Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Robust Vision-Based Framework for Traffic Sign and Light Detection in Automated Driving Systems

1 School of Electronic and Control Engineering, Chang’an University, Xi’an, 710064, China

2 Department of Mechatronics Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Sana’a University, Sana’a, 11311, Yemen

3 Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Computing and Information Technology, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 21589, Saudi Arabia

4 School of Computer Science and Engineering, Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210094, China

5 School of Resources and Environment, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, 610054, China

6 School of Information, Xi’an University of Finance and Economics, Xi’an, 710100, China

* Corresponding Authors: Mohammed Al-Mahbashi. Email: ; Abdolraheem Khader. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Machine Learning and Deep Learning-Based Pattern Recognition)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 40 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.075909

Received 11 November 2025; Accepted 25 December 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

Reliable detection of traffic signs and lights (TSLs) at long range and under varying illumination is essential for improving the perception and safety of autonomous driving systems (ADS). Traditional object detection models often exhibit significant performance degradation in real-world environments characterized by high dynamic range and complex lighting conditions. To overcome these limitations, this research presents FED-YOLOv10s, an improved and lightweight object detection framework based on You Only look Once v10 (YOLOv10). The proposed model integrates a C2f-Faster block derived from FasterNet to reduce parameters and floating-point operations, an Efficient Multiscale Attention (EMA) mechanism to improve TSL-invariant feature extraction, and a deformable Convolution Networks v4 (DCNv4) module to enhance multiscale spatial adaptability. Experimental findings demonstrate that the proposed architecture achieves an optimal balance between computational efficiency and detection accuracy, attaining an F1-score of 91.8%, and mAP@0.5 of 95.1%, while reducing parameters to 8.13 million. Comparative analyses across multiple traffic sign detection benchmarks demonstrate that FED-YOLOv10s outperforms state-of-the-art models in precision, recall, and mAP. These results highlight FED-YOLOv10s as a robust, efficient, and deployable solution for intelligent traffic perception in ADS.Keywords

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and computer vision (CV) have significantly influenced modern transportation engineering, particularly in the development of autonomous driving systems (ADS). Deep learning–based methods now play a central role in key tasks such as lane detection [1], vehicle and pedestrian detection [2], and driver distraction detection [3–5]. Among these applications, automatic traffic sign detection (TSD) has become especially important. By enabling real-time identification of traffic signs, TSD systems provide both drivers and ADS with immediate updates on road conditions, thereby enhancing situational awareness and supporting timely and reliable decision-making in complex traffic environments.

Despite substantial progress, achieving robust TSD performance in real-world conditions remains challenging. Small and distant traffic signs, variations in illumination, and adverse weather conditions continue to degrade detection accuracy. Many existing models perform well in controlled environments but exhibit significant performance drops when confronted with motion blur, rain, fog, or low-light scenarios. Furthermore, limitations in adapting to scale variations and environmental noise often result in missed detections or false positives. These persistent gaps highlight the need for more adaptive and resilient detection frameworks capable of generalizing to the diverse and unpredictable conditions encountered in practical driving environments.

TSD techniques are generally divided into two main parts: traditional machine learning and deep learning (DL)-based approaches. Machine learning (ML) techniques depend on manually designed feature information [6] to identify attributes such as color, shape, and contour [7]. However, this process requires extensive prior knowledge and effort, and the resulting models often lack robustness and generalization, particularly in complex environments. In contrast, DL has revolutionized the field of object detection by allowing neural networks to automatically learn hierarchical features from large datasets, thereby improving model stability and adaptability [8]. DL-based techniques can be further classified into two categories: two-stage and one-stage detection frameworks. Two-stage detectors, such as Cascaded R-CNN, Faster R-CNN, and Mask R-CNN [9–11], offer high accuracy but demand significant computational resources, limiting their real-time applicability. In contrast, one-stage detectors, including SSD [12] and the YOLO series [13–15], achieve faster detection speeds but often struggle with small object recognition, leading to higher miss rates and reduced precision.

The YOLO family of detectors has undergone continuous architectural improvements and remains one of the most widely used object detection frameworks due to its balance of speed and accuracy. Building on this foundation, the present study enhances YOLO’s effectiveness for traffic sign and light (TSL) detection through the integration of attention mechanisms and improved feature extraction designed to increase robustness under varying lighting conditions. Considering these challenges, we propose an innovative deep learning framework, FED-YOLOv10s, which is more robust, adaptive, and comprehensive. This model incorporates significant modifications to the YOLOv10 architecture, leading to higher detection accuracy compared with other state-of-the-art methods. Furthermore, data augmentation techniques, including zooming and brightness adjustments, were applied to enhance dataset diversity and improve generalization. The experimental findings demonstrate that FED-YOLOv10s can accurately detect TSLs under diverse lighting conditions, enabling reliable and timely decision-making in ADS. The essential contributions of this research can be summarized as follows:

1. Conducted a comprehensive and critical review of existing literature on TSL detection, identifying key limitations in accuracy, robustness, and adaptability under complex environmental conditions.

2. Developed a new TSL dataset in Xi’an, encompassing a diverse range of real-world samples and illumination scenarios to better represent the challenges of practical autonomous driving environments.

3. Designed a lightweight FED-YOLOv10s model by optimizing the YOLOv10 architecture to reduce computational complexity and parameter count while enhancing detection accuracy and robustness for real-time TSL recognition.

4. Implemented and evaluated the proposed model on Jetson Nano and Jetson Xavier NX embedded platforms, demonstrating its high efficiency, low latency, and suitability for real-time intelligent transportation applications.

The proposed model in this study demonstrates significant improvement over existing state-of-the-art approaches. Section 2 provides a brief overview of relevant research on traffic sign and public object detection. Section 3 details the methodology of the proposed TSL detection model, which is based on an improved YOLOv10 framework. Section 4 presents an analysis of the experimental outcomes. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the main findings and conclusions of this research.

TSD has been an active research area since the 1970s, evolving significantly from early handcrafted approaches to modern DL-based frameworks. Traditional methods primarily relied on low-level visual features such as color, shape, or a combination of both to identify traffic signs [16,17]. For instance, de la Escalera et al. [18] utilized color segmentation followed by shape analysis to detect signs, while Fleyeh [19] converted RGB images into the IHLS color space to enhance the effectiveness of color-based segmentation. Although these techniques were straightforward to implement, their performance was often hindered by environmental variables such as lighting changes, weather conditions, occlusions, and sign degradation. Additionally, internal factors, including limited processing speed and classification accuracy further constrained their applicability in real-time systems.

The introduction of ML techniques marked a turning point in the evolution of TSD. Models like support vector machines (SVMs) enabled more sophisticated classification based on extracted features. For instance, Maldonado-Bascón et al. [20] applied SVMs to shape classification and content recognition tasks, demonstrating improved performance over earlier methods. More recently, the emergence of DL, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have revolutionized the field. CNNs enable automatic extraction of hierarchical, data-driven information directly from raw images, eliminating the need for manual feature design and substantially enhancing detection accuracy and generalizability across diverse scenarios [21].

With the growing adoption of artificial intelligence in intelligent transportation systems (ITS), DL techniques, particularly CNNs, have become fundamental in TSD as a result of their ability to efficiently extract features and process images through local connectivity and weight sharing. R-CNN, one of the earliest CNN-based detection models, utilizes selective search to create region proposals. Each candidate region is then cropped, processed through a CNN for feature extraction, and classified using separate classifiers and regression models. While effective, this method suffers from slow processing speeds due to redundant computations, as demonstrated by Girshick et al. [22]. To enhance efficiency, Girshick [23] introduced the Fast R-CNN framework, an end-to-end training model that includes a Region of Interest (ROI) pooling layer, which standardizes candidate regions of various sizes into fixed-size feature maps. This model significantly improves computational efficiency by enabling shared feature extraction across all regions on the feature map. The evolution continued with Faster R-CNN, proposed by Ren et al. [24], which replaced selective search with a CNN-based method for generating high-quality region proposals in real-time. This advancement not only improved detection speed but also reduced redundant computations. Collectively, these methods are known as two-stage detection models, as they divide the detection process into three steps: generating region proposals, classifying objects, and refining boundaries through regression.

In the same specific context of traffic sign recognition, Han et al. [25] developed an improved Faster R-CNN approach tailored for recognizing small traffic signs in real-time. This model introduced a specialized small-area proposal generator to better capture features from small-scale signs and incorporated Online Hard Example Mining (OHEM) to enhance robustness in detecting challenging traffic signs. This approach led to a 12.1% increase in mAP compared to the baseline model. Nevertheless, the computational intensity of two-stage models limits their real-time applicability. To overcome these obstacles, Wu and Liao [26], based on the work of Liu et al. [27], proposed a novel approach that integrates the Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD) with the Path Aggregation Network (PANet). This model achieved an excellent mAP of 95.9% on the CCTSDB dataset. Despite its high precision, the model’s substantial computational and storage requirements pose challenges for resource-constrained environments.

For single-stage detection methods, the YOLO series models have gained popularity in industrial detection due to their remarkable speed and high precision, in addition to its high architectural scalability. Gheorghe et al. [28] presented a comprehensive review of the YOLO algorithm for real-time object detection in automotive applications, emphasizing its rapid advancements and impact on modern transportation, particularly autonomous vehicles. The study includes a bibliometric analysis that classifies YOLO applications into three main domains: road traffic, autonomous vehicle development, and industrial settings. Their findings indicate that the YOLOv8 architecture achieves a mAP of 0.99, highlighting its high effectiveness in these applications. Fan et al. [29] modified YOLOv3 by incorporating DenseNet as the backbone network, enabling more efficient feature extraction to enhance detection speed. Jia et al. [30] presented a lightweight convolutional structure that integrates a spatial pyramid pooling fusion module. This model replaces conventional convolution layers in the detector head with depth-separable convolution, significantly minimizing computational complexity without compromising accuracy, achieving a 6.7% increase in mAP compared to the baseline model. Likewise, Yan et al. [31] sought to improve YOLOv5’s small object detection performance by introducing a supplementary information enhancement module. Their model incorporates a context improvement mechanism to capture both global and local image information and integrates high- and low-frequency features extracted via wavelet transform into the PANet, facilitating better multi-scale feature representation. This strategy effectively addresses the issue of small object features being lost during down-sampling and pooling operations, leading to a 9.5% increase in mAP compared to the benchmark method. Yu et al. [32] integrated YOLOv3 with the VGG19 network, enhancing the correlation between input sequences and images and improving detection efficiency. Similarly, Song and Suandi [33] employed the K-means++ clustering technique to refine anchor boxes for traffic light dimensions in a YOLOv4-based approach. Additionally, they presented a module of lightweight Brain-Environment Cross-Attention (BECA) attention to improve detection performance under adverse weather and varying lighting conditions. These developments demonstrate YOLO’s ability to achieve reliable and accurate detection outcomes even in complex traffic sign recognition scenarios. Small traffic sign objects, in particular, are prone to missed detections, as they occupy only a small portion of an image’s pixel count. To solve this issue, Hu et al. [34] introduced a deformable convolution module within the YOLOv5 framework, improving small-object traffic signs recognition by enhancing the model’s adaptability. Wang et al. [35] proposed AF-FPN, an advanced feature pyramid network built upon YOLOv5, designed specifically for multi-scale traffic sign detection. By combining a feature improvement module and an adaptive attention mechanism, the model reduces information loss during feature mapping and improves focus on critical features. Experimental results on the TT-100K dataset demonstrated superior detection performance across varying sign scales, although challenges such as false positives and missed detections persist.

Attention mechanisms have become a critical component in improving model performance by focusing on essential features while filtering out irrelevant ones. Based on that, several studies have explored ways to integrate attention mechanisms into TSD frameworks. YOLOv4-Tiny, Shen et al. [36] proposed an enhanced lightweight traffic sign recognition algorithm by incorporating depthwise separable convolution and the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) to improve the information extraction capability of both the backbone and detection head, leading to a 6.52% increase in mAP compared to the baseline method, though it introduced challenges related to excessive memory access. Similarly, Qu et al. [37] presented a modified YOLOv5s model for small object detection, embedding a lightweight coordinate attention module within the backbone. By encoding positional information directly into channel attention, their approach enhanced the algorithm’s ability to capture fine-grained features, achieving a mAP of 82.8% on the CCTSDB database. In the same year, Wang et al. [38] addressed feature refinement at the channel level by developing C2Net, which presents Squeeze-and-Excitation Attention (SE) into channel attention. With this refinement, their model reached a mAP of 84.2% on the TT-100K database, although SE attention remains limited to channel-level adjustments without addressing spatial dimensions. To further advance small object detection, Zhou et al. [39] presented a new TSD method that integrates explicit visual center fusion and Selective Kernel (SK) attention within a YOLOv5-based framework. By leveraging SK attention to extract and weight multi-scale features [40] and capturing localized features with visual center fusion, this model significantly improved small object detection, achieving a mAP of 88.5% on the TT-100K database. Despite these advances, YOLO-based models still face notable limitations in complex environments, particularly in detecting small, densely packed objects, where precision often deteriorates due to feature loss from repeated down-sampling and pooling operations. These challenges underscore the need for further refinement of YOLO’s architecture to improve its robustness and accuracy under real-world conditions.

This study proposes a real-time TSL detection system to improve environmental perception and decision-making in ADS. The proposed model is implemented on embedded computing platforms (Jetson Xavier NX and Jetson Nano) and is based on an improved YOLOv10 architecture, referred to as FED-YOLOv10s, which is specifically optimized for TSL detection in autonomous vehicles. While retaining the core structure of YOLOv10, FED-YOLOv10s integrates several architectural enhancements to improve detection efficiency, accuracy, and adaptability under diverse real-world conditions.

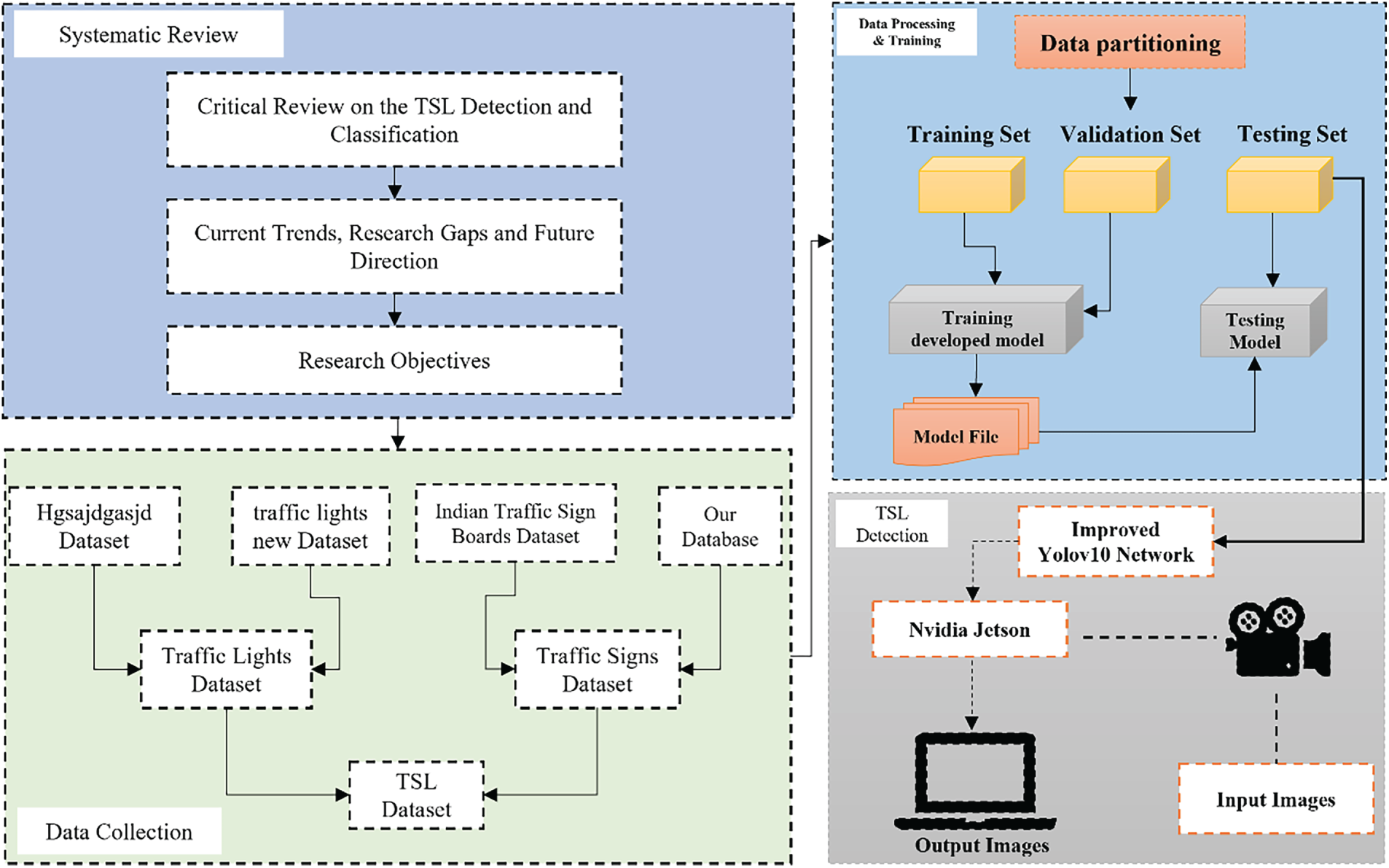

The study was structured into three sequential phases: systematic analysis, dataset preparation, and TSL detection model development. First, a comprehensive review of existing TSL methodologies was conducted to identify prevailing research gaps, methodological limitations, and performance constraints under real-world driving conditions. Insights from this analysis guided the definition of the study objectives and informed the design of the proposed detection framework. Second, a hybrid TSL database was constructed by integrating three publicly available datasets [41–43], two containing traffic sign images and one containing traffic light images, along with a set of images manually collected under varying lighting conditions. The resulting database includes both near- and far-field TSL images to support detection at various ranges. We augmented the dataset using brightness normalization, inversion, cropping, geometric transformations, and noise injection to improve generalization. Finally, we developed and optimized the FED-YOLOv10s algorithm for accurate, real-time TSL detection on embedded platforms. The overall workflow and system architecture are illustrated schematically in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The proposed methodology framework for real-time TSL detection system

3.2 Construction of TSL Detection Model

In real-world autonomous driving scenarios, lighting conditions significantly influence the accuracy and stability of TSL detection. TSLs are often captured under varying illumination levels, such as strong sunlight, shadows, or low-light environments, requiring detection algorithms to maintain both high precision and speed under changing light intensities. Therefore, designing a network architecture that ensures robust detection accuracy and real-time performance under diverse lighting conditions remains a key challenge. These variations can introduce background interference and reduce contrast, making it crucial to optimize information extraction and improve the model’s ability to focus on essential targets while suppressing irrelevant visual information.

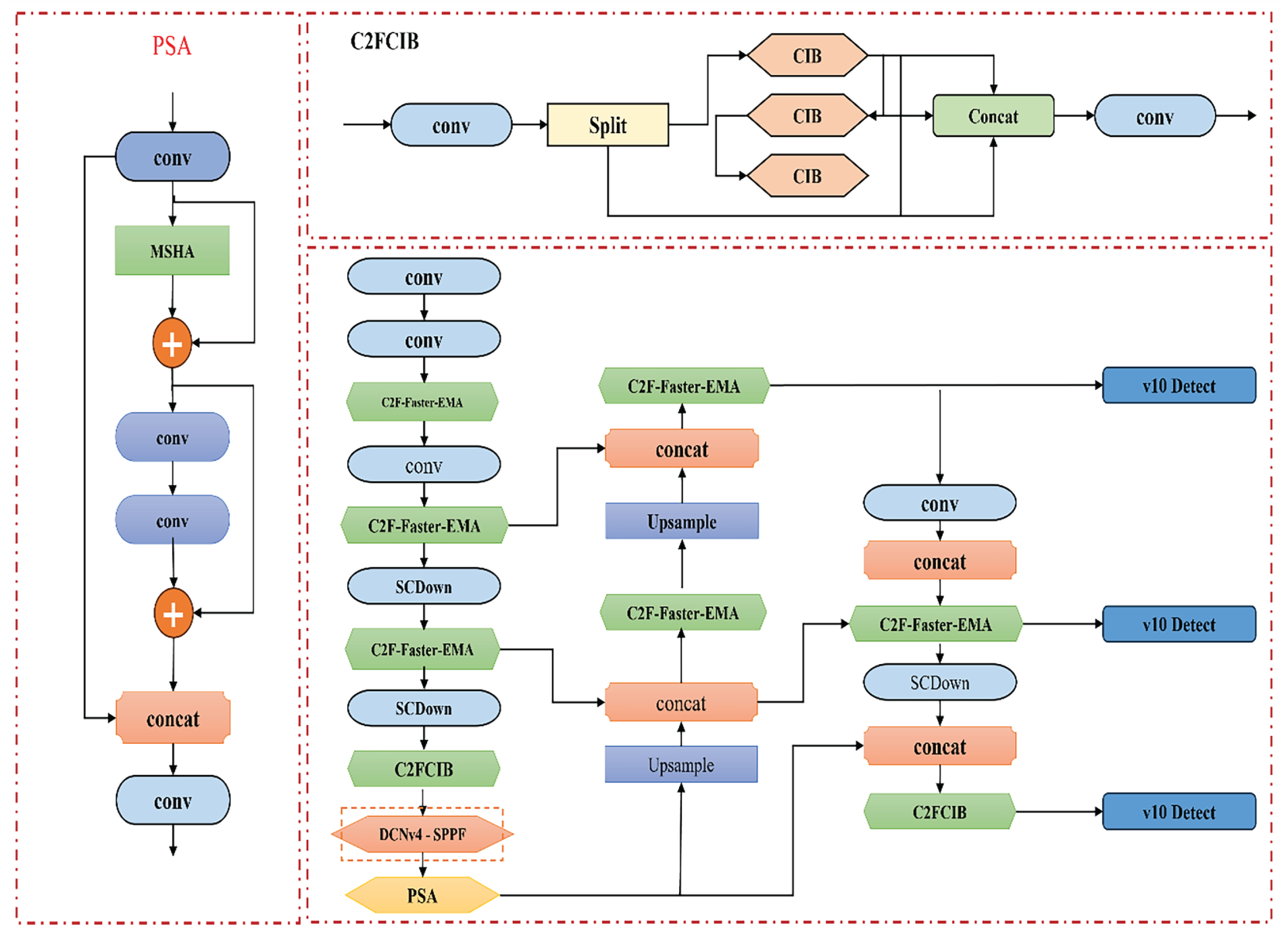

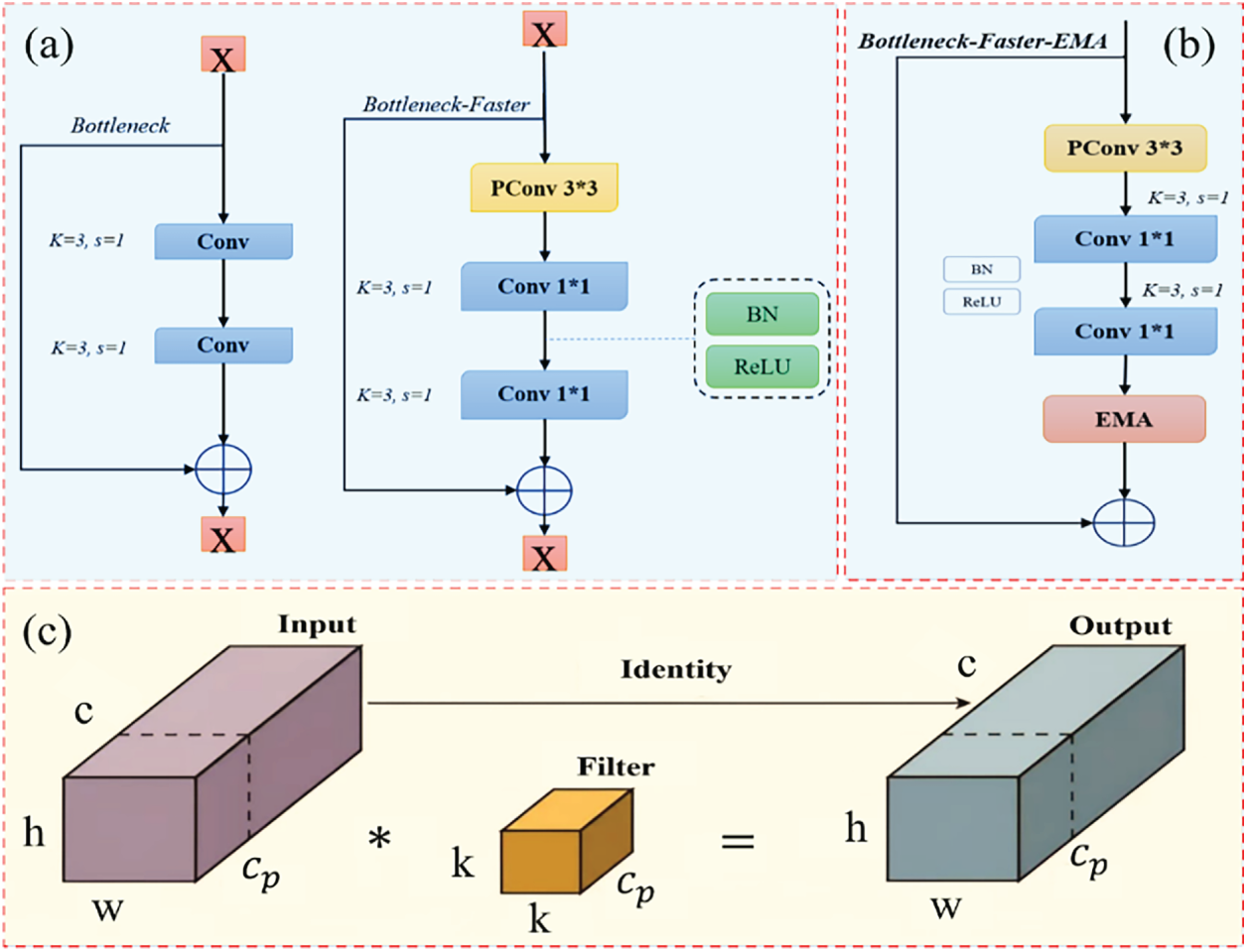

In this study, the backbone and detection head are redesigned based on the YOLOv10 architecture to improve adaptability to lighting variations. The goal is to develop a TSL detection algorithm that maintains high precision, robustness to changing lights, and efficient real-time inference. All original C2f modules in YOLOv10 are replaced with a unified C2f-Faster-EMA structure, designed specifically to address key limitations of YOLOv10 when applied to real-world TSL detection. The C2f-Faster module, derived from FasterNet, is employed to reduce redundant computation and memory access inherent in traditional C2f blocks. By using partial convolution (PConv) and optimized feature reuse, it significantly improves inference speed on embedded devices while preserving sufficient representational capacity.

To enhance multi-scale contextual modeling without incurring the computational burden of transformer-based self-attention, the Efficient Multiscale Attention (EMA) module is integrated into the backbone. EMA enables hierarchical cross-spatial interaction with substantially lower memory overhead, making it well-suited for detecting small and distant traffic signs and for handling severe illumination changes commonly found in outdoor environments. This combination strengthens feature fusion and improves the model’s sensitivity to both bright and low-light conditions, thereby reducing detection failures caused by overexposure, glare, or shadows.

Within the YOLOv10 core network, the Spatial Pyramid Pooling—Fast (SPPF) continues to play a critical role by expanding the receptive field and aggregating multi-scale spatial information, enabling efficient detection of objects across varying sizes. To further address geometric distortions, non-frontal views, and partial occlusion, frequent challenges in TSL imagery, the proposed architecture incorporates DCNv4, an improved deformable convolutional operation. DCNv4 adaptively adjusts sampling offsets to align with irregular object shapes, while its removal of SoftMax normalization enhances memory access and routing efficiency. When combined with the improved SPPF, DCNv4 facilitates faster convergence and delivers high robustness, particularly in scenes with perspective distortion or motion blur. Experimental results confirm that this principled integration of C2f-Faster, EMA, and DCNv4 collectively enhances both detection accuracy and inference speed. Fig. 2 presents the overall structure of FED-YOLOv10s and its key modules.

Figure 2: The scheme of the FED-YOLOv10s model’s network structure

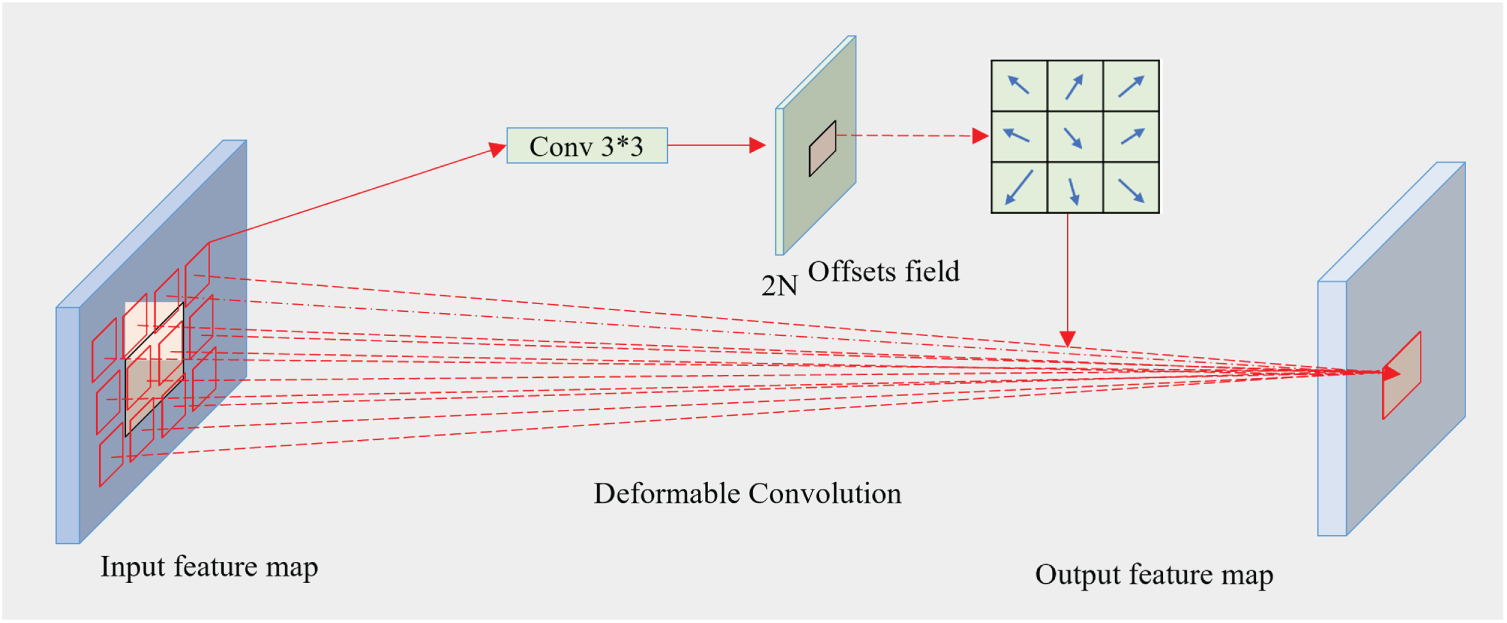

3.2.1 Deformable Convolution DCNv4 Modul

Deformable Convolution v4 (DCNv4) is a state-of-the-art operator that enhances vision tasks by building on the capabilities of its predecessors, such as DCNv2 and DCNv3. It introduces significant innovations to improve both computational efficiency and task performance, addressing challenges in dynamic representation and processing speed.

In the YOLOv10 core network, the SPPF plays an important role in improving multi-scale feature extraction, enabling better detection of objects of different sizes while maintaining computational efficiency. It also expands the receptive field, aggregates spatial information, and works seamlessly with feature fusion networks, improving accuracy without slowing down inference. This makes YOLOv10 powerful and effective for real-time object detection tasks, even in complex scenarios. In this paper, we conducted an experiment to validate the detection accuracy and inference speed. Through this process, we found that combining the efficient deformable convolution DCNv4 with YOLOv10 achieves faster convergence and higher performance by improving SPPF, which results in optimal optimization results. DCNv4 removes SoftMax normalization, improves memory access, and improves routing speed, which enhances its robustness.

The purpose of using DCN is to improve the model’s capacity to extract invariant features. DCN enables the convolutional kernel to learn an offset at each sampling point during training, allowing it to adjust to the object’s geometric shape. DCN improves the feature extraction performance for infrared objects of various scales by learning several optimal convolutional kernel structures based on various object data. The 3 × 3 deformable convolutions are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Deformable convolutions

To demonstrate the effectiveness of DCNv4, we will consider the input x

where

In terms of SoftMax normalization, a key distinction between Convolution and DCNv3 lies in their treatment of spatial pooling weights. DCNv3 applies the SoftMax function to normalize the weights m, aligning with the self-attention mechanism’s convention for normalized point-wise multiplication. In contrast, Convolution does not utilize SoftMax for its weights yet still achieves strong performance. The necessity of SoftMax in attention mechanisms is evident: self-attention for normalized point-wise multiplication, involving

N represents the number of points within the same attention window, which can be either global or local, and d denotes the hidden dimension. The matrices Q, K, V correspond to the query, key, and value respectively, calculated from the input. The SoftMax operation is essential in Eq. (3) for attention mechanisms. Without SoftMax,

In DCNv4, the SoftMax normalization used in DCNv3 has been eliminated, and the normalization metrics, previously bounded between 0 and 1, are replaced with unbounded dynamic weights similar to convolution. This modification enhances the dynamic nature of DCN, addressing limitations found in other operators, such as restricted value ranges (as in attention/DCNv3) or fixed pooling windows with input-independent weights (as in convolution). As a result, DCNv4 achieves significantly faster convergence compared to DCNv3 and other widely-used operators, including convolution and attention mechanisms [44].

3.2.2 Lightweight Module C2f-Faster-EMA

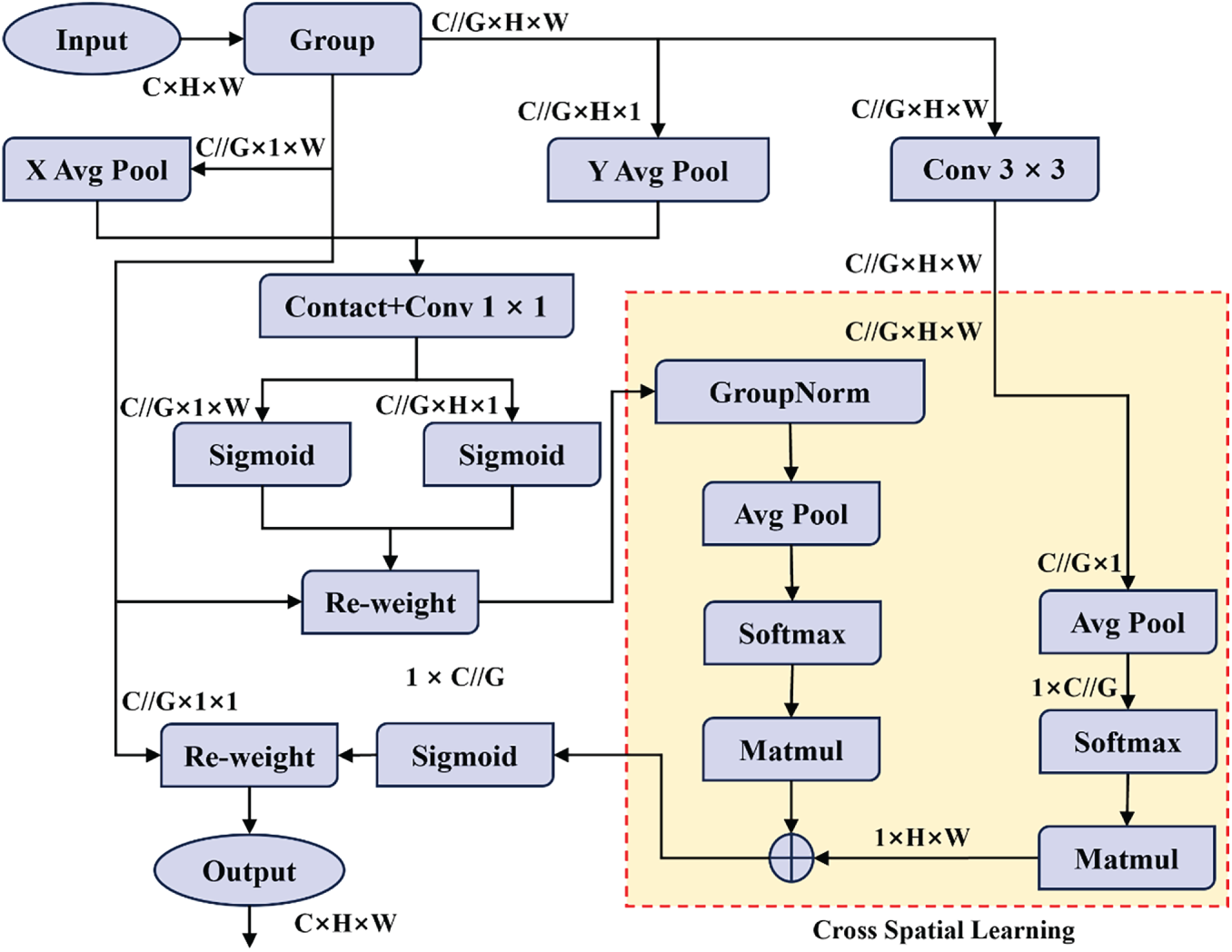

Efficient Multi-Scale Attention

The EMA module represents an advanced attention mechanism specifically engineered to retain comprehensive channel information while minimizing computational complexity. This is accomplished by transforming a portion of the feature channels into batch dimensions and subsequently dividing them into multiple sub-feature groups. Through this structured partitioning, the module enables different feature subsets to capture distinct semantic representations. Such a design ensures that essential channel information is preserved while significantly enhancing computational efficiency [45]. Furthermore, the EMA module integrates parallel subnetworks capable of capturing multi-scale spatial dependencies, thereby refining attention weight descriptors and substantially improving the discriminative capacity of feature representations.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the operational principle of the EMA module begins with dividing the input feature map X into G sub-features, denoted as

Figure 4: Efficient Multi-Scale Attention (EMA) module

In addition, the EMA module incorporates cross-spatial learning, enabling it to capture interdependencies between channels and spatial locations. This mechanism facilitates the aggregation of cross-spatial information across multiple dimensions, enhancing the model’s ability to represent both local and long-range contextual relationships. Within each feature group, output computation is achieved through the fusion of two spatial attention weight maps, followed by a Sigmoid activation function. This design allows the EMA module not only to dynamically adjust channel significance but also to embed precise spatial structural cues within the feature maps.

Ultimately, the EMA (Exponential Moving Average) module produces outputs identical in size to the input feature map X, ensuring seamless integration with modern deep learning architectures. In applications such as land-use change detection—where cropland often coexists with forested, grassy, or shrub-covered terrain, the complexity of feature differentiation is notably high. By leveraging the EMA attention mechanism, the MADNet framework effectively exploits discriminative regional information, enhancing its capacity to distinguish complex mixed land-use areas and achieving substantial improvements in detection accuracy.

Lightweight Module C2f-Faster

In the original YOLOv10 model architecture, the C2f (CSPDarknet53 to 2-Stage FPN) module serves as an essential component that fuses low-level and high-level feature maps. This design enables the model to simultaneously utilize detailed and semantic information, thereby improving detection accuracy and robustness. Additionally, the C2f module helps reduce information loss and enhances the model’s capability to perceive image details. However, due to the required feature fusion operations, this module increases the model’s computational complexity, resulting in higher training and inference time costs. Moreover, the inclusion of multiple C2f modules adds to the number of parameters, increasing storage and computational demands.

The YOLOv10 algorithm employs numerous standard convolutions and C2f modules, which, while enhancing detection accuracy, also slow down inference speed and inflate model parameters. In motion detection scenarios, where the scene changes rapidly, maintaining sufficient detection accuracy is crucial. However, the YOLOv10 algorithm demonstrates limitations in real-time TSL detection, often producing false or missed detections. To enable real-time detection of fast-moving targets on embedded onboard platforms, the model must achieve a high frame rate Frames Per Second (FPS) and reduced parameter complexity, ensuring lightweight performance without compromising accuracy.

Traditionally, the design of fast neural networks has focused on reducing the number of floating-point operations (FLOPs). However, recent research indicates that a reduction in FLOPs does not necessarily yield proportional latency improvements due to inefficiencies in floating-point computation. To address this issue, a PConv was proposed, effectively extracting spatial features by minimizing redundant computation and memory access. Building upon this concept, FasterNet was developed, offering significantly improved inference speed and reduced computational cost while maintaining detection accuracy.

Inspired by FasterNet, this study adopts the concept of PConv to design a new Bottleneck-Faster structure, which replaces the bottleneck structure in the YOLOv10 C2f module. The modified module is referred to as C2f-Faster. Each Bottleneck-Faster module consists of one PConv layer followed by two 1 × 1 convolution layers. Together, these layers form an inverted residual block, where the intermediate layer expands the number of channels, and a shortcut connection reuses the input features [46]. The comparison between the original bottleneck structure and the Bottleneck-Faster structure is illustrated in Fig. 5a. In this figure, the original bottleneck employs conventional convolution layers throughout, while our Bottleneck-Faster design replaces the first standard convolution with a PConv layer, significantly reducing computational complexity while maintaining feature representational capacity.

Figure 5: Network module structures: (a) Bottleneck and Bottleneck-Faster structures, (b) Bottleneck-Faster-EMA structure, (c) Partial convolution structure

Compared with ordinary Conv, PConv applies standard convolution operations to only 1/4 of the input channels for spatial feature extraction, while the remaining 3/4 of the channels remain unchanged and are subsequently convolved with the processed subset. The resulting 1/4 channel output is then concatenated with the unprocessed channels. Thus, some convolutional layers preserve the number of input channels and the feature map scale, allowing the network to retain original information while reducing redundant computation. Although 3/4 of the channels are not directly convolved, they are not discarded; the subsequent 1 × 1 convolution operation extracts additional useful information from these channels. To minimize potential information loss, the output feature map channels are expanded to twice the original value during the pointwise convolution (1 × 1 Conv) operation. Meanwhile, the unutilized portion of the PConv layer is reused to prevent information waste. The final 1 × 1 convolution restores the channel dimension to its original size, ensuring consistency between the input and output feature maps in the backbone network.

Fig. 5c illustrates the architecture of the PConv layer, where (H) and (W) denote the input height and width, (K) the filter size, (C) the total number of input channels, and

because the channel ratio of PConv to ordinary convolution is:

Thus,

where r represents the channel ratio. Therefore, the FLOPs of PConv are only 1/16 of those in ordinary convolution, and the corresponding memory access is significantly lower, approximately expressed as:

Fig. 5b presents our enhanced Bottleneck-Faster-EMA structure, which integrates the EMA module into the Bottleneck-Faster design. This integration occurs after the initial PConv layer, allowing the model to capture multi-scale contextual information while preserving the efficiency gains of PConv [47]. The EMA mechanism enables hierarchical cross-spatial interaction with minimal memory overhead, enhancing the model’s ability to detect small and distant traffic signs under varying illumination conditions.

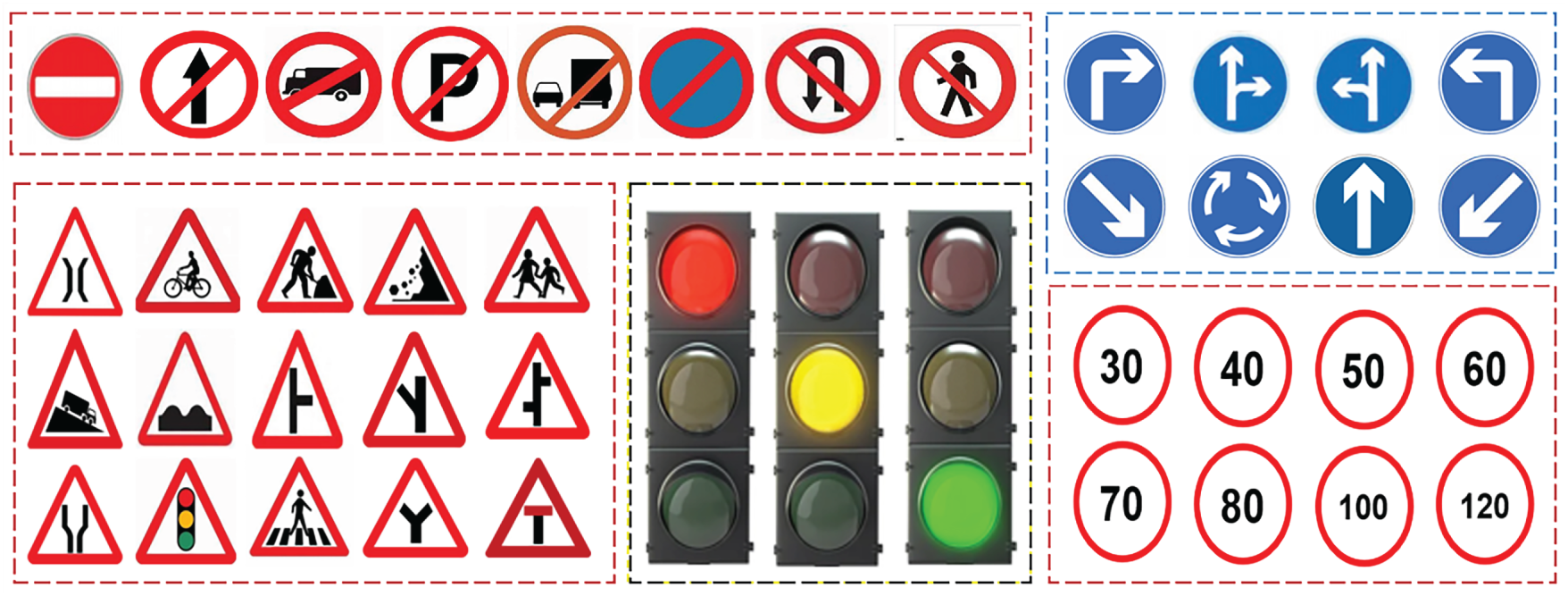

The customized TSL dataset used in this study comprises 7673 images, including 5137 traffic-sign samples and 2539 traffic-light samples spanning 78 categories. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the final hybrid dataset was constructed by integrating four sources: our newly collected images and three publicly available datasets obtained from Roboflow. Although a portion of the data was acquired using a single smartphone model, the incorporation of multiple external datasets captured under resolutions, backgrounds, and environmental conditions significantly enhances domain diversity and mitigates the risk of device-specific bias. The traffic-light subset was created by merging two publicly available datasets, Hgsajdgasjd dataset [41] with 1739 images and an additional dataset [42] with 800 images, and standardizing them into three signal classes (red, yellow, and green). Likewise, the traffic-sign subset was formed by combining 783 newly collected images with the Indian Traffic Sign Board dataset [43], containing 4354 real-world samples across 75 categories. All images were standardized to a resolution of 640 × 640 pixels, and the resulting dataset was divided into training, validation, and testing splits using a 7:2:1 ratio. Because the combined dataset exhibits a long-tailed class distribution with several underrepresented categories, we applied a Weighted Dataloader [48] during training to ensure more balanced sampling. This method adjusts sampling probabilities so that minority classes are encountered more frequently, while retaining all available data and providing smoother and more stable gradient updates than loss reweighting or under-sampling. This strategy effectively reduces class-imbalance-induced bias and supports more consistent learning across the full set of categories.

To prevent data leakage and ensure a fair assessment of model generalization, the train, validation, and test split was performed strictly before any preprocessing or augmentation. All augmentations were applied dynamically at runtime within the training and validation dataloader, ensuring that no augmented variants of training images appear in the testing set. This procedure guarantees that model evaluation is conducted on entirely unseen, unaltered data, thereby maintaining the integrity and reliability of the reported results. Representative samples from the hybrid dataset are displayed in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Sample images for the hybrid TSL dataset

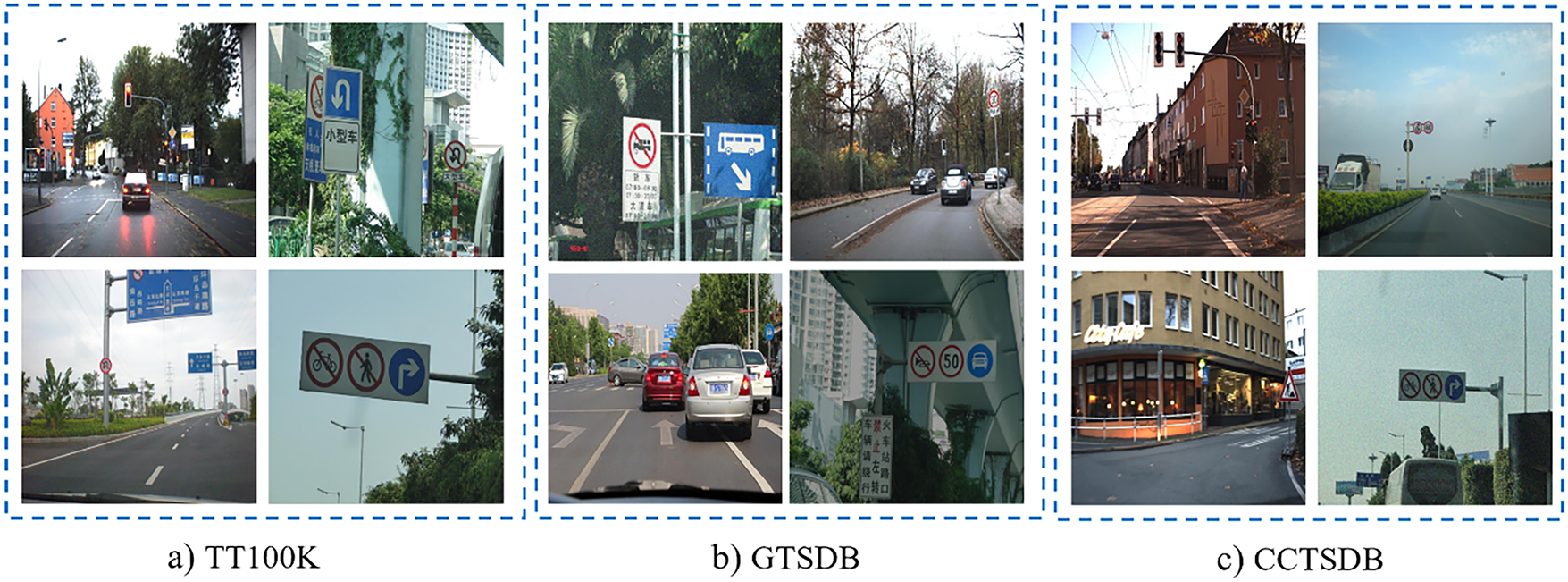

To rigorously evaluate the performance and generalization capability of the proposed FED-YOLOv10s model, comparative experiments were conducted on three widely used benchmark datasets: TT-100K [49], CCTSDB [50], and GTSDB [51]. These datasets differ substantially in imaging conditions, annotation quality, scene complexity, and class distributions, enabling a comprehensive assessment of the model across diverse traffic environments. Representative samples from each dataset are shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Sample images for all comparison datasets (a) TT-100K, (b) GTSDB and (c) CCTSDB

The CCTSDB dataset contains approximately 20,000 images with nearly 40,000 annotated traffic signs across the mandatory, prohibitory, and warning categories, collected from diverse environments in China. Although the dataset covers a wide range of lighting, resolution, and weather conditions, it contains annotation issues such as missing labels, inaccurate bounding boxes, and occasional class misclassification errors. These imperfections can penalize correct detections as false positives or false negatives, particularly for small or partially occluded signs, thereby biasing performance evaluation. To reduce these effects, we employed a refined and re-annotated subset of the dataset for the final comparative analysis, consisting of 7219 training images, 902 validation images, and 902 test images.

The TT100K dataset contains roughly 100,000 images covering 128 traffic sign categories—including prohibition, warning, and instruction signs, captured under diverse weather and illumination conditions. Despite its scale, the dataset exhibits substantial class imbalance, which complicates the training of robust detectors. To obtain a more balanced distribution, we selected 42 classes with more than 70 samples. The traffic sign instances range from 16 × 16 to 160 × 160 pixels, making the dataset suitable for evaluating long-distance, small-object detection performance. The resulting subset consisted of 8438 images, divided into 7538 for training, 473 for validation, and 472 for testing. In contrast, the GTSDB dataset contains 1149 training images and 54 test images with comparatively clean and consistent annotations, captured at a resolution of 1360 × 800 pixels. Traffic signs in GTSDB range from 16 to 128 pixels, providing a reliable benchmark for assessing detection stability under controlled label quality.

This approach provides a more stable and reliable basis for evaluating model performance despite the known limitations of the original datasets. By integrating multiple datasets and conducting experiments across their diverse characteristics, we were able to assess the robustness and generalizability of the proposed model under both ideal, well-annotated conditions and the more challenging, imperfect labeling scenarios that commonly occur in real-world applications.

We evaluated the model using precision, recall, and F1-score, defined in Eqs. (8)–(10), where a True Positive (TP) is a correct detection, a False Positive (FP) is an incorrect detection, and a False Negative (FN) is a missed instance.

In object detection assessment, two prominent performance metrics commonly used are average precision (AP) and mean average precision (mAP). The AP metric measures the area under the precision-recall curve for each class, while mAP represents the average AP value across all detection classes. The value of AP and mAP is calculated from Eqs. (11) and (12).

where N is the total number of classes, P indicates the precision, R indicates the recall, and

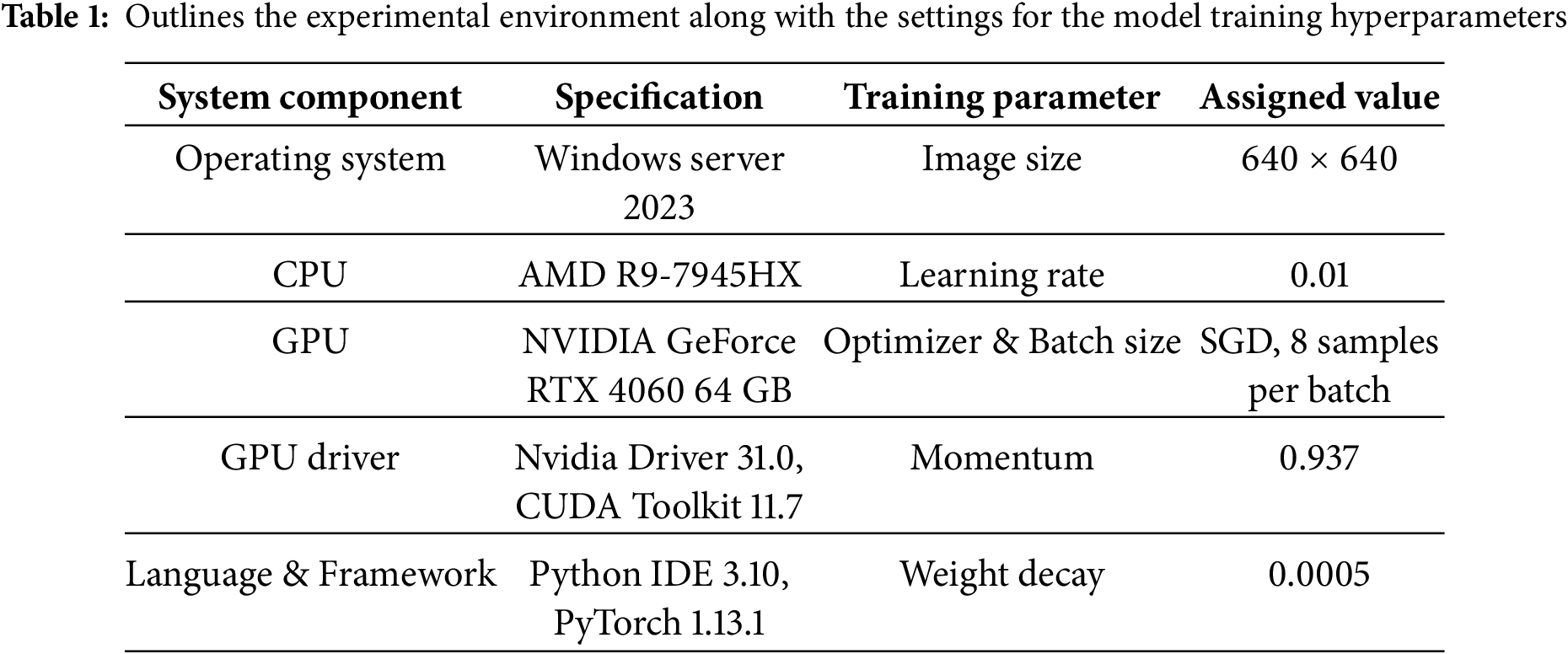

All experiments were conducted using the PyTorch deep learning framework on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU running Windows Server 2023. Python served as the primary development environment, and CUDA 11.7 was employed to enable GPU-accelerated computation. The models were trained for 100 epochs using the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer with a learning rate of 0.01, a momentum of 0.937, a batch size of 8, and a weight decay of 0.0005. These hyperparameters follow standard YOLOv10s training conventions and were consistently applied across all experiments to ensure comparability. The hybrid TSL dataset was trained using a unified augmentation strategy that included brightness adjustment, random scaling, cropping, horizontal flipping, geometric transformations, and Gaussian noise to enhance the model’s robustness to real-world variations. To account for stochastic variability, all experiments were repeated three times using different random seeds by setting seed = −1 for each run, allowing the framework to generate a new random seed automatically. For each run, metrics including precision, recall, F1-score, and mAP were recorded. We report the mean ± standard deviation and additionally estimate 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for mAP@0.5 using 1000 resamples. This procedure ensures that reported improvements are statistically meaningful and not attributable to randomness in weight initialization or data shuffling.

All models, including the proposed FED-YOLOv10s and the baseline detectors, were trained independently on each dataset to avoid cross-dataset bias. No automated hyperparameter search was performed; instead, the same standard training settings were adopted for all models to ensure methodological consistency. In contrast, publicly available subsets of the datasets (TT100K, CCTSDB, GTSDB) were used without additional augmentation to preserve their native distributional characteristics and maintain comparability with prior studies. This configuration provides a transparent and reproducible experimental environment aligned with current best practices in the field. The experimental setup and hyperparameters are detailed in Table 1.

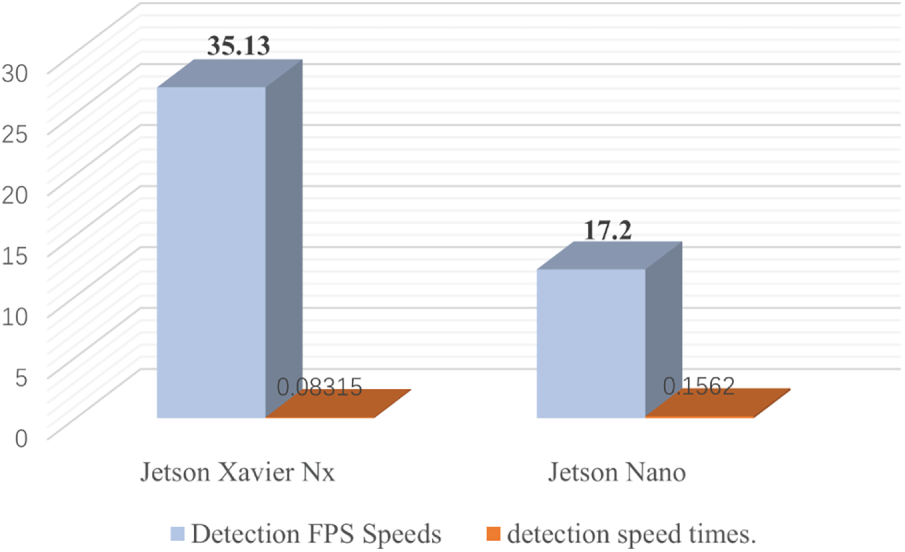

4.2.2 Embedded Devices Selection

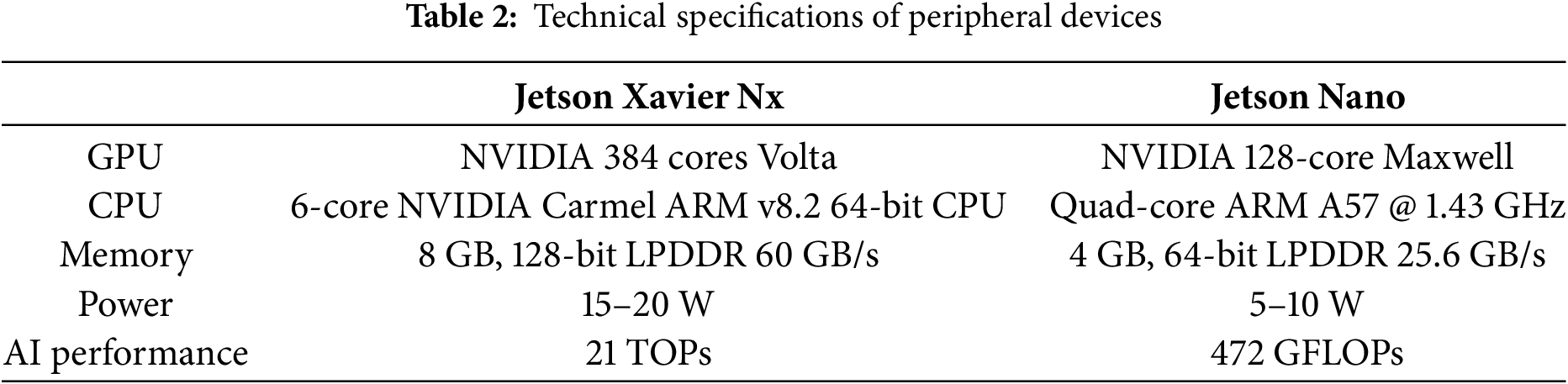

Recent developments in lightweight embedded devices have markedly increased their computational capabilities, allowing the execution of complex deep learning inference tasks. In this study, we propose and implement the FED-YOLOv10s algorithm for real-time TSL detection on mobile GPU platforms. Among contemporary embedded solutions, NVIDIA’s series of platforms demonstrates notable market presence and performance. Real-time video stream processing imposes stringent computational demands, which can be challenging to meet on single-chip embedded devices. To assess the inference speed of the proposed model, experiments were conducted on the Jetson Xavier NX and Jetson Nano platforms. The technical specifications of these devices are summarized in Table 2, indicating their ability to perform real-time operations with power consumption ranging from 5 to 20 W. A comparative analysis of key hardware components, including RAM, GPU, and CPU, was performed across platforms. The results demonstrate that the proposed FED-YOLOv10s achieves high efficiency and reliable real-time performance on embedded systems. Representative images of the Jetson Xavier NX and Jetson Nano boards are presented in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: The board for (a) the Jetson Xavier Nx, and (b) the Jetson Nano

5 Experimental Results Analysis on TSL

In implementing the YOLOv10 algorithm for TSL detection, the computational limitations of mobile hardware must be taken into account. Consequently, larger variants such as YOLOv10b, YOLOv10l, and YOLOv10x are impractical for deployment, despite their superior detection accuracy, due to their high computational complexity and latency. Since real-time inference is essential in TSL recognition within ADSs, this study adopts YOLOv10s as the optimized baseline model. Model training was executed on a GPU platform, with the training parameters configured according to Section 4.2.1. The experimental findings confirm that the enhanced YOLOv10s framework effectively improves the detection of TSL, emphasizing the significance of the proposed lightweight module in enhancing overall algorithmic efficiency and performance.

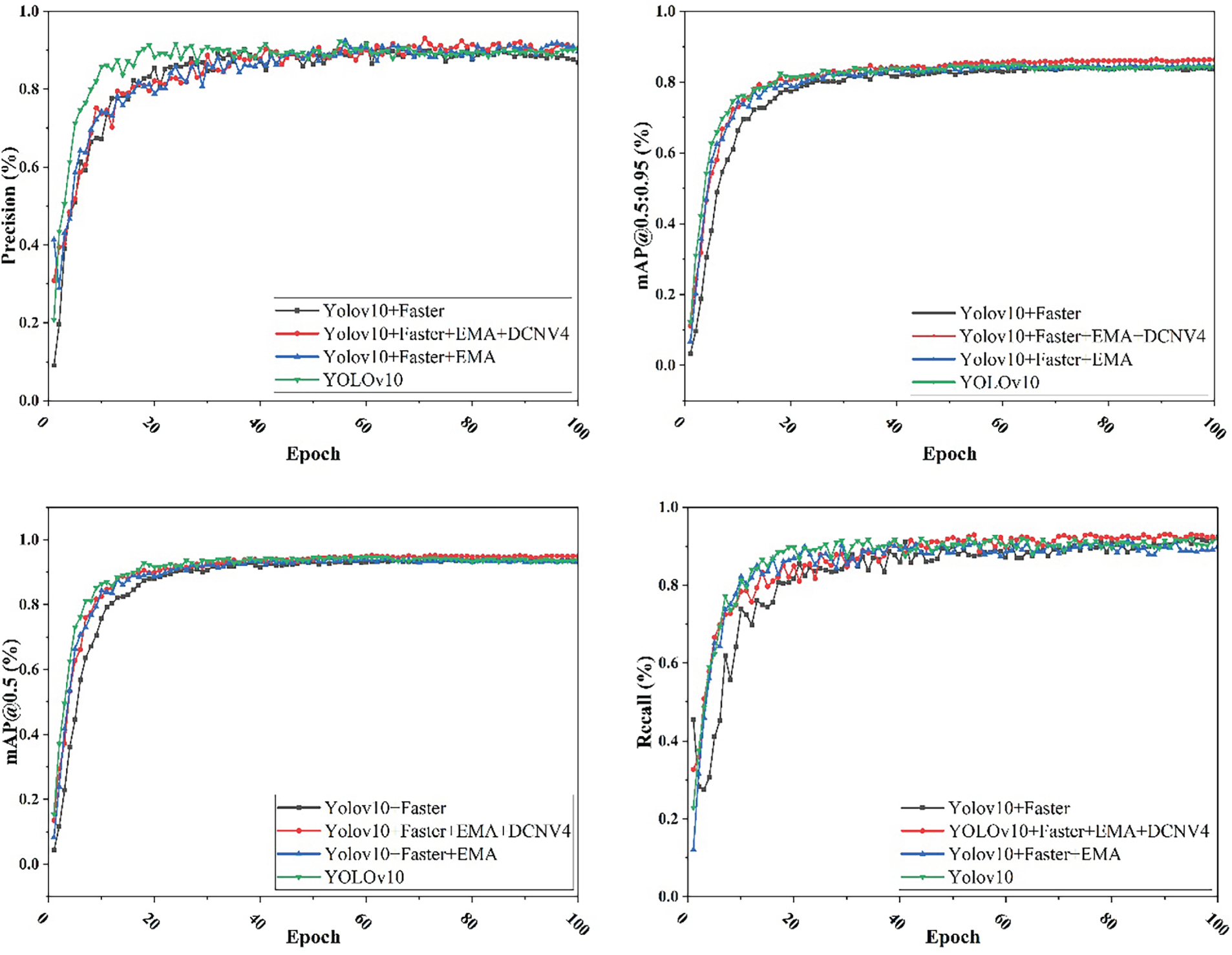

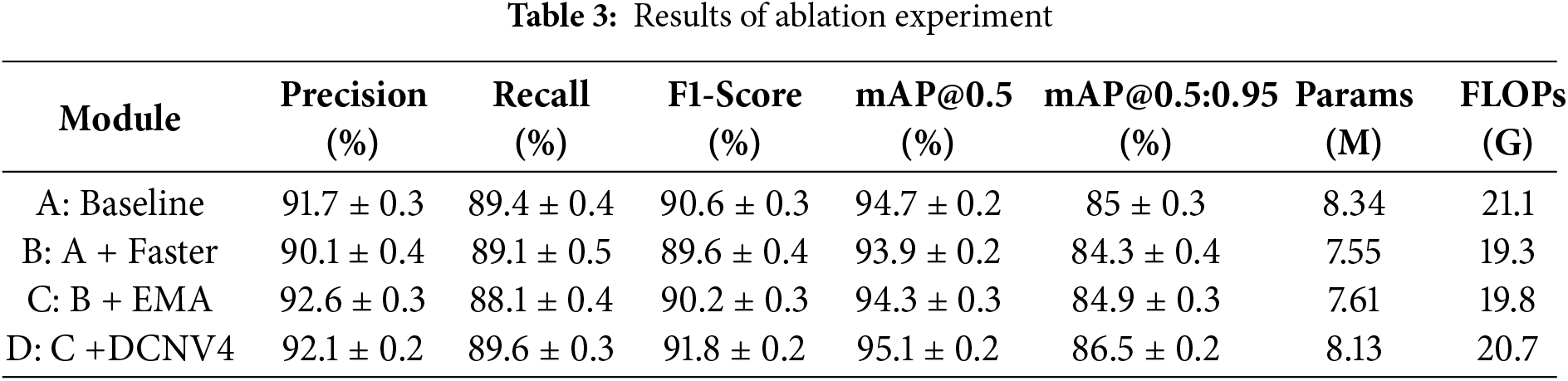

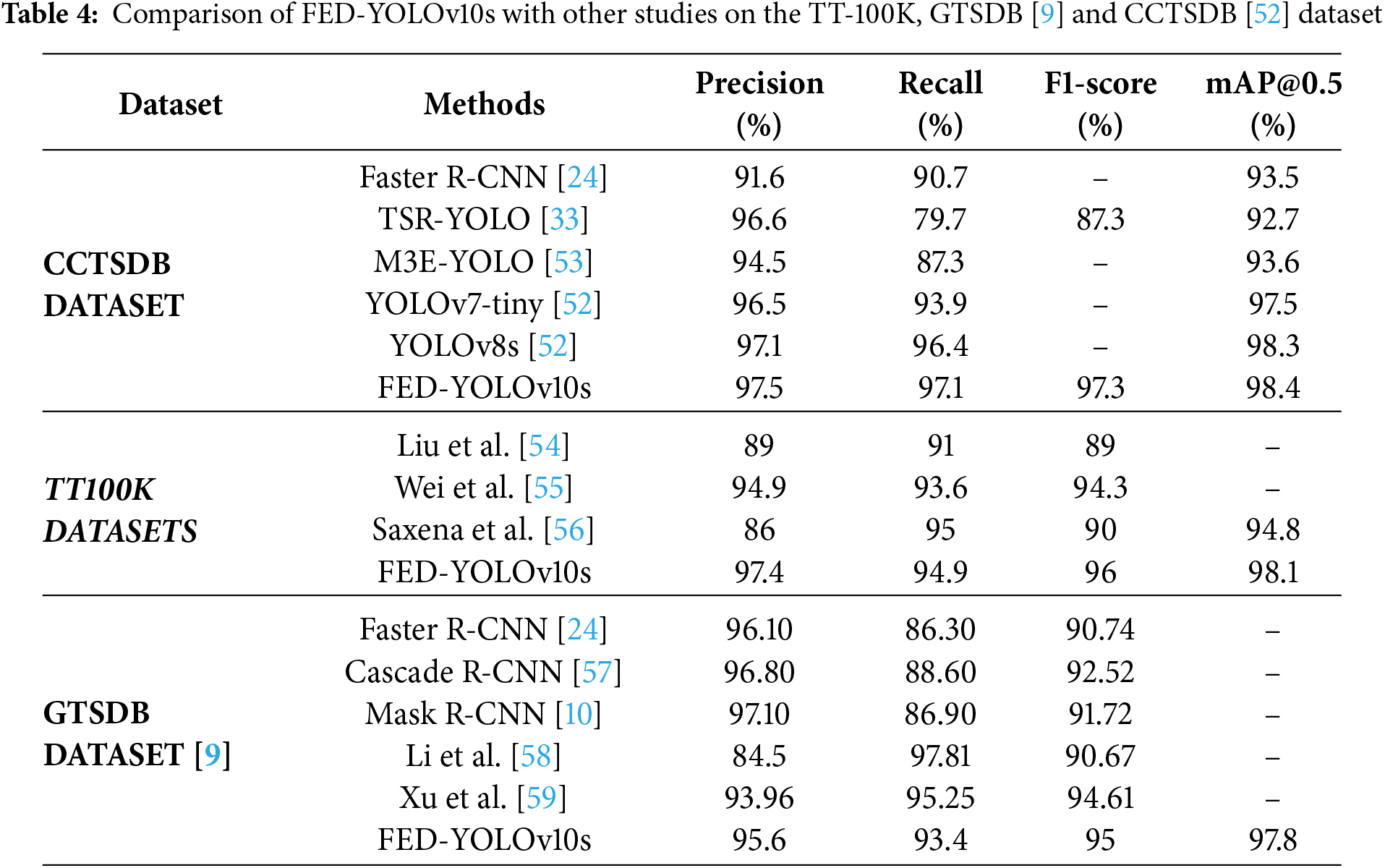

The experimental results systematically analyzed the contributions of each proposed module, the lightweight C2f-Faster module, the EMA Attention Mechanism, and DCNv4, to detection accuracy and immediate performance. The outcomes demonstrate the framework’s effectiveness for real-time TSL detection. An ablation study (Fig. 9, Table 3) quantifies the impact of each module. The baseline model (Module A) achieved a precision of 91.7%, recall of 89.4%, F1-score of 90.6%, and mAP@0.5 of 94.7%, serving as the reference for evaluating performance improvements introduced by subsequent configurations.

Figure 9: Curves of ablation experimental indexes

Incorporating the Faster module (Module B) reduced parameters from 8.34 to 7.55 M and FLOPs from 21.1 to 19.3 G, indicating higher computational efficiency. However, this also slightly reduced precision (90.1%) and F1-score (89.6%), illustrating a trade-off between efficiency and accuracy. The integration of the EMA attention mechanism (Module C) with the Faster module enhanced the model’s representational power by improving precision to 92.6% and achieving an F1-score of 90.2%, with only a marginal increase in parameters (7.61 M) and FLOPs (19.8 G). This demonstrates that the inclusion of attention mechanisms effectively compensates for minor accuracy losses associated with lightweighting, thereby improving feature focus without significantly increasing computational load. Finally, the addition of the DCNv4 module (Module D) further elevated the model’s detection capability, yielding the highest F1-score (91.8%) and mAP@0.5 (95.1%). The improved mAP@0.5:0.95 (86.5%) reflects enhanced multi-scale target recognition, while the moderate parameter and FLOP increments (8.13 M and 20.7 G, respectively) confirm that this enhancement does not impose excessive computational burden.

To ensure that the reported improvements are not due to random initialization or training stochasticity, all experiments were repeated three times using different random seeds. The results, reported as mean ± standard deviation, show that the performance differences observed in the ablation study are consistent across runs. Importantly, the improvements introduced by the proposed modules remain larger than the observed seed-to-seed variance, indicating that the gains are statistically reliable. The final model achieves a mAP@0.5 of 95.1 ± 0.2%, with a narrow 95% bootstrap confidence interval (94.8%–95.4%), confirming the stability of the architecture modifications. Collectively, the ablation results validate our modular design. The sequential integration of Faster, EMA, and DCNv4 optimizes the trade-off between efficiency and accuracy, confirming the robustness and practicality of FED-YOLOv10s for real-time detection. Qualitative detection results are shown in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Qualitative detection results of the proposed model on the TSL dataset

5.2 Comparative Database Results

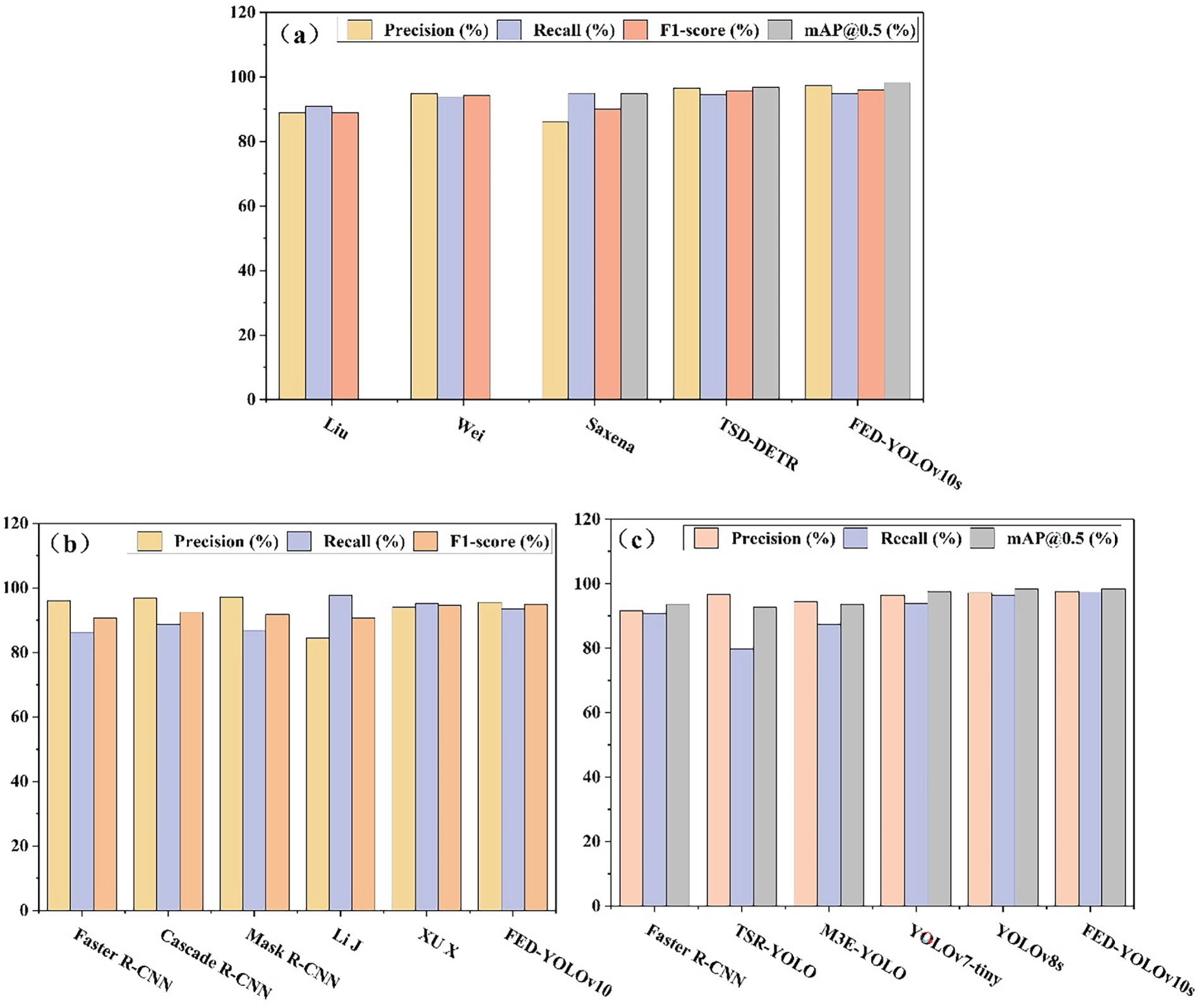

To assess the generalization capabilities of FED-YOLOv10s, we evaluated its performance on three publicly available datasets: CCTSDB, TT-100K, and GTSDB, as summarized in Table 4. FED-YOLOv10s consistently outperformed existing benchmark models in terms of key metrics such as precision, recall, F1-score, and mAP@0.5, demonstrating its robustness and adaptability across diverse datasets. The models used for comparison in this study were not retrained; rather, we evaluated the performance of our proposed FED-YOLOv10s model against the results reported by the original authors, who trained these models under specific experimental conditions. For transparency and reproducibility, the references for each model are provided next to their corresponding names in Table 4.

On CCTSDB, which contains prohibitory, mandatory, and warning signs, FED-YOLOv10s demonstrated robustness to diverse sign shapes and colors. It outperformed models like Faster R-CNN, TSR-YOLO, and YOLOv8s across all key metrics. Its precision (97.5%) represents a 5.9% improvement over Faster R-CNN and a 0.4% improvement over YOLOv8s. A recall of 97.1% indicates a low miss-rate and high sensitivity for small, distant targets. The high F1-score (97.3%) and mAP@0.5 (98.4%) confirm its balanced and accurate detection capability. These results demonstrate that our attention and lightweight modules enhance multi-scale feature extraction, enabling reliable performance in complex environments. On the TT-100K dataset, FED-YOLOv10s again showed improved performance. Its precision (97.4%) surpassed methods from Liu et al., Wei et al., Saxena et al., and TSD-DETR by 8.4%, 2.5%, 11.4%, and 0.8%, respectively. Recall also improved significantly, and the model achieved a high F1-score of 96% and mAP@0.5 of 98.1%. These findings validate the model’s high adaptability to diverse data distributions and its robustness in complex real-world conditions. The evaluation on GTSDB further confirms the model’s excellent transferability. FED-YOLOv10s attained an F1-score of 95%, improving upon Mask R-CNN, Cascade R-CNN, and Faster R-CNN by 4.26%, 2.48%, and 3.28%, respectively. A mAP@0.5 of 97.8% also exceeded that of other models, underscoring its good recognition capability across varying traffic environments.

Fig. 11a–c presents a graphical comparison of the proposed FED-YOLOv10s model and existing detection frameworks across the three benchmark datasets. The outcomes clearly show that the FED-YOLOv10s achieves well and consistent performance, exceeding state-of-the-art detectors in precision, recall, mAP, and F1-score. Owing to its lightweight architecture, the proposed model exhibits exceptional efficiency in detecting small-scale targets, which is essential for high-accuracy applications in autonomous driving. These outcomes highlight the model’s strong generalization ability, stability across diverse data distributions, and practical value for real-world intelligent transportation systems. Fig. 12 shows a visual representation of the implementation of the proposed model on the three databases.

Figure 11: Performance metrics of the proposed model on the three databases: (a) TT-100K dataset; (b) GTSDB dataset; (c) CCTSDB dataset

Figure 12: Visual representation of the proposed model on the three databases: (a) TT-100K dataset; (b) GTSDB dataset; (c) CCTSDB dataset

Fig. 13 presents a graphical analysis comparing the real-time detection FPS rates of the Jetson Xavier NX and Jetson Nano platforms under a consistent evaluation protocol. The FPS was measured as the end-to-end pipeline throughput, which includes image preprocessing (resizing to 640 × 640 pixels and normalization), model inference, and post-processing (Non-Maximum Suppression). Latency was averaged over 1000 consecutive frames to ensure statistical reliability. The results confirm that the Jetson Xavier NX substantially outperforms the Jetson Nano, reflecting its superior computational capacity. This demonstrates that the real-time processing capability of the Xavier NX significantly enhances both efficiency and overall system performance in deep learning-based perception tasks. The tests further verify that the FED-YOLOv10s system maintains high detection accuracy while achieving practical inference speeds suitable for real-world embedded applications.

Figure 13: Comparison analysis of detection FPS speeds and speed times in real-time

Both platforms were configured with Jetpack Ubuntu 20.04, and necessary libraries—including CUDA, CUDNN, and PyTorch, were installed to ensure full hardware acceleration. Throughout the evaluation, the system exhibited consistent stability and operational reliability under varying workloads. These outcomes highlight the effectiveness of FED-YOLOv10s as a portable and efficient solution for embedded intelligent transportation systems, with the Jetson Xavier NX delivering the highest processing throughput during real-time detection.

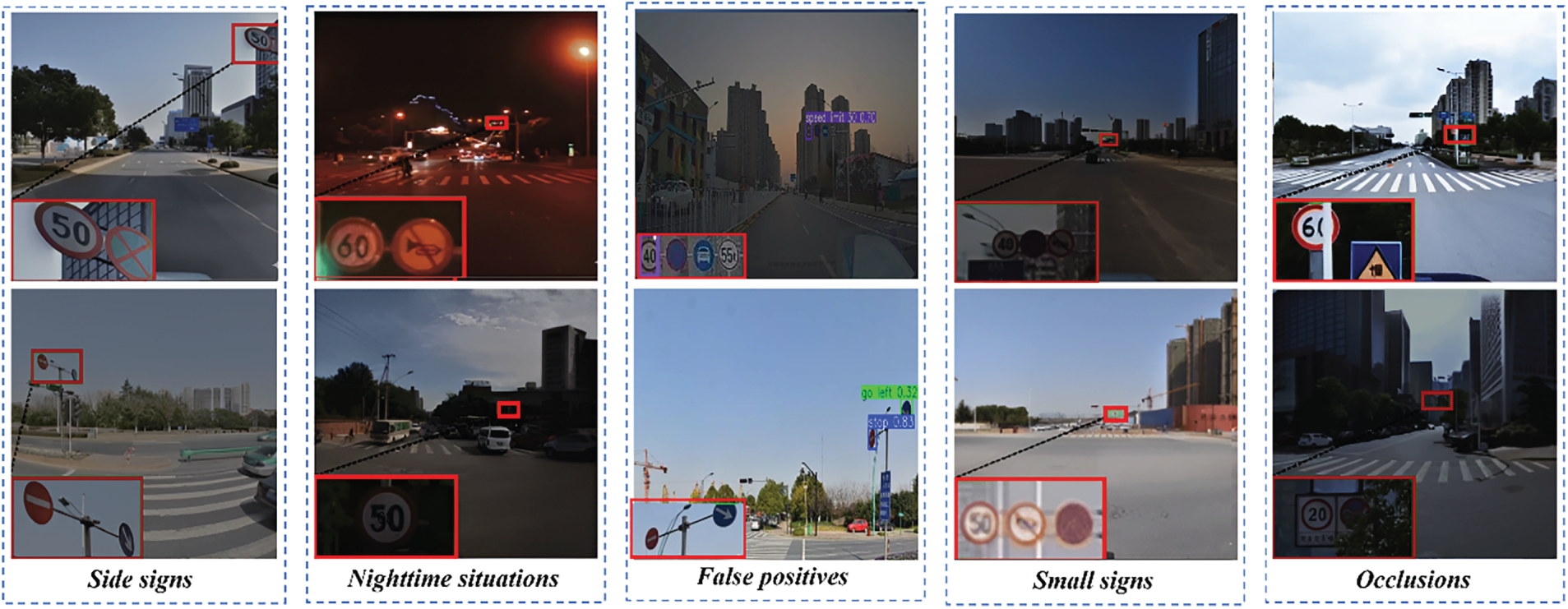

5.3 Error Analysis and Safety Considerations

To evaluate the operational reliability of FED-YOLOv10s in safety-critical contexts, we conducted a systematic error analysis and robustness assessment. This analysis focuses on failure modes under challenging conditions and discusses their implications for real-world autonomous driving systems. Fig. 14 shows examples of potential failure cases.

Figure 14: The challenges of traffic sign detection, including size, side signs, false positive, occlusion, and lighting issues

The model exhibits predictable yet important failure patterns consistent with vision-based detection in complex environments. False negatives primarily occur under low-visibility conditions such as nighttime, extreme backlighting, or partial occlusion (e.g., signs obscured by vegetation or vehicles), particularly for small or distant targets where feature representation is inherently weak. False positives are often triggered by urban clutter with sign-like visual characteristics, including circular advertisements, triangular architectural elements, and high-intensity reflections from vehicle headlights or building windows. These cases highlight the model’s reliance on local shape and luminance cues, which can be misleading without sufficient semantic or contextual validation.

5.3.2 Robustness under Challenging Conditions

We quantified the degradation in detection performance under synthetically generated challenging conditions. Simulated low-light and nighttime scenarios (applied via gamma correction) resulted in a 12%–15% relative reduction in mAP@0.5, driven mainly by increased false negatives as color and edge information diminished. Under synthetic occlusions (random masks covering up to 30% of object area), performance declined progressively; beyond this threshold, detection reliability dropped sharply, indicating a dependence on holistic object appearance. The introduction of motion blur and sensor noise led to an 8%–10% decrease in recall, underscoring the sensitivity of small-object detection to high-frequency feature preservation.

5.3.3 Safety Implications and System Integration

The identified failure modes have important safety implications for Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS). False negatives on critical regulatory signs or traffic lights pose direct collision risks, while false positives may trigger unnecessary interventions, potentially causing abrupt braking or reduced driver trust. Misclassification of speed-limit signs likewise undermines situational awareness and regulatory compliance. For this reason, vision-based detectors such as FED-YOLOv10s are not deployed in isolation; rather, they function as components within a broader perception stack that incorporates multi-sensor fusion (e.g., LiDAR, radar) and temporal filtering to mitigate transient errors and provide redundancy. In practice, confidence thresholds are tuned to favor high precision and minimize false positives in safety-critical categories, consistent with fail-safe design principles. Nonetheless, enhancing robustness under challenging conditions, such as nighttime, heavy occlusion, and adverse weather, remains essential to approaching the reliability required for real-world autonomous decision-making.

This study introduces FED-YOLOv10s, a novel and efficient detection framework specifically optimized for real-time TSL recognition under diverse illumination conditions. The proposed architecture integrates three key components to enhance both performance and efficiency: the C2f-Faster module, which minimizes redundant computation and reduces model complexity; the EMA mechanism, which strengthens feature extraction and improves robustness to illumination variations; and the DCNv4 module, which enhances spatial adaptability and multiscale feature learning.

Comprehensive evaluations demonstrate that FED-YOLOv10s achieves a good balance between computational cost and precision. It outperformed state-of-the-art models on the CCTSDB, TT-100K, and GTSDB benchmarks. These results confirm its strong generalization capability and reliability in detecting small targets under varying lighting. Deployment on Jetson Nano and Jetson Xavier NX platforms validated its real-time performance, with low latency and energy consumption suitable for intelligent driving systems.

Despite the good performance of the proposed method, several limitations should be acknowledged. Although the evaluation utilized diverse datasets, they may not fully represent the complexity and variability of real-world driving conditions, particularly in extreme adverse weather such as heavy rain, snow, or dense fog, as well as in scenarios involving heavy occlusion, complex nighttime reflections, or highly congested environments. Moreover, the datasets used, while rich in illumination conditions, lack broad geographic diversity, which may limit the model’s generalizability across different regions and operational contexts. Future work should therefore include broader cross-domain validation and incorporate more challenging environmental factors such as fog, rain, and occlusion, alongside exploring model compression and quantization strategies to enhance deployment efficiency on low-power embedded platforms.

Acknowledgement: This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia under Grant No. IPP: 172-830-2025. The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

Funding Statement: This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia under Grant No. IPP:172-830-2025.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Mohammed Al-Mahbashi and Abdolraheem Khader; methodology, Mohammed Al-Mahbashi; software, Mohammed Al-Mahbashi; validation, Mohamed A. Damos, Ahmed Abdu, and Shakeel Ahmad; investigation, Abdolraheem Khader; resources, Mohammed Al-Mahbashi and Ahmed Abdu; data curation, Mohammed Al-Mahbashi, Shakeel Ahmad and Mohamed A. Damos; writing—review and editing, Mohammed Al-Mahbashi and Abdolraheem Khader; visualization, Ali Ahmed; supervision, Ali Ahmed. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zheng T, Huang Y, Liu Y, Tang W, Yang Z, Cai D, et al. CLRNet: cross layer refinement network for lane detection. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr52688.2022.00097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Qie K, Wang J, Li Z, Wang Z, Luo W. Recognition of occluded pedestrians from the driver’s perspective for extending sight distance and ensuring driving safety at signal-free intersections. Digit Transp Saf. 2024;3(2):65–74. doi:10.48130/dts-0024-0007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Al-Mahbashi M, Li G, Peng Y, Al-Soswa M, Debsi A. Real-time distracted driving detection based on GM-YOLOv8 on embedded systems. J Transp Eng Part A Syst. 2025;151(3):04024126. doi:10.1061/jtepbs.teeng-8681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhao S, Peng Y, Wang Y, Li G, Al-Mahbashi M. Lightweight YOLOM-net for automatic identification and real-time detection of fatigue driving. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;82(3):4995–5017. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.059972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Debsi A, Ling G, Al-Mahbashi M, Al-Soswa M, Abdullah A. Driver distraction and fatigue detection in images using ME-YOLOv8 algorithm. IET Intell Transp Syst. 2024;18(10):1910–30. doi:10.1049/itr2.12560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ho C, Won K, Koo K, Taeg L. ADM-Net: attentional-deconvolution module-based net for noise-coupled traffic sign recognition. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022;81(16):23373–97. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-12219-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Saadna Y, Behloul A. An overview of traffic sign detection and classification methods. Int J Multimed Inf Retr. 2017;6(3):193–210. doi:10.1007/s13735-017-0129-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Woźniak M, Zielonka A, Sikora A. Driving support by type-2 fuzzy logic control model. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;207(3):117798. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.117798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang J, Xie Z, Sun J, Zou X, Wang J. A cascaded R-CNN with multiscale attention and imbalanced samples for traffic sign detection. IEEE Access. 2020;8:29742–54. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2972338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. He K, Gkioxari G, Dollar P, Girshick R. Mask R-CNN. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2020;42(2):386–97. doi:10.1109/tpami.2018.2844175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Li X, Xie Z, Deng X, Wu Y, Pi Y. Traffic sign detection based on improved faster R-CNN for autonomous driving. J Supercomput. 2022;78(6):7982–8002. doi:10.1007/s11227-021-04230-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. You S, Bi Q, Ji Y, Liu S, Feng Y, Wu F. Traffic sign detection method based on improved SSD. Information. 2020;11(10):475. doi:10.3390/info11100475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang H, Yu H. Traffic sign detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv4. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 9th Joint International Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence Conference (ITAIC); 2020 Dec 11–13; Chongqing, China. doi:10.1109/itaic49862.2020.9339181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Snegireva D, Perkova A. Traffic sign recognition application using Yolov5 architecture. In: Proceedings of the 2021 International Russian Automation Conference (RusAutoCon); 2021 Sep 5–11; Sochi, Russian Federation. doi:10.1109/rusautocon52004.2021.9537355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang X, Zhang Z. Traffic sign detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv7. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Image, Signal Processing, and Pattern Recognition (ISPP 2023); 2023 Feb 24–26; Changsha, China. doi:10.1117/12.2681271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wali SB. A unified color and shape based algorithm for traffic sign detection system. J Energy Environ. 2020;12(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

17. Handoko H, Pratama JH, Yohanes BW. Traffic sign detection optimization using color and shape segmentation as pre-processing system. TELKOMNIKA Telecommun Comput Electron Control. 2021;19(1):173. doi:10.12928/telkomnika.v19i1.16281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. de la Escalera A, Moreno LE, Salichs MA, Armingol JM. Road traffic sign detection and classification. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 1997;44(6):848–59. doi:10.1109/41.649946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Fleyeh H. Color detection and segmentation for road and traffic signs. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent Systems, 2004; 2004 Dec 1–3; Singapore. p. 809–14. doi:10.1109/iccis.2004.1460692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Maldonado-Bascon S, Lafuente-Arroyo S, Gil-Jimenez P, Gomez-Moreno H, Lopez-Ferreras F. Road-sign detection and recognition based on support vector machines. IEEE Trans Intell Transport Syst. 2007;8(2):264–78. doi:10.1109/tits.2007.895311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hechri A, Mtibaa A. Two-stage traffic sign detection and recognition based on SVM and convolutional neural networks. IET Image Process. 2020;14(5):939–46. doi:10.1049/iet-ipr.2019.0634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Girshick R, Donahue J, Darrell T, Malik J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2014 Jun 23–28; Columbus, OH, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2014.81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Girshick R. Fast R-CNN. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015 Dec 7–13; Santiago, Chile. doi:10.1109/iccv.2015.169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/tpami.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Han C, Gao G, Zhang Y. Real-time small traffic sign detection with revised faster-RCNN. Multimed Tools Appl. 2019;78(10):13263–78. doi:10.1007/s11042-018-6428-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wu J, Liao S. Traffic sign detection based on SSD combined with receptive field module and path aggregation network. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022;2022:4285436. doi:10.1155/2022/4285436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Liu S, Qi L, Qin H, Shi J, Jia J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2018.00913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Gheorghe C, Duguleana M, Boboc RG, Postelnicu CC. Analyzing real-time object detection with YOLO algorithm in automotive applications: a review. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;141(3):1939–81. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.054735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Fan W, Yi N, Hu Y. A traffic sign recognition method based on improved YOLOv3. In: Advances in intelligent automation and soft computing. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 846–53. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-81007-8_97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jia Z, Sun S, Liu G. Real-time traffic sign detection based on weighted attention and model refinement. Neural Process Lett. 2023;55(6):7511–27. doi:10.1007/s11063-023-11271-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Yan B, Li J, Yang Z, Zhang X, Hao X. AIE-YOLO: auxiliary information enhanced YOLO for small object detection. Sensors. 2022;22(21):8221. doi:10.3390/s22218221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Yu J, Ye X, Tu Q. Traffic sign detection and recognition in multiimages using a fusion model with YOLO and VGG network. IEEE Trans Intell Transport Syst. 2022;23(9):16632–42. doi:10.1109/tits.2022.3170354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Song W, Suandi SA. TSR-YOLO: a Chinese traffic sign recognition algorithm for intelligent vehicles in complex scenes. Sensors. 2023;23(2):749. doi:10.3390/s23020749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Hu J, Wang Z, Chang M, Xie L, Xu W, Chen N. PSG-Yolov5: a paradigm for traffic sign detection and recognition algorithm based on deep learning. Symmetry. 2022;14(11):2262. doi:10.3390/sym14112262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wang J, Chen Y, Dong Z, Gao M. Improved YOLOv5 network for real-time multi-scale traffic sign detection. Neural Comput Appl. 2023;35(10):7853–65. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-08077-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Shen J, Liao H, Zheng L. A lightweight method for small scale traffic sign detection based on YOLOv4-Tiny. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(40):88387–409. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-17146-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Qu S, Yang X, Zhou H, Xie Y. Improved YOLOv5-based for small traffic sign detection under complex weather. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):16219. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-42753-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Wang X, Tian Y, Zheng K, Liu C. C2Net-YOLOv5: a bidirectional Res2Net-based traffic sign detection algorithm. Comput Mater Contin. 2023;77(2):1949–65. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.042224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhou F, Zu H, Li Y, Song Y, Liao J, Zheng C. Traffic-sign-detection algorithm based on SK-EVC-YOLO. Mathematics. 2023;11(18):3873. doi:10.3390/math11183873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Li X, Wang W, Hu X, Yang J. Selective kernel networks. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2019.00060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Roboflow. hgsajdgasjd computer vision project: roboflow; 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://universe.roboflow.com/yapay-zeka-enkjg/hgsajdgasjd. [Google Scholar]

42. Roboflow. Traffic lights new computer vision project; 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://universe.roboflow.com/ripo-ce6cm/traffic-lights-new. [Google Scholar]

43. Roboflow. Indian traffic signboards computer vision project; 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://universe.roboflow.com/major-project-166na/indian-traffic-signboards. [Google Scholar]

44. Xiong Y, Li Z, Chen Y, Wang F, Zhu X, Luo J, et al. Efficient deformable ConvNets: rethinking dynamic and sparse operator for vision applications. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr52733.2024.00540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ouyang D, He S, Zhang G, Luo M, Guo H, Zhan J, et al. Efficient multi-scale attention module with cross-spatial learning. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023—2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2023 Jun 4–10; Rhodes Island, Greece. doi:10.1109/icassp49357.2023.10096516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Chen J, Kao SH, He H, Zhuo W, Wen S, Lee CH, et al. Run, don’t walk: chasing higher FLOPS for faster neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. doi:10.1109/cvpr52729.2023.01157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Du D, Xie Y. Vehicle and pedestrian detection algorithm in an autonomous driving scene based on improved YOLOv8. J Transp Eng Part A Syst. 2025;151(1):04024095. doi:10.1061/jtepbs.teeng-8446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Yasin’s Keep. Balance classes during YOLO training using a weighted dataloader. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://y-t-g.github.io/tutorials/yolo-class-balancing/. [Google Scholar]

49. Zhu Z, Liang D, Zhang S, Huang X, Li B, Hu S. Traffic-sign detection and classification in the wild. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2016.232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Zhang J, Zou X, Kuang L, Wang J, Sherratt R, Yu X. CCTSDB 2021: a more comprehensive traffic sign detection benchmark. Hum-Centric Comput Inf Sci. 2022;12:23. [Google Scholar]

51. Houben S, Stallkamp J, Salmen J, Schlipsing M, Igel C. Detection of traffic signs in real-world images: the German traffic sign detection benchmark. In: Proceedings of the 2013 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); 2013 Aug 4–9; Dallas, TX, USA. doi:10.1109/ijcnn.2013.6706807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Wang Q, Li X, Lu M. An improved traffic sign detection and recognition deep model based on YOLOv5. IEEE Access. 2023;11:54679–91. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3281551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Guo H, Li F, Kuang P, Xiong G. M3E-yolo: a new lightweight network for traffic sign recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2022 19th International Computer Conference on Wavelet Active Media Technology and Information Processing (ICCWAMTIP); 2022 Dec 16–18; Chengdu, China. doi:10.1109/iccwamtip56608.2022.10016618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Liu Z, Du J, Tian F, Wen J. MR-CNN: a multi-scale region-based convolutional neural network for small traffic sign recognition. IEEE Access. 2019;7:57120–8. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2913882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wei L, Xu C, Li S, Tu X. Traffic sign detection and recognition using novel center-point estimation and local features. IEEE Access. 2020;8:83611–21. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2991195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Saxena S, Dey S, Shah M, Gupta S. Traffic sign detection in unconstrained environment using improved YOLOv4. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238(2):121836. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Cai Z, Vasconcelos N. Cascade R-CNN: delving into high quality object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2018.00644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Li J, Wang Z. Real-time traffic sign recognition based on efficient CNNs in the wild. IEEE Trans Intell Transport Syst. 2019;20(3):975–84. doi:10.1109/tits.2018.2843815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Xu X, Jin J, Zhang S, Zhang L, Pu S, Chen Z. Smart data driven traffic sign detection method based on adaptive color threshold and shape symmetry. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2019;94:381–91. doi:10.1016/j.future.2018.11.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools