Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of Cognitive Stimulation Intervention on Cognitive Function and Depression in Older Adults with Mild Dementia: A Quasi-Experimental Study

1 Department of Nursing, Yuanlin Christian Hospital, Yuanlin City, 51052, Taiwan

2 Institute of Long Term Care, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung City, 402306, Taiwan

3 Department of Family Medicine, Taichung Hospital, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taichung City, 40343, Taiwan

4 Department of Nursing, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung City, 402306, Taiwan

5 Department of Medical Administration, The Islands Healthcare Complex-Macao Medical Center of Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Taipa, Macao, 999078, China

6 Department of Nursing, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung City, 402306, Taiwan

7 Institute of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung City, 402306, Taiwan

* Corresponding Authors: Ching-Pyng Kuo. Email: ; Shu-Hsin Lee. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Social and Behavioral Determinants of Mental Health: From Theory to Practice)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(7), 979-994. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.066026

Received 27 March 2025; Accepted 30 June 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

Background: Cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) is a non-pharmacological intervention designed to improve cognitive function and emotional well-being in individuals with dementia. However, limited studies have evaluated its efficacy in Chinese-speaking populations. This study aimed to assess the effects of a 12-week cognitive stimulation intervention on cognitive function and depression in older adults with mild dementia. Methods: This quasi-experimental study employed a repeated measures design with a non-randomized experimental and control group. Participants (N = 40) 65 years and older with mild dementia (clinical dementia rating (CDR) = 0.5–1) were recruited from a regional hospital and dementia care center in Taiwan. The experimental group (n = 20) received a structured CST intervention for 12 weeks (two sessions per week, 120 min per session), while the control group (n = 20) received routine care. Cognitive function was assessed using the Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) exam, and depression was measured using the Chinese version of the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD-C). Data were collected at baseline, 4, 8, and 12 weeks and analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA and generalized estimating equation (GEE) modeling. Results: The experimental group showed significant improvements in cognitive function compared to the control group (SLUMS score: baseline 16.1 ± 4.8 to 12th week 19.3 ± 5.0, p < 0.001). Depression levels decreased significantly in the experimental group but not in the control group (p < 0.05). The GEE analysis showed that the improvement in cognitive function was positively associated with education level and duration, but declined with increasing age. Similarly, depression was lower in participants with higher educational levels and in men. Conclusions: The findings support the efficacy of CST in improving cognitive function and reducing depression in older adults with mild dementia. The results highlight the importance of the duration of the intervention and individual cognitive reserve in modulating treatment outcomes.Keywords

Dementia represents a significant global public health challenge, with rising prevalence and profound impacts on individuals, families, and healthcare systems. According to the Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI), more than 55 million people worldwide are currently living with dementia, and this number is projected to increase to 139 million by the year 2050 [1]. A 2023 national survey conducted by Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare reported a dementia prevalence rate of 7.99% among community-dwelling older adults. The prevalence was notably higher in women (9.36%) than in men (6.35%) and increased progressively with age [2]. Dementia is characterized by a progressive decline in cognitive function, leading to impairments in activities of daily living and reduced quality of life. Recent studies indicate that cognitive decline is influenced by various genetic and environmental factors, highlighting the need for early intervention [3–5].

Among older adults, dementia and depression are the most common mental health concerns. There exists a complicated and bidirectional association between dementia and depression, involving overlapping symptoms and shared risk factors [3,6]. Recent research has highlighted the bidirectional relationship between cognitive impairment and depression, with evidence suggesting that untreated depression can accelerate cognitive decline. The study by Zabihi et al. demonstrated that depression is a significant early clinical indicator associated with the development of dementia, including mild cognitive impairment (MCI). About 10% of people with depression exhibit cognitive impairment, leading to frequent misdiagnoses such as dementia and the risk of inadequate treatment [7].

As dementia prevalence continues to increase worldwide, the selection of effective intervention strategies to improve cognitive function, alleviate depressive symptoms, and improve quality of life for both patients and caregivers has become a critical healthcare priority [8]. Despite the progressive nature of dementia, current pharmacological treatments cannot fully cure or halt the disease. However, research has shown that non-pharmacological interventions, particularly cognitive stimulation therapy (CST), can enhance physical activity levels, improve cerebral blood flow, and mitigate cognitive deficits. CST is an evidence-based, structured psychosocial intervention designed to improve cognitive function and quality of life in people with mild to moderate dementia. It consists of engaging activities that stimulate various cognitive domains, including memory, attention, language, and problem-solving skills. CST sessions typically involve group discussions, reality orientation exercises, music-based activities, word association games, and creative tasks that encourage mental engagement. Therapy is based on the principles of neuroplasticity, suggesting that the brain can adapt and reorganize itself in response to cognitive challenges [5,9].

Studies have consistently demonstrated that cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) improves cognitive performance, mood, and social engagement in people with dementia [5,9–12]. However, most evidence comes from Western populations, and there is limited research examining the application of CST in Chinese-speaking communities. Additionally, few studies have focused on community-based implementation or evaluated long-term effects across multiple follow-up points. To address these gaps, the present study investigates the effects of a 12-week CST intervention for older adults with mild dementia in a community-based dementia care center in Taiwan. By evaluating cognitive function and depressive symptoms at baseline and at 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-intervention, this study provides a longitudinal, culturally contextualized assessment of CST. Aligned with Taiwan’s Long-Term Care 2.0 Program, which emphasizes integrated community-based dementia services [13], this research aims to generate localized evidence to inform future models of community dementia prevention and care.

1. The cognitive stimulation intervention will improve cognitive function in older adults with mild dementia.

2. The cognitive stimulation intervention will reduce depressive symptoms in older adults with mild dementia.

This study employed a quasi-experimental repeated measures design, with participants non-randomly assigned to either the experimental or control group. This study followed the TREND (Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs) reporting guidelines for non-randomized intervention studies [14].

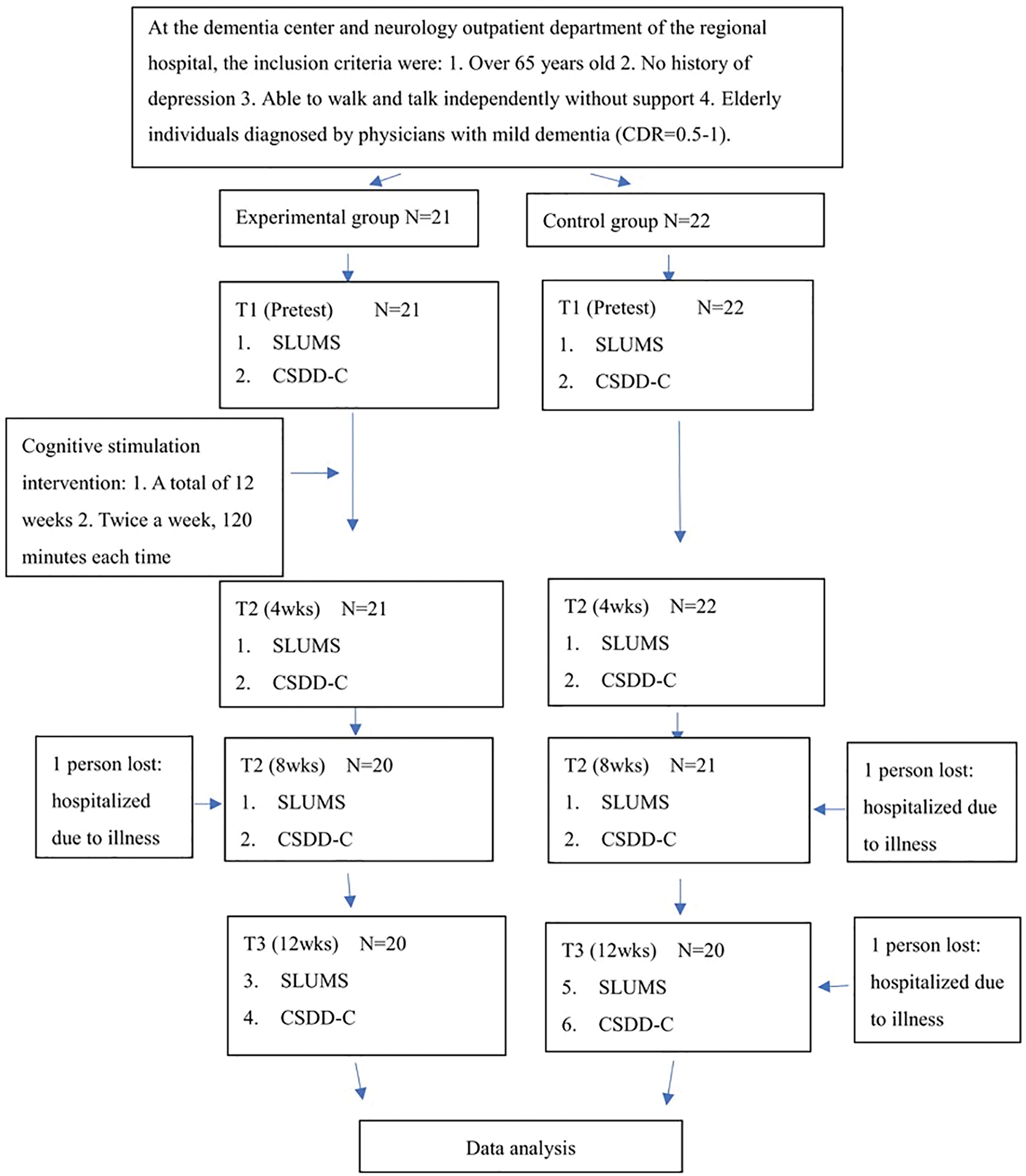

The inclusion criteria were as follows: people 65 years or older diagnosed with mild dementia by a physician, with a clinical dementia rating (CDR) of 0.5–1, able to walk independently without assistance, and capable of verbal communication. The excluded criteria included a history of diagnosed depression. The sample size was estimated using G*Power 3.1, applying a repeated measures approach (between factors) with an alpha level of 0.05, beta value of 0.2, correlation among repeated measures of 0.5, and moderate effect size (f = 0.35). With four repeated measurements, the required sample size was determined to be 44 participants. A total of 43 participants were recruited, with 21 assigned to the experimental group and 22 to the control group. During the course of the study, three participants (one from the experimental group and two from the control group) withdrew due to hospitalization. This resulted in a final sample size of 40 participants (20 in each group), achieving a study completion rate of 93%. Despite this slight attrition, the final sample size retained sufficient statistical power (77%) to detect a moderate effect, which is considered acceptable for exploratory intervention research.

3.3 Data Collection Procedures

Between January and June 2020, participants were recruited from a neurology outpatient clinic at a regional hospital in central Taiwan, where eligible individuals were assigned to the control group, and from the dementia care unit affiliated with the same hospital, where participants were assigned to the experimental group. This group assignment strategy was adopted to reflect real-world care delivery settings and to avoid contamination between intervention and control conditions. Before the intervention, all participants underwent baseline assessments, including demographic data collection, the Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) exam [15], and the Chinese version of the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD-C) [16]. The experimental group received a cognitive stimulation intervention twice a week for 120 min per session for 12 weeks, while the control group received routine care without CST intervention. Routine care included standard services such as medication and health monitoring, assistance with daily living activities, occasional recreational or social interaction activities, and caregiver support, but did not involve any structured cognitive stimulation. Follow-up evaluations were conducted at weeks 4, 8, and 12 (Fig. 1). Although participants and facilitators were not blinded due to the nature of the intervention, outcome assessments at all time points were conducted by independent evaluators who were blinded to group assignments, thereby minimizing assessment bias. Data collection was conducted via structured, face-to-face interviews to accommodate participants with varying literacy levels. Trained research assistants, who remained consistent throughout the study, administered all assessments using standardized protocols. They underwent preparatory training that included instruction on instrument administration (SLUMS and CSDD-C), mock interviews, and communication skills specific to working with older adults with cognitive impairment. This procedure helped ensure data reliability and minimize interviewer bias. Both the SLUMS and CSDD-C instruments were administered in structured interviews to minimize subjectivity and enhance the reliability of the data collection process.

Figure 1: Research flow chart. Note: CDR, clinical dementia rating; SLUMS, Saint Louis University Mental Status; CSDD-C, Chinese version of the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; wks, weeks

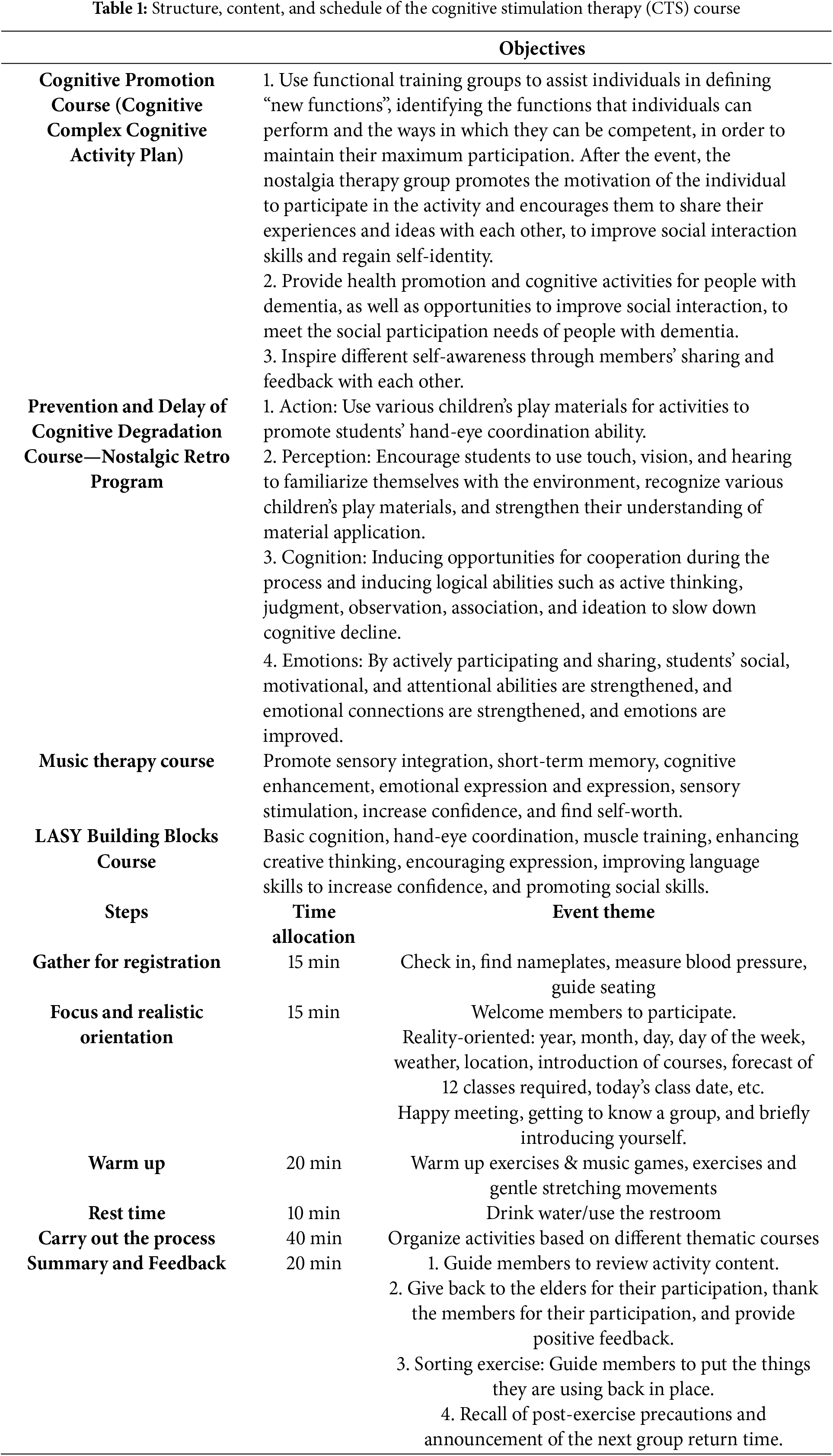

The cognitive stimulation intervention for the experimental group was designed based on the Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST) guidelines proposed by the UK National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in 2006 [17]. The program was structured as a 12-week course, with sessions held twice a week, each lasting 120 min. To minimize potential fatigue among older participants, each session was carefully segmented into multiple shorter components (e.g., cognitive enhancement activities, music-assisted therapy, and block building exercises), interspersed with brief rest and hydration breaks. Participants were also encouraged to take additional rests as needed. The intervention was designed and implemented by a multidisciplinary team, including occupational therapists, professional art and music instructors from a community college, and trained dementia care facilitators. Prior to implementing the intervention, all members of the multidisciplinary team completed an 8-h structured training program conducted by dementia care experts. The training included topics such as dementia care principles, CST methodology, effective communication with older adults, and role-playing simulations to ensure consistent intervention delivery. The intervention included cognitive enhancement activities, courses designed to prevent cognitive decline, music-assisted therapy, and block building exercises. The intervention sessions were carried out in a group format (20–21 participants per group). The details of the course content and the implementation procedures are listed in Table 1.

Demographic information was collected using a structured questionnaire developed based on the relevant literature and clinical experience of the research team. Variables included sex, age, marital status, education level, and medical diagnosis.

4.2 Saint Louis University Mental Status Exam (SLUMS)

The SLUMS was developed by Morley and Tumosa in 2002 and has been translated into numerous languages around the world. The traditional Chinese version was officially authorized by Hu [15]. This tool assesses orientation, attention, numerical calculations, immediate and short-term memory, size differentiation, animal naming, and clock drawing, with a total of 11 items scored from 0 to 30. The cutoff scores for normal cognition, mild neurocognitive disorder, and dementia vary based on educational background. The SLUMS has been shown to be more sensitive than the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in detecting mild cognitive impairment and is less influenced by the level of education [15].

4.3 Chinese Version of the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD-C)

The CSDD was developed by Alexopoulos et al. [18] in 1988 to assess depression in individuals with dementia. It consists of 19 items covering emotional symptoms, physical symptoms, cyclical functions, behavioral disturbances, and ideational disturbances, with scores ranging from 0 to 38. A score below 6 is considered normal, 7–9 indicate mild depression, a score of 10 or higher suggests major depression, and 18 or higher confirms severe depression. It was translated and validated by Lin and Wang in 2008, demonstrating a content validity index (CVI) of 0.92 and internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.84, making it a reliable tool to assess depressive symptoms in Chinese-speaking dementia patients [16].

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Changhua Christian Hospital (IRB number: 191104). All participants provided their informed consent prior to participating. The study adhered to ethical principles, ensuring the autonomy, nonmaleficence, and fairness of participants. If participants experienced discomfort or wanted to withdraw from the study at any time, their decision was fully respected. The study followed these ethical principles: (1) compliance with nursing research ethics, including autonomy, non-maleficence, and fairness; (2) data collected through interviews were used solely for research purposes; (3) a detailed explanation of the purpose, methods, and procedures was provided to participants and/or their caregivers before obtaining consent; and (4) all collected data were anonymized and coded to protect participants’ privacy.

Collected data were coded and entered into a computer for statistical analysis using SPSS V22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The significance level was established at p < 0.05. The descriptive statistics included frequency (N), percentage (%), mean, and standard deviation. Inferential statistics included t-tests, chi-square tests, repeated measures ANOVA, and generalized estimating equations (GEE) to assess the effects of cognitive stimulation intervention on cognitive function and depression at weeks 4, 8, and 12.

5.1 Demographic, Lifestyle, and Disease Characteristics of the Experimental and Control Groups

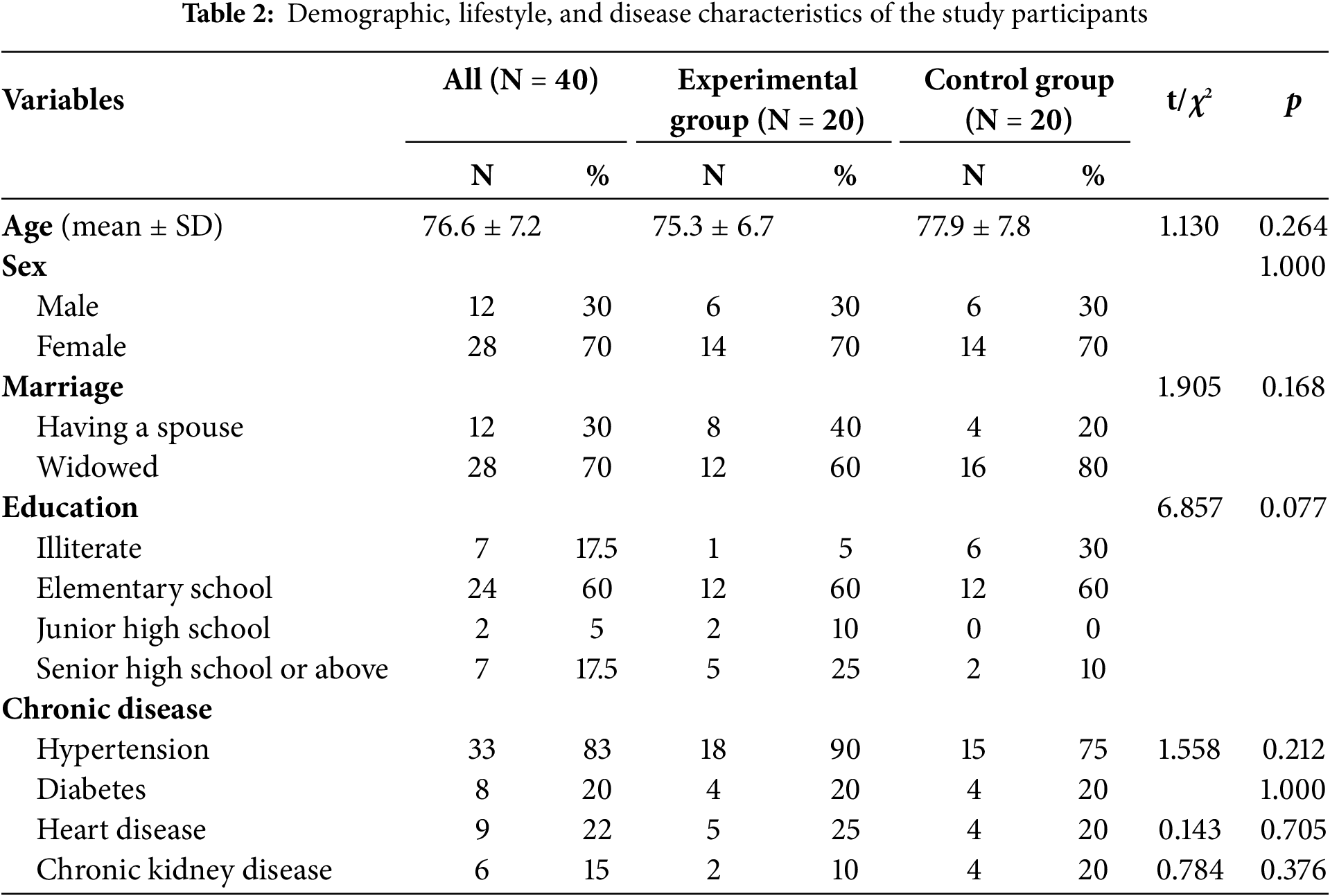

The study included 40 participants, 20 in the experimental group and 20 in the control group. The average age of the participants was 76.6 ± 7.2 years, the experimental group averaging 75.3 ± 6.7 years and the control group averaging 77.9 ± 7.8 years. The majority of the participants were female (70.0%). Regarding marital status, 70.0% were widowed. The most common educational level was elementary school (60.0%), while 17.5% of the participants were illiterate. Among chronic diseases, hypertension was the most prevalent (83.0%), followed by diabetes (20.0%), heart disease (22.5%), and chronic kidney disease (15.0%). No significant differences were found between the experimental and control groups in terms of demographic characteristics, lifestyle, and disease status, indicating high homogeneity between the two groups (Table 2).

5.2 Effect of Cognitive Stimulation Intervention on Cognitive Function and Depression: Repeated Measures ANOVA Analysis

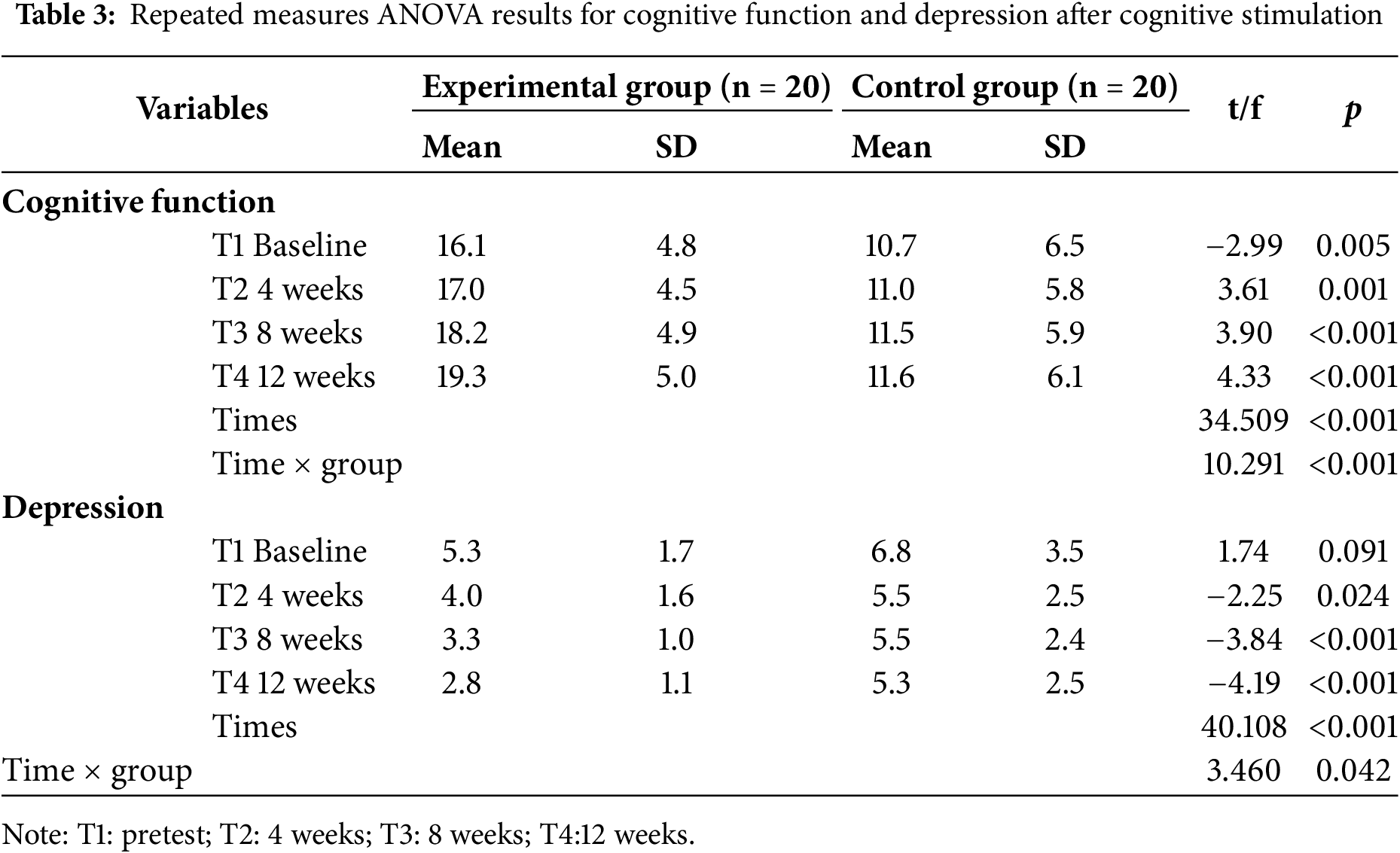

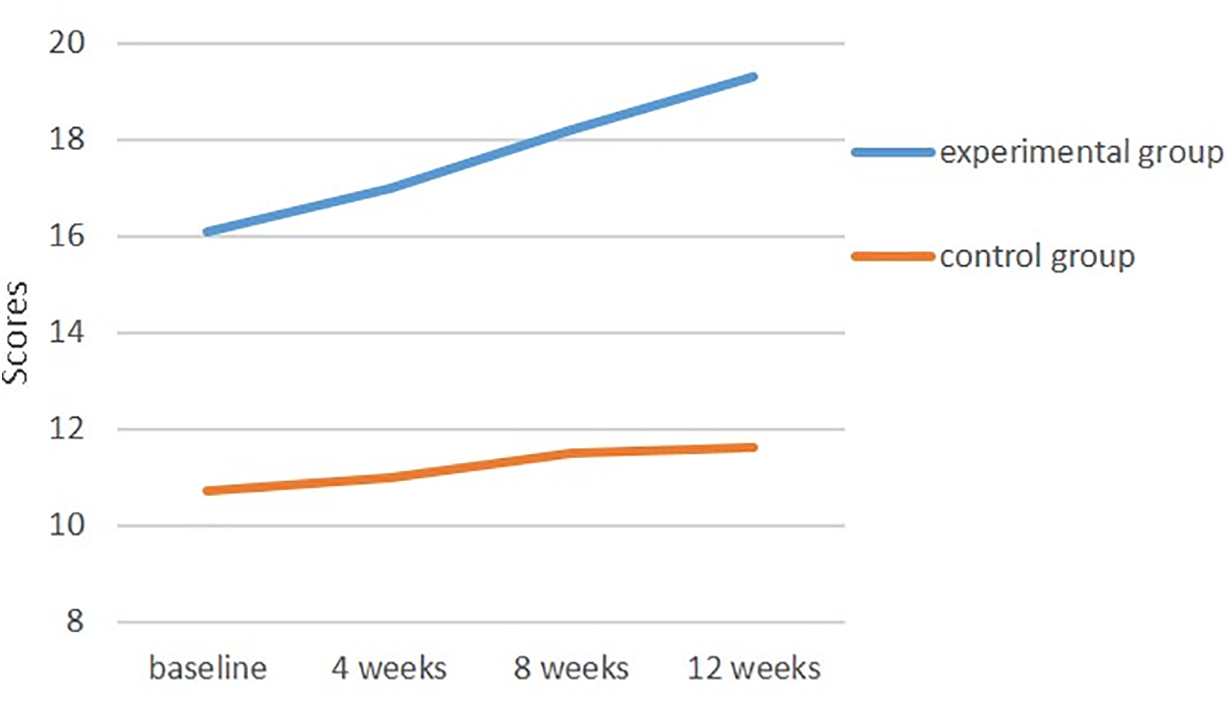

At baseline (T1), the cognitive function score of the experimental group was 16.1 ± 4.8, which was significantly higher than that of the control group (10.7 ± 6.5) (t = −2.99, p = 0.005), indicating that the experimental group had better cognitive performance before the intervention. At subsequent time points (T2, T3 and T4), cognitive function in the experimental group continued to improve, while no significant changes were observed in the control group. The time effect analysis revealed a significant improvement in cognitive function over time in all participants (p < 0.001). The time × group interaction effect indicated a significant difference in the trajectory of cognitive function between the experimental and control groups, demonstrating the statistically significant impact of the cognitive stimulation intervention on the improvement of cognitive function (p < 0.001) (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Changes in cognitive function scores over time in the experimental and control groups

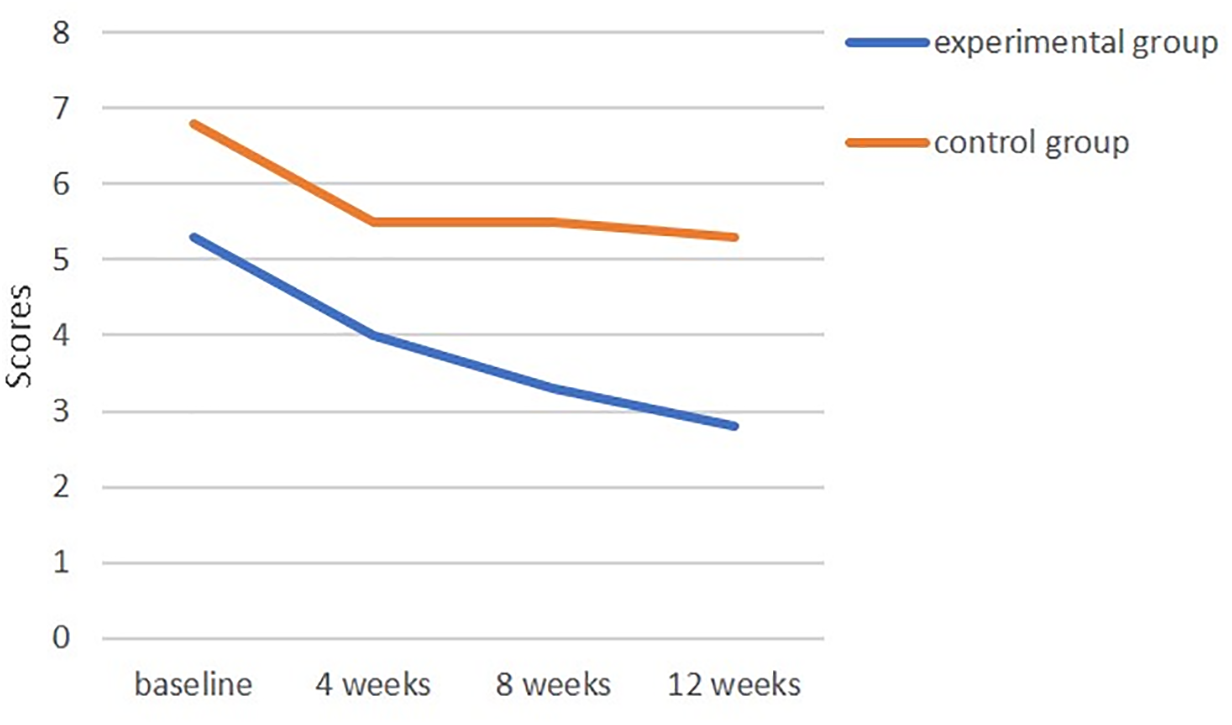

Regarding depression status, the mean baseline score in the experimental group was 5.3 ± 1.7, compared to 6.8 ± 3.5 in the control group, with no significant differences (t = 1.74, p = 0.091). After the CST intervention, the depression scores in the experimental group gradually decreased over T2, T3 and T4, whereas little change was observed in the control group. Time-effect analysis indicated a significant reduction in depression levels over time (p < 0.001). The time × group interaction revealed a significant difference in depression changes between the experimental and control groups, confirming that the cognitive stimulation intervention had a statistically significant effect on reducing depression levels (p < 0.05) (Table 3, Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Changes in depression scores over time in the experimental and control groups

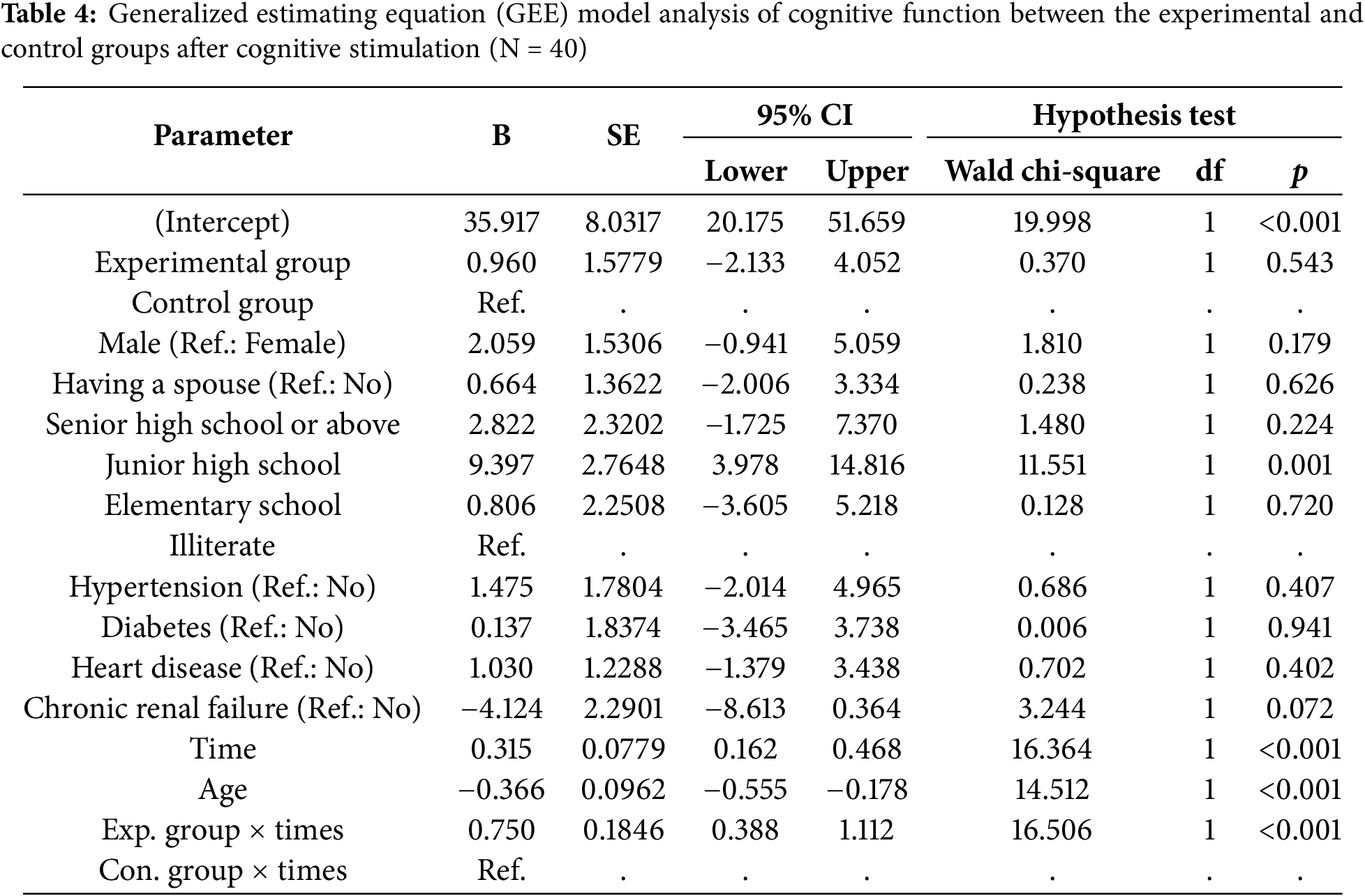

5.3 Effect of Cognitive Stimulation Intervention on Cognitive Function: GEE Model Analysis

The analysis of the changes in cognitive function of the GEE model in older adults with mild dementia indicated that the experimental group showed a significant improvement in cognitive function over time (B = 0.750, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the effects of interaction of education level, age, and time interaction effects were significantly associated with changes in cognitive function changes (p < 0.05). Participants with a middle school education level had a significantly greater cognitive improvement (B = 9.397, p = 0.001) compared to illiterate participants. Furthermore, for each additional year of age, cognitive function decreased by 0.366 points (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

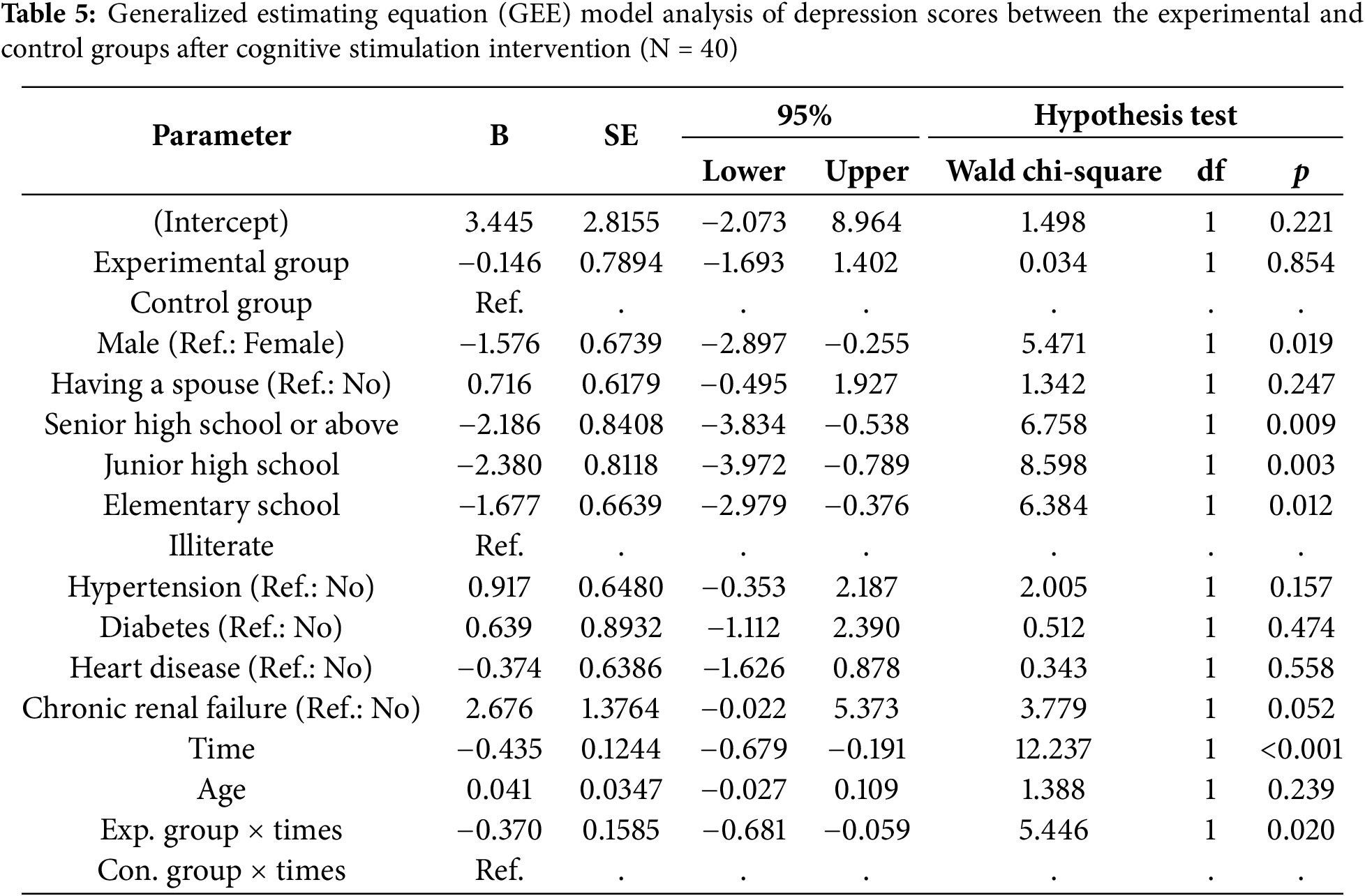

5.4 Effect of Cognitive Stimulation Intervention on Depression: GEE Model Analysis

Analysis of depression changes in older adults with mild dementia demonstrated that the experimental group had significantly lower depression scores compared to the control group (B = −0.370, p = 0.020). Additionally, male participants and those with higher education levels exhibited significantly lower depression scores (Table 5).

This study examined the effects of a 12-week cognitive stimulation intervention on cognitive function and depression in older adults with mild dementia. The results demonstrated that: (1) The experimental group, which received cognitive stimulation therapy (CST), exhibited significant improvements in cognitive function compared to the control group. SLUMS test scores in the experimental group increased with time (baseline: 16.1 ± 4.8; 12th week: 19.3 ± 5.0, p < 0.001), while the control group remained relatively stable. (2) Depression levels, measured using CSDD-C, decreased significantly in the experimental group but not in the control group (p < 0.05). (3) The GEE model showed that cognitive function was positively associated with education level and duration of the intervention, while it declined with increasing age. Similarly, depression was lower in participants with higher educational levels and in men. These findings suggest that cognitive stimulation interventions can effectively enhance cognitive function and reduce depression in older adults with mild dementia.

Our findings align with previous studies demonstrating the effectiveness of CST in improving cognitive function and emotional well-being in individuals with dementia [5,9,19]. CST has been recognized as an evidence-based non-pharmacological approach to dementia, with multiple studies supporting its effectiveness [10,20]. The significant improvement in cognitive function observed in the experimental group is consistent with a systematic review by Woods et al. [5], which found that CST led to improvements in memory, language, and executive functions. Similarly, Spector et al. [9] reported that an 8-week CST program significantly improved cognitive function in dementia patients. Our 12-week intervention yielded comparable results, suggesting that extending the duration of the intervention may further enhance cognitive benefits.

Age was negatively associated with cognitive improvement, with each additional year leading to a decline in cognitive function. Liu et al. (2019) reported a significant increase in dementia and Alzheimer’s incidence with advancing age based on a 7-year national study in Taiwan [21]. Similarly, Wu et al. (2015) observed rising dementia prevalence across East Asia, largely attributed to population aging [22]. These findings support the interpretation that advanced age not only increases dementia risk but may also limit the effectiveness of cognitive interventions. However, education level played a crucial role, with participants having middle school or higher education demonstrating significantly greater cognitive gains compared to illiterate individuals. According to the cognitive reserve hypothesis, individuals with higher educational backgrounds may possess more efficient or adaptable neural networks, which support better compensation in the face of cognitive challenges. These findings suggest that educational attainment may enhance the effectiveness of cognitive training, especially in aging populations, highlighting the need to tailor interventions based on cognitive reserve indicators [3,23,24].

The reduction in depression symptoms in the experimental group further supports the psychological benefits of CST. In addition to cognitive benefits, CST has been found to exert positive effects on psychological well-being, particularly in reducing depressive symptoms. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Desai et al. [25] demonstrated that CST delivered according to the original protocol resulted in not only moderate improvements in cognition but also significant reductions in depressive symptoms among individuals with mild to moderate dementia. These findings are in line with earlier evidence from Woods et al. [5], who reported that cognitive stimulation may contribute to emotional well-being by enhancing social interaction, fostering a sense of achievement, and promoting positive affect. Such mechanisms are especially relevant in dementia care, as depressive symptoms are commonly comorbid and have a profound impact on both quality of life and care burden. Therefore, the observed mood improvements in this study may be attributable not only to cognitive gains but also to the emotionally enriching and socially engaging nature of CST, supporting its role as a holistic non-pharmacological intervention. Interestingly, both groups showed reduced depression scores at 4 weeks, possibly due to repeated measurements, regression to the mean, or psychosocial benefits from study participation and routine care, such as staff attention or basic social interaction. These non-specific effects should be considered when interpreting results.

Our findings that men exhibited lower depression scores compared to women are consistent with prior large-scale meta-analyses and a cross-national surveys [26,27]. Salk et al. [26], in a comprehensive review of gender differences in depression, found that females consistently report higher levels of depressive symptoms and are more likely to receive a diagnosis of depression across various age groups and populations. Calatayud et al. [28] investigated sex differences in anxiety and depression in older adults and their relationship with cognitive impairment. The study found that depression in men was associated with lower cognitive levels. Therefore, when CST interventions enhance cognition in men with MCI, the resulting improvement in depression may be more pronounced than in women. This gender disparity may reflect a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors, including hormonal fluctuations, gender role expectations, and differential coping strategies. In the context of dementia care, women may experience a greater emotional burden or be more likely to express affective symptoms. Tailored interventions that consider gender-specific risk profiles may help enhance the emotional well-being and care outcomes of people living with cognitive impairment. Furthermore, individuals with higher education levels exhibited lower depression scores, supporting the notion that cognitive reserve may offer protective effects against emotional distress in MCI.

The sustained improvements in cognitive function observed between the eighth and 12th weeks suggest that the benefits of CST may accumulate over time. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that cognitive interventions can produce lasting effects when implemented over extended durations [19,29–31]. While shorter CST programs (e.g., 6–8 weeks) have demonstrated efficacy, extending the intervention to 12 weeks or beyond may yield more robust and durable improvements in both cognitive function and mood. These findings highlight the importance of intervention length as a critical factor influencing therapeutic outcomes. Overall, our results reinforce the effectiveness of CST in enhancing both cognitive and emotional well-being in individuals with mild dementia, supporting its broader integration into comprehensive dementia care strategies.

This study was conducted in a Taiwanese context where cultural values strongly emphasize family responsibility in elder care and high respect for authority figures in structured group settings. Such values may enhance participant engagement with CST, as older adults are generally receptive to organized community programs delivered by professionals. Moreover, traditional stigma toward mental illness may lead to underreporting of depressive symptoms, particularly among men, potentially influencing the observed gender differences in emotional outcomes. The integration of music, storytelling, and group discussion—familiar and culturally resonant activities—likely contributed to the intervention’s acceptability and emotional impact. These findings underscore the importance of culturally tailoring CST interventions to ensure relevance and effectiveness in non-Western populations.

7 Implications for the Care of Dementia

This study makes several significant contributions to dementia care and non-pharmacological interventions. Although CST has been widely studied in Western populations, this study demonstrates its effectiveness in a Chinese-speaking population, supporting its global applicability. The findings suggest that the improvements in cognitive function and depression become more pronounced after 8–12 weeks, highlighting the need for an extended CST program. The study highlights the role of education level in intervention effectiveness, suggesting that personalized strategies based on individual cognitive and demographic characteristics may improve outcomes. Given the increasing prevalence of dementia, these findings support the inclusion of CST in long-term care policies and community-based dementia program. The results align with global dementia care recommendations, such as those of the WHO [8] and NICE [17]. This study was implemented under the framework of Taiwan’s Long-Term Care 2.0 initiative, supporting its relevance to ongoing national policy directions in dementia care.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that should be addressed in future research. The study included only 40 participants from a single regional hospital and dementia care center, limiting its generalizability. In addition, the use of a quasi-experimental design without randomization may introduce potential selection bias and reduce internal validity. To reduce the risk of contamination, group assignment was based on distinct recruitment sites; although demographic characteristics between groups were not statistically different, clinically meaningful variations (e.g., age and education level) may have influenced outcomes. However, future studies should consider randomized controlled trials to strengthen causal inference. While structured tools were used to assess cognition and depressive symptoms, elements of self-report may still be subject to social desirability bias or underreporting, especially within the cultural context. This study assessed cognitive and depression outcomes only up to 12 weeks. Future longitudinal studies should investigate whether the observed benefits persist beyond this period. Factors such as physical activity, social support, and baseline cognitive reserve may have influenced the results. Future research should control for these variables to isolate the effects of CST. Additionally, repeated assessments at multiple time points may have introduced potential recall bias, although structured instruments and independent raters were used to help mitigate this issue.

This study provides strong evidence that a 12-week cognitive stimulation intervention significantly improves cognitive function and reduces depression in older adults with mild dementia. The findings are consistent with previous research and support the integration of CST into dementia care strategies. Future studies should focus on larger samples, long-term follow-up, and comparative analyses to further refine and optimize cognitive interventions for dementia patients.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the participants from Yuanlin Christian Hospital, Taiwan, for their generous contribution to this study.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by a grant from Chung Shan Medical University (Grant No.: CSMU-INT-109-06).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Ya-Wen Chang, Ching-Pyng Kuo, Shu-Hsin Lee; data collection: Ya-Wen Chang, Hsiu-Chuan Chen; analysis and interpretation of results: Shih-Chi Chung, Wai-Lam Lao, Shu-Hsin Lee; draft manuscript preparation: Ya-Wen Chang, Hsiu-Chuan Chen, Shih-Chi Chung, Ching-Pyng Kuo, Shu-Hsin Lee. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Changhua Christian Hospital (IRB number: 191104). All participants provided their informed consent prior to participating.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Alzheimer’s Disease International. Dementia facts and figures [Internet]. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2025 [cited 2025 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.alzint.org/about/dementia-facts-figures/. [Google Scholar]

2. Ministry of Health and Welfare (Taiwan). Results of the 2023 National Community-Based Dementia Epidemiological Survey [Internet]. Taipei: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2023 [cited 2025 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.mohw.gov.tw/cp-16-78102-1.html. [Google Scholar]

3. Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020 Aug;396(10248):413–46. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30367-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Nichols E, Steinmetz JD, Vollset SE, Fukutaki K, Chalek J, Abd-Allah F, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022 Feb;7(2):e105–25. doi:10.1002/alz.051496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Woods B, Rai HK, Elliott E, Aguirre E, Orrell M, Spector A. Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Jan;2023(1):CD005562. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005562.pub2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Stafford J, Chung WT, Sommerlad A, Kirkbride JB, Howard R. Psychiatric disorders and risk of subsequent dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022 May;37(5):315. doi:10.1002/gps.5711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Zabihi S, Bestwick JP, Jitlal M, Bothongo PL, Zhang Q, Carter C, et al. Early presentations of dementia in a diverse population. Alzheimers Dement. 2025 Feb;21(2):e14578. doi:10.1002/alz.14578. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. World Health Organization. Dementia: a public health priority [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2012 [cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/dementia-a-public-health-priority. [Google Scholar]

9. Spector A, Thorgrimsen L, Woods B, Royan L, Davies S, Butterworth M, et al. Efficacy of an evidence-based cognitive stimulation therapy programme for people with dementia: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2003 Sep;183(3):248–54. doi:10.1192/bjp.183.3.248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Aguirre E, Woods RT, Spector A, Orrell M. Cognitive stimulation for dementia: a systematic review of the evidence of effectiveness from randomised controlled trials. Ageing Res Rev. 2013 Jan;12(1):253–62. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2012.07.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Orrell M, Aguirre E, Spector A, Hoare Z, Woods RT, Streater A, et al. Maintenance cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia: single-blind, multicentre, pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2014 Jun;204(6):454–61. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.113.137414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Apóstolo JLA, Cardoso DFB, Rosa AI, Paúl C. The effect of cognitive stimulation on nursing home elders: a randomized controlled trial. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2014 May;46(3):157–66. doi:10.1111/jnu.12072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Ministry of Health and Welfare (Taiwan). Introduction to the Long-Term Care Services 2.0 Program [Internet]. Taipei: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 24]. Available from: https://1966.gov.tw/LTC/cp-6572-69919-207.html. [Google Scholar]

14. Haynes AB, Haukoos JS, Dimick JB. TREND reporting guidelines for nonrandomized/quasi-experimental study designs. JAMA Surg. 2021 Sep;156(9):879–80. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0552. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Hu MH. New choice of a screening tool for cognitive function: the SLUMS test. J Long-Term Care. 2010 Dec;14(3):267–76. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

16. Lin JN, Wang JJ. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the cornell scale for depression in dementia. J Nurs Res. 2008 Sep;16(3):202–10. doi:10.1097/01.jnr.0000387307.34741.39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers [Internet]. London: NICE; 2018 [cited 2025 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97. [Google Scholar]

18. Alexopoulos GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, Shamoian CA. Cornell scale for depression in dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 1988 Feb;23(3):271–84. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(88)90038-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Carbone E, Gardini S, Pastore M, Piras F, Vincenzi M, Borella E. Cognitive stimulation therapy for older adults with mild-to-moderate dementia in Italy: effects on cognitive functioning, and on emotional and neuropsychiatric symptoms. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021 Oct;76(9):1700–10. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbab007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Hall L, Orrell M, Stott J, Spector A. Cognitive stimulation therapy (CSTneuropsychological mechanisms of change. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013 Mar;25(3):479–89. doi:10.1017/s1041610212001822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Liu CC, Li CY, Sun Y, Hu SC. Gender and age differences and the trend in the incidence and prevalence of dementia and alzheimer’s disease in Taiwan: a 7-year national population-based study. Biomed Res Int. 2019 Nov;2019:5378540. doi:10.1155/2019/5378540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Wu YT, Brayne C, Matthews FE. Prevalence of dementia in East Asia: a synthetic review of time trends. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015 Aug;30(8):793–801. doi:10.1002/gps.4297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Stern Y. What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002 Mar;8(3):448–60. doi:10.1017/s1355617702813248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Stern Y. Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia. 2009 Aug;47(10):2015–28. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.03.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Desai R, Leung WG, Fearn C, John A, Stott J, Spector A. Effectiveness of cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) for mild to moderate dementia: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of randomised control trials using the original CST protocol. Ageing Res Rev. 2024 Jun;97(6):102312. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2024.102312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull. 2017 Aug;143(8):783–822. doi:10.1037/bul0000102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Seedat S, Scott KM, Angermeyer MC, Berglund P, Bromet EJ, Brugha TS, et al. Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Jul;66(7):785–95. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Calatayud E, Marcén-Román Y, Rodríguez-Roca B, Salavera C, Gasch-Gallen A, Gómez-Soria I. Sex differences on anxiety and depression in older adults and their relationship with cognitive impairment. Semergen. 2023 May–Jun;49(4):101923. doi:10.1016/j.semerg.2023.101923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Orrell M, Spector A, Thorgrimsen L, Woods B. A pilot study examining the effectiveness of maintenance Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (MCST) for people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005 May;20(5):446–51. doi:10.1002/gps.1304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Justo-Henriques SI, Otero P, Torres AJ, Vázquez FL. Effect of long-term individual cognitive stimulation intervention for people with mild neurocognitive disorder. Rev Neurol. 2021 Aug;73(4):121–9. doi:10.33588/rn.7304.2021114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Justo-Henriques SI, Pérez-Sáez E, Marques-Castro AE, Carvalho JO. Effectiveness of a year-long individual cognitive stimulation program in Portuguese older adults with cognitive impairment. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2023 May;30:321–35. doi:10.1080/13825585.2021.2023458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools