Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Influence of Leisure-Time Physical Activity and Peer Relationships on Cyberbullying among Adolescents: A One-Year Longitudinal Investigation

1 School of Physical Education, Leshan Normal University, 778 Binhe Road, Shizhong District, Leshan, 614000, China

2 Xiangshui Teacher Development Center, No. 98, Huanghai Road, Xiangshui County, Yancheng, 224600, China

3 Postgraduate School, Harbin Sport University, 1 Dacheng Street, Nangang District, Harbin, 150001, China

* Corresponding Author: Jun Hu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Exploring the Impact of School Bullying, Aggression and Childhood Trauma in the Digital Age: Influencing Factors, Interventions, and Prevention Methods)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(5), 717-735. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.061576

Received 27 November 2024; Accepted 24 March 2025; Issue published 05 June 2025

Abstract

Background: With the rapid growth of internet usage, adolescent cyberbullying has become a pressing issue. This study examines the longitudinal impact of leisure-time physical activity and peer relationships on cyberbullying over a one-year period, drawing on the Stage-Environment Fit Theory and the Interpersonal Relationship Theory. Methods: A three-wave longitudinal study was conducted over one year, involving 896 middle school students from five schools in Sichuan, Jiangsu, and Guangdong, China, selected to ensure regional diversity. Participants were recruited using stratified random sampling, and data were collected at four-month intervals. Leisure-time physical activity, peer relationships, and cyberbullying behaviors were assessed using validated scales. Data were analyzed using latent growth modeling (LGM) and structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine longitudinal effects and mediation relationships. Results: (1) Leisure-time physical activity, peer relationships, and cyberbullying behaviors remained relatively stable over time. (2) Both leisure-time physical activity and peer relationships significantly reduced future cyberbullying incidents, with physical activity also enhancing subsequent peer relationships. (3) Peer relationships partially mediated the effect of leisure-time physical activity on cyberbullying, indicating that improved peer interactions contributed to a reduction in cyberbullying behaviors. Conclusion: This study found that leisure-time sports activities and peer relationships are important factors affecting cyberbullying, and peer relationships play a partial mediating role in it. The results provide empirical support for understanding the formation mechanism and influencing factors of cyberbullying.Keywords

The Global Cyberbullying Report, spanning 28 nations, reveals a concerning statistic: over 17% of children have fallen victim to cyberbullying, with especially high rates in South Africa, Turkey, and across Latin America [1]. This phenomenon has emerged as a critical issue affecting adolescent mental health, posing significant challenges for both society and families. In China, the prevalence of cyberbullying among adolescents is estimated at approximately 27.7% [2,3], with victims often grappling with diminished self-esteem, depression, and anxiety [4]. Cyberbullying, which occurs through electronic media, manifests in various forms, including text messages, phone calls, photos, videos, and other digital methods [5].

Unlike traditional bullying, which is often confined to physical spaces such as schools, cyberbullying occurs in digital environments where anonymity and rapid content dissemination intensify its psychological impact on victims [6]. Additionally, the persistence of harmful content online means that victims may repeatedly experience distress, making cyberbullying more enduring than face-to-face aggression [7]. Adolescents, being highly susceptible to external influences and experiencing imbalances in cognitive control and emotional responses, are particularly prone to engaging in cyberbullying [8,9]. Over time, cyberbullying has evolved from early forms such as email harassment and anonymous messaging to more complex behaviors involving social media, doxxing (publicly revealing private information), and deepfake content manipulation [10]. Prior studies indicate that cyberbullying often originates in middle school, peaks between the ages of 12 and 16, and persists into college years [11,12]. Moreover, research has highlighted how the diversity and subtlety of cyberbullying significantly threaten adolescent mental health, increasing risks of depression and suicidal ideation [13,14].

Despite extensive research on cyberbullying, existing studies mainly rely on cross-sectional designs, which fail to capture the dynamic and evolving nature of cyberbullying behaviors over time. Cross-sectional studies provide only a snapshot of the problem, limiting the ability to infer causal relationships or examine longitudinal trajectories of cyberbullying involvement. Given the continuous expansion of digital communication platforms, understanding how cyberbullying patterns change over time is essential for designing effective prevention and intervention strategies [15]. To address this gap, this study employs a longitudinal design to explore the long-term impact of leisure-time physical activity and peer relationships on cyberbullying among adolescents. A longitudinal approach is particularly well-suited to studying cyberbullying because it allows for the examination of temporal stability, the establishment of causal relationships, and the identification of mediation effects over time.

To fill this research gap, this study employs a longitudinal multi-wave design to investigate the associations among participation in leisure-time physical activities, peer relationships, and adolescent cyberbullying. Specifically, the main objectives are: (1) To examine the temporal stability and measurement reliability of cyberbullying across multiple time points. (2) To explore the direct effects of leisure-time physical activity participation and peer relationships on cyberbullying. (3) To investigate whether peer relationships mediate the association between leisure-time physical activity participation and cyberbullying. Through a longitudinal multi-wave survey, this study aims to analyze the developmental trajectories and predictors of adolescent cyberbullying. The findings will offer empirical evidence and theoretical insights to inform school-based interventions aimed at fostering adolescents’ psychological well-being and prosocial development.

1.1 Leisure-Time Physical Activity and Cyberbullying

In recent years, the role of leisure-time physical activity has garnered significant attention, particularly as an effective intervention for preventing and reducing antisocial behaviors such as cyberbullying [16]. Leisure-time physical activity, which refers to sports activities engaged in by adolescents during breaks, after school, or on weekends, not only enhances physical fitness but also serves as a healthy emotional outlet, easing emotional tension and psychological stress [17]. Research indicates that adolescents who regularly engage in physical exercise demonstrate improved emotional regulation, which in turn reduces impulsive behaviors such as violence or bullying [18]. Furthermore, evidence suggests that leisure-time physical activity stimulates the release of neurotransmitters like dopamine and endorphins, significantly enhancing emotional well-being, alleviating negative emotions such as anxiety and depression, and consequently diminishing the probability of aggressive behaviors [19].

Moreover, sports, particularly team sports, enhance adolescents’ social interactions and bolster their social skills and self-efficacy, playing a pivotal role in curbing cyberbullying behaviors [20]. Studies have found that adolescents who engage in fewer sports activities are at a higher risk of feeling isolated and lacking effective emotional regulation strategies, which may increase their propensity to express dissatisfaction online and bully others [21]. Sports activities also provide a healthy environment for competition and cooperation, enabling adolescents to experience competition within a structured framework, learn to control impulsive behaviors and reduce cyberbullying stemming from emotional dysregulation or social setbacks [22]. Longitudinal studies have further demonstrated that regular participation in physical exercise by adolescents not only diminishes the frequency of cyberbullying behaviors [23]. These findings underscore the importance of leisure-time physical activity in reducing cyberbullying among adolescents.

1.2 Peer Relationships and Cyberbullying

Peer relationships are a significant factor influencing the psychological development and behavioral performance of adolescents during puberty. Peer relationships refer to the social connections and interactions that adolescents have with individuals of similar age or status, which play a crucial role in shaping their social skills, emotional well-being, and identity development [24]. The quality of peer relationships is crucial for emotional regulation and behavioral norms among adolescents [25]. Research indicates that positive peer relationships offer emotional support and a sense of belonging, which enhances subjective well-being and mental health, effectively preventing antisocial behaviors such as cyberbullying [26]. Research further suggests that positive peer relationships can significantly reduce the occurrence of cyberbullying behaviors, especially among adolescents with weaker emotional regulation skills, where good peer relationships serve as a buffer and protective factor [27]. Adolescents who feel secure, trusted, and valued within their peer relationships are more inclined to seek support from their peers when facing adversity or stress, rather than resorting to online channels to vent or attack [28].

Conversely, poor peer relationships, especially social isolation or exclusion, can lead to intense negative emotions like depression, anger, or anxiety, increasing the risk of adolescents engaging in cyberbullying [29]. Research indicates that adolescents who suffer from peer exclusion or bullying are more likely to retaliate or seek outlets through cyberbullying, a trend that is especially pronounced among those with strained peer relationships [30]. The social ecological model suggests that the development of adolescent behavior is influenced not only by individual internal factors but also, to a significant extent, by external environments, with peer relationships being a critical component [31]. Consequently, the quality of peer relationships in schools, including the frequency and quality of peer interactions, has a direct bearing on adolescents’ emotional regulation capabilities and their online conduct.

1.3 Leisure-Time Physical Activity and Peer Relationships

Leisure-time physical activity plays a constructive role in fostering and maintaining peer relationships [16]. By engaging in sports activities, particularly team sports, adolescents can establish closer interactions and cooperative relationships with their peers, which not only strengthen trust and a sense of belonging among peers but also effectively enhance adolescents’ social skills and self-efficacy [18]. Studies indicate that adolescents who participate in sports activities are more likely to form positive social interactions with their peers, which improves the quality of peer relationships and mitigates cyberbullying behaviors arising from social isolation or emotional deprivation [19].

Furthermore, leisure-time physical activity offers a relaxed and informal social setting where adolescents can deepen mutual understanding and friendships through cooperation, competition, and communication [32]. This social interaction not only improves individuals’ emotional regulation abilities but also assists adolescents in better managing daily conflicts and stress, thereby reducing the occurrence of cyberbullying behaviors [16]. Research demonstrates that the social support and emotional recognition adolescents receive through sports activities can significantly boost their sense of self-efficacy and subjective well-being, thus reducing the likelihood of cyberbullying [33]. Additionally, positive interactions in physical exercise can empower adolescents to utilize social skills more effectively when confronted with conflicts or setbacks, steering clear of online attacks or retaliation [34].

This study is anchored in the Stage-Environment Fit Theory and the Social Ecological Model. The Stage-Environment Fit Theory suggests that individual development is intricately linked to the alignment with one’s environment, especially during the pivotal phase of adolescence. Within this context, support, interaction, and autonomy are deemed essential for adolescents’ healthy development [17]. In the educational sphere, leisure-time physical activity and peer relationships, as critical components of adolescents’ daily lives, offer platforms for interaction and avenues for emotional regulation, aiding youth in coping with the challenges and stresses of puberty [25]. The theory underscores that the quality of emotional support and social interaction within the school environment is tightly coupled with adolescents’ mental health and behavioral outcomes, implying that leisure-time physical activity and peer relationships can mitigate cyberbullying by enhancing the social milieu of adolescents [26].

Conversely, the Social Ecological Model broadens the perspective to encompass a wider socio-environmental scope in explaining the genesis of cyberbullying behavior. It posits that the behavioral development of adolescents is shaped by a confluence of factors across different strata, encompassing personal attributes, familial settings, peer dynamics, school climate, and the overarching socio-cultural backdrop [28]. Within this framework, leisure-time physical activity and peer relationships emerge as pivotal environmental determinants in the behavioral trajectory of adolescents. They exert a direct influence on mental health and indirectly modulate online conduct through emotional regulation mechanisms [29]. Theoretically, then, leisure-time physical activity and peer relationships are posited to significantly curtail cyberbullying by bolstering adolescents’ capacities for emotional regulation and the robustness of their social support networks [30].

While a plethora of studies has dissected the nexus between leisure-time physical activity, peer relationships, and adolescent cyberbullying from a cross-sectional vantage point, these have predominantly centered on descriptive analyses, neglecting a profound exploration of their longitudinal developmental dynamics [30]. Prevailing research has primarily probed the correlation between an individual’s engagement in sports or the quality of peer relationships at a given moment and instances of cyberbullying. However, such cross-sectional methodologies are inadequate for elucidating the long-term causal interplay between these variables [31]. Furthermore, research elucidating the precise mechanisms through which leisure-time physical activity and peer relationships modulate emotions, and specifically, how they attenuate the prevalence of cyberbullying through emotional regulation over time, remains sparse [35].

The Interpersonal Theory of Aggressive Behavior posits that deficient interpersonal relationships and adverse social milieus substantially amplify the risks of emotional dysregulation and cognitive distortions, precipitating aggressive conduct [33]. In detrimental school settings, adolescents, bereft of emotional succor and social proficiency, may gravitate toward online channels to perpetrate bullying or aggression [34]. Moreover, a dearth of leisure-time physical activity may result in adolescents lacking viable emotional outlets, escalating the propensity for cyberbullying [36]. Hence, while current research accentuates the role of leisure-time physical activity and peer relationships in attenuating aggressive behaviors, there is an imperative need for further investigation into their capacity to diminish cyberbullying through emotional regulatory mechanisms over time [37].

In conclusion, this study is poised to delve into the enduring effects of leisure-time physical activity and peer relationships on adolescent cyberbullying through a longitudinal approach, uncovering the mediating role of these factors in emotional regulation. By scrutinizing data across multiple longitudinal time points, this study aspires to furnish novel theoretical and empirical insights, deepening our comprehension of the intricate interplay between leisure-time physical activity, peer relationships, and adolescent cyberbullying. Grounded in the Stage-Environment Fit Theory and the Social-Ecological Model, this study proposes the following hypotheses: (H1) Leisure-time physical activity will exhibit longitudinal stability; (H2) Peer relationships will exhibit longitudinal stability; (H3) Adolescent cyberbullying behavior will exhibit longitudinal stability; (H4) Leisure-time physical activity will negatively predict cyberbullying behavior over time; and (H5) Peer relationships will mediation the relationship between leisure-time physical activity and cyberbullying over time.

This study encompassed seventh and eighth-grade students from five middle schools located in Leshan City, Sichuan Province, Yancheng City, Jiangsu Province, and Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province. These cities were selected to ensure geographical diversity, representing western, eastern, and southern regions of China, which enhances the generalizability of the findings. The selected schools varied in urban and suburban settings, covering a range of educational environments. Participants were randomly selected using a stratified random sampling method. In each city, two to three schools were chosen based on their student population size and willingness to participate. Within each selected school, entire classes were randomly drawn from seventh and eighth grades to ensure a representative sample of students. The survey was conducted over a one-year period with three data collection points, spaced four months apart. The initial survey commenced in November 2023, distributing 1426 questionnaires and garnering 1043 valid responses, comprising 652 male students (62.51%) and 391 female students (37.49%). The second follow-up survey was conducted with the original cohort, excluding students who were absent, boarded, transferred, or dropped out, yielding 619 male responses (64.01%) and 348 female responses (35.99%), with a retention rate of 92.71%. The third follow-up survey targeted students who had advanced to eighth and ninth grades, with attrition primarily due to absence, boarding, transfer, or dropout, resulting in 568 male responses (63.39%) and 328 female responses (36.61%), maintaining a retention rate of 92.66%. To ensure the validity of the dataset, Levene’s test for equality of variances confirmed no significant differences across the points (p > 0.05). The average age of the participants, based on the third follow-up data, was 14.62 ± 0.48 years.

2.2.1 Leisure-Time Physical Activity

The study utilized the Physical Activity Scale, developed by Liang [38], to assess adolescents’ engagement in leisure-time physical activity. This self-report scale evaluates the past week’s physical activity across three dimensions: duration, frequency, and intensity, scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = always). The scale consists of 3 items, such as: “In the past week, how often did you engage in physical activity for at least 30 min?” Higher scores indicate greater physical activity participation. The scale has been validated internationally and is widely used in the monitoring of adolescent physical activity. It has demonstrated adequate internal consistency and test-retest reliability of 0.80 [39] and correlates significantly with variables such as cyberbullying behavior [35], confirming its suitability for adolescent cyberbullying research. To ensure the reliability of the scale in this study, Cronbach’s α was calculated, yielding coefficients of 0.83, 0.78, and 0.88 across the three observation periods. Test-retest reliability was 0.80, demonstrating temporal stability.

The Peer Relationship Questionnaire, originally developed by Hymel et al. [40] and later translated and revised by Chen et al. at East China Normal University [41], was used to assess peer relationship quality. This self-report scale consists of 18 items, rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree), with higher scores reflecting better peer relationships and lower scores indicating poorer relationships. A sample item is: “I feel that my classmates respect and support me.” The Cronbach’s α coefficients were 0.86, 0.87, and 0.88. The test-retest reliability between the first (T1) and second (T2) measurements was 0.87, indicating good stability over time.

The Cyberbullying Questionnaire, developed by Calvete et al. [42], was employed to measure the prevalence of cyberbullying behavior among adolescents. This self-report instrument consists of 16 items, rated on a 3-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = often), with higher scores indicating more frequent cyberbullying experiences. A sample item is: “In the past three months, have you received hurtful messages online?” The scale has been widely used in cyberbullying research and has demonstrated strong reliability in previous studies. The Cronbach’s α coefficients in the study were 0.85, 0.84, and 0.84, respectively, and the test-retest reliability between the first (T1) and second (T2) administrations was 0.85, indicating the stability of the scale over time.

2.3 Research Procedures and Data Processing

The study employed a cluster random sampling method for the survey. Before the study began, ethical approval was obtained from the Academic Ethics Committee of Leshan Normal University (Approval No. LSNU:1031-24-12RO). The entire research process adhered to the relevant guidelines and requirements of the American Psychological Association (APA). Prior to the survey, communication and guidance were provided to homeroom teachers and grade-level teachers, covering aspects such as obtaining informed consent from participants, addressing doubts during the process, and random filling of questionnaires. Parents provided informed consent for their child’s participation, and children provided assent.

Subsequently, after the questionnaires were collected, two groups of students were assigned to data sorting and entry to prevent bias and omissions caused by individual information barriers, ensuring the completeness and accuracy of information entry and sorting across different groups. Furthermore, data cleaning and sorting were conducted to exclude individuals with excessively short filling times or inconsistent information across the points. Complete and accurate respondents were then selected as the sample size for data analysis, and the unidimensionality of the scale was assessed. Standardized scores of the scales were selected for subsequent calculations.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 and Mplus 8.3. First, the means, standard deviations, and probability distributions of demographic variables were computed to describe the basic characteristics of the data. Second, statistical significance tests were conducted for key variables. Additionally, repeated measures ANOVA was employed to examine changes in variables over time, including tests of main effects and post hoc least significant difference (LSD) tests to compare differences across time points. Finally, a cross-lagged panel model (CLPM) was employed to investigate the longitudinal association between childhood psychological abuse and adolescent depressive symptoms, examining their bidirectional influences over time. The model was estimated using the maximum likelihood (ML) method, with both standardized and unstandardized path coefficients reported. Model fit was evaluated using multiple indices: chi-square (χ2) for overall model fit, comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) for relative model performance, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) for absolute fit, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) for residual discrepancies. A model was considered to have acceptable fit if CFI and TLI exceeded 0.90, RMSEA was below 0.08, and SRMR was below 0.08, while values above 0.95 for CFI/TLI and below 0.06 for RMSEA indicated good fit.

To further examine the presence of common method bias and to prevent systematic issues from compromising the reliability of the research findings, this study employed Harman’s single-factor test to assess the quality of all variables [43]. The results indicated that there was no common method bias across the three time points of the study, as the first maximum factor explained a rate well below the control standard of 40%. The findings confirm that this study is free from common method bias.

3.2 Reliability and Validity Test

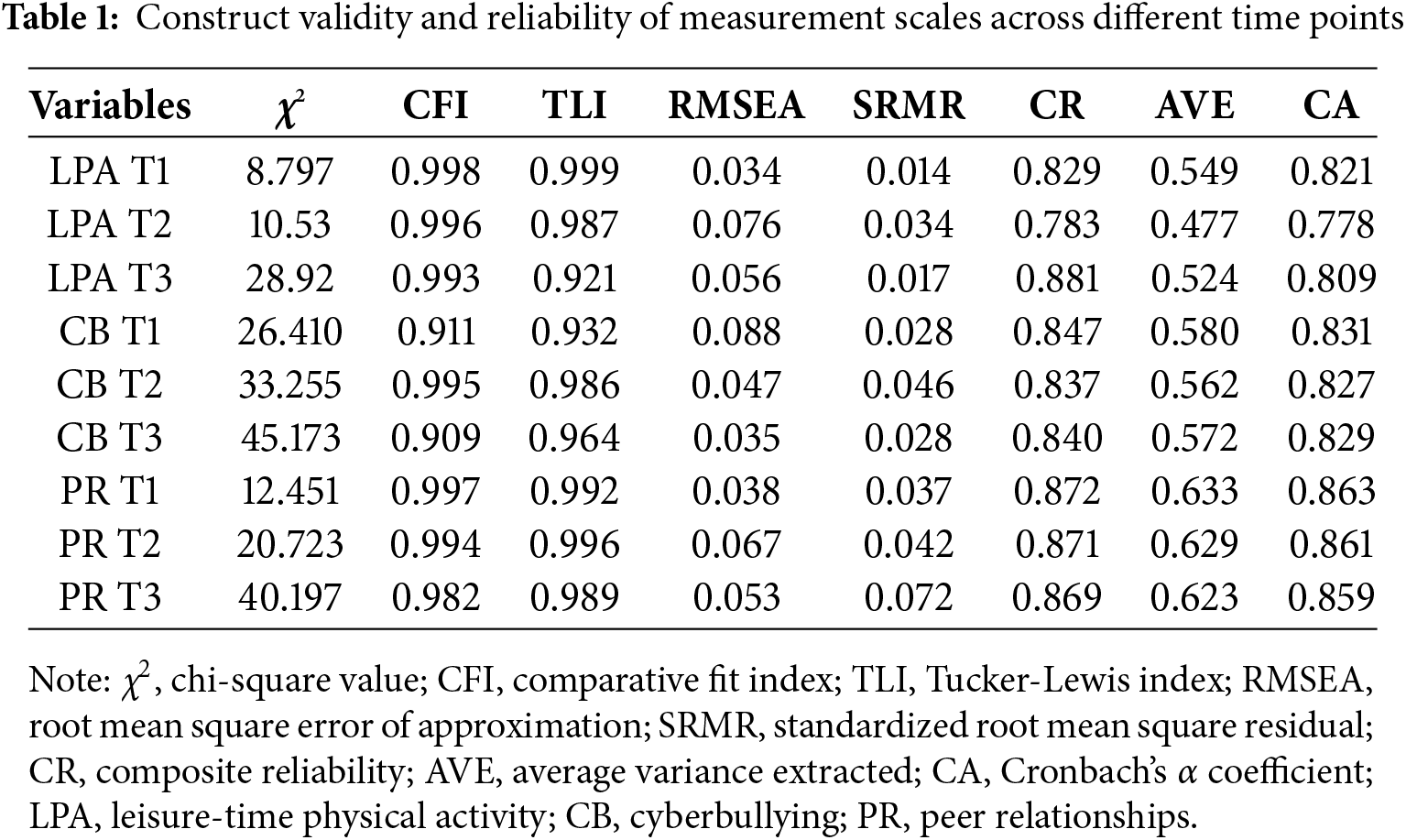

The overall model fit indices for the variables of leisure-time physical activity, peer relationships, and cyberbullying observed at three time points are shown in Table 1. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) ranges from 0.477 to 0.633, well above the minimum standard of 0.3, indicating a medium to high degree of correlation. Overall, the variables observed at three time points demonstrate good reliability and validity.

3.3 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Descriptive statistical results for leisure-time physical activity, peer relationships, and cyberbullying from three measurements are presented in Table 2. The correlation matrix reveals significant correlations among the three variables across two time periods, with both cross-sectional and longitudinal time points showing significant associations. These findings suggest that the three variables demonstrate stability over the three periods spanning six months. Concurrently, one-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted for leisure-time physical activity, peer relationships, and cyberbullying with the observation period as the independent variable. The results indicated a significant main effect of the measurement period for leisure-time physical activity (p < 0.001), while the main effects for peer relationships and cyberbullying were not significant (p > 0.05). Post-hoc tests (LSD test) revealed that the atmosphere of leisure-time physical activity at Time Point 1 was significantly higher than the scores at Time Point 2 (p < 0.01).

3.4 Cross-Lagged Panel Analysis

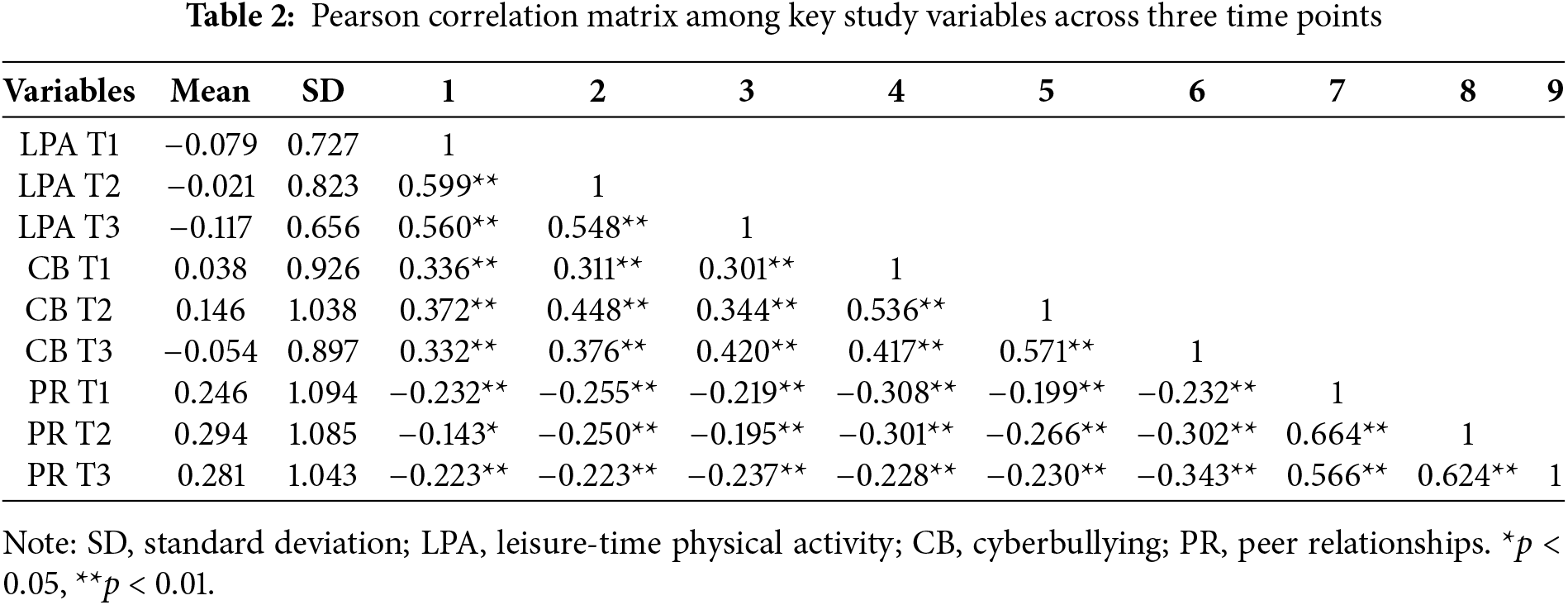

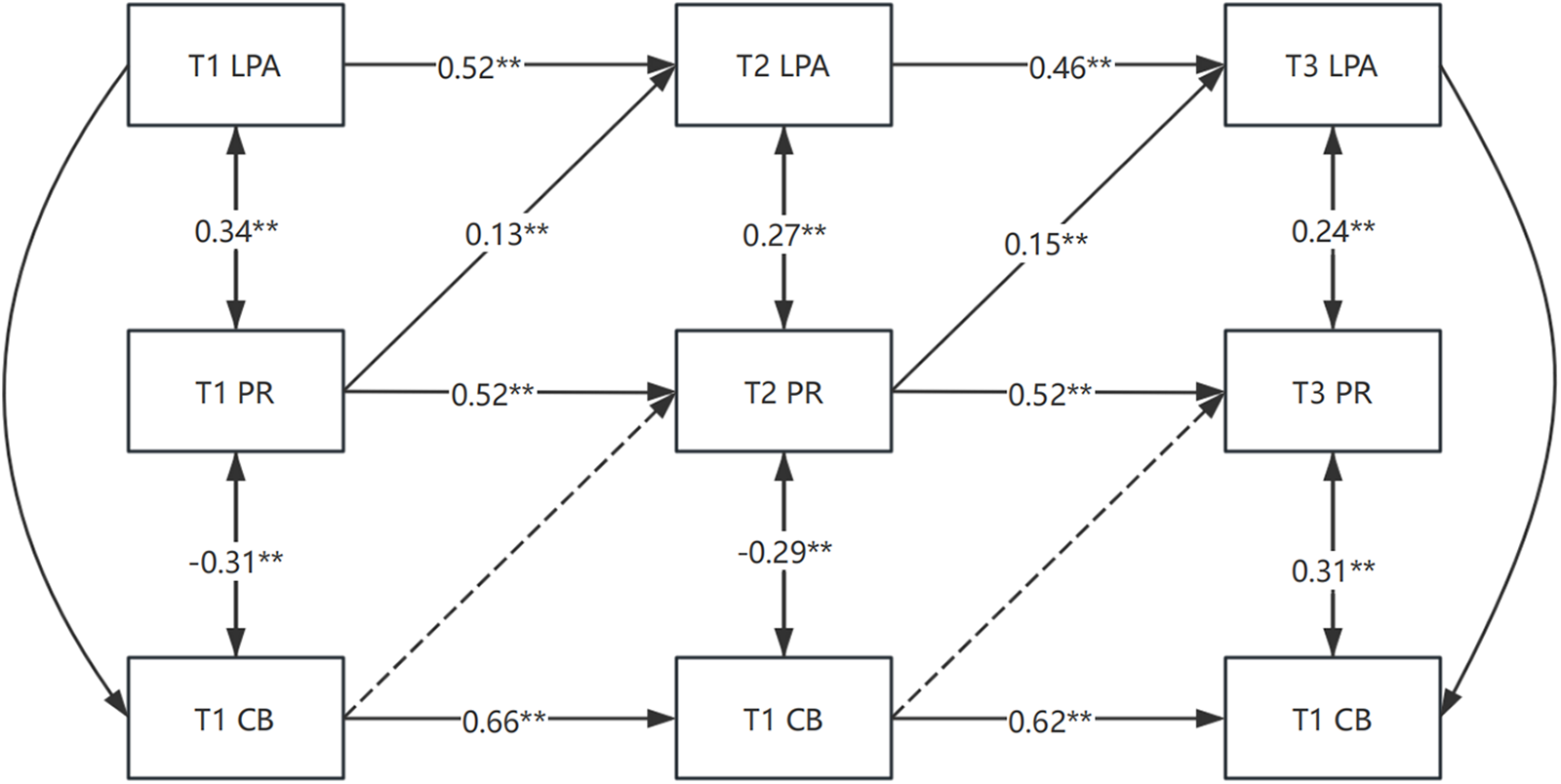

To investigate the cross-lagged effects of leisure-time physical activity on cyberbullying across the three observation periods, while controlling for age and grade, the results are depicted in Fig. 1. The findings indicate that both leisure-time physical activity and cyberbullying behaviors significantly predict changes in the next period, suggesting the stability of these variables. Additionally, leisure-time physical activity significantly and negatively predicts cyberbullying behavior in the subsequent period, while cyberbullying does not significantly predict leisure-time physical activity behavior. This suggests that leisure-time physical activity may play a causal role in reducing cyberbullying behavior.

Figure 1: The path coefficients in Model 1. Note: LPA, leisure-time physical activity; CB, cyberbullying; PR, peer relationships. **p < 0.01

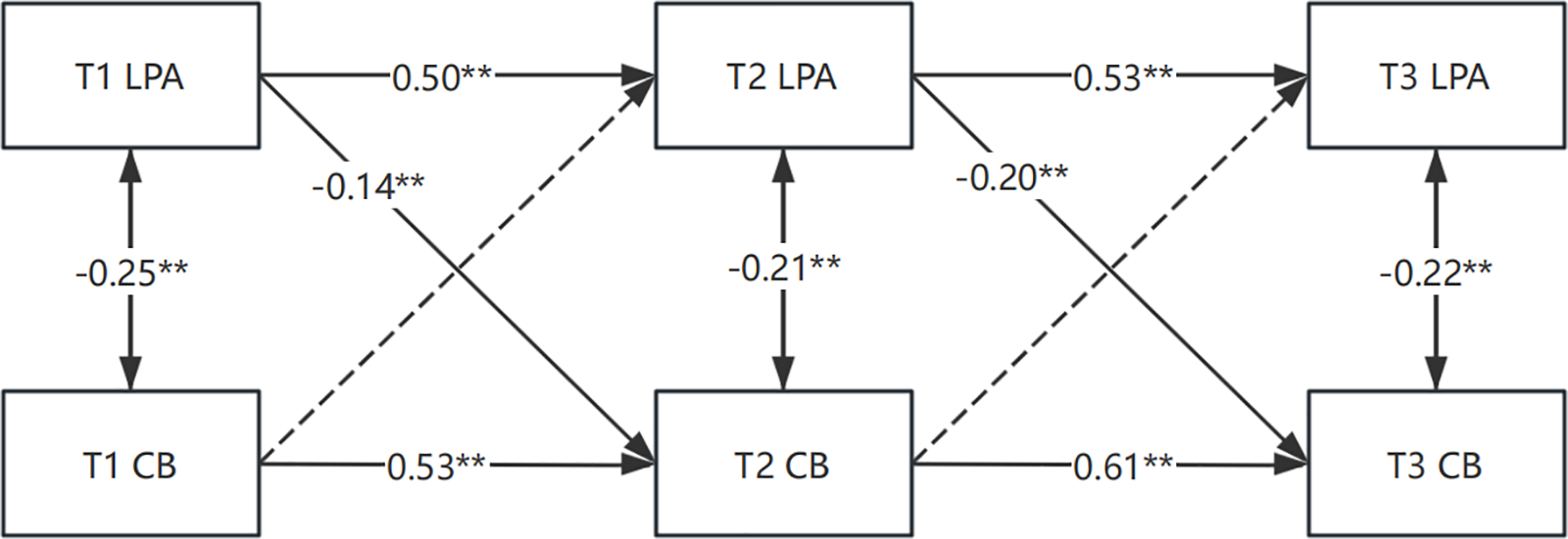

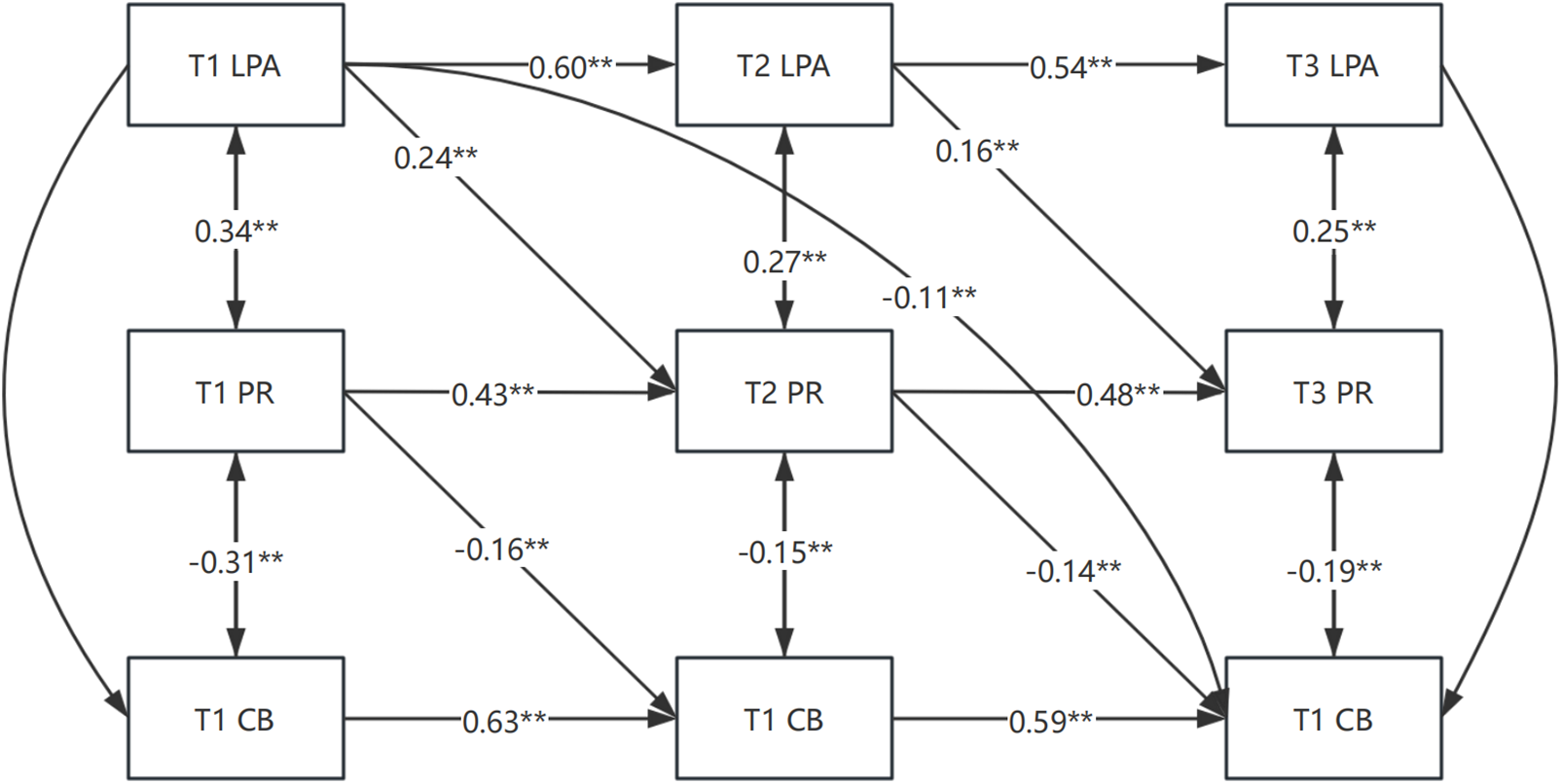

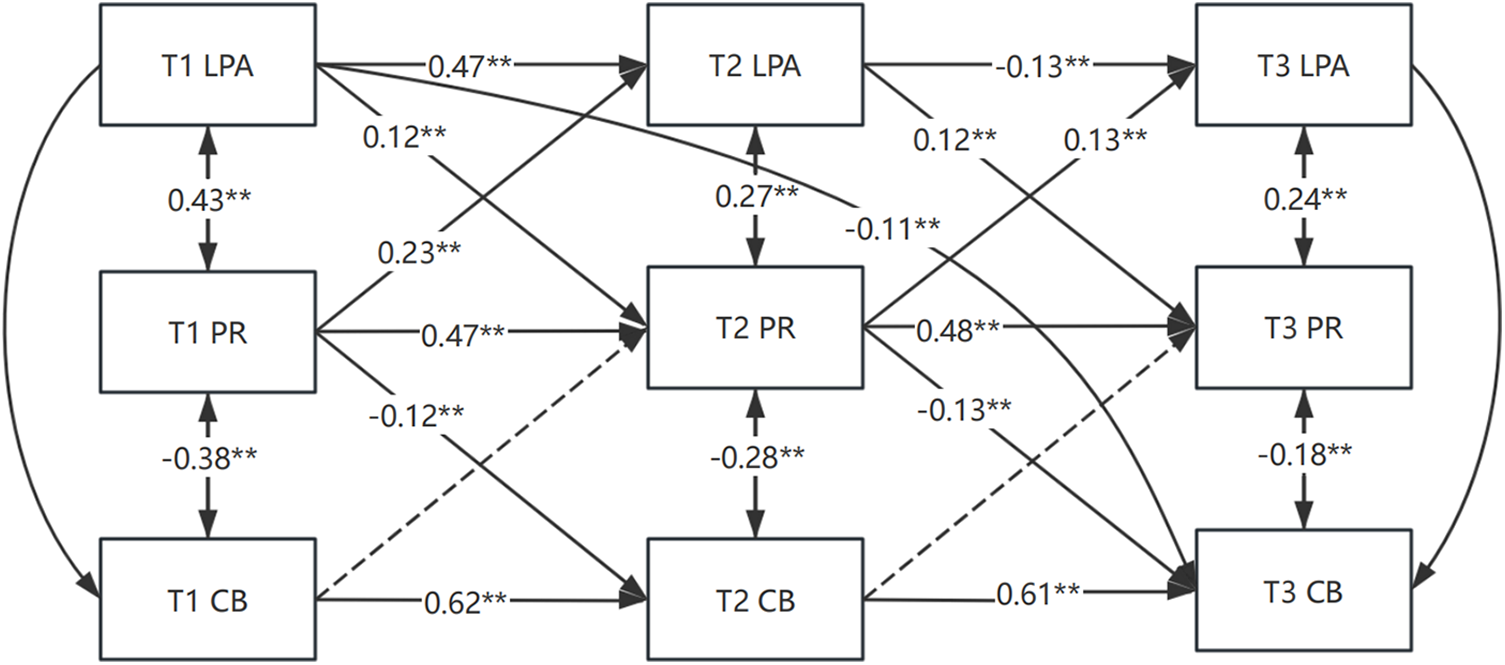

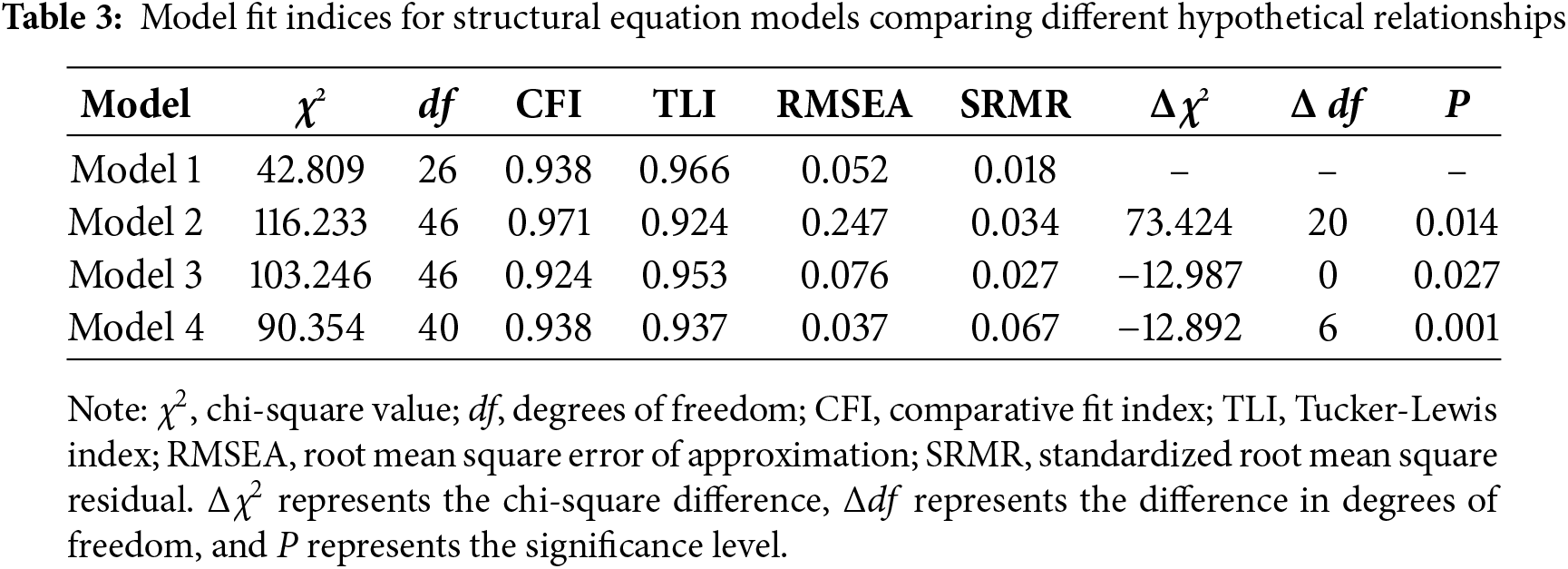

To further clarify the intercorrelations between variables over time and the underlying mechanisms, a model was constructed with age and grade as control variables. Taking the impact of leisure-time physical activity on cyberbullying as the baseline model, peer relationship variables were included to examine their mediating role in this relationship (Model 2, as shown in Fig. 2). Additionally, Model 3 (Fig. 3) was constructed to explore whether cyberbullying influences leisure-time physical activity and the extent of its significance. To provide a comprehensive analysis of variable interactions over time, a full-path model (cross-lagged effect model) was developed to examine the mediating role of peer relationships over three time periods in the impact of leisure-time physical activity on cyberbullying (Model 4, as shown in Fig. 4).

Figure 2: The path coefficients in Model 2. Note: LPA = leisure-time physical activity; CB = cyberbullying; PR = peer relationships. **p < 0.01

Figure 3: The path coefficients in Model 3. Note: LPA = leisure-time physical activity; CB = cyberbullying; PR = peer relationships. **p < 0.01

Figure 4: The path coefficients in Model 4. Note: LPA = leisure-time physical activity; CB = cyberbullying; PR = peer relationships. **p < 0.01

Table 3 presents the effects of different cross-lagged models compared to the baseline model, all demonstrating good model fit indices. Figs. 2–4 display standardized path coefficients (β) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each model, clearly distinguishing between significant and non-significant paths to enhance interpretability. Based on the model fit indices in Table 3, Model 4 exhibits the best fit.

The results indicate that leisure-time physical activity at T1 and T2 significantly predicts peer relationships at T2 and T3, which in turn significantly and negatively predicts cyberbullying at T2 and T3. Moreover, leisure-time physical activity at T1 significantly and negatively predicts cyberbullying at T3, with peer relationships at T2 playing a partial mediating role in this effect, highlighting the key mediating role of peer relationships in this process.

Schools serve as pivotal environments for the holistic development of adolescents’ physical and mental well-being. leisure-time physical activity and the quality of peer relationships are key factors influencing adolescent cyberbullying [44]. This study, involving 896 seventh and eighth graders, employed a biannual tracking survey to thoroughly investigate the longitudinal relationship between leisure-time physical activity and cyberbullying. The findings revealed that leisure-time physical activity significantly predicts cyberbullying in subsequent periods, but not the other way around. Additionally, it was discovered that peer relationships exhibit a longitudinal mediating effect between leisure-time physical activity and cyberbullying.

4.1 Stability and Trends in Leisure-Time Physical Activity, Peer Relationships, and Adolescent Cyberbullying

The study identified cross-period stability for all three variables, both horizontally and longitudinally, indicating that variables from one period can significantly predict those in the following period. This finding supports Hypothesis 1 (H1), Hypothesis 2 (H2), and Hypothesis 3 (H3), which predicted the longitudinal stability of leisure-time physical activity, peer relationships, and adolescent cyberbullying behavior, respectively. Across the three periods, the overall trend showed a decline in peer relationships and cyberbullying, albeit not significantly. Leisure-time physical activity experienced a more pronounced change in the second period compared to the first, yet the overall change was not significant. Despite fluctuations, the three variables exhibited relatively stable trends over time. This aligns with the Social-Ecological Model, which posits that adolescent behaviors are shaped by stable environmental and social factors, ensuring continuity in behavioral patterns. This aligns with previous scholars’ assertions that the school environment remains relatively stable and does not undergo significant changes with time or shifts in interpersonal relationships [45]. On one hand, school physical education not only imparts sports skills to adolescents but also provides joy and serves as a vital tool for their physical and mental health. As academic pressures and emotional turbulence during adolescence intensify, middle school students increasingly seek out leisure-time physical activities. Over time, these activities become ingrained habits, contributing to the longitudinal stability of this variable [46]. On the other hand, the emotional turbulence of adolescence and the need for physical and mental health development are priorities for the party and the state. School education management systems mandate comprehensive physical education classes, ensuring adolescents have ample time for physical activity, which from a policy management perspective, secures the continuity and stability of adolescent leisure-time physical activity [47]. This is also a significant reason for the variable’s longitudinal stability. Furthermore, the study confirmed the stability of peer relationships over time, consistent with research hypotheses and scholarly opinions [48]. The school environment, being a relatively fixed social setting with limited external social interactions, allows adolescents to form high-quality interpersonal relationships, leading to stable and robust friendships that do not change significantly in the short term [49]. Additionally, middle school students, focusing primarily on academics and living in a collective setting, spend considerable time together, understanding each other’s personalities, character, and approaches to handling situations, which fosters stable and enduring peer relationships [50].

Moreover, this study corroborates the stability of adolescent cyberbullying, aligning with scholarly research [51]. Cyberbullying behavior, a manifestation of pathological emotional expression, often stems from long-term negative emotional interference rather than short-term outbursts [52]. Such behavior, driven by indirect friction, requires short-term adjustment or intervention to resolve, contributing to its short-term stability [53]. Additionally, adolescents’ emotional volatility during puberty makes them susceptible to peer influence and group attack mentality, which can lead to bullying and aggressive behavior without clear constraints and discipline [54]. This is a primary reason for the persistence of school violence in the middle school era. Therefore, based on the perspectives and conclusions of scholars, we can deduce that leisure-time physical activity, peer relationships, and cyberbullying in the adolescent school environment are relatively stable and do not change significantly with emotional fluctuations, demonstrating overall stability in the short term.

4.2 The Delayed Predictive Effect of Leisure-Time Physical Activity on Cyberbullying Behavior

This study reveals significant insights into the relationship between leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) and cyberbullying behavior, demonstrating that LTPA not only predicts its own developmental trajectory but also exerts a negative predictive effect on cyberbullying over time. These findings substantiate Hypothesis 4 (H4), confirming that increased engagement in LTPA correlates with reduced involvement in cyberbullying behaviors.

The theoretical framework supporting these findings integrates the Stage-Environment Fit Theory and the Social-Ecological Model. According to the Stage-Environment Fit Theory [17], adolescent development thrives when environmental resources align with their evolving psychological and social needs. LTPA serves as an optimal platform for emotional expression, stress management, and social interaction, effectively addressing these developmental requirements. The Social-Ecological Model further complements this perspective by highlighting how external factors, particularly school environments and peer networks, influence adolescent behavior. A positive campus atmosphere enriched with LTPA opportunities strengthens peer relationships, enhances social cohesion, and reduces aggressive tendencies, including cyberbullying [35].

The study also validates Hypothesis 5 (H5) regarding the mediating role of peer relationships in the LTPA-cyberbullying dynamic. Adolescents who regularly participate in physical activities tend to develop stronger peer bonds, characterized by enhanced emotional support, improved communication skills, and greater social competence. These robust social connections serve as protective factors against cyberbullying, as adolescents with well-established peer networks are less likely to resort to online aggression as an emotional outlet.

Furthermore, the observed delayed effect corroborates Hypothesis 3 (H3), which posited the longitudinal stability of cyberbullying behavior. The persistence of cyberbullying tendencies over time can be attributed to the reinforcement of aggressive patterns and the perceived anonymity of online environments. This underscores the critical importance of early intervention strategies to disrupt the cycle of cyber aggression.

While the study primarily examines the preventive role of physical activity, it is crucial to consider potential reverse causality. Existing research indicates that victims of cyberbullying may experience social withdrawal, potentially reducing their participation in LTPA [21]. Future investigations should explore whether psychological distress, social anxiety, or peer exclusion mediates this relationship and whether early LTPA interventions can mitigate the adverse effects of cyberbullying.

From an emotional regulation perspective, LTPA participation facilitates improved social interactions, communication skills, cooperative behaviors, and emotional stability [55]. These benefits contribute to reduced academic burnout and emotional distress [56], thereby decreasing the likelihood of aggressive behaviors, including cyberbullying. The gradual development of emotional regulation strategies and inhibitory control [57] further enables adolescents to manage negative emotions effectively and prevent aggressive online behaviors over extended periods.

From an intervention perspective, implementing regular LTPA programs is essential for enriching campus life, enhancing students’ cultural literacy, and fostering individual initiative. A vibrant and supportive campus environment can cultivate stable emotional states, positive character development, and healthy personality formation [58]. Such positive emotional development serves as a protective factor against verbal aggression and cyberbullying behaviors [34]. Therefore, establishing comprehensive management mechanisms, creating nurturing campus environments, and promoting diverse LTPA opportunities are crucial for supporting adolescents’ physical and mental well-being.

4.3 The Delayed Predictive Effect of Peer Relationships on Adolescent Cyberbullying

By integrating cross-lagged models and path coefficients, our research reveals that peer relationships exhibit a delayed predictive effect on subsequent cyberbullying behavior over a half-year period with three observations. This demonstrates a lagged negative predictive effect, aligning with scholarly consensus. The findings provide empirical support for Hypothesis 2 (H2), confirming the longitudinal stability of peer relationships. This stability enables peer relationships to maintain their influence on adolescent behaviors, including cyberbullying, across various developmental stages. Furthermore, the results substantiate Hypothesis 3 (H3), demonstrating the persistent nature of cyberbullying behavior over time. This persistence suggests that, in the absence of effective interventions, aggressive online behaviors may become entrenched through repeated reinforcement and the lack of corrective mechanisms.

The reasons may be based on several levels: (1) From the perspective of school management, the policy requirement to fully implement physical education classes can meet the needs of students’ leisure life and has a certain effect on individual interaction, which indeed promotes the quality of friendship among adolescents living in communities, greatly enhancing unity, mutual assistance, and trust, and alleviating the emotional instability of the adolescent developmental stage [59]. Emotional fluctuations may lead to indirect verbal attacks [60], conflicts, physical contact, and covert bullying, all of which can be resolved and eliminated through friendship [61], also becoming one of the main measures for emotional intervention during adolescence [62]. (2) From the perspective of differences in family upbringing styles, the physical and mental health of adolescents during the developmental stage is closely linked to the surrounding environment and interpersonal relationships, a point on which scholars generally agree. However, the quality of family education, the overall cultural literacy of parents, the standard of material life in the family, and the degree of family harmony are all important variables affecting individual psychological health and emotional stability. A warm and comfortable family environment can fend off external harm and interference, prompting individuals to seek confession and protection from family members [63], and when timely responses are received, emotions may stabilize and ease [64], indirectly curbing the occurrence of cyberbullying behavior, verbal violence, physical attacks, and other adverse behaviors. (3) From the perspective of individual social development, adolescents in the developmental stage are full of curiosity about the unknown world and urgently hope for more care and attention from society, teachers, parents, and peers to gain more social resources and support. When resource conditions are limited, cognitive biases, emotional imbalances, and improper regulatory strategies are inevitable [65]. With the help and support of others, contradictions in life will not intensify and deteriorate [66], nor will they lead to verbal attacks, abuse, and cyberbullying behavior in a short period, which is also in line with the psychological development characteristics and social resource allocation needs theory of adolescents during puberty. Therefore, in subsequent studies, it is necessary to compensate for more variables to avoid regrets and deficiencies in the study due to the lack of controllable variables.

4.4 The Cross-Temporal Mediating Role of Peer Relationships

Based on the cross-lagged regression model, a full-path model was constructed, showing that peer relationships have a partial cross-temporal mediating effect between leisure-time physical activity and cyberbullying. That is, leisure-time physical activity at time point T1 may indirectly affect cyberbullying behavior at time point T3 through peer relationships at time point T2, rather than directly affecting cyberbullying behavior at time point T3 through leisure-time physical activity at time point T1. This finding supports Hypothesis 5 (H5), which posited that peer relationships mediate the relationship between leisure-time physical activity and cyberbullying over time.

This result, to some extent, reveals the mechanism by which school leisure-time physical activity behavior and peer relationships affect adolescent cyberbullying behavior on a longitudinal level. The impact of middle school students’ leisure-time physical activity behavior and peer relationships on individuals does not directly affect cyberbullying behavior but transitions through a cross-lagged mediating effect, indicating a delay. In summary, the exploration of adolescent cyberbullying behavior, verbal bullying, and other problematic behaviors should not be confined to the diagnosis of current period issues but should consider relevant factors from previous periods.

In this study, leisure-time physical activity behavior and peer relationships are part of the school environment and an indispensable part of the adolescent living environment. The quality, frequency, and participation in recreational life determine the satisfaction and happiness index of adolescents’ lives and are the main factors affecting adolescent problematic behaviors [67]. Combining the interpersonal relationship theory in aggressive behavior, we can explain that in the school environment, if adolescents have a lack of cultural life, low cultural literacy, difficulty in releasing mental pressure, and a lack of communication and interaction among peers, it is highly likely to cause an imbalance and mismatch in social needs, leading to resistance, rebellion, and negative emotions [68].

Long-term accumulation of negative emotions can easily lead to bullying and attacks on vulnerable groups, and lead to frequent cyberbullying behavior in the internet era [69]. On the contrary, with participation in leisure-time physical activity activities, adolescents’ enthusiasm for activities can be greatly improved, releasing the innate nature and pressure of the group. Activities can enhance the group’s ability to interact and help each other, and long-term participation will provide a compensatory mechanism for the brain, causing a sustained period of influence, and the creation of a warm environment also requires the accumulation of time [70].

Over time, as activities are carried out in depth, peer relationships are further strengthened, and the school environment becomes warmer [24], individuals’ emotional regulation strategies and cognitive levels are significantly improved, ultimately leading to a decline in cyberbullying and other aggressive behaviors. In summary, this study highlights the delayed effect of leisure-time physical activity on cyberbullying behavior through peer relationships, supporting a cross-temporal mediation mechanism. This aligns with Hypothesis 5 (H5), reinforcing the notion that interventions targeting peer relationships may serve as an effective strategy to mitigate cyberbullying over time.

4.5 Study Limitations and Future Directions

While this study contributes to the understanding of the relationship between leisure-time physical activity and cyberbullying, several limitations should be acknowledged, along with corresponding directions for future research.

First, the geographical scope was restricted to middle schools in selected prefecture-level cities within Sichuan, Jiangsu, and Guangdong provinces due to budgetary constraints. This limited sampling may affect the generalizability of findings. Future research should incorporate broader geographical coverage and cross-cultural comparisons to enhance the robustness and applicability of results.

Second, the exclusive reliance on self-reported measures may introduce response biases and discrepancies between reported and actual behaviors. To improve data reliability, subsequent studies should employ multi-informant approaches, including teacher reports, peer evaluations, and systematic behavioral observations during physical activities. Additionally, integrating qualitative methods such as interviews and focus groups with students, teachers, and parents could provide deeper insights into behavioral patterns and contextual factors.

Third, the study did not examine potential reverse causality, particularly whether cyberbullying victimization affects participation in leisure-time physical activities. Future longitudinal research should investigate how psychological distress, social anxiety, or peer exclusion might mediate this relationship. This exploration could inform the development of integrated intervention programs that combine psychological support with physical activity promotion to mitigate the negative effects of cyberbullying.

Finally, future studies should investigate potential moderating factors in the relationship between physical activity and cyberbullying, such as socioeconomic status, parental involvement, and school climate. These factors may significantly influence adolescent behavior patterns. For instance, structured sports programs and peer-led physical activities, combined with digital literacy education, could be implemented as part of comprehensive school policies [71]. Collaborative efforts among educators, psychologists, and policymakers are essential to develop effective strategies that simultaneously address cyberbullying prevention and physical activity promotion.

The conclusions are as follows. Firstly, leisure-time physical activity, peer relationships, and cyberbullying all demonstrate cross-temporal stability, with the variables in one period being predictive of changes in subsequent periods. Notably, leisure-time physical activity significantly predicts the following period’s peer relationships and instances of cyberbullying. Secondly, on a longitudinal basis, adolescents who engage more in leisure-time physical activity and have stronger peer relationships tend to exhibit lower levels of cyberbullying. Thirdly, leisure-time physical activity at time point T1 can indirectly influence cyberbullying behavior at time point T3 through the mediating role of peer relationships at time point T2. Additionally, there is a direct effect, indicating that leisure-time physical activity, peer relationships, and cyberbullying are interconnected through cross-temporal mediation effects. These findings underscore the importance of promoting physical activity and fostering positive peer interactions as part of cyberbullying prevention strategies. By understanding these mechanisms, educators and policymakers can design more targeted interventions to mitigate cyberbullying and support adolescent well-being.

Acknowledgement: The research team would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Education Bureaus and related schools in Leshan, Sichuan Province, Yancheng, Jiangsu Province, and Guangzhou, Guangdong Province for their strong support and assistance. Special thanks are extended to the Student Service Team of Leshan Normal University for their active participation and selfless dedication in this study.

Funding Statement: This study was funded by the following projects: National Social Science Fund Project “The Empowerment Mechanism of Physical Exercise on Emotional Regulation in Adolescents” (23BTY116), Leshan Normal University 2024 Research Cultivation Project: “Research on the Trajectory Effect of Family Cumulative Risk and Home-based Activity of Adolescents” (KYPY2025-0014), Key Humanities and Social Sciences Cultivation Project of Leshan Normal University: “Research on the Sequence Difference of Knowledge and Behavior of Physical Activity among Adolescents and the Compensation Mechanism”; and Sichuan Province College Students’ Sports Association Annual Project “The Trajectory Effect of Family Cumulative Risk and Adolescents’ Home Physical Activity” (23CDTXQ004).

Author Contributions: Jingtao Wu was responsible for data analysis, study design, data interpretation, and drafting the manuscript. Wanli Zang contributed to study design, coordination, and assisted in drafting the manuscript. Yanhong Shao and Jun Hu were responsible for reviewing, editing, and approving the final manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was ethically approved by the Academic Ethics Committee of Leshan Normal University, with the approval number LSNU:1031-4-12RO, and the entire process of the subjects followed the relevant regulations and requirements of the American Psychological Association (APA).

Informed Consent: Parents provided informed consent for their child’s participation, and children provided assent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sorrentino A, Esposito A, Acunzo D, Santamato M, Aquino A. Onset risk factors for youth involvement in cyberbullying and cybervictimization: a longitudinal study. Front Psychol. 2023;13:1090047. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1090047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Alvarez C, Sabina C, Brockie T, Perrin N, Sanchez-Roman MJ, Escobar-Acosta L, et al. Patterns of adverse childhood experiences, social problem-solving, and mental health among Latina immigrants. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(23–24):NP22401–27. doi:10.1177/08862605211072159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Li J, Sidibe AM, Shen X, Hesketh T. Incidence, risk factors and psychosomatic symptoms for traditional bullying and cyberbullying in Chinese adolescents. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2019;107(2):104511. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chu XW, Fan CY, Liu QQ, Zhou ZK. Cyberbullying victimization and symptoms of depression and anxiety among Chinese adolescents: examining hopelessness as a mediator and self-compassion as a moderator. Comput Hum Behav. 2018;86(4):377–86. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Doumas DM, Midgett A. Witnessing cyberbullying and suicidal ideation among middle school students. Psychol Sch. 2023;60(4):1149–63. doi:10.1002/pits.22823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Vandebosch H. Cyberbullying prevention, detection and intervention. In: Vandebosch H, Green L, editors. Narratives in research and interventions on cyberbullying among young people. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 29–44. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04960-7_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Tokunaga RS. Following you home from school: a critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26(3):277–87. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lee JM, Choi HH, de Lara E. Parental care and family support as moderators on overlapping college student bullying and cyberbullying victimization during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2022;19(6):684–99. doi:10.1080/26408066.2022.2094744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Adebayo DO, Ninggal MT. Relationship between social media use and students’ cyberbullying behaviors in a west Malaysian pubic university. J Educ. 2022;202(4):524–33. doi:10.1177/0022057421991868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Fauman MA. Cyber bullying: bullying in the digital age. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(6):780–1. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gan X, Wang P, Huang C, Li H, Jin X. Alienation from school and cyberbullying among Chinese middle school students: a moderated mediation model involving self-esteem and emotional intelligence. Front Public Health. 2022;10:903206. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.903206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Evangelio C, Rodríguez-González P, Fernández-Río J, Gonzalez-Villora S. Cyberbullying in elementary and middle school students: a systematic review. Comput Educ. 2022;176(12):104356. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Amin SM, Mohamed MAE, Metwally El-Sayed M, El-Ashry AM. Nursing in the digital age: the role of nursing in addressing cyberbullying and adolescents mental health. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2025;32(1):57–70. doi:10.1111/jpm.13085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Paschke K, Thomasius R. Digital media use and mental health in adolescents-a narrative review. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2024;67(4):456–64. (In German). doi:10.1007/s00103-024-03848-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ang RP. Adolescent cyberbullying: a review of characteristics, prevention and intervention strategies. Aggress Violent Behav. 2015;25:35–42. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2015.07.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ouyang Y, Peng J, Luo J, Teng J, Wang K, Li J. Research on the influence of sports participation on school bullying among college students—chain mediating analysis of emotional intelligence and self-esteem. Front Psychol. 2022;13:874458. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.874458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Jiménez-Barbero JA, Jiménez-Loaisa A, González-Cutre D, Beltrán-Carrillo VJ, Llor-Zaragoza L, Ruiz-Hernández JA. Physical education and school bullying: a systematic review. Phys Educ Sport Pedagogy. 2020;25(1):79–100. doi:10.1080/17408989.2019.1688775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Guerra AM, Montes F, Useche AF, Jaramillo AM, González SA, Meisel JD, et al. Effects of a physical activity program potentiated with ICTs on the formation and dissolution of friendship networks of children in a middle-income country. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5796. doi:10.3390/ijerph17165796. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Arazi H, Dadvand SS, Suzuki K. Effects of exercise training on depression and anxiety with changing neurotransmitters in methamphetamine long term abusers: a narrative review. Biomed Hum Kinet. 2022;14(1):117–26. doi:10.2478/bhk-2022-0015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Rusillo-Magdaleno A, Moral-García JE, Brandão-Loureiro V, Martínez-López EJ. Influence and relationship of physical activity before, during and after the school day on bullying and cyberbullying in young people: a systematic review. Educ Sci. 2024;14(10):1094. doi:10.3390/educsci14101094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Marengo N, Borraccino A, Charrier L, Berchialla P, Dalmasso P, Caputo M, et al. Cyberbullying and problematic social media use: an insight into the positive role of social support in adolescents—data from the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study in Italy. Public Health. 2021;199(4):46–50. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2021.08.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Schütz J, Bäker N, Koglin U. Bullying in school and cyberbullying among adolescents without and with special educational needs in emotional-social development and in learning in Germany. Psychol Sch. 2022;59(9):1737–54. doi:10.1002/pits.22722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Chen S, Gu X. Toward active living: comprehensive school physical activity program research and implications. Quest. 2018;70(2):191–212. doi:10.1080/00336297.2017.1365002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wong RS, Tung KT, Chan DY, Ip P. Correction: susceptibility to peer relationship problems: does sociability play a role? J Pediatr Neuropsychol. 2024;10(4):340–39. doi:10.1007/s40817-024-00174-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Fu X, Li S, Shen C, Zhu K, Zhang M, Liu Y, et al. Effect of prosocial behavior on school bullying victimization among children and adolescents: peer and student-teacher relationships as mediators. J Adolesc. 2023;95(2):322–35. doi:10.1002/jad.12116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Deng Y, Wang X. The impact of physical activity on social anxiety among college students: the chain mediating effect of social support and psychological capital. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1406452. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1406452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Sahi RS, Eisenberger NI, Silvers JA. Peer facilitation of emotion regulation in adolescence. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2023;62(4):101262. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2023.101262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ssewamala FM, Brathwaite R, Neilands TB. Economic empowerment, HIV risk behavior, and mental health among school-going adolescent girls in Uganda: longitudinal cluster-randomized controlled trial, 2017–2022. Am J Public Health. 2023;113(3):306–15. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2022.307169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Song Q, Vicman JM, Doan SN. Changes in attachment to parents and peers and relations with mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg Adulthood. 2022;10(4):1048–60. doi:10.1177/21676968221097167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Lim H, Lee H, Bridgewater SSUUSA. Cyberbullying: its social and psychological harms among schoolers. Int J Cybersecur Intell Cybercrime. 2021;2021:25–45. doi:10.52306/04010321knsz7360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Milnes K, Turner-Moore R, Gough B. Towards a culturally situated understanding of bullying: viewing young people’s talk about peer relationships through the lens of consent. J Youth Stud. 2022;25(10):1367–85. doi:10.1080/13676261.2021.1965106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Strindberg J, Horton P. Relations between school bullying, friendship processes, and school context. Educ Res. 2022;64(2):242–56. doi:10.1080/00131881.2022.2067071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Miyagawa Y, Taniguchi J. Sticking fewer (or more) pins into a doll? The role of self-compassion in the relations between interpersonal goals and aggression. Motiv Emot. 2022;46(1):1–15. doi:10.1007/s11031-021-09913-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Benítez-Sillero JD, Armada Crespo JM, Ruiz Córdoba E, Raya-González J. Relationship between amount, type, enjoyment of physical activity and physical education performance with cyberbullying in adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):2038. doi:10.3390/ijerph18042038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang Q, Deng W. Relationship between physical exercise, bullying, and being bullied among junior high school students: the multiple mediating effects of emotional management and interpersonal relationship distress. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):2503. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-20012-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Aizenkot D, Kashy-Rosenbaum G. The effectiveness of safe surfing intervention program in reducing WhatsApp cyberbullying and improving classroom climate and student sense of class belonging in elementary school. J Early Adolesc. 2021;41(4):550–76. doi:10.1177/0272431620931203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Lee H, Yi H. Intersectional discrimination, bullying/cyberbullying, and suicidal ideation among South Korean youths: a latent profile analysis (LPA). Int J Adolesc Youth. 2022;27(1):325–36. doi:10.1080/02673843.2022.2095214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Liang DQ. The stress level of college students and its relationship with physical exercise. Chin Ment Health J. 1994;8(1):5–6. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

39. Bai MZ, Yao SJ, Ma QS, Wang XL, Liu C, Guo KL. The relationship between physical exercise and school adaptation of junior students: a chain mediating model. Front Psychol. 2022;13:977663. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.977663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Hymel S, Franke S. Children’s peer relations: assessing self-perceptions. In: Schneider BH, Rubin KH, Ledingham JE, editors. Children’s peer relations: issues in assessment and intervention. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 1985. p. 75–91. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-6325-5_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Chen GP, Zhu XL, Ye LL, Tang YM. The revision of the Shanghai norm of the self-description questionnaire. J Psychol Sci. 1997;6:499–503. (In Chinese). doi:10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.1997.06.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Calvete E, Orue I, Estévez A, Villardón L, Padilla P. Cyberbullying in adolescents: modalities and aggressors’ profile. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26(5):1128–35. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Tang DD, Wen ZL. Statistical approaches for testing common method bias: problems and suggestions. J Psychol Sci. 2020;1:215–23. (In Chinese). doi:10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20200130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. McCuddy T, Esbensen FA. Delinquency as a response to peer victimization: the implications of school and cyberbullying operationalizations. Crime Delinq. 2022;68(5):760–85. doi:10.1177/00111287211005398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Opdenakker MC, Maulana R, den Brok P. Teacher-student interpersonal relationships and academic motivation within one school year: developmental changes and linkage. Sch Eff Sch Improv. 2012;23(1):95–119. doi:10.1080/09243453.2011.619198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Aryslanbaeva A, Niyazova O, Niyazova A. Features of emotional stability of adolescents in sports activities. ACADEMICIA Int Multidiscip Res J. 2021;11(5):993–6. doi:10.5958/2249-7137.2021.01499.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Lane C, Nathan N, Reeves P, Sutherland R, Wolfenden L, Shoesmith A, et al. Economic evaluation of a multi-strategy intervention that improves school-based physical activity policy implementation. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):40. doi:10.1186/s13012-022-01215-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Liu L, Wu Y, Li Y. Linking family relationships with peer relationships based on spillover theory: a positive perspective. J Soc Pers Relatio. 2022;39(7):2094–116. doi:10.1177/02654075221074399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Ronchi L, Banerjee R, Lecce S. Theory of mind and peer relationships: the role of social anxiety. Soc Dev. 2020;29(2):478–93. doi:10.1111/sode.12417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Berkowitz R, Winstok Z. The association between teacher-student and peer relationships and the escalation of peer school victimization. Child Indic Res. 2022;15(6):2243–65. doi:10.1007/s12187-022-09961-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Paez GR. Assessing predictors of cyberbullying perpetration among adolescents: the influence of individual factors, attachments, and prior victimization. Int J Bullying Prev. 2020;2(2):149–59. doi:10.1007/s42380-019-00025-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Costa Ferreira PD, Veiga Simão AM, Martinho V, Pereira N. How beliefs and unpleasant emotions direct cyberbullying intentions. Heliyon. 2022;8(12):e12163. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Jin S, Miao M. Family incivility and cyberbullying perpetration among college students: negative affect as a mediator and dispositional mindfulness as a moderator. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(23–24):NP21826–49. doi:10.1177/08862605211063000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Elbedour S, Alqahtani S, El Sheikh Rihan I, Bawalsah JA, Booker-Ammah B, Turner JF. Cyberbullying: roles of school psychologists and school counselors in addressing a pervasive social justice issue. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;109(8):104720. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Kolanowski W, Ługowska K, Trafialek J. The impact of physical activity at school on eating behaviour and leisure time of early adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(24):16490. doi:10.3390/ijerph192416490. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Gwon H, Shin J. Effects of physical education playfulness on academic grit and attitude toward physical education in middle school students in the Republic of Korea. Healthcare. 2023;11(5):774. doi:10.3390/healthcare11050774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Chen S, Wang Q, Wang X, Huang L, Zhang D, Shi B. Self-determination in physical exercise predicts creative personality of college students: the moderating role of positive affect. Front Sports Act Living. 2022;4:926243. doi:10.3389/fspor.2022.926243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Liao Y, Cheng X, Chen W, Peng X. The influence of physical exercise on adolescent personality traits: the mediating role of peer relationship and the moderating role of parent-child relationship. Front Psychol. 2022;13:889758. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.889758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Demkowicz O, Panayiotou M, Qualter P, Humphrey N. Longitudinal relationships across emotional distress, perceived emotion regulation, and social connections during early adolescence: a developmental cascades investigation. Dev Psychopathol. 2024;36(2):562–77. doi:10.1017/S0954579422001407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Murray-Close D, Lent MC, Sadri A, Buck C, Yates TM. Autonomic nervous system reactivity to emotion and childhood trajectories of relational and physical aggression. Dev Psychopathol. 2024;36(2):691–708. doi:10.1017/S095457942200150X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Caceres J, Holley A. Perils and pitfalls of social media use: cyber bullying in teens/young adults. Prim Care. 2023;50(1):37–45. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2022.10.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Lyng ST. The social production of bullying: expanding the repertoire of approaches to group dynamics. Child Soc. 2018;32(6):492–502. doi:10.1111/chso.12281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Sudarsana IK, Lali Yogantara IW, Ekawati NW. Cyber bullying prevention and handling through Hindu family education. J Penjaminan Mutu. 2019;5(2):170. doi:10.25078/jpm.v5i2.1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Fang J, Wang W, Gao L, Yang J, Wang X, Wang P, et al. Childhood maltreatment and adolescent cyberbullying perpetration: a moderated mediation model of callous-unemotional traits and perceived social support. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(7–8):NP5026–49. doi:10.1177/0886260520960106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Herd T, Kim-Spoon J. A systematic review of associations between adverse peer experiences and emotion regulation in adolescence. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2021;24(1):141–63. doi:10.1007/s10567-020-00337-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Ciccarelli M, Nigro G, D’Olimpio F, Griffiths MD, Cosenza M. Mentalizing failures, emotional dysregulation, and cognitive distortions among adolescent problem gamblers. J Gambl Stud. 2021;37(1):283–98. doi:10.1007/s10899-020-09967-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Livingston CP, Schneider DE, Melanson IJ, Martinez SE, Anderson H, Bryan SJ. Variables influencing physical activity for children with developmental disabilities who exhibit problem behavior. Behav Interv. 2025;40(1):e2067. doi:10.1002/bin.2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Anderson SF, Sladek MR, Doane LD. Negative affect reactivity to stress and internalizing symptoms over the transition to college for Latinx adolescents: buffering role of family support. Dev Psychopathol. 2021;33(4):1322–37. doi:10.1017/S095457942000053X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Rey L, Quintana-Orts C, Mérida-López S, Extremera N. The relationship between personal resources and depression in a sample of victims of cyberbullying: comparison of groups with and without symptoms of depression. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(24):9307. doi:10.3390/ijerph17249307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Azeredo CM, Marques ES, Okada LM, Peres MFT. Association between community violence, disorder and school environment with bullying among school adolescents in Sao Paulo—Brazil. J Interpers Violence. 2023;38(3–4):2432–63. doi:10.1177/08862605221101201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Saif ANM, Purbasha AE. Cyberbullying among youth in developing countries: a qualitative systematic review with bibliometric analysis. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2023;146(1):106831. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2023.106831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools