Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Potential Vicious Cycle between School Refusal and Depression among Chinese Adolescents: A Cross-Lagged Panel Model Analysis

1 Zhejiang Provincial Clinical Research Center for Mental Health, The Affiliated Wenzhou Kangning Hospital, Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, 325000, China

2 Key Laboratory of Alzheimer’s Disease of Zhejiang Province, Institute of Aging Wenzhou Medical University, Oujiang Laboratory (Zhejiang Laboratory for Regenerative Medicine, Vision, and Brain Health), Wenzhou, 325035, China

3 Teaching and Research Center, Bureau of Education, Linhai, Taizhou, 317000, China

4 School of Mental Health, Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, 325015, China

5 Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G 2R3, Canada

6 Department of Psychology, University of Toronto, Scarborough, ON M5S 1A1, Canada

7 School of Public Health, Fudan University, Shanghai, 200433, China

8 Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Macau, Taipa, Macau, 999078, China

9 Centre for Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Institute of Collaborative Innovation, University of Macau, Macau, 999078, China

10 Center for Public Mental Health, Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, 325015, China

* Corresponding Authors: Joseph T. F. Lau. Email: ; Deborah Baofeng Wang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(10), 1423-1437. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.068840

Received 07 June 2025; Accepted 22 September 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

Background: Adolescent depression and school refusal (SR) are prevalent and important global concerns that need to be understood and addressed. Cross-sectional associations have been reported but prospective relationships between them remain unclear. This longitudinal study investigated the bidirectional relationships between these two problems among Chinese adolescents. Methods: A longitudinal study was conducted in Taizhou, China, surveying students of three junior high schools, three senior high schools, and one vocational high school. A total of 3882 students completed the questionnaire at baseline (T1); 3167 of them completed an identical follow-up questionnaire after 6 months (T2). Depression was assessed via the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and SR via the modified Chinese version of The School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised (SRAS-R). Cross-lagged panel modeling (CLPM) analysis was conducted to test the reciprocal relationships, adjusting for socio-demographic factors. Multiple group analysis was conducted to test whether the CLPM differed by gender and grade. Results: Statistically significant bidirectional relationships were found. A higher level of SR assessed at T1 is prospectively associated with a higher level of depression at T2 (β = 0.07, p = 0.006); a higher level of depression at T1 also is prospectively associated with a higher level of SR at T2 (β = 0.14, p < 0.001). Such models differed significantly by neither gender nor grade. Conclusion: SR and depression should be seen as each other’s mutually reinforcing association. The bidirectional relationships potentially result in a vicious cycle. Early interventions may target both problems concurrently. Future studies may involve more time points and test some mediators.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileGlobally, mental disorders accounted for 31.1 million of the 153.6 million years lived with disabilities (YLDs) [1]. Depression, anxiety and behavioral disorders are among the leading causes of adolescent illness and disability [2]. According to the World Health Organization key facts, one in seven of the 10–19-year-olds experiences a mental disorder, accounting for 13% of the global burden of disease in this age group. The prevalence of lifetime prevalence of depression was between 11% and 14% among American adolescents aged 15 to 18 [3,4], and was 24.6% among Chinese adolescents according to a meta-analysis and 28.4% according to a national report [5,6]. Depression is prospectively associated with suicidal acts among adolescents and untreated adolescent depression may persist into adulthood [7]. School refusal (SR) is closely related to adolescent depression [8,9] but is it a cause or a consequence or both? This study investigated this interesting and implicative research question.

SR and absenteeism are related but unidentical constructs. Absenteeism refers to the habitual pattern of total absences from schools [8]. SR involves a wider scope and refers to intention and behaviors related to difficulties attending classes or remaining in school for the entire day [10], tardiness, skipped classes, morning misbehaviors to miss school, and school attendance with reluctance [11]. SR often involves strong negative emotions [12]. Also, students may use SR to fulfill specific socio-emotional functions that are not considered in absenteeism. According to the Functional Behavioral Model [10], SR is maintained by four primary reinforcement avoidance/reward-related functions: avoidance of negative affectivity, escape from aversive social-evaluative situations, attention-seeking, and pursuit of tangible rewards. A validation study conducted in Chinese adolescents modified them into five dimensions (i.e., avoiding negative emotions at school, pursuit of reinforcement outside school, frequent absenteeism to reduce psychosocial problems, conditions that would increase motivation to go to school, and preference to stay with family over going to school) [9]. Such functions or ‘reasons’ of SR are informative in understanding the causes or consequences of depression. For instance, the SR function of avoiding negative emotions and reduction of psychosocial problems may imply unpleasant experiences at school, which are expected to be associated with depression. The push factors (e.g., reinforcement outside of the school or staying with family or low reinforcement at school) may reflect unrewarding school experiences (e.g., boredom and frustrations) that may be associated with depression. Gonzálvez et al. [13] found differential effects between specific function and depression—adolescents reporting avoidance-based SR functions reported significantly higher depression than others. The study hence allows testing the relative strengths of the bidirectional associations between specific SR functions and depression. Thus, by utilizing the validated multidimensional scale of SR (SRAS-R) [9], this study moved beyond using generic absenteeism metrics to investigate whether depression and specific SR functions affect each other reciprocally. Knowledge of such relationships with depression would facilitate design of interventions.

The prevalence of SR ranged from 28% to 35% in the children and adolescents in the U.S. and at global level [14,15] and was 22.5% to 30% in various parts of China [16]. According to Havik and Ingul [12], school refusers are more likely than others to develop internalizing symptoms and mental health problems (e.g., anxiety and depression). Our literature found over a dozen cross-sectional studies reporting associations between SR and depression conducted in countries such as China [9,17,18], Ecuador [13,19], Germany [20], Netherland [21], U.S. [22–24], Britain [25], Sweden [26,27] and Turkey [28]. To our knowledge, however, no longitudinal studies have looked at the causal relationships from depression to SR and from SR to depression, although two longitudinal studies investigated the casual directions between absenteeism and adolescent depression in the U.S. [29,30]. In the first study, a cross-lagged panel analysis found bidirectional relationships between absenteeism and depression [29]. In the second study, level of depression at the spring term of the fifth grade was significantly correlated with absenteeism at the fall term of the sixth grade [30]. There are cultural differences and more studies are needed. As mentioned, absenteeism and SR are not equivalent. It is hence warranted to clarify the causal relationships between SR functions and depression among Chinese adolescents.

Another novel feature of this study was investigating moderations of the potential reciprocal relationships between SR and depression. Literature has found moderations between risk factors and depression by gender and school grade [31,32]. It is known that prevalence of depression and level of academic stress are higher among females [33,34] than males and increase with age [31,32] and both SR and depression are related to emotion regulation/coping [35]. Depression-related experiences are stressors, and stressors may induce maladaptive coping and maladaptive emotion regulation that may lead SR. Conversely, SR are often emotion driven [10,19] and such negative emotions increase the risk of depression. As previous studies found that females and higher school grade students were more likely than their counterparts to adopt maladaptive emotion regulation such as rumination [36], there are reasons to believe that the bidirectional relationships between SR and depression would be stronger among females and higher grade students than those among males and lower grade students. Possibly for the first time, such moderation hypotheses were tested in this study.

This longitudinal study investigated prevalence of depression and level of SR functions at two time points six months apart among secondary school students in a southeastern Chinese city. Its cross-lagged panel analysis investigated the prospective reciprocal relationships between the level of depression and SR. First, it was hypothesized that a higher level of depressive symptoms at Time 1 (T1) is prospectively associated with a higher level of SR at Time 2 (T2). Second, it was hypothesized that a higher level of SR at T1 would is prospectively associated with a higher level of depressive symptoms at T2. Multiple group analysis was also conducted to investigate whether the cross-lagged panel model differed significantly by gender and across school grades. It is hypothesized that relationships between SR and depression would be stronger in the group of females than males and in the group students of higher grades than lower grades.

2.1 Participants and Data Collection

A 2-wave longitudinal survey was conducted in seven schools from March 2022 to September 2022 located in Taizhou city, Zhejiang Province, China. All grades 1 and 2 students of three junior middle schools, all grade 2 students of three senior high schools, and all grade 1 students of a vocational high school were invited to join the study. In the classroom, the fieldworkers provided a brief explanation of the purpose of the study to the students and informed them that the return of the completed questionnaire implied informed consent to participate in the study. The participants were reminded that they could quit anytime without bearing negative consequences. This information was also printed on the cover page of the questionnaire. They then self-administered the structured questionnaire in the absence of teachers. Furthermore, parents were notified about the study and given the option to decline their child’s participation by sending a note to the teachers, in which case the child would not be invited to participate in the study. Such a procedure has been used in other studies [37]. No incentives were provided to the participants. The questionnaires were passed directly to the researchers without being copied to the schools. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Kangning Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (No. KNLL-2022007).

A total of 3882 students completed the baseline survey (T1) in March 2022. The follow-up survey (T2) was administered in September 2022. Data obtained from 3167 of these students were matched by their grade, class, and seat number for the two waves (81.6%) and were used for data analysis.

Background information included school type (junior middle school, senior high school, vocational high school), age, gender, and perceived family financial situation (five-point response from very poor to very good).

Depression was assessed at both two-time points. The 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to evaluate depression [38], which is a multipurpose tool for screening, diagnosing, and monitoring the severity of depression. It has been validated in Chinese adolescents and showed excellent psychometric properties [38–40]. A sample item is “Feeling down, depressed or hopeless”. Participants were asked to evaluate the frequency of each of the 9 items over the last two weeks on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day). The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.89 at T1 and 0.92 at T2. The results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), including model fit indices and factor loading for depression T1 and T2 were demonstrated in the supplementary information (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

The validated Chinese version School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised (SRAS-R) was used to assess SR [9], modified from the 24-item English version SRAS-R [41,42]. It is a 21-item scale consisting of five subscales: avoiding negative emotions at school, pursuit of reinforcement outside school, frequent absenteeism to reduce psychosocial problems, conditions that would increase motivation to go to school, and preference to stay with family over going to school. Sample items are “How often do you have bad feelings about going to school because you are afraid of something related to school (e.g., tests, school bus, teacher, fire alarm)?”. “When you are not in school during the week (Monday to Friday), how often do you leave the house and do something fun?”. “How often do you stay away from school because it is hard to speak with the other kids at school?”. “How much would you rather be taught by your parents at home than by your teacher at school?”. “How often do you feel you would rather be with your parents than go to school?”. The items were rated with 7-point Likert scales (0 = never to 7 = always). The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.88 and 0.91 for T1 and T2, respectively. The McDonald’s Omega of the scale was 0.89 and 0.92 for T1 and T2, respectively. The results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), including model fit indices and factor loading for the SR T1 and T2 were presented in the Supplementary Tables S1 and S3.

Descriptive statistics were presented. Attrition analysis was performed by using independent sample t-test and chi-square test. SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for such analyses. In the descriptive and correlation analyses, listwise deletion was used to handle missing data. Given the low proportion of missing data (less than 1%), this method was considered suitable, as it was unlikely to introduce bias or meaningfully impact statistical power.

Cross-lagged panel model (CLPM) analysis using Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation was conducted to test the longitudinal association between SR and depression, with the adjustment of the covariates (school type, age, gender, and perceived family financial situation). The latent variable of SR was derived from the five subscales. Satisfactory model fit indices included χ2/df ≤ 5, the values of CFI and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) ≥ 0.90, and the values of RMSEA and SRMR ≤ 0.08 [43]. Multi-group analyses were further conducted to test the differences in the CLPM models between the two genders and across school types (i.e., junior middle school, senior high school, and vocational high school); a series of models, each constraining a specific individual path, were fit and compared to the unconstrained model which tested all the paths freely. Measurement invariance was tested in the multiple group analysis. A good configural model should demonstrate acceptable fit indices, including the values of Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥ 0.90; the values of Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) ≤ 0.08. Compared to the configural model, changes in CFI and RMSEA should not exceed the critical thresholds (i.e., ΔCFI ≤ 0.01, ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.015) to indicate metric and scalar measurement invariance [44]. A Wald test result of p < 0.05 denotes that there was a significant gender or school type difference in one of the paths. The present study reported standardized regression coefficients (βs). These analyses were conducted using Mplus 8.3. The proportion of missing was low (<1%). Listwise deletion was used to handle missing data in the descriptive and correlation analyses. In the SEM analyses. the Mplus version 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA) was used and its Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation used all the available data to generate efficient and unbiased parameter estimates [45] without the need for imputation. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed p-value < 0.05.

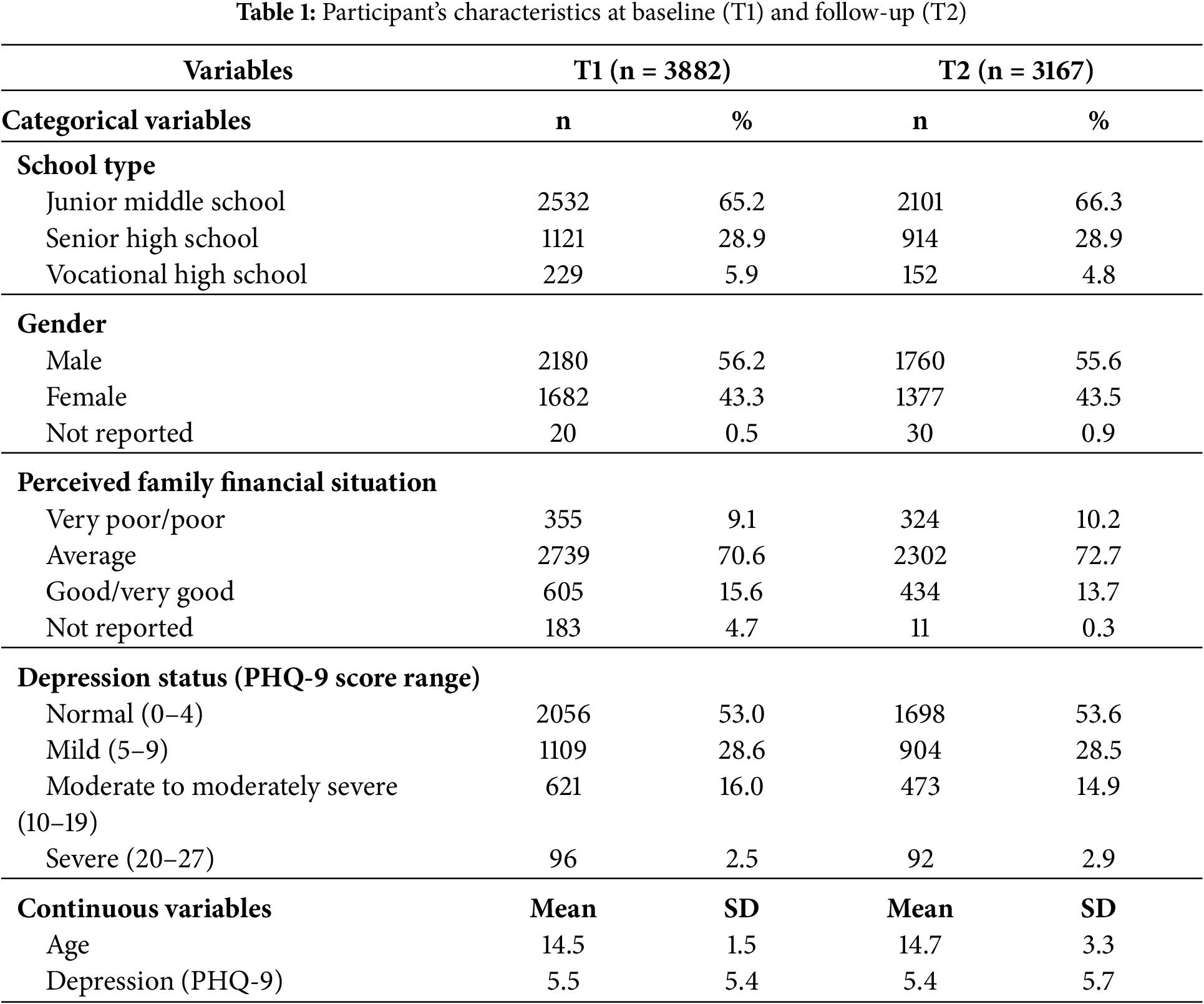

As shown in Table 1, the characteristics of the two waves’ samples were largely stable over time. The two surveys’ proportions of students sampled from junior middle schools (~65%), male gender (~56% male), self-reported poor/very poor conditions (~10%), and no depression (~53%) were comparable.

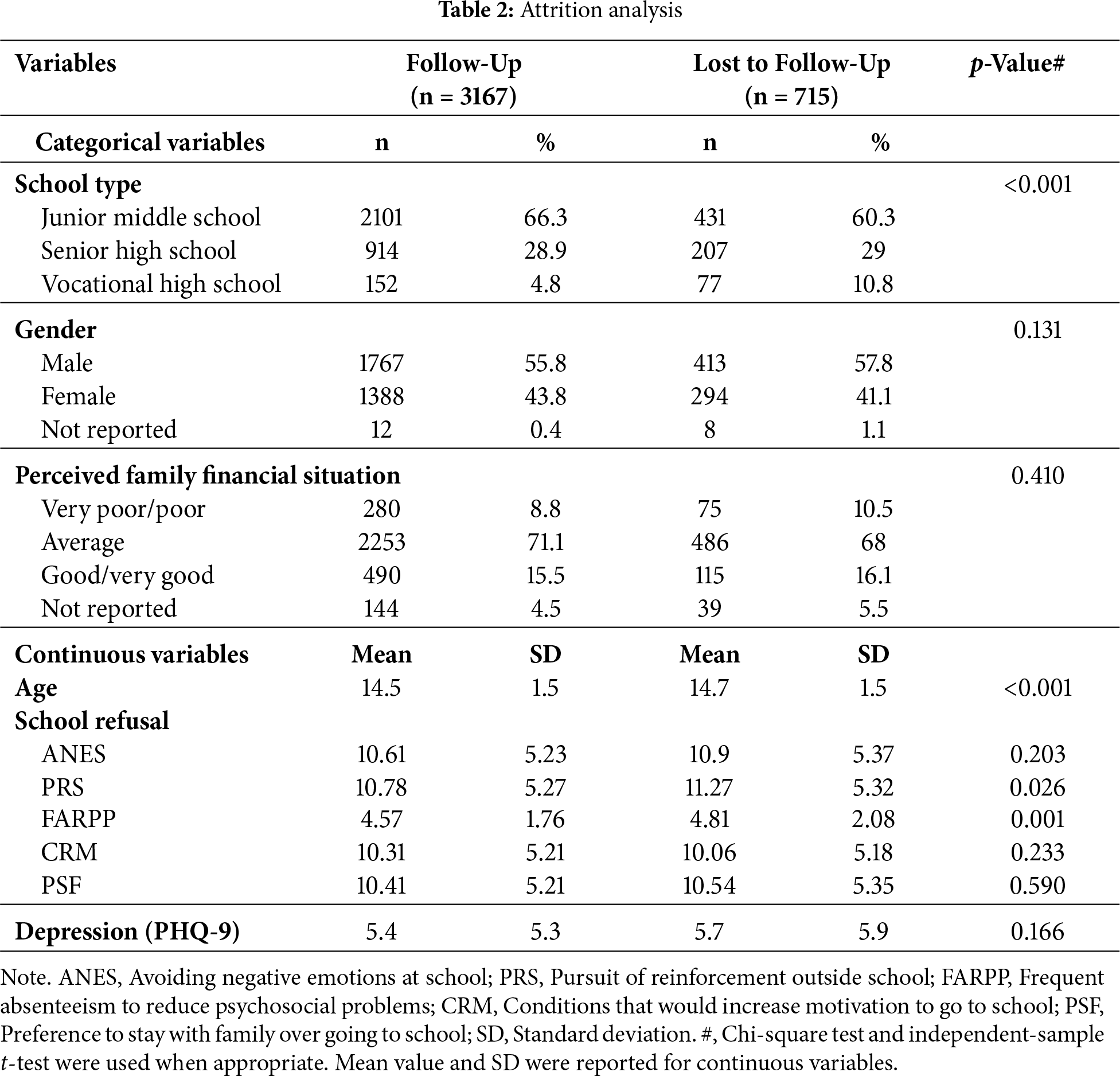

The results are presented in Table 2. Attrition analysis comparing those being followed up and loss to follow-up found statistically significant differences in age (p < 0.001) and school type (p < 0.001); older age and higher proportions of vocational high school students (33.6%) were found in the loss-to-follow-up group than the junior middle (17.0%) and senior high (18.5%). The gender difference, family financial background, and depression levels were non-significant. Significant group differences of small effect sizes (Cohen’s d of −0.09 and −0.12) were observed in the variables of pursuit of reinforcement outside school (p = 0.026) and frequent absenteeism to reduce psychosocial problems (p < 0.001), respectively. Comparisons of the other three SR functions were statistically non-significant (p = 0.203 to 0.590). The results are presented in Table 2.

Second, loss-to-follow-up (about 20%) may introduce attrition bias to the findings as the loss-to-follow-up group involved older students and more vocational high school students than junior middle and senior high schools. However, since school type did not significantly moderate the cross-lagged models, the magnitude of the bias might be relatively small. The attrition group also showed higher scores in two SR functions which are understandable as the survey was conducted in the school setting and would not involve absent students. The effect sizes were, however, small and would not have caused a strong bias in the analysis.

3.3 Measurement Invariance across Gender and School Type

Measurement invariance between gender and between school type demonstrated good fit indices for configural invariance (all values of CFI > 0.90; all values of RMSEA SRMR < 0.08), indicating consistent factor structures between gender and between school type. Metric invariance was supported with ΔCFI ≤ 0.01 and ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.015, confirming equivalent factor loadings across gender. Scalar invariance was also established (ΔCFI ≤ 0.01, ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.015), suggesting that item intercepts were equivalent, and any group differences in variables could be attributed to true differences, not measurement bias (Supplementary Tables S4 and S5).

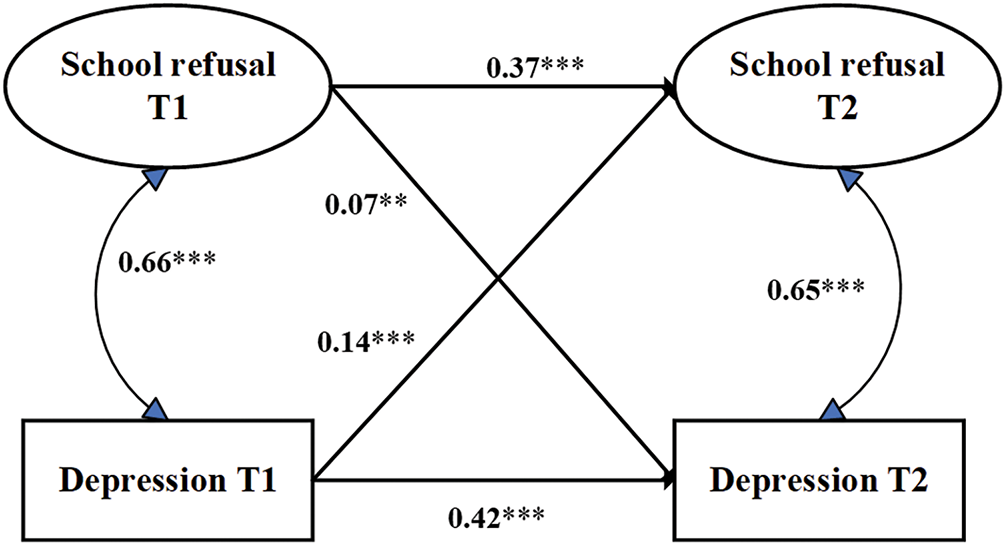

Fig. 1 showed the results of the CLPM. The model adjusted covariates including school type, age, gender, and perceived family financial situation. It showed satisfactory goodness of fit to the data, with χ2(74) = 1315.98, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.924, TLI = 0.901, RMSEA = 0.073, and SRMR = 0.063. Level of SR at T1 is prospectively associated with level of depression at T2 (β = 0.07, p = 0.006) and level of depression at T1 also is prospectively associated with level of SR at T2 (β = 0.14, p < 0.001). Within-time or synchronous correlations between level of SR at T1 and level of depression at T1 (β = 0.66, p < 0.001) and between level of SR at T2 and level of depression at T2 were also statistically significant (β = 0.65, p < 0.001). The two autoregressive effects were statistically significant (SR: β = 0.37, p < 0.001; depression: β = 0.42, p < 0.001).

Figure 1: The cross-lagged panel model with bidirectional effects between school refusal and depression, with adjustment of school type, age, gender, and perceived family financial situation. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

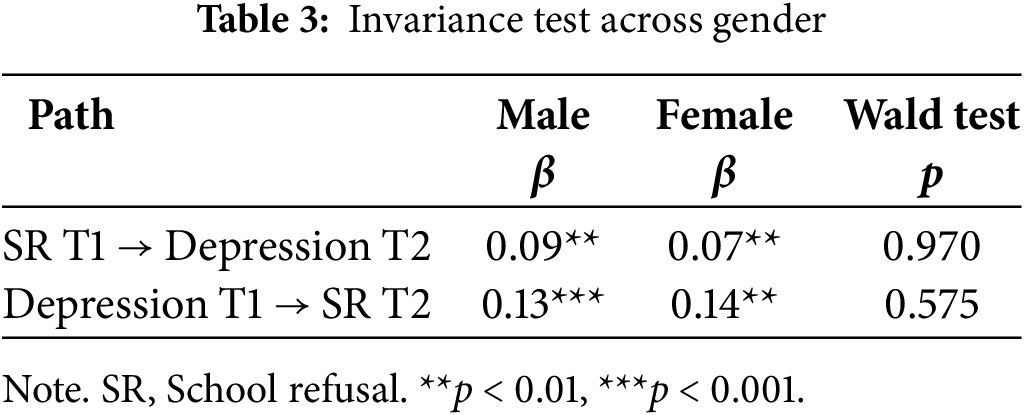

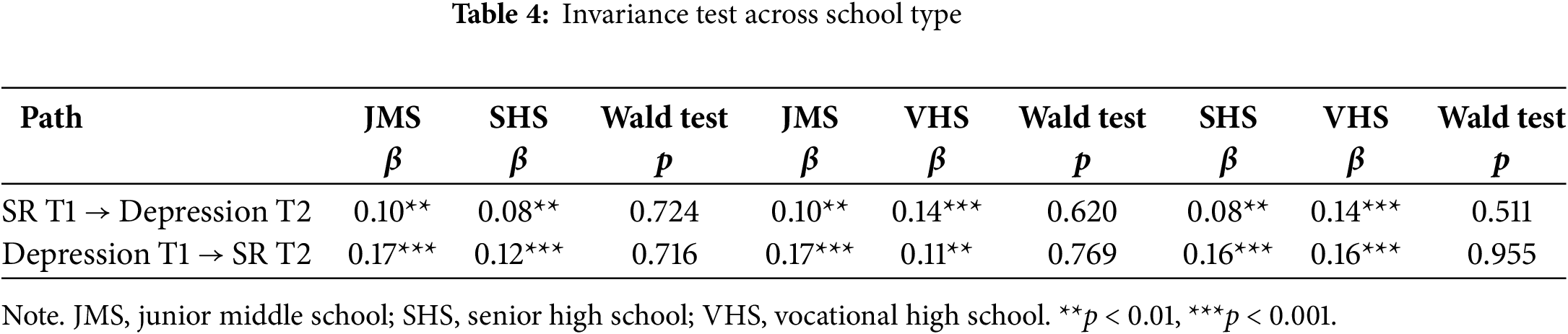

As presented in Table 3, gender did not moderate the path from SR at T1 to depression at T2 (p = 0.970) and the path from depression at T1 to SR at T2 (p = 0.575). Similarly, Table 4 shows that school type (junior middle school, senior high school, and vocational high school) did not moderate the path from SR at T1 to depression at T2 (p = 0.724, 0.620, and 0.511, respectively) and the path from depression at T1 to SR at T2 (p = 0.716, 0.769, and 0.955, respectively).

The present study finds prevalence of probable moderate or above depression of close to 20% at T1 and T2. These findings corroborate previous studies [5,6,46], reinstating that adolescent depression has become a severe and pervasive issue. The prevalence further increased with grade [47]. The high prevalence obtained from this and other studies signify an urgent need for early and targeted interventions to address the mental health challenges faced by adolescents. The results found bidirectional significant prospective associations between SR and depression, with level of depressive symptoms at T1 prospectively associated with level of SR at T2 and level of SR at T1 also prospectively associated with level of depression at T2. It has added to literature knowledge about temporalities between these two variables. The present study also extends the findings presented by Wood et al. [29] and Kingery et al. [30], which documented reciprocal relationships between absenteeism and depression.

Apparently, the significant cross-lagged coefficients look ‘small’. However, as discussed in Orth et al. [48], cross-lagged effects in longitudinal panel models are typically modest and benchmarks have been proposed (β = 0.03 as small; β = 0.07 as medium, and β = 0.12 (large). In our study, the cross-lagged effects from SR to depression (β = 0.07) and from depression to SR (β = 0.14) fell within the medium-to-large range according to the guideline. The reason for the modest coefficients is that the cross-lagged effects are net of the auto-regressive effects, which are expected to be quite large in most circumstances. Such net cross-lagged effects are, however, important as they are capturing unique contributions to the non-autoregressive prospective associations, which is the essential statistics assessing directions of such prospective associations. The findings are hence meaningful.

The two significant bidirectional relationships between SR and depression have strong theoretical and conceptual foundations. Thambirajah et al. [49] highlight that when youths experience SR, they may lose peer support and face social isolation. They may also fall behind academically, making it harder to reintegrate into school and intensifying their fear of failure. These losses in both the peer and academic domains elevate the risk of depression. Specifically, SR deprives adolescents of positive reinforcement, such as peer support and academic rewards, while amplifying negative self-appraisals, such as feelings of incompetence and alienation. As a result, avoidance behaviors like SR, which initially reduce negative emotions (such as anxiety and depression), can exacerbate depression in the long term. This is because the inactivity, social isolation, and poor academic performance stemming from SR may further increase the risk of depression [4]. Stressors related to SR experiences may also trigger maladaptive emotional regulation, such as rumination, which in turn heightens the risk of depression [50]. Thambirajah et al. [49] and Havik and Ingul [12] propose that behavioral avoidance directly fuels negative affectivity, creating conditions conducive to the onset and escalation of depression. Therefore, the path from SR to depressive symptoms illustrates how avoidance behaviors can initiate a harmful psychosocial cascade.

Conversely, the pathway from depressive symptoms to SR is also theoretically grounded. Depression is often closely linked with low self-confidence [51], and the systemic integrated cognitive model [12] suggests that depression can lead to SR. When adolescents encounter stressors, they may appraise the situation as unmanageable, generating mental distress, such as depression. This distress can trigger negative behavioral responses, from emerging SR to social alienation, eventually leading to established SR [12]. Depressive symptoms—such as social withdrawal, loss of motivation, sleep disturbances, and low energy—can impair an adolescent’s ability to attend school. Furthermore, the experience of depression creates stressors, such as stigma, which may further reinforce maladaptive avoidance behaviors, including SR. Future studies are needed to explore mediators of these bidirectional associations and to test the proposed theories.

Havik and Ingul [12] identified several factors contributing to the vicious cycle of SR. The systemic cognitive model posits that depressive emotions lead to avoidant coping, which then triggers emerging SR, alienation from school, and eventually established SR. SR, in turn, fosters social isolation, fear of academic failure, low self-confidence, and mental distress, which further exacerbates depressive symptoms. This mental distress fuels additional avoidance behaviors, thereby solidifying SR. The reciprocal relationships found by the cross-lagged analysis thus suggest that a potential vicious cycle of depression → SR → depression may occur, i.e., students with depression would have a higher likelihood of developing SR, which would in turn increase depressive symptoms, resulting in a ‘spiral’ vicious cycle. As the study cannot establish causality, it remains a speculation but if such is true, the already high prevalence of SR of 23% to 35% [4,15,19,52] would soar further as the prevalence of depression has been increasing over time [53]; unfortunately, the increase in SR would then cause more depression cases. To break the potential vicious cycle, stakeholders (clinicians, educators, and parents) need to work together to create comprehensive treatment plans that include not only mental health support to prevent depression but also strategies to help students gradually re-engage with school. Interestingly, the multi-group cross-lagged models did not differ between genders and across age groups. Similar intervention strategies may be employed to break the potential vicious cycle in students of different genders and age groups. The initial hypotheses that females would show stronger prospective associations were not supported by the data. It is beyond the scope of this preliminary study to explain the non-significance of the hypothesis as this study did not measure emotional regulation. Further research may test moderated mediations of the two prospective paths.

The present study incurs practical implications. The findings call for a paradigm shift toward integrated, multi-targeted prevention and intervention strategies. Specifically, evidence-based mental health interventions should concurrently address depressive symptoms and SR (e.g., via functional behavioral assessment, and targeted academic/social support). Effective depression prevention programs include those involving family, peer, and teacher support [50,54], mindfulness stress reduction [55,56], academic support [57,58], social emotional development [59], emotional regulation [60] and cognitive behavioral therapy [55,61]. Some effective interventions have been able to reduce SR, including cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) [49], social work programs, multi-systemic interventions [62–65]. Interventions reducing SR need to be socio-ecological and involve various levels [66]. At the personal level, in particular, it is essential to understand the causes (or functions) of the SR, such as avoidance of emotional distress, escape from stressful social relationship, and attention seeking [41] and to develop tailored interventions to remove such obstacles. Three of the SR functions are related to incentive of attendance versus absence; it is hence important to shift the reward structure from outside/home back to the school. Research has shown that application of generative AI learning tools has been able to boost learning motivation [67]; teaching needs to be innovative and make use of new technologies. Family support is also important in reducing the SR of home-staying. If the SR function were related to avoidance of emotional avoidance, training on emotional regulation is potentially important [36]. For those with a SR function involving social relationships, training for social acceptance and communication skills may also be important [68]. Training to foster socio-emotional skills is potentially important in reducing both emotional and interpersonal problems. Interpersonal issues such as bullying need to be address as it is potentially related to the SR function of avoidance of emotional problems and psychosocial problems [69]. Effective interventions are available. At the school level, improvements in school climate and school identification are useful as they were negatively associated with SR [70] and may counteract the SR functions of reward obtained outside the school. At the clinical level, back-up is important. As depression predicted SR, parents and teachers need to understand that SR may have a clinical base [71,72]. It should be considered within a mental health context and professional help seeking may sometimes be necessary to treat school refusers [73]. Stakeholders’ involvement is very essential. Teachers and parents need to understand that blaming the school refusers is not a good strategy as it might increase the already heightened risk of depression [12,74]. As frontline workers, teachers require support and mandatory training to identify the co-occurrence of SR and depression and to implement stigma-free re-engagement support. To prevent depression potentially caused by SR, the emotional state of the school refusers may be monitored through careful observations and periodic screening for depression, if possible, and followed up by counselling, secondary interventions, diagnostic assessment, and treatment if necessary.

This study is novel but has several limitations. First, the self-reported data may introduce a bias, as students might underreport or overreport their depressive symptoms or SR due to social desirability. Second, loss-to-follow-up (about 20%) may introduce attrition bias to the findings as the loss-to-follow-up group involved older students and more vocational high school students than junior middle and senior high schools. However, since school type did not significantly moderate the cross-lagged models, the magnitude of the bias might be relatively small. The attrition group also showed slightly higher scores in two SR functions which are understandable as the survey was conducted in the school setting and would not involve absent students; the effect sizes of the difference in SR scores were, however, small and would not have caused a strong bias. Third, although the 6-month interval between T1 and T2 allowed us to capture bidirectional relationships, a longer follow-up period and more points of time would be preferred. Fourth, the current study employed CLPM to examine the longitudinal associations among the study variables. This approach, however, cannot distinguish between within-person and between-person effects. The Random Intercept Cross-Lagged Panel Model (RI-CLPM) is more suitable for separating various sources of variance. Its estimation, however, requires at least three waves of data [75]. It was not feasible as this study only involved two time-points. Despite its limitations, the traditional CLPM remains a valid and widely accepted method for analyzing directional associations over time in two-wave panel data [76]. The findings should be interpreted with caution, as the observed effects might reflect stable between-person differences instead of pure within-person changes. Fifth, this study only looked at the temporal relationships between SR and depression and did not investigate mediators between the two problems. Also, the present study only tested two moderators (gender and school type) and it would be useful to test other moderators such as resilience. Sixth, the study was limited to adolescents in one region of China, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions or countries with different educational and cultural contexts.

In conclusion, this longitudinal study provides valuable evidence of the bidirectional positive prospective relationships between SR and depression in Chinese adolescents. Our findings suggest that SR not only would exacerbate depressive symptoms, but SR may also be fueled by the elevated symptoms, creating a vicious cycle potentially. This research underscores the need for early detection and comprehensive dual treatment strategies that address both SR and depression simultaneously, paying attention to the SR functions of individual students. Future cross-lagged studies may involve a longer follow-up period, more time points, some other mediators, and cross-cultural comparisons.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Taizhou psychology teachers, participants and Mr. Hongshen Yang at Wenzhou Kangning Hospital for their support in the entire data collection process.

Funding Statement: This project was funded by Science and Technology Program of Wenzhou (Y20220843).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Joseph T. F. Lau, Xiaojun Xu and Deborah Baofeng Wang; Methodology: Hui Lu, Yanqiu Yu, Yang Wang, Anise M. S. Wu, Guohua Zhang and Joseph T. F. Lau; Investigation: Xiaojun Xu, Mingyan Liu, Deborah Baofeng Wang, Lei Qian, Chunyan Shan, Jianan Xu, Mengni Du and Guohua Zhang; Software: Hui Lu and Yanqiu Yu; Formal analysis: Hui Lu and Joseph T. F. Lau; Validation: Joseph T. F. Lau; Resources: Xiaojun Xu, Mingyan Liu, Lei Qian, Jianan Xu, Mingyan Liu, Mengni Du and Chunyan Shan; Writing—original draft: Deborah Baofeng Wang, Hui Lu, Joseph T. F. Lau, Xiaojun Xu and Guohua Zhang; Writing—review & editing: Joseph T. F. Lau, Yang Wang, Deborah Baofeng Wang and Hui Lu; Supervision: Joseph T. F. Lau; Funding acquisition: Xiaojun Xu and Deborah Baofeng Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable requests.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Kangning Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (No. KNLL-2022007).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process: During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT to help refine and make the abstract more concise. All content was subsequently reviewed and edited by the authors, who take full responsibility for the final version of the publication.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.068840/s1.

References

1. Kieling C, Buchweitz C, Caye A, Silvani J, Ameis SH, Brunoni AR, et al. Worldwide prevalence and disability from mental disorders across childhood and adolescence: evidence from the global burden of disease study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81(4):347–56. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.5051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. World Health Organization. Key facts: mental health of adolescents. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2025. [Google Scholar]

3. Mendelson T, Tandon SD. Prevention of depression in childhood and adolescence. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin. 2016;25(2):201–18. [Google Scholar]

4. Avenevoli S, Swendsen J, He JP, Burstein M, Merikangas KR. Major depression in the national comorbidity survey-adolescent supplement: prevalence, correlates, and treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(1):37–44. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Liu F, Song X, Shang X, Wu M, Sui M, Dong Y, et al. A meta-analysis of detection rate of depression symptoms among middle school students. Chin Ment Health J. 2020;34(2):123–8. [Google Scholar]

6. Fu X, Zhang K, Chen X, Chen Z. Report on national mental health development in China (2019–2020). Beijing, China: Social Sciences Academic Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

7. Mullen S. Major depressive disorder in children and adolescents. Ment Health Clin. 2018;8(6):275–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

8. Finning K, Ukoumunne OC, Ford T, Danielsson-Waters E, Shaw L, Romero De Jager I, et al. The association between child and adolescent depression and poor attendance at school: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:928–38. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Yu Y, Chen JH, Lau JTF, Wu AMS, Du M, Chen Y, et al. Validation of the school refusal assessment scale-revised (SRAS-R) in the general adolescent population in china. Sch Ment Health. 2024;16(2):436–46. doi:10.1007/s12310-024-09647-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kearney CA. School refusal behavior in youth: a functional approach to assessment and treatment. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

11. Kearney CA. Managing school absenteeism at multiple tiers: an evidence-based and practical guide for professionals. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

12. Havik T, Ingul JM. How to understand school refusal. Front Educ. 2021;6:715177. doi:10.3389/feduc.2021.715177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Gonzalvez C, Kearney CA, Jimenez-Ayala CE, Sanmartin R, Vicent M, Ingles CJ, et al. Functional profiles of school refusal behavior and their relationship with depression, anxiety, and stress. Psychiatry Res. 2018;269(7):140–4. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Kearney CA, Albano AM. When children refuse school: a cognitive-behavioral therapy approach. In: Parent workbook. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

15. UIS U. New-methodology-shows-258-million-children-adolescents-and-youth-are-out-school. Montreal, QC, Canada: UNESCO Institute for Statistics; 2019 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/new-methodology-shows-258-million-children-adolescents-and-youth-are-out-school.pdf. [Google Scholar]

16. School CTFL. 32% of Chinese middle school students have psychological problems; Beijing Students’ “School Refusal Rate” at 30% 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.tangwai.com/sitehtml/news/jy/2005/32709.htm. [Google Scholar]

17. Zhao G, Wang B, Li H, Ren H, Jiao Z. The relationship between depressive and anxious symptoms and school attendance among adolescents seeking psychological services in a public general hospital in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):456. doi:10.1186/s12888-023-04813-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wu X, Liu F, Zhu L, Shi S. Impact of different treatment methods of school refusal among adolescents. China J Sch Health. 2007;28(6):519–20. [Google Scholar]

19. Gonzálvez C, Inglés CJ, Sanmartín R, Vicent M, Calderón CM, García-Fernández JM. Testing factorial invariance and latent means differences of the school refusal assessment scale-revised in Ecuadorian adolescents. Curr Psychol. 2018;39(5):1715–24. doi:10.1007/s12144-018-9871-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Walter D, von Bialy J, von Wirth E, Doepfner M. Psychometric properties of the German school refusal assessment scale—revised. J Psychoeduc Assess. 2018;36(6):644–8. doi:10.1177/0734282916689641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Heyne DA, Vreeke LJ, Maric M, Boelens H, Van Widenfelt BM. Functional assessment of school attendance problems: an adapted version of the school refusal assessment scale-revised. J Emot Behav Disord. 2017;25(3):178–92. doi:10.1177/1063426616661701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Egger HL, Costello EJ, Angold A. School refusal and psychiatric disorders: a community study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(7):797–807. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000046865.56865.79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Kearney CA. Depression and school refusal behavior: a review with comments on classification and treatment. J Sch Psychol. 1993;31(2):267–79. doi:10.1016/0022-4405(93)90010-g. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Dube SR, Orpinas P. Understanding excessive school absenteeism as school refusal behavior. Child Sch. 2009;31(2):87–95. doi:10.1093/cs/31.2.87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Green H, McGinnity A, Meltzer H, Ford T, Goodman R. Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain, 2004. London, UK: The Office for National Statistics; 2005. [Google Scholar]

26. Leduc K, Tougas AM, Robert V, Boulanger C. School refusal in youth: a systematic review of ecological factors. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2024;55(4):1044–62. doi:10.1007/s10578-022-01469-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Flakierska-Praquin N, Lindstrom M, Gillberg C. School phobia with separation anxiety disorder: a comparative 20-to 29-year follow-up study of 35 school refusers. Compr Psychiatry. 1997;38(1):17–22. doi:10.1016/s0010-440x(97)90048-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Tekin I, Erden S, Şirin Ayva AB, Büyüköksüz E. The predictors of school refusal: depression, anxiety, cognitive distortion and attachment. J Hum Sci. 2018;15(3):1519–29. doi:10.14687/jhs.v15i3.5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wood JJ, Lynne-Landsman SD, Langer DA, Wood PA, Clark SL, Eddy JM, et al. School attendance problems and youth psychopathology: structural cross-lagged regression models in three longitudinal data sets. Child Dev. 2012;83(1):351–66. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01677.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Kingery JN, Erdley CA, Marshall KC. Peer acceptance and friendship as predictors of early adolescents’ adjustment across the middle school transition. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2011;57(3):215–43. [Google Scholar]

31. Brody DJ, Hughes JP. Depression prevalence in adolescents and adults: United States, August 2021–August 2023. Hyattsville, MD, USA: National Center for Health Statistics; 2025. Report No.: 527. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/index.htm2025. [Google Scholar]

32. Gonzalvez C, Ingles CJ, Kearney CA, Vicent M, Sanmartin R, Garcia-Fernandez JM. School refusal assessment scale-revised: factorial invariance and latent means differences across gender and age in spanish children. Front Psychol. 2016;7:2011. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.02011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Singh G, Sharma S, Sharma V, Zaidi SZH. Academic stress and emotional adjustment: a gender-based post-COVID study. Ann Neurosci. 2023;30(2):100–8. doi:10.1177/09727531221132964. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Kristensen SM, Larsen TMB, Urke HB, Danielsen AG. Academic stress, academic self-efficacy, and psychological distress: a moderated mediation of within-person effects. J Youth Adolesc. 2023;52(7):1512–29. doi:10.1007/s10964-023-01770-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Chen J, Feleppa C, Sun T, Sasagawa S, Smithson M, Leach L. School refusal behaviors: the roles of adolescent and parental factors. Behav Modif. 2024;48(5–6):561–80. doi:10.1177/01454455241276414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Sanchis-Sanchis A, Grau MD, Moliner AR, Morales-Murillo CP. Effects of age and gender in emotion regulation of children and adolescents. Front Psychol. 2020;11:946. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00946. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Yu Z, Jiang X. How school climate affects student performance: a fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis based on the perspective of education system. Math Probl Eng. 2022;2022(1):7975433. doi:10.1155/2022/7975433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams JB. The PHQ-9 validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Wang W, Bian Q, Zhao Y, Li X, Wang W, Du J, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(5):539–44. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.05.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Leung DYP, Mak YW, Leung SF, Chiang VCL, Loke AY. Measurement invariances of the PHQ-9 across gender and age groups in Chinese adolescents. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2020;12(3):e12381. doi:10.1111/appy.12381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Kearney CA. Identifying the function of school refusal behavior: a revision of the school refusal assessment scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2002;24(4):235–45. doi:10.1023/a:1020774932043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kearney CA. Confirmatory factor analysis of the school refusal assessment scale-revised: child and parent versions. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2006;28(3):139–44. doi:10.1007/s10862-005-9005-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Shi D, Lee T, Maydeu-Olivares A. Understanding the model size effect on SEM fit indices. Educ Psychol Meas. 2019;79(2):310–34. doi:10.1177/0013164418783530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct Equ Model. 2002;9(2):233–55. doi:10.1207/s15328007sem0902_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct Equ Model. 2001;8(3):430–57. doi:10.1207/s15328007sem0803_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Rao WW, Xu DD, Cao XL, Wen SY, Che WI, Ng CH, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents in China: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:790–6. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Fu X, Zhang K, Chen X, Chen Z. Report on national mental health development in China (2021–2022). Beijing, China: Social Sciences Academic Press; 2023. [Google Scholar]

48. Orth U, Meier LL, Bühler JL, Dapp LC, Krauss S, Messerli D, et al. Effect size guidelines for cross-lagged effects. Psychol Methods. 2024;29(2):421. doi:10.1037/met0000499. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Thambirajah MS, Granduson KJ, De-Hayes L. Understanding school refusal: a handbook for professionals in education, health and social care. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

50. Stice E, Rohde P, Gau J, Ochner C. Relation of depression to perceived social support: results from a randomized adolescent depression prevention trial. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49(5):361–6. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.02.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Orth U, Robins RW. Understanding the link between low self-esteem and depression. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22(6):455–60. doi:10.1177/0963721413492763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Kearney C. Helping school refusing children and their parents: a guide for school-based professionals. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

53. Moreno-Agostino D, Wu YT, Daskalopoulou C, Hasan MT, Huisman M, Prina M. Global trends in the prevalence and incidence of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:235–43. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Thompson EA, Eggert LL, Herting JR. Mediating effects of an indicated prevention program for reducing youth depression and suicide risk behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2000;30(3):252–71. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278x.2000.tb00990.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Werner-Seidler A, Spanos S, Calear AL, Perry Y, Torok M, O’Dea B, et al. School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;89(8):102079. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102079. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Tsang HW, Cheung WM, Chan AH, Fung KM, Leung AY, Au DW. A pilot evaluation on a stress management programme using a combined approach of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for elementary school teachers. Stress Health. 2015;31(1):35–43. doi:10.1002/smi.2522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Zeng Q, Liang Z, Zhang M, Xia Y, Li J, Kang D, et al. Impact of academic support on anxiety and depression of Chinese graduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic: mediating role of academic performance. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:2209–19. doi:10.2147/prbm.s345021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Jin X, Sangwoo H. Using online information support to decrease stress, anxiety, and depression. KSII Trans Internet Inf Syst. 2021;15(8):2944–58. [Google Scholar]

59. Garaigordobil M, Jaureguizar J, Bernaras E. Evaluation of the effects of a childhood depression prevention program. J Psychol. 2019;153(2):127–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

60. Ritkumrop K, Surakarn A, Ekpanyaskul C. The effectiveness of an integrated counseling program on emotional regulation among undergraduate students with depression. J Health Res. 2022;36(2):186–98. doi:10.1108/jhr-03-2020-0067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Hetrick SE, Cox GR, Merry SN. Where to go from here? An exploratory meta-analysis of the most promising approaches to depression prevention programs for children and adolescents. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2015;12(5):4758–95. doi:10.3390/ijerph120504758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Maynard BR, Brendel KE, Bulanda JJ, Heyne D, Thompson AM, Pigott TD. Psychosocial interventions for school refusal with primary and secondary school students: a systematic review. Campbell Syst Rev. 2015;11(1):1–76. doi:10.4073/csr.2015.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Lyon AR, Cotler S. Multi-Systemic intervention for school refusal behavior: integrating approaches across disciplines. Adv Sch Ment Health Promot. 2009;2(1):20–34. doi:10.1080/1754730x.2009.9715695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Elsherbiny MM. Using a preventive social work program for reducing school refusal. Child Sch. 2017;39(2):81–8. doi:10.1093/cs/cdx005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Kearney CA, Albano AM. When children refuse school: a cognitive-behavioral therapy approach: therapist guide. 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

66. Finan SJ, Yap MBH. Engaging parents in preventive programs for adolescent mental health: a socio-ecological framework. J Fam Theory Rev. 2021;13(4):515–27. doi:10.1111/jftr.12440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Monzon N, Hays FA. Leveraging generative artificial intelligence to improve motivation and retrieval in higher education learners. JMIR Med Educ. 2025;11(1):e59210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

68. Slotkin R, Bierman KL, Jacobson LN. Impact of a school-based social skills training program on parent-child relationships and parent attitudes toward school. Int J Behav Dev. 2023;47(6):475–85. doi:10.1177/01650254231198031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Balakrishnan RD, Andi HK. Factors associated with school refusal behaviour in primary school students. Muall J Soc Sci Humanit. 2019;3:1–13. [Google Scholar]

70. Hendron M, Kearney CA. School climate and student absenteeism and internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems. Child Sch. 2016;38(2):109–16. doi:10.1093/cs/cdw009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. McShane G, Walter G, Rey JM. Characteristics of adolescents with school refusal. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35(6):822–6. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00955.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Li G, Niu Y, Liang X, Andari E, Liu Z, Zhang KR. Psychological characteristics and emotional difficulties underlying school refusal in adolescents using functional near-infrared spectroscopy. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):898. doi:10.1186/s12888-023-05291-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Richardson K. Family therapy for child and adolescent school refusal. Aust New Zealand J Fam Ther. 2016;37(4):528–46. doi:10.1002/anzf.1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Kljakovic M, Kelly A, Richardson A. School refusal and isolation: the perspectives of five adolescent school refusers in London. UK Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;26(4):1089–101. doi:10.1177/13591045211025782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Hamaker EL, Kuiper RM, Grasman RP. A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychol Methods. 2015;20(1):102–16. doi:10.1037/a0038889. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Little TD. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools