Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Challenges of Adolescence: Depressive Symptoms and Associated Family and Sociodemographic Factors in 15–18-Year-Olds in Vojvodina, Serbia

1 Department of Social Medicine and Health Statistics with Informatics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, 21000, Serbia

2 Center for Analysis, Planning and Organization of Health Care, Institute of Public Health of Vojvodina, Novi Sad, 21000, Serbia

3 Service for the Health Care of Women and Children, Primary Health Care Centre “Dr Milorad Mika Pavlović”, Indjija, 22320, Serbia

4 Center for Health Promotion, Institute of Public Health of Vojvodina, Novi Sad, 21000, Serbia

* Corresponding Author: Dušan Čanković. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mental Health and Subjective Well-being of Students: New Perspectives in Theory and Practice)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(8), 1071-1086. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.066430

Received 08 April 2025; Accepted 18 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Depression is one of the most common mental health disorders in adolescence. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of depressive symptoms (DS) in adolescents aged 15–18 years in the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina (APV) and to analyze the association of sociodemographic and family factors with DS. Methods: The sample consisted of 986 students (47.4% females and 52.6% males) from ten government high schools in all seven districts of the APV. The Kutcher Adolescents Depression Scale (KADS) was used as a screening test for DS. Sociodemographic data were assessed using a self-reported questionnaire. A three-level binary logistic regression model was conducted to explore the association between sociodemographic and family factors and DS. Results: Symptoms of depression were presented in 27.9% of females (95% CI = 23.9%–32.2%) and 14.7% of males (95% CI = 11.7%–18.0%) (χ2 = 25.129, p < 0.001). In terms of parents’ employment, DS were more prevalent among students whose fathers were unemployed or retired (31.4%, 95% CI = 20.9%–43.6%) (χ2 = 4.376, p = 0.036). In the multilevel logistic regression model, males had 56% lower odds of having DS compared to females (odds ratio [OR] = 0.44, 95% CI = 0.30–0.65). Students with fathers who completed high school had 46% lower odds of depression compared to those whose fathers had the lowest education level (OR = 0.54, 95% CI = 0.30–0.98), and having an employed mother was associated with 40% lower odds of DS in students compared to those whose mothers were unemployed (OR = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.38–0.95). Conclusions: The study revealed a high prevalence of DS among adolescents. Girls have significantly higher values of prevalence of DS than boys, and adolescents whose fathers are without employment or retired. Gender, the father’s education, and the mother’s employment status are significant predictors of DS. Screening programs and the adoption of targeted prevention programs intended for vulnerable populations are extremely important.Keywords

Adolescence represents the phase of human development during which the changes in a person are the fastest and most visible [1]. The understanding of adolescence as a critical phase in life for achieving human potential is also confirmed by the fact that approximately 75% of adult mental health disorders first appear before the age of 24 [2]. Depression, anxiety and behavioral challenges are among the primary contributors to illness and disability in adolescents. Globally, one in seven 10–19-year-olds experiences a mental disorder, accounting for 15% of the global burden of disease in this age group [3]. Many authors have cited worrying data on the increase in the frequency of depressive symptoms (DS) among adolescents in the past two to three decades [4–6], with the information that this increase is at a greater rate than in adults [7].

Depression ranks among the most prevalent psychological conditions affecting youth. It is a multifaceted disorder presenting with emotional, cognitive, and social manifestations [8]. Characteristic signs include feelings of sadness, dissatisfaction, loss of interest in everyday activities, poor concentration, decreased energy, suicidal thoughts, changes in appetite, insomnia, guilt, self-rejection, and reduced self-esteem. The diagnosis of depressive disorder in adolescents is more difficult than in adults, especially if the primary problems that occur in the individual are unexplained physical symptoms, appetite changes, anxiety, refusal to attend school, academic decline, substance abuse, or behavioral issues [1,9]. A recent Global Burden of Diseases Study indicates that the global incidence, prevalence, and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) linked to depression in youth have increased between 1990 and 2019 [10]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, among adolescents in the United States ages 12–17 in 2021–2022, 17% reported symptoms of depression in the past two weeks [11]. Within the European region, the World Health Organization estimates that depression affects 8.3% of adolescents, while nearly a third have subclinical DS [12].

DS can be associated with several health consequences, both physical and mental. In the first place, the risk of suicide is increased, and depression is a well-known risk factor for suicidal behaviours [13,14]. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among individuals aged 10–14 and 25–34 in the United States and the fourth among 15–19-year-olds globally [15,16]. Further, depression can negatively affect general physical health [17]. Young people suffering from depression are more likely to use tobacco, alcohol, or drugs, which can lead to addiction and other health problems [18–20]. Numerous studies have confirmed that DS in adolescence may cause changes in an individual’s organism, which can have long-term consequences for adult health. Adolescent depression was associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk, nervous system diseases, higher levels of anxiety and illicit drug use disorders and also with worse health, criminal, and social functioning in adulthood [21–23]. These findings highlight the urgent need for early identification and appropriate intervention strategies to mitigate lasting impacts.

It is essential to identify factors that precede and are associated with the development of DS in this vulnerable group of individuals in order to develop specific and compelling techniques and strategies to reduce the frequency of this disorder. Some key factors that are precursors of DS in adolescents include biological factors/genetic factors, temperament, cognitive vulnerability, family factors, academic stress, changing social milieu, school factors, peer group and social networking, and sociodemographic factors [24]. There is evidence from the literature that social factors, such as a lower level of parental education, less paid parental occupations, living in a single-parent home or unemployed parents, are risk factors for the development of DS among children [25–27].

The Autonomous Province of Vojvodina (APV) is the northern Province within the Republic of Serbia with an estimated population of 1,734,129 inhabitants [28]. Although the Republic of Serbia has a relatively low mortality rate due to suicides in adolescents aged 15–19 years (2.81 per 100,000 in 2021), it is important to note that the rates of moderate/severe DS among the population aged ≥15 years were the highest in this part of the Serbia (2.7%), and the suicide rate has been continuously high in previous decades [29–31]. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have analyzed the prevalence of DS in adolescents aged 15–18 years in APV, especially considering social inequalities in mental health. The only data on DS from the available literature refers to research that included only first-grade secondary school students in the Republic of Serbia, using a different questionnaire [32]. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of DS in adolescents aged 15–18 years in APV and to examine the association of sociodemographic and family characteristics with DS.

2.1 Study Design and Participants

This cross-sectional survey included adolescents from 10 secondary schools (8 vocational schools and 2 gymnasiums) from all seven districts of APV. The sampling was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, high schools were randomly selected from the institutional registry list of the Provincial Secretariat for Education, Regulations, Administration and National Minorities—National Communities. In the second stage, one class from each year was randomly selected from each of the selected schools. A total of 40 high school classes were included in the sample. A priori power calculation was performed to determine the minimal sample size using G*Power software (Version 3.1.9.7). Based on the total number of independent variables (N = 11) to run the regression model, an effect size of f2 = 0.15 at a significance level of α = 0.05 and a power of 0.95, we needed to recruit at least 178 subjects for the survey.

The study protocol received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Novi Sad (No. 01-39/198/1) and by the principals of the secondary schools that participated in the research, with the prior consent of the Parents’ Advisory Board. In accordance with the Law on the Rights of Patients, which refers to research in public health involving a child who has reached the age of 15, the subjects themselves gave their written consent to participate in the study [33].

Data collection took place from September to December 2021. Questionnaires were distributed to students from the first to the fourth grade of selected high schools during one school hour. Before starting the research, all respondents were informed that filling out the questionnaire was anonymous and voluntary. Informed consent forms were submitted separately to maintain confidentiality. A total of 986 high school students (519 males and 467 females) participated in the research. The research included students who were present in class on the day of the study. Exclusion criteria were students younger than 15 and older than 19, exempt from physical education classes on the day of the research and in the period of 7 days before the study.

The questionnaire used in the research includes questions related to sociodemographic background (gender, age, residence type, level of education and employment of parents), family structure (family type and family size), and questions about the success one achieved in schooling, class and type of high school. Then, follow the questions belonging to the 6-Item Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale (KADS-6). Brooks et al. developed a self-report scale to identify adolescents with depressive disorders and determine changes in that disorder over time [34]. The scale was created based on the experience and studies of experts dealing with adolescent medicine and was designed in such a way as to be sensitive to changes, and over time, it was applied as a screening instrument and for research purposes. The questionnaire was used in public health and clinical research to identify young people at risk for depression [35–37]. This questionnaire is available in three versions, containing 6, 11, and 16 questions, respectively. The 6-question form was used in this research. Each question offered four response options, scored from 0 (hardly ever) to 3 (all of the time), assessing mood, hopelessness, motivation, dissatisfaction and concern, and finally, a question about thoughts related to self-harm, all referring to a week prior to the study. A score of 6 points or higher indicates a risk of depression [38]. Researchers have confirmed the validity and reliability of the KADS-6 questionnaire for assessing the presence of DS in adolescents [36,39,40].

Permission to use all forms of the KADS questionnaire was obtained for the purposes of this research from Professor Stanley Kutcher, who is the leading creator of this instrument. After obtaining permission, the Serbian version of the KADS-6 questionnaire was used in this study [41].

The proportion of missing data for variables was below the cutoff value of 5% (with a maximum of 2.0% for the father’s work status); therefore, the authors did not perform any method for treating missing data [42]. Standard methods of descriptive and inferential statistics were used in the statistical analysis of the data. The prevalence and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were estimated according to gender, high school, residence type, high school grade, family type, number of family members, mother’s and father’s education, and mother’s and father’s work status. The results are derived from a Chi-Square analysis, with effect sizes based on Cramer’s V [43]. To maintain the hierarchical nature of the data, a three-level binary logistic regression model was conducted with individuals/students (level 1) nested within grades (level 2, with grades ranging from 1 to 4), which are in turn nested within schools (10 schools). To estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs for the association between DS (outcome) and sociodemographic and family factors as individual factors (predictors). Among 11 predictors, categorical were gender (male; female), type of high school (gymnasium; vocational school), residence type (rural; suburban; urban), family type (single-parent; complete), and mother’s and father’s employment status; ordinal were school performance, mother’s and father’s education; and interval were age and number of family members. All categorical variables were sorted as descending. The initial model (i.e., empty model) was with individual, grade, and school levels but without predictor variables, while the full model included predictors. Model fit was compared using deviance and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), with lower values indicating a better-fitted model. Statistical analysis was carried out using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

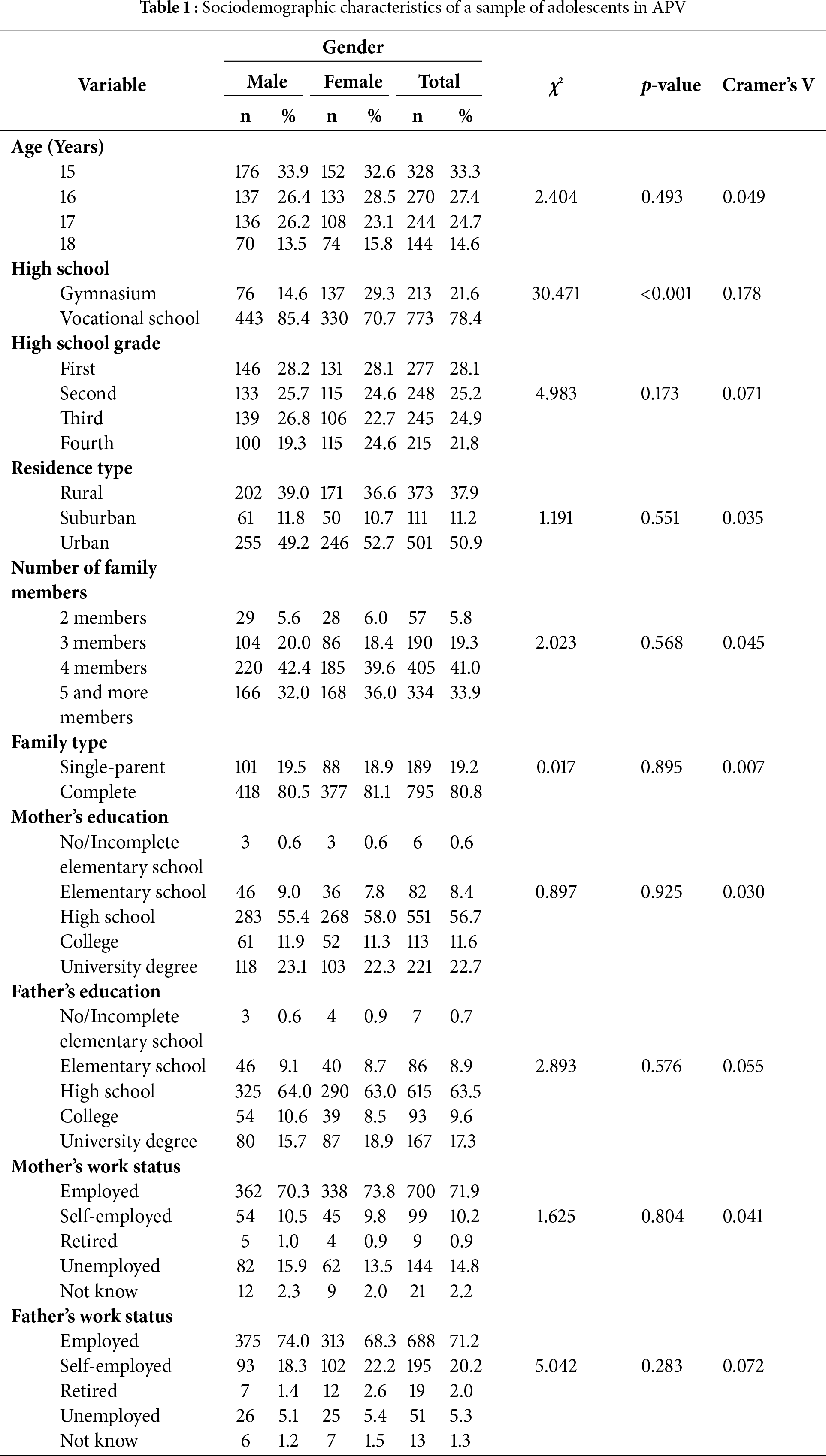

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants. The table summarizes the gender distribution of respondents according to age, type of school and grade, family characteristics, and parents’ educational level and work status. Every second respondent (50.9%) was living in urban areas. Statistically, more females attended the gymnasium than males (29.3% vs. 14.6%) (χ2 = 30.471, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.178). In most cases (41.0%), the family had four members. By parents’ educational level, 56.7% of the students’ mothers and 63.5% of their fathers had high school as the highest level of education. Almost 15% of students’ mothers and 5.3% of students’ fathers were unemployed.

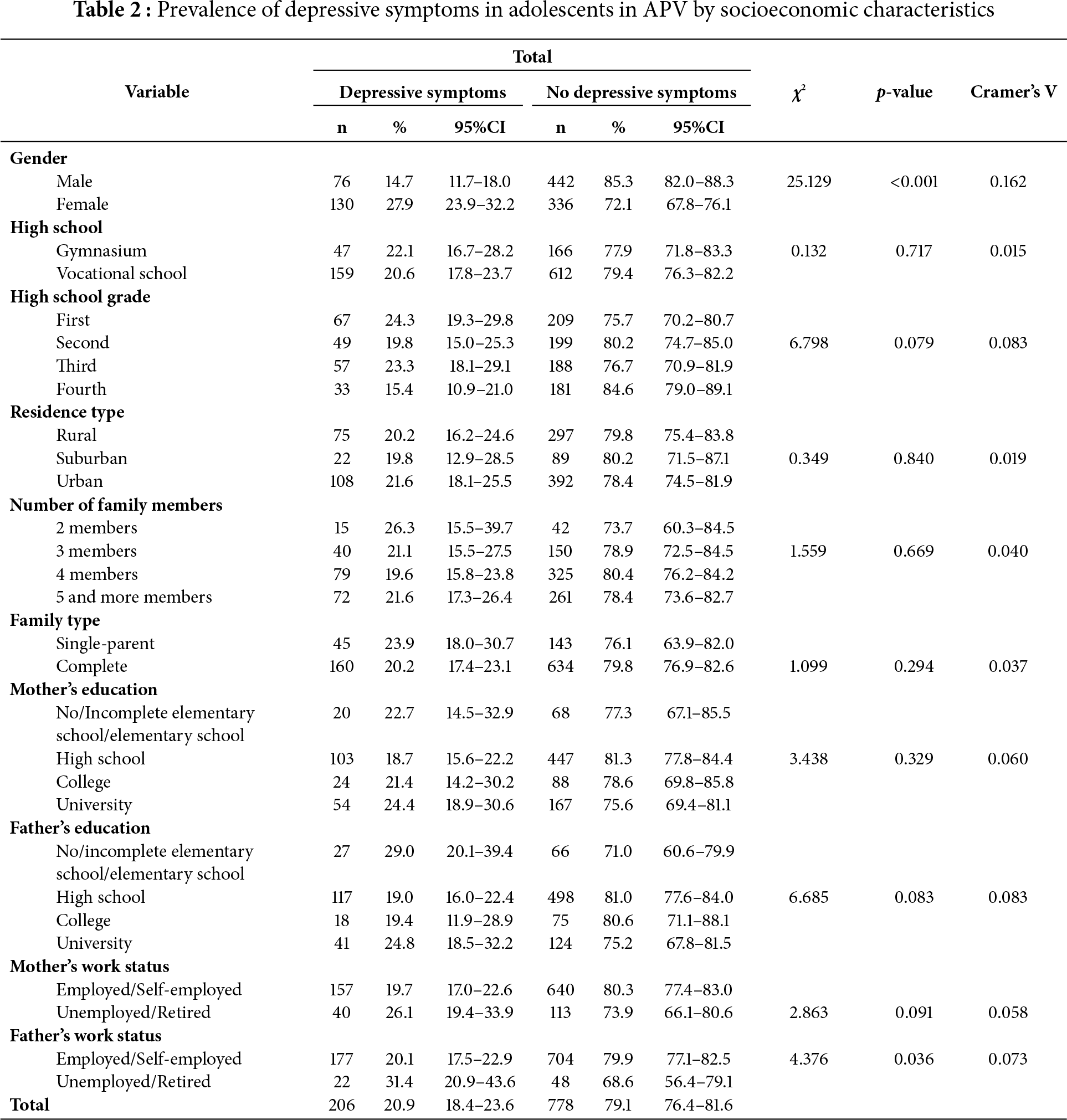

Table 2 presents the prevalence of DS among high-school students in APV. One-fifth of all respondents (20.9%, 95% CI = 18.4–23.6%) had DS, statistically significant more females (27.9%, 95% CI = 23.9%–32.2%) than males (14.7%, 95% CI = 11.7%–18.0%) (χ2 = 25.129, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.162) with small effect size. The highest prevalence was among first-grade students (24.3%), but the differences were not statistically significant. Although the prevalence of DS was the highest among students whose fathers had the lowest level of education, the differences were not statistically significant. In terms of parents’ employment, DS were significantly more prevalent among students whose fathers were unemployed or retired (31.4%, 95% CI = 20.9%–43.6%) (χ2 = 4.376, p = 0.036, Cramer’s V = 0.073). The same pattern was observed regarding mothers, although the difference was not significant.

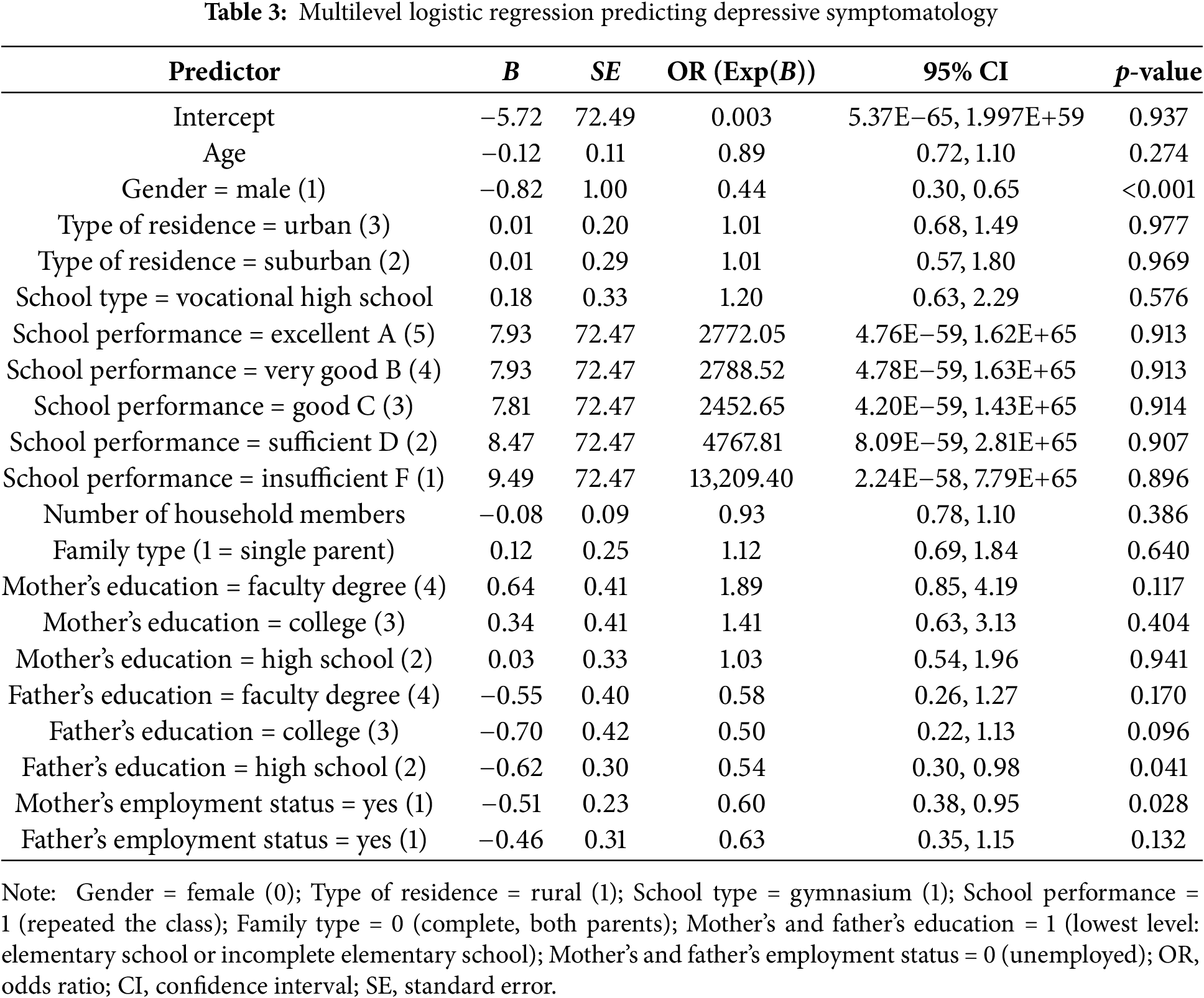

Table 3 presents multilevel logistic regression analysis. For the initial model, the results were: random effect covariance for school level was 0.07, standard error [SE] = 0.12, p = 0.578, and for school × grade level was 0.28, SE = 0.14, p = 0.047; AIC = 4582.52. For the full model, results are: random effect covariance for school × grade level was 0.24, SE = 0.13, p = 0.063, and for school level only, the parameter was redundant, suggesting that once predictors were included, the between-school variance was fully explained; AIC = 4355.58. Thus, a model with predictors was better according to lower values of deviance and AIC. Furthermore, Intraclass Correlation Coefficient [ICC] (school) was 0.019, meaning that 1.9% of the variance is attributable to differences between schools, while ICC (school × grade) was 0.077, meaning that 7.7% of the variance is at the school × grade level.

The results suggest that gender, the father’s education, and the mother’s employment status are significant predictors of the presence of DS (coded as 1) relative to no symptoms (coded as 0). First, the odds ratio (OR = 0.44, p < 0.001) indicates that males had 56% lower odds of having DS compared to females (reference group). In other words, females were more likely to report DS. Second, students with fathers who completed high school had 46% lower odds of depression compared to those whose fathers had the lowest education level (OR = 0.54, p = 0.041). In other words, students with fathers with elementary school or had incomplete elementary school were more likely to report DS compared to students with fathers who had completed high school. Third, having an employed mother is associated with 40% lower odds of DS in students compared to those whose mothers were unemployed (OR = 0.60, p = 0.028). Thus, students with unemployed mothers were more likely to report DS. Other demographic and family factors did not show statistically significant effects in the current model (Table 3).

This study aimed to reveal the prevalence of DS in adolescents aged 15–18 years in the northern province of Serbia and to examine the association of family and sociodemographic factors with DS. Globally, it is estimated that as many as 34% of adolescents aged 10–19 are at risk of developing clinical depression. Female adolescents who showed a significantly greater increase and adolescents from the Middle East, Africa, and Asia who have the highest risk of developing depression stand out [44,45]. Data from the China Family Panel Studies showed that in 2020, 26.6% of adolescents were found to have a depressed mood or DS [46].

In a Polish study, 23.0% of the students were found to have depressive disorders [47]. However, lower values were recorded in a survey conducted in Germany in adolescents aged 12 to 17, where about one in twelve adolescents experienced DS [48]. Moreover, the literature states that in the previous decade European countries experienced the decline of DS that is most noticeable in the elderly, while it is discreet in younger adults [49].

Our study showed that the prevalence of DS in adolescents in APV was 20.9% using the KADS-6 instrument. In a Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study conducted in 2018 and involving first-grade secondary school students in Serbia, it was determined that 26.1% of respondents reported DS [32], which is almost at the level of values for first-grade students in our study (24.3%). In a study using the same HBSC methodology conducted in Sweden, 28.0% of respondents had DS [50]. Research data on the presence of DS in different adolescent populations vary, probably due to the different instruments used, the various age ranges of respondents in the adolescent category itself, and various cultural factors.

The authors cannot consider the connection between the COVID-19 pandemic and DS among adolescents in Vojvodina because the survey did not include questions linked to pandemic-related mental health effects (e.g., economic slump, family bereavement). This research was conducted during the period when the COVID-19 epidemic was still ongoing in Serbia, but not with the intensity it had in the first waves [51]. Other research has confirmed that during the period of the pandemic, the frequency of depression among adolescents was significantly higher compared to the period before the pandemic, especially emphasizing that this increase was more significant among girls [52,53]. In the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic 1 in 4 youth globally were experiencing clinically elevated DS, further stating that prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of clinically significant DS were 12.9% [53,54]. Research conducted in Iceland highlights that adolescents aged 16–18 years are the most negatively affected during the COVID-19 pandemic [55]. Many authors have linked the pandemic with the increase in DS, not only due to loneliness, especially in girls, fear, school closures, and social distancing, exposure to family violence and parental substance use disorders during lockdowns, but also due to economic decline, financial hardship, or family bereavement [56,57].

In line with previous research [4,44,45], our results showed that the prevalence of DS was greater among female individuals compared to male individuals (27.9% vs. 14.7%). Additionally, in the multilevel logistic regression, males had 56% lower odds of having DS compared to females. There are several suggestions as to why girls are at higher risk for DS. Some authors claim that boys and girls have similar risks for depression during childhood, but girls begin to have a higher risk when they reach adolescence [58]. According to Hamilton et al., higher rates of depression in girls were explained by their greater exposure to total stress, particularly interpersonal dependent stress [59]. In addition, another research also indicated that emotional abuse and domestic violence increase the risk of depression in young girls [60]. According to the Report of the American Psychological Association, in girls, concern with physical appearance, body dissatisfaction, and exposure to sexualization may be the reasons that affect their mental health [61]. Further, other research showed that girls are oversensitive and tend to worry more than boys, which can lead to the development of depression among girls [62]. Research conducted among high school students in Serbia on how students spend their free time confirmed the already-known gender stereotypes. It was established that girls are more school-oriented; they spend more time at home, grooming, and going out to shop, and are more likely to do housework. In contrast, boys are oriented towards the outside world, sports, technology, and earning money [63]. It was also observed in the other literature that boys are better at meeting physical activity guidelines than girls [64], and it is known that the odds of depression were lower when people met or exceeded the recommended levels of physical activity [65]. Additionally, in a Swedish study, it was found that girls are especially susceptible to DS if they live in families of parents with a low level of education [25]. The literature indicates that the mother’s education is a crucial protective factor in helping daughters recover from bullying victimisation [66].

Our results showed that students with fathers who completed high school had 46% lower odds of depression compared to those whose fathers had the lowest education level. This finding is in line with another study, which revealed that with the increase in the education level of parents, the level of depression in their children decreased [67]. According to a German study, this also relates to overall mental health because the results showed that children from families with higher-educated parents showed a lower risk of developing mental health problems than their peers with lower-educated parents, explained by the fact that children of higher-educated parents are less affected by a stressful life situation [68]. On the other hand, a study conducted in Iran among female students aged 15–18 found no association between the parents’ level of education and students’ depression [69]. Moreover, in the Spanish study, there was no connection between the level of education of the parents and the mental health of adolescents, but there was in group 4- to 11-year-olds [70]. It is clear that the education of parents has multiple positive effects on the health of children. Although, when it comes to mental health, the literature also states that in addition to the protective effect that we already mentioned, there are also negative ones, such as the fact that children whose parents have a higher level of education have a higher level of academic stress and pressure, which can increase the risk of developing DS [71].

The prevalence of DS among adolescents in our study was significantly higher in students whose fathers were unemployed or retired (31.4%). Still, in the multilevel model, we did not find the father’s employment status to be a significant predictor of DS in adolescents. A possible explanation for the nonsignificant paternal association in the multilevel model could be the overestimation of prevalence due to the small sample size effect. Having an unemployed mother was associated with higher odds of DS in students compared to those whose mothers were employed. A potential reason for this relation is that DS extends beyond the boundaries of the individual, significantly affecting the family’s ability to experience these symptoms. The literature speaks of a bidirectional relationship. Disorders that occur in parents influence and shape the environment in which children live, leading to the manifestation of disorders in children. Consequently, changes that occur in children are often reflected in their parents, creating a bidirectional effect. In this way, DS in adolescents could influence maternal work capacity [72]. In a study conducted in Greece, the mother’s employment status was not associated with depressive episodes [73]. Piko et al. have discussed the employment of parents in the context of impact on children’s mental health, explaining that the father is often seen as the head of the family and that usually, his unemployment is seen as a negative factor in the general health and well-being of the family. At the same time, in the case of an unemployed mother, in some societies the role of the housewife becomes dominant, which can positively affect the psychosocial health of children [74]. In cases where parental education does not play a protective role, other factors may be more dominant, such as the moderating and mediating effects of various family characteristics, including parents’ mental health, parenting practices, and the parent-child relationship.

Others suggest that children living in a household with only one parent are more likely to report DS [75], while our research found that family type did not prove to be a significant predictor of DS. It has been observed that the risk for DS in adolescents is deepened by the fact that single parents themselves are at greater risk of developing depression due to the difficulties they face either due to divorce or the loss of a spouse, the stress caused by raising a child independently, and the financial challenges they face [76]. In addition to single parenthood, a non-significant association was found between school performance and DS in adolescents. However, other research has found that better academic achievement is positively associated with mental health [77]. Based on this, it can be concluded that other factors may have moderated the relationship between academic achievement and DS among our respondents.

Although the current study did not collect data on different adversities, with the aim of a broader overview of possible factors that are associated with DS, it is undoubtedly necessary to mention that exposure to hostile acts in the school environment, such as verbal bullying, social exclusion or isolation, physical bullying, bullying through lies and false rumours, having money or other things taken or damaged, threats or being forced to do things, sexual bullying and negative experiences in the family, psychosomatic health complaints, etc. would increase the probability of DS among adolescents [78]. Recent data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which includes 15-year-olds in Serbia, showed that 19% of girls and 17% of boys reported being victims of bullying at least several times a month [79]. On the other hand, peer relationship is recognized as a buffer against depression in adolescents. It is interesting to note that in this case, too, there is a gender difference, where bad social relations or their lack thereof have a greater impact on girls than on boys, considering the occurrence of DS [80]. Similarly, family support was associated with lower levels of DS resulting from persistent bullying victimization among girls, but with no evidence of a moderating role of family support among boys [81].

This study has some limitations. Its cross-sectional design makes it impossible to draw any conclusions about cause and effect. Younger students were more willing to participate in the study than the older ones (Age 15: 33.3% vs. Age 18: 14.6%), which could lead to the masking of age-related DS trends. A higher participation rate among younger students could impact the sample’s representativeness. Moreover, the research did not anticipate the use of school attendance records to indirectly assess potential biases. The research was conducted in a school, not in households; the authors limited themselves to parental occupation and education questions, believing that household income, assets or other poverty indicators would likely result in high levels of missing or invalid data. In future research, alternative socioeconomic proxies (e.g., parental occupation prestige, asset ownership) and additional factors (e.g., scales for academic pressure and adverse childhood experiences) could be incorporated to provide a more comprehensive assessment of factors related to DS among adolescents. The lack of our research could be due to recall bias, as all measures were self-reported. Additionally, other variables such as previous or actual psychiatric illness of respondents or their parents that might influence the findings were not included. Finally, exclusion bias since students who were absent on the day of the survey were excluded, potentially leading to an underestimation of the true prevalence.

The prevalence of DS among adolescents in Vojvodina is high. Gender differences are prominent; girls have significantly higher values of prevalence of DS than boys, and adolescents whose fathers were unemployed. Furthermore, girls had significantly higher odds of DS. Parental factors such as the father’s education and the mother’s employment status also showed a significant association with DS. The implementation of screening programs for early identification, especially in vocational schools, as well as the adoption of other special prevention programs intended for vulnerable categories, and the dedicated implementation of the defined goals are of utmost importance. Equally important is the reinforcement of psychological services within the educational system, with an emphasis on analytical practices that enhance mental well-being. This includes creating safer school environments, ensuring equal availability, and expanding the role of youth counselling centres within healthcare centres, all of which are key to establishing effective multisectoral collaboration.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank all the students who participated in this study and all schoolteachers who helped organize the data collection.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Sonja Čanković, Vesna Petrović; Methodology: Sonja Čanković, Vesna Petrović; Formal analysis and investigation: Sonja Čanković, Vesna Petrović; Writing—original draft preparation: Sonja Čanković; Writing—review and editing: Vesna Mijatović Jovanović, Tanja Tomašević, Dragana Milijašević, Dušan Čanković; Resources: Sonja Čanković, Vesna Petrović; Supervision: Vesna Mijatović Jovanović, Tanja Tomašević, Dragana Milijašević, Dušan Čanković. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data will be provided upon request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Novi Sad (No. 01-39/198/1) and by the principals of the secondary schools that participated in the research, with the prior consent of the Parents’ Advisory Board. In accordance with the Law on the Rights of Patients, which refers to research in public health involving a child who has reached the age of 15, the subjects themselves gave their written consent to participate in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lloyd CB. Growing up global: the changing transitions to adulthood in developing countries. Washington, DC, USA: The National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

2. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM IV disorders in the National Co-morbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. World Health Organization. Mental health of adolescents [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2024 [cited 2025 Feb 9]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health. [Google Scholar]

4. Daly M. Prevalence of depression among adolescents in the U.S. from 2009 to 2019: analysis of trends by sex, race/ethnicity, and income. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70(3):496–9. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.08.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Li JY, Li J, Liang JH, Qian S, Jia RX, Wang YQ, et al. Depressive symptoms among children and adolescents in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:7459–70. doi:10.12659/MSM.916774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Goodwin RD, Dierker LC, Wu M, Galea S, Hoven CW, Weinberger AH. Trends in U.S. depression prevalence from 2015 to 2020: the widening treatment gap. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63(5):726–33. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2022.05.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Miller L, Campo JV. Depression in adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(5):445–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2033475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Mullen S. Major depressive disorder in children and adolescents. Ment Health Clin. 2018;8(6):275–83. doi:10.9740/mhc.2018.11.275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Bozzola E, Barni S, Ficari A, Villani A. Physical activity in the COVID-19 era and its impact on adolescents’ well-being. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):3275. doi:10.3390/ijerph20043275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Yang CH, Lv JJ, Kong XM, Chu F, Li ZB, Lu W, et al. Global, regional and national burdens of depression in adolescents and young adults aged 10–24 years, from 1990 to 2019: findings from the 2019 global burden of disease study. Br J Psychiatry. 2024;225(2):311–20. doi:10.1192/bjp.2024.69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. U.S. Centers for disease control and prevention. Data and statistics on children’s mental health [Internet]. Atlanta, GA, USA: U.S. Centers for disease control and prevention; 2025 [cited 2025 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/data-research/index.html. [Google Scholar]

12. European Commission. Prevention of depression in children and adolescents. 2021 [cited 2025 Feb 10]. Available from: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/health-promotion-knowledge-gateway/depression-children-adolescents_en. [Google Scholar]

13. World Health Organization. Depressive disorder (depression) [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2023 [cited 2025 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression. [Google Scholar]

14. Gili M, Castellví P, Vives M, de la Torre-Luque A, Almenara J, Blasco MJ, et al. Mental disorders as risk factors for suicidal behavior in young people: a meta-analysis and systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord. 2019;245(9937):152–62. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. U.S. Centers for disease control and prevention. Leading cause of death. [cited 2025 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html. [Google Scholar]

16. United Nations Children’s Fund. The state of the world’s children 2021: on my mind—promoting, protecting and caring for children’s mental health. New York, NY, USA: UNICEF; 2021 [cited 2025 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/114636/file/SOWC-2021-full-report-English.pdf. [Google Scholar]

17. National Institute of Mental Health. Depression. [Internet]. Bethesda, MD, USA: National Institutes of Health; 2024 [cited 2025 Feb 17]. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/sites/default/files/health/publications/depression/depression.pdf. [Google Scholar]

18. Cioffredi LA, Kamon J, Turner W. Effects of depression, anxiety and screen use on adolescent substance use. Prev Med Rep. 2021;22(5):101362. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Sjödin L, Larm P, Karlsson P, Livingston M, Raninen J. Drinking motives and their associations with alcohol use among adolescents in Sweden. Nordisk Alkohol Nark. 2021;38(3):256–69. doi:10.1177/1455072520985974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Pozuelo JR, Desborough L, Stein A, Cipriani A. Systematic review and meta-analysis: depressive symptoms and risky behaviors among adolescents in low- and middle-income countries. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;61(2):255–76. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2021.05.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Korczak DJ, Cleverley K, Birken CS, Pignatiello T, Mahmud FH, McCrindle BW. Cardiovascular disease risk factors among children and adolescents with depression. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:702737. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.702737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Leone M, Kuja-Halkola R, Leval A, D’Onofrio BM, Larsson H, Lichtenstein P, et al. Association of youth depression with subsequent somatic diseases and premature death. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(3):302–10. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Copeland WE, Alaie I, Jonsson U, Shanahan L. Associations of childhood and adolescent depression with adult psychiatric and functional outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60(5):604–11. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2020.07.895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Malhotra S, Sahoo S. Antecedents of depression in children and adolescents. Ind Psychiatry J. 2018;27(1):11–6. doi:10.4103/ipj.ipj_29_17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Wirback T, Möller J, Larsson JO, Galanti MR, Engström K. Social factors in childhood and risk of depressive symptoms among adolescents—a longitudinal study in Stockholm. Sweden Int J Equity Health. 2014;13(1):96. doi:10.1186/s12939-014-0096-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Xiang Y, Cao R, Li X. Parental education level and adolescent depression: a multi-country meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2024;347(4):645–55. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.11.081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Lund J, Andersen AJW, Haugland SH. The social gradient in stress and depressive symptoms among adolescent girls: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Nor Epidemiol. 2019;28(1–2):27–37. doi:10.5324/nje.v28i1-2.3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. The Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Estimated population, 2023 [Internet]. Belgrade, Serbia: The Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia; 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.stat.gov.rs/en-US/vesti/statisticalrelease/?p=15196. [Google Scholar]

29. Eurostat. Suicide death rate by age group. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 27]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00202/default/bar?lang=en. [Google Scholar]

30. Mijatović-Jovanović V, Milijašević D, Čanković S, Tomašević T, Šušnjević S, Ukropina S. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and association with sociodemographic factors among the general population in Serbia. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2024;81(5):269–78. doi:10.2298/VSP231023005M. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kačavenda-Babović D, Đurić P, Babović R, Dugandžija T, Đekić-Malbaša J, Rajčević S. Epidemiological characteristics of suicide in the autonomous province of Vojvodina. Med Pregl. 2018;71(9–10):277–83. doi:10.2298/MPNS1810277K. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Skoric D, Rakic JG, Jovanovic V, Backovic D, Soldatovic I, Zivojinovic JI. Psychosocial school factors and mental health of first grade secondary school students-results of the health behaviour in School-aged children survey in Serbia. PLoS One. 2023;18(11):e0293179. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0293179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia No. 45/2013, 25/2019. The low of patients’ rights [Internet]. Belgrade, Serbia: Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia; 2019 [cited 2025 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_pravima_pacijenata.html. (In Serbian). [Google Scholar]

34. Brooks SJ, Krulewicz SP, Kutcher S. The Kutcher adolescent depression scale: assessment of its evaluative properties over the course of an 8-week pediatric pharmacotherapy trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13(3):337–49. doi:10.1089/104454603322572679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Lowe GA, Lipps GE, Gibson RC, Jules MA, Kutcher S. Validation of the Kutcher adolescent depression scale in a Caribbean student sample. CMAJ Open. 2018;6(3):E248–53. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20170035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Romero-Acosta K, Lipps GE, Lowe GA, Gibson R, Ramirez-Giraldo A. The validation of the Kutcher adolescent depression 6-item scale in a sample of Colombian preadolescents and adolescents. Eval Health Prof. 2024;47(1):27–31. doi:10.1177/01632787231175931. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Sarman A, Çiftci N. Relationship between smartphone addiction, loneliness, and depression in adolescents: a correlational structural equation modeling study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2024;76(3):150–59. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2024.02.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Kossewska J, Tomaszek K, Macałka E. Time perspective latent profile analysis and its meaning for school burnout, depression, and family acceptance in adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(8):5433. doi:10.3390/ijerph20085433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Mojs E, Bartkowska W, Kaczmarek Ł., Ziarko M, Bujacz A, Warchoł-Biedermann K. Psychometric properties of the Polish version of the brief version of Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale-assessment of depression among students. Psychiatr Pol. 2015;49(1):135–44. (In Polish). doi:10.12740/PP/22934. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. LeBlanc JC, Almudevar A, Brooks SJ, Kutcher S. Screening for adolescent depression: comparison of the Kutcher adolescent depression scale with the beck depression inventory. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002;12(2):113–26. doi:10.1089/104454602760219153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Sun Life Financial Chair in Adolescent Mental Health. The Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale (KADShow to use the 6-item KADS [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 28]. Available from: https://mentalhealthliteracy.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Serbian_KADS-2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

42. Heymans MW, Twisk JWR. Handling missing data in clinical research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;151(2):185–8. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.08.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

44. Shorey S, Ng ED, Wong CHJ. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;61(2):287–305. doi:10.1111/bjc.12333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Blomqvist I, Henje Blom E, Hägglöf B, Hammarström A. Increase of internalized mental health symptoms among adolescents during the last three decades. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29(5):925–31. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckz028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Gu J. Physical activity and depression in adolescents: evidence from China family panel studies. Behav Sci. 2022;12(3):71. doi:10.3390/bs12030071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Dziedzic B, Sarwa P, Kobos E, Sienkiewicz Z, Idzik A, Wysokiński M, et al. Loneliness and depression among polish high-school students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1706. doi:10.3390/ijerph18041706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Wartberg L, Kriston L, Thomasius R. Depressive symptoms in adolescents. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(33–34):549–55. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2018.0549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Beller J, Regidor E, Lostao L, Miething A, Kröger C, Safieddine B, et al. Decline of depressive symptoms in Europe: differential trends across the lifespan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2021;56(7):1249–62. doi:10.1007/s00127-020-01979-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Hena M, Leung C, Clausson EK, Garmy P. Association of depressive symptoms with consumption of analgesics among adolescents. J Pediatr Nurs. 2019;45(2):e19–23. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2018.12.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Medic S, Anastassopoulou C, Lozanov-Crvenkovic Z, Dragnic N, Petrovic V, Ristic M, et al. Incidence, risk, and severity of SARS-CoV-2 reinfections in children and adolescents between March 2020 and July 2022 in Serbia. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e2255779. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.55779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Madigan S, Racine N, Vaillancourt T, Korczak DJ, Hewitt JMA, Pador P, et al. Changes in depression and anxiety among children and adolescents from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177(6):567–81. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.0846. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1142–50. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Lu W. Adolescent depression: national trends, risk factors, and healthcare disparities. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(1):181–94. doi:10.5993/AJHB.43.1.15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Thorisdottir IE, Asgeirsdottir BB, Kristjansson AL, Valdimarsdottir HB, Jonsdottir Tolgyes EM, Sigfusson J, et al. Depressive symptoms, mental wellbeing, and substance use among adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iceland: a longitudinal, population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(8):663–72. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00156-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(11):1218–39.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Samji H, Wu J, Ladak A, Vossen C, Stewart E, Dove N, et al. Review: mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth—a systematic review. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2022;27(2):173–89. doi:10.1111/camh.12501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(1):128–40. doi:10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Hamilton JL, Stange JP, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Stress and the development of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression explain sex differences in depressive symptoms during adolescence. Clin Psychol Sci. 2015;3(5):702–14. doi:10.1177/2167702614545479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Gallo EAG, De Mola CL, Wehrmeister F, Gonçalves H, Kieling C, Murray J. Childhood maltreatment preceding depressive disorder at age 18 years: a prospective Brazilian birth cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2017;217(1):218–24. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. American Psychological Association. Report of the APA task force on the sexualization of girls. Report of the APA Task force on the sexualization of girls [Internet]. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association; 2007 [cited 2025 Feb 28]. Available from: http://www.apa.org/pi/women/programs/girls/report-full.pdf. [Google Scholar]

62. Chaplin TM, Gillham JE, Seligman ME. Gender, anxiety, and depressive symptoms: a longitudinal study of early adolescents. J Early Adolesc. 2009;29(2):307–27. doi:10.1177/0272431608320125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Videnović M, Pešić J, Plut D. Young people’s leisure time: gender differences. Psihologija. 2010;43(2):199–214. [Google Scholar]

64. Brazo-Sayavera J, Aubert S, Barnes JD, González SA, Tremblay MS. Gender differences in physical activity and sedentary behavior: results from over 200,000 Latin-American children and adolescents. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0255353. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0255353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Mammen G, Faulkner G. Physical activity and the prevention of depression: a systematic review of prospective studies. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(5):649–57. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Jang H, Park H, Son H, Kim J. The asymmetric effects of the transitions into and out of bullying victimization on depressive symptoms: the protective role of parental education. J Adolesc Health. 2024;74(4):828–36. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.11.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Sandal RK, Goel NK, Sharma MK, Bakshi RK, Singh N, Kumar D. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress among school going adolescent in Chandigarh. J Family Med Prim Care. 2017;6(2):405–10. doi:10.4103/2249-4863.219988. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Reiss F, Meyrose AK, Otto C, Lampert T, Klasen F, Ravens-Sieberer U. Socioeconomic status, stressful life situations and mental health problems in children and adolescents: results of the German BELLA cohort-study. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213700. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0213700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Moeini B, Bashirian S, Soltanian AR, Ghaleiha A, Taheri M. Prevalence of depression and its associated sociodemographic factors among Iranian female adolescents in secondary schools. BMC Psychol. 2019;7(1):25. doi:10.1186/s40359-019-0298-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Sonego M, Llácer A, Galán I, Simón F. The influence of parental education on child mental health in Spain. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(1):203–11. doi:10.1007/s11136-012-0130-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Jang YJ, Lee SY, Song JH, Hong SH. The effects of parental educational attainment and economic level on adolescent’s subjective happiness: the serial multiple mediation effect of private education time and academic stress. Korean J Youth Stud. 2020;27(12):249–73. doi:10.21509/KJYS.2020.12.27.12.249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Pérez-Edgar K, LoBue V, Buss KA. From parents to children and back again: bidirectional processes in the transmission and development of depression and anxiety. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38(12):1198–200. doi:10.1002/da.23227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Magklara K, Bellos S, Niakas D, Stylianidis S, Kolaitis G, Mavreas V, et al. Depression in late adolescence: a cross-sectional study in senior high schools in Greece. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):199. doi:10.1186/s12888-015-0584-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Piko B, Fitzpatrick KM. Does class matter? SES and psychosocial health among Hungarian adolescents. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(6):817–30. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00379-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Wang X, Wang Y, Zhang X, Yang W, Yang J. A large-scale cross-sectional study on mental health status among children and adolescents—Jiangsu Province, China, 2022. China CDC Weekly. 2023;5(32):710–4. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Kareem OM, Oduoye MO, Bhattacharjee P, Kumar D, Zuhair V, Dave T, et al. Single parenthood and depression: a thorough review of current understanding. Health Sci Rep. 2024;7(7):e2235. doi:10.1002/hsr2.2235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Monzonís-Carda I, Rodriguez-Ayllon M, Adelantado-Renau M, Moliner-Urdiales D. Bidirectional longitudinal associations of mental health with academic performance in adolescents: DADOS study. Pediatr Res. 2024;95(6):1617–24. doi:10.1038/s41390-023-02880-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Malinauskiene V, Malinauskas R. Predictors of adolescent depressive symptoms. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4508. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094508. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. PISA 2022 results (Volume I and II)—Country Notes [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 12]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/pisa-2022-results-volume-i-and-ii-country-notes_ed6fbcc5-en/serbia_961b99f9-en.html. [Google Scholar]

80. Adedeji A, Otto C, Kaman A, Reiss F, Devine J, Ravens-Sieberer U. Peer relationships and depressive symptoms among adolescents: results from the German BELLA study. Front Psychol. 2022;12:767922. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.767922. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Son H, Jang H, Park H, Subramanian SV, Kim J. Exploring the Trajectories of depressive symptoms associated with bullying victimization: the intersection of gender and family support. J Adolesc. 2025;97(3):746–57. doi:10.1002/jad.12450. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools