Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

MALAT1 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pancreatic cancer cells through the miR-141-5p-TGF-ß-TGFBR1/TGFBR2 axis

Department of Pancreatic Surgery, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, 610041, Sichuan, China

#

Those authors are both to be considered as first authors

* Corresponding Author: Huimin Lu,

European Cytokine Network 2024, 35(3), 28-37. https://doi.org/10.1684/ ecn.2024.0495

Accepted 06 February 2024;

Abstract

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is one of the leading causes of cancer deaths, associated with a high risk of metastasis and mortality. The long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1) is highly expressed in multiple types of tumour tissues and may be associated with the growth of PC cells. In this study, we aimed to assess the role and possible mechanisms of MALAT1 in PC progression. Methods: Expression of MALAT1 was studied by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) in PC tissues. The dual-luciferase assay was performed to validate binding between MALAT1 and miR-141-5p in HEK293 cells. Western blot analysis was performed to examine the expression of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and its receptors, TGFBR1 and TGFBR2. Invasiveness and migration of cultured PANC-1 cells were studied using transwell invasion and migration assays, respectively. Results: A high level of miR-141-5p and low level of MALAT1 were detected in PC tissues, and the level of MALAT1 was shown to significantly correlate with tumour growth and metastasis. In HEK293 cells, miR-141-5p overexpression inhibited the expression of TGFBR1 and TGFBR2, and this inhibition was reversed by overexpression of MALAT1. In PANC-1 cells, MALAT1 was shown to act as a competing endogenous RNA, as the direct target of miR-141-5p. Furthermore, in PANC-1 cells, miR-141-5p overexpression suppressed TGF-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), cell migration, and cell invasion through direct binding to the 3’UTR of TGFBR1 and TGFBR2. Conclusions: Our results indicate that, in PC cells, miR-141-5p suppresses TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 expression and further inhibits TGF-β-induced EMT, cell migration, and cell invasion, which are reversed by overexpression of MALAT1, demonstrating that MALAT1 and miR-141-5p may be important regulators in the initiation and metastasis of PC.Keywords

As the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the United States, pancreatic cancer (PC) is a deadly disease with a very low five-year survival rate due to difficulties in early diagnosis, resistance to drug therapy, and high propensity for metastasis [1–4]. In the past two decades, the number of PC diagnoses has doubled [5]. Furthermore, the incidence and mortality rates of patients with PC have only decreased slightly over the past 30 years due to late diagnosis, resistance to therapies, and insufficient effective treatments [6]. Despite significant advances in the understanding of PC genetics, biology, physiology, and pharmacology, the treatments for PC are far from satisfactory since neither chemotherapy nor radiotherapy provide significant effects in PC patients, and no effective therapies are feasible at the time of diagnosis in most cases [7, 8]. This is in line with clinical statistics showing that only 24% and 5% of all patients with PC will survive for one year and five years after diagnosis, respectively [9, 10].

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), originally identified in embryogenesis, is a process through which epithelial cells undergo remarkable morphological changes characterized by a transition from an epithelial cobblestone phenotype to an elongated fibroblastic phenotype [9]. Recent studies have shown that EMT-type cells share similar characteristics to cancer stem cells, and play critical roles in cancer metastasis and drug resistance in a variety of cancers including PC. Indeed, previous studies have reported the EMT phenomenon in several PC cell lines and surgically resected PCs, and L3.6pl, Colo357, BxPC-3, and HPAC cell lines have been shown to exhibit strong expression of epithelial marker, E-cadherin, while another group of PC cells (MiaPaCa-2, Panc-1, and Aspc-1 cells) has been shown to exhibit strong expression of mesenchymal markers, including vimentin and zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 (ZEB-1), at the mRNA and protein level. The existence of these EMT cells in PC, to some extent, is responsible for the progressive characteristics of PC [11, 12]. Various bone mesenchymal stem cell (BMSC) populations (mainly VSELs and MSCs) occur in the peripheral blood (PB) of PC patients, indicating that the involvement of MSCs and other types of stem cells is of significance in the clinical setting of PC [13, 14].

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) is a group of multifunctional polypeptides with four different isoforms (β1, β2, β3, and β4, with β1 being the most abundant), and plays an important role in regulating cell differentiation, migration, invasion, and metastasis [15, 16]. TGF-β has received substantial attention as a major inducer of EMT during cancer progression through binding to its receptors, TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 [17]. In normal epithelium cells and early-stage human carcinoma cells, TGF-β demonstrates tumour-suppression effects. However, in the later stage of tumour development, it promotes cell proliferation and metastasis [18]. EMT is the transition during which epithelial cells lose cell-to-cell adhesion and start to become MSCs, and this is a crucial step for cell invasion during tumourigenesis [19]. This process is known to be initiated by TGF-β by binding to the transmembrane protein, TGFBR [20]. Binding of TGF-β and TGFBR1 activates TGFBR2 to trigger autophosphorylation of receptor-regulated Smad2 and Smad3 (R-Smads) [21, 22]. The phosphorylated R-Smads further form a complex with Smad4 and translocate into the nucleus. This complex then promotes the activation of transcription factors that induce EMT, such as Snail1, Snail2, and Snail3, as well as Smad-related proteins, ZEB2, Twist-related protein 1 (Twist1), and Twist2 [19]. TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 were found to be overexpressed in PC cells and may be associated with disease progression [23].

The long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are RNA molecules longer than 200 nucleotides that play important roles in regulating gene expression. One of the common functions of lncRNAs is to attenuate the expression of micro-ribonucleic acids (miRNAs) by acting as an endogenous sponge [24]. Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1) is one of the most well-known lncRNA members, which is found to be abundantly expressed in multiple types of tumour tissues [25, 26] and highly associated with the growth of cancer cells [27, 28]. In addition, overexpression of MALAT1 in PC cells is considered to positively correlate with the stage of tumour growth and metastasis [29].

In this study, we hypothesized that the metastatic effect of MALAT1 in PC may be related to the process of EMT involving related signal mediators. As one of the most studied pathways, the role of TGF-TGFBR1/TGFBR2 in inducing EMT was investigated. Furthermore, the underlying mechanisms in PC metastasis were examined by investigating the regulatory role of lncRNA in metastasis-related gene expression. Advances in our knowledge of the underlying mechanisms of PC metastasis and drug resistance relating to EMT, that are believed to be critical, will likely shed light on the discovery of novel drugs and aid in the design of therapeutic strategies for the treatment of PC.

We present the following article in accordance with the MDAR reporting checklist.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

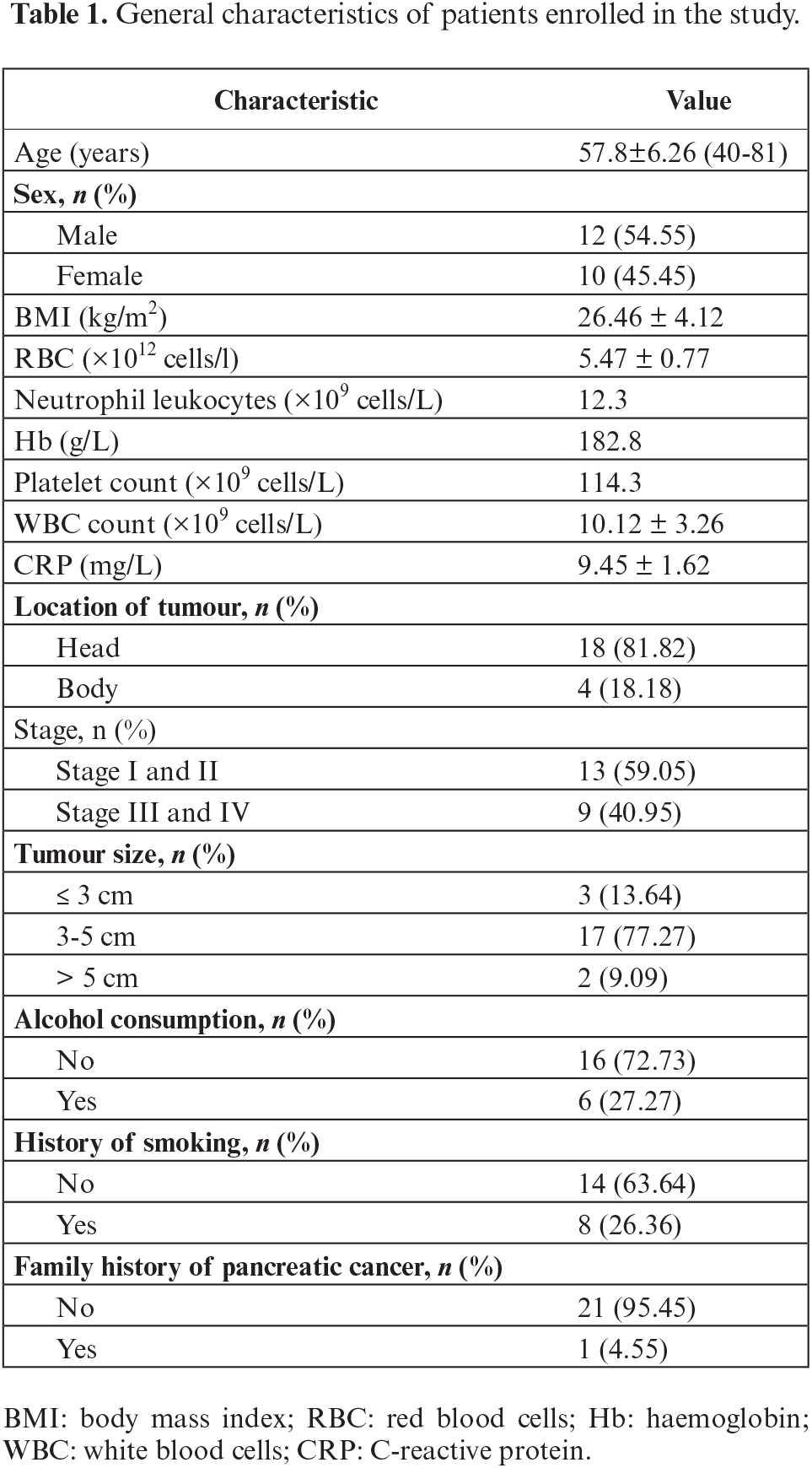

A total of 22 individuals were diagnosed with PC using computed tomography (CT) and enrolled in this study. PC tissues and adjacent non-cancerous pancreas tissues were obtained from patients in West China Hospital between 2015 and 2017. Patients diagnosed with PC were selected from all age groups and genders, excluding patients who were diagnosed with other malignant or benign pancreatic tumours. Diagnoses were performed following the conventional diagnostic criteria of the World Health Organization. All tissue samples were obtained from untreated patients during surgery, frozen immediately with liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C before use for further experiments. General characteristics of the individuals enrolled in this study are presented in table 1.

Human embryonic kidney cells 293 (HEK293) and PANC-1 were purchased from Shanghai Institutes for Biological Science (Shanghai, China). Both HEK293 and PANC-1 cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Both cell lines were incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C with saturated moisture.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

The expression of MALAT1 and miR-141-5p in PC tissues and cell lines was examined using qRT-PCR. Briefly, cryogenic grinding was performed on tissue samples, followed by total RNA extraction by adding 1 mL of Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA purity of the extracts was examined by measuring the optical density (OD) value. Sample extracts with OD 260/280 ratio between 1.8 and 2.0 were selected for use in the experiments. Reverse transcription was carried out using a High Capacity RNA-

to-cDNA kit (Takara Bio Inc. Kusatsu, Japan), with no more than 500 ng RNA per 10 μL PCR mix as the template. For the measurement of the expression of MALAT1 and miR-141-5p, real-time PCR was performed according to the standard SYBR Green protocol. cDNA was transcribed from total RNA using random primers. qPCR was performed at 95 °C for 10 seconds, then 60 °C for 60 seconds for 40 cycles, in 10 μL of reaction mix containing 3 μL of the cDNA, 2 μL of primers and 5 μL of SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), using an ABI 7900 thermocycler. The expression of miR-141-5p was normalized to that of U6. Expression of MATALT1 was normalized to that of GAPDH. Quantification of each gene was performed using the △△Ct method. Primers for miR-141-5p (MIRAP00173-250RXN) were purchased from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Other primers were the following. MALAT1: 5’-AAAGCAAGGTCTCCCCACAAG-3’ (forward), 5’-GGTCTGTGCAGATCAAAAGGCA-3’ (reverse); U6: 5’-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3’ (forward), 5’-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3’ (reverse); GAPDH: 5’-TTGGCCAGGGGTGCTAAG-3’ (forward), GAPDH: 5’-AGCCAAAAGGGTCATCATCTC-3’ (reverse).

RNA oligoribonucleotides and cell transfection

The MALAT1 sequence was designed and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (pcDNA3.1- MALAT1) to overexpress MALAT1. The small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting human MALAT1 (si-MALAT1, 5’-CACACGGAAGGCGAGUGGGUGGUC-3’), the negative control (siControl), miR-141-5p mimic (sense: 5’-CAUCUACCAGUAGAGUGUUCGA-3’, antisense 5’-CACCACGUUAUCGGAUGAUGCU-3’), miRNA negative control (miRNA-NC, 5’-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU-3’), and miR-141-5p inhibitor (5’-UAACAUCCGGCUGGUGAACAUGG-3’) were purchased from RiboBio (Guangzhou, China). The negative control for the miRNA mimic or siRNA was not homologous to any human genome sequences. Transfection of the RNA oligoribonucleotides (100 nmol/L) and plasmids was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were evaluated at 48 hours after transfection under an inverted fluorescence microscope to assess transfection efficiency and then harvested for the subsequent experiments.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

The interactions between miR-141-5p and MALAT1, and miR-141-5p and TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 were investigated using the dual-luciferase reporter assay. The psiCHECK2 dual-luciferase vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was used to generate a series of constructs. A fragment of MALAT1 consisting of the predicted target sites for miR-141-5p (WT) or a mutant variant (MUT) was directly synthesized (Shenggong, Shanghai, China) and then subcloned into the psiCHECK-2 vector to create the constructs. Each construct was then co-transfected with the miR-141-5p mimic or the negative control into HEK293 cells. In a separate experiment, the wild-type and mutant MALAT1 constructs were each co-transfected with a miR-141-5p inhibitor or the negative control into HEK293 cells for comparison. To analyse the binding of miR-141-5p on TGFBR1 and TGFBR2, the 3’-UTRs of TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 containing the putative binding sites for miR-141-5p (WT) or the mutant variants (mut) were each synthesized and subcloned into the psiCHECK-2 vector. Each construct was co-transfected with either the miR-141-5p mimic or the miRNA NC into HEK293 cells. All transient transfections were carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 hours of transfection, cells were harvested and luciferase activities were determined using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Each experiment was performed in triplicate. Results are presented as relative renilla luciferase activity, normalized to firefly luciferase activity.

Cell samples were lysed, and total proteins were extracted. Total protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 30 μL of each protein sample was loaded for separation via sodium decyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The gel was then transferred onto a Poly vinylidene fluoride (PVDF) transfer membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% fat-free dry milk for 2 hours, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with the primary antibodies, anti-TGFBR1, TGFBR2, N-cadherin, vimentin, E-cadherin, and GAPDH (1:1000 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). The membranes were then washed, followed by a one-hour incubation with the secondary antibody, HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). The membranes were then washed again and evaluated by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) using test kits (KeyGEN BioTech, Jiangsu, China).

Transwell migration and invasion assay

The invasive and migrated features of cultured cells were studied using transwell migration and invasion assays. Cell samples were suspended in FBS-free DMEM and density adjusted to 5×105 cells/mL. For testing the effect of miR-141-5p on TGF-β-mediated EMT, PANC-1 cells were transfected with miR-141-5p mimic, miRNA NC, or a mock vector, followed by treatment with 5 ng/mL TGF-β or blank solvent for 24 hours. To analyse the effect of MALAT1 together with the effect of miR-141-5p, PANC-1 cells were co-transfected with either pcDNA3.1-MALAT1 or a mock vector, each with or without miR-141-5p mimic, followed by treatment with 5 ng/mL TGF-β or blank solvent for 24 hours. The cell migration test was performed by adding 200 μL of the suspended cells to the upper chamber and adding 500 μL of DMEM with 10% FBS to the lower chamber. For cell invasion assays, Matrigel was first thawed overnight at 2-8 °C and diluted at a 1:4 ratio with pre-chilled FBS-free DMEM. Prior to adding the suspended cells, 50 μL of the diluted Matrigel was first added from the upper chamber to cover the membrane. Next, the chamber was incubated overnight at 37 °C, followed by the addition of 500 μL DMEM with 10% FBS to the lower chamber. For both the migration assay and invasion assay, the suspended cells were incubated for 48 hours. Medium from the upper chamber was discarded. A swab was used to remove excess cells on the upper surface of the membrane, and 4% paraformaldehyde was then added to the chamber to fix cells for 10 minutes, followed by washing three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The membrane was then washed after being stained for 20 minutes using crystal violet staining solution. For each membrane, five randomized views under an inverted microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) were chosen for cell counting to evaluate migration and invasion.

All statistical data in this study are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 19.0 statistics software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, UA). Comparison between multiple groups was analysed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The student’s t-test was used for comparison of MALAT1 and miR-141-5p expression between tumour tissue samples and adjacent non-cancerous pancreas tissues, and for comparison of TGF-β1-induced EMT, cell migration, and cell invasion between miR-141-5p mimic or miR-NC groups. All pairwise multiple comparison procedures were performed using Holm-Sidak method. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

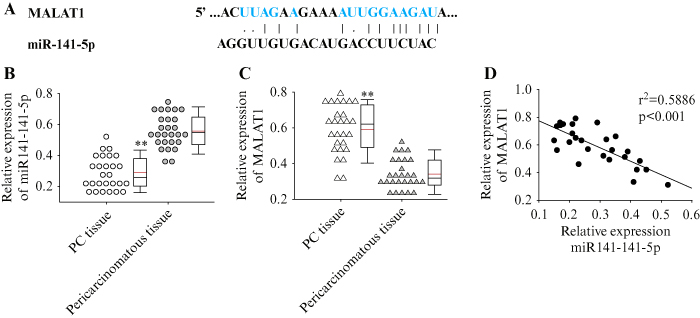

Negative correlation of MALAT1 and miR-141-5p expression in PC tissue

To assess the role of MALAT1 in PC, MALAT-1 expression in tumour tissue samples and adjacent non-cancerous pancreas tissues was first investigated. The results showed that MALAT-1 was highly expressed in various types of tumours, and was associated with the expression of miR-141-5p. A putative binding site between MALAT1 and miR-141-5p was identified using Blast sequence analysis (figure 1A), indicating that these genes might correlate with each other in terms of expression, signalling, and/or functionality. Therefore, their expression in both PC and pericarcinomatous tissues was analysed. Results showed a lower level of miR-141-5p (figure 1B) but higher level of MALAT1 (figure 1C) in PC tissues, compared to normal pancreatic tissues (p<0.05). Further correlation analysis showed that the expression levels of miR-141-5p and MALAT1 negatively correlated with each other in PC tissues (p<0.05) (figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Expression of MALAT1 and miR-141-5p in pancreatic cancer tissue. A) Blast analysis of the putative binding site between MALAT1 and miR-141-5p. B) Expression of MALAT1 in pancreatic tissue and pericarcinomatous tissue. C) Expression of miR-141-5p in pancreatic tissue and pericarcinomatous tissue. D) Correlation between the expression of MALAT1 and miR-141-5p in pancreatic tissue. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, **p<0.01.

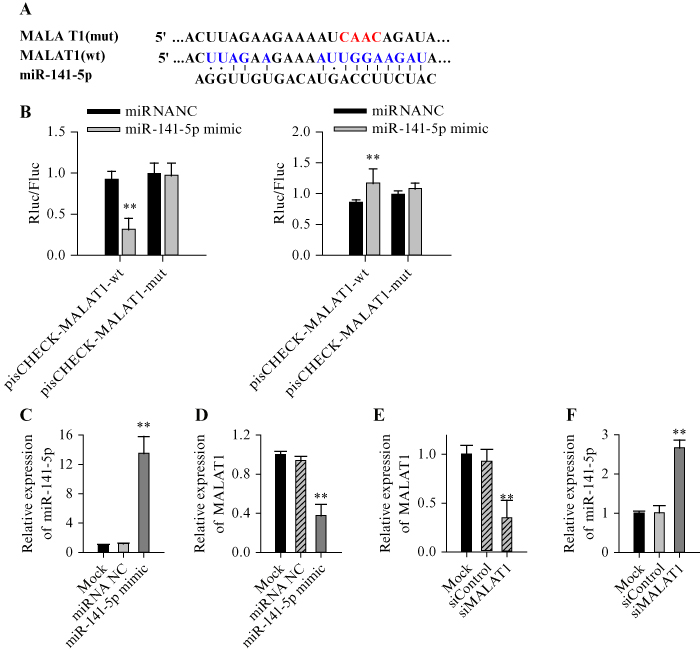

MiR-141-5p directly binds to MALAT1 in PANC-1 cells

Using HEK293 cells, we performed the dual luciferase assay to investigate whether MALAT1 interacts with miR-141-5p in vitro. The fragment containing the wild-type (WT) putative binding sequence of MALAT1 and the mutant (mut), as well as the sequence of miR-141-5p, subcloned into the psiCHECK-2 luciferase vector, are shown in figure 2A. The results showed that miR-141-5p significantly reduced luciferase activity when co-transfected with wild-type MALAT1 (p<0.05) (figure 2B). In addition, co-transfecting wild-type MALAT1 with miR-141-5p inhibitor into HEK293 cells showed increased luciferase activity compared to transfection with the miRNA negative control (p<0.05). These results indicate that miR-141-5p directly binds to MALAT1. To further investigate the interaction between miR-141-5p and MALAT1 in PC cells, miR-141-5p mimic were transfected into PANC-1 cells and the change in MALAT1 expression was monitored. Results indicated that transfection with miR-141-5p mimic increased the expression of miR-141-5p

(figure 2C) and suppressed the expression of MALAT1 (p<0.05) (figure 2D). On the other hand, knockdown of MALAT1 in PANC-1 cells using siRNA (figure 2E) significantly increased the expression of miR-141-5p (p<0.05) (figure 2F). The above results suggest that lncRNA MALAT1 acts as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) and a target for miR-141-5p in PC cells.

Figure 2.

Direct sequence-specific binding between MALAT1 and miR-141-5p and their effect on each other. A) The fragment containing the wild-type (wt) putative binding sequence of MALAT1 and the mutant (mut), as well as the sequence of miR-141-5p, were subcloned into the psiCHECK-2 luciferase vector. B) Luciferase activity in HEK293 cells co-transfected with the wild-type or mutant MALAT1, with miR-141-5p mimic or inhibitor. Cells co-transfected with mutant MALAT1 and miRNA NC were used as control. C, D) qRT-PCR showing the relative expression of miR-114-5p and MALAT1 in PANC-1 cells transfected with miR-141-5p mimic or miRNA-NC. E, F) qRT-PCR showing the relative expression of miR-114-5p and MALAT1 in PANC-1 cells transfected with siMALAT1 or siControl. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, **p<0.01.

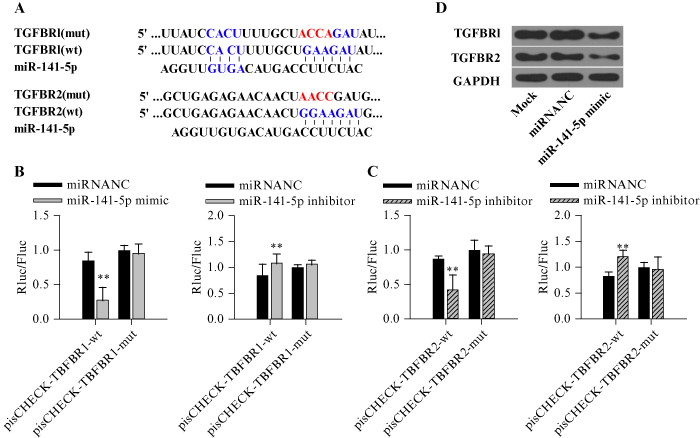

miR-141-5p directly binds to the 3’-UTR of TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 and suppresses their expression

TargetScan analysis revealed possible binding sites of miR-141-5p in the 3’-UTR of the TGF-β receptor genes, TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 (figure 3A). Therefore, a dual-luciferase experiment was further performed to determine whether miR-141-5p interacts with TGFBR1 and/or TGFBR2 in HEK293. Overexpression of miR-141-5p was shown to significantly suppress luciferase activity with wild-type TGFBR1 (figure 3B) or TGFBR2 (figure 3C) in HEK293 cells (p<0.05). Moreover, western blot analysis revealed that miR-141-5p mimic significantly reduced the expression of both TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 (figure 3D). These results therefore suggest that miR-141-5p binds directly to the 3’UTR of TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 to suppress their gene expression.

Figure 3.

Direct binding of miR-141-5p to the 3’-UTR of TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 inhibits protein expression in HEK293 cells. A) Fragments containing the wild-type (wt) putative binding site of TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 and their mutant (mt) variant, as well as the sequence for miR-141-5p mimic, were subcloned into the luciferase vector. B) Luciferase activity in cells co-transfected with miRNA-NC or the miR-141-5p mimic, with wild-type or mutant TGFBR1. C) Luciferase activity in cells co-transfected with miRNA-NC or miR-141-5p mimic, with wild-type or mutant TGFBR2. D) Western blot of TGFBR1 and TGFBR2. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, **p<0.01.

Overexpression of miR-141-5p inhibits TGF-β-induced EMT in PANC-1 cells

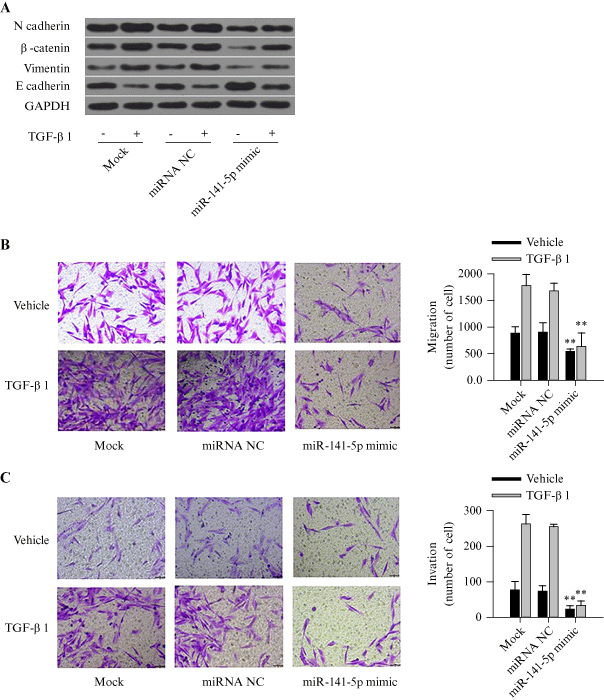

We further investigated whether miR-141-5p and MALAT1 play important roles in TGF-β-induced EMT and cell migration and invasion. After PANC-1 cells were transfected with either miR-141-5p mimic or miR-NC, and further induced with TGF-β1, the expression of a series of EMT-related markers was measured and analysed, including mesenchymal markers, N-cadherin and vimentin, and the epithelial marker, E-cadherin. When cells were transfected with miR-NC, TGF-β1 significantly downregulated E-cadherin but upregulated N-cadherin and vimentin expression. In contrast, these effects were inhibited by transfecting with miR-141-5p mimic (p<0.05) (figure 4A). Furthermore, overexpression of miR-141-5p significantly reduced TGF-β1-induced cell migration (figure 4B) and invasion (figure 4C) compared to those cells transfected with miR-NC (all p<0.05).

Figure 4.

Overexpression of miR-141-5p inhibits TGF-β-induced EMT, cell migration, and cell invasion in PANC-1 cells. A) Western blot analysis showing the expression of EMT-related proteins, after transfecting with miR-141-5p mimic, miRNA-NC, or the mock, followed by TGF-β1 treatment. B) Transwell migration assay in cells transfected with miR-141-5p mimic, miRNA-NC, or mock, followed by treatment with TGF-β1 or blank solvent. C) Invasion assay with Matrigel in cells transfected with miR-141-5p mimic, miRNA-NC, or mock, followed by treatment with TGF-β1 or blank solvent. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, **p<0.01.

Overexpression of MALAT1 suppresses the inhibitory effect of miR-141-5p on TGF-β-induced EMT, cell migration, and cell invasion in PANC-1 cells

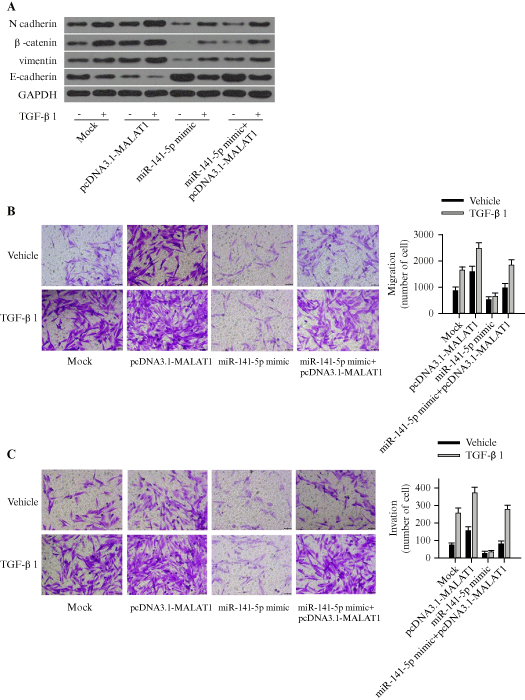

To investigate whether MALAT1 affects the inhibitory role of miR-141-5p in PC cell migration and invasion, either pcDNA3.1-MALAT1 or a mock vector was co-transfected with miR-141-5p mimic in PANC-1 cells, and the cells were then treated with TGF-β1 or blank solvent. Western blot results revealed that, compared to the mock vector, overexpression of MALAT1 significantly upregulated N-cadherin and vimentin expression, but downregulated E-cadherin expression (p<0.05) (figure 5A). These changes indicated that MALAT1 suppressed the inhibitory effect of miR-141-5p on TGF-β-induced EMT. Experiments on cell migration and invasion demonstrated that miR-141-5p reduced cell migration (figure 5B) and invasion (figure 5C) induced by TGF-β, while MALAT1 reversed metastatic effects of TGF-β (all p<0.05). It should be noted that there was a significant difference in the effects of miR-141-5p between vehicle and TGF-1-βtreated groups (p<0.05).

Figure 5.

MALAT1 suppresses the inhibitory effect of miR-141-5p on EMT, cell migration, and cell invasion induced by TGF-β in PANC-1 cells. A) Western blot showing the expression of EMT-related proteins in cells co-transfected with either pcDNA3.1-MALAT1 or a mock vector, with or without miR-141-5p mimic, followed by treatment with TGF-β1 or blank solvent. B) Transwell migration assay in cells transfected with either pcDNA3.1-MALAT1 or mock vector, with or without miR-141-5p mimic, followed by treatment with TGF-β1 or blank solvent. C) Invasion assay with Matrigel in cells transfected with either pcDNA3.1-MALAT1 or mock vector, with or without miR-141-5p mimic, followed by treatment with TGF-β1 or blank solvent. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. **p<0.01.

DISCUSSION

The role of lncRNA in gene regulation has been a popular topic in disease-related research, particularly oncology. Numerous researchers have found that lncRNAs play important roles and are crucial in PC initiation and progression [26–28]. The lncRNA, MALAT1, acts as a molecular scaffold for various riboprotein complexes and functions as a transcriptional and epigenetic regulator [29]. There are studies indicating that overexpression of MALAT1 in PC is associated with poor prognosis [30–34]. It was found that MALAT1 binds with the RNA-binding protein, HuR, and promotes autophagy via the HuR-TIA-1 pathway [33]. Moreover, MALAT1 is known to regulate the expression of Kras via competitive binding to miR-217, which promotes tumourigenesis [34].

The present study focused on analysing the sequence-specific binding between MALAT1 and miR-141-5p, providing the hypothesis that MALAT1 plays a role in miRNA expression via endogenous sponging. We initially revealed a correlation between MALAT1 and miR-141-5p in clinical tissue samples, followed by further confirmation of their binding in HEK293 cells, and finally we validated the negative correlation in terms of their expression within PANC-1 cells.

EMT is one of the crucial steps in metastasis of tumour cells. A few studies have provided evidence of increased expression of EMT markers (N-cadherin) and transcription factors (Snail, Slug and Twist, fibronectin, and vimentin) in surgically resected PC specimens [35–37]. Additionally, the presence of EMT in PC is often associated with an undifferentiated phenotype and overall poor survival compared to tumours without EMT [38]. TGF-β is needed to balance interactions between cells and the extracelluar matrix [39]. In recent years, TGF-β signalling has been found to play central roles in PC through EMT [40]. In order to initiate EMT, TGF-β must activate downstream signalling, including the Smad signalling pathway, through the tetramer unit formed by its two receptor proteins, TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 [21, 22]. Based on our experiments, we have shown that miR-141-5p can directly target TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 genes, and inhibit their expression. By suppressing the TGF-β pathway, miR-141-5p also regulates EMT-related protein expression, and inhibits TGF-β-induced cell migration and invasion in PANC-1 cells.

LncRNA is known to bind miRNAs and attenuate their activity by preventing their binding to target mRNAs, which indirectly promotes the expression of mRNA during the progression of PC [41, 42]. Studies have explored the use of miR-141-5p to treat a range of diseases [43, 44]. Our study reveals that overexpression of MALAT1 reduces free miR-141-5p via endogenous sponging, which in turn activates the TGF-β pathway through upregulation of TGFBR1 and TGFBR2. The overall effects promote TGF-β-induced EMT and increase cell migration and invasion.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, miR-141-5p inhibits TGF-β-induced PC cell migration, invasion, and metastasis by suppressing the expression of TGFBR1 and TGFBR2, and this inhibitory effect is reversed by MALAT1. Overexpression of MALAT1 in PC cells may be responsible for the initiation of metastasis during PC progression. Down-regulation of MALAT1 and/or upregulation of miR-141-5p may be a potential therapeutic strategy for PC treatment. Overall, our study may shed light on the discovery of novel drugs and aid the design of new therapeutic strategies for the treatment of PC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: We would like to thank Anna Wang from the USA for her help in preparing the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE

Financial support: This research was supported by the 1.3.5 project for Disciplines of Excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, China (No.ZYJC18027) and Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology Supporting Project, China (No.2018SZ0381). Conflicts of interest: none.

Author contributions. Conception and design: Zhenlu Li and Chao Yue. Administrative support: Zhenlu Li and Shengzhong Hou. Provision of study materials or patients: Chao Yue and Zihe Wang. Collection and assembly of data: Xing Huang, Weiming Hu and Huimin Lu. Data analysis and interpretation: Zhenlu Li and Chao Yue. Manuscript writing: All authors. Final approval of manuscript: all authors.

Ethical Statement. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of West China Hospital (No.2020[652]). Written informed consent was obtained from all adults for participation in this study.

Availability of data and material. All data generated or analysed during this study were included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

1. Freelove R, Walling AD. Pancreatic cancer: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 2006;73:485-92. [Google Scholar]

2. Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Epidemiology and risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2006;20:197-209. [Google Scholar]

3. Matsubayashi H, Takaori K, Morizane C, et al. Familial pancreatic cancer: concept, management and issues. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:935-48. [Google Scholar]

4. Hu JX, Zhao CF, Chen WB, et al. Pancreatic cancer: a review of epidemiology, trend, and risk factors. World J Gastroenterol 2021;27:4298-321. [Google Scholar]

5. Klein AP. Pancreatic cancer epidemiology: understanding the role of lifestyle and inherited risk factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;18:493-502. [Google Scholar]

6. Hu HF, Ye Z, Qin Y, et al. Mutations in key driver genes of pancreatic cancer: molecularly targeted therapies and other clinical implications. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2021;42:1725-41. [Google Scholar]

7. McGuigan A, Kelly P, Turkington RC, et al. Pancreatic cancer: a review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol 2018;24:4846-61. [Google Scholar]

8. Pereira SP, Oldfield L, Ney A, et al. Early detection of pancreatic cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:698-710. [Google Scholar]

9. Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2011;378:607-20. [Google Scholar]

10. Ribatti D, Tamma R, Annese T. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: a historical overview. Transl Oncol 2020;13:100773. [Google Scholar]

11. Sarkar FH, Li Y, Wang Z, Kong D. Pancreatic cancer stem cells and EMT in drug resistance and metastasis. Minerva Chir 2009;64:489-500. [Google Scholar]

12. Derynck R, Akhurst RJ. Differentiation plasticity regulated by TGF-beta family proteins in development and disease. Nat Cell Biol 2007;9:1000-4. [Google Scholar]

13. Ma ZL, Hua J, Liu J, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell-based targeted therapy pancreatic cancer: progress and challenges. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:3559. [Google Scholar]

14. Starzyńska T, Dąbkowski K, Błogowski W, et al. An intensified systemic trafficking of bone marrow-derived stem/progenitor cells in patients with pancreatic cancer. J Cell Mol Med 2013;17:792-9. [Google Scholar]

15. Bierie B, Moses HL. Tumour microenvironment: TGF-beta: the molecular Jekyll and Hyde of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:506-20. [Google Scholar]

16. Hata A, Shi Y, Massague J. TGF-beta signaling and cancer: structural and functional consequences of mutations in Smads. Mol Med Today 1998;4:257-62. [Google Scholar]

17. Neuzillet C, de Gramont A, Tijeras-Raballand A, et al. Perspectives of TGF-β inhibition in pancreatic and hepatocellular carcinomas. Oncotarget 2014;5:78-94. [Google Scholar]

18. Xu J, Lamouille S, Derynck R. TGF-beta-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cell Res 2009;19:156-72. [Google Scholar]

19. Truty MJ, Urrutia R. Basics of TGF-beta and pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology 2007;7:423-35. [Google Scholar]

20. Shi Y, Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 2003;113:685-700. [Google Scholar]

21. Feng XH, Derynck R. Specificity and versatility in tgf-beta signaling through Smads. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2005;21:659-93. [Google Scholar]

22. Lu Z, Friess H, Graber HU, et al. Presence of two signaling TGF-beta receptors in human pancreatic cancer correlates with advanced tumor stage. Dig Dis Sci 1997;42:2054-63. [Google Scholar]

23. Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, et al. A ceRNA hypothesis: the Rosetta Stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell 2011;146:353-8. [Google Scholar]

24. Hirata H, Hinoda Y, Shahryari V, et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 promotes aggressive renal cell carcinoma through Ezh2 and interacts with miR-205. Cancer Res 2015;75:1322-31. [Google Scholar]

25. Gutschner T, Hämmerle M, Eissmann M, et al. The noncoding RNA MALAT1 is a critical regulator of the metastasis phenotype of lung cancer cells. Cancer Res 2013;73:1180-9. [Google Scholar]

26. Jiao F, Hu H, Yuan C, et al. Elevated expression level of long noncoding RNA MALAT-1 facilitates cell growth, migration and invasion in pancreatic cancer. Oncol Rep 2014;32:2485-92. [Google Scholar]

27. Li L, Chen H, Gao Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 promotes aggressive pancreatic cancer proliferation and metastasis via the stimulation of autophagy. Mol Cancer Ther 2016;15:2232-43. [Google Scholar]

28. Zhao G, Wang B, Liu Y, et al. miRNA-141, downregulated in pancreatic cancer, inhibits cell proliferation and invasion by directly targeting MAP4K4. Mol Cancer Ther 2013;12:2569-80. [Google Scholar]

29. Zhang X, Hamblin MH, Yin KJ. The long noncoding RNA Malat1: its physiological and pathophysiological functions. RNA Biol 2017;14:1705-14. [Google Scholar]

30. Xu J, Xu WX, Xuan Y, et al. Pancreatic cancer progression is regulated by IPO7/p53/LncRNA MALAT1/miR-129-5p positive feedback loop. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021;9:630262. [Google Scholar]

31. Xie ZC, Dang YW, Wei DM, et al. Clinical significance and prospective molecular mechanism of MALAT1 in pancreatic cancer exploration: a comprehensive study based on the GeneChip, GEO, Oncomine, and TCGA databases. Onco Targets Ther 2017;10:3991-4005. [Google Scholar]

32. Wang WL, Lou WY, Ding BS, et al. A novel mRNA-miRNA-lncRNA competing endogenous RNA triple sub-network associated with prognosis of pancreatic cancer. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11:2610-27. [Google Scholar]

33. Xie ZC, Dang YW, Wei DM, et al. Clinical significance and prospective molecular mechanism of MALAT1 in pancreatic cancer exploration: a comprehensive study based on the GeneChip, GEO, Oncomine, and TCGA databases. Onco Targets Ther 2017;10:3991-4005. [Google Scholar]

34. Liu PP, Yang HY, Zhang J, et al. The lncRNA MALAT1 acts as a competing endogenous RNA to regulate KRAS expression by sponging miR-217 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep 2017;7:5186. [Google Scholar]

35. Nakajima S, Doi R, Toyoda E, et al. N-cadherin expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:4125-33. [Google Scholar]

36. Hotz B, Arndt M, Dullat S, et al. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition: expression of the regulators snail, slug, and twist in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:4769-76. [Google Scholar]

37. Javle MM, Gibbs JF, Iwata KK, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (p-Erk) in surgically resected pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:3527-33. [Google Scholar]

38. Masugi Y, Yamazaki K, Hibi T, et al. Solitary cell infiltration is a novel indicator of poor prognosis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer. Hum Pathol 2010;41:1061-8. [Google Scholar]

39. Xu M, He JB, Li J, et al. Methyl-CpG-binding domain 3 inhibits epithelial–mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer cells via TGF-β/Smad signaling. Br J Cancer 2017;116:919. [Google Scholar]

40. Gasior K, Wagner NJ, Cores J, et al. The role of cellular contact and TGF-beta signaling in the activation of the epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT). Cell Adh Migr 2019;13:63-75. [Google Scholar]

41. Romano R, Picca A, Eusebi LHU, et al. Extracellular vesicles and pancreatic cancer: insights on the roles of mirna, lncrna, and protein cargos in cancer progression. Cells 2021;10:1361. [Google Scholar]

42. Zhang GL, Pian C, Chen Z, et al. Identification of cancer-related miRNA-lncRNA biomarkers using a basic miRNA-lncRNA network. PloS One 2018;13:e0196681. [Google Scholar]

43. Liu P, Zou YT, Li X, et al. circGNB1 facilitates triple-negative breast cancer progression by regulating miR-141-5p-IGF1R axis. Front Genet 2020;11:193. [Google Scholar]

44. Wei ZM, Hu Y, He X, et al. Knockdown hsa_circ_0063526 inhibits endometriosis progression via regulating the miR-141-5p/EMT axis and downregulating estrogen receptors. Aging (Albany NY) 2021;13:26095-117. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools