Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of Pre-Class Acute Exercise on Executive Function in University Students

1 Body-Brain-Mind Laboratory, School of Psychology, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, 518060, China

2 Shenzhen College of International Education, Shenzhen, 518043, China

3 Department of Sport, Exercise and Health, Division Sport and Psychosocial Health, University of Basel, Grosse Allee 6, Basel, 4052, Switzerland

4 Department of Physical Education, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai, 200240, China

5 School of Biomedical Engineering, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z3, Canada

6 Aging, Mobility, and Cognitive Health Laboratory, Department of Physical Therapy, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 2B5, Canada

7 Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z3, Canada

8 Centre for Aging Solutions for Mobility, Activity, Rehabilitation and Technology (SMART) at Vancouver Coastal Health, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, Vancouver, BC V5Z 1M9, Canada

9 Center for Cognitive and Brain Health, Northeastern University, Boston, MA 02115, USA

10 Department of Psychology, Northeastern University, Boston, MA 02115, USA

11 Department of Physical Therapy, Movement, and Rehabilitation, Northeastern University, Boston, MA 02115, USA

12 AdventHealth Research Institute, Department of Neuroscience, AdventHealth, Orlando, FL 32101, USA

13 Beckman Institute, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801, USA

14 Epidemiology of Psychiatric Conditions, Substance Use and Social Environment (EPiCSS), Department of Public Health Sciences, Karolinska Institute, Solna, 171 77, Sweden

15 Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition (IPAN), Deakin University, Melbourne, VIC 3125, Australia

16 School of Education, Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia

17 Department of Psychology, Education, and Child Studies, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, P.O. Box 1738, The Netherlands

18 School of Education, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 1466, Australia

19 Canadian Centre for Activity and Aging, University of Western Ontario, London, ON N6A 3K7, Canada

20 School of Kinesiology, University of Western Ontario, London, ON N6A 3K7, Canada

21 Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, HMU Health and Medical University Erfurt, Erfurt, Thuringia, 99089, Germany

* Corresponding Author: Liye Zou. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(10), 1439-1455. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.069633

Received 27 June 2025; Accepted 27 August 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

Background: There is growing evidence that an acute bout of exercise positively influences executive function (EF). However, the existing evidence primarily originates from laboratory-based studies, and only a limited number of studies have extended this work to real-world classroom settings. Accordingly, in the present study, we aimed to employ a real classroom setting to determine whether acute exercise-induced effects on EF emerged. Methods: All 49 students who enrolled in a real-world course agreed to participate in the experimental protocol and the final sample was composed of 43 individuals (13 male and 30 female participants). Participants were asked to perform an acute bout of exercise (i.e, 10 min at moderate intensity) before a real classroom, and on a separate day, complete a non-exercise control condition. EF was assessed via Naming, Inhibition, and Switching variants of the Stroop task. We used a paired-samples t-test to compare participants' cognitive load between two conditions and a repeated-measures ANOVA to investigate changes in RPE. What's more, a repeated measures ANOVA was used to examine potential pre- to post-class changes in EF-related parameters (e.g., inverse efficiency scores, reaction times, and error rates). Results: A pre- to post-class benefit in performance efficiency across all Stroop task variants was shown. In both exercise and control conditions, there was a significant main effect of time, with lower inverse efficiency scores (IES) (p = 0.003) and shorter reaction times (RT) (p < 0.001) observed from pre- to post-class. Moreover, performance gains varied by Stroop task-type, with the Switching task showing the longest RTs and largest IES, reflecting its greater cognitive demands. Importantly, a marginally significant three-way interaction among task-type, intervention, and time (p = 0.052) indicated that the exercise intervention enhanced post-class performance on the Switching task. Post-hoc analyses revealed significantly lower IES and faster RTs at post-class for both the Naming and Switching tasks, particularly in the exercise group (e.g., Switching IES: p < 0.001; Switching RT: p < 0.001). Conclusions: These findings suggest that pre-class acute exercise enhances EF and provides a benefit to cognitive flexibility. Accordingly, our results extend previous knowledge by indicating that the cognitive benefits of acute exercise observed primarily in laboratory settings can be translated to real-world educational contexts.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileExecutive function (EF) is a set of higher-order cognitive functions that include the core components of inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility [1]. EF is necessary to regulate goal-directed behavior and is a significant predictor of academic performance, health behavior (e.g., smoking, alcohol, and drug use), and future career success in college-aged populations [1,2]. In this context, there is a growing interest in understanding how modifiable lifestyle factors, such as sedentary behavior and physical activity, can shape EF, especially in younger ages [1,3–5].

Sedentary behaviour (SB) is defined as any waking behavior in a sitting, reclining, or lying posture with an energy expenditure of 1.5 METs (metabolic equivalents) or lower [6,7]. In industrialized societies, prolonged sitting (e.g., sitting over 30 min) is one of the most prevalent and pervasive forms of SB [6,7] and is particularly salient in educational settings wherein students are required to sit for the duration of a lecture or classroom demonstration [8–11]. Previous studies have reported that prolonged seating is associated with reduced inhibitory control as measured via the Flanker [12] and Stroop tasks [13]. Thus, convergent evidence indicates the negative effects of SB on EF.

Physical activity (PA) is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscle contractions that results in energy expenditure of >1.5 METs, and includes planned and structured forms of PA—typically referred to as physical exercise [14,15]. Previous meta-analytical reviews have consistently reported small but significant improvements in EF across various age groups following long-term exercise interventions [16–19]. Such an effect has also been observed following a single bout of exercise (also referred to as acute exercise) [20–22].

Acute exercise interventions have emerged as a promising approach to improve EF [20,21,23,24]. However, it remains unclear as to whether acute exercise reliably ameliorates the deleterious impact of prolonged sitting in a classroom. To this end, Yu et al. had college students complete a single 15-min session of light-intensity exercise (i.e., cycling) between two 45-min periods of sitting [25]. Results showed that acute exercise produced increased functional connectivity within the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and was linked to improved inhibitory control. Similarly, Heiland et al. found that healthy young adults who performed 3 min of acute exercise every 30 min during 3 h of sitting showed decreased right PFC activation and improved working memory, mood, and alertness [26]. In turn, Yu et al. reported that young adults who completed a 15-min exercise break during 115 min of sitting showed improved EF and increased activity within EF-related brain regions [27]. Given that acute SB, namely prolonged sitting, can be detrimental to EF [12,13] and acute exercise can effectively improve EF [20,22], the present study aimed to explore whether pre-class acute exercise effectively circumvents or ameliorates the documented negative effects of prolonged sitting on EF.

Notably, the majority of work to examine whether the interruption of prolonged sitting via acute exercise impacts EF was conducted in controlled laboratory settings [28–30]. Thus, it is unclear whether such findings can be generalized to real-world settings. Additionally, previous studies in this domain have focused on individual exercises (e.g., cycling) [28,29] and are thus not practical or implementable with a real-world (and group-based) classroom setting. What is more, previous studies often did not provide a basis to evaluate the cognitive load associated with class learning during prolonged sitting. This represents an important consideration because cognitive load is a construct for assessing available EF resources. Indeed, although cognitive load has been widely studied in the context of information processing [31], a recent review suggested that it may also serve as a potential mechanism influencing the cognitive benefits of exercise interventions [32]. Therefore, carefully controlling for cognitive load—particularly that induced by classroom content—is crucial for ensuring the precision and validity of findings in real-world educational settings. As such, in the current study, all participants were exposed to the same real-world classroom as a method to control for cognitive load between pre- and post-intervention assessments of EF.

Collectively, the present study employed group-based, equipment-free exercises (e.g., synchronized aerobic dance workouts) to examine the potential effect of a period of SB interspersed with a 10-min session of exercise impacts EF. As well, the present study used a standardized sequence of interventions and systematically measured cognitive load after each session to provide a more direct examination of the cognitive effects of acute exercise in realistic educational contexts. To simulate a real-world scenario, a 10-min exercise intervention and a 45-min classroom-based sitting period were set to coincide with a lecture period delivered at a Chinese university. Our primary aims were to (1) investigate the impact of classroom-based prolonged sitting on different aspects of EF (e.g., inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility); and (2) determine whether a single pre-class bout of exercise can alleviate or reverse the purported negative effects of prolonged sitting on EF.

Students were recruited at Shenzhen University located in the Southern area of China, and were included based on the following criteria: (1) between 18 and 25 years of age [33–36]; (2) normal or corrected-to-normal vision [37]; (3) self-reported being right-handed [38]; (4) not pregnant or lactating [39]; (5) no major chronic illnesses, psychiatric histories, or intellectual deficits; and (6) at a low risk for PA-related adverse events as assessed by the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) [40].

The required sample size for this study was determined using G*Power 3.1 [41], and input parameters from previous research stating that acute exercise generally has a small-to-medium effect on cognition [20,23]. Accordingly, taking a medium effect size of f = 0.25, with a significance level of α = 0.05, and a two-factor repeated-measures ANOVA within-participant design, 36 participants were required to achieve 95% statistical test power. To ensure ecological validity, we implemented the study in a natural classroom setting, and all 49 students enrolled in the course agreed to participate in the experimental protocol. Valid data were obtained from 43 participants, reflecting an attrition rate of 12% (6 out of 49), which exceeded the minimum sample size of 36. This study adhered to the principles outlined in the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee of Shenzhen University (SZU_PSY_2024_171). All participants provided written informed consent before their participation.

Before the start of the experiment, all participants were required to complete a comprehensive baseline questionnaire that included the assessment of demographic information, PA levels, workday sedentary time, sleep quality, and mental health status (e.g., depression, anxiety, and stress), given that such variables influence cognitive outcomes [7,27,42–44]. In addition, for the exercise intervention used here (see details below), participants reported their subjective exercise intensity to validate whether the intervention effectively induced changes in perceived effort. As well, participants rated their perceived cognitive load during the lecture to assess whether the instructional content introduced varying cognitive demands between the exercise and control interventions used here.

2.2.1 Regular Physical Activity Level

PA and SB were assessed using the Chinese version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF) [45], which captures levels of PA and SB on working days. Total physical activity was quantified in metabolic equivalents (METs) by calculating a weighted sum of activity duration based on intensity, following the standard approach outlined by Macfarlane et al. [46].

2.2.2 Subjective Sleep Quality

Sleep quality was evaluated using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [47], which assesses subjective sleep quality over the past month. The PSQI consists of 19 self-report items across 7 dimensions: sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, daytime dysfunction, and overall subjective sleep quality. Each dimension is scored on a 0–3 Likert scale, yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality.

Mental health status—including symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress—was measured using the 21-item version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21) [48]. The depression subscale reflects low mood, low self-esteem, and an absence of positive affect; the anxiety subscale captures somatic and cognitive symptoms of anxious arousal; and the stress subscale assesses tension, worry, and irritability. Responses were rated on a 4-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater emotional distress.

The intensity associated with the exercise intervention (see details below) was assessed using the Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) [49]. Participants rated their fatigue on a scale from 6 to 20, with 6 representing minimal exertion and 20 indicating maximal exertion. Previous research has shown that the RPE provides a valid proxy for objective measures of exercise intensity [50].

Cognitive load was assessed using the Cognitive Load Scale [51], a single-item measure (i.e., Likert Scale) allowing for a time-efficient and easily administrable assessment of university students’ individual level of cognitive engagement in a university course(s). As in previous studies [51,52], participants rated their level of cognitive load on a 9-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very low mental effort) to 9 (very high mental effort).

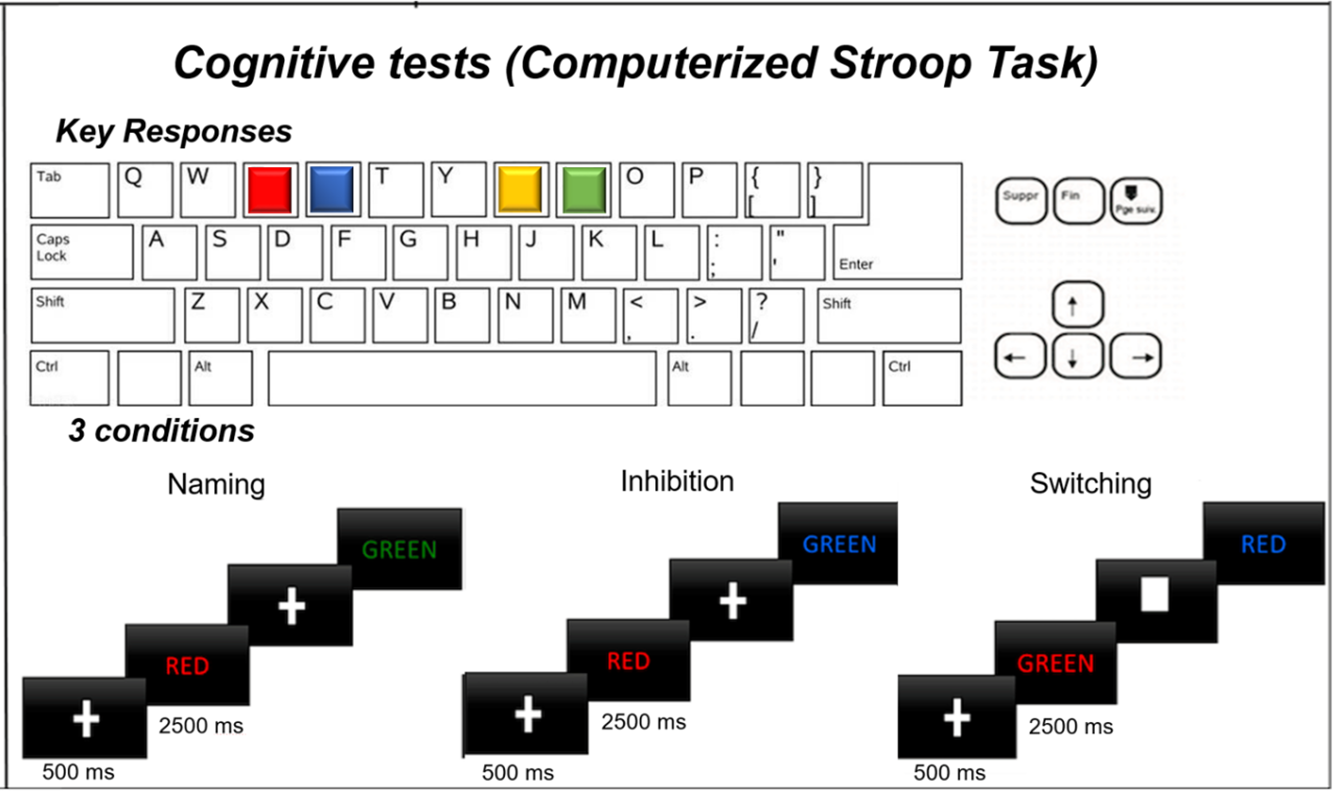

In the current study, we used a modified computerized Stroop Task to investigate the effects of exercise on EF [53–55]. The following variants of the Stroop task were used to assess EF: (1) Naming task, (2) Inhibition task, and (3) Switching task. Each task was administered in a separate block, presented in a fixed order (Naming → Inhibition → Switching), and included 60 trials/block. For the Stroop task, stimuli were presented in a randomized order using PsychoPy (version 2021.1) [56–58].

For Naming and Inhibition tasks, each trial began with a central fixation cross (“+”) presented for 500 ms, followed by a color word (RED, BLUE, GREEN, or YELLOW) displayed in colored font for 2500 ms. Participants were instructed to respond to the font color in both tasks. In the Naming task (i.e., standard task), all stimuli were congruent (e.g., the word “RED” displayed in red), providing a measure of basic color-naming performance under minimal cognitive interference. In the Inhibition task (i.e., non-standard task), the meaning of the word and the colour of the ink in which the word was presented were incongruent (e.g., the word “RED” displayed in blue). Accordingly, the task required participants to suppress the automatic tendency to complete a standard response and instead evoke a non-standard volitional response (i.e., inhibitory control).

The Switching task required participants to alternate between two response rules. As in the previous tasks, each trial began with a fixation cue, but now the nature of the cue signaled the associated task rule. Specifically, a central cross (i.e., “+”) indicated a non-standard color-naming trial, whereas a central filled rectangle (i.e., “■”) indicated a standard word-naming trial. The ratio of colour- and word-naming trials was 3:1 and ensured a high level of response conflict and sustained EF demands. Stimulus timing remained consistent across all Stroop task variants. Fig. 1 presents a schematic of the timeline and response requirements associated with the different variants of the Stroop task. Across all Stroop task variants, reaction time (RT, ms) and error rate (ER, %) were recorded. To obtain a composite measure accounting for response speed and accuracy, we computed an Inverse Efficiency Score (IES) (see Eq. (1) below), with a lower score indicating better performance [59]:

Figure 1: Schematic illustration of the modified computerized Stroop task widely used in previous studies [53–55]

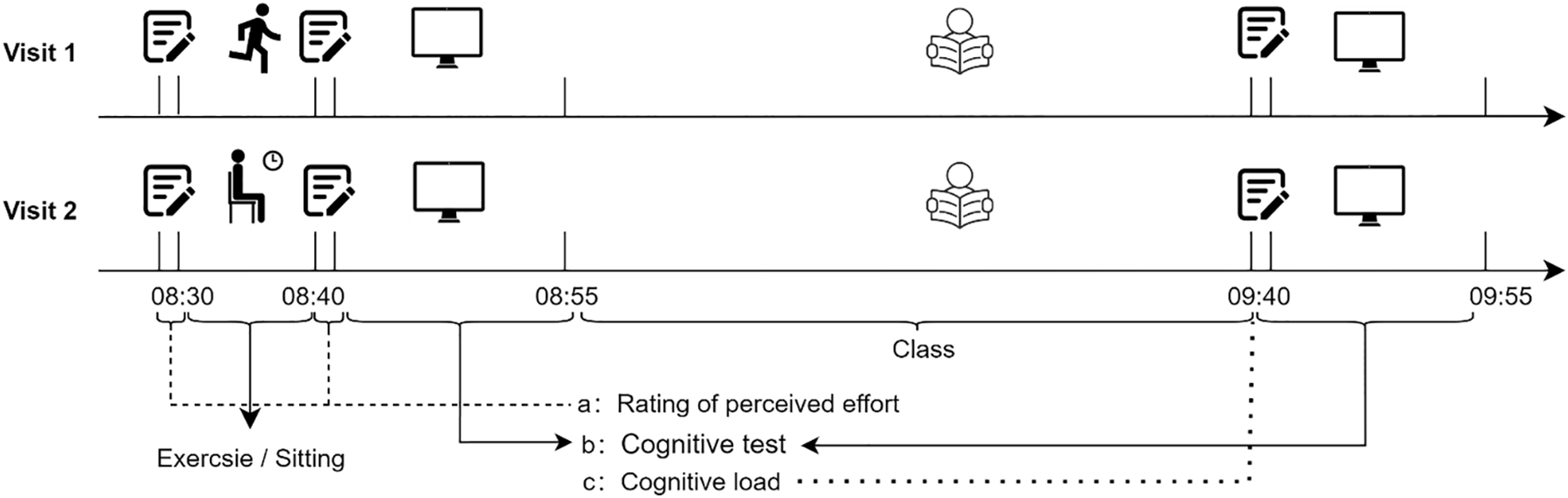

In the exercise intervention, all 49 participants arrived in the classroom and began the intervention before class started. The exercise intervention consisted of a 90-s standardized warm-up, 450 s of moderate-intensity exercise incorporating movements such as running in place, knee lifts, and deep squats, and a final 60-s recovery session. To validate the exercise intensity, participants provided their RPE on a 6-20 Borg Scale [49] at a pre-exercise baseline (8:30 a.m.) and immediately after the exercise intervention (8:40 a.m.). In the control intervention, participants remained seated in the same classroom as was used for the exercise intervention and for the same time frame as the exercise, but without engaging in exercise. To standardize between-intervention, RPE was also recorded in the control intervention (see Fig. 1).

In both interventions, participants completed a pre-class assessment of EF via the above-mentioned variants of the Stroop (~15-min to complete) followed by a 45-min standardized academic lesson, delivered by a trained instructor, during which all participants remained seated. Immediately after the lesson, participants reported their perceived cognitive load of the lesson using the Cognitive Load Scale [51]. Lastly, participants completed a second 15-min Stroop task (9:40–9:55 a.m.) to evaluate post-class cognitive performance. A room temperature environment of 22 ± 2°C was maintained throughout the experiment. To standardize the experimental procedures and control for the effects of circadian rhythms, exercise and control interventions were conducted at the same time period in the morning (8:30–10:15 a.m.), which corresponds to the Chinese university students' schedule.

This experiment utilized a 2 (test time: pre-/post-class) × 3 (Stroop task-type: Naming task/Inhibition task/Switching task) × 2 (condition: exercise/sedentary) repeated measures design. As our study was conducted in a real-world setting, we did not perform a parallel-group or randomized controlled trial because such study designs would have necessitated splitting a class into different groups engaging in different conditions (e.g., exercise vs. sitting) within the same classroom. In addition, to preserve ecological validity, we adopted a fixed-order within-subjects design (i.e., all participants were uniformly assigned to the exercise condition at the first visit, and after 14-day intervals, they engaged in the sitting condition at the second visit). Such an arrangement would have been impractical and may have introduced some specific bias (e.g., placebo responses or behavioral shifts due to participants observing peers in alternate conditions), which, in turn, would have compromised the study’s internal validity [60]. Furthermore, the within-subjects design, as used in this study, minimized the confounding effects of between-subject variability (e.g., baseline cognitive level or aerobic fitness), which is inherent to parallel group studies [22,61]. While this fixed sequence limits our ability to fully disentangle potential carryover effects, such an approach ensured the feasibility of conducting such a study in a real-world setting while maintaining consistency across sessions and minimizing contextual interference (see Fig. 2 for a visualization of the experimental procedures).

Figure 2: Schematic illustration of the experimental procedures

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS (Version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were first computed for participants' demographic characteristics, movement behaviors, and mental health. To assess the distributional properties of the data, normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and homogeneity of variance was verified with Levene's test. Sphericity was evaluated using Mauchly’s test, and where appropriate, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied if the epsilon value was <0.75, whereas the Huynh-Feldt correction was used if the epsilon value was >0.75.

We used paired-samples t-tests to compare participants’ cognitive load between two conditions to ensure that putative pre- to post-class changes in EF were not confounded by variations in class design. In addition, a two (condition: exercise vs. control) × two (test time: before vs. after intervention) repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to investigate changes in RPE.

A repeated measures ANOVA was used to examine potential pre- to post-class changes in EF-related parameters (e.g., inverse efficiency scores, reaction times, and error rates). Significant interactions identified in the ANOVA were examined using simple effects analyses. Effect sizes were reported where relevant: partial η2 for ANOVA and Cohen’s d for t-tests. Specifically, Cohen’s d: low (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), and large (d = 0.8); partial η²: low (η2 = 0.01), medium (η2 = 0.06), and large (η2 = 0.14) [62]. All statistical tests were two-tailed with a significance level set at α < 0.05.

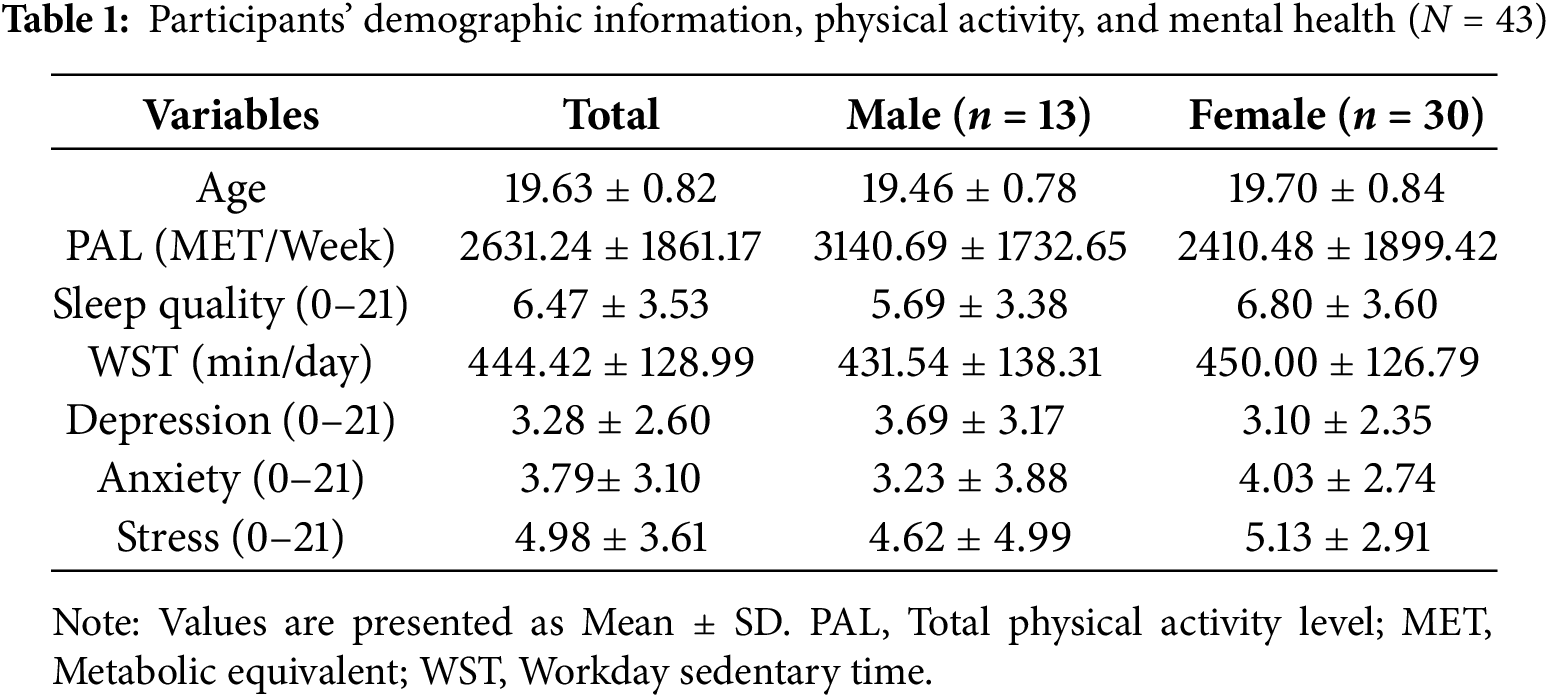

3.1 Participants Characteristics

The final sample was composed of 43 individuals (13 male and 30 female participants), for whom demographic characteristics, movement behaviour (i.e., PA, sleep, and SB), and mental health are shown in Table 1. Six of the original 49 participants were excluded from our analyses because they failed to complete the exercise intervention (n = 2) or achieve less than 70% response accuracy on the EF task (n = 4). The exclusion criterion for accuracy was based on previous research indicating that performance falling more than three standard deviations below a mean level of accuracy indicates possible misunderstanding of task goals [54,63–65].

3.2 Manipulation of Cognitive Load and RPE

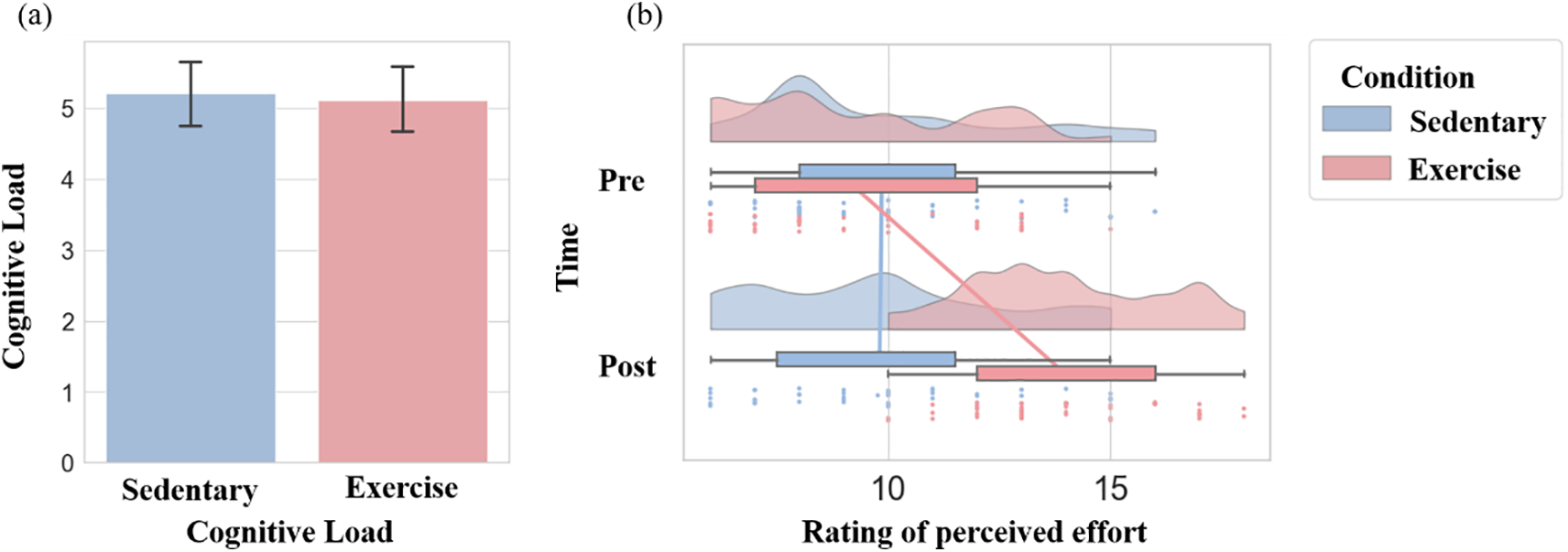

A paired samples t-test for cognitive load revealed no statistically significant difference between control (Mean = 5.21, SD = 1.55) and exercise (Mean = 5.12, SD = 1.50) interventions, t(42) = 0.64, p = 0.52, Cohen’s d = 0.06—a result indicating no confounding effect of class on cognitive outcomes for the two interventions.

In terms of RPE, results yielded a significant main effect of intervention, F(1, 42) = 32.26, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.43, and an interaction between intervention and time, F(1, 42) = 79.79, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.66. In the exercise intervention, RPE increased from before (Mean = 9.21, SD = 2.61) to after the intervention (Mean = 13.98, SD = 2.19), t(42) = 10.06, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.83, whereas the control intervention showed no statistically significant before (Mean = 9.86, SD = 2.84) to after intervention change (Mean = 9.81, SD = 2.72), t(42) = 0.18, p = 0.86, Cohen’s d = 0.02. Manipulation of cognitive load and RPE are demonstrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Manipulation check results for cognitive load and rating of perceived exertion. (a) Paired t-test for cognitive load, visualizing mean and standard error across conditions. (b) Repeated-measures ANOVA results for rating of perceived exertion. The half-violin plot shows data density; scatter dots represent individual data points; and the boxplot with connecting lines indicates trends. The legend between intervention conditions indicates condition color coding

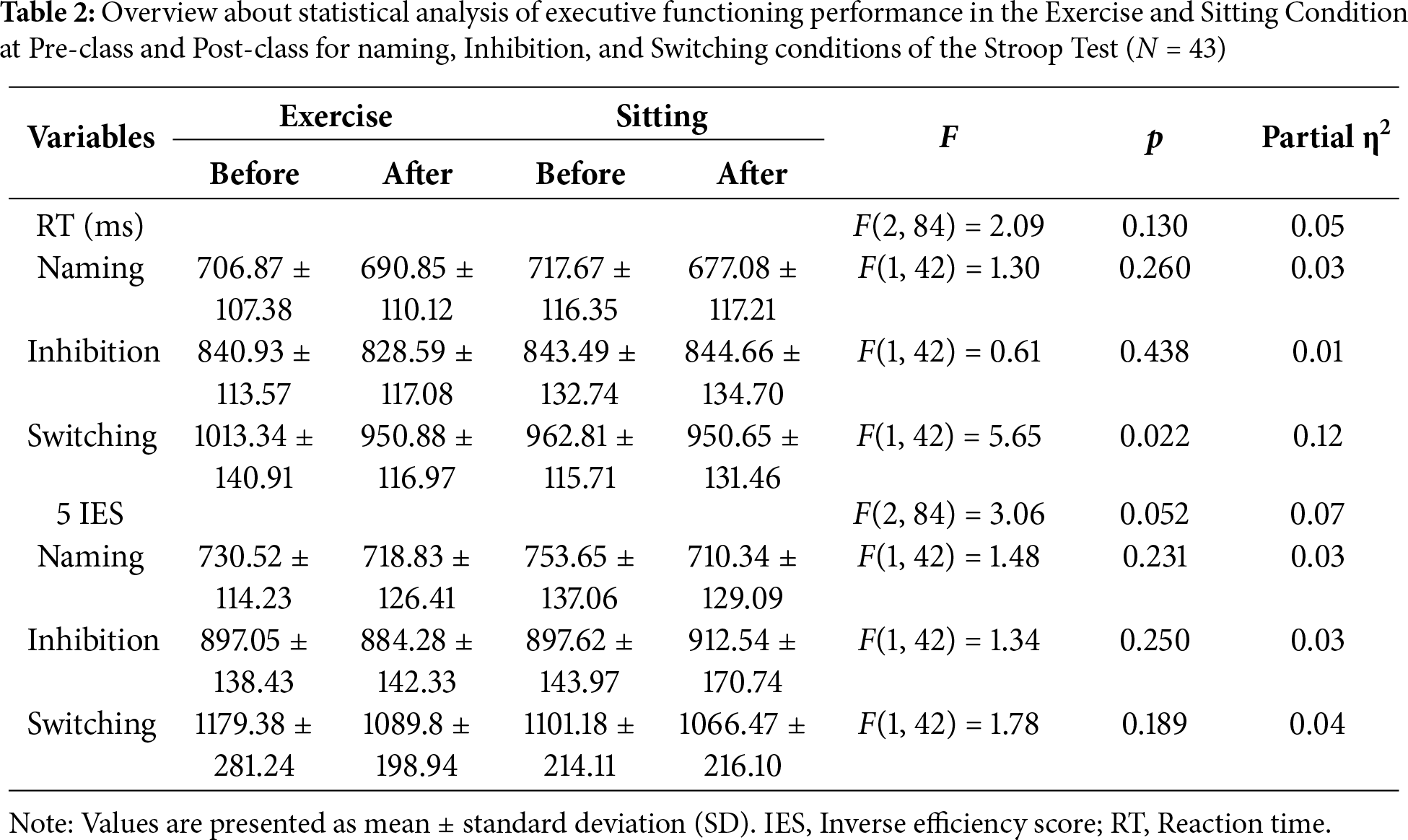

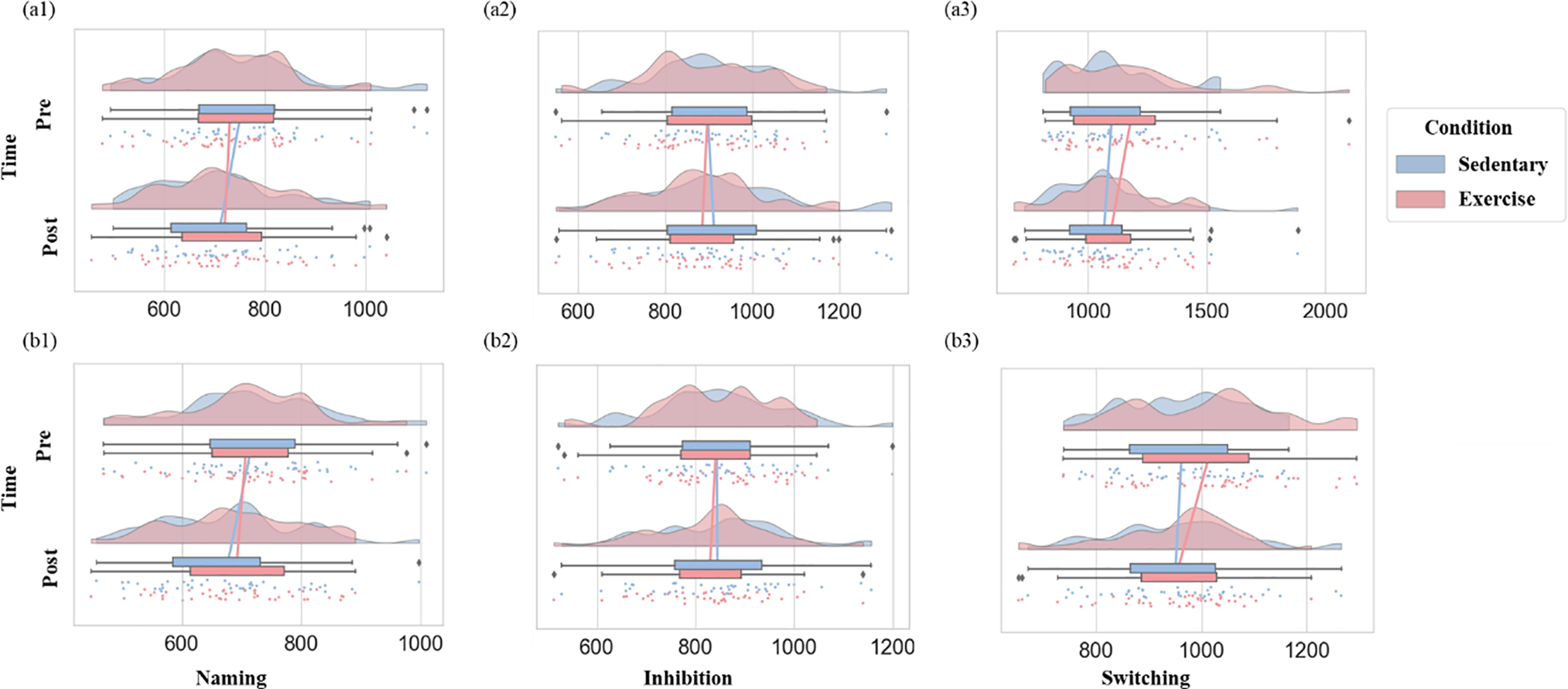

3.3 Executive Function before and after a Real Class under Exercise and Sitting Conditions

For IES and RT, both the normality test and Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance were satisfied. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2. Nevertheless, the normality tests revealed that error rates were not normally distributed across the different Stroop task variants. As a result, a non-parametric approach was used to analyze, and the final results are available in Supplementary Materials.

3.3.1 Inverse Efficiency Score

For IES, there was a significant main effect of task type (F(1.4, 58.1) = 220.30, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.84). The Naming task yielded significantly lower IES compared to Inhibition (Δ = −169.54, p < 0.001) and Switching (Δ = −380.87, p < 0.001) tasks, and this result indicates that tasks with higher cognitive demand were associated with higher IES and thus poorer cognitive performance. A main effect of intervention was not significant (F(1,42) = 0.61, p = 0.44, partial η2 = 0.014); however, a significant main effect of test time was detected (F(1,42) = 9.71, p = 0.003, partial η2= 0.19), indicating that overall IES was improved from pre- to post-class assessments (Δ = 29.52, p = 0.003).

The ANOVA revealed no significant interaction effects of task type, intervention condition, and test time (F(2,84) = 2.09, p = 0.13, partial η2 = 0.05). In light of the non-significant three-way interaction, 2 (intervention condition: exercise/sitting) × 2 (test time: before class/after class) analyses were conducted separately for each task to better understand potential task-specific patterns. For the Naming task, a significant main effect of test time was found (F(1, 42) = 6.05, p = 0.02, partial η2 = 0.13), indicating that IES was significantly higher at pre- than post-class (Δ = 27.50, p = 0.02, Cohen’s d = 0.23). Similarly, for the Switching task, a significant main effect of test time (F(1, 42) = 10.57, p = 0.002, partial η2 = 0.20) demonstrated that IES values were greater at pre- than post-test (Δ = 62.14, p = 0.002, Cohen’s d = 0.33). For the Switching task, a significant interaction between intervention condition and time was observed (F(1, 42) = 5.65, p = 0.02, partial η2 = 0.12). In the exercise condition, participants showed significantly higher IES values at pre- compared to post-test (Δ = 62.46, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.26), whereas for the control condition pre- and post-class values did not differ (Δ = 12.16, p = 0.35, Cohen’s d = 0.06) (see Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Executive function results. (a1) inverse efficiency scores (IES) in naming task; (a2) IES for inhibition task; (a3) IES for switching task; (b1) reaction time (RT) for naming task; (b2) RT for inhibition task; (b3) RT for switching task. The half-violin plot shows data density; scatter dots represent individual data points; and the boxplot with connecting lines indicates trends. The legend indicates condition color coding. Abbreviations. Pre, Pre-class; Post, Post-class

For RT, the intervention condition did produce a significant main effect (F(1, 42) = 0.55, p = 0.463, partial η2 = 0.013). In contrast, test time showed a significant main effect (F(1, 42) = 15.62, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.27) with RTs showing a pre- to post-class reduction (Δ = 24 ms, p < 0.001). Task type also had a significant main effect (F(1.607, 67.504) = 327.49, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.89): RTs were significantly shorter for the Naming task than for Inhibition (Δ = −141 ms, p < 0.001) and Switching (Δ = −271 ms, p < 0.001) tasks.

A three-way interaction between task type, intervention condition, and test time approached a conventional level of statistical significance (F(2, 84) = 3.06, p = 0.052, partial η2 = 0.07). Simple effects analyses revealed that for Naming task, RTs in the sitting condition were significantly longer at pre- than post-class assessment (Δ = 41 ms, p = 0.01, Cohen’s d = 0.40), whereas in the exercise condition, pre- and post-class RTs did not differ (Δ = 16 ms, p = 0.175, Cohen’s d = 0.19). In contrast, for the Switching task, significantly longer pre-class RTs were observed in the exercise condition (Δ = 62 ms, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.61), whereas no significant difference was found in the sitting condition (Δ = 12 ms, p = 0.35, Cohen’s d = 0.13). Separate 2 (intervention condition: exercise vs. sitting) × 2 (test time: before class vs. after class) ANOVAs for the three tasks indicated a significant main effect of test time for the Naming task (F(1, 42) = 11.60, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.22) with RTs significantly longer at the pre- than post-class assessment (Δ = 28.30 ms, p = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.28). Similarly, for the Switching task, a significant main effect of test time was found (F(1, 42) = 21.56, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.34) with RTs significantly higher pre-class than post-class (Δ = 37.31 ms, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.31).

This study investigated the effects of a single bout of pre-class exercise on university students’ EF in a real-world classroom setting. RPE scores obtained after exercise were significantly higher in the exercise (Mean = 13.98, SD = 2.19) than in the control condition (Mean = 9.81, SD = 2.72). Moreover, the mean RPE following the exercise intervention corresponded to moderate-to-vigorous intensity levels [50,66,67]. As well, exercise (Mean = 5.12, SD = 1.50) and control (Mean = 5.21, SD = 1.55) conditions showed comparable levels of cognitive load during the real-world classroom setting; that is, the classroom experience associated with both conditions produced a comparable level of cognitive load. As we did not observe significant differences in subjective cognitive load between the two conditions, which required a relatively low level of cognitive engagement, it is unlikely that variance in cognitive load during the intervention contributed meaningfully to the effects observed in IES and RT.

In terms of EF performance, error rates showed floor effects across all Stroop task variants and thus indicate that the tasks were relatively easy for young adults [53,55]. Moreover, as task demands increased (i.e., Naming → Inhibition →Switching), participants exhibited longer RTs and lower IES. Most notably, our RT and IES findings revealed task-specific effects of exercise and control interventions. First, class-based SBs led to improvements in the Naming and Switching variants of the Stroop task, but not the Inhibitory task-type, and this result was consistent across exercise and control conditions. Second, in comparison to the control condition, the pre-class exercise intervention improved performance in the Naming and Switching task-types; however, no significant change was associated with the Inhibitory task-type. These findings and their broader implications are discussed below in more detail.

Although some previous studies have reported that acute bouts of prolonged sitting can impair cognitive performance [12,13], the present study demonstrates that university students engaged in prolonged sitting during a real class scenario showed improved post-class performance on attention and cognitive flexibility (as measured by Naming and Switching task-types, respectively) in both exercise and control conditions. It is, however, important to distinguish between different SB types based on the level of mental engagement: mentally active (e.g., reading, attending lectures) vs. mentally passive (e.g., watching TV) SB [7,68]. This is a salient consideration because in prior studies, participants who engaged in mentally passive SB (i.e., watching videos during prolonged sitting) showed decreased cognitive performance [12,13]. Given this consideration, the class-based SB in our study can be classified as mentally active, and this mentally stimulating environment may have rendered an EF benefit [69]. Moreover, our sessions were scheduled before students’ first class of the day and represent a time when physical and cognitive arousal are typically low [70,71]. Accordingly, the 45 min of mentally active SB during the class may have provided a period of cognitive stimulation that served to elicit a post-class EF benefit.

Although no statistically significant difference was observed between exercise and control conditions for performance on the Inhibition task type, we found that the exercise intervention showed more pronounced cognitive benefits for the Switching task type. Such a result is in line with other work showing that an exercise intervention improved cognitive flexibility as a key component of EF [20,22,72,73]. In turn, for the Naming task (i.e., a measure of attention), the exercise intervention did not produce a pre- to post-class change in performance, whereas a post-class cognitive benefit was observed in the control condition. This finding might be explained by the arousal theory, suggesting that over-arousal may be determinant for cognitive performance [74]. However, whether pre-class exercise may contribute to an over-arousal remains speculative, so further studies are required to confirm or refute this observation.

We recognize that the interpretation of our findings was limited by several methodological and interpretive constraints. First, some work has reported that 20 min of exercise provides the most robust post-exercise EF benefit, and as such, the 10-min exercise intervention used in the present study may have precluded the manifestation of more robust exercise-related EF benefits [22]. To address this limitation and better understand potential dose-response relationships, we suggest that future research investigate whether factors such as duration (e.g., 10, 15, or 30 min), density (e.g., multiple short bouts during class breaks), and time of day (e.g., morning vs. afternoon), intensity (e.g., mild, moderate, or vigorous) influence the effects of acute exercise on EF [27,71,75]. A more nuanced understanding of these factors could help inform the effective implementation of exercise interventions in real-world educational settings. Second, the present study focused on domain-general EF, assessed via the Stroop task. Although this approach captures a broad spectrum of self-regulatory abilities, it offers limited explanatory power for specific academic skills that are of greater relevance in real-world educational contexts [76,77]. Therefore, future research should continue examining domain-general EF and also incorporate domain-specific tasks tied to classroom learning (e.g., such as math-related working memory or reading comprehension-related inhibitory control) to evaluate more precisely how acute exercise supports subject-specific cognitive performance in real-world classroom settings [78]. Last, the intervention conditions were arranged in a fixed order to ensure feasibility in a real-world setting (with the exercise condition at the first visit and control condition at the second visit). This may have introduced practice-related bias in Stroop task performance, which may limit the ability of the present study to isolate exercise-related effects and reduce the generalizability of our findings. To address this limitation, future studies should consider multi-class designs with counterbalanced task orders. In particular, we suggest that future studies should: (1) contrast between mentally-passive and mentally-active SB in determining exercise-based changes in EF [7], and (2) evaluate each core component of EF (i.e., inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility) to examine whether an acute exercise intervention moderates the effects of a subsequent SB [76].

This study investigated whether a single bout of exercise conducted before 45 min of class-based prolonged sitting impacted EF. Results showed that cognitive flexibility in the selected participants was improved following exercise and in the control condition. Further, the former condition demonstrated a larger magnitude of benefit. Accordingly, this study provides initial evidence that acute exercise-induced cognitive benefits observed in laboratory settings can be transferred to classroom environments.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank all students for their participation in this study.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Shenzhen Educational Research Funding (grant number zdzb2014), Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission (grant number 202307313000096), Social Science Foundation from China's Ministry of Education (grant number 23YJA880093), Post-doctoral Fellowship (grant number 2022M711174), National Center for Mental Health (grant number Z014), and Research Excellence Scholarships of Shenzhen University (grant number ZYZD2305).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Weijia Zhu, Zhihao Zhang, Liye Zou; data collection: Weijia Zhu, Linjing Zhou, Zijun Liu, Kaiqi Guan, Meijun Hou, Xun Luo, Yifei Dong, Ziquan Cai, Jinming Li, Qian Yu, Jiahui Wang, Tai Ji, Liye Zou; analysis and interpretation of results: Weijia Zhu, Liye Zou; draft manuscript preparation: Weijia Zhu, Sebastian Ludyga, Ryan S. Falck, Charles H. Hillman, Kirk I. Erickson, Arthur F. Kramer, Mats Hallrgen, Myrto F. Mavilidi, Fred Paas, Matthew Heath, Fabian Herold. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was conducted according to theguidelines laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shenzhen University, China (ID: SZU_PSY_2024_171).

Informed Consent: All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.069633/s1.

References

1. Diamond A. Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64(1):135–68. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex Frontal Lobe tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cogn Psychol. 2000 Aug;41(1):49–100. doi:10.1006/cogp.1999.0734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Liu J, Wei M, Li X, Ablitip A, Zhang S, Ding H, et al. Substitution of physical activity for sedentary behaviour contributes to executive function improvement among young adults: a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2024 Nov 29;24(1):3326. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-20741-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Northey JM, Raine LB, Hillman CH. Are there sensitive periods for physical activity to influence the development of executive function in children? J Sport Health Sci. 2024 Nov 28;14:101015. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2024.101015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Van Oeckel V, Poppe L, Deforche B, Brondeel R, Miatton M, Verloigne M. Associations of habitual sedentary time with executive functioning and short-term memory in 7th and 8th grade adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2024 Feb 16;24(1):495. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-18014-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Carson V, Choquette L, Connor Gorber S, Dillman C, et al. Canadian sedentary behaviour guidelines for the early years (aged 0–4 years). Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012 Apr;37(2):370–80. doi:10.1139/h2012-019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Zou L, Herold F, Cheval B, Wheeler MJ, Pindus DM, Erickson KI, et al. Sedentary behavior and lifespan brain health. Trends Cogn Sci. 2024 Apr 1;28(4):369–82. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2024.02.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Benzo RM, Gremaud AL, Jerome M, Carr LJ. Learning to stand: the acceptability and feasibility of introducing standing desks into college classrooms. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016 Aug;13(8):823. doi:10.3390/ijerph13080823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Castro O, Bennie J, Vergeer I, Bosselut G, Biddle SJH. How sedentary are university students? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Sci. 2020 Apr;21(3):332–43. doi:10.1007/s11121-020-01093-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Edelmann D, Pfirrmann D, Heller S, Dietz P, Reichel JL, Werner AM, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior in university students-the role of gender, age, field of study, targeted degree, and study semester. Front Public Health. 2022 Jun 16;10:1602. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.821703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Garn AC, Simonton KL. Prolonged sitting in university students: an intra-individual study exploring physical activity value as a deterrent. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Jan 19;20(3):1891. doi:10.3390/ijerph20031891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Baker BD, Castelli DM. Prolonged sitting reduces cerebral oxygenation in physically active young adults. Front Cognit. 2024 Aug 12;3:20906. doi:10.3389/fcogn.2024.1370064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Horiuchi M, Pomeroy A, Horiuchi Y, Stone K, Stoner L. Effects of intermittent exercise during prolonged sitting on executive function, cerebrovascular, and psychological response: a randomized crossover trial. J Appl Physiol. 2023 Dec 1;135(6):1421–30. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00437.2023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):126–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Falck RS, Davis JC, Khan KM, Handy TC, Liu-Ambrose T. A wrinkle in measuring time use for cognitive health: how should we measure physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep? Am J Lifestyle Med. 2023 Mar 1;17(2):258–75. doi:10.1177/15598276211031495. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Xue Y, Yang Y, Huang T. Effects of chronic exercise interventions on executive function among children and adolescents: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019 Nov 1;53(22):1397–404. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099825. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Haverkamp BF, Wiersma R, Vertessen K, van Ewijk H, Oosterlaan J, Hartman E. Effects of physical activity interventions on cognitive outcomes and academic performance in adolescents and young adults: a meta-analysis. J Sports Sci. 2020 Dec 1;38(23):2637–60. doi:10.1080/02640414.2020.1794763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Ludyga S, Gerber M, Pühse U, Looser VN, Kamijo K. Systematic review and meta-analysis investigating moderators of long-term effects of exercise on cognition in healthy individuals. Nat Hum Behav. 2020 Jun;4(6):603–12. doi:10.1038/s41562-020-0851-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Hoffmann CM, Petrov ME, Lee RE. Aerobic physical activity to improve memory and executive function in sedentary adults without cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med Rep. 2021 Jul 16;23(2):101496. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Chang YK, Ren FF, Li RH, Ai JY, Kao SC, Etnier JL. Effects of acute exercise on cognitive function: a meta-review of 30 systematic reviews with meta-analyses. Psychol Bull. 2025 Feb;151(2):240–59. doi:10.1037/bul0000460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Mavilidi MF, Vazou S, Lubans DR, Robinson K, Woods AJ, Benzing V, et al. How physical activity context relates to cognition across the lifespan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2025;151(5):544–79. doi:10.1037/bul0000478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Pontifex MB, McGowan AL, Chandler MC, Gwizdala KL, Parks AC, Fenn K, et al. A primer on investigating the after effects of acute bouts of physical activity on cognition. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2019 Jan;40(16):1–22. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.08.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Chang YK, Labban JD, Gapin JI, Etnier JL. The effects of acute exercise on cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Brain Res. 2012 May 9;1453(1–2):87–101. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Samani A, Heath M. Executive-related oculomotor control is improved following a 10-min single-bout of aerobic exercise: evidence from the antisaccade task. Neuropsychologia. 2018 Jan 8;108:73–81. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.11.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Yu Q, Herold F, Ludyga S, Cheval B, Zhang Z, Mücke M, et al. Neurobehavioral mechanisms underlying the effects of physical exercise break on episodic memory during prolonged sitting. Complement Therap Clini Pract. 2022 Aug;48:101553. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2022.101553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Heiland EG, Tarassova O, Fernström M, English C, Ekblom Ö, Ekblom MM. Frequent, short physical activity breaks reduce prefrontal cortex activation but preserve working memory in middle-aged adults: ABBaH study. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021 Sep 16;15:38. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2021.719509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Yu Q, Zhang Z, Ludyga S, Erickson KI, Cheval B, Hou M, et al. Effects of physical exercise breaks on executive function in a simulated classroom setting: uncovering a window into the brain. Adv Sci. 2025;12(3):2406631. doi:10.1002/advs.202406631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Chueh TY, Chen YC, Hung TM. Acute effect of breaking up prolonged sitting on cognition: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022 Mar 15;12(3):e050458. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Li J, Herold F, Ludyga S, Yu Q, Zhang X, Zou L. The acute effects of physical exercise breaks on cognitive function during prolonged sitting: the first quantitative evidence. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2022 Aug;48(2):101594. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2022.101594. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Herold F, Ludyga S, Mavilidi MF, Benzing V, Vazou S, Tomporowski PD, et al. The other side of the coin—a call to investigate the influence of reduced levels of physical activity on children’s cognition. Educ Psychol Rev. 2025 Jun 17;37(3):62. doi:10.1007/s10648-025-10031-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Sweller J, van Merriënboer JJG, Paas F. Cognitive architecture and instructional design: 20 years later. Educ Psychol Rev. 2019 Jun 1;31(2):261–92. doi:10.1007/s10648-019-09465-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zou L, Zhang Z, Mavilidi M, Chen Y, Herold F, Ouwehand K, et al. The synergy of embodied cognition and cognitive load theory for optimized learning. Nat Hum Behav. 2025 May;9(5):877–85. doi:10.1038/s41562-025-02152-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–80. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kuang J, Zhong J, Arnett JJ, Hall DL, Chen E, Markwart M, et al. Conceptions of adulthood among chinese emerging adults. J Adult Dev. 2024 Mar;31(1):1–13. doi:10.1007/s10804-023-09449-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Kuang J, Jensen Arnett J, Chen E, Demetrovics Z, Herold F, Cheung YM, et al. The relationship between dimensions of emerging adulthood and behavioral problems among chinese emerging adults: the mediating role of physical activity and selfcontrol. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2023;25(8):937–48. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2023.029187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kuang J, Zhong J, Yang P, Bai X, Liang Y, Cheval B, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the inventory of dimensions of emerging adulthood (IDEA) in China. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2023 Jan;23(1):100331. doi:10.1016/j.ijchp.2022.100331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Daffner KR, Haring AE, Alperin BR, Zhuravleva TY, Mott KK, Holcomb PJ. The impact of visual acuity on age-related differences in neural markers of early visual processing. NeuroImage. 2013;67:127–36. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.089. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Somers M, Shields LS, Boks MP, Kahn RS, Sommer IE. Cognitive benefits of right-handedness: a meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015 Apr;51:48–63. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.01.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Nathan N, Elton B, Babic M, McCarthy N, Sutherland R, Presseau J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of physical activity policies in schools: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2018 Feb;107(7):45–53. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.11.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Adams R. Revised physical activity readiness questionnaire. Can Fam Physician. 1999 Apr;45:992–1005. [Google Scholar]

41. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007 May;39(2):175–91. doi:10.3758/bf03193146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Falck RS, Sorte Silva NCB, Balbim GM, Li LC, Barha CK, Liu-Ambrose T. Addressing the elephant in the room: the need to examine the role of social determinants of health in the relationship of the 24-hour activity cycle and adult cognitive health. Br J Sports Med. 2023 Nov;57(22):1416–8. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2023-106893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Kong C, Chen A, Ludyga S, Herold F, Healy S, Zhao M, et al. Associations between meeting 24-hour movement guidelines and quality of life among children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Sport Health Sci. 2023 Jan;12(1):73–86. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2022.08.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Taylor A, Kong C, Zhang Z, Herold F, Ludyga S, Healy S, et al. Associations of meeting 24-h movement behavior guidelines with cognitive difficulty and social relationships in children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactive disorder. Child Adolesc Psych Ment Health. 2023 Mar 27;17(1):42. doi:10.1186/s13034-023-00588-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exer. 2003 Aug;35(8):1381. doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Macfarlane DJ, Lee CCY, Ho EYK, Chan KL, Chan DTS. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of IPAQ (short, last 7 days). J Sci Med Sport. 2007 Feb 1;10(1):45–51. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2006.05.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989 May;28(2):193–213. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995 Mar;33(3):335–43. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Borg G. Ratings of perceived exertion and heart rates during short-term cycle exercise and their use in a new cycling strength test. Int J Sports Med. 1982 Aug;3(3):153–8. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1026080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011 Jul;43(7):1334–59. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Paas FGWC. Training strategies for attaining transfer of problem-solving skill in statistics: a cognitive-load approach. J Educat Psychol. 1992;84(4):429–34. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.84.4.429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Ayres P, Lee JY, Paas F, van Merriënboer JJG. The validity of physiological measures to identify differences in intrinsic cognitive load. Front Psychol. 2021 Sep 10;12:161. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.702538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Dupuy O, Gauthier CJ, Fraser SA, Desjardins-Crèpeau L, Desjardins M, Mekary S, et al. Higher levels of cardiovascular fitness are associated with better executive function and prefrontal oxygenation in younger and older women. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015 Feb 18;9(314):4005. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Dupuy O, Douzi W, Theurot D, Bosquet L, Dugué B. An evidence-based approach for choosing post-exercise recovery techniques to reduce markers of muscle damage, soreness, fatigue, and inflammation: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2018 Apr 26;9:372. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.00403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Goenarjo R, Dupuy O, Fraser S, Berryman N, Perrochon A, Bosquet L. Cardiorespiratory fitness and prefrontal cortex oxygenation during Stroop task in older males. Physiol Behav. 2021 Dec 1;242(1):113621. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2021.113621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Peirce JW. PsychoPy—psychophysics software in python. J Neurosci Methods. 2007 May 15;162(1):8–13. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.11.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Peirce JW. Generating stimuli for neuroscience using Psychopy. Front Neuroinform. 2009 Jan 15;2. doi:10.3389/neuro.11.010.2008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Peirce J, Gray JR, Simpson S, MacAskill M, Höchenberger R, Sogo H, et al. PsychoPy2: experiments in behavior made easy. Behav Res. 2019 Feb 1;51(1):195–203. doi:10.3758/s13428-018-01193-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Bruyer R, Brysbaert M. Combining speed and accuracy in cognitive psychology: is the inverse efficiency score (IES) a better dependent variable than the mean reaction time (RT) and the percentage of errors (PE)? Psycholog Belgica. 2011 Feb 1;51(1):5. doi:10.5334/pb-51-1-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Colloca L, Miller FG. How placebo responses are formed: a learning perspective. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011 Jun 27;366(1572):1859–69. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al., editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2nd ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [Google Scholar]

62. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: Routledge; 2013. 567 p. doi:10.4324/9780203771587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Van Selst M, Jolicoeur P. A solution to the effect of sample size on outlier elimination. Quart J Experim Psychol A Human Experim Psychol. 1994;47A(3):631–50. doi:10.1080/14640749408401131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Goenarjo R, Bosquet L, Berryman N, Metier V, Perrochon A, Fraser SA, et al. Cerebral oxygenation reserve: the relationship between physical activity level and the cognitive load during a stroop task in healthy young males. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Jan;17(4):1406. doi:10.3390/ijerph17041406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Siritzky EM, Cox PH, Nadler SM, Grady JN, Kravitz DJ, Mitroff SR. Standard experimental paradigm designs and data exclusion practices in cognitive psychology can inadvertently introduce systematic shadow biases in participant samples. Cogn Research. 2023 Oct 21;8(1):66. doi:10.1186/s41235-023-00520-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Parfitt G, Evans H, Eston R. Perceptually regulated training at RPE13 is pleasant and improves physical health. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012 Aug;44(8):1613–8. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31824d266e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Scherr J, Wolfarth B, Christle JW, Pressler A, Wagenpfeil S, Halle M. Associations between Borg’s rating of perceived exertion and physiological measures of exercise intensity. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013 Jan 1;113(1):147–55. doi:10.1007/s00421-012-2421-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Hallgren M, Dunstan DW, Owen N. Passive versus mentally active sedentary behaviors and depression. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2020 Jan;48(1):20. doi:10.1249/JES.0000000000000211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Nguyen L, Murphy K, Andrews G. Immediate and long-term efficacy of executive functions cognitive training in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2019 Jul;145(7):698–733. doi:10.1037/bul0000196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Evans MDR, Kelley P, Kelley J. Identifying the best times for cognitive functioning using new methods: matching university times to undergraduate chronotypes. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017 Apr 19;11:188. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2017.00188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Ingham-Hill E, Hewitt A, Lester A, Bond B. Morning compared to afternoon school-based exercise on cognitive function in adolescents. Brain Cogn. 2024 Mar 1;175(4):106135. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2024.106135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Heath M, Shukla D. A single bout of aerobic exercise provides an immediate boost to cognitive flexibility. Front Psychol. 2020 May 29;11:4005. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Shukla D, Al-Shamil Z, Belfry G, Heath M. A single bout of moderate intensity exercise improves cognitive flexibility: evidence from task-switching. Exp Brain Res. 2020 Oct 1;238(10):2333–46. doi:10.1007/s00221-020-05885-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. McMorris T. History of research into the acute exercise-cognition interaction: a cognitive psychology approach. In: Exercise-cognition interaction: neuroscience perspectives. San Diego, CA, USA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2016. p. 1–28. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800778-5.00001-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Herold F, Zou L, Theobald P, Manser P, Falck RS, Yu Q, et al. Beyond FITT: addressing density in understanding the dose-response relationships of physical activity with health—an example based on brain health. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2025 Jun 26;8(10):e800. doi:10.1007/s00421-025-05858-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Lubans DR, Smith JJ, Eather N, Leahy AA, Morgan PJ, Lonsdale C, et al. Time-efficient intervention to improve older adolescents’ cardiorespiratory fitness: findings from the ‘Burn 2 Learn’ cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2021 Jul 1;55(13):751–8. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-103277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Raine LB, Hopman-Droste RJ, Padilla AN, Kramer AF, Hillman CH. The benefits of acute aerobic exercise on preadolescent children’s learning in a virtual classroom. Pediat Exerc Sci. 2024 Oct 9;21(1):1–9. doi:10.1123/pes.2024-0049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Zhang Z, Yu Q, Chen Y, Zou L, Ludyga S, Mavilidi M, et al. A dual-process framework for understanding how physical activity enhances academic performance through domain-general and domain-specific executive functions. Educ Psychol Rev. 2025 Jul 5;37(3):68. doi:10.1007/s10648-025-10049-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools