Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Relationship between Mobile Phone Dependency and Academic Burnout in Middle and High School Students

1 Faculty of Psychology, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, 300387, China

2 Mental Diseases Prevention and Treatment Institute of Chinese PLA, No. 988 Hospital of Joint Logistics Support Force, Jiaozuo, 454003, China

3 Key Research Base of Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education, Academy of Psychology and Behavior, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, 300387, China

4 Center of Cooperative Innovation for Assessment and Promotion of National Mental Health under the Ministry of Education, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, 300387, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhansheng Xu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mental Health and Subjective Well-being of Students: New Perspectives in Theory and Practice)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(8), 1165-1180. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.067133

Received 25 April 2025; Accepted 31 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Background: With the proliferation of smartphones, adolescent mobile phone dependency has intensified, potentially precipitating academic burnout and other adverse outcomes among students. Contemporary study mostly examines college populations, resulting in a lack of exploration on the internal mechanisms connecting mobile phone dependency to academic burnout. In addition to analysing the chain-mediated effects of sleep quality and cognitive flexibility, this study sought to provide theoretical insights for prevention by applying the Conservation of Resources theory to examine the relationship between academic burnout and mobile phone dependency among middle and high school students. Methods: A cluster convenience sampling approach was adopted. Data were collected from 811 middle and high school students in Tianjin, China, using a paper-based questionnaire battery comprising the Mobile Phone Addiction Index, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, the Cognitive Flexibility Scale, and the Adolescent Academic Burnout Scale. Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were conducted using SPSS 25.0. Chain mediation effects were examined via the PROCESS macro, with significance assessed using bias-corrected bootstrap 95% confidence intervals. Results: A statistically significant positive link exists between mobile phone dependency and academic burnout among middle and high school students (r = 0.575, p < 0.001). Dependence on mobile phones had a substantial direct impact on academic burnout (β = 0.303, p < 0.001). Chain mediation analysis revealed that mobile phone dependency had a substantial direct impact on academic burnout (β = 0.303, p < 0.001). Sleep quality and cognitive flexibility mediated the link between mobile phone dependency and academic burnout. These indirect pathways represent 44.18% of the total effect. Conclusions: Mobile phone dependency contributes to academic burnout among middle and high school students, mediated sequentially by sleep quality and cognitive flexibility. These findings suggest a potential intervention strategy to mitigate academic burnout by targeting excessive mobile phone use, enhancing sleep hygiene, and implementing cognitive flexibility training.Keywords

In accordance with the 54th Statistical Report on Internet Development released by the China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), China’s internet user base had reached approximately 1.1 billion by June 2024, including 298 million adolescent users. Notably, 99.7% of these young internet users accessed the internet primarily through mobile devices [1], indicating a substantial growth in mobile phone adoption among Chinese youth. Pervasive mobile technology in our hyper-connected society has established adolescent mobile phone dependency as a significant predictor of multifaceted psychological and behavioral maladjustment [2].

Mobile phone dependency is a cyclical state of fascination resulting from the habitual use of mobile phones, accompanied by a strong and persistent sense of need and reliance [3]. Substantial empirical research confirms that students’ academic achievement and social competence are significantly compromised by mobile phone dependency [4,5]. Moreover, it exhibits strong correlations with psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression [6–8] and may precipitate maladaptive behavioral patterns [9].

Although prior studies have examined the mediating pathways connecting smartphone overuse to affective disorders, including depressive symptomatology [10] and behavioral maladjustment, including pathological procrastination patterns [11], a critical gap remains regarding its impact on academic adaptation, particularly academic burnout. Academic burnout induces detrimental emotional and cognitive changes, manifesting as diminished learning motivation [12] and behavioral disengagement from academic tasks, including alienation, withdrawal, or chronic procrastination [13]. Chronic academic burnout may further lead to reduced subjective well-being [14].

During this formative developmental period centered on scholastic success, secondary education students experience academic burnout as a significant detrimental outcome of excessive smartphone engagement [9]. Consequently, investigating the effects of mobile phone dependency on academic burnout among adolescent students constitutes an urgent research priority.

2.1 Relationship between Mobile Phone Dependency and Academic Burnout

Students are predominantly affected by academic burnout—a chronic, adverse psychological condition stemming from learning contexts [15]. Three defining characteristics emerge in this syndrome: (1) depletion of emotional resources, (2) detachment from academic work (or cynicism), and (3) diminished sense of accomplishment [16]. Empirical research indicates that academic burnout precipitates a range of detrimental outcomes, including: physical impairments (e.g., headaches, appetite loss, musculoskeletal disorders, and general fatigue), behavioral maladjustments (e.g., truancy and school dropout), and psychological disturbances (e.g., heightened anxiety and depressive symptoms) [12,17,18]. The etiology of academic burnout is multifaceted, influenced by family dynamics [19], peer and teacher-student relationships [20], individual traits [21], and psychological symptoms [22]. Furthermore, the proliferation of digital technology has exacerbated problematic internet use, which has emerged as a significant predictor of academic burnout [23].

The Demand-Resource Model posits that academic burnout occurs if school environments impose excessive demands on students while providing insufficient learning resources [24]. First, the Cognitive Processes Model of Addiction [25] suggests that adolescents with mobile phone dependency develop automatic stimulus-response associations through habitual device use, exhibiting an attentional bias toward mobile phone-related cues. For middle and high school students with pronounced mobile phone dependency, this cognitive bias may divert limited attentional resources away from learning activities, thereby contributing to academic burnout [26]. Second, mobile phone-dependent students frequently engage in social media browsing due to internal factors (e.g., fear of missing out, boredom), in addition to the external factors (e.g., the highly social nature of networking platforms, rapid information dissemination) [27]. This behavior not only disrupts sustained attention and promotes academic procrastination [28] but also elevates vulnerability to academic burnout. Empirical evidence demonstrates that vocational college students exhibit progressively worsening mobile phone dependency throughout their academic tenure, paralleling increases in academic burnout [29]. Similarly, adolescent-focused research confirms a robust association between mobile phone dependency and academic burnout [9]. Based on these findings, this study hypothesizes that (Hypothesis 1) mobile phone dependency positively predicts academic burnout.

2.2 The Mediating Role of Sleep Quality

Sleep quality serves as a critical indicator of sleep efficacy, encompassing multidimensional components such as sleep onset latency, sleep continuity, frequency of nocturnal awakenings, and subjective restorative perception upon waking [30]. As a fundamental biological process, sleep plays an indispensable role in sustaining both physiological and psychological well-being [10,31]. Empirical evidence demonstrates that sleep deprivation adversely impacts cognitive performance, including memory consolidation and executive functioning [32,33].

Previous studies have shown a significant negative correlation between mobile phone dependency and sleep quality [34–37]. Aligned with the Sleep Displacement Theory, individuals exhibiting excessive mobile phone engagement disproportionately allocate time to nocturnal internet use, thereby curtailing sleep duration and compromising sleep quality [38]. Furthermore, longitudinal data indicate that prolonged mobile phone overuse serves as a predictive factor for subsequent sleep disturbances [10].

Previous studies have demonstrated that poor sleep quality significantly predicts academic burnout [39,40]. The Conservation of Resources model posits that individuals possess an inherent motivation to preserve and accumulate resources, with resource depletion constituting the fundamental cause of burnout [41]. According to the Conservation of Resources theory, resources encompass entities that individuals value or pathways facilitating the acquisition of valued assets [42]. Expanding on this conceptualization, Halbesleben et al. defined resources as elements perceived by individuals to aid in goal attainment [43]. Sleep quality represents a critical component of self-regulatory resources, and its deterioration may precipitate burnout [42]. An empirical investigation involving 196 medical students confirmed that sleep quality negatively predicts academic burnout [44], indicating an inverse relationship wherein diminished sleep quality corresponds to elevated academic burnout levels.

Based on the aforementioned evidence, this study posits that (Hypothesis 2) sleep quality acts as a mediating factor in the relationship between mobile phone dependency and academic burnout among middle and high school students. More specifically, mobile phone dependency not only encroaches upon sleep duration but also compromises sleep quality and depletes personal resources, thereby potentially contributing to academic burnout in this student population.

2.3 The Mediating Role of Cognitive Flexibility

Cognitive flexibility, a core component of executive functioning, refers to the mental ability to shift between conceptual frameworks, adapt to dynamic environments, and approach problems from novel perspectives beyond conventional paradigms [45]. The Conservation of Resources theory conceptualizes resources as four distinct categories: (1) object resources like vehicles and work tools; (2) condition resources such as employment status and tenure; (3) personal resources exemplified by core competencies (e.g., self-efficacy, optimism); and (4) energy resources like knowledge and financial capital [42]. Within this framework, cognitive flexibility functions as a critical energy resource that facilitates stress adaptation [46]. Consequently, individuals exhibiting heightened cognitive flexibility display superior adaptability to environmental changes and demonstrate enhanced divergent thinking capabilities. Moreover, they exhibit superior capacity to identify and mobilize alternative resources in response to changing circumstances [47].

Students with higher cognitive flexibility demonstrate enhanced cognitive adaptability, greater availability of cognitive resources, and increased self-efficacy, thereby potentially mitigating academic burnout [48]. Empirical evidence indicates that middle school students experiencing pronounced academic burnout exhibit significantly lower cognitive flexibility than their less-affected counterparts [49]. Research has established that addictive behaviors compromise cognitive functioning, with mobile phone dependence exerting particularly detrimental effects on cognitive flexibility [50–52]. A recent study identified a robust inverse relationship between mobile phone addiction and cognitive flexibility, where higher addiction severity predicted greater impairment in cognitive flexibility [53]. The cognitive resource limitation theory posits that excessive mobile phone use exacerbates cognitive load and substantially depletes finite cognitive resources [54]. This depletion not only induces cognitive failures through resource exhaustion [55] but also precipitates academic burnout when insufficient cognitive resources remain available to cope with academic demands.

Based on this cumulative evidence, we hypothesize that (Hypothesis 3) cognitive flexibility mediates the relationship between mobile phone dependency and adolescent academic burnout.

2.4 The Chain Mediation of Sleep Quality and Cognitive Flexibility

The Conservation of Resources (COR) model posits that resources (e.g., self-esteem and self-efficacy) are inherently interconnected [56]. Empirical studies have demonstrated that prolonged sleep deprivation significantly impairs adolescents’ cognitive flexibility [57]. Sleep deficiency adversely affects cognitive functions in healthy individuals, including learning, memory, and executive functioning. A key underlying mechanism of this relationship is that poor sleep quality reduces the clearance rate of amyloid proteins in the brain, thereby accelerating cognitive decline [58].

Similarly, research on college students indicates that restorative sleep mitigates the negative effects of sleep deprivation on cognitive flexibility [59]. These findings highlight the substantial impact of sleep quality on cognitive flexibility. Consequently, it is hypothesized that (Hypothesis 4) sleep quality and cognitive flexibility serve as sequential mediators in the association between mobile phone dependency and adolescent academic burnout.

The Conservation of Resources model, introduced by Hobfoll and Buckley, has exerted a significant influence on burnout-related research [60]. The Conservation of Resources theory conceptualizes stress coping as a dynamic, bidirectional process of resource exchange between individuals and their environments [61]. Central to this theory is the proposition that individuals persistently pursue the acquisition, retention, and safeguarding of valued resources. These resources fall into four classes: Object resources, Status-based conditions, Personal capacities, and Energy reserves [42]. Valuable resources serve as motivational drivers and enable individuals to cope effectively with stress-inducing challenges in occupational settings [62]. However, when these resources are depleted, threatened, or insufficient to meet personal demands or expectations, adverse psychological outcomes—such as job burnout—may emerge [63].

Sleep constitutes a fundamental physiological necessity for human functioning, with high-quality sleep significantly enhancing students’ academic performance [64]. Cognitive flexibility, a critical psychological resource for task execution, plays an indispensable role in facilitating learning processes and academic achievement [65]. Individuals exhibiting high cognitive flexibility demonstrate an enhanced capacity to adapt to dynamic environmental demands and engage in divergent problem-solving strategies. Grounded in the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory [43], both sleep quality and cognitive flexibility serve as pivotal personal resources that contribute to the attainment of academic objectives. However, excessive reliance on mobile phones has been shown to impair sleep quality [34] and undermine cognitive flexibility [53]. Drawing upon the COR framework, the present study investigates the mediating roles of sleep quality and cognitive flexibility in the relationship between mobile phone dependency and academic burnout among adolescent students.

Although prior research has established a robust association between mobile phone dependency and academic burnout, most studies have predominantly focused on university students, leaving younger populations—particularly middle and high school students—relatively underexplored. Furthermore, existing literature seldom integrates both physiological and cognitive dimensions to elucidate the underlying mechanisms linking mobile phone dependency to academic burnout in adolescents. To address these gaps, this study develops a chain mediation model that incorporates individual physiological and cognitive factors, thereby offering a comprehensive examination of how mobile phone dependency influences academic burnout in middle and high school students. The evidence offers empirical-theoretical foundations for addressing adolescent academic burnout during pervasive smartphone penetration.

Utilizing cluster sampling, this study administered paper-and-pencil questionnaires to seventh/eighth-grade junior high and first-year senior high students in Tianjin, China (January 2024). Participants and legal guardians were explicitly informed of their voluntary involvement and their unconditional right to withdraw, and formal informed consent was obtained after institutional permission. Participants self-administered paper-based questionnaires during class time under research assistant supervision. Completion time varied according to academic level: junior high students required 25–30 min, while senior high students needed 20–25 min. Responses were retrieved immediately on-site by the lead investigator following survey finalization. Of 956 questionnaires distributed, 811 valid responses were retained after eliminating incomplete, inattentive, or anomalous submissions—yielding an 84.83% valid response rate. All materials and protocols received ethical clearance from Tianjin Normal University (Ethics Approval No. 2025041505) and complied with established guidelines.

3.2.1 Mobile Phone Addiction Index

This research employed the Mobile Phone Addiction Index (MPAI) scale, originally developed by Leung (2008) [66] and subsequently modified by Huang et al. (2014) [67]. The 17 elements on this scale are categorized into four groups: inefficiency, disengagement, escape, and loss of control. In a Likert scale with five points, a score of 1 signifies “never,” while a score of 5 indicates “always.” Elevated scores suggest a greater propensity for mobile phone dependency. The scale demonstrated high internal consistency, evidenced by a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.906 in this research.

3.2.2 Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Scale

This study utilized the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scale, created by Buysse et al. (1989) [68]. The 18-item scale assesses subjective sleep quality, onset time, efficiency, disorders, hypnotic drug use, and daytime dysfunction. Responses are assessed on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3, with the sum of the seven components yielding the overall score. Increased overall scores signify poorer sleep quality. This scale in this study has an adequate reliability of 0.802, Cronbach’s α coefficient.

3.2.3 Cognitive Flexibility Scale

Developed by Martin and Rubin (1995) [69] and modified by Qi et al. (2012) [70], the Chinese version of the Cognitive Flexibility Scale (CFS) was employed in this study. The measure comprises 12 items that encompass three dimensions: “flexible choice,” “flexible willingness,” and “flexible effectiveness.” Cognitive flexibility is measured by rating responses from 1 (extremely inconsistent) to 6 (highly consistent). This scale in this study has an adequate reliability of 0.837, Cronbach’s α coefficient.

3.2.4 Adolescent Academic Burnout Scale

This study utilized the self-rating scale modified by Wu et al. (2011) [71], based on Maslach’s burnout inventory. This scale assesses three dimensions: “physical and mental fatigue,” “academic disconnection,” and “diminished sense of accomplishment.” It utilizes a five-point Likert scale, with responses varying from “very inconsistent” (1) to “very consistent” (5). The cumulative score is derived from the aggregation of individual item scores, with elevated values signifying increased academic burnout. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale in this investigation was 0.835, signifying good reliability.

SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Hayes’ PROCESS macro tool [72] were utilized for data analysis. Harman’s single-factor test was initially employed to assess potential common method bias. Subsequently, Pearson’s correlation analyses were employed to examine relationships among the key variables. Further analysis utilized PROCESS Model 6 to investigate a mediation model where mobile phone dependency served as the predictor, students’ sleep quality and cognitive flexibility acted as sequential mediators, and academic burnout was the outcome variable. To test this chained mediation effect of sleep quality and cognitive flexibility linking mobile phone dependency to academic burnout, 5000 bias-corrected bootstrap resamples were generated. Mediation effects were deemed significant when the 95% confidence interval (CI) for indirect effects did not contain zero.

In accordance with Harman’s common method bias principle, factor analysis revealed that the variance explained by the first factor was 21.57%, which is below the critical threshold of 40%, indicating that common method bias was not a significant issue in the present study.

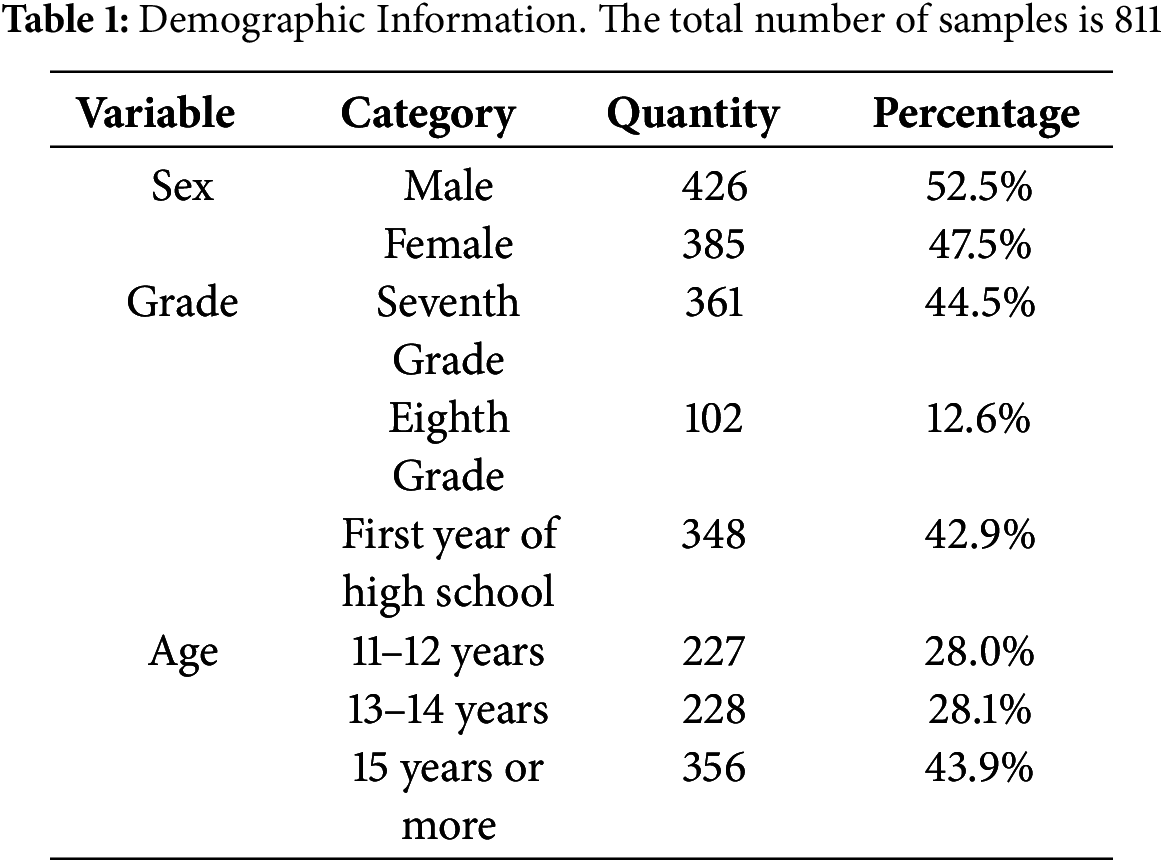

4.2 Demographic Characteristics

A total of 811 responses were included in the analysis, with the demographic characteristics of students presented in Table 1. Participants ranged in age from 11 to 17 years, with a mean age of 13.84 (SD = 1.55). The sample included 426 boys (52.5%) and 385 girls (47.5%). More than half of the students in middle school (57.1%).

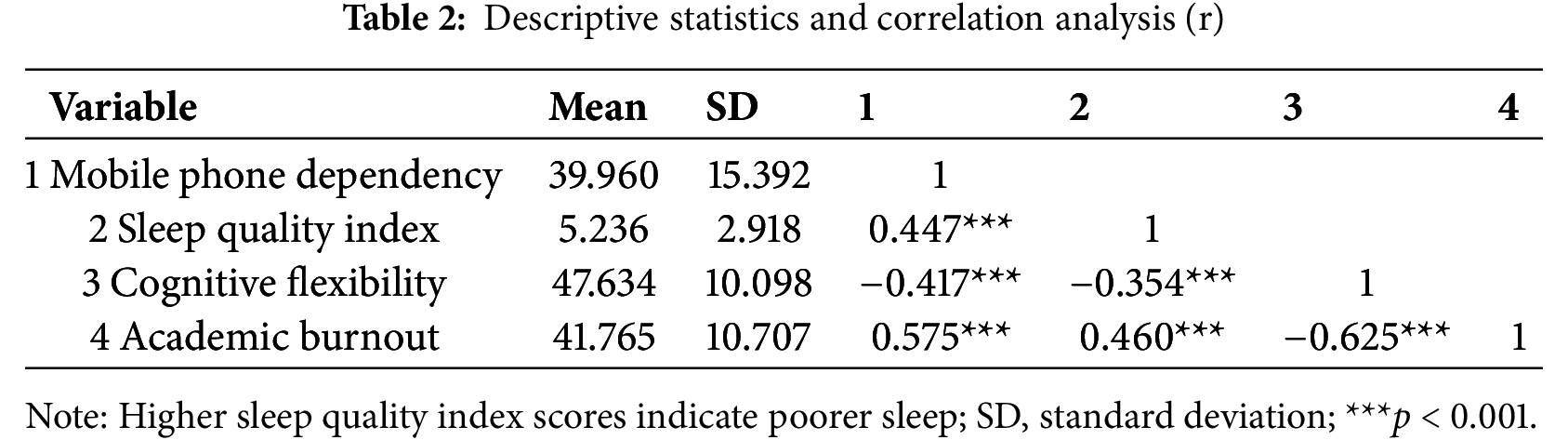

4.3 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

The means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients of the variables examined in this investigation are shown in Table 2. The findings show a substantial correlation between academic burnout, cognitive flexibility, sleep quality index, and mobile phone dependency. Mobile phone dependency is significantly and positively correlated with the sleep quality index (r = 0.447, p < 0.001). Cognitive flexibility is significantly and negatively correlated with both mobile phone dependency (r = –0.417, p < 0.001) and the sleep quality index (r = –0.354, p < 0.001). Academic burnout shows a significant positive correlation with mobile phone dependency (r = 0.575, p < 0.001) and the sleep quality index (r = 0.460, p < 0.001), while it is significantly and negatively correlated with cognitive flexibility (r = –0.625, p < 0.001).

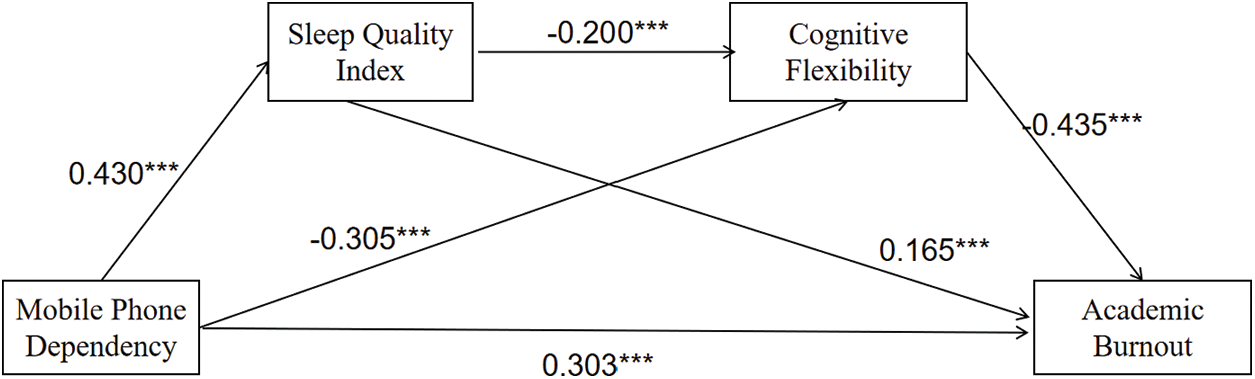

4.4 Analysis of Chain Mediation Effects of Sleep Quality and Cognitive Flexibility

To investigate the hypotheses, Hayes’s SPSS PROCESS macro’s Model 6 was utilized [72]. Academic burnout was identified as the dependent variable, mobile phone dependency as the independent variable, and cognitive flexibility and the sleep quality index as chain mediators. Fig. 1 displays the path coefficients that were obtained after demographic variables were taken into account. R2 = 0.34, p < 0.001, indicated that the regression model as a whole was statistically significant. The analysis revealed that mobile phone dependency significantly predicted sleep quality index (β = 0.430, p < 0.001) and cognitive flexibility (β = −0.305, p < 0.001). Furthermore, mobile phone dependency also significantly predicted academic burnout (β = 0.303, p < 0.001). Sleep quality index significantly predicted cognitive flexibility (β = −0.200, p < 0.001) and academic burnout (β = 0.165, p < 0.001). Lastly, cognitive flexibility was found to significantly predict academic burnout (β = −0.435, p < 0.001).

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of chain mediation. Note: Path coefficients are standardized; ***p < 0.001

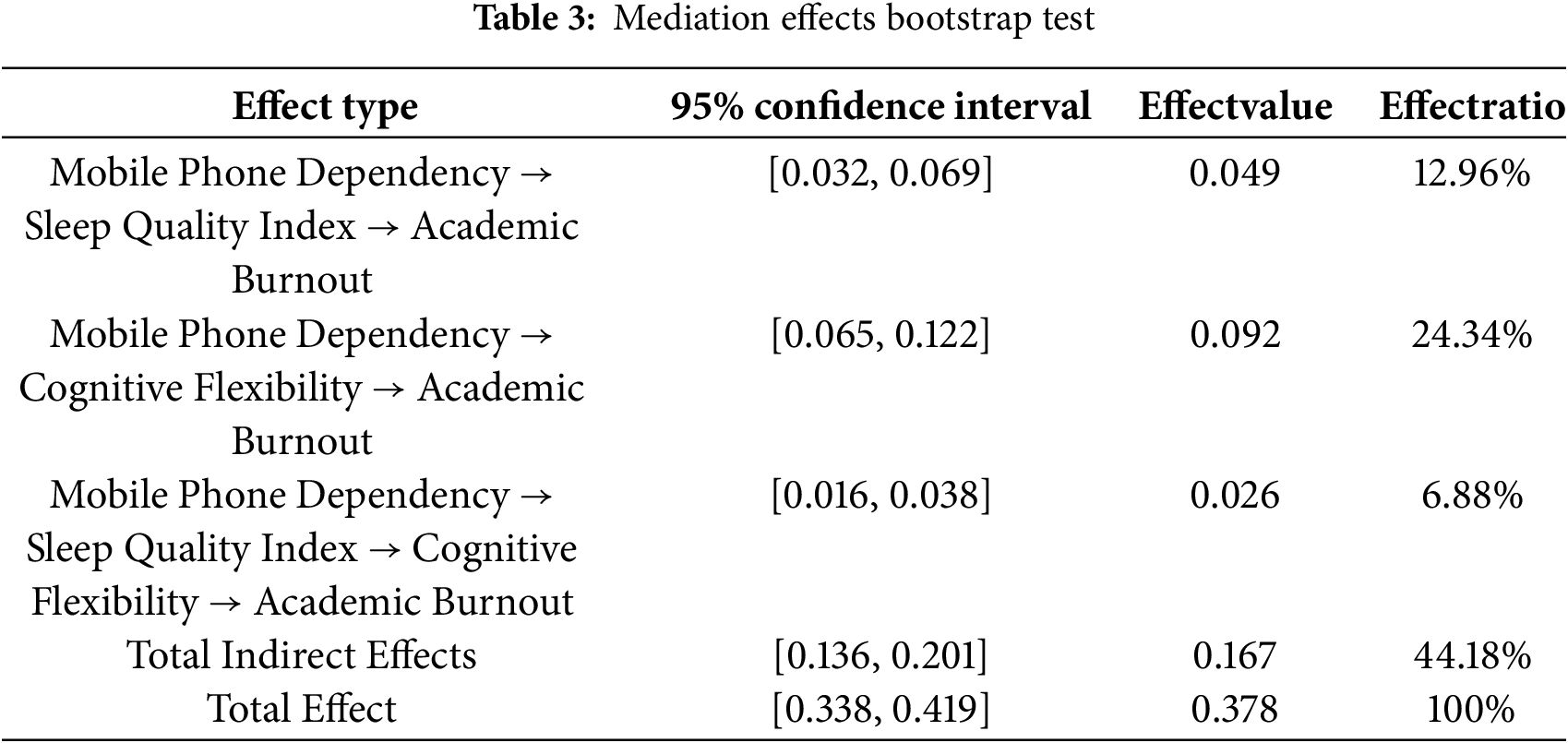

Furthermore, for a bootstrap confidence interval test, 5000 bootstrap samples were chosen at random. The results are shown in Table 3. The bootstrap 95% confidence interval for the chain mediation effect of sleep quality index and cognitive flexibility was [0.016, 0.038], which does not include 0, indicating the chain mediation model is valid. Similarly, the bootstrap 95% confidence interval for the independent mediating effect of the sleep quality index was [0.032, 0.069], which does not include 0, indicating that the mediating effect of sleep quality is significant. The bootstrap 95% confidence interval for cognitive flexibility was [0.065, 0.122], which does not include 0, indicating the independent mediating effect of cognitive flexibility is also significant.

The detrimental effect of mobile phone dependency on academic burnout has been well-documented in prior research [19]. Nevertheless, the underlying psychological mechanisms mediating this relationship remain insufficiently understood. While existing studies have predominantly focused on self-related factors, including self-esteem, self-efficacy, and self-control as potential mediators [29], cognitive aspects of this association have been relatively understudied. Based on the conservation of resources theory, this study systematically investigates the influence of mobile phone dependency on academic burnout among adolescents (middle and high school students). This study clarifies the sequential mediating roles of sleep quality and cognitive flexibility in this connection, so filling a notable gap in the current knowledge.

5.1 The Relationship between Mobile Phone Dependency and Adolescent Academic Burnout

This study’s findings robustly validate Hypothesis 1, which asserts that mobile phone dependency is a strong predictor of academic burnout among adolescents, aligning with other research in this field. These results provide robust support for the Conservation of Resources theoretical framework [41], which establishes a fundamental association between individuals’ resource reservoirs and their adaptive functioning. The Conservation of Resources model specifically postulates an inverse relationship between resource availability and maladaptation, suggesting that resource depletion leads to poorer psychological adjustment. Within this theoretical framework, resources are operationally defined as any psychological, social, or material assets that facilitate goal attainment [46]. These resources are not isolated but rather form interconnected networks, conceptualized in the Conservation of Resources theory as “resource caravans”. When the equilibrium between resource gain and loss is disrupted through excessive resource depletion, critical psychological constructs, including self-efficacy and self-evaluation, become compromised. This process ultimately erodes self-identity and manifests in negative psychological outcomes, particularly burnout [73]. The current findings illustrate how mobile phone dependency contributes to academic burnout among middle and high school students through multiple pathways of resource depletion [74]. Empirical evidence indicates that problematic mobile phone use leads to: significant reductions in productive study time due to excessive digital engagement [75]; decreased academic motivation and learning efficacy [76]; impaired self-esteem and diminished social support networks [77]; and compromised cognitive flexibility. These interrelated effects collectively create a resource depletion spiral that heightens vulnerability to academic burnout during this critical developmental period.

5.2 The Mediating Role of Sleep Quality and Cognitive Flexibility

The study’s findings validate Hypothesis 2, indicating that mobile phone dependency negatively predicts sleep quality, which in turn mediates its detrimental impact on academic burnout in middle and high school students. The most obvious physiological ramifications of excessive mobile phone use are sleep insufficiency and reduced sleep quality [78]. Consistent with self-depletion theory, inadequate sleep may deplete cognitive and emotional resources, impairing daytime functioning and academic engagement. As a result, students frequently experience fatigue prior to learning activities, exacerbating their susceptibility to academic burnout [79].

Our findings supported Hypothesis 3, suggesting that cognitive flexibility mediates dependency and academic burnout in middle and high school students. The mediation analysis demonstrated that mobile phone dependency significantly and negatively predicted cognitive flexibility, which subsequently mediated its adverse effect on academic burnout among middle and high school students. Given that learning is fundamentally a cognitive process, cognitive ability represents the most critical resource for academic engagement. Empirical evidence consistently indicates that cognitive flexibility serves as a key determinant of learning outcomes and academic performance [80]. According to the conservation of resources theory, while various resources in the resource pool are interconnected, their proximity to specific goals may vary substantially [76]. Different goal pursuits require distinct sets of critical resources, and the depletion of these goal-relevant resources shows particularly strong associations with burnout in corresponding domains. In the context of academic achievement, cognitive flexibility likely constitutes the most proximal and essential resource. The current findings demonstrate that excessive mobile phone use leads to diminished cognitive flexibility. Neurocognitive research suggests that addictive behaviors may induce structural and functional changes in the brain, promoting a present-oriented focus while simultaneously impairing cognitive flexibility [81].

Additionally, the findings provide robust support for Hypothesis 4. This study elucidates the sequential mediating pathway through which sleep quality and cognitive flexibility transmit the effects of mobile phone dependency to academic burnout in adolescents. These findings not only corroborate existing literature but also provide stronger theoretical integration by applying the conservation of resources framework. The results demonstrate that mobile phone dependency exerts indirect effects on both cognitive flexibility and academic burnout through its detrimental impact on sleep quality. The analysis revealed three key mechanisms: First, mobile phone dependency showed significant negative predictive effects on sleep quality. Specifically, adolescents with higher dependency levels engaged in prolonged nighttime mobile phone use, which directly reduced sleep duration and contributed to both sleep procrastination and degraded sleep quality. Second, compromised sleep quality led to measurable declines in cognitive flexibility among middle and high school students. Given that adolescence represents a critical period for neurocognitive development, adequate sleep is essential for maintaining optimal physiological and psychological functioning. Neurobiological research indicates that sleep facilitates activation of the midbrain limbic dopamine system, with elevated dopamine levels serving as a neural substrate for cognitive processes [82]. Conversely, sleep deprivation and poor sleep quality have been shown to impair multiple dimensions of executive function. Specifically, sleep deficiency diminishes alertness, constrains the flexible allocation of attentional resources, and ultimately compromises cognitive flexibility [83]. Finally, diminished cognitive flexibility was associated with elevated academic burnout. As a core component of adaptive functioning, cognitive flexibility plays a pivotal role in stress management and emotional regulation [84–86]. When facing academic demands, students with reduced cognitive flexibility tend to employ less effective coping strategies, thereby increasing their vulnerability to burnout. In conclusion, this investigation systematically examines the chain mediation mechanism linking mobile phone dependency to academic burnout through sleep quality and cognitive flexibility, while providing a theoretical foundation grounded in conservation of resources theory.

5.3 Contributions and Limitations

This study makes significant theoretical and practical contributions. Theoretically, it advances current understanding by integrating physiological and cognitive perspectives to examine the complex interplay among mobile phone dependency, sleep quality, cognitive flexibility, and academic burnout. By elucidating the psychological mechanisms through which mobile phone dependency affects students’ academic burnout, this research addresses a critical gap in existing literature. Previous studies have predominantly focused on college students while largely overlooking younger adolescent populations. Our findings extend the conservation of resources theory by demonstrating its applicability to digital-age adolescents and providing new insights into the development of academic burnout in this vulnerable demographic. From a practical perspective, the study empirically demonstrates that mobile phone dependency exacerbates academic burnout in adolescents through the mediating pathways of diminished sleep quality and impaired cognitive flexibility. These findings offer compelling evidence for implementing targeted interventions to mitigate mobile phone overuse and its detrimental academic consequences. Importantly, the results suggest novel intervention approaches that simultaneously address sleep hygiene and cognitive enhancement, providing a more comprehensive strategy for reducing academic burnout among middle and high school students with problematic mobile phone use.

Meanwhile, this study contains a number of noteworthy shortcomings. This cross-sectional analysis investigates the correlation between mobile phone dependency and academic burnout among junior and senior high school students; however, it cannot prove a causal relationship between these variables. The cross-sectional approach confines our data to associative patterns at one time point, rendering it impossible to ascertain the causal relationship between cell phone dependency and academic stress. Therefore, future longitudinal studies are essential to determine chronological precedence and clarify the underlying causative mechanisms. Secondly, the sole dependence on self-reported metrics may engender response bias and inconsistencies between stated and real behaviors. To improve data dependability, subsequent studies should include additional assessment methods, including psychophysiological assessments and experimental procedures.

This study revealed a significant chain mediation effect of sleep quality and cognitive flexibility on the relationship between mobile phone dependency and academic burnout in middle and high school students. The findings underscore the detrimental effect of cell phone use on students’ academic achievement. In the digital era, problematic mobile phone usage poses novel developmental challenges for adolescents. Specifically, mobile phone dependency substantially impairs academic adaptation in secondary education students through both physiological and cognitive pathways, consequently affecting their overall physical and mental health. The results indicate that comprehensive prevention and intervention strategies should be developed to mitigate adolescent academic burnout in digital environments. Such programs should incorporate controlled mobile phone usage, sleep quality enhancement, and cognitive flexibility training. These empirical findings call for concerted efforts from families, educational institutions, and policymakers to address the growing concern of academic burnout in secondary education. Proactive measures should be implemented to safeguard students’ psychological well-being and foster their holistic development in technology-saturated learning environments.

Acknowledgement: We sincerely thank the anonymous participants for their invaluable contributions to this study, their responses were essential to the research.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Foundation of Tianjin (Grant No. TJJX22-006).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Miao Wang and Zhansheng Xu; Methodology, Dangyang Ma and Xinyu Ji; Formal Analysis, Miao Wang; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Miao Wang; Investigation, Menglin Zhao; Data Curation, Menglin Zhao and Dangyang Ma; Writing—Reviewing and Editing, Donghe Li and Zhansheng Xu; Funding Acquisition, Zhansheng Xu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Email: xzsbrain-140111@tjnu.edu.cn, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The current research was approved by the ethics committee of Tianjin Normal University (No. 2025041505), and informed consent of all participants was obtained.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. The 54th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development-China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC); 2024. [cited 2025 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2024/0829/c88-11065.html. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

2. Chang FC, Chiu CH, Chen PH, Chiang JT, Miao NF, Chuang HY, et al. Children’s use of mobile devices, smartphone addiction and parental mediation in Taiwan. Comput Human Behav. 2019 Apr 1;93(6):25–32. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yen CF, Tang TC, Yen JY, Lin HC, Huang CF, Liu SC, et al. Symptoms of problematic cellular phone use, functional impairment and its association with depression among adolescents in Southern Taiwan. J Adolesc. 2009 Aug;32(4):863–73. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.10.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zhao K, Liu Y, Shi Y, Bi D, Zhang C, Chen R, et al. Mobile phone addiction and interpersonal problems among Chinese young adults: the mediating roles of social anxiety and loneliness. BMC Psychol. 2025 Apr 11;13(1):372. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-02686-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Sapci O, Elhai JD, Amialchuk A, Montag C. The relationship between smartphone use and students` academic performance. Learn Individ Differ. 2021 Jul 1;89(1):102035. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2021.102035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Cheng KT, Hong FY. Study on relationship among university students’ life stress, smart mobile phone addiction, and life satisfaction. J Adult Dev. 2017 Jun 1;24(2):109–18. doi:10.1007/s10804-016-9250-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Gao T, Li J, Zhang H, Gao J, Kong Y, Hu Y, et al. The influence of alexithymia on mobile phone addiction: the role of depression, anxiety and stress. J Affect Disord. 2018 Jan 1;225(1):761–6. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Lian SL, Sun XJ, Niu GF, Yang XJ, Zhou ZK, Yang C. Mobile phone addiction and psychological distress among Chinese adolescents: the mediating role of rumination and moderating role of the capacity to be alone. J Affect Disord. 2021 Jan 15;279(3):701–10. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. He A, Wan J, Hui Q. The relationship between mobile phone dependence and mental health in adolescents: the mediating role of academic burnout and the moderating role of coping style. Psycholog Develop Educat. 2022;38(3):391–8. (In Chinese). doi:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2022.03.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Thomée S, Härenstam A, Hagberg M. Mobile phone use and stress, sleep disturbances, and symptoms of depression among young adults—a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2011 Jan 31;11(1):66. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Zarrin SA, Gracia E, Paixão MP. Prediction of academic procrastination by fear of failure and self-regulation. Kuram Ve Uygulamada Egitim Bilimleri. 2020 Jul;20(3):34–43. doi:10.12738/jestp.2020.3.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Madigan DJ, Curran T. Does burnout affect academic achievement? A meta-analysis of over 100,000 students. Educ Psychol Rev. 2021 Jun;33(2):387–405. doi:10.1007/s10648-020-09533-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Seibert GS, Bauer KN, May RW, Fincham FD. Emotion regulation and academic underperformance: the role of school burnout. Learn Individ Differ. 2017 Dec 1;60(1):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2017.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Raiziene S, Pilkauskaite-Valickiene R, Zukauskiene R. School burnout and subjective well-being: evidence from cross-lagged relations in a 1-year longitudinal sample. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014 Feb 21;116(2):3254–8. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hu Q, Schaufeli WB. The factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey in China. Psychol Rep. 2009 Oct;105(2):394–408. doi:10.2466/PR0.105.2.394-408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):397–422. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Bask M, Salmela-Aro K. Burned out to drop out: exploring the relationship between school burnout and school dropout. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2013;28(2):511–28. doi:10.1007/s10212-012-0126-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wang MT, Chow A, Hofkens T, Salmela-Aro K. The trajectories of student emotional engagement and school burnout with academic and psychological development: findings from Finnish adolescents. Learn Instr. 2015;36:57–65. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Liu C, She X, Lan L, Wang H, Wang M, Abbey C, et al. Parenting stress and adolescent academic burnout: the chain mediating role of mental health symptoms and positive psychological traits. Curr Psychol. 2024 Feb 1;43(8):7643–54. doi:10.1007/s12144-023-04961-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Luo Y, Liang J. Teacher-student relationships and adolescent academic burnout: the moderating role of general self-concept. Psychol Behav Sci. 2021 Nov;10(6):220–5. doi:10.11648/j.pbs.20211006.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Seong H, Lee S, Chang E. Perfectionism and academic burnout: longitudinal extension of the bifactor model of perfectionism. Pers Individ Dif. 2021 Apr 1;172(1):110589. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Koutsimani P, Montgomery A, Georganta K. The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2019;10:284. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wei Z, Hassan NC, Hassan SA, Ismail N, Gu X, Dong J. The relationship between Internet addiction and academic burnout in undergraduates: a chain mediation model. BMC Public Health. 2025 Apr 24;25(1):1523. doi:10.1186/s12889-025-22719-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2001 Jun;86(3):499–512. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wiers RW, Stacy AW. Implicit cognition and addiction. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2006;15(6):292–6. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00455.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chen C, Zhang KZK, Gong X, Lee M. Dual mechanisms of reinforcement reward and habit in driving smartphone addiction: the role of smartphone features. Internet Res. 2019 Jun 7;29(6):1551–70. doi:10.1108/INTR-11-2018-0489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yali Z, Sen LI, Guoliang YU. The relationship between social media use and fear of missing out: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychol Sin. 2021 Mar 25;53(3):273. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2021.00273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kärki K. Digital distraction, attention regulation, and inequality. Philos Technol. 2024 Jan 12;37(1):8. doi:10.1007/s13347-024-00698-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang B, Cheng S, Zhang Y, Xiao W. Mobile phone addiction and learning burnout: the mediating effect of self-control. China J Health Psychol. 2019;27(3):435–8. doi:10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2019.03.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Litwiller B, Snyder LA, Taylor WD, Steele LM. The relationship between sleep and work: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2017 Apr;102(4):682–99. doi:10.1037/apl0000169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Altchuler SI. Sleep and quality of life in clinical medicine. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009 Aug;84(8):758. doi:10.4065/84.8.758-a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Balkin TJ, Rupp T, Picchioni D, Wesensten NJ. Sleep loss and sleepiness: current issues. Chest. 2008 Sep;134(3):653–60. doi:10.1378/chest.08-1064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Killgore WDS. Effects of sleep deprivation on cognition. Prog Brain Res. 2010;185(5):105–29. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53702-7.00007-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Demirci K, Akgönül M, Akpinar A. Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. J Behav Addict. 2015 Jun;4(2):85–92. doi:10.1556/2006.4.2015.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Li L, Mei SL, Niu ZM, Song YT. Loneliness and sleep quality in university students: mediator of smartphone addiction and moderator of gender. Chin J Clinic Psychol. 2016;24(2):345–8+320. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2016.02.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Sahin S, Ozdemir K, Unsal A, Temiz N. Evaluation of mobile phone addiction level and sleep quality in university students. Pak J Med Sci. 2013 Jul;29(4):913–8. doi:10.12669/pjms.294.3686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Jin L, Pan C, Zhao C, Li D, Wu Y, Zhang T. Perceived social support and symptoms of depression and anxiety among Chinese adolescents: a moderated chain mediation model. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2025 Jan 31;27(1):29–40. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2025.057962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Exelmans L, Van den Bulck J. Bedtime, shuteye time and electronic media: sleep displacement is a two-step process. J Sleep Res. 2017 Jun;26(3):364–70. doi:10.1111/jsr.12510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Evers K, Chen S, Rothmann S, Dhir A, Pallesen S. Investigating the relation among disturbed sleep due to social media use, school burnout, and academic performance. J Adolesc. 2020 Oct;84(1):156–64. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.08.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Ghods AA, Ebadi A, Nia HS, Allen KA, Ali-Abadi T. Academic burnout in nursing students: an explanatory sequential design. Nurs Open. 2023 Feb;10(2):535–43. doi:10.1002/nop2.1319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Hobfoll SE. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing Conservation of Resources theory. Appl Psychol. 2001;50(3):337–70. doi:10.1111/1464-0597.00062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Hobfoll S, Halbesleben J, Neveu JP, Westman M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2018 Apr 23;5(1):103–28. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Halbesleben JRB, Neveu JP, Paustian-Underdahl SC, Westman M. Getting to the COR: understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J Manag. 2014 Jul;40(5):1334–64. doi:10.1177/0149206314527130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Arbabisarjou A, Hashemi SM, Sharif MR, Haji Alizadeh K, Yarmohammadzadeh P, Feyzollahi Z. The relationship between sleep quality and social intimacy, and academic burn-out in students of medical sciences. Glob J Health Sci. 2015 Nov 5;8(5):231–8. doi:10.5539/gjhs.v8n5p231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Hohl K, Dolcos S. Measuring cognitive flexibility: a brief review of neuropsychological, self-report, and neuroscientific approaches. Front Hum Neurosci. 2024 Feb 19;18:1331960. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2024.1331960. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Liao H, Huang L. Conservation of resources theory in the organizational behavior context: theoretical evolution and challenges. Adv Psychol Sci. 2022;30(2):449–63. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2022.00449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Wu D, Gao L, Duan J. The mechanism of job engagement on voice behavior: the moderating effects of cognitive flexibility and power motive. Chin J Appl Psychol. 2014;20(1):67–75. doi:10.20058/j.cnki.cjap.2014.01.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Nakhostin-Khayyat M, Borjali M, Zeinali M, Fardi D, Montazeri A. The relationship between self-regulation, cognitive flexibility, and resilience among students: a structural equation modeling. BMC Psychol. 2024 Jun 7;12(1):337. doi:10.1186/s40359-024-01843-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Ma G, Wang Z, Zhang S, Luo Y. The relationship between academic burnout and cognitive flexibility of middle school students. J Longdong Univ. 2017;28(6):132–5. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-1730.2017.06.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Brand M, Young KS, Laier C, Wölfling K, Potenza MN. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: an Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016 Dec 1;71(2):252–66. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Dong G, Potenza MN. A cognitive-behavioral model of Internet gaming disorder: theoretical underpinnings and clinical implications. J Psychiatr Res. 2014 Nov 1;58:7–11. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.07.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Hadar A, Hadas I, Lazarovits A, Alyagon U, Eliraz D, Zangen A. Answering the missed call: initial exploration of cognitive and electrophysiological changes associated with smartphone use and abuse. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180094. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180094. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. İnal Ö, Selen Arslan S. Investigating the effect of smartphone addiction on musculoskeletal system problems and cognitive flexibility in university students. Work. 2021;68(1):107–13. doi:10.3233/WOR-203361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Yasin S, Altunisik E, Tak AZA. Digital danger in our pockets: effect of smartphone overuse on mental fatigue and cognitive flexibility. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2023 Aug 1;211(8):621–6. doi:10.3233/WOR-203361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Hong W, Liu RD, Ding Y, Sheng X, Zhen R. Mobile phone addiction and cognitive failures in daily life: the mediating roles of sleep duration and quality and the moderating role of trait self-regulation. Addict Behav. 2020 Aug 1;107(1):106383. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Hobfoll SE. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev Gen Psychol. 2002;6(4):307–24. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Zhang X, Feng S, Yang X, Peng Y, Du M, Zhang R, et al. Neuroelectrophysiological alteration associated with cognitive flexibility after 24 h sleep deprivation in adolescents. Conscious Cogn. 2024 Sep 1;124(2):103734. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2024.103734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Mander BA, Winer JR, Jagust WJ, Walker MP. Sleep: a novel mechanistic pathway, biomarker, and treatment target in the pathology of alzheimer’s disease? Trends Neurosci. 2016 Aug;39(8):552–66. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2016.05.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Couyoumdjian A, Sdoia S, Tempesta D, Curcio G, Rastellini E, Gennaro DE, et al. The effects of sleep and sleep deprivation on task-switching performance. J Sleep Res. 2010 Mar;19(1-Part-I):64–70. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00774.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Halbesleben JRB, Buckley MR. Burnout in organizational life. J Manag. 2004 Dec;30(6):859–79. doi:10.1016/j.jm.2004.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Hobfoll S. Resource caravans and resource caravan passageways: a new paradigm for trauma responding. Interven J Ment Health Psychosoc Supp Conf Affect Areas. 2014;12(4):21–32. doi:10.1097/WTF.0000000000000067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J Occup Organ Psych. 2011;84(1):116–22. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Park HI, Jacob AC, Wagner SH, Baiden M. Job control and burnout: a meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources model. Appl Psychol. 2014;63(4):607–42. doi:10.1111/apps.12008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Seoane HA, Moschetto L, Orliacq F, Orliacq J, Serrano E, Cazenave MI, et al. Sleep disruption in medicine students and its relationship with impaired academic performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2020 Oct;53(Suppl 1):101333. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Titz C, Karbach J. Working memory and executive functions: effects of training on academic achievement. Psychol Res. 2014 Nov;78(6):852–68. doi:10.1007/s00426-013-0537-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Leung L. Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. J Child Media. 2008 Jul 1;2(2):93–113. doi:10.1080/17482790802078565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Huang H, Niu L, Zhou C, Wu H. Reliability and validity of mobile phone addiction index for Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2014;5:835–8. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2014.05.062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989 May;28(2):193–213. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Martin MM, Rubin RB. A new measure of cognitive flexibility. Psychol Rep. 1995;76(2):623–6. doi:10.2466/pr0.1995.76.2.623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Qi B, Zhao B, Wang K, Liu H. Revision and preliminary application of cognitive flexibility scale for college students. Stud Psychol Behav. 2012;1:120–3. [Google Scholar]

71. Wu Y, Dai X, Wen Z, Cui H. The development of adolescent student burnout inventory. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2011;2:152–4. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2010.02.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Hayes A. PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling 1; 2012. [cited 2025 Jul 30]. Available from: http://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/aa753b543c78d6c4f344fb431c6683edaa062c07. [Google Scholar]

73. Hu X, Yeo GB. Emotional exhaustion and reduced self-efficacy: the mediating role of deep and surface learning strategies. Motiv Emot. 2020 Oct 1;44(5):785–95. doi:10.1007/s11031-020-09846-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Wang JL, Rost DH, Qiao RJ, Monk R. Academic stress and smartphone dependence among Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020 Nov 1;118(1):105029. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Siebers T, Beyens Ine, Pouwels JL, Valkenburg PM. Social media and distraction: an experience sampling study among adolescents. Media Psychol. 2022 May 4;25(3):343–66. doi:10.1080/15213269.2021.1959350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Zhang J, Zeng Y. Effect of college students’ smartphone addiction on academic achievement: the mediating role of academic anxiety and moderating role of sense of academic control. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024 Mar 6;17:933–44. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S442924. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Zhou H, Liang Y, Liu X. The effect of the life satisfaction on internet addiction of college students: the multiple mediating roles of social support and self-esteem. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2020;28(5):919–23. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2020.05.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Kadian A, Mittal R, Gupta M. Mobile phone use and its effect on quality of sleep in medical undergraduate students at a tertiary care hospital. Open J Psych All Sci. 2019;10(2):128. doi:10.5958/2394-2061.2019.00028.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Horvat M, Tement S. Self-reported cognitive difficulties and cognitive functioning in relation to emotional exhaustion: evidence from two studies. Stress Health. 2020;36(3):350–64. doi:10.1002/smi.2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Bertsimas D, Gupta S, Lulli G. Dynamic resource allocation: a flexible and tractable modeling framework. Eur J Oper Res. 2014 Jul 1;236(1):14–26. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2013.10.063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Dong G, Lin X, Zhou H, Lu Q. Cognitive flexibility in internet addicts: fMRI evidence from difficult-to-easy and easy-to-difficult switching situations. Addict Behav. 2014;39(3):677–83. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.11.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Salehinejad MA, Ghanavati E, Reinders J, Hengstler JG, Kuo MF, Nitsche MA. Sleep-dependent upscaled excitability, saturated neuroplasticity, and modulated cognition in the human brain. eLife. 2022 Jun 6;11:e69308. doi:10.7554/eLife.69308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Sen A, Tai XY. Sleep duration and executive function in adults. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2023 Nov;23(11):801–13. doi:10.1007/s11910-023-01309-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Zheng W, Akaliyski P, Ma C, Xu Y. Cognitive flexibility and academic performance: individual and cross-national patterns among adolescents in 57 countries. Pers Individ Dif. 2024 Feb 1;217(2):112455. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2023.112455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Ma C, Song M, Zhao X. The impact of executive functions on English academic performance among Chinese primary school students: a network analysis. Learn Instr. 2025 Oct 1;99(3):102174. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2025.102174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Harel O, Hemi A, Levy-Gigi E. The role of cognitive flexibility in moderating the effect of school-related stress exposure. Sci Rep. 2023 Mar 31;13(1):5241. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-31743-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools