Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Unpacking Societal Stigma toward Schizophrenia: Development of a Multidimensional Scale with Sociodemographic Insights

1Rheumatology Servive, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, 08035, Spain

2 Psychology Department, Universidad Europea, Canarias, 38300, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Carlos Suso-Ribera. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(7), 929-951. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.065646

Received 18 March 2025; Accepted 13 June 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Schizophrenia is a profoundly stigmatized mental health condition, characterized by misconceptions that affect societal attitudes, policy development, and the lived experiences of individuals with the condition. This study aimed to develop and validate a multidimensional scale for assessing societal stigma towards schizophrenia, while exploring how demographic factors influence such attitudes. Methods: Drawing on an extensive literature review and consultations, the study identified five domains of stigma: Workplace Capability, Intimate Relationships, Autonomy, Risk Perception, and Recovery. Using a two-phase methodology, a preliminary 38-item scale was administered to 729 participants from the general Spanish population, refining the measure through descriptive and exploratory factor analysis. Subsequently, a revised 34-item scale was validated through confirmatory factor analysis with an independent sample of 417 participants. Results: The final model showed good fit (RMSEA = 0.056, CFI = 0.938, TLI = 0.933) and strong internal consistency (α = 0.73–0.86). Findings revealed that stigma was most pronounced in the domain of Autonomy (Mean = 2.83, SD = 0.91), reflecting pervasive doubts about individuals’ ability to live independently and achieve meaningful integration into society. Stigma varied significantly across demographic variables, with higher levels reported among men, older individuals, married participants, and those outside health professions (p < 0.01). Conversely, healthcare professionals, younger individuals, and those familiar with someone with schizophrenia generally reported less stigma (p < 0.01). Conclusion: This study developed and validated a robust multidimensional scale for assessing societal stigma toward schizophrenia. The five-factor model—Workplace Capability, Intimate Relationships, Autonomy, Risk Perception, and Recovery—was empirically supported. Autonomy and Recovery emerged as the most stigmatized domains across the Spanish general population. The scale demonstrated strong psychometric properties and effectively captured stigma patterns linked to key sociodemographic variables.Keywords

Schizophrenia is a severe and complex mental disorder, affecting approximately 1 in 300 adults globally, and is associated with significant challenges for individuals, families, and societies [1]. Characterized by disruptions in thought processes, emotional regulation, and behavior, it is among the most disabling psychiatric conditions identified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V) [2], contributing to a reduced life expectancy of 15 to 25 years due to comorbidities, suicide risk, and systemic healthcare disparities [3,4]. Additionally, the disorder imposes considerable societal costs, including lost productivity, caregiver burdens, and increased healthcare expenditures [5]. Addressing schizophrenia effectively requires a multifaceted approach that includes clinical treatment, policy changes, and an understanding of the broader social determinants influencing the disorder.

One critical yet underexplored social factor is societal stigma, which operates on a broader scale than self-stigma [6,7]. Societal stigma toward mental health encompasses negative stereotypes, prejudiced attitudes, and discriminatory behaviors toward individuals with mental disorders [8,9]. This type of stigma shapes public perceptions, policy development, access to care, and opportunities for inclusion [10,11] and exacerbates health disparities by increasing stress responses, deterring help-seeking behaviors, and fostering social exclusion [10,12]. By contrast, community participation has been shown to enhance the subjective perception of recovery and quality of life among individuals with serious mental illnesses by reducing self-stigma and fostering a sense of belonging and empowerment [13].

Schizophrenia has long been one of the most stigmatized mental disorders, with widespread misconceptions perpetuated by media portrayals and societal beliefs of the disorder’s symptoms, causes, and prognosis [14,15], frequently depicting individuals with schizophrenia as violent, unpredictable, or incapable of leading productive lives [16,17]. These misconceptions perpetuate discrimination in critical domains such as employment, housing, and healthcare, while also increasing self-stigma, social isolation, and psychological distress [10,18].

Extensive research has documented various aspects of stigma, including public, structural, and self-stigma [19,20]. While self-stigma has been studied in depth [21], societal stigma remains a pervasive and deeply ingrained issue that continues to shape the experiences of individuals with schizophrenia. Despite increased advocacy and public awareness campaigns, stigma persists across multiple domains, influencing employment opportunities, healthcare access, and social interactions [22,23]. Furthermore, stigma does not operate uniformly—it is shaped by demographic factors such as age, gender, and cultural background [24], yet the ways in which these factors intersect to reinforce or mitigate stigma remain underexplored. Understanding these dynamics is essential for designing more effective interventions.

A critical factor influencing stigma is mental health literacy, which refers to the ability to recognize symptoms, understand causes, and navigate treatment options [25,26]. While improving mental health literacy has been a central focus of stigma-reduction efforts, research suggests that knowledge alone is insufficient to challenge deeply entrenched stereotypes about schizophrenia [27,28]. In fact, despite growing awareness and knowledge of mental health issues, stigma against schizophrenia remains notably severe [29,30] and, unlike conditions like depression, public misconceptions of schizophrenia, such as being inherently violent, have intensified over time [12]. Addressing this enduring stigma requires not only educational efforts but also the development of multidimensional assessment tools that capture the complexity of stigma. However, existing stigma scales often lack rigorous psychometric validation, dimensional specificity, or a targeted focus on schizophrenia [16,31,32], highlighting the urgent need for more precise and robust measurement instruments.

1.2 The Multidimensional Nature of Stigma

Schizophrenia stigma operates across multiple domains, each influencing different aspects of social participation and quality of life [11,33,34]. A thorough review of the literature in the field identified five key stigma domains: Workplace Capability, Intimate Relationships, Autonomy, Recovery, and Risk Perception [32,34–37], which guided the development of the stigma scale.

While prior research has examined some of these dimensions individually [38,39], there is a need to comprehensively analyze them within a single framework. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework highlights that stigma is not a singular construct but a complex interplay of social, psychological, and structural forces [40]. The five domains identified in this study—Workplace Capability, Intimate Relationships, Autonomy, Recovery, and Risk Perception—align with the framework’s emphasis on stigma manifestations and their consequences for affected individuals.

1.3 Sociodemographic Determinants of Stigma

Effective interventions, such as psychoeducation and contact-based programs, rely on a nuanced understanding of the demographic and cultural determinants of stigma to maximize their impact [36]. Tailoring these interventions requires identifying the specific populations and contexts where stigma is most prevalent. Research has consistently demonstrated that certain demographic factors influence stigma levels. For instance, men and older individuals tend to exhibit higher levels of stigma, while closer relationships with individuals with the condition and professional experience in health-related occupations are linked to reduced stigma and discrimination [41–44]. These findings suggest that both personal and occupational experiences significantly shape attitudes toward mental illness.

1.4 Study Objectives and Significance

This study seeks to address gaps in the literature by developing and validating a multidimensional scale for assessing societal stigma toward schizophrenia. It examines stigma across five domains identified after an extensive review of the literature—Workplace Capability, Intimate Relationships, Autonomy, Recovery, and Risk Perception. The study also aims to evaluate the scale’s psychometric properties and analyze how stigma varies across demographic groups in a diverse Spanish population, a country where approximately 3.7% of people are affected by schizophrenia [45]. The findings will provide evidence-based insights to inform stigma reduction initiatives and improve societal inclusion for individuals with schizophrenia, aligning with global efforts to address the social determinants of mental health [11].

This study employed a two-phase cross-sectional observational design to develop and validate a multidimensional stigma scale for schizophrenia. The study aimed to ensure a rigorous psychometric evaluation, incorporating both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. To enhance the conceptual foundation of the scale, a review of existing stigma research on schizophrenia stigma was conducted to identify key stigma domains.

Participants were recruited from the general Spanish population (ages 18 and older) through online convenience sampling (virtual snowball approach using social media and paid advertisements). The participants did not receive any compensation to participate. Inclusion criteria required participants to be Spanish residents with proficiency in Spanish. Exclusion criteria included a self-reported history of schizophrenia or related psychotic disorders to prevent response bias.

Respondent anonymity was ensured, and data collection adhered to informed consent protocols. The study was approved by the Ethics committee at the Jaume I University (CD/43/2021). All the participants provided their written online consent to participate.

Study 1 (Scale Development): A preliminary 38-item scale was administered to 729 participants. Items were refined based on exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and psychometric criteria.

Study 2 (Scale Validation): The revised 34-item scale was administered to an independent sample of 417 participants for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

Total Sample: Combined, 1146 participants provided data, with sociodemographic characteristics analyzed across both studies to ensure representativeness.

To assess sample adequacy, the ratio of participants to items was examined, ensuring compliance with best practices in psychometric research. The final 34-item scale had a participant-to-item ratio exceeding 10:1, reinforcing the robustness of factor analysis outcomes.

2.3.1 Stigma Scale Development

The stigma scale was developed through a three-step process:

(1) Systematic Review and Expert Consultation: A review of existing stigma measures and qualitative studies was conducted to define stigma domains. Expert consultations (three mental health professionals, two researchers, and three individuals with lived experience) refined the conceptual framework.

(2) Item Generation and Selection: An initial pool of items was developed for each of the five identified domains: Workplace Capability, Intimate Relationships, Autonomy, Risk Perception, and Recovery. Items were refined based on expert feedback and pilot testing. Items were newly developed, but they were also based on prior research, as described in the following lines. Both direct and reversed items were created to reduce acquiescence:

- Workplace Capability: Individuals with schizophrenia are often viewed as incapable of professional success or burdensome to colleagues [46]. Employment discrimination remains a major barrier to social inclusion and recovery, despite evidence showing that individuals with schizophrenia can succeed in supportive work environments [10]. Based on this literature, items were created to reflect widely held public perceptions about the competence, reliability, and employability of individuals with schizophrenia, as well as beliefs about whether workplace accommodations or supervision are necessary for their success.

- Intimate Relationships: Doubts about the competence of individuals with schizophrenia to maintain meaningful relationships or fulfill roles such as partners and parents are still frequent and create significant interpersonal barriers, perpetuating isolation and emotional burdens [8,47]. According to this previous research, items here were developed to evaluate common assumptions about the desirability, trustworthiness, and suitability of individuals with schizophrenia as romantic partners or parents, including beliefs about their ability to maintain stable, healthy intimate relationships.

- Autonomy: Stereotypes often depict individuals with schizophrenia as perpetually dependent or incapable of managing daily life, which can have significant social consequences and lead to social distancing [48,49]. Based on these prior studies, items were developed to capture public beliefs about the capacity of individuals with schizophrenia to make independent life decisions, manage daily activities, and exercise personal agency without constant supervision or external control.

- Recovery: Public ignorance about advances in treatment contributes to skepticism about the potential for meaningful recovery [33], ultimately impacting recovery-oriented practices in mental healthcare [50]. Items were constructed to assess beliefs about the possibility of improvement, recovery, and reintegration for individuals with schizophrenia, including whether the public perceives treatment, support, and rehabilitation as effective pathways to meaningful life outcomes.

- Risk Perception: Public views associating schizophrenia with unpredictability and violence have intensified, with over 60% of respondents in a recent study linking severe mental illness to violent behavior, despite evidence showing minimal actual risk [12]. This dimension is particularly pervasive and damaging, as it contributes to both public and institutional discrimination [51,52]. Here, items were designed to reflect societal fears and stereotypes about the potential danger, unpredictability, or violence associated with schizophrenia, as well as assumptions about whether individuals with the condition pose a threat to themselves or others.

(3) Psychometric Testing: Items were assessed for reliability, validity, and factor structure through EFA (Study 1) and CFA (Study 2).

While some previous research has used vignettes to examine perceptions of schizophrenia and other mental disorders [53], in this study it was chosen to use statements about social stigma instead to ensure that the results reflected the imaginative landscape people already associate with the disorder. Vignettes, while useful for standardization, might constrain responses by providing a fixed narrative that may not fully capture the diverse and often stereotypical ways in which schizophrenia is perceived. By using statements, the participants were allowed to engage with broader, more abstract beliefs and assumptions, ensuring that the findings were grounded in the spontaneous and subjective impressions people hold. This approach aligns with the idea that stigma is largely shaped by societal narratives and media portrayals rather than direct, detailed case descriptions [54], making it more relevant for understanding how schizophrenia is perceived in an everyday context.

2.3.2 Sociodemographic Variables

Participants provided data on sex, age, marital status, occupation, and relational experience with people with schizophrenia. Given the significant impact of demographic factors on stigma, the previous variables were analyzed in relation to stigma scores to identify potential predictors.

Data collection was conducted via an online survey hosted on Qualtrics, ensuring anonymity and voluntary participation. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before completing the survey. The survey included a study information sheet and consent form, the stigma scale items, and a sociodemographic questionnaire.

EFA-Study 1 An EFA was conducted using Principal Axis Factoring with Promax rotation. Factor retention was guided by Eigenvalues greater than 1.0, scree plot analysis, and the conceptual clarity of emerging factors. Items were removed if they had low loadings (<0.40), strong cross-loadings (>0.30), or problematic distribution (e.g., negative skewness, high kurtosis). Inter-item correlations and corrected item-total correlations were used to further refine item quality and internal consistency.

An EFA was conducted on the initial 38-item scale to identify the underlying factor structure. Items with low factor loadings, cross-loadings, or poor psychometric properties were removed, resulting in a refined 34-item scale.

CFA-Study 2 Cronbach’s alpha values for each domain indicated strong internal consistency: Workplace Capability (α = 0.82), Intimate Relationships (α = 0.84), Autonomy and Supervision (α = 0.86), Risk Perception (α = 0.81), and Recovery and Societal Roles (α = 0.78).

A CFA was performed to validate the five-factor structure. Model fit was assessed using the Chi-square test (χ2, expected to be significant due to sample size), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (≤0.06 indicating good fit), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) (≥0.90 indicating acceptable fit). Taking reliability, the Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each stigma domain, with values above 0.70 considered acceptable [55]. Item inter-correlations were also computed.

Differences in stigma scores across demographic groups (sex, age, familiarity, marital status, occupation) were examined using t-tests for binary variables and ANOVAs with post-hoc tests for multi-category variables.

Statistical analyses were conducted using Mplus 6.12 for factor analyses and SPSS 26 for descriptive and group comparisons. Significance levels were set at p < 0.05.

3.1 Study 1: Scale Development and Administration and Refinement through Descriptive and Exploratory Factor Analyses (n = 729)

A preliminary 38-item scale was developed through literature review and expert consultations and administered to 729 participants from the Spanish general population (mean age = 38.66, SD = 15.78). The sample included 67.2% women, 32.6% men, and one intersex individual, with most participants born (89.1%) or residing (93.8%) in Spain.

Educational levels varied: 9% completed secondary education or less, 15.9% held a high school diploma, 16.4% completed technical studies, 35.3% held a university degree, and 22.7% obtained a master’s or doctoral degree. Regarding relationship status, 32.6% were in a relationship, 32.6% were married, and 34.8% were single, widowed, or divorced.

Employment status included 60.6% actively employed, 21.2% students, and 18.2% non-working. Common fields of work were health (20.8%), education (11.4%), sales (5.5%), and administration (4.0%). Most participants (77.2%) reported no close friends or relatives with schizophrenia, while 22.8% had varying levels of familiarity with the condition.

3.1.2 Initial Refinement through Descriptive Analyses

The scale was refined by analyzing item statistics (mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis). Three items (“I wouldn’t mind being friends with someone who has schizophrenia,” “It is important to promote the rehabilitation and recovery of people with schizophrenia,” and “It is possible for people with schizophrenia to achieve a lot of autonomy and independence thanks to rehabilitation”) due to overwhelmingly positive responses (means: 4.57, 4.81, and 4.44 on a 5-point scale) and problematic psychometric properties, including strong negative skewness and high kurtosis, indicating limited variability and insufficient discriminatory power. Removing these items improved the scale’s validity and reliability for subsequent EFA.

3.1.3 Initial Assessment of Model Fit and Item Distribution through Exploratory Factor Analysis

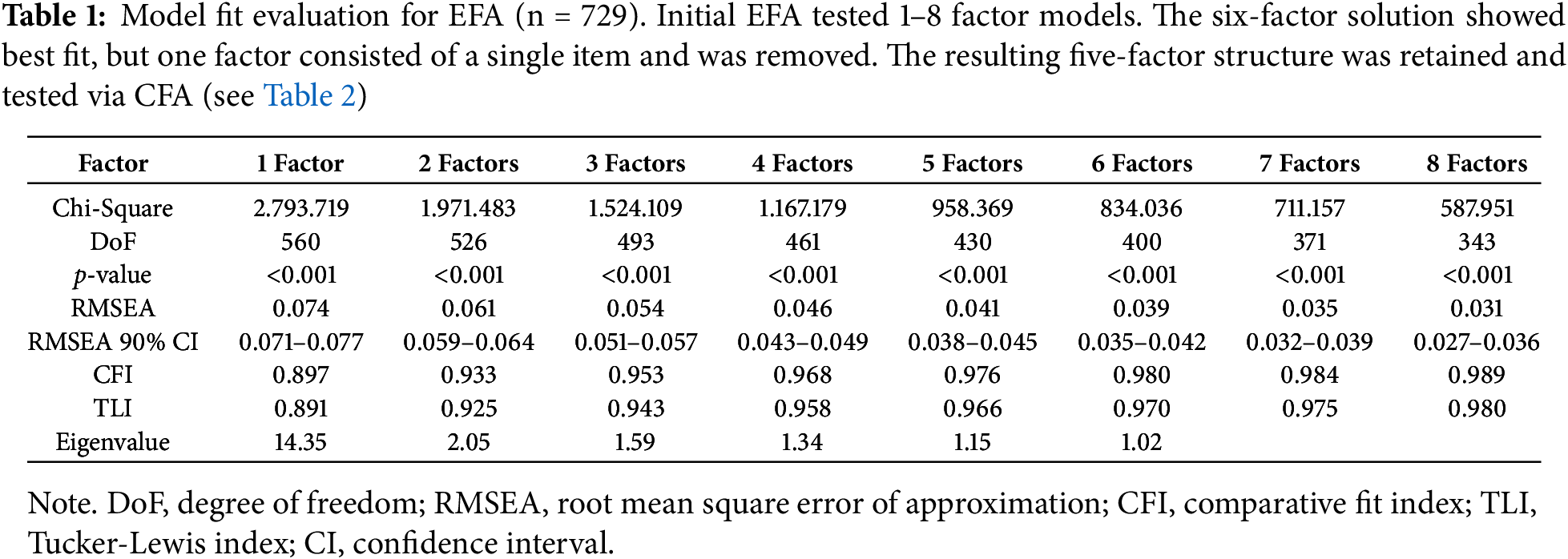

The EFA identified a six-factor solution as the initial best fit, balancing statistical fit, conceptual coherence, and minimal cross-loadings (Table 1). Factors beyond the sixth one had eigenvalues less than 1 (e.g., 0.903 for the seventh factor), indicating that they may not contribute substantively to the overall factor structure. Single-factor and two- to five-factor models had poor fit indices or conceptual limitations, while seven- and eight-factor models included weak factors with limited item contributions.

In the six-factor model, one factor was represented by a single item, “The job prospects for people with schizophrenia are the same as those of others,” which was removed due to insufficient representation. In fact, the eigenvalue for this model was 1.018, just above the threshold, suggesting that the explanatory power of this factor is relatively weak. This refinement led to testing a five-factor model, which was evaluated in a confirmatory manner. The first five factors in the exploratory analyses explained approximately 58.53% of the total variance in the dataset based on the eigenvalues. The results of this revised model are discussed in the subsequent section.

3.2 Study 2: Final Assessment of Model Fit and Item Distribution through CFA and Factor Labeling (n = 417)

The final scale was administered to a new sample of 417 individuals from the Spanish general population (mean age = 38.95, SD = 16.07), closely resembling the initial sample. The group included 66.2% women, 33.6% men, and one intersex individual, with most participants born (95.7%) or residing (90.9%) in Spain.

Educational attainment included 8.8% with secondary education or less, 20.4% with a high school diploma, 15.9% with technical studies, 33.4% with a university degree, and 20.4% with a master’s or doctoral degree. Relationship statuses were 26.4% in a relationship, 31.9% married, and 41.5% single, widowed, or divorced.

Employment patterns showed 59.5% actively working, 23.3% students, and 17.0% in non-working situations. Common occupations included healthcare (23.6%), education (8.2%), administration (6.2%), and sales (3.1%).

Participants were asked about their familiarity with schizophrenia, with 75.9% reporting no personal connection, 17.8% knowing one person, 2.6% knowing two people, 1.2% knowing three people, and 2.4% knowing more than three individuals.

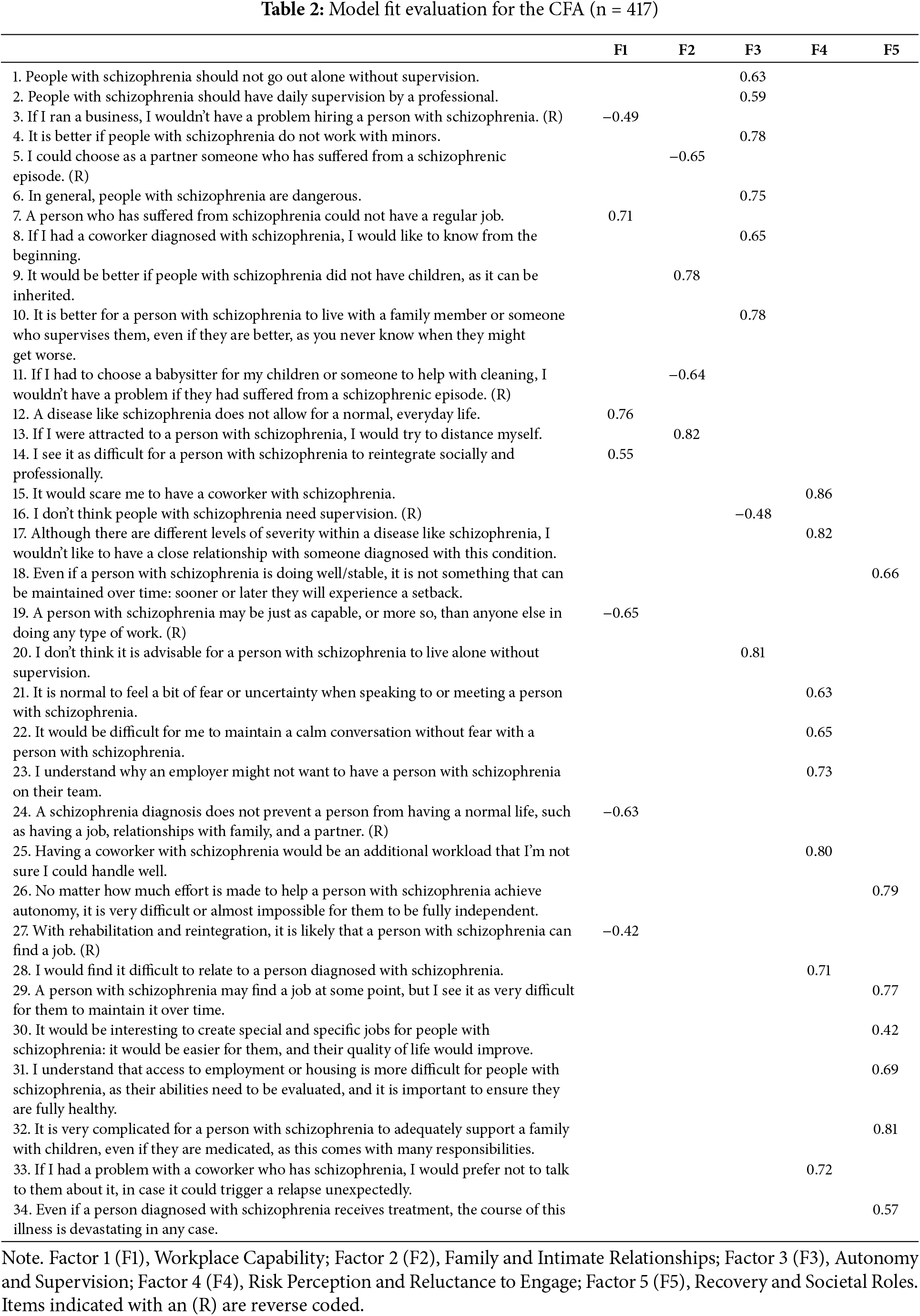

The CFA assessing the structural validity of the final scale demonstrated a good model fit. The chi-square value was significant, χ2(517) = 1191.465, p < 0.001, which is expected for the sample size. The RMSEA was 0.056 (90% CI: 0.052–0.060), and incremental fit indices (CFI = 0.938, TLI = 0.933) exceeded the 0.93 threshold, indicating a satisfactory fit. Item distributions and loadings are detailed in Table 2.

{\raggedright\arraybackslash}p{100mm}}?> {\raggedright\arraybackslash}X}?>The factors identified in the analysis were labeled based on the content of the items and the underlying themes they represent.

Factor 1: Workplace Stigma and Capability addresses perceptions about the professional abilities of people with schizophrenia. It evaluates beliefs about the capacity of individuals with schizophrenia to succeed in the workplace and the potential burden they might place on coworkers.

Factor 2: Family and Intimate Relationships focuses on attitudes towards people with schizophrenia forming close personal relationships. It evaluates whether people believe that individuals with schizophrenia can be considered as partners or live with family members for support.

Factor 3: Autonomy and Supervision evaluates societal attitudes and beliefs about the ability of individuals with schizophrenia to live independently, make their own decisions, and manage daily life without constant supervision.

Factor 4: Risk Perception and Reluctance to Engage captures fears and stereotypes about individuals with schizophrenia as potentially dangerous, unpredictable, or problematic in interpersonal settings.

Factor 5: Recovery and Societal Roles measures skepticism and stigma related to the potential for individuals with schizophrenia to achieve meaningful recovery, sustained wellness, and integration into society.

These factors together reflect a complex array of attitudes and beliefs about people with schizophrenia, ranging from perceptions of danger and incapacity to a recognition of the potential for recovery and autonomy.

3.3 Internal Consistency and Item Inter-Correlations

The Workplace Stigma subscale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.74), with all inter-item correlations significant (p < 0.001) and small in magnitude (r = 0.19–0.30). The Family and Intimate Relationships subscale showed similar reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.73), with significant inter-item correlations ranging from small to moderate (r = 0.25–0.56). The Autonomy and Supervision subscale exhibited good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.81), with significantly small-to-moderate inter-item correlations (r = 0.22–0.55). The Risk Perception and Reluctance to Engage subscale showed high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.86), with significantly small-to-moderate inter-item correlations (r = 0.24–0.66). Finally, the Recovery and Societal Roles subscale demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.82), with significantly small-to-moderate inter-item correlations (r = 0.32–0.56).

3.4 Differences in Stigma across Sex, Age, Familiarity with the Condition, Marital Status, and Type of Occupation in the Whole Sample (n = 1130)

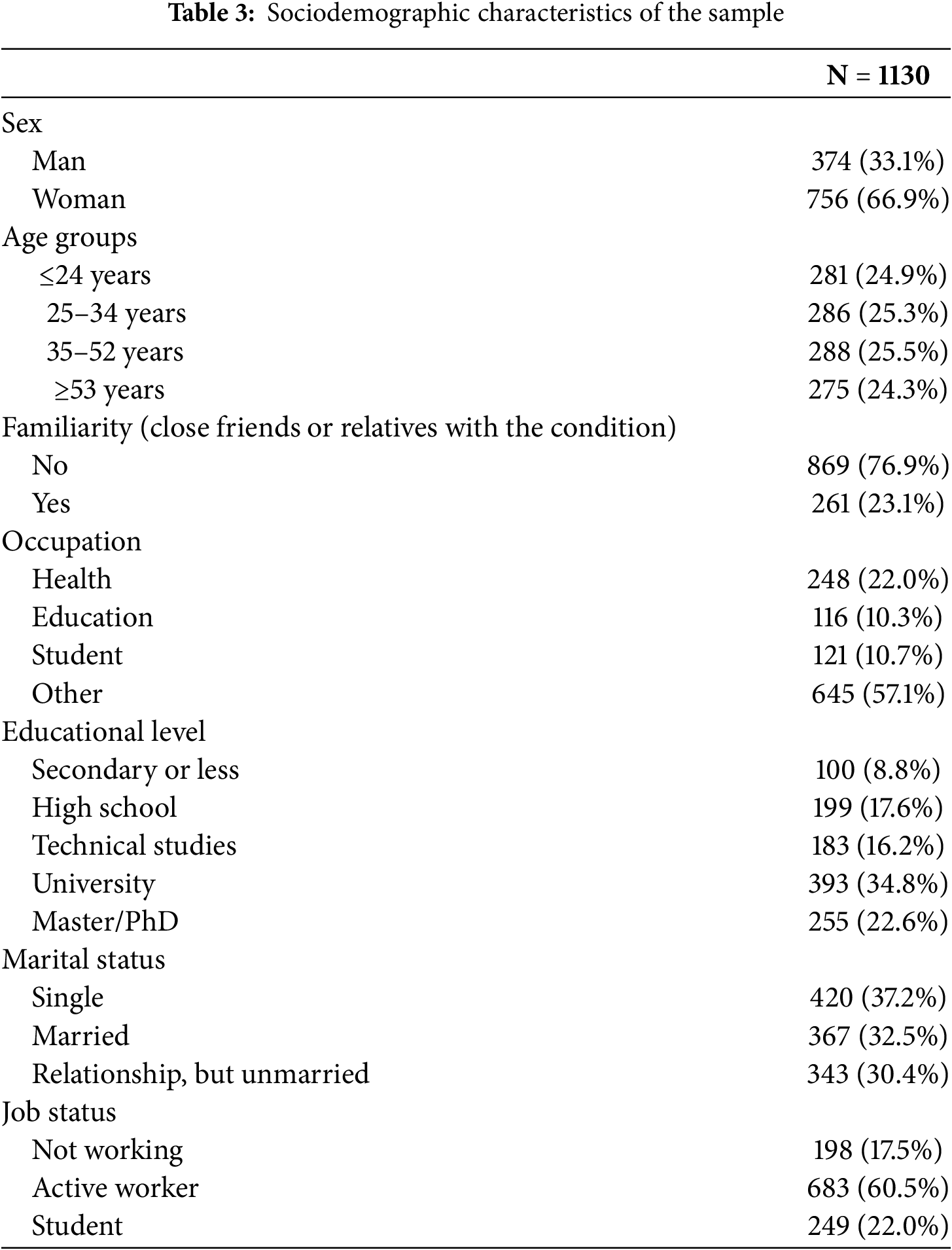

From the combined sample of Studies 1 and 2 (n = 1146), sociodemographic data were available for 1130 participants (98.6%), as detailed in Table 3. Most participants were women (66.9%) and reported no close friends or relatives with schizophrenia (76.9%). Occupations were grouped into health (n = 248), education (n = 116), student (n = 121), and other (n = 645). Age groups, based on quartiles, were ≤24 years (24.9%), 25–34 years (25.3%), 35–52 years (25.5%), and ≥53 years (24.3%).

Mean stigma scores for each area, adjusted to a 1-to-5 range, revealed the highest stigma in Autonomy and Supervision (Mean = 2.83, SD = 0.91), followed by Recovery and Societal Roles (Mean = 2.38, SD = 0.84) and Family and Intimate Relationships (Mean = 2.37, SD = 0.93). The lowest scores were observed in Workplace Stigma and Capability (Mean = 2.00, SD = 0.72) and Risk Perception and Reluctance to Engage (Mean = 2.00, SD = 0.82). These results highlight the contextual nature of stigma, with autonomy-related interactions as the most concerning area.

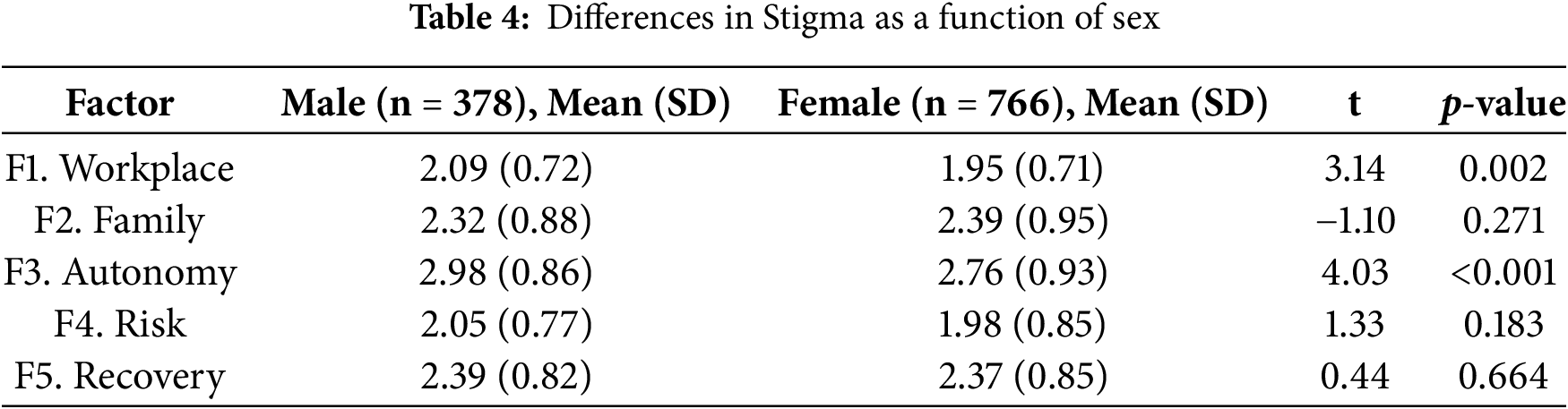

3.4.1 Differences in Stigma as a Function of Sex

Significant differences in stigma were found between men and women for Workplace Stigma, Capability, and Autonomy and Supervision, with men scoring higher (Table 4). No significant differences were observed for Family and Intimate Relationships, Risk Perception and Reluctance to Engage, and Recovery and Societal Roles.

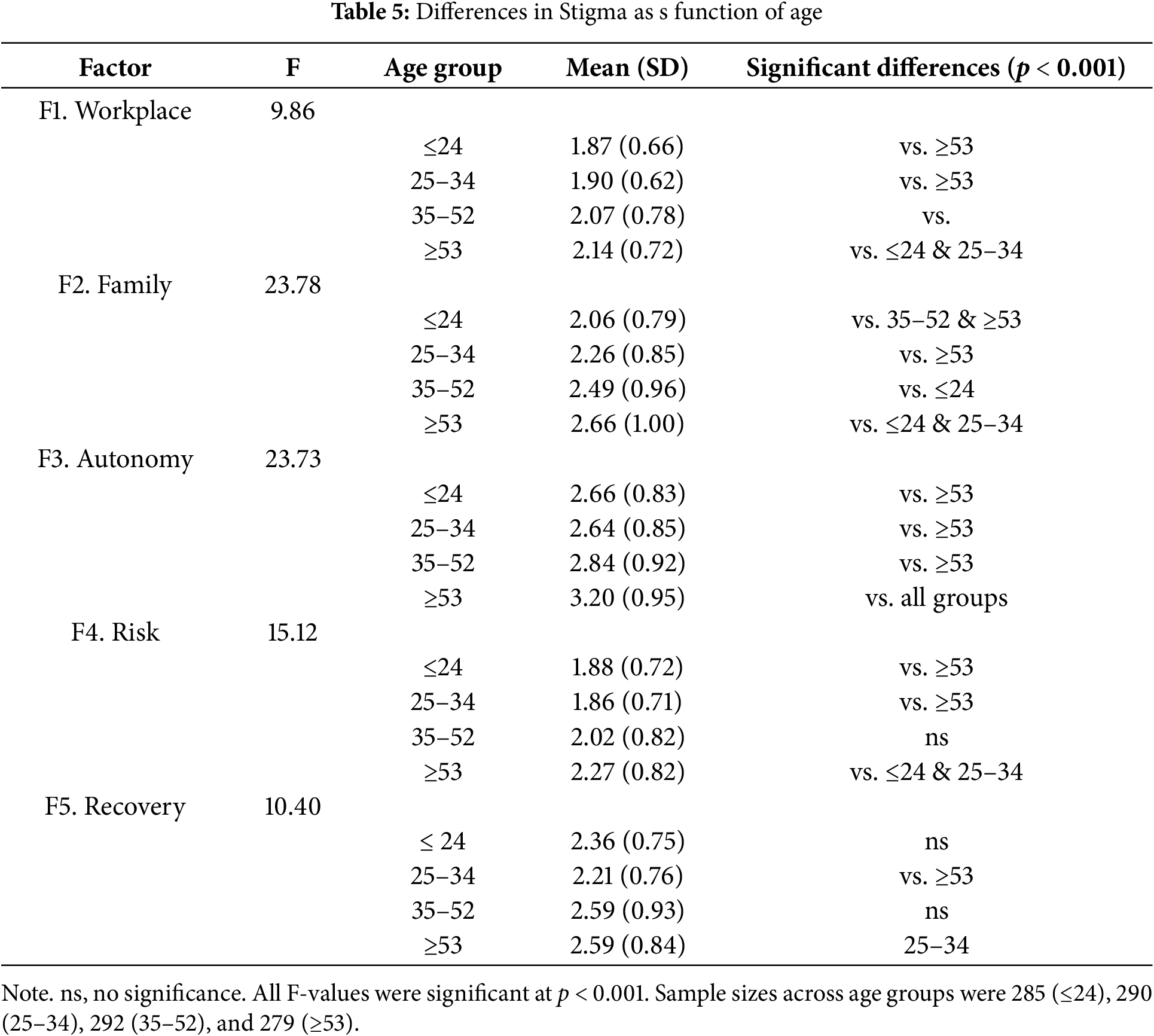

3.4.2 Differences in Stigma as a Function of Age

Stigma levels increased with age, with the ≥53 years group showing the highest stigma across all domains (Table 5). Younger groups (≤24 years and 25–34 years) had significantly lower stigma than the oldest group. The 35–52 years group had stigma scores between the youngest and oldest groups, with mostly non-significant differences. Notable differences were observed in Family and Intimate Relationships and Autonomy and Supervision, indicating a progressive increase in stigma with age, especially in the oldest group.

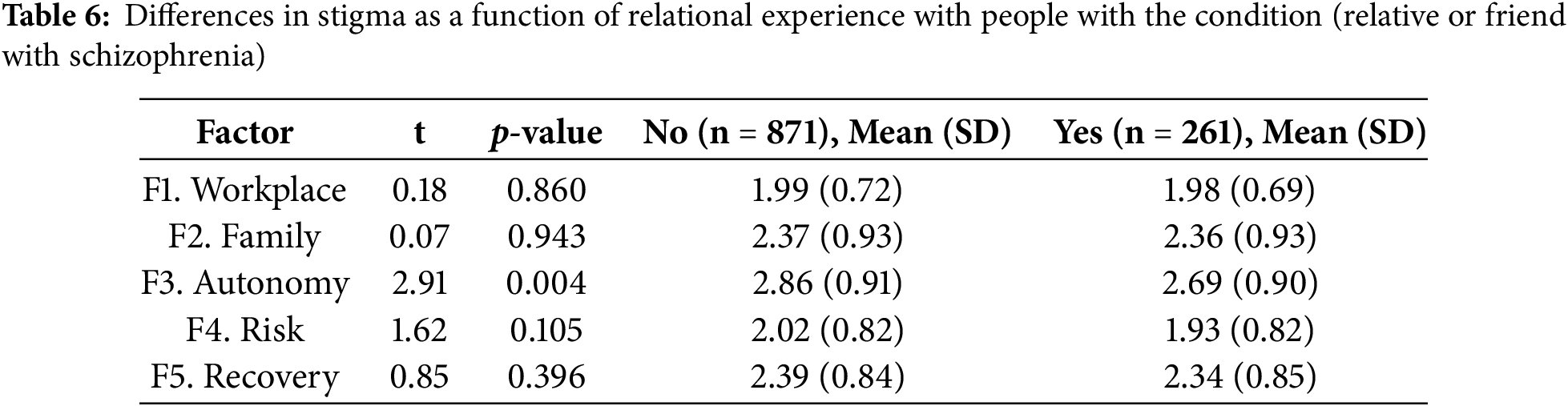

3.4.3 Differences in Stigma as a Function of Relational Experience with People with Schizophrenia (Relative or Friend)

Individuals with a close relationship to someone with schizophrenia (i.e., first-degree family or long-term personal connection) reported significantly lower stigma in Autonomy and Supervision compared to those without familiarity. No significant differences were found in other stigma dimensions (Table 6).

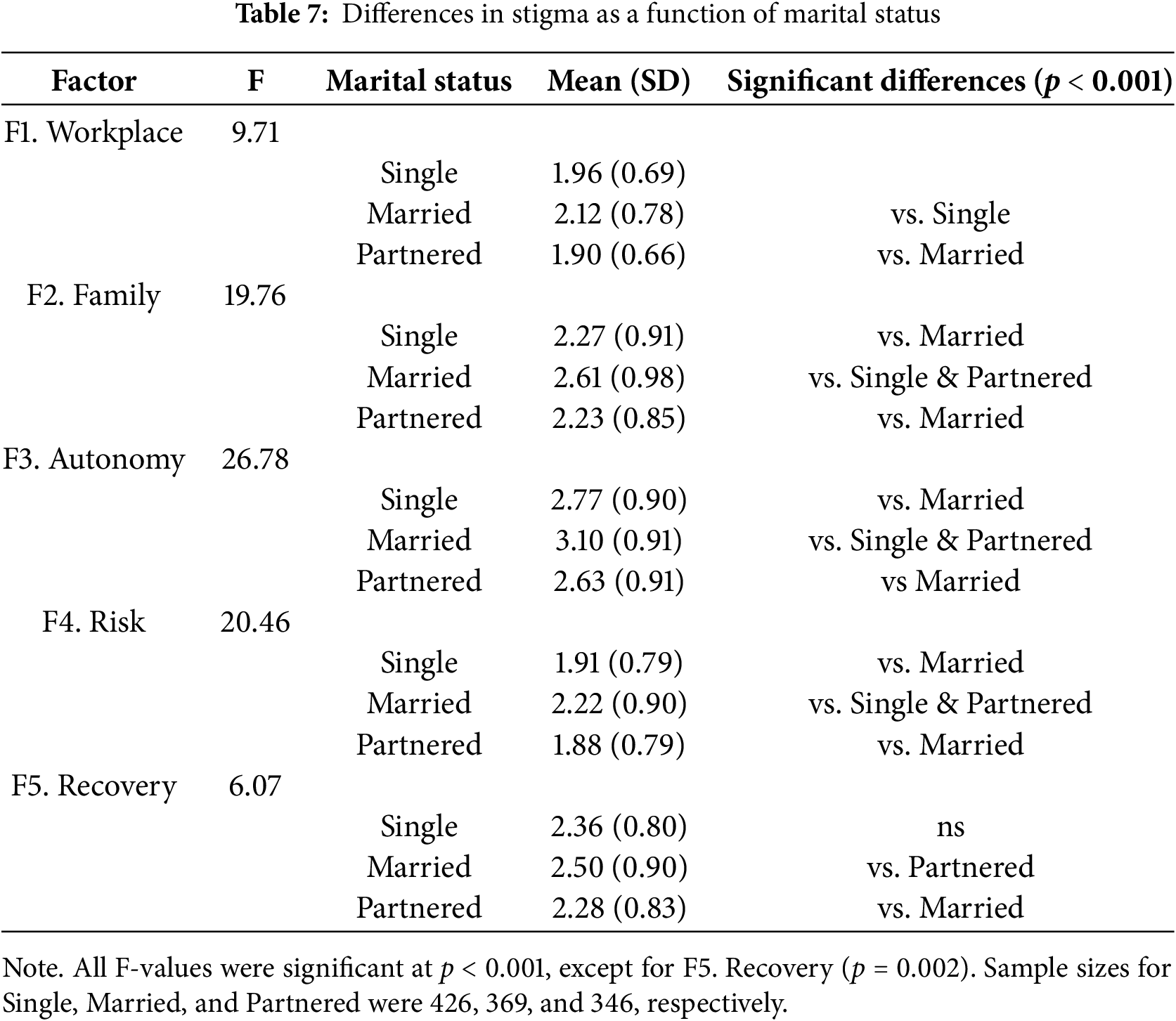

3.4.4 Differences in Stigma as a Function of Marital Status

Married individuals reported higher stigma across all areas, with significant differences from single and partnered groups (Table 7). Single and partnered individuals had similar, lower stigma levels, with no significant differences between them. The largest differences were found in Autonomy and Supervision, Perception and Reluctance to Engage, and Family and Intimate Relationships. When age was included as a covariate in the ANCOVA, the previously observed group differences were no longer significant for the Workplace, Family, and Autonomy factors. However, significant group differences remained for the Risk Perception and Recovery factors.

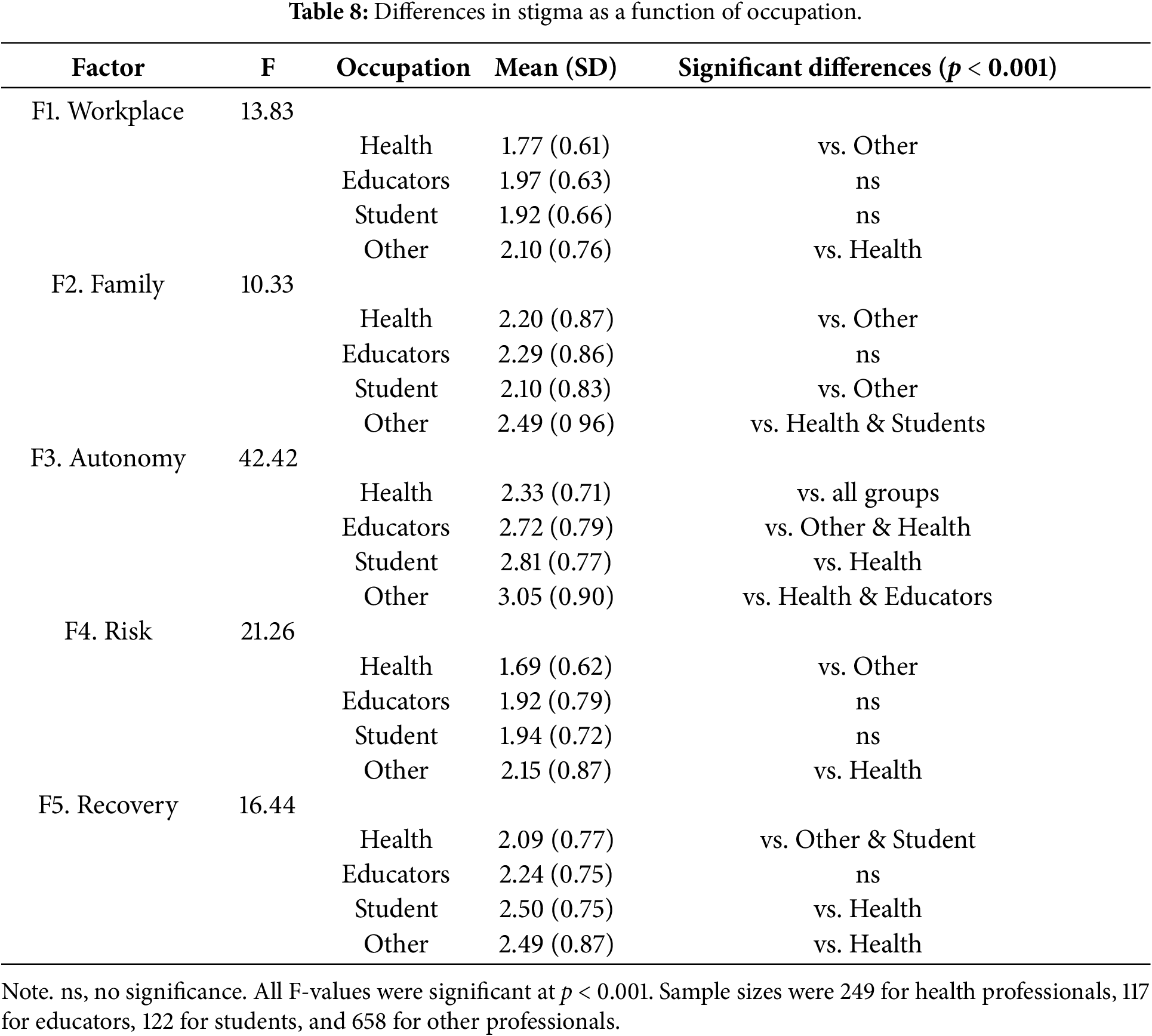

3.4.5 Differences in Stigma as a Function of Occupation

Health professionals, which included a broad range of roles such as physicians, nurses, psychologists, and other healthcare workers—without distinguishing between mental health specialists and general health staff, consistently reported the lowest stigma across most factors, while other occupations had the highest stigma scores (Table 8). Education and Student groups showed variable results depending on the stigma domain. Significant differences were observed between health professionals and other occupations in Workplace Stigma, Capability and Risk Perception, and Reluctance to Engage. Both health professionals and students had lower stigma in Family and Intimate Relationships, differing significantly from other professionals. In Recovery and Societal Roles, students and other professionals reported higher stigma than health professionals and educators. The most pronounced group difference was in Autonomy and Supervision, where health professionals reported significantly lower stigma than all other groups.

This study provides new empirical evidence on how societal stigma toward schizophrenia is structured and expressed across multiple dimensions. By developing and validating a multidimensional stigma scale, the research revealed that public attitudes toward schizophrenia are far from uniform but rather cluster into distinct domains reflecting beliefs about workplace capability, intimate relationships, autonomy, risk perception, and recovery. These findings underscore the multifaceted nature of stigma, indicating that societal biases are not monolithic but span various aspects of life, such as work, personal relationships, and perceived personal independence. The five-factor model was statistically supported, demonstrating that these stigma domains are both conceptually and empirically distinct from one another, which provides a more nuanced understanding of public attitudes toward schizophrenia. Additionally, the scale demonstrated strong psychometric properties, indicating that it can serve as a reliable tool for assessing stigma patterns in diverse populations, and thus can be utilized for future large-scale studies or intervention assessments.

Importantly, the study also identified significant sociodemographic predictors of stigma, highlighting how factors such as age, occupation, sex, and marital status shape public perceptions. For example, older individuals, men, and married individuals were found to report higher levels of stigma, which suggests that generational, cultural, and demographic factors play a crucial role in shaping public attitudes. These findings are critical for understanding how stigma is not only influenced by individual experiences but is also shaped by broader societal factors. They further emphasize the need for tailored interventions that consider sociodemographic variables to more effectively reduce stigma within different segments of the population.

4.1 Workplace Stigma and Capability

Stigma related to workplace capability reflects entrenched biases about the ability of individuals with schizophrenia to sustain employment [10]. This belief that people with schizophrenia cannot contribute meaningfully to the workforce still remains today a significant barrier to their social inclusion [56]. Interestingly, the findings indicated that workplace stigma is even higher in specific populations, particularly among men, older individuals, and those outside health and education fields, highlighting the need for tailored campaigns. Addressing these beliefs requires workplace policies that promote inclusion and accommodations, together with educational initiatives targeting employers and colleagues to foster understanding of schizophrenia and recovery potential [10].

4.2 Family and Intimate Relationships

Stigma in family and intimate relationships was evident in doubts about relational competence, particularly among older and married participants. These beliefs perpetuate stereotypes of emotional instability and social isolation, limiting opportunities for integration and fostering self-stigma [8,57]. Targeted public health campaigns and psychoeducational interventions focusing on relational success stories can help reduce stigma in this domain and encourage supportive family environments [58].

Autonomy-related stigma reflects societal doubts about the ability of individuals with schizophrenia to live independently [46]. Such views reinforce stereotypes of unpredictability and dependency, contributing to exclusion in housing and social interactions [12,48]. Public education campaigns emphasizing the ability of individuals with schizophrenia to manage symptoms effectively and achieve independence are crucial. Evidence-based messaging can challenge entrenched myths of instability or risk [59,60].

4.4 Risk Perception and Reluctance to Engage

This domain captures societal fears of individuals with schizophrenia as dangerous or unpredictable [61], which lead to avoidance, self-stigma, and reduced opportunities for meaningful interactions [21,47,62]. Interventions targeting these stereotypes must go beyond improving mental health literacy to actively challenge irrational beliefs about violence and unpredictability [12]. Contact-based initiatives promoting direct engagement with individuals who have lived experience are particularly effective in reducing stigma [63].

4.5 Recovery and Societal Roles

Skepticism about recovery perpetuates the belief that schizophrenia inevitably results in insuperable challenges, ignoring advancements in treatment and numerous success stories [64,65]. Integrated care programs, including therapy, housing assistance, and employment support, demonstrate the potential for significant societal participation [66]. Public campaigns should emphasize recovery-oriented narratives and highlight real-life examples of individuals thriving with adequate support, while policies promoting equitable access to resources can dismantle systemic barriers to inclusion [30,67].

4.6 Sociodemographic Differences

A final contribution of this study was its exploration of sociodemographic differences in societal stigma. As expected, significant differences were observed, with men and older individuals generally reporting higher levels of stigma, while those with close relationships to individuals with schizophrenia and healthcare professionals showed less stigma [42,43,68]. Additionally, married individuals were more likely to endorse stigmatizing beliefs. Interestingly, stigma differences were more pronounced in some stigma domains than others.

Men exhibited higher levels of stigma, particularly in domains of Workplace Stigma and Autonomy. This aligns with research suggesting that women’s greater empathy and mental health literacy contribute to more accepting attitudes [69,70]. Conversely, traditional masculine norms emphasizing independence may exacerbate stigma by reinforcing biases against perceived vulnerabilities [71,72]. Interventions targeting men should focus on challenging these norms and enhancing empathy and mental health literacy.

Older individuals reported higher stigma, particularly in Family and Intimate Relationships and Autonomy domains. This is consistent with findings that younger individuals exhibit lower social distancing and perceive mental health disorders as less severe [73], while older adults often view schizophrenia as a personal weakness [74], reflecting more traditional attitudes. While some research with small sample sizes (n = 80) suggests less stigma in older adults compared to adolescents, possibly due to greater mental health literacy and personal experience with mental illness [75], recent evidence challenges the notion that literacy improves with age [73]. Furthermore, persistent stigma, such as reluctance to accept mentally ill individuals in close family roles, has remained stable over the past 20 years, regardless of generational shifts [12]. These findings suggest that, in addition to generational norms, age-related personality changes, such as increased conservatism and reduced openness to experience, may contribute to higher stigma among older individuals [76,77]. Moreover, it is possible that older participants’ higher stigma reflects greater lifetime exposure to individuals with mental illness, which may influence attitudes and reinforce existing stereotypes. This exposure, combined with a long history of societal stigmatization, could amplify negative perceptions of schizophrenia, despite potential increases in mental health literacy.

4.9 Relational Experience with People with Schizophrenia

Close personal relationships with individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia were associated with reduced stigma, particularly in Autonomy and Supervision. However, relational experience with people with schizophrenia alone may not suffice to eliminate stigma. For example, while early exposure to psychiatric training and personal experiences with mental illness positively influence stigma and career choices [78], even mental health professionals with high exposure to schizophrenia often hold subtle biases [28,63]. In fact, the positive impact of mental health literacy is harder to achieve with schizophrenia compared to conditions like depression [44]. This underscores the need for comprehensive strategies that combine education with efforts to challenge cultural norms and stereotypes. In this line, relatability has been identified as a key factor that could help bridge the gap between understanding and stigma reduction [79].

Married individuals reported higher stigma across several domains, reflecting the influence of societal pressures and traditional norms that perpetuate stigmatizing beliefs [80]. Traditionalism, which is linked to, may explain this trend. Lower openness is associated with greater stigma, especially toward mental illness, as traditional attitudes perpetuate stigmatizing beliefs [81]. Additionally, individuals who marry earlier tend to have lower openness and stronger adherence to traditional norms [82]. This suggests that traditionalism, shaped by personality traits and life choices, may contribute to heightened stigma in married individuals, highlighting the need for culturally tailored anti-stigma interventions. Anti-stigma interventions for this group should address traditional attitudes and emphasize the benefits of inclusive perspectives for familial and community well-being.

Interestingly, when age was included as a covariate, the previously observed group differences across the Workplace, Family, and Autonomy domains were no longer significant. This suggests that age may partially explain the variations in stigma perceptions within these areas, particularly when exploring differences across marital status, highlighting the potential influence of generational and developmental factors on societal attitudes toward schizophrenia. However, significant differences between married and non-married individuals persisted for the Risk Perception and Recovery domains, indicating that these perceptions of schizophrenia may be less influenced by age and probably reflecting more deeply ingrained societal beliefs and misconceptions. These findings emphasize the need for targeted stigma reduction strategies that account for both age-related and marital status factors, while also addressing the persistent stigma in the areas of risk and recovery, which remain key dimensions for intervention.

Consistent with previous research [72], healthcare professionals reported lower stigma levels compared to individuals in other occupations, likely due to greater exposure to mental health conditions and professional training. However, subtle biases persist, particularly among psychiatrists, highlighting the need for targeted stigma reduction initiatives within healthcare professions [83]. Expanding mental health training in non-healthcare occupations can also help reduce stigma. However, despite this lower reported stigma, subtle or structural biases still persist [84]. These biases may not always be overt, but they can influence the way individuals with schizophrenia are treated. Research has shown that even professionals with extensive training may harbor stereotypes or misconceptions about mental illness that can affect their interactions with patients [85]. Such biases can lead to unintentional discrimination, resulting in diminished care or a failure to fully support patients in their recovery [86].

This study provides valuable insights but has limitations. The use of self-administered online questionnaires may introduce selection bias, as participants with internet access and greater mental health awareness were more likely to respond, potentially underrepresenting older individuals or those with limited digital literacy. Social desirability bias may have influenced responses, as participants might have reported socially acceptable attitudes rather than their true beliefs. Future research should incorporate mixed methods, including interviews and observational approaches, and recruit more diverse samples through randomized surveys. Additionally, while the study focused on the Spanish population, cultural, regional, and systemic differences should be explored through cross-cultural comparisons to enhance the generalizability of findings. Ethnic and cultural background data were not collected in this study, and future research should consider including these variables to better understand how cultural and ethnic diversity might influence stigma perceptions. While Spain is not particularly diverse in terms of cultural and ethnic groups (with a majority White Caucasian population), it is important to assess potential differences in stigma attitudes across diverse cultural and ethnic contexts to deepen our understanding of societal stigma. Furthermore, the study did not compare scores with existing stigma instruments or personality measures, limiting evidence for construct validity. Also, while the scale focused on schizophrenia, other mental health conditions (such as depression) and prior personal or family mental health experiences were not fully accounted for, though they could significantly shape stigma attitudes.

Although marital status was acknowledged, it is important to note that the potential influence of parenthood on stigma perceptions—particularly how having children may shape individuals’ attitudes toward schizophrenia—was not explored. Parenthood could influence stigma through heightened concerns about safety, family roles, or social functioning, and may intersect with age and marital status to further shape public perceptions. Future research should examine how parental status and concerns related to caregiving responsibilities influence stigma, which could help refine intervention strategies targeting family and community contexts. Additionally, the role of healthcare professionals in shaping stigma, including their specialization, was not fully explored. Future research could benefit from investigating how different healthcare professionals (e.g., psychiatrists, psychologists, or social workers) and their specializations influence stigma toward schizophrenia, as their perspectives may significantly differ and impact patient outcomes. Finally, while the scale demonstrated strong psychometric properties, some structural refinements—such as reducing item complexity, addressing valence imbalance, or shortening the 34-item length—could enhance clarity, response consistency, and feasibility for use in large-scale or cross-cultural studies. Developing a short-form version may be particularly valuable for epidemiological research and intervention evaluations.

This study provides valuable insights into the complex nature of societal stigma toward schizophrenia by developing and validating a multidimensional scale and identifying key sociodemographic predictors. The findings confirm that stigma is not a uniform construct but spans distinct domains, including workplace capability, intimate relationships, autonomy, risk perception, and recovery. Notably, autonomy and supervision emerged as the most stigmatized areas, reflecting widespread doubts about individuals with schizophrenia’s ability to live independently and manage daily responsibilities. While stigma in areas like workplace capability and risk perception appears to be decreasing, deep-seated misconceptions continue to affect broader societal attitudes, particularly regarding recovery and interpersonal relationships.

The study also highlights important demographic patterns, with men, older individuals, and married participants reporting higher stigma, while women, younger individuals, healthcare professionals, and those with personal connections to schizophrenia exhibited lower stigma. These findings underscore the need for targeted interventions that account for sociodemographic factors, promoting greater understanding and challenging misconceptions in specific groups. Addressing schizophrenia stigma is a critical public health concern, as it can hinder access to treatment, social integration, and employment opportunities. Future research should focus on cross-cultural validation, exploring intervention effects, and expanding conceptual frameworks to foster more inclusive attitudes and improve mental health outcomes for individuals with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgement: Special recognition for the experts and colleagues who were consulted for the development of the scale.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data will be shared by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the Jaume I University (CD/43/2021), which was the lead author’s institutional affiliation during the planning and data collection phases of this research.

Informed Consent: All the participants provided their written online consent to participate.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. World Health Organization. Schizophrenia [Internet]. 2022. World Health Organization. [cited 2025 Jun 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia. [Google Scholar]

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. 947 p. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hjorthøj C, Stürup AE, McGrath JJ, Nordentoft M. Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(4):295–301. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30078-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wildgust HJ, Hodgson R, Beary M. The paradox of premature mortality in schizophrenia: new research questions. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(4_suppl):9–15. doi:10.1177/1359786810382149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Jin H, Mosweu I. The societal cost of schizophrenia: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(1):25–42. doi:10.1007/s40273-016-0444-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Degnan A, Berry K, Humphrey C, Bucci S. The relationship between stigma and subjective quality of life in psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;85(1):102003. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Vass V, Sitko K, West S, Bentall RP. How stigma gets under the skin: the role of stigma, self-stigma and self-esteem in subjective recovery from psychosis. Psychosis. 2017;9(3):235–44. doi:10.1080/17522439.2017.1300184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Boysen GA. Stigma toward people with mental illness as potential sexual and romantic partners. Evol Psychol Sci. 2017;3(3):212–23. doi:10.1007/s40806-017-0089-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Colizzi M, Ruggeri M, Lasalvia A. Should we be concerned about stigma and discrimination in people at risk for psychosis? A systematic review. Psychol Med. 2020;50(5):705–26. doi:10.1017/S0033291720000148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Brouwers EPM. Social stigma is an underestimated contributing factor to unemployment in people with mental illness or mental health issues: position paper and future directions. BMC Psychol. 2020;8(1):36. doi:10.1186/s40359-020-00399-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Thornicroft G, Sunkel C, Alikhon Aliev A, Baker S, Brohan E, El Chammay R, et al. The lancet commission on ending stigma and discrimination in mental health. Lancet. 2022;400(10361):1438–80. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01470-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Pescosolido BA, Manago B, Monahan J. Evolving public views on the likelihood of violence from people with mental illness: stigma and its consequences. Health Aff. 2019;38(10):1735–43. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Liu Y, Li Y. Community participation and subjective perception of recovery and quality of life among people with serious mental illnesses: the mediating role of self-stigma. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2024;60(6):1335–45. doi:10.1007/s00127-024-02754-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Adil M, Atiq I, Ellahi A. Stigmatization of schizophrenic individuals and its correlation to the fear of violent offence. Should we be concerned? Ann Med Surg. 2022;82:104666. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang H, Firdaus A. What does media say about mental health: a literature review of media coverage on mental health. J Media. 2024;5(3):967–79. doi:10.3390/journalmedia5030061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Infante-Torres D, Muñoz-Contreras L, Peña-Bravo S, Ramírez-Pérez M, Ferrer-Urbina R. Construction and validation of a scale of stigma against individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. Terap Psicol. 2023;41(3):343–61. doi:10.4067/s0718-48082023000300343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Mannarini S, Taccini F, Sato I, Rossi AA. Understanding stigma toward schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2022;318(6):114970. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med. 2015;45(1):11–27. doi:10.1017/S0033291714000129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Hatzenbuehler ML. Structural stigma: research evidence and implications for psychological science. Am Psychol. 2016;71(8):742–51. doi:10.1037/amp0000068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Vrbova K, Prasko J, Holubova M, Kamaradova D, Ociskova M, Marackova M, et al. Self-stigma and schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:3011–20. doi:10.2147/NDT.S120298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Fond G, Vidal M, Joseph M, Etchecopar-Etchart D, Solmi M, Yon DK, et al. Self-stigma in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 37 studies from 25 high- and low-to-middle income countries. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28(5):1920–31. doi:10.1038/s41380-023-02003-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Fusar-Poli P, Estradé A, Stanghellini G, Venables J, Onwumere J, Messas G, et al. The lived experience of psychosis: a bottom-up review co-written by experts by experience and academics. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):168–88. doi:10.1002/wps.20959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. The Lancet. Time for renewed optimism for schizophrenia? Lancet. 2024;403(10422):117. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00047-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Ahad AA, Sanchez-Gonzalez M, Junquera P. Understanding and addressing mental health stigma across cultures for improving psychiatric care: a narrative review. Cureus. 2023;15(5):e39549. doi:10.7759/cureus.39549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Furnham A, Swami V. Mental health literacy: a review of what it is and why it matters. Int Perspect Psychol. 2018;7(4):240–57. doi:10.1037/ipp0000094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kutcher S, Wei Y, Coniglio C. Mental health literacy: past, present, and future. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(3):154–8. doi:10.1177/0706743715616609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Cummings JR, Lucas SM, Druss BG. Addressing public stigma and disparities among persons with mental illness: the role of federal policy. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):781–5. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Valery K-M, Prouteau A. Schizophrenia stigma in mental health professionals and associated factors: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113068. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Boysen GA, Osgood PN, Price C, Rollins A. Affordance management theory and stigma toward schizophrenia. Stigma Health. 2022;7(3):280–8. doi:10.1037/sah0000385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Fleischhacker WW, Arango C, Arteel P, Barnes TRE, Carpenter W, Duckworth K, et al. Schizophrenia—time to commit to policy change. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(Suppl 3):S165–94. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbu006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Fox AB, Earnshaw VA, Taverna EC, Vogt D. Conceptualizing and measuring mental illness stigma: the mental illness stigma framework and critical review of measures. Stigma Health. 2018;3(4):348–76. doi:10.1037/sah0000104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wei Y, McGrath P, Hayden J, Kutcher S. The quality of mental health literacy measurement tools evaluating the stigma of mental illness: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27(5):433–62. doi:10.1017/S2045796017000178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Angermeyer MC, Grausgruber A, Hackl E, Moosbrugger R, Prandner D. Evolution of public beliefs about schizophrenia and attitudes towards those afflicted in Austria over two decades. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2021;56(8):1427–35. doi:10.1007/s00127-020-01963-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Clay J, Eaton J, Gronholm PC, Semrau M, Votruba N. Core components of mental health stigma reduction interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e164. doi:10.1017/S2045796020000797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Feldman DB, Crandall CS. Dimensions of mental illness stigma: what about mental illness causes social rejection? J Soc Clin Psychol. 2007;26(2):137–54. doi:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.2.137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Fujii T, Hanya M, Murotani K, Kamei H. Scale development and an educational program to reduce the stigma of schizophrenia among community pharmacists: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):211. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03208-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Grandón P, Aguilera AV, Bustos C, Alzate EC, Saldivia S. Evaluation of the stigma towards people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia using a knowledge scale. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr (Engl Ed). 2018;47(2):72–81. doi:10.1016/j.rcpeng.2018.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Hooley JM. Social factors in schizophrenia. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2010;19(4):238–42. doi:10.1177/0963721410377597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Jankowski SE, Yanos P, Dixon LB, Amsalem D. Reducing public stigma towards psychosis: a conceptual framework for understanding the effects of social contact based brief video interventions. Schizophr Bull. 2023;49(1):99–107. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbac143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH, Van Brakel W, Simbayi LC, Barré I, et al. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):31. doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Baba Y, Nemoto T, Tsujino N, Yamaguchi T, Katagiri N, Mizuno M. Stigma toward psychosis and its formulation process: prejudice and discrimination against early stages of schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;73(9661):181–6. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.11.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Mackenzie CS, Heath PJ, Vogel DL, Chekay R. Age differences in public stigma, self-stigma, and attitudes toward seeking help: a moderated mediation model. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(12):2259–72. doi:10.1002/jclp.22845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Mueser KT, DeTore NR, Kredlow MA, Bourgeois ML, Penn DL, Hintz K. Clinical and demographic correlates of stigma in first-episode psychosis: the impact of duration of untreated psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;141(2):157–66. doi:10.1111/ACPS.13102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Svensson B, Hansson L. How mental health literacy and experience of mental illness relate to stigmatizing attitudes and social distance towards people with depression or psychosis: a cross-sectional study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2016;70(4):309–13. doi:10.3109/08039488.2015.1109140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Subdirección General de Información Sanitaria. Salud mental en datos: prevalencia de los problemas de salud y consumo de psicofármacos y fármacos relacionados a partir de los registros clínicos de atención primaria (BDCAP Series 2). Madrid, Spain: Ministerio de Sanidad; 2021. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

46. Corrigan PW, Druss BG, Perlick DA. The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2014;15(2):37–70. doi:10.1177/1529100614531398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Lloyd C, Sullivan D, Williams PL. Perceptions of social stigma and its effect on interpersonal relationships of young males who experience a psychotic disorder. Aust Occup Ther J. 2005;52(3):243–50. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1630.2005.00504.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Lampropoulos D, Apostolidis T. Be autonomous or stay away! Providing evidence for autonomy beliefs as legitimizing myths for the stigma of schizophrenia. Int J Soc Psychol. 2022;37(2):362–82. doi:10.1080/02134748.2022.2040864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zamorano S, Sáez-Alonso M, González-Sanguino C, Muñoz M. Social stigma towards mental health problems in Spain: a systematic review. Clín Salud. 2023;34(1):23–34. doi:10.5093/clysa2023a5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Avdibegović E, Hasanović M. The stigma of mental illness and recovery. Psychiatr Danub. 2017;29(Suppl 5):900–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

51. Hsu C, Tseng P, Tu Y. Associating violence with schizophrenia—risks and biases. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(7):739. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Jorm AF, Reavley NJ, Ross AM. Belief in the dangerousness of people with mental disorders: a review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46(11):1029–45. doi:10.1177/000486741244240653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. O’Connor C, Brassil M, O’Sullivan S, Seery C, Nearchou F. How does diagnostic labelling affect social responses to people with mental illness? A systematic review of experimental studies using vignette-based designs. J Ment Health. 2022;31(1):115–30. doi:10.1080/09638237.2021.1922653. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Competiello SK, Bizer GY, Walker DC. The power of social media: stigmatizing content affects perceptions of mental health care. Soc Media Soc. 2023;9(4):368. doi:10.1177/20563051231207847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Taber KS. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ. 2018;48(6):1273–96. doi:10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Hampson ME, Watt BD, Hicks RE. Impacts of stigma and discrimination in the workplace on people living with psychosis. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):288. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02614-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Budziszewska MD, Babiuch-Hall M, Wielebska K. Love and romantic relationships in the voices of patients who experience psychosis: an interpretive phenomenological analysis. Front Psychol. 2020;11:570928. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.570928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Kuhney FS, Miklowitz DJ, Schiffman J, Mittal VA. Family-based psychosocial interventions for severe mental illness: social barriers and policy implications. Policy Insights Behav Brain Sci. 2023;10(1):59–67. doi:10.1177/23727322221128251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Corrigan PW, Gelb B. Three programs that use mass approaches to challenge the stigma of mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(3):393–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Corrigan PW, Shapiro JR. Measuring the impact of programs that challenge the public stigma of mental illness. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(8):907–22. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Bizumic B, Gunningham B. Prejudice toward people with mental illness, schizophrenia, and depression: measurement, structure, and antecedents. Schizophr Bull Open. 2022;3(1):sgac060. doi:10.1093/schizbullopen/sgac060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Li XH, Zhang TM, Yau YY, Wang YZ, Wong YLI, Yang L, et al. Peer-to-peer contact, social support and self-stigma among people with severe mental illness in Hong Kong. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;67(6):622–31. doi:10.1177/0020764020966009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Warpinski AC, Gracia G. Implications of educating the public on mental illness, violence, and stigma. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(5):577–80. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.55.5.577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Catalan A, Salazar De Pablo G, Vaquerizo Serrano J, Mosillo P, Baldwin H, Fernández-Rivas A, et al. Annual research review: prevention of psychosis in adolescents—systematic review and meta-analysis of advances in detection, prognosis and intervention. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;62(5):657–73. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Correll CU, Abi-Dargham A, Howes O. Emerging treatments in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;83(1):SU21024IP1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

66. Wander C. Schizophrenia: opportunities to improve outcomes and reduce economic burden through managed care. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(Suppl 3):S62–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

67. Morgan AJ, Wright J, Reavley NJ. Review of Australian initiatives to reduce stigma towards people with complex mental illness: what exists and what works? Int J Ment Health Syst. 2021;15(1):10. doi:10.1186/s13033-020-00423-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Dessauvagie A, Dang HM, Truong T, Nguyen T, Hong Nguyen B, Cao H, et al. Mental health literacy of university students in Vietnam and Cambodia. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2022;24(3):439–56. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2022.018030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Farina A. Are women nicer people than men? Sex and the stigma of mental disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 1981;1(2):223–43. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(81)90005-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Gibbons RJ, Thorsteinsson EB, Loi NM. Beliefs and attitudes towards mental illness: an examination of the sex differences in mental health literacy in a community sample. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1004. doi:10.7717/peerj.1004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Oliffe JL, Phillips MJ. Men, depression and masculinities: a review and recommendations. J Mens Health. 2008;5(3):194–202. [Google Scholar]

72. Smith AL, Cashwell CS. Social distance and mental illness: attitudes among mental health and non-mental health professionals and trainees. Prof Couns. 2011;1(1):13–20. doi:10.15241/als.1.1.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Clarkin J, Heywood C, Robinson LJ. Are younger people more accurate at identifying mental health disorders, recommending help appropriately, and do they show lower mental health stigma than older people? Ment Health Prev. 2024;36(11):200361. doi:10.1016/j.mhp.2024.200361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Farrer L, Leach L, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF. Age differences in mental health literacy. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):125. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Bradbury A. Mental health stigma: the impact of age and gender on attitudes. Community Ment Health J. 2020;56(5):933–8. doi:10.1007/s10597-020-00559-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Cornelis I, Van Hiel A, Roets A, Kossowska M. Age differences in conservatism: evidence on the mediating effects of personality and cognitive style. J Pers. 2009;77(1):51–88. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00538.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Donnellan MB, Lucas RE. Age differences in the Big Five across the life span: evidence from two national samples. Psychol Aging. 2008;23(3):558–66. doi:10.1037/a0012897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Man Yeung Tai A, Suen J, Mamdouh Kamel M, Schomerus G, Giovanni Icro Maremmaniz A, Michael Krausz R. Medical students’ views on psychiatry in Germany and Italy: survey. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2023;25(9):985–93. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2023.030087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Schomerus G, Kummetat J, Angermeyer MC, Link BG. Putting yourself in the shoes of others—relatability as a novel measure to explain the difference in stigma toward depression and schizophrenia. Soc Psych Psych Epid. 2024;203(1):146. doi:10.1007/s00127-024-02807-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Alonso J, Buron A, Rojas-Farreras S, De Graaf R, Haro JM, De Girolamo G, et al. Perceived stigma among individuals with common mental disorders. J Affect Disord. 2009;118(1–3):180–6. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Yuan Q, Seow E, Abdin E, Chua BY, Ong HL, Samari E, et al. Direct and moderating effects of personality on stigma towards mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):358. doi:10.1186/s12888-018-1932-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Sasudevan S. Personality traits and transition to first marriage [master’s thesis]. London, ON, Canada: Western University; 2020. [Google Scholar]

83. Lauber C, Nordt C, Braunschweig C, Rössler W. Do mental health professionals stigmatize their patients? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(s429):51–9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00718.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Knaak S, Mantler E, Szeto A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthc Manag Forum. 2017;30(2):111–6. doi:10.1177/0840470416679413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Stuber JP, Rocha A, Christian A, Link BG. Conceptions of mental illness: attitudes of mental health professionals and the general public. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(4):490–7. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201300136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Meidert U, Dönnges G, Bucher T, Wieber F, Gerber-Grote A. Unconscious bias among health professionals: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(16):6569. doi:10.3390/ijerph20166569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools