Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The role of IL-33 in immunotherapy for breast cancer: targets and signalling pathways

1

Department of General Surgery, The People’s Hospital of Yuhuan, Taizhou 317600, Zhejiang Province, China

2

Department of General Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (Yuhuan Branch), Taizhou 317600, Zhejiang

Province, China

3

Department of Surgery, Second Affiliated Hospital of School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, China

* Corresponding Author: F. Zhou,

European Cytokine Network 2025, 36(1), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1684/ecn.2025.0500

Accepted 01 February 2025;

Abstract

Interleukin-33 (IL-33), a key member of the IL-1 family, plays a significant role in inflammation and cancer. Its classic receptors, ST2 and IL-1 receptor accessory protein (IL-1RAcP), are predominantly expressed in immune cells such as T helper 2 (Th2) cells and mast cells. Recent studies have highlighted the involvement of IL-33 in breast cancer, demonstrating its ability to exert dual functional effects by modulating both innate and adaptive immune responses within the tumour microenvironment. However, the precise molecular mechanisms linking IL-33 to breast cancer pathogenesis and its potential as a target for molecularly targeted therapies remain incompletely understood. This review aims to provide a comprehensive summary of the current understanding of IL-33 in breast cancer immunotherapy.Keywords

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common malignancy among women worldwide, significantly impacting both physical and mental health [1]. Between 2015 and 2019, the incidence of BC increased at a rapid rate of 0.6%-1% per year, garnering widespread attention [1]. According to the 2024 Global Cancer Statistics, BC accounts for approximately 2.3 million new cases annually, placing a substantial disease burden on the global population [2]. Current BC treatment strategies have evolved into a multimodal approach encompassing surgery, chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and targeted therapy to optimize therapeutic outcomes [3, 4]. However, despite these advancements, BC mortality remains high, with recurrence and metastasis being the main contributors to poor prognosis [5]. Due to the striking heterogeneity and complex immune microenvironment of BC, as well as the presence of innate and acquired drug resistance, researchers are increasingly focusing on identifying novel immune targets to enhance therapeutic efficacy [6, 7].

The IL-33 gene is located on human chromosome 9p24.1 (mouse chromosome 19qC1 region), and its mRNA encodes a 270-amino acid polypeptide (266 amino acids in mice), which exerts diverse biological functions [8]. Structurally, IL-33 possesses unique dual features, including an N-terminal region with a nuclear localization signal and DNA-binding domains, a C-terminal region with IL-1-like cytokine domains, and a distinct helix-turn-helix motif in the middle [9, 10]. The primary receptors for IL-33 are specific receptor 2 (ST2) and IL-1 receptor accessory protein (IL-1RAcP), which are mainly expressed by immune cells such as T helper 2 (Th2) cells and mast cells [11]. Upon receptor binding, IL-33 functions both as an extracellular alarm cytokine and an intracellular nuclear factor, contributing to tumour progression and drug resistance [12]. Accumulating evidence suggests that IL-33 levels are significantly elevated in the serum of BC patients, particularly in those with stage IV disease [12–15]. Moreover, several studies have demonstrated that IL-33 inhibition enhances tumour immune surveillance and attenuates BC progression [15–17]. However, conflicting reports suggest that IL-33 overexpression within tumours can inhibit tumour growth and remodel the tumour microenvironment [18, 19]. Notably, Viana et al. [19, 20] observed that ST2 deletion in male mice led to increased BC growth, a finding that was inconsistent with the effects of ST2 deletion in female mice. Overall, IL-33 is predominantly regarded as an oncogenic cytokine that promotes BC progression and immune evasion. However, its precise role in pathogenesis and its potential as a target remain to be fully elucidated.

In this review, we provide an overview of the mechanisms of IL-33 in BC and summarize its potential for therapeutic targeting. We particularly focus on preclinical studies exploring IL-33-based therapeutic combinations.

THE MECHANISTIC ROLE OF IL-33 IN BC

The type 2 immune response is primarily mediated by type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) and Th2 cells, which help maintain immune homeostasis by secreting cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 [21]. ILC2 activation is primarily driven by IL-25, IL-33, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) [22]. A study by Ophir et al. [23] demonstrated that IL-33 derived from cancer-associated fibroblasts can stimulate a type 2 immune response within the tumour microenvironment (TME), leading to the recruitment of eosinophils, neutrophils, and inflammatory monocytes to the lungs, ultimately promoting lung metastasis. Conversely, Hollande et al. [24] reported that IL-33 is essential for eosinophil-mediated anti-tumour responses and that targeting this pathway may provide new insights into synergistic chemoimmunotherapy strategies [25]. However, in a mouse model of BC lung metastasis, IL-33 was found to enhance TNF-α production by macrophages, leading to an increased expression of IL-33/ST2 on natural killer (NK) cells. IL-33-induced NK cell activation has been shown to facilitate eosinophil and CD8+ T cell accumulation in the lungs and to trigger the release of CCL5, promoting NK cell recruitment to the tumour microenvironment. The administration of different doses of recombinant human (rh) IL-33 inhibited the progression of advanced pulmonary metastatic BC in one study [19]. These findings suggest that the therapeutic implications of IL-33 inhibition in advanced metastatic BC are complex and require further investigation.

The type 1 immune response is mediated by type 1 innate lymphoid cells, NK cells, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTLs), and type 1 CD4+ T helper (Th1) cells. These cells produce IFN-γ, which activates mononuclear phagocytes, thereby exerting immune functions [26]. Recent studies suggest that IL-33 supplementation can promote intratumoral eosinophil infiltration and CD8+ T cell activation, thereby enhancing the response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Interestingly, IL-33 has been identified as a key cytokine that drives CD4+ T cell activation through IL-5, leading to eosinophil recruitment and CD8+ T cell activation [27]. Other studies have demonstrated that IL-33 enhances the proportion of CD8+ T cells and NK cells, as well as IFN-γ production within tumour tissues, creating a TME more favourable for tumour eradication [28]. IL-33 has also been shown to synergize with T-cell receptor (TCR) signalling or IL-12 to stimulate IFN-γ production and enhance effector functions in CD8+ T and Th1 cells [29]. Therefore, both type 1 and type 2 immune responses contribute to the anti-tumour effects of IL-33 and may act synergistically to control tumour growth in certain contexts [24].

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a heterogeneous population of bone marrow-derived cells that suppress immune responses by secreting arginase-1 (Arg-1), nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2), and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Additionally, they promote regulatory T cell (Treg) proliferation, further dampening the immune response [30]. Tumour-infiltrating MDSCs exhibit greater immunosuppressive capacity than peripheral MDSCs. IL-33 has been identified as a critical factor in promoting the proliferation and survival of tumour-infiltrating MDSCs through GM-CSF signalling. This process activates NF-κB and MAPK pathways, thereby suppressing immune responses and facilitating tumour immune evasion [16]. In line with these findings, Jovanovic et al. [17] reported that IL-33 administration led to an increased accumulation of immunosuppressive CD11b+ Gr-1+ MDSCs in both breast tumours and the spleen. Furthermore, IL-33 was found to induce CD4+ Foxp3+ IL-10+ Tregs, promoting the differentiation of tolerogenic or immature dendritic cells, which in turn inhibited NK cell cytotoxicity and facilitated BC growth and metastasis.

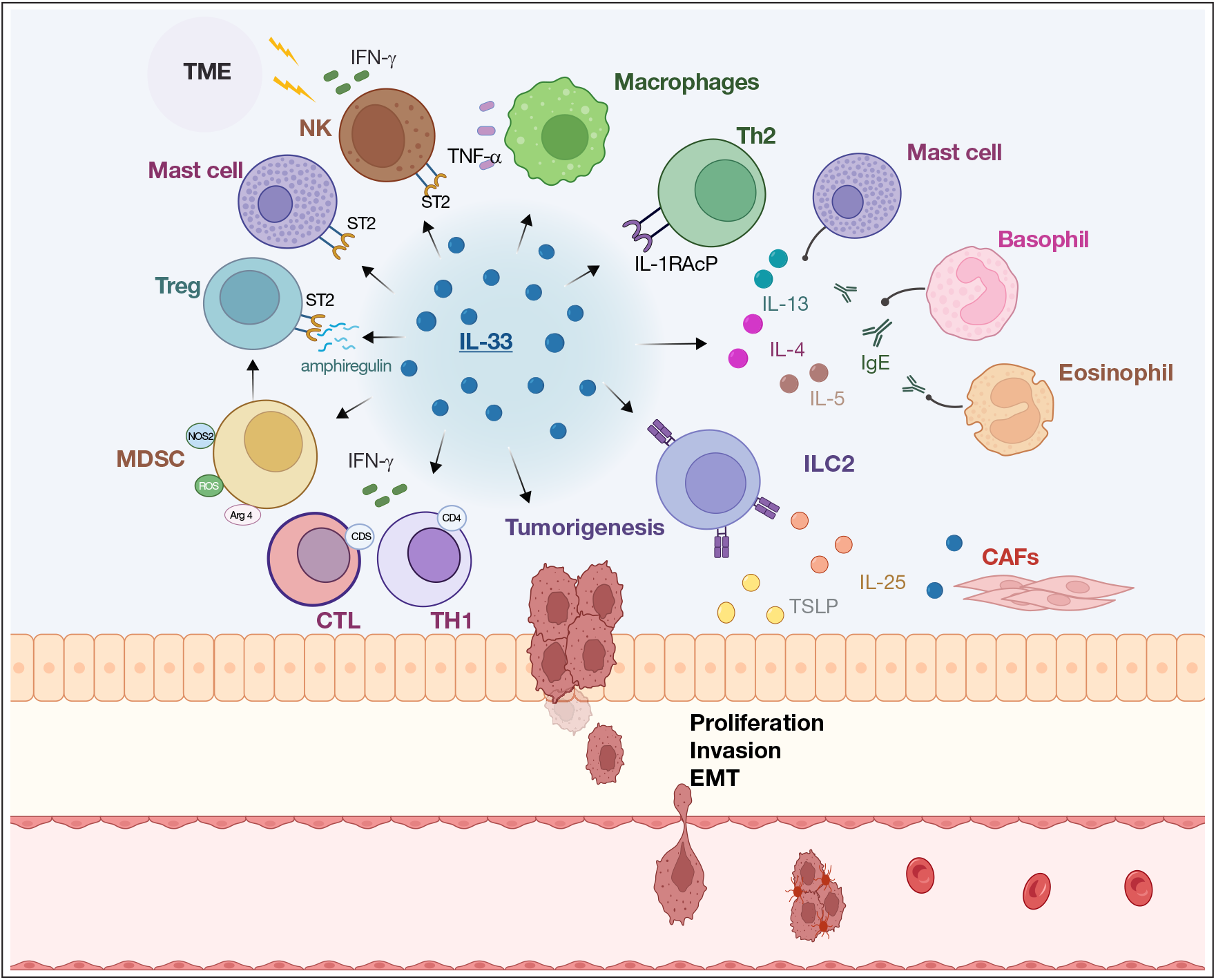

In the TME, Tregs, as a specialized subset of lymphocytes, can facilitate immune evasion by suppressing anti-tumour immunity through epigenetic reprogramming and signal cascade regulation [31]. Tregs not only contribute to the growth of primary tumours but also accelerate the progression of metastatic tumours. In a preclinical study, ST2+ Tregs were identified as the primary target of IL-33-mediated production of amphiregulin, a growth factor involved in tumour progression [32]. However, while this study suggested that amphiregulin is primarily derived from ST2+ Tregs, it is also produced by mast cells, basophils, and ILC2s, indicating that further research is needed to fully elucidate the connection between IL-33, Tregs, and the type 2 immune response [33, 34]. Additionally, a strong correlation between IL-33 expression and FOXP3+ Tregs has been observed in TNBC [35]. Figure 1 provides a summary of the interactions between IL-33, immune cells, and cytokines.

Figure 1:

The IL-33 immune network in the tumour microenvironment (TME). NK: natural killer cell; Treg: regulatory T cell; MDSC: myeloid-derived suppressor cell; CTL: cytotoxic T cell; Th1: T helper cell; ILC2: type 2 innate lymphoid cell; Th2: T helper cell; CAFs: cancer-associated fibroblasts; TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor-α; IFN-γ: interferon-γ; ST2: specific receptor 2; NOS2: nitric oxide synthase 2; Arg-1: Arginase-1; ROS: reactive oxygen species; TSLP: thymic stromal lymphopoietin; IL-1RAcP: IL-1 receptor accessory protein; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

Inherent and acquired resistance

Inherent and acquired resistance represent significant challenges in BC treatment. To better understand the mechanisms underlying drug resistance, extensive research has been conducted to develop strategies aimed at overcoming treatment resistance [36, 37]. Preclinical studies have revealed that IL-33 plays a crucial role in inducing endocrine resistance in BC. Specifically, IL-33 overexpression in BC cells has been shown to confer stem cell-like properties, leading to resistance against tamoxifen-induced tumour growth inhibition [12].

Preclinical data indicate that IL-33-induced activation of the ST2-Cancer Osaka Thyroid (COT) interaction enhances epithelial cell transformation and breast tumorigenesis through the MEK-ERK, JNK-cJun, and STAT3 signalling pathways [14]. Additionally, the IL-33/ST2/COT/JNK1/2 signalling axis has been found to accelerate breast tumorigenesis by regulating LPIN1 mRNA and protein expression [38]. Furthermore, activation of the IL-33/IL-33R pathway plays a crucial role in mammary tumour development by promoting the expression of pro-angiogenic VEGF and reducing necrosis in breast carcinoma [39]. Notably, Yes-associated protein (YAP), a well-established cancer regulatory gene, has been linked to IL-33 expression. The YAP/IL-33 axis has been implicated in obesity-mediated tumorigenesis and regulatory T cell infiltration, further highlighting the potential role of IL-33 in BC progression [36, 40].

Potential therapeutic combinations with IL-33 in preclinical studies

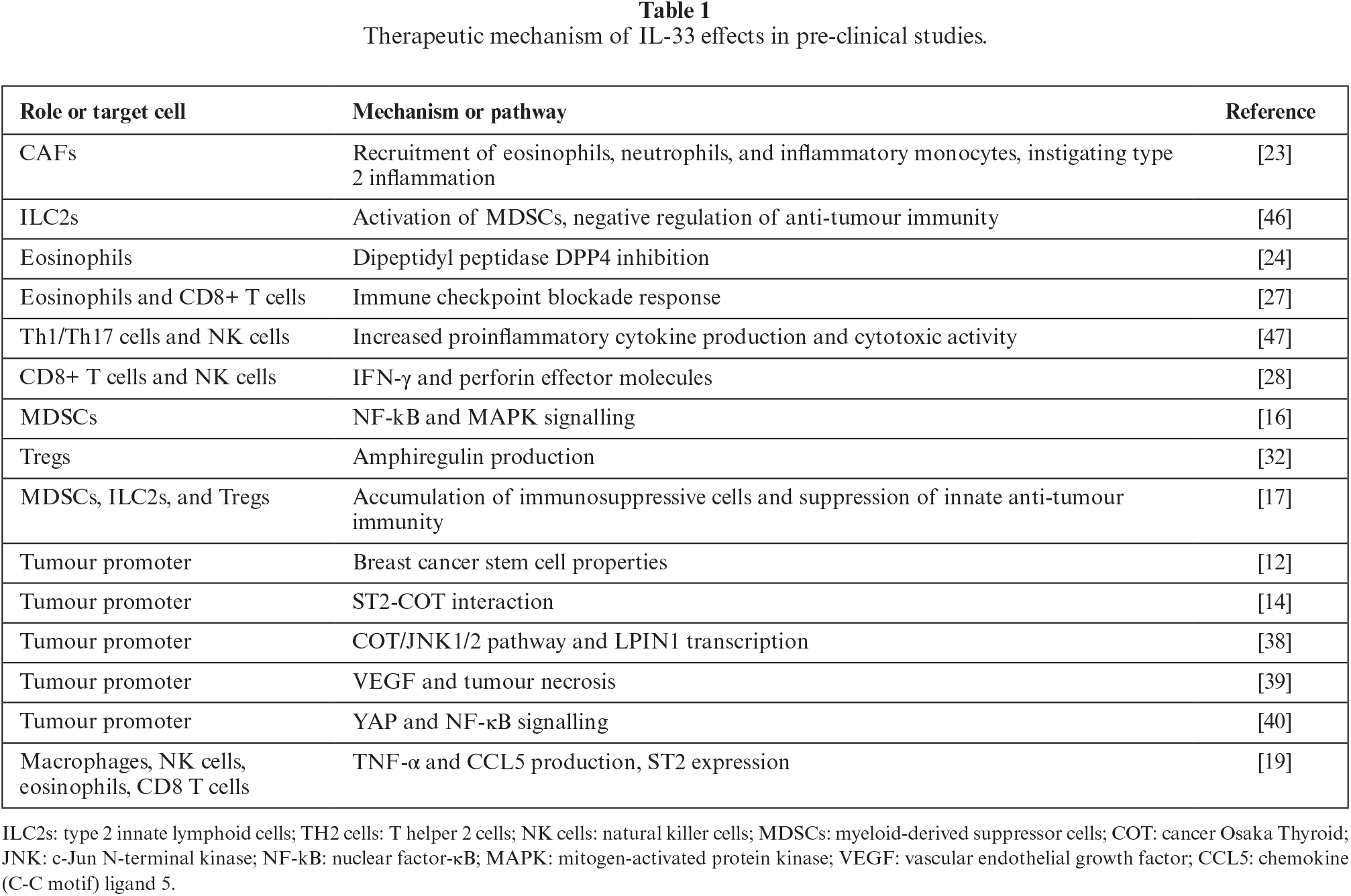

While CTLA-4 and PD-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb)-based immunotherapies have achieved significant success for haematological malignancies, their efficacy for solid tumours remains limited [24]. Due to the complexity of the immune microenvironment in solid tumours, which includes spontaneous T-cell responses, combination strategies incorporating IL-33 as an adjuvant may enhance therapeutic outcomes [29]. A preclinical study reported that combined inhibition of PD-L1/PD-1 and IL-33/ST2 increased the expression of miRNA-150 and miRNA-155, augmented NK cell cytotoxicity, and upregulated the NF-κB and STAT3 pathways, ultimately leading to activation of the perforin/granzyme B-mediated apoptotic pathway [41]. Furthermore, sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibitor, demonstrated a synergistic effect when combined with PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibition, which was mediated by IL-33 [24]. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy remains a standard treatment for BC [42]. A study found that BC patients who did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy exhibited higher IL-33 mRNA levels compared to those who underwent chemotherapy. This suggests that neoadjuvant chemotherapy may reduce IL-33 expression and activate IL-33-mediated anti-tumour immune responses [43]. Table 1 summarizes the therapeutic mechanisms of IL-33 that have been documented in preclinical studies.

DISCUSSION

Historically, IL-33 has been primarily recognized for its role in regulating type 2 immune responses, including interactions with ILC2 and Th2 cells, which contribute to immunity and immune evasion. Notably, type 1 and type 2 immune responses often exert opposing effects. While ILC2 is generally associated with tumour progression by activating MDSCs, MDSCs themselves are known to negatively regulate anti-cancer immunity [44, 45]. The role of IL-33 in BC appears to be context-dependent, with the cytokine capable of either promoting or inhibiting tumour progression by influencing different immune cell populations. IL-33 exerts multifaceted effects within the tumour microenvironment, where its impact is shaped by factors such as tumour stage, pathology, the source of IL-33, tissue-resident immune cells, and specific characteristics of the tumour microenvironment. In early-stage BC, IL-33 secretion from tumour tissue may modulate the immune microenvironment by regulating ILC2 and Th2 cells, thereby facilitating tumour cell survival and metastasis [46, 47]. Consequently, IL-33 inhibition may be effective in preventing tumour initiation. However, as the tumour progresses, the local immune microenvironment becomes increasingly unstable, leading to excessive IL-33 expression and dysregulation of ILC2 and other immune cells, which may explain the discrepancies observed in previous studies. A major challenge remains in distinguishing different immune microenvironment stages in individual patients and optimizing patient-specific responses to IL-33-targeted treatments. IL-33 inhibition appears to be a viable candidate for combination strategies with immune checkpoint inhibitors or endocrine therapy to enhance therapeutic efficacy. Ongoing clinical trials are necessary to evaluate the potential of IL-33-targeted therapies as adjuvant immunotherapy approaches.

DISCLOSURE

Financial support: The research was supported by the Yuhuan City Science and Technology Plan Project (No.202301).

Conflicts of interest: none.

All authors conceived and designed the hypotheses underlying this study. Fu Zhang and Miao Lin drafted the article and revised the manuscript. Fangjian Zhou and Yuancong Jiang critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that they have not used Artificial Intelligence in this study.

REFERENCES

1. Harris MA, Savas P, Virassamy B, et al. Towards targeting the breast cancer immune microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer 2024;24:554-77. [Google Scholar]

2. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74:229-63. [Google Scholar]

3. Qiu J, Qian D, Jiang Y, et al. Circulating tumor biomarkers in early-stage breast cancer: characteristics, detection, and clinical developments. Front Oncol 2023;13:1288077. [Google Scholar]

4. Dvir K, Giordano S, Leone JP. Immunotherapy in Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25:14. [Google Scholar]

5. Jin X, Mu P. Targeting Breast Cancer Metastasis. Breast Cancer Basic Clin Res 2015;9(Suppl 1):23-34. [Google Scholar]

6. Khan MM, Yalamarty SSK, Rajmalani BA, et al. Recent strategies to overcome breast cancer resistance. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2024;197:104351. [Google Scholar]

7. Shen F, Wang S, Yu S, et al. Small intestinal metastasis from primary breast cancer: a case report and review of literature. Front Immunol 2024;15:1475018. [Google Scholar]

8. Roussel L, Erard M, Cayrol C, et al. Molecular mimicry between IL-33 and KSHV for attachment to chromatin through the H2A-H2B acidic pocket. EMBO Rep 2008;9:1006-12. [Google Scholar]

9. Stojanovic B, Gajovic N, Jurisevic M, et al. Decoding the IL-33/ST2 Axis: Its Impact on the Immune Landscape of Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:18. [Google Scholar]

10. Jiang Y, Kong D, Miao X, et al. Anti-cytokine therapy and small molecule agents for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Eur Cytokine Netw 2021;32:73-82. [Google Scholar]

11. Liu A, Hayashi M, Ohsugi Y, et al. The IL-33/ST2 axis is protective against acute inflammation during the course of periodontitis. Nat Commun 2024;15:2707. [Google Scholar]

12. Hu H, Sun J, Wang C, et al. IL-33 facilitates endocrine resistance of breast cancer by inducing cancer stem cell properties. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017;485:643-50. [Google Scholar]

13. Lu DP, Zhou XY, Yao LT, et al. Serum soluble ST2 is associated with ER-positive breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2014;14:198. [Google Scholar]

14. Kim JY, Lim SC, Kim G, et al. Interleukin-33/ST2 axis promotes epithelial cell transformation and breast tumorigenesis via upregulation of COT activity. Oncogene 2015;34:4928-38. [Google Scholar]

15. Liu J, Shen JX, Hu JL, et al. Significance of interleukin-33 and its related cytokines in patients with breast cancers. Front Immunol 2014;5:141. [Google Scholar]

16. Xiao P, Wan X, Cui B, et al. Interleukin 33 in tumor microenvironment is crucial for the accumulation and function of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncoimmunology 2016;5:e1063772. [Google Scholar]

17. Jovanovic IP, Pejnovic NN, Radosavljevic GD, et al. Interleukin-33/ST2 axis promotes breast cancer growth and metastases by facilitating intratumoral accumulation of immunosuppressive and innate lymphoid cells. Int J Cancer 2014;134:1669-82. [Google Scholar]

18. Larsen KM, Minaya MK, Vaish V. The Role of IL-33/ST2 Pathway in Tumorigenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:9. [Google Scholar]

19. Qi L, Zhang Q, Miao Y, et al. Interleukin-33 activates and recruits natural killer cells to inhibit pulmonary metastatic cancer development. Int J Cancer 2020;146:1421-34. [Google Scholar]

20. Viana CTR, Orellano LAA, Pereira LX, et al. Cytokine Production Is Differentially Modulated in Malignant and Non-malignant Tissues in ST2-Receptor Deficient Mice. Inflammation 2018;41:2041-51. [Google Scholar]

21. Spits H, Mjösberg J. Heterogeneity of type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2022;22:701-12. [Google Scholar]

22. McKenzie ANJ, Spits H, Eberl G. Innate lymphoid cells in inflammation and immunity. Immunity 2014;41:366-74. [Google Scholar]

23. Shani O, Vorobyov T, Monteran L, et al. Fibroblast-Derived IL33 Facilitates Breast Cancer Metastasis by Modifying the Immune Microenvironment and Driving Type 2 Immunity. Cancer Res 2020;80:5317-29. [Google Scholar]

24. Hollande C, Boussier J, Ziai J, et al. Inhibition of the dipeptidyl peptidase DPP4 (CD26) reveals IL-33-dependent eosinophil-mediated control of tumor growth. Nat Immunol 2019;20:257-64. [Google Scholar]

25. Zerdes I, Matikas A, Foukakis T. The interplay between eosinophils and T cells in breast cancer immunotherapy. Mol Oncol 2023;17:545-7. [Google Scholar]

26. Taggenbrock R, van Gisbergen K. ILC1: Development, maturation, and transcriptional regulation. Eur J Immunol 2023;53:e2149435. [Google Scholar]

27. Blomberg OS, Spagnuolo L, Garner H, et al. IL-5-producing CD4(+) T cells and eosinophils cooperate to enhance response to immune checkpoint blockade in breast cancer. Cancer Cell 2023;41:106-23.e110. [Google Scholar]

28. Gao X, Wang X, Yang Q, et al. Tumoral expression of IL-33 inhibits tumor growth and modifies the tumor microenvironment through CD8+ T and NK cells. J Immunol 2015;194:438-45. [Google Scholar]

29. Yang Q, Li G, Zhu Y, et al. IL-33 synergizes with TCR and IL-12 signaling to promote the effector function of CD8+ T cells. Eur J Immunol 2011;41:3351-60. [Google Scholar]

30. Hegde S, Leader AM, Merad M. MDSC: Markers, development, states, and unaddressed complexity. Immunity 2021;54:875-84. [Google Scholar]

31. Vilbois S, Xu Y, Ho PC. Metabolic interplay: tumor macrophages and regulatory T cells. Trends Cancer 2024;10:242-55. [Google Scholar]

32. Halvorsen EC, Franks SE, Wadsworth BJ, et al. IL-33 increases ST2(+) Tregs and promotes metastatic tumour growth in the lungs in an amphiregulin-dependent manner. Oncoimmunology 2019;8:e1527497. [Google Scholar]

33. Aron JL, Akbari O. Regulatory T cells and type 2 innate lymphoid cell-dependent asthma. Allergy 2017;72:1148-55. [Google Scholar]

34. Cayrol C, Girard JP. Interleukin-33 (IL-33A nuclear cytokine from the IL-1 family. Immunol Rev 2018;281:154-68. [Google Scholar]

35. Goda N, Nakashima C, Nagamine I, et al. The Effect of Intratumoral Interrelation among FOXP3+ Regulatory T Cells on Treatment Response and Survival in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers 2022;14:9. [Google Scholar]

36. Kong D, Jiang Y, Miao X, et al. Tadalafil enhances the therapeutic efficacy of BET inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma through activating Hippo pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2021;1867:166267. [Google Scholar]

37. Jiang Y, Miao X, Wu Z, et al. Targeting SIRT1 synergistically improves the antitumor effect of JQ-1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Heliyon 2023;9:e22093. [Google Scholar]

38. Kim JY, Kim G, Lim SC, et al. IL-33-Induced Transcriptional Activation of LPIN1 Accelerates Breast Tumorigenesis. Cancers 2021;13:9. [Google Scholar]

39. Milosavljevic MZ, Jovanovic IP, Pejnovic NN, et al. Deletion of IL-33R attenuates VEGF expression and enhances necrosis in mammary carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016;7:18106-15. [Google Scholar]

40. Dai JZ, Yang CC, Shueng PW, et al. Obesity-mediated upregulation of the YAP/IL33 signaling axis promotes aggressiveness and induces an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in breast cancer. J Cell Physiol 2023;238:992-1005. [Google Scholar]

41. Jovanovic MZ, Geller DA, Gajovic NM, et al. Dual blockage of PD-L/PD-1 and IL33/ST2 axes slows tumor growth and improves antitumor immunity by boosting NK cells. Life Sci 2022;289:120214. [Google Scholar]

42. Kroemer G, Chan TA, Eggermont AMM, et al. Immunosurveillance in clinical cancer management. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74:187-202. [Google Scholar]

43. Albuquerque RB, Borba M, Fernandes MSS, et al. Interleukin-33 Expression on Treatment Outcomes and Prognosis in Brazilian Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:22. [Google Scholar]

44. Qiu J, Jiang Y, Ye N, et al. Leveraging the intratumoral microbiota to treat human cancer: are engineered exosomes an effective strategy? J Transl Med 2024;22:728. [Google Scholar]

45. Kopp EB, Agaronyan K, Licona-Limón I, et al. Modes of type 2 immune response initiation. Immunity 2023;56:687-94. [Google Scholar]

46. Ito A, Akama Y, Satoh-Takayama N, et al. Possible Metastatic Stage-Dependent ILC2 Activation Induces Differential Functions of MDSCs through IL-13/IL-13Rα1 Signaling during the Progression of Breast Cancer Lung Metastasis. Cancers 2022;14:13. [Google Scholar]

47. Jovanovic I, Radosavljevic G, Mitrovic M, et al. ST2 deletion enhances innate and acquired immunity to murine mammary carcinoma. Eur J Immunol 2011;41:1902-12. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools