Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Comparative Benchmark of Deep Learning Architectures for AI-Assisted Breast Cancer Detection in Mammography Using the MammosighTR Dataset: A Nationwide Turkish Screening Study (2016–2022)

Department of Computer Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Architecture and Design, Kayseri University, Kayseri, 38280, Türkiye

* Corresponding Author: Nuh Azginoglu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Image Segmentation and Object Detection: Innovations, Challenges, and Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 38 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2026.075834

Received 09 November 2025; Accepted 05 January 2026; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

Breast cancer screening programs rely heavily on mammography for early detection; however, diagnostic performance is strongly affected by inter-reader variability, breast density, and the limitations of conventional computer-aided detection systems. Recent advances in deep learning have enabled more robust and scalable solutions for large-scale screening, yet a systematic comparison of modern object detection architectures on nationally representative datasets remains limited. This study presents a comprehensive quantitative comparison of prominent deep learning–based object detection architectures for Artificial Intelligence-assisted mammography analysis using the MammosighTR dataset, developed within the Turkish National Breast Cancer Screening Program. The dataset comprises 12,740 patient cases collected between 2016 and 2022, annotated with BI-RADS categories, breast density levels, and lesion localization labels. A total of 31 models were evaluated, including One-Stage, Two-Stage, and Transformer-based architectures, under a unified experimental framework at both patient and breast levels. The results demonstrate that Two-Stage architectures consistently outperform One-Stage models, achieving approximately 2%–4% higher Macro F1-Scores and more balanced precision–recall trade-offs, with Double-Head R-CNN and Dynamic R-CNN yielding the highest overall performance (Macro F1Keywords

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers among women worldwide and remains a leading cause of cancer-related death. According to World Health Organization data, approximately 2.3 million women were diagnosed with breast cancer in 2022, and approximately 670,000 people died from it. A significant portion of cases occur without any clear or identifiable risk factors, other than unmodifiable underlying characteristics such as gender and age [1].

Early diagnosis is crucial for improving survival and reducing treatment costs in breast cancer. Mammography, thanks to its high sensitivity in detecting early-stage lesions, remains the gold standard. However, accurate interpretation of mammograms is challenging, and inconsistencies often occur due to inter-radiologist variability. Factors such as dense breast tissue, workload, or subjective differences in interpretation can cause even experienced radiologists to miss subtle anomalies [2–4].

In recent years, rapid advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Deep Learning (DL) have led to significant breakthroughs in medical imaging. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transformer-based architectures have achieved remarkable performance in core computer vision tasks, including image analysis, Object Detection (OD), classification, and segmentation [5–7]. In mammography, these approaches have been increasingly adopted to improve diagnostic accuracy, reduce False Negatives (FN), and alleviate the workload of large-scale breast cancer screening programs [8,9]. Beyond imaging-based methods, recent studies have also demonstrated the potential of DL when combined with alternative, physics-driven sensing modalities, such as graphene-based terahertz absorbers for breast tissue classification [10].

Among widely adopted OD models, architectures such as You Look Only Once (YOLO), REgion-based Two-stage Inspired Network for Accurate NeT detection (RetinaNet), and Faster Region Based CNN (R-CNN) have shown superior performance in detecting malignant lesions compared to traditional computer-aided detection systems [11]. Transformer-based architectures have further enabled end-to-end OD through attention mechanisms, emerging as a strong alternative to conventional CNN-based pipelines [12]. In parallel, recent research has explored lightweight and non-Transformer designs, including state-space and segmentation-oriented architectures, demonstrating that efficient modeling paradigms can offer complementary advantages, particularly in terms of computational efficiency and localization-driven learning [13].

Despite these advances, the effectiveness of DL-based mammography systems remains highly dependent on the availability of large, well-balanced, and carefully annotated datasets. Many widely used public datasets, such as INbreast [14], CBIS-DDSM [15], and MIAS [16], are limited by relatively small sample sizes, heterogeneous image quality, and incomplete clinical metadata. These constraints hinder the generalizability and robustness of AI models when deployed in real-world screening environments. To address these limitations, this study utilizes the MammosighTR dataset [17], a large-scale and nationally representative mammography dataset developed within the Turkish National Breast Cancer Screening Program [18–22].

This study conducts a comprehensive comparative evaluation of open-source OD architectures on the MammosighTR dataset and represents one of the first benchmarking efforts on this resource. Three main architectural groups are examined:

1. One-Stage Architectures (YOLOv3, YOLOv9, YOLOv10, YOLOv11, RetinaNet, FCOS, ATSS, VFNet),

2. Two-Stage Architectures (Faster R-CNN, Cascade R-CNN, Dynamic R-CNN, Double-Head R-CNN),

3. Transformer-based Architectures (DEtection TRansformer (DETR), Deformable DETR).

These architectural families represent diverse trade-offs between computational efficiency, detection accuracy, and robustness to class imbalance, enabling a systematic assessment of their clinical suitability in large-scale mammography screening scenarios [18–22].

The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows;

• compares a wide range of open-source DL-based OD models trained on different datasets and presents a reproducible evaluation framework for AI-assisted mammography analysis using the MammosighTR dataset.

• performs hyperparameter optimization by determining the most appropriate confidence threshold for each model, thus ensuring a fair and consistent comparison.

• performs both patient-based and breast-based evaluations to reflect the applicability of the models in real clinical settings.

• provides important findings regarding diagnostic challenges arising from tissue characteristics by quantitatively examining the effect of breast density on model performance.

In conclusion, this study systematically compares current DL architectures using a highly representative dataset and contributes to the development of AI-enabled breast cancer screening systems. The results are expected to support radiologists’ clinical decision-making processes and contribute to the development of reliable and highly accurate detection models that can be seamlessly integrated into national screening programs. Despite substantial advances in DL–based breast imaging, the existing literature has predominantly focused on individual model architectures, limited datasets, or a single level of performance evaluation. To date, there has been no systematic study that comparatively analyzes modern one-stage, two-stage, and Transformer-based OD architectures on a large-scale, nationally representative breast cancer screening dataset such as MammosighTR. This study aims to address this gap by providing a comprehensive, multi-level comparative evaluation within a unified experimental framework.

To facilitate a clear and coherent understanding of the analysis, the overall workflow of the study is organized as follows. First, the structure and main characteristics of the MammosighTR dataset are introduced to establish the clinical context of the research. Subsequently, DL–based OD models are categorized according to their architectural paradigms and evaluated within a unified experimental framework. The evaluation is conducted at both the patient level and the breast level to better reflect real-world clinical practice. Finally, model performance across different breast density categories is examined in order to assess their consistency under varying tissue characteristics.

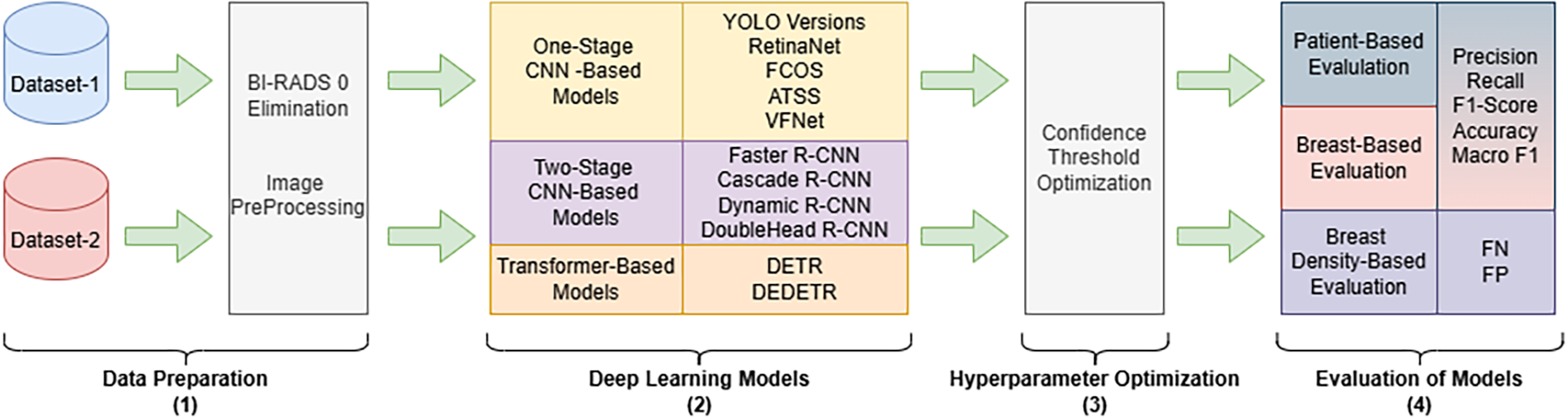

This section first presents general information about the dataset and describes the preprocessing steps applied to mammography images. Next, the DL models used in this study are grouped based on their architecture and described individually. The overall workflow of the study is visually presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the work process. The workflow consists of four main stages: (1) preprocessing of mammograms in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine format belonging to the MammosighTR dataset, (2) running DL models with different architectures, (3) performing confidence threshold optimization, and (4) patient- and breast-based performance evaluation, as well as determining the effect of breast density on model performance

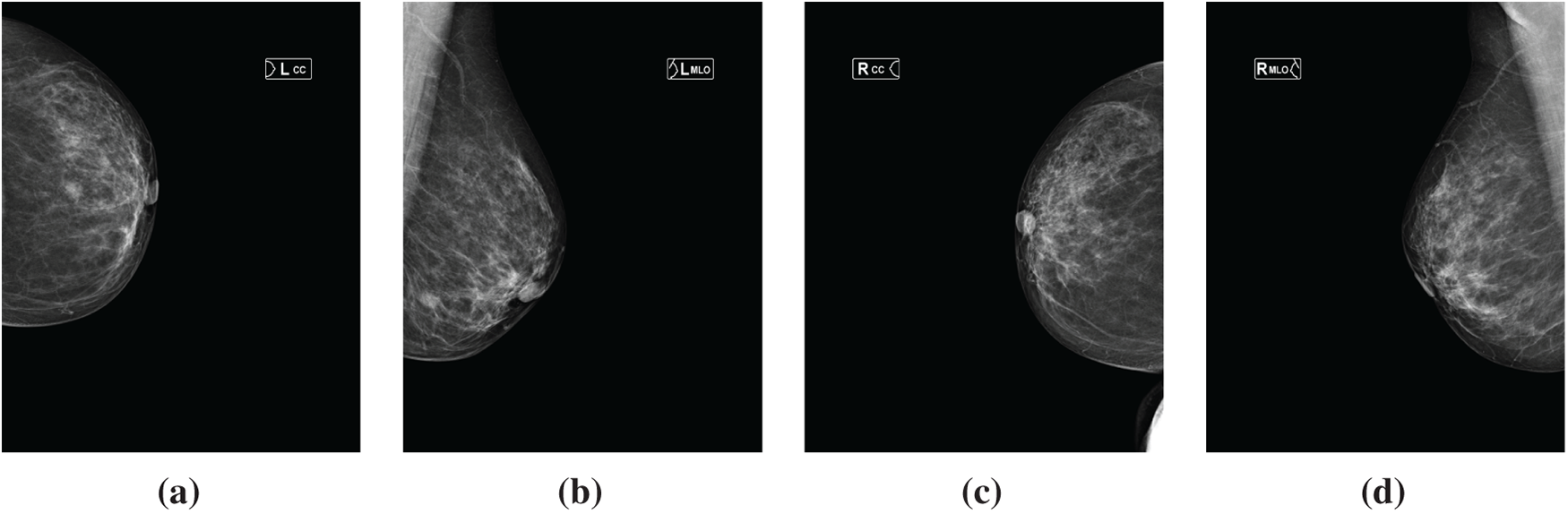

This study used the MammosighTR dataset [17], developed within the Turkish National Breast Cancer Screening Program. This dataset is a comprehensive, publicly available resource designed for AI-based breast imaging research. It includes 12,740 patient cases collected from 347 Cancer Early Diagnosis, Screening, and Training Centers across Turkey between 2016 and 2022. Each case is presented with BI-RADS categories, breast density levels, and quadrant information labels indicating lesion locations. Each case also includes four baseline images representing standard mammography acquisition angles: left craniocaudal (LCC), left mediolateral oblique (LMLO), right craniocaudal (RCC), and right mediolateral oblique (RMLO).

Fig. 2 shows a sample mammogram image from Dataset-1 of a patient diagnosed with BI-RADS 4. The four standard mammography positions are presented in the following panels, respectively: (a) LCC, (b) LMLO, (c) RCC, and (d) RMLO.

Figure 2: Sample mammographic views from the MammosighTR dataset of a patient diagnosed as BI-RADS 4. (a) LCC view; (b) LMLO view; (c) RCC view; and (d) RMLO view

Radiologists conducted the dataset labeling process in a multistage, blinded review to ensure consistency and reliability. Rare but clinically significant cases of BI-RADS 4–5 were confirmed by biopsy, and these cases were included in the dataset with a balanced ratio to increase the representativeness of positive samples.

The dataset includes training and test subsets that were created as part of the TEKNOFEST 2023 Healthcare AI Competition [23]. Following the competition, all subsets were made publicly available. These data were originally released through a national AI competition and later curated for research purposes. In this study, the Training-1 set (hereafter referred to as Dataset-1) and the Test set (hereafter referred to as Dataset-2) were used. Dataset-1 comprised a total of 15,916 mammogram images (four images per patient) from 3979 patients, while Dataset-2 contained 8000 images from 2000 patients.

Dataset-1 and Dataset-2 correspond to two predefined, non-overlapping partitions of the MammosighTR dataset originally designated for blind evaluation. This split was preserved in the present study to ensure a consistent and unbiased evaluation protocol and to prevent data leakage. Although both subsets originate from the same nationwide screening program, they are treated as independent evaluation sets without implying external validation on different populations.

The dataset covers three primary BI-RADS categories: BI-RADS 0, BI-RADS 1–2, and BI-RADS 4–5. It also includes four different breast density categories (A, B, C and D). Another important feature of the dataset is the inclusion of quadrant information indicating the location of the lesion within the breast. All features in the dataset were used in all experimental analyses in the study.

The MammosighTR dataset was originally in DICOM format ( [24]). During the preprocessing phase, the images were normalized by scaling their pixel intensities to the range 0–255. Then, the images were converted to PNG format, preserving the original file names.

The study utilized pre-trained models using The Digital Eye for Mammography (DEM) [25], an open-source toolkit developed for the detection and classification of masses in mammography images. These models are grouped under two main open-source benchmarks: MMDetection [26] and YOLO [27]. The models used are categorized into three architectural groups: One-Stage, Two-Stage, and Transformer-based architectures.

Two-Stage detectors were first introduced with the R-CNN [28] model and subsequently significantly improved with Faster R-CNN [29]. In this architecture, OD is accomplished in two sequential steps. In the first stage, a Region Proposal Network (RPN) identifies potential object regions (anchors or proposals) in the image. In the second stage, the detection head, candidate regions are classified and the bounding box coordinates are refined more precisely. While two-stage models generally provide high detection accuracy, they are slower due to their computationally intensive nature.

One-stage detectors combine the steps of the traditional two-stage architecture into a single, end-to-end process. In this approach, the model directly predicts both class labels and bounding boxes, eliminating the need for a separate region proposal stage [27].

Transformer-based architectures [12], on the other hand, rely entirely on attention. These models learn the relationships between all elements in the array through self-attention, without using convolutional or recurrent layers. Typically, feature maps extracted by a CNN are processed through an encoder-decoder architecture; the encoder captures the overall context, while the decoder performs object prediction.

The models used in this study are described in detail in the following subsections.

2.3.1 One-Stage CNN-Based Architectures

• YOLO is a DL-based algorithm designed for real-time OD. Unlike traditional region-based approaches, YOLO processes the entire image in a single forward pass and performs object classification and localization simultaneously. This combined structure gives YOLO significantly higher speed and computational efficiency compared to traditional methods.

The YOLO architecture divides the input image into a grid structure, with each cell responsible for predicting possible object centers and corresponding bounding boxes. This structure allows YOLO to demonstrate strong performance in autonomous driving, robotic systems, and other time-critical applications. The YOLO framework has evolved into multiple versions with architectural improvements over time.

This study evaluated a total of 21 models from five different generations of the YOLO family:

(a) YOLOv11 (n, s, m, l, x)

(b) YOLOv10 (n, s, m, l, x)

(c) YOLOv9 (t, s, m, c, e)

(d) YOLOv8 (n, s, m, l, x)

(e) YOLOv3

Each generation includes several variants that offer different trade-offs between accuracy, model size, and inference speed. While all versions share a common architectural foundation, they differ in network depth, layer width, and computational complexity. Furthermore, YOLOv3 is included as the baseline model for comparison purposes to evaluate performance differences between different generations and architectural designs.

• RetinaNet [30] is a DL architecture that strikes a strong balance between high accuracy and efficient inference in OD tasks. The key innovation of this model is its focal loss function. This loss function was developed to improve the ability to learn from underrepresented examples by reducing class imbalance. As a One-Stage detector, RetinaNet aims to maintain accuracy while offering faster inference times compared to two-stage approaches. Its architecture, built on the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN), enables reliable detection of objects at different scales. These advantages make RetinaNet widely preferred in real-time OD applications.

• FCOS (Fully Convolutional One-Stage Object Detector) [31] is an anchor-free OD architecture. Unlike anchor-based methods, it treats each pixel in the feature map as a possible object center and directly predicts the class label and bounding box for the location. This design simplifies the training process by eliminating the need for predefined anchors and complex matching processes, while maintaining high detection accuracy.

• ATSS (Adaptive Training Sample Selection) is a dynamic sample selection strategy proposed by Zhang et al [18]. This approach uses an automated method based on statistical analysis of IoU distributions, rather than manually determined IoU (Intersection over Union) thresholds, to identify positive and negative samples in One-Stage detection frames. This enables adaptive sample selection and increases the stability and balance of the training process, resulting in more consistent and accurate detection performance.

• VarifocalNet (VFNet) [19] is an anchor-free One-Stage detection model that builds on and extends the capabilities of previous frameworks such as FCOS and ATSS. VFNet introduces an IoU-aware classification mechanism and a new loss function called Varifocal Loss, directly relating classification confidence to the location quality of detected objects. This design allows the model to assign higher confidence scores to predictions with high IoU values while suppressing low-quality detections. These improvements allow VFNet to achieve significant gains in accuracy and training stability compared to traditional One-Stage detectors.

2.3.2 Two-Stage CNN-Based Architectures

• Faster R-CNN is a model representing a two-stage DL architecture, considered one of the most significant milestones in OD [29]. Its key innovation is the direct integration of the RPN component into the network structure. This allows region proposals to be generated within the network without the need for external algorithms. In the first stage, the RPN identifies potential object candidate regions; in the second stage, these regions are classified according to relevant object categories, and the positions of the bounding boxes are refined.

• Cascade R-CNN is an extension of the Faster R-CNN architecture. The model is based on the observation that fixed Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds can limit performance in OD tasks. To address this issue, Cascade R-CNN introduces successive detection stages (cascade stages) trained with increasing IoU thresholds. This stepwise training strategy progressively eliminates low-quality bounding box predictions, resulting in more accurate and reliable detections [20].

• Dynamic R-CNN [32] is a two-stage OD model built on the Faster R-CNN model. The primary goal of this model is to increase the adaptability of traditional detectors that use fixed IoU thresholds and static loss weights during training. Dynamic R-CNN dynamically adjusts both IoU thresholds and loss weights throughout training, allowing the model to better adapt to the data distribution. This approach has been found to provide significant improvements in detection accuracy and robustness.

• Double-Head R-CNN Double-Head R-CNN is another two-stage detection model derived from the Faster R-CNN architecture. The model’s starting point is the assumption that classification and localization tasks require different feature representations. Therefore, Double-Head R-CNN replaces the traditional single Region of Interest (RoI) header with two separate headers: a classification header using fully connected layers and a boundary box regression header using convolutional layers. This decoupled structure allows for more efficient learning of task-specific features, resulting in significantly improved overall detection performance.

2.3.3 Transformer-Based Architectures

• DETR is a Transformer-based architectures that offers a new perspective on OD tasks [12]. Unlike traditional CNN-based detectors, DETR eliminates the need for hand-designed components such as anchors, region proposals, and Non-Maximum Suppression. Instead, it processes feature maps obtained from a CNN backbone through the Transformer encoder-decoder architecture. In this architecture, each object query in the decoder corresponds to a possible object in the image, allowing the model to directly predict a fixed number of class labels and bounding boxes. By defining OD as a set prediction problem, DETR enables completely end-to-end training and inference, thus eliminating the reliance on heuristic post-processing steps.

• Deformable DETR [33] is an improved and more efficient variant of the DETR architecture. This model was developed to overcome the fundamental limitations of the original DETR, such as slow convergence and high computational cost. The global attention mechanism used in the original DETR, which takes all spatial information into account, results in high computational overhead and long training times. To address this issue, Deformable DETR uses a deformable attention mechanism, ensuring that each query focuses only on a limited number of relevant sample points. This sparse attention approach significantly reduces the model’s computational complexity and speeds up the training process while maintaining detection accuracy.

This section presents the experimental results obtained from the comparative analysis. It begins with a description of the evaluation metrics and the process of optimizing confidence thresholds, followed by a detailed assessment of model performance at both the patient and breast levels. Finally, the impact of breast density on model stability is examined.

To reflect clinical screening workflows, model performance is evaluated at two complementary granularities: patient-based and breast-based. Patient-based evaluation corresponds to the screening decision per patient, where a case is considered positive if a suspicious finding (BI-RADS 4–5) is detected in at least one breast. Breast-based evaluation, in contrast, treats each breast independently to assess lesion localization accuracy and unilateral findings. This dual evaluation strategy enables a clearer interpretation of detection performance and its relationship to patient-based diagnostic outcomes.

All computational and visualization experiments were performed on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i9-12900F processor, 64 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX A4000 GPU with 16 GB of dedicated memory.

Precision is a fundamental performance metric in classification tasks that measures the proportion of correctly identified positive predictions among all positive predictions made by the model. It is calculated as the ratio of true positives (TP) to the total number of positive predictions, as shown in Eq. (1). In essence, Precision represents the accuracy of the model’s positive outputs [21].

This metric is particularly critical in applications where false positives (FP) can have serious consequences—such as medical diagnosis, cybersecurity threat detection, or automated content filtering. A Precision value close to 1 indicates that the model produces very few FPs, reflecting high reliability. However, for a more comprehensive assessment of model performance, Precision should be considered together with complementary metrics such as Recall and F1-Score.

Recall quantifies the model’s ability to correctly identify TP instances. In other words, it measures how effectively the model captures all relevant samples belonging to the positive class. Recall is calculated as the ratio of TPs to the total number of actual positive cases (TP + FN), where FN represents FN—instances that are truly positive but misclassified as negative—as shown in Eq. (2).

F1-Score is a performance metric that captures the balance between Precision and Recall by calculating their harmonic mean (Eq. (3)). It is particularly useful in scenarios where a trade-off exists between these two metrics, as improving one often results in a reduction in the other. For instance, a model may achieve high Precision but low Recall, or vice versa. By combining these complementary measures into a single value, the F1-Score provides a concise and informative indicator of a model’s overall ability to accurately identify positive instances while maintaining comprehensive coverage of all actual positives.

Accuracy is one of the most fundamental performance metrics used to evaluate the overall correctness of a classification model. It is defined as the ratio of correctly classified instances to the total number of instances in the dataset. In other words, Accuracy represents the proportion of the model’s total predictions that are correct, as expressed in Eq. (4).

This metric is particularly informative when the dataset has a balanced class distribution. However, when the dataset is imbalanced, such as when positive samples are significantly fewer than negative ones, Accuracy can be misleading. For example, if most samples belong to the negative class, a model that predicts every instance as negative could still achieve a deceptively high Accuracy score while failing to capture meaningful distinctions. Therefore, Accuracy should be interpreted together with other complementary metrics, such as Precision, Recall, and F1-Score, to obtain a more comprehensive evaluation of model performance.

The Macro Average F1-Score (also referred to as the Macro F1-Score) is a metric used in multi-class classification problems and represents the arithmetic mean of the F1-Scores calculated separately for each class (Eq. (5)). In this approach, each class is assigned equal weight, regardless of the number of instances it contains. This metric evaluates the model’s overall performance across all classes, ensuring that minority classes contribute equally to the final score. In other words, it assesses how well the model performs on both majority and minority classes. A high Macro F1-Score indicates that the model delivers consistent performance across all classes, demonstrating balanced and reliable classification capability even when class imbalance is present.

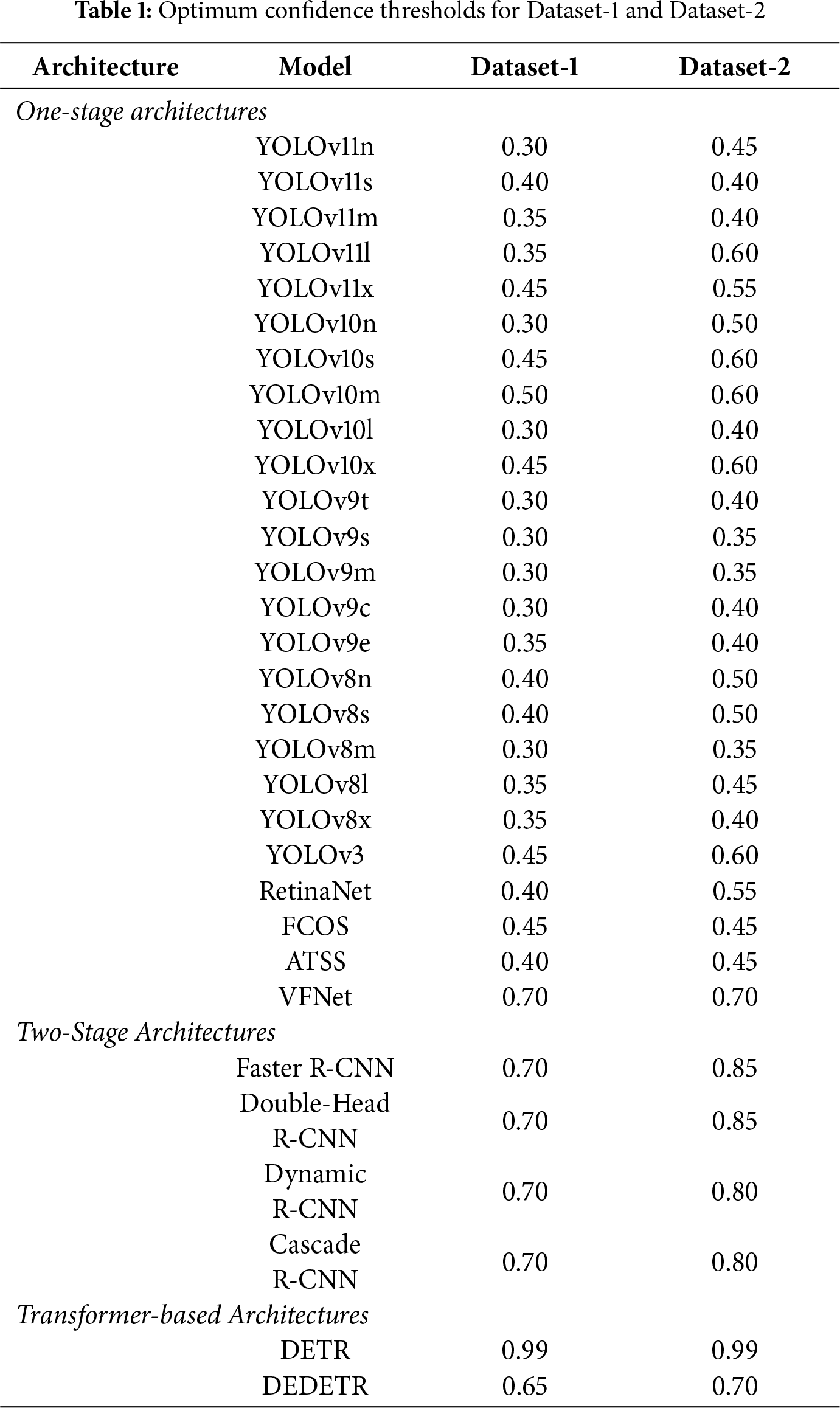

3.2 Determination of the Optimum Confidence Threshold

Predictions were generated for both datasets using the OD models employed in this study, and the results were recorded accordingly. For each detected lesion, the following information was extracted for subsequent analyses: patient_id, confidence score, mammographic view (LCC, LMLO, RCC, RMLO), bounding box coordinates, and class label. The initial confidence threshold was set to the default value of 0.25.

Following prediction, an optimization procedure was performed to identify the optimal confidence threshold for each model and dataset. Thresholds were increased from 0.25 to 0.9 in steps of 0.05, with detections below each threshold labeled as negative (BI-RADS 1–2). Among the evaluated levels, optimal thresholds were selected based on performance. For the DETR model, the optimal value lay outside the initial range; therefore, the threshold was extended to 0.9–1.0, resulting in an optimal value of 0.99. The selected thresholds for each model and dataset, determined using the Macro F1-score, are reported in Table 1.

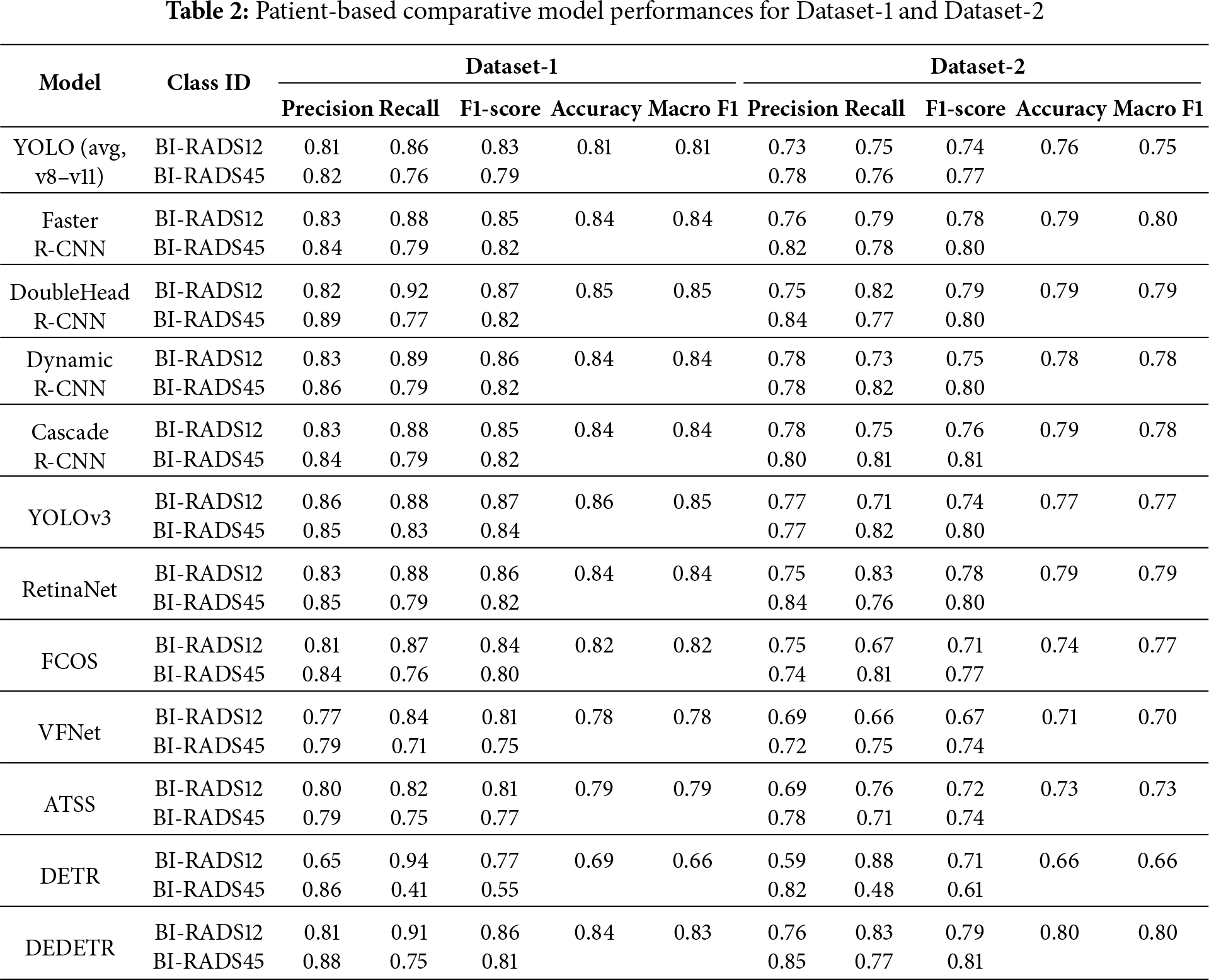

Patient-based evaluation results are presented in Table 2. The table reports class-wise performance for BI-RADS12 and BI-RADS45 together with overall Accuracy and Macro F1-Score for both Dataset-1 and Dataset-2. This evaluation reflects the clinical screening decision at the patient level, where a case is considered positive if a suspicious finding is detected in at least one breast.

In the patient-based experiments conducted on Dataset-1, the highest overall performances were achieved by YOLOv3, Double-Head R-CNN, Dynamic R-CNN, and Deformable DETR. These models demonstrate strong balance between benign and malignant classes, achieving Macro F1-Scores in the upper performance range.

When analyzed by architectural paradigm, clear performance differences emerge. One-Stage detectors, including recent YOLOv8–YOLOv11 variants, achieve competitive Recall values but exhibit slightly reduced Precision due to occasional false positives. As a result, their average Macro F1-Scores typically fall within the 0.80–0.83 range.

In contrast, Two-Stage architectures consistently demonstrate higher stability and improved class balance, with Macro F1-Scores generally ranging between 0.84 and 0.85. Among these, Double-Head R-CNN and Dynamic R-CNN provide the most balanced performance across BI-RADS categories, underlining their robustness for patient-based diagnosis.

A performance drop is observed for most models when transitioning from Dataset-1 to Dataset-2, reflecting increased heterogeneity and distributional differences in the test set. Nevertheless, the relative ranking of model families remains largely unchanged, indicating consistent generalization behavior.

Overall, patient-based evaluation highlights the diagnostic reliability of Two-Stage and Transformer-based architectures, while One-Stage models retain practical relevance due to their uniform performance and suitability for high-throughput screening workflows.

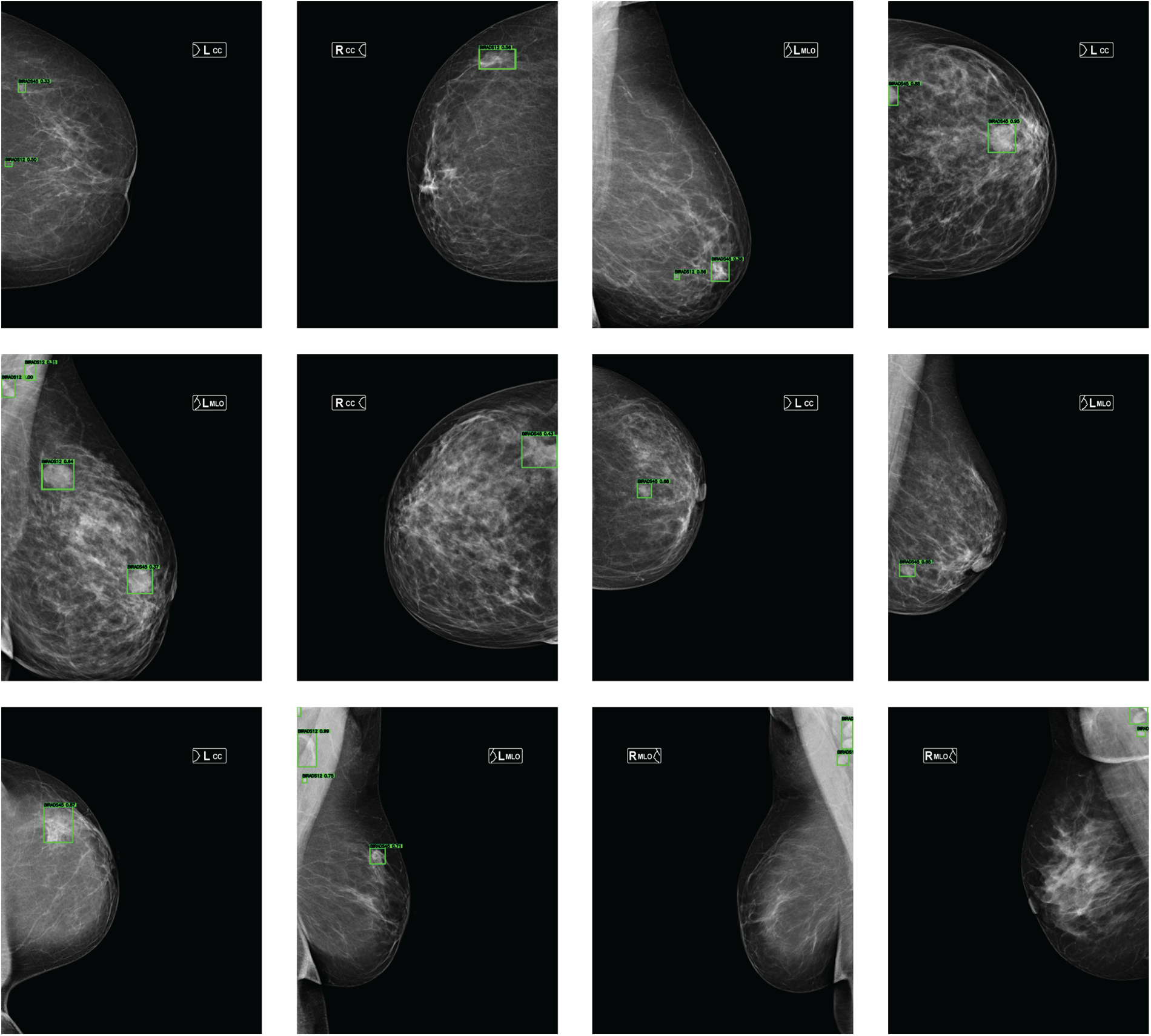

Fig. 3 presents represe + ntative detection examples obtained from mammograms of different patients. The Double-Head R-CNN successfully localizes lesion regions across both low- and high-density breast tissues, demonstrating consistent detection behavior under varying anatomical conditions.

Figure 3: Lesion detection examples on mammograms from different patients in the MammosighTR dataset. Detected regions are highlighted with green bounding boxes

Breast-based evaluation assesses model performance by treating each breast as an independent sample, enabling a more granular analysis of lesion localization and asymmetric findings. In this setting, the Macro F1-Score serves as the most reliable indicator, as it equally weights benign (BI-RADS12) and malignant (BI-RADS45) classes.

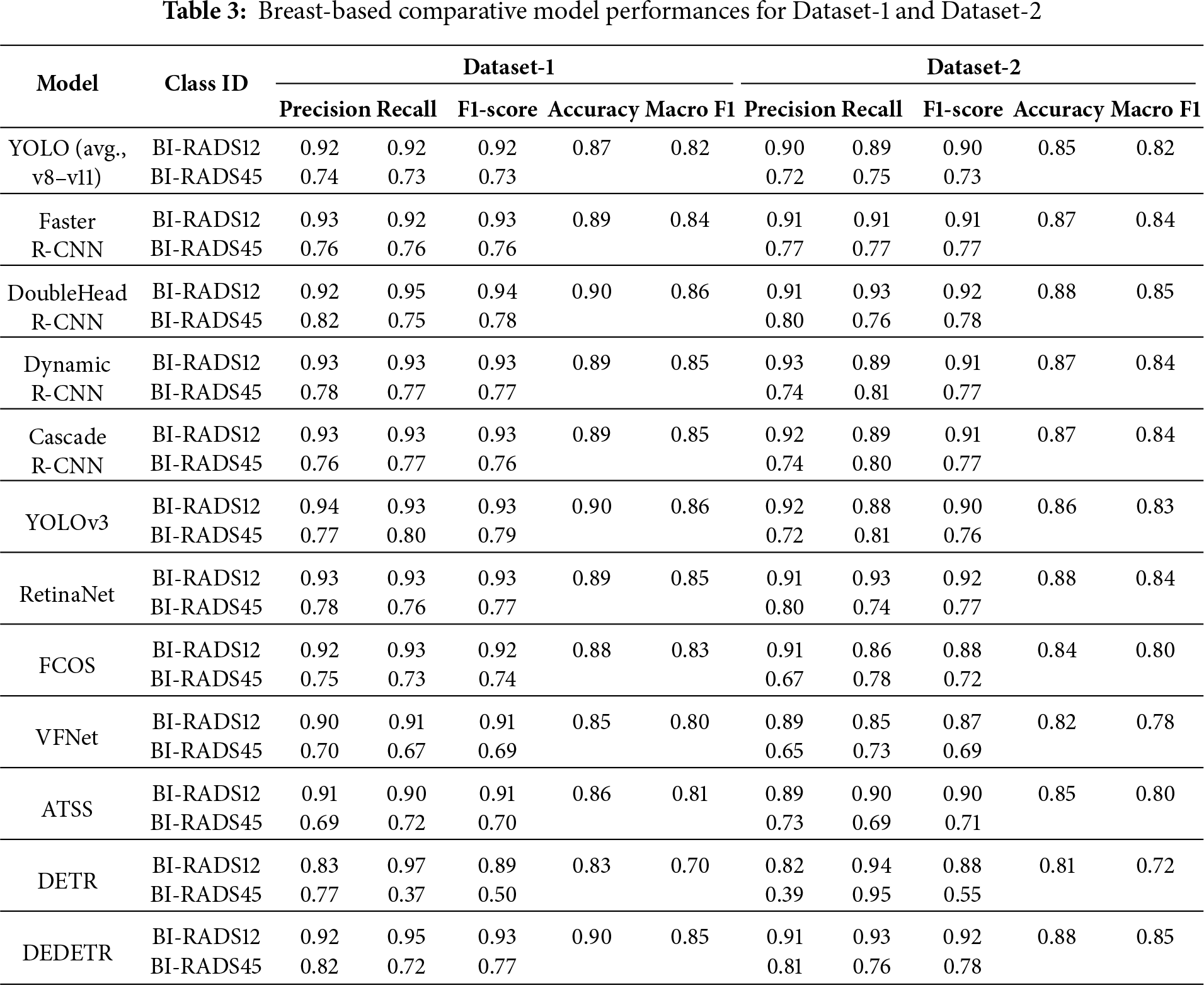

Breast-based evaluation results are summarized in Table 3, which reports Precision, Recall, F1-Score, Accuracy, and Macro F1-Score for both Dataset-1 and Dataset-2.

Across all evaluated models, breast-based Macro F1-Scores range between approximately 84%–86% for Dataset-1 and 83%–85% for Dataset-2. This indicates that most architectures achieve strong lesion-level discrimination and maintain balanced performance across classes.

The modest decrease of around 1%–2% observed in Dataset-2 can be attributed to increased variability and heterogeneity in the test data, rather than a fundamental degradation in model capability.

When examined by architectural family, Two-Stage detectors consistently achieve the highest average Macro F1-Scores. These models exhibit enhanced sensitivity for the BI-RADS45 category while preserving high Precision for benign cases, resulting in clinically reliable performance.

One-Stage models achieve comparable but slightly lower Macro F1-Scores, typically trailing Two-Stage approaches by 1–2%. This difference suggests that One-Stage architectures are more sensitive to class imbalance, despite their computational efficiency advantages.

Among Transformer-based architectures, Deformable DETR demonstrates stable breast-based performance across both datasets, whereas the classical DETR exhibits pronounced imbalance between Recall and Precision. This contrast highlights the importance of deformable attention mechanisms for robust lesion localization.

From a class-specific perspective, F1-Scores for BI-RADS12 consistently exceed those for BI-RADS45 across all architectures. While benign cases are identified with high accuracy, malignant cases remain more challenging due to visual ambiguity and lower prevalence. Nevertheless, overall Macro F1-Scores remain above 80% for all models, confirming robust inter-class balance.

These findings indicate that breast-based evaluation provides a reliable foundation for clinical decision-support systems and complements patient-based diagnosis by offering detailed localization insight.

3.5 Analysis of Model Stability across Breast Density Types

In this section, the diagnostic stability of the AI-based BI-RADS classification models was examined at the patient level under different breast density categories (A–D). Breast density is classified from least dense to most dense as A, B, C and D, and each category exhibits distinct imaging characteristics. The effect of high breast density on the performance of both radiologists and AI systems has been widely studied in previous research [36]. In this context, variations in FP and FN rates across breast density levels were evaluated to assess the models’ sensitivity and generalizability to dense tissue.

Accordingly, patient-based errors of the models were analyzed in relation to breast density. FP represents cases where the model incorrectly labels a benign patient as “at risk,” while FN refers to cases where a malignant patient is mistakenly classified as “normal.”

An analysis of the density ratios in both datasets revealed that, in Dataset-1, the proportions of categories A, B, C, and D were 15.38%, 38.24%, 31.25%, and 15.13%, respectively. In Dataset-2, the corresponding ratios were 12.45%, 41.75%, 35.65%, and 10.15%. These distributions indicate that, in both datasets, categories B and C are predominant, whereas categories A and D are underrepresented.

In the following sections, the influence of breast density is analyzed first for patient-based classification and then for breast-based classification.

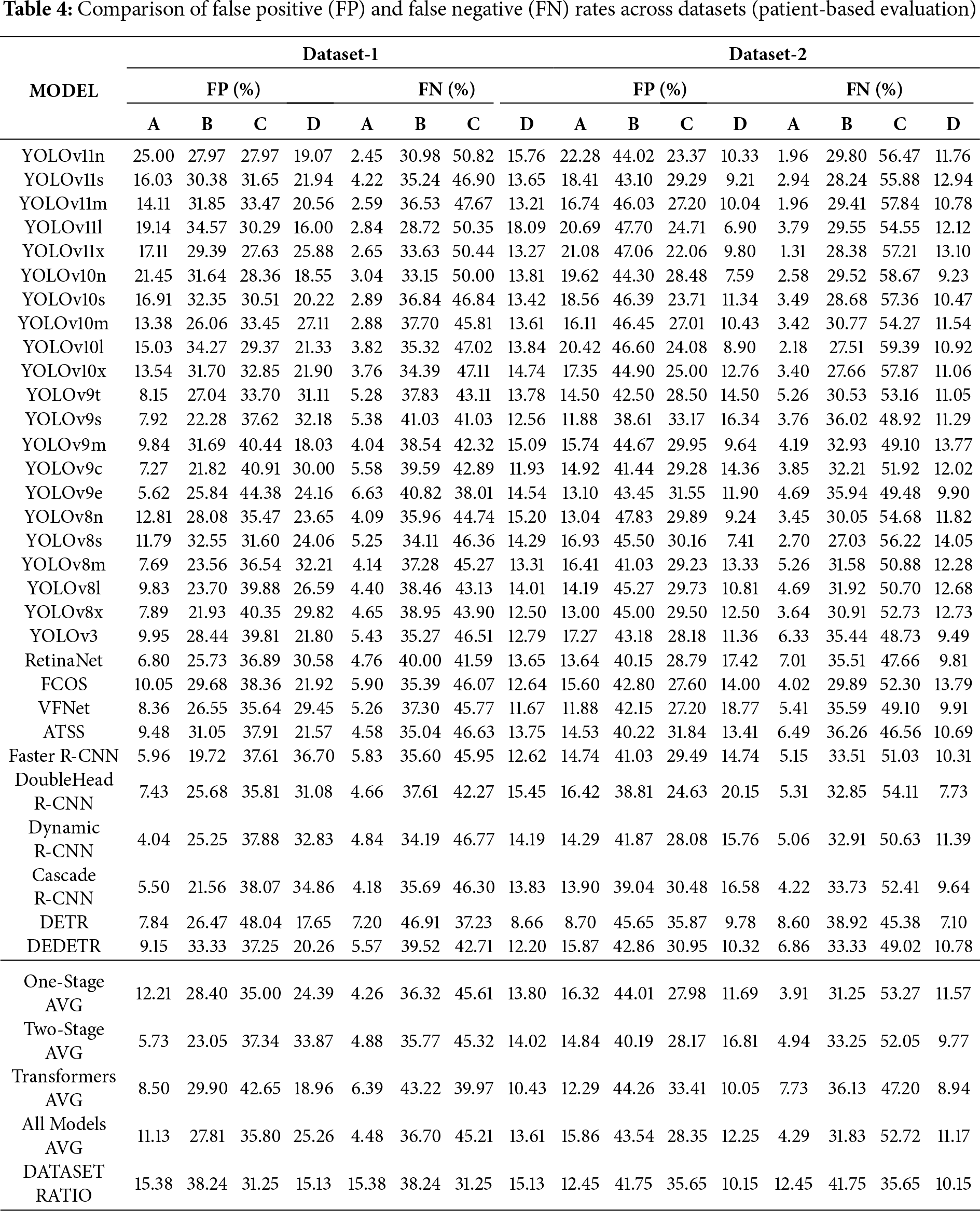

3.5.1 Patient Based Breast Density

Patient-based evaluation results are presented in Table 4. The tables present the proportional FP and FN values generated by all models according to breast density. At the bottom of each table, the architecture-based average results and the overall average values obtained from all models are listed. The dataset ratio row represents the ground-truth breast density distribution within the dataset.

The experimental results on Dataset-1 show that as breast density increases, both FP and FN rates vary notably. In type A breasts, FP and FN values are the lowest across all model groups. In types B and C, the error rates increase considerably, while in type D breasts, FP tends to decrease and FN, particularly in the transition from C to D, either partially decreases or stabilizes. These findings suggest that higher breast density may reduce FPs while slightly decreasing the likelihood of missing true lesions. Hence, tissue density appears to influence model errors in a differential rather than uniform manner.

When examined by architecture, One-Stage models generally produce more FPs than Two-Stage models but exhibit lower FN rates. This indicates that One-Stage models are more sensitive, with higher Recall but lower specificity. Two-Stage models maintain lower FP rates but slightly higher FN values relative to One-Stage models, which may result from the more conservative prediction strategy inherent to region-proposal-based architectures. In high-density categories (C and D), the increase in FP is more limited, suggesting that these architectures are more resistant to false-positive escalation caused by dense tissue. Transformer-based architectures demonstrate the most balanced FP performance and moderate FN levels. As density increases, FP fluctuations are more controlled compared with other groups, indicating that the global attention mechanism helps mitigate the adverse effects of dense tissue. All three architecture types show a noticeable performance drop within the B–C density range; however, in type D breasts, Transformer-based architectures, in particular, effectively limit performance degradation. This finding suggests that the adaptability of different model architectures to tissue complexity varies.

The Dataset Ratio presented at the bottom of the table is an important factor in interpreting model performance. The predominance of B and C categories in the dataset leads to greater variability in FP and FN values for these groups. This observation suggests that class imbalance may increase models’ sensitivity to density variations and cause errors to concentrate within these categories.

In the experiments conducted on Dataset-2, FP rates increased significantly for breasts with B-level density, whereas a decrease in FP rates was observed in categories C and D. In Dataset-2, the models exhibited excessive sensitivity in A–B cases but produced more conservative predictions in higher-density categories (C–D). This behavior indicates that the models developed more stable decision mechanisms when dealing with dense tissue structures. The shift between datasets resulted in varying performance changes across architectural groups, which can be attributed to differences in data distribution between the two datasets.

When both datasets are considered together, a systematic relationship between breast density and model errors becomes apparent. As density reaches intermediate levels (B–C), both FP and FN rates increase, showing that model decisions are most uncertain in this range. At high-density levels (D), models—particularly Transformer-based architectures—exhibit markedly greater stability. The error behavior of the same architectures varies significantly across datasets, revealing that the distributional characteristics of the data strongly influence performance.

In conclusion, breast density affects model performance by increasing both FP and FN rates at moderate density levels. Transformer-based architectures demonstrate higher robustness under dense conditions compared with other architectures, whereas One-Stage architectures show greater sensitivity to errors in medium-density cases.

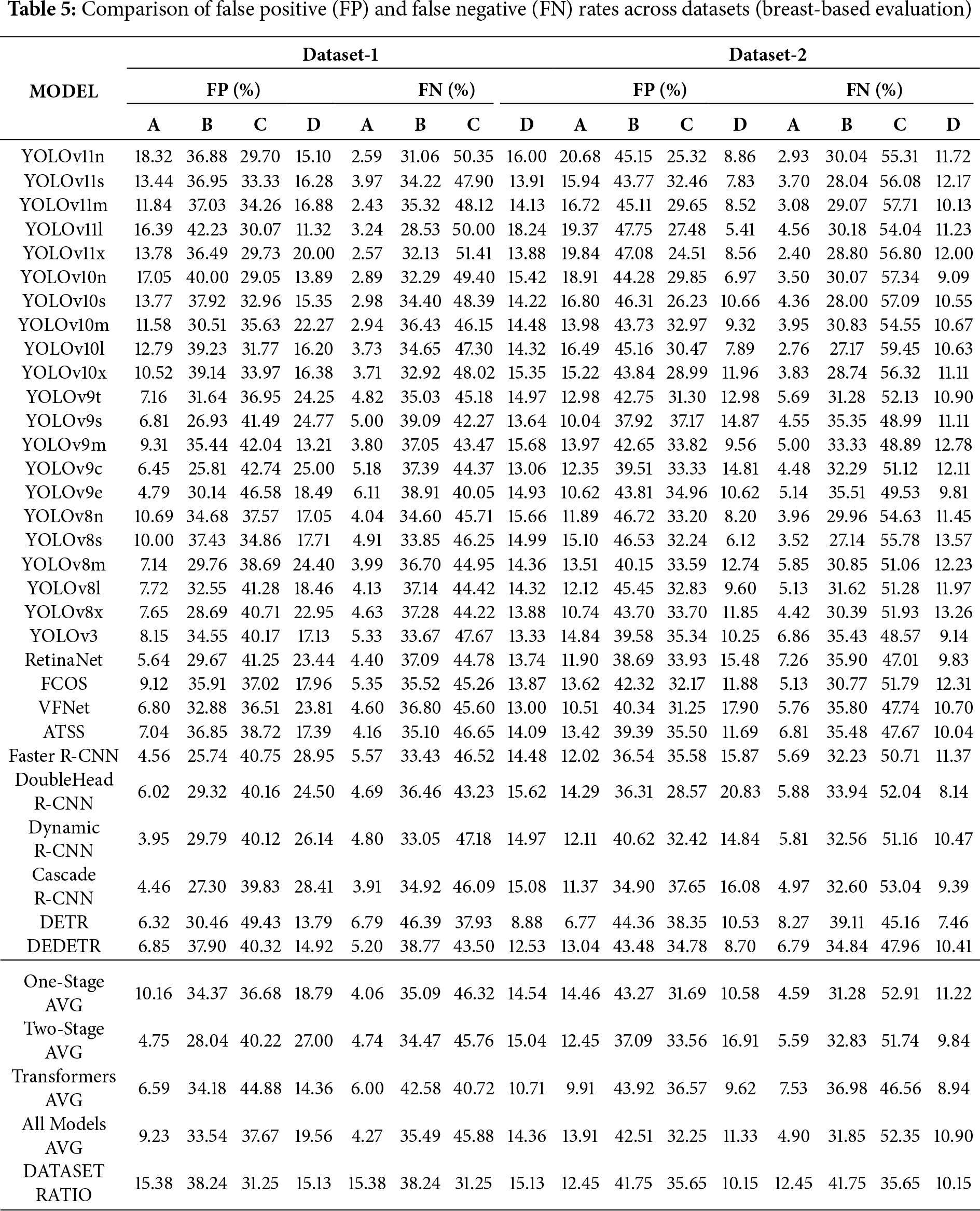

3.5.2 Breast Based Breast Density

In this section, the effect of breast density on breast-based classification is examined. The results show that breast density has a significant impact on the performance of AI models. In particular, both FP and FN rates increase noticeably in moderately dense (B and C) breasts. This pattern can be attributed to the structural complexity of tissues within this density range, which tends to blur the models’ decision boundaries. In contrast, the models perform more consistently in low-density (A) and extremely dense (D) breasts, resulting in lower error rates.

Breast-based evaluation results are presented in Table 5. The table reports, for each detection model, the percentage of FPs and FNs across the four density subcategories (A–D). For both Dataset-1 and Dataset-2, FP and FN rates are provided side by side, enabling direct comparison across datasets and model families. This presentation allows for a clearer analysis of model tendencies toward over-detection or under-detection under different data distributions and breast density configurations.

When the two datasets are compared, the higher representation of B and C categories corresponds to increased error rates within these density levels. This finding suggests that the models’ error behavior is influenced not only by architectural differences but also by the distribution of data. From an architectural standpoint, One-Stage models appear to be the most sensitive to changes in breast density, while Two-Stage models yield more stable performance in low-density cases. Transformer-based architectures, particularly in high-density (D) categories, achieve the most balanced results by maintaining the lowest FP and FN rates.

Overall, breast-based evaluation provides more realistic and consistent results compared with patient-based analysis. The findings indicate that the models experience performance degradation in moderately dense breasts but regain stability in highly dense tissue. Future research should therefore focus on data balancing and adaptive modeling strategies specifically designed to address the challenges presented by B and C density levels.

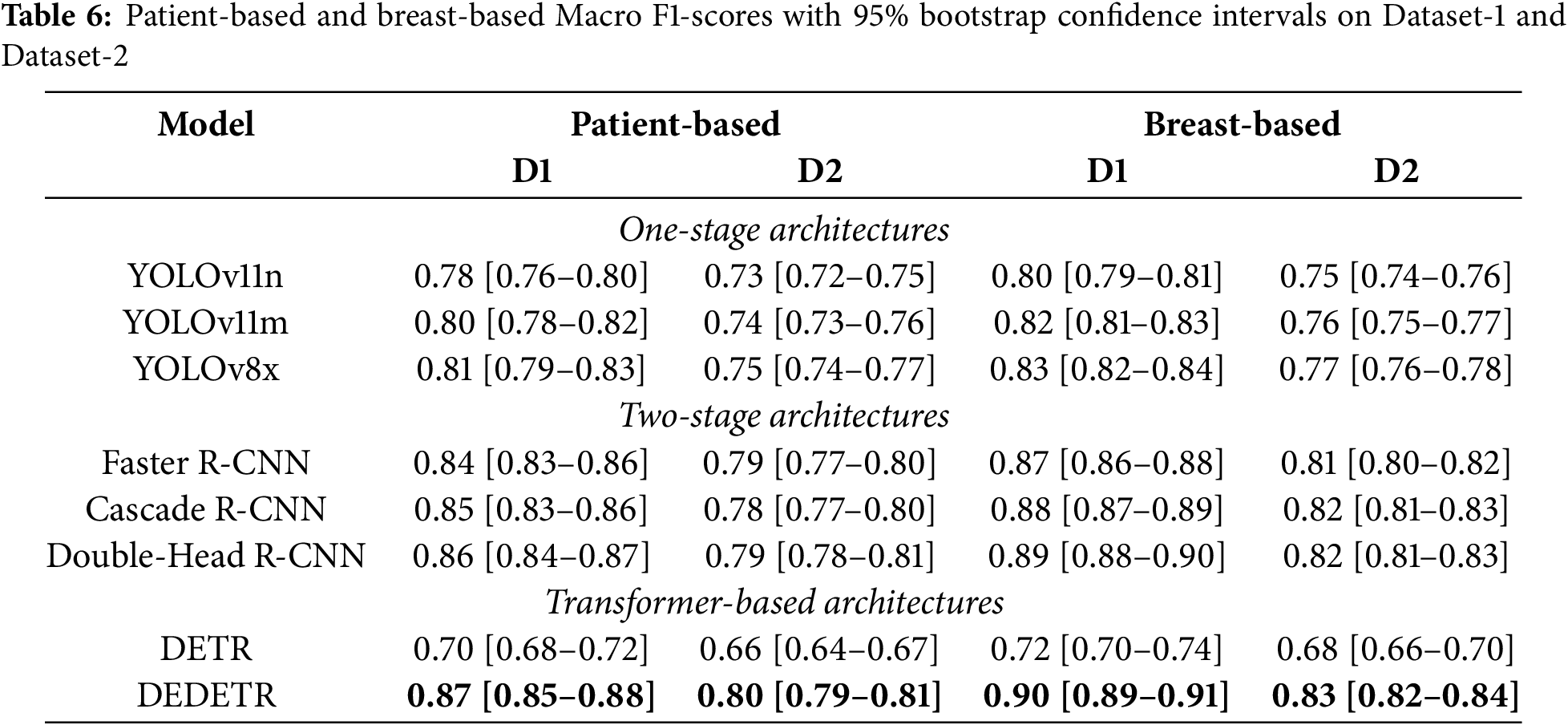

3.6 Bootstrap-Based Statistical Validation

Table 6 summarizes the patient-based and breast-based Macro F1-scores together with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) for representative models evaluated on Dataset-1 and Dataset-2. Bootstrap analysis was conducted for all investigated detection models; however, to ensure clarity and readability, the main table reports a subset of representative architectures selected from each detector family, including One-Stage, Two-Stage, and Transformer-based architectures.

For patient-based analysis, the summarized results indicate that models achieving higher average performance also tend to exhibit relatively narrow confidence intervals, suggesting stable behavior under resampled test conditions. In particular, Two-Stage detectors consistently maintain high Macro F1-scores with limited performance variability across both datasets, highlighting their robustness across different data distributions.

A noticeable performance degradation is observed when transitioning from Dataset-1 to Dataset-2 for most architectures, reflecting the increased difficulty and distributional shift of the independent test set. Nevertheless, the relative ranking of models remains largely consistent, and the substantial overlap among the confidence intervals of top-performing approaches indicates comparable performance levels rather than isolated superiority of a single model.

Similar to the patient-based analysis, breast-based bootstrap evaluation was performed for all models, with the main table presenting representative results for clarity. Compared to patient-based evaluation, breast-based analysis yields slightly higher Macro F1-scores and narrower confidence intervals across all architectural families. This behavior is expected due to the increased number of evaluation samples at the breast-based and further confirms the robustness and consistency of the observed performance trends.

The findings of this study provide important insights into the use of DL–based OD models for automated mammography analysis. Across both datasets, Two-Stage detectors consistently demonstrate superior diagnostic reliability, characterized by higher Precision and more stable Macro F1-Scores. This behavior highlights the continued relevance of region-proposal–based architectures in clinical screening scenarios, where reducing false positives and avoiding unnecessary biopsies are critical considerations.

Transformer-based architectures, particularly the Deformable DETR, emerge as a strong alternative to conventional CNN-based detectors. Unlike the classical DETR, which exhibits notable performance instability, the Deformable DETR achieves competitive accuracy with improved robustness across datasets and evaluation granularities. These results suggest that attention mechanisms can enhance spatial reasoning and contextual understanding in complex breast tissue. Nevertheless, the higher computational cost of Transformer-based architectures currently limits their scalability in large-scale screening, motivating future exploration of hybrid or lightweight attention-based designs.

The bootstrap-based statistical validation further supports these observations. The relatively narrow 95% confidence intervals obtained for Two-Stage models indicate limited performance variability under resampling, reinforcing their stability. In contrast, Transformer-based architectures display more heterogeneous behavior, with Deformable DETR showing substantially improved confidence bounds compared to the original DETR. The overall narrower intervals at the breast level additionally suggest consistent lesion localization across evaluation granularities.

The observed performance degradation on Dataset-2 underscores the challenge of domain generalization in real-world screening environments. Variations in data distribution, imaging conditions, and annotation characteristics likely contribute to this decline. These findings highlight the importance of future work on domain adaptation, transfer learning, and contrast normalization strategies to improve robustness under distributional shifts.

Breast density remains a key factor influencing detection performance. Higher error rates in moderate-density breasts (BI-RADS B–C) are consistent with challenges reported in clinical practice. However, this analysis is affected by the inherent imbalance of density categories in the dataset, where B and C densities are substantially overrepresented. As a result, the observed trends may partially reflect greater statistical power rather than intrinsic detection difficulty alone. Despite this limitation, consistent architectural performance patterns across density categories suggest that the reported findings are not driven solely by sample size effects.

From a clinical workflow perspective, the results emphasize the complementary roles of different evaluation granularities. Patient-based performance directly supports screening and recall decisions, whereas breast-based evaluation provides detailed lesion localization that aids interpretability during radiological review. Accordingly, reporting both perspectives offers a more comprehensive assessment of clinical utility rather than prioritizing a single evaluation level.

Despite the comprehensive evaluation presented, several methodological considerations should be acknowledged. The models evaluated in this study were adopted from open-source implementations and utilized in their pre-trained form rather than being trained from scratch on the MammosighTR dataset. As a result, some of the observed performance differences may be influenced by dataset compatibility and pre-training biases, rather than reflecting purely architectural superiority.

In addition, confidence threshold optimization was performed separately for Dataset-1 and Dataset-2 in order to reflect realistic deployment conditions for each evaluation setting. While this approach improves within-dataset fairness, it may also introduce dataset-specific tuning effects that limit direct cross-dataset generalization claims. Nevertheless, the primary objective of this study is to benchmark architectural behavior under clinically relevant operating conditions using a large, nationally representative screening dataset, rather than to identify universally optimal hyperparameter configurations.

Overall, the performance ranges observed in this study are consistent with recent large-scale investigations of AI-assisted screening reported in the literature [37,38]. While direct numerical comparisons across studies remain limited by differences in datasets and evaluation protocols, the alignment of performance trends supports the external relevance of our findings. Future research should focus on external validation across diverse populations, density-balanced evaluation, and the integration of explainability mechanisms to facilitate safe and effective clinical adoption.

This study presents a comprehensive benchmark analysis of state-of-the-art OD architectures using the nationally representative MammosighTR dataset, which contains more than 12,700 patient cases collected through Türkiye’s National Breast Cancer Screening Program. The evaluation encompassed One-Stage (YOLO, RetinaNet, FCOS, ATSS, VFNet), Two-Stage (Faster R-CNN, Cascade R-CNN, Dynamic R-CNN, Double-Head R-CNN), and Transformer-based (DETR, Deformable DETR) architectures to assess their diagnostic effectiveness in AI-assisted mammography.

Experimental results demonstrate that Two-Stage architectures consistently achieved the highest and most stable performance across both patient-based and breast-based analyses. In particular, Double-Head R-CNN and Dynamic R-CNN reached Macro F1-Scores in the range of approximately 0.84–0.86, outperforming One-Stage detectors by approximately 2%–4%. This performance advantage is mainly attributed to the region proposal mechanism and the improved balance between Precision and Recall, which resulted in more reliable discrimination between benign and malignant cases.

Transformer-based architectures showed a clear architectural progression. While the classical DETR model underperformed, the Deformable DETR variant achieved Macro F1-Scores of approximately 0.83–0.85, with less than 1%–2% performance variation across datasets, indicating strong robustness to data heterogeneity and distributional shifts. In contrast, One-Stage architectures, particularly YOLOv8–v11, maintained high sensitivity with Recall values frequently exceeding 0.88 and superior computational efficiency, making them well suited for real-time screening scenarios, albeit with minor reductions in Precision and overall accuracy (

Breast density–based analysis further revealed that diagnostic errors were most pronounced in intermediate-density tissue types (B and C), where both false positive and false negative rates peaked across all architectures. Conversely, performance was more stable in high-density type D breasts, especially for Transformer-based architectures, which exhibited reduced error fluctuations. These findings quantitatively confirm that tissue characteristics significantly influence model behavior and that architectural adaptability varies across detector families.

In conclusion, this study establishes a reproducible and quantitatively grounded framework for benchmarking AI-based mammography detection systems. The results highlight that while Two-Stage detectors offer superior accuracy and class balance, and One-Stage models provide speed and sensitivity, Transformer-based architectures contribute robustness and contextual modeling capacity. Combining these complementary strengths may enable the development of next-generation, clinically deployable breast cancer screening systems that are both highly accurate and explainable.

Despite the comprehensive scope of this benchmark, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study evaluates pre-trained object detection models without additional task-specific training or fine-tuning on the MammosighTR dataset; therefore, the reported performance reflects architectural robustness rather than dataset-adaptive optimization. Second, while predefined and non-overlapping dataset partitions were intentionally preserved to ensure unbiased evaluation, the absence of external datasets limits direct assessment of cross-population generalizability.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research received no external funding.

Availability of Data and Materials: The MammosighTR dataset used for this study is publicly available as described in the cited reference [17]. Additional data or analysis code can be provided upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. World Health Organization. Breast Cancer. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer. [Google Scholar]

2. Dromain C, Balleyguier C, Adler G, Garbay JR, Delaloge S. Contrast-enhanced digital mammography. Eur J Radiol. 2009;69(1):34–42. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.07.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Widely I. Variability in the interpretation of screening mammograms by US radiologists. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(2):209–13. doi:10.1001/archinte.1996.00440020119016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Pisano ED, Gatsonis C, Hendrick E, Yaffe M, Baum JK, Acharyya S, et al. Diagnostic performance of digital versus film mammography for breast-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17a):1773–83. doi:10.1056/nejmoa052911. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Litjens G, Kooi T, Bejnordi BE, Setio AAA, Ciompi F, Ghafoorian M, et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med Image Anal. 2017;42(13):60–88. doi:10.1016/j.media.2017.07.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Tasyurek M, Gul E. A new deep learning approach based on grayscale conversion and DWT for object detection on adversarial attacked images. J Supercomput. 2023;79(18):20383–416. doi:10.1007/s11227-023-05456-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Sagiroglu S, Terzi R, Celtikci E, Börcek AÖ, Atay Y, Arslan B, et al. A novel brain tumor magnetic resonance imaging dataset (Gazi Brains 2020initial benchmark results and comprehensive analysis. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2025;11(1):e2920. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.2920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Chen Y, Shao X, Shi K, Rominger A, Caobelli F. AI in breast cancer imaging: an update and future trends. Semin Nucl Med. 2025;55(3):358–70. doi:10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2025.01.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jairam MP, Ha R. A review of artificial intelligence in mammography. Clin Imaging. 2022;88(9855):36–44. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2022.05.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Zamzam P, Rezaei P, Khatami SA, Appasani B. Super perfect polarization-insensitive graphene disk terahertz absorber for breast cancer detection using deep learning. Opt Laser Technol. 2025;183(10):112246. doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2024.112246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chen JL, Cheng LH, Wang J, Hsu TW, Chen CY, Tseng LM, et al. A YOLO-based AI system for classifying calcifications on spot magnification mammograms. Biomed Eng Online. 2023;22(1):54. doi:10.1186/s12938-023-01115-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Carion N, Massa F, Synnaeve G, Usunier N, Kirillov A, Zagoruyko S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. p. 213–29. [Google Scholar]

13. Kim J, Kim J, Dharejo FA, Abbas Z, Lee SW. Lightweight mamba model for 3D tumor segmentation in automated breast ultrasounds. Mathematics. 2025;13(16):2553. doi:10.3390/math13162553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Moreira IC, Amaral I, Domingues I, Cardoso A, Cardoso MJ, Cardoso JS. Inbreast: toward a full-field digital mammographic database. Acad Radiol. 2012;19(2):236–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Lee RS. Curated breast imaging subset of DDSM (CBIS-DDSM). The cancer imaging archive. 2016 [cited 2026 Oct 16]. Available from: https://wiki.cancerimagingarchive.net/display/Public/CBIS-DDSM. [Google Scholar]

16. Suckling J, Parker J, Astley S, Hutt I, Boggis C, Ricketts IW, et al. The mammographic images analysis society digital mammogram databases. In: Excerpta Medica International Congress Series. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Excerpta Medica Foundation; 1994. p. 375–8. [Google Scholar]

17. Koç U, Karakaş E, Sezer EA, Beşler MS, Özkaya YA, Evrimler Ş, et al. MammosighTR: nationwide breast cancer screening mammogram dataset with BI-RADS annotations for artificial intelligence applications. Radiol Artif Intell. 2025;7(6):e240841. doi:10.1148/ryai.240841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang S, Chi C, Yao Y, Lei Z, Li SZ. Bridging the gap between anchor-based and anchor-free detection via adaptive training sample selection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2020; 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 9759–68. [Google Scholar]

19. Zhang H, Wang Y, Dayoub F, Sunderhauf N. Varifocalnet: an IoU-aware dense object detector. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 8514–23. [Google Scholar]

20. Cai Z, Vasconcelos N. Cascade R-CNN: delving into high quality object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 6154–62. [Google Scholar]

21. Terzi R, Azginoglu N. A novel pipeline on medical object detection for bias reduction: preliminary study for brain MRI. In: Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Innovations in Intelligent Systems and Applications (INISTA); 2021 Aug 25–27; Kocaeli, Turkey. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

22. Terzi R, Azginoglu N, Terzi DS. False positive repression: data centric pipeline for object detection in brain MRI. Concurr Comput Pract Exp. 2022;34(20):e6821. doi:10.1002/cpe.6821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. TEKNOFEST. Official website. 2025 [cited 2026 Oct 16]. Available from: https://www.teknofest.org/en/. [Google Scholar]

24. Mustra M, Delac K, Grgic M. Overview of the DICOM standard. In: Proceedings of the 2008 50th International Symposium ELMAR; 2008 Sep 12–18; Zadar, Croatia. p. 39–44. [Google Scholar]

25. Terzi R, Kılıç AE, Karaahmetoğlu G, Özdemir OB. The digital eye for mammography: deep transfer learning and model ensemble based open-source toolkit for mass detection and classification. Signal Image Video Proc. 2025;19(2):170. doi:10.1007/s11760-024-03737-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chen K, Wang J, Pang J, Cao Y, Xiong Y, Li X, et al. MMDetection: open mmlab detection toolbox and benchmark. arXiv:190607155. 2019. [Google Scholar]

27. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 779–88. [Google Scholar]

28. Girshick R, Donahue J, Darrell T, Malik J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2014 Jun 23–28; Columbus, OH, USA. p. 580–7. [Google Scholar]

29. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2016;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/tpami.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Lin TY, Goyal P, Girshick R, He K, Dollár P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2980–8. [Google Scholar]

31. Tian Z, Shen C, Chen H, He T. Fcos: fully convolutional one-stage object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 9627–36. [Google Scholar]

32. Zhang H, Chang H, Ma B, Wang N, Chen X. Dynamic R-CNN: towards high quality object detection via dynamic training. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. p. 260–75. [Google Scholar]

33. Zhu X, Su W, Lu L, Li B, Wang X, Dai J. Deformable detr: deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv:201004159. 2020. [Google Scholar]

34. Sokolova M, Lapalme G. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Inf Process Manag. 2009;45(4):427–37. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2009.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Opitz J, Burst S. Macro f1 and macro f1. arXiv:191103347. 2019. [Google Scholar]

36. Kwon M, Chang Y, Ham SY, Cho Y, Kim EY, Kang J, et al. Screening mammography performance according to breast density: a comparison between radiologists versus standalone intelligence detection. Breast Cancer Res. 2024;26(1):68. doi:10.1186/s13058-024-01821-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. McKinney SM, Sieniek M, Godbole V, Godwin J, Antropova N, Ashrafian H, et al. International evaluation of an AI system for breast cancer screening. Nature. 2020;577(7788):89–94. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1799-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Marinovich ML, Wylie E, Lotter W, Lund H, Waddell A, Madeley C, et al. Artificial intelligence (AI) for breast cancer screening: breastScreen population-based cohort study of cancer detection. EBioMedicine. 2023;90(12):104498. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools