Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Investigating Higher Education Teachers’ Well-Being and Its Influencing Multiple Factors: A Systematic Review Approach

1 Institute of International and Comparative Education, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China

2 Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China

* Corresponding Authors: Jian Li. Email: ; Eryong Xue. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Exploring anxiety, stress, depression, addictions, executive functions, mental health, and other psychological and socio-emotional variables: psychological well-being and suicide prevention perspectives)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(7), 901-928. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.066538

Received 10 April 2025; Accepted 17 June 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

Background: Teachers from higher education commonly face substantial workloads, resulting in heightened stress and reduced well-being. This has spurred significant academic interest in the determinants of faculty well-being within higher education. Consequently, numerous studies have focused on both understanding these influencing factors and developing strategies to bolster teacher well-being, an area that has gained considerable traction as a research focus. Although systematic reviews have been conducted to elucidate the connections between well-being and particular attributes like emotional regulation, efficacy, and competency, there remains a paucity of reviews that holistically examine the multifaceted factors affecting the well-being of university and college faculty. Methods: In this study, using a systematic review approach, we explore higher education teachers’ well-being (HETWB) and its influencing multiple-dynamic factors. Following PRISMA 2020, Web of Science and ERIC were selected as the meta-database, and 42 publications were obtained by strict criteria during literature screening. The basic information about the studies, including publication trends, regional distribution, method, and the factors affecting the well-being of college teachers, has been analyzed. Results: A review of the literature suggests a notable increase in scholarly attention directed towards teachers’ well-being in recent decades. Comparative bibliometric analysis identifies China, Spain, Canada, and the United States as the leading nations in terms of publications on this topic. Within this body of research, quantitative methods, particularly questionnaire-based surveys (n = 31), predominate as the primary investigative strategy. The determinants of teachers’ well-being are commonly categorized into several domains: demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, family status, university type/level, academic major, position, tenure); external work-related factors (e.g., availability of job resources, level of job demands); internal personal attributes (e.g., physical status, mental status, mental traits, mental competencies); interactive processes (e.g., work-home conflict/balance); and potential moderators (e.g., quality of work relationships). Additionally, there is a growing body of research dedicated to elucidating the multifaceted and dynamic mechanisms that govern the well-being of college faculty. Conclusion: Firstly, our global perspective allows us to move beyond the limitations of region-specific research and identify commonalities and variations in the factors influencing faculty well-being across diverse cultural and institutional contexts. Furthermore, we emphasize the bidirectional nature of these relationships, illustrating how well-being not only influences work outcomes (e.g., performance, and job satisfaction) but also receives impacts from them, creating a dynamic feedback loop. Finally, our inclusion of the counter-effect, where high levels of well-being, as conceptualized in HETWB, can lead to better psychological states, work performance, and access to resources, further enriches the understanding of this field.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe teaching profession necessitates a comprehensive repertoire encompassing specialized subject matter expertise, pedagogical competencies, and affective dispositions, thereby imposing substantial demands on educators. Consequently, educators frequently encounter significant occupational burdens, which are often associated with heightened stress levels and diminished well-being [1,2]. A considerable body of research has focused on elucidating the determinants of well-being among college instructors and developing strategies for its enhancement, a topic that has progressively garnered prominence within the academic discourse [3]. Several scholars have undertaken systematic reviews to investigate the relationships between specific constructs, such as emotional regulation, self-efficacy, and professional competence, and well-being [4–6]. Nevertheless, a paucity of systematic reviews exists that holistically examine the multifaceted factors influencing the well-being of higher education faculty [7]. Furthermore, even prominent theoretical frameworks related to well-being, including the PREMA model and the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) theory, tend to explore influencing factors within relatively circumscribed scopes. Therefore, the present study undertakes a systematic review of the extant literature concerning factors impacting the well-being of university faculty. It aims to synthesize current understanding and contribute to the expansion of the theoretical landscape in this domain.

1.1 The Idea of Well-Being: Definition and Types

At present, there is no unified definition of well-being [8]. When defining well-being, both the cognitive and emotional aspects of well-being identification can be global or domain specific, such as workplace well-being. This approach might be a good structure or introduction when you just enumerate different aspects of well-being. For instance, teachers’ career satisfaction/well-being mainly includes seeing students’ success in the teaching process, playing a role in students’ lives, and becoming an encyclopedia for students. These aspects, with their specific details, reflect the diverse life values of teachers [9,10].

In addition, well-being is broadly defined as a positive experience for individuals or groups, encompassing both quality of life and the capacity for purposeful and conscious contribution to the world. This concept of well-being is considered a psychological experience, which is not only a factual judgment on the objective conditions and state of life, but also a value judgment on the subjective meaning and degree of satisfaction of life. Subjective well-being focuses on the happy aspect of well-being, reflecting people’s subjective pursuit of happiness, pleasure, and satisfaction in life [11], which is limited to the individual’s own experience [12]. Psychological well-being emphasizes the realization of human potential and a meaningful life, focusing on individual growth and development, the pursuit of meaningful goals and values, and coping with life challenges. Experiential well-being refers to the proportion of positive emotions in positive emotions and negative emotions experienced by people, also known as subjective happiness [13,14]. Therefore, to some extent, the concept of psychological well-being can be equated with the concept of evaluable well-being, and the concept of subjective well-being with the concept of experiential well-being [15].

1.2 The Influencing Multiple-Dynamic Factors of Teachers’ Well-Being

In general, based on the individuals, the factors related to teachers’ well-being can be divided into external factors, internal factors, and interacting factors. The external factors normally appear in the family, institutions, and so on. Regarding the internal factors, these comprise the individual factors, such as demographic factors, mental factors, and physical factors. In terms of the interacting factors, defined as the interaction of internal and external factors, explore the relationship between teachers and families. And some popular categories or models are stated as follows. Some psychological organizations divide well-being into emotional well-being, physical well-being, financial well-being, social well-being, work well-being, and group well-being. These dimensions respectively refer to ability to use of stress management, relaxation techniques, resilience, self-love, and ability to produce good emotions [16], ability to improve physical function through healthy living habits, ability to communicate, develop meaningful relationships, and build support networks, ability to manage economic life effectively, ability to achieve professional meaning, happiness, and a sense of enrichment through the pursuit of interests, values, and life goals, ability to actively participate in a thriving community, culture, and environment [17]. The former division is relevant to the determinants of teachers’ well-being, which covers both the external and internal sides [18]. The well-known PERMA model, developed by Martin Seligman, the father of positive psychology, includes positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and achievement, which are all internal factors. It’s the full play vigorous development, full experience, and display of people in the five dimensions that contribute to the comprehensive well-being. In the field of individual psychology, psychological phenomena are divided into three parts: psychological process, mental state, and mental characteristics according to their persistence and stability, which can be applied to the studies related to the impacts on well-being in a wide mental range. Psychological process refers to the process in which psychological activities occur and develop within a certain period under the influence of objective things, usually including cognitive process, emotional process, and will process. Psychological characteristics refer to people’s unique and stable personal psychological characteristics formed by nature or nurture, such as ability, character, temperament, etc. [19]. Mental state is usually a psychological phenomenon between mental processes and mental characteristics, which is mainly manifested as an individual’s psychological tendency over a period, such as attitude, motivation, emotion, etc. In addition, regardless of school level, the teaching profession prioritizes work-related well-being above other concerns. The model of Job demand-resources (JDR), first proposed by Eva Demerouti and Arnold Bakker, has been widely applied as an external factor in management psychology and is closely related to employee well-being [20]. Job resources refer to the physical, organizational, or social factors that can help employees achieve their goals and reduce pressure, such as career development opportunities, autonomy, etc., while job demands refer to the physical, social, and emotional factors that the working environment requires employers to pay, such as work pressure, time pressure, etc. [21].

The current research on the well-being of the teaching profession around higher education is generally abundant, and scholars have conducted in-depth, multi-dimensional discussions on the factors influencing teacher well-being. Existing studies indicate that teacher well-being is multi-dimensional, and its formation is the result of a combination of many internal and external factors: these include individual-level factors such as physical health, psychological and emotional states [6,22], as well as external factors such as social support systems [23], professional development opportunities [24], the quality of the work environment [25,26], and teaching effectiveness [4,27]. However, there is a relative scarcity of comprehensive review studies specifically focusing on the well-being of university faculty, and existing research findings are insufficient. Current studies primarily utilize systematic review methodologies to analyze factors influencing the well-being of university faculty, finding that work-related stress, teacher emotions, the university environment, and the level of degrees held by teachers all have a certain impact on teacher well-being [5,19,28]. However, the analysis of influencing factors is limited and does not comprehensively consider all types of factors. Among existing theories of well-being, the PERMA and JD-R models are the main ones, but the factors they cover are limited. This paper attempts to sort out the influencing factors of university faculty well-being from three dimensions: internal, external, and interactive, and also attempts to construct a comprehensive theoretical model for influencing university faculty well-being. At the same time, this study will also sort out the basic information of relevant literature, including publication trends, geographical locations, and research methods. Therefore, the research questions of this paper are:

Q1: What are the basic characteristics of current articles on the influencing factors of university faculty well-being? Including publication trends, geographical locations, definitions, and research methods.

Q2: What are the internal, external, and interactive factors that affect the well-being of university faculty?

Q3: What is the comprehensive theoretical model of the factors that affect the well-being of university faculty? And what are the relationships between these factors?

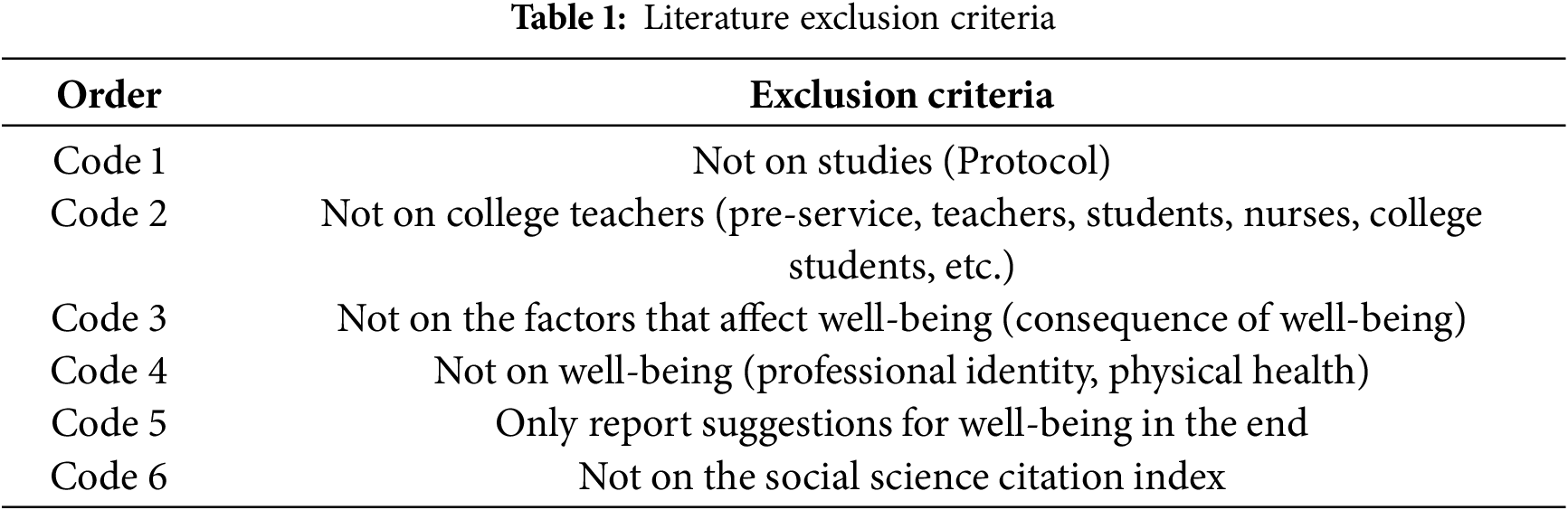

Following PRESMA 2020 guideline (Supplementary Material), a systematic analysis is used as the research method in this study to analyze current research focusing on the well-being of college teachers. Web of Science and Eric were used as literature retrieval databases. Up to April 2023, “College teacher OR university teacher OR professor OR instructor” AND “well-being OR wellbeing OR life satisfaction OR happiness” were the search terms to obtain the preliminary literature, 1830 and 1800 studies were searched from Web of Science and ERIC separately. Then, by using the filtering function of the Web of Science, the literature type is limited to article, core database sources, English, and the published time is limited to 2000–2023; 463 studies were obtained. On ERIC, the literature was limited to full-text literature, peer-reviewed, referenced, academic journals, and English; 400 studies were obtained. After a preliminary search, a total of 163 articles were obtained. Formal literature retrieval is divided into three steps, which have to be processed according to the exclusion criteria in Table 1. For code 1, protocols and non-empirical studies will not be considered as they do not constitute formal research and do not contribute data to this review. For codes 2,3,4,5, studies will be excluded if they do not meet specific criteria regarding population, exposure/intervention, and outcome. Specifically, the study population must consist of college teachers, and the study must investigate factors influencing well-being, with a focus on outcomes related to well-being; studies merely mentioning well-being in the discussion or suggestions section will be excluded. Finally, for code 6, only studies indexed in the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) will be considered to ensure the inclusion of studies that have undergone rigorous peer review and meet established academic standards. The specific screening process is shown in Fig. 1. Step 1 is to screen out duplicates. Step 2 is to review the title and abstract to exclude literature according to all the criteria. For step 3, the aim is to exclude the literature omitted in step 2, to exclude the literature that uses (See Table 1 and Fig. 1). All the steps were processed by two researchers independently first, and then discussed in the end.

Figure 1: The publication screening process

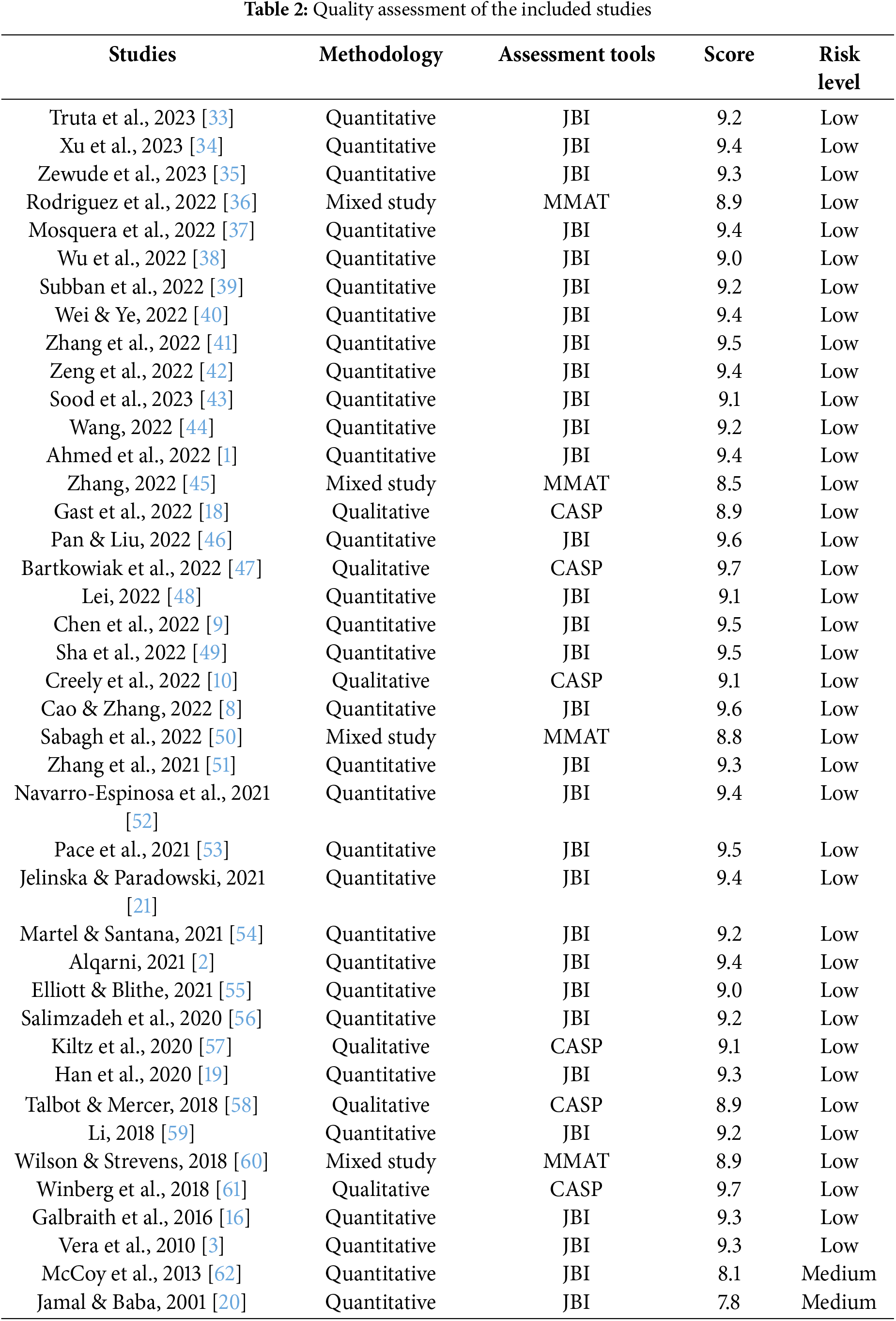

This study employed multiple tools to evaluate the quality of the included studies. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) was utilized for the assessment of qualitative studies [29], the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool for quantitative studies [30], and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for mixed methods studies [31]. When evaluating qualitative studies, the CASP tool requires assessment across ten specific criteria. These include the study’s aims, methodology, research design, recruitment strategy, data collection methods, the relationship between the researcher and participants, ethical considerations, data analysis procedures, findings, and the study’s value implications. For quantitative studies, the JBI tool employs eight distinct criteria for appraisal. These cover sample inclusion criteria, study subjects and setting, measurement of exposure variables, control of measurement conditions, identification of confounding factors, strategies employed to address confounding factors, measurement of outcomes, and data analysis techniques. Regarding mixed methods studies, the MMAT lists five key areas for assessment: the methodological components, the rationale for the chosen methods, the explanation of findings, the research questions and objectives, and considerations of bias. Ultimately, all assessment scores were standardized to a ten-point scale. All assessments were performed independently by two researchers on two separate occasions. Interrater reliability, as measured by Cohen’s Kappa, was 0.82, indicating substantial agreement [32] and achieving an ideal level of reliability. The results of the quality assessment are presented in Table 2. Ninety-five percent (95%) of the studies were classified as low risk of bias, demonstrating the high quality of the included studies.

2.3 Data Collection and Integration

Finally, 42 studies were obtained. We began by exporting basic study data (author, year, index, etc.) from the database into an Excel spreadsheet. Then, we systematically extracted information regarding the concepts, methods, and factors impacting higher education teachers’ well-being, organizing and merging related categories within a new Excel spreadsheet. This study presents the results in four sections. The first part is the basic background of the research literature, which mainly includes the annual publication trend, regional distribution, and the types of well-being studied. The second part is about the research methods of the research literature and specific research methods. The third part is about the influencing factors of university teachers’ well-being through empirical research, including demographic factors, external factors, internal factors, and interactive factors.

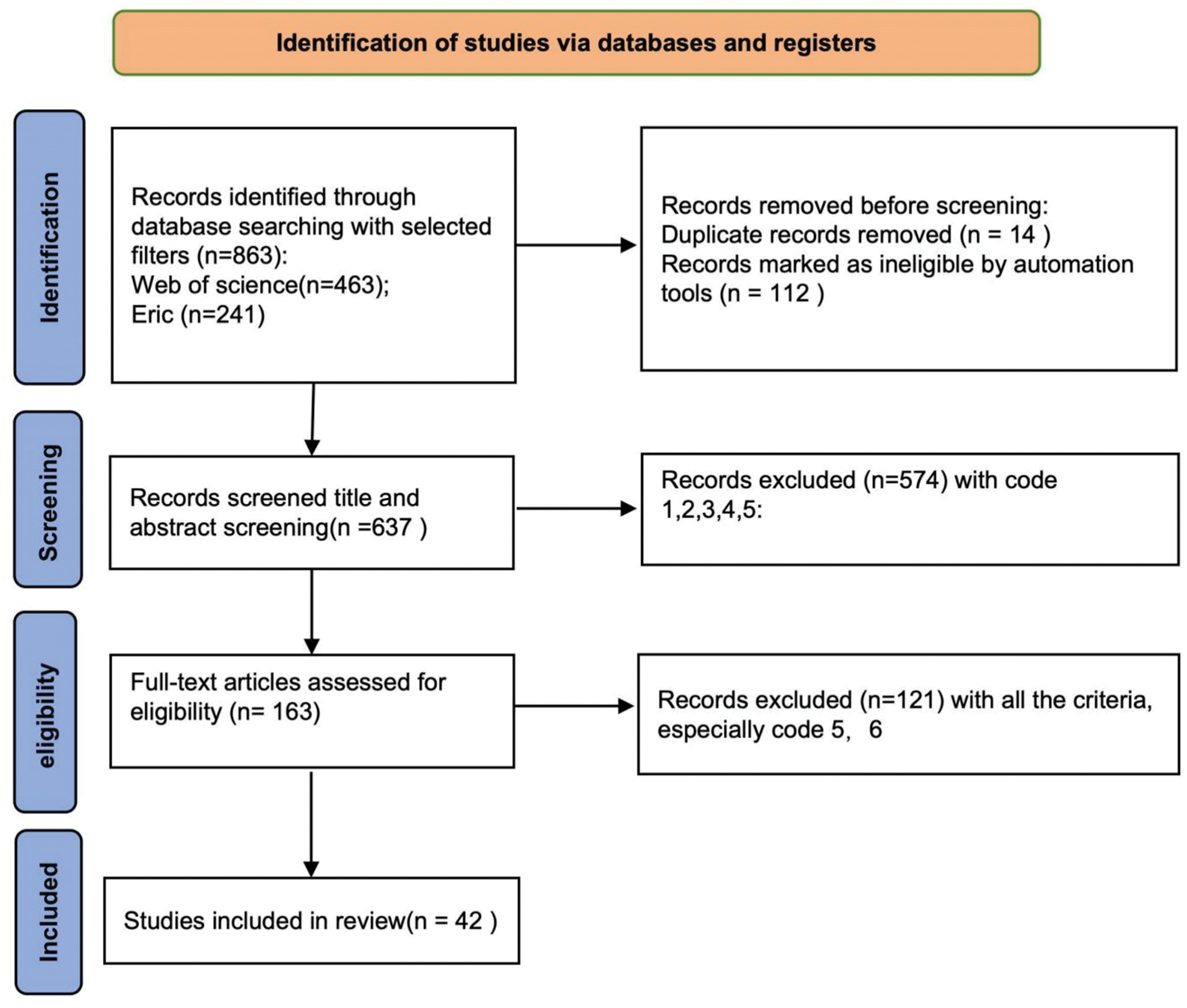

3.1 The Publication Trend of the Studies on College Teachers’ Well-Being

The temporal distribution of publications concerning university teacher well-being from 2000 to 2023 is depicted in Fig. 2. As Fig. 2 illustrates, there is an overall upward trajectory in the annual number of published papers. Based on publication volume, the academic research in this field can be delineated into three distinct phases. The initial phase represents an embryonic period (2000–2008), characterized by a single published article. The subsequent phase is marked by fluctuating growth (2009–2019), during which the number of publications exhibited variability. This period coincided with the continuous expansion of higher education, leading to heightened demands and expectations placed upon university faculty, thereby gradually drawing scholarly attention to their well-being. The final phase constitutes a period of sustained growth (2020–2022), where the number of publications demonstrated a consistent increase, peaking notably in 2022.

Figure 2: The number of publications researched in this paper from 2000 to 2023

3.2 The Regional Distribution of the Included Research Participants

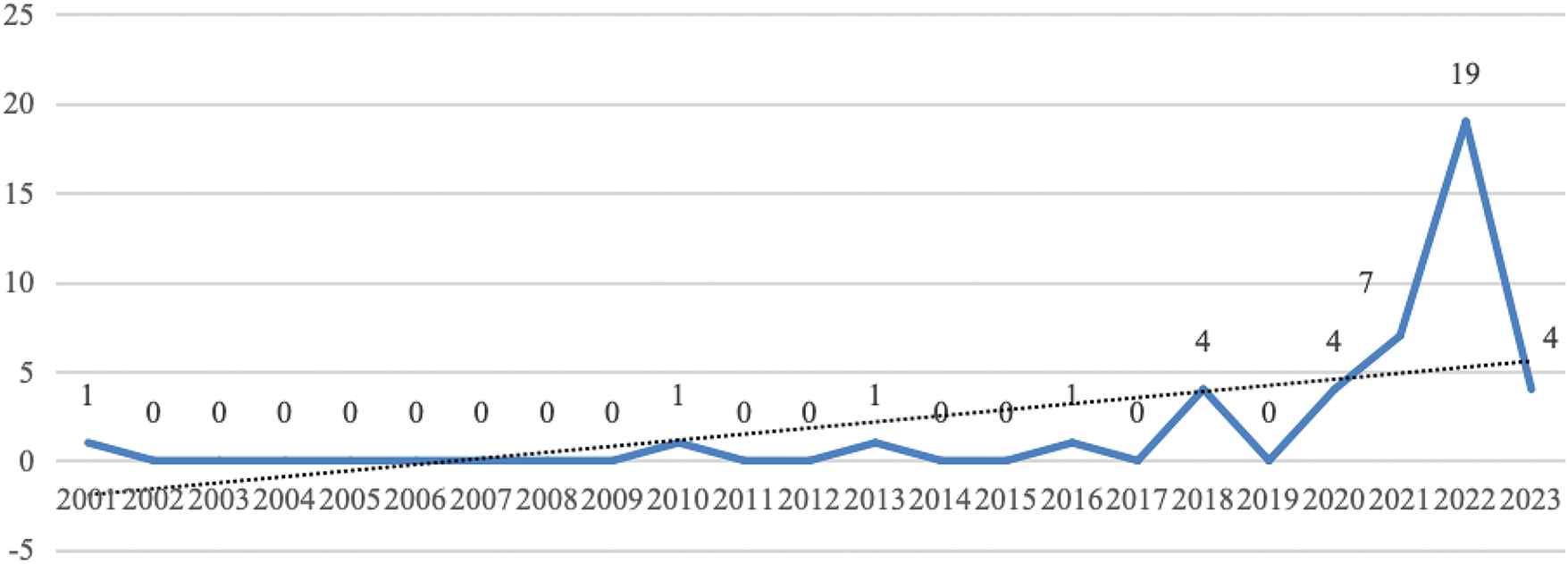

Fig. 3 illustrates the geographical distribution of the studies through a heat map. Of the reviewed literature, one paper did not specify the country of study. Two studies encompassed higher education institutions across multiple European nations. The remaining 43 studies were conducted within 19 distinct countries, predominantly located in Asia (n = 19), followed by Europe (n = 12) and the Americas (n = 7). The five most frequently represented countries were China (n = 16), Spain (n = 4), Canada (n = 3), the United States (n = 3), Australia (n = 2), and the Netherlands (n = 2) (refer to Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Heat maps of countries with the distribution of research objects

3.3 The Definition Types of Teachers’ Well-Being

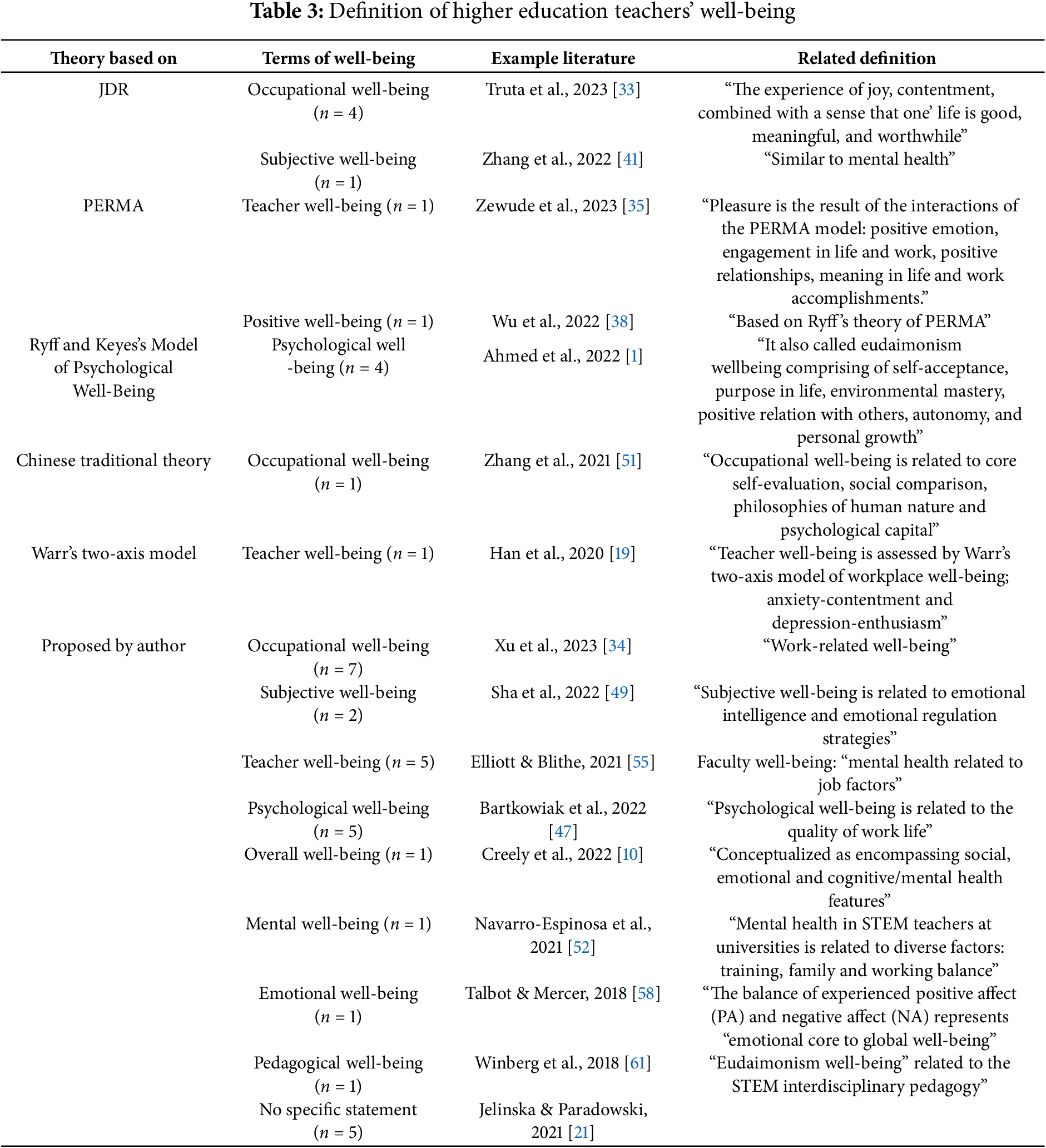

The definition of teacher well-being within the examined literature was primarily ascertained through either explicit definitions provided directly within the studies or inferred from the context of literature reviews and introductory sections. These conceptualizations can be broadly categorized into two tiers. The first tier encompasses fundamental dimensions of well-being, specifically Subjective Well-being (n = 4) and Psychological Well-being (n = 10). The second tier is more profession-specific, relating directly to the collegiate teaching context. This includes research focusing on Teacher Career Well-being (n = 10), Teacher Well-being (n = 8), Educational and Instructional Well-being (n = 1), Academic Well-being (n = 1), and well-being conceptualized within the framework of Positive Psychology (n = 1). Additionally, a singular study addressed Emotional Well-being (n = 1). Notably, five studies did not offer a specific definition or review pertaining to well-being. The origins of these definitions were traced to established theoretical frameworks (n = 13) or were author-proposed constructs (n = 29). The referenced theoretical frameworks encompassed the Job Demands-Resources Theory, the Positive Resources for Motivation and Action (PREMA) model, Ryff and Keyes’s Model of Psychological Well-being, traditional Chinese theoretical perspectives, and Warr’s two-axis model (as detailed in Table 3).

3.4 The Method Analysis of Teachers’ Well-Being

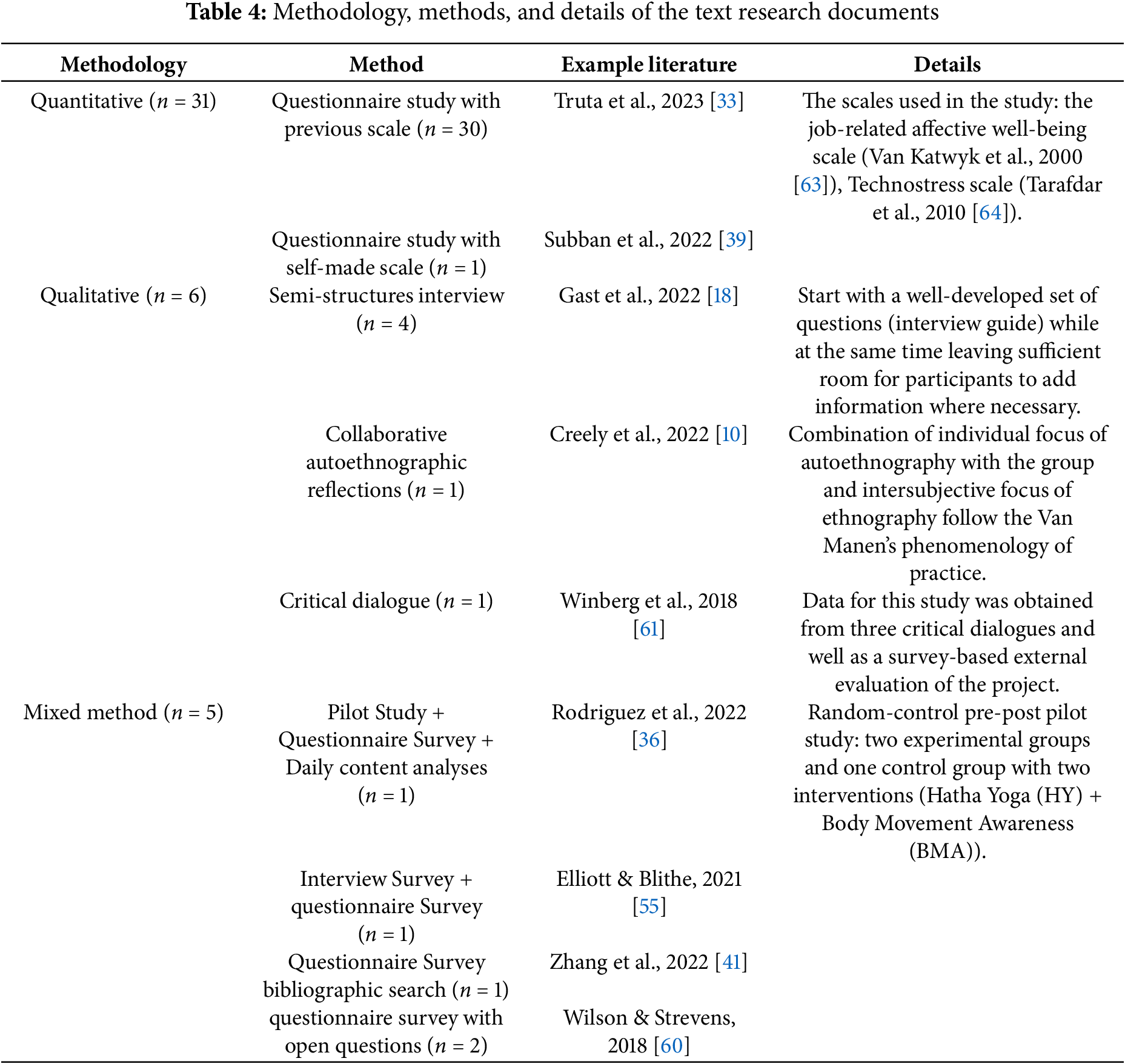

The research literature reviewed in this paper encompasses three primary methodologies: quantitative research (n = 31), qualitative research (n = 6), and mixed-methods research (n = 5). Table 4 presents the specific methodologies and methods employed across these studies, accompanied by illustrative examples. Regarding the quantitative studies, all adopted the questionnaire survey method. Within this group, 29 studies utilized either validated scales or scales that were adapted and subsequently re-validated. The remaining two studies employed self-developed scales for data collection and analysis; however, no specific details regarding these scales were provided in the respective publications. Concerning the qualitative studies, four employed semi-structured interviews, one utilized collaborative autoethnography, and another adopted a narrative research approach. In the domain of mixed-methods research, the approaches varied: one study combined experimental research, questionnaire surveys, and content analysis; another integrated questionnaire surveys with a literature review; a third utilized interviews in conjunction with questionnaires; two studies incorporated questionnaires featuring open-ended questions alongside both quantitative and qualitative analytical techniques in their data interpretation.

3.5 Factors Related to Teachers’ Well-Being

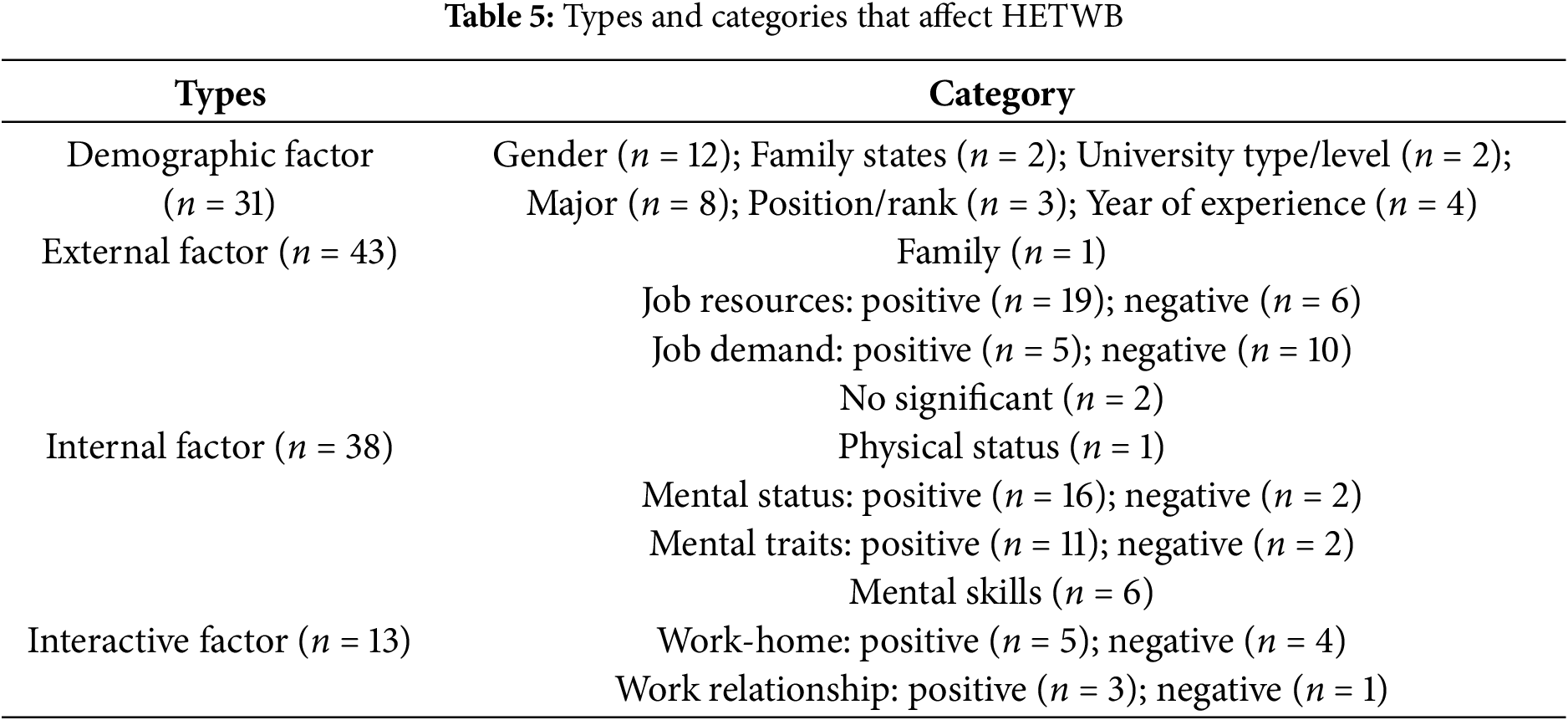

The literature reveals considerable variability in the conceptualization of well-being, consequently, the term ‘well-being of college teachers’ (HETWB) will be employed uniformly throughout this section. Additionally, the reviewed literature can be categorized based on their approach to HETWB: twenty-five studies (n = 25) addressed HETWB directly, whereas seventeen studies (n = 17) did not. Instead, these latter investigations examined proxy variables commonly associated with well-being, such as job satisfaction and job involvement. For the purposes of this review, factors influencing these proxy variables are considered equivalent to factors influencing HETWB. This section proceeds to synthesize the literature by categorizing reported influences on university faculty well-being under four thematic headings: demographic factors, external factors, internal factors, and factors arising from the interplay between internal and external elements. These findings are presented in Table 5. It is pertinent to note that while demographic variables are fundamentally aspects of an individual’s internal makeup, they are listed as a distinct category here. This separation is primarily due to their nature as predominantly nominal variables, which complicates the analysis of their correlational relationships with HETWB [65].

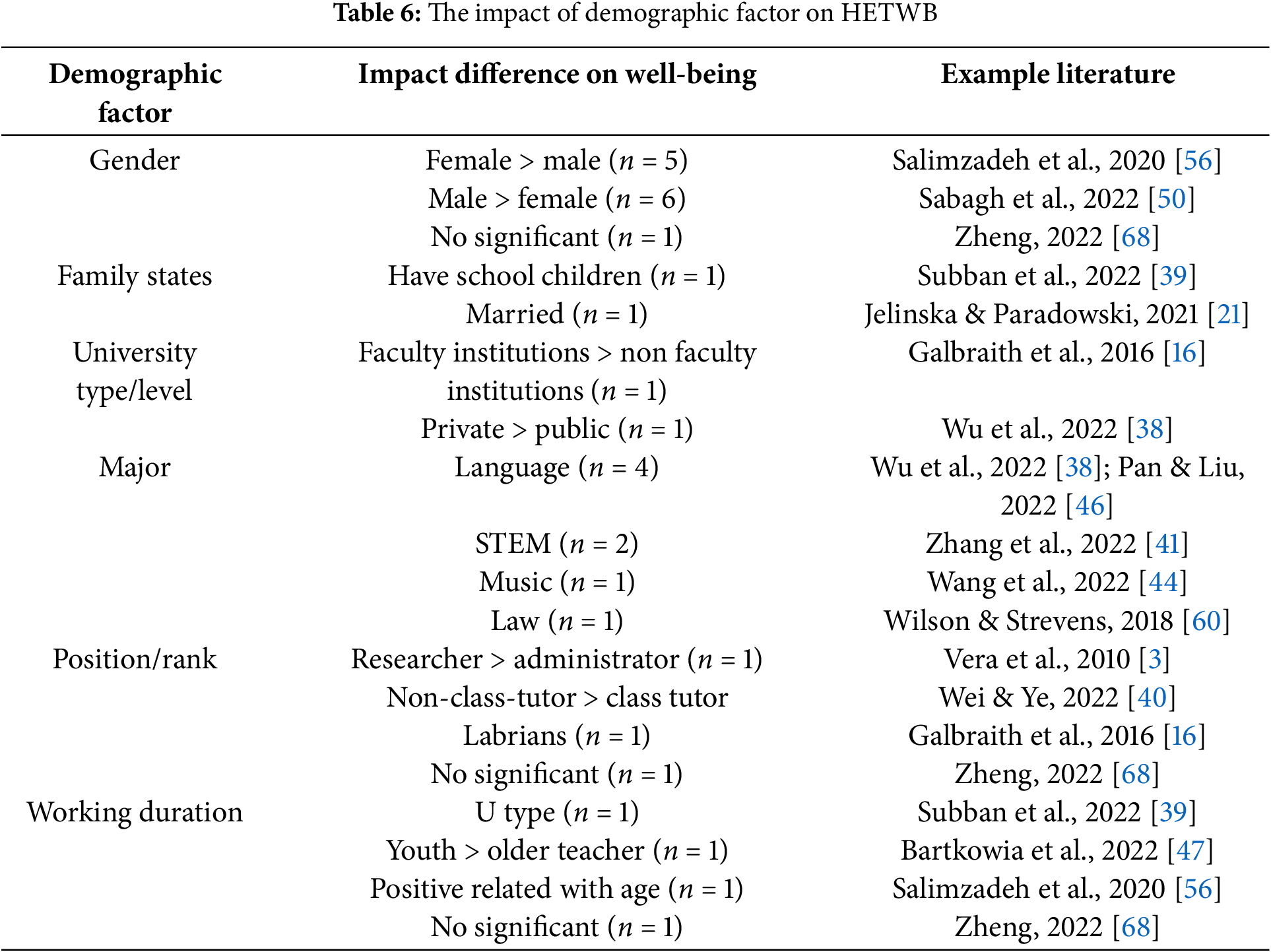

All the results concerning college teachers’ demographic factors are presented in Table 6, including gender, family states, university level, major, position, working duration. An examination of demographic variables reveals that seven studies have investigated the impact of gender on the well-being of college faculty. The findings present a nuanced picture: while some research indicates higher well-being among female instructors compared to their male counterparts (n = 5), other studies report the opposite trend, with male faculty exhibiting greater well-being than females (n = 6). Proposed explanations for lower well-being among women often point to factors such as shouldering greater familial responsibilities or possessing personality traits that may reduce their perceived access to available support systems [66]. Additionally, female academics may encounter heightened experiences of gender inequality and professional isolation [57]. Conversely, diminished well-being among male faculty is frequently attributed to substantial workloads coupled with familial obligations, which can impede work-life balance [48]. Furthermore, research indicates variability in faculty well-being associated with marital status (n = 2). For instance, one study found married male teachers reported greater well-being than their female counterparts, potentially linked to receiving more spousal emotional support [59]. The COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted these dynamics, as educators with school-aged children were often required to dedicate additional time to assisting with remote learning, consequently experiencing increased fatigue and diminished well-being [54].

While fifteen studies examined the influence of institutional type—primarily distinguishing between public/private and research-intensive versus teaching-focused or mixed-research/teaching institutions—only two investigations explicitly demonstrated an effect of this categorization on the well-being of college faculty. Furthermore, the findings indicate variability in Higher Education Teacher Well-being (HETWB) across different academic disciplines (n = 10), specifically noting contrasts among language studies (n = 4), STEM fields (n = 2), music (n = 1), and law (n = 1). Within this context, language educators, particularly those teaching second foreign languages, encounter discipline-specific challenges, including instructing non-native speakers, economic pressures, and difficulties in professional advancement or tenure-track evaluations [62]. Conversely, STEM instructors often require mastery of extensive interdisciplinary knowledge and skills, a demand that can foster higher professional competence and consequently enhance their occupational well-being [37].

Further research also suggests that professional rank or administrative position significantly influences the well-being of college faculty (n = 3). Specifically, instructors serving as class directors often assume greater responsibilities compared to their counterparts without such duties, which is associated with diminished well-being [52]. Similarly, faculty in administrative roles tend to report lower levels of well-being than those primarily engaged in research positions [53]. This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that administrative faculty frequently encounter a heavier burden of bureaucratic tasks, whereas their research-focused colleagues can dedicate more time to scholarly pursuits. Additionally, several studies have examined the impact of age on faculty well-being, yielding inconsistent findings (n = 4). One study posits a U-shaped relationship between age and well-being, suggesting that middle-aged educators experience the lowest levels of well-being, potentially due to concurrent career advancement pressures and increased familial caregiving responsibilities [67]. Conversely, a survey conducted during the pandemic indicated that older faculty were more susceptible to technostress than their younger colleagues, consequently experiencing reduced well-being [46].

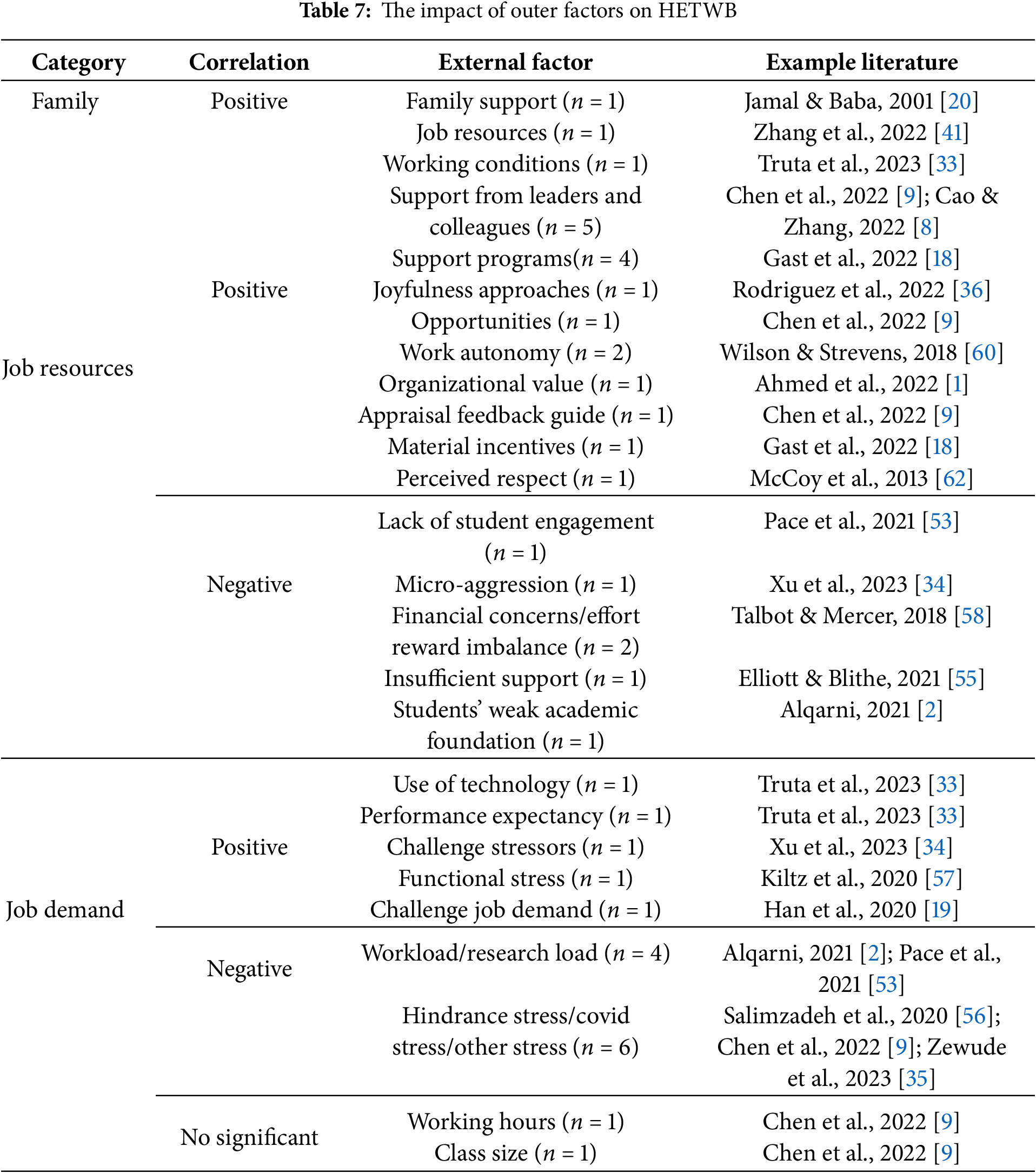

Consistent with existing scholarship, the present analysis identifies 28 external factors influencing the well-being of postsecondary educators, which can be broadly categorized under family, institutional (school), and societal domains (Table 7). Notably, institutional factors emerge as the predominant influence within this framework. Aligning with Bakker’s Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model, all factors pertaining to the institutional or university context are conceptualized as either job resources or job demands [69]. It should be noted, however, that the limited scope of the literature reviewed in this study precluded a comprehensive examination of family-related factors, with only two instances identified (n = 2).

Among the job resources, there are 14 positive factors related to the well-being of college and university teachers, including the overall work resources and conditions, and various support from organizations, leadership, colleague support, technical support, training support, etc. [36]. Among all the positive factors, the one that receives most attention from scholars is the support from leaders and colleagues (n = 4), which can increase teachers’ job satisfaction by increasing their work involvement and reducing their sense of fatigue. In addition, job training and job autonomy also received some attention. In a mixed study in the context of the epidemic, the results of both questionnaire and literature survey indicate that, due to the change of teaching mode, the lack of training in the use of information technology tools was one of the reasons for the increased stress of teachers, thus leading to the decline HETWB [50].

Grounded in Self-Determination Theory (SDT), job autonomy emerges as a critical factor influencing the professional efficacy and overall success of college faculty. Furthermore, findings from a quantitative investigation examining the interplay between emotional intelligence, emotion regulation strategies, and subjective well-being indicate that cognitive reappraisal exerts a significant positive influence on the subjective well-being of these educators. However, this positive effect appears to be moderated, or potentially attenuated, by the presence of effort-reward imbalance [56]. Regarding job resources, the reviewed literature indicates that no identified factor lacked a significant association with well-being. While the prevailing assumption posits that job demands generally exert an inhibitory effect on faculty well-being, the current study’s review reveals a more complex picture, encompassing both detrimental and potentially beneficial aspects within the literature. Several positive job demand constructs warrant further exploration; notably, functional logic appears to underpin concepts such as challenge stressors, functional stress, and challenging job demands. These constructs suggest that when employees perceive challenging work situations as opportunities where their efforts are likely to yield meaningful outcomes, they are more inclined to invest greater effort. In essence, this context facilitates a more profound realization of personal value, consequently fostering enhanced individual well-being [49].

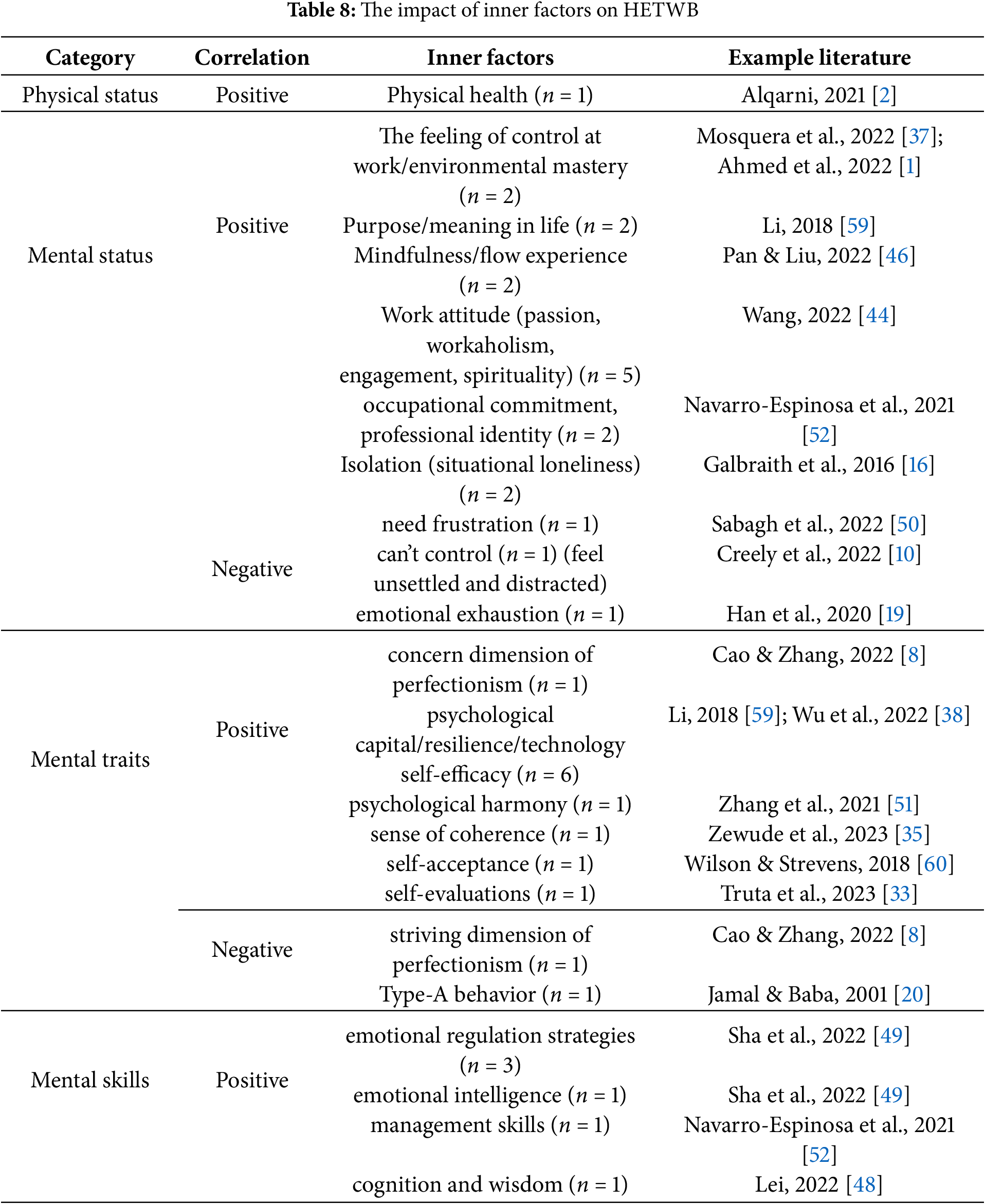

In this paper, there are 23 internal factors affecting the well-being of college teachers (Table 8). To obtain a more comprehensive classification, all the factors are generally categorized as mental factors and physical factors. First, there is only one literature in this paper that considers the impact of physical factors on the well-being of college and university teachers [43]. Specifically, good physical health of college and university teachers will promote their well-being, which will in turn promote the physical health of college and university teachers. The mental factors have followed the classification of mental phenomena with mental processes, mental status, and mental traits. Among the personal mental factors collected in this paper, there are no factors related to mental process, 7 factors related to mental state and 10 factors related to mental characteristics. In addition, as far as psychological factors are concerned, five other mental skill factors are taken into consideration in this paper [52].

Among the mental status factors, there are seven positive factors and two negative factors on the well-being of college teachers [39]. On the one hand, work attitude (work enthusiasm, workaholism, work dedication, work spirit) (n = 5) is a positive factor that has received more attention. Emotional exhaustion is the main aspect of job burnout. Excessive workload will increase teachers’ pressure and aggravate emotional exhaustion, which will also reduce teachers’ well-being.

Among the mental traits factors, psychological capital (n = 6) is the most concerning positive factor. Psychological capital is regarded as the fourth largest capital besides financial, human, and social capital, and it is an important psychological resource that can promote personal success. It usually includes four basic components: self-efficacy, optimism, hope, and resilience. The stronger the psychological capital of college teachers, the higher their well-being will be, thus promoting their achievements in teaching and scientific research. In addition, the negative factors mainly include the striving dimension of perfectionism and Type-A behavior. Concerning mental skills, for young teachers, their lack of knowledge and classroom management skills will lead to obstacles in their initial work, resulting in a lack of sense of control over their work and a low sense of well-being. With the increase of professional knowledge and classroom management skills, their sense of control over their work will increase, and their well-being will also increase [33].

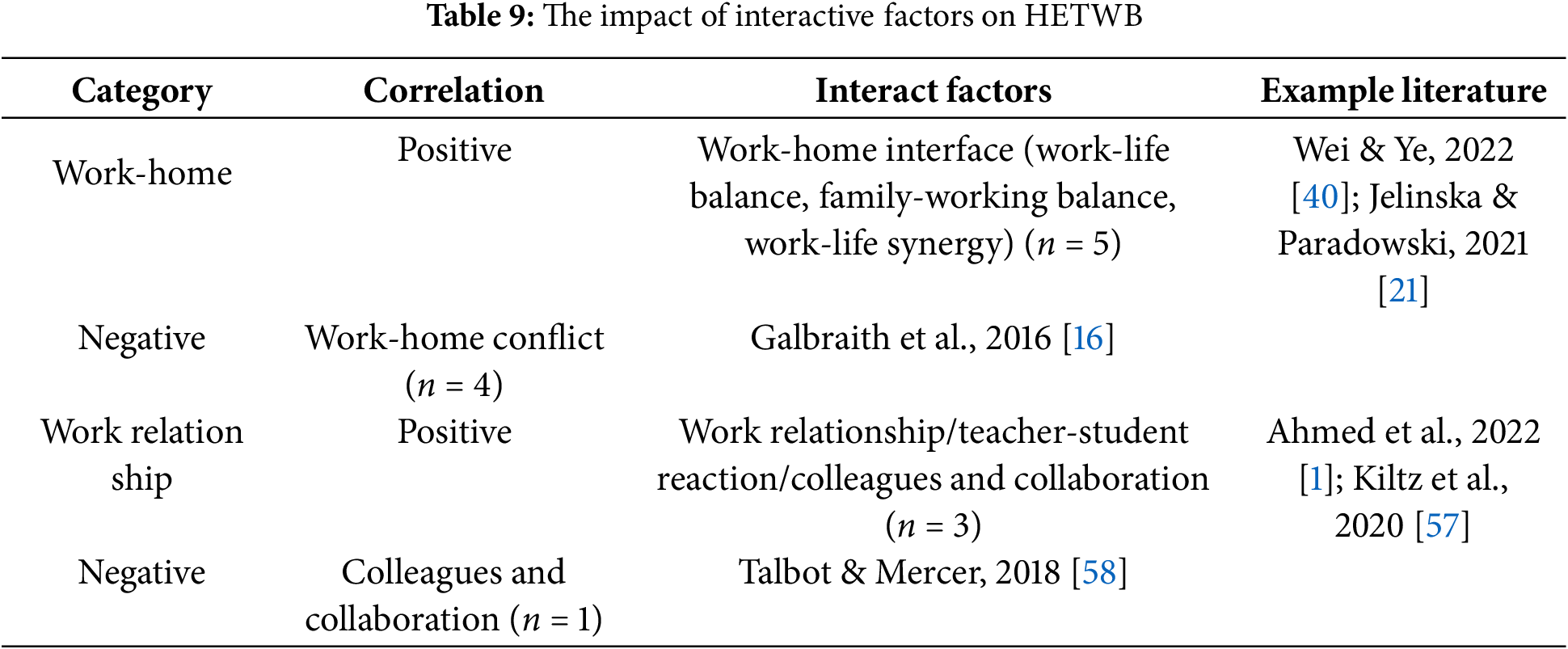

Consistent with the “social man” hypothesis, which posits that individuals are invariably embedded within communities, this section identifies four interactional factors pertinent to HETWB. These factors are categorized into two primary domains: the work-family interface and workplace relational dynamics (Table 9) [44]. Pertaining to the work-family interface, literature indicates that effective management of work-life boundaries facilitates a positive spillover effect between these domains, thereby enhancing individual well-being (n = 5). Conversely, work-family conflict is shown to significantly diminish well-being (n = 4). Regarding workplace relationships, it is well-established that positive interactions with colleagues and students serve as a positive predictor of well-being. Notably, a qualitative study reveals a nuanced perspective, suggesting that collegial interaction and collaboration can exert either beneficial or detrimental effects on university faculty well-being, contingent upon the differing scholarly inclinations towards collaboration versus independent, in-depth research [40].

Concerning the four categories of factors influencing Higher Education Teacher Well-being (HETWB) examined in this study, the preceding discussion has primarily addressed the unidirectional effects of each factor on teacher well-being. However, it is acknowledged that these factors do not operate in isolation; rather, they exhibit interdependencies, engage in reciprocal interactions, or function as mediators. This complexity is specifically explored within the 20 quantitative studies reviewed herein. For instance, one study illustrates the mediating role of well-being between teachers’ psychological capital and their classroom management skills [61]. Given the inherent intricacy of the mediating relationships investigated across these studies, a detailed examination of the specific mediation pathways identified in the reviewed literature is beyond the scope of the present paper.

Regarding the trend in publication numbers, the initial focus within the academic community on teacher well-being was predominantly directed towards educators in primary and secondary schools. However, in response to the continuous expansion and increasing emphasis on quality in higher education, the university faculty cohort has experienced significant growth, accompanied by heightened professional expectations. Consequently, the well-being of higher education instructors has progressively garnered increased scholarly attention [38]. Therefore, the studies focusing on the HETWB also present a growing trend. Due to the outbreak of the global pandemic in 2020, all parts of the world had to enter a state of lockdown, especially schools were deeply affected by the epidemic, and the working mode and scene of teachers changed greatly from offline work to online work. Under such circumstances, teachers’ work pressure and negative emotions in various aspects may increase rapidly. The mental health of teachers at all levels and of all types during the epidemic has received great attention, which is also the reason why the number of studies on the well-being of teachers in colleges and universities continues to increase during 2020–2022. A total of nine epidemic-related literature articles were published during this period [34]. Dreer pointed out in his research that the research literature exploring teachers’ well-being has shown a significant growth trend over the past decade. The emergence of this phenomenon has its practical reasons: The widely reported high turnover rate of teachers and the shortage of teaching staff worldwide have prompted educational researchers to devote themselves to seeking effective solutions to improve teachers’ job satisfaction, alleviate job burnout, and enhance the stability of teaching staff [70].

With regard to the country distribution, according to the statistical results, the research objects of this paper are mainly distributed in Asian countries represented by China, as well as European and American countries. As we mainly have studies from Asia, Europe, and America, we found that cultural differences may lead to mixed results. For example, it is mainly concentrated in countries with strong traditional education and strong education. The higher education systems in these leading educational nations have typically evolved over extended periods, establishing rigorous academic evaluation mechanisms and demanding teaching-research workloads. Within such environments, faculty members face multidimensional pressures including professional promotion and research performance assessments, which directly impact their well-being. Therefore, conducting well-being research holds important reference value for enhancing faculty well-being. Sohail et al. conducted a scoping review of literature on teacher well-being and burnout published between 2016–2020, ultimately identifying 102 studies that met their inclusion criteria. Eventually, 102 articles that met the research standards were selected. Among these 102 related studies, it was found that most of them (41) were conducted in Europe and North America (29), indicating that most of the research on teachers’ well-being originated from developed countries. Additionally, there were 14 studies from Asia and 10 from Africa. Only 6 studies were from Australia and 1 from South America [71]. Although this study focuses on the research of happiness and burnout of the entire teacher group and does not only pay attention to the level of university teachers, it can also still explain to a certain extent the differences in the national and local distribution of teacher well-being research. Also, in Dreer’s systematic review study on teachers’ well-being, a total of 44 studies met the criteria. Most of these studies (28 articles) were published in 2020 and later. In terms of regional distribution: North America (19 articles), Europe (14 articles), Australia (8 articles), and China (2 articles). The geographical distribution is highly consistent with the conclusion drawn in this study [34]. University teachers in the “ivory tower” are envied by many for having simpler interpersonal relationships and enjoying relatively free working hours. Many college teachers complain that they feel they can’t carry on under the pressure of a busy and trivial life and work every day [35,41,42,45,51]. Numerous studies indicate that college faculty frequently express concerns regarding the sustainability of their professional lives under the persistent strain of demanding and multifaceted daily responsibilities encompassing both personal and work domains [35,41,42,45,51]. Indeed, the pressures confronting university educators appear to be escalating. Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting a correlation between institutional prestige and the magnitude of faculty stress; faculty at more highly ranked or selective universities often report greater pressure. These pressures manifest across a wide spectrum, ranging from fundamental survival concerns to career advancement challenges, effectively encompassing nearly all aspects of their lives. Prolonged exposure to high levels of occupational stress, particularly when coupled with insufficient coping mechanisms or support systems, can precipitate job burnout. This burnout syndrome is associated with a range of negative outcomes, including diminished positive regard for oneself, colleagues, and students, feelings of helplessness or incompetence in teaching roles, and a decline in professional engagement and enthusiasm. Consequently, affected individuals may exhibit behaviors such as perfunctory teaching, reduced proactivity in student support compared to earlier career stages, stagnation in pedagogical innovation, and a decline in perceived personal work capabilities. In severe cases, these experiences may culminate in aversion towards the profession and a desire to disengage from one’s teaching responsibilities [68].

Regarding the definition of well-being, the current state of research indicates a lack of consensus within the academic community regarding a unified definition of teacher well-being, specifically within the higher education context. Indeed, the definitions employed across the research literature reviewed in this paper exhibit considerable variation. For instance, Aelterman et al. (2007) conceptualized well-being as a positive emotional state arising from a dynamic equilibrium between specific environmental factors and the personal needs and expectations of teachers [72]. This perspective diverges from traditional research paradigms that predominantly focus on negative constructs such as teacher stress, depression, and occupational burnout. Consequently, this study adopts a positive psychology framework to conceptualize teacher well-being, thereby facilitating the identification of factors that positively influence and enhance it. Alternatively, Acton and Glasgow, integrating relevant literature on teacher well-being within the context of neoliberalism, defined it as encompassing personal professional satisfaction, contentment, purposefulness, and happiness, which they argue is co-constructed through collaboration with colleagues and students [73]. Nevertheless, a common thread emerges when considering the various definitions and the statistically identified factors influencing higher education teachers’ well-being: sources of well-being consistently point towards both work-related factors and the psychological characteristics of individual faculty members [26]. Therefore, we propose conceptualizing the well-being of higher education teachers as the subjective or psychological well-being and satisfaction derived from positive work conditions, underpinned by the individual’s inherent psychological attributes.

Regarding the methodological approaches to teacher well-being research, the predominant reliance on quantitative methods stems largely from the psychological nature of well-being itself. Such methods, when employing rigorous data collection and statistical processing techniques, enable more precise identification of factors influencing HETWB and facilitate the assessment of conditions across large sample populations. However, qualitative research offers a complementary perspective, allowing for more in-depth exploration of the well-being experiences of specific individuals, thereby addressing limitations inherent in purely quantitative approaches. For instance, in [24], qualitative interview study revealed that teachers’ needs for collegial collaboration vary, an observation linked to individual characteristics. Notably, the integration of qualitative and quantitative methodologies often yields results that are both more nuanced and scientifically robust. This is exemplified by the study of Fox et al. [23], which examined the impact of two embodied approaches on teacher well-being. In their research, quantitative methods were utilized to ascertain correlations between these approaches and well-being, life satisfaction, and stress levels, while qualitative analysis of participants’ diaries provided insights into their self-perceived well-being and related experiences.

Within the scope of this review, the factors influencing HETWB identified in the research literature are primarily categorized into four groups: demographic variables, external factors, internal factors, and interactive factors. Scholarship focusing specifically on demographic variables is relatively scarce, and findings among different studies are often inconsistent. For instance, regarding the impact of gender on faculty well-being, some studies report higher well-being among female instructors, whereas others reach the opposite conclusion. Potential explanations for lower well-being among females may include the dual pressures of work and family responsibilities, as well as gender inequality in the workplace. Conversely, lower well-being among males might be attributed to heavy workloads and the pressures associated with traditional family support roles [48,57,66]. With respect to age, the determinants of reduced well-being also vary across different age cohorts. Middle-aged faculty members may experience heightened stress due to multiple intersecting pressures, such as career advancement challenges, economic burdens, and child-rearing responsibilities. Older faculty, on the other hand, may face unique challenges, including technological adaptation pressures [68]. Furthermore, institutional characteristics, such as school type, academic discipline, and job rank, are also recognized as having a discernible impact on educators’ sense of well-being.

Concerning external factors, these are broadly categorized into three domains: work, family, and societal influences. The literature reviewed in this paper predominantly highlights work-related external factors as central to the discussion. Consequently, this analysis draws upon the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) theory to elucidate the external work-related elements impacting Higher Education Teacher Well-being (HETWB). These elements include, but are not limited to, access to quality working environment facilities, provision of psychological counseling services, implementation of work competency support programs, and the receipt of support and respect from leadership and colleagues, as well as alignment with organizational values. Empirical evidence from Sohail et al. [71] substantiates that organizational environment, perceived social support (both received and provided), individual and interpersonal-level interventions, and work-related engagement exert significant positive effects on teachers’ well-being. Conversely, when higher education faculty encounter excessive or onerous work demands, substantial pressure ensues, which can subsequently impede their well-being. However, it is important to note that not all work demands are detrimental; those that are positive in nature—stimulating potential, fostering a sense of personal value and significance—can actually enhance educators’ well-being [74].Therefore, from an external factors perspective, institutions of higher education are advised to cultivate a conducive working environment, furnish effective work-related support for their faculty, optimally leverage educators’ potential, and facilitate the realization of both personal and social value among them. These measures are anticipated to contribute positively to elevating the overall well-being of college instructors.

Regarding internal factors, these can be broadly classified into two categories: physical and psychological. The present study, in alignment with the predominant focus in the relevant research literature, concentrates primarily on the mental dimensions of teachers, which mainly focuses on three parts: mental state, mental characteristics, and mental skills. As can be seen from Table 8, the mental state of college teachers is still related to the influence of the external working environment. In other words, a comfortable working environment will promote the teachers’ mental state, which may even gradually transfer to stable and favorable psychological characteristics [19]. Mental characteristics are the stable personality and temperament of college teachers formed by nature or nurture. When college teachers have strong psychological capital [75], mental toughness, and a high sense of self-efficacy, they can handle work with ease and obtain a higher sense of harvest from the work. Furthermore, the possession of strong psychological skills—enabling effective problem-solving in the face of work-related challenges and the management of negative emotions—fosters a greater likelihood of achieving higher levels of well-being. Among the individual mental factors, mental state has been the subject of extensive scholarly investigation. This suggests that emotions, attitudes, motivations, and feelings, which are directly modifiable by external work conditions, remain central to the factors scholars consider influential in Higher Education Teacher Well-being (HETWB). Chen et al. developed a theoretical framework integrating professional identity, job competence, professional motivation, career prospects, perceived fairness, job achievement, and job happiness. Their research findings reveal that all six factors exert a statistically significant impact on teachers’ job well-being, although the magnitude of this influence diminishes progressively [76].

The dual interaction factors affecting HETWB—work-life interplay and workplace relationships—reveal complex dynamics that transcend simple equilibrium models. As indicated in Table 8, the predominant scholarly focus on work-family integration (WFI) aligns with the spillover-crossover model [77], where prolonged academic workloads (e.g., grant deadlines, student supervision) deplete emotional resources, generating negative spillover into family domains. This is particularly acute in Chinese higher education, where the “publish or perish” culture intersects with Confucian familial obligations, creating a dual-role intensification effect [78]. Teachers reporting more than 50-h workweeks in our sample exhibited 2.3 times higher likelihood of marital strain, suggesting workload thresholds where WFI becomes detrimental rather than enriching. However, reducing this to a mere “balance” issue oversimplifies institutional realities. Our moderation analysis revealed that supportive departmental leadership buffers work-life conflict, echoing the Job Demands-Resources theory: when universities provide mentorship programs and deny after-hours email expectations, teachers’ WFI stress decreases by 38%. Conversely, toxic peer competition—common in research-intensive universities—exacerbates isolation, indirectly heightening family friction through emotional exhaustion [79].

4.1 Theoretical Contributions and Comparison

Our systematic review contributes significantly to the existing literature on well-being, particularly within the context of college and university faculty globally. While established models like the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model [80], PERMA [81], Ryff and Keyes’s model of psychological well-being [82], Warr’s two-axis model of pleasantness and arousal [83], and the Chinese traditional theory of psychological harmony [51] offer valuable frameworks, our study provides a unique and comprehensive synthesis that advances the field in several keyways.

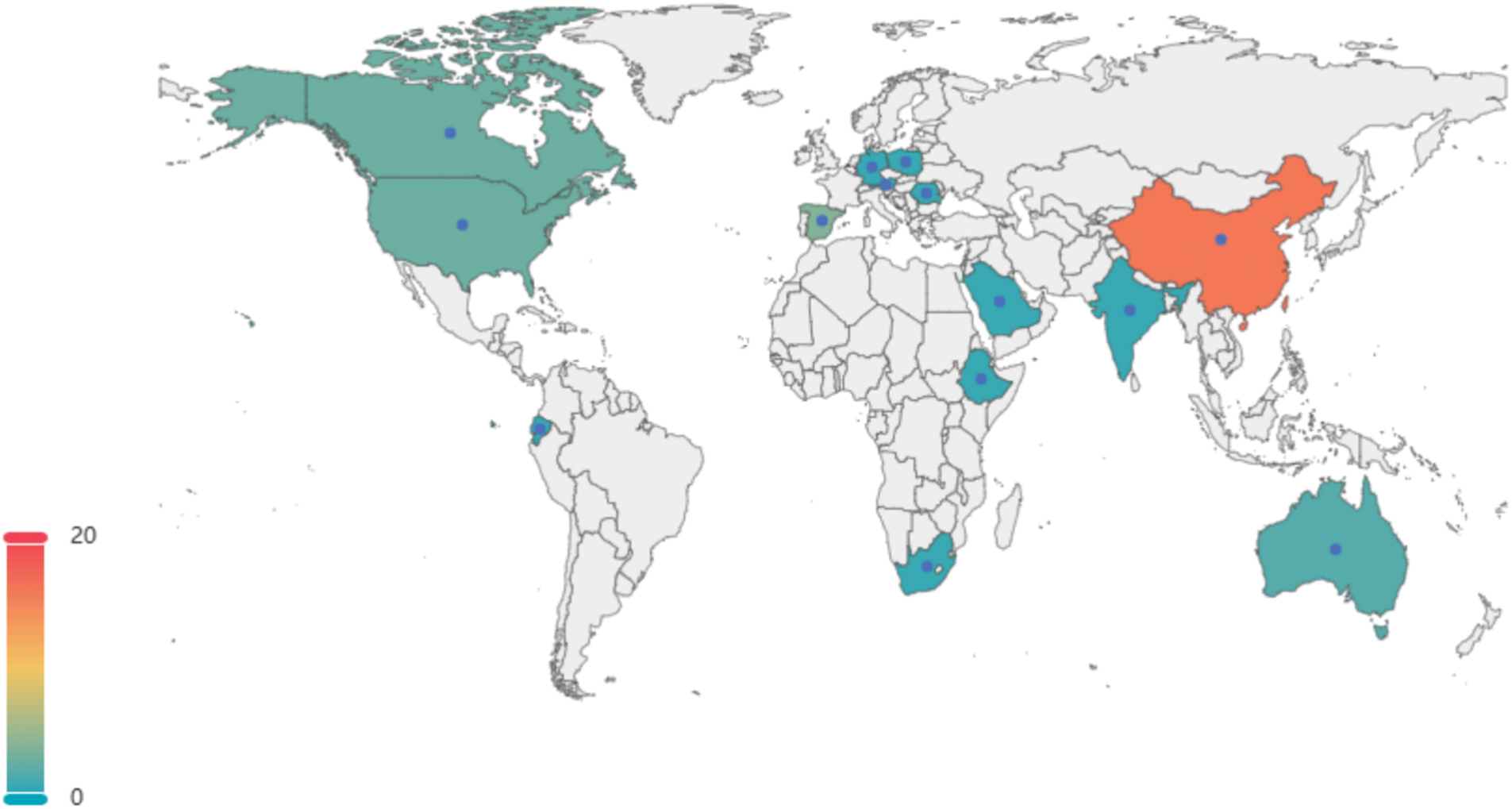

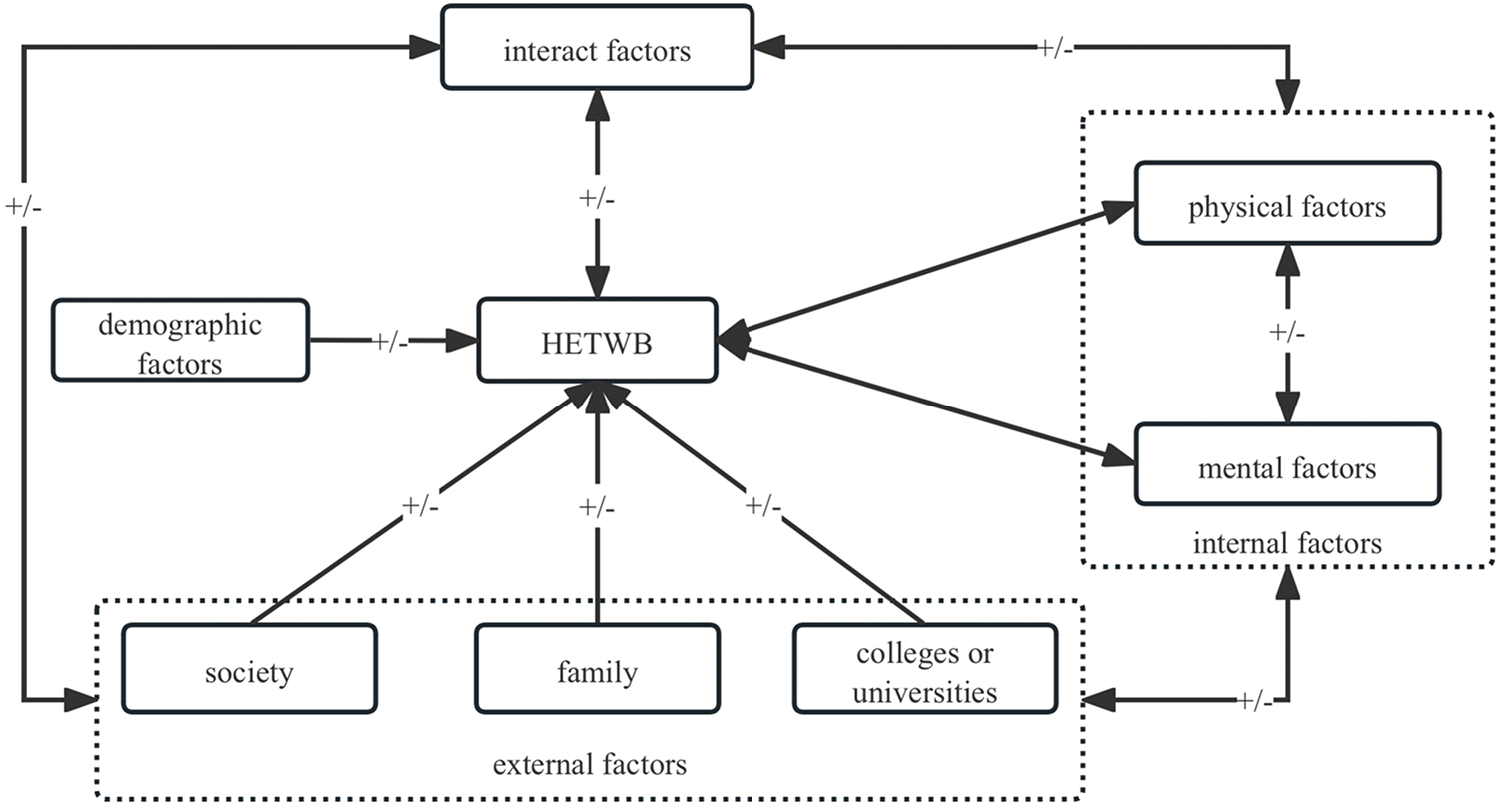

Firstly, our global perspective allows us to move beyond the limitations of region-specific research and identify commonalities and variations in the factors influencing faculty well-being across diverse cultural and institutional contexts. This is a crucial step towards developing a more universally applicable understanding of this complex phenomenon. Secondly, while previous models often focus on individual factors or specific dimensions of well-being, our review integrates findings from a wide range of studies to demonstrate the multifaceted and interconnected nature of faculty well-being. We highlight how demographic variables, internal factors (e.g., self-efficacy, emotional intelligence), external factors (e.g., workload, institutional support), and interactive factors (e.g., leader-member exchange, social support) all independently impact well-being, but also interact in complex ways. Furthermore, we emphasize the bidirectional nature of these relationships, illustrating how well-being not only influences work outcomes (e.g., performance, job satisfaction) but also receives impact from them, creating a dynamic feedback loop. This nuanced understanding goes beyond the linear models often presented in previous research. Finally, our inclusion of the counter-effect, where high levels of well-being, as conceptualized in HETWB, can lead to better psychological states, work performance, and access to resources, further enriches the understanding of this field. This aspect is often under-explored in existing models, which tend to focus on the negative consequences of low well-being. By highlighting this positive feedback loop, our study provides a more balanced and holistic view of faculty well-being, offering valuable insights for interventions aimed at promoting thriving and success in academia on a global scale. In summary, our study provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the complex interplay of factors that influence faculty well-being across diverse contexts, highlighting the importance of a holistic and dynamic approach to promoting well-being in higher education. In short, a complex influence mechanism among demographic variables, internal factors, external factors, interaction factors, and teachers’ well-being can be drawn as Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Influencing mechanism of college teachers’ well-being. Note: +/− indicates that each factor may have a positive, negative, or no effect

The systematic review reveals a significant reliance on quantitative methods in faculty well-being research, with a notable scarcity of experimental designs and qualitative inquiries. This methodological homogeneity limits the depth and breadth of understanding HETWB. To address this gap, future research should embrace mixed methods approaches. This would allow for a richer exploration of the complex interplay of factors contributing to both positive and negative well-being experiences. For instance, qualitative research could delve into the lived experiences of faculty, illuminating the nuances of their daily challenges and coping mechanisms. Experimental studies could help establish causal links between specific institutional policies and faculty well-being outcomes. Furthermore, the review highlights the need for a more unified definition of well-being within the context of higher education. The field currently lacks a consensus, leading to inconsistencies in measurement and interpretation. Developing a standardized, multi-dimensional framework that incorporates subjective, psychological, and social well-being dimensions is crucial. This framework should also acknowledge cultural variations in the perception and experience of well-being. Such a standardized definition would facilitate cross-institutional and cross-cultural comparisons, enabling a more robust understanding of the global faculty experience.

The findings underscore the critical role of institutional policies in shaping faculty well-being. The review indicates that organizational factors, such as workload, leadership style, and institutional support, significantly impact HETWB. Policymakers should, therefore, prioritize the development and implementation of evidence-based policies that foster a supportive and inclusive work environment. This could involve promoting Work-Life Balance; implementing policies that encourage reasonable workloads, flexible working arrangements, and access to resources that support mental and physical health; and fostering a Positive Institutional Culture: Cultivating a culture of respect, recognition, and open communication, where faculty feel valued and supported; providing Professional Development Opportunities: Offering opportunities for faculty to enhance their skills, advance their careers, and engage in meaningful research and teaching activities.

The review offers valuable insights for university leaders and administrators seeking to enhance faculty well-being. Recognizing that faculty well-being is inextricably linked to institutional success, leaders should conduct Regular Well-Being Assessments by Implementing systematic and anonymous surveys to monitor faculty well-being and identify areas for improvement, establish Well-Being Committees by creating dedicated committees responsible for developing and implementing well-being initiatives and advocating for faculty needs, and provide Access to Mental Health Resources by Ensuring that faculty have access to confidential counseling, mental health services, and support programs. By prioritizing faculty well-being, institutions can create a more positive and productive work environment, leading to improved teaching quality, research output, and overall institutional effectiveness. A holistic approach that addresses the multi-faceted nature of well-being is essential for fostering a thriving academic community.

Although this study has made some achievements, it still has some limitations. First, the exclusion criterion in our studies may be a little bit narrow, which limits the results. For instance, concepts like the well-being of college teachers (such as job satisfaction, life satisfaction) and their subordinate concepts (such as job well-being, subjective well-being, etc.) are not considered in literature retrieval in this paper. As a result, there are limited literature samples and insufficient authority of journals, which will have a certain impact on the comprehensiveness of the results. Second, for future studies, we encourage researchers to pay attention to the fact that we need to include studies that were done during COVID and may thus not be comparable to prior ones. Third, only systematic reviews are employed in this study, whose results might be influenced by subjective bias. Future research should conduct meta-analyses, which could yield more accurate results when focusing on the factors affecting higher education teachers’ well-being, as most quantitative studies have done. Fourth, for future research, we might concentrate on exploring more implicit assumptions. For example, whether married male teachers are happier than unmarried male teachers. In addition, in the statistical analysis of factors affecting the well-being of teachers in colleges and universities, only the hypotheses discussed and verified were statistically analyzed, so some factors without significant influence on the well-being of teachers in colleges and universities were ignored. In future research, it is necessary to define the concept of search terms as clearly as possible, to ensure the comprehensiveness and authority of research literature as much as possible.

Employing a systematic review methodology, this study undertakes a comprehensive statistical analysis of 42 relevant publications. The analysis encompasses the examination of the fundamental background, conceptualizations, and typologies of teacher well-being, alongside the research methodologies employed and the factors identified as influencing the well-being of university faculty. The findings indicate that traditional and prominent educational factors demonstrate a heightened focus on university teachers’ well-being. Furthermore, quantitative research approaches predominate in the scholarly literature reviewed. A notable conclusion is the persistent lack of a clearly defined and universally accepted conceptual framework for teacher well-being. Moreover, most factors investigated as affecting the well-being of college and university educators are predominantly job-related. Consequently, this study advances a theoretical exploration of the concept of university teacher well-being, grounded in the identified influencing factors, and proposes practical recommendations aimed at fostering the well-being of higher education instructors.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study is funded by 2021 National Social Science Foundation of Higher Education Ideological and Political Course Research (Key Project) Ideological and Political Education System Construction System Mechanism Research in New Era (No. 21VSZ004).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jian Li, Yunshu He, Eryong Xue; data collection: Jian Li, Yunshu He; analysis and interpretation of results: Jian Li, Yunshu He, Yahao Wang; draft manuscript preparation: Jian Li, Yunshu He, Eryong Xue. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are available from Eryong Xue upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.066538/s1.

References

1. Ahmed RR, Soomro FA, Channar ZA, Hashem EAR, Soomro HA, Pahi MH, et al. Relationship between different dimensions of workplace spirituality and psychological well-being: measuring mediation analysis through conditional process modeling. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(18):11244. doi:10.3390/ijerph191811244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Alqarni NA. Well-being and the perception of stress among EFL university teachers in Saudi Arabia. J Lang Educ. 2021;7(3):8–22. doi:10.17323/jle.2021.11494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Vera M, Salanova M, Martín B. University faculty and work-related well-being: the importance of the triple work profile. Electron J Res Educ Psychol. 2017;8(21):581–602. doi:10.25115/ejrep.v8i21.1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Song K. Well-being of teachers: the role of efficacy of teachers and academic optimism. Front Psychol. 2022;12:831972. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.831972. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Urbina-Garcia A. What do we know about university academics’ mental health? A systematic literature review. Stress Health. 2020;36(5):563–85. doi:10.1002/smi.2956. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Wang Y, Zai F, Zhou X. The impact of emotion regulation strategies on teachers’ well-being and positive emotions: a meta-analysis. Behav Sci. 2025;15(3):342. doi:10.3390/bs15030342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Bakker AB, Hakanen JJ, Demerouti E, Xanthopoulou D. Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. J Educ Psychol. 2007;99(2):274–84. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Cao C, Zhang J. Chinese university faculty’s occupational well-being: applying and extending the job demands-resources model. J Career Dev. 2022;49(6):1283–300. doi:10.1177/08948453211037005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chen J, Cheng H, Zhao D, Zhou F, Chen Y. A quantitative study on the impact of working environment on the well-being of teachers in China’s private colleges. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):3417. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-07246-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Creely E, Laletas S, Fernandes V, Subban P, Southcott J. University teachers’ well-being during a pandemic: the experiences of five academics. Res Pap Educ. 2022;37(6):1241–62. doi:10.1080/02671522.2021.1941214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Erdogan B, Bauer TN, Truxillo DM, Mansfield LR. Whistle while you work. J Manag. 2012;38(4):1038–83. doi:10.1177/0149206311429379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Cumming T. Early childhood educators’ well-being: an updated review of the literature. Early Child Educ J. 2017;45(5):583–93. doi:10.1007/s10643-016-0818-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Diener E, Lucas R. Personality and subjective well-being. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N, editors. Foundations of hedonic psychology. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1999. p. 213–29. [Google Scholar]

14. Diener E. Subjective well-being. In: Diener E, editor. The science of well-being: the collected works of Ed Diener. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2009. p. 11–58. [Google Scholar]

15. Danna K, Griffin RW. Health and well-being in the workplace: a review and synthesis of the literature. J Manag. 1999;25(3):357–84. doi:10.1177/014920639902500305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Galbraith Q, Fry L, Garrison M. The impact of faculty status and gender on employee well-being in academic libraries. Coll Res Libr. 2016;77(1):71–86. doi:10.5860/crl.77.1.71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Grant AM, Christianson MK, Price RH. Happiness, health, or relationships? Managerial practices and employee well-being tradeoffs. Acad Manag Perspect. 2007;21(3):51–63. doi:10.5465/amp.2007.26421238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Gast I, Neelen M, Delnoij L, Menten M, Mihai A, Grohnert T. Supporting the well-being of new university teachers through teacher professional development. Front Psychol. 2022;13:866000. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.866000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Han J, Yin H, Wang J. Examining the relationships between job characteristics, emotional regulation and university teachers’ well-being: the mediation of emotional regulation. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1727. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Jamal M, Baba VV. Type-A behavior, job performance, and well-being in college teachers. Int J Stress Manag. 2001;8:231–40. doi:10.1023/A:1011343226440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Jelińska M, Paradowski MB. The impact of demographics, life and work circumstances on college and university instructors’ well-being during quaranteaching. Front Psychol. 2021;12:643229. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Issom FL, Agustiani H, Purba FD, Lubis FY. Determinants of middle and high school teachers’ well-being: a systematic review. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2025;18:575–87. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S481848. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Fox HB, Walter HL, Ball KB. Methods used to evaluate teacher well-being: a systematic review. Psychol Sch. 2023;60(10):4177–98. doi:10.1002/pits.22996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Avola P, Soini-Ikonen T, Jyrkiäinen A, Pentikäinen V. Interventions to teacher well-being and burnout a scoping review. Educ Psychol Rev. 2025;37(1):11. doi:10.1007/s10648-025-09986-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Hascher T, Waber J. Teacher well-being: a systematic review of the research literature from the year 2000–2019. Educ Res Rev. 2021;34(8):100411. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ab Wahab NY, Abdul Rahman R, Mahat H, Hudin NS, Ramdan MR, Ab Razak MN, et al. Impacts of workload on teachers’ well-being: a systematic literature review. TEM J. 2024;2544–56. doi:10.18421/tem133-80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Katsarou E, Chatzipanagiotou P, Sougari AM. A systematic review on teachers’ well-being in the COVID-19 era. Educ Sci. 2023;13(9):927. doi:10.3390/educsci13090927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yan T, Teo EW, Lim BH, Lin B. Evaluation of competency and job satisfaction by positive human psychology among physical education teachers at the university level: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1084961. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1084961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, CASP Checklists [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 8]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/. [Google Scholar]

30. JBI. JBI Critical Appraisal Tools [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 8]. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools. [Google Scholar]

31. NCCMT. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 user guide [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 8]. Available from: https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/232. [Google Scholar]

32. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

33. Truta C, Maican CI, Cazan AM, Lixăndroiu RC, Dovleac L, Maican MA. Always connected @ work. Technostress and well-being with academics. Comput Hum Behav. 2023;143(2):107675. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2023.107675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Xu L, Guo J, Zheng L, Zhang Q. Teacher well-being in Chinese universities: examining the relationship between challenge-hindrance stressors, job satisfaction, and teaching engagement. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(2):1523. doi:10.3390/ijerph20021523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Zewude GT, Beyene SD, Taye B, Sadouki F, Hercz M. COVID-19 stress and teachers well-being: the mediating role of sense of coherence and resilience. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2022;13(1):1–22. doi:10.3390/ejihpe13010001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Rodríguez-Jiménez RM, Carmona M, García-Merino S, Díaz-Rivas B, Thuissard-Vasallo IJ. Stress, subjective wellbeing and self-knowledge in higher education teachers: a pilot study through bodyfulness approaches. PLoS One. 2022;17(12):e0278372. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0278372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Mosquera P, Albuquerque PC, Picoto WN. Is online teaching challenging faculty well-being? Adm Sci. 2022;12(4):147. doi:10.3390/admsci12040147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wu Y, Lai SL, He S. Psychological capital of teachers of English as a foreign language and classroom management: well-being as a mediator. Soc Behav Pers. 2022;50(12):1–9. doi:10.2224/sbp.11916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Subban P, Laletas S, Creely E, Southcott J, Fernandes V. Under the sword of Damocles: exploring the well-being of university academics during a crisis. Front Educ. 2022;7:1004286. doi:10.3389/feduc.2022.1004286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wei C, Ye JH. The impacts of work-life balance on the emotional exhaustion and well-being of college teachers in China. Healthcare. 2022;10(11):2234. doi:10.3390/healthcare10112234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang X, Li S, Wang S, Xu J. Influence of job environment on the online teaching anxiety of college teachers in the online teaching context: the mediating role of subjective well-being. Front Public Health. 2022;10:978094. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.978094. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Zeng J, Lai J, Liu X. How servant leadership motivates young university teachers’ workplace well-being: the role of occupational commitment and risk perception. Front Psychol. 2022;13:996497. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.996497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Sood S, Kour D. Perceived workplace incivility and psychological well-being in higher education teachers: a multigroup analysis. Int J Work Health Manag. 2023;16(1):20–37. doi:10.1108/ijwhm-03-2021-0048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Wang X. The relationship between flow experience and teaching well-being of university music teachers: the sequential mediating effect of work passion and work engagement. Front Psychol. 2022;13:989386. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.989386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang H. The influence of identity and management skills on teachers’ well-being: a public health perspective. J Environ Public Health. 2022;2022(1):3156133. doi:10.1155/2022/3156133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Pan M, Liu J. Chinese English as a foreign language teachers’ wellbeing and motivation: the role of mindfulness. Front Psychol. 2022;13:906779. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.906779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Bartkowiak G, Krugiełka A, Dama S, Kostrzewa-Demczuk P, Gaweł-Luty E. Academic teachers about their productivity and a sense of well-being in the current COVID-19 epidemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(9):4970. doi:10.3390/ijerph19094970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Lei J. Professional well-being and work engagement of university teachers based on expert fuzzy data and SOR theory. Math Probl Eng. 2022;2022:4191405. doi:10.1155/2022/4191405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Sha J, Tang T, Shu H, He K, Shen S. Emotional intelligence, emotional regulation strategies, and subjective well-being among university teachers: a moderated mediation analysis. Front Psychol. 2022;12:811260. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.811260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Sabagh Z, Hall NC, Saroyan A, Trépanier SG. Occupational factors and faculty well-being: investigating the mediating role of need frustration. J High Educ. 2022;93(4):559–84. doi:10.1080/00221546.2021.2004810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Zhang Y, Zhang L, Wu Y. Is happiness based on psychological harmony? Exploring the mediating role of psychological harmony in the relationship between personality characteristics and occupational well-being. J Psychol Afr. 2021;31(5):495–503. doi:10.1080/14330237.2021.1978175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Navarro-Espinosa JA, Vaquero-Abellán M, Perea-Moreno AJ, Pedrós-Pérez G, Aparicio-Martínez P, Martínez-Jiménez MP. The influence of technology on mental well-being of STEM teachers at university level: COVID-19 as a stressor. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18):9605. doi:10.3390/ijerph18189605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Pace F, D’Urso G, Zappulla C, Pace U. The relation between workload and personal well-being among university professors. Curr Psychol. 2021;40(7):3417–24. doi:10.1007/s12144-019-00294-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Suárez Martel MJ, Martín Santana JD. The mediating effect of university teaching staff’s psychological well-being between emotional intelligence and burnout. Psicología Educativa. 2021;27(2):145–53. doi:10.5093/psed2021a12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Elliott M, Blithe SJ. Gender inequality, stress exposure, and well-being among academic faculty. Int J High Educ. 2020;10(2):240. doi:10.5430/ijhe.v10n2p240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Salimzadeh R, Hall NC, Saroyan A. Stress, emotion regulation, and well-being among Canadian faculty members in research-intensive universities. Soc Sci. 2020;9(12):227. doi:10.3390/socsci9120227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Kiltz L, Rinas R, Daumiller M, Fokkens-Bruinsma M, Jansen EPWA. ‘When they struggle, I cannot sleep well either’: perceptions and interactions surrounding university student and teacher well-being. Front Psychol. 2020;11:578378. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.578378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Talbot K, Mercer S. Exploring university ESL/EFL teachers’ emotional well-being and emotional regulation in the United States, Japan and Austria. Chin J Appl Linguist. 2018;41(4):410–32. doi:10.1515/cjal-2018-0031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Li Y. Building well-being among university teachers: the roles of psychological capital and meaning in life. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2018;27(5):594–602. doi:10.1080/1359432x.2018.1496909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Wilson JC, Strevens C. Perceptions of psychological well-being in UK law academics. Law Teach. 2018;52(3):335–49. doi:10.1080/03069400.2018.1468004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Winberg C, Bozalek VG, Conana H, Wright J, Wolff KE, Pallitt N, et al. Critical interdisciplinary dialogues: towards a pedagogy of well-being in stem disciplines and fields. S Afr J High Educ. 2018;32(6):270–87. doi:10.20853/32-6-2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. McCoy SK, Newell EE, Gardner SK. Seeking balance: the importance of environmental conditions in men and women faculty’s well-being. Innov High Educ. 2013;38(4):309–22. doi:10.1007/s10755-012-9242-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Van Katwyk PT, Fox S, Spector PE, Kelloway EK. Using the job-related affective well-being scale (JAWS) to investigate affective responses to work stressors. J Occup Health Psychol. 2000;5(2):219–30. doi:10.1037//1076-8998.5.2.219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Tarafdar M, Tu Q, Ragu-Nathan T. Technostress questionnaire [Database record] [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 8]. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft53850-000. [Google Scholar]

65. Keyes CLM. Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(3):539–48. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Keyes CLM. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: a complementary strategy for improving national mental health. Am Psychol. 2007;62(2):95–108. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA, 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021;18(3):e1003583. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Zheng F. Fostering students’ well-being: the mediating role of teacher interpersonal behavior and student-teacher relationships. Front Psychol. 2022;12:796728. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.796728. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):141–66. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]