Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Preliminary Efficacy of an Immersive Virtual Reality Meditation Intervention in Reducing Perceived Stress and Anxiety among University Students

1 Department of Recreation Sciences and Sport Management, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27858, USA

2 Department of Health Behavior, School of Public Health, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77840, USA

3 Department of Recreation and Leisure Studies, California State University, Long Beach, CA 90840, USA

4 HI Fertility Center, 436 Gangseo-ro, Gangseo-gu, Seoul, 07696, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Na Young Kim. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(8), 1087-1099. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.064617

Received 20 February 2025; Accepted 27 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Background: While traditional meditation practices are known for their mental health benefits, they often face limitations such as restricted access and environmental distractions. To address these challenges and enhance meditation effectiveness, this study implemented an immersive virtual reality meditation (IVRM) program and examined its potential mental health benefits among university students—a population that frequently experiences significant psychological distress. Methods: Nineteen university students participated in eight 15-min sessions of an IVRM program designed to promote mindfulness and relaxation over the course of one month. Perceived stress and anxiety levels were assessed using validated self-report measures at baseline (T1) and post-intervention (T2). Two-tailed paired t-tests were conducted to evaluate the preliminary efficacy of the program, and effect sizes were reported using Cohen’s d. Results: Significant reductions were observed from pre- to post-intervention in perceived stress (t(18) = 3.694, p < 0.001, SE = 0.17, d = −0.85) and perceived anxiety (t(18) = 5.113, p < 0.01, SE = 0.10, d = −1.20), both indicating large effect sizes. Conclusion: Our findings provide preliminary evidence that the IVRM program can reduce stress and anxiety levels in university students. The positive results suggest that IVRM has the potential to serve as a novel, technology-based meditation intervention for individuals at elevated risk for developing mental health disorders. Furthermore, our study suggests important implications for future research.Keywords

The mental health challenges experienced by university students are a critical public health issue, as mental health is integral to their academic success and social and emotional well-being [1,2]. According to the report released by the American University Health Association [3], stress (40.2%) and anxiety (34.0%) were the top two ongoing or chronic medical conditions diagnosed or treated in the last 12 months in university students, and only 1.4% reported that they perceived no stress within the last 30 days. Due to high levels of stress and anxiety, research indicates that university students are more likely to experience psychological distress compared with non-students of the same age [4]. Improving the mental health of university students has received a critical attention from multiple stakeholders such as campus counselors, educators, policy makers, and researchers because high stress and anxiety levels have been associated with the academic performance and retention of university students [5,6], as well as with their health and wellbeing [7]. In addition, mental health problems have been shown to lead to unhealthy behaviors, such as suicide attempts [3], alcohol and drug consumption [8,9].

Considering the detrimental effects related to the mental health challenges experienced by university students, institutions of higher education strive to provide them with effective resources, counseling programs, and relevant activities [10]. While there are available resources and programs, research has provided evidence that university students have difficulties related to managing and coping with stressors and underutilized mental counseling programs [11]. In addition, recent studies indicate that, post-COVID, university students experienced higher levels of psychological challenges and concerns (e.g., depression, anxiety, and loneliness), and that they had limited opportunities to experience positive social interactions and develop social skills on campus [12]. Thus, there is an urgent need to provide support to university students to prevent the onset of mental health issues in an effective manner.

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have been demonstrated to be one of the most effective programs that have been used to reduce mental health challenges and subsequently improve mental health and quality of life [13]. MBIs have been widely applied across various settings and have provided relaxation, a reduction in elevated stress levels, and improved mental health [14,15]. Prior studies have provided evidence that the use of MBIs contributed to better participant mental health and quality of life [16]. For example, Ren et al. [17], who conducted a meta-analysis, found that mindfulness meditation resulted in medium to large immediate effects on mitigating anxiety. Also, Cheng [18] conducted an integrative review of 356 reviewed publications and found mindfulness-based meditation to be not only beneficial to the mental health of adolescents, but also that it could be incorporated with other activities such as physical activities, art, music, and dance to provide a synergistic effect.

While traditional MBIs have been found to be effective in promoting mental health and wellbeing, the participation of university students in such programs has been limited by practical challenges including limited accessibility to meditation programs, a lack of individualization and customizability of such programs, a shortage of meditation instructors, and environmental distractions [19–22]. To address these barriers and facilitate more effective meditation practices, there is growing interest in the application of digital health technologies as a facilitator in reducing mental health problems and improving mental health across a wide variety of clinical settings [23–25]. Among available types of digital health technology applications, virtual reality (VR) is a user-friendly and cost-effective application that offers non-pharmacological mental health care [26,27].

VR-based meditation programs provide an intervention that delivers a unique and immersive application for individuals to fully engage in MBIs and gain relaxation [28]. Due to its structure and adaptability, immersive VR-based meditation programs (IVRM) may minimize practical barriers and challenges and allow participants to fully engage in a variety of immersive meditation programs [29]. Recent systematic reviews of studies on IVRM programs found that VR-based mindfulness training was more effective in improving mental health than conventional mindfulness programs [30,31]. Specifically, the effectiveness of IVRM programs has been demonstrated primarily across many clinical populations, including individuals with schizophrenia [32], cardiovascular disease [33], and anxiety disorders [34]. These studies reported improvements in stress and depression levels, positive emotion, mood, relaxation, and sleep quality.

Based on the demonstrated efficacy of IVRM programs in improving mental health, our study explored the potential benefits of an IVRM program in reducing stress and anxiety among university students. The IVRM program used in this study focused on a variety of personalized meditation programs that allowed participants to select meditation settings (e.g., nature scenery, background music, and mindfulness programs). Thus, the purpose of our study was to investigate the impact of the use of the IVRM program on the stress and anxiety of university students. We hypothesized that IVRM participants would report significantly lower levels of stress and anxiety following the completion of the 4-week IVRM program.

1.1 Traditional Mindfulness-Based Interventions

The English word ‘Mindfulness’ was derived and translated from the Buddhist technical term Sati by T.W. Rhys Davids [35]. Sati refers to awareness or attention so that mindfulness is not simply remaining passively seated, but maintaining clear awareness of one’s body, feelings, and mind in the present moment. Due to its’ philosophy, MBIs have been receiving significant attention from both academics and practice in the past several decades [36]. While MBIs can be delivered in various forms, mindfulness-based stress reduction [37] and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy [38] are one of the widely adopted MBIs [39]. The primary goals of these interventions are a) to nurture one’s ability to aware present moments and openness and acceptance toward one’s experience, and b) to incorporate its practice to into everyday life [40]. In line with these goals, both interventions are typically designed as 8-week group programs that not only educate participants on emotional awareness and healthy coping strategies but also involve direct practice of mindfulness techniques such as meditation, mindful movement, and yoga.

Substantial research over the past several decades demonstrated that MBIs can be beneficial to diverse populations, especially individuals with mental health conditions as well as chronic pain [39]. Klainin-Yobas et al. [41], for example, conducted a meta-analysis on 39 studies from 10 different countries. The results demonstrated that MBIs were more effective standard care to alleviate depressive symptoms. Additionally, multiple studies reported treatment of anxiety disorders [42] and mood-disorders [43]. Moreover, through a systematic review, Hilton et al. [44] found small but significant decrease in pain from the chronic pain patients in 30 out of 38 randomized controlled trials. Segal et al. [39] suggested that MBIs help individuals mitigate the negative impacts of stress and support the discovery of a greater sense of purpose through objective self-evaluation. Moreover, consistent mindfulness practices have been shown to activate brain regions associated with self-regulation, body awareness, emotional regulation, and memory processing as well as several physiological markers related to stress and immune functions.

Despite the growing evidence supporting MBIs, traditional delivery formats present some limitations that can hinder accessibility and engagement. Since each session of MBIs takes two to three hours, it could be burdensome for individuals with physical constraints (e.g., health conditions or limited functional abilities) or environmental barriers (e.g., time limitations or caregiving responsibilities), as well as for staff responsible for preparing and delivering the sessions [45]. Also, the group-based nature of traditional MBIs may not adequately address individuals’ differences in learning styles and needs. For example, some participants might need more personalized attention or uncomfortable sharing their experiences or emotions with others [45,46]. These limitations or challenges highlight the need to explore more adaptable and individualized approaches to delivering MBIs.

1.2 Immersive Virtual Reality Mindfulness Interventions

IVRM interventions have gained significant attention across various health-related fields and have helped address challenges commonly associated with traditional MBIs, such as limited access and environmental distractions. Researchers have examined the feasibility and effectiveness of IVRM programs across diverse populations, particularly among individuals living with mental illness. For example, Navarro-Haro et al. [47] integrated VR technology into an existing mindfulness training program to address common challenges such as external distractions and mind-wandering. They proposed that VR could serve as an effective tool to enhance individuals’ attention and increase their sense of presence (i.e., being fully in the present moment) during mindfulness practice. The results indicated various benefits of the VR mindfulness program, including increased mindfulness and reductions in negative emotions such as sadness, anger, and anxiety. The findings demonstrated a high acceptance for using VR technology in mindfulness training programs.

Wren et al. [48] conducted a pilot and feasibility study to examine the preliminary efficacy of an IVRM intervention among children and young adults with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). The results indicated a significant reduction in both anxiety and pain levels among participants with IBD after a single 6-min session. Additionally, the qualitative component of the study, conducted through brief semi-structured interviews, revealed that participants responded positively to the IVRM program, reporting high levels of enjoyment and relaxation. Moreover, participants were generally open to using IVRM as a tool for managing stress and pain symptoms both during treatment in medical settings and in their leisure time outside the hospital. Wren et al.’s findings align with previous research demonstrating that the 3D computer-generated environments used in IVRM can enhance the user experience by increasing participants’ sense of immersion and presence within the virtual setting. Even brief sessions of IVRM—lasting approximately five minutes—have been shown to effectively promote mindfulness, reduce anxiety, and improve psychological well-being [49–52].

Sigmon et al. [53] conducted a study implementing a longer-term IVRM program (8 weeks) to assess its feasibility and acceptability among students, residents, and fellows at a university medical campus. Participants were instructed to complete an 8–10-min IVRM session using the TRIPP program at least 3–5 days per week via a VR headset over the 8-week period. The TRIPP IVRM program was found to be effective in reducing perceived stress and increasing mindful awareness and self-compassion. Additionally, qualitative interview data revealed participants’ positive responses to VR mindfulness, with specific features of the TRIPP program, such as its immersive environment, gamification, and guided breathing exercises. In sum, previous research has identified the effectiveness of the IVRM programs. Those programs were varied in the number of sessions provided and in populations studied. Based on the literature review above, we call for further studies that focus on non-patient populations who yet still are at higher risk of psychological distress, such as college students. Moreover, there is a need for more longer terms and regular provisions of IVRM (e.g., over several weeks of IVRM programs) and pilot test its effectiveness on mental health.

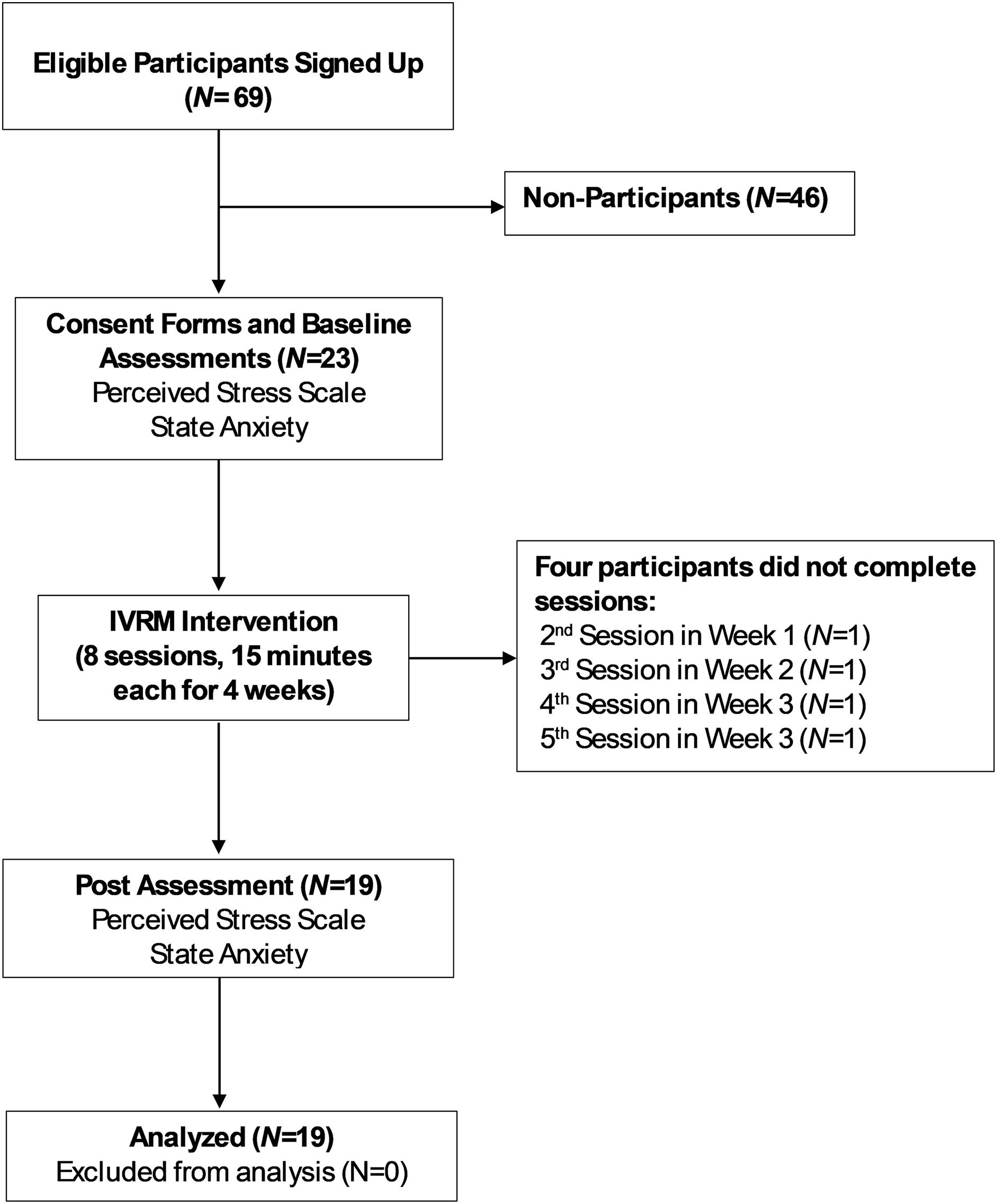

The participants in this study were 19 university students in eastern North Carolina in the United States. Our inclusion criteria required participants to be at least 18 years of age, to speak and read English at an 8th-grade reading level. Exclusion criteria included a history of head injury, seizure activity, or major mental health concerns (schizophrenia or bipolar disorder), and those who had experience with the IVRM called TRIPP. All participants provided written informed consent. Study recruitment and flow are presented in Fig. 1. The mean age was 20.09 (SD = 3.13) and ranged from 18 to 30. There were seven men (36.8%) and 12 women (63.2%). Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of East Carolina University (UMCIRB 22-002566). All participants provided written informed consent.

Figure 1: Study recruitment and flow

2.2.1 Recruitment of Participants

Eligible participants were recruited from on-campus university residence halls. The researcher contacted residence hall directors to receive permission to contact and recruit potential participants, and then posted fliers in the selected residence halls. The investigator also recruited participants through an e-mail in which they were provided with necessary forms and information (e.g., consent/assent form, explanation of the purpose of the study, and withdrawal procedures). Once interested participants had contacted a researcher after receiving an email invitation or seeing a flyer, they were asked to answer screening questions regarding their past medical history to determine final eligibility. Potential participants were also recruited from research methods and recreation therapy courses on campus. Contact information (e.g., name, email) was collected, and the researcher contacted them and provided more detailed information about the research project. Once any interested students agreed to participate in the project, they scheduled their sessions through a scheduling system. Recruitment efforts resulted in the participation of nineteen university students in eight sessions of IVRM.

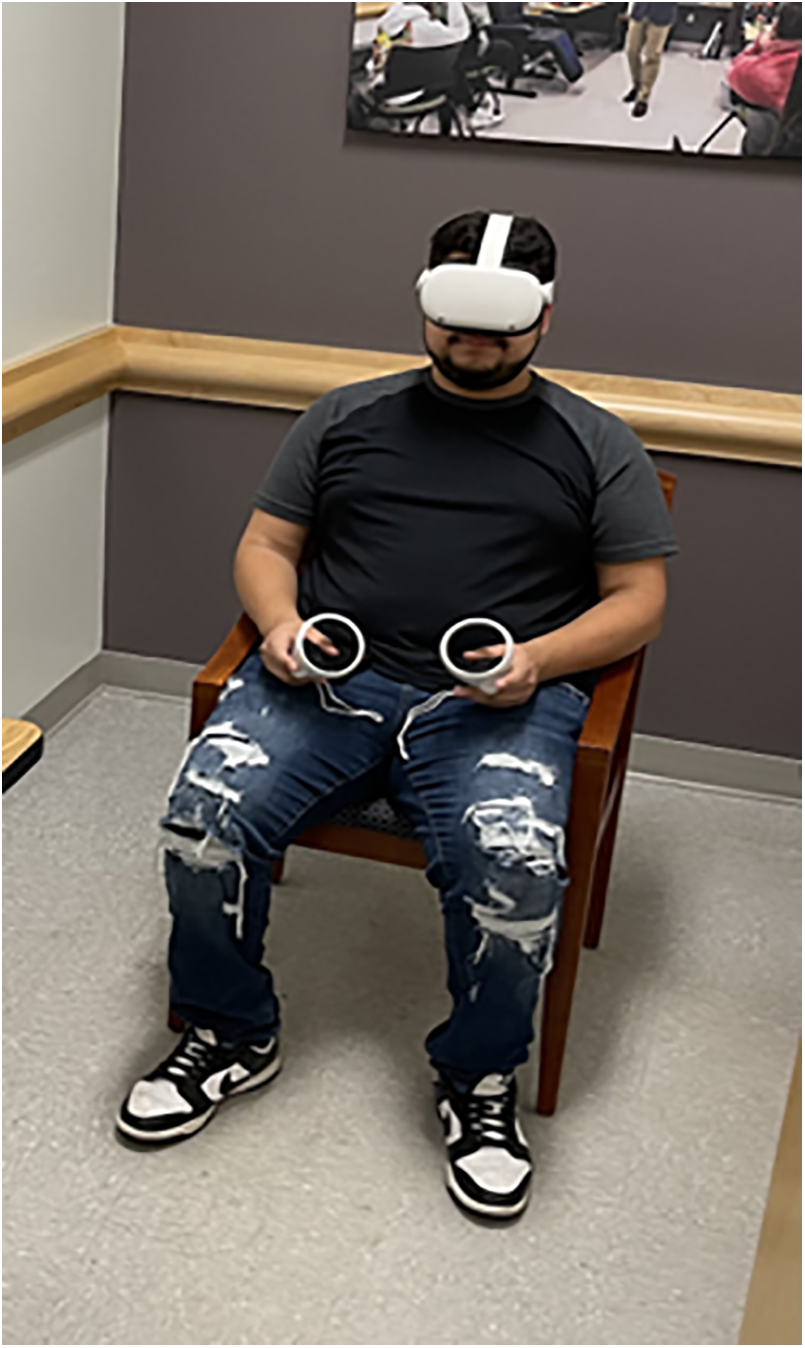

IVRM intervention was delivered using the Oculus Quest 2 (Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), the most advanced all-in-one, easy-to-set-up and navigate VR system that provides virtual worlds that are adaptable to participant engagement. University students (n = 19) received eight sessions, each lasting 15 min, over a four-week period. Participants were asked to complete all relevant questions on a survey instrument at baseline (T1) and at the conclusion of the program (T2). The IVRM sessions were implemented in a dedicated VR research lab at the researcher’s university (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Set-Up for Mindfulness-Based Virtual Reality (IVRM). The TRIPP IVRM application was pre-installed on an Oculus Quest 2 VR headset. Participants remained seated upright in a chair

This study used TRIPP (https://www.tripp.com), a VR meditation program designed to promote mindfulness and relaxation. TRIPP offers access to more than 40 immersive meditation environments that involve beautiful, inspiring, abstract visuals that can reduce user anxiety and provide calming sensations. The program features guided mindfulness exercises in which participants can practice breathwork, helping them enhance their awareness of the present moment and cultivate emotional regulation. Additionally, TRIPP provides interactive mindfulness activities, such as brief games that reinforce sustained attention. For example, participants must avoid colliding with incoming obstacles by successfully adjusting their head position. Thus, the TRIPP program helps users engage in a mindfulness-based VR experience, enhancing immersion through multiple sensory modalities and potentially contributing to stress and anxiety reduction. Sample TRIPP scenery is presented in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: TRIPP VR program. (A) The visual cue ‘EXHALE’ is designed to help participants pace their breathing; (B) Visual Elements and Scenes are designed to promote relaxation and mindfulness

Perceived stress was assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), developed by Cohen et al. [54]. The scale is comprised of 10 items that are categorized into a negativity subscale, comprised of six items, and a positivity subscale, comprised of four items. Participants rated how often they experienced stressful situations in the past month on a 5-point scale, from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Sample items include: “In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and stressed?” and “In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?” The total score was calculated by reverse-coding the positive items and summing all the scores, with a higher score indicating higher levels of perceived stress. The PSS-10 scale has been used in previous studies to measure perceived stress among college students [55,56]. The perceived stress scale showed high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.90–0.92 between T1 and T2.

Momentary feelings of anxiety (i.e., state anxiety) were assessed using the State Anxiety Inventory (SAI) scale developed by Spielberger [57], which includes 20 items. Example items include: “I am tense,” “I am worried,” and “I feel calm.” Participants were asked to rate how they felt at a certain time and under certain conditions on a 4-point Likert scale, from 1 (Not at all) to 4 (Very much). Therefore, a higher total score indicated a higher level of anxiety. The SAI scale has been used in previous research to measure perceived anxiety levels among university students [58,59]. The SAI scale demonstrated high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.92 to 0.93 between T1 and T2.

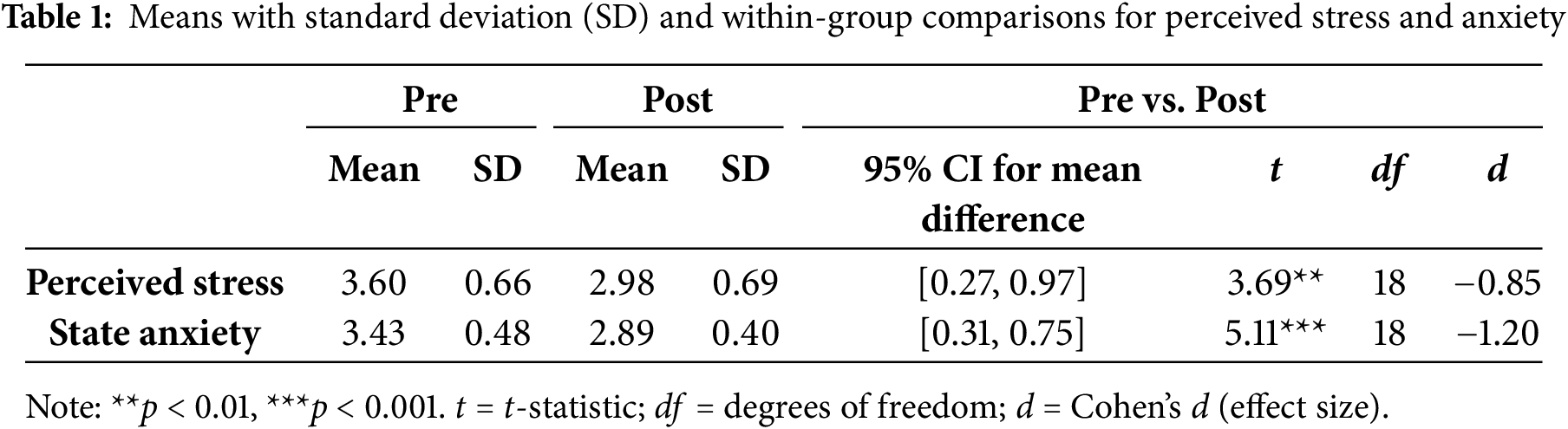

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize perceived stress and state anxiety levels (Table 1). Two-tailed paired t-tests were conducted to assess preliminary efficacy by measuring changes in the perceived stress and anxiety level of participants before and after participating in the IVRM. This analytic method was used to test whether there were statistically significant differences in perceived stress and anxiety levels before and after participation in the IVRM program. It is appropriate for comparing pre- and post-intervention scores within the same group of participants over time. This approach is commonly used in intervention studies to detect changes in outcomes and, consequently, evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention. Additionally, effect sizes with Cohen’s d are reported. Effect sizes were interpreted using the following thresholds: 0.2 as small, 0.5 as medium, and 0.8 as large. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Perceived Stress. Descriptive statistics revealed a statistically significant reduction in perceived stress following participation in the IVRM program. As shown in Table 1, mean perceived stress scores decreased from M = 3.12, SD = 0.48 at pre-intervention to M = 2.61, SD = 0.45 post-intervention. A paired-samples t-test confirmed that this mean change of 0.51 was significant, t (18) = 3.69, p < 0.01, SE = 0.17. The results also indicated a large effect size, Cohen’s d = −0.85; the negative direction reflects a reduction in stress. Further analysis of the data showed that 84.0% (16 out of 19) of participants reported lower stress levels after the intervention, while only three reported an increase. These findings support the statistical evidence for the effectiveness of the IVRM program in reducing perceived stress.

State Anxiety. Participants also showed significantly lower levels of perceived anxiety following the IVRM program (Table 1). Mean state anxiety scores decreased from M = 3.45, SD = 0.53 at pre-intervention to M = 2.68, SD = 0.47 post-intervention. A paired-samples t-test indicated that this mean reduction of 0.77 was highly significant, t (18) = 5.11, p < 0.01, SE = 0.10, with a very large effect size, Cohen’s d = −1.20. The change in perceived anxiety was highly consistent across participants, with 18 out of 19 (94.0%) reporting decreased anxiety levels. These results suggest a robust and consistent benefit of the IVRM program in reducing anxiety among participants.

This study assessed the preliminary efficacy of the use of an IVRM program on the targeted outcomes (perceived stress and anxiety) by focusing on university students who are at higher risk for mental disorders. Our findings provide evidence that IVRM program use can reduce the stress and anxiety levels of these high-risk individuals. Our findings are aligned with previous research demonstrating the effectiveness of MBI programs in improving mental health outcomes across diverse clinical populations, including patients with physical disorders and mental illnesses [32–34]. Through a systematic review and meta-analysis, for example, Gonzalez-Martin et al. [60] explore the effects of MBIs on the mental health of university students. All 21 related studies found the positive benefits of MBIs on college students’ stress, mindfulness, depression, anxiety, psychological distress, attention, and cognitive awareness. These findings are particularly important given that college students often report higher levels of stress and anxiety compared to other age groups [3]. Prior research has shown that such psychological distress can negatively impact academic performance as well as the overall health and well-being of college students [5–7]. In this context, there is a growing need to develop digital interventions aimed at promoting mental health among university students. Given these positive preliminary results, the IVRM program shows potential as an effective tool to support the psychological well-being of college students. Further studies in larger randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are warranted to determine whether IVRM use can reduce stress and anxiety levels among more diverse individuals at higher risk for mental disorders, such as individuals with spinal cord injury, cancer, chronic pain, and cardiovascular disease. Environmental distractions are considered a significant limitation in traditional meditation practices as they can disrupt concentration and diminish the effectiveness of meditation [19,20,22]. Given our positive preliminary findings, we believe that integrating VR technology with a meditation program can effectively address the challenges commonly faced in traditional meditation practices, such as environmental distractions and participant difficulties in maintaining focus. Although our study did not specifically measure the acceptability of VR technology, none of the participants reported encountering challenges with the use of VR technology and the IVRM program during their eight IVRM sessions. In addition, previous VR research has documented that the immersive nature of VR technology can improve the efficacy of mindfulness practices by creating a distraction-free virtual setting that promotes deep mental engagement and relaxation [29]. Additional qualitative studies are warranted to examine participant satisfaction, perceptions of appropriateness, interest and willingness to participate, and any adverse experiences through in-depth formative and summative interviews in addition to quantitative measures. Moreover, while the present study focused on non-clinical participants (i.e., college students), some clinical studies have provided evidence that MBIs can be an effective tool to promote mental health among clinical patient populations, such as patients with borderline personality disorder [34]. Considering that clinical populations often experience difficulty maintaining attention and practicing mindfulness, IVRM may provide a context conducive to grabbing attention and improving a sense of immersion, which can enhance the overall mindfulness experience. Previous research has suggested that universities should provide students with a broader range of opportunities to lower their psychological stress levels and improve their life satisfaction during their university years [21,61]. Based on our findings, we suggest that providing IVRM program availability on campus can play a significant role in improving the mental health of university students. Given the high levels of stress and anxiety experienced by university students, especially during exam periods and transitional phases, IVRM program use can serve as an innovative and immersive tool to enhance traditional university mental health services. To enhance the feasibility of offering IVRM programs on campus, universities should first establish dedicated VR meditation spaces on campus, such as within student wellness centers. It is also essential to provide access to trained facilitators who can lead MVBR sessions. Additionally, we propose that promoting the availability of VR meditation through awareness campaigns or health education sessions led by instructors, and integrating it into orientation programs for new students, can lead to the widespread engagement of university students and facilitate the full integration of IVRM programs into the mental health resources available on campus. Overall, our findings provide valuable insights to campus recreation administrators and mental health service providers who wish to design mental health promotion programs for university students.

The findings from our study also suggest an important implication for future research. We recommend exploring the impact of varying levels of use of an IVRM intervention on mental health outcomes. For example, Rowland et al. [62] examined 37 studies on the effectiveness of virtual reality interventions (VRI) for mental health disorders including generalized anxiety, panic, and depressive disorders in which they found inconsistencies in the dosage, duration, and frequency of VRI. For example, treatment frequency varied from a single session to twenty sessions, and session lengths ranged from 5 to 120 min. We provided eight IVRM sessions over four weeks, each lasting 15 min, and found significant reductions in stress and anxiety levels after four weeks. The broad range of treatment parameters in previous research make it challenging to identify the ideal dosage, duration, and frequency of IVRM sessions for mental disorders. Therefore, further research that seeks to determine the optimal IVRM dose will help health professionals develop appropriate guidelines and recommendations based on individual responses to various doses. Establishing such a standard will ultimately lead to more effective, personalized, evidence-based interventions for individuals at higher risk for mental disorders.

We acknowledge multiple limitations in our study. This study is a feasibility study with a limited sample size (n = 19) in which there was no control group or random assignment. That is, it is difficult to determine whether the positive preliminary efficacy findings are due to the IVRM intervention or to other external factors (e.g., better attention during the intervention). Therefore, larger RCTs will be needed to clarify the effect of IVRM on mental health. Furthermore, we acknowledge that this study has limitations associated with the lack of follow-up assessments, which may limit the generalizability of our findings on the intervention’s effectiveness. A long-term study would be beneficial in determining whether the observed benefits of the intervention in the present study are sustained over time. Lastly, this study measured mental health outcomes solely through survey instruments. Self-reported data may be subject to limitations such as recall bias and the subjective nature of participant responses. Future research should integrate objective physiological measures of mental health outcomes, such as heart rate variability, electroencephalography (EEG), and cortisol levels, to enhance the robustness of the findings.

Our study found significant decreases in the perceived stress and anxiety levels of participants following eight sessions of IVRM over four weeks. These positive preliminary findings indicate that IVRM has the potential to be a novel technology-based mediation practice for clients who are at higher risk for developing mental disorders. This preventive approach is essential, as early intervention can help prevent stress and anxiety from developing into more serious mental health challenges. Health professionals can use IVRM as an effective tool for preventing mental health disorders before clients develop clinical symptoms. Additional investigations, such as larger RCTs, will be needed to determine whether IVRM can reduce stress and anxiety levels among a more diverse population of individuals at higher risk for mental disorders.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Jaehyun Kim conceptualized the study, led the project administration, and contributed to the methodology, data analysis, and writing of the original draft. Junhyoung Kim contributed to the study design, supervision, and critical review and editing of the manuscript. Chungsup Lee was involved in statistical analysis and manuscript revision. Marcos Ardon Lobos assisted with data collection and participant coordination. Na Young Kim supported literature review, data collection, data management, supervision, and formatting of the manuscript for submission. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of East Carolina University (UMCIRB 22-002566). All participants provided written informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chen T, Lucock M. The mental health of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: an online survey in the UK. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0262562. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Salimi N, Gere B, Talley W, Irioogbe B. College students mental health challenges: concerns and considerations in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Coll Stud Psychother. 2023;37(1):39–51. doi:10.1080/87568225.2022.2122102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. American College Health Association. American college health association-national college health assessment III: undergraduate student reference group data report spring 2023 (PDF). Silver Spring, MD, USA: American College Health Association; 2023. [Google Scholar]

4. Lo SM, Wong HC, Lam CY, Shek DT. Common mental health challenges in a university context in Hong Kong: a study based on a review of medical records. Appl Res Qual Life. 2020;15(1):207–18. doi:10.1007/s11482-018-9673-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Jaisoorya TS, Rani A, Menon PG, Jeevan CR, Revamma M, Jose V, et al. Psychological distress among college students in Kerala, India—Prevalence and correlates. Asian J Psychiatry. 2017;28(2):28–31. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2017.03.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Ishii T, Tachikawa H, Shiratori Y, Hori T, Aiba M, Kuga K, et al. What kinds of factors affect the academic outcomes of university students with mental disorders? A retrospective study based on medical records. Asian J Psychiatry. 2018;32(6):67–72. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2017.11.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Ribeiro IJ, Pereira R, Freire IV, de Oliveira BG, Casotti CA, Boery EN. Stress and quality of life among university students: a systematic literature review. Health Prof Educ. 2018;4(2):70–7. doi:10.1016/j.hpe.2017.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. McConaha CD, McCabe BE, Falcon AL. Anxiety, depression, coping, alcohol use and consequences in young adult college students. Subst Use Misuse. 2024;59(2):306–11. doi:10.1080/10826084.2023.2270550. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Papp LM, Kouros CD, Armstrong L, Curtin JJ. College students’ momentary stress and prescription drug misuse in daily life: testing direct links and the moderating roles of global stress and coping. Stress Health. 2023;39(2):361–71. doi:10.1002/smi.3191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Nair B, Otaki F. Promoting university students’ mental health: a systematic literature review introducing the 4m-model of individual-level interventions. Front Public Health. 2021;9:699030. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.699030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Bryant J, Welding L. College student mental health statistics [Internet]. BestColleges. 2024. [cited 2025 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.bestcolleges.com/research/college-student-mental-health-statistics/. [Google Scholar]

12. Dingle GA, Han R, Carlyle M. Loneliness, belonging, and mental health in Australian university students pre-and post-COVID-19. Behav Change. 2022;39(3):146–56. doi:10.1017/bec.2022.6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Simpson R, Posa S, Langer L, Bruno T, Simpson S, Lawrence M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis exploring the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions on quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2023;270(2):726–45. doi:10.1007/s00415-022-11422-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Goldberg SB, Tucker RP, Greene PA, Davidson RJ, Wampold BE, Kearney DJ, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;59(5):52–60. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang D, Lee EK, Mak EC, Ho CY, Wong SY. Mindfulness-based interventions: an overall review. Br Med Bull. 2021;138(1):41–57. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldab002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Han A. Effects of mindfulness-based interventions on depressive symptoms, anxiety, stress, and quality of life in family caregivers of persons living with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Aging. 2022;44(7–8):494–509. doi:10.1177/01640275221104290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ren Z, Zhang Y, Jiang G. Effectiveness of mindfulness meditation in intervention for anxiety: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychol Sin. 2018;50(3):283–95. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2018.00283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Cheng FK. Is meditation conducive to mental well-being for adolescents? An integrative review for mental health nursing. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2016;4(1):7–19. doi:10.1016/j.ijans.2016.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Anderson T, Suresh M, Farb NA. Meditation benefits and drawbacks: empirical codebook and implications for teaching. J Cogn Enhanc. 2019;3(2):207–20. doi:10.1007/s41465-018-00119-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Chandrasiri A, Collett J, Fassbender E, De Foe A. A virtual reality approach to mindfulness skills training. Virtual Real. 2020;24(1):143–9. doi:10.1007/s10055-019-00380-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kim J, Park C, Fish M, Kim YJ, Kim B. Are certain types of leisure activities associated with happiness and life satisfaction among college students? World Leis J. 2024;66(1):12–25. doi:10.1080/16078055.2023.2222701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Liu K, Madrigal E, Chung JS, Parekh M, Kalahar CS, Nguyen D, et al. Preliminary study of virtual-reality-guided meditation for veterans with stress and chronic pain. Altern Ther Health Med. 2023;29(6):42–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

23. Jacobson NC, Weingarden H, Wilhelm S. Using digital phenotyping to accurately detect depression severity. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2019;207(10):893–6. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Kim SJ, McHugo GJ, Unützer J, Bartels SJ, et al. Health behavior models for informing digital technology interventions for individuals with mental illness. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2017;40(3):325–35. doi:10.1037/prj0000246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Patel NA, Butte AJ. Characteristics and challenges of the clinical pipeline of digital therapeutics. npj Digit Med. 2020;3(1):159. doi:10.1038/s41746-020-00370-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Chirico A, Gaggioli A. When virtual feels real: comparing emotional responses and presence in virtual and natural environments. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2019;22(3):220–6. doi:10.1089/cyber.2018.0393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Park MJ, Kim DJ, Lee U, Na EJ, Jeon HJ. A literature overview of virtual reality (VR) in treatment of psychiatric disorders: recent advances and limitations. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:505. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Seabrook E, Kelly R, Foley F, Theiler S, Thomas N, Wadley G, et al. Understanding how virtual reality can support mindfulness practice: mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(3):e16106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

29. Salminen M, Järvelä S, Ruonala A, Harjunen VJ, Hamari J, Jacucci G, et al. Evoking physiological synchrony and empathy using social VR with biofeedback. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2019;13(2):746–55. doi:10.1109/taffc.2019.2958657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ma J, Zhao D, Xu N, Yang J. The effectiveness of immersive virtual reality (VR)-based mindfulness training on improvement mental-health in adults: a narrative systematic review. EXPLORE. 2023;19(3):310–8. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2022.08.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Mitsea E, Drigas A, Skianis C. Virtual reality mindfulness for meta-competence training among people with different mental disorders: a systematic review. Psychiatry Int. 2023;4(4):324–53. doi:10.3390/psychiatryint4040031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Barry TJ, Hernandez-Viadel JV, Ricarte JJ. An investigation of mood and executive functioning effects of brief auditory and visual mindfulness meditations in patients with schizophrenia. Int J Cogn Ther. 2020;13(4):396–407. doi:10.1007/s41811-020-00071-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Lee SY, Kang J. Effect of virtual reality meditation on sleep quality of intensive care unit patients: a randomised controlled trial. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;59(9):102849. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Navarro-Haro MV, Modrego-Alarcon M, Hoffman HG, Lopez-Montoyo A, Navarro-Gil M, Montero-Marin J, et al. Evaluation of a mindfulness-based intervention with and without virtual reality dialectical behavior therapy® mindfulness skills training for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in primary care: a pilot study. Front Psychol. 2019;10:414878. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Gethin R. On some definitions of mindfulness. Contemp Buddh. 2011;12(1):263–79. doi:10.1080/14639947.2011.564843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Goldberg SB. A common factors perspective on mindfulness-based interventions. Nat Rev Psychol. 2022;1(10):605–19. doi:10.1038/s44159-022-00090-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Constr Human Sci. 2003;8(2):73. [Google Scholar]

38. Sipe WEB, Eisendrath SJ. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: theory and practice. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(2):63–9. doi:10.1177/070674371205700202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Segal Z, Williams M, Teasdale J. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

40. Shapero BG, Greenberg J, Pedrelli P, de Jong M, Desbordes G. Mindfulness-based interventions in psychiatry. Focus. 2018;16(1):32–9. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20170039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Klainin-Yobas P, Cho MAA, Creedy D. Efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions on depressive symptoms among people with mental disorders: a meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(1):109–21. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.08.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Vøllestad J, Nielsen MB, Nielsen GH. Mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions for anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2012;51(3):239–60. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02024.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(2):169–83. doi:10.1037/a0018555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, Newberry S, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(2):199–213. doi:10.1007/s12160-016-9844-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Marks E, Moghaddam N, De Boos D, Malins S. A systematic review of the barriers and facilitators to adherence to mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for those with chronic conditions. Br J Health Psychol. 2023;28(2):338–65. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Walker ER, Obolensky N, Dini S, Thompson NJ. Formative and process evaluations of a cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness intervention for people with epilepsy and depression. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;19(3):239–46. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.07.032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Navarro-Haro MV, López-Del-Hoyo Y, Campos D, Linehan MM, Hoffman HG, García-Palacios A, et al. Meditation experts try Virtual Reality Mindfulness: a pilot study evaluation of the feasibility and acceptability of Virtual Reality to facilitate mindfulness practice in people attending a Mindfulness conference. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0187777. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187777. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Wren AA, Neiman N, Caruso TJ, Rodriguez S, Taylor K, Madill M, et al. Mindfulness-based virtual reality intervention for children and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease: a pilot feasibility and acceptability study. Children. 2021;8(5):368. doi:10.3390/children8050368. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Tennant M, Youssef GJ, McGillivray J, Clark TJ, McMillan L, McCarthy MC. Exploring the use of immersive virtual reality to enhance psychological well-being in pediatric oncology: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;48(1):101804. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101804. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Sliwinski J, Katsikitis M, Jones CM. A review of interactive technologies as support tools for the cultivation of mindfulness. Mindfulness. 2017;8(5):1150–9. doi:10.1007/s12671-017-0698-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Chavez LJ, Kelleher K, Slesnick N, Holowacz E, Luthy E, Moore L, et al. Virtual reality meditation among youth experiencing homelessness: pilot randomized controlled trial of feasibility. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(9):e18244. doi:10.2196/18244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Crescentini C, Chittaro L, Capurso V, Sioni R, Fabbro F. Psychological and physiological responses to stressful situations in immersive virtual reality: differences between users who practice mindfulness meditation and controls. Comput Human Behav. 2016;59:304–16. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Sigmon CAN, Park SY, Bam D, Rimel SE, Boeldt DL. Feasibility and acceptability of virtual reality mindfulness in residents, fellows, and students at a university medical campus. Mayo Clin Proc Digit Health. 2023;1(4):467–75. doi:10.1016/j.mcpdig.2023.07.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96. doi:10.1007/BF00844860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Makhubela M. Assessing psychological stress in South African university students: measurement validity of the perceived stress scale (PSS-10) in diverse populations. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(5):2802–9. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-00784-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Slimmen S, Timmermans O, Mikolajczak-Degrauwe K, Oenema A. How stress-related factors affect mental wellbeing of university students: a cross-sectional study to explore the associations between stressors, perceived stress, and mental wellbeing. PLoS One. 2022;17(11):e0275925. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275925. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Spielberger CD. State-trait anxiety inventory (Form Y) manual. Redwood City, CA, USA: Mind Garden; 1983. [Google Scholar]

58. Capdevila-Gaudens P, García-Abajo JM, Flores-Funes D, García-Barbero M, García-Estañ J. Depression, anxiety, burnout and empathy among Spanish medical students. PLoS One. 2021;16(12):e0260359. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Jenaro C, Flores N, Frías CP. Anxiety and depression in cyberbullied college students: a retrospective study. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36(1–2):579–602. doi:10.1177/0886260517730030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. González-Martín AM, Aibar-Almazán A, Rivas-Campo Y, Castellote-Caballero Y, Carcelén-Fraile MD. Mindfulness to improve the mental health of university students. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1284632. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1284632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Chang Y, Davidson C, Conklin S, Ewert A. The impact of short-term adventure-based outdoor programs on college students’ stress reduction. J Adv Educ Outdoor Learn. 2019;19(1):67–83. doi:10.1080/14729679.2018.1507831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Rowland DP, Casey LM, Ganapathy A, Cassimatis M, Clough BA. A decade in review: a systematic review of virtual reality interventions for emotional disorders. Psychosoc Interv. 2022;31(1):1–11. doi:10.5093/pi2021a8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools