Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

ChatGPT, Loneliness, and Well-Being among International PhD Students in Malaysia: A Mixed-Methods Study

1 Faculty of Nursing, Shangqiu Medical College, Shangqiu, 476100, China

2 Faculty of Education, City University Malaysia, Petaling Jaya, 46100, Malaysia

3 Department of Education Management, Planning and Policy, Faculty of Education, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Kenny S. L. Cheah. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Self-Concept in the Digital Era: Exploring Its Interplay with Internet Use Patterns, Mental Health, and Physical Well-Being)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(12), 2023-2038. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.071322

Received 05 August 2025; Accepted 16 October 2025; Issue published 31 December 2025

Abstract

Background: Despite access to university counseling services, many students underutilize them due to cultural stigma, language barriers, and perceived irrelevance. As a result, ChatGPT has emerged as an informal, always-available support system. This study investigates how international PhD students in Malaysia navigate loneliness, mental well-being, and social disconnection through interactions with Generative AI (mainly ChatGPT. Methods: Using a mixed-methods design, the study surveyed 155 international doctoral students and analyzed quantitative responses across four dimensions: loneliness, well-being (WHO-5), perceived social support, and AI-facilitated emotional support. Additionally, open-ended responses were examined using Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) to identify emergent themes. Results: Quantitative findings showed that ChatGPT use was modestly associated with greater loneliness (r = 0.17) and lower perceived social support (r = −0.16), with only a weak positive link to well-being (r = 0.11). Regression analysis confirmed these small effects, while qualitative themes revealed that students used ChatGPT mainly for emotional venting and productivity, underscoring its value as short-term support but also its potential to displace human interaction. More specifically, thematic analysis revealed two dominant student experiences: (1) emotional venting and calmness, and (2) productivity through non-judgmental dialogue. Conclusions: These findings suggest that while ChatGPT offers emotional reprieve and academic clarity, it may also displace human interaction. This study highlights the promise and pitfalls of AI-driven mental support in higher education. It urges institutions to enhance peer networks, foster culturally responsive mentoring, and develop ethical AI usage guidelines to support international doctoral students holistically.Keywords

International PhD students in Malaysia often face unique psychological challenges, particularly feelings of isolation, academic stress, and social disconnection. These challenges tend to intensify during academic milestones such as proposal defense, thesis writing, or the adjustment to unfamiliar cultural and institutional norms. Prior studies have consistently highlighted that such students are at risk of developing emotional fatigue and loneliness due to their separation from family support systems and limited engagement in social communities [1,2].

Despite the availability of counseling services, international students underutilize these resources due to several cultural and structural barriers. These include fear of stigma associated with mental health, discomfort with expressing personal struggles in a second language, and the perception that such services are tailored to local students [3,4]. Consequently, there is a growing need to explore alternative, accessible, and culturally neutral modes of support that international students are more likely to engage with. On the other hand, Generative AI platforms such as ChatGPT have introduced a new dimension of psychological engagement in education. These tools offer 24/7 accessibility, a judgment-free conversational space, and instant feedback on both academic and personal queries. Emerging evidence suggests that students are not only using these platforms for writing assistance or knowledge clarification but also as informal tools for emotional processing, encouragement, and self-motivation (Danieli et al. [5]). Building on this context, the following Section 1.2 examines prior research on international doctoral students’ mental health and the emerging role of generative AI as a source of emotional and academic support.

Recent studies highlight ChatGPT’s ability to produce counseling-like responses, offering empathy, interpretability, and psychoeducational benefits that make it appealing as a supplemental support tool [6]. These features are especially valuable for international doctoral students who seek clarity and stigma-free communication when traditional therapy is difficult due to language or cultural barriers. Researchers also note ChatGPT’s potential as a psychoeducational resource, enhancing learning, reflection, and self-management strategies (Maurya et al. [7]). Yet, concerns remain that conversational agents can oversimplify or misinterpret subtle issues, reinforcing the view that AI should complement, not replace, human oversight (Weitz [8]).

On the other hand, Wang et al. [9] conducted a systematic review evaluating the capabilities and limitations of generative AI in mental health. Others scholars like Chenneville et al. [10] raised multiple ethical dilemmas in the context of generative AI use in psychological science. For doctoral students, this means AI can provide initial relief and structure but risks masking the need for professional or peer support. Ongoing debates reflect this tension, with some practitioners welcoming AI’s accessibility while others remain skeptical of its reliability [11,12]. Collectively, these findings align with our results: ChatGPT can deliver rapid, stigma-free support, but its role must be carefully bounded by ethical safeguards and complemented with human-centered systems.

To situate this study within existing scholarship, recent research highlights the growing importance of AI companions in addressing emotional support needs across diverse populations, from adolescents to older adults. These tools are valued because they are always accessible, non-judgmental, and adaptive to users’ emotional states (Dhimolea et al. [13]). Previous research indicates that international graduate students often underutilize counseling services due to cultural stigma and communication barriers, as noted by Hyun et al. [3] and Boafo-Arthur et al. [4]. Relating to the context of this study, International doctoral students could be confronted with a lot of academic work and social isolation at the same time. Thus, ChatGPT could be accepted as AI companion, because it provides an avenue to share their thoughts and get support without worrying about being judged or having their information leaked. Other scholars also warn that the emotional advantages of AI partners may have significant drawbacks. Although these platforms mimic empathy and offer temporary solace, they fail to reproduce the profound connection and mutual development inherent in peer and mentor relationships [14,15]. There are trending studies that indicate habitual dependence on AI for companionship may unintentionally strengthen tendencies to disengage from authentic support networks, thereby intensifying feelings of alienation and dependency over time (Danieli et al. [5]). In the PhD environment, this risk is heightened, as students who already inadequately utilize institutional services may increasingly rely on AI, thus alienating them from essential academic and social support systems.

Consequently, the growing body of research portrays AI companions as a double-edged sword: they diminish stigma-related obstacles to assistance while also prompting concerns regarding the erosion of human connection and the viability of AI-mediated coping mechanisms. It is evident that our study context is relevant—international PhD students in Malaysia are using ChatGPT not only for academic aid but also as a way to deal with loneliness and stress. However, without deliberate institutional initiatives to promote peer networks and culturally attuned mentorship, dependence on AI may obscure rather than address the fundamental issues of social integration and well-being [16,17]. Subsequent research should investigate the ways in which AI might enhance, rather than replace, human-centered support systems in higher education. Given the increasing use of ChatGPT among university students, it is critical to understand how these AI conversations affect users’ mental states and social behaviors. While early feedback highlights the usefulness of AI for venting and coping, concerns remain regarding its potential to replace human interaction or contribute to digital dependency [14]. For international PhD students who already face limited social embeddedness, as this duality presents both an opportunity and a psychological risk. This study, therefore, investigates the role of talking to Generative AI, specifically ChatGPT, in shaping students’ psychological well-being, emotional support perception, and experiences of loneliness. Focusing on international PhD students in Malaysian universities, the research seeks to explore both the promise and limitations of AI-supported engagement in higher education. It responds to a growing demand for alternative support systems that are scalable, stigma-free, and capable of addressing emotional challenges in a transnational academic context [3,4].

Despite the availability of university counseling services and institutional support mechanisms, international PhD students in Malaysia continue to experience significant psychological challenges, including persistent loneliness, academic anxiety, and emotional disconnection [1,2]. Previous studies have not adequately addressed the role of alternative digital tools (specifically Generative AI such as ChatGPT) as a source of emotional and academic support, especially in the context of doctoral-level international students navigating transnational learning environments (Danieli et al. [5]). Without intervention or deeper understanding, this issue may lead to worsening mental health outcomes, increased emotional isolation, and a diminished sense of belonging among this vulnerable population [16,17]. Therefore, this study seeks to explore the psychological experiences of international PhD students in Malaysia, investigate their interactions with ChatGPT for emotional and academic support, and evaluate how the frequency of AI use relates to reported levels of loneliness, perceived support, and overall well-being. The following research questions (RQs) were listed for this study:

RQ1: What psychological challenges do international PhD students face in Malaysia, and how do these relate to loneliness?

RQ2: How do international PhD students describe their experience of using ChatGPT as a form of emotional and academic support?

RQ3: What is the relationship between the frequency of ChatGPT use and students’ reported levels of loneliness, support, and well-being?

This study employed a mixed-methods research design to examine the psychological challenges faced by international PhD students in Malaysia and explore the role of Generative AI (ChatGPT) as a self-guided emotional support tool. The mixed-methods approach integrates quantitative survey data with qualitative open-ended responses to offer both breadth and depth of understanding [18]. This design is particularly suitable for educational and mental health research where subjective experience, behavioral trends, and social factors interact [19]. With academic discernment, only language polishing and APA formatting checks were supported using AI-based tools (ChatGPT and Grammarly), limited to grammar correction, analysis reporting format, and citation and referencing consistency. No AI was used in the generation of research content, data interpretation, or conceptual development. Table 1 summarizes the methodology used for this study:

Table 1: Overview of study design, data collection, and analytical procedures.

| Component | Details |

|---|---|

| Design | Mixed-methods explanatory design combining quantitative survey and qualitative content analysis. |

| Participants | Participants were full-time international doctoral students in Malaysian universities, aged 21 or above, proficient in English, and had tried conversing with ChatGPT before. Exclusions included visiting scholars, coursework-only postgraduates, and incomplete survey responses. Eventually, 155 international PhD students from public and private universities in Klang Valley, Malaysia, completed the data collection stage. |

| Data Collection | Data were collected between October 2024 and February 2025, coinciding with proposal defences and thesis writing stages common to doctoral students. |

| Phase 1—Quantitative | Structured online survey comprising: • Frequency of ChatGPT usage (self-developed scale) • UCLA Loneliness Scale (short version) • WHO-5 Well-being Index • AI Emotional Support Scale (pilot-tested for internal consistency) • Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (peer-focused version). |

| Phase 2—Qualitative | Open-ended written responses from the same survey exploring emotional and academic uses of ChatGPT. LDA topic modeling and word cloud visualization were used for pattern analysis. Open-ended responses averaged 58 words (median = 52, range = 12–210). Short, trivial entries under 10 words were excluded from thematic coding. |

| Analysis Tools | Jamovi Software (Version 2.4.8) for descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations, and regression. ATLAS.ti and LDA for thematic text analysis. |

| Ethical Note | Participation was voluntary with informed consent. Students were reminded that ChatGPT is not a mental health provider. Referral contact to the university counseling centers was included. |

As summarized above, a total of 155 international PhD students from public and private universities located in the Klang Valley region of Malaysia participated in the study. Participants were recruited through institutional email lists and postgraduate student associations. Eligibility criteria included being a full-time international doctoral candidate and currently enrolled in a Malaysian university. Convenience sampling was adopted due to accessibility and constraints imposed by institutional permissions, but efforts were made to ensure diversity in discipline and university type [20].

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Education, University of Malaya (Reference No.: UM.TNC2/UMREC_3591). The research complied with the ethical standards outlined in the Malaysian Personal Data Protection Act 2010. All participants provided informed consent before taking part in the study, and anonymity and confidentiality were ensured throughout the research process.

To measure AI-mediated emotional support, this study developed a dedicated scale for international doctoral students, drawing from existing digital mental health and technology acceptance measures [5,21]. Items were refined through expert consultation and cognitive interviews to ensure clarity, cultural appropriateness, and content validity [22]. Pilot testing showed satisfactory reliability (Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω > 0.70). Reliability and validity were confirmed through standard psychometric criteria such as composite reliability and factor loadings, consistent with Hair et al. [23]. Convergent and discriminant validity were assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and HTMT ratios, as recommended by Fornell and Larcker [24] and Henseler et al. [25]. In addition, the criterion-related validity was supported by expected correlations and known-groups differences. Full instrument details, reliability evidence, and validity tables are provided in Appendix A (See Table A1 and Table A2).

Quantitative data were collected through a structured online survey built using Google Forms. In this study, the use of Google Forms may privilege participants with reliable internet and digital skills. This potential bias was mitigated by offering mobile access and multilingual clarifications, but limitations remain. Loneliness was assessed using the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3), developed and validated by Russell [26], while Mental well-being was measured using the WHO-5 Well-being Index, a widely validated tool developed by Topp et al. [27]. Also added is a custom-developed AI Emotional Support Scale (inspired by the Technology Acceptance Model; Davis [21]), and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [28]. All scales used Likert-type responses and were adapted to ensure cultural and linguistic clarity for an international audience. Composite scores were computed for each construct to facilitate correlation and regression analysis.

The mixed-methods design ensured triangulation, thus increasing the reliability and interpretive strength of the findings [29]. The qualitative component consisted of one open-ended question where participants described their experiences using ChatGPT (or similar AI tools) for emotional or academic support. As justification, the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic modeling was used alongside manual thematic coding. LDA is a machine learning technique that identifies latent topics in text by clustering frequently co-occurring words, thereby providing an objective, data-driven check on human coding [30]. In this study, LDA helped surface patterns across short open-ended responses, which were then refined into broader themes through thematic analysis. Using LDA in combination with manual interpretation reduced coder bias and ensured that the reported themes reflected both statistical structure and contextual meaning.

All statistical analyses were carried out using JAMOVI software (version 2.4.8). Prior to inferential testing, the dataset was screened for missing values and outliers, and the assumptions of normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity were tested using descriptive diagnostics such as skewness and kurtosis indexes. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and frequency) were used to characterize participants’ demographic and study data. We used two-tailed tests with a significance level of p < 0.05 for inferential analyses such as Pearson correlation, multiple regression, and independent-sample t-tests. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d, r, or R2, if appropriate) were supplied to supplement significance tests and reflect the magnitude of observed connections. These statistical methods were chosen for their applicability to the study’s design and data characteristics, and they are described in enough detail for competent readers to assess their suitability and replicate the reported results.

A group comparison study was also performed to see whether students’ living circumstances impacted their psychological well-being. Independent-sample t-tests were used to assess the mean differences between students living in university-provided housing and those who live off-campus. The study examined four composite psychological measures: loneliness, mental well-being (WHO-5), AI emotional support, and perceived social support. All tests were two-tailed with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were used to measure group differences. These analyses were carried out using JAMOVI, after data was screened for normality, outliers, and variance homogeneity (Levene’s test). This method allowed us to determine if the living situation contributed significantly to differences in emotional and social adjustment among foreign PhD students.

To better understand the psychological landscape of international PhD students in Malaysia, a descriptive statistical analysis was conducted based on data collected from 155 participants enrolled in public and private universities across the Klang Valley. This initial analysis serves as a crucial foundation, providing insights into how these students perceive their emotional well-being, social connectedness, and engagement with AI tools like ChatGPT. The questionnaire items were designed to measure four key constructs: loneliness, mental health (as indicated by the WHO-5 Well-being Index), AI emotional support, and perceived social support from peers. Each item was rated using a Likert scale appropriate to the construct, and the results offer a compelling snapshot of how these doctoral candidates are coping with the academic and social demands of transnational education. The survey collected responses from 155 international PhD students across public and private universities in Klang Valley. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) for each item are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Means and standard deviations for survey items measuring loneliness, mental health (WHO-5), AI emotional support, and perceived social support (N = 155).

| Item | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Loneliness_Q1 | 2.690 | 1.029 |

| Loneliness_Q2 | 2.471 | 1.164 |

| Loneliness_Q3 | 2.471 | 1.107 |

| Loneliness_Q4 | 2.529 | 1.124 |

| Loneliness_Q5 | 2.594 | 1.073 |

| WHO5_Q1 | 2.465 | 1.645 |

| WHO5_Q2 | 2.774 | 1.723 |

| WHO5_Q3 | 2.394 | 1.692 |

| WHO5_Q4 | 2.600 | 1.731 |

| WHO5_Q5 | 2.497 | 1.676 |

| AI_Q1 | 2.852 | 1.376 |

| AI_Q2 | 3.026 | 1.405 |

| AI_Q3 | 2.935 | 1.408 |

| AI_Q4 | 2.994 | 1.523 |

| AI_Q5 | 3.045 | 1.518 |

| Social_Q1 | 3.142 | 1.434 |

| Social_Q2 | 2.865 | 1.433 |

| Social_Q3 | 2.948 | 1.432 |

| Social_Q4 | 3.174 | 1.382 |

| Social_Q5 | 2.987 | 1.396 |

As summarized in Table 2, the mean scores for loneliness items hovered around 2.5 on a 4-point scale, suggesting moderate levels of social isolation among respondents. Mental health indicators revealed similar patterns, with WHO-5 scores ranging from 2.39 to 2.77 on a 6-point scale, pointing to fluctuating but generally average emotional well-being. Interestingly, responses related to AI emotional support scored slightly higher, with means above 2.85 and reaching as high as 3.05, implying that students found ChatGPT to be a reasonably useful outlet for emotional expression or guidance. Perceived social support also reflected moderate agreement, indicating that while peer networks exist, they may not be consistently strong or accessible. These descriptive trends underscore the nuanced and hybrid nature of support systems shaping the lives of international PhD students in a digital and multicultural academic setting.

To deepen our understanding of the interconnections between psychological variables, Pearson correlation analysis was employed to examine the relationships among four core constructs: Loneliness, Mental Well-being (WHO-5), AI Emotional Support (ChatGPT), and Perceived Social Support. This analysis is crucial as it helps reveal how these psychological and behavioral dimensions interact within the lived experiences of international PhD students. Table 3 presents the correlation matrix, offering a bird’s-eye view of both positive and negative associations among the variables based on a sample of 155 participants.

Table 3: Pearson correlation matrix among composite scores of loneliness, mental well-being (WHO-5), AI emotional support, and social support (N = 155).

| Loneliness | WHO-5 | AI Support | Social Support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | 1.000 | −0.079 | 0.211 | −0.111 |

| WHO-5 | −0.079 | 1.000 | 0.099 | −0.141 |

| AI Support | 0.211 | 0.099 | 1.000 | −0.154 |

| Social Support | −0.111 | −0.141 | −0.154 | 1.000 |

A weak negative correlation was found between Loneliness and Mental Well-being (r = −0.079), indicating a slight inverse relationship between students’ experiences of loneliness and their reported well-being scores. This suggests that higher loneliness was weakly associated with lower well-being within the sample. In addition, a moderate positive correlation was observed between Loneliness and AI Emotional Support (r = 0.211, r2 = 0.04). Students who reported higher levels of loneliness also reported higher usage of ChatGPT as a source of emotional or academic support.

Moreover, Perceived Social Support was negatively correlated with Loneliness (r = −0.111, r2 = 0.01), suggesting that students who reported stronger peer support experienced slightly lower levels of loneliness. Additionally, Perceived Social Support showed a negative correlation with AI Emotional Support (r = −0.154, r2 = 0.02), indicating that those with higher social support reported slightly less reliance on AI tools like ChatGPT. Collectively, these effect sizes reflect small but meaningful associations, consistent with behavioral science conventions that recognize r2 values between 0.01 and 0.09 as modest yet practically relevant in psychological and educational contexts. In essence, the overall pattern of correlations provides a descriptive overview of the relationships between students’ psychological indicators and their engagement with both human and AI-based support systems. These findings highlight variations in how international PhD students report their experiences of support, well-being, and AI tool usage.

3.3 Group Comparison: University Residence vs. Non-Residence

Independent samples t-tests were conducted to compare psychological outcomes between two groups of international PhD students: those residing in university-provided accommodations and those living off-campus. The comparison focused on four composite scores: Loneliness, Mental Well-being (WHO-5), AI Emotional Support, and Perceived Social Support. The results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4: Independent samples t-test comparing university residence and non–residence groups on composite scores of loneliness, mental well-being (WHO-5), AI emotional support, and social support (N = 155).

| Construct | Residence Mean | Non-Residence Mean | t-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | 2.561 | 2.542 | 0.225 | 0.823 |

| WHO-5 | 2.450 | 2.638 | −1.694 | 0.092 |

| AI Support | 2.916 | 3.023 | −1.043 | 0.299 |

| Social Support | 2.976 | 3.068 | −0.888 | 0.376 |

For Loneliness, students living in university residences had a mean score of 2.561, while those living off-campus reported a mean of 2.542. The difference between the two groups was minimal, with a t-statistic of 0.225 and a p-value of 0.823, indicating no statistically significant difference. Regarding Mental Well-being (WHO-5), students in university residences had a mean score of 2.450, compared to 2.638 for non-resident students. The t-statistic was −1.694 with a p-value of 0.092. Although the difference approached significance, it did not meet the conventional threshold of p < 0.05.

In the case of AI Emotional Support, resident students had a mean of 2.916, while non-residents had a slightly higher mean of 3.023. Similarly, the t-test result (t = −1.043, p = 0.299) showed no significant difference. Similarly, Perceived Social Support scores were 2.976 for residents and 3.068 for non-residents (t = −0.888, p = 0.376). Therefore, across all variables tested, no statistically significant differences were found between the two groups at the 0.05 level.

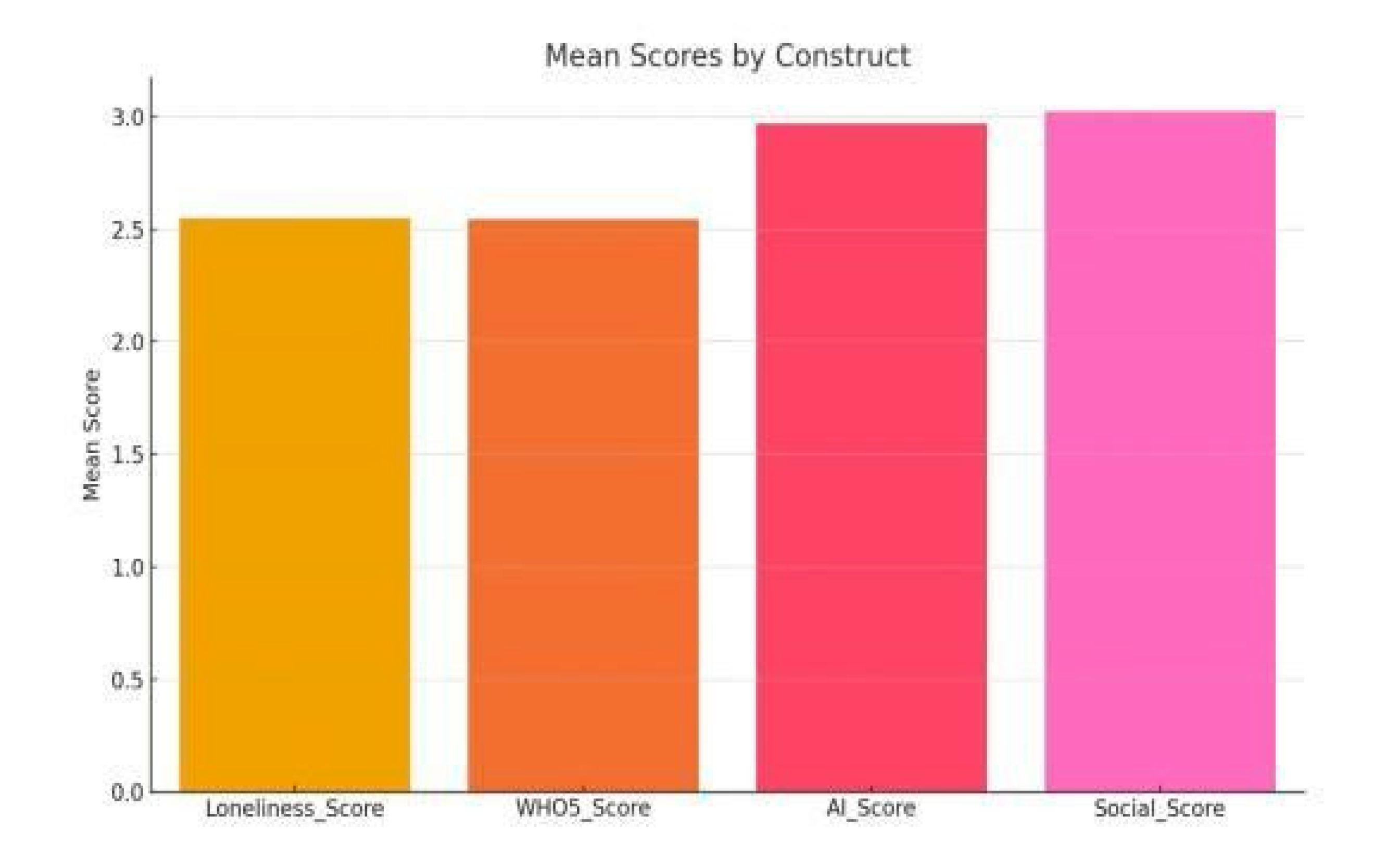

3.4 Visual Summary of Mean Scores

A visual summary was generated to provide an at-a-glance comparison of the average scores across all four psychological constructs measured in the study: Loneliness, Mental Well-being (WHO-5), AI Emotional Support, and Perceived Social Support. Fig. 1 presents a bar chart that illustrates the mean score for each construct based on responses from 155 international PhD students.

Figure 1: Visual comparison of the mean scores for each construct measured in this study.

Among the constructs, Social Support recorded the highest average score, followed closely by AI Emotional Support, with mean values above 2.9 on a 5-point scale. Mental Well-being (measured using the WHO-5 Index) had a moderate mean value of approximately 2.56 on a 6-point scale, while Loneliness, measured on a 4-point scale, yielded an average score of 2.56 as well.

The visual chart effectively summarizes the central tendencies of each psychological domain and supports the descriptive statistics reported earlier. This summary enables a clearer understanding of how students rate their experiences in relation to emotional support systems and overall mental well-being.

3.5 Addressing Research Questions (RQs)

3.5.1 Findings from RQ1: Psychological Challenges and Loneliness

The descriptive analysis of the latest data reveals that the mean loneliness score among international PhD students is 2.55 on a 4-point scale, reflecting moderate levels of loneliness. Likewise, the average WHO-5 Well-being score is 2.55 on a 6-point scale, indicating a similarly moderate level of emotional well-being. A Pearson correlation analysis between loneliness and well-being yielded r = −0.08, suggesting a weak negative relationship. Although statistically small, the result indicates that students experiencing greater loneliness may also report slightly lower emotional well-being. These patterns point to underlying emotional detachment and perceived lack of support, which may be particularly pronounced among those without access to structured university housing or community spaces.

3.5.2 Findings from RQ2: Experiences Using ChatGPT for Emotional and Academic Support

To examine how international PhD students in Malaysia utilize ChatGPT as a form of emotional and academic support, qualitative data from the survey’s open-ended responses as analyzed using thematic analysis. The coding process followed Braun and Clarke’s six-step framework [31] and adhered to trustworthiness criteria outlined by Nowell et al. [32] (see Table A3 in Appendix A). This process began with familiarizing with the data, followed by generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing those themes, defining them, and finally producing the report. In addition, LDA topic modeling was used to support the manual coding process, ensuring consistency and rigor in identifying patterns. Two central themes emerged: (1) Emotional Venting and Calmness, and (2) Productivity and Non-judgmental Support. These themes captured how ChatGPT serves as more than a digital assistant; it is also experienced as a flexible, emotionally supportive resource when traditional support networks are absent or insufficient.

The first theme, Emotional Venting and Calmness, reveals that many students turned to ChatGPT during moments of emotional discomfort, stress, or loneliness. Responses frequently mentioned that interacting with the platform offered a sense of calm, clarity, and presence. For example, one student wrote, “I use it to talk when my chest feels heavy” (Respondent 1), conveying the use of ChatGPT as a relief valve for emotional buildup. Another student expressed, “It helps me calm down after a long day” (Respondent 5), while a third stated, “This space lets me feel safe when I feel weak” (Respondent 6). Furthermore, another participant reflected, “During lonely nights, I talk to it for comfort” (Respondent 13). These excerpts were coded under categories such as “emotional burden”, “comfort”, and “non-judgmental presence”, which together formed a coherent theme illustrating ChatGPT as a surrogate for human emotional connection during periods of isolation.

The second theme, Productivity and Non-judgmental Support, highlights how students also viewed ChatGPT as a supportive partner in managing academic challenges. Students reported using the platform to sort through complex thoughts, plan tasks, and reflect on emotionally charged academic situations. For instance, one participant noted, “It helps me prepare for emotional days ahead” (Respondent 15), suggesting that they used the tool not just reactively but proactively for emotional planning. Another shared, “ChatGPT helps me be kind to myself” (Respondent 2), demonstrating how the tool reinforced self-compassion in a high-pressure environment. These types of reflections were commonly associated with codes such as “academic planning”, “motivation”, and “affirmation”. Together, they support the theme that ChatGPT functions as a reliable and unbiased space where students can articulate academic anxieties without fear of judgment.

In summary for the second research objective, the thematic analysis offers a detailed and multifaceted view of how international PhD students interact with ChatGPT beyond its informational capabilities. It becomes clear that students are actively repurposing this technology into a form of personal support (both emotionally and cognitively). Rather than seeking only academic clarification, many turn to ChatGPT for reassurance, routine structuring, and private emotional expression. The findings suggest that in the absence of consistent human support, particularly for students facing cultural and linguistic barriers, ChatGPT serves a unique dual role. It is both an academic companion and an emotionally stabilizing force in the lives of many international doctoral students.

3.5.3 Findings from RQ3: Relationship between ChatGPT Use and Well-Being, Loneliness, and Support

As shown in the previous section, Pearson correlation analysis was performed using composite scores for Loneliness, Mental Well-being (WHO-5), and Perceived Social Support to examine the relationship between ChatGPT usage and key psychological outcomes. To further examine the directional relationship between ChatGPT usage and psychological outcomes, three simple linear regression analyses were conducted. Table 5 indicates that ChatGPT use showed a small positive prediction for Loneliness (β = +0.17, R2 = 0.045), suggesting that higher reliance was modestly associated with greater feelings of isolation, though the effect explained only a limited amount of variance. Similarly, ChatGPT use showed only a very small positive prediction for Mental Well-being (β = +0.11, R2 = 0.010), an effect too weak to draw firm conclusions but indicative of a possible minimal association. Also, ChatGPT use showed only a very small positive prediction for Mental Well-being (β = +0.11, R2 = 0.010), an effect too weak to draw strong conclusions but suggestive of a limited potential association. Conversely, ChatGPT use was a small negative predictor of Perceived Social Support (β = −0.16, R2 = 0.024), implying that frequent use was modestly linked with reduced perceptions of peer support, though this relationship was also weak in magnitude.

Table 5: Regression analysis: Predicting psychological outcomes from ChatGPT use.

| Dependent Variable | Standardized Coefficient (β) | R2 | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | +0.17 | 0.045 | More ChatGPT use predicts higher loneliness |

| Mental Well-being | +0.11 | 0.010 | Slight positive effect on well-being |

| Social Support | −0.16 | 0.024 | More ChatGPT use predicts lower peer support |

This study shines a spotlight on an urgent and often overlooked issue: the emotional and psychological terrain navigated by international PhD students in Malaysia. It captures the quiet crisis of academic loneliness, emotional fatigue, and the nuanced ways students are turning to digital tools like ChatGPT as coping mechanisms. These findings emerge at a critical moment, where mental health challenges intersect with rapid technological adoption in higher education. The data reveals that while traditional support systems remain underused, students are finding solace in spaces not originally designed for therapy; yet are fulfilling therapeutic needs nonetheless.

The prevalence of moderate loneliness and emotional strain among participants reinforces a troubling narrative: cultural displacement, isolation from peers, and relentless academic pressure continue to erode the well-being of doctoral scholars [1,2]. In response, many students have adopted ChatGPT not only as an academic assistant but as a surrogate confidant. This reflects a growing reliance on AI-driven platforms for emotional self-regulation, a trend consistent with emerging literature that positions conversational AI as both a mental support outlet and a personalized self-guidance tool (Danieli et al. [5]).

Table 6 shows a combination presentation of quantitative and qualitative findings to demonstrate how ChatGPT use affects emotional and intellectual well-being among foreign PhD students. The use of 95% confidence intervals (CIs) improves the interpretative clarity of quantitative data and helps readers to assess the precision of effect estimates. Each qualitative topic correlates to the statistical patterns found, adding to the interpretation by demonstrating how participants’ tales explain or contextualize the measured connections. This integrative presentation demonstrates that, while the quantitative benefits were minimal, the qualitative data demonstrated significant psychological engagement patterns with AI technologies, particularly during times of emotional stress and academic pressure.

Table 6: Joint display of quantitative findings and qualitative themes on ChatGPT use, loneliness, and well-being.

| Quantitative Finding (Effect, 95% CI) | Qualitative Theme | Representative Quotation (Respondent, R) | Interpretation/Hypothesized Mechanism | Implication for Practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher ChatGPT use → higher loneliness (β = +0.17, r = 0.21, 95% CI [0.04, 0.38]; small effect) | Emotional Venting and Calmness | “I use it to talk when my chest feels heavy… it helps me calm down after a long day”. (R1, R5) | Students tended to rely on ChatGPT most during periods of isolation or stress. The emotional relief gained from these interactions may temporarily substitute for human connection. | Integrate AI literacy and emotional regulation modules within postgraduate orientation; encourage peer-mentoring when heavy ChatGPT use coincides with loneliness indicators. |

| Higher ChatGPT use → lower perceived peer support (β = –0.16, r = –0.16, 95% CI [–0.32, –0.01]; small effect) | Productivity and Non-judgmental Support | “It helps me prepare for emotional days ahead… and be kind to myself”. (R2, R15) | Frequent use of ChatGPT may reduce informal interactions with peers or supervisors, reinforcing solitary coping patterns. | Promote structured peer check-ins and supervision meetings alongside AI tool use; encourage balance between self-reliance and collegial engagement. |

| Minimal association with well-being (β = +0.11, r = 0.11, 95% CI [–0.06, 0.28]; trivial effect) | Task Structuring and Academic Reassurance | “ChatGPT helps me break tasks down and focus when I feel overwhelmed”. (R8) | ChatGPT provided task clarity and momentary calm, but did not produce sustained improvements in well-being. | Use AI for task scaffolding and academic coaching while monitoring WHO-5 trends for emotional well-being. |

| No significant residence-based differences (p > 0.05, 95% CI [–0.27, 0.29]) | Access and Availability | “Whether in hostel or off-campus, it’s always there when I need to talk”. (R13) | Round-the-clock accessibility of ChatGPT made physical living location less relevant for emotional support. | Focus interventions on academic stress periods (e.g., proposal defense, thesis submission) rather than residence-based support differences. |

| Small R2 across models (R2 = 0.07–0.10, 95% CI [0.02, 0.15]) | Multiple Unmeasured Influences | “Loneliness spikes around milestones like proposal defense and write-up”. (Anonymous respondent) | Psychological outcomes appear influenced by unmeasured variables such as personality, academic culture, and social networks, with ChatGPT use serving mainly as a contextual marker. | Implement milestone-timed mental health outreach and mixed-support models integrating online and offline well-being systems. |

However, beneath the surface of convenience lies a complex psychological trade-off. A moderate positive correlation between ChatGPT use and loneliness signals a paradox: students are using AI more when they feel emotionally adrift. The very tool that offers momentary relief may also be reinforcing digital dependency, distancing users from deeper, more meaningful interpersonal engagement. The interaction between humans and AI systems often mirrors social behavior patterns, as noted by Nass and Moon [14] and further discussed by Oritsegbemi [15], but it cannot replicate human connection, and excessive reliance may contribute to emotional detachment.

Crucially, the regression analysis uncovers a deeper concern. Students who turn to ChatGPT more frequently report lower levels of perceived social support. This suggests that the AI may be filling a void rather than supplementing an existing network. The takeaway is sharp: institutions must not only acknowledge AI’s growing presence in students’ emotional lives but must also double down on strengthening real-world community ties. Peer mentoring, intercultural bonding activities, and supervisor-student dialogue must not be sidelined. Technology is not the enemy, but it must not be mistaken for a human safety net, especially as concerns about over-reliance, clinical limitations, and ethical use of AI in mental health care remain active areas of debate (Terra et al. [33]).

The findings of this study extend beyond academic insight, serving as a call for institutions to strengthen support systems for international PhD students. Emotional distress and reliance on digital coping tools highlight the need for deliberate strategies to foster belonging and psychological well-being. The path forward requires not just acknowledgment of these challenges, but structured action framed through a People–Process–Platform approach. To enhance operational feasibility, the recommendations were reformulated into a People–Process–Platform framework with measurable indicators. This framework moves beyond broad suggestions by outlining specific targets and timelines that institutions can monitor and evaluate. Table 7 presents sample key performance indicators (KPIs) to demonstrate how universities can systematically implement, assess, and refine interventions that support the well-being of international doctoral students while promoting responsible AI use.

Table 7: Sample KPI framework for implementing the people–process–platform recommendations.

| Pillar | Indicator | Target | Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| People | Number of peer mentors recruited and trained | At least 20 peer mentors trained per semester | By the end of Semester 1, the ongoing |

| People | Participation rate in peer-mentoring sessions | ≥70% of new doctoral students engaged | Each semester |

| Process | Supervisors completing cultural responsiveness training | ≥80% of supervisors trained | Within the first academic year |

| Process | Supervisor competency scores on empathy/rubrics | Average rubric score ≥4 on 5-point scale | Annual review |

| Platform | AI literacy workshops delivered | Minimum of 3 workshops per semester | Each semester |

| Platform | Student self-reported confidence in responsible AI use | ≥75% reporting confidence levels of 4 or above (5-point scale) | End of each academic year |

Under People, universities should prioritize peer mentoring, discussion circles, and inclusive community spaces, recognizing that doctoral isolation is structural rather than incidental. Process calls for culturally responsive supervision, where faculty are trained to address mental health risks, linguistic challenges, and transitional stressors, supported by assessment rubrics to track empathetic engagement [22]. Finally, Platform emphasizes AI literacy: students should be taught to use ChatGPT responsibly and ethically through structured workshops and clear guidelines. Each pillar should be tied to measurable KPIs (such as participation rates, improvements in well-being scores, and peer-network involvement), ensuring institutions monitor outcomes and adapt practices. In this way, generative AI can be responsibly integrated into higher education while balancing innovation with institutional accountability.

4.2 Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study offers valuable insights but has several limitations. The cross-sectional design captures responses at one point in time, restricting causal inference and preventing analysis of changes in emotions or ChatGPT use across the doctoral journey. The geographically limited sample, drawn only from the Klang Valley, also reduces generalizability to other regions and institutional settings. Reliance on self-reported data further raises the possibility of bias in reporting mental health or AI use. In addition, the self-developed AI Emotional Support scale, while context-specific, requires fuller psychometric validation, and the brevity of open-ended responses limited thematic depth. Future research should consider longitudinal designs, multi-site samples, and richer qualitative methods such as interviews or focus groups.

From the findings, the regression models accounted for only a small proportion of the variance, indicating that important unmeasured factors such as personality traits, offline peer networks, and academic milestone stressors likely influenced outcomes. Moreover, the cross-sectional design restricts causal inference, and as such, the findings should be interpreted as descriptive associations rather than definitive causal relationships. The results are limited to international doctoral students in Malaysia’s Klang Valley, a region with major universities but not representative of the country’s full institutional diversity. Students elsewhere may face different supervisory styles, academic cultures, and support systems, and this study also did not stratify participants by discipline, cultural background, or digital literacy, all of which may shape ChatGPT use and perceptions of support. Future research should therefore adopt multi-site designs across public, private, and international campuses, and employ stratified sampling to capture subgroup variations. Such approaches would strengthen external validity and reveal whether the links between ChatGPT use, loneliness, and peer support are consistent across contexts or differ by field, culture, and digital competence, thereby offering more actionable insights for policy and practice

This study provides important insights into how international PhD students in Malaysia experience psychological challenges and increasingly turn to Generative AI tools, particularly ChatGPT; as a means of emotional and academic support. Through the integration of quantitative findings and thematic analysis, the research highlights moderate levels of loneliness and emotional strain, the perceived utility of ChatGPT for stress relief and productivity, and the nuanced relationships between AI use, well-being, and social connection. While ChatGPT appears to serve as an accessible and judgment-free outlet, the data also point to a concerning link between high reliance on AI and reduced perceptions of real-world social support.

These findings mark a critical step toward understanding the evolving emotional landscape of doctoral education in the digital age. However, much remains unexplored. Future research should adopt longitudinal designs to investigate how prolonged engagement with AI platforms influences mental health across time; especially during key academic stress points such as proposal defense, thesis writing, and submission. Additionally, studies should examine differences across subgroups, including fields of study, digital literacy levels, and cultural backgrounds, to understand how ChatGPT’s role may vary across diverse doctoral populations.

To advance empirical rigor, scholars are encouraged to develop and validate a standardized measurement tool specifically focused on perceived emotional support from AI. This scale should capture elements such as trust, satisfaction, and perceived empathy. Further, future work should explore the interplay between AI use and human support systems, asking whether AI complements or competes with traditional peer and mentor relationships. Researchers should also incorporate behavioral usage data (e.g., interaction logs, frequency, prompt types) to triangulate self-report findings. Lastly, interdisciplinary collaboration will be key. Working with developers, ethicists, and clinical psychologists, future studies should contribute to the creation of ethical frameworks and usage guidelines to ensure AI tools are adopted responsibly in higher education’s mental health landscape.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Kenny S. L. Cheah; Data collection: Tianyu Zhao, Xiaoli Zhao; Analysis and interpretation of results: Kenny S. L. Cheah, Ye Zhang, Xiaoli Zhao; Draft manuscript preparation: Ye Zhang, Xiaoli Zhao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [Kenny S. L. Cheah], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study involved human participants and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Education, University of Malaya (Reference No.: UM.TNC2/UMREC_3591). The research complied with the ethical standards outlined in the Malaysian Personal Data Protection Act 2010.

Informed Consent: All participants provided informed consent before taking part in the study, and anonymity and confidentiality were ensured throughout the research process.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Table A1: Item loadings, item—total correlations, and alpha-if-deleted for the AI emotional support scale (N = 155).

| Item | Standardized Factor Loading | Corrected Item—Total Correlation | α If Item Deleted |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ChatGPT helps me feel calmer when stressed | 0.72 | 0.54 | 0.81 |

| 2. ChatGPT provides non-judgmental support | 0.78 | 0.59 | 0.8 |

| 3. ChatGPT helps me express emotions I cannot share with others | 0.74 | 0.52 | 0.81 |

| 4. ChatGPT motivates me to manage academic challenges | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.82 |

| 5. ChatGPT offers reassurance when I feel isolated | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.8 |

Table A2: Convergent and discriminant validity indices for the AI emotional support scale.

| Construct | CR | AVE | Loneliness (r) | Social Support (r) | Well-Being (r) | HTMT Ratios |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI Emotional Support | 0.85 | 0.55 | 0.21* | −0.16* | 0.11 | <0.85 with all constructs |

Table A3: Thematic analysis of international PhD students’ experiences using ChatGPT for emotional and academic support.

| Theme | Code Categories | Illustrative Quotes (with Respondent ID) | Interpretation/Analytical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Emotional Venting and Calmness | Emotional burden, comfort, non-judgmental presence, emotional release, solitude coping | “I use it to talk when my chest feels heavy”. (R1) “It helps me calm down after a long day”. (R5) “This space lets me feel safe when I feel weak”. (R6) “During lonely nights, I talk to it for comfort”. (R13) | ChatGPT provided an emotionally safe and private outlet for students experiencing stress, loneliness, or anxiety. Its constant availability and perceived empathy offered users a sense of calm and relief, functioning as a substitute for immediate human support during emotionally charged moments. |

| Theme 2: Productivity and Non-judgmental Support | Academic planning, motivation, affirmation, self-compassion, reflective thinking | “It helps me prepare for emotional days ahead”. (R15) “ChatGPT helps me be kind to myself”. (R2) “It helps me think clearly before doing my assignments”. (R9) “I use it to plan my week and focus when I’m overwhelmed”. (R12) | ChatGPT was perceived as a non-judgmental and reliable partner that helped users manage emotional and academic pressures. Students used it both as a planning aid and as an emotional regulator, demonstrating how AI can foster reflective thinking, self-care, and motivation within academic contexts. |

References

1. Ahrari S , Krauss SE , Suandi T , Abdullah H , Sahimi AHA , Olutokunbo AS , et al. A stranger in a strange land: experiences of adjustment among international postgraduate students in Malaysia. Issues Educ Res. 2019; 29( 3): 611– 32. [Google Scholar]

2. Liu M . Addressing the mental health problems of Chinese international college students in the United States. Adv Soc Work. 2009; 10( 1): 69– 86. doi:10.18060/164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hyun J , Quinn B , Madon T , Lustig S . Mental health need, awareness, and use of counseling services among international graduate students. J Am Coll Health. 2007; 56( 2): 109– 18. doi:10.3200/JACH.56.2.109-118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Boafo-Arthur S , Boafo-Arthur A . Help seeking behaviors of international students: stigma, acculturation, and attitudes towards counseling. In: Global perspectives and local challenges surrounding international student mobility. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global; 2016. p. 262– 80. doi:10.4018/978-1-4666-9746-1.ch014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Danieli M , Ciulli T , Mousavi SM , Riccardi G . A conversational artificial intelligence agent for a mental health care app: evaluation study of its participatory design. JMIR Form Res. 2021; 5( 12): e30053. doi:10.2196/30053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Liu Y , Wang X , Zhou Y . Evaluating ChatGPT’s capability in providing mental health support: an empirical study. Front Psychol. 2023; 14: 1267767. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1267767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Maurya RK , Montesinos S , Bogomaz M , DeDiego AC . Assessing the use of ChatGPT as a psychoeducational tool for mental health practice. Couns Psychother Res. 2025; 25( 1): e12759. doi:10.1002/capr.12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Weitz K . Towards human-centered AI: psychological concepts as foundation for empirical XAI research. IT-Inf Technol. 2022; 64( 1–2): 71– 5. doi:10.1515/itit-2021-0047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang L , Bhanushali T , Huang Z , Yang J , Badami S , Hightow-Weidman L . Evaluating generative AI in mental health: systematic review of capabilities and limitations. JMIR Ment Health. 2025; 12: e70014. doi:10.2196/70014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chenneville T , Duncan B , Silva G . More questions than answers: ethical considerations at the intersection of psychology and generative artificial intelligence. Transl Issues Psychol Sci. 2024; 10( 2): 162– 78. doi:10.1037/tps0000400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Schönberger M . Integrating artificial intelligence in higher education: enhancing interactive learning experiences and student engagement through ChatGPT. In: The evolution of artificial intelligence in higher education: challenges, risks, and ethical considerations. Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing Limited; 2024. p. 11– 34. doi:10.1108/978-1-83549-486-820241002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shahzad MF , Xu S , Liu H , Zahid H . Generative artificial intelligence (ChatGPT-4) and social media impact on academic performance and psychological well-being in China’s higher education. Eur J Educ. 2025; 60( 1): e12835. doi:10.1111/ejed.12835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Dhimolea TK , Kaplan-Rakowski R , Lin L . Supporting social and emotional well-being with artificial intelligence. In: Bridging human intelligence and artificial intelligence. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 125– 38. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-84729-6_8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Nass C , Moon Y . Machines and mindlessness: social responses to computers. J Soc Issues. 2000; 56( 1): 81– 103. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Oritsegbemi O . Human intelligence versus AI: implications for emotional aspects of human communication. J Adv Res Soc Sci. 2023; 6( 2): 76– 85. doi:10.33422/jarss.v6i2.1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Marginson S . Student self-formation in international education. J Stud Int Educ. 2014; 18( 1): 6– 22. doi:10.1177/1028315313513036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sverdlik A , Hall NC , McAlpine L , Hubbard K . The PhD experience: a review of the factors influencing doctoral students’ completion, achievement, and well-being. Int J Dr Stud. 2018; 13: 361– 88. doi:10.28945/4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Creswell JW , Plano Clark VL . Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

19. Ivankova NV , Creswell JW , Stick SL . Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: from theory to practice. Field Meth. 2006; 18( 1): 3– 20. doi:10.1177/1525822x05282260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Etikan I , Musa SA , Alkassim RS . Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat. 2016; 5( 1): 1– 4. doi:10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Davis FD . Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989; 13( 3): 319– 40. doi:10.2307/249008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Haynes SN , Richard DCS , Kubany ES . Content validity in psychological assessment: a functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychol Assess. 1995; 7( 3): 238– 47. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hair JF , Black WC , Babin BJ , Anderson RE . Multivariate data analysis. 8th ed. Andover, UK: Cengage Learning; 2019. [Google Scholar]

24. Fornell C , Larcker DF . Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981; 18( 1): 39– 50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Henseler J , Ringle CM , Sarstedt M . A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci. 2015; 43( 1): 115– 35. doi:10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Russell DW . UCLA loneliness scale (version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996; 66( 1): 20– 40. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Topp CW , Østergaard SD , Søndergaard S , Bech P . The WHO-5 well-being index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2015; 84( 3): 167– 76. doi:10.1159/000376585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zimet GD , Dahlem NW , Zimet SG , Farley GK . The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988; 52( 1): 30– 41. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Johnson RB , Onwuegbuzie AJ , Turner LA . Toward a definition of mixed methods research. J Mix Meth Res. 2007; 1( 2): 112– 33. doi:10.1177/1558689806298224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Blei DM , Ng AY , Jordan MI . Latent dirichlet allocation. J Mach Learn Res. 2003; 3: 993– 1022. [Google Scholar]

31. Braun V , Clarke V . Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006; 3( 2): 77– 101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Nowell LS , Norris JM , White DE , Moules NJ . Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Meth. 2017; 16( 1): 1– 13. doi:10.1177/1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Terra M , Baklola M , Ali S , et al. Opportunities, applications, challenges and ethical implications of artificial intelligence in psychiatry: a narrative review. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2023; 59: 80. doi:10.1186/s41983-023-00681-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools