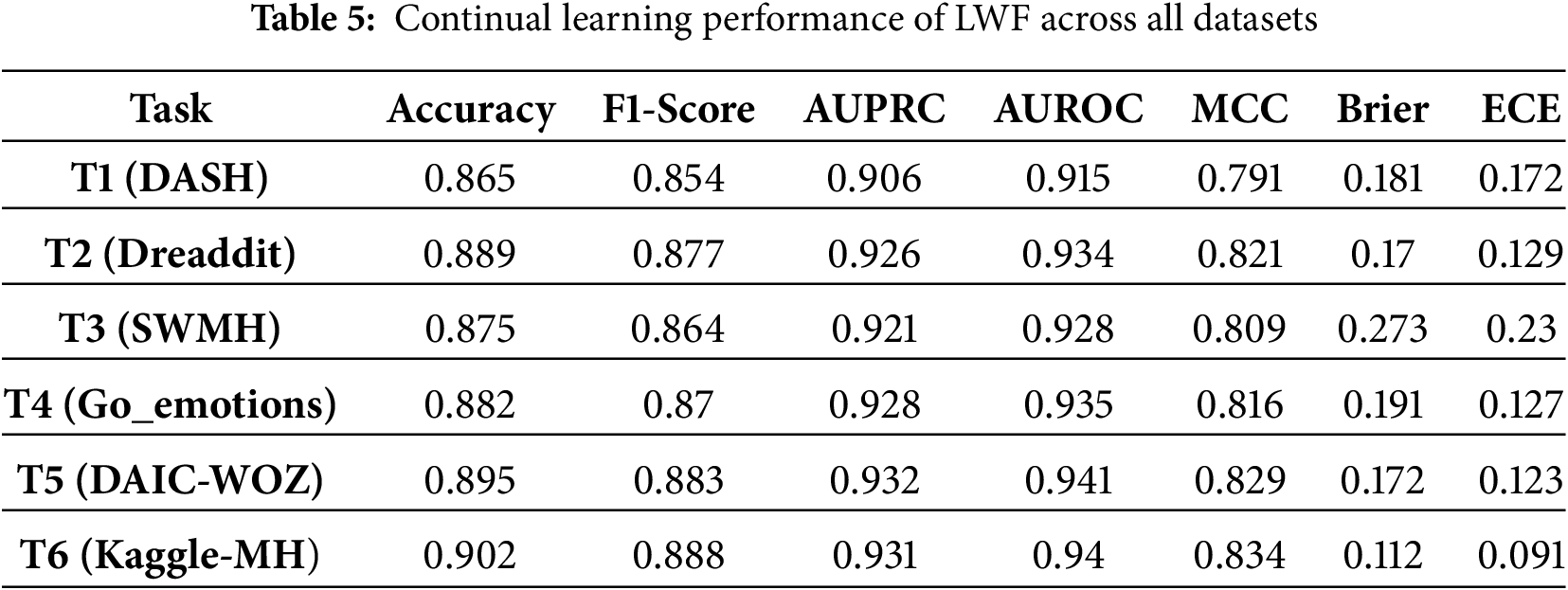

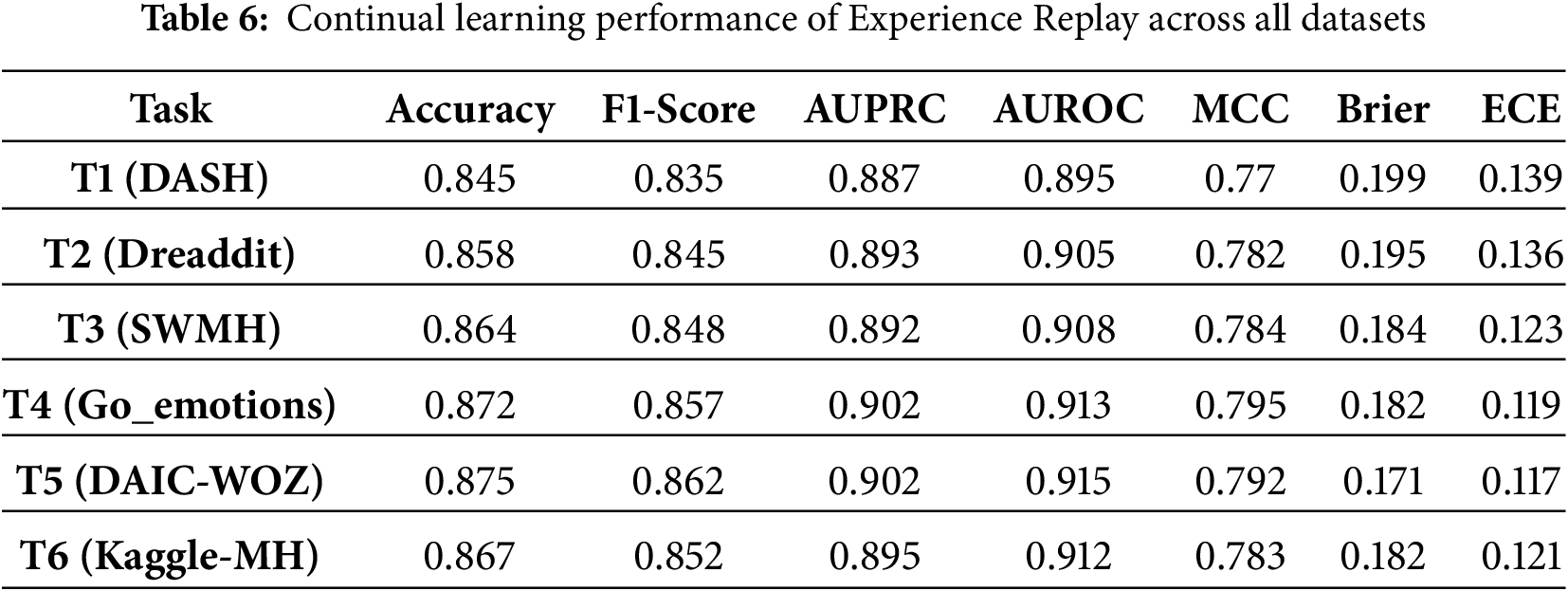

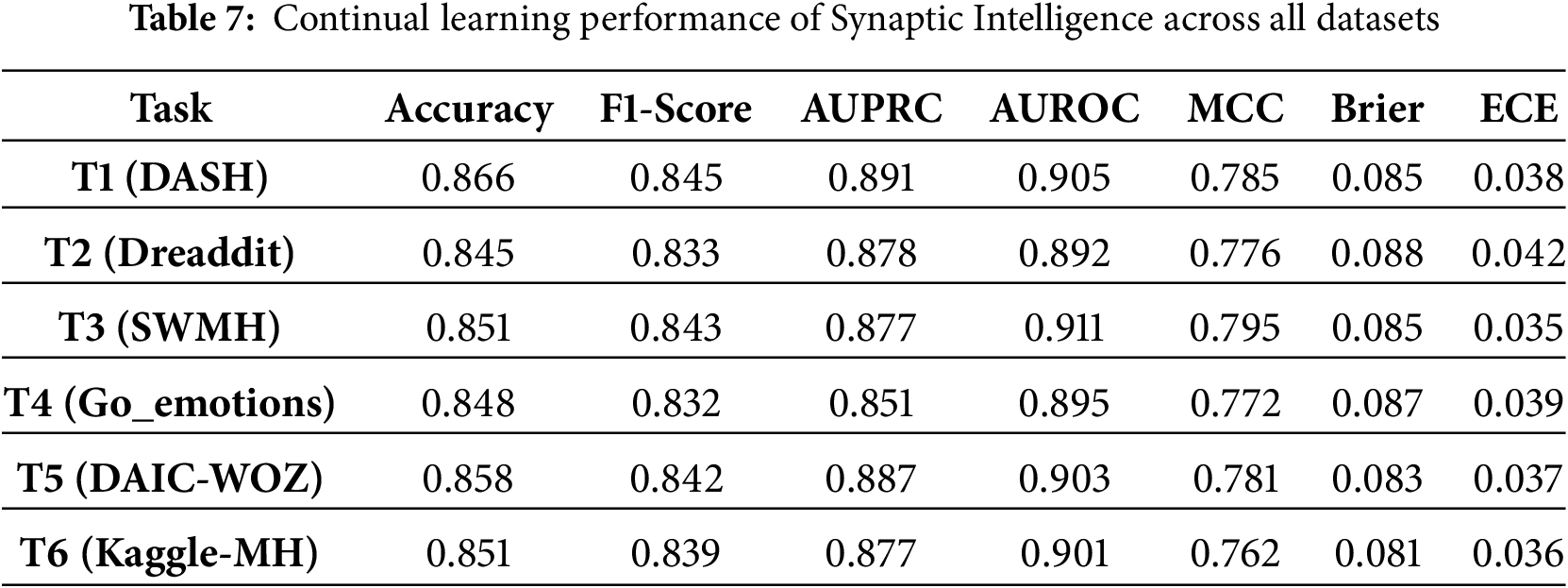

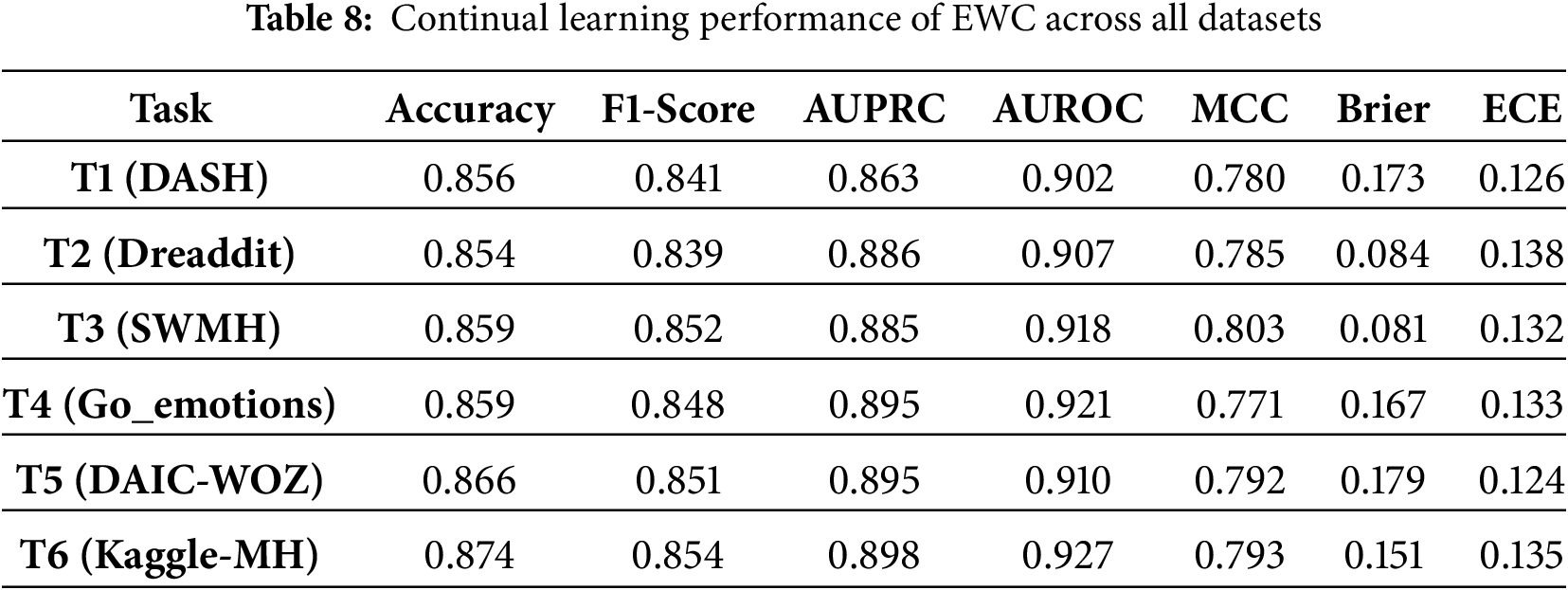

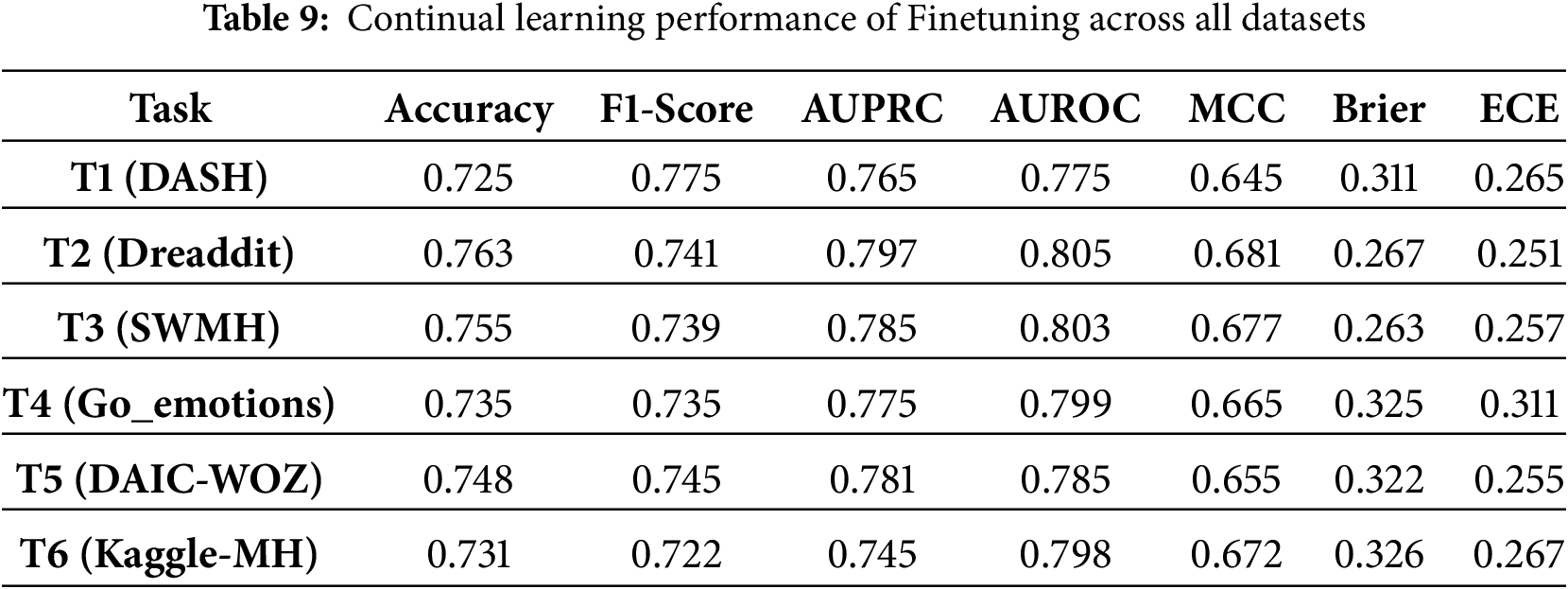

Among the CL baselines used for comparison, GEM performs better, attaining moderately high AUROC (0.94–0.95) and balanced MCC values, though it gains plateau beyond mid-sequence tasks. LWF exhibits reasonable F1-scores but suffers from high calibration error and inconsistent reliability across datasets. Experience Replay and Synaptic Intelligence provide stable yet lower performance, with AUROC typically below 0.91 and limited robustness to domain shifts. EWC achieves comparable mid-range results but shows greater sensitivity to task transitions, while Finetuning performs worst overall, displaying rapid accuracy decay (0.73–0.76) and high Brier/ECE values indicative of severe forgetting. In contrast, MH-Freeze sustains near-optimal metrics across all six tasks, confirming that its frozen encoder with task-specific heads yields superior retention, adaptation, and calibration in continual-learning environments. The detailed results for each continual-learning baseline are presented in Tables 4–9, providing a comprehensive comparison across all tasks. Experience Replay and Synaptic Intelligence show early performance saturation, as seen in Tables 6 and 7, respectively. This likely reflects limited forward transfer and calibration instability under domain shift. A plausible cause is that ER’s small replay buffer cannot adequately represent later datasets, while SI’s weight-importance penalty restricts the flexibility needed to adapt. Consistently higher Brier and ECE on the final tasks (T4-T6) reinforce this interpretation, indicating less reliable probabilities and weaker calibration as the data distribution changes. While MH-Freeze exhibits a monotonic increase in MCC from T1 to T6, GEM stabilizes at a slightly lower range (Table 4). Brier and ECE generally decline for MH-Freeze, indicating progressively better calibration, whereas replay and regularization-based baselines (ER, EWC, SI) show smaller or inconsistent reductions.

Methods that incorporate explicit memory mechanisms or parameter regularization, such as GEM and EWC, demonstrate better retention than Finetuning or LWF across all six tasks, confirming that constraining weight drift mitigates forgetting. However, these approaches still exhibit limited calibration stability, as indicated by elevated Brier and ECE values across late tasks. Synaptic Intelligence achieves moderate balance between accuracy and calibration, but its adaptation saturates beyond mid-sequence datasets, revealing difficulty in scaling to domain shifts. In contrast, MH-Freeze consistently maintains high discriminative accuracy while achieving the lowest calibration errors.

From T1 (DASH) to T6 (Kaggle-MH), most baselines show mild fluctuations in F1-Score and AUROC due to changing dataset characteristics and label imbalance. However, MH-Freeze exhibits smooth performance progression, achieving improvements in accuracy and F1-Score compared with the strongest baseline (GEM). This trend demonstrates strong forward transfer and minimal backward interference. Moreover, the consistently low Brier (

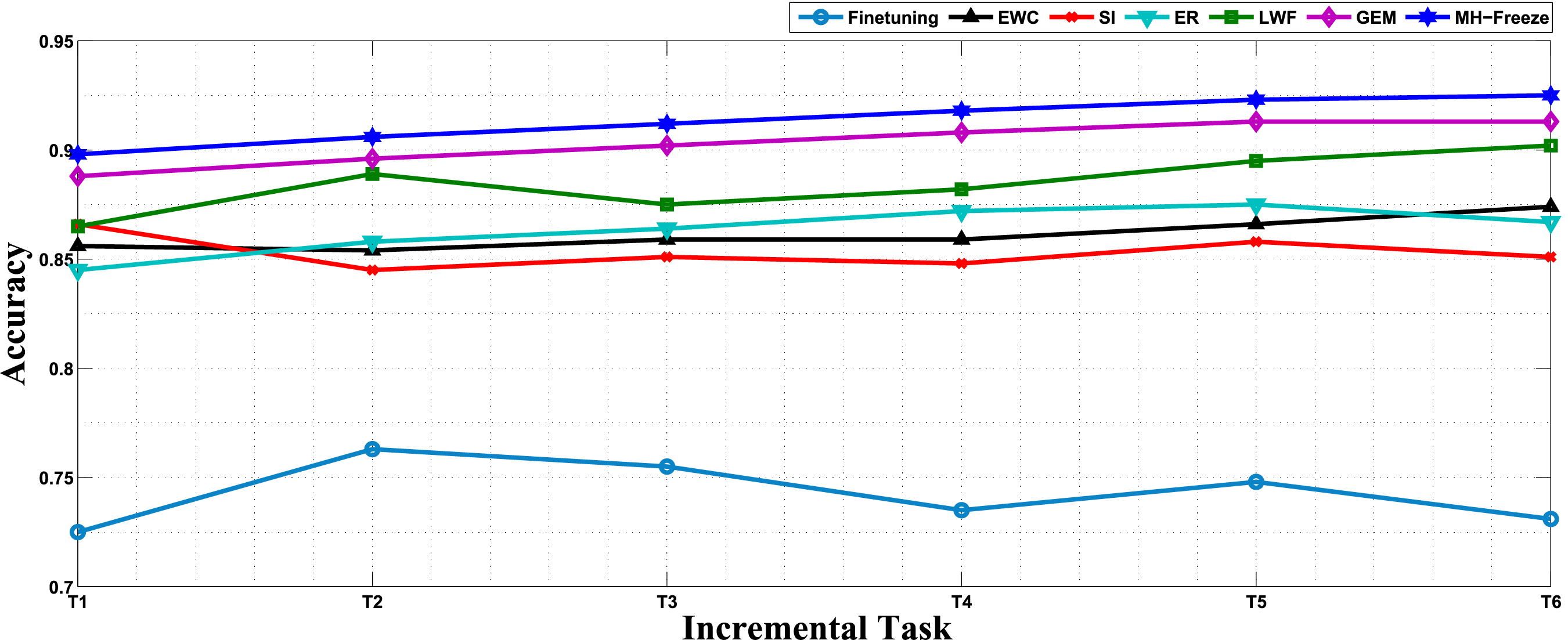

Fig. 3 shows accuracy trends for all methods across the six datasets in sequence. The accuracy curves show a clear and persistent margin for the proposed MH-Freeze approach on every task. From

Figure 3: Performance comparison of Continual Learning techniques in terms of Accuracy

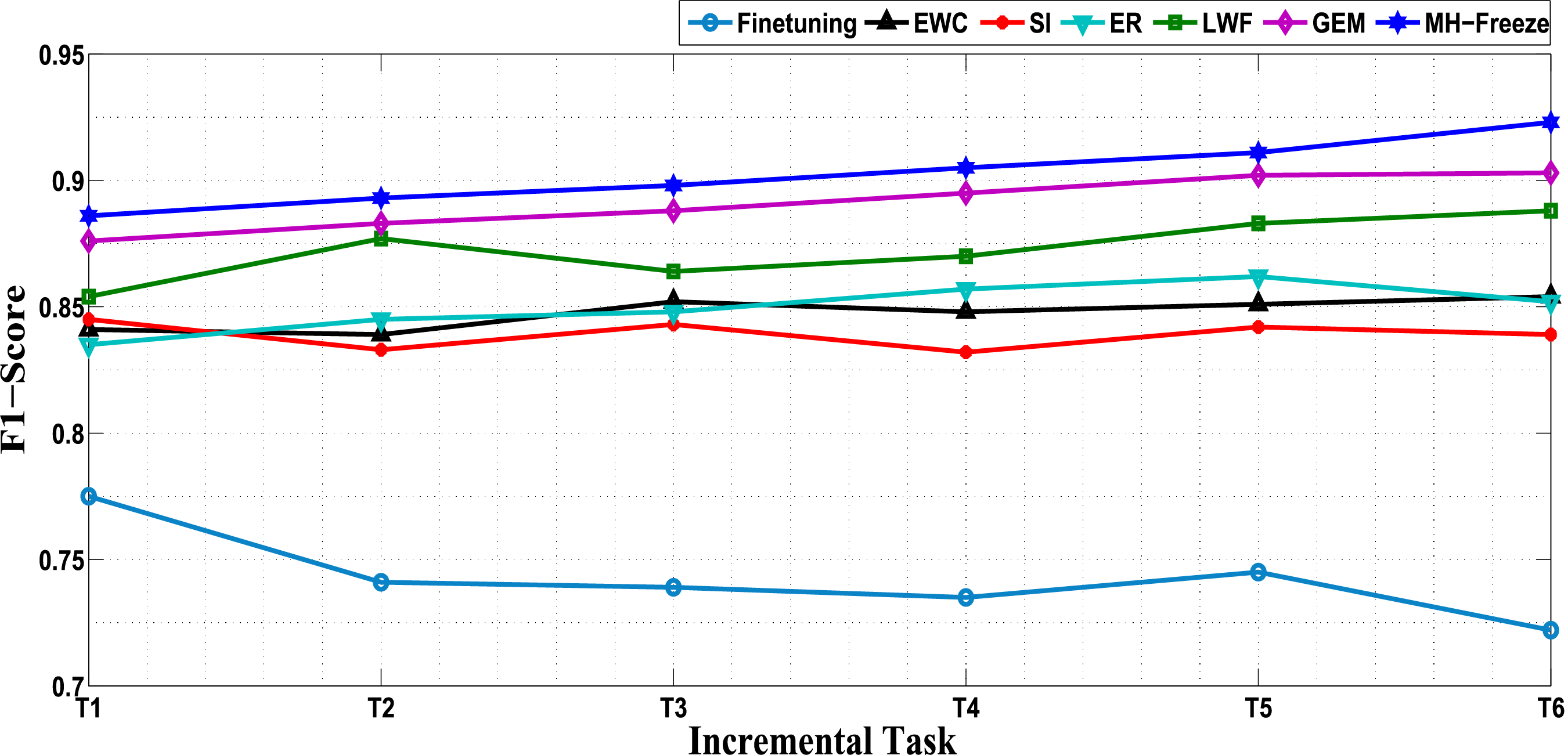

Similarly, a comparison based on F1-Score is presented in Fig. 4. This metric is informative under class imbalance and helps assess whether decisions remain balanced as new datasets are introduced. The F1-Score of MH-Freeze increases from 0.886 at

Figure 4: Performance comparison of Continual Learning techniques in terms of F1-Score

In addition, ROC curves are presented to provide an intuitive visualization of classification trade-offs across varying decision thresholds. Unlike single-value metrics, ROC curves reveal how each model balances the true-positive and false-positive rates, offering a deeper understanding of their discriminative behavior. The ROC curves shown in Fig. 5 illustrates the comparative classification performance of all continual-learning baselines and the proposed MH-Freeze model across six sequential tasks (T1–T6). Each subplot corresponds to a specific task, where the x-axis represents the False Positive Rate (FPR) and the y-axis represents the True Positive Rate (TPR). The ROC trajectories of all models are plotted within each panel, while only the area under the ROC curve (AUC) of the MH-Freeze model, representing the top-performing method, is explicitly annotated. The solid black curve corresponds to MH-Freeze and demonstrates its consistently superior separability across all tasks. In contrast, baseline models such as Finetuning, EWC, and SI are depicted with thinner colored curves to provide visual benchmarking and highlight relative performance differences. This visualization clearly demonstrates that MH-Freeze maintains stable and near-optimal discriminative capability across all incremental tasks, confirming its strong resistance to catastrophic forgetting and enhanced adaptability in continual-learning environments.

Figure 5: ROC curves across six sequential tasks (T1–T6) for continual-learning baselines and the proposed MH-Freeze model. Each task corresponds to a distinct dataset used in the continual-learning sequence

4.5 Computational Efficiency and Model Complexity

The CNSGL framework is designed to remain computationally efficient while still using the same encoder as the continual-learning baselines. The shared encoder, comprising a two-layer GCN (hidden size 128) and a single Transformer attention block with four heads (

All continual-learning baselines use the same encoder architecture for a fair comparison, so their inference FLOPs are identical to CNSGL. However, they differ substantially in how many parameters are updated during each new task and in the resulting training time. CNSGL (MH-Freeze) updates only 129 parameters per new task, yielding the lowest per-task training time, whereas baselines must update the full encoder (

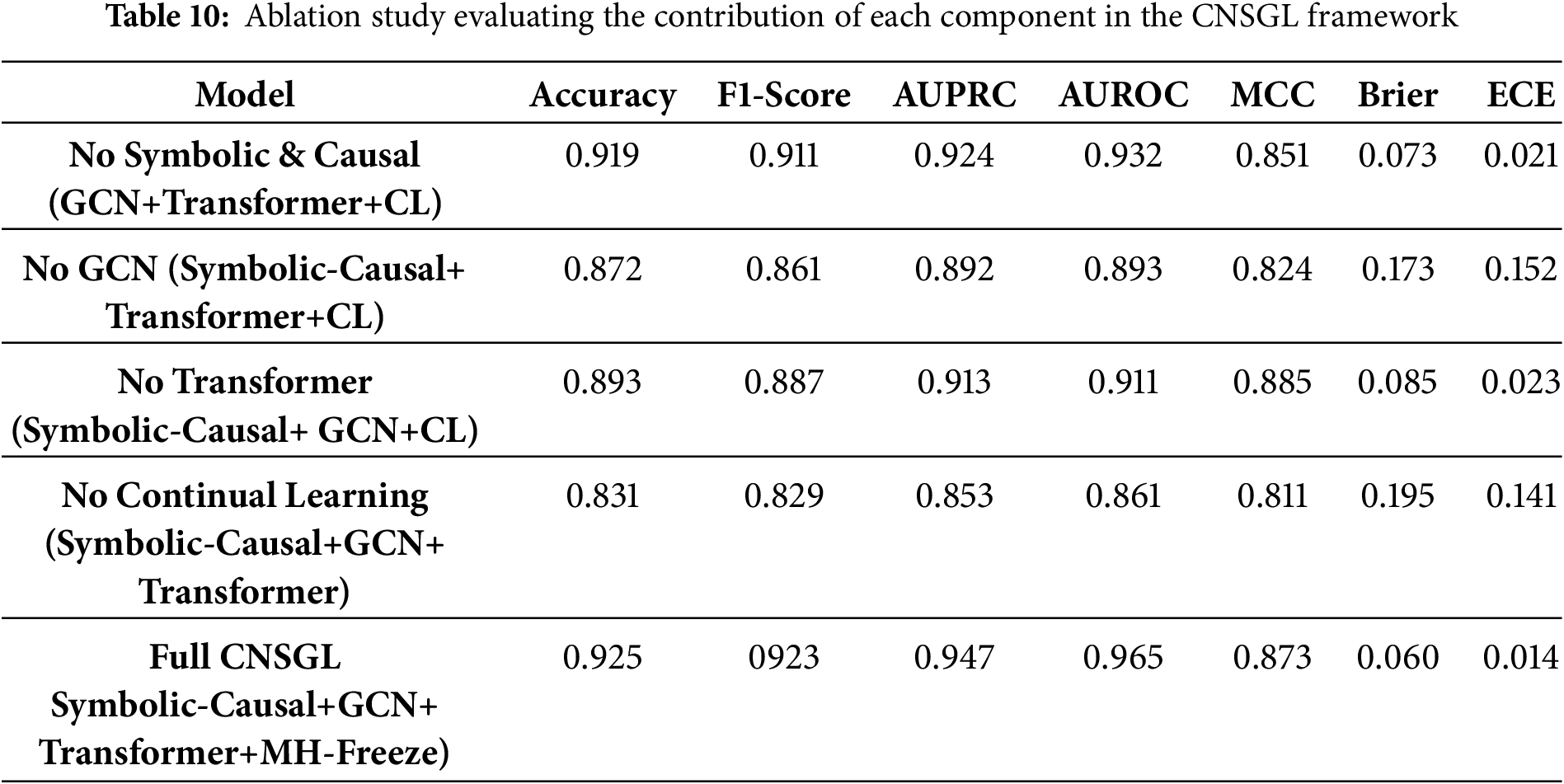

An ablation study was performed to examine individual contribution of each component in the proposed CNSGL framework, where symbolic reasoning, causal enrichment, GCN-based message passing, Transformer attention pooling, and the continual-learning mechanism are removed one at a time. Table 10 summarizes the performance of these variants.

Removing symbolic tags and causal edges (“No Symbolic & Causal”) yields a model that operates purely on GCN + Transformer embeddings without structured risk concepts. While performance remains reasonably strong (F1 = 0.911, AUPRC = 0.924), a noticeable drop appears compared to the full system, particularly in calibration (Brier = 0.073 vs. 0.060). This confirms that symbolic grounding provides clinically meaningful structure that enhances predictive reliability. When the GCN encoder is removed (“No GCN”), performance declines sharply across all metrics (F1 = 0.861, AUPRC = 0.892), and calibration degrades significantly (ECE = 0.152). This indicates that graph-based message passing is essential for leveraging symbolic–causal structure; replacing it with flat representations harms both accuracy and stability. Removing the Transformer attention pooler (“No Transformer”) further demonstrates the role of attention in extracting concept-level importance. Although the model still performs moderately well due to symbolic–causal structure (F1 = 0.887), it shows lower AUROC (0.911) and poorer calibration relative to the full framework.

The performance degrades drastically when continual learning is removed (“No Continual Learning”), where sequential fine-tuning leads to catastrophic forgetting (F1 = 0.829, AUPRC = 0.853, Brier = 0.195). This highlights the necessity of the MH-Freeze strategy; without it, performance on earlier tasks collapses, and calibration becomes unstable. At last, the full CNSGL model, integrating symbolic tags, directional associations, GCN encoding, Transformer pooling, and MH-Freeze, achieves the strongest and most consistent performance across all metrics (F1 = 0.923, AUROC = 0.965, Brier = 0.060, ECE = 0.014). These results confirm that each component contributes meaningfully and that the full architecture offers the best balance of predictive accuracy, stability, and interpretability.

The proposed Continual Neuro-Symbolic Graph Learning framework successfully integrates symbolic reasoning, causal inference, and continual learning to address the evolving nature of mental-health risk detection. By constructing symbolic graphs enriched with directional causal edges, the framework enables interpretable reasoning about risk factors and their interrelations. The hybrid encoder, comprising a two-layer GCN and a Transformer-based attention pooler, effectively captures both structural and contextual dependencies, producing discriminative yet interpretable graph-level embeddings. The MH-Freeze strategy, which freezes the shared encoder and attaches task-specific heads, ensures strong retention of prior knowledge while allowing efficient adaptation to new datasets. Experimental results across six tasks (datasets) validate its robustness, showing that MH-Freeze consistently achieves the highest AUROC and F1-Score values, alongside superior calibration metrics (Brier and ECE), compared to all other continual-learning baselines. These findings confirm that MH-Freeze mitigates catastrophic forgetting and sustains stable, generalizable decision boundaries across diverse domains. Ablation analysis further confirms that each component contributes meaningfully to overall performance and calibration, and that the MH-Freeze continual-learning scheme is particularly critical for preserving performance and stability as new tasks are introduced.

Despite its advantages, this work also has a few limitations. The symbolic tag vocabulary is kept intentionally small and manually curated to ensure clarity and cross-dataset consistency. This focused design works well for the current scenario, but future extensions could incorporate richer or domain-specific tags to capture more subtle risk cues in broader clinical or social media data. In addition, the directional PMI module models precedence-based associations rather than fully validated causal relations. Future work can address these points by learning richer tag sets in a data-driven way and by integrating stronger causal discovery or longitudinal validation to refine the directed edges.

Future extensions will broaden the scope of the framework in several ways. Integrating multimodal signals, such as speech, facial expressions, and physiological markers can enrich early detection by complementing text with non-textual cues. Enhancing causal graph enrichment with temporal and counterfactual reasoning can deepen interpretability and strengthen the reliability of causal claims. Adopting federated or other privacy-preserving continual learning schemes can enable secure training across distributed mental-health datasets without direct data sharing. These advances would move CNSGL toward a more explainable, adaptive, and ethically deployable system for real-world mental-health risk assessment.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2025-00518960) and in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2025-00563192).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Monalisa Jena and Noman Khan; methodology, Monalisa Jena; software, Monalisa Jena and Noman Khan; validation, Monalisa Jena and Noman Khan; formal analysis, Mi Young Lee; investigation, Seungmin Rho; data curation, Monalisa Jena; writing—original draft preparation, Monalisa Jena; writing—review and editing, Monalisa Jena and Noman Khan; visualization, Monalisa Jena and Noman Khan; supervision, Mi Young Lee and Seungmin Rho; project administration, Mi Young Lee; funding acquisition, Mi Young Lee and Seungmin Rho. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The SWMH (SuicideWatch and Mental Health), E-DAIC (DAIC-WOZ), and DASH-2020 datasets are available on request from the respective authors due to ethical and access restrictions (SWMH: https://10.5281/zenodo.6476178, accessed on 16 May 2025; E-DAIC: https://dcapswoz.ict.usc.edu/wwwedaic/, accessed on 16 May 2025; DASH-2020: https://zenodo.org/record/4278895#.X7T6cgzY2w, accessed on 18 May 2025), whereas the Dreaddit, Kaggle Mental_Health, and GoEmotions datasets are openly available via public repositories on Kaggle (Dreaddit: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/rishantenis/dreaddit-train-test, accessed on 20 May 2025; Kaggle Mental Health: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/entenam/reddit-mental-health-dataset?resource=download-directory, accessed on 22 May 2025; GoEmotions: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/debarshichanda/goemotions, accessed on 22 May 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| AUPRC | Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representation from Transformers |

| CL | Continual Learning |

| CNSGL | Continual Neuro-Symbolic Graph Learning |

| DASH | Data Analytics for Smart Health |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| EWC | Elastic Weight Consolidation |

| ECI | Event Causality Identification |

| ECE | Expected Calibration Error |

| ER | Experience Replay |

| FP | False Positive |

| FPR | False Positive Rate |

| FN | False Negative |

| FFN | Feed-Forward Network |

| FLOP | Floating Point Operations Per second |

| GEM | Gradient Episodic Memory |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network |

| HAN | Hierarchical Attention Network |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LWF | Learning without Forgetting |

| MCC | Matthews Correlation Coefficient |

| MH-Freeze | Multi-Head Freeze |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NLP | Natural Language processing |

| PMI | Point-wise Mutual Information |

| SI | Synaptic Intelligence |

| SVD | singular value decomposition |

| SWMH | SuicideWatch and Mental Health Collection |

| TF-IDF | Term Frequency Inverse Document Frequency |

| TPP | Temporal Point Process |

| TN | True Negative |

| TP | True Positive |

| TPR | True Positive Rate |

References

1. Li Y, Mihalcea R, Wilson SR. Text-based detection and understanding of changes in mental health. In: Social informatics (SocInfo 2018). Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 176–88. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01159-8_17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hossain E, Alazeb A, Almudawi N, Alshehri M, Gazi M, Faruque G, et al. Forecasting mental stress using machine learning algorithms. Comput Mater Contin. 2022;72(3):4945–66. doi:10.32604/cmc.2022.027058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Xu X, Yao B, Dong Y, Gabriel S, Yu H, Hendler J, et al. Mental-LLM: leveraging large language models for mental health prediction via online text data. Proc ACM Interact Mob Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2024;8(1):1–32. [Google Scholar]

4. Hossain MM, Hossain MS, Mridha MF, Safran M, Alfarhood S. Multi-task opinion enhanced hybrid BERT model for mental health analysis. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):3332. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-86124-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Omarov B, Narynov S, Zhumanov Z. Artificial intelligence-enabled chatbots in mental health: a systematic review. Comput Mater Contin. 2023;74(3):5105–22. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.034655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Tejaswini V, Sathya Babu K, Sahoo B. Depression detection from social media text analysis using natural language processing techniques and hybrid deep learning model. ACM Trans Asian Low-Resour Lang Inf Process. 2024;23(1):1–20. doi:10.1145/3569580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Vajrobol V, Saxena GJ, Pundir A, Singh S, Gaurav A, Bansal S, et al. A comprehensive survey on federated learning applications in computational mental healthcare. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;142(1):49–90. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.056500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Thekkekara JP, Yongchareon S, Liesaputra V. An attention-based CNN-BiLSTM model for depression detection on social media text. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;249:123834. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.123834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Mazurets O, Tymofiiev I, Dydo R. Approach for using neural network BERT-GPT2 dual transformer architecture for detecting persons depressive state. In: VI International Scientific and Practical Conference; 2024 Nov 15; Bologna, Italy. p. 147–51. [Google Scholar]

10. Helmy A, Nassar R, Ramdan N. Depression detection for Twitter users using sentiment analysis in English and Arabic tweets. Artif Intell Med. 2024;147:102716. doi:10.1016/j.artmed.2023.102716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Kodati D, Tene R. Advancing mental health detection in texts via multi-task learning with soft-parameter sharing transformers. Neural Comput Appl. 2025;37(5):3077–110. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-10753-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yang Y, Zhou J, Ding X, Huai T, Liu S, Chen Q, et al. Recent advances of foundation language models-based continual learning: a survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2025;57(5):1–38. doi:10.1145/3705725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Thuseethan S, Rajasegarar S, Yearwood J. Deep continual learning for emerging emotion recognition. IEEE Trans Multimedia. 2021;24:4367–80. doi:10.1109/tmm.2021.3116434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Han J, Zhang Z, Mascolo C, André E, Tao J, Zhao Z, et al. Deep learning for mobile mental health: challenges and recent advances. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 2021;38(6):96–105. doi:10.1109/msp.2021.3099293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hemmatirad K, Bagherzadeh H, Fazl-Ersi E, Vahedian A. Detection of mental illness risk on social media through multi-level SVMs. In: Proceedings of the 8th Iranian Joint Congress on Fuzzy and Intelligent Systems (CFIS); 2020 Sep 2–4; Mashhad, Iran. p. 116–20. [Google Scholar]

16. Zhou S, Mohd M. Mental health safety and depression detection in social media text data: a classification approach based on a deep learning model. IEEE Access. 2025;13:63284–97. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3559170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Garg M. Mental health analysis in social media posts: a survey. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2023;30(3):1819. doi:10.1007/s11831-022-09863-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Skaik R, Inkpen D. Using social media for mental health surveillance: a review. ACM Comput Surv. 2020;53(6):1–31. doi:10.1145/3422824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Benrouba F, Boudour R. Emotional sentiment analysis of social media content for mental health safety. Soc Netw Anal Min. 2023;13(1):17. doi:10.1007/s13278-022-01000-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ding Z, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Cao Y, Liu Y, Shen X, et al. Trade-offs between machine learning and deep learning for mental illness detection on social media. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):14497. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-99167-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. De Choudhury M, Kiciman E. The language of social support in social media and its effect on suicidal ideation risk. In: Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2017. p. 32–41. [Google Scholar]

22. Zhang Y, Cao D, Liu Y. Counterfactual neural temporal point process for estimating causal influence of misinformation on social media. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2022;35:10643–55. [Google Scholar]

23. Cheng Q, Zeng Z, Hu X, Si Y, Liu Z. A survey of event causality identification: taxonomy, challenges, assessment, and prospects. ACM Comput Surv. 2025;58(3):59. doi:10.1145/3756009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kipf TN. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv:1609.02907. 2016. [Google Scholar]

25. Hamilton W, Ying Z, Leskovec J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. In: NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2017. p. 1025–35. [Google Scholar]

26. Yao L, Mao C, Luo Y. Graph convolutional networks for text classification. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2019. Vol. 33. p. 7370–7. doi:10.1609/aaai.v33i01.33017370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Subakan C, Ravanelli M, Cornell S, Bronzi M, Zhong J. Attention is all you need in speech separation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 21–5. [Google Scholar]

28. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2017. p. 6000–10. [Google Scholar]

29. Devlin J, Chang M-W, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of the Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NAACL-HLT). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2019. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

30. Yang Z, Yang D, Dyer C, He X, Smola A, Hovy E. Hierarchical attention networks for document classification. In: Proceedings of the Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NAACL-HLT). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2016. p. 1480–9. [Google Scholar]

31. Gamel SA, Talaat FM. SleepSmart: an IoT-enabled continual learning algorithm for intelligent sleep enhancement. Neural Comput Appl. 2024;36(8):4293–309. doi:10.1007/s00521-023-09310-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Lee CS, Lee AY. Clinical applications of continual learning machine learning. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2(6):e279–81. doi:10.1016/s2589-7500(20)30102-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Li C-H, Jha NK. DOCTOR: a multi-disease detection continual learning framework based on wearable medical sensors. ACM Trans Embed Comput Syst. 2024;23(5):1–33. doi:10.1145/3679050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Nie W, Chang R, Ren M, Su Y, Liu A. I-GCN: incremental graph convolution network for conversation emotion detection. IEEE Trans Multimedia. 2021;24:4471–81. doi:10.1109/tmm.2021.3118881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Kaur S, Bhardwaj R, Jain A, Garg M, Saxena C. Causal categorization of mental health posts using transformers. In: Proceedings of the 14th Annual Meeting of the Forum for Information Retrieval Evaluation. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2022. p. 43–6. [Google Scholar]

36. Kodati D, Tene R. Identifying suicidal emotions on social media through transformer-based deep learning. Appl Intell. 2023;53(10):11885–11917. doi:10.1007/s10489-022-04060-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kumar A. Neuro Symbolic AI in personalized mental health therapy: bridging cognitive science and computational psychiatry. World J Adv Res Rev. 2023;19(2):1663–79. doi:10.30574/wjarr.2023.19.2.1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Tang X, Guo R, Zhang C, Zhuang X, Qian X. A causality-driven graph convolutional network for postural abnormality diagnosis in Parkinsonians. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2023;42(12):3752–63. doi:10.1109/tmi.2023.3305378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Bhuyan BP, Ramdane-Cherif A, Singh TP, Tomar R. Neuro-Symbolic AI: the integration of continuous learning and discrete reasoning. In: Neuro-symbolic artificial intelligence: bridging logic and learning. Singapore: Springer; 2024. p. 29–44. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-8171-3_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Dalkic H. CognEmoSense: a continual learning and context-aware EEG emotion recognition system using transformer-augmented brain-state modeling. J Brain Sci Ment Health. 2025;1(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

41. Patanè G, Sorrenti A, Bellitto G, Palazzo S. Continual learning strategies for personalized mental well-being monitoring from mobile sensing data. In: Proceedings of the International Workshop on Personalized Incremental Learning in Medicine. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2025. p. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

42. Febrinanto FG, Simango A, Xu C, Zhou J, Ma J, Tyagi S, et al. Refined causal graph structure learning via curvature for brain disease classification. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(8):222. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11231-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Gosala B, Singh AR, Tiwari H, Gupta M. GCN-LSTM: a hybrid graph convolutional network model for schizophrenia classification. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2025;105(1):107657. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2025.107657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Chen L-C. An extended TF-IDF method for improving keyword extraction in traditional corpus-based research: an example of a climate change corpus. Data Knowl Eng. 2024;153(2):102322. doi:10.1016/j.datak.2024.102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ma D, Chang KC-C, Chen Y, Lv X, Shen L. A principled decomposition of pointwise mutual information for intention template discovery. In: Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM). New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2023. p. 1746–55. [Google Scholar]

46. Ghorbani M, Baghshah MS, Rabiee HR. MGCN: semi-supervised classification in multi-layer graphs with graph convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 208–11. [Google Scholar]

47. Wu X, Lao Y, Jiang L, Liu X, Zhao H. Point Transformer V2: grouped vector attention and partition-based pooling. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2022;35:33330–42. [Google Scholar]

48. Terven J, Cordova-Esparza D-M, Romero-González J-A, Ramírez-Pedraza A, Chávez-Urbiola EA. A comprehensive survey of loss functions and metrics in deep learning. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(7):195. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11198-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Ghosh S, Misra J, Ghosh S, Podder S. Utilizing social media for identifying drug addiction and recovery intervention. In: 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 3413–22. [Google Scholar]

50. Demszky D, Movshovitz-Attias D, Ko J, Cowen A, Nemade G, Ravi S. GoEmotions: a dataset of fine-grained emotions. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2020. p. 4040–54. [Google Scholar]

51. Rani S, Ahmed K, Subramani S. From posts to knowledge: annotating a pandemic-era Reddit dataset to navigate mental health narratives. Appl Sci. 2024;14(4):1547. doi:10.3390/app14041547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Turcan E, McKeown K. Dreaddit: a Reddit dataset for stress analysis in social media. arXiv:1911.00133. 2019. [Google Scholar]

53. Ji S, Li X, Huang Z, Cambria E. Suicidal ideation and mental disorder detection with attentive relation networks. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34:10309–19. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06208-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Ringeval F, Schuller BW, Valstar M, Cowie R, Kaya H, Amiriparian S, et al. AVEC 2019 workshop and challenge: state-of-mind, detecting depression with AI, and cross-cultural affect recognition. In: Proceedings of the 9th International on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge and Workshop. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2019. p. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

55. Gratch J, Lucas GM, King A, Morency L-P. The Distress Analysis Interview Corpus of human and computer interviews. In: Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2014). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2014. p. 3123–8. [Google Scholar]

56. Kirkpatrick J, Pascanu R, Rabinowitz N, Veness J, Desjardins G, Rusu AA, et al. Overcoming catastrophic forgetting in neural networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(13):3521–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1611835114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Lopez-Paz D, Ranzato M. Gradient episodic memory for continual learning. In: NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2017. p. 6470–9. [Google Scholar]

58. Li Z, Hoiem D. Learning without forgetting. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;40(12):2935–47. doi:10.1109/tpami.2017.2773081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Rolnick D, Ahuja A, Schwarz J, Lillicrap T, Wayne G. Experience replay for continual learning. In: Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2019. p. 350–60. [Google Scholar]

60. De Lange M, Aljundi R, Masana M, Parisot S, Jia X, Leonardis A, et al. A continual learning survey: defying forgetting in classification tasks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;44(7):3366–85. doi:10.1109/tpami.2021.3057446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Zenke F, Poole B, Ganguli S. Continual learning through synaptic intelligence. In: ICML’17: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2017 Aug 6–11; Sydney, NSW, Australia. p. 3987–95. [Google Scholar]

62. Chicco D, Jurman G. The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):6. doi:10.1186/s12864-019-6413-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools