Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Physical Fitness and Mental Health Three Months after COVID-19 Infection in Young and Elderly Women

1 Faculty of Education, University of Macau, Macao, 999078, China

2 UCLA Center for Human Nutrition, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90024, USA

3 Whole Person Education Centre, Beijing Normal University-Hong Kong Baptist University United International College, Zhuhai, 519087, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhaowei Kong. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Determinants and Subsequences of Subjective Well-being as a Microcosm of Social Change)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(3), 363-378. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.060875

Received 12 November 2024; Accepted 18 February 2025; Issue published 31 March 2025

Abstract

Background: This study evaluated physical fitness and mental health in young and elderly women 3 months after mild COVID-19 infection, and examined the impact of infection and age on long COVID occurrence and trajectory. Methods: There were 213 eligible female volunteers (107 young, 106 elderly) recruited approximately three months after the significant outbreak of COVID-19 in China. Participants completed a fitness test and mental health assessment using the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Self-Assessment Scale (PTSD) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Inventory (PSQI). Results: Despite no significant difference in physical fitness, infected young and elderly females experienced poorer sleep quality related to mental health compared to their uninfected peers (+22% in young participants, p = 0.027; +10% in elderly participants, p = 0.005). The elderly scored significantly higher in sleep quality than the young (p < 0.05). Age, previous infection, and PTSD were significant predictors of sleep quality, explaining 60.6% of the variance in PSQI scores. Conclusions: Three months following COVID-19 infection, infected women experienced poorer sleep quality compared to their uninfected peers. Irrespective of being infected, older individuals exhibited higher rates of sleep disorders compared to younger women, suggesting the importance of addressing post-COVID-19 sleep issues among at-risk individuals.Keywords

The global impact of the COVID pandemic on human health has been significant, with more than 660 million confirmed cases and over 6.6 million deaths worldwide by February 2023 [1]. China initially implemented a strict dynamic zero-COVID approach, which effectively suppressed local outbreaks compared to other countries [2]. In mid-November 2022, a pivotal shift occurred with the relaxation of this policy, driven by extensive vaccination coverage and the emergence of less severe Omicron subvariants. This strategic adjustment led to a rapid spread of Omicron, accounting for over 90% of SARS-CoV-2 infections nationwide [2,3].

While acute respiratory illness has been the primary focus during the outbreak [4], the effects of COVID have exceeded the initial infection, impacting physical and mental health, as well as quality of life during recovery [5]. Despite the World Health Organization declaring an end to the pandemic in 2023 [6], there is a growing awareness of the long-term health impacts of COVID-19 on various populations [7]. While critical illness is the immediate focus, the persistence and severity of long-term effects, even after mild infections, continues to gain attention. Sustained physical and mental health impacts have become established post-infection issues facing survivors [8], given that 10%–30% of infected individuals experience persistent symptoms or “long COVID” [9,10].

“Long COVID” refers to a range of persistent symptoms that continue to afflict individuals for weeks or months after initial infection [10,11]. Commonly reported sequelae substantially reducing quality of life include fatigue, dyspnea, cognitive dysfunction, muscular pain, and sleep abnormalities [8]. At 3 months post-infection, 23% of individuals had not fully regained normal exercise capacity, experiencing ongoing fatigue, breathlessness, and a reduction of quality of life [12]. By the 6-month mark, up to 50% of infected individuals may still be coping with debilitating symptoms such as fatigue, respiratory issues, memory deficits, and neurological challenges [8,13,14]. A meta-analysis has revealed that more than half of COVID-19 survivors continue to experience lingering fatigue and respiratory limitations 6–12 months after infection [5], with 96% of over 400 survivors reporting at least one persistent symptom at 6 months, including fatigue, dyspnea, and memory impairment [14].

Among the concerning sequelae of long COVID are sleep abnormalities such as insomnia, hypersomnia, and disruptions in circadian rhythm [13]. Given that sleep plays a crucial role in immune regulation and recovery, these disruptions may exacerbate cognitive and emotional impairments. Recent research has linked sleep disturbances in COVID-19 survivors to heightened levels of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a sample of over 24,000 individuals [15]. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated a correlation between poor sleep and accelerated cognitive decline in older populations [16]. The relationship between long COVID and sleep disruptions appears to be bidirectional, with viral infection and inflammation disrupting sleep patterns, while sleep disturbances, in turn, worsen symptoms of long COVID [8]. The direct impact of the virus can impair restorative slow wave and rapid eye movement sleep, crucial for tissue recovery and memory consolidation [17], thus contributing to a negative spiral where symptoms of long COVID such as fatigue, mood disorders, and cognitive dysfunction that further deteriorate sleep quality.

Demographic factors importantly influence the occurrence and trajectory of long COVID. Limited studies have examined the functional impacts of COVID across various age groups when compared to uninfected populations. Current research primarily focuses on middle-aged adults [14,18], leaving a noticeable gap in understanding the effects of long COVID on young adults or the elderly. Some analyses indicate that infected adults, including young low-risk groups, may experience enduring exercise intolerance and cardiovascular deficits compared to uninfected controls [19]. However, a study on the elderly population showed no post-infection health differences from controls without severe initial illness [20]. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that the elderly may undergo synergistic declines such as sleep, mental health, and physical biomarkers [21]. This susceptibility may increase the risk of impairment and neurodegenerative outcomes in elderly individuals with long COVID. Even after a mild infection, recovering infected individuals may exhibit persistent inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiovascular changes [22].

To simplify analysis amid multifaceted demographic risks, this cross-sectional study aimed to evaluate physical and mental health at 3 months following mild COVID-19 infection across young and elderly female cohorts. It was hypothesized that, (1) individuals with COVID-19 infection would experience physical impairment and sustained sleep disruption compared to their uninfected peers; and (2) worse impairment would be found in the infected elderly group.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) volunteering to participate in the research; (2) young females aged 18–30 years, as well as elderly females aged 60–75 years, regardless of whether they were diagnosed with COVID-19 infection confirmed through Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), rapid test or antigen test; (3) mild infection of COVID-19 (mild clinical symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, cough, anorexia, malaise, muscle pain, sore throat, dyspnea, nasal congestion, headache) with no abnormal chest imaging findings [23], and can be managed at home without hospitalization; (4) had no diagnosed endocrine, metabolic, osteoarticular, cardiovascular diseases; (5) had no psychiatric illness and no physical barriers to exercise; (6) received at least two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine prior to enrollment.

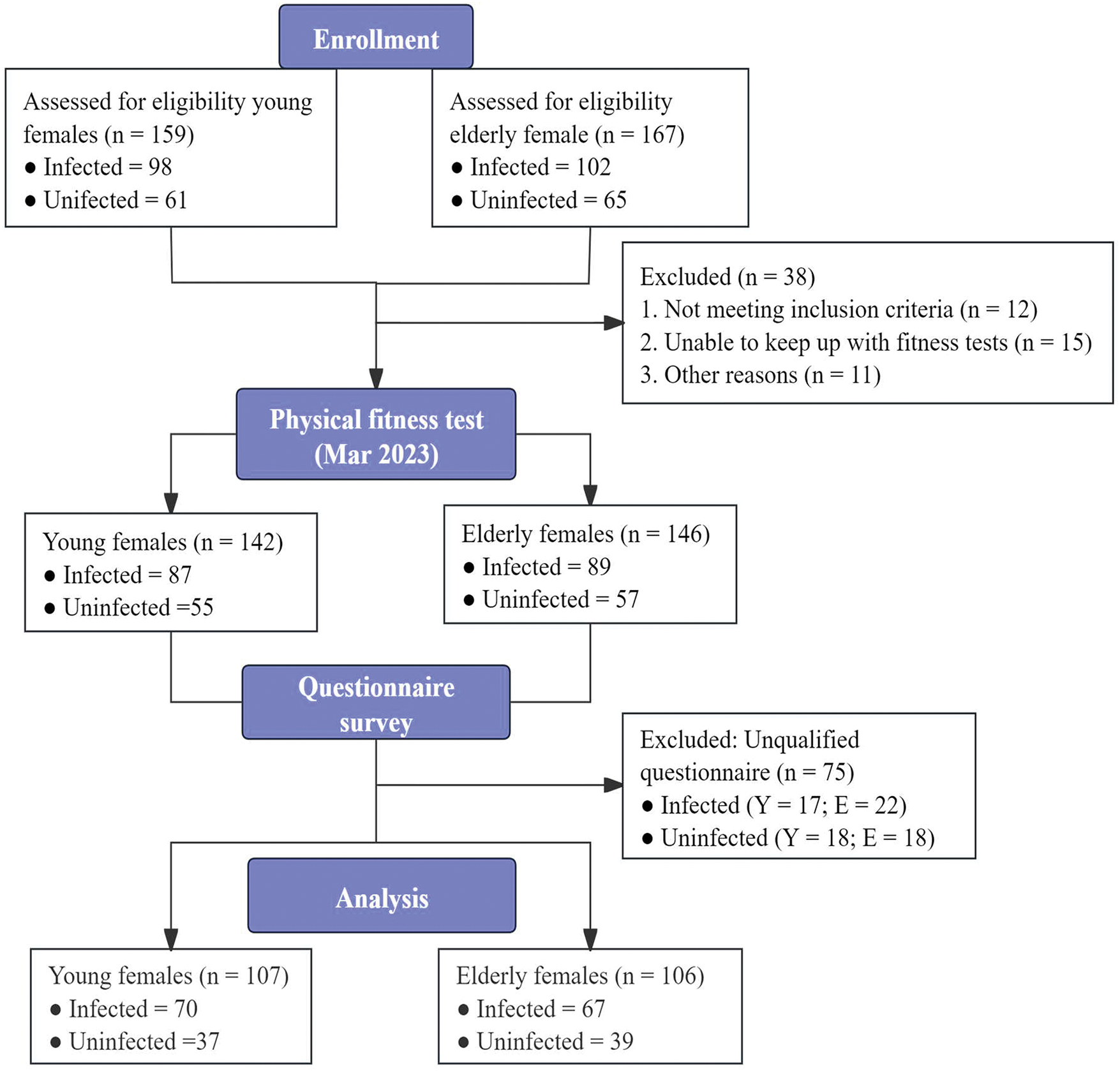

To compare the difference between the infected young and elder participants, G*power (Version 3.1) software was used to perform power analysis and determine the sample size, by setting the effect size (d) to 0.5 (medium), the alpha error probability (α) to 0.05, and the power (1-β) to 0.8 for power. A sample size of 64 for each infected group was necessary. Considering the potential dropout rate, a total sample size of 200 infected individuals was anticipated. Participants were recruited three months after the large-scale COVID-19 infection by inviting both infected and uninfected young and elderly volunteers from a university and an activity center. Initially, 167 elderly females and 159 young females enrolled in this study. However, during the course of the study, 38 participants were excluded before the fitness test, and 75 participants declined to complete the questionnaire, resulting in their exclusion. Consequently, a total of 213 eligible female volunteers were recruited. The participants consisted of 107 young females (Meanage = 18.7 ± 1.0 years; infected = 70; uninfected = 37) and 106 elderly females (Meanage = 64.8 ± 3.4 years; infected = 67; uninfected = 39) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Schematic diagram for research process

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Macau (RC Ref. no. SSHRE23-APP117-FED) and carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to enrollment in the study, the purpose of the research was clearly explained to the participants, and written informed consent was obtained from those who were willing to participate. Nevertheless, participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time. To ensure confidentiality, coding was used instead of names for all collected information. The original paper records of all identifiable data were stored in locked cabinets and rooms. Additionally, electronic copies of this data were securely saved on cloud storage, with access limited exclusively to the principal investigator and authorized personnel.

2.2 Study Design and Procedures

The cross-sectional study was conducted between March 2023 and April 2023, three to three and half months after the Chinese government had announced the downgrade management of the disease from “Class A” to a less strict “Class B” in late December 2022 [24]. This change demonstrated the transition from strict restrictions to reopening. Considering its vaccination rate, medical resources and experience in prevention and control, China had the appropriate conditions for downgrading the management. “Class B” management indicated the end of centralized quarantine, close contact tracing, and mass nucleic acid testing [25]. The outbreak led to a rapid increase in symptomatic COVID cases nationwide, with estimates suggesting that 60%–80% of people in major cities were infected. This highlights the widespread impact of the outbreak during that period [2]. The prevalence of virus infections in China has largely been made up of Omicron variants (mainly strains BA.5.2 and BF.7) during this time [26].

The outcomes included personal information (age, COVID-19 infection status) and the results of the physical fitness test. Considering the potential impact of COVID-19 on mental health, secondary outcomes were evaluated using scales such as the PTSD and the PSQI Scale.

The average indoor environment was maintained at a constant temperature of 22.2°C ± 1.5°C and relative humidity of 21.9% ± 5.8%. The physical fitness test was conducted by PE teachers, with assistance from postgraduate students majoring in physical education who had undergone systematic training and long-term experience in physical fitness testing. There was a 10-min break between each test item.

Following the fitness test, participants were categorized into uninfected and infected groups based on their infection status. Subsequently, they were required to complete an online questionnaire under the supervision of teaching assistants. Only after their submitted questionnaires had been checked on-site were they permitted to leave.

Prior to the commencement of the testing protocol, all participants were instructed to adhere to specific guidelines. On the day before the test, participants were asked to refrain from engaging in excessive exercise, consuming alcohol, nicotine, caffeine, and taking analgesics or sedatives. On the test day, volunteers were instructed to fast for 2.5 h before the scheduled test time and to abstain from eating or drinking during this period. Participants were also reminded to inform the investigators if they had any physical discomfort. A 10-min warm-up was required before the test to minimize the risk of sports injuries.

2.3.1 Measurement of Physical Fitness

Physical fitness tests are used to assess physical fitness of participants, including anthropometric characteristics, muscle strength, flexibility and cardiovascular fitness level (CRF). Initially, a comprehensive assessment of the participants’ anthropometric characteristics was conducted, including measurements of body weight, height, and body mass index (BMI). These measurements were taken using electronic instruments, with participants wearing lightweight clothing and removed their shoes and socks. The height was determined through a calibrated stadiometer.

Muscle strength was measured using a Hand Grip Dynamometer (5401 Hand Grip Dynamometer, Takei, Japan) to measure hand grip strength (HGS). Participants held the tester with one hand and gripped it vertically with full force. Three grip strength tests were performed, and the highest value was taken for analysis.

Flexibility was assessed using the sit and reach test. The participant sat with legs straight and feet flat against the test plate (NL-500 Pro, Naili, China). With both arms and fingers extended forward, the participant gradually advanced the vernier to its maximum forward position, while ensuring that the legs remained flat against the floor. Three trials were conducted, and the highest measurement was recorded.

The Three-Minute Step Test (3MST) was used to assess cardiovascular fitness level (CRF) in young females. Participants were required to step up and down on the 30 cm box 90 times in 3 min following a metronome with a speed of 120 beats per minute (4 beats up and down), leading to a stepping rate of 30 steps per minute. Heart rates were measured at 1, 2 and 3 min after the 3MST exercise via a finger pulse oximeter (YX306, Yuwell, China). The step index is calculated using Eq. (1) as follows [27]:

The Two-Minute Step Test (TMST) was used to assess cardiorespiratory fitness in elderly females. Participants were instructed to step in place for two minutes, ensuring each knee to a designated height with each step. The score was determined by the number of right knee lifts that met the required height completed in two minutes.

The CRF levels were classified into five categories (1 = very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = average, 4 = good, 5 = very good) for young and elderly females, based on age and score [28].

2.3.2 Measurement of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Sleep Quality

The PTSD questionnaire and the PSQI questionnaire were used to assess mental health [29], and sleep quality [30], respectively. The PTSD symptoms identified in previous research served as a crucial reference for our study. PTSD is considered a potential long-term consequence of COVID-19. COVID-19 exposure is a unique, multidimensional severe stressor (direct like life-threatening physical discomfort and indirect like witnessing others’ struggle), and though some related experiences’ status as traumatic stressors is controversial, they can lead to symptoms similar or identical to PTSD symptoms [31]. During pandemics, people rely on the media for information due to lockdown policies, and media exposure during major public events may cause varying degrees of vicarious trauma to audiences, further triggering trauma and anxiety [32].

The PTSD scale consists of 17 self-report items, each scored on a scale from level 1 to level 5. The diagnosis of PTSD is determined based on the total score, which is categorized into ranges indicating the presence and severity of symptoms. The Chinese version of the PTSD has been thoroughly validated and is extensively utilized within Chinese populations. The scale has good internal and test-retest reliability and validity, the Cronbach’α was 0.95 [33]. The scale is reliable and valid for undergraduate students and the elderly [34,35].

The PSQI consists of 19 self-reported questions and 5 questions answered by others. The total score is calculated based on self-answered questions, with the score range being from 0 to 21. Higher scores on this scale indicate poorer sleep quality. The Chinese version of PSQI showed good reliability and validity, with a Cronbach’α of 0.79 in undergraduate students [36] and elderly individuals [37].

Data are expressed as mean ± SD and were analyzed using SPSS software (version 26.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). All variables were found to conform to the normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Independent sample t-tests were carried out on each of the variables to determine the difference in physical fitness outcomes, PTSD, and PSQI between infected individuals and compared to their uninfected peers in both young and elderly groups. A two-way repeated measures (Two-Way ANOVA) analysis of variance (age × infection) was used to determine the main effects (age) and interaction effects (age × infection) on the outcome variables. A generalized linear model was performed with infection condition, physical outcome and PTSD as independent variables, while sleep quality (PSQI) was defined as a dependent variable. To build the regression model, variables that had a significant correlation with outcome variables at a p-value of 0.05 were included. A stepwise regression method was employed to identify the best-fitting model, and since the outcome variables were continuous, linear regression was applied. As for effect size (ES) measures of the main effect and the interaction effect, partial eta squared was considered small if

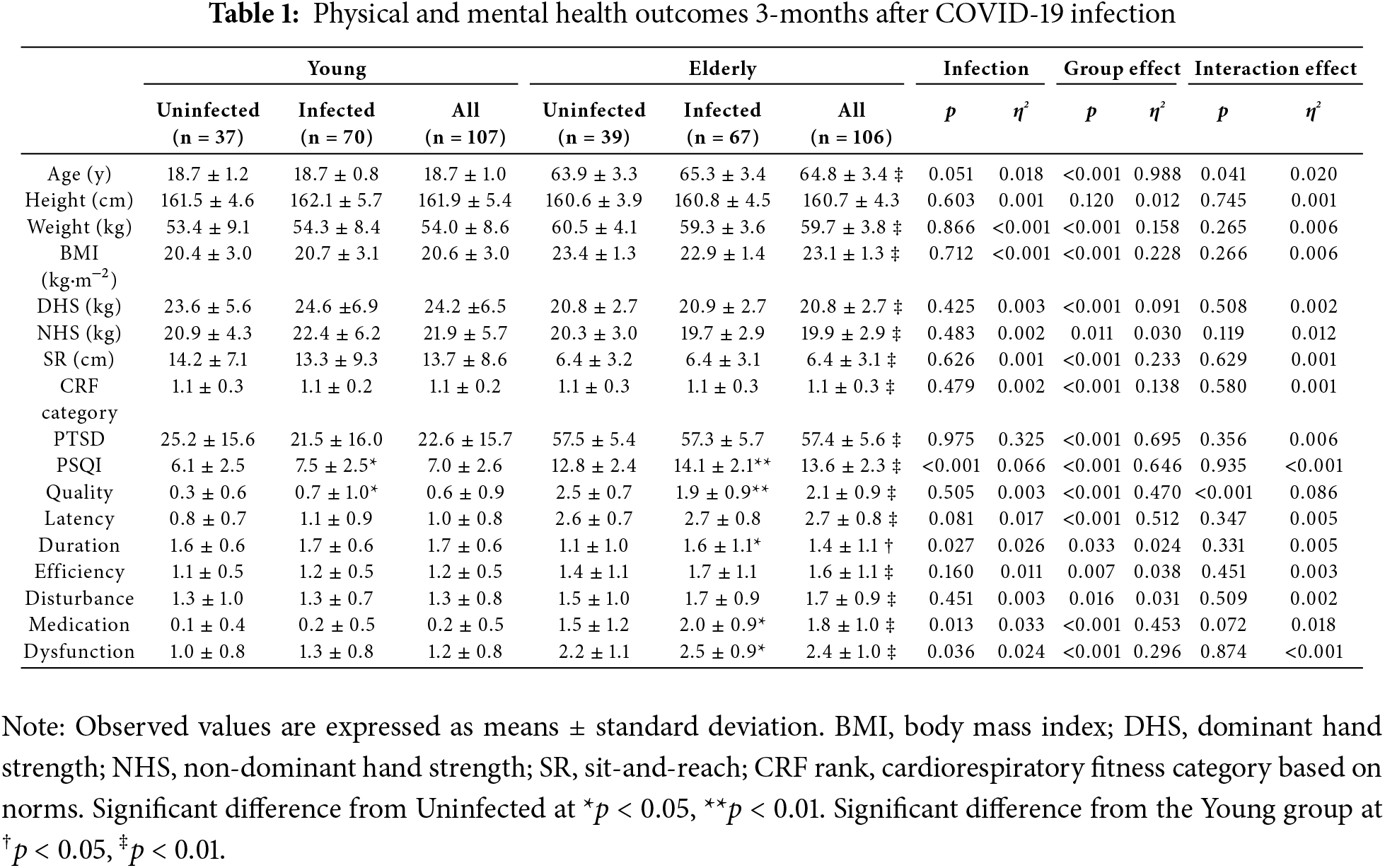

Participants’ demographic characteristics and physical fitness outcomes measured 3 months after COVID-19 infection are provided in Table 1. Regardless of age, there was no difference in body mass and BMI between the infected and non-infected groups (p > 0.05). Moreover, the COVID-19 infection did not significantly impair hand grip strength, flexibility, and cardiorespiratory fitness in either young or elderly females compared to their uninfected peers (p > 0.05).

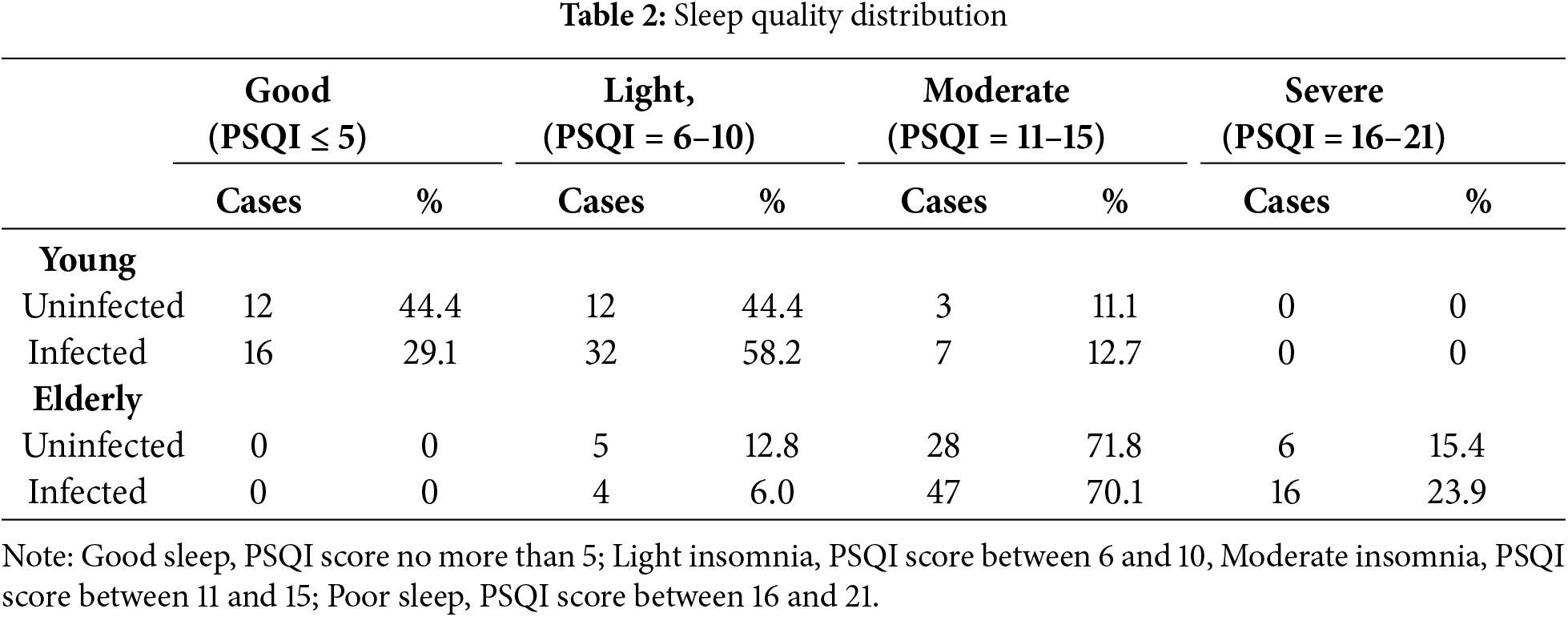

There was no significant difference in PTSD observed in infected individuals compared to uninfected individuals in either of the two groups at 3 months post-infection (p > 0.05, Table 1). The elderly group scored significantly higher in PTSD compared to the young group (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.695). At the same time, a significant effect on sleep quality was observed (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.066, Table 1). Specifically, infected groups in both young and elderly groups had a significant sleep quality decline (p < 0.05 in the young group, p < 0.01 in the elderly group). Infected young females exhibited a sleep quality score 22.0% higher compared to their uninfected peers (d = 0.56). Moreover, in the elderly group, infected individuals had sleep quality scores 10.0% higher than those who were not infected (d = 0.58). Regarding PSQI dimensions, infected elderly participants reported poorer sleep duration, use of sleep medication and daytime dysfunction. Furthermore, the elderly group scored significantly higher in PSQI compared to the young group (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.646), including all seven dimension scores. Additionally, 70.91% of infected young women and 55.56% of uninfected young women experienced insomnia, whereas all elderly women reported insomnia, regardless of infection status (Table 2).

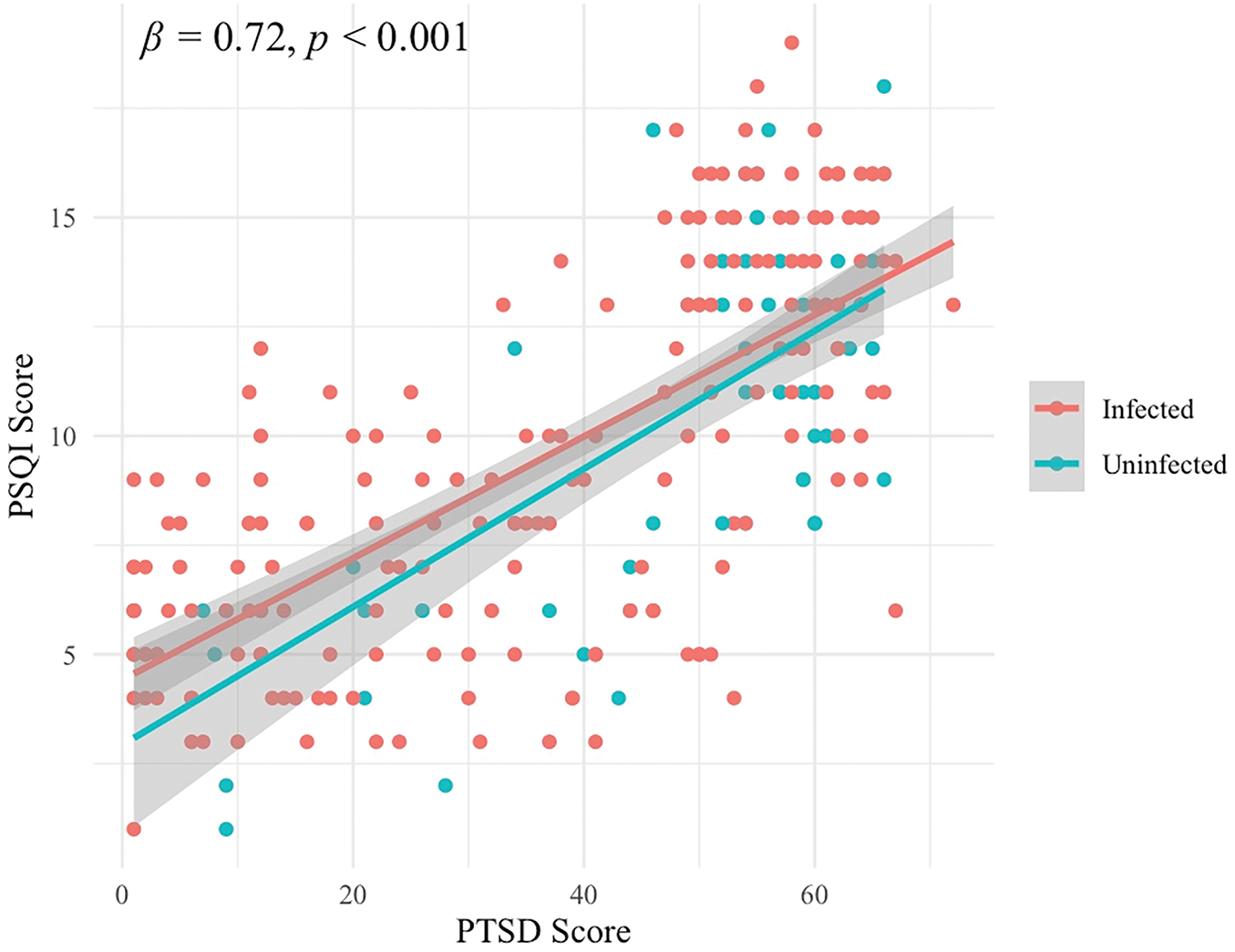

3.3 Associations between Infection Status, Physical Fitness and PTSD with PSQI

A moderate correlation (β = 0.367, p = 0.042) was observed between the PSQI score and the PTSD score among the young group, but no significant correlation was observed in the elderly or the combined groups. A strong correlation (β = 0.72, p < 0.001) was observed between the PSQI score and the PTSD score in both the infected and uninfected group (Fig. 2). Greater traumatic stress (PTSD scores) predicted poorer sleep quality in the young group. Infection status had a positive effect on the PSQI score in the young group (β = 0.245, p = 0.027) and the elderly group (β = 0.272, p = 0.005).

Figure 2: Regressions between PSQI (Y-axis) scores and PTSD (X-axis) scores in infected and uninfected individuals

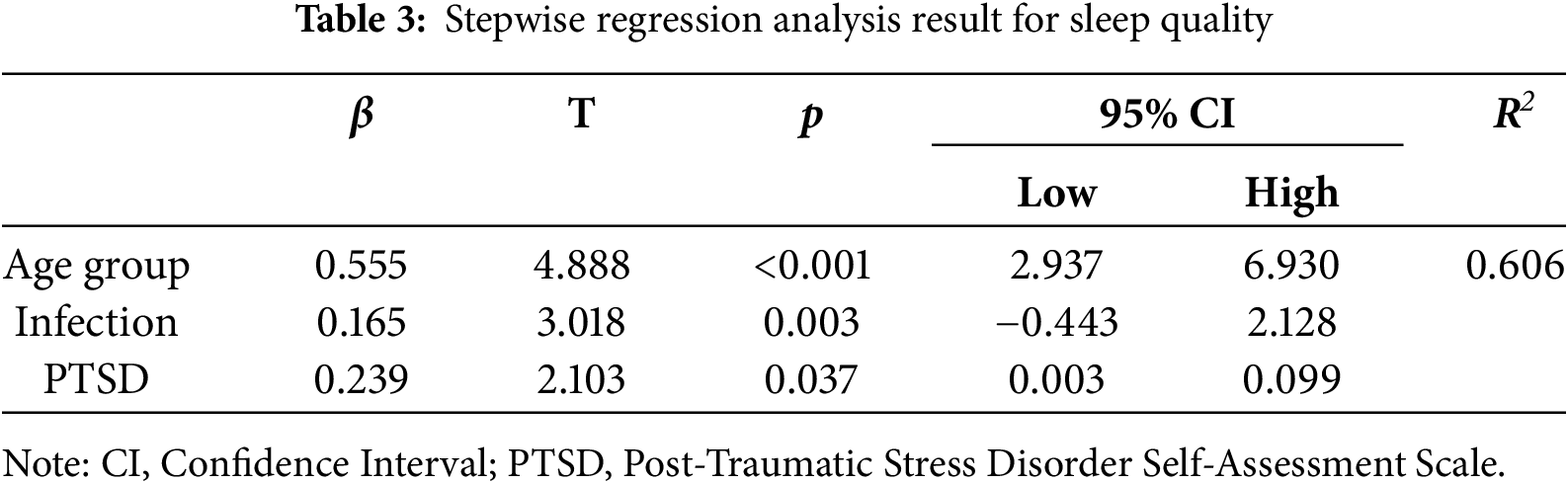

Stepwise regression analysis was conducted using age group (young = 0, elderly = 1), infection status (uninfected = 0, infected = 1) and physical and mental health indicators as predictor variables to predict the PSQI scores. The results demonstrated that age group (β = 0.555, p < 0.001), previous infection (β = 0.165, p = 0.003) and PTSD (β = 0.239, p = 0.037) were significant predictors in the model, accounting for 60.6% of the variance in PSQI scores (Table 3).

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine physical health and sleep quality three months after mild COVID-19 infection across age groups, compared with a matched uninfected population. The main findings of this study were that both young and elderly infected individuals experienced even worse sleep quality compared to their uninfected peers three months following COVID-19 infection. However, there was no significant impairment in physical fitness among the infected participants when compared to their uninfected peers. Additionally, the study found that older individuals were more likely to experience sleep disorders than younger individuals. The severity of sleep disorders was significantly worse in the elderly infected group compared to the young infected group.

4.1 Physical Fitness and Sleep Quality between Infected and Uninfected Peers

Given the fact that physical exertion malaise is a common symptom in the aftermath of COVID-19 [38,39], in this study, objective measurements were used to evaluate and assess the physical health indicators of individuals, with a focus on hand grip strength, flexibility, and cardiorespiratory fitness. This finding indicates that, within this time frame, the COVID-19 infection did not have a long-lasting detrimental effect on the physical fitness of the participants, regardless of their age. Both young and elderly women who recovered from COVID-19 demonstrated comparable physical fitness levels to those who were never infected, indicating the impact of the infection is temporary and reversible in relatively healthy females.

The fast recovery in physical fitness post-COVID-19 seems potentially facilitated by factors such as differences in physical active levels [40–43], SARS-CoV-2 variants [44], lockdown policy [45] and time for testing after acute infection (1–12 months) [5,10,46]. Reports have highlighted those adults who remained physical active during the COVID-19 pandemic had a reduced likelihood of developing long COVID [41]. Thus, it cannot be excluded that active exercise habits of the recruited individuals in this study likely promote recovery, mitigating temporary physical impairments. Moreover, the prevalence of virus infections in China has largely been made up of Omicron variants (mainly strains BA.5.2 and BF.7) since November 2022 [26]. Given that Omicron variants have a lower risk of severe COVID-19, particularly in vaccinated individuals [47], compared to Delta variants [48], mild viral infections may not cause a significant reduction in physical fitness. However, it is important to note that while physical fitness level appears to have normalized, this does not encompass other dimensions of health, such as sleep quality and mental health.

The results of the self-reported sleep quality (PSQI score) indicated that both young and elderly individuals had worse sleep quality three months after infection with COVID-19 compared to their uninfected peers. This study is in line with previous observations conducted by Peixoto et al. [49], Ahmed et al. [50] and Taquet et al. [8]. Sleep disturbances were identified as one of the most frequently documented and longest-lasting post-COVID-19 symptoms, causing continuing issues at the time of infection and during rehabilitation [49,51]. Notably, prior studies have noted the importance of the higher likelihood of the presence of post-COVID-19 conditions in infected female and the elderly. Women were at higher risk of developing long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms, including anxiety, depression, or poor sleep quality [52,53]. They were more likely to have persistent post-COVID-19 symptoms with age [49,54,55]. This information was highly relevant to the present study as it highlights the need for a gender-specific and age-sensitive approach in the treatment and management of post-COVID-19 conditions. By identifying women and the elderly as high-risk groups, interventions can be tailored to address their specific needs and vulnerabilities.

4.2 Sleep Quality between Youth and the Elderly

This study revealed poorer sleep quality among both younger individuals and the elderly after three months compared to non-infected individuals. The elderly had poorer sleep quality compared to the younger population, with more than 90% of the elderly continuing to experience moderate or severe insomnia, a condition that was independent of whether or not they had contracted the virus. Previous data have shown that the prevalence of sleep problems in the general population reached approximately 40% during the COVID-19 pandemic, significantly higher than the 15% rate reported in a meta-analysis [56]. In addition, 65% of infected individuals reported decreased sleep quality compared with healthy controls [57], highlighting the common decrease in sleep quality during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially among infected individuals.

Consistent with previous research, a higher prevalence of sleep problems or a worse sleep quality was reported in infected individuals [58,59], with symptoms lasting even after 12 months of recuperation [60,61]. Infected individuals, particularly those in severe or hospitalized conditions, experienced poorer sleep quality [62]. This study further suggests that even COVID-19 infection with the relatively mild Omicron variant still had an impact on sleep quality, underscoring the importance of long-term research efforts.

Whether age has an impact on sleep quality remains inconclusive. A meta-analysis has shown that age and gender are not significant predictors of the prevalence of sleep disorders [63]. However, research indicates that younger adults in their twenties and thirties frequently encounter more disruptions in sleep patterns compared to older age groups [61]. Additionally, Gui et al. [57] reported that poor sleep quality is more common in older infected individuals, suggesting that age can influence sleep quality. On the other hand, Abuhammad et al. [61] revealed that the prevalence of poor sleep quality increases with age [61]. The relationship between age and sleep quality during the COVID-19 pandemic appears complex and inconclusive, potentially influenced by various factors and interactions with each other. Discrepancies could be due to differences in socioeconomic status [50,61] assessment instruments [56], recovery periods [60,64] and underlying health conditions [65–67].

4.3 Association between PTSD and Sleep Quality

In the present study, age, history of infection, and PTSD were determinants of sleep quality, together explaining 60.6% of the PSQI score. Among these three factors, infection with COVID-19 had a generalized effect on sleep quality across age groups, while PTSD primarily negatively influenced sleep quality in young women.

This study demonstrated a significant association between PTSD symptoms and sleep quality in young women. Consistent with the recent studies conducted during the pandemic reporting associations between poor sleep and PTSD [68,69], infected individuals with PTSD not only struggled with falling asleep but were also at a higher risk of experiencing nightmares and insomnia [68]. Additionally, research has suggested that the increase in nightmare frequency during the pandemic is partially mediated by post-traumatic stress symptoms [70]. Consequently, PTSD symptoms appear to emerge as a unique predictor of sleep quality during the COVID-19 pandemic [68]. On the other hand, infected individuals face direct threats to their physical health, in addition to discomfort caused by symptoms and physiological fears, which exacerbate PTSD symptoms. These mental health issues and sleep quality have a bidirectional relationship [8]. Conversely, uninfected individuals face relatively fewer health threats, which may reduce their risk of enduring lasting psychological trauma.

Interestingly, PTSD scores were not significantly correlated with sleep quality among the elderly population, regardless of COVID-19 infection status. A possible explanation for this finding could be that fears related to COVID-19 detrimentally affected sleep quality, as heightened anxiety and worry exacerbate sleep disturbances [65]. Both uninfected and infected elderly individuals may share concerns about COVID-19, with infected individuals worrying about the direct effects of the virus and uninfected individuals fearing potential infection. Despite these different concerns, similar scores on PTSD measures were observed, and thus, there was no observable association between PTSD and sleep quality. Worries about COVID-19 infection and the inability to return to normal daily life due to the COVID-19 pandemic may lead to poorer sleep quality in this vulnerable group. Given the higher mortality risk, older adults are under considerable physical and psychological stress, potentially making them more susceptible to issues such as insomnia and depression [67]. Notably, the psycho-social burden seems to have influenced sleep quality more than the infection itself during the COVID-19 pandemic [49]. These findings highlight the need for targeted interventions to address insomnia and related psychological impacts for elderly individuals post-COVID-19 [71].

In this study, age group, history of previous infection, and PTSD were found to be significant predictors of sleep quality, providing clinicians with a basis for risk assessment. During the treatment and rehabilitation of individuals with COVID-19, doctors can assess the risk of sleep disorders based on the infected individuals’ age, infection history, and psychological state and take appropriate preventive measures. Health education for infected individuals recovering from COVID-19 can be strengthened to raise their awareness of sleep problems and encourage them to adopt a positive lifestyle, such as regular work and rest, moderate exercise, and a reasonable diet, to prevent the occurrence of sleep disorders.

The results of this study provide a new direction for further research on the long-term effects of COVID-19 infections. Future studies could explore the mechanisms of the occurrence of sleep quality problems after COVID-19 infection, including the effects of the virus on the nervous system and the relationship between immune response and sleep regulation. This will help to better understand the pathophysiological process of COVID-19 infection and provide a theoretical basis for developing more effective treatments.

This study has a few limitations. First, although it utilizes a cross-sectional research design, the sampling of the older adult population may not be fully representative of their group. Future studies may need to consider older adults with medical conditions. Second, due to the sample being restricted to females, there may be limitations in generalizing the research findings to the entire population. Third, the confirmed cases in this study were self-reported by the infected individuals and then confirmed by PCR testing or antigen testing. However, antigen testing has some limitations in terms of accuracy compared to PCR testing. Therefore, asymptomatic carriers could not be ruled out in this study, and future research could include regular, continuous testing of study subjects, with dynamic monitoring helping to identify potential carriers more accurately. Furthermore, future research could prioritize longitudinal studies to track and evaluate participants, enabling prompt identification of the ongoing effects of COVID-19 infection.

After three months of infection with COVID-19, both young and elderly women experienced even worse sleep quality compared to their uninfected peers, despite no further impairment in physical fitness. Regardless of infection, the elderly individuals had more sleep disorders than their younger counterparts, highlighting the need to address the long-term health implications of COVID-19 and to provide sufficient assistance to vulnerable populations.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our gratitude to all volunteer participants and thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their constructive suggestions.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization and study design: Frankie U Kei Wong, Water Soi Po Wong, and Zhaowei Kong; data collection: Meng Wang, Frankie U Kei Wong, Water Soi Po Wong, Walter Heung Chin Hui, Gasper Chi Hong Leong, and Wenze Fang; data analysis and interpretation: Meng Wang, Onkei Lei, and Zhaowei Kong; draft preparation: Meng Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that supports the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Macau (RC Ref. no. SSHRE23-APP117-FED) and carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The written informed consent was obtained from those who were willing to participate.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. WHO Coronavirus Dashboard. WHO COVID-19 dashboard. [cited 2023 Mar 15]. Available from: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c. [Google Scholar]

2. Zheng L, Liu S, Lu F. Impact of national omicron outbreak at the end of 2022 on the future outlook of COVID-19 in China. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2023;12(1):2191738. doi:10.1080/22221751.2023.2191738. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Pan Y, Wang L, Feng Z, Xu H, Li F, Shen Y, et al. Characterisation of SARS-CoV-2 variants in Beijing during 2022: an epidemiological and phylogenetic analysis. Lancet. 2023;401(10377):664–72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00129-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Vendramin B, Bergamin GS, Freeman EE. Face masks for COVID-19: implications for ocular health. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;234:16–26. [Google Scholar]

5. Peter RS, Nieters A, Kräusslich HG, Brockmann SO, Göpel S, Kindle G, et al. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 six to 12 months after infection: population based study. BMJ. 2022;379:e071050. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-071050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. World Health Organization. WHO director-general declares COVID-19 pandemic over, but warns against complacency. [cited 2023 Feb 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/14-02-2023-who-director-general-declares-covid-19-pandemic-over-but-warns-against-complacency. [Google Scholar]

7. Rocha RPS, Andrade ACdeS, Melanda FN, Muraro AP. Post-COVID-19 syndrome among hospitalized COVID-19 patients: a cohort study assessing patients 6 and 12 months after hospital discharge. Cadernos De Saúde Pública. 2024;40(2):e00027423. doi:10.1590/0102-311XEN027423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiat. 2021;8(2):130–40. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Groff D, Sun A, Ssentongo AE, Ba DM, Parsons N, Poudel GR, et al. Short-term and long-term rates of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2128568. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28568. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Huang L, Yao Q, Gu X, Wang Q, Ren L, Wang Y, et al. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398(10302):747–58. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01755-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. The Lancet. Facing up to long COVID. Lancet. 2020;396(10266):1861. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32662-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Raman B, Cassar MP, Tunnicliffe EM, Filippini N, Griffanti L, Alfaro-Almagro F, et al. Medium-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on multiple vital organs, exercise capacity, cognition, quality of life and mental health, post-hospital discharge. eClinicalMedicine. 2021;31(10223):100683. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Mahase E. Long covid could be four different syndromes, review suggests. BMJ. 2020;371:m3981. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Carvalho-Schneider C, Laurent E, Lemaignen A, Beaufils E, Bourbao-Tournois C, Laribi S, et al. Follow-up of adults with noncritical COVID-19 two months after symptom onset. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(2):258–63. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang Q, Shang L, Wu M, Li J, Gu J, Liu J, et al. Sleep disturbances and post-traumatic stress, depressive symptoms following COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res. 2022;31(3):e13529. [Google Scholar]

16. Denison HJ, Harvey NC, Cooper C, Sayer AA, Bayer AJ. Physical activity, sleep and physical function in older people with osteoporosis: baseline findings from a fitness for health trial in UK primary care. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

17. Arnardottir ES, Mackey M, Jackson A, Stone SE, Andriessen CJ, O’Brien AJ, et al. Frequency and impact of sleep disturbances at 12 months following mild COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Sleep. 2022;45(12):zsac246. [Google Scholar]

18. Petersen MS, Kristiansen MF, Hanusson KD, Danielsen ME, á Steig B, Gaini S, et al. Long COVID in the Faroe islands: a longitudinal study among nonhospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(11):e4058–63. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Rinaldo RFT, Menni C, Sudre CH, Varsavsky T. Early detection of post-vaccination risk of COVID-19 using routine testing for healthcare workers combined with symptoms surveys and machine learning. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11:1–14. [Google Scholar]

20. Stavem K, Ghanima W, Olsen MK, Gilboe HM, Einvik G. Persistent symptoms 1.5–6 months after COVID-19 in non-hospitalised subjects: a population-based cohort study. Thorax. 2021;76(4):405–7. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Freak R, Ali F, Solomon C. Long covid in older people: more vulnerable, disproportionately affected. Age Ageing. 2023;52(1):afac337. [Google Scholar]

22. Puntmann VO, Carerj ML, Wieters I, Fahim M, Arendt C, Hoffmann J, et al. Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients recently recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(11):1265–73. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Gao Z, Xu Y, Sun C, Wang X, Guo Y, Qiu S, et al. A systematic review of asymptomatic infections with COVID-19. J Microbiol, Immunol Infect. 2021;54(1):12–6. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2020.05.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. National Health Commission of the China. Notice on the issuance of the “Class B infectious disease Class B management” general plan for the implementation of novel coronavirus infection. [cited 2024 Dec 20]. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-12/27/content_5733739.htm. [Google Scholar]

25. The Lancet Regional Health–Western Pacific. The end of zero-COVID-19 policy is not the end of COVID-19 for China. Lancet Reg Health: Western Pacific. 2023;30:100702. doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Bai Y, Peng Z, Wei F, Jin Z, Wang J, Xu X, et al. Study on the COVID-19 epidemic in mainland China between November 2022 and January 2023, with prediction of its tendency. J Biosaf Biosecur. 2023;5(1):39–44. doi:10.1016/j.jobb.2023.03.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Ofusa Y, Golding LA. YMCA fitness testing and assessment manual. Champaign, IL, USA: Human Kinetics Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

28. Sport Administration, Ministry of Education. National physical fitness—physical fitness health dictionary zone. [cited 2024 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.sa.gov.tw/PageContent?n=4628. [Google Scholar]

29. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD checklist (PCLreliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. In: Annual convention of the international society for traumatic stress studies; 1993. [Google Scholar]

30. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Elkayam S, Łojek E, Sękowski M, Żarnecka D, Egbert A, Wyszomirska J, et al. Factors associated with prolonged COVID-related PTSD-like symptoms among adults diagnosed with mild COVID-19 in Poland. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1358979. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1358979. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Liu C, Liu Y. Media exposure and anxiety during COVID-19: the mediation effect of media vicarious traumatization. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(13):4720. doi:10.3390/ijerph17134720. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Jin Y, Xu J, Liu H, Liu D. Posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth among adult survivors of Wenchuan earthquake after 1 year: prevalence and correlates. Arch Psychiat Nurs. 2014;28(1):67–73. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2013.10.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Mao J, Wang C, Teng C, Wang M, Zhou S, Zhao K, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of PTSD symptoms after the COVID-19 epidemic outbreak in an online survey in China: the age and gender differences matter. Neuropsych Dis Treat. 2022;18:761–71. doi:10.2147/NDT.S351042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Tang W, Hu T, Hu B, Jin C, Wang G, Xie C, et al. Prevalence and correlates of PTSD and depressive symptoms one month after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in a sample of home-quarantined Chinese university students. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Guo S, Sun W, Liu C, Wu S. Structural validity of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index in Chinese undergraduate students. Front Psychol. 2016;7(e116383):1126. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Li N, Xu G, Chen G, Zheng X. Sleep quality among Chinese elderly people: a population-based study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;87(6):103968. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2019.103968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Alqahtani H, Aljouiee T, Alsultan M, Ayyash M, Abu-shaheen A. Exercise capacity and fatigue in post-COVID-19 patients. J Med, Law Public Health. 2024;4(3):399–402. doi:10.52609/jmlph.v4i3.125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Patare S, Harishchandre (PT) DM, Ganvir (PT) DS. Consequences of COVID-19 in the status of physical fitness in post COVID patients: a cross sectional study. Vims J Phys Ther. 2022;4(1):46–52. doi:10.46858/VIMSJPT.4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. de la Guía-Galipienso F, Palau P, Berenguel-Senen A, Perez-Quilis C, Christle JW, Myers J, et al. Being fit in the COVID-19 era and future epidemics prevention: importance of cardiopulmonary exercise test in fitness evaluation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2024;83(15):84–91. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2024.03.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Feter N, Caputo EL, Delpino FM, Leite JS, da Silva LS, de Almeida Paz I, et al. Physical activity and long COVID: findings from the prospective study about mental and physical health in adults cohort. Public Health. 2023;220(5):148–54. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2023.05.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Brawner CA, Ehrman JK, Bole S, Kerrigan DJ, Parikh SS, Lewis BK, et al. Inverse relationship of maximal exercise capacity to hospitalization secondary to coronavirus disease 2019. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(1):32–9. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.10.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Liu J, Guo Z, Lu S. Baseline physical activity and the risk of severe illness and mortality from COVID-19: a dose-response meta-analysis. Prev Med Rep. 2023;32(8):102130. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Zabidi NZ, Liew HL, Farouk IA, Puniyamurti A, Yip AJW, Wijesinghe VN, et al. Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 variants: implications on immune escape, vaccination, therapeutic and diagnostic strategies. Viruses. 2023;15(4):944. doi:10.3390/v15040944. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Ingram J, Hand CJ, Hijikata Y, Maciejewski G. Exploring the effects of COVID-19 restrictions on wellbeing across different styles of lockdown. Health Psychol Open. 2022;9(1):20551029221099800. doi:10.1177/20551029221099800. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. de Oliveira Almeida K, Nogueira Alves IG, de Queiroz RS, de Castro MR, Gomes VA, Santos Fontoura FC, et al. A systematic review on physical function, activities of daily living and health-related quality of life in COVID-19 survivors. Chronic Illn. 2023;19(2):279–303. doi:10.1177/17423953221089309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Sigal A. Milder disease with Omicron: is it the virus or the pre-existing immunity? Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22(2):69–71. doi:10.1038/s41577-022-00678-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Petrone D, Mateo-Urdiales A, Sacco C, Riccardo F, Bella A, Ambrosio L et al. Reduction of the risk of severe COVID-19 due to omicron compared to Delta variant in Italy (November 2021–February 2022). Int J Infect Dis. 2023;129:135–41. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2023.01.027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Peixoto VGMNP, Facci LA, Barbalho TCS, Souza RN, Duarte AM, Almondes KM. The context of COVID-19 affected the long-term sleep quality of older adults more than SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front Psychiat. 2024;15:1305945. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1305945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Ahmed GK, Khedr EM, Hamad DA, Meshref TS, Hashem MM, Aly MM. Long term impact of COVID-19 infection on sleep and mental health: a cross-sectional study. Psychiat Res. 2021;305(4):114243. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Islam MdK, Molla MdMA, Hasan P, Sharif MdM, Hossain FS, Amin MdR, et al. Persistence of sleep disturbance among post-COVID patients: findings from a 2-month follow-up study in a Bangladeshi cohort. J Med Virol. 2022;94(3):971–8. doi:10.1002/jmv.27397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Martín-Guerrero JD, Pellicer-Valero ÓJ, Navarro-Pardo E, Gómez-Mayordomo V, Cuadrado ML, et al. Female sex is a risk factor associated with long-term post-COVID related-symptoms but not with COVID-19 symptoms: the long-COVID-exp-cm multicenter study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(2):413. doi:10.3390/jcm11020413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Beyer S, Haufe S, Meike D, Scharbau M, Lampe V, Dopfer-Jablonka A, et al. Post-COVID-19 syndrome: physical capacity, fatigue and quality of life. PLoS One. 2023;18(10):e0292928. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0292928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Jimeno-Almazán A, Pallarés JG, Buendía-Romero Á., Martínez-Cava A, Franco-López F, Sánchez-Alcaraz Martínez BJ, et al. Post-COVID-19 syndrome and the potential benefits of exercise. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5329. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Tsampasian V, Elghazaly H, Chattopadhyay R, Debski M, Naing TKP, Garg P, et al. Risk factors associated with post−COVID-19 condition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(6):566–80. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.0750. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Jahrami H, BaHammam AS, Bragazzi NL, Saif Z, Faris M, Vitiello MV. Sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic by population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(2):299–313. doi:10.5664/jcsm.8930. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Gui Z, Wang YY, Li JX, Li XH, Su Z, Cheung T, et al. Prevalence of poor sleep quality in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiat. 2024;14:1272812. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1272812. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Shaik L, Boike S, Ramar K, Subramanian S, Surani S. COVID-19 and sleep disturbances: a literature review of clinical evidence. Medicina. 2023;59(5):818. doi:10.3390/medicina59050818. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Islam MdS, Ferdous MZ, Islam US, Mosaddek ASMd, Potenza MN, Pardhan S. Treatment, persistent symptoms, and depression in people infected with COVID-19 in Bangladesh. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1453. doi:10.3390/ijerph18041453. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Alkodaymi MS, Omrani OA, Fawzy NA, Shaar BA, Almamlouk R, Riaz M, et al. Prevalence of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome symptoms at different follow-up periods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28(5):657–66. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2022.01.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Abuhammad S, Alzoubi KH, Khabour OF, Hamaideh S, Khasawneh B. Sleep quality and sleep patterns among recovered individuals during post-COVID-19 among Jordanian: a cross-sectional national study. Medicine. 2023;102(3):e32737. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000032737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Carnes-Vendrell A, Piñol-Ripoll G, Ariza M, Cano N, Segura B, Junque C et al. Sleep quality in individuals with post-COVID-19 condition: relation with emotional, cognitive and functional variables. Brain Behav Immun-Health. 2024;35:100721. doi:10.1016/j.bbih.2023.100721. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Jahrami HA, Alhaj OA, Humood AM, Alenezi AF, Fekih-Romdhane F, AlRasheed MM, et al. Sleep disturbances during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Sleep Med Rev. 2022;62(10):101591. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Salfi F, Amicucci G, Corigliano D, Viselli L, D’Atri A, Tempesta D, et al. Poor sleep quality, insomnia, and short sleep duration before infection predict long-term symptoms after COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. 2023;112(24):140–51. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2023.06.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Pakpour AH. The association between health status and insomnia, mental health, and preventive behaviors: the mediating role of fear of COVID-19. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6(4):2333721420966081. doi:10.1177/2333721420966081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Tedjasukmana R, Budikayanti A, Islamiyah WR, Witjaksono AMAL, Hakim M. Sleep disturbance in post COVID-19 conditions: prevalence and quality of life. Front Neurol. 2023;13:1095606. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.1095606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Xu F, Wang X, Yang Y, Zhang K, Shi Y, Xia L, et al. Depression and insomnia in COVID-19 survivors: a cross-sectional survey from Chinese rehabilitation centers in Anhui province. Sleep Med. 2022;91(4):161–5. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2021.02.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Hyun S, Hahm HC, Wong GTF, Zhang E, Liu CH. Psychological correlates of poor sleep quality among U.S. young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Med. 2021;78(10):51–6. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2020.12.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiat Res. 2020;288:112954. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Holzinger B, Nierwetberg F, Chung F, Bolstad CJ, Bjorvatn B, Chan NY, et al. Has the COVID-19 pandemic traumatized us collectively? The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and sleep factors via traumatization: a multinational survey. Nat Sci Sleep. 2022;14:1469–83. doi:10.2147/NSS.S368147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Zhang QQ, Li L, Zhong BL. Prevalence of insomnia symptoms in older Chinese adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis. Front Med. 2021;8:779914. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.779914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools