Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Development and Factorial Structure of the Green Crescent Life Skills Scale for Turkish Adolescents

1 Department of Guidance and Psychological Counseling, Hasan Ali Yücel Faculty of Education, Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, Istanbul, 34500, Türkiye

2 Department of Educational Sciences, Faculty of Education, Istanbul Medeniyet University, Istanbul, 34720, Türkiye

3 Member of the Turkish Green Crescent Society Scientific Committee, Istanbul, 34110, Türkiye

* Corresponding Author: Ayşe Esra İşmen Gazioğlu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Exploring anxiety, stress, depression, addictions, executive functions, mental health, and other psychological and socio-emotional variables: psychological well-being and suicide prevention perspectives)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(5), 683-700. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.062650

Received 24 December 2024; Accepted 11 April 2025; Issue published 05 June 2025

Abstract

Background: The effectiveness of life skills-based prevention programs to prevent substance addiction has been underexplored in Türkiye, likely in part due to the lack of validated measurement tools developed specifically for that purpose. Therefore, the aim of this study is to develop a tool to measure life skills for middle school students. The present study aims to test the factorial structure, reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, and measurement invariance across gender and age groups of the Green Crescent Life Skills (GCLS) Scale. Methods: The study was conducted in Istanbul with two different sample groups. The first sample consisted of 566 and the second sample consisted of 885 middle school students. In the study, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was applied to the first sample, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was applied to the second sample to test the factorial structure of the scale. Convergent and discriminant validity were examined to provide evidence for construct-based validity. The reliability of the scale was assessed with Cronbach’s α, composite reliability, McDonald’s ω, and test-retest. Results: The EFA results showed that the scale consisted of four factors (self-awareness, coping with negative emotions, thinking skills, and peer relations). CFA results also confirmed this structure. The results revealed a significant positive correlation (r = 0.52, p < 0.01) between life skills and avoidance self-efficacy scores, as well as a significant negative correlation (r = −0.53, p < 0.01) between life skills and attitude toward drug use scores. Additionally, it was found that measurement invariances based on gender and age groups were provided. It was determined that all sub-dimensions had sufficient reliability levels. Conclusion: The findings of this validation study show that the GCLS Scale, which assesses four skills in a self-reported format, is a valid and reliable scale with considerable potential utility in monitoring life skills in Turkish adolescent populations.Keywords

Life skills programs have been utilized since the 1960s to provide knowledge of skills that can be transferred to multiple areas of an individual’s life [1]. There are many accepted definitions for the broad category of life skills. Life skills are defined as “abilities for adaptive and positive behavior that enable individuals to deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life” [2].

Life skills are often enhanced by a psychoeducational program called “Life Skills Training”. These programs employed in different venues might have focused on different life skills and were implemented in different aspects of an individual’s life. For example, they have been implemented in the areas of antipoverty, HIV/AIDS, violence against children, the status of women, educational settings, multiple sports settings, individuals with developmental disabilities, improving the mental health of hospitalized patients, and drug and alcohol prevention.

Previous studies on the life skills approach have demonstrated it to be effective in preventing cigarette smoking, alcohol, and marijuana use [3]. Life skill programs focus on multiple age groups, ranging from youth through adulthood. However, considering alcohol and drug use prevention, the most effective prevention approaches target individuals at the beginning of adolescence. Smoking, drinking, and illicit drug use often begin during adolescence in Western countries. Research regarding the age of onset of drug use in Türkiye is consistent with Western societies. While the age of 15 is considered a critical age for the onset of drug use [4], more recent studies have reported an earlier age of initiation [5]. Alcohol is the most widely used drug among adolescents in Türkiye [6]. Smoking and alcohol use are less prevalent among Turkish adolescents than in European countries, and illicit drug use remains below the global average. However, studies report an increase in the use of these substances compared with previous years [7]. Although the prevalence of drug, alcohol, and tobacco use is still far lower than that reported in most European Union countries and the United States, the rising rates of use highlight the need for adolescent prevention and intervention programs in Türkiye [6–8].

There are few life skills-based prevention programs to prevent drug use in Turkish adolescents [8,9]; only one effectiveness study was reported [10]. Effectiveness studies of prevention programs can be effectively implemented when appropriate measurement tools are available.

Measurement tools aiming to measure life skills are also limited in Türkiye. Life skills scales developed or adapted in Türkiye generally include skills such as coping with emotions and stress, empathy and self-awareness, decision-making and problem-solving, creative thinking and critical thinking, and communication, and their target groups are mostly high school and university students. However, there are relatively few valid and reliable life skills scales that can be used in early adolescence. It can be attributed to the fact that there is no self-report survey with adequate psychometric properties that assesses constructs targeted by a particular drug prevention program for Turkish adolescents. Limitations of current instruments include inadequate information on psychometric properties or assessment of generic constructs, but they are not specific to drug prevention. Another limitation is that they do not examine the measurement invariance in gender and age. Whereas, previous research with Turkish secondary school students has shown age and gender differences in life skills [11]. Thus, it is hard to directly compare the performance of these groups on the life skills scales without being able to estimate the impact of potential structural differences. A valid comparison of the life skills across age or gender groups requires that the instrument be comparable in these groups. If measurement invariance cannot be confirmed, mean scores cannot be compared meaningfully. This is because groups probably interpret the question items differently.

A limited number of instruments are available that exclusively measure a cluster of life skills among adolescents in Western cultures such as the Youth Leadership Life Skills Development Scale [12], Life Skills Development Scale-Adolescent Form [13], Life Skills Development Inventory-College Form [14], Life Skills Training Questionnaire [15], The Life Skills Evaluation Instrument [16], National Youth Life Skills Evaluation Scale [17], Youth Life Skills Inventory [18], Youth Life Skills Scale [19], PLANEA Independent Life Skills Scale [20], and in non-western cultures such as Life Skills Scale [21], The Life Skills Scale [22], Life Skills Assessment Scale [23], Life Skills Scale for Adolescents and Adults [24], and Life Skills Scale [25]. These scales varied in terms of their objectives (e.g., needs of the target population), targeted age groups (e.g., elementary, high school, or college students and adults), and sub-factors (e.g., life skill categories). None of them were developed to measure the outputs of a special drug prevention life skills program in Türkiye. Although most of these instruments have adequate psychometric properties, only some of them confirmed gender measurement invariance [26,27].

Life skills education differs in its objectives and contents from country to country and from one locality to another. For this reason, it is more appropriate to test the effectiveness of life skills programs with measurement tools suitable for the culture in which they were developed. Life skills programs in non-Western countries require appropriate tools to measure their effectiveness, which help to develop their potential. An instrument to evaluate life skills developed for secondary school students in Türkiye will be a useful guide in developing a drug prevention program, implementing a program, and creating a measurable and valid evaluation of a specific life skills program and will also provide data to funders and decision-makers about life skills and the impacts of programs on youth.

The purpose of this research is to develop the Green Crescent Life Skills (GCLS) Scale for its use in the psychoeducational field, under a drug prevention framework. We sought to examine the factorial structure, measurement invariance, convergent and discriminant validity finally reliability of the GCLS Scale. In this way, the psychometric properties of the GCLS Scale in Turkish adolescents were estimated. We hypothesize that the resulting instrument will feature different dimensions based on the WHO [2]. Skills-based health education approach, the factor structure model will explain a latent second-order variable and measure invariance across gender and age, as well as adequate psychometric properties. Sufficient evidence of validity in relation to other variables is expected to be found from the study of the correlation between the instrument’s scores with attitudes toward drug use and avoidance self-efficacy.

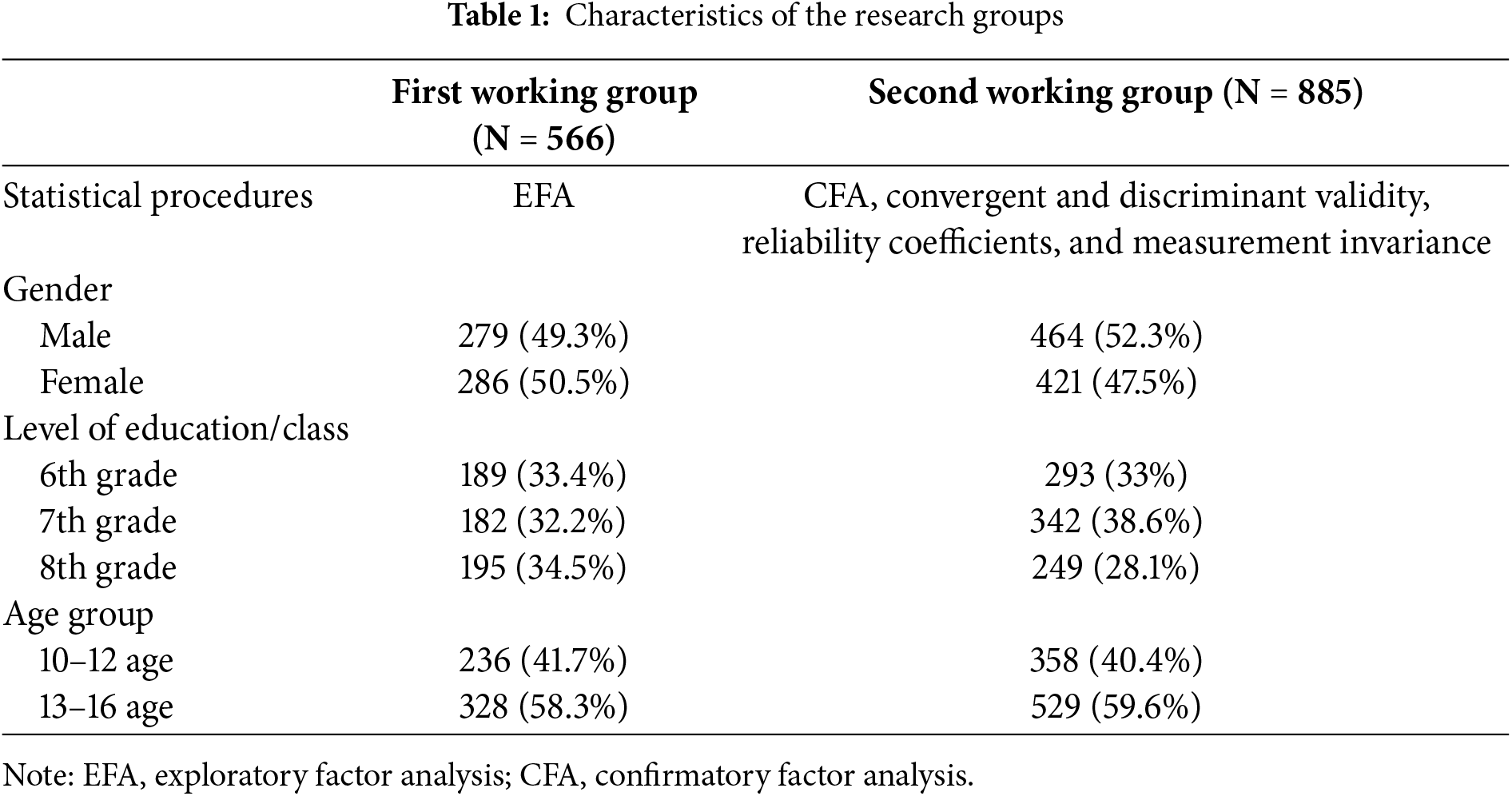

Data were collected from two independent samples in Istanbul, a city highly representative of its socioeconomic structure. In both samplings, a probabilistic sampling strategy was used. In the first sample, six public middle schools in two central districts of Istanbul were initially selected. The first sample consisted of 566 middle school students aged between 10 and 16, including 286 females and 279 males (one missing information), with an average age of 12.80 years (SD = 1.08). Students as participants were distributed across three grade levels: 6th (n = 189, 33.4%), 7th (n = 182, 33.2%), and 8th (n = 195, 28.1%).

The second sample of the present study consisted of 885 (421 female, 464 male) middle school students aged between 10 and 16. The mean age of the participants was 12.81 years (SD = 1.09). Among the participants, 293 (33%) of them were 6th graders, 342 (38.6%) of them were 7th graders, and 249 (28.1%) of them were 8th graders (one missing information).

To test the factor structure and construct validity of the scale, an EFA was conducted on the first sample, while a CFA was performed on the second sample to validate the model. Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω, Composite Reliability Coefficient (CR), measurement invariance, and convergent and discriminant validity were also tested on the second sample.

The socioeconomic composition of the participants was quite similar to the first sample. In the second sample, six different schools were selected from two central districts of the same city, with a total of 885 participants involved. All 1451 students were Turkish citizens, and they were native Turkish speakers. The characteristics of the research groups are given in Table 1.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. To collect data, necessary permissions were obtained for 12 secondary schools by applying to the Ministry of National Education. The administrators of the selected schools were contacted, and the letter containing a parental consent form and information about the research was sent home with students to give to the parents. In addition, this letter included an email address and a phone number that parents can use if they want to ask questions before signing the consent form. Printed questionnaires were distributed to only students with parental written consent to participate in the research. In addition, the students were informed that they had the free will to fill in the questionnaire and could withdraw from it at any point they wished. All procedures were approved by the Istanbul Institutional Review Board (No. E.21319083).

2.3 Measurement Instruments for Assessing Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Favorable attitudes toward drug use and low avoidance self-efficacy are individual risk factors associated with adolescent substance use [28]; it has been found that training youth in life skills improves their self-efficacy to prevent substance use [29]. In the present study, correlations between the GCLS Scale, the Self-Efficacy for Adolescents Protecting Substance Abuse Scale [30], and the Drug Attitude Scale [31].

2.3.1 The Self-Efficacy for Adolescents Protecting Substance Abuse Scale (SEAPSAS)

SEAPSAS, developed by Eker et al. [30] to measure the self-efficacy of high school students in preventing substance addiction, consists of four subscales with a five-point Likert-type rating and 23 items. Each item was answered on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. The psychometric properties of the SEAPSAS for middle school students were examined by İşmen Gazioğlu [32]. The SAEPSAS middle school version’s four-factor model has the following goodness-of-fit indices: comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.99, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.04. Also, the SAEPSAS middle school version’s subscales’ Cronbach’s α coefficients ranged from 0.93 to 0.62. The high total score on the scale indicates high self-efficacy in protection from substance addiction.

2.3.2 Drug Attitude Scale (DAS)

DAS, developed by Aksoy [31] to measure high school students’ attitudes towards addictive substances, consists of 45 items with a Likert-type rating with responses varying from 1 (absolutely inappropriate) to 5 (absolutely appropriate). The scale has two dimensions: “positive attitude-21 items” and “negative attitude-24 items”. Psychometric properties of the DAS for middle school students were examined by İşmen Gazioğlu [32]. DAS middle school version’s two-factor model has the following goodness-of-fit indices: CFI = 0.96, RMSEA 0.05. The internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s α) of the DAS middle school version are 0.92 for a positive attitude and 0.932 for a negative attitude.

2.4 Item Pool Preparation and Pre-Pilot Testing

The item pool preparation process followed DeVellis’ [33] guidelines for scale development, which consisted of identification of the construct to be measured, generating an item pool, determining the format for measurement, expert review of the initial item pool, including validation items, and administration of the scale to a developmental sample. These stages are described in detail below.

To clarify the range of life skills to be assessed, an intensive literature review was carried out. Regarding instruments for evaluating the outcomes of drug prevention life skills programs, several researchers have developed a variety of instruments to measure life skills in each component. In 1990, Botvin et al. [3] developed life skills training (LST) to prevent drug abuse through a multimodal cognitive-behavioral approach. The LST program includes three main modules for drug resistance, personal self-management, and social skills. According to WHO, life skills programs to prevent the use of alcohol, cigarettes, and illicit drugs should include three skill domains: interpersonal relations and communication, critical thinking and decision-making, and coping and self-management skills [2].

According to a recent meta-analysis [34], interpersonal skills, assertiveness, and problem-solving skills are three of the active components that are consistently associated with the overall effectiveness of preventive interventions to reduce risk behaviors in adolescents. These domains were taken into consideration while creating the item pool. Additionally, since one of the developmental characteristics specific to early adolescence is “worrying about physical appearance”, the domain of self-awareness skills (awareness of the changing body and healthy life choices) has been added to the three domains defined by WHO. Consequently, the item pool was formed based on these skill domains:

(1) Self-awareness (awareness of the changing body, healthy life choices) Example item: “I am aware of the consequences of not taking proper care of my body.” (Item 8)

(2) Coping with negative emotions (coping with negative emotions, coping with challenging life events, positive thinking, self-control) Example item: “I can overcome challenges by using my strengths.” (Item 18)

(3) Thinking skills (problem-solving, critical thinking, decision-making) Example item: “I think carefully before attempting to solve a problem.” (Item 30)

(4) Peer relations (relationship initiation and maintenance skills, resistance to peer pressure, distinguishing between safe and unsafe areas). Example item: “I can share my thoughts with others, even if they don’t agree with me.” (Item 50)

Similar to other scale development studies, the authors of the present study sought to develop an item pool that would be considerably larger than the final scale. In total, 89 items were developed, which represented the four life skills domains. Then, developed items were evaluated for face validity. Five experts, three of whom were from the field of assessment and evaluation and two of whom were from the field of education programs and training, reviewed the initial item pool.

All items were comprehensively reviewed to ensure their relevance in measuring life skills in adolescence. This process involved assessing each item’s conceptual alignment with the target construct, ensuring clarity and readability, and avoiding ambiguous, overlapping, or irrelevant meanings. Special attention was given to ensure that the language used was both developmentally suitable for adolescents and free from potential misinterpretations. Then all items in the item pool were phrased as declarative statements and measured on a “1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree” response set.

However, to further assess the clarity and comprehensibility, a pre-pilot test was conducted with a sample of 60 students who closely resembled the target population. The objective of this phase was to evaluate the clarity of the items and statements, assess the average response time, and identify any items that might be unclear to respondents. The average completion time for the scale was determined to be approximately 40–45 min. Following this process, the scale was finalized for administration to the study groups after necessary adjustments had been made. To ensure ethical compliance, informed consent was obtained from parents before administering the self-reported questionnaires, and assent was also provided by the children for their participation.

The factorial structure of the GCLS was examined using EFA and CFA. In EFA, a principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted via SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA), whereas in CFA, the covariance and asymptotic covariance matrix were used with the robust maximum likelihood method as the parameter estimation method via LISREL 8.8 (Scientific Software International, Chicago, IL, USA). To test the equivalence (invariance) of the model across gender and age groups, multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (MG CFA) was employed. This analysis was conducted in R Studio 4.2.2 (Posit, PBC, Boston, MA, USA, ABD) with R 4.2.2 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria) with the ‘Lavaan’ and ‘semTools’ packages. Additionally, Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s ω, and composite reliability coefficients were estimated for sub-dimensions and the overall scale to examine reliability.

Prior to conducting EFA, the following fundamental assumptions were evaluated: First, the adequacy of the sample size was ensured. In general, a minimum of five to ten participants per item is recommended, with a total target of at least 100 to 200 participants [34]. To determine the suitability of the data for factor analysis, a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test were conducted. The KMO value must exceed 0.60, and the results of Bartlett’s test must be statistically significant. Ensuring these assumptions is essential for producing valid and reliable results from the EFA.

To assess the fit of the CFA model derived from the EFA results, the following fit indices were used: The chi-square statistic to the degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df) should be less than three, indicating an acceptable fit of the model. It is recommended that both the CFI and the non-normed fit index (NNFI) exceed 0.90 [35,36]. RMSEA should be less than 0.05, and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) should not exceed 0.05 [35,37]. It is critically important to confirm the model’s validity and reliability by verifying that it meets these criteria.

3.1 Exploratory Factor Analysis

To assess the structural validity of the GCLS, EFA was performed using PCA with varimax rotation. This approach was selected to maximize factor variances. The KMO measure was 0.89, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a χ2 value of 6410.938 (p < 0.01), indicating adequacy for factor analysis. The primary criterion for determining the number of factors to retain was based on extracting factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.00 [38]. Consequently, four factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1.00 were retained for further analysis.

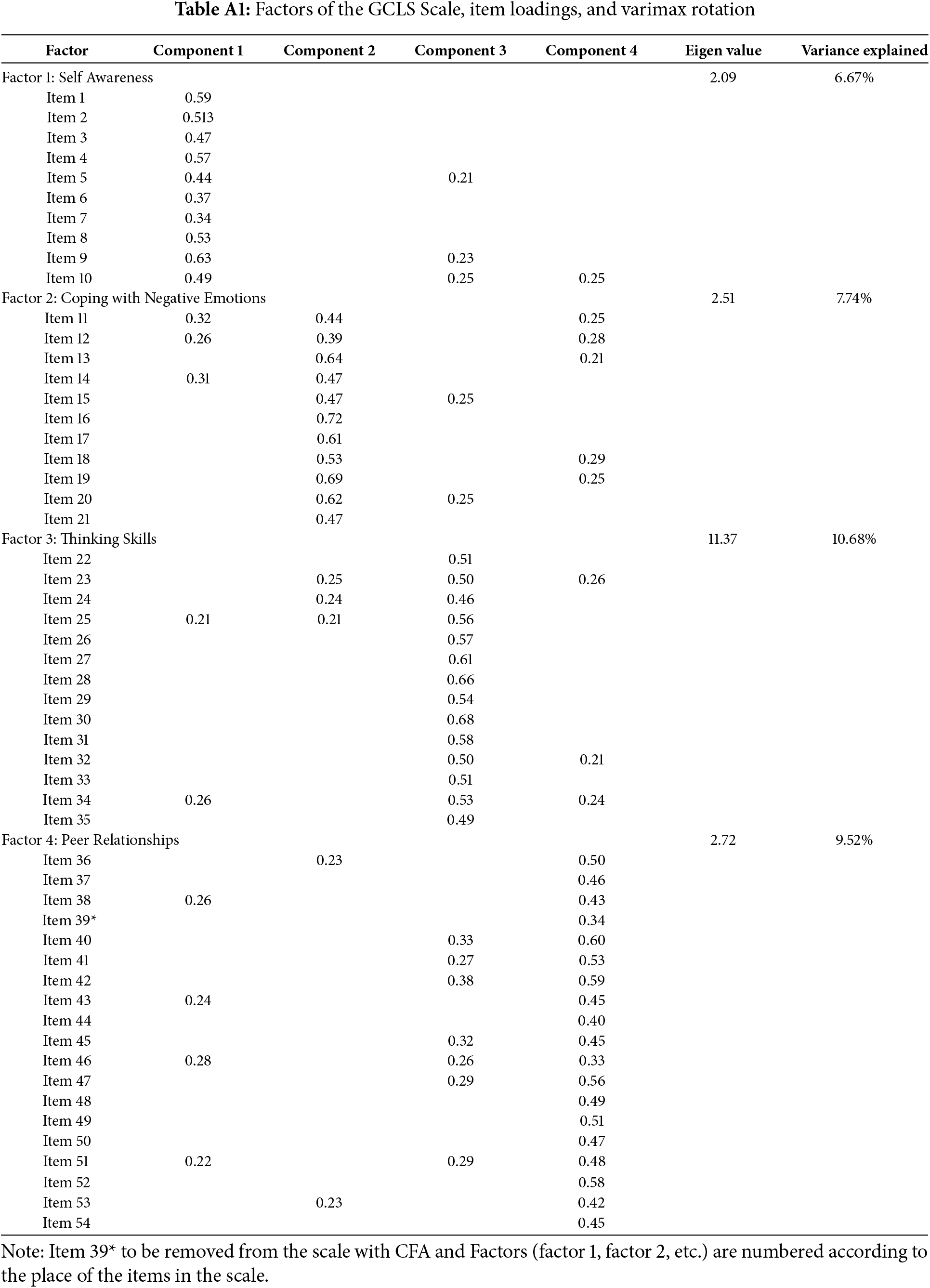

Following the EFA, a total of 89 items were included in the analysis, and the items were systematically eliminated based on their factor loadings and the 0.30 threshold in the rotated component matrix. Following the performance of PCA on the remaining 54 items, four components were identified as making a significant contribution to the overall variance. The PCA results revealed four factors, namely self-awareness, coping with negative emotions, thinking skills, and peer relationships. The factor loadings for these factors ranged from 0.33 to 0.72, with the total variance explained by these factors amounting to 34.60%. The detailed factor loadings, eigenvalues, and the explained variance for each scale are presented in Table A1 in Appendix A.

3.2 Confirmatory Factor Analysis

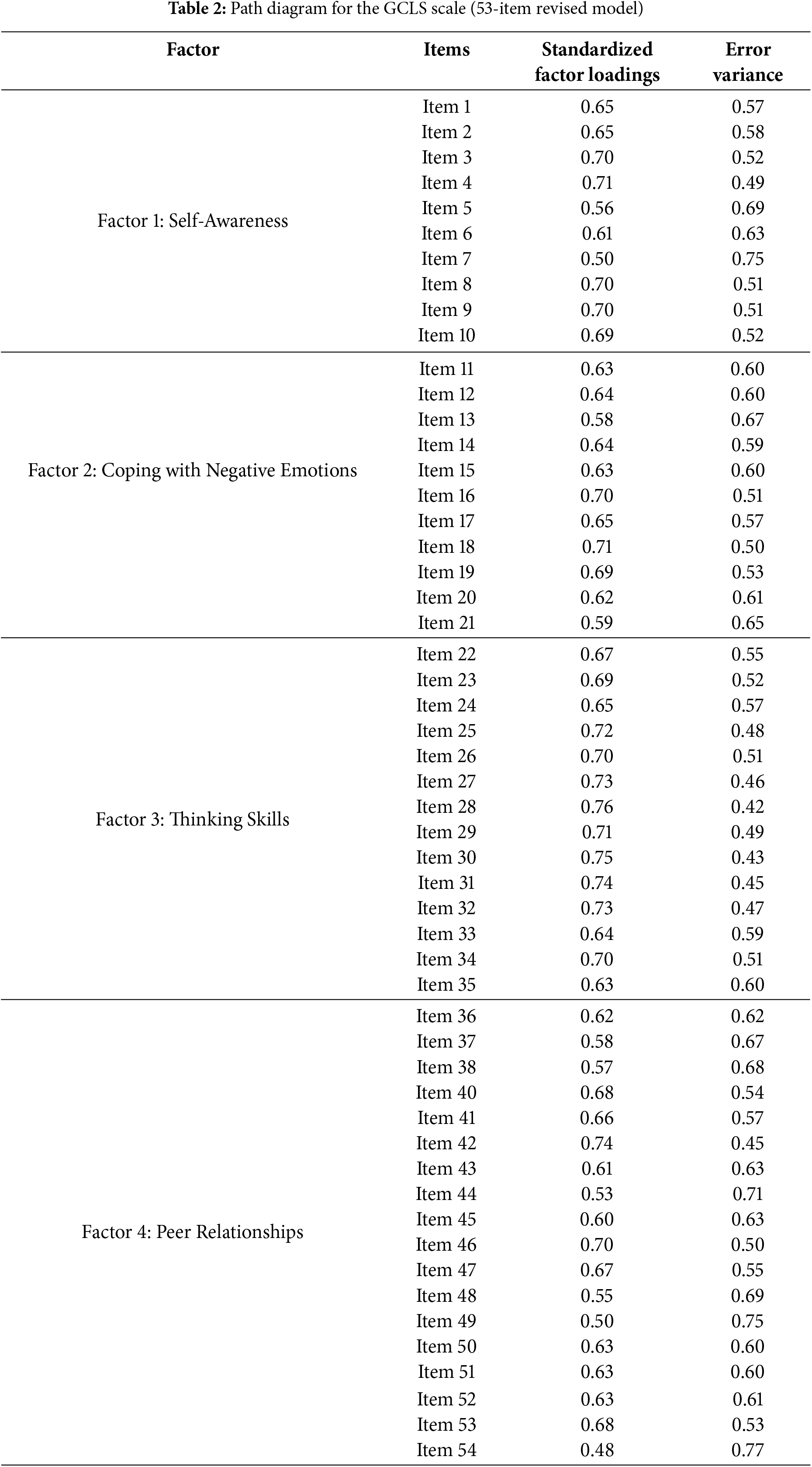

CFA was conducted to assess whether the data collected from the second sample (N = 885) confirmed the structure consisting of 54 items and four factors obtained as a result of EFA. The fit indices for the GCLS Scale indicated a satisfactory model fit: χ2/df = 2.54, CFI = 0.98, NFI = 0.97, NNFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.04, SRMR = 0.05. The significance of the factors in the four-factor model was evaluated using t-values. Due to the 39th item (“It is almost impossible for me to reject others”) showing a non-significant t-value and high error variance, it was removed from the model.

Following this adjustment, a revised model consisting of 53 items (excluding the 39th item) was evaluated, resulting in a path diagram displaying the standardized factor loadings (see Table 2). The fit indices for the revised four-factor model confirmed that the GCLS Scale provided a satisfactory fit to the data, further supporting the validity of the model [37].

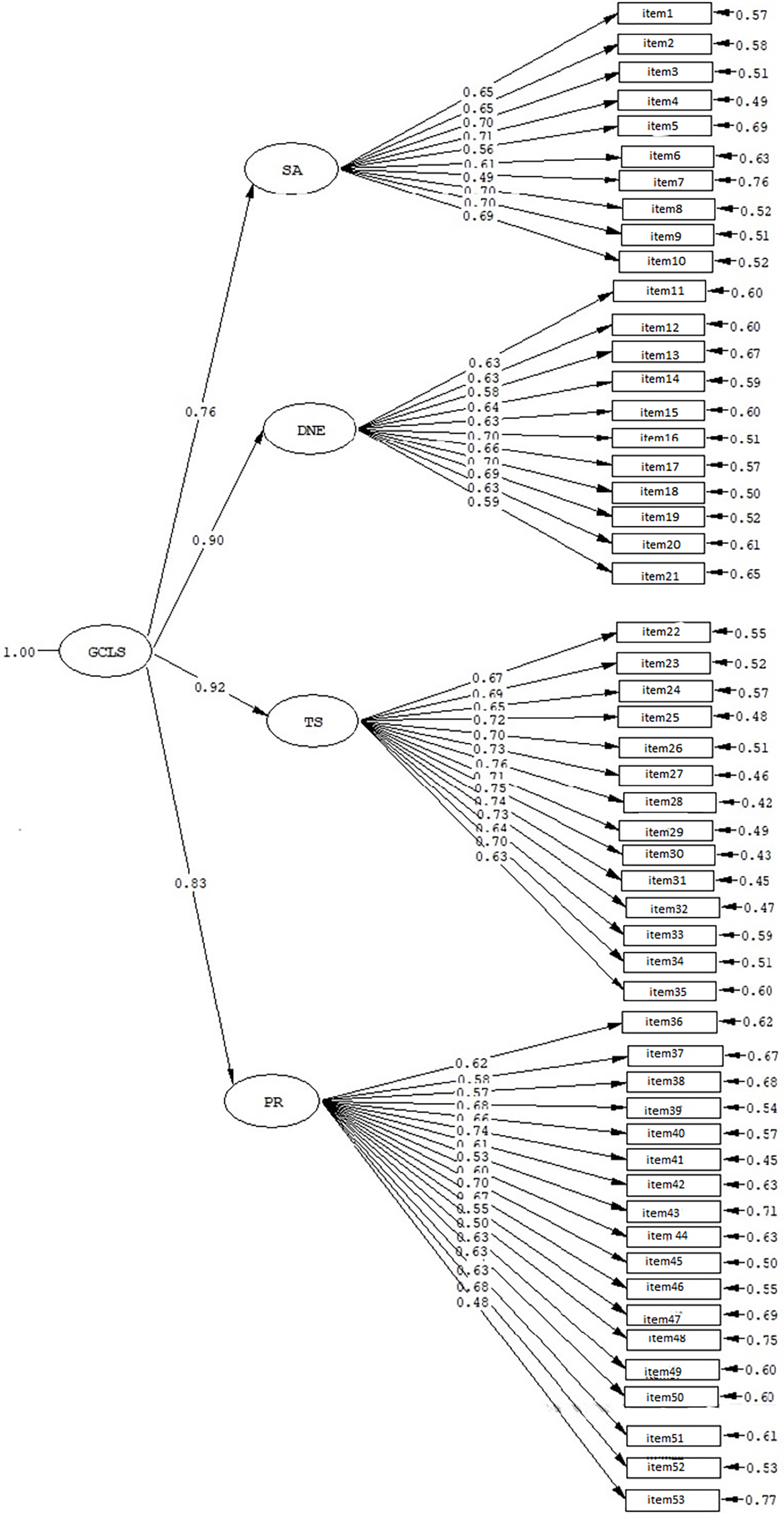

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to test the relationships between the subfactors of the GCLS Scale. The correlation coefficients between the subscales ranged from 0.60 to 0.75. It was concluded that the existence of a second-order factor could explain the common source among these factors, as indicated by the high correlations between the subfactors in the first-order CFA model. Consequently, a second-order CFA was conducted to test the hypothesis that the four factors of the GCLS Scale-self-awareness, coping with negative emotions, thinking skills, and peer relationships-load onto a single, broader latent life skills factor [39].

Second-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis

A second-order CFA was conducted to test the hypothesis that the four factors of the GCLS Scale load onto a single, broader latent factor. The purpose of this analysis was to evaluate the structural integrity of the model by examining the relationships between factors and aggregating them under a second-order construct.

The results demonstrated that the model showed a good fit according to the criteria specified in references [36,37]. In particular, the ratio of the chi-square to the degrees of freedom (χ2/df) was 2.51, with a statistically significant p-value. The SRMR was 0.05, and the RMR was 0.06. Furthermore, the CFI was 0.99, the NFI was 0.98, and the NNFI was 0.99, which indicates an excellent fit for the model. The RMSEA value of 0.04 provides further evidence that the model provides a close approximation to the data.

These results support the validity of the GCLS Scale, indicating that the four factors can be aggregated into a single, higher-order construct with a robust alignment to the data (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Second-order CFA path diagram of the GCLS Scale. Note. SA: Self-Awareness, CNE: Coping with Negative Emotions, TS: Thinking Skills, PR: Peer Relationships

3.3 Convergent and Discriminant Validity

To assess the convergent and discriminant validity of the GCLS Scale, Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) were computed between the GCLS Scale, SEAPSAS, and DAS. The analysis revealed a significant negative correlation between the GCLS Scale and DAS (r = −0.53, p < 0.01), indicating that students with higher life skills exhibit more negative attitudes towards drugs. Also, as expected, a positive correlation was identified between the GCLS Scale and SEAPSAS (r = 0.52, p < 0.01), indicating that individuals with higher life skills also demonstrate higher self-efficacy in protecting themselves from drug addiction. The results provide substantial evidence to support the convergent and discriminant validity of the GCLS Scale.

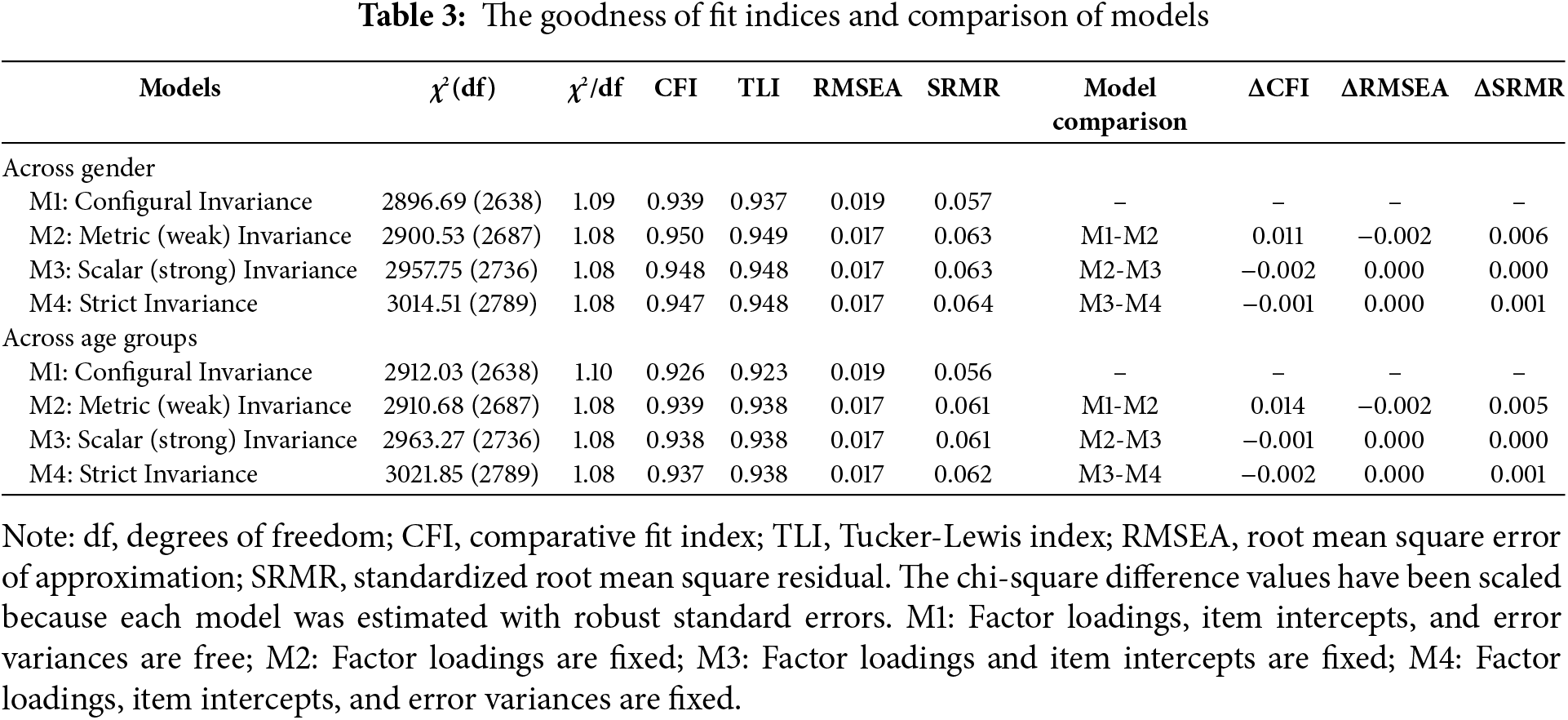

Measurement invariance is the process of evaluating whether a measurement tool maintains a consistent construct and meaning across different groups, such as gender and age. This is crucial for ensuring that the measurement is fair and reliable across diverse populations and is typically evaluated using MG CFA [40]. In this study, measurement invariance was tested across gender and age groups using Sample 2.

The assessment was conducted through MG CFA (see Table 3), with various models being tested at different stages of the analysis. There is no universal consensus on the best-fit indices or cutoff values for measurement invariance. In this study, the cutoff values suggested by Chen [41] and Rutkowski and Svetina [42] were used.

The configural invariance model was initially tested (using Sample 2) across gender and age groups. The fit indices obtained from this model met the criteria for configural invariance, with CFI ≥ 0.90, TLI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.08, and SRMR ≤ 0.06, thereby confirming that configural invariance was achieved [35]. The subsequent stage involved the assessment of metric invariance. The fit indices for the metric invariance model (M1–M2: ΔCFI = 0.011, ΔRMSEA = 0.002 for gender; ΔCFI = 0.014, ΔRMSEA = 0.002, ΔSRMR = 0.005 for age groups) demonstrated that the model fit was satisfactory. This result indicates that factor loadings were similar across gender and age groups [43]. The subsequent stage of the analysis involved testing scalar invariance. The next stage involved testing scalar invariance. The differences between the fit indices for scalar invariance and metric invariance (M2–M3: ΔCFI = 0.002, ΔRMSEA = 0.000, ΔSRMR = 0.000 for gender; ΔCFI = 0.001, ΔRMSEA = 0.000, ΔSRMR = 0.000 for age groups) showed that the cutoff points were met. This indicates that scalar invariance was achieved and that regression constants were similar across groups [41]. Finally, strict invariance was tested. The fit indices for strict invariance (M3–M4: ΔCFI = 0.001, ΔRMSEA = 0.000, ΔSRMR = 0.001 for gender; ΔCFI = 0.002, ΔRMSEA = 0.000, ΔSRMR = 0.001 for age groups) confirmed that the error terms were similar across gender and age groups, and strict invariance was achieved [39].

In summary, the GCLS Scale demonstrated full measurement invariance across gender and age groups. These findings suggest that the GCLS Scale provides consistent meaning and measurement across these groups.

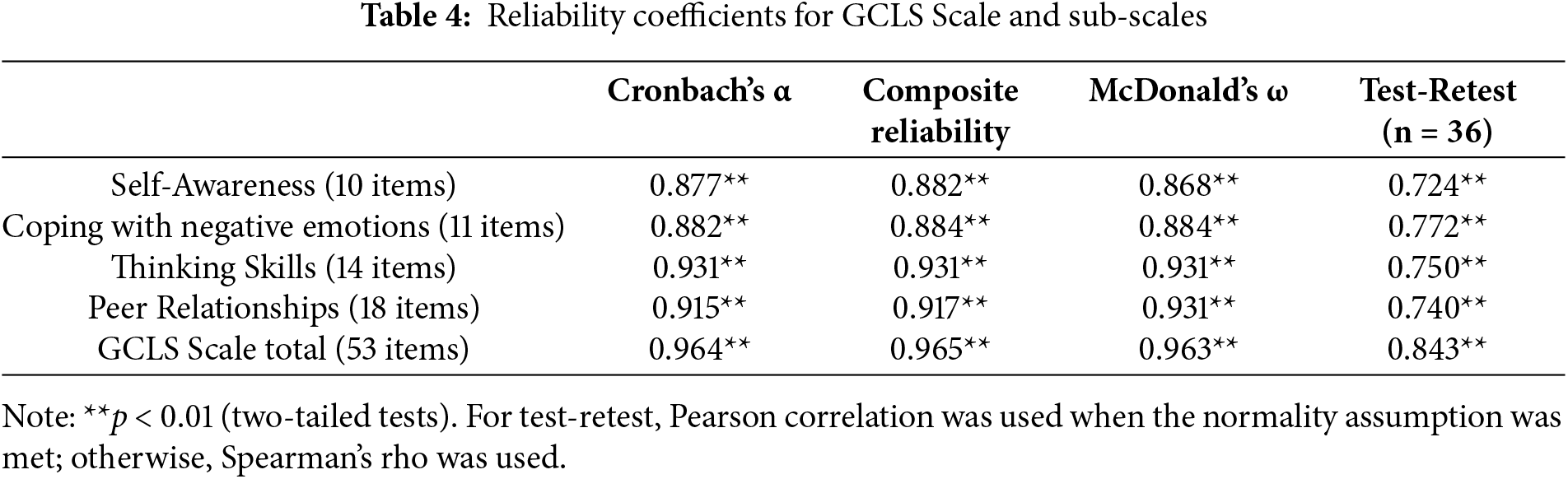

The reliability of the GCLS Scale was assessed using Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s ω, composite reliability, and test-retest reliability methods. The Cronbach’s α reliability coefficients for Self-Awareness (SA), Coping with Negative Emotions (CNE), Thinking Skills (TS), Peer Relationships (PR), and the total GCLS Scale were 0.87, 0.88, 0.93, 0.91, and 0.96, respectively. The scores are considered to be reliable in terms of high internal consistency. Another coefficient that is frequently recommended for the evaluation of reliability in measurement constructs is omega (ω), as proposed by McDonald [44]. McDonald’s ω coefficients for SA, CNE, TS, and PR dimensions and total score were 0.868, 0.884, 0.931, 0.931, and 0.963, respectively. The GCLS Scale’s stability over time was examined through a test-retest reliability assessment with a three-week interval. The results indicated that the subscales’ reliability coefficients ranged from 0.72 to 0.77, indicating an adequate level of reliability. Also, the analysis showed that the GCLS Scale’s test-retest reliability was at a good level.

Additionally, composite reliability, which is crucial for accurately estimating the internal consistency of a construct by accounting for both factor loadings and error variances [45], was computed based on the factor loadings and error variances obtained from CFA. The composite reliability coefficients for SA, CNE, TS, PR, and the total GCLS Scale were 0.88, 0.88, 0.93, 0.91, and 0.96, respectively (see Table 4).

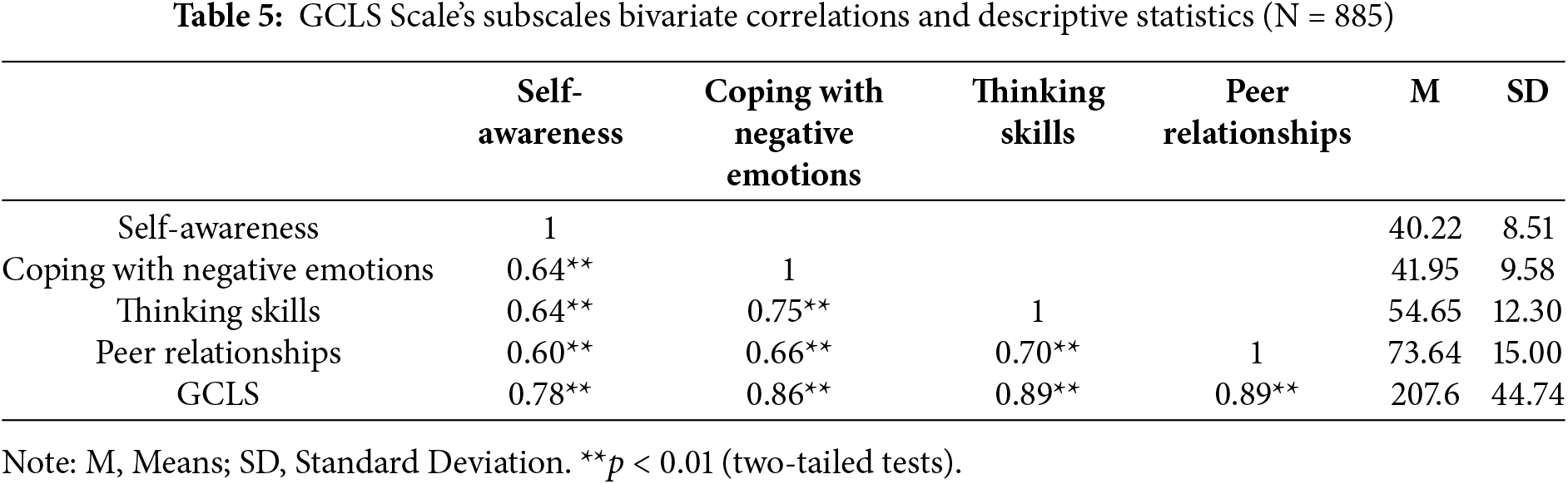

Finally, the mean scores for the GCLS Scale (Mean = 207.65, SD = 44.74), as well as for the sub-scales of Self-Awareness (Mean = 40.22, SD = 8.51), Coping with Negative Emotions (Mean = 41.95, SD = 9.58), Thinking Skills (Mean = 54.65, SD = 12.30), and Peer Relationships (Mean = 73.64, SD = 15.00) were relatively high (see Table 5).

The bivariate relationships between the GCLS Scale and its subscales indicate that life skills consist of interrelated dimensions. Positive high correlations were found between GCLS and self-awareness, coping with negative emotions, thinking skills, and peer relationships (r = 0.78, 0.86, 0.89, 0.89; p < 0.01). Furthermore, the intercorrelations among the subscales ranged from 0.60 to 0.75, with all relationships positive and statistically significant. Significant correlations were observed between all sub-scale scores and the total scale score, providing further support for the reliability of the GCLS Scale (see Table 5).

This study sought to expand the literature on life skills for adolescents in non-Western countries by developing a self-reported instrument to evaluate constructs targeted by a particular drug prevention program for Turkish adolescents. The construct validity of the GCLS Scale via EFA and CFA and the measurement invariance of the related models were tested across age and gender groups. The findings supported the conceptual framework underlying the GCLS Scale with four sub-scales (self-awareness, coping with negative emotions, thinking skills, and peer relationships) that are subsumed under a single broader latent factor of the GCLS Scale. Measurement invariance results indicate that the scores obtained from this scale can be used to compare gender and age groups.

As a result of EFA, a 4-factor structure consisting of 54 items that explain 34.60% of the total variance was obtained. The theoretically constructed measurement model verified by the data was tested with CFA. It was determined that the GLCS Scale with 53 items under a 4-factor structure was confirmed as a model. However, due to the high correlation values between factors, it was thought that a second-order structure could be defined and a second-level CFA was performed. Considering the fit indices estimated and the standardized factor loadings as a result of the second-order CFA analysis, it was found that the fit indices were sufficient and the factor loadings were between 0.76 and 0.92. Accordingly, it was determined that the 4-factor structure of the GCLS Scale, consisting of 53 items, was verified as a model under the Life Skills second order and adapted to the data at a good level. As a result, it can be stated that the measurements obtained from the GCLS Scale provided construct validity. In addition, the study aims to assess the measurement invariance of the GCLS Scale across gender and age groups. Results revealed that full invariance (model equivalency) was achieved in the gender and age subsamples. Information on measurement invariance provides evidence of the degree to which an instrument measures the same latent dimension(s) in all age and gender groups.

Results of the present study revealed that the life skills scores of adolescents were relatively high. Some authors have indicated higher levels of life skills in the adolescent population [25], whereas others have reported average levels [21]. These contradictory results may be because the life skills scales were developed for different constructs and also have different subscales or not to ensure measurement invariance between age groups. In the present study, the high life skills scores may be due to the fact that the mean age of the participants is below the age of 15 considered a critical age for the onset of drug use.

Some studies have found significant differences in adolescents’ social [25] and life skill levels [21,46] regarding gender, whereas others have found no difference [47]. The subscales of the GCLS Scale are self-awareness, coping with negative emotions, thinking skills, and peer relationship skills, which are gender-sensitive skills. In previous studies, boys exhibited more positive attitudes toward their bodies than did girls [48]. Girls coped more maladaptively with common stressors than boys [49]. Gender-related difference in problem-solving ability is an issue of great controversy, but Zach et al. [50] reported that boys performed better than girls on the problem-solving task. Girls reported higher levels of interpersonal functioning and are more concerned about the quality of their interpersonal relationships [29] in addition, boys and girls differ in nature. To what extent these different findings in the literature about gender differences in life skills are realistic, they are correct in proportion to the comparability of the relevant structure in the gender groups. Strict measurement invariance across gender was obtained in the present study that indicated the GCLS was assessing the same latent structure in girls and boys. In other words, observed scores from the GCLS Scale can be compared more realistically across gender groups.

For the convergent and discriminant validity study, the correlation among the GCLS Scale, SEAPSAS, and DAS was calculated. Correlation analysis results were in line with the previous studies examining the relationship between life skills self-efficacy and attitudes [51,52]. Individuals with high self-efficacy make more effort to avoid harmful behaviors such as addiction and cope more effectively with the challenges they encounter. Individuals with high self-efficacy are more resilient to drug use and use life skills more effectively [53,54]. Furthermore, it is stated in the literature that individuals with high life skills can evaluate the possible harms of substance use more accurately and develop more negative attitudes towards substance use and that there is a strong negative correlation between life skills and attitudes towards drug use [55]. Therefore, it can be said that provided GCLS Scale’s convergent and discriminant validity.

The reliability of the GCLS Sale was examined by Cronbach’s α. McDonald’s ω and composite reliability methods. The Cronbach α reliability of the scale was calculated as 0.96. Measurements with a reliability coefficient of 0.70 and above are considered to be reliable.

5 Limitation and Future Research

The current study is not without limitations. First, because the GCLS Scale is a self-report measure. The responses may have been influenced by social desirability attitudes, which often endanger self-report scales. Second, it is necessary to expand the sample to allow a broader generalization of the findings. There is a need to assess the generalizability of the findings in different samples in different cities in Türkiye. Future research might provide a more in-depth exploration of the GCLS Scale’s psychometric properties, such as test-retest reliability, divergent validity, and response styles. We would encourage future research to assess the temporal stability of the GCLS Scale over time and with different adolescent populations (e.g., homeless. and immigrants). Despite those limitations described above, the present study makes further contributions to the literature focused on creating a measurable and valid evaluation of a life skills-based drug prevention program and also will provide data to funders and decision-makers about life skills and the impacts of programs on youth. Ultimately, the GCLS Scale proves a useful instrument for researchers and practitioners interested in prevention and intervention programs based on skills training in adolescence.

In summary, the findings arising from this validation study were generally encouraging and robust. The GCLS Scale, which assesses four skills in a self-reported format, is a valid and reliable scale and a cost-effective tool with considerable potential utility in monitoring life skills in adolescent populations. It is also a potentially useful tool for evaluating interventions aimed at improving and developing these skills in different groups of adolescents in school. The use of the GCLS Scale before and after interventions would also help to measure their impact on strengthening life skills.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank the participants who responded to our instruments.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Turkish Green Crescent Society under Grant [41402653-160-6/333].

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Ayşe Esra İşmen Gazioğlu, Halime Yıldırım Hoş; data collection: Ayşe Esra İşmen Gazioğlu; analysis and interpretation of results: Ayşe Esra İşmen Gazioğlu, Halime Yıldırım Hoş, Şener Büyüköztürk; draft manuscript preparation: Ayşe Esra İşmen Gazioğlu, Halime Yıldırım Hoş, Şener Büyüköztürk. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: All procedures were approved by the Istanbul Institutional Review Board (No. E.21319083). Informed consent was obtained from all participants’ parents included in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Husted J, Garland G. The validity of the TMR as a measure of achievement in life adjustment skills. J Inst Psyc. 1977;4:28–32. [Google Scholar]

2. World Health Organization. Skills for health: skills-based health education including life skills: an important component of a child-friendly/health-promoting school. Geneva, Switzerland: The World Health Organization’s Information Series on School Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]

3. Botvin GJ, Baker E, Dusenbury L, Tortu S, Botvin EM. Preventing adolescent drug abuse through a multimodal cognitive-behavioral approach: results of a 3-year study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58(4):437–46. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.58.4.437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Türkiye Uyuşturucu ve Uyuşturucu Bağımlılığı İzleme Merkezi-TUBİM. Avrupa uyuşturucu ve uyuşturucu bağımlılığı izleme merkezi ulusal raporu [European monitoring center for drugs and drug addiction national report]. Ankara, Türkiye: TUBİM; 2013. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

5. Bilaç Ö, Kavurma C, Önder A, Doğan Y, Uzunoğlu G, Ozan E. A clinical and sociodemographic evaluation of youths with substance use disorders in a child and adolescent inpatient unit of a mental health hospital. J Clin Psy. 2019;22(4):463–71. doi:10.5505/kpd.2019.30075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ogel K, Tamar D, Evren C, Cakmak D. Prevalence of cigarette, alcohol and substance use among high school youth. Turk Psych. 2001;12(2):47–52. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

7. Yoldaş C, Demircioğlu H. Madde kullanımı ve bağımlılığını önlemeye yönelik psikoeğitim programlarının incelenmesi. Bağımlılık Derg. 2020;21:72–91. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

8. Aslan TK, Batı S. Addiction among high school students: determination of nicotine, substance, game, and Internet addiction levels. J Subst Use. 2024;2024(4):1–7. doi:10.1080/14659891.2024.2412580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Cinar RK. Psychoactive substance use and related factors among high schools. Haydarpasa Numune Med J. 2019;61(1):58–64. doi:10.14744/hnhj.2019.71677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Şirin H, Uzun ME. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adolescent patients treated in ÇEMATEM with the diagnosis of substance use disorders: Bursa sample. Turk J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2021;28(2):151–8. doi:10.4274/tjcamh.galenos.2021.46330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Coskuner Z, Büyükçelebi H, Kurak K, Açak M. Examining the impact of sports on secondary education students’ life skills. Int J Prog Edu. 2021;17(2):292–304. [Google Scholar]

12. Seevers BS, Dormody TJ, Clason DL. Devleoping a scaled to research and evaluate youth leadership like skills development. J Agric Educ. 1995;36(2):28–34. doi:10.5032/jae.1995.02028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Darden CA, Ginter EJ. Life-skills development scale—adolescent form: the theoretical and therapeutic relevance of life-skills. J Ment Health Couns. 1996;18(2):1–18. [Google Scholar]

14. Picklesimer B, Miller T. Life-skills development inventory—college form: an assessment measure. J Coll Stud Dev. 1998;39(1):100–10. [Google Scholar]

15. MacAulay AP, Griffin KW, Botvin GJ. Initial internal reliability and descriptive statistics for a brief assessment tool for the Life Skills Training drug-abuse prevention program. Psychol Rep. 2002;91(2):459–62. doi:10.2466/pr0.2002.91.2.459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Bailey SJ, Deen MY. Development of a web-based evaluation system: a tool for measuring life skills in youth and family programs. Fam Relat. 2002;51(2):138–47. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2002.00138.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Mincemoyer CC, Perkins DF. Measuring the impact of youth development programs a national online youth life skills evaluation system. Forum Fam Consum Issues. 2005;10(2):1–9. [Google Scholar]

18. Robinson CW, Zajicek JM. Growing minds: the effects of a one-year school garden program on six constructs of life skills of elementary school children. HortTechnology. 2005;15(3):453–7. doi:10.21273/HORTTECH.15.3.0453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Greene HA. Learn from yesterday, live for today, hope for tomorrow: the development of a life skills scale [master’s thesis]. Oxford, OH, USA: Miami University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

20. García-Alba L, Postigo Á, Gullo F, Muñiz J, Del Valle J. PLANEA independent life skills scale: development and validation. Psicothema. 2021;2(33):268–78. doi:10.7334/psicothema2020.450. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Vranda MN. Development and standardization of life skills scale. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2009;20:17–28. [Google Scholar]

22. Erawan P. Developing life skills scale for high school students through mixed methods research. Eur J Sci Res. 2010;47(2):169–86. [Google Scholar]

23. Subasree DR, Nair DAR. The life skills assessment scale: the construction and validation of a new comprehensive scale for measuring life skills. IOSR J Humanit Soc Sci. 2014;19(1):50–8. doi:10.9790/0837-19195058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kase T, Bannai K, Oishi K. Behavior and thought constructing life skills in Japanese adults: an exploratory study using quantitative text analysis. Jpn J Soc Psychol. 2016;32:60–7. doi:10.14966/jssp.0929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Erduran-Avcı D, Korur F. Evaluation of the life skills of students in adolescence: scale development and analysis. J Sci Learn. 2022;5(2):226–41. doi:10.17509/jsl.v5i2.41071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mehta N, Kapoor H. Validating tools to measure life skills among adolescents in India. Monk Pray Work Pap. 2024;20(3):221–8. doi:10.1177/09731342241236304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Vergara-Torres AP, Ortiz-Rodríguez V, Reyes-Hernández O, López-Walle JM, Morquecho-Sánchez R, Tristán J. Validation and factorial invariance of the life skills ability scale in Mexican higher education students. Sustainability. 2022;14(5):2765. doi:10.3390/su14052765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ellickson PL, Morton SC. Identifying adolescents at risk for hard drug use: racial/ethnic variations. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25(6):382–95. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00144-X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Moeini B, Hazavehei SMM, Faradmal J, Ahmadpanah M, Dashti S, Hashemian M, et al. The relationship between readiness for treatment of substance use and self-efficacy based on life skills. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2022;21(1):364–76. doi:10.1080/15332640.2020.1772930. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Eker F, Akkus D, Kapisiz O. The development and psychometric evaluation study of self-efficacy for protecting adolescences from substance abuse scale. Psi Hem Derg. 2013;4(1):7–12. doi:10.5505/phd.2013.74936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Aksoy K. Lise öğrencilerinin bağımlılık yapan maddelere ilişkin tutumları ve bu tutumlara etki eden değişkenlerin incelenmesi (Malatya ili örneği) [High school students’ attitudes towards addictive substances and investigation of the variables affecting these attitudes (Malatya city sample)] [master’s thesis]. Malatya, Türkiye: İnönü University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

32. İşmen-Gazioğlu E. Scope and content of green crescent life skills programme. In: 2nd International Symposium on Drug Policy and Public Health; 2018 Nov 26–27; İstanbul, Türkiye. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

33. DeVellis RF. Scale development: theory and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage; 2017. [Google Scholar]

34. Skeen S, Laurenzi CA, Gordon SL, du Toit S, Tomlinson M, Dua T, et al. Adolescent mental health program components and behavior risk reduction: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2):e20183488. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Kline TJB. Psychological testing: a practical approach to design and evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

36. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY, USA: Guilford; 2015. [Google Scholar]

38. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. London, UK: Pearson Education; 2013. [Google Scholar]

39. Iversen MM, Norekvål TM, Oterhals K, Fadnes LT, Mæland S, Pakpour AH, et al. Psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the fear of COVID-19 scale. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2022;20(3):1446–64. doi:10.1007/s11469-020-00454-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Byrne BM, van de Vijver FJR. Testing for measurement and structural equivalence in large-scale cross-cultural studies: addressing the issue of nonequivalence. Int J Test. 2010;10(2):107–32. doi:10.1080/15305051003637306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Chen FF. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct Equ Model. 2007;14(3):464–504. doi:10.1080/10705510701301834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Rutkowski L, Svetina D. Assessing the hypothesis of measurement invariance in the context of large-scale international surveys. Educ Psyc Meas. 2014;74(1):31–57. doi:10.1177/0013164413498257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ogden T, Olseth A, Sørlie MA, Hukkelberg S. Teacher’s assessment of gender differences in school performance, social skills, and externalizing behavior from fourth through seventh grade. J Edu. 2023;203(1):211–21. doi:10.1177/00220574211025071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. McDonald RP. Test theory: a unified treatment. Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. [Google Scholar]

45. Hancock GR, Mueller RO. The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences. 2nd ed. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge; 2021. [Google Scholar]

46. Salavera C, Usán P, Jarie L. Emotional intelligence and social skills on self-efficacy in Secondary Education students. Are there gender differences? J Adolesc. 2017;60(1):39–46. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.07.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Koff E, Rierdan J, Stubbs ML. Gender, body image, and self-concept in early adolescence. J E Adoles. 1990;10(1):56–68. doi:10.1177/0272431690101004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Hampel P, Petermann F. Age and gender effects on coping in children and adolescents. J Youth Adoles. 2005;34(2):73–83. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-3207-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Mefoh PC, Nwoke MB, Chukwuorji JC, Chijioke AO. Effect of cognitive style and gender on adolescents’ problem solving ability. Think Ski Creat. 2017;25(1):47–52. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2017.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Zach S, Yazdi-Ugav O, Zeev A. Academic achievements, behavioral problems, and loneliness as predictors of social skills among students with and without learning disorders. Sch Psyc Int. 2016;37(4):378–96. doi:10.1177/0143034316649231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Shaluhiyah Z, Indraswari R, Kusumawati A, Musthofa SB. Life skills education to improvement of teenager’s knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy and risk health behavior. Kemas. 2021;17(1):1–8. doi:10.15294/kemas.v17i1.22474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Panahi S, Seifi H, Garousi A, Eghbalpour F, Noroozi Fard A. Impact of life skills education on changing atti-tudes toward substance abuse and promoting healthy lifestyle behaviors in female students. Razavi Interna-Tional J Med. 2024;12(2):24–32. [Google Scholar]

53. Fertman CI, Primack BA. Elementary student self efficacy scale development and validation focused on student learning, peer relations, and resisting drug use. J Drug Educ. 2009;39(1):23–38. doi:10.2190/DE.39.1.b. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Lipien L, Ismajli F, Rigg KK. Psychometric properties of the LifeSkills Training middle school health survey. Psychol Sch. 2021;58(12):2374–91. doi:10.1002/pits.22598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Bonyani A, Safaeian L, Chehrazi M, Etedali A, Zaghian M, Mashhadian F. A high school-based education concerning drug abuse prevention. J Educ Health Promot. 2018;7(1):88. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_122_17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools