Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Family Organization and Resilience in Chinese Primary Students: Mediating Effects of Proactive Coping and Mindfulness

School of Humanities, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, 214000, China

* Corresponding Author: Xueyan Wei. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Risk and Protective Factors in Child and Adolescent Mental Health: Insights for Research and Practice)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(12), 1929-1948. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.071233

Received 02 August 2025; Accepted 10 November 2025; Issue published 31 December 2025

Abstract

Background: Chinese elementary students face mental health challenges due to excessive academic pressures. Previous research has indicated that resilience is crucial for improving their mental health, which is fostered by a supportive family environment. This study, therefore, explored the impact of family organization on children’s resilience and examined whether proactive coping and mindfulness mediate this relationship. Methods: Data were collected from 702 elementary school students (grades 3–6) in 3 cities in China using a multi-stage sampling procedure. Validated scales measured family organization, proactive coping, mindfulness, and resilience. The hypothesized model was tested using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in Mplus. Results: Resilience was strongly correlated with family organization (r = 0.655, p < 0.001), proactive coping (r = 0.482, p < 0.001), and mindfulness (r = 0.639, p < 0.001). Proactive coping and mindfulness mediated the relationship between family organization and resilience, with the direct effect accounting for 42.88% of the total effect. Indirect effects were distributed through two pathways: via mindfulness (41.41%) and via the “proactive coping → mindfulness” chain mediation (10.72%). Conclusions: This study reveals that effective family organization significantly enhances resilience among Chinese elementary students. Moreover, proactive coping and mindfulness serve as pivotal mediators in this relationship. These findings underscore the importance of understanding family organization and self-regulation, and their effects on the resilience of elementary pupils within the context of Chinese culture.Keywords

Adolescent mental health has emerged as a critical global concern, with increasing educational pressures identified as one of the significant contributing factors worldwide [1]. In China, this trend is particularly pronounced, as an escalating number of primary school students are experiencing mental health issues [2,3]. Consequently, enhancing the psychological well-being of adolescents has become a pivotal objective within China’s framework of basic education. Previous research has demonstrated that an individual’s capacity to withstand adversity is crucial, as it enables them to manage external stressors and safeguard their psychological health [3,4,5,6]. These findings indicate that bolstering children’s mental health through enhanced resilience is both feasible and effective. Resilience refers to the dynamic process of positive adaptation in the context of significant stress or adversity, which serves to protect an individual’s psychological function [7,8]. This construct is often conceptualized as comprising multiple dimensions, such as external support, internal strengths, and self-efficacy [8,9]. Studies suggest that cohesive, well-managed, and structured families are more likely to support children in overcoming adversity and strengthening their resilience [9,10,11]. It is evident that family dynamics significantly influence individual resilience [12,13].

Well-organized families, characterized by cohesiveness, effective management, and structured relationships, play a crucial role in this context [14,15]. Family organization is defined as the process through which family members collaborate to confront stress, mobilize resources, and adjust organizational structures to effectively manage crises [16,17]. A well-organized family promotes positive actions between primary school students and their environments, which is essential for successfully navigating Erikson’s psychosocial crisis of ‘Industry vs. Inferiority’ [18], thereby enhancing their confidence and life satisfaction, ultimately contributing to resilience development [19,20]. Moreover, within such environments, children have the opportunity to develop self-regulation [19], which further fosters resilience [8,21,22,23]. Both future-oriented self-regulation (e.g., proactive coping) and present-oriented strategies (e.g., mindfulness) mediate the relationship between family dynamics and resilience [24,25], thereby forming an endogenous regulatory system for individuals when confronting stress and adversity. As a result, proactive coping and mindfulness are recognized as key mechanisms through which family organization impacts resilience.

In summary, investigating how family and individual processes together shape resilience is of practical importance for enhancing the psychological health of Chinese primary school students, who face distinct academic and familial pressures [26,27]. However, empirical research on how the structured protective factor of family organization influences resilience remains in its formative stages. Additionally, the internal mechanisms governing these relationships are largely unexplored. Thus, this study investigates the influence of family dynamics (i.e., family organization) in conjunction with self-regulatory processes (i.e., proactive coping and mindfulness) on the resilience of Chinese primary school students.

1.1 The Influencing Factors of Resilience: The Resilience-as-Regulation Model

MacPhee et al.’s model [10] provides a theoretical foundation for the design of this study. The framework posits that resilience emerges not merely from isolated protective factors but through a dynamic interaction between family-level regulation and individual self-regulation [10]. Specifically, effective family organization and children’s adaptive self-regulation act as scaffolds in the development of resilience.

This model further suggests that family regulatory processes influence individual adaptive self-regulation and facilitate its internalization. Family organization enables parents to model flexible problem-solving and to provide emotional warmth, offering children tangible opportunities to observe and practice self-regulation skills in a supportive environment. Over time, as these behaviors are consistently reinforced, children internalize them, developing proactive coping habits and enhancing their capacity for mindfulness. This underscores the theoretical proposition that proactive coping and mindfulness are significant mediators through which family organization impacts resilience. Subsequent studies have corroborated this theoretical framework [24,28]. In summary, this model presents a comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding the interplay among family organization, proactive coping, mindfulness, and individual resilience.

While this model offers a universal framework, its application is invariably influenced by specific socio-cultural contexts. The Chinese context, marked by deeply ingrained familism and intense academic competition starting from primary school, provides a unique backdrop distinctly different from Western settings [3,29]. Consequently, there is an urgent need not only to validate the model in China but also to explore potential unique pathways through which family and individual regulatory processes promote resilience, potentially differing from those identified in Western contexts.

1.2 Family Influences on Resilience: Family Organization

Research has demonstrated that family members’ resilience is shaped by family resilience, which includes aspects such as family organization [12,13]. As mentioned previously, family organization serves as a buffer against the impact of crises and is conceptualized as the structural and functional capacity of a family system to maintain stability, adapt to challenges, and provide a coherent and supportive environment for its members [16]. This multifaceted construct encompasses several interconnected dimensions that collectively contribute to resilience. These dimensions include: (1) Leadership and Structure, characterized by strong authoritative leadership, clear expectations, and a firm yet congenial management style [14]; and (2) Relational Cohesion, which involves the flexibility of family roles and the emotional connectedness among members, as emphasized by Walsh [16]. A critical aspect of this organized system ’s effectiveness is its capacity to mobilize resources [14,16]. Thus, (3) Resource Integration, defined as the management and utilization of both social and economic capital, is considered a functional dimension of family organization that enables the translation of structural and relational strengths into tangible support [14,16].

Numerous studies have underscored the critical role of flexibility and connectedness in children’s resilience [19,30,31]. Specifically, the functionality of a family is profoundly influenced by its flexibility and cohesion, which are closely associated with resilience [31,32]. Families that exhibit high levels of flexibility and connectedness are capable of adapting to crises by adjusting roles and strengthening interpersonal bonds, thereby creating a supportive environment that enhances children’s resilience [10,16,19]. Additionally, authoritative parenting, which is characterized by a balance between high expectations and responsive engagement, has consistently been linked to the promotion of resilience in children [11,33,34,35]. This parenting style also mirrors the firm yet amicable management indicative of effective family organization [14]. In terms of family structuring, where parents establish clear expectations, enforce rules, and maintain effective control, it has been demonstrated to significantly bolster children’s resilience [10]. In contrast, inadequate family organization can lead to a chaotic and disorganized environment, potentially undermining children’s resilience [36]. Moreover, the integration of resources plays a crucial role in this context. It allows families to convert their internal strengths into practical outcomes. Families with robust organizational skills not only provide emotional support during economic hardships but are also more adept at leveraging external resources to overcome challenges, thus further enhancing children’s resilience in economically adverse conditions [37,38,39].

These findings highlight the significance of family organization and its various dimensions in fostering resilience during childhood. However, the existing body of research has predominantly focused on parenting styles and family functioning, with a notable deficiency in the comprehensive exploration of the integrated and systematic concept of “Family Organization”. Furthermore, there is a paucity of discourse that considers the unique sociocultural context of China. Consequently, the present study aims to examine how family organization and its dimensions positively influence resilience among elementary school children, thereby addressing this gap in the research.

1.3 Individual Influences on Resilience: Proactive Coping and Mindfulness

While family organization lays a vital environmental foundation for adolescent resilience through structured management and flexible functioning, existing research highlights that individual factors, particularly proactive coping and mindfulness, serve as the “internal scaffolding” crucial for the development of resilience [8,22]. The subsequent sections will detail how these two mediators facilitate the relationship between family organization and resilience, employing a dynamic interaction model.

1.3.1 Proactive Coping as a Mediator

Proactive coping represents a goal-oriented self-regulatory process through which individuals amass resources, gather feedback, learn from experiences, and ultimately achieve self-development and goal attainment [23,40,41,42]. This process is structurally conceptualized as a multifaceted construct that integrates cognitive planning with goal-directed behavior [40,42]. As these future-oriented actions are sustained over time, proactive coping evolves into a stable personal trait [40,43].

Butler et al. [23] underscored the pivotal role of proactive coping in enhancing resilience, highlighting its future-oriented and growth-focused attributes. These characteristics not only prepare individuals for adversity but also diminish potential difficulties. Proactive coping bolsters resilience through proactive engagement and resource utilization [44,45]. Furthermore, it is strongly associated with improved emotional regulation and mental health, both of which are essential for resilience [40,46,47]. Additionally, family support plays an integral role in shaping adolescents’ coping strategies. Yang et al. [48] demonstrated that the manner in which families organize and mobilize their members against risks and stress significantly impacts the development of proactive coping strategies. A well-structured family, characterized by a robust social support system, facilitates the formation of these coping strategies [42,49].

Consequently, there is a positive correlation between family organization, proactive coping, and individual resilience. According to MacPhee’s model [10], the organization and functioning of the family create a supportive environment that fosters the development of self-regulatory capacities such as proactive coping in adolescents. Proactive coping, which then enhance their competence to manage stress and confront adversity—a clear manifestation of resilience [42,49]. The literature indicates that well-functioning families promote positive behavioral outcomes in children by fostering effective coping strategies [25,50]. This suggests that coping strategies serve as mediators in this context.

While existing research confirms the mediation role of positive coping strategies between family organization and resilience, it often fails to recognize the distinct role of proactive coping. Unlike reactive approaches, proactive coping is a future-oriented strategy focused on resource accumulation and goal-setting. Therefore, we hypothesize that proactive coping mediates the relationship between family organization and resilience, exerting a significant influence on the operational dynamics of this relationship.

1.3.2 Mindfulness as a Mediator

Mindfulness entails a present-centered awareness process [51,52,53]. This capacity is comprised of several integrated skills: the ability to observe various stimuli; to describe experiences verbally; to engage in tasks with full focus, or act with awareness; to adopt a non-judging attitude toward one’s inner world; and to practice non-reactivity by letting go of distressing thoughts rather than being controlled by them [54].

According to the Monitor and Acceptance Theory [55], mindfulness augments resilience by fostering attentional monitoring (sustained present-moment awareness) and acceptance (nonjudgmental acknowledgment of experiences). These processes diminish rumination and mitigate negative emotions, thereby promoting resilience [56,57,58,59]. Empirical research substantiates the pivotal role of mindfulness in enhancing resilience [22,52]. Conversely, a well-organized family environment can bolster children’s capacity for mindfulness. Research suggests that family resilience can elevate adolescents’ mindfulness [24]. In essence, an effectively organized family, characterized by close bonds and structured practices, cultivates adolescent mindfulness [14,16]. Warm, secure relationships enhance mindful awareness [60,61,62], while clear rules and rituals support its development by improving self-regulation [63,64,65].

In summary, there is a positive association among family organization, mindfulness, and resilience. Empirical studies have demonstrated that mindfulness serves as a significant mediator between familial factors and individual adjustment [24,62]. In well-structured families, parents intentionally create a warm and structured home environment, laying the groundwork for the development of mindfulness in children [10,24,62,65]. This environment enables children to concentrate on their current feelings and form positive evaluations, which in turn facilitates their ability to maintain effective performance under adversity [22,24]. Thus, we hypothesize that mindfulness serves as a mediator between family organization and resilience.

1.3.3 The Chain Mediation of “Proactive Coping → Mindfulness”

In summary, both proactive coping and mindfulness mediate the relationship between family organization and individual resilience, respectively. As an exogenous regulatory system, family organization necessitates through endogenous self-regulatory processes, notably mindfulness and proactive coping, to achieve resilience outcomes [10]. Although both proactive coping and mindfulness are widely acknowledged in the literature as crucial strategies for mitigating stress and enhancing resilience [43,66], the internal sequence of their effects remains a critical unanswered question in current research.

Proactive coping, as an effective self-regulatory process, involves implementing proactive strategies to achieve goals [40], which enable to serve as an important prerequisite for mindfulness [67,68]. Drawing on Masicampo and Baumeister’s research, making progress toward goals quiets the mind by reducing goal-related intrusive thoughts, thereby creating the internal conditions for mindful awareness [67]. At the same time, by enabling tangible goal progress, proactive coping engenders positive emotions, like self-efficacy [69,70]. Based on the Broaden-and-Build Theory [68], this process expands individuals’ awareness (e.g., through mindfulness) and cultivate enduring personal resources over time, particularly resilience.

Empirical studies further support this sequential relationship. For instance, Polk et al. [43] discovered that the advantages of proactive coping in both younger and older adults predominantly depend on subsequent mindfulness. However, these insights, primarily derived from adult populations, prompt questions about whether this sequential process is similarly applicable in childhood, especially among primary school students, who are developmentally capable of both mindfulness and proactive coping [71,72]. Understanding how children transition from external family regulation to autonomous self-regulation is crucial.

Therefore, based on the above theoretical and empirical evidence, it is proposed that “Proactive Coping → Mindfulness” sequentially mediate the relationship between family organization and resilience. Specifically, a well-organized family environment fosters the development of proactive coping skills in children; the exercise of these skills, in turn, creates the cognitive and emotional conditions necessary for mindful awareness to flourish; ultimately, this heightened mindfulness serves as a key mechanism in building lasting resilience.

The present study aims to examine the relationship between family organization and individual resilience, with a particular focus on the chain mediation effect of proactive coping and mindfulness. Specifically, we investigate whether family organization significantly influences individual resilience and whether this relationship is sequentially mediated by proactive coping and mindfulness. This investigation not only provides evidence-based intervention strategies for parents but also enhances our understanding of resilience development among elementary school students.

Accordingly, we have formulated the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Family organization, proactive coping, mindfulness, and individual resilience are positively correlated.

Hypothesis 2: Family organization positively predicts individual resilience.

Hypothesis 3: Proactive coping and mindfulness mediate the relationship between family organization and individual resilience.

Hypothesis 4: Proactive coping and mindfulness play a chain mediating role in the relationship between family organization and individual resilience.

The participant selection process employed a multi-stage sampling method to enhance the representativeness of the sample. In the first stage, three cities were selected through simple random sampling from a broader urban list. Subsequently, within these cities, elementary schools were chosen using a stratified random sampling approach, ensuring that schools of varying sizes were proportionally represented.

The study included students in grades 3–6. This range was methodologically chosen to ensure valid self-reports of complex psychological constructs. Younger children (grades 1–2, aged 6–8) have developing cognitive and metacognitive abilities that may limit their capacity to provide reliable response [73]. Consistent with this, our pretests showed that first and second graders had difficulty understanding key questions. The sample was therefore limited to grades 3–6 to ensure psychometric quality.

A total of 738 elementary school students (grades 3 to 6) were recruited for this questionnaire survey, and after excluding invalid questionnaires, 702 elementary school students were retained as the final sample. This sample size well exceeds the minimum of 119 determined by an a priori power analysis, ensuring adequate statistical power for the study [74]. The effective recall rate was 95.1%. Among the study subjects, 52.0% (n = 365) were male and 48.0% (n = 337) were female, and the proportion of students in each grade was 28.9% (n = 203), 22.2% (n = 156), 28.1% (n = 197), and 20.8% (n = 146) respectively. Table 1 provides comprehensive demographic data.

Table 1: Demographic variables of the samples (n = 702).

| Variables | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 365 | 52.0 |

| Female | 337 | 48.0 |

| Grade | ||

| Third Grade | 203 | 28.9 |

| Fourth Grade | 156 | 22.2 |

| Fifth Grade | 197 | 28.1 |

| Sixth Grade | 146 | 20.8 |

| Place of Origin | ||

| Urban | 445 | 63.4 |

| Township | 126 | 17.9 |

| Rural | 131 | 18.7 |

According to our data integrity criteria, 36 responses were excluded primarily for the following reasons: (a) excessively short response time on either questionnaire, (b) patterned responses (e.g., straight-lining) in either questionnaire, and (c) more than 10% missing data in either questionnaire. This exclusion helped ensure data quality.

Furthermore, to mitigate potential confounding bias from comorbid conditions, participant inclusion was contingent upon parent-reported confirmation of no prior psychiatric or neurodevelopmental diagnoses (e.g., attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], depression). Additionally, participants were excluded if they were (a) receiving active psychological treatment, or (b) had a known intellectual disability (IQ < 70). These criteria ensure that the measurements of mindfulness and coping strategies are not distorted by unaccounted clinical conditions.

Informed consent was first obtained from the participating schools and all participants before administering the questionnaire. Since the subjects of this study were minors, informed consent was also obtained from their guardians. Following approval from the participating schools and consent from students and their parents, data were collected using structured online questionnaires. Students completed questionnaires assessing their family organization, proactive coping, mindfulness and resilience during school hours in computer classrooms under teacher supervision.

To adhere to ethical research practices, all questionnaires included a standardized introductory statement outlining the study’s purpose, participation guidelines, and assurances of anonymity, which aimed to encourage participants to provide honest responses. The studies were conducted in accordance with Jiangnan University Medical Ethics Committee (Reference No. JNU202506RB068). This research adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki.

The family organization scale was adapted from the Family Organization Assessment Scale [75], grounded in Walsh’s family resilience model [16]. There were 18 elements on the scale in four different dimensions. The four dimensions include flexibility, connectedness, economic resources and social support. A 5-point Likert scale was employed, with higher scores indicating more effective family organization. The sample item for each dimension is provided in the Appendix A.

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses demonstrated strong psychometric properties. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was 0.921. The overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.908, and sub-dimension reliability coefficients ranged from 0.685 to 0.831, affirming the scale’s reliability and validity for further use. Fit indices included Chi-square divided by degrees of freedom (χ2/df) = 2.018, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.056, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.942, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.931, adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) = 0.895, goodness of fit index (GFI) = 0.921, incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.943. These findings demonstrated strong psychometric properties suitable for further analysis.

The Proactive Coping Scale was adopted from a revised version of the Proactive Coping Styles Questionnaire (PCS) developed by Chen [76]. The scale consists of 12 questions divided into 3 dimensions, namely goal setting, coping behavior, and proactive cognition. The scale is based on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating a greater tendency to adopt proactive coping. The sample item for each dimension is provided in the Appendix A.

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses demonstrated strong psychometric properties. The KMO value was 0.914, and the overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.668, and sub-dimension reliability coefficients ranged from 0.720 to 0.883, affirming the scale’s reliability and validity for further use. Fit indices included χ2/df = 1.971, RMSEA = 0.055, CFI = 0.971, TLI = 0.963, normed fit index (NFI) = 0.944, IFI = 0.971, relative goodness-of-fit index (RF = 0.927. These findings demonstrated strong psychometric properties suitable for further analysis.

Mindfulness were assessed using a short version of the Five-Factor Positive Mindfulness Scale revised by Deng et al. [77], which consists of 5 dimensions and 20 items. The five dimensions are observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience and non-reactivity to inner experience. The scale is a 5-point scale, and the higher the score, the higher the level of positive mindfulness of the children who fill out the questionnaire. The sample item for each dimension is provided in the Appendix A.

Factor analyses indicated robust psychometric properties. The KMO value was 0.868. The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.875, supporting its reliability and validity. Fit indices included χ2/df = 22.049, RMSEA = 0.057, CFI = 0.941, TLI = 0.930, GFI = 0.941, IFI = 0.942. These findings demonstrated strong psychometric properties suitable for further analysis.

The Resilience Scale was developed by Hu and Gan [78] and contains 5 dimensions and 22 items. The five dimensions are goal planning, emotional control, family support, interpersonal assistance, and positive cognition. The scale is a 5-point scale, with higher scores representing higher levels of resilience. The sample item for each dimension is provided in the Appendix A.

Factor analyses confirmed the scale’s suitability. The KMO value was 0.894. The overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.899, with sub-dimension reliability coefficients ranging from 0.750 to 0.884. Fit indices included χ2/df = 1.740, RMSEA = 0.048, CFI = 0.952, TLI = 0.945, AGFI = 0.888, GFI = 0.912, IFI = 0.953. These findings demonstrated strong psychometric properties suitable for further analysis.

Data were statistically analyzed using SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), MPLUS 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA). First, the findings of this study are not considered to be substantially impacted by common method bias, as assessed by Harman’s single-factor test. An exploratory factor analysis incorporating all items from the four measurement scales was conducted using SPSS 27.0 and MPLUS 8.3. The analysis revealed that the primary factor accounted for only 29.850% of the total variance, which is well below the 40% threshold, thereby confirming the absence of significant common method variance.

Subsequently, the means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations for all variables were calculated and examined to characterize the sample and evaluate bivariate relationships, utilizing SPSS 27.0 for this analysis. The significance of correlation coefficients was assessed using a two-tailed test with an alpha level of 0.05. A series of hierarchical multiple regression analyses were employed using SPSS 27.0 to explore the predictive power of the sub-dimensions of family organization, proactive coping, and mindfulness on resilience. The sub-dimensions of each construct were entered as independent variables to predict the total score of resilience, with the adjusted R2 used to evaluate the variance explained and the statistical significance of individual regression coefficients was determined at p < 0.05.

The core mediation hypotheses were tested using path analysis in MPLUS 8.3. Three models were examined: (1) a simple mediation model with proactive coping as the mediator; (2) a simple mediation model with mindfulness as the mediator; and (3) a chain mediation model specifying the path from family organization to proactive coping, then to mindfulness, and finally to resilience. A bias-corrected bootstrap approach with 5000 resamples was applied to test all effects. The 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals were examined, and effects for which these intervals did not contain zero were considered statistically significant.

3.1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

We used correlation analysis and descriptive statistics to examine the links among the research variables. The findings indicate that resilience was significantly and positively correlated with family organization (r = 0.655, p < 0.001), proactive coping (r = 0.482, p < 0.001), and mindfulness (r = 0.639, p < 0.001), with the strongest relationship between resilience and mindfulness. Table 2 presents the results, which support Hypothesis 1.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics and correlations analysis for study variables (n = 702).

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Organization | 73.80 | 12.90 | 1 | |||

| Proactive Coping | 42.32 | 6.77 | 0.571*** | 1 | ||

| Mindfulness | 76.77 | 13.80 | 0.663*** | 0.535*** | 1 | |

| Resilience | 84.70 | 16.36 | 0.655*** | 0.482*** | 0.639*** | 1 |

In order to further investigate the predictive power and impact of family organization, proactive coping, and mindfulness on the resilience of elementary school students in grades 3–6, regression analyses were conducted. The results are shown in Table 3. Regression analyses were conducted with the sub-dimensions of family organization, proactive coping, and mindfulness as independent variables and resilience as the dependent variable.

Table 3: Regression analysis for variables predicting children’s resilience (n = 702).

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | R | R2 | ΔR2 | F | β | Durbin-Watson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience | Connectedness | 0.601 | 0.361 | 0.361 | 395.210*** | 0.387*** | |

| Social Support | 0.656 | 0.430 | 0.069 | 85.207*** | 0.255*** | ||

| Economic Resources | 0.666 | 0.443 | 0.013 | 15.806*** | 0.143*** | 1.761 | |

| Goal Setting | 0.690 | 0.475 | 0.475 | 634.599*** | 0.373*** | ||

| Coping Behavior | 0.762 | 0.580 | 0.105 | 174.01*** | 0.367*** | ||

| Proactive Cognition | 0.773 | 0.598 | 0.018 | 30.651*** | 0.193*** | 1.643 | |

| Describing | 0.645 | 0.417 | 0.417 | 499.691*** | 0.313*** | ||

| Acting with Awareness | 0.744 | 0.553 | 0.137 | 213.572*** | 0.362*** | ||

| Non-reactivity | 0.759 | 0.576 | 0.023 | 37.880*** | 0.184*** | ||

| Non-judging | 0.763 | 0.583 | 0.007 | 10.883*** | 0.087*** | ||

| Observing | 0.766 | 0.586 | 0.004 | 5.887* | 0.076* | 1.724 |

Among the dimensions of family organization, connectedness, social support, and economic resources entered the regression equation together, and all of them had significant positive predictive effects. Based on the regression analyses, the three dimensions accounted for 44.3% of the variance in the total scores, and in terms of the individual explanations, connectedness had the most significant predictive effect, which was 36.1% (β = 0.387, p < 0.001). In the dimensions of proactive coping, goal setting, coping behavior and proactive cognition entered the regression equation together, and all of them had significant positive predictive effects. The regression analysis revealed that the three constituent dimensions collectively accounted for 59.8% of the variance observed in the aggregate scores, thereby elucidating their predictive capacity, and in terms of the individual interpretations, goal setting had the most significant predictive effect at 47.5% (β = 0.373, p < 0.001). In the aspect of mindfulness, describing, acting with awareness, non-reactivity and non-judgment entered the regression equation with a significant positive predictive effect, and according to the results of the regression analysis, the predictive explanation of the four dimensions on the total score was 58.6%, and in terms of the individual explanations, describing had the most significant predictive effect at 41.7% (β = 0.313, p < 0.001). Hypothesis 2 was tested.

To further examine the role of proactive coping, mindfulness in the relationship between family organization and resilience, we conducted mediation effects analyses using MPLUS 8.3.

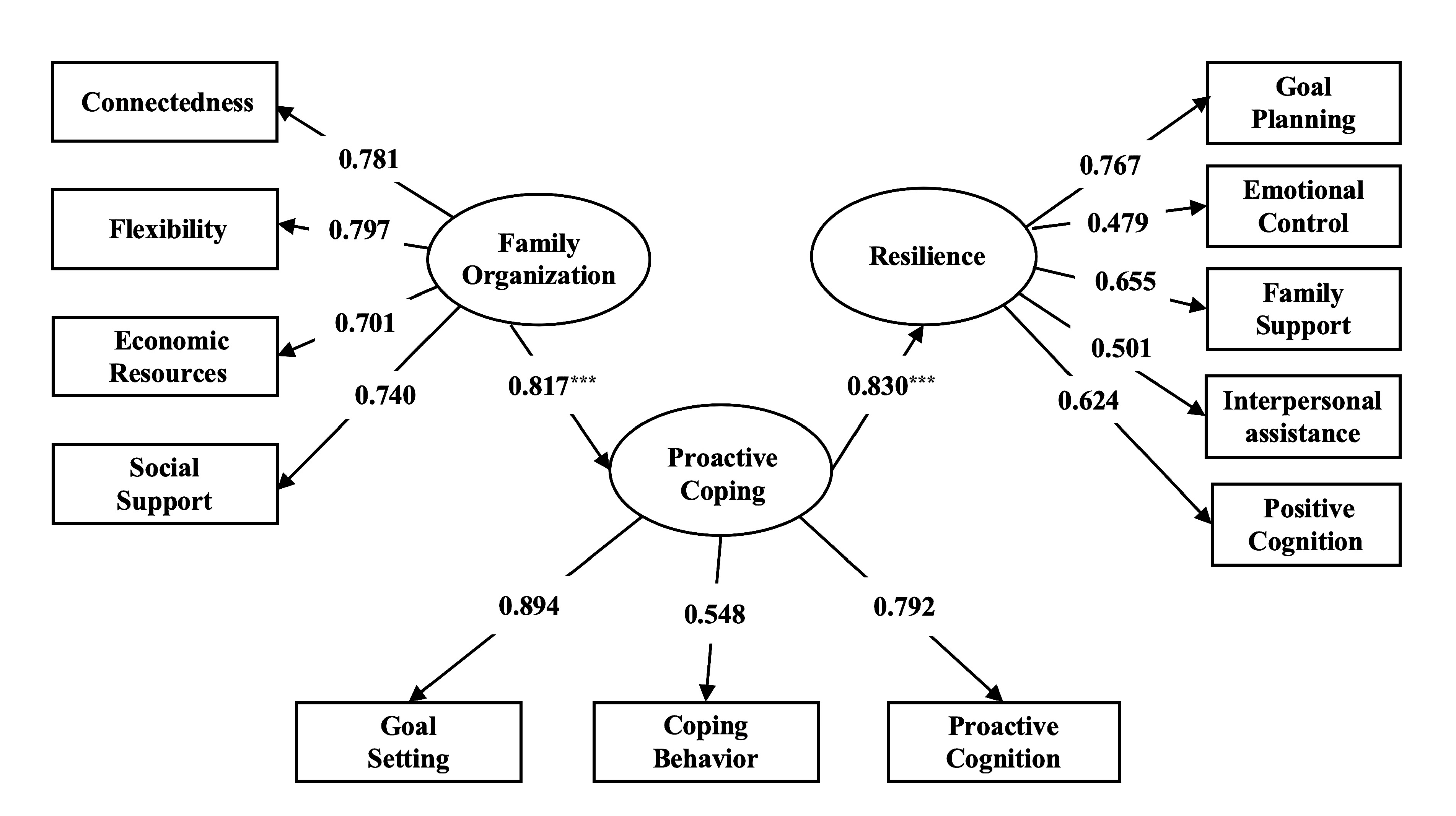

3.3.1 Analysis of Mediating Effects of Proactive Coping

First, we tested the mediating effects with family organization as the independent variable, elementary school students’ resilience as the dependent variable, and proactive coping as the mediating variable. The results of the analysis are presented in Fig. 1. Hypothesis 3 was tested.

Figure 1: Diagram of the mediating model of proactive coping between family organization and resilience. Note: ***p < 0.001.

The test found that the path coefficients in the above figure reached the significant level, and the family organization mode can promote the generation of resilience (β = 0.817, p < 0.001) through the positive effect on proactive coping (β = 0.830, p < 0.001), which verifies the mediating pathway of “Family Organization → Proactive Coping → Resilience”. To robustly test the mediating effect, we employed a bias-corrected bootstrap procedure (5000 repetitions) which is recommended as it does not assume a normal distribution for the indirect effect. The path of “Family Organization → Proactive Coping → Resilience” is significant (see Table 4), and its 95% confidence interval is [0.519, 0.855], which indicates that proactive coping is a mediator between family organization and resilience. Also, the path of “Family Organization → Resilience” is not significant, and its 95% confidence interval is [−0.017, 0.352] that includes zero, suggesting that family organization has an effect on resilience through proactive coping in this model.

Table 4: Mediating effect of proactive coping between family organization and resilience.

| Path Effect | 95% Confident Interval | Estimate | S.E. | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boot CI Lower Limit | Boot CI Upper Limit | ||||

| Family Organization → Resilience | −0.017 | 0.352 | 0.170 | 0.095 | 0.074 |

| Family Organization → Proactive Coping → Resilience | 0.519 | 0.855 | 0.678 | 0.087 | <0.001 |

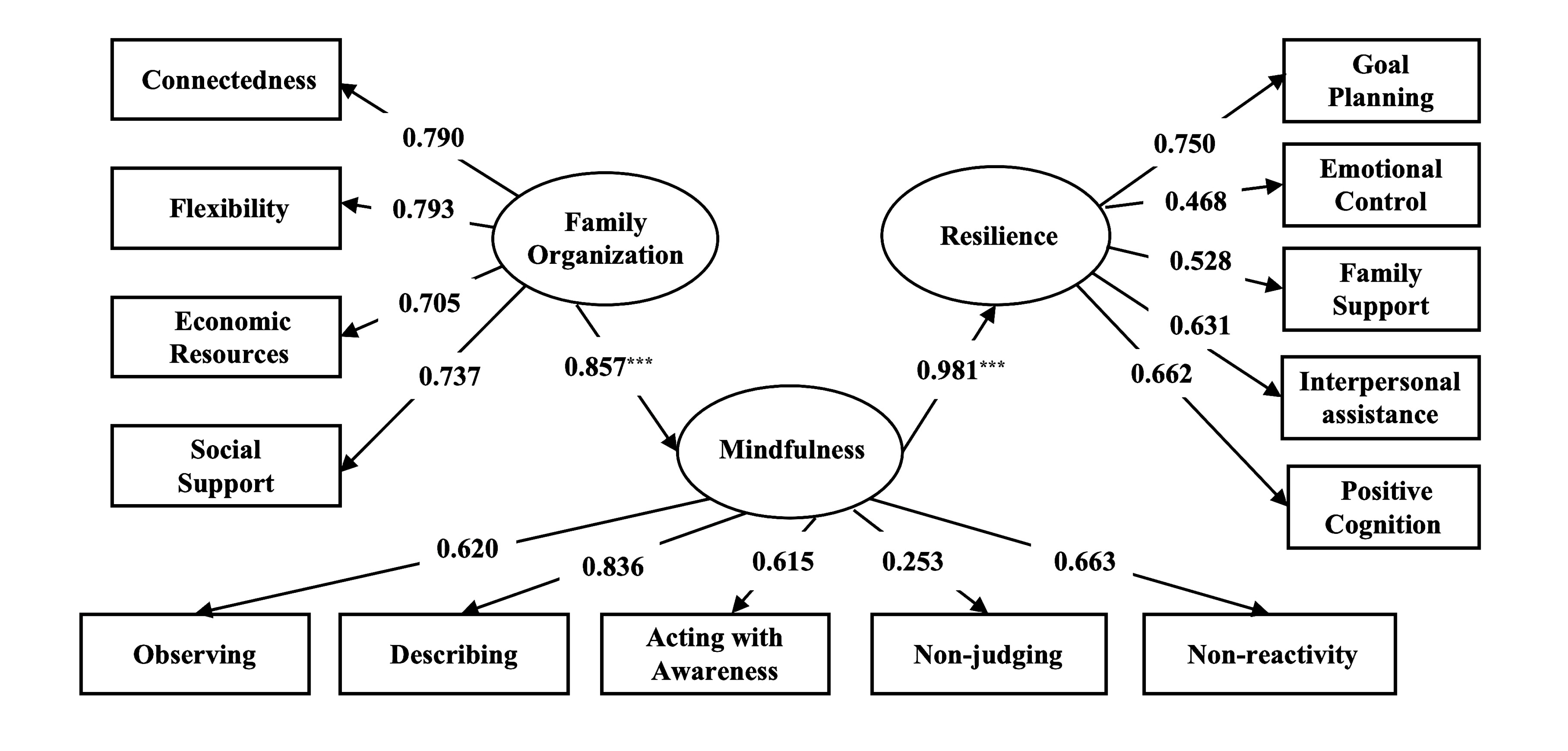

3.3.2 Analysis of Mediating Effects of Mindfulness

Then, we conducted a mediation effect test with family organization as the independent variable, resilience of elementary students as the dependent variable, and mindfulness as the mediating variable. The results are showed in Fig. 2. Hypothesis 3 was tested.

Figure 2: Diagram of the mediating model of mindfulness between family organization and resilience. Note: ***p < 0.001.

All path coefficients were significant. Family organization can promote the enhancement of resilience (β = 0.990, p < 0.001) through the positive influence on mindfulness (β = 0.849, p < 0.001), which verifies the mediation path of “Family Organization → Mindfulness → Resilience”. The mediating effect was further examined by the Bootstrap test (5000 repetitions). The path of “Family Organization → Mindfulness → Resilience” is significant (see Table 5), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.632, 1.136], suggesting that mindfulness have a mediating effect between family organization and resilience. In addition, the path of “Family Organization → Resilience” is not significant, with a 95% confidence interval of [−0.280, 0.232], which contains 0, indicating that family organization has an effect on resilience through mindfulness in this model.

Table 5: Mediating effect of mindfulness between family organization and resilience.

| Path Effect | 95% Confident Interval | Estimate | S.E. | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boot CI Lower Limit | Boot CI Upper Limit | ||||

| Family Organization → Resilience | −0.280 | 0.232 | 0.012 | 0.132 | 0.929 |

| Family Organization → Mindfulness → Resilience | 0.632 | 1.136 | 0.841 | 0.128 | <0.001 |

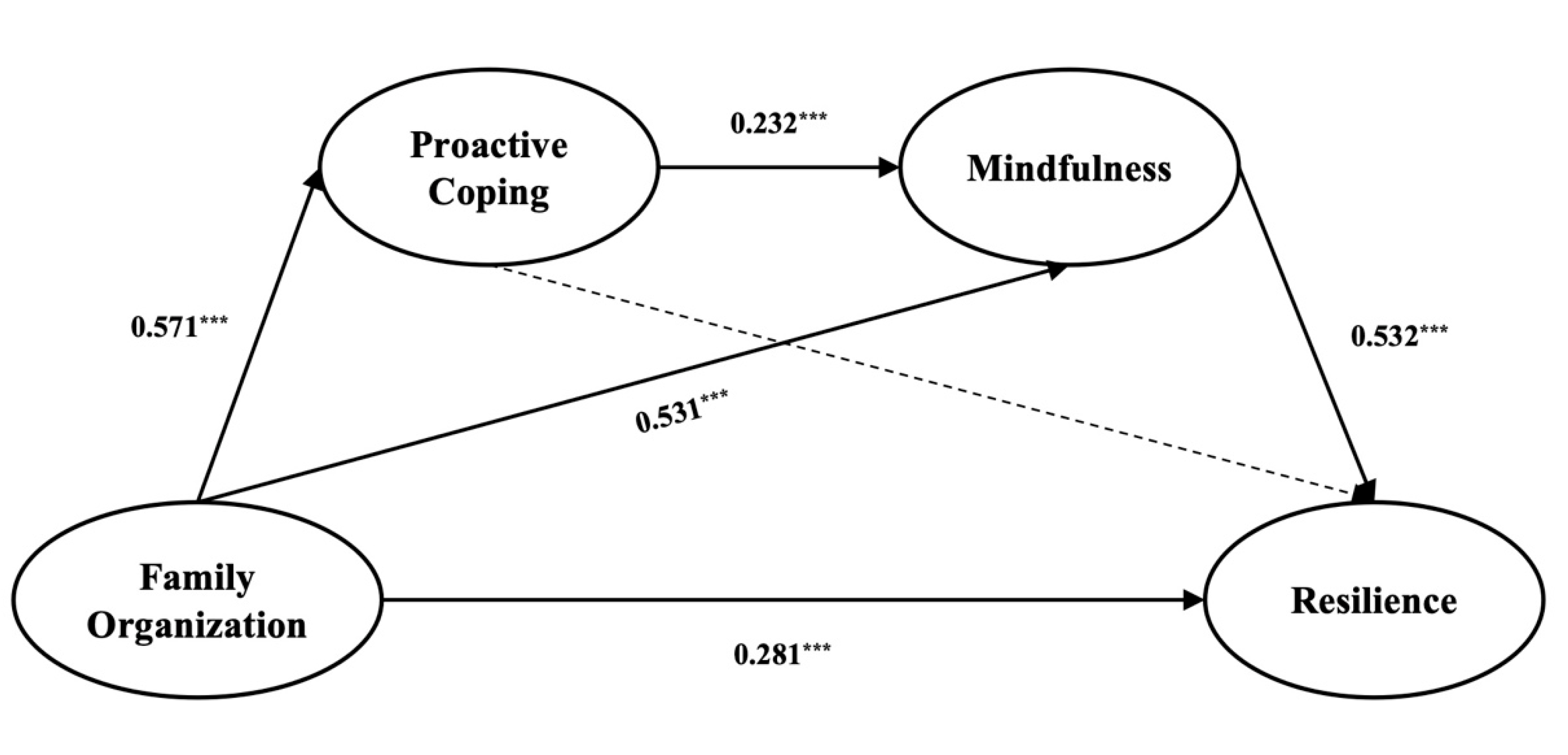

3.3.3 Analysis of Mediating Effects of “Proactive Coping → Mindfulness”

Following the preliminary confirmation of simple mediation, we proceeded to examine our central sequential mediation hypothesis, which proposes that the “proactive coping → mindfulness” pathway serves as a chain mediator between family organization and resilience. The findings showed in Fig. 3, which support Hypothesis 4.

Figure 3: Chain-mediated model. Note: ***p < 0.001.

First, family organization could positively predict resilience, with an effect value of. Second, family organization could positively predict mindfulness, and mindfulness could positively predict resilience. Third, family organization could positively predict proactive coping, proactive coping was able to positively predict mindfulness, and mindfulness were also able to significantly and positively predict resilience. However, proactive coping was not a significant predictor of resilience.

The robustness of the mediation model was confirmed using a bootstrap method with 5000 resamples. As can be seen from the Table 6. (1) The direct effect is significant, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.221, 0.363], excluding 0. (2) The path of “Family Organization → Mindfulness → Resilience” has a 95% confidence interval of [0.242, 0.348], excluding 0, indicating that mindfulness has a significant mediating effect between family organization mode and resilience. (3) The 95% confidence interval of the pathway “Family Organization → Proactive Coping → Resilience” is [−0.017, 0.063]. Given that the 95% confidence interval encompasses zero, this suggests that proactive coping does not play a statistically significant mediating influence within the relationship between family organization and resilience. (4) Finally, the 95% confidence interval for the path of “Family Organization → Proactive Coping → Mindfulness → Resilience” is [0.049, 0.100], which indicates that the chain of “Proactive Coping → Mindfulness” has a significant mediating effect between family organization and resilience.

Table 6: Mediating effect of proactive coping and mindfulness between family organization and resilience.

| Model Path | Effect | Boot SE | 95% Confident Interval | Ratio of Indirect to Total Effect | Ratio of Indirect to Direct Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boot CI Lower Limit | Boot CI Upper Limit | |||||

| Direct Effect | ||||||

| Family Organization → Resilience | 0.292 | 0.036 | 0.221 | 0.363 | 42.88% | - |

| Indirect Effect | ||||||

| Path 1: Family Organization → Mindfulness → Resilience | 0.282 | 0.027 | 0.242 | 0.348 | 41.41% | 96.60% |

| Path 2: Family Organization → Proactive Coping → Resilience | 0.022 | 0.020 | −0.017 | 0.063 | ||

| Path 3: Family Organization→ Proactive Coping → Mindfulness →Resilience | 0.073 | 0.013 | 0.049 | 0.100 | 10.72% | 25.00% |

| Total Effect | 0.681 | 0.027 | 0.630 | 0.734 | - | - |

Drawing upon the Resilience-as-Regulation model [10], the Monitor and Acceptance Theory [55], the Broaden-and-Build Theory [68], and the research on mindfulness [67], our investigation centered on the link between family organization and resilience in Chinese primary school students. A key focus was testing the proposed serial mediation involving proactive coping and mindfulness. Our findings indicate that family organization, proactive coping, and mindfulness are all significantly and positively correlated with resilience in Chinese primary school children, and each factor can predict children’s resilience. Notably, the pathway “proactive coping → mindfulness” demonstrated a significant chain-mediated effect.

4.1 The Direct Relationship between Family Organization and Chinese Elementary Students’ Resilience

Our initial finding reveals that family organization fosters the development of resilience, corroborating the results of Dou et al. [19] and Zhang et al. [31]. More importantly, this outcome not only validates the Resilience-as-Regulation model [10] by emphasizing the pivotal role of family regulation but also expands upon it by elucidating distinct pathways to resilience within the unique cultural and socioeconomic context of China.

Regression analyses have shown that connectedness, social support, and economic resources are significant predictors of resilience. From a cultural perspective, the finding that connectedness serves as the strongest predictor holds profound cultural significance. Within the family-centric culture of China, connectedness transcends simple emotional intimacy to encompass a deeper sense of belonging and identity [29]. It provides the secure foundation necessary for children to engage in exploration, face challenges, and cultivate self-efficacy [41] and an internal locus of control [79], which are essential for resilience. At the same time, this aspect of family environment is critical for elementary school students who are at the stage of navigating Erikson’s psychosocial crisis of ‘Industry vs. Inferiority’ [18]. Thus, reinforcing and deepening these culturally significant family bonds is a crucial strategy in promoting resilience among students.

Moreover, regression analyses have also identified social support and economic resources as important predictors of resilience, consistent with studies by Yamamoto et al. [39] and Bruno et al. [38]. In a society that values guanxi (relational networks) [80], social support functions as a practical support system that offers not only emotional support but also essential information and practical assistance. This support helps to stabilize the family environment and shield children from external pressures [39,81]. Concurrently, economic resources enable families to transform financial capital into developmental assets, thereby reducing uncertainty and enhancing a sense of security [38,82]. Collectively, these organized efforts are vital components of family organization, equipping children with both tangible and psychological tools to manage adversity and enhance their resilience.

4.2 The Indirect Prediction on Chinese Elementary Students’ Resilience

Our second significant finding elucidates the mediating roles of proactive coping and mindfulness in the relationship between family organization and individual resilience. This revelation extends the Resilience-as-Regulation model [10]. We identified two distinct modes of individual self-regulation that foster resilience development: future-oriented self-regulation (proactive coping) and present-oriented self-regulation (mindfulness). Our study demonstrates how these modes are influenced by family organization. In other words, within a supportive and well-organized family environment, individuals gradually develop both behavioral and cognitive regulatory skills, which in turn enhance their resilience, enabling them to better withstand and adapt to adversity [10].

Concerning future-oriented self-regulation, proactive coping serves as a variable link between family organization and resilience. Specifically, connected and flexible family dynamics, accompanied by economic and social supports, equip children with the necessary resources and social communication skills to anticipate challenges and plan effective responses. This finding aligns with the research conducted by Yang et al. [62] and Jurek et al. [49]. Proactive coping further bolsters resilience through goal setting, experience adjustment, and resource mobilization, as supported by Butler et al. [23]. Regarding present-oriented self-regulation, mindfulness acts as a mediating influence in the operational dynamics between family organization and resilience. Particularly, well-organized families, characterized by emotional warmth and secure attachment cues, provide an optimal context for the development of mindfulness [61]. Mindfulness then enables individuals to maintain ongoing awareness of their current thoughts and emotions, thereby fostering a more thoughtful and adaptable response to stress [55]. This conclusion is corroborated by the findings of Aydin Sünbül and Yerin Güneri [22].

4.3 “Proactive Coping → Mindfulness” as Chain Mediator

In this study, we discovered that family organization influences children’s resilience through the chain mediation of “Proactive Coping → Mindfulness”. This sequential mechanism elucidates a critical development process of resilience: as an exogenous system, family organization can foster the endogenous self-regulatory capacity, and then enhance the resilience among Chinese primary school students [10]. Specifically, by achieving goals, proactive coping induces a process of reducing mental noise and intrusive thoughts, thereby enabling mindfulness to emerge. Therefore, this finding also substantiates the Masicampo & Baumeister’s research [67] and Broaden-and-Build Theory [68].

It is noteworthy that within our chain mediation model, the pathway “Family Organization → Proactive Coping → Resilience” did not yield significant results. It suggests that proactive coping alone did not show a significant direct effect on resilience, highlighting the critical mediating role of mindfulness in this chain mediator model. While proactive coping is effective for goal achievement, it cannot be directly equated with the capacity for emotional regulation and acceptance when facing adversity, the distinctive advantage of mindfulness resides in its ability to foster reality acceptance and diminish ruminative thinking through non-judgmental awareness, consequently facilitating adaptive regulation of negative internal experiences and strengthening resilience [43,55]. Therefore, in our model, elementary school students’ proactive coping efforts only culminate in durable resilience when coupled with the development of mindfulness. This observation is supported by Polk et al. [43] who discovered that the benefits of proactive coping depend substantially on subsequent mindfulness in adults. Further, our study empirically confirms this causal sequence within the context of child development.

Furthermore, it is crucial to emphasize that family organization can also enhance child resilience by directly fostering mindfulness, independent of proactive coping. This direct pathway underscores the power of family environment as a foundational source of psychological security and life satisfaction, especially for primary school students [19,38]. Its positive effect does not necessitate goal-directed action to take effect. Thus, beyond the sequential chain, family organization can also directly nurture the inner state of mindfulness that is fundamental to enduring resilience.

4.4 Limitations and Future Direction

The present study analyzed a theoretical model linking family organization, proactive coping, mindfulness, and resilience among Chinese elementary school students. However, certain limitations must be acknowledged when interpreting the findings.

Firstly, the sample comprised only 702 elementary school students and may not accurately reflect the demographic diversity of the wider Chinese population, particularly students from other regions with different socioeconomic backgrounds. This spatial constraint underscores the geographically circumscribed sample suggests the need for broader recruitment in future work. Secondly, this study relied on self-report instruments. While these are appropriate for capturing internal states such as mindfulness, this method is susceptible to common method bias. Future research could benefit from incorporating perspectives from teachers, parents, or friends to supplement student self-reports. Finally, While the primary aim of this study was to explore a general pattern of resilience development among 3rd to 6th graders under the influence of family organization, the developmental heterogeneity within this group is also of significant value. It reflects the diversity in individual growth trajectories and represents a promising direction for future research. Specifically, a promising avenue for future research would be to explicitly model these developmental differences, examining how the relative strength of family, school, and peer-based mechanisms might shift across specific developmental stages [83,84]. Such an approach could further expand the self-stabilization component of the Resilience-as-Regulation model [10].

This study makes crucial contributions, particularly within the context of Chinese family culture. Based on empirical evidence, the study concludes that effective family organization has a profound impact on the resilience of Chinese elementary students. Notably, family organization directly enhances children’s resilience and also promotes it indirectly by boosting their proactive coping and mindfulness skills. More importantly, it facilitates resilience through the chain mediation of “Proactive Coping → Mindfulness”.

To foster children’s resilience effectively, it is advisable to focus on enhancing family organization processes and cultivating children’s proactive coping and mindfulness skills. Parents should work on strengthening family connectivity and flexibility, and seek external support to transition from passive protection to active empowerment in resilience cultivation. Schools should offer counseling and group activities designed to teach mindfulness and proactive coping skills for managing academic stress. Furthermore, policies should aim to balance academic achievement with psychological well-being by reducing excessive academic pressures and promoting family involvement, thereby promoting the holistic well-being of Chinese elementary students.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was supported by Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (22YJAZH109).

Author Contributions: Jingyuan Yu, Xueyan Wei: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, visualization, writing—original draft, review & editing; Jinghui Wang: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, visualization, writing—original draft. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Ethics Approval: The studies involving humans were approved by Jiangnan University Medical Ethics Committee (Reference No. JNU202506RB068). This research adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from students, head teachers, schools, and the legal guardians of the students.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Study Constructs, Dimensions, and Sample Items

This appendix provides the operational definitions of the main constructs and corresponding sample measurement items of their sub-dimensions. All measures used a Likert scale (e.g., from 1 “Strongly Disagree” to 5 “Strongly Agree”).

Resilience: Resilience refers to the dynamic process of positive adaptation in the context of significant stress or adversity, which serves to protect an individual’s psychological function. [7,8].

Family Organization: Family organization is defined as the process through which family members collaborate to confront stress, mobilize resources, and adjust organizational structures to effectively manage crises [16,17].

Proactive Coping: Proactive coping represents a goal-oriented self-regulatory process through which individuals amass resources, gather feedback, learn from experiences, and ultimately achieve self-development and goal attainment [40].

Mindfulness: Mindfulness is a present-centered awareness process in which individuals consciously and continuously focus on their current experiences [51,53].

Table A1: Dimensions and measurement of resilience.

| Dimension | Sample Item |

|---|---|

| Goal Planning | I have clear goals in my life. |

| Emotional Control | *I have difficulty controlling my unpleasant emotions. |

| Family Support | My parents always encourage me to do my best. |

| Interpersonal Assistance | When I have difficulties, I take the initiative to talk to someone. |

| Positive Cognition | I believe that adversity can motivate people. |

Table A2: Dimensions and measurement of family organization.

| Dimension | Sample Item |

|---|---|

| Connectedness | My family adjusts its approaches to tasks and communication styles across different stages to maintain family stability. |

| Flexibility | Everyone in my family always provides each other with the greatest help and support. |

| Economic Resource | Our family’s living expenses are sufficient for our needs. |

| Social Support | When my family needs help, we can obtain assistance from relatives and friends. |

Table A3: Dimensions and measurement of proactive coping.

| Dimension | Sample Item |

|---|---|

| Goal Setting | I make an effort to clarify what is necessary for my success. |

| Coping Behavior | *I often let things happen without interference. |

| Proactive Cognition | When I encounter problems, I actively think of various solutions. |

Table A4: Dimensions and measurement of mindfulness.

| Dimension | Sample Item |

|---|---|

| Observing | I notice some of my sensations, such as the wind blowing through my hair or the sunlight on my face. |

| Describing | I am good at using words to describe my emotions. |

| Acting with Awareness | *I have difficulty focusing my attention on what is happening in the present moment. |

| Non-judging | When I have painful thoughts or images, I usually just acknowledge them and let them be. |

| Non-reactivity | *I tell myself that I shouldn’t be feeling the way I am feeling. |

References

1. UNICEF . Adolescent Mental Health [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/china/en/reports/adolescent-mental-health. [Google Scholar]

2. Cui Y , Li F , Leckman JF , Guo L , Ke X , Liu J , et al. The prevalence of behavioral and emotional problems among Chinese school children and adolescents aged 6–16: a national survey. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021; 30( 2): 233– 41. doi:10.1007/s00787-020-01507-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yao C , Ma L . Anxiety transmission of educational involution, lottery enrollment and new policy of burden reduction. Contemp Youth Res. 2022; 4: 85– 93. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

4. Liu W , Yu ZY , Lin DH . Resilience and mental health in children and youth: a meta-analysis. Stud Psychol Behav. 2019; 17( 1): 31– 7. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2019.01.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mesman E , Vreeker A , Hillegers M . Resilience and mental health in children and adolescents: an update of the recent literature and future directions. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021; 34( 6): 586– 92. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. McMahon EL , Wallace S , Samuels LR , Heerman WJ . The relationships between resilience and child health behaviors in a national dataset. Pediatr Res. 2025; 97( 7): 2296– 304. doi:10.1038/s41390-024-03664-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Davydov DM , Stewart R , Ritchie K , Chaudieu I . Resilience and mental health. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010; 30( 5): 479– 95. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Masten AS , Barnes AJ . Resilience in children: developmental perspectives. Children. 2018; 5( 7): 98. doi:10.3390/children5070098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tian L , Liu L , Shan N . Parent-child relationships and resilience among Chinese adolescents: the mediating role of self-esteem. Front Psychol. 2018; 9: 1030. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. MacPhee D , Lunkenheimer E , Riggs N . Resilience as regulation of developmental and family processes. Fam Relat. 2015; 64( 1): 153– 75. doi:10.1111/fare.12100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Adnan H , Rashid S , Aftab N , Arif H . Effect of authoritative parenting style on mental health of adolescents: Moderating role of resilience. Multicult Educ. 2022; 8( 4): 1– 8. doi:10.5281/zenodo.6486191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Feng L , Jin J , An Y , Zhao J , Zhu Y , Li X . The dyadic effects of individual resilience on family resilience among Chinese parents and children during COVID-19. Psych J. 2023; 12( 6): 868– 75. doi:10.1002/pchj.687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Qi C , Yang N . An examination of the effects of family, school, and community resilience on high school students’ resilience in China. Front Psychol. 2024; 14: 1279577. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1279577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Walsh F . The concept of family resilience: crisis and challenge. Fam Process. 1996; 35( 3): 261– 81. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.1996.00261.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Amatea E , Smith-Adcock S , Villares E . From family deficit to family strength: viewing families’ contributions to children’s learning from a family resilience perspective. Prof Sch Couns. 2006; 9( 3): 177– 89. doi:10.1177/2156759X0500900305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Walsh F . Family resilience: a developmental systems framework. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2016; 13( 3): 313– 24. doi:10.1080/17405629.2016.1154035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Voydanoff P , Fine MA , Donnelly BW . Family structure, family organization, and quality of family life. J Fam Econ Issues. 1994; 15( 3): 175– 200. doi:10.1007/BF02353627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Erikson EH . Identity: youth and crisis. New York, NY, USA: Norton; 1968. 336 p. [Google Scholar]

19. Dou D , Shek DTL , Tan L , Zhao L . Family functioning and resilience in children in mainland China: life satisfaction as a mediator. Front Psychol. 2023; 14: 1175934. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1175934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Brajša-Žganec A , Džida M , Kućar M . Family resilience and children’s subjective well-being: a two-wave study. Children. 2024; 11( 4): 442. doi:10.3390/children11040442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Xie S , Li H . Self-regulation mediates the relations between family factors and preschool readiness. Early Child Res Q. 2022; 59: 32– 43. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.10.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Aydin Sünbül Z , Yerin Güneri O . The relationship between mindfulness and resilience: the mediating role of self compassion and emotion regulation in a sample of underprivileged Turkish adolescents. Pers Individ Differ. 2019; 139: 337– 42. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.12.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Butler CG , O’Shea D , Truxillo DM . Adaptive and proactive coping in the process of developing resilience. In: Harms PD , Perrewé PL , Chang CH , editors. Research in occupational stress and well being. Vol 19. Boston, MA, USA: Emerald Publishing; 2021. p. 19– 46. doi:10.1108/S1479-355520210000019002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yuan GF , Zhong S , Liu C , Liu J , Yu J . The influence of family resilience on non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: the mediating roles of mindfulness and individual resilience. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2025; 54: 46– 53. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2025.01.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Shao L , Zhong JD , Wu HP , Yan MH , Zhang JE . The mediating role of coping in the relationship between family function and resilience in adolescents and young adults who have a parent with lung cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2022; 30( 6): 5259– 67. doi:10.1007/s00520-022-06930-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang Y , Yin XL , Xiao ZY , Guo N , Qiao CJ , Chen XB , et al. The “Psychological Resilience” curriculum in China to enhance the frustration tolerance of primary and secondary school students: an intervention study. In: Fu XL , Zhang K , editors. Report on national mental health development in China (2021~2022). Beijing, China: Social Sciences Academic Press; 2023. p. 285– 99. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

27. He JL , Xu XM , Wang W , Chen JM , Zhang Q , Gan Y , et al. Study pressure and self harm in Chinese primary school students: the effect of depression and parent-child relationships. Front Psychiatry. 2025; 16: 1580527. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1580527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Lobo FM , Lunkenheimer E , Lucas-Thompson RG , Seiter NS . Parental emotion coaching moderates the effects of family stress on internalizing symptoms in middle childhood and adolescence. Soc Dev. 2021; 30( 4): 1023– 39. doi:10.1111/sode.12519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Xia Y , Fu R , Li D , Wu L , Chen X , Sun B . Development and initial validation of the contemporary Chinese Familism Scale. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2025; 31( 3): 579– 94. doi:10.1037/cdp0000682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wang QY , Huang QM , Liu XF , Chi XL . The association between family functioning and externalizing behavior in early adolescents: the mediating effect of resilience and moderating effect of gender. Stud Psychol Behav. 2020; 18( 5): 659– 65. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2020.05.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang S , Cai XB , Deng XY , Zhao X . The relationship between family functioning and psychological resilience of adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Stud Psychol Behav. 2022; 20( 2): 204– 211. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

32. Olson D . FACES IV and the circumplex model: validation study. J Marital Fam Ther. 2011; 37( 1): 64– 80. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00175.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Baumrind D . Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Dev. 1966; 37( 4): 887. doi:10.2307/1126611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kritzas N , Ann G . The relationship between perceived parenting styles and resilience during adolescence. J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2005; 17( 1): 1– 12. doi:10.2989/17280580509486586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhai Y , Liu K , Zhang L , Gao H , Chen Z , Du S , et al. The relationship between post-traumatic symptoms, parenting style, and resilience among adolescents in Liaoning, China: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2015; 10( 10): e0141102. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhao J , Cui H , Zhou J , Zhang L . Influence of home chaos on preschool migrant children’s resilience: a moderated mediation model. Front Psychol. 2023; 14: 1087710. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1087710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Conger RD , Conger KJ . Resilience in Midwestern families: selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. J Marriage Fam. 2002; 64( 2): 361– 73. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00361.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Bruno W , Dehnel R , Al-Delaimy W . The impact of family income and parental factors on children’s resilience and mental well-being. J Community Psychol. 2023; 51( 5): 2052– 64. doi:10.1002/jcop.22995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Yamamoto T , Nishinaka H , Matsumoto Y . Relationship between resilience, anxiety, and social support resources among Japanese elementary school students. Soc Sci Humanit Open. 2023; 7( 1): 100458. doi:10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Aspinwall LG , Taylor SE . A stitch in time: self-regulation and proactive coping. Psychol Bull. 1997; 121( 3): 417– 36. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Schwarzer R , Knoll N . Positive coping: mastering demands and searching for meaning. In: Lopez SJ , Snyder CR , editors. Positive psychological assessment: a handbook of models and measures. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association; 2003. p. 393– 409. doi:10.1037/10612-025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Greenglass ER , Fiksenbaum L . Proactive coping, positive affect, and well-being: testing for mediation using path analysis. Eur Psychol. 2009; 14( 1): 29– 39. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.14.1.29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Polk MG , Smith EL , Zhang LR , Neupert SD . Thinking ahead and staying in the present: implications for reactivity to daily stressors. Pers Individ Differ. 2020; 161: 109971. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.109971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Van der Hallen R , Jongerling J , Godor BP . Coping and resilience in adults: a cross-sectional network analysis. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2020; 33( 5): 479– 96. doi:10.1080/10615806.2020.1772969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Liu S , Xiao H , Qi P , Song M , Gao Y , Pi H , et al. The relationships among positive coping style, psychological resilience, and fear of falling in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2025; 25( 1): 51. doi:10.1186/s12877-025-05682-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Serrano C , Andreu Y , Greenglass E , Murgui S . Future-oriented coping: dispositional influence and relevance for adolescent subjective wellbeing, depression, and anxiety. Pers Individ Differ. 2021; 180: 110981. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2021.110981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Gil-Juliá B , Serrano C , Murgui S , Soto-Rubio A , Picazo C , Andreu Y . Future-oriented coping: gender and adolescent stage as modulators of its use, dispositional profile and relationship with emotional adjustment outcomes. Behav Psychol. 2024: 339– 55. doi:10.51668/bp.8324207n. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Yang C , Gao H , Li Y , Wang E , Wang N , Wang Q . Analyzing the role of family support, coping strategies and social support in improving the mental health of students: evidence from post COVID-19. Front Psychol. 2022; 13: 1064898. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1064898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Jurek K , Niewiadomska I , Chwaszcz J . The effect of received social support on preferred coping strategies and perceived quality of life in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep. 2024; 14( 1): 21686. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-73103-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Collins CC , Kwon E , Kogan SM . Parenting practices and trajectories of proactive coping assets among emerging adult Black men. Am J Community Psychol. 2024; 74( 3–4): 210– 26. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Kabat-Zinn J . Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003; 10( 2): 144– 56. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bpg016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Tang YY , Hölzel BK , Posner MI . The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015; 16( 4): 213– 25. doi:10.1038/nrn3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Brown KW , Ryan RM , Creswell JD . Mindfulness: theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychol Inq. 2007; 18( 4): 211– 37. doi:10.1080/10478400701598298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Baer RA , Smith GT , Hopkins J , Krietemeyer J , Toney L . Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006; 13( 1): 27– 45. doi:10.1177/1073191105283504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Lindsay EK , Creswell JD . Mechanisms of mindfulness training: monitor and acceptance theory (MAT). Clin Psychol Rev. 2017; 51: 48– 59. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Thompson RW , Arnkoff DB , Glass CR . Conceptualizing mindfulness and acceptance as components of psychological resilience to trauma. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2011; 12( 4): 220– 35. doi:10.1177/1524838011416375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Garland EL , Farb NA , Goldin PR , Fredrickson BL . The mindfulness-to-meaning theory: extensions, applications, and challenges at the attention–appraisal–emotion interface. Psychol Inq. 2015; 26( 4): 377– 87. doi:10.1080/1047840X.2015.1092493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Bajaj B , Pande N . Mediating role of resilience in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and affect as indices of subjective well-being. Pers Individ Differ. 2016; 93: 63– 7. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Johnson LK , Nadler R , Carswell J , Minda JP . Using the broaden-and-build theory to test a model of mindfulness, affect, and stress. Mindfulness. 2021; 12( 7): 1696– 707. doi:10.1007/s12671-021-01633-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Pepping CA , Duvenage M . The origins of individual differences in dispositional mindfulness. Pers Individ Differ. 2016; 93: 130– 6. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Stevenson JC , Emerson LM , Millings A . The relationship between adult attachment orientation and mindfulness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness. 2017; 8( 6): 1438– 55. doi:10.1007/s12671-017-0733-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Yang X , Fan C , Liu Q , Chu X , Song Y , Zhou Z . Parenting styles and children’s sleep quality: examining the mediating roles of mindfulness and loneliness. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020; 114: 104921. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Fiese BH . Who took my hot sauce? Regulating emotion in the context of family routines and rituals. In: Calkins LV , Morris AS , editors. Family contexts of parent-child regulation. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2006. p. 269– 90. doi:10.1037/11468-013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Chen F . Everyday family routine formation: a source of the development of emotion regulation in young children. In: Fleer M , González Rey F , Veresov N , editors. Perezhivanie, emotions and subjectivity. Singapore: Springer; 2017. p. 129– 43. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-4534-9_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Selman SB , Dilworth-Bart JE . Routines and child development: a systematic review. J Fam Theory Rev. 2024; 16( 2): 272– 328. doi:10.1111/jftr.12549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Kriakous SA , Elliott KA , Lamers C , Owen R . The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the psychological functioning of healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Mindfulness. 2021; 12( 1): 1– 28. doi:10.1007/s12671-020-01500-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Masicampo EJ , Baumeister RF . Relating mindfulness and self-regulatory processes. Psychol Inq. 2007; 18( 4): 255– 8. doi:10.1080/10478400701598363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Fredrickson BL . The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004; 359( 1449): 1367– 78. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Wang J , Li Z , Li Q , Zhang M , Chen Y , Chen A . Preparation enhances the effectiveness of positive emotion regulation. Emotion. 2025. doi:10.1037/emo0001582 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Wang S , Wei J , Zhang P , Song J , Chen J , Li G . The chain mediating effect of self-efficacy and health literacy between proactive personality and health-promoting behaviors among Chinese college students. Sci Rep. 2025; 15( 1): 16101. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-00936-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Phan ML , Renshaw TL , Caramanico J , Greeson JM , MacKenzie E , Atkinson-Diaz Z , et al. Mindfulness-based school interventions: a systematic review of outcome evidence quality by study design. Mindfulness. 2022; 13( 7): 1591– 613. doi:10.1007/s12671-022-01885-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Fenwick-Smith A , Dahlberg EE , Thompson SC . Systematic review of resilience-enhancing, universal, primary school-based mental health promotion programs. BMC Psychol. 2018; 6( 1): 30. doi:10.1186/s40359-018-0242-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Borgers N , de Leeuw E , Hox J . Children as respondents in survey research: cognitive development and response quality 1. Bull Sociol Methodol/Bull De Méthodologie Sociol. 2000; 66( 1): 60– 75. doi:10.1177/075910630006600106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Faul F , Erdfelder E , Lang AG , Buchner A . G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007; 39( 2): 175– 91. doi:10.3758/bf03193146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Chow TS , Tang CSK , Siu TSU , Kwok HSH . Family resilience scale short form (FRS16): validation in the US and Chinese samples. Front Psychiatry. 2022; 13: 845803. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.845803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Chen Z . The impact of hope on proactive coping among college students: the mediation effects of family function [ master’s thesis]. Zheng Zhou, China: Henan University; 2010. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

77. Deng YQ , Liu XH , Rodriguez MA , Xia CY . The five facet mindfulness questionnaire: psychometric properties of the Chinese version. Mindfulness. 2011; 2( 2): 123– 8. doi:10.1007/s12671-011-0050-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Hu YQ , Gan YQ . Development and psychometric validity of the resilience scale for Chinese adolescents. Acta Psychol Sin. 2008; 40( 8): 902– 12. (In Chinese). doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2008.00902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Kronborg L , Plunkett M , Gamble N , Kaman Y . Control and resilience: the importance of an internal focus to maintain resilience in academically able students. Gift Talent Int. 2017; 32( 1): 59– 74. doi:10.1080/15332276.2018.1435378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Li X , Bian Y . Social networks in China: a thematic review of guanxi scholarship in the past decade. Chin J Sociol. 2024; 10( 4): 531– 62. doi:10.1177/2057150x241282563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Zhang L , Roslan S , Zaremohzzabieh Z , Jiang Y , Wu S , Chen Y . Perceived stress, social support, emotional intelligence, and post-stress growth among Chinese left-behind children: a moderated mediation model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19( 3): 1851. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Wang L , Zhao J . Longitudinal association between perceived economic stress and adolescents’ depression in rural China: the mediating roles of hope trajectories. J Affect Disord. 2025; 383: 290– 7. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2025.04.130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Rubin KH , Dwyer KM , Kim AH , Burgess KB , Booth-Laforce C , Rose-Krasnor L . Attachment, friendship, and psychosocial functioning in early adolescence. J Early Adolesc. 2004; 24( 4): 326– 56. doi:10.1177/0272431604268530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Wang H , Xu J , Fu S , Tsang UK , Ren H , Zhang S , et al. Friend emotional support and dynamics of adolescent socioemotional problems. J Youth Adolesc. 2024; 53( 12): 2732– 45. doi:10.1007/s10964-024-02025-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools