Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Self-Esteem as a Mediator: Analyzing Its Impact on Parental Attachment and Adolescent Delinquency

1 Department of Psychology, Amity University Dubai Campus, Dubai International Academic City, Dubai, 345019, United Arab Emirates

2 Faculty of Human Ecology, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, 43400, Malaysia

3 Department of Internal Medicine, Section Nursing Science, Erasmus University Medical Center (Erasmus MC), Rotterdam, 3015 GD, The Netherlands

4 Research Centre Innovations in Care, Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences, Rotterdam, 3015 EK, The Netherlands

5 Department of Early Childhood and Family Education, National Taipei University of Education, Taipei, 106320, Taiwan

6 Faculty of Human and Social Sciences, Hassiba Benbouali University of Chlef, Chlef, 02076, Algeria

7 Department of Psychiatric Nursing and Mental Health, Faculty of Nursing, Alexandria University, Smouha, Alexandria, 21527, Egypt

8 Institute of Allied Health Sciences, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan City, 701401, Taiwan

9 School of Nursing, College of Nursing, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, 807378, Taiwan

* Corresponding Authors: Mahshid Manouchehri. Email: ; Chung-Ying Lin. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Father/Mother Absence and Moral Emotion)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(7), 1013-1028. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.061088

Received 17 November 2024; Accepted 01 July 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

Background: While various factors contributing to delinquency have been explored, the role of self-esteem in this specific context has received little attention. Hence, this study aims to investigate the complex issue of adolescent delinquency in Iran by focusing on the mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between parental attachment and delinquent behavior. Methods: Using the multistage cluster random sampling method, the research involved 528 high school students in Tehran. Each student completed validated scales assessing their parental attachment, self-esteem, and delinquency at school. Multiple regression analyses with the Sobel test and bootstrapping method were used to examine mediated effects. Results: The findings reveal that self-esteem significantly mediates the relationship between maternal attachment and delinquency (standardized coefficient = −0.0292; p = 0.04). Adolescents with secure maternal attachments tend to exhibit higher self-esteem, which reduces the likelihood of delinquent behavior. In contrast, paternal attachment did not show a significant mediating effect in this study. These results underscore the importance of cultivating secure maternal relationships and fostering positive self-esteem to address adolescent delinquency. Conclusion: The study suggests that targeted interventions that strengthen maternal attachment and boost self-esteem could effectively mitigate delinquent behaviors among Iranian adolescents. These interventions should prioritize the emotional support and value of secure maternal bonds as key factors in promoting healthy adolescent development.Keywords

Juvenile delinquency (here after delinquency also indicates juvenile delinquency), defined as unlawful acts committed by individuals under the age of 18, remains a significant global challenge with profound implications for public safety, economic stability, and social cohesion [1,2]. The complexity of juvenile delinquency arises from an interplay of social, psychological, and environmental factors, including family dynamics, peer influence, and broader societal conditions [3]. Delinquent behaviors range from minor infractions to serious criminal offenses such as theft, assault, and homicide [4]. While definitions of juvenile delinquency vary across legal systems and cultural contexts, it generally encompasses offenses committed between the minimum age of criminal responsibility and legal adulthood, typically set at 18 years [3,4].

Among the many factors contributing to juvenile delinquency, family dynamics—particularly parental attachment—play a crucial role in shaping adolescent behavior [5]. Research indicates that strong parental bonds, effective supervision, and positive parent-child relationships serve as protective factors against delinquency [6]. Conversely, inadequate parental monitoring, inter-parental conflict, and weak emotional attachments increase adolescents’ susceptibility to delinquent behaviors [7]. Secure parental attachment, particularly with mothers, fosters emotional stability, self-control, and moral development, thereby reducing delinquency risks [8,9]. Additionally, self-esteem mediates this relationship, with higher self-esteem reinforcing resilience against negative influences such as peer pressure and external stressors [10].

Empowerment strategies that strengthen family relationships and enhance adolescents’ self-esteem have proven effective in mitigating delinquency, particularly in specific cultural contexts such as Iranian society [11]. However, delinquency is not shaped solely by family factors—external influences such as socioeconomic status, peer associations, and exposure to violence must also be considered [12]. Therefore, a comprehensive approach that integrates parental attachment, self-esteem development, and broader social interventions is essential for effectively addressing juvenile delinquency [13].

As conceptualized by Rosenberg, self-esteem represents a core evaluative dimension of self-concept, encompassing individuals’ global perceptions of their worth and significance. It is a stable yet dynamic construct influenced by internal evaluations and external experiences, reflecting a balance between self-competence and self-value [14]. Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) operationalizes this concept, assessing global self-esteem through ten items designed to capture positive and negative self-perceptions, thus preventing response bias [14,15]. The scale has robust psychometric properties and is widely validated across diverse populations and cultural contexts, making it the most commonly used measure of self-esteem in psychological research [16]. Rosenberg’s framework underscores self-esteem’s pivotal role in mental health and life satisfaction, highlighting its function as both an outcome and a determinant of social and psychological experiences [17]. This theoretical perspective forms a foundation for understanding self-esteem as a multidimensional construct, integral to addressing its implications for individual development and behavioral outcomes.

Research demonstrated that self-esteem exerts a stronger causal influence on delinquency than delinquency does on self-esteem, particularly in lower-class youth, supporting the theory that delinquent behavior can serve self-enhancing functions for those with low self-esteem [18]. Similarly, findings emphasized that delinquency among adolescents with low self-esteem often acts as a compensatory mechanism, while self-esteem has a limited direct influence on teenage orientations [19]. However, the assumption of a linear relationship was challenged, showing that high self-esteem is not always a protective factor against delinquency and calling for further exploration of the mechanisms underlying these dynamics [20]. These studies underscore the complexity of self-esteem’s role in adolescent behavior and its broader developmental implications. In addition to self-esteem theory, the parent-child relationship [21] forms the cornerstone of a child’s emotional and social development, with attachment playing a central role in shaping these dynamics [22].

Attachment Theory, as proposed by John Bowlby in 1982, highlights the importance of early relationships with caregivers in shaping emotional development and resilience [23]. Secure attachment provides a foundation for emotional regulation, social competence, and exploration while also serving as a haven of safety during distress. In contrast, insecure attachment, often resulting from neglect or abusive parenting, can lead to emotional insecurity, diminished self-esteem, and vulnerability to risks such as delinquency due to a lack of stability and support during critical developmental phases [24,25]. Research demonstrates that strong parent-child bonds mediate the effects of family emotional expressiveness on adolescents’ psychological well-being, emphasizing the role of positive family dynamics in fostering resilience [26]. Secure attachments are also linked to higher interpersonal neural synchrony (INS), reflecting stronger relational quality, while insecure attachment is associated with atypical neural patterns [27]. Furthermore, both mother- and father-child attachment quality predict better emotion regulation in children, underscoring the importance of nurturing caregiving behaviors [28].

Parent-child attachment significantly reduces delinquent behavior, as strong bonds foster trust, communication, and emotional security. Poor attachment to parents has been consistently linked to higher levels of delinquency, with studies highlighting that better respondents lower the likelihood of misbehavior, vandalism, and substance use among adolescents [9]. A meta-analysis revealed a small-to-moderate effect size (r = 0.18) between weak parental attachment and delinquency [9]. Additionally, family attachment mediates delinquency by promoting adolescent self-disclosure and enhancing parental knowledge, demonstrating the importance of reciprocal family dynamics [29].

Research has consistently highlighted the differential roles of fathers and mothers in shaping juvenile delinquency. Studies show that attachment to mothers has a stronger relationship with delinquency compared to attachment to fathers [9]. Adolescents tend to trust their mothers more than their fathers, particularly regarding communication and alienation, which negatively correlate with delinquent behaviors [9]. Moreover, while maternal and paternal behavioral control reduces delinquency levels, paternal behavioral control may paradoxically predict faster growth in delinquency over time [30]. These findings underscore the nuanced influence of maternal and paternal dynamics, necessitating a differentiated approach when addressing adolescent delinquency.

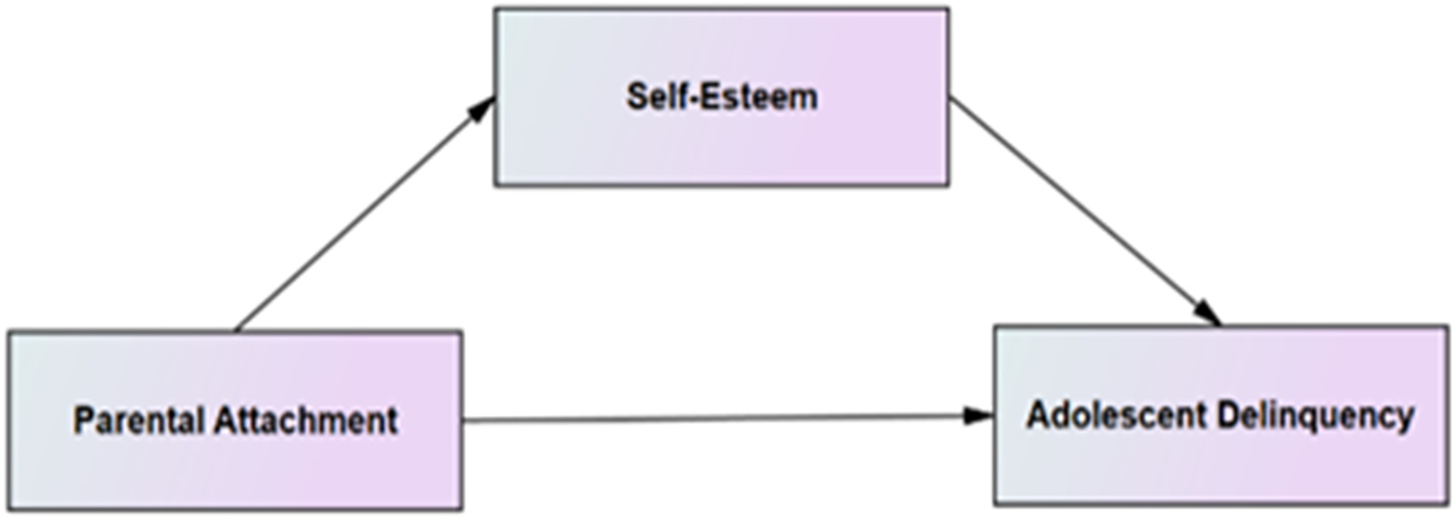

Social Control Theory, developed by Travis Hirschi in 1969, emphasizes the significance of social bonds in mitigating delinquent behavior [31]. The theory asserts that individuals are less inclined to engage in delinquency when they possess robust social connections. These connections include attachments to family, educational institutions, and other societal entities [31]. Insecure attachments can undermine these social bonds, particularly within familial contexts, rendering adolescents more vulnerable to adverse influences [32]. In the absence of strong affiliations with positive social structures, individuals may experience a deficiency in the constraints necessary to deter them from engaging in delinquent activities [33]. Social Control Theory highlights the critical role of fostering strong social bonds as a protective measure against delinquency, thereby underscoring the preventive function of positive social relationships in influencing behavior [31]. Fig. 1 shows the theoretical framework of this study.

Figure 1: The theoretical framework

In Iran, juvenile delinquency poses a growing challenge, driven by a combination of socio-cultural factors, strained family relationships, and low self-esteem. Iran’s unique cultural and societal norms, such as familial honor, religious expectations, and social pressures, shape adolescents’ behaviors and interactions within their environments. These dynamics help us understand the interplay between parental attachment, self-esteem, and delinquency.

Although previous studies have examined the relationships between parental attachment, self-esteem, and delinquency, significant gaps remain in understanding how these factors interact across diverse cultural contexts. Much of the existing global literature has focused on Western populations, leaving an insufficient understanding of these dynamics in non-Western societies, particularly in regions like Iran. Previous findings indicate that low self-esteem among Iranian adolescents increases vulnerability to delinquent behaviors [34]. Moreover, insecure attachment styles—stemming from neglect, abuse, or inconsistent parenting—have been linked to both diminished self-esteem and a greater likelihood of engaging in deviant actions [10,34]. Hence, building on prior research, this study aims to investigate the mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between parental attachment and adolescent delinquency.

This study posits that both paternal and maternal attachment are directly associated with delinquent behavior among adolescents, consistent with research showing the importance of secure parental bonds in fostering emotional and social well-being [21]. Additionally, self-esteem is hypothesized to mediate the relationship between parental attachment and delinquency, with higher self-esteem as a protective factor against deviant behaviors [23,35]. By addressing these gaps, the current study contributes to the broader understanding of adolescent delinquency by exploring these relationships within a non-Western context. Given the significant role of family dynamics and individual psychological factors in shaping adolescent behavior, this study explores how parental attachment and self-esteem influence delinquency among Iranian youth. While extensive research has examined juvenile delinquency in various cultural contexts, there remains a need to understand how these factors operate within Iran’s unique socio-cultural framework. The collectivist nature of Iranian society, along with distinct family structures and social norms, may shape the ways in which parental attachment and self-esteem impact delinquent behavior.

This study investigates the mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between maternal and paternal attachment and adolescent delinquency. Specifically, it seeks to determine how parental bonds influence self-esteem and, in turn, how self-esteem affects the likelihood of delinquent behavior. By examining these relationships, the study intends to provide culturally relevant insights that can inform intervention strategies to reduce delinquency among Iranian adolescents. The findings are expected to contribute to developing targeted, evidence-based approaches that emphasize strengthening parental attachments and fostering self-esteem as protective factors against delinquency.

4.1 Study Design, Setting, and Sampling Procedures

This observational study recruited middle and late adolescents aged 15 to 17 in Tehran. The total population of high school students in Tehran is 170,205, with a slightly higher number of females (n = 90,368) than males (n = 79,837). A multistage cluster random sampling method was employed to identify potential respondents, ensuring that the sample selection followed random selection principles. Initially, the geographical distribution of schools in Tehran, as provided by the Ministry of Education, was categorized into five distinct regions: North, West, East, South, and Centre. Each region encompasses several districts: the North includes districts 1, 2, and 3; the West comprises districts 5, 9, and 10; the East consists of districts 4, 8, 13, and 14; the South includes districts 15, 16, 17, 18, and 19; and the Centre comprises districts 6, 7, 11, and 12. Subsequently, one educational district was randomly selected from each geographical region, followed by the selection of one girls’ school and one girls and boys’ school from each district. Each school has three grades—first, second, and third—containing multiple classes. One class was randomly chosen from each grade, and all students within the selected class were invited to participate in the study. Informed consent was obtained from participants and their guardians. Ethical approval from the Ethics Research Committee of Universiti Putra Malaysia (ERGS/1/2012/SS03/UPM/01/1) was obtained. We confirm that all methods related to the human participants were conducted following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

4.2 Determination of Sample Size

To estimate the sample size for this study, we employed the methodology proposed by Schoemann et al. [36], which emphasizes the relationships among variables in mediation analysis. The required sample size was calculated to be 118, based on standardized coefficients of 0.3 for both the a (from parental attachment to self-esteem) and b (from self-esteem to adolescent delinquency) paths and 0.1 for the c′ (from parental attachment to adolescent delinquency) path, with a Type I error rate (alpha) set at 0.05 and a desired statistical power of 0.80. Furthermore, we utilized a general sample size estimation formula appropriate for survey studies to ensure a robust sample size calculation. Given a population size of 170,205, the application of this formula yielded an estimated sample size of 384.

where N is the population size (170,205), Z is the Z-value (set at 1.96 for a 95% confidence level), p is the estimated proportion (set at 0.5 for maximum variability), and E is the margin of error (set at 0.05).

This integrated approach yields a comprehensive and precise estimate of the required sample size by incorporating the demands of mediation analysis and population considerations. Given that 384 exceeds 118, we established 384 as the necessary sample size for the current study. Furthermore, to account for potential non-response and incomplete data from certain participants, we employed the method proposed by Salkind [37] to adjust for the anticipated unavailability of respondents: Sample size (n) = 384 + (384 × 0.5) = 576. As a result, the total number of questionnaires distributed for this study was 576, targeting school-aged adolescents in Tehran, Iran.

A pilot study was conducted to evaluate the instruments’ reliability involving 100 high school students from Tehran, comprising female and male participants aged 15 to 17 (refer to the Instrumentation section below for further details). Data collection occurred within a specified timeframe (December 5th–12th), employing random cluster sampling to ensure participant consistency. The data quality was further enhanced by administering questionnaires in controlled classroom settings. Throughout the study, participant confidentiality and anonymity were rigorously maintained. Following data collection, the data were securely recorded and subsequently analyzed.

A 31-item scale assessed delinquent behaviors among Iranian adolescents over the past 12 months, comprising 15 items adapted from Harris [38] and 16 newly developed items. School discipline reports, and Islamic literature informed the items. The pilot study indicated that all items of the delinquency scale were reliable, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88, leading to their retention in the current study. The scale used a four-point Likert format, from “not at all” (1) to “5 times or more” (4). Total scores, derived from summing all items, reflect the level of delinquent behavior. Examples of items in the delinquency scale include:

(a) In the past 12 months, how often did you get into a serious physical fight?

(b) In the past 12 months, how often were you loud, rowdy, or unruly in a public place?

(c) In the past 12 months, how often did you possess forbidden personal property (i.e., ornaments, a Walkman, a cell phone, a camera, improper books, magazines, a CD, or an MP3 player)?

(d) In the past 12 months, how often did you not abide by the rules of Islamic clothing (hejab) for girls and decent appearance for boys?

4.4.2 Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA)

The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA) by Armsden and Greenberg [39] assessed respondents’ perceptions of their relationships with their mother and father. The scale originally included peer relationships and focused on this study’s mother and father sub-scales. Each scale contained 25 items rated on a five-point Likert scale from Never or Never True (1) to Always or Always True (5). Total scores were calculated by summing the items after reversing negatively worded items (3, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 14, 17, 18, 23). High scores indicate secure attachment. The IPPA has a reliability of 0.93 [39], while the current study found maternal and paternal Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.89 and 0.90, respectively.

Furthermore, the IPPA proved to have good construct validity. Examples of items included in the mother and father attachment scale are

(a) My mother/father respects my feelings.

(b) I feel my mother/father does a good job as a parent.

(c) I wish I had a different mother/father.

The 10-item Self-Esteem Scale by Rosenberg [40] was used to assess adolescents’ self-esteem levels in this study. A four-point Likert scale, from five items (2, 5, 6, 8, and 9) was reverse scored to determine the total score, with higher scores reflecting higher self-esteem. In this research in Iran, Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.68. Examples of items in the scale include:

(a) On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.

(b) At times, I think I am no good at all.

(c) I feel that I have several good qualities.

Multiple regression analyses were employed to ascertain the significance of these variables in examining the interrelationships among paternal and maternal attachment, self-esteem, and delinquency. Specifically, the entry method of multiple regression was utilized to evaluate each variable’s contributions systematically. To ensure the validity and robustness of the findings, multicollinearity was evaluated using variance inflation factors (VIF). A VIF threshold of 10 was established to identify potential multicollinearity issues that could compromise the results [41].

The present study utilized a three-step regression analysis alongside the Sobel test to investigate the mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between paternal and maternal attachment and delinquency. The mediation effect was examined using a regression model following Baron and Kenny’s [42] four-step method and supported by a theoretical framework. Adhering to the framework established by Baron and Kenny in 1986, the analysis comprised three essential steps: first, examining the relationship between paternal and maternal attachment and self-esteem; second, assessing the impact of self-esteem on delinquency; and third, evaluating whether the inclusion of self-esteem in the model diminished the effect of paternal and maternal attachment on delinquency, indicated by a beta ratio of less than 1.0. The Sobel test was employed to ascertain the significance of this mediating effect, thereby providing a more nuanced understanding of how self-esteem mediates the relationship between parental attachment and delinquency. The data analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 24) and Microsoft Excel 2016.

6.1.1 Respondents’ Demographic Characteristics

Among the 576 participants invited to participate in the study, 528 high school students completed the questionnaires, resulting in a response rate of 88.3%. The mean age of the sample was 16.04 years (standard deviation (SD) = 0.80), with ages ranging from 15 to 17 years. Regarding family characteristics, most fathers (69.5%) were aged between 40 and 54 years, while most mothers (63.1%) were under 40. Regarding educational attainment, approximately 40% of fathers and 49% of mothers had completed their diploma (high school).

6.2 Levels of Delinquency, Parental Attachment, and Self-Esteem

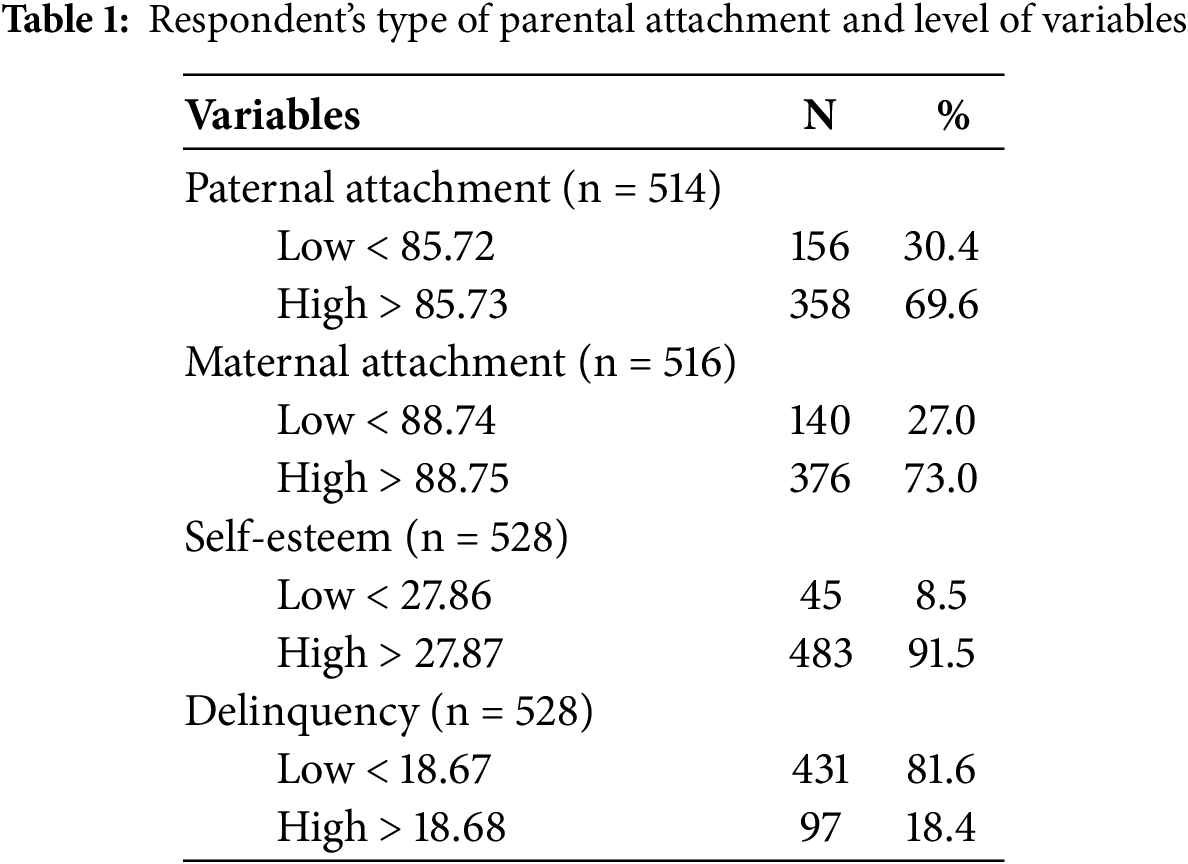

The analysis of the sample and the distribution of normative data reveals significant patterns concerning parental attachment, self-esteem, and delinquency. Specifically, for paternal attachment, scores exceeding 85.73 indicate a high level of attachment, with 69.6% of respondents categorized within this range. Conversely, scores below 85.72 reflect a low level of attachment, comprising 30.4% of the sample. In maternal attachment, scores above 88.75 are classified as high, with 73.0% of respondents falling into this category, while scores below 88.74 are deemed low, accounting for 27.0% of the sample. Regarding self-esteem, scores above 27.87 signify high self-esteem, encompassing 91.5% of participants, whereas scores below this threshold indicate low self-esteem, representing 8.5% of the sample. In terms of delinquency, scores exceeding 18.68 are associated with delinquent behavior, observed in 18.4% of respondents, while scores below 18.67 denote low levels of delinquent behavior, constituting 81.6% of the sample (Table 1). These findings underscore a predominantly well-adjusted cohort of students characterized by robust familial bonds, exceptional self-regulatory capabilities, and low incidences of delinquent behavior, presenting a favorable assessment of their psychological and behavioral health.

6.2.1 Testing the Multicollinearity

Significant variables from the correlation table were used for multivariate linear regression analysis. Based on the correlation values, there was no evidence of multicollinearity in the data sample, as the bivariate correlations between all independent variables were less than the 0.8 to 0.9 threshold. Additionally, the results of collinearity statistics showed no multicollinearity problem (VIF ranged between 1.040 and 4.758).

6.2.2 Self-Esteem Significantly Mediates the Relationships between Paternal Attachment and Delinquency

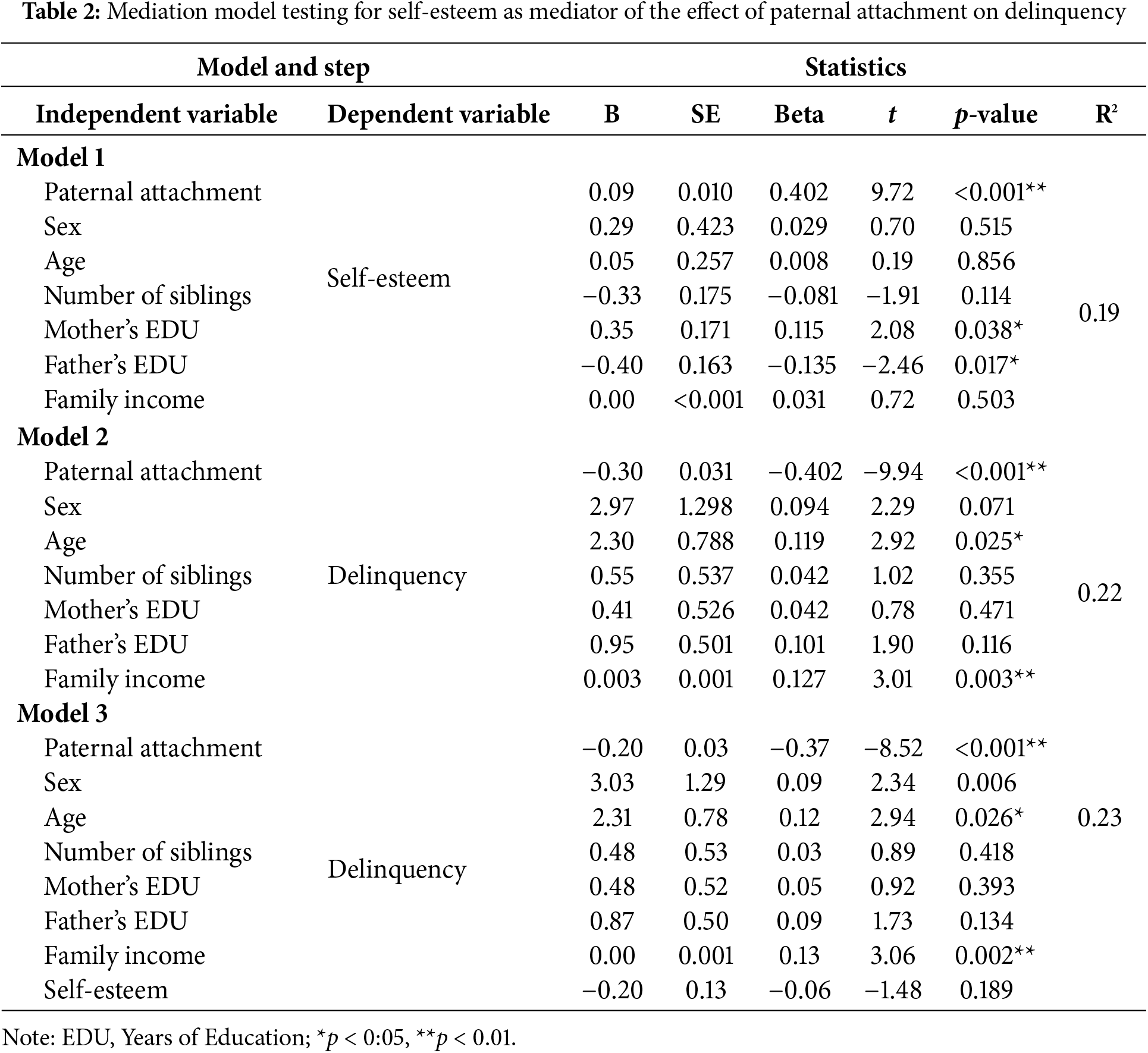

Table 2 below outlines three statistical models examining the relationships between independent variables (such as paternal attachment, sex, age, number of siblings, and parental education) and dependent variables (self-esteem and delinquency). Each model has a corresponding R2 value that indicates how much of the dependent variable’s variance is explained by that model’s independent variables. The table also includes regression coefficients β, standard errors (SE), beta coefficients, t-statistics, p-values, and R2 values for each variable.

In Model 1, the dependent variable is self-esteem. The results show that paternal attachment significantly and positively affects self-esteem. This means that higher levels of paternal attachment are associated with increased self-esteem. Additionally, the mother’s education is positively related to self-esteem, suggesting that children whose mothers have higher levels of education tend to have higher self-esteem. Interestingly, the father’s education has a significant negative effect on self-esteem, which may warrant further investigation to understand this unexpected relationship. Other variables like sex, age, number of siblings, and family income do not significantly affect self-esteem. The R2 value of 0.19 indicates that about 19.0% of the variation in self-esteem is explained by the independent variables included in the model.

Model 2 focuses on delinquency as the dependent variable, excluding self-esteem as a mediator. In this model, paternal attachment is found to have a strong negative effect on delinquency, meaning that individuals with higher levels of paternal attachment are less likely to engage in delinquent behavior. Age is positively associated with delinquency, suggesting that older individuals tend to exhibit more delinquent behavior. Family income also shows a positive and significant effect on delinquency, which is somewhat counterintuitive and might indicate that higher-income families experience certain dynamics contributing to delinquency. Other variables, such as sex, number of siblings, and parental education, do not significantly influence delinquency in this model. The R2 value of 0.22 indicates that the independent variables explain nearly one-fourth of the variation in delinquency.

In Model 3, self-esteem is introduced as a mediator between paternal attachment and delinquency. Paternal attachment remains a significant negative predictor of delinquency, consistent with the results from Model 2. Age and family income also maintain their significant positive effects on delinquency. However, self-esteem does not show a statistically significant effect on delinquency, which suggests that it may not play a strong mediating role between paternal attachment and delinquency. Other variables, such as sex, number of siblings, and parental education, continue to have no significant impact on delinquency. The R2 value of 0.23 shows that this model explains 23.0% of the variation in delinquency.

Table 2 comprehensively analyzes the relationships between paternal attachment, self-esteem, and delinquency. The models indicate that paternal attachment plays a significant role in both self-esteem and delinquency, with stronger paternal attachment associated with higher self-esteem and lower delinquency. Additionally, age and family income are important predictors of delinquency, though their exact roles may require further exploration. While expected to be a mediator in the relationship between paternal attachment and delinquency, self-esteem does not show a significant effect in Model 3, which raises questions about its role in this context. Still, it is essential to interpret these results carefully, considering the potential for other variables not included in the models to influence the outcomes.

The Sobel test was utilized to determine whether self-esteem mediated the relationship between paternal attachment and delinquency. Initially, results from a simple linear regression indicated that self-esteem was not a statistically significant predictor of delinquency (B = −0.20, SE = 0.13, p = 0.18). However, paternal attachment was found to have a significant positive relationship with self-esteem (B = 0.09, SE = 0.010, p < 0.01). The Sobel test was conducted to examine the mediating role of self-esteem. The results revealed that self-esteem did not significantly mediate the relationship between paternal attachment and delinquency (Z = −1.51, SE = 0.011, p = 0.12). Furthermore, a 95% confidence interval (CI) with a lower bound of −0.0054 and an upper bound of 0.0414 indicates that self-esteem does not mediate the relationship between paternal attachment and delinquency.

6.2.3 Self-Esteem Significantly Mediates the Relationships between Maternal Attachment and Delinquency

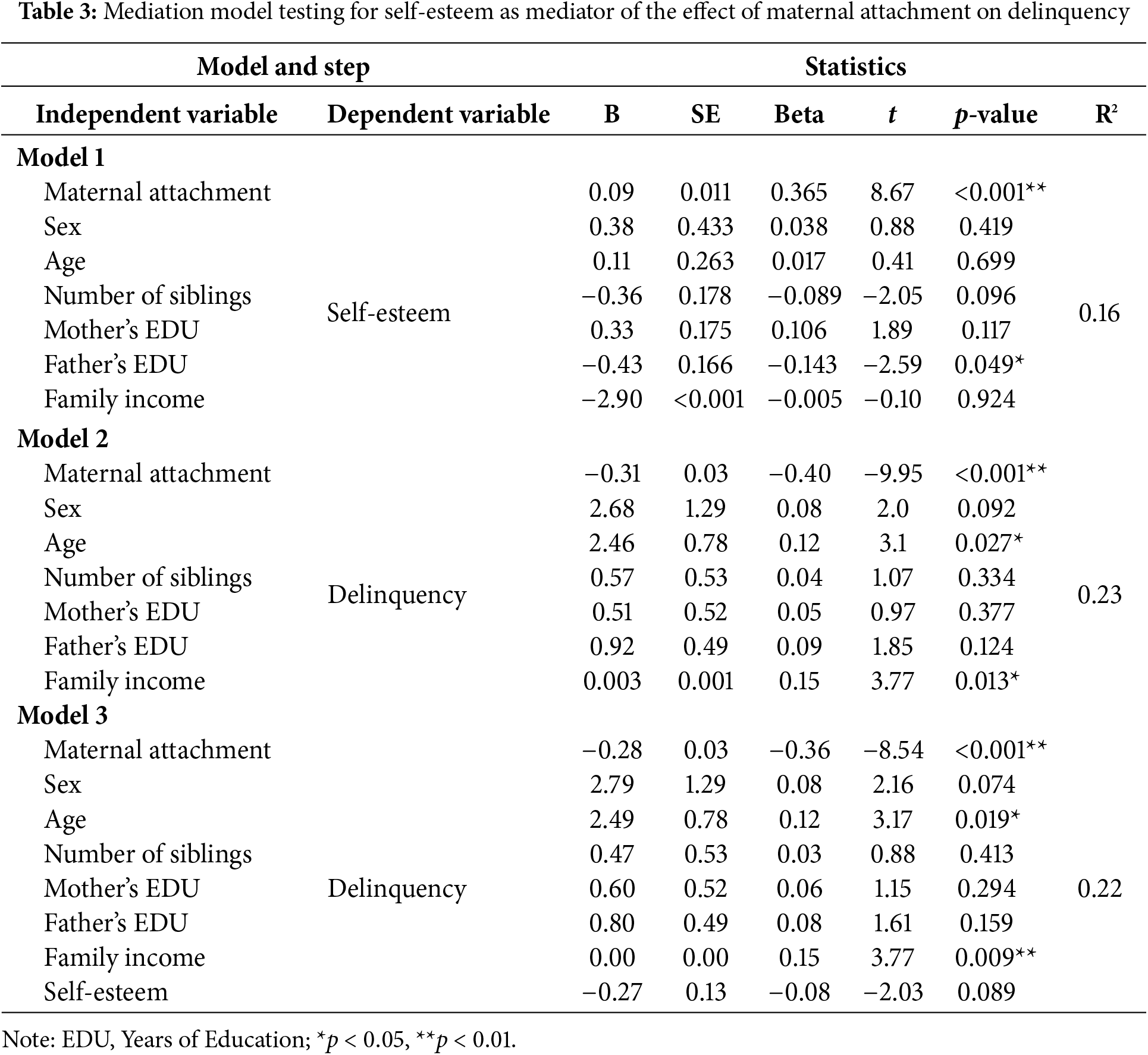

Table 3 explores the relationship between maternal attachment, self-esteem, and delinquency across three models. These models aim to determine whether self-esteem mediates the impact of maternal attachment on delinquency. Each model includes various factors, such as sex, age, number of siblings, parental education, and family income, to explore how these elements influence self-esteem and delinquency.

In Model 1, the goal is to understand how maternal attachment affects self-esteem. Other variables, such as sex, age, number of siblings, and parental education, are also included to explore their influence. The results show that maternal attachment significantly and positively impacts self-esteem. This means that higher levels of maternal attachment are associated with higher self-esteem. In contrast, the father’s education significantly negatively impacts self-esteem, suggesting that higher levels of the father’s education are linked to lower self-esteem. This result may seem unusual and could need further investigation. Other variables, such as sex, age, number of siblings, mother’s education, and family income, have not been statistically significant in their impact on self-esteem. The overall model explains 16.0% of the variation in self-esteem (indicated by the R2 value of 0.16).

In Model 2, delinquency is examined as the dependent variable without considering self-esteem. This model aims to directly understand how maternal attachment and other variables impact delinquent behavior. Maternal attachment shows a significant negative effect on delinquency, indicating that individuals who report higher levels of maternal attachment tend to engage less in delinquent behaviors. Additionally, age is positively associated with delinquency, suggesting that older individuals are more likely to engage in delinquent acts.

Similarly, family income has a small but significant positive impact on delinquency, meaning that individuals from wealthier families may exhibit more delinquent behavior, which could be counterintuitive and deserves further exploration. However, variables such as sex, number of siblings, and parental education do not show a statistically significant influence on delinquency. The model explains 23.0% of the variation in delinquency.

In Model 3, self-esteem is introduced as a mediator between maternal attachment and delinquency to test whether it explains the relationship between these two factors. Even with self-esteem included in the model, maternal attachment maintains its significant negative effect on delinquency, meaning that stronger maternal attachment still leads to lower delinquency. Age and family income continue to be significant predictors, with age positively influencing delinquency and family income showing a significant positive association with delinquency. Interestingly, while self-esteem has a negative relationship with delinquency, its effect is not statistically significant. This suggests that although individuals with higher self-esteem may engage in less delinquent behavior, self-esteem does not appear to be a crucial mediator between maternal attachment and delinquency in this context.

Table 3 presents three models that collectively explore the impact of maternal attachment on delinquency, with self-esteem as a potential mediator. Across all models, maternal attachment consistently shows a strong negative effect on delinquency, suggesting that higher levels of maternal attachment are associated with lower delinquency. Age and family income also emerge as significant predictors of delinquency, with older individuals and those from higher-income families exhibiting higher levels of delinquent behavior.

The introduction of self-esteem as a mediator in Model 3 reveals that while self-esteem is negatively associated with delinquency, this relationship is not statistically significant. This suggests that self-esteem may not play as crucial a mediating role as hypothesized in the relationship between maternal attachment and delinquency. Overall, the findings from the three models indicate that maternal attachment plays a key role in reducing delinquent behavior, while age and family income also significantly affect delinquency. Self-esteem, though expected to mediate the relationship between maternal attachment and delinquency, does not significantly influence delinquent behavior in this particular analysis. Overall, the results emphasize the protective role of maternal attachment in preventing delinquency, while the roles of age and family income in delinquency warrant further investigation.

The Sobel test was performed to assess whether self-esteem mediated the relationship between maternal attachment and delinquency. Initial findings from a simple linear regression revealed that self-esteem was not a statistically significant predictor of delinquency (B = −0.27, SE = 0.13, p = 0.089). However, maternal attachment was found to have a significant positive association with self-esteem (B = 0.09, SE = 0.011, p < 0.01).

To test the mediating effect of self-esteem, the Sobel test was conducted. The results showed that self-esteem significantly mediates the relationship between maternal attachment and delinquency (Z = −2.01, SE = 0.012, p = 0.04). Additionally, bootstrapping analysis indicated a 95% CI with a lower bound of −0.0480 and an upper bound of −0.0006, suggesting that self-esteem is a mediator in the relationship between maternal attachment and delinquency.

Parental attachment is critical in shaping adolescents’ emotional well-being and behavioral tendencies [43]. The mediating role of self-esteem is crucial for understanding how parental attachment affects adolescent behavior [44]. Mediation refers to how an adolescent’s attachment to their parents affects the likelihood of delinquent behavior through self-esteem [45]. A secure attachment is associated with a positive self-concept, which protects against delinquency [46]. Previous research showed that strong familial bonds foster self-esteem, reducing the risk of problematic behaviors [40,47,48].

This study found that maternal attachment significantly mediates the relationship between attachment and adolescent delinquent behavior, whereas paternal attachment does not significantly mediate. Self-esteem was identified as a key mediator in this relationship.

Previous research has demonstrated that adolescents with secure maternal attachments tend to have higher self-esteem, which protects them against delinquent behaviors [43–45]. This aligns with the current study’s findings, where adolescents who feel securely attached to their mothers are more likely to develop a positive self-concept, which in turn helps reduce the likelihood of engaging in delinquent behavior [47,48].

On the other hand, paternal attachment did not show a significant mediating effect in this study. This is in contrast to prior studies suggesting that both parental figures can influence adolescents’ behaviors, but in this case, only maternal attachment appeared to be a significant factor [9,30].

These results underscore the importance of maternal attachment in fostering self-esteem among adolescents. Strong maternal relationships can serve as protective factors, promoting a healthy self-concept that reduces the risk of delinquent behavior. This study highlights the role of self-esteem as a mediator in the maternal attachment-delinquency relationship, emphasizing that positive maternal attachment fosters self-worth, which can act as a buffer against negative behaviors.

In practical terms, interventions should focus on enhancing maternal involvement and strengthening mother-child relationships to promote positive self-esteem in adolescents. This can be achieved through family counseling programs, educational workshops for parents, and initiatives that enhance the emotional bonds between mothers and their children.

Educators and counselors need to understand the significant role of maternal attachment in adolescents’ self-esteem and behavior. Programs encouraging active parental engagement, especially from mothers, can enhance self-esteem and reduce delinquency. Moreover, public health initiatives should prioritize family-based interventions to support healthy family dynamics, promoting strong maternal attachments to improve adolescents’ psychological well-being and reduce delinquent behavior.

Future research could explore additional factors influencing delinquency, such as peer influence, socioeconomic status, and the role of paternal attachment in different cultural contexts. Longitudinal studies could provide deeper insights into how maternal attachment and self-esteem influence adolescent behavior over time, contributing to the development of more targeted prevention and intervention strategies.

This study has several limitations. First, the reliance on self-reported measures may introduce bias, suggesting the need for multiple data sources. Second, its cross-sectional design limits causal interpretations, highlighting the importance of longitudinal research. Third, cultural differences in parental roles may affect generalizability, requiring further cross-cultural studies. Finally, other potential mediators, such as peer influence and emotional regulation, should be explored to provide a more comprehensive understanding of adolescent delinquency.

The current research focuses on the relationship between parental attachment, self-esteem, and delinquency in teenagers. The results show that secure attachment to mothers strongly mediates the attachment-delinquency relationship, and self-esteem plays an important part. Teenagers with secure mother attachment are more likely to develop a strong self-image, further reducing the propensity to engage in delinquent behavior. Attachment to fathers, nevertheless, failed to show a large mediating effect in the current study.

The study demonstrates how maternal attachment enhances self-worth as a protective mechanism against delinquency. Close maternal attachments enable adolescents to be emotionally cared for and loved, which fosters a positive self-concept as a protective mechanism against bad behavior. Though paternal attachment matters, its mediating effect on delinquency via self-esteem was not as evident in this study.

The current study highlights the role of stable parental relationships, particularly maternal relationships, in promoting adolescent self-esteem while at the same time dampening delinquent behaviors. Secure parent-child relationships are vital for healthy emotional development, with self-esteem significantly mediating the relationship between attachment and delinquency.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study. This publication fee for the research was supported in part by the Higher Education Sprout Project, Ministry of Education, to the Headquarters of University Advancement at National Cheng Kung University (NCKU).

Author Contributions: Conception and design of the study, Mahshid Manouchehri; Analysis and interpretation of data, Mahshid Manouchehri, Chung-Ying Lin, and Musheer A. Aljaberi; Investigation, Mahshid Manouchehri, Musheer A. Aljaberi, and Chung-Ying Lin; Resources, Mahshid Manouchehri, Aiche Sabah, Yi-Ching Lin, Musheer A. Aljaberi, and Amira Mohammed Ali; data curation, Mahshid Manouchehri; Writing—original draft preparation, Mahshid Manouchehri, Musheer A. Aljaberi, Yi-Ching Lin, Aiche Sabah, Amira Mohammed Ali, and Chung-Ying Lin; Writing—review and editing, Mahshid Manouchehri, Musheer A. Aljaberi, Yi-Ching Lin, Aiche Sabah, Amira Mohammed Ali, and Chung-Ying Lin; Critically revising its important intellectual content, Mahshid Manouchehri, Musheer A. Aljaberi, Yi-Ching Lin, Aiche Sabah, Chung-Ying Lin, and Amira Mohammed Ali. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets supporting this study’s findings are not openly available. It will be made available from the first author upon reasonable academic and research use request.

Ethics Approval: Ethical approval from the Ethics Research Committee of University Putra Malaysia (ERGS/1/2012/SS03/UPM/01/1) was obtained. We confirm that all methods related to the human participants were conducted following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from participants and their guardians.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Siegel LJ, Senna JJ, Welsh B. Juvenile delinquency: theory, practice, and law. Belmont, CA, USA: Wadsworth; 2000. [Google Scholar]

2. Abhishek R, Balamurugan J. Impact of social factors responsible for Juvenile delinquency—a literature review. J Educ Health Promot. 2024;13(1):102. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_786_23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Frazier JD, Schreck C, Rogers EM. Delinquency. In: Troop-Gordon W, Neblett EW, editors. Encyclopedia of adolescence. 2th ed. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2024. p. 174–86. [Google Scholar]

4. Gupta MK, Mohapatra S, Mahanta PK. Juvenile’s delinquent behavior, risk factors, and quantitative assessment approach: a systematic review. Indian J Community Med. 2022;47(4):483–90. doi:10.4103/ijcm.ijcm_1061_21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Weng X, Ran M-S, Chui WH. Juvenile delinquency in Chinese adolescents: an ecological review of the literature. Aggress Violent Behav. 2016;31(1):26–36. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2016.06.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mohammad T, Nooraini I. Routine activity theory and Juvenile delinquency: the roles of peers and family monitoring among Malaysian adolescents. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2021;121(1):105795. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Guo S. A model of religious involvement, family processes, self-control, and juvenile delinquency in two-parent families. J Adolesc. 2018;63(1):175–90. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.12.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Manouchehri M, Harun MM, Baber C. Differential impacts of maternal and paternal attachments on adolescent delinquency: implications for counselling. Pertanika J Soc Sci Humanit. 2024:32. [Google Scholar]

9. Hoeve M, Stams GJJM, van der Put CE, Dubas JS, van der Laan PH, Gerris JRM. A meta-analysis of attachment to parents and delinquency. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40(5):771–85. doi:10.1007/s10802-011-9608-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Grenadi KM, Rahayu MNM. The self-esteem of Dayak ethnic adolescents reviewed from the attachment relationship of parents. Psikoborneo: J Ilm Psikol. 2024;12(3):351–8. doi:10.30872/psikoborneo.v12i3.15649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Aghajani S, Beheshti Motlagh A, Mohamadnezhad Devin A, Ghobadzade S. The mediating role of family cohesion in the relationship between attitude towards drug addiction and personal empowerment in Iranian college students. J Prev Med. 2024;10(4):386–97. [Google Scholar]

12. Gaik LP, Abdullah MC, Elias H, Uli J. Parental attachment as predictor of delinquency. Malays J Learn Instr. 2013;10:99–117. doi:10.32890/mjli.10.2013.7653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Roshandel J, Sadeghi F, Tadrisi S. Gender equality and empowerment in Iran: a comparison between Ahmadinejad’s and Rouhani’s governments. J South Asian Middle East Stud. 2019;42(3):35–53. [Google Scholar]

14. Moksnes UK, Espnes GA, Eilertsen MEB, Bjørnsen HN, Ringdal R, Haugan G. Validation of Rosenberg self-esteem scale among Norwegian adolescents—psychometric properties across samples. BMC Psychol. 2024;12(1):506. doi:10.1186/s40359-024-02004-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Niveau N, New B, Beaudoin M. Self-esteem interventions in adults—a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Res Personal. 2021;94(2):104131. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2021.104131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Pedersen AB, Edvardsen BV, Messina SM, Volden MR, Weyandt LL, Lundervold AJ. Self-esteem in adults with ADHD using the Rosenberg self-esteem scale: a systematic review. J Atten Disord. 2024;28(7):1124–38. doi:10.1177/10870547241237245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Rosenberg M, Schooler C, Schoenbach C. Self-esteem and adolescent problems: modeling reciprocal effects. Am Sociol Rev. 1989:1004–18. [Google Scholar]

18. Rosenberg FR, Rosenberg M, McCord J. Self-esteem and delinquency. J Youth Adolesc. 1978;7(3):279–94. doi:10.1007/bf01537978. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Bynner JM, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Self-esteem and delinquency revisited. J Youth Adolesc. 1981;10(6):407–41. doi:10.1007/bf02087937. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Tzeng SP, Yi CC. The effects of self-esteem on adolescent delinquency over time: is the relationship linear? In: Yi CC, editor. The psychological well-being of East Asian youth. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2013. p. 243–61 doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4081-5_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. van Bakel HJA, Hall RAS. Parent-child relationships and attachment. In: Sanders MR, Morawska A, editors. Handbook of parenting and child development across the lifespan. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 47–66 doi:10.1007/978-3-319-94598-9_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: retrospect and prospect. Am J Orthopsychiat. 1982;52(4):664–78. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall SN. Patterns of attachment: a psychological study of the strange situation. Oxfordshire, UK: Psychology Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

24. Main M, Solomon J. Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth strange situation. Attachment in the preschool years: theory, research, and intervention. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur foundation series on mental health and development. Chicago, IL, US: The University of Chicago Press; 1990. p. 121–60. [Google Scholar]

25. Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. In: Hazan C, Shaver P, editors. Interpersonal development. 1st ed. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge; 2017. p. 283–96 doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sabah A, Alduais A. Intersections of family expressiveness and adolescent mental health: exploring parent-adolescent relationships as a mediator. Ment Health Soc Incl. 2025;29(3):246–58. doi:10.1108/mhsi-06-2024-0104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Nguyen T, Kungl MT, Hoehl S, White LO, Vrtička P. Visualizing the invisible tie: linking parent-child neural synchrony to parents’ and children’s attachment representations. Dev Sci. 2024;27(6):e13504. doi:10.1111/desc.13504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ferreira T, Matias M, Carvalho H, Matos PM. Parent-partner and parent-child attachment: links to children’s emotion regulation. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2024;91(6):101617. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2023.101617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Jiang X, Chen X, Liang B, Liu J. Family attachment and delinquency among Chinese adolescents: the mediating roles of adolescent self-disclosure and parental knowledge. Crime Delinq. 2024;3(1):00111287241276522. doi:10.1177/00111287241276522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Shek DTL, Zhu X. Paternal and maternal influence on delinquency among early adolescents in Hong Kong. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2019;16(8):1338. doi:10.3390/ijerph16081338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. New York, NY, USA: Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

32. Warr M. Companions in crime: the social aspects of criminal conduct. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

33. Laub JH, Sampson RJ. Shared beginnings, divergent lives. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

34. Ghodsi SE, Ghadami Azizabad M. Preventing the confession of crimes against chastity in Iranian jurisprudence and law in the light of criminological theories. Comp Crim Jurisprud. 2021;1(2):55–68. [Google Scholar]

35. Branden N. The six pillars of self-esteem. New York, NY, USA: Penguin Books; 2016. [Google Scholar]

36. Schoemann AM, Boulton AJ, Short SD. Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2017;8(4):379–86. doi:10.1177/1948550617715068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Salkind NJ. Encyclopedia of research design. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

38. Harris KM. The national longitudinal study of adolescent health: research design [Internet]; 2011 [cited 2025 Jan 5]. Available from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design. [Google Scholar]

39. Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 1987;16(5):427–54. doi:10.1007/bf02202939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

41. Sabah A, Aljaberi MA, Hassan SA. Examining benign and malicious envy and flourishing among Muslim university students in Algeria: a quantitative study. Soc Sci Humanit Open. 2025;11(9–10):101293. doi:10.1016/j.ssaho.2025.101293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1986;516(6):1173–82. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. McCoby EE. Socialization in the context of the family: parent-child interaction. Handb Child Psychol. 1983;4:1–101. [Google Scholar]

44. Carlson EA, Sampson MC, Sroufe LA. Implications of attachment theory and research for developmental-behavioral pediatrics. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24(5):364–79. doi:10.1097/00004703-200310000-00010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1991;61(2):226. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Barry CT, Kim H. Parental monitoring of adolescent social media use: relations with adolescent mental health and self-perception. Curr Psychol. 2024;43(3):2473–85. doi:10.1007/s12144-023-04434-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Baumeister RF. Violent pride. Sci Am. 2001;284(4):96–101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

48. Ahn J, Yang Y. Relationship between self-esteem and risky sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review. Am J Sex Educ. 2023;18(3):484–503. doi:10.1080/15546128.2022.2118199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools