Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Associations between Rejective Parenting Style and Academic Anxiety among Chinese High School Students: The Chain Mediation Effect of Self-Concept and Positive Coping Style

1 School of Education, Liaoning Normal University, Dalian, 116029, China

2 Faculty of Education, East China Normal University, Shanghai, 200062, China

3 Faculty of Education, University of Macau, Macau, 100084, China

4 College of Psychology, Liaoning Normal University, Dalian, 116029, China

* Corresponding Authors: Xin Lin. Email: ; Xingchen Zhu. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.058744

Received 19 September 2024; Accepted 29 November 2024; Issue published 31 January 2025

Abstract

Background: The phenomenon of academic anxiety has been demonstrated to exert a considerable influence on students’ academic engagement, leading to the emergence of a phenomenon known as “learned helplessness” and undermining the self-confidence and motivation of high school students. Using acceptance-rejection theory, this study elucidated how a rejective parenting style affects Chinese high school students’ academic anxiety and explored the urban-rural heterogeneity of this relationship. Methods: Data were analyzed using a stratified whole-cluster random sampling method. There are a total of 30,000 high school students in the three regions of northern and central China (from Shanxi, Hebei and Henan). A sample of 2286 high school students aged 14–19 years was ultimately selected from 2760 respondents for this investigation, which was conducted at the beginning of the 2023 school year. Pearson correlation, ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis, path analysis, and Fisher’s permutation test (FPT) were used to examine the effects of rejective parenting style on high school students’ academic anxiety. Results: Results indicated a significant positive predictive effect between rejective parenting style and academic anxiety among high school students (β = 0.815, t = 116.211, p < 0.001). Students’ self-concept was significantly positively related to positive coping style (β = 0.424, t = 21.208, p < 0.001) and chain-mediated this relationship. Therefore, this parenting style may indirectly mitigate academic anxiety through these mediators. The study also found that the effect of rejective parenting style on academic anxiety varied by students’ residential background and was more pronounced in urban areas (0.226) than in rural areas (0.130). Conclusion: The research underscores the imperative for Chinese families to re-examine their utilization of rejection parenting and to prioritize the cultivation of students’ intrinsic attributes. These findings offer a theoretical framework and practical evidence for policymakers and educators to develop efficacious and targeted interventions. In particular, greater attention should be directed towards the discrepancies in the manifestation of emotional and academic anxiety between urban and rural students, and prompt guidance should be furnished.Keywords

Addressing concerns over excessive academic pressure, the Chinese government issued a policy in July 2021 aimed at reducing homework burdens while promoting more learning opportunities at home [1]. Furthermore, the enactment of the Law on the Promotion of Family Education in October 2021 marked a legislative milestone, highlighting the importance of balanced and supportive parenting practices [2]. Consequently, parental involvement [3,4] and parenting styles [5] have gained increasing importance in shaping individual development. Family education has thus transitioned from a private concern to a public focus, with parenting styles emerging as pivotal factors in addressing the academic and emotional challenges faced by adolescents [6].

High school years are a unique period marked by both challenges and rapid personal growth. However, this period also presents heightened psychological vulnerability, characterized by the “maturity gap”-the discrepancy between young people’s psychological maturity and their societal responsibilities and rights [7]. Adolescents’ energetic disposition and desire for recognition often render them prone to emotional disturbances and mood fluctuations when faced with frustrations [8].

Parental rejection or denial within the family context significantly heightens adolescents’ anxiety [9]. When high expectations clash with reality, anxiety often escalates, potentially leading to behavioral or psychological issues [10]. Adolescents exposed to prolonged rejective parenting are more likely to internalize feelings of inadequacy and academic failure, further intensifying their anxiety [11]. In contrast, supportive parenting styles help alleviate anxiety and foster resilience [12].

Rejective parenting style and academic anxiety among high school students

The concept of parenting styles was first systematically developed in the 1970s by Baumrind, who categorized them into democratic, authoritarian, and permissive based on the level of parental control and responsiveness [13]. Recent studies, such as those by Jiang et al., have adapted these categories to better reflect the current characteristics of family education in China [14]. They identify rejective, emotional warmth, and overprotective as key dimensions of parenting styles, providing nuanced and actionable insights for educational practices [15]. Different parenting styles influence individual development in various ways, reflecting the shared emotional experiences and expressions parents wish to cultivate in their children [16]. Wells identified parenting style as one of the most significant determinants of children’s psychological and behavioral development [17].

The pervasive influence of multimedia and advancements in science and technology affect every family and individual, reflecting the ongoing evolution of environmental structures and societal changes [18]. In his theory of capital, Bourdieu posited that capital is characterized by its ability to reproduce and be transmitted across generations, marking the genesis of social inequality [19]. The investment perspective highlights the significant impact of parents’ socio-economic status—indicative of family social class—on the allocation of educational resources for children. This allocation is closely tied to children’s academic performance and personal achievements [20].

In the context of traditional Chinese family culture, which is characterized by strong collectivism, ritual indoctrination, and power differentials, Chinese parents believe that leveraging capital and educational resources derived from family income can enhance the quality of education for their children, thus improving the social adaptability [21]. Many parents dedicate significant time to their careers under the mistaken belief that providing material resources and access to prestigious schools will secure their children’s futures and improve the quality of family education [22,23]. This misconception is particularly prevalent among Chinese families, especially in small and medium-sized cities where the phenomenon of “half-left-behind children” occurs, with parents and children sharing living spaces but only spending time together during meals due to conflicting schedules [24].

Compounding this issue is the tendency for family members to become absorbed in virtual electronics, which further diminishes the quality of parent-child interaction [25]. Family conflicts have surged, notably during periods of home confinement in epidemics [26,27]. Furthermore, studies indicate that a rejective parenting style—characterized by parental apathy, lack of affection, neglect, and criticism—is prevalent in China and disproportionately affecting adolescents [28,29]. Such parental behaviors and emotional deficits cause both physical and psychological harm on children, undermining their self-confidence and leading them to view themselves as failures, particularly when they perceive their parents as uncaring or unloving [30].

Children and adolescents from families characterized by unhappiness or parental violence are more likely to develop chronic anxiety, which can lead to psychological disorders, depressive symptoms, transgressive behavior, and suicidal tendencies [31]. The academic demands and varied subjects in high school can also trigger emotional instability, particularly as students experience fluctuations in performance [32]. When high school students perceive rejection or disapproval from their parents during such times, the absence of familial support exacerbates their psychological distress, plunging them into a state of academic anxiety where they feel overwhelmed by the pressures of their studies [33]. This state not only hampers their educational progress but also increases the likelihood of school disengagement, boredom, and truancy [34].

The theory of acceptance-rejection offers a framework for understanding these dynamics [35]. Humans are evolutionarily inclined to seek love, affection, care, comfort, and nourishment from their attachment figures [36]. When these emotional needs are not met, individuals often exhibit a pattern known as the acceptance-rejection syndrome, which manifests as anger, hostility, aggression, negative self-esteem, emotional instability, unresponsiveness, and a pessimistic worldview [37]. The manifestation of these adverse traits correlates strongly with the nature, frequency, duration, and intensity of perceived parental rejection [38]. When students perceive their parents as uncaring or overly critical, they are more likely to develop low self-esteem, hostility, and destructive behaviors, which in turn severely undermine their commitment to school, leading to academic underachievement [39].

In sum, family dynamics that center around a rejective parenting style often prove dysfunctional, failing to support adolescents’ academic and interpersonal development and potentially leading to psychological maladjustment, depressive symptoms, and substance abuse [40–42]. Our first hypothesis (H1) is that a rejective parenting style in the home environment may increase the intensity and duration of academic anxiety in high school students.

Self-concept as a mediator between rejective parenting style and academic anxiety

In philosophical discourse, the “self” is often viewed as a cohesive entity tied to consciousness, awareness, and decision-making [43]. George Herbert Mead’s symbolic interactionism suggests that the self is formed through socialization, primarily by internalizing family and societal attitudes [44]. Parental Acceptance-Rejection Theory (PART) builds on this by highlighting the family’s essential role in shaping self-concept. As the core social unit, the family significantly impacts personality development [45].

Research shows that a rejecting parenting style—characterized by harshness and limited communication—can hinder positive self-concept, leading to increased internalizing behaviors such as anxiety and depression in adolescents [46]. This effect is particularly strong in high school years, where rejective parenting intensifies academic anxiety through restrictive disciplinary practices [47]. Conversely, warmth and acceptance in parenting support self-confidence and a healthy self-concept, promoting resilience and academic success [48].

PART aligns with Mead’s perspective, as both emphasize that external social factors, particularly family, are central to self-concept development. A strong self-concept enables effective coping and resilience, whereas a weakened self-concept, often seen in those exposed to rejective parenting, heightens vulnerability to anxiety [49]. Thus, PART provides a foundational framework for understanding how rejective parenting increases academic anxiety by negatively impacting self-concept, supporting our hypothesis (H2) that self-concept mediates this relationship.

Positive coping style as a mediator between rejective parenting style and academic anxiety

Adolescence is a challenging period in which coping styles play a crucial role in development and social adaptation [50]. Positive coping includes active efforts to manage stress and solve problems, which can reduce negative outcomes like academic anxiety and depression. High school students who adopt positive coping strategies, such as problem-solving and seeking support, are more likely to experience well-being and academic success [51]. Conversely, those relying on negative coping styles often experience higher levels of depression, social anxiety, and academic stress [52].

PART provides insight into how family dynamics influence adolescents’ coping styles and mental health. Studies indicate that students from rejecting or unsupportive families are less likely to adopt positive coping than those from supportive households [53]. According to PART, children who experience rejection from parents tend to develop defensive and hostile behaviors such as self-protection [54]. In contrast, supportive parenting promotes resilience and effective problem-solving skills, which help adolescents cope with academic challenges [55].

Within the PART framework, rejective parenting is linked to negative coping styles and higher academic anxiety. Adolescents who feel rejected may lack emotional security, making them more likely to respond to stress with avoidance or denial, which can exacerbate anxiety [56,57]. Positive coping can, however, mitigate the adverse effects of rejective parenting on academic anxiety, suggesting that a student’s coping style may mediate this relationship (Hypothesis 3).

The chain mediating role of self-concept and positive coping style between rejective parenting style and academic anxiety

Self-concept has been recognised as a predictor of positive coping style [58]. When confronted with stressful events, individuals engage in secondary appraisals to evaluate the adequacy of resources available to cope with these events, ultimately influencing their future behaviors [59]. This assessment of resource adequacy may be influenced by one’s self-concept and positive coping style [60]. The Personality Functioning Theory (PFT) suggests that personality traits significantly affect an individual’s ability to manage life stressors [61]. Notably, self-concept is recognized as a key component of personality, linking it to a positive coping style [62]. Uncertain events can deplete self-resources, thereby reducing an individual’s capacity to cope [63].

An individual’s self-concept significantly influences their positive coping strategies. Empirical research supports the notion that enhancing positive coping style is associated with improvements in self-concept [64,65]. Several studies have examined the relationship between perceived stressors, stress symptoms, self-concept, and coping styles. Results indicate that individuals who maintain a positive self-concept tend to use effective and positive coping styles and are adept at transforming problems into concrete, actionable events. Such groups typically experience a lesser amount of stress symptoms and have fewer or milder symptoms of anxiety, all of which contribute to psychological well-being [66]. However, a decline in positive self-concept may increase vulnerability to stress and symptoms of mental disorders, which adversely affects the individual’s ability to process information positively, further impeding effective coping [67]. Consequently, a student’s self-concept plays a crucial role in how they manage and respond to academic stress during high school [68]. Adolescents with a positive self-concept are more likely to approach stressful situations with confidence and optimism, which can help mitigate anxiety, particularly when they develop a positive coping style following stressful events [69].

In sum, we expect that the rejective parenting style may indirectly impact students’ academic anxiety through the mediating influences of self-concept and positive coping style. Our fourth hypothesis (H4) posits that students’ individual self-concept and positive coping style act as chain mediators in the relationship between rejective parenting style on their academic anxiety.

Given the layered and interdependent nature of variables like rejective parenting style, self-concept, positive coping style and academic anxiety, path analysis enables us to construct and test a model that represents not only individual relationships but also the combined impact of multiple mediating factors.

Urban-rural variations in the impact of rejective parenting style on students’ academic anxiety

A growing body of research has examined the influence of parenting styles on students’ psychological and academic outcomes, with particular attention to the differential impact of these styles across diverse socio-environmental contexts. Emerging evidence suggests that the intensity and consequences of these parenting practices vary significantly between urban and rural environments [70,71].

Urban areas are often characterized by higher levels of socioeconomic pressure, competition, and academic expectations. In these environments, urban students subject to rejective parenting styles tend to experience heightened levels of self-blame, fear, and academic anxiety [72]. Previous studies have highlighted that urban parents frequently prioritize academic success in their children’s lives, which may exacerbate family conflicts and diminish parental support for the academic process, thereby intensifying academic anxiety [73]. In contrast, despite having fewer educational opportunities, rural students often benefit from more supportive family dynamics and closer relationships with family members, which help them navigate academic challenges with less anxiety [74].

Furthermore, the social and cultural dynamics prevalent in urban environments may amplify the stressors students face, thereby strengthening the relationship between parental disapproval and academic anxiety [75]. Research indicates that urban students, who typically encounter socio-spatial segregation and family conflict, are at a greater risk of developing academic problems due to rejective parenting styles, which can trigger confrontational feelings of academic anxiety among high school students [76]. Conversely, rural environments, typically characterized by close-knit communities and lower levels of academic pressure, may offer protective factors that mitigate the adverse effects of negative parenting [77]. This suggests that social stratification in urban environments, parenting styles, and individual socialization processes develop simultaneously and interact with each other.

Given these observations, our fifth hypothesis (H5) posits that if a rejective parenting style leads to higher academic anxiety in students, this effect will be more pronounced in urban areas than in rural areas.

In this study, we focus on the group of Chinese high school students. Due to the uniqueness of the cultural and social background, the parenting styles commonly adopted by Chinese families may differ significantly from those in Western countries. In particular, the impact of rejective parenting style on children’s academic anxiety may be particularly complex in the specific cultural context of China. For example, traditional Chinese culture emphasises respect for elders and authority, which may mean that criticism and negation in rejective parenting style have a deeper emotional shock on children, which in turn exacerbates their academic anxiety. At the same time, the highly competitive nature of the Chinese education system and the emphasis placed on academic performance may also cause students who are raised in a rejective way to experience greater psychological pressure, worrying that they will not be able to meet the expectations of their parents or society. Therefore, by thoroughly analysing the specific impact of rejective parenting style on academic anxiety among Chinese high school students, we aim to reveal the intrinsic link between family parenting style and adolescent mental health under cultural characteristics, and provide empirical evidence and intervention strategies to promote psychological well-being.

Understanding the causes of academic anxiety in high school students is complex due to the many factors involved, such as family dynamics, individual traits, and external environmental conditions. Among these factors, parenting style is a key predictor of academic anxiety in adolescents. Specifically, a rejective parenting style may increase academic anxiety, with this effect potentially influenced by students’ self-concept and positive coping style. Additionally, the influence of rejective parenting style on academic anxiety may differ based on whether students live in urban or rural areas.

To date, there has been limited research on how rejective parenting style, self-concept, and positive coping style together affect academic anxiety. Furthermore, previous studies have not adequately addressed the differences between urban and rural students in this context. Through this research, we aim to gain a deeper understanding of the factors and mechanisms that contribute to academic anxiety in high school students.

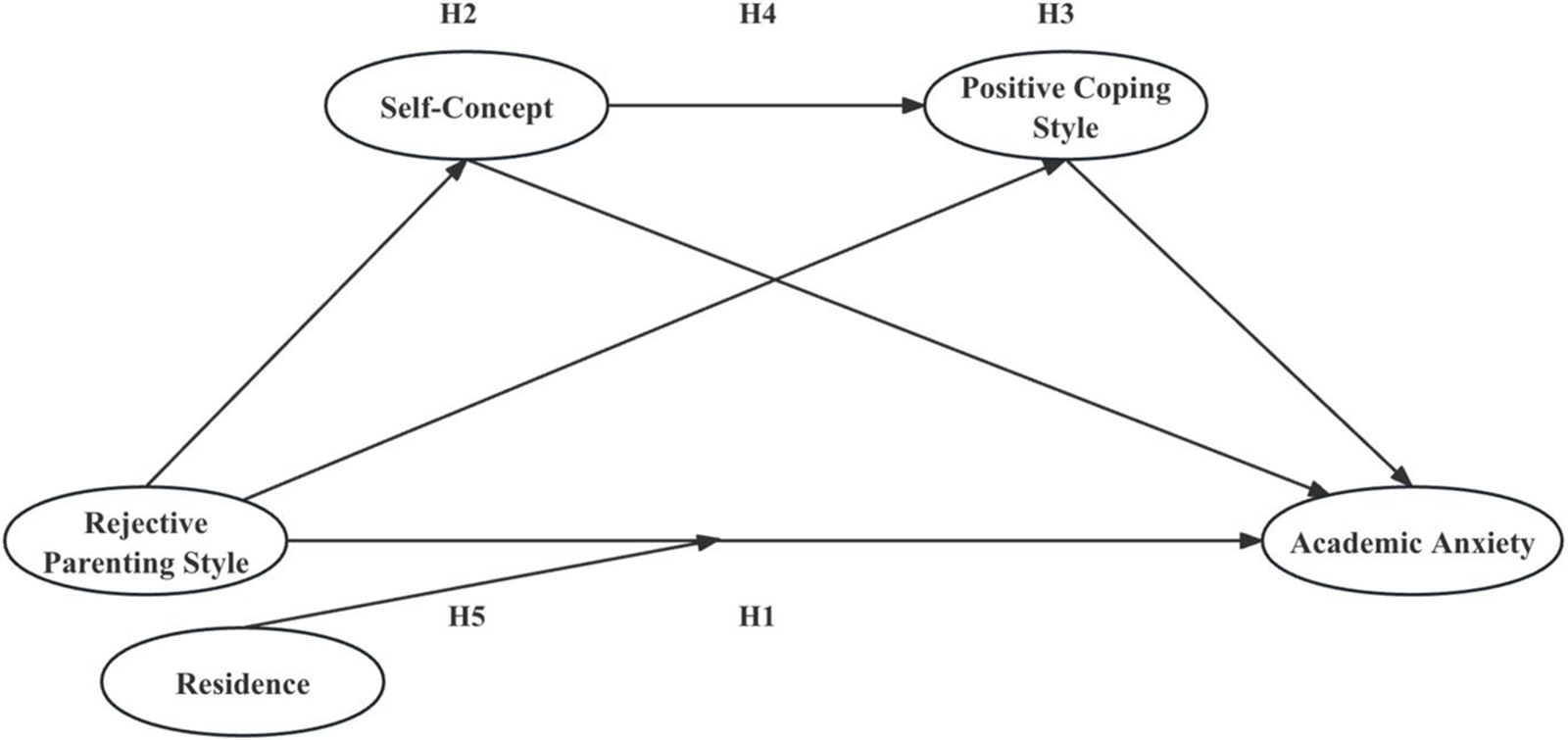

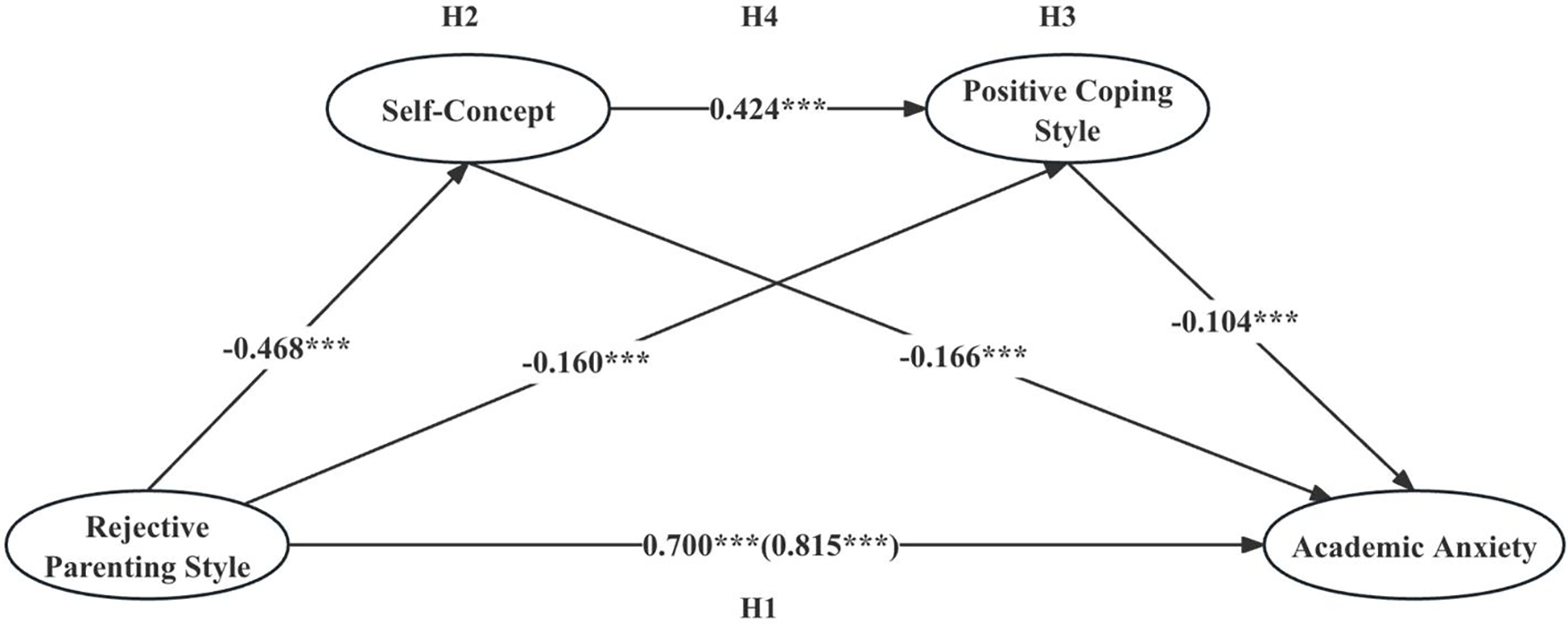

Based on the research objectives, Hypotheses H1 to H5 were formulated. They are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Research hypothesis model.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Rejective parenting style may increase high school students’ academic anxiety.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Self-concept serves as a mediating factor in the influence of rejective parenting style on students’ academic anxiety.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Positive coping style serves as a mediating factor in the influence of rejective parenting style on students’ academic anxiety.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Self-concept and positive coping style act as chain mediators in the relationship between rejective parenting style on their academic anxiety.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): If rejective parenting style leads to higher academic anxiety in students, this effect may be more pronounced in urban areas compared to rural areas.

In order to increase the generalisability and rigour of the study, the total statistical population for this study comprised approximately 30,000 high school students from the two geographical regions of northern and central China. The initial target population consisted of 2760 students (n = 960 from Shanxi, 750 from Hebei, and 1050 from Henan) from 12 high schools in three provinces of China who completed questionnaires. A stratified random cluster sampling method was used in this study, and the sampling process was carried out in three stages. First, the population was divided into three different strata based on year level, ensuring that each stratum represented a unique year group with no overlap. Next, it was decided to sample 920 students from each year group. Therefore, a minimum of 77 students were selected from each year group in each secondary school. Finally, whole clusters were randomly selected from each year group. The selected clusters were combined to form the total sample. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Education at Liaoning Normal University (IRB number: LSDJYXY2023001). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

The survey was conducted at the beginning of the 2023 academic year. Following approval from the participating schools, we obtained written consent from both the participants and their guardians. The consent forms were designed to protect anonymity by not including signatures or student names. Participants were informed that participation was voluntary and they had the right to withdraw at any time.

Data was collected using paper-and-pencil questionnaires, which students completed independently under the supervision of trained research assistants during class time. To ensure privacy, completed questionnaires were sealed in envelopes immediately. As an incentive, small gifts such as pens or cards were offered to the participants. After reviewing the data, we excluded 474 questionnaires due to inconsistencies, resulting in a final response rate of 82.826% and 2286 valid questionnaires for analysis. The participants’ ages ranged from 14 to 19 years, with an average age of 16.50 (SD = 1.64). The sample consisted of 1249 boys (54.637%) and 1037 girls (45.363%). All research materials and procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Liaoning Normal University, China (Ref. No. LSDJYXY2023001).

We utilized the Academic Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (AASA) developed by Xie to measure academic anxiety in adolescents [78]. The AASA comprises 18 items divided into three dimensions: academic evaluation anxiety (questions 1–5), academic performance anxiety (questions 6–12), and academic situational anxiety (questions 13–18). Sample items include: ‘Being a poor student sometimes makes me feel sorry for my family and myself,’ ‘Every time I am confronted with the ranking of my exam results, I get an inexplicable feeling of nervousness,’ and ‘I get annoyed when my parents keep talking about me studying.’ Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represents ‘not at all’ and 5 represents ‘very much’. Higher scores indicate greater anxiety. This scale has been validated in prior research and is recognized for its reliability and validity in measuring academic anxiety among high school students [79]. In the current study, the scale achieved a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.863.

This scale is based on the Egma Minnen av Bardndosnauppforstran (EMBU) scale, which assessed perceptions of parenting behavior [80]. To adapt it to the Chinese cultural context, the scale underwent modifications by Yue in 1993 [81]. Further revisions led to the creation of the EMBU (S-EMBU-C) scale by Hou et al., reflecting the characteristics of contemporary Chinese family upbringing [15]. To enhance respondent participation and improve the scale’s validity and reliability, the revised scale maintains the core questions from the original EMBU dimensions while omitting repetitive and overly lengthy items. The S-EMBU-C scale has gained widespread adoption in research both nationally and internationally, and has been validated through numerous studies. The S-EMBU-C comprises 21 items divided into three dimensions: rejective, emotional warmth, and overprotective. Specifically, six items (questions 1, 4, 7, 12, 14, and 19) focus on assessing the tendency of Chinese parents to reject their children, which was a primary focus of our analyses. Responses are recorded on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always), with higher scores indicating a more rejective parenting style. This style is characterized by negative behaviors that children often perceive, such as parental criticism, disrespect, and excessive and inappropriate punishment. For example, one item states: ‘My parents often criticize me in front of others for being lazy and useless, and they often treat me in a way that makes me feel ashamed.’ Recent research confirms that the S-EMBU-C possesses high reliability and robust psychometric properties for use among Chinese high school students [82]. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.861.

We measured self-concept using the Self-Description Questionnaire (SDQ), developed by Marsh. The SDQ includes 23 items across five dimensions: academic, physical, interpersonal, emotional, and general self-concept [83]. Higher scores on this scale indicate a more positive self-concept. In our analysis, we looked at students’ self-concept as a whole, without separating the different dimensions. An example item from the scale is: “I can do anything that I want to do if I really put my mind to it.” Students rated reach item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (fully), reflecting their daily perceptions, attitudes, feelings, and behaviors. This method has been shown to be psychometrically valid [84], with higher scores denoting a stronger self-concept. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale in this study was 0.879.

The current study utilized the Secondary School Students’ Coping Styles Inventory (SSCSI) developed by Huang et al., which comprises 30 items [85]. Among these items, there is a subscale for positive coping style that includes 12 items (specifically 1–11 and 20). This subscale evaluates an individual’s capacity to adopt positive attitudes and behaviors in response to challenges, dilemmas, and adversities. For instance, one item states: “Make a plan to overcome difficulties and stick to it.” Responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 denotes “never” and 5 denotes “always.” Higher scores reflect a greater propensity to engage in positive behaviors and employ effective coping strategies. This scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties within Chinese populations and is well-regarded in both educational and psychological research contexts [86]. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the positive coping style dimension was 0.967, indicating a high reliability.

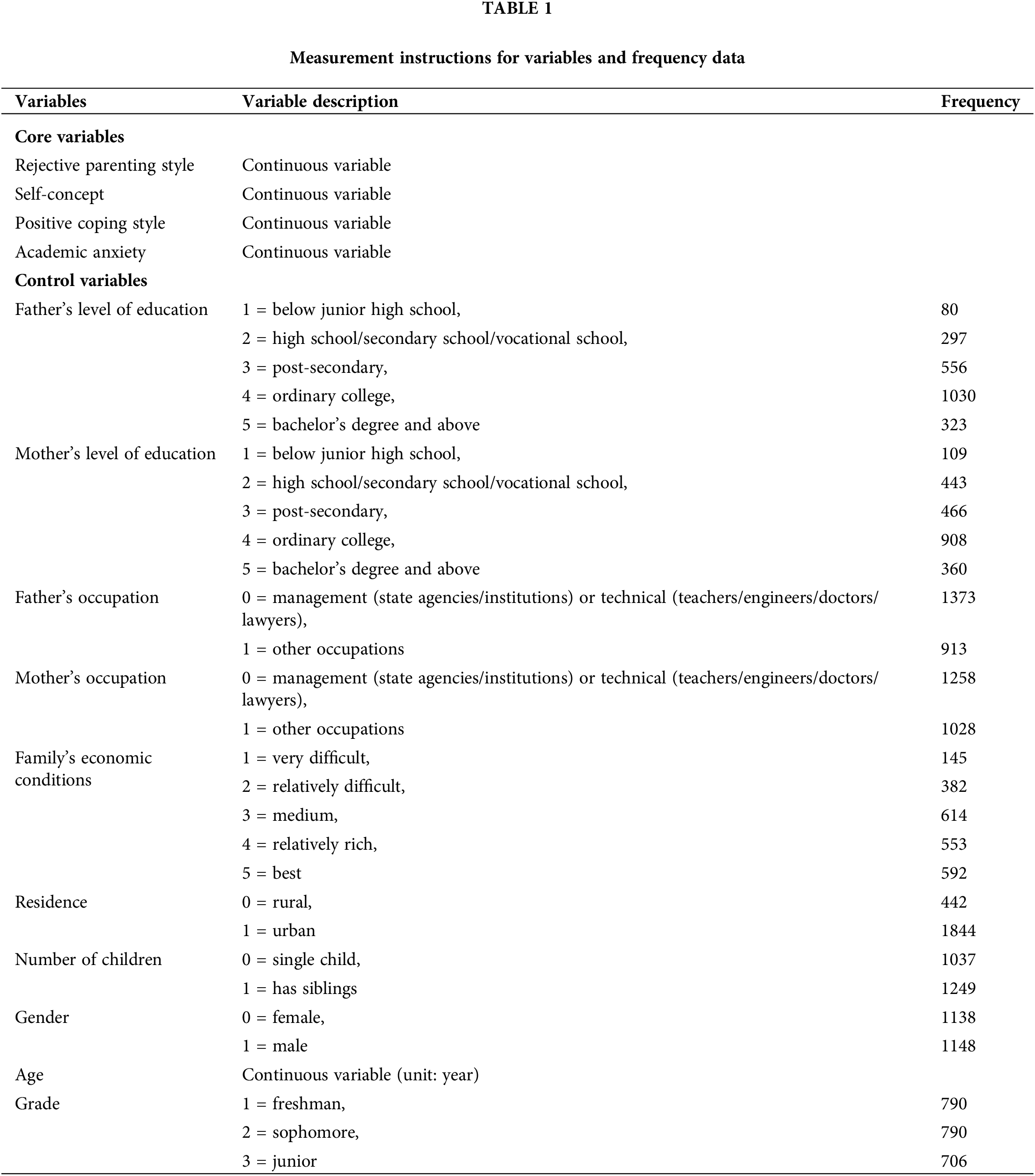

The selection of control variables was informed by prior research [87–89]. The variables are classified into two categories: family characteristics and personal characteristics associated with high school students’ academic anxiety. The measurement instructions of the aforementioned variables and the frequency data related to demographic variables are detailed in Table 1.

In this project, we used SPSS version 26.0, STATA version 16.0, and Mplus version 8.3 for data analysis and model construction. Initially, to address potential general method bias arising from the self-reported nature of the data, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. Next, we examined the relationships between the variables of interest by performing Pearson’s correlation analyses. Additionally, the hypothesized chain mediation model was examined using path analysis, where rejective parenting style was the predictor variable, and students’ self-concept and positive coping style served as mediator variables, with academic anxiety as the outcome variable. The presence of a mediating effect was inferred if the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the indirect effect did not include zero. To confirm the chain mediating role of self-concept and positive coping style in the relationship between rejective parenting style and academic anxiety, 5000 bootstrap resamples were completed using bias-corrected bootstrapping, enhancing the reliability of the mediation model. Finally, the sample was stratified between urban and rural areas to identify potential heterogeneity. Fisher’s permutation test was applied to explore the significance of heterogeneity in the analyses.

In this study, Harman’s single-factor test was initially employed to assess the presence of general method bias, following the methodology described by Zhou and Long [90]. To thoroughly explore the range of themes related to the primary study variables, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted. This analysis yielded ten factors, each with an eigenvalue exceeding one. The principal factor accounted for 22.625% of the variance, which was below the critical threshold of 40%. Consequently, this study did not exhibit significant common method bias. The homological bias appeared to have a minimal impact on the study results, thereby supporting the validity of the data analysis continuation.

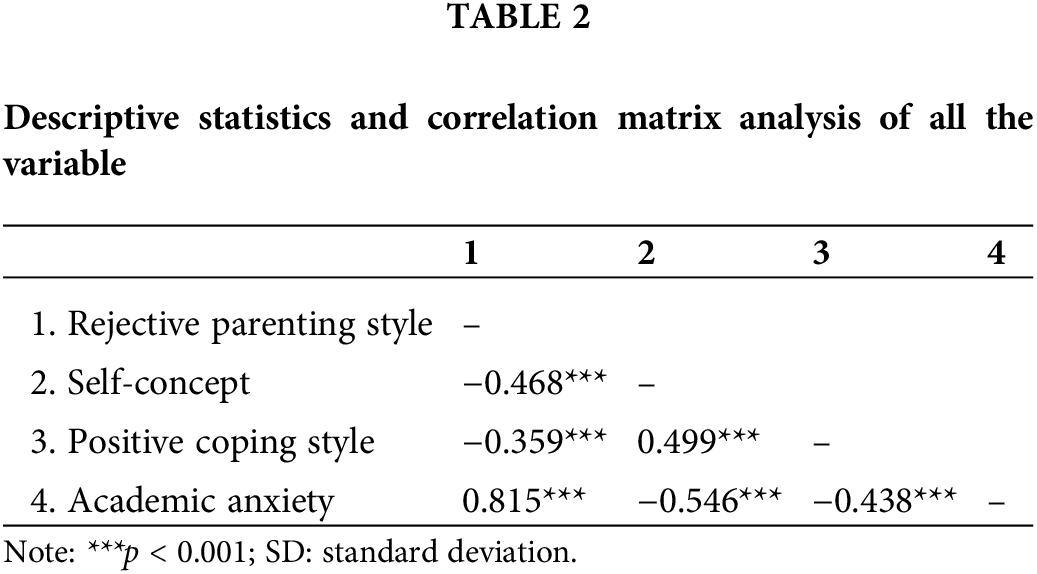

Correlation analysis of variables

Pearson’s correlation analysis was employed to measure the binary correlations among the core variables. The results, including the means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlation coefficients of the core variables, are presented in Table 2. All core variables were found to be significantly correlated. The academic anxiety of high school students demonstrated a positive correlation with rejective parenting style (r = 0.815, p < 0.001). Conversely, students’ academic anxiety was negatively correlated with self-concept (r = −0.546, p < 0.001) and positive coping style (r = −0.438, p < 0.001). Additionally, rejective parenting style was negatively related to self-concept (r = −0.468, p < 0.001) and negatively related to positive coping style (r = −0.359, p < 0.001). Furthermore, self-concept showed a positive relationship with positive coping style (r = 0.499, p < 0.001).

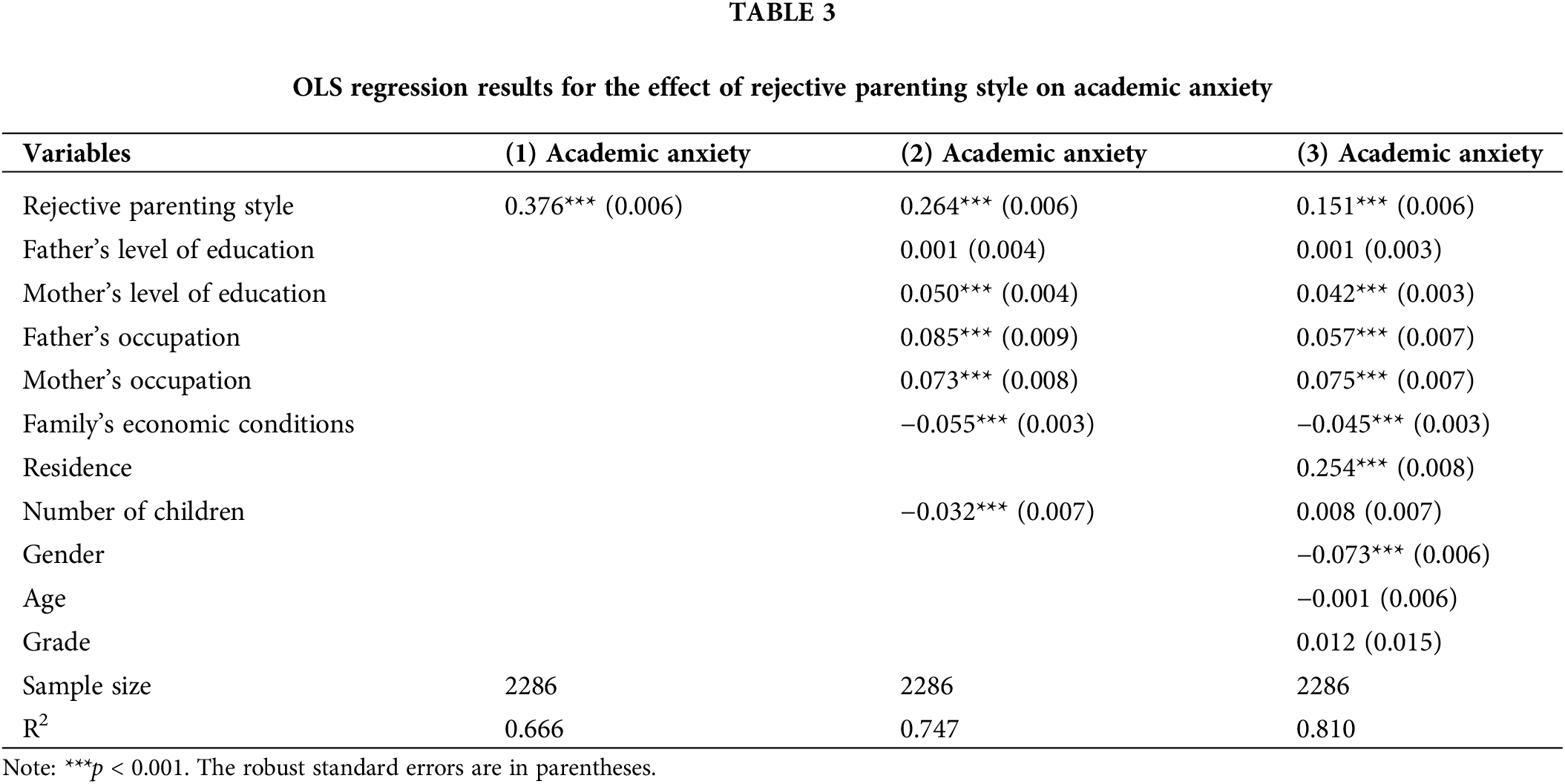

The results presented in Table 3 indicate that a rejective parenting style positively influences academic anxiety. Model (1) considered only the independent variable representing rejective parenting. Model (2) expanded on Model (1) by including variables characterizing family features. Subsequently, Model (3) further included variables related to individual characteristics, thus extending Model (2). Across Models (1) through (3), the estimated coefficients for rejective parenting style were 0.376 (p < 0.001), 0.264 (p < 0.001), and 0.151 (p < 0.001), respectively. These coefficients consistently demonstrate that rejective parenting style is a significant predictor of academic anxiety.

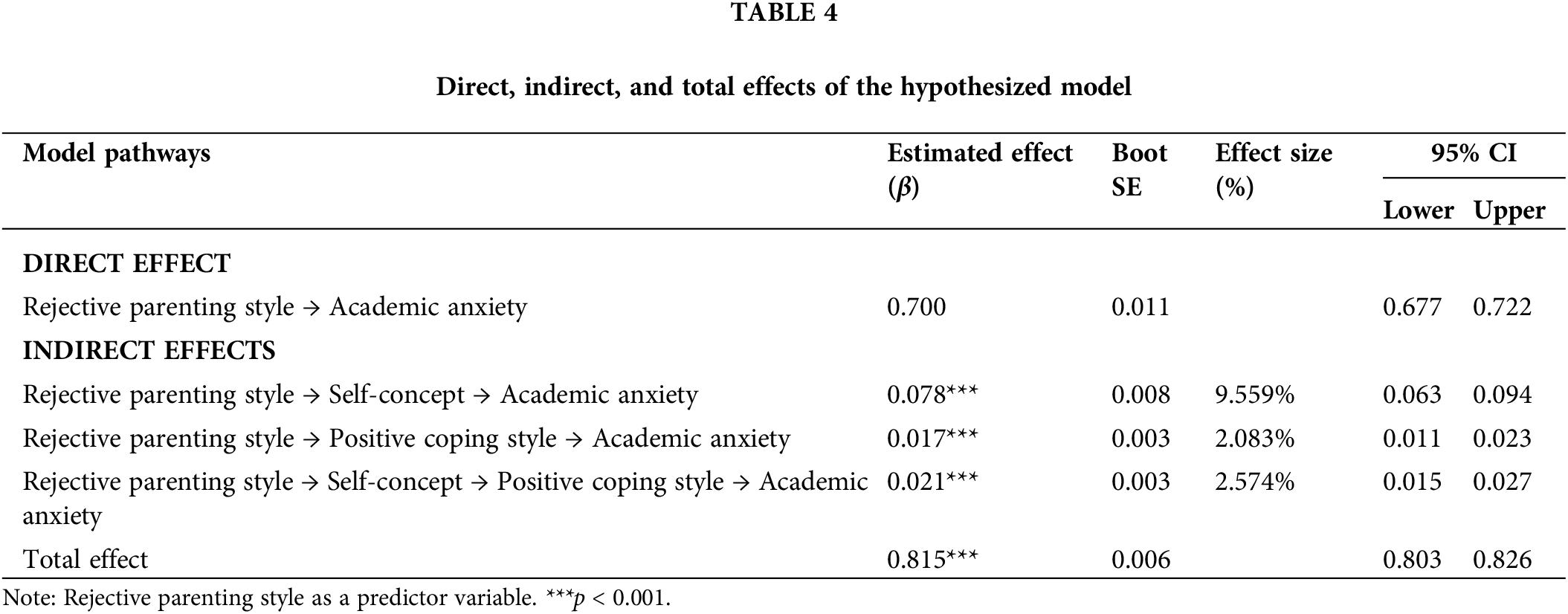

A Structural Equation Model (SEM) was established by calculating the mean values of the variables under investigation. The fit of the model was evaluated using several indices: The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) both yielded values of 1, while the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) were both 0. These metrics indicated strong predictive validity of the research model employed in this study. Consequently, a chain mediation model was implemented, which is a type of SEM that incorporates three indirect effects: (1) self-concept mediated the relationship between rejective parenting style and high school students’ academic anxiety; (2) positive coping style also mediated this relationship; and (3) jointly, self-concept and positive coping style mediated the effect of rejective parenting style on academic anxiety (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The mediating roles of self-concept and positive coping style between rejective parenting style and academic anxiety. ***p < 0.001.

First, the total effect analysis revealed a strong positive relationship between rejective parenting style and academic anxiety among high school students (β = 0.815, t = 116.211, p < 0.001), as illustrated in Fig. 2. Second, the chain mediation model indicated that the positive predictive effect of rejective parenting style on academic anxiety remained significant (β = 0.700, t = 61.014, p < 0.001) even after accounting for the effects of the control variables, with only a slight decrease in significance.

Moreover, rejective parenting style exhibited a significant negative predictive effect on both self-concept (β = −0.468, t = −29.478, p < 0.001) and positive coping style (β = −0.160, t = −7.735, p < 0.001) in students. Furthermore, self-concept was a significant negative predictor of academic anxiety among high school students (β = −0.166, t = −10.980, p < 0.001), and positive coping style also significantly negatively predicted academic anxiety (β = −0.104, t = −7.692, p < 0.001). Additionally, there was a significant positive relationship between high school students’ self-concept and positive coping style (β = 0.424, t = 21.208, p < 0.001).

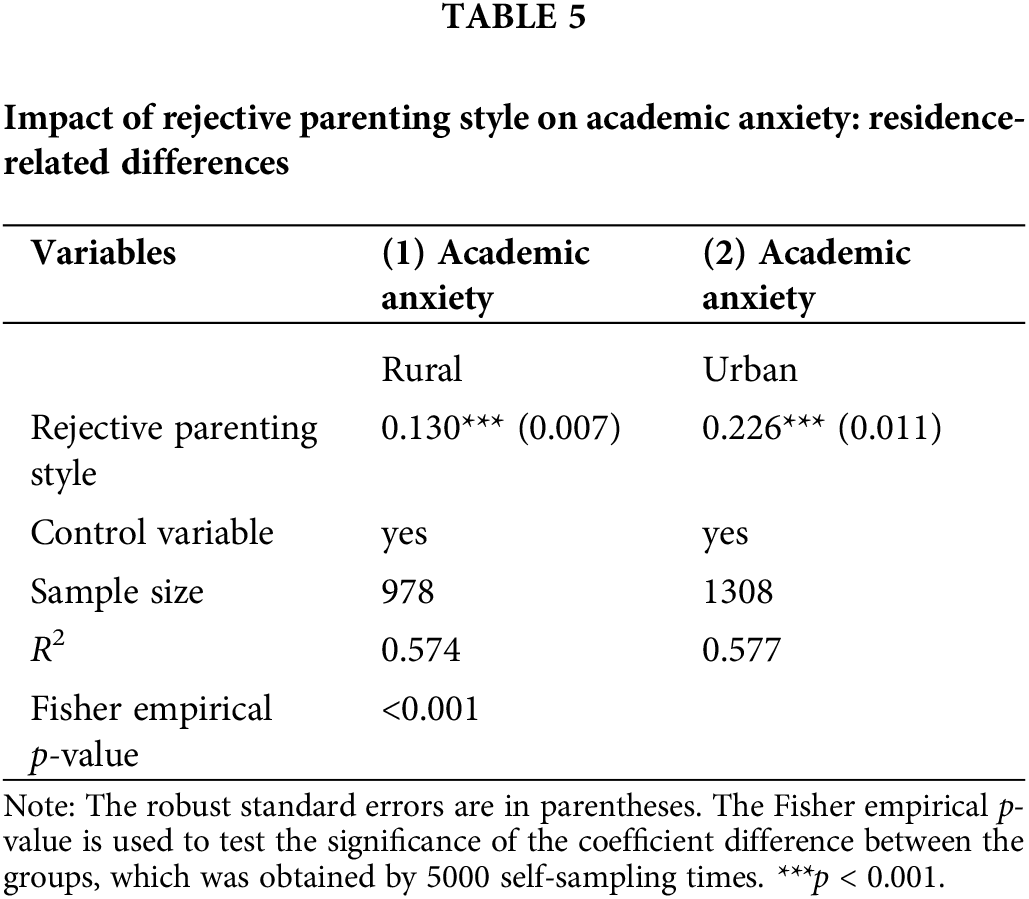

Finally, the results from the bias-corrected bootstrap mediation tests (presented in Table 4) demonstrated that the overall effect of rejective parenting style on high school students’ academic anxiety was substantial, with an effect size of 0.815 (SE = 0.006, 95% CI [0.803,0.826], p < 0.001). The direct effect was also significant at 0.700 (SE = 0.011, 95% CI [0.677,0.722], p < 0.001), indicating robust overall and direct effects. Regarding the mediation pathways, the pathway from rejective parenting style to academic anxiety through self-concept showed an indirect effect of 0.078 (SE = 0.008, 95% CI [0.063,0.094], p < 0.001), accounting for 9.559% of the total effect (0.816). In the pathway from rejective parenting style to academic anxiety via positive coping style, the indirect effect was 0.017 (SE = 0.003, 95% CI [0.011,0.023], p < 0.001), which represented 2.083% of the total effect. Additionally, in the pathway incorporating both self-concept and positive coping style (rejective parenting style → self-concept → positive coping style → academic anxiety), the indirect effect was 0.021 (SE = 0.003, 95% CI [0.015,0.027], p < 0.001), making up 2.574% of the total effect. Given that the bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals did not include zero, these indirect effects were statistically significant. The analysis indicated that the influence of rejective parenting style on students’ academic anxiety operated indirectly through the negative partial mediation of students’ self-concept and positive coping style.

Models (1) and (2) in Table 5 demonstrated the impacts of rejective parenting style on academic anxiety for urban and rural students, respectively. In both models, the coefficients were statistically significant at the 1‰ level and were positive. Notably, the effect of rejective parenting style on academic anxiety in urban students (0.226) exceeded that for rural students (0.130). Additionally, Fisher’s exact test confirmed that the difference in residence-specific coefficients regarding the influence of rejective parenting style on academic anxiety was significant at the 1‰ level. These results suggested that academic anxiety responses among urban students were more pronounced than those among rural students. Moreover, there was evidence of heterogeneity based on residence in the effect of rejective parenting style on academic anxiety, with a more pronounced impact observed in urban students compared to rural students.

Rejective parenting style exacerbates the risk of academic anxiety in high school students

The findings of this research support the initial hypothesis (H1), demonstrating that rejective parenting style directly worsens academic anxiety among high school students. The current findings suggest that rejective parenting style is associated with more internalizing problems in adolescents, especially exacerbating the occurrence of excessive academic anxiety in high school students. First, as time passes, parenting style is a significant influence that cannot be ignored in the characterization and emotional formation of adolescents. This is supported by the literature, Motamedi applied multi-stage random sampling method to analyse data from 9728 students in different regions of the Middle East. The results showed that differences in students’ cognitive, affective and behavioral development were due to the diversity of their family environments [91]. And parenting styles are the primary manifestation of how parents relate to their children. One of the core features of the rejective parenting style is the lack of emotional support [92]. When students experience academic difficulties or setbacks, they long for encouragement and support from their parents. However, in the rejective parenting style, parents tend to be indifferent or negative towards their children’s achievements, which can lead to students feeling emotionally isolated [93]. According to attachment theory, children who are chronically emotionally unsupported by their parents may develop insecure attachments, which could make them more anxious in the face of academic pressure because they lack an object to rely on and confide in [94]. Severe academic anxiety threatens students’ mental health and lives in the long term. Rejective parenting style exacerbates the risks associated with a variety of emotional characteristics and problem behaviors in students. The most common is falling deeper into the morass of excessive academic anxiety and being devastated by unsupportive and disapproving parents [95].

In the present study, rejective parenting style was identified as a direct influence in worsening high school students’ academic anxiety, and even more, as a single influencing factor that we tend to neglect. Such discoveries indicate that although school environments and peer groups become more involved in students’ life development as they mature, parenting styles at the micro level seem to be the starting point for exploring individual diversity [96]. It is well documented that a rejective parenting style of excessive denial and neglect may be the best catalyst for high school students to suffer from excessive academic anxiety [97]. It is worth noting that many parents recognize that rejective parenting is incorrect, but in their practical approach to raising their children, they are paranoid that a harsh and strict parenting style is more conducive to the development of independence and problem-solving skills [98]. This can be attributed to two factors. On the one hand, Chinese parents do not have a comprehensive knowledge of the rejective parenting style and simply believe that rejection gives students the opportunity to acquire independent behavior and self-growth. On the other hand, Chinese parents lack knowledge of educational psychology, and the rejective parenting style exacerbates students’ academic anxiety over a period of time and combines it with other influences. Students’ academic anxiety cannot be directly observed in the daily parent-child relationship, nor can it be easily measured with objective instruments. Unfortunately, in the sample group of students with depressive disorders, the researchers found that they were also accompanied by excessive academic anxiety and that there was a relationship with negative parenting styles [99]. Thus, these results of the present study suggest that regardless of the development of an intervention mechanism for students’ academic anxiety at any academic level, parenting styles should be a priority intervention area, and families with rejective parenting style should not be ignored.

In conclusion, the results of this study implicate that rejective parenting style may exacerbate the risk of excessive academic anxiety in high school students causing some adverse effects on adolescent development. Simultaneously, this provides strong empirical support for the family acceptance-rejection theory, emphasizing the profound harmful consequences of parental rejection on adolescent growth [100]. It is evident that for students prone to academic anxiety, parental indifference, resentment, and neglect can be especially harmful. To prevent the escalation of academic anxiety and avoid irreversible consequences, raising awareness about the effects of rejective parenting style on academic anxiety among parents, educators, and the community is essential [98]. Schools and mental health professionals should design and implement intervention programs aimed at educating parents about the impact of their parenting style on their children’s academic performance and mental health.

The mediating effect of self-concept and positive coping style between rejective parenting style and academic anxiety in high school students

The very important and differentiating point of this research, which is beyond the simple and separate relationships of variables among students and it is necessary to pay attention to it, is the integrated and chain model of the relationship between these components. The integrated model presented in this study confirmed the second hypothesis (H2), demonstrating that self-concept serves as a mediating factor in the influence of rejective parenting style on students’ academic anxiety. This finding suggests that the detrimental effects of rejective parenting style on students’ academic anxiety can be mitigated by a positive self-concept, which serves as a buffer by influencing intrinsic individual characteristics.

Importantly, this mediation aligns with the principles of self-schema theory, which posits that self-concept structures influence how individuals process information and respond behaviorally in various contexts [101]. Further support for this mediation comes from Dermitzaki et al. [102]. Their research revealed that adolescents with a strong belief in their capabilities were more effective in utilizing available resources, which helped reduce their anxiety levels. Conversely, individuals with a negative self-concept tended to perceive difficult tasks or social interactions as unfair, leading to anxiety and internalizing behaviors.

The manner in which parents raise their children profoundly shapes their self-concept and their perception of personal strengths and weaknesses [103]. For instance, collectivist Chinese families tend to impose pressure on their children and consider overexpression of negative emotions or impulsive behavior as signs of immaturity [104]. In many Chinese families, stern parenting can undermine family intimacy and lead children to doubt their abilities, resulting in feelings of depression and anxiety [105]. This often results in two types of student attitudes towards learning: disengagement and lack of motivation, or a tendency to give up in the face of academic challenges due to severe anxiety. Conversely, a supportive and harmonious family environment can foster strong emotional bonds and a positive self-concept during adolescence, providing children with significant socio-emotional resources that enhance their social interactions and academic motivation [106]. Such an environment enables students to approach academic challenges with confidence and resilience, further affirming their self-worth and contributing to academic success.

Thus, self-concept not only serves as a protective factor in mental health but also as a potent internal resource that can mitigate the negative impacts of adverse parenting styles on academic anxiety. This study underscores the importance of fostering a mature self-concept to buffer against the negative effects of rejective parenting style. The findings offer valuable insights for educational psychologists, counselors, and policymakers focused on enhancing the well-being and educational outcomes of young people.

Our findings support the third hypothesis (H3), indicating that the negative effects of rejective parenting style on students’ academic anxiety can be mitigated by the adoption of a positive coping style. This aligns with Wang et al., who found that effective coping strategies can moderate the adverse effects of stressors on adolescents’ psychological outcomes [107]. A positive coping style enables effective monitoring and regulation of learning, enhancing problem-solving abilities that are crucial for reducing academic anxiety and promoting academic success [108]. According to the transactional model of coping, students’ response behaviors when facing stressful academic situations can mitigate the effects of those stressors. Successful resolution fosters a positive mindset and self-confidence, whereas failure to resolve stress can lead to an overload of learning anxiety [109].

However, the development of this coping style is partly influenced by parenting style [110]. The way parents educate their children—characterized by their parenting style—significantly affects adolescents’ ability to cope with stress and develop a positive self-concept [111]. A rejective parenting style can lead to negative self-evaluations and coping styles, making students attribute their academic success or failure to external factors such as luck, which diminishes their engagement in active learning [112].

By demonstrating that a positive coping style can mitigate the effects of rejective parenting style on academic anxiety, our study suggested that schools and educational institutions should prioritize the teaching of effective coping mechanisms as part of their curriculum. Programs that teach students how to manage stress, solve problems, and develop resilience can help create a supportive academic environment.

This study demonstrates the chain-mediated effects of self-concept and positive coping style between rejective parenting style and academic anxiety among high school students (H4). Specifically, it suggests that by developing a robust self-concept and employing positive coping strategies, adolescents subjected to rejective parenting style can effectively mitigate their academic anxiety. Although Wang et al. identified positive coping as a mediating factor between parenting style and children’s emotional well-being, their study overlooked the role of self-concept [113]. According to self-determination theory, students need to recognize that they can effectively use necessary strategies and resources. This, in turn, encourages the establishment of positive coping style and actions to enhance initiative in accomplishing tasks [114]. This demonstrates the critical requirement for students to maintain a clear self-awareness of what benefits them and the positive paths they can take to deal with academic dilemmas in their own learning process. Students’ belief in their own competencies enhances their ability to perform and build a system of positive coping style through the management of their self-concept [115]. Obviously, focusing more on academic problem solving reduces the risk of academic anxiety and further increases the sense of academic achievement and motivation of this group of students. Consequently, a well-developed self-concept is a fundamental prerequisite for the effective implementation of positive coping strategies. Negative self-concept can undermine students’ confidence in taking appropriate strategic actions.

Our mediation model incorporates both students’ self-concept and positive coping style, creating a comprehensive framework that explains the impact of rejective parenting style on academic anxiety. From the perspective of educational theories, our findings enrich the scholarly conversation about parents’ responsive attitudes and parenting behaviors toward their children in terms of their academic performance and emotional adjustment. It also provides a strong advocate for the family acceptance-rejection theory in empirical research, and moreover, it contributes to theoretical research on academic anxiety in high school students. In terms of educational practice, the findings of these studies advocate individual characteristics and qualities, such as the formation of a correct self-concept and the cultivation of a positive coping style, should be actively considered in the process of cooperative education and positive psychological intervention programs at home and school, in accordance with the core educational philosophy of “people oriented”. In addition, lectures on the pedagogy and psychology of parenting styles will be held to warn parents against rejective parenting style and to learn about proper parenting behavior and high-quality interactions. Enhancing students’ self-concept and cultivating positive coping mechanisms may thus serve as effective interventions to alleviate academic anxiety among adolescents experiencing rejective parenting style.

Variations between urban and rural areas in the impact of rejective parenting style on students’ academic anxiety

Our findings supported the hypothesis that rejective parenting style is linked to higher academic anxiety in students, with this effect being more pronounced in urban areas compared to rural areas (H5). Our study builds on existing research that identifies rejective or negative parenting practices as significant predictors of increased anxiety in adolescents [116] by further demonstrating that the impact of these parenting styles varies in intensity between rural and urban areas.

The stronger effect observed in urban settings may be related to the unique challenges these environments pose, such as increased academic pressures and social expectations [117]. Building on previous findings that urban students often encounter more intense stressors than their rural peers [118], our results provide plausible explanations for this phenomenon by specifically linking these stressors to rejective parenting practices.

In contrast, the less pronounced effect in rural areas suggests that lower academic competition or stronger community support networks might serve as protective factors that reduce the negative impacts of rejective parenting. This finding is consistent with the work of Olivos who noted that rural settings could mitigate the effects of adverse parenting due to these protective factors [76].

Overall, our study contributes to the literature by highlighting the importance of considering environmental contexts when examining the relationship between parenting styles and academic anxiety. Future research should explore these contextual influences in more detail to develop targeted interventions that address the specific needs of students in different settings.

Theoretical Contribution and Implications for the Practice

This study contributes significantly to both theoretical and practical perspectives. Theoretically, it clarifies the mechanisms through which a rejective parenting style impacts students’ academic anxiety. It expands current understanding for families and educational institutions concerning this influence and enriches existing literature. Additionally, this research serves as a valuable resource for scholars investigating familial parenting practices and academic emotions. It delves into the deeper internal mechanisms that shape students’ academic anxiety, highlighting the critical roles of self-concept and positive coping style. Practically, the findings guide the development of effective interventions designed to alleviate academic anxiety and psychological disorders among high school students. Importantly, this study elucidates the interconnections between self-concept, positive coping style, urban-rural disparities, and rejective parenting style, demonstrating their collective impact on the manifestation of students’ academic anxiety.

The results of this study have significant practical implications. The family is a crucial environment for the cultivation of individual qualities and emotional development, exerting a fundamental, enduring, and profound influence on individuals. Parents, as the most influential members within the family, serve as both initial and lifelong mentors to their children. Their attitudes, perceptions, and behavioral responses significantly shape their children’s development. Accordingly, this research underscores the need for Chinese families to adopt healthier parenting styles. It alerts Chinese parents to the risks of high school students’ academic anxiety and emotional volatility, particularly in families with a rejective parenting style. Firstly, it is essential for parents to help their children develop a clear self-concept and positive coping strategies. Parents should involve their children in decision-making processes, thereby fostering their sense of responsibility and improving their problem-solving and resilience skills. Secondly, establishing regular emotional sharing sessions within the family is recommended. Such sessions enable parents to better understand their children’s mental states and unexpressed emotions through open communication. Lastly, active parental involvement in their children’s academic and personal lives is crucial. High school is a critical period where students greatly benefit from emotional support and affirmation. Parental praise and validation can significantly enhance a student’s self-confidence and emotional agency, facilitating the use of positive coping mechanisms to manage academic conflicts through effective emotional regulation.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample was confined to three provinces: Shanxi, Hebei, and Henan. Consequently, the results may not be generalizable to a broader population. To enhance external validity, future studies should aim to include a nationally representative sample. Additionally, variations in rejective parenting style and students’ academic anxiety could exhibit heterogeneity not captured in this study. Secondly, the cross-sectional design of this study limits the ability to draw causal inferences between variables. Cross-sectional research design: During data collection, all variables are collected at the same time or within a short period of time. This means that we cannot assume that a rejective parenting style will definitely cause academic anxiety in high school students. The research cannot determine the time sequence between the variables, and there may be the influence of other unknown factors at different times. In other words, it is impossible to determine which variable is the cause and which variable is the effect. Therefore, it cannot establish a causal relationship. Parenting styles and their effects may vary over time and across different cultures, and the development of self-concept and positive coping style are dynamic processes. Future research should consider employing a longitudinal design or a lagged crossover model to better delineate causality and the relationship between rejective parenting style and high school students’ academic anxiety [119]. Third, the necessity to control for multiple variables and the extensive workload constrained our analysis to the effects of a singular method. Future studies could adopt an integrated research methodology to enhance the accuracy of measurements. Fourth, this study focused solely on the mediating mechanism of rejective parenting style on students’ academic anxiety. However, a growing body of literature suggests a strong link between family education and adolescent mental and physical health risk behaviors [120,121]. Future research should also consider other potential protective factors in adolescents to more precisely target educational interventions aimed at managing academic anxiety in high school students.

Findings underscore the adverse effects of a rejective parenting style on students’ mental well-being, highlighting the need for culturally sensitive interventions within family education in China. To address these challenges, we recommend training programs for parents to foster supportive communication, reduce criticism, and promote positive encouragement. Schools should integrate mental health support into curricula and establish collaborative mechanisms with families to monitor and improve students’ home environments. Additionally, policymakers are encouraged to prioritize adolescent mental health by promoting supportive parenting practices. In sum, these findings call for action from families, educators, and society to enhance parenting approaches and foster students’ mental health and holistic development.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the reviewers and editorial team for their valuable comments and suggestions, which greatly improved the quality of this article. We are also deeply grateful to all the anonymous participants who took part in this research. Their contributions have been invaluable to the successful completion of this study.

Funding Statement: This study was funded by the Key Discipline Construction Project of the Liaoning Provincial Social Science Planning Fund (grant ID: L24ZD042).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Dexian Li, Xin Lin, Xingchen Zhu; data collection: Wencan Li; analysis and interpretation of results: Wencan Li, Xingchen Zhu; draft manuscript preparation: Dexian Li, Wencan Li, Xin Lin, Xingchen Zhu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Participants were informed during the data collection process that their information would remain confidential and that no one outside the research team would have access to the data, so the datasets generated and analyzed in this study cannot be shared publicly as this was explicitly stated in the consent forms.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Liaoning Normal University (IRB number: LSDJYXY2023001). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Xu T. From academic burden reduction to quality education: a case study of students’ and parents’ perceptions and experiences under the double-reduction policy in China. Lingnan University: Hong Kong; 2023. [Google Scholar]

2. Liu N, Wu S. Codification of family education promotion law in education code. J East China Norm Univ (Educ Sci). 2022;40(5):100–7. [Google Scholar]

3. Tan CY, Lyu M, Peng B. Academic benefits from parental involvement are stratified by parental socioeconomic status: a meta-analysis. Parenting. 2020;20(4):241–87. doi:10.1080/15295192.2019.1694836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hornby G, Lafaele R. Barriers to parental involvement in education: an explanatory model. In: Mapping the field. New York: Routledge; 2023. p. 121–36. [Google Scholar]

5. Garcia OF, Fuentes MC, Gracia E, Serra E, Garcia F. Parenting warmth and strictness across three generations: parenting styles and psychosocial adjustment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7487. doi:10.3390/ijerph17207487. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Cheng KY. China’s family education promotion law: family governance, the responsible parent and the moral child. Chin J Comp Law. 2023;11(2):cxad004. doi:10.1093/cjcl/cxad004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Jacobsen B, Nørup I. Young people’s mental health: exploring the gap between expectation and experience. Educ Res. 2020;62(3):249–65. doi:10.1080/00131881.2020.1796516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Vandenkerckhove B, Vansteenkiste M, Brenning K, Boncquet M, Flamant N, Luyten P, et al. A longitudinal examination of the interplay between personality vulnerability and need-based experiences in adolescents’ depressive symptoms. J Pers. 2020;88(6):1145–61. doi:10.1111/jopy.v88.6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Herd T, Kim-Spoon J. A systematic review of associations between adverse peer experiences and emotion regulation in adolescence. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2021;24(1):141–63. doi:10.1007/s10567-020-00337-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Xie S, Zhang X, Cheng W, Yang Z. Adolescent anxiety disorders and the developing brain: comparing neuroimaging findings in adolescents and adults. Gen Psychiatr. 2021;34(4):1–13. [Google Scholar]

11. Lorence B, Hidalgo V, Pérez-Padilla J, Menéndez S. The role of parenting styles on behavior problem profiles of adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(15):2767. doi:10.3390/ijerph16152767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kamran M, Iqbal K, Zahra SB, Javaid ZK. Influence of parenting style on children’s behavior in Southern Punjab. Pakistan IUB J Soc Sci. 2023;5(2):292–305. [Google Scholar]

13. Baumrind D. Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Dev. 1966;37:887–907. doi:10.2307/1126611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jiang J, Lu ZR, Xu Y. Preliminary revision of Chinese version of parenting style questionnaire. Psychol Dev Educ. 2010;26(1):94–9 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

15. Hou Y, Xiao R, Yang X, Chen Y, Peng F, Zhou S, et al. Parenting style and emotional distress among Chinese college students: a potential mediating role of the Zhongyong thinking style. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1774–13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: an integrative model. In: Interpersonal development. New York: Routledge; 2017. p. 161–70. [Google Scholar]

17. Rankin JH, Wells LE. The effect of parental attachments and direct controls on delinquency. J Res Crime Delinq. 1990;27(2):140–65. doi:10.1177/0022427890027002003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Estiningsih D. The role of the family in facing the impact of advances in information technology on the lives of children and adolescents (Review of Islamic Psychology). Al Misykat J Islam Psychol. 2023;1(1):40–62. doi:10.24269/almisykat.v1i1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Gunn S. Translating Bourdieu: cultural capital and the English middle class in historical perspective. Br J Sociol. 2005;56(1):49–64. doi:10.1111/bjos.2005.56.issue-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li M, Chzhen Y. Parental investment or parenting stress? Examining the links between poverty and child development in Ireland. Eur Soc. 2023;26(4):911–51. [Google Scholar]

21. Mistry RS, Biesanz JC, Chien N, Howes C, Benner AD. Socioeconomic status, parental investments, and the cognitive and behavioral outcomes of low-income children from immigrant and native households. Early Child Res Q. 2008;23(2):193–212. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Harris A, Goodall J. Do parents know they matter? Engaging all parents in learning. Educ Res. 2008;50(3):277–89. doi:10.1080/00131880802309424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. LaRocque M, Kleiman I, Darling SM. Parental involvement: the missing link in school achievement. Prev Sch Fail. 2011;55(3):115–22. doi:10.1080/10459880903472876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Lu N, Lu W, Chen R, Tang W. The causal effects of urban-to-urban migration on left-behind children’s well-being in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(5):4303. doi:10.3390/ijerph20054303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Bao K, Zhang X, Cai L. The closed loop between parental upbringing and online game addiction: a narrative study of rural children’s growth in China. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024;17:1703–16. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S457068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Guo Z, Zhang Y, Liu Q. Bibliometric and visualization analysis of research trend in mental health problems of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2023;10:1040676–14. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.1040676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Amin S, Raudhoh S. The role of readiness of work-home resources and work motivation in minimizing work-family conflict in the COVID-19 pandemic era. J Appl Manag. 2021;19(4):738–50. [Google Scholar]

28. Meng F, Cheng C, Xie Y, Ying H, Cui X. Perceived parental warmth attenuates the link between perceived parental rejection and rumination in Chinese early adolescents: two conditional moderation models. Front Psychiat. 2024;15:1294291–13. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1294291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Hu J, Zheng Q, Zhou T, Huang Z. Development and initial validation of the parental response to adolescents’ emotions scale: a mixed methods approach. J Res Adolesc. 2024;34(2):599–613. doi:10.1111/jora.v34.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Sroufe LA, Fleeson J. Attachment and the construction of relationships. In: Relationships and Development. London: Psychol Press; 2013. p. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

31. Basu S, Banerjee B. Impact of environmental factors on mental health of children and adolescents: a systematic review. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;119:105515. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Xie K, Vongkulluksn VW, Cheng SL, Jiang Z. Examining high-school students’ motivation change through a person-centered approach. J Educ Psychol. 2022;114(1):89–112. doi:10.1037/edu0000507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Johnson KC, LeBlanc AJ, Sterzing PR, Deardorff J, Antin T, Bockting WO. Trans adolescents’ perceptions and experiences of their parents’ supportive and rejecting behaviors. J Couns Psychol. 2020;67(2):156–70. doi:10.1037/cou0000419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Tus J. The influence of study attitudes and study habits on the academic performance of the students. Int J All Res Writ. 2020;2(4):11–32. [Google Scholar]

35. Khaleque A, Rohner RP. Perceived parental acceptance-rejection and psychological adjustment: a meta-analysis of cross-cultural and intracultural studies. J Marriage Fam. 2002;64(1):54–64. doi:10.1111/jomf.2002.64.issue-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Hazan C, Shaver PR. Attachment as an organizational framework for research on close relationships. Psychol Inq. 1994;5(1):1–22. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0501_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yakın D. Parental acceptance-rejection/control and symptoms of psychopathology: Mediator roles of personality characteristics (Master’s Thesis). Middle East Technical University: Çankaya Ankara, Turkey; 2011. [Google Scholar]

38. Giovazolias T. The relationship of rejection sensitivity to depressive symptoms in adolescence: the indirect effect of perceived social acceptance by peers. Behav Sci. 2023;14(1):10. doi:10.3390/bs14010010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Deb S, Strodl E, Sun H. Academic stress, parental pressure, anxiety and mental health among Indian high school students. Int J Psychol Behav Sci. 2015;5(1):26–34. [Google Scholar]

40. Gardner AA, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Rejection sensitivity and responses to rejection: serial mediators linking parenting to adolescents and young adults’ depression and trait-anxiety. J Relat Res. 2018;9:e9. doi:10.1017/jrr.2018.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Matejevic M, Jovanovic D, Ilic M. Patterns of family functioning and parenting style of adolescents with depressive reactions. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015;185:234–9. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Matejevic M, Jovanovic D, Lazarevic V. Functionality of family relationships and parenting style in families of adolescents with substance abuse problems. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;128:281–7. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Peacocke C. Mental action and self-awareness (I). Contemp Debates Philos Mind. 2023;6:341–58. [Google Scholar]

44. Poole M. Socialisation: how we become who and what we are. Public Sociol. 2023;5:94–122. [Google Scholar]

45. Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. J Marriage Fam. 2010;72(3):685–704. doi:10.1111/jomf.2010.72.issue-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Haw YH, Lee N, Yashnevathy G. Parent-child relationship, perceived social support, perceived discrimination as predictors of well-being among LGBTQ emerging adults in Malaysia (Doctoral Dissertation). Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman: Kampar, Malaysia; 2023. [Google Scholar]

47. Du Y, Zheng C, Kao T, Yu Y, Chen Z, Hsu P. Study on the influencing mechanism of parental psychological control on adolescents. In: Educ Awareness Sustain; Amsterdam: Atlantis Press; 2020. p. 753–8. [Google Scholar]

48. Marsh HW, Martin AJ. Academic self-concept and academic achievement: relations and causal ordering. Br J Educ Psychol. 2011;81(1):59–77. doi:10.1348/000709910X503501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Nawaz D, Jahangir N, Khizar U, John H, Ilyas Z. Impact of anxiety on self-esteem, self-concept and academic achievement among adolescent. Elem Educ Online. 2021;20(1):3458–8. [Google Scholar]

50. Topps AK, Jiang X. Exploring the moderating role of ethnic identity in the relation between peer stress and life satisfaction among adolescents. Contemp Sch Psychol. 2023;27(4):634–45. doi:10.1007/s40688-023-00454-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Oubibi M, Chen G, Fute A, Zhou Y. The effect of overall parental satisfaction on Chinese students’ learning engagement: role of student anxiety and educational implications. Heliyon. 2023;9(3):1–11. [Google Scholar]

52. Zuppardo L, Serrano F, Pirrone C, Rodriguez-Fuentes A. More than words: anxiety, self-esteem, and behavioral problems in children and adolescents with dyslexia. Learn Disabil Q. 2023;46(2):77–91. doi:10.1177/07319487211041103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Smokowski PR, Kopasz KH. Bullying in school: an overview of types, effects, family characteristics, and intervention strategies. Child Sch. 2005;27(2):101–10. doi:10.1093/cs/27.2.101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Rohner RP, Rohner EC. Antecedents and consequences of parental rejection: a theory of emotional abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1980;4(3):189–98. doi:10.1016/0145-2134(80)90007-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wolfradt U, Hempel S, Miles JN. Perceived parenting styles, depersonalisation, anxiety and coping behavior in adolescents. Pers Individ Dif. 2003;34(3):521–32. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00092-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Skinner EA. The development of coping: implications for psychopathology and resilience. In: Cicchetti D, editor. Developmental psychopathology: Risk, resilience, and intervention (3rd ed). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2016. p. 485–545. [Google Scholar]

57. da Matos MG, Gaspar T, Cruz J, Neves AM. New highlights about worries, coping, and well-being during childhood and adolescence. Psychol Res. 2013;3(5):252–67. [Google Scholar]

58. Bayrak R, Güler M, Şahin NH. The mediating role of self-concept and coping strategies on the relationship between attachment styles and perceived stress. Eur J Psychol. 2018;14(4):897–913. doi:10.5964/ejop.v14i4.1508. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

60. Liu W, Li Z, Ling Y, Cai T. Core self-evaluations and coping styles as mediators between social support and well-being. Pers Individ Dif. 2016;88(4):35–9. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Carver CS, Connor-Smith J. Personality and coping. Annu Rev Psychol. 2010;61(1):679–704. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Kardum I, Krapić N. Personality traits, stressful life events, and coping styles in early adolescence. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;30(3):503–15. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00041-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Turner JC, Onorato RS. Social identity, personality, and the self-concept: a self-categorization perspective. In: The psychology of the social self. New York: Psychol Press; 2014. p. 11–46. [Google Scholar]

64. Zhou T, Wu D, Lin L. On the intermediary function of coping styles: between self-concept and subjective well-being of adolescents of Han, Qiang and Yi nationalities. Psychology. 2012;3(2):136–43. doi:10.4236/psych.2012.32021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Güler K, Faraji H, Arslan G. The role of stress coping styles in the relationship between separation individualization and sexual self-schema. Eur Res J. 2023;9(2):416–27. doi:10.18621/eurj.1182932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Li W, Guo Y, Lai W, Wang W, Li X, Zhu L, et al. Reciprocal relationships between self-esteem, coping styles and anxiety symptoms among adolescents: between-person and within-person effects. Child Adolesc Psychiat Ment Health. 2023;17(1):21–37. doi:10.1186/s13034-023-00564-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Coelho VA, Marchante M, Jimerson SR. Promoting a positive middle school transition: a randomized-controlled treatment study examining self-concept and self-esteem. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46:558–69. doi:10.1007/s10964-016-0510-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Khan A, Alam S. Influence of academic stress on students self-concept, adjustment and achievement motivation (Thesis). Aligarh Muslim University: India; 2016. [Google Scholar]

69. Xu J, Yang X. The influence of resilience on stress reaction of college students during COVID-19: the mediating role of coping style and positive adaptive response. Curr Psychol. 2024;43(13):12120–31. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-04214-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Chen X, Zhou J, Li D, Liu J, Zhang M, Zheng S, et al. Concern for mianzi: relations with adjustment in rural and urban Chinese adolescents. Child Dev. 2024;95(1):114–27. doi:10.1111/cdev.v95.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Albulescu I, Labar AV, Manea AD, Stan C. The mediating role of anxiety between parenting styles and academic performance among primary school students in the context of sustainable education. Sustainability. 2023;15(2):1502–39. [Google Scholar]

72. Şengönül T. A review of the relationship between parental involvement and children’s academic achievement and the role of family socioeconomic status in this relationship. Pegem J Edu Instr. 2022;12(2):32–57. [Google Scholar]

73. Sisk LM, Gee DG. Stress and adolescence: vulnerability and opportunity during a sensitive window of development. Cur Opini Psychol. 2022;44:286–92. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.10.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Fuligni AJ, Zhang W. Attitudes toward family obligation among adolescents in contemporary urban and rural China. Child Dev. 2004;75(1):180–92. doi:10.1111/cdev.2004.75.issue-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. McLeod BD, Wood JJ, Weisz JR. Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:155–72. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Olivos F. Motivation, legitimation, or both? Reciprocal effects of parental meritocratic beliefs and children’s educational performance in China. Soc Psychol Q. 2021;84(2):110–31. doi:10.1177/0190272520984730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Choa RK. Extending research on the consequences of parenting styles for Chinese and European Americans. Child Dev. 2001;72(6):1832–43. doi:10.1111/cdev.2001.72.issue-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Xie MQ. A study on the relationship between personality traits, structural needs and academic anxiety of high school students. Doctoral dissertation (Master’s Thesis). Fujian Normal University: Chinese; 2017 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

79. Huang KY, Cheng S, Calzada E, Brotman LM. Symptoms of anxiety and associated risk and protective factors in young Asian American children. Child Psychiatr Hum Dev. 2012;43:761–74. doi:10.1007/s10578-012-0295-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Perris C, Jacobsson L, Linndström H, von Knorring L, Perris H. Development of a new inventory for assessing memories of parental rearing behavior. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1980;61(4):265–74. doi:10.1111/acp.1980.61.issue-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Yue DM, MiG Li, Jin KH, Ding BK. Parenting styles: preliminary revision of the EMBU and its application in neurotic patients. Chin Ment Health J. 1993;7:97–101 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

82. Zhang L, Han J, Liu M, Yang C, Liao Y. The prevalence and possible risk factors of gaming disorder among adolescents in China. BMC Psychiat. 2024;24(1):381–92. doi:10.1186/s12888-024-05826-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Marsh HW. The structure of academic self-concept: the Marsh/Shavelson model. J Educ Psychol. 1990;82(4):623–36. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.82.4.623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]