Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Influence of Gratitude on Coping Strategies: Indirect Effect Testing from Longitudinal Data

1 School of Business Administration, Tourism College of Zhejiang, Hangzhou, 311231, China

2 College of Education, Sehan University, Yeongam County, Jeollanam-do, 650106, Republic of Korea

3 School of Educational Science, Anhui Normal University, Wuhu, 241000, China

* Corresponding Author: Jun Zhang. Email:

# Jun Zhang and Junqiao Guo share the co-first authors

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mental Health Promotion and Psychosocial Support in Vulnerable Populations: Challenges, Strategies and Interventions)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(2), 193-214. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.058022

Received 02 September 2024; Accepted 10 December 2024; Issue published 03 March 2025

Abstract

Background: The academic community is increasingly interested in understanding the mechanisms through which gratitude influences coping strategies. In addition, the role of gratitude in fostering long-term resilience and mental health outcomes has garnered significant attention. This study explores the mechanisms through which gratitude affects problem-focused coping strategies and emotion-focused coping strategies by constructing models involving gratitude, perceived social support, self-esteem, and problem-focused coping strategies, as well as models involving gratitude, perceived social support, self-esteem, and emotion-focused coping strategies. Methods: A longitudinal survey was conducted on 1666 Chinese university students using highly reliable and valid scales, including the Gratitude Scale, Perceived Social Support Scale, Self-Esteem Scale, and Brief Coping Strategies Scale. To examine whether perceived social support and self-esteem play a significant indirect role in the relationship between gratitude and problem-focused coping strategies, as well as between gratitude and emotion-focused coping strategies. Differences in variables based on demographic variables: We used one-way ANOVA to test the differences in gratitude, perceived social support, self-esteem, problem-focused coping strategies, and emotion-focused coping strategies among students of different grades and ages. Additionally, independent samples t-tests were used to examine the differences between students of different genders and household registrations. Results: The study found that (1) Gratitude significantly positively predicted perceived social support (β = 0.661, p < 0.001), self-esteem (β = 0.234, p < 0.001), and problem-focused coping strategies (β = 0.130, p < 0.001); (2) Perceived social support significantly positively predicted self-esteem (β = 0.440, p < 0.001; β = 0.439, p < 0.001), problem-focused coping strategies (β = 0.443, p < 0.001), and emotion-focused coping strategies (β = 0.279, p < 0.001); (3) Self-esteem significantly positively predicted problem-focused coping strategies (β = 0.172, p < 0.001) and significantly negatively predicted emotion-focused coping strategies (β = −0.205, p < 0.001); (4) Gratitude can influence problem-focused coping strategies through the dual indirect effect of two mediating variables. After the inclusion of the mediating variables, the effect of problem-focused coping strategies in the indirect model was further strengthened. (5) Gratitude can influence emotion-focused coping strategies through a completely indirect effect on perceived social support and self-esteem. After inserting the mediating variables, the effect of emotion-focused coping strategies in the mediating model is enhanced. Conclusion: Gratitude can directly and positively predict problem-focused coping strategies, and it can also positively predict problem-focused coping strategies through the dual indirect effect of two mediating variables. Gratitude does not significantly predict emotion-focused coping strategies directly, but it can influence emotion-focused coping strategies via a double indirect pathway.Keywords

Gratitude is a social emotion that involves a positive response to the actions of others. It encompasses not only the recognition of favors received but also the positive evaluation of and desire to reciprocate to the benefactor. Gratitude is believed to contribute to the overall well-being of individuals and society, enhancing interpersonal relationships and social cohesion. Structurally, gratitude comprises three dimensions: cognitive, emotional, and behavioral. The cognitive dimension involves recognizing oneself as the recipient of a favor; the emotional dimension manifests as a feeling of gratitude for the favor received; and the behavioral dimension involves the desire or actual behavior of reciprocating the favor, collectively constituting the complete experience of gratitude [1]. The broaden-and-build theory implies that grateful persons tend to break free from conventional thinking patterns, expand their cognitive frameworks, and build strong personal resources, thereby altering their coping strategies [2]. Specifically, people with a sense of gratitude are more prone to utilize problem-focused coping strategies in the face of life stress and challenges, rather than emotion-focused coping strategies (For instance, shunning and guilt). This is because gratitude can enhance individuals’ positive emotions, improve their ability to cognitively reassess problems, and thus more effectively cope with stressful situations [3]. Moreover, gratitude is closely related to better social support and interpersonal relationships [4]. This means that when individuals face stress, gratitude emotions can help them rely on and utilize social resources more effectively. Grateful individuals tend to receive high levels of social support, which positively impacts them by increasing the use of proactive coping strategies [5]. However, gratitude may be moderated by individual differences and cultural backgrounds. For example, different cultures vary in their acceptance of expressing and experiencing gratitude, which may affect the coping strategies they adopt [6]. In China, gratitude, as a value and cultural tradition, is deeply rooted in social and individual behaviors [7]. In recent years, with social changes and cultural exchanges, expressions, and experiences of gratitude may have changed, but it remains an important part of interpersonal communication and moral education.

Coping strategies represent the behavioral approaches individuals adopt when faced with setbacks or stress [8]. In academia, coping strategies are often designated as two types: problem-focused coping strategies and emotion-focused coping strategies. Avoidance or escape is a common emotion-focused coping strategy, where individuals attempt to avoid or escape from the source of stress rather than confronting and resolving the problem [9]. For example, an individual may try to evade work pressure by indulging in electronic games or oversleeping, which may temporarily alleviate stress but could lead to accumulating problems and further increase stress in the long run. Another emotion-focused coping strategy is self-blame or negative self-evaluation, where individuals excessively criticize themselves or attribute blame to themselves when facing difficulties, often resulting in low mood and damaged self-esteem [10]. For instance, a student may continuously blame themselves and believe they are not smart or hardworking enough after not achieving expected exam results, further reducing their sense of self-efficacy and motivation. Additionally, substance abuse is also a common emotion-focused coping strategy in contemporary society. Some individuals may resort to drinking, smoking, or drug abuse to alleviate stress and discomfort, but these behaviors can lead to health issues, dependency, and problems in other life domains [11]. Although maladaptive coping strategies may provide temporary relief for the time being, over time, they can exacerbate individuals’ stress and health problems [12].

Gratitude theory posits gratitude as a theoretical framework for experiencing positive emotions and psychological states. Gratitude is the emotional experience of appreciation and acknowledgment of kindness, support, or assistance from others. It is not only a response to the actions of others but also a positive evaluation of oneself and society. Gratitude can boost an individual’s mental health, happiness, and relationships [13]. Furthermore, it is considered a form of positive psychological capital that facilitates the selection of problem-focused coping strategies when facing life challenges and adversities [14,15]. A study involving 589 Chinese adolescents completed surveys on gratitude, coping strategies, and aggression, revealing significant correlations between gratitude and problem-focused coping strategies. The authors suggested that individuals with gratitude possess more resources, exhibit broader thinking, actively discard unrealistic fantasies and social withdrawal, earnestly reassess negative events they experience, and employ problem-focused coping strategies to confront reality [1]. The theory of emotion regulation posits that individuals attempt to regulate their emotions in response to challenges and stressors to adapt to their environment. Emotion-focused coping strategies emphasize regulating individual emotions and feelings rather than addressing the problem itself. Gratitude can bring about several positive emotions, like joy, contentment, and love, increasing an individual’s psychological resilience. These emotions, in turn, can mitigate the impact of negative emotions and augment an individual’s capacity for positive stress management [16]. When an individual’s ability to cope positively with difficulties improves, their tendency to cope negatively with difficulties decreases [17]. Therefore, it can be seen that gratitude may positively correlate with problem-focused coping strategies and adversely correlate with emotion-focused coping strategies [18]. Based on previous research, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Gratitude significantly positively predicts problem-focused coping strategies.

Hypothesis 2: Gratitude significantly negatively predicts emotion-focused coping strategies.

1.1 Indirect Effect of Perceived Social Support

Social support concerns humans’ perception or experience of the external environment, namely, being cared for and valued by others, being part of a social network, and being able to seek assistance when needed [19]. Perceived social support is the emotional experience of receiving recognition, empathy, and support from the environment. Compared to tangible social support, it exerts a more profound positive influence on mental health [20,21]. This perceived social support involves beliefs about getting affective, informational, material, or companionship support from family members, friends, colleagues, or a broader social network. Perceived social support emphasizes individuals’ subjective evaluations of the existence of support, rather than the actual amount of support received. Specifically, perceived social support is often manifested as trusting that others will provide help when needed, feeling accepted by the social group, and trusting that others will provide emotional and material support [22]. These beliefs can be observed through individuals’ positivity in social interactions, seeking help behaviors, and sharing experiences. A wealth of research has found that gratitude and social support are considered processes through which individuals provide or exchange resources with others. Individuals with high levels of gratitude feel respected and cared for, leading to more stable emotions and greater acceptance by others in social interactions, thereby bringing higher levels of social support and increased happiness to the individual [23,24]. At the same time, expressing gratitude to others also leads to recognition from others, which in itself contributes to receiving more social support [25,26]. In other words, individuals who understand gratitude tap into the potential of their minds, consciously raising their levels of social support and happiness.

The “Broaden-and-Build” theory posits that optimistic affect are not merely feelings of pleasure, they expand individuals’ cognitive and behavioral abilities. When individuals experience positive emotions, their attention becomes broader and more flexible, their thinking becomes more open and creative, and their behavior becomes more flexible and exploratory. Additionally, they build more psychological resources. Individuals can establish more emotional capital, social support, and interpersonal relationships, enhance their sense of self-worth and confidence, and improve psychological resilience and adaptability, thereby leading to a series of positive effects [2]. Researchers conducted a study on 330 nurses and found that nurses with religious beliefs consistently believed that they could receive unlimited support and assistance from God, maintained gratitude towards God and the people around them, and had relatively low levels of depression. In addition, women are more susceptible to anxiety and depression [27]. This may be because men tend to have a more optimistic mindset, and they end to adopt problem-focused coping strategies when dealing with setbacks and difficulties [28], rather than dwelling on negative emotions [29]. Emotional support, including care, encouragement, and understanding, boosts individuals’ self-esteem and confidence, assisting them in managing stress and overcoming challenges. This kind of support assists individuals in maintaining a positive mindset and adopting problem-focused coping strategies. However, at times, social support may manifest as overprotection or interference. This ineffective support can lead individuals to depend on others, lacking the ability to independently solve problems, thereby increasing the likelihood of using emotion-focused coping strategies. In summary, there is a significant correlation between social support and problem-focused coping strategies, as well as between social support and emotion-focused coping strategies [30]. However, based on existing research, we cannot fully determine whether perceived social support can predict coping strategies, which requires further validation through subsequent studies. Drawing from this, the current study proposes:

Hypothesis 3: Perceived social support is a significant indirect role between gratitude and problem-focused coping strategies.

Hypothesis 4: Perceived social support is a significant indirect role between gratitude and emotion-focused coping strategies.

1.2 Indirect Effect of Self-Esteem

Self-esteem indicates an individual’s overall evaluation or attitude toward their own worth and abilities, and it is an essential component of personal self-concept [31]. It reflects how much individuals consider themselves worthy and capable, typically formed through internal self-evaluation and external feedback. Social investment theory posits that individuals interact with the social environment, which expects them to play certain roles in interpersonal relationships. When individuals assume these roles, they exhibit corresponding cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses, thereby influencing personality and self-esteem [32,33]. Self-esteem can manifest in various ways, including individuals’ confidence levels, resilience in facing challenges, proactivity in social interactions, and responses to criticism. People with high self-esteem typically display greater confidence and are more capable of confronting challenges, those who have low self-esteem often avoid challenges and are particularly sensitive to criticism [34]. A wealth of research has found close associations between individual self-esteem and their occupational development, physical and mental health, and interpersonal relationships [31,35]. Good self-esteem is linked to greater happiness, fewer feelings of depression and anxiety, and stronger interpersonal skills [36]. Therefore, self-esteem is a core element in individual psychological development and social behavior, playing a significant role in promoting psychological health and social adaptation.

Gratitude is considered as an emotional attitude of appreciation towards the kindness of others or positive aspects of life. Currently, there is extensive research on its impact on individuals’ self-esteem. Theoretically, it is suggested that gratitude enhances one’s positive outlook on both themselves and their environment, thereby boosting self-esteem. When individuals have substantial amounts of gratitude, they are more likely to recognize that they are cared for and supported, which can strengthen their sense of self-worth [37]. Moreover, gratitude directs individuals’ attention to the positive elements of their lives and reduces comparisons with others, which also contributes to enhancing self-esteem [4]. Research has shown a significant positive correlation between gratitude and self-esteem. Individuals with gratitude tend to have positive views of themselves and experience fewer negative emotions, which helps to maintain and enhance self-esteem. By enhancing individuals’ awareness of their self-worth and reducing negative comparisons, gratitude helps to establish and maintain higher levels of self-esteem [38].

Self-verification Theory emphasizes that individuals tend to seek confirmation and validation from others for their existing self-concept. According to this theory, individuals are more inclined to interact with those who can validate their self-concept and seek interaction with them to maintain and reinforce the stability and consistency of self-awareness. This means that people with elevated gratitude levels are more prone to showing positive behavior, as they feel more cared for and supported [39]. Researchers carried out a study with 981 adolescents to explore whether self-esteem plays a significant indirect role in spanning life events to coping strategies. The results indicate that this indirect effect is indeed significant [40,41]. People with elevated self-esteem typically favor problem-focused coping strategies, for example, they believe they are fully capable of solving real-life problems by seeking social support. In contrast, individuals with lower self-esteem have a higher probability of using emotion-focused coping strategies, as they often hold negative attitudes towards their abilities and future, do not believe in their ability to independently solve problems, and thus choosing avoidance, denial, and other emotion-focused coping strategies to resolve stress and difficulties. Additionally, individuals with lower self-esteem are greater prone to exhibit bad feelings, such as anxiety and Sorrow, when facing stress, which further drives them to adopt emotion-focused coping strategies. Such a vicious cycle exacerbates their psychological distress, further lowering self-esteem, forming a negative feedback loop [30]. Additionally, scholars conducted a questionnaire survey of 427 Chinese college students to explore the relationships among social support, self-esteem, gratitude, and life satisfaction. The results indicate that there is a strong correlation between gratitude and life satisfaction, with self-esteem playing a significant mediating role between them [42]. Expressing gratitude not only helps improve individuals’ subjective well-being and life satisfaction [43], but also has a positive effect on physical health [44]. Grateful people show a higher tendency to receive greater social support, and those with higher social support scores tend to have higher life satisfaction [45]. We hypothesize that individuals with gratitude are more inclined to adopt coping strategies, as they perceive greater love and social support. Based on the above viewpoints, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 5: Self-esteem mediates the relationship between gratitude and problem-focused coping strategies.

Hypothesis 6: Self-esteem mediates the relationship between gratitude and emotion-focused coping strategies.

1.3 Sequential Mediating Role of Perceived Social Support and Self-Esteem

Perceived social support represents people’s perception of comprehension, concern, and practical assistance provided by others [46]. Research demonstrates that individuals’ self-esteem is positively affected by perceived social support. Perceived social support fosters a sense of belonging to a supportive and understanding social network, which in turn facilitates the establishment of a positive identity, thus maintaining psychological well-being. The enhancement of psychological well-being enables individuals to be more optimistic and confident, thereby bolstering their self-esteem [47]. When individuals perceive support from others, feel valued members of society, or perceive increased social support, their levels of self-esteem often rise, enabling them to face challenges with greater confidence and a sense of worth [48].

Based on existing research, we can preliminarily conclude that Gratitude may have an impact on both types of coping strategies [1,25]. However, few studies have elucidated the mechanism through which Gratitude influences coping strategies. This study attempts to understand this relationship from the perspective of self-verification. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 7: The chain-mediated effect of perceived social support and self-esteem between gratitude and problem-focused coping strategies is significant.

Hypothesis 8: The chain-mediated effect of perceived social support and self-esteem between gratitude and emotion-focused coping strategies is significant.

2.1 Participants and Procedure

Convenience sampling is a non-random sampling method characterized by the convenience of sample acquisition and low-cost advantages [49]. In this study, participants were recruited using convenience sampling method from three universities in China. All participants signed the informed consent in this study. During the survey involving human participants, this study was performed in line with the ethical standards established by the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tourism College of Zhejiang (IRB number: ZT783590). We recruited all first-, second-, and third-year university students who were present on the day of recruitment. We conducted three longitudinal data collections at the aforementioned universities, each with a 3-month interval. The first survey distributed 1695 questionnaires (09 March 2023); the second survey distributed 1686 questionnaires (08 June 2023); and the third survey distributed 1680 questionnaires (08 September 2023). Some students were not present for the three surveys due to reasons such as leave. Since the study is longitudinal, it is necessary to ensure that each participant has valid scores for gratitude, coping strategies, perceived social support, and self-esteem in each survey. Therefore, only participants who completed all three surveys had their data retained for analysis. We extracted gratitude data from the first survey, perceived social support and self-esteem data from the second survey, and the data on the two types of coping strategies obtained from the third survey.

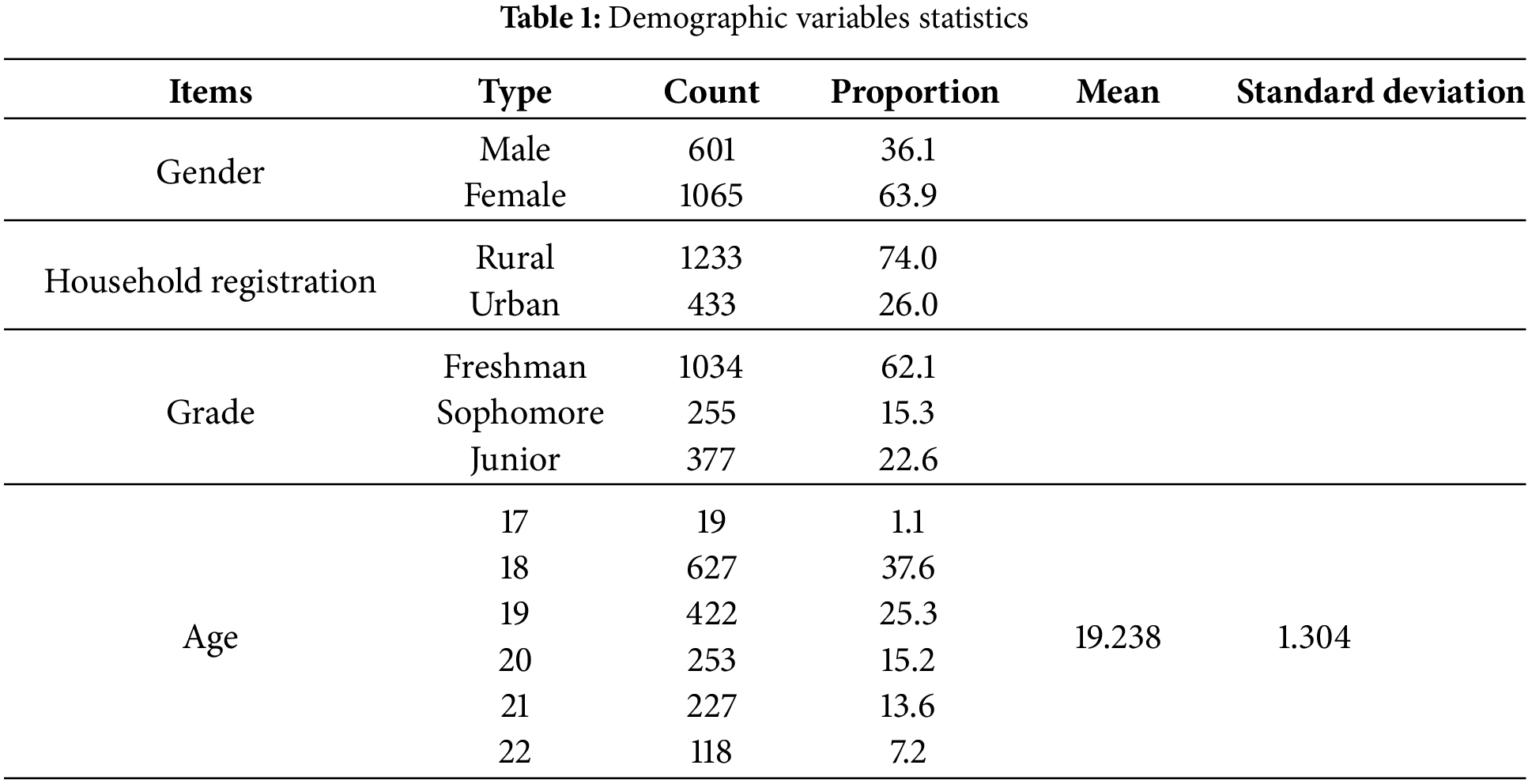

We obtained 1666 valid questionnaires in total. Among them, there were 601 male participants (36.1%) and 1065 female participants (63.9%). 433 participants (74.0%) were from urban areas, while 1233 participants (26.0%) came from townships. The sample’s mean age was 19.238 ± 1.304 years, with an average age of 19.685 ± 1.403 years for males and 18.985 ± 1.172 years for females. This study conducted descriptive statistics on the demographic characteristics of the participants, as shown in Table 1.

2.2.1 Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6)

We utilized the Gratitude Scale developed by McCullough [50]. This questionnaire was primarily used to measure the subjects’ level of gratitude, which consists of a single factor with 6 items. For each item, there are 7 possible response options. Participants who select “Strongly Disagree” are assigned 1 point, whereas those who select “Strongly Agree” are assigned 7 points, with the remaining options being scored on a scale between these two extremes. The questionnaire contains 4 forward-scoring questions and 2 reverse-scoring questions, the scores of the reverse-scoring questions need to be processed in reverse, and then all the scores of the questions are summed to obtain the overall score of the questionnaire, which ranges from 7 to 42 points. Higher scores indicate a greater understanding of gratitude [51]. Through statistical analysis, we determined that Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.733, indicating that the scale demonstrates satisfactory internal consistency. According to the factor analysis, the model shows a strong fit with the data: Comparative Fit Index = 0.997, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation = 0.031, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual = 0.010, Tucker-Lewis Index = 0.993.

2.2.2 Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS)

We utilized the PSSS created by Zimet [52]. The questionnaire consists of three factors: Support from family members, close friends, and other forms of support. Participants were required to select one option from the seven available choices for each item, based on their true situation. A score of 1 point was assigned for selecting “Strongly Disagree,” while selecting “Strongly Agree” earned the highest score of 7 points. The participants’ scores on the questionnaire ranged from a minimum of 12 to a maximum of 84. Those who scored higher on the questionnaire reported perceiving more social support [21,22]. Cronbach’s α for the scale was found to be 0.954. The outcomes of the confirmatory factor analysis displayed that it has good construct validity: CFI = 0.972, RMSEA = 0.078, SRMR = 0.025, TLI = 0.964.

We used the Rosenberg SES [53], comprising a single factor with 10 items, including 5 reverse-scored items. For each item, participants can choose one from the options below: “Strongly Disagree,” “Disagree,” “Agree,” and “Strongly Agree,” with corresponding scores of 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The combined total of the scores for all items is the total score of the questionnaire. After completing the questionnaire, participants receive a score ranging from 10 to 40. Higher scores are generally associated with higher levels of self-esteem [54]. We conducted a reliability analysis and its Cronbach’s α of 0.842. The outcomes of the confirmatory factor analysis are as follows: CFI = 0.994, TLI = 0.990, RMSEA = 0.038, SRMR = 0.020.

2.2.4 Simplified Coping Strategies Questionnaire (SCSQ)

We employed a SCSQ developed by Lazarus and Folkman [55], it is frequently used in related studies among the Chinese population. This questionnaire comprises two factors: problem-focused coping strategies (e.g., “Seeking advice from others who have faced similar difficulties”) and emotion-focused coping strategies (e.g., “Attempting to forget the entire thing”), The 20 items include four response options: “Do not engage,” “Occasionally engage,” “Sometimes engage,” and “Frequently engage,” Participants are required to select an answer from the options. Individuals’ scores on all items were summed to obtain a total questionnaire score, which ranged from 0 to 60. Higher scores on the scale indicate more proactive coping strategies by individuals [56]. The reliability coefficient of the positive coping strategies was Cronbach’s α = 0.923. The analysis of the confirmatory factor analysis indicated that it has good construct validity: CFI = 0.962, TLI = 0.951, RMSEA = 0.070, SRMR = 0.030. The reliability coefficient of the negative coping strategies was Cronbach’s α = 0.767, and the confirmatory factor analysis results showed it also has good construct validity: CFI = 0.969, TLI = 0.955, RMSEA = 0.052, SRMR = 0.028.

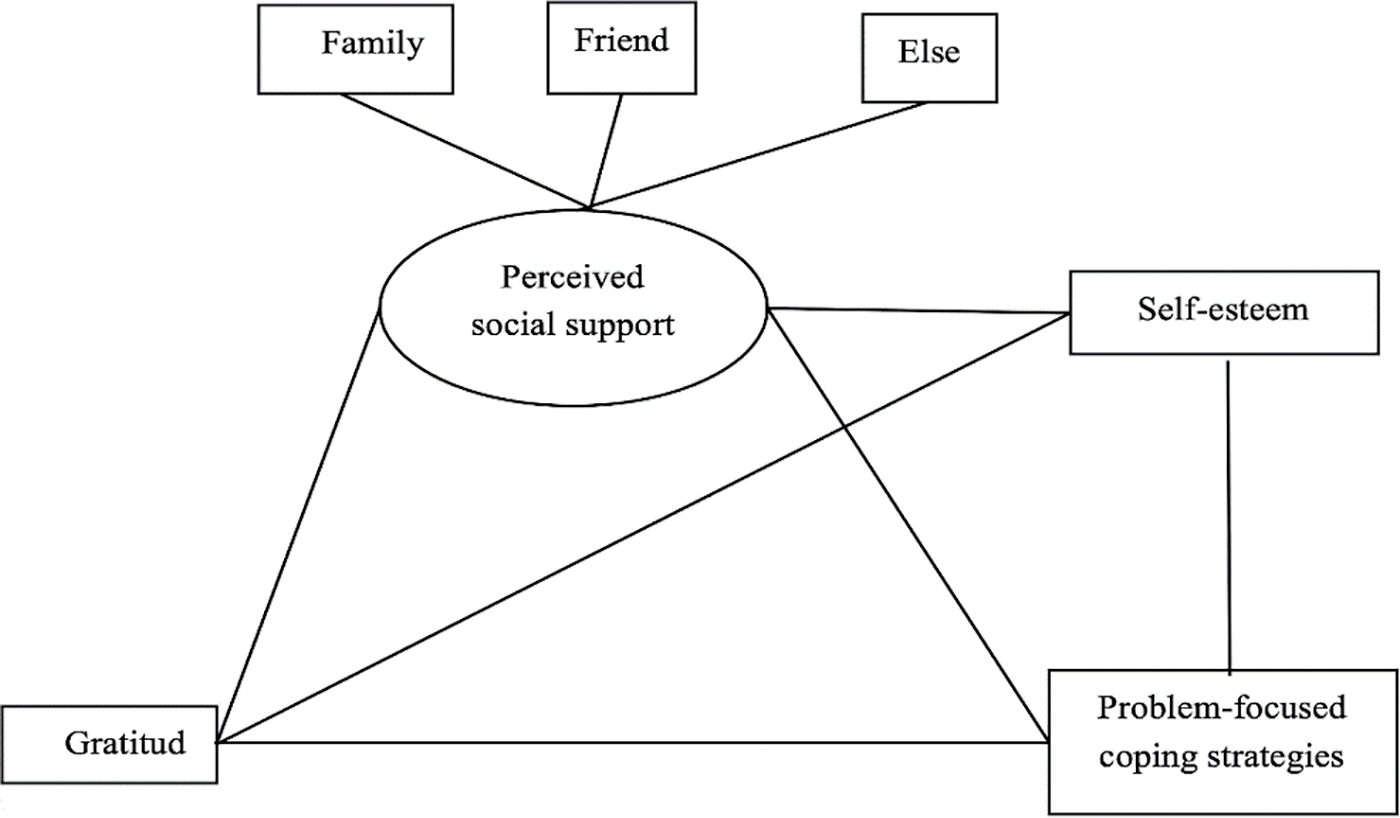

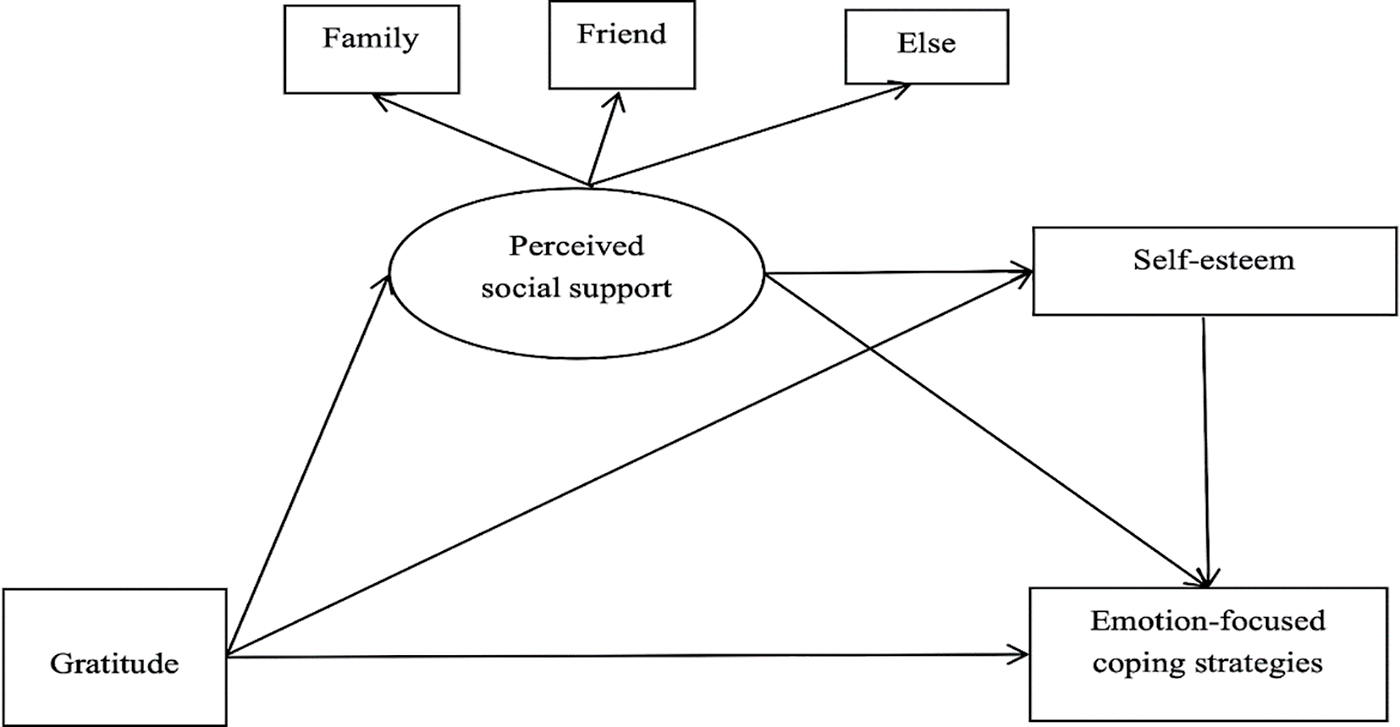

We used SPSS 25.0 software to calculate the differences of different variables across demographic variables, including the means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlation coefficients of the variables. We assessed the model fit by performing confirmatory factor analysis and handled missing data using Maximum Likelihood Estimation Upon confirming that the structural validity indices of the measurement tools were reasonably fitted. We constructed two path analysis models: In the first model, we explored the mechanism through which gratitude influences problem-focused coping strategies (Model 1). We included demographic variables as covariates in the model to examine whether perceived social support and self-esteem significantly mediate the relationship between gratitude and problem-focused coping strategies (as shown in Fig. 1). In the second model, similarly, we included demographic variables as covariates to test the significance of perceived social support and self-esteem as mediators in the relationship between gratitude and emotion-focused coping strategies (Model 2), as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 1: The chain indirect effect of gratitude on problem-focused coping strategies (Model 1)

Figure 2: The chain indirect effect of gratitude on emotion-focused coping strategies (Model 2)

In assessing the model fit, we adopted the criteria proposed by Wen et al. to evaluate the fit of the model [53], The RMSEA and SRMR values should be less than 0.1, while the TLI and CFI values should be greater than 0.9 to be considered indicators of good fit.

Common method biases (CMB) refer to the phenomenon where researchers using the same type of measurement tools, the same measurement environment, or the same subjects lead to false common variance among different traits. This bias is commonly observed in data collected through self-report questionnaires [57]. Since it is difficult to control for the variation in data caused by traits, the variation in data caused by research methods often becomes the primary concern for researchers.

Harman’s single-factor test was utilized, where all items involved in the assumptions were subjected to factor analysis together. Eight factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1 were extracted, explaining a total variance of 64.48%. The first factor revealed 33.96% of the variance, which is lower than 40%, indicating no significant common method bias [58].

3.1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

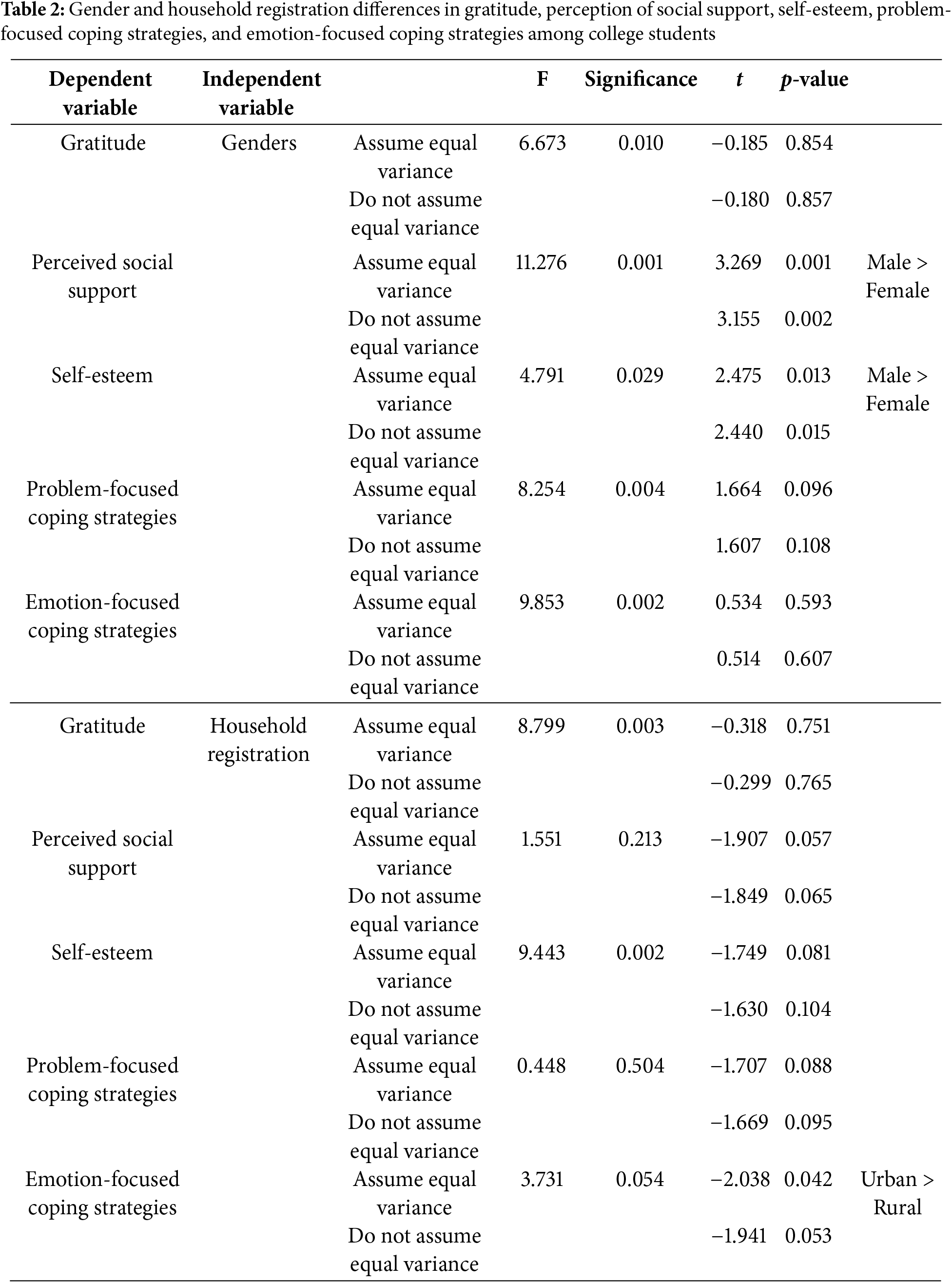

We tested the differences in different variables based on gender and household registration. The results revealed that there were no significant differences between males and females in Gratitude, problem-focused coping strategies, and emotion-focused coping strategies (p > 0.05). However, significant differences were found in Self-esteem and Perceived social support (p < 0.05). Similarly, there were no substantial differences between urban and rural university students in Gratitude, Perceived social support, Self-esteem, and problem-focused coping strategies (p > 0.05), but considerable differences in emotion-focused coping strategies (p < 0.05), as detailed in Table 2.

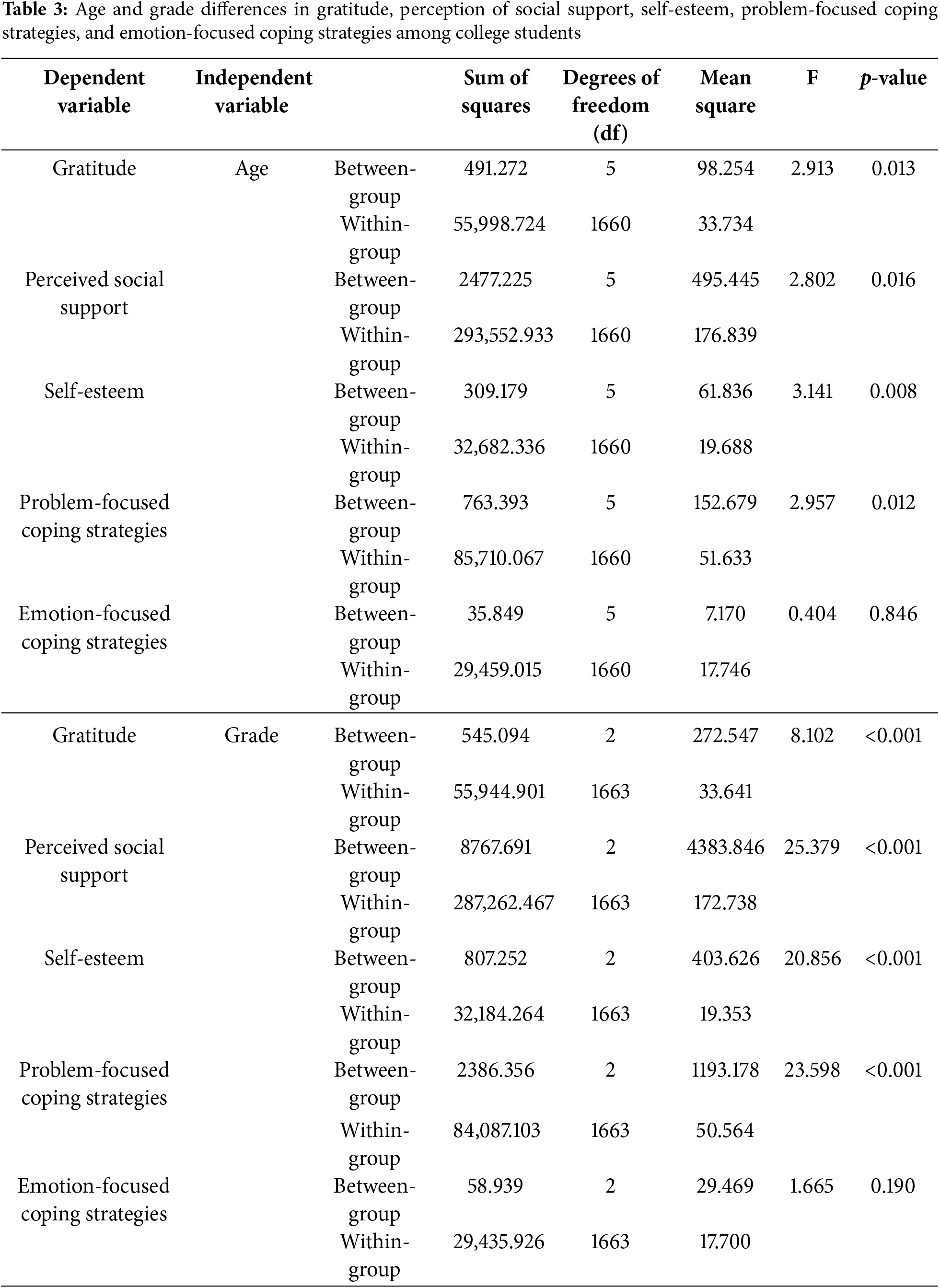

The differences in gratitude, perceived social support, self-esteem, problem-focused coping strategies, and emotion-focused coping strategies based on age and grade were examined using ANOVA. Pronounced differences were found among university students of different age groups in Gratitude, Perceived social support, Self-esteem, and problem-focused coping strategies (p < 0.05), while no relevant differences in emotion-focused coping strategies (p > 0.05). Similarly, distinct differences among students of different grades in Gratitude, Perceived social support, Self-esteem, and problem-focused coping strategies (p < 0.001), with no marked differences in emotion-focused coping strategies (p > 0.05). Please refer to Table 3 for details.

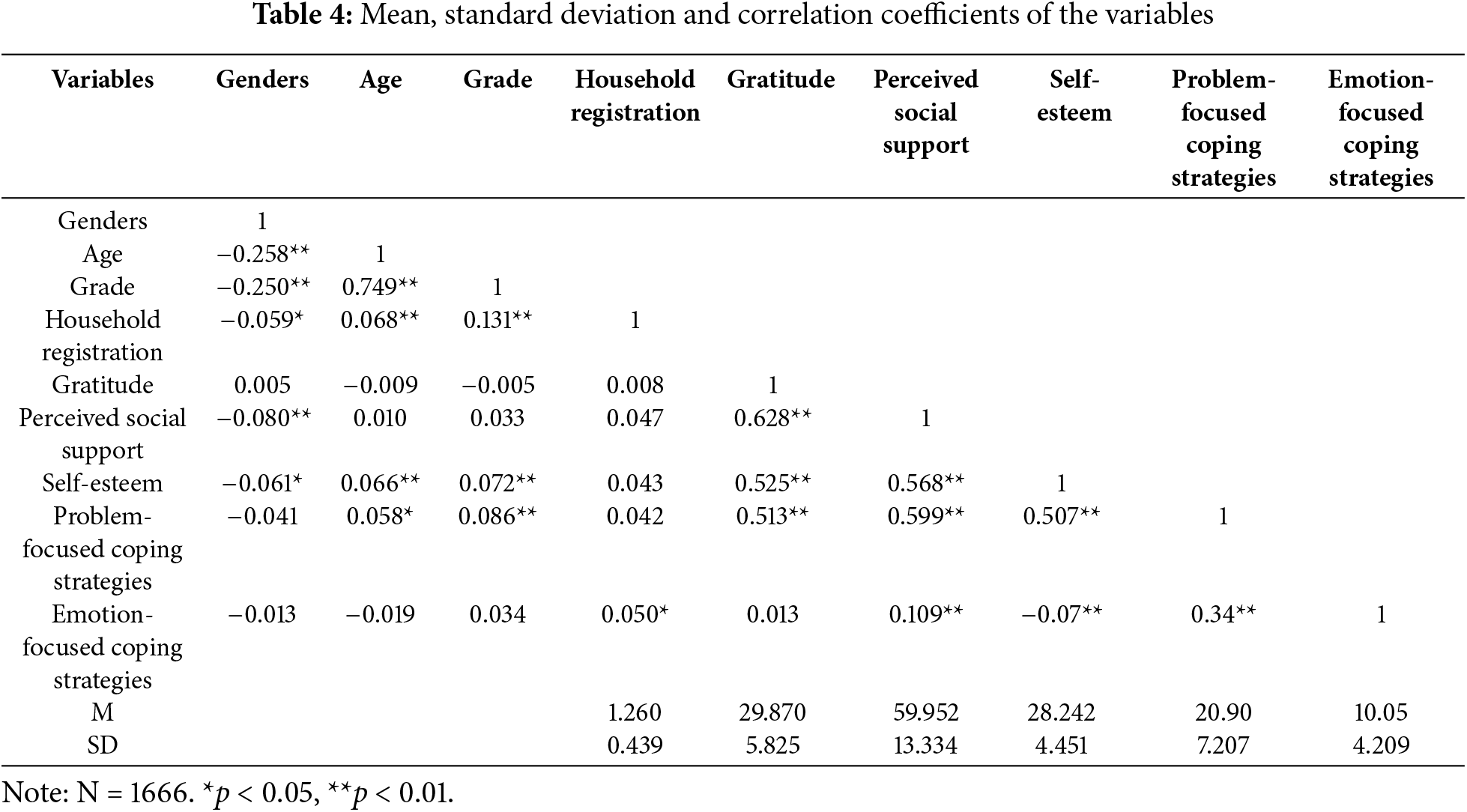

Analysis of the variables’ means, standard deviations, and correlations for the observed values in this study (N = 1666) was conducted, as shown in Table 4. Regarding demographic variables, gender was significantly negatively correlated with age (r = −0.258, p < 0.01), grade (r = −0.250, p < 0.01), household registration (r = −0.059, p < 0.05), Perceived social support (r = −0.080, p < 0.01), and Self-esteem (r = −0.061, p < 0.05). Age was significantly positively correlated with grade (r = 0.749, p < 0.01), household registration (r = 0.068, p < 0.01), Self-esteem (r = 0.066, p < 0.01), and problem-focused coping strategies (r = 0.058, p < 0.05). Grade was significantly positively correlated with household registration (r = 0.131, p < 0.01), Self-esteem (r = 0.072, p < 0.01), and problem-focused coping strategies (r = 0.086, p < 0.01). Household registration was significantly positively correlated with emotion-focused coping strategies (r = 0.050, p < 0.05). No significant correlation was found among emotion-focused coping strategies and gratitude (r = 0.013, p > 0.05). However, a negative correlation was observed between emotion-focused coping strategies and self-esteem (r = −0.070, p < 0.05). Significant positive correlations were found in the midst of the other primary variables (p < 0.01).

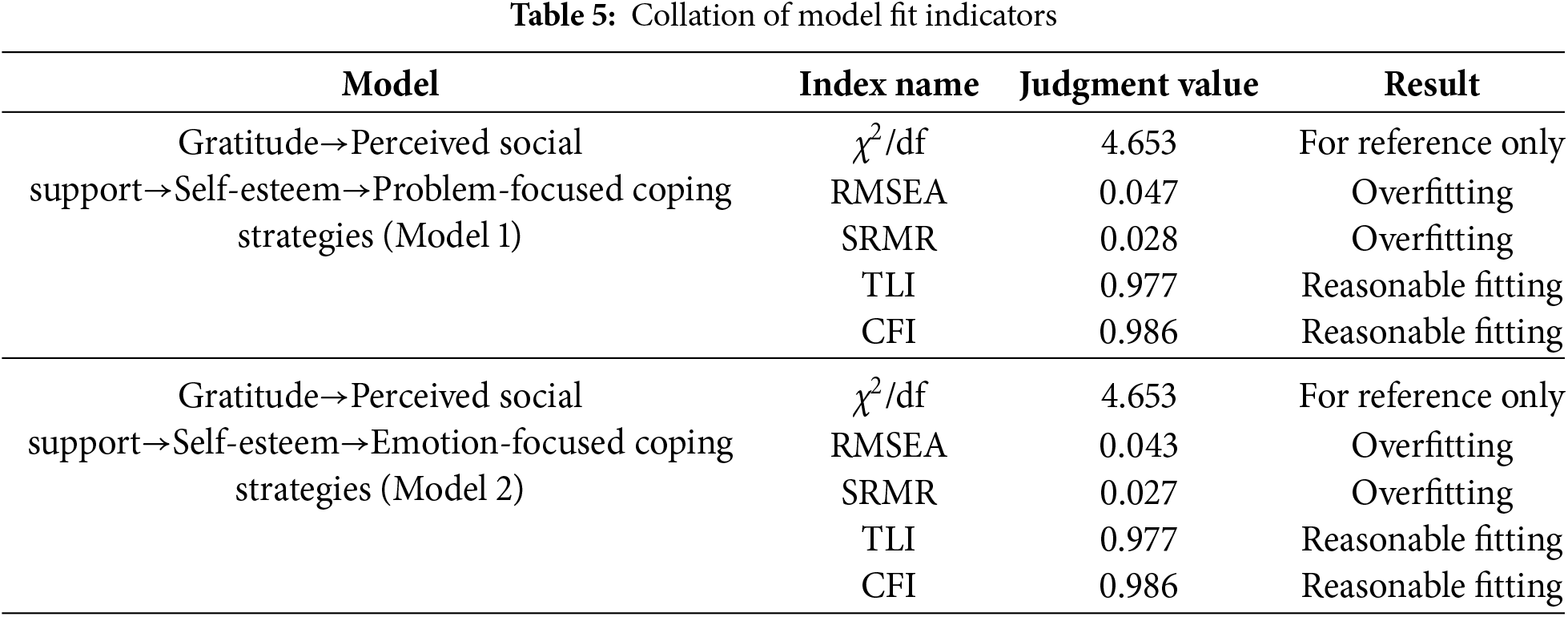

3.2 Construction and Testing of Structural Equation Models

In this study, since the PSSS contains many items, we used a bundling method to model them with the aim of ensuring the quality of the model [59]. As demographic variables may have a potential impact on the study results, we included them in the model.

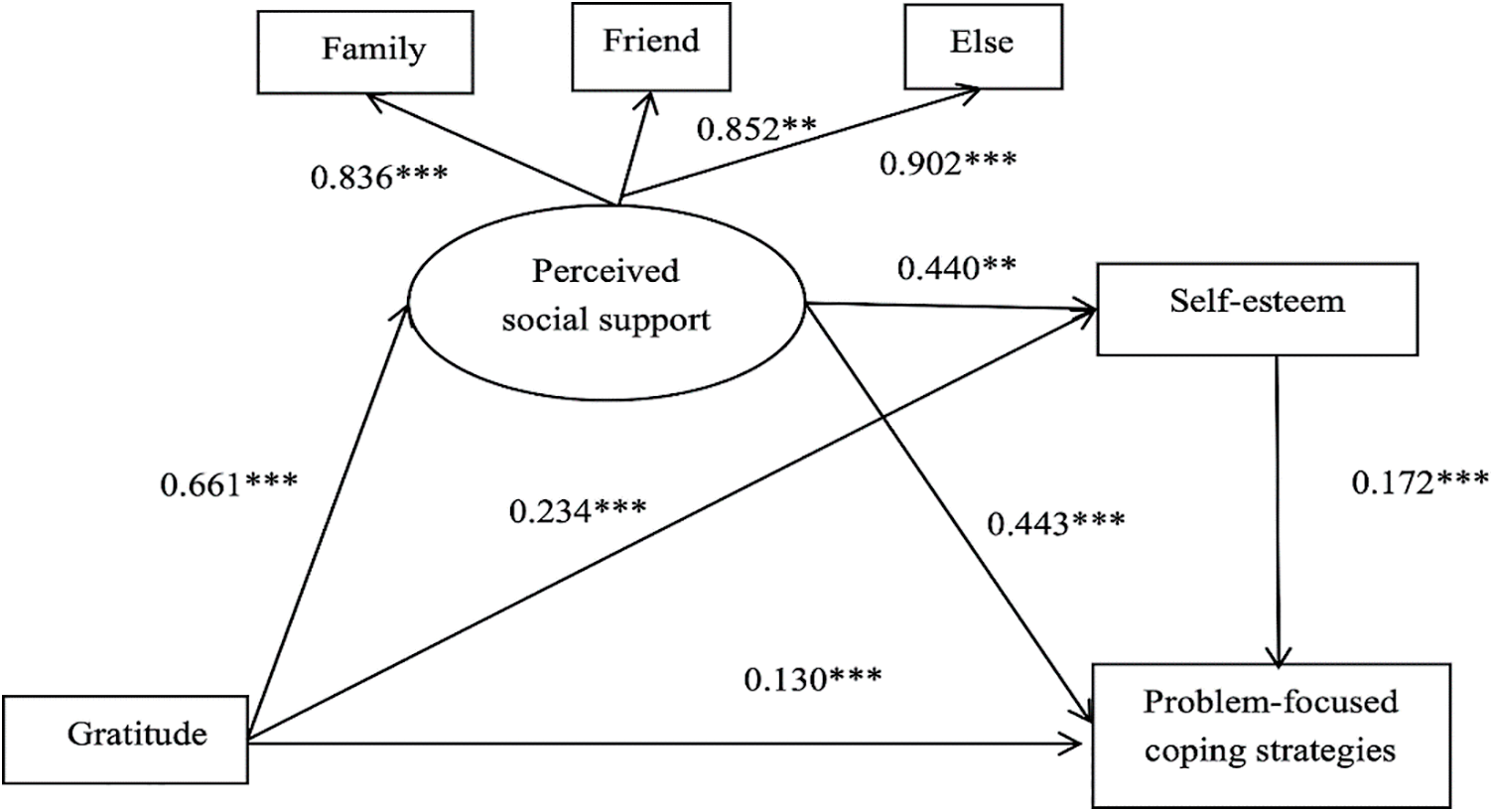

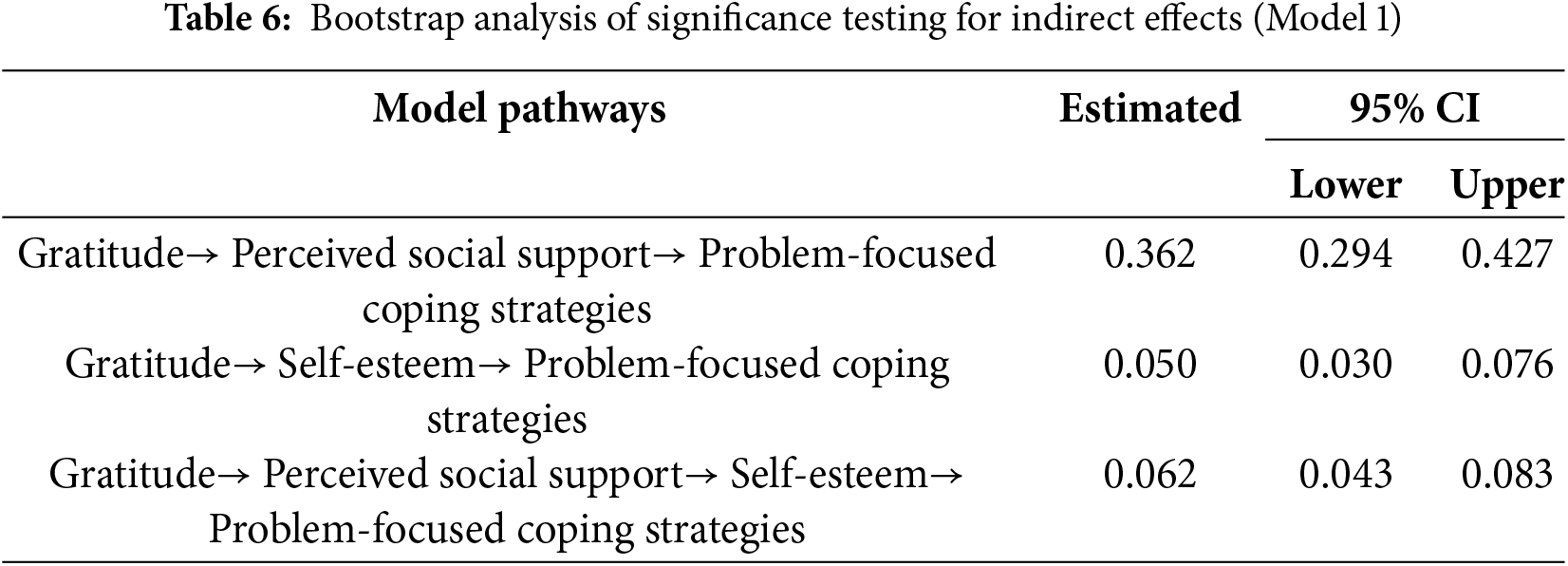

In Model 1, we established a model in which gratitude served as the independent variable, problem-focused coping strategies as the response variable, and perceived social support and self-esteem as intermediate variables. The results revealed that the model fit the data well (as presented in Table 5), the overall effect value of gratitude on problem-focused coping strategies is 0.634, and gratitude had a significant direct effect on problem-focused coping strategies (β = 0.130, p < 0.001). Gratitude positively predicted Perceived social support (β = 0.661, p < 0.001) and Self-esteem (β = 0.234, p < 0.001), Perceived social support positively predicted Self-esteem (β = 0.440, p < 0.001) and problem-focused Coping strategies (β = 0.443, p < 0.001), and Self-esteem positively predicted problem-focused Coping strategies (β = 0.172, p < 0.001), as illustrated in Fig. 3. We employed Bootstrap resampling 1000 times to test the chain indirect effect and calculate the 95% confidence intervals. Perceived social support and self-esteem played indirect effect in the relationship between gratitude and problem-focused coping strategies. Specifically, the model path coefficients were as follows: Gratitude → Perceived social support → problem-focused coping strategies had a path coefficient of 0.362, Gratitude → Self-esteem → problem-focused coping strategies had a path coefficient of 0.050, and Gratitude → Perceived social support → Self-esteem → problem-focused coping strategies had a path coefficient of 0.062. None of their Bootstrap 95% confidence intervals included 0, indicating that all three indirect effects reached significance levels (see Table 6). Therefore, Hypotheses 3, 5, and 7 were supported in this study.

Figure 3: The chain indirect effect of gratitude on problem-focused coping strategies (Model 1). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Gratitude: Data collected on 09 March 2023; Perceived social support and Self-esteem: Data collected on 08 June 2023; Problem-focused coping strategies and Emotion-focused coping strategies: Data collected on 08 September 2023

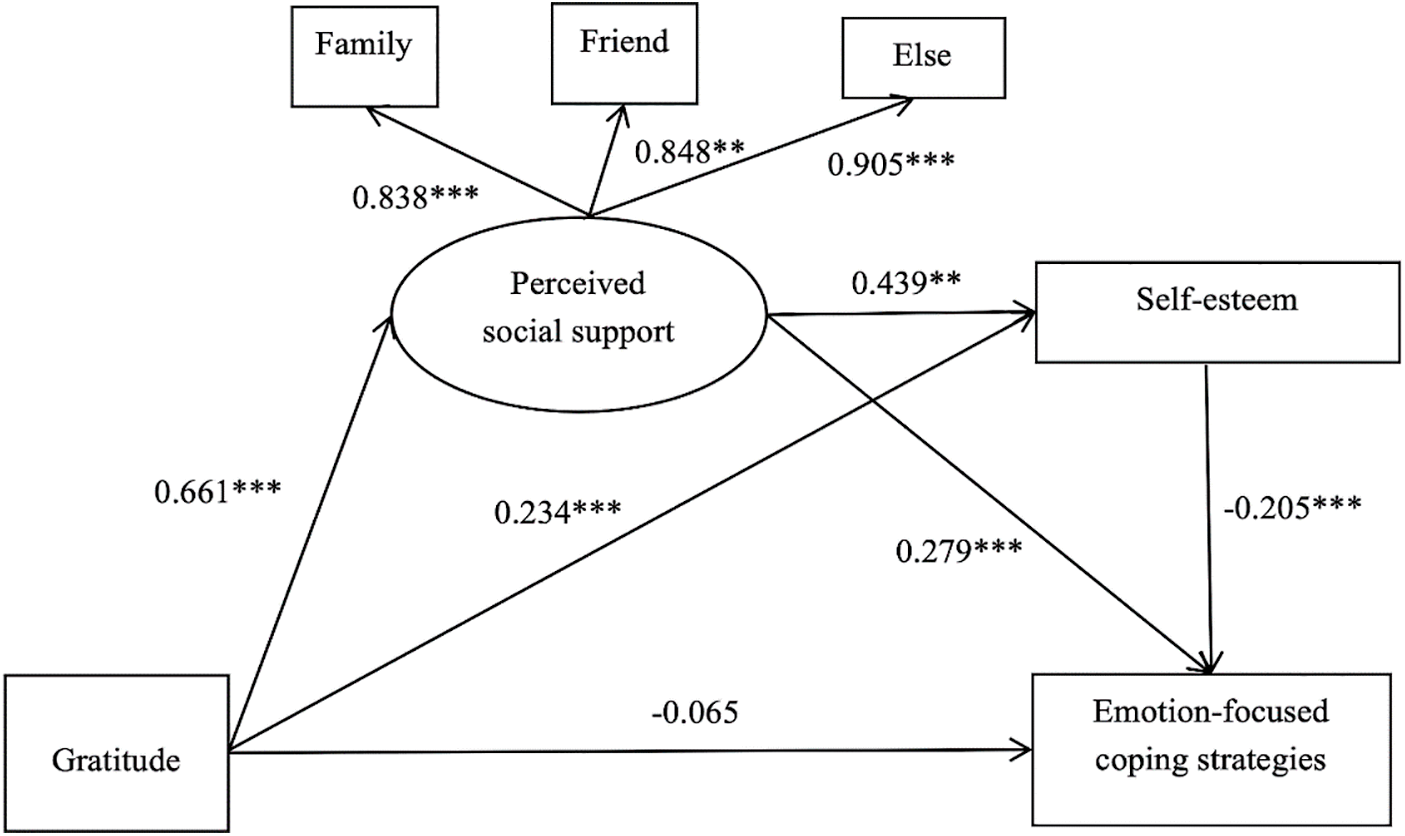

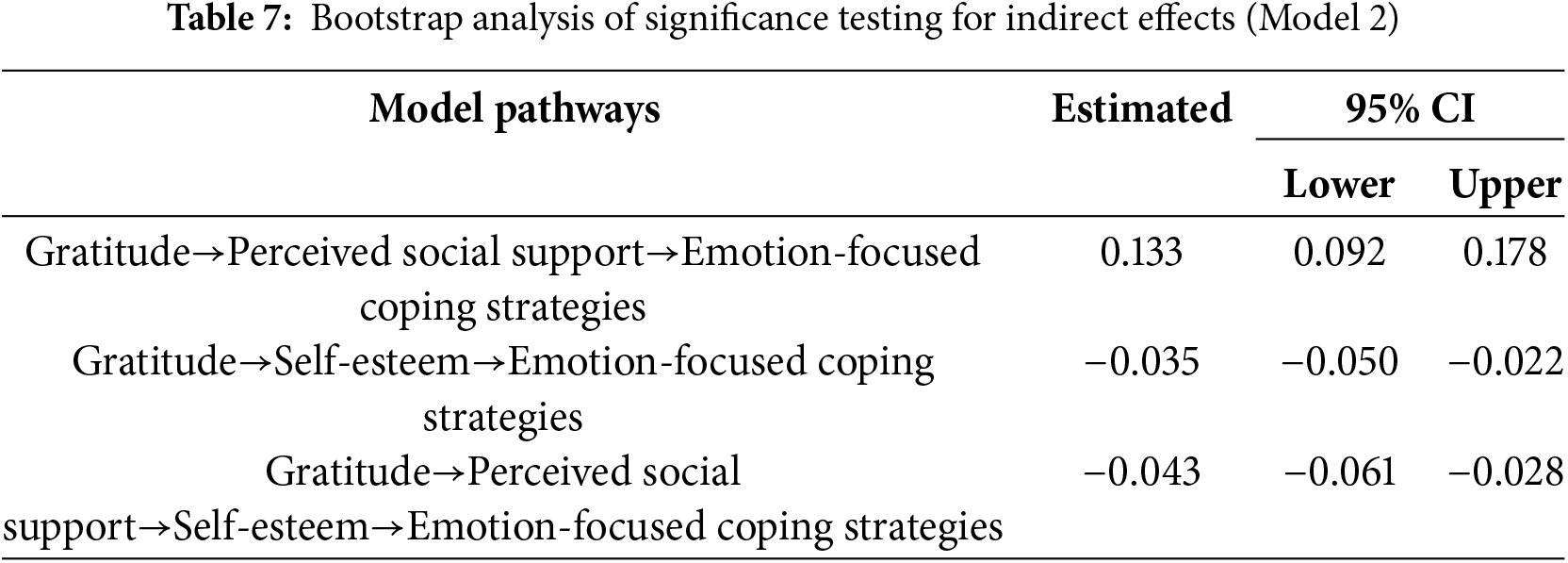

In Model 2, we created a model with gratitude as the independent variable, emotion-focused coping strategies as the target variable, and perceived social support and self-esteem as the transmission variables. The model exhibited good fit indices, as indicated in Table 5, the overall effect value of gratitude on emotion-focused coping strategies is 0.009, and the direct effect of gratitude on emotion-focused coping strategies was also not significant (β = −0.065, p > 0.05). Gratitude positively predicted Perceived social support (β = 0.661, p < 0.001) and Self-esteem (β = 0.234, p < 0.001), Perceived social support positively predicted Self-esteem (β = 0.439, p < 0.001) and emotion-focused coping strategies (β = 0.279, p < 0.001), and Self-esteem negatively predicted emotion-focused coping strategies (β = −0.205, p < 0.001), as illustrated in Fig. 4. We employed Bootstrap resampling 1000 times to evaluate the cumulative indirect effect and calculate the 95% confidence intervals. Perceived social support and self-esteem played indirect effects in the context of gratitude and emotion-focused coping strategies. Specifically, the model path coefficients were as follows: Gratitude → Perceived social support → emotion-focused coping strategies had a path coefficient of 0.133, Gratitude → Self-esteem → emotion-focused coping strategies had a path coefficient of −0.035, and Gratitude → Perceived social support → Self-esteem → emotion-focused coping strategies had a path coefficient of −0.043. None of their Bootstrap 95% confidence intervals included 0, indicating that all three indirect effects reached significance levels (see Table 7). Therefore, Hypotheses 4, 6, and 8 were supported in this study.

Figure 4: The chain indirect effect of gratitude’s impact on emotion-focused coping strategies (Model 2). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Gratitude: Data collected on 09 March 2023; Perceived social support and Self-esteem: Data collected on 08 June 2023; Problem-focused coping strategies and Emotion-focused coping strategies: Data collected on 08 September 2023

This research revealed that gratitude significantly positively predicts problem-focused coping strategies, supporting Hypothesis 1. Gratitude does not significantly negatively predict emotion-focused coping strategies, rejecting Hypothesis 2. Theoretical expectations in psychology suggest that individuals form expectations about others’ behaviors during interactions, which may be based on their past experiences, sociocultural backgrounds, and personal beliefs. When others’ behaviors exceed individuals’ expectations, it can trigger emotional responses such as surprise, disappointment, or gratitude. Individuals possessing higher gratitude exhibit a stronger tendency to exhibit positive emotional responses of goodwill [60]. According to the perspective of social resource theory, the resources that individuals may obtain through a sense of gratitude include social support, emotional support, and informational support, among others. These resources can provide individuals with the information and support they need to cope with challenges and difficulties, thus enhancing their tendency to employ problem-focused coping strategies [38,61], This justifies why gratitude significantly and positively predicts problem-focused coping strategies. Additionally, we found in this study that gratitude mediates emotion-focused coping strategies through perceived social support and self-esteem, which may be a result of the intricate psychological mechanisms of individuals. Throughout, the original intention of gratitude education in schools and families has been to foster children’s problem-focused coping strategies. However, the reality is that individuals’ levels of gratitude are not easily significantly improved solely through gratitude education. Therefore, schools and families should also consider other factors that influence children’s engagement in positive behaviors, such as cultivating high levels of self-esteem. This approach may lead to more desirable outcomes.

This study confirmed that perceived social support mediates the relationships between gratitude and both problem-focused coping strategies, along with gratitude and emotion-focused coping strategies, supporting Hypotheses 3 and 4. The theory of social support seeks to explain how individuals manage stress and challenges by leveraging the social support resources available to them. According to this theory, social support can be provided to individuals through emotional, informational, instrumental, and tangible support, thereby enhancing individuals’ psychological well-being and happiness, strengthening their coping and adaptive abilities, and helping them cope with stress and challenges positively [62]. Gratitude is believed to enhance positive interactions and relationships between individuals, by that means boosting their perceived levels of social support. When individuals experience gratitude, they more easily recognize goodwill from others, which helps build and enhance social support [63]. It can also improve people’s overall happiness and mental health [38]. Therefore, people tend to adopt coping strategies, including seeking emotional support, reinterpreting situations positively, and dealing with practical problems [64]. Therefore, promoting perceived social support through gratitude can indirectly enhance individuals’ overall well-being. Based on this, it is easy to understand why perceived social support in this study positively predicts problem-focused coping strategies. However, we may have doubts about whether perceived social support also positively predicts emotion-focused coping strategies. The adaptive burden hypothesis suggests that when individuals perceive themselves to have more social support available, they show a stronger inclination to choose more emotion-focused coping strategies, for instance, evasion, disavowal, or emotional responses. Behind this phenomenon is an adaptive psychological mechanism, wherein individuals believe they have more resources to cope with stress and challenges, thus they may not need to adopt active, problem-solving coping strategies [65]. This study suggests that the seemingly contradictory research findings may be related to individuals’ personal styles of dealing with tasks. If an individual has a decisive style, when their perceived social support is high, they might actively engage with social support resources to manage and solve the problems they confront. Nevertheless, if an individual has a procrastinating style, even if their perceived social support is high, they may not be willing to rush to solve immediate problems because they believe that when they need to address the issue, there will always be someone to help them. This also underscores that individuals’ coping strategies are influenced not only by gratitude, perceived social support, and self-esteem, but also by their personal approaches to task management. Based on this, schools and families should also focus on cultivating highly self-disciplined living habits in children. When children exhibit procrastination behavior, parents and teachers should help them correct it.

Self-esteem was found to mediate the relationships between gratitude and both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies in this study, supporting Hypotheses 5 and 6. The self-affirmation theory posits that individuals maintain and enhance self-esteem by affirming their positive aspects, such as emphasizing their strengths, achievements, and worth, which enables them to better adopt positive behaviors to cope with challenges and difficulties [66]. Individuals with gratitude tendencies are inclined to give more positive evaluations and assistance to others, which in turn strengthens their sense of internal worth and self-efficacy [37]. When people perceive life as hopeful, their levels of self-esteem tend to increase, thereby enhancing their confidence and ability to face life challenges, reducing the detrimental effect of stress, and serving a protective function in stressful situations [67]. Higher self-esteem is generally associated with a greater tendency to engage in proactive coping strategies, as an example, actively solving problems and seeking emotional support, as opposed to passive avoidance or self-destructive behaviors [68]. This relationship likely explains why self-esteem is a significant positive predictor of problem-focused coping strategies and a significant negative predictor of emotion-focused coping strategies in this study. Therefore, it is evident that cultivating children’s self-esteem is a highly important task for parents and educators. This includes providing children with positive feedback and affirmation during the educational process, emphasizing their strengths and achievements, acknowledging their efforts and progress, granting them appropriate autonomy and decision-making power, respecting their opinions and feelings, giving them sufficient listening and understanding, and making them feel valued and accepted. All of these efforts contribute to the establishment of positive self-esteem.

Gratitude significantly predicts problem-focused coping strategies and emotion-focused coping strategies through the chained mediation of perceived social support and self-esteem, hypothesis 7 and hypothesis 8 are confirmed. Social identity theory suggests that individuals’ self-esteem is partly built on their identification with the social groups to which they belong. Individuals shape their self-esteem by comparing themselves with the group, thereby gaining a sense of belonging and receiving social support and recognition from the group [69]. Individuals with gratitude tendencies are more inclined to recognize and appreciate the kindness of others, which promotes the formation of closer and more supportive social networks. In other words, gratitude enhances individuals’ social relationships and enhances perceived social support [38]. Perceiving social support typically accompanies positive emotional experiences such as satisfaction, happiness, and a sense of security. These positive emotional experiences help individuals maintain a good emotional state, and enhance their psychological resilience when facing stress, this leads to an increase in their self-esteem, while also prioritizing the application of problem-focused coping strategies [70]. At the same time, higher levels of self-esteem facilitate individuals in establishing and maintaining supportive social relationships, thereby assisting them in increasing their perceived levels of social support [37,64]. Our study validates the above viewpoint, which indicates that self-esteem significantly and positively predicts problem-focused coping strategies, while negatively predicting emotion-focused coping strategies. At the same time, we also observed that perceived social support has a significant positive predictive effect on both coping strategies. Why do we see such results? When individuals perceive that they have ample social support resources, they are prone to believing that others will provide help when needed, feel accepted by their social group, and trust that others will offer emotional and material support, thus motivating them to adopt problem-focused coping strategies [22]. However, excessive reliance on social support may lead to feelings of insecurity when facing challenges, increasing the need for support from others and forming a psychological dependence, resulting in more passive coping strategies when encountering difficulties.

5 Limitations and Implications

Several limitations in the research design must be noted. To begin with, the focus is on college students, which does not extend to various demographic groups in society. Future research could broaden the participant range to include different populations and adopt multiple sampling methods, such as stratified sampling and cluster sampling, to enhance the representativeness of the sample. Next, this study employs a longitudinal research design with a 3-month interval, and we are uncertain whether this interval is appropriate. Future studies could utilize continuous tracking methods to further validate the research findings.

Despite these limitations, the use of longitudinal data in this study is more scientifically rigorous than cross-sectional data. Moreover, the results of this study help us gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between gratitude and coping strategies, and also validate the perspectives of expectancy theory, social support theory, and self-esteem theory. In future family education and school education, we recommend that teachers and parents place emphasis on cultivating minors’ self-esteem during the educational process, this can foster their problem-focused coping strategies. Furthermore, it is essential to cultivate a decisive style of action in children. When procrastination behavior is observed, parents and teachers should help them correct it, as procrastination may lead children to engage in emotion-focused coping strategies more easily.

Gratitude can significantly and directly predict problem-focused coping strategies, and it can also predict problem-focused coping strategies through the mediating roles of perceived social support and self-esteem. Furthermore, the hypothesis that Gratitude significantly negatively predicts emotion-focused coping strategies was not supported. Instead, Gratitude influences emotion-focused coping strategies through the indirect effects of perceived social support and self-esteem. We observed that individuals with high self-esteem tend to adopt problem-focused coping strategies. Those with strong perceived social support may adopt problem-focused coping strategies due to their high self-confidence, while also relying on available support resources to help solve problems. As a result, they may also be inclined to use emotion-focused coping strategies. We refer to this pattern as the social support-coping strategies dichotomy. Based on the above findings, we believe that in the practices of school education and family education, it is not sufficient to simply strengthen Gratitude education to cultivate children’s problem-focused coping strategies. Instead, more emphasis should be placed on fostering children’s self-independence and Self-esteem.

Acknowledgement: We thank Junqiao Guo for completing the translation work and the research participants for their involvement in this study.

Funding Statement: Tourism College of Zhejiang Fund provided financial support for this research (Project Number: 2023CGYB05).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jun Zhang; data collection: Junqiao Guo; analysis and interpretation of results: Junqiao Guo; draft manuscript preparation: Jun Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the Tourism College of Zhejiang (IRB number: ZT783590). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviation

| GQ-6 | Gratitude Questionnaire |

| PSSS | Perceived Social Support Scale |

| SES | Self-Esteem Scale |

| SCSQ | Simplified Coping Strategies Questionnaire |

| CMB | Common method biases |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| TLI | Tucker-Lewis Index |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| ANOVA | One-way Analysis of Variance |

References

1. Sun PZ, Sun YD, Jiang HY, Jia R, Li ZY. Gratitude and problem behaviors in adolescents: the mediating roles of positive and emotion-focused coping strategiess. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1547. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):218–26. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Bryan JL, Young CM, Lucas S, Quist MC. Should I say thank you? Gratitude encourages cognitive reappraisal and buffers the negative impact of ambivalence over emotional expression on depression. Personal Ind Diff. 2018;120:253–8. [Google Scholar]

4. Ding K, Liu JT. Comparing gratitude and pride: evidence from brain and behavior. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2022;22(6):1199–214. doi:10.3758/s13415-022-01006-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Lin CC. The roles of social support and coping style in the relationship between gratitude and well-being. Pers Indiv Differ. 2016;89(1):13–8. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Morgan B, Gulliford L, Kristjansson K. Gratitude in the UK: a new prototype analysis and a cross-cultural comparison. J Posit Psychol. 2014;9(4):281–94. doi:10.1080/17439760.2014.898321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Tian L, Du M, Huebner ES. The effect of gratitude on elementary school students’ subjective well-being in schools: the mediating role of prosocial behavior. Soc Indic Res. 2015;122(3):887–904. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0712-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Santarnecchi E, Sprugnoli G, Tatti E, Mencarelli L, Neri F, Momi D, et al. Brain functional connectivity correlates of coping styles. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2018;18(3):495–508. doi:10.3758/s13415-018-0583-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Chen J, Tarizadeh A. The ideal avoidance property. J Pure Appl Algebra. 2024;228(3):107500. doi:10.1016/j.jpaa.2023.107500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Birhan GS, Belete GT, Eticha BL, Ayele FA. Magnitude of maladaptive coping strategy and its associated factors among adult glaucoma patients attending tertiary eye care center in Ethiopia. Clin Ophthalmol. 2023;17:711–23. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S398990. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Wang RJ, Wang TY, Ma J, Liu MX, Su MF, Lian Z, et al. Substance use among young people in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2017;390:S14. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33152-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Krueger PM, Chang VW. Being poor and coping with stress: health behaviors and the risk of death. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(5):889–96. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.114454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Nelson C. Appreciating gratitude: can gratitude be used as a psychological intervention to improve individual well-being? Couns Psychol Rev. 2009;24(3–4):38–50. doi:10.53841/bpscpr.2009.24.3-4.38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Froh JJ. Review of ‘Thanks! How the new science of gratitude can make you happier. J Posit Psychol. 2008;3:80–2. [Google Scholar]

15. Wood AM, Maltby J, Gillett R, Linley PA, Joseph S. The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: two longitudinal studies. J Res Pers. 2008;42(4):854–71. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2007.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wedberg NA, Geher G, McQuade B, Thomas DM. Positive evolutionary psychology: the new science of psychological growth. In: AI-Shawai L, Shackelford TK, editors. The oxford handbook of evolution and the emotions; online edition. Oxford Academic; 2024 May 22. p. 929–43. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197544754.013.45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhao L, Zhang LY, Xu CJ. Effects of psychological intervention on military personnel’s social support, coping styles and psychosomatic health and their relationships. Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci. 2013;22(3):233–6 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

18. Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(2):217–37. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Tomoko F, Kumiko O, Katsuyasu K, Tomoki M, Chiemi M, Katsumasa M, et al. Association of social support with gratitude and sense of coherence in Japanese young women: a cross-sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2017;10:195–200. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S137374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Wu N, Ding F, Ai B, Zhang R, Cai Y. Mediation effect of perceived social support and psychological distress between psychological resilience and sleep quality among Chinese medical staff. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):19674. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-70754-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Chen M, Che C. Perceived social support, self-management, perceived stress, and post-traumatic growth in older patients following stroke: chain mediation analysis. Medicine. 2024;103(29):38836. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000038836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhao Y, Huang LH, Li Y. Influence of physical exercises on pilot students emotional stability: chain mediation effects of perceived social support and self-efficacy. China J Health Psychol. 2023;31(3):446–51 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

23. Algoe SB, Way BM. Evidence for a role of the oxytocin system, indexed by genetic variation in CD38, in the social bonding effects of expressed gratitude. Soc Cogn Affect Neur. 2014;9(12):1855–61. doi:10.1093/scan/nst182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lambert NM, Fincham FD, Stillman TF. Gratitude and depressive symptoms: the role of positive reframing and positive emotion. Cognit Emot. 2012;26(4):615–33. doi:10.1080/02699931.2011.595393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Swickert R, Bailey E, Hittner J, Spector A, Benson-Townsend B, Silver NC. The mediational roles of gratitude and perceived support in explaining the relationship between mindfulness and mood. J Happiness Stud. 2018;1–14(3):815–28. doi:10.1007/s10902-017-9952-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. You SY, Lee J, Lee Y, Kim E. Gratitude and life satisfaction in early adolescence: the mediating role of social support and emotional difficulties. Pers Individ Dif. 2018;130(2):122–8. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ates E, Canyilmaz E, Cakir NG, Yurtsever C, Yoney A. Assessment of depression and anxiety states of cancer patients and their caregivers. Ank Med J. 2018;18(1):61–7. doi:10.17098/amj.408965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Chaplin TM, Aldao A. Gender differences in emotion expression in children: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2013;139(4):735–65. doi:10.1037/a0030737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Matud MP. Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Pers Individ Differ. 2004;37(7):1401–15. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Henriksen IO, Ranoyen I, Indredavik MS, Stenseng F. The role of self-esteem in the development of psychiatric problems: a three-year prospective study in a clinical sample of adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiat Ment Health. 2017;11(1):68. doi:10.1186/s13034-017-0207-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Stephenson E, Watson PJ, Chen ZJ, Morris RJ. Self-compassion, self-esteem, and irrational beliefs. Curr Psychol. 2017;37:809–15. [Google Scholar]

32. Hemerijck A. The uses of social investment. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

33. Tong W, Fang R, Nie R, Deng Y, Jia J, Fang X. The relationship between marriage and self-esteem: insights from the person-centered approach. J Psychol Sci. 2023;46(3):726–33 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

34. Cameron JJ, Granger S. Does self-esteem have an interpersonal imprint beyond self-reports? A meta-analysis of self-esteem and objective interpersonal indicators. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2018;23(1):73–102. doi:10.1177/1088868318756532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Johnson MD, Galambos NL, Finn C, Neyer FJ, Horne RM. Pathways between self-esteem and depression in couples. Dev Psychol. 2017;53(4):787–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

36. Zdemir T, Karada G, Kul S. Relationship of gratitude and coping styles with depression in caregivers of children with special needs. J Relig Health. 2022;61(2):214–27. doi:10.1007/s10943-021-01389-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Voci A, Veneziani CA, Fuochi G. Relating mindfulness, heartfulness, and psychological well-being: the role of self-compassion and gratitude. Mindfulness. 2019;10(2):339–51. doi:10.1007/s12671-018-0978-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zhou X, Zhen R, Wu XC. Understanding the relation between gratitude and life satisfaction among adolescents in a post-disaster context: mediating roles of social support, self-esteem, and hope. Child Indic Res. 2019;12(5):1781–95. doi:10.1007/s12187-018-9610-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Cheng JT, Tracy JL, Foulsham T, Kingstone A, Henrich J. Two ways to the top: evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2013;104(1):103–25. doi:10.1037/a0030398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Li WY, Guo YF, Lai WJ, Wang WX, Li XW, Zhu LW, et al. Reciprocal relationships between self-esteem, coping styles, and anxiety symptoms among adolescents: between-person and within-person effects. Child Adol Psych Men. 2023;17(1):21. doi:10.1186/s13034-023-00564-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Li J, Chen YP, Zhang J, Lv MM, Vlimki M, Li YF, et al. The mediating role of resilience and self-esteem between life events and coping styles among rural left-behind adolescents in China: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:560556. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.560556. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Kong F, Ding K, Zhao J. The relationships among gratitude, self-esteem, social support and life satisfaction among undergraduate students. J Happiness Stud. 2015;16(2):477–89. [Google Scholar]

43. Zhang L, Zhang S, Yang Y, Li C. Attachment orientations and dispositional gratitude: the mediating roles of perceived social support and self-esteem. Pers Indiv Differ. 2017;114(2):193–7. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Gallagher S, Creaven AM, Howard S, Ginty AT, Whittaker AC. Gratitude, social support and cardiovascular reactivity to acute psychological stress—science direct. Biol Psychol. 2021;162(3):108090. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2021.108090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Keshky MESE, Khusaifan SJ, Kong F. Gratitude and Life Satisfaction among older adults in Saudi Arabia: social support and enjoyment of life as mediators. Behav Sci. 2023;13(7):527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

46. Naseri L, Mohamadi J, Sayehmiri K, Azizpoor Y. Perceived social support, self-esteem, and internet addiction among students of Al-Zahra University, Tehran, Iran. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2015;9(3):421. doi:10.17795/ijpbs-421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Emadpoor L, Lavasani MG, Shahcheraghi SM. Relationship between perceived social support and psychological well-being among students based on mediating role of academic motivation. Int J Ment Health Ad. 2016;14(3):284–90. doi:10.1007/s11469-015-9608-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Uchino BN. Social support and physical health: understanding the health consequences of relationships. 2nd ed. New Haven,CT, USA: Yale University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

49. Peterson RA, Merunka DR. Convenience samples of college students and research reproducibility. J Bus Res. 2014;67(5):1035–41. [Google Scholar]

50. McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(1):112–7. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Emmons RA, Crumpler CA. Gratitude in the digital age: understanding the role of social media in gratitude expression and its association with well-being. J Posit Psychol. 2022;17(1):98–109. [Google Scholar]

52. Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(3–4):610–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

53. Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

54. Liu Q, Niu G, Fan C, Zhou Z. Passive use of social network site and its relationships with self-esteem and self-concept clarity: a moderated mediation analysis. Acta Psychol Sin. 2017;49(1):60–71 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

55. Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

56. Chen W, Wang H, Zhao M. The relationship between childhood abuse and lack of pleasure in college students: the chain mediating role of problem-focused coping strategiess and stress perception. China J Health Psychol. 2023;31(11):1690–5. [Google Scholar]

57. Zhang J, Li XW, Tang ZX, Xiang SG, Tang Y, Hu WX, et al. Effects of stress on sleep quality: multiple mediating effects of rumination and social anxiety. Psicol Reflex E Crit. 2024;37(10):1–10. doi:10.1186/s41155-024-00294-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Tang D, Wen Z. Statistical approaches for testing common method bias: issues and suggestions. J Psychologic Sci. 2020;43(1):215–23 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

59. Wen Z, Huang BD, Tang DD. Preliminary work for modeling questionnaire data. J Psychol Sci. 2018;41(1):204–10 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

60. Rudman LA, Glick P. The social psychology of gender: how power and intimacy shape gender relations. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

61. Sookwah RD, Gholizadeh S. Experiences of two exemplar women with coping self-efficacy during undergraduate engineering. In: 2023 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE); 2023; College Station, TX, USA. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/FIE58773.2023.10342949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Uchino BN, Bowen K, Carlisle M, Birmingham W. Psychological pathways linking social support to health outcomes: a visit with the ghosts of research past, present, and future. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(7):949–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

63. Jin L, Zhu T, Wang Y. Relationship power attenuated the effects of gratitude on perceived partner responsiveness and satisfaction in romantic relationships. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):21090. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-71994-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Canboy B, Tillou C, Barzantny C, Guclu B, Benichoux F. The impact of perceived organizational support on work meaningfulness, engagement, and perceived stress in France. Eur Manag J. 2023;4(1):90–100. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2021.12.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. House JS, Umberson D, Landis KR. Structures and processes of social support. Annu Rev of Sociol. 2003;14(1):293–318. [Google Scholar]

66. Cohen GL, Sherman DK. The psychology of change: self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65(1):333–71. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Barbalat G, Plasse J, Gauthier E, Verdoux H, Quiles C, Dubreucq J, et al. The central role of self-esteem in the quality of life of patients with mental disorders. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):7852. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-11655-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Harter S. The construction of the self: developmental and sociocultural foundations. 3rd ed. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

69. Greenaway KH, Cruwys T, Haslam SA. Social identities promote well-being because they satisfy global psychological needs. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2015;46(3):294–307. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Baker JP, Berenbaum H. Emotional approach and problem-focused coping: a comparison of potentially adaptive strategies. Cogn Emot. 2007;21(1):95–118. doi:10.1080/02699930600562276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools