Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Challenge and Hindrance Academic Stressors and University Students’ Well-Being: The Chain Mediating Roles of Meaning in Life and Academic Self-Efficacy

1 Faculty of Education, East China Normal University, Shanghai, 200062, China

2 Institute of Higher Education, Tongji University, Shanghai, 200092, China

* Corresponding Author: Yezi Zeng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mental Health Promotion in Higher Education: Interventions and Strategies for the Psychological Well-being of Teachers and Students)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(11), 1663-1679. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.072125

Received 20 August 2025; Accepted 30 October 2025; Issue published 28 November 2025

Abstract

Background: Academic stress is a critical factor influencing university students’ well-being. However, research has shown that stress is not a unidimensional construct; different types of stressors (challenge vs. hindrance) may lead to distinct outcomes. This study constructed a structural equation model (SEM) to examine the relationships between challenge and hindrance academic stressors and students’ well-being, as well as the mediating mechanisms. Methods: Data were collected from 836 undergraduates at six universities in China (58.4% female, 41.6% male; Mean age = 20.47 ± 1.46 years). Descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations, and SEM with 5000 bootstrap resamples were conducted to test hypothesized paths and mediating effects. Results: Direct path analysis revealed that challenge stressors positively predicted meaning in life (β = 0.329, p < 0.001) but not academic self-efficacy (β = –0.004, p = 0.915), while hindrance stressors negatively predicted meaning in life (β = –0.371, p < 0.001). Meaning in life strongly predicted academic self-efficacy (β = 0.543, p < 0.001) and well-being (β = 0.301, p < 0.001), and academic self-efficacy further contributed to well-being (β = 0.190, p < 0.001). Bootstrapping confirmed that meaning in life significantly mediated the effects of both challenge (β = 0.099, 95% CI [0.063, 0.144]) and hindrance stressors (β = –0.112, 95% CI [–0.162, –0.076]) on well-being. The serial mediation pathway was also significant for both models (challenge: β = 0.034, 95% CI [0.019, 0.049]; hindrance: β = –0.038, 95% CI [–0.057, –0.024]). Conclusions: This study partially validates the dual-pathway model of academic stress in higher education and highlights the pivotal roles of meaning in life and academic self-efficacy in the stress–well-being relationship.Keywords

The university stage represents a critical developmental transition from adolescence to early adulthood, during which students face multiple challenges related to academic demands, career planning, interpersonal relationships, and identity formation [1]. Against the backdrop of expanding global higher education and intensifying competition, mental health concerns among university students have become increasingly prominent [2,3]. Academic stress is one of the most influential determinants of students’ mental health and well-being (WB) [4]. It affects not only academic performance and persistence [5,6] but also emotional states, social adaptation, and overall quality of life [7].

Early conceptualizations defined academic stress as the set of students’ subjective perceptions and responses to threatening stimuli within the academic environment [8], providing an analytical pathway from stressors to individual reactions. Subsequent studies identified seven primary sources of academic stress, including pressure from teachers, academic performance, examinations, group work, peers, time management, and self-imposed expectations [9]. With the emergence of the Transactional Model of Stress, academic stress has been reconceptualized as the cognitive appraisal outcome of the interaction between environmental demands and personal resources [10], emphasizing the “demand–resource” evaluation process. For instance, research on Korean high school students viewed academic stress as a dynamic interaction shaped by time pressure and academic requirements through cognitive appraisal [11], while studies in Vietnam further incorporated cultural context, defining academic stress as a comprehensive cognitive appraisal of academic demands, family expectations, and social norms within a collectivist culture [12]. Collectively, these perspectives underscore that academic stress is not a static response to external pressure but a dual evaluative process in which individuals assess academic demands—such as task difficulty and performance pressure—against their perceived resources, including time, ability, and social support.

Traditional research has typically conceptualized academic stress as a unitary negative stimulus, linking it with anxiety, depression, and emotional exhaustion [13,14]. However, contemporary stress theories increasingly emphasize that stress is not universally detrimental; rather, different types of stressors may lead to divergent psychological and behavioral outcomes [15,16,17,18]. According to the Transactional Model of Stress, when individuals assess stressors as manageable growth opportunities through their evaluation of demands and resources, adaptive responses are generated. However, when stressors are perceived as insurmountable obstacles to goals, negative reactions arise [10]. Early on, the Yerkes-Dodson Law identified an inverted U-shaped relationship, indicating that moderate pressure enhances performance, while excessive pressure inhibits performance [19]. This distinction has since evolved, with stress further categorized into eustress (positive stress), which stimulates individual potential, and distress (negative stress), which impairs health [20]. The classification of challenge versus hindrance academic stressors (HAS) used in this study reflects this dual cognitive appraisal process, serving as a manifestation of the Transactional Model of Stress within academic contexts.

The challenge-hindrance stressors (CHS) framework, first proposed by Cavanaugh et al. [16], distinguishes between stressors that may foster personal growth and development (challenge stressors) and those that constrain resources and hinder goal attainment (hindrance stressors). It is important to note that the categorization of stressors is not an objective definition of stress sources, but rather a dynamic process that changes according to individuals’ resource appraisals. Challenge stressors are perceived as stress-inducing demands that, although requiring effort, present opportunities for growth and achievement. The core attributes of challenge stressors include potential gains, such as skill enhancement and goal attainment, and controllability, where individuals believe their resources can meet the demands. In contrast, hindrance stressors are perceived as stress-inducing demands that obstruct goal achievement without offering any growth value. The defining characteristics of hindrance stressors are goal interference, such as disruptions to academic progress, and resource depletion, where resources are consumed without providing any benefits [16,18]. In organizational behavior research, challenge stressors have been positively linked to motivation, innovative performance, and job satisfaction [21,22,23], whereas hindrance stressors are consistently associated with diminished motivation, emotional exhaustion, and lower performance [24,25,26]. Recently, the CHS framework has been introduced into educational contexts to explain differential effects of academic stress [21,27,28]. This classification provides valuable insights into how different types of stressors impact learners’ behaviors and psychological states [29]. However, empirical research applying the CHS framework to academic stress remains limited, particularly studies that systematically differentiate between the two types of academic stressors in undergraduate populations.

WB, as a multidimensional construct of mental health, encompasses positive emotions, life satisfaction, psychological functioning, and social connectedness [30]. Coping strategies and social support can moderate students’ perceptions of WB in the face of stress. Emotion-focused coping, such as avoidance or denial, can amplify the negative impact of academic stress on WB, while problem-focused coping, such as time management or seeking advice, acts as a buffering mechanism [31]. Both informational support, such as academic advice, and emotional support, such as empathetic expression, can weaken the negative relationship between academic overload and WB [32]. Naturally, individual perceptions of WB in response to the same stress are also influenced by differences in gender, age, and personality traits [33,34]. When academic stress is classified using the Challenge-Hindrance Stressor framework, it has been found that challenge stressors can enhance WB by promoting goal-setting, academic self-efficacy (ASE), and a sense of achievement [23,35], whereas hindrance stressors, by increasing emotional burden and reducing perceived control, undermine WB [36,37]. Psychological capital, including self-efficacy, hope, optimism, and resilience, mediates the relationship between challenge stressors and student WB, but does not exhibit the same effect with hindrance stressors [38]. However, the impact and mechanisms of this relationship within the context of Chinese university students have yet to be fully explored in the higher education sector. Additionally, some studies suggest that cultural context shapes individuals’ meaning-making of stressors, thereby influencing the relationship between stress and WB [39]. However, few studies have systematically analyzed how cultural dimensions, such as individualism-collectivism, affect the relationship between challenge-HAS and WB, leaving the underlying cultural differences behind students’ WB largely unexplained.

From the perspective of positive psychology, meaning in life (ML) is a core predictor of WB, reflecting individuals’ sense of purpose, values, and direction [40,41]. In academic settings, ML is reflected in students’ recognition of the value of their studies and clarity about long-term goals [42]. When students perceive their academic activities as purposeful and socially meaningful, they are more likely to reappraise academic demands as positive challenges, thereby generating adaptive emotional outcomes [43]. Conversely, a lack of meaning—even under moderate stress levels—may lead to alienation and diminished WB [44]. In East Asian educational contexts, individuals’ sense of meaning and value in life tends to emphasize relational meaning, which is closely connected to family expectations, collective identity, and social responsibility [12]. For instance, family pressure can intensify the negative impact of academic stress, whereas family support can strengthen students’ sense of life meaning and psychological resilience [45]. This relational dimension plays a crucial role in students’ learning and development during higher education.

Social cognitive theory [46] further posits that self-efficacy—the belief in one’s ability to accomplish tasks under specific conditions—directly shapes emotional states, motivational processes, and behavioral persistence. In higher education, ASE has been shown to influence how students respond to challenge and hindrance stressors [23,47]. High self-efficacy students are more likely to interpret challenge stressors as opportunities for growth, while those with low self-efficacy are more prone to helplessness and negative affect under hindrance stressors [23,48].

In summary, although the CHS framework has been widely applied in organizational and, more recently, educational research, gaps remain in the literature. First, many studies in educational psychology continue to treat academic stress as a unitary negative construct [4], overlooking the nuanced, differential impacts of challenge and hindrance stressors. Existing studies that adopt the CHS framework rarely focus on undergraduates’ mental health outcomes, with more emphasis placed on innovation or performance [23,27,49]. Second, few studies have integrated perspectives from positive psychology and social cognitive theory to examine mediating mechanisms, such as ML and ASE, in a single serial mediation model. Addressing these gaps, the present study proposes and tests an integrative model that explores how challenge and HAS influence university students’ WB through the parallel and serial mediating roles of ML and ASE. This study not only advances theoretical understanding of academic stress processes but also provides practical implications for designing academic and psychological interventions in higher education.

2.1 Challenge and Hindrance Academic Stressors and Well-Being

In higher education contexts, academic stressors faced by students can be categorized into challenge and hindrance stressors. Challenge academic stressors (CAS) typically arise from demanding coursework, research and innovation tasks, competition for academic performance, and pressures related to postgraduate study and career development [21,50]. Although such demands require considerable effort and commitment, students often appraise them as opportunities to enhance competence and realize personal goals [23]. For example, engaging in research projects, participating in academic competitions, or completing challenging assignments may generate tension, but these experiences foster engagement, reinforce self-efficacy, and contribute to positive achievement outcomes.

By contrast, HAS originate from institutional barriers such as unreasonable regulations, unbalanced course schedules, unclear evaluation standards, excessive administrative workload, and inequitable resource allocation [27,51]. These stressors are perceived as constraints rather than opportunities, offering little developmental value and instead leading to negative emotions, disengagement, and academic burnout [4]. Therefore, academic stress is not a unidimensional construct but instead reflects a dual nature—promotive or obstructive—depending on situational appraisal. This duality provides an important theoretical foundation for exploring how academic stress influences WB and its underlying psychological mechanisms.

Empirical evidence indicates that challenge stressors may enhance WB by facilitating goal setting, strengthening motivation, and promoting self-realization [35], whereas hindrance stressors may undermine WB by eroding perceived control and increasing emotional exhaustion [36]. Among university students, this bidirectional relationship is particularly salient because the academic environment encompasses both developmental opportunities and restrictive constraints [14,44]. For instance, Steinert found that challenge stressors were more strongly associated with performance outcomes, whereas hindrance stressors were more closely related to declines in satisfaction and health indicators [52]. Based on the above theoretical and empirical evidence, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a): Challenge academic stressors are positively associated with students’ well-being.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b): Hindrance academic stressors are negatively associated with students’ well-being.

2.2 The Mediating Role of Meaning in Life

Positive psychology emphasizes ML as a core predictor of WB [40,41]. Meaning reflects students’ sense of purpose, value, and direction in their academic pursuits. When individuals find personal or societal value in their studies, they are more likely to reappraise stress as an opportunity for growth, leading to positive affect and greater satisfaction [43]. Challenge stressors, often embedded in goal-directed tasks, can reinforce meaning by fostering purpose and commitment. Conversely, hindrance stressors may diminish students’ sense of academic value, leaving them feeling helpless and disconnected [53]. Based on the above theoretical and empirical evidence, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a): Meaning in life mediates the positive relationship between challenge academic stressors and well-being.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b): Meaning in life mediates the negative relationship between hindrance academic stressors and well-being.

2.3 The Mediating Role of Academic Self-Efficacy

Social cognitive theory highlights self-efficacy as a central determinant of how individuals respond to stressors, shaping emotional states, motivation, and behavioral persistence [46]. ASE directly predicts students’ achievement, persistence, and coping strategies [48,54]. Students with high self-efficacy are more likely to perceive challenge stressors as opportunities for skill development and engage in adaptive coping, whereas those with low self-efficacy are more prone to avoidance and negative outcomes under hindrance stressors [23]. Based on the above theoretical and empirical evidence, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 3a (H3a): Academic self-efficacy mediates the positive relationship between challenge academic stressors and well-being.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b): Academic self-efficacy mediates the negative relationship between hindrance academic stressors and well-being.

2.4 Serial Mediation of Meaning in Life and Academic Self-Efficacy

Notably, ML and ASE may function as a sequential mediation process. A strong sense of meaning provides students with clear goals and values, thereby enhancing intrinsic motivation [55]. This motivational resource can, in turn, strengthen students’ confidence in their academic abilities, ultimately contributing to higher WB [56]. Thus, incorporating both ML and ASE into a single model allows for a more comprehensive understanding of how academic stressors influence WB through both motivational and cognitive pathways. Based on the above ideas, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 4a (H4a): Meaning in life and academic self-efficacy jointly form a serial mediation pathway between challenge academic stressors and well-being.

Hypothesis 4b (H4b): Meaning in life and academic self-efficacy jointly form a serial mediation pathway between hindrance academic stressors and well-being.

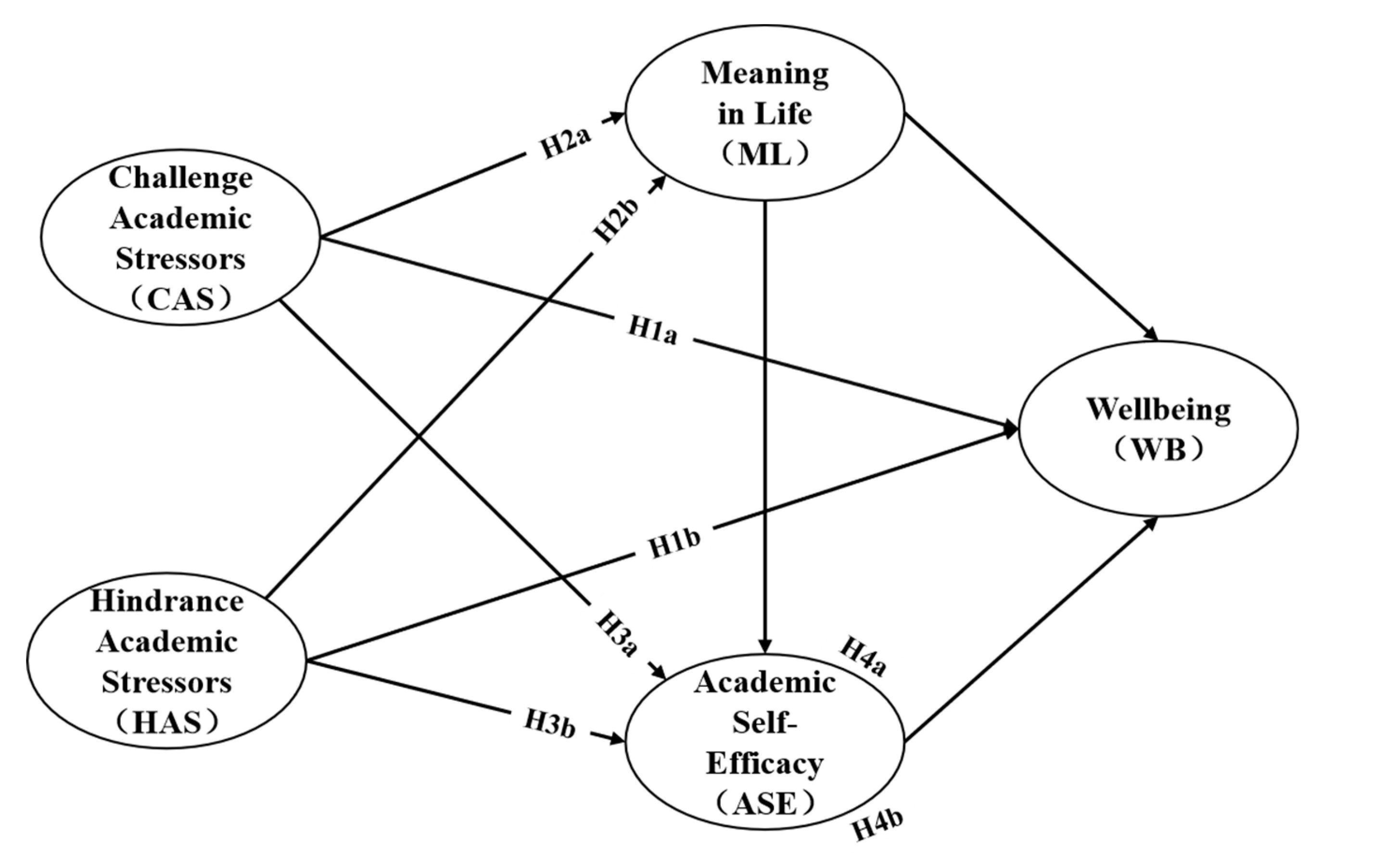

Building on the CHS framework, positive psychology, and social cognitive theory, this study proposes an integrative model explaining how academic stress affects college students’ WB through internal psychological resources.

According to the CHS framework, academic stressors are appraised as challenges that promote growth or hindrances that obstruct goal attainment. This distinction forms the basis for exploring how stress perceptions trigger distinct psychological mechanisms. Drawing on positive psychology, ML functions as a motivational resource that helps students reinterpret academic pressure as purposeful engagement, enhancing emotional stability and goal persistence. Informed by social cognitive theory, ASE represents a capability resource that enables effective coping and sustained learning confidence. Integrating these perspectives, the model also proposes a chain mediation mechanism whereby challenge and hindrance stressors influence WB through ML and ASE. For theoretical coherence and analytical focus, this study did not include other classical variables commonly used in stress and WB research, such as coping strategies or social support. The study is positioned as a foundational exploration of the core mechanism through which challenge and hindrance stressors affect WB via psychological resources—ML and ASE. Incorporating behavioral or environmental variables would dilute the explanatory power of this internal resource–based framework and risk conceptual redundancy. Therefore, these variables were intentionally excluded to provide a clearer view of the central psychological pathways.

This framework advances the CHS model by emphasizing internal psychological transformation rather than direct stress effects. It also introduces a cultural refinement: in the collectivist Chinese context, ML plays a primary role in converting stress into growth-oriented outcomes, highlighting a “meaning–efficacy–WB” pathway distinctive to this cultural setting. Based on the above theoretical framework and hypotheses, Fig. 1 illustrates the research framework of the present study.

Figure 1: Research framework.

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design, with data collected during the spring semester of 2025. A total of 878 questionnaires were distributed and returned via the Wenjuanxing online survey platform. To ensure data quality, consistency checks and control items were embedded in the survey to identify and exclude invalid or low-quality responses. After rigorous screening and data cleaning, 836 valid responses were retained, yielding a valid response rate of 95.2%. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling with stratification by region and university type to ensure diversity across institutional contexts. They were recruited from six universities located in eastern, central, and western China, covering different institutional types, including comprehensive, science and engineering, and normal universities. Importantly, the sample encompassed both elite universities (i.e., those included in national “Double First-Class” initiatives) and non-elite regional universities, thereby ensuring that the findings capture perspectives from diverse institutional tiers. This diversity helps clarify the scope and strengthens the potential generalizability of the results within the Chinese higher education context.

Eligibility criteria required participants to (1) be full-time undergraduate students, (2) have enrolled in at least four courses during the previous semester, and (3) provide informed consent and complete the entire questionnaire. The survey link was distributed via institutional email lists, course groups, and student organizations. Among the valid respondents, 58.4% were female and 41.6% were male. Participants ranged in age from 17 to 25 years (Mean = 20.47, standard deviation [SD] = 1.46). In terms of year of study, 24.3% were first-year students, 28.7% were sophomores, 26.1% were juniors, and 20.9% were seniors. Disciplinary backgrounds included humanities and social sciences (32.6%), science and engineering (51.8%), and arts and other disciplines (15.6%), indicating relatively balanced representation across academic fields. All participants reviewed and electronically signed an informed consent statement before beginning the survey, which clarified the study purpose, anonymity, and data use. Only those who selected “I voluntarily agree to participate” were able to proceed. The study adhered strictly to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Tongji University (No. tjdxsr2025015).

All constructs were measured using validated scales that had been translated into Chinese following a forward–backward translation procedure conducted by bilingual experts, with wording adapted to the academic context of Chinese university students. Responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater levels of the construct.

CAS and HAS were measured using the scale originally developed by Cavanaugh et al. [16] and later refined by Rodell and Judge [57]. The items were adapted to reflect academic contexts (e.g., “High course difficulty and strict requirements” for challenge stressors; “Administrative procedures hinder learning efficiency” for hindrance stressors). Each subscale consisted of six items. Previous studies have validated the two-factor structure and reliability of the scale among Chinese university students [27]. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.96 for challenge stressors and 0.91 for hindrance stressors. Although the scale exhibited relatively high Cronbach’s α coefficients (≥0.95), this level of reliability is theoretically acceptable and consistent with prior research. The high internal consistency reflects the careful linguistic and contextual adaptation of the instruments to the Chinese higher education setting, where the items are designed to capture closely related yet distinct aspects of the same underlying construct. Similar reliability coefficients have also been reported in previous studies published in the International Journal of Mental Health and Promotion, particularly in multidimensional scales assessing constructs such as academic stressors [58,59].

ML was assessed with the 10-item Meaning in Life Questionnaire [55]. A sample item is “I understand my life has a clear purpose”. The ML has demonstrated robust cross-cultural applicability in student populations [60]. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.92.

ASE was measured using the 8-item ASE Scale developed by Chemers et al. [61]. A sample item is “I am confident in my ability to meet the academic demands of my courses”. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.94.

WB was measured using the Flourishing Scale (FS) [62], which consists of eight items assessing overall psychological functioning and eudaimonic WB (e.g., “I lead a meaningful and purposeful life”). The FS emphasizes positive psychological functioning rather than transient affective states, making it suitable for educational psychology research [63]. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.89.

Data analyses were conducted using AMOS 23 and SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation analyses were first performed to examine variable distributions and associations. Structural equation model (SEM) was then employed to test the hypothesized pathways, with bias-corrected bootstrapping (5000 resamples) used to estimate the significance and confidence intervals of indirect effects. The model simultaneously estimated the direct effects of challenge and HAS on WB and the indirect effects through ML and ASE, including the proposed serial mediation pathway.

To address the potential issue of common method variance, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test, given that all key constructs were measured through self-reported questionnaires. Results from the exploratory factor analysis showed that the first unrotated factor accounted for 32.09% of the variance, which is well below the commonly accepted threshold of 40%. This suggests that common method bias was unlikely to pose a serious concern in the present study.

4.1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlation coefficients of all study variables. On average, CAS were at an above-moderate level (Mean = 3.51, SD = 1.02), whereas HAS were at a below-moderate level (Mean = 2.28, SD = 1.01). Both ML (Mean = 3.90, SD = 0.82), ASE (Mean = 4.22, SD = 0.74), and WB (Mean = 4.06, SD = 0.69) were at moderately high levels.

Table 1: Means, standard deviations and correlations among variables in the research.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Challenge Academic Stressors | 1 | ||||

| 2. Hindrance Academic Stressors | −0.793** | 1 | |||

| 3. Meaning in Life | 0.537** | −0.549** | 1 | ||

| 4. Academic Self-Efficacy | 0.377** | −0.403** | 0.591** | 1 | |

| 5. Well-being | 0.564** | −0.615** | 0.605** | 0.503** | 1 |

| Mean | 3.51 | 2.28 | 3.90 | 4.22 | 4.06 |

| SD | 1.02 | 1.01 | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.69 |

Correlation results indicated that CAS were positively associated with WB (r = 0.564, p < 0.01), ML (r = 0.537, p < 0.01), and ASE (r = 0.377, p < 0.01). In contrast, HAS were negatively correlated with WB (r = −0.615, p < 0.01), ML (r = −0.549, p < 0.01), and ASE (r = −0.403, p < 0.01). Moreover, ML and ASE were strongly positively correlated (r = 0.591, p < 0.01), and both were significantly related to WB (r = 0.605 and r = 0.503, respectively; p < 0.01). These results provide preliminary support for the hypothesized mediation effects and are consistent with theoretical expectations that motivational and competence-related resources are positively linked to psychological outcomes.

4.2 Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

The hypothesized structural model demonstrated good overall fit to the data (χ2/df = 5.011, goodness of fit index [GFI] = 0.905, comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.919, Tucker–Lewis index [TLI] = 0.908, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.074). Although the χ2/df value slightly exceeded the conventional threshold, this is acceptable given the large sample size, as χ2 is highly sensitive to sample size. The remaining indices all met or exceeded commonly accepted cutoffs. To some extent, it suggests that the model provides an overall acceptable representation of the observed data. The fit is adequate but not optimal.

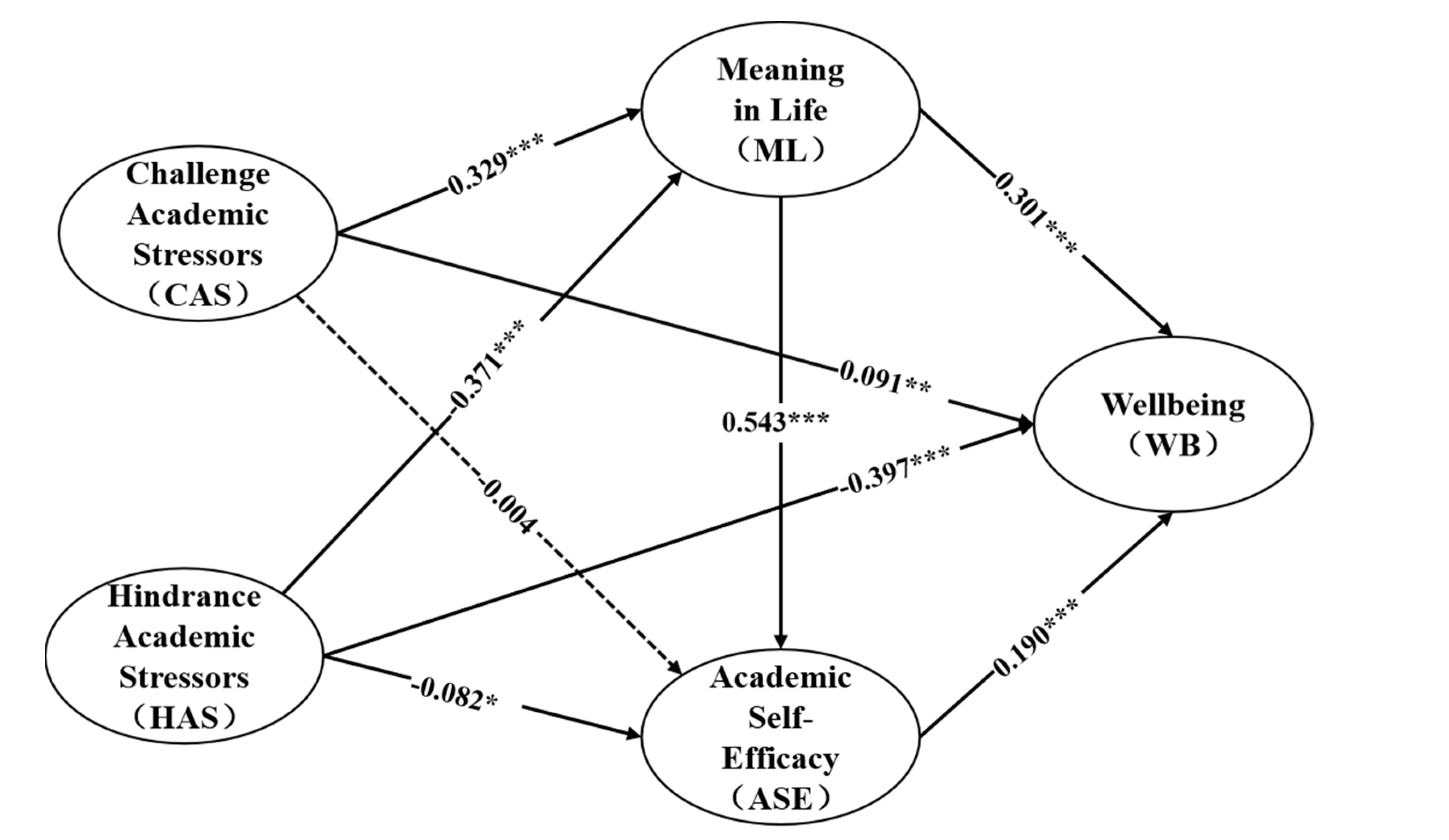

As shown in Fig. 2, regarding direct pathways, CAS significantly and positively predicted ML (β = 0.329, p < 0.001), which supports H1a. However, CAS showed no significant direct effect on ASE (β = −0.004, p = 0.915), suggesting that ASE in this pathway may be influenced indirectly. HAS exhibited a significant negative direct effect on ML (β = −0.371, p < 0.001), consistent with H1b.

Among the mediators, ML significantly predicted ASE (β = 0.543, p < 0.001), confirming the role of motivational resources in enhancing competence beliefs. WB was significantly predicted by both ML (β = 0.301, p < 0.001) and ASE (β = 0.190, p < 0.001). Overall, the effects associated with challenge stressors were stronger and more stable than those of hindrance stressors, suggesting that fostering positive challenge perceptions may be more effective for promoting WB than merely reducing hindrances.

Figure 2: Model verification. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

To further examine mediation effects, bias-corrected bootstrapping (5000 resamples) was employed to estimate indirect effects and their confidence intervals (see Table 2).

Table 2: Mediating results in the SEM.

| Mediation Effect Test | β | BootStrap SE | Z | Bootstrapping 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| CAS→WB | ||||||

| Total effect | 0.223 | 0.059 | 3.780 | 0.119 | 0.326 | 0.007 |

| Direct effect | 0.091 | 0.055 | 1.655 | −0.002 | 0.186 | 0.104 |

| Indirect effect (CAS→ML→WB) | 0.099 | 0.024 | 4.125 | 0.063 | 0.144 | 0.007 |

| Indirect effect (CAS→ASE→WB) | −0.001 | 0.011 | −0.091 | −0.016 | 0.023 | 0.924 |

| Indirect effect (CAS→ML→ASE→WB) | 0.034 | 0.009 | 3.778 | 0.019 | 0.049 | 0.013 |

| HAS→WB | ||||||

| Total effect | −0.563 | 0.051 | −11.039 | −0.649 | −0.479 | 0.007 |

| Direct effect | −0.397 | 0.054 | −7.352 | −0.484 | −0.305 | 0.011 |

| Indirect effect (HAS→ML→WB) | −0.112 | 0.025 | −4.480 | −0.162 | −0.076 | 0.005 |

| Indirect effect (CAS→ASE→WB) | −0.016 | 0.012 | −1.333 | −0.038 | 0.001 | 0.149 |

| Indirect effect (CAS→ML→ASE→WB) | −0.038 | 0.010 | −3.800 | −0.057 | −0.024 | 0.006 |

For the pathway from CAS to WB, the total effect was significant (β = 0.223, p = 0.007), whereas the direct effect was not (β = 0.091, p = 0.104), indicating that the effect was largely explained through mediators. The indirect effect via ML was significant (β = 0.099, 95% CI [0.063, 0.144]), whereas the indirect effect via ASE alone was not (β = −0.001, 95% CI [−0.016, 0.023]). Importantly, the serial mediation pathway “ML → ASE” was significant (β = 0.034, 95% CI [0.019, 0.049]). These results support H2a and H4a, while H3a was not supported.

For the pathway from HAS to WB, the total effect was significantly negative (β = −0.563, p = 0.007), and the direct effect remained significantly negative (β = −0.397, p = 0.011), suggesting that the detrimental effect of hindrance stressors on WB was only partially mediated. The indirect effect through ML was significant and negative (β = −0.112, 95% CI [−0.162, −0.076]), whereas the indirect effect through ASE alone was nonsignificant (β = −0.016, 95% CI [−0.038, 0.001]). The serial mediation pathway “ML → ASE” was also significant and negative (β = −0.038, 95% CI [−0.057, −0.024]). These results support H2b and H4b, while H3b was not supported.

Taken together, the findings largely confirmed the hypothesized model: challenge stressors positively influenced WB through enhanced ML and ASE, whereas hindrance stressors negatively influenced WB through reductions in these psychological resources.

Grounded in the CHS framework, this study examined the direct and indirect mechanisms through which academic stressors influence the WB of university students. The findings highlight the dual-pathway nature of academic stress, which is particularly salient in higher education settings where both growth-enhancing challenges and progress-inhibiting barriers coexist [28,50].

First, challenge stressors were positively associated with WB, whereas hindrance stressors demonstrated a significant negative relationship with WB. These results are consistent with findings from organizational contexts [17,64] and extend their applicability to undergraduate populations. Challenge stressors often stem from demanding coursework, frequent academic evaluations, research and innovation tasks, and future career expectations. Despite increasing academic load, such stressors can stimulate intrinsic motivation and promote self-realization, thereby enhancing engagement and WB [52,65]. By contrast, hindrance stressors primarily reflect systemic constraints, unreasonable curriculum designs, redundant requirements, and lack of institutional support, which undermine students’ sense of control, induce anxiety and emotional exhaustion, and ultimately diminish their psychological WB [37]. Besides, the relatively high negative correlation between challenge and hindrance stressors also deserves further reflection. Although conceptually distinct within the CHS framework, the two categories of stressors may be experienced as intertwined in academic contexts, where demanding tasks often encompass both facilitative and obstructive features. Rather than indicating conceptual redundancy, this correlation may reflect students’ holistic appraisal of stress as a dynamic and context-dependent experience. This finding suggests that, in educational settings—particularly within collectivist cultures where achievement and pressure are tightly coupled—the challenge–hindrance distinction might operate more as a continuum than as a dichotomy, inviting future refinement of measurement approaches.

Importantly, the direct positive effect of challenge stressors on WB became nonsignificant once mediators were introduced, suggesting that their benefits are contingent on the mobilization of psychological resources rather than a direct impact. This supports Crawford et al.’s “resource gain” perspective [24], which posits that positive stress enhances WB only when translated into meaning-making and competence development. Conversely, hindrance stressors not only eroded WB indirectly via reduced psychological resources but also retained a significant direct detrimental effect. This indicates a stronger and less compensable destructive force of hindrance stressors, echoing prior findings outside educational contexts [25]. In higher education, this has important implications, as systemic barriers and inequitable resource allocation are often structural and long-lasting, making them difficult to mitigate through short-term interventions.

Second, ML played a significant mediating role in the relationship between both types of stressors and WB, supporting the positive psychology perspective that meaning is a fundamental predictor of WB [40,41]. This suggests that the extent to which students can construct meaning from academic demands critically determines whether stress leads to growth or impairment. The core value of this finding lies in further confirming that the pathways to achieving WB under stress differ between Western and Chinese university students. Western students tend to focus on individual coping strategies, such as time management [66] and personal mindfulness practices [67], while Chinese students primarily seek meaning. Within the Chinese cultural context, the essence of this meaning-making process is rooted in social values and collective significance. Specifically, challenge stressors encourage students to reappraise academic tasks as meaningful opportunities, thereby enhancing WB; whereas hindrance stressors, by depleting resources and fostering helplessness, erode students’ sense of meaning and consequently undermine WB [43]. These findings align with recent cross-cultural research: Kero et al. demonstrated that during the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals with a strong sense of meaning maintained higher WB despite heightened stress [68].

Interestingly, ASE did not function as a significant independent mediator in either pathway, suggesting that in academic stress contexts, efficacy beliefs may be more a consequence of motivational resources (ML) rather than directly shaped by stress levels. It reflects a hierarchical pattern in which motivation precedes capability. Rather than reflecting a measurement issue, this pattern may reveal a deeper motivational hierarchy embedded in the cultural context. In Western research, self-efficacy is often conceptualized as a proximal cognitive resource that directly buffers stress and fosters psychological WB [23]. However, in the Chinese higher education context, self-efficacy appears to function as a downstream outcome shaped by students’ perceived ML. In other words, efficacy beliefs may not spontaneously translate into WB unless they are grounded in a sense of purpose and social value. This hierarchy suggests that meaning serves as a motivational foundation for the activation of efficacy, consistent with the collectivist orientation in which achievement motivation is often tied to family expectations, social contribution, and moral purpose. Thus, the indirect pathway—whereby challenge stress enhances meaning, which in turn strengthens efficacy and WB—captures a culturally coherent sequence of psychological adaptation rather than a lack of efficacy’s importance.

Third, this study simultaneously tested the roles of challenge and hindrance stressors within a single model, confirming their opposing predictive effects on WB. This underscores the “double-edged sword” nature of academic stress and supports the growing consensus in higher education research that academic stress should not be viewed as a uniformly negative burden but rather as contingent upon cognitive appraisals and resource activation [52,65]. Moreover, challenge and hindrance stressors are not strictly dichotomous but dynamically interrelated [15]. For instance, when challenge demands are unmet by sufficient support, they may transform into hindrance stressors; conversely, institutional reforms that reduce hindrances can reframe experiences into positive challenges for students.

The findings of this study contribute to understanding the mechanisms linking academic stress and WB in the Chinese higher education context. In Western higher education studies, ASE is often viewed as a core mechanism fostering learning engagement and psychological resilience. By contrast, the present findings indicate that, within the Chinese cultural context, self-efficacy is largely derived from students’ sense of ML. This suggests that to promote the WB of Chinese university students, efforts should focus on fostering a sense of meaning, on the basis of enhancing challenge stressors and reducing hindrance stressors, thereby forming the “stress–meaning–efficacy–WB” chain consistent with the empirical model.

Universities should design programs and activities grounded in collectivist cultural values such as family orientation, social responsibility, and communal contribution. Linking academic meaning with family expectations can provide students with clearer value direction and emotional support. For instance, annual “Study–Family Workshops” can invite students to share how their academic projects align with family aspirations, such as career stability and intergenerational advancement. Similarly, academic programs should be embedded within broader social and national goals. Engineering courses can integrate graduation projects with local infrastructure initiatives, whereas humanities disciplines may design modules such as “Academic Engagement for Rural Revitalization”.

At the institutional level, policies should aim to minimize hindrance stressors while empowering challenge stressors. Reducing bureaucratic procedures, simplifying administrative processes through digital platforms [69], and easing excessively competitive evaluation systems can mitigate students’ sense of low control and emotional exhaustion. Because unclear expectations amplify stress [70], universities should also replace ambiguous grading rules with competence-growth and social-value–oriented assessment criteria, enabling students to interpret evaluations as purposeful challenges rather than arbitrary pressures. Transparent expectations and value-based feedback can effectively reduce anxiety associated with uncertainty and enhance perceived academic control. Guide students to shift from obstructive stress to challenging stress.

At the same time, creating constructive challenge environments is essential. High-level coursework, academic competitions, and research opportunities should be accompanied by sufficient institutional support to prevent these experiences from becoming sources of hindrance. Examples include student research grants, structured faculty–student mentorship programs (e.g., one faculty member to five students), and peer learning communities. Curriculum design should also integrate knowledge acquisition with meaning cultivation through 2–3 credit service-learning courses that connect academic knowledge with community service. Elective courses and alumni lectures can further guide students to relate their academic expertise to socially valuable career pathways, fostering a stronger sense of purpose and direction.

For students experiencing high hindrance stress and diminished ML, universities should offer specialized counseling programs emphasizing collective reflection and value reconstruction rather than adopting Western individual-centered models. Activities such as family value mapping and stress reframing exercises can help students reinterpret academic challenges within their familial and social value systems. Collectively, these measures can promote a culturally grounded, meaning-centered educational environment in which students’ sense of meaning nurtures self-efficacy and, ultimately, sustainable WB in the face of academic stress.

This study advances the understanding of how academic stress relates to WB among Chinese undergraduates through a contextual adaptation, mechanism refinement, and practical transformation of the CHS framework. Rather than constructing a new theoretical model, it contributes to the localization and extension of an established framework within a non-Western higher education setting, offering both theoretical enrichment and applied implications for student mental health promotion. Theoretically, the study reconstructs the attributes of academic stressors and integrates the “individual–collective” goal appraisal logic rooted in Chinese collectivist culture, refining the CHS framework and aligning it more closely with academic psychological contexts. Empirically, it provides the quantitative evidence that hindrance stress exerts stronger detrimental effects than challenge stress and that ASE does not serve as an independent mediator. Instead, self-efficacy functions as a downstream outcome shaped by students’ sense of ML, extending the CHS mechanism and enhancing its explanatory boundary. Practically, the study translates the CHS framework’s organizational intervention logic into strategies suited to Chinese universities—specifically, a dual mechanism of “meaning–competence support” and a structural approach of “administration–teaching optimization”. These culturally grounded strategies transform theoretical insights into feasible approaches for promoting student mental health. Collectively, the research represents an incremental yet contextually significant innovation, demonstrating that the CHS framework can be refined, validated, and applied within collectivist educational contexts to enhance both theory and practice.

Despite these contributions, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the use of stratified convenience sampling limits the representativeness of the sample. While participants were drawn from multiple universities across different regions and university types and tiers, the sample may still not fully capture the diversity of the broader undergraduate population. More rigorous random or longitudinal sampling approaches would enhance the generalizability of the findings.

Second, the cross-sectional design restricts causal inference and temporal interpretation. For example, without longitudinal data, it remains uncertain whether challenge stress enhances ML or whether students with stronger meaning are more likely to perceive stress as a challenge. And the sample was limited to Chinese undergraduate students. Consequently, the findings may not generalize to other cultural or educational contexts. Longitudinal and cross-cultural studies are needed to examine the temporal dynamics and contextual variability of the observed mechanisms.

Third, several measurement constraints apply. Our instruments treated academic stress as a largely static construct, overlooking its multicomponent and dynamic nature, and specifically the experiential loop in which stress-evoked feelings (physical, psychological, social) both result from stress and, when consciously appraised, become new stressors.

Finally, although the SEM achieved acceptable fit indices, certain parameters (e.g., RMSEA) suggested room for improvement. This may be due to the complexity of the proposed chain mediation model and the multidimensional nature of the variables. Future research could test alternative model specifications or use or multilevel data to enhance robustness and parsimony. In addition, potential confounders were not controlled for, even though they may simultaneously influence stress appraisal and WB.

Future research should address these limitations through several directions. First, future studies should adopt more rigorous sampling strategies—such as multi-stage random sampling or longitudinal panel tracking—to improve representativeness and capture developmental changes in students’ stress and WB. Second, implementing multi-wave longitudinal or ecological momentary assessment designs could help establish causal ordering and capture real-time dynamics of academic stress across the academic cycle, thereby elucidating how meaning-making and efficacy beliefs evolve over time. Third, refining the measurement of academic stress is an important direction. Future studies could incorporate both the intensity and duration of stressors and capture their dynamic feedback loops, where emotional and physiological responses may further reinforce perceived stress. Finally, future comparative studies across cultural contexts could further elucidate how cultural values shape the challenge–hindrance–WB pathway, refining the CHS framework’s boundary conditions and its cross-cultural applicability.

This study applied the CHS framework to investigate the mechanisms through which academic stressors influence student WB. Results demonstrated that CAS were positively related to WB, whereas HAS were negatively related. ML played a central mediating role in both pathways, while ASE alone did not emerge as a significant mediator but contributed significantly within the serial mediation chain. These findings validate the dual-pathway model of CHS in higher education and deepen our understanding of the complex relationship between academic stress and WB. The study highlights that in the cultural context of China, fostering psychological WB among university students requires not only reducing hindrance stressors but also cultivating appropriate challenge stressors, particularly by enhancing ML to stimulate intrinsic motivation and strengthen efficacy beliefs.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Yezi Zeng and Yufei Cong; methodology: Yezi Zeng; software: Yezi Zeng; validation: Yufei Cong; data curation: Yezi Zeng and Yufei Cong; writing—original draft preparation: Yezi Zeng and Yufei Cong; writing—review and editing: Yezi Zeng and Yufei Cong. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author.

Ethics Approval: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the. Institutional Review Board of the Tongji University (No. tjdxsr2025015). All participants were informed that the survey was voluntary and anonymous before filling in the questionnaire. They were told they could quit at any time. All the students responded by volunteering to participate in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Arnett JJ . College students as emerging adults: the developmental implications of the college context. Emerg Adulthood. 2016; 4( 3): 219– 22. doi:10.1177/2167696815587422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Auerbach RP , Mortier P , Bruffaerts R , Alonso J , Benjet C , Cuijpers P , et al. WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2018; 127( 7): 623– 38. doi:10.1037/abn0000362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Pedrelli P , Nyer M , Yeung A , Zulauf C , Wilens T . College students: mental health problems and treatment considerations. Acad Psychiatry. 2015; 39( 5): 503– 11. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0205-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Pascoe MC , Hetrick SE , Parker AG . The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2020; 25( 1): 104– 12. doi:10.1080/02673843.2019.1596823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Talib N , Zia-ur-Rehman M . Academic performance and perceived stress among university students. Educ Res Rev. 2012; 7( 5): 127– 32. [Google Scholar]

6. Tus J . Academic stress, academic motivation, and its relationship on the academic performance of the senior high school students. Asian J Multidiscip Stud. 2020; 8( 11): 29– 37. [Google Scholar]

7. Bewick B , Koutsopoulou G , Miles J , Slaa E , Barkham M . Changes in undergraduate students’ psychological well-being as they progress through university. Stud High Educ. 2010; 35( 6): 633– 45. doi:10.1080/03075070903216643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Helms BJ , Gable RK . School situation survey. Palo Alto, CA, USA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1989. doi:10.1037/t06495-000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Lin YM , Chen FS . Academic stress inventory of students at universities and colleges of technology. World Trans Eng Technol Educ. 2009; 7( 2): 157– 62. [Google Scholar]

10. Lazarus RS , Folkman S . Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY, USA: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

11. Yun J , Kim MJ , Kim JS . The mediating effect of academic stress in the relationship between time pressure and subjective well-being of high school students. Korean J Educ Probl. 2018; 36( 4): 49– 69. doi:10.22327/kei.2018.36.4.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Van TD . Academic stress, psychological well-being and depression of Vietnamese high school students. Multidiscip Sci J. 2025; 7( 10): 142– 58. doi:10.31893/multiscience.2025485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Mahmoud JSR , Staten RT , Hall LA , Lennie TA . The relationship among young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, life satisfaction, and coping styles. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012; 33( 3): 149– 56. doi:10.3109/01612840.2011.632708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Misra R , Castillo LG . Academic stress among college students: Comparison of American and international students. Int J Stress Manag. 2004; 11( 2): 132– 48. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.11.2.132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Podsakoff NP , Freiburger KJ , Podsakoff PM , Rosen CC . Laying the foundation for the challenge–hindrance stressor framework 2.0. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2023; 10( 1): 165– 99. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-080422-052147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Cavanaugh MA , Boswell WR , Roehling MV , Boudreau JW . An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among US managers. J Appl Psychol. 2000; 85( 1): 65– 74. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. LePine JA , Podsakoff NP , LePine MA . A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Acad Manag J. 2005; 48( 5): 764– 75. doi:10.5465/amj.2005.18803921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Webster JR , Beehr TA , Love K . Extending the challenge–hindrance model of occupational stress: The role of appraisal. J Vocat Behav. 2011; 79( 2): 505– 16. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2011.02.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yerkes RM , Dodson JD . The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit formation. J Comp Neurol Psychol. 1908; 18: 459– 82. doi:10.1002/cne.920180503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Selye H . The stress of life. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill; 1956. [Google Scholar]

21. Yao H , Chen S , Liu A . Exploring the relationship between academic challenge stress and self-rated creativity of graduate students: Mediating effects and heterogeneity analysis of academic self-efficacy and resilience. J Intell. 2023; 11( 9): 176. doi:10.3390/jintelligence11090176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kim M , Beehr TA . Challenge and hindrance demands lead to employees’ health and behaviours through intrinsic motivation. Stress Health. 2018; 34( 3): 367– 78. doi:10.1002/smi.2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Travis J , Kaszycki A , Geden M , Bunde J . Some stress is good stress: The challenge–hindrance framework, academic self-efficacy, and academic outcomes. J Educ Psychol. 2020; 112( 8): 1632– 43. doi:10.1037/edu0000478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Crawford ER , LePine JA , Rich BL . Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: a theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J Appl Psychol. 2010; 95( 5): 834– 48. doi:10.1037/a0019364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Podsakoff NP , LePine JA , LePine MA . Differential challenge stressor–hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2007; 92( 2): 438– 54. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Amah OE . Challenge and hindrance stress relationship with job satisfaction and life satisfaction: The role of motivation-to-work and self-efficacy. Int J Humanit Soc Sci. 2014; 4( 6): 26– 37. [Google Scholar]

27. Yao H , Yu Q . Graduate student challenge–hindrance scientific research stress and creativity: Mediating effect of creative self-efficacy. J Psychol Afr. 2023; 33( 5): 448– 54. doi:10.1080/14330237.2023.2246277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. McCauley KD , Hinojosa AS . Applying the challenge–hindrance stressor framework to doctoral education. J Manag Educ. 2020; 44( 4): 490– 507. doi:10.1177/1052562920924072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Li C , Yang LQ , Wang XHF , Johnson RE , Chang CHD , Zhou Z . Feeling the approach to challenges and the avoidance of hindrances: Stressors, affective shift, and employee behaviors. J Occup Health Psychol. 2025; 30( 4): 272– 89. doi:10.1037/ocp0000405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Diener E , Oishi S , Tay L . Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat Hum Behav. 2018; 2( 4): 253– 60. doi:10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. del Pino MJ , Matud MP . Stress, mental symptoms and well-being in students: a gender analysis. Front Psychol. 2024; 15: 1492324. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1492324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Aloia AM , McTigue EM . Social support types and academic stress: Buffering effects on college students’ psychological well-being. J Youth Adolesc. 2019; 48( 12): 2345– 60. [Google Scholar]

33. Ruiz-Camacho C , Gozalo M . Predicting university students’ stress responses: The role of academic stressors and sociodemographic variables. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2025; 15( 8): 163. doi:10.3390/ejihpe15080163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Anglim J , Horwood S , Smillie LD , Marrero RJ , Wood JK . Predicting psychological and subjective well-being from personality: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2020; 146( 4): 279– 323. doi:10.1037/bul0000226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. O’Sullivan G . The relationship between hope, eustress, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction among undergraduates. Soc Indic Res. 2011; 101( 1): 155– 72. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9662-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Glozah FN . Effects of academic stress and perceived social support on the psychological wellbeing of adolescents in Ghana. Open J Med Psychol. 2013; 2( 4): 143– 50. doi:10.4236/ojmp.2013.24022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Al-Dalaeen AS , Shoqeirat MDA , Alshawawreh S , Alzaben MB . Challenge and hindrance stressors and mental health influencing psychological well-being: Moderation of psychological capital. Pak J Life Soc Sci. 2023; 21( 1): 155– 72. doi:10.57239/PJLSS-2023-21.1.0013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Al Sultan AA , Alharbi AA , Mahmoud SS , Elsharkasy AS . The mediating role of psychological capital between academic stress and well-being among university students. Pegem J Educ Instr. 2023; 13( 2): 335– 44. doi:10.47750/pegegog.13.02.37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Marques-Pinto A , Fernandes AR , Martins MP , Nunes B . Perceived stress, well-being, and academic performance during the first COVID-19 lockdown: Portuguese, Spanish, and Brazilian students. Healthcare. 2025; 13( 4): 371. doi:10.3390/healthcare13040371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Steger MF . Making meaning in life. Psychol Inq. 2012; 23( 4): 381– 85. doi:10.1080/1047840X.2012.720832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Seligman MEP . Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY, USA: Free Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

42. van der Walt C . The relationships between first-year students’ sense of purpose and meaning in life, mental health and academic performance. J Stud Aff Afr. 2019; 7( 2): 109– 21. doi:10.24085/jsaa.v7i2.3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Schippers MC , Ziegler N . Life crafting as a way to find purpose and meaning in life. Front Psychol. 2019; 10: 2778. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Li J , Han X , Wang W , Sun G , Cheng Z . How social support influences university students’ academic achievement and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Learn Individ Differ. 2021; 89: 102015. [Google Scholar]

45. Deng Y , Cherian J , Khan NUN , Liu X . Family and academic stress and their impact on students’ depression level and academic performance. Front Psychiatry. 2022; 13: 869337. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.869337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Bandura A . Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York, NY, USA: W. H. Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

47. Kristensen SM , Larsen TMB , Urke HB , Danielsen AG . Academic stress, academic self-efficacy, and psychological distress: a moderated mediation of within-person effects. J Youth Adolesc. 2023; 52( 7): 1512– 29. doi:10.1007/s10964-023-01770-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Putwain DW , Sander P , Larkin D . Academic self-efficacy in study-related skills and behaviours: Relations with learning-related emotions and academic success. Br J Educ Psychol. 2013; 83( 4): 633– 50. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02084.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Ahmad A . Navigating challenge-stress and hindrance-stress: Implications for well-being. Int J Manag Econ Fundam. 2024; 4( 4): 27– 33. [Google Scholar]

50. Bao D , Mydin F , Surat S , Lyu Y , Pan D , Cheng Y . Challenge–hindrance stressors and academic engagement among medical postgraduates in China: a moderated mediation model. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024; 17: 1115– 28. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S448844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Zhu Y , He W , Wang Y . Challenge–hindrance stress and academic achievement: Proactive personality as moderator. Soc Behav Pers. 2017; 45( 3): 441– 52. doi:10.2224/sbp.5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Steinert JK . The impact of perceived challenge and hindrance stress on individual well-being, role satisfaction, and role performance [ dissertation]. Miami, FL, USA: Florida International University; 2011. 343 p. [Google Scholar]

53. Wood SJ , Michaelides G . Challenge and hindrance stressors and wellbeing-based work–nonwork interference: a diary study of portfolio workers. Hum Relat. 2016; 69( 1): 111– 38. doi:10.1177/0018726715580866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Honicke T , Broadbent J . The influence of academic self-efficacy on academic performance: a systematic review. Educ Res Rev. 2016; 17: 63– 84. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2015.11.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Steger MF , Frazier P , Oishi S , Kaler M . The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J Couns Psychol. 2006; 53( 1): 80– 93. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Yuen M , Datu JAD . Meaning in life, connectedness, academic self-efficacy, and personal self-efficacy: a winning combination. Sch Psychol Int. 2021; 42( 1): 79– 99. doi:10.1177/0143034320973370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Rodell JB , Judge TA . Can “good” stressors spark “bad” behaviors? The mediating role of emotions in links of challenge and hindrance stressors with citizenship and counterproductive behaviors. J Appl Psychol. 2009; 94( 6): 1438– 51. doi:10.1037/a0016752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Li P , Chen L . College students’ academic stressors on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparison between graduating students and non-graduating students. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2022; 24( 4): 479– 93. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2022.019406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Han R , Xu T , Shi Y , Liu W . The risk role of defeat on the mental health of college students: a moderated mediation effect of academic stress and interpersonal relationships. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2024; 26( 9): 731– 44. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2024.054884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Steger MF , Dik BJ , Duffy RD . Measuring meaningful work: the work and meaning inventory (WAMI). J Career Assess. 2012; 20( 3): 322– 37. doi:10.1177/1069072711436160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Chemers MM , Hu LT , Garcia BF . Academic self-efficacy and first-year college student performance and adjustment. J Educ Psychol. 2001; 93( 1): 55– 64. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.93.1.55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Diener E , Wirtz D , Tov W , Kim-Prieto C , Choi DW , Oishi S , et al. New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 2010; 97( 2): 143– 56. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Howell AJ , Buro K . Measuring and predicting student well-being: further evidence in support of the flourishing scale and the scale of positive and negative experiences. Soc Indic Res. 2015; 121( 3): 903– 15. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0663-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. LePine MA , Zhang Y , Crawford ER , Rich BL . Turning their pain to gain: charismatic leader influence on follower stress appraisal and job performance. Acad Manag J. 2016; 59( 3): 1036– 59. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.0778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Acharya V , Rajendran A . A holistic model of resources to enhance the doctoral student’s well-being. Int J Educ Manag. 2023; 37( 6/7): 1445– 80. doi:10.1108/IJEM-11-2022-0457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Clabaugh A , Duque JF , Fields LJ . Academic stress and emotional well-being in United States college students. Front Psychol. 2021; 12: 628787. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.628787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Xue P , Abdullah SMS . A systematic review of mindfulness-based stress reduction on university students’ well-being. Open Psychol J. 2025; 18: e18743501379520. doi:10.2174/0118743501379520250716121048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Kero K , Podlesek A , Kavcic V . Meaning in challenging times: Sense of meaning supports well-being despite pandemic stresses. SSM Ment Health. 2023; 4: 100226. doi:10.1016/j.ssmmh.2023.100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Xia Q , Zhang L , Wang Y , Chen J . Burnout among VET pathway university students: the role of academic stress. BMC Psychol. 2025; 13( 1): 10583. doi:10.1186/s12889-025-22769-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Olson N , Sørensen MV , Pedersen AK , Madsen KH . Stress, student burnout and study engagement: implications for well-being. BMC Psychol. 2025; 13( 1): 2602. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-02602-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools