Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Structural Relationships between Perceived Psychological Well-Being, Social Support, Academic Engagement, and School-Life Satisfaction among Students Participating in School Esports Activities

1 Asia Esports Industry Support Center, Chosun University, 31 Chosundae 5-Gil, Dong-gu, Gwangju Metropolitan City, 61452, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Physical Education, Gwangju National University of Education, Gwangju Metropolitan City, 61204, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Elementary Education, College of First, Korea National University of Education, Cheongju-si, 28173, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Myeong-Hun Bae. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Enhancing Mental Health through Physical Activity: Exploring Resilience Across Populations and Life Stages)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(11), 1729-1745. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.071944

Received 16 August 2025; Accepted 29 October 2025; Issue published 28 November 2025

Abstract

Background: With the rapid growth of digital learning environments, esports has emerged as a popular form of school-based activity that promotes teamwork, motivation, and engagement. However, limited research has examined how participation in esports relates to students’ psychological and academic development. To address this gap, the present study identified structural relationships between perceived psychological well-being, social support, academic engagement, and school-life satisfaction among students participating in school-based esports activities. Methods: We surveyed 588 students who competed in on-campus esports tournaments across 15 secondary schools in Gwangju Metropolitan City, South Korea. Psychological well-being, social support, academic engagement, and school-life satisfaction were measured using five-point Likert scales. Confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling (SEM) were employed to test the hypotheses, and mediation effects were assessed via bootstrapping (1000 resamples, 95% confidence interval) and competing model analysis. Results: The results showed that psychological well-being has significant positive effects on social support (β = 0.899, p < 0.001) and academic engagement (β = 0.427, p < 0.01). Social support positively predicted school-life satisfaction (β = 0.804, p < 0.001). Psychological well-being did not directly influence this outcome; instead, it exerted an indirect effect via social support (indirect effect = 0.676, 95% confidence interval [0.549, 0.782]), indicating that social support functioned as a full mediator. Conclusion: Overall, the results demonstrate that school-based esports activities may serve as educational contexts that enhance students’ overall satisfaction with school experiences through increased social support. Importantly, these findings highlight the unique psychosocial mechanisms of esports participation, including digital identity, online belonging, and virtual collaboration, which extend beyond traditional educational activities. Because the impact of academic engagement may depend on the quality of participation, future esports programs should incorporate support systems that foster autonomous and collaborative engagement and include digital-citizenship education.Keywords

With the rapid advancement of digital technologies, esports is emerging as one of the most popular leisure pursuits and co-curricular activities among students [1]. Debuting as an official medal event in the 2022 Asian Games has further brought esports in a positive light worldwide [2,3]. According to recent findings, school-based esports activities foster collaborative problem-solving and self-regulation among students [4]. School-based esports activities are not only a form of entertainment; under appropriate conditions, but they may also serve as educational contexts that can contribute to students’ holistic growth and development.

With the advent of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, school systems increasingly seek learners who possess future-oriented competencies such as self-directed learning, digital literacy, and collaborative problem-solving [5]. Esports, now widely regarded as an effective vehicle for cultivating these abilities, is gradually being integrated into educational settings. Game-based learning and esports have been found to enhance students’ creativity and motivation, while simultaneously boosting their academic engagement [6]. Recent works further emphasize the educational value of esports, including its potential to cultivate 21st-century skills [7], shape learning trajectories in team-based contexts [8], and inform global higher-education curricula [9]. Moreover, because esports unfolds in virtual environments, it transcends temporal and spatial constraints and allows students from diverse cultural backgrounds to collaborate toward common goals, thereby fostering the broad range of competencies required in an increasingly globalized era.

Psychological well-being is an essential construct that helps students maintain a stable and positive state during stressful circumstances and achieve healthy developmental outcomes [10]. Higher levels of psychological well-being foster self-acceptance, positive interpersonal relationships, personal growth, and a sense of purpose in life, which, in turn, enhance students’ overall quality of life and satisfaction with school [11,12]. Recent longitudinal studies have further demonstrated that well-being is closely associated with greater social resources and academic engagement [13,14]. Additional evidence confirms that social support functions as a critical protective factor in promoting good mental health and well-being in adolescents [15]. Consequently, schools are encouraged to prioritize enhancing students’ psychological well-being, and esports activities may serve as a potentially useful tool under appropriate conditions, though further empirical validation is needed to confirm this possibility. While many studies highlight the benefits of esports in fostering communication, teamwork, and engagement, other studies have cautioned against potential risks, including excessive gaming, gender disparities, digital divides, and toxic behaviors within competitive environments [16,17]. These mixed findings suggest that the educational value of esports is not inherent but depends on careful program design and contextual safeguards.

Although numerous studies have explored the interrelations among psychological well-being, social support, academic engagement, and school-life satisfaction, most of them have been conducted in conventional classroom or sports settings. Consequently, little is known about how these dynamics operate in digitally mediated, team-based environments such as school esports. The present study addresses this gap by conceptualizing esports as a digital educational ecology in which students build virtual identities, collaborate strategically, and negotiate social belonging through technology-enabled interaction.

Accordingly, this study was not intended to assume that esports inherently produce positive outcomes, but rather to empirically examine the structural pathways linking psychological well-being, social support, academic engagement, and school-life satisfaction. By focusing on these relationships, this study aims to clarify both the potential benefits and limitations of esports as an educational practice, and to specify the psychosocial mechanisms—such as peer interaction, digital identity formation, and collaborative engagement—through which participation in sports may influence student well-being.

Social support is a vital resource that enables individuals to sustain a positive psychological state when confronted with stress [18]. Empirical evidence has shown that higher levels of social support are associated with greater resilience and heightened academic motivation among students, which improve academic performance and adaptation to school life [19,20]. More recently, researchers have confirmed that social support enhances the adjustment and school satisfaction in adolescents across diverse cultural contexts [21,22]. Additionally, adequate social support encourages students’ participation in their schooling, provides psychological stability, and facilitates positive educational experiences. Esports activities through their team-based structure can provide students with opportunities to build supportive relationships with their peers, which in turn enhance resilience and school adjustment.

Academic engagement refers to the degree of physical and psychological energy students invest in pursuing their educational goals [23,24]. Students exhibiting higher levels of engagement not only achieve superior academic outcomes but also report greater satisfaction with school life and stronger social achievements after graduation [25,26]. A systematic review further confirmed that engagement is positively linked to both academic success and subjective well-being [27]. More recent work also indicates that academic engagement mediates the relationship between social belonging and school satisfaction [28]. As esports programs can heighten students’ intrinsic motivation and psychological immersion, they may serve as an important educational strategy for enhancing academic engagement.

School-life satisfaction is a key indicator of students’ emotional and social adjustment to the school environment [29]. Students who report high levels of satisfaction tend to maintain positive attitudes toward interpersonal relationships and academic performance, which directly promotes academic persistence and reduces the risk of school dropout [30,31]. Recent studies also suggest that engagement may mediate the link between social relationships and school satisfaction [25,28]. School-based esports activities may enhance students’ satisfaction with school by offering enjoyable, non-academic experiences. Beyond entertainment, these activities can foster a positive school climate that supports overall adjustment [32].

Despite growing interest in esports in education, prior studies have largely emphasized either isolated benefits or descriptive outcomes. Few studies have simultaneously examined the structural pathways linking psychological well-being, social support, academic engagement, and school-life satisfaction in the context of school-based esports. Moreover, the limited discussion of potential risks and boundary conditions leaves the overall picture incomplete. This gap underscores the need for an integrative approach that clarifies both the benefits and limitations of esports participation in schools.

Unlike conventional extracurricular activities, esports takes place in digitally mediated environments where students develop virtual identities and engage in cooperative as well as competitive interactions. [16]. These features align with emerging theoretical frameworks such as digital citizenship [33], gamification theory [34], and virtual collaboration theory [35], which emphasize how digital participation can foster responsibility, motivation, and peer connectedness. Hence, in this study, we aimed to replicate established psychological relationships and extend them into the novel context of esports as a digital educational arena.

Furthermore, to sharpen the theoretical contribution, this study incorporates Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [36]. SDT identifies three basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—that are essential for fostering intrinsic motivation, psychological well-being, and high-quality engagement. Applying SDT to the esports context offers a nuanced lens: esports may provide autonomy through role selection and self-directed play, competence through skill mastery and performance feedback, and relatedness through peer bonding and teamwork. Prior research has shown that fulfilling these needs promotes sustained motivation and positive psychosocial outcomes in digital gaming environments [37,38]. By integrating SDT, this study extends traditional well-being–support–satisfaction pathways into the unique digital and collaborative ecology of esports, thereby clarifying its distinct theoretical and educational significance.

Theoretically, this research extends traditional well-being–support–satisfaction frameworks by integrating SDT and digital-collaboration perspectives to explain how autonomy, competence, and relatedness are enacted in virtual team contexts. By applying SDT to esports participation, we highlight the unique psychosocial mechanisms—digital identity formation, peer connectedness, and gamified cooperation—that differentiate esports from traditional extracurricular activities. This approach clarifies both the opportunities and boundary conditions of esports as an educational medium, thereby providing a novel theoretical contribution to studies of student well-being and engagement in technology-driven learning environments.

In this study, four major constructs were examined and defined as follows. Psychological well-being refers to a positive psychological state characterized by self-acceptance, personal growth, autonomy, purpose in life, environmental mastery, and positive relations with others [11]. Social support denotes the emotional, informational, instrumental, and appraisal assistance that students perceive from their peers and teachers, which enables them to cope with stress and foster resilience [18]. Academic engagement is conceptualized as a multidimensional construct comprising vigor, dedication, and absorption in learning activities [39]. Finally, school-life satisfaction represents students’ overall evaluation of their school experiences, including academic, peer, teacher, and environmental domains [40]. In the hypothesized model, psychological well-being was conceptualized as a personal resource that not only enhances students’ internal states but also fosters their external relationships. Higher levels of well-being may encourage students to seek and maintain supportive ties with peers and teachers, providing the emotional and informational resources needed for meaningful academic engagement. In turn, such engagement—when supported by strong relational networks—is more likely to translate into overall satisfaction with school life. This study aimed to elucidate the educational significance of school-based esports activities by identifying the structural relationships between psychological well-being, social support, academic engagement, and school-life satisfaction among students participating in school-based esports activities. In particular, we tested the following hypotheses.

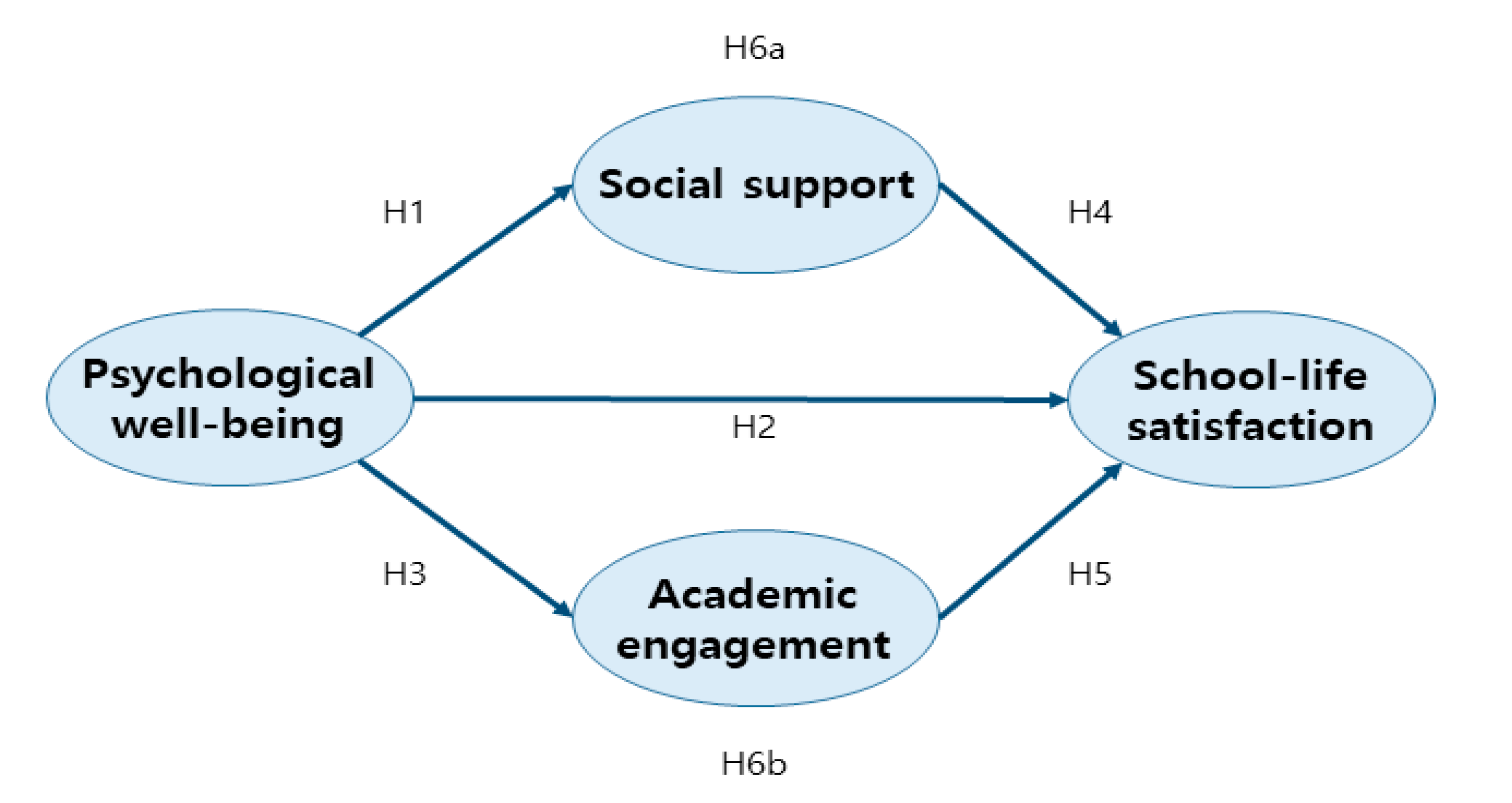

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Psychological well-being positively influences social support.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Psychological well-being positively influences school-life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Psychological well-being positively influences academic engagement.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Social support positively influences school-life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Academic engagement positively influences school-life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 6a (H6a): Social support mediates the relationship between psychological well-being and school-life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 6b (H6b): Academic engagement mediates the relationship between psychological well-being and school-life satisfaction.

Fig. 1 presents the hypothesized structural model developed for this study. The model was constructed based on established theoretical frameworks and prior empirical findings linking psychological well-being, social support, academic engagement, and school-life satisfaction. It illustrates the hypothesized relationships that were empirically tested using structural equation modeling (SEM), rather than results already obtained.

Figure 1: Hypothesized structural model.

The proposed model is not merely a reapplication of traditional well-being–support–satisfaction pathways. Rather, it interprets these relationships within the distinctive environment of esports, where gamified interaction and digital collaboration shape students’ social and academic experiences. By exploring these associations, we sought to provide empirical evidence of the need to integrate esports into school settings and to offer practical guidance on fostering students’ holistic development.

2.1 Participants and Data Collection

From May to December 2024, we surveyed 600 participants, of whom 375 (63.8%) and 213 (36.2%) were middle and high school students, respectively, who participated in intramural esports tournaments across 15 schools in Gwangju Metropolitan City. Participant age range was 13–18 years (Mean = 15.2, standard deviation [SD] = 1.4). The gender distribution was 480 males (81.6%) and 108 females (18.4%). After excluding 12 questionnaires with missing or careless responses, 588 responses were retained for analysis. Students were recruited through school announcements and direct invitations by esports advisors and physical education teachers. All eligible students were invited to participate, with participation being voluntary. We surveyed the students using an anonymous, self-administered questionnaire. The students completed this questionnaire in classrooms during a designated period under teacher supervision. Before conducting the survey, we obtained assent from the students and permission from their parents or guardians. No personally identifiable information was collected, and confidentiality was emphasized in the information sheet. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Korea National University of Education Ethics Review Committee (approval number: KNUE-202309-SB-0329-01).

The questionnaire collected data on five demographic and esports-related characteristics: school level, gender, the esports game played, the frequency of watching esports, and the reason for watching esports. It also comprised scales assessing psychological well-being, social support, academic engagement, and school-life satisfaction. All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). All scales demonstrated acceptable internal consistency and were considered suitable for the study sample.

2.2.1 Psychological Well-Being

Building on validated measures by Kim and Yoo [41] and Seong and Won [42], we adapted a scale for measuring psychological well-being in secondary-school contexts. It comprised 19 items across six dimensions: environmental mastery (three items; e.g., “I find daily tasks rewarding and enjoyable”), personal growth (three items; e.g., “I continually think about ways to improve or change my life”), self-acceptance (three items; e.g., “Looking back, I am satisfied with the course my life has taken”), positive relations with others (three items; e.g., “Maintaining close relationships is easy and enjoyable for me”), autonomy (three items; e.g., “I tend to make decisions without being influenced by others”), and purpose in life (four items; e.g., “I have a clear idea of what I want to accomplish in life”). The Cronbach’s α for the dimensions ranged from 0.710 to 0.787.

To measure social support, we adapted 14 items from Lee [43] to make them suitable for adolescents. The items measured emotional support (four items; e.g., “People around me make me feel loved and cared for”), informational support (three items; e.g., “People around me praise me when I do well”), instrumental support (three items; e.g., “When I face difficulties, people around me suggest wise solutions”), and appraisal support (four items; e.g., “If they are unable to help me directly, people around me connect me with someone who can”). The Cronbach’s α coefficients ranged from 0.708 to 0.729.

Academic engagement was measured using 13 items adapted from Choo and Sohn [44]. Specifically, they assessed vigor (four items; e.g., “Even when my study tasks do not go well, I keep working on them”), dedication (four items; e.g., “Studying is difficult, but it challenges me in a meaningful way”), and absorption (five items; e.g., “When I study, I forget everything happening around me”). The reliability coefficients ranged from 0.721 to 0.806.

2.2.4 School-Life Satisfaction

Twenty-two items adapted from Choi [45] assessed five domains concerning school-life satisfaction: academic satisfaction (four items; e.g., “I enjoy learning the material taught in class”), school environment (five items; e.g., “I am satisfied with our classroom’s environment, layout, and facilities”), school life (four items; e.g., “Most of my classmates adapt well and have fun at school”), teacher satisfaction (five items; e.g., “Teachers provide appropriate information to help me solve problems”), and peer satisfaction (four items; e.g., “My classmates respect my opinions and respond positively”). The Cronbach’s α coefficients ranged from 0.778 to 0.810.

All measurement tools were adapted from validated scales previously developed in the field. Minor wording modifications were made to ensure clarity and appropriateness for Korean middle- and high-school students, particularly in the context of school-based esports activities. The adaptation process involved simplifying technical terms into age-appropriate language, aligning items with the cultural and educational context, and pilot-testing the items with a small group of students for comprehensibility.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic and esports-related variables. Using confirmatory factor analysis, we evaluated the construct validity of the scales employed in this study. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s α coefficients. Next, descriptive statistics were determined for the four main variables, and correlation analysis was performed to identify relationships among them. Finally, SEM was employed to test the overall fit of the proposed research model and verify causal relationships. To test mediating effects, we performed a comparison of competing model fit indices and Bootstrapping. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS and AMOS (version 24.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3.1 Descriptive Statistics for Demographic and Esports-Related Variables

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for demographic and esports-related variables.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics for demographic and esports-related variables.

| Variable | Categories | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| School level | Middle school | 375 | 63.8 |

| High school | 213 | 36.2 | |

| Gender | Male | 480 | 81.6 |

| Female | 108 | 18.4 | |

| Esports game | League of Legends | 240 | 40.8 |

| Valorant | 282 | 48.0 | |

| FC Online | 33 | 5.6 | |

| KartRider (Drift) | 33 | 5.6 | |

| Frequency of watching esports | Non-viewer | 147 | 25.0 |

| Once a week | 138 | 23.5 | |

| Two to three days a week | 147 | 25.0 | |

| Four to six days a week | 66 | 11.2 | |

| Daily | 90 | 15.3 | |

| Reason for watching esports | Enjoyment | 213 | 36.2 |

| Analysis & preparation | 144 | 24.5 | |

| Team support | 177 | 30.1 | |

| Leisure pastime | 54 | 9.2 | |

| Total | 588 | 100.0 |

3.2 Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to examine the validity of the scales employed in the study. First, model fit was evaluated using the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR < 0.08), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA < 0.08), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI > 0.90), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI > 0.90) [46,47]. In addition, convergent validity was assessed by inspecting standardized factor loadings (>0.50), average variance extracted (AVE > 0.50), and construct reliability (>0.70) [48]. The results indicated that the scales used in this study met all criteria for model fit and convergent validity (Table 2). Specifically, all standardized factor loadings exceeded 0.60 and were statistically significant (p < 0.001), and all AVE and Composite Reliability (CR) values met the recommended thresholds, confirming construct reliability. For clarity, Table 2 presents only standardized loadings (β), AVE, and CR values, as these indices sufficiently demonstrate the constructs’ reliability and validity.

Table 2: Results of confirmatory factor analysis of the measurement scales used in the study.

| Variable | β | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological well-being | Environmental mastery | 0.630–0.729 | 0.819 | 0.601 |

| Personal growth | 0.682–0.835 | 0.870 | 0.691 | |

| Self-acceptance | 0.675–0.801 | 0.835 | 0.629 | |

| Positive relations with others | 0.670–0.760 | 0.854 | 0.661 | |

| Autonomy | 0.649–0.836 | 0.750 | 0.503 | |

| Purpose in life | 0.684–0.808 | 0.843 | 0.573 | |

| Social support | Emotional support | 0.787–0.886 | 0.929 | 0.767 |

| Informational support | 0.611–0.894 | 0.901 | 0.756 | |

| Instrumental support | 0.774–0.837 | 0.896 | 0.743 | |

| Appraisal support | 0.798–0.834 | 0.888 | 0.666 | |

| Academic engagement | Vigor | 0.722–0.886 | 0.885 | 0.660 |

| Dedication | 0.665–0.920 | 0.883 | 0.658 | |

| Absorption | 0.783–0.908 | 0.909 | 0.668 | |

| School-life satisfaction | Academic satisfaction | 0.775–0.907 | 0.887 | 0.663 |

| School environment | 0.711–0.927 | 0.908 | 0.667 | |

| School life | 0.594–0.871 | 0.907 | 0.714 | |

| Teacher satisfaction | 0.830–0.895 | 0.950 | 0.791 | |

| Peer satisfaction | 0.868–0.884 | 0.937 | 0.789 | |

3.3 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Coefficients of the Key Variables

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients of the four main variables. All inter-factor correlation coefficients were below 0.80, indicating the absence of multicollinearity. Additionally, for every construct, the AVE (0.641–0.762) exceeded the squared inter-factor correlation coefficients (0.183–0.530), thereby confirming discriminant validity [49]. Tests of normality also supported the data’s distribution, as skewness and kurtosis values were within ±2.

Table 3: Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients of the key variables.

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Psychological Well-Being | Social Support | Academic Engagement | School-Life Satisfaction | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological well-being | 3.79 (0.44) | 0.643# | — | — | — | 0.166 | −0.171 |

| Social support | 3.83 (0.51) | 0.530** (0.281) | 0.762# | — | — | −0.048 | −0.109 |

| Academic engagement | 3.49 (0.64) | 0.242** (0.059) | 0.259** (0.067) | 0.653# | — | −0.024 | −0.313 |

| School-life satisfaction | 3.83 (0.52) | 0.474** (0.225) | 0.429** (0.183) | 0.183** (0.033) | 0.641# | −0.049 | −0.651 |

3.4 Verification of the Research Model

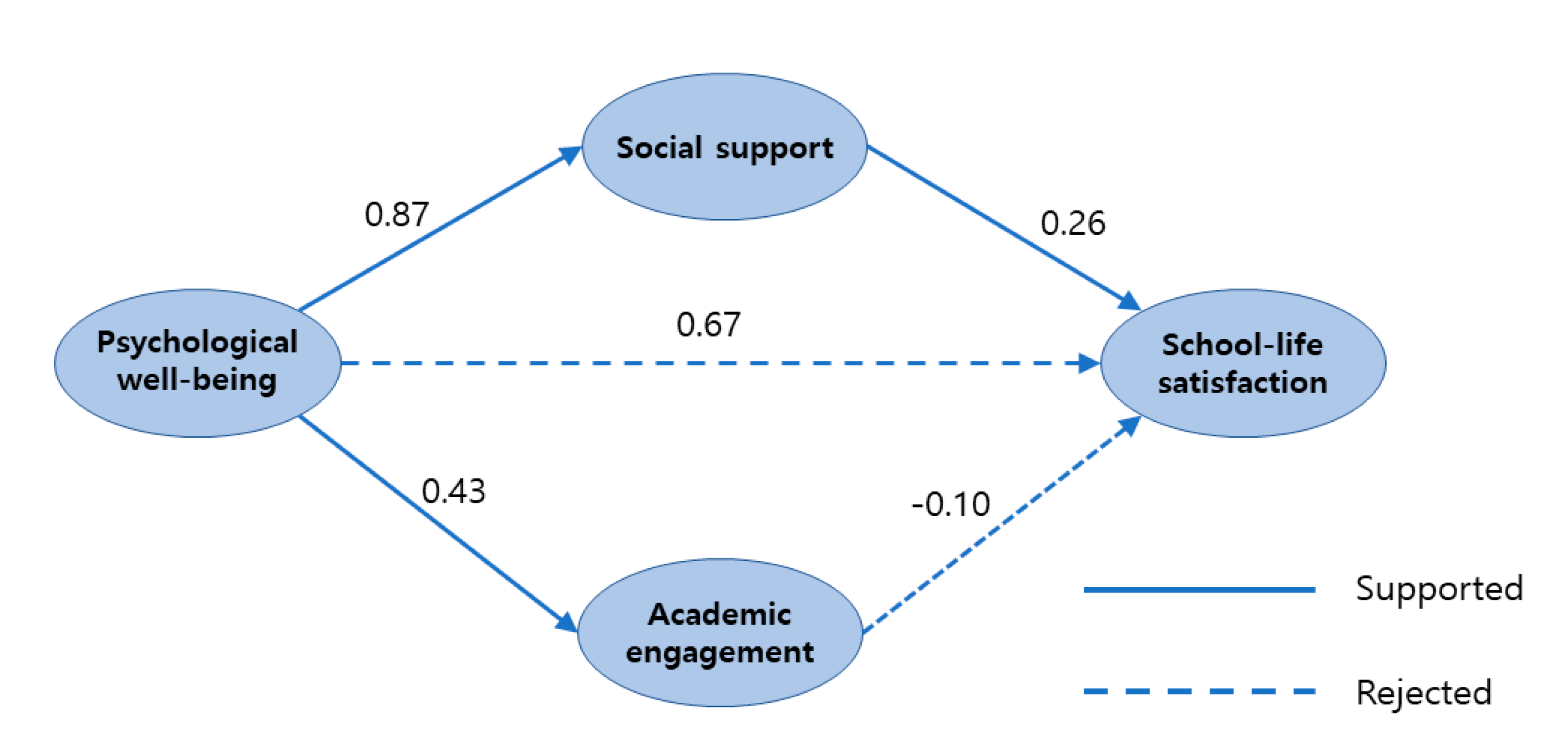

To clarify the relationships between psychological well-being, social support, academic engagement, and school-life satisfaction among students participating in school-based esports activities, we conducted an SEM analysis. The model-fit indices indicated adequate fit (SRMR = 0.075, CFI = 0.930, TLI = 0.903, and RMSEA = 0.065), and CFI, TLI, and RMSEA exceeded commonly accepted thresholds, confirming the suitability of the proposed model for hypothesis testing.

Table 4 presents the results of the hypothesis testing. H1 was supported, as a significant positive causal effect was found (β = 0.871, t = 5.549, p < 0.001). However, H2 was not supported (β = 0.666, p > 0.05), indicating that the effect of psychological well-being on school-life satisfaction may be entirely mediated by social support. Both H3 (β = 0.435, t = 3.060, p < 0.001) and H4 were supported (β = 0.258, t = 2.302, p < 0.01), showing that psychological well-being also predicted academic engagement and that social support positively influenced school-life satisfaction By contrast, H5 was not supported (β = −0.097, t = −1.022), suggesting that academic engagement did not contribute directly to school-life satisfaction in this sample. Collectively, these findings highlight the central role of social support as a mediator, while questioning the direct contribution of academic engagement to students’ satisfaction with school life.

Table 4: Results of testing hypotheses.

| Hypothesis | Path | β | SE | t | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Psychological well-being → Social support | 0.871 | 0.157 | 5.549*** | Supported |

| 2 | Psychological well-being → School-life satisfaction | 0.666 | 0.362 | 1.843 | Rejected |

| 3 | Psychological well-being → Academic engagement | 0.435 | 0.142 | 3.060** | Supported |

| 4 | Social support → School-life satisfaction | 0.258 | 0.112 | 2.302** | Supported |

| 5 | Academic engagement → School-life satisfaction | −0.097 | 0.095 | −1.022 | Rejected |

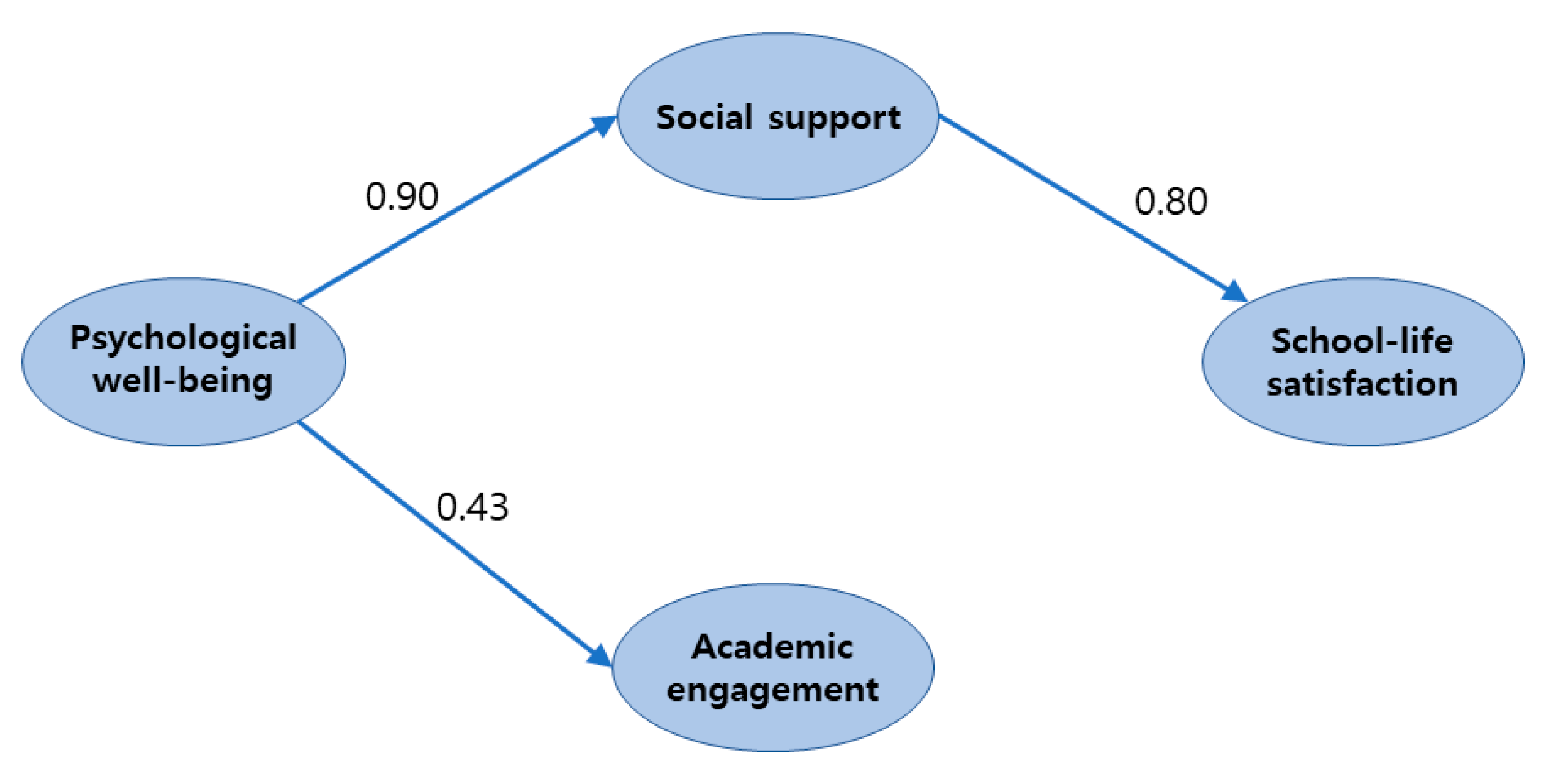

3.5 Selection and Analysis of the Final Model

After testing the proposed model, we removed the two non-significant paths corresponding to Hypotheses 2 and 5. The removal of these paths was justified to improve model parsimony and clarify the mediating role of social support. The revised model exhibited an acceptable fit (SRMR = 0.075, CFI = 0.927, TLI = 0.903, and RMSEA = 0.065), and fit indices remained stable compared to the initial model, confirming the adequacy of the revised specification. In the revised model, psychological well-being exerted a significant positive effect on social support (β = 0.899, t = 5.164, p < 0.001; H1) and a moderate positive effect on academic engagement (β = 0.427, t = 3.054, p < 0.01; H3). Social support, in turn, strongly predicted school-life satisfaction (β = 0.804, t = 5.093, p < 0.01; H4) (Table 5). These effect sizes highlight the central role of social support in linking psychological well-being to students’ satisfaction with school life, while academic engagement exerted a comparatively smaller influence.

Table 5: Results of testing hypotheses in the revised model.

| Hypothesis | Path | β | SE | t | Decision | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Psychological well-being → Social support | 0.899 | 0.153 | 5.164*** | Supported | 0.897 | — | 0.897 |

| 3 | Psychological well-being → Academic engagement | 0.427 | 0.140 | 3.054** | Supported | 0.353 | — | 0.353 |

| 4 | Social support → School-life satisfaction | 0.804 | 0.158 | 5.093*** | Supported | 0.753 | — | 0.753 |

Table 6 shows the results of the comparison of competing model fit indices and bootstrapping analysis to test the mediating effect of social support. Because the direct path from academic engagement to school satisfaction was not statistically significant, we did not test the mediating effect of academic engagement. According to MacKinnon [50] and Kline [51], when the chi-square difference (Δχ2) between a partial-mediation model and a full-mediation model is ≤3.84 at 1 degree of freedom, full mediation can be assumed. In this study, the comparison yielded a Δχ2 of 3.779 with Δdf = 2, which indicates that social support fully mediates the relationship between psychological well-being and school-life satisfaction.

Table 6: Results of competing model analysis and bootstrapping.

| Model | χ2 | df | SRMR | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial mediation model | 236.513 | 130 | 0.075 | 0.903 | 0.930 | 0.065 | |||

| Full mediation model | 240.292 | 132 | 0.075 | 0.903 | 0.927 | 0.065 | |||

| Model | Path | 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||

| Indirect effect | sig | Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Full mediation | Psychological well-being → Social support → School-life satisfaction | 0.676 | 0.008 | 0.549 | 0.782 | ||||

| Model comparison: Δχ2 = 3.779, Δdf = 2 | |||||||||

In the bootstrapping analysis (1000 resamples; 95% confidence interval), the 95% confidence interval did not include zero (lower bound = 0.597, upper bound = 0.870), indicating a statistically significant indirect effect at p < 0.05 (α = 0.002) and confirming full mediation [52]. These results suggested that social support completely mediates the relationship between psychological well-being and school-life satisfaction among students participating in school-based esports activities, thereby partially supporting H6. In other words, H6a was supported, whereas H6b was not supported by our results. Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 present the results of SEM and full mediation analyses.

Figure 2: Results of structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis. Note: All values represent standardized path coefficients (β).

Figure 3: Results of full mediation analysis. Note: All values represent standardized path coefficients (β).

This study examined the structural relationships between psychological well-being, social support, academic engagement, and school-life satisfaction among students participating in school-based esports activities. The results revealed that psychological well-being exerts significant positive effects on social support and academic engagement, while social support has a significant positive effect on school-life satisfaction. The results also demonstrated that social support fully mediates the relationship between psychological well-being and school-life satisfaction.

These results can be further interpreted through the lens of SDT, which posits that individuals’ motivation and well-being depend on the fulfillment of three basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness [36]. Within school-based esports, students frequently experience autonomy by selecting game roles, strategies, and collaborative methods; they gain a sense of competence through continuous skill improvement and performance feedback; and they fulfill relatedness through teamwork and shared achievements. The satisfaction of these needs provides a theoretical basis for understanding how esports participation promotes psychological well-being and engagement when implemented in structured and supportive environments [37,38].

These findings suggest that the mechanisms identified in this study cannot be fully accounted for by the frameworks of conventional classroom instruction or traditional sports activities. Esports, as a digitally mediated team-based activity, reinforces the role of social support through dynamic processes such as online collaboration, strategic performance, and digital identity formation. In this regard, the theoretical contribution of the present study lies in extending established psychological constructs into the domain of esports, thereby demonstrating that digital citizenship and gamified collaboration operate as distinctive pathways to students’ psychological well-being and school-life satisfaction.

First, psychological well-being strongly predicted social support (β = 0.899, p < 0.001). This finding is consistent with a Swiss longitudinal study showing that decreases in well-being coincide with reduced emotional and tangible support [53], a study conducted in the United States of America indicates that higher well-being enhances social well-being [54]. An Italian study further demonstrated that greater emotional stability fosters prosocial behavior, which increases peer support [55]. Together, these findings suggest that well-being enables students to cultivate emotional, informational, and instrumental support, a pattern also evident in esports contexts. This finding resonates with the need for relatedness, a central component of SDT. Students who experience higher levels of psychological well-being tend to communicate more openly and empathetically, fulfilling their relational needs through mutual support, trust, and shared team goals. In esports settings, digital collaboration allows adolescents to satisfy this need for relatedness by developing cohesive, emotionally supportive peer networks [37].

Second, psychological well-being significantly predicted academic engagement (β = 0.427, p < 0.01). Similar effects have been observed among Swiss adolescents, where well-being boosted school engagement and improved grades [14], and in the Philippines, where well-being was a direct predictor of academic engagement [56]. A meta-analysis of youth samples confirmed a positive correlation between subjective well-being and engagement [27], with comparable patterns reported in higher education [57,58]. These results indicate that psychological well-being functions as an emotional infrastructure that provides the vigor and focus needed for academic persistence, which can be reinforced through esports-related flow and mastery experiences. This association can also be interpreted through the need for competence in SDT [36]. When students experience success and mastery in esports—such as improving gameplay strategy, achieving in-game milestones, or receiving recognition from teammates—they satisfy their competence need. These experiences enhance their confidence and persistence, which may generalize to academic learning contexts and sustain engagement even when challenges arise.

Third, social support strongly predicted school-life satisfaction (β = 0.804, p < 0.001). This result aligns with evidence that relational resources serve as benchmarks in students’ evaluations of their school environment [19,25]. Emotional, informational, and instrumental support from peers and teachers help students interpret academic and social demands positively, consistent with the stress-buffering perspective [18]. Our study extends this supportive effect from classrooms and traditional sports into the esports setting.

Fourth, the direct effect of psychological well-being on school-life satisfaction was not significant, but an indirect effect through social support was confirmed (indirect effect = 0.676, 95% CI [0.549, 0.782]). This suggests that satisfaction depends less on internal well-being than on the relational support experienced in school. Even students with high well-being may fail to feel satisfied without peer and teacher support. Similar findings in collectivist contexts emphasize that relational cues are central in shaping school satisfaction [19,25].

Fifth, academic engagement did not significantly predict school-life satisfaction (β = −0.097, p > 0.05). While prior studies in Romania, the U.S., and Angola have reported positive links between engagement and satisfaction [25,28,59], our results indicate that this relationship is not universal. In our sample, engagement may have been driven by externally regulated or test-oriented participation, limiting its impact on satisfaction. According to SDT, only autonomous, intrinsically motivated engagement enhances school satisfaction, whereas controlled motivation undermines it [56,60].

Taken together, these non-significant findings suggest that the pathways from psychological well-being and academic engagement to school-life satisfaction are contingent on contextual and cultural conditions. In collectivist educational settings, students often rely on relational cues such as peer and teacher support when evaluating school satisfaction, which explains why well-being did not predict satisfaction without the mediating role of social support [19,25]. Similarly, when academic engagement is externally regulated or test-oriented, it may fail to foster school attachment and can contribute to fatigue or burnout. Prior studies based on SDT confirm that only autonomous, intrinsically motivated engagement yields positive outcomes, whereas controlled motivation undermines satisfaction [56,60]. These findings underscore the importance of focusing on the quality rather than the quantity of engagement.

From the perspective of autonomy, this non-significant relationship may suggest that much of the engagement observed among participants was controlled rather than autonomous—driven by external pressures such as academic evaluation or competitive ranking rather than intrinsic interest. According to SDT, only autonomous engagement, which satisfies the need for self-endorsement and volition, fosters genuine satisfaction and well-being [36]. Future esports programs should therefore cultivate autonomy-supportive conditions that encourage voluntary participation, reflection, and choice.

Although psychological well-being positively predicted both social support and academic engagement, esports should not be regarded as inherently beneficial. Its positive impact depends on contextual safeguards, such as structured program design, supportive coaching, and digital-citizenship education. Without these, esports may also involve risks, including excessive play, gender disparities, or toxic interactions [17]. Beyond these risks, it is equally important to consider the protective factors that can maximize the educational benefits of esports while minimizing potential harm. International research conducted in Western contexts has emphasized that the quality of program design and coach supervision critically determines whether esports participation leads to positive developmental outcomes or problematic behavior [8,61]. In collectivist educational environments such as South Korea—where social cohesion and teacher authority are highly valued—structured program design can function as a protective scaffold, transforming competition into opportunities for cooperation and shared growth [5]. Similarly, supportive coaching, characterized by autonomy support, emotional guidance, and feedback on teamwork, helps students internalize positive values and maintain balance between gaming and academic responsibilities [36,37]. Digital-citizenship education also serves as a crucial safeguard, equipping students with the awareness and skills to navigate online interactions responsibly and to prevent toxic or exclusionary behavior [62,63]. Collectively, these protective mechanisms contribute to a psychologically safe and educationally meaningful esports ecosystem that nurtures both engagement and well-being.

Furthermore, cross-cultural comparisons indicate that while Western students often value autonomy and self-expression in esports participation, students in collectivist settings tend to emphasize team harmony, relational belonging, and peer approval [12,21,22]. These cultural distinctions highlight that effective esports education must adopt a context-sensitive approach—one that balances individual motivation with collective responsibility and adapts program structures to the surrounding educational culture [61]. In this respect, we conceptualized esports as a digital collaborative space—a digitally mediated, team-based environment in which students coordinate strategies, communicate in real time, and solve problems collectively. Under appropriate conditions, these processes can promote persistence, focus, and cooperative learning. However, poorly managed environments may instead generate conflict or disengagement.

Overall, the evidence suggests that esports should not be regarded as a guaranteed pathway to improved well-being and engagement, but as a conditional educational context that requires careful structuring. By integrating both positive findings [4,6] and critical perspectives [29], this study highlights that the educational value of esports depends on balancing opportunities for collaboration with strategies to mitigate potential risks. Collectively, these interpretations reaffirm the explanatory value of Self-Determination Theory, demonstrating that the fulfillment of autonomy, competence, and relatedness constitutes the key psychological mechanism linking well-being, social support, and engagement in school-based esports.

4.1 Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study has several methodological constraints that also suggest directions for future refinement. First, the sample was drawn exclusively from Gwangju Metropolitan City, a region characterized by a collectivist educational culture and a highly competitive school environment. Such contextual features may shape how students perceive well-being, social support, and school satisfaction, potentially leading to results that differ from those observed in more individualistic or less competitive educational systems. Consequently, the generalizability of these findings should be interpreted with caution.

Second, the sample was heavily male-dominated (over 80%), reflecting the current gender imbalance in school-based esports participation. This imbalance may have influenced the observed outcomes, as male students often emphasize competition and achievement-oriented play, which could amplify engagement and peer-support dynamics while underrepresenting the perspectives of female participants. Future research should therefore include gender-balanced samples across multiple regions and examine whether the structural pathways among psychological well-being, social support, engagement, and satisfaction differ by gender or cultural background.

Third, the structural model did not incorporate esports-specific variables such as game genre, interaction quality, or team role dynamics. Including these contextual factors could clarify how digital collaboration shapes well-being and satisfaction.

Finally, although constructs were treated as composite variables for model parsimony, future research could conduct dimension-level or multi-group analyses to capture nuanced effects across subdimensions and demographic groups. Together, these refinements will help advance a more comprehensive understanding of how school-based esports contribute to adolescents’ psychosocial and academic development.

The results of this study suggest the following practical applications. First, schools should strengthen relationship-based support systems, considering that psychological well-being enhanced social support, which fully mediates the effect of psychological well-being on school-life satisfaction. Programs aimed at esports team coaching, peer mentoring, and teacher–student emotional coaching ought to be institutionalized so that students can experience structured support. Second, clear educational guidelines are needed for esports. Given that esports demand cooperation, strategy, and communication, they should be explicitly linked to curricular and co-curricular learning objectives to embed a positive feedback loop that reinforces school-life satisfaction. Third, it is essential to manage the quality of participation and to deliver digital-citizenship instruction. The absence of a direct effect of academic engagement on satisfaction suggests that qualitative dimensions—such as autonomy and meaningfulness—are more critical than the sheer amount of participation, and digital-citizenship and conflict-mediation training can preempt the online conflicts and flaming that sometimes arise in esports settings.

While these applications are primarily school-based, their scope and generalizability may be limited. Considering cultural and national differences in educational practices and attitudes toward esports, the suggested strategies should be adapted flexibly to local contexts. Future initiatives should therefore emphasize adaptability and responsiveness, ensuring that program design, coaching approaches, and digital-citizenship education can be tailored to diverse cultural and institutional environments.

This study investigated the structural relationships among psychological well-being, social support, academic engagement, and school-life satisfaction in school-based esports. The findings supported Hypotheses 1, 3, and 4, while Hypotheses 2 and 5 were not supported.

Psychological well-being was a strong predictor of social support and a moderate predictor of academic engagement. Social support, in turn, significantly predicted school-life satisfaction and fully mediated the effect of well-being on satisfaction. By contrast, academic engagement did not directly influence satisfaction, highlighting the importance of distinguishing between the quality and quantity of engagement in future research.

These results suggest that esports can serve as an educational context under structured conditions. Their positive impact depends on program design, supportive coaching, and explicit digital-citizenship education. Without such safeguards, esports participation may also involve risks such as excessive play, gender disparities, or toxic interactions.

Overall, the findings extend established psychological constructs into digitally mediated, team-based environments. When thoughtfully implemented, esports can strengthen relational resources and foster students’ satisfaction with school life. These results underscore the practical implication that integrating structured esports programs with supportive coaching can promote both well-being and school satisfaction, while adaptability to cultural and institutional contexts remains essential for broader applications.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Study design: Myeong-Hun Bae; conceptualization: Gwang-Soo Oh; study conduct: Gwang-Soo Oh, Je-Seong Lee; data collection: Je-Seong Lee, Myeong-Hun Bae; data analysis: Gwang-Soo Oh, Je-Seong Lee; data interpretation: Je-Seong Lee, Myeong-Hun Bae; drafting the manuscript: Gwang-Soo Oh, Je-Seong Lee; revising manuscript content: Je-Seong Lee, Myeong-Hun Bae. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: All participants signed the informed consent in this study. The survey collection process was approved by the Korea National University of Education Ethics Review Committee (approval number: KNUE-202309-SB-0329-01) and conducted according to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kwan J . The impact of esports on the development of 21st-century skills and academic performance for youths. Biomed J Sci Tech Res. 2025; 62( 1): 54291– 309. doi:10.26717/BJSTR.2025.62.009694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Cui L , Kim EJ , Kim J . How Chinese media addresses esports issues: a text mining comparative analysis of online news and viewers’ comments on the Hangzhou Asian Games. Electronics. 2023; 12( 24): 4961. doi:10.3390/electronics12244961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Lee Y , Park S , Na S . The impact of novelty seeking on media consumption intentions in esports: a study of the 2022 Hangzhou Asian Games using the model of goal-directed behavior. Int J Bus Sports Tour Hosp Manag. 2024; 5( 2): 21– 40. [Google Scholar]

4. North America Scholastic Esports Federation (NASEF) . Scholastic Esports as Resilient Safe Spaces: Promoting Positive Pro-Social Programs in Inspiring Social Environments [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 27]. Available from: https://www.nasef.org/blog/scholastic-esports-as-resilient-safe-spaces [Google Scholar]

5. Ahiaku PKA , Muyambi G . Empowering learners for the fourth industrial revolution: the crucial role of teachers and school management. Soc Sci Humanit Open. 2024; 10: 101141. doi:10.1016/j.ssaho.2024.101141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhong Y , Guo K , Fryer LK , Chu SKW . More than just fun: Investigating students’ perceptions towards the potential of leveraging esports for promoting the acquisition of 21st-century skills. Educ Inf Technol. 2025; 30: 1089– 121. doi:10.1007/s10639-024-13146-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wimmer S , Denk N , Pfeiffer A , Fleischhacker M . On the use of esports in educational settings: how can esports serve to increase interest in traditional school subjects and improve the ability to use 21st century skills? In: Proceedings of the 15th International Technology, Education and Development Conference; 2021 Mar 8–9; Online. p. 5782– 7. doi:10.21125/inted.2021.1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Rusk F , Ståhl M , Silseth K . Player agency, team responsibility, and self-initiated change: an apprentice’s learning trajectory and peer mentoring in esports. In: Harvey M , Marlatt R , editors. Esports research and its integration in education. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global; 2021. p. 103– 26. doi:10.4018/978-1-7998-7069-2.ch007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jenny SE , Gawrysiak J , Besombes N . Esports.edu: an inventory and analysis of global higher education esports academic programming and curricula. Int J Esports. 2021: 1– 48. [Google Scholar]

10. Kuykendall L , Tay L , Ng V . Leisure engagement and subjective well-being: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2015; 141( 2): 364– 403. doi:10.1037/a0038508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Ryff CD . Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989; 57( 6): 1069– 81. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tian L , Chen H , Huebner ES . The longitudinal relationships between basic psychological needs satisfaction at school and school-related subjective well-being in adolescents. Soc Indic Res. 2014; 119( 1): 353– 72. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0495-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Puiu S , Udriștioiu MT , Petrișor I , Yılmaz SE , Pfefferová MS , Raykova Z , et al. Students’ well-being and academic engagement: a multivariate analysis of the influencing factors. Healthcare. 2024; 12( 15): 1492. doi:10.3390/healthcare12151492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Schnell J , Saxer K , Mori J , Hascher T . On the longitudinal relationship between Swiss secondary students’ well-being, school engagement, and academic achievement: a three-wave random intercept cross-lagged panel analysis. Educ Sci. 2025; 15( 3): 383. doi:10.3390/educsci15030383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Cherewick M , Lama R , Rai RP , Dukpa C , Mukhia D , Giri P , et al. Social support and self-efficacy during early adolescence: dual impact of protective and promotive links to mental health and wellbeing. PLoS Glob Public Health. 2024; 4( 12): e0003904. doi:10.1371/journal.pgph.0003904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Reitman JG , Anderson-Coto MJ , Wu M , Lee JS , Steinkuehler C . Esports research: a literature review. Games Cult. 2020; 15( 1): 32– 50. doi:10.1177/1555412019840892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Aguerri JC , Santisteban M , Miró-Llinares F . The enemy hates best? Toxicity in League of Legends and its content moderation implications. Eur J Crim Pol Res. 2023; 29( 3): 437– 56. doi:10.1007/s10610-023-09541-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Cohen S , Wills TA . Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985; 98( 2): 310– 57. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Azpiazu L , Antonio-Aguirre I , Izar-de-la-Funte I , Fernández-Lasarte O . School adjustment in adolescence explained by social support, resilience and positive affect. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2024; 39( 4): 3709– 28. doi:10.1007/s10212-023-00785-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Chen C , Bian F , Zhu Y . The relationship between social support and academic engagement among university students: the chain mediating effects of life satisfaction and academic motivation. BMC Public Health. 2023; 23( 1): 2368. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-17301-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sullanmaa J , Tikkanen L , Ulmanen S , Pyhältö K . Life satisfaction, relatedness, and study engagement in the upper secondary school transition: the function of social support. Soc Psychol Educ. 2025; 28( 1): 128. doi:10.1007/s11218-025-10081-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Castelli L , Marcionetti J . Life satisfaction and school experience in adolescence: the impact of school supportiveness, peer belonging and the role of academic self-efficacy and victimization. Cogent Educ. 2024; 11( 1): 2338016. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2024.2338016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Stoeber J , Childs JH , Hayward JA , Feast AR . Passion and motivation for studying: predicting academic engagement and burnout in university students. Educ Psychol. 2011; 31( 4): 513– 28. doi:10.1080/01443410.2011.570251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Astin AW . Student involvement: a developmental theory for higher education. J Coll Stud Dev. 1999; 40( 5): 518– 29. [Google Scholar]

25. Jiang X , Shi D , Fang L , Ferraz RC . Teacher–student relationships and adolescents’ school satisfaction: behavioural engagement as a mechanism of change. Br J Educ Psychol. 2022; 92( 4): 1444– 57. doi:10.1111/bjep.12509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Symonds JE , D’Urso G , Schoon I . The long-term benefits of adolescent school engagement for adult educational and employment outcomes. Dev Psychol. 2023; 59( 3): 503– 14. doi:10.1037/dev0001458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wong ZY , Liem GAD , Chan M , Datu JAD . Student engagement and its association with academic achievement and subjective well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Educ Psychol. 2024; 116( 1): 48– 75. doi:10.1037/edu0000833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Bălțătescu S , Cernea-Radu AE . Age-related variations in school satisfaction: the mediating role of school engagement. Hung Educ Res J. 2025; 15( 1): 67– 87. doi:10.1556/063.2024.00302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Baker JA , Maupin AN . School satisfaction and children’s positive school adjustment. In: Furlong MJ , Gilman R , Huebner ES , editors. Handbook of positive psychology in schools. New York, NY, USA: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2009. p. 207– 14. doi:10.4324/9780203884089-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Danielsen AG , Breivik K , Wold B . Do perceived academic competence and school satisfaction mediate the relationships between perceived support provided by teachers and classmates, and academic initiative? Scand J Educ Res. 2011; 55( 4): 379– 401. doi:10.1080/00313831.2011.587322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Pedditzi ML . School satisfaction and self-efficacy in adolescents and intention to drop out of school. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024; 21( 1): 111. doi:10.3390/ijerph21010111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Reitman JG , Gardner RT , Campbell K , Cho A , Steinkuehler C . Academic and social-emotional learning in high school esports. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Connected Learning Summit. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: ETC Press; 2021. p. 148– 59. [Google Scholar]

33. Choi M . A concept analysis of digital citizenship for democratic citizenship education in the internet age. Theory Res Soc Educ. 2016; 44( 4): 565– 607. doi:10.1080/00933104.2016.1210549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Deterding S , Dixon D , Khaled R , Nacke L . From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. In: Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference; 2011 Sep 28–30, Tampere, Finland. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2011. p. 9– 15. doi:10.1145/2181037.2181040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Kozlowski SW . Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2018; 13( 2): 205– 12. doi:10.1177/1745691617697078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Deci EL , Ryan RM . Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY, USA: Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. 371 p. [Google Scholar]

37. Ryan RM , Rigby CS , Przybylski A . The motivational pull of video games: a self-determination theory approach. Motiv Emot. 2006; 30( 4): 344– 60. doi:10.1007/s11031-006-9051-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Qian TY , Wang JJ , Zhang JJ , Hulland J . Fulfilling the basic psychological needs of esports fans: a self-determination theory approach. Commun Sport. 2022; 10( 2): 216– 40. doi:10.1177/2167479520943875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Schaufeli WB , Salanova M , González-Romá V , Bakker AB . The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two-sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J Happiness Stud. 2002; 3( 1): 71– 92. doi:10.1023/A:1015630930326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhuang H , Zhao H , Wang Y , He C , Zhai J , Wang B . Development and validation of a school satisfaction scale for medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2025; 25: 379. doi:10.1186/s12909-025-06962-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Kim KS , Yoo SM . The influence of self-efficacy, psychological well-being, and stress management on subjective well-being. Brain Educ Res. 2010; 6: 19– 53. [Google Scholar]

42. Seong GB , Won JY . Effects of multidimensional perfectionism, self-esteem, and interpersonal competence on university students’ psychological well-being. J Learn-Centered Curric Instr. 2024; 24( 17): 553– 71. (In Korean). doi:10.22251/jlcci.2024.24.17.553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Lee JY . The effect of social support on the innovation behavior of social entrepreneurs: focused on mediating effects of self-leadership [ dissertation]. Seoul, Republic of Korea: Hanyang University; 2023. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

44. Choo HT , Sohn WS . A validating academic engagement as a multidimensional construct for Korean college students: academic motivation, engagement, and satisfaction. Korean J Sch Psychol. 2012; 9( 3): 485– 503. (In Korean). doi:10.16983/kjsp.2012.9.3.485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Choi JH . The effects of academic emotion and academic self-efficacy on self-regulated learning ability and school life satisfaction of middle school students [ dissertation]. Seoul, Republic of Korea: Myongji University; 2021. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

46. Browne MW , Cudeck R . Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA , Long JS , editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA, USA: Sage; 1993. p. 136– 62. [Google Scholar]

47. Hu LT , Bentler PM . Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999; 6( 1): 1– 55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Bagozzi RP , Yi Y . On the evaluation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci. 1988; 16( 1): 74– 94. doi:10.1007/BF02723327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Fornell C , Larcker DF . Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J Mark Res. 1981; 18( 3): 382– 8. doi:10.1177/002224378101800313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. MacKinnon DP . Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY, USA: Routledge; 2008. 488 p. [Google Scholar]

51. Kline RB . Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Publications; 2023. 554 p. [Google Scholar]

52. Shrout PE , Bolger N . Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002; 7( 4): 422– 45. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Debnar C , Peter C , Morselli D , Michel G , Bachmann N , Carrard V . Reciprocal association between social support and psychological distress in chronic physical health conditions: a random intercept cross-lagged panel model. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2024; 16( 1): 376– 94. doi:10.1111/aphw.12495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Joshanloo M . Longitudinal associations between psychological and social well-being: exploring within-person dynamics. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2024; 34( 1): e2768. doi:10.1002/casp.2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Affuso G , Picone N , De Angelis G , Dragone M , Esposito C , Pannone M , et al. The reciprocal effects of prosociality, peer support and psychological well-being in adolescence: a four-wave longitudinal study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024; 21( 12): 1630. doi:10.3390/ijerph21121630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Datu JAD , King RB . Subjective well-being is reciprocally associated with academic engagement: a two-wave longitudinal study. J Sch Psychol. 2018; 69: 100– 10. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2018.05.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Boulton CA , Hughes E , Kent C , Smith JR , Williams HTP . Student engagement and wellbeing over time at a higher education institution. PLoS One. 2019; 14( 11): e0225770. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0225770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Wang X , Wan Jaafar WM , Sulong RM . Building better learners: exploring positive emotions and life satisfaction as keys to academic engagement. Front Educ. 2025; 10: 1535996. doi:10.3389/feduc.2025.1535996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Gutiérrez M , Tomás JM , Romero I , Barrica JM . Perceived social support, school engagement and satisfaction with school. Rev Psicodidact. 2017; 22( 2): 111– 7. doi:10.1016/j.psicod.2017.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Deci EL , Ryan RM . The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000; 11( 4): 227– 68. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Brus A . Social gaming and esports in a health-competent and citizenship-enhancing framework: children and young people’s path to better digital well-being. In: Proceedings of the BARN Conference II—methodological Humility and Ethical Conundrums: Collaborative Explorations in Nordic Childhood Studies; 2025 Aug 14–15; Trondheim, Norway. [Google Scholar]

62. Jones LM , Mitchell KJ , Beseler CL . The impact of youth digital citizenship education: insights from a cluster randomized controlled trial outcome evaluation of the Be Internet Awesome (BIA) curriculum. Contemp Sch Psychol. 2024; 28( 4): 509– 23. doi:10.1007/s40688-023-00465-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Zheng Y , Zhang J , Li Y , Wu X , Ding R , Luo X , et al. Effects of digital game-based learning on students' digital etiquette literacy, learning motivations, and engagement. Heliyon. 2023; 10( 1): e23490. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools