Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Effect of proinflammatory cytokines on blood-brain barrier integrity

Department of Biophysics, Physiology & Pathophysiology, Medical University of Warsaw, 5 Chalubinskiyi Str., 02-004 Warsaw, Poland

* Corresponding Author: Dariusz Szukiewicz,

European Cytokine Network 2024, 35(3), 38-47. https://doi.org/10.1684/ecn.2024.0498

Accepted 19 October 2024;

Abstract

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) consists of a unique system of brain microvascular endothelial cells, capillary basement membranes, and terminal branches (“end-feet”) of astrocytes. The BBB’s primary function is to protect the central nervous system from potentially harmful or toxic substances in the bloodstream by selectively controlling the entry of cells and molecules, including nutrients and immune system components. During neuroinflammation, the BBB loses its integrity, resulting in increased permeability, mostly due to the activity of inflammatory cytokines. However, the pathomechanism of structural and functional changes in the BBB caused by individual cytokines is poorly understood. This review summarizes the current state of knowledge on this topic, which is important from both the pathophysiological and clinical-therapeutic point of view. The structure and function of each of the components of the BBB are discussed with particular attention to phenotypic differences between brain microvascular endothelial cells and the vascular endothelium at other locations of the circulatory system. The protein composition of the inter-endothelial tight junctions in the context of regulating BBB permeability is presented, as is the role of the pericyte-BMEC interaction in the exchange of metabolites, ions, and nucleic acids. Finally, the documented actions of proinflammatory cytokines within the BBB are summarized.Keywords

The blood-brain barrier (BBB), which is a specialized internal barrier, plays an important role in ensuring the normal functioning of the central nervous system (CNS), which is responsible for the vital functions of the body as a whole [1]. The BBB is a complex structure consisting of endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocytes, located between the brain parenchyma and the vascular system, and is highly connected to surrounding neurons and microglia [2, 3]. Loss of division between blood and nervous tissue can damage the central nervous system and change the composition of the cerebrospinal fluid. BBB disturbances are commonly found in neuronal dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration, as well as substance use disorders [4, 5]. A precise understanding of the structure of the BBB and the pathomechanism in which pro-inflammatory cytokines influence the disruption (loss of integrity) of the BBB may contribute to improving existing preventive and therapeutic methods (reviewed in [6, 7]).

The majority of studies consider the disruption of this barrier structure in the context of pathogenesis of certain diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, psychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus, herpes simplex encephalitis and cerebrovascular ischaemia or other pathological conditions and processes, including stress, traumatic brain injury, subarachnoid haemorrhage and sepsis [8–10].

Wątroba et al. reviewed the literature regarding the impact of dysglycaemia associated with diabetes mellitus on BBB structure, revealing that impaired blood sugar stability, especially when exceeding normal levels, causes damage to BBB structure and CNS cells, leading to neurodegeneration and dementia [11]. High blood sugar was found to raise the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-1, IL-4, and IL-6, although no information as to how these cytokines affect the integrity and permeability of the BBB was mentioned. Using a mouse model with BBB disruption due to congenital traumatic brain injury, Lesniak et al. showed that the loss of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, as a result of BBB disruption, correlated with depression-like behaviour [12]. The authors, however, only studied behavioural changes caused by BBB damage and did not investigate the mechanisms leading to barrier structure damage. Nevertheless, this mouse model of BBB rupture may be useful to investigate the in vivo effect of cytokines on BBB disruption.

Małkiewicz et al. reviewed studies showing that drugs, such as methamphetamine, can activate microglia and induce the release of proinflammatory cytokines, leading to BBB disruption [13]. The authors also highlighted the role of oxidative stress and MMP activation in this process. In order to determine whether serum levels of proteins are associated with BBB function in patients with epilepsy, Bronisz et al. reported that increased serum levels of MMP-9, MMP-2, TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and S100B, but not of CCL-2, ICAM-1, P-selectin, and TSP-2, were associated with the chronic processes of disruption and restoration of BBB integrity, indicating their direct relationship with barrier permeability [14, 15]. However, the study did not provide a detailed description of the nature of the mechanism(s) underlying these relationships.

Since proinflammatory cytokines cause systemic inflammation as a response to pathological changes associated with the development of diseases, some of which are the cause and others the consequence of BBB, they may be directly related to BBB structural damage [16–18]. Therefore, the current review paper aims to summarize the current state of knowledge on the influence of proinflammatory cytokines on the disruption of the integrity and permeability of the BBB, based on data relating to its structural features that are important from both a pathophysiological and clinical-therapeutic point of view.

Materials and Methods

To investigate BBB structure and the effect of proinflammatory cytokines on disruption of the BBB, we focussed on the structure and function of the BBB, including pathways and factors leading to BBB disorders, pathways of proinflammatory cytokines that pass through the BBB without disrupting its structure, and the effect of proinflammatory cytokines on BBB disorders. Analysis was based on medical scientific literature sources on anatomy, neurology, immunology, and microbiology published in the electronic databases of PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus. The search that included information on the structure and function of the BBB was carried out using the following key words: “blood-brain barrier structure”, “capillary endothelium”, “basement membrane”, “astrocytes”, and “blood-brain barrier functions”. The search resulted in 33 sources that were relevant to the topic. These search terms identified scientific papers that dealt with causes of BBB disorders and how these disorders can be treated, and were grouped into three main categories: “mechanisms of BBB damage”, “factors influencing BBB disorders”, and “diseases causing BBB disorders”.

Priority was given to papers that contained observational or experimental data. Six publications of interest were selected for analysis. Sources for the review of proinflammatory cytokines that can cross the BBB without damaging its structure were selected from the list of studies containing both theoretical developments and experimental components using the key words “proinflammatory cytokines and the blood-brain barrier”, “types of proinflammatory cytokines that cross the blood-brain barrier”, and “ways of crossing the blood-brain barrier by proinflammatory cytokines”. Four sources corresponded to the given topic. The search for scientific papers on the role of proinflammatory cytokines in the disruption of BBB integrity was carried out using the key words “the role of the inflammatory process in blood-brain barrier integrity disruption”, “negative impact of proinflammatory cytokines on the blood-brain barrier”, and “impact of proinflammatory cytokines on blood-brain barrier structure disruption”. In total, 32 sources were selected that contained theoretical information and the results of practical developments on this topic. A total of 75 scientific sources, published between 1994 and 2023, were selected for analysis. Data relating to the objective of the study were then prepared in order to generate information on the mechanism by which proinflammatory cytokines affect the disruption of BBB structure.

This information was summarised to determine the positive and negative effects of proinflammatory cytokines on BBB structure and further identify how damage due to such negative effects may be controlled and overcome.

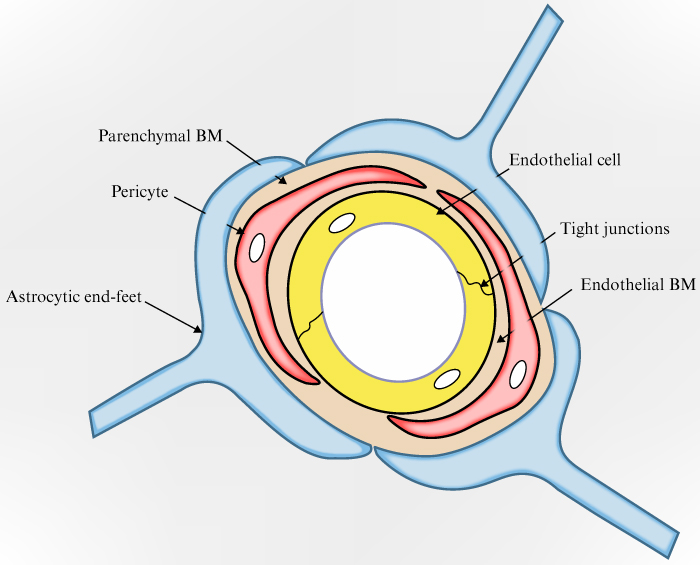

The BBB is structurally designed to provide its main, protective and regulatory, functions. Any damage to it can negatively affect the neurological system, as loss of integrity disrupts how the the blood and nervous tissue are separated, abolishing the boundary between the central nervous system and dangerous substances in the blood, leading to changes in the stability of cerebrospinal fluid. To study how the BBB is damaged, it is necessary to get acquainted with its structure in detail, to understand how and what can disrupt it. The BBB is not located in the entire central nervous system; it is absent in those parts of the central nervous system in which the chemical composition of the blood is controlled, its main parameters are regulated, and the presence of toxins are detected. These parts include the hypothalamus and the vomiting centre in the medulla oblongata. The BBB structure is made up of three main parts: the capillary endothelium, the capillary basement membrane, and the perivascular membrane, which is made up of glial cell processes (the round “legs” of astrocytes). The capillary endothelium, together with pericytes, is located on the basement membrane, on the opposite side to that with glial cell processes.

The normal (undisturbed) structure of the BBB is a “layering” of biostructures, each of which acts as a level of protection, isolating blood from nerve tissue. The first level of protection is provided by the capillary endothelium, the second level by the basement membrane, and the third level by the perivascular membrane formed from astrocyte processes. The capillary endothelium restricts the access of bacteria and other microscopic objects, as well as large hydrophilic molecules, while also ensuring the diffusion of small hydrophilic molecules and the transport of metabolic products. The basement membrane’s tasks are to preserve the barrier’s structure and ensure signal exchange between its components. The perivascular membrane maintains the normal structure of the BBB due to contact with brain capillaries and astrocyte processes [19–21] (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the BBB.

The capillary endothelium consists of firmly and tightly connected endothelial cells that are linked by inter-endothelial tight junctions. Phenotypically, the endothelial cells of the BBB differ from endothelial cells localised in other parts of the body as they have a more flattened appearance, a larger number of mitochondria, and a significantly smaller number of caveolae [22, 23]. These features, as well as playing a role in communication between cells in the capillary endothelium, affect the level of BBB permeability.

The capillary endothelium blocks the transport of hydrophilic molecules to the nervous system and separates the capillary lumen from the basolateral complex. However, it allows small lipophilic molecules to pass by making it easier for nutrients (like glucose through the GLUT1 channel, essential amino acids, and some electrolytes), oxygen, carbon dioxide, lipids, anaesthetics, ethanol, and nicotine to diffuse, and insulin, transferrin, and leptin to pass the barrier via receptor-mediated endocytosis [24–26].

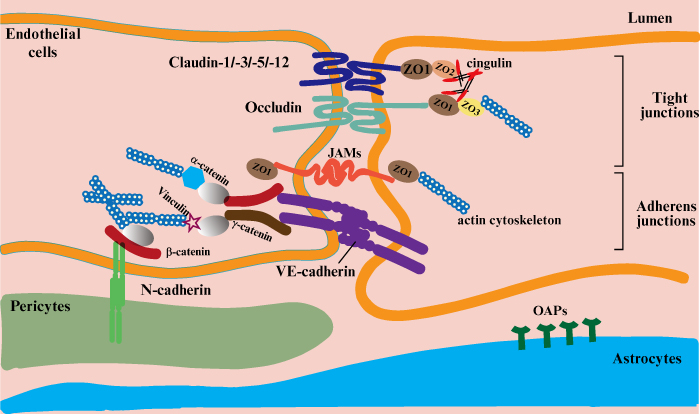

Tight contacts, which ensure a strong contact between endothelial cells, are formed from the main membrane proteins (claudin, occludin, junctional adhesion molecules [JAMs], and cadherin) and several additional cytoplasmic proteins (Zonula occludens-1, -2, -3; cingulin; α-catenin; β-catenin; γ-catenin; vinculin and others) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the tight contact made by endothelial cells [27].

Tight junctions (TJs) consist of auxiliary cytoplasmic proteins that tether the main membrane proteins to the main cytoskeleton protein (actin), which allows the integrity of the capillary endothelium and the required level of permeability to be maintained [27, 28].

Claudin proteins form a strong seal, involving bonds with each other between the endothelial cells on which they are located and Zonula occludens proteins (ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3). The strength of the bonds affects the degree of BBB permeability under conditions of inflammation, exposure to harmful substances, trauma, and other pathological conditions. As a result, damage to claudin negatively affects the barrier’s permeability, allowing monocytes to pass through in some inflammatory diseases [29–34].

The occludin protein has a molecular weight of 65 kDa and is a much bigger molecule compared to the claudins (20-27 kDa). It is thus composed of more amino acids than the latter (522 and 102-150 amino acids, respectively), depending on the transmembrane domains. Along with claudin, occludin creates intramembrane filaments that enable hydrophilic molecules and ions to move through cells that control the amount of fluid which can pass through between cells [35–37]. JAMs are immunoglobulin proteins with a molecular weight of 40 kDa. JAMs are known to provide adhesion density by binding to actin via ZO-1, but data on their role in monocyte migration across the BBB have not been conclusively confirmed, and research in this area is still ongoing [38].

Cadherin is an important part of tight junctions that binds to the cell’s cytoskeleton with the help of catenins to form a tight adhesive contact. The main task of additional cytoplasmic proteins is to establish a strong connection between membrane proteins and the cell cytoskeleton. Zonula occludens ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3 bind claudins, and ZO-1 binds occludins and JAMs. ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3 establish a connection between claudin and occludin and intracellular actin via cingulin [39]. It is the role of β-catenin and γ-catenin to link cadherin to the cytoskeleton through α-catenin or its related protein, vinculin [40–42].

Pericytes are localised outside the capillary endothelium, sharing a basement membrane with it, and are involved in the synthesis of its constituents. With their ability to contract and the processes they use to cover the endothelium, pericytes control how easily fluids can pass through the interendothelial junction. Due to the close contact with the capillary endothelium, metabolites, ribonucleic acid (RNA), and ions are exchanged between cells, and this exchange is ensured by the ability of pericytes to phagocytose, which allows them to neutralise toxic metabolites [43].

Pericytes play an important role in the activation of endothelial and astrocyte functions in BBB regulation (reviewed in [44]). They express vasopressin, angiotensin, and endothelin receptors that control the expression of BBB-specific genes in endothelial cells and cause polarisation of astrocytes that surround the capillaries in the central nervous system. Damage to pericytes occurs in many neurological disorders, especially degenerative diseases, such as dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis. This can lead to a decrease in the resistance of endothelial cells to apoptosis, as a result of a loss of their connection with pericytes, thereby compromising the integrity of the BBB.

The basement membrane of capillaries, which is a form of extracellular matrix, is located under endothelial and epithelial cells. Its primary functions are cell fixation on its surface, BBB structure maintenance, and signal transmission between its elements [45]. The basement membrane consists of four proteins, collagen IV, laminin, nidogen and perlecan, that form a plate, 50 to 100 nm thick [46]. These proteins are synthesised by the endothelial cells of the brain vessels, pericytes, and astrocytes. Collagen IV is the most abundant basement membrane protein that maintains the basement membrane structure and also plays an important role in maintaining vessel integrity [47–49].

Laminin is produced in different isoforms depending on the type of cell that synthesizes it. Astrocytes, in particular, synthesize specific isoforms of laminin that play an important role in maintaining the BBB, which is indispensable for its integrity. Collagen IV and laminin are stabilised by the protein, nidogen (entactin).

The perivascular membrane, formed by glial cell processes, consists of astrocytes that are the most common cells in the central nervous system which play an important role in the inflammatory process during the development of neurodegenerative diseases [51]. Given that astrocytes are formed in the postnatal period, i.e., after the BBB has formed and thickened, it can be assumed that these cells are not involved in the formation of the barrier itself. However, an important role in maintaining BBB structure is played by the processes (“legs”) of astrocytes, which are in close contact with the brain capillaries. It has not yet been established whether astrocytes affect the level of BBB permeability, although some studies confirm the involvement of these cells in the formation of TJs by modulating the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and angiotensin-1 [50].

Having examined the main structural units of the BBB, we now turn to how proinflammatory cytokines affect their integrity.

Influence of proinflammatory cytokines on disorders associated with abnormal BBB structure

The effect of cytokines on BBB structure is dependent on the barrier penetration mechanism. When entering the body exogenously, for example, via injection, cytokines can quickly and easily cross the BBB without disrupting its structure. This process can occur via retrograde axonal transport, saturated influx transport, or simple diffusion in areas of the brain where the BBB is leaky. The interleukins, IL-1α and IL-6, and TNF-α can cross the barrier via these pathways. Usually, the exogenous route of cytokines into the body is controlled such that when the barrier is crossed, its structure is not disturbed, or the disturbance is insignificant. However, it is worth noting that such a crossing, even without structural disruption, can compromise the integrity of the BBB by activating free calcium and potentially disrupting homeostasis in the brain (review in [52]).

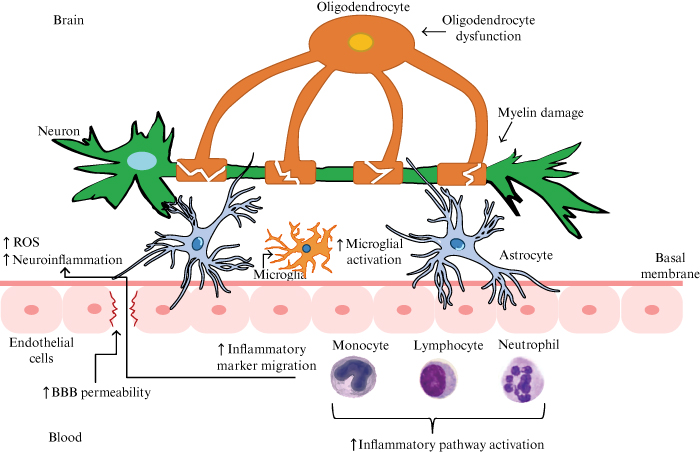

The endogenous pathway of proinflammatory cytokines through the BBB may be more harmful to the barrier’s structural integrity, which is often damaged, resulting in increased permeability due to the occurrence of neurological disorders, neurodegenerative diseases or infectious diseases of the CNS. These conditions cause the level of proinflammatory cytokines to rise (figure 3).

Figure 3.

The endogenous pathway of proinflammatory cytokines through the BBB. Note: in this case, the scheme of BBB disruption is related to a mental disorder (bipolar affective disorder) [16].

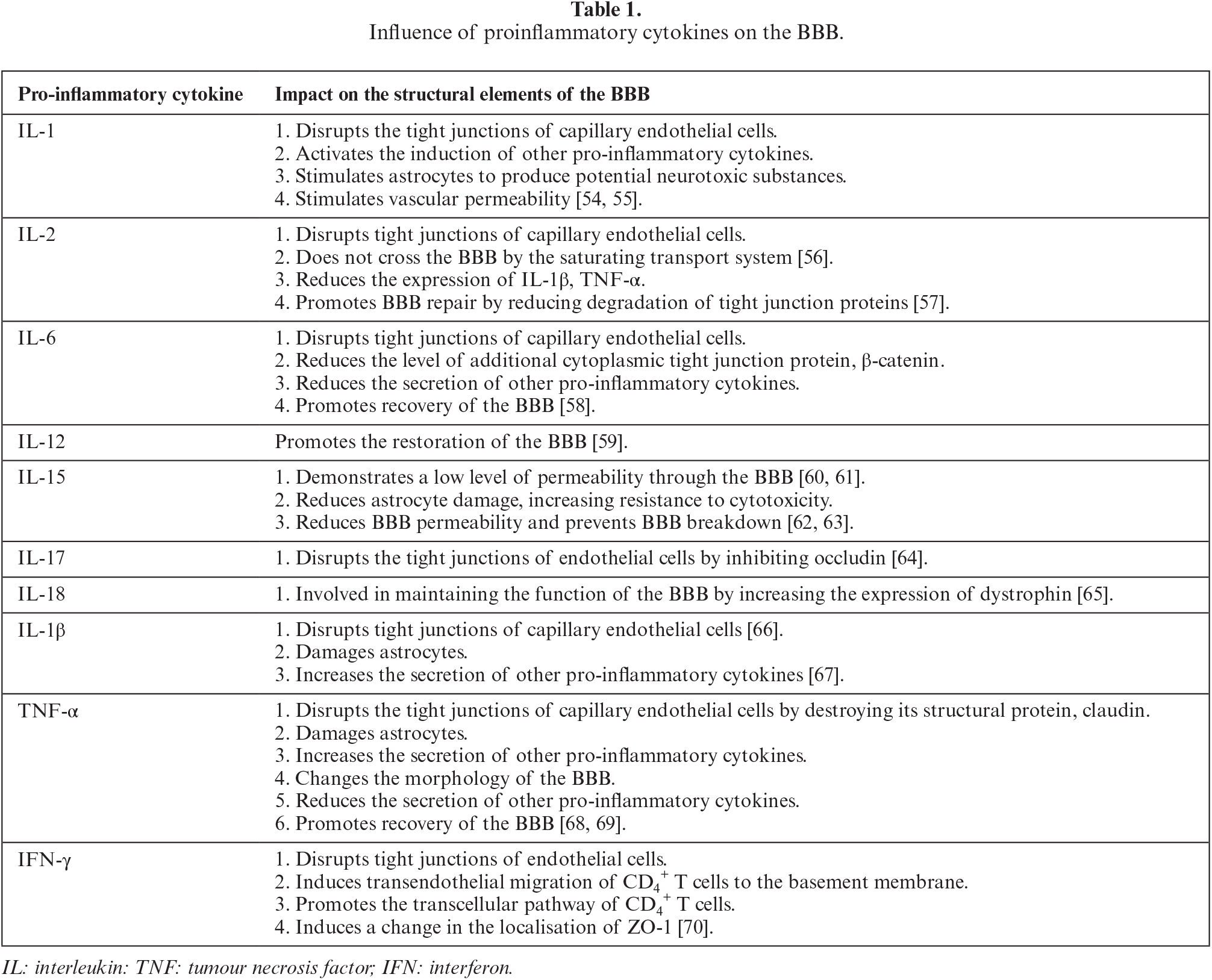

Pathological conditions in the CNS are often, if not always, accompanied by an inflammatory response involving proinflammatory cytokines produced by macrophages, leukocytes, neutrophils, or other cells, depending on the pathological process. For example, in response to stroke or lipopolysaccharides, microglia produce IL-1 and TNF-α, as a result of neuroinflammation, and induce the generation of reactive astrocytes that adopt the same proinflammatory phenotype [53]. The effect of proinflammatory cytokines on BBB disorders is shown in table 1.

The increase in the levels of proinflammatory cytokines depends on the nature and character of pathological processes and nervous system conditions. The permeability of the BBB is indirectly affected by autoimmune diseases, as they lead to an increase in cytokine levels. Thus, certain changes in the immune system cause a violation of BBB permeability, resulting in the generation of autoreactive T lymphocytes entering the central nervous system and increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1, TNF-α, and interferon [IFN]-γ. As a result, the process of autoimmune attack on the myelin sheath is triggered, which leads to the development of multiple sclerosis [71, 72].

In ischaemic stroke, cytokines, oxidants, and proteolytic enzymes are also released which, upon reaching the brain, can cause cytotoxic oedema, thereby rendering the BBB less permeable. This allows leukocytes to migrate into brain tissue through the capillary endothelium and damage healthy neurones [73]. The neuroinflammatory process is considered to be one of the underlying causes of epilepsy which is initiated by IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α when the CNS is affected by pathological conditions such as the presence of a brain tumour, a traumatic brain injury (TBI), or following drug exposure. However, it is important to determine which is the primary process– damage to the BBB or seizures. Considering one of the most common causes of epilepsy, TBI, it is important to investigate how BBB damage is associated with seizures. Depending on the consequences of TBI, BBB disruption occurs either mechanically or as a result of the action of proinflammatory cytokines activated in response to trauma. Blood components, one of which is thrombin, enter the cerebrospinal fluid through a haemorrhage, where they provoke neuronal excitability and, accordingly, seizures [74, 75].

The increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, TNF-α and IFN-γ) is also associated with the occurrence of some mental disorders, including depression. This inflammatory activity can both start and sustain this production, implying that prolonged exposure of the nervous system to this state can damage the BBB and cause other neurological disorders and diseases [76]. Activation of astrocytes and increased levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α are observed following the administration of neurotoxic drugs. Damage to the BBB and an increase in its permeability caused by methamphetamine neurotoxicity is manifested by a decrease in the levels of claudin and occludin, swelling of astrocytes and their processes, a decrease in pericyte coverage, and loss of TJs of endothelial cells [77–79]. Factors that stimulate increased production of IL-6 and TNF-α reportedly include engagement of the histamine H4 receptor, expressed on many cell types of the immune system, thereby indirectly activating mast cells, which, in addition to cytokines, actively produce chemokines and histamine [80].

Chemokines are cytokines with chemotactic activity that are involved in the physiological and pathological processes of the CNS [81, 82]. In healthy, non-pathological conditions, chemokines, such as CCL2, CCL19, CCL20, CCL21, and CXCL12, allow intracellular communication, turn on signalling pathways, and maintain the CNS in a state of homeostasis [83, 84]. CX3CL1 (fractalkine) acts as a growth or maintenance factor for adult neurones, maintains homeostasis, and can also lower levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α [85, 86]. CXCL12, CCL19, CCL20 and CCL21, are expressed in the vascular system associated with the BBB (review in [87]). In pathological conditions of the CNS, chemokines exhibit the property of mediators of cell migration and participate in the regulation of inflammatory and autoimmune (differentiation and growth of cells, including that of tumours) processes [88]. The mechanism of the effect of CX3CL1 on BBB integrity depends on the cell type involved in migration. For example, one mechanism is triggered by a significant accumulation of CD16+ monocytes on inflamed cerebral endothelial cells due to their transendothelial migration in response to CX3CL1 expression [89]. Alternatively, the migration of CD4+ T cells is ensured by the chemoattractant activity of CX3CL1 [90]. Changes in BBB permeability are affected by an increase in CXCL13 levels, which may occur as a result of the development of tumours with cerebral metastases. This leads to an increase in the capillary endothelium’s paracellular permeability and a decrease in the expression and localization of the tight junction proteins, claudin-5 and occludin [91].

It is also important to consider the role of histamine and its impact on BBB integrity. The histamine molecule is not small enough to penetrate the capillary endothelium, and thus cannot cross the BBB [92, 93]. However, it can increase BBB permeability by downregulating the major tight junction membrane proteins, claudin-5 and occludin, as well as the additional cytoplasmic protein, Zonula occludens-1. Moreover, the expression of histamine H2 receptor can be used as a predictive indicator of barrier permeability provoked by histamine [94, 95]. An investigation of the structure of the BBB and the effect of proinflammatory cytokines on its damage revealed that interleukins IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α were most often involved in barrier disruption. The development of therapeutic approaches should address the mechanism of the effect of proinflammatory cytokines on the BBB in order to preserve its integrity and prevent neurological disorders caused by the ingress of blood elements into the nervous tissue [96, 97].

The study of the BBB has revealed that its main functions (protection and regulation) are performed primarily due to the structure and combination of all elements, from the specific shape of endothelial cells and specific tight connections between them, to the placement of astrocyte processes in a tight ring around the basement membrane [98, 99]. When the nervous system is damaged, as in multiple sclerosis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, or myasthenia gravis, the immune system reacts by causing systemic inflammation, which is sparked by proinflammatory cytokines [100, 101]. According to studies, an increase in the concentration of these cytokines in the blood can damage the BBB structure and increase its permeability by disrupting the tight junctions of capillary endothelial cells and other barrier components. This data may be used as a foundation for the development of therapeutic methods, to control the level of proinflammatory cytokines in order to preserve the integrity of the BBB.

This issue was addressed by Takeshita et al. [102]. The authors built static BBB models to study long-term barrier function, and based on this, they demonstrated that IL-6 blockade suppresses BBB dysfunction, preventing the onset of visual spectrum neuromyelitis. The authors found that inhibition of T-cell migration to nervous tissue of the spinal cord was influenced by blocking IL-6 signal transduction, which prevented the expansion of BBB permeability. IL-6 blockade was achieved by transferring immunoglobulin G (NMO-IgG) and satralizumab through the BBB using a triple culture system, which mimics the close contact with endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocyte processes. Using this BBB model, methods to block other pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, may be developed.

It is important to consider the ability of proinflammatory cytokines to penetrate the BBB, not only as a means to control it, but also as a tool to overcome the BBB as an obstacle to drug penetration into nervous tissue. Italian researchers, Corti et al., investigated how tumour necrosis factor (TNF-α) could be used as a “conductor” for drugs to cross the BBB, to travel directly to a brain tumour for treatment [103]. The authors studied the capabilities and properties of the drug, NGR-TNF, a product of peptide and cytokine fusion, which includes the NGR-TNF molecule combined with the peptide Cys-Asn-Gly-Arg-Cys-Gly (CNGRCG) (denoted as NGR in the drug’s name) and the ligand of aminopeptidase N (CD13) of tumour blood vessels. The results of preclinical and clinical trials have shown the drug’s effectiveness in altering tumour BBB selectivity, which has improved the quality of chemotherapy and led to increased patient survival. Although it was noted that the drug’s instability and molecular heterogeneity could give rise to unwanted side effects, this therapeutic approach to enhance BBB permeability, allowing the delivery of drugs at the tumour site, is promising [103].

In addition to exogenous disrupting factors (brain injury, infection, radiation), internal causes, such as stress or sleep loss, may also affect BBB integrity. The effect of sleep on the regulation of the BBB was studied by Hurtado-Alvarado et al. who reported that sleep loss in an experimental mouse model provoked a low-grade inflammatory state [104]. According to the study results, increased BBB permeability was found in the group of experimental mice with limited sleep time. The hippocampus of these animals showed an increase in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF and IFN-γ, as well as adenosine receptor. As a result of prolonged sleep loss or disruption, the damaged BBB structure may therefore be limited in its ability to recover, leading to complex nervous disorders and neurodegenerative diseases [47].

The COVID-19 acute respiratory disease pandemic has sparked scientists’ interest in the impact of the highly transmissible, pathogenic coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 on various body systems. Zhang et al. reported that SARS-CoV-2 crosses the BBB, accompanied by the destruction of the basement membrane without affecting TJs [105]. SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in vivo in the vascular wall, perivascular space and microvascular endothelial cells in the brain of infected mice, whereas BBB breakdown was observed in SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters. The study reveals that the SARS-CoV-2 virus damages the BBB through a transcellular pathway that bypasses TJs and breaks the barrier through endothelial cells.

COVID-19 can trigger hyperactivation of the immune system and an uncontrolled release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in pulmonary tissues, a process known as a “cytokine storm”, which may ultimately result in multi-organ failure and death. The effect of a cytokine storm on BBB integrity is poorly understood, and at present there are no studies that identify the type of damage to the BBB and the level of its recovery after successful treatment of the cytokine storm [106–108].

Chen et al. examined the role of IL-17 in neuroinflammation in an animal model of nitroglycerin-induced chronic migraine and reported that nitroglycerin administration increased BBB permeability and peripheral IL-17A permeation into the medulla oblongata, resulting in activated microglia and neuroinflammation, and causing hyperalgesia and migraine attack [109]. The results of this study suggest that IL-17A might be a novel target in the treatment of migraine.

Conclusions

This review was conducted to describe the structure of the BBB and the deleterious effect of proinflammatory cytokines on its function. Proinflammatory cytokines, in particular IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, following their interaction with structural elements of the BBB, lead to the disruption of TJs of capillary endothelial cells, destruction of the structural protein claudin, reduced levels of catenin, and damage to astrocytes. These inflammatory actions have deleterious effects on the structure and permeability of the BBB, and are associated with pathological processes in the nervous system. Taken together, understanding the mechanism of the effect of proinflammatory cytokines on the BBB may be useful in developing therapeutic methods to neutralise their deleterious action.

Disclosure

Financial support: none. Conflicts of interest: none.

LIST Of ABBREVIATIONS

| BBB | blood-brain barrier structure (BBB) |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| IL | interleukin |

| TJs | tight junctions |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid |

| TBI | traumatic brain injury. |

REFERENCES

1. Dyrna F, Hanske S, Krueger M, Bechmann I. The blood-brain barrier. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2013;8:763-73. [Google Scholar]

2. Khan E. An examination of the blood-brain barrier in health and disease. Br J Nurs 2005;14:509-13. [Google Scholar]

3. Abbott NJ, Patabendige AA, Dolman DE, Yusof SR, Begley DJ. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis 2010;37:13-25. [Google Scholar]

4. Kim JH, Byun HM, Chung EC, Chung HY, Bae ON. Loss of integrity: Impairment of the blood-brain barrier in heavy metal-associated ischemic stroke. Toxicol Res 2013;29:157-64. [Google Scholar]

5. Yang C, Hawkins KE, Doré S, Candelario-Jalil E. Neuroinflammatory mechanisms of blood-brain barrier damage in ischemic stroke. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2019;316:135-53. [Google Scholar]

6. Akata F, Nakagawa S, Matsumoto J, Dohgu S. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction amplifies the development of neuroinflammation: Understanding of cellular events in brain microvascular endothelial cells for prevention and treatment of BBB dysfunction. Front Cell Neurosci 2021;15:661838. [Google Scholar]

7. Zhao B, Yin Q, Fei Y, Zhu J, Qiu Y, Fang W, Li Y. Research progress of mechanisms for tight junction damage on blood-brain barrier inflammation. Arch Physiol Biochem 2022;128:1579-90. [Google Scholar]

8. Li X, Cai Y, Zhang Z, Zhou J. Glial and vascular cell regulation of the blood-brain barrier in diabetes. Diabetes Metab J 2022;46:222-38. [Google Scholar]

9. Cai Z, Qiao PF, Wan CQ, Cai M, Zhou NK, Li Q. Role of blood-brain barrier in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2018;63:1223-34. [Google Scholar]

10. Nikolopoulos D, Manolakou T, Polissidis A, Filia A, Bertsias G, Koutmani Y, Boumpas DT. Microglia activation in the presence of intact blood-brain barrier and disruption of hippocampal neurogenesis via IL-6 and IL-18 mediate early diffuse neuropsychiatric lupus. Ann Rheum Dis 2023;82:646-57. [Google Scholar]

11. Wątroba M, Grabowska AD, Szukiewicz D. Effects of diabetes mellitus-related dysglycemia on the functions of blood-brain barrier and the risk of dementia. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:10069. [Google Scholar]

12. Lesniak A, Poznański P, Religa P, Nawrocka A, Bujalska-Zadrozny M, Sacharczuk M. Loss of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) resulting from congenital – Or mild traumatic brain injury-induced blood-brain barrier disruption correlates with depressive-like behaviour. Neuroscience 2021;458:1-10. [Google Scholar]

13. Małkiewicz MA, Małecki A, Toborek M, Szarmach A, Winklewski PJ. Substances of abuse and the blood brain barrier: Interactions with physical exercise. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2020;119:204-16. [Google Scholar]

14. Bronisz E, Cudna A, Wierzbicka A, Kurkowska-Jastrzębska I. Blood-brain barrier-associated proteins are elevated in serum of epilepsy patients. Cells 2023;12:368. [Google Scholar]

15. Bartoszewicz M, Czaban SL, Bartoszewicz K, Kuzmiuk D, Ladny JR. Bacterial bloodstream infection in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2023;10:20499361231207178. [Google Scholar]

16. Patel JP, Frey BN. Disruption in the blood-brain barrier: The missing link between brain and body inflammation in bipolar disorder? Neural Plast 2015;2015:708306. [Google Scholar]

17. Yarlagadda A, Alfson E, Clayton AH. The blood brain barrier and the role of cytokines in neuropsychiatry. Psychiatry 2009;6:18-22. [Google Scholar]

18. Haley MJ, Lawrence CB. The blood-brain barrier after stroke: Structural studies and the role of transcytotic vesicles. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017;37:456-70. [Google Scholar]

19. Xu L, Nirwane A, Yao Y. Basement membrane and blood-brain barrier. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2018;4:78-82. [Google Scholar]

20. Erickson MA, Banks WA. Transcellular routes of blood-brain barrier disruption. Exp Biol Med 2022;247:788-96. [Google Scholar]

21. Persidsky Y, Ramirez SH, Haorah J, Kanmogne GD. Blood-brain barrier: Structural components and function under physiologic and pathologic conditions. J Neuro Pharm 2006;1:223-36. [Google Scholar]

22. Xie Y, He L, Lugano R, et al. Key molecular alterations in endothelial cells in human glioblastoma uncovered through single-cell RNA sequencing. JCI. Insight 20216. [Google Scholar]

23. Langen UH, Ayloo S, Gu C. Development and cell biology of the blood-brain barrier. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2019;35:591-613. [Google Scholar]

24. Ozgür B, Helms HCC, Tornabene E, Brodin B. Hypoxia increases expression of selected blood-brain barrier transporters GLUT-1, P-gp, SLC7A5 and TFRC, while maintaining barrier integrity, in brain capillary endothelial monolayers. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022;19:1. [Google Scholar]

25. Bhowmick S, D’Mello V, Caruso D, Wallerstein A, Abdul-Muneer PM. Impairment of pericyte-endothelium crosstalk leads to blood-brain barrier dysfunction following traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol 2019;317:260-70. [Google Scholar]

26. Kakava S, Schlumpf E, Panteloglou G, et al. Brain endothelial cells in contrary to the aortic do not transport but degrade low-density lipoproteins via both LDLR and ALK1. Cells 2022;11:3044. [Google Scholar]

27. Kadry H, Noorani B, Cucullo L. A blood-brain barrier overview on structure, function, impairment, and biomarkers of integrity. Fluids Barriers CNS 2020;17:69. [Google Scholar]

28. Kniesel U, Wolburg H. Tight junctions of the blood-brain barrier. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2000;20:57-76. [Google Scholar]

29. Feng S, Zou L, Wang H, et al. RhoA/ROCK-2 pathway inhibition and tight junction protein upregulation by catalpol suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced disruption of blood-brain barrier permeability. Molecules 2018;23:2371. [Google Scholar]

30. Haseloff RF, Dithmer S, Winkler L, et al. Transmembrane proteins of the tight junctions at the blood-brain barrier: Structural and functional aspects. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2015;38:16-25. [Google Scholar]

31. Koumangoye R, Penny P, Delpire E. Loss of NKCC1 function increases epithelial tight junction permeability by upregulating claudin-2 expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2022;323:1251-63. [Google Scholar]

32. Yamamoto TM, Webb PG, Davis DM, et al. Loss of Claudin-4 reduces DNA damage repair and increases sensitivity to PARP inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther 2022;21:647-57. [Google Scholar]

33. Kim NY, Pyo JS, Kang DW, Yoo SM. Loss of claudin-1 expression induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition through nuclear factor-κB activation in colorectal cancer. Pathol Res Pract 2019;215:580-85. [Google Scholar]

34. Greene C, Hanley N, Campbell M. Claudin-5: Gatekeeper of neurological function. Fluids Barriers CNS 2019;16:3. [Google Scholar]

35. Günzel D, Fromm M. Claudins and other tight junction proteins. Compr Physiol 2012;2:1819-52. [Google Scholar]

36. Komarova YA, Kruse K, Mehta D, Malik AB. Protein interactions at endothelial junctions and signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Circ Res 2017;120:179-206. [Google Scholar]

37. Liu WY, Wang ZB, Zhang LC, et al. Tight junction in blood-brain barrier: An overview of structure, regulation, and regulator substances. CNS Neurosci Ther 2012;18:609-15. [Google Scholar]

38. Bergmann S, Lawler SE, Qu Y, et al. Blood-brain-barrier organoids for investigating the permeability of CNS therapeutics. Nat Protoc 2018;13:2827-43. [Google Scholar]

39. Hartsock A, Nelson WJ. Adherens and tight junctions: Structure, function and connections to the actin cytoskeleton. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008;1778:660-69. [Google Scholar]

40. Kuo WT, Odenwald MA, Turner JR, Zuo L. Tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1 as regulators of epithelial proliferation and survival. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2022;1514:21-33. [Google Scholar]

41. Wang Q, Huang X, Su Y, et al. Activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway mitigates blood-brain barrier dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2022;145:4474-88. [Google Scholar]

42. Liebner S, Gerhardt H, Wolburg H. Differential expression of endothelial beta-catenin and plakoglobin during development and maturation of the blood-brain and blood-retina barrier in the chicken. Dev Dyn 2000;217:86-98. [Google Scholar]

43. Armulik A, Genové G, Mäe M, et al. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature 2010;468:557-61. [Google Scholar]

44. Alarcon-Martinez L, Yemisci M, Dalkara T. Pericyte morphology and function. Histol Histopathol 2021;36:633-43. [Google Scholar]

45. Khalilgharibi N, Mao Y. To form and function: On the role of basement membrane mechanics in tissue development, homeostasis and disease. Open Biol 2021;11:200360. [Google Scholar]

46. Halder SK, Sapkota A, Milner R. The importance of laminin at the blood-brain barrier. Neural Regen Res 2023;18:2557-63. [Google Scholar]

47. Latka K, Zurawel R, Maj B, et al. Iatrogenic lumbar artery pseudoaneurysm after lumbar transpedicular fixation: Case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep 2019;7:2050313X19835344. [Google Scholar]

48. Alisheva A, Mamyrbekova S, Kamkhen V. Diseases of the circulatory system: Structure and dynamics of mortality and survival. Z Gefassmed 2023;20:9-13. [Google Scholar]

49. Latka K, Kolodziej W, Pawlak K, et al. Fully endoscopic spine separation surgery in metastatic disease-case series, technical notes, and preliminary findings. Medicina-Lithuania 2023;59:993. [Google Scholar]

50. Vyshka G, Seferi A, Myftari K, Halili V. Last call for informed consent: confused proxies in extra-emergency conditions. Indian J Med Ethics 2014;11:252-4. [Google Scholar]

51. Clarke LE, Barres BA. Emerging roles of astrocytes in neural circuit development. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013;14:311-21. [Google Scholar]

52. Varatharaj A, Galea I. The blood-brain barrier in systemic inflammation. Brain Behav Immun 2017;60:1-12. [Google Scholar]

53. Liu LR, Liu JC, Bao JS, et al. Interaction of microglia and astrocytes in the neurovascular unit. Front Immunol 2020;11:1024. [Google Scholar]

54. Versele R, Sevin E, Gosselet F, et al. TNF-α and IL-1β modulate blood-brain barrier permeability and decrease amyloid-β peptide efflux in a human blood-brain barrier model. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:10235. [Google Scholar]

55. Sjöström EO, Culot M, Leickt L, et al. Transport study of interleukin-1 inhibitors using a human in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier. Brain Behav Immun Health 2021;16:100307. [Google Scholar]

56. Waguespack PJ, Banks WA, Kastin AJ. Interleukin-2 does not cross the blood-brain barrier by a saturable transport system. Brain Res Bull 1994;34:103-9. [Google Scholar]

57. Gao W, Li F, Zhou Z, et al. IL-2/Anti-IL-2 complex attenuates inflammation and BBB disruption in mice subjected to traumatic brain injury. Front Neurol 2017;8:281. [Google Scholar]

58. Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Broadwell RD. Passage of cytokines across the blood-brain barrier. Neuroimmunomodulation 1995;2:241-8. [Google Scholar]

59. Serna-Rodríguez MF, Bernal-Vega S, de la Barquera JAO et al. The role of damage-associated molecular pattern molecules (DAMPs) and permeability of the blood-brain barrier in depression and neuroinflammation. J Neuroimmunol 2022;371:577951. [Google Scholar]

60. Pan W, Wu X, He Y, et al. Brain interleukin-15 in neuroinflammation and behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2013;37:184-92. [Google Scholar]

61. Pan W, Hsuchou H, Yu C, Kastin AJ. Permeation of blood-borne IL-15 across the blood-brain barrier and the effect of LPS. J Neurochem 2008;106:313-9. [Google Scholar]

62. Li Z, Han J, Ren H, et al. Astrocytic Interleukin-15 Reduces Pathology of Neuromyelitis Optica in Mice. Front Immunol 2018;9:523. [Google Scholar]

63. Burrack KS, Huggins MA, Taras E, et al. Interleukin-15 complex treatment protects mice from cerebral malaria by inducing interleukin-10-producing natural killer cells. Immunity 2018;48:760-72. [Google Scholar]

64. Huppert J, Closhen D, Croxford A, et al. Cellular mechanisms of IL-17-induced blood-brain barrier disruption. FASEB J 2010;24:1023-34. [Google Scholar]

65. Jung HK, Ryu HJ, Kim MJ, et al. Interleukin-18 attenuates disruption of brain-blood barrier induced by status epilepticus within the rat piriform cortex in interferon-γ independent pathway. Brain Res 2012;1447:126-34. [Google Scholar]

66. Souza PS, Gonçalves ED, Pedroso GS, et al. Physical exercise attenuates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibiting peripheral immune response and blood-brain barrier disruption. Mol Neurobiol 2017;54:4723-37. [Google Scholar]

67. Balzano T, Dadsetan S, Forteza J, et al. Chronic hyperammonemia induces peripheral inflammation that leads to cognitive impairment in rats: Reversed by anti-TNF-α treatment. J Hepatol 2020;73:582-92. [Google Scholar]

68. Zhang W, Tian T, Gong SX, et al. Microglia-associated neuroinflammation is a potential therapeutic target for ischemic stroke. Neural Regen Res 2021;16:6-11. [Google Scholar]

69. Han EC, Choi SY, Lee Y, et al. Extracellular RNAs in periodontopathogenic outer membrane vesicles promote TNF-α production in human macrophages and cross the blood-brain barrier in mice. FASEB J 2019;33:13412-22. [Google Scholar]

70. Sonar SA, Shaikh S, Joshi N, et al. IFN-γ promotes transendothelial migration of CD4+ T cells across the blood-brain barrier. Immunol Cell Biol 2017;95:843-53. [Google Scholar]

71. Rochfort KD, Cummins PM. The blood-brain barrier endothelium: A target for pro-inflammatory cytokines. Biochem Soc Trans 2015;43:702-6. [Google Scholar]

72. Lee JI, Choi JH, Kwon TW, et al. Neuroprotective effects of bornyl acetate on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis via anti-inflammatory effects and maintaining blood-brain-barrier integrity. Phytomedicine 2023;112:154569. [Google Scholar]

73. Pawluk H, Woźniak A, Grześk G, et al. The role of selected pro-inflammatory cytokines in pathogenesis of ischemic stroke. Clin Interv Aging 2020;15:469-84. [Google Scholar]

74. Savotchenko АВ. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction and development of epileptic seizures. Bull Nat Acad Sci Ukr 2021;1:53-61. [Google Scholar]

75. Kamali AN, Zian Z, Bautista JM, et al. The potential role of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in epilepsy pathogenesis. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 2021;21:1760-74. [Google Scholar]

76. Diener H-C, Gaul C, Holle-Lee D, et al. Headache – An update 2018. Laryngorhinootologie 2019;98:192-217. [Google Scholar]

77. Huang J, Ding J, Wang X, et al. Transfer of neuron-derived α-synuclein to astrocytes induces neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier damage after methamphetamine exposure: Involving the regulation of nuclear receptor-associated protein 1. Brain Behav Immun 2022;106:247-61. [Google Scholar]

78. Jayanthi S, Daiwile AP, Cadet JL. Neurotoxicity of methamphetamine: Main effects and mechanisms. Exp Neurol 2021;344:113795. [Google Scholar]

79. Zareifopoulos N, Skaltsa M, Dimitriou A, et al. Converging dopaminergic neurotoxicity mechanisms of antipsychotics, methamphetamine and levodopa. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2021;25:4514-9. [Google Scholar]

80. Thangam EB, Jemima EA, Singh H, et al. The role of histamine and histamine receptors in mast cell-mediated allergy and inflammation: The hunt for new therapeutic targets. Front Immunol 2018;9:1873. [Google Scholar]

81. van der Vorst EP, Döring Y, Weber C. Chemokines. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2015;35:52-6. [Google Scholar]

82. Miller MC, Mayo KH. Chemokines from a structural perspective. Int J Mol Sci 2017;182088 [Google Scholar]

83. Liu W, Jiang L, Bian C, Liang Y, Xing R, Yishakea M, Dong J. Role of CX3CL1 in Diseases. Arch Imm Exper Ther 2016;64:371-83. [Google Scholar]

84. Vérité J, Janet T, Chassaing D, et al. Longitudinal chemokine profile expression in a blood-brain barrier model from Alzheimer transgenic versus wild-type mice. J Neuroinflamm 2018;15:182. [Google Scholar]

85. Bachstetter AD, Morganti JM, Jernberg J, et al. Fractalkine and CX3CR1 regulate hippocampal neurogenesis in adult and aged rats. Neurobiol Aging 2011;32:2030-44. [Google Scholar]

86. Rogers JT, Morganti JM, Bachstetter AD, et al. CX3CR1 deficiency leads to impairment of hippocampal cognitive function and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci 2011;31:16241-50. [Google Scholar]

87. Williams JL, Holman DW, Klein RS. Chemokines in the balance: maintenance of homeostasis and protection at CNS barriers. Front Cell Neurosci 2014;8:154. [Google Scholar]

88. Legler DF, Thelen M. Chemokines: Chemistry, biochemistry and biological function. Chimia (Aarau) 2016;70:856-9. [Google Scholar]

89. Ancuta P, Moses A, Gabuzda D. Transendothelial migration of CD16+ monocytes in response to fractalkine under constitutive and inflammatory conditions. Immunobiology 2004;209:11-20. [Google Scholar]

90. Bertin J, Jalaguier P, Barat C, et al. Exposure of human astrocytes to leukotriene C4 promotes a CX3CL1/fractalkine-mediated transmigration of HIV-1-infected CD4+ T cells across an in vitro blood-brain barrier model. Virology 2014;454-5:128-38. [Google Scholar]

91. Curtaz CJ, Schmitt C, Herbert SL, et al. Serum-derived factors of breast cancer patients with brain metastases alter permeability of a human blood-brain barrier model. Fluids Barriers CNS 2020;17:31. [Google Scholar]

92. Alstadhaug KB. Histamine in migraine and brain. Headache 2014;54:246-59. [Google Scholar]

93. Smashna O. Influence of cognitive functioning on the effectiveness of treatment of veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder and mild traumatic brain injury. Int J Med Med Res 2023;9:30-41. [Google Scholar]

94. Wang Z, Cai XJ, Qin J, et al. The role of histamine in opening blood-tumor barrier. Oncotarget 2016;7:31299-310. [Google Scholar]

95. Vadzyuk S, Tabas P. Cardio-respiratory endurance of individuals with different blood pressure levels. Bull Med Biol Res 2023;5:30-8. [Google Scholar]

96. Navruzov SN, Polatova DS, Geldieva MS, et al. Possibilities of study of the main cytokines of the immune system in patients with osteogenic sarcoma. Vopr Onkol 2013;59:599-602. [Google Scholar]

97. Diaferio L, Parisi GF, Brindisi G, et al. Cross-sectional survey on impact of paediatric COVID-19 among Italian paediatricians: Report from the SIAIP rhino-sinusitis and conjunctivitis committee. Ital J Pediatr 2020;46:146. [Google Scholar]

98. Gilhus NE, Verschuuren JJ. Myasthenia gravis: Subgroup classification and therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:1023-36. [Google Scholar]

99. Younger DS. The blood-brain barrier: Implications for vasculitis. Neurol Clin 2019;37:235-48. [Google Scholar]

100. Ortiz GG, Pacheco-Moisés FP, Macías-Islas MÁ, et al. Role of the blood-brain barrier in multiple sclerosis. Arch Med Res 2014;45:687-97. [Google Scholar]

101. Khan AW, Farooq M, Hwang MJ, et al. Autoimmune neuroinflammatory diseases: Role of interleukins. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:7960. [Google Scholar]

102. Takeshita Y, Fujikawa S, Serizawa K, et al. New BBB model reveals that IL-6 blockade suppressed the BBB disorder, preventing onset of NMOSD. Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 20218. [Google Scholar]

103. Corti A, Calimeri T, Curnis F, et al. Targeting the blood-brain tumor barrier with tumor necrosis factor-α. Pharmaceutics 2022;14:1414. [Google Scholar]

104. Hurtado-Alvarado G, Becerril-Villanueva E, Contis-Montes de Oca A, et al. The yin/yang of inflammatory status: Blood-brain barrier regulation during sleep. Brain Behav Immun 2018;69:154-66. [Google Scholar]

105. Zhang L, Zhou L, Bao L, et al. SARS-CoV-2 crosses the blood-brain barrier accompanied with basement membrane disruption without tight junctions alteration. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021;6:337. [Google Scholar]

106. Salyha N. Regulation of oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation induced by epinephrine: The corrective role of L-glutamic acid. Int J Med Med Res 2023;9:32-8. [Google Scholar]

107. Primasatya CAI, Awalia A. Small vessel vasculitis, an uncommon presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus: A case report. Gac Med Caracas 2023;131:198-205. [Google Scholar]

108. Gómez J, Lozada CC. Public health bioethics: Digievolution proposal. Gac Med Caracas 2023;131:434-48. [Google Scholar]

109. Chen H, Tang X, Li J, et al. IL-17 crosses the blood-brain barrier to trigger neuroinflammation: A novel mechanism in nitroglycerin-induced chronic migraine. J Headache Pain 2022;23:1. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools