Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Linking Filial Piety to Adolescent Autonomy: The Sequential Mediating Roles of Depression and Well-Being in Taiwanese University Students

1 Center for Teacher Education, National Changhua University of Education, Changhua, 500207, Taiwan

2 Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, National Changhua University of Education, Changhua, 500207, Taiwan

3 Department of Electrical and Mechanical Technology, National Changhua University of Education, Changhua, 500208, Taiwan

4 Department of Guidance and Counseling, National Changhua University of Education, Changhua, 500207, Taiwan

5 Graduate Institute of Technology Management, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung City, 40227, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Shu-Hua Lin. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(8), 1181-1202. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.066515

Received 10 April 2025; Accepted 22 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Background: Recent scholarly attention has increasingly focused on filial piety beliefs’ impact on youth’s psychological development. However, the mechanisms by which filial piety indirectly influences adolescent autonomy through depression and well-being remain underexplored. This study aimed to test a sequential mediation model among filial piety beliefs, depression, well-being, and autonomy in Taiwanese university students. Methods: A total of 566 Taiwanese undergraduate and graduate students, comprising 390 females and 176 males, and including 399 undergraduates and 167 graduate students, were recruited through convenience sampling. Data were collected via an online questionnaire. Validated instruments were employed, including the Filial Piety Scale (FPS), the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Chinese Well-being Inventory (CHI), and the Adolescent Autonomy Scale-Short Form (AAS-SF). Statistical analyses included group comparisons, correlation analyses, and structural equation modeling to examine the hypothesized relationships and mediation effects. Results: The results revealed that filial piety beliefs exerted a significant positive impact on adolescent autonomy, with depression and well-being serving as key mediators in this relationship. A sequential mediation effect was confirmed through structural equation modeling (β = 0.052, 95% CI [0.028, 0.091]), with good model fit indices (χ2/df = 4.25, RMSEA = 0.076, CFI = 0.968), supporting the hypothesized pathway from filial piety to autonomy via depression and well-being. In terms of demographic differences, male students showed significantly higher autonomy than females (p < 0.001); students from single-parent families reported significantly higher depression levels than those from two-parent families (p < 0.05); and graduate students exhibited significantly higher autonomy and well-being than undergraduates (p < 0.05). Conclusions: These findings underscore not only the importance of filial piety beliefs for developing youth autonomy but also the critical role that mental health factors, such as depression and well-being, play in this process. The study concludes with a discussion of both theoretical implications and practical recommendations. These include strategies to foster reciprocal filial piety, strengthen parent-child relationships, and promote mental health. Additionally, the study outlines its limitations and proposes directions for future research.Keywords

In contrast to Western societies that emphasize individualism, Taiwan’s sociocultural context is deeply influenced by Confucian thought. It highlights a relational orientation and role-based ethics, core Chinese cultural values [1]. In Chinese familial contexts, filial piety belief is regarded as a fundamental cohesive force in parent-child relationships [2–4] and associated with psychological well-being [5]. Yeh introduced the Dual Filial Piety Model (DFPM), positing that filial piety beliefs can be divided into reciprocal filial piety (RFP) and authoritarian filial piety (AFP). RFP emphasizes children’s spontaneous expression of care, support, and concern for their parents, which stems from gratitude for their upbringing. RFP emphasizes voluntary, context-transcending normative beliefs rooted in Confucian interpersonal principles. RFP beliefs contribute to developing individuated and relationally oriented autonomy in adolescents. In contrast, AFP focuses on obedience to authority, asserting that children should unconditionally comply with their parents’ expectations and demands, often at the expense of suppressing or sacrificing their needs. AFP focuses on children’s role identity and the hierarchical nature of parent-child relationships in Chinese society [6,7]. These two dimensions form a rich and complex Chinese parent-child interaction model [8].

According to Erikson’s psychosocial development theory, a primary developmental task for university students transitioning into adulthood is balancing intimacy with isolation. The primary psychological task at this stage is to form close, trusting, and lasting relationships with others. Failure to establish such intimacy may lead to feelings of loneliness and isolation, which can negatively affect mental health [9]. As adolescents move toward adulthood, the parent-child relationship gradually shifts from an authoritarian model to one characterized by interaction and mutual understanding; through appropriate involvement and emotional support, this shift fosters the development of autonomy and expands students’ capacity to care for others [10]. Reciprocal and AFP were positively associated with a stronger sense of meaning in life among late adolescents. It helps promote the development of adolescents’ psychological tasks and mental health [11].

Self-determination theory contends that individuals’ capacity for self-choice arises from satisfying basic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Autonomy refers to the feeling that one’s actions are self-initiated and self-controlled. Competence means believing that one can successfully handle the activities one engages in. Relatedness involves feeling connected to others, experiencing acceptance, and receiving care [12]. The research indicated that basic psychological needs significantly mediated the relationships between parental autonomy support and university students’ academic engagement. Autonomous motivation also significantly mediated the relationships between parental autonomy support and academic engagement [13].

According to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, individual development is shaped by the dynamic interplay of multiple environmental systems. These systems encompass the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem. The microsystem refers to the environments that directly impact individuals’ psychological development, such as family, peers, or school. The mesosystem involves the interactions between two microsystems, such as the connections between the family and school. The exosystem exerts an indirect influence on individuals, including various social policies. The macrosystem refers to broader contextual systems, such as cultural values and the filial piety culture. The theory indicates that university students are influenced by their family members, interactions among multiple systems, and broader sociocultural influences on students [14]. These dynamic interactions collectively shape both filial piety beliefs and autonomy.

As they transition from adolescence to adulthood, university students represent a group particularly influenced by concepts of autonomy. Although existing research has identified associations among filial piety beliefs, depression, and well-being, the influence of these relationships on adolescent autonomy and the interconnections among the three variables remains insufficiently understood. Based on the aforementioned theoretical background and empirical findings, the primary objective of the present study is to examine the relational model among filial piety belief, depression, well-being, and adolescent autonomy. This research explores how filial piety belief, within the context of Eastern Chinese culture, influences the development of autonomy in youth, and it aims to provide substantive theoretical and practical recommendations for future studies on the interrelationships among filial piety, adolescent autonomy, depression, and well-being.

2 Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1 Theoretical Foundation for the Current Study

The theoretical basis of this study integrates the DFPM [6], Ecological Systems Theory [14], psychosocial development theory for university students [9], Self-Determination Theory [12], and the cultural characteristics of Chinese family functioning and parent-child interactions [2]. The DFPM distinguishes filial piety belief into two dimensions: RFP and AFP. RFP emphasizes a voluntary, cross-context normative belief grounded in gratitude for parental rearing, which engenders intimate interpersonal relationships and is founded on an inherently benevolent human nature [2,15]. AFP emphasizes fulfilling children’s social role obligations, often necessitating the subordination of personal needs to parental expectations. This includes glorifying parents and preserving family traditions, reflecting a passive and culturally specific form of filial piety. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory states that an individual’s developmental context comprises the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem. These interactive layers, including family members, educators, peers, and broader societal forces, play a critical role in shaping individuals’ behavior, beliefs, and cognitive development through direct and indirect pathways [16].

Furthermore, Chickering and Reisser’s Seven Vectors Model of psychosocial development posits that one of the major developmental tasks for university students aged 18 to 24 is the shift from independence toward interdependence [17]. This form of autonomy encompasses emotional independence (transitioning from dependency on parents to trusting peers and independent critical thinking), instrumental autonomy (the ability to handle problems and life challenges autonomously), and an awareness of interdependence (recognizing the mutual dependence between the individual, family, peers, and society). Self-determination theory further asserts that autonomy is a basic psychological need universally present across cultures and that parenting practices that foster autonomy significantly influence an individual’s psychological well-being [12].

Within the Chinese cultural context, Research has noted that family functioning emphasizes filial obedience and compliance, with disciplinary practices often characterized by nonverbal and implicit communication, prioritizing family harmony over individual psychological needs [18]. Moreover, Cheng et al. have indicated that Chinese children experience complex internal emotional processes when confronted with parental discipline and expectations [19]. Empirical studies have demonstrated that RFP can facilitate high-quality parent-child interactions, enhance emotion regulation capabilities, and improve life satisfaction [20], with higher levels of RFP associated with greater autonomy. Conversely, AFP may impede the development of cognitive autonomy, thereby exacerbating psychological stress and increasing the risk of depression [21]. Other studies have found that while RFP is negatively correlated with depression, anxiety, and aggressive behaviors, AFP is negatively correlated with suicidal ideation and may elevate the risk of eating disorders [22]. Nevertheless, Yan and Chen have noted that both reciprocal and AFP positively correlate with life satisfaction [23], and research by Mai and Le further indicates that these two forms of filial piety are not inherently contradictory but can effectively predict family well-being [24]. In summary, the present theoretical framework explores how filial piety belief within the Chinese cultural context influences the development of university students’ autonomy through psychological health factors (i.e., depression and well-being).

2.2 Research Framework and Hypotheses

2.2.1 The Relationship between Filial Piety Belief and Depression

RFP has been found to provide a significant protective effect against depressive symptoms in adolescents through both direct and indirect pathways. A negative correlation exists between filial piety belief and depressive symptoms, such that stronger filial piety is associated with a lower risk of depression [21,22,25].

2.2.2 The Relationship between Filial Piety Belief and Well-Being

Filial piety reflects an individual’s psychological needs and the patterns of interaction with their parents [2,26]. Variations in one’s perception of filial piety can lead to different interpretations and responses to parental behavior. Research has shown that Chinese children with higher levels of RFP tend to perceive maternal interference as a form of care and support, which reduces conflict between mother and child [27]. Furthermore, RFP is associated with higher levels of well-being [15,28,29]. RFP and authoritative filial piety are positively associated with life satisfaction [30]. Emotional filial responsibilities, on the other hand, were positively linked to life satisfaction and negatively associated with depression [31].

2.2.3 The Relationship between Filial Piety Belief and Adolescent Autonomy

Adolescent autonomy develops through both increasing personal decision-making and shifts in family relationships. Adolescents gradually gain control over individual choices, with autonomy shaped by the quality of parent-child interactions [32]. Similarly, emotional separation and independent decision-making are key to psychosocial adjustment, highlighting that autonomy evolves alongside changes in relationships with parents [33]. Individuals with higher levels of RFP tend to exhibit greater individuated autonomy [34]. Recognition and gratitude for parental upbringing contribute to the development of autonomy [35]. Research by Jen et al. indicates that Chinese adolescents who espouse strong RFP tend to exhibit greater cognitive flexibility and are better equipped to adapt to life challenges [36]. Conversely, individuals who overly emphasize AFP may struggle to meet situational demands. Regarding family harmony, mature relational autonomy enables adult children to better understand their parents’ expectations and adopt interaction strategies that help maintain harmonious relationships, fostering proactive care and support [37].

2.2.4 The Relationship between Depression and Well-Being

Empirical findings indicate a moderate negative correlation between well-being and depression [38]. Extensive empirical evidence suggests that individuals with higher levels of subjective well-being are substantially less prone to depression, a pattern consistently observed across diverse age groups and populations [38]. This relationship has also been confirmed in clinical samples [39], and genetic research has demonstrated a strong negative genetic correlation between well-being and depression [40]. An optimistic disposition is significantly associated with lower depressive symptoms and positively predicts an individual’s life satisfaction, indicating that optimism promotes mental health and overall well-being [41]. Additionally, constructs such as psychological capital and subjective well-being have been found to mediate the relationship between mindfulness and depression [36], with subjective well-being serving a similar mediating role between psychological capital and depression.

2.2.5 The Relationship between Depression and Adolescent Autonomy

Higher levels of autonomy are associated with better physical and mental health, primarily due to the adaptive functions of autonomy in daily life [42]. Conversely, when university students receive less functional care and experience greater emotional neglect and inequity, their physical and mental well-being deteriorates [43]. The adverse effects of depression may, therefore, undermine adolescent autonomy.

2.2.6 The Relationship between Well-Being and Adolescent Autonomy

Both individuated independence and relational connectedness are closely linked to individual adaptation and subjective well-being [44,45]. Well-being arises from satisfying basic psychological needs, one of which is harmony in interpersonal relationships (e.g., the parent-child relationship) [46]. Indeed, research has demonstrated that both individual and relational forms of autonomy are positively associated with subjective well-being [42]. The dual autonomy model emphasizes that individuals can simultaneously pursue personal independence and harmonious relationships; these two forms of autonomy are moderately correlated, and individuals tend to adopt the form of autonomy most advantageous for maintaining their well-being in a given context [47].

2.2.7 The Mediation Role of Depression on the Relationship between Filial Piety Belief and Adolescent Autonomy

Numerous studies have indicated that parent-child conflict exerts a negative impact on psychological and behavioral adaptation and can predict depressive symptoms in adolescents [48,49]. Although adolescents strive for independence and seek an egalitarian, reciprocal, and cooperative relationship with their parents, conflicts often arise when parents adhere to traditional authoritarian roles, leading to relationship imbalances [50]. While prior research has predominantly focused on the effects of filial piety belief or adolescent autonomy on adaptation, there is relatively little exploration of the emotional mechanisms of adaptation. Yeh found that adolescents’ perceptions of threat and self-blame regarding conflict mediate the negative effects of parent-child conflict on both internalizing and externalizing outcomes [6]. Moreover, adopting accommodative or suppressive responses in the face of prolonged family conflict may exacerbate negative emotions, stress accumulation, and negative emotional expression.

2.2.8 The Mediating Role of Well-Being in the Relationship between Filial Piety Belief and Adolescent Autonomy

Lu et al. emphasized that the emphasis on family harmony in Chinese familial relationships is a major source of an individual’s well-being [51]. In a study of Hong Kong university students, Chen found that RFP positively influenced students’ life satisfaction [52]. Further, Lu et al. indicated that children’s well-being is influenced by their own and their parents’ filial piety beliefs, with well-being mediating the relationship between RFP and the social support parents provide [51]. When parents adopt need-satisfying parenting practices, adolescents are likelier to exhibit higher autonomy and better adaptive functioning [53]. In other words, need-satisfying parenting, mediated by individuated autonomy, impacts personal adaptation outcomes (e.g., well-being and anxiety).

2.2.9 The Mediation Roles of Depression and Well-Being on the Relationship between Filial Piety Belief and Adolescent Autonomy

The influence of filial piety extends beyond the familial sphere, affecting not only parent-child conflict [54] but also individual psychological adaptation, such as well-being [55], mental health [36], and life satisfaction [52,56]. Supportive parenting practices via RFP mediate the relationship between parental support and adolescent well-being and the quality of parent-child relationships [55]. Research on the association between filial piety and mental health has further shown that RFP positively correlates with adolescents’ life satisfaction and social competence [56].

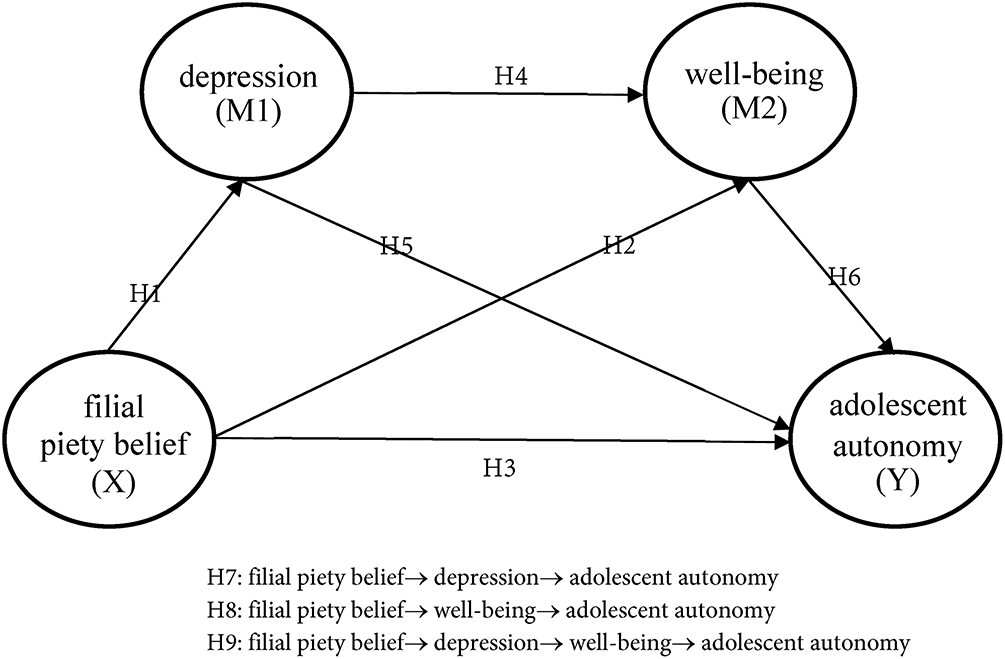

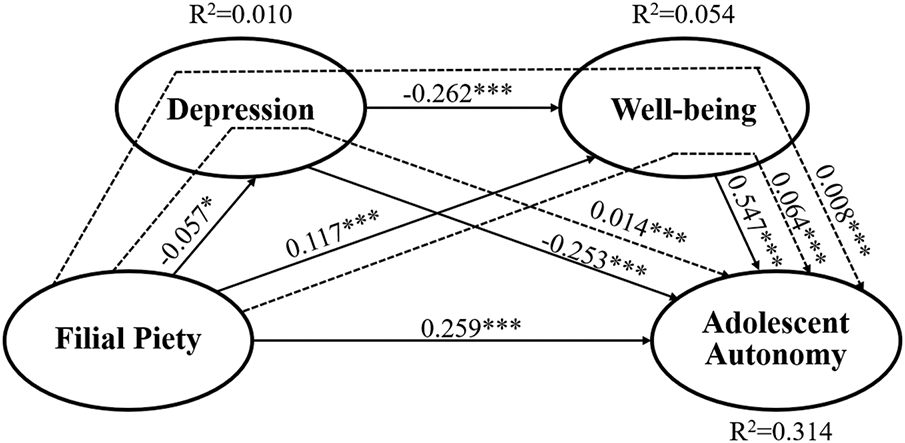

In summary, this study proposed a hypothesized model, as illustrated in Fig. 1, to examine the relationships among filial piety belief, depression, well-being, and adolescent autonomy. Filial piety belief is hypothesized to negatively predict depression (H1) and positively predict both well-being (H2) and adolescent autonomy (H3). Depression is expected to negatively predict well-being (H4) and adolescent autonomy (H5), while well-being is hypothesized to positively predict adolescent autonomy (H6). In addition to these direct effects, three mediating pathways are proposed: depression mediates the relationship between filial piety belief and autonomy (H7); well-being serves as a second mediator (H8); and a sequential mediation pathway is hypothesized, in which filial piety belief affects autonomy through depression and subsequently through well-being (H9). The following hypotheses are proposed in this study:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Filial piety belief negatively predicts depression.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Filial piety belief positively predicts well-being.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Filial piety belief positively predicts adolescent autonomy.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Depression negatively predicts well-being.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Depression negatively predicts adolescent autonomy.

Hypothesis 6 (H6): Well-being positively predicts adolescent autonomy.

Hypothesis 7 (H7): Depression mediates the relationship between filial piety belief and adolescent autonomy.

Hypothesis 8 (H8): Well-being mediates the relationship between filial piety belief and adolescent autonomy.

Hypothesis 9 (H9): Depression and well-being sequentially mediate the relationship between filial piety belief and adolescent autonomy.

Figure 1: Research framework for the current study

3.1 Participants and Procedures

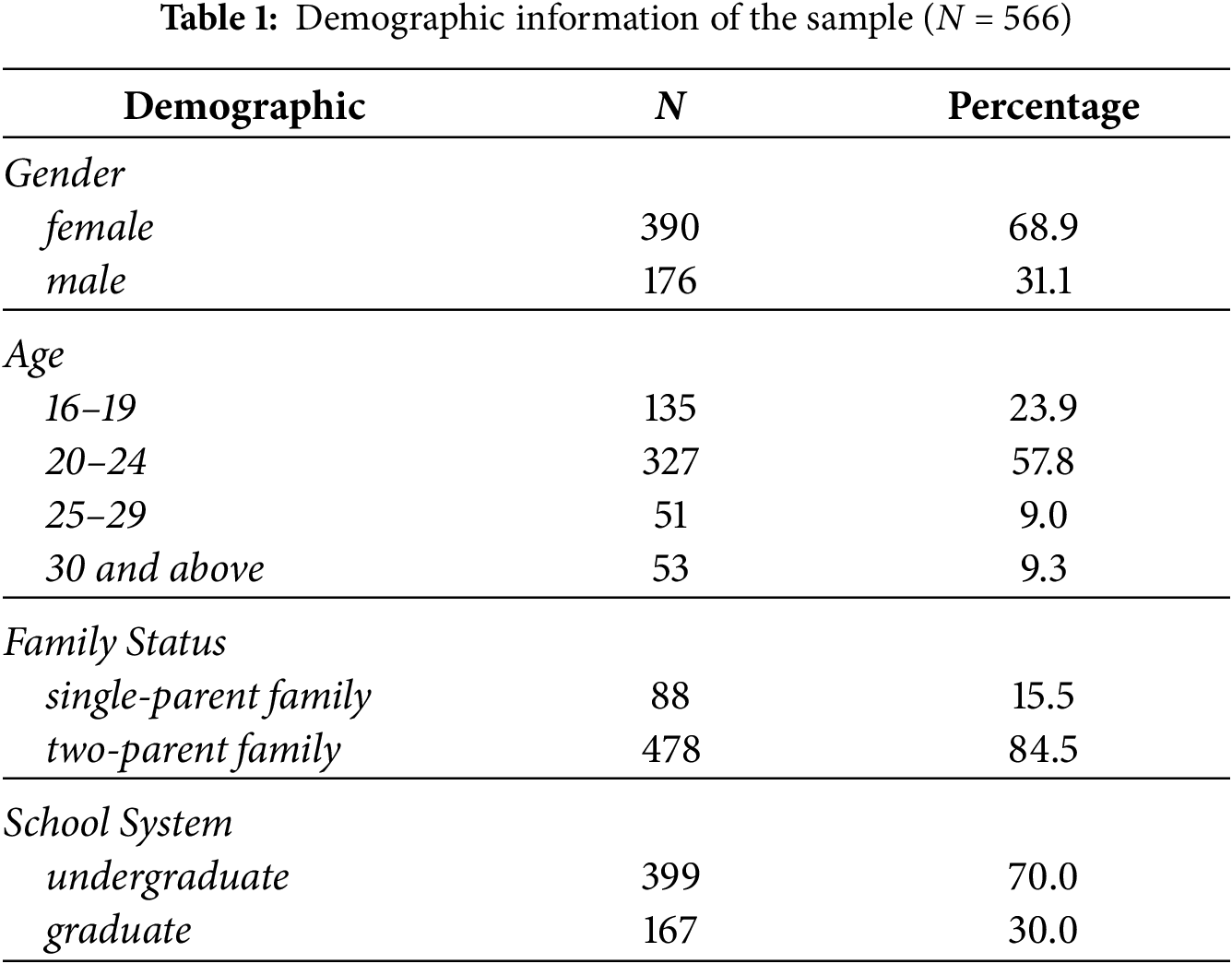

This study employed a cross-sectional observational design to examine the relationships among filial piety belief, depression, well-being, and autonomy among university students in Taiwan. In 2022, a total of 566 undergraduate and graduate students from 46 universities across Taiwan were recruited for this study using non-probability convenience sampling. The sample comprised 390 females and 176 males. Recruitment was conducted via multiple online channels, including university professors distributing the survey through educational platforms, academic communities and student networks. To reduce sampling bias, efforts were made to include students from diverse educational levels, institutions, and family backgrounds, thereby increasing the heterogeneity and generalizability of the sample. This research was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of both institutional and national research committees, as well as the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical standards. Before participating, all respondents were required to read and electronically sign an informed consent form, which detailed the study’s purpose, voluntary participation, confidentiality measures, and data withdrawal options. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the participants’ backgrounds, 68.9% were female and 31.1% were male; 15.5% came from single-parent families, while 84.5% were from two-parent families; 70.0% were undergraduate students and 30.0% were graduate students. The mean age was 23.2 years.

Scales that have been published in academic journals were used as measurement instruments. Three of the four scales, originally in English, were translated by five Taiwanese experts using the back translation method [57], and all scales were reviewed and revised to maintain high content validity.

3.2.1 Filial Piety Scale (FPS)

The Filial Piety Scale (FPS), developed by Yeh and Bedford, was adapted to measure university students’ filial piety beliefs [2]. The scale comprises 15 items divided into two subscales: RFP (7 items) and AFP (8 items). Responses were recorded on a 6-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating stronger filial piety beliefs.

3.2.2 Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) by Radloff was revised to assess depression among university students [58]. This scale contains 19 items categorized into four subscales: physical symptoms (7 items), melancholy (6 items), interpersonal troubles (2 items), and positive emotion (4 items). Responses were recorded on a 4-point Likert scale, with higher scores signifying more severe depressive symptoms.

3.2.3 Chinese Well-Being Inventory (CHI)

The Chinese Well-being Inventory (CHI), developed by Lu, was modified to measure the well-being of university students [59]. The CHI consists of 20 items covering five dimensions: optimism (4 items), positive affect (5 items), sense of control (3 items), satisfaction with self (3 items), and peace of mind (5 items). Participants responded using a 4-point Likert scale, with higher scores reflecting greater well-being.

3.2.4 Adolescent Autonomy Scale–Short Form (AAS-SF)

The Adolescent Autonomy Scale–Short Form (AAS-SF), developed by Yeh, was adapted to measure adolescent autonomy among university students [60]. This scale comprises seven items divided into two subscales: individuating autonomy (4 items) and relating autonomy (3 items). Responses were collected using a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater personal autonomy.

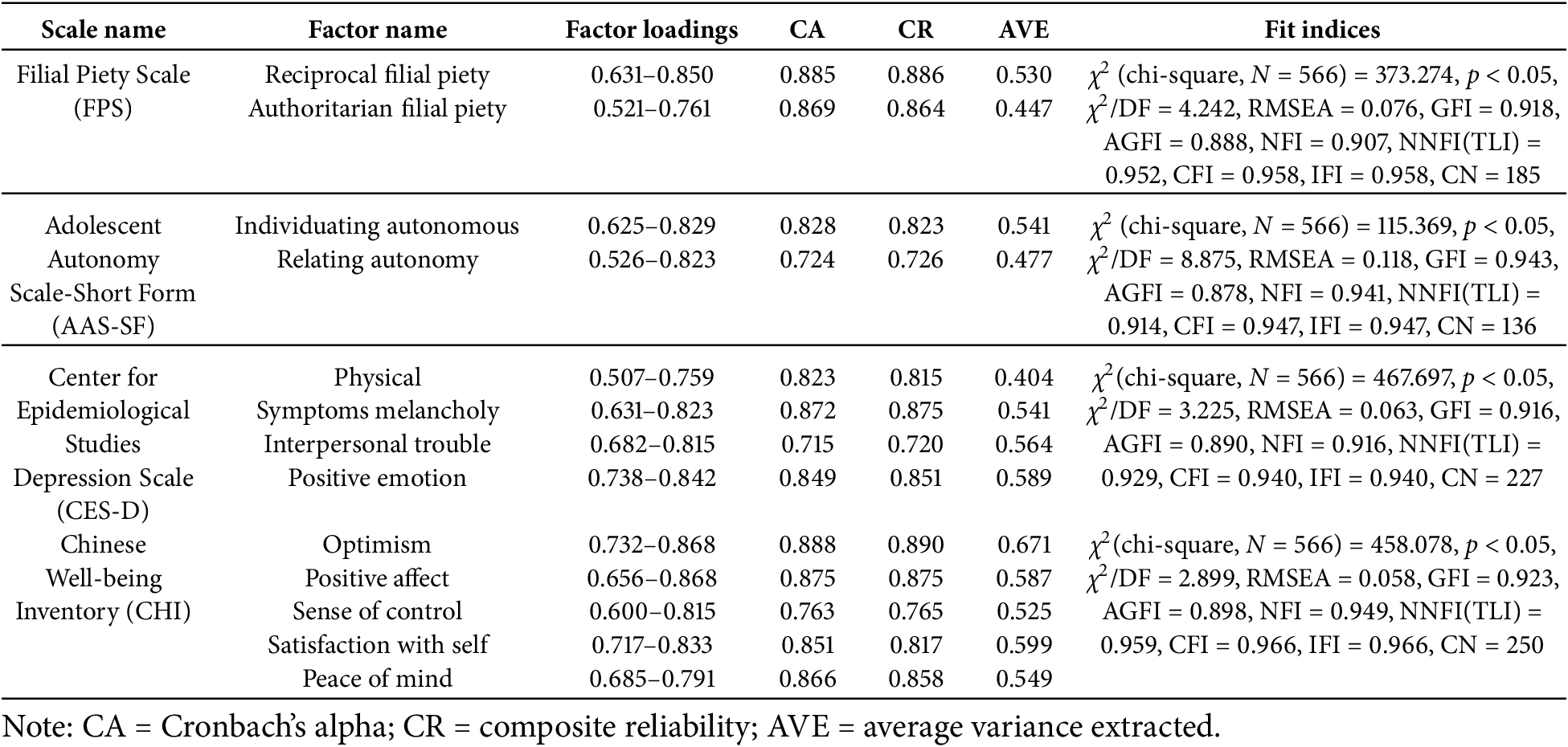

3.3 Confirmatory Factor Analysis for the Research Questionnaire

To assess the reliability and validity of the scales, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on data from all 566 participants. As shown in Table 2, the fit indices for the instruments were within acceptable ranges: factor loadings ranged from 0.521 to 0.868, Cronbach’s α values ranged from 0.715 to 0.888, construct reliability ranged from 0.726 to 0.890, and the average variance extracted (AVE) ranged from 0.404 to 0.671. The χ2/df ratios ranged from 2.899 to 8.875, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ranged from 0.058 to 0.118, the goodness of fit index (GFI) ranged from 0.916 to 0.943, the adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) ranged from 0.878 to 0.898, the normed fit index (NFI) ranged from 0.907 to 0.949, the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) ranged from 0.914 to 0.959, and both the comparative fit index (CFI) and incremental fit index (IFI) ranged from 0.940 to 0.966. These results indicate that the measurement model demonstrates acceptable levels of validity and reliability [61–63]. Please refer to Appendix A for a detailed breakdown of the scales and their CFA results.

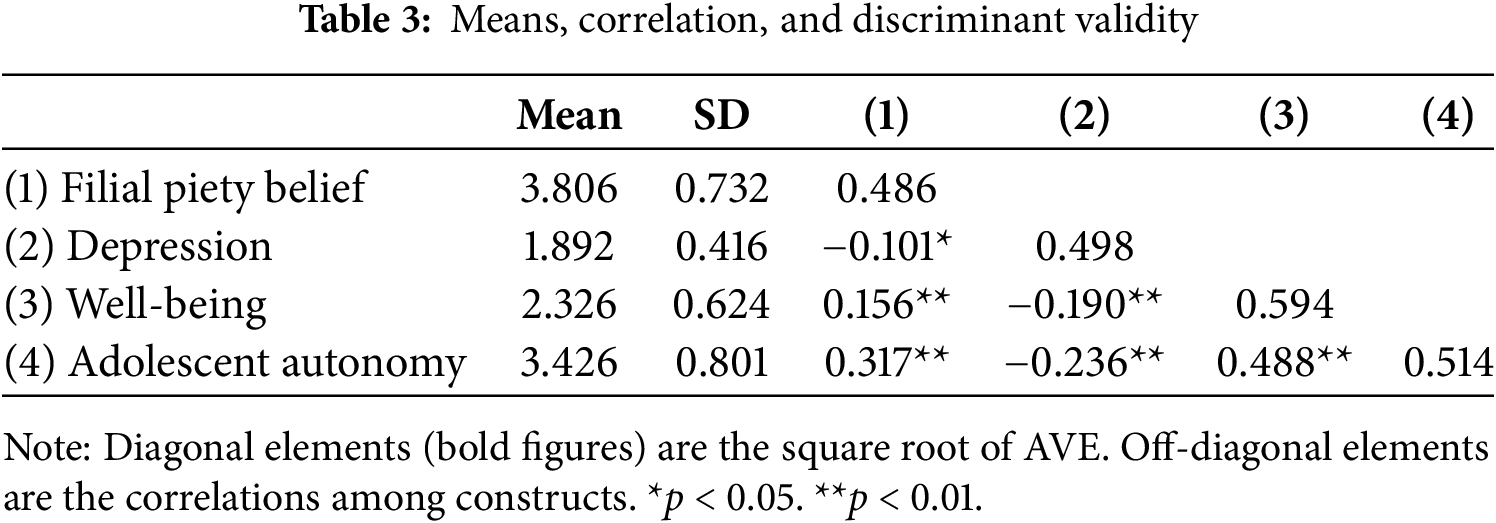

4.1 Assessment of Common Method Variance (CMV)

Two established procedures were implemented to evaluate the potential impact of common method variance (CMV). First, we examined the intercorrelations among all main study constructs. As shown in Table 3, none of the correlation coefficients exceeded 0.80, indicating that multicollinearity and CMV were unlikely to be of concern [64]. Second, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test using unrotated exploratory factor analysis. The analysis revealed that the first unrotated factor accounted for 29.76% of the total variance, well below the conventional 50% threshold. This result suggests that no single latent factor dominated the variance, and therefore, the presence of significant CMV was not supported [65]. In addition, the dataset contained no missing values across any key variables. All 566 responses were complete, and no imputation or listwise deletion was necessary. This completeness strengthens the reliability and interpretability of the statistical models tested in subsequent analyses.

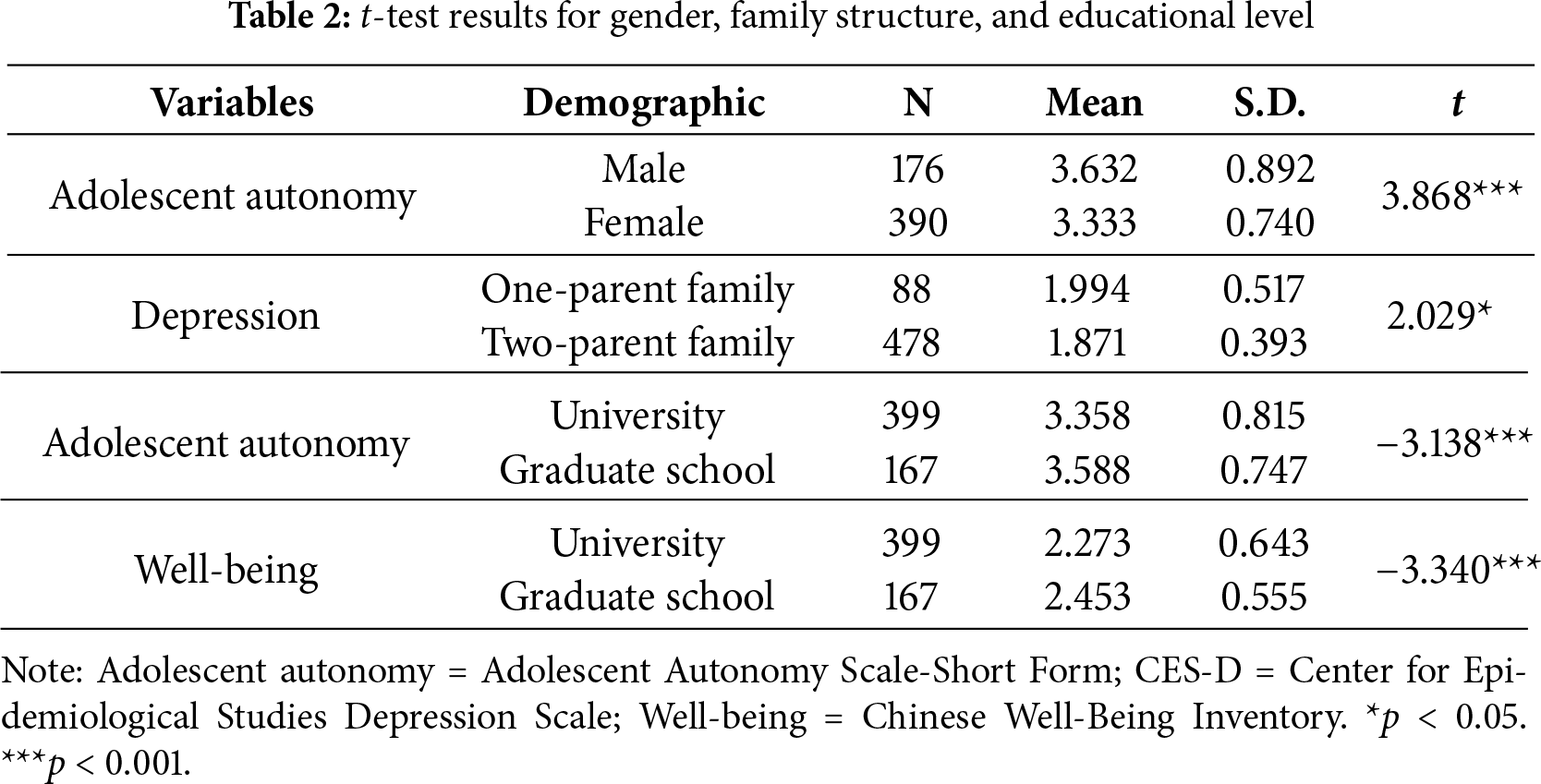

4.2 Differences in Research Variables by Demographic Characteristics

As presented in Table 2, independent-sample t-tests revealed that adolescent autonomy was significantly higher in males than in females (t = 3.868, p < 0.001). In terms of family background, participants from single-parent families reported substantially higher levels of depression than those from two-parent families (t = 2.029, p < 0.05). Regarding academic level, both adolescent autonomy (t = −3.138, p < 0.001) and well-being (t = −3.340, p < 0.001) were significantly higher among graduate students compared to undergraduates.

4.3 Correlation Analysis and Descriptive Statistics

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships among the study variables. As shown in Table 3, all correlation coefficients were below 0.80, suggesting no serious multicollinearity [64]. Regarding discriminant validity, the AVE for each construct was compared with the inter-construct correlations. According to Fornell and Larcker, if the square root of a construct’s AVE exceeds its correlations with other constructs, it demonstrates good discriminant validity [66].

4.4 Structural Equation Model Testing

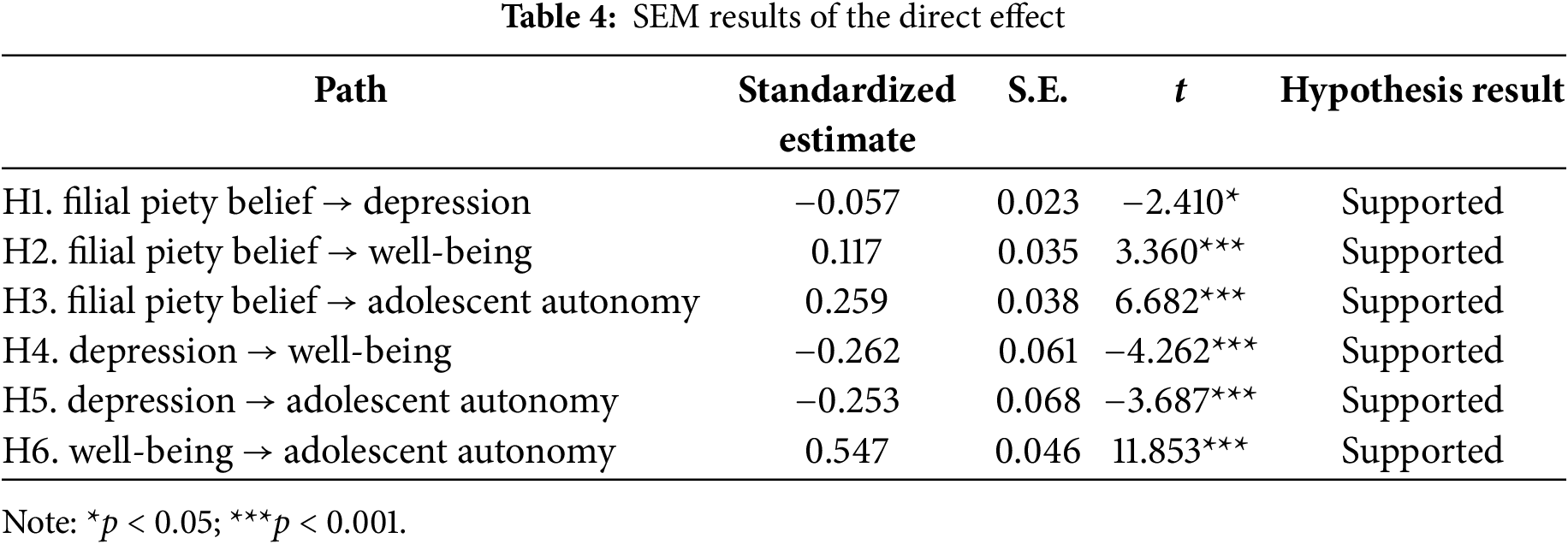

The results of the structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis are shown in Fig. 2, which displays the explained variance (R2) of the endogenous variables, the standardized path coefficients (β), and the indirect effects. This study employed the bootstrapping method [56], drawing 5000 samples and using a 95% confidence interval to test all hypotheses in the path model. A mediating effect was considered statistically significant at the 0.05 level if the bias-corrected 95% confidence interval did not include zero [67]. The analysis yielded a well-fitting path model, as assessed by multiple commonly used fit indices. The chi-square (χ2) value was 246.460 (df = 58, N = 566, p < 0.05), with a χ2/df ratio of 4.249, which is considered marginally acceptable in SEM literature. RMSEA was 0.076, indicating an adequate error level. Other absolute and incremental fit indices also demonstrated good model fit: GFI = 0.940, AGFI = 0.907, NFI = 0.958, non-normed fit index (NNFI/TLI) = 0.957, CFI = 0.968, and IFI = 0.968. The critical N (CN) value was 198, slightly below the recommended threshold of 200, yet still within a tolerable range.

Figure 2: The structural equation model of the study. Note: Solid lines represent direct effects, and dashed lines represent indirect (mediated) effects. Standardized path coefficients are shown. R2 values indicate the explained variance in each endogenous variable. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001

Table 4 and Fig. 2 present the hypothesis testing results. The findings indicate that filial piety belief significantly negatively affects depression (β = −0.057, p < 0.05), thereby supporting H1. Similarly, filial piety belief exerts a significant positive effect on well-being (β = 0.117, p < 0.001), which supports H2, and it has a significant positive effect on adolescent autonomy (H3: β = 0.259, p < 0.001), thereby supporting H3. Furthermore, depression significantly negatively affects well-being (H4: β = −0.262, p < 0.001), supporting H4, and it also shows a significant negative effect on adolescent autonomy (H5: β = −0.253, p < 0.001), supporting H5. In contrast, well-being has a significant positive effect on adolescent autonomy (H6: β = 0.547, p < 0.001), supporting H6, suggesting it is the strongest predictor among the variables.

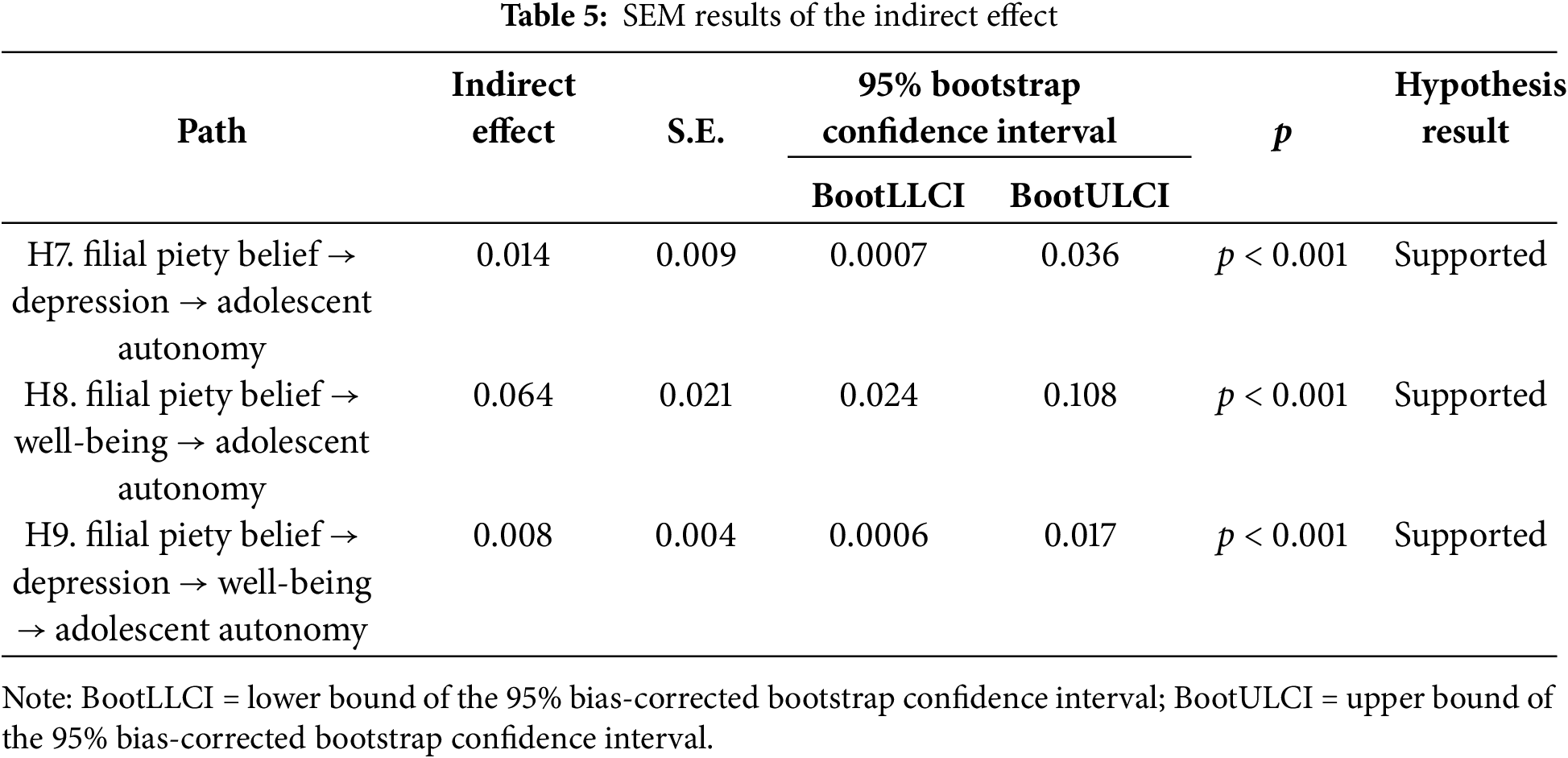

In addition, as shown in Table 5, the mediation hypotheses were confirmed. Specifically, depression partially mediated the relationship between filial piety belief and adolescent autonomy; the bias-corrected 95% confidence interval for the specific indirect effect ranged from 0.0007 to 0.036, thereby supporting H7. Similarly, well-being mediates the relationship between filial piety belief and adolescent autonomy, as indicated by a bias-corrected confidence interval ranging from 0.024 to 0.108, confirming H8. Finally, the multiple mediation model demonstrated that depression and well-being sequentially mediate the relationship between filial piety belief and adolescent autonomy, with the bias-corrected confidence interval ranging from 0.0006 to 0.017, confirming H9.

5.1 Implications of Demographic Variables Difference for the Study Constructs

The results indicate that adolescent autonomy is significantly higher among males than females (t = 3.868, p < 0.001). In Chinese societies, where gendered social experiences are deeply embedded, males are encouraged to exhibit autonomous and independent behaviors. They are often viewed as the key figures in inheriting family businesses and establishing households. According to Erikson’s psychosocial development theory, although the developmental focus for university students centers on intimate relationships, females receive less encouragement to develop autonomy and tend to maintain close ties with their families or other interpersonal networks [68]. Research has confirmed that females are generally more satisfied with dependency and affiliative needs; however, excessive reliance on interpersonal relationships for security may impede the development of autonomy [69]. Thus, the development of autonomy is more pronounced in males than in females, a finding that is consistent with previous research.

Regarding family status, individuals from one-parent families exhibit significantly higher levels of depression than those from two-parent families (t = 2.029, p < 0.05). Beyond physiological factors, environmental influences also contribute to depression; family settings marked by divorce or the loss of a parent are considered risk factors for adolescent depression [70,71]. Lin et al. found that family conflict and low autonomy in one-parent households may lead to declining family functioning. At the same time, excessive maternal care and emotional involvement can increase stress among children, thereby heightening depressive symptoms [72]. Therefore, our findings indicate that depression tendencies are significantly higher among individuals from one-parent families compared to those from two-parent families, which aligns with earlier studies.

In terms of school system, both adolescent autonomy (t = −3.138, p < 0.001) and well-being (t = −3.340, p < 0.001) were significantly higher among graduate students than undergraduates. This may be attributed to the fact that graduate students typically experience more stable physical development and have begun entering the workforce, which enhances their appreciation for parental care and enables them to share economic burdens. Moreover, graduate students generally have more choices, greater financial independence, and a higher level of education and experience than undergraduates, all of which can positively affect well-being. For instance, individuals with higher incomes usually report greater well-being than those with lower incomes. Additionally, because graduate students often live away from home and opt for off-campus housing, the parent-child relationship is less impacted by personal growth and environmental factors. When individual needs are adequately met, higher levels of autonomy and adaptation in life tend to follow. These results are consistent with those reported by Yeh et al. [73].

5.2 Filial Piety Belief Positively Influences Adolescent Autonomy

The study’s findings reveal a significant positive relationship between filial piety and autonomy (β = 0.259, p < 0.001), which concurs with previous research [74,75]. RFP is reflected in the naturally established intimate bond and affection between parents and children, embodying both the gratitude for parental care and the recognition of parental sacrifice [54]. Children who exhibit high levels of RFP can perceive and appreciate their parents’ efforts, support, and sacrifices and reciprocate these through respect and love [54]. Filial piety is closely linked to harmonious interpersonal relationships. It also facilitates positive social and behavioral development, such as empathy and self-disclosure [2]. When adolescents perceive that their parents express expectations and care that support autonomy, they are more likely to internalize these expectations as personal goals and motivations, enhancing their decision-making capabilities and fostering active participation in family and social domains [74]. Consequently, autonomy-supportive parenting practices that foster trust and encouragement in the parent-child relationship are likely to promote the development of adolescent autonomy and self-efficacy [75], with RFP further facilitating this developmental process.

5.3 Depression as a Mediator between Filial Piety Belief and Adolescent Autonomy

The results indicate that depression plays a mediating role in the relationship between filial piety belief and adolescent autonomy. When individuals perceive a weakening or violation of filial obligations, they may experience elevated levels of psychological stress and an increased risk of suicidal ideation, particularly in cultural contexts where filial expectations are strongly emphasized [20]. Moreover, research by Li and Dong suggests that a reduction in the perception of filial piety is associated with an increased risk of depression [25], a finding that is consistent with previous literature [20]; hence, a negative correlation exists between the perception of filial piety and the risk of depression. Empirical studies have further shown that perceived support from others, including care provided by family and broader social networks, has a significantly positive impact on the psychological well-being of older adults [39]. Individuals who uphold strong RFP are less likely to experience depression and other mental health issues. Additionally, a strong parent-child connection and autonomy-supportive parenting are crucial for developing adolescent autonomy, as they enhance communication skills, emotional regulation, and self-efficacy [76,77]. Thus, RFP contributes to the development of autonomy in children. In sum, by examining the relationship between filial piety belief, depression, and autonomy, this study makes a novel contribution by confirming that depression mediates the relationship between filial piety belief and adolescent autonomy.

5.4 Well-Being as a Mediator between Filial Piety Belief and Adolescent Autonomy

The findings also indicate that well-being mediates the relationship between filial piety belief and adolescent autonomy. Kim et al. argue that the perception of support from others is a critical factor influencing the psychological well-being of older adults [39], and empirical research has found that receiving emotional support and care from family or society enhances subjective well-being and reduces the risk of depression. Filial piety, which emphasizes children’s obedience and understanding toward their parents, is associated with a lower risk of depression among those who endorse strong RFP. Moreover, when adolescents internalize filial values and integrate them into their attitudes toward life, their overall life satisfaction and emotional well-being are improved [20]. Therefore, by examining the relationships among filial piety belief, well-being, and autonomy, this study confirms that well-being mediates the relationship between filial piety belief and adolescent autonomy.

5.5 Sequential Mediation of Depression and Well-Being in the Relationship between Filial Piety Belief and Adolescent Autonomy

Several studies have established a stable negative relationship between subjective well-being and depression, with this association playing a potential mediating role in research on filial piety and the development of adolescent autonomy [38,39]. Elevated levels of perceived filial piety are associated with a reduced risk of depression [21,25]. Among adolescents, RFP strongly correlates with life satisfaction. This association can be further strengthened by fostering greater autonomy and enhancing the quality of parent-child relationships [20,78]. The emotional bond between parents and children and parental support for autonomy are essential for developing adolescent autonomy, as they enhance psychological adaptation and the quality of interpersonal relationships [76,77]. Therefore, RFP is conducive to the development of autonomy. Filial piety belief, depression, well-being, and autonomy are closely intertwined. By examining these relationships, this study provides novel insights and confirms that depression and well-being sequentially mediate the relationship between filial piety belief and adolescent autonomy.

This study found that among youth, perceptions of filial piety are associated with a lower risk of depression and are positively correlated with the severity of internet addiction among adolescents [79]. Recent research further indicates that parental autonomy support is negatively associated with pathological Internet use, with filial piety serving as a partial mediator in this relationship [80]. In addition, RFP is negatively related to youth psychological problems, such as internet addiction and behavioral issues, suggesting that filial piety may serve as a protective factor against mental health symptoms [22,81]. Furthermore, RFP moderated the relationship between meaning in life and Internet addiction [82]. Based on the findings of this study, filial piety beliefs appear to influence both autonomy and internet addiction, warranting further investigation. Emphasizing the role of RFP may offer meaningful pathways to alleviate internet addiction among adolescents.

This study offers meaningful theoretical contributions by elucidating the relationships among filial piety belief, autonomy, depression, and well-being, enhancing the explanatory power, and integrating relevant psychological and cultural theories. First, our findings reveal a significant positive association between filial piety belief and adolescent autonomy. This result reaffirms previous observations [20,75] and indicates that the relationship is not solely direct; rather, it is realized through mediating processes involving psychological health indicators such as depression and well-being. This discovery advances our theoretical understanding of how filial piety belief influences adolescents’ psychological development, filling existing gaps in the literature by exploring how filial piety beliefs influence autonomy through psychological mechanisms. Second, the study confirms a negative relationship between filial piety belief and depressive tendencies, which is highly consistent with earlier research [21,25]. Notably, by focusing on the positive aspect of RFP, our study further clarifies how family values within a Chinese cultural context shape psychological health and serve as a protective factor that promotes adolescent adaptation and emotional regulation. These results bolster the view of filial piety as a culturally specific psychological resource and delineate its position and function within contemporary mental health theory. Incorporating well-being into the mediating framework through which filial piety belief influences autonomy deepens our theoretical understanding of its regulatory and transformative roles in psychological processes. Our results indicate that well-being is a crucial bridge between filial piety belief and autonomy and is also closely linked to overall life satisfaction [78], further emphasizing the interplay between mental health and psychosocial development. By integrating depression and well-being into a sequential mediation model, our study offers a more comprehensive and systematic mechanistic framework, enhancing the model’s explanatory power and predictive validity. Employing SEM enabled us to clearly distinguish and test the direct and indirect relationships among constructs. SEM’s statistical rigor and structural modeling capability have improved the precision with which latent pathways in the theoretical framework are interpreted, thus enhancing the filial piety belief theory’s overall consistency and logical coherence.

In summary, the theoretical contribution of this study lies in the explicit construction of a theoretical model incorporating depression and well-being as mediators, thereby unveiling the psychological processes through which filial piety belief impacts autonomy. This model addresses the previous lack of integration among filial piety, autonomy, and mental health theories and provides a theoretical foundation and research direction for future investigations into the dynamic relationship between cultural values and psychological adaptation. Moreover, the study underscores the cross-cultural applicability of filial piety belief theory, reinforcing its theoretical appropriateness and potential for broader dissemination in global psychological research.

The family is the most critical initial environment in individual development, exerting profound and lasting influences on personal growth [14]. In Chinese society, parent-child relationships are particularly shaped by cultural values centered on filial piety. This concept has evolved over thousands of years into an indispensable ethical norm in modern interpersonal interactions [51]. This study’s findings highlight the key role of filial piety in shaping mental health and autonomy. These findings offer clear, actionable implications for family education, psychological counseling, and educational practice. The study indicates that within the dual filial piety framework, a stable and positive relationship exists between RFP and individual well-being [83]. RFP emphasizes mutual respect and emotional support. Practically, this suggests that promoting such values in families may help foster better psychological outcomes [26]. Accordingly, this indicates that initiatives such as emotional development courses, family counseling, or therapeutic services could be implemented to promote the concept of RFP, thereby helping parents and children build closer, more supportive relationships that enhance family well-being and promote the development of adolescent autonomy.

Our study also found that the effects of AFP are relatively complex and can yield both positive and negative outcomes [2]. When applied appropriately, AFP can provide clear social norms that promote harmonious interpersonal relationships and facilitate the development of autonomy. However, if overemphasized or misapplied, it may be perceived as domineering or restrictive, negatively affecting individual autonomy [2]. Consequently, in family education and counseling practices, exercising caution in employing AFP and avoiding overly strict or controlling parenting styles is important. Modern education and mental health fields emphasize environments and parenting approaches that support autonomy while balancing respect for individual differences with normative expectations to fulfill psychological needs and foster healthy development [75]. The transition from secondary education to higher education or the labor market is a critical developmental phase that shapes the formation of autonomy and carries long-term implications for future adaptation and well-being [21]. Promoting filial piety during this stage, particularly through a bidirectional model emphasizing mutual respect and support, can significantly enhance university students’ autonomy and psychological well-being. Lu contends that filial piety promotes harmonious interpersonal relationships and effective social interactions and facilitates the effective transmission of experiences [84]; these functions can be realized through school curricula and psychological counseling practices. For instance, schools could offer courses on life education or mental health to guide students in understanding and reflecting on the various dimensions of filial piety and its impact on self-development. At the same time, counselors could explore family interaction patterns and provide concrete, actionable strategies to support individual psychological growth. From a policy perspective, this study offers important practical insights for governments and related agencies. In developing family or mental health policies, governments should consider the differential impacts of various forms of filial piety on diverse populations and strive to integrate traditional cultural values with modern ideologies, ensuring that the needs and interests of different generations are balanced. This study addresses contemporary challenges families and society face by offering clear and specific practical recommendations. It contributes to the positive transformation and innovative development of family systems and social structures.

7 Limitations and Future Directions

This study examined the relationships among filial piety belief, depression, well-being, and autonomy in Taiwanese university students, providing important preliminary insights; however, several limitations remain that future research should address and explore further. First, the study relied predominantly on self-report questionnaires for data collection, which may have introduced common method bias. Respondents might have been influenced by social desirability or self-protective inclinations during the survey process, potentially compromising the accuracy and interpretability of the findings [85]. To enhance data quality, future studies might consider adopting a mixed-methods design by incorporating qualitative interviews, behavioral observations, or obtaining information from multiple sources (e.g., teachers, parents, peers) to bolster the diversity and reliability of the data.

Second, this study employed a cross-sectional design that only revealed correlations among the variables, precluding any conclusions about causality. Future research should consider utilizing a longitudinal design to track psychological changes in participants over time, applying advanced statistical methods such as cross-lagged panel models and growth curve analyses to strengthen causal inferences. Although the sample was exclusively drawn from Taiwanese higher education institutions and is relevant to the research context, its cultural specificity limits the generalizability of the findings. Given that filial piety belief is deeply rooted in East Asian Confucian culture, its meanings and functions may vary across different cultural contexts. Future studies could expand the sample to other cultural backgrounds and conduct cross-cultural comparisons to examine the universality and variations in the relationships between filial piety belief, mental health, and autonomy [86].

Third, although the full age distribution was reported and supplementary analyses were provided, the broader age span may introduce variability. Prior research has shown that autonomy develops unevenly across adolescence and early adulthood, with notable age-related differences in behavioral and motivational dimensions [87,88]. These findings underscore the importance of aligning inclusion criteria with developmental frameworks. Future studies should apply stricter age-based criteria and consider age-specific trajectories in interpreting autonomy-related outcomes.

Fourth, this study involved participants over 30, whose retrospective accounts may reflect current experiences or shifting interpretations rather than accurate memories [89,90]. Emotional salience and reinterpretation over time can further undermine report validity [91]. Adolescent autonomy typically develops between ages 12 and 18, a period of growing independence and identity formation. For individuals well past this stage, recall accuracy may vary widely. Future research should adopt prospective longitudinal designs following individuals from adolescence into adulthood to enhance validity and enable causal inference. When using retrospective designs, restricting samples to younger adults nearer to adolescence may reduce memory bias [92]. Future studies should also compare retrospective and concurrent reports across age groups to evaluate recall consistency and validity [93].

Finally, although the scales used in this study demonstrated good reliability and validity, the AVE for certain constructs (e.g., well-being and autonomy) was slightly below the recommended threshold of 0.50, suggesting room for improvement in measurement precision. Future research could develop culturally sensitive and psychometrically refined measurement instruments to strengthen further discriminant validity and the overall structural stability of the model. This study constructed a sequential mediation model in which filial piety belief influences autonomy through mental health indicators. To better capture real-world dynamics, future research may incorporate potential moderator variables (e.g., gender, family structure, socioeconomic status) to explore their potential moderating effects on the hypothesized model. It offers more operational, practical recommendations to promote mental health and personal development among young individuals.

By validating a sequential mediation model, this study provides an in-depth examination of how filial piety belief among Taiwanese university students influences the development of adolescent autonomy through depression and well-being. The findings reveal a significant positive association between filial piety belief and autonomy, with depression and well-being serving as key mediators in this relationship. These findings suggest that filial piety significantly influences psychological development and behavior as a cultural and familial value. RFP, in particular, contributes to improved mental health and reduced depressive tendencies, thereby enhancing overall well-being and the development of autonomy. Theoretically, this study extends existing literature on filial piety within Eastern cultures by uncovering the underlying emotional regulation mechanisms that promote individual autonomy. Practically, the findings offer concrete, empirically supported recommendations for family education, psychological counseling, and youth empowerment programs. Cultivating a family and social atmosphere that fosters RFP can alleviate psychological distress among adolescents and help create a positive, supportive environment that enables young people to balance traditional values with modern self-determination. Importantly, the significance of this study lies not only in revealing the impact of Eastern cultural values on youth psychological development but also in emphasizing that, while pursuing individual independence and freedom, maintaining deep interpersonal connections is an essential foundation for mental health. In the context of globalization, this understanding encourages contemporary youth to re-examine the dynamic balance between individual freedom and group belonging, ultimately exploring the profound meaning of life and the shared values of human coexistence.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editorial board for their insightful comments and constructive feedback, which greatly enhanced the clarity and scholarly quality of this manuscript. We also extend our sincere appreciation to all anonymous participants, whose involvement and contributions were essential to the successful completion of this research. In addition, we gratefully acknowledge the National Changhua University of Education for its outstanding research infrastructure and administrative support, both of which played a vital role in facilitating this study.

Funding Statement: This study was partially funded by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, under Grant No. NSTC 113–2410-H-018-027 awarded to the first author, Yao-Chung Cheng.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Yao-Chung Cheng: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing, Funding Acquisition. Wei-Sho Ho: Data Curation, Analysis, Validation, Writing—Original Draft. Shu-Hua Lin: Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing. Kai-Jie Chen: Validation, Writing—Original Draft. Angel Hii: Writing—Original Draft. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Participants were informed that their data would be treated with strict confidentiality, accessible only to the research team, and destroyed three years after publication. As stated in the informed consent, the datasets generated and analyzed during the study are not publicly available to protect participant privacy.

Ethics Approval: This study adhered to the ethical standards of both institutional and national research committees and the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Scales

References

1. Hwang KK. Foundations of Chinese psychology: confucian social relations. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

2. Yeh KH, Bedford O. Filial piety: a test of the dual filial piety model. Asian J Soc Psychol. 2003;6(3):215–28. doi:10.1046/j.1467-839X.2003.00122.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang YF, Daoh M, Kasim NM, Lim SP. Focusing on filial piety: a scoping review study from cultural differences to educational practices. Quantum J Soc Sci Humanit. 2025;6(3):561. doi:10.55197/qjssh.v6i3.561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhang L, Han Y, Fang Y. Eastern perspectives on roles, responsibilities and filial piety: a case study. Nurs Ethics. 2020;28(3):414–30. doi:10.1177/0969733020934143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Liu J, Wu B, Dong X. Psychological well-being of Chinese immigrant adult-child caregivers: how do filial expectation, self-rated filial performance, and filial discrepancy matter? Aging Ment Health. 2020;24(3):489–96. doi:10.1080/13607863.2018.1544210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Bedford O, Yeh K-H. Evolution of the conceptualization of filial piety in the global context: from skin to skeleton. Front Psychol. 2021;12:570547. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.570547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Bedford O, Yeh KH, Tan CS. Editorial: filial piety as a universal construct: from cultural norms to psychological motivations. Front Psychol. 2022;13:980060. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.980060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Lin L, Wang Q. Adolescents’ filial piety attitudes in relation to their perceived parenting styles: an urban-rural comparative longitudinal study in China. Front Psychol. 2022;12:750751. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.750751. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Erikson EH. Childhood and society. New York, NY, USA: W. W. Norton; 1950. [Google Scholar]

10. Wintre MG, Yaffe M, Crowley J. Perception of Parental Reciprocity Scale (POPRSdevelopment and validation with adolescents and young adults. Soc Dev. 1995;4(2):129–48. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.1995.tb00056.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sun P, Yang Z, Jiang H, Chen W, Xu M. Filial piety and meaning in life among late adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2023;147(1):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2023.106837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Li Y, Sueb R, Said Hashim K. The relationship between parental autonomy support, teacher autonomy support, peer support, and university students’ academic engagement: the mediating roles of basic psychological needs and autonomous motivation. Front Psychol. 2025;16:1503473. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1503473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

15. Yeh KH. Intergenerational exchange behaviors among Taiwanese people: an exploration from the perspective of filial piety. Indig Psychol Res Chin Soc. 2009;31:97–141. (In Chinese). doi:10.6254/2009.31.97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chiu MM, Chow BWY. Classmate characteristics and student achievement in 33 countries: classmates’ past achievement, family socioeconomic status, educational resources, and attitudes toward reading. J Educ Psychol. 2015;107(1):152–69. doi:10.1037/a0036897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chickering AW, Reisser L. Education and identity. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA, USA: Jossey-Bass; 1993. [Google Scholar]

18. Lee S, Matthews B, Torres J. Cultural silence and emotional suppression in Asian-American families: a phenomenological exploration. Appl Fam Ther J. 2025;6(2):135–44. doi:10.61838/kman.aftj.6.2.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Cheng XL, Lin SH, Wu LJ. A study on the relationships between college students’ perceptions of parental authoritativeness and their anger processes and depressive tendencies. J Educ Psychol. 2001;32(2):19–44. doi:10.6251/BEP.20001112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sun P, Fan X, Sun Y, Jiang H, Wang L. Relations between dual filial piety and life satisfaction: the mediating roles of individuating autonomy and relating autonomy. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2549. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Pan Y, Tang R. The effect of filial piety and cognitive development on the development of adolescents’ depressive symptoms: a longitudinal study. Front Psychol. 2021;12:751064. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.751064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Han X, Cheung MC. The relationship between dual filial piety and mental disorders and symptoms among adolescents: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Adolesc Res Rev. 2025;10(1):31–45. doi:10.1007/s40894-024-00234-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yan J, Chen WW. The relationships between filial piety, self-esteem, and life satisfaction among emerging adults in Taiwan. In: Demir M, Sümer N, editors. Close relationships and happiness across cultures. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 151–64. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-89663-2_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mai VH, Le VH. The interdependence of happiness and filial piety within the family: a study in Vietnam. Health Psychol Rep. 2024;12(2):124–32. doi:10.5114/hpr/172091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Li M, Dong X. The association between filial piety and depressive symptoms among US Chinese older adults. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2018;4(1):1–7. doi:10.1177/2333721418778167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Bedford O, Yeh KH. The history and the future of the psychology of filial piety: chinese norms to contextualized personality construct. Front Psychol. 2019;10:100. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Wong SM, Leung ANM, McBride-Chang C. Adolescent filial piety moderates perceived maternal control and mother-adolescent relationship quality in Hong Kong. Soc Dev. 2010;19(1):187–201. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00523.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Guo X, Li J, Niu Y, Luo L. The relationship between filial piety and the academic achievement and subjective wellbeing of Chinese early adolescents: the moderated mediation effect of educational expectations. Front Psychol. 2022;13:747296. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.747296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Liu F, Chui H, Chung MC. Reciprocal/authoritarian filial piety and mental well-being in the Chinese LGB population: the roles of LGB-specific and general interpersonal factors. Arch Sex Behav. 2022;51:3513–27. doi:10.1007/s10508-021-02227-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wang Z, Xi J, Huang T, Xu Y. The association between dual filial piety and life satisfaction: a meta-analysis. J Fam Theory Rev. 2025;120(1):349. doi:10.1111/jftr.12614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Leung JTY, Shek DTL. Filial responsibilities and psychological wellbeing among Chinese adolescents in poor single-mother families: does parental warmth matter? Front Psychol. 2024;15:1341428. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1341428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Smetana JG. The development of autonomy during adolescence: a social-cognitive domain theory view. In: The Oxford handbook of moral development. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

33. Alonso-Stuyck P, Zacarés JJ, Ferreres A. Emotional separation, autonomy in decision-making, and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence: a proposed typology. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27(2):443–54. doi:10.1007/s10826-017-0980-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang Z, Chen WW. Chinese intimacy: filial piety, autonomy, and romantic relationship quality. Pers Relatsh. 2022;29(4):675–92. doi:10.1111/pere.12460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. An Y, Lu A, Chen W, Liu S, Li J, Ke X. Using network analysis to explore the key bridge indicators between parental autonomy support and filial piety among Xinjiang adolescents: moderation of gender. Curr Psychol. 2025. doi:10.1007/s12144-024-06563-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Jen CH, Chen WW, Wu CW. Flexible mindset in the family: filial piety, cognitive flexibility, and general mental health. J Soc Pers Relatsh. 2019;36(6):1715–30. doi:10.1177/0265407518770912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wu CW, Yeh KH. Becoming a caregiver for aging parents: filial piety beliefs, the ability to integrate intergenerational multitemporal and spatial experiences, and role identification as intergenerational caregivers among adult children. Chin J Couns Guid. 2020;59:1–33. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

38. Li C, Xia Y, Zhang Y. Relationship between subjective well-being and depressive disorders: novel findings of cohort variations and demographic heterogeneities. Front Psychol. 2023;13:1022643. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1022643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Kim JH, Lee J, Kim YB, Han AY. Subjective well-being and depressive symptoms in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(3):708–13. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.11.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Okbay A, Baselmans BM, De Neve JE, Turley P, Nivard MG, Fontana MA, et al. Genetic associations with subjective well-being also implicate depression and neuroticism. bioRxiv:032789. 2015. doi:10.1101/032789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wong S, Lim T. Hope versus optimism in Singaporean adolescents: contributions to depression and life satisfaction. Pers Individ Dif. 2009;46(5):648–52. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Wu CW, Yeh KH. The coexistence and differential operational mechanisms of dual autonomy: reducing common method variance through information discrimination performance. Chin J Psychol. 2011;53(1):59–77. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

43. Chen HS, Wu LJ. A study on the relationships among parentalization phenomena, the degree of individualization, and indicators of physical and mental health in college students. J Educ Psychol. 2013;45(1):103–20. (In Chinese). doi:10.6251/BEP.20130121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Brewer MB, Gardner W. Who is this “we”? Levels of collective identity and self-representation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71(1):83. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.1.83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Trafimow D, Triandis HC, Goto SG. Some tests of the distinction between the private self and the collective self. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60(5):649. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.60.5.649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Kwan VS, Bond MH, Singelis TM. Pancultural explanations for life satisfaction: adding relationship harmony to self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(5):1038. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.5.1038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Yeh KH, Liu YL, Huang HS, Yang YJ. Individuating and relating autonomy in culturally Chinese adolescents. In: Casting the individual in societal and cultural contexts. Seoul, Republic of Korea: Kyoyook-Kwahak-Sa Publishing; 2007. p. 123–46. [Google Scholar]

48. Casey-Cannon S, Pasch LA, Tschann JM, Flores E. Nonparent adult social support and depressive symptoms among Mexican American and European American adolescents. J Early Adolesc. 2006;26(3):318–43. doi:10.1177/0272431606288592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Shek DT, Ma HK. Parent-adolescent conflict and adolescent antisocial and prosocial behavior: a longitudinal study in a Chinese context. Adolescence. 2001;36(143):545–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

50. Bi X, Yang Y, Li H, Wang M, Zhang W, Deater-Deckard K. Parenting styles and parent-adolescent relationships: the mediating roles of behavioral autonomy and parental authority. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2187. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Lu L, Gao XF, Chen FY. The effects of traditionality, modernity, and filial piety beliefs on well-being: a parent-child dyadic design. Indig Psychol Res Chin Soc. 2006;25:243–78. (In Chinese). doi:10.6254/IPRCS.200604_(25).0006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Chen WW. The relationship between perceived parenting style, filial piety, and life satisfaction in Hong Kong. J Fam Psychol. 2014;28(3):308. doi:10.1037/a0036819. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Chuang SY, Yeh KH, Wu CW. Ability and affection: differentiating parental cognitive and emotional trust and exploring their functions. Chin J Psychol. 2016;58(3):169–85. (In Chinese). doi:10.6129/CJP.20160825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Yeh KH, Bedford O. Filial belief and parent-child conflict. Int J Psychol. 2004;39(2):132–44. doi:10.1080/00207590344000312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Chen WW, Wu CW, Yeh KH. How parenting and filial piety influence happiness, parent-child relationships and quality of family life in Taiwanese adult children. J Fam Stud. 2016;22(1):80–96. doi:10.1080/13229400.2015.1027154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Leung ANM, Wong SSF, Wong IWY, McBride-Chang C. Filial piety and psychosocial adjustment in Hong Kong Chinese early adolescents. J Early Adolesc. 2010;30(5):651–67. doi:10.1177/0272431609341046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Brislin RW. Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In: Triandis HC, Berry JW, editors. Handbook of cross-cultural psychology. Vol. 2. Boston, MA, USA: Allyn & Bacon; 1980. p. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

58. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Lu L. An exploration of the connotations, measurement, and related factors of happiness among Chinese people. Bull Res Natl Sci Counc Humanit Soc Sci. 1998;8(1):115–37. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

60. Yeh KH. Filial piety and autonomous development of adolescents in the Taiwanese family. In: The family and social change in Chinese societies. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2014. p. 29–38. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7445-2_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Fornell CR, Larcker DF. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981;18(3):39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Bentler PM. Confirmatory factor analysis via noniterative estimation: a fast, inexpensive method. J Mark Res. 1982;19(4):417–24. doi:10.1177/002224378201900403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate data analysis. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall; 2010. [Google Scholar]

64. Van Belle G. Statistical rules of thumb. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

65. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012;63(1):539–69. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–91. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(4):422–45. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Enns CZ. Self-esteem groups: a synthesis of consciousness-raising and assertiveness training. J Couns Dev. 1992;71(1):7–13. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1992.tb02162.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Miller PM, Ingham JG. Friends, confidants, and symptoms. Soc Psychiatry. 1976;11(2):51–8. doi:10.1007/BF00578738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, Rohde P. Major depression in community adolescents: age at onset, episode duration, and time to recurrence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(6):809–18. doi:10.1097/00004583-199407000-00006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Petersen AC, Compas BE, Brooks-Gunn J, Stemmler M, Ey S, Grant KE. Depression in adolescence. Am Psychol. 1993;48(2):155. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Lin YS, Li JH, Wu YC. An examination of the relationships among parental attitudes, family functioning, and depressive tendencies in adolescents. J Clin Psychol. 2006;3(1):35–45. (In Chinese). doi:10.6550/ACP.200606_3(1).0004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Yeh KH, Wu CW, Wang MH. The effects of perceived needs-satisfying parenting on adolescents’ adaptive performance: a longitudinal examination of the mediating role of dual autonomy. Indig Psychol Res Chin Soc. 2016;45:57–92. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

74. Çelik O. Academic motivation in adolescents: the role of parental autonomy support, psychological needs satisfaction, and self-control. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1384695. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1384695. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Guo M, Wang L, Day J, Chen Y. The relations of parental autonomy support, parental control, and filial piety to Chinese adolescents’ academic autonomous motivation. Front Psychol. 2021;12:724675. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.724675. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Clark KE, Ladd GW. Connectedness and autonomy support in parent-child relationships. Dev Psychol. 2000;36(4):485–98. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.36.4.485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Jiao J. Autonomy and parent-child relationship satisfaction: the mediating role of communication competence. Commun Res Rep. 2020;37(2):99–109. doi:10.1080/08824096.2020.1768060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Tan S, Nainee S, Tan CS. The mediating role of reciprocal filial piety in the relationship between parental autonomy support and life satisfaction among adolescents in Malaysia. Curr Psychol. 2021;40(2):804–12. doi:10.1007/s12144-018-0004-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Cangelosi G, Biondini F, Sguanci M, Nguyen CTT, Ferrara G, Diamanti O, et al. Anhedonia in youth and the role of internet-related behavior: a systematic review. Psychiatry Int. 2025;6(1):1. doi:10.3390/psychiatryint6010001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Ma C, Ma Y, Lan X. Parental autonomy support and pathological internet use among Chinese undergraduate students: gratitude moderated the mediating effect of filial piety. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2022;19(5):2644. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052644. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Wan J, Zhang Q, Mao Y. How filial piety affects Chinese college students’ social networking addiction: a chain-mediated effect analysis. Comput Hum Behav Rep. 2024;14(1):100378. doi:10.1016/j.chbr.2024.100378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Li Y, Yue P, Zhang M. Alexithymia and Internet addiction in children: meaning in life as mediator and reciprocal filial piety as moderator. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;16:3597–606. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S423200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Yu SJ. Harmony at home, prosperity in all things? A perspective on Chinese happiness through filial piety. Posit Psychol Couns Educ. 2024;3:98–115. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

84. Lu G. Filial piety is the pursuit of happiness. Beijing, China: China Youth Press; 2013. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

85. King MF, Bruner GC. Social desirability bias: a neglected aspect of validity testing. Psychol Mark. 2000;17(2):79–103. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(200002)17:2<79::AID-MAR2>3.0.CO;2-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Jager J, Putnick D, Bornstein MII. More than just convenient: the scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2017;82(2):13–30. doi:10.1111/mono.12296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Dutra-Thomé L, Marques LF. Autonomy development: gender and age differences from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Rev Iberoam Diagn Eval Psicol. 2019;2(52):27–38. doi:10.22201/fpsi.20074719e.2019.2.259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Modrek AS, Hass R, Kwako A, Sandoval WA. Do adolescents want more autonomy? Testing gender differences in autonomy across STEM. J Adolesc. 2021;90(1):58–68. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.09.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. McCurdy AL, Williams KN, Lee GY, Benito-Gomez M, Fletcher AC. Measurement of parental autonomy support: a review of theoretical concerns and developmental considerations. J Fam Theory Rev. 2020;12(4):517–32. doi:10.1111/jftr.12389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Inguglia C, Ingoglia S, Liga F, Lo Coco A, Lo Cricchio MG. Autonomy and relatedness in adolescence and emerging adulthood: relationships with parental support and psychological distress. J Adult Dev. 2015;22(1):1–13. doi:10.1007/s10804-014-9206-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Palermo TM, Putnam J, Armstrong G, Daily S. Adolescent autonomy and family functioning are associated with headache-related disability. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(5):458–65. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31805f70e2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Pavlova MK, Haase CM, Silbereisen RK. Early, on-time, and late behavioural autonomy in adolescence: psychosocial correlates in young and middle adulthood. J Adolesc. 2011;34(2):361–70. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Teuber Z, Tang X, Sielemann L, Otterpohl N. Autonomy-related parenting profiles and their effects on adolescents’ academic and psychological development: a longitudinal person-oriented analysis. J Youth Adolesc. 2022;51(1):34–50. doi:10.1007/s10964-021-01538-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools