Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Anti-inflammatory action and effects on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism: an understudied role of interleukin-6

Division of Biological and Health Science (DCBS), Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana Unidad Iztapalapa (UAM-I); Laboratory of Pharmacology, Department of Health Sciences. CBS. UAM-I

* Corresponding Author: Fortis-Barrera A.,

European Cytokine Network 2024, 35(4), 48-55. https://doi.org/10.1684/ecn.2024.0499

Accepted 18 October 2024;

Abstract

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a cytokine with pleiotropic effects that plays a significant role in the transition from the innate immune response to adaptive response. IL-6 is of interest due to its proinflammatory action, however, it also exhibits anti-inflammatory effects, supporting metabolism and suppressing associated diseases, such as obesity, diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome. The IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) is a type I transmembrane glycoprotein in the plasma membrane of only some cell types, such as macrophages, neutrophils, hepatocytes, and T cells. The function of IL-6R requires another transmembrane glycoprotein of 130 kDa (gp130) which, in contrast to IL-6R, is expressed in many cell types. In addition, a soluble form of the IL-6 receptor (sIL-6R) also plays a role in the function of IL-6. These receptors, gp130 and sIL-6R, are involved in the trans pathway of IL-6 signalling, the activation of which is associated with high IL-6 concentrations, promoting proinflammatory processes that are well known. In contrast, the physiological effects of IL-6 associated with increased insulin secretion, fatty acid oxidation and decreased adipose tissue, which occur due to activation of the IL-6 anti-inflammatory signalling pathway, have been poorly explored. Some studies using IL-6 knockout models suggest that some of the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-6 may be stimulated by low concentrations of IL-6, and are essential to suppressing metabolic alterations. This review seeks to highlight the importance of the anti-inflammatory role of IL-6 in metabolic diseases.Keywords

Interleukin 6 (IL-6) is a protein of the IL-6 type cytokine family [1, 2]. It consists of 212 amino acid residues, including a 28-residue signal peptide, forming a bundle-shaped structure of four α-helices of 21 to 28 kDa [1, 3]. IL-6 was discovered and identified when the cDNA encoding for B-cell stimulatory factor 2 (BSF-2) was cloned in 1986. It was then named BSF-2, as well as hepatocyte-stimulating factor, hybridoma-plasmacytoma growth factor, interferon β2, and the 26-kDa protein [4, 5]. IL-6 is associated with the transition from an innate immune response towards an adaptive response and has been proposed as a modulator of the immune response [4, 6].

IL-6 is associated with pro-inflammatory processes. The overproduction of this cytokine leads to alterations in tissues, favouring the development of multiple chronic inflammatory diseases that include rheumatoid arthritis [7], Castleman’s disease [8], polymyalgia rheumatica [9], giant cell arteritis [10], and colon cancer [11]. In contrast, IL-6 also exhibits anti-inflammatory effects and participates in the regulation of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism [12]. In this review, the results of recent investigations on this cytokine are presented and the main molecular mechanisms of action of IL-6 are discussed.

REGULATION OF IL-6 GENE EXPRESSION

IL-6 acts before an event emerges. Many cell types, including stromal and immune cells, produce IL-6 in response to exogenous stimuli, including bacterial, viral or fungal antigens that activate pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like receptors [13]. The concentration of circulating IL-6 in the normal human adult bloodstream fluctuates between 1 and 5 pg/mL, however, this concentration dramatically increases under inflammatory conditions [14]. IL-6 participates in tissue damage through damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), involving molecules synthesized from mitochondrial DNA, high mobility group proteins (HMGB1) or s100 proteins, which are released by damaged or dead cells during non-infectious processes, triggering inflammatory events [15].

The regulatory factors of IL-6 gene expression have been described to several levels. In the upstream promotor region of the IL-6 gene, there are different DNA cis elements that interact with several proteins or trans elements [16]. The transcription factor NF-κB is the main regulator of IL-6 expression. NF-κB binds to specific sequences located in the -75 to -64 upstream region of the IL-6 promoter [17, 18]. The binding and activation of NF-κB occurs in response to stimuli from bacterial or viral infections and, consequently, by TNFα and IL-1β [19].

Another site within the IL-6 promoter is the cAMP response element (CRE) [20], which allows for binding of CREB transcription factor, activated by β-adrenergic agonists which are mediated by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Norepinephrine can induce IL-6 secretion in gastric epithelial cells [21]. Synthetic agonists, such as isoproterenol, also induce IL-6 secretion in Balb/c mouse cardiac fibroblasts [22]. In this region where the CRE is located, there is a binding site for another transcription factor, C/EBPβ (also called NF-IL6) [23]. All these sequences are together located between -164 and -145 bp [24], and present a high degree of homology between mice and humans [25].

Other elements that regulate the expression of IL-6 have also been reported, such as an activation protein 1 (AP-1) binding motif [26], also known as a TPA response element, located at -283 to -277 bp [19]. When AP-1 binds to its DNA consensus binding site, it exerts a significant effect on IL-6 expression [27].

Steroid hormones are also capable of exerting effects on the expression of IL-6. When a steroid binds to its receptor, it migrates to the nucleus and binds to a DNA consensus sequence known as a steroid response element, which is present in the promoter region of the IL-6 gene. In humans, a pair of glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) are located at positions -557 to -552 and -446 to -441 bp [28]. When the alpha subunit of glucocorticoid receptor binds to GREs, it acts as a negative regulator of proinflammatory cytokine expression, in addition to binding to transcription factors, such as NF-κB or AP-1 [29, 30]. Therefore, glucocorticoids may play a role in the anti-inflammatory action of IL-6.

On the other hand, oestrogens can negatively regulate the expression of IL-6 through the interaction of oestrogen receptor with the DNA-binding domains of transcription factors, such as NF-κB or NF-IL6 [31]. This regulation of IL-6 is also mediated by androgens [32].

The IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) is an 80-kDa type I transmembrane glycoprotein. The α subunit of the receptor is also known as CD126 [33, 34]. This protein is expressed on the plasma membrane of a very limited number of cell types, including macrophages, neutrophils, hepatocytes, and some types of T cells [6, 33, 35].

A particular characteristic of IL-6R is that it requires another 130-kDa transmembrane glycoprotein, the β subunit of the receptor, called gp130 (or CD130), which is responsible for initiation of signal transduction within the cell [3, 33, 34, 35]. It is important to note that IL-6R is not capable of activating signalling if gp130 is not present.

Contrary to the expression of IL-6R, restricted to very few cell types, gp130 is expressed in practically all cell types present in the body [1, 35]. Functional and structural studies suggest that the formation of a hexameric complex formed by two molecules of IL-6, IL-6R and gp130 (IL-62/IL-6R2/gp1302) is necessary [36, 37]. Another model proposed involves the formation of a tetrameric complex (IL-61/IL-6R1/gp1302) [38].

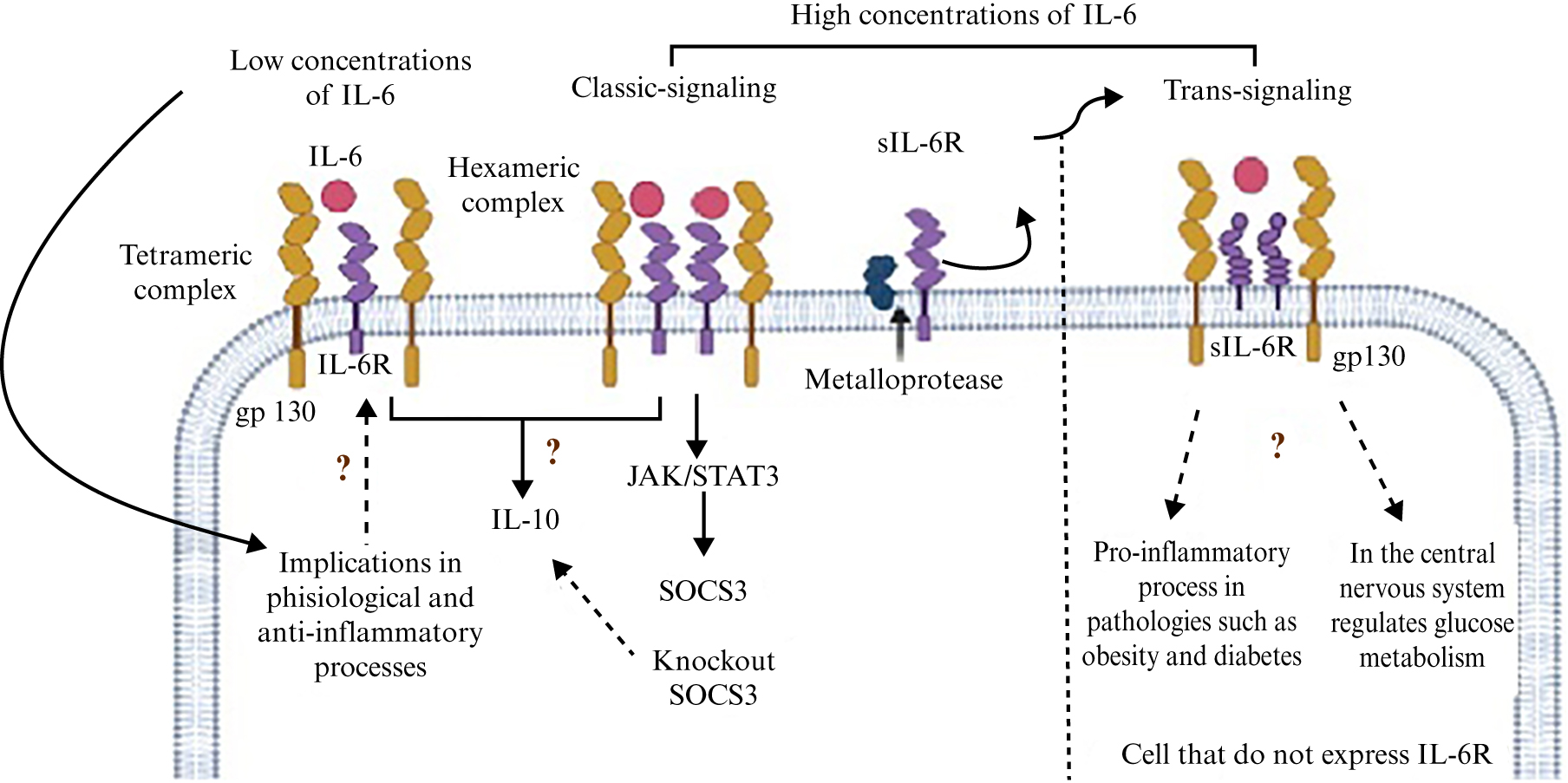

These models indicate that the type of complex formed depends on the concentration of circulating IL-6, since high concentrations of IL-6 appear to favour the formation of the hexameric complex, while low concentrations favour formation of the tetrameric complex (figure 1) [39–41]. The study of these complexes between IL-6 and its receptors is of interest because they are possibly involved in activating specific signals responsible for the attributed pleiotropic action of IL-6. Moreover, IL-6 signalling, involving gp130, is implicated in the regulation of insulin sensitivity, leading to disorders such as obesity and diabetes [42].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram showing IL-6 receptor complexes and their signalling. At high concentrations of IL-6, the hexameric complex (IL-62/IL-6R2/gp1302) of IL-6 forms and activates the trans pathway or the canonical pathway involved in the inflammatory process, although the trans pathway may positively regulate glucose metabolism. However, in the anti-inflammatory pathway, the complex formed and the associated signalling pathway are unclear. Interestingly, upon activation of the IL-6 receptor in SOCS3 knockout cells, the expression of IL-10 (an anti-inflammatory cytokine) is increased, which would indicate that IL-6 could play an anti-inflammatory role in the absence of SOCS3, however, evidence for this is lacking.

The canonical signalling pathway of IL-6 is activated when the cytokine binds to its receptor in the cell plasma membrane (mbIL-6R) [3, 1, 34], however, another mechanism called “trans-signalling” has been described, in which a soluble form of IL-6R (sIL-6R) also plays a role [1, 3, 6]. There are two mechanisms that are believed to be involved in the formation of sIL-6R. The first is via metalloproteases of the ADAM family (particularly ADAM10 and ADAM17), which are responsible for “cutting” the receptor in the membrane of cells that express and release it. The second mechanism involves alternative splicing of the IL-6R, causing a change in the reading frame which results in a protein without a transmembrane and cytosolic domain, but with the ability to interact with its ligand and form the IL-6/sIL-6R complex. Interestingly, the IL-6/sIL-6R complex can freely circulate and bind to gp130 of cells that do not express IL-6R on their surface, and thus respond to IL-6 stimulation [6, 33, 35].

Also, a soluble form of gp130 (sgp130) has been detected in human blood [43]. This soluble form is produced mainly via alternative splicing [44] and can interact with the IL-6/sIL-6R complex, acting as a specific inhibitor of trans-signalling, while having no significant effect on the classic IL-6/sIL-6R signalling complex [45].

The binding of IL-6 to its receptor activates different signal transduction pathways, and the JAK/STAT pathway is the main and best studied. The group of tyrosine kinases, known as janus kinases (JAKs), participate in this pathway and phosphorylate tyrosine residues in the intracellular domain of gp130. Another group of proteins, known as signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs), mainly STAT1 and STAT3, are recruited to gp130 and interact with it through specific phosphorylated tyrosine residues [46]. STATs are then also phosphorylated at their specific tyrosine residues, allowing homodimers or heterodimers to form which are translocated to the nucleus, acting as transcription factors that regulate the expression of different target genes, many of which are involved in the immune response [3, 47]. In the liver, this IL-6 signalling pathway promotes the synthesis of a group of proteins known as “acute-phase proteins”, including C-reactive protein (CRP), serum amyloid A (SAA), fibrinogen, haptoglobin, and haptoglobin anti-chymotrypsin α [48].

A particular aspect of STAT signalling is that it exhibits negative feedback, regulating the transcription of proteins that act as inhibitors of the pathway at different levels. The main proteins are suppressors of cytokine-mediated signalling (SOCS), for example, SOCS1 that binds to phosphorylated tyrosine residues of JAKs to inhibit their kinase activity [49] or SOCS3 that binds to phosphorylated tyrosine residues on gp130 [50]. SOCS3 knockout macrophage cell lines [51] and hepatocytes differ in the duration of signalling after stimulation with IL-6, which does not affect the initiation of signalling but results in prolonged activation of STAT1 and STAT3 [52].

The proinflammatory effect of IL-6 appears to be strongly related, most of the time, to trans-signalling [53]. sIL-6R allows cells to react to signals induced by pathogens or by some type of damage. At high concentrations of IL-6, sIL-6R binds to IL-6 to activate trans-signalling [54]. Therefore, it may be deduced that the activation of signalling will depend on the concentration of IL-6. Few studies have addressed anti-inflammatory signalling of IL-6, therefore, research should focus on studies to identify signalling molecules downstream of the activated pathway (canonical or trans).

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY EFFECT OF IL-6 ON CELLS OF THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

In one of the first studies in which the anti-inflammatory effect of IL-6 was demonstrated, IL-6+/+ and IL-6-/- mice were subjected to systemic and local endotoxemia in the lungs. In IL-6-/- mice, the levels of proinflammatory cytokines (TNFα, MIP-2, IFNγ) were significantly higher than those in IL-6+/+ mice. Also, administration of IL-6 to IL-6-/- mice further decreased the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, endogenous IL-6 plays an anti-inflammatory role by controlling the levels of proinflammatory cytokines without the involvement of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10 [55].

In macrophages, IL-6 induces an anti-inflammatory effect in the absence of SOCS3. In macrophages from SOCS3 knockout mice exposed to LPS, the production of TNFα and IL-12 is suppressed by IL-6 and IL-10. Therefore, the absence of SOCS3 promotes the production of TNFα and IL-12. IL-6 generates an anti-inflammatory response, similar to that of IL-10. Both IL-6 and IL-10 act through STAT3, but SOCS3 selectively inhibits STAT3 activity only when it is induced by IL-6 and not by IL-10 [51].

IL-6 acts synergistically with TGF-β to induce IL-10 expression in Th-17 cells [56]. Naïve CD4+ cells exposed to IL-6 generate a phenotypic change similar to that of type 1 regulatory T cells (Tr1), and are capable of secreting IL-10, in the absence of TGF-β. Based on an in vivo model of multiorgan inflammation, blocking IL-6-mediated signalling resulted in decreased production of IL-10 in T cells and increased inflammation in the lungs and intestine [57]. In contrast to pro-inflammatory studies of IL-6, anti-inflammatory effects have been poorly studied, and there is a wide scope for further studies to clarify the signalling pathways involved and effects on cells.

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY EFFECT OF IL-6 IN MUSCLE TISSUE

Skeletal muscle is the most abundant tissue in the human body and plays a relevant role in the secretion of IL-6, induced by physical activity and exercise. IL-6 is the first cytokine to appear in the serum of subjects subjected to high-intensity exercise, and its concentration can increase up to 100 times and decrease after such activity [58]. Although it was postulated that this increase in IL-6 was a consequence of the damage caused to muscle fibres, other major proinflammatory markers, such as TNFα and IL-1β, do not increase. Therefore, cytokine secretion during exercise is different to that occurring during an infection [59].

During exercise, an increase in circulating IL-6 leads to a rise in IL-10 concentration and the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) [60], as well as release of the soluble TNFα receptor, which has an inhibitory effect on TNFα [61]. Administration of recombinant human IL-6 (rhIL-6) mimics the effect of exercise, promoting IL-6 secretion and inhibiting the increase in plasma TNFα production induced by endotoxemia in humans [62].

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY EFFECT OF IL-6 IN THE LIVER

In hepatocytes, IL-6 can induce the production of some acute-phase proteins with anti-inflammatory activity, including IL-1Ra [63] or CRP. The latter also slightly increases in plasma after exercise, inducing anti-inflammatory cytokine secretion in circulating monocytes and suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine synthesis in tissue-resident macrophages [64].

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY EFFECT OF IL-6 IN ADIPOSE TISSUE

During obesity, a low-grade inflammatory disease develops that is mediated by adipose tissue macrophages, which can be classified according to their phenotype, as M1 or proinflammatory and M2 or anti-inflammatory. Adipose tissue macrophages from lean subjects express genes associated with the M2 phenotype, while those from overweight or obese subjects predominately express genes associated with the M1 phenotype. This latter phenotype contributes to characteristic inflammation of adipose tissue, through the release of many proinflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6) and chemokines that attract more cells, such as monocytes and neutrophils, to adipose tissue [65].

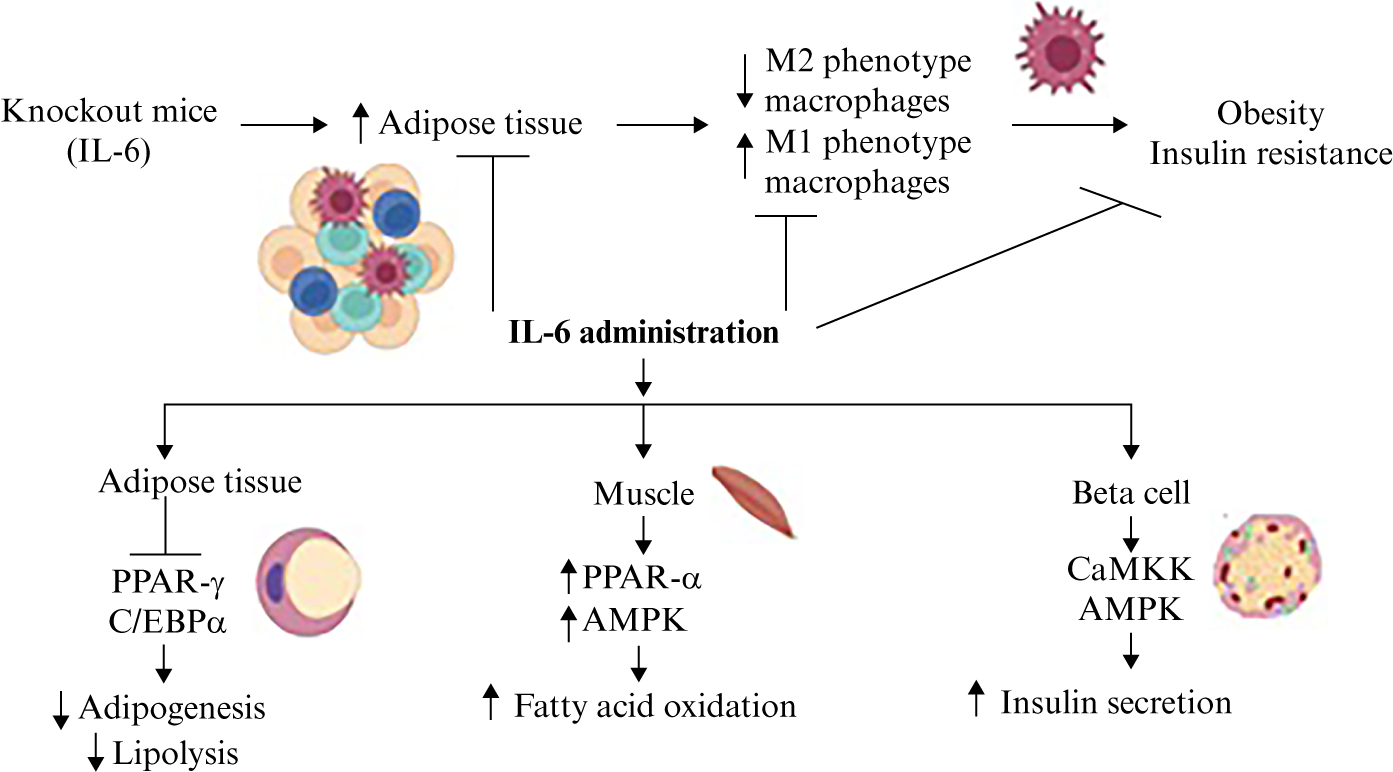

In experiments carried out in myeloid cells lacking the IL-6R α subunit, a pattern of gene expression was observed similar to that of macrophages with the M1 phenotype, in vitro and in vivo, and treatment with recombinant IL-6 contributed to the acquisition of an M2 phenotype, mediated also by IL-4, another anti-inflammatory cytokine. In IL-6Rα knockout mice fed with a high-fat diet, many macrophages acquired an M1 phenotype, inducing inflammation in adipose tissue, while the number of M2 macrophages was greatly reduced, suggesting that IL-6 has an important effect on the acquisition of a proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory phenotype (figure 2) [66].

Figure 2.

Anti-inflamatory and metabolic effects of IL-6. IL-6 knockout mice exhibit increased adipose tissue, M1 macrophages, inflammation, obesity, and insulin resistance. However, the administration of IL-6 induces an anti-inflammatory effect associated with an increase in M2 macrophages. IL-6 may inhibit adipogenesis and suppress the develomment of obesity, and in muscle, may increase fatty acid oxidation by regulating PPAR and AMPK. AMPK may also be modulated by IL-6 in the pancreas, improving insulin secretion.

EFFECT OF IL-6 ON LIPID METABOLISM

IL-6 also appears to play a role in lipid metabolism. Wallenius et al. showed that IL-6 knockout mice develop a very advanced obesity phenotype and IL-6 administration decreases adipose tissue [67]. Preadipocytes obtained from the adipose tissue of obese patients treated with IL-6 showed decreased expression of PPARγ and C/EBPα, with a lower adipogenic capacity [68]. In human adipocytes, IL-6 administration regulates lipid metabolism, increasing lipolysis in the absence of insulin, and increases leptin expression [69]. In lean and obese men, anti-IL-6 therapy impaired fat mobilization, which might contribute to an increase in adipose tissue mass and, thus, affect the health of individuals [70].

Peterson et al. observed that the administration of IL-6 in older adults produces an increase in the metabolism of fatty acids without affecting insulin sensitivity. However, in the model of 3T3-L1 adipocytes treated with IL-6, an increase in lipolysis was observed through the quantification of glycerol released in the medium [71]. IL-6 also exerts effects on transcription factors that regulate lipid metabolism, such as PPARα, a nuclear receptor. By binding to saturated or unsaturated fatty acids, PPARα promotes the expression of enzymes involved in fatty acid oxidation, such as SREBP-1c, which is responsible for regulating the expression of lipogenic enzymes, favouring lipid synthesis. In Hep3B cells treated for 24 hours with IL-6, there was a significant increase in PPARα mRNA and a decrease in SREBP-1c. This same result was observed in mice after administration of IL-6 [72]. On the other hand, in humanized rodent liver models, activation of IL-6R and gp130 decreased lipid accumulation in hepatocytes, and independent activation of gp130 was sufficient to prevent the development of steatosis. In addition, Kupffer cells play an important role in the production of IL-6 and activation of the signalling pathway controlling lipid droplet accumulation in hepatocytes [73]. Therefore, IL-6, by regulating PPARs, has an important role in the regulation of lipid metabolism, however, it is important to clarify the pathways involved.

EFFECT OF IL-6 ON CARBOHYDRATE METABOLISM

Regarding the effects of IL-6 on the metabolism of carbohydrates, results are contradictory because IL-6 generates insulin resistance in both 3T3-L1 adipocytes in vitro [74] and experimental mouse models [75]. In contrast, the induction of IL-6 expression in human myotubes in vitro does not inhibit the effect of insulin or glycogen synthesis [76]. Moreover, acute administration of rhIL-6 to healthy subjects does not alter glucose internalization into adipose tissue or its endogenous generation [77]. In patients with type 2 diabetes, who received rhIL-6, plasmatic insulin levels decreased, suggesting that the administration of IL-6 improves sensitivity to insulin [71]. In IL-6 knockout mouse, insulin resistance and mature-onset obesity was observed, that was partly reversed after IL-6 administration, and it was concluded from this study that centrally acting IL-6 exerts anti-obesity effects in rodents [67]. In β-cells, the secretion of insulin was increased at IL-6 concentrations of 25 to 100 pg, after 20 minutes and 24 hours of treatment. In pancreatic islets isolated from C57BL/6J mice, an increase in insulin was observed after a two-hour incubation at a concentration of 100 to 1000 pg of IL-6. In addition, IL-6 is reported to induce insulin secretion through calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase (CaMKK) and subsequent AMPK activation [78].

Studies indicate that IL-6 trans-signalling is involved in signalling of the central nervous system in obese mice, exerting beneficial effects on glucose metabolism even under conditions of leptin resistance [79]. These contradictory data, regarding the fact that this pathway is involved in proinflammatory processes in obesity and may enhance metabolism at the level of the central nervous system, illustrate the complexity of IL-6 in relation to its pleiotropic action on different cell types.

In mice with a low and high-fat diet, IL-6 decreased blood glucose and mRNA expression of gluconeogenic genes, and increased phosphorylation of AKT. Moreover, a single injection of IL-6 improved glucose tolerance, decreased hepatic gluconeogenic gene expression, and increased hepatic phosphorylation of AKT in lean and obese mice [80].

IL-6 AS A REGULATOR OF METABOLISM THROUGH AMPK

Knowledge of the role of IL-6 signalling in metabolic regulation is lacking and there are still many unknown interesting aspects. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) appears to play a key role in the effects of IL-6 on metabolism. This protein has the function of acting as a sensor of the energy state in cells, stimulating pathways involved in energy production and turning off those where it is consumed. AMPK is a heterotrimeric complex with a catalytic subunit (α) and two regulators (β and γ), which controls the ATP/AMP ratio in the cell, with AMP being an allosteric activator of AMPK. Phosphorylation at threonine residue 172 of the α subunit by kinases, such as LKB1 when AMP concentration rises or CaMKKβ in the presence of Ca+2, also activates AMPK, which can phosphorylate various proteins and regulate transcription of genes that participate in the regulation of metabolism, by activating catabolic pathways and turning off anabolic pathways [81].

L6 myotubes treated with IL-6 and 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside (AICAR), one of the main AMPK agonists, have both been shown to increase palmitate oxidation compared to control group. Therefore, increased fatty acid oxidation has a positive effect on energy production induced by IL-6 and AMPK [67].

TREATMENT WITH IL-6 AS AN ANTI-INFLAMMATORY AGENT

Treatments for different pathologies with chronic inflammation, such as rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and Crohn’s disease, have focused on drugs that interfere with IL-6 and IL-6R function [82, 83]. Recently, tocilizumab, a monoclonal anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, was used to treat COVID, resulting in an improvement in the hyperinflammatory state associated with severe COVID [84]. It is interesting to note that some new studies are focussing on the anti-inflammatory action of IL-6-related treatments. A recent study at phase II clinical stage was established based on the hypothesis that soluble gp130 inhibits IL-6 trans-signalling without affecting canonical IL-6 signalling [85]. Indeed, it has been suggested that treatment with soluble gp130 is superior to that with drugs which target IL-6, because blocking IL-6 trans-signalling does not compromise canonical IL-6 signalling and therefore the body’s defence against bacterial infections [85]. The action of soluble gp130 is important as it only inhibits the trans-signalling pathway, however, the canonical IL-6 pathway is believed to activate subsequent anti-inflammatory processes.

Additionally, inhibition of IL-6/sIL-6R trans-signalling has been proposed as a treatment for the COVID-19 cytokine storm. Although the effect of treatments that inhibit IL-6 may be unclear, pre-clinical models show that tocilizumab may reduce vascular dysfunction [86].

For other pathologies, such as cancer and coronary heart disease, the role of IL-6 is under investigation and new therapies may be proposed [87, 89]. In the case of coronary heart disease, in vascular endothelial cells, the pathways induced by IL-6 classic signalling and trans-signalling in these cells are distinct but overlap with different biological effects. In vitro and in vivo studies on the inhibition of IL-6 trans-signalling and activation of classic signalling demonstrate a cytoprotective effect [87]. Studies in transgenic mice expressing high levels of soluble gp130, inhibiting trans-signalling, have shown that gp130 plays an important role in the development of cancer, however, further studies are needed to determine exactly which mechanisms of the classic pathway are involved that could be targeted to treat this pathology [88]. In addition, it is important to mention that this type of therapy should also be investigated for metabolic diseases due to the significant role of IL-6 in the regulation of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism.

CONCLUSIONS

IL-6 is a cytokine that plays an important anti-inflammatory role in the body’s response to endogenous and exogenous threats. The effect of IL-6 on metabolism of carbohydrates and lipids is an important factor in the different chronic inflammatory pathologies. Hence, continued study of this pleiotropic cytokine is important in order to understand its effect on signalling pathways and cellular function, as a potential target for the treatment of various metabolic disorders.

DISCLOSURE:

Financial support: none. Conflicts of interest: none.

REFERENCES

1. Scheller J, Chalaris A, Schmidt-Arras D, et al. The pro-and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1813:878-88. [Google Scholar]

2. Lutoslawska G. Interleukin-6 as an adipokine and myokine: the regulatory role of cytokine in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle metabolism. Hum Mov 2012;13:372-9. [Google Scholar]

3. Glund S, Krook A. Role of interleukin-6 signalling in glucose and lipid metabolism. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2008;192:37-48. [Google Scholar]

4. Rose-John S. Interleukin-6 family cytokines. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2018;10:a028415. [Google Scholar]

5. Hirano T, Yasukawa K, Harada H, et al. Complementary DNA for a novel human interleukin (BSF-2) that induces B lymphocytes to produce immunoglobulin. Nature 1986;324:73-6. [Google Scholar]

6. Pal M, Febbraio MA, Whitham M. From cytokine to myokine: the emerging role of interleukin-6 in metabolic regulation. Immunol Cell Biol 2014;92:331-9. [Google Scholar]

7. Hirano T, Matsuda T, Turner M, et al. Excessive production of interleukin-6/B cell stimulatory factor-2 in rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Immunol 1988;18:1797-801. [Google Scholar]

8. Yoshizaki K, Matsuda T, Nishimoto N, et al. Pathogenic significance of interleukin-6 (IL-6/BSF-2) in Castleman’s Disease. Blood 1989;74:1360-7. [Google Scholar]

9. Mori S, Koga Y. Glucocorticoid-resistant polymyalgia rheumatica: pretreatment characteristics and tocilizumab therapy. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:1367-75. [Google Scholar]

10. Weyand CM, Hicok KC, Hunder GG, et al. Tissue cytokine patterns in patients with polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:484-91. [Google Scholar]

11. Rose-John S, Mitsuyama K, Matsumoto S, et al. Interleukin-6 trans-signaling and colonic cancer associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Pharm Des 2009;15:2095-103. [Google Scholar]

12. Knudsen JG, Joensen E, Bertholdt L, et al. Skeletal muscle IL-6 and regulation of liver metabolism during high-fat diet and exercise training. Physiol Rep 2016;4:e12788. [Google Scholar]

13. Kumar H, Kawai T, Akira S. Pathogen recognition by the innate immune system. Int Rev Immunol 2011;30:16-34. [Google Scholar]

14. Waage A, Brandtzaeg P, Halstensen A, et al. The complex pattern of cytokines in serum from patients with meningococcal septic shock. J Exp Med 1989;169:333-8. [Google Scholar]

15. Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014;6:a016295. [Google Scholar]

16. Wolf J, Rose-John S, Garbers C. Interleukin-6 and its receptors: a highly regulated and dynamic system. Cytokine 2014;70:11-20. [Google Scholar]

17. Libermann TA, Baltimore D. Activation of interleukin-6 gene expression through the NF-kappa B transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol 1990;10:2327-34. [Google Scholar]

18. Shimizu H, Mitomo K, Watanabe T, et al. Involvement of a NF-kappa B-like transcription factor in the activation of the interleukin-6 gene by inflammatory lymphokines. Mol Cell Biol 1990;10:561-8. [Google Scholar]

19. Edbrooke MR, Burt DW, Cheshire JK, et al. Identification of cis-acting sequences responsible for phorbol ester induction of human serum amyloid A gene expression via a nuclear factor kappaB-like transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol 1989;9:1908-16. [Google Scholar]

20. Dendorfer U, Oettgen P, Libermann TA. Multiple regulatory elements in the interleukin-6 gene mediate induction by prostaglandins, cyclic AMP, and lipopolysaccharide. Mol Cell Biol 1994;14:4443-54. [Google Scholar]

21. Yang R, Lin Q, Gao HB, et al. Stress-related hormone norepinephrine induces interleukin-6 expression in GES-1 cells. Braz J Med Biol Res 2014;47:101-9. [Google Scholar]

22. Chen C, Du J, Feng W, et al. β-Adrenergic receptors stimulate interleukin-6 production through Epac-dependent activation of PKCδ/p38 MAPK signalling in neonatal mouse cardiac fibroblasts. Br J Pharmacol 2012;166:676-88. [Google Scholar]

23. Matsusaka T, Fujikawa K, Nishio Y, et al. Transcription factors NF-IL6 and NF-kappa B synergistically activate transcription of the inflammatory cytokines, interleukin-6 and interleukin-8. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993;90:10193-7. [Google Scholar]

24. Ray A, Sassone-Corsi P, Sehgal PB. A multiple cytokine- and second messenger-responsive element in the enhancer of the human interleukin-6 gene: similarities with c-fos gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol 1989;9:5537-47. [Google Scholar]

25. Tanabe O, Akira S, Kamiya T, et al. Genomic structure of the murine IL-6 gene. High degree conservation of potential regulatory sequences between mouse and human. J Immunol 1988;141:3875-81. [Google Scholar]

26. Lee W, Mitchell P, Tjian R. Purified transcription factor AP-1 interacts with TPA-inducible enhancer elements. Cell 1987;49:741-52. [Google Scholar]

27. Wisdom R. AP-1: one switch for many signals. Exp Cell Res 1999;253:180-5. [Google Scholar]

28. Isshiki H, Akira S, Tanabe O, et al. Constitutive and interleukin-1 (IL-1)-inducible factors interact with the IL-1-responsive element in the IL-6 gene. Mol Cell Biol 1990;10:2757-64. [Google Scholar]

29. Almawi WY, Melemedjian OK. Molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoid antiproliferative effects: antagonism of transcription factor activity by glucocorticoid receptor. J Leukoc Biol 2002;71:9-15. [Google Scholar]

30. Smoak KA, Cidlowski JA. Mechanisms of glucocorticoid receptor signaling during inflammation. Mech Ageing Dev 2004;125:697-706. [Google Scholar]

31. Liu H, Liu K, Bodenner DL. Estrogen receptor inhibits interleukin-6 gene expression by disruption of nuclear factor κB transactivation. Cytokine 2005;31:251-7. [Google Scholar]

32. Ershler WB, Keller ET. Age-associated increased interleukin-6 gene expression, late-life diseases, and frailty. Annu Rev Med 2000;51:245-70. [Google Scholar]

33. Hunter CA, Jones SA. IL-6 as a keystone cytokine in health and disease. Nat Immunol 2015;16:448-57. [Google Scholar]

34. Akbari M, Hassan-Zadeh V. IL-6 signalling pathways and the development of type 2 diabetes. Inflammopharmacology 2018;26:685-98. [Google Scholar]

35. Scheller J, Rose-John S. Interleukin-6 and its receptor: from bench to bedside. Med Microbiol Immunol 2006;195:173-83. [Google Scholar]

36. Boulanger MJ, Chow DC, Brevnova EE, et al. Hexameric structure and assembly of the interleukin-6/IL-6 alpha-receptor/gp130 complex. Science 2003;300:2101-4. [Google Scholar]

37. Skiniotis G, Boulanger MJ, Garcia KC, et al. Signaling conformations of the tall cytokine receptor gp130 when in complex with IL-6 and IL-6 receptor. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2005;12:545-51. [Google Scholar]

38. Grötzinger J, Kernebeck T, Kallen KJ, et al. IL-6 type cytokine receptor complexes: hexamer, tetramer or both? Biol Chem 1999;380:803-13. [Google Scholar]

39. van Dam M, Müllberg J, Schooltink H, et al. Structure-function analysis of interleukin-6 utilizing human/murine chimeric molecules. Involvement of two separate domains in receptor binding. J Biol Chem 1993;268:15285-90. [Google Scholar]

40. Kallen KJ, Grötzinger J, Lelièvre E, et al. Receptor recognition sites of cytokines are organized as exchangeable modules. Transfer of the leukemia inhibitory factor receptor-binding site from ciliary neurotrophic factor to interleukin-6. J Biol Chem 1999;274:11859-67. [Google Scholar]

41. Viswanathan S, Benatar T, Rose-John S, et al. Ligand/receptor signaling threshold (LIST) model accounts for gp130-mediated embryonic stem cell self-renewal responses to LIF and HIL-6. Stem Cells 2002;20:119-38. [Google Scholar]

42. White UA, Stephens JM. The gp130 receptor cytokine family: regulators of adipocyte development and function. Curr Pharm Des 2011;17:340-6. [Google Scholar]

43. Narazaki M, Yasukawa K, Saito T, et al. Soluble forms of the interleukin-6 signal-transducing receptor component gp130 in human serum possessing a potential to inhibit signals through membrane-anchored gp130. Blood 1993;82:1120-6. [Google Scholar]

44. Müllberg J, Dittrich E, Graeve L, et al. Differential shedding of the two subunits of the interleukin-6 receptor. FEBS Lett 1993;332:174-8. [Google Scholar]

45. Jostock T, Müllberg J, Özbek S, et al. Soluble gp130 is the natural inhibitor of soluble interleukin-6 receptor transsignaling responses. Eur J Biochem 2001;268:160-7. [Google Scholar]

46. Gerhartz C, Heesel B, Sasse J, et al. Differential activation of acute phase response factor/STAT3 and STAT1 via the cytoplasmic domain of the interleukin-6 signal transducer gp130. I. Definition of a novel phosphotyrosine motif mediating STAT1 activation. J Biol Chem 1996;271:12991-8. [Google Scholar]

47. Kishimoto T. The biology of interleukin-6. Blood 1989;74:1-10. [Google Scholar]

48. Heinrich PC, Castell JV, Andus T. Interleukin-6 and the acute phase response. Biochem J 1990;265:621-36. [Google Scholar]

49. Naka T, Narazaki M, Hirata M, et al. Structure and function of a new STAT-induced STAT inhibitor. Nature 1997;387:924-9. [Google Scholar]

50. Schmitz J, Weissenbach M, Haan S, et al. SOCS3 exerts its inhibitory function on interleukin-6 signal transduction through the SHP2 recruitment site of gp130. J Biol Chem 2000;275(1):2848-56. [Google Scholar]

51. Yasukawa H, Ohishi M, Mori H, et al. IL-6 induces an anti-inflammatory response in the absence of SOCS3 in macrophages. Nat Immunol 2003;4:551-6. [Google Scholar]

52. Croker BA, Krebs DL, Zhang JG, et al. SOCS3 negatively regulates IL-6 signaling in vivo. Nat Immunol 2003;4:540-5. [Google Scholar]

53. Rose-John S, Heinrich PC. Soluble receptors for cytokines and growth factors: generation and biological function. Biochem J 1994;300:281-90. [Google Scholar]

54. Kang S, Kishimoto T. Interplay between interleukin-6 signaling and the vascular endothelium in cytokine storms. Exp Mol Med 2021;53:1116-23. [Google Scholar]

55. Xing Z, Gauldie J, Cox G, et al. IL-6 is an antiinflammatory cytokine required for controlling local or systemic acute inflammatory responses. J Clin Invest 1998;101:311-20. [Google Scholar]

56. McGeachy MJ, Bak-Jensen KS, Chen YI, et al. TGF-β and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain TH-17 cell-mediated pathology. Nat Immunol 2007;8:1390-7. [Google Scholar]

57. Jin JO, Han X, Yu Q. Interleukin-6 induces the generation of IL-10-producing Tr1 cells and suppresses autoimmune tissue inflammation. J Autoimmun 2013;40:28-44. [Google Scholar]

58. Febbraio MA, Pedersen BK. Muscle-derived interleukin-6: mechanisms for activation and possible biological roles. FASEB J 2002;16:1335-47. [Google Scholar]

59. Pedersen BK, Hoffman-Goetz L. Exercise and the immune system: regulation, integration, and adaptation. Physiol Rev 2000;80:1055-80. [Google Scholar]

60. Steensberg A, Fischer CP, Keller C, et al. IL-6 enhances plasma IL-1ra, IL-10, and cortisol in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2003;285:E433-7. [Google Scholar]

61. Tilg H, Dinarello CA, Mier JW. IL-6 and APPs: anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive mediators. Immunol Today 1997;18:428-32. [Google Scholar]

62. Starkie R, Ostrowski SR, Jauffred S, et al. Exercise and IL-6 infusion inhibit endotoxin-induced TNF-α production in humans. FASEB J 2003;17:884-6. [Google Scholar]

63. Gabay C, Smith MF, Eidlen D, et al. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) is an acute-phase protein. J Clin Invest 1997;99:2930-40. [Google Scholar]

64. Pue CA, Mortensen RF, Marsh CB, et al. Acute phase levels of C-reactive protein enhance IL-1β and IL-1Ra production by human blood monocytes but inhibit IL-1β and IL-1Ra production by alveolar macrophages. J Immunol 1996;156:1594-600. [Google Scholar]

65. Caslin HL, Bhanot M, Bolus WR, et al. Adipose tissue macrophages: unique polarization and bioenergetics in obesity. Immunol Rev 2020;295:101-13. [Google Scholar]

66. Mauer J, Chaurasia B, Goldau J, et al. Signaling by IL-6 promotes alternative activation of macrophages to limit endotoxemia and obesity-associated resistance to insulin. Nat Immunol 2014;15:423-30. [Google Scholar]

67. Wallenius V, Wallenius K, Ahrén B, et al. Interleukin-6-deficient mice develop mature-onset obesity. Nat Med 2002;8:75-9. [Google Scholar]

68. Almuraikhy S, Kafienah W, Bashah M, et al. Interleukin-6 induces impairment in human subcutaneous adipogenesis in obesity-associated insulin resistance. Diabetologia 2016;59:2406-16. [Google Scholar]

69. Trujillo ME, Sullivan S, Harten I, et al. Interleukin-6 regulates human adipose tissue lipid metabolism and leptin production in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:5577-82. [Google Scholar]

70. Trinh B, Peletier M, Simonsen C, et al. Blocking endogenous IL-6 impairs mobilization of free fatty acids during rest and exercise in lean and obese men. Cell Rep Med 2021;2:100396. [Google Scholar]

71. Petersen EW, Carey AL, Sacchetti M, et al. Acute IL-6 treatment increases fatty acid turnover in elderly humans in vivo and in tissue culture in vitro. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2005;288:E155-62. [Google Scholar]

72. Hashizume M, Mihara M. IL-6 and lipid metabolism. Inflamm Regen 2011;31:325-33. [Google Scholar]

73. Carbonaro M, Wang K, Huang H, et al. IL-6-GP130 signaling protects human hepatocytes against lipid droplet accumulation in humanized liver models. Sci Adv 2023;9:eadf4490. [Google Scholar]

74. Rotter V, Nagaev I, Smith U. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) induces insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and is, like IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor-α, overexpressed in human fat cells from insulin-resistant subjects. J Biol Chem 2003;278:45777-84. [Google Scholar]

75. Kim HJ, Higashimori T, Park SY, et al. Differential effects of interleukin-6 and -10 on skeletal muscle and liver insulin action in vivo. Diabetes 2004;53:1060-7. [Google Scholar]

76. Weigert C, Brodbeck K, Staiger H, et al. Palmitate, but not unsaturated fatty acids, induces the expression of interleukin-6 in human myotubes through proteasome-dependent activation of nuclear factor-κB. J Biol Chem 2004;279:23942-52. [Google Scholar]

77. Steensberg A, Fischer CP, Sacchetti M, et al. Acute interleukin-6 administration does not impair muscle glucose uptake or whole-body glucose disposal in healthy humans. J Physiol 2003;548:631-8. [Google Scholar]

78. da Silva Krause M, Bittencourt A, Homem de Bittencourt PIJr et al.Physiological concentrations of interleukin-6 directly promote insulin secretion, signal transduction, nitric oxide release, and redox status in a clonal pancreatic β-cell line and mouse islets. J Endocrinol 2012;214:301-11. [Google Scholar]

79. Timper K, Denson JL, Steculorum SM, et al. IL-6 improves energy and glucose homeostasis in obesity via enhanced central IL-6 trans-signaling. Cell Rep 2017;19:267-80. [Google Scholar]

80. Peppler WT, Townsend LK, Meers GM, et al. Acute administration of IL-6 improves indicators of hepatic glucose and insulin homeostasis in lean and obese mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2019;316:G166-78. [Google Scholar]

81. Daval M, Foufelle F, Ferré P. Functions of AMP-activated protein kinase in adipose tissue. J Physiol 2006;574:55-62. [Google Scholar]

82. Adachi Y, Yoshio-Hoshino N, Nishimoto N. The blockade of IL-6 signaling in rational drug design. Curr Pharm Des 2008;14:1217-24. [Google Scholar]

83. Raimondo MG, Biggioggero M, Crotti C, et al. Profile of sarilumab and its potential in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017;11:1593-603. [Google Scholar]

84. Quartuccio L, Sonaglia A, Pecori D, et al. Higher levels of IL-6 early after tocilizumab distinguish survivors from nonsurvivors in COVID-19 pneumonia: A possible indication for deeper targeting of IL-6. J Med Virol 2020;92:2852-6. [Google Scholar]

85. Rose-John S. The soluble interleukin-6 receptor: advanced therapeutic options in inflammation. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2017;102:591-8. [Google Scholar]

86. Chen LYC, Biggs CM, Jamal S, et al. Soluble interleukin-6 receptor in the COVID-19 cytokine storm syndrome. Cell Rep Med 2021;2:100269. [Google Scholar]

87. Montgomery A, Tam F, Gursche C, et al. Overlapping and distinct biological effects of IL-6 classic and trans-signaling in vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2021;320:C554-65. [Google Scholar]

88. Chalaris A, Garbers C, Rabe B, et al. The soluble interleukin-6 receptor: generation and role in inflammation and cancer. Eur J Cell Biol 2011;90:484-94. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools