Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Do Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Relate to Psychological Health of People with Cataracts?

1 School of Physical Education, Hunan University of Science and Engineering, Yongzhou, 425000, China

2 College of Physical Education and Sports, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiangqin Song. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(8), 1101-1116. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.066316

Received 04 April 2025; Accepted 10 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Adults with cataracts are often reported with mental health issues, which has driven researchers to identify modifiable factors so that effective intervention programs can be timely implemented. Thus, we investigated associations of physical activity (PA) and sedentary behavior (SB) with stress, anxiety, and sleep problems among adults with cataracts. Methods: In this cross-sectional study, a total of 2219 participants with cataracts completed self-reported measures on demographic characteristics (e.g., age and sex), PA, SB, anxiety, stress and sleep problems. Multiple linear regression and logistic analyses adjusted for covariates were employed to examine the associations of PA and SB with outcomes of interest. Results: Meeting PA recommendation was significantly associated with lower stress score (β = −2.920, 95% CI: −3.880 to −1.959; p < 0.001), a 51.2% reduction in the odds of sleep problems (OR = 0.488, 95% CI: 0.389 to 0.612; p < 0.001). Limiting SB to ≤8 h/day was significantly associated with reduced stress score (−5.191, 95% CI: −6.378 to −4.004; p < 0.001), lower odds of anxiety symptoms (OR = 0.481, 95% CI: 0.354 to 0.655; p < 0.001), and sleep problems (OR = 0.540, 95% CI: 0.420 to 0.693; p < 0.001). The greatest benefit appeared when both PA and SB recommendations were achieved simultaneously. Compared with individuals who met neither recommendation, those who were sufficiently active and sat less than 8 h/day showed a 9.307-point lower stress score (95% CI: −11.12 to −7.49; p < 0.001), a 54.9% lower odds of anxiety symptoms (OR = 0.451, 95% CI: 0.262 to 0.776; p = 0.004), and a 66.4% lower odds of sleep problems (OR = 0.336, 95% CI: 0.206 to 0.550; p < 0.001). Conclusions: Meeting PA and SB recommendations could provide substantial psychosocial benefits for adults with cataracts.Keywords

Cataracts, a second leading cause of visual impairment or blindness globally, primarily affect aging populations, with over 80% of cases occurring in individuals aged 50 years and older [1,2]. In 2010, cataracts caused blindness in 10.8 million persons globally [3]. Due to accelerating global population aging and rising life expectancy, this figure may climb to about 40 million by 2025 [4]. Despite cataract surgery can fully restore vision in most patients, large inequities in service delivery remain, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where surgical coverage rarely exceeds 50%, compared to over 90% in high-income countries [5–7]. Individuals living in LMICs (e.g., Africa and South Asia) experience 2–3 times higher cataract-related blindness rates than high-income regions [5,6]. Metabolic disorders, notably diabetes, further amplify disease burden, with East Asian populations showing genetic overlap between type 2 diabetes and cataract development [8,9].

The cataract disability model offers a useful perspective for understanding how cataracts trigger a progressive chain reaction, ranging from tissue damage (lens opacity) to functional limitations (decreased contrast sensitivity and depth perception). These visual limitations lead to restricted participation in daily physical activities and an increase in sedentary behavior for patients [10]. In turn, this reduction in physical activity (PA) and the increase in sedentary behavior (SB) lead to an increased risk of cataracts, creating a cycle of declining physical and mental health [10]. For example, some studies conducted in the United States have demonstrated that individuals with cataract or severe vision loss tend to engage in less PA and more sedentary time [11,12]. A cross-sectional study in Sweden included 52,660 participants aged between 45 and 83 years showed that a long-term high level of PA (>45.5 MET-h/day) significantly reduced the cataract risk by 24% compared to a long-term low PA level [13]. Another study observed a significant association between higher PA levels and reduced cataract risk [14]. Moreover, cataracts are also associated with significant psychological challenges, including elevated stress, anxiety, and sleep disturbances, which collectively diminish quality of life and functional independence [15,16]. For example, a longitudinal study by Zhang et al. [17] identified a 1.6-fold increased risk of significant depression among adults with untreated cataracts compared to peers without visual impairment.

To promote the physical and mental health of patients with cataracts and improve their quality of life in the future, effective measures are needed to be taken to alleviate the psychological problems of these population. The researchers suggest that individuals with cataracts should maintain a healthy lifestyle, as higher PA levels and limiting SB are positively correlated with better mental health (e.g., depression, stress) [18–21]. The recommendations of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) on movement behaviors have been increasingly utilized to examine associations of meeting PA and SB recommendations with various health outcomes across different age groups [22–25]. Emerging evidence suggests that PA exerts multifaceted influences on chronic disease prevention, psychological health promotion, and sleep homeostasis by lowering systemic inflammation, and stimulating neurotrophic and endocrine pathways [26–29]. Large cohort studies show that adults who meet the WHO guidelines (≥150 min/week moderate-to-vigorous PA) associated with 30%–40% lower odds of depressive disorder [30–32] and generalized anxiety disorder among cataracts patients [33]. Conversely, SB (≥8 h/day) has emerged as an independent risk factor for poor health, likely mediated by inflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and reduced opportunities for enjoyable physical and mental activities [34,35]. Epidemiological studies demonstrate that adults engaging in >8 h/day of sitting time exhibited 20%–30% higher risks of cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and all-cause mortality compared to those with <8 h/day, even after adjusting for PA levels [34,36]. In particular, an increasing amount of empirical evidence indicates that individuals with or without chronic disease who maintain the health behavior recommendations (i.e., PA and SB) of the WHO had a lower incidence of stress, depression, and sleep problems [37–40].

Although these independent associations have been well established, little is known about how combination of PA and SB (e.g., sitting time) relate to stress, anxiety, and sleep problems among individuals with cataracts. Therefore, we will assess whether the combination of higher PA level and lower sedentary time are associated with reduced stress, lower levels of anxiety symptoms, and less sleep problems in adults with cataracts in this present study. We hypothesized that (1) achieving the recommended 150 min per week of moderate-to-vigorous PA or less than 8 h/day of sedentary time will correspond to reduced stress, lower risk of anxiety symptoms, and lower risk of sleep problems; and (2) the combination of enough PA and limited sedentary time will relate to reduced stress, lower risk of anxiety symptoms, and lower risk of sleep problems. By clarifying these relationships, the study aims to inform healthy behaviors that can complement surgical services and reduce the psychosocial burden of cataract, especially in resource-limited settings where delays to surgery are common.

This study utilized data from the WHO’s Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE), a cross-sectional, population-based survey conducted between 2007 and 2010 across six low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia, and South Africa. The SAGE initiative employed a nationally representative sampling framework to collect data on aging-related health outcomes, sociodemographic factors, and psychological health. Trained personnel administered standardized instruments through in-person interviews, including domains such as chronic disease prevalence, psychological health symptoms, and lifestyle behaviors. National response rates ranged from 51% (Mexico) to 93% (China), reflecting variability in participation across regions. The study protocol rigorously adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, with approval granted by the WHO Ethical Review Committee and local institutional review boards in all participating countries. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

In the SAGE Survey, participants (total n = 52,390) who failed to complete the data on sociodemographic, PA, sedentary behavior, stress, anxiety symptoms, and sleep problems were excluded (n = 29,333) using listwise deletion method. Cataracts were assessed using two questions: “In the last 12 months have you experienced any cloudy or blurry vision?” and “In the last 12 months have you experienced any vision problems with light, such as glare from bright lights, or halos around lights?”. When the respondents clearly answered “Yes” to both of these questions, they were defined as cataracts [41,42]. The sample of this study includes adults with cataracts aged 50 years and above from six LMICs (n = 2663). There was a total of 2663 observations.

2.2 Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior

Leisure-time PA was assessed using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) to evaluate engagement in sports, fitness, and recreational activities. Participants reported the frequency (days/week) and duration (minutes/day) of both vigorous-intensity (e.g., running, football) and moderate-intensity (e.g., brisk walking, cycling, swimming) leisure activities during a typical week. Total weekly moderate-to-vigorous PA was computed by summing time spent in these activities. According to the mainstream recommendations for weekly leisure-time PA volume [43,44], the total leisure-time PA in this study was categorized into two groups: high level of PA (>150 min/week) or low level of PA (≤150 min/week), consistent with established thresholds from prior research [45]. In addition, SB was operationalized using a single-item measure derived from the GPAQ: “How much time do you usually spend sitting or reclining on a typical day? Here are examples: working at a desk, socializing while seated, commuting by car, bus, or train, reading, playing cards, or watching television” [46]. Participants reporting <8 h/day were classified as meeting sedentary guidelines, while those with ≥8 h/day were categorized as non-compliant, consistent with established public health guidelines [47]. Notably, the combination of >150 min/week PA and <8 h/day of sedentary behavior was considered as meeting the PA and SB recommendations.

Stress was measured using two questions, which were followed by the validated perceived stress scale [48]. The questions were: “How often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?”; and “How often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?” Response options were: “never = 1”, “almost never = 2”, “sometimes = 3”, “fairly often = 4”, and “very often = 5”. We conducted factor analysis using the polychoric correlation coefficient to incorporate the covariance structure of the answers provided for each question aimed at measuring a similar structure. The principal component approach was employed for factor extraction, and the factor scores were obtained through the regression scoring method. These factor scores were then converted into scores ranging from 0 to 100; the higher scores represented a higher level of perceived stress [49].

The presence of sleep problems was assessed using the following question: “During the past 30 days, how much of a problem did you have with sleeping, such as falling asleep, waking up frequently during the night, or waking up too early in the morning?” Response options were: “none = 1”, “mild = 2”, “moderate = 3”, “severe = 4” and “extreme/cannot do = 5”. According to previous publications that used the same dataset of questions, we generated a binary variable by combining “no”, “mild”, and “moderate” to represent “no sleep problems = 0” and “severe” and “extreme/cannot do” to represent “sleep problems = 1” [50,51].

Anxiety symptoms were assessed by the question: ‘Overall in the past 30 days, how much of a problem did you have with worry or anxiety?’ Response options were: “none = 1”, “mild = 2”, “moderate = 3”, “severe = 4”, and “extreme = 5”. According to previous publications that used the same dataset of questions, those who responded “severe” and “extreme” were regarded as anxiety (coded 1), the other responses were regarded as non-anxiety (coded 0) [52,53].

The control variables contained demographic and health-related covariates: age (continuous), sex (male/female), educational attainment, residential setting (urban/rural), smoking status, alcohol use, and the cumulative count of chronic conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, stroke, lung disease). Educational attainment was classified as four tiers: no formal education (0 years), primary education (1–6 years), secondary education (7–12 years; encompassing junior/senior high school equivalency), and higher education (>12 years; university or postgraduate training). Smoking status was classified as never, current, or past smokers, while alcohol consumption was classified as never or past drinker. Chronic disease burden was derived from the sum of self-reported, physician-confirmed diagnoses [54].

The statistical analyses were conducted with Stata 17.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The Shapiro-Wilk test and the normal-probability plot were used to examine the normality. The variance inflation factors were used to examine the multicollinearity. The descriptive characteristics were summarized and presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), count and percentages. A multiple linear regression analysis was employed to examine the associations between PA, sedentary behavior, and stress while controlling for covariates such as age, sex, educational attainment, residential environment, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and number of chronic diseases. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was employed to examine the associations between PA, SB, sleep problems, and anxiety symptoms after controlling for the covariates. The results were presented in the form of β coefficients or odd ratio (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI).

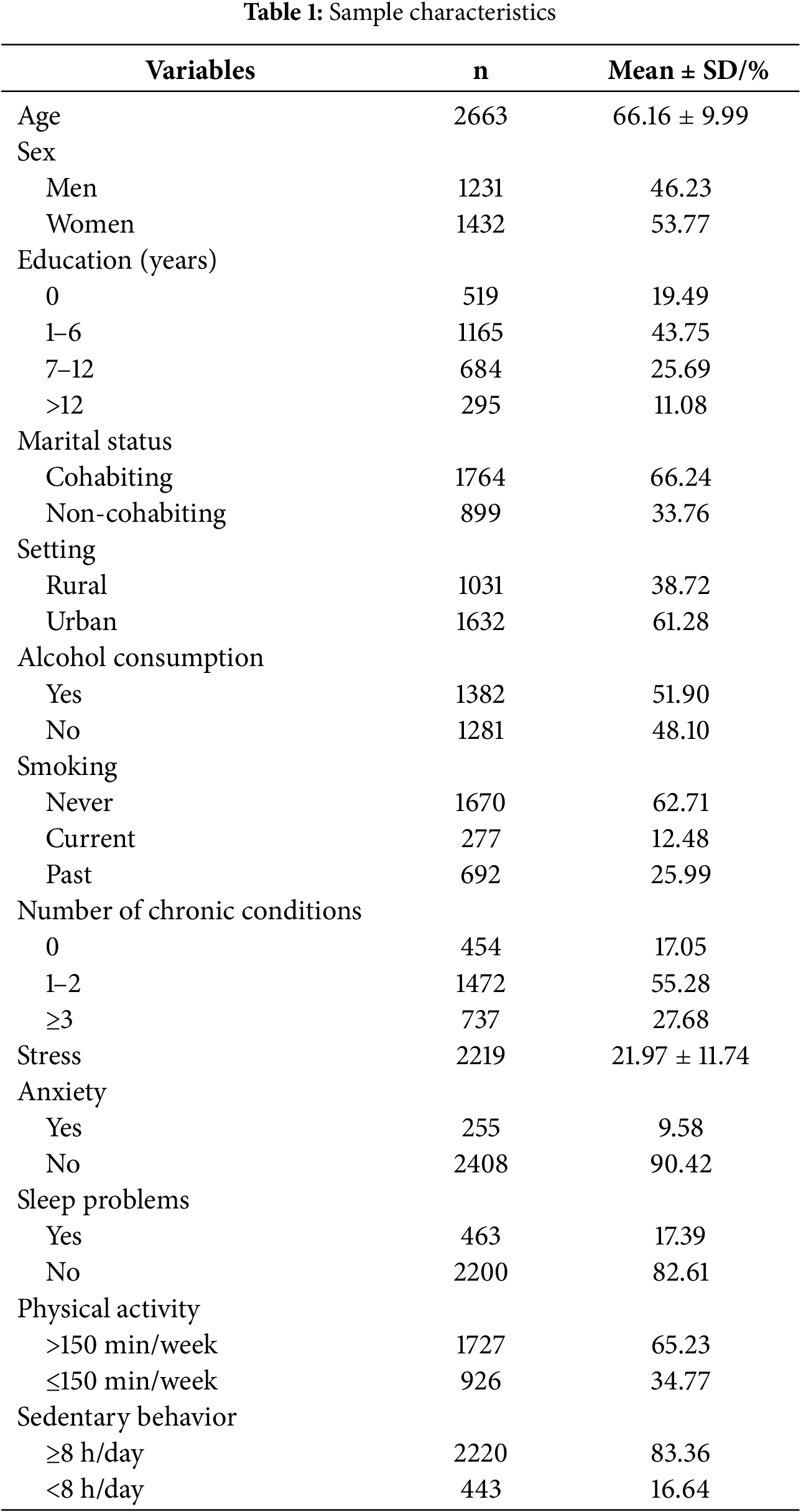

3.1 Participant Characteristics

To verify the appropriateness of the model, we conducted a series of diagnostic tests. The Shapiro-Wilk test and the normal-probability plot did not reveal any substantial deviation of the residuals from a normal distribution (p ≥ 0.05). The variance inflation factors were below 2. The model explained 18%–28% of the variance in pressure (R2 = 0.18–0.28). Overall, the analytic assumptions were met and that the models provided acceptable fit and explanatory strength.

The study included 2663 individuals with cataracts (mean age = 66.16 ± 9.99 years; 53.77% women). Most participants resided in urban settings (61.28%) and were cohabiting (66.24%). Educational attainment varied: 43.75% reported 1–6 years of formal education, 25.69% had 7–12 years, and 11.08% completed >12 years, while 19.49% reported no formal education. Health behaviors indicated that half of the sample (51.90%) consumed alcohol, and the majority were non-smokers (69.85%), with 12.48% reporting current smoking and 25.99% past smoking. 55.28% had 1–2 chronic conditions, and 27.68% had ≥3, while only 17.05% reported none. Mean stress score was 21.97 ± 11.74, the prevalence of anxiety and sleep problems was 9.58% and 17.39%, respectively physical activity levels were relatively high, with 65.23% meeting the recommended threshold of >150 min/week. However, sedentary behavior was widespread, as 83.36% reported sitting ≥8 h/day (Table 1).

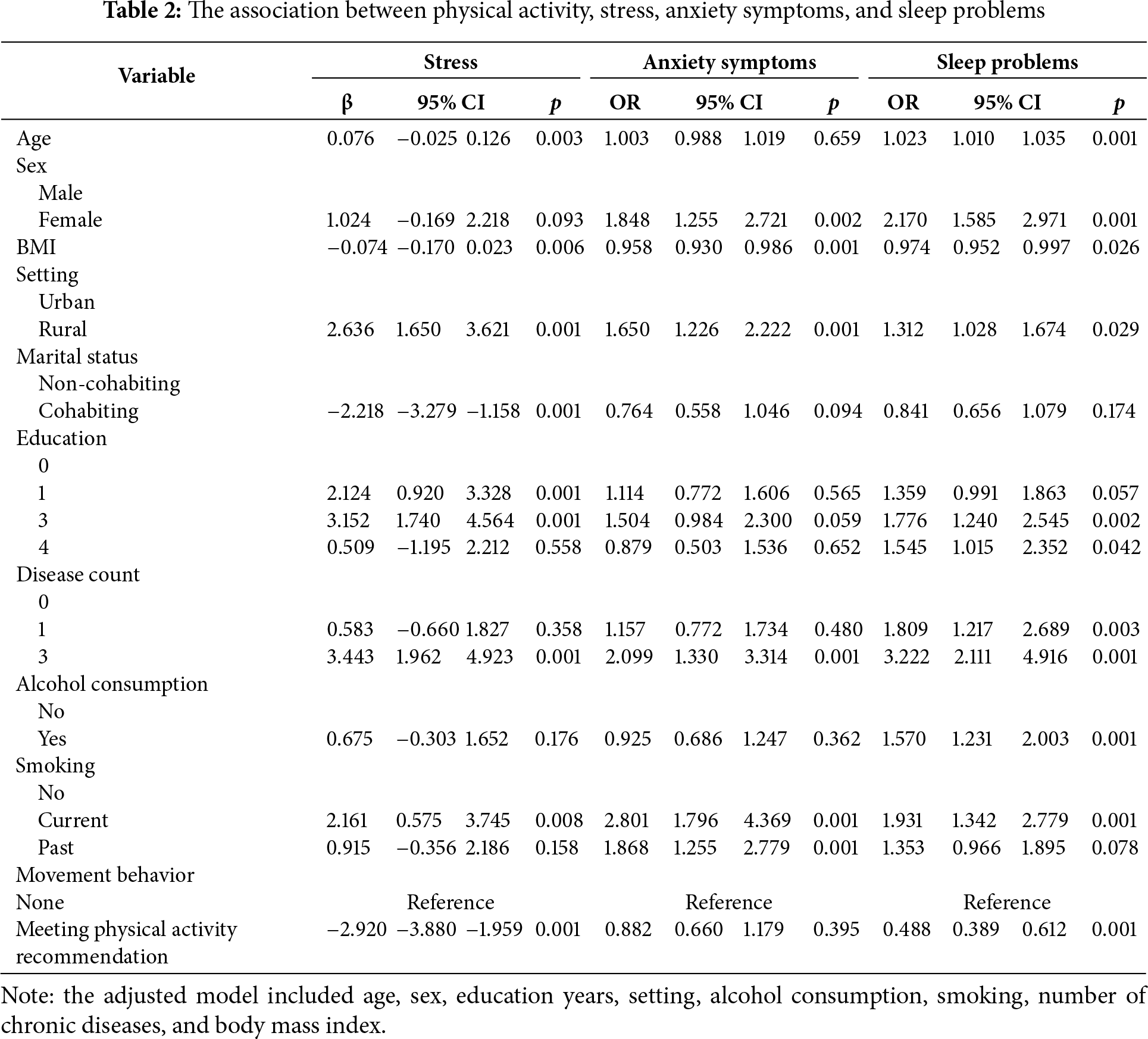

3.2 Associations between Physical Activity, Stress, Anxiety, and Sleep Problems

Table 2 depicts the results of the associations between meeting physical activity recommendations (>150 min/week) and stress score, anxiety symptoms, and sleep problems among the participants. Specifically, participants who met the recommendations were associated with lower stress score (β = −2.920, 95% CI: −3.880 to −1.959, p < 0.001) and lower odds of reporting sleep problems (OR = 0.488, 95% CI: 0.389 to 0.612, p < 0.001) compared to those with non-meeting physical activity recommendations. However, meeting physical activity recommendations was non-significantly associated with reduced odds of anxiety symptoms (OR = 0.882, 95% CI: 0.660 to 1.179, p = 0.395). Overall, participants with meeting physical activity recommendation were likely to have less stress and a lower risk of sleep problems.

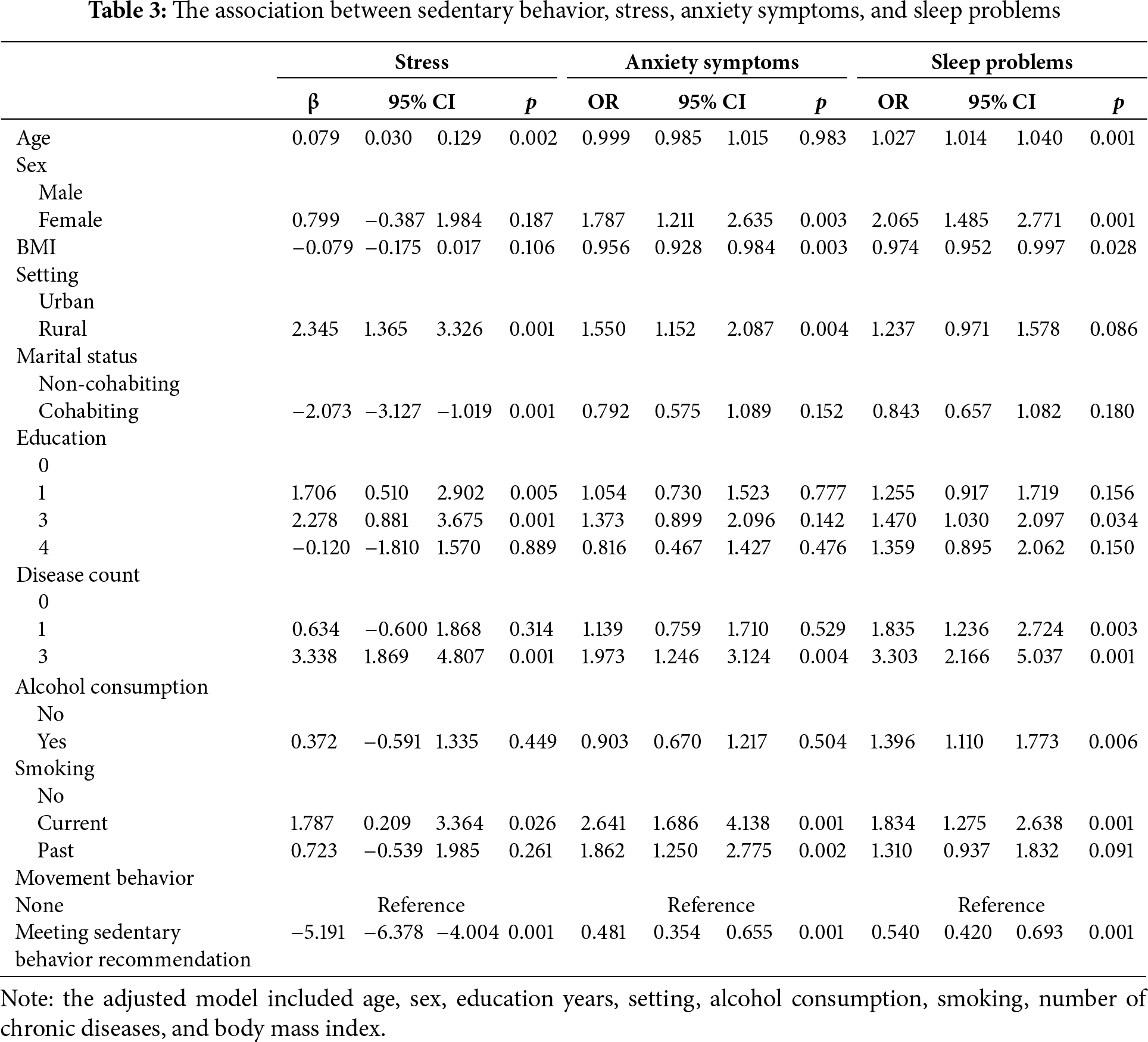

3.3 Associations between Sedentary Behavior, Stress, Anxiety, and Sleep Problems

Table 3 depicts the results of the associations between meeting sedentary behavior recommendation and stress score, anxiety symptoms, and sleep problems among the participants. Participants who met the sedentary behavior recommendation (<8 h/day) were associated with lower stress score (β = −5.191, 95% CI: −6.378 to −4.004, p < 0.001), lower odds of anxiety symptoms (OR = 0.481, 95% CI: 0.354 to 0.655, p < 0.001), and lower odds of sleep problems (OR = 0.540, 95% CI: 0.420 to 0.693, p < 0.001) compared to those with non-meeting sedentary behavior recommendation. Overall, participants with meeting sedentary behavior recommendation were likely to have less stress, anxiety symptoms and a lower risk of sleep problems.

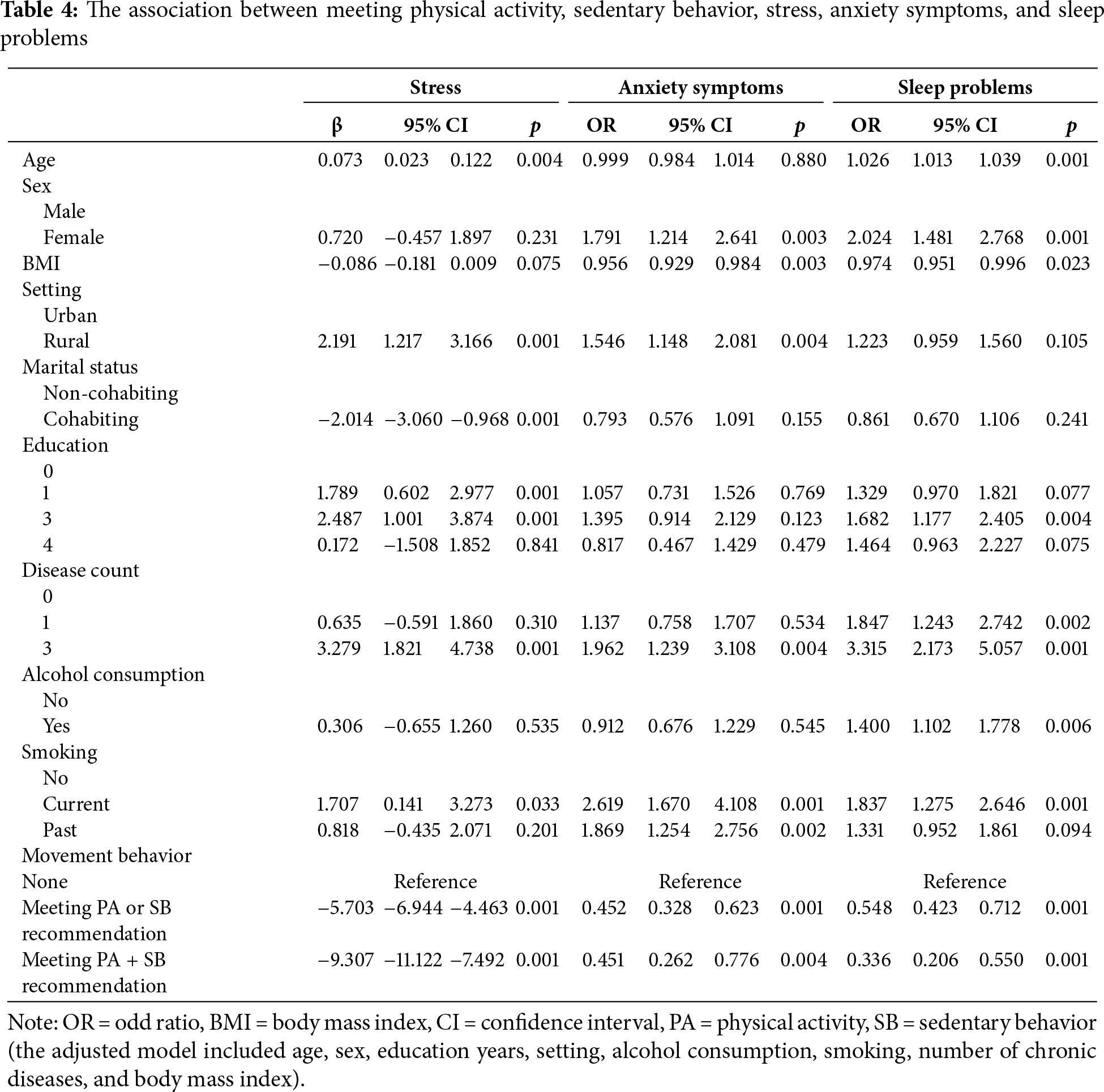

3.4 Combined Effects of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior

Table 4 shows the results of associations of physical activity and sedentary behavior with stress score, anxiety symptoms, and sleep problems after controlling for covariate. Participants who met either the physical activity recommendation (>150 min/week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity) or the sedentary behavior recommendation (<8 h/day) were associated with lower stress score (β = −5.703, 95% CI: −6.944 to −4.463, p < 0.001), lower odds of anxiety symptoms (OR = 0.452, 95% CI: 0.328 to 0.623, p < 0.001), and lower odds of sleep problems (OR = 0.548, 95% CI: 0.423 to 0.712, p < 0.001)compared to those non-meeting recommendation. Additionally, meeting both physical activity and sedentary behavior recommendations was associated with reduced stress (β = −9.307, 95% CI: −11.122 to −7.492, p < 0.001), lower odds of anxiety symptoms (OR = 0.451, 95% CI: 0.262 to 0.776, p = 0.004), and sleep problems (OR = 0.336, 95% CI: 0.206 to 0.550, p < 0.001) compared to those with non-meeting recommendation. Overall, participants with meeting both physical activity and sedentary behavior recommendations were more likely have the lowest levels of stress, anxiety symptoms, and sleep problems.

This study was conducted to examine the associations of physical activity and sedentary behavior with psychological health outcomes, specifically stress, anxiety, and sleep problems among adults with cataracts. The findings of this study indicate that physical activity and sedentary behavior are independently and jointly associated with stress, anxiety symptoms, and sleep problems in adults with cataracts. Specifically, meeting physical activity recommendations (>150 min/week) was associated with a 2.92 points lower stress score and 51.2% lower odds of sleep problems. Limiting sedentary behavior to <8 h/day showed even stronger associations: stress scores were 5.191 points lower and the odds of anxiety (51.9%) and sleep problems (46%) were reduced compared to participants who sat longer. The largest gains arose when the two behaviors were combined. Adults who both met the physical activity and sedentary behavior recommendations had a 9.307 points lower stress score, 54.9% lower odds of anxiety symptoms, and 66.4% lower odds of sleep problems compared with those who met neither recommendation, indicating clear additive benefits.

Consistent with previous literature [27,55,56], our findings support existing evidence that regular physical activity positively affects psychological health outcomes. Studies across diverse populations consistently demonstrate that engaging in regular physical activity significantly reduces stress levels and sleep problems. For example, systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that individuals meeting physical activity recommendations generally report lower stress [27,55]. Our observed association, a reduction of stress symptoms, aligns with these established findings. The inverse relationship between physical activity and stress in cataract patients may be explained by both biological and psychosocial mechanisms. Biologically, physical activity enhances neuroplasticity through increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) secretion and elevated dopaminergic activity, which modulates stress reactivity and emotional regulation [57–59]. In previous study, elevated BDNF was reported to be associated with reduced amygdala hyperactivity (a key node in stress pathways) and improved prefrontal cortex function [60], which may counteract the heightened stress response often observed in visually impaired individuals. Additionally, physical activity stimulates the production of endorphins, neurotransmitters that are closely linked to alleviates perceived stress and improves mood [61,62]. Moreover, the significant inverse association between physical activity and sleep problems identified in this study also mirrors previous research. Previous studies have highlighted the role of physical activity in reducing sleep disturbances, improving sleep efficiency, and increasing total sleep duration [63,64]. Similarly, in a longitudinal study by Gerber et al. [65], increasing in physical activity over time resulted in reduced sleep problems. The identified reduction in sleep problems in our study resonates with this literature, indicating the potential of physical activity as a non-pharmacological approach for sleep issues, particularly among clinical populations such as those with cataracts.

Regarding sedentary behavior, our findings are in line with the growing body of evidence highlighting its detrimental effects on psychological health [66,67]. Earlier research indicates that prolonged sedentary behavior increases risks for stress, anxiety, and poor sleep quality [26,68,69]. For example, Chauntry et al. observed significant associations between increased sedentary behavior and heightened stress and anxiety symptoms [70], supporting the strong inverse relationship found in this study. Furthermore, a systematic review by Yang et al. underscored that prolonged sedentary time was consistently associated with poorer sleep quality and increased insomnia [69], consistent with the present findings that limiting sedentary behavior substantially improved sleep outcomes. Our results extend this literature by demonstrating substantial reductions in stress, anxiety, and sleep problems when sedentary behavior is limited to <8 h/day. The particularly pronounced impact on stress and sleep problems emphasizes the critical importance of not only promoting physical activity but also actively discouraging prolonged sedentary behaviors, particularly in vulnerable populations. It is likely that prolonged sedentary behavior may negatively affect psychological health through increased systemic inflammation, poor metabolic regulation, and altered cortisol secretion patterns [71]. Consequently, reducing sedentary behavior could independently mitigate these pathways, providing additional protective effects beyond physical activity. The magnitude of these effects underscores the clinical relevance of emphasizing sedentary behavior reduction in health promotion strategies.

A novel finding of this study was the additive effect observed when combining physical activity with sedentary behavior recommendations. While prior literature has largely examined physical activity and sedentary behavior separately, the interactive effect observed herein suggests that optimal psychological health outcomes may require concurrent attention to both movement behaviors. Similarly, Hofman et al. [28] suggested in their cross-sectional study that the combination of sufficient physical activity and limited sedentary behavior was beneficial in improving psychological health outcomes. Likewise, Kandola et al. [72] observed additive benefits of combining higher levels of physical activity with lower sedentary behavior for reducing anxiety symptoms, suggesting that integrated lifestyle behaviors might yield the greatest psychosocial benefits.

These findings have significant clinical and public health implications. Given the strong association between adhering to physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior recommendations and improved psychosocial outcomes, health promotion efforts should specifically target adults with cataracts to increase their physical activity levels and reduce sedentary time. Intervention strategies may include a combination of structured physical activity programs and behavior modification techniques to reduce prolonged sitting, such as regular breaks, and behavioral prompts. Healthcare providers can advise and guide cataracts patients to engage in >150 min/week of physical activity and limit sedentary behavior to <8 h per day during routine cataract care and consultations. In addition, they can also encourage patients to follow the principle of “more movement and less sitting” to manage their physical and psychological health.

There are some limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, this study is of cross-sectional survey nature and cannot determine whether there is a causal relationship between physical activity and sedentary behavior and the reduction of stress, anxiety and sleep problems. Because individuals with better psychological health may be more active and less sedentary. For example, a prospective study suggested a greater physical activity associated with better psychological health and vice versa in older adults [73]. Therefore, longitudinal studies or randomized controlled trials need to be conducted to test whether the combined physical activity and sedentary behavior recommendations can improve psychological health. Second, the reliance on self-reported measures of visual issues, physical activity and sedentary behavior introduces potential recall bias, which could affect the accuracy of the reported associations. Future studies should employ objective measurement methods, such as accelerometers, Color Doppler imaging, to collect more precise data and diagnose cataract disease. Third, since this study analyzed pooled data sets, our estimates represent average effects and may mask the unique patterns of each country. Differences in cultural expectations regarding gender, different income, and health condition could alter the magnitude and even the direction of the association between physical activity and sedentary behavior and psychological health. Future research should examine the interaction effects by country and urban-rural environment, and explore mediating factors such as social support. Fourth, as the study subjects were limited to cataract patients, the generalizability of the study results may be restricted. Replicating these study results in a broader and more diverse population will enhance their external validity.

In this study we investigated associations between physical activity and sedentary behavior related to stress, anxiety, and sleep problems among adults with cataracts. This study provides useful information to support the independent and joint associations between physical activity, sedentary behavior, and psychological health outcomes, specifically stress, anxiety symptoms, and sleep problems. These observations add to the growing evidence that movement behaviors may influence psychological health in people with cataracts. Because the data are cross-sectional and all key variables were self-reported, the direction of the associations cannot be confirmed. Longitudinal and intervention studies that use device-based movement measures and validated clinical assessments are needed to test whether changing physical activity and sedentary behavior truly improves psychological health in this population.

This paper uses data from WHO’s Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE). SAGE is supported by the U.S. National Institute on Aging through Interagency Agreements OGHA 04034785, YA1323-08-CN-0020, Y1-AG-1005-01 and through research grants R01-AG034479 and R21-AG034263.

Acknowledgement: This paper employs data from WHO’s Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE), which is supported by the U.S. National Institute on Aging through Interagency Agreements OGHA 04034785, YA1323-08-CN-0020, Y1-AG-1005-01 and through research grants R01-AG034479 and R21-AG034263.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Zhiyan Xiao and Xiangqin Song are responsible for idea conceptualization, data analysis, result integration, manuscript writing, and revision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available at https://www.who.int/data/data-collection-tools/study-on-global-ageing-and-adult-health (accessed on 09 July 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Cicinelli MV, Buchan JC, Nicholson M, Varadaraj V, Khanna RC. Cataracts. Lancet. 2023;401(10374):377–89. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01839-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Pesudovs K, Lansingh VC, Kempen JH, Tapply I, Fernandes AG, Cicinelli MV, et al. Global estimates on the number of people blind or visually impaired by cataract: a meta-analysis from 2000 to 2020. Eye. 2024;38(11):2156–72. doi:10.1038/s41433-024-02961-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Jonas JB, Bourne RRA, White RA, Flaxman SR, Keeffe J, Leasher J, et al. Visual impairment and blindness due to macular diseases globally: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158(4):808–15. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2014.06.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Bourne RRA, Cicinelli MV, Sedighi T, Tapply IH, McCormick I, Jonas JB, et al. Effective refractive error coverage in adults aged 50 years and older: estimates from population-based surveys in 61 countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10(12):e1754–63. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00433-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Jiang B, Wu T, Liu W, Liu G, Lu P. Changing trends in the global burden of cataract over the past 30 years: retrospective data analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023;9:e47349. doi:10.2196/47349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. McCormick I, Butcher R, Evans JR, MacTaggart IZ, Limburg H, Jolley E, et al. Effective cataract surgical coverage in adults aged 50 years and older: estimates from population-based surveys in 55 countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10(12):e1744–53. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00419-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Ruiss M, Findl O, Kronschläger M. The human lens: an antioxidant-dependent tissue revealed by the role of caffeine. Ageing Res Rev. 2022;79:101664. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2022.101664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Go JA, Mamalis CA, Khandelwal SS. Cataract surgery considerations for diabetic patients. Curr Diab Rep. 2021;21(12):67. doi:10.1007/s11892-021-01418-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang H, Xiu X, Xue A, Yang Y, Yang Y, Zhao H. Mendelian randomization study reveals a population-specific putative causal effect of type 2 diabetes in risk of cataract. Int J Epidemiol. 2022;50(6):2024–37. doi:10.1093/ije/dyab175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Rimmer JH, Riley B, Wang E, Rauworth A, Jurkowski J. Physical activity participation among persons with disabilities: barriers and facilitators. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(5):419–25. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.02.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. van Landingham SW, Willis JR, Vitale S, Ramulu PY. Visual field loss and accelerometer-measured physical activity in the United States. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(12):2486–92. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.06.034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Cai Y, Schrack JA, Wang H, E JY, Wanigatunga AA, Agrawal Y, et al. Visual impairment and objectively measured physical activity in middle-aged and older adults. J Gerontol A. 2021;76(12):2194–203. doi:10.1093/gerona/glab103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Zheng Selin J, Orsini N, Ejdervik Lindblad B, Wolk A. Long-term physical activity and risk of age-related cataract: a population-based prospective study of male and female cohorts. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(2):274–80. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.08.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Jiang H, Wang LN, Liu Y, Li M, Wu M, Yin Y, et al. Physical activity and risk of age-related cataract. Int J Ophthalmol. 2020;13(4):643–9. doi:10.18240/ijo.2020.04.18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wang S, Du Z, Lai C, Seth I, Wang Y, Huang Y, et al. The association between cataract surgery and mental health in older adults: a review. Int J Surg. 2024;110(4):2300–12. doi:10.1097/JS9.0000000000001105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Hwang G, Lee SH, Lee DY, Park C, Roh HW, Son SJ, et al. Age-related eye diseases and subsequent risk of mental disorders in older adults: a real-world multicenter study. J Affect Disord. 2025;375:306–15. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2025.01.128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang X, Bullard KM, Cotch MF, Wilson MR, Rovner BW, McGwin GJr, et al. Association between depression and functional vision loss in persons 20 years of age or older in the United States, NHANES 2005–2008. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(5):573–81. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.2597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Hou M, Herold F, Werneck AO, Teychenne M, Paoli AGD, Taylor A, et al. Associations of 24-hour movement behaviors with externalizing and internalizing problems among children and adolescents prescribed with eyeglasses/contact lenses. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2024;24(1):100435. doi:10.1016/j.ijchp.2023.100435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Gao Y, Yu Q, Schuch FB, Herold F, Hossain MM, Ludyga S, et al. Meeting 24-h movement behavior guidelines is linked to academic engagement, psychological functioning, and cognitive difficulties in youth with internalizing problems. J Affect Disord. 2024;349:176–86. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2024.01.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Cheng Z, Aikeremu A, Gao Y, Zhang Z, Paoli AGD, Cunha PM, et al. Linking 24-h movement behavior guidelines to cognitive difficulties, internalizing and externalizing problems in preterm youth. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2024;26(8):651–62. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2024.055351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang Z, Wang T, Kuang J, Herold F, Ludyga S, Li J, et al. The roles of exercise tolerance and resilience in the effect of physical activity on emotional states among college students. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2022;22(3):100312. doi:10.1016/j.ijchp.2022.100312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Herold F, Zou L, Theobald P, Manser P, Falck RS, Yu Q, et al. Beyond FITT: addressing density in understanding the dose-response relationships of physical activity with health-an example based on brain health. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2025;8:e800. doi:10.1007/s00421-025-05858-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Taylor A, Kong C, Zhang Z, Herold F, Ludyga S, Healy S, et al. Associations of meeting 24-h movement behavior guidelines with cognitive difficulty and social relationships in children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactive disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2023;17(1):42. doi:10.1186/s13034-023-00588-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Rollo S, Antsygina O, Tremblay MS. The whole day matters: understanding 24-hour movement guideline adherence and relationships with health indicators across the lifespan. J Sport Health Sci. 2020;9(6):493–510. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2020.07.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zhao M, Zhang Y, Herold F, Chen J, Hou M, Zhang Z, et al. Associations between meeting 24-hour movement guidelines and myopia among school-aged children: a cross-sectional study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2023;53:101792. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2023.101792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Wright LJ, Williams SE, Veldhuijzen van Zanten JJCS. Associations between physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and stress using ecological momentary assessment: a scoping review. Ment Health Phys Act. 2023;24:100518. doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2023.100518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Schuch FB, Vancampfort D. Physical activity, exercise, and mental disorders: it is time to move on. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2021;43(3):177–84. doi:10.47626/2237-6089-2021-0237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Hofman A, Voortman T, Ikram MA, Luik AI. Substitutions of physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep: associations with mental health in middle-aged and elderly persons. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2022;76(2):175–81. doi:10.1136/jech-2020-215883. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Abete I, Konieczna J, Zulet MA, Galmés-Panades AM, Ibero-Baraibar I, Babio N, et al. Association of lifestyle factors and inflammation with sarcopenic obesity: data from the PREDIMED-Plus trial. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10(5):974–84. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Pearce M, Garcia L, Abbas A, Strain T, Schuch FB, Golubic R, et al. Association between physical activity and risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(6):550–9. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Kim SY, Park JH, Lee MY, Oh KS, Shin DW, Shin YC. Physical activity and the prevention of depression: a cohort study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;60:90–7. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.07.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Firth J, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, Silva ES, et al. Physical activity and incident depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(7):631–48. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17111194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Brunes A, Flanders WD, Augestad LB. Physical activity and symptoms of anxiety and depression in adults with and without visual impairments: the HUNT Study. Ment Health Phys Act. 2017;13:49–56. doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2017.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Dempsey PC, Owen N, Biddle SJH, Dunstan DW. Managing sedentary behavior to reduce the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14(9):522. doi:10.1007/s11892-014-0522-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Björk M, Dragioti E, Alexandersson H, Esbensen BA, Boström C, Friden C, et al. Inflammatory arthritis and the effect of physical activity on quality of life and self-reported function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2022;74(1):31–43. doi:10.1002/acr.24805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Patterson R, McNamara E, Tainio M, de Sá TH, Smith AD, Sharp SJ, et al. Sedentary behaviour and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality, and incident type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose response meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33(9):811–29. doi:10.1007/s10654-018-0380-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Wanjau MN, Möller H, Haigh F, Milat A, Hayek R, Lucas P, et al. Physical activity and depression and anxiety disorders: a systematic review of reviews and assessment of causality. AJPM Focus. 2023;2(2):100074. doi:10.1016/j.focus.2023.100074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Singh B, Olds T, Curtis R, Dumuid D, Virgara R, Watson A, et al. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: an overview of systematic reviews. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57(18):1203–9. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2022-106195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Chen ST, Guo T, Yu Q, Stubbs B, Clark C, Zhang Z, et al. Active school travel is associated with fewer suicide attempts among adolescents from low-and middle-income countries. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2021;21(1):100202. doi:10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.11.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Yu L, Li J, Zou L, Chen Y, Werneck AO, Herold F, et al. Associations of physical activity and sedentary behavior with internalizing problems among youth with chronic pain. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2025;27(2):97–110. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2025.061237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Li X, Guo Y, Liu T, Xiao J, Zeng W, Hu J, et al. The association of cooking fuels with cataract among adults aged 50 years and older in low- and middle-income countries: results from the WHO Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). Sci Total Environ. 2021;790:148093. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Smith L, López Sánchez GF, Veronese N, Soysal P, Tully MA, Gorely T, et al. Association between self-reported visual symptoms (suggesting cataract) and self-reported fall-related injury among adults aged ≥65 years from five low- and middle-income countries. Eye. 2024;38(15):2920–5. doi:10.1038/s41433-024-03181-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Sparling PB, Howard BJ, Dunstan DW, Owen N. Recommendations for physical activity in older adults. BMJ. 2015;350:h100. doi:10.1136/bmj.h100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. p. 60. [Google Scholar]

45. Jacob L, Gyasi RM, Oh H, Smith L, Kostev K, López Sánchez GF, et al. Leisure-time physical activity and sarcopenia among older adults from low- and middle-income countries. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2023;14(2):1130–8. doi:10.1002/jcsm.13215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Chen S, Li Z, Zhang Y, Chen S, Li W. Food insecurity, physical activity, and sedentary behavior in middle to older adults. Nutrients. 2025;17(6):1011. doi:10.3390/nu17061011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451–62. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

49. Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Veronese N, Schofield P, Lin PY, Tseng PT, et al. Multimorbidity and perceived stress: a population-based cross-sectional study among older adults across six low- and middle-income countries. Maturitas. 2018;107:84–91. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.10.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Rani R, Arokiasamy P, Selvamani Y, Sikarwar A. Gender differences in self-reported sleep problems among older adults in six middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study. J Women Aging. 2022;34(5):605–20. doi:10.1080/08952841.2021.1965425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Smith L, Shin JI, Jacob L, Carmichael C, López Sánchez GF, Oh H, et al. Sleep problems and mild cognitive impairment among adults aged ≥50 years from low- and middle-income countries. Exp Gerontol. 2021;154:111513. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2021.111513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Herring MP, Hallgren M, Koyanagi A. Sedentary behavior and anxiety: association and influential factors among 42, 469 community-dwelling adults in six low- and middle-income countries. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018;50:26–32. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.09.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Hallgren M, Veronese N, Mugisha J, Probst M, et al. Correlates of physical activity among community-dwelling individuals aged 65 years or older with anxiety in six low- and middle-income countries. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(5):705–14. doi:10.1017/S1041610217002216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Xie H, Chen E, Zhang Y. Association of walking pace and fall-related injury among Chinese older adults: data from the SAGE survey. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2023;50:101710. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2022.101710. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Schuch FB, Stubbs B, Meyer J, Heissel A, Zech P, Vancampfort D, et al. Physical activity protects from incident anxiety: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36(9):846–58. doi:10.1002/da.22915. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, Taylor P, del Pozo Cruz B, van den Hoek D, et al. Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2024;384:e075847. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Fakhoury M, Eid F, El Ahmad P, Khoury R, Mezher A, El Masri D, et al. Exercise and dietary factors mediate neural plasticity through modulation of BDNF signaling. Brain Plast. 2022;8(1):121–8. doi:10.3233/BPL-220140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Küster OC, Laptinskaya D, Fissler P, Schnack C, Zügel M, Nold V, et al. Novel blood-based biomarkers of cognition, stress, and physical or cognitive training in older adults at risk of dementia: preliminary evidence for a role of BDNF, irisin, and the kynurenine pathway. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;59(3):1097–111. doi:10.3233/JAD-170447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Hou M, Herold F, Zhang Z, Ando S, Cheval B, Ludyga S, et al. Human dopaminergic system in the exercise-cognition link. Trends Mol Med. 2024;30(8):708–12. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2024.04.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Phillips C. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, depression, and physical activity: making the neuroplastic connection. Neural Plast. 2017;2017:7260130. doi:10.1155/2017/7260130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Hossain MN, Lee J, Choi H, Kwak YS, Kim J. The impact of exercise on depression: how moving makes your brain and body feel better. Phys Act Nutr. 2024;28(2):43–51. doi:10.20463/pan.2024.0015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Chan JSY, Liu G, Liang D, Deng K, Wu J, Yan JH. Special issue—therapeutic benefits of physical activity for mood: a systematic review on the effects of exercise intensity, duration, and modality. J Psychol. 2019;153(1):102–25. doi:10.1080/00223980.2018.1470487. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Kredlow MA, Capozzoli MC, Hearon BA, Calkins AW, Otto MW. The effects of physical activity on sleep: a meta-analytic review. J Behav Med. 2015;38(3):427–49. doi:10.1007/s10865-015-9617-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Atoui S, Chevance G, Romain AJ, Kingsbury C, Lachance JP, Bernard P. Daily associations between sleep and physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;57:101426. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Gerber M, Börjesson M, Jonsdottir IH, Lindwall M. Association of change in physical activity associated with change in sleep complaints: results from a six-year longitudinal study with Swedish health care workers. Sleep Med. 2020;69:189–97. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2019.01.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Guan K, Yang J, Cheval B, Health M, Herold F, Werneck Aé O, et al. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between sedentary behavior and behavioral problems in children with overweight/obesity. Ment Health Phys Act. 2025;29(1):100698. doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2025.100698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Zou L, Herold F, Cheval B, Wheeler MJ, Pindus DM, Erickson KI, et al. Sedentary behavior and lifespan brain health. Trends Cogn Sci. 2024;28(4):369–82. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2024.02.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Hallgren M, Nguyen TTD, Owen N, Vancampfort D, Smith L, Dunstan DW, et al. Associations of interruptions to leisure-time sedentary behaviour with symptoms of depression and anxiety. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):128. doi:10.1038/s41398-020-0810-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Yang Y, Shin JC, Li D, An R. Sedentary behavior and sleep problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Med. 2017;24(4):481–92. doi:10.1007/s12529-016-9609-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Chauntry AJ, Bishop NC, Hamer M, Kingsnorth AP, Chen YL, Paine NJ. Sedentary behaviour is associated with heightened cardiovascular, inflammatory and Cortisol reactivity to acute psychological stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2022;141:105756. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2022.105756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Pinto AJ, Bergouignan A, Dempsey PC, Roschel H, Owen N, Gualano B, et al. Physiology of sedentary behavior. Physiol Rev. 2023;103(4):2561–622. doi:10.1152/physrev.00022.2022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Kandola AA, Del Pozo Cruz B, Osborn DJ, Stubbs B, Choi KW, Hayes JF. Impact of replacing sedentary behaviour with other movement behaviours on depression and anxiety symptoms: a prospective cohort study in the UK Biobank. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):133. doi:10.1186/s12916-021-02007-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Steinmo S, Hagger-Johnson G, Shahab L. Bidirectional association between mental health and physical activity in older adults: whitehall II prospective cohort study. Prev Med. 2014;66:74–9. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.06.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools