Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Extension of Goal-Directed Behavior Model for Post-Pandemic Korean Travel Intentions to Alternative Local Destinations: Perceived Risk and Knowledge

1 College of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Sejong University, Seoul, 143-747, Korea

2 School of Tourism, University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City, 700000, Vietnam

3 Department of Hotel & Restaurant Management, Kyunghee Cyber University, Seoul, 130-739, Korea

4 Major in Tourism Management, College of Business Administration, Keimyung University, Daegu, 42601, Korea

* Corresponding Author: Sanghyeop Lee. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(4), 449-469. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.025379

Received 08 July 2022; Accepted 28 September 2022; Issue published 01 March 2023

Abstract

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, tourists have been increasingly concerned over various risks of international travel, while knowledge of the pandemic appears to vary significantly. In addition, as travel restrictions continue to impact adversely on international tourism, tourism efforts should be placed more on the domestic markets. Via structural equation modeling, this study unearthed different risk factors impacting Korean travelers’ choices of alternative local destinations in the post-pandemic era. In addition, this study extended the goal-directed behavior framework with the acquisition of perceived risk and knowledge of COVID-19, which was proven to hold a significantly superior explanatory power of tourists’ decisions of local alternatives over foreign countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, desire was found to play an imminent mediating role in the conceptual model, maximizing the impact of perceived risk on travel intentions. Henceforth, this research offers meaningful theoretical implication as the first empirical study to deepen the goal-directed behaviour framework with perceived risk and knowledge in the context of post-COVID-19 era. It also serves as insightful knowledge for Korean tourism authorities and practitioners to understand local tourists’ decision-making processes and tailor effective recovery strategy for domestic tourism.”Keywords

Ever since the outbreak of COVID-19, which has drastically raised the health-related risks of traveling overseas, the international tourism industry and its various beneficiaries have faced severe financial risks derived from a significant decrease in customers [1–3]. Global air travel demands historically dropped by almost 70% year over year [4] and hotels worldwide experienced the worst revenue per available room (RevPar), with Italy and Korea performing 93% and 75% lower than pre-pandemic time, respectively [5]. Undoubtedly, COVID-19 has had an immensely adverse effect on international tourism as national leaders across countries are imposing strict mobility policies on their citizens and foreign entries. China has the most stringent travel restrictions under the de facto international travel ban forbidding both inbound and outbound non-essential trips [6]. Furthermore, more than 170 countries are still upholding strict travel restrictions to prevent pandemic infection [7]. These restrictions culminated in a striking 75% revenue loss, from 1.5 billion in 2019 to merely 380 million in 2020 [8]. Despite the Korean government’s and tourism authorities’ continued endeavors to boost the domestic tourism industry, the country has seen a deficit in tourism and related businesses for the past few decades, which Park [9] attributed to a growing level of Korean outbound tourism, particularly to China. Korean tourism was affected even more drastically starting from the beginning of 2020 owing to the global pandemic COVID-19, whose numerous risks have placed significantly negative impacts on trust and satisfaction of international tourists [10]. In 2020, under the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic, Koreans took 4.95 domestic trips per person on average, which was eight trips down from 2019. Moreover, Korean individual spending on tourism was cut roughly in half [11]. Another key reason for the suffering of Korean domestic tourism is that 35% of tourists in Korea were not locals but in fact, Chinese travelers, accounting for 8.1 million tourists in Korea in 2016 [12], who however, are currently in strict national quarantine under the de facto international travel ban. Henceforth, from the tourism management perspective, it is urgently essential to secure the Korean tourism industry from the pandemic crisis, and the design of local destinations in Korea that domestic travelers appeal to as a safer and more comfortable alternative to visiting China/other countries is therefore of utmost significance for the strategic development of the industry in the foreseeable future [13].

Undeniably, the recent contraction of domestic as well as international tourism is mainly related to the overall risk of COVID-19, which tourists perceive could be potentially encountered at tourism destinations [14,15]. Since risk perception is critical in explicating international tourist behaviors [10], understanding the types of risk that Korean travelers perceive when traveling abroad in the post-pandemic era is essential to gain a deeper insight about the Korean tourist decision-making process and behaviors [16,17]. Yet, little empirical research has assessed the possible effect of perceived risk and knowledge pertinent to COVID-19 on a socio-psychology theoretical framework (i.e., goal-directed behavior framework) [18–20], which is vital in travelers’ decision formation [13]. Particularly, the linkages between perceived risk, perceived knowledge, and the dimensions within the goal-directed behavior framework (i.e., volitional, non-volitional, emotional, and motivational dimensions) have not been unearthed. Therefore, the objective of this study is to investigate how perceived risk and perceived knowledge of the pandemic contribute to activating Korean travelers’ alternative local destination choices instead of China in the post-pandemic era. Specifically, the possible associations between factors within the goal-directed behavior framework, perceived risk, and perceived knowledge are tested. In addition, how such relationships influence the formation of travelers’ intentions to travel to alternative local destinations in Korea is assessed. This research is also designed to identify the relative criticality among study variables in determining intention and to examine how desire as a mediator maximizes the effect of perceived risk on traveler intention. Moreover, the adequacy of the higher-order framework of perceived risk is evaluated.

As such, theoretically, this study contributes by confirming the first-order variables of risk perception towards COVID-19 and deepening the goal-directed behavior model with relevant constructs, allowing the model to have more precise prediction capability of travel intention in the case of the post-pandemic trips. Meanwhile, from a practical standpoint, the significance of the study is undeniable among national and local tourism ministries, strategists and practitioners in Korea, whose pressing goals are to strategically map out the most effective plans for domestic tourism to quickly recover from COVID-19. Utilizing the results of this study, tourists’ understanding of the pandemic and decision processes are better understood, which are fundamental insights to set up effective and superior precautionary practices at the local destinations and competitive tourism products and services to win over domestic markets in these vulnerable times. This is particularly essential for countries whose tourism in the past had been over-reliant on international tourists, such as Korea, and therefore urgently need an efficacious strategic transformation to capture local tourists’ revenue potential.

2.1 Model of Goal-Directed Behavior

In order to explicate the drivers underlying consumer behaviors and decisions, well-established theories in social psychology are typically utilized. One of the earliest and most prevalent would be the theory of reasoned action (TRA) and its extended model, the theory of planned behavior (TBP) [21]. Nonetheless, the limitations of these models have been later identified by recent studies as unable to sufficiently capture the complexity of the consumer decision-making process and its constituents such as affective and experiential factors [22–25]. Consequently, a new conceptual framework was deemed essential, and hence the introduction of the goal-directed model (MGB) by Perugini et al. [18] was put forward, which aims to elucidate behaviors and decisions as a means to achieve certain goals. The MGB model has been consistently proven across studies to hold stronger prediction power and explication capability in comparison to the aforementioned conceptualizations [24–30].

Before understanding the fundamentals of MGB, it is of critical importance to break down the key components of TRA and TPB, the foundations upon which the MGB is proposed. The TRA denotes that a person’s behavioral intention, the most proximal determinant towards the demonstration of actual behavior, can be predicted via analysis of two key variables: attitude towards the behavior. According to Eagly et al. [31], TRA is referred to as “a psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor”. On the other hand, the subjective norm, is comprehended as the perceived social pressure to perform or not perform a certain activity [32]; or in a more succinct manner, the social approval or disapproval of a specific behavior [33]. Meanwhile, TPB expands this framework by postulating that one’s behavior is not only built on volitional factors, analogous to those included in the TRA but also on the non-volitional driver, that is, the perceived behavioral control explicated as the perceived level of ease or adversity one may encounter while carrying out an action [34]. Although these two models have repeatedly demonstrated their efficacy in various studies, they inarguably neglected some vital constructs affecting human behaviors, such as emotion and habits [18,19,24], hindering the accuracy of human behavior explication, and leaving a persistent theoretical gap that the adaptation of MGB could fulfill. Specifically, MGB, despite bearing high resemblance to TRA and TPB characteristics, emerges as a novel and more improved framework by incorporating three additional conceptual pillars, i.e., desire, past behavior and anticipated emotion [13], under the core belief that a particular behavior always is elicited in order for a goal or purpose to be accomplished. As such, the MGB model encompasses the highest number of predicting variables and constructs, i.e., motivational (desire), volitional (attitude towards behavior and subjective norm), non-volitional (perceived behavioral control), emotional (positive and negative anticipated emotion), and habitual (frequency of past behaviors) [18,19], culminating such an intricate yet parsimonious model.

Desire is the focal and most imperative construct of MGB, often unearthed as the closest proxy towards intention and directly determining force of intention [24,30]. It is defined as the “a state of mind whereby an agent has personal motivation to perform an action or to achieve a goal” [18], and “wherein appraisals and reasons to act are transformed into a motivation to do so” [19]. On the other hand, anticipated emotions evidently represent the emotional process in this theorization, particularly one’s expected attainment of favorable or unfavorable feelings when a behavior is conducted or suppressed. A person’s anticipated emotion is generally theorized into two dimensions: either positive or negative [21]. Due to the prominence of desire in the decision-making process, various studies in the social sciences and psychology have made attempts to identify the impetuses leading to the arousal of human desire; and across multiple studies, variables rooted in the aforementioned social-psychological frameworks (i.e., attitude towards the behavior, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, anticipated emotions and past experiences) all play the role of an immediate antecedent of desire [18,19,25,26,35]. In tourism studies, according to Kim et al. [36] in their study of international travel, behavioral intention was influenced by a plethora of factors that are part of the MGB model (i.e., attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control and anticipated emotions) in which desire was the mediating variable. This finding was reconfirmed in a study conducted by Song et al. [24] to understand festival visitors’ pro environmental behaviors. Specifically, desire is the most prominent mediator bridging between visit intentions and other factors including attitude towards behaviors and perceived behavioral control. Meanwhile, Wang et al. [30] adopted the original MGB model and proposed an extended model of MGB, discovering that desire has the strongest effect on behavioral intentions to travel domestically with positive and negative anticipated emotion being the influencer towards level of desire. As such, the proposal of the first six hypotheses is listed below:

H1: Attitude toward the behavior has a significant effect on desire.

H2: Subjective norm has a significant effect on desire.

H3: Perceived behavioral control has a significant effect on desire.

H4: Positive anticipated emotion has a significant effect on desire.

H5: Negative anticipated emotion has a significant effect on desire.

H6: Desire has a significant effect on intention to travel to alternative destinations in Korea.

2.2 Integration of Perceived Risk and Knowledge into the Model of Goal-Directed Behavior

2.2.1 Perceived Risk of the Pandemic

The concept of perceived risk is conceptualized as a multi-dimensional variable that denotes an individual’s subjective expectation and evaluation of the uncertainty and negative outcomes or losses potentially resulting from a specific decision or behavior that he/she conducts [37–39]. Its impact is particularly imminent in hospitality and tourism, which was first mentioned by Cheron et al. [40], who aimed to discover the perceived risks of tourists participating in leisure activities. Due to the unique characteristics of tourism products, it comes as no surprise that this conceptualization and its influence on behavior has been extensively stressed in the last four decades by academicians and practitioners in the field [41–56]. First, the intangible nature of tourism services and products, which in layman’s terms means that consumers are mandated to make upfront payments without having first-hand experiences during the decision evaluation process, is inherently viewed as a potential risk in scenarios like the service delivery is unsatisfactory or does not live up to guest’s expectations. Second, it is paramount to note that this construct refers to human perception rather than actual risks, and so it can differ drastically across demographic profiles and travel contexts, e.g., gender, age, travel experiences, travel geography, etc. [48]. For example, female tourists tend to have greater perception of health and food risks [43] as well as concern over sex-related issues [49], while tourists who have prior experiences in travelling would be less aware of any particular potential risks [50]. In addition, the impact of perceived risk is even heightened at international tourism spaces where the traveler is placed in cross-cultural settings and is evidently exposed to various safety and health risks such as political chaos, religious instability, and global epidemics [44,51,52].

In the current climate in which the entire world is affected by COVID-19, locking down the world for almost one-third of a decade and causing millions of casualties, the significance of perceived risk in tourism is in fact bolstered and overwhelmingly profound [42,53–56]. In a study by Han et al. [13], investigating the drivers of Korean tourists’ avoidance behavior towards traveling to China amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, perceived risk is categorized into 6 key variables, i.e., human crowding risk, spatial crowding risk, quality risk, psychological risk, health and safety risk, and lastly financial risk. However, for Zhu et al. [56], who analyzed the influence of perceived risks of COVID-19 on tourist’s approach behavior towards local rural tourism in China, this perception of risk is explained by 6 manifest variables: physical risk (e.g., natural catastrophes, public security), equipment risk (e.g., public infrastructure, hygiene and tourism facilities), cost risk (e.g., time and money concerns), psychological risk (e.g., stress and anxiety), social risk (e.g., family and peer opinions) and performance risk (e.g., food and beverage, natural landscapes). A substantial amount of the extant tourism literature has evidenced the correlation of one or multiple aforementioned perceived risk factors with a person’s behavioral intention generation [10,53–56], which is reflected in this paper by the 6 core variables embedded in the proposed MGB model: attitude toward the behavior, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, positive and negative anticipated emotion, desire, and lastly travel intention. More specifically, the more potential risks are perceived by tourists during the decision-making process, the more negative attitudes and emotions are elicited, deterring the individual to set foot on new and foreign lands, especially for leisure purposes, and instead seeking for alternative locations that could offer less risks. Therefore, the following hypotheses are pushed forward:

H7: Perceived risk has a significant effect on attitude toward the behavior.

H8: Perceived risk has a significant effect on subjective norm.

H9: Perceived risk has a significant effect on perceived behavioral control.

H10: Perceived risk has a significant effect on positive anticipated emotion.

H11: Perceived risk has a significant effect on negative anticipated emotion.

H12: Perceived risk has a significant effect on desire.

H13: Perceived risk has a significant effect on intention to travel to alternative local destinations in Korea.

2.2.2 Perceived Knowledge of the Pandemic

Risk knowledge or awareness, referred to as the perception of how much a person is aware about the risks they might face, has a major impact on their risk perception and behavioral intention generation [16,54,56–59]. Similar to perceived risk, perceived knowledge could vary depending on the subjective awareness of each individual and not the actual conditions [60]. Knowledge attainment can be broken down into a few key types: social information (obtained by interacting with the outside world), major-oriented knowledge (obtained through the study of specialized courses and related to a specific learning field of knowledge information) and general knowledge (access to information by foraging, not limited to a specific area). When it comes to a new, highly dangerous and unfamiliar risk equivalent to the COVID-19 pandemic, traveler’s risk knowledge depends primarily on the government’s official announcements and news across media channels [60,61]. This also means the public’s level of perceived uncertainty is drastically higher in such circumstances due to constant modifications in government policy in a short period of time [62].

The theory of perceived risk knowledge is rather a new conceptualization and has been mostly investigated in relation to perception of risk as well as behavioral intention, denoting the salience of such a concept in predicting one’s behaviors in the presence of one or more potential risks [54,56,63,64]. This correlation between perceived knowledge, perceived risk, and behavioral intention has been often examined within the tourism sector in order to better understand traveler behavioral responses toward the pandemic. In Zhu et al. [56] study, which examined the impact of tourist knowledge on travel intention in rural areas, the authors mentioned two types of knowledge, namely tourism risk knowledge (accounting for information about potential risks that are exposed to a tourist) and pneumonia risk knowledge (constituting the level of one’s risk awareness of the COVID-19 pandemic), both of which were found to place a significant impact on risk perception and travel final decision. On the other hand, in a study exploring tourism in Indonesia during COVID-19 conducted by Rahmafitria et al. [54], when an individual attains inadequate knowledge of a risk, their level of perceived risk is in fact reduced, leading to less urgency in practicing physical distancing and increased motivation in traveling. Evidently, the previous literature paves a firm foundation for this paper to draw a relationship between the degree to which a tourist knows about the COVID-19 pandemic risks with their desire to switch to local tourism and their travel intention regarding local destinations. Thus, the last two hypotheses are proposed as follows:

H14: Perceived knowledge of the pandemic has a significant effect on desire.

H15: Perceived knowledge of the pandemic has a significant effect on intention to travel to alternative local destinations in Korea.

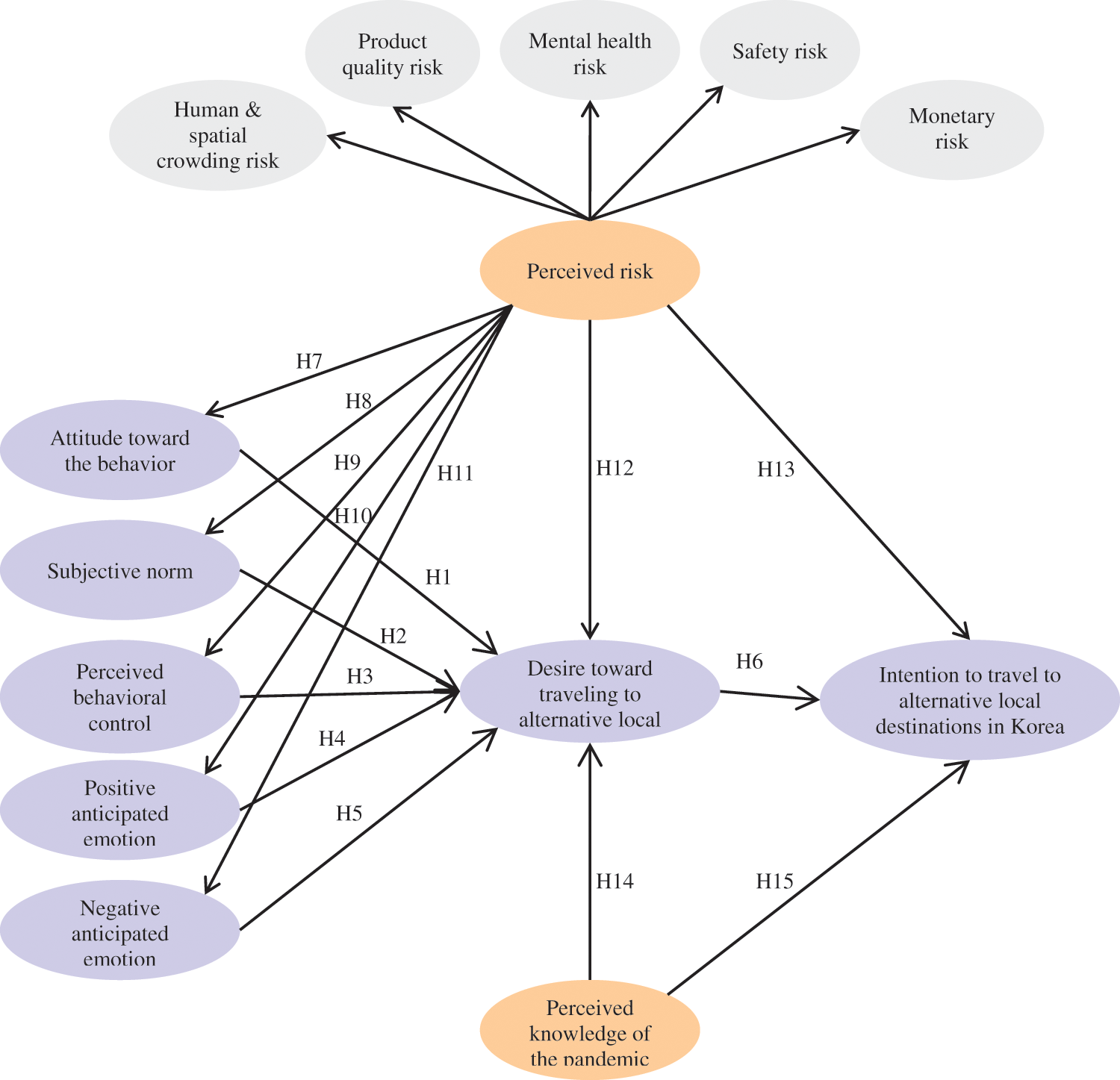

The proposed conceptual model is shown in Fig. 1. This model includes perceived risk factors, volitional (attitude and subjective norm) and non-volitional (perceived behavioral control) factors, affective factors (positive and negative anticipated emotions), a motivational factor (desire), and a knowledge perception factor for the prediction of individuals’ intention to travel to alternative local destinations in Korea. Perceived risk contained human and spatial crowding, product quality, mental health, safety, and monetary dimensions. These factors are integrated as the first-order dimensions of perceived risk. The framework also encompasses 15 research hypotheses linking the study variables.

Figure 1: Proposed theoretical framework

The measurement items for study constructs were developed on the basis of the extant literature [10,13,18,24,32,51,65–67]. Multi-item measures along with a 7-point scale were utilized for all research variables of this study. In particular, measures for human and spatial crowding risk (e.g., “Too many people are at tourist sites of China”) were adopted from Wei et al. [65] and Yin et al. [67]. Product quality risk (e.g., “I am worried that the quality of tourism products in China becomes lower in the post-pandemic era”) was measured with two items, employed from Al-Ansi et al. [10] and Yin et al. [67]. Three items for mental health risk (e.g., “The thought of traveling to China in the post-pandemic era makes me feel psychologically uncomfortable”) was adopted from Reisinger et al. [51]. Safety risk (e.g., “Traveling to China in the post-pandemic era is still unsafe”) was measured with three items employed from Han et al. [13]. In addition, monetary risk (e.g., “I worry that visiting China would involve unexpected extra expenses in the post-pandemic era”) is assessed with two items adopted from Yin et al. [67].

Attitude toward behavior was adopted from Ajzen [32]. Five items were used to measure attitude (e.g., “For me, traveling to alternative local destinations instead of China in the near future is bad [1]–good [7]”). We employed three items for the evaluation of subjective norm (e.g., “People whose opinions I value would prefer me to visit alternative local destinations instead of China”), and used three items for the assessment of perceived behavioral control (e.g., “Whether or not I travel to alternative local destinations is completely up to me”). The measures were adopted from Ajzen [32] and Perugini et al. [18]. To measure positive (e.g., “Imagine that you are traveling to alternative local destinations instead of China in the near future. How would you feel?–I would feel excited”) and negative (“Imagine that you are traveling to alternative local destinations instead of China in the near future. How would you feel?-I would feel regretful”) anticipated emotions, we used four items, respectively. The measures were adopted from Perugini et al. [18]. In addition, we employed three items for the evaluation of desire toward behavior (e.g., “I desire to travel to alternative local destinations instead of China–False [1]–True [7]”), and used three items for the assessment of intention to travel to alternative local destinations (e.g., “I will travel to alternative local destinations instead of China in the post-pandemic era”). We adopted these measures from Song et al. [24] and Perugini et al. [18]. Perceived knowledge of the pandemic was measured with three items (e.g., “Compared with the average person, I know the facts about the consequences of the COVID-19 on health/economy/society”). This measure was employed from Wong et al. [66].

3.2 Data Collection and Demographic Profiles of the Samples

The survey questionnaire contains the measures of the study variables along with an introductory letter and questions for personal characteristics. The questionnaire was pre-tested with tourism academics and industry experts. The final version of the survey questionnaire was modified and developed based on their feedback. The English version of the survey questionnaire was translated into Korea using a back-translation method. The translated version was also pre-tested and improved based on tourism academics’ and practitioners’ feedback. For the assessment of the proposed conceptual model, this research adopted a Web-based survey approach. Using a market research company’s system, the online version of the questionnaire was created. The survey invitation was sent to potential respondents through the system of the survey company. The potential respondents were those travelers who had visited China for a vacation within the last 5 years. The participants were asked to read the research purpose and the introductory letter in a thorough manner. For the completion of the online survey, the respondents should fill out all questions of the questionnaire.

Through this data collection procedure, a total of 351 responses were collected. We obtained 342 usable cases for this study after removing nine multivariate outliers (Mahalanobis’D, p < .001). Before the data analysis and the research framework assessment, the values of kurtosis and skewness were evaluated. Our investigation showed no significant kurtosis and skewness problems. Hence, these 342 cases were utilized for data analysis. Among the respondents, 49.7% were women and 50.3% were men. About 44.4% of the respondents reported that they are college graduates, followed by high school graduates or less (24.6%), graduate degree holders (18.4%), and two-year/some college graduates (12.6%). Regarding annual income level, about 35.4% indicated their income between $30,000–$49,999, followed by $29,999 or less (33.9%), between $50,000–$69,999 (19.0%), $70,000–$79,999 (7.0%), and $90,000 or more (4.7%). In terms of age, about 29.5% of the respondents reported that their age is between 30–39 years old, followed by 50 years or older (24.9%), 20 years or younger (24.0%), and between 40–49 years old (21.6%).

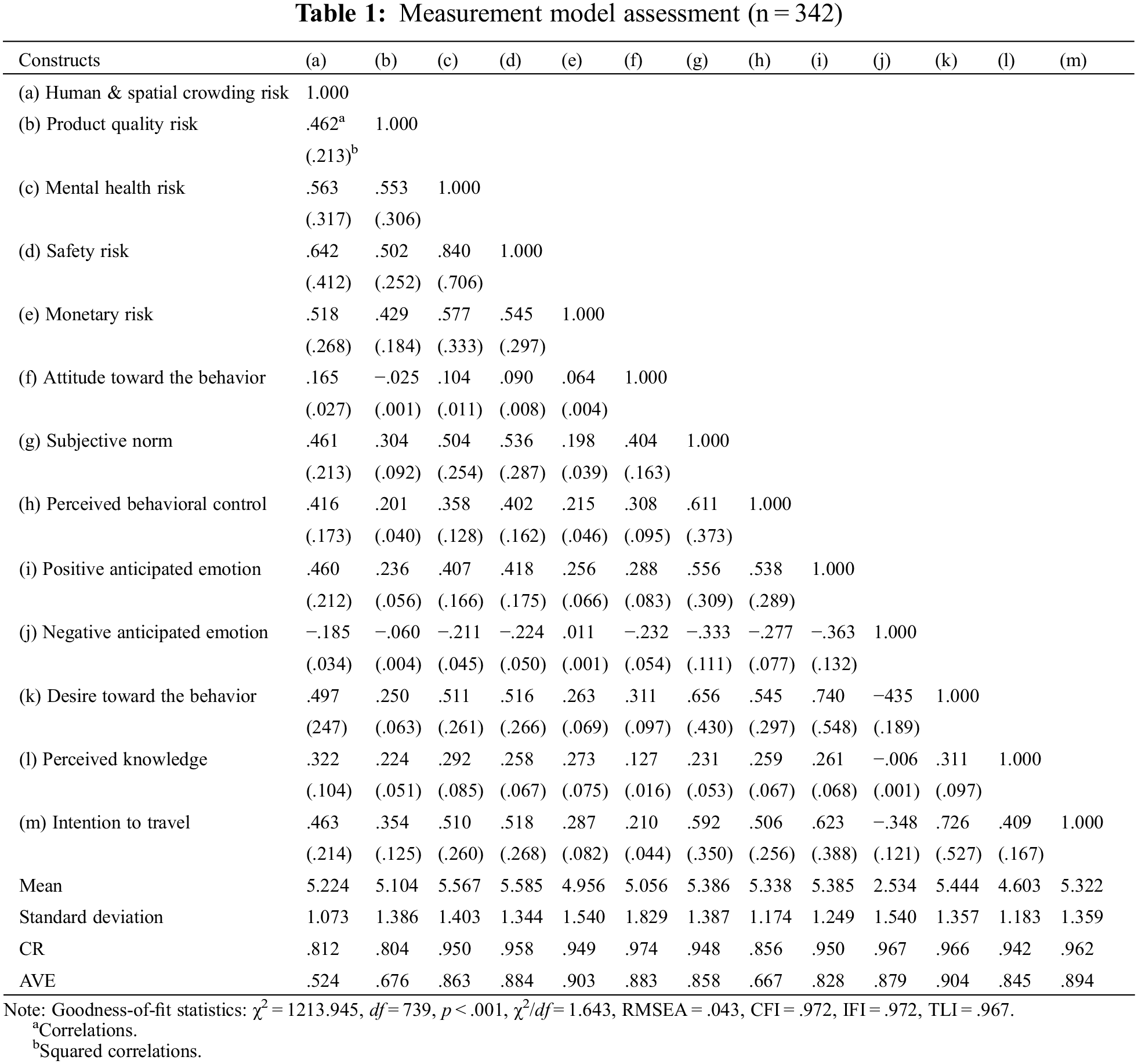

A measurement model was created by utilizing confirmatory factor analysis. The model contained an acceptable fit to the data (χ2 = 1213.945, df = 739, p < .001, χ2/df = 1.643, RMSEA = .043, CFI = .972, IFI = .972, TLI = .967). Details about the measurement model assessment results are exhibited in Table 1. Each observed variable was loaded to its associated latent construct significantly at the level of p < .01. A composite reliability was evaluated. The values exceed the minimum threshold of .70 (human and spatial crowding risk = .812; product quality risk = .804; mental health risk = .950; safety risk = .958; monetary risk = .949; attitude toward the behavior = .974; subjective norm = .948; perceived behavioral control = .856; positive anticipated emotion = .950; negative anticipated emotion = .967; desire toward the behavior = .966; perceived knowledge = .942; intention to travel = .962), suggested by Hair et al. [68]. Average variance extracted values were evaluated. All values were above the minimum threshold of .50 (human and spatial crowding risk = .524; product quality risk = .676; mental health risk = .863; safety risk = .884; monetary risk = .903; attitude toward the behavior = .883; subjective norm = .858; perceived behavioral control = .667; positive anticipated emotion = .828; negative anticipated emotion = .879; desire toward the behavior = .904; perceived knowledge = .845; intention to travel = .894), suggested by Hair et al. [68]. Thus, convergent validity was evident. In addition, these AVE values were all greater than the between-construct correlations (squared) (see Table 1). Therefore, the discriminant validity for all variables was empirically supported. That is, measures for each study construct were not unduly related.

Further analysis was performed to evaluate if the measures are under the impact of common method variance. One common factor (latent variable) within the measurement model was created, and its associations with other observed factors were tested. Results indicated that none of the measures were influenced by common method variance.

4.2 Evaluation of the Proposed Theoretical Framework and Test for Research Hypotheses

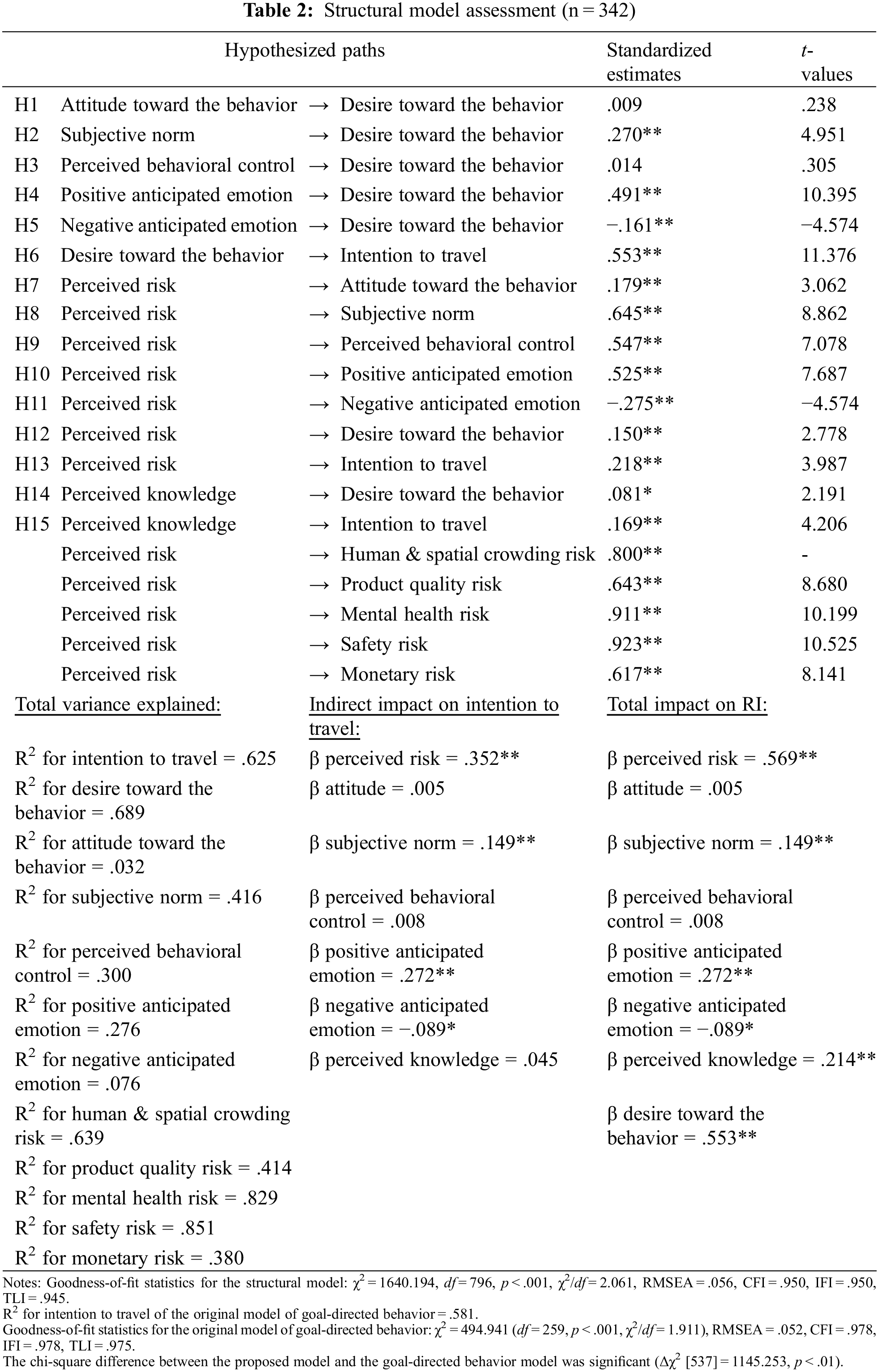

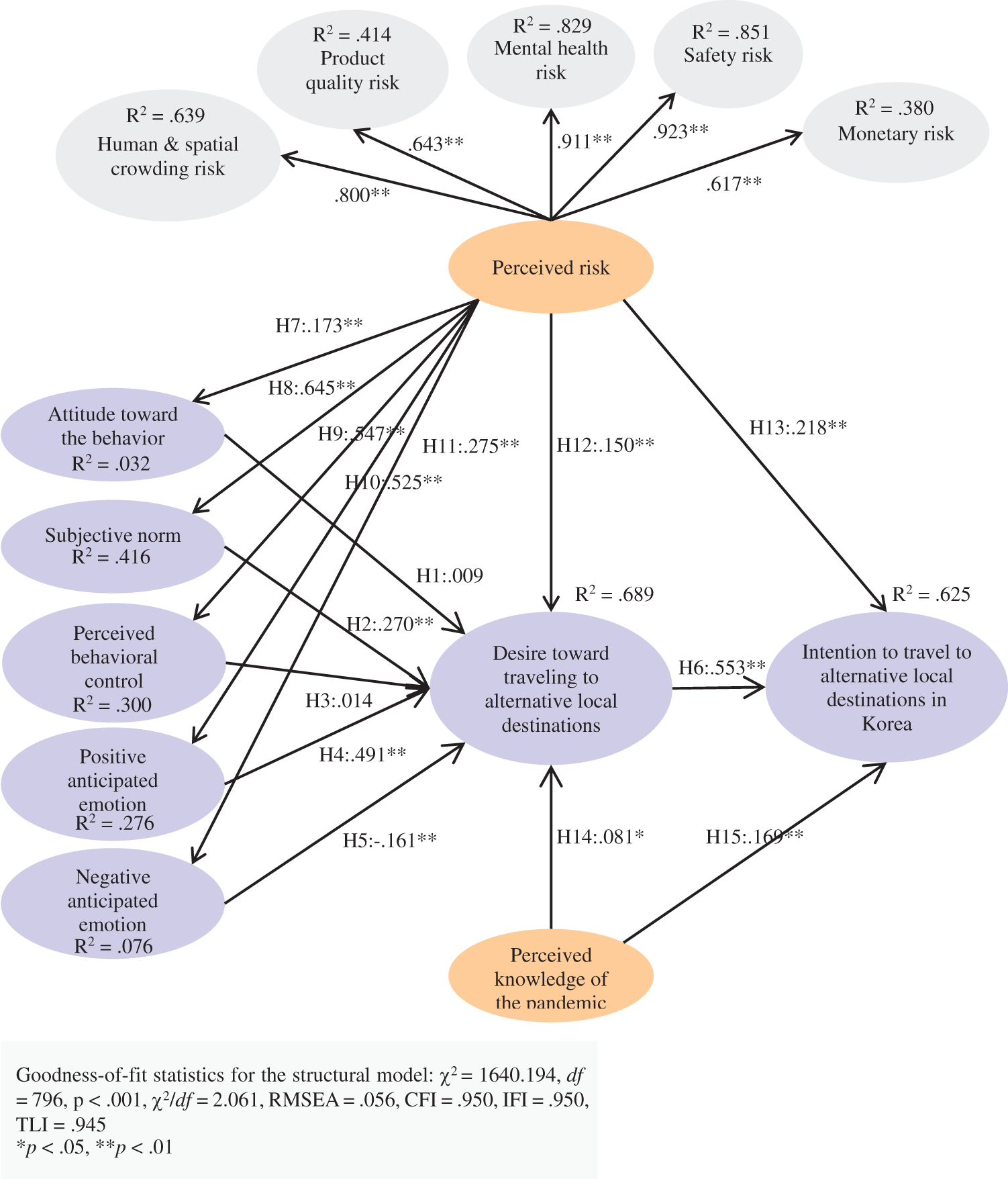

The proposed model was evaluated with the use of structural equation modeling. The model was found to fit the data satisfactory (χ2 = 1640.194, df = 796, p < .001, χ2/df = 2.061, RMSEA = .056, CFI = .950, IFI = .950, TLI = .945). The R2 for intention to travel to alternative local destinations in Korea was .625. That is, the model sufficiently accounted for about 62.5% of the total variance of traveler intention. The goodness-of-fit statistics of the original model of goal-directed behavior assessment was also acceptable (χ2 = 494.941 (df = 259, p < .001, χ2/df = 1.911), RMSEA = .052, CFI = .978, IFI = .978, TLI = .975). However, its prediction power for traveler intention (R2 = .581) was significantly weaker than our proposed theoretical model. This means that the proposed conceptual framework has a more sufficient level of explanatory power for traveler intention as compared to the original goal-directed behavior framework. Details about the structural model analysis are presented in Table 2.

As exhibited in Fig. 2 and Table 2, the higher-order framework for travelers’ perceived risk showed that the inclusive second-order variable is linked to the five first-order dimensions in a significant manner (human and spatial crowding risk, product quality risk, mental health risk, safety risk, and monetary risk). The values for coefficients were .800 (human and spatial crowding risk), .643 (product quality risk), .911 (mental health risk), .923 (safety risk), and .617 (monetary risk). All coefficients were significant at the level of p < .01. The explanatory power of the global higher-order construct for first-order factors were .639 (human and spatial crowding risk), .414 (product quality risk), .829 (mental health risk), .851 (safety risk), and .380 (monetary risk). That is, the global higher-order latent variable satisfactorily accounted for each first-order dimension. Overall, this result evidenced the appropriateness and efficacy of the second-order structure of perceived risk within the hypothesized theoretical model.

Figure 2: Assessment of the proposed theoretical framework

Hypotheses 1–5 were tested. Our result indicated that subjective norm (β = .270, p < .01), positive anticipated emotion (β = .491, p < .01), and negative anticipated emotion (β = −161, p < .01) significantly affected desire toward traveling to alternative local destinations. However, attitude toward the behavior (β = .009, p > .05) and perceived behavioral control (β = .014, p > .05) were not significantly associated with desire. Hence, Hypotheses 2, 4, and 5 were supported, whereas Hypotheses 1 and 3 were not supported. The hypothesized link between desire and intention to travel was also found to be significant (β = .553, p < .01), and therefore supporting Hypothesis 6. The proposed effect of perceived risk was assessed. The result revealed that perceived risk significantly influenced attitude toward the behavior (β = .173, p < .01), subjective norm (β = .645, p < .01), perceived behavioral control (β = .547, p < .01), positive anticipated emotion (β = .525, p < .01), and negative anticipated emotion (β = −275, p < .01). Therefore, Hypotheses 7–11 were supported. In addition, perceived risk exerted a significant effect on desire (β = .150, p < .01) and intention (β = .218, p < .01). Hence, Hypotheses 12 and 13 were supported. The proposed effect of perceived knowledge was assessed. The result showed that perceived knowledge of the pandemic significantly influenced desire (β = .081, p < .05) and intention (β = .169, p < .01). This result supported Hypotheses 14 and 15.

The indirect effect of research constructs on intention to travel was tested. Our result showed that perceived risk (β = .352, p < .01), subjective norm (β = .149, p < .01), and positive anticipated emotion (β = .272, p < .01), and negative anticipated emotion (β = −.089, p < .05) included a significant indirect influence on intention. This means that desire toward the behavior played a crucial mediating role within the proposed conceptual framework. A total influence of research constructs was examined. As reported in Table 2, the total influence of perceived risk on intention to travel to alternative local destinations (β = .569, p < .01) was the highest, followed by desire toward the behavior (β = .553, p < .01), positive anticipated emotion (β = .272, p < .01), perceived knowledge (β = .214, p < .01), subjective norm (β = .149, p < .01), and negative anticipated emotion (β = .089, p < .05).

The tourism industry inherently includes a high frequency of domestic and international human mobility, is often accused of spreading unfamiliar pathogens and causing infectious disease transmission [69,70]. Some of the most phenomenal and deadly outbreaks in history that often appear in tourism studies are the Spanish flu, Swine flu, HIV/AIDS, SARS, Ebola and most recently COVID-19 [71]. Compared to past epidemics, COVID-19 is ranked as one of the most serious and detrimental [71,72]. By the end of 2021, COVID-19 mortality rate was up to five million, which outperformed all other viral epidemics in the 20th and 21st century [73]. Due to the severity of this pandemic with various implications in the tourism industry, the amount of research focusing on COVID-19, has seen an unprecedented growth, especially those relating to behavioral intentions [53,55], perception of risk [13,56], strategic adaptation, response and recovery [74,75]. While sharing some commonalities with other global contagious diseases in the past, COVID-19 evidently left modern societies with unique economic, social, and cultural impacts [71], proving the salience of empirical studies of COVID-19 to accurately understand the implications of this pandemic and future similar incidents in local and international tourism.

Indeed, the COVID-19 outbreak has definitely hit the tourism industry hard, particularly during the period between the end of 2019 up to the first quarter of 2022, as the world was faced with extremely strict social distancing practices and global lockdown policies, prohibiting most inbound and outbound movements if not proved essential [2,7]. Although the global implementation of vaccinations has been implemented and international borders are opening, allowing travel activities to resume, the current post-COVID time presents new challenges for tourism practitioners and destination managers as the consumers’ mentality and preferences towards traveling has undergone major changes, such as choices of outbound travels [76] or preference of non-crowded to crowded places [77]. Most notably, due to the fear of being infected by the pandemic, many are more concerned about health and safety risks before making their travel decisions [13,56,78]. This means that the refrain from riskier outbound tourism is presumably more pronounced [44], whereas preference towards inbound tourism, where COVID-19 is thought to be better contained, will naturally arise.

As a result, this calls for studies investigating local tourists’ decision-making processes in post-COVID 19 settings and suggests strategies that can take full advantage of it; yet little research to this point has attended to such a need. Thus, with the focus placed on Korean tourists, this paper was the first empirical attempt to determine the influence of perceived risk and perceived knowledge, when integrated into the MGB framework, had on Korea’s preference to travel domestically rather than to China in the post-pandemic era. Using a quantitative approach based on SEM, this paper presents a meaningful theorization for domestic tourism and offers practical implications for Korea’s tourism leaders to effectively manage local destinations and quickly bounce back from the so-called ‘tourism nightmare’.

First, to the knowledge of the authors, this is the first study to establish an intricate conceptual model to understand local Korean tourists’ intentions of traveling within Korea as an alternative to China via the analysis of the dynamic relationships between various perceived risk factors of traveling in post-COVID-19 times (i.e., human and spatial, product quality, mental health, safety and monetary risk), perceived knowledge of the pandemic, key elements of the MGB (i.e., attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, positive and negative anticipated emotions, and desire) and travel intentions. When comparing between the original and proposed model of MGB, it appears that the latter not only has strong forecast capability but is also far more superior than the former version, reflected by a significantly greater total variance of traveler intention. This result reaffirms the prominence of adding more constructs and latent variables when adapting social-psychological conceptualization, which often results in a higher level of total variance for behavioral intention [18,32]. In previous tourism studies, the MGB model has been extended to reflect specific contexts and circumstances (e.g., museums, festivals, hotels, etc.), hence deepening and enriching the theory to great lengths [24,30,36,79–82]. For instance, Meng et al. [82] conducted a study of environmental perception of bicycle travelers in China utilizing an extended MGB model with the addition of environmental connectedness and environmental behavior, which were relevant in this case as they are important constructs in bicycle tourism. Also, understanding the necessity of enriching the model, Wang et al. [30] proposed an extended MGB, which adds two other constructs, namely smog policy and protection motivation, into the original MGB to better explain impact of smog-related factors on domestic tourists’ decision-making formation in Korea. Likewise, in the case of this study, perceived risk and perceived risk knowledge are the newly integrated variables of the MGB model that fit well into the post-COVID era context and rationalize better the antecedents of behavioral intentions (i.e., attitude towards the behavior, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, anticipated emotion and desire). Under the circumstances of large-scale and widespread epidemics such as SARS and COVID-19, which pose an array of unknown risks, risk perception tends to be drastically higher and more influential than those existing in times of normalcy [83]. Besides, the impact of perceived knowledge living in the so-called unknown era is inevitable in this case. During and after the outbreak, it is highly likely that people will obtain contradictory and perplexing information due to the variance of media coverage as well as word-of-mouth [84], resulting in vastly varied perceived knowledge and beliefs of these public health crises. Overall, it is believed that the extended MGB model of this study broadens the literature of not only domestic travel intentions after COVID-19 [85,86] but also theories on extending social-psychological models, specifically the MGB [80,82,87].

In addition, the explanatory power of the extended MGB was enhanced because of the inclusion of five sub-constructs of the formative second order factor (i.e., perceived risk) in the context of the traveling in post-pandemic times, with mental health risk and safety risk being the most influential predictors. This model is believed to be the one of the first attempts to identify relevant risk variables within the context of traveler’s perception after COVID-19 and public health crises in general. It is found that tourism studies looking into other past epidemics such as SARS and Avian Flu had not determined specific risk types, but rather investigated it as one single construct. For example, the study of Mao et al. [88] concluded that perceived risk differently influenced Japanese, American, and Hong Kong tourists’ travel intentions to Taiwan during the post-SARS period, but they did not elaborate on the particular risks. Nevertheless, scholars interested in perceived risks of COVID-19 have made some efforts in categorizing perceived risks of travelers [13,56,89]. While there are some differences in terms of the risk types, most studies display consistencies with the current study, specifically being the prominence of safety-related and psychological perceived risks of travelers under the influence of COVID-19. Besides, perceived risk has the strongest total impact on travel intention towards local destinations as an alternative to outbound travels. In other words, the total contribution of risk perception to the decision to travel domestically is far greater than that of desire, positive and negative anticipated emotion, perceived knowledge and subjective norm. This is rather different from a few previous studies deploying the model of MGB to understand pro-environmental behaviors [24,30,82] in which desire tends to have the highest level of total impact on behavioral intention. This finding aligns well with past studies asserting the staggering importance of perceived risk of tourists coping with from global crisis and public health incidents [47,90].

Another meaningful finding of this study is that it brought to light the decision formation processes of Korean travelers when choosing a local destination as an alternative to other countries. Among the core components of MGB, subjective norm, positive and negative anticipated emotion were shown to have a strong connection with the desire of Koreans to choose an alternative local destination, whereas attitude and perceived behavioral control were insignificant in this matter. This result differs from previous research in which desire was strongly correlated with both attitude and perceived behavioral control [24,82,91,92]. However, these studies did not analyze intentions in the context of the post-pandemic era. This means that when considering the MGB model, the vital factors encouraging or deterring tourists to choose a local region than an overseas one during and after COVID-19 are subjective norms and anticipated positive and negative emotions. Perceived risk and knowledge are also significantly related to desire. As such, this paper provides an important theoretical implication as the model adds to current scholastic bodies on post-pandemic reducers of travel intentions towards inbound/outbound travels [13,89,93]. Most importantly, desire is frequently the direct antecedent of behavioral intention tying other predictors and mediating the impact of which on the ultimate intention [18,19,25,26,35]. Without exception, this mediating framework is also observed in this paper, positing the significance of desire as a crucial mediator, acting as a bridge to connect intention to travel to alternative local destinations in Korea with four significant predictors: subjective norm, positive and negative anticipated emotion, and perceived risk. With the limited literature on the relationship between desire and its mediating effect on travel intentions after COVID-19, this preliminary study evidently proves as a fundamental foundation for future studies exploring different key factors impacting the decision-making process of post-pandemic travelers.

First, the study revealed that perceived risk was the most influential factor on Korean travel intentions of alternative local destinations. Particularly, this implies that when they perceive more human and spatial, product quality, mental health, safety and monetary risks in the international tourism spaces, their travel intentions of local destinations as an alternative are higher. Additionally, it was also found that perceived risk plays a crucial role in affecting traveler’s desire to travel locally in the times of post-pandemic. This broadly suggests that if the local destination can position itself as less risky alternatives to international ones, tourists’ travel intentions to these domestic areas will be heightened. Further, among the five risk variables, safety and mental health risks are identified as the most accurate predictor of risk perception in this study, which means that strategies and resources should be to minimize these risks as a priority. In post-pandemic era, local authorities and tourism and hospitality enterprises can reduce safety and mental health risks by ensuring that strict social distancing practices (e.g., wearing mask, using hand sanitizer, managing crowds, offering contactless services, monitoring mobile applications, vaccination green cards, etc.) and well-equipped quarantine facilities and policies are in place. Apart from that, destination marketing organizations (DMOs) should develop and invest in tourism types that can address to the increasing safety demands of tourists, such as smart or contactless tourism, which limit human contact and face-to-face interactions at the tourism spaces, facilitated by the advent of technology in the digital era [53].

In this study, along with perceived risk, perceived knowledge of the pandemic also clearly attributes to desire and travel intentions of alternative local destinations in Korea. This bolsters the role of governments and tourism organizations to provide clear and updated information so that traveler’s awareness of the pandemic risks as well as preventive measures is increased, and at the same time, unnecessary fear of safe and well controlled regions is omitted. For example, specific statistics of infectious cases in Korea in comparison to those in other countries, China in particular, should be frequently updated so that tourists can understand the magnitude and complexity of this pandemic’s danger outside of Korea, and thus are more inclined towards local destinations. On the other hand, in order to reduce stress and anxiety of traveling, information regarding self-protective practices should be emphatically communicated with Korean tourists (e.g., getting vaccinated and booster shots, wearing masks, using hand sanitizers, and maintaining 2-meter distance with other people) in addition with the knowledge of the collective efforts at the local destinations to contain the virus. Considering the fact that there is a drastic increase in social media engagement when a crisis or pandemic hits [94], it is essential that information is timely updated on popular social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter alongside government official websites and articles to maximize reach.

Within the model of MGB, subjective norm and positive and negative anticipated emotions were shown to place considerable impact on desire to travel to alternative local destinations in Korea, while attitude and perceived behavioral control did not. Among the influential factors, positive anticipated emotions had the greatest impact on desire. Moreover, desire was confirmed in this study to be significantly and positively correlated with travel intentions. These findings imply that desire is a key element in understanding tourists’ post-pandemic decision formation towards domestic tourism. Thus, from a practical perspective, it is recommended that DMOs design content that can first elicit positive feelings and sentiment of target readers and travelers in anticipation of a trip. Under a novel study of Li et al. [95], investigating hospitality and tourism firms’ digital announcements in times of crises, a combination of innovative responses (e.g., innovative approach to bolster hygiene standards), argument quality (e.g., strong arguments of the firm with regards to its capability of combating the virus infection), and assertive language (e.g., confident and bold messages from the firm) was found to suppress negative tourist emotions and strengthen positive ones. Moreover, advanced technology such as virtual reality (VR), allowing users to experience and interact with the local tourism destinations in three dimensions and at the most authentic level, should be fully taken advantage of in post-pandemic times to induce consumer’s positive emotions and desire to visit them in real life [96,97]. Also, it is equally paramount that similar marketing attention is placed on the target markets’ most significant people within his/her social networks (e.g., family, friends, managers, coworkers, etc.) as the prominence of subjective norm has been clearly proven in this study.

5.3 Limitations and Future Research

This research is the first to our knowledge that empirically uncovered the specific role of perceived risk and knowledge of COVID-19 within the MGB framework in explaining visitors’ decision-making processes for alternative local tourism destinations rather than overseas locations. Building on the extant literature in post-outbreak tourism behavior, this research contributes to enriching both researchers’ and industry practitioners’ understanding of visitors’ decision formation for inbound rather outbound travel in the post-pandemic era. Nevertheless, as with most empirical studies, the current research is not free from limitations. First, as mentioned earlier, it is essential to deepen the theory by adding other instrumental variables into the model [18,32], and as such, although this paper offers theoretical significance by adding two additional concepts into the original MGB model, perceived risk and perceived knowledge, there are other important factors that should be identified and integrated into the model in future research to enhance theory in post-outbreak context. Second, the drawback of only investigating one nationality, Korean, is obvious: the data can highly vary due to the cultural differences and cannot be generalized in a larger population. The impact of other demographic factors (e.g., gender, education and income background, marital status, etc.) should not also be overlooked. Hence, another improvement in future studies is the change in different demographic profiles, such as the perception of European or Asian tourists, perception of young and older tourists, or perception of male and female, so as to bolster validity and the effectiveness of the proposed theoretical framework across conditions and settings. Third, the sample size in this study (n = 342) was greater than Hair et al.’s [68] suggested size of between 200 and 400 cases when running the CFA and SEM. Nevertheless, considering the total number of parameters of the proposed framework, the sample size of this study was not large enough. A larger sample size is, therefore, recommended for future research.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5A2A01046684).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Arbulú, I., Razumova, M., Rey-Maquieira, J., Sastre, F. (2021). Measuring risks and vulnerability of tourism to the COVID-19 crisis in the context of extreme uncertainty: The case of the balearic islands. Tourism Management Perspectives, 39, 100857. DOI 10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. UNWTO (2022). Impact assessment of the COVID-19 outbreak on international tourism. United Nations World Tourism Organizations (UNWTO). https://www.unwto.org/impact-assessment-of-the-COVID-19-outbreak-on-international-tourism. [Google Scholar]

3. Yang, Y., Zhang, H., Chen, X. (2020). Coronavirus pandemic and tourism: Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium modeling of infectious disease outbreak. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102913. DOI 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. IATA (2021). Airline industry statistics confirm 2020 was worst year on record. International Air Transport Association (IATA). https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/pr/2021-08-03-01/. [Google Scholar]

5. Fjällman, B. A. (2020). The global hotel industry following COVID-19 and what hoteliers can do. Atomize. https://atomize.com/blog/hotel-industry-COVID-19-hoteliers/. [Google Scholar]

6. Yeung, J. C. (2022). Ban on international travel tightened in China as lockdown anger rises. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2022/05/13/china/china-COVID-outbound-travel-restriction-intl-hnk-mic/index.html. [Google Scholar]

7. DTM (Displacement Tracking Matrix) (2022). DTM global mobility restrictions overview: Monitoring restrictions on international air travel. https://dtm.iom.int/reports/dtm-COVID-19-global-mobility-restrictions-overview-31-october-2022. [Google Scholar]

8. Oum, S., Kates, J., Wexler, A. (2022). Economic impact of COVID-19 on PEPFAR countries. KFF. https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/issue-brief/economic-impact-of-COVID-19-on-pepfar-countries/. [Google Scholar]

9. Park, Y. S. (2016). Determinants of Korean outbound tourism. Journal of Economics, Business and Management, 4(2), 92–98. [Google Scholar]

10. Al-Ansi, A., Olya, H. G. T., Han, H. (2019). Effect of general risk on trust, satisfaction, and recommendation intention for halal food. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 83, 210–219. DOI 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.10.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yonhap News Agency (2021). Domestic trips decline 35 pct in 2020 due to pandemic. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20210627000900320. [Google Scholar]

12. OECD (2019). OECD Tourism Trends and Policies: Korea. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Republic Korea (MOFA). http://surl.li/dxhnx. [Google Scholar]

13. Han, H., Che, C., Lee, S. (2021). Facilitators and reducers of Korean travelers’ avoidance/hesitation behaviors toward China in the case of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 182, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

14. Matiza, T. (2020). Post-COVID-19 crisis travel behaviour: Towards mitigating the effects of perceived risk. Journal of Tourism Futures, 8(1), 99–108. DOI 10.1108/JTF-04-2020-0063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yu, J., Lee, K., Hyun, S. S. (2021). Understanding the influence of the perceived risk of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) on the post-traumatic stress disorder and revisit intention of hotel guests. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 46, 327–335. DOI 10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Han, H., Lee, S., Kim, J. J., Ryu, H. B. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19traveler behaviors, and international tourism businesses: Impact of the corporate social responsibility (CSRknowledge, psychological distress, attitude, and ascribed responsibility. Sustainability, 12(20), 8639. DOI 10.3390/su12208639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Miao, L., Im, J., Fu, X., Kim, H., Zhang, Y. E. (2021). Proximal and distal post-COVID travel behavior. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103159. DOI 10.1016/j.annals.2021.103159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Perugini, M., Bagozzi, R. P. (2001). The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviors: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behavior. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 79–98. DOI 10.1348/014466601164704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Perugini, M., Bagozzi, R. P. (2004). The distinction between desires and intentions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 34, 69–84. DOI 10.1002/(ISSN)1099-0992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Tassiello, V., Tillotson, J. S. (2020). How subjective knowledge influences intention to travel. Annals of Tourism Research, 80, 102851. DOI 10.1016/j.annals.2019.102851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Han, H. (2021). Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in hospitality and tourism: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(7), 1021–1042. DOI 10.1080/09669582.2021.1903019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Han, H., Hwang, J., Woods, D. P. (2014). Choosing virtual–rather than real–leisure activities: An examination of the decision–making process in screen-golf participants. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 19(4), 428–450. DOI 10.1080/10941665.2013.764333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Poels, K., Dewitte, S. (2008). Hope and self-regulatory goals applied to an advertising context: Promoting prevention stimulates goal-directed behavior. Journal of Business Research, 61(10), 1030–1040. DOI 10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.09.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Song, H., Lee, C., Kang, S., Boo, S. (2012). The effect of environmentally friendly perceptions on festival visitors’ decision-making process using an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Tourism Management, 33, 1417–1428. DOI 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.01.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Taylor, S. A., Ishida, C., Wallace, D. W. (2009). Intention to engage in digital piracy: A conceptual model and empirical test. Journal of Service Research, 11(3), 246–262. DOI 10.1177/1094670508328924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Carrus, G., Passafaro, P., Bonnes, M. (2008). Emotions, habits and rational choices in ecological behaviours: The case of recycling and use of public transportation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(1), 51–62. DOI 10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Han, H., Kim, W., Hyun, S. S. (2014). Overseas travelers’ decision formation for airport-shopping behavior. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 31(8), 985–1003. DOI 10.1080/10548408.2014.889643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Han, H., Myong, J., Hwang, J. (2016). Cruise travelers’ environmentally responsible decision-making: An integrative framework of goal-directed behavior and norm activation process. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 53, 94–105. DOI 10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.12.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Lee, C. K., Song, H. J., Bendle, L. J., Kim, M. J., Han, H. (2012). The impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions for 2009 H1N1 influenza on travel intentions: A model of goal-directed behavior. Tourism Management, 33(1), 89–99. DOI 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.02.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wang, J., Kim, J., Moon, J., Song, H. (2020). The effect of smog-related factors on Korean domestic tourists’ decision-making process. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3706. DOI 10.3390/ijerph17103706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Eagly, A. H., Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers. [Google Scholar]

32. Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. DOI 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Jacobson, R. P., Mortensen, C. R., Cialdini, R. B. (2011). Bodies obliged and unbound: Differentiated response tendencies for injunctive and descriptive social norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(3), 433. DOI 10.1037/a0021470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Madden, T. J., Ellen, P. S., Ajzen, I. (1992). A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(1), 3–9. DOI 10.1177/0146167292181001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Bagozzi, R. P., Dholakia, U. M. (2006). Antecedents and purchase consequences of customer participation in small group brand communities. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 23(1), 45–61. DOI 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2006.01.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kim, M. J., Lee, M. J., Lee, C. K., Song, H. J. (2012). Does gender affect Korean tourists’ overseas travel? Applying the model of goal-directed behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 17(5), 509–533. DOI 10.1080/10941665.2011.627355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Dowling, G. R., Staelin, R. (1994). A model of perceived risk and intended risk-handling activity. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1), 119–134. DOI 10.1086/209386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Mitchell, V. W. (1999). Consumer perceived risk: Conceptualisations and models. European Journal of Marketing, 33(1/2), 163–195. DOI 10.1108/03090569910249229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Quintal, V. A., Lee, J. A., Soutar, G. N. (2010). Risk, uncertainty and the theory of planned behavior: A tourism example. Tourism Management, 31(6), 797–805. DOI 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.08.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Cheron, E. J., Ritchie, J. B. (1982). Leisure activities and perceived risk. Journal of Leisure Research, 14(2), 139–154. DOI 10.1080/00222216.1982.11969511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Chew, E. Y. T., Jahari, S. A. (2014). Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post-disaster Japan. Tourism Management, 40, 382–393. DOI 10.1016/j.tourman.2013.07.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Joo, D., Xu, W., Lee, J., Lee, C. K., Woosnam, K. M. (2021). Residents’ perceived risk, emotional solidarity, and support for tourism amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100553. DOI 10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Lepp, A., Gibson, H. (2003). Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 606–624. DOI 10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00024-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Lepp, A., Gibson, H. (2008). Sensation seeking and tourism: Tourist role, perception of risk and destination choice. Tourism Management, 29(4), 740–750. DOI 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.08.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Lepp, A., Gibson, H., Lane, C. (2011). Image and perceived risk: A study of Uganda and its official tourism website. Tourism Management, 32(3), 675–684. DOI 10.1016/j.tourman.2010.05.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Maser, B., Weiermair, K. (1998). Travel decision-making: From the vantage point of perceived risk and information preferences. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 7(4), 107–121. DOI 10.1300/J073v07n04_06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Yang, E. C. L., Nair, V. (2014). Tourism at risk: A review of risk and perceived risk in tourism. Asia-Pacific Journal of Innovation in Hospitality and Tourism, 3(2), 1–21. DOI 10.7603/s40930-014-0013-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Simpson, P. M., Siguaw, J. A. (2008). Perceived travel risks: The traveller perspective and manageability. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10(4), 315–327. DOI 10.1002/jtr.664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Yao, H. B., Hou, P. P. (2019). A study on female tourism risk perception dimension. Consumer Economic, 3, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

50. Kozak, M., Crotts, J. C., Law, R. (2007). The impact of the perception of risk on international travellers. International Journal of Tourism Research, 9(4), 233–242. DOI 10.1002/(ISSN)1522-1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Reisinger, Y., Mavondo, F. (2005). Travel anxiety and intentions to travel internationally: Implications of travel risk perception. Journal of Travel Research, 43(3), 212–225. DOI 10.1177/0047287504272017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Rittichainuwat, B. N., Chakraborty, G. (2009). Perceived travel risks regarding terrorism and disease: The case of Thailand. Tourism Management, 30(3), 410–418. DOI 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Bae, S. Y., Chang, P. J. (2021). The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’ tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic (March 2020). Current Issues in Tourism, 24(7), 1017–1035. DOI 10.1080/13683500.2020.1798895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Rahmafitria, F., Suryadi, K., Oktadiana, H., Putro, H. P. H., Rosyidie, A. (2021). Applying knowledge, social concern and perceived risk in planned behavior theory for tourism in the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Review, 76(4), 809–828. [Google Scholar]

55. Sánchez-Cañizares, S. M., Cabeza-Ramírez, L. J., Muñoz-Fernández, G., Fuentes-García, F. J. (2021). Impact of the perceived risk from COVID-19 on intention to travel. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(7), 970–984. DOI 10.1080/13683500.2020.1829571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Zhu, H., Deng, F. (2020). How to influence rural tourism intention by risk knowledge during COVID-19 containment in China: Mediating role of risk perception and attitude. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3514. DOI 10.3390/ijerph17103514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Lin, C. A., Xu, X., Dam, L. (2021). Information source dependence, presumed media influence, risk knowledge, and vaccination intention. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 29(2), 53–64. DOI 10.1080/15456870.2020.1720022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Aggarwal, N., Albert, L. J., Hill, T. R., Rodan, S. A. (2020). Risk knowledge and concern as influences of purchase intention for internet of things devices. Technology in Society, 62, 101311. DOI 10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Granderath, J. S., Sondermann, C., Martin, A., Merkt, M. (2020). Actual and perceived knowledge about COVID-19: The role of information behavior in media. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 5648. [Google Scholar]

60. Faasse, K., Newby, J. (2020). Public perceptions of COVID-19 in Australia: Perceived risk, knowledge, health-protective behaviors, and vaccine intentions. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 551004. DOI 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.551004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Holland, K., Blood, R. W., Imison, M., Chapman, S., Fogarty, A. (2012). Risk, expert uncertainty, and Australian news media: Public and private faces of expert opinion during the 2009 swine flu pandemic. Journal of Risk Research, 15(6), 657–671. DOI 10.1080/13669877.2011.652651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Mulder, N. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism sector in latin america and the Caribbean, and options for a sustainable and resilient recovery. https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/publication/files/46502/S2000751_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

63. Chen, R., He, F. (2003). Examination of brand knowledge, perceived risk and consumers’ intention to adopt an online retailer. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 14(6), 677–693. DOI 10.1080/1478336032000053825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Klerck, D., Sweeney, J. C. (2007). The effect of knowledge types on consumer-perceived risk and adoption of genetically modified foods. Psychology & Marketing, 24(2), 171–193. DOI 10.1002/(ISSN)1520-6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Wei, Q., Han, H. (2019). How crowdedness affects Chinese customer satisfaction at Korean restaurants? Korean Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 28(8), 161–177. DOI 10.24992/KJHT.2019.12.28.08.161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Wong, J. Y., Yeh, C. (2009). Tourist hesitation in destination decision making. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(1), 6–23. DOI 10.1016/j.annals.2008.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Yin, J., Cheng, Y., Bi, Y., Ni, Y. (2020). Tourists perceived crowding and destination attractiveness: The moderating effects of perceived risk and experience quality. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 18, 100489. DOI 10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Hair, J. F., Ortinau, D. J., Harrison, D. E. (2010). Essentials of marketing research, vol. 2. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. [Google Scholar]

69. Hall, C. M. (2006). Tourism, disease and global environmental change: The fourth transition? In: Tourism and global environmental change, pp. 173–193. London, UK: Routledge. DOI 10.4324/9780203011911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Richter, L. K. (2003). International tourism and its global public health consequences. Journal of Travel Research, 41(4), 340–347. DOI 10.1177/0047287503041004002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Ozbay, G., Sariisik, M., Ceylan, V., Çakmak, M. (2021). A comparative evaluation between the impact of previous outbreaks and COVID-19 on the tourism industry. International Hospitality Review, 36(1), 65–82. [Google Scholar]

72. Zoppi, B. L. A. (2021). How does the COVID-19 pandemic compare to other pandemics? News Medical. https://www.news-medical.net/health/How-does-the-COVID-19-Pandemic-Compare-to-Other-Pandemics.aspx. [Google Scholar]

73. Medical Xpress (2021). COVID-19 compared with other deadly viruses. https://medicalxpress.com/news/2021-11-COVID-deadly-viruses.html. [Google Scholar]

74. Villacé-Molinero, T., Fernández-Muñoz, J. J., Orea-Giner, A., Fuentes-Moraleda, L. (2021). Understanding the new post-COVID-19 risk scenario: Outlooks and challenges for a new era of tourism. Tourism Management, 86, 104324. DOI 10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Yeh, S. S. (2021). Tourism recovery strategy against COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(2), 188–194. DOI 10.1080/02508281.2020.1805933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Huang, S. S., Shao, Y., Zeng, Y., Liu, X., Li, Z. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 on Chinese nationals’ tourism preferences. Tourism Management Perspectives, 40, 100895. DOI 10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Park, I. J., Kim, J., Kim, S. S., Lee, J. C., Giroux, M. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on travelers’ preference for crowded versus non-crowded options. Tourism Management, 87, 104398. DOI 10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Chan, C. S. (2021). Developing a conceptual model for the post-COVID-19 pandemic changing tourism risk perception. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9824. DOI 10.3390/ijerph18189824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Han, H., Yoon, H. (2015). Customer retention in the eco-friendly hotel sector: Examining the diverse processes of post-purchase decision-making. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(7), 1095–1113. DOI 10.1080/09669582.2015.1044535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Meng, B., Choi, K. (2016). Extending the theory of planned behaviour: Testing the effects of authentic perception and environmental concerns on the slow-tourist decision-making process. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(6), 528–544. DOI 10.1080/13683500.2015.1020773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Song, H., Lee, C. K., Reisinger, Y., Xu, H. L. (2017). The role of visa exemption in Chinese tourists’ decision-making: A model of goal-directed behavior. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(5), 666–679. DOI 10.1080/10548408.2016.1223777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Meng, B., Han, H. (2016). Effect of environmental perceptions on bicycle travelers’ decision-making process: Developing an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(11), 1184–1197. DOI 10.1080/10941665.2015.1129979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Godovykh, M., Pizam, A., Bahja, F. (2021). Antecedents and outcomes of health risk perceptions in tourism, following the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Review, 76(4). DOI 10.1108/TR-06-2020-0257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Voeten, H. A., De Zwart, O., Veldhuijzen, I. K., Yuen, C., Jiang, X. et al. (2009). Sources of information and health beliefs related to SARS and avian influenza among Chinese communities in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, compared to the general population in these countries. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 16(1), 49–57. DOI 10.1007/s12529-008-9006-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Arbulú, I., Razumova, M., Rey-Maquieira, J., Sastre, F. (2021). Can domestic tourism relieve the COVID-19 tourist industry crisis? The case of Spain. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 20, 100568. DOI 10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Moya Calderón, M., Chavarría Esquivel, K., Arrieta García, M. M., Lozano, C. B. (2022). Tourist behaviour and dynamics of domestic tourism in times of COVID-19. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(14), 2207–2211. DOI 10.1080/13683500.2021.1947993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Bui, N. A., Kiatkawsin, K. (2020). Examining Vietnamese hard-adventure tourists’ visit intention using an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Sustainability, 12(5), 1747. DOI 10.3390/su12051747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Mao, C. K., Ding, C. G., Lee, H. Y. (2010). Post-SARS tourist arrival recovery patterns: An analysis based on a catastrophe theory. Tourism Management, 31(6), 855–861. DOI 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Perić, G., Dramićanin, S., Conić, M. (2021). The impact of serbian tourists’ risk perception on their travel intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Tourism Research, 27, 2705–2705. DOI 10.54055/ejtr.v27i.2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. McKercher, B., Chon, K. (2004). The over-reaction to SARS and the collapse of asian tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 716–719. DOI 10.1016/j.annals.2003.11.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Platania, S., Woosnam, K. M., Ribeiro, M. A. (2021). Factors predicting individuals’ behavioural intentions for choosing cultural tourism: A structural model. Sustainability, 13(18), 10347. DOI 10.3390/su131810347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Kim, M. J., Lee, C. K., Petrick, J. F., Kim, Y. S. (2020). The influence of perceived risk and intervention on international tourists’ behavior during the Hong Kong protest: Application of an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 622–632. DOI 10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Liu, Y., Shi, H., Li, Y., Amin, A. (2021). Factors influencing Chinese residents’ post-pandemic outbound travel intentions: An extended theory of planned behavior model based on the perception of COVID-19. Tourism Review, 76(4), 871–891. DOI 10.1108/TR-09-2020-0458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Pachucki, C., Grohs, R., Scholl-Grissemann, U. (2022). Is nothing like before? COVID-19–evoked changes to tourism destination social media communication. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 23, 100692. DOI 10.1016/j.jdmm.2022.100692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Li, S., Wang, Y., Filieri, R., Zhu, Y. (2022). Eliciting positive emotion through strategic responses to COVID-19 crisis: Evidence from the tourism sector. Tourism Management, 90, 104485. DOI 10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Kim, H., So, K. K. F., Mihalik, B. J., Lopes, A. P. (2021). Millennials’ virtual reality experiences pre-and post-COVID-19. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 48, 200–209. DOI 10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.06.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

97. Yang, T., Lai, I. K. W., Fan, Z. B., Mo, Q. M. (2021). The impact of a 360 virtual tour on the reduction of psychological stress caused by COVID-19. Technology in Society, 64, 101514. DOI 10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools