Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Understanding Academic Evaluation Anxiety in Portuguese Adolescents: A Psychosocial and Educational Perspective

1 Egas Moniz School of Health & Science, Monte da Caparica, 2829-511, Portugal

2 Faculdade de Motricidade Humana, Universidade de Lisboa, Cruz Quebrada-Dafundo, 1499-002, Portugal

3 ISAMB/Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, 1649-028, Portugal

4 CRC-W/FCH, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisboa, 1649-023, Portugal

5 Faculdade de Ciências da Saúde, Universidade Europeia, Lisboa, 1500-210, Portugal

6 Equipa Aventura Social, Lisboa, 1400-415, Portugal

7 Direção-Geral de Estatísticas da Educação e Ciência, Lisboa, 1399-054, Portugal

* Corresponding Author: Marta Reis. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Adolescent and Youth Mental Health: Toxic and Friendly Environments)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(10), 1457-1470. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.070318

Received 13 July 2025; Accepted 08 September 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Academic Evaluation Anxiety is a significant psychological concern among adolescents, with well-documented impacts on academic performance, emotional well-being, and school engagement. In Portugal, recent evidence suggests growing pressure on students to achieve high academic standards, with psychosocial variables such as resilience, perceived support, and school environment playing a crucial role. This study aims to examine the prevalence and psychosocial predictors of Academic Evaluation Anxiety in Portuguese students, and to identify risk and protective factors that inform educational practice. Methods: This cross-sectional, quantitative study analysed data from 3083 students (5th to 12th grade) from the 2024 National Study by the Observatory of Psychological Health and Well-Being. Validated instruments were used, including the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 items (DASS-21), the Social and Emotional Skills Scale (SSES), the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) psychological symptoms and well-being indices, the Positive Youth Development (PYD) scale, and the School Environment Scale. Statistical analyses included descriptive measures, one-way ANOVAs, and multivariate linear regression. Results: Academic Evaluation Anxiety was significantly higher among female students (Mean = 2.80, SD = 0.93) compared to male students (Mean = 2.16, SD = 1.10), representing approximately 30% higher mean levels of anxiety in girls (F = 306.206, p < 0.001). Resilience (β = −0.38, p < 0.001), self-confidence (β = −0.07, p = 0.02), and creativity (β = −0.06, p = 0.01) emerged as protective factors, whereas cooperation (β = 0.23, p < 0.001), teacher relationships (β = 0.08, p < 0.001), bullying (β = 0.07, p < 0.001), and school environment (β = 0.05, p = 0.03) were positively associated with anxiety levels. Conclusions: Academic Evaluation Anxiety is highly prevalent among Portuguese adolescents, with girls reporting significantly higher levels than boys. Resilience, self-confidence, and creativity act as protective factors, while bullying, teacher relationships, cooperation, and negative school climate increase vulnerability. These findings highlight the need for whole-school strategies that strengthen socio-emotional competencies and create psychologically safe learning environments to support both well-being and academic success.Keywords

Academic Evaluation Anxiety is a widespread phenomenon in school contexts, particularly during adolescence, and is defined as a set of physiological, emotional, and cognitive responses triggered by evaluative academic situations [1,2]. While some degree of anxiety can be adaptive, high Academic Evaluation Anxiety interferes with students’ learning, well-being, and academic performance [3].

Recent research in the Portuguese educational context highlights the increasing relevance of Academic Evaluation Anxiety as a public health concern in schools, with academic pressure, low emotional regulation, and limited psychological flexibility acting as amplifying factors [4,5]. In addition, lack of social support and poor self-management strategies have been associated with heightened anxiety in academic settings [6,7].

Academic Evaluation Anxiety has been consistently linked to reduced academic achievement, lower self-esteem, school avoidance, and increased psychological distress [8–10]. At a neurocognitive level, it impairs working memory, attention, and test performance, particularly when students experience perfectionistic thinking or fear of a negative evaluation [11].

Gender differences have been consistently documented in both national and international studies, with girls reporting higher levels of Academic Evaluation Anxiety than boys [12,13]. These differences may be explained by a combination of biological mechanisms—such as heightened hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis reactivity to stress [14]—and sociocultural factors, including internalised performance expectations, fear of failure, and greater societal acceptance of emotional expression in girls [15]. In Portugal, where educational attainment is often associated with social mobility and family honour, female students may experience additional pressure to achieve academically, further exacerbating anxiety symptoms [16].

Furthermore, adolescence represents a period of heightened vulnerability due to rapid neurobiological development, identity exploration, and increased exposure to evaluative and competitive academic contexts [17]. These processes may interact with gender norms, leading to distinct coping styles—such as greater reliance on relational validation among girls—that can influence the intensity and expression of Academic Evaluation Anxiety [1].

Understanding the psychosocial predictors of Academic Evaluation Anxiety is crucial for identifying vulnerable students and informing targeted interventions. Emerging approaches based on Positive Youth Development and mindfulness have shown promising outcomes in mitigating Academic Evaluation Anxiety and promoting coping strategies [18,19]. However, despite the growing literature, there remains a need for large-scale, population-based studies in Portugal that simultaneously examine individual, relational, and contextual predictors of this form of anxiety.

This study seeks to fill existing gaps in the Portuguese context by providing large-scale evidence on the prevalence, predictors, and gender differences in Academic Evaluation Anxiety, integrating individual, relational, and school-environmental factors.

1.1 Theoretical Background: Understanding Academic Evaluation Anxiety in Adolescence

1.1.1 Defining Academic Evaluation Anxiety: A Multidimensional Construct

Academic Evaluation Anxiety is conceptualized as a multidimensional construct comprising three interrelated components: emotionality (physiological arousal), cognitive worry (ruminative thoughts and fear of failure), and behavioural avoidance [20,21]. These components interact to affect how students perceive academic challenges and respond to evaluative situations.

Students with high Academic Evaluation Anxiety tend to overestimate the threat of academic failure while underestimating their capacity to cope, resulting in a cycle of avoidance, disengagement, and self-criticism [22]. These cognitive distortions are exacerbated when self-worth becomes overly tied to academic performance [15].

This multidimensional perspective provides a foundation for understanding how both individual traits (e.g., resilience, self-confidence) and environmental conditions (e.g., school climate, teacher expectations) can shape the onset and intensity of anxiety symptoms. To deepen this understanding, it is important to consider developmental factors that make adolescents particularly susceptible to this form of anxiety.

1.1.2 Developmental Vulnerability in Adolescence

Adolescence is a critical developmental period characterized by heightened emotional sensitivity, identity exploration, and increased exposure to evaluative social contexts [17]. These features make adolescents particularly vulnerable to academic anxiety, especially during transitional phases or in high-stakes academic environments [12].

In Portugal, transitions between basic and secondary education, alongside the pressure to succeed in national exams and secure future opportunities, contribute significantly to anxiety symptoms [4,23]. Research has also shown that retained students and those experiencing academic failure report lower self-esteem and greater psychological vulnerability [23].

Understanding these developmental dynamics sets the stage for examining how demographic and psychosocial factors intersect with academic demands. One of the most consistent demographic correlates identified in the literature is gender.

1.1.3 Gender Differences and Sociocultural Pressures

Girls consistently report higher levels of Academic Evaluation Anxiety than boys, both in Portugal and internationally [12,13]. This may reflect both biological stress sensitivity and cultural norms around emotional expression and academic perfectionism. This gender gap has been attributed to a combination of biological mechanisms—such as heightened hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis reactivity to stress—and sociocultural expectations that promote academic perfectionism, fear of failure, and greater acceptance of emotional expression among girls [14,15].

In the Portuguese context, educational attainment is highly valued and often linked to social mobility and family expectations [16]. These sociocultural pressures may result in increased self-monitoring, fear of failure, and internalized stress—particularly among high-performing female students [7].

These sociocultural pressures may result in increased self-monitoring, fear of failure, and internalised stress—particularly among high-performing female students [7].

1.1.4 Integrating Individual, Relational, and Contextual Predictors

Existing research suggests that Academic Evaluation Anxiety does not emerge solely from individual predispositions; rather, it reflects the interaction of personal skills, relational dynamics, and broader school conditions. For example, resilience and creativity may serve as protective buffers, whereas negative peer interactions (e.g., bullying) or performance-contingent relationships with teachers can heighten anxiety. School climate also plays a pivotal role, with supportive environments fostering psychological safety and hostile climates exacerbating stress [6,7].

This integrated perspective underpins the present study’s focus on identifying not only risk factors but also protective mechanisms, recognising that effective intervention must operate at multiple levels of the school ecosystem. These theoretical considerations directly informed the study design and the formulation of its hypotheses, presented in the Section 1.2 “Aims of the Study”.

The present study aims to understand and characterize Academic Evaluation Anxiety among Portuguese students by examining its prevalence and identifying key psychological symptoms, emotional competences, and perceived academic demands that act as risk or protective factors, in order to develop informed and actionable guidelines for educational intervention.

The present study addresses this gap by: (1) examining the prevalence of Academic Evaluation Anxiety among Portuguese adolescents; (2) identifying psychosocial risk and protective factors at the individual, relational, and school-environment levels; and (3) exploring gender differences in these associations. Based on previous research, we hypothesised that: (Hypothesis 1) girls would report significantly higher levels of Academic Evaluation Anxiety than boys; (Hypothesis 2) resilience, self-confidence, and creativity would be negatively associated with anxiety levels; and (Hypothesis 3) bullying, poorer school climate, and performance-contingent relationships with teachers would be positively associated with anxiety.

The second National Study of the Psychological Health and Well-being Observatory [24] began in October 2023 with the aim of monitoring the psychological health and well-being of different groups within the school ecosystem. This included students from preschool to 12th grade, as well as parents/guardians, teachers, school leaders, psychologists, and other professionals. In January 2024, school clusters were randomly selected by NUTS III regions and subsequently contacted by email or telephone. The questionnaires were administered online between 23 January and 9 June 2024, under the coordination of teachers and psychologists appointed by each school or school cluster.

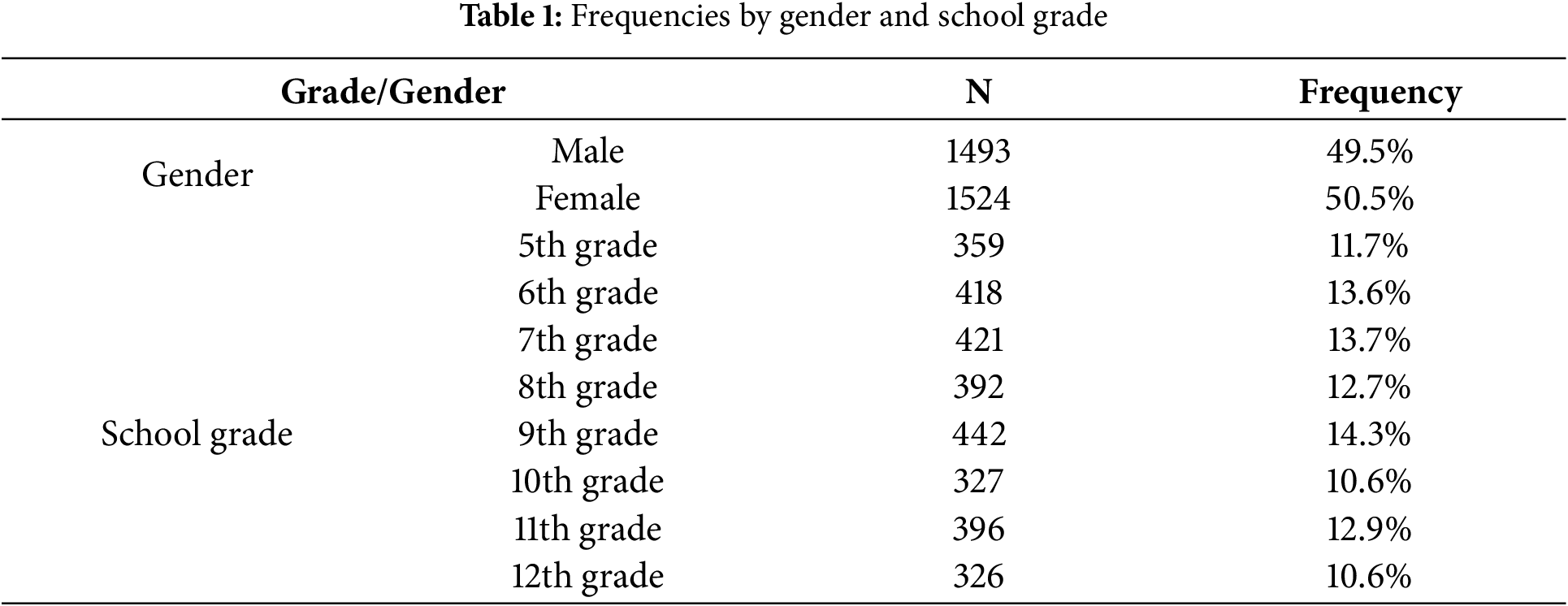

For the present study, a total of 3083 students from lower and upper secondary education participated (2nd and 3rd cycles and secondary education). Of these, 49.5% identified as male and 50.5% as female, with a mean age of 13.64 years (SD = 2.53), ranging from 9 to 20 years old. Regarding school grade distribution: 11.7% were in 5th grade, 13.6% in 6th grade, 13.7% in 7th grade, 12.7% in 8th grade, 14.3% in 9th grade, 10.6% in 10th grade, 12.9% in 11th grade, and 10.6% in 12th grade (see Table 1).

The full description of the instrument can be found in the study report [24], and for this in-depth study, the following questions were used: gender, grade, HBSC symptoms of psychological distress scale, HBSC who-5 perceived quality of life, SSES scale | socio-emotional skills, including the Academic Evaluation Anxiety; DASS scale, PYD scale | positive development, and school environment scale.

Brief descriptions of the key instruments are provided below for clarity: HBSC Psychological Distress Scale—measures frequency of psychosomatic complaints (e.g., headaches, difficulty sleeping) in the past six months; responses range from 0 (“rarely or never”) to 4 (“almost every day”), α = 0.83; HBSC WHO-5 Well-being Index—assesses positive well-being with items such as “I have felt cheerful and in good spirits” rated from 0 (“at no time”) to 5 (“all of the time”), α = 0.87; SSES—Academic Evaluation Anxiety subscale—evaluates feelings of tension and worry in evaluative situations (e.g., “I feel nervous before a test”), using a 0–4 Likert scale, α = 0.88; DASS-21—measures depression, anxiety, and stress over the previous week, using a 0–3 scale; Depression α = 0.91; Anxiety α = 0.86; Stress α = 0.88; PYD Scale—assesses positive youth development across competence, confidence, connection, and contribution, using a 0–4 scale, α = 0.89; School Environment Scale—measures students’ perceptions of safety, relationships, and support within the school, α = 0.85. All instruments have demonstrated good psychometric properties in previous Portuguese validation studies, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.74 to 0.91.

Ethical approval was obtained from the National Data Protection Commission and the Ethics Committee of the Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Lisboa. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians for students under 18, and directly from students aged 18 or older. All participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity, and no personally identifiable information was collected. Data were stored securely in encrypted files accessible only to the research team.

The dependent variable in all analyses was Academic Evaluation Anxiety. Independent variables included demographic factors (gender, grade), socio-emotional skills (SSES subscales), well-being, psychological distress, DASS-21 subscales, positive youth development dimensions, bullying, and school environment.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequencies) were used to characterise the sample. Group differences in Academic Evaluation Anxiety were analysed using one-way ANOVAs. Before inferential analyses, data were screened for accuracy, missing values, and outliers. Assumptions of normality (Shapiro-Wilk test, skewness, kurtosis) and homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test) were assessed. For regression models, multicollinearity was evaluated using tolerance and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values, with all VIF scores below 2 indicating acceptable levels. Potential confounding variables (gender, grade) were included as control variables in the multivariate regression. Effect sizes were calculated (η2 for ANOVAs, standardized β for regression analyses), and the level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors utilized ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4o, June 2025 version) for language polishing, including suggestions of synonyms and improvements in clarity and style. The tool was not used for data analysis, interpretation of results, or generation of scientific content. All sections of the manuscript were critically reviewed, revised, and approved by the authors, who take full responsibility for the final content.

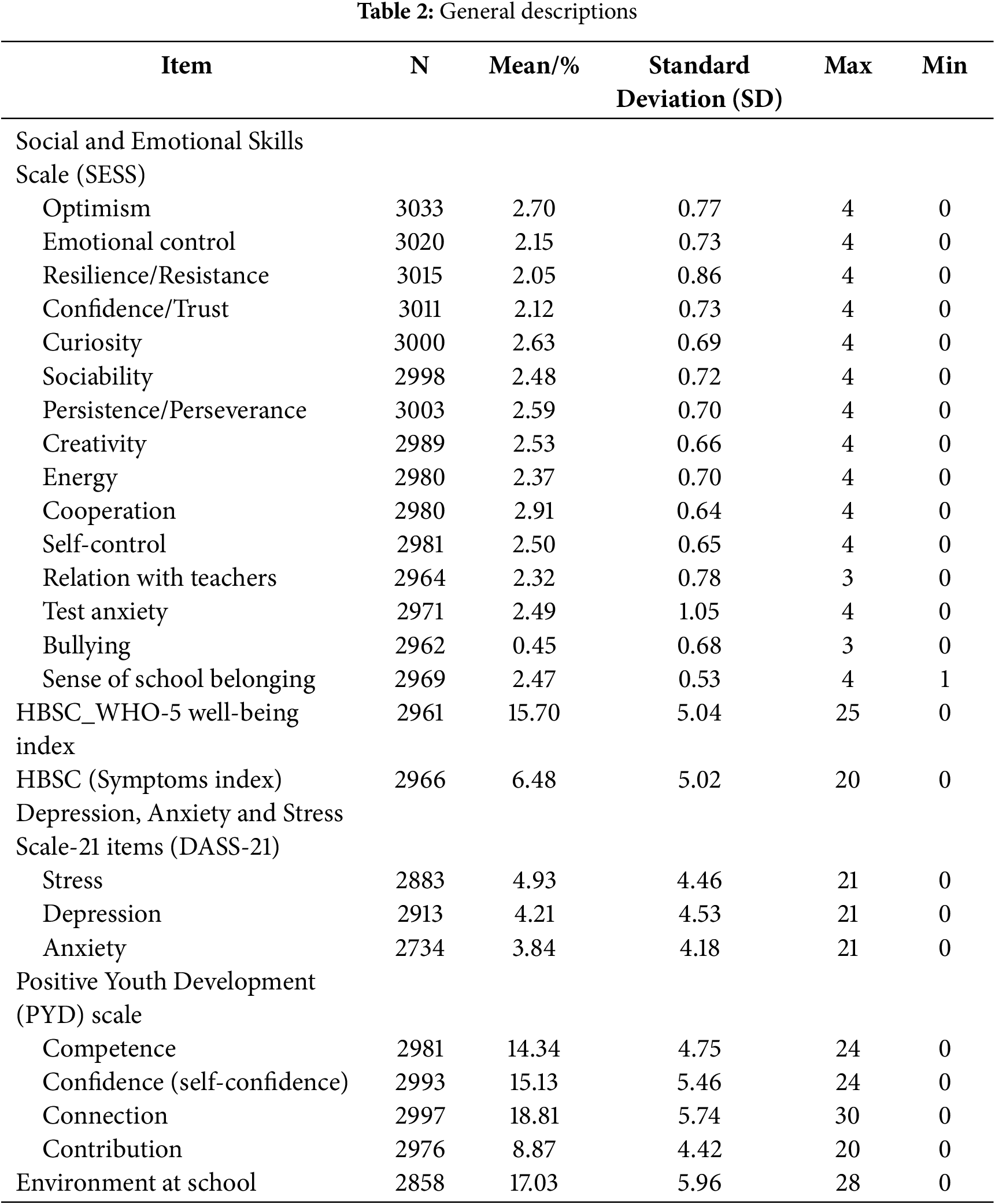

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the variables used in the study, including the number of participants (N), means, standard deviations (SDs), and observed ranges. Overall, students reported a moderate mean level of Academic Evaluation Anxiety (Mean = 2.49, SD = 1.05), with higher average scores in socio-emotional skills such as cooperation (Mean = 2.91) and optimism (Mean = 2.70), and lower scores in bullying (Mean = 0.45). Well-being levels, as measured by the WHO-5 index, were moderate (Mean = 15.70), while stress, anxiety, and depression scores from the DASS-21 were generally low to moderate. These descriptive patterns provide an initial overview of potential protective and risk factors associated with Academic Evaluation Anxiety.

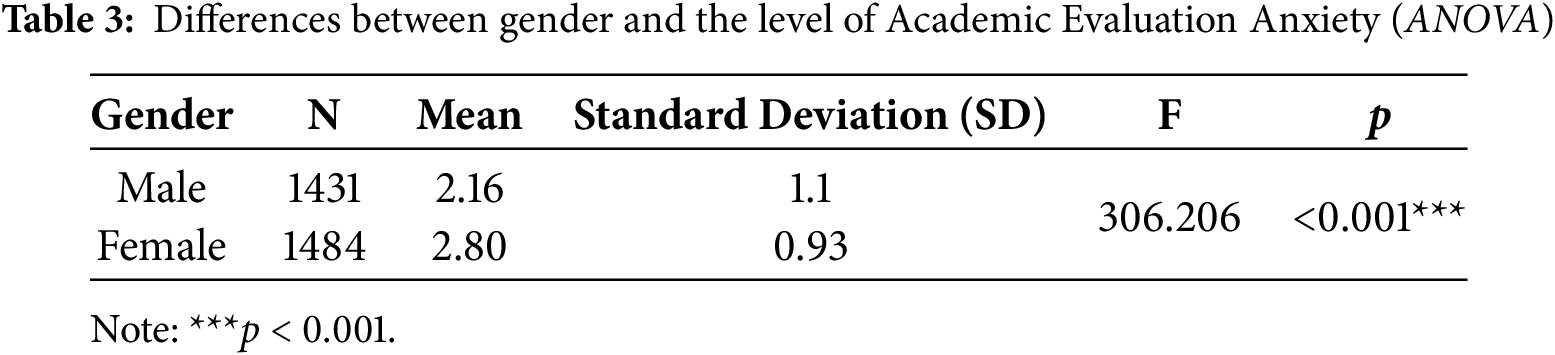

There are statistically significant differences between the genders in the level of Academic Evaluation Anxiety (F = 306.206, p < 0.001), with female students (Mean = 2.80, SD = 0.93) presenting a higher level of Academic Evaluation Anxiety compared to male students (2.16 ± 1.1) (see Table 3).

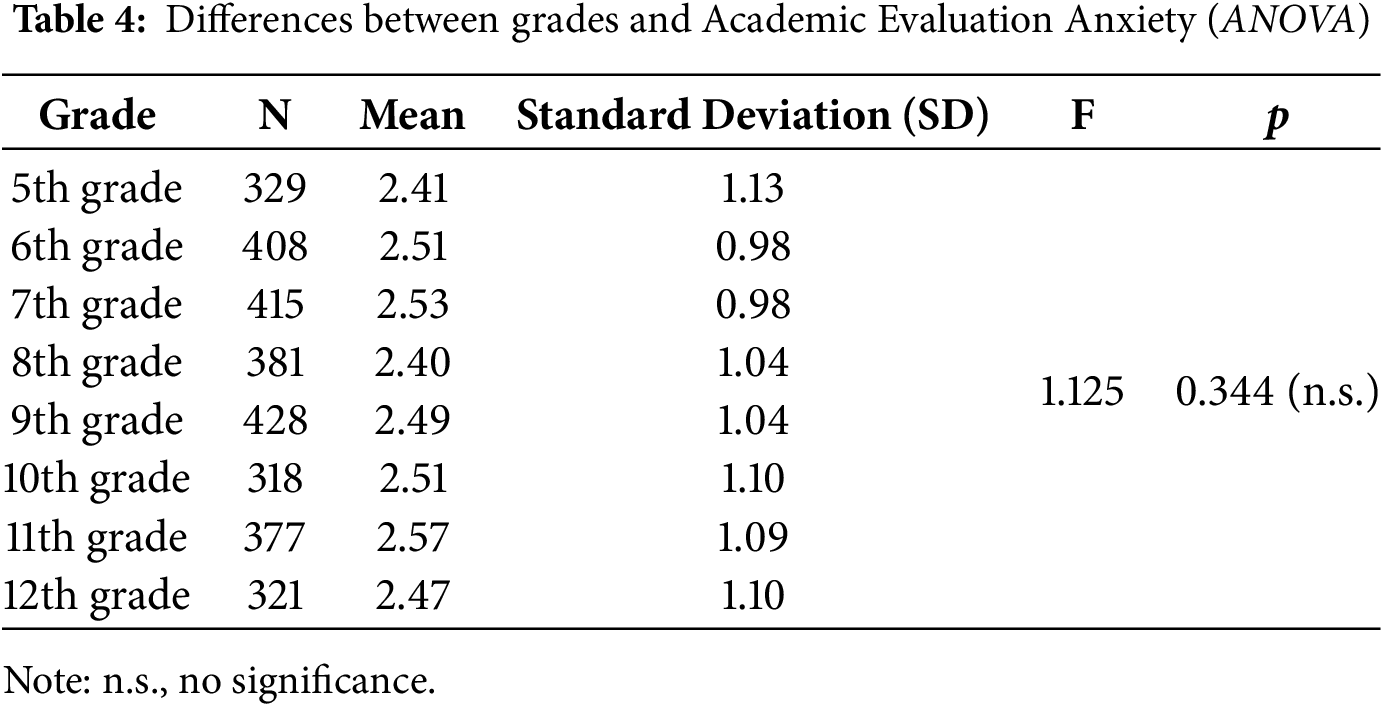

Considering the differences between the grades in relation to the average level of Academic Evaluation Anxiety, illustrated in Table 4, there are no statistically significant differences.

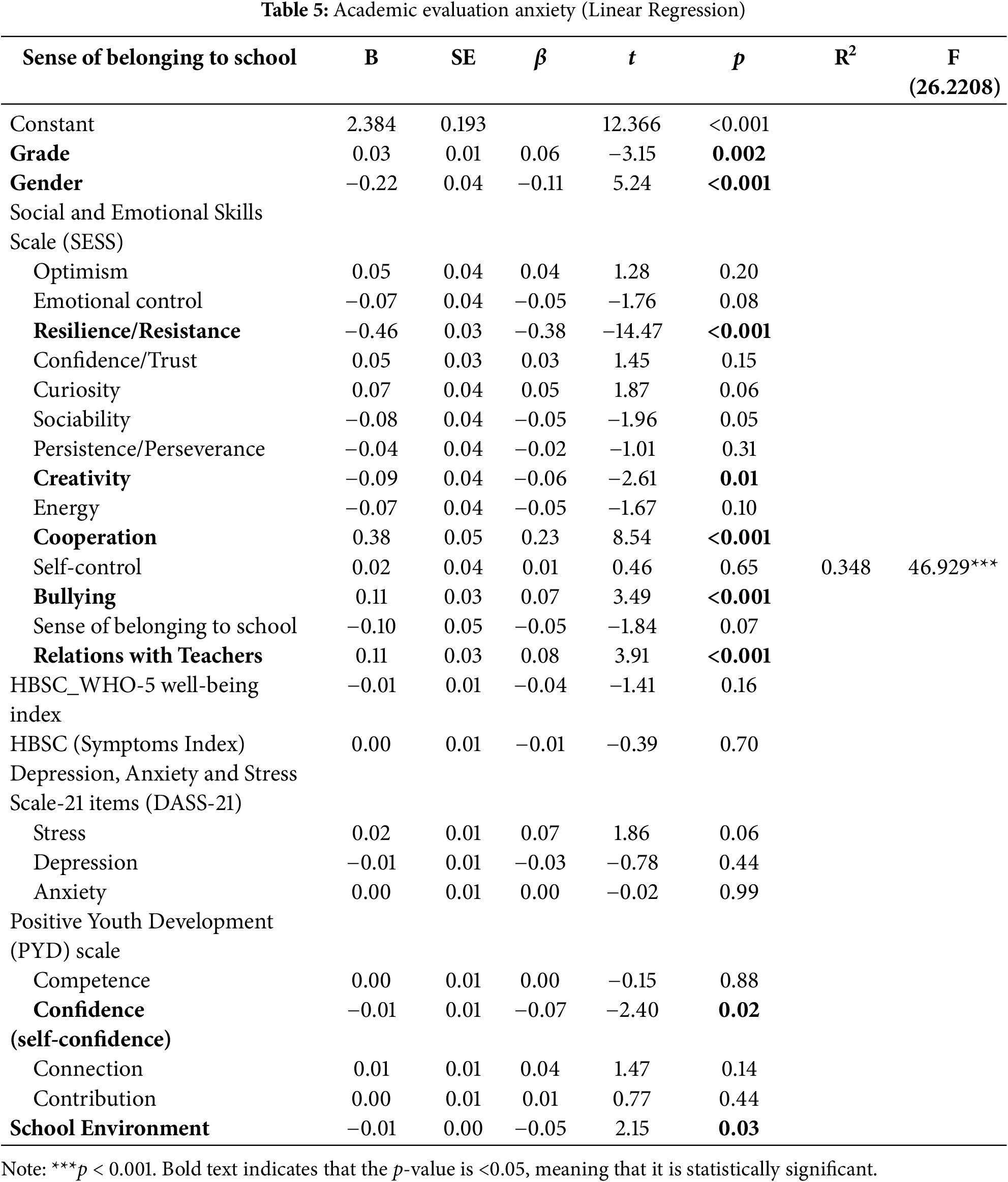

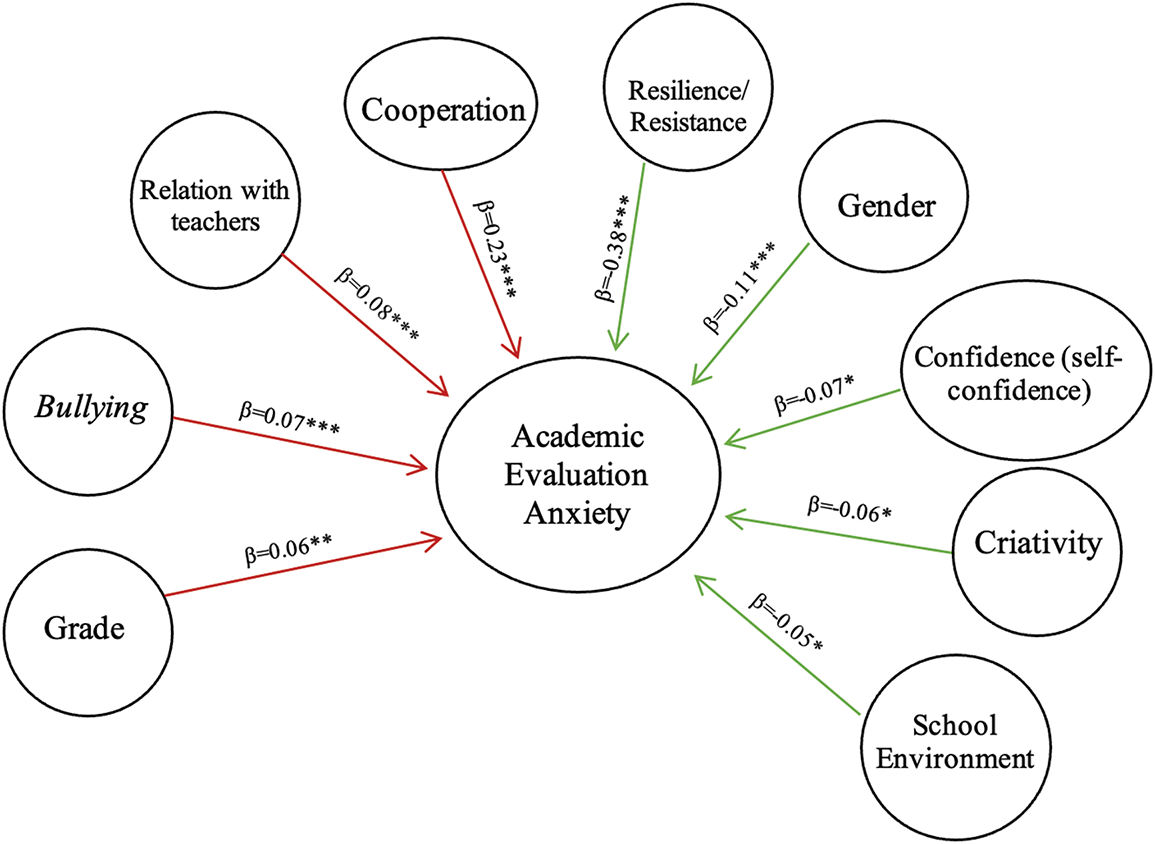

A multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to identify the variables most strongly associated with Academic Evaluation Anxiety (Table 5 and Fig. 1). The adjusted model was statistically significant, F (26.2208) = 46.93, p < 0.001, explaining 34.8% of the variance in the dependent variable (R2 = 0.348). All predictors in the model showed acceptable multicollinearity values, with VIF scores ranging from 1.02 to 1.78, well below the commonly accepted threshold of 5.

Figure 1: Academic evaluation anxiety (only with statistically significant variables) (Linear regression model). Red: risk factors; green: protective factors. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Among the predictors, resilience/resistance emerged as the strongest protective factor (β = −0.38, p < 0.001), indicating that students with higher resilience scores reported substantially lower levels of Academic Evaluation Anxiety. Creativity (β = −0.06, p = 0.010) and self-confidence (β = −0.07, p = 0.020) also acted as protective factors, albeit with smaller effect sizes.

In contrast, cooperation was the most prominent risk factor (β = 0.23, p < 0.001), followed by relationships with teachers (β = 0.08, p < 0.001) and bullying (β = 0.07, p < 0.001). Interestingly, school environment showed a small but significant positive association with anxiety (β = 0.05, p = 0.030), suggesting that even in generally supportive contexts, certain environmental dynamics may contribute to evaluative stress.

Gender differences remained significant in the multivariate model, with female students reporting higher anxiety scores than male students (β = 0.11, p < 0.001), even after controlling for other variables.

These findings highlight the complex interplay between individual competencies, interpersonal relationships, and school context in shaping students’ experience of Academic Evaluation Anxiety.

The findings of this study confirm that Academic Evaluation Anxiety is a significant concern among Portuguese students, particularly for female adolescents. The results support previous literature indicating gender differences in emotional response to academic pressure [12,13]. Girls report higher levels of Academic Evaluation Anxiety, potentially due to sociocultural norms around emotional expression, performance expectations, and fear of failure [7]. This finding provides direct support for Hypothesis 1, which predicted that girls would report significantly higher levels of Academic Evaluation Anxiety than boys.

Although descriptive analyses indicated that older students presented slightly higher mean levels of anxiety, the differences by school grade were not statistically significant. In contrast, gender emerged as the only significant demographic predictor in the multivariate model, with female students consistently reporting higher anxiety scores. This distinction highlights that age-related patterns observed at a descriptive level may not hold when controlling for other psychosocial variables.

Resilience emerged as the strongest protective factor. Students with higher resilience scores were significantly less likely to report elevated levels of Academic Evaluation Anxiety. This finding corroborates developmental frameworks that position resilience and emotional regulation as core competencies in adolescent adaptation [18,25]. Creativity also appeared as a protective factor, suggesting that students with greater creative flexibility may cope more adaptively with evaluative challenges [26,27]. Together with the inverse association of self-confidence, these results confirm Hypothesis 2, which anticipated that resilience, self-confidence, and creativity would be negatively associated with Academic Evaluation Anxiety.

Conversely, cooperation and teacher-student relationships, while generally considered positive, were positively associated with Academic Evaluation Anxiety. This paradox may reflect a context of performance-driven cooperation or external validation needs, where students feel compelled to meet others’ expectations. Similarly, teacher relationships might become sources of pressure when academic expectations are high [15].

Bullying and school environment also significantly predicted higher levels of Academic Evaluation Anxiety. These results reinforce the importance of relational safety and a supportive school climate in shaping students’ emotional experiences. As such, preventive strategies should integrate not only individual coping but also structural and relational components [6,7]. These findings are consistent with Hypothesis 3, which predicted that bullying, poorer school climate, and performance-contingent relationships with teachers would be positively associated with Academic Evaluation Anxiety.

Finally, confidence—a dimension of Positive Youth Development—was inversely related to anxiety. This supports the role of intrapersonal strengths in buffering stress and highlights the need to embed youth development principles into educational policies [19,28].

Unexpectedly, general anxiety symptoms (as measured by the DASS-21) were not significantly associated with Academic Evaluation Anxiety. This suggests that the anxiety reported by students is not indicative of a generalised internalising disorder, but rather reflects a specific, performance-related form of situational anxiety [2,3,21]. This distinction underscores the importance of differentiating between general anxiety and evaluation-specific anxiety in both assessment and intervention planning.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, its cross-sectional design precludes causal inference; longitudinal designs are needed to establish temporal relationships between predictors and Academic Evaluation Anxiety. Second, the reliance on self-report measures may introduce social desirability or recall bias. Third, although the sample was large and nationally representative by region, it did not account for possible variations across specific school types or curriculum tracks. Finally, some potentially relevant factors—such as family dynamics or personality traits—were not assessed and could complement the present findings in future research.

The results have direct implications for educational practice and policy. Schools should integrate socio-emotional learning (SEL) into the curriculum, emphasising resilience, self-confidence, and creativity as protective skills. Teacher training should address how to provide academic support without inadvertently increasing evaluative pressure. Anti-bullying programmes and strategies to improve school climate should be prioritised to enhance relational safety. Assessment practices should shift towards more formative, process-oriented approaches that reduce high-stakes stress while maintaining academic standards.

4.3 Future Research Directions

Future studies should adopt longitudinal and mixed-method approaches to explore the causal mechanisms linking socio-emotional skills, school environment, and Academic Evaluation Anxiety. Qualitative studies could provide deeper insights into how students perceive and experience teacher relationships, cooperation, and performance expectations. Cross-cultural comparisons would also help to understand how sociocultural norms shape gender differences and coping strategies in different educational systems.

In light of the findings and their implications, a set of multi-level recommendations can be proposed to address Academic Evaluation Anxiety in Portuguese schools. First, schools should promote emotional education across the curriculum by integrating structured socio-emotional learning (SEL) programmes from early grades onward, with a particular emphasis on skills such as emotional regulation, self-awareness, stress management, and psychological flexibility [18,25]. Second, educational policies should reinforce Positive Youth Development (PYD) principles by explicitly promoting competence, confidence, connection, and character [29], and by encouraging participatory pedagogies that allow students to experience success beyond academic metrics. Third, teacher training should include professional development focused on recognising the emotional signs of anxiety and on equipping educators with strategies to reduce evaluative pressure while maintaining high expectations.

Furthermore, assessment practices should be reframed towards more diverse, formative, and growth-oriented approaches that promote learning without excessive performance anxiety. Relational safety and school climate should be enhanced through anti-bullying programmes, inclusive policies, and systematic monitoring that involves students in co-creating emotionally safe environments. Targeted support must be ensured for vulnerable groups—particularly female students, older adolescents, and those reporting low resilience or confidence—through accessible psychological services and validated screening tools such as the TA-AAQ-A [5].

At a broader level, family and community involvement is essential by educating parents and caregivers on the nature of Academic Evaluation Anxiety and promoting community engagement in school-based mental health initiatives. Policy alignment and accountability should also be strengthened, ensuring that national and regional educational strategies explicitly integrate mental health promotion, allocate dedicated funding for SEL, teacher training, and anti-bullying initiatives, and establish monitoring frameworks to evaluate their impact. Finally, the definition of student success should be broadened to include socio-emotional, creative, and collaborative competencies [29], moving beyond a narrow focus on academic achievement.

Together, these recommendations provide actionable pathways for fostering more balanced and emotionally supportive learning environments where all students can thrive both academically and psychologically.

This study contributes to the growing body of research on adolescent mental health by highlighting the psychosocial dimensions of Academic Evaluation Anxiety in Portuguese schools. It identifies not only the emotional toll of academic pressure but also the personal and relational resources that buffer its impact.

From a scientific perspective, the study confirms international evidence that Academic Evaluation Anxiety is more prevalent among girls, and that resilience and confidence serve as protective factors—thereby reinforcing the developmental relevance of socio-emotional competencies [26,29]. These findings validate the application of Positive Youth Development frameworks and emotional regulation theory within the school context [5,18].

Furthermore, the study draws attention to less intuitive findings—such as the association of Academic Evaluation Anxiety with perceived cooperation and teacher relationships—highlighting the need to critically reflect on how support systems are structured. Support that is contingent upon performance may inadvertently increase anxiety, particularly in achievement-focused environments [15].

At the ecological level, the predictive role of bullying and a negative school climate underscores the necessity of creating emotionally safe school environments, where belonging, respect, and psychological security are cultivated alongside academic goals [6,7].

Theoretically, these findings expand our understanding of Academic Evaluation Anxiety as not merely an internal experience, but as an interaction between individual characteristics, relational dynamics, and the broader school ecosystem. This perspective can inform more holistic educational policies that address both learning outcomes and student well-being.

In practical terms, the results support the development of national educational guidelines that integrate mental health promotion into the core curriculum. Policy actions could include embedding socio-emotional learning (SEL) in all school years, reforming assessment methods to reduce excessive performance pressure, and mandating anti-bullying and school climate improvement programmes. These measures align with current Portuguese educational reforms aimed at fostering inclusion, reducing school dropout, and promoting student well-being as a foundation for academic success.

Importantly, current international literature advocates for a shift away from viewing academic achievement as the sole indicator of student success, toward a more integrative perspective that values multiple competencies, including socio-emotional, creative, and collaborative skills [29]. This broader framework reinforces the need to align educational reforms with a holistic vision of student development, ensuring that academic environments nurture both learning outcomes and overall well-being.

In conclusion, addressing Academic Evaluation Anxiety requires coordinated action between policymakers, educators, families, and communities to create learning environments where students can thrive academically and psychologically.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the participating schools, teachers, and students for their collaboration in the National Study of the Observatory of Psychological Health and Well-Being. The authors are also grateful to the administrative and technical teams that supported data collection and management. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors utilized ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4o, June 2025 version) for language editing support, specifically to refine wording, improve clarity, and enhance readability. The authors have carefully reviewed and revised all AI-assisted outputs and accept full responsibility for the content of the article.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Marta Reis, Margarida Gaspar de Matos; data collection: Nuno Neto Rodrigues; analysis and interpretation of results: Marta Reis, Catarina Noronha, Gina Tomé, Marina Carvalho; draft manuscript preparation: Marta Reis, Catarina Noronha, Gina Tomé. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (Marta Reis), upon reasonable request. Due to ethical restrictions regarding confidentiality and anonymity of student responses, data are not publicly available.

Ethics Approval: This study involved human participants. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Lisboa, and from the National Data Protection Commission (CNPD). The research complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and national regulations for studies with minors. Informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians for students under 18, and directly from students aged 18 or older.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Putwain DW, Symes W. Teachers’ use of fear appeals in the Mathematics classroom: worrying or motivating students? Br J Educ Psychol. 2011;81(3):456–74. doi:10.1348/2044-8279.002005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Zeidner M. Test anxiety: the state of the art. New York: plenum [Internet]. Glendale, CA, USA: Scientific Research Publishing; 1998 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=845527. [Google Scholar]

3. von der Embse N, Barterian J, Segool N. Test anxiety interventions for children and adolescents: a systematic review of treatment studies from 2000–2010. Psychol Sch. 2013;50(1):57–71. doi:10.1002/pits.21660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Veríssimo L, Dias P, Santos D, Carneiro A. Low academic achievement as a predictor of test anxiety in secondary school students. Neuropsychiatrie de l’Enfance et de l’Adolescence. 2022;70(5):270–6. doi:10.1016/j.neurenf.2021.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Pires CP, Putwain DW, Hofmann SG, Martins DS, MacKenzie MB, Kocovski NL, et al. Assessing psychological flexibility in test situations: the test anxiety acceptance and action questionnaire for adolescents. Rev De Psicopatol Y Psicol Clínica. 2020;25(3):147. doi:10.5944/rppc.29014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Camacho A, Correia N, Zaccoletti S, Daniel JR. Anxiety and social support as predictors of student academic motivation during the COVID-19. Front Psychol. 2021;12:644338. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.644338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Pontes A, Coelho V, Peixoto C, Meira L, Azevedo H. Academic stress and anxiety among Portuguese students: the role of perceived social support and self-management. Educ Sci. 2024;14(2):119. doi:10.3390/educsci14020119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Arens AK, Morin AJS, Watermann R. Relations between classroom disciplinary problems and student motivation: achievement as a potential mediator? Learn Instr. 2015;39:184–93. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Costa A, Moreira D, Casanova J, Azevedo Â, Gonçalves A, Oliveira Í, et al. Determinants of academic achievement from the middle to secondary school education: a systematic review. Soc Psychol Educ. 2024;27(6):3533–72. doi:10.1007/s11218-024-09941-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Segool NK, Carlson JS, Goforth AN, von der Embse N, Barterian JA. Heightened test anxiety among young children: elementary school students’ anxious responses to high-stakes testing. Psychol Sch. 2013;50(5):489–99. doi:10.1002/pits.21689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Owens M, Stevenson J, Hadwin JA, Norgate R. Anxiety and depression in academic performance: an exploration of the mediating factors of worry and working memory. Sch Psychol Int. 2012;33(4):433–49. doi:10.1177/0143034311427433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Torrano R, Ortigosa JM, Riquelme A, Méndez FJ, López-Pina JA. Test anxiety in adolescent students: different responses according to the components of anxiety as a function of sociodemographic and academic variables. Front Psychol. 2020;11:612270. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.612270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Van Mier HI, Schleepen TMJ, Van den Berg FCG. Gender differences regarding the impact of math anxiety on arithmetic performance in second and fourth graders. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2690. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02690. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Stroud LR, Salovey P, Epel ES. Sex differences in stress responses: social rejection versus achievement stress. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(4):318–27. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01333-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Putwain DW, Daly AL. Do clusters of test anxiety and academic buoyancy differentially predict academic performance? Learn Individ Differ. 2013;27(2):157–62. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2013.07.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Acquah E, Ainscow M, Cerna L, Rutigliano A. Review of inclusive education in Portugal: reviews of national policies for education. Paris, France: OECD; 2022. doi:10.1787/a9c95902-en. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Steinberg L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9(2):69–74. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Carvalho M, Branquinho C, Moraes B, Cerqueira A, Tomé G, Noronha C, et al. Positive youth development, mental stress and life satisfaction in middle school and high school students in Portugal: outcomes on stress, anxiety and depression. Children. 2024;11(6):681. doi:10.3390/children11060681.doi:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Gonzaga LRV, Ramos FP, de Lara Machado W, Cordeiro CR, Enumo SRF. Coping with test anxiety and academic performance in high school and university: two studies in Brazil. In: Handbook of stress and academic anxiety. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 93–113. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-12737-3_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Everson HT, Millsap RE, Rodriguez CM. Isolating gender differences in test anxiety: a confirmatory factor analysis of the test anxiety inventory. Educ Psychol Meas. 1991;51(1):243–51. doi:10.1177/0013164491511024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Spielberger CD, Vagg PR. Test anxiety: theory, assessment, and treatment. Washington, DC, USA: Taylor & Francis; 1995. [Google Scholar]

22. Cassady JC, Johnson RE. Cognitive test anxiety and academic performance. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2002;27(2):270–95. doi:10.1006/ceps.2001.1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Pipa J, Peixoto F. One step back or one step forward? Effects of grade retention and school retention composition on Portuguese students’ psychosocial outcomes using PISA 2018 data. Sustainability. 2022;14(24):16573. doi:10.3390/su142416573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Matos MG, Branquinho C, Moraes B, Domingos L, Noronha C, Raimundo M, et al. Saúde psicológica e bem-estar 2024 [Internet]. Bormla, Malta: FlippingBook. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://info.dgeec.medu.pt/saude-psicologica-e-bem-estar-2024/. (In Portugal). [Google Scholar]

25. Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: current status and future prospects. Psychol Inq. 2015;26(1):1–26. doi:10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Silvia PJ, Beaty RE, Nusbaum EC, Eddington KM, Levin-Aspenson H, Kwapil TR. Everyday creativity in daily life: an experience-sampling study of “little c” creativity. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts. 2014;8(2):183–8. doi:10.1037/a0035722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zenasni F, Besançon M, Lubart T. Creativity and tolerance of ambiguity: an empirical study. J Creat Behav. 2008;42(1):61–73. doi:10.1002/j.2162-6057.2008.tb01080.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Lerner RM, Almerigi JB, Theokas C, Lerner JV. Positive youth development a view of the issues. J Early Adolesc. 2005;25(1):10–6. doi:10.1177/0272431604273211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Mašková I, Kučera D, Nohavová A. Who is really an excellent university student and how to identify them? A development of a comprehensive framework of excellence in higher education. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2024;39(4):4329–63. doi:10.1007/s10212-024-00865-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools