Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Social Media Addiction, Perceived Social Support, Sleep Disorder, and Job Performance in Healthcare Professionals: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model

1 Department of Guidance and Psychological Counselling, Ağrı İbrahim Çeçen University, Ağrı, 04100, Türkiye

2 Vocational School, Department of Property Protection and Security, Ağrı İbrahim Çeçen University, Ağrı, 04100, Türkiye

3 Department of Therapy and Rehabilitation, Ağrı İbrahim Çeçen University, Ağrı, 04100, Türkiye

4 Department of Measurement and Assessment, Yüzüncü Yıl Üniversitesi Kampüsü, Tuşba, 65090, Türkiye

5 Department of Sociology, Social Work and Public Health, Faculty of Labour Sciences, University of Huelva, Huelva, 21007, Spain

6 Safety and Health Postgraduate Program, Universidad Espíritu Santo, Guayaquil, 092301, Ecuador

7 Department of Psychology, Faculty of Science and Letters, Ağrı İbrahim Çeçen University, Ağrı, 04100, Türkiye

8 Psychology Research Center, Khazar University, Baku, 1009, Azerbaijan

* Corresponding Authors: Juan Gómez-Salgado. Email: ; Murat Yıldırım. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Causes, Consequences and Interventions for Emerging Social Media Addiction)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(8), 1149-1163. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.067388

Received 01 May 2025; Accepted 04 August 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Background: Social media addiction, one of the behavioural addictions, is a significant predictor of job performance. It has also been posited that individuals whose fundamental requirements (e.g., sleep) are not sufficiently met and who lack adequate support (e.g., perceived social support) are incapable of effectively harnessing their potential. The primary objective of this study is to examine the mediating effects of sleep disorder and perceived social support on the relationship between social media addiction and job performance. Furthermore, it seeks to explore the moderating effects of perceived social support on sleep disorders and job performance. Methods: The data were collected through the questionnaire method, and data analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0. Moreover, statistical analysis encompasses correlation analysis, mediation, and moderation analysis. The data were gathered from 488 healthcare professionals (57.2% female), whose ages ranged from 24 to 56 years (Meanage ± SD = 37.86 ± 6.71), using a convenience sample approach. Results: The results revealed significant relationships between social media addiction, job performance, perceived social support, and sleep disorder. The findings indicate that social media addiction negatively predicts job performance (β = −0.11, p < 0.05). Sleep disorder (effect size = −0.02, 95% CI = [−0.04, −0.00]) and perceived social support (effect size = −0.01, 95% CI = [−0.02, −0.00]) mediate this relationship. Furthermore, perceived social support moderates the pathway between sleep disorder and job performance (index of moderated mediation: −0.0040, 95% CI = [−0.0070, −0.0010]). Conclusions: This study suggests that social media addiction negatively affects job performance through sleep disorders and perceived social support among healthcare professionals. The study’s findings are significant, as they suggest that treatments aimed at alleviating sleep disorders and enhancing perceived social support among medical workers may improve their job performance.Keywords

People have basic needs, such as the desire to belong and establish relationships. Interpersonal communication plays a key role in meeting these needs [1]. Due to the rapid development of information technologies, particularly social media platforms on the internet (e.g., Twitter and Instagram), interpersonal communication has undergone significant changes over the past few years [2]. Social media tools have become increasingly popular, leading to more research regarding the possibility of excessive and addictive usage [3,4]. Moreover, many mobile devices are used regularly, and the ability to access social network tools has become a norm, available anywhere and at any time [5]. It thus leads to some individuals overusing social media to the point of developing addiction symptoms [6,7].

Social media addiction is related to a range of emotional, performance, and health problems [8,9]. It can reduce individuals’ real-life social interactions. Research indicates that excessive social media use can reduce face-to-face communication, negatively impacting individuals’ social skills [4]. Social media platforms offer numerous applications to their users due to the content they provide and the opportunities they offer [10]. Additionally, the speed of these platforms and the abundance of content prompt users to stay updated on social media developments [11]. Therefore, it creates pressure and stress on social media users [12].

Social media platforms are frequently used by healthcare professionals [13]. Individuals in this profession often use social media for relaxation or as a distraction from their critical duties in the healthcare sector [13,14]. Using social media problematically may lead to social media addiction, which can be linked to depression, stress, anxiety, or sleep problems [15]. Moreover, social media platforms may lead individuals to constantly compare themselves with others, resulting in constant unhappiness and dissatisfaction [16,17]. As a result, social media addiction affects individuals’ psychological health and well-being [18]. These negative consequences harm these individuals’ social and professional lives, who are in a critical period to fulfil various roles and duties (e.g., job performance or career-related duties) [19].

The extent to which people contribute to the needs of the organization in which they work determines their performance. When employees use social media platforms inappropriately, they cannot adequately meet the organization’s expectations. Additionally, social media usage can lead to distractions for users, potentially impacting their work performance. Social media platforms can potentially distract individuals by stimulating them via messages and notifications [11]. Allowing unrestricted access to platforms like Facebook during work hours has been associated with a measurable decline in organizational productivity, estimated at around 1.5% [20]. Similarly, another study reported that the productivity and engagement of employees are hindered by social media addiction [21]. A further potential problem caused by excessive use is social isolation, which often contributes to depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders. Furthermore, the Conservation of Resources Theory (COR) emphasizes that individuals strive to maintain their values even in stressful environments (e.g., hospitals) [22]. It also suggests that they are encouraged to accumulate resources that will help them manage stress and secure their well-being [22]. This may lead them to use social media platforms excessively and in a problematic manner.

Social media addiction-related problems (e.g., attention disorder, insomnia, and depression) have devastating effects on job performance [15]. Several studies reported that diminished focus and sleep disorders occur when people use social media problematically [23,24]. Sleep disorders and insufficient sleep duration result in individuals working drowsily during the day [25]. Research indicates that social media addiction disrupts sleep patterns and may result in adverse consequences such as impairments in interpersonal relationships, deficiencies in self-care skills, and increased loneliness [26,27]. Individuals with social media addiction often encounter considerable anxiety regarding the potential to miss important updates or events on these platforms. This encourages them to depend on social media sources consistently. Despite the late hours, this instinct may lead them to prioritize social media platforms over getting enough sleep. This can create significant problems with sleep duration, sleep onset, and quality, reducing the well-being of social media addicts [27]. Moreover, daytime sleepiness also affects employee performance. A study reported that social media addiction has a negative effect on sleep efficiency [28]. An analysis of a large sample of U.S. adults revealed that those with six or seven hours of sleep duration were likelier to have a fair or poor self-rated health status [25]. Consequently, being distracted from the task harms job performance [29]. Young adults and professionals in a variety of industries are particularly affected by social media addiction, which adversely impacts sleep quality and mental health.

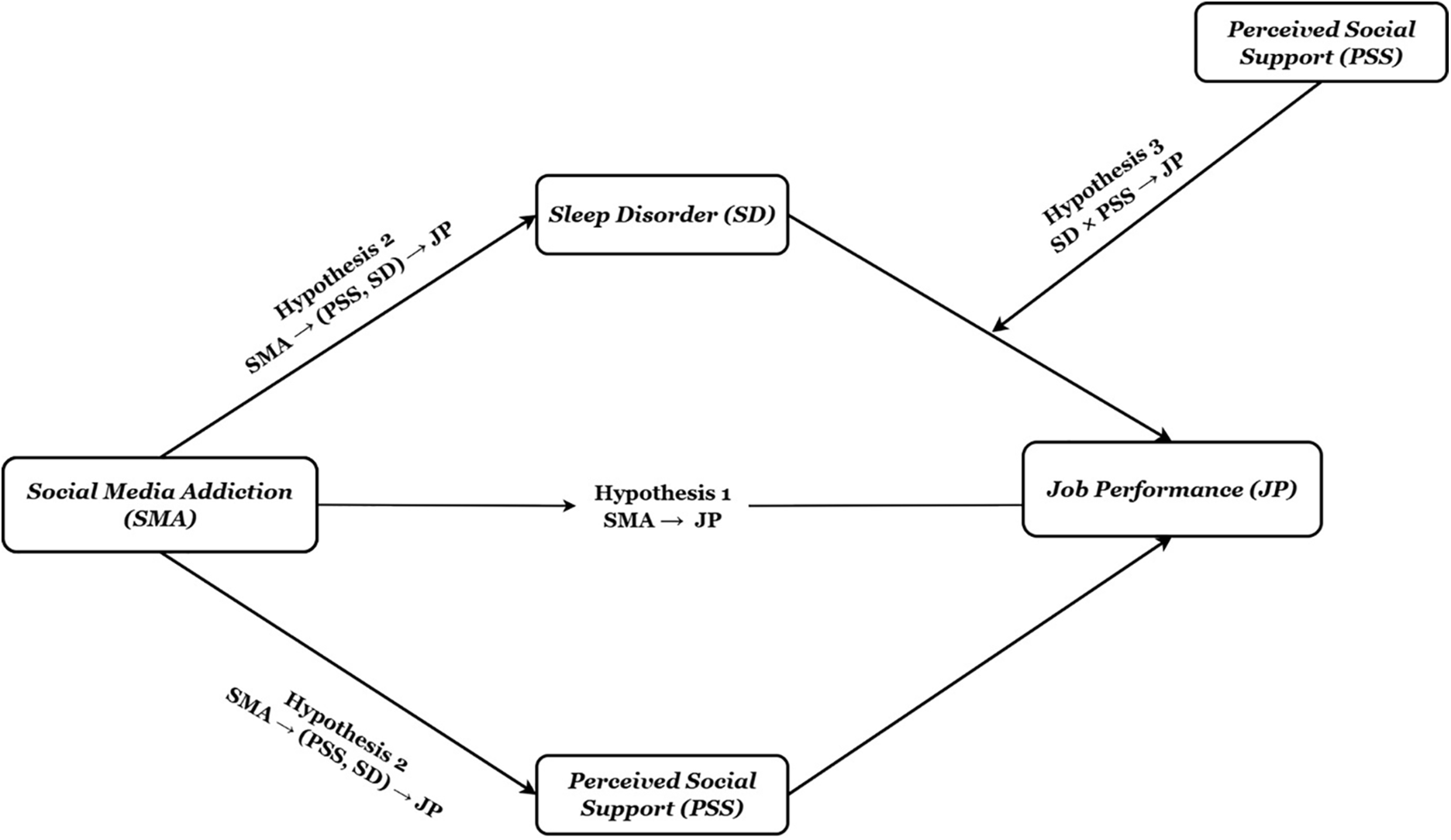

It is common for healthcare workers to engage in rigorous work and must carry out complex duties with great meticulousness. Their performance at work will likely be significantly impaired by their family responsibilities and other potential distractions [23]. As a result, their perception of social support has a significant impact on their work performance [30]. When individuals with challenging work environments (e.g., similar to employees in healthcare) lack sufficient resilience and coping skills, they are more likely to suffer adverse mental and psychological consequences [31]. Similarly, empirical study results showed that social media addiction negatively affects people’s job performance [32]. Similarly, another study indicated that using social media in the workplace has a detrimental effect on job performance [33]. People have also been shown to maintain emotional balance in the face of threats and stressful events when they receive support from peers, colleagues, friends, and family members [34]. Individuals can resolve conflicts and balance their personal and professional lives by receiving this support [23]. Social support is a crucial factor in buffering and mitigating the effects of negative life events, thereby enhancing individuals’ psychological well-being and mental health outcomes [31,34]. Similarly, social media addiction has a negative relationship with perceived social support. Moreover, perceived social support was one of the predictors of social media addiction [35] and a variety of well-being and mental health outcomes [36–38]. Healthcare professionals often struggle to dedicate enough time to their families due to high job performance expectations, long hours, lack of sleep, rest, and heavy workloads [39]. Additionally, using social media to meet their social needs increases the risk of addiction [40]. Therefore, this study was conducted because it identifies them as a high-risk group. Based on the theoretical and empirical evidence, this study aims to examine the mediating effects of perceived social support and sleep disorder on the relationship between social media addiction and job performance. Based on this aim, the following hypotheses are proposed: (Hypothesis 1) Social media addiction predicts job performance; (Hypothesis 2) Perceived social support and sleep disorder would have a mediating effect in the association between social media addiction and job performance; and (Hypothesis 3) Perceived social support would moderate the effect of sleep disorder on job performance (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Structure of the proposed model

Participants comprised 488 Turkish healthcare professionals recruited through a convenience sampling method (57.2% female). Their ages ranged from 24 to 56, with an average age of 37.86 (standard deviation [SD] = 6.71). Over three-quarters of the sample comprises married individuals (i.e., 375). Out of the participants, 102 (20.9%) were doctors, 239 (49.0%) were nurses, and 147 (30.1%) were other healthcare personnel (e.g., patient caregivers, anaesthetic technicians, and paramedics). 41 (8.4%) individuals worked fewer than 6 h per day, 327 (67.0%) worked 6–9 h, 68 (13.9%) worked 9 > –12 h, and 52 (10.7%) worked more than 12 h. The number of participants who stated that they use social media hourly is 216 (44.3%), while the number of participants who stated that they use social media many times each day is 242 (49.6%). 422 respondents indicated that they use one device to access social media platforms, with a mean of 1.15. Healthcare workers aged 18 or older who volunteered to participate and met the inclusion criteria, including being a healthcare professional, were eligible. Those who participated in the research were queried regarding their voluntary willingness to participate. Individuals who declared themselves to have not voluntarily participated in the study were not allowed to participate.

The power analysis was conducted to effectively and powerfully emphasise the associations between the predictor and the predicted variable. To calculate the required sample size, the G*Power (version 3.1.9.7) package program was used for the analysis. As a result, “r = 0.20” has been determined as a small effect size. Moreover, the significance level is defined as 0.05, and the power is 0.80 [41]. According to the analysis results, a total of 395 samples were required. Once an adequate number of samples was reached, the same analysis was performed as a post-hoc method under the same conditions. The sample size of the research was determined to have a power of 0.88 (1−β error probe), and with an observed effect size of f2 = 0.11 (corresponding to R2 = 0.10). As indicated by the findings of this study, the sample had sufficient power to conduct the analysis.

The Brief Perceived Social Support Questionnaire (BPSSQ) was used to assess perceived social support. English version [42] and the scale was previously validated in Turkish; the Turkish adaptation of BPSSQ [43]. The scale has 6 items. There is a range of 1 (not true at all) to 5 (very true) (e.g., “There are always friends and neighbours who are willing to lend me items when I need them”, or “Several people I know enjoy doing things together”.). Increasing scores indicate an increase in perceived social support. Cronbach’s α was found to be 0.79. McDonald’s ω was 0.80 in the present study.

Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS) was used to assess social media addiction. English version [44] and the scale was previously validated in Turkish [45]. The BSMAS has 6 items that are scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (rarely) to 5 (very often) (e.g., “When you had a personal issue, did you use social media to get it out?” and “If you could not access social media, would you feel uncomfortable and upset?”). A higher score indicates a greater degree of social media addiction. Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω were found to be 0.83 in the current study.

Job Performance Scale-4 items JPS- was used to assess participants’ job performance (e.g., “I am confident that I have more than reached the standards in the quality of service I offer” or “When a problem comes up, I find a solution in the fastest way possible”) ranging from 1 (not suitable for me) to 5 (totally suitable for me). English version [46] and the scale was previously validated in Turkish [47]. A higher score means greater job performance. The present study’s Cronbach’s α was 0.81, and McDonald’s ω was also 0.81.

Sleep Disorder Scale (SDS) [48]. The SDS, originally developed for use in Turkish culture, was employed to assess the level of sleep disorder. The scale consisted of 8 items ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (every time) (e.g., “I had trouble falling asleep” or “I had a restful sleep”). The higher the score on the scale, the greater the sleep disorder. Cronbach’s α was 0.87, and McDonald’s ω was 0.87.

The Ethics Committee supervised all stages of the research. The Ağrı Ibrahim Cecen University’s ethics committee approved the study (Number: E.86893). The recruitment period took place from 01 January 2024 to 31 January 2024. Data was collected through an online survey. The four instructions were included in the survey to measure participants’ attention and detect inattentive responses. which would adversely affect the study results. “Please mark ‘2’ on these instructions”. The online survey provided participants with an overview of the study’s objectives. A text/email invitation was sent to healthcare workers from various hospitals in Turkey, detailing the study and including an informed consent form. This document outlines the purposes and duration of the study, as well as the promises of anonymity and confidentiality, and includes an invitation to participate voluntarily. Furthermore, it is specified that each participant is only allowed to complete one survey. The distribution of the questionnaires commenced solely after the participants’ informed consent was acquired. The participants were explicitly told that they could withdraw from the study at any stage if they did not wish to complete the questionnaires or experienced any discomfort. To alleviate potential distrust issues that may arise during the scale response process, participants have been advised to refrain from providing any identifiable data on the online form. Ensuring the confidentiality and anonymity of the responses was the highest priority. We adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki throughout the study.

Initially, 630 participants were invited to participate in the study. However, only 524 completed the questionnaires completely (attrition rate: 16.83%). To eliminate outliers from the sample, the Mahalanobis distance was calculated, and it was determined that 16 individuals should be removed from the sample. Mahalanobis distance is frequently used to identify outliers. Twenty participants who provided incorrect responses to these questions were excluded from the study. After removing incorrect answers and outliers from the study, analyses were started with 488 participants. Normality was tested through skewness and kurtosis statistics. Variance inflation factors (VIFs) were used to test the assumptions of multicollinearity. Following these preliminary assumptions, Model 4 with the PROCESS macro was utilized to determine whether or not there is a mediation effect [49]. The mediation model used to determine if sleep disorders and perceived social support mediated the association between social media addiction and job performance. In order to detect moderation effect (to test Hypothesis 3), we utilized Model 14 using the PROCESS macro to carry out moderated mediation or conditional process analysis. The indirect effects of the proposed model were explained using a 95% confidence interval. A bias-corrected bootstrapping approach was employed to determine whether indirect effects were statistically significant. The bootstrap threshold was set at 5000. SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyze all the data. The parallel mediation and moderated mediation analyses were computed using the PROCESS macro for SPSS.

3.1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

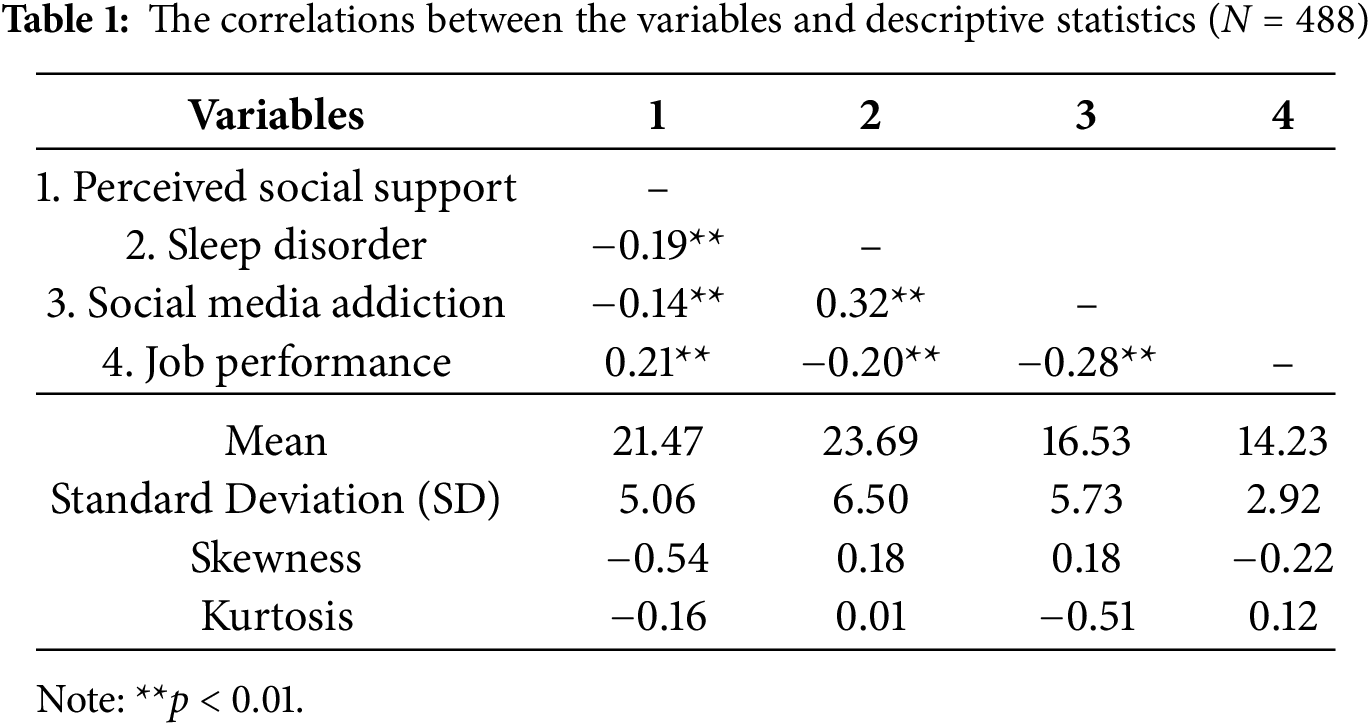

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for the variables. There was no indication that the normality assumption had been violated, as both skewness and kurtosis were under the recommended threshold value of 2. Correlation analysis revealed that job performance was associated with perceived social support, while being significantly negatively associated with social media addiction and sleep disorder. The study’s findings revealed that all variables were either low or moderately associated.

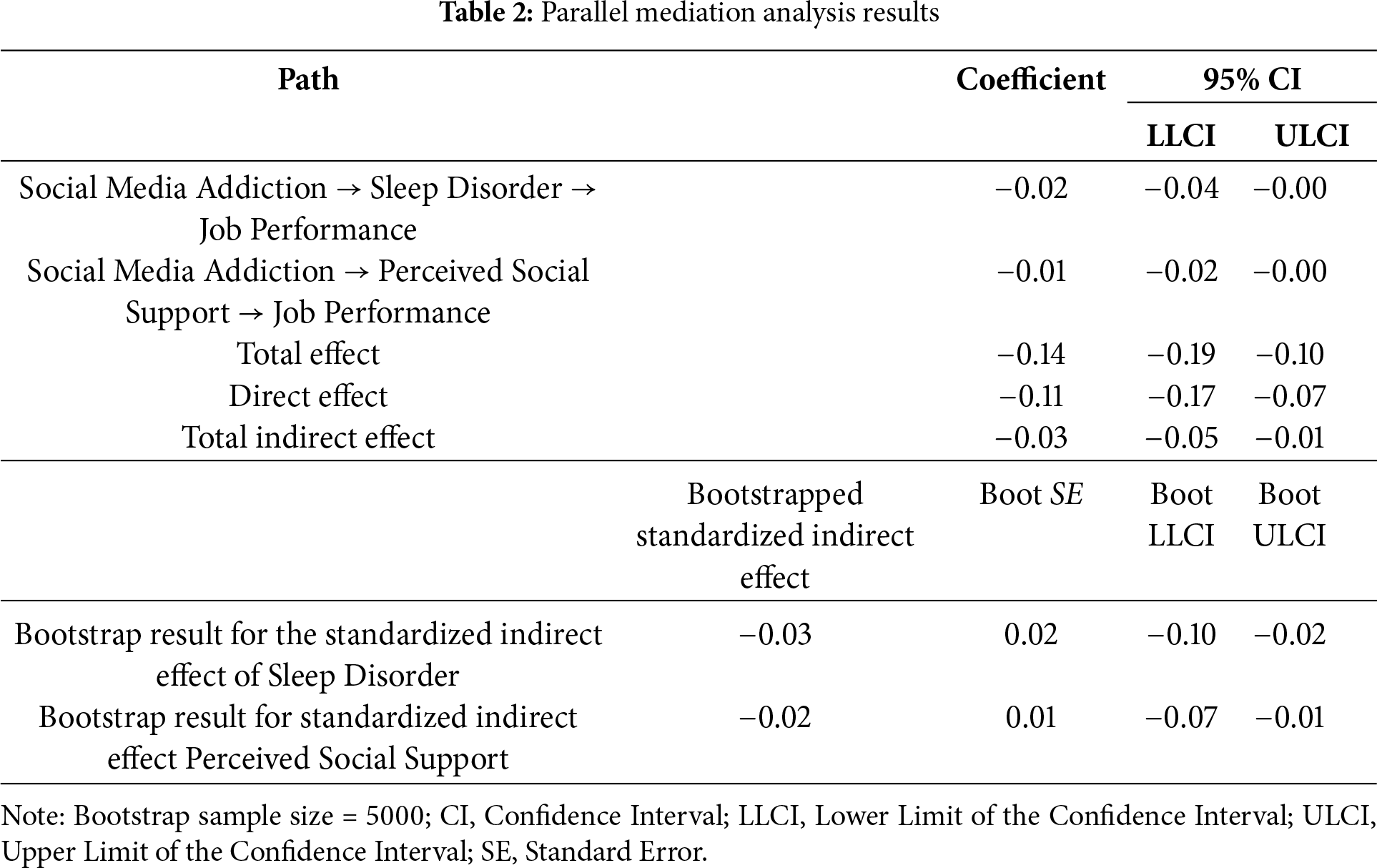

Parallel mediation analysis was conducted to determine whether perceived social support and sleep disorder have a parallel mediating role in the association between job performance and social media addiction. A direct effect of social media addiction on job performance (total effect, β = −0.14, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.19, −0.10]) has been found. The results confirmed Hypothesis 1. Moreover, social media addiction was found to be a negative predictor of perceived social support (β = −0.12, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.20, −0.05]). Social media addiction was also a positive predictor of sleep disorder (β = 0.36, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.26,0.46]). Results showed that the data were eligible for mediation analysis. Thus, mediators (i.e., perceived social support and sleep disorder) were included in the model simultaneously. The results revealed that the coefficient of regression was significant (indirect effect, β = −0.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.05, −0.01]). According to the result, Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2 have been confirmed (see Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The proposed model presents parallel mediation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

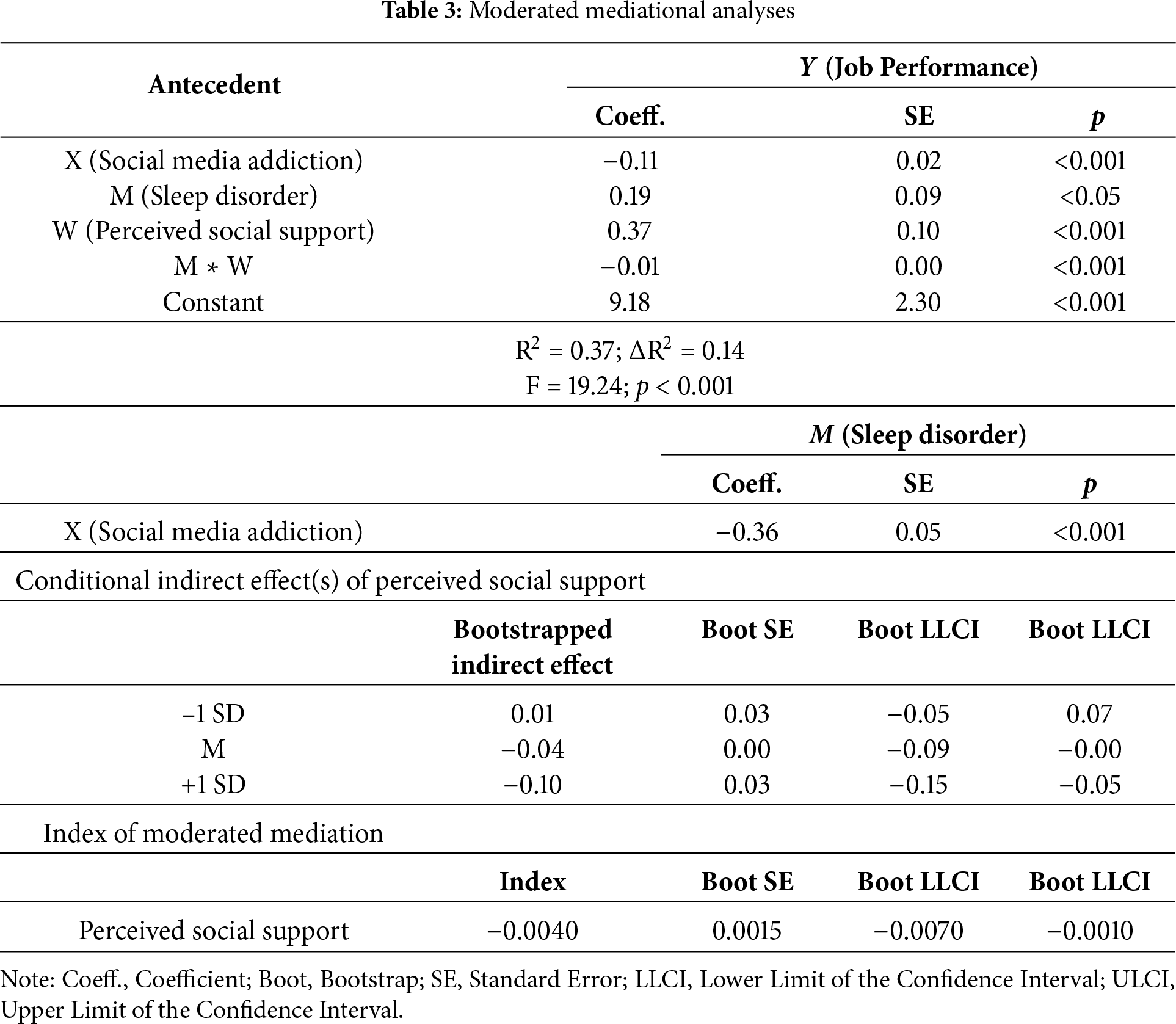

3.3 Moderated Mediational Analysis—Modeling Data

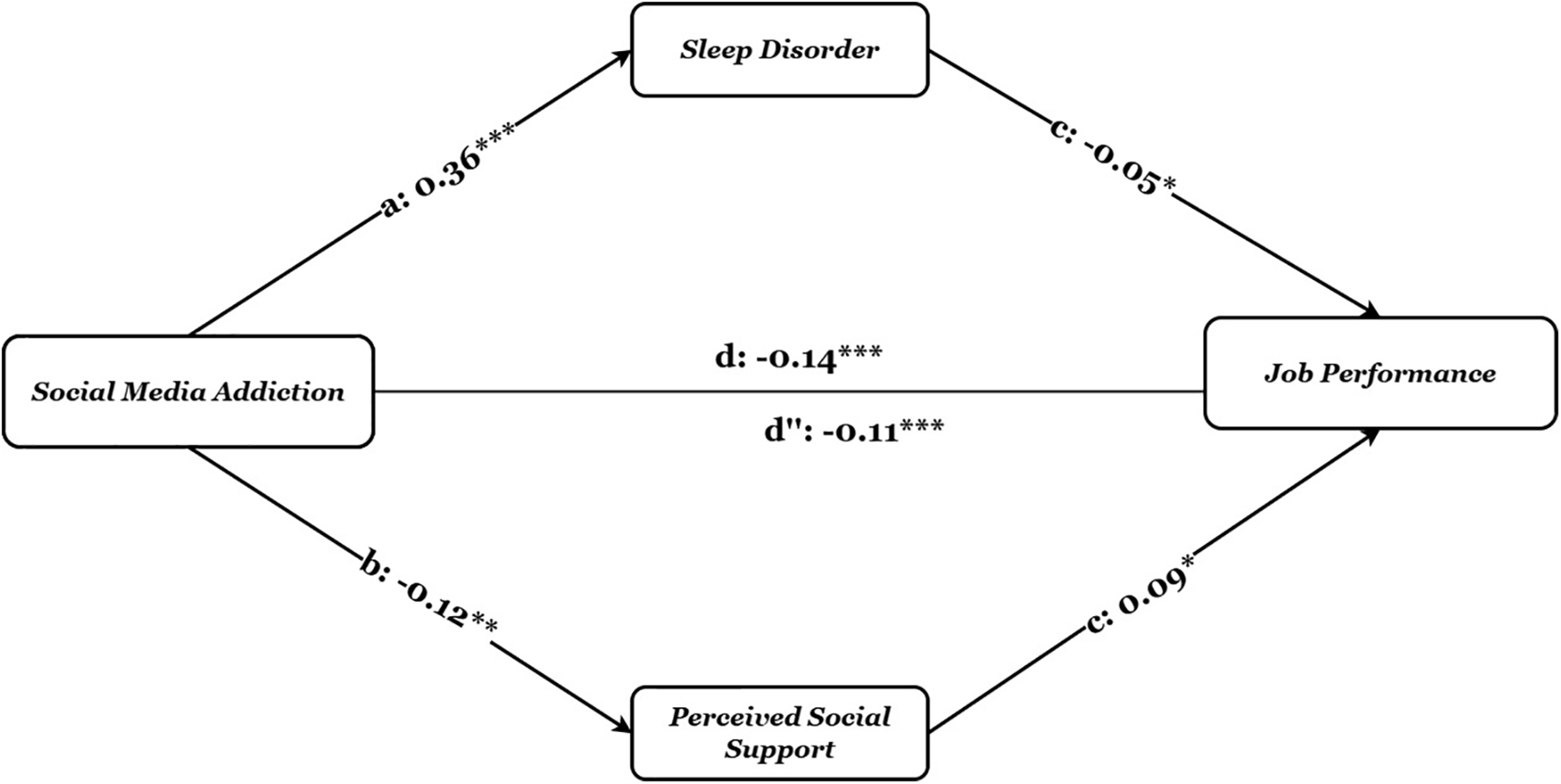

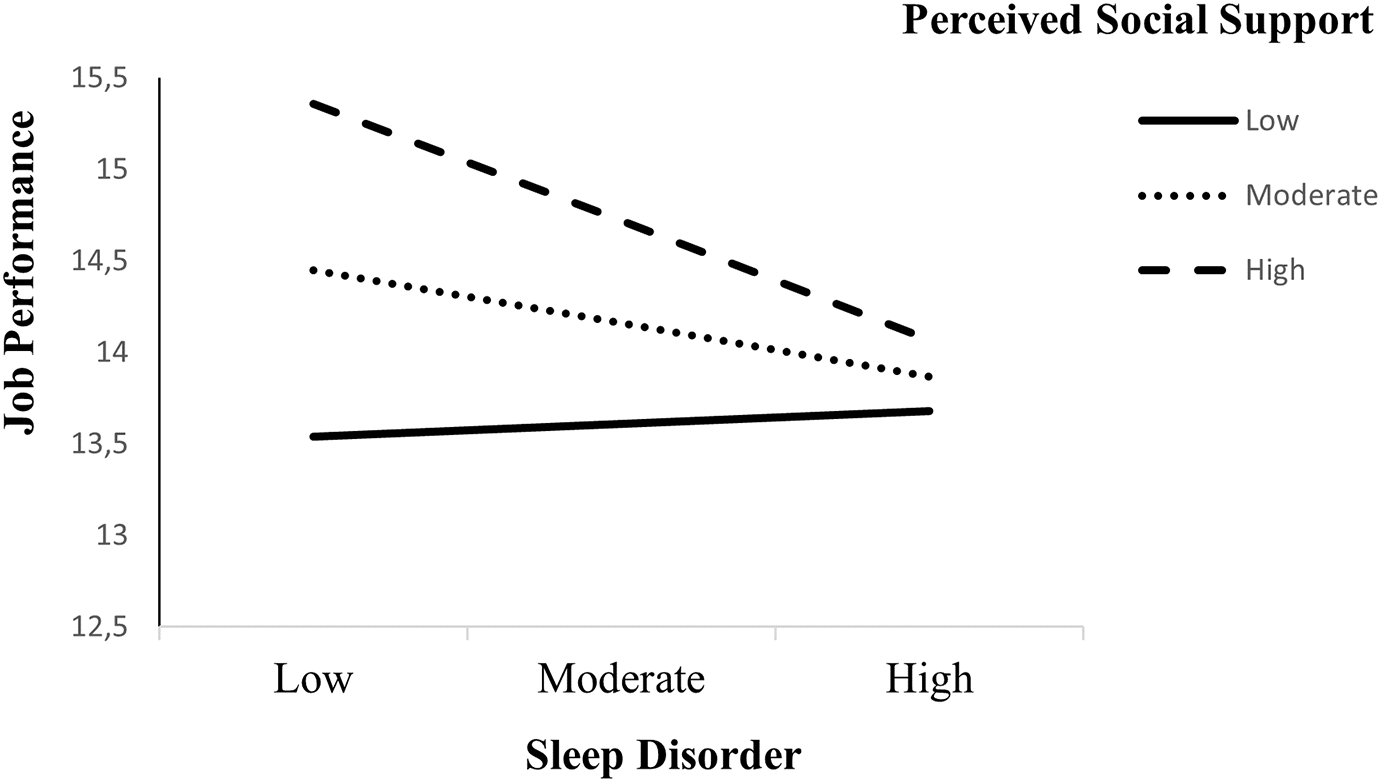

The moderated mediation analysis was conducted to investigate whether perceived social support mediated the effect of sleep disorder on job performance. Perceived social support moderated the mediating effect of sleep disorder in this association. In the moderated mediation model, sleep disorder and perceived social support serve as both mediators and moderators. The moderator alters the strength of the association between two variables simultaneously. Upon examining Table 3, it is found that the results are consistent with Hypothesis 3. Perceived social support significantly affected the association between sleep disorder and job performance (interaction = 0.01, p < 0.001). Additionally, the Index of moderated mediation was significant (Coefficient = −0.0040, 95% CI = [−0.0070, −0.0010]) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Proposed model presenting the moderation effect

The present study sought to explore the mediating effects of sleep disorder and perceived social support between social media addiction and job performance. As a result of the findings, it was demonstrated that social media addiction predicted job performance and social support, and positively predicted sleep disorder. These findings supported Hypothesis 1. The results are consistent with previous research showing negative associations between social media addiction and job performance [50,51]. Using social media at work has been the subject of numerous studies, with negative results [50,52]. A common criticism raised against social media in the workplace is that it has the potential to decrease employee performance while simultaneously creating an environment of unease, tension, and emotional weariness [50,53]. In support of this, a study found that using social media addiction in the workplace had a significant impact on employees’ mental and physical health, resulting in eye strain and back pain. It also causes dissatisfaction, superficiality, and jealousy in bilateral relationships [54]. Employee performance was shown to be adversely affected by smartphone addiction in a recent study focused on healthcare workers [55]. Another study reported that using social media triggers the emergence of technostress in employees and negatively affects task performance [56]. The findings of these studies show that there is a strong relationship between social media addiction and decreased job performance.

The present study has examined the path coefficients between social media addiction and job performance in healthcare workers. Even after social support and sleep disorder were added to the model simultaneously. The path coefficients were still found to be significant, showing the parallel mediating effects of perceived social support and sleep disorder. According to the result, Hypothesis 2 was confirmed. A study showed that prolonged use of social media is detrimental to an individual’s sleep quality [57]. A study found that people who are addicted to social media may have a decline in their performance at work [50]. Furthermore, Yazdi et al. [58] reported that sleep disorders negatively impact work performance. Distraction-Conflict Theory suggests that when attention is divided, it induces a form of internal conflict, which may lead to stress and hinder optimal performance [59]. Social media platforms often send users frequent notifications, which can distract them and make them feel like they are constantly missing out. As a result, long-term exposure to these notifications can raise a person’s stress levels [60]. Moreover, studies have demonstrated that excessive use of social media negatively impacts sleep quality. Social media addiction also may lead to depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem [60,61]. As a result, the individual may feel isolated and receive less support from others. Mecha et al. [62] reported that people’s perception of social support decreases when they are experiencing adverse conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety, and stress). Similarly, Nazari et al. [63] found that perceptions of social support correlated with job performance among hospital nurses. In addition, employees with higher perceived social support performed better and were more engaged at work [64]. Research results have shown that social media addiction can result in sleep disorders, thus reducing the level of support that users receive from their social network, which negatively impacts their job performance.

The study has found that perceived social support moderated the mediating effect of sleep disorder on the relationship between social media addiction and job performance. The result supported Hypothesis 3. The findings suggest that a healthcare professional with increased levels of social media addiction, sleep disorders, and poor social support is more likely to perform less effectively at work. As a result, communication problems can arise at work, efficiency and productivity can be reduced, and relationships can be negatively affected. Negative emotions may also be triggered by these conditions (for instance, stress and anxiety) [65]. COR posits that individuals inherently tend to preserve and augment their resources, such as energy, time, and social support, particularly when experiencing stress [66]. Social media addiction leads users to repeatedly use social media, which drains their resources and results in feelings of burnout [51]. Experiencing burnout can lead to less tolerance for social interactions, thereby contributing to the deterioration of interpersonal relationships and a reduction in perceived social support [67]. Several studies have shown that social support similarly influences sleep quality, supporting these findings [68,69]. Perceived social support as a preventative mechanism may mitigate the impact of poor sleep quality and psychological distress based on Zhang et al.’s [70] findings. Another study reported that as social support increases, sleep quality also increases. In addition, social support is negatively associated with irritability, sleep quality, and loneliness [71]. These unfavorable conditions can reduce employees’ focus and productivity [44]. As a result, high levels of perceived social support and low levels of sleep disorder may help people deal with irritating situations (e.g., work stress and social isolation) and encourage greater productivity among healthcare workers. Taken together, the study’s findings indicate that higher levels of social support and lower levels of sleep disorder improve an employee’s efficiency. Therefore, perceived social support might moderate the mediating effect of sleep disorder on the association of social media addiction and job performance.

This study provides insight into the relationship between social media addiction, job performance, perceived social support, and sleep disorder. However, this study has limitations, as with all research. The study employed a cross-sectional design. Therefore, detecting causality between variables gets increasingly difficult. To address this problem, researchers should look at long-term investigations that influence the results. Future research investigating the associations between variables could employ a variety of designs, incorporating both qualitative and quantitative approaches. One further limitation of this study is that it utilizes self-reported measures to gather data. Furthermore, confounding variables may have impacted the data due to demographic factors, including gender, years of employment, and age. While evaluating the data gathered, it is important to consider these demographic factors. Furthermore, applying the study results to all healthcare professionals poses a challenge. Furthermore, the study was conducted with healthcare professionals, and it is important to acknowledge the potential for social desirability bias. In future studies, researchers should recruit healthcare personnel more representative of the population in terms of demographic variables. Future studies should also address this limitation by employing evaluation methods that may include third parties to minimize social desirability bias.

The current study greatly extends our understanding of the association between social media addiction and job performance by demonstrating the mediating effect of sleep disorder and social support. The performance of healthcare workers in the workplace is significantly influenced by their perception of social support and sleep disorders [72,73]. Because healthcare is inherently demanding and stressful, inadequate sleep and a lack of social support may significantly compromise both physical and mental well-being. This, in turn, can adversely affect job performance and the quality of patient care. An increase has been found in sleep disorders and decreased job performance due to social media addiction. Sleep disorders and job performance were associated with higher levels of social media addiction and lower levels of social support. Therefore, it is essential to implement targeted interventions that enhance sleep quality and create supportive work environments. Healthcare facilities and hospital employees require specialized training programs. Organizational policies should prioritize flexible scheduling, stress management, and peer support to mitigate sleep disturbances and enhance social connectedness. Additionally, healthcare institutions can consider incorporating sleep quality and social support evaluations into their employee health assessments. This approach allows them to more effectively identify individuals who may require additional assistance and tailor support efforts to meet their specific needs.

The present study revealed that several factors, both positive and negative, such as social media addiction, social support, and sleep disorder, had significant roles in determining job performance among healthcare workers. Due to their higher likelihood of experiencing sleep deprivation, those who work night shifts in the healthcare sector may face a higher degree of risk. Nevertheless, healthcare professionals working in departments with a low workload might increase the duration of their social media platforms. Hence, they may have the potential to develop an addiction to social media. Furthermore, employees who are compelled to work long hours and are moving from their social environment may encounter substantial declines in their work productivity. Social media platforms can potentially serve as a way for individuals to obtain the social support they desire. The results imply that increasing social support and decreasing sleep disorder may help with low job performance. Ultimately, professionals and hospital management in the health industry can utilize these buffering aspects to enhance their intervention programs to mitigate the impact of social media addiction on job performance.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank all healthcare professionals who devoted their valuable time to participating in our study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Alican Kaya and Emre Seyrek; data collection: Emre Seyrek; analysis and interpretation of results: Alican Kaya and Mehmet Şata; draft manuscript preparation: Alican Kaya, Emre Seyrek, Mehmet Şata, and Abdulselami Sarıgül; statistical expertise: Alican Kaya and Mehmet Şata; administrative, technical, and material support: Emre Seyrek, Alican Kaya, and Juan Gómez-Salgado; supervision: Murat Yıldırım and Juan Gómez-Salgado; writing—review and editing: Murat Yıldırım and Juan Gómez-Salgado. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Authors, [Juan Gómez-Salgado, Murat Yıldırım], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: We adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki at all phases of the study. Ethics approval was obtained for this study from The Ağrı Ibrahim Cecen University’s ethics committee (Reference number: E.86893). Formal participants’ informed consent was acquired.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Glossary

| BSMAS | Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale |

| DCT | Distraction-Conflict Theory |

| COR | Conservation of Resources Theory |

| JPS | Job Performance Scale |

| SDS | Sleep Disorder Scale |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| LLCI | Lower Limit Confidence Interval |

| ULCI | Upper Limit Confidence Interval |

| β | Beta coefficient (used in regression analysis) |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination (explained variance) |

| ΔR2 | Change in R-squared |

| F | F-statistic (used in ANOVA and regression analysis) |

| p | p-value (statistical significance level) |

| N | Sample size |

| ORCID | Open Researcher and Contributor ID |

| G*Power | Statistical software for power analysis |

| PROCESS macro | Add-on tool for SPSS used for mediation and moderation analysis |

References

1. Wang Q. The autobiographical self in time and culture. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 2013. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199737833.001.0001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Stone CB, Wang Q. From conversations to digital communication: the mnemonic consequences of consuming and producing information via social media. Top Cogn Sci. 2019;11(4):774–93. doi:10.1111/tops.12369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Kırcaburun K, Griffiths MD. Problematic instagram use: the role of perceived feeling of presence and escapism. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2019;17(4):909–21. doi:10.1007/s11469-018-9895-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kuss D, Griffiths M. Social networking sites and addiction: ten lessons learned. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(3):311. doi:10.3390/ijerph14030311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Kuss D. Mobile technology and social media: the “extensions of man” in the 21st century. Hum Dev. 2017;60(4):141–3. doi:10.1159/000479842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Dhir A, Yossatorn Y, Kaur P, Chen S. Online social media fatigue and psychological wellbeing—a study of compulsive use, fear of missing out, fatigue, anxiety and depression. Int J Inf Manag. 2018;40(3):141–52. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.01.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. van den Eijnden RJJM, Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM. The social media disorder scale. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;61(3):478–87. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Marino C, Gini G, Vieno A, Spada MM. A comprehensive meta-analysis on problematic facebook use. Comput Hum Behav. 2018;83(2):262–77. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kenyhercz V, Mervó B, Lehel N, Demetrovics Z, Kun B. Work addiction and social functioning: a systematic review and five meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2024;19(6):e0303563. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0303563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Tanhan F, Özok Hİ, Kaya A, Yıldırım M. Mediating and moderating effects of cognitive flexibility in the relationship between social media addiction and phubbing. Curr Psychol. 2023;43(1):192–203. doi:10.1007/s12144-023-04242-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Turan ME, Adam F, Kaya A, Yıldırım M. The mediating role of the dark personality triad in the relationship between ostracism and social media addiction in adolescents. Educ Inf Technol. 2024;29(4):3885–901. doi:10.1007/s10639-023-12002-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yang S, Tinmaz H. Exploring workplace fear of missing out (FoMOa systematic literature review. Environ Soc Psychol. 2024;9(7):213–29. doi:10.59429/esp.v9i7.2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Craig W, Boniel-Nissim M, King N, Walsh SD, Boer M, Donnelly PD, et al. Social media use and cyber-bullying: a cross-national analysis of young people in 42 countries. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66(6S):S100–8. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.03.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Bandyopadhyay S, Baticulon RE, Kadhum M, Alser M, Ojuka DK, Badereddin Y, et al. Infection and mortality of healthcare workers worldwide from COVID-19: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(12):e003097. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Meshi D, Ellithorpe ME. Problematic social media use and social support received in real-life versus on social media: associations with depression, anxiety and social isolation. Addict Behav. 2021;119(2):106949. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106949. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Boursier V, Gioia F, Griffiths MD. Do selfie-expectancies and social appearance anxiety predict adolescents’ problematic social media use? Comput Hum Behav. 2020;110(2):106395. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2020.106395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hawes T, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Campbell SM. Unique associations of social media use and online appearance preoccupation with depression, anxiety, and appearance rejection sensitivity. Body Image. 2020;33:66–76. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.02.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Boer M, van den Eijnden RJJM, Boniel-Nissim M, Wong SL, Inchley JC, Badura P, et al. Adolescents' intense and problematic social media use and their well-being in 29 countries. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66(6S):S89–99. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Majeed M, Irshad M, Fatima T, Khan J, Hassan MM. Relationship between problematic social media usage and employee depression: a moderated mediation model of mindfulness and fear of COVID-19. Front Psychol. 2020;11:557987. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.557987. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Ibrahim M, Yusra Y, Shah NU. Impact of social media addiction on work engagement and job performance. Pol J Manag Stud. 2022;25(1):179–92. doi:10.17512/pjms.2022.25.1.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Clark LA, Roberts SJ. Employer’s use of social networking sites: a socially irresponsible practice. J Bus Ethics. 2010;95(4):507–25. doi:10.1007/s10551-010-0436-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Schaufeli WB, Taris TW. A critical review of the job demands-resources model: implications for improving work and health. In: Bridging occupational, organizational and public health. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2013. p. 43–68. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5640-3_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Obrenovic B, Jianguo D, Khudaykulov A, Khan MAS. Work-family conflict impact on psychological safety and psychological well-being: a job performance model. Front Psychol. 2020;11:475. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Wong HY, Mo HY, Potenza MN, Chan MNM, Lau WM, Chui TK, et al. Relationships between severity of Internet gaming disorder, severity of problematic social media use, sleep quality and psychological distress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):1879. doi:10.3390/ijerph17061879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kader SB, Shakurun N, Janzen B, Pahwa P. Impaired sleep, multimorbidity, and self-rated health among Canadians: findings from a nationally representative survey. J Multimorb Comorb. 2024;14(1):26335565241228549. doi:10.1177/26335565241228549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Stirnberg J, Margraf J, Precht LM, Brailovskaia J. Problematic smartphone use, depression symptoms, and fear of missing out: can reasons for smartphone use mediate the relationship? A longitudinal approach. J Soc Media Res. 2024;1(1):3–13. doi:10.29329/jsomer.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Langlais M, Bigalke J, Bigalke J. Relationship stress and sleep: examining the mediation of social media use for objective and subjective sleep quality. J Soc Media Res. 2025;2(1):1–12. doi:10.29329/jsomer.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sümen A, Evgin D. Social media addiction in high school students: a cross-sectional study examining its relationship with sleep quality and psychological problems. Child Indic Res. 2021;14(6):2265–83. doi:10.1007/s12187-021-09838-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Kühnel J, Diestel S, Melchers KG. An ambulatory diary study of mobile device use, sleep, and positive mood. Int J Stress Manag. 2021;28(1):32–45. doi:10.1037/str0000210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jolly PM, Kong DT, Kim KY. Social support at work: an integrative review. J Organ Behav. 2021;42(2):229–51. doi:10.1002/job.2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ivbijaro G, Brooks C, Kolkiewicz L, Sunkel C, Long A. Psychological impact and psychosocial consequences of the COVID 19 pandemic Resilience, mental well-being, and the coronavirus pandemic. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62(Suppl 3):S395–403. doi:10.4103/psychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_1031_20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Ibrahim M, Kong Y, Adam DR. Linking service innovation to organisational performance. Int J Serv Sci Manag Eng Technol. 2022;13(1):1–16. doi:10.4018/ijssmet.295558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Shepherd C. Does social media have a place in workplace learning? Strateg Dir. 2011;27(2):3–4. doi:10.1108/02580541111103882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ye Z, Yang X, Zeng C, Wang Y, Shen Z, Li X, et al. Resilience, social support, and coping as mediators between COVID-19-related stressful experiences and acute stress disorder among college students in China. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2020;12(4):1074–94. doi:10.1111/aphw.12211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Bilgin O, Taş İ. Effects of perceived social support and psychological resilience on social media addiction among university students. Ujer. 2018;6(4):751–8. doi:10.13189/ujer.2018.060418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Alshehri NA, Yildirim M, Vostanis P. Saudi adolescents’ reports of the relationship between parental factors, social support and mental health problems. Arab J Psychiatry. 2020;31(2):130–43. doi:10.12816/0056864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yildirim M, Turan ME, Albeladi NS, Crescenzo P, Rizzo A, Nucera G, et al. Resilience and perceived social support as predictors of emotional well-being. J Health Soc Sci. 2023;8:59–75. [Google Scholar]

38. Yıldırım M, Ahmad Aziz I, Vostanis P, Hassan MN. Associations among resilience, hope, social support, feeling belongingness, satisfaction with life, and flourishing among Syrian minority refugees. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2024;23(1):166–81. doi:10.1080/15332640.2022.2078918. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Saintila J, Soriano-Moreno AN, Ramos-Vera C, Oblitas-Guerrero SM, Calizaya-Milla YE. Association between sleep duration and burnout in healthcare professionals: a cross-sectional survey. Front Public Health. 2024;11:1268164. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1268164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Prasetya TAE, Wardani RWK. Systematic review of social media addiction among health workers during the pandemic Covid-19. Heliyon. 2023;9(6):e16784. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Lachenbruch PA, Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84(408):1096. doi:10.2307/2290095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kliem S, Mößle T, Rehbein F, Hellmann DF, Zenger M, Brähler E. A brief form of the Perceived Social Support Questionnaire (F-SozU) was developed, validated, and standardized. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(5):551–62. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Yıldırım M. Çelik Tanrıverdi F. Social support, resilience and subjective well-being in college students. J Posit Sch Psychol. 2021;5(2):127–35. doi:10.47602/jpsp.v5i2.229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Andreassen CS, Billieux J, Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Demetrovics Z, Mazzoni E, et al. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(2):252–62. doi:10.1037/adb0000160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Demirci İ. The adaptation of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale to Turkish and the evaluation its relationships with depression and anxiety symptoms. Anadolu Psikiyatri Derg. 2019;20(Supple 1):15–22. doi:10.5455/apd.41585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Kirkman BL, Rosen B. Beyond self-management: antecedents and consequences of team empowerment. Acad Manag J. 1999;42(1):58–74. doi:10.2307/256874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Çöl G. The effects of perceived empowerment on employee performance. J Doğuş Üniversitesi Derg. 2008;9(1):35–46. [cited 2025 Jul 1]. (In Turkish). Available from: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/2151906. [Google Scholar]

48. Yüzeren S, Herdem A, Aydemir Ö, Grubu D. Reliability and validity of Turkish form of sleep disorder scale. Anadolu Psikiyatri Derg. 2017;18(2):79. doi:10.5455/apd.241499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. 3rd ed. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

50. Cao X, Yu L. Exploring the influence of excessive social media use at work: a three-dimension usage perspective. Int J Inf Manag. 2019;46(1):83–92. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.11.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Zivnuska S, Carlson JR, Carlson DS, Harris RB, Harris KJ. Social media addiction and social media reactions: the implications for job performance. J Soc Psychol. 2019;159(6):746–60. doi:10.1080/00224545.2019.1578725. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Kock N, Moqbel M. Social networking site use, positive emotions, and job performance. J Comput Inf Syst. 2021;61(2):163–73. doi:10.1080/08874417.2019.1571457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. van Zoonen W, Verhoeven JWM, Vliegenthart R. Social media’s dark side: inducing boundary conflicts. J Manag Psychol. 2016;31(8):1297–311. doi:10.1108/jmp-10-2015-0388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Priyadarshini C, Dubey RK, Kumar YLN, Jha RR. Impact of social media addiction on employees’ wellbeing and work productivity. Qual Rep. 2020;25(1):181–96. [Google Scholar]

55. Alan H, Bekar EO, Güngör S. An investigation of the relationship between smartphone addiction and job performance of healthcare employees. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2022;58(4):1918–24. doi:10.1111/ppc.13006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Brooks S. Does personal social media usage affect efficiency and well-being? Comput Hum Behav. 2015;46(9):26–37. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Graham S, Mason A, Riordan B, Winter T, Scarf D. Taking a break from social media improves wellbeing through sleep quality. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2021;24(6):421–5. doi:10.1089/cyber.2020.0217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Yazdi Z, Sadeghniiat-Haghighi K, Loukzadeh Z, Elmizadeh K, Abbasi M. Prevalence of sleep disorders and their impacts on occupational performance: a comparison between shift workers and nonshift workers. Sleep Disord. 2014;2014(6):870320. doi:10.1155/2014/870320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Baron RS. Distraction-conflict theory: progress and problems. In: Advances in experimental social psychology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1986. p. 1–40. doi:10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60211-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Acar IH, Avcılar G, Yazıcı G, Bostancı S. The roles of adolescents’ emotional problems and social media addiction on their self-esteem. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(10):6838–47. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-01174-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Arikan G, Acar IH, Ustundag-Budak AM. A two-generation study: the transmission of attachment and young adults' depression, anxiety, and social media addiction. Addict Behav. 2022;124(4):107109. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Mecha P, Martin-Romero N, Sanchez-Lopez A. Associations between social support dimensions and resilience factors and pathways of influence in depression and anxiety rates in young adults. Span J Psychol. 2023;26:e11. doi:10.1017/SJP.2023.11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Nazari S, Zamani A, Afshar PF. The relationship between received and perceived social support with ways of coping in nurses. Work. 2024;78(4):1247–55. doi:10.3233/WOR-230337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Yildirim D, Darican Ş. The effect of perceived social support on work-life balance and work engagement: a case of banking sector. Yönetim Bilimleri Dergisi. 2024;22(52):758–84. doi:10.35408/comuybd.1422526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Shensa A, Escobar-Viera CG, Sidani JE, Bowman ND, Marshal MP, Primack BA. Problematic social media use and depressive symptoms among U.S. young adults: a nationally-representative study. Soc Sci Med. 2017;182:150–7. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Hobfoll SE, Freedy J, Lane C, Geller P. Conservation of social resources: social support resource theory. J Soc Pers Relatio. 1990;7(4):465–78. doi:10.1177/0265407590074004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Velando-Soriano A, Ortega-Campos E, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Ramírez-Baena L, De La Fuente EI, La Fuente GAC. Impact of social support in preventing burnout syndrome in nurses: a systematic review. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2020;17(1):e12269. doi:10.1111/jjns.12269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Lei G, Yang C, Ge Y, Zhang Y, Xie Y, Chen J, et al. Community workers’ social support and sleep quality during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19a moderated mediation model. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2021;23(1):119–38. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2021.013072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Chen YC, Lu TH, Ku EN, Chen CT, Fang CJ, Lai PC, et al. Efficacy of brief behavioural therapy for insomnia in older adults with chronic insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis from randomised trials. Age Ageing. 2023;52(1):afac333. doi:10.1093/ageing/afac333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Zhang C, Xiao S, Lin H, Shi L, Zheng X, Xue Y, et al. The association between sleep quality and psychological distress among older Chinese adults: a moderated mediation model. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):35. doi:10.1186/s12877-021-02711-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Grey I, Arora T, Thomas J, Saneh A, Tohme P, Abi-Habib R. The role of perceived social support on depression and sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293(4):113452. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Hou T, Zhang T, Cai W, Song X, Chen A, Deng G, et al. Social support and mental health among health care workers during Coronavirus Disease 2019 outbreak: a moderated mediation model. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233831. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Liu Y, Zhang Q, Jiang F, Zhong H, Huang L, Zhang Y, et al. Association between sleep disturbance and mental health of healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:919176. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.919176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools