Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Digital Distraction or Creative Catalyst? Parental Smartphone Use and Adolescent Creativity among Chinese Vocational Students

1 Faculty of Education, Qufu Normal University, Qufu, 273165, China

2 English Teaching and Research Group, No. 18 Senior High School of Zaozhuang, Zaozhuang, 277200, China

3 School of Information Engineering, Shandong Youth University of Political Science, Jinan, 250103, China

4 Student Development Office, Changzhou Wujin Lijia Senior High School, Changzhou, 213100, China

5 Yancheng Mechatronic Branch, Jiangsu Union Technical Institute, Yancheng, 224005, China

6 International College, Krirk University, Bangkok, 10110, Thailand

7 Chinese Academy of Education Big Data, Faculty of Education, Qufu Normal University, Qufu, 273165, China

8 Jiangxi Psychological Consultant Association, Nanchang, 330000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Xuelian Wang. Email: ; I-Hua Chen. Email:

# These two authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Causes, Consequences and Interventions for Emerging Social Media Addiction)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(7), 1029-1044. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.065876

Received 24 March 2025; Accepted 20 June 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

Background: Despite growing research on parental technology use and its impacts on adolescent development, the influence of parental smartphone behavior on creativity remains understudied. This study addresses this gap by examining how parental phubbing affects adolescent creativity, exploring both direct and indirect pathways through creative self-efficacy as a mediator and problematic smartphone use (PSU) as a moderator. Methods: A total of 9111 Chinese vocational school adolescents (60.3% male; mean age = 16.88 years) were recruited via convenience sampling. Participants completed validated self-report questionnaires assessing creativity, parental phubbing, creative self-efficacy, and PSU. A moderated mediation model was tested using jamovi with bootstrapping procedures (2000 resamples), controlling for gender, age, sibling status, and school type. Results: Creative self-efficacy significantly mediated the relationship between parental phubbing and adolescent creativity (indirect effect = 0.061, 95% CI [0.013, 0.109]), while the direct effect was non-significant. PSU moderated both pathways, revealing contrasting patterns: for adolescents with high PSU, parental phubbing showed positive associations with creative self-efficacy and creativity, whereas among those with low PSU, parental phubbing demonstrated negative associations with both outcomes. Conclusion: This study reveals the complex influence of parental phubbing on adolescent creativity, with effects contingent upon adolescents’ own digital engagement patterns. It emphasizes the need to balance guidance and autonomy in fostering creativity. While not endorsing phubbing, the findings challenge simplistic views of technology’s impact and stress the importance of individual differences. The results offer valuable insights for parents, educators, and policymakers supporting youth development in today’s digital family environments.Keywords

Creativity is the ability to generate novel, useful, and contextually appropriate ideas or solutions, shaped by cognitive processes, domain knowledge, and environmental factors within sociocultural contexts [1,2]. Historically viewed as the domain of artistic or scientific innovation, creativity is now recognized as vital to everyday problem-solving and adaptive behaviors across various life domains [3,4]. This broader perspective is exemplified by “Little-C” creativity, a concept proposed by Kaufman and Beghetto [5], which refers to innovative thinking in ordinary situations. Examples include showing creativity in interpersonal problem-solving (e.g., developing unique approaches to help others navigate challenges) and applying creative thinking in scholarly work or daily artistic expression. “Little-C” underscores that creativity extends beyond rare genius to include adaptive, novel solutions in routine life.

The development of such everyday creativity is profoundly influenced by environmental contexts, with family dynamics playing a particularly crucial role [6,7]. Family interactions shape creative potential during adolescence—a critical period coinciding with cognitive maturation and identity formation [8,9]. As teens develop abstract thinking, independence, and engage with diverse environments, these creative abilities become valuable assets impacting their future educational and professional success [7,10].

While creativity development has traditionally been studied in relatively stable environments, today’s adolescents are growing up in a rapidly evolving technological landscape. With technological advancement accelerating in recent decades, the prevalence of electronic devices in households has increased significantly [11], transforming smartphones into indispensable necessities in modern family life. This technological integration has fundamentally altered family interaction patterns and parental behaviors, creating new dynamics that could impact adolescents’ creative development in complex ways. Of particular interest is “parental phubbing”—defined as parents’ frequent smartphone use during daily communications with their children [12]—which captures instances when parents divert their attention to smartphones during face-to-face interactions with their adolescents. Unlike general measures of screen time or technology use, phubbing potentially serves as a critical environmental factor that directly influences parent-child interactions during developmentally significant moments [13]. This behavior specifically captures smartphone use within interpersonal contexts [14], representing a direct social-environmental input that may significantly shape creative development.

Despite extensive research on parental phubbing’s impacts on adolescents’ problematic internet use [15] and mental health [16–18], its effects on creativity development remain largely unexplored. The present study addresses this gap by focusing specifically on adolescents’ perceptions of parental phubbing—whether interpreted as rejection, disinterest, or acceptable behavior—which likely influence creativity development more strongly than objective behaviors. This emphasis on perceived parental smartphone use aligns with current methodological approaches in phubbing research [13] and recognizes the critical role of subjective interpretation in developmental outcomes.

1.1 Theoretical Framework: Social Cognitive Theory

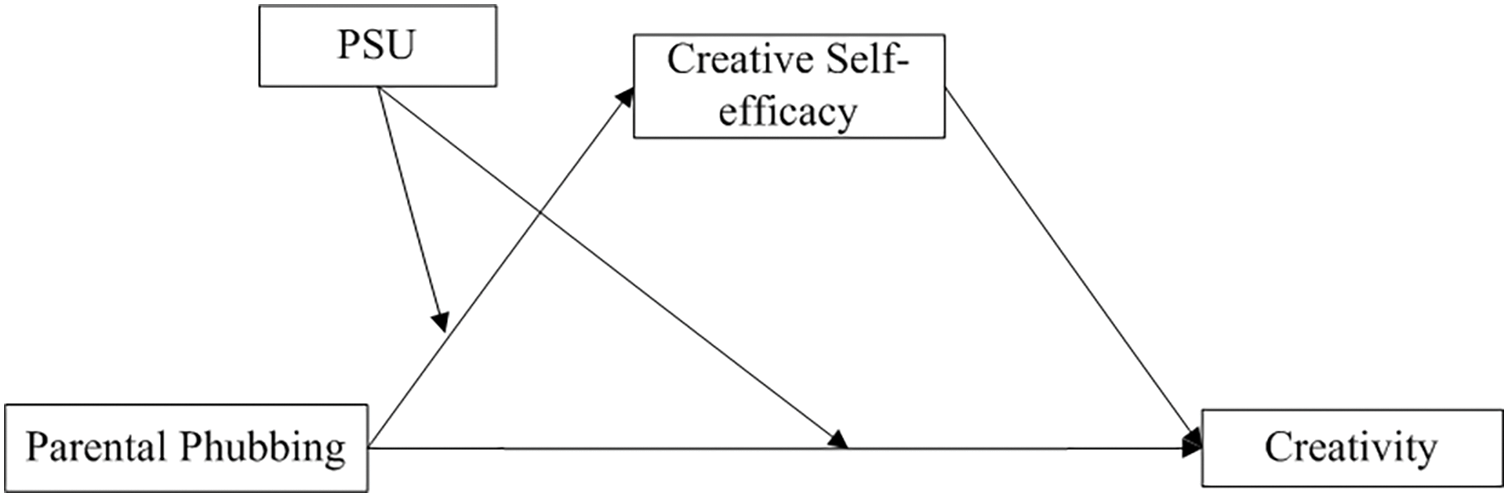

To investigate the relationship between parental phubbing and adolescent creativity, we propose a theoretical model based on Social Cognitive Theory (SCT). As illustrated in Fig. 1, this model examines both the direct association between parental phubbing and adolescent creativity and explores creative self-efficacy as a mediator and problematic smartphone use (PSU) as a moderator. Bandura’s SCT [19] provides a framework through triadic reciprocal determinism, where parental phubbing (environmental factor) influences adolescents’ psychological characteristics (personal factors) and creative behaviors (behavioral components) through the mediating and moderating pathways specified in our model.

Figure 1: The proposed theoretical framework. PSU, Problematic smartphone use

SCT provides an ideal framework for understanding this relationship through three key mechanisms. First, SCT emphasizes observational learning, through which adolescents acquire knowledge and behaviors by observing their parents [19]. When parents engage with smartphones during family interactions, they model specific patterns of technology use that adolescents may internalize, influencing how adolescents perceive technology’s role in creative pursuits.

Second, SCT highlights how environmental opportunities shape behavioral development [19]. Parental phubbing alters the family environment by changing parent-adolescent interaction quality [13], potentially reducing creative modeling and scaffolding opportunities. Alternatively, it might necessitate greater adolescent autonomy—possibly fostering self-reliance and innovative thinking when adolescents must develop creative projects without immediate guidance [20].

Third, SCT identifies psychological mechanisms mediating between environmental influences and behavioral outcomes, particularly self-efficacy—individuals’ beliefs about their capabilities to perform specific tasks [19]. Self-efficacy develops through mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and physiological states [21], all potentially affected by parental phubbing. Because self-efficacy strongly influences effort and achievement [21], these psychological processes provide valuable pathways for understanding how parental smartphone behaviors influence adolescent creative development.

1.2 Creative Self-Efficacy as a Mediator

Building on the self-efficacy concept central to SCT, our research model proposes creative self-efficacy as a theoretically grounded mediator between parental phubbing and adolescent creativity. Creative self-efficacy—defined as an individual’s beliefs about their capability to generate novel and useful ideas, solutions, or products [22,23]—represents a domain-specific application of Bandura’s self-efficacy construct. According to SCT, environmental factors (such as parental behaviors) influence performance outcomes (such as creativity) substantially through their impact on self-efficacy beliefs.

When examining the potential influence of parental phubbing on adolescents’ creative self-efficacy specifically, competing perspectives merit consideration. Primary research suggests that parental smartphone distraction might reduce quality interactions [24,25] necessary for developing creative confidence in adolescents. However, reduced parental oversight might increase adolescents’ autonomy and independent problem-solving, potentially enhancing their beliefs in their creative capabilities through self-directed experiences [20]. Empirical studies have demonstrated that self-direction and autonomy are critical factors for creativity development [26]. Thus, although somewhat paradoxical, parental phubbing might increase opportunities for independent mastery experiences that build creative self-efficacy through autonomous practice and problem-solving. Additionally, in contemporary digital environments, adolescents observing parents’ technological engagement might develop increased comfort with technology as a creative medium, possibly strengthening their creative self-efficacy in digital contexts.

These competing theoretical perspectives, suggesting both potentially negative and positive impacts of parental phubbing on adolescents’ creative self-efficacy, highlight the necessity of conducting empirical research to clarify the actual relationship between these variables. Understanding these pathways has significant implications for family dynamics in increasingly technology-integrated households and for developing effective strategies to foster creative development in digital-native generations.

1.3 Adolescents’ Problematic Smartphone Use as a Moderator

While the mediational pathway through creative self-efficacy offers a primary mechanism through which parental phubbing may influence creativity, additional factors may affect the strength or direction of these relationships. In this study, we propose that adolescents’ own PSU might moderate both the direct and indirect relationships between parental phubbing and creative outcomes. SCT provides a theoretical basis for understanding this moderation effect. Bandura’s triadic reciprocal determinism model emphasizes that personal factors (including individuals’ own behavioral patterns) interact with environmental influences to determine developmental outcomes [19]. In this case, adolescents’ PSU represents a personal behavioral pattern that may alter how they respond to and are affected by the environmental influence of parental phubbing.

More specifically, PSU is defined as excessive and compulsive smartphone usage patterns that interfere with daily functioning and psychological well-being [27,28]. Research consistently shows that adolescents with high PSU devote substantial time to online activities, with studies reporting that problematic users spend significantly more hours on their devices than non-problematic users [29]. These patterns of technology use may significantly moderate how parental phubbing affects creativity through both potential pathways.

For adolescents with low PSU, the negative pathway may predominate. Since these adolescents engage less with digital environments [29], the family context remains their primary source for observational learning and creative development. When experiencing parental phubbing, these adolescents have fewer alternative models and sources of creative stimulation to compensate for reduced quality interactions with parents. Consequently, the reduced feedback, modeling, and emotional support resulting from parental phubbing might more strongly diminish their creative self-efficacy and creative performance.

Conversely, for adolescents with high PSU, the potentially positive pathway may become more influential. These adolescents spend considerably more time engaged with their smartphones [29], which potentially exposes them to a wider range of digital experiences and information sources beyond their immediate family environment. They may have developed digital skills, online social connections, and technology-mediated creative practices that reduce their dependence on parental modeling and feedback. Furthermore, when parental phubbing creates opportunities for autonomous exploration, high-PSU adolescents may be better positioned to capitalize on this independence through their established digital capabilities. For these adolescents, parental phubbing might not only have minimal negative effects but could potentially enhance creative self-efficacy by creating synergistic conditions for digital autonomy and exploration.

Based on this SCT framework, the present study aims to address the following research questions:

i) What is the influence mechanism through which parental phubbing affects adolescents’ creativity? Specifically, does parental phubbing exert a direct effect on adolescent creativity, and/or does it operate indirectly through creative self-efficacy as a mediating variable?

ii) Does adolescents’ PSU moderate the relationship between parental phubbing and adolescent creativity? More specifically, does PSU moderate both the direct pathway from parental phubbing to creativity and the indirect pathway through creative self-efficacy?

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Jiangxi Psychological Consultant Association (IRB ref: JXSXL-2022-CL15). Informed consent has been obtained in electronic form from all participants and their guardians involved in the study.

Participants were recruited using a convenience sampling strategy with administrative support from four vocational schools in Jiangsu Province, China. Data collection occurred through an online questionnaire administered via the Wenjuanxing platform. The platform’s required-response feature ensured complete data for all submitted questionnaires. To maintain data quality, responses with completion times under 120 s were deemed invalid and excluded from analysis. The final sample consisted of 9111 adolescents (60.3% male, 39.7% female) with a mean age of 16.88 years (standard deviation [SD] = 1.15). This gender distribution is consistent with the broader vocational school population in China. According to data released by the National Bureau of Statistics in January 2025 [30], females account for 44.8% of students in vocational schools overall, with 42.2% in secondary vocational schools and 47.4% in higher vocational institutions. Our observed female ratio of 39.7% differs only slightly from these national statistics, suggesting that our sample provides a reasonably representative reflection of the overall gender distribution across vocational schools in China. Regarding family composition, 38.3% of participants reported being only children. Within the vocational education system, 45.5% of participants were enrolled in secondary vocational programs, while the remaining 54.5% were in higher vocational programs.

The study examined creativity, creative self-efficacy, parental phubbing, and PSU using the following scales. Background information, including gender, age, sibling status, and school type, was also collected. The psychometric properties of each measure in the present study are reported below.

2.2.1 20-Item Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scales (20-K-DOCS)

The present study employed the 20-K-DOCS [31], an adaptation of the original 50-item Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale [32], to assess creativity across multiple domains. This 20-item instrument conceptualizes creativity as a multidimensional construct that manifests across various life contexts, consistent with contemporary domain-specific approaches to creativity. The scale employs a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Much Less Creative) to 5 (Much More Creative), asking participants to rate their creative abilities relative to peers in different situations. Importantly, the scale measures self-perceived creative potential rather than actual creative products, allowing participants to evaluate their creative capabilities even in scenarios they might not have directly experienced by imagining how they would approach such situations with novel and effective solutions.

The 20-K-DOCS captures creativity across five distinct domains, reflecting Kaufman’s comprehensive framework of creativity. Sample items such as “Helping other people cope with a difficult situation” assess creativity in the Everyday domain (requiring novel solutions to interpersonal problems), while “Understanding how to make myself happy” measures creativity in the Self/Everyday domain (requiring innovative approaches to personal well-being). Other domains include Scholarly creativity, assessed through items like “Writing a nonfiction article for a newspaper” (requiring original analysis and integration of ideas); Performance creativity, measured by items such as “Spontaneously creating lyrics to a rap song” (requiring novel interpretations and expressions); and Mechanical/Scientific creativity, evaluated through items like “Building something mechanical” (requiring innovative problem-solving approaches in technical contexts).

The instrument has been extensively validated across diverse student populations, including university and secondary school students [31,33]. More specifically, the 20-K-DOCS was recently validated by Cao et al. [34] for use with Chinese adolescents, demonstrating strong factorial validity and item validity through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and Rasch analysis. In the current study, the scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.974).

2.2.2 Creative Self-Efficacy Student Scale (CSESS)

Creative self-efficacy was assessed using the CSESS developed by Hung [35]. This 12-item scale utilizes a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 4 (Strongly Agree), with higher scores indicating greater levels of creative self-efficacy. Sample items include “When suffering difficult problems, I believe I can try another way to solve it”, “When suffering difficult problems, I believe I can propose surprising answer that others cannot”, “I can creatively use ordinary things to enhance my reports” and “I believe I am capable of producing refreshing and original work when preparing a report”. Previous research has demonstrated this scale’s applicability to university and secondary school students, exhibiting strong psychometric properties [35,36]. In the present study, the scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.955).

2.2.3 Parents Phubbing Scale (PPS)

Parental phubbing was measured using the PPS, adapted by Ding et al. [37] from the partner phubbing scale originally developed by Roberts and David [38]. The PPS was designed to measure children’s perceptions of parental phubbing behavior. This unidimensional scale comprises nine items assessed on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always), with higher scores indicating greater perceived frequency of parental phubbing. Sample items include “During a typical mealtime that my parents and I spend together, my parents pull out and check their cell phones” and “My parents glance at their cell phones when talking to me”. Previous research has established the high reliability and validity of this scale with adolescent populations [37,39]. In the present study, the scale demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.924).

2.2.4 Smartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale (SABAS)

PSU was assessed using the Smartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale (SABAS), adapted by Csibi et al. [40]. This unidimensional scale comprises six items measuring PSU levels. Sample items include “Conflicts have arisen between me and my family (or friends) because of my smartphone use” and “If I cannot use or access my smartphone when I feel like, I feel sad, moody, or irritable.” Responses are recorded on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 6 (Strongly Agree), with higher scores indicating greater severity of PSU. The SABAS has demonstrated strong psychometric properties and has been validated among young populations in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan [41,42]. In the present study, the scale exhibited high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.944).

In this study, potential common method bias was assessed through CFA that included a common method factor. In line with the recommendation by Podsakoff et al. [43], the difference in the Comparative Fit Index (ΔCFI) was adopted as the evaluation criterion. A ΔCFI value below the threshold of 0.01 suggests that common method bias is unlikely to pose a significant threat.

After confirming the absence of substantial common method bias, we proceeded with the main data analyses. Descriptive statistical analysis (means and standard deviations of the core variables) and partial correlation analyses were conducted using SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), while moderated mediation analysis was performed using the GLM Mediation Model module in jamovi 2.6.13 (The jamovi project, retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org). In the proposed research model, parental phubbing was specified as the independent variable, creativity as the dependent variable, creative self-efficacy as the mediator, and PSU as the moderator. Specifically, PSU was hypothesized to moderate both the first stage of the mediation pathway (the relationship between parental phubbing and creative self-efficacy) and the direct effect of parental phubbing on creativity. To test the mediating effect, bootstrapping with 2000 resamples was employed to generate bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals. Additionally, gender, age, sibling status, and school type were included as control variables to account for potential confounding effects on the research findings.

3.1 Descriptive Statistical Analysis and Partial Correlation Analysis

Before conducting the main analysis, we assessed common method bias using a method factor model. The results showed that the ΔCFI was 0.004, which is well below the threshold of 0.01, indicating that the inclusion of the method factor did not substantially improve model fit. Therefore, common method bias was not considered a significant concern in this study.

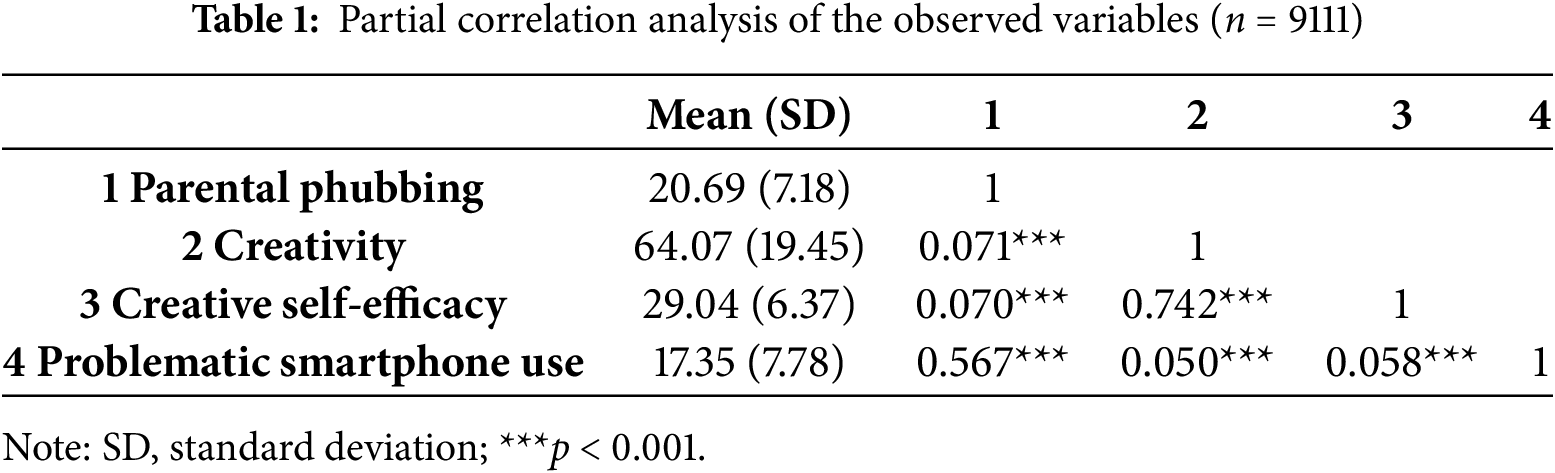

Gender, age, sibling status, and school type demonstrated varying degrees of significant correlations with the core variables, potentially confounding the interrelationships among primary constructs. Consequently, partial correlation analysis was implemented to control for these demographic variables. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and partial correlation matrix. Results revealed significant positive correlations among parental phubbing, creativity, creative self-efficacy, and PSU, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.050 to 0.742.

3.2 Moderated Mediation Analysis

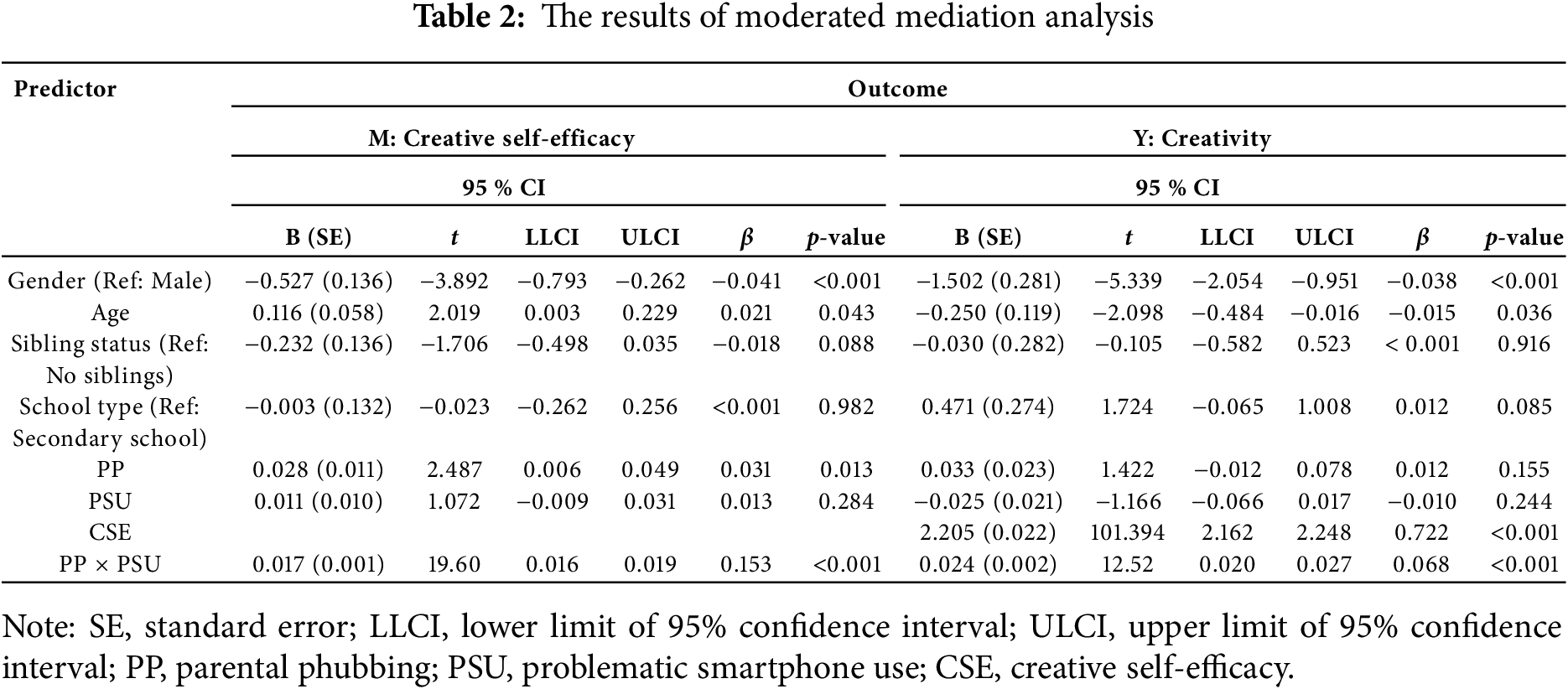

Table 2 presents the moderated mediation analysis results. After controlling for gender, age, sibling status, and school type, parental phubbing demonstrated a significant positive effect on creative self-efficacy (β = 0.031, t = 2.487, p = 0.013). However, the direct effect of parental phubbing on creativity was not statistically significant (β = 0.012, t = 1.422, p = 0.155). Creative self-efficacy exhibited a significant positive effect on creativity (β = 0.722, t = 101.394, p < 0.001). Further analysis confirmed that creative self-efficacy mediated the relationship between parental phubbing and creativity, with an estimated indirect effect of 0.061. The bootstrap confidence interval (lower limit of 95% confidence interval, LLCI; upper limit of 95% confidence interval, ULCI) = [0.013,0.109] did not include zero, substantiating the statistical significance of the mediation effect.

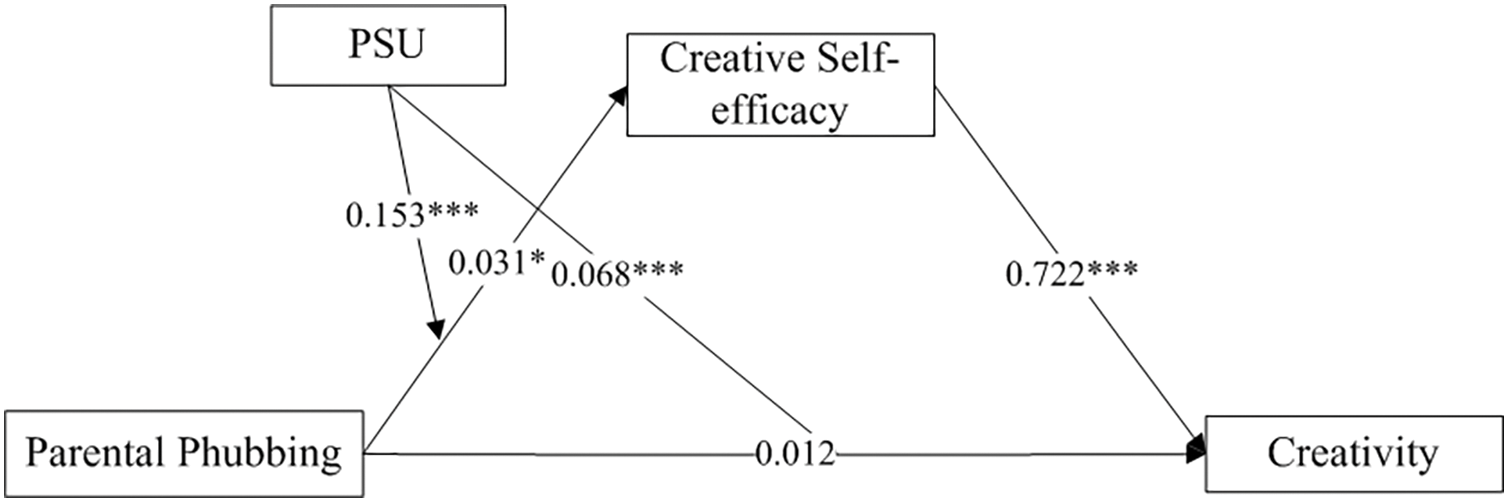

The moderated mediation analysis revealed a significant moderating effect of PSU in the initial stage of the mediation process. Specifically, in the relationship between parental phubbing and creative self-efficacy, the interaction term (parental phubbing × PSU) was statistically significant (β = 0.153, t = 19.60, p < 0.001), indicating that PSU amplified the effect of parental phubbing on creative self-efficacy. Additionally, results demonstrated that PSU moderated the direct effect of parental phubbing on creativity, with a significant interaction effect (β = 0.068, t = 12.52, p < 0.001). To provide a clearer visualization of these findings, the path coefficients representing the effect sizes of relationships among the core variables are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: The path coefficients among core variables. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. PSU, Problematic smartphone use

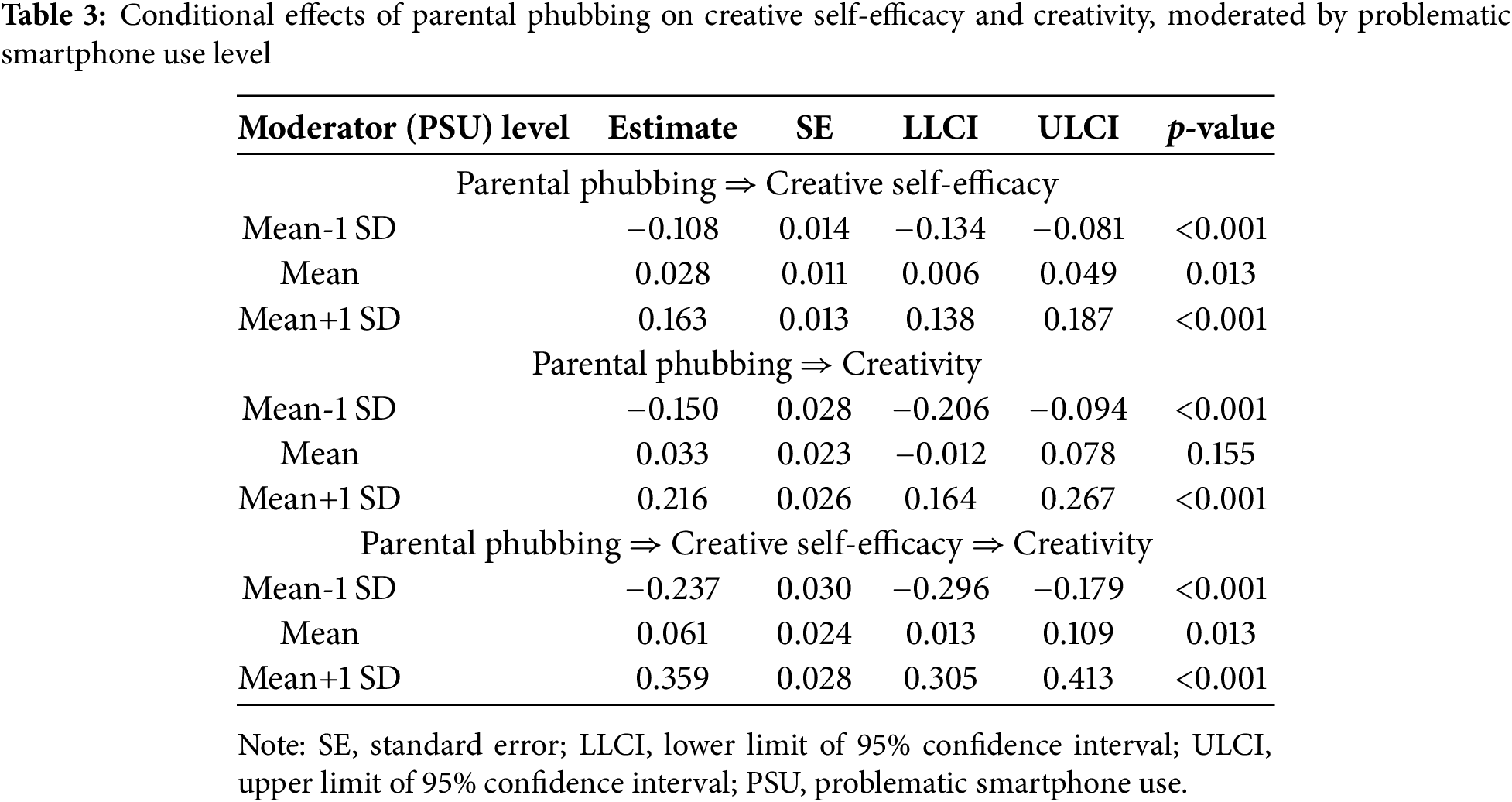

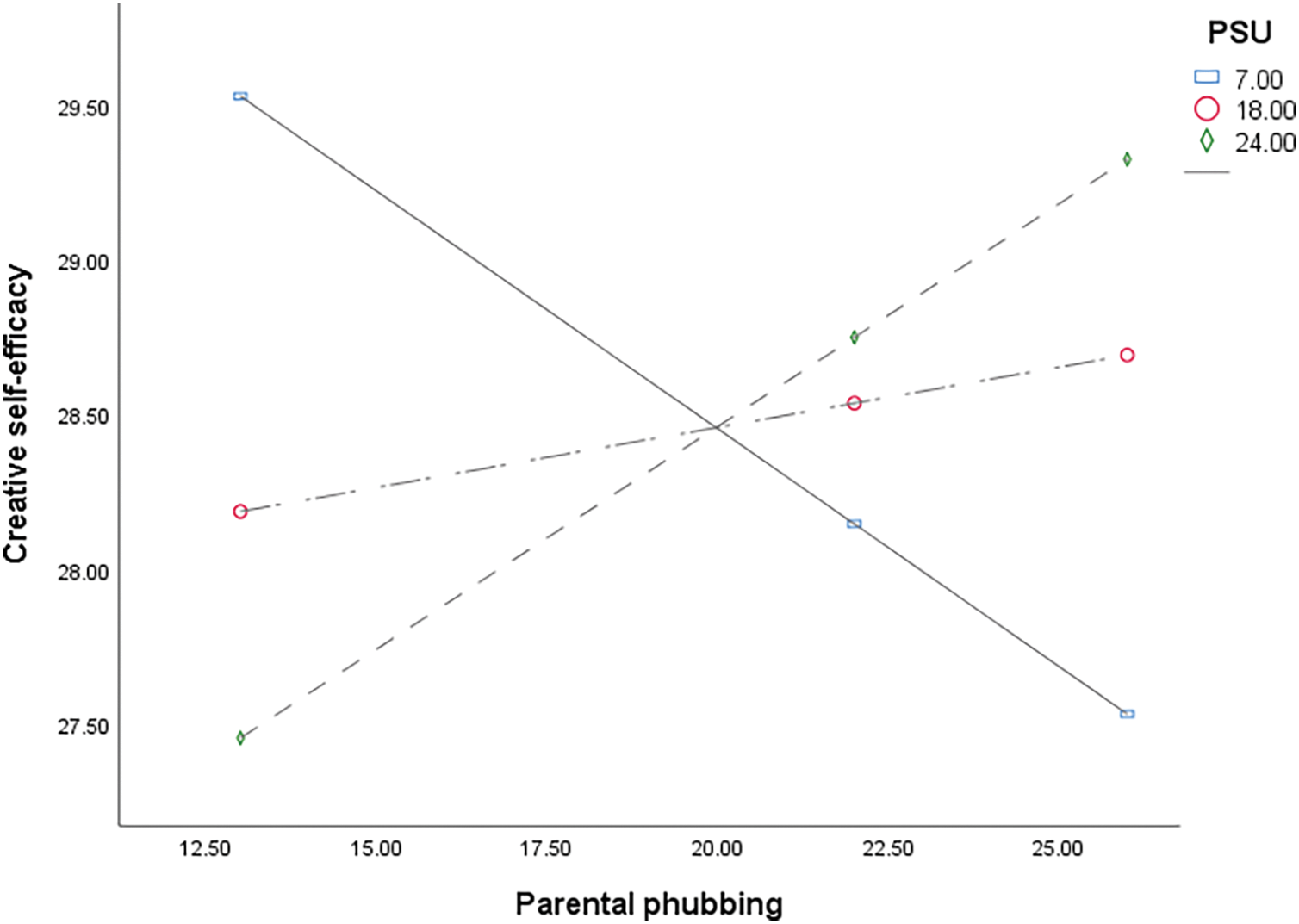

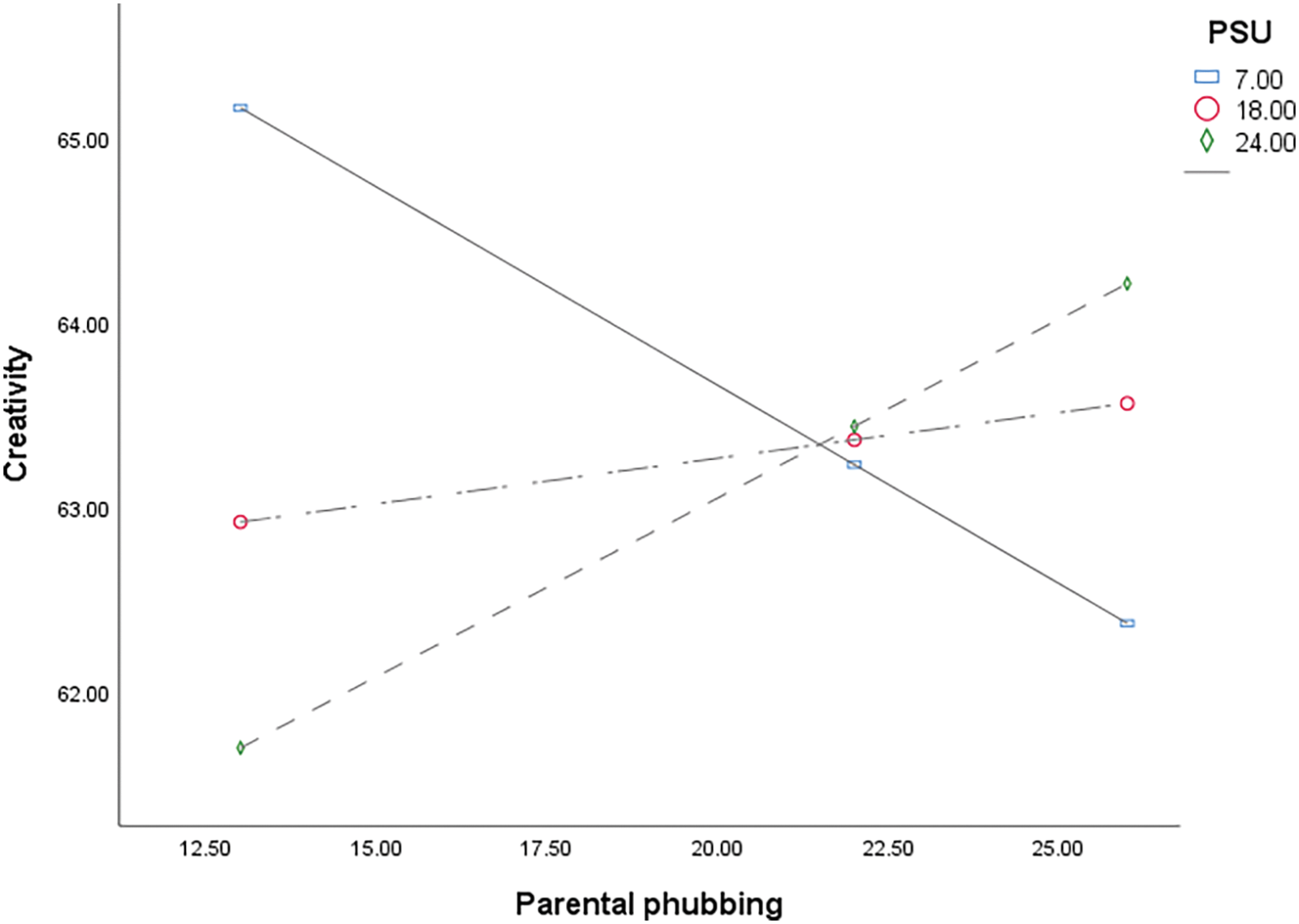

Table 3 and Fig. 3 present the results of the conditional mediation effect analysis. The findings indicate that when levels of PSU are high, the positive effect of parental phubbing on creative self-efficacy becomes more pronounced, suggesting that participants with higher PSU experience a stronger positive relationship between parental phubbing and creative self-efficacy. Moreover, a similar pattern was observed in the direct effect of parental phubbing on creativity (see Table 3 and Fig. 4). Specifically, when PSU levels are high, the positive impact of parental phubbing on creativity is more significant, further reinforcing the moderating role of PSU in this relationship. Conversely, among participants with lower PSU, parental phubbing demonstrated negative associations with both creative self-efficacy and creativity.

Figure 3: The association between parental phubbing and creative self-efficacy at different levels of problematic smartphone use (PSU). The horizontal line indicates the levels of parental phubbing

Figure 4: The association between parental phubbing and creativity at different levels of problematic smartphone use (PSU). The horizontal line indicates the levels of parental phubbing

The present study investigated the relationship between parental phubbing and adolescent creativity, examining the mediating role of creative self-efficacy and the moderating association with PSU. Our findings contribute to understanding how parents’ smartphone use behaviors relate to adolescents’ creativity development through complex pathways. Drawing on SCT [19], we explored how this specific environmental factor (parental phubbing) relates to adolescents’ creative development through both direct and indirect pathways.

4.1 The Mediating Role of Creative Self-Efficacy

Our analysis revealed that creative self-efficacy significantly mediated the association between parental phubbing and adolescent creativity while also confirming there is no direct relationship between phubbing and creativity. This finding aligns with SCT’s emphasis on self-efficacy as a psychological mechanism connecting environmental influences with behavioral outcomes [19]. The observed indirect pathway suggests that parental phubbing relates to adolescents’ creativity primarily through its association with their beliefs about their own creative capabilities, consistent with previous research highlighting self-efficacy as a critical intermediary between social contexts and creative performance [22,44].

Notably, our findings differ from some previous research on family interactions and creativity. While studies by Park et al. [45] and Pérez-Fuentes et al. [46] found that traditional positive parent-child interactions directly related to enhanced creative performance in adolescents, our results suggest a more nuanced relationship in digitally-mediated family contexts. The non-significant direct association between parental phubbing and creativity in our study highlights that technology-disrupted interactions may operate through different mechanisms than the face-to-face parenting dynamics examined in previous research. Unlike traditional parenting studies that typically focus on intentional parenting dimensions such as encouragement, behavioral control, monitoring, or autonomy support [46], our investigation of parental phubbing represents a distinctive contemporary context where technology interrupts parent-adolescent engagement. This digital dimension introduces unique elements not present in conventional parent-child interaction studies, potentially explaining why the relationship between parental behavior and creativity manifests differently in our research compared to studies of traditional parenting practices.

These differences in findings prompt consideration of potential mechanisms through which the observed mediating pattern might operate, though our cross-sectional design prevents causal interpretations. Drawing on Zimmerman’s self-regulated learning perspective within SCT [47], parental phubbing may coincide with increased psychological space for autonomous exploration, potentially allowing adolescents to develop creative self-efficacy through independent problem-solving without immediate evaluation. Additionally, adolescents who observe parents using smartphones may develop technological familiarity that transfers to creative confidence in digital contexts, aligning with research showing positive associations between technological fluency and domain-specific creative self-efficacy [48,49]. These interpretations raise the possibility that parental phubbing could, in some contexts, differ from simple lower quality interaction with adolescents; it may depend on the family’s digital context, adolescents’ own technology engagement, and individual responses to autonomy. For some adolescents, especially those with digital skills, reduced direct parental involvement might create opportunities for self-directed creative exploration that builds self-efficacy. Further research is needed to verify the complex relationship between parental phubbing and adolescent development across different contexts and to identify the conditions under which it may have varying implications for creativity and other developmental outcomes.

The small effect sizes observed in our mediation analysis warrant cautious interpretation. The indirect effect of parental phubbing on creativity through creative self-efficacy (0.061) and the association between parental phubbing and creative self-efficacy (β = 0.031), while statistically significant, were modest in magnitude. These findings suggest that creative self-efficacy represents just one of many factors in the complex relationship between family digital behaviors and adolescent creativity. The same applies to parental phubbing, which appears to be only one of several environmental factors related to creative development. These small associations align with meta-analytic findings by Fan et al. [50], who reported similarly small relationships between parental involvement and children’s/adolescents’ creativity (average r = 0.10), highlighting the multifaceted nature of creative development and the need to consider multiple influencing factors when examining creativity in adolescents.

4.2 The Moderating Role of Problematic Smartphone Use

Another key finding from our study was the significant moderating association of PSU with both the direct and indirect pathways between parental phubbing and adolescent creativity. This moderation manifested in distinctly different patterns depending on adolescents’ levels of problematic smartphone engagement, suggesting that the relationship between parental digital behaviors and creative outcomes varies based on adolescents’ own technology use patterns.

For adolescents with low PSU, parental phubbing showed negative associations with both creative self-efficacy and creativity, aligning with the perspective that parental smartphone distraction might reduce quality interactions [24,25] necessary for developing creative confidence. Conversely, for adolescents with high PSU, parental phubbing showed stronger positive associations with creative outcomes, supporting our theoretical framework that reduced parental oversight might increase adolescents’ autonomy and independent problem-solving [20]. These contrasting patterns can be understood through SCT’s triadic reciprocal determinism model [19], wherein personal factors (including smartphone use patterns) interact with environmental influences to shape developmental outcomes. For low-PSU adolescents, parental phubbing may represent a disruption to crucial modeling opportunities, as these adolescents have fewer alternative models for creative behavior. In contrast, high-PSU adolescents, who spend considerably more time engaged with smartphones [29], likely have developed digital self-efficacy that allows them to benefit from the autonomy created by parental phubbing. This interpretation aligns with SCT’s emphasis on how environmental opportunities are processed differently depending on individuals’ existing capabilities and alternative sources of efficacy information [21], explaining the differential associations observed across PSU levels.

We strongly caution against interpreting our findings as suggesting that parental phubbing or adolescent PSU are beneficial for creativity development. Both parental phubbing [12] and PSU [27,28], despite very few studies connecting them with adolescents’ creativity, are associated with numerous negative outcomes documented in previous research. Our moderated mediation analysis merely reveals differential statistical associations that vary by adolescents’ PSU levels, not beneficial causal relationships. Any explanations for why high-PSU adolescents showed different statistical patterns than low-PSU adolescents remain entirely speculative and outside our study’s scope. While we might hypothesize that digitally engaged adolescents potentially develop alternative creative pathways when faced with reduced parental attention, such mechanisms were not measured in our study. Our cross-sectional, questionnaire-based design cannot determine causality or underlying processes. Future research should explore the specific conditions and mechanisms through which family digital behaviors relate to adolescent development using more appropriate longitudinal approaches or targeted questionnaires that specifically measure the relevant variables only hypothesized in our discussion.

Our findings have significant practical implications for parents, educators, and policymakers. The results highlight the complex relationship between parental smartphone use and adolescent creativity development. Parents should be attentive to their smartphone use patterns during interactions with their children, as parental phubbing generally represents a missed opportunity for quality interactions that support creative development. These findings emphasize that creativity development requires a balance between supportive guidance and sufficient autonomy for independent exploration. Understanding the potential influence of parental smartphone use on adolescents’ creative self-efficacy may help parents make more informed decisions about technology use during family interactions.

Educational programs might consider approaches to enhance adolescents’ creative self-efficacy, which our study identified as a mediating factor between parental phubbing and creativity. Given our finding that adolescents’ own smartphone use patterns moderated these relationships, family guidance initiatives could benefit from addressing both parental and adolescent technology use. While our study did not directly test intervention approaches, the observed patterns suggest that supporting creative self-efficacy development might be valuable across different family digital contexts. Future research should explore specific strategies for promoting creative development in increasingly digital environments and test their effectiveness through intervention studies.

Despite the contributions of this study, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the small effect sizes observed in the mediation analysis suggest that parental phubbing is only one of many factors within the complex ecosystem influencing adolescent creative development. Other parental variables—such as family socioeconomic status, and parents’ digital behaviors (e.g., co-use of technology, digital mentoring)—may also play significant roles. Future research should further explore these factors to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the parental influences on adolescent creativity. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the ability to draw causal inferences from the observed relationships. To better understand the temporal dynamics and potential causal pathways, future research would benefit from employing longitudinal designs. Third, the participants were recruited through a convenience sampling strategy with administrative support from four vocational schools. The recruitment approach may limit the overall representativeness of the sample and, consequently, the generalizability of the findings. Finally, cultural factors may moderate the mechanisms through which parental phubbing affects adolescent creativity. Variations in parental education, family values, technology usage norms, and social expectations across different cultural contexts may influence these effects. Future studies should explore these potential moderators to refine the explanatory model, and cross-cultural research is therefore warranted to explore the applicability and variability of these relationships across diverse sociocultural backgrounds.

This study highlights the complex and multifaceted influence of parental phubbing on adolescent creativity, revealing tensions between digital distraction and potential catalytic effects. Our findings demonstrate that creative self-efficacy plays a crucial mediating role between parental phubbing and adolescent creativity, while adolescents’ own PSU significantly moderates this relationship. The results indicate that creativity development fundamentally requires both nurturing guidance and space for autonomous exploration—a balance best achieved through mindful parent-child engagement rather than digital disengagement. Despite the varied outcomes across different patterns of technology use, our findings should not be interpreted as endorsing parental phubbing. This investigation provides fresh perspectives on family digital behaviors and creativity development while offering implications for education and guidance. As technology becomes increasingly embedded in family life, finding equilibrium between digital engagement and meaningful interpersonal interactions presents ongoing challenges. Future research should continue to verify the relationship between parental phubbing and adolescents’ creativity. Additionally, investigations into how different technology usage patterns, individual characteristics, and cultural contexts influence these dynamics would enhance our understanding of these complex relationships, ultimately informing more nuanced approaches to fostering creativity in our digital age.

Acknowledgement: We express our gratitude to all contributors and participants who took part in this study.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by a special grant from the Taishan Scholars Project (Project No. tsqn202211130).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Min Qu, Xiumei Chen and I-Hua Chen; data collection: Xuelian Wang and Yue Zhou; methodology, Xiumei Chen and I-Hua Chen; analysis and interpretation of results: I-Hua Chen and Xuelian Wang; draft manuscript preparation: Min Qu and I-Hua Chen; review and editing: Min Qu, Xiumei Chen, Yue Zhou, Xuelian Wang and I-Hua Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Jiangxi Psychological Consultant Association (IRB ref: JXSXL-2022-CL15). Informed consent has been obtained in electronic form from all participants involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York, NY: HarperPerennial; 1996. [Google Scholar]

2. Runco MA, Jaeger GJ. The standard definition of creativity. Creat Res J. 2012;24(1):92–6. doi:10.1080/10400419.2012.650092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Glăveanu VP. Rewriting the language of creativity: the Five A’s framework. Rev Gen Psychol. 2013;17(1):69–81. doi:10.1037/a0029528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Beghetto RA, Kaufman JC. Toward a broader conception of creativity: a case for “mini-c” creativity. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts. 2007;1(2):73–9. doi:10.1037/1931-3896.1.2.73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kaufman JC, Beghetto RA. Beyond big and little: the four c model of creativity. Rev Gen Psychol. 2009;13(1):1–12. doi:10.1037/a0013688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Jankowska DM, Karwowski M. Family factors and development of creative thinking. Pers Individ Differ. 2019;142(4):202–6. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.07.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Runco MA. Creativity: Theories and themes: Research, development, and practice. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Academic Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

8. Kleibeuker SW, De Dreu CK, Crone EA. The development of creative cognition across adolescence: distinct trajectories for insight and divergent thinking. Dev Sci. 2013;16(1):2–12. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2012.01176.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Barbot B, Lubart TI, Besançon M. “Peaks, slumps, and bumps”: individual differences in the development of creativity in children and adolescents. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2016;2016(151):33–45. doi:10.1002/cad.20152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Kaufman JC. Creativity in education: teaching learners to think outside the box. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

11. Radesky JS, Schumacher J, Zuckerman B. Mobile and interactive media use by young children: the good, the bad, and the unknown. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):1–3. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Wei H, Ding H, Huang F, Zhu L. Parents’ phubbing and cyberbullying perpetration among adolescents: the mediation of anxiety and the moderation of Zhong-Yong Thinking. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2022;20(5):2609–22. doi:10.1007/s11469-021-00535-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kang MJ, Ryu S, Kim M, Kang KJ. The effects of parental phubbing on adolescent children: scoping review. J Korean Acad Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2023;32(2):203–15. doi:10.12934/jkpmhn.2023.32.2.203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Niu G, Yao L, Wu L, Tian Y, Xu L, Sun X. Parental phubbing and adolescent problematic mobile phone use: the role of parent-child relationship and self-control. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;116(6):105247. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Geng J, Lei L, Ouyang M, Nie J, Wang P. The influence of perceived parental phubbing on adolescents’ problematic smartphone use: a two-wave multiple mediation model. Addict Behav. 2021;121(1–2):106995. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106995. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Bai Q, Lei L, Hsueh FH, Yu X, Hu H, Wang X, et al. Parent-adolescent congruence in phubbing and adolescents’ depressive symptoms: a moderated polynomial regression with response surface analyses. J Affect Disord. 2020;275(2):127–35. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Harianti WS, Kurniawan IN. Parental phubbing and mental well-being: preliminary study in Indonesia. Commun Humanit Soc Sci. 2022;2(2):53–9. doi:10.21924/chss.2.2.2022.34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Pancani L, Gerosa T, Gui M, Riva P. “Mom, dad, look at me”: the development of the Parental Phubbing Scale. J Soc Pers Relat. 2021;38(2):435–58. doi:10.1177/0265407520964866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):1–26. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Jin X, Jiang Q, Xiong W, Pan X, Zhao W. Using the online self-directed learning environment to promote creativity performance for university students. Educ Technol Soc. 2022;25(2):130–47. [Google Scholar]

21. Zimmerman BJ. Self-efficacy: an essential motive to learn. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000;25(1):82–91. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Tierney P, Farmer SM. Creative self-efficacy: potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Acad Manag J. 2002;45(6):1137–48. doi:10.2307/3069429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Beghetto RA. Creative self-efficacy: correlates in middle and secondary students. Creat Res J. 2006;18(4):447–57. doi:10.1207/s15326934crj1804_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. McDaniel BT, Radesky JS. Technoference: parent distraction with technology and associations with child behavior problems. Child Dev. 2018;89(1):100–9. doi:10.1111/cdev.12822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Xie X, Chen W, Zhu X, He D. Parents’ phubbing increases adolescents’ mobile phone addiction: roles of parent-child attachment, deviant peers, and gender. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2019;105(1):104426. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Liu D, Chen XP, Yao X. From autonomy to creativity: a multilevel investigation of the mediating role of harmonious passion. J Appl Psychol. 2011;96(2):294–309. doi:10.1037/a0021294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Elhai JD, Dvorak RD, Levine JC, Hall BJ. Problematic smartphone use: a conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J Affect Disord. 2017;207:251–9. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Panova T, Carbonell X. Is smartphone addiction really an addiction? J Behav Addict. 2018;7(2):252–9. doi:10.1556/2006.7.2018.49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Haug S, Castro RP, Kwon M, Filler A, Kowatsch T, Schaub MP. Smartphone use and smartphone addiction among young people in Switzerland. J Behav Addict. 2015;4(4):299–307. doi:10.1556/2006.4.2015.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Statistical monitoring report on the Outline for Women’s Development in China (2021-2030). China Statistics Press. [cited 2025 Jun 19]. Available from: https://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/sjfb/zxfb2020/202501/t20250124_1958439.html. [Google Scholar]

31. Tan CS, Tan SA, Cheng SM, Hashim IHM, Ong AWH. Development and preliminary validation of the 20-item Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale for use with Malaysian populations. Curr Psychol. 2021;40(4):1946–57. doi:10.1007/s12144-019-0124-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kaufman JC. Counting the muses: development of the Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale (K-DOCS). Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts. 2012;6(4):298–308. doi:10.1037/a0029751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Tan CS, Ong AWH, Tan SA, Cheng SM. Psychometric evaluation of the Malay version Self-Rated Creativity Scale among secondary school students in Malaysia. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(8):5264–71. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-00772-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Cao CH, Wang XL, Ji YP, Chen I-H. Psychometric validation of the 20-item K-DOCS in Chinese adolescents: a multi-method approach. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):4875. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-88980-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Hung SP. Validating the creative self-efficacy student scale with a Taiwanese sample: an item response theory-based investigation. Think Skills Creat. 2018;28(3):190–203. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2018.02.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Liu GongXX, Zhou SY, Wang ZJ, XY. Relationship between parental autonomy support, psychological control, and junior high school students’ creative self-efficacy: the mediating role of academic emotions. Psychol Dev Educ. 2020;36(1):45–53. (In Chinese). doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1028722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ding Q, Wang ZQ, Zhang YX. Revision of the parent phubbing scale among Chinese adolescents. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2020;28(5):942–5. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

38. Roberts JA, David ME. My life has become a major distraction from my cell phone: partner phubbing and relationship satisfaction among romantic partners. Comput Human Behav. 2016;54(1):134–41. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ding Q, Zhang YX, Zhou ZK. The relationship between parental phubbing and mobile phone addiction among middle school students: the moderating role of parental monitoring. Chin J Spec Educ. 2019;1:66–71. (In Chinese). doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1117221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Csibi S, Griffiths MD, Cook B, Demetrovics Z, Szabo A. The psychometric properties of the smartphone application-based addiction scale (SABAS). Int J Ment Health Addict. 2018;16(2):393–403. doi:10.1007/s11469-017-9787-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Chen IH, Ahorsu DK, Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD, Lin CY, Chen CY. Psychometric properties of three simplified Chinese online-related addictive behavior instruments among mainland Chinese primary school students. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:875. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00875. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Leung H, Pakpour AH, Strong C, Lin Y-C, Tsai M-C, Griffiths MD, et al. Measurement invariance across young adults from Hong Kong and Taiwan among three internet-related addiction scales: bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMASSmartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale (SABASand Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-Short Form (IGDS-SF9) (Study Part A). Addict Behav. 2020;101(2):105969. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York, NY, USA: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

45. Park H, Kim S. Effects of perceived parent-child relationships and self-concept on creative personality among middle school students. Behav Sci. 2024;14(1):58. doi:10.3390/bs14010058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Pérez-Fuentes MDC, Molero Jurado MDM, Oropesa Ruiz NF, Simón Márquez MDM, Gázquez Linares JJ. Relationship between digital creativity, parenting style, and adolescent performance. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2487. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02487. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Zimmerman BJ. Becoming a self-regulated learner: an overview. Theory Pract. 2002;41(2):64–70. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Shadiev R, Liu T, Shadiev N, Wang X, Yang MK, Fayziev M, et al. The effects of familiarity with mobile-assisted language learning environments on creativity. In: 2022 International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT); 2022; Bucharest, Romania. p. 242–4. doi:10.1109/ICALT55010.2022.00079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Liu X, Gu J, Xu J. The impact of the design thinking model on pre-service teachers’ creativity self-efficacy, inventive problem-solving skills, and technology-related motivation. Int J Technol Des Educ. 2024;34(1):167–90. doi:10.1007/s10798-023-09809-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Fan H, Feng Y, Zhang Y. Parental involvement and student creativity: a three-level meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1407279. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1407279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools